BROWN

Calder Piece

for Four Percussionists and Mobile

Score

Score

Earle Brown

For four percussionists and mobile (expressly made for this work) by Alexander Calder

For Carol and Sandy

This work was first conceived and “designed” in the spring of 1963 while was in Paris finishing the work on TIMES FIVE for the Service de la Recherche of the French Radio. At that time, the Paris Percussion Quartet commissioned me to compose a work for the group.

Those who are familiar with my work are aware that the original impulse and influence that led me to create “open form” works (which, in 1952 I called “mobile” compositions) came from observing and reflecting upon the mobiles of Alexander Calder. I later met Calder at his home in Connecticut (in 1953 ) and he therefore knew of my work and my indebtedness to his concept and work.

In Paris began the work for the quartet with the idea that it would be “conducted” by a mobile in the center of the space with the four percussionists placed equidistantly around it, the varying configurations of the elements of the mobile being “read” by the performers and the evolving “open form” of each performance different and changing perspectives in relation to it.

Calder was immediately intrigued and excited by the idea. The final scoring for the piece had to wait for the mobile to be finished because various aspects of the score and performance were directly based on the number of elements and their physical placement in the structure of the mobile. It was not until 1966 that everything came together and the work was finished. Calder named the mobile Chef d’ Orchestre

CALDER PIECE was first performed at the Théâtre de l’Atelier in Paris, early in 1967 In addition to the mobile functioning as a conductor, the musicians actually use it as an instrument. One is not conditioned to tolerate the striking of a work of art and the sounds of breath-holding could be heard in the audience when the musicians first approached and played the mobile. One of Calder’s slightly disappointed comments after that first performance was, “I thought that you were going to hit it much harder –with hammers.”

The piece is one of a kind, and the music must never be independent of that particular mobile. It is my very deeply felt homage to “one of a kind” Sandy Calder and to his life and work.

Earle Brown January 1980

Page 1 is self explanatory. Go to MOBILE in indicated sequence ( 1-3-2-4 ). Continue friction sounds on “skin” instruments until each percussionist leaves for MOBILE

At MOBILE light friction sounds and light striking with the wrong end of sticks. About 80% friction sounds, as in opening ‘metal to wood to skin’ sequence.

Leave MOBILE in indicated sequence, returning to indicated pitched instruments.

