table of contents

part one 1 introduction 2 where are you from? 5 mestiza panamericana 6 am(é)rica 8 nos casamos 10 terremoto 12 el cerrejón 14 mejorando la raza 16 in utero // in flight 18 part two 19 american(a) 22 spectrum of self 24 in the heights 25 echando flores 26 in closing, an opening 27 notes 28

Bahía Portete, Colombia, 1982.

Bahía Portete, Colombia, 1982.

part one

Ecuador, 1975.

Inset: Guatemala, 1976.

I come to this project by way of myself, by way of the meanderings of my lineage, by way of an enduring love story tangled up in even more enduring problematics I’m just beginning to question.

In this project I come to myself through story, through poetics, through the power of imagination to make love, power, and violence both real and abstract. I channel the conflicts and pluralities of the borderlands in Gloria Anzaldúa’s “mestiza consciousness.”1 I channel the acts of counterhistorical resistance and loving recovery in Saidiya Hartman’s “critical fabulation.”2 I dig the root of every universal story in some subjective truth in an effort to “collect and combine the fragments… and function as a witness to the conditions of individual lives.”3 I investigate racial formation both at the level of “sociohistorical process”4 and mestizaje specifically as a “lived process that operates within the embodied person and within networks of family and kinship relationships.”5 I navigate with care and trepidation the overlapping “privilege-penalty experiences”6 that have given structure to my own life, presented in and through well-worn family tales, extrapolated narratives, and the intimate poetics of selfhood and belonging.

I see myself and my life come into being through the eyes and hands of my parents, through the wonder, curiosity, joy, and love with which they captured and created their world. By looking back, I can look forward; but more importantly, I can look here, now, and reflect on the constancy of change and the ephemeral interconnections of self, life, and world. As identity becomes epistemology,7 self becomes subject—both world-made product and world-making agent. These are the scattered bits of a photographic history, a critically reflexive8 autoethnographic genealogy that freely crosses and recrosses constructed boundaries of fiction and truth.

This is an interrogation by storytelling a reckoning or an apology a coping mechanism an excavation a conduit a spiral a bridge a feedback loop a flight of the mind an opening of the heart an ongoing work in progress a mere scratching of the surface

but toucan

Boise, Idaho, 1981.

where are you from?

I hate this question. I have no good answer–not one that satisfies anyone, at least. (Nowhere. Everywhere. All over the place. I’m here now. It’s a long story.)

I’m always struck by the audacity of this question, how often it rolls out immediately following “What’s your name?” A big question with small talk expectations. No matter how I answer, there are always follow up questions. “Where were you born?”

“Where did you grow up?”

“Where is your family from?”

“No but like where are you fromfrom?” (that’s the racial dimension that lurks beneath this question)

The trouble with “from” is that I don’t have it. The trouble with race is that I don’t feel it.

What’s it supposed to feel like anyway? Where does it reside? is it cellular–in my blood? is it genetic–in my family? is it physical–in my features? is it cultural–in my traditions, my languages, my habits, my transnational upbringing? or is it all just an elaborate illusion?

I feel my body, I know my family, I am my story. I see myself reflected in my multiple origins, in my ever-changing perspectives and experiences, and in the people and places I’ve encountered along the way. My mixedness may make me uncertain of which box to check, but it makes me no less certain of who I am—it’s the boxes that don’t know and can’t contain what I mean when I say: mi raza no cabe. It’s why lately I feel my selfhood reside in the broad sweep and long-winded complexity of my heritage rather than neatly-defined yet always-messy racial constructs. Because heritage is not just in the blood or on the skin, it’s in life—it’s alive, it’s living. It’s being steeped equally en las aguas tibias del Pacífico ecuatorial and the dark icy depths of the Great Lakes. It’s coming inside from the snow to instant cocoa and arroz con leche. It’s being raised on Celia Cruz and Bob Dylan, on tamales and apple pie. It’s living the seasons of the temperate north and their exact inversion en sudamérica; it’s finding comfort in the daily rhythms of light and patterns of clouds in the tropical rainy season. It’s feeling “home” everywhere, nowhere, and anywhere all at once.

It’s the soft “r” and playful lilt of “Sarita” that brightens where my given name pales in its plainness. It’s having my dad’s build and my mom’s face so clearly that when you see us together it all makes sense.

one can’t, but two can make a blend it complicates the racial end one box to check is not enough exoticism can be rough multiracial is not a trend

you say that I’m ambiguous my mixedness is conspicuous half this, half that? I’m not a pie divide me up? but how? and why? to me it’s all continuous

born and raised and raised and raised movement and change in every phase america: a hemisphere north, central, south–each one, I’m here as landscapes rise to meet my gaze

nothing in this I’d ever trade even though memories will fade my features may belie my roots through my many circuitous routes look close—you’ll see how I was made

