IMPETUS

31.08.23 – 30.09.23

Insurmountable anguish marks the surface of paper and canvas with sharp angular lines and uneven textures, with unrestrained gestural intensity. Jagath Weerasinghe’s work is characterised by a cognitive and emotional struggle to comprehend the brutal violence and bloodshed that defined Sri Lanka’s post-independence landscape. His works exhibit an awareness of the deep-seated failures of human civilisation and Sri Lanka’s state and religious institutions between 1983 and 1989.

Impetus presents a selection of woodcut prints from 1989 in conjunction with works from the early 1990s that express an outcry filled with despair – made discernible through the deep furrows chiselled into woodblock and the fervent blackness of charcoal. Created in the years preceding his 1992 Anxiety (Kansawa) show, it locates the visual, intellectual and thematic precursors that defined Jagath Weerasinghe’s three-decade-long year career.

The woodcut prints from 1989-91, created during his time at the American University, were a cumulative reaction. Coinciding with the massacres in Sri Lanka between 1987 and 1989, they mirror the visual responses by German Expressionists of the post-war era – both in medium and aesthetic qualities. They mark a characteristic departure from the melancholic poetry that is reflected in his earlier works. For instance, the plunging darkness in the painting Death Under the Bo Tree (1986), created in the aftermath of the 1985 Anuradhapura massacre, evokes unending despondency and despair. In the years that followed, this sense of despair was replaced by a tormented fervour and a kind of perpetual restlessness became the dominant style of Weerasinghe’s oeuvre – adapting the physical expressiveness involved in the woodcuts to the rapid, energetic strokes of paint. Impetus moves back and forth between thirty years of art production to trace the history and trajectories of the cathartic imagination that guides the spontaneous and erratic nature of Weerasinghe’s visual language.

Kansawa (Anxiety), Weerasinghe’s first public exhibition since returning to Sri Lanka from his academic training in the US, underscored his disillusionment at the state of affairs in the island, through the repertoire of broken stupas and disembodied heads. Commenting on the collapse of moral and ethical order, his series, I’ve Got Enough Guilt to Start My Own Religion, Crucify Me featured decapitated heads devoid of any features that make them recognizably human. The erasure of familiar features from the human face has become a device in Weerasinghe’s work through which he delves into the human–inhuman dichotomy. Mauled by jagged lines that run along the entire length of the portraits in Faces (1989) are deliberate attempts to destroy traces of any identifying features. Inasmuch as it was a physical act of destroying any markers of identity, it also showed his cognitive inability to associate himself with the label of being a Sinhala Buddhist. It sought to disengage and dissociate from a reality made unbearable by the manifestation of brutality housed within humankind. It preludes the vocabulary of absence that we find in Who Are You, Soldier? (2007), which dwells on the human propensity for carnage and their reduction into a tool that can mindlessly actualise barbaric motives.

Anoli Perera observed that Weerasinghe’s work criticises the justification of state-led violence, interlaced with religious extremism and nationalism, as a necessary tool for maintaining stability and peace within the country. It is a theme that echoes in his contorted Long-Necked Man - a figure that translates mental anguish into a more visible and physical form. It reflects on the intertwined relationship between vulnerability and masculinity, and its association with violence - which in his subsequent works diverges into Man with Kitchen Knife (2009), a light installation created for the exhibition Celestial Fervour and his series of paintings Shiva (1990s - 2009). Shiva is a compelling image of the activity, beautiful, elegant, and violent, which probes into the necessity of destruction to create an environment of peace and tranquillity. Man with Kitchen Knife, on the other hand, links the destructive nature of Sinhalese ethnonationalism with the celebratory aspect of Vesak pandals is a subtle commentary on the lethal aspect of religious fundamentalism.

This up-close interrogation of masculinity is preceded by Weerasinghe’s Long-Necked Man in Light Stop (1989). The flabbergasted image of the Long-Necked Man, with his flaccid genitalia, overwhelmed at the sight of something unfamiliar is an acknowledgement of fear and weakness. It shows a kind of vulnerable acceptance that is overridden by a culturally rooted fear of being perceived as weak, giving rise instead to the assertion of phallic dominance.

