Portfolio Note

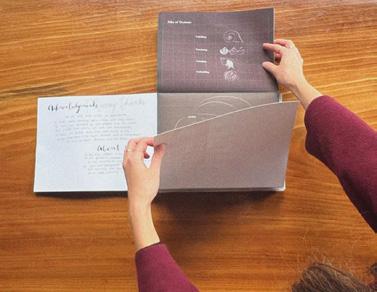

My aim with this portfolio is to showcase my ability to carefully craft a question that can lead to greater understanding and towards even better questions.

There is not a single project shown here that does not reflect the care and attention that I bring to my work. However, the format of a portfolio fails to capture what I enjoy most about landscape architecture – the dialogue and community that attends every site and proposal. My goal as a budding landscape architect is to be in community, always bringing my best to the table and trying to bring out the best in others.

The works shown in this portfolio are a sampling of studio projects, exhibitions, publications, and events that I worked on throughout my time at UVA. In every project, I challenged myself to work deeply with archival materials and approach each site with awareness

of my preconceptions and biases. My approach to these projects is a direct result of my previous years working in art, photography, and film, which I’ve also shared a bit of at the end of this portfolio.

I arrived at landscape architecture with the intention to meld together historical and archival research, careful and exhaustive documentation, and care of community towards the goal of creating or revealing beautiful and meaningful sites. I have learned that this means paying close attention to the details while keeping sight of the whole. This portfolio reflects the last three years of research, growth, and development of this mode of practice. I am immensely grateful for the mentors who helped guide me along the way.

The result of all this work is a constellation of images and themes, composing a rich world of coincidences, relations, and unexpected points of connection.

+1 (305) 972 1533 samanthajrosner@gmail.com qhv6je@virginia.edu Contact

2

Table of Contents

Thesis

American Beach, Amelia Island, FL

Research Studios Grant Park, Chicago, IL

Sparrow’s Point, Baltimore, MD

Research Work

Coastal Parklands

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument (HATU)

Coastal Parklands

Assateague National Seashore (ASIS)