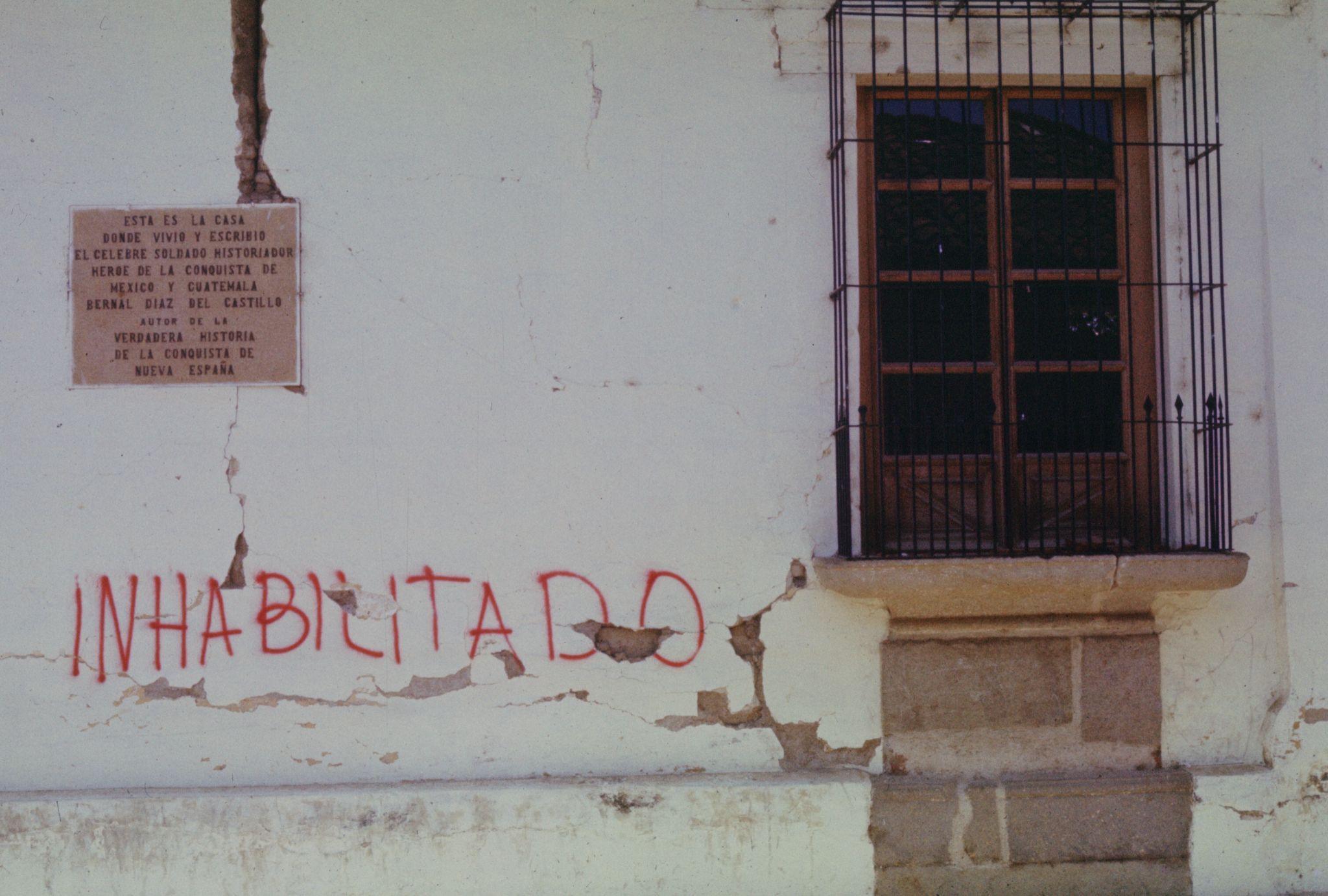

Top: Guatemala, 1976.

Bottom: Austin, Texas, 1979-80.

Inset, top (L-R): Boise, Idaho, 1981-83; Detroit, Michigan, 1984; Texas, 1981.

Inset, bottom (L-R): Honduras, 1977; Volcán Tungurahua, Ecuador, 1978; Quimiag, Ecuador, 1977-79.

am(é)rica

1975-1977 | Moravia, Costa Rica

A long way from his native Detroit, Mark Ellis Bukowski (Peace Corps member), meets Ana Cecilia Cerdas Castillo (hotel receptionist) at a bar in her native San José. He’s practicing his Spanish, she’s practicing her English—in love they speak the same language.

1977-1979 | Riobamba, Ecuador

Mark joins the International Voluntary Service to avoid going home. Cecilia teaches English. They live in a little house in thin air, above the Andean clouds. They hitchhike and wander their way through Mexico, Honduras, Guatemala, Peru, Bolivia, and Colombia. They climb some mountains (big ones!).

1979-1980 | Austin, Texas

Mark gets his Masters in Civil Engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Cecilia works in the rare book collection of the University library. Everyone assumes he’s Texan. Everyone assumes she’s Mexican. Everyone is wrong.

1980-1982 | Boise, Idaho

Cecilia attends formal school consistently for the first time in her life at Boise State University. She finds solace and camaraderie with the international students association, though it seems wherever she goes she’ll always be the only Costa Rican. Mark tinkers away and climbs more mountains, longing for the unknown.

1982-1986 | Albania, Colombia

Mark gets his big break on the Cerrejón coal mining project in the coastal Colombian desert. He gets his hands dirty again. Cecilia domesticates herself along with all the other engineers’ wives. Born: Jessica Frances (1984) and Sarah Cecilia (1986).

1986-1997 | Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania

Mark is transferred to company headquarters. Cecilia learns how to drive. Born: Paul Bernard (1988). Domesticity becomes further entrenched with family life in idyllic suburbia: a proper lawn, brown bag lunches, tupperware parties, parent-teacher conferences, snow days, bake sales, etc.

1997-2000 | Buenos Aires, Argentina

Mark gets a new job and a new post cleaning up some filthy urban rivers. The kids can finally learn Spanish properly (sort of). Cecilia feels uprooted and disoriented. When she answers the door, strangers assume she’s the maid. The family crisscrosses the continent in a navy blue 1991 Dodge Caravan. The kids won’t stop complaining, but they’ll also never forget it.

