Thank you to our Champion & Impact Partners

Thank you to our Champion & Impact Partners

It is my great pleasure to present to you the inaugural edition of The Giving List Women

Did you know that only 1.8% of all U.S. philanthropic dollars currently go to women’s and girls’ organizations? That this number has been relatively static for over five years?

It is this staggering statistic that inspired the launch of The Giving List Women. As did coming to understand that whether we give $50 a year or $50 million a year, our greatest chance of moving the needle on any issue we care about is by supporting women and girls – by far the most powerful lever for change in almost every key area of philanthropic focus.

The Giving List Women’s central mission is to urge donors, no matter their age or giving capacity, to view women and girls as a lens, not a lane, in philanthropy.

This book was created to help donors apply this lens to their giving. It also exists to help nonprofits on the ground floor of our world’s most vital work tell their powerful stories in a way that can help us all better understand and appreciate the critical services they provide.

Our world is filled with nonprofits, of all types and sizes, that must compete for limited resources. The organizations written about in the pages of this book are certainly not the only ones doing great work. But they do represent our nation’s and our world’s vibrant nonprofit and philanthropic culture. They are working to give power to women and girls at a critical moment in our world’s history, and we believe that they are, each of them, worthy of your support.

I am grateful to our Champion and Impact Partner organizations, also profiled in this book, who enthusiastically linked arms in partnership with The Giving List Women. The women and men at these partner organizations helped not only to curate and to underwrite the cost of this effort, but deepened our understanding of why it matters so much to support women and girls.

Our partner organizations are focused, day in and day out, on investing in women and girls locally, nationally, and globally. They do this work because they understand the huge contribution being made by women and girls to the creation of a vision for a better world. They know that the idea is no longer for us all to fit into a world created by and for men. It is about building a world that will be better for us all, for every human on our planet. A world where we protect the Earth, where we rethink what good leadership looks like, where everyone is seen and protected and valued and included. And the only road to achieving this vision is that which leads to gender equity.

A special thanks to the 10 Giving List Women Trailblazers also interviewed for this publication. The life work of these philanthropic and movement leaders has made – and continues to make – an indelible impact on our world. They are part of the chorus of courageous voices in the powerful push for equity, compassion, and justice for all.

We hope that this publication will help you break through some of the confusion created by so many pressing needs. That you will use this book as a resource as you decide where to invest your much-needed support. Budgets are moral documents; they reflect our values and our understanding of what matters. We hope that you will consider applying the lens of women and girls to your giving, because in doing so, you will be a part of making the world a better place for us all.

In solidarity,

Gwyn Lurie Co-founder & CEO, The Giving List Women

Gwyn Lurie Co-founder & CEO, The Giving List Women

We are all many things. We may be women, mothers, daughters. Fathers, sons, brothers. We are of every shape, size, color. We come from all walks of life, backgrounds, and places. We have our own proclivity for whom we love, whom or what we worship. And to view the world any other way is to leave out critical pieces of ourselves and others.

Like people, nonprofits are multifaceted. They focus on a plethora of critical, overlapping issues. In these pages, we have organized these 48 nonprofits and 19 Champion Partners across 10 chapters, though we understand that each aligns with many of the book’s themes. Our hope is that their placement helps us think differently about every important challenge we face and to better understand the complexities these organizations tackle. This is the reason, for example, you will find themes of social justice and racial justice interwoven throughout the book, not as separate chapters.

The title “How to Use This Book” is intentional, as we also hope that you will engage with it, and not merely read it. Our goal is for each story to inspire us to feel something, whether it be compassion for the human beings at the story’s center, an urgency to tackle a critical challenge, or indignance at the inequities reflected.

Mostly, we hope you feel compelled to act. That you will reach out to the organizations you are curious about; you will re-tell these stories to your colleagues, families, and friends; you will reflect on your own giving and the lens you currently use. That you will join the movement we are building with our partners to help unlock billions of dollars towards female-facing organizations. The word – or acronym – “List” in the title of this book reflects our intention at The Giving List Women: “Let’s Ignite Something Transformational!” To do that, we need your involvement.

Many people helped bring this inaugural book to life, from our commissioned artists to the writers who interviewed each nonprofit and Champion/Impact Partner and wrote the stories you’ll read in the following pages.

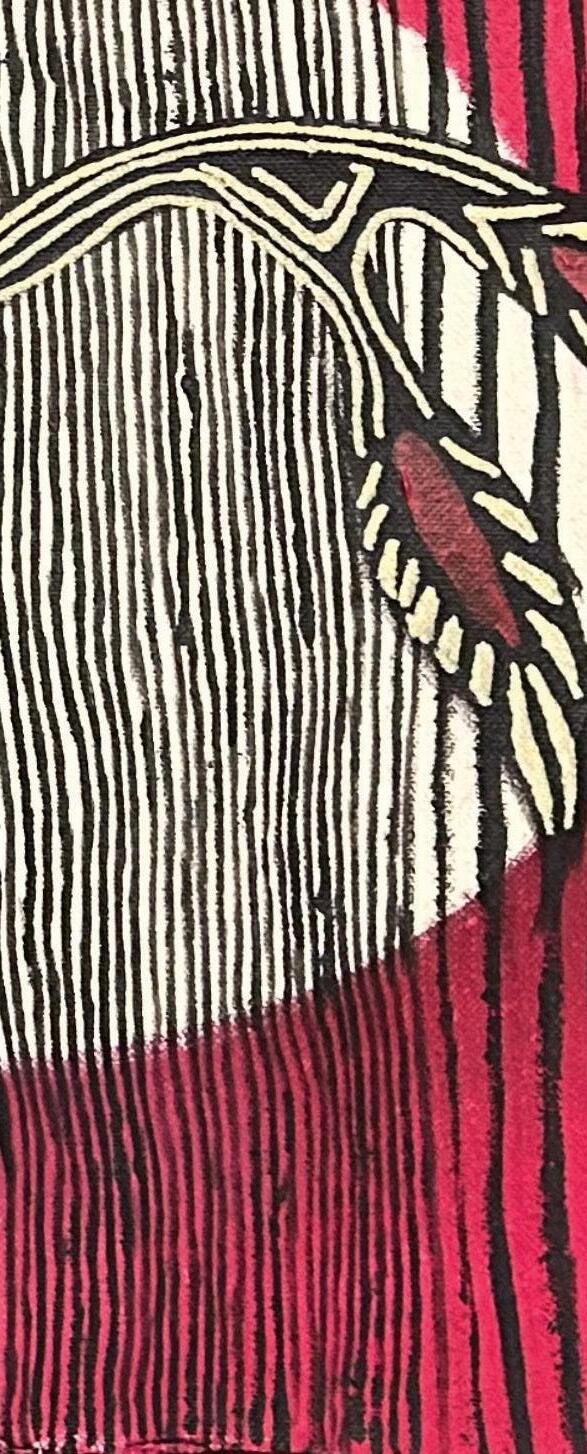

A special thanks to three talented individuals who made this book ready for your coffee table. Natalie Johnson’s beautiful images open each chapter of the book, while Ebony Osun Morris made a Giving List Women quilt, the 10 swatches of which are sewn together in real life, but for the book you’ll find each swatch in a chapter bar.

Finally, Dayna Bowers' centerfold visually summarizes the essence of what we are building together with our partners. So, tear it out and pin it on your wall! And don’t forget to read the back where you’ll find the bios of all our contributors.

A final note as you use this book. Please read the often overlooked masthead where we identify our team. Building something new is no easy feat. These individuals kept stepping up as the book expanded beyond our expectations as additional partners came aboard and as we navigated the challenges that come with creating anything new.

With much anticipation –

Janine Berridge President, The Giving List Women

Janine Berridge President, The Giving List Women

You’ve read The Giving List Women and hopefully you’re now wondering how you can become part of our network of networks. You’ve come to the right page and we have some ideas for you:

“Can we be featured next year as a nonprofit organization?”

• For our inaugural year, organizations were identified and selected through our own networks and recommendations from our Champion Partners and Thought Partners. The organizations featured in these pages represent a tiny selection that are undertaking critical work for women and girls around the world. To be featured in our 2025 edition, we invite organizations to apply online at www.givinglistwomen.com. Through a committee composed of a diverse selection of our 2024 partners, we will identify our next cohort of organizations to be featured.

“We are a foundation or collective giving organization and would like to partner with The Giving List Women.”

• The Champion Partners you read about in this book are all fueling our collective pursuit of gender equality in many different ways, whether through funding, research, membership networks, giving circles, campaigns, and more. They also fueled our ability to produce this book. If you’d like to become part of our growing list of Champion Partners, please email janine@thegivinglist.com.

“Our company is prioritizing women and girls through our impact initiatives or core business. We want ‘in’ too!”

• We seek Impact Partners who understand that ethical business is successful business. That doing well is doing good. Our Impact Partners are innovators and disruptors; they are evolving as our world evolves; they execute bold ideas and learn and grow through challenge; and above all else, they are committed to excellence and impact and gender equity.

• If this sounds like your company and you want to learn more, email janine@thegivinglist.com.

“I have a great idea for a Trailblazer who readers should know about.”

• We welcome your ideas, and especially those with diverse experiences, who might be unknown, but should be known.

