COVERT

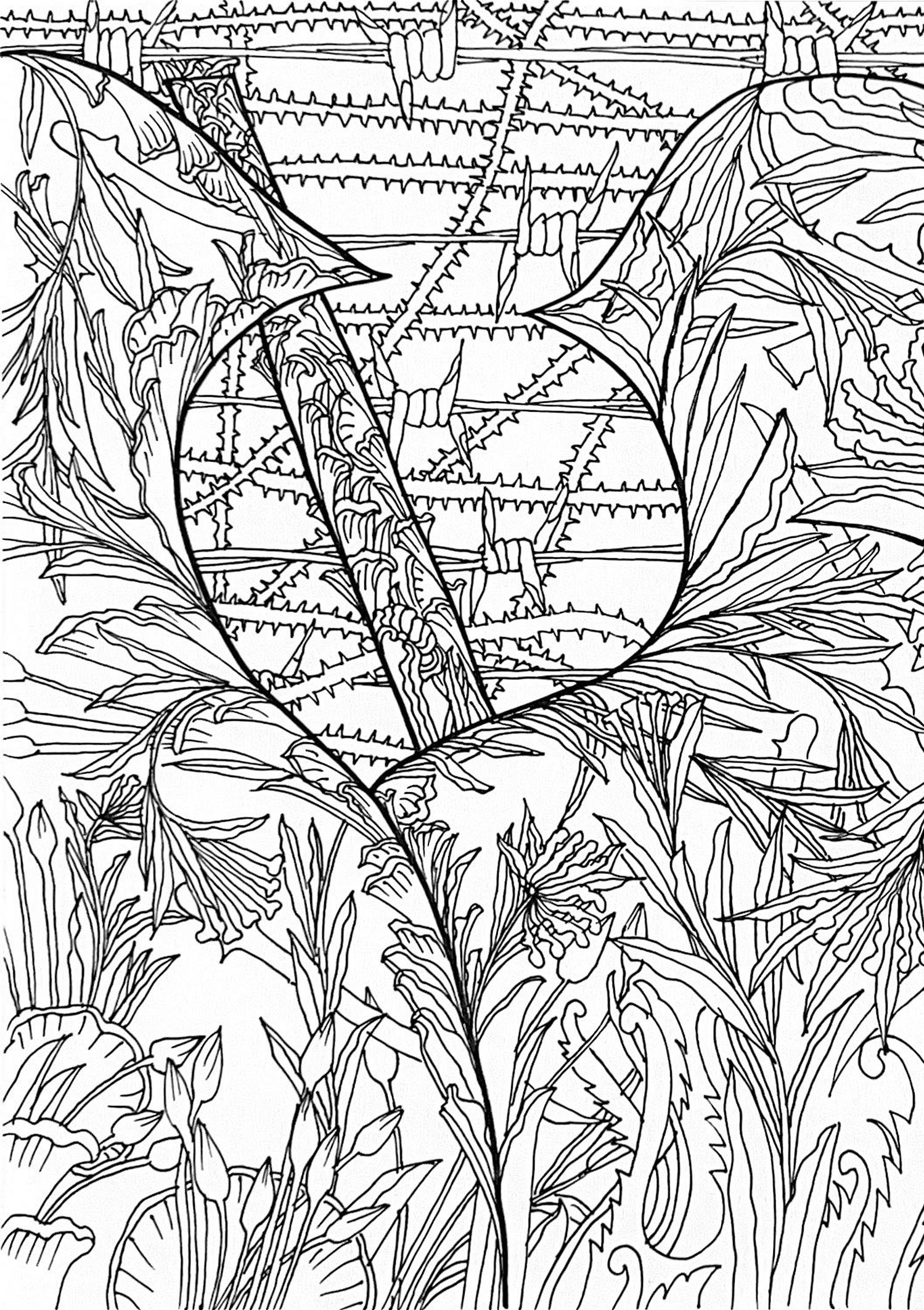

A monumental column, Chandraguptha Thenuwara’s Covert (2021-23) is composed of intricate and interlocking iron filigree symbols painted black: lotus buds, bodies, barbed wire, thorns, stupas, lion tails, weapons, vehicles. Exhibited at the Venice Biennale last year, it travelled to Colombo’s Lionel Wendt Art Gallery in 2023, where a new floor sculpture sprouts out from its base like tree roots. The installation marks Thenuwara’s annual memorial show dedicated to Black July, the anti-Tamil pogrom at the start of Sri Lanka’s civil war (1983-2009), exactly forty years ago. The cylinder towers over its viewers at 222.5 cm in height and 91.4 cm in diameter, while inter weaving lines on the ground cover a 550x550 cm area. On the walls are large-scale black and white drawings, showing similar patterns in ink: expansive landscapes in which icons associated with the conflict recur in two-dimensions.

