The Physics of Us

Physicists are studying how living matter works, and find that it breaks the standard rules and produces

By Susan Ahlborn

By Susan Ahlborn and Blake Cole

Blake Cole

Duyen Nguyen

OMNIA is published by the School of Arts & Sciences Office of Advancement

EDITORIAL OFFICES

School of Arts & Sciences

University of Pennsylvania

3600 Market Street, Suite 300 Philadelphia, PA 19104-3284

P: 215-746-1232

F: 215-573-2096

E: omnia-penn@sas.upenn.edu

STEVEN J. FLUHARTY

Dean, School of Arts & Sciences

LORAINE TERRELL

Executive Director of Communications

BLAKE COLE

Editor

SUSAN AHLBORN

Associate Editor

LUSI KLIMENKO

Art Director

HEMANI KAPOOR

LUSI KLIMENKO

ANDREW NEALIS

Designers

CHANGE OF ADDRESS

Alumni: visit MyPenn, the Penn alumni community, at mypenn.upenn.edu. Non-alumni: email Development and Alumni Records at record@ben.dev. upenn.edu or call 215-898-8136.

The University of Pennsylvania values diversity and seeks talented students, faculty and staff from diverse backgrounds. The University of Pennsylvania does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, religion, creed, national or ethnic origin, citizenship status, age, disability, veteran status or any other legally protected class status in the administration of its admissions, financial aid, educational or athletic programs, or other University-administered programs or in its employment practices. Questions or complaints regarding this policy should be directed to the Executive Director of the Office of Affirmative Action and Equal Opportunity Programs, Sansom Place East, 3600 Chestnut Street, Suite 228, Philadelphia, PA 19104-6106; or (215) 898-6993 (Voice) or (215) 898-7803 (TDD).

Cover Illustration: Marina Muun

OMNIA

The Energy of New Beginnings

The start of the academic year always brings new energy to campus, and this year the energy has been exceptional. Faculty and students are fully engaged in a way we haven’t seen since before the pandemic. In their teaching and learning, as well as in discussion, engagement, and actions, they demonstrate to me every day their passion and desire to make a difference.

The campus is drawing a great deal of this energy from the presence of our new president, Liz Magill. The entire Penn community, including students, faculty, administration, and alumni, came together to officially celebrate this new beginning at President Magill’s inauguration festivities on October 21. We were honored to have her spend two days this fall getting to know about the School of Arts & Sciences through a series of meetings with faculty from the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences, as well as graduate students, undergraduates, and staff. In addition, she has been

spending time one-on-one with each of our 27 department chairs. Through her inspiring words at her inauguration, as well as through this substantial commitment of her own time and energy, our new president’s commitment to the arts and sciences comes through loud and clear.

Energy has also been on the front of our minds as the campus is mobilizing around the need to address critical environmental challenges. Two School of Arts & Sciences faculty, Joseph Francisco of Earth and Environmental Science and Chemistry and Kathleen Morrison of the Anthropology department, are co-leaders of the Provost’s Environmental Innovations Initiative, which is working to advance innovation and collaboration in the Penn research community. Earlier this fall, in coordination with this initiative, the School issued a statement confirming our commitment to address the threat of climate change to humans and to our planetary environment through a broad array of existing and

emerging programs. These efforts include the work of many faculty you can read about in this publication, such as Anthropology’s Nikhil Anand (p. 46), who is leading interdisciplinary initiatives that provide insight on worldwide climate disasters and water crises, or History’s Jared Farmer, whose new book considers the world’s oldest trees in the context of our climate crisis (p. 8), and Chemistry’s Andrew Rappe, whose research continues to help us forge a path toward clean energy technologies (p. 10). I hope that you draw as much inspiration from these stories as I do.

Dean and Thomas S. Gates, Jr. Professor of Psychology,

Pharmacology, and Neuroscience

Godfrey

Organic Learning

As we head into the holiday season, we are excited to again deliver OMNIA in printed form. One focus of this issue is connection with nature. In our cover story, “The Physics of Us” (p. 16), we explore how living matter works— whether it’s the vasculature in leaves or the neurons in our brains—and find that it breaks standard rules and produces fascinating phenomena that could impact everything from medicine to robotics.

Our focus on nature also includes an examination of issues surrounding climate change, a central priority for the School (p. 2). “Beyond the Margins of Land and Water” (p. 46) follows two interdisciplinary research initiatives that provide insight on worldwide climate disasters and water crises, analyzing everything from melting glaciers to intensifying monsoon cloud bursts. “Tree Wisdom” (p. 8) profiles a new book that examines 5,000 years of living trees through the lens of science, religion, and history, as well as the long-term relationships between people and individual trees. And in our Last Look visual feature (p. 65), a postdoctoral researcher collects coral samples to study how ocean acidification—caused by rising CO₂ levels—is affecting the health of reefs.

Though the election season will be behind us by the time you read this, concerns over the economy and global affairs will certainly remain. In “OMNIA 101: The Federal Reserve Bank” (p. 12), we speak with a former Fed employee turned professor to learn more about why the

institution is especially relevant in times of financial crisis. We also learn how a fateful trip to Eastern Europe in 1989 inspired a professor to pursue a career studying the impact of the Cold War and its aftermath on the lives of individuals in “Ordinary Lives, Extraordinary Times” (p. 24), and how the Department of Russian and East European Studies is helping to bring Ukrainian scholars to Penn.

One of the strengths of Penn Arts & Sciences learning is the diverse classroom experiences our students share. With this in mind, our In the Classroom segment explores the “flipped classroom,” a learning model in which lectures and presentations are delivered outside of class time while in-person learning features active student engagement (p. 14). “Moments in Time” (p. 34) tells the story of a long-form nonfiction class that met over dinner, following two students as they create detailed portraits of life around campus, while “Threading the Needle” (p. 52) highlights an initiative in the College of Liberal and Professional Studies’ online Bachelor’s of Applied Arts and Sciences degree program that guides students in curating a digital collection of materials to showcase their academic abilities. This portfolio has helped graduates build their careers, including a professional ballerina who parlayed her new-found confidence into a leadership role at her ballet company.

In our Movers & Quakers alumni profile (p. 60), we speak with Victor Scotti, C’13, who is harnessing technology to work

towards a future where diversity, equity, and inclusion are the norm. Scotti also operates his own company, which “accelerates Black boys’ self-efficacy” through professional experiences, job shadowing, mentorship, and socio-emotional support.

A number of programs in the Penn Arts & Sciences community recently celebrated anniversaries, among them Kelly Writers House, the Center for the Advanced Study of India and its counterpart in New Delhi, the University of Pennsylvania Institute for the Advanced Study of India, and the Barbara and Edward Netter Center for Community Partnerships.

In “Celebrating the Past—and Planning for the Future” (p. 32) we explore how these initiatives’ combined 110 years of experience, research, education, and collaboration continue to have enormous impact at Penn and in the world.

We also share in the campus-wide welcome of Elizabeth Magill, the new President of the University of Pennsylvania. Magill recently met with Penn Arts & Sciences faculty, students, and staff to learn about highlights and priorities across the School (p. 5).

We hope you enjoy all the issue has to offer. Happy holidays.

Blake Cole, Editor

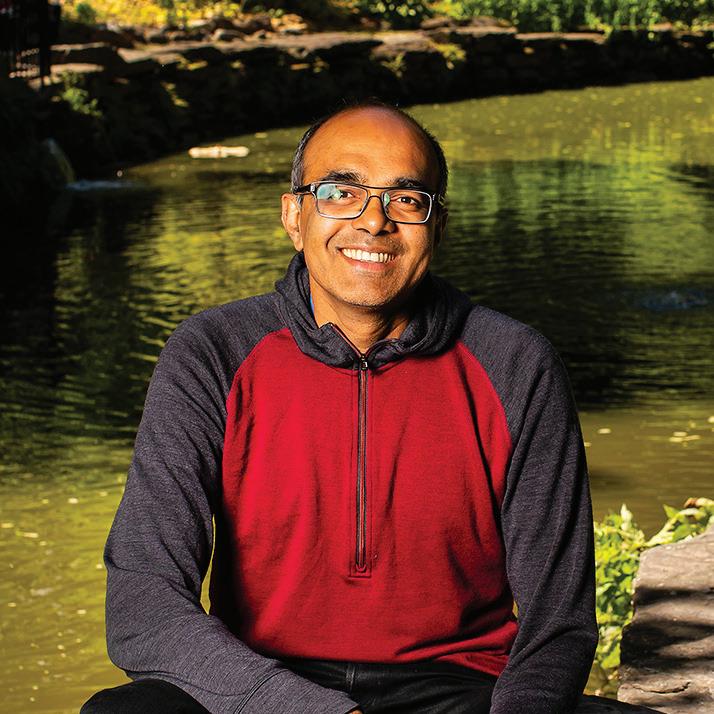

Ramanan Raghavendran Named Chair of Board of Advisors

Ramanan Raghavendran, Chair of the School of Arts and Sciences Board of Advisors

Ramanan Raghavendran, ENG’89, W’89, LPS’15, was appointed the new chair of the School of Arts and Sciences Board of Advisors, effective July 1, 2022. Raghavendran succeeded Michael Price, W’79, who stepped down from the Board after more than 20 years of service.

Raghavendran has been a member of the Board of Advisors for a decade and is also a University Trustee. He is a member of the Advisory Board for the Center for the Advanced Study of India and chair of the University of Pennsylvania Institute for the Advanced Study of India. He is the Global Coordinator of the Penn Alumni Interview Program and a member of the Orrery Society, and has long been a champion of financial aid.

“Ramanan truly walks the walk when it comes to his commitment to the liberal arts, and even earned a Master of Liberal Arts degree from our division of Liberal and Professional Studies while a member of our Board,” says Steven J. Fluharty, Dean and Thomas S. Gates, Jr. Professor of Psychology, Pharmacology, and Neuroscience. “He has always been extremely thoughtful and imaginative in his engagement with the School, and I am looking forward to his continued counsel and involvement as our Board’s new chair.”

Raghavendran is the co-founder of Amasia, a venture capital firm that invests in companies that help fight the climate crisis and enhance sustainability through behavior change. He is also active on the boards of several charities and NGOs.

New Faculty

Penn Arts & Sciences welcomed 14 new faculty members for the 2022–23 academic year.

