As we move into the final months of 2022, I look back on this year with pride and humility.

Both our campuses have offered visitors from near and far a dazzling array of exhibits, experiences, and programs that showcase the extraordinary beauty, wonder, and fragility of the natural world. Our new Dive In: Our Changing Channel exhibit at the Sea Center contextualizes each of the marine animals in our care within their unique habitats in the Santa Barbara Channel. What looks to our eyes like just one unbroken expanse of water, the channel is in reality home to a number of highly specialized ecosystems, each supporting a rich diversity of life.

At the Museum, I hope each of you had a chance to experience the arresting beauty of the world-class mineral specimens on display in our Rare Earth exhibit. As many visitors attested, it not only surpassed their expectations, it was unlike anything they had ever seen before. And while the minerals in all their awesome beauty remained comfortably grounded, the winged wonders in our Butterflies Alive! exhibit this summer likewise surpassed all previous Sprague Butterfly Pavilion displays. The Costa Rican and other Central American species—from the flashy Blue Morpho to the diaphanous Glasswings—mesmerized and delighted thousands of guests. It was indeed a very good summer at the Museum!

I encourage you to keep a close eye out for the exciting upcoming lectures and adult programs that we will once again be offering this fall after a two-year hiatus. Many in Santa Barbara have always looked to the Museum as a place that provides current and rigorous nature and science education for lifelong learners. We are delighted to bring those offerings back to you again.

Yes, I am proud, but I am humble as well. I know it is your generosity and your belief in the work we do that sustains this entire enterprise. Thank you for your support!

Sincerely, Luke J. Swetland President & CEOMany in Santa Barbara have always looked to the Museum as a place that provides current and rigorous nature and science education for lifelong learners.

Top: A VolunTEEN reveals the Mystery Box to guests in the Backyard.

Middle: Collections care is a top priority and vital to our work.

Bottom: Sea Center Director Richard Smalldon helps a young volunteer on Coastal Cleanup Day.

In November 2019, the SBMNH Board of Trustees adopted a five-year strategic plan to guide our work. The plan was built on the Museum’s roles as steward of a century-old legacy, an internationally recognized and trusted scientific institution, and a beloved regional cultural attraction. Yet we operate in a culture with widespread skepticism about science and a relentless global assault on nature and its resources. Our plan needed to articulate the Museum’s response to those two threats while honoring our past and our professional, ethical, and moral obligations.

After much self-reflection, we realized we did not need a grand new initiative or direction. Quite the opposite. We were enjoying great success and recognition for our work and the best way forward was to leverage our accomplishments to date—and commit to take them even further.

While the global pandemic required our attention, we did not lose sight of these commitments—indeed, they provided a powerful tool for helping us adjust our operations and offerings to continue to meet our mission in an incredibly difficult set of circumstances.

Continually strive to provide every guest with a compelling nature and science experience by:

• Sustained focus on each aspect of our interactions with every guest to establish trust and connection with SBMNH and its mission.

• Nourishing authentic excitement and curiosity about nature and science for each guest by providing age- and interest-appropriate opportunities to increase their knowledge of the natural world, how nature changes over time, and the complex human relationship within it.

Become the best possible science interpreters we can be by:

• Equipping staff and volunteers with the skills and resources necessary to comfortably and effectively engage with guests—to make nature and science knowledge accessible— and to explain complex, and sometimes controversial subjects.

• Working with strategic partners to convene rigorous community conversations on the state of our region’s biodiversity and the human relationship with it.

• Making SBMNH the recognized and trusted go-to expert that can meaningfully explain our region’s natural history and changes to it.

Become an ever more operationally and financially sustainable organization by:

• Increasing revenues and managing expenses without sacrificing our commitment to excellence.

• Investing in our staff and providing them a healthy and inclusive work environment.

• Protecting the collections and investing in the care of the facilities that make our work possible.

These commitments reaffirm that the Museum is a center for conversation and learning, a place where rigorous science is made understandable and accessible, and a place to engage with our visitors on the pressing and vexed environmental issues we face.

By enlarging a shared understanding of our region’s ecological change over time and how our activities impact the workings of our natural systems, we invite engagement, reflection, and ultimately, a willingness to act.