2000-2011 | Lenexa, Kansas Mark is transferred back to company headquarters, this time in the most boring place imaginable. Frequent trips to project sites abroad help. Cecilia goes back to school to become a paralegal to work on immigration, asylum, and international adoption cases. She becomes a U.S. citizen, taking the naturalization oath standing on one foot. The kids graduate from high school; the middle one (the restless artist) flees immediately for the big city and never looks back. Wonder where she got her wanderlust from?

2011-present | Ottawa Lake, Michigan Mark takes one last project before retiring, bringing him back to his native state and aging mother. They buy a big weird house in the middle of nowhere. Cecilia successfully cultivates a potted mango tree and unsuccessfully cultivates chayotes in her garden. They still travel every chance they get, both for leisure and humanitarian purposes. For their 40th wedding anniversary they take a weeks-long voyage to retrace the steps of their pan-American love story. And the story continues.

Riobamba,

Inset (left): Tres Ríos, Costa Rica, 1976.

Inset (right): Detroit, Michigan, 1983.

Ecuador, September 16, 1978.nos casamos

16 de septiembre 1978

Riobamba, Ecuador

Querida Mami, Hoy Mark y yo nos casamos, nada más aquí en el registro civil de Riobamba.

Usted sabe que nos queremos mucho y que le echo de menos en este día más que nunca. Me hice la falda y el bordado de la blusa como me enseñó y salieron preciosos.

Con tanta distancia entre nosotros y nuestras familias pensamos que sería mejor así, entre los dos. Esperamos visitarle pronto, no sé cuando, pero siempre le mantengo aquí en mi corazón.

Un beso, Cecilia

September 16, 1978 Riobamba, Ecuador

Dear Mom and Dad, Cecilia and I got married today in a civil ceremony here in Ecuador. We figured it was time.

I’ve got some projects to finish and plenty of mountains left to climb before returning stateside. After all I’ve seen, Tigers stadium will feel small.

Your wandering son, Mark

Top: Chocavi-Mocha, Chimborazo, Ecuador, 1979.

Bottom: Gaushi, Ecuador, 1977-79.

Inset: Gaushi, Ecuador, 1977-79.

I’ve never liked just conceptualizing a project, and I’ve never liked just telling people what to do. You know, like that guy in an office drafting blueprints or standing off to the side “supervising” with his hands in his pockets. I might need to be that guy sometimes, but mostly I like to feel the life in a project, and that means getting down on my knees and getting my hands dirty.

When it comes to being a “foreigner” or facing others different from me, I’ve come to realize you don’t really know someone until you’ve sweat beside them, gotten dirty with them, pooled your weight and strength and will to accomplish something together. That’s why I do this work. Because skin color, culture, and language be damned—work is universal.

Building a pipeline in the Ecuadorian scrub desert with a handful of Quechua Indians and a couple lazy gringos is no easy feat. In the shadows of majestic Mount Chimborazo, the air is thin and the temperatures are extreme, and after a few days I learn from the soft spoken, hardy native men around me what to wear, what to eat, and when to rest. We spend days surveying the landscape, measuring out the ideal placement for the pipeline to bring life-giving mountain water to the arid fields and dusty villages below.

With the glaciers shrinking further and further up the mountain, it’s become increasingly difficult for the Quechua hieleros to mine and carry their frozen cargo to their families and communities as they have for generations. Piping down the glacial meltwaters signals both the changing landscape and the progressive modernization of this remote Andean outpost. Hieleros have become ideal tour guides for expeditions to the glaciers and summits (I’ve got another attempt at Tungurahua planned next month). The men who work alongside me now lend their labor at the expense of their subsistence farms and ranches, all with the quiet hope that their sweat will earn a future for their families. This I cannot guarantee.

As the project progresses from surveying to digging, it slowly subsumes the whole curious community. Things here are done together. Stocky matriarchs and wiry, round-faced boys join the effort, which is only fitting given their knowledge of this land and experience coaxing their livelihoods from its dry, hard soil. Every morning I’m unsure of what we might accomplish together, but bit by bit we’re getting there.

Last Tuesday only a few hands showed up, the regulars who hiked up without a truck, excusing the absence of their wives, sons, and cousins—preparations for an upcoming festival were being made, and elaborate costumes, feasts, and musical performances needed to be prepared. We toiled in near silence, fitting and sealing long, cumbersome lengths of black pipe that would soon become a lifeline. It was clear, warm, and the air was oddly still.

When the earth began to shake, the men rose instantly from their crouches, dropping their hands at their sides and raising their senses to read the landscape. As the shaking intensified, I felt my blood rise as I scrambled to gather tools, supplies, and hardware in my rusty truck. No sooner had I yelled a command than I turned to see their backs as they ran down the hill in unspoken consensus. Despite their steadfast commitment to the project over the past weeks, for these men their families, homes, and livestock could not compare in value to this gringo and his pipes.

As the dust settled, I was left standing alone to survey the damage and wonder whether this project is an advance worth celebrating or a burden made necessary in the name of Progress.

el cerrejón

aguas caribeñas llanos guajireños montaña sagrada tierra indígena

raw materials abound ripe for the taking in a “backward nation”10 in a “lunar landscape”11

a deep water port an open pit coal mine a railway to export a road to connect and divide

“The white man eats coal… but neither us nor our animals eat coal, that’s not our life.”12

“Any process of development logically does violence to social structures [and produces] cultural ethnocides.”13

local concerns ignored market interests favored tax write-offs and contract loopholes cheap labor exploited this is economic advancement (for whom?) all in the name of modernization globalization colonization settlement extraction native land is raped while national credit improves

burial grounds are excavated14 while profit margins rise

mejorando la raza

Bukowski: Mark and Cecilia

Holliday: Bob and María

Walther: Klaus and Alina gringo con su joya latina todo entre familia

all shades of brown (but never black) they traveled far to bring them back in home and heart they made good wives building pan-American lives for light brown babies who’d never lack

Their settlement was a peaceful one, ready-made for a life of comfortable austerity in shared isolation. The wives were left alone and incommunicado for days as the husbands were called to the port or the mine, traveling that long dusty stretch of road they knew served a dual purpose as a landing strip for cartel planes. Their shared circumstances eased their worry, just as their shared fecundity brought small pleasures each day: planting gardens and harvesting their fruits, watching their bellies and babies grow.

