To Mom and Dad also Nusi, wish you could see this.

To Mom and Dad also Nusi, wish you could see this.

Written by Esin Karaosman

Written by Esin Karaosman

Aesthetics

written by Esin Karaosman

Within the corridors of the architecture schools, we can all agree that we are endlessly staging new realities. What is interesting, however, is that we often locate these new realities in the foreground. The backdrop, which we often name as the “real” world, appears as if it is a fundamental ground for our perception. We talk about “reality” and our perceptions of it, but mainly as if it were a dead one - already chopped into pieces, cooked, packaged, and perhaps already consumed. Yet we don’t realize that everything we consume is already full of abstraction - an abstraction that conceals the theatricality that is usually hidden in the acts of consumption.

Somewhere in between the kitchen and the restaurant, the restaurant and the museum, this staged reality shakes this fundamental belief. Here, what we thought was dead still carries within it the taste of the living.

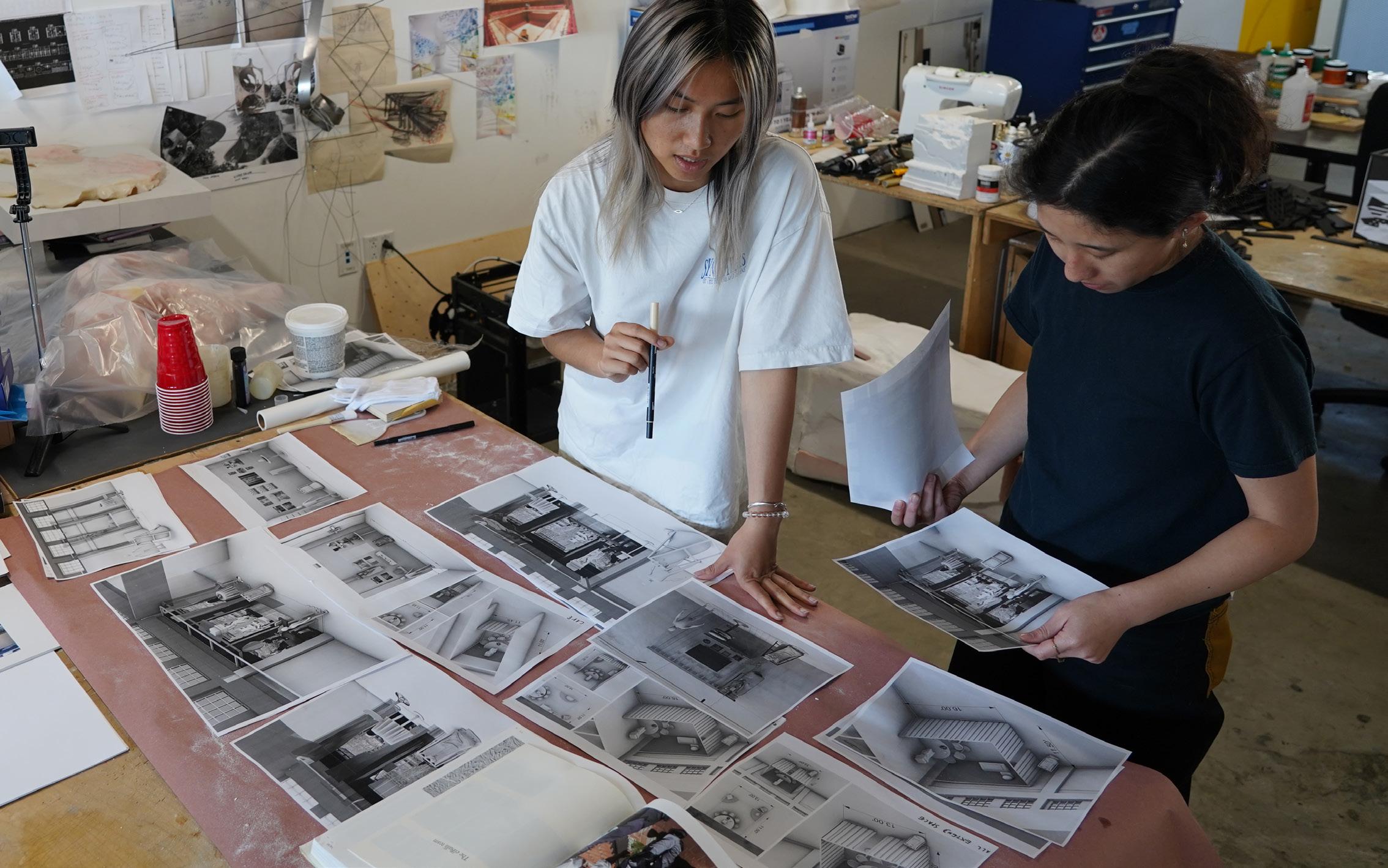

As an associate curator, it is a pleasure to introduce our Chef Curator - Chief Curator, Yi Cheung. Yi intervenes with the problem with reality and our perception like a surgeon. She thinks like an architect, operates like a chef, constructs like an artist and a sculptor, curates not only the courses of the menu but also the realities that move between a stage and a museum, among many others. With all this, the images that she remakes -virtual, physical, visceral- make us feel unsettled, creating discomfort.

With her guidance, you will encounter the strangeness of the “real”, the construction of it. You will feel the anxiety as our distinctions and artificial boundaries that we make between the world, ourselves and the other living beings slowly disappear, our interactions start to lose the hierarchy where we become one among many others. You will find yourself within this lingering space between the dead worlds that we inhabit and the ones that have been brought to life once again.

A space where you will be tasting the magical remaking and transformation of realities and their living imagese of life.

EXPERIMENTATION. “PARROT-LOBSTER-CRAB”, YI (2024)

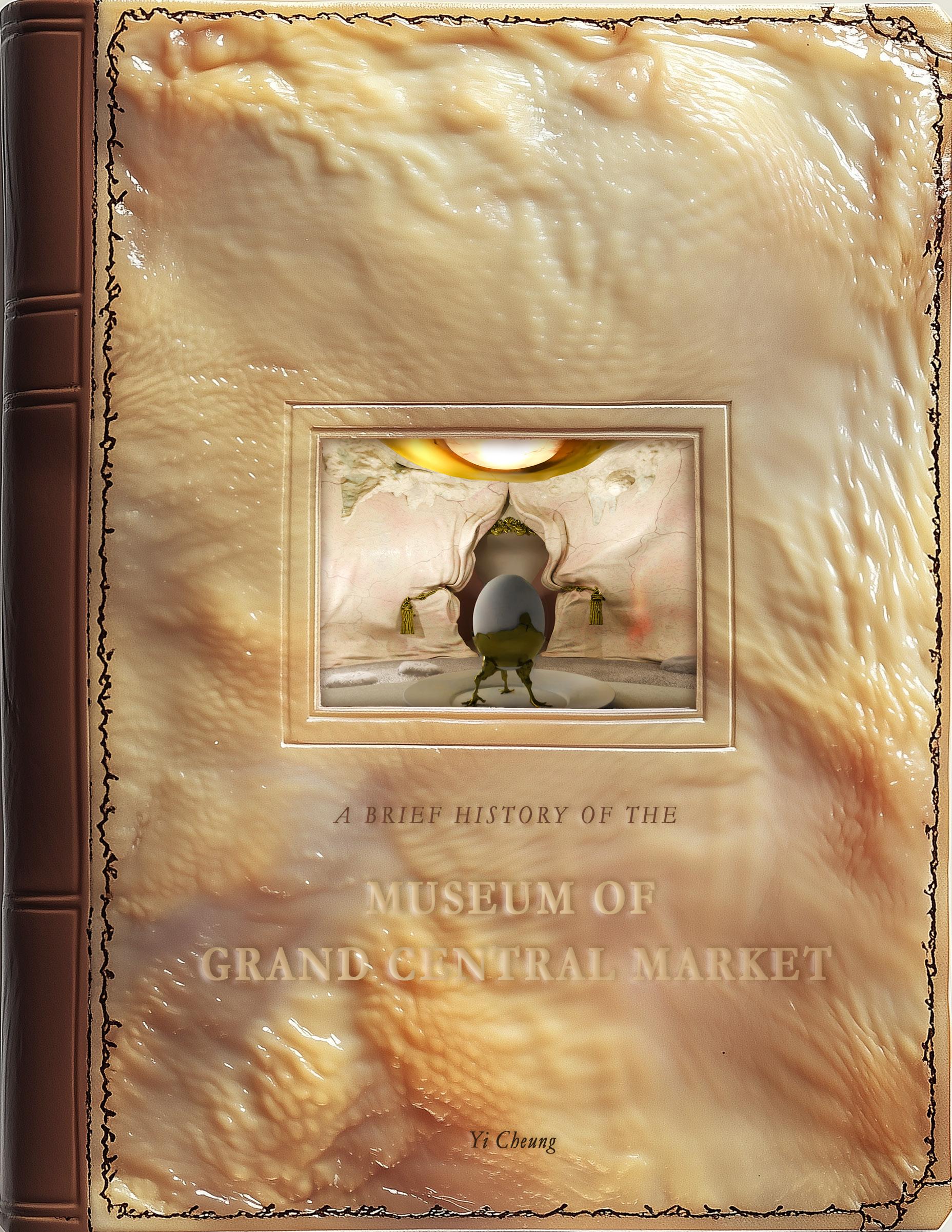

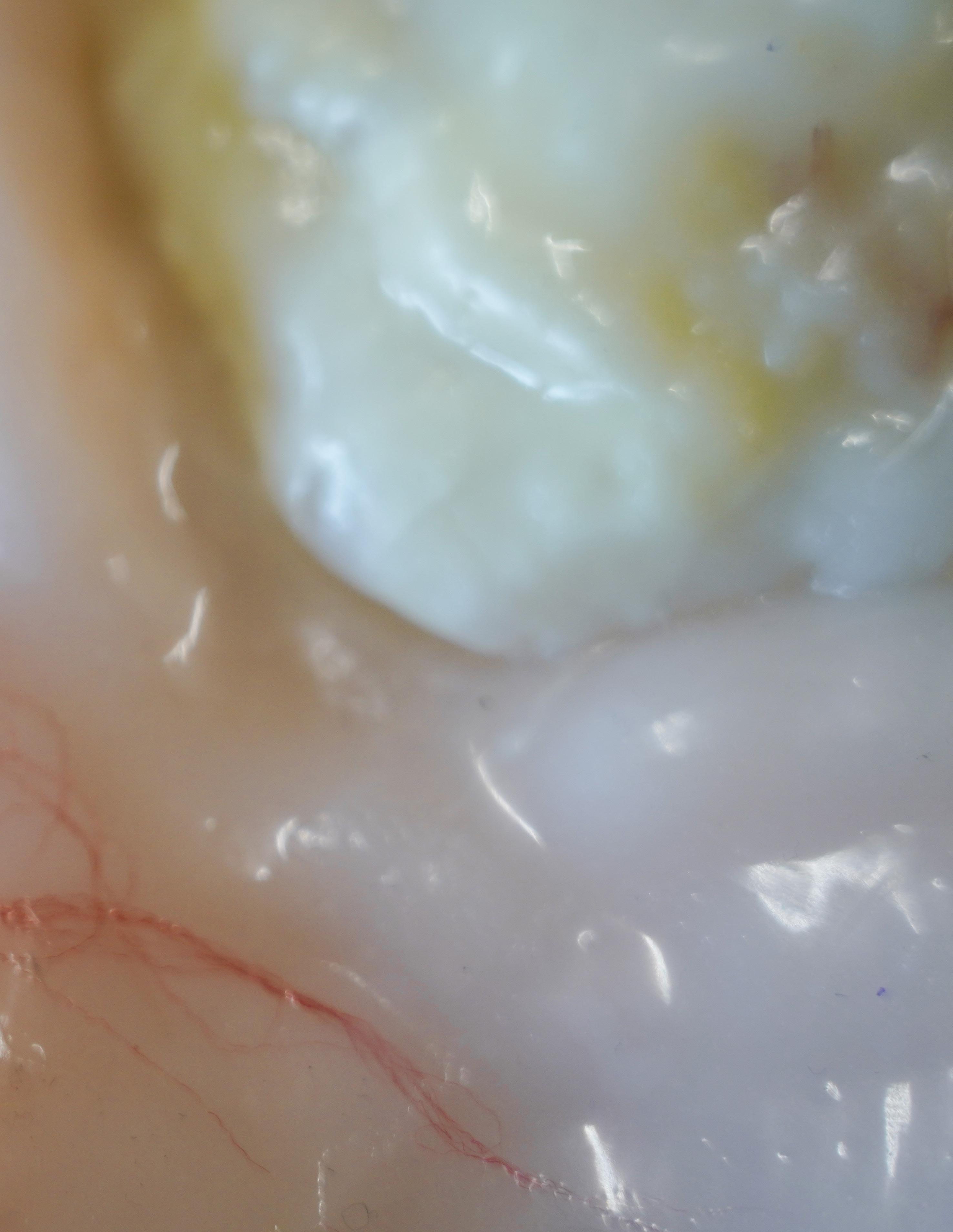

When a chicken becomes a meal, it is of course dead. Yet when the meal is still in the form of its raw material—the chicken meat, it somehow still feels alive. This lingering sense of life, I propose, seems to persist in the aesthetic qualities of rawness itself: a primal materiality that resists full abstraction.

It all started with a series of material exploration and sculptural pieces I made in the Fall of 2024. It followed by the discovery of a personal interest, if not (fetish), towards the raw meat — not the typical beef steak that imbues gore and blood. Yet the peachy pink, glistening wet, chicken breast flesh, that is honestly sort of “cute” and seducing.

This paradox—finding beauty in what should repulse, tenderness in what represents death—became the central tension driving my work. The chicken breast’s surface, with its subtle marbling and yielding texture, seemed to hover between states: neither fully living nor entirely objectified.

Living in downtown Los Angeles, Grand Central Market is one of the to-go places for a typical international student. It has its brutal history that not many are aware of or care too much about (not that brutal afterall, gentrification happens everywhere). The place once offered humble sustance to the local community and hosted lively exchanges of fresh livestocks. Today stands as a highly curated, marketed, “multi-cultural” food hub — a stage for consumption severed from its origins. This aesthetic inquiriy quickly became a museum project of that very place that embodies capitalist history. A museum not of artifacts, but of appetite. I figured its prominent location and brand would make the perfect site for a public institution that investigates: What it means to eat?

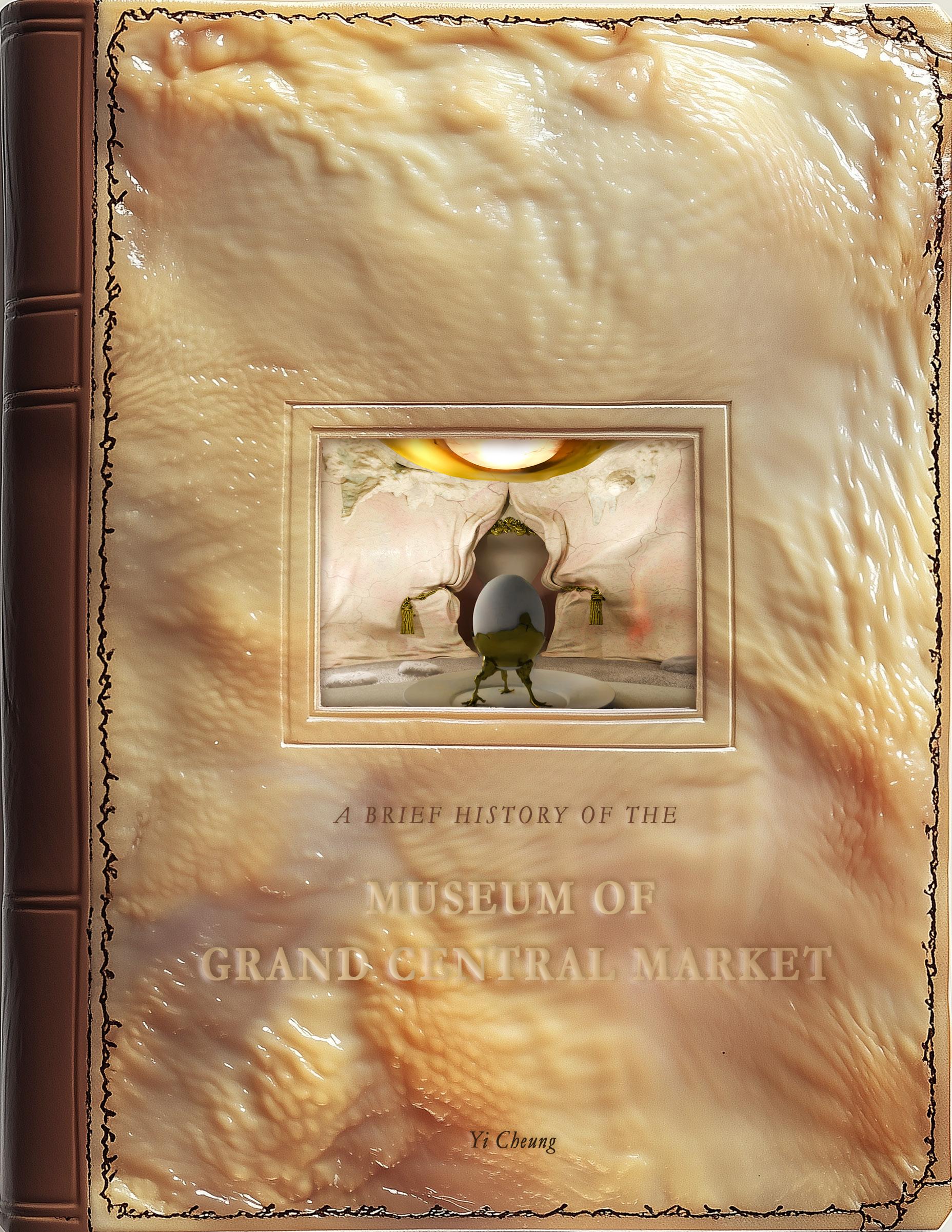

This book is a record of the pseudo-history of that museum: The Museum of the Grand Central Market. It is part theatre, part field study. Through architectural interventions, culinary artifacts and speculative recipes, it continues to situate as a spectacle, but seeks to provide a different lesson, to whom it may concern.

