SOUTHERN SEMINARY MAGAZINE

v90 n2 4 Confessional Integrity in A Time of Theological Crisis R.

JR. 20 A Confessional People and Their Confession of Faith PETER BECK 36 A Confessing People JOE HARROD We Believe CONFESSING OLD TRUTHS IN A NEW AGE

ALBERT MOHLER

The D.Min. is an extension of your current ministry, not a distraction from it. It’s about helping church leaders improve what you’re actively doing every day—faithfully ministering in the place you’ve been called. With professors that are practitioners as well as scholars, you can be sure that every aspect of your education is designed to fully equip you for more faithful service.

2825 Lexington Road Louisville, KY 40280

SOUTHERN SEMINARY MAGAZINE VOLUME 90, NUMBER 2: WE BELIEVE: CONFESSING OLD TRUTHS IN A NEW AGE SBTS.EDU

MPresident’s Message

r. albert mohler jr.

artin Luther rightly observed that the church house is to be a “mouth house” where words, not images or dramatic acts, stand at the center of the church’s attention and concern. We live by words, and we die by words.

Truth, life, and health are found in the right words. Paul will instruct Timothy that sound words come to us in a revealed pattern. “Follow the pattern of sound words that you have heard from me, in the faith and love that are in Christ Jesus. By the Holy Spirit who dwells within us, guard the good deposit entrusted to you” (2 Tim. 1:13–14).

Theological education is a deadly serious business. The stakes are so high. A theological seminary that serves faithfully will be a source of health and life for the church, but an unfaithful seminary will set loose a torrent of trouble, untruth, and sickness upon Christ’s people. Inevitably, the seminaries are the incubators of the church’s future. The teaching imparted to seminarians will shortly be inflicted upon congregations, where the result will be either fruitfulness or barrenness, vitality or lethargy, advance or decline, spiritual life or spiritual death.

Sadly, the landscape is littered with theological institutions that have poorly taught and have been poorly led. Theological liberalism has destroyed scores of seminaries, divinity schools, and other institutions for the education of the ministry. Many of these schools are now extinct, even as the churches they served have been evacuated. Others linger on, committed to the mission of revising the Christian faith to make peace with the spirit of the age.

How does this happen? Rarely does an institution decide, in one comprehensive moment of decision, to abandon the faith and seek after another. The process is far more dangerous and subtle. A direct institutional evasion would be instantly recognized and corrected, if announced honestly at the onset. Instead, theological disaster usually comes by means of drift and evasion, shading and equivocation. Eventually, the drift

accumulates into momentum, and the school abandons doctrine after doctrine, truth claim after truth claim, until the pattern of sound words, and often the sound words themselves, are mocked, denied, and cast aside in the spirit of theological embarrassment.

As James Petigru Boyce, founder of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, argued, “It is with a single man that error usually commences.” When he wrote those words in 1856, he knew that pattern by observation of church history. All too soon, he would know this sad truth by personal observation.

By the time Southern Baptists were ready to establish a theological seminary, many schools for the training of ministers had already been lost to theological liberalism. Drawing upon the lessons of the past, Southern Baptists were determined to establish schools bound by covenant and constitution to a confession of faith—to the pattern of sound words.

Confessional seminaries require professors to sign a statement of faith, designed to safeguard by explicit theological summary. The sad experience of fallen and troubled schools led Southern Baptists to require that faculty members must teach in accordance with the confession of faith and not contrary to anything therein.

We are living in an anti-confessional age. Our society and its reigning academic culture are committed to individual autonomy and expression as well as to an increasingly relativistic conception of truth. The language of higher education is overwhelmingly dominated by claims of academic freedom rather than academic responsibility. But, among us, a confession of faith must be seen as a gift and covenant. It is a sacred trust that guards revealed truths. A confession of faith never stands above the Bible, but the Bible itself mandates concern for the pattern of sound words.

1 fall 2022

@ALBERTMOHLER

ALBERTMOHLER.COM

The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary

from the editor

JEFF ROBINSON

A little over 25 years ago, I embraced confessional evangelical Christianity after attending a church that was rather proud of the fact that it had no confession of faith. The church adopted a slogan in place of a confession, a slogan attributed to various well-known figures from church history: “In essentials, unity; in non-essentials, liberty; in all things, charity.”

To modern ears, that cliché has a ring of wisdom, but here’s the problem: the essentials and non-essentials were intentionally left undefined.

The consequences of the church’s theological murkiness emerged in a conversation I had with a man in the final few months I attended this church.

One Sunday morning I greeted a man who’d been visiting for several weeks and for the past two weeks sat in the back of Sunday school class I taught. I asked him where he had been attending church, and he answered: “I’ve been going to the Mormon church for many years now.” I was stunned. Aware of the monumental distance between Mormon doctrine and what the people in our church believed, I asked him what made him comfortable attending

an evangelical church. “You don’t seem to make anyone believe any particular doctrines, and I find that attractive.”

Almost instantly, I was transformed into a budding confessional Christian. I realized that if a church stands for everything, then it stands for nothing. A church or evangelical institution needs to communicate its theological and ethical convictions to a watching world for numerous reasons, not the least of which being so it can establish precisely what it believes about God and man and Scripture and salvation and much more.

As you will learn or be reminded in this issue of the Southern Seminary Magazine, we believe that a healthy church or a healthy seminary is one that clearly confesses what it believes and then commits to teach in accord with and not contrary to that statement of faith. The Bible teaches a very certain body of truth that is able to make one “wise unto salvation,” and a strong confession of faith will make those things clear.

In an age that denies the very possibility of absolute truth, an age that prefers a sentimental form of love to doctrinal precision, there is no place for ambiguity on such vital matters.

Fall 2022. vol. 90, no. 2. Copyright ©2022

The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary

Vice President of Communications:

Dustin W. Benge

Managing Editor: Jeff Robinson

Copy Editor: C. Rebecca Rine

Creative Director: Stuart Hunt

Production Manager: Evan Sams

Graphic Designers: Dustin Benge, Stuart Hunt, Benjamin Aho

Photographer: Trevor Wheeker

Contributing Writers: R. Albert Mohler Jr., Peter Beck, Eric C. Smith, Joe Harrod, Stephen Presley, Raymond Johnson, Jarvis Williams, Jeff Robinson, Travis Hearne

Subscription Information:

Southern Seminary Magazine is published by the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2825 Lexington Road, Louisville, KY 40280. The magazine is distributed digitally at equip.sbts.edu/magazine. If you would like to request a hard copy, please reach out by emailing communications@sbts.edu

Mail:

The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2825 Lexington Road, Louisville, KY 40280 Online: www.sbts.edu Email: communications@sbts.edu Telephone: 800-626-5526, ext. 4000

@TheSBTS @SBTS @SouthernSeminary

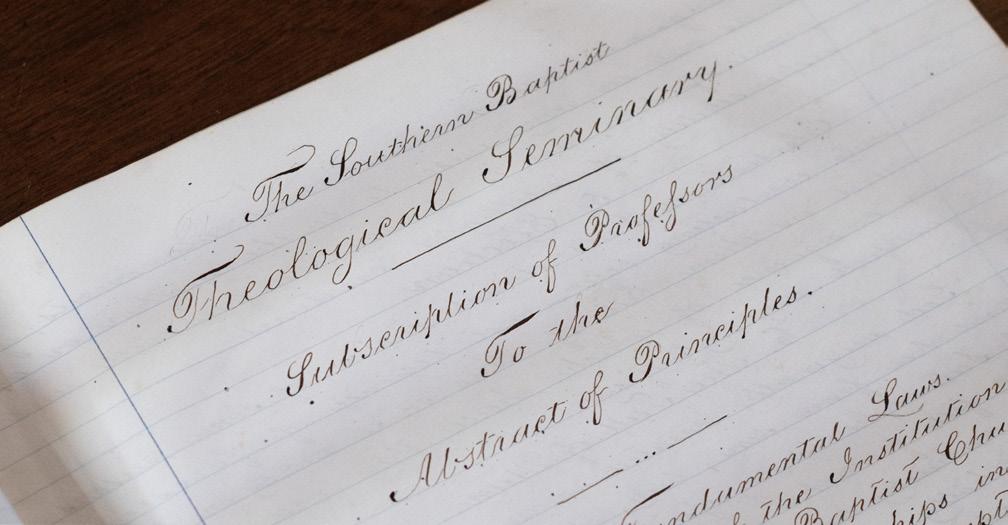

About the Cover:

