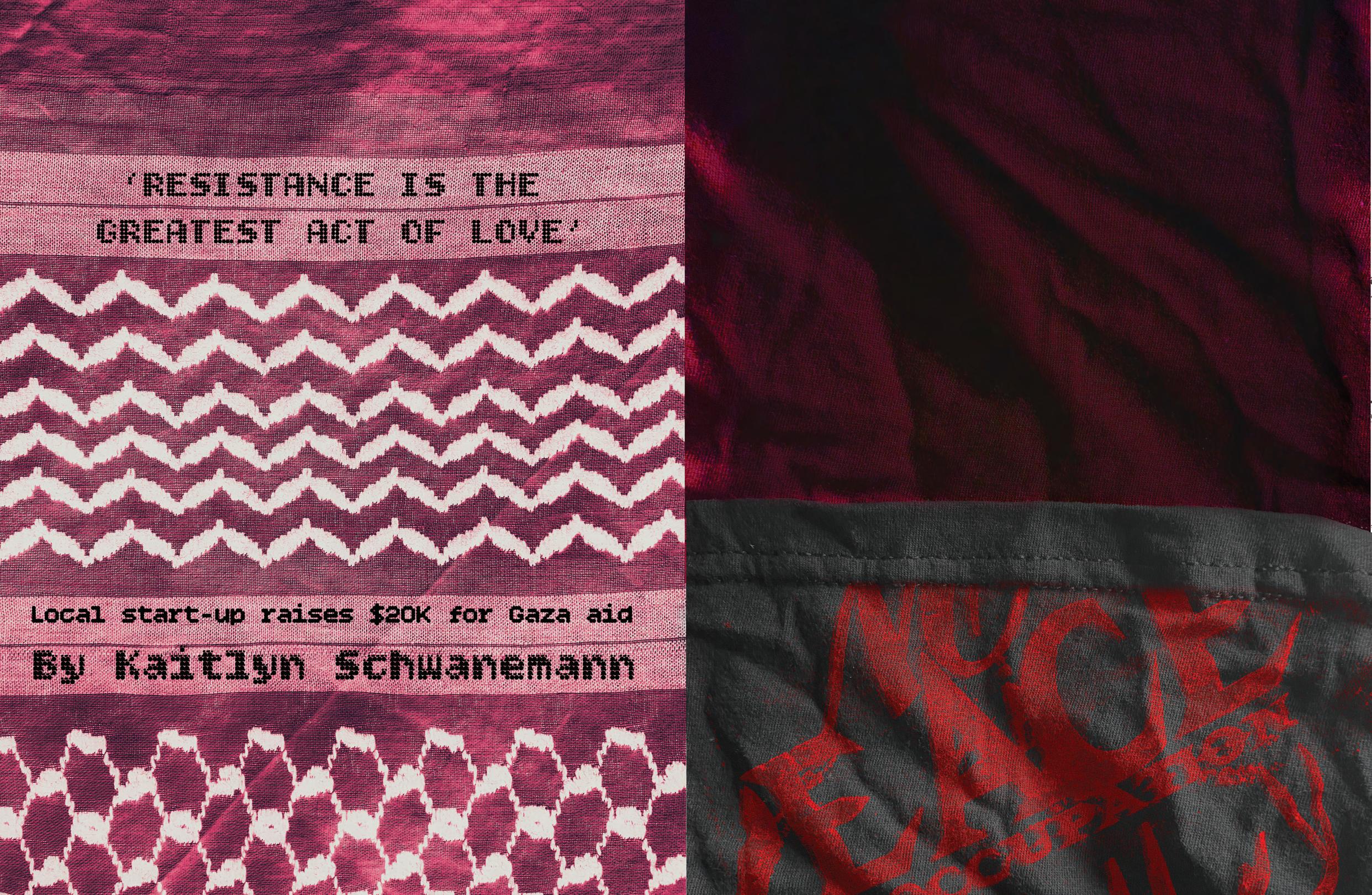

Kaitlyn Schwanemann

Kaitlyn Schwanemann

By Liam Hinck

For a few years, I would see an older gentleman near my house, walking his canine counterpart. A golden retriever whose face was just like his owner’s, covered in white hair. They never moved quickly, at least from what I saw. As the dog stopped to investigate something, his owner followed suit. Years went by. I grew a beard, graduated from high school, got into college, I was somehow elected Executive Editor for this magazine. Yet, occasionally, I’d see the man and his dog walking at the same pace as they always had. I never once interacted with them — not a good morning, a smile, a wave, as I never had the time to. Racing in my car to school or work or wherever I was heading, I never once slowed down and learned the name of the old man walking his dog.

Over this summer, I saw the man once again on a walk, alone this time. Maybe the dog was asleep, or he was at home eating a hearty meal. I’m not sure what he was doing, but this time, he wasn’t there and it concerned me. If I weren’t so wrapped up in life over the last few years, maybe I could’ve learned the name of the older man and his dog or why the dog wasn’t with him that day. I’m afraid that many of us suffer this fate; we get too busy for our own good and forget to slow down sometimes and investigate the things around us, just as the old man and his dog did. I haven’t seen the old man or his dog since that day.

This makes me wonder how many people will stop and investigate this page and my letter, and how many people have read this far in my letter. Oh… you have… this is awkward. I think everyone should take the time to appreciate small things like these. Life, to me, can get way too serious too quickly. Whether your job is giving you hell or school makes you want to rip your hair out, I’ve realized that the NUMBER ONE solution to help avert some stress is to be a troll. Troll everyone you know, everyone you interact with, troll them just a little bit. Don’t do it maliciously; there is a major difference between trolling and being mean. I’m not going to give any examples because I’m not here to spit free game. All jokes aside, if you have made it this far, I hope you can appreciate the time and effort we put into this magazine. You don’t have to agree with any of our opinions or the words we say. But I hope you, the reader, can achieve your goals just as we achieved the goal of producing the very thing you are holding right now.

August/September 2025

Executive Editor

Managing Editor

Associate Editor

Business Manager

Culture Editors

Features Editors

Opinions Editor

Music Editor

Graphics Editors

Ombud Team

Liam Hinck

Kaan Ozcan

Tui Katoanga

Brian Chen

Sonia Zahid

Samantha Sanso

Tyler Rieger

Christiana Hadjipavlis

Vik Pepaj

Steven Ospina Delgado

Annabelle Gilman

Sonia Zahid

Antonio Mochmann

Kaitlyn Schwanemann

Ali Jacksi

Shelly Gupta

Marie Lolis

Aman Rahman

Jessica Castagna

Ivan Vuong

Layne Groom

Elene Mokhevishvili

Emma Ehrhard

Jane Montalto

Rafael Cruvinel

Leanne Pastore

Sammie Aguirre

Sydney Corwin

The Press is located on the third floor of the SAC and is always looking for artists, writers, graphic designers, critics, photographers and creatives!

Meetings are Wednesdays in SAC 307K at 1 PM and 7:30 PM.

Scan with Spotify to hear what we’ve been listening to lately:

Dr. Syed Sayeed, a plastic surgeon practicing on Long Island, met Steve Sosobee while working in a hospital in Gaza last summer. Sayeed had been working with a 3-year-old girl whose body — at least 20 to 30% of it — was covered in burns. Her family was displaced due to a bomb strike, Sayeed said. She needed medical care immediately, and the state of health care in Gaza was bleak; the few hospitals still operating lacked adequate resources, and in the midst of a famine, there simply wasn’t enough food to keep her healthy enough to recover.

“One of the doctors I met in Gaza was from the United States,” Sayeed said. “He actually had a joint venture with HEAL Palestine to enter Gaza. And he said, you know… reach out to Steve Sosobee, and, ‘If anyone can get the child out of Gaza, Steve will be able to do it.’”

Sosobee co-founded HEAL Palestine — HEAL being an acronym for health, education, aid and leadership — in January 2024. The organization is a non-profit that provides aid to Palestinian refugees in the United States and in Gaza. He started the Palestinian Children’s Relief Fund (PCRF) 30 years ago as well, but when the organization’s board no longer reflected his values, he left and created HEAL.

“Using my own connections and some of Steve’s connections, we were able to get the child accepted to Boston Shriners’ Hospital for burn care, and they were able to get the child a passport from the West Bank,” Sayeed said. “A few days before she was going to be

transferred out, I actually had to leave — I was pulled out because there was a plan for an attack on the Rafah border. And then two days before she was going to leave, the Rafah border was overtaken, and the possibility of her leaving was gone, and that’s when she died.”

There are more stories like the girl’s. More cases than Sosobee can take on — but HEAL is taking things one step at a time.

Nearly half the population of Gaza is under the age of 18. In the approximately 25-mile strip of land that makes up the territory, more than 50,000 people have been killed, the Palestinian Health Ministry reported in March. A study published in The Lancet in July estimated that the death toll could exceed 186,000 when accounting for “indirect” deaths. These include deaths that occurred as a result of the bombings of Gazan hospitals, deaths by starvation due to the Israeli blockade of aid and food into the region, as well as people who are considered missing (as opposed to dead) and are buried under rubble.