As part of Thenuwara’s longstanding anti-war activism and artistic practice, Covert considers the way collective violence puts pressure on the aesthetic field as visual culture is co-opted into militaristic iconography. But while the series works to reveal such strategies, it also strives to undermine them: to appropriate and reinvent such symbolism in protest against its weaponization and the profound violence that accompanies it. Begun just before the 2022 Aragalaya protests, Covert is also deeply committed to the imaginative potential of contemporary art to picture political possibilities in alliance with wider social movements.

Draft of motifs used throughout Covert, 2021

Sri Lanka’s multi-ethnic social uprising in 2022 deposed the then-president Gotabaya Rajapaksa, a military-officer-turned-politician accused of war crimes, who oversaw one of the island’s worst financial crises since independence from British rule in 1948. The 2019 Easter bombings, covid pandemic, money creation, tax cuts, and farming policy all combined to create severe shortages of medical supplies, unprecedented inflation, increased prices for basic commodities, and depletion of foreign exchange reserves. Last summer Thenuwara spoke about seeing society change rapidly, having spent decades challenging the civil war and its legacies in his artistic practice and activism. ‘The movement is unprecedented, even organic’ – he explained – ‘shedding old school thinking. The whole country understands we need to free ourselves from the entrapment of militarization’.1 Psychology studies scholar Shamala Kumar insisted Aragalaya shall ‘ignite our imaginations, and produce an awesome force, once again – but bigger – that leads to a radically different system of democracy’.2 Thenuwara’s art has long pre-dated but is ultimately also part of that imaginative force.

Sociologist Sasanka Perera has praised his ability to communicate: a practice that appeals to a wide public, able to decode its meaning, blurring boundaries between art and activism.3

For Thenuwara, art can contest and create new conceptual associations between images and political movements, by using beautiful cultural forms to draw in viewers and then provoke shifts in their perception.4 Thenuwara is concerned with putting pressure on the aesthetic field by emphasising it as a site of ideological staging itself. Covert’s delicatelytraced lines seek to reveal and disrupt political strategies which naturalise symbolism to covertly conceal operations of power, often by drawing on metaphysical icons taken from the natural world. The lion’s tail in Covert implicitly refers to beliefs that Sri Lanka’s first Sinhalese king, Prince Vijaya (r.543-505 BCE), was descended from the animal – as told by historical chronicles like the Mahāvaṃsa (5th century CE).5 Although similar iconography was associated with Tamil dynasties in Sri Lanka and South India such as the Pallava (275897 CE) and Chola (300s BCE-1279 CE), certain textual accounts sought to develop a distinct Sinhalese consciousness through ideological myth-making to support the elite ruling classes.6 But the contours of the island’s many ethnic groups have been mutable and porous for thousands of years. Connections between Tamils and Sinhalese people have been defined by cohabitation, conflict, cultural exchange, as well as integration and assimilation.7

Buddhism – evoked by the lotus bud in Covert – took on a particular meaning for Sinhalese identity after the 7th century CE, but in modern times it was British colonialism from 1796 that played a fundamental role in institutionalising ethnic differences.8 Despite the term ‘Sinhalese Buddhist’ being coined in c.1906, the two have never been mutually exclusive.9 If British rule laid foundations for later civil war, the war’s proponents used Sri Lanka’s deep past to legitimise contemporary conflict.10

Covert’s stupa depicts Anuradhapura’s Buddhist Ruwanweli Maha Seya temple, built by Sinhalese king Dutugemunu in c.140 BCE, after defeating Tamil Chola king Elāra. Rajapaksa’s decision to swear his 2019 presidential oath at the site angered Thenuwara.11 Covert uses two-dimensional lines to emphasise political symbolism as a cultural practice that requires reduction or simplification alongside repetition to create impact. But for all that specific motifs recur throughout Thenuwara’s sculpture and drawings with an appearance that evokes the diagrammatic, his illustrated forms constantly threaten to overwhelm and collapse their neatly demarcated boundaries. Thorns spill into barbed wire, bodies slip into swords. Covert put pressures on the mechanisms that underpin militarism by unmasking its attempt to naturalise social divisions.