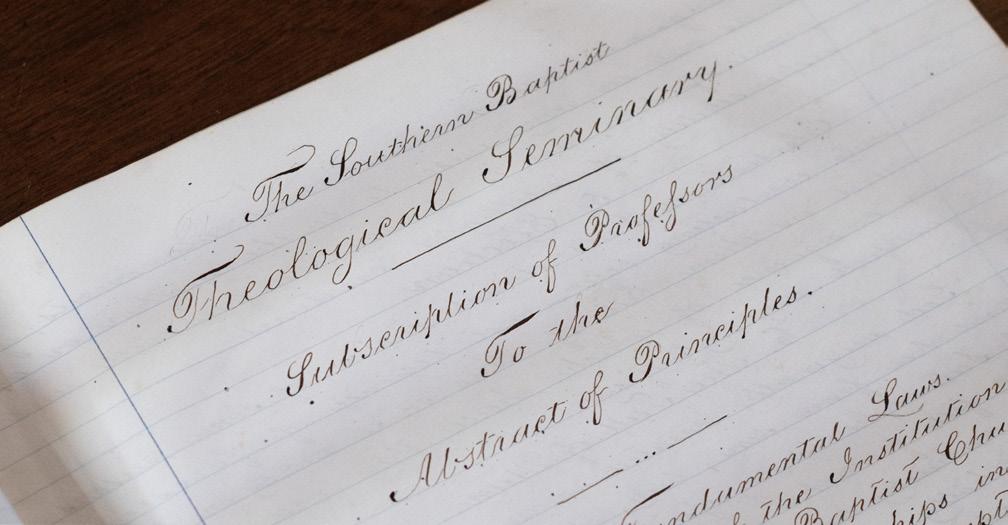

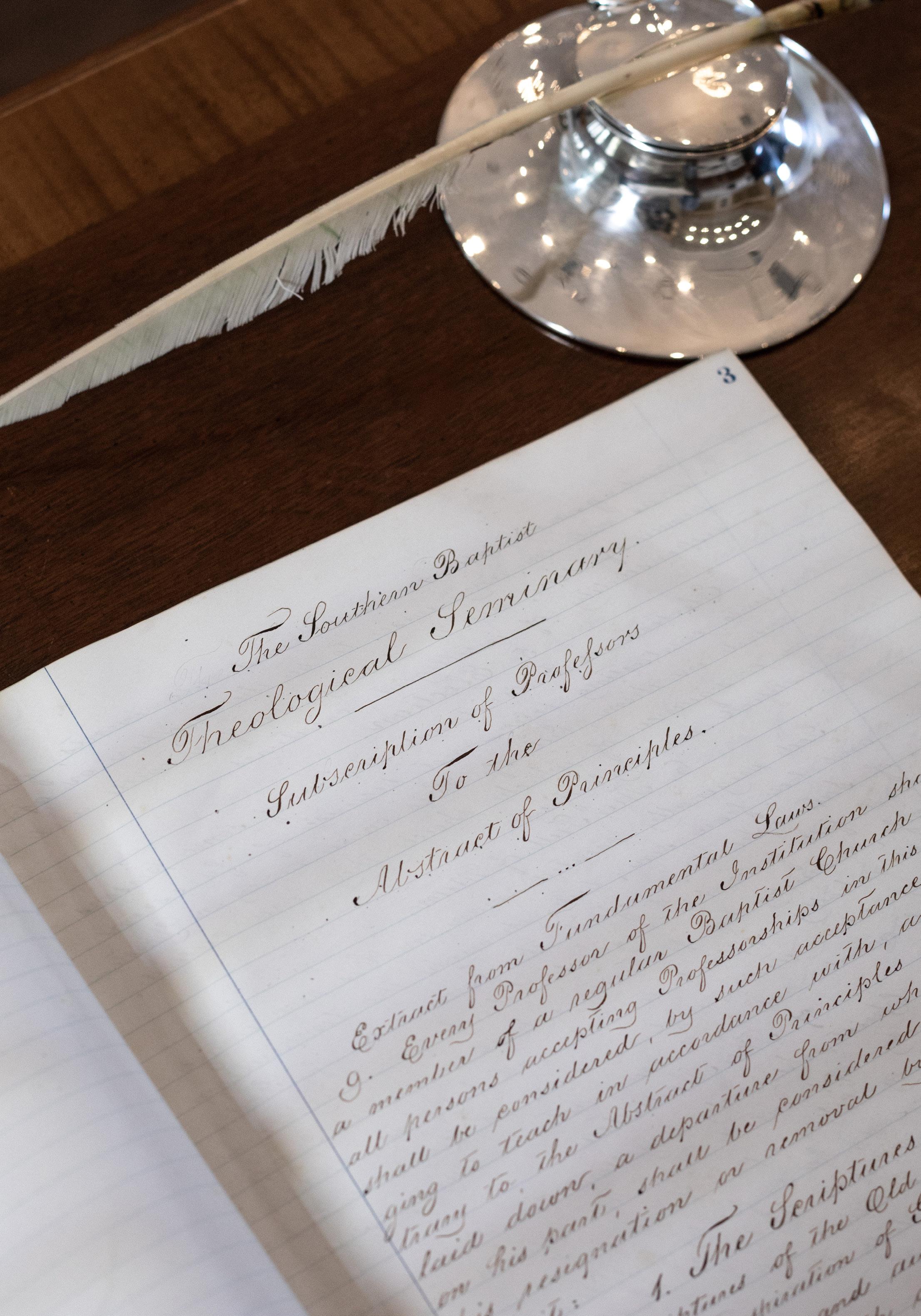

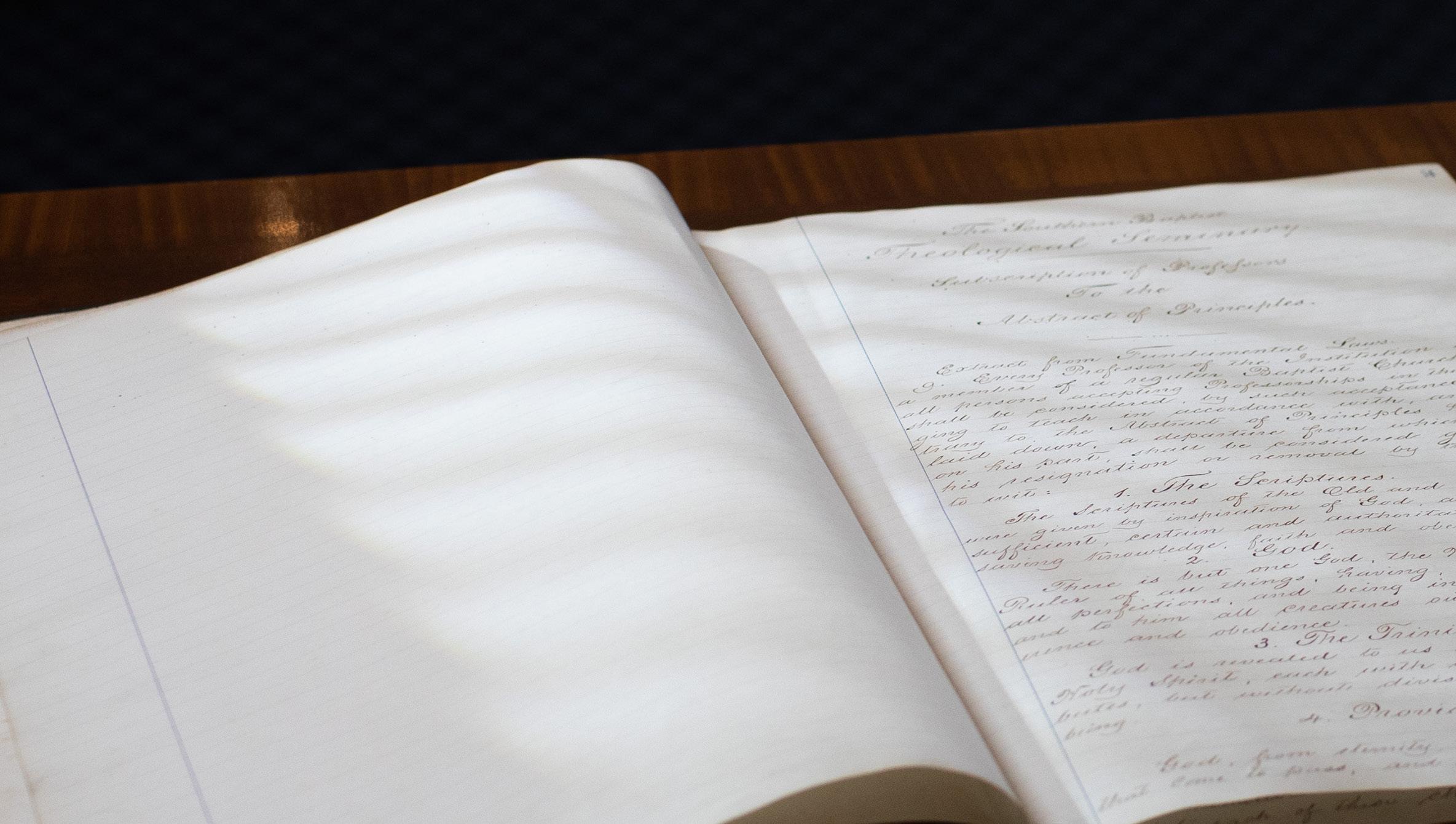

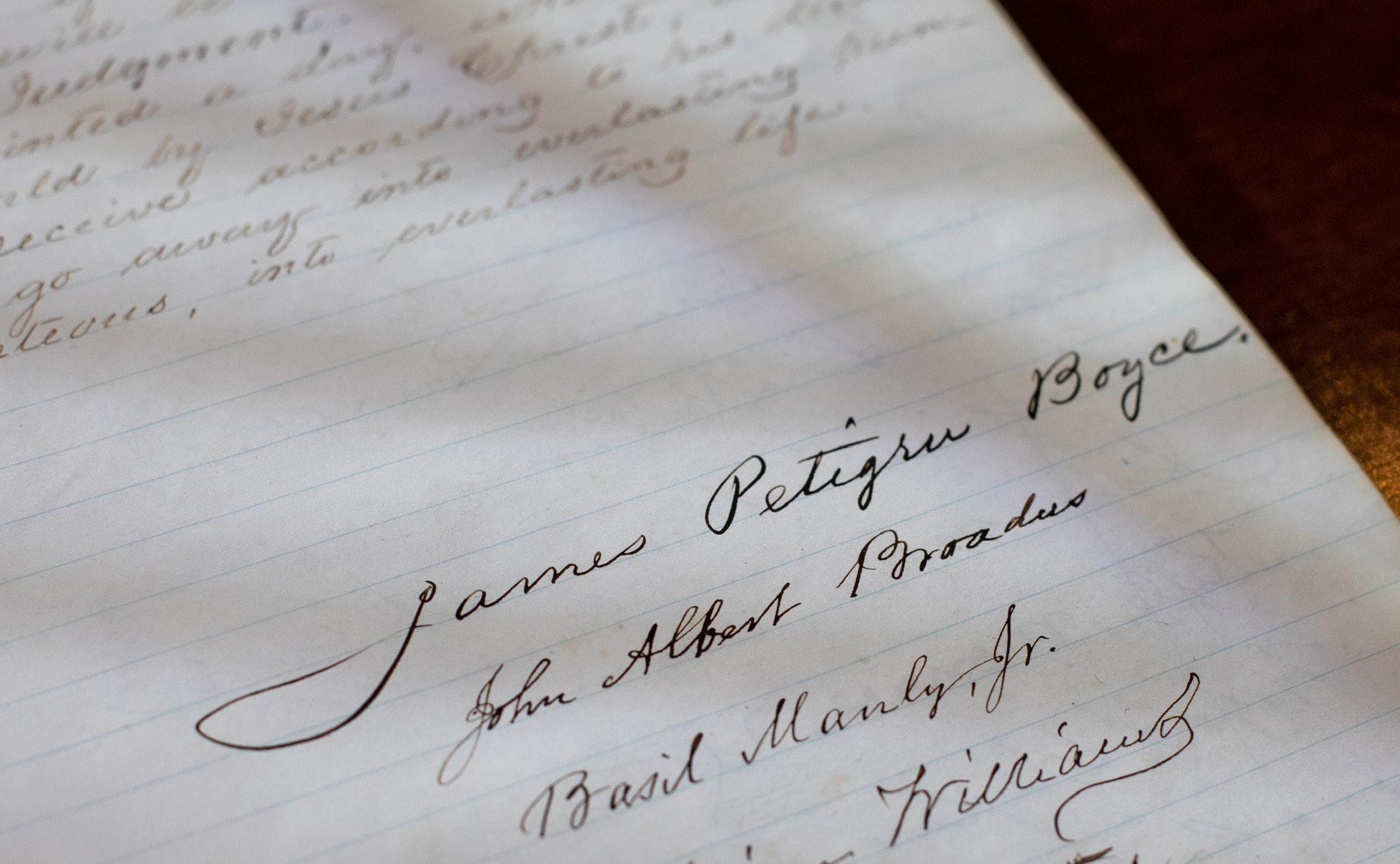

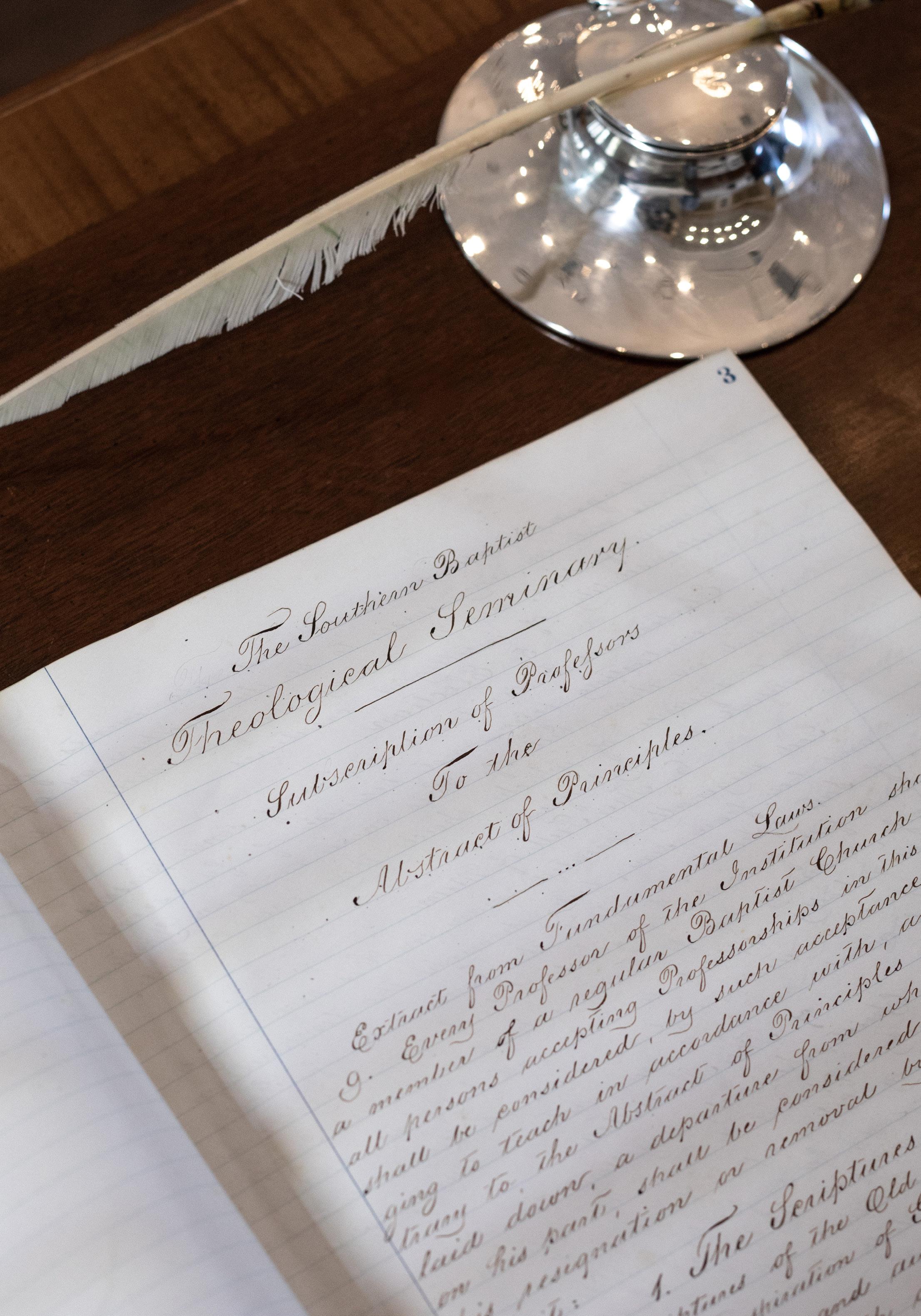

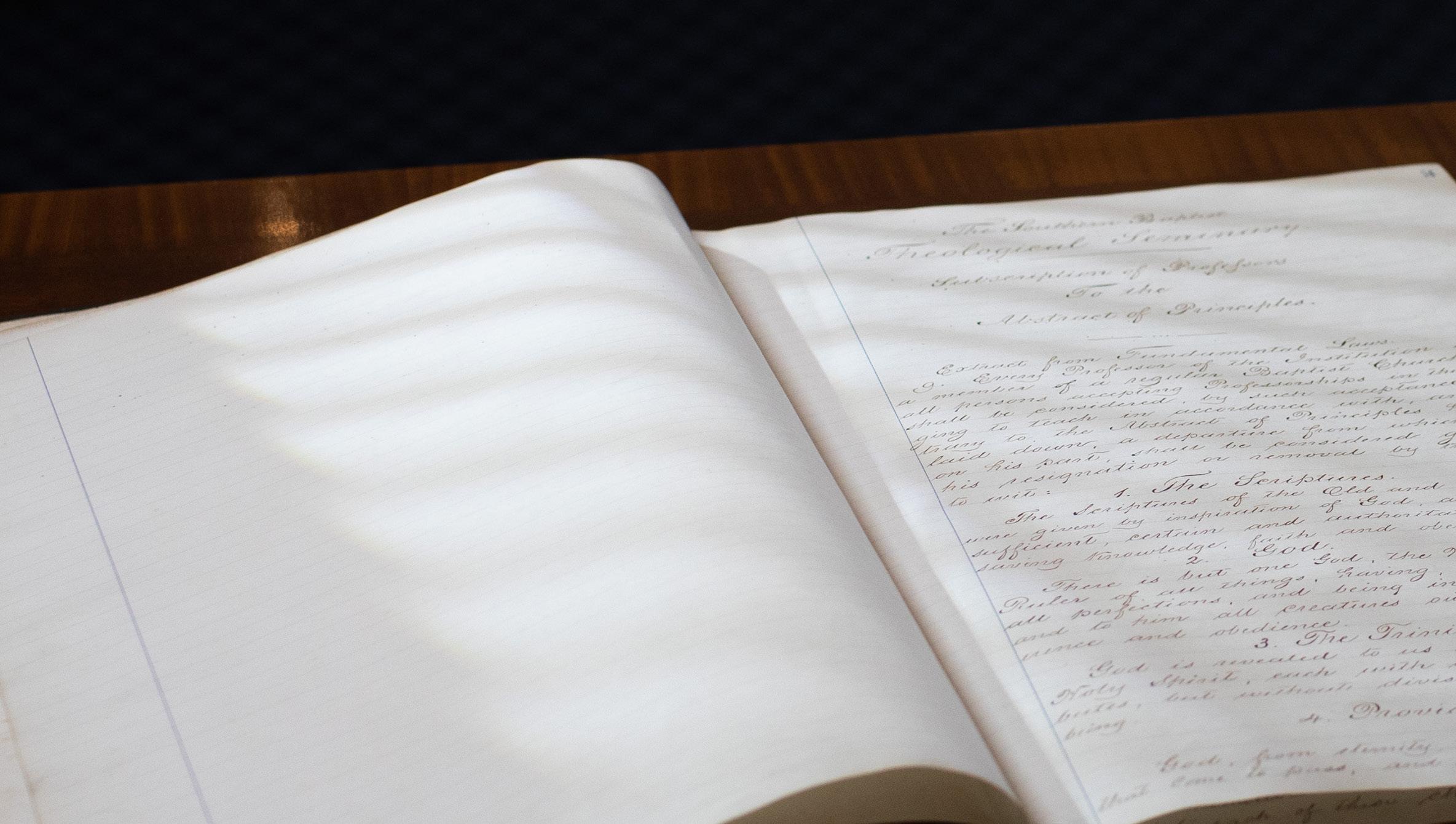

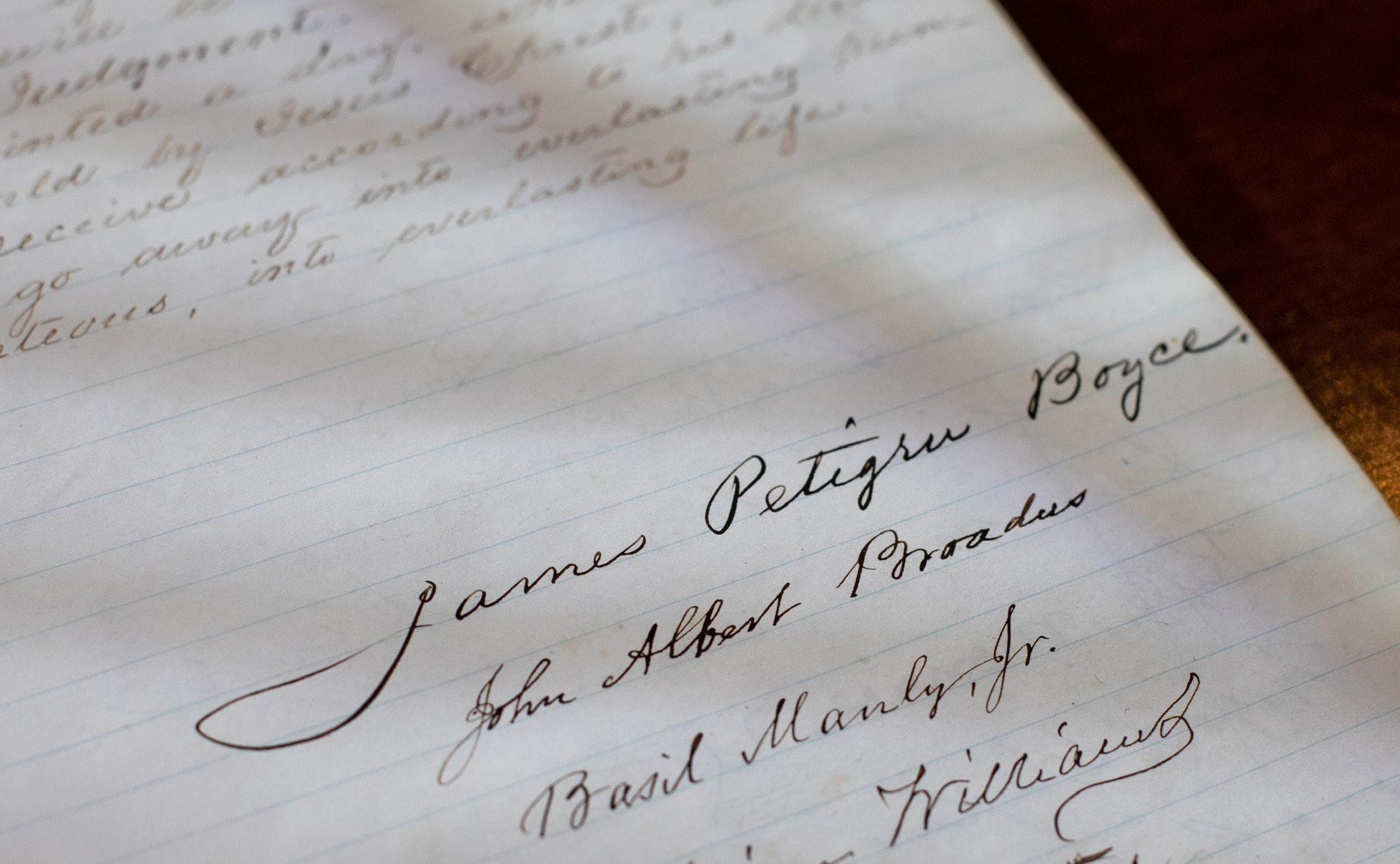

The original Professors’ Subscription Book to the Abstract of Principles, Southern Seminary’s confession of faith. Every professor on the SBTS’ faculty agrees to “teach in accord with and not contrary to” the Abstract. It was written and adopted in 1858 as part of the seminary’s original charter.

2 the southern baptist theological seminary

R. Albert Mohler Jr.

R. Albert Mohler Jr.

am

R. Albert Mohler Jr.

by Peter Beck

by Eric C. Smith

by Peter Beck

by Eric C. Smith

3 fall 2022 1 president’s message 2 from the editor 32 six ways confessions promote church health by Jeff Robinson 36 a confessing people: a brief history of baptist confessions of faith by Joe Harrod 42 how did the fathers use creeds? by Stephen Presley 45 how do you cast a confessional vision in a nonconfessional church? by Raymond Johnson contents WE BELIEVE • CONFESSING OLD TRUTHS IN A NEW AGE v90 n2 4 Confessional Integrity in a Time of Theological Crisis THE ABSTRACT OF PRINCIPLES THEN AND NOW by

48 how narrow should a confession be? by Jeff Robinson 52 seminary wives institute: 25 years of god’s faithfulness by Jeff Robinson 57 news & features 62 faculty books 64 gospel light shines on my old eastern kentucky home by Jarvis J. Williams 10 Don’t Just Do Something; Stand There! SOUTHERN SEMINARY AND THE ABSTRACT OF PRINCIPLES

20 “I

Southern

A CONFESSIONAL PEOPLE AND THEIR CONFESSION OF FAITH

26 1922: Northern Baptists Lose Their Confession

by

Baptist”:

redeeming the time with

r . albert mohler jr .

FConfessional Integrity in a Time of Theological Crisis: The Abstract of Principles Then and Now

r . albert mohler jr .