We look forward to sharing more updates on how we are continuing to implement these priorities on our journey from good to great.

Our strategic plan commits the Museum and Sea Center to focus on three priorities over the next five to seven years.Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris) skull with teeth stained purple from eating sea urchins

Teaching a room of teenagers is like being in a swarm of bees. Lucky for me—and the 15 students I supervise in the Quasars to Sea Stars program—I love bees. I’ve found that in both groups, there is more than first meets the eye. Bees have incredible biodiversity, and every teenager has individual perspectives and curiosities.

Quasars is a work/study/volunteer program at the Museum, a perfect fit for any teenager who loves science. My quasar connection started at 13, when I applied to be a quasar myself. I liked science, but didn’t know where it could take me. During four years in the program, I tried everything. I taught people of all ages through camps, outreach, and planetarium shows. I helped sort bones of long-ago owl prey, curated mollusks, and finally fell in love with bees and education. I combined the two, writing and teaching my own bee-focused camp curriculum.

Middle: The author netting bees during his research at the Museum.

Photo by Jerry Thrift

Bottom: Return to Lobo Canyon on Santa Rosa Island with current quasars.

Photo by Jenna Hamilton-Rolle

Middle: The author netting bees during his research at the Museum.

Photo by Jerry Thrift

Bottom: Return to Lobo Canyon on Santa Rosa Island with current quasars.

Photo by Jenna Hamilton-Rolle

For my senior project, I studied two wild hives of honey bees at the Museum. With help from Schlinger Chair & Curator of Entomology Matt Gimmel, Ph.D., Museum Librarian Terri Sheridan, and Lead Naturalist Christine Melvin, I collected bees to analyze pollen loads and floral resources. I learned that honey bees—although cool—were but one of thousands of bee species, and I resolved to study the others in college.

As a UCSB undergrad, I studied biology and education, worked in a bee-focused lab at the Cheadle Center for Biodiversity and Ecological Restoration, and clicked refresh on the Museum’s careers page. I served as Hearst intern in Teen Programs, developing and teaching original curriculum for quasars. After my first lecture, I was ecstatic. Of my three

jobs that summer—curating UCSB’s bees, scooping McConnell’s ice cream, and teaching Museum teens—it felt the least like work. I looked forward to every class. When the pandemic hit the following year, I taught through Zoom, replacing field trips with games. My students managed hypothetical dams. They roleplayed solving a whodunitstyle environmental crisis, with less murder and more internet connectivity problems.

When the Teen Programs manager position became available, I still had a year of college to go. But I couldn’t let the opportunity pass, so I applied anyway. I got the job. At 21, I took charge of the same meetings I used to attend. Remaining part of the Museum—such a valuable education resource for the community—is a dream come true.

Over the next year, I graduated and planned the return of quasar programming to prepandemic levels, life-changing field trips included. With the support of colleagues and mentors, I took our 15 quasar teens back to Santa Rosa Island. It was my third time on the island, having spent one week there as a quasar, and a second as Hearst intern. During this trip full of exploring, tide pooling, birding, sandy beach monitoring, hiking, and laughter, I confirmed what I’ve known all along: this program positively impacts young scientists and leaders, just like it did for me. And it will continue to do so. I’ll bee sure of it.

Visit sbnature.org/quasars for more information.

Left and above: The author examining bee specimens during his research at CCBER. Photos by Christin Palmstrom A pinned specimen of Apis mellifera, laden with pollen. Photo by Charlie Thrift

Krissie Cook remembers when Gladwin Planetarium was analog. In 1995, when she started volunteering here as a teen in the Quasars to Sea Stars program, the planetarium was home to the Spitz A3P projector known as the “starball.” “It looked like a mechanical ant,” she recalls, one of many specialized machines—including 16 overlapping Kodak slide projectors—used to create an analog immersive experience. After a summer watching six planetarium shows a week, Cook fell in love with astronomy and the Museum’s interpretive

facilities. In the decades that followed, she’s taken on a variety of positions in Education Division and repeatedly worked to build Astronomy Programs capacity.