Caroline Batten, Assistant Professor of English

Jane Esberg, Assistant Professor of Political Science

Chloe Estep, Assistant Professor of East Asian Languages and Civilizations

Jasmine Henry, Assistant Professor of Music

Aman Husbands, Assistant Professor of Biology

Corine Labridy, Assistant Professor of Francophone Studies

Melissa Lee, Klein Family Presidential Assistant Professor of Political Science

Dylan Rankin, Assistant Professor of Physics and Astronomy

Javier Samper Vendrell, Assistant Professor of German

Tahseen Shams, Assistant Professor of Sociology

Sabina Vaccarino Bremner, Assistant Professor of Philosophy

Beans Velocci, Assistant Professor of History and Sociology of Science

Secil Yilmaz, Assistant Professor of History

New Penn President Gets to Know Penn Arts & Sciences

Elizabeth Magill, the new President of the University of Pennsylvania, met with Penn Arts & Sciences faculty, students, and staff to learn about highlights, priorities, and challenges across the School. Magill held discussions with faculty and staff from all departments, and a virtual session with students in the online BAAS degree program for working adults & other non-traditional students. She also met with members of the First-Generation, Low-Income Dean’s Advisory Board and the College Dean’s Advisory Board (above), groups of undergraduate volunteers who work with Paul Sniegowski, Stephen A. Levin Family Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, on initiatives to serve undergrads.

School

Funds Faculty

Initiatives in Global Change and Social Justice

Penn Arts & Sciences has awarded grants for six projects through the Making a Difference in Global Communities and the Klein Family Social Justice initiatives.

Making a Difference in Global Communities supports multidisciplinary, faculty-led projects that involve students and address societal challenges internationally, including inequities in race, gender, sexual identity, socioeconomic mobility, education, health care, and political representation, as well as the grand challenges of climate change, poverty, and immigration.

The 2022 Making a Difference in Global Communities projects are:

LAVA: Laboratorio para apreciar la vida y el ambiente, led by Michael Weisberg, Professor and Chair of Philosophy.

Using Animated Video to Address Sea Level Rise, led by Simon Richter, Class of 1942 Endowed Term Professor of German.

Regional Collaboration for Better Crime Policy, led by Anthony Braga, Jerry Lee Professor of Criminology and Director of the Crime and Justice Policy Lab.

Klein Family Social Justice Grants offer awards for academic activities that use the arts and sciences to contribute to positive social change in the United States, including Penn’s engagement with its surrounding community. They are intended to stimulate scholarship and education on topics of anti-racism, inclusion, diversity, and social justice and to promote additional opportunities for community engagement.

The 2022 Klein Family Social Justice Grants are:

Personalized, Accelerated Science Learning, led by Lori Flanagan-Cato, Associate Professor of Psychology.

Free State Slavery and Bound Labor: Pennsylvania, led by Sarah Barringer Gordon, Professor of History and Arlin M. Adams Professor of Constitutional Law, and Kathleen Brown, David Boies Professor of History.

Kitchen Science: A Platform for Inclusive and Accessible Outreach, led by Arnold Mathijssen, Assistant Professor of Physics and Astronomy.

Alex Schein

Faculty Honors

The outstanding work of the Penn Arts & Sciences faculty continues to be recognized with notable honors and awards. Here are just a few.

Anthea Butler, Geraldine R. Segal Professor in American Social Thought and Chair of Religious Studies, received the Martin Marty Award for the Public Understanding of Religion from the American Academy of Religion.

Diana C. Mutz, Samuel A. Stouffer Professor of Political Science and Communication, was co-winner of the 2022 Best Book Award from the American Political Science Association for Winners and Losers: The Psychology of Foreign Trade. Two members of the Department of History of Art were honored by the Society of Cinema and Media Studies for their books. Karen Redrobe, Elliot and Roslyn Jaffe Endowed Professor in Film Studies, received the Best Edited Collection Award for Deep Mediations: Thinking Space in Cinema and Media Cultures (co-edited with Jeff Scheible of King’s College, London), and Chenshu Zhou,

Assistant Professor of History of Art, won Best First Book Award for Cinema Off Screen: Moviegoing in Socialist China.

Evelyn Thomson, Professor of Physics and Astronomy, was named an American Physical Society Fellow, who are chosen for their outstanding advances in physics through original research and publication or significant innovative contributions in the application of physics to science and technology.

Several faculty members were recognized for their work in chemistry. The American Chemical Society’s (ACS) Physical Chemistry division established a new award, the Marsha I. Lester Award for Exemplary Impact in Physical Chemistry, in honor of Lester, Christopher H. Browne Distinguished Professor of Chemistry. Karen Goldberg, Vagelos Professor in Energy Research, won the 2023 William H. Nichols Medal from the ACS for outstanding contributions in the field of chemistry. Joseph Francisco, President’s Distinguished Professor of Earth and Environmental Science,

received the 2022 Centenary Prize from the Royal Society of Chemistry and the Philadelphia Section Award from the ACS. Eric Schelter, Professor of Chemistry, and his team won the 2022 Anders Gustaf Ekeberg Tantalum Prize, awarded to the lead author of the published paper, book, or patent that is judged to have made the greatest contribution to understanding the processing, properties, or applications of tantalum.

(L–R) Anthea Butler, Geraldine R. Segal Professor in American Social Thought and Chair of Religious Studies; Chenshu Zhou, Assistant Professor of History of Art; Marsha I. Lester, Christopher H. Browne Distinguished Professor of Chemistry; Diana C. Mutz, Samuel A. Stouffer Professor of Political Science and Communication; Joseph Francisco, President’s Distinguished Professor of Earth and Environmental Science; Karen Goldberg, Vagelos Professor in Energy Research; Evelyn Thomson, Professor of Physics and Astronomy; Eric Schelter, Professor of Chemistry; Karen Redrobe, Elliot and Roslyn Jaffe Endowed Professor in Film Studies

Asian American Studies Program Expands

The Asian American Studies Program will welcome three new core faculty members next year, expanding the range of topics and classes the program offers.

Tahseen Shams, currently an assistant professor at the University of Toronto who studies international migration, race and ethnicity, and religion, is due to arrive in the spring of 2023 as a member of the Department of Sociology. Hardeep Dhillon, a legal historian who recently earned her Ph.D. from Harvard University, will join the Department of History in fall 2023. Dhillon is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the American Bar Foundation researching law and inequality. Bakirathi Mani will also arrive during fall 2023 as a member of the Department of English specializing in Asian American studies, postcolonial studies, and

transnational feminist and queer studies. Mani, who currently teaches at Swarthmore College, is a founding member of the Tri-College Asian American Studies program at Swarthmore, Bryn Mawr, and Haverford Colleges.

The Asian American Studies Program was established in 1996 as a result of collective student, faculty, and alumni action, and celebrated its 25th anniversary this year. It is an interdisciplinary program that offers a minor as well as a broad range of courses, events, and research opportunities to contextualize the history, experiences, and contributions of Asian immigrants and persons of Asian ancestry in North America and the diaspora. It is led by Faculty Director David Eng, Richard L. Fisher Professor of English, and Co-Director Fariha Khan

David Eng, Asian American Studies Program Faculty Director and Richard L. Fisher Professor of English, and Fariha Khan, Program Co-Director

Tree Wisdom

In his new book, Jared Farmer, Walter H. Annenberg Professor of History, examines what trees can teach us about the climate crisis and our relationship with time.

BY KATELYN SILVA

Humans have a long history of venerating ancient trees. That reverence and caretaking took a modern turn in the 18th century, when scientists embarked on a quest to locate and date the oldest living things on Earth, as Jared Farmer, Walter H. Annenberg Professor of History, narrates in Elderflora: A Modern History of Ancient Trees. The book takes readers from Lebanon to New Zealand to California, looking at the complex history of the world’s oldest trees, their relationship to time, and how they can help us address the climate crisis.

Humans are remarkably skilled at looking into our deep history, says Farmer, but they’re not particularly adept at thinking about the long future. Trees, however, are ideal for long-term climate thinking. Trees can persist for thousands of years. Their wood rings store valuable data about past climates, weather events, and natural disasters, and offer insight into events on a planetary to regional to local level that can be tied to calendrical dates and therefore historical chronicles. This makes trees powerful timekeepers, says Farmer.

“Ancient trees are bridges between short time and deep time, between lived human time and abstract geological time,”

continues Farmer, whose book looks at 5,000 years of living trees through the lens of science, religion, and history, as well as the long-term relationships between people and individual trees.

Elderflora joins a growing group of arboreal science- and tree-themed books released in the past decade, including the forest ecologist Suzanne Simard’s best-selling memoir, Finding the Mother Tree; the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Overstory by Richard Powers; and Barkskins, by Pulitzer-winner Annie Proulx.

Farmer believes this surging popularity relates to both the human desire for the connection that trees embody through their mycorrhizal network, as well as the increasing urgency surrounding the climate crisis, which has already killed or damaged ancient sequoias, ancient olives, ancient kauris, and other longlived tree species. He says, “The ‘mother tree’ is a metaphor for connectivity based on mutualism and care. This idea is very attractive in our current moment of miscommunication, disinformation, animosity, distrust, and political breakdown. This notion that there are beings out there who have a wholly different model of sharing and cooperating is inspiring.”

Farmer highlights Indigenous groups and religious figures who serve as caretakers for ancient trees. He also quotes from his conversations with scientists, who agree there’s a “real crisis right now for forests and trees, especially old trees, and most especially big old trees, whose climate of establishment is now long gone.”

Humans have already changed the climate going forward centuries, perhaps millennia, Farmer notes. He hopes that understanding ancient trees and our relationship to them will develop our capacity for hindsight and foresight and create emotive connections to the far future in order to work together on climate now.

“There is much to learn about how to best live on Earth from trees,” he says. “Trees are solar-powered, vegetarian, and committed to their locale. There’s something deeply inspiring and deeply Earth-appropriate about that way of living. There’s no reason to think our species can’t have at least a few million more years in its future, if we learn to live appropriately alongside life-forms that preceded us and will surely outlast us.”

Listen on Repeat

Mary Channen Caldwell, Assistant Professor of Music, explores the medieval refrain in song outside of vernacular contexts.

BY DUYEN NGUYEN

hile working on a directed study on medieval dance in graduate school, Mary Channen Caldwell, Assistant Professor of Music, kept coming across references to Latin songs with refrains. In contemporary music, the refrain refers to a song’s repeated lines, or its chorus— think of the part that you somehow always remember and sing along to.

But the refrain in the repertoire that caught Caldwell’s attention is distinctive in a number of ways. “You can have the same refrain in different songs, for example,” Caldwell says, explaining that there is more to the medieval refrain than its association with dance. Her new book

Devotional Refrains in Medieval Latin Song explores these possibilities, tracing how the Latin refrains and refrain songs were created, transmitted, and performed.