rom the very beginning, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has been a confessional institution. Every professor must sign our confession of faith, the Abstract of Principles, agreeing to teach “in accordance with and not contrary to all that is contained therein.” This pledge has remained unchanged since 1859, but the history of Southern Seminary is a history with many twists and turns. The men who founded Southern Seminary understood themselves as confessional Protestants standing in a line of theological orthodoxy that found its quintessential shape in the Reformation of the 16th century and the Princeton Theology of the 19th century. They were also unapologetically

Baptist, and they perceived the need for a Baptist seminary in the South that would serve as the great central theological institution for the expanding Southern Baptist Convention. Though the convention was established in 1845, the dream of a seminary would be deferred until 1859.

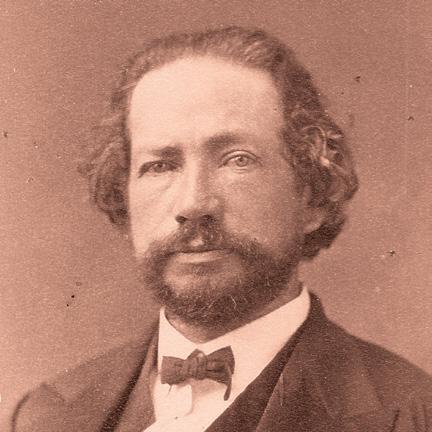

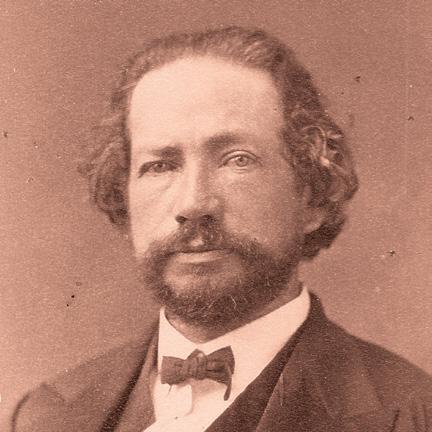

Basil Manly Sr., long pastor of First Baptist Church in Charleston, South Carolina, had urged Southern Baptists to establish a seminary, but it was a young man from his own congregation, James Petigru Boyce, who would become the driving force in Southern Seminary’s founding and, for many years, its very existence. On July 31, 1856, Boyce, then a new professor of theology at Furman University, would deliver the address that became the Magna Carta of Southern Seminary,

5 fall 2022

“Three

Changes in Theological Institutions.”

Boyce called for a central theological institution that would serve the entire denomination and beyond. He drew upon his experience at Princeton Theological Seminary, but he went beyond the Princeton model in calling for one school that would offer all ministers some level of theological education and would also offer the highest level of academic achievement available anywhere in the world. Such an institution would require, Boyce advised, an excellent faculty and adequate support, including a great theological library.