Covert’s intricate lines also recall the illustrations in British-Sri Lankan art historian Ananda Coomaraswamy’s book Medieval Sinhalese Art (1908). Reproducing traditional craft through carefully-drawn diagrams, the publication recorded 18th- and 19th-century religious iconography from temple murals to sculptural reliefs. Coomaraswamy’s writing was fundamentally driven by his socialist anti-colonialism: conceptualising Sri Lanka in ways that were expansive and open in the context of South Asia, while agitating against British rule. He proclaimed: ‘Sinhalese art is essentially Indian, but possess this especial interest, that it is in many ways of an earlier character, and more truly Hindu – though Buddhist in intention, – than any Indian art surviving on the mainland’.12

While such analysis is contested and contentious, it evokes an understanding of a Sri Lankan imagination unbound by the ethnic exclusivity that later defined the island’s civil war. If Covert alludes to Medieval Sinhalese Art, it is to imply that Sri Lanka’s cultural histories have been shaped by constantly shifting concepts of identity: while they can and have been put to sectarian ends, the aesthetic field also offers a space to radically reimagine the very political structures that produce such profound violence. Coomaraswamy himself believed ‘craftsmanship is a mode of thought’.13

For Coomaraswamy, 18th- and 19th-century Sri Lankan visual culture ‘was the art of a people for whom husbandry was the most honourable of all occupations, amongst whom the landless man was a nobody, and whose ploughmen spoke as elegantly as courtiers’.14

Whether or not this claim is strictly speaking true, it is important to recognise the role landscape played in the island’s collective imagination from imperial conquest to anticolonial struggles.

Coomaraswamy’s focus was on Kandy in particular: a Sinhalese kingdom inherited in its final decades by Tamil monarchs, who practised Hinduism while patronising Buddhism.15 The polity was the last in Sri Lanka to be conquered by European powers, having maintained a ring of defensive forests with thorn gates until 1815.16 British rule subsequently cut down common lands, once used as a source of subsidence living and folk medicine, and installed mass tea or coffee plantations to extract wealth back to the UK.17 Environmental destruction would continue in later decades after independence, while the civil war itself was waged over territorial control.18 In Thenuwara’s own work, barrels have been reclaimed as artistic symbols: once associated with infrastructure development under British colonialism, later used for roadblocks as oppressive tools of military architecture.19 Covert’s floor sculpture suggests the very ground under visitors’ feet is politically contested.

Curator Sandhini Poddar, who has supported the project’s development, recognises the way it ‘draws our attention to the fragile and fraught dystopia of contemporary Sri Lanka’.20 For art historian Sharmini Pereira, Thenuwara’s drawings of thorns and spikes amidst other kinds of conflict debris employ landscape as a metaphor in a manner that ‘juxtaposes the apparatus of war with decaying nature as if to suggest peace will, wishfully, return through a cycle of growth or rebirth’.21 But the artist does not take nature for granted as an uncritical metaphor for Sri Lankan society after 2009, rather Covert challenges the way political symbols are often naturalised as part of larger structures of social control and oppression. Pereira notes that Thenuwara pictures natural landscapes in transition or transformation, while art critic Azara Jaleel sees similar states of flux or fervour and commends his active artistic participation in Aragalaya.22 Covert’s symbols swell and seep across sculptures and drawings, as though they are aesthetic forms in constant motion: congealing into certain shapes before shattering and reconstituting. The work suggests that cultural symbols can never be entirely co-opted for sectarian ends: not only can icons be reclaimed, but more importantly throughout history Sri Lankans and their collective imagination have never neatly fallen exclusively between irreconcilably or impermeably-bounded ethnic groups.