Cook’s history gives her the perspective to appreciate both the crushing impact of the pandemic, and the astonishing rebound of the last year. “I remember that week when everything shut down. That Saturday, there was supposed to be a Star Party and a Girl Scout Astronomy Club meeting, and it all melted away.” Girl Scouts and the Santa Barbara Astronomical Unit (SBAU) continued on Zoom, but the Museum

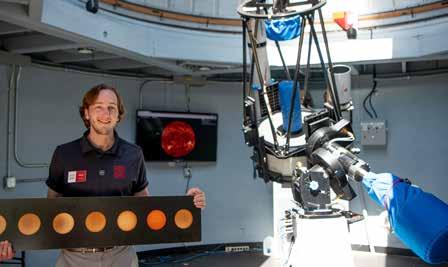

Dr. Kiman presenting a planetarium show. Photo credit Jeff Liang and the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics at UCSB Cook maneuvers the big telescope in Palmer Observatory for solar viewing.was greatly constrained. Cook’s successor, longtime Astronomy Programs

Manager Javier Rivera, retired, as did many volunteers. During the subsequent period of uncertainty, Astronomy Programs lagged behind in reopening, but with Cook’s persistent advocacy, it’s coming back in full force.

“I knew there was a deep need in the community, not just for information, but for human connection with these topics. The community needs this space.”

Gladwin Planetarium reopened with shows free and ticketless for all guests, and the proof of community

Top: Volunteer Noah Swimmer interpreting in the observatory “Our volunteers are spectacular. They’re so good at sharing information with the public in an approachable, friendly way. It makes a big difference to visitors.”

approval is in the attendance numbers: a record-breaking 6,687 show attendees this summer. Every Sunday at 1:00 PM, there’s a live, interactive Spanish-language show. This summer, native speaker and UCSB Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics Postdoc Rocio Kiman, Ph.D., presented many shows. Dr. Kiman is one of the highly-skilled and qualified volunteers bringing astronomy to life at the Museum. Thanks to volunteer support, we opened Palmer Observatory for hours at a time on Fridays and Saturdays, inviting guests to enjoy safe solar viewing. Cook has high praise for the people who make it all possible:

Star Parties—in partnership with SBAU and Santa Barbara City College—returned, bringing a jubilant and festive atmosphere to the observatory on the second Saturday of every month. Girl Scout meetings are back, with small but growing numbers. Astronomy-based school programs are one of the last puzzle pieces.

Cook and School & Teacher Services developed new content and activities to meet kindergarten through fifth-grade standards for solar system mechanics, so teachers can now book astronomy field trips.

“The backbone of the Museum—people who love this place—is still here,” says Cook. “People making a special experience for our visitors, and doing important scientific work that will last for generations. It warms my heart to no end.”

Find out what’s on offer at sbnature.org/astronomy

Star Parties are back at the Museum!Metz's Sea Center curriculum spotlights the egg cases of local shark species.

Before the pandemic, the Sea Center was a destination for schoolchildren learning about marine science. The popular beach-based curriculum focused on watershed and oceanographic concepts. New field trips debuting in fall 2022 are based in zoology and ecology, with a strong tie to live exhibits.

“These programs are scientifically rigorous and Next Generation Science Standards-aligned, and at the same time interactive, sensory experiences,” says School & Teacher Services Manager Charlotte Zeamer, Ph.D.

The curriculum was developed from the fresh perspective of new Sea Center School & Teacher Services Coordinator Rachel Metz, M.S. Her master’s degree is in philosophy with a specialization in environmental ethics, which, Metz notes, “explores questions of stewardship: How should we interact with Earth’s natural resources? Do we have responsibilities to other species, and future generations? Is nature intrinsically valuable?”

Metz constructed animal-focused curriculum to help children build personal connections to local ecosystems: “Most kids seem to naturally desire personal, intimate connections with animals—this seemed the perfect starting point to inspire further wonder and care for our ocean and local marine life.”

Students will learn with their whole class during an outdoor lesson with interactive activities on the wharf, before splitting into small groups and touring the Sea Center. The lessons offer background knowledge that will enrich their experience of the hands-on exhibits. “I think that’ll give them a cool connection, learning something and then getting to see it contextualized,” says Metz. Thanks to the Museum Access Funds program, students receive free passes to return with family and share their new expertise.

Visit sbnature.org/fieldtrip for more information.

Having camps back in person this summer was a treat for all.