But Boyce’s third major point in his address was a warning that theological education must be guarded by a clear confession of faith, required of all faculty. Already, a host of theological schools had been lost to various heresies and the influence of theological liberalism—starting with Harvard Divinity School, founded in orthodoxy but largely lost to Unitarianism by the end of the 18th century. Basil Manly Jr., another of the founding faculty, had been urged by his father to leave the Newton Theological Institute, a Baptist school in Massachusetts, and to enroll at Princeton, a Presbyterian school, because Princeton was more orthodox and held to a higher view of the Bible. Boyce saw a theological crisis on the horizon:

A crisis in Baptist doctrine is evidently approaching, and those of us who still cling to the doctrines which formerly distinguished us, have the important duty to perform of earnestly contending for the faith once delivered to the saints. Gentlemen, God will call us to judgment if we neglect it.1

Boyce called for a confession of faith, clear and explicit, that would define the theological commitments of the school and its faculty. Every faculty member would be required not only to sign the statement but to believe all that it contained, without reservation. In his words:

But of him who is to teach the ministry, who is to be the medium through which the fountain of Scripture truth is to flow to them—whose opinions more than those of any living man, are to mold their conceptions of the doctrines of the Bible, it is manifest that much more is requisite. No difference, however slight, no peculiar sentiment, however speculative, is here allowable. His agreement with the standard should be exact. His declaration of it should be based on no mental reservation, upon no private understanding with those who immediately invest him into office; but the articles to be taught having been fully and distinctly laid down, he should be able to say

from his knowledge of the Word of God, that he knows these articles to be an exact summary of the truth therein contained. If the summary of truth established be incorrect, it is the duty of the Board to change it, if such change be within their power; if not, let an appeal be made to those who have the power, and if there be none such, then far better is it that the whole endowment be thrown aside than that the principle be adopted that the Professor sign any abstract of doctrine with which he does not agree, and in accordance with which he does not intend to teach. No Professor should be allowed to enter upon such duties as are there undertaken with the understanding that he is at liberty to modify the truth, which he has been placed there to inculcate.2

Boyce had learned that pattern of confessional subscription at Princeton Theological Seminary, where he was influenced by the example set by that institution and the arguments taught by Professor Samuel Miller. Miller warned especially against the right of a professor to sign the confession with reservations or by a private understanding with those who assign him to teach.3 Princeton Theological Seminary’s own historic charter and bylaws required the professors to “solemnly promise to engage not to inculcate, teach, or insinuate anything which shall appear to me to contradict or contravene, either directly or indirectly, any thing taught in the said confession of faith or catechism … while I shall continue a Professor in this Seminary.”4

All this should indicate beyond question that confessional subscription was to be without any “hesitation or mental reservation,” in Boyce’s words, and without any private understanding between a faculty member and the president or Board of Trustees.

And yet, by the time I arrived at Southern Seminary as a student in 1980, that understanding of confessional commitment was absent from the majority of the faculty. Indeed, some professors openly expressed their disagreement with the Abstract of Principles. In my second year I took Systematic Theology with Professor Dale Moody, a titanic figure, who passed out his own revision of the Abstract early in the term.5 Moody considered himself a biblicist who would not defer to any human confession of faith over his own interpretation of the Scriptures. He also claimed to have entered the faculty in the 1940s by a private understanding with President John R. Sampey over Article XIII, “Perseverance of the Saints.”

As a student, I was surprised by Professor Moody’s candor, to say the least. At the same time, I was also aware that many other faculty members contradicted the

6 the southern baptist theological seminary

confessional integrity in a time of theological crisis

confession without Moody’s candor.

By the early 1970s open theological warfare broke out within the Southern Baptist Convention, and by the time I arrived as a seminary student, Southern Seminary was a prime battlefield. The Abstract of Principles was once again the focus of controversy, as Dale Moody was terminated from his teaching contract by President Roy L. Honeycutt due to Moody’s open contradiction of the Abstract of Principles. Nevertheless, the majority of the faculty expressed opposition to the Abstract as a regulative confession, and many argued in public that the statement of faith was open to individual interpretation. In essence, the argument was that the only way a professor could be found in conflict with the confession of faith is for the professor to declare that conflict.

That argument was made repeatedly in a book by retired Southern Seminary professors published in 1993 by Review & Expositor, then the Seminary’s faculty journal. Professor Dale Moody directly addressed the Abstract of Principles yet again. He recited the controversy that led to his termination and claimed that three successive presidents of Southern Seminary (John R. Sampey, Ellis Fuller, and Duke K. McCall) had allowed him to offer revisions or footnotes to the Abstract when signing it. Professor Willis Bennett, who had also served as provost of the seminary, looked back to his interview

with the Academic Personnel Committee of the Board of Trustees: “In 1959, when I was interviewed by a trustee committee before my election to the faculty, I was questioned about the confessional statement of the seminary, the Abstract of Principles. I provided my own interpretation and my comments satisfied the trustees. They viewed the Abstract, as did I, as a broad statement which provided room for differences of opinion while still accepting the parameters.”6 The problem is that while differences of opinion were certainly allowed, open conflict with the clear language of the Abstract was also allowed, and sometimes celebrated.

The issues of biblical inerrancy, inspiration, and authority were central to the controversy that so reshaped the Southern Baptist Convention in the last decades of the 20th century and into the 21st, but the controversy also ranged across the full spectrum of theological issues.

When the search committee looking for a new president came to me in 1993, a conservative majority on the Board of Trustees was looking to elect a conservative president. By that point, a majority of trustees had come to understand and affirm the necessity of reforming the seminary and of recovering theological orthodoxy. Many did not yet understand the centrality of the Abstract of Principles to that process.

Early in 1993, the search committee identified four

“I understood that one of my most significant responsibilities as the new president was to make the confessional nature of the seminary unmistakably clear. I also understood that the convocation message traditionally presented by the president for the opening of the new academic year was the right moment for such a public declaration.”

7 fall 2022

r . albert mohler jr .

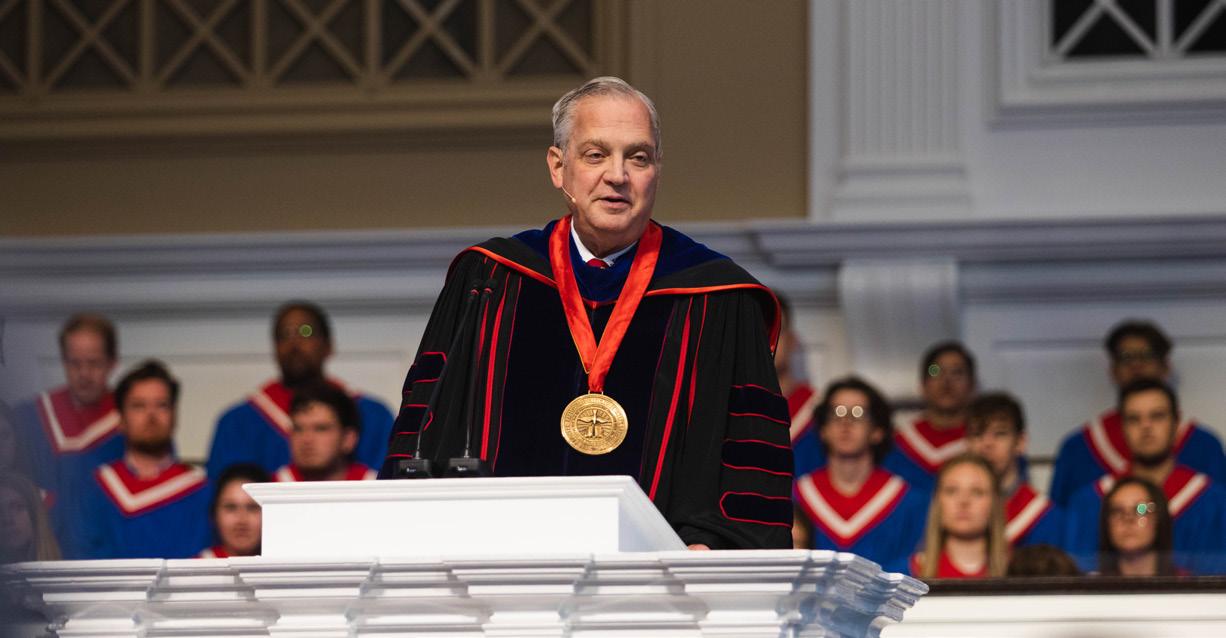

candidates to be interviewed. I was one of the four. In preparation for the interview, we were each asked for a statement on the Abstract of Principles. In response, I submitted a 42-page commentary covering each article of the confession. In the many hours of interview, I made clear that orthodoxy would require confessional correction, as understood by James P. Boyce and the other founders. The search committee eventually invited me to accept their nomination, and I made the same presentation over many hours with the full Board of Trustees. I was elected president on March 26, 1993.

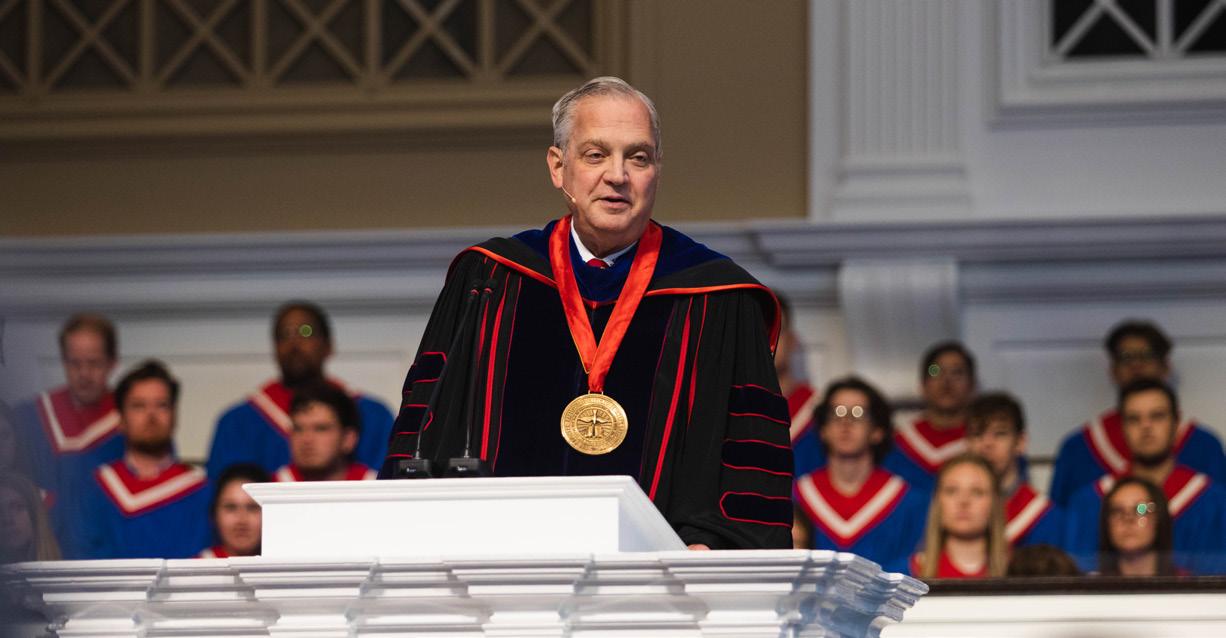

I understood that one of my most significant responsibilities as the new president was to make the confessional nature of the seminary unmistakably clear. I also understood that the convocation message traditionally presented by the president for the opening of the new academic year was the right moment for such a public declaration.

There was more to the story. I also perceived that many of the seminary’s faculty and the vast majority of the students had virtually no idea of the founders’ vision of the Abstract of Principles and no real understanding of the school’s confessional history—much less an awareness of the confessional subscription and fidelity that was so central to the seminary’s founding and still required by contract of all faculty.

Boyce had actually added to the precedent of Princeton by requiring that the Abstract of Principles be signed

by every professor, and not merely affirmed verbally. So every single member of the faculty in 1993 had signed that very statement, agreeing to teach “in accordance with and not contrary to” all that it contained. At the very least, I was going to remind them of that commitment to which they had affixed their name by their own hand. Beyond that, I wanted to make very clear the path I would take as president, bringing the school into consistency with the confession of faith.

I entitled my address, “Don’t Just Do Something; Stand There,” using an expression I remembered from reading a biography of William F. Buckley Jr. That address was my manifesto of Southern Seminary’s identity, taking us back to the crisis in Baptist doctrine that James P. Boyce saw on the horizon in 1856 and making the argument that we were then engaged in that very crisis. That address is included in this issue.

More than 25 years later, I can only thank God for what has happened at Southern Seminary in this generation. The theological recovery for which we had longed, prayed, and worked has come to pass. This very volume is evidence of that. In this generation, every professor elected to the faculty gladly signs the Abstract of Principles in full public view during a convocation and gladly teaches all that it contains. Confessional fidelity is made clear at every stage in the hiring process and is a living and public commitment held in trust by the president, the faculty, and the Board of Trustees.