University of Liberia Field School, Fluvanna County, VA

Finding Freetowns, Albemarle County, VA

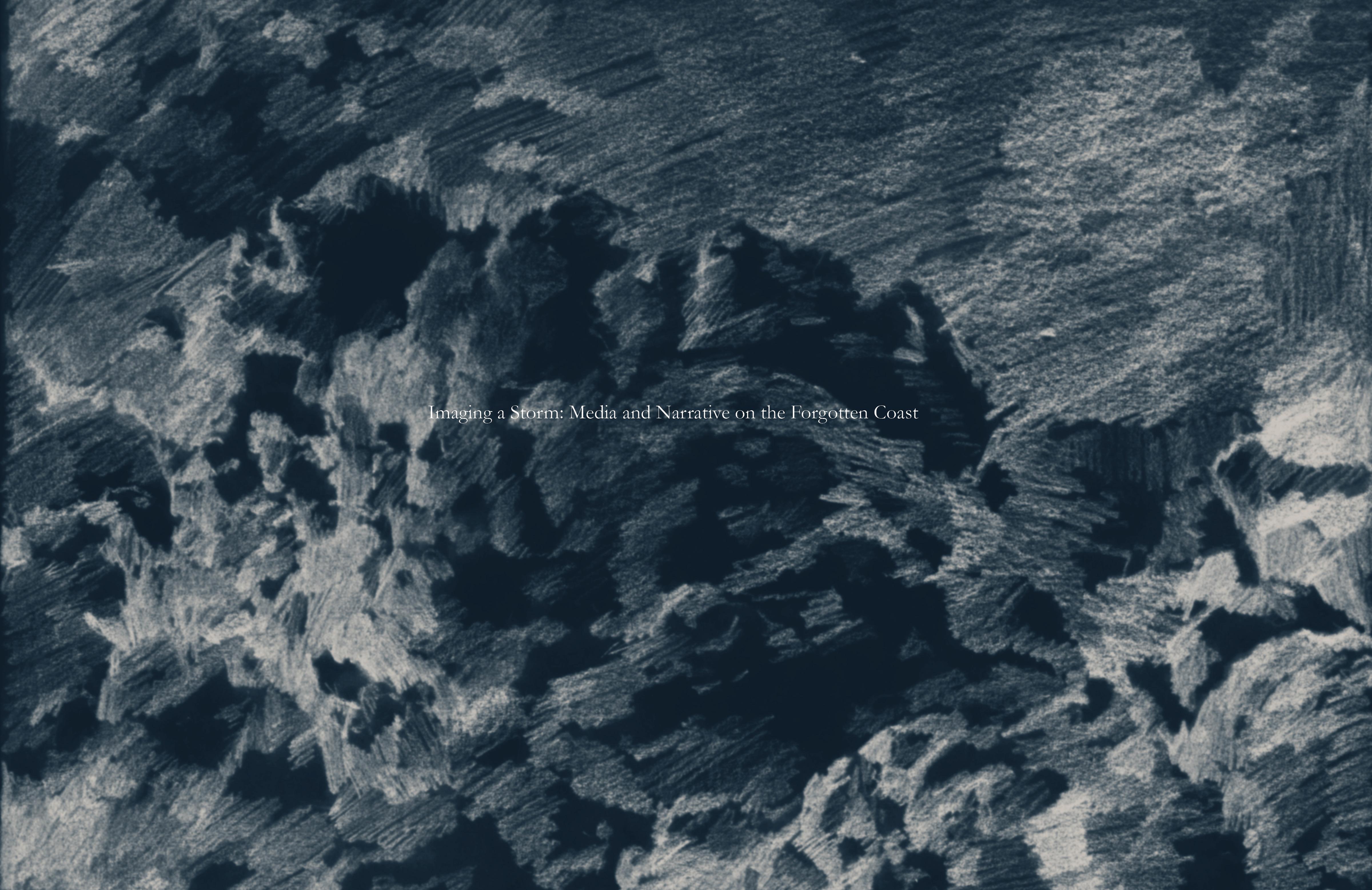

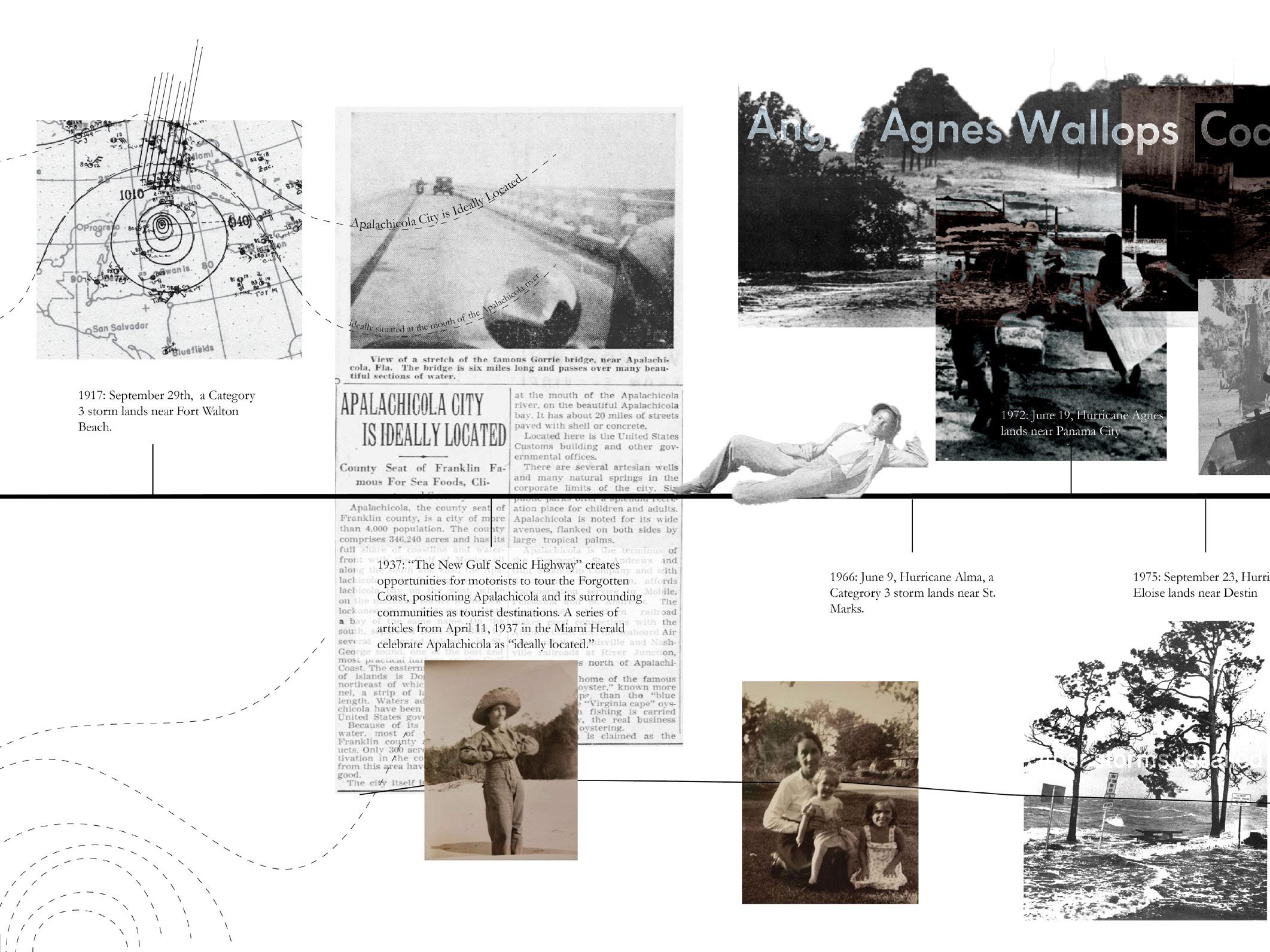

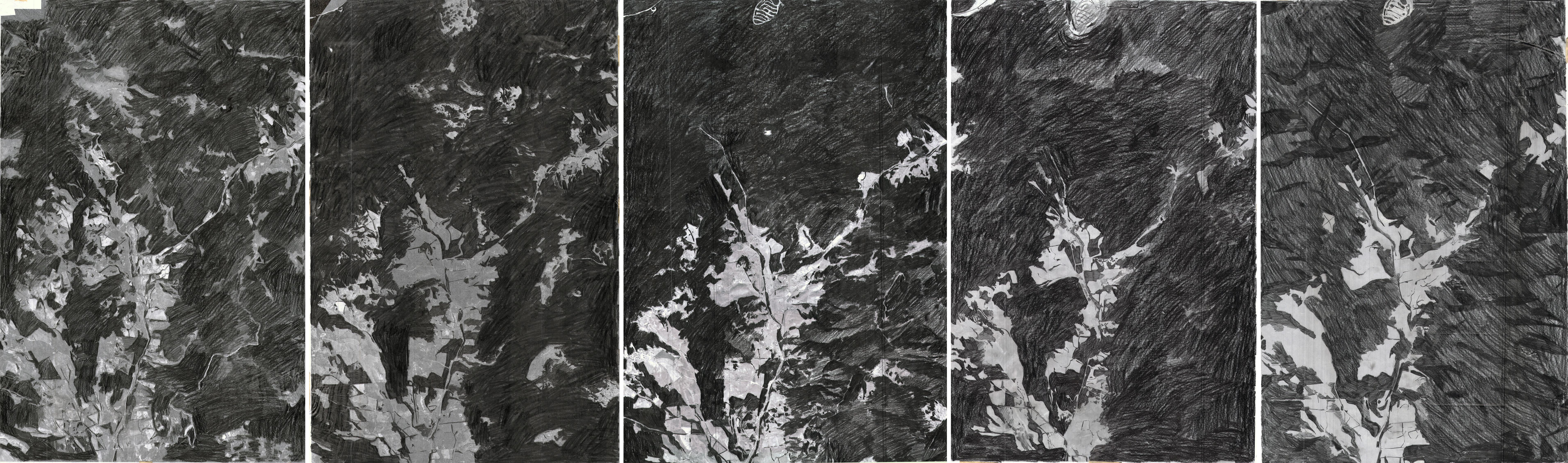

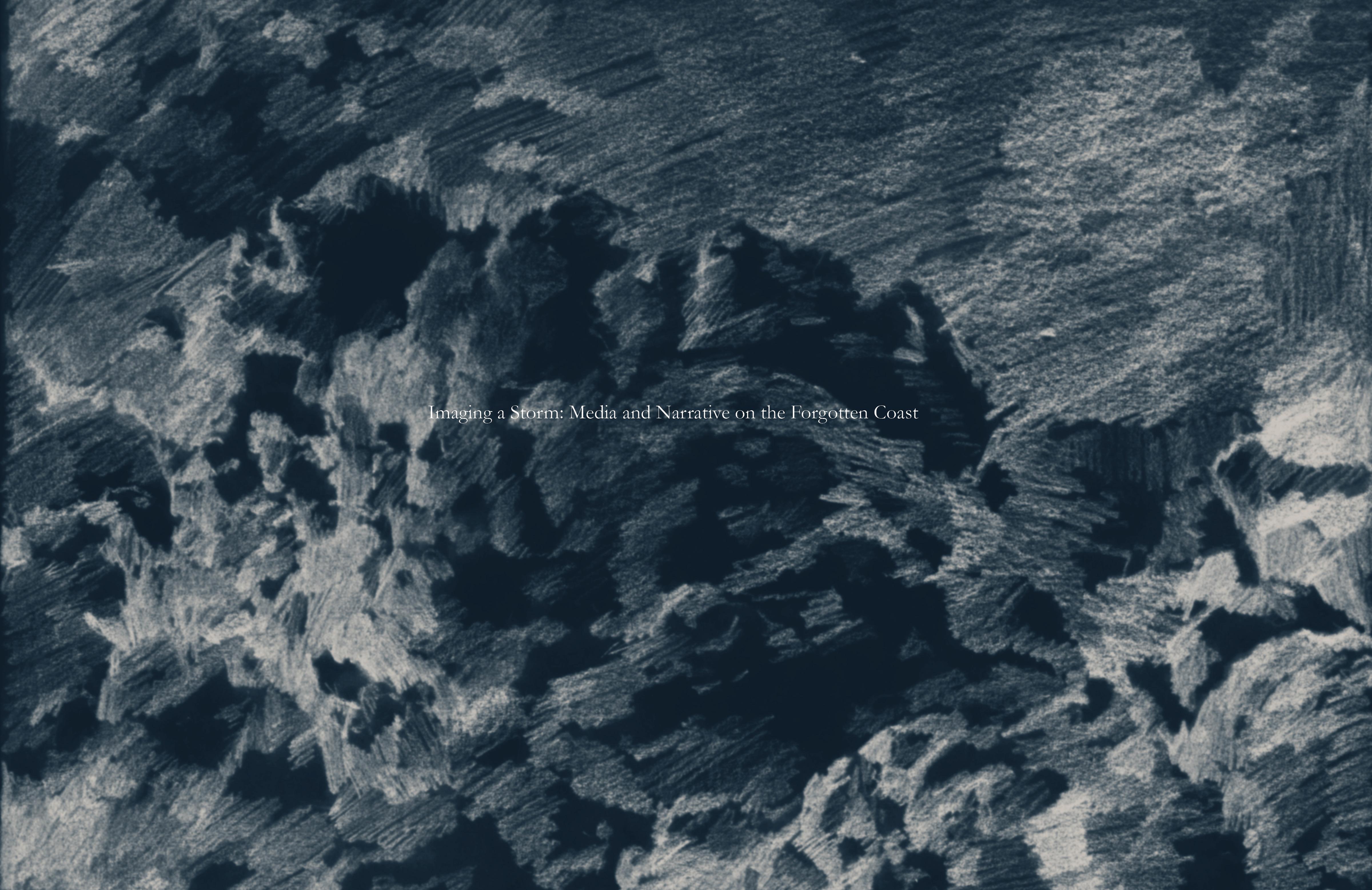

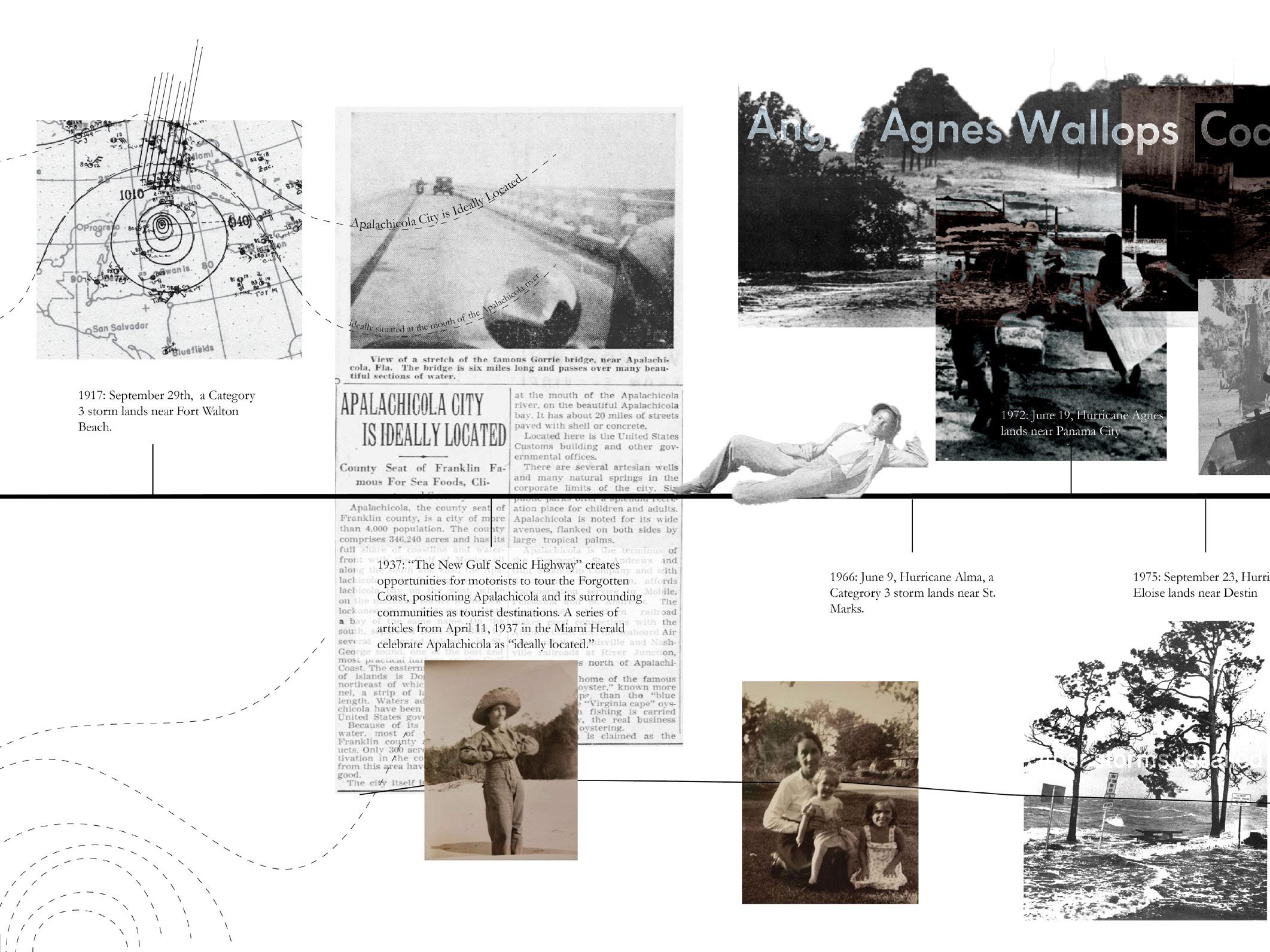

Visioning a Storm, Forgotten Coast, FL