In their modest, identical homes they played card games, said rosaries for distant relatives, and exchanged recipes from their various motherlands, native and adopted. Every other week they were escorted in an armed car to Maicao, the black market town, returning with housewares, textiles, and big blocks of dark chocolate they’d hack apart with machetes and kitchen knives to make chocolate chip cookies. The native girls and women brought in to help with household chores and childcare were surprised at first to see so few gringas among their señoras. They soon became comadres and confidants, particularly for those señoras unaccustomed to servants, or who’d at one time been servants themselves.

Every month the pregnant and breastfeeding wives—which each and every one was at some point or multiple points—would board a tiny plane bound for the nearest real hospital in Barranquilla. They’d hold hands and pray quietly, their wriggling babies and toddlers immune to the undercurrent of fear that permeated these ventures. Each safe arrival brought relief, and they breathed easier as they waited in a neat row to see the doctor, their bellies bulging progressively down the line.

The one closest to her due date stayed behind in the company’s tiny apartment in town to await her baby’s arrival, never certain whether her husband would get word in time to arrive for the birth. The rest made the return voyage with sweating palms and shallow breaths. The next day they would collectively set about preparing the absent soon-to-be mother’s home for the new baby, stitching and repairing the same tiny clothes that would circulate through their insular community over and over through the years.

They could not gaze to the home from which they came, and many knew nothing of the home that awaited them after this temporary desert idyll. Together they were suspended in time and space, tasked only with creating life and home in a foreign, sometimes hostile place.

Bottom:

Top: Arequipa, Ecuador, 1975.

Top: Arequipa, Ecuador, 1975.

“¿Cómo te sientes?”

“Nerviosa.”

“¿Pero por qué? Es tu segundita, ¿será más fácil, no? Y te faltan unos meses ya.”

“Supongo que sí, pero lo que pasa es que estoy pensando en Gumercinda, ¿sabes? La mujer guajira que me ayuda en casa y con la niña, you know.”

“Ah, la mucama. La criada. La empleada esa, your maid, ya sé.”

“Pfsh, you know I can’t call her that. Es casi cómo familia. Don’t you miss your family?”

“Pues sí, por supuesto.”

“Sometimes I wish I had Mami here, pero al menos nosotras lo pasamos juntitas.”

“Criar hijos nunca se debería hacer solita.”

“Sabes que la hija de Gumercinda está embarazada, a los siete meses, pienso. Tiene como quince o dieciséis años, la pobre. Y con lo que Gumercinda me cuenta, parece que no anda bien.”

“No me digas… pero así se hace, ¿no? ¿Y por qué no viene con nosotras a la clínica?

“Ay no, eso se reserva solamente para nosotras las esposas de los ingenieros, ¿no sabes? Y además, creo que ella nunca se subiría a este avioncito.”

“A los guajiros no les gusta abandonar su terreno. Las mujeres no salen nunca.” “¿Aunque sea por su salud?”

“Pues su salud depende de la tierra y el hogar, en ser matriarcas. Y es por la salud que tienen sus hierbas y ritos y no sé qué.”

“Gumercinda me dió unas ramitas de hierbas la semana pasada, me dijo que su hija se las tomaba por la náusea y los dolores. Tienen otras que asisten con el parto, supuestamente.”

“¿Y te las vas a tomar?”

“Pues veremos lo que recomienda el doctor en la clínica.”

“Ya sabes lo que el doctor te va a decir. Que eso no es medicina, que te hará daño a ti y a la bebita. Siempre te lo van a contar eso. ¿Y tu Mami? ¿Ella te daría hierbas?”

“Quizás. Pero me parece que así no se hace aquí.”

“Yes yes yes, ya tenemos estos hijitos bien A-mer-i-can. Limpiecitos y sanitos, nacidos en camita de hospital con sábanas blanquitas y doctores con guantes y batas antisépticas.” “La mamá de Mark piensa que es un hospital bien salvaje.”

“¡Salvaje! Eso sí. Todo fuera de A-mer-i-ca les parece así. ¿Y qué tú harías si estuvieras en tu país?”

“No sé… no estoy ahí, y no hay otra opción, ¿no? Aquí estamos, con nuestros A-mer-i-can esposos en este desierto salvaje, sin familia, sin raíces, sin teléfono, sin nada.”

“Ay, pero nosotras nos tenemos. Estamos creando algo juntitas, ¿no ves? No te desesperes. Todo saldrá bien. It’s the American dream, ¿no?”