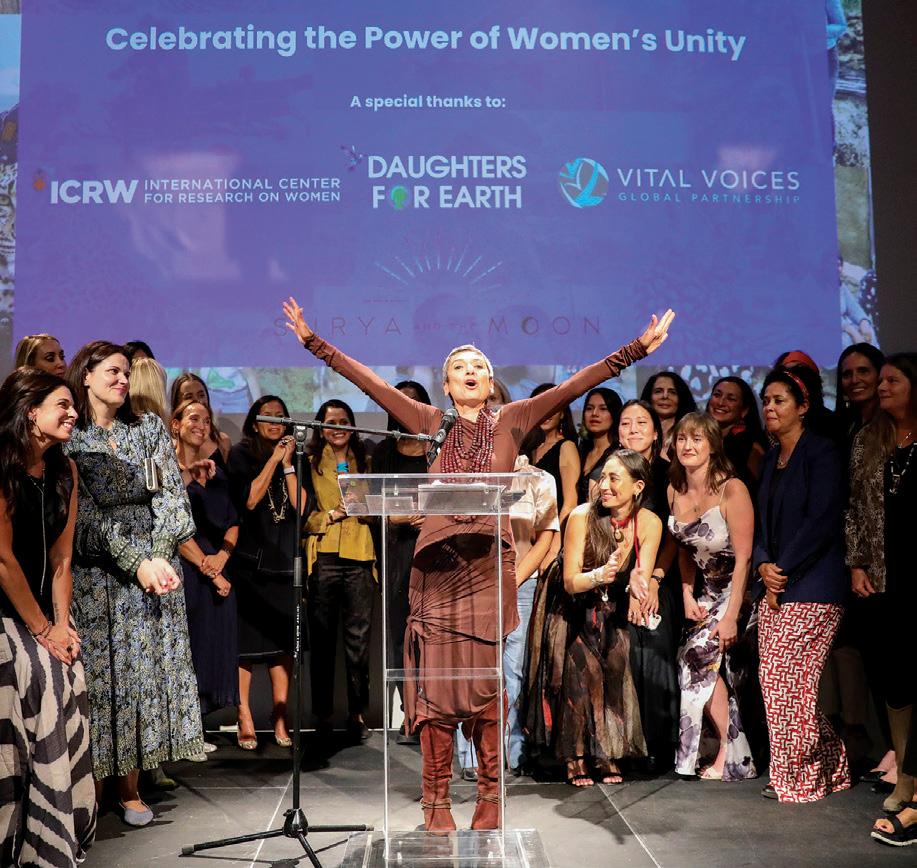

“I heard there is an intimate annual convening of philanthropic and impact leaders that brings the book to life. That sounds like something I need to attend!”

• The inaugural Giving List Women Summit took place April 2024 in Montecito, California. With the goal of building relationships and passion around intersectional feminist philanthropy, the summit intends to broaden the tent of people who understand that when women and girls thrive, we all win – men and boys included. Learn more at www.givinglistwomen.com.

“I need to help drive up the dismal 1.8% of charitable giving that goes to women’s and girls’ organizations.”

• First, approach the featured organizations that you’re curious about. Next, keep track of data released by the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. And don’t forget to support Give to Women and Girls Day on October 11!

“I love this book and want to share it with others.”

• Individuals can receive a complimentary copy of The Giving List Women by visiting www.givinglistwomen.com/signup.

• If you’d like to help distribute larger quantities of the inaugural book – or future editions – to your employees or members, please email jmoran@montecitojournal.net.

CHAMPION PARTNERS:

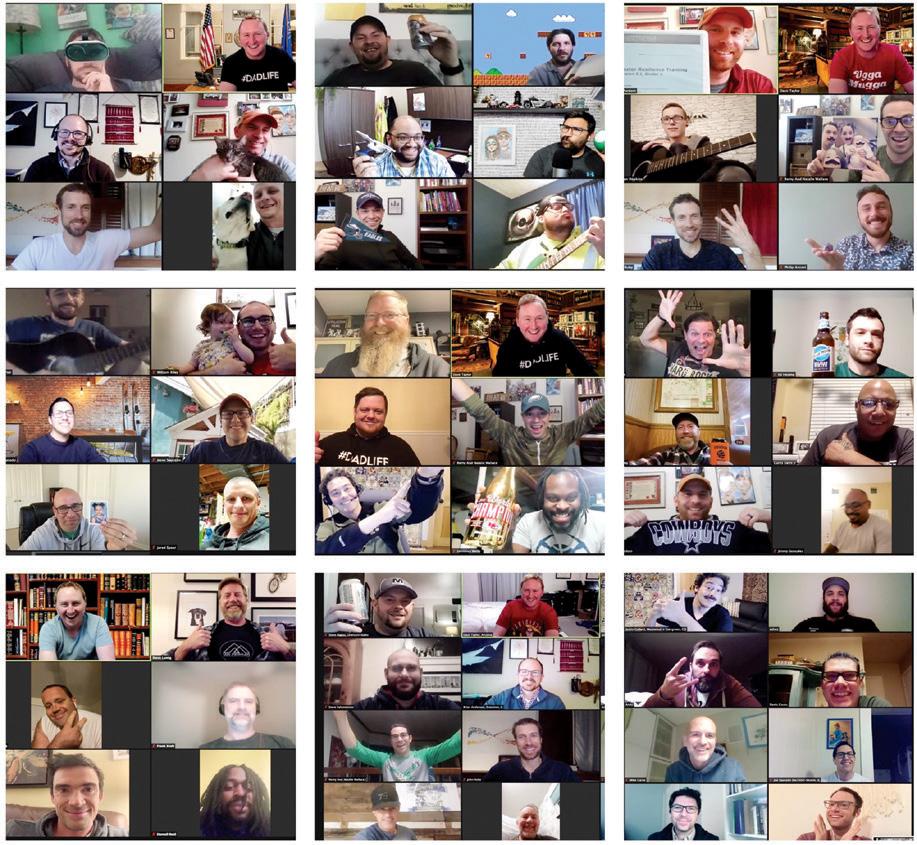

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Grassroots and Grasstops. P.14

Women’s Philanthropy Institute

An Entrepreneurial Approach to Growing Women’s Philanthropy P.18

Women Moving Millions

Taking Bold Risks and Championing Leadership. P.22

CHAPTER 1

Our World P.24 Women Rise to the Challenge

Q&A: Pat Mitchell

Connecting Women for Greater Opportunities and Maximum Power. P.26

CHAMPION PARTNER:

Global Greengrants Fund

Collaborating with Communities, Catalyzing Movements. P.28

Daughters for Earth mobilizes all women to actively engage in climate action by supporting on-the-ground, women-led efforts around the world to protect and restore the Earth. P.30

“…Women are the ones carrying the innovations forward at the front lines. And when they’re in positions of influence, the evidence is clear that they have better environmental policies and certainly better gender and family-focused policies.”

– Pat Mitchell, P.26

“…When you think about all the issues that philanthropy works on, women and girls are at the center, and now in leading nonprofits, leading social change movements in government, and certainly in the issues to which philanthropy seeks to respond… Many of the movement leaders are women. And that lens is very much part of how we think about these issues.”

– Miguel Santana, P.126

Pastoral Women’s Council promotes the cultural, environmental, and educational development of pastoralist women and children to facilitate their access to essential social services and economic empowerment. P.31

WECAN International engages women worldwide in policy advocacy, on-the-ground projects, training, and movement-building for global climate justice. P.32

Pacific Island Feminist Alliance for Climate Justice leads a participatory grantmaking program to resource, connect, and amplify feminist climate action across the region. P.33

Akashinga protects endangered wildlife and ecosystems in Zimbabwe by conducting antipoaching operations, delivering ranger training, supplying equipment and technological solutions, and providing critical project management and administrative support to local communities engaged in preventing poaching and trafficking. P.34

CHAMPION PARTNER: Global Center for Gender Equality

A Dynamic Gender Equality Collective Tackles the Hierarchy of Patriarchy. P.36

Our Democracy P.38

Women’s Equality Is at the Heart of Democracy

Q&A: Kimberlé Crenshaw

What “Intersectionality” Really Means and Why It’s So Crucial for Racial Equality. P.42

CHAMPION PARTNER:

Global Fund for Women

Shifting Power to Gender Justice Movements. P.44

Feminist Majority Foundation develops bold, new strategies and programs, advances women’s equality, non-violence, economic development, and, most importantly, empowers women and girls in all sectors of society. P.46

International Women’s Media Foundation unleashes the potential of women journalists as champions of press freedom to transform the global news media. P.47

The Ascend Fund, powered by Panorama Global, works with organizations to improve the gender composition of state legislatures. P.48

National Women’s Law Center advances gender justice – working across issues that are central to the lives of women and girls. It uses the law in all its forms to change culture and drive solutions toward gender equity. P.49

ERA Coalition works with its partner organizations to provide a strong, multigenerational, inclusive forum for all voices, and to build the groundswell moving toward a more equal future for all. P.50

“...So now we are not sure about feminism. We’re not sure what women’s rights are. We’re not sure how to frame it. We’re not sure about intersectionality. We’re not sure about democracy. All these things are up for grabs right now, and it is our failure to articulate a common narrative and aspiration that is our Achilles’ heel.”

– Kimberlé Crenshaw, P.42

“ When we’re looking at things from different angles, it’s very useful to have some of those angles seen through a woman’s lens.”

– Sara Miller McCune, P.158

Our Security P.52

Accessing Pathways to Build a Thriving Future

Q&A: Kavita Ramdas

The Prism of Philanthropy. P.54

CHAMPION PARTNER: New Moon Network

Leading with Lived Experience: Sex Workers & Survivors Working Together. P.56

The Cupcake Girls provides confidential support to those involved in the sex industry, as well as trauma-informed outreach, advocacy, holistic resources, and referral services to provide prevention and aftercare to those affected by sex trafficking. P.58

Downtown Women’s Center works toward ending homelessness for women and genderdiverse individuals by providing safe housing and supportive services centered on wellness, employment, and advocacy. P.59

Elman Peace Center promotes peace, cultivates leadership, and empowers the marginalized members of society to be decision-makers in the processes that ensure their wellbeing. P.60

Grameen America helps low-income entrepreneurial women build businesses to enable financial mobility. P.61

Friendship Bridge creates opportunities that empower Guatemalan women to build a better life. P.62

CHAMPION PARTNER: California Community Foundation

Creating a Stronger Los Angeles by Boosting Marginalized Communities. P.64

Our Safety P.66

Allies in the Protection and Safety of Women and Girls

Q&A: Hali Lee

The Power of Collective Giving P.68

CHAMPION PARTNER:

Gibson Dunn

Leading the Way to a More Equitable and Inclusive World. P.70

Futures Without Violence works to prevent and end violence against women and children around the world. P.73

Equality Now achieves legal and systemic change that addresses violence and discrimination against women and girls around the world. P.74

Nadia’s Initiative partners with local communities and local and international organizations to design, support, and implement projects that promote the restoration of education, healthcare, livelihoods, WASH (water, sanitation, and hygiene), culture, and women’s empowerment in the Sinjar region of Iraq. P.75