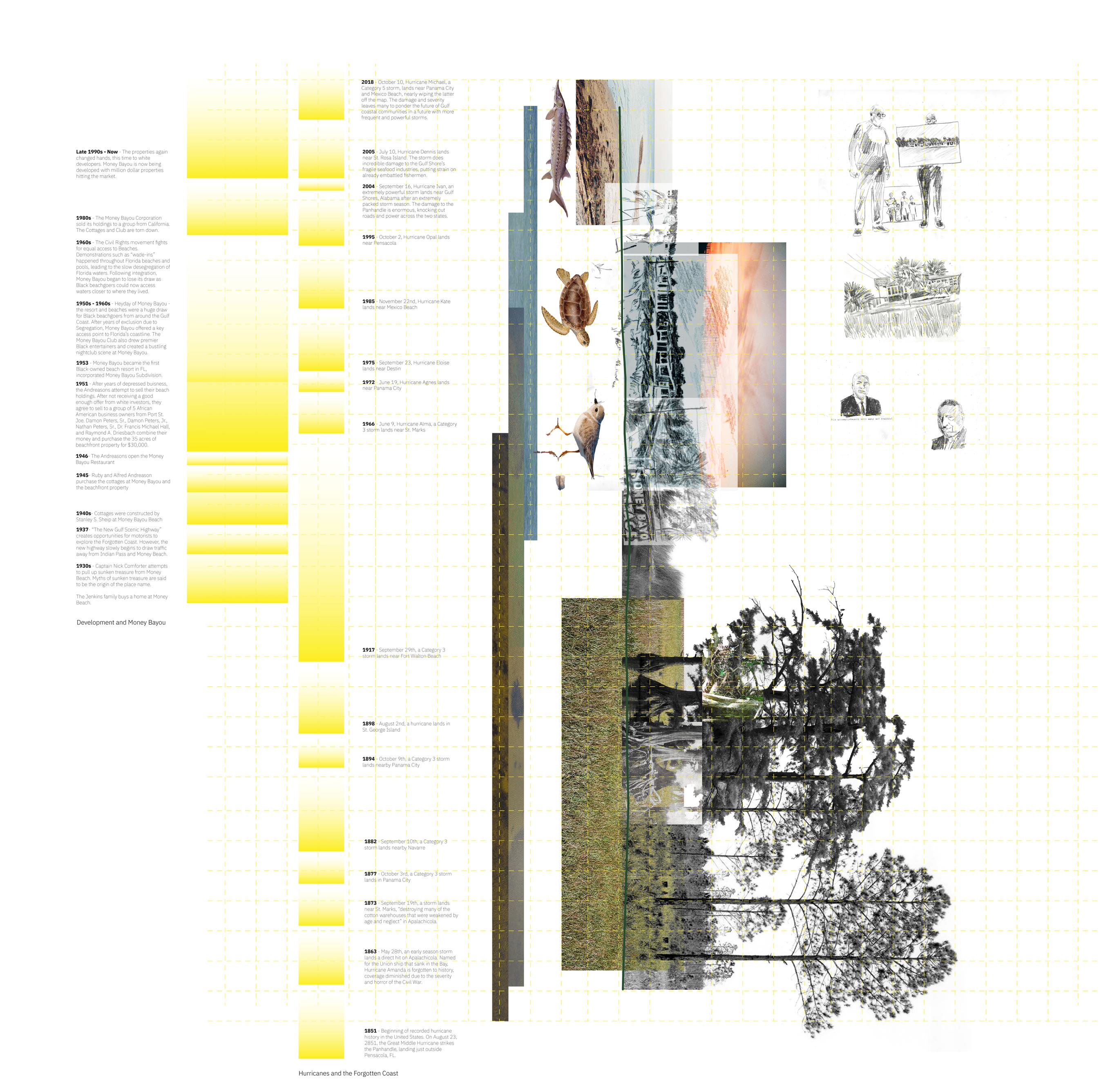

Foundation Studios Money Bayou, Apalachicola, FL

Black Bus Stop Charlottesville, VA

Community Design Arrival on Grounds, Charlottesville, VA

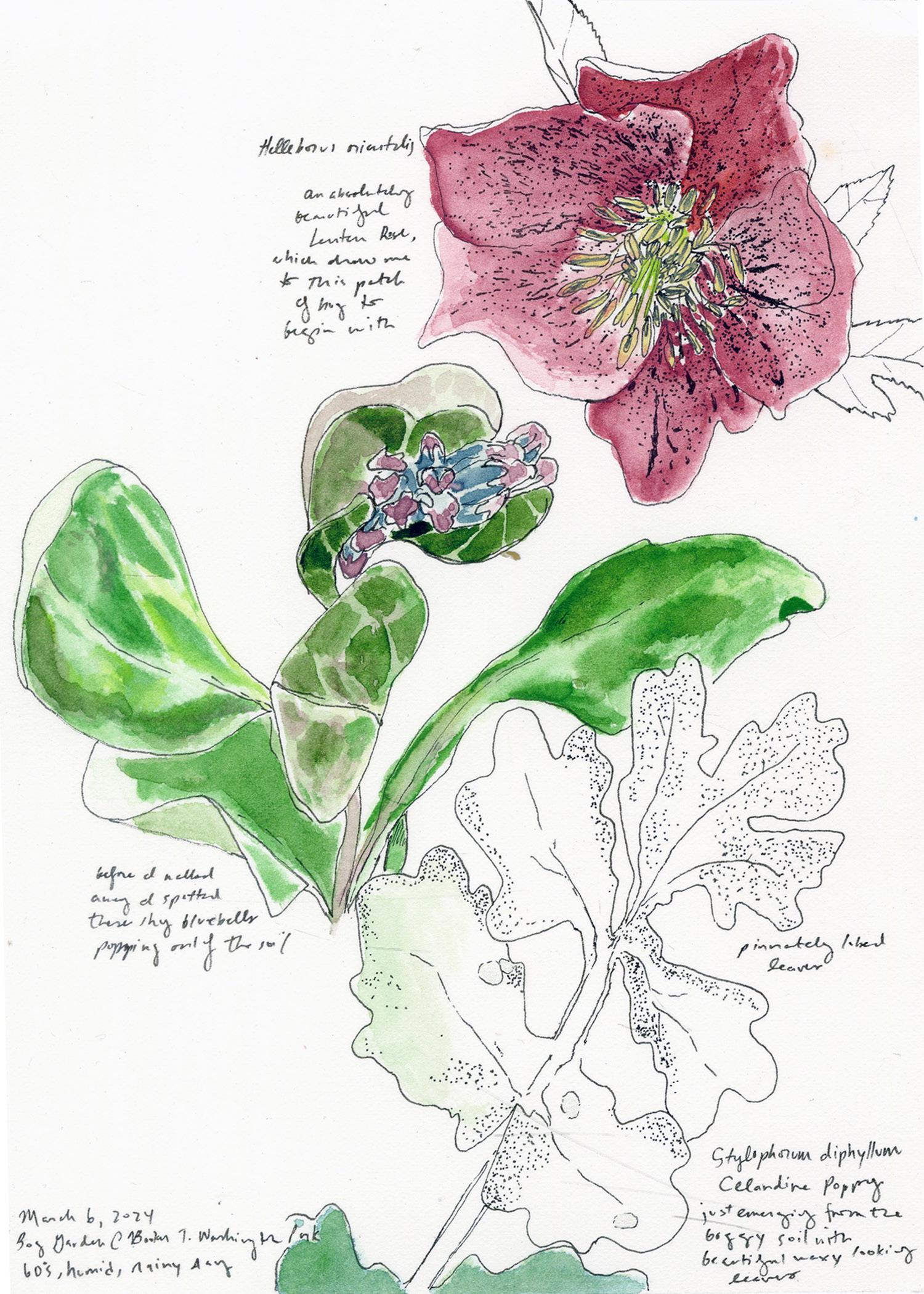

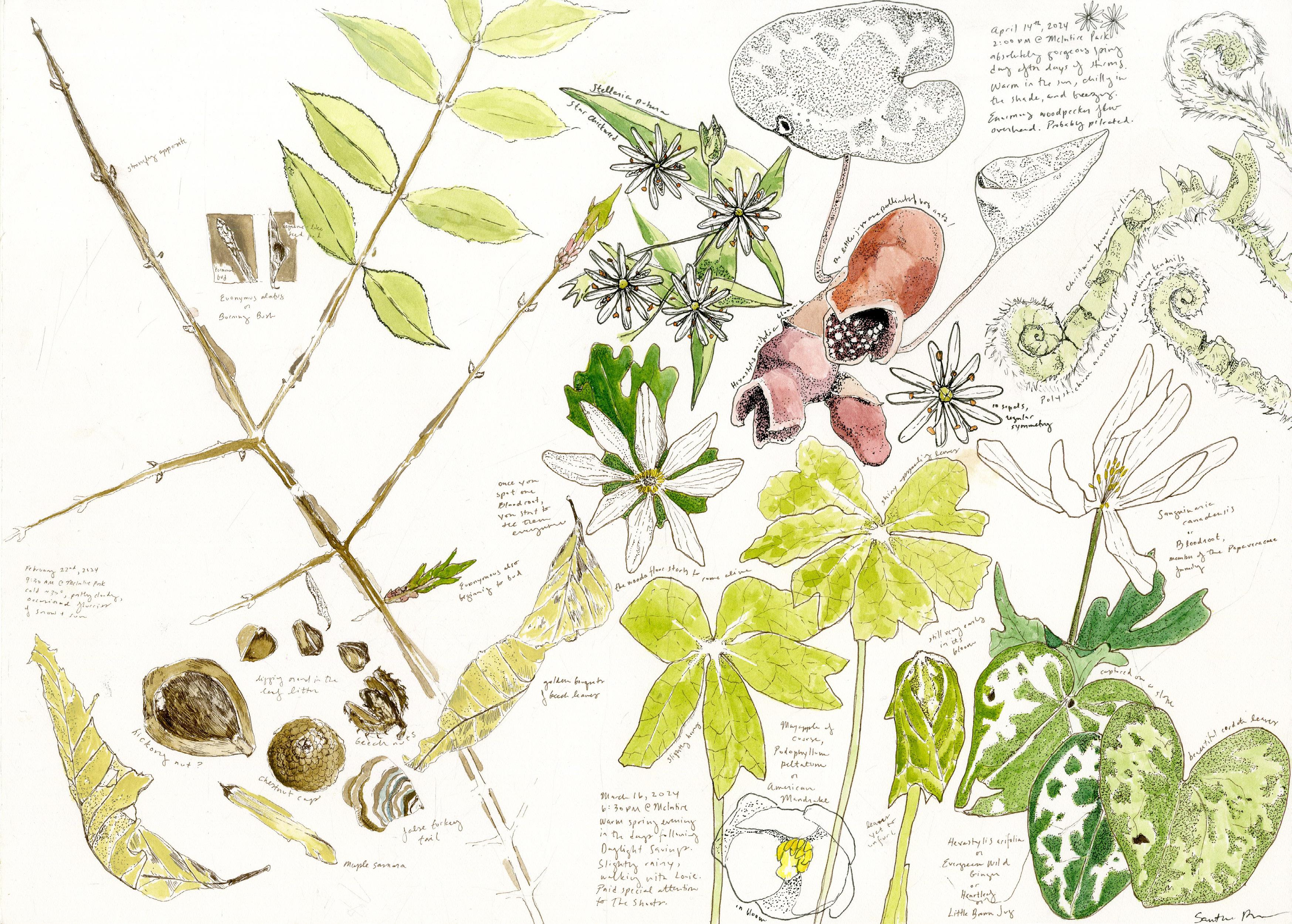

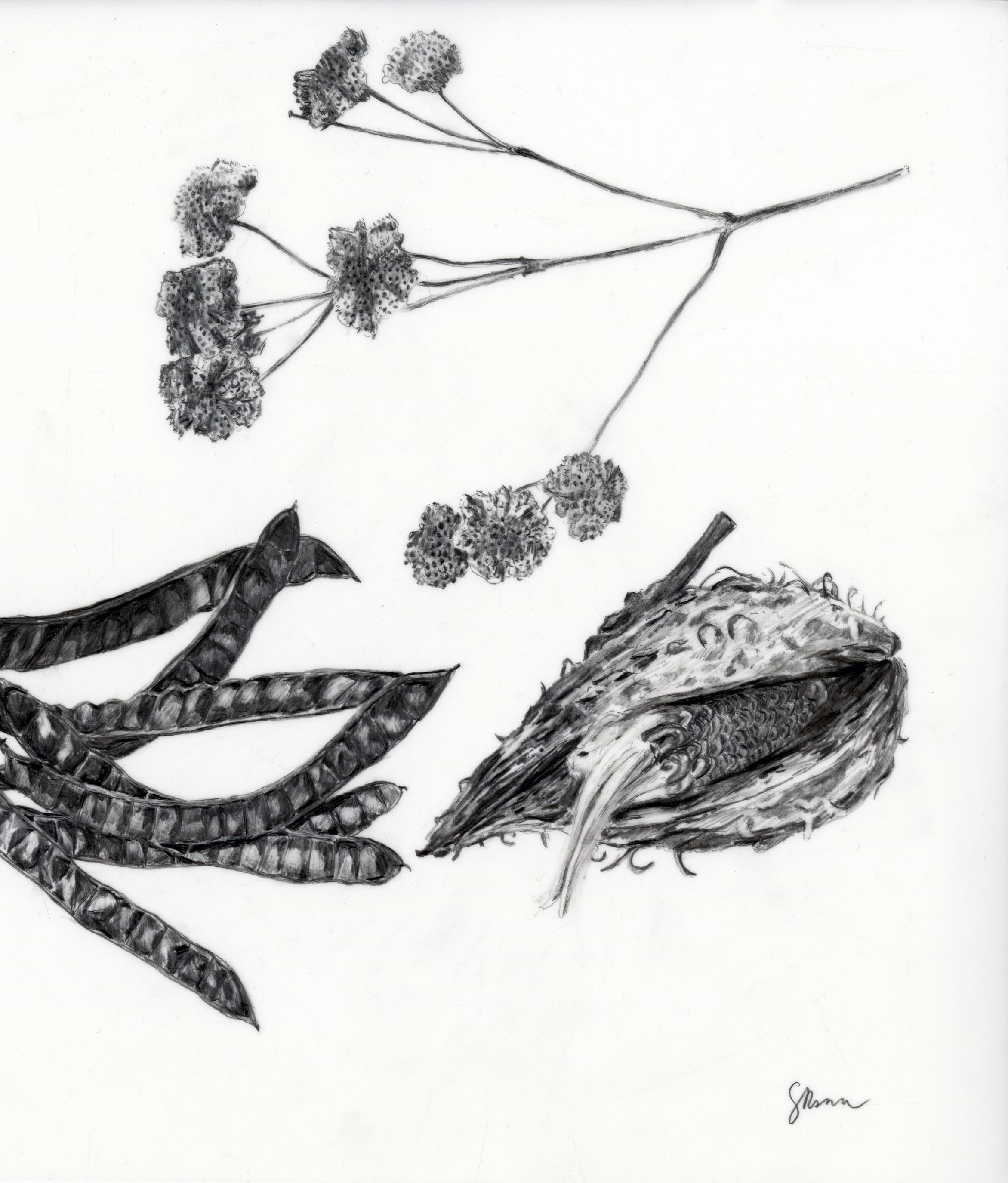

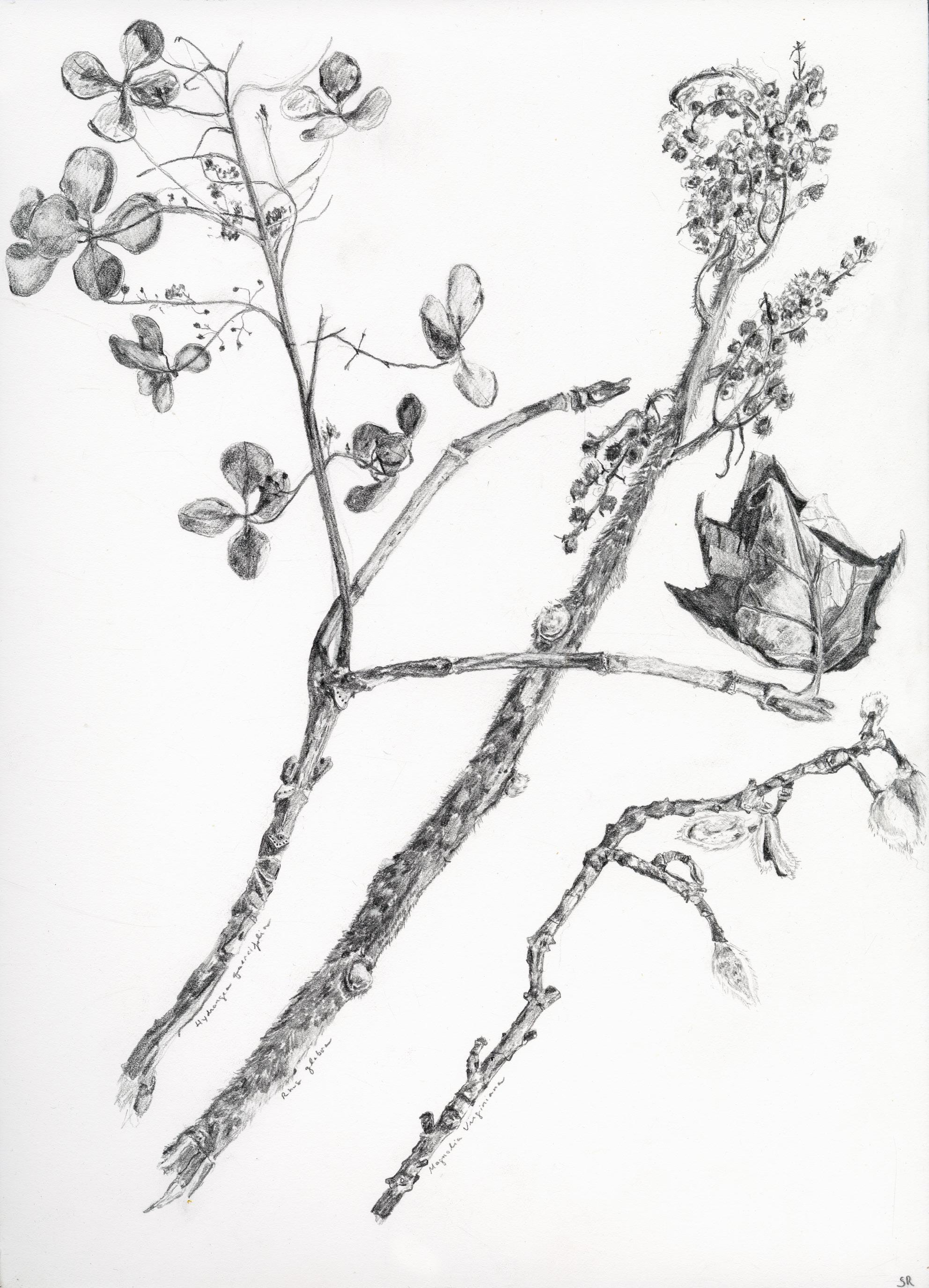

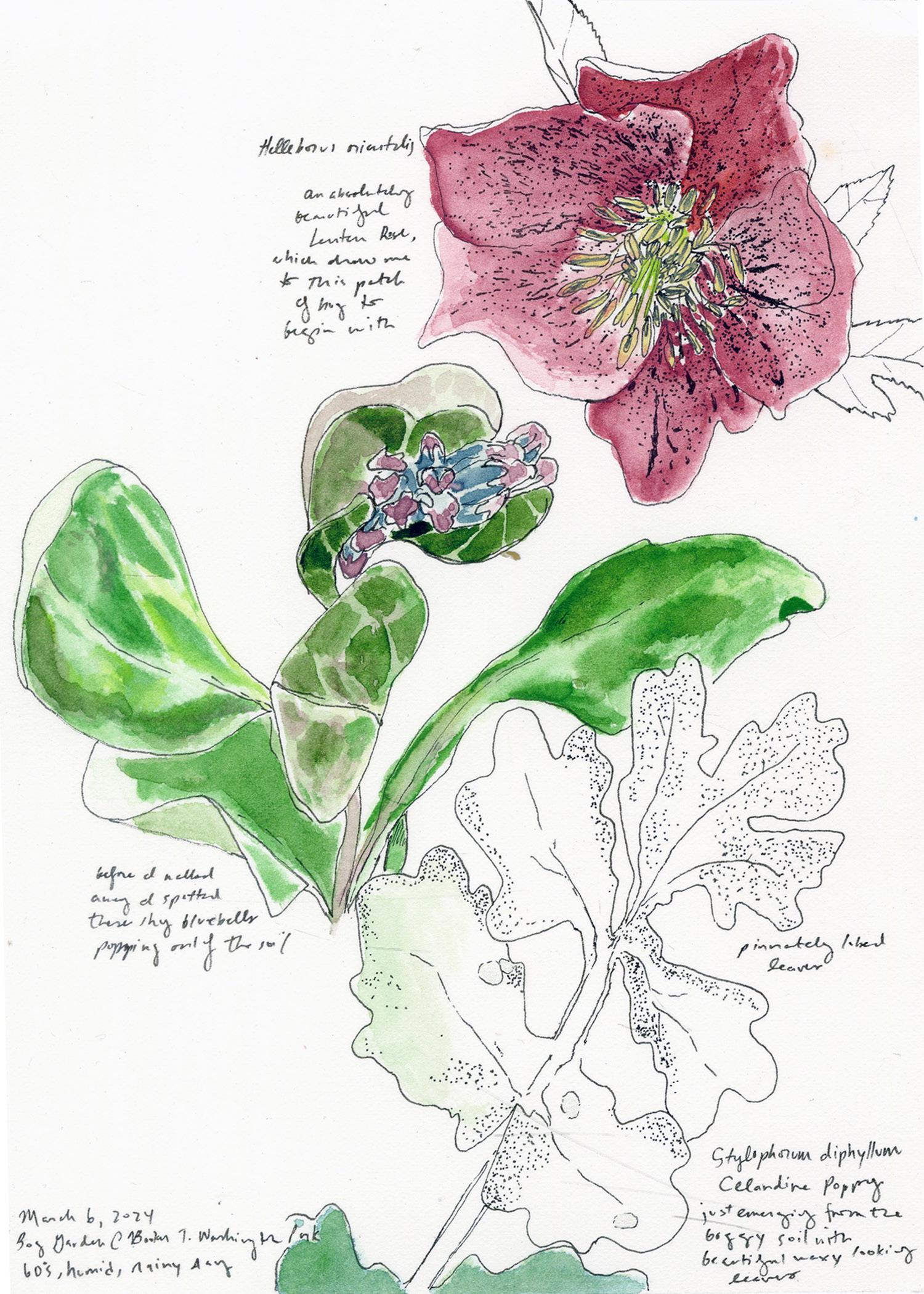