It is not a lesson that teaches, but rather an experience that makes you feel something. I discovered my interest in altering perceptions through multiple artworks I made previously, each attempting to create what I call “alternative perspectival speculation”—moments where the familiar becomes foreign enough to be seen anew, thus foregrounding and reminding the existing. My fascination with magical realism rooted frankly, from my frustration towards the daily life that has been made banal. Like Gabriel García Márquez’s matter-of-fact approach to the extraordinary, I seek to present the uncomfortable aspects of the living with the same casual intimacy we might describe breakfast. Within these alluring yet slightly off-puting scenes, these difficult truths about appetite, desire, and commodity culture are smuggled without the defensive barriers that direct critique often erects.

The third chapter of the book ‘More Stories’ laid down my works of inspiration. I have always been interested in the fantastical and whimsical—even better if there are tensions between familiar realities. Donna Haraway’s posthumanism work on kinship was a crucial backbone for the project. Her insistence on “staying with the trouble” of our entangled relationships with other species— including those we consume—helped me understand that this museum project isn’t about solving the ethical dilemmas of eating, but about dwelling more consciously within them. They aren’t problem to be resolved but a relationship to be examined.

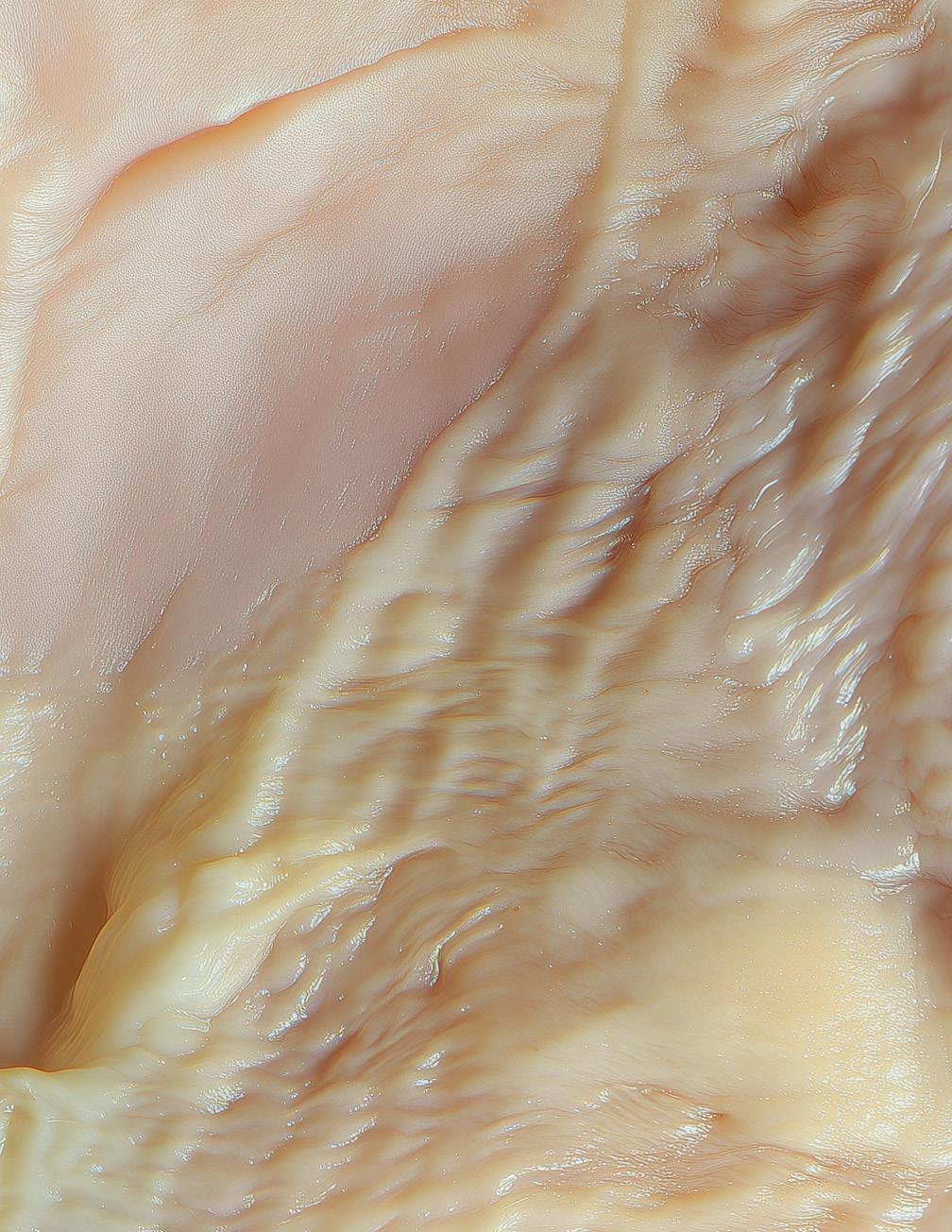

The project continues my broader inquiry into enchantment and estrangement—what I explored in “For the First Time: Encountering the Enchanting Nature.” There, I asked how subtle dislocations of the familiar might reactivate our sense of wonder when approaching nature-related topics or crisis. Here, I ask it again—but in the realm of the edible. Through fleshy interiors, strange dishes, and meat columns, I attempt to enchant the grotesque, to make the familiar built environment strange, and perhaps, to let the consumer encounter themselves anew.

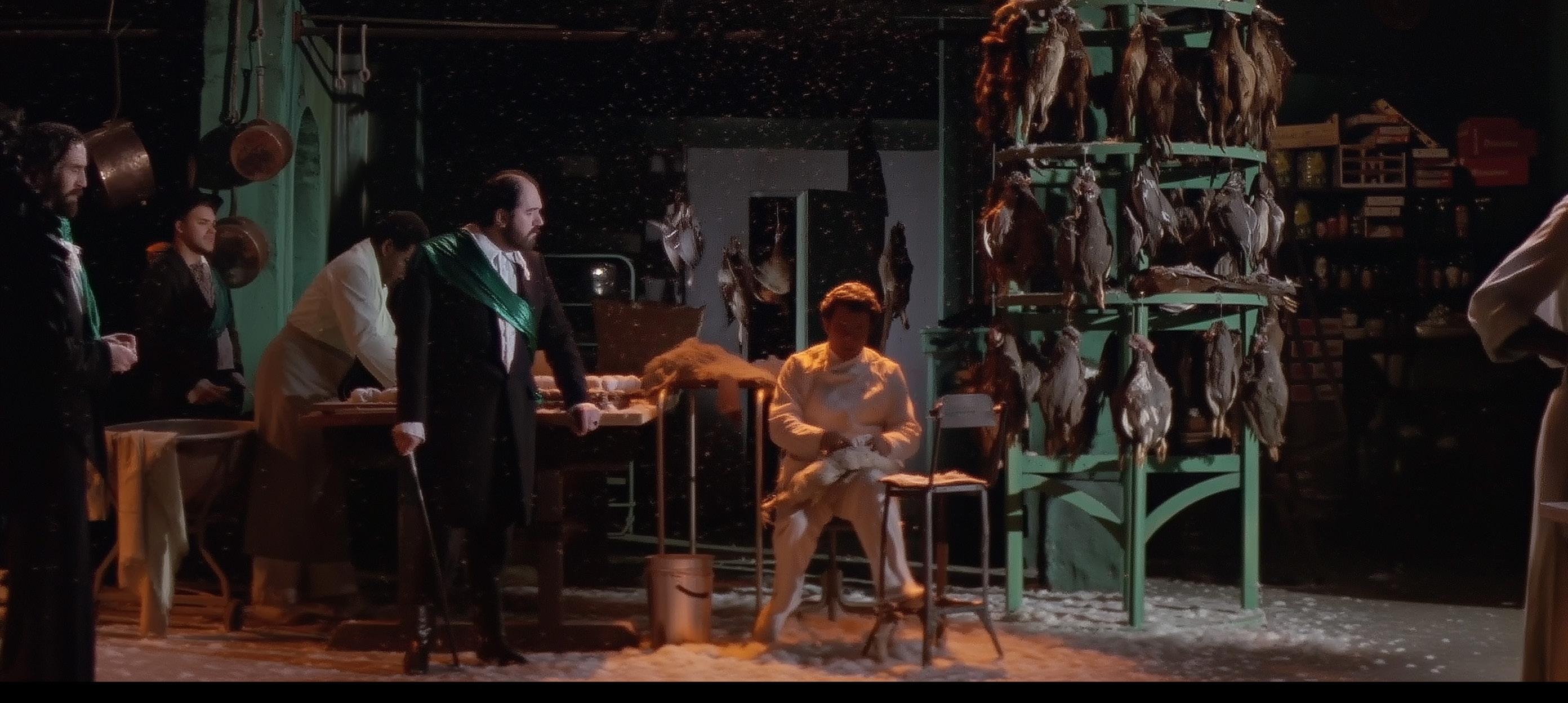

A common thread I found in my work is the creation of theatrical moments and scene staging. This realization led me deeper into Peter Greenaway’s work, particularly his understanding of cinema as architecture and architecture as performance. His film “The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover” became especially relevant—its color-coded rooms and ritualistic consumption creating spaces where eating becomes both intimate act and public spectacle. The last part of this book details how I curated this project in real life (the thesis presentation and exhibition), drawing from these cinematic strategies to transform documentation into performance.

This is not a book about food. It is a book about the conditions under which food becomes theatre, facts becomes fiction and

EXHIBITION OPENING. “FOR THE FIRST TIME: ENCOUNTERING THE ENCAHNTED NANTURE”, YI (2024)

How it all started:

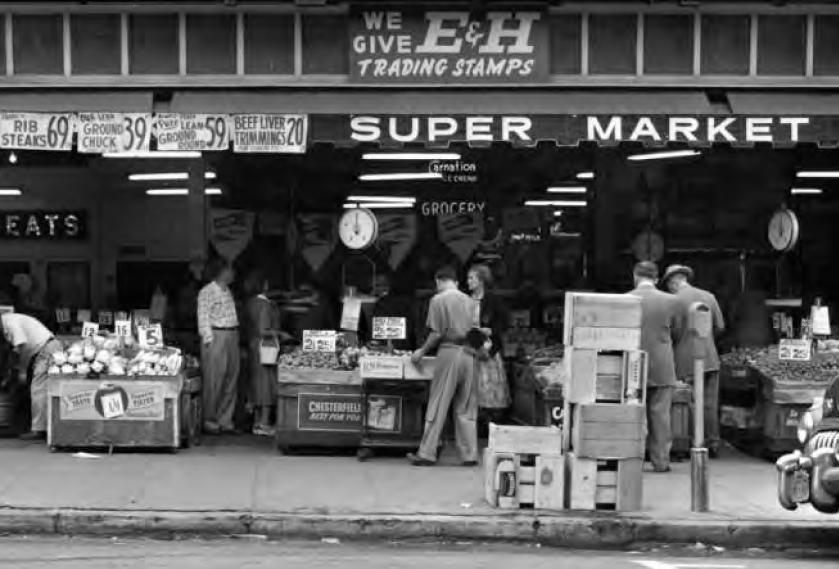

The ground floor of Homer Lauglin Building housed Coulter’s Dry Goods, selling fabrics, clothing, and household items to downtown Los Angeles residents. The space operated as a traditional department store until 1917, when it was converted into the Wonder Market, later renamed Grand Central Market.

The location was chosen because of its proximity to the Angels Flight Railway allowing for easy access to the well-off citizens of Bunker Hill. Initially serving wealthy Bunker Hill residents who descended via the funicular, the market gradually became a hub for immigrant communities and working-class families.

When the doors first opened in October 1917, the “Wonder Market” as a public market embodied liveliness. As a marketplace, it thrived on sensory immediacy encompassing fresh groceries. Butchers displayed whole carcasses and fresh cuts, fishmongers sold daily catch on ice, and produce vendors offered vegetables still bearing soil. The encounter with living stocks is unmediated and the process is visible.

EXHIBITION OPENING. “FOR THE FIRST TIME: ENCOUNTERING THE ENCAHNTED NANTURE”, YI (2024)

A communal aliveness was nurtured through selection, negotiation and exchange emcompassing fresh groceries. Vendors called out prices and offerings in multiple languages while customers examined the livestock directly. Regular customers developed relationships with specific vendors who remembered their preferences and saved quality items. The market operated as both commercial space and community hub.

New ownership initiated a modernization campaign aimed at competing with suburban shopping centers. Originally built in the Beaux Arts style, it underwent subsequent modifications that stripped away ornate details and installed contemporary aluminum storefronts. However, community resistance from longtime vendors and customers eventually pressured management to restore elements of the original character. By the late 1960s, some traditional features were reinstated, creating the hybrid aesthetic that would define the market for decades.

THE EXILES - GRAND CENTRAL MARKET, CITYSLEUTH. REELSF (1963)

“...it thrived on sensory immediacy encompassing fresh groceries. Encounters with living stocks are unmediated and process is visible.”

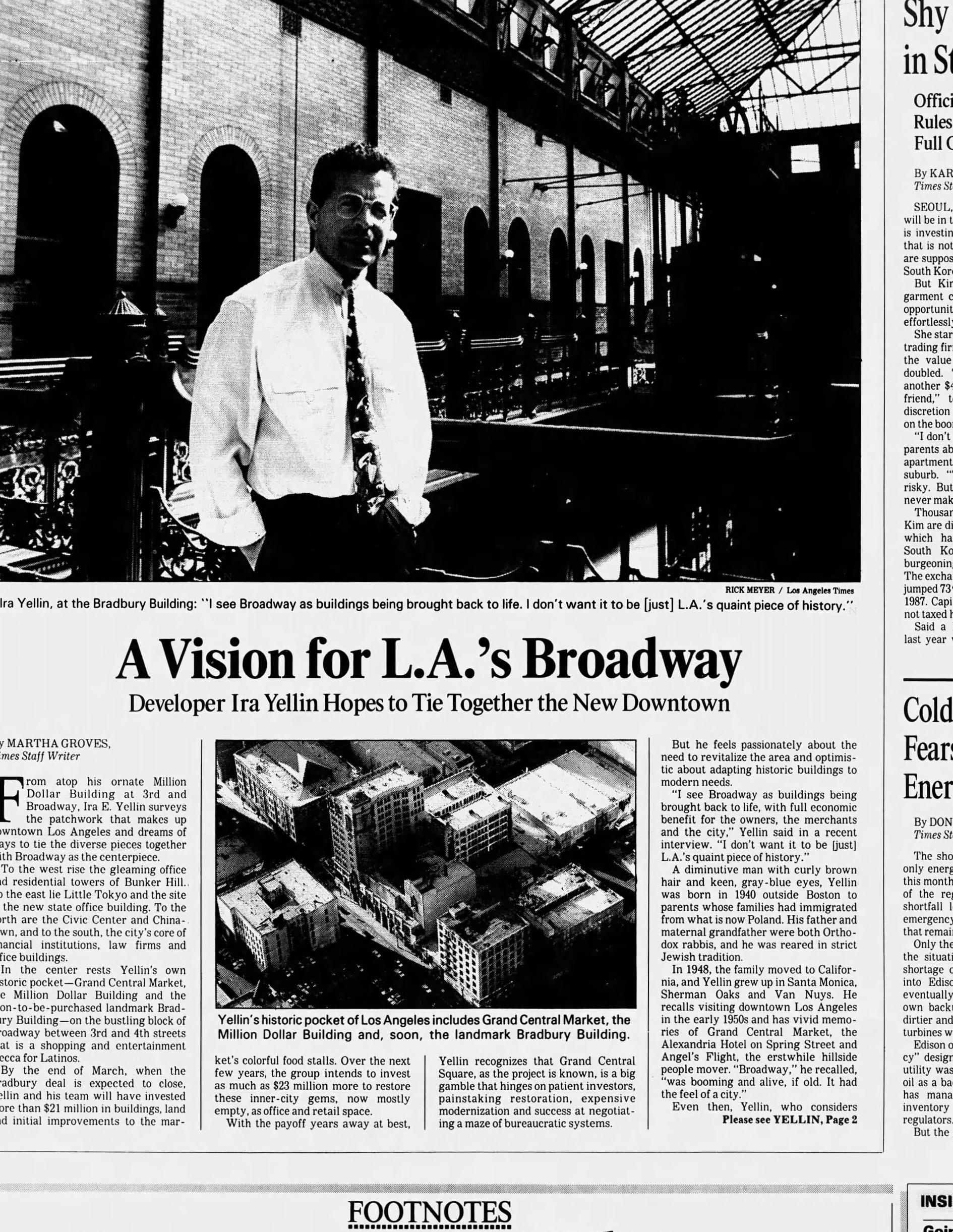

In the late 1980s, developer Ira Yellin became interested in the possibility of renovating the historic market, along with the adjacent Million Dollar Theater building. Yellin refurbished by stripping away a 1970s façade, adding neon signage and new parking. The 611,000 square-foot transformation was intended as the staging ground for the revived downtown residential and shopping district. Yellin’s plan was to create a Grand Central Square, combining historic preservation with modern urban living in what would become a model for downtown revitalization.