“Nothing compares to being in person,” says Nature Adventures Manager Ty Chin, Ph.D. “We really enjoy having the kids back, and the kids are much happier, being able to talk to someone.” Parents scored a win as well.

Their desire to get kids out of the house echoed loud and clear in the speed with which they signed up for spots. Camps for little kids filled in a single day.

Nature Adventures also offers programs for children ages 10–12, often overlooked amid stiff competition for that age group’s time. “I think we’re unique,” says Dr. Chin, who draws on our exhibits and expertise for her curriculum. Next year, with the return of Sea Center camps, Chin may restore a special opportunity for older campers.

“We introduce a concept—like a climate change concept, or specific animals—and intensively research it. Then they build an exhibit from scratch and interpret it to the public.”

This approach builds confidence and sophistication. “The older kids are asked to reflect more, they learn to be more analytical.” When they use equipment like microscopes, they learn more of the science behind how the tools actually work.

Chin has been here long enough to watch some of her older campers grow up to careers in science and education. “That’s really rewarding to see. We hope that we all had a part in that success.”

Visit sbnature.org/natureadventures for more information.

In 2007, the Museum hosted an exhibition of photographs by Edward S. Curtis with the eyebrowraising title Romancing the Indian “It had an intentionally controversial title,” remembers Museum Librarian Terri Sheridan. “Once you got inside, you started getting why it was called that.” During the 100 years between the photographs’ publication in the 20-volume book series The North American Indian, much of their power has stemmed from their idealized romanticism.

Images from that ambitiously illustrated series powerfully affected global perceptions of Native America in ways that are still discussed today. Artists, scholars, and activists—with and without Native heritage—continue to unpack and remake the legacy of these images. Taken at the turn of the century, they remain timely in how they are continually reinterpreted.

The photographs’ complexity stems from inherent contradictions. “Curtis himself was conflicted,” Sheridan explains. First taught that Native people were savages, Curtis—through study and exposure to reality—came to hold “a deep respect for the people he was living next to.” He was keenly aware of the wide range of government-sanctioned pressures aiming to destroy Native people and

their ways of life, including land seizure, environmental destruction to devastate economies, language and religion suppression, legal disenfranchisement, and the division of families. “Curtis was thinking that these cultures and people were going to be erased. He brought it on himself to be the person who was going to record all this.”

His obsession with documentation was colossally expensive. To finance it, Curtis “needed to come up with images that the American bankroll could accept.” Banker J.P. Morgan patronized the project on the condition that Curtis create, in Morgan’s words, “the most beautiful set of books ever published.” To the books’ audience, beauty lay in imagery that flattened cultures to warrior stereotypes and romanticized the very

disappearance Curtis feared. His portraits of men from Plains cultures in feathered war bonnets, or as distant mounted figures dominated by bleak landscapes, fed into “vanishing race” stereotypes. These stereotypes are still damaging today, since their omnipresence often conceals the persistence of living Native people and the diversity of Native cultures.

Romancing sought to expose the artistic manipulations which gave stereotypical images flattening power. This year’s exhibit— Storytelling: Native People Through the Lens of Edward S. Curtis further contextualizes Curtis and the people he photographed. A strong infusion of lesser-seen imagery and new interpretation provide “a broader exhibit for people, in terms of what’s

on the walls as well as what their takeaways might be.” The most important takeaway, according to Sheridan? “Respect.” In particular, she hopes to invite greater respect and understanding of the women who agreed to be photographed. “Because of the patriarchal place Curtis was coming from, he would usually talk with the men, not realizing that often the women were people of power in particular cultures. He also very rarely named women, so their photographs often are just ‘wife of’ or ‘sister of.’ Although we rarely know their names, these women should be seen.”

Storytelling runs through April 30, 2023 at the Museum. Visit sbnature.org/storytelling for details.

“Gossiping – San Juan,” 1905

“East Mesa Girls,” 1921

“East Mesa Girls,” 1921

“Short-eared Owl,” John Gould, The Birds of Europe, 1837

Any excuse to look at owls will do. When a generous donor recently contributed his prints—many of which were owls—Maximus Gallery Curator Linda Miller flew at the chance to convene A Parliament of Owls. Owls are particularly wellrepresented in our collection of antique nature illustration prints. “They’re instantly recognizable,” says Miller, who considered about 100 candidates for the exhibition, finally settling on about 25 images spanning 13 artists, 6 countries, and 3 centuries. You won’t even find scientific names on the earliest pieces; they were drawn before Carl Linnaeus developed the scientific conventions of binomial nomenclature.