In Gaza, there are 16 at least partially-functioning hospitals with a total of 1,822 hospital beds as of January 2025, according to the World Health Organization. In Nassau County, for reference, there are 13 hospitals and more than 5,600 hospital beds. The population of the Gaza Strip is nearly twice that of Nassau County.

Sayeed spent the spring in Gaza, primarily helping people who were suffering from burn injuries as a result of

Israeli air strikes. He went to the West Bank, and then to Jordan to try to enter Gaza again. Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) wouldn’t allow him in, he said.

“They don’t really give reasons why they don’t allow people in,” Sayeed said. Foreign doctors of Palestinian descent are not allowed in. This includes any person whose parents or grandparents were born in or lived in Palestine, whether or not they had a Palestinian ID.

Sayeed said the IDF allowed him to bring medical supplies during his first trip to Gaza, but nothing more than one bag for personal items and one bag for food on the second trip. Along with the other doctors, he stayed in a safe house, which is considered “de-conflicted.” He still woke up to the sounds of bombs nearby.

Sayeed recalled a moment in which he went up to the roof of the safe house. Below him, for miles, all he could see were tents. In them were thousands of displaced Palestinian families seeking refuge. When the sun set, they were left in complete darkness; Israel cut off electricity into Gaza soon after Oct. 7, 2023. Occasionally, a small light would peek through — usually a cell phone light or flashlight powered by a generator or a solar panel.

During the day, he would drive to the hospital campus, which was surrounded by makeshift shelters of sheets and strings. People had set up stations outside: barber shops, tailoring shops to sew up tattered clothes, cell phone charging ports connected to car bat-

teries.

“Everyone is trying to seek shelter, but also trying to live their life the best that they could in those circumstances,” Sayeed said. Minimal aid is flowing into Gaza, and when the Biden administration gave the Israeli government a deadline to begin sending more or risk losing their arms transfers in 2024, Israel didn’t meet it. Earlier this month, a ship carrying aid into Gaza was hit by drone strikes. Activist groups accused Israel of the strikes, but the Israeli government has not yet commented on the matter. No consequences were issued after Israel missed the aid deadline and the country remains the largest recipient of American aid since World War II.

Inside the hospital, the deprivation was especially hard to work around. Given the shortage of medical supplies faced by the doctors — both Gazan natives and foreigners there on aid missions — treating patients sometimes meant abandoning standard medical practice.

With displaced people living in the hallways of the hospital, it was hard to keep things sanitary, Sayeed said.

“You can just imagine thousands and thousands of people using these facilities on a regular basis… and in the operating room itself, the supplies are lacking. There are flies because sanitary conditions are poor. So operating on patients, you’d have flies landing on

them. Some of the patients would have maggots growing out of their wounds, because the flies would lay eggs.”

Most of the patients were women and children, Sayeed said. The United Nations’ Human Rights Office reported in November that nearly 70% of the fatalities of the war on Gaza were women and children.

Even for those who do receive adequate medical care, recovering from their injuries is made harder by the lack of food in Gaza.

“They don’t have adequate nutrition. There’s no access to regular quality food and protein. So they may be getting aid of rice and flour and these things, but it’s not what the human body needs to heal these large wounds.”

The situation in Gaza is catastrophic, which is why HEAL takes a qualitative approach over a quantitative one.

“I’m looking for qualitative work in which we can identify ways that we can save the lives of kids,” Sosobee said. The process of getting a child out of Gaza and into the U.S. is extensive, and costly, so the in-depth focus on each case is necessary.

“You have to submit their names to an evacuation list, which, in the case of an American organization, the state department will then submit it to the Israelis on our behalf. And that gets approved or not approved,” Sosobee

explained. “So first you have to obviously arrange the care for them. And once they get the care arranged, then you submit their case for treatment abroad, and hopefully we can get them out depending on the U.S.’ ability to push them, and then the Israelis’ approval. At the end of the day, the Israelis have full approval.”

Sosobee said they have dozens of children waiting to get approval to be sent to the U.S. for medical care. Through their work, though, HEAL has already transformed and even saved lives. As a grassroots organization, HEAL has over 30,000 donors.

“Not a few wealthy ones, but people from all backgrounds,” Sosobee said of HEAL’s donors.

With the money they’ve raised, they saved 18-year-old Sara Bseiso’s life. Bseiso grew up in the neighborhood of Rimal in Gaza.

“My life before the war was normal… I lived in a cozy house with my family — four sisters and four brothers,” Bseiso said at “Voices from Gaza and the West Bank: Healthcare in Crisis,” an event held at Stony Brook University on Sept. 19, 2024.

Bseiso lost two of her brothers to an air strike on her home: 15-year-old Ahmed, and 8-year-old Mohammed. She was severely burned on her face and body and remained in the bombed remnants

of her home for 90 days without proper medical care. Bseiso moved to an out-of-service hospital, and then began her trek south until she reached the Rafah border, where she was evacuated to the U.S. and spent three months in the intensive care unit at Northwell Health.

“We arranged a medical evacuation flight for $180,000… we saved her life with the thanks to the doctors in the hospital. Of course, all [of HEAL’s evacuees] deserve all the recognition and appreciation, but it was that kind of work that really, for me, symbolizes the kind of organization I want to work on,” Sosobee said.

Ahmed, an English and Arabic translator for HEAL who requested she be referred to by her last name over privacy concerns, said “[Sara’s] the first kid to be here — not kid, because she hates the word kid. She was only the first patient to the U.S.”

Ahmed, who is from Gaza but currently resides in the U.S., said she feels connected to every patient she works with.

“Whenever we provide support and treatment for such kids, it makes me feel that I’m giving back, I’m helping my people,” Ahmed said. “I’m not — I felt hopeless, like by the time the war started, but I decided to put all my energy just to give back and to help my people and support them.”

“I guess this makes my life easier these days,” she added.

HEAL brought a brother and a sister to Philadelphia for medical care, and Ahmed followed up with every step of the case. At first, the doctors said they would have to amputate the brother’s leg. After several surgeries, they decided they could save it.

“Whenever we have this success story for one of our kids, or we have another solution that is less harmful for the family… it makes my heart feel so happy that they’re getting the right treatment in the right place,” Ahmed said.

Working on these cases can be emotionally draining, she noted, but it brings her more peace than doing nothing would. For those on the ground in the Gaza Strip, the job is life-threatening: In September, HEAL program manager Islam Hijazy was shot and killed, and in October, teacher and journalist Omar Al Balawi was also fatally shot.

Sayeed said his time in Gaza was difficult — but more than anything, he felt an urge to go back once he had left. He returned to Gaza in December.

“I think it’s just, you develop these personal connections to the people that you meet there, whether they’re healthcare providers or people in the

communities that we cross paths with and made friends with, and we still stay in touch with,” he said.

Sayeed stressed the collective responsibility of people to contribute to aid in Palestine.

“First, put it in your mind, and put it in your heart. Second, put it in your words and in your action,” he said at the “Voices from Gaza” event.

“We have a moral responsibility to care for these children and to get them back on track for as much as they can have a normal life when they’ve lost limbs or been burned. These are all factors that students in Stony Brook and everywhere around the country and around the world need to be aware and take action on, that we can’t stay silent,” Sosobee said. ■

Do these lyrics hit a little too close to home? Well, American Football’s self-titled, debut studio album, retrospectively known as LP1 is just for you. American Football is a Midwest emo band originating in Urbana, Illinois. Led by frontman Mike Kinsella, they released LP1 in September 1999 — a record that paved the way for many of the melancholic emo records we know and love today.

LP1 does it all right. It’s the shoulder you cry on, but the one that hits your back a little too hard when you’re having a coughing fit. To truly understand what makes LP1 stand out, you have to understand the genre at large.

The lust for sadness present in moody teenagers inevitably brought about emo — a loud, emotional genre stem-

ming from hardcore punk. While emo does have the same anarchic ideology as its punk predecessors, the music is often more focused on the artist’s hate towards their high school ex-partner who probably moved on years ago. The first emo bands originated around the 1980s in Washington, D.C., with bands such as Embrace, Fugazi and Rites of Spring being credited with starting the genre. It’s also worth noting that this genre of music wasn’t always called emo. Originally, many considered emo an altered version of hardcore, a genre more closely associated with punk. Thrasher Magazine used “emotional hardcore” in a 1986 issue, but the term was eventually shortened to “emo-core.” Ian Mackaye of Fugazi called emocore “the stupidest fucking thing I’ve ever heard in my entire life.”