Militarism sorts people into hierarchical categories of us-and-them as a tool for structuring power. But violence can transform all those who encounter it: spiralling out of their control, shattering boundaries between bodies.23 Covert’s delicately-drawn details give way to a mass of contorting forms at a distance, as seemingly unstable concepts and corporeal forms cascade into each other. The cylindrical tower also recalls barrel motifs or monumental designs used across Thenuwara’s practice. In 2000, the artist created the Monument for the Disappeared on the Raddoluwa intersection of the Colombo-Katunayake Road in a memorial to those abducted and killed as a result of the civil war.24 In recent years, Thenuwara has spoken about memorialisation as a means to critically reflect on the causes and consequences of conflict as a form of collective mourning and warning.25

Although begun before the Aragalaya movement erupted in 2022, Covert prompts questions about how its legacy might be recorded in visual culture – particularly following brutal police crackdowns, IMF bailouts with austerity conditions, and ongoing economic suffering. In such a climate, Thenuwara’s work remains as urgent as ever. Covert seeks to both diagnose and disrupt certain aesthetic techniques of power: the artistic series aims to dramatize and denaturalise the creation or consolidation of sectarian iconography in contemporary Sri Lankan politics.

Dr Edwin Coomasaru is a historian of modern and contemporary UK and Sri Lankan art: researching gender, sexuality, and race. He has been awarded Postdoctoral and Research Fellowships at Edinburgh University, The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, and The Courtauld Institute of Art.

It’s lovely to have this conversation on the brink of this very important exhibition, starting on the 23rd of July, at the Lionel Wendt Center. I am an adjunct curator at the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi project, and I had the pleasure of visiting Sri Lanka in January last year. This is a region of the world that’s very important to my ongoing research. I visited Thenu’s studio and he very kindly shared his ongoing project Covert, which is the centerpiece of this exhibition.

This is the work that we’re going to be discussing today, but of course in in the context of his larger worldview as a professor, activist and a studio artist.

Thenu from what I know, this is a very intricate and collaborative project that you started back in 2021. And of course, when visitors come to the Lionel Went Center, they will experience it as a final installation also in dialogue with a number of works on paper that you have been developing at the same time. But what I think audiences miss is the kind of long intellectual journeys that artists go through in order to form their personal vocabularies and iconographies. And one could think of it as a glossary or a dictionary of ideas. So even before we start to talk about covert as a final work, if you could just talk about what the genesis of the project was and how you came to think about this piece, perhaps as an amalgamation of many of the other ideas or forms that you had been toying with in your practice, perhaps, for either years or decades before that.

It is kind of a continuation of my responses to un-commemorated commemorations. You can’t separate my thinking patterns. I have a lot of experience this time, with the Covert three-dimensional structure, plus the floor. I wanted to have the drawing as a three-dimensional work, such that it is standing. Unconsciously, it came out as a larger version of the barrel form. I introduced Barrelism in 1997. The barrel form is embedded in me. That too is the reason why the cylindrical shape came in, I think, when I analyze it. Another connection might be that - I wanted to draw on the floor. I did road paintings after the 1999 killing of Neelam Thiruchelvam at Kinsey Road. I painted that road every year until 2013, which is when the authorities tarnished the road painting. That’s the last moment I painted. But that experience also gives me a connection with the floor. I also think that working with the floor and drawing is close to art forms in Asia. Other than paintings and installations, drawings are also a very important part of my practice.

At the same time like kolam and rangoli. I am inspired by them. There is a connection I share with drawing. When people saw my work in Italy they exclaimed that it was very Sri Lankan! I have not made it Sri Lankan intentionally. I was not picking up forms from the old paintings or old drawings. Instead I was trying to do it like the old artists - one curve followed by two curves and a dot and another curve - the Wakkade, a continuous form which became the form of the Covert work.

And I guess also when you work on drawings of different skills, they also become more nomadic, right? So, you can work on those drawings. They become almost diaristic. You could be sitting anywhere in the world. And you are still kind of going over those ideas and those forms and those images and making new connections, but you don’t have to be sitting in the studio in order to continue that practice. It gives you that kind of flexibility and mobility that perhaps painting and installation-based work doesn’t give you. It’s a kind of riyaaz or a kind of practice where there are certain forms and ideas that keep churning in your mind. And every time you make a drawing, you are trying to create new connections not just formally, but also, you know, contextually. Because you’ve done a number of these drawings and they are, you know, some of them are quite miniature, but then also a lot of them are quite large.

But the beauty of paper is that you can roll it up and practice it anywhere in the world. So, you don’t have to be just in the context of Colombo in order for you to continue those works. But in terms of the smaller details - let’s talk about the micro before we come back into the macro. But you have these repeating forms. You’ve spoken to me about them even when I came to visit you in January last year. You’ve got the lotus flower, you’ve got the stupa, you’ve got the cannon, you’ve got the fallen body, you’ve got barbed wire. How did you come up with this glossary of images?

