VELLUM, PAPER AND IVORY: PORTRAITS AND PORTRAIT MINIATURES

1550-1950

VELLUM, PAPER AND IVORY: PORTRAITS AND PORTRAIT MINIATURES

1550-1950

28TH APRIL TO 9TH MAY 2025

Monday to Friday 10am to 6pm

Weekends and evenings by appointment

Riverwide House, 6 Mason’s Yard Duke Street, St James’s, London SW1Y 6BU

Front Cover: (43) Anna Tonelli (c.1763-1846)

Portrait of Amelia and Harriet Harding-Newman of Nelmes, Essex at their Music Lesson

Rear Cover: (1) Attributed to Levina Teerlinc (1510-1576) King Edward VI (1537-1553); circa 1550

Opposite: (30) Richard Cosway, R.A. (1742-1821)

Portrait miniature of Thomas Augustus Hervey (1775-1796), wearing a dove grey coat and a white cravat, his hair worn down and curled; 1793

THE LIMNER COMPANY was established in 2023 by leading consultant Emma Rutherford, who has specialised in portrait miniatures for 25 years. She has worked in museums, with art dealers and in the auction world, her research and discoveries published in articles in academic publications as well as national media. Emma is also a curator, lecturer and writer. Based in London, The Limner Company works with researchers and restorers, while also holding a carefully curated selection of original works for sale. The works in this catalogue have been catalogued by Emma Rutherford, Rebecca Ingram and Emma Blane, with additional research by Phoebe Griffiths.

Works on ivory: Portrait miniatures painted on ivory before 1918, with a surface area smaller than 320cm, are exempt from the Ivory Act of 2018, but must be registered with the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). All of the portrait miniatures with this criteria in the catalogue are registered and the reference number will be provided to the buyer.

Opposite: (17) John Smart (1741-1811)

Mrs Fenton, wearing a white dress, a red surcoat trimmed with ermine, a drop-pearl brooch and sapphires at her corsage, her upswept, powdered hair dressed with white ribbon; 1774

Edward VI (1537-1553); circa 1550

Watercolour on vellum, laid down on card

Set into a turned ivory box

Circular, 43 mm (1 ¾ in) high

Provenance

Dr John Lumsden Propert (1834-1902), London, by 1887; Christie’s, London, 23 October 1989, lot 152 (as English School); Dr Erika Pohl-Ströher (1919-2016), until 2018; Private Collection, UK.

Exhibited

London, Spencer Club, Art Exhibition at Spencer House, 1887, no.467 (as Levina Teerlinc);

London, Burlington Fine Arts Club, Exhibition of Portrait Miniatures, 1889, case XXXIV, no.21 (as Levina Teerlinc);

London, The New Gallery, The Royal House of Stuart, 1889; London, The New Gallery, The Royal House of Tudor, 1890; London, The New Gallery, The Royal House of Guelph, 1891; London, The Fine Art Society, Historical Collection of Miniatures formed by Mr. J. Lumsden Propert, 1897, no.11 (as Levina Teerlinc); Philip Mould Gallery, ‘Jewel in the Hand; Early Portrait Miniatures from Private and Noble Collections’, 12 March – 18 April 2019, cat. no. 1; Compton Verney House, Exhibition ‘The Reflected Self; Portrait Miniatures 1550-1850’, September 2024-February 2025 as Attributed to Levina Teerlinc.

Literature

J. L. Propert, A History of Miniature Art (London and New York, 1887), ill. opp. p.66 (as L. Teerlinc); B. Long, British Miniaturists (London, 1929), p.433 (as Attributed to Levina Teerlinc).

The present portrait would appear to be one of only two portrait miniatures painted during Edward’s short reign. The other, a smaller version of the present work, appeared at a Christie’s auction 26 May 1879 and is recorded in the Heinz archive at the National Portrait Gallery in a colour photograph. Both images of Edward are almost certainly by the same hand, and belong to a small but cohesive group currently attributable to Levina Teerlinc, who was working at the English Court from 1545.

As the daughter of the celebrated Bruges manuscript illuminator, Simon Benninck or Bening, Teerlinc seems to have been highly praised for her artistic skills. Georgio Vasari (1511-1574) stated that she was ‘…held in estimation by Queen Mary, even as she is now by Queen Elizabeth’.1 The master of illumination Giulio Clovio (1498-1578) seems to have owned a portrait of Elizabeth I by Teerlinc. The present portrait, along with the other reduced version, would, perhaps unsurprisingly, firmly link Teerlinc to the court of Edward VI.

At Edward’s accession, Teerlinc may have been the only viable option as an artist to paint his portrait in miniature. Hans Holbein the Younger had died in 1543, Gerard Horenbout in 1541, and his son Lucas in 1544. Teerlinc may also have been the teacher of Nicholas Hilliard (1547-1619), although there is no firm evidence for her involvement in his training as a limner.2 Teerlinc’s £40 annuity from the crown for limning, which began in the reign of Henry VIII, continued until her death in 1576. It is notable that this was the same amount given to Gerard Horenbout and is evidence of both her status as an artist and her output as a limner.

The scarcity of portraits of Edward are testament to both his short reign and the fact that many would have been given away as gifts, likely to foreign rulers. The rarity of his image ‘in little’ can also be explained by the religious turmoil which followed his reign, spearheaded by his Catholic half-sister Mary I. Portraits of Edward would have been

destroyed or hidden away during this time, with his portraiture in demand again when his half-sister, the Protestant Elizabeth, became Queen.

The present portrait was likely painted between 1550 and 1553 when Edward died. The young King was often presented as being more mature than his actual age, adding a sense of security and strength, and a natural line from the only legitimate son of the powerful Henry VIII. As was the established practice with portrait miniatures, even from their inception, the sitter was expected to be present for the sitting. It is therefore no surprise that this portrait shows Edward in costume unique to the two portrait miniatures, with a heavily goldembroidered hat and tunic.

Later copies of this portrait, including one by Bernard Lens III, show that this miniature was considered a notable likeness of Edward.3 In all recorded copies of this portrait, including those 18th-century versions in the collections of the Duke of Buccleuch and the Earl of Beauchamp (as of 1965), the precise detailing on the costume has been translated faithfully and it is clear that whoever made the copies had either the present work, or another example from the period, close to hand.

As a rare ad vivum portrait miniature of Edward VI, the historical importance of this image cannot be overstated. Dying at the age of fifteen, Edward had looked to fulfil the legacy of his father, but, given his youth, his reign was dominated by infighting amongst the nobility, all looking to seize power. Although portrait miniatures were important tools in diplomacy, they also performed a more intimate role in Tudor relationships. It should not be overlooked that this miniature portrait may have been intended as a gift to a member of Edward’s family. Intended recipients may have been his halfsisters Mary and Elizabeth, his uncle Edward Seymour, the self-styled Duke of Somerset who would also serve as the Lord Protector, or even his successor, his fated cousin Lady Jane Grey.

1 Vere, Gaston du C. De (translated), Vasari, Giorgio, Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, 1996 Edition, Vol. 2, p. 865.

2 This has been most recently discussed in Dr. Elizabeth Goldring’s book, Nicholas Hilliard, Life of an Artist, published by Yale in 2019. Dr. Goldring notes that Teerlinc received a gift of plate each New Year from Elizabeth I, often from the workshop of Charles Brandon, Hilliard’s father-in-law and Goldsmith master.

3 A version of this portrait, signed by Bernard Lens III, sold at Christie’s, London, 7 December 2005, lot 95.

A Lady of the French Court, wearing pearl earring and large, lace ruff

Pencil and coloured chalks on laid paper; watermark: Grapes with narrow stem, surmounted by the letters "III" (Briquet 13196: Lyon, 1582) and later inscription

Polished cassetta frame with burr walnut inlay

Rectangular (trimmed) 240 x 195 mm (9 ½ x 7 ⅔ in)

Provenance

Private Collection, UK.

This sensitive drawing is a rare example of a 16thcentury portrait drawing which has survived in remarkably good condition. Possible artists would be Daniel Dumonstier (1574-1646) or the Edinburgh-born François Quesnel (1543-1619), both of whom were working at the French court in the final decade of the 16th century, attempting to fill the role of the mighty Francois Clouet who had died in 1572.1

The sitter seems to be following the influential fashion of Gabrielle d'Estrées, Marquise de Monceaux, mistress of Henri IV, King of France (1571-99).2 She was usually portrayed with her hair combed back high over her head, with a large pearl earring, including in the famous double painting in the Louvre, dated 1594, where she sits in a bath with her sister, Julienne-Hippolyte-Joséphine, Duchess of Villars, pinching her nipple in a gesture assumed to relate to the fertility or pregnancy of the twenty-one year old.3

The watermark on this drawing is identical to one found on a drawing, currently catalogued as ‘School of François Clouet, Portrait of Marguerite de Valois’, now in the Morgan Library and Museum, the paper identified as made in Lyon in 1582 (Briquet, 13196).4

Although, as with so many French drawings of this period, both the sitter and artist are yet to be identified, the work still retains the immediacy of an ad vivum sitting.

1 If by Daniel Dumonstier, this would be a juvenile work as the earliest dated work by him is 1605. Large groups of portraits by Dumonstier are in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris (J. Adhémar, 'Les dessins de Daniel Dumonstier au Cabinet des Estampes', Gazette des Beaux-Arts, March 1970, LXXV, pp. 129-150) and in the Louvre (J. Guiffrey and P. Marcel, Inventaire général des dessins du Musée du Louvre et du Musée de Versailles, Ecole Française, Paris, 1949, V, nos. 3799-3827).

2 A group of portraits of women from the same date were illustrated in the catalogue ‘Les Clouet de Chantilly’, Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Paris, Mai-Jun 1971, as ‘Quelques Dames de la fin du siècle, nos 339-344, p. 329.