“I see Broadway as building being brought back to life.”

After more than a century, Grand Central Market was rebranded into a curated food hall, polished into a spectacle of urban consumption. Neon-signs and utilitarian steel delis filled the long hallway.

After more than a century, Grand Central Market was rebranded into a curated food hall, polished into a spectacle of urban consumption. The present market feels strangely static. Consumption occurs behind glazed storefronts and within compartmentalized zones — food has been severed from both process and presence. Polished partitions and self-contained vendor stalls sanitize the act of eating. They erect conceptual walls between diner and ingredient.

Today, eating at the market has become a solitary act performed within a choreographed routine: arrive, select a vendor, order from a menu, then proceed to a designated seating zone. While once a communal experience shaped by dialogue and exchange, eating is now linear, private, and transactional. There is little sense of wandering or negotiation. Each step is streamlined, targeting individualized preferences. The ritual resembles a techenabled errand, rather than a sensory or communal event. The market now accommodates the efficient eater—one who consumes quickly, quietly, and often alone.

“Glazed storefronts, polished partitions and fragmented zones reinforce the conceptual wall between us and the living entities we consume.”

“A neighbourly gathering spot turned into a spectacle in a blink of an eye — intimacy traded for performance.”

Grazing

Curated Fine Dining

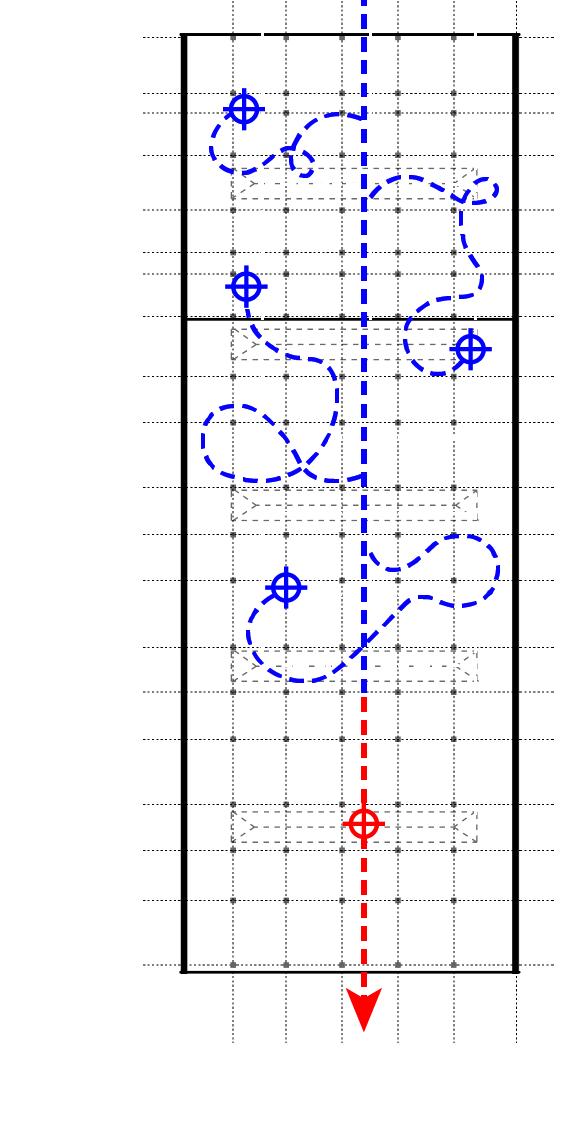

CIRCULATION DIGRAM.

COMPARISON OF EATING RITUAL OF EXISTING AND PROPOSAL. YI (2025)

Much of the food arrives not as freshly harvested or butchered, but as pre-prepared, cold, and lifeless packages. Refrigerated displays glow with vacuum-sealed proteins and wilt-resistant vegetables. There is no longer a smell of fish or blood, nor the soil from uprooted greens—only the clinical hum of refrigeration. The ‘deadness’ of the offerings is not just literal but symbolic: a distancing from the visceral, the perishable, the unpredictable. What once provoked a direct encounter with life now presents a controlled image of food as product—sanitized, aestheticized, and ready to be consumed without thought.

+ Martin Picard – Au Pied de Cochon Sugar Shack

+ Federico Campagna – Technic and Magic

+ David Wilson – Museum of Jurassic Technology

+ David Foster Wallace – Consider the Lobster

+ Peter Greenaway – The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover

+ Donna Haraway – Staying with the Trouble

+ The Menu – Mark Mylod

+ Salvador Dalí – Lobster Telephone

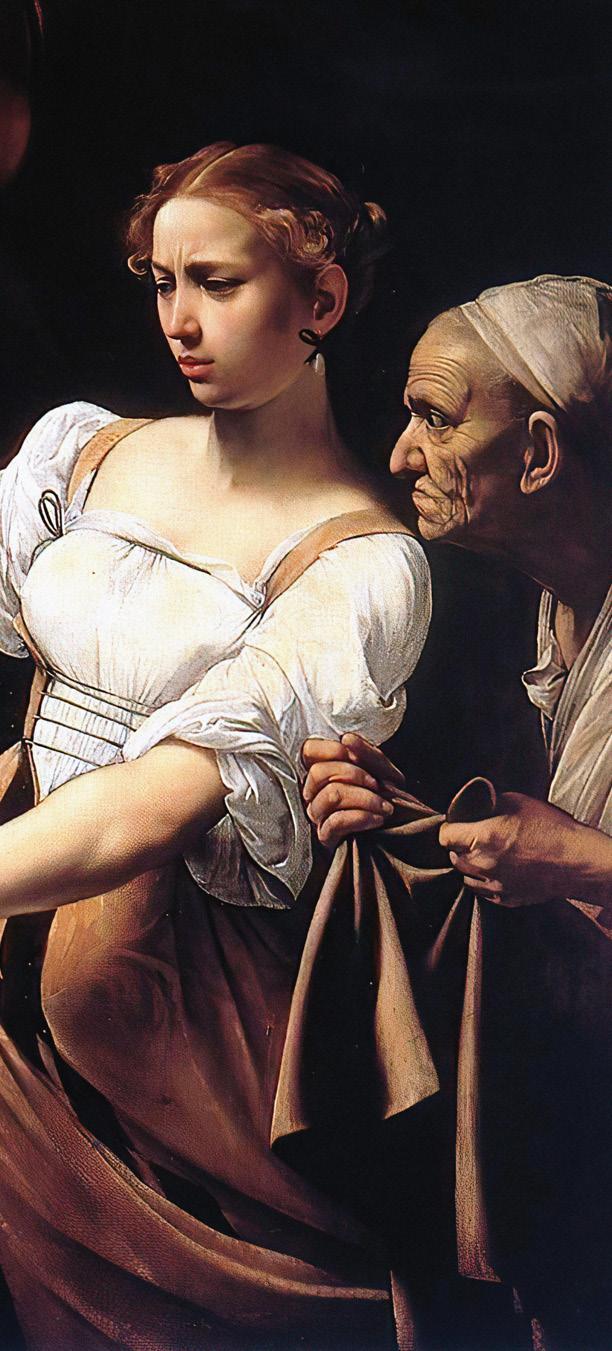

+ Caravaggio – Judith Beheading Holofernes

+ Monty Python – The Architect’s Sketch

+ Matthew Barney – Cremaster Cycle

+ Ivana Bašić – Throat Wanders Down the Blade...

+ Giacomo Puccini – La Bohèm

+ Meret Oppenheim – Object (Le Déjeuner en fourrure)

+ Bernini – The Rape of Proserpina

+ Ursula K. Le Guin – Carrier Bag Theory

+ Aaron Betsky – the Alpha and the Omega

+ Matte Collishaw – Venal Muse Left, Viridor

+ Jon Foncuberta – Fauna

consumption

Au

spectacle

fiction

re-enchantment

kinship

non-linearity

Consider the Lobster

AESTHETIC

Ivana Bašić

Throat Wanders Down the Blade...

deception

raw authenticity theatricality

absurdity

Matte Collishaw

Venal Muse Left, Viridor

visceral

David Wilson Museum of Jurassic Technology

Carravagio Judith Beheading Holofernes

humour

Mark Mylod The Menu

sattire

Peter Greenaway The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover

Monty Python The Architect’s Sketch

From moss-dusted plates in Copenhagen to alien geometries in Los Angeles, and finally to a squirrel sprawled across sushi rice in Montreal — these three restaurants speak of food’s origin, but in radically different dialects. Each claims to honor nature by foregrounding where food comes from. Yet their methods reveal as much about their cultural stance toward consumption as about the food itself.

Noma remains the poster child of the “new Nordic” ideal: hyper-seasonal, hyper-local, intensely foraged. Its reverence for nature comes wrapped in a narrative of purity and place. Even its famous duck, served with the feathers still on and the brain still in its skull, gestures toward confronting origin. Redzepi frames this as a zero-waste ethic: to honor the whole animal, not just the market-ready cuts, to challenge diners to open their minds. Yet for all its sincerity, the gesture was perceived as art-directed and massively critqued on its sacraficion on its taste. It is a romance of origin, designed to be admired, not necessarily to be confronted.

Vespertine speaks in an even more rarefied register. Jordan Kahn’s sci-fi cathedral of dining abstracts food origin into cosmic metaphor. Ingredients are transfigured into alien forms: coral-like lattices, blackened meteorites, silvered shards. The connection to nature is encoded, not visible — a conceptual puzzle that demands diners play along. It is, perhaps, the most polite and pretentious of the three, not because the cooking lacks vision, but because it distances the eater from the raw fact of food’s life before the plate. Origin becomes myth rather than memory.

Then there is Au Pied de Cochon, where Martin Picard dispenses with euphemism altogether. Here, reverence for nature is expressed not through suggestion, but through confrontation. The infamous squirrel sushi is emblematic: the animal is present, whole, staring back. No polite plating to soften the truth. To eat here is to acknowledge that something has died for the plate in front of you — a gesture that, in its frankness, feels oddly more respectful than the hushed theater of foraging narratives or cosmic abstractions.

All three reframe the same idea — that knowing the origin of food deepens the experience of eating. Yet for me, it is Au Pied de Cochon’s blunt honesty that resonates most. By stripping away the polite fictions around consumption, it makes visible what dining culture often hides. Perhaps the truest respect to nature is not in romanticizing its beauty, but in confronting its cost.

“High-end culinary practice is a familiar form of spectacle.”

‘A DUCK BRAIN SERVE IN ITS OWN SKULL, SCOOP WITH ITS OWN TONGUE.” RENÉ REDZEPI. NOMA.

David Foster Wallace’s “Consider the Lobster” begins as a seemingly straightforward assignment—covering Maine’s annual Lobster Festival for a food magazine—before slowly transforming into a profound philosophical meditation on the ethics of consumption through a humorous tone. Inspired by this, this architectural thesis that appears to be a building proposal for Grand Central Market becomes a vehicle for examining our relationship with food we consume. Both works operate as wolves in sheep’s clothing: Wallace’s journalistic piece and an architectural school review setting provide respectable frameworks to smuggle in deeper, more uncomfortable inquiries. Where Wallace uses rigorous textual analysis to pierce what I call “cultural anesthesia,” my spatial intervention is a bolder extension, embodying an enchanted yet slightly discomfort experience rather than intellectual contemplation.

Both works fundamentally challenge the “aesthetic abstraction” that defines contemporary culinary culture. Wallace exposes how the Maine Lobster Festival’s festive atmosphere—complete with carnival rides and corporate sponsorship—serves to mask the reality of boiling sentient creatures alive. This mirrors this critique of high-end dining culture, where “thinly sliced scallops are sculpted into delicate art pieces, plated on minimal vessels and dressed with lavish syrup—so much of it abstracted away from the living origin.” Wallace’s detailed investigation into lobster neuroanatomy and pain response parallels the architectural strategy of making “the physical reality of life and death legible (and edible), once again.” Both works identify spectacle as a mechanism of separation—Wallace noting how the festival’s “upscale and legitimate” veneer disguises ethical violence, while I target pretentious high-end restaurant settings and rituals that reinforces the conceptual wall between us and the flesh that we consume.” Wallace’s central question—”Is it all right to boil a sentient creature alive just for our gustatory pleasure?”—finds its spatial equivalent in the museum’s climactic moment where visitors confront an actual dish and must decide: “do we eat or do we not?”

The methodological divergence between our approaches reveals both similarity and distinction in how we deploy discomfort as a pedagogical tool. Wallace maintains his journalistic persona while systematically dismantling it through footnotes, scientific research, and philosophical digressions—his humor emerges from the absurdity of applying rigorous academic analysis to a popular food festival. This architectural intervention operates through what I call “absurd enchantment”—the Grand Central Market’s familiar elements transformed into “bone-like, fleshy” columns and “pulsing wall of inflatable tiles.” Where Wallace’s unexpected shock comes through intellectual revelation wrapped in sarcastic jokes, mine aims for spectacle with a more serious tone designed for maximum visceral impact. Both approaches share an element of the surreal— Wallace’s deadpan dissection of festival rhetoric mirrors my strategy of making the everyday strange. His humor stems from exposing contradictions through logic; mine from the architectural uncanny, where familiar spaces become viscerally alien. Yet both create an “off-putting yet alluring” experience that refuses easy dismissal. Wallace’s readers cannot simply close the essay and forget its implications, just as the museum visitors cannot maintain comfortable distance from the ethical questions posed by its spatial provocations.

What really distinguishes my project most significantly from Wallace’s work lies in our approaches towards this paradigm for interspecies ethics. Wallace’s consideration remains fundamentally anthropocentric—he carefully examines lobster consciousness and capacity for suffering, but continues to center human moral responsibility toward other creatures. Detailed explanations of lobster neuroanatomy serves to establish their worthiness of moral consideration based on their similarity to human pain experience. The proposed architectural feast suggests something more radical: “kinship between the fleshconsuming animal and the raw flesh that we consume” based not on similarity but on “shared precarity” across all forms of life. Rather than arguing for lobster rights, this intervention seeks to collapse the distinction between consumer and consumed that the culture dreads to mediate. The museum’s hybrid architectural elements—spaces that are simultaneously familiar and viscerally other—embody this collapse of categorical boundaries. Where Wallace maintains the investigative distance necessary for ethical judgment, this spatial intervention eliminates distance altogether, forcing physical participation in the very contradictions it exposes.

Both works do not seek to provide comfortable answers but by sustaining productive discomfort. Wallace’s essay deliberately ends without resolution, its final paragraphs maintaining the tension between gustatory pleasure and ethical responsibility. Similarly, this architectural feast culminates not in moral clarity but in an unavoidable question posed by the act of eating itself. Both works demonstrate the value of sustained attention to what contemporary culture renders systematically invisible—whether through intellectual rigor or spatial provocation, we refuse the luxury of looking away from the violence that sustains us.

Disguised at first as an extravagant fine dining experience, “The Menu” gradually reveals itself to be a planned massacre scheme by a psychotic chef. The film starts with an introduction of the farms and kitchen spaces which are highly sterile and unnervingly controlled, establishing a chilling tone. Guests are then settled and served the first courses, before serving each of the plates, the chef claps demanding silence to commence a dramatic monologue introduction. These dishes soon reveal themselves to be a composed theatrical act of judgment, exposing the guests’ personal moral decay. The movie ends with a forceful participation of the guests in the dessert, where they are crowned with marshmallow-threaded collars, then being ‘plated’ together with ‘unethically sourced chocolate’ and ‘gelatinized sugar water’, finally burnt into flames – replicating the classic family snack, “s’mores.” The final course pinpoints the movie’s critique – a brutal yet clever ironic critique on consumerism that often disguises as high art.