8 the southern baptist theological seminary

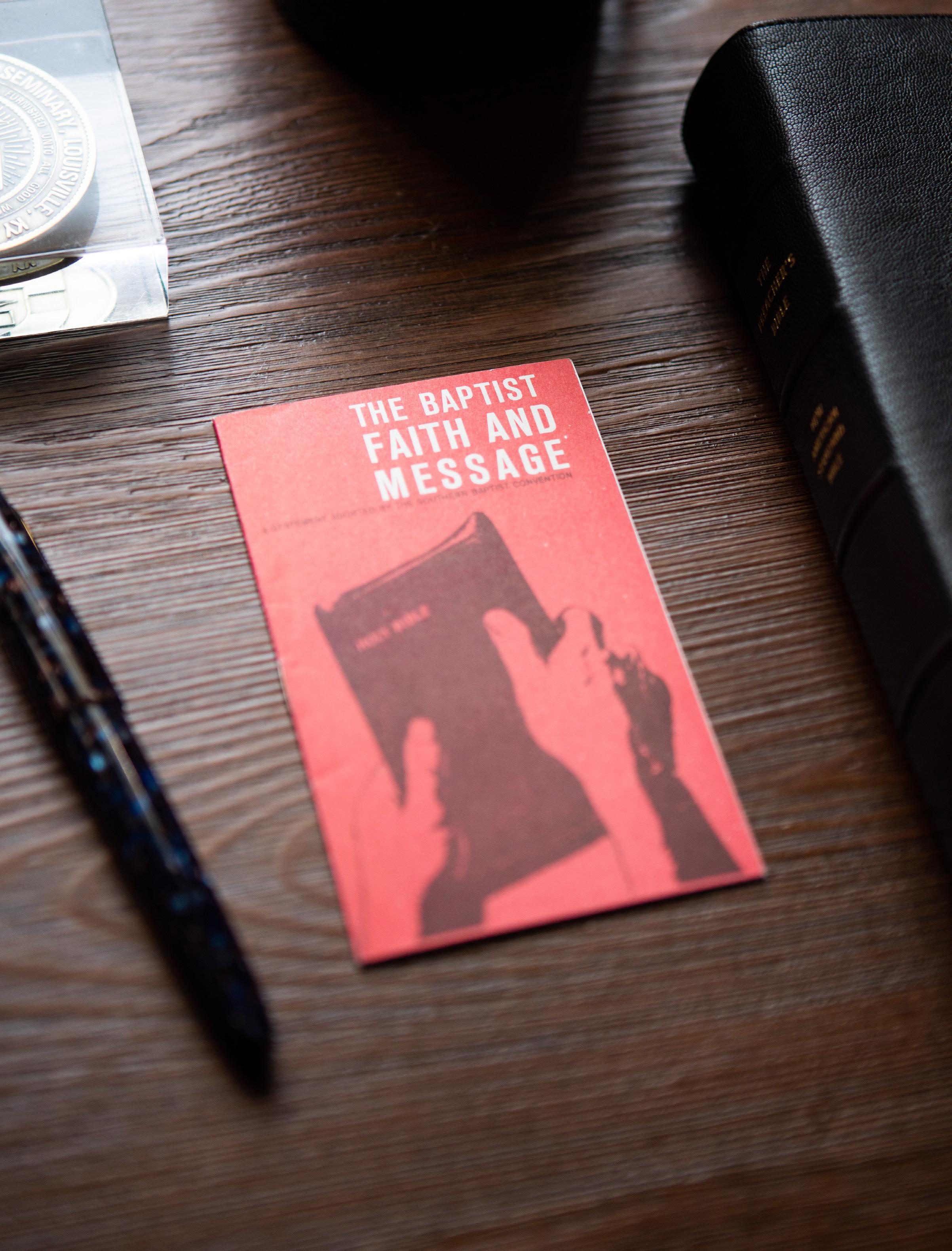

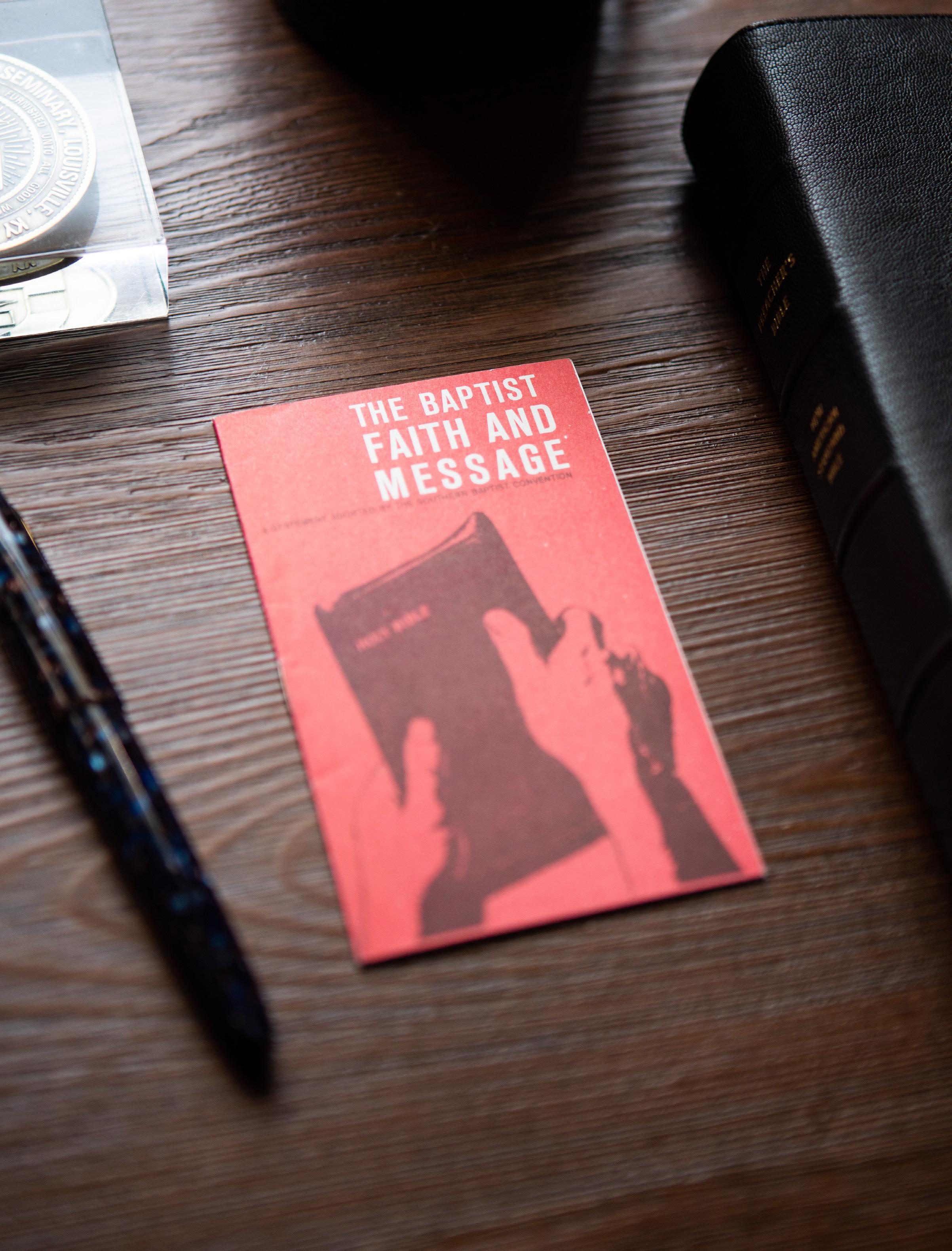

Every faculty member makes the sacred commitment to teach in accordance with and not contrary to the Abstract of Principles and the Baptist Faith and Message as adopted by the Southern Baptist Convention in 2000. We elect to this faculty only professors who are eager to teach our confessional beliefs, not those who would be merely willing to do so. Our determination is to maintain this school for evangelical orthodoxy and Baptist faithfulness for generations to come.

In 1874, James P. Boyce recalled the establishment of the seminary and the adoption of the Abstract of Principles, reminding the Southern Baptist Convention that the confession of faith had been adopted not only by the seminary’s Board of Trustees, but by the special action of the 1858 Education Convention of the Southern Baptist Convention. He also reminded Baptists that the Abstract had been adopted as a statement of doctrines held nearly universally among Southern Baptists at the time.7

The Abstract of Principles was instrumental in the recovery of this seminary. We were able to point to the moral and contractual obligation agreed to by every professor, and to the very language that the founders used to frame this sacred commitment. Thus, this commitment is more than a doctrinal exposition or devotional exercise. It is the display of public fidelity to a confession of faith, to the faith once for all delivered to the saints, and to the gospel of Jesus Christ.

R. Albert Mohler Jr. is president of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and daily host of The Briefing.

Notes

1. James P. Boyce, Three Changes in Theological Institutions: An Inaugural Address Delivered to the Board of Trustees of the Furman University, July 31, 1856 (Greenville: C. J. Elford’s Book and Job Press, 1856), 34.

2. Boyce, Three Changes, 35.

3. See Samuel Miller, “The Utility and Importance of Creeds and Confessions: An Address Delivered at Princeton Theological Seminary,” 1824.

4. “Of the Professors,” Charter and By-Laws, Princeton Theological Seminary, Article III, Section 3.

5. The fact that Professor Moody passed out this revision to students in his classes was denied by some seminary authorities at the time, but copies are contained within the Moody papers in the James P. Boyce Centennial Library, and Moody provided the same revision to the Board of Trustees in 1982. Interestingly, it later became known that President Duke K. McCall had asked at least some members of the faculty to provide proposed revisions to the Abstract of Principles in 1979, presumably in a more liberal direction. Moody responded with a long, multi-page letter, also found in the Moody papers collection. See also Gregory A. Wills, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary 1859-2009 (New York: Oxford University Press), 438-44.

6. Willis Bennett in “How I Changed My Mind: Essays by Retired Professors of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary” (Louisville: Review & Expositor, 1993), 88.

7. James P. Boyce, “Two Objections to the Seminary,” Western Recorder, June 20, 1874.

9 fall 2022

r . albert mohler jr .

10 the southern baptist theological seminary Don’t Just Do Something; Stand There! Southern Seminary and the Abstract of Principles

inaugural convocation address

A convocation address delivered by R. Albert Mohler Jr., president of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, August 31, 1993, in Alumni Memorial Chapel

“But we should always give thanks to God for you, brethren, beloved by the Lord, because God has chosen you from the beginning for salvation through sanctification by the Spirit and faith in the truth. And it was for this He called you through our gospel, that you may gain the glory of our Lord Jesus Christ. So then, brethren, stand firm and hold to the traditions which you were taught, whether by word of mouth or by letter from us.”

(2 Thess. 2:13–15, NASB)

The seminary convocation, which opens each academic year, constitutes a unique gathering of the seminary community, assembled to welcome new students and new faculty, and to solemnize the beginning of a new seminary term. The roots of such an academic convocation are found in the British universities of Oxford and Durham, where for centuries the university communities have assembled to mark the inauguration of formal studies.

At Southern Seminary, the tradition is as old as the institution itself, for the very earliest minutes of the school record formal services at the start of each academic year. A convocation of the Southern Seminary family, gathered for worship and commemoration, is a fitting hallmark of the seminary’s tradition and is the cause of our gathering this day.

Today, you have witnessed a ceremony which has been a central part of this institution’s life and commitment for 134 years—the signing of the original Abstract of Principles.

The convergence of this ceremony as the first convocation of my service as president and as the occasion of placing my own signature on this sacred document prompts me to reflect upon the meaning of this confession, on its role as the seminary’s charter of fidelity, on the priceless heritage of faithfulness of those who have preceded us, and on the responsibility we collectively bear to keep faith with this body of biblical doctrine.

Russell Reno, professor of moral theology at Creighton University, recently reflected on the role of confessions in the church:

The impulse behind confessions of faith is doxological, the desire to speak the truth about God, to give voice to the beauty of holiness in the fullest possible sense. However, the particular forms that historical confessions take are shaped by confrontation. Their purpose is to respond to the spirit of the age by rearticulating in a pointed way the specific content of Christianity so as to face new challenges as well as new forms of old challenges. As a result, formal confessions are characterized by pointed distinctions. They are exercises in drawing boundaries where the particular force of traditional Christian claims is sharpened to heighten the contrast between orthodoxy and heresy, between true belief and false belief…. As they shape our beliefs, confessions structure our identities.1

My design today—on this day, which will ever remain sacred in my memory as the occasion of my own public attestation of this confession—is for us to consider the central role of the Abstract of Principles in structuring the identity of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary.