3 Louvre Museum, accession number RF 1937-1.

4 Briquet, Les Filigranes: Dictionnaire historique des marques du papier dès leur apparition vers 1282 jusqu'en 1600.

Lady Anne Cobham (d. 1612), wearing embroidered black and gold dress, wired, white standing ruff and black cap with gold trim, circa 1595

Watercolour and bodycolour on vellum, on card

Oval, 48 mm (1 ⅞ in) high

Silver locket frame

Provenance

Mrs P. B. K. Daingerfield of Baltimore Collection; Sotheby’s, London, 9 February 1961, lot 24 (as a Lady, called Lady Cobham, by Hilliard); Edward Grosvenor Paine (1911-1989) Collection, New Orleans, inv. no. 186; Christie's, London, 20 March 1989, lot 161 (as Lady Cobham by Rowland Lockey);

With D. S. Lavender (Antiques) Ltd., in 2000 (as Anne, Wife of Sir Henry Cobham by Rowland Lockey);

The Collection of the late Mrs. T. S, Eliot, Christie’s, London, 20 November 2013, lot 88 (as Anne Cobham née Sutton (d. c. 1612)); Private Collection, UK.

Exhibited

Victoria and Albert Museum, Artists of the Tudor Court, (London, 1983), no. 124 (as an Unknown Lady, attributed to Roland Lockey).

Literature

Strong, R. (1983) The English Renaissance Miniature, London: Thames & Hudson. Illustrated p. 139 (as an Unknown Lady by Rowland Lockey) and p. 140.

Portrait miniatures attributable to Rowland Lockey are extremely rare, but the present example has been given to his hand by many eminent art historians, including Sir Roy Strong. The case for this particular Rowland Lockey is based on the stylistic and technical similarities between this work and those miniatures by his master, Nicholas Hilliard.1

Technically, the present miniature is complex – the black silk of the gown is drawn in lattice ribbons over an embroidered under gown, with an intricate thread weaved in loops. Each pearl on the sitter’s neck and cap is carefully highlighted with silver (now blackened through oxidisation). Shell gold is added to the cap to give the jewelled element weight, and the ruff is carefully drawn with each layer carefully delineated (albeit in a much thinned down white pigment compared to Hilliard’s three-dimensional depiction of lace). Clearly the artist of this miniature had an intimate understanding of the technical elements which Hilliard guarded so carefully. The fact that the two men worked alongside each other, meant that, unlike Isaac Oliver (c.1565-1617), Lockey was a colleague, not a rival.

Lockey is recorded as joining the household of Nicholas Hilliard in 1581 as apprentice to the artist who would only have been in his mid-30s, but who was already considered the chief image-maker of Elizabeth I. Since his childhood therefore, Lockey was also likely learning his craft from Hilliard’s mastery.2 In his Treatise concerning the Arte of Limning, Hilliard comments on the difficulties in

finding good assistants who can work to his exceptional standard. ‘The good workman also which is so excellent dependeth on his own hand, and can hardly find any workmen to work with him, to help him to keep promise, and work as well as himself, which is a great mischief to him’.3 As Elizabeth Goldring notes, many of Hilliard’s ‘schollers’ would have been trained in an unofficial capacity, freeing the ever insolvent Hilliard from paying for their board and lodging.4

Despite the circumstantial and documented evidence, which places both Lockey and Isaac Oliver as successors to their former master, it is only Isaac Oliver who leaves a body of recognised and recognisable work. As Otto Kurz stated in his article of 1957, ‘a number of elusive or shadowy personalities remain. One of them is Rowland Locky (sic)’.5 As was the case of his former master, Lockey was making a living outside the sphere of limning.6 Lockey is also noted as an independent artist in contemporary literature – his name appears in Richard Haydocke’s preface to A Tracte Containing the Artes of Curious Paintinge, Carvinge & Buildinge (1598); he is also mentioned by Francis Meres, in his Palladis tamia (1598), among the eminent artists then living in England, and in Edward Norgate’s Miniatura (1627-28), as using a third technique of crayons, or ‘dry colours’.7 The antiquary William Burton calls him Hilliard’s ‘expert scholler…who was both skilful in limning and in oilworks and perspectives’.8

1 Lockey’s signed and dated, visual family tree of the More family of 1593 is one of the most important paintings by him (National Portrait Gallery, NPG 2765).

A cabinet miniature copy of this oil painting, dated slightly later, is in the Victoria and Albert Museum; a further oil version is at Nostell Priory (West Yorkshire).

2 This information was first given by Edmond, M, Hilliard & Oliver: The Lives and Works of Two Great Miniaturists, (London: Robert Hale, 1983), p. 72, where she quotes the 1588 will of Dutch student Pieter Mathewe which referred to ‘my twoe fellowes Isac Olivyer and Rouland Lacq’.

3 P. Norman, ed., ‘Nicholas Hilliard’s Treatise concerning ‘The Arte of Limning’, with Introduction and Notes by Philip Norman, LL.D.,” The Walpole Society 1 (1911-12), p. 41.

4 Goldring, E, Nicholas Hilliard: Life of an Artist (London: Yale University Press, 2019), p. 181.

5 Kurz, O, ‘Rowland Locky’, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 99, (1957), no. 646, p. 12.

6 Elizabeth Goldring notes that at the time of Lockey’s apprenticeship: ‘Hilliard and his workshop produced not just miniatures but paintings in great (portraits as well as ‘story work’), seals, medals, illuminations, designs for prints and miscellaneous decorative painting’, see; Goldring, (2019) Hilliard, p. 170. Lockey was also responsible for designing title-page borders for the Bishop’s Bible in 1602 – evidence that he was supplementing his income outside of painting oils or miniatures.

7 Burnette, A. (2010). ‘Lockey, Rowland (c. 1566-1616), painter and goldsmith’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography [online] Available at: https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-16897 [accessed 9 Feb 2021]. This technique presumably refers to the type of drawing in chalks used by Holbein and later at the French court by Jean Clouet and others. In France they were often preliminary life drawings for miniatures or oils.

8 Murdoch, J The English miniature, (London: Yale University Press, 1981), p. 60.

By 1589 it is likely that Lockey was a freeman of the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths and in 1600, his brother Nicholas joined Hilliard as an apprentice.9 In the exhibition Artists of the Tudor Court (1983), the curator Roy Strong attempted to assemble his oeuvre.10 The written plaudits afforded to Lockey by his contemporaries have not been matched by documented portrait miniatures, but Strong used as his basis the More series and an oil of Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby, of 1598, inscribed ‘Rolandus Lockey pinxit Londini’.11 He also compared a miniature of an unknown noblewoman by Hilliard and a contemporary copy of the same subject; the latter he attributed to Lockey.12 However, unlike the work of Laurence Hilliard (1582-1648), there are simply no signed works with which to compare those mysterious, non-Hilliard miniatures of the later 16th century.13

Although Lockey clearly made a living through his oil copies, he was fully trained to paint ad vivum miniatures. As Strong pointed out, the presumed sitter of the present miniature is of the type of aristocratic rank who appears to have employed Lockey, as he is recorded as working for both Elizabeth (‘Bess’) of Hardwick. Anne Cobham married Walter Haddon (c. 1514-1571) but had no children, and secondly Sir Henry Cobham (15381591/2), with whom she had three children.

9 The exact date is unknown but it was certainly after 1589 and no later than the summer of 1592, as by then Lockey was employing an apprentice of his own.

10 Strong, R. and Murrell, V.J, Artists of the Tudor court: the portrait miniature rediscovered, 1520–1620. (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1983).

11 The Mater and Fellows of St John’s College, Cambridge. This painting is a copy of an earlier work.

12 Strong and Murrell, p. 94.

13 Miniature of an unknown lady by Nicholas Hilliard, collection of the Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry KT and second version in the National Museum, Stockholm (NMB 1694).

after JOHN DE CRITZ THE

(1551/2-1642)

King James VI/I of Scotland and England, wearing a silver doublet, white lace ruff, and a black hat with the ‘Mirror of Great Britain’; circa 1635

Oil on copper

Turned ebonised wood frame

Oval, 85mm (3 ⅓ in) high

Provenance

Private Collection, UK.

Although generally considered to be a vain man, James VI/I of Scotland and England did not enjoy having his likeness taken. Sir A. Weldon, author of a work on the Court of James from 1650, said that the King ‘could never be brought to sit for the taking of that [picture], which is the reason of so few good pieces of him’.1 This may be part of the reason that so much of the iconography of James is based on certain ‘types’ of portraits, painted by artists close to the monarch. In the present miniature, the likeness has been taken from the well-known ‘De Critz’ type, of which at least 20 full-length portraits are known. John De Critz was Serjeant Painter to the King, a post that he shared with Robert Peake the Elder. James was also known to have employed Isaac Oliver, as his Painter in Miniature, as well as Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger. The De Critz portraits (and versions) are scattered in collections across the world, including the Dulwich Picture Gallery, the Prado, and the Pitti Palace. These full-scale portraits are first recorded to have been painted in 1606.

On the reverse of the miniature, the name of the artist ‘Gonzales Coques’ is engraved. Coques was known as the ‘little van Dyck’ for the influence he took from the great portrait painter and trained under Pieter Breughel III. Like van Dyck, he was an Antwerp-born artist, but it is thought that he worked in England between 1635 and 1640, so he may have encountered and copied this portrait of the King at this later date. The robust nature of oil on a copper support means that the present work has remained vibrant and animated, as is usually the case with smaller works painted by Coques.