Lobster Telephone stages an encounter that is both immediate and absurd. A domestic object—ordinary, practical—is overlaid with the anatomy of a crustacean. Its humor and dissonance lie in the precise fit of the lobster on the handset: at once ridiculous, intimate, and oddly plausible. This surreal collision reframes perception, making the familiar strange without entirely severing its recognizability. The receiver becomes the lobster’s underbelly; the tail curves naturally into the mouthpiece, as if this pairing had always been inevitable. It hovers between function and interruption, a tool rendered useless yet still tempting to hold.

This strategy is applied in this thesis: objects in the market are reassembled in illogical pairings—meat columns, edible furnishings—keeping just enough of their original role to remain legible. Like the lobster on the phone, these hybrids quietly infiltrate the familiar, making the ordinary feel unstable without ever declaring themselves unreal.

Matthew Barney’s Cremaster Cycle is a sprawling, five-part cinematic work in which sculptural tableaux, ritualized gestures, and surreal environments merge into a mythic narrative about transformation, desire, and constraint. Across its films, Barney fuses performance, costume, and meticulously constructed sets into a symbolic world—one where the body is both protagonist and architecture.

The Cremaster films are organized as ceremonial acts—processions, competitions, and metamorphoses—whose logic feels both alien and inevitable. These rites transform materials and gestures into symbols of a closed, self-sustaining world. In my thesis, dining is reframed as a theatrical ritual: each room-course operates as a staged act in which consumption becomes a performance of desire, disgust, and intimacy. The audience is drawn into an invented order where food is not simply eaten but enacted—mirroring Barney’s transformation of athletic or sexual acts into sacred choreographies.

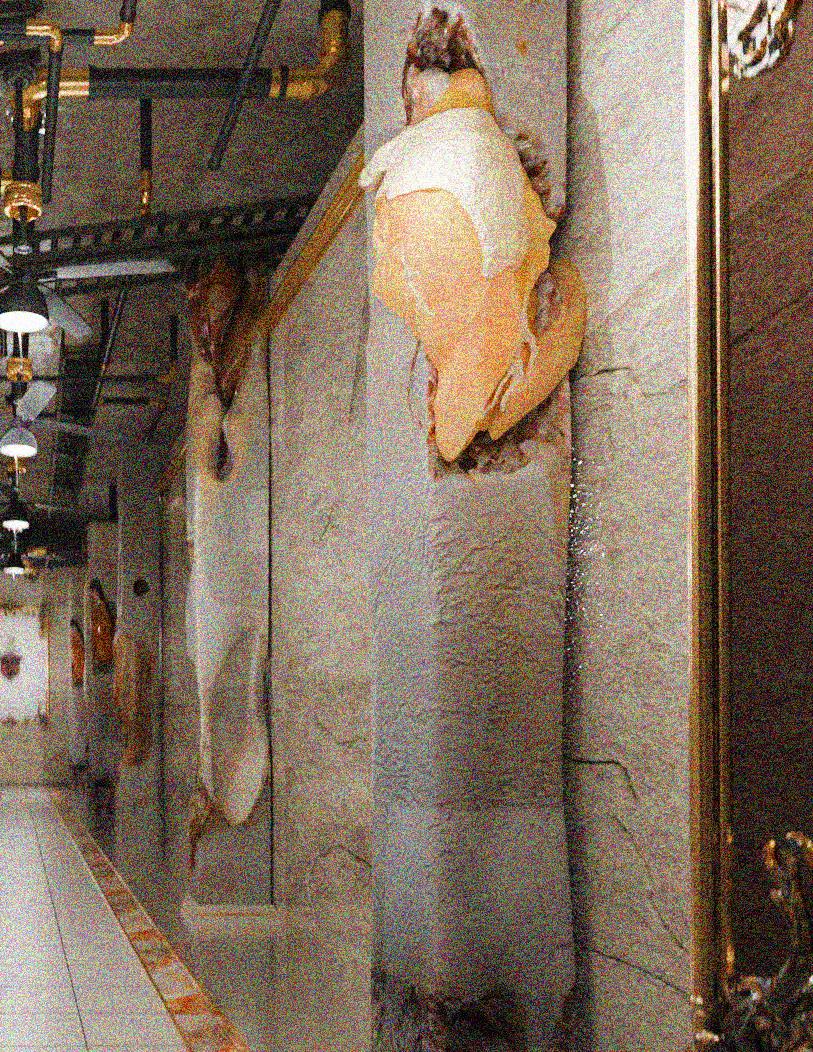

A crucial device in Cremaster is how spatial tension is composed through thresholds and framing. The work often situates the viewer at the edge of an opening— peering through a doorway, a crack in a wall, or a gap between monumental forms. In one image, a cathedrallike space is glimpsed through a monumental wax surface, the framing compressing and intensifying the architectural vista beyond. In another, a trio of suited figures in a tight, wood-paneled room appear both claustrophobically enclosed and theatrically presented, as if the walls themselves conspire to make the tableau inevitable. These perspectives pull the viewer into an active role—caught between spectator and participant— hovering at the edge of entry.

In my thesis, similar spatial framings are key. Each dining space is staged as a distinct “act” in a meal, but the progression between them is charged by thresholds— curtains, narrow corridors, sudden openings—that force the viewer to inhabit a state of anticipation. These are not neutral transitions; they are spatial cues that condition how the next encounter will be perceived, much like Barney’s framing devices charge each scene with narrative and symbolic weight before the viewer even fully enters it.

The Cremaster Cycle also demonstrates the theatrical power of proximity and staged perspective. Objects and figures are placed in deliberate spatial relationships to their backgrounds, blending flat, illusionistic backdrops with tangible, volumetric forms. This produces an uncanny extension of the stage into real space, dissolving the boundary between set and action. In my project, I similarly manipulate proximity between backdrop and object to fold the viewer into the performance of dining.

The work also shifts visual resolution and scale fluidly—from hyper-detailed close-ups of waxy textures and object surfaces, to medium shots of architectural fragments, to sweeping wide views of entire rooms or structures. This movement between scales creates a visual rhythm that oscillates between intimacy and monumentality. It allows viewers to inhabit the work on multiple registers at once—feeling both embedded in the material and aware of the grand, encompassing space. My project adopts this strategy, alternating between tactile close encounters with food-like forms and expansive views of staged dining environments.

Ultimately, Barney’s work inspires my thesis through its mastery of ritual, spatial thresholds, and theatrical framing. It shows that the tension of “what lies beyond” can be as compelling as the event itself, and that staging consumption— whether of narrative, spectacle, or food—can be an architecture in itself.

The painting captures a scene of tense yet suspended violence. The composition conveys a timely narrative, with characters spreaded across the canvas to suggest the sequence of an unfolding event. The head was framed at the center of attention. Holofernes, caught mid-death, does not scream but gazes upward in shock, leading the audience towards the top right of the painting, where the young female killer, slightly irritated, performs the act with surprising calm. Behind her stands an old servant, on the edge of the canvas, holding a fabric awaiting to hold the head. The tension lies at the center of the frame, where the head is resisting to be slaughtered against the arms —his posture suggests he’s half-risen from bed escaping from fate. High contrast foregrounds flesh and expression while letting the weapon of violence itself exist subtly. Emotion and movement evoke horror more than gore. A silky red fabric dominates almost half of the painting, amplifying the scene’s visceral intensity. The sensation of violence is distilled through highly realistic expressions and gestures articulated with lighting.

JUDITH BEHEADING HOLOFERNES. CARRAVAGIO.

The sculpture presents a creature-like figure punctured by a steel rod through its torso and fixated on the wall. It features distorted appendages resembling two dangling legs and a pair of arms wrapping around its body, curling inwards as if in pain. Abject art like this one is generally deemed as discomforting or simply rejected by public audiences, considering it as pure violence or pessimistic abstraction of reality. It may be easier to dismiss than to stay with its visceral intensity, bypassing what the work here dares to confront.

The steel rod that pierces the entire form is a brutal anchor that simultaneously crucifies and supports. This paradox— where the instrument of violence becomes the very means of suspension—embodies the work’s central tension between fragility and endurance. Sculpted in detail with wax, the sculpture presents delicate muscle anatomy and accentuated by grey oil painting shadows crevices, recalling one of Bernini’s marble sculptures, exemplifies the strength embodied in the figure. Yet, the flesh appears bruised, soft and almost decaying. It is presenting not grotesquery for its own sake, but a profound meditation on vulnerability and endurance as a shared condition across species and forms of life.

The abstract phantom is neither fully human nor entirely other. Its hybrid form and punctuation with metal collapses distinctions between organism and object, machine and flesh. A phantom caught in slow decomposition, it resists categorical clarity and instead insists on kinship through shared precarity. This refusal to provide easy consolation constitutes the work’s curatorial power. While contemporary culture excels at making violence palatable—transforming slaughter into cuisine, otherlife’s suffering into spectacle—Throat wanders down the blade… maintains an uncomfortable proximity to pain. The figure’s suspended animation freezes transformation mid-process, brutally demanding sustained attention to what is typically veiled: the slow violences of existence and the intimate connections between vulnerability and resilience.

The spatial condition of the piece intensifies the encounter. It’s impossible posture—simultaneously falling and suspended— defies immediate comprehension. Viewers must move around it, their bodies compelled into engagement. This physical participation collapses the safe distance of spectatorship,

implicating the viewer in the contradiction of support and harm. Bašić’s sculpture is not merely an object then, but a demand for an alternative mode of seeing as we encounter otherness. It shapes a form of attention that refuses the luxury of distance, insisting instead on recognition across differences. The figure’s hybrid nature—human yet other, organic yet penetrated by industrial materials—suggests new forms of kinship based not on similarity but on shared fragility. It offers an ethics of care that begins with acknowledging mutual precarity rather than transcending it. Ultimately, piercing through cultural anesthesia and restoring what has been systematically obscured.

It shapes a form of attention that refuses the luxury of distance, insisting instead on recognition across differences. The figure’s hybrid nature—human yet other, organic yet penetrated by industrial materials—suggests new forms of kinship based not on similarity but on shared fragility. It offers an ethics of care that begins with acknowledging mutual precarity rather than transcending it. Ultimately, piercing through cultural anesthesia and restoring what has been systematically obscured.

Like many other Monty Python’s skids, The Architect’s Sketch is a surreal comedy casted on mundane situations, absurdly but with wit. It opens with a seemingly formal meeting between clients and architects discussing a proposal for an apartment complex. The tone grows increasingly farcical—from the exaggeratedly formal introductions to the architects’ pretentious presentations using scale models and theatrical visual effects. The first architect presents a design that gradually reveals itself to be a repurposed slaughterhouse, complete with rotating blades and blood drains. His deadpan justification—“I mainly design slaughterhouses”—turns the macabre into something hilariously logical. The second architect does no better: the model collapses mid-way while he praises its structural integrity, and bursts into flames as he describes its fireproofing. The sketch escalates into brilliant chaos, culminating in classic Monty Python dark humour, as the clients, utterly unbothered, select the second burning model as the winning design.

Like many other Monty Python’s skids, The Architect’s Sketch is a surreal comedy casted on mundane situations, absurdly but with wit. It opens with a seemingly formal meeting between clients and architects discussing a proposal for an apartment complex. The tone grows increasingly farcical—from the exaggeratedly formal introductions to the architects’ pretentious presentations using scale models and theatrical visual effects. The first architect presents a design that gradually reveals itself to be a repurposed slaughterhouse, complete with rotating blades and blood drains. His deadpan justification—“I mainlmour, as the clients, utterly unbothered, select the second burning model as the winning design.

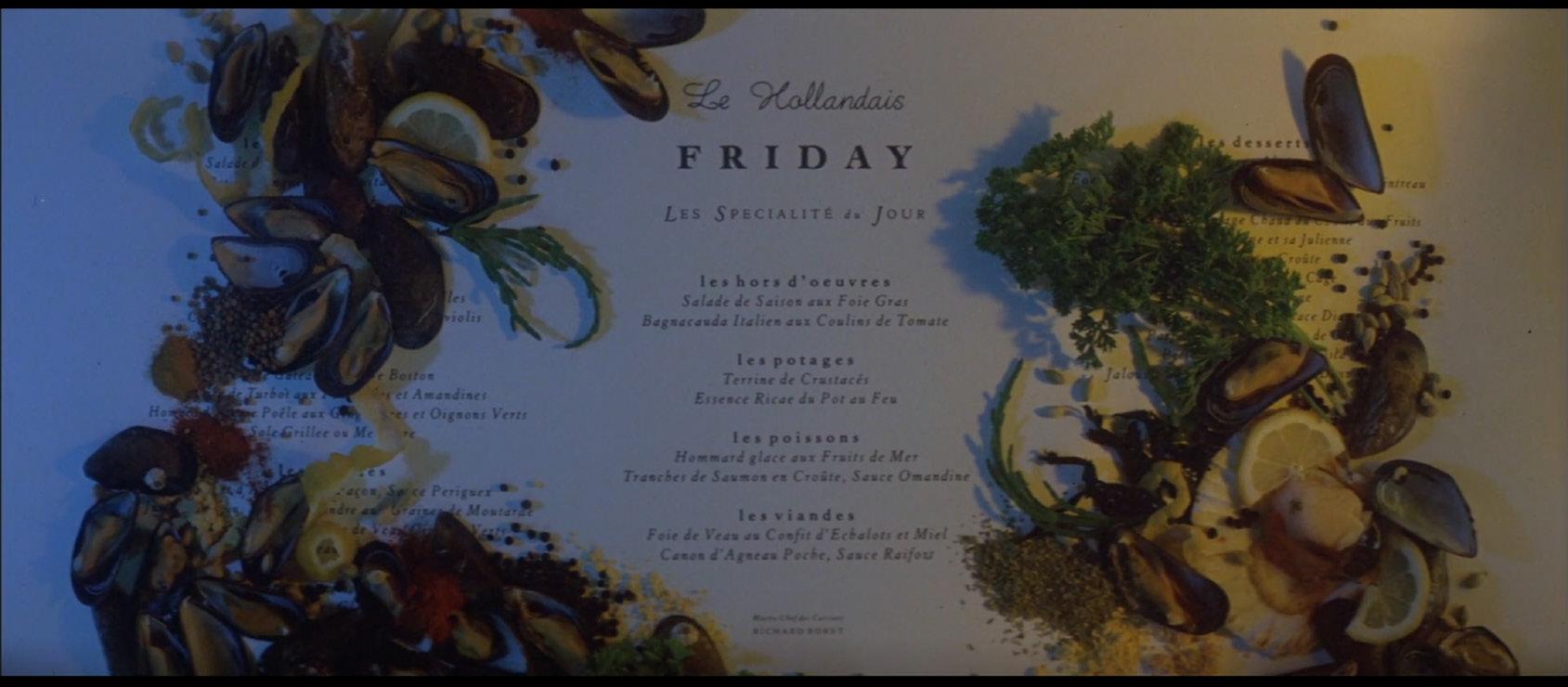

THE COOK, THE THEIF, HIS WIFE, HER LOVER.(1989) PETER GREENAWAY.

Peter Greenaway’s The Cook, The Thief, His Wife & Her Lover is an exemplar of cinematic staging, where each room is treated almost as a theatrical set, defined by highly controlled lighting, choreographed movement, and an exaggerated color palette that changes as characters cross thresholds. This spatial dramaturgy finds its architectural parallel in the thesis project, where dining rooms are not merely backdrops for consumption, but active scenes that manipulate mood, pace, and desire. Each architectural room-course is defined by a singular lighting condition, distinct material vocabulary, and spatial rhythm—much like Greenaway’s hyperstylized mise-en-scène.

The film’s genius lies in how it moves laterally through spaces, almost like a slow horizontal pan from room to room— through kitchen, restaurant, corridor, bathroom—without the need for hard cuts. These fluid transitions elevate the restaurant into a stage, and the act of dining into a choreographed ritual. In a similar manner, the thesis uses sequentially linked dining environments where one’s passage through spaces is experienced as a narrative unfolding—a meal not eaten, but enacted. This continuous spatial dramaturgy helps sustain a theatrical momentum that blurs the line between viewer and participant, performance and habit.

Moreover, the film’s use of physical props—rotting food, luxurious fabrics, dangling carcasses—adds texture and symbolic weight to each space. These objects are not passive décor but act as narrative agents, staging class, gluttony, power, and violence. Inspired by this, the architectural interiors in the thesis are populated with exaggerated material artifacts—flesh columns, inflatable skins, blood-colored walls—that expose the visceral mechanics of food and desire. The spatiality becomes dense, sculptural, and sensorially charged.

