OA Student Publication

OA Student Publication

Managing Editors

Alexandra Jade Garcia

Jacqueline Canchola-Martinez

Art & Design Leads

Armando Gutierrez

Jessalyn Fong

Jacqueline Canchola-Martinez

OUR CONTRIBUTORS

Angie Chen

Angie (she/they) is a second year student from South Florida (and later the South Bay) studying Environmental Economics & Policy, Society and the Environment, and minoring in Sustainable Business and Policy She is passionate about the role of neoliberalism and capitalism in environmental and social marginalization and degradation She's also passionate about centering marginalized voices in fantasy books!

Krishna Parekh

Krishna (she/they) is a fourth year from LA County studying Environmental Science and History. They are passionate about ecology, conservation, Palestinian liberation, and reading She is currently writing a thesis about habitat restoration and its effects on biodiversity, and a comparative thesis about colonial hunting practices in British India and British East Africa

Sydney Lee

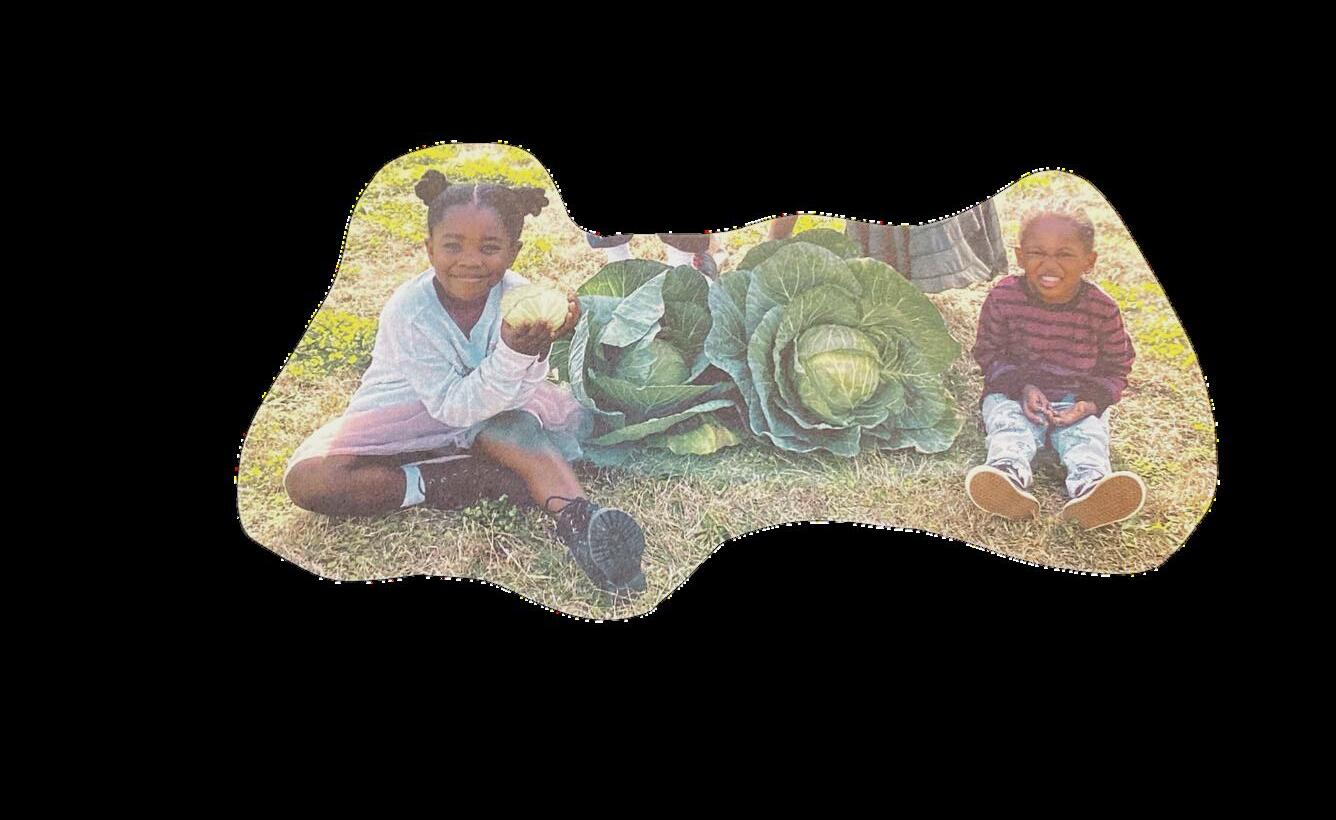

Syd (she/they) is a third year from Los Angeles studying Society and Environment with a minor in City Planning. They are passionate about food systems and agriculture as a way to analyze human health and well-being.

Kavina Peters

Kavina (she/her) is a third year studying Environmental Economics and Policy with a minor in Food Systems She is passionate about decolonizing narratives around agriculture, and is currently working on a project to incentivize regenerative agricultural practices

Zora Uyeda-Hale

Zora Uyeda-Hale (she/her) is a passionate leader, activist, and creative from Albany, California She is a second-year at UC Berkeley, double majoring in Society & Environment and Ethnic Studies. Zora strives to use storytelling, artivism, and culture to spark community-informed change.

Mia Soumbasakis

Mia Soumbasakis (they/them) is a 2nd year Ethnic Studies major, avid bird photographer, and activist with the League of Filipino Students They fight for national democracy in the Philippines, the death of US imperialism, and for land to be returned to their rightful indigenous owners across the globe! Makibaka, Huwag Matakot, Free Palestine!

Jacqueline Canchola-Martinez

Jacqueline Canchola-Martinez (she/her/ella) is a geographer, environmental promotora, reader, and artist from the California San Joaquin Valley Her majors are Conservation & Resource Studies and Geography and she is deeply passionate about the politics of place, social movement studies, decolonial environmental perspectives, and community care.

Alexandra Jade Garcia

Alexandra Jade (she/her) is a fourth year from the Bay Area studying Society & Environment with a minor in Political Economy Her environmentalism is shaped by community organizing efforts, student activism, and feminist frameworks on environmental justice

Jed Lee

Jessica Arenas

Jessica (she/they) is a third year from Chula Vista studying Public Health After undergrad, they plan on becoming a physician and organizing with other medical professionals to provide free healthcare access to under-resourced communities in the San Diego region

Jed Terrence Lee 李家誠 is an activist, artist, and filmmaker of the Chinese Diaspora from the Bay Area in California Jed organizes for the Student Environmental Resource Center at UC Berkeley, their alma mater, as a Wellness and Environmental Justice Community Engagement Manager to continue pursuing environmental, climate, and development justice Jed strongly believes that we can always look to nature to find inspiration for our interpersonal relationships, collective movements, and personal healing, and that there is always love, life and hope in this world. Jed is a proud alumni of SCEC and so proud of the work SCEC carries on through #OE!

Shreya Chaudhuri

Shreya (she/her) is a third year undergrad student from the Bay Area studying Environmental Science & Geography with minors in Data Science and Global Poverty + Practice She is deeply passionate about Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Indigenous sciences around the world She facilitates the DeCal: Decolonizing Environmentalism and runs Project Planet, a non-profit about creating decolonial environmental educational content

Megan Mehta

Megan Mehta (she/her) is a third year undergraduate from the East Bay Area studying Data Science (Applied Math & Modeling Concentration) and Society & Environment (Global Environmental Politics Concentration). She works to utilize data science, machine learning, and policy analysis principles in climate change research to help build a greener future. She is a zealous supporter of decentralized clean energy-based electric grids, and hopes to continue to research sustainable water infrastructure, deforestation, natural resource management, and agroecology.

Jessalyn Fong

Jessalyn (she/her) is a third year from San Diego, California studying Conservation and Resource Studies with a minor in Human Rights. With a concentration in "Environmental Justice Law & Advocacy," she is driven by a passion to explore how policy and law can serve as effective tools for promoting environmental justice and amplifying the voices and experiences of BIPOC communities

In 2017, the Students of Color Environmental Collective (SCEC) at UC Berkeley held a demonstration in Mulford Hall of the College of Natural Resources. Standing in front of photographs of mostly White faculty in the college, students asked, "Where are the Professors of Color?" This demonstration was part of SCEC’s #EnvironmentalismSoWhite campaign, a movement that sought to challenge the racist roots and praxis of the environmental movement and reclaim environmentalism for people of color. Campus environmentalism could no longer freely ignore or suppress our voices and experiences. The #OurEnvironmentalism campaign is rooted in this same radical spirit. Rather than try to fit ourselves into the traditional mold of (White) environmentalism, we are instead redefining what it means to be an advocate for so-called nature, telling our stories, and creating space for ourselves and those students who will come after us.

OurEnvironmentalism is part of this #OE campaign and is a first-ofits-kind publication made by BIPOC environmental students at UC Berkeley. While as undergraduate students we typically spend hours of our semesters writing papers, doing research, and completing academic deliverables for courses, these works typically go unseen after being submitted for grades at the end of the semester. In an effort to uplift our rich academic work, specifically as BIPOC environmental students, we have created this academic journal. Also part magazine and part zine, you’ll find that our approach transcends any easy label and that this first volume is a sweeping one.