Weerasinghe’s works also identify mothers as victims of a failed society caught in the crossfire of political ideologies, ethno-linguistic wars, and the overt expression of masculine power. Charged with empathy for their suffering, he essayed their harrowing experience through the dishevelled figures of mothers in his woodcut prints – corresponding with Woman with Dead Child (1903) a deeply moving image of a mother grieving the death of her young son by Kathe Kollwitz. It is a concern that also guides the creation of works such as the Shrine of the Innocents and Yantra Gala that ponder on the countless deaths of innocent youth and their mothers’ search for the missing children at sites of worship.

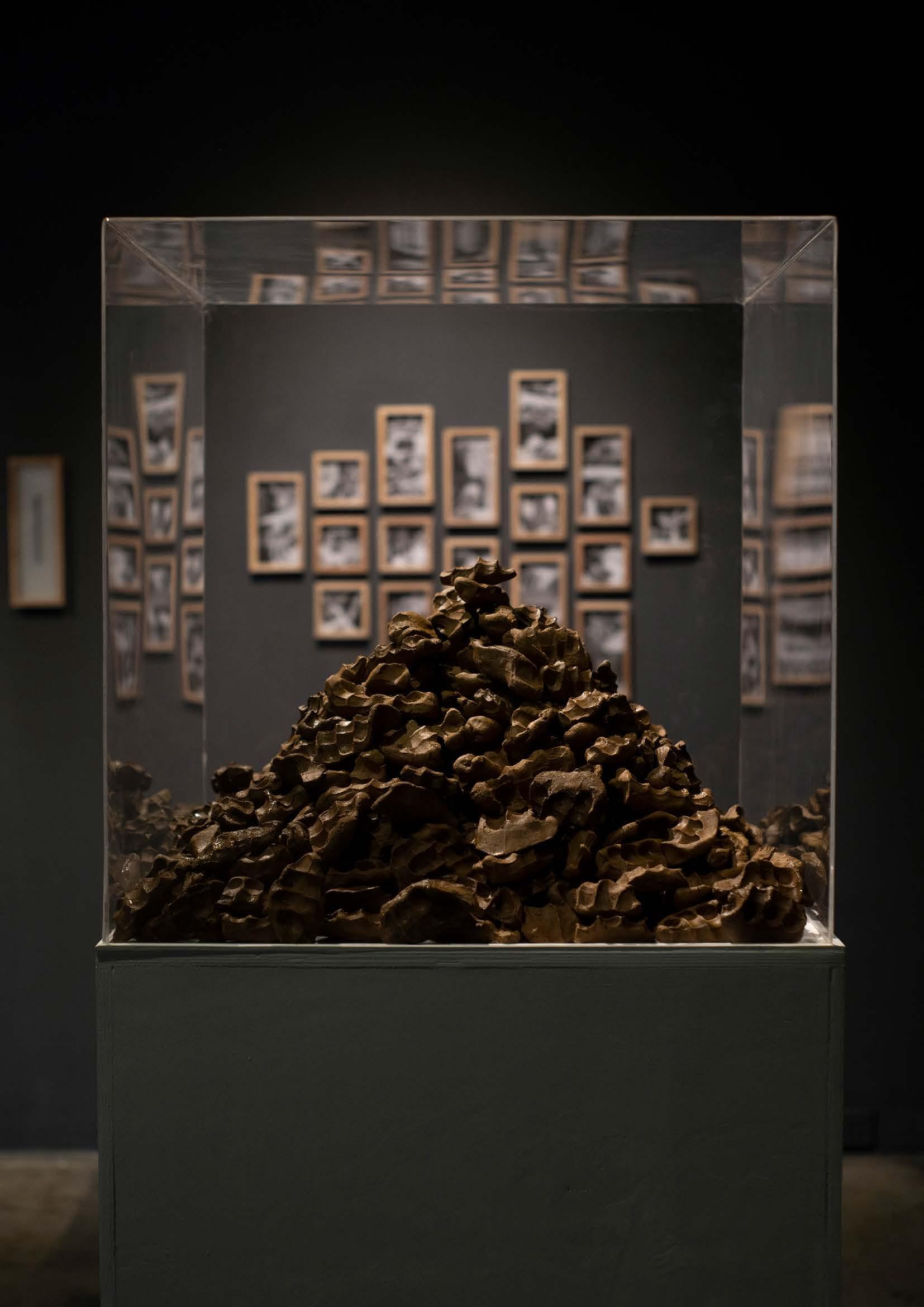

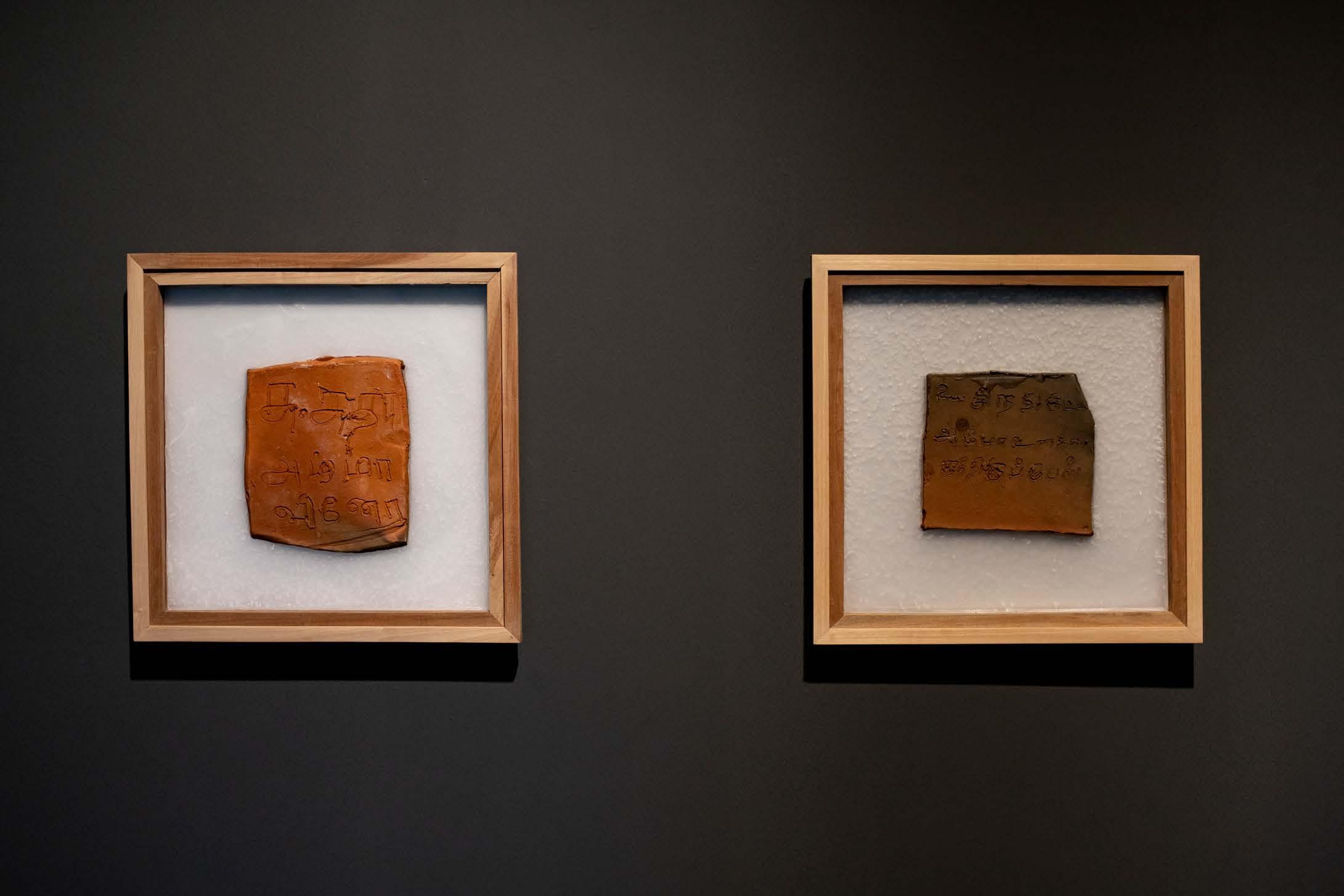

For this exhibition, Jagath Weerasinghe revisited the demolished 1999 public monument Shrine of the Innocents, which was built at Battaramulla to commemorate the Embilipitiya Massacre. Shrine of the Innocents, Kilinochchi: Where is my Child? (2023) was created through a collaborative process involving the bereaved mothers from Kilinochchi who left imprints of their grief on wet clay in a momentary transmission of pain. Love, anguish and hope are made visible through the clenched expression of the fist, a gesture that expresses emotional restraint. Unlike its previous iterations, the clay work is left unburnt in the hope and belief that their children are alive and will someday return. The work is accompanied by terracotta tablets on which the women have inscribed their thoughts in Tamil with the help of a nail. The language which is foreign to individuals who are unfamiliar with the script reminds them once again of a suffering and pain that they have been largely oblivious to, lost as it is in the ethnolinguistic dimension of the war.