The different versions of the De Critz portrait type vary, specifically in the jewel that the King wears on his hat, whether this hat has a feather on it, whether or not his shoulders are covered by a coat, and, very specifically, whether his collar has ties

1 Sir A W[eldon], The Court and Character of King James, 1650, reprinted by G. Smeeton, (London, 1817), pp. 55-59.

2 Roy Strong, The Tudor and Stuart Monarchy, volume III, Jacobean and Caroline, p. 73.

falling down from its centre. Looking at these details, it has been possible to identify that this miniature must have been taken by Coques from the De Critz portrait now in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, as this is the only full-scale portrait which matches the present composition in all these details.

King James wears the hat jewel known as the ‘Mirror of Great Britain’, which had been created, Strong believes, from jewels held by the Elizabethan court.2 Other formal jewels include those known as ‘The Three Brothers’ and ‘The Feather’. All of these jewels were pawned off at the end of James’s reign. ‘The Mirror’ was formed of a rhombus made from three diamonds, and a ruby, surmounted by two diamonds. Below this rhombus sat the famous ‘Sancy’ diamond, which is reputed to have been owned by numerous royals throughout history.

The rest of the King’s attire does not go unadorned; he wears a necklace with pearls and what appear to be more diamonds, and from this hangs a George of the Garter, likely to have also been encrusted with diamonds.

King James is predominately remembered in popular culture for his scandalous behaviour within his court. He had numerous ‘favourites’ who rose to gain extraordinary power and privilege at court, sometimes well beyond their abilities. The son of Mary, Queen of Scots, he became King of Scotland in 1567 when his mother was forced to abdicate the throne. In 1603 he became the King of England, following the death of his cousin Elizabeth I, who had been responsible for the execution of his mother. As a monarch in both countries, he created a ‘dynastic union’, a precursor to the political union of the nations of Britain in 1707.

A Gentleman, traditionally called Charles Fleetwood, later Lord Fleetwood (circa 1618-1692), wearing armour and lawn collar; circa 1655

Watercolour on vellum

Inscribed verso, in a later hand, ‘11 / General Fleetwood’

Oval, 57 mm (2 ¼ in) high

Turned wood frame with later scroll plate

Provenance

Sotheby’s, London, 6 June 2007, lot 153 (as Portrait of an Officer); Private Collection, UK.

1 Yale Center for British Art, accession number B1974.2.12.

2 Rosenbach Foundation, Philadelphia.

The previous identification of this miniature portrait stems from an inscription on the reverse of the original backing, which appears to have been added at a later date. Identifying the portrait as one of General Charles Fleetwood, it is probable that this name was added to the miniature during the nineteenth century, when interest in the interregnum and Oliver Cromwell experienced a revival. Fleetwood was one of the Lord Protector’s most notorious generals, as well as his son-in-law. He had fought at Naseby (1645), Dunbar (1650), and Worcester (1651), and played a major role in governing England when Cromwelll became the Lord Protector. Comparisons to known portraits of Fleetwood, by Samuel Cooper (1607/8-1672)1 and Thomas Flatman (1635-1688)2, indicate that this is not the name of the gentleman portrayed here.

The painter of this portrait was John Hoskins the Younger, son of the well-known elder artist. For a long time, differentiating the hands of the two was seen as almost impossible. The younger is believed to have worked in his father’s studio for over ten years as an apprentice before being employed as an assistant.3 Compared to his father, John Hoskins the Younger lived in a far more peaceful and politically stable climate. Hoskins the Elder was employed by the Court before the outbreak of the English Civil war and had adapted to paint during the war, capturing those on opposing sides and then into the Interregnum.

3 E Rutherford, et. al. Warts and All: The Portrait Miniatures of Samuel Cooper, London, Philip Mould & Company, 2013, p.98.

Hoskins the younger was likely taught the art of limning alongside his older cousin Samuel Cooper. The similarity between their styles attests to this, but Cooper soon became the most sought-after miniaturist in England and garnered an International reputation. The workshop of Hoskins, which had been so successful during the reign of Charles I, suffered from the success of its most promising pupil. Family loyalty to Hoskins the elder might be behind the commission of this officer, painted against a distinctive half-sky blue background.

King Charles II (1630-85), wearing a decorated doublet under an armour breastplate, blue sash of the Order of the Garter, and a lawn collar; circa 1651

Watercolour on vellum

Signed with initials and dated DDG

Original turned stained wood frame

Oval, 57 mm (2 ¼ in) high

Provenance

Christie’s, London, 9th December 2008, lot 221; Private Collection, UK.

Exhibited Compton Verney House, Warwickshire, ‘The Reflected Self; Portrait miniatures 1540-1850’, September 2024-February 2025.

This portrait by David des Granges is one of a series commissioned by the young Charles while fleeing into exile. Here, his official title was ‘King of Scots’, as after his father Charles I’s execution in January 1649, The Scottish Parliament proclaimed Charles II as king.

This title was not a comfortable fit, as Charles’s relationship with the Scottish Parliament was fraught to say the least. The young king refused to bow to demands concerning religion, union, and the peace of Scotland, according to the covenants. After a final attempt to invade England, Charles’s army was defeated at Worcester in 1651. That year had begun with Charles’s coronation as ‘King of Scots’ in January but he now became a fugitive, hunted through England (hiding from the army’s search in, among other places, the famous oak tree at Boscobel), protected by a handful of his loyal subjects until he escaped to Normandy, France in October 1651.

Based back in Perth, the artist des Granges was tasked with painting miniatures of Charles to distribute to those who were loyal to the monarchy and providing much needed funds to the royal family.1 New research into the life of des Granges and his family has shown that the artist had relocated from London to Edinburgh by 1649, where they baptised a son named Samson, after his grandfather, in Canongate. Although it has been suggested that des Granges followed Charles II to Edinburgh, when the future king arrived in the city in June 1650, Des Granges had actually already been based there for at least a year.

The dire financial circumstances of the monarchy are well illustrated by des Granges’s own plea to be paid for portrait miniatures, such as the present example, in the Treasury Papers of 1671. Called ‘A Schedule of Work done by David de Grange Intertained Limner to His Majty during Y or Royal abode at St.Johnstons at Scotland’. The artist had

already waited two decades to be remunerated for his work. The only gain for des Granges, other than this expression of his loyalty to the crown, was the title of King’s Limner.

One of barely a dozen portraits gifted to those closest to the royal family, the remaining extant miniatures have ended up in large and important collections across the country, including the Buccleuch collection, Ham House collection, and the National Portrait Gallery. Without the King to hand, des Granges took his visage from oil portraits. The lost oil by by Adriaen Hanneman is the likely source here.2 Des Granges also seems to have gained inspiration from the portraits by Champaigne for his own composition, featuring similar tassels on Charles’s lawn collar, and slightly flattening the King’s hair too.

Two years after the death of Oliver Cromwell, in 1660, Charles returned to England to begin the process of restoring the crown. Portraits, particularly portrait miniatures, were a key feature in this transition – they had kept the image of the King and his claim to the throne alive during the Protectorate. Given that portrait miniatures were deemed to represent the absent sitter ‘by proxy’ (i.e. as if they were bodily present), they invoked the loyalty of the owner far more than other portrait formats. Their size also meant that they could be hidden and secretly gifted. The original stained wood case would originally have had a lid, which would have kept the portrait both protected and concealed.

The present work is both a rare survival and a key object in the story of the Restoration of the monarchy.

1 Des Granges is known to have been based as St Johnston’s, the 17th century name for Perth, the city closest to Scone Palace where Charles II had just been crowned King.

2 O. Ter Kuile, Utrecht, Adriaen Hanneman, 1604-1671: A Portrait Painter in the Hague, 1976, p. 68.

King James II as Duke of York (1633-1701); circa 1649/50

Watercolour and bodycolour on vellum

Silver frame, likely contemporary, inscribed verso ‘REMEMBER DEATH’ with a border of engraved bones

Oval, 61 mm (2 ¾ in) high

Provenance

The Collection of Edward Grosvenor Paine, Christie’s, 23 October 1979, lot 29; Private Collection, UK.

Exhibited

London, Philip Mould Gallery, Warts and All: Portrait Miniatures of Samuel Cooper (title in italics), 13 November - 7 December 2013, cat. no. 29.

Literature

E Rutherford, et. al. Warts and All: The Portrait Miniatures of Samuel Cooper, London, Philip Mould & Company, 2013, p.88.

After the shocking execution of their father, King Charles I, in January 1649, his two eldest sons fled into exile on the Continent. It was assumed that the ‘Divine right of Kingship’ would be restored by one, or eventually, both of the young men. This portrait miniature likely marks the point at which James, like his brother Charles, was abroad but keeping the memory of the monarchy very much alive while Cromwell ruled as Lord Protector over England’s new Commonwealth.

The dating of this miniature can be evidenced by several factors. Firstly, it aligns closely with Sir Peter Lely’s oil portrait of the three younger children of Charles I, painted while they were in the custody of the Duke of Northumberland in 1647. In the year following, Lely painted the double portrait of Charles I and his son James (who was by then in captivity). Like the portraits painted in the early 1650s, also by des Granges, this image of James was constructed from earlier images, as he could not be present for the miniature. Although this bucked the tradition of having the sitter in attendance for his or her portrait miniature, the recipient (often a highly valued member of the royal household or important royalist) was still given a sense of the sitter’s presence. As well as being highly portable and easily hidden, the intimate nature of portrait miniatures was well-established by this date and the recipient would have been rewarded for their loyalty by this decidedly personal gift.1

Contemporary accounts show that des Granges was working in Scotland (Perth) for the Royal Household at this date. His appointment as ‘His Majesty's Limner in Scotland’ in 1651 kept him busy producing portrait miniatures for those closest to the royal family. Stylistically, this portrait of James conforms to the known portraits of his brother Charles, further confirming the likely dating to the early 1650s.2

The unusual frame is a further clue to the dating of this miniature, as it would have reminded the owner of the death of James’s father, Charles I (note the bones which act as a border, engraved into the silver). A type of ‘vanitas’, this message would have been clear – the time in which a legitimate line of monarchs to be restored was not infinite.