Our theme, “all of us: Radically Imagining Past, Present, and Environmental Futures”, is purposefully wide and airy, emphasizing that the

“all” in so many spaces, whether it be environmental history, the environmental movement, or elite academic institutions, has not meant “us”: Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. These works, from poems to photographs, policy briefs to research essays, voice the critical and beautiful lenses through which we, as environmentalists of color, see the world.

PAST examines those legacies that are colonial, imperial, and White supremacist and how they reverberate in today’s world. PRESENT examines the current crises that weigh heavy on our hearts, from the ongoing genocide of Palestinians to the slow violence inflicted on our communities here in California, as well as examples of resistance and personal reflection. FUTURE asks what it would look like to dismantle our systemic enemies racism, colonialism, neoliberalism, and dualisms—while peering into other worlds and possibilities.

We’d like to thank and celebrate every single contributor to this volume. May rage, inspiration, and a profound sense of hope flow through you as you read their works. Thank you to the Green Initiative Fund (TGIF) for funding the #OurEnvironmentalism project. And, of course, thank you to the Student Environmental Resource Center for believing in and supporting this publication since the beginning.

With love and in solidarity,

Becoming a “Wasteful American” by Kavina

Mother, Mother by Zora

Implicating the Epidemic of Burnout in the Collective “War Against Imagination” by Jed Lee......................................63

“Pani:” Case Studies of the Jalanidhi Project and Jal Jeevan Mission for Water Infrastructure Development in India by Megan Mehta.................................................71

Environmental Degradation as a Consequence of Neoliberalism by Angie Chen..................................................77 Indigenous Rights to the Land and Narratives of Western Science: An Environmental Politics Case Study of Mauna Kea and the Thirty Meter Telescope by Meg Kalaw......................................81

“Whether we want to or not, we are traveling in a spiral, we are creating something new from what is gone.”

- Ocean Vuong

Immigration policy in the 18th and early 19th centuries remained lax until large waves of immigrants moved to the US in search of employment or to evade increasingly unstable home environments. In 1790, the Nationality Act outlined eligibility for citizenship and defined eligibility rights as applying to “free white persons”, excluding non white people. This restriction was in place until 1952 and numerous legal decisions were based upon this precedent. Exclusion acts reinforced the narrative that immigrants were stealing jobs from white Americans and made white population purity a conscious goal for legislators and citizens In 1911, over 400,000 Japanese Americans lived in the states and primarily settled in Hawaii and California. Geopolitical tensions between Japan and the U.S. were used to justify land grabs based on eligibility for citizenship that had been set in 1790 The 1913 and 1920 Alien Land Laws along with formal Japanese internment in 1942 are responsible for the setback of Asian food sovereignty within the United States as land was forcibly handed over to white farmers and commercial agriculture. The loss of Asian American farming businesses due to legal discrimination on the basis of aliens ineligible to citizenship laws has displaced them from farming livelihoods, making cultural foods less accessible.

There has been a longstanding narrative that immigrants have been stealing white Americans’ jobs The logic most commonly employed is that if an immigrant did not hold that job, then someone else (presumably born in the US) would be able to have work. The lump of labor fallacy assumes there is a “fixed amount of work to be done” 1 . Assuming a fixed amount of labor implies that no new jobs are being created but that there is only redistribution During the 1950s, 33% of the labor within San Francisco was completed by Chinese men, making it easy for Americans to point out and criticize immigration as the source of unemployment. The Page Act of 1975, more commonly referred to as the Chinese Exclusion Act, barred laborers from “China, Japan or any Oriental country” 2 from entering. The exclusion of people from “any Oriental country” created a clear distinction and disdain for non-west cultures and identities 3 which later manifested itself in various education and work policies

I. IntroductionAs the Japanese population increased, antiJapanese sentiment developed similarly to the way it impacted Chinese populations. In 1906, the San Francisco school board mandated that Japanese and Korean students must attend “Oriental school” with the already separate Chinese student population This separation and intense ‘othering’ of Asian populations illustrates the resistance towards a diversifying population. Exclusion policies had formally established western superiority over unfamiliar eastern culture and framed its people to be a threat to American society and the American economy

Japanese immigrants entered America at the bottom of the economic ladder and had to find a means to survive and establish themselves Families gravitated towards farming and agriculture for economic stability since there was prevalent backlash against Asian immigrants in other labor markets. Shifting to agriculture was thought to reject the takeover and job theft narrative that had contributed to anti-Asian sentiments In addition, cultivation was a vessel for cultural and community preservation.

Over time, Japanese farmers turned their small acreage into some of the most productive and fertile farmlands. Their presence was most notable in the California agricultural scene, with 39% of California farms being operated by Nikkei 4 farmers 5 . The average value per acre of all farms was $37.94 and Japanese-owned farms were valued at $279.96 6 . At that same time, Japanese-owned farms were responsible for cultivating 35 to 50 percent of vegetables in California, which constituted to being “between one-to two-thirds of the county’s vegetable production” 7.

The increased amount of land held by Japanese farmers was perceived to foreshadow a total takeover. The concern around a growing foreign population was rooted in preserving white racial purity During the time, progressives in California connected economic self-preservation to racial preservation. Therefore, witnessing the success of Japanese farms fostered the belief that “it would only be a matter of time before they would make racial inroads” 8 . Progressives of the Republican party in California, such as Chester Rowell, were specifically worried about “Japanese immigrants taking over much of the state’s agricultural land” 9 and expressed interest in preventing these perceived outcomes.

The concern over white Americans losing land was a heavily discussed topic for California legislators

“Over time, Japanese farmers turned their small acreage into some of the most productive and fertile farmlands. Their presence was most notable in the California agricultural scene, with 39% of California farms being operated by Nikkei farmers . ”

between 1907 and 1913. The “emotional pleas of [white] farmers stole the show” 10 at town halls and highlighted the specific concern over white farmers’ prosperity as a reason to deny Japanese immigrants land ownership In 1913, the Alien Land Act was passed and effectively targeted “aliens ineligible to citizenship” 11 . This intentional phrasing targeted Asian immigrants from owning land. In 1913, when the bill was introduced, only Caucasians or people of African descent were allowed to naturalize into the United States It specified that aliens “eligible to citizenship” were able to own land which “effectively prohibited Japanese and a few other Asian residents in the state from doing the same” 12 . An attempt to remedy this denial of land ownership was by allowing ineligible aliens to lease land for up to three years The three-year lease limitation made it difficult for Japanese families to solidify themselves in the agricultural scene by establishing multigenerational farms. Families began to set up joint operations, where multiple families cooperatively operated land. This would allow families to pass the land lease between each other to maintain longevity and claim to their land In 1920, Japanese Americans held their peak amount of land at 458,056 acres. Therefore, American-born children were barred from leasing land as well. Asian Americans were therefore not able to lease, own, or control land in California It was also extended to prevent Asian corporations or businesses from owning land, extending land laws beyond fields. Two years later, 330,653 acres of land were held 13 . The 1920 land laws strategically prevented Asian and Asian Americans from owning agricultural or commercial land in California

On February 19, 1942, Executive Order 9066 was enacted and removed Japanese immigrants and

Americans of Japanese descent from the West Coast after Pearl Harbor was attacked. The attack on Pearl Harbor coupled with building concerns over economic competition and non-white population growth quickly spurred on relocation Executive Order 9066 did not explicitly name Japanese populations, however, John L DeWitt explicitly enforced a curfew for Japanese Americans. From there, DeWitt verbalized support for Japanese Americans to voluntarily leave but only 7% of the population did so. Later, on March 29, 1942, DeWitt enforced Public Proclamation No 4 which forced the removal of Japanese-Americans from the West Coast within only 48 hours. The Food for Freedom Program reassured Americans that they would not fall short on their harvests during wartime and boasted that “America has the best informed farmer and the best agricultural leadership” 14 All the while, Japanese-operated farms were the ones yielding 35-50% of the county’s vegetable harvest.

The 1790 Nationality Act created the classification of “aliens ineligible for citizenship” that targeted Asian immigrants’ rights to property ownership and employment. The law exclusively outlined “free white men” as those being eligible during an era where race was viewed in a black-white paradigm Asian immigrants were deemed to be nonwhite and therefore ineligible to citizenship. This status-race perspective utilizes a “common sense” rationale to determine where people stand socially and economically 15 relative to each other Status-race rationale uses race as a comparative measure and thus creates an inferior-superior dualism. The usage of status-race emphasizes the racial hierarchy and shows how inferiority ends up limiting one’s access to social, economic, and political resources. Whiteness, as

defined in the 1790 law, operates as an identity that has various privileges aligned with it. Apart of these privileges are property rights, or “legal entitlements [that] arise from that status” 16 Cheryl Harris argues that property is a right rather than a physical or tangible asset 17 . She argues that property entails “all of a person’s legal rights” 18 . Therefore, one’s racial status determines their ability to own any properties. Value and freedom have always been adjacent to whiteness As mentioned earlier, only whites or those of African descent were allowed to naturalize, showing that the “aliens ineligible for citizenship” phrasing of the land laws was intentionally attacking Asian immigrants and their attempt to stabilize themselves through agriculture

B. The Alien Land Laws were Designed to Shift Asian-owned Land into White Hands

The sociolegal construction of property allowed for race-based land laws to develop and actively shift Asian-owned land to white farmers and operations

The support to pass the Alien Land Laws initially in 1913 was rooted in the interest to preserve white farmers’ economic endeavors. This success occurred at a time when the US President had shared concern over creating a “homogenous population out of people who do not blend with the Caucasian race ” 19 Since white economic stability was tied to racial purity, it was imperative to Progressives that the economic sector remain in control of white citizens. The fruitful success on Japanese farms was thought to have deeper implications for overall racial success that would bleed into their obtaining of other rights The land laws were a clear attempt to prevent this from happening

“ Value and freedom have always been adjacent to whiteness.”