The guilt he expressed in the broken stupas in Kansawa (1992) is foregrounded in his woodcut print Self-portrait with Dambulla (1989) and Ruined Stupa (1989). Dambulla is of autobiographical relevance to the artist, as it sits at the cusp of his aspirations as a young conservationist and his love for the homeland. It marks his return from the conservation site in 1983 to witness the violence unfolding in the city – of burning vehicles and people. The artist, for a moment, thought the violence was justified. But this is also the moment that made him instantly aware of the nationalistic tendencies within him and filled him with deep remorse.

Dambulla thus becomes a metaphor for the accompanying sense of disillusionment – about his self, beliefs and the island that was his home. The artist identifies this moment as a turning point when his ideals were shattered. It is echoed in The Rock (1991) which depicts a quivering figure of a man, presumably a self-portrait of the artist. A painting filled with pathos, it calls for pity as the man presses his knees against his chest, drawing them tightly with his arms to stop himself from disintegrating. Sitting on top of the very mound which represents Dambulla with dark red and grey clouds overhead, it underlines the unsettling emotions that the artist recalls feeling on returning from restoration work.

Dambulla and the Broken Stupa become the spark that also ignites a dialogue between the interconnectedness of heritage conservation and nationalism in Sri Lanka. The violence that is inherent in it becomes apparent as state-driven attempts at celebrating the Buddhist history and legacy in Sri Lanka cast away the histories of the ethnic and religious minorities in the country. Series such as Public Rally (1994 - 2005) and Snakes and Mikes (2005) are charged commentaries on religious extremism which ironically is perpetuated by the guardians of Buddhist philosophy. It chronicles the contradictions between principles and practice - where the Buddhist doctrine of non-violence or ahimsa crumbles under the weight of their violent campaigns against the minorities, sponsored and supported by the state. It reminds one of the vulnerability that Weerasinghe attempted to explore through the Long-Necked Man which represents the precarious position of the Sri Lankan Buddhist whose acts of violence endanger the very identity he attempts to uphold.

Jagath Weerasinghe’s three-decade-long career is a cathartic unfolding of an internal turmoil. He seeks respite through his woodcuts and its demands of repetition, strenuous concentration and the physical motions of chipping away at the material. His recurrent engagement with the themes encapsulated in Shiva and Dambulla attempts to comprehend the cruelty that lurks within each human being - channelled as it is by an attachment to one’s personal beliefs and notions of culture. In short, they are artworks by an individual who is responding to the crisis of his time and place - where the inseparability of the self from one’s habitus leads him to seek rationales that can in someway legitimise his existence as a part of a larger community and the culpability he feels on behalf of it.

Mariyam Begum1. Getty Art + Ideas. Cultural Heritage Under Attack: Who Defines Heritage? Hosted by Jim Cuno Featuring guest speakers Neil Macgregor and Kavita Singh. Jan 18, 2023. Podcast.

2. Johnson, Holly. 2012. “When Feminism Meets Evolutionary Psychology.” Homicide Studies 16 (4): 332–45. https://doi. org/10.1177/1088767912457169. http://blogs.getty.edu/iris/cultural-heritage-under-attack-who-defines-heritage/

3. Dhar, Jyoti. 2017. “Jagath Weerasinghe - States of Psychosis.” 115 -121. Art Asia Pacific, Issue 105.

4. Manuratne, Prabha. 2007. “The Celestial Underwear and the Challenges of Postcolonial Art- Jagath Weerasinghe.” South Asia Journal for Culture, Vol (1), 70 - 92. Colombo: Colombo Institute for Advanced Study of Society and Culture Theertha International Artists’ Collective

5. Pathak, Dev Nath, and Sasanka Perera. 2019. Intersections of Contemporary Art, Anthropology and Art History in South Asia: Decoding Visual Worlds, 11-12. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

6. Pereira, Sharmini. 1994. New Approaches in Contemporary Sri Lankan Art. Colombo: The Art Gallery of Colombo. Exhibition catalog

7. Perera, Anoli. 2009. “ A Prelude to an Exhibition.” In Art of Jagath Weerasinghe - Celestial Fervour Colombo: Theertha Dot Gallery. Exhibition catalog