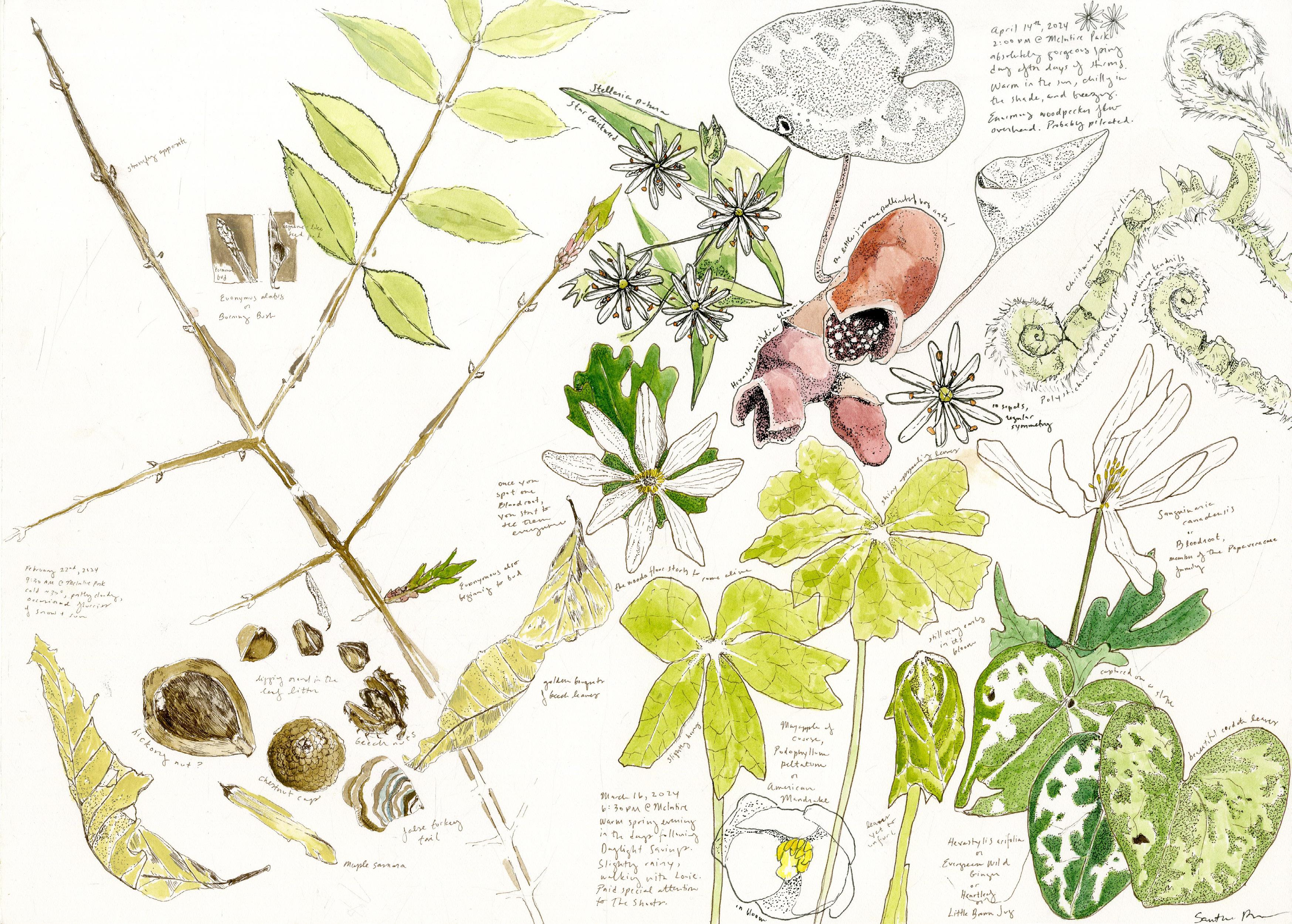

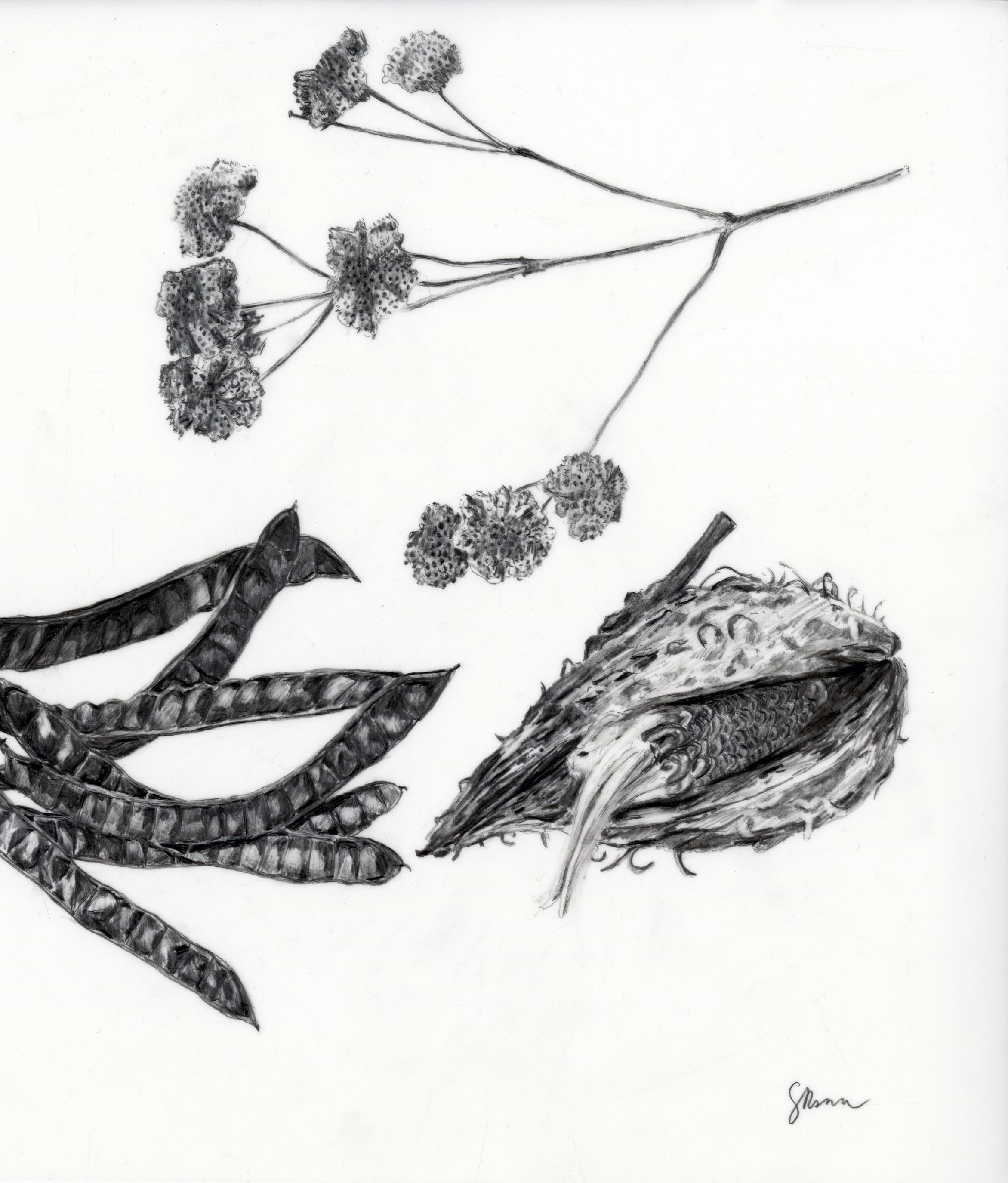

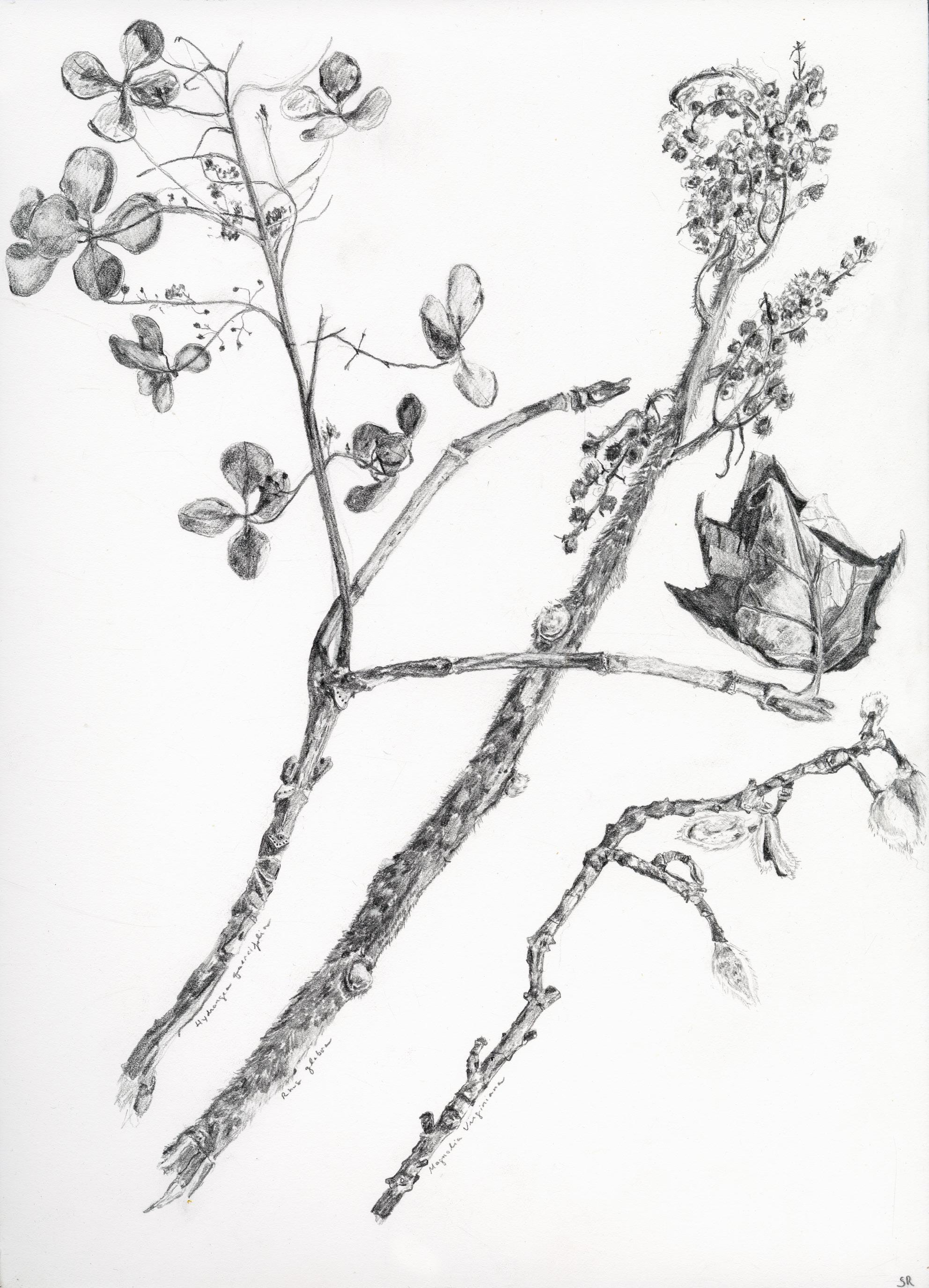

ManifestA Community Design Roundtable, Charlottesville, VA Selected Art Works Seeing Plants - Botanical Sketches Selected Films 6 52 66 80 84 88 92 96 102 112 126 132 136 140 3

Thesis Research: Refusal to Fade

Yucca aloifolia Andropogon glomeratus Ilex vomitoria Muhlenbergia capillaris Dalea feayi Panicum amarum Quercus myrtifolia Acacia farnesiana Myrica cerifera Caltis laevigata Sideroxylon tenax

4

Limonium

Ipomopsis rubra

Opuntia stricta

Flaveria linearis

Ipomoea sagittata

Sabatia stellaris

Croton punctatus

Borrichia arborescens

Solidago sempervirens

Batis maritima

Serenoa repens

Ipomoea pes-caprae

Uniola paniculata

carolinianum

Baccharis halimifolia

Distichlis spicata

Sporobolus virginicus

5

Physalis walteri

Refusal to Fade: Inscribing Memory on the Historically Black Beaches of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor

Thesis Research presented in May 2024 Advisor: Dr. CL Bohannon Amelia Island, FL - Wilmington, NC

