Tribute to Paolo Sorrentino

16-20/08/2025

Saturday, 16/08/2025

Meeting Point Cinema, 15:00

Parthenope

Italy, France, 2024, 136 min

Director: Paolo Sorrentino

Cineplexx 4, 16:30

The Consequences of Love

Italy, 2004, 100 min

Director: Paolo Sorrentino

Sunday, 17/08/2025

Meeting Point Cinema, 15:00

One Man Up

Italy, 2001, 100 min

Director: Paolo Sorrentino

Cineplexx 4, 16:30

Il Divo

Italy, France, 2008, 113 min

Director: Paolo Sorrentino

Monday, 18/08/2025

Meeting Point Cinema, 15:00

The Hand of God

US, Italy, 2021, 130 min

Director: Paolo Sorrentino

Cineplexx 4, 16:30

The Family Friend

Italy, France, 2006, 110 min

Director: Paolo Sorrentino

Coca-Cola Open Air Cinema

The Great Beauty

Italy, France, 2013, 141 min

Director: Paolo Sorrentino

Tuesday, 19/08/2025

Meeting Point Cinema, 15:00

Youth

UK, Switzerland, Italy, France, 2015, 124 min

Director: Paolo Sorrentino

Cineplexx 4, 16:30

This Must Be The Place

Italy, Ireland, France, 2011, 118 min

Director: Paolo Sorrentino

Wednesday, 20/08/2025

Cineplexx 4, 15:00

Loro

Italy, France, 2018, 151 min

Director: Paolo Sorrentino

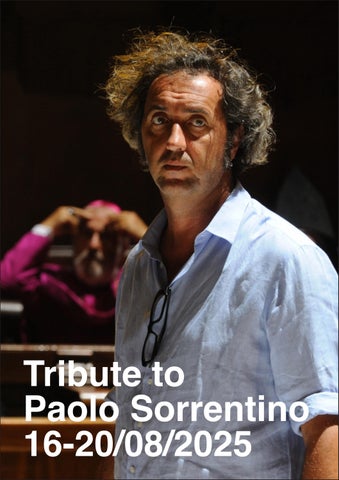

Paolo Sorentino on Beauty, Loss, and Cinema

In conversation with Bianca Lucas

Paolo Sorrentino charged onto the global cinema stage in 2001 with his directorial debut, ONE MAN UP, and has firmly held his position as a prolific and lauded film auteur ever since. Born in Naples in 1970, Sorrentino started studying economics before quitting to pursue his dream of making cinema. His talent was quickly apparent, and his early efforts led to a collaboration with Italian filmmaker Antonio Capuano, with whom he co-wrote THE DUST OF NAPLES (1998).

ONE MAN UP- a dual narrative about two men both named Antonio Pisapia- differed from the traditions expected of Italian cinema. Its unusual approach and distinct character earned the film a premiere at the Venice Film Festival and set the tone for Sorrentino’s recurring themes: duality, guilt, nostalgia, and the decadent actions of both the rich and the ordinary as they battle a common adversary - the passage of time.

Sorrentino’s roots in Naples are not just biographical- they’re foundational to his worldview. His characters often walk through opulent ruins, metaphors for a country and consciousness shaped by centuries of Catholicism, beauty, and burden. Or, perhaps more astutely, the burden of beauty. But what he by his own admission owes most to Naples, is his sense of humour. His work never takes itself too seriously. Sorrentino has made it his signature to find comedy in grief, absurdity in holiness, and tenderness in decay

ONE MAN UP also marked the beginning of a loving collaboration with actor Toni Servillo, who would go on to become Sorrentino’s creative muse across many projects.

In THE CONSEQUENCES OF LOVE (2004), Servillo plays a lonely, isolated man entangled with the mafia. A slow-burning character study, it is with this film that Sorrentino garnered international acclaim. It premiered in competition at Cannes, as did his third feature. THE FAMILY FRIEND (2006) follows Geremia, an old, ‘repulsive’ moneylender who calls himself a “family friend” as he preys on poor families by lending them money at exploitative rates. Laced with bitter irony, the film further explores hallmarks of Sorrentino’s early work, but feels like a bookend for the next chapter of his filmmaking.