This hardcore era of emo is known as “first-wave emo.” That’s right — emo comes in waves, and there are more installments than Lord of the Rings. From first-wave emo arises its dorky cousin, Midwest emo, also known as second-wave emo. Midwest emo is a subgenre that has the same emotional themes as emo but shifts away from its hardcore punk origin and instead takes inspiration from math rock,

a style of rock characterized by complex rhythmic structures — like if a rock star took a jazz class. If you’ve ever two-stepped to names such as Cap’n Jazz, Mineral or Sunny Day Real Estate, you’ve danced to Midwest emo. It attracts listeners with its crisp approach to sadness. The band that brought together many of the angsty teens in the ‘90s through the sound of Midwest emo is no other than American Football.

Third-wave emo came in the early 2000s, where pop-punk and emo intertwined. It’s unimportant to American Football’s history though — so save that for a Google search later. Fourth-wave emo, known as emo revival, is what most teenagers today are familiar with. If you’re wondering why everyone who bullied emos a decade ago now posts “Death Cup” by Mom Jeans on their Instagram notes, you can thank fourthwave emo. This genre takes heavy inspiration from Midwest emo and blends it with indie rock. Among the excitement surrounding the mid-2010s emo revival, fans dug up the decade-old LP1. The contemporary style of LP1 is what makes it as loved as it is today, influencing modern artists you may have cried to, such as Title Fight, Modern Baseball and TRSH.

Though American Football’s sound is unique, bands such as Slowdive, Red House Painters and Tortoise helped mold it. The slow nature of LP1 is a reflection of its inspirations. The somber ambiance of the music is accompanied by deceivingly complicated guitar riffs, which sound simple enough that you can cry to them — but will have you scratching your head when you try to cover the song with your band that doesn’t know what an arpeggio is.

Brendan Gamble, a singer-songwriter who worked with American Football as an au-

dio engineer, produced LP1. The twinkly, comforting guitar riffs are the work of lead guitarist Steve Holmes and Kinsella, who also delivers melancholic vocals and simple yet effective bass lines. Drummer Steve Lamos plays the quick, complex drum patterns and beautifully delivers the trumpet in a couple of songs on the album.

Though LP1 is now seen as an emo masterpiece, it was initially shrouded in obscurity. While it did receive positive reviews and the occasional college radio play, the album was quickly forgotten along with the band. American Football broke up soon after the album’s release, with each member pursuing other musical projects. Over time, however, they amassed a cult following. Fortunately for fans, the band found the old master tapes of LP1, and released them on streaming services as a deluxe edition of LP1 for its 25th anniversary. Thanks to TikTok’s use of songs such as “Honestly?” and the well-known “Never Meant” as audios after the emo revival, the popularity of LP1 continued to flourish.

But why LP1? Sure, the album is fantastic for romanticizing your own sadness with its poignant lyrics and bittersweet instrumentals, but why specifically this album — 25 years later? Can’t one cry to any other emo album? Well, LP1 is depressing, but not for the same reason that, say, Sunny Day Real Estate is depressing. LP1 stands out from other emo records for one reason: it’s real.

Picture this: You’re in your bedroom, crying because the person you love is leaving you. You reread the last text you sent them, pleading for forgiveness as your eyes slowly drift to the “Seen 4 minutes ago” note below the text bubble. They aren’t picking up any of your phone calls, and your friends are telling you to leave the situation alone. No matter how long you wait, and no matter how much you’d want to believe it’s not over, you know deep down, it’s over. Has this situation happened to me? No, I’m just writing an article about emo music — but this same feeling resonates with just about everyone that enjoys American Football’s music, or emo music in general.

LP1 encapsulates this situation, which is unlike what other emo records try to develop in their sound. The emo of the ‘90s was upbeat and aggressive, but LP1 takes it slow and plays with your heart strings through its regretful sound. What makes this album so distinct from other emo records is that it parts from the feeling of hatred you experience months after a failed relationship, and it instead connects with you minutes after you get your essay left on delivered. It delivers a feeling that isn’t quite hatred, but anguish.

Kinsella perfectly captures the initial feeling of heartbreak in LP1. He plays a character who is a direct reflection of how one feels after losing that one situationship you had in high school. Like most people going through this exact situation, Kinsella tries to portray an indifferent, mellow persona through his lyrics, but oftentimes reveals his bitter self with tear-jerking lines such as, “Considering. Everything. Me leaving. With regrets. Only makes sense.” While Kinsella doesn’t directly admit to his depression towards the failed relationship he alludes to, the familiarity of saltiness in his lyrics while reflecting on the happiest time of his life is what touchethe hearts of emos around the world.

Despite the album touching more on the sadness one experiences during a breakup, Kinsella doesn’t fail to put complete blame on his partner, demonstrating a sense of spite; could LP1 really be an emo record if he didn’t? This is present throughout the album, but is most heavily touched upon in, “I’ll See You When We’re Both Not So Emotional.”

Kinsella’s ability in combining lyrics that are spiteful and depressing has become famous not only in emo culture but also in the rock scene. Songs like, “Never Meant” and “But The Regrets are Killing me” are present in social media posts. The contemporary relevance of the heart-rending lyrics in the record is evident, with lines such as, “Let’s just forget everything said, and everything we did” and “But The

Regrets Are Killing me” proving that, despite generation differences, many people could relate to the angst present in the music. This is why these lyrics, despite being from the ‘90s, have solidified themselves in modern music. And if you ask the nearest friend of yours who fumbled that one person in fall semester, they’d agree these lyrics are reminiscent of the bottled-up sadness many feel when going through heartbreak.

The album tops off the self-pitying

result of the twinkly instruments, polyrhythmic beats, and layered lyrics is the landmark album of midwest emo and what most people would agree is the forefather of sadness fetishization.

Now you’re at the end of the album, still wiping your tears from “The One With the Wurlitzer.” You’re contemplating texting your ex back. You are one of millions of other people who spend a little too much time bragging about how you listen to American Football on Instagram. But after all the tears, you’ll

cries with a few instrumental tracks, including trumpets that sound like they’re being played by angels who listened to a bit too much Elliot Smith. These songs, “You Know I Should Be Leaving Soon” and the song with the Wurlitzer, “The One With The Wurlitzer” prove that American Football doesn’t need lyrics to make you cry. Instruments that are able to tell a story without words are essential not only to emo but to music as a whole. American Football’s ability of storytelling through instrumental music can be credited to the band’s aforementioned jazzy background. All in all, the grand

feel a bit better. You’ll know that you aren’t alone; this feeling will fade, and you’ll move on. Despite the album feeling self-deprecating, listening to LP1 in its entirety is a therapeutic experience. Perhaps it’s the feeling of knowing that you’re not the only person going through tough times.

There will never be another LP1 ever again. American Football reformed in 2014, but will they ever release a record that has at least the same level of influence as LP1 did? Your local emo will say no. ■

A few moons ago, I saw posts on X of users boasting the newest additions to their trinket collections. To my dismay, what the posters deemed trinkets were Calico Critters: durable plastic figurines you can find at nearly every bigbox store. They are bought with names, genders and identities assigned to them by their manufacturer which can only be uncovered after tearing apart the plastic boxes they are sold in. Despite their antiquated look — Calico Critters often don Victorian-era clothes — and their miniature size, I was not convinced that they could or should be considered trinkets.

My strife with the Calico Critters was resurrected when I saw a bumper sticker that read “On my way to find a trinket that will fix me on the inside.” On the sticker were cartoonish graphics of a rabbit, a flower-decal mug, a dog, a Russian nesting doll and a tea kettle. It was adorable, but I thought about how some of these objects seemed too big, and more importantly, too alive, to be a trinket. My immediate thought was, “These items do not check the boxes of what a trinket is,” until I came to the startling realization that I was unsure what the classification of a trinket even was.

I have come to anthropomorphize trinkets, referring to them as small ornamental objects bought or found any-

where – they usually have a past life and an alluring story. A trinket can be obtained in numerous ways; visiting antique shops or second-hand stores allows one to find a trinket with unknown connections, leaving a sense of mystery to them. Or trinkets can be passed down generationally, favoring history over mystery with predetermined connections to the item. To me, all trinkets have an air of age to them, and if they have not yet fumbled in the hands of others and are instead bought untouched or in mint condition like Calico Critters are, they do not fit that criteria.

Trinkets have served as a multitude of things to a multitude of people, which is where I find value in them. While their utilitarian purpose may be minute, if existent at all, their decorative presence adds character to one’s personal space. My bedroom is filled with items that I consider to be trinkets, all bought or found second-hand, none of them alike. They have stories and sentimental attachments to them, making them more interesting to look at. Scattered across nearly every flat surface in my personal space are small items that I have attached a piece of myself to. I own a miniature porcelain horse figurine, hardly larger than a Calico Critter, that I found at an antique shop. Even though I have never been on a horse, I was drawn to this particular object due

to its painted eye that amusingly appears to be made up with eyeliner. This miniature grey horse stands behind a thimble of a hand-painted cat that resembles my beloved pet. Next to these two trinkets sits a small and surprisingly heavy golden apple gifted to me by my mom, which was given to her with the purchase of a bamboo plant at a now-closed flea market.