Minnesota Indian Women’s Sexual Assault

Coalition strengthens the sovereignty of its Tribal coalition members and uplifts the voices of survivors and service providers. P.76

Rape Treatment Center provides comprehensive treatment for adult and child victims of rape, sexual assault, and other forms of sexual abuse; prevention and education initiatives that reduce the prevalence of these forms of violence; and training programs for law enforcement and other service providers to enhance the treatment victims receive wherever they turn for help. P.77

CHAMPION PARTNER:

The New York Women’s Foundation

Bringing About an Era of Radical Generosity. P.78

Our Bodies P.81

The Anatomy of Valuing All Bodies

CHAMPION PARTNER:

Linked Foundation

Investing in Women to Change the World. P.82

Q&A: Dr. Jean Berchmans Uwimana

Innovating Equity in Rwanda Through a Trailblazing “Cooking” Show. P.84

Black Mamas Matter Alliance centers Black mamas and birthing people to advocate, drive research, build power, and shift culture for Black maternal health, rights, and justice. P.87

Breast Cancer Alliance improves survival rates and quality of life for those impacted by breast cancer through better prevention, early detection, treatment, and cure research. P.88

Plan C transforms access to abortion in the U.S. by normalizing the self-directed option of abortion pills by mail. P.89

One Heart Worldwide saves the lives and promotes the well-being of mothers and their newborns in underserved areas of rural Nepal. P.90

CHAMPION PARTNER: #HalfMyDAF

An Innovator Inspiring More Giving: Jennifer Risher. P.92

“I’m trying to make the case that giving circles are one important way for us to reanimate and reclaim our democracy –a way to exercise our democracy and civic engagement muscles. Especially when participation in churches, PTAs [parent–teacher associations], the Elks – all those civic associations that animated American culture two generations ago –are plummeting.”

– Hali Lee, P.68

“It’s honestly astonishing because again and again, we see research that says if you invested more in women, particularly women contributing to the economy, trillions more would go to global GDP. That investing in women tends to not only pay back in an economic sense, but also because of the trickle-down effect – the intergenerational [effect], the community effect, of a woman doing well in her community.”

– Cherie Blair,P.138

Our Minds P.94

A Healthier Coming of Age

Q&A: Kara Nortman & Julie Uhrman Women in Sports: Passion, Purpose, and Profitability. P.96

CHAMPION PARTNER: Grantmakers for Girls of Color Guiding Liberated Futures. P.100

Girls on the Run North Bay inspires girls to be joyful, healthy, and confident by using a fun, experience-based curriculum that creatively integrates running. P.102

Girls Inc. of Greater Santa Barbara inspires all girls to be strong, smart, and bold. P.103

Pine Ridge Girls’ School radically changes the trajectory of Lakota girls’ lives by equipping them with vital foundations for new and promising futures full of choice and opportunity. P.104

Stand with Trans empowers and supports transgender youth and their loved ones. P.105

Tools & Tiaras shows girls that Jobs Don’t Have Genders™. P.106

CHAMPION PARTNER:

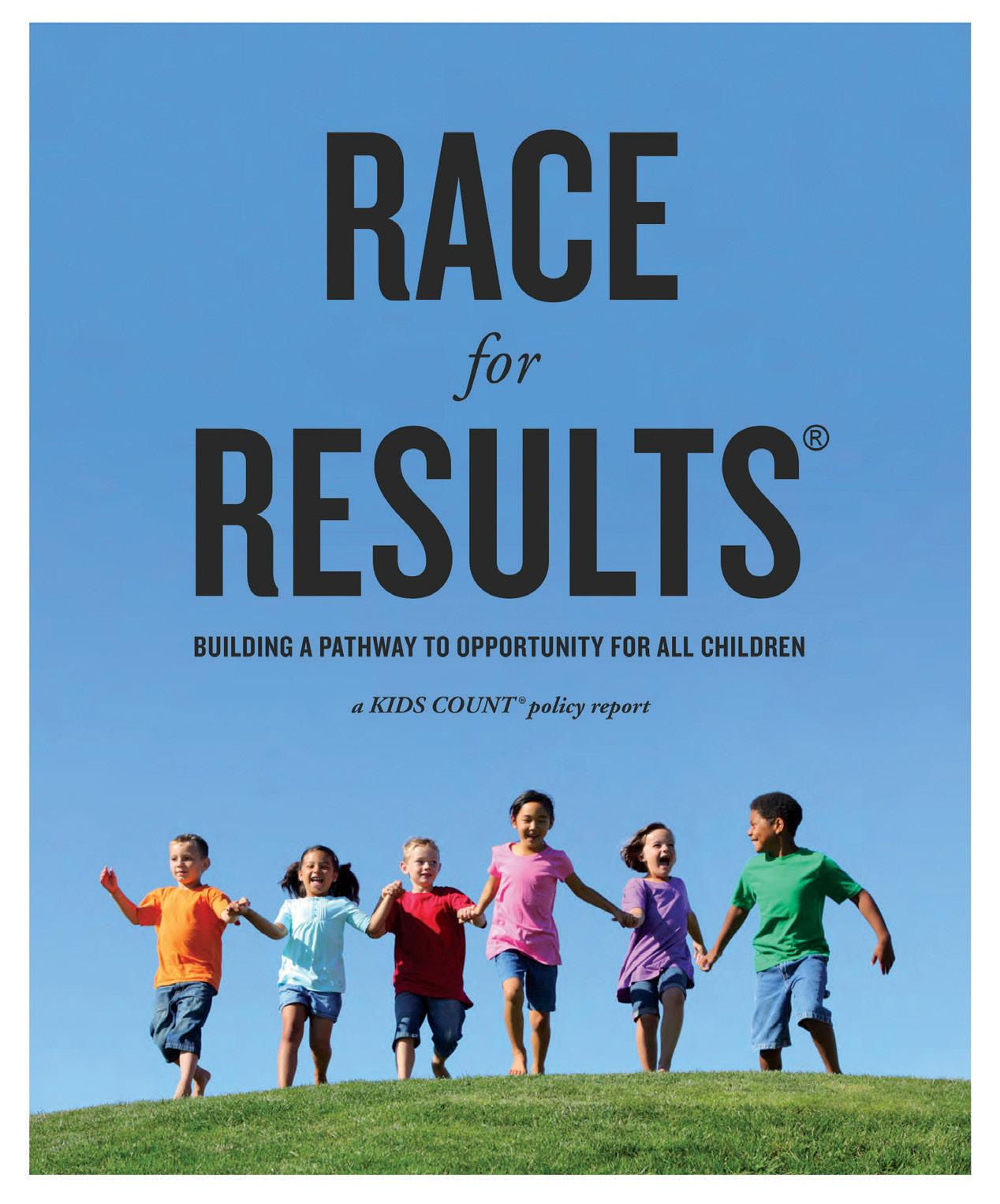

The Annie E. Casey Foundation Overcoming the Barriers to Success. P.108

Our Culture P.110

Lifting Up Women and Girls in the Arts Is Vital to Cultural Progress

Q&A: Franco Stevens Creating Representation. P.112

National Women’s History Museum educates, inspires, empowers, and shapes the future by integrating women’s distinctive history into the culture and history of the United States. P.114

Queer Women of Color Media Arts Project uses film to shatter stereotypes and bias, reveal the lived truth of inequality, and challenge the roots of inequity and injustice through art and activism. P.115

The Representation Project builds a world where all people can achieve their potential and be seen for their full humanity. P.116

V-Day responds against violence toward women, girls, and the Earth. It unifies and strengthens existing anti-violence efforts, and it lays the groundwork for new educational, protective, and legislative endeavors throughout the world. P.117

Girls Make Beats empowers girls by expanding the female presence of music producers, DJs, and audio engineers. P.118

CHAMPION PARTNER:

The Curve Foundation Championing Lesbian and Queer Women’s Stories and Culture. P.120

“Empowering more women directly, giving them more opportunities for education, and helping society know that by doing so, it does not only benefit the woman, but it benefits the country – it benefits the society and everyone who is part of the society.”

– Dr. Jean Berchmans Uwimana, P.84

Our Solidarity P.122

One of the Most Important Social Justice Movements You’ve Probably Never Heard Of

Q&A: Miguel Santana Forever Changed and Engaged by the Strong Women Who Shaped His Life. P.126