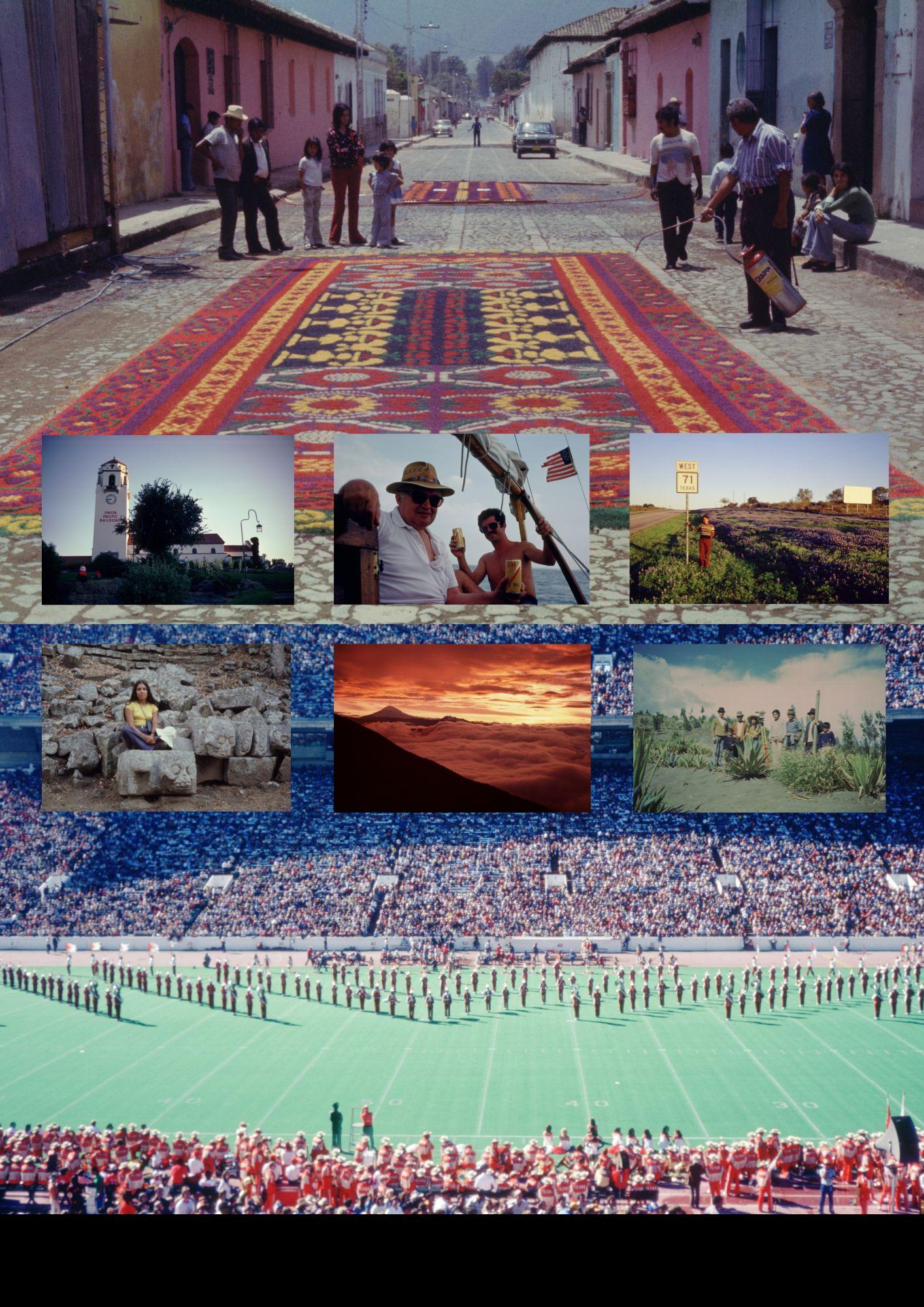

Background: Argentina-Chile border, 1999.

From top: Albania, Colombia, 1986; Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania,1996; Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1998; Lenexa, Kansas, 2001.