My trinkets all emotionally resonate with me as they reflect my own stories and memories. If another individual owned these items, they would attach their own personal history to them, elevating the trinkets’ value in a different way.

A miniature horse stands behind a thimble with a hand-painted cat, next to a golden apple. By Samantha Sanso

Amusingly, when I looked up the dictionary definition of what a trinket is, the X poster and I were both incorrect. Referred to as “a small ornament (such as a jewel or ring)” and “a thing of little value” by Merriam Webster, a trinket can be semantically confined, yet it has expanded in many of our minds through a personal definition. Trinkets are not so easily categorized, transcending their dictionary definition and transforming them into objects with value determined by their possessors.

Personally, I have no attachment to

Calico Critters, and I wondered if this is what antagonized me against their trinket classification. I asked family, friends, coworkers and fellow members of The Press if they considered a Calico Critter a trinket. For each firm “no” I received, there was an emphatic “yes!” that agreed with the X poster. There is a surprising amount of discrepancy in what we consider a trinket, and the opposing views we have towards each of these figuratively —and literally— small affairs led me down a rabbit hole. On my way down, thimbles, jewelry, Calico Critters, porcelain boxes and tea kettles — all objects people felt were trinkets, flashed before me. They tempted me to address the question: does the personal value projected on an item transform it from mere object to the desirable trinket?

To learn more about how trinkets are classified outside of personal spaces and the value we tie into them, I reached out to Emily Weiss, the owner of the eclectic vintage shop Beyond the Beaten Path in Eastport, New York. The items in Weiss’s shop live up to the store’s name, as there is a wide array of vintage clothing, furniture and ornamental objects that could not easily be replicated or found anywhere else. Weiss has curated quite an impressive collection of quaint antiques, and at every turn there is the guarantee of finding a trinket.

When I asked her what she

considered a trinket, she took it upon herself to walk around the store and search for something that would fit her definition: “It would be something small that… Some of them are porcelain, some of them are metal, some of them are egg-shaped. I would consider those trinkets.” She asked me what the dictionary definition of a trinket is, and was surprised by her own disagreement with it. She said “Wow, that’s weird!” after denying that a trinket is meant to be worn.

Carrying on around the store on her search for an answer, Weiss found more examples of items she considered trinkets. “I have Victorian dresser drawers. I think those would be trinkets also. They’re small and most of them have a sterling silver top. And I found a case that has some stuff in it, very small perfume bottles... I think those would fit into the category also.”

After finding items in the shop that she considered trinkets, I asked if she believed personal history and sentimental value were necessary criteria.

“Personally I do, but I’m sure others will disagree.” She also said that she considers trinkets antiques that “could even be something that you give to someone as a gift. And maybe someone passed it down to you in your family.”

However, the further down the rabbit hole she went in trying to define what a trinket was to her, she said,

laugh- ing, “I don’t know where to draw the line.”

I also inquired what trinkets in the store, or at home, Weiss feels the most connected to. She told me she has “about 5million things” and could not think of her favorite off the top of her head, but she knew it would definitely be in her home. “Most of them would be in my bedroom, because it lends itself to that.”

Like me, Weiss has placed her most valuable trinkets in her room, serving as totems of expression in the space that many of us feel the most comfortable.

Even though her most valued trinkets are at home, Weiss finds value in all the things she sells. “I am a collector first. I am not a dealer, and I don’t have a dealer mentality. When people come in and something isn’t for sale, they’ll say to me, ‘Oh everything is for sale!’ and I’m like, ‘No, it’s not!’ I’m a collector who sells, so for me, it’s collecting first, and I can’t part with my stuff because I’m emotionally involved. I left a note of apology for my kids in the attic.”

It appears most people have differing opinions on what they consider a trinket and it truly does reflect back on what the possessor deems valuable. Many of us feel a similar emotional involvement to our items like Weiss, which is why language sometimes fails

us in accurately describing them.

Occasionally, trinkets are deemed interchangeable with other small objects, like tchotchkes, but the elusive trinket remains its own abstraction. The definition of tchotchke incorporates trinket to assist its definition, turning these objects into subsects of the trinket and potentially complicating the idea of what a trinket is. While the nature of the tchotchke is just as questionable, there is a kitschier connotation attached to a tchotchke as opposed to the daintiness of objects like trinkets. Tchotch-

kes are typically more durable than trinkets, composed from materials that do not easily shatter like plastic, rubber or silicone –hence the appearance of tchotchke shops in tourist-dense areas. Because they are not easily breakable and quickly replaceable, tchotchkes are sold more for kicks than sentimentality.

Further, the zaniness often associated with tchotchkes allows places like TGI Fridays to flourish, which depends on the whimsiness of tchotchkes to create a persona-based corpo-

ration. Walls adorned with pool balls, road signs, masks and the occasional Gumby figurine have items removed from their intended environment to project Americana-based ideas and values. Additionally, Fridays often have totems of local schools and sports teams to create a sense of familiarity amongst diners. Relying on America’s consumer market — which allows a fascination with small, purchasable objects to flourish — and the wholesome idea of a community united in a dining space, hokeyness becomes a marketing tool.

Because sentimentality is either underrepresented and nonexistent in places dependent on the tchotchke essence, like Friday’s, this faux flair explains why a tchotchke remains semantically related to the trinket.

Knick knacks have also come to be considered interchangeable with trinkets despite often lacking sentimental value. Like tchotchkes, knickknacks are defined as items of lower value and quality, making them accessible and not difficult to find. Things that we often consider knick knacks include toys

in cereal boxes, Happy Meals and the items found when waiting in line in a big-box store. I would also venture to say that knick knacks can be obtained through quarter machines and range from sticky-hand toys to colorful ninja figurines. Knickknacks are typically made of plastic or some other polymer-based material, allowing them to be mass-produced and accessible in a variety of places. Because of this, a Calico Critter could more closely be associated with a knickknack. Knickknacks are something to fumble with in our

hands in times of idleness and could even be disposable when our interest in them dwindles. Unlike the tchotchke, which is founded on quirk, and the trinket, which is valued for its sentimentality, the knick knack depends on accessibility for its appeal.

The artificial tchotchke charm of TGI Fridays and the access to collectible knick knacks in our most frequented stores make places like Beyond the Beaten Path essential in the exploration of small objects we can connect with, specifically the trinket. Charming

shops that preserve days past do not intend to craft a narrative for you in their trinkets. Instead, you are invited to find the trinket that most speaks to you and create your own, modern connection with these items. I do not know who owned the small porcelain horse before me, but that trinket has come to be one of the most beloved on my shelf. These small items often contain so much of our own personal history — and the history of others — that they cannot be replicated or sold for simple amusement. Whether obtained for an aesthetic purpose or not, they speak to and of the person who possesses them.

Trinkets continue to have an intangible quality that elevates them from other decorative items. They are not always bought for their functionality but for their ability to communicate an idea or memory that is in the making. Tchotchkes and knickknacks are potentially on the path to becoming trinkets, probably only a few heartbeats away, and if given time they could transcend that popular barrier. However, the allure of the trinket rests in its sentimentality. Our trinkets contain personal value that immortalizes our emotions in a tangible object, preventing our own histories from being lost down the rabbit hole of memory. ■