Yes, the first time I came up with the flowers was when the water lily was announced as the Sri Lankan national flower. Around the same time, the rebels in Jaffna also announced their flower, the Gloriosa lily, known as Niyangala in Sinhala. It was like creating a shadow flower: there is a national flower in Sri Lanka and a national flower in Elam. That is why I played with these two flowers. They are embedded in my mind.

The form of the Gloriosa lily later became a creeper, with the flower coming down from top to bottom. I also developed the form of the bodies in my work. After 2015, more lotuses appeared in my work. The lotus was a very innocent symbol. It was more Buddhist, and it was the peace symbol for Chandrika’s period. It’s a white lotus. But then the lotus became a political symbol of the oppression of some people by Mahinda Rajapaksa and his regime. So, they connected it with the Buddhist realm and with the political realm. It was hypnotizing.

So I took that hypnotism and hypnotized my viewers with that flower, the Niyangala form, the dead bodies, and sometimes with pieces of bones, fractions. But you can’t immediately see those things. If you are scrutinising them enough, then you’ll find them.

And isn’t the intention also, Thenu, that you want the visitors to come very up close to the sculpture? We had spoken in the past that you wanted them to walk on the drawing and to be almost in this space of the glitch where you are looking at the images and trying to decode them. But there is a certain kind of confusion because the trellis work that you’ve done in iron, in metal, is so intricate. It’s on one level extremely handmade. The whole work is a drawing but it’s in three-dimensional form. But is this also something that you will be doing at the Lionel Wendt Center? Will you let people come and actually stand on the drawing and come up very close to the column? Is that something that you’ll be doing?

Yes, because if you look at the drawing on the floor from far away, then you will see the perspective and the distorted drawing. But when you are walking on the drawing, then you can closely look at that drawing and at the same time you are within the drawing. And that connection is very important. At the same time when you go toward the column and see the other side too, it becomes confusing. You are in and out of it, and on it. You go through all the levels of the space. It is a kind of living atmosphere, and with your movement, you become air and light. When you look at the work of heavy metal, what you are seeing seems very light. It will be like you are on a cloud and at the same time entering a natural forest. You find your own map, your own roads, and you have to find where to walk, go around it, and come back.

At the same time, it allows touch. This was also very important. When I started, the first time I used that effect in my artwork was when I made the wall. People came in and lit the lamps on the sculpture. It was then that I felt that people also felt it and that share a connection with the work. That it is not isolated, although there was a “Do not touch” label on it. This is a very important feeling. At the same time, you get to feel the hypnotism that exists — it looks beautiful.

Where I was going to go next with the question was if we zoom out, I mean we’ve talked about the different imagery that one can start to discern even though it’s not apparent, one has to look for it within this kind of maze or trellis. But then if you zoom out, you know, one of the things that’s important for visitors to understand, of course, they would be aware of this in the context of Colombo, because you’ve been holding these annual exhibitions for many years in commemoration of plaque July. But I think for visitors who are perhaps less familiar with the political history of what happened in the Civil War if you could just, you know, perhaps zoom out for a second and just share with everyone why is this exhibition held in July and why is Covert seen as such a paradigmatic work, now politically, what does it mean, what is its symbolism? If we could talk about the symbolism of the work, vis-a-vis what is current in the politics of Sri Lanka now, but then also just perhaps refer back a little bit to the political history of the last 30 - 35 years.

When I started in 1997, I had finished my early studies in art. When I came back to Sri Lanka, I had to find my own way and my own language. I was a figurative painter. I knew how to do it in 19th-century techniques - kind of like a classical painter. I was trained in the Russian kind of practice. When I came here, I did not find any human figures. Instead, I found figures of barrels because of the war that was going on. Thus, I moved away from the human figures but I found a new figure with Barrelism and other things. I had been away from Sri Lanka since 1983.

I came back to Colombo the same day when the program took place. It happened in front of my eyes. When I got the news, I was travelling to Colombo from Kandy. On that day, 23rd of July, 1997, 13 soldiers were killed.The military had advised, “Don’t bring the dead bodies to Colombo. Otherwise, this will be a problem and there will be unrest among the Sinhalese people.” But the politicians insisted on bringing the bodies. I think that is what created the pogrom. In that sense, it was kind of an organized crime. The people who came, burnt and tortured people, were not from Colombo.