Devotional Refrains in Medieval Latin Song focuses on devotional songs that would have been part of the musical practices of the Latin-literate communities attached to churches, abbeys, and schools across medieval Europe. The book, which includes five chapters, as well as an introduction and conclusion, highlights the versatility of the Latin refrain as a devotional tool in these communities— and as an interpretive framework for modern-day scholars. Each chapter analyzes a specific aspect of the Latin refrain, from its relationship to medieval notions of time to the refrain’s role in the formation of devotional communities. To carry out her study, Caldwell compiled and studied over 400 vocal works from dozens of manuscripts located in archives in France, Italy, Ireland, and elsewhere.

The book considers songs chiefly from the 11th to the 16th century, first examining the relationship between the Latin refrain and perceptions of time in the

Middle Ages. “Latin refrain songs and the refrains in them negotiate different poetic and musical temporalities,” Caldwell explains. While medieval Christians understood time through liturgical celebrations like Christmas or Easter, Caldwell says that Latin refrain songs merged the liturgical calendar with the seasonal experience of time—spring, summer, winter, and fall.

Another notable feature of the Latin refrain appears in the manuscripts themselves as inscriptions, rubrics, and marginalia. This is significant for both scholars studying medieval music and those trying to reconstruct medieval cultural traditions. Caldwell says, “One of the hardest things about studying medieval music is that we don’t know how it’s performed. We can make educated guesses— we can study the theoretical treatises and make interesting hypotheses—but at the end of the day, there’s a lot that we just don’t know.”

The annotated manuscripts of many Latin refrain songs shed some light on these unknowns, sometimes indicating who would sing what or even explaining why a collection included a certain song. One of the sources that Caldwell examines—the Moosburger Graduale, a manuscript containing Latin chant and devotional songs from 14th-century Moosburg, Germany— includes a preface written by the dean of the local church’s song school. “Textual introductions to songs are pretty rare, but this gives us insight into the medieval perspective on this repertoire from someone who is actively involved in the musical life of, in this case, choir boys,” says Caldwell. Songs like those in the Moosburger Graduale would have likely been adapted to other contexts. A key finding of Caldwell’s research, then, is that Latin refrains were rarely fixed, despite their repeatability. “From the 12th to the 16th centuries in Europe, you have these refrains that appear across multiple songs and each time they appear in any song, you have the possibility of remembering what it was in the original song and also creating a new context for that same refrain,” Caldwell says, explaining how the Latin refrain moved across time and space while simultaneously creating “networks of memory and allusion.”

“Some of these songs continue to be sung for hundreds of years and a couple of them actually end up getting translated into vernacular and sung as Christmas carols,” Caldwell explains. “These are songs that have had a lifespan of millennia and that’s really unusual. But this speaks to the idea that these little units of text and music were somehow meaningful—they were meaningful enough to continue being part of traditions that in other ways had changed dramatically.”

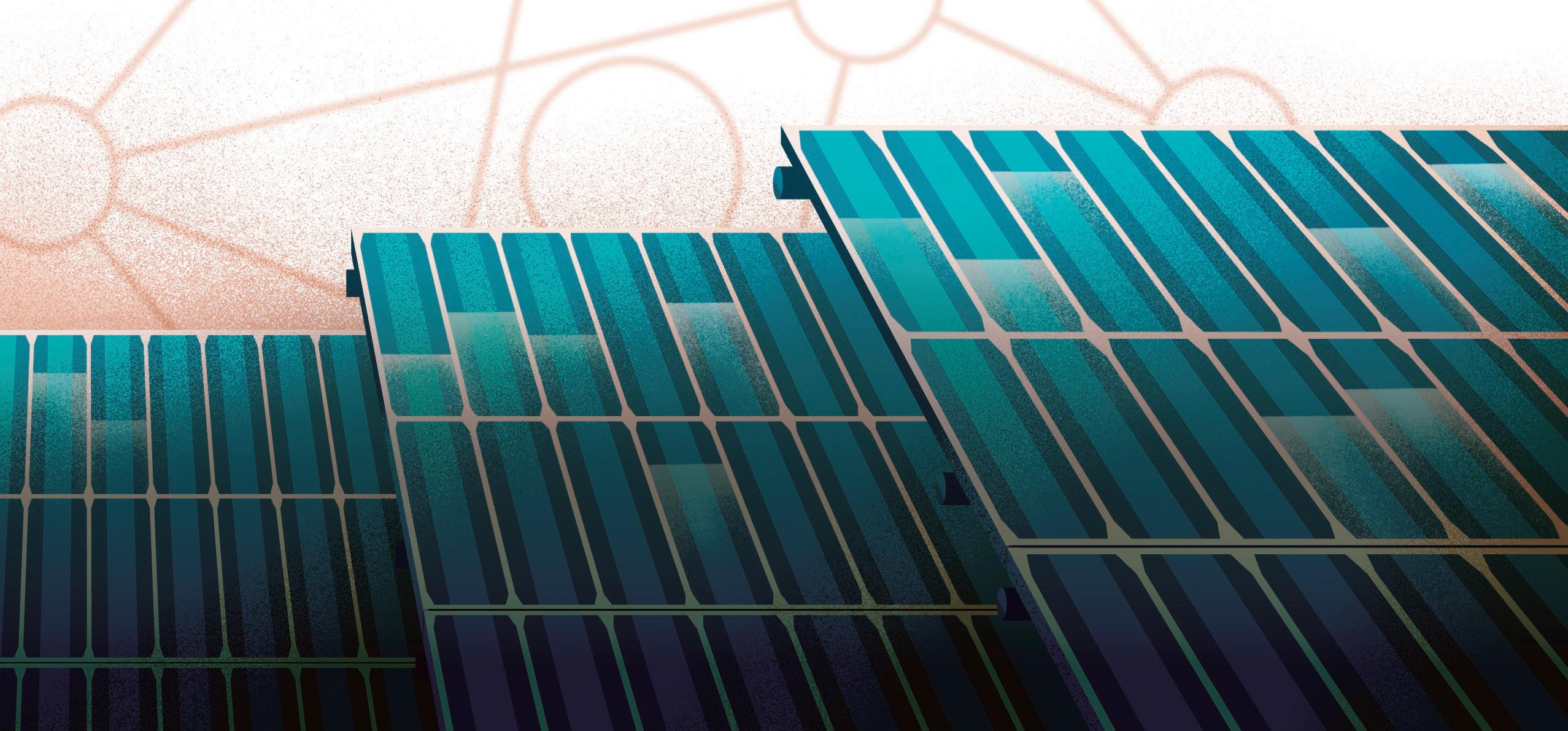

Marrying Models With Experiments to Build More Efficient Solar Cells

Andrew M. Rappe, Blanchard Professor of Chemistry, and postdoctoral researcher Arvin Kakekhani lend their expertise to a study on solar cell efficiency.

BY LUIS MELECIO-ZAMBRANO

n a single day, enough sunlight strikes Earth to power the world for an entire year. While the cost of solar energy has decreased dramatically, current silicon-based solar cells are expensive and energy-intensive to manufacture, prompting researchers to look for alternatives. One of the prime contenders for the next generation of this renewable energy is called perovskite solar cells. These synthetic materials are cheaper and require less energy to produce, but fall behind many silicon-based cells in terms of their stability and efficiency.

Now, a paper published in Nature Communications from the groups of Andrew M. Rappe, Blanchard Professor of Chemistry at Penn, and Yueh-Lin Loo of Princeton University, gives insight into how the molecular make-up of certain perovskites might affect their efficiency and offers a path forward to better solar cells using a simple metric.

“The world currently needs more efficient and cost-effective photovoltaic cells, and 3D hybrid perovskite PVs have taken the world by storm,” says Rappe, who also co-directs Penn’s undergraduate Vagelos Integrated Program in Energy Research. “But they are irreversibly damaged by water, which is a showstopper for practical applications.”

In the study, researchers investigated a certain class of perovskites called 2D

hybrid perovskites. Initially, the Princeton team prepared a set of 2D perovskites with different organic molecules, studying how those molecules affected the inorganic layer’s alignment and the solar cell efficiency. They noticed that the type of molecule influenced the structure and energy efficiency of the solar cells but didn’t exactly know why or how. They needed an atomistic insight to complement the experimental findings and hypotheses, so they reached out to Rappe and Arvin Kakekhani, then a postdoc in the Rappe group, both experts in using computers to model chemical interactions.

From the current quantum mechanical calculations and charge modeling work, Kakekhani and Rappe found that the molecules in the organic layer could interact with each other, lining up in pairs or in zigzags between the metal-based layers of the perovskites. When forming these pairs or zigzags, the organic molecules interacted less with the metal-based layer, giving the layer space to align properly and improving the performance of the resulting solar cells.

But Kakekhani wondered whether he could find a way to capture this phenomenon in a simple value that described the interaction between the organic and inorganic layers. After testing various models, he landed on one that described how far away the interactions in the

organic layer pulled the positive charge from the inorganic layer. Then he tested it to see whether it might predict how well the inorganic layer would align and how well the solar cells might perform.

Kakekhani predicted the real-life trends with surprisingly high fidelity. In mathematical terms, his model gives a coefficient of determination of >0.95, almost a perfect linear correlation. Because this metric only needs a computer to predict solar cell performance, it could allow scientists to choose which molecules might work best in perovskites before stepping into the lab, helping researchers narrow their efforts to only the most promising candidates.

“There are literally millions of molecules that people could try. But it’s not so easy to make millions of solar cells,” says Rappe. “This gives people a simple scoring rule, where they could analyze whether a molecule they’re considering is likely to enhance the productivity of the solar cell.”

In the future, Rappe says these insights might also help with perovskite LEDs. If these perovskites can turn light into energy efficiently, they should be able to do something similar when turning energy to light. More generally, he says, “This study shows that we are learning how to assemble materials, atom by atom and molecule by molecule, that can solve the world’s most pressing energy challenges.”