part two

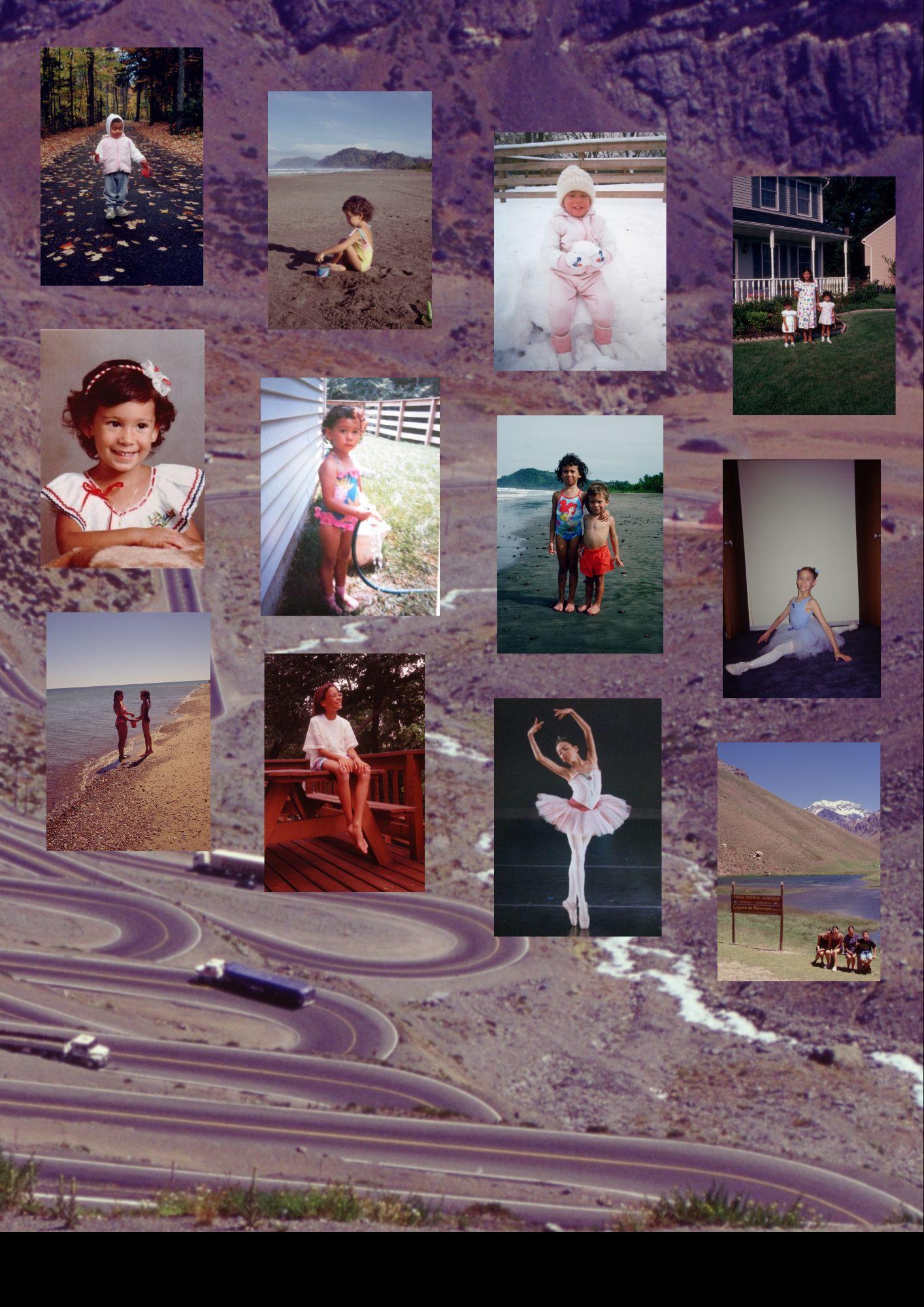

Top row L-R: Pennsylvania, 1987; Playa Jacó, Costa Rica, 1989; Pennsylvania, 1989; Pennsylvania, 1988.

Middle row L-R: Pennsylvania, 1991; Pennsylvania, 1990; Playa Coronado, Costa Rica, 1991; Pennsylvania, 1995.

Bottom row L-R: Lake Huron, Michigan, 1995; Pennsylvania, 1995; Pennsylvania, 1996; Parque Aconcagua, Argentina, 1999.

Background: Nicaragua, 1977.

Inset: Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, 1992.

1986 | Albania, Colombia

I have no memories here. At two days old, I have my ears pierced by nuns in Barranquilla. They are holes that will never close. I’m napping in my passport photo, a tiny new U.S. citizen.

1986-1997 | Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania

Childhood contained in a suburban cul de sac, catching fireflies in a jar and sledding down ever-steeper hills. Car trips and plane trips to see family—some I could talk to, some I could not. On one side, we’re the brown ones; on the other side, the foreigners. Rubbing lime leaves between my fingers en el patio de Abuelita, playing pinball in Nanna and Grandpa’s basement. I fall in love with dancing before I can quite remember, and all my subsequent memories bear this imprint. Dancing I learn to be myself. Dancing I discover my body. Dancing I am forced to confront that I somehow look different from others, and that this isn’t necessarily a good thing.

1997-2000 | Buenos Aires, Argentina

Eleven years old is the perfect time for a big change–everything is changing anyway. Awareness opens as the world unfolds. I’m in a small international school surrounded by a mix of multiracial, multilingual, multinational kids whose fast friendships and fearless cosmopolitanism start to scrub off my suburban shyness. It’s a gently cushioned experience of culture shock and reclamatory language immersion for a flacucha with morenita looks and a gringuita tongue. Dancing anchors me as a physical language I speak fluently across borders.

2000-2004 | Lenexa, Kansas

This is my biggest culture shock to date. I begin to notice things: the tight clutches of Black kids in the school cafeteria’s sea of whiteness; the ESL classrooms filled with brown kids, hidden away in the dank basement next to Special Ed; my Anglo American Spanish teachers’ relentless fixation on grammar tables and rules que nunca aprendí (no one is actually speaking); the way my dancing body looks dark and gangly next to the pretty blonde girls who wear pink like they were born to it; the ways I begin to be subtly exoticized. After graduation I flee immediately for the big city and never look back. Wonder where I got my wanderlust from?

2004-2009 | New York, New York

I arrive at Barnard College as a wide-eyed 18-year-old and leave two semesters later for the wide world of dance. I am lucky to find a home at Dance Theatre of Harlem, a predominantly Black ballet company, where I learn the power of flesh tone tights and shoes. I never feel the same about pink again. For the first time I am empowered by my difference, and I never let that go.

2009-2014 | San Francisco/Oakland, California

Long accustomed to change, I feel the itch. California casts a spell. A spell of love, a spell of opportunity, a spell of fertile creativity, a spell of fog and sun and wild Pacific Ocean and a blue blue blue sky like none other. The beauty seeps in and feels like home. I inadvertently discover that marrying a Black man somehow makes me Black by association. I’m the only non-Black-identifying person in the Black cast of San Francisco Opera’s “Showboat.” Weeks of side-eye later, I’m relieved to be a cover—I never have to go on stage.

2014-2016 | Portland, Oregon

I grow out my short hair and sharpen my pointes to land my dream job, only to be slyly told I’m once again a (mis)racialized token: “I didn’t hire you because of your race, but it looks good to have a woman of color in the company.” Reentering the world of classical ballet, I’m thrown by how what should feel familiar seems oppressive instead. I’m pigeonholed, typecast, and exoticized—still Black by association, or just because I’m the darkest woman around—and sent straight to the back every time the tutus and pink tights roll out. When Swan Lake hits, I run for the exit. My heart breaks, and to hide the pain I rage instead.