The unusually wide swath of time surveyed by the exhibition made it particularly difficult to winnow the final selection of works shown. Contemplating a candidate, Miller muses: “Look at his alert little ear tufts and his bright eyes.” It’s a fine specimen of French technique. Many other equally fine owls remain in the collection room’s drawers for now. Yet exclusivity pays off in the contrasts between the owls that remain. As in Beneath a Wild Sky, the birds

are grouped by species rather than chronologically. “Seeing them displayed together should invite comparison,” says Miller. “The range and diversity of the portrayals is fascinating, from crude and eccentric to fully realized and naturalistic.”

Many of these artists worked primarily from specimens rather than drawing from life, and none of them had the benefit of drawing from reference photos. Some artists were wealthy aristocrats, others were self-taught amateurs. Some worked in cottage industry, with different household members working together on different parts of the printmaking process: sketching, engraving tiny lines in a metal plate, hand-painting colors atop printed black. Alexander Wilson endured poverty as he pursued his passion for documenting American birds; Prideaux John Selby was an Oxford-educated gentleman who received drawing lessons from Audubon. Contrasting their Snowy Owls, you can appreciate both Wilson’s charming attention to detail and Selby’s depth and shading. Selby had the advantage of working later, when larger paper sizes became commercially available.

The pièce de résistance will be Audubon’s Barn Owl, on the massive double elephant folio paper size. “Audubon wanted all his birds the size of life.”

This hand-colored engraving (produced with Robert Havell, Jr.) reinforces the deservedness of Audubon’s reputation for artistry. The dramatic moment—the exchange of a predated chipmunk between two owls—reveals the beautiful details of all parts of the body, cunningly composed in a naturalistic scene motivating their poses. It illustrates Miller’s thesis that the advance of ornithology was supported by advances in illustration. As printing technology developed and skilled artists were attracted to the field, the resulting imagery offered not only great aesthetic pleasure, but more information about the animals for science. A printed gallery guide will highlight the works that are significant milestones in the history of bird illustration.

From the majestic to the modest, all these owls have distinctive character and expression, a joy to behold. Stand in the presence of A Parliament of Owls through February 5, 2023.

One of the best places to experience the seasons at the Museum is entering a new season of life: the Sukinanik’oy Garden is celebrating 20 years of growth and renewal. “I’ve had many people tell me the garden has never looked better,” says Curator Emeritus of Ethnography Jan Timbrook, Ph.D. The garden is a living link in a chain of plant knowledge extending from Chumash ancestors to their modern descendants, and a true labor of love for Dr. Timbrook. Twentieth-

century Elders Fernando Librado Kitsepawit, María Solares, Mary Yee, and others relayed Chumash culture to anthropologist J.P. Harrington, whose notes were the basis of Dr. Timbrook’s book Chumash Ethnobotany.

The garden was an outgrowth of her research and collaboration with Chumash advisors. Yee’s descendants chose the name—meaning “bringing back to life”—from among the words Yee taught Harrington. Yee’s daughter, Barbareño Chumash Elder Ernestine Ygnacio DeSoto, sees Sukinanik’oy’s early

Chumash advisors who consulted on the garden’s creation, left to right: Elise Tripp, Beverly Folkes, Julie Tumamait-Stenslie, Art Lopez, Adelina Alva Padilla, Lei Lynn Olivas Odom, Ernestine Ygnacio DeSoto

Chumash advisors who consulted on the garden’s creation, left to right: Elise Tripp, Beverly Folkes, Julie Tumamait-Stenslie, Art Lopez, Adelina Alva Padilla, Lei Lynn Olivas Odom, Ernestine Ygnacio DeSoto

Left, right: the garden in 2002, and 2022 with Timbrook and Volunteer Toni McQueen Circle: Gina Mosqueda-Lucas gathers Wewey (Coastal Sagebrush).