The restructuring of the land laws in 1920 to prevent Asian Americans from even leasing land shows that even those born in the states are only viewed as foreigners. The legal and social norms surrounding Asian identities are reduced to a foreign, immigrant status 20 This race-based legal discrimination provided the foundation for the full restriction of Asian property rights in 1920. Around two decades later in 1940, there were 125,928 white farm operators and only 6,730 nonwhite operators in California. White operators ran 30,168,554 acres of farmland while nonwhite farmers ran 355,770 acres 21 , showing an aggressive loss resulting from the land laws. The census’ separation of white and nonwhite operators also depicts the distinction of race within data points, contributing to the concept of “othering”. The “nonwhite” category doesn’t break down into more specific racial categories but still shows the shift in land ownership throughout the country. Most new

andowners were “naturalized European immigrants, or Americans from the Dust Bowl region” 22 This was an intentional effort to ensure land remained in white hands.

By the time internment ended in 1946, many Japanese families left California or failed to return to their farmland. Their exclusion from the West Coast forced them to give up their source of income and cut their history in US agriculture short Fear of social discrimination and violence prevented people from returning. Sugimoto, an archivist, states that “After the war, very few farmers came back” and that “People had to restart their lives” 23 . Beyond social exclusion and potential violence, they were still unable to own any property, as the land laws did not end until 1952

By the time the land laws were repealed, it was hard for Japanese farmers to reenter the agricultural scene, let alone compete with white farmers and new agribusinesses that have developed. The term “agribusiness” was first used in 1955 to describe a massive conglomerate of operations that controlled both the production and distribution of food 24 These businesses dictated the price that their produce could be sold at and have eliminated the communal aspect that farming has had since the beginning of time. This vertical integration made it nearly impossible for independent farmers to compete

The networks that Japanese farmers had previously maintained prior to internment were shattered. There was no land to return to and starting over was too risky both socially and economically.

They had previously utilized “ethnic networks” 25 grow and transport produce, thus demonstrating some level of food sovereignty. Before the land laws and internment, Japanese farmers had control over what they grew and who it could be distributed to. They grew and shared a wide variety of fruits and vegetables throughout their networks and their farms were a source of social and economic value

The hundreds of thousands of acres that were operated by Japanese farmers became backyard gardens. Those passionate about farming were able to enhance their land on a comparatively smaller scale for themselves and their neighbors Kiyoko Nakatsui’s family writes that the farm was just a memory of their early years in the states. Her family was unable to return to their land after their means of social reproduction and economic stability were shattered. Despite this, they still cultivated an abundant garden that grows their favorite fruits and vegetables every season The persimmons, kumquats and avocados are better than store bought, as her family knows how to be patient with the natural growing cycles and tend to their plot. The families all share their harvests with one another, emulating the heart of food sovereignty connections on a smaller scale

Food is commonly referred to as one of the most powerful vessels of cultural preservation. Cultural values can be relayed through food access and cultivation. To challenge a group’s agricultural efforts is to suppress their culture. Food sovereignty advocates emphasize the importance of cultural ingredients that are cultivated and enjoyed locally Cultural foods in many supermarkets throughout the country are found in a single aisle. These ingredients must be bought at specific grocery markets that import ingredients from home countries abroad. There is no diverse food network within the United States that is as reflective of the diversity of its population Food is no longer grown based on local need or capacity. Our systems have become a one-size-fits-all model that hastens natural growing processes in search of profits and is reliant on globalized networks. It is nearly impossible to trace back the various sources and stages that our food is channeled through in its lifetime. The homogenized food system within America is due to the prevention of diverse bodies from cultivating the land and the subsidizing of large agribusinesses.

The widespread belief that Asian communities were stealing white populations’ economic opportunities led to the enactment of Anti-Asian land laws The social construction of property rights and race-based rationale paints Asians as non white foreigners, preventing them from exercising social and legal mobility. Even though Japanese farmers were able to successfully work with the land, their economic contributions came secondary to racial purity Additionally, the social and physical othering of Japanese communities during internment actively removed them from their farmland in an era where agricultural mechanization and homogenization took flight. After internment, it was near impossible to restart their farming initiatives under growing social and economic burdens. The social deterioration of Japanese farm networks through race-based rationales has directly setback and prevented a diverse and local agricultural scene in California

9.

Van Nuys, Frank “A Progressive Confronts the Race Question : Chester Rowell, the California Alien Land Act of 1913, and the Contradictions of Early Twentieth-Century Racial Thought” (2)

10.

11.

12.

13

14

Van Nuys, Frank (4)

Immigration History, “Alien Land Laws in California (1913 & 1920)” 2019

Van Nuys, Frank (5)

Yuji Ichioka, “Japanese Immigrant Response to the 1920 California Alien Land Law” Agricultural History, Vol 58, No 2 (Apr 1984) pp 169

United States Department of Agriculture, “Food for Freedom”, 1943 https://naldc.nal.usda.gov/download/1789419/PDF

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20

Neil Gotanda, “A Critique of ‘Our Constitution is Color-Blind’”, 1991 (18)

Cheryl Harris, “Whiteness as Property” Harvard Law Review, Vol. 106, No. 8, 1993, (1725)

Cheryl Harris, 1725

Cheryl Harris, 1726

Don Wolfensberger, “Woodrow Wilson, Congress and Anti-Immigrant Sentiment in America An Introductory Essay” Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 12 Mar 2007

Chang, Michael “Exclusion and the Law”, University of California, Berkeley, 9 Feb 2023

Lecture

21.

Census of Agriculture - California, State Table 1. “Farms and Farm Acreage, by Color and Tenure of Operator, and by Size of Farm 1910-1940; and Farm Land According to Use, 1924 to 1939”

22.

23.

John G. Brucato, The News, “War Hits the Farm Lands” 1948

Morino, Douglas “Preserving the Legacy of Japanese American Farms in Southern California”, The New York Times, 1 May 2023

24 Immigration History, “Alien Land Laws in California (1913 & 1920)” 2019

Bill Ganzel, “Farming in the 1950s & 60s - Agribusiness” The Ganzel Group, 2007

25

“ To challenge a group’s agricultural efforts is to suppress their culture. Food sovereignty advocates emphasize the importance of cultural ingredients that are cultivated and enjoyed locally. Cultural foods in many supermarkets throughout the country are found in a single aisle. These ingredients must be bought at specific grocery markets that import ingredients from home countries abroad. There is no diverse food network within the United States that is as reflective of the diversity of its population.”

Azuma, E. “Japanese Immigrant Farmers and California Alien Land Laws: A Study of the Walnut Grove Japanese Community ” California History, vol 73, no 1, 1 Apr 1994, pp 14–29, https://doi org/10 2307/25177396 Accessed 2 Dec 2019

Brucato, John G. War Hits the Farm Lands : City Folks Urged to Harvest Crops’ during Vacation Back-To-Land Movement Takes on a New Importance. The News, May 1998, www sfmuseum org/hist9/harvest html#:~:text=The%20World%20War%20II%20evacuation,%2 DJapanese%E2%80%9D%20owners%20and%20lessees

Chang, Michael. Exclusion and the Law. 9 Feb. 2023. Lecture given at the University of California, Berkeley.

--- Immigration Politics, Policies and Practices 2 Mar 2023 Lecture given at the University of California, Berkeley.

Chin, Gabrial J. , and Anna Ratner. “The End of California’s Anti-Asian Alien Land Law: A Case Study in Reparations and Transitional Justice ” Asian American Law Journal, vol 29, no 1, 9 Nov 2022, pp 1–17, https://doi org/10 15779/Z383775W4G

Ganzel, Bill. Farming in the 1950s & 60s. The Ganzel Group, 2007, livinghistoryfarm.org/farminginthe50s/farminginthe1950s.html.

Gotanda, Neil “A Critique of “Our Constitution Is Color-Blind ”” Stanford Law Review, vol 44, no 1, Nov. 1991, p. 1, https://doi.org/10.2307/1228940.

Harris, Cheryl I. “Whiteness as Property.” Harvard Law Review, vol. 106, no. 8, June 1993, pp. 1707–1791, https://doi org/10 2307/1341787

Ichioka, Yuji. Japanese Immigrant Response to the 1920 California Alien Land Law. Duke University Press, Apr. 1984.

Immigration History “Alien Land Laws in California (1913 & 1920) ” Immigration History, 2019, immigrationhistory org/item/alien-land-laws-in-california-1913-1920/

--. “Nationality Act of 1790.” Immigration History, 2019, immigrationhistory.org/item/1790nationality-act/.

--- “Page Law (1875) - Immigration History ” Immigration History, 2019, immigrationhistory.org/item/page-act/.

Kashima, Tetsuden. Personal Justice Denied : Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians Washington, D C , Civil Liberties Public Education Fund ; Seattle ; London, 1997, pp 117–134

Le Pore, Herbert P “Prelude to Prejudice: Hiram Johnson, Woodrow Wilson, and the California Alien Land Law Controversy of 1913 ” Southern California Quarterly, vol 61, no 1, Apr 1979, pp 99–110, https://doi.org/10.2307/41170813. Accessed 23 June 2020.