8. Raffel, Suhanya. 1999. “ Jagath Weerasinghe - Embodied Terror: Yantra Gala and the Round Pilgrimage.” In Beyond the Future: The Third Asia-Pacific Triennale of Contemporary Art. Queensland: Queensland Art Gallery. Exhibition catalog

9. Turner, Caroline, and Jen Webb. 2016. “War, Violence, and Divided Societies.” In Art and Human Rights - Contemporary Asian Contexts, 81 - 87. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Bheeshanaya - A House, Artist’s Proof, Woodcut Print on Paper, 56 x 38 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Bheeshanaya - A House, Artist’s Proof, Woodcut Print on Paper, 56 x 38 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Something Burnt in the Country, Woodcut Print on Paper, 57 x 39 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Something Burnt in the Country, Woodcut Print on Paper, 57 x 39 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Bheeshanaya - Face, Woodcut Print on Paper, 51 x 33 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Bheeshanaya - Face, Woodcut Print on Paper, 51 x 33 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Faces, Woodcut Print on Paper, 57 x 39 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Faces, Woodcut Print on Paper, 57 x 39 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1994, The Face, Mixed media on Paper, 52 x 75 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1994, The Face, Mixed media on Paper, 52 x 75 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Self Portrait with Dambulla, Woodcut Print on Paper, 56 x 38 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Self Portrait with Dambulla, Woodcut Print on Paper, 56 x 38 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Self Portrait, Artist’s Proof, Woodcut Print on Paper, 56 x 38 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Self Portrait, Artist’s Proof, Woodcut Print on Paper, 56 x 38 cm