Born in 1633 and named after his grandfather James I, James II grew up in exile after the Civil War (in France, the Dutch Republic and Germany) . During this time James proved a brave and effective soldier in both the French and Spanish armies, and saw action at the Battle of the Dunes. In 1673, by which time he was an open Catholic, the Test Act debarred him from public office and forced his resignation as Lord High Admiral. Charles, who had characterized his stubborn inflexibility as 'la sottise de mon frère' (the stupidity of my brother), had predicted that if James became king he would not remain so for more than four years. He lasted only three. In 1688, a highly placed Protestant cabalfearing a new civil war - engineered the almost bloodless ‘Glorious Revolution’ which replaced him with his Protestant daughter Mary and her Dutch husband, Prince William of Orange, as joint monarchs William III and Mary II.

1 A recent discovery of provenance for another version of cat. no. 6 shows that it was commissioned by Charles, Prince of Wales, for Henry Seymour (Langley) (1612-1686), a loyal Gentleman of the Bedchamber who was the last member of the royal household to see King Charles I alive and entrusted to take messages from the late king to his family in exile.

2 Des Grange’s career can be traced back to when he was still in his teens, when stylistically he followed the path of the elder Hoskins and Peter Oliver. The present work is quite different in technique and very close in style to his output while in Scotland.

Probably a self-portrait of the Artist, wearing lawn collar, his hair long and curled; circa 1660

A counter-proof, black and red chalks, possibly reworked, on laid paper prepared with a pink wash

Inscribed verso: ‘Mr Gibson the Dwarf / Husband to Mrs. Gibson the Dwarf’

Rectangular, 162 by 126 mm (6 2⁄5 x 5 in)

Provenance

Probably Mrs Richard Gibson, née Anne Shepherd (d. 1707), the artist’s wife; probably Susannah-Penelope Rosse (d. 1700), the artist’s daughter; probably Michael Rosse (d. circa 1735), her husband; probably his sale, London, Cecil Street, April-May 1723, unknown lot number; (according to family tradition) Christopher Tower of Huntsmoor Park, Buckinghamshire (1657-1728); possibly Christopher Tower (1692-1771); possibly Christopher Tower (1747-1810); possibly the Rev. William Tower of Weald Hall, Essex (1789-1847); Mrs William Henry Harford, née Ellen Tower (1832-1907);

Hugh Wyndham Luttrell Harford (1862-1920); Arthur Hugh Harford (1905-1985); Sotheby’s, London, 5 July 2023, lot 17.

While we cannot be completely certain that this is a self-portrait, the features of Richard Gibson are well-known from other portraits of him, including a drawing by Sir Peter Lely (1618-1680). This drawing, now in the British Museum, was previously thought to have been a self-portrait by Gibson, but is now firmly attributed to Lely.1

The re-attribution of the present work to Gibson himself is based on other chalk drawings by the artist, two of which are also in the British Museum.2 These drawings, both of young girls, show strong similarities in the drawing of the sitter’s eyes with the current work, with the eye furthest from the viewer shown on a slightly lower pane and the eyes also drawn with heavy upper and lower lids. Although there are differences in these finished and coloured portraits of girls, the drawing of the faces shows a consistent pattern in the handling of the eyes.3

If accepted as a self-portrait, it would be the only one by Gibson, who clearly, like his fellow miniaturists, drew his immediate family and friends for pleasure. Datable to circa 1660, the pose shows a knowledge of Lely’s own self-portrait from the same date.4 Although Lely’s image is far grander, with his hand gesturing towards his own countenance, the stance of the body, with the eyes toward the viewer (presumably looking into a mirror) are all suggestive of a study of the self. Furthermore, the portrait was probably sold in the sale of Michael Rosse, son-in-law of the artist (married to Gibson’s daughter, Susannah-Penelope), in 1723.5 Its presence in the Tower/s family collection, is also suggestive of a self portrait, as Tower was said to be close to the artist.6 Part of a group of drawings by Cooper, Gibson and Susannah-Penelope Rosse, they remained together for 300 years before an auction sale in 2023.

Richard Gibson (1605/15-1690) had a long and fascinating life and a successful career as a miniaturist or limner.7 As a dwarf, who was 3 feet

10 inches in height, he was unique in breaking from the servitude of English court life to direct his own profession. What is clear is that he was a talent to nurture from an early age - his early training was under Francis Cleyn (c. 1582-1658) and from the late 1630s he entered the service of the Lord Chamberlain, Philip, 4th Earl of Pembroke. It was in Lord Pembroke’s household that Gibson met his future wife, Anne Sheppard (d. 1707), who was also a dwarf. Their marriage, in February 1641, was one of the last court festivities in London before the onset of the Civil War.

After his death in 1650, Lord Pembroke’s patronage was taken up by his grandson, the 2nd Earl of Carnarvon. Throughout this period and after the Restoration in 1660, Gibson’s work was much in demand. It is thought that this self-portrait could have been taken during this high point of Gibson’s career, although before being made ‘picture maker’ to Charles II after the death, in 1672, of the previous incumbent, Samuel Cooper. The following year, Gibson relinquished the post when he was appointed drawings master to the daughters of James, Duke of York. In 1677, he accompanied Princess Mary to the Hague at the time of her marriage to Prince William of Orange, remaining in the Netherlands for over ten years. He returned to London when Princess Mary and William of Orange acceded to the British throne 1688. Of the five surviving children of Richard and Anne Gibson, one was the miniaturist Susannah-Penelope Rosse, who may have been the original recipient of this drawing given that it most likely appeared in her husband’s possessions in the auction of 1723.

1 For a discussion of the re-attribution see https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1881-0611-157 Lely's double portrait of Richard Gibson with his wife Anne Sheppard (formerly Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth), probably painted about 1649-50, and another portrait by Lely of 1658 (an early copy of which is in the National Portrait Gallery, London), all concur with the features in the present drawing. Sir Oliver Millar also suggested that a painting of a sleeping dwarf (Millar (1978) 16) is also a portrait of Gibson, datable in the late 1640s.

2 Museum numbers 1900,0717.40 and 1900,0717.41.

3 This distinctive handling of the eye area can also be seen in a fine drawing by Gibson of an unknown young woman, also once in the possession of William Towers (d. 1693). See L. Stainton & C. White, Drawing in England from Hilliard to Hogarth, British Museum catalogue, 1987, p. 102.This distinctive handling of the eye area can also be seen in a fine drawing by Gibson of an unknown young woman, also once in the possession of William Towers (d. 1693). See L. Stainton & C. White, Drawing in England from Hilliard to Hogarth, British Museum catalogue, 1987, p. 102.

4 Sold from a Private Collection at Sotheby’s, 6 July 2016, lot 216.

5 Sotheby’s, London, July 5 2023, lot 17.

6 D. Foskett, London, Samuel Cooper, 1609-1672, 1974, p.85.

7 Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Gibson, Richard [called Dwarf Gibson] , J. Murdoch, 2004.

A Lady, called Lady Lonsdale, probably Katherine Lowther Lowther [née Thynne], later Viscountess Lonsdale (1653-1713) wearing white chemise and blue cloak, her blonde hair curled and loose; circa 1680

Watercolour and bodycolour on vellum

Inscribed verso ‘wife of John Lord Lonsdale/ Bought from Byram/ A Pair with Minit of/ Lord Lonsdale CB’

Turned wood frame with inner metal border

Oval, 70 mm (2 ¾ in) high

Provenance

Pierre de Regaini Collection, Paris; Christie's, London, 11 May 1994, lot 6 (as a Lady by Charles Beale); Christie's London, 28 November 2012, lot 373; Private Collection, UK.

Literature

‘Gages d’amour. Les Miniatures’, ABC Decor, no.153-154, July-August 1977, illustrated in colour following p.10 (as by Lawrence Crosse).

The present portrait miniature aligns very closely with the work of both Charles Beale Junior and his mother, Mary Beale (1633-1699). Noted as ‘a good copyst in miniature’, many of his works are taken from paintings by Sir Peter Lely.1 Charles learned to draw and paint by practising in his mother’s studio from a young age and took lessons with the miniaturist Thomas Flatman (1637–1688) one of the earliest and closest friends of the Beales. Flatman shared with Beale a preference for naturalistic likenesses and the idea of painting ‘out of love and friendship or for study and improvement’.2 The attribution of the present portrait to Charles Beale is based on the portrait of his mother, Mary (now in the collection at Tate Britain), which through a reassessment of documentation, was shown to be by his hand.3 Sharing the same technique and palette, this work can be added to a small oeuvre by him.

It is difficult to pinpoint whether the present work is copied from an oil painting, possibly one by Mary, or painted ‘out of love’. Certainly, the sitter shows a close resemblance to portraits painted at this period by the court artist Sir Peter Lely, who painted his female subjects with a sensual allure which also translated, perhaps almost more successfully, to portrait miniatures of the period.

The great protagonists for this ‘sensual’ style of portraiture were of course the mistresses of King Charles II, and here we see a direct correlation between this portrait and those of Nell Gwyn. Gwyn was the favourite mistress of King Charles II and one of the most colourful characters of the Restoration age. Her image was widely sought after, but high demand both in her own lifetime and later has led to great confusion in her iconography, with a proliferation of portraits showing unknown, sultry-looking Stuart beauties misidentified as Nell.