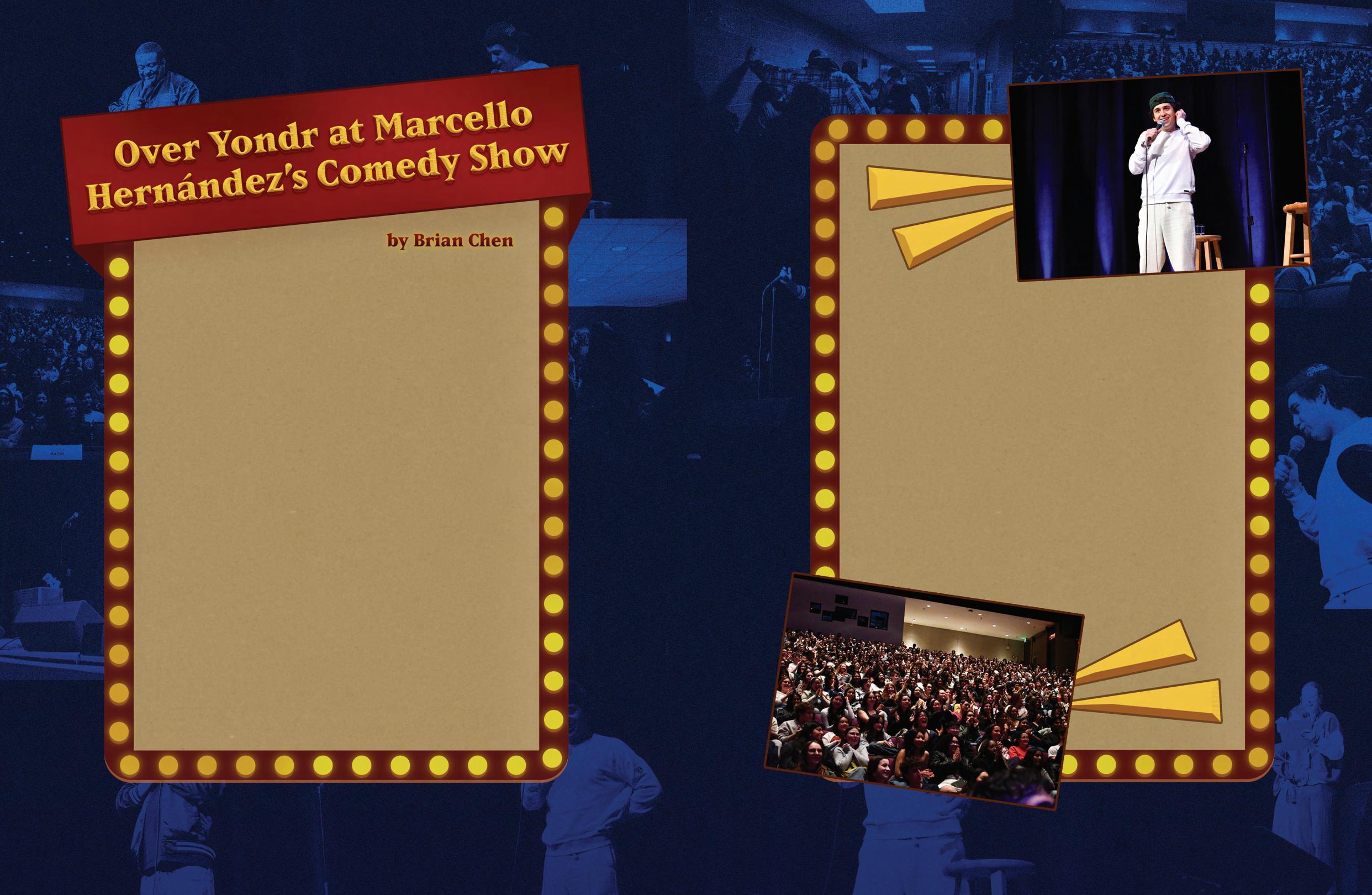

It’s hard to believe Stony Brook could sell out anything on a weekend, especially a Sunday show with doors opening at 7:00 p.m. Still, on March 9, lines for the much-anticipated Marcello Hernández Comedy Show snaked from the top floor of the Staller Center all the way down to the lobby. When I finally made my way to the front, a Nikon camera strapped around my neck and my media pass dangling, a security guard took my phone and slipped it into a Yondr pouch before handing it back to me with a casual, “You’re good to go, bossman.”

Yondr pouches, which use magnets to lock and seal mobile devices, are becoming more popular for creating phone-free spaces. This was the first time SBU’s Undergraduate Student Government (USG) used them at an event. Typically, the annual comedy show features a lineup of comedians, like the Impractical Jokers in 2023, so this was a sort of experimental solo performance.

“I was wondering how that was going to be received,” said Tanisa Rahman, vice president of student life.

Threading the delicate balance between enforcing a no-phone policy and addressing practical issues, like students needing to leave for the bathroom, added complexities for management.

“It was mainly just figuring out the logistics behind it, especially because we were doing e-tickets,” explained Jenn Tsuchiya, senior programming coordinator.

Cast in a deep blue light, there was a noticeable awkwardness during the hour leading up to the show. Accustomed to always having my phone in hand with TikTok on standby, I found myself needing to ask the security guards for time updates. But the absence of devices created a unique opportunity for us to catch up with friends in the crowd and meet new people. When Matt Richards took the stage to open the show, the energy in the room was instant. His rather accurate Trump impressions, paired with his raunchy jokes about sex while high, set the tone for the night ahead.

Then, Hernández finally stepped on stage. The room roared with cheers, and the enthusiasm was instant.

“I haven’t laughed that hard in a long time,” said Rahman, reflecting on the night. ,

“It was incredible, I’ve seen his SNL content, but seeing him live?” Tsuchiya said, “I’m really happy with the feedback from students. A lot of people were really excited to see him here.”

At a school with so many first-generation students, it was clear that Hernández’s stories about growing up in an immigrant household resonated with his audience. Tales of an authoritarian mother, getting disciplined for misbehaving and the mythical stories his parents told about their treks to school seemed to hit home for many.

After the show, SBU sophomore Gabe Villacres-Balseca shared his thoughts, “He took a different routine, which felt a lot more personal, especially as someone who identified with a lot of his points about Latin American communities and families.”

Without the distractions of screens and the temptation to document everything, a unique energy was present in the room. Laughs rang out without any interruptions. People weren’t just present physically; they were mentally engaged, and that made the comedy feel more intimate, more connected. It was apparent the engagement was reciprocal, with both the comedians and the crowd feeding off each other’s energy.

I couldn’t help but wonder if this was how entertainment was always meant to

be. It felt old-fashioned, in a way. When the show ended, it was nice to see how much the crowd engaged with each other. Conversations were lively, and it seemed like everyone had shared an experience they would talk about for days.

Though the Yondr process is still new, it’s becoming increasingly common at shows and concerts. Looking ahead, I’m excited to see the technology used more frequently in future events. It has the potential to make performances feel more authentic, raw, unfiltered and real. And honestly, that kind of vibe is hard to come by nowadays. ■

Far-right parties began to gain influence in Europe after the economic crisis in 2008 and an increase in migrant populations after instability in the Middle East. France’s National Rally saw a surge in popularity after electing Marine Le Pen as their leader, from 10.4% in 2007 to 17.9% in 2012. The Alternative for Germany party then formed in 2013, using anti-immigrant sentiment to fuel their campaigns. In the U.S., President Donald Trump gave this movement a model for legitimacy and power when he won his first presidential election in 2016. His brand of far-right populism spoke to a working class still grappling with the effects of 2008, while bringing anti-immigration legislation and trade protectionism to the forefront. Throughout Europe and the U.S., this brand has spread like wildfire, allowing for other populist parties like Alternative for Germany to comfortably take the second-most seats in government, and far-right movements like the Proud Boys to get tacit approval from the president — telling them to “stand back and stand by.” Centrist parties often build coalitions to stop the far-right from gaining power, a popular strategy that was just used in Germany known as the “firewall.” But far-right parties are gaining in votes and popularity, and are becoming increasingly hard to ignore.

The historical causes for the rise of fascist politics stem from economic strife, lack of information and growing hatred for an “outsider” group from the “native” or natural citizen group. The Nazi Party, for example, rose from a crippled economy. After they gained power, they increased censorship and propaganda to distort reality and found a scapegoat for these issues in the Jewish people. Economic strife worldwide in 2020 allowed for far-right parties to capitalize on voters looking for a way out. These parties often take economic ideas from the left, promoting affordability and an increased standard of living. The far-right party in Denmark, the Danish People’s Party, maintains the platform on their website that maintaining social safety nets is essential, and that the country must ensure safe working environments. Le Pen decried the government’s aid of the 1% and austerity measures at the expense of working people at a May Day rally in 2014. But a key element of fascism is the use of nationalist and isolationist ideas to promote the internal supremacy of their own people.

These ideas often look like anti-immigration legislation, with fascist politicians promoting the idea that migrants

are less civilized, promote lawlessness and take jobs from citizens of the country; these parties aim to convince the public that the government cares more about migrants than the native population. The far-right is isolationist in regards to foreign relations, especially with the extended conflict between Ukraine and Russia. They also often hold Islamophobic views, as the migrants they often encounter come from Muslim-majority countries in political turmoil such as Syria or Afghanistan. Geert Wilders, the leader of the farright Party for Freedom in the Netherlands, likened the Quran to Mein Kampf and proposed a “head rag tax” against women who wear the hijab. These parties become popular as they challenge the status quo, serving as the alternative for centrist parties that maintain control of government.

This is especially true with younger voters. Young voters were long thought to be a stronghold for left-wing parties, especially on climate issues, which put them at the forefront of the fight for their future. However, while facing an affordability crisis due to the lingering effects of COVID-19, an alternative that promises reform for the country and scapegoats migrants becomes increasingly attractive. This population meets all the criteria to create an environment that promotes the far-right, especially with the ease in which new generations can find themselves in information echo chambers. One-third of young voters in France said they rely on TikTok for information on the election campaign of the far-right party, National Rally. This party ranked the highest in popularity among voters aged 18-25, with 32% saying they would vote for the party if the elections were held in the next week after the poll was taken.