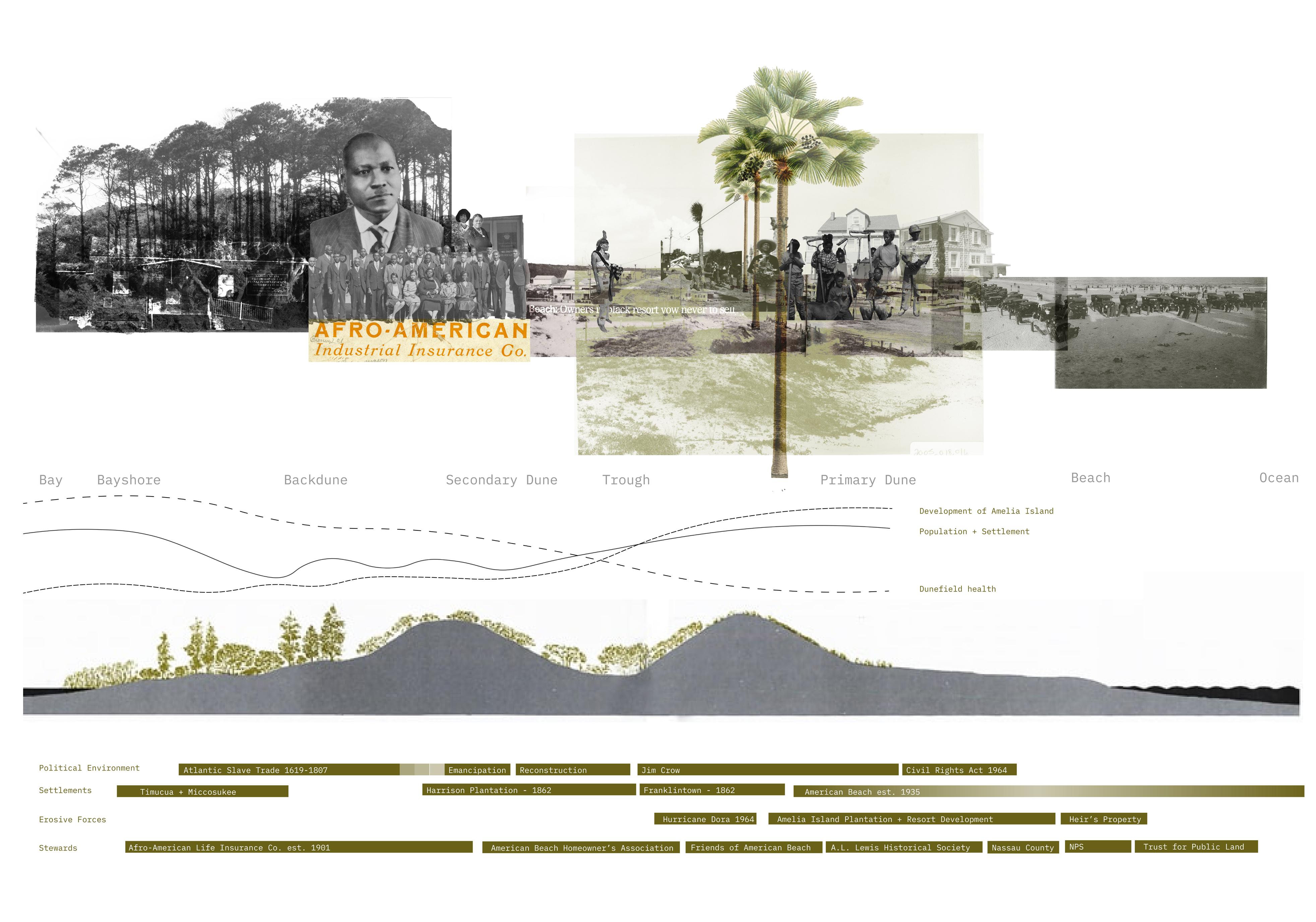

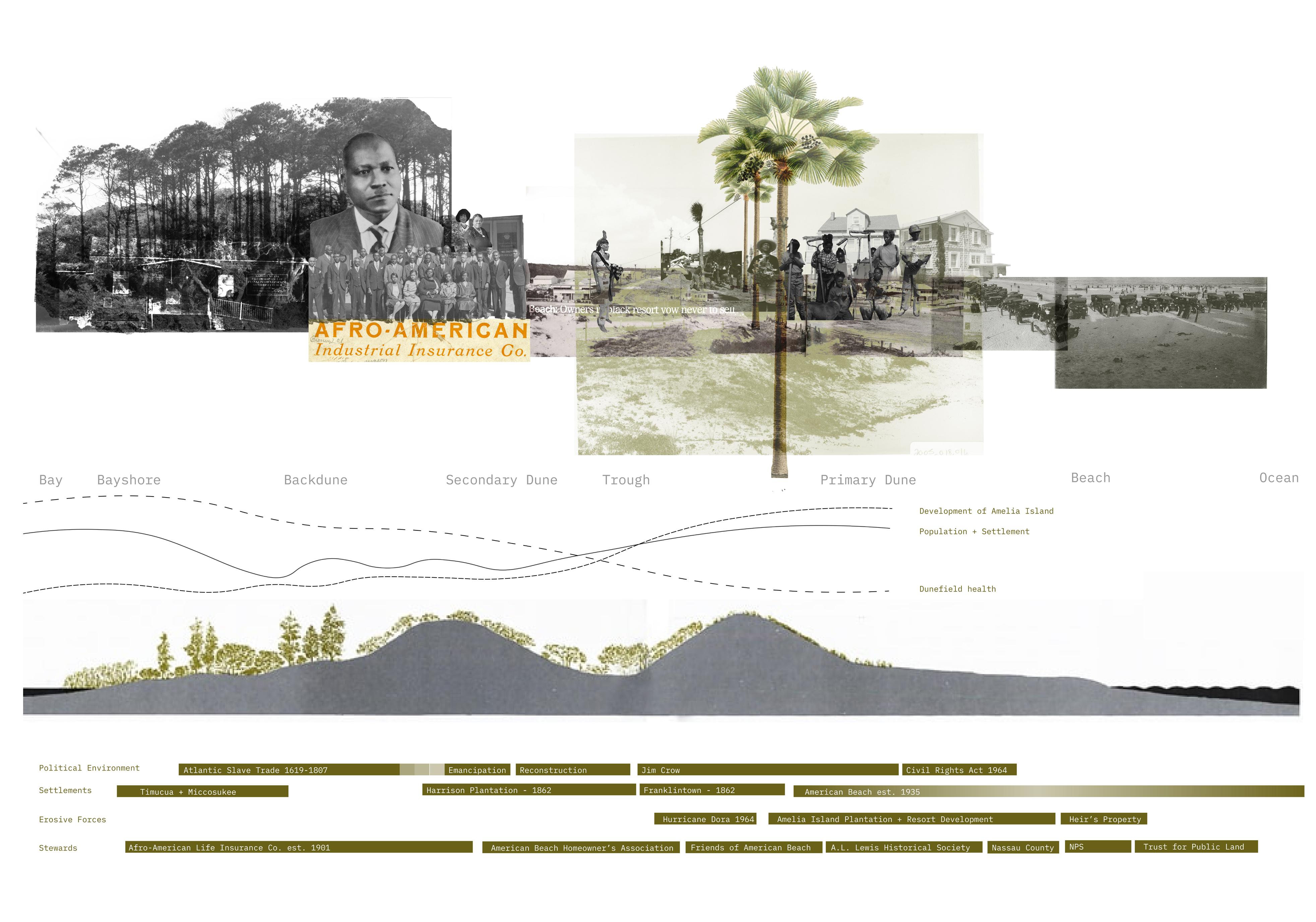

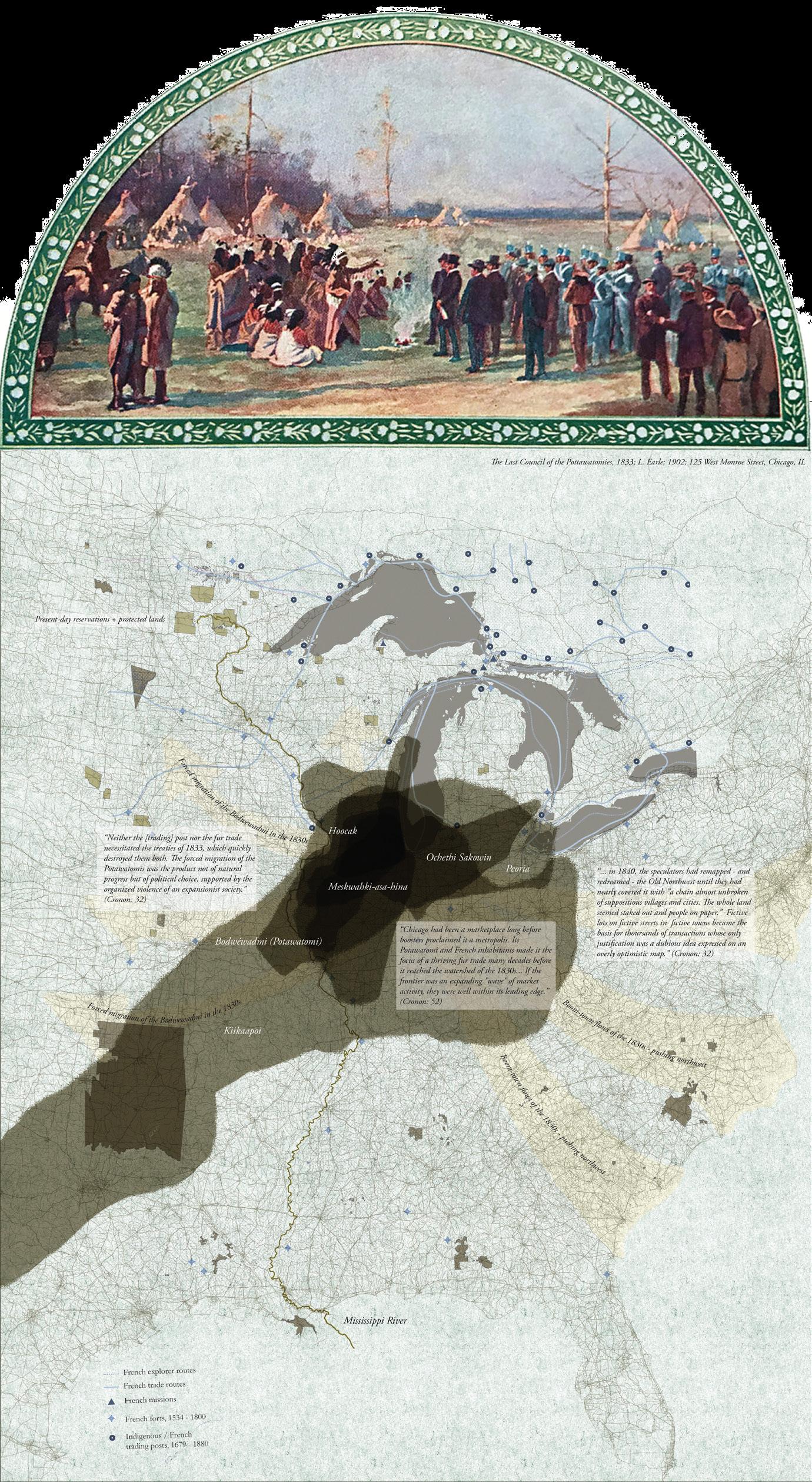

This thesis examines the trajectories of Seabreeze (Wilmington, NC), Atlantic Beach (Myrtle Beach, SC), and American Beach (Amelia Island, FL) - three historically Black beaches along the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor (GGCHC). It seeks to preserve these unique histories by designing landscapes that draw from historical forms and narratives and celebrate Black joy, prosperity, and community-building. Historically Black beaches are coastal resort communities that were established during the Jim Crow era by Black entrepreneurs to provide waterfront leisure opportunities on a segregated shoreline. Beaches along the GGCHC are distinct because many families who established the resorts have long-standing claims to the land. Gullah people have been stewards and landowners along the Lowcountry South since the 18th century when their West African ancestors were enslaved and forced overseas to import their agricultural knowledge and develop the landscape into rice plantations. The endurance of Gullah culture reflects the strength and resiliency of a people who built sovereign communities dedicated to education and prosperity. Inspired by this legacy, my research challenges normative methods of marking and memorializing and centers counternarratives of Black prosperity and placemaking to encode memory in these fragile landscapes through a restoration approach informed by community interviews, archival images, and oral histories.

These beaches were sites of resistance during the dark era of segregation that punished and destroyed thriving Black communities such as Tulsa’s Black Wall Street. While the heyday of these beaches concludes with the 1964 Civil Rights Act, their communities are intact, though suffer from the erosive forces of gentrification, hurricanes, and aging populations. The beaches are distinct in the coastal suburban fabric, featuring low-density neighborhoods surrounded by encroaching highrises and exclusive resorts. Seabreeze, Atlantic Beach, and American Beach have sought to preserve their histories through applications to the

National Register of Historic Places, which often results in placing historical markers or preserving a few structures. The inefficacy of this practice can be seen at Atlantic Beach, where one finds a patchwork of crumbling, mid-century buildings amongst vacant lots and a few newly constructed luxury homes. This preservation method does not reflect the richness of what was once a densely built and popular destination. Certainly, it does not celebrate and support the endurance and resilience of the community. I argue that preservation should push beyond markers and move towards inscribing memory through the design of landscapes that are informed by present and future needs and participate in everyday life.

This design thesis culminates in (1) an atlas of the three beaches comprising archival materials from local historical societies and interviews conducted with community members from travel research completed in Summer of 2023; (2) design propositions to restore connections between the neighborhood and the shore, marking these beach sections as significant and distinct from the surrounding shoreline; and (3) a proposal to design community laboratories using the framework of ecological reparation that support the vibrancy of present and future communities.