2016-2020 | San Francisco/Oakland, California

Pain, rage, and rebellion bounce me right back from where I came, only changed. I cut my hair off and dive in with gusto. I’m initially triumphant, then all at once I’m injured, broken, cut open, divorced, disabled, unhoused, unwanted, alone. I battle persistent demons, internal and external, stumbling my way to recovery.

2020-present | New York, New York

It’s that same old itch again. Change everything. New York calls me back. And the story continues.

Background: still from “Ellipsis” by John Sanborn, 2017.

Background: still from “Ellipsis” by John Sanborn, 2017.

spectrum of self

I must be just that right shade of brown (variable by season), with just that right curl to my hair, fullness in my lips, almonds of my eyes.

A chameleon—just right to mystify and elude your easy definitions. Media tica, media gringa, toda confusa (at least for you).

Exotic features and a Polish last name. At your insistence, I confess my mix. You tilt your head like you’re looking at a hologram, squinting to parse out refractions of hazy images overlaid in your mind.

What are you trying to see?

I used to think it was fun to make it a guessing game, because you’ll never guess.

Brazilian? Nope. Creole? Nope. Puerto Rican? Nope. Dominican? Nope. Indian? Nope. Biracial? Not quite. How about Colombian-born-Costa Rican-Polish-Irish-American? Fat chance. I’ve been typecast downcast outcast miscast I’ve been festishized exoticized tokenized otherized

A spectral spectrum of self made spectacle by your racialized illusions, assumptions, and expectations.

My privilege grants me entry, at least some of the way— conditional to (and conditioned by) your privilege.

I can measure up, “despite” my color. I can be your diversity badge, but at heart you know I’ll still never fit the part.

But it’s ok–I’ll make my own.

in the heights

I first moved to Inwood in 2007 at the tough and tender age of twenty-one. A looming, blocky brown-bricked building two blocks east of Broadway from the last stop on the A train, right in the middle of Little Dominican Republic. Somehow the dingy but spacious one bedroom apartment was all mine (if you didn’t count the mice). Its third floor windows faced onto the neglected, overgrown concrete courtyard–essentially an unused void that filled the center of the cuadra–and my $850 each month came with an unexpected bonus: free nightly admission to the club across the yard that blasted bachata hasta las cuatro de la mañana. That’s how I learned to sleep through anything.

Those heady years passed in bright blurs, workdays never below 145th street, nights and weekends in the Village slurred to greasy drunken smudges ending in black sleep empty of dreams. Through all my adventures and risk-taking, I always felt safe in Inwood, no matter what people (read: white people) liked to say about anywhere above 110th street. I felt seen, held, quietly known by neighbors and strangers who perhaps saw su hermanita, su hija, o su prima in me. I’ll never remember the face of the man who steadied my arm and walked me home one night at that dark, disoriented hour after the fun wore off and I still had two long blocks to go. I walk that stretch and still think I see her sometimes, that bright-faced, hard-eyed, soft-hearted girl who thought she knew everything and thought she needed no one.

Despite its moniker, Little DR is not all barrio. Inwood is a neighborhood divided–neatly bisected by that most New York of thoroughfares: Broadway. Una frontera urbana que nos divide por clase, color, lengua, y tradición. The divide is alarmingly evident in the condition of structures and surroundings, in the individual faces and conglomeration of sights and sounds that intermingle in the commercial districts only to diverge suddenly on residential blocks. As a working-class artist living east of Broadway, the only thing to ever draw me westward was the park, that crown of green hills and sloping paths that could almost transport me out of the city. But I never quite felt I had the right to meander the other blocks west of Broadway, as if they weren’t quite mine. I had certainly heard about them–people lived in co-ops there, they had families and cars and gardens and survived exclusively on organic produce. West of Broadway was like a mythical wonderland, an aspirational paradise I could never afford.

Fast forward thirteen years and here I am again. West of Broadway, this time. In a co-op, this time (one my parents helped me purchase). Still can’t afford the organic produce, though. But here I am. High up on a hill with windows overlooking my past life. Still a working artist, still barely scraping by–just older now. I often pass by my old building while walking to the gym or running errands, and I sense the change in the neighborhood over those eight blocks along with the changes in myself and the ways I’m perceived. West of Broadway I’m recognized by neighbors who say “good morning.” I pause to admire the well-kept front gardens of each building or stop by the gated community garden to read a book. East of Broadway I’m mostly looking down, dodging dog shit and weaving between the mats, tables, and tents of informal street vendors. The weed guy on the corner recognizes me but seems like doesn’t quite know what to do with me.

I love my neighborhood and wish I could say I feel a sense of belonging throughout it, but the truth is that I don’t. I feel like an impostor. I feel like a gentrifier. I feel like a traitor, like by crossing Broadway I’ve betrayed some part of myself and acquiesced to some other part. The more I try to make myself fit, the more I feel like I’ll always be straddling this line, fated to walk this cultural tightrope on tiptoe forever. When will I belong?