Mann, Alana. “Food Sovereignty: Alternatives to Failed Food and Hunger Policies.” Contemporanea, vol. 18, no. 3, 2015, pp 445–468, www jstor org/stable/24654154 Accessed 11 May 2023

Morehouse, Lisa. “Farming Behind Barbed Wire” Npr.org, 2017, www npr org/sections/thesalt/2017/02/19/515822019/farming-behind-barbed-wire-japanese-americans-rem ember-wwii-incarceration.

Morino, Douglas “Preserving the Legacy of Japanese American Farms in Southern California”, The New York Times, 1 May 2023

Nakatsui, Kiyoko “Japanese American Farming in California: A Personal History – Sherman Library and Gardens ” Thesherman.org, 27 May 2022, thesherman org/2022/05/27/japanese-american-farming-in-california-a-personal-history/ Accessed 11 May 2023.

National Archives “Executive Order 9066: Resulting in Japanese-American Internment (1942) ” National Archives, 22 Sept 2021, www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/executive-order-9066.

Quinnell, Kenneth “Asian Pacific American Heritage Month Profiles: Chinese Railroad Laborers | AFL-CIO ” Aflcio org, 9 May 2019, aflcio.org/2019/5/9/asian-pacific-american-heritage-month-profiles-chinese-railroad-laborers.

Tokunaga, Yu “Japanese Internment as an Agricultural Labor Crisis ” Southern California Quarterly, vol 101, no 1, Feb 2019, pp. 79–113, https://doi.org/10.1525/scq.2019.101.1.79. Accessed 29 Feb. 2020.

U S Census Bureau Census of Agriculture - California. 1940, agcensus library cornell edu/wp-content/uploads/1940California-STATE TABLES-1264-Table-01.pdf.

United States Department of Agriculture. Food for Freedom : Informational Handbook. 1943, naldc.nal.usda.gov/download/1789419/PDF.

Van Nuys, F. W. “A Progressive Confronts the Race Question: Chester Rowell, the California Alien Land Act of 1913, and the Contradictions of Early Twentieth-Century Racial Thought ” California History, vol 73, no 1, 1 Apr 1994, pp 2–13, https://doi org/10 2307/25177395 Accessed 11 Feb 2020

Wolfensberger, Don Woodrow Wilson, Congress and Anti-Immigrant Sentiment in America : An Introductory Essay 2007 Wolla, Scott A. “Examining the “Lump of Labor” Fallacy Using a Simple Economic Model.” Research.stlouisfed.org, Nov. 2020, research stlouisfed org/publications/page1-econ/2020/11/02/examining-the-lump-of-labor-fallacy-using-a-si mpleeconomic-model#:~:text=The%20lump%20of%20labor%20fallacy.

For ASAMST 145AC Politics, Public Policy, and Asian American Communities Prof. Michael Chang, Spring 2023

Prompt: Imagine that you are a curator in a museum, and you have been given an empty cabinet to fill. Your job is to find 4-6 objects that when placed together in that cabinet provoke questions, confound conventional wisdom, evoke telling comparisons or contrasts, or otherwise illuminate the history we've been exploring this semester. You may use any relevant object other than a simple text. Material artifacts, paintings, codexes, maps - use your imagination and aim to combine very different kinds of objects.

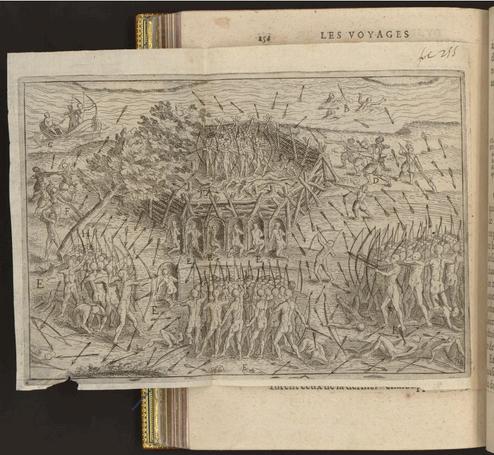

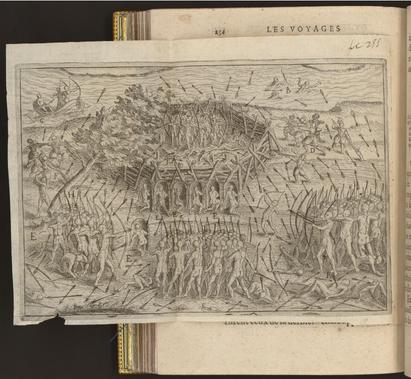

The story of encounter and conquest in America can be seen through the lens of Indigenous resilience and agency. The exhibit that I propose will contain art and objects from different contact zones around America and range from the period of 1510 to 1770. The exhibit will showcase Tabula Geographica Regni Chile by Alonso de Olvalle, La Virgen del Cerro Rico (The Virgin of the Mountain of Potosí), Lienzo de Tlaxcala by Anonymous, Les voyages du sieur de Champlain Xaintongeois, capitaine ordinaire pour le Roy, en la marine (The voyages of de Champlain Xaintongeouis, the ordinary captain for the King in the navy) by Samuel de Champlain, Zemi by Anonymous, and Portrait of a Mameluca Womanby Albert Eckhout. All these objects showcase how the period of European conquest

in the Americas was dominated by stories of Indigenous resilience and agency. By highlighting these stories, we can subvert the stereotypical notion that Indigenous peoples were powerless and solely the subjects of European coercion and exploitation, and we can undermine the erasure of Indigenous peoples and cultures today.

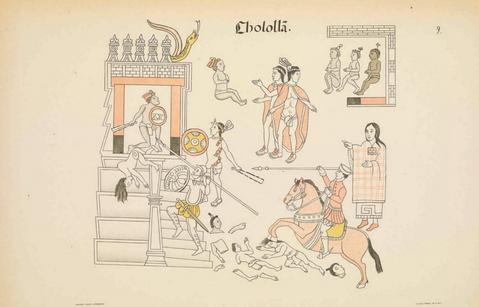

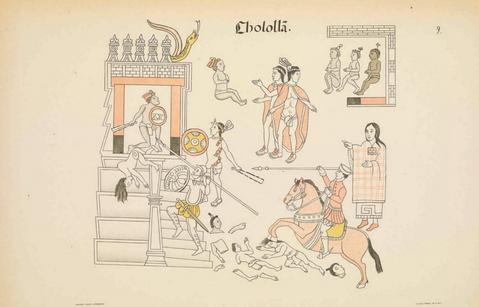

On the subject of Indigenous agency, I first turn to the Lienzo de Tlaxcala, the Les voyages du sieur de Champlain, Tabula Geographica Regni Chile, and Portrait of a Mameluca Woman. The Lienzo de Tlaxcala showcases the creation of the alliance between the Tlaxcala and the Spanish. In particular, I propose showing a depiction of the Cholula Massacre. 1 The Cholula Massacre is an example of Indigenous agency, as it was a moment in which the Tlaxcala utilized their newly founded alliance with the Spanish to enact violent retribution against an ally turned enemy Furthermore, the depiction of the Cholula Massacre will highlight how Indigenous peoples often joined in alliances with European conquerors of their own choice, often in hopes of expanding their territory or undermining their enemies. In contrast, Les voyages du sieur de Champlain is an account written and details his travels around Canada, including his interactions i h h I di l h I hat

illustration by Champlain that depicts an attack by the French, and their Indigenous allies, the Anishinaabe, Wendat, and Innu, against a Haudenosaunee fort. 2 Similarly, to the Lienzo de Tlaxcala, this illustration depicts how Indigenous peoples utilized alliances with Europeans to subvert their enemies. Tabula Geographica Regni Chile is a map that was created by Fr. Alonso de Ovalle, a Chilean Jesuit. 3 The map shows the country of Chile and includes vignettes of the Parliament of Quillín which took place in 1641. The Parliament of Quillín was a meeting between the Mapuche peoples and the Spanish during the Arauco War. The Mapuche held a series of campaigns against the Spanish that eventually led to a peace treaty and recognition of the Mapuche by the Spanish crown. 4 This shows Indigenous agency, as it demonstrates an instance in which Indigenous peoples were able to form treaties with colonizing forces that recognized their sovereignty. Finally, Portrait of a Mameluca Woman depicts a mixedrace woman born of a Portuguese and Indigenous union. 5 During the colonial era in South and Central America, mixed-race marriages and children were popular.