The identification of the sitter as Katherine, Viscountess Lonsdale (1653-1713) would date the portrait to around her age of twenty-seven and after her marriage to John Lowther. It is likely that she was in London up until 1680, where several of her children were born. Her husband became Viscount Lonsdale in 1696 and a member of the House of Lords, but after his death she took the unusual step (for a woman at that date) of continuing his political influence in North-West England.

1 Basil Long, British Miniaturists, (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1924), pp. 20–21.

2 Helen Draper, ‘Mary Beale and her ‘paynting roome’ in Restoration London, (Institute of Historical Research and Courtauld Institute, 2020), p. 98.

3 Tate Britain, T14107. The portrait was sold to Tate Britain by Philip Mould & Co. – for a full catalogue description see http://www.historicalportraits.com/Gallery.asp?Page=Item&ItemID=1817&Desc=Mary-Beale-%7C-Charles-Beale-II

Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619-1683), First Minister of State, wearing black robes, lace jabot and the blue sash of the order of the Saint-Esprit; circa 1676

Watercolour and bodycolour on vellum

Silver-gilt frame with spiral cresting

Oval, 45 mm (1 ¾ in) high.

Provenance

By descent within the artist’s family to; Gaspard-Louis, Duke of Clermont-Tonnerre (d. 1889); by family descent until; Professor Théophile Alajouanine (d. 1980); his executor’s sale, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, 30 March 1981, lot 37; with Edwin Bucher, Trogen; Collection Dr. Erika Pohl-Ströher.

Exhibited Evreux, 1864, Exposition d'objets d'art et de curiosité à Evreux1 Paris, Exposition Universelle, 1867.

Originally part of a set of twenty-four miniatures of courtiers, this important miniature is a fine example of the work of Samuel Bernard, painter to Louis XIV, and father of the well-known French financier, also Samuel Bernard (1651-1739). This set of miniatures remained together for a significant period of time and have been exhibited historically, including at the International Exhibition in Paris in 1867.2, Another two of these miniatures, with the same provenance, were sold at Sotheby’s in 2019.3

Samuel Bernard had been trained by Louis du Guernier and Simon Vouet and, through his success in art, ended up being one of the founders of the academy of painting and sculpture in Paris in 1848. At the same time, the sitter of this portrait, Colbert, was rising to his first political rank. Known as Le Grand Colbert, he developed an economic approach during his time as the First Minister to Louis XIV that became known as Colbertism. This

was a form of mercantilism designed to serve the state, with actions including reducing the number of people benefitting from possessing titles of nobility, increasing the international power of France to compete with the Netherlands, and introducing import tariffs. These tariffs included one on foreign lace, which was banned completely in 1667. It is possible, then, that the unusually large lace Jabot that Colbert is seen to wear here, something that he was often depicted in, was intended to represent his loyalty to national production.

The present miniature shows Colbert circa 1676 and shares some similarities with the depiction of the sitter’s clothing in the pastel portrait in the Musée Condé, Chantilly by the Parisian artist Robert Nanteuil (1623-1678).

Colbert’s close relationship with Louis XIV, also known as ‘The Sun King’, cannot be understated. He held almost all the great offices of State - as Comptroller-General of Finances, Secretary of State for the King’s Household, Secretary of State for the Merchant Navy and Superintendent of Royal Buildings, Arts and Manufactories. He met with the monarch five times a week and kept up regular correspondence with him. Colbert’s allegiance to the nation often put him at odds with those in business. Merchants, he repeatedly declared, were little men with only “little private interests”. Colbert’s ideas on taxation were those of almost every minister of finance everywhere, except they were more clearly and far more candidly expressed: “The art of taxation,” he said, “consists in so plucking the goose as to obtain the largest amount of feathers with the least amount of hissing.”

Colbert’s influence extended far and wide during Louis’s reign, even impinging on the people’s leisure activities. Personally, he preferred the Italian opera form to the French ballet and so doomed the latter to the benefit of the Italian import. He also created

1 Catalogue available online, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Notice no. FRBNF31844983.

2 Two of which are for sale with the Limner Company.

3 Sotheby’s, London, 5 December 2019, lots 225 and 226.

4 E. Clermont-Tonnerre, Histoire de Samuel Bernard et de ses enfants, 1914.

a theatrical monopoly. In 1673, he forced two existing theatres to unite: when a third troupe was later forced to join them, the Comédie française was thereby formed in 1680. The Comédie française was given a monopoly of all dramatic performances in Paris and was subjected to tight state regulation and control, as it was aided by state funds.

As a man, Colbert gave his entire life to the service of the King, even performing the most personal and sometimes demeaning tasks – for example, he searched for the King’s missing swans, supplied Louis with his favourite oranges, took on arrangements for the birth of Louis’s illegitimate children, and bought jewels for mistresses on the King’s behalf. Colbert’s personal philosophy was best summed up in his advice to his beloved son, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Marquis de Seignelay (1651–1690), on how to get ahead in the world. He told his son that “the chief end that he should set himself is to make himself agreeable to the king, he should work with great industry, during his whole life to know well what might be agreeable to His Majesty”.

Apart from painting his portrait, Samuel Bernard also had other connections with Colbert. In 1681, the artist was forced to leave the academy of painters and sculptors as he was a protestant, a religious persecution that Colbert had not opposed as the King’s first secretary. From this information it is possible to suggest that the miniature was painted earlier than this date, most likely in the 1670s when Bernard had a comfortable amount of influence within the academy. Furthermore, Bernard’s son would go on to become a famed financier, and it is possible that his path crossed with that of the present sitter.

A member of the artist’s family who previously owned this set of miniatures, Elisabeth, Duchess of Clermont-Tonnerre, published a work on Bernard and his children in 1914.4

A Lady, wearing white silk dress over white lace chemise, pearl and diamond clusters at her corsage and shoulder, blue cloak, further pearls at her neck and drop earrings; circa 1675

Watercolour on vellum

Oval, 60 mm (2 ⅓ in) high

Provenance

Walter, 5th Duke of Buccleuch (1806-1884); Private Collection, UK.

Exhibited London, South Kensington Museum, 1865, no. 1624 (as ‘Nell Gwyn’ lent by Walter, 5th Duke of Buccleuch (1806-1884)).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the present miniature has long been thought to be a portrait of the infamous Nell Gwyn, mistress of King Charles II. Nicholas Dixon succeeded the short tenure held by Richard Gibson, following the long career of Samuel Cooper, as King’s Limner to Charles II in 1673. Despite his obscure origins and apparent intermittent poverty (he is documented as paying the ‘poor rate’ from his London home in the 1670s) he belongs, in style and quality, to the small, distinctive circle of Restoration court miniaturists, and was adept at transferring to miniature the languorous court beauties portrayed on the King’s walls by Peter Lely and Godfrey Kneller.

The present miniature can be dated to Dixon’s time at court, when he would have been granted the patronage of this elite assemblage. Although the sitter in this portrait is unknown, her gown and jewels mark her as a wealthy noblewoman. The present work can be compared in quality to the portrait of an unknown lady in the Victoria and Albert Museum [P.4-1942], dated to c. 1675 (previously identified as Frances Theresa Stuart

(1657-1701)). Similarly, the portrait now thought to represent Anne Hyde, Countess of Ossory (d.1685) [Royal Collection 420938], sports a parallel dark background and monogram. At this date, Dixon was clearly entrenched in the task of producing fashionable portraits of the King’s immediate circle, including his mistresses, imbuing his sitters with a sensuality that directly reflected the mood of the court.

Dixon was not only the King’s Limner but also the Keeper of the King’s Picture Closet and as such had access to the royal collection of paintings. This portrait marks a high point of his career, as it would only be a matter of years before he had lost his royal appointment to Peter Cross (c. 1645-1724) in 1678. Dixon’s work thereafter is often viewed as a decline from his glittering court career, ending with a lottery of his cabinet miniatures in 1698 that failed to attract public interest. The present miniature marks a point in Dixon’s life of great prosperity and patronage to which, sadly, he was never able to return.

The Head of a Lady, traditionally identified as Barbara Villiers, 1st Duchess of Cleveland (1640-1709); circa 1680

Black lead and ink on laid paper

Stained black wood frame

Rectangular, 126 mm (5 in) high

Provenance

Howard Collection (according to an inscription verso).

The artist of this portrait, which dates to the 1680s, was likely influenced by artists such as Sir Peter Lely, Samuel Cooper and Richard Gibson, all of whom produced drawings which were highly valued in the 17th century. Several drawings which remained in Lely’s studio after his death, were subsequently sold as framed and appreciated as works of art in their own right (as opposed to preparatory studies).

The unfinished nature of the drawing would have been much appreciated in this period as an insight into the artist’s creative processes. In an intimate portrait, such as this, might have made the recipient feel closer to the sitter - the artist’s concentration on the face focusing attention on the sitter’s expression as she looks directly out of the portrait. Evidence shows that there was considerable interest in obtaining examples of the miniaturist Samuel Cooper’s unfinished work after his death in 1672. Cosimo III, Grand Duke of Tuscany, who had been painted by Cooper in 1669, opened negotiations for the purchase of the sketches belonging to Mrs Cooper in 1674 but declined to buy, because of the price. A sketch by Cooper of

Barbara Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland c. 1660-61, was described in 1683 by Francesco Terriesi, an agent acting for Cosimo III de’ Medici, as ‘Duchess of Cleveland, face and head finished and beautiful, but nothing else’ and was priced at £30, slightly lower than the £50 demanded for other sketches from the same group.

Traditionally, this drawing has been identified as Barbara Villiers, 1st Duchess of Cleveland. Villiers achieved fame as the mistress to King Charles II (1630-1685). Her influence remained throughout the 1660s, until in 1671 Louise de Keroualle caught the eye of the King and she replaced Villiers as his principal mistress. However, a facial comparison to other known portraits of Villiers confirms that the present is unlikely to represent her, but closely conforms to the ideals of beauty in this period.