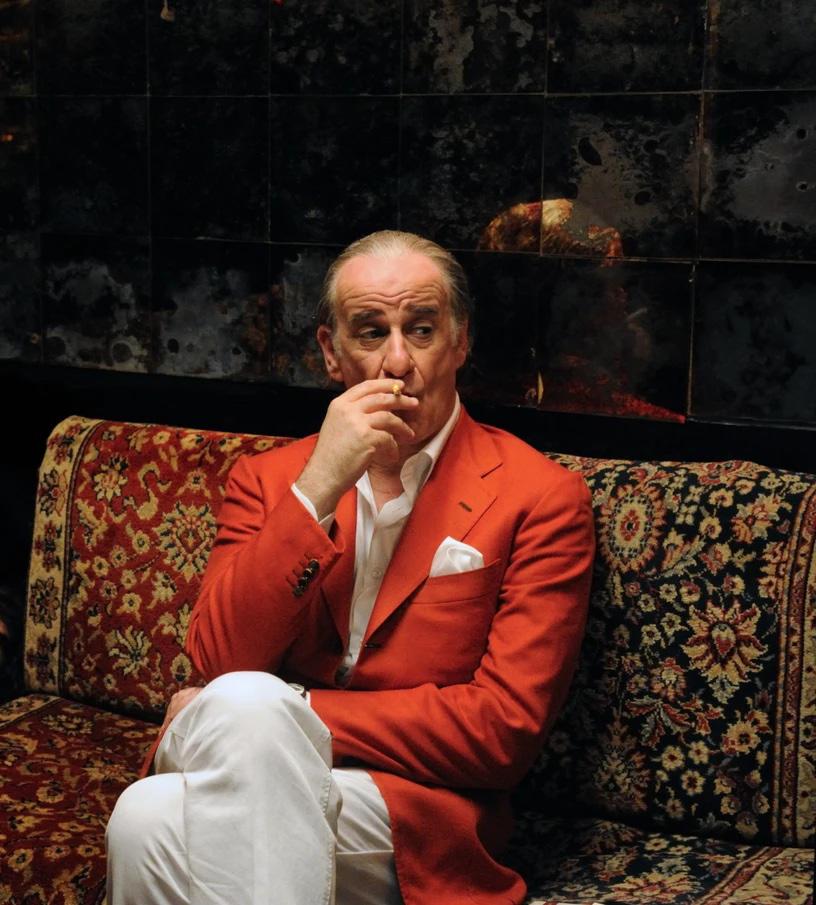

IL DIVO (2008) marks that transition in that it ventures into a political portrait of former Italian Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti, which won the Jury Prize at Cannes and cemented Sorrentino’s reputation for provocative storytelling. By turning dry politics into something akin to a gothic opera, he further honed his mastery of cinematic rhythm and visual choreography.

Sorrentino later revisited the seedy backstage of Italian politics with another one of Servillo’s brilliant embodiments - this time as infamous Silvio Berlusconi in LORO (2018). The gothic opera continued, evermore awash with abstractions, its power-players teetering in a house of cards built on delusion and disconnection from reality

It didn’t take long for Hollywood superstars to reel him in. In THIS MUST BE THE PLACE (2011), he odysseyed into America’s belly of the beast, with Sean Penn as tour guide. Penn donned the creation of a Robert Smith-esque retired rock star who, upon

learning of his estranged, holocaust survivor father’s death, travels through rural America in an effort to hunt down his nazi tormentor. As in the case of Sorrentino’s previous three films, it premiered in Cannes’ Competition section where he casually collected his second Jury Prize. He also proved that his fabrication of worlds and characters is immune to the difficulties that come with working in a different cultural context. He can seamlessly shift from making films in his native surroundings to more distant environments - and from working with Italian actors to anglophone Hollywood icons. We see it again with Sir Michael Caine and Harvey Keitel in YOUTH (2015), a quiet meditation on aging, time, memory, and meaning at a Swiss spa. And when Jude Law’s sexy, revolutionary Pope Pius (THE YOUNG POPE, 2016) faces off with the eccentric, unpredictable genius of John Malkovich’s John Paul III (THE NEW POPE, 2020) in the HBO series.