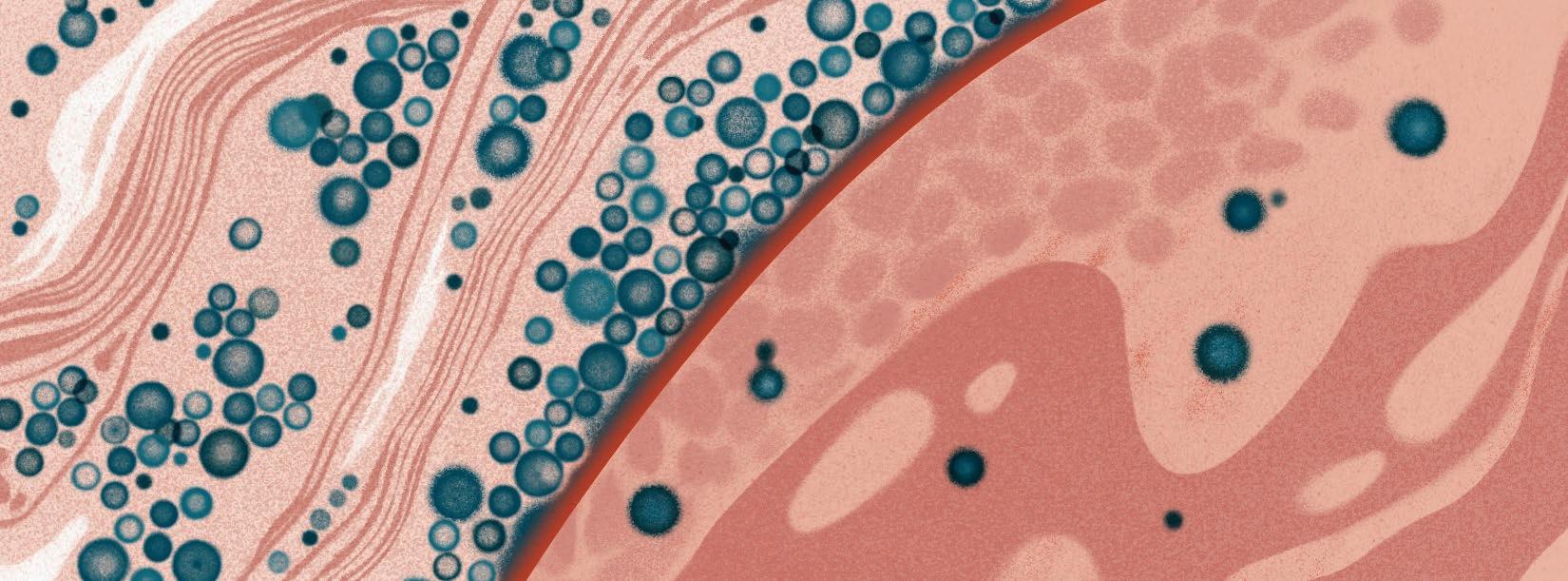

Cancer Cells Selectively Use ‘Drones’ to Keep T Cells From Infiltrating Tumors

Wei Guo, Class of 1965 Term Professor of Biology, identifies a new tool to help predict how a patient might respond to checkpoint inhibitor drugs.

BY KATHERINE UNGER BAILLIE

Checkpoint inhibitor drugs have been a gamechanger for many cancer patients. Yet around 70 percent don’t respond to these medications, which work by removing the “brakes” on the immune system’s response to a tumor. In some non-responders, the immune system’s killer T cells can’t penetrate the tumor boundaries.

In a new study, Wei Guo, Class of 1965 Term Professor of Biology, identified a mechanism responsible for keeping killer T cells from infiltrating a tumor. The work, published in Nature Communications, offers a new tool to predict how a patient might respond to checkpoint inhibitor drugs.

“Infiltration of the tumor is crucial for the success of checkpoint blockade therapy,” says Guo, senior author on the work. “Because this T cell infiltration is so crucial, it’s also important to know the molecular mechanism of how it works and when it doesn’t.”

Guo’s lab has explored how cancerous tumors secrete exosomes, small vesicles that serve as biological drones that do battle with the immune system at sites well away from the primary tumor. Exosomes loaded with the protein PD-L1 can interact with T cells’ PD-1 protein, causing the T cells to tire before they reach the tumor. “If you consider exosomes as drones, then PD-L1

is the weapon loaded on the drone,” Guo says.

Many checkpoint inhibitor drugs block this interaction, aiming to keep T cells invigorated and ready for a fight. Guo and colleagues wanted to understand how cancer cells load their “drones” with PD-L1, and whether this activity prevents T cells from infiltrating tumors.

Turning their focus to the process by which cancer cells generate exosomes, the researchers paid particular attention to a molecule called HRS, a member of a large complex called ESCRT involved in sorting the “cargo” placed in exosomes. In the lab, they looked in metastatic melanoma cells and found that frequently ERK, an enzyme well known to be activated in melanomas, added a phosphate group to HRS.

“We hypothesized that the tumor is regulating HRS, which has a major role in generating

exosomes and uploading PD-L1 to their exosomes,” Guo says.

Guo and colleagues created different cancer cell lines, some of which had regular HRS, and some of which had HRS with either reduced or elevated levels of phosphorylation. Mice exposed to the more highly phosphorylated HRS developed tumors that grew significantly faster; these animals also had lower levels of T cell infiltration in their tumors.

When the researchers gave these mice a checkpoint inhibitor drug that blocked PD-1, the tumors did not respond. Yet when they added an ERK inhibitor drug, the tumors shrank. Further studies showed that exosomes processed by phosphorylated HRS had cargos enriched with PD-L1, promoting resistance to the checkpoint blockade.

In tissue samples from melanoma patients, different areas of the tumors had varying levels of phosphorylated HRS. “In the

areas of the tumor with a lot of phosphorylation, the T cells stayed outside the border,” says Guo. “They just could not cross.”

The findings suggest that screening cancer patients’ tumors for HRS phosphorylation may help predict their responsiveness to checkpoint inhibitors. And reducing HRS phosphorylation could be a strategy for boosting the immune system’s defenses against cancer. While ERK inhibitors alone could be toxic, says Guo, an approach that blocked phosphorylation of HRS specifically could prevent it from loading PD-L1 to exosomes in the first place.

Guo’s group will continue investigating how tumor cells can be so selective in choosing which cargo to send out in exosomes—and how T cells, in turn, can selectively send out their own exosomes to fight back.

“It’s a clash of two titans,” Guo says.

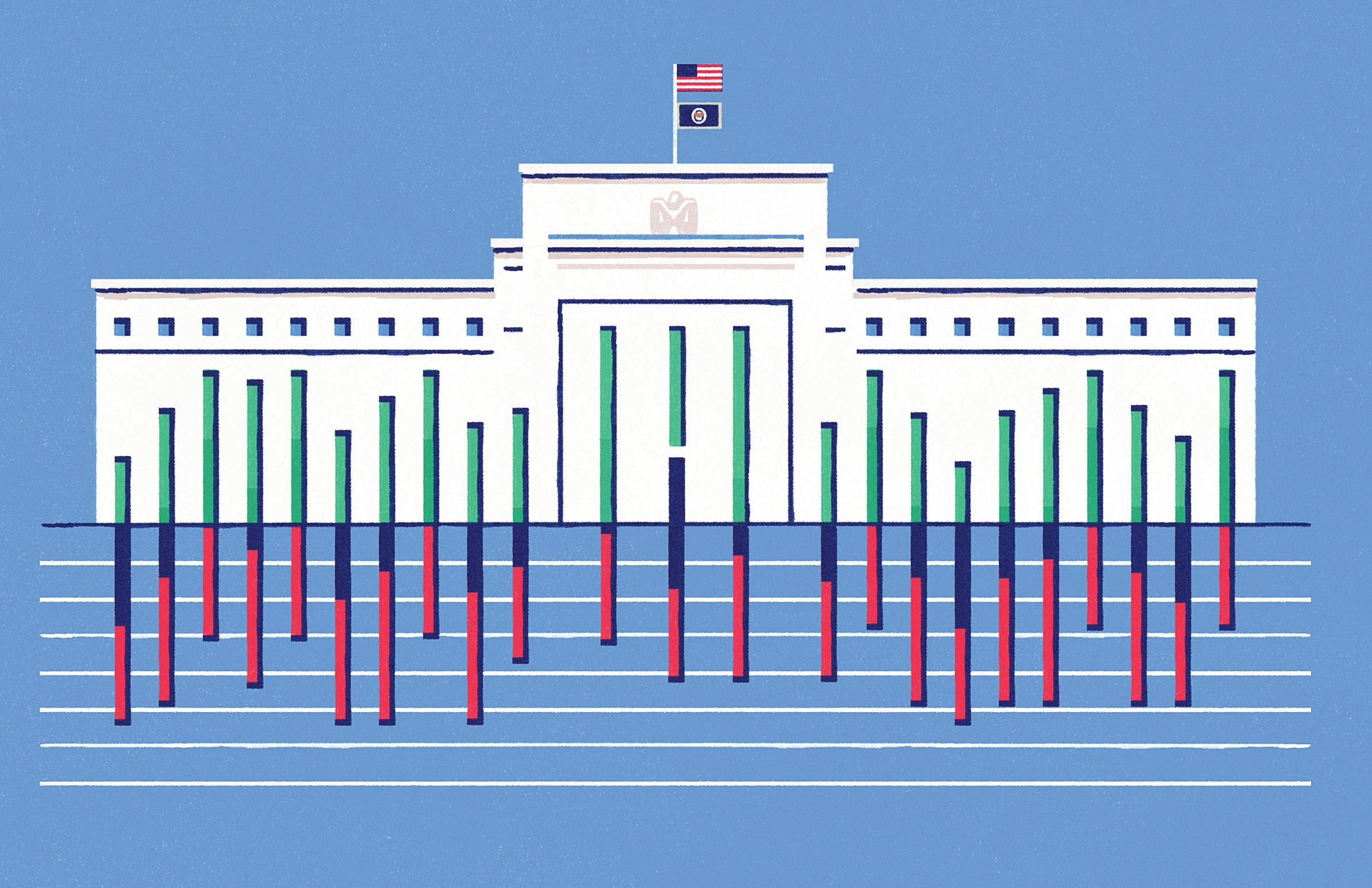

THE FEDERAL RESERVE BANK

We speak with Harold Cole, James Joo-Jin Kim Professor of Economics, to learn more about the Fed’s structure, objectives, and capabilities—and why it is especially relevant in times of financial crisis.

By Blake Cole

Illustration by Gracia Lam

OMNIA 101 offers readers a peek into what faculty do each day in their classrooms and how their research and expertise are inspiring the next generation. he Federal Reserve Bank, more affectionately known as the Fed, impacts many important aspects of our everyday lives, from purchasing power to job security. We spoke with Harold Cole, James Joo-Jin Kim Professor of Economics, who worked at the Minneapolis Federal Reserve for more than a decade, to learn more about the Fed’s structure, objectives, and capabilities— and why it is especially relevant in times of financial crisis.

What is the role of the Fed— historically and now?