“Lienzo de Tlaxcala” by Unknown (1550)This image highlights Indigenous agency as it portrays the Tupi concept of cunhadismo. Cunhadismo was a process in which kinship was created through the marriage of Tupi women with foreigners in their society, therefore highlighting Indigenous agency 6 Through marriage, kinship ties would be created, which effectively made the foreigner part of Tupi society. Thus, marriage was not just a way in which European men were able to create alliances with Indigenous peoples, but rather a way in which Indigenous peoples were able to make Europeans their kin and therefore subject them to the social obligations of being part of their larger family Similarly, Portrait of a Mameluca Woman is also a show of Indigenous agency during this time. By showing these illustrations, we can disrupt traditional notions that Indigenous peoples were naïve, innocent peoples who were being coerced or exploited by European conquerors This long-held belief strips Indigenous peoples of their agency, and by showing the aforementioned images, we can demonstrate how the era is much more complicated. Instead, through these images, we can see how Indigenous peoples maintained their agency in a variety of different ways

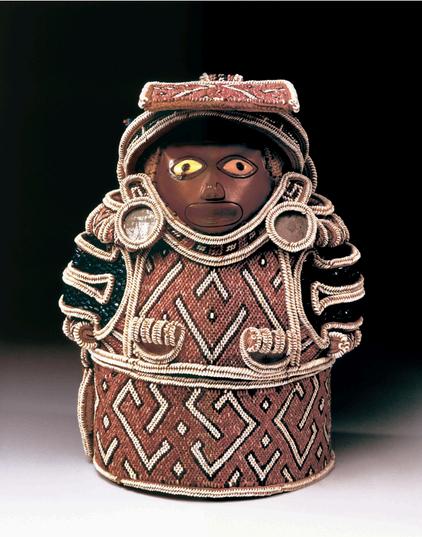

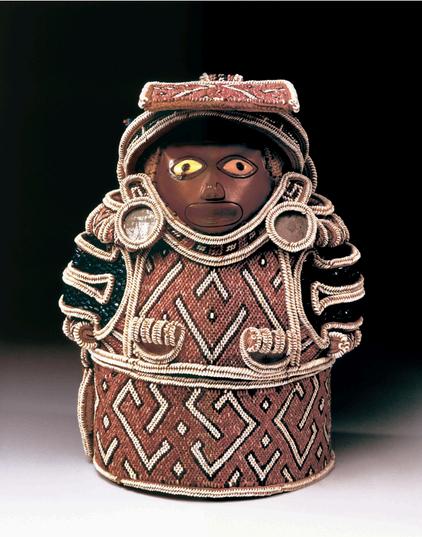

On the other hand, Indigenous resilience can be seen through La Virgen del Cerro Rico, a Zemi figure, Tabula Geographica Regni Chile, and a Portrait of a Mameluca Woman. La Virgen del Cerro Rico is a devotional image of the Virgin Mary that originates from Bolivia. 7 In Bolivia, Pachamama is a goddess that was worshipped by Indigenous peoples Associated with the Earth, mountains, fertility, and harvest, La Virgen del Cerro Rico is an example of Indigenous resilience through cultural syncretism. 8 La Virgen del Cerro Rico depicts the mountain of Potosí merged with the Virgin Mary. The depiction of the Virgin Mary as a mountain draws parallels between her and Pachamama In Latin America, the Virgin Mary was commonly used as a way to merge Indigenous beliefs with Catholicism. Thus, through cultural and religious syncretism, Indigenous beliefs and traditions were able to survive throughout colonization. Zemis were believed to be spirits or objects representing/housing spirits amongst Taíno people in the Caribbean The zemi that I propose to showcase is decorated with intricate beadwork and is likely made up of rhinoceros bone from Africa. 9 This zemi showcases Indigenous resilience in two parts. The first is that its pristine condition is reminiscent of other zemi figures that have been found in caves, as Indigenous peoples would hide them there away from Spanish colonizers who would destroy them. In addition, the use of rhinoceros bone shows how, even in an increasingly global world dominated by colonialism, Indigenous peoples exhibited resilience in keeping their cultural and religious traditions alive The depiction of the Parliament of Quillín in the Tabula Geographica Regni Chile is another example of Indigenous resilience, as

Mapuche peoples were able to resist Spanish conquest for over two hundred and fifty years, primarily through violent resistance against colonizing forces

Finally, Portrait of a Mameluca Woman shows Indigenous resilience as it pushes against the narrative that Indigenous peoples are extinct. Through identification with an Indigenous heritage, this notion of Indigenous extinction is proven false 10 All in all, through this art, we can highlight how ideas of Indigenous extinction are false; Indigenous communities were able to demonstrate their resilience through armed resistance, preservation of culture and religion, and visible indigeneity.

Overall, by showing the images that I have proposed, we can create a narrative that subverts false notions that Indigenous peoples were helpless and went extinct during the encounter and conquest era in America. By showing art that demonstrates Indigenous resilience and agency, we complicate traditional narratives about this era and provoke our audience to question what they have been told about the conquest era in America.

Lienzo de Tlaxcala, 1550, National Library of Anthropology and History, Mexico City, Mexico.

1. Les voyages du sieur de Champlain. 1613. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa, Canada. 2. De Ovalle, Alonso. 1601. Tabula Geographica Regni Chile. Museo Nacional de Arte, La Paz, Bolivia.

3. Clément, Vincent. “Conquest, Natives, and Forest: How Did the Mapuches Succeed in Halting the Spanish Invasion of Their Land (1540–1553, Chile)?” War in History 22, no. 4 (2015): 428–47. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26098447.

4. Eckhout, Albert. 1641. Portrait of a Mameluca Woman. National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen, Denmark.

5. Moreira, Vânia Maria. “Territorialidade, Casamentos Mistos e Política Entre Índios e Portugueses.” Revista Brasileira de História 35, no. 70 (2016): 17–39. https://doi.org/10.1590/180693472015v35n70006.

6. La Virgen del Cerro Rico. 1740. Museo Nacional de Arte, La Paz, Bolivia.

7. “Virgin of the Mountain of Potosí.” VistasGallery. Accessed April 27, 2023. https://vistasgallery.ace.fordham.edu/items/show/1924#:~:text=It%20is%20currently%20in%20the ,Arte%20in%20L a%20Paz%2C%20Bolivia.

8. Zemi. 1510. Museo Nazionale Preistorico ed Etnografico "Luigi Pigorini". 9.

For History 135B: Encounter & Conquest in Indigenous America, Prof. Brian DeLay, Spring 2023

“Tabula Geographica Regni Chile” by Alonso de Olvalle (16501651), Chile, currently at John Carter Brown Library: This map was created by Alonso de Olvalle, a Chilean Jesuit priest. The map contains a compass rose, the location of rivers, settlements, the dividing line between Mapuche and Spanish territory, various wild animals, and the Spanish coat of arms. The excerpts on the map show one vignette of the Parliament of Quillín and another of warfare between Spanish and Indigenous peoples and the plans of San Jacob and Valdivia. The depiction of the Parliament of Quillín highlights Indigenous agency and resilience as it demonstrates a moment in which Indigenous peoples were able to resist Spanish colonization and were able to advocate for themselves through the creation of a peace treaty that recognized Mapuche sovereignty

“La Virgen del Cerro Rico” by Unknown (1740-1770), Bolivia, currently at Casa de Murillo in La Paz, Bolivia: This oil painting shows the Virgin of the Mountain, which is a merging of the Virgin Mary with Potosí Mountain in Bolivia. At the top of the painting is the Holy Trinity blessing Mary, and at the bottom are various saints and the artist’s patron. Climbing the mountain are mineworkers and llamas The depiction of the Virgin of the Mountain highlights Indigenous resilience, as the illustration of the Virgin Mary is reminiscent of the Indigenous goddess Pachamama who presides over fertility, mountains, and the Earth. The depiction of the Virgin of the Mountain is an example of Indigenous resilience through syncretism, in which Indigenous peoples combined elements of their religion and culture with Catholicism to keep their traditions alive.

“Lienzo de Tlaxcala” by Unknown (1550), Mexico, currently at the National Library of Anthropology and History, Mexico: The original Lienzo de Tlaxcala was commissioned by the town council of Tlaxcala Three copies were made, one for King Carlos I, another for Mexico City, and the last for the Tlaxcalan council However, all three versions were lost, and only a reproduction by Manuel de Yllánez (1773) exists. The Lienzo de Tlaxcala was created using canvas. The Lienzo de Tlaxcala shows the creation of the alliance between the Tlaxcala and the Spanish until the fall of Tenochtitlan and the end of the Triple Alliance This artwork specifically depicts the Cholula Massacre, which took place shortly after the formation of the TlaxcalanSpanish alliance. The Cholula Massacre was a moment of retribution by the Tlaxcala against the Cholulans, who had defected from their alliance to join the Triple Alliance This instance shows how Indigenous groups were able to utilize European alliances to establish dominance in the region.