But Sorrentino is firmly tethered to Italy. If he weren’t, THIS MUST BE THE PLACE might have led to him being ingested by the Hollywood machine. Instead, he made THE GREAT BEAUTY (2013). Shot in Rome, it follows an aging writer Jep Gambardella (Servillo) as he floats through Roman high society, paying his respects to all the beauties (in the larger sense of the word) that have shaped his life and career. As always in the case of Sorrentino, behind the glamour is nostalgia, and behind nostalgia is grief in response to arguably the only given truth of life: decay. It won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, along with a BAFTA and Golden Globe, and drew comparisons to Fellini’s LA DOLCE VITA. But make no mistake. Sorrentino’s work is always unequivocally his. And frequently drawing on his own life.

Nowhere is that clearer than in THE HAND OF GOD (2021), the film with which he comes home to Naples, and in which Young Fabbieto embodies the director’s younger self. It is here that Sorrentino fully reveals himself. In the Vomero neighborhood, where he grew up, Fabietto’s childhood is depicted through unforgettable, sweet, almost saccharine - but never kitsch - vignettes. They make us long to be there in the sweltering Neapolitan heat with him, basking in the freedom of his tender years rendered almost tactile through Sorrentino’s sensual depiction of Naples in the 70s and 80s. But the film also lets us in on the tragedy that shaped the director’s acute sense of loss and grief: at 16, both his parents died of carbon monoxide poisoning. Despite the suffering it eventually depicts (or is it because of it?), THE HAND OF GOD makes us want to stay in Naples, with Fabietto, forever.

Sorrentino’s penultimate film (so far), PARTHENOPE (2024) partially grants our wishes. We stay in Naples. And, for the first time, Sorrentino puts himself in the shoes of a female protagonist who takes centre-stage. Some obsessions are forever though. Parthenope has ‘everything’- beauty, recognition, power. But what of it when - once again - one is haunted by ghosts past for whom one’s painful longing makes all achievements eventually pale.

It is timely that the 31st Sarajevo Film Festival pays tribute this year to Sorrentino’s extraordinary filmography just ahead of his latest film, GRAZIA, opening the 82nd International Venice Film Festival. We sat down and picked his brain with a rapid-fire exchange that allowed us to understand a little bit of his elusive genius in anticipation of his visit to Sarajevo.