The roots of that role are integral to the founding of this institution in the 1850s. The very idea of a central Baptist seminary was controversial then, and so it remained for over half a century. Baptists, though increasingly convinced of the need for an educated ministry, were suspicious of centralized structures and had long established a pattern of uneven cooperation in educational endeavors. The decline and loss of Columbian College was but the most celebrated embarrassment to Baptist educational efforts.

On the other hand, virtually all of the Baptist colleges and universities founded in the 19th century were established for the express purpose

11 fall 2022

of training ministers of the gospel and had developed theological departments of varying size and impact. Each had a loyal following, however, and none was ready to surrender its own institutional identity in order to meld a larger school. That was true, at least, until the rise of James Petigru Boyce.

Boyce, the son of a patriarchal South Carolina businessman and financier, brought together the threads of seminary aspiration left untied by so many others. As a 29-year-old theology professor at Furman University, Boyce delivered his inaugural address as what became the Magna Carta of Southern Seminary, “Three Changes in Theological Institutions.”

Educated at Brown University and Princeton Seminary, Boyce had followed a privileged educational pathway. In presenting his vision for a uniquely Southern Baptist theological institution, he drew from his own experiences at Brown and Princeton, his tenure as a newspaper editor, his deep rootage in what historian Walter Shurden has identified as the “Charleston Tradition” in Southern Baptist life, and the wisdom which had been imparted to him by the influence of others.

authority, was a necessary precondition to Southern Baptist support for a theological seminary.

Boyce delivered his weighty address, uncertain that Southern Baptists would ever respond to his call, but certain of his rectitude in pointing the denomination toward a vision for theological education that was open at some level to all persons, regardless of their educational preparation, offered the most strenuous programs to persons of exceptional preparation, and was firmly rooted in a confession of doctrinal principles binding upon all who would teach therein.

James

P. Boyce (1827–1888)

Southern’s First President

Among those who influenced Boyce, surely none exerted a more powerful moral, theological, and ministerial impact than Boyce’s former pastor and future trustee chairman, Basil Manly Sr. Manly, who had been pastor of First Baptist Church, Charleston, during Boyce’s boyhood, was one of the towering figures of the South, and of the Southern Baptist Convention. Manly was also an ardent confessionalist who believed that a confession of faith, clearly articulated and endowed with institutional

This last point, the third of Boyce’s three proposed changes, is our concern today. Boyce’s call was answered in the Educational Convention of 1857 and in the eventual founding of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, and Boyce was himself to be the central stack pole of the founding faculty.

But Boyce did not dream or serve alone. The most critical role in bringing the Abstract of Principles to final form was served by Basil Manly Jr., another of the four founding faculty members. The younger Manly had also enjoyed a Princeton Seminary education. Though he began his studies for the ministry at Newton Theological Institution, a Baptist school, he was directed to Princeton by his father, at least in part because Princeton was governed by a regulative confession of faith.

At Princeton, both Manly and Boyce had studied under the imposing figure of Samuel Miller, a stalwart defender of Presbyterian theological and ecclesiastical standards, who argued that “the necessity and importance of creeds and confessions appears from the consideration

“Every elected and tenured faculty member of this institution has freely and willfully affixed his or her name to this historic record and to this confession of faith.”

12 the southern baptist theological seminary

don ’ t just do something ; stand there !

that one great design of establishing a church in our world was that she might be, in all ages, a depository, a guardian, and a witness of the truth.”2

That same conviction drove Boyce, both Manlys, John A. Broadus, and those who deliberated with the, to propose an Abstract of Principles based upon the Second London Confession, which was itself a Baptist revision of the Westminster Confession. The Second London Confession had been adopted in slightly revised form by the Baptist associations in Philadelphia and Charleston and had thus greatly influenced Baptists of both the North and the South.

Writing in 1874, Boyce detailed the principles which guided the drafting committee:

The Abstract of Principles must be: 1. A complete exhibition of the fundamental doctrines of grace, so that in no essential particular should they speak dubiously; 2. They should speak out clearly and distinctly as to the practices universally prevalent among us; 3. Upon no point, upon which the denomination is divided, should the convention, and through it, the seminary, take any position.3

This explanation clarifies the Abstract’s originating process and underlines the incredible theological unity of Southern Baptists at the middle of the 19th century. The members of the drafting committee were certain that Southern Baptists were undivided on “the fundamental doctrines of grace” and that the matters which threatened denominational unity—and were thus avoided by the confession—dealt with issues related to the Landmark

controversies, in particular to questions of baptism, alien immersion, and to related issues.

The committee protected the integrity of the confession’s witness to the doctrines of grace and, as Boyce indicated, spoke dubiously on no essential particular. Indeed, the Abstract remains a powerful testimony to a Baptist theological heritage that is genuinely evangelical, Reformed, biblical, and orthodox.

When the Committee on the Plan of Organization brought its report in 1858—just one year before classes would begin—the fundamental laws of the institution stipulated that the Abstract of Principles, “selected as the fundamental principles of the gospel, shall be subscribed to by every professor elect, as indicative of his concurrence in its correctness as an epitome of biblical truth; and it shall be the imperative duty of the board to remove any professor of whose violation of the pledge they feel satisfied.”4

In that spirit, every elected and tenured faculty member of this institution has freely and willfully affixed his or her name to this historic record and to this confession of faith.

In publishing their report, the committee also indicated that the Abstract “will always be a guarantee as to the safety of the funds now contributed, against any perversion from their original intention.” The confession was designed to be compact, but “without obscurity or weakness.” Its articles begin with the issue of Holy Scripture, and there is affirmed the basis of all Christian knowledge—the knowledge of the true God who has graciously and freely revealed himself to his creatures— in Scripture inspired by God which is sufficient, certain,

13 fall 2022

r . albert mohler jr .

Nassau Hall, Princeton University, 1836

“The founders of this institution were quite ready to speak of orthodoxy and heterodoxy, of evangelical truth and heresy. This was a vocabulary used with individuals certain of the reality of divine revelation and the necessity of orthodox teaching. These issues were taken with deadly seriousness.”

and authoritative. In their certainty they bear witness to the perfection and unblemished truthfulness of God’s self-revelation through the written Word.

From there the Abstract is bold to confess that this God who has spoken is none other than the one sovereign Lord and creator of the universe, infinite in all his divine perfections, “the maker, Preserver, and Ruler of all things.”

Furthermore, God is revealed to be a Trinity of three divine persons, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, “without division of nature, essence, or being.” Those who voice assaults ancient or modern upon the integrity of the Trinity will find no comfort here.

This God revealed as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit “decrees or permits all things that come to pass, and perpetually upholds, directs, and governs all creatures and all events.” No more comprehensive witness to the reality of divine providence is imaginable. This God is neither inert nor inactive nor ineffectual. The relationship between divine sovereignty and human freedom is beyond our limited understanding, but God is God, and his sovereignty is unconditioned.

The Abstract testifies to the grace-filled doctrine of election as “God’s choice of some persons into everlasting life—not because of unforeseen merit in them, but of his mere mercy in Christ.” But of his mere mercy in Christ! Could there be any more eloquent affirmation of God’s saving purpose in election?

The confession also points directly to the issue of

human sin through the fall, whereby human beings created in the image of God and thus free from sin “transgressed the command of God” and fell from perfection and holiness, such that all now inherit a nature “corrupt and wholly opposed to God and his law,” and become actual transgressors when capable of moral action. Therein is our condemnation.

But Jesus Christ, the “divinely appointed Mediator,” took on human form, yet without sin, and “suffered and died upon the cross for the salvation of sinners.” This same Jesus was buried, rose again the third day, and ascended to his Father, from whose right hand he “ever liveth to make intercession for his people.” Beyond all this, he is “the only Mediator, the Prophet, Priest, and King of the Church, and Sovereign of the universe.”

God’s salvific purpose is demonstrated in regeneration, whereby the sinful heart, wholly opposed to God in itself, is quickened and enlightened “spiritually and savingly,” as “a work of God’s free and special grace alone.” Therein is our salvation.

Then the Abstract points to repentance, by which we are “made sensible of the manifold evil” of our individual sin and respond by means of this “evangelical grace” so that, with sorrow, detestation of sin, and self-abhorrence, we seek to “walk before God so as to please him in all things.”

Faith is then believing on God’s authority the gospel concerning Christ, “accepting and resting on him alone for justification and eternal life.” This too is a

14 the southern baptist theological seminary

don ’ t just do something ; stand there !

divine gift wrought by the Holy Spirit to those who are unworthy and, on their own part, unable to conjure faith unaided by the Spirit.

Those who have trusted in Christ by faith are then justified and acquitted before God through the satisfaction that Christ has made, “not for anything wrought in them or done by them; but on account of the obedience and satisfaction of Christ, they receiving and resting on him.”

Thereafter comes sanctification, by which the redeemed are granted divine strength so as to press “after a heavenly life in cordial obedience to all Christ’s commands.”

Those whom God has redeemed in Christ “will never totally nor finally fall away from the state of grace but shall certainly persevere to the end.” Even though they may fall, they are “kept by the power of God through faith unto salvation.”

In successive articles the Abstract affirms and confesses Jesus Christ as the head of the church; the church as the possessor of all “needful authority for administering that order, discipline, and worship which he hath appointed”; baptism by immersion in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit as the sign of fellowship with the death and resurrection of Christ, of remission of sin, and of consecration unto God; the Lord’s Supper as the church’s ordinance of commemoration of Christ’s death and as “a bond, pledge, and renewal of their communion with him”; of the Lord’s Day as a regular observance of worship, both public and private; of liberty of conscience on issues “which are in anything contrary to his Word, or not contained in it,” and yet of subjugation to civil magistrates in all lawful things.

The Abstract also confesses that our bodies return to dust after death, but our spirits return immediately to God—“the righteous to rest with him; the wicked, to be reserved under darkness to the judgment.” At the last day, the bodies of both the just and the unjust will be raised. On the appointed Day of Judgment, God will judge the world by Jesus Christ, and “the wicked shall go into everlasting punishment; the righteous into everlasting life.”

In this we have inherited a priceless and grace-filled testimony to the gospel of Jesus Christ and to the eternal truths revealed in Holy Scripture.

Philip Schaff, whose great work The Creeds of Christendom remains an indispensable classic, defined a creed, however it is labeled, as “a confession of faith for public use, or a form of words setting forth with authority certain articles of belief which are regarded by the framers as necessary for salvation, or at least for the well-being of the Christian Church.”5

Schaff well described the purpose of the founders of Southern Seminary in framing the Abstract of Principles.

It is a testimony to those central doctrines necessary to salvation, and to other issues essential to the well-being of the Christian church.

What operative convictions are revealed in the Abstract and in the testimony of those who framed the confession?

First, that truth is always confronted with error, and that the doctrinal depository of the church is ever in danger of compromise. The founders of this institution were quite ready to speak of orthodoxy and heterodoxy, of evangelical truth and heresy. This was a vocabulary used with individuals certain of the reality of divine revelation and the necessity of orthodox teaching. These issues were taken with deadly seriousness.

They offered no apology for stipulating doctrinal issues, nor for demanding theological fidelity. In fact, Boyce specifically aimed his critical sights at “that sentiment, the inevitable precursor, or the accompaniment of all heresy—that the doctrines of theology are matters of mere speculation, and that its distinctions only logo machines and technicalities…”6 There is no theological indifference to be found here—no doctrinal minimalism or lowest common doctrinal denominator is the focus or sentiment.

This is a robust, full-orbed faith from beginning to end; a faith which would establish Southern Seminary on its rightful course.

Southern Seminary was established in the very year Darwin published his The Origin of Species. Critical philosophies were already spreading from Europe to the United States. Harvard had fallen to Unitarianism and Transcendentalism. Established seminaries in the North, once considered secure in the faith, were now seen to be wavering. Boyce and his colleagues saw a “crisis in Baptist doctrine” approaching, and they were determined that Southern Seminary be ready.7

Second, that a confession of faith is a necessary, proper, and instrumental safeguard against theological atrophy or error. As Boyce argued, “It is based upon principles and practices sanctioned by the authority of Scripture and by the usage of our people.” Further, “you will receive by this assurance that the truth committed unto you by the founders is fulfilled in accordance with their wishes, that the ministry that go forth have here learned to distinguish truth from error, and to embrace the former….”

Beyond this, the confession is a safeguard to trustees, to faculty, to students, and to the denomination:

It seems to me … that you owe this to yourselves, to your professors, and to the denomination at large; to yourselves because your position as

15 fall 2022

r . albert mohler jr .