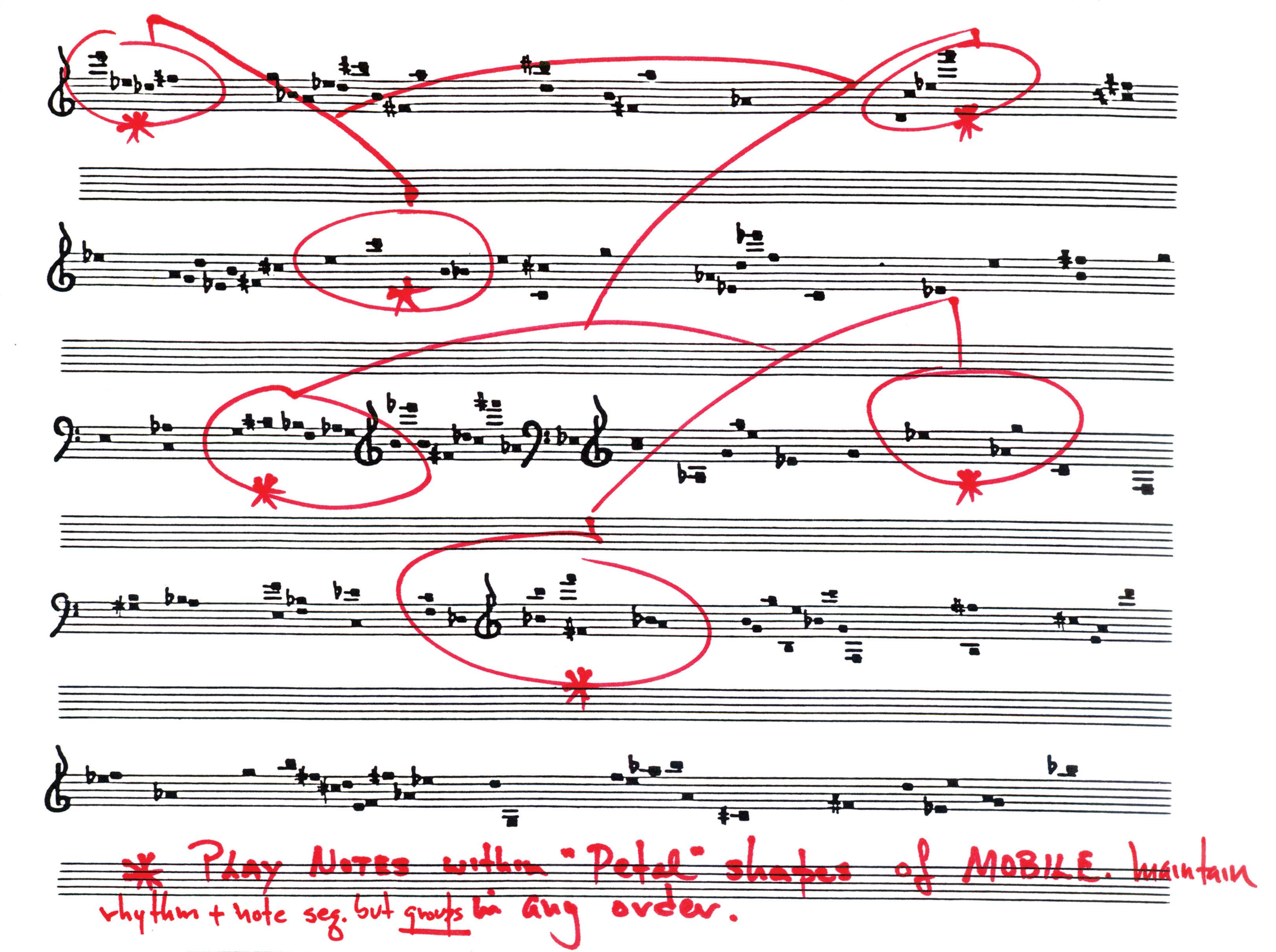

Page 2: “Read” the MOBILE Visualize (imagine) a configuration of the “petals” as being superimposed over the field of pitch figurations of page 2 and play the figurations that the “petals” would cover at that instant, in any order you wish. When the MOBILE is moving or at rest, glance at its total configuration at that instant and play the corresponding areas on page 2

See below, drawing in explanation of above “reading” of MOBILE

Total time on page 2 will be determined in rehearsal. Practice all musical figures on page 2 at various tempi.

Page 3: Ensembles as indicated: non-pitched and pitched instruments. Each system is read horizontally across the whole page.

Go to MOBILE as indicated at bottom right of page. Gong-like sounds with mediumsoft mallets.

Leave MOBILE in following sequence: percussion 2-3-4-1

Page 4 (A), 4 (B): Above sequence to solo passages in above sequence.

Solos should connect to each other but not overlap.

Percussionists should remain at MOBILE until time to (slowly) return to instruments for solos.

4th solo to be followed by duet by 1 & 2 , followed by duet by 3 & 4

After 1 & 2 finish their duet, they go to MOBILE and play on it with soft mallets when duet by 3 & 4 is finished. 1 & 2 leave MOBILE moving (moderately), while 3 & 4 begin page 5 on glockenspiel and vibraphone.

Page 5: 1 & 2 return to instruments and all “read” MOBILE ( 1 & 2 also on glockenspiel and vibraphone.) All players move to marimbas and xylophones to finish page 5

Page 6: Synchronize beginning on non-pitched instruments only.

Freely “converse,” exchanging solos, duets, trios and all four together, as in jazz.

General dynamic shape during this section:

Page 7: Synchronize explosive drums, as indicated. All play as fast as possible, beginning on highest pitched drums and descending to tympani or lowest pitches. Highest to lowest in a period of approximately 4 seconds.

EXTREMELY metallic sound ( fff ) at end of page: Vibraphones L.V. (pedal sustain) until silence.

Glockenspiels to MOBILE when their sound ceases.

Vibraphones to MOBILE when vibraphone resonances cease.

All use very soft tympani mallets on MOBILE tremolo etc., for maximum resonance of MOBILE (It will be dynamically soft but resonant.)

MOBILE must begin to rotate slowly and gradually increase in speed until it is rotating as fast as possible. (Do not destabilize the tripod.)

LEAVE MOBILE MOVING AS FAST AS POSSIBLE; return quickly to instruments in sequence, 1-3-2-4 to page 8

Page 8: “Read” the MOBILE as on pages 2 and 5 soloistically Play any of the written figurations (do not improvise), maintaining the given timbre and dynamics but do not synchronize as on page 3 Free solo-polyphony of any figures on the page.

As the MOBILE comes to rest, the sound slows down, quiets down, and stops in sync with the MOBILE

( 3 to 4 minutes)

Earle Brown was born in 1926 in Lunenburg, Massachusetts, and in spirit remained a New Englander throughout his life. A major force in contemporary music and a leading composer of the American avantgarde since the 1950s, he was associated with the experimental composers John Cage, Morton Feldman and Christian Wolff, who – together with Brown – came to be known as members of the New York School. Brown died in 2002 at his home in Rye, New York.

Earle Brown wurde 1926 in Lunenburg, Massachusetts, geboren und blieb im Geist ein Leben lang Neuengländer. Ab den 1950er Jahren war er eine treibende Kraft in der zeitgenössischen Musik und einer der führenden Komponisten der amerikanischen Avantgarde. Enge Verbindung unterhielt er zu den experimentellen Komponisten John Cage, Morton Feldman und Christian Wolff, mit denen gemeinsam er später der sogenannten New York School zugerechnet wurde. Brown starb 2002 in seinem Haus in Rye, New York.