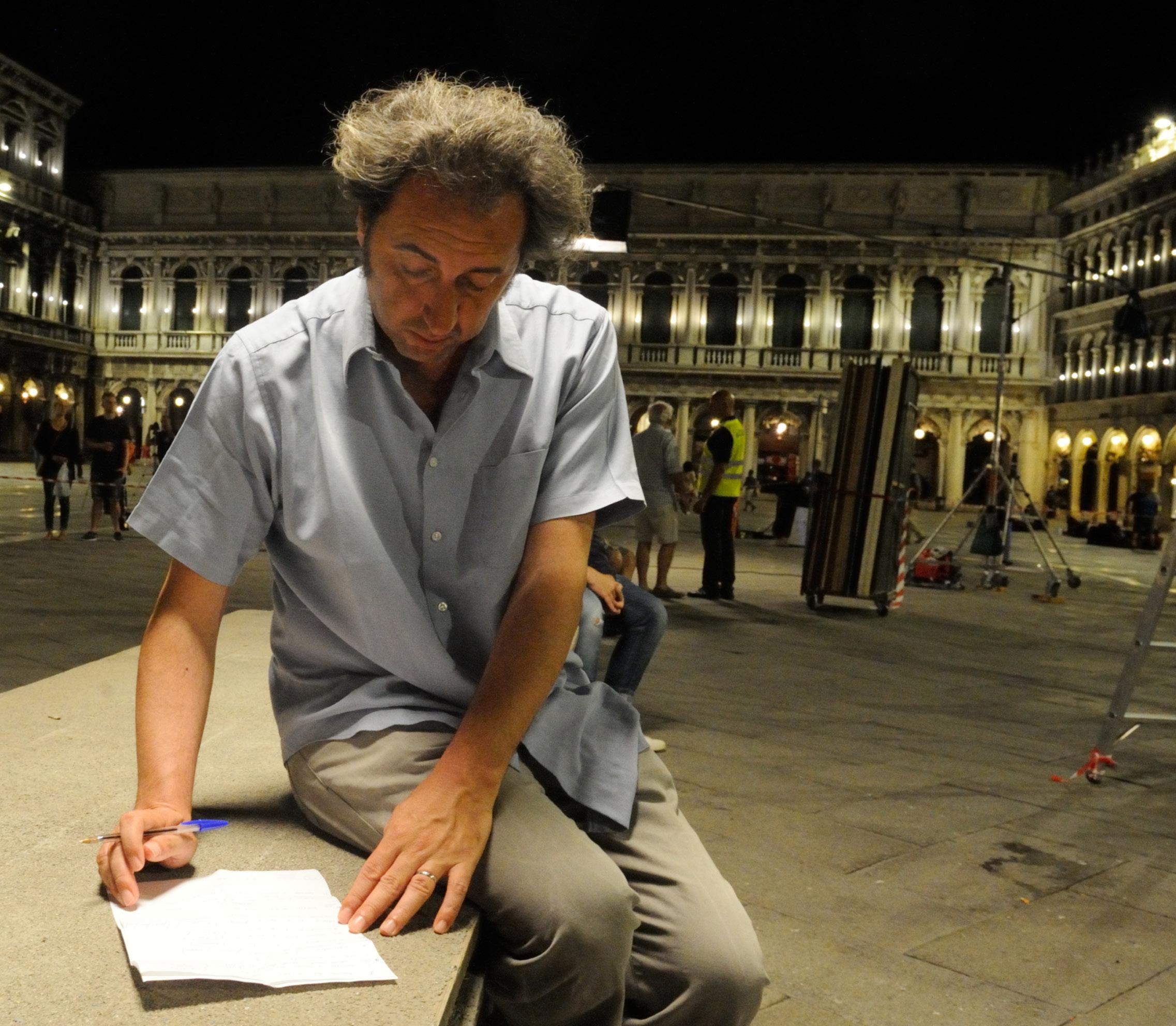

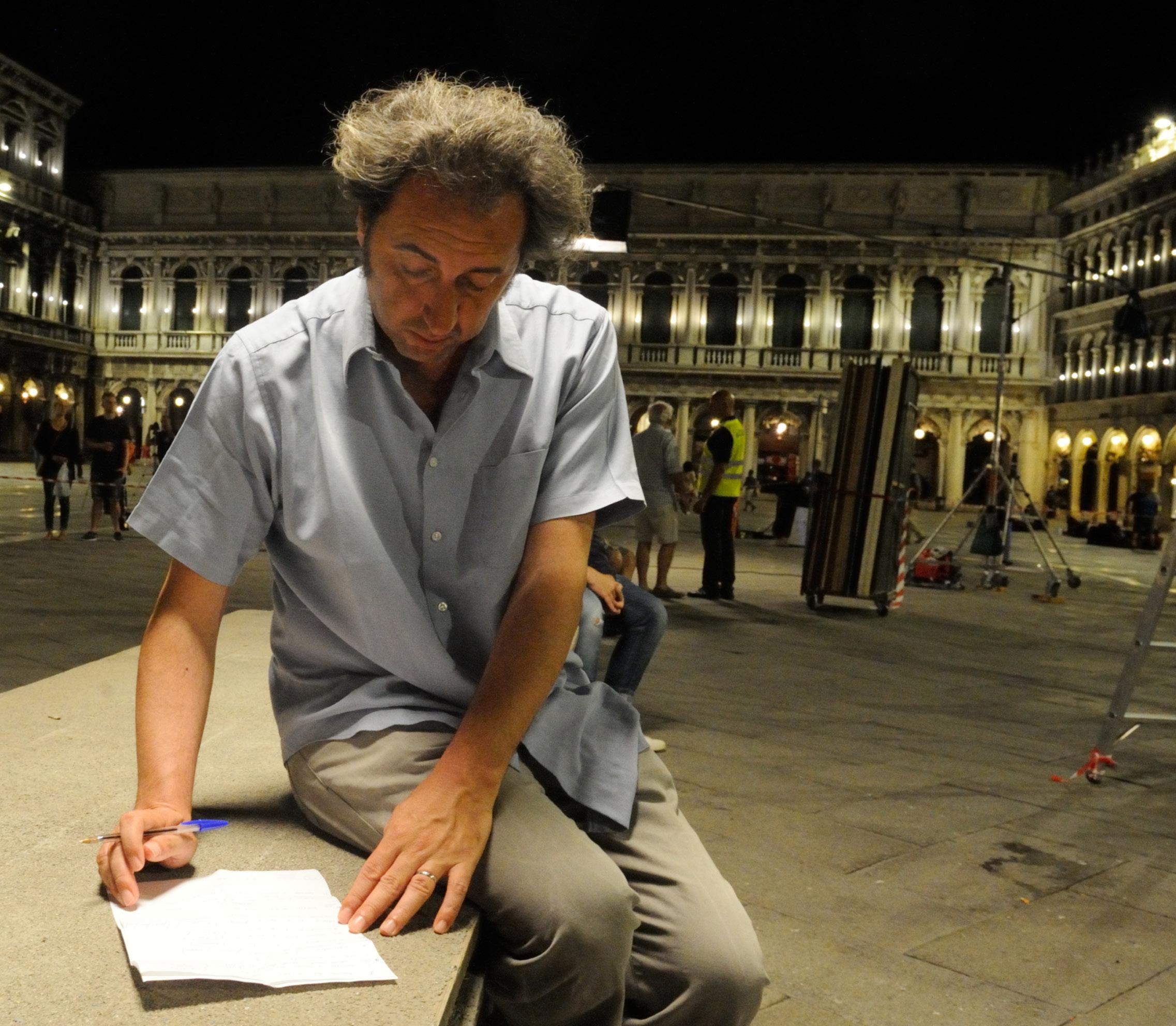

Paolo Sorrentino on the set of YOUTH, photo by Gianni Fiorito

ONE MAN UP

I had the immense pleasure of revisiting your entire filmography to prepare for this interview. When I think of your work, three words come to mind: Decadence, Destiny, and Pain. What’s remarkable, though, is that as philosophical, tender, or decadent as your work can be, it never takes itself too seriously. You manage to make us smile about some of life’s deepest wounds: loss, the passage of time, and the inner battle of conflicting desires. Where does your sense of humor come from? Is there someone or something you credit for your stoic yet ironicperspective? I think my sense of humor comes from the people in my city. Naples is a city that, for various reasons, has always embraced humor. Over the centuries, its people have been subjected to whichever powerful figure was in charge. Being servile was a necessity—but even servility has its shortcuts. Making the powerful laugh is one of those shortcuts to win favor. I believe that’s the origin of Neapolitan humor.