“Les voyages dv sievr de Champlain Xaintongeois, capitaine ordinaire pour le Roy, en la marine Divisez en devx livres ou, Iovrnal tres-fidele des observations faites és descouuertures de la Nouuelle France: tant en la descriptiõ des terres, costes, riuieres, ports, haures, leurs hauteurs, & plusieurs declinaisons de la guide-aymant; qu ʾ en la creãce des peuples, leur superstition façon de viure & de guerroyer: enrichi de quantité de figures. Ensemble deux cartes geografiques: la premiere seruant à la nauigation, dressée selon les compas qui nordestent, sur lesquels les mariniers nauigent: lʾautre en son vray Meridien, auec ses longitudes & latitudes: à laquelle est adiousté le voyage du destroict qu ʾont trouué les Anglois, au dessus de Labrador, depuis le 53e degré de latitude, iusques au 63e en lʾ an cerchans vn chemin par le Nord, pour aller à la Chine ” By Samuel De Champlain (1613), Canada, currently at Library and Archives Canada: Samuel de Champlain was a French explorer who traveled throughout Canada This image depicts a joint attack by the French, Innu, Wendat, and Anishinaabe against a Haudenosaunee fort This artwork highlights Indigenous agency as it highlights that Indigenous alliances with Europeans were beneficial to Indigenous peoples as it allowed them to extend their dominance throughout the region, in this case through violent attacks against enemy groups

Zemi by Unknown (1510-1515), the Caribbean, currently at the National Museum of Prehistory and Ethnography “Luigi Pigorini”: In Taíno culture, zemis were believed to be both spirits and objects housing spirits This zemi is made of rhinoceros horn from Africa and decorated with Caribbean shells that are woven into a pattern Many zemis were found hidden in caves, away from European colonizers who wanted to destroy pre-Colombian religions This figure shows Indigenous resilience, one through its immaculate condition and its survival until the present, and because the use of rhinoceros horn shows how, in the face of increased European influences in Taíno culture, Indigenous peoples were still able to keep their cultural and religious traditions alive

“Portrait of a Mameluca Woman” by Albert Eckhout (1641), Brazil, currently at the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen, Denmark: Albert Eckhout was a Dutch painter who lived in Dutch Brazil for some time This is an oil painting on canvas. The painting depicts a mixedrace woman of European and Indigenous heritage. Other elements include a guinea pig, a basket of flowers, and a variety of greenery. This image shows both Indigenous agency and resilience Indigenous agency is depicted here as mixed-race unions that benefitted both Indigenous peoples and Europeans In Brazil, the concept of cunhadismo in Tupi culture is the giving away of a woman to strangers or foreigners to create kinship ties. Through the newly created kinship, Indigenous groups could subject Europeans to societal obligations. By forging these bonds with Europeans, Indigenous groups displayed agency Indigenous resilience is depicted in the mere visualization of a woman with Indigenous heritage, contradicting the idea that Indigenous people are extinct.

Caption: Runit Dome with Protestors Source: @sanna6789998212 on X

While the Oscar-award-winning film Oppenheimer may shed light on America's nuclear testing history, we must recognize and go beyond the surface of the overlooked and ongoing injustices inflicted upon vulnerable communities by these reckless experiments. Often untold, the Marshall Islands serve as a key example of the devastating nuclear legacy of the U S

The Marshall Islands is situated between Hawaii and Australia, consisting of two chains of 29 coral atolls. Marshallese people have inhabited the Marshall Islands

since the second millennium BCE, building a rich cultural and historical tapestry interwoven with the islands’ ecosystems In the 20th century, Marshallese people began to experience the detrimental impacts of military occupation as the Japanese came in 1914, followed by the U.S. in 1944.

From 1946-1958, the U.S. used the Marshall Islands as a testing ground for 67 nuclear weapon tests, leaving widespread contamination of nuclear fallout across the islands. Operation Crossroads was the first testing series deployed by the U.S. The largest of the nuclear detonations was “Castle Bravo,” at Bikini Atoll in 1954 – a bomb 1,000 times more powerful than the explosion at Hiroshima (Atomic Heritage Foundation 2022). Today, the Runit Dome on Enewetak Atoll holds more than 3.1 million cubic feet – or 35 Olympic-sized swimming pools – of U.S.-produced radioactive debris (Atomic Heritage Foundation 2022)

Moreover, Marshallese people were forcibly removed from their homes. A 2012 United Nations report affirmed the irreversible environmental contamination caused by nuclear testing, and those who stayed faced increased risk of nuclear exposure A Nationwide Radiological Study found that between 1993

and 1997, 60-69% of the entire Marshallese population was potentially exposed to fallout from nuclear testing (United Nations 2012).

This exposure resulted in increased rates of cancers, such as thyroid cancer

A 2007 report to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 17 of 19 children exposed before age 10 on the Rongelap Atoll were diagnosed with thyroid lesions by 1974 (Thomas 1999). As a symptom of thyroid cancer, patients experience hypothyroidism – a decreased production of the thyroid hormone, resulting in slower metabolisms (Raj 2019). The Marshall Islands Nuclear Claim Tribunal collects a list of additional cancers related to nuclear exposure and found that cancers are hereditary, continuing from generation to generation Despite these generational impacts, many Marshallese remain undiagnosed and without adequate treatment.

Increased cancer rates have also unraveled the intricate cultural tapestry of the Marshallese. Thyroid cancers affecting the throats of Marshallese people have weakened their ability to practice traditional songwriting and singing, a crucial component of Marshallese storytelling (Raj 2019).

When the Marshall Islands Nuclear Claim Tribunal was formed in 1988, the U.S. was supposed to financially compensate radiation victims and those undergoing post-treatment However, the U S failed to sufficiently fund the tribune (Atomic Heritage Foundation 2022). Cancer patients who seek assistance from the tribunal are left facing financial hardships. With limited research and resources, Marshallese activists continue to advocate for thorough investigation and compensation regarding the health impacts of nuclear testing.

Reports of U.S. Military Personnel confirmed that they observed leaking fallout from the Runit Dome, yet no action by the U S was taken (Atomic Heritage Foundation 2022) Now facing escalating sea levels caused by climate change and the gradual deterioration of its concrete structure, the

Runit Dome reveals itself as a temporary fix to this issue. Despite the need for medical support and the concerning future of the Runit Dome, the U.S. maintains that they are no longer liable for these nuclear impacts

Why were the Marshall Islands appealing to military forces? Apparently, the U.S. saw the Marshall Islands as a prime testing site due to its remote location, “sparse” population, and the islands’ existing military infrastructure Yet, the better question to ask is why did the U S deem native Marshallese communities dispensable? Native communities around the world are facing similar environmental injustices at the hands of imperialist powers. We must transform our dominant paradigms to center the stories and lived experiences of these communities

The U S must be held responsible for its detrimental nuclear impacts and negligence in attending to the health of the Marshall Islands’ people and ecosystems. This nuclear legacy has disrupted the Marshallese indigenous ways of being, and the U.S. must work closely with Marshallese communities to find culturally appropriate solutions that initiate an

“ The U.S. must be held responsible for its detrimental nuclear impacts and negligence in attending to the health of the Marshall Islands’ people and ecosystems.”

“Marshall Islands.” Nuclear Museum, Atomic Heritage Foundation, ahf.nuclearmuseum.org/ahf/location/marshallislands/#:~:text=Operation%20Crossroads, %2C%20on%20July%201%2C%201946. Accessed 16 Mar. 2024.

Raj, Ali. “In Marshall Islands, Radiation Threatens Tradition of Handing down Stories by Song.” Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 10 Nov. 2019, www.latimes.com/projects/marshall-islands-radiation-effects-cancer/.

“Nuclear Legacy in the Marshall Islands: “nomads in Their Own ... ” United Nations, United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2012/03/nuclear-legacy-marshall-islands-nomadstheir own-country-un-expert. Accessed 17 Mar. 2024.

Thomas, G., et al. Radiation and Thyroid Cancer: Proceedings of an International Seminar on Radiation and Thyroid Cancer. World Scientific, 1999.

For ESPM 167 Environmental Health & Development, Prof. Kurt Spreyer Spring 2024

The trees seem to whisper with the wind. They sway into each other, laughing with their deep hearty guffaws. I wonder what stories they tell when we aren’t listening. As I watch them dance, I think how surreal it is that sixty years ago, a previous Berkeley student who might now be a grandparent saw these same trees gently swing with the breeze in the same apartment - but in 1963. What a different world it must’ve been here in the 60s with revolution at every corner of Berkeley; maybe this student who watched the same trees as I am today also saw Mario Savio’s address and arrest or Martin Luther King Jr’s speech in Sproul. Maybe they marched for civil rights, anti-war, or pro-roe protests.

I always think of the past as a place that only exists in our memories, but thinking of the trees, I now realize that perhaps the past instead coexists with the present. The student might have graduated and left, but the trees didn’t - they are living history. Through each change within our history, our wise wooden relatives have stood here sturdy and have seen us born and grow, walk and fall, love and hurt. Their shade has provided us solace, but most importantly, they have literally breathed life into us.

But still somehow, we so freely and casually butcher our terrestrial cousins to make way for our own comfort. The knowledge seeps out with each

By Shreya Chaudhurihack, years of history lost. Without the foundation that trees gift us, what will we stand on? Our culture and our identity will be lost.

The ecosystem present in the trees is an entire universe. The tree in my backyard is a White Alder. She stands tall at nearly 82 feet with branches reaching to the sky. The white alder is a buffet for all the creatures that live in this now urban forest. Muskrats, deer, and hares munch on the leaves, while birds like redpolls and goldfinches feast on the alder seeds and buds. The trees themselves are sturdy and vital for this ecosystem. White alders are known to increase nitrogen levels in the soil, thus increasing the nutrient content and allowing more life to thrive on this land. The white alder is not picky and is able to persist in spite of infertile soil conditions. The average life of a white alder is around 75 years, so the ones in my apartment’s backyard have truly seen Berkeley’s evolution across most decades in the past century. Berkeley’s landscape transitioned from rural to urban and became home to thousands and now, hundreds of thousands of people. Trees like the white alder have been chopped to make room for more people. Trees that have withstanded droughts and bomb cyclones are demolished instantly by our weapons of saws that they cannot defend themselves from. There are examples around us of this silent violence. From the stadium that used to be a redwood grove to the buildings that were once an oak grove, the past is present all around us, and the memory of the forest lives on in our soil. It was in these same trees that

the tree-sitting activists built a home, the same trees that monks held with their own bodies. We have to listen to these earthly guardians and respect the land they inhabit. I understand that Berkeley’s landscape is complicated and exists within contradiction, but I believe that the question is not if a tree’s life is more important than a human’s but rather how do we recognize that both are intertwined in a city at a crossroads between nature and urbanization?