The Fed was created well before the Great Depression and basically was a response to various banking crises. In particular, the government was worried about the kind of bank run you see in the film It’s a Wonderful Life with Jimmy Stewart, where everyone panics and withdraws their money all at once, and the bank has to sell its assets at a fire sale. Then, suddenly, you’re not going to get your money back. So, the Fed was designed to try to stabilize the banking system—to buy up assets and underpin their value, to make emergency loans to banks that they think are solvent, and to try and prevent these crises from snowballing.

Historically, the Fed also had a supervisory role where they would go out and inspect the banks. In 1933, Roosevelt basically shut down the U.S. banking system because of runs. He had auditors inspect all the banks in fairly short order, and had them start reopening, and it stopped the banking crisis.

Over time, the Fed’s role has expanded, where they now look to stabilize the price level, keep the financial system stable, and also maintain the economy running at a high level. However, all of these goals are in opposition to each other. One classic example of this

is that stabilizing the price level to prevent inflation could have employment consequences, and that’s the big one we’re talking about right now.

The main Fed, also known as the U.S. central bank, is made up of 12 smaller Feds divided into geographic districts. Why?

The smaller Feds were created as part of an effort to decentralize the power structure within the Federal Reserve system. I was at the Minneapolis Fed from 1990 to 2000—a dinky, regional Fed—but they had fantastic people working there and fantastic people visiting. The number of Nobel prizes that are associated with the Minneapolis Fed is amazing. So, it was a very different intellectual environment than you would see at the Federal Reserve board. It was much more open and academic, and it became a conduit by which new ideas flowed into the Fed. I think your average Fed chairman is probably more conscious of the public good than I would argue a lot of politicians are, because of how they’re able to react to the community’s needs.

One of the Fed’s key duties is to set interest rates. What does this entail?

If the Fed raises interest rates, that discourages consumption today versus consumption tomorrow, because you’re saying, “If I put aside $1 today, that translates into more money in the future.” But if you’re undertaking any finance activity, like buying a house, mortgage rates are higher, so it tends to depress economic activity. But, the hope is that by cranking up interest rates, it will bring the demand side more in line with the supply.

What are some of the potential effects on everyday citizens when interest rates are adjusted?

When we put in very low interest rates during the Great Recession and the COVID crisis, that hurt a lot of conservative savers. If you were in the stock

market, though, it’s been very good to you. We know that wealth is very skewed in this country, but another factor is what form of wealth people have. As you go up the income distribution, people tend to hold much more stock and private equity—a bunch of things that are going to be responding positively to reductions in the interest rate. But if you were someone who was saving using these interest-bearing assets, you have not done so well.

One ripple effect in terms of inflation is that some prices adjust right away, but others, like wages, are much slower to adjust. So, real earnings might be doing pretty well, but then turn down. That’s because even though nominal earnings are going up, they’re not keeping pace with inflation. If you’re on social security, for instance, because that adjusts slowly, you’ll take a significant hit.

What is your opinion on how the Fed is addressing the dual challenges of inflation with threat of recession?

I think right now, there’s a lot of uncertainty. We had some shocks that they didn’t anticipate—the Ukraine war would be a big example of that. The stock market also came down a lot, so that’s going to make people poorer directly. I think what’s relatively obvious is if inflation continues to be high, they’re going to continue this policy of ratcheting up the Fed funds rate until they bring it down.

Should there be a push for increased public awareness in regard to the Fed and the impact that changes in interest rates have?

One thing that really strikes me is we have all these high schools that are advising kids on where they should go on to college, but maybe we should take a few minutes and talk about debt and interest rates. You’re investing in yourself, which is a good thing, but if you’re going to take on all this debt, you need something that’s going to offset it—you need a return on it.

WHEN SOMETHING CLICKS

How Structured, Active, In-class Learning is changing the calculus on teaching.

By Jane Carroll

Photography by Brooke Sietinsons

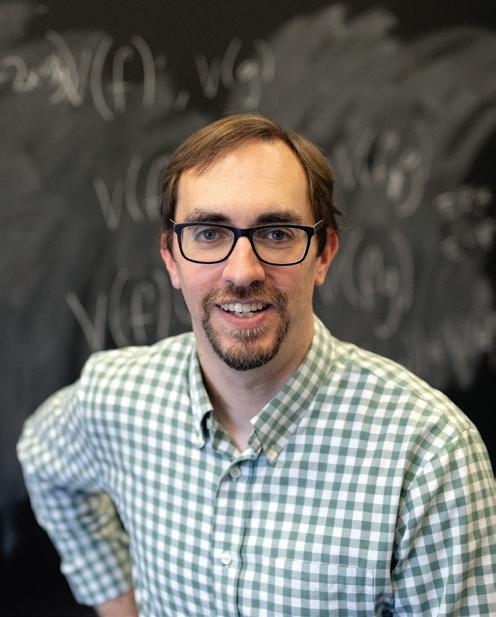

Philip Gressman, Professor of Mathematics

he idea of the “flipped classroom”—in which lectures and presentations are delivered outside of class time and in-person learning features active student engagement—is becoming a familiar concept to many in education, but Professor of Mathematics Philip Gressman says that’s only one example of a more comprehensive teaching approach called SAIL.

The idea is that anything you’re doing that’s getting your students engaged, that’s having their thinking happen in that classroom— that’s SAIL.

“Structured, Active, In-class Learning, or SAIL, is an acronym that’s unique to Penn,” explains Gressman. “It describes a whole host of ideas for how to run a classroom. The idea is that anything you’re doing that’s getting your students engaged, that’s having their thinking happen in that classroom—that’s SAIL,” he says.

In the humanities, students have long been accustomed to coming to class ready to discuss pre-assigned readings, but that’s not always the case in math and science classes. Gressman says, “STEM students are often treated by instructors like empty vessels—that the information should be poured into them, and what we’re trying to do is push back against that. So, I might say, ‘Please read this section, try these exercises, and then come to class and let’s do the next steps together.’”

Gressman uses the SAIL approach primarily in his Calculus I course, and he puts a heavy emphasis on group work. Students tackle exercises together, slowly building on the basics of a new concept. The aim is to capture that “aha” moment in real time, to be present with students when something clicks.

It’s not easy to do, and Gressman says getting it right requires trial and error. “You’re balancing on a knife edge,” he says. “If you go too far, if you make it too hard, then you have to deal with frustration and you create unnecessary problems. It takes a while to get a sense of exactly where the line is, because being right on the edge of failure—but succeeding—that’s the optimal spot for learning.”

Gressman was drawn to SAIL out of a desire to “bring his teaching where it’s needed most.”

“Penn is a place where there are plenty of students who are very strong, and they can do well in any class without much help, but in a traditional calculus class, some students really struggled,” he says.

After switching to SAIL, Gressman says his grade distributions in Calculus I became much more compact, and the grades of students at the lower end jumped up. Overall averages were higher, too, suggesting that everyone benefits. Gressman says SAIL also helped him create a more inclusive environment that addresses persistent stereotypes about who is good at math and who is not.

Gressman also has adopted a few of the technological tools he used for remote learning during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, such as having students collaboratively edit documents on Google Docs outside of class time. He also moved his office

hours online, which he says is much more accessible for students and easier for him.

Some students are initially uncomfortable with the SAIL approach, Gressman notes, not only because it’s unfamiliar, but also because they may sense that they are not “getting” the material.

One theory, he says, is that a good lecture that’s pleasant to listen to creates a cognitive fluency effect— it’s entertaining, but it may not stick. Another possibility is that students are not used to confronting the feeling of struggle in the company of their peers and instructors. “It can be an uncomfortable thing, but that’s exactly what we want,” Gressman says. “We want that struggle to happen in the classroom, so that it is done and overcome when the exam comes. You have to explain that that’s not a mistake—it’s a feature.”

Gressman explains the SAIL approach to his students at the outset of the course, including the research behind it. He says this transparency has pedagogical benefits. “When students have an opportunity to examine the way you’re thinking about the course, and see for themselves what the evidence is, they’re more willing to go along.”

This transparency carries over to the students. For instance, to counter concerns they are experiencing more difficulty than their peers, Gressman asks students to openly share how much time they spend on problems.

“I actually have the whole class go up and make a histogram,” he says, “so that everybody can see what everyone else’s experience is like.”

Most, he says, ultimately embrace the SAIL approach. “I have students come up to me at the end of the semester and say, ‘I need to take the next course in the sequence. Which one is being offered in this format?’”

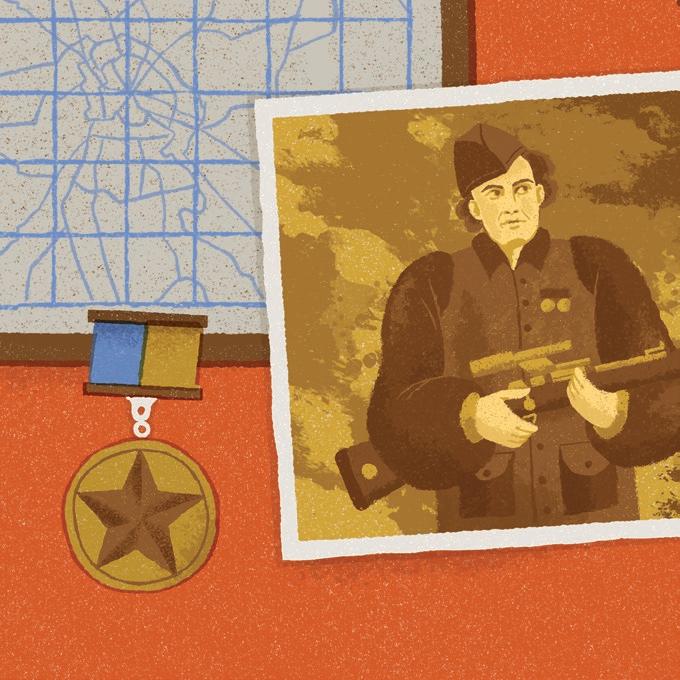

The Physics of Us

Physicists are studying how living matter works, and find that it breaks the standard rules and produces fascinating new phenomena.

By Susan Ahlborn | Illustrations by Marina Muun

The James Webb telescope is showing us our universe in vibrant new detail. Some physicists, though, are looking in another direction: at us and other living matter here on Earth, from the cilia in lungs to the vasculature in leaves to the neurons in brains. What they’re finding is equally marvelous, and it’s challenging some of the current understanding of physics.

How can an intelligent system arise from the collective dynamics of its basic components?