For example, I walked from Nugegoda to Colombo and from Colombo to Wellawatte. I saw what happened on 23rd of July. It was burning from early morning till evening. I couldn’t do anything at that time. I was 23 years old. I had just graduated as an artist - a freelance artist, but I couldn’t even make the opening amount. It was a tense situation. You became an onlooker, and you were just watching. You have so many feelings inside of you. It was a political problem. A political solution should have been given - not by vote nor by killing but by listening to the grievances. By sharing and discussing it to find a solution. But the government at that time wanted to have a solution that called for war.Even when I was in Moscow, I painted my compositions related to the Sri Lankan theme from 1988 to 1989 - the horror and death of losing your relatives. I had once come for a short visit in 1989. My brother said, “Don’t speak a word. You are from the Soviet Union and you shouldn’t use any socialist words because even the walls can listen to you.” That is the kind of silence I kept. I stayed for over one month without saying anything. You couldn’t freely express yourself. Those are the things that are within you. That’s the only way I co express it. So, it was released as art. And it came late actually from 1983, the real form of my language - in 1997 with Barrelism – creating a signature to my work.

Covert 14, 2022, Ink on Paper, 30 x 42 cm

Covert 14, 2022, Ink on Paper, 30 x 42 cm

What was the impetus behind the commemorative exhibition, the annual exhibitions? Because I think it was an opportunity to also create a discursive space by dialoguing with other artists. Isn’t that, right? With younger artists and inviting them to respond. So, is that something that you’re still thinking about?

Yeah, always. Especially since 2015, which is when I moved to Saskia Fernando Gallery, I have always organized the voices of other artists parallel to my work at the space at Lionel Wendt. Because of my political work, some people think I’m not an artist but that I am a politician. I know there is always politics in my art. But a lot of young people are inspired. Social consciousness is very important. That’s the thing we did - Jagath and me. We were doing socially conscious work through our art, but at the same time, keeping our own identity.That thought process and dedication became my language.

It’s hard to talk about the significance of an event in the present tense because you always need a few years, to look back in order to do that kind of thorough analysis of the meaning of something. But if you had to just try to think about the significance of the exhibition this year, 40 years later, and also with Covert completed as a finished project, what is your hope for this iteration of the exhibition in 2023?

I think the problem has not been solved permanently. Last year, the president spoke about the 13th Amendment. Again, the Buddhist monks and the so-called extremist Sinhalese people are trying to go against it and not giving into the 13 Amendment – that is the devolution of power. At this point, it is very important for people to think about what we would gain and what we have learnt from history - that it shouldn’t happen again. Not at all. And no blood should be spilt in this land in the name of ethnicity and other things. We have a right to life or not be a victim of a bullet or a victim of unknown political forces.

It is rare - the life we have gotten. And we have to live peacefully. That’s the thing we have to talk about. The barbed wires – remind you of an unforgettable history. People can easily forget everything. Sometimes ten days is enough to forget everything, but then you can start. It might be the mobs again, and politicians who try to trigger these kinds of situations. That is why it’s very important to talk about this. They can criticize me. But anyway, that process is also very important – going against me and at the same time artistically. They can think about what I’m saying - wrong or good. And this is not a provocative, you know…

No, it’s a discursive space, a discussion. It’s an invitation for a gathering. It’s an invitation for collective thinking. And it’s not about one person’s position. It’s more about trying to create an opportunity to think together and to feel safe in that company.

That is very important.

Thank you so much Thenu.

Thank you for giving me the time to talk here.

No, I’ve learned so much, and it’s always a privilege to speak to you because we learn about these events either through, of course, reading about political histories or by reading about certain practices or artist biographies, but it’s always such an honour to speak to an artist live and in the present tense. And I know that this project has been a very all-consuming process for you over the last two years. And I think it’s wonderful that you are opening up the studio process to the visitor and showing also how there are so many different collaborators that you have worked with - that these projects don’t emanate from a blank slate. But they are very much processes of accumulation through your lived experience and what you’ve read and who you’ve met and what you think about politics, but also places that you’ve travelled and what you’ve seen - forms of art history that have inspired you from Europe, as well. These are always amalgamations of many processes, both external and internal. And the more we can share these with the public, I think it’s always wonderful for them because it’s a very generous invitation for them to come and participate in one aspect of your practice. So, thank you so much.