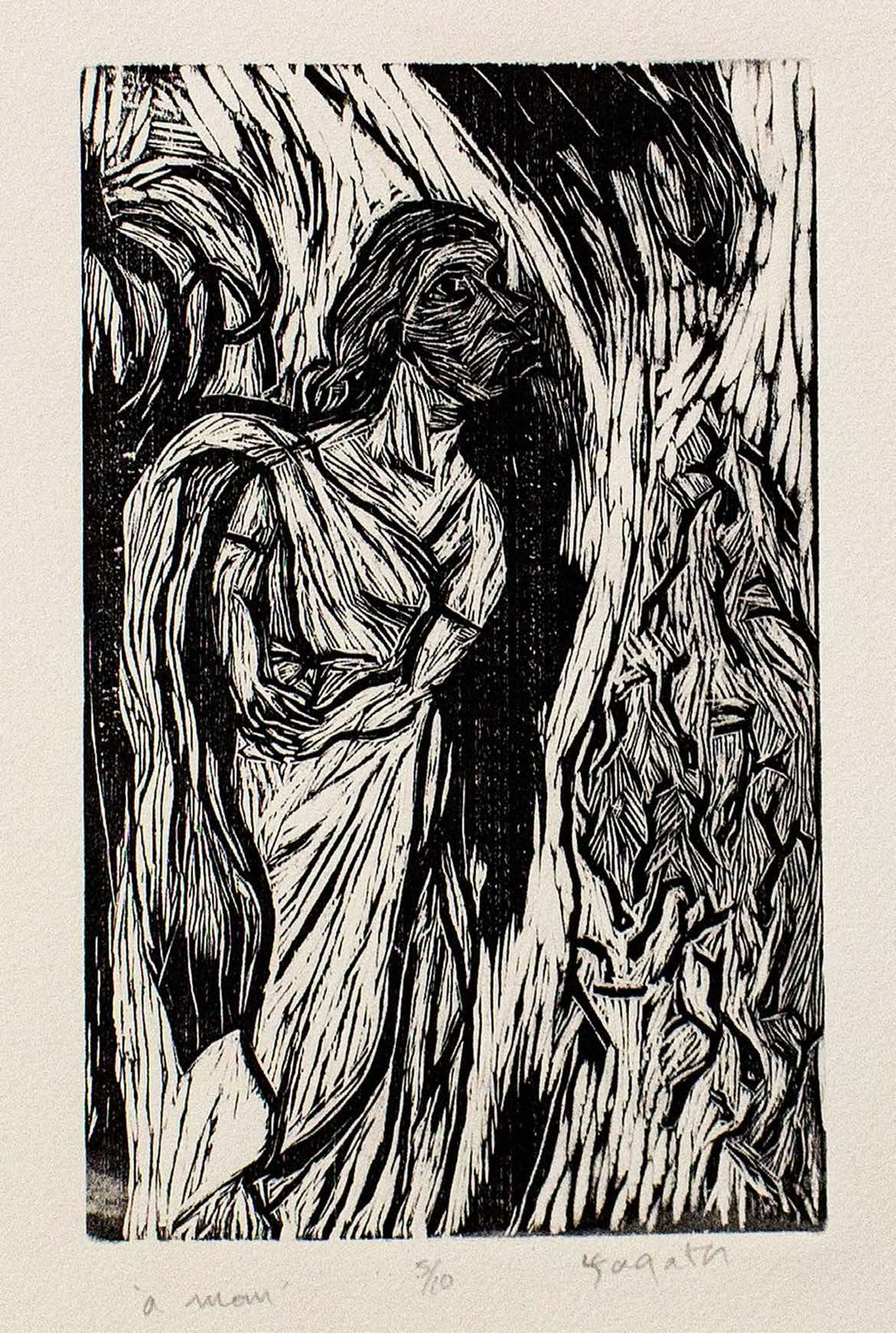

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1993, A Man, Mixed Media on Paper, 77 x 56 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1993, A Man, Mixed Media on Paper, 77 x 56 cm