But hope is not lost; we are slowly returning to indigenous principles of honoring trees as a crucial part of our community. From the Green Belt movement to the Chipko activists, a revolution is rising around the world, and especially in Berkeley, environmental activists are still fighting for our future at every corner. I can only hope that one day, another Berkeley student sixty years from now will glance at the same trees from the apartment I onced lived in and wonder what stories the trees hold. Perhaps, the trees will whisper back: “They tried to break us, but we never fell.”

“ But hope is not lost; we are slowly returning to indigenous principles of honoring trees as a crucial part of our community. From the Green Belt movement to the Chipko activists, a revolution is rising around the world, and especially in Berkeley[.]”

For the UC Berkeley Art of Environmental Writing Fellowship

"May we have the strength, the love, the endurance to keep on to fight for a life worth living and a future worthy of our children."

-Noura Erakat

The Israeli military’s widespread aerial bombardment and ground invasion of the Gaza Strip for the past six months, killing over 34,000 people1 (not accounting for those missing under the rubble), has resulted in an ecological catastrophe that will scar the Strip and its people, already marred by an almost 17-year blockade, for decades to come. Often, the devastating impacts of war, or in this case, violence that could plausibly amount to genocide (according to the International Court of Justice)2, on the environment is rarely discussed but is a vital conversation to be had

Since the start of the war, the Israeli army has destroyed and damaged many waste management facilities in Gaza, with the UN Environment Assembly estimating at least 100,000 cubic meters of sewage and wastewater being dumped daily onto land or into the Mediterranean Sea This will likely exacerbate an already high level of chlorophyll and suspended organic matter in Gaza’s coastal waters caused by a history of marine pollution incidents.3 Due to the lack of municipality vehicles and sanitation workers, garbage lines the streets in Rafah In a video filmed by Palestinian journalist Bisan Owda, we see an overflowing container in front of a maternity hospital, spilling bloody bandages into an already trash-filled street. This leads to hazardous substances from solid

waste leaching into the soil and the sewage water, further polluting the streets. The 1.5 million refugees living there have limited access to clean water and sewage services due to 70% of Gaza’s infrastructure being destroyed As of February 11th, 2024, it was estimated that there were 45,000 metric tons of unmanaged solid waste in Gaza. Much of this unmanaged is burned, releasing hazardous gasses and particulate matter into the air.3

Not only is Gaza’s water supply being contaminated by unbridled waste pollution, but it is also being poisoned by the Israeli military’s use of white phosphorus weapons.4 White phosphorus exposure is highly dangerous; when in contact with human flesh, it can burn down to the bone, as well as set fields and structures on fire When these chemicals reach rivers and aquifers, they can be incredibly toxic to humans who rely on these sources of water,5 especially considering Gaza’s water scarcity as Israel continues to severely limit humanitarian aid, falling 15 liters short of the survival levels required by humanitarian standards 6 The contaminated waterways will affect Gaza’s ecosystem, fisheries, and the livelihoods of fishers; even before this genocide, Gazan fishers could only access six to fifteen nautical miles offshore due to the almost 17-year blockade.5 As of right now, 70% of Gaza’s fishing fleet has already been destroyed by the Israeli army White phosphorus also results in a

buildup of phosphoric acid in the soil, which depletes soil fertility and increases erosion, as well as contaminates the local crops and livestock on agricultural land,5 leaving Palestinians in Gaza with even fewer options for food. To add extra strain, 22% of farms in Northern Gaza have already been destroyed.6

In addition to the water, soil, and land pollution from chemical weapons and thousands of metric tons of solid waste, on January 7th there were an estimated 22.9 million metric tons of unexploded weapons, rubble, and debris from destroyed buildings,3 a number that has certainly since increased. There are also tens of thousands of bodies decomposing under the rubble,6 which pose a significant health risk due to disease, already spreading rapidly among the population. Building debris also contains pollutants like asbestos, heavy metals, fire contaminants, and hazardous chemicals (3) that could severely impact the health of millions of Gazans who have no safe place to go and are surrounded by destruction

Furthermore, Israel’s assault on Gaza has released copious amounts of carbon emissions into the atmosphere. During the first week alone, 29,000 bombs, the majority 2,000-pound bombs,6 were dropped on Gaza During just the first two months of the war in Gaza, 281,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions were released, which is greater than the annual carbon emissions of 20 of the world’s climate-vulnerable nations. The Israeli State’s aerial bombardment and ground invasion of Gaza is responsible for 99% of carbon emissions released during the first two months of the war; this number is most certainly higher (previous studies suggest the true carbon footprint could be five to eight times higher) and doesn’t account for the emissions released after the first 60 days of the Israeli State’s assault,7 most notably as this genocide is entering its seventh month. These emissions come from aircraft missions, tanks, fuel from vehicles, and making and exploding bombs, artillery, and rockets.

Almost half of the CO2 emissions were caused by United States cargo planes flying military supplies to Israel. In addition, it is estimated that to rebuild Gaza’s destroyed infrastructure, the construction of over 100,000 buildings would require the release of at least 30 million metric tons of greenhouse gasses, which is higher than the annual emissions of 135 countries and territories,7 or around 0 5% of 2022 US emissions

In February 2022, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) announced that the temperatures in the Mediterranean are rising 20% faster than the global average, already 1 5 degrees Celsius higher than preindustrial levels, compared to 1.1-1.3 degrees globally.8 As a result, even before this war, Gaza was already highly vulnerable to climate change, with these increasing temperatures as well as more frequent cold snaps (a brief period of very cold weather) during the winter Additionally, according to the International Committee of the Red Cross’s new report, Gaza is projected to see decreased rainfall by 20% by 2050.6 These climate risks will endanger over one million unhoused Gazans currently living in tents, destroyed shelters, or in the streets who are already threatened with bombardment, execution, starvation, disease, and insurmountable loss Omar Shoshan, the President of the Jordan Environment Union, put it simply: “Wars have a direct impact on climate change by increasing carbon emissions and destroying infrastructure. The Gaza Strip is a stark example in the face of a complex crisis from a humanitarian, environmental, health, and climate perspective due to the repeated wars it has experienced in recent years.”6

It’s important to know that environmental abuse in occupied Palestine did not start with the military invasion. In Gaza, it is estimated that around 90-95% of the water supply was contaminated and unfit for human consumption before this genocide started. In Gaza and the illegally occupied West Bank, Israeli military authorities have complete power over all water resources and water-related infrastructure; in November of 1967, they issued Military Order 158, preventing Palestinians from constructing any new water installation without a permit from the Israeli military, which is almost impossible to obtain Palestinians in the West Bank are not able to access the Jordan River and freshwater springs, and Israel controls the collection of rainwater throughout most of the West Bank and Gaza. About 180 Palestinian communities in rural areas of the West Bank have no running water, and if they do, taps often run dry Due to so many restrictions, Palestinians in the West Bank often have to pay for water brought in from trucks, and may even pay half a family’s income for water.9 Meanwhile, Israel develops its own water infrastructure for its settlers in the West Bank, who are there illegally under international law 10 The water inequity is so great that Israeli settler (9) communities in the West Bank, such as Ma’ale Adumim, have swimming pools

“Since 2000, it has destroyed over 3,000,000 trees through uprooting, poisoning, burning, or bombing, due to their cultural significance and indigeneity to Palestine.”

accessing a water supply four times greater than provided to Palestinian communities. In some West Bank communities, the water consumption can be as low as 20 liters per day, while the average Israeli water consumption is 300 liters of water per day 9

The Israeli State also disrupts Palestinian food sovereignty and agriculture. Since 2000, it has destroyed over 3,000,000 trees through uprooting, poisoning, burning, or bombing,11 due to their cultural significance and indigeneity to Palestine Often, certain organizations plant non-native trees in their place (this will be discussed further in the paper).12 The military also often bulldozes and displaces Palestinians from their homes and agricultural land to make room for more illegal settlers or military activity. In addition, many barriers have been placed to separate the State of Israel and Palestinian land, such as the apartheid wall in the West Bank and the walls that keep Gaza in an open-air prison. Many Palestinians have thus lost land on the Israeli side of borders, and are forced to try to obtain a permit to farm their own land, which is incredibly difficult to get This prevents Palestinians from being able to plant the food they need, and thus Palestinian markets are forced to rely on imports and exports from Israel. The barrier surrounding Gaza known as the buffer zone takes away 29% of Gazan farming land. Before the establishment of the Israeli State, farming was an integral part of the Palestinian economy, particularly in selling plums, olives and olive oil, oranges, grapes, and dates, producing more than current-day Israel.13 Gaza was a historically agrarian-dependent society, but the blockade has prevented the export of agricultural products such as fertilizer, farming, and irrigation equipment,6 leading to food insecurity Israel’s enforcement of the buffer zone through military encroachments leads to further environmental damage. The building of the iron wall itself, separating Gaza from the Israeli State, contributed to almost 274,000 metric tons of CO2, on par with almost all the 2022 emissions by the Central African Republic, one of the most climate-vulnerable countries in the world.7