blooming as the forerunner to a wider flowering: “Everybody’s really getting interested in indigenous plants, especially since they’re water-friendly and we’re in a lot of trouble now for water.” Ygnacio DeSoto is actively involved in the cultural side of restoration projects at North Campus Open Space and San Marcos Foothills Preserve. The Sukinanik’oy Garden shares the cultural significance of our region’s plants with all guests, while serving as a harvesting site for Chumash people. Gina Mosqueda-Lucas (S h amala Chumash) reflects on the ease of access, compared to the remote and secluded places where she often gathers plants: “One of the fondest memories

I have is bringing my tribal Elder Pita Macias here. To be here with Pita, and for her to gather her own materials, was important to me. It’s important to keep our elders continuing these traditions, and this is easy access for them.” They gathered Tok (Dogbane) that day, and soon found themselves talking with a young guest about processing the plant “to make cordage, and we use it for netting, jewelry making, and all that good stuff, to this day.”

Last year was marked by extra activity made possible by a generous gift from Susan Williams. Throughout fall 2021 and the following winter, Dr. Timbrook and volunteers dug up

compacted beds, applied mulch for water efficiency, and added plants. They dug up and replanted Tok, as well as Mo’moy (a.k.a. Datura or Jimsonweed), a plant of profound spiritual importance and the only one to appear as a person in Chumash myth. Both plants are thriving. W ɨlɨ (Santa Cruz Island Ironwood) is a new addition, its strong wood preferred for harpoons, canoe paddles, and other specialized uses.

Timbrook’s focus is on plants and people, but ongoing renovations may also update infrastructure. The signs have held up amazingly over 20 years, but a few need to be repaired.

Learn more at sbnature.org/garden.

Top: Colombian Emerald Moths (Nemoria darwiniata) from the Russell Collection

Circle: Paul and Sandy Russell with their collection in the Museum’s Invertebrate Zoology Department

How do you build a collection? Slowly, and with patience. The Museum’s research collections are built in many ways, and usually over many years. They start small and grow through the collecting efforts and encouragement by generations of curators, donations from private collectors, from other museums, and the public who bring in something interesting or important. If well cared for and made accessible, they can become significant to our understanding of the natural world we live in.

The Museum’s current Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths) collection started with a few cabinets salvaged from a fire in 1962. Sandy Russell

volunteered as a docent in 1999 when she and her husband Paul moved to Santa Barbara. Eric Hochberg, Ph.D., a curator in the Department of Invertebrate Zoology at that time, suggested that she also come work on the longneglected insect collection. She has been tending the collection and adding specimens ever since. The addition of the Schlinger Chair of Entomology in 2001 has been a gamechanger since it signaled a long-term commitment to insects by the Museum. Since that time the collection has grown manyfold through donations from Tom Dimock, Ken Denton, Ed Pfeiler, and others. John Carson donated specimens and a significant bequest.

Now a major gift from Paul and Sandy Russell, longtime Museum volunteers and patrons, is taking it to a new level. The Russell Collection more than doubles the size of the Museum’s Lepidoptera holdings. It includes over 50,000 specimens housed in about 500 drawers, amassed over 50 years in North America, mostly from the West, and particularly from the South Coast area. The largest segment is moths collected by light trap year-round for more than 30 years at their homes in Malibu and Santa Barbara. The comprehensiveness of this collection makes it particularly valuable toward a full understanding of our local moth fauna. It also provides a unique record over time and seasons of the local fauna, and a reference point for comparing future changes from climate change, drought, wildfire, and other calamities. Moths are much less collected and

known than butterflies, even though they are 10 times more numerous and diverse. Who knew there could be 900 different species of moths from a single location in the Santa Barbara foothills?

The transfer of the Russell Collection accelerated four years ago, and now the rest has been donated, along with funding to assure the care and encourage the research use of this collection. The butterflies have already been integrated into the Museum collection. The moths are coming in on a weekly basis as the Russells combine their collection with existing Museum holdings, and reorganize and curate all of it to conform to the most recent taxonomic thinking.

The Russells also have an extensive collection from South America and other continents, which are being donated to the Peabody Museum at Yale University.