In a particularly memorable motif, Greenaway shifts between narrative scenes using still frames of menus and ingredients laid out like ritual offerings, top-down in painterly compositions. Each still is highly curated, with the selection of ingredients, placement and quantity of them, and the lighting that cast on the menu. The thesis mirrors this strategy in its graphic and spatial transitions between each courseroom: each new scene is preceded by a still “menu moment”—a flat-lay tableau of ingredients, interior fragments, and objects rendered in architectural drawings or staged photography. These moments serve not only as palate resets but as conceptual pauses, reminding the viewer that every course is a constructed spectacle—a performance built from consumption, longing, and excess.

Staging, Framing, Lighting

In this La Bohème garret scene, the stage design demonstrates how theatrical devices can compress physical space while expanding imaginative space. The room’s geometry subtly funnels toward the back wall, using perspectival narrowing to suggest greater depth than the stage allows. Angled ceiling beams, slanted wall lines, and foreshortened side planes guide the audience’s eye inward, producing the illusion of a long, attic-like volume.

The interplay of real, textured elements with the illusionary backdrop anchors the scene in material authenticity. The weathered timber door, peeling plaster walls, and warped windowpanes are physically built, not merely painted. Their surfaces catch and scatter light in ways flat scenery cannot, deepening the realism and inviting tactile recognition.

This realism is heightened through layering of space. In the foreground, personal and domestic objects—bed, table, stove—are arranged with the informality of real life. The mid-ground holds the performers in loose groupings, their movements naturally threading between zones. The background, with its glowing window and shadowed loft ledge, extends the garret into unseen depths. This blend of tangible and implied space allows the audience’s imagination to spill beyond the proscenium.

Lighting shapes and divides these zones without resorting to hard physical barriers. A warm, concentrated pool on the bed draws emotional focus toward Mimi, while cooler light isolates the painter at his easel, underscoring his parallel but detached activity. The corners remain dim, their partial obscurity hinting at further recesses of the room and lives lived beyond the immediate drama.

The set’s strength lies in its seamless blending of illusion with the physical world. Perspectival design, textured surfaces, and calibrated lighting merge into a convincing whole, transforming a finite stage into an attic whose emotional and spatial depth feels limitless—an intimate, believable Paris that breathes just beyond the footlights.

This realism is heightened through layering of space. In the foreground, personal and domestic objects—bed, table, stove—are arranged with the informality of real life. The mid-ground holds the performers in loose groupings, their movements naturally threading between zones. The background, with its glowing window and shadowed loft ledge, extends the garret into unseen depths. This blend of tangible and implied space allows the audience’s imagination to spill beyond the proscenium.

The set’s strength lies in its seamless blending of illusion with the physical world. Perspectival design, textured surfaces, and calibrated lighting merge into a convincing whole, transforming a finite stage into an attic whose emotional and spatial depth feels limitless—an intimate, believable Paris that breathes just beyond the footlights.

“familiar but very weird, slightly uncomfortable but somehow cute, almost alive”

impermanence

imperfections

blemishes residue moisture

growth

freshness

visceral realistic

vein muscle skin hair or fur

bright colors resistance

fatty tissue softness expression

liveliness

motion breathing

MUSEUM DIRECTORY, ALSO DAILY REGULAR MENU. GOUT VITALE, YI (2025)

MUSEUM ENTRANCE. GOÛT VITALITÉ, YI (2025)

The ‘whimsical’ pig-head sculpture, usually neglected, stand in front of the entrance of Grand Central Market. It was a bike rack commissioned by the Los Angeles Land Department in 1995 as part of a larger urban program ‘The Bike Stops Here’. The design, created by students from SCI-Arc has stood the test of time, and hopefully will continue to do so with a retextured touch.

This Beaux-Art styled arch door, now only one remaining on the farthest bay as entry to the upper apartments, once stretched through the whole facade of Grand Central Market. It is now relocated and brought back to mark the mysterious entrance of the New Museum of Grand Central Market.

The open ceiling of Grand Central Market reveals a dense weave of exposed pipes, hulking fans, and industrial lights. Mechanical pipes entangles with column structure, now reappears in the new Musuem.

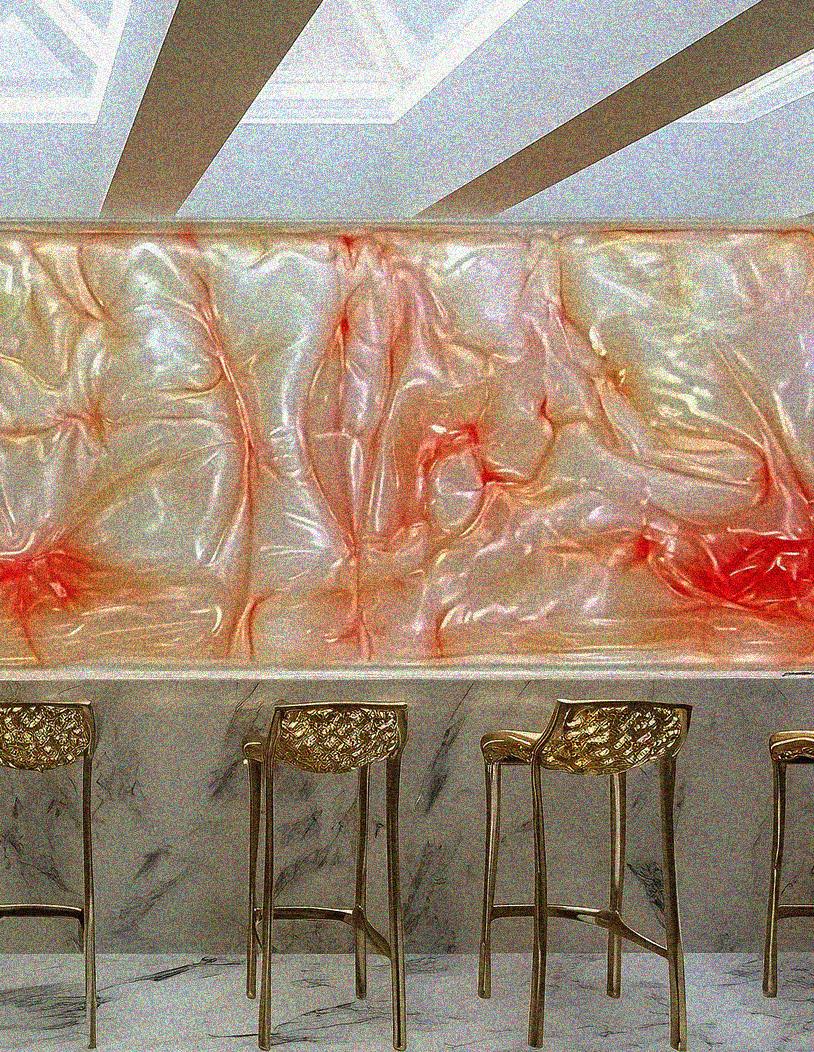

A starter often pacifies, after the deliberately alienated rituals of a high-end restaurant to detach from reality outside. Tinted with a pale peachy color, this starter pacifies as well - to some extent. Here, the preserved counter, fleshy fittings, and meaty columns sets the tone of the meal — a slightly unsettling visceral prelude.

Preserved Eggslut counter, tiled in pink-veined ceramic and sealed in ribbed metal, served on a base of worn stone. ζ

Exposed mechanical pipes, lacquered in pearl glaze, laced in fatty tissue, dressed with brass jointed fittings.

Baroque-handled beer taps in aged brass, set on veiny marble tabletops.

Bar stools, upholstery stuffed with pork thigh upholstery.

Columns cooked in the manner of grilled bone marrow, streaked in cream and crimson, trimmed with a gilt crown.

WAITING ROOM.

GOÛT VITALITÉ, YI (2025)

Eggslut opened its first permanent location at Grand Central Market in November 2013, transforming Alvin Cailan’s famed food truck into a full stall inside the historic 1917 marketplace. Almost immediately, it became an anchor vendor—its celebrated egg sandwiches inspired long queues and widespread media acclaim.

In 2014, Bon Appétit named Grand Central Market one of America’s Top 10 new restaurants, citing Eggslut as a key driver in the market’s renaissance. That recognition elevated the market’s profile, catalyzing a wider renovation that welcomed dozens of new chef-driven vendors in the years that followed.

Eggslut’s stall became synonymous with LA breakfast culture—teams of young people and foodies lining up early for its signature dish “The Slut”, a coddled egg over potato in a toasted brioche bun. Its presence has helped redefine Grand Central Market from a century-old food hall into a culinary destination celebrated both locally and internationally.

Eggslut’s stall became synonymous with LA breakfast culture—teams of young people and foodies lining up early for its signature dish “The Slut”, a coddled egg over potato in a toasted brioche bun. Its presence has helped redefine Grand Central Market from a century-old food hall into a culinary destination celebrated both locally and internationally.

A salad refreshes and cleanses, offering a bright contrast before heavier dishes. This hall’s pearlescent fish-bladder wall and marble bar serve as the palate-cleanser, their cool tones and airy light cutting through the richness of the preceding room.

White framed wall wrapped in inflated fsih-bladder sheathing, glazed in pearlescent and red veins, cured in diffused sunlight.

Preserved Beaux-art style cooked prismic skylight, infused with daylight, served in parralel bays.

Bar bench topped with ivory marble, garnished with gold-tinted ornamentation.

French-style bar stools, baked with gold-lattice cast in open filigree.

The pitched skylight in equildistanced bays slices through Grand Central Market’s ceiling, letting in natural light along the market’s spine. It frames the linearity from above while spotlighting textures below, balancing industrial rigidity with ephemeral moments of warmth and illumination.

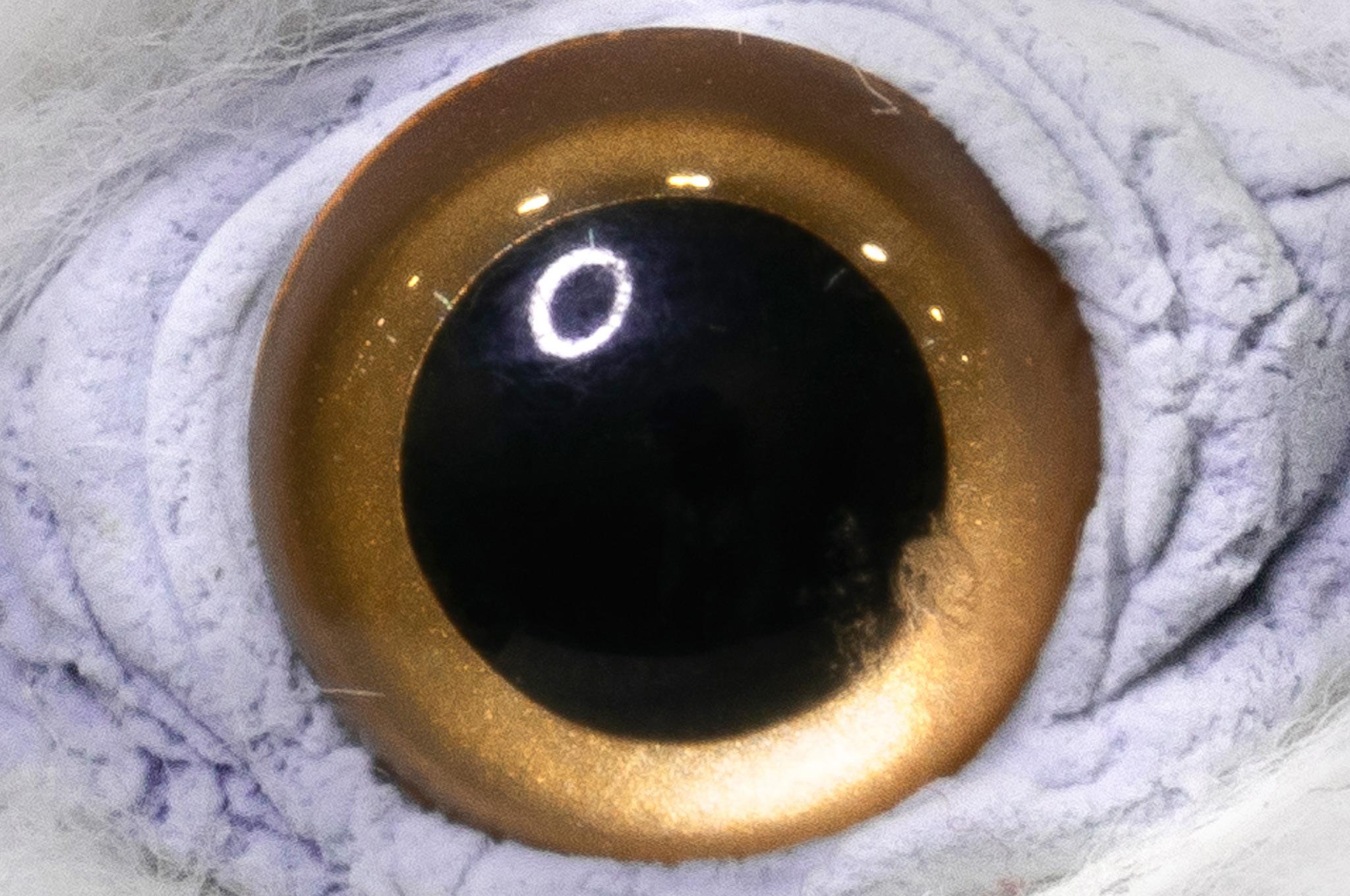

Soup warms and comforts, enveloping the diner in a focused, singular flavor. Within these fur-lined walls, solitary counters invite quiet consumption, making the act of dining an intimate ritual. Individualized deli counters reminds the quiet sipping of thick broth in a high-end diner.

Individual deli counters, finished in stainless steel, poahed to a brushed finish, each served with a recessed service tray at centre.

Long-pile freshhly-plugged chicken feather in tawny and cream, basted and stitched into vertical seams, lining the enclosure in a continuous coat.

Relocated aged clock framed in metal, suspended above center aisle, flanked with original exposed piping for garnish.

GOÛT

A strong datum line anchors Grand Central Market’s linear form, guiding movement and sightlines. Alongside it, fuzzy edges—neon signs, eclectic stall fronts—rupture the order, layering a vibrant, chaotic rhythm that animates the space with playful dissonance.

The main course satisfies — the centerpiece of the meal, rich and complete. Here, golden-trimmed stalls and overflowing vitrines create a theatrical abundance, the room itself plated as the feast.

Market stalls in golden trim, roasted to a warm sheen, glazed with polished metal edge-banding, served in an unbroken row.

Industrial fans and signage cooked in the manner of suspended rotisserie, drawing perspective lines down the market’s spine.

Glass vitrines filled with hybrid crustacean cuts, plated on carved trays, interspersed with fur-trimmed presentation platters.

Chandeliers, dressed with cut-glass pendants, drizzled with warm brass light across the length of the hall.

Dessert closes the meal with delight and softness. Beneath its glowing membrane dome, this room’s cushioned floor and womb-like drapery reminds innocence and kinship with the 'living', acting a gentle reminder before departure.

Pouch draped in fat infused skin, tied back with gold tassels revealing entrance of chamber.

Ceiling crowned with yellow translucent membrane, poached under bakclight, stretched to a shallow dome.

Interspersed cushions, cured in pale-peach soft fluff

ζ Beanbags, blanched in smooth membrane and filled with warm fluid. ζ

Old Grand Central Market's red-carpeted stair, flambéed in situ, leading to a raised platform dressed in matching fatlined drapery.

The iconic red carpeted stairs are aligned to the center of Grand Central Market’s plan, marking the height difference of the two ends - Hill Street and the Grand, hence the slopy topography of where it sits, the Bunker Hill. Brass ornated handrails indicates its Beaux Art style.

Yi Cheung Founder, Executive Director, Chief Curator

My sincere gratitude to all the beautiful souls that support the project and wish it success.