This trend has also found its way into American politics. Trump initially gained popularity in large part due to his populist calls to action to working class voters. Like the far-right parties in Europe, he presented a solution to a country that people felt had left them behind in favor of immigrants that take their jobs and promote lawlessness. He promised Americans that he would deport immigrants, impose tariffs on countries that we import goods from and make living in the U.S. more affordable. He’s depended on the far-right, conspiracy theory-promoting echo chambers to gain voters that are scared for their well-being. He’s long demonized media organizations that criticize him, most recently accusing CNN and MSNBC of illegal behavior. Trump has echoed far-right sentiments, saying,

“I need the kind of generals that Hitler had,” according to The Atlantic. He too has created the perfect environment to shift the Republican Party to a far-right movement. His recent executive orders have proved Project 2025 to be his blueprint to cripple the administrative and regulatory state along with it. Young men in the U.S. have followed the European trend towards the right. Predominantly male spaces like sports and gaming are led by influencers that lean towards the right and are open about their views like Dave Portnoy and Adin Ross. An NBA 2K fan may have followed Adin Ross initially for his gaming content, but will inevitably be exposed to his collaborations with Nick Fuentes, a white supremacist, or misogynists like Sneako and Andrew Tate. One of the biggest appeals of the far-right is the obsession with aesthetics of the past and reactionary fringe culture issues over practical solutions and issues that real Americans face. They capitalize on young men that have not yet cemented their identity.

Dave Portnoy founded one of the most popular sports media organizations, Barstool Sports, in 2003, and since has used the site to platform his right-wing views. He publicly supported Trump’s presidential campaign in 2015, writing, “I am voting for Donald Trump. I don’t care if he’s a joke. I don’t care if he’s racist. I don’t care if he’s sexist. I don’t care about any of it. I hope he stays in the race and I hope he wins. Why? Because I love the fact that he is making other politicians squirm. I love the fact he says shit nobody else will say, regardless of how ridiculous it is.”

In the years since that post, Portnoy intertwined his popular media platform for sports news with conservative culture and political incorrectness. Young men that may have just loved sports now have the association that sports culture comes with conservative culture; they’re inevitably exposed to conservatism by engaging with certain hobbies. These right leaning corners of the internet serve as a foray into conservatism — which may then devolve into the alt-right movement.

The far-right only gains legitimacy as traditional parties begin to capitulate on issues they hold. Germany’s center-right Christian Democratic Party passed a resolution for strict immigration laws in January by working with Alternative for Germany, breaching a decadeslong consensus to not work with far-right parties. In the 2024 U.S. presidential elections, the Democratic Party capitulated on the issues of immi-

gration and fracking — two issues long thought to be positions the Democratic Party would oppose Republicans on. But to appeal to more voters in the center, Kamala Harris ran on the platform of a strict border and increased fracking. Instead of the intended effect of leeching Republican voters away from Trump, it gave his platform more legitimacy. People trusted the candidate that long held these opinions over the party that seemingly has just now realized their mistake. Polling from NPR in February shows 49% of Americans believe we need to build a border wall along the Southern border, up from 38% in January 2018. Now, 46% believe we should give legal status to undocumented immigrants brought in as children, down from 65% in 2018.

The left in the U.S. has seemingly nowhere to go. The Democratic Party aims to move further to the center as polls found Kamala Harris to be “too progressive.” The far-right has taken hold of young male voters with right-wing influencers at the forefront of predominantly male spaces. Though the future

may seem bleak, far-right parties eventually fall in power and return to the fringes of society. We must remember that the scapegoats the far-right uses are just that: scapegoats. They distract people from the real issues at hand, and while Trump worries about diversity, equity and inclusion funding and pronouns in email signatures, the American people have to contend with eggs costing record high prices. Soon people will realize that they are still struggling after DOGE budget cuts and decreased government spending — in fact, many will find they are struggling even more.

With tariffs imposed and immigrants being deported en masse, the U.S. country is set to face a massive economic crisis — with stock prices already plummeting. The U.S. does not have the infrastructure to create most goods at the rate that other countries do, and losing millions of immigrant workers currently in the labor market would cripple the farming and construction sectors of the economy. Agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration are

necessary not only for human health crises, but for day-to-day consumption. Trump will soon find that fundamentally changing how our economy and government function will be politically toxic, or will face electoral consequences.

The Republican Party does not have a feasible plan for a post-Trump society. The coalition of political incorrectness could only be combined through a populist leader like himself. There is no popular movement in the GOP that could replace the direction that Trump took the party, and once his term is over, his lack of concrete policy in favor of populist calls will leave Republicans fumbling to keep their support.

The American people Trump used for electoral success will likely abandon the party that failed to fulfill its promise for a more affordable country, and the far-right movement will fall as fast as it rose. The American left need to focus less on every transgression of the Constitution he makes, and more on how to act when people wake up.

Left in the dust

On Feb. 6, David Hogg, Vice Chair of the Democratic National Convention, posted a graphic on X, formerly known as Twitter, outlining what Democrats had done that day. They had held the floor for 30 hours to speak out against Russell Vought, who was then the nominee for the director of the Office of Management and Budget. They introduced an act to protect people’s data from Musk and Trump. Nearly 100 House Democrats sent a letter to the Education secretary asking for transparency on the Department of Education’s plans. They delayed the vote for Kash Patel, who was the nominee for the head of the FBI. They investigated why Community Health Centers did not have access to funding after Trump’s freeze.

Both nominees were voted in without a hitch. They do not have the votes for a bill against Trump to pass. Noth-

ing came of the “100 Democrats sending a letter” except a photo-op and a headline when they tried entering the Department of Education building. Despite a court order to stop the freezing of federal funds, the Trump administration has failed to comply. Democrats are scattered and ineffective, unsure of how to contend with a total loss in both houses and the presidency. They lack the momentum and outrage that they had in 2016. In losing the popular vote, they lost the argument that they were the party that the U.S. wanted. It is less a story of this election being stolen by the electoral college and old establishment rules and more one of the people rejecting Democratic rule. Though it is likely the far right’s platform will face drastic electoral consequences in 2026, what will the Democratic Party that people come back to look like?

Ideally, a party that can win. Not the

party of former President Joe Biden — of the safe establishment pick that will right the course and knows what’s best after the mess Trump made. Party politics must evolve past the flipping of power as a reaction, and instead elect candidates with policies people actually like. The Democrats need to return to their roots as the working class party. But two challenges stand in the way of this ideal: feasibility and messaging.

After Democrats lost the election, the New York Times released a story documenting the loss of a voter base that used to be a Democratic stronghold: working class Americans. In an effort to reorient the American economy towards more international trade in a post Cold War world, our country engaged in more trade with China. This bolstered the total American economy through increased production and cheap labor that American companies

could export. It made goods cheaper, which should have been better for the working class in theory. But as the Times puts it, “Democratic policies focused on people as consumers instead of as workers.” The exported labor meant a sharp decrease in blue-collar work, with the number of people in manufacturing dropping from 17.6 million in 1998 to 11.5 million in 2010. Trump was able to capitalize on the fear that jobs were being taken away and the strain these people felt in the long recovery from the 2008 financial crisis. He won in 2016 due to his ability to effectively speak to the working class. Biden took cues from this in his own

presidency. It may not have been why he won — at least not compared to the allures of name recognition and normalcy. But during his time as president, he understood the importance of domestic production, and reoriented Democrat- ic policies to ensure the work- ing class was well represented. Biden kept many of the tariffs against China that Trump had enacted, nominated Lina Khan to fight against corpo- rate monopo- lies and many of the

bills he passed were to bolster American infrastructure and blue-collar work. He was the first president to walk a picket line and sided with union leaders against a Japanese company attempting to take over U.S. Steel. In an attempt to avoid the tepid and drawn out response to an economic crisis that the Obama administration had attempted, Biden spent trillions to hasten the recovery.

It’s more than feasible to orient policy towards the working class. And yet, this massive demographic still overwhelmingly voted for Trump. A candidate’s economic record as president can be perfect on paper, but if people

When the dust settles, Trump’s messaging about taking America back and being the party for the economy will backfire when the working class is still hurting. When Democrats pick up the

are still suffering, they will lose elections. Some analysts say people who voted for Trump did so due to the economy, but for many people, “the economy” is less about policy and more about a feeling of material well-being. Implementing policies that are aimed at helping working-class Americans is important, but what wins elections is the messaging attached. Much of the feelings of prosperity that people felt under Trump were due to the aftereffects of the recovery from the Obama administration. What was more important was his messaging — his catering to the working class that was left behind.

pieces, their policies still need that working-class orientation, but their messaging needs to follow. People are hungry for a leader that speaks up and is willing to help. It’s not luck that helped Sen. Bernie Sanders pack thousands of people into a room to “fight oligarchy” hundreds of miles away from his home state of Vermont. It’s not a coincidence that multiple town halls in Republican districts erupted into outcry. People are ready to fight. They need a party that’s ready to fight for them. ■

The midrange shot is an art form. There’s nothing quite like watching a post-fade rise above the outstretched defender’s hand. As Michael Jordan told Detroit Pistons legend Rip Hamilton, “Rip add that to your game. That’s the hardest play in the game of basketball to guard.” But some think the midrange is dying. The NBA is shooting more three-pointers than ever before, and fans think players have forgotten this pivotal part of basketball. In reality, the midrange game has never been more beautiful.