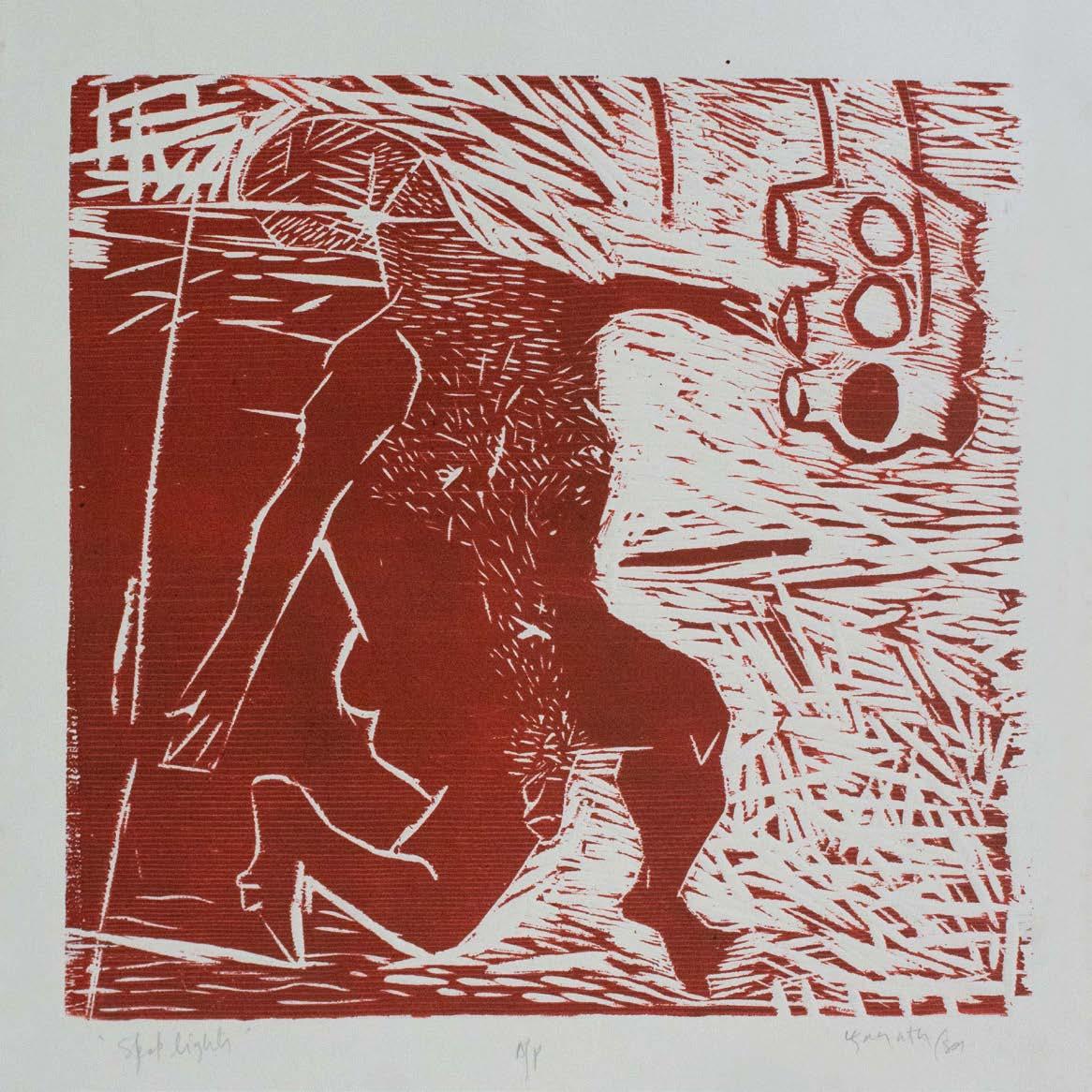

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Stop Lights, Artist’s Proof, Woodcut Print on Paper, 46 x 33 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Stop Lights, Artist’s Proof, Woodcut Print on Paper, 46 x 33 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Long Necked Man, Woodcut Print on Paper, 38 x 33 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Long Necked Man, Woodcut Print on Paper, 38 x 33 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Long Necked Man, Charcoal on Paper, 76.5 x 91.5 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Long Necked Man, Charcoal on Paper, 76.5 x 91.5 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Stop Light, New York City, Mixed Media on Paper, 74 x 59 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Stop Light, New York City, Mixed Media on Paper, 74 x 59 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1995, Dancing Shiva, Acrylic on Canvas, 91 x 76 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1995, Dancing Shiva, Acrylic on Canvas, 91 x 76 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1995, Public Rally 2, Acrylic on Canvas, 91 x 66 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1995, Public Rally 2, Acrylic on Canvas, 91 x 66 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 2005, Dambulla 21, Mixed Media on Paper, 30 x 42 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 2005, Dambulla 21, Mixed Media on Paper, 30 x 42 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 2005, Dambulla 15, Mixed Media on Paper, 30 x 42cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 2005, Dambulla 15, Mixed Media on Paper, 30 x 42cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1991, The Rock, Watercolour on Paper, 76 x 57 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1991, The Rock, Watercolour on Paper, 76 x 57 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Ruined Landscape with a Stupa, Charcoal on Paper, 76.5 x 91.5 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Ruined Landscape with a Stupa, Charcoal on Paper, 76.5 x 91.5 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Ruined Stupa, Woodcut Print on Paper, 56 x 38 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Ruined Stupa, Woodcut Print on Paper, 56 x 38 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1993, Broken Stupa, Mixed Media on Paper, 54 x 39 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1993, Broken Stupa, Mixed Media on Paper, 54 x 39 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Ruined Stupa, Charcoal on Paper, 76.5 x 91.5 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1989, Ruined Stupa, Charcoal on Paper, 76.5 x 91.5 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1990, A Mom II, Woodcut Print on Paper, 56 x 38 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1990, A Mom II, Woodcut Print on Paper, 56 x 38 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1990, A Mom, Woodcut Print on Paper, 56 x 38 cm

Jagath Weerasinghe, 1990, A Mom, Woodcut Print on Paper, 56 x 38 cm

The Association for Relatives of Enforced Disappearance (ARED) was founded in Kilinochchi in the years following the end of Sri Lanka’s civil war. Sri Lanka has the second-highest number of enforced disappearances in the world. According to the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances, as many as 100,000 people have been reported missing since the 1980s, the majority of them during the civil war. Several human rights organizations, including Amnesty International, have documented the use of enforced disappearances by the Sri Lankan authorities as a tool to silence dissent.

Shrine of the Innocents, Kilinochchi: Where is My Child?, Installation

Jagath Weerasinghe with Bandu Manamperi, Sivasubramaniam Kajendran, G. Ranjith Perera, Kadurkamanathan Kokilawani, Sellaththurai Soothy, Balan Malar, Suerenthiran Veno, Kanthasamay Malar, Uthayakumar Sewanthy, and Yogeshwaran Vijayalakshmi

2023, Shrine of the Innocents, Kilinochchi: Where is My Child? Installation

Shrine of the Innocents, Kilinochchi: Where is My Child?, Installation (detail)

Shrine of the Innocents, Kilinochchi: Where is My Child?, Installation (detail)

Shrine of the Innocents, Kilinochchi: Where is My Child?, Installation (detail)

Shrine of the Innocents, Kilinochchi: Where is My Child?, Installation (detail)