How did you get your first film, ONE MAN UP, off the ground? Have you ever felt, or do you still feel, psychologically worn down or drained by cinema? Is there a mantra or thought that helps you keep going, film after film? I’m trying to understand how you’ve managed to be so incredibly prolific—cinema is tough and all-consuming. Do you just have boundless energy, or do you have a secret that keeps you going?

ONE MAN UP came about thanks to the persistence of myself and my friend and producer Nicola Giuliano. We worked and struggled a lot, but in the end, we managed to do something that, at the time, was unusual in the landscape of Italian cinema. I’m productive because, ultimately, cinema is fun to me—and it’s the only thing I know how to do.

Sean Penn, David Byrne and Paolo Sorrentino on the set of THIS MUST BE THE PLACE

IL DIVO

“ I’m productive because, ultimately, cinema is fun to me— and it’s the only thing I know how to do.”

In THE HAND OF GOD, Fabietto meets a director he admires, Antonio Capuano. Their meeting is both instrumental and painful. Fabietto ignores Capuano’s advice to stay in Naples and leaves for Rome. What are your thoughts on the mentor-protégé relationship in art? Looking back now, as a famous and prolific director, what advice would you give young Fabietto? Is there something you wish you’d been warned about?

I don’t think advice is very useful. You come to understand things on your own. And anyway, advice is made to be forgotten or ignored.

When you look back at your films and the creative choices that inspired them, do you have any regrets?

I’d say no. Regret is a feeling that doesn’t really belong to me.

I’ve read that you’re not a religious person, and yet your films often include moments of divine intervention. Is this a nod to Italian romanticism, or does mysticism play a deeper role in your creativity?

I’m not religious, but I’ve always been morbidly curious about how much religion occupies a vital space in many people’s lives.

The “sweetness of doing nothing” is completely at odds with today’s dominant economic and social structures. Yet your films allow us to immerse ourselves in that sweetness: being fully present in a purposeless moment, with no profitable outcome. It’s beautiful, but also makes us (or at least me...) long for a mindset that’s disappearing. Bittersweet idleness. Do you also feel this tension?

Idleness is still in fashion, but you have to be rich to enjoy it.

I can’t think of many directors who exude love for their country the way you do for Italy. It’s not about idealism or lack of criticism, but rather an unconditional love rooted in both beauty and flaws—it’s integral to your artistic practice. Yet you’ve also made films outside Italy and with nonItalian actors (YOUTH, THIS MUST BE THE PLACE, partly THE YOUNG POPE and THE NEW POPE). How does working abroad or with non-Italian actors affect your process, and what challenges have you faced? Are you able to connect with cultural and human vulnerabilities in the same way?

I don’t really distinguish between Italian and non-Italian actors. Italy, for all its flaws, still seems to me the best place in the world to live. What’s harder is to penetrate the cultural fabric of other countries and shape it into a cinematic narrative. In those cases, you have to tread very carefully.

THE GREAT BEAUTY

YOUTH

YOUTH

Paolo Sorrentino and Michael Caine on the set of YOUTH, photo by Gianni Fiorito

What usually sparks a new project: images, a situation you’ve witnessed, or simply writing? Do you have a set writing routine or rituals? Do you write with actors in mind, or do you create the characters first and then cast them precisely?

A new project is born when a character—or more rarely, a story—becomes more dominant in my mind than anything else, taking it over completely. I only write in the morning. I usually have only the lead actor in mind, but not always.

You are also a novelist. How does your literary writing influence your screenwriting, and vice versa?

I’ve always written screenplays as if they were novels, and novels as if they were novels.

Can you tell us a bit about your creative team? People like Luca Bigazzi, Cristiano Travaglioli, and Toni Servillo seem like an artistic family unit. At what point in the pro-

cess do you bring them in?

I involve them after I’ve written the script, never before. Only with Toni do I occasionally mention the idea of a film I’d like to make.