“Hollow Bone, Tender Flesh”

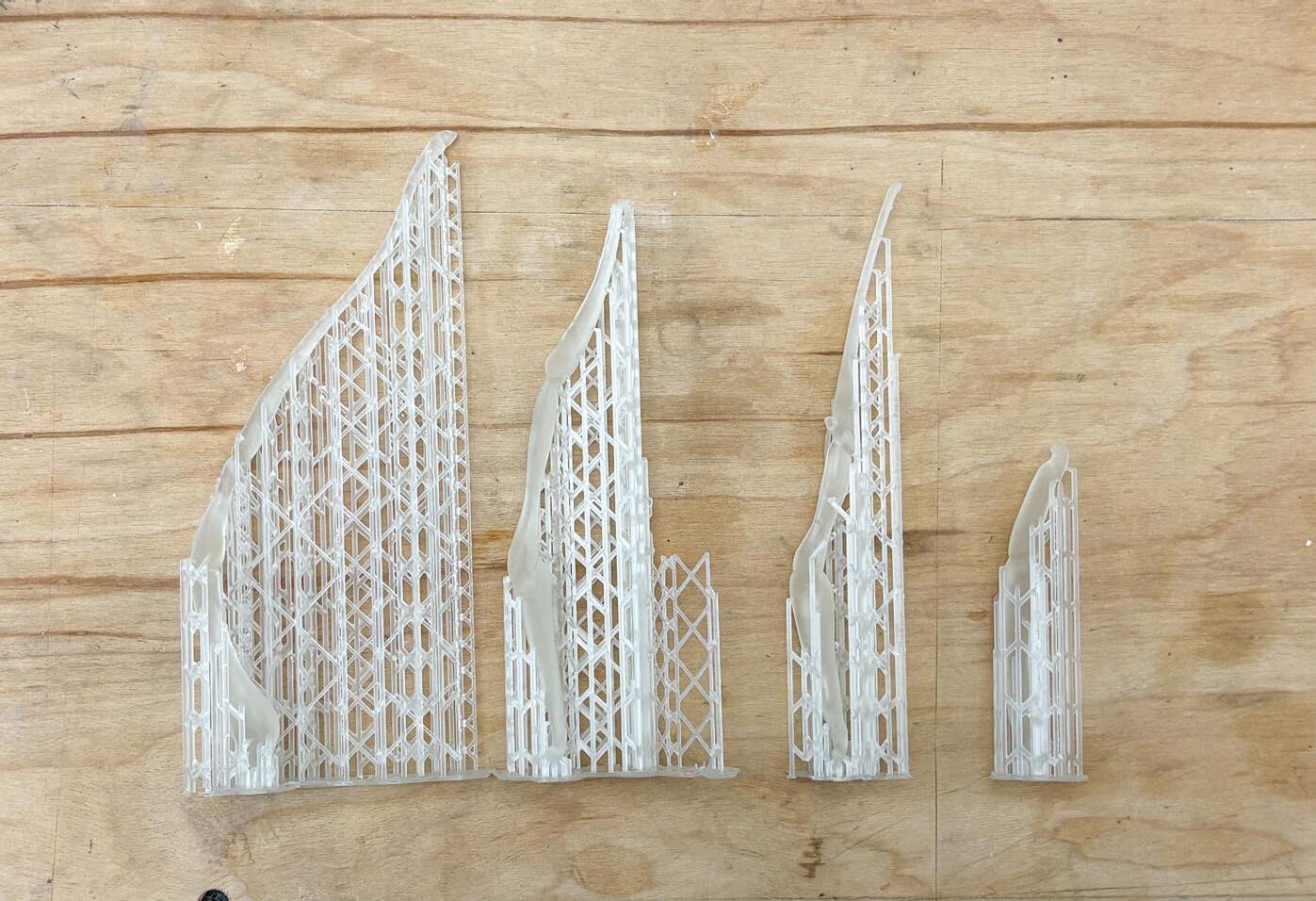

4 x

8 x 1 x

2 x 2x

low density insulation foam

4lbs, 32’x17’

Polyacid Filament, Matte White

Medium-density fibreboard 11’x10’ irregular

10A Silicone

16lbs DragonSkin Fast Curing

35A Silicone 2lbs EcoFlex

Silicone Dye

5 colors: white, peach, burgundy, umber, yellow

conduit box

electric pipe socket

light switch

Spray Paint gold

Sand Puddy

NOTE: WEAR GLOVES BEFORE COOKING, SOME INGREDIENTS ARE CORROSIVE

1. Collect anatomical references of both animal and human skeletal forms. Focus on spinal cavities, marrow voids, and fracture patterns.

2. 3D Sculpting in ZBrush, start with overall bone structure, then adding detailed textures.

3. Export and process mesh for CNC milling. Simulate toolpaths and adjust topology as needed.

4. Calibrate bit choice depending on detail regions. 1” bit for rough mill, 1/2” bit for second pass.

5. Send to CNC router. Wait with patience. Milling duration: 7 days.

6. Retrieve milled foam. Remove tabs and off-cuts with multi-tool.

7. Rework foarm and add resolution using Dremel rotary tool and chisel.

NOTE: DOWNLOAD EXISTING BRUSH FROM ART STATION DO NOT ATTEMPT 1/4” BIT, DURATION LENGTHENS DISTINCTIVELY

1. Prepare the glaze by mixing a generous layer of spackle—this will act as the bone’s outer rind.

2. Spread the coating across the foam using a spatula, as one would ice a cake, pressing gently into the pores.

3. Whip texture into the surface with a damp sponge, creating grain, pull, and ripple to mimic fossil striations.

4. Rest at room temperature until the surface sets to the touch (approx. 1 hour).

NOTE:

AVOID LIQUITEX MODELLING PASTE. DESPITE SILKY SMOOTH TEXTURE, APPLYING AND SANDING IS EXTREMELY TRICKY. PRIORITIZE DAX ALL PURPOSE SPACKLING PASTE.

1. Align the slabs and apply Gorilla glue generously along the seams, like binding the edges of a roulade.

2. Insert steel pins into the foam structure to hold weight-bearing joints.

3. Clamp structure firmly with wood clamps.

4. Let cure for 4 hours, tightening incrementally every 30 minutes to ensure compression and adhesion.

NOTE:

ADDITIONAL STRUCTURAL SUSPPORT WITH MDF. ALLOW FOR FUTURE HANGING PURPOSE.

1. Pipe putty into all seams and imperfections.

2. Sand with gradually increasing grit. (80 > 150 > 400)

3. Spray on intial primer coat. ensuring even coverage and slight absorption.

1. Prepare the aging glaze by mixing acrylic pigments (burnt umber, raw umber and unbleached titanium in 0.5:1:10 ratio)

2. Add water gradually to the mixture to achieve a silky, cream-like consistency.

3. Using a dampened sponge, apply a thick base coat of the mixture with gentle dabbing motions

4. Once the surface is set but not dry, begin layering translucent washes of burnt umber and raw umber. Dilute heavily with water for each layer. Apply using a sponge, then immediately blot with a dry kitchen towel in irregular swipes. This stains the reliefs and wipes the flats—mimicking the uneven aging of ancient bone or oxidized gold foil.

5. Repeat the wash-and-wipe process 2–3 times, letting partial drying occur between each layer. The result should resemble an object touched by time, with pigment settled in cracks and edges slightly smudged by imagined hands.

1. Brush liquid latex generously over areas meant to remain untouched—this masking acts like marbling fat preserved in a dry-aged cut. Allow to dry until tacky.

2. Dust the entire surface with a matte black undercoat. This burnt layer of crust enhances depth, mimicking oxidized crevices in aged bronze or charred bones.

3. Layer the metallic glossy gold spray, keep distance.

4. Once dry, peel off the latex mask to reveal bone.

1. Prepare two glazes in separate bowls: - Matte Medium – for powdered, bone-dry finish - Glossy Medium – for softened light reflection and skin-like tack

2. Using a fine round brush or fingertip sponge, apply the matte medium selectively over regions intended to appear calcified, powdered, or sun-bleached. Avoid pooling.

3. On smoother planes or fleshy protrusions, dab on the glossy medium to imitate subcutaneous oil. Let irregularities remain — the contrast mimics skin under tension.

4. In areas where slime or mucus is suggested (e.g. folds, ruptures, meat-fat junctures), pour a thin coat of epoxy resin. Let it settle naturally into crevices.

5. Tip the piece slightly to allow epoxy to pool unevenly, then lay flat. Allow to self-level and cure undisturbed for at least 24 hours.

This step is the key to a successful ‘Os Creusé, Chair Tendre’. It embodies the spontaneousness and experimental, yet highly clincal and precise impression.

NOTE: SILICONE PICKS UP THE SMALLEST DETAIL OF THE MOULD. APPLYING EPOXY TO MOULD RESULTS IN GLOSSY FINISH IN COOKED SILICONE.

“It requires spontaneity and experimentality, yet a high level of control and precision.”

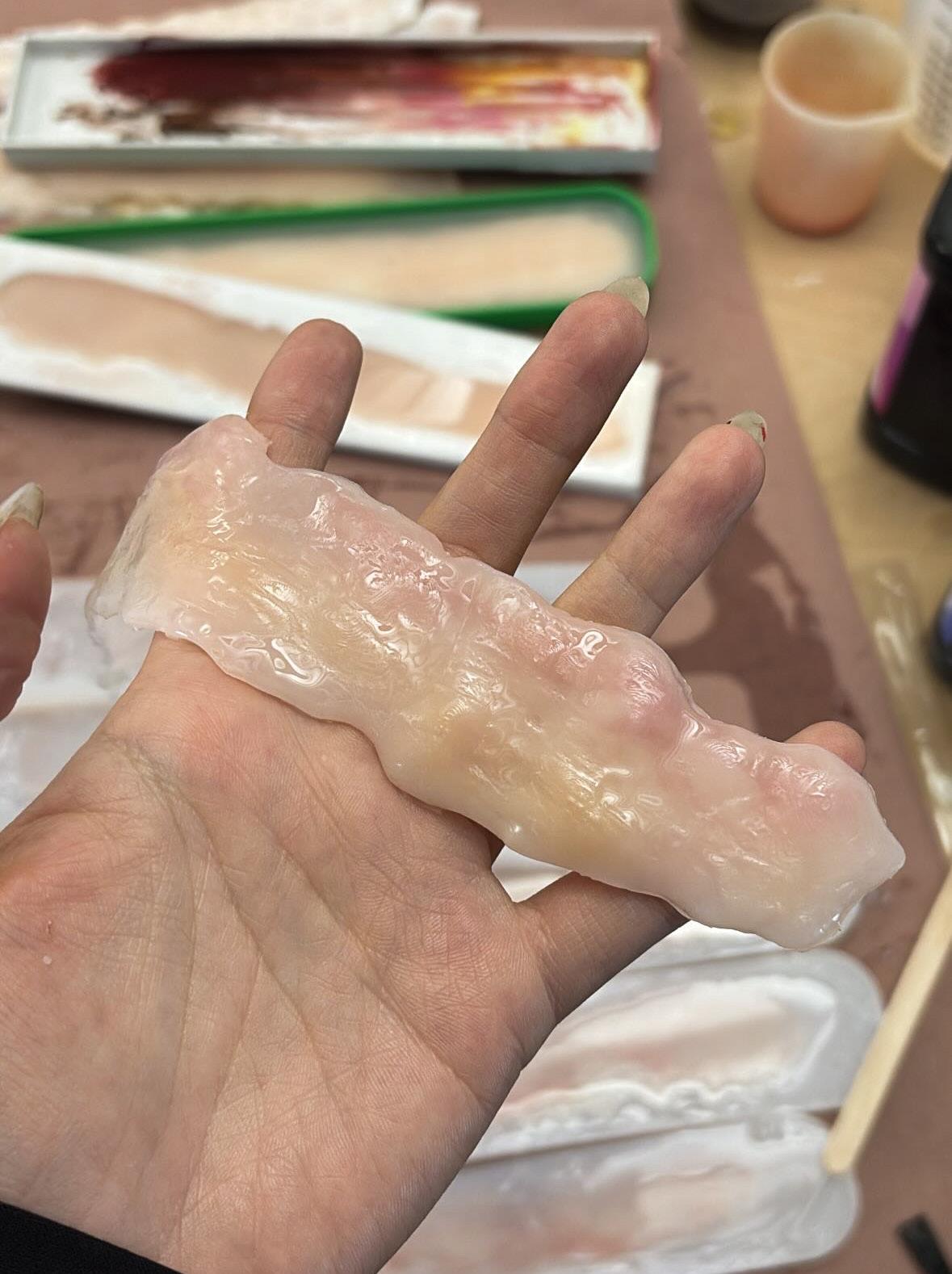

Flesh making shares uncanny kinship with the Japanese craft of sampuru—hyperrealistic fake food models displayed in restaurant windows. Both practices blur the line between life and imitation, demanding a strange mix of experimentation and rigor. In sampuru making, an artist might flick droplets of colored wax into water to mimic tempura batter mid-fry, capturing a moment in motion. Similarly, in flesh casting, the artist must pour, brush, or inject silicone to simulate the translucency of skin, fat, or viscera—working against time before the material sets.

NOTE: PLAT-CAT. PLATINUM CATYLISER FOR SHORTENING CURING TIME. THI-VEX. AN ADDITIVE THICKENER.

5% Patinum Catalyser + 18 min.

2% Patinum Catalyser + 7 min.

This technique is essential to massaging realistic flesh. Adding thickness and control of cure time allows specific palettes to fall onto and seeps in desired areas. For example, muscle tenders, capillary-abundant areas, fatty tissue.

In both practices, the artist must choreograph imperfection: a misplaced pore, a hint of capillary, a glisten of fat. These details are not accidents but mastery lies in knowing how to control those accidents. The silicone artist, like the sampuru craftsman, choreographs imperfections: a vein here, a speckled bruise there, a subtle shine of gloss to evoke sweat or blood. Both crafts demand precise timing, steady hands, and a forensic eye for detail.

What emerges is something simultaneously appetizing and off-putting, familiar and strange. This tension—between control and chaos, between illusion and embodiment—is what makes silicone flesh casting not just a technique, but a craft that breathes uncanny life into inert matter.

NOTE: ONE AT A TIME. DO NOT RUSH. CHEMICAL REACTION HAPPENS IN UNPREDICTABLE MANNERS DEPENDING ON VARIOUS FACTORS. GREAT CARE IS REQUIRED FOR EACH BATCH.

1. Prepare flesh base (silicone) by mixing part A and part B silicone in exactly the same portions. Use electrical weight to ensure precision.

2. Take a moment to observe with reference: what color goes on the most surface level? How will mixture react to gravity after pouring in mould?

3. After drafting a color-making sequence, only make one color tone at a time. Estimate the amount needed for each color.

4. Adding silicone pigments small drops at a time, after mixture starts appearing to be blended with color, add more if needed.

5. Using stainless steel scapals or fingertip, apply the mixture in desired cavities.

6. Cure time depend on amount of catylse added.

NOTE: SPRAY ON MOULD RELEASE BEFORE CASTING.

VASELINE IS LESS PREFERRED DUE TO ITS TEXTURED NATURE THAT SILICONE WILL CATCH.

NOTE: TEST FAILURE. (D-55) ECOFLEX REACTS ABSORBS PIGMENTS WAY SLOWER THAN DRAGONSKIN, RESULTED IN ADDING EXCESSIVE AMOUNT OF PIGMENT.

Just like in culinary arts where each ingredient demands its own preparation—slow braise for tendon, quick sear for liver—silicone casting requires a deep understanding of how different materials behave before entering production. Not all silicone is the same. Some are firmer, others impossibly soft; each serves a different purpose when mimicking skin, fat, or flesh.

Researching material properties is not optional—it is foundational. Silicone is typically categorized by its Shore hardness scale, with 15A being the most commonly used in special effects and prop-making. But when the goal is to imitate tender tissue or sagging skin, softer variants— sometimes even negative Shore values—are required. These softer silicones behave differently in mixing, curing, and tinting, and must be chosen deliberately.

Trial and error in small test batches is essential. Matching the right silicone softness to the specific anatomical area being imitated allows for a more believable tactile experience. A cheek might need a soft bounce; a cartilage detail, firmer definition. Choosing the wrong grade compromises the illusion and wastes costly material.

In this craft, experimentation is like recipe testing—precise, iterative, and rooted in understanding. Only through this process can one cook up flesh that truly lives.

Just like in culinary arts where each ingredient demands its own preparation—slow braise for tendon, quick sear for liver—silicone casting requires a deep understanding of how different materials behave before entering production. Not all silicone is the same. Some are firmer, others impossibly soft; each serves a different purpose when mimicking skin, fat, or flesh.

Researching material properties is not optional—it is foundational. Silicone is typically categorized by its Shore hardness scale, with 15A being the most commonly used in special effects and prop-making. But when the goal is to imitate tender tissue or sagging skin, softer variants— sometimes even negative Shore values—are required. These softer silicones behave differently in mixing, curing, and

tinting, and must be chosen deliberately.

Trial and error in small test batches is essential. Matching the right silicone softness to the specific anatomical area being imitated allows for a more believable tactile experience. A cheek might need a soft bounce; a cartilage detail, firmer definition. Choosing the wrong grade compromises the illusion and wastes costly material.

In this craft, experimentation is like recipe testing—precise, iterative, and rooted in understanding. Only through this process can one cook up flesh that truly lives.

“Every experiment with a new material entails unfathomable joy.”

There is a peculiar delight in the first contact with an unfamiliar substance—the way it reacts, resists, or yields. Whether it oozes like syrup or snaps like brittle sugar, each material holds secrets waiting to be unlocked through touch and time. The moment silicone overflows, or a mold peels back to reveal a perfect imprint, feels like witnessing alchemy.