The excellent condition of the present work suggests that it too may have come from an artist’s studio or preserved in a folio.

Self-portrait; circa 1690

Oil on card

Inscribed on label, verso: ‘peint / par Fairgusen / de Toulouse / son portrait’

Oval, 75 mm (3 in) high

Provenance

Private collection, Toulouse.

Recently discovered in Toulouse, where the artist worked for much of his career, this newly identified self-portrait by the Anglo-Dutch landscape painter Henry Ferguson is now the only known example of his foray into portraiture.

Likely painted when the artist was working in the studio of Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723) during his formative years as an artist in London, it must have been considered an important keepsake for the artist, presumably travelling with him from England to France, where it would remain for over 300 years.

Henry Ferguson (or ‘Vergazon’ as he was known in Europe) was almost certainly the son of the Scottish emigrée artist William Gouw Ferguson (1632–1695) who spent most of his career in the Netherlands after being admitted to the Guild of St Luke in Utrecht in 1648. A migratory artist like William, Henry was one of several Anglo-Dutch artists working in late 17th-century London London, where he painted backgrounds for Kneller’s portraits, but later settled in Toulouse. While William specialised in still-lifes of dead game, Henry was best known for his darkly atmospheric capriccio compositions of architectural ruins, often with fragments of monumental sculpture.

This self-portrait could easily be confused for a work by the artist’s master Kneller, with its strong colouring and effective use of chiaroscuro. The confidence in its handling – especially considering its miniature scale - and the immediacy of the subject’s gaze would suggest that it was an exercise purely for the artist’s own use.

Its historic Toulouse-based provenance would also indicate that this remained with the artist until his death there in 1730, suggesting it was of great sentimental value to him.

A Lady, wearing ‘Turkish-style’ dress; 1748

Enamel on copper

Signed and dated on the counter-enamel ‘G. Spencer. pinx./1748’

Oval, 44 mm (1 ¾ in) high

Gilt metal mount with stamped detail

Provenance

Sotheby’s, London, Silver, Portrait Miniatures, and Objects of Vertu, 7 November 1996, lot 226. Bonham’s, London, Fine Portrait Miniatures, 23 November 2005, lot 32; Private Collection, UK.

This miniature is an example of how Gervase Spencer excelled at painting portraits of women in enamel. As a miniature painter, he also worked on ivory, though most of his portraits were on copper, or sometimes gold, using the difficult medium of enamel. The unidentified woman in this portrait wears fashions inspired by the Ottoman Empire, which were also common amongst portraits of women by Spencer. A notable comparison is the portrait of another unknown woman in the Victoria and Albert Museum1, previously identified as Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689-1762).

Britain had a long history with the Ottoman Empire, being one of the first countries to establish an embassy in Istanbul in 1535. In the 1740s, the war of Austrian Succession meant that British troops were fighting closer to the Ottomancontrolled Mediterranean2. Though this did not spell good news for British-Ottoman relations, it did mean that more and more British men were gaining exposure to the cultures, and more importantly in this case fashions, of the empire. The robe that the lady in this miniature wears is known in Turkish as a Kurdi, and typically takes the form of a floor-length robe trimmed with fur. Such robes became popular amongst western women, as did hair turbans, also seen in this portrait.

Whereas later works were often signed on the obverse, this miniature has been signed and dated on the counter-enamel. Therefore, it is a rarer and earlier example of Spencer’s work. He became known for his fashionable portraits, and this is certainly not an exception. Though the colours of the woman’s outfit are more subdued than in other examples, such as the V & A portrait, she has still been depicted as a glamorous and wealthy sitter.

1 Victoria and Albert Museum, London, accession number P.4-1943.

2 M. Talbot, British-Ottoman Relations, 1713-1779: Commerce, Diplomacy, and Violence, Gale Internation, online at https://www.gale.com/intl/essays/michael-talbot-british-ottoman-relations-17131779-commerce-diplomacy-violence

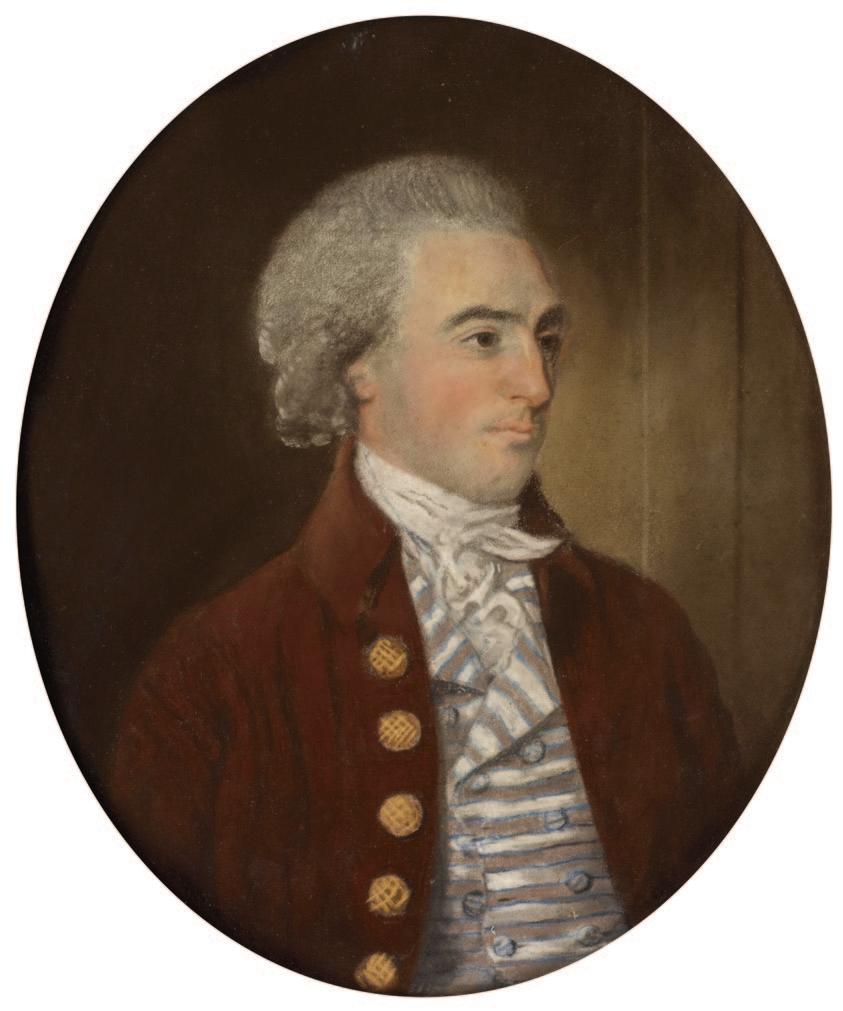

A Gentleman, believed to be James Dunlop of Garnkirk (1741-1816), wearing a green coat, embroidered waistcoat, solitaire, and white stock, with pink powdered hair; 1770

Watercolour on Ivory

Signed with initials and dated ‘J.S/1770’

Oval, 40 mm (1 ½ in) high

Provenance

The family of the sitter; Moore Allen & Innocent, April 2005; Private collection.

James Dunlop of Garnkirk has been identified as the sitter of this portrait through an inscription that was sold with the miniature when it left his descendants’ collection in 2005. There are other portraits known to depict the sitter, including one by George Romney (1734-1802), sold from the Paul Mellon collection in 1989.

The son of Colin Dunlop, Lord Provost of Glasgow, James purchased Garnkirk from his uncle, also James. Four years following the completion of this miniature, he would marry his cousin, Marion Buchanan of Mount Vernon (1754-1828), the daughter of George Buchanan of Mount Vernon (1728-1762) and Lilias Dunlop of Garnkirk. There are some focal differences between the portrait by Romney and this miniature, however this could be down to artistic licence, and a difference in the age of the sitter at the time of both of these portraits.

One of the most notable features of this portrait is the colour of Dunlop’s hair. Coloured powder, in this case pink, was fashionably applied to wigs in the late 18th century by both men and women. Though we are mostly used to seeing this done with white powder, many portrait miniatures by Smart provide examples of just how many different colours were also used. Contemporary advertisements attest to the fact that various colours and scents in powder were available.

In 1770, Smart was at an early stage in his career as a miniature painter, but clearly already fluent in the highly detailed, highly coloured portraits he would become renowned for painting. Not only has he managed to capture a fine level of textural details across the different fabrics that the sitter wears, but Smart has also created an immense amount of depth in Dunlop’s complexion. If this is who the portrait depicts, the miniature may have been presented to Dunlop’s wife as a wedding gift, to be worn around her wrist or on her person.

A pair of portraits, probably Husband and Wife; circa 1779

Watercolour on ivory

Gold frames

Ovals, 67 mm (2 ⅝ in) high (2)

Provenance

Sotheby’s, London, 7 February 1996, lot 236; Private Collection, UK.

It is extremely rare to find a surviving pair of portraits given their reciprocal purpose. Here, a pair of portraits, likely showing husband and wife, have been painted in a relatively large format as a duo and may have always hung together. Although we do not know the names of the sitters, the miniatures, based on their costume and technique, would appear to date to the late 1770s when Meyer was at the height of his career.

Born in Germany, Meyer moved to England at an early age and settled with his family in London. His early training was with the enamellist Christian Friedrich Zincke, but his mature works, such as these, display little of the hard, stippled bright colours of enamel painting. Instead, Meyer was one of the first miniaturists to exploit the support of ivory, using transparent washes to allow the delicate tones of the ivory to show luminescence through the paint. He only used opaque colours for detail – the thicker white paint used here to describe the delicate lace of the lady’s cap and gentleman’s cravat is typical of his technique.