Your characters aren’t exactly textbook heroes—some might even be described as morally questionable. Catholicism is a recurring theme in your work, so allow me to quote something often heard at weddings in Poland: “Love is patient and kind... it does not delight in evil, but rejoices with the truth. ”That seems to reflect your approach to your protagonists. You reveal the truth of their flaws in brutal and absurd ways, yet remain deeply loving, even forgiving. Today there’s a lot of debate and criticism around whether such “sinful” characters deserve the spotlight. Harsh critics might say this glorifies historical wrongdoers (e.g., patriarchal figures, abusers, religious fanatics, con artists, sexual predators, etc.). Have you faced this criticism, and/or how would you respond?

If cinema is meant to reflect life, then life—as we know—contains everything.

A recurring theme in your work is the loss of a brother and survivor’s guilt, often tied to parental guilt (ONE MAN UP, THE NEW POPE, PARTHENOPE). Is this theme personal, symbolic, or both?

It’s personal. Everything in my films is personal. Often autobiographical.

Another theme is the emptiness that corrodes those who seemingly “have it all”: power, fame, money, beauty. Your characters lose or abandon these privileges, yet continue to struggle for meaning. Could you speak more about this theme and what you’d like the audience to take from it?

Life is about conquest at first, and loss later. That’s the theme. Almost always. You lose your hair first, then your memory, then your strength, and finally even your money and power. I don’t want the audience to take anything away from it. That’s just how things go.

Paolo Sorrentino and Elena Sofia Ricci on the set of LORO, photo by Gianni Fiorito

Paolo Sorrentino, Toni Servillo and Giovanni Esposito on the set of LORO, photo by Gianni Fiorito

“ If cinema is meant to reflect life, then life— as we know— contains everything.”

THE HAND OF GOD THE HAND OF GOD

THE HAND OF GOD

THE HAND OF GOD

Most interviews focus only on cinematic influences. I’m curious about your visual, literary, and philosophical inspirations. Could you open Paolo Sorrentino’s treasure chest for us? Which writers changed your thinking? What artworks or images left you awestruck or sparked a project? Which ideas or public figures have fueled your anger and rebellion?

I’m grown now. Over a lifetime there have been many influences. I wouldn’t know how to give a comprehensive summary of who and what has inspired me.

A classic question, but I’ll tailor it to cinema: if you could have dinner with any film artist—actor, director, cinematographer, writer—dead or alive, who would it be? And what would you eat and drink?

I’d go with Fellini to Naples and eat pizza.

Are you hopeful about humanity? How does this extend to your hopes (or anxieties) about art?

I think we’re living through a very dark period. But usually, after darkness comes light.

Some memories are like cathedrals: whether painful or joyful, we pray at their altars for life. Your films seem guided by this. Which memories are you grateful for?

The memory of my mother.

What’s the difference between art and entertainment for you?

None. Art must also entertain—otherwise, it’s masturbation.

And an easy final question to close the interview before our audience interrogates you during your Sarajevo masterclass: Paolo Sorrentino — What is the meaning of life for someone who’s aware of what and who they’ve survived?

I’d prefer to answer that in Sarajevo, so I’ll have time to prepare the response.

Bianca Lucas is a filmmaker and film programmer. Born to an Australian father and Polish mother in Switzerland, she grew up in Warsaw, Poland. She got her first degree in Media & Communications with a specialisation in Film at Goldsmiths College, University of London. In 2017, she graduated from film. factory- a three-year filmmaking course helmed by Béla Tarr in Sarajevo, Bosnia & Herzegovina. She has worked as a film programmer and department head at various international institutions, mostly notably the Sarajevo Film Festival and Eye Filmmuseum in Amsterdam. In 2022, her first feature film, LOVE DOG, premiered at the Locarno Film Festival where it received a Special Mention. Since her studies Bianca has lived and worked in Berlin, Istanbul, Paris, Mexico City and Amsterdam. She is currently based in Los Angeles.

PARTHENOPE PARTHENOPE

Tribute to Paolo Sorrentino / 31st Sarajevo