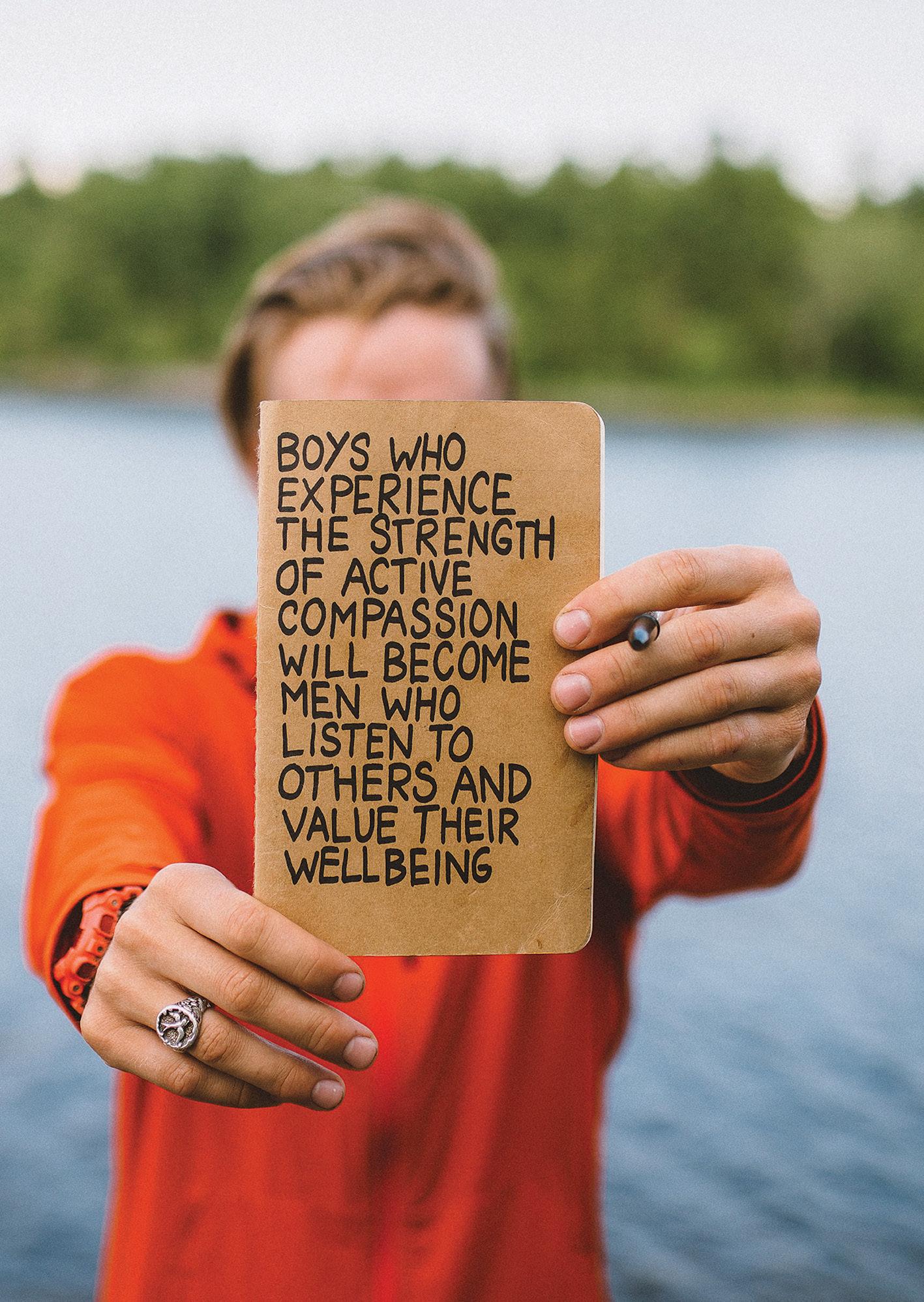

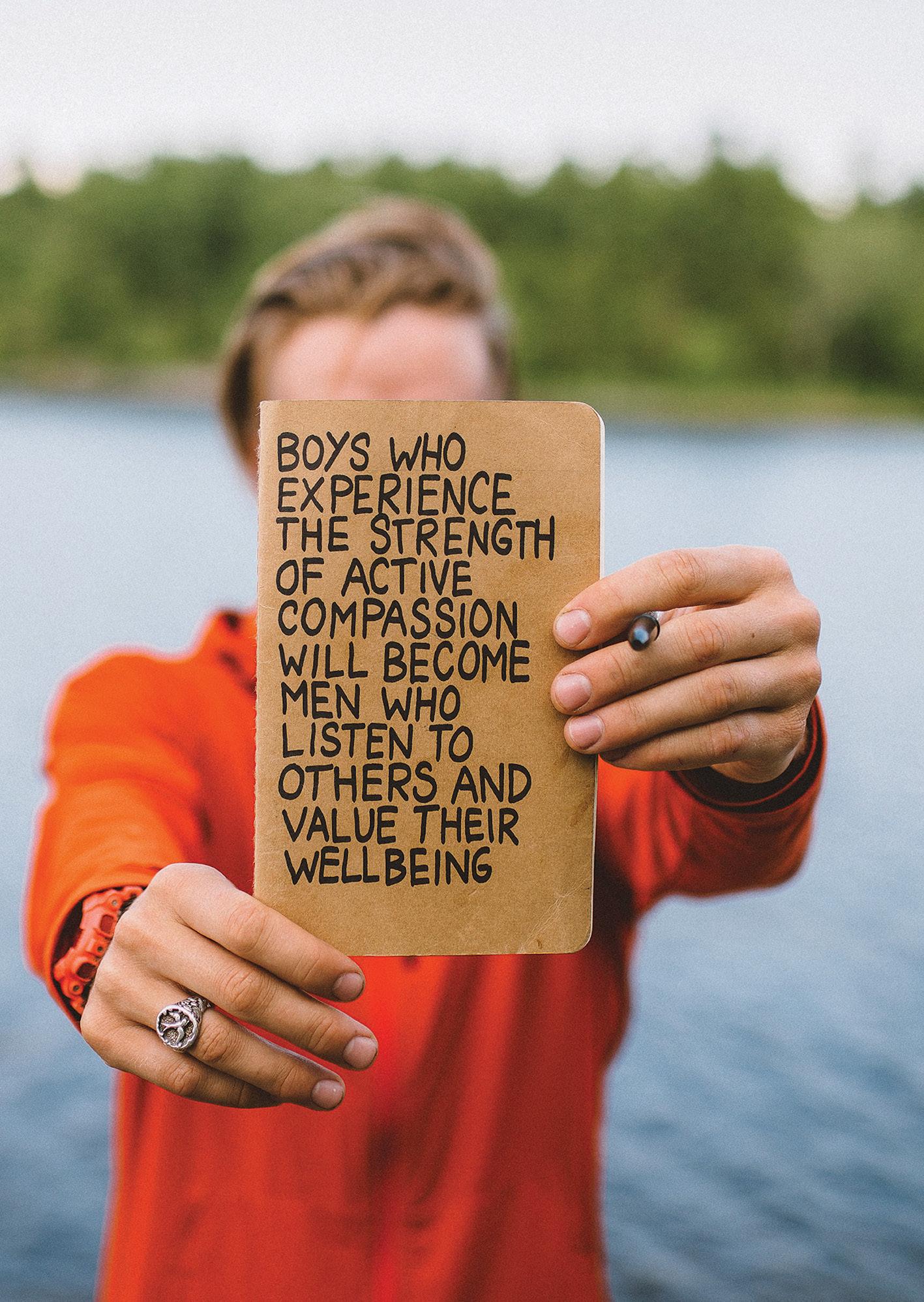

A Call to Men transforms society by promoting healthy, respectful manhood and offering training and educational resources for companies, government agencies, schools, and community groups. P.128

Equimundo works to promote gender equality and create a world free from violence by engaging men and boys in partnership with women, girls, and individuals of all gender identities. P.129

Fathering Together turns dads into positive change agents. P.130

Men 4 Choice unconditionally supports the women and impacted individuals leading the pro-choice movement by activating, educating, and mobilizing male allies in the fight to protect and expand reproductive freedom. P.131

Next Gen Men works to change how the world sees, acts, and thinks about masculinity. P.132

CHAMPION PARTNER: Philanthropy Together Changing Philanthropy’s Narrative Through Community Involvement. P.134

“For me, feminism has nothing to do with what’s between your legs; it’s what’s between your ears.”

– Kavita Ramdas, P.54

“…So little funding is devoted to gay people, and then there’s no accurate demographics on how much money is given to lesbian causes because nobody keeps track of that kind of stuff.”

– Franco Stevens, P.112

Our Careers P.136

Opening Doors to Prosperity

Q&A: Cherie Blair The Woman Behind the Business Revolution for Women. P.138

Cherie Blair Foundation for Women empowers women in low- and middle-income countries to start, sustain, and grow successful businesses, and it builds fair and inclusive business environments. P.140

Equal Rights Advocates protects and advances rights and opportunities for women, girls, and people of all gender identities through groundbreaking legal cases and bold legislation that sets the stage for the rest of the nation. P.141

Lift Our Voices changes toxic workplace cultures. P.142

Women’s Economic Ventures cultivates the power within each woman to realize her dreams, achieve financial independence, and succeed on her own terms. P.143

National Domestic Workers Alliance works for the respect, recognition, and rights for more than 2.2 million nannies, house cleaners, and home care workers who do the essential work of caring for our loved ones and our homes. P.144

CHAMPION PARTNER: Women Connect4Good Lifting Up Women 4 the Future. P.146

Our Leadership P.148

It’s Time for a New Definition of Leadership

Leadership Women empowers and advances women leaders by providing transformative programs, networking opportunities, and leading-edge information on state, national, and global issues. P.151

CHAMPION PARTNER:

illumyn

Elevating Board Candidates to Diversify the Boardroom. P.152

Him For Her accelerates diversity on corporate boards. P.154

Rise Up partners with women, girls, and allies who are transforming their communities and countries as part of a global movement for justice and equity. P.155

Girls for Gender Equity works intergenerationally, through a Black feminist lens, to achieve gender and racial justice by centering the leadership of Black girls and gender-expansive young people of color to reshape culture and policy through advocacy, youth-led programming, and shifting dominant narratives. P.156

Q&A: Sara Miller McCune

Building Sage and Productive Change. P.158

CHAMPION PARTNER:

The Annenberg Foundation

Inspiring Innovative Change and Empowering Women from All Generations. P.160

“ Women’s sports is a cultural institution that brings people joy, that moves their mind, body, and spirit. It moves things forward by getting people to show up, getting their butts in seats, and making them feel part of something that isn’t connected to a screen – part of a community in the real world – and all that makes us feel human and present.” – Kara Nortman, P.96

To learn more about joining The Giving List Women movement, please visit: www.givinglistwomen.com

CEO & Co-Founder

Gwyn Lurie gwyn@montecitojournal.net

COO & Co-Founder Tim Buckley tim@thegivinglist.com

President Janine Berridge janine@thegivinglist.com

Executive Editor Vicki Horwits vicki@thegivinglist.com

Production Manager/Associate Editor

Maya Becker

Elizabeth Long

Art Director Trent Watanabe

Copy Editor Lily Buckley Harbin

Graphic Design/Layout Stevie Acuña

Operations Jessikah Fechner jmoran@montecitojournal.net

Illustrators

Dayna Bowers, Natalie Johnson

Photography Lisa Kristine

Contributors

Aliya Bashir, Alyssa Wright, Anna Lind-Guzik, Aviva Dove-Viebahn, Brenda Gazzar, Brett Simpson, Carrie N. Baker, Cecile Garcia, Dan Schifrin, Ebony Osun Morris, Hannah Murphy, Holly C. Corbett, Isabella Rolz, Janell Hobson, Jen Christensen, Lauren Brathwaite, May Jeong, Nadra Nittle, Rob Okun, Wendy Eley Jackson

the giving list women

is published by: The Giving List Women, LLC. Corporate offices located at: 1206 Coast Village Circle, Suite H, Montecito, CA 93108

Even among nonprofit giants, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is a behemoth. With an $8.6 billion budget for 2024 – larger than the GDP of many small island nations – the Gates Foundation exists in its own stratosphere. As of December 2022, their endowment was $67.3 billion. But here’s what really makes them a giant among giants: ey plan to give all that money away. In his annual letter, CEO Mark Suzman announced a new goal to raise the budget to $9 billion by 2026 in furtherance of Bill and Melinda Gates’ commitment to spend down the endowment within 20 years of their deaths. And they’re calling on other billionaires to do the same via the Giving Pledge, which is a promise by the world’s wealthiest individuals and families to dedicate the majority of their wealth to charitable causes.