Ultimately, they’re working to discover the rules that govern how matter lives and evolves, and their research may lead to better medicine, robotics based on biology, and an expanded understanding of the physical and biological world.

“We’re using physics principles to understand life and living matter,” says Eleni Katifori, Associate Professor of Physics and Astronomy, who studies vasculature in plants and animals. “But we are also using living matter as an inspiration to discover new physics, for asking the right questions or new questions.”

“Biology has already invented a lot of things. Living matter, from bacteria to leaves to humans, works in ways that physicists don’t understand, much less can duplicate,” adds Arnold Mathijssen, Assistant Professor of Physics and Astronomy. His goal is to unravel the physics of pathogens, design biomedical materials, and understand the collective functionality of living systems out of equilibrium. “It’s fundamental research. For example, how can an intelligent system arise from the collective dynamics of its basic components? It’s also directly relevant to our society, as in, what is the probability of SARS-CoV-2 transmission within a food supply chain?”

Leading the Way

The study of biophysics is not new; Luigi and Lucia Galvani were already investigating animal electricity in the late 1700s. In the last 20 years, though, technological advances have allowed researchers to see microscopic phenomena in living tissue with unprecedented detail, record simultaneously from thousands of neurons, and even track the large-scale behavior of ecosystems. All of these new methods produce vast amounts of quantitative data from which we can infer the laws of living matter. But it wasn’t until 2022 that the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine recognized biological physics as a separate field.

Penn Arts & Sciences physicists have been studying living matter for decades, bringing Penn to the front of this area. Philip Nelson, Professor of Physics and Astronomy, wrote key books in the field, starting with Biological Physics: Energy, Information, Life in 2014. He’s been honored with the Emily Gray Award of the Biophysical Society for his “far-reaching and significant contributions.” Arjun Yodh, James M. Skinner Professor of Science, has received the Michael S. Feld Biophotonics Award of the Optical Society of America for his pioneering work in demonstrating and clinically translating biomedical optics. A.T. Charlie Johnson, Rebecca W. Bushnell Professor of Physics and Astronomy, is using biological molecules as chemical recognition elements in disease diagnosis, security, and environmental monitoring. Marija Drndic, Fay R. and Eugene L. Langberg Professor of Physics, explores mesoscopic and nanoscale structures, including the detection and analysis of DNA and microRNA.

In 2021, Penn Arts & Sciences and Penn Engineering made a unique investment in this interdisciplinary study with the new Center for Soft and Living Matter. Led by Director Andrea J. Liu, Hepburn Professor of Physics, and Associate Director Douglas J. Durian, Mary Amanda Wood Professor of Physics and Astronomy, the center brings together more than 60 faculty from the two schools. And Penn’s Computational Neuroscience Initiative, cofounded by Vijay Balasubramanian, Cathy and Marc Lasry Professor of Physics and Astronomy, involves researchers from Arts & Sciences, the Perelman School of Medicine, and Engineering.

“If you look at a different scale or regime, new phenomena always pop up,” says Balasubramanian, a theoretical physicist who also holds a secondary appointment in neuroscience in the Perelman School of Medicine. “It’s the interactions between the components of living systems that make them so interesting, unlike, for example simple gases in a room. The brain contains a hundred billion interacting neurons. Molecules can talk to the whole organism, pheromones can change the behavior of entire colonies of organisms, stress can change gene expression. So, living systems interact across scales of organization unlike most physical systems that we are used to.”

What Is Living?

Physicists don’t all agree on how to define living matter, but Balasubramanian gives it three characteristics: It is complex, it adapts according to circumstances, and it often acts as if it has a purpose like staying alive or reproducing.

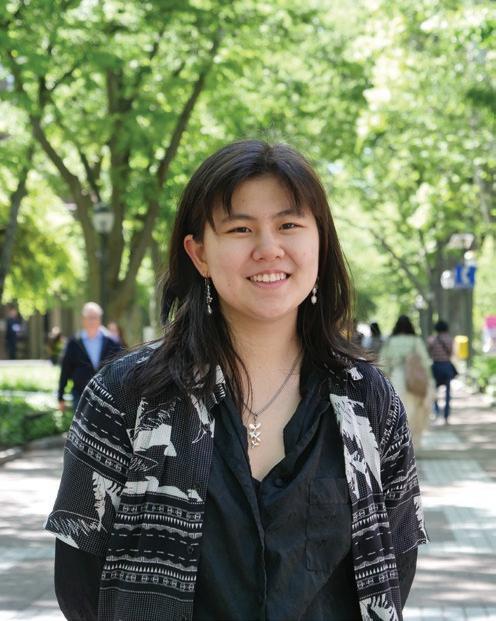

Eleni Katifori, Associate Professor of Physics and Astronomy; Arnold Mathijssen, Assistant Professor of Physics and Astronomy; Vijay Balasubramanian, Cathy and Marc Lasry Professor of Physics and Astronomy

(L-R) Brooke Sietinsons; Wanying Wang; Eric Sucar, University Communications

It is also unique because its components work together is such complicated ways. “A single molecule, you cannot really call alive,” says Mathijssen. “But when you put a bunch of enzymes and proteins and molecular motors in a membrane and we call that a cell, then suddenly these things have shared functions and they will cooperate with each other in such a way that we call that living.”

We know very little about how to deal with systems that interact to produce a collective effect across a range of scales from genes to ecosystems, and that are exceedingly complex with many different interacting parts. Molecules work together to form organelles and cells; cells form tissues, and tissues give rise to organs and eventually organisms. “And even these organisms will work together, like bird flocks to confuse predators,” says Mathijssen, who was named one of Scientific American’s 30 Under 30 in 2012 and received the Charles Kittel Award from the American Physical Society in 2019.

“This notion of cooperativity and shared functionality is something that, in physics, we don’t know how to explain. But that’s exactly what we try to do in physics, to find rules of universality, to see if a school of fish behaves the same as a school of bacteria.”

Inspiration for this work is everywhere; one of Mathijssen’s projects grew out of a conference dinner at the Georgia Aquarium. “We were looking at this school of fish, and there were these little particles in between them, and we were really just curious,” he says. “Does the school push these particles forward, or are the tails of the fish pushing the particles back instead?”

How materials are transported in a group is a question of survival for microbes like bacteria, which run out of food and oxygen quickly because they live in very high concentrations. “So, it can be curiosity, but then you think, hey, wait, this is actually not just applicable to this one aquarium, but it ranges across a set of questions in microbiology,” says Mathijssen.

“But then also maybe you can use this in microrobotics. Because if you want to deliver drugs, then you can also use this to move things from A to B.”

Mathijssen studied particle physics in college but began working on biophysics while earning his doctorate, “because life itself fascinates me.” He and his lab move back and forth between microorganisms and microrobotics, collaborating with researchers in Penn Engineering and the Singh Center for Nanotechnology. They’ll sometimes build a device based on a biological finding, and sometimes try to build a model to help figure out a biological function.

“It’s entirely possible to come up with a thought on a Monday, and then by Friday you may already have tested something in the lab,” he says. “This close connection of going back and forth all the time and testing your idea and then maybe changing your theory again, that dialogue is something that really attracted me.”

One recent project was based on long filaments, called microtubules, found inside cells. Molecular motors can move along these filaments against a flow. In the past, free-swimming microrobots have been explored as a way to deliver therapeutics within a blood vessel, but these can disperse in the strong flows. Mathijssen and his group made a system using filaments with embedded magnets, which would allow precise delivery and could someday treat blocked blood vessels or cancerous tumors.

The lab’s study of how bacteria move in and are cleared out of the lungs, inspired by the COVID-19 pandemic, led them to build another device: tiny magnetic beating hairs that pump liquid, emulating the cilia that are the main driving force behind mucus clearance in lungs. They’re trying to learn if there is a connection between the alignment of the cells and the efficiency of bacterial clearance, something that links to conditions like cystic fibrosis.

The Math of Life

Eleni Katifori also studies flows in the context of understanding the topology and architecture of vascular networks, whether it’s the xylem and phloem in leaves and plants, or the arterial, venous, or lymphatic system in animals.

“Everything that is larger than, let’s say, a millimeter has to have some sort of vascular system. We can’t have life without it,” she says. “And yet there is still so much we don’t understand. I get up in the morning, I brush my teeth, go to work, and the whole system seems to work. So, this idea that something that is very everyday is still so mysterious is quite intriguing to me.”

Katifori became “enamored with plants” while earning her Ph.D., and began working on biological flow networks in plant leaves during a postdoctoral appointment. Then she realized that for dynamics, animal vasculature was more interesting

mathematically. She received an NSF Career Award—the National Science Foundation’s most prestigious award in support of early-career faculty— in 2016, and was named a Simons Investigator in the Mathematical Modeling of Living Systems in 2018. She and her lab are seeking to uncover the physical principles behind how these complex networks build themselves and what functions they’re optimizing through evolution.

You have to talk about everything from the whole colony down to the individual neurons.

The vasculature in our bodies is not entirely genetically directed, she says, but instead self-organizes according to a set of equations she’s trying to discover. “We are asking, is this consistent with optimizing efficiency? Is this consistent with optimizing robustness? And if it’s not, what constraints came in the way? Maybe the absolutely optimal architecture would look different, but this biology cannot build that version.”

Ultimately, she wants to be able to predict how the vasculature will form—or malform, like when an artery narrows, or how a vessel will change downstream from a blockage. “If I put in what I’m trying to optimize and what my constraints and costs are, basically, I crank the machine and I get some principles,” she says. “This is what makes it very exciting for me, just discovering what kind of math biology is using to solve a particular problem.”

Katifori says her biggest challenge is deciding what to leave out. “There is a tremendous amount of stuff going on inside the vessel. It’s not just water flowing through a pipe.” Vessel walls are elastic and every time the heart beats, a pulse is transmitted to the rest of the body, something she believes impacts how the network builds itself.

There are also different kinds of cells interacting with each other inside the fluid, and the potential for coagulation. “It’s a living thing. So, figuring out which of that information is relevant is something I struggle with.”

Seeing Life in Action

Along with faster computers and machine learning, new technological tools for biophysics include ways to record and analyze neurons, or to genetically modify them to fire under laser light or to glow when they fire. DNA and nanostructures can be manipulated. Cameras can take hundreds of images per second, and there are new ways to bring light to microscopes which allow researchers to study living systems.