Sandhini Poddar is a London-based art historian and Adjunct Curator at the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi Project, where she is responsible for acquisitions, commissions, and research for the future museum. Previously, Poddar served on the curatorial team at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Foundation from 2007 until 2016 as part of its international Asian Art Initiative. Poddar writes on contemporary art, aesthetics, and politics and has contributed articles for magazines such as Artforum, ArtAsiaPacific, and Art India. She has post-graduate degrees from New York University and Mumbai University. Poddar recently curated ‘Indra’s Net’ for Frieze London.

April 2021

The concept for the Covert project was shared with curators of the European Cultural Centre, Venice for the 59th Venice Biennale and approved for inclusion in the Personal Structures exhibition to be presented at Palazzo Mora.

December 2021

Thenuwara begins construction of the column section of the Covert project. It is decided that the entire concept cannot be included, and the work will need to be constructed in a manner in which it can fit through the Palazzo Mora entrance.

The Covert drawing is projected onto a large drawing board (8’x10’) at the actual scale required for the cylindrical metal drum. Using the projection the artist then outlined the drawing onto tracing paper. This traced drawing provided the blueprint for the sculptural installation.

January 2022

Sandhini Poddar visits Sri Lanka on a research trip and is introduced to the project; the drum at this point is still in the form of a plastic column.

The drum arrives and the traced blueprint is transferred onto the drum using white carbon and carbon trace fixed (redraw) with typing correction ink pens.

Welding of the iron rods onto the drum surface begins. Each 6mm, 4.9mm and a few 4mm iron rods are cut and bent to trace the lines of the work.

The metal drum is then separated from the welded column. Covert is then completed, primed and ready to be shipped to Venice.

Following the presentation of the Covert project to Sandhini Poddar, adjunct curator of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, Thenuwara & SFG are invited to present the drawings of Covert at Frieze London 2022.

February 2022

Covert is temporarily installed at SFG before being disassembled for crating and transport to Venice. Due to the tiny entrances of the ECC Palazzo Mora the piece had to be made into four parts to be carried into the exhibition room.

March 2022

Protests erupt in Sri Lanka in response to the worsening economic crisis.

April 2022

Due to worldwide shipping delays, the installation does not arrive in Venice in time for the opening nights of the biennale. The drawing used for the creation of the work was hand carried as a backup and installed in the space.This drawing later became an essential part of the installation as it illustrated the way in which this column was created.

May 2022

Protests erupt in Sri Lanka in response to the worsening economic crisis.

November 2022

October 2022

Covert Drawings is presented by Saskia Fernando Gallery at Frieze London 2022. Indra’s Net is featured in the New York Times.

The 59th Venice Biennale concludes, and the column is packed for return to Sri Lanka. In the meantime, Thenuwara begins work on the floor extension of Covert to be presented at his annual memorial exhibition in 2023 which will mark 40 years since Black July 1983.

The floor extension of the Covert column is created by first completing the drawing on wooden boards laid on the floor. They are traced for reference and after that, the same process of welding is used to trace the drawings on each wooden square.

July 2023

Due to the scale of the project, Saskia Fernando Gallery will present this project in the main gallery of the Lionel Wendt Art Centre alongside hosting his annual show at their Horton Place gallery. A third exhibition curated by Thenuwara will be shown at the JDA Perera Gallery. The group exhibition will feature visual responses of the war by six Sri Lankan artists. These three exhibitions will open on 23 July 2023.

1 Chandraguptha Thenuwara and Sanjana Hattotuwa, ‘SFG Interview: Chandraguptha

Thenuwara and Sanjana Hattotuwa’, Saskia Fernando Gallery, 16 May 2022, https:// www.saskiafernandogallery.com/video/44-sfg-interview-chandraguptha-thenuwara-andsanjana-hattotuwa, accessed 7 May 2023.

2 Marianne David, ‘Emergency Regulations are the epitome of instability’, The Sunday Morning, 31 July 2022, https://www.themorning.lk/emergency-regulations-are-theepitome-of-instability-prof-shamala-kumar, accessed 31 July 2022.

3 Sasanka Perera, Artists Remember; Artists Narrate: Memory and Representation in Contemporary Sri Lankan Visual Arts (Colombo and Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte: Colombo Institute for the Advanced Study of Society and Culture and Theertha International Artists’ Collective, 2011), p.67, p.96.