This might be where the magic meets the technic, perhaps?

1. Prepare the cured silicone flesh It should resist slightly under pressure, and non-sticky.

2. Mark incision lines with non-erasable marker to avoid unwanting smerring.

3. Using a scalpel, insert the bladde into sublater, letting it glide with resistance of tendon.

NOTE: SILICONE CATCHES DUST EASILY. ALWAYS COVER WITH PVC SHEETS TO PRESERVE SURFACE SHININESS. HOLLOW BONE, TENDER FLESH

“When the chicken becomes a meal, it is of course dead. Yet when it is still in the form of its raw material, it somehow feels alive.”

“When she starts climbing up and down ladders we know it’s gonna be good.”

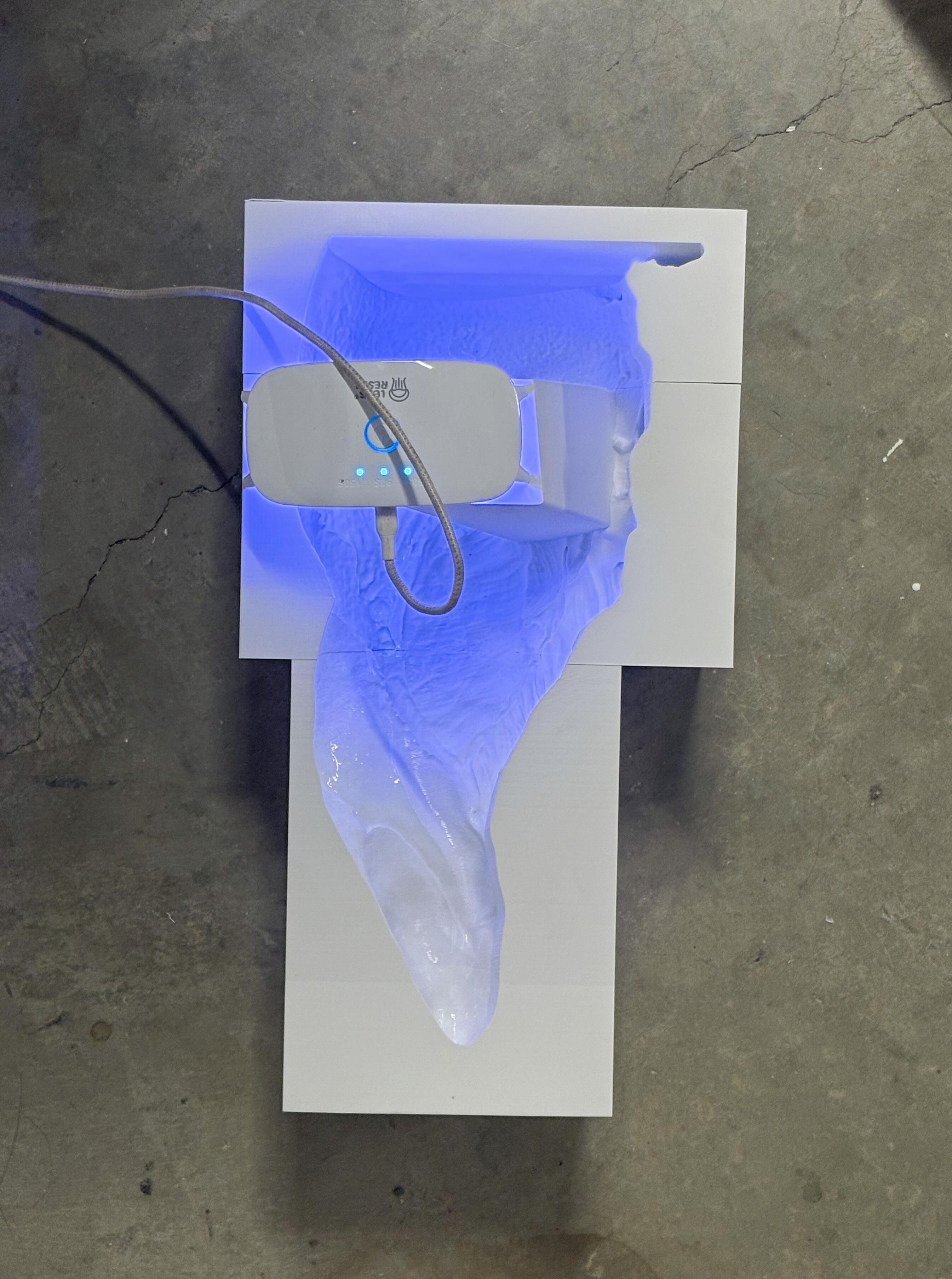

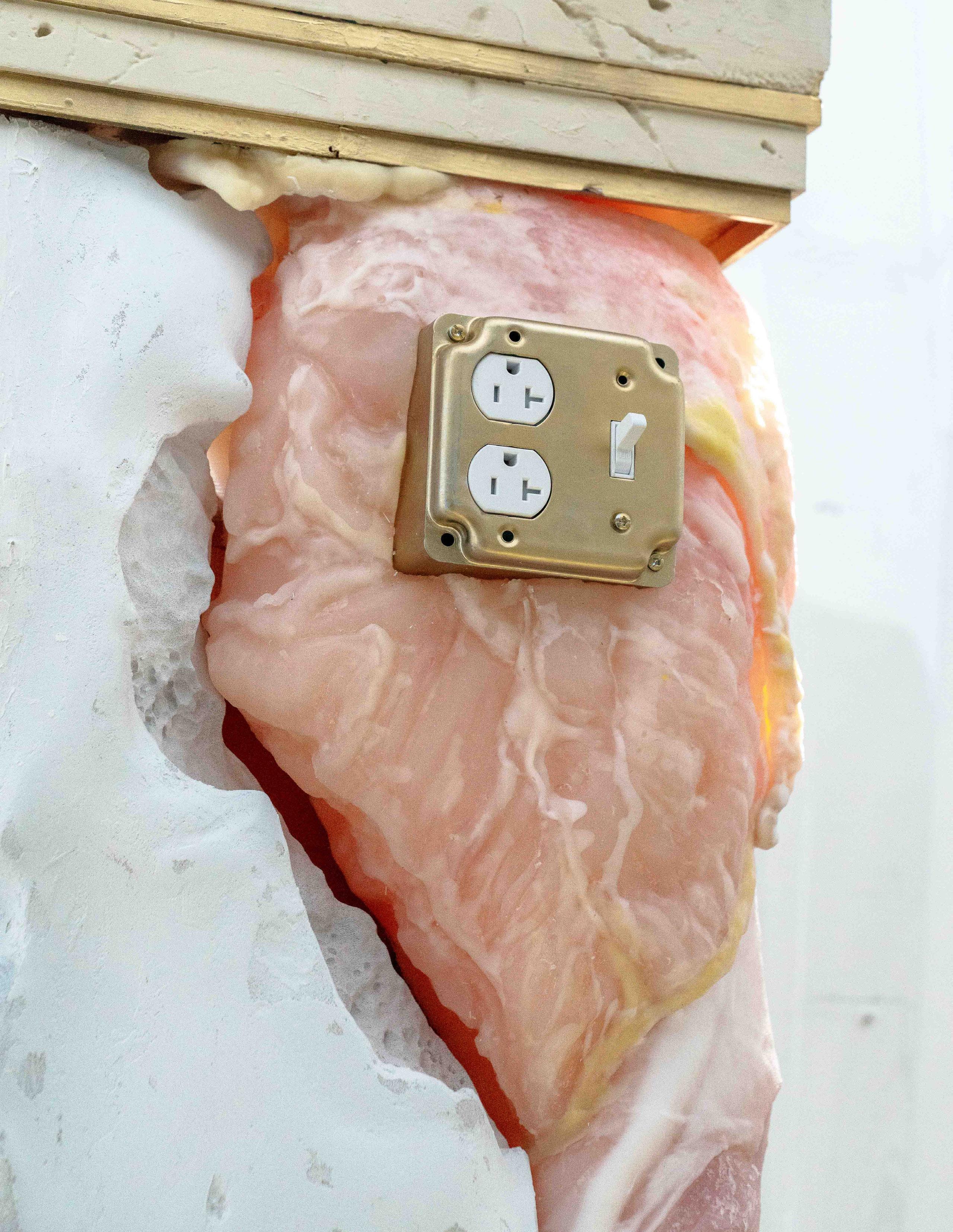

This sculptural column hovers between classical architecture and bodily absurdity, grafting visceral silicone flesh into the ruptured cavity of a neoclassical pedestal. Where there should be structure, there is sag; instead of stone solidity, we encounter fatty translucency, muscle-toned blushes, and the gleam of sweat-like gloss. A golden electrical socket is embedded in the flesh, as if flesh itself were infrastructural, wired into our systems of use and function.

The piece entangles enchantment and discomfort in equal measure. The glossy folds and seductive materiality lure us in with the promise of tactile pleasure—yet what we see is raw and too real. It simulates something edible, or maybe surgical. It is familiar—like supermarket meat, like our own bodies—and yet estranged, hybridized with architecture and utility. The socket, absurdly placed, renders the body not sacred but plugged-in, expendable, domestic.

This is not merely a critique of aesthetic norms or bodily taboos; it’s an encounter with reality entangled. The column refuses to resolve into metaphor. It is a thing—too real to ignore—yet too odd to assimilate. It triggers a mimetic response, activating our sensorium to fill in temperature, softness, even smell. In doing so, it reveals the slippage between object and subject, flesh and façade.

Meat Column invites us to dwell in that slippage—not to decode it, but to feel it. It proposes that enchantment arises not from fantasy, but from the strange familiarity of altered realities. This is enchantment with stakes: one rooted in texture, affect, and the uncanny proximity between our built environments and our mortal forms.

This is not merely a critique of aesthetic norms or bodily taboos; it’s an encounter with reality entangled. The column refuses to resolve into metaphor. It is a thing—too real to ignore—yet too odd to assimilate. It triggers a mimetic response, activating our sensorium to fill in temperature, softness, even smell. In doing so, it reveals the slippage between object and subject, flesh and façade.

“Where bone collapses, tenderness begins. Where banality of existing realities are pierced through, enchantment seeps in.”

7 yards

2 x

2 x 2 x 2x 1x

Clear vinyl sheet (in roll)

6 mil

Cornstarch 36oz

Birch plywood sheet 1/4”

10A Silicone 16lbs DragonSkin Fast Curing

35A Silicone 2lbs EcoFlex

Epoxy Resin (slow cure) 16oz

NOTE: ENSURE DISPOSAL SOLUTION BEFORE MAKING. EGG WHITE ROTS WITHIN 7 DAYS.

Muslin (test fabric)

3M Scotch double-sided water sealant tape

Polyacid Filament

Silicone Dye

Colors: flesh pink, ivory white, vein blue, deep red, fat yellow

Air gun with 2” nails

Water-soluble pigment

Colors: white, amber

When a chicken becomes a meal, it is of course dead. Yet when the meal is still in the form of its raw material—the chicken meat, for example—it somehow still feels alive. This lingering sense of life seems to persist in the aesthetic qualities of rawness itself: the primal and visceral materiality that resists full abstraction.

1. 3D Print a mock up scale of bean bag finish form. 1:8 is used here.

2. Tape masking tape around the print. Be sure to lelt it cling to all contours.

3. Once fully laminated, draw around tentaive seams.

4. Using an exacto knife, slice the mask and peel out the pattern.

5. Repeat above steps until a pattern that yields desired seams and forms is produced.

NOTE: WEAR GLOVES BEFORE COOKING

4. Using an exacto knife, slice the mask and peel out the pattern.

5. Repeat above steps until a pattern that yields desired seams and forms is produced.

6. Lay pattern flat. If bumps apears, darts could be useful. Cut slits to flatten bumps.

7. Identify joinery seams on different pattern. Make sure they are of the same length.

8. Scale to larger size. Test sewing on fabrics.

1. Select your PVC sheeting based on flexibility. Test several mils (e.g. 4mil, 6mil, 10mil) to assess stiffness and form memory. The ideal sheet should fold with tension yet drape with weight — not too rigid, not too slack.

2. Divide each seam edge into equal-length notches — these are your markers for alignment. Every segment must have a twin on its adjoining piece.

3. Line each seam with 3M Scotch doublesided water-sealant tape.

4. Carefully press two seams together, marker by marker, gently stretching the curve where needed.

5. Avoid using a sewing machine — it create micro-holes.

NOTE: 3M WATER SEALANT TAPE IS PRESSURE-SENSITIVE AND ALLOWS MICRO-FLEXIBILITY, ENSURING PVC CONFORM AND SEAL WITHOUT AIR BUBBLES OR GAPS.

RESULTS

TEST 1: Stitch only

did not leak

NOTE: GLUE REQUIRE CLAMPING TO AID DRYING. RELEASING CLAMP MAY TEAR PVC RESULTING IN LEAK HOLES.

The idea of breaking down the old to make way for the new is very important in creative discipline. Only when parts of the old is let go of then could the new bleeds in. This concept is embodied in the curation of the Museum project of Grand Central Market as well as through out the making of its exhibit artifacts, or, the dishes.

1. Prepare clean water in a sterilized mixing vessel.

2. Calculate the required cornstarch by weight.

3. Begin by adding water gradually to the cornstarch. Stir slowly with a whisky to avoid air bubbles.

4. Introduce water-soluble pigments drop by drop. Aim for cloudy transclucency like protein clogs.

5. Set mixture aside for 10 minutes for final consistency.

NOTE: ALWAYS ADD WATER TO CONSTARCH, NEVER REVERSE. POURING CORNSTARCH INTO WATER WILL CAUSE INSTANT CLUMPING.

NOTE: TOUCH AND FEEL. RESULT SHOULD RESEMBLE SOFT-SET VISCOSITY, NOT GELATION. THE IDEAL TEXTURE IS SLIGHTLY RUNNY, WITH SUSPENDED WEIGHT.

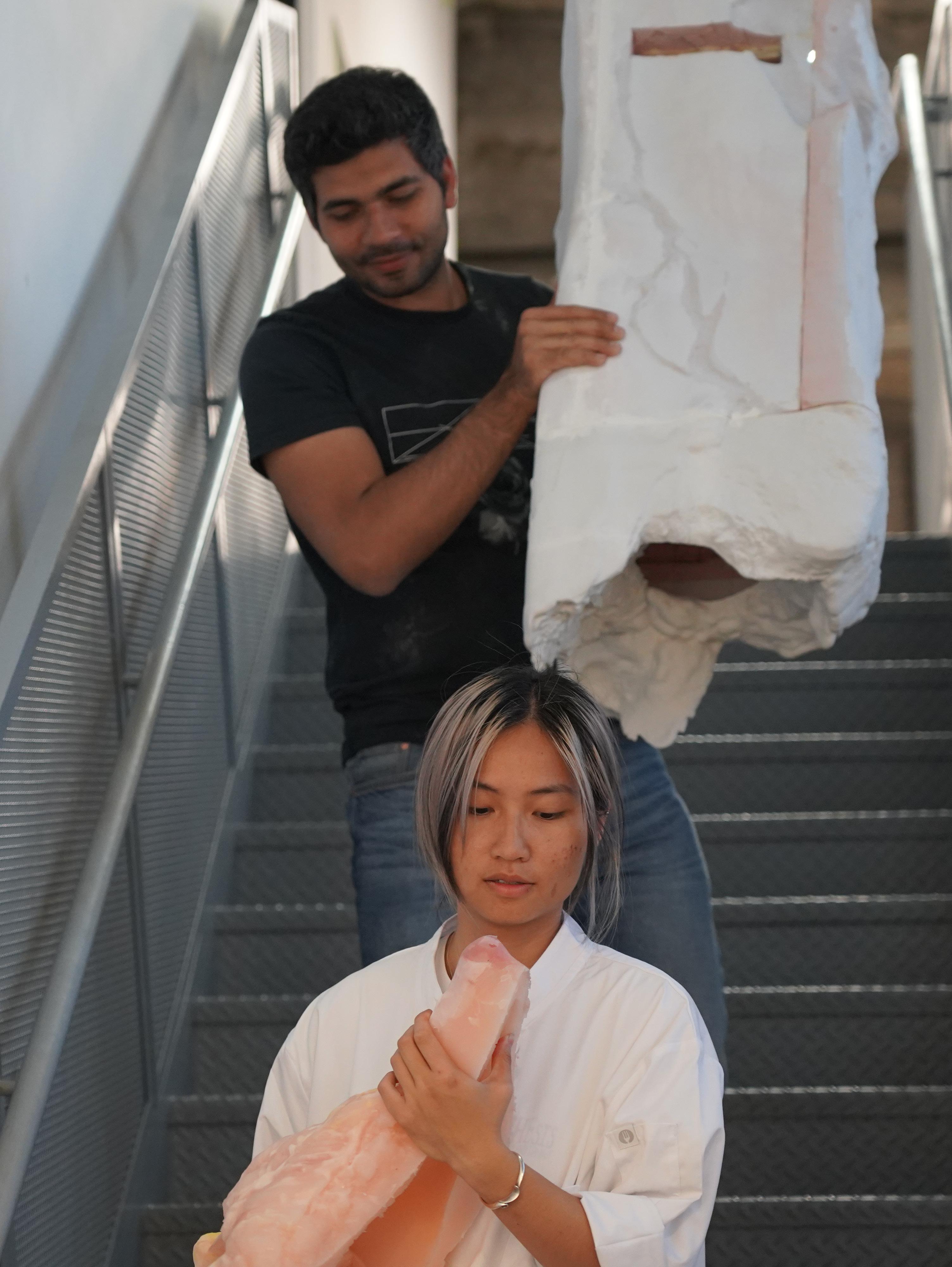

Success of a large-scale project is never accomplished by one person. Handling the 1:1 beanbag—spanning full scale and weighing 35 gallons—required synchronized teamwork, careful choreography, and collective strength to lift, maneuver, ensuring its final form.