Technology is allowing Balasubramanian to go to the birds—he’s collaborating with Marc Schmidt, Professor of Biology; and Kostas Daniilidis, Ruth Yalum Stone Professor of Computer and Information Science at the School of Engineering, to study how cowbirds pair bond at Schmidt’s aviary at the Pennovation Center. “At the beginning of the season, you have 10 males and 10 females. You introduce them into the aviary,” Balasubramanian says. “The males sing. The females evaluate them: Is that a good song, is that not a good song? And they decide whose song is better.” The cowbirds use this information to form a social hierarchy that guides their interactions. By the end of the season, they’re mostly pair bonded, and the success of these bonds affects the success of the egg laying. The process is a little reminiscent of high school, complete with cliques and bullying if we anthropomorphize the behavior, but it has serious implications for the long-term success of the flock.

Previously, to analyze the birds’ behavior, researchers would need to sit outside an aviary and make notes on what they saw and heard. Now they’re close

to getting a 24/7 recording of all of the birds’ poses and songs, and automating the analysis of the data. “It’s a complex system, and it crosses scales,” says Balasubramanian. “You have to talk about everything from the whole colony down to the individual neurons. It takes neuroscientists, physicists, and engineers all working together to do this kind of thing. This is not the kind of collaboration you could have envisioned 20 years ago.”

Balasubramanian talked his way out of every biology course after sixth grade, arguing he wouldn’t need it. In college he earned degrees in physics and computer science, then an M.S. in computer science, with the goal of understanding information processing, including by the brain, the computer inside our heads. He then realized that the engineering approach wasn’t answering the questions he had, and switched to physics for his Ph.D. An advisor suggested that he might be interested in systems neuroscience as a field, and he began working more and more with biologists. Now his research focuses on how natural systems manipulate and process information to produce new forms of self-organization.

Balasubramanian, a Fellow of the American Physical Society, has worked on neural systems that are involved in the senses of sight, hearing, and smell; control of the body; spatial navigation; and decision-making. Recently, he realized that some ideas on molecular sensing in his work on olfaction (the sense of smell) could also be used to understand aspects of adaptive immune systems in vertebrates and bacteria. For example, his work with postdoctoral fellows Hanrong Chen, now at the Genome Institute

of Singapore, and Andreas Mayer, now at University College London, led to a paper identifying a new scaling law for immune memory in the CRISPR-based system used by bacteria to defend against recurrent viruses.

A Team Effort

The collaboration available at Penn, with all its schools on a single campus, is vital to the study of living matter. “You get to talk to people that have a very different view about things and very different backgrounds than you,” says Katifori.

She is working with researchers who have been able to digitize the vessels in the brain, from capillaries to arteries. This lets her see data and use machine learning to examine, for example, statistical differences between different areas, or how disease affects the vasculature. “We know that Alzheimer’s, for example, correlates with microvascular phenotypes in the diseased brain,” she says. “I’m not claiming this is the reason for Alzheimer’s, but there’s definitely a lot going on that we don’t understand. And these types of techniques to image the micro-vasculature will be revolutionary for understanding flow, for understanding the biology, but also for disease.”

“I’ve been working on hydrodynamics for maybe two or three years, and I had never seen the bacteria under the microscope,” says Mathijssen. “And you realize for the first time you look through those goggles that, wow, this is somewhat what I expected, but there are really different things going on as well.

And you need the right people to come together for that, and the right facilities and tools. The Singh Center for Nanotechnology is unparalleled when it comes to the nanofabrication techniques that they can do here.”

Biology found a similar solution to the same physical problem, transport, using very different tools, very different biology.

There are challenges to collaboration in that researchers from different areas need to learn each other’s lingo. “You have to pick these things up by working with somebody, or reading enough papers,” says Balasubramanian. “And you learn how to talk to each other.”

There is also often a degree of luck in finding a pathway to biophysics during graduate school and after. Mathijssen believes that Ph.D. programs should try to give students that training to bring fields together and help them get out of silos, “but that’s often easier said than done. And so, the risk is then that you could get stuck in your own area because you don’t understand what someone else is doing.”

The Big Picture

Balasubramanian has long theorized about William of Occam’s “razor,” which states that causes should not be multiplied beyond necessity. Scientists now use it as a rule of thumb that says when you don’t have much data, a simple explanation is better than a more complicated one. He’s working on a paper with former postdoc Philip Fleig, now at a Max Planck institute in Germany, in which they argue that systems making decisions with limited information—for example, bacterial colonies deciding which

phenotype to express—do better by implicitly using simpler models of the world.

Beyond bacteria, Balasubramanian says that data are showing that both humans and machine learning systems working with limited information implicitly implement a tendency toward simplicity. “Probability theory says to prefer simple explanations when you don’t have much data. And these two learning systems, the human brain and deep learning networks, seem to learn such biases against complexity without being told that they should. I think these common features of learning in animals and machines are very exciting.”

Looking ahead, he says, “Anything involving the theory of learning directly affects the question of what kind of learning engines can be built, what can they learn, and why they learn. Understandings of how the brain works always have potential applications, in medicine as well as in things like building neuro-prosthetics. You could build a replacement retina, if you knew how it worked. You could also put in a robot.”

The study of living matter suggests nearly endless avenues of usefulness. Understanding immune systems would have applications from making yogurt by helping the relevant bacteria to better survive bacteriophage

attacks to designing vaccines to help defend humans against seasonal viruses. We could develop materials that heal themselves or learn, or even an item that can become a different toy depending on what a child wants.

Katifori also sees universality in her work. “You look at vasculature in these wildly different organisms with entirely different genes that evolved completely independently, in a plant leaf and in our bodies. And yet you see the same core principles emerging. And that is very, very exciting. Biology found a similar solution to the same physical problem, transport, using very different tools, very different biology. The physical truth is the same.”

“We don’t know how to describe, for example, what is the temperature of an active system,” says Mathijssen. “It does not follow the same laws of physics. And we don’t know what those new laws of physics could be, and so that’s why we try to come up with the simplest possible models to remove all the redundancies and really just think of the essence of the material and see if we can write down equations. And I think the field is now in a state where we don’t know whether this would work.”

He compares it to the beginning of quantum mechanics. “Now we are in a similar state, but we try a lot of different things and maybe we can solve small systems first and then see how it generalizes. In science, by definition, you head into the unknown. But what we do know is that there is progress every day, and there are really good new theories being developed in this field,” like equations that explain how the motion of individual birds in a flock affects the motion of neighboring birds. “And I think that’s why it’s so exciting to work in this field, because it is now really coming together.”

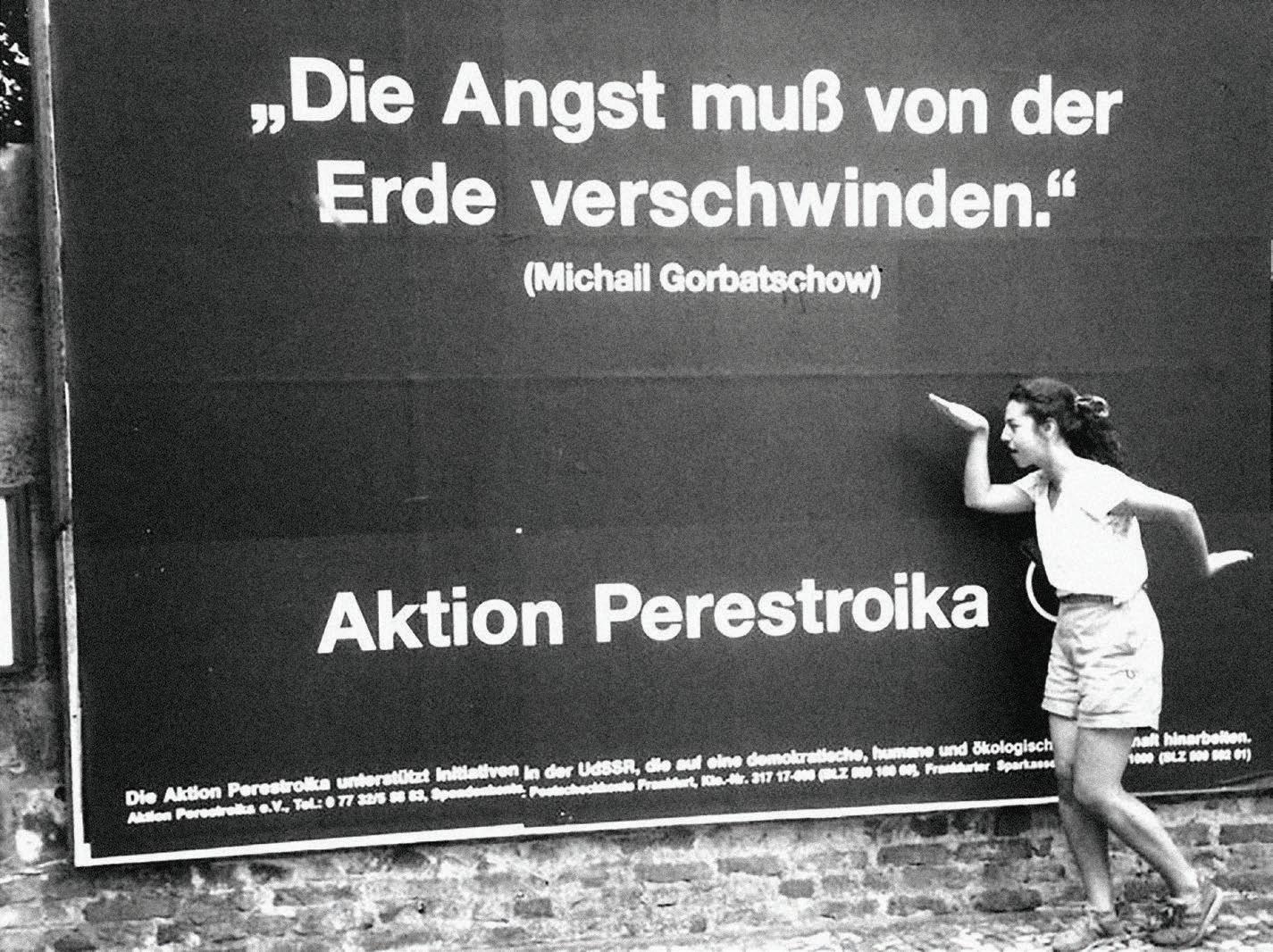

Ordinary Lives, Extraordinary Times

A fateful trip to Eastern Europe in 1989 inspired Kristen Ghodsee, Professor and Chair of Russian and East European Studies, to pursue a career studying the impact of the Cold War and its aftermath on the lives of ordinary people.