F rom its perch atop the philanthropic ecosystem, the Gates Foundation acts as a convener and catalyst, and in the last decade, one of its top priorities has been gender equality. It’s a deeply felt belief that resonates throughout the foundation. When asked why it matters to lift up women and girls, Alex Jakana, a former journalist and now senior program officer for Philanthropic Partnerships at the Gates Foundation, cites the women in his life and his experiences in Uganda, the U.K., and the U.S., witnessing the same challenges for women repeat themselves and how little progress has been made. He also makes an elegant, practical case for gender equality: “If you go to the gym and you work out your left side more than your right side, [the imbalance] is going to affect your entire system. Anything other than equality is the definition of self-harming.”

“ When women and girls are lifted up, they lift up an entire community with them. It’s proven over and over again that women invest in community and the world around us. It’s a ‘rising tides lift all boats’ scenario.”

– Katelen Kellogg

Katelen Kellogg, communications officer at the foundation, credits her education in gender theory and feminist philosophy, and the explanatory power of a gender lens for steering her into philanthropy, first in LGBTQ+ rights and now at the Gates Foundation. “When women and girls are lifted up, they lift up an entire community with them. It’s proven over and over again that women invest in community and the world around us. It’s a ‘rising tides lift all boats’ scenario.”

Although women and girls have always benefited from the foundation’s programming more broadly, it wasn’t until 2014 that the Gates Foundation made its first set of explicit investments in gender equality. Following the 2015 adoption of the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – world development goals that call for a concerted effort toward building an inclusive, sustainable, and resilient future for the people and the planet – the foundation began to scale its investment in gender equality. In 2018, the Gates Foundation launched its first strategy on gender equality, and by 2020, gender equality had its own division. is increasing commitment meant more funding to partners working directly on gender equality, and also an internal structural shift to intentionally and explicitly apply a gender lens and track relevant data across all of the foundation’s divisions.

The foundation serves a number of roles within the feminist funder space, this includes a Philanthropic Partnerships strategy to inspire and enable donors to give more generously. According to Jakana, their team’s goal is to facilitate philanthropy by asking, “What mechanisms would make giving easier and more frictionless?” eir

target audience is the donor who says, “I want to fund this issue, but I don’t know where to write the check.” As Jakana argues, “Gender inequality, for example, is universe-sized,” and people are easily put off from acting.

e Gates Foundation is there to provide community and support. is includes providing research and data, and partnering with learning communities like Greenwood Place, where they’ve planned a deep dive for donors on gender equality as defined by SDG 5.

One data point they’re tracking: Women are poised to inherit a massive amount of wealth in the coming decades as older generations pass. According to the management consulting firm McKinsey, women in just the U.S. are expected to inherit around $30 trillion by 2030. e Gates Foundation sees this wealth transfer to women as an opportunity to build philanthropic networks, pool community resources, and fund programs for gender equality. e foundation takes a similar approach to all its partnerships: “We’re trying to bring resources together and be a convener in a way that’s so often missing in terms of gaps in the market and the larger ecosystem.” is fits within the Gates Foundation’s ethos that we need both “grassroots and grasstops.” Kellogg describes their theory of systemic change: “You not only need power, brilliance, and expertise from community, but that needs

to then be transferred up to the people in government who are making policy decisions and funding decisions related to what those communities are actually receiving.”

On the funder side, what does that look like? Susan Sherrerd was part of a pilot cohort learning journey sponsored by the Foundation to participate in and reflect together on the Women Deliver 2023 Conference. When asked why she funds gender equality, she says, “I believe in a gender equal world without sexism, discrimination, and gender-based violence. Gender equality -- besides being a fundamental human right -- benefits everyone, men as well as women.” It’s essential, she says, to achieve peaceful societies and a sustainable world. As for what message she would share with prospective Giving List Women donors? Don’t wait until you think you’re ready. “Confidence and skill come from making the grants,” she says. Also, manage your expectations and think long-term because social change work isn’t like vaccine development, for example, with a clearly defined problem and solution. No one organization, institution, or donor can solve gender equality on their own. Don’t duplicate efforts. “Giving collaboratively with other donors leverages my grants and catalyzes my impact to address the scale and complexity of gender inequality.”

– Grantee Partners as Critical Intermediaries

Increasingly the money going to fuel gender equality is being directed to collaborative funds, critical intermediaries with local relationships, cultural context, and skills in advocacy and communications. ese collaboratives increasingly practice Trust-Based Philanthropy and are often led by women and people of color. e end goal is to close the distance between donors and grassroots organizations already doing the work in

We’re trying to bring resources together and be a convener in a way that’s so often missing in terms of gaps in the market and the larger ecosystem.

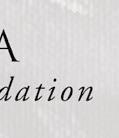

Walking the Talk in a visual – or what an ideal feminist foreign policy (FFP) may look like according to 70+ participants at an FFP Community Festival held in the Netherlands in October 2023. (image: Holland Park Media)

their own communities. To do that, the foundation seeks out grantee partners that build bridges – nonprofit partners, regional funds, feminist collectives that are best positioned to act as intermediaries. “Bridge-building reduces the likelihood of losing things in translation. It speeds up the ability to be able to connect. It reduces the likelihood of hurting while you’re trying to help,” says Jakana.

One grantee, Komboa, is an African regional collective of feminist funds whose name translates to “transform” in Arabic, “liberate” in Swahili, and “resist” in Creole. Komboa describes itself and its mission as follows: “Each institution in the collective exists to resource different communities within the dynamic and broad demographic of African women, girls, and gender-diverse peoples, with evidence-based and community-informed strategies that advance gender justice and center the experiences of their target communities. Our collective mission is to resource and strengthen feminist resistance, movements, and collectives across Africa, enabling them to advance gender justice and be inclusive, and resilient to the attacks from anti-rights movements.”

Another grantee, Walking the Talk, is a European consortium of organizations advocating the full potential of feminist foreign policy. Like Komboa, Walking the Talk is a regional collective responding to the global backlash against

women’s rights. ey’ve united to unlock “a feminist foreign policy that places gender equality and the rights of women, LGBTIQ+ people, and other marginalized groups at the heart of all areas of foreign policy – be it trade, diplomacy, global health, climate justice, or security. From the four Rs –Rights, Representation, Resources, Reality Check – Walking the Talk focuses on getting more Resources into the hands of feminist movements in the Global South.”

e Gates Foundation’s pledge to “spend it all down” will have a tremendous, enduring impact across philanthropy. But their efforts to inspire billions to intersectional feminist collaboratives enabling grassroots activists to make continental-scale systemic change will likely have a global transformative impact driving progress for women and girls around the world.

Jeannie Infante Sager, director of the Women’s Philanthropy Institute (WPI) situated within the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, brings a unique perspective as a seasoned frontline fundraiser and nonprofit leader. “What drew me to the institute was this entrepreneurial approach to improving behaviors in the (philanthropic) field and growing women’s philanthropy in a much more focused and intentional way,” says Sager.

WPI, founded in 1991 as the National Network of Women as Philanthropists, conducts, curates, and disseminates in-depth research so that women’s philanthropy, and philanthropy dedicated to uplifting women and girls, can grow.

WPI is part of the acclaimed Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, the world’s first school dedicated solely to the study and teaching of philanthropy. e Lilly Family School of Philanthropy is a treasure trove of philanthropic resources, research, and learning opportunities for those interested in pursuing a career in philanthropy.

A Global Hub for Harnessing the Power of Women’s Philanthropy

Sager joined WPI in early 2020 amidst global health challenges. She immediately focused on enhancing WPI’s global standing as a hub for women’s philanthropy, study, and education. With an existing audience of fundraisers and wealth advisors, she aimed to expand the network of donors and women philanthropists, instilling confidence by showcasing their role in the research. Sager believes a philanthropist’s identity is reflected in how they give and express generosity.

“Where I hope the work of translational research impacts the practice is that more women continue to self-identify as philanthropists. And that they can confidently contribute new and expanded resources to and for the public good, and that they’re showing up in different ways,” says Sager.

While there is great enthusiasm surrounding the increased visibility of prominent women – such as MacKenzie Scott and Melinda French Gates – who openly express their philanthropic agency, to unlock the full potential of women’s philanthropy, WPI knows that we must understand how gender shapes giving. eir research seeks to answer why women give where they give.

Sager firmly believes the ongoing growth of women’s wealth will drive more philanthropy, an underpinning of WPI’s research. However, she expresses the importance of delving deeper into understanding how women make financial decisions, not just in their philanthropy but also in managing their other finances.

“Reports suggest that 90% of women say that they’re the chief financial officer of their households, so we want to continue to better understand why women seem more inclined than men to use their wealth for philanthropy,” says Sager.

She states that figures like French Gates stress that supporting women and girls translates to supporting communities and society, given that women often set goals considering both their families and the broader community.

W PI is the only academic institute committed to furthering understanding of gender and philanthropy through research, education, and data. WPI’s research can help fundraisers and donors understand context for giving and can provide evidence-based data to help both groups proceed with confidence.

Among their stellar research is their signature series, Women Give, a compilation

Philanthropic support for women’s and girls’ organizations totaled $8.8 billion in 2020, remaining less than 2% of overall charitable giving.