“que dios te bendiga, mami.” a familiar refrain to me somewhere between catcall and prayer menos niña y más mujer “oye flaca, vente pa’quí” “ey, mírate esa nena” blanca, mestiza, morena, mulata, o negra: ¿quién soy? choose your flavor: ¿cuál será hoy? me caben todas: soy plena deep bronze and blonde all summer long shades that fade once the heat is gone “¡me gustabas de rubia!” he yelled over his cumbia what’s natural to me is wrong ¿y me encuentro dónde, ya? ni de aquí ni de allá in between, like I’ve always been never quite right, not blending in mezcla de color y raza

in closing, an opening

if “race” is a defining fact if “fromness” is essential to knowing, locating, and deciphering if “home” is meant to be singular, simple, and comfortable this has never been my world this is not my life these are not my terms

la conciencia de la mestiza becomes la resistencia de la mestiza to resist your definitions to complicate your assumptions to find out for myself where I come from who I come from where I am who I am where I will be who I will be undefined and undefinable but if you must define me know that I am multiple and always will be

1 Anzaldúa, Gloria. “Laconcienciadelamestiza: Towards a New Consciousness.” Borderlands/LaFrontera. San Francisco, Aunt Lute Books, 1999, pp. 99-120. Anzaldúa’s Chicana mestiza consciousness operates primarily around the physical borderlands of South Texas. I extend this narrative through multiple crossings and straddlings of borders, both physical and social, and their implications on identity formation. I am interested in the mestiza’s transcendental desire to be “healed so that we are on both shores at once” through an internalized and inhabited “tolerance for ambiguity” (100-101). This lens allows for the crafting of “new images of identity, new beliefs about ourselves” which I seek to initiate for myself in this project (109).

2 Hartman, Saidiya. “Venus in Two Acts.” smallaxe, vol. 26, June 2008, p. 11. “Critical fabulation” entails the construction of a story that is capable of “re-presenting the sequence of events in divergent stories and from contested points of view… to jeopardize the status of the event, to displace the received or authorized account, and to imagine what might have happened or might have been said or might have been done” (11). This method interrogates and disrupts hegemonic constructions of history by using imagination to surface suppressed narratives.

3 Irving, Toni. “Borders of the Body: Black Women, Sexual Assault, and Citizenship.” Women’sStudiesQuarterly, vol. 35, Spring 2007, p. 72. Here Irving speaks to the agentive power of literature to represent subaltern histories and experiences, which allows a reader to “separate and distill out structural forces” from traditional or stereotypical characterizations of marginalized groups, as outlined in Irving’s exposition on the Philadelphia Police Department Sex Crimes Unit’s systematic dismissal of rape cases involving poor Black female victims (80). My project merges family lore, storytelling, and poetics with theory, criticism, and media to project subaltern narratives within and adjacent to my parents’ lived experiences that created and shaped my life.

4 Omi, Michael and Howard Winant. “Racial Formation.” RacialFormationintheUnitedStates, 1994, p. 55.

5 Wade, Peter. “Rethinking ‘Mestizaje’: Ideology and Lived Experience.” JournalofLatinAmericanStudies, vol. 37, no. 2, May 2005, p. 239.

6 Hughes, Sherick A. and Julie L. Pennington. “Autoethnography: Introduction and Overview.” Autoethnography:Process, Product,andPossibilityforCriticalSocialResearch. SAGE Publications, 2017, pp. 4-33. The framing of privilege-penalty experiences examines patterns and variances of oppression among overlapping and intersecting social identities. My project seeks to pull apart the origins of my inherited privilege-penalty statuses and experiences as a mixed heritage woman of color and U.S. citizen born into a middle class household.

7 ibid.

8 ibid.

9 Poems “mestiza panamericana,” “mejorando la raza,” and “echando flores” are composed in décima style a Spanish poetic form of ten octosyllabic lines with an abbaaccddcrhyme scheme. Décima traditions have been transposed onto a variety of Afro-Caribbean song forms such as rumba, son, punto guajiro, guaguancó, and merengue. For more on décima, see Pasmanick, Philip. “‘Décima’ and ‘Rumba’: Iberian Formalism in Afro-Cuban Song.” Latin AmericanMusicalReview/RevistadeMúsicaLatinoamericana, vol. 18, no. 2, 1997, pp. 252-277.

10 Gonzalez, Gilbert G. “The rape of Colombia.” Race&Class, Vol. 23, Iss. 4, 1982, pp. 321.

11 “Coal Strip Mine Lifts Colombia’s Export Hopes.” LosAngelesTimes, Nov. 8, 1984. The depiction of native lands rich in geological resources as wastelands is a colonialist discourse used to justify the appropriation of land and exploitation of resources. The Guajira region of coastal Colombia is a scrub desert with limited fresh water and arable land, yet the native people of the region have thrived for generations by living in harmony with the ecology.

12 Gutierrez, Alberto Rivera. “Exxon and the Guajiro.” CulturalSurvivalQuarterly, Vol. 8, Iss. 2, 1984. This quote from a Guajiro Indian woman “underscored the basic incompatibility between the Guajiro notion of well-being and the Western notion of development” (1). This is in line with how Leanne Betasamosake Simpson illustrates the ecologically harmonious principles practiced by the Indigenous peoples of North America in “Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation.” Decolonization:Indigeneity,Education&Society, vol. 3, no. 3, 2014, pp. 1-25.

13 ibid. This quote from Ricardo Plata, Deputy Manager of El Cerrejón, illustrates how corporate and state powers are implicated in “clinically diagnosing the death of a people” in the name of progress. This “technocrat ethnocide” shrugs off the social, economic, and ecological damage inflicted on native people and their land as the “unavoidable costs” of globalized modern capitalism (2).

14 “Colombia to become major coal exporter.” TheGlobeandMail, Mar. 18, 1985. “To secure land for the road and railway, dozens of cemeteries belonging to Guajira Indians had to be moved. ‘The feasts to rebury the dead lasted up to one week but we paid for it all,” Mr. Teicher [Carbocoal’s marketing manager] said.” For more on Guajira burial practices, see Pulowi. Edited by Grupo Cinco, Cromotip, Caracas, 1984. Guajira bury their dead twice: once at the time and place of death, and again after eight to ten years, when the bones are ceremonially excavated, cleaned, and reinterred. “El muerto está tranquilo / cuando sus huesos están limpios.” (135)

All photographs unless otherwise marked courtesy of Mark and Cecilia Bukowski.