By Duyen Nguyen

Illustrations by Mariya Pilipenko

Kristen Ghodsee collects Cold War-era typewriters. Some in her collection are even older, dating back to the 1920s. The majority were manufactured in the former socialist countries of Eastern Europe. Over the summer, while completing a fellowship at the Freiburg Institute for Advanced Studies (FRIAS) in Germany, she added three more to her collection.

“Each typewriter tells a unique story,” says Ghodsee, Professor of Russian and East European Studies. In a recent talk titled “Cold War Keys: The Curious Lives of East European Typewriters,” she explained how the machines— once strictly regulated in many parts of the region—shed light on the lived experiences of socialism and post-socialism. A Marista 11 model that she found at a flea market in Sofia, Bulgaria, for instance, invokes bitter memories of the corrupt privatization and liquidation of the country’s onceflourishing typewriter industry.

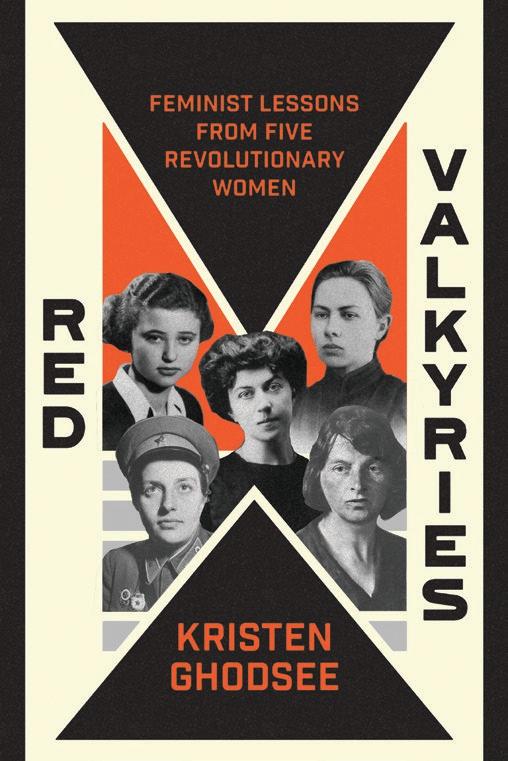

Ghodsee, who was recently appointed Department Chair of Russian and East European Studies, is a prolific author for both academic and general audiences. She also harnesses other media, like podcasting. Her newest book, Red Valkyries: Feminist Lessons From Five Revolutionary Women, focuses on the lives of five socialist women and their legacy for modern-day feminists, including one from Ukraine—a region which Ghodsee has been reflecting upon of late, given current events.

An award-winning ethnographer, Ghodsee is also interested in the stories that people tell— particularly those of ordinary people living in Eastern Europe during the region’s transition from state socialism to capitalism in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Ghodsee joined Penn in 2017. She was previously a professor at Bowdoin College, where she directed the gender, sexuality, and women’s studies program. Throughout her career, she

has sought to understand from Eastern Europeans themselves how the end of the Cold War changed their lives. Much of her research involves fieldwork, specifically in the Balkans and the former German Democratic Republic, where she has lived for months at a time, meeting with locals and learning about the countries’ social, cultural, and political histories. For her first book, The Red Riviera: Gender, Tourism and Postsocialism on the Black Sea, an ethnography of women working in Bulgaria’s popular sea and ski resorts, Ghodsee spent 18 months living in Bulgaria, conducting survey research, and interviewing the women she met, including a waitress, a tour operator, and a travel agent. The book was published in 2005. Ghodsee began this fieldwork as a doctoral candidate in social and cultural studies at UC Berkeley, but the origins of her interest in Eastern Europe date further back—to the summer of 1989.

A Fateful Trip

That year, Ghodsee, who’d just completed her freshman year at UC Santa Cruz, decided to drop out of college. Convinced that the Cold War would eventually escalate to a point that would make any travel impossible, she bought a one-way ticket to Spain.

But on November 9, only a few months after she’d arrived in Europe, the Berlin Wall came down, marking the end of the decades-long geopolitical conflict. The timing, Ghodsee says, seemed serendipitous. She began making her way to Germany, eager to witness and take part in the hope and exuberance spreading across the region. Setting off from Turkey, Ghodsee traveled through Bulgaria, former Yugoslavia, Romania, Hungary, and former Czechoslovakia, before finding herself on Alexanderplatz, the plaza in East Berlin where nearly a million people had recently gathered to demonstrate for political reforms. Ghodsee was there with thousands of revelers in the summer of 1990 when East and West Germany unified their currencies.

“It was huge—to be there and to feel the possibility of what the world was going to be like,” Ghodsee remembers, describing the experience as a turning point in her life.

Though she didn’t yet know it at the time, the trip would also go on to shape her career in profound ways. “I did not at all in any way have a traditional path into academia,” Ghodsee says, explaining that, after she returned to UC Santa Cruz the following year, she’d had no clear plans except to pursue opportunities that would allow her to continue engaging with the world. She studied abroad at the University of Legon in Accra, Ghana, during her junior year and spent three years teaching English in Japan after completing her undergraduate studies in creative writing and theater arts. While she’d been interested in political and economic issues since high school, describing herself as “a model United Nations dork,” Ghodsee says that she applied to graduate school on a lark.

A Prolific Career

To date, Ghodsee has held residential research fellowships at several institutions, including FRIAS; the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars; the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey; the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University; the Imre Kertész Kolleg at the FriedrichSchiller-Universität in Jena, Germany; the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research in Rostock, Germany; and the Aleksanteri Institute of the University of Helsinki in Finland. Back in 2012, she won a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship for her work in Anthropology and Cultural Studies, and she was an invited professor at Sciences Po in Paris, France, in 2021.

Ghodsee is the author of 11 books, eight of which are academic explorations of the lives of ordinary people, especially women, in the former Eastern Bloc both under socialism and in the aftermath of the Cold War. Her most recent book, Red Valkyries, which was mentioned in the New York Times Book Review, profiles five socialist women who were prominent activists in the 19th and 20th centuries but whose stories are lesser-known than those of their male compatriots. The book

reflects another focus of Ghodsee’s work: the forgotten stories of “people who have these incredible moments of meaning and profundity in their lives and actually end up changing the world.”

Kristen

In the summer of 1990, Ghodsee joined revelers in Berlin when East and West Germany united their currencies.

(L) Kristen Ghodsee, Professor and Chair of Russian and East European Studies

Courtesy of Kristen Ghodsee

Red Valkyries: Feminist Lessons From Five Revolutionary Women

By

Ghodsee Professor and Chair of Russian and East European Studies

Lyudmila Pavlichenko, a Ukrainianborn sniper whose 309 confirmed kills in World War II makes her the most successful female sniper in history, is one of these extraordinary figures. “Ukraine has a long history of women in the army,” says Ghodsee, who writes about Pavlichenko’s resistance of traditional women’s roles in Red Valkyries

The implications of this history are visible today as the ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine continues to disrupt the lives of millions of Ukrainians. “Legislation adopted in 2018 gave Ukrainian women the same legal status as men in the armed forces, and today there are over 50,000 women serving in the armed forces,” in both combatant and non-combatant roles, Ghodsee explains. Since the war began on February 24, 2022, many women have remained in or returned to the country to fight against Russian forces. While in residence at FRIAS this summer, Ghodsee met a psychologist from Ukraine who counseled soldiers at the frontlines of the war via Zoom. “She said that many women are more committed

fighters than the young men who were draftees and forced to fight. The women who volunteered are well-trained and deeply committed to the defense of their homeland,” Ghodsee recalls.

The Diversity of Human Experiences

While at UC Berkeley, Ghodsee received a Fulbright grant to conduct fieldwork that would shape the focus of her own interest in Eastern Europe.

“I always knew I wanted to go back—it was just a question of which country,” Ghodsee says. Several factors tipped her in the direction of Bulgaria. At the time, few scholars in the field were focusing their studies on Bulgaria, let alone its tourism industry, the subject of Ghodsee’s dissertation and subsequently her first book, Red Riviera. Because of her own mixed heritage—half Puerto Rican and half Persian—she’d initially considered a transatlantic comparison of Bulgaria’s

and Cuba’s tourism industries. But the complications of working around U.S. sanctions against Cuba meant that she would’ve had to shift her research method away from ethnography—the immersive approach to studying a culture or society that would eventually become indispensable to her academic pursuits.

“Ethnography was the motivating thing for me,” Ghodsee remembers. In 2016, she published From Notes to Narrative: Writing Ethnographies that Everyone Can Read, a guide to writing accessible ethnographic texts.

Ghodsee’s first exposure to ethnography came in graduate school, where she learned the importance of fieldwork. In order to fully understand and write about a people’s way of life, “You’ve got to live with those people, speak the language, you have to fully immerse yourself in that culture,” Ghodsee explains. At UC Berkeley, with the fall of the Berlin Wall still fresh in her mind, Ghodsee took a class on the anthropology of Eastern Europe with Alexei Yurchak. “That class, combined with the methods classes I had with these

two powerhouse female anthropologists, Carol Stack and Jean Lave, really shifted me in that direction,” she says, explaining her motivations to return to the region in 1998.

In order to

fully

understand and write about a people’s way of life, you’ve got to live with those people, speak the language, you have to fully immerse yourself in that culture.

For Ghodsee, the greatest draw of ethnography is that it “helps us get in touch with the diversity of human experiences in a way that is deeper and more profound.” Ethnography captures and preserves different peoples’ ways of life, Ghodsee explains, fighting against what anthropologist Wade Davis calls “ethnocide,” or the gradual loss of human cultures and societies. Her second book, Muslim Lives in Eastern Europe: Gender, Ethnicity, and the Transformation of Islam in Postsocialist Bulgaria, which came out in 2010, follows the Pomaks, a group of Slavic Muslims in Southern Bulgaria, and explores how the community’s gender relations shifted in the aftermath of the Cold War. The book won numerous awards, including the 2011 William A. Douglass Prize in Europeanist Anthropology and the 2011 Harvard Davis Center Book Prize in Political and Social Studies. Today, Ghodsee is a member of the Graduate Groups in Anthropology, Comparative Literature, and the Lauder Institute for Management and International Studies, and advises a wide variety of Ph.D. students doing work in or on Eastern Europe.

(Top to bottom) Ghodsee stands in front of the Bulgarian Parliament in 1998. An award-winning ethnographer, Ghodsee’s research involves extensive fieldwork; Ghodsee in Sofia, Bulgaria in 1999. For her first book, The Red Riviera: Gender, Tourism and Postsocialism on the Black Sea, Ghodsee spent 18 months living in Bulgaria, interviewing the women she met and conducting survey research.

Courtesy of Kristen Ghodsee