“Let those who would understand Southern Seminary understand this: That our faith is not in the Abstract of Principles, but in the God to whom it testifies; that the revealed text we seek rightly to divide is not the Abstract of Principles, but Holy Scripture, but that this Abstract is a sacred contract and confession for those who teach here—who willingly and willfully affix their signatures to its text and their conscience to its intention. They pledge to teach ‘in accordance with and not contrary to’ its precepts.”

r . albert mohler jr .

16 the southern baptist theological seminary

trustees makes you responsible for the doctrinal positions of your professors, and the whole history of creeds has proved the difficulty without them of correcting errorists of perversions of the Word of God—to your professors, that their doctrinal sentiments may be known and approved by all, that no charges of heresy be brought against them; that none shall whisper of peculiar notions which they hold, but that in refutation of all charges they may point to this formulary as one which they hold ex animo, and teach in its true import and to the denomination at large, that they may know in what truths the rising ministry are instructed, may exercise full sympathy with the necessities of the institution, and may look with confidence and affection to the pastors who come forth from it.8

Here is where the institution would stand, before God and before the churches of the Southern Baptist Convention. The founders were certain that this was solid ground, and in this they were surely right.

Third, that a theological institution bears a unique responsibility to protect the integrity of the gospel, and that its professors should give their unmixed and public attestation to the confession of faith. As Boyce commented:

You will infringe the rights of no man, and you will secure the rights of those who have established here an instrumentality for the production of a sound ministry. It is no hardship to those who teach here to be called upon to sign the declaration of their principles, for there are fields of usefulness open elsewhere to every man, and none need accept your call who cannot conscientiously sign your formulary.

Fourth, that those who teach the ministry bear the greatest burden of accountability to the churches and to the denomination.

Boyce delivered his address as the ghost of Alexander Campbell still haunted the Baptist mind. Campbell criticized confessions of faith as assaults upon freedom of conscience and, as Boyce lamented, “threatened at one time the total destruction of our faith.” As Boyce feared, “Had he occupied a chair in one of our theological institutions, that destruction might have been completed.”

“It is with a single man that error usually commences,” argued Boyce. “Scarcely a single heresy has ever blighted the church which has not owed its existence to one man of power and ability whose name has always been associated with its doctrines.” Boyce specifically identified

Campbellism and Arminianism.

Those who founded this institution were painfully and solemnly aware of the history of heresy, which included Arianism, Nestorianism, Pelagianism, Socinianism—a parade of doctrinal deviation. And they were determined to safeguard the institution they would establish, insofar as human determination would suffice. They knew nothing of radical revisionist theologies which would follow, of process philosophy and deconstructionism, of demythologization and logical positivism. But they knew the pattern of compromise and deviation which marked the checkered history of the church and its testimony to the truth. They had seen the radical Enlightenment and the French Revolution, and they had seen enough to understand the challenge.

The faculty of Southern Seminary would be held to a standard higher than that required of the churches, higher than that required of students, higher than that required of those who would teach at many sister institutions. As Boyce stipulated:

But of him who is to teach the ministry, who is to be the medium through which the fountain of Scripture truth is to flow to them—whose opinions more than those of any living man, are to mold their conceptions of the doctrines of the Bible, it is manifest that more is requisite. No difference, however slight, no peculiar sentiments, however speculative, is here allowable. His agreement with the standard should be exact. His declaration of it should be based upon no mental reservation, upon no private understanding with those who immediately invest him into office; but the articles to be taught being distinctly laid down, he should be able to say from his knowledge of the Word of God that he knows these articles to be an exact summary of the truth therein contained.

Let those who would understand Southern Seminary understand this: that our faith is not in the Abstract of Principles, but in the God to whom it testifies; that the revealed text we seek rightly to divide is not the Abstract of Principles, but Holy Scripture, but that this Abstract is a sacred contract and confession for those who teach here—who willingly and willfully affix their signatures to its text and their conscience to its intention. They pledge to teach “in accordance with and not contrary to” its precepts.

The Abstract is not something foreign which has been imposed upon this institution—it is the charter of its existence and its license to teach the ministry. Its purpose is unity, not disunity; its heart is bent toward

17 fall 2022

r . albert mohler jr .

common confession.

In some sectors of theological education, confessionalism is assumed and charged to be dead—a fossil of an ancient era when the church claimed and proclaimed objective truth on the basis of divine revelation.

Some would now celebrate what Edward Farley has identified as the “collapse of the house of authority.”9 Confessions, creeds, doctrines, truth claims, supernaturalism, theism, commands—all these are swept away by the acids of modernity.

It cannot be so here. Not because we are unaware of the currents of modern knowledge; not because we do not understand the challenges of a relativistic and secular age, where all issues of truth and meaning are automatically privatized and politicized; not because we are unaware of the hermeneutics of suspicion, but precisely because we have faith in God, and in his truth unchanged and unchanging. Our motive is not to seek false refuge in an antiquarian past absolved of all its faults and blemishes, but to keep the faith once for all delivered to the saints. We fear no charges of foundationalism, positivism, or authoritarianism. We do fear God and his divine judgment.

The Abstract is our most fundamental centering covenant with each other as faculty, students, president,

and trustees. For students, it is the framework within which you should expect to receive instruction and education. You will not be tested by the Abstract upon your arrival nor your departure, but it should frame your expectations and assure the confessional parameters of your study here. It is a pledge your professors have made before they enter your classroom to teach, and it is because they so highly esteem their calling to teach the ministers of the church that they have come here and committed their lives to serve the church and the cause of Christ by investing their lives in you. They do so gladly, heartily, and with consecration. They deserve your utmost respect, affection, and dedicated attention. For faculty, the Abstract is the charter to teach and the standard of confessional judgment. Southern Seminary is a confessional institution, a pre-committed institution. Teachers here should expose students to the full array of modern variants of thought related to their courses of study. But these options are not value-neutral. The standard of judgment is found within the parameters of the Abstract. In this charter is found the platform for true academic excellence, where all fields of study are submitted to the most rigorous and analytical study; but also found here is the standard for confessional fidelity to the churches and the denomination, for these fields

18 the southern baptist theological seminary

don ’ t just do something ; stand there !

The Abstract of Principles signed by the founding faculty of Southern Seminary.

of study and research are conducted by those who have established their own confessional commitments and who make these plain and evident to those who come here to study and to learn.

But the importance and impact of the Abstract of Principles and of Southern Seminary reaches much farther. We have arrived at a critical moment for the Southern Baptist Convention and its churches. A denomination once marked by intense theological commitment and a demonstrable theological consensus has seen that doctrinal unity pass into a programmatic consciousness. We are in danger of losing our theological grammar and, more seriously by far, of forfeiting our theological inheritance.

This crisis far outweighs the controversy which has marked the Southern Baptist Convention for the last fourteen years. That controversy is a symptom rather than the root cause. As Southern Baptists, we are in danger of becoming God’s most unembarrassed pragmatists—much more enamored with statistics than invested in theological substance.

The Abstract is a reminder that we bear a responsibility to this great denomination, whose name we so proudly bear as our own. We bear the collective responsibility to call this denomination back to itself and its doctrinal inheritance. This is a true reformation and revival only the sovereign God can accomplish, but we must strive to be acceptable and usable instruments of that renewal.

The Abstract represents a clarion call to start with conviction rather than mere action. It cries out “Don’t just do something; stand there!” This reverses the conventional wisdom of the world, but it puts the emphasis rightly. Southern Baptists are now much more feverishly concerned with doing than with believing—and thus our denominational soul is in jeopardy. This people of God must reclaim a theological tradition which understands all of our denominational activity to be founded upon prior doctrinal commitments. This is true for the denomination at every level—and of the local churches as well.

But this message is also critical for the future of theological education and of Southern Seminary. We can never measure our life and work in terms of activity and statistics. In the view of eternity, we will be judged most closely not on the basis of how many courses were taught, how many students were trained, how many syllabi were printed, or how many books were published, but on whether or not we kept the faith.

The other issues are hardly irrelevant, and they are valid markers of institutional stewardship and ministry. But there is a prior question: Does the institution and those who teach here stand for God’s truth, and do so without embarrassment? May we answer that question with the humble confidence of Martin Luther and say, “Here we stand; we can do no other. God help us.”

R. Albert Mohler Jr. is president of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and daily host of The Briefing.

Notes

1. Russell Reno, “At the Crossroads of Dogma,” in Reclaiming the Faith, ed. Ephraim Radner and George R. Sumner (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1993), 105. Inaugural Convocation Address xvii.

2. Samuel Miller, Doctrinal Integrity (Philadelphia, 1824), 11.

3. James P. Boyce, “The Doctrinal Position of the Seminary,” The Western Recorder, June 20, 1874. Fifth in a series of articles. This article was reprinted in Review & Expositor, January 1944, 18–24.

4. “Report of the Committee on Organization,” The Southern Baptist, May 11, 1858, 1.

5. Philip Schaff, The Creeds of Christendom: With a History and Critical Notes, Three volumes (New York: Harper and Row, 1931), I:3.

6. James Petigru Boyce, “Three Changes in Theological Institutions,” in James Petigru Boyce: Selected Writings, ed. Timothy E George (Nashville: Broadman Press, 1989), 49.

7. Ibid., 49.

8. Ibid., 52. All further citations from James P. Boyce are from this address, ad passim, unless otherwise noted.

9. Edward Farley, Ecclesial Reflection: An Anatomy of Theological Method (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1982), see esp. 165–70.

10. Phrase borrowed from Martyn Lloyd-Jones, Truth Unchanged, Unchanging (Westchester, IL: Crossway Publishers, 1993.

“The Abstract is a reminder that we bear a responsibility to this great denomination, whose name we so proudly bear as our own. We bear the collective responsibility to call this denomination back to itself and its doctrinal inheritance.”

19 fall 2022

r . albert mohler jr .

“I am Southern Baptist”: A Confessional People and Their Confession of Faith

“Who are you?”, the criminal once asked Batman. “Who are you?”, the Who once asked their generation.

In one sense, the answer should be obvious. We ought to be able to answer as Popeye did: “I am who I am, and that’s all that I am.” But, is it really? Can your identity be boiled down to one easy statement? “I’m Peter.” Or, “I’m a pastor.” “I’m Karis’ father.” “I’m Melanie’s husband.” You get the idea. Who you are is not one thing or another. It’s the aggregate of many things.

If that’s true of each of us as individuals, how much more complex must the answer be when we answer as a body, as a gathering of diverse yet somehow like-minded folk who share a common identity? Now, think of the complexity of the answer to that question when the answer represents the collective sentiments of millions of people in a denomination or even a movement that spans the globe.

Yet people ask us all the time, “Who are you? What’s a Baptist? How are you different than any other church or religious group?”

One would hope that any church-going Southern Baptist could answer such questions with

aplomb. But can they?

I regularly begin a class on Baptist theology by asking doctoral students, “What does it mean to be Baptist?” I get all the expected answers. “We practice believer’s baptism by immersion.” So? So do many evangelical groups who aren’t Baptists. “We believe in congregational polity.” Yeah, so do some of your charismatic neighbors. “We hold to regenerate church membership.” And? Around and around we go.

They eventually get my point just as you did. Baptists are all those things. And more. Thus, the answer to the question, “Baptists, who are you?”, is complex. The answer to that question is found in our corporate identity and, as Southern Baptists, in our corporate confession of faith.

Southern Baptists and Their Confession of Faith

The founding president of the Southern Baptist Convention, William B. Johnson, famously and erroneously said Baptists have no creed but the Bible. The irony, of course, is such a statement is a creedal statement, a summary statement of belief, personal or otherwise. He said it because he believed it. Most Baptists didn’t.

21 fall 2022

peter beck

From the start Baptists have been a confessional people. This was true of Baptists in Europe. It was true of Baptists in America. In fact, as Baptists began to form unions for cooperation, they did so around confessional statements like the Philadelphia Confession or the Charleston Confession. For Baptists further north, it was the New Hampshire Confession of Faith. This was true for churches, associations, and denominations.

Not even a generation after Johnson’s profession, Baptists in his own state of South Carolina produced a confession of faith for the founding of what became the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in 1859. Thus, the Abstract of Principles became the theological statement of what it meant to be a Southern Baptist in the South for generations as pastors and denominational leaders were taught “in accordance with and not contrary to” the Abstract of Principles. Virtually from the outset, Southern Baptists professed a corporate faith that defined them as a movement and shaped their disciplemaking endeavors.