TOTAL CHARITABLE GIVING: $486.3 B $8.8B 2020 1.8%

“ Where I hope the work of translational research impacts the practice is that more women continue to self-identify as philanthropists. And that they can confi dently contribute new and expanded resources to and for the public good, and that they’re showing up in different ways.”– Jeannie Infante Sager

of yearly research reports that highlight vital factors that shape gender-based giving (such as age, religion, and income) to help to encourage transformative philanthropy.

Sager believes that WPI’s research has the potential to uplift, amplify, and inspire more women to fully embrace and step into these influential roles.

Another WPI flagship research project is the Women & Girls Index (WGI), which provides the only comprehensive data on organizations dedicated to women and girls and tracks the philanthropic support they receive. U.S. nonprofits focused on advancing these causes received $8.8

EquitableGivingLab.org/WGI #GiveToWomenAndGirls

billion in philanthropic support in 2020. is amount constitutes just 1.81% of the total charitable giving landscape.

“What the fifth annual Women & Girls Index says about the current state of funding for women and girls is that there is huge room to grow,” says Sager. “We now have a benchmark to work towards. anks to the WGI, we’ve defined what a women’s and girls’ serving organization is here in the United States, which wasn’t defined before. We could put some parameters around this question about giving to women and girls and then create a data point around it. It has resonated for the sector that these women’s and girls’ organizations were excited to be recognized as such, to know that they’re part of this index, and to be able to use that data point as a call to action for support.”

Sager underscores the significance of the less than 2% figure for organizations ranging from well-known entities like Women Moving Millions to smaller grassroots organizations serving local communities. is figure has been instrumental in generating momentum for charitable contributions. However, she acknowledges that the sector has grappled with the stagnation of the percentage, as there hasn’t been any notable movement beyond the less than 2% threshold since WPI began tracking it.

Sager stresses that WPI works to translate research into practice. Given its location at a large state-sponsored research institution, WPI turns to its strategic partners and creative initiatives to advocate for increased philanthropy towards women and girls.

Sager also highlights a rising concern over heightened politicization of women’s issues. She reflects on her onetime mentor’s perspective, who framed it as part of the “moral imagination,” where philanthropy navigates a crossroads between diverse agendas. She acknowledges that both organizations that uplift women, like the Ms.

Foundation for Women, and extremist groups that target women operate within their own “moral imagination.”

“We want to do research that shares answers to questions based on the facts and without preconceived agendas. Wherever those answers end up, we also know that we have a responsibility to give voice to these organizations that are doing well and to women donors who want to be more outspoken,” Sager says.

Sager acknowledges a unique gap in dedicated giving communities for women and girls, unlike initiatives supporting causes like climate or animal welfare. To that end, WPI’s creation of Give to Women and Girls Day, supported by anchor partners like Pivotal Ventures, Women Moving Millions, and the National Women’s Hall of Fame, has been impactful. Aligned with the International Day of the Girl on October 11, it exemplifies a collaborative journey, and has been well-received but still has room for growth. Sager emphasizes the promotion of Give to Women and Girls Day through a gender lens, advocating for an abundance mindset.

“[Let’s] grow and not worry about the fact that the pie is somehow only going to be a certain size. Make a bigger pie! Give us a bigger slice! e more people who are talking about it, the better. And I think everybody understands that, and that’s why coalescing around Give to Women and Girls Day has been a really great collaboration,” she says.

Sager engages audiences in discussions about WPI’s research and finds it intriguing that, despite her familiarity with the data, many people approach her after presentations, having encountered the research for the first time.

“It’s important to support women and girls. We need to move the needle on this less than 2% [statistic] because other research indicates that by supporting women and girls and all the different intersections of causes they operate in, we’ll get more impact for our investment,” says Sager. “ e consequences of inaction in this field of work are there are less resources going to important missions. at’s the consequence.

“It is about changing donor behavior, and that’s hard. We must examine social norms and how we inspire people to operate differently and within their authenticity to allow them to live their values. Success for WPI continues to be more researchers looking at gender as a variable and an important concept in philanthropy and giving.”

Please contact us to learn more about:

Jacqueline Ackerman Interim DirectorPost O ce Box 6460 Indianapolis, IN 46206

Tax ID# 35-6018940

(*Indicate Women’s Philanthropy Institute as direction for gift)

We had just finished distributing the first edition of e Giving List – Bay Area when I received a call from Stacey Keare, a Silicon Valley philanthropist and Board Chair of Women Moving Millions (WMM).

“I love e Giving List book; my family uses it for our giving,” Keare began. en came the question that would change the trajectory of my life’s work and that of our company. “Would you ever consider doing a Giving List Women?” Keare posited.

And so began my years-long journey into understanding how profoundly underfunded nonprofit organizations are that primarily focus on women and girls.

More importantly, as I talked with Women Moving Millions, whose mission is to catalyze unprecedented resources for a gender-equal world, I began to understand that the irony of the perpetual underfunding of women and girls is that women and girls are widely understood to be the most powerful lever for the very impact most philanthropists and donors seek to bring about.

“Investing in women and girls is the smartest social change strategy. If you care about impact, why are you not investing

in the

most effective and proven and researched way to accelerate change? When you invest in women, everybody benefits.”

Women Moving Millions inspired me to think more deeply about how we can support donors at every level to understand the importance of treating women and girls as a lens, and not a lane, in philanthropy. I became motivated to consider what it would take to drive billions of donor dollars to organizations that focus primarily on this demographic.

And so e Giving List Women was born. We are grateful to WMM for joining us as our first partner in this exciting new venture.

“Women have the unique combination of skill sets that the world presently needs,” says Sarah Haacke Byrd, CEO of WMM, a vibrant, dynamic network of nearly 400 female philanthropists committed to building a gender-equal world.

In its 15 years, WMM has catalyzed an impressive $1 billion in funding from its members specifically benefiting organizations and initiatives that empower women, girls, and gender-expansive people. Now the organization is committed to unlocking the next $1 billion at an accelerated pace.

WMM sees itself as a convener, educator, and resource advocate, uniting changemakers around a shared cause while also building their capacity for greater impact and pushing forward the broader movement for women’s rights.

“Members join Women Moving Millions because they want to be part of a supportive peer network with other philanthropists who care deeply about improving the lives of women and girls,” Haacke Byrd explains. “ ey also seek out this com-

munity to enhance their own philanthropic education.”

Mona Sinha, former WMM Board Chair and current Global Executive Director of Equality Now, agrees. “My community at Women Moving Millions both challenges me to be better and brings me so much joy,” says Sinha. “It is understanding the power that each one of us has, what we can do together, and how we can meet the urgency of our times. e support and closeness that the WMM community offers is a wonderful model to share with other communities and spaces that I engage with.” e organization champions core values of trust-based philanthropy, encouraging members to take bold risks and move major resources while giving grantees more flexibility. is contrasts starkly with the wider landscape, where less than 2% of all U.S. philanthropic dollars goes specifically towards organizations empowering women and girls.

A critical message WMM pushes is just how strategically smart – and profoundly ethical – it is to invest in women-focused programs. “Investing in women and girls is the smartest social change strategy. If you care about impact, why are you not investing in the most effective and proven and researched way to accelerate change? When you invest in women, everybody benefits. From strengthening public health to reducing poverty, research clearly shows lifting up women creates a halo effect benefiting families and communities more broadly,” says Haacke Byrd.

WMM spotlights members’ stories to inspire others to join the movement. Profiles of young inheritors like WMM members Elsa Soderberg and Vanessa Evans showcase how women are driving social change wherever they are in their own unique philanthropic journey. ese narratives also counter staid assumptions that female philanthropists are inherently more risk averse. “Women are truly leading a new approach to giving, using their voice and influence, embracing bold collaborations, and taking risks in their giving all the time,” says Haacke Byrd.

By positioning members as forward-thinking leaders in this space, WMM focuses on building the confidence of its members to dream even bigger. is capacity building connects to the enormous intergenerational wealth transfer currently underway, with women set to inherit over $30 trillion in the next decade. Haacke Byrd wants to leverage this milestone to make women’s giving even more visible and accessible and by supporting women to step into their leadership.

“I think that women inherently are more inclined to build consensus, collaborate, and ensure everyone has a seat at the table,” says Haacke Byrd. “Rather than making unilateral decisions, women tend to lead through compassion, respecting complexity, and elevating alternate standpoints.” ese inclusive leadership traits prove doubly important considering the escalating crises our society currently faces. “ e challenges before the world today are too complex for us to manage alone, or by a small group of men in some back room,” says Haacke Byrd. “It’s just

WMM Board Chair, Stacey Keare, participates in WMM’s Annual Member Day in May 2023. (Photo by Myleen Hollero Photography)

simply not possible to actually meet the moment and what’s being required of humanity.”

Instead, realizing change requires unlocking women’s collective leadership and influence across public, private, and social sectors. rough community building and capacity-expanding platforms like WMM, Haacke Byrd sees immense potential to advance gender equality through bold, trust-based philanthropy. True to its name, Women Moving Millions seeks to exponentially accelerate resources benefiting women and girls worldwide by catalyzing women’s innate power to transform lives.

According to Keare, WMM is only starting its journey to positively impact the rights of girls and women in this country and across the world. “Women and girls are beginning to make a huge imprint on the vision of a better world,” says Keare. “ e goal is no longer fitting into a man’s world but creating one that will be better for everyone. A world in which we protect the Earth, include everyone, create new forms of leadership, and work together to make life better and fairer for us all.”

Please contact us to explore membership opportunities:

Amanda Gri n Director of Community Engagement agri n@womenmovingmillions.orgWomen Moving Millions

New York, NY

TaxID# 45-2576859

womenmovingmillions.org

As temperatures rise around the world, one thing is clear: Women are paying an outsized price. The United Nations estimates that 80% of those displaced by climate change are women. Women are likelier victims of natural disasters, and pregnant women and babies are especially vulnerable to climate change. Black, brown, and Indigenous women, as well as women in the Global South, bear an even heavier burden due to systemic inequities wrought by centuries of racism and colonialism.

But there’s another side to this story: The same forces that make women more vulnerable uniquely equip them to lead solutions. In the Global South, women collect two-thirds of water supplies and are responsible for up to 80% of food production. As they are on the front lines of water and food scarcity, disaster recovery, and biodiversity loss, women are well-positioned to identify root causes and dream up solutions. Through the process, research shows that they’re core agents for peacemaking and likelier to work to improve their entire community.