Meyer was the oldest of a group of artists, including Richard Cosway, John Smart and Richard Crosse, all born around the same date, who attended William Shipley’s new drawing school, the first such school in London. After his expensive apprenticeship with Zincke, it seems that he also spent time at the informal St. Martin’s Lane ‘Academy’ run by William Hogarth. As one of the founding members of the Royal Academy, which opened in 1769, Meyer was one of a new generation of miniaturists who would present their art form in direct competition with oil painters. In 1774, one critic noted ‘[His] miniatures excell all others in pleasing Expression, Variety of Tints and Freedom of Execution’.

In 1764, Meyer was appointed miniature painter to Queen Charlotte and painter in enamel to King George III. This secured his place as primary miniaturist for the royal family and improved his ability to secure this position as he was much in demand. The scale of this pair would have been rare at this date and suggests an expensive commission of importance.

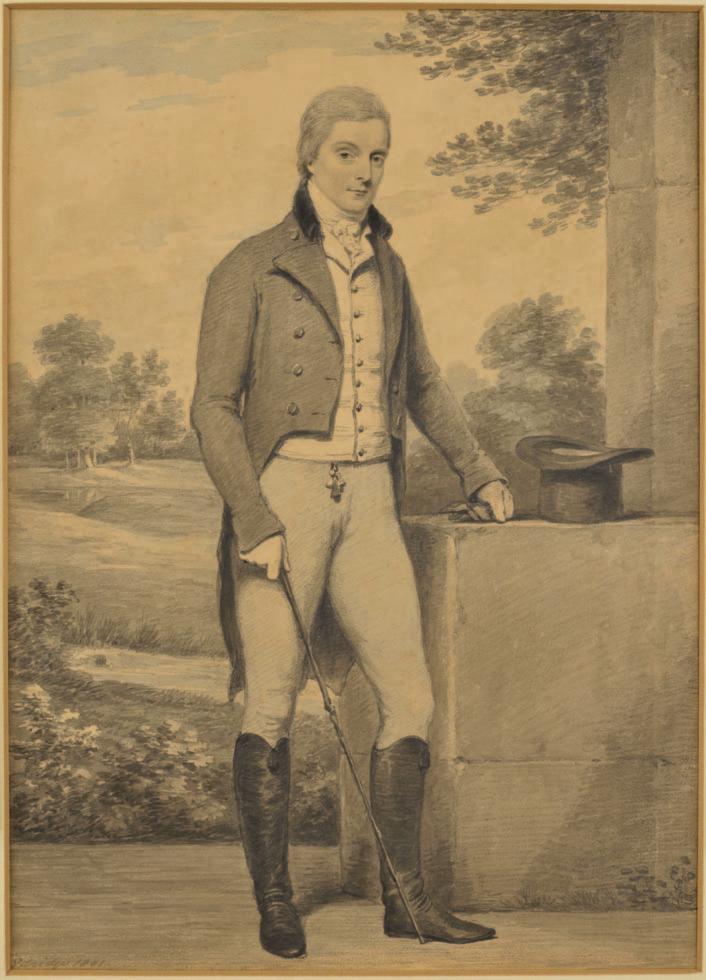

Mrs Fenton, wearing a white dress, a red surcoat trimmed with ermine, a drop-pearl brooch and sapphires at her corsage, her upswept, powdered hair dressed with white ribbon; 1774

Watercolour on ivory

Signed and dated, ‘J.S . 1774’

Associated gold frame with red guilloché enamel and rough-cut diamond surround

Oval, 51 mm (2 in) high

Provenance

The Rt. Hon. The Earl of Lanesborough; Sotheby’s London, 15 July 1968, lot 77 (as ‘unknown Lady’); Christie’s London, Important Portrait Miniatures Including the Walter and Gertrude Rappolt Collection, 14 October 1998, lot 68 (as ‘a young Lady’); Karin Henninger-Tavcar, 1999; Private Collection, Germany; Philip Mould & Co., 2014; Cheffins, The Fine Art Sale, 30 November 2016, lot 839 (as ‘a Lady’); Cheffins, 9 March 2017, lot 422 (as ‘a noblewoman’); Private Collection, UK.

Exhibited

Philip Mould & Company, John Smart: A Genius Magnified, 25 November – 9 December 2014 (as ‘a Lady’).

Literature

Foskett, D., John Smart: The Man and His Miniatures (London: Cory, Adams & Mackay, 1964), p.66; E. Rutherford et. al., John Smart: A Genius Magnified, Philip Mould & Company, 2014, cat. no. 13, pp. 38-39 (as ‘A Young Lady’).

The present sitter can be identified from a pair of preparatory drawings depicting ‘Mr and Mrs Fenton’. The drawings have now been separated, with the preparatory work for the present miniature now in the Albertina Museum, Vienna, and Mr Fenton’s drawing having been sold at Galerie Bassenge, Berlin in 2022.12A Mrs Fenton is recorded among Smart’s known sitters in Daphne Foskett’s monograph, although no date is given, and a Mr Thomas Fenton recorded and dated 1776.3 The present finished miniature is dated 1774 and it is therefore likely that the drawings became a pair at a later date.4 It may be that it was only after this miniature was presented to her husband – possibly as part of their courtship or betrothal - that he decided to sit for the same artist who had captured her so beautifully.

John Smart has been described as ‘the finest miniaturist in 18th-century Britain’; no major collection of miniatures can be considered complete if this artist is not represented.5 He was still a young man when he painted this portrait, and his career was progressing steadily. Having exhibited at the Society of Artists since 1762, he was made Director in 1771. Later, he would be appointed Vice President in 1777 and President in 1778. He was working in an affluent area of London and a decade later would travel to India, one of many British portraitists who journeyed there in search of the lucrative patronage of the ‘wealthy English residents and native princes’.6 Indeed he was appointed miniature painter to the family of the Nawab of Arcot and was in great demand.7 Smart returned home in 1795 and exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1797 until his death in 1811.

1 Illustrated in Keil, N., Die Miniaturen der Albertina in Wien, Vienna, 1977, pp.47-48, n° 41.

2 Galeria Bassenge, Berlin, Old Master Paintings, 1 December 2022, lot 6044.

3 Foskett, D., John Smart: The Man and His Miniatures (London: Cory, Adams & Mackay,1964), p.66.

We are grateful to Dr Bodo Hofstetter, curator of the Miniatures Cabinet in the Museum Liaunig, Neuhaus, Carinthia, for identifying the sitter of this portrait.

4 Smart’s preparatory drawings were likely left in the artist’s studio after his death and later sold, some being cut down and framed like oval miniatures. Many were passed down through the generations and eventually sold at auction in the 20th century.

5 Rutherford, E., & Hendra, L., John Smart: A Genius Magnified (Philip Mould & Company), a catalogue for the exhibition held at Philip Mould & Co. 25 November – 9 December 2014, p.8

6 Foskett, D., British Portrait Miniatures (The Hamlyn Publishing Group), 1968 edition, p.112.

7 Ibid.

A Lady, almost certainly Suzanne Elisabeth de Gaulmyn (1752-after 1804), Countess-Canoness of Saint-Denis Church, Alix (later married name Puy de Semur), wearing white satin dress, a red moiré silk sash, an order and gold epaulette, seated, holding a letter in her right hand and her left arm resting on a table with marble top, maroon covered book beside her; blue silk curtain background; circa 1777

Watercolour on ivory

Silver frame stamped with a coin pattern

Circular, 75 mm (3 in) diam.

Provenance

Christie’s, London, 24 May 2000, lot 100 (as ‘A fine miniature of a young lady called the Chanoinesse de Golmin’); Private Collection, UK.

Previously called the Chanoinesse de Golmin by Christie’s, London, this fascinating portrait shows a young woman, who can now be identified as Suzanne Elisabeth de Gaulmyn.1 Like many other teenage girls, she became a noble canoness at St Denis in Alix (in the Lyonnais region of France). In 1771, Suzanne entered the ‘Chapter’ of the church, after the highly selective process to prove her nobility.2 At the age of 23, in 1775, she left to marry Jacques Augustin du Puy de Semur, a musketeer in the King's Guard, which she did in 1777.3 The portrait here likely marks the occasion of her marriage, but she still wears the insignia of her Chapter: an enamelled gold cross attached to a ribbon worn as a sash for church services.

The option of entering a Chapter would have had much appeal to young women of the period, where choices were limited to the authority of a husband or a bishop. A canoness, however, remained free to determine her own destiny. Upon entering the Chapter, she would acquire the title of Countess, and kept it for the rest of her life, whereas in civilian life she lost (unlike her brothers) her father’s title of nobility to take that of her husband. She was not cut off from the world and regularly stayed with her family. At the age of 25, she could choose to return to live in the society with which she had not broken ties, or took vows, and from then on was able to benefit from a portion of the Chapter’s income. Once a professed canoness, a semi-religious, semi-worldly lifestyle could be lived until her death.

During the Revolution, the chapters, which combined clergy and nobility, were the first to be dissolved. The canonesses of Alix fought to keep

their houses and their income, but many returned to their families, and their houses were eventually sold as national property.

The traditional identification of the artist of this portrait as the elusive Nicolas Hallé still stands. The painting of the silks of the sitter’s dress fit with the description of his painting by Bernd Pappe, given when discussing a miniature attributable to Hallé in the Tansey Collection. Pappe states that Hallé’s miniatures ‘show an individual painting style which is easily recognised: the facial features are painted very precisely and sharply, the face is often directly turned to the viewer, and the clothes appear almost metallic because of the conspicuously placed highlights with their rich contrasts. Fur ther hallmarks of his style are a mouth that appears pinched because of the narrow brown dividing line of the lips, together with striking red accents in the corners of the eyes’.4

This portrait of the Countess de Gaulmyn is typical of the clientele who were attracted to Hallé’s precise yet grand style of miniature painting. Apparently married to a Baroness, Hallé found a patron in the Duc de Penthiève (1725-1793), the illegitimate grandson of Louis XIV.