1991 Master of Fine Arts Degree in Painting, American University, Washington D.C.

1988 Conservation of Rock Art, Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles, USA

1985 Conservation of Wall Paintings, International Center for the Scientific Study and Restoration of Cultural Property

1981 Bachelors of Fine Arts. Honors in Painting (Second Class Upper Pass) Minor: Sculpture, Institute of Aesthetic Studies University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka

Solo Exhibitions (selected)

2020 April Works: Backpacks, Bombs & Borders | Saskia Fernando Gallery, Colombo, Sri Lanka

2018 Writing a letter to you | Curated by Liz Fernando | KHOJ, India

2018 Belief: The Promise of Absence | Saskia Fernando Gallery, Colombo, Sri Lanka

2018 Days without a Night | Curated by Kanika Kuthiala and Leonhaerd Emmeling, Goethe Institute, New Delhi, India

2018 Dream for Me | Curated by Liz Fernando | KHOJ, New Delhi, India

2016 With or Without Me/aning | Saskia Fernando Gallery, Colombo, Sri Lanka

2015 Paradise Road Galleries, Colombo, Sri Lanka

2014 Decorated Breese Little | London, United Kingdom

2014 Decorated | Saskia Fernando Gallery, Colombo, Sri Lanka

2009 Shiva Nataraja | Saskia Fernando Gallery, Colombo, Sri Lanka

2006 The Reading Room: Thousand Shivas and Thousand Mikes | Singapore Biennale curated by Fumio

Nanjo, Sharmini Perera, Eugene Tan and Roger McDonald, Singapore

2005 The Celestial Underwear | Phenomenal Space Gallery, Colombo, Sri Lanka

2004 Urban and the Individual | Group Show, Phenomenal Space Gallery, Colombo

2003 Paradise Road Galleries, Colombo, Sri Lanka

2000 (My) Inability of Painting Woman’ | Gallery 706, Colombo, Sri Lanka

1997 Recent Paintings | Paradise Road Galleries, Colombo, Sri Lanka

1997 Yantragala and the round pilgrimage | Heritage Gallery, Colombo, Sri Lanka

1995 Lionel Wendt Art Gallery, Colombo, Sri Lanka

1992 Anxiety | National Gallery of Art, Colombo, Sri Lanka

Group Exhibitions (selected)

2023 India Art Fair | New Delhi, India

2019 Shades of Black and White | J.D.A Perera Gallery, Colombo, Sri Lanka

2019 Crossing Place | Baik Art Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

2018 Art Dubai | Saskia Fernando Gallery, Dubai, UAE

2017 A Tale of Two Cities: India & Sri Lanka | Gallery Espace, New Delhi, India

2017 Portraits of Intervention: Contemporary Art form Sri Lanka | Curated by Bansie Vasvani

Aicon Gallery, New York

2016 Serendipity Arts Festival Goa | Goa, India

2016 Portraits of Resistance | India International Centre, New Delhi, India

2016 India Art Fair, New Delhi, India

2015 Cinnamon Colomboscope: Shadow Scenes | Rio Hotel and Cinema, Colombo, Sri Lanka

2012 Drawings | Breese Little, London, UK

2012 Mediated (Data Art) | Saskia Fernando Gallery, Colombo, Sri Lanka

2012 Art of Resistance | Espace Gallery, New Delhi, India

2012 Colombo Art Biennale | Colombo, Sri Lanka

2011 Contemporary Art from Sri Lanka 2011 | Asia House, London, UK

2009 Artful Resistance: Crisis and Creativity in Sri Lanka | Museum fur Volkerkunde Wien, Vienna, Austria

2009 Designing Peace | Marian Pasat Roces, MCDA, Manila, Philippines

2007 Theertha Red Dot Gallery, Sri Jayawardanepura, Sri Lanka

2005 Ten Artists from Sri Lanka | Group show, Milles Garden, Stockholm, Sweden

2004 Aham Puram | Jaffna Library, Jaffna

2002 Arts South Asia Show | Liverpool University Gallery, Liverpool

1999 Asia-Pacific Triennial, Queensland Gallery, Australia

1997 Dialogue | With Christa Webber, Gallery Mount Castle, Colombo, Sri Lanka

1996 Die Welt zu Gast | Spiel Bank, Dortmund, Germany

1994 4th Asian Art Show | Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, Fukuoka, Japan

1994 New Approaches in Contemporary Sri Lankan Art | National Art Gallery, Colombo, Sri Lanka

Residencies

2019 Baik Art Residency, Davidson College Art Galleries, North Carolina, USA