Women in higher-income countries are better advocates for the environment, too. One study found that, in Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, women, who make over 80% of consumer purchasing decisions, are more likely to recycle, buy eco-friendly products, and focus on lifestyle changes to combat climate change. A 2021 survey of European Union citizens revealed that women are slightly more concerned about –and likely to have taken action against – climate change than men.

At the highest level, women leaders make more climate-forward decisions. A 2005 study indicated that countries with more female representation in their parliaments are more likely to ratify international environmental treaties. Research in 2019 suggests that the election of more women to parliaments can lead to countries adopting more rig-

orous climate policies and lowering carbon dioxide emissions.

If global disempowerment of women has been bad for the Earth, the era of climate change is also an opportunity to rethink the systems that got us here. From fossil fuel reliance, to wasteful or crumbling water infrastructure, to an unsustainable and inequitable global food supply, it’s clear that the status quo is failing. As we leave behind extractive systems of the past, we have an opportunity to do away with the gender inequities they perpetuate and build a more just future.

Despite the evidence in favor of investing in women, less than 2% of environmental funding goes to women-led projects. At the highest level of climate leadership, women decision-makers are still underrepresented: In 2023, only 15 of the 133 world leaders at the 28th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28) were women. In 2024, COP29 host Azerbaijan announced an allmale 28-member conference organizing committee. (After criticism, the government included 12 women.)

The challenges of climate change can feel overwhelming, and it’s tempting to feel hopeless. But women on the front lines of the planet’s most drastic changes – who are responsible for the well-being of the most vulnerable and often for entire communities – don’t have the choice of despair.

And women around the world are acting. They are rewilding forests, feeding their communities, and protecting wildlife. They are rebuilding after cyclones, constructing seawalls, and educating their communities on reproductive health and biodiversity. These women, and their allies, are leading the transition out of an era of extraction and exploitation, and dreaming up new systems of support, regeneration, and care.

These are some of the women – and the organizations supporting them – who are taking on the responsibility of hope with courage and ingenuity.

Pat Mitchell is a pioneering figure in the media industry, a dedicated advocate for women’s rights, and a firm believer that gender justice and environmental health go hand in hand.

As the first woman president of PBS and CNN Productions, Mitchell oversaw the production of documentaries and series that received 37 Emmy Awards, five Peabody Awards, and two Academy Award nominations. Her Emmy-winning TV talk show Woman to Woman was the first national program produced and hosted by a woman, and she personally received a Primetime Emmy Award in 1996 for Survivors of the Holocaust on TBS.

Mitchell is chair emerita of the Women’s Media Center; chaired the board of the Sundance Institute; and, in partnership with TED, launched TEDWomen in 2010. She continues to serve as TEDWomen’s editorial director, curator, and host. Among many honors, she has received the WICT Network Woman of the Year Award and the CINE Golden Eagle for Lifetime Achievement.

Mitchell’s impact has become increasingly global, as she continues to connect the stories and leadership potential of women around the world through projects like V-Day, a movement to end violence against women and girls; the WOW – Women of the World Festival in London; and the Connected Women Leaders initiative, which brings together women leaders in government and civil society. Among the initiative’s key ventures is Project Dandelion, a women-led global climate justice campaign.

Mitchell is the author of the 2019 memoir Becoming a Dangerous Woman: Embracing Risk to Change the World.

Giving List Women: You served as the [president and] CEO of PBS and of the Paley Center for Media when few women held such positions. Did that inform your choice to spend much of your life working to support women and girls?

Pat Mitchell: Growing up in the rural South, the expectations for girls were severely limited. I was almost

always the first or only, as was any girl or woman who wished to break through those boundaries and expectations. That never felt right, and always [felt] lonely. So, the first commitment I made internally without recognizing it was to bring other women into those spaces with whatever influence I had.

Creating opportunities for women to tell their own stories and ideas was embedded in my work. That’s not altruism. That was the feeling that if I have this power or influence, I must use it to create another opportunity for another woman or elevate her accomplishments. And then moving from being a journalist to being an executive who got to hire people and make decisions about programming, I felt that as a woman of privilege and good fortune, it was my responsibility to bring more along.

GLW: Were you leading differently than the men with whom you were working?

PM: Absolutely. I believe all women do if they allow themselves to be in touch with their full selves. Women and men bring different skills to leadership. But often women leave them behind as they attempt to succeed on the same terms as the men they replace or who hire them. But if we don’t bring different skills and interests to the table, then the argument for having more equal leadership falls away. It’s the differences that make it imperative to have both women and men in leadership positions for the best, most balanced use of power.

If you look at transformative women leaders, they bring their full intuition, capacity, and interest in collaboration – their ability to build consensus. We come to positions with experiences that are part of being a woman. Part of being a mother, a wife, a partner.

GLW: Why did you decide there needed to be a TEDWomen?

PM: As a TED audience member for years, watching mostly man after man go on that stage and give a TED

Talk about an idea, there were very few women. So, I asked [TED Curator] Chris Anderson, “How can you not be interested in the ideas of half of the world’s population?” He said, “I’d love to, but I can’t find them.” Well, that’s all you have to say to somebody who spends her life connecting women. I said, “I can find them.” And he said, “I’m looking for a rocket scientist for the next TED.” I found him 10 women without breaking a sweat – five of them women of color. So, I said, “Why don’t we try and create a TED platform featuring women giving TED Talks, and we’ll invite men, too?” We thought the first one would be the last. Then 1,700 people showed up on the coldest day of the year in D.C.

“If you look at transformative women leaders, they bring their full intuition, capacity, and interest in collaboration – their ability to build consensus. We come to positions with experiences that are part of being a woman. Part of being a mother, a wife, a partner.”

GLW: Women are not monolithic. But can our life experiences bring important leadership assets like collaboration and respectful discourse?

PM: You’ve just described the rules for our convenings with the Connected Women Leaders forums. We often have different political views. We certainly have different priorities and commitments. But in this room, we can collectively problem-solve, we can find consensus, we can lead. And out of that has come astonishing innovations including Project Dandelion, which grew out of a group of climate leaders and non-climate leaders saying this competition for resources is keeping the work siloed. We needed connective tissue over the silos to connect the women to each other in positive ways. And that’s been our work for the last 18 months – connecting frontline women leaders, across every sector of social justice issues, intersectional with the climate and nature crisis.

GLW: Project Dandelion is a good example of applying a female lens to a critical issue.

PM: When [former President of Ireland] Mary Robinson first came to me and said, “We have to make climate the key work of the Connected Women Leaders,” I said, “But gender equality must remain our top gender justice issue.” “Gender justice is climate justice, as is racial justice and digital rights justice,” she said. Getting

out of that siloed mindset is why we decided to start a movement rather than another organization, which could be seen competitively.

We started realizing how little people knew about the disproportionate negative impact of the climate crisis on women and girls. Education is disrupted, more girls are married off, reproductive health is seriously threatened. Eighty-four percent of those who’ve died from climate-related disasters are women and girls.

We have over 800 climate organization partners, and we elevate their work and tell their stories. Our message is, climate is everyone’s issue, just as gender is everyone’s lens on how we spend our money.

GLW: Would you say that Project Dandelion is one of the most impactful efforts of which you’ve been a part?

PM: I would say if we don’t get this one right, we won’t have a habitable planet. It’s the most important work that anyone can be involved in because we are at that crossroads where if we go this way, we’re looking at a catastrophic future. And if we go this way, we’re on the cusp of getting it right. And from what I’ve witnessed, we’re going to get it right if women are in leading positions. Because women are the ones carrying the innovations forward at the front lines. And when they’re in positions of influence, the evidence is clear that they have better environmental policies and certainly better gender and family-focused policies. That’s the premise of Project Dandelion. It’s integrated, intersectional work that speaks to a more just, peaceful, and prosperous world where men and women share power.

The water was rising: On the western coast of Bangladesh in the early 2000s, communities deep in the Sundarbans mangrove forest began tasting salt in their drinking water and watching their elds ood and crops choke and die. It was a crisis coming to coasts around the globe: the steady creep of sea level rise.

In the Global North, the crisis didn’t go unnoticed. Year after year, major investors were pouring millions of dollars into the construction of seawalls around the villages. And year after year, as storm surges increased, those seawalls were crumbling.

But locals knew that their villages once had a natural defense: the mangroves. is once-dense barrier, diminished by decades of logging and development, had shielded their communities from the sea for generations. In the early 2010s, one group of women began their own movement to restore it – mobilizing their community to plant and protect the trees. As the forest came back, slowly but surely, it began to slow the ooding.

“It’s an example of how top-down approaches fail to closely observe what’s happening,” says Laura García, president and CEO of Global Greengrants Fund. “ ese communities live there, experience the problem, and understand why those multimillion-dollar initiatives do not work.”

Today, Sundarbans reforestation is one of thousands of projects supported by Global Greengrants Fund, which connects philanthropic dollars to grassroots organizations ghting for human rights and environmental justice around the world.

Before 1993, when Global Greengrants Fund was founded, there would have been virtually no way for philanthropy in the Global North to nd, let alone sup-

“ We need to take a transformative approach. To tap into the feminist theories of economic sustainability and equality that are countering the systems of oppression that generated the climate crisis in the fi rst place.”

port, the communities in the Sundarbans. Paradoxically, the highest-impact, lowest-investment work seemed the most di cult to support.

“ ere’s a huge gap between resources needed by hundreds of thousands of small-scale organizations and the large amounts of funding sitting in the Global North given through traditional large-scale investments,” García says.

Global Greengrants Fund works to close this gap.

eir “people and planet” approach acknowledges that those living on and caring for the land are best equipped to identify and create ways to protect it.

Across Africa, the Arctic, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, and the Paci c Islands, they are supporting more than 1,300 grassroots environmental organizations annually in areas from youth, disability rights to gender justice, organizations that would likely previously never have otherwise found support.

“Global Greengrants Fund was born out of the great opportunity to democratize the funding from the philanthropic sector to be able to advance environmental justice globally,” García says.