4 Thenuwara and Hattotuwa.

5 R.A.L.H.Gunawardana,‘The People of the Lion:The Sinhala Identity and Ideology in History and Historiography’, in Jonathan Spencer ed., Sri Lanka: History and the Roots of Conflict (London: Routledge, 2004), pp.45-86, p.48-52.

6 Gunawardana, p.55-57.

7 Gunawardana, p.58-66; Sujit Sivasundaram, Islanded: Britain, Sri Lanka, and the Bounds of an Indian Ocean Colony (Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press, 2013), p.32, p.45-46, p.160-161, p.251-252; Steven Kemper, The Presence of the Past: Chronicles, Politics, and Culture in Sinhala Life (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991), p.13.

8 Gunawardana, p.60, p.70-78; Sivasundaram, p.17-18, p.283, p.286, p.292, p.317.

9 Gunawardana, p.61, p.76.

10 On the 19th and 20th century history of this practice, see: Kemper, p.8-9, p.79, p.95, p.111-112, p.117-118, p.122, p.126-127, p.131, p.133.s

11 Thenuwara and Hattotuwa.

12 Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, Medieval Sinhalese Art (New York, NY: Pantheon Books, 1956), p.v.

13 Sria Chatterjee, ‘Postindustrialism and the Long Arts And Crafts Movement: between Britain, India, and the United States Of America’, British Art Studies, Issue 15, https://doi. org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-15/schatterjee.

Coomaraswamy, p.v.

15 Sivasundaram, p.32; Robert Aldrich, ‘Out of Ceylon: The Exile of the Last King of Kandy’, in Ronit Ricci ed., Exile in Colonial Asia: Kings, Convicts, Commemoration (Honolulu: Hawaii University Press, 2016), pp.48-70, p.53.

16 James S. Duncan, In the Shadows of theTropics: Climate, Race and Biopower in Nineteenth Century Ceylon (London:Routledge,2016),p.28;James L.A.Webb,Tropical Pioneers:Human Agency and Ecological Change in the Highlands of Sri Lanka, 1800-1900 (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2002), p.50.

17 Duncan, p.7, p.37; Webb, p.41, p.48-49, p.72, p.149.

18 For example, see: Tariq Jazeel, Sacred Modernity: Nature, Environment and the Postcolonial Geographies of Sri Lankan Nationhood (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2013), p.2, p.16, p.65-66, p.76-83.

19 Sharmini Pereira,‘This Island:The Idea of Landscape in Contemporary Sri Lankan Art’, in Sujatha Arundathi Meegama ed., Sri Lanka: Connected Art Histories (Mumbai: The Marg Foundation, 2017), pp.128-145, p.136-137.

20 ‘Watch Now: Chandraguptha Thenuwara’, Frieze, 16 September 2022, https://www. frieze.com/video/watch-now-chandraguptha-thenuwara, accessed 12 July 2023.

21 Pereira, p.139.

22 Pereira, p.139; Azara Jaleel, ‘Cader & Thenuwara Draw Upon Sri Lanka’s Beauty & Bereavement’, ARTRA, 12 October 2022, https://www.artra.lk/visual-art/caderthenuwara-draw-upon-sri-lankas-beauty-bereavement-at-frieze-london-oct-12-16-2022, accessed 14 May 2023.

23 Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (London: Verso, 2006), p.24, p.28-29, p.46.

24 Perera (2011), p.65-67; Sasanka Perera, Violence and the Burden of Memory: Remembrance and Erasure in Sinhala Consciousness (Hyderabad: Orient BlackSwan, 2016), p.255-262, p.268-273.

25 ‘Memory is the process; its result, the memorial: A chat with Prof. Chandraguptha Thenuwara’, The Sunday Morning, 24 January 2021, https://www.themorning.lk/ articles/115522, accessed 13 May 2023.

Thank you to everyone who has contributed to this project over the last two years.

Sandhini Poddar

Dr. Janaka de Silva

Rita Mannella

Anojie Amerasinghe & Hugues Marchand

European Cultural Centre Venice

Italian Embassy in Sri Lanka

Edwin Coomarasu

Udaya Hewawasam

Melanie Taylor

Amila Udara Dias

Archana Gunarathna Bandula

Manjusri Aluthge

Chandrika Wanniarachci

Daya Suriyaarachci

Kusal Gunasekara

Shyama Jayawardena

Wishwanatha Thenuwara