If basketball was like boxing, then the midrange is your uppercut. It should be used situationally, thrown in a few times to make your opponent worry about it, opening up more chances for your bread and butter: 3-pointers and layups. It shouldn’t be the only tool in your arsenal; a boxer isn’t going to win their fight by only throwing uppercuts.

The best scorers to touch the court maximize their opportunities to take the highest percentage shots. An elite midrange ability is a frightening weapon, as defenders must stay aware of it as they guard. If at any moment, a player can fire a midrange over your outstretched hand and make them at a 50% success rate, you’re going to worry. This worry is what separates the best scorers from the rest of the league, they can attack from anywhere on the court.

The caveat to the midrange is that it’s, to put it simply, too hard. Most midrange shots entail an off-thedribble, contested jumpshot while the momentum of your body carries you away from the basket. Middies are also shot from odd angles, and the strength needed to make them feels awkward for most people. They require a soft, elegant touch, so you don’t overshoot them, but they’re not close to the basket like layups. Trying to keep that same touch over the typical midrange distance is extraordinarily difficult to master.

Your reward for conquering the extreme difficulty of making a contest midrange fadeaway 18 feet from the basket? Two points. The same as a wide-open layup directly under the basket that would have been easier to do. The risk-to-reward ratio is just

not worth it for 99% of players, and the league has come to understand this in the last 25 years. According to the NBA, during the 2000-01 season, teams attempted 30.1 midrange shots per game. Compare this to the 202324 season, where teams on average shot only 8.8 midranges a game.

Players in the early 2000s were relying on the midrange too heavily, and soon, the “well” of the midrange was beyond dry. If you combine the overuse of middies with the shot’s high degree of difficulty, the league was disrespecting the art of the midrange — and the numbers back this up. In what people ironically herald as the prime of the midrange, Jerry Stackhouse chucked 895 middies and made a measly 35% of them. This calculates to about 0.7 points per shot, which is around the same value as a 24% 3-point shooter gets on the threes they jack up. Now, Stackhouse was shooting 11.5 middies a game; could you imagine if Zion Williamson, a 23% 3-point shooter, was averaging 11.5 threes a game? Fans would be calling for his head.

It was astonishing how many middies were jacked up throughout the league that season. Almost 100 players had over 250 attempts from the midrange in the 2000-01 season, with many of them going well beyond that number, while only 16 managed to hit that mark in the 2023-24 season.

Based on this, the 2000-01 season surely had more players making 45% or more from the midrange than the 2023-24 season. The 2000-01 season had almost 85 more players qualify, so they had to have more players over the 45% threshold, right? Both seasons had nine players meet those criteria. If we bump this number to 48%, the 2023-24 season had seven players meet the criteria, while the 2000-01 season had just two.

Offensive efficiency during the early 2000s was a victim of the overdose of midrange shooting. The average offensive rating in the NBA in the 200001 season was a measly 103.8 — the second lowest it has ever been. Some argue the poor shooting was because defenses back then were more physical, so players couldn’t get to the rim as easily as they do now and had to settle for midranges. However, there was something bigger in play. It all

goes back to “his airness”’, Michael Jordan.

Six NBA Finals wins and zero losses were all everyone needed to see, they wanted to be like Mike. In 1996, Jordan shot 48.9% on over 1200 midrange attempts in what may be considered the greatest midrange season we’ve ever seen. All of the success and glory that came to Jordan inspired everyone to try and replicate him — but they couldn’t.

The midrange is an upper-echelon skill for players, but nobody will ever reach Jordan’s ability. It took a while for players to realize his ultra-high volume and efficiency may never be seen again. But, once they did, the 3-pointer became more prominent and the league’s average offensive rating skyrocketed to 116.1 in 202324. This has created the belief that the 3-pointer killed the midrange, but despite its underuse, the midrange is still alive and well today, but in a different way.

Two players in particular carry the torch when it comes to Jordan-esque midrange efficiency. Kevin Durant and Gilgeous-Alexander were the most efficient high-volume midrange shooters last year at 51.8% and 49.4%, respectively. Besides Jordan, the NBA is reaching the pinnacle of midrange shooting. Players are using it in the way it’s supposed to be. Instead of being milked dry, the midrange is now the ultimate tool in the belt of the league’s best scorers. The number of midranges that are now shot is healthy, and the efficiency matches that. The midrange lives on not as a crutch, but as a calculated weapon in an evolving game. ■

“Nothing is of its own explanation. Is there a better description of a cube than that of its construction?”

Laszlo Toth, the protagonist of Brady Corbet’s 2024 film The Brutalist, asks this essential question at a glamorous dinner party where he is decidedly out of place. For Toth, an accomplished yet tortured architect with a grand vision for how he can shape the world around him, the end result is the only thing that matters; the only justification needed. Corbet offers audiences a film equally unapologetic in its conception. For some, watching the movie may feel like an arduous undertaking, but it triumphs as a film brimming with perceptive ideas and impressive craftsmanship upon completion.

The Brutalist is refreshing in its originality. Unlike all the spinoffs, sequels and superhero movies that thrive at the box office, or the stylish comedies and horror films that have come to dominate pop culture, Corbet’s film unabashedly embraces its artistic indulgences. Every moment presented on screen attempts to tell the audience something, sometimes through deeply uncomfortable and intimate means. At times, it can feel excessive and over the top, but it never compromises. Through this unrepentant direction, Corbet manages to provide audiences with undiluted artistry, rife with audacious and aspirant storytelling and masterful filmmaking strokes.

The film chronicles the life of Toth, played by an evocative and striking Adrien Brody, after he flees the horrors of a wartorn

Europe in the aftermath of World War II. As he arrives in the United States, the Jewish-Hungarian immigrant is quickly swallowed up by the all-consuming futility of the American dream, only to escape his stateside anonymity when he encounters wealthy businessman Harrison Van Buren, depicted by Guy Pearce, in a deft performance that swirls with notes of menace and insecurity. Van Buren tasks Toth with a massive architectural endeavor, and from there, the two men engage in a timelessly complicated artist-benefactor relationship.

Despite critical acclaim — including an Oscar win — The Brutalist was received meagerly by general audiences. The film earned just over $15 million at domestic box offices, an underwhelming number considering the independent production cost $10 million.

Exactly why the film has fallen short of breaking into the mainstream likely has to do with how it was made. Corbet created a film that feels like it came out of a time capsule. Shot almost entirely on VistaVision, a widescreen format last used in Hollywood in the 1960s, The Brutalist has a granular, antiquated aesthetic. It also runs a staggering three and a half hours, including a 15-minute intermission — a runtime just short of Lawrence of Arabia. Besides these technical aspects, its subject matter is

somehow both painfully intimate and exceedingly vast, something more akin to The Godfather than to Wolverine & Deadpool.

These aren’t convincing selling points to entice the modern-day moviegoer, as evidenced by the highest grossing films in 2024. Every movie that finished in the top 10, from Inside Out 2 to Sonic the Hedgehog 3, is either a sequel, spinoff or retread of familiar intellectual property. It seems a growing number of audiences want to know what’s in store for them before they even step into the theater.

But it’s precisely because Corbet makes his movie exactly the way he wants, to his unique idiosyncratic inclinations, that the film flourishes. Every decision seems to be deliberate. The decision to film with older equipment creates an ambiance transcending time, steadily blurring the lines between what once was and now is. Despite the extended length of the movie, it never really drags; each moment is meticulously crafted and brimming with complex ideas, although the intermission is a welcome break to stretch your legs. And while the story does not entertain in the way, let’s say, a Marvel movie might,

or even another indie film like best picture winner Anora, it serves a greater purpose — it provides a thought-provoking, intellectually rigorous cinematic experience that feels increasingly rare nowadays.

The film anchors itself to the architectural style of brutalism, a minimalist approach that prioritizes functionality over decoration. The style was first popularized in Europe in the 1950s during postwar reconstruction. It often produces blocky, monochromatic concrete buildings adorned with harsh edges and peculiar angles. Brutalism is a divisive aesthetic; some find beauty in its raw and unconventional nature, while others are put off by its domineering austerity. This polarizing aspect makes it the ideal vessel for Corbet’s complicated yet ultimately rewarding story.

Like brutalist architecture, The Brutalist is raw and blunt. Yet, the film overflows with vast thematic purpose: it’s an exploration of identity, of reconciling one’s own self in the context of the American experience, specifically for immigrants; it’s trying to figure out how art is meant to survive in an increasingly commercialized world.