Grassroots Movements Take the Lead

How does a global fund nd organizations that are, by de nition, hyperlocal and movement-based? By working from the grassroots up. For three decades, Global Greengrants Fund has steadily grown their network of more than 215 advisors who are deeply connected to local communities and environmental justice causes around the world. Advisors bring their nominations to one of 30 regional or thematic advisory boards that connect these groups to the funding.

“ e decentralized grantmaking decision system is unique in the philanthropic space,” García says. “It’s about participation and treating grantees as true partners.”

Another core aspect of these grants is their exibility. By leaving the terms of the agreement more open ended, Global Greengrants Fund puts trust in the community to confront and be exible to new challenges as they arise.

Flexible funding also allows for unconventional ap-

proaches. As an example, Global Greengrants Fund’s Latin American advisory board recently observed a pivot taken by a group of Indigenous women grantees organizing their communities to oppose mine approvals. During the pandemic, as a food security crisis emerged, these women began using their funds to set up community kitchens. After the worst of the pandemic was over, they had built up so much credibility in their communities that they saw a surge in meeting attendance and newfound support from initially skeptical male leaders.

Building a new philanthropy model requires confronting both new and age-old systemic challenges like gender injustice. Global Greengrants Fund recognizes that climate change disproportionately a ects women, who receive only a minuscule fraction of climate investment. Since 2014, they’ve rapidly increased their grantmaking to projects that address the gendered e ects of climate change. Today they are one of the world’s top public foundations supporting gender-just environmental initiatives, which comprise over 50% of their grants. “We need to take a transformative approach,” García says. “To tap into the feminist theories of economic sustainability and equality that are countering the systems of oppression that generated the climate crisis in the rst place.”

Global Greengrants Fund was built for this work. To nd those in need who are working towards a new vision for their world and connect them directly with those who can support it. ey are extending their advisory board grantmaking model to underfunded areas like Central Asia, and launching thematic boards for Indigenous Peoples’ rights, plastics, and zero waste among others. But at the center of all of their work is gender.

García says, “We cannot really expect to tap into that magic of imagining equality and justice if we don’t fund those who have been ghting for it for a very long time: women.”

Please contact us to learn more about Global Greengrants Fund:

Kézha Hatier-Riess Vice President of External Relations kezha@greengrants.orgwww.greengrants.org

Global Greengrants Fund LLC Tax ID# 84-1612422

What part can I play in the climate ght?

To answer this question, the late Kenyan environmentalist Wangari Maathai, who won the 2004 Nobel Peace Prize, told the parable of the hummingbird: As a wild re tears through a forest, all of the animals stand frozen, immobilized by fear. All except the hummingbird, which ies to the river, lls its beak with water, and drops it on the re. e other animals ridicule it as it zips back and forth, ghting the re one droplet at a time. e tiny bird looks at each of them and says, “I am doing the best I can – are you?”

For Zainab Salbi, co-founder of Daughters for Earth, the hummingbird story is key to her organization’s mission: to elevate women around the world who are proving that no e ort is too small.

“With everything going on in the world, every day can become fear oriented,” Salbi says. “ e Hummingbird [story] is about shifting the focus and putting it on hope.”

Take Flávia Neves Maia, a Brazilian urban planner. And a Hummingbird. When Neves Maia moved to Barra Grande, a shing village threatened by both climate change and tropical deforestation, she joined a local women’s circle that took a personal approach to discussing climate action. Together, they devised a plan to regenerate local mangrove forests – and created a model to spread and scale community-led climate responses.

Funding is only the rst step. Step two: “We celebrate the heck out of them.” Neves Maia is now the hero of a colorful graphic novel. ese “Hummingbird Community” novels come out weekly, forming a series that shares stories of women like her.

Reframing the Narrative

I

n philanthropic giving, Salbi says she’s seen the bias against women-led, small-scale solutions rsthand. She says philanthropists often prefer to invest in expensive, high-tech solutions over small-scale, human ones.

“Other donors chase after the inventions, the ‘let’s extract carbon from the sky,’” she says. “We say, ‘Let’s get back down to Earth and see what people are doing to solve this.’”

And they’re gathering data to help show that investing in local, women-led solutions is not just the right thing to do – it will be essential to global climate-related goals.

In 2023, Daughters for Earth teamed up with Vital

Voices to power Foreign Policy’s FP Analytics division report “Accelerating Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change rough Women’s Leadership.” is report helped prove that both women-led and nature-based solutions remain under-prioritized and underfunded. Yet research shows that women act as multipliers leading nature-based solutions around the world. If used widely, nature-based solutions could provide roughly 30% of the cost-e ective mitigation necessary to keep warming below two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by 2030.

“Women don’t need to be empowered. ey are in their power,” Salbi says. “What they need is to be reinforced, echoed, heard, supported, and celebrated.”

Today, Daughters for Earth has funded 103 women-led organizations in 37 countries, with plans to expand. Every Hummingbird and their story, Salbi hopes, will help mobilize women around the world.

Daughtersforearth.org

Casey Rogers Chief Mobilizing O cer (201) 308-3044

casey@daughtersforearth.org

Ways to Give...

By Check or DAF:

NEO Philanthropy, Inc. 1001 Avenue of the Americas 12th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Tax ID# 13-3191113

*NEO Philanthropy (Fiscal Sponsor of Daughters for Earth)

While Maanda Ngoitiko was growing up in her Maasai community in northern Tanzania, a blade of grass was the symbol of a woman’s place in society, growing quietly. If she had the privilege to attend a meeting, waiting for a man’s invitation would be her only opportunity to speak.

At five years old, Ngoitiko was one of only two girls her age selected to begin school. Later, with help from a local member of Parliament, she rejected a forced marriage and left her village to continue school.

“I was so scared, so lonely, and felt powerless,” she says. “But with education, I learned self-reliance and resourcefulness.”

A Crisis of Natural Resources

In 1995, Ngoitiko returned to her village, hoping to help the Maasai women and girls enhance their voice, agency, and rights. What she found was a land crisis. e Maasai of Tanzania are one of the few Indigenous pastoral communities raising livestock on the country’s northern plains. With growing pressures on natural resources, including land, water, and forests, plus harsh droughts from climate change, life for pastoralists is hard. Additionally, women bear the brunt of feeding families and caring for children with dwindling resources and few opportunities to escape poverty.

Ngoitiko knew that women needed to be part of the solution. After all, she says, in this culture, it is women who know the land best, as they search for and collect water, food, and medicine. Ngoitiko helped organize a meeting of 500 local women. ey united with the mission of bringing education, economic opportunity, and property ownership to Maasai women – to empower new female leadership to save their pastoral way of life.

“As Maasai women, we focus on education because it helps us to become decision-makers, innovators, and to respond to the climate crisis,” Ngoitiko says.

Transforming from Within

Nearly 30 years later, that group, now the Pastoral Women’s Council, reaches and transforms the lives of over 20,000 Indigenous women annually. ey fund girls’ scholarships, enhance women’s rights and agency, change negative social norms, drill for clean water, support women’s economic empowerment, and women’s health and wellness.

Maasai women are now business owners and commu-

nity leaders and they negotiate with local and federal governments on issues ranging from sustainable water management to climate change adaptation.

Solidarity sits at the center of this work – and the Pastoral Women’s Council works hard to include men and boys to change traditional attitudes. “If women and men are collaborating, doesn’t that make for greater success and happiness?” Ngoitiko asks.

Y et the challenges for the Maasai continue to grow, from ongoing land rights challenges, to increased uncertainty and worsening droughts. e Pastoral Women’s Council seeks long-term strategic partners and to empower ever more highly motivated young women to stand up for their rights and make a lasting difference to their community.

Maasai women have come a long way from that single blade of grass, says Ngoitiko. “We have created a model of constant learning that will produce the leaders of the future. Together, we planted a tree. Now, it is bearing fruit.”

Women’s Council

pastoralwomenscouncil.org

Ruth Kihiu Head of Programs+255 767 237 470 pwctanzania@gmail.com

Friends of Pastoral Women’s Council P.O. Box 5406

Incline Village, NV 89450 Tax ID# 92-1204704

The image made headlines around the world: five Indigenous women in traditional regalia standing outside the imposing facade of a European bank. It was 2017, and the Indigenous Women’s Divestment Delegation had formulated because of the Dakota Access Pipeline protest at Standing Rock. Sitting at conference tables, these women faced down Norwegian, German, and Swiss bankers, and told stories of their fight to protect water and experiences of law enforcement abuse. Citing international human rights law, they made a straightforward request: Stop financing the destruction of their land.

“Women were able to look decision-makers directly in the eye and tell their stories of harm to their lives, bodies, and homelands,” says Osprey Orielle Lake, founder and executive director of Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN), who co-coordinated these meetings with Divest Invest Protect leadership. Collective pressure worked: Hundreds of millions of dollars were divested from the project. Since its inception, WECAN has facilitated various types of delegations of frontline women worldwide to stop fossil fuel expansion and deforestation.

WECAN’s programs reach more than 50 countries, uniting women in the fight for social and climate justice. From reforestation projects in the Congo and Amazon rainforests to the protection of nine million acres of old-growth forest in Alaska, from fossil fuel divestment to United Nations climate policy advocacy, from Indigenous rights to food sovereignty projects, WECAN gets behind women on the frontlines tackling the root causes of environmental degradation and socioeconomic inequalities.

“We need to have Indigenous, Black, and Brown women, in the room, directly engaging with government leaders and financial institutions. Communities being impacted must be heard,” Lake says. “Simultaneously, while we are working to stop destructive projects, we need to be building the healthy and equitable world we know is possible.”

Women’s leadership can, quite literally, change the climate. So demonstrated the more than 1,000 women of the WECAN Women for Forests program in the Democratic Republic of Congo, who have planted

more than 300,000 trees in the Itombwe Rainforest. ere, women carry native saplings on their heads, strategically planting them to yield a 94.7% survival rate. ese carbon-sequestering trees have influenced the local climate, lowering temperatures and bringing rain to parched landscapes. e reforestation effort has also increased available habitat for gorillas, golden cats, and rare birds. And women responsible are emerging as newly respected leaders of their communities.