In the ensuing years, statements of faith like the Abstract were also used to protect the denomination from theological drift. Such was the case with the dismissal of Lottie Moon’s onetime fiancé, Crawford Howell Toy, in 1879. Toy lost his professorial appointment at Southern Seminary not simply because he refused to adhere to the Abstract but because his own faith commitments had moved beyond it. He was, in essence, no longer a Southern Baptist, as evidenced by his failure to teach in accordance with the confession of that people. In due time, Toy left Baptist life behind altogether for Unitarianism.

Those ideals which informed Toy’s departure from Southern Baptist life impacted other denominations at the end of the 19th century as well. Modernism in its many forms led pastors like Presbyterian David Swing to reject all confessional statements before leaving his own denomination. A generation later, the Baptist Harry Emerson Fosdick could pastor a Presbyterian church, because the orthodoxy of one generation no longer held any authority over the next. Many in that day agreed and saw no problem with the pastoral arrangement. Some even went so far as to encourage Fosdick to simply become a Presbyterian to end the turmoil. He refused, left the church, and founded a nondenominational church with the backing of John D. Rockefeller.

Rise of the BF&M

Denominational and theological laxity were not the only challenges confronting Southern Baptists in the opening decades of the 20th century. Modernism’s dalliance with Darwinism also struck close to home. As the so-called Scopes Monkey Trial upheld a Tennessee law enforcing the teaching of creationism in public schools, public sentiment was beginning to shift on the matter. Creationists won in the court of law but lost ground in the court of public opinion. As these events unfolded, Southern Baptists were caught positionally unaware. It’s not that Southern Baptists didn’t have an opinion about Darwinian evolution. In true Baptist form, they had many, but they didn’t have any official position.

At the same time, calls for reconciliation with Northern Baptists 60 years after the Civil War were growing

“Denominational and theological laxity were not the only challenges confronting Southern Baptists in the opening decades of the 20th century. Modernism’s dalliance with Darwinism also struck close to home.”

22 the southern baptist theological seminary

a confessional people and their confession of faith

louder from some quarters. Southern Baptists sent representatives to the Northern Baptist Convention to further these discussions and explore the idea of reunification.

In light of all this, Edgar Young Mullins, then president of Southern Seminary and president of the SBC, called for the formation of a committee to formalize the denomination’s theological views—in essence to define what it meant to be Southern Baptist. In 1925, even as Northern Baptists rejected a similar call to adopt a denominational confession of faith, one based on the long-revered New Hampshire Confession, Southern Baptists adopted their own based on that same confession. That year they affirmed the Baptist Faith and Message as a statement of their collective beliefs, a “consensus of opinions.”

Troubling Revision of the BF&M

Not 40 years later, Southern Baptists would again answer the call to define and refine their faith in light of theological controversy. In the 1960s, debate raged within the convention over how one reconciles the creation narrative of Genesis with the scientific narrative of evolution.

One might ask: if this was part of the impetus for the creation of the BF&M in the first place in 1925, why must it be dealt with again? The answer is easy. While the Preamble affirmed a supernatural reading of Scripture and the world around us, an explicit statement regarding evolution and Scripture was deleted from the initial draft of the Baptist Faith and Message before it was ratified by the denomination. Thus, the problem remained unresolved and had to be addressed again by a later generation.

Under the leadership of Herchel Hobbs, the SBC formed another committee and issued an updated version of the BF&M in 1963. A firmer, though still not concrete, statement on theological commitments about the controversies of the age emerged. The updated statement presented a compromise meant to narrow the boundaries of Southern Baptist theological life in such a way as to answer the present concern without constraining the idea of liberty of conscience Baptists hold dear. As a result, while church members were being discipled according to the teachings of the BF&M via Hobbs’ own commentary on the confession, others in the seminaries and elsewhere were able to claim adherence to the revised doctrinal statement while also holding views contrary to the faith of the rank-and-file membership of the SBC, those things they claimed “with which they have been and are now closely identified.”

In a very real sense, the Baptist Faith and Message (1963) failed to unite the denomination in faith. The controversies that prompted the formation of a committee to revisit the statement festered for nearly another

decade due to political maneuvering by some involved. The result was that the denomination’s faith statement no longer accurately represented the united faith of the denomination as a whole. Such theological diversity led to theological division. Within a decade and a half, the movement that would become the Conservative Resurgence was birthed, and the battle for the heart of the convention was on.

This denominational tug-of-war drug on into the 1990s. When it was over, the conservatives reclaimed the denomination’s entities from the theologically broaderminded Moderates. More importantly, they saw the opportunity to reaffirm the Southern Baptist faith they believed was compromised over the preceding 70 years and called the convention back to its theological roots.

Y2K and the End of the World As We Know It

The year 2000 was burdened with great theological and prophetic significance. Such was already the case for hundreds of years before the coming of the new millennium. As the historical moment drew closer, it appeared Nostradamus and others might be right.

Of course, the apocalypse didn’t begin on January 1 any more than did all the computers in the world crash as predicted. Yet the year 2000 and the years surrounding it did usher in an era of change for Southern Baptists.

Firmly in the hands of the conservatives, the SBC experienced significant change in its leadership and its institutions. New trustees were elected, new presidents hired. And, in one sense, the old faith was rediscovered. However, as the millennium was set to begin, Southern Baptists had yet to address definitively the issue that led to the donnybrook recently ended: the Baptist Faith and Message. To prevent yet another round of theological controversy, something had to change.

An important step was taken in the closing years of the 1990s to do just that. Then SBC President Tom Elliff presciently appointed a committee in 1997 to bring a proposal back to the convention addressing the coming social storm over the nature of the family as defined by the Bible. This proposal came in the form of new article on “The Family” that was to be added to the Baptist Faith and Message. The convention affirmed this proposal in 1998. While it caused a minor denominational dustup, its impact would pale in comparison to what was just over the theological horizon. It proved to be an omen of things to come.

In 1999, Paige Patterson, president of Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary and the Southern Baptist Convention, appointed a “blue ribbon committee,” a veritable who’s who of the Conservative Resurgence, to review the BF&M and present any recommendations to

23 fall 2022

peter beck

“Creeds and confessions are meant to be inclusive. They identify those doctrines or theological hallmarks that characterize a particular body of believers. In other words, creeds and confessions define or identify those within a religious body by their shared system of beliefs. If one shares those beliefs, they are included as part of that body.”

the convention at its annual meeting in 2000. This committee would return with a revision that would address many of the perceived flaws that allowed for the divisions only recently resolved.

As the committee observed in their final report, “Baptists are a people of deep beliefs and cherished doctrines. Throughout our history we have been a confessional people, adopting statements of faith as a witness to our beliefs and a pledge of our faithfulness to the doctrines revealed in Holy Scripture.” Moreover, they added, “Our confessions of faith are rooted in historical precedent, as the church in every age has been called upon to define and defend its beliefs.”

Working from the position of historical precedent, the committee reviewed the BF&M in light of the earlier versions and “the ‘certain needs’ of our own generation.” In other words, doing what Baptists have always done, they revisited the Baptist faith as it had been handed down to them with a view toward clarifying and amending it to address the challenges of the present age.

Unlike its predecessors at certain points, the 2000 update of the Baptist Faith and Message addressed the “certain needs” head on and narrowed the theological definitions provided. In places, language was clarified. In others, articles were modified to reflect contemporary debates earlier writers could not have foreseen. Beyond that, the current version of the BF&M largely mirrors the wording of earlier editions.

The most significant changes brought forward for consideration were arguably found in the introduction to

the confession, the Preamble. There the committee omitted the language of 1963 which stated, “The sole authority for faith and practice among Baptists is Jesus Christ whose will is revealed in the Holy Scriptures.” For many, such a hermeneutical principle proved too subjective and allowed for theological variances that might be cloaked in pious claims of Christlikeness that pitted long-held views against modern concerns.

Such a possible interpretation is highlighted by the next statement the new version of the Preamble also deleted: “A living faith must experience a growing understanding of truth and must be continually interpreted and related to the needs of each new generation.” Whether it was the intent of the 1963 framers or not, such was the language of those like Toy who abandoned the ancient faith in the name of modernizing it for their generation, something many believed to have continued to happen in the 20th century SBC. Instead, the new Preamble simply states, “Our living faith is established upon eternal truths.” Thus, the Baptist Faith and Message as adopted in 2000 seeks to ground “those articles of the Christian faith which are most surely held among us” in unchangeable truth.

While the proposed updates were broadly accepted within the SBC, some took exception to the latest revision of the BF&M. A number of individuals and churches left the denomination over what they perceived to be violations of other key Baptists ideals such as soul competency and liberty of conscience. Such people were no longer convinced that the Baptist Faith and Message

24 the southern baptist theological seminary

a confessional people and their confession of faith

was no longer truly Baptist. Still others chose to remain within the Southern Baptist Convention but retained the use of the Baptist Faith and Message (1963) as their personal or congregational confession of faith.

At the end of the day, while affirmation of the Baptist Faith and Message (2000) is not a requirement of fellowship within the Southern Baptist Convention, it is the official confessional document of the denomination. It is theological self-portrait of a people called Southern Baptists. It is who we think we are.

Baptist Identity Defined and Defended

In the aftermath of 2000 and the ratification of the latest version of the Baptist Faith and Message, some claimed the denomination’s confessional statement moved beyond confession and consensus to creed. Using the concept of creed as a pejorative, they meant to imply the BF&M was now being used as a test of orthodoxy, a litmus test for the purpose of exclusion rather than inclusion. Such an argument betrays a theological and political bias that ignores the meaning of the word itself and the historical use of creeds through the ages.

The term “creed” is drawn from the ancient term credo which simply means “I believe.” Or, as one modern dictionary defines it: a set of fundamental beliefs. The historical and contemporary use of confessions of faith in Southern Baptist life echoes these definitions.

Likewise, church history is replete with examples of the twofold use of confessional statements found in 21st century Southern Baptist life.

First, creeds and confessions are meant to be inclusive.

They identify those doctrines or theological hallmarks that characterize a particular body of believers. In other words, creeds and confessions define or identify those within a religious body by their shared system of beliefs. If one shares those beliefs, they are included as part of that body.

Second, creeds and confessions are meant to be exclusive. They are used to identify those who do not belong to such bodies, not in a punitive sense but a protective one. Those who do not identify with the body with their rejection of that body’s beliefs are prevented from joining or changing that body. They are excluded from membership because they refuse to identify with the members.

Thus, as one looks at Southern Baptist history, we have adopted confessions of faith to define this unique body of believers by identifying those doctrines that give us our unique identity within the larger Christian church. These confessions were then used to train our pastors and disciple our parishioners as to what we believe the Bible teaches. In so doing, the Baptist Faith and Messages does more than provide a summary of what Southern Baptists believe. It shapes what we believe. It defines who we are. It defends our convictions and our churches from external challenge.

Peter Beck serves as lead pastor of Doorway Baptist Church in North Charleston, SC, and as associate professor of Christian studies at Charleston Southern University. Peter is a Ph.D. graduate of Southern Seminary.

25 fall 2022

peter beck

1922: Northern Baptists Lose Their Confession

eric c . smith

One hundred years ago, Harry Emerson Fosdick preached one of the most controversial sermons of the 20th century. Delivered on May 21, 1922, “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” immediately ignited a national firestorm. Today, historians remember it as a defining moment in the Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy of the 1920s. The occasion of the infamous message, however, has been largely forgotten.

Fosdick, reared in a conservative Baptist home, preached with the annual gathering of the Northern Baptist Convention—meeting just three weeks later—squarely in his sights. Formed in 1907, the Northern Baptist Convention was still a relatively young denomination in 1922. Yet tensions between the NBC’s fundamentalist and modernist factions had been escalating since the end of World War I. The modernists were eager to update the Christian faith with contemporary ideas about evolutionary science and the historical-critical study of the Bible. In the process, they radically altered or discarded many tenets of traditional theology, from the complete accuracy of the Scriptures to the bodily resurrection of Jesus. The modernist project had begun within Baptist colleges and seminaries in the late 19th century; by 1922, it had progressed into many of the denomination’s leading churches.

Standing in their path were the fundamentalists, described by their own Curtis Lee Laws as “aggressive conservatives who feel that it is their duty to contend for the faith.” Alarmed at the rapid advance of liberal theology in American culture and in their denomination (northern Presbyterians, led by J. Gresham Machen, waged

a simultaneous battle throughout the decade), a diverse assortment of these “aggressive conservatives” banded together after the Great War to recover what they had lost.

Both factions in the Northern Baptist Convention sensed that their 1922 annual meeting in Indianapolis, Indiana, would determine the future of the denomination. The modernists had clearly been on the ascent for more than a decade, but many in their number, including Fosdick, feared a reversal in Indianapolis. To pull it off, the fundamentalists would need an orthodox confession of faith.

Decline of Baptist Confessionalism