Lepidoptera have long been important in our Museum exhibits, even more so since the Butterfly Pavilion opened. They have been important to education through classes and camps. A child gains a new perspective when holding a wriggling caterpillar in their hand. Sandy Russell has been supplying live insects and other critters to Museum camps and classes for many years.

Schlinger Chair & Curator of Entomology Matthew Gimmel, Ph.D., is immensely grateful that the Russells are giving not only their specimens, but the time and expertise to ensure those specimens are perfectly integrated into our collections:

“From a curatorial perspective, what they’re doing here now is amazing, and that example should be followed by other donors.”

The Russells believe that donors don’t have to die before contributing to the Museum, and it is much more satisfying to see one’s collection properly cared for, used, and integrated into the Museum’s mission.

As Dr. Gimmel summarizes, “They’re doing it early, they’re working on it actively, and they’re financially planning for its future.”

The Museum is grateful to the Russells for their incredibly generous and scientifically significant gift. We are honored to be caretakers of their collection and look forward to learning from the research they will support.

Luke J. Swetland President & CEO Montana Six-plume Moth (Alucita montana) from the Russell Collection. Photo by Lucie GimmelAs a benefit of membership in the Leadership Circles of Giving, the Museum hosts an annual dinner of thanks for our Leadership Circles Members. This past May we moved the dinner outdoors overlooking the Museum’s beautiful Backyard, and the evening’s focus was our organization’s longstanding efforts in ocean conservation and education— past and present.

Dinner guests were treated to tables decorated with unique Museum specimen centerpieces and the premiere of “How We Sea It,” a video highlighting our important ocean conservation efforts and

collaborations (now available among the videos at sbnature.org/youtube). The event also honored this year’s Legacy Award recipients: Elaine Gibson, Bobbie and John Kinnear, and Diane Waterhouse. Leadership Circles Members serve as a core foundation for all we do: from research, to collections, to education across both campuses. If you’re interested in learning more about this important membership level and want to join the fun, contact Diane Devine at ddevine@sbnature2.org or 805-682-4711 ext. 124.

Above: President & CEO Luke Swetland, honorees Elaine Gibson, Diane Waterhouse, Bobbie and John Kinnear. Photos by Baron Spafford

Above: President & CEO Luke Swetland, honorees Elaine Gibson, Diane Waterhouse, Bobbie and John Kinnear. Photos by Baron Spafford

Diane Wondolowski is a central figure at the Museum and Sea Center. Her passion for nature and love of learning have grounded 20 years of service.

Diane and her husband Mike graduated from UC Berkeley and moved to Santa Barbara where he attended graduate school. Soon after, Mike gave his then-fiancée a gift of Museum membership, the first time they’d officially have their names together. Diane was hired by a local CPA firm and became the partner in charge of the Museum’s annual audit, and was later offered the Museum’s director of finance and administration position.

When not working on budgets, investments, or multi-million-dollar construction projects, Diane loves walking around campus and seeing children’s reactions. Whether it’s a child throwing a tantrum because they don’t want to leave or a fouryear-old saying it’s the best day of

their life, witnessing these interactions is inspiring and gratifying. Diane is also lifted by her colleagues’ passion for keeping the Museum a relevant, creative, and innovative institution. Diane’s favorite project so far has been incorporating materials from the Dibblee Foundation— responsible for the legacy of “rock star” geologist Tom Dibblee—into the Museum’s collections in 2002. The transfer allowed Museum employee John Minch to digitize and make accessible 419 geologic maps of California. Through this experience, and a few geology field trips, Diane discovered she “really likes rocks.”

She’s also proud of how the Museum, with support from its board of trustees, committed to providing job security, work, and payment for staff throughout the pandemic shutdown. Thanks to Diane’s financial acumen and a supportive, skilled board and staff, the Museum is in a strong financial position to continue our mission to inspire passion for the natural world.

2559 Puesta del Sol

Santa Barbara, CA 93105

SBnature Journal is a publication of the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History. As a Member benefit, issues provide a look at the Museum’s exhibits, collections, research, and events. The Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History is a private, non-profit, charitable organization. Our mission is to inspire a thirst for discovery and a passion for the natural world. For information about how to support the Museum, contact Director of Development Caroline Baker at 805-682-4711 ext. 109 or cbaker@sbnature2.org.

sbnature.org

@sbnature@sbmnh