Making of the 1:1 beanbag was a full-body endeavor. At 35 gallons, its weight and scale exceeded what one person could handle. Every step—stuffing, flipping, sealing—became a collaborative act, turning labor into choreography and making into shared authorship.

The making is always the most exciting and enjoyable. Dealing with different forms of meat that unevitably require close observation allows one to discover more about the beauty of beings.

1. While the mold rests, prepare the silicone mixture as described in “Silicone Base Preparation” (see page 185).

2. Note that mixture consistency here must be looser and more fluid to allow for marbling technique and striation.

3. Begin the pour by layering large patches of the tinted silicone mixture in flesh tones.

4. Build a marbled palette by alternating with white and ivory swirls, imitating fatty tissue and muscle grain.

5. Use a spatula or wooden skewer to lightly drag through layers.

6. Do not overmix.

7. Allow to cure for at least 6 hours before attempting removal. Gently peel the ham slab from the mold.

NOTE: PREPARE EXTRA MIXTURE, THIN SHEET ON BIG SURFACE AREA WORKS ARE HARD TO ESTIMATE. THIS IS REQUIRED TO FULLY SUBMERGE AND REVEAL THE EMBOSSED LETTERING ONCE DEMOLDED.

1. Begin by constructing a mold using linear plywood pieces. Cut all sides to size with a table saw, leaving the top face open.

2. Assemble the mold into a box using an air gun to tack the pieces together.

3. Mount the box onto a flat baseboard. Apply downward pressure while sealing all bottom edges — this will prevent silicone leakage during the pour.

4. Glaze the inner walls of the mold with a thin layer of epoxy. Allow to cure fully for 24 hours.

5. Once cured, lay a 3D-printed letterform at the bottom of the mold, mirrored. This create embossed effect on final ham surface.

The making of the ham was another material experimentation. Applying the same logic and methodology as the flesh piece in previous recipe. This time the craft lies in carefully replicating realistic section cut of meat. The interplay of muscle tissues and fatty tissue in between.

The beanbag project began as an exploration of soft form and bodily tactility—an object meant to evoke fleshiness, comfort, and surrender. Constructed from stitched PVC skins, it was filled with a viscous liquid intended to give weight and fluid adaptability. However, the material reality of the object quickly unraveled the initial concept.

One of the first challenges was weight. Though visually soft and pliable, the liquid interior added an unexpected heaviness, making the piece difficult to handle, transport, or shape. What was imagined as a yielding surface became physically burdensome. Structural integrity was compromised as the weight placed pressure on seams and stitching.

Shortly after completion, leaks began to appear. Despite multiple attempts at sealing, the liquid continued to find escape routes, oozing through minute gaps and weakening the latex over time. The beanbag became sticky, unstable, and ultimately began to rot. The interior mixture reacted with air, producing an unpleasant odor and visual decomposition.

Despite these failures, the process offered valuable insight. The collapsing, leaking, and decaying object unexpectedly echoed the very qualities it sought to simulate—fragility, impermanence, and corporeal unpredictability. In this sense, the flaws were instructive, revealing the tension between design intention and material agency. The experiment became less about perfection and more about embracing instability.

Waiting,

and

with Defects and

is also a careful design act

NOTE: ALWAYS ADD WATER TO CONSTARCH, NEVER REVERSE. POURING CORNSTARCH INTO WATER WILL CAUSE INSTANT CLUMPING.

“Sometimes it takes so much precision that I thought I’m about to get sick of it but I never did.”

NOTE: THE CONSISTENCY HERE MUST BE LOOSER AND MORE FLUID. TO ALLOW FOR CLEAN MARBLING AND STRIATION.

Out of the many joyous moments, none surpass the magic of releasing fresh fat from the mold. Still warm from chemical reaction, its glossy surface glistens; edges soften, tender like flesh meeting air for the first time.

This is surely a high resolution version of the flesh in Os Creusé, Chair Tendre . The clear distinction of fat and flesh is achieved by seperation of mesh while sculpting of 3D model, taking account of its function as a mold. Red and purple veins are prepared by damping with silicone mixture to create branching quality.

This melting slab—a translucent silicone sheet dyed in meat tones and imprinted with the institutional title Museum of Grand Central Market—is draped over a a bulging yellow liquid sac anchored by a common A-framed menu signage, often found on the streets in front of delis. Its surface recalls raw meat or supermarket packaging, yet its posture suggests signage, authority, or display. The result is absurd and unsettling: a museum label that refuses to stand straight, sliding off its own pedestal, leaking, sagging, and pooling onto the floor.

The work operates through a deliberate estrangement of materials. The glossiness of silicone mimics organic fluids; the marbled pinks and yellows suggest fat, sweat, and skin. But these visceral references are not dramatized—they are banal, almost clinical, like the cut meats of everyday consumption. Much like Meret Oppenheim’s Object—the fur-lined teacup that turned utility into something feral—this piece destabilizes our habitual reading of function. A museum label becomes a body. A plastic sac becomes an organ. Furniture becomes flesh.

There is no clear metaphor here, only friction. The tension arises from material behavior: the strain of weight against structure, of liquid against skin, of surface against legibility. What once signified order—the museum, the market, the label—is reduced to a leaking, collapsing form.

By extracting textures and forms from daily life and reassigning their material logic, the piece achieves a subtle estrangement. It does not scream; it sags. In this soft collapse, absurdity emerges— not as comedy, but as quiet resistance to the clean, fixed boundaries of design, display, and reality. This is not a museum artifact. It is an anti-monument: perishable, ambiguous, and wet.

There is no clear metaphor here, only friction. The tension arises from material behavior: the strain of weight against structure, of liquid against skin, of surface against legibility. What once signified order—the museum, the market, the label—is reduced to a leaking, collapsing form.

By extracting textures and forms from daily life and reassigning their material logic, the piece achieves a subtle estrangement. It does not scream; it sags. In this soft collapse, absurdity emerges—not as comedy, but as quiet resistance to the clean, fixed boundaries of design, display, and reality. This is not a museum artifact. It is an anti-monument: perishable, ambiguous, and wet.

“An institution label that refuses to stand straight, sliding off its own pedestal, leaking, sagging, and pooling onto the floor.”

“Parrot-Lobster-Crab”

7 yards

8 x 1 x 2 x 2x

clear vinyl sheet (in roll)

6 mil

Polyacid Filament, Matte White

Medium-density fibreboard 11’x10’ irregular

10A Silicone 16lbs DragonSkin Fast Curing

35A Silicone 2lbs EcoFlex

NOTE: WEAR GLOVES BEFORE COOKING

3M Scotch double-sided water sealant tape

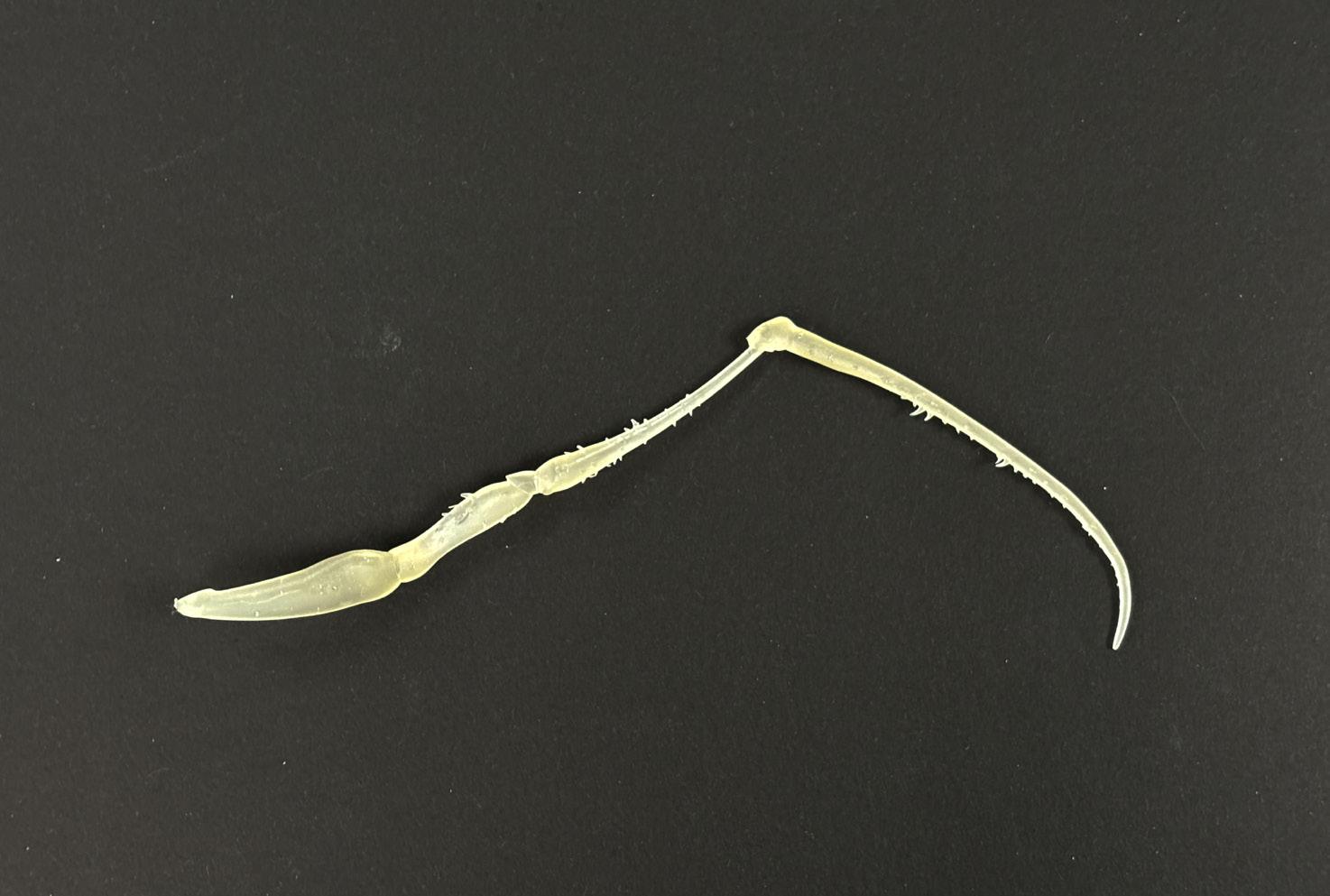

Foraging our ingredients from the local stalls on Maple Street. We make sure our parrot feather comes in fresh. —still tousled by wind, not box. Lumpy defects are discarded into the chicken farm in our studio backyard as a part of the hatching station. Shell segments are inspected for textural rigidity and hue. Only those with translucence, marrow-soft pinks, and exoskeleton tension are selected for binding and grafting.

1. Retrieve the resin-printed legs from curing chamber. Let rest at room temperature for 30 minutes until surface hardens to a crisp shell.

2. Remove all supports carefully with clippers. Trim flush at the joint to maintain surface continuity.

3. Apply a uniform layer of white base primer over all surfaces to allow airbrush pigment to stay.

4. With an airbrush, apply successive light coats of pigment. Begin with the palest tone and gradually layer darker shades.

5. Garnish with teased wool fibers, adhere with modelling paste. Apply with spatula. Press gently to embed.

Physical fabrication process undergo multiple tests to ensure result doies not lose resolution from its virtual form.

Painting begins with close observation: studying tone, hue, saturation, and brightness to match he living creature. precise color mixing to match tone, hue, and brightness—too much saturation breaks the illusion. Each brushstroke is adjusted based on paint consistency: thin layers for translucency, thickened with modeling paste for texture. A toothbrush is used to splatter spots, adding blemishes and lifelike irregularity. Careful observation guides every decision, balancing accuracy with expressive surface treatment. The process is slow, deliberate, and always responsive to the form beneath— ensuring the creature feels both constructed and alive.

The bacon was the dish where silicone casting was first employed. Due to its small hand-held scale, coming off flimsy and malleable, it was the most fun speciment out of other flesh dishes. It’s making technique was comparatively the most intuitive and, of course “raw”.

We keep our silicone residue samples archived in the display drawer of the test lab. You’d be surprised— despite referencing the same image, each batch yields drastically different hues. Slight shifts in pigment ratio, curing time, or lighting conditions produce unexpected results. What emerges from these experiments is not what you might call inconsistency, but a vibrant, living palette—a spectrum of fleshy tones born from error, instinct, and iteration. This archive becomes a record of this vibrant process.

A team is very important blaballab 1. Mix creamy filling. Beat the mascarpone, cream, sugar, and vanilla together until stiff peaks.

Being the very first batch to test with silicone casting, our original methodology was negative casting of a silicone mold out of a positive bacon print. Later realising that due to the flexibility of such a small piece, it does not require the mold to be in silicone. Our methodology was refined to a more efficient and direct way, leaving time and care to the silicone brush on process.

TEST BATCH 04. CASTING WITH VACUME FORMED PETG MOLD.

Once cast, the ham flesh is left to rest on a wire rack. Over time, surface moisture evaporates, and subtle crystallization appears along the ridges. What was once glossy begins to dull, gaining realism. Aging is not decay—it is the final conversion from raw to believable.

Final composition demands delicacy. Each appendage is positioned with tweezers, rotated until anatomical tension is achieved. The torso is laid last—slightly tilted for presence. The frame cradles the creature like a reliquary. Serving is visual, not edible; a ritual of arranging the unfamiliar into something nearly natural.

“A crab leg, once armored for survival, now slumps in tangled wool—softness wrapped around something that resists in another life.”

PARROT LOBSTER CRAB

Parrot Lobster Crab is a sculptural dish presented as a specimen—an absurd fusion of familiar animal parts: the flamboyant head of a parrot, the armored tail of a lobster, and the bent, splayed limbs of a crab. Served in a shadow box frame reminiscent of Victorian natural history collections, the dish invites not hunger, but critical reflection. This is not food—it is food theatre. A confrontation. A seduction. A discomfort.

The form is uncanny, built from elements that are easily identified yet wrongly arranged. Each part appears real—plucked, steamed, or boiled— yet together they create a chimera that hovers between meal and memorial. The dish critiques the logic of consumption by pushing it to its grotesque extreme: what happens when food is presented not as nourishment, but as spectacle?

There’s an impact intended here, one that draws from the traditions of abject art and post-natural taxonomy. It asks the diner/viewer to confront the constructedness of nature as it appears on their plate. Just as taxidermy has long reflected human attempts to dominate and aestheticize animals, Parrot Lobster Crab exaggerates that impulse into absurdity. It forces an awareness of how animal parts are isolated, named, and commodified, only to be reassembled in ways that erase their original identity.

The dish is also about enchantment—through texture, gloss, and eerily lifelike detail. It mimics wetness, sinew, softness, and shell, drawing viewers close before revealing the deceit. Silicone, resin, and faux feathers replace flesh. This sensory contradiction—real yet not real—provokes an estranged intimacy. You know the parts, but not the creature.

Ultimately, Parrot Lobster Crab destabilizes the boundaries between food, body, and object. It is not meant to be consumed but considered. It doesn’t aim to disgust, but to disarm. Through its fragile theatricality, it reawakens an ancient instinct: to question what we kill, what we eat, and how we classify life for our pleasure.

“It is not a dish meant to be consumed, but considered.”

But first, Let’s pay

the bills.

A team is very important blaballab 1. Mix creamy filling. Beat the mascarpone, cream, sugar, and vanilla together until stiff peaks.

A team is very important blaballab 1. Mix creamy filling. Beat the mascarpone, cream, sugar, and vanilla together until stiff peaks.

A team is very important blaballab 1. Mix creamy filling. Beat the mascarpone, cream, sugar, and vanilla together until stiff peaks.

A team is very important blaballab 1. Mix creamy filling. Beat the mascarpone, cream, sugar, and vanilla together until stiff peaks.