By examining the toils of Toth and the relentless commitment the character demonstrates, Corbet forces the audience to confront the enduring legacy of art in the face of unseemly exploitation. Toth’s attempt to execute Van Buren’s grand and impetuous dream in the vein of his own artistic integrity sets up a mighty clash of ideals: it exposes the fraught balance of navigating individuality amidst the consuming nature of assimilation. This conflict also underscores the tragedy inherent to Toth’s character. All at once, he must internalize the debilitating traumas he has suf-

fered while pushing toward a new, almost inconceivable future.

The film nearly falters because it almost feels too broad in its scope. In every other scene, it seems Corbet is trying to unpack several highly complicated and nuanced ideas. What saves it from being a drawn-out mess of indulgent patterings, like Francis Ford Coppola’s poorly received Megalopolis — although it’s always appreciated when a legendary filmmaker takes a big swing — is the uncompromising vision Corbet cultivated with the film’s distinct stylistic underpinnings. Its award-winning cinematography, helmed by Lol Crawley, beautifully captures the grandeur of artistic enterprise simultaneously at odds with the agonizing intimacy of the characters. Opening shots of a shaky, upside-down, then flipped sideways Statue of Liberty, as a haggard yet hopeful Toth enters America, set the tone early of a film unafraid of its prescience.

The movie’s score is also instrumental in grounding the story. Orchestrated by Daniel Blumberg — the former frontman of the band Yuck, whose hit song “Get Away” is a jam — the musical composition of the film lends itself entirely to the story being told. Combining melodic piano lines with a sweeping, incongruous orchestra, Blumberg evokes the epic scale at hand by casting the story in sounds of emphatic ambition jumbled with mesmeric hints of imperiling doom. Corbet’s devotion to scrupulously shaping the film in its entirety pays dividends. Every component is carefully considered and fosters an atmosphere compatible with a script that’s saturated with innumerable intentions.

It’s quite fitting that The Brutalist has been acclaimed for its artistic ingenuity, as it demonstrably celebrates precisely that. Ironically, although the film lambasts the oppressive cultural controls pervading the art world, it has been mired in controversy for its use of artificial intelligence. Corbet’s team used generative artificial intelligence to enhance the accents of Brody and Felicity Jones, who plays Toth’s

wife, in the few scenes where they speak in Hungarian. Corbet says there was no alteration in their performances for the parts where the characters speak in English, which is most of the movie.

While it’s forgivable to touch up an accent to add a layer of authenticity to a performance, it sets a complicated precedent for when and how artists should use these technologies. On shoestring budgets, independent filmmakers are focused on crafting the best, most genuine films they can conceive as quickly and cheaply as possible. However, by using AI, Corbet opened up a broader conversation about the acceptable convergence of art and generative technologies that circumvent human origination. The use of AI was a sticking point for Hollywood actors and screenwriters when they went on strike only a couple of years ago. Most people don’t want to lose their jobs to a machine or have algorithms replace human creativity.

However, an evident problem with a zero-tolerance approach to technologies like AI in creative spaces is that it may ultimately limit the breadth of the art-making process. The utilization of this type of technology in filmmaking seems inevitable. Rather than wholly denying its use in film studios, the industry should take care to safeguard the artistic process while allowing AI to assist in areas that are generally more expensive and time-consuming. This will help to democratize the film industry, enabling independent production companies to pursue more ambitious projects that otherwise would not be feasible, toppling big-budget studios’ monopolistic hold on large-scale productions.

The begrudging acceptance of groundbreaking technologies in film isn’t new. On the set of Jurassic Park, Steven Spielberg famously had a computer-generated imagery (CGI) team compete against a practical effects team to create the best T-Rex design. After seeing the results, the head of the practical effects team reportedly said, “I think I’m extinct.”

That

clearly wasn’t the case, as practical effects are still widespread and instill an irreplaceable air of reality in any movie. Still, it’s obvious that CGI has played an essential role in reshaping how stories are told through film. Although one could easily argue that CGI has become too prevalent in modern cinema, it’s undeniable that it has pushed movie-making forward, expanding what filmmakers can manufacture from their imaginations. Similarly, AI can coexist with contemporary movie-making practices as long as it doesn’t start replacing the innate human ingenuity that makes art indispensable.

The AI post-production alteration to Brody’s voice caused many to suggest

he was undeserving of the best actor award, which he won. However, his performance was far more than a few lines of perfectly spoken Hungarian. Playing the beleaguered Toth, Brody is enigmatic in the best way possible. He’s hypnotic and emotive, effortlessly carrying the complexity of a character entrenched in a toxic American dreamscape. Brody eloquently displays both the triumphant highs of successful endeavor and the tumultuous lows of spiritual defeat. A minor editorial change to Brody’s Hungarian accent does not diminish the luster of his consummate performance.

Towards the film’s end, a character says, “No matter what the others try

and sell you, it is the destination, not the journey.” The story of The Brutalist is, in fact, a decades-spanning journey filled with miserable yearning and captivating aspiration. But, the ultimate reward for both Toth and the audience is the redemptive nature of an enduring legacy — a destination that supersedes the finite struggle of getting there in the first place. ■

Namal, then a student at Stony Brook University (SBU), had nothing to do for a while. She had just been suspended from the University and barred from campus because of her involvement in the May 2024 Gaza solidarity encampment on the Staller Steps. While at Stony Brook, she stayed busy: Namal was the president and co-founder of Stony Brook’s Students for Justice in Palestine chapter (SJP), which has repeatedly been in trouble with the University administration.

But now it was summer, and she could be subject to arrest if she stepped foot on campus. She thought back to the encampment, sometimes fondly. Before the police and state troopers flooded in, before Vice President of Student Affairs Rick Gatteau issued the first suspension (to the SJP chapter’s designated mediator), before students and professors were carted off to holding centers in SBU buses — there were moments of peace, and a sense of community. Namal gave out hand warmers when everyone slept on the grass, muddied in the cold rain. She argued with university officials when they said that protesters weren’t allowed to have

blankets, until they caved. She passed out halal chicken and rice platters from a local restaurant to fellow protesters.

When graduate instructor Callen Zimmerman brought their screen printing class to the encampment, Namal learned how to apply the technique on T-shirts. She and Zimmerman’s students sat in a circle on the grass, lush in the warmth of late spring. Together they designed graphics and slathered white T-shirts in red, black and green ink, leaving them to dry in the sun. One protester would later go for a run and return with Aquaphor to help another who fell asleep and woke up sunburnt.

“As a relatively simple art form, it’s a communal activity and a great way to get messaging out through both aesthetics and words,” Zimmerman said. “My intention with bringing screen printing to the encampment was to share with this group of brilliant, committed and caring young people and other members of the Stony Brook community, a skill that I have often turned to in political organizing when things feel desolate and hopeless, as art is a means of expression and connec-

tion, especially to our shared humanity.” That moment was the “major spark” for Inteefada Shirts, Namal said.

Inteefada Shirts, a clothing brand that sells T-shirts and sweaters with pro-Palestine designs by Namal herself (barring one collection), has raised over $20,000 in aid for Gaza relief. Some of the money went to a Gazan teenager, Ibraheem, whom Namal met on social media. They bonded over art, and he’s gone on to create some of his own designs for Inteefada Shirts.

“Right now, the food prices in Gaza and Palestine overall are just astronomical. I remember him telling us that a kilogram of sugar goes for, like, $70 in USD, and so a lot of the money is being spent on food for him and his families, as well as neighboring families,” Namal said. “He also teaches the children… If you go to his page, you’ll see he’s always doing videos with the school kids. They’re doing art projects and things like that.”

Some of the money also goes to HEAL Palestine, a non-profit organization dedicated to providing Palestinian refugees with relief. They’ve helped evac-

uate people from Gaza and rebuild their lives in New York. In one case, HEAL Palestine evacuated a teenage girl, Sara Bseiso, from Gaza to New York to save her life. She was suffering from life-threatening burns after surviving an Israeli airstrike on her home which killed several of her family members.

“We arranged a medical evacuation flight for $180,000. We brought her, and she spent three months in an intensive care unit, and we saved her life with thanks to the doctors in the hospital,”

Steve Sosobee, co-founder of HEAL Palestine said.

Whether to Ibraheem or HEAL Palestine, 100% of the brand’s proceeds are dedicated to Gaza relief no matter what, and Namal doesn’t give herself a wage for her work.

The brand has gained traction on Instagram, where they posted photos of their clothing and flyers for pop-up sales events on college campuses throughout New York.

A Stony Brook professor in the department of anesthesiology who was arrested at the May encampment, Josh Dubnau, is pictured on the brand’s Instagram wearing a shirt that says “Free Palestine.”

“Inteefada is a clever brand name. It merges the Arabic word for ‘struggle’ with the T-shirts they sell,” Dubnau said. “The T-shirt that I bought from Inteefada Shirts has a beautiful drawing of a peace dove with a Palestinian keffiyeh motif and the words ‘Free Palestine.’ So my Inteefada shirt shows

a struggle for peace with justice.”