Often, Israeli media, governmental officials, and military try to cover up their crimes and justify their claim to the land through forms of greenwashing This is done by portraying Israel as environmentally progressive and land conscious while simultaneously denying Palestinian indigeneity and portraying them as “backward” or “primitive,” and therefore less deserving of that land, reinforcing Israel’s claim to it This is juxtaposed by Israel’s severely detrimental effects on the environment, as well as organizations and settlers that repurpose the land in a way it was not meant for. For example in November 2023, at COP28 in Dubai, Gideon Behar, a special convoy for climate change and sustainability, claimed that Israel’s “biggest contribution to the climate crisis comes in the forms of “solutions” due to the presence of a climate technology industry with carbon capture and storage, water harvesting infrastructure, and the implementation of more plant-based meat.7 However, Israel has released several tons of carbon emissions through military activity, much more than Palestine; in 2019, seven million metric tons of carbon dioxide was released from the military alone, which was 55% more emissions than the whole of Mandatory Palestine.7

Another example of greenwashing is a nonprofit called the Jewish National Fund, which controls around 11% of Palestinian land.5 It has uprooted thousands of Palestinian olive trees, an integral part of the ecosystem, and has planted more than 250 million imported, non-native trees in their place to “make the desert bloom.” This prevents villagers from returning to their homes, “while also hiding the evidence that those homes ever existed,” according to the Washington Report on Middle East Affairs 12 Furthermore, illegal settlers in the occupied West Bank often uproot Palestinian olive trees in olive groves and agricultural plots, sometimes during harvest season.14 In Hebron, certain areas in Palestine are polluted with garbage that Israeli settlers constantly throw down at them from their settlements.15 These behaviors are only an aspect of the increasingly brutal settler violence that Palestinians in the West Bank face.

Olives hold deep cultural significance not only to the people of Palestine but in the wider Levant, including Lebanon and Syria. To the Palestinians, they are a symbol of peace, rootedness, and connectedness to the land. The uprooting of these native olive trees is a violent colonial tactic that not only destroys the native ecosystem but also attempts to deny any existence of Palestinian culture and indigeneity to this land. Indigenous peoples know their native plants and cherish them; colonists often do not. In an attempt to establish their claim to Palestinian land in the West Bank and deny Palestinian culture, illegal settlers and Israeli soldiers uproot the plants native to the land itself.

“After the partition plan and the Nakba, Palestinians lost much of their agricultural land to the Israeli State, the value of which is estimated to be $5 billion by today’s standards.”

Before the establishment of the State of Israel, Palestinians had a flourishing economy based on agriculture, producing wheat, barley, olives, citrus fruits 12 (Yaffa is known for their oranges), and more, which comprised up to 40% of their agricultural exports in the early 20th century. They grew vegetables, including potatoes, and often used systems of subsistence farming. After the partition plan and the Nakba, Palestinians lost much of their agricultural land to the Israeli State, the value of which is estimated to be $5 billion by today’s standards 16

Zionism is a form of colonialism that disrupts Palestinian indigenous practices and violently uproots people from their land in the name of supposed safety To understand social and environmental justice movements, we must come from an understanding of what colonialism is, how it has impacted indigenous communities, and how it has resulted in a loss of indigenous practices that care for the land; Palestine is no exception. To understand colonialism is to understand the exploitation of land and the devastating impacts it holds over the environment and the native peoples and people of color who are disproportionately affected by environmental abuses We cannot call for the safety of all people as long as this colonial system that has resulted in apartheid, genocide, and ethnic cleansing continues to ravage the Palestinian people. No one can ever truly be safe in the Holy Land as long as these systems are still in place. If we want safety, justice, and freedom for all peoples, regardless of ethnicity, nationality, religion, or skin color, we must dismantle these systems of oppression that devalue and dehumanize Palestinian life. Global justice and freedom for all can be secured when we recognize that we must all be free We must understand that a ceasefire is not enough; we need justice, clarity, and a right of return for the Palestinian people There is no more “progressive” without Palestine None of us are free from oppression until the Palestinians are.

9. References

1.

Usaid Siddiqui, “In Numbers: 200 Days of Israel’s War on Gaza,” Al Jazeera, April 23, 2024, https://www .aljaz eera.com/news/2024/4/23/by-the-numbers-200-days-of-israels-war-on-gaza.

2.

OHCHR, “Gaza: ICJ Ruling Offers Hope for Protection of Civilians Enduring Apocalyptic Conditions, Say UN Experts,” n.d., https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2024/01/gaza-icj-ruling-offers-hopeprotection-civilians-enduring-apocalyptic#:~:text=The%20ICJ%20found%20it%20pla usible,under%20sie ge%20in%20Gaza%2C%20and.

3 “Israel: White Phosphorus Used in Gaza, Lebanon,” Human Rights Watch, October 13, 2023, https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/10/12/israel-white-phosphorus-used-gaza-lebanon.

Lottie Limb, “The UN Is Investigating the Environmental Impact of the War in Gaza. Here’s What It Says so Far,” Euronews, March 6, 2024, https://www.euronews.com/green/2024/03/06/the-un-isinvestigating-the-environmental-impact-of-the-war-in-gaza-heres-what-it-says-so-

4. Isaiah, “War Has Poisoned Gaza’s Land and Water. Peace Will Require Environmental Justice.,” The Century Foundation, December 19, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/war-has-poisonedgazas-land-and-water-peace -will-require-environmental-justice/

5. Amali Tower, “The Not-So-Hidden Climate Risks for Gaza’s Displaced Climate Refugees,” Climate Refugees, February 19, 2024, https://www climaterefugees org/spotlight/2023/1/11/gaza#:~: text=In%20addition%20to%20the%20humanitarian,anywhere%20else%20in%20the%20world.

6. Nina Lakhani, “Emissions From Israel’s War in Gaza Have ‘Immense’ Effect on Climate Catastrophe,” The Guardian, January 10, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/jan/09/emissions-gazaisrael-hamas-war-climatechange#:~:text=3%20months%20old-,Emissions%20from%20Israel's%20war%20in%20Gaza,immen se'%20effect%20on%20climate%20catastrophe&text=The%20planet%2Dwarming%20emissions%2 0generated,vulnerable%20nations%2C%20new%20research%20reveals

7. Glenn Scherer, “Cradle of Transformation: The Mediterranean and Climate Change,” Mongabay Environmental News, April 28, 2022, https://news.mongabay.com/2022/04/cradle-of-transformationthe-mediterranean-and-climate-change/.

8. Amnesty International, “The Occupation of Water,” August 5, 2022, https://www.amnesty org/en/latest/campaigns/2017/11/the-occupation-of-water/

10. Amnesty International, “Chapter 3: Israeli Settlements and International Law,” July 29, 2021, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/campaigns/2019/01/chapter-3-israeli-settlements-and-internationallaw/#:~:text=Most%20states%20and%20international%20bodies,are%20illegal%20under%20internati onal%20law.

11 Conflict and Environment Observatory, “Tree Planting as Resistance in Palestine,” CEOBS, September 8, 2021, https://ceobs.org/tree-planting-as-resistance-in-palestine/.

12. WRMEA, “Film Uncovers Truth About JNF’s Tree Planting in Israel,” August 18, 2023, https://www.wrmea.org/israel-palestine/film-uncovers-truth-about-jnfs-tree-planting-in-israel.html.

13. “Food Insecurity in Palestine: A Future for Farmers,” Wilson Center, n.d., https://www.wilsoncenter.org /article/food-insecurity-palestine-future-farmers.

14. Doha Asous, “‘They Ransack Our Village for Sport’: One Palestinian Farmer’s Story of Israeli Settler Violence,” The Guardian, March 10, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/mar/05/palestinian-farmer-israeli-settlers-west-bank-wipedout-olive

15. AJ+, “How Israeli Apartheid Destroyed My Hometown,” October 27, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aEdGcej-6D0.

16. Wikipedia contributors, “History of Agriculture in Palestine,” Wikipedia, April 22, 2024, https://en.wikip edia.org/wiki/History of_agriculture_in_Palestine.

Tijuana’s aging sewage infrastructure has resulted in significant coastal water pollution, leading to prolonged beach closures and heightened health risks across the California-Mexico border. Recreational exposure to polluted water contributes to approximately 90 million cases of water-related illness annually in the US (DeFlorio-Barker, Wing, et al , 2018) While the South Bay International Wastewater Treatment Plant (SBIWTP)

Expansion Project aims to double sewage treatment capacity in the US, the current proposal focuses primarily on physical infrastructure improvements, lacking funds for community outreach and research. This brief advocates for a more comprehensive approach that integrates physical infrastructure improvements with community involvement to reduce human exposure to pollutants in the ocean and health risks.

Over the past four decades, Tijuana, Mexico, has seen substantial population and industrial growth, leading to rapid urbanization This expansion has strained the aging sewage infrastructure in the region over time, causing recurring sewage issues. Sewage problems involve Mexicangenerated sewage flowing into California impacting water quality and posing health risks to people on both sides of the border.

The San Diego South Bay and Tijuana region has significant water quality issues due to inflows of untreated sewage from two sources: the Tijuana River Estuary (TJRE) and the San Antonio de los Buenos outfall at Pt. Bandera (SAB/PTB) (Fedderson, et al , 2021)

Over the past five years alone, 100 billion gallons of toxic waste have flowed into US coastal waters from Tijuana (Murga, 2023). The contaminated water has resulted in the closure of local beaches for over 700 consecutive days (Rios, 2023)