Hallé was working at the same time as the successful artist Pierre Adolphe Hall. The similarities in their names, techniques and statuses as artists caused some confusion and rivalry, culminating in an incident where, one year after the outbreak of the French Revolution, Hallé’s wife had allegedly thrown apples from her opera box on patriotically minded fellow citizens, but the blame was cast on Hall’s wife.

1 This identification is a new reading of a handwritten old label on the backing paper, which previously identified the sitter as ‘Chanoinesse de Golmin trisaïeule de Ary Chevallier homme de lettres’. The spelling of ‘Golmin’ is phonetic for ‘Gaulmyn’ and her identity is further proved by the order of the Chapter of a canoness of Alix that she wears on her sash.

2 Before the letters patent of Louis XV in 1753, proof of nobility was testimonial, but the king imposed five generations of paternal nobility. The Chapter’s own statutes, written in 1756, went beyond royal prescriptions and required eight degrees of paternal nobility.

The evidence was presented to the Canon-Counts of Lyon designated by the Prioress of Alix, and studied by a genealogist.

3 Suzanne and Jacques had several children, including Jacques Claude Augustin, born in 1778, Gilbert in 1780, Marie Louise, born around 1781, and Charles in 1783.

4 See https://tansey-miniatures.com/en/collection/10244 (accessed March 2025). Very few signed works are known, but one is illustrated in J. de Bourgoing, Die Französische Bildnisminiatur, Vienna, 1928, pl. 45.

A Lady, Traditionally identified as Viscountess Townshend, later Anne, 1st Marchioness Townshend (circa 1752-1819), wearing a blue fur-trimmed coat, white embroidered dress, her hair powdered auburn and worn up; 1777

Watercolour on ivory

Signed with initials and dated ‘J.S/1777’

Gold reeded frame

Oval, 45 mm (1 ¾ in) high

Provenance

Karin Henninger-Tavcar, 1995, as ‘Viscountess Townshend’; Private collection, Germany; Private Collection, UK.

Literature

E. Rutherford et.al., John Smart: A Genius Magnified, London, 2014, p. 46-47.

Exhibited

London, Philip Mould & company, John Smart: A Genius Magnified, 25 November-9 December 2014, cat.no. 17.

This portrait resembles both another portrait of Viscountess Townshend by Smart and portraits of the Viscountess by Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807) and Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792).1 The second portrait by Smart is illustrated in Foskett’s 1964 monograph of the artist, and bears the date 1775.2 In both miniature portraits, she wears a high updo, fur-trimmed coat and a similar style of dress underneath. However, the sitter in the present example is much more subdued in her style, possibly reflecting a change in her lifestyle following some years of marriage since the first portrait was painted.

Anne was the second wife of George, 4th Viscount and later 1st Marquess Townshend (1724-1807). She had been born to Sir William Montgomery, 1st Baronet of Magbiehill (1717-1788) and Hannah Tomkyns in the early 1750s, and was known for her beauty, something that is certainly reflected in this work. Smart had an incredible amount of skill in depicting fine details, such as the sitter’s eyelashes and the baby hairs framing her face. The result here is an extremely delicate rendering of Anne, who gazes softly out of the frame of the portrait. She adopts the same position in Smart’s earlier portrait, though this is slightly larger, so it is possible that the second version was commissioned as a more portable and intimate option.

John Smart painted similarly skillful portraits of important members of society throughout his career as a miniature painter. These included, for a period beginning in 1785, citizens in India, where he travelled to continue receiving commissions at a time when portrait miniatures were popular amongst members of the East India Company. His bright, lifelike, and sensitive works are seen as some of the finest examples of miniature painting of his period.

1 D. Foskett, John Smart: The Man and His Miniatures, London, 1964, p.36, ill. fig.29, plate X; At Burghley House, reference PIC155.

2 At M H De Young Memorial Museum, San Francisco, 75.2.13.

Lady Betty (Elizabeth) Foster (née Hervey) (later Cavendish) (1757-1824); circa 1787

Watercolour on Ivory

Oval, 50 mm (2 in) high

Provenance

Possibly collection of Sir Augustus William James Clifford, 1st Baronet (1788-1877); By descent to Lord Charles Walter James Dormer (1903-1975);

Christie’s, London, 27 March 1984, lot 165 (as Henry Edridge after Sir Joshua Reynolds); Christie’s, London, 21 April 1998, lot 71.

Literature

Dorothy Margaret Stuart, Dearest Bess: The Life and Times of Lady Elizabeth Foster, afterwards Duchess of Devonshire from Her Unpublished Journals and Correspondence, London, 1955, ill. op. p. 116.

The sitter in this portrait, Lady Elizabeth Foster, born Hervey and later Cavendish (from 1809), led an extremely interesting life, the story of which has since been told through films, books, and television. Born in Suffolk, her childhood was not a prosperous one. In 1776 she was married to Thomas Foster (d.1796), an Irish MP. She had two sons with Foster, but the marriage was not happy and soon ended.

Only a few years after her separation from Foster, she became acquainted with William Cavendish, 5th Duke of Devonshire, and his wife, Georgiana. Their relationship soon developed into a ménage à trois, and in 1786 Elizabeth gave birth to William’s son. The affair had not ruined her relationship with Georgiana, however, and when the Duchess fell pregnant with another man’s son, Elizabeth followed her in her exile. When Georgiana died in 1806, she named Elizabeth as the sole guardian of her papers, meaning that her future was secured. Only three years later, she married the Duke of Devonshire.

The trio became known due to the questions surrounding their relationship at the time, which has remained a subject of intrigue since. In 2008, the film ‘The Duchess’, featuring Kiera Knightley, Ralph Fiennes, and Hayley Atwell as Elizabeth, was released and follows the relationship from the perspective of Georgiana. For contemporaries, the gaudish and scandalous behaviour, particularly of Georgiana and Elizabeth, was often satirised and the subject of comment. Aside from being involved in this scandal, they were society hostesses, with Georgiana responsible for receptions at Chatsworth. This exposure meant that their relationship became well known in society. Both Elizabeth and Georgiana were painted by numerous important artists from the period, including Angelica Kauffman, who painted Elizabeth only a year before this miniature is presumed to have been painted.1

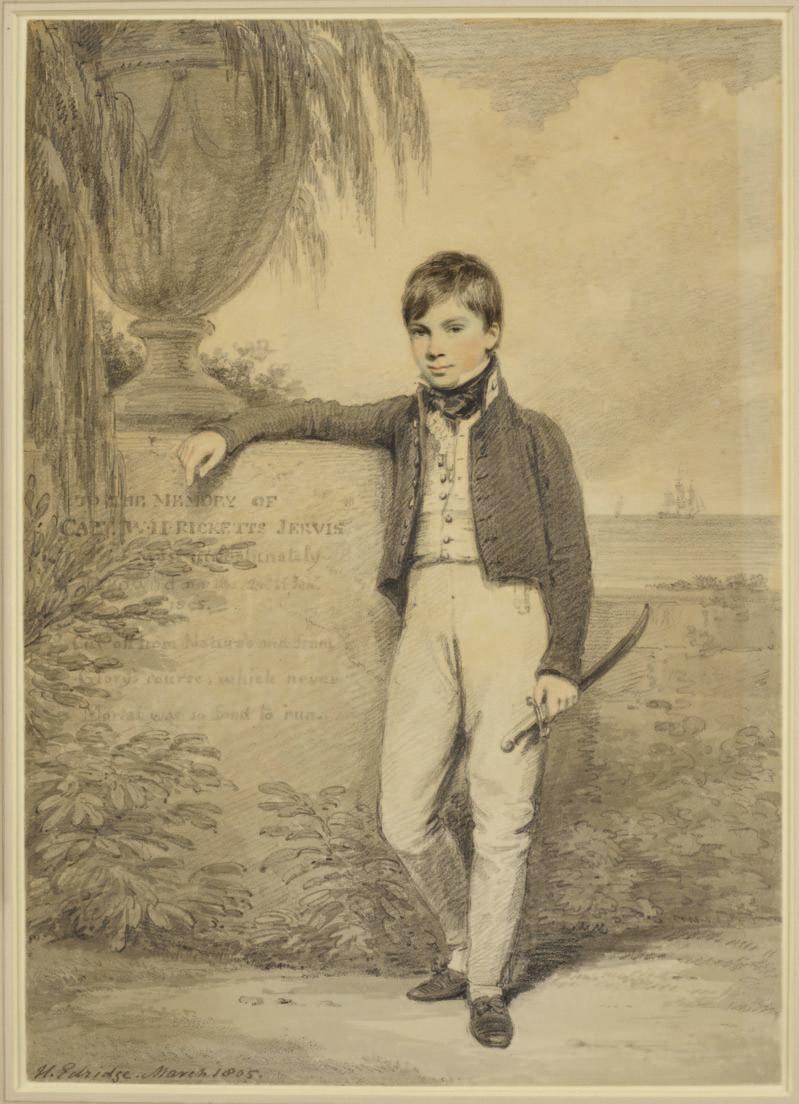

According to George Engleheart’s fee book, he painted 3 portraits of a ‘Forster, Lady E’ in 1787. The miniature has previously been sold as by Henry Edridge, but sits much more comfortably within the oeuvre of Engleheart, and matches the other two portrait miniatures painted by him. Though the spelling of the surname is different, transcriptions of his fee book consistently spell the surname in this way, and there are no ‘Fosters’ included, and it is certain that he painted Foster. Historically, then, it has been assumed that the present work is one of those recorded to have been painted in this year.