6

7

DRAWING

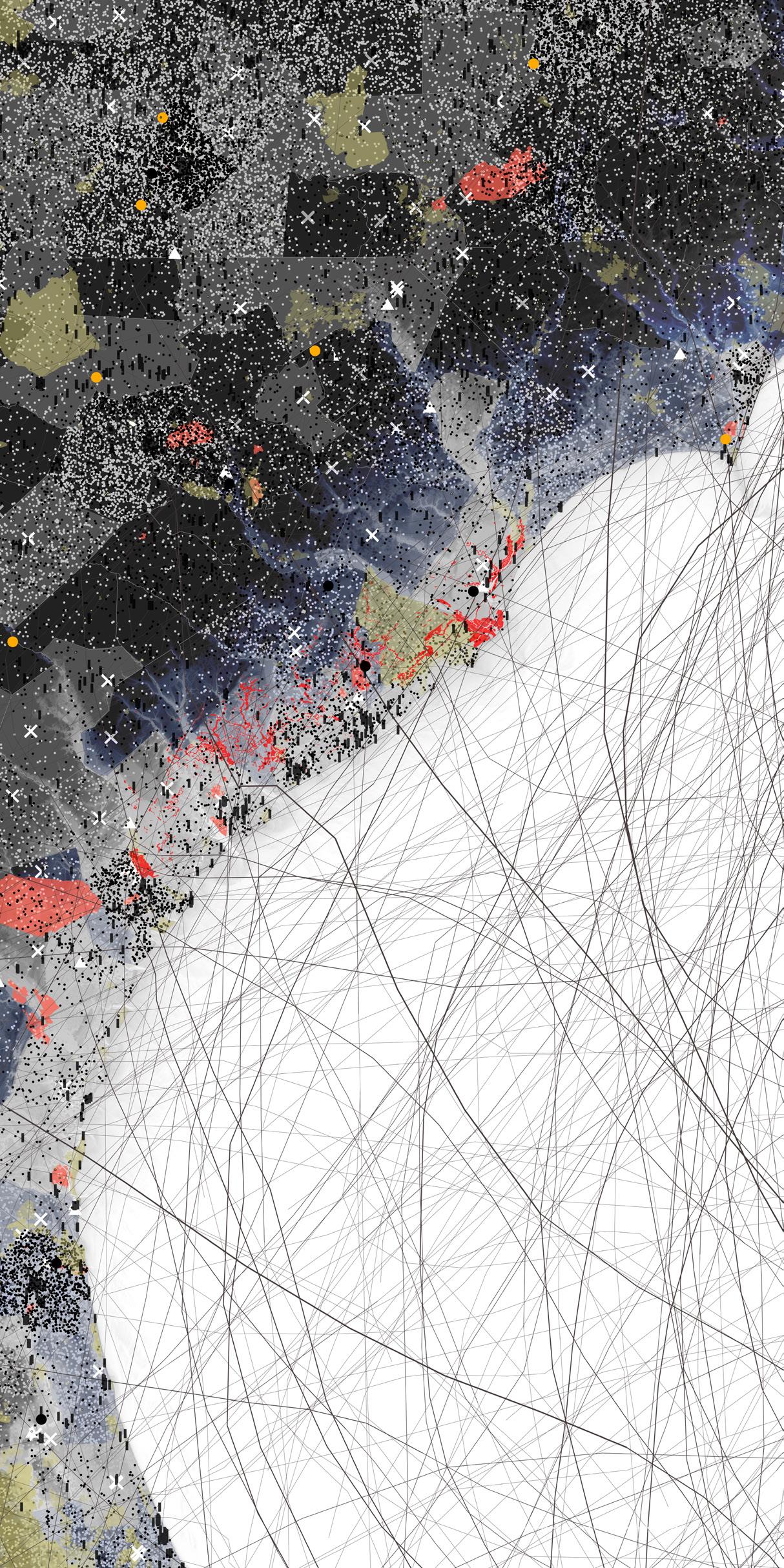

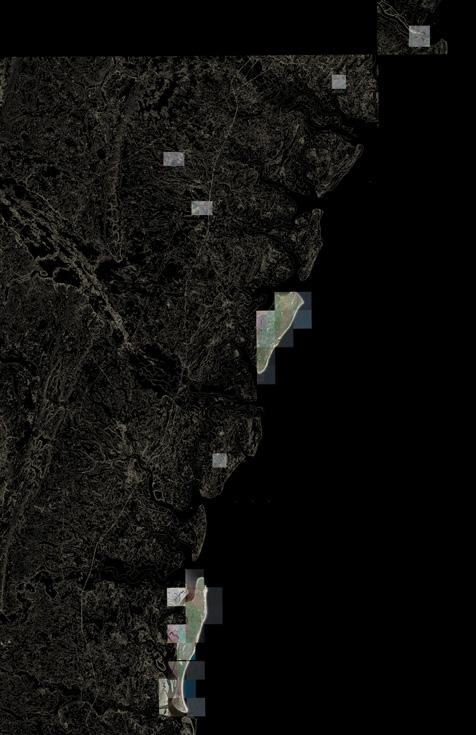

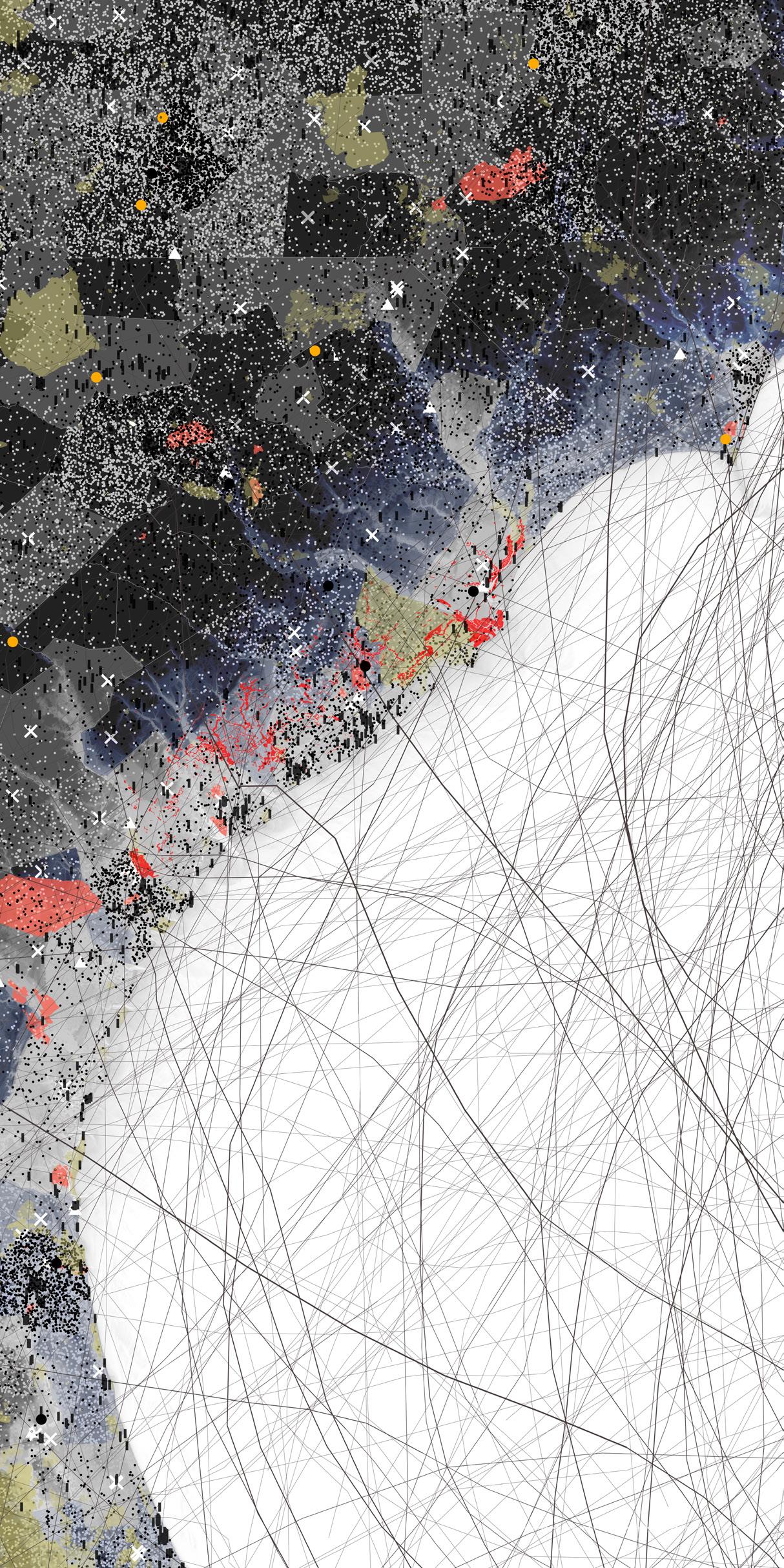

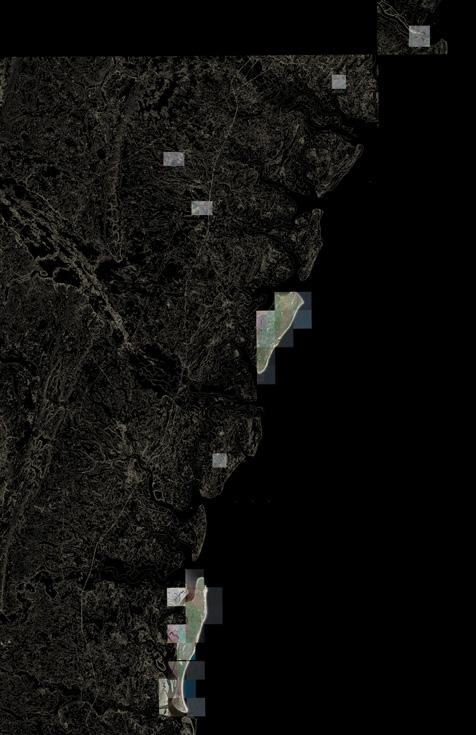

Thick map of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor, showing the pressures and harms that mark the territory.

Race (Black dots = 200 Black Residents, Peach dots = 200 White Residents)

Military Bases

Prisons (Xs), Pulp Mills (Triangles), Powerplants (Circles)

Parks

Historic Hurricane Tracks (thick line = more powerful storm)

Historic Rice Fields (SC only) Hog Agriculture

Elevation (-20 ft to 40ft)

Thick map of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor, showing the pressures and harms that mark the territory.

Race (Black dots = 200 Black Residents, Peach dots = 200 White Residents)

Military Bases

Prisons (Xs), Pulp Mills (Triangles), Powerplants (Circles)

Parks

Historic Hurricane Tracks (thick line = more powerful storm)

Historic Rice Fields (SC only) Hog Agriculture

Elevation (-20 ft to 40ft)

A

10

CORRIDOR

Poplar Grove, Pender County, Typology: Plantation Moores Creek National Battlefield, Currie, Typology: Civil War Battlefield Bellamy Mansion Museum, Wilmington, NC Typology: Colonial House Brunswick Town/Fort Anderson, Winnabow, NC Typology: Confederate Fort Brookgreen Gardens, Murrel’s Inlet, SC Typology: Former plantation, current-day botanical garden Gullah Museum, Georgetown, SC Hobcaw Barony, Georgetown, SC Typology: Former plantation, current-day McLeod Plantation Historic Site, Charleston, Typology: Former plantation Fort Moultrie/Sumter, Charleston, SC Typology: Naval Fort Typology: Witness tree Typology: Historic School for Freed People Gullah Museum Hilton Head, Hilton Head, SC Typology: Cultural museum Mitchelville, Hilton Head, Typology: Freetown Caw Caw Interpretive Center, Ravenel, SC Phillip Simmons House Museum, Charleston, Typology: Plantation mansion Aiken-Rhett House, Charleston, Typology: Plantation mansion Avery Research Center, Charleston, SC Typology: African American School Magnolia Plantation Gardens, Charleston, SC Typology: Rice plantation Charles Pinckney National Historic Site, Mt. Pleasant, Typology: Plantation Boone Hall Plantation Gardens, Mt. Pleasant, Typology: Plantation Scanlonville, Mt. Pleasant, Typology: Historically Black Beach Drayton Hall, Charleston, SC Typology: Rice plantation The Rice Museum, Georgetown, Typology: Agri-historical museum Seabreeze, New Hanover County, NC Typology: Historically Black Beach Resort Town Shell Island, Wrightsville Beach, Typology: Historically Black Beach Resort Town Atlantic Beach, Horry County, Typology: Historically Black Beach Resort Town American Beach, Amelia Island, FL Typology: Historically Black Beach Resort Town Pinpoint Museum, Savannah, GA Typology: Cultural museum Fort Pulaski National Monument, Savannah, Dorchester Academy and Museum, Midway, GA Typology: Historic School for Freed People Years Active: 1871 1940s Typology: Cultural museum Years Active: 1871 1940s Sapelo Island, GA Typology: Wildlife refuge Typology: Wildlife refuge Cumberland Island National Seashore, Typology: National park Timuacan Ecological and Historical Preserve Typology: National park Red Bank Plantation House, Jacksonville, Fort Mose Historic State Park, St. Augustine, Typology: Free-Slave Settlement Lincolnville Historic District, St. Augustine, FL Typology: Historically Black neighborhood Years Active: 1866 Historical Harrington School, Brunswick, Typology: African American school Years Active: 1920s 1960s Butler Beach, St. Augustine, Typology: Historically Black Beach Manhattan Beach, Jacksonville, FL (location unknown) Typology: Historically Black Beach Resort Town Typology: Historically Black Beach Hilton Head, SC Typology: Historically Black beaches Poplar Grove, Pender County, NC Typology: Plantation Moores Creek National Battlefield, Currie, NC Typology: Civil War Battlefield Bellamy Mansion Museum, Wilmington, Typology: Colonial House Brunswick Town/Fort Anderson, Winnabow, Typology: Confederate Fort Brookgreen Gardens, Murrel’s Inlet, Typology: Former plantation, current-day botanical garden Gullah Museum, Georgetown, Typology: Cultural museum Hobcaw Barony, Georgetown, Typology: Former plantation, current-day research preserve McLeod Plantation Historic Site, Charleston, SC Typology: Former plantation Fort Moultrie/Sumter, Charleston, Typology: Naval Fort Angel Oak Tree, Johns Island, Typology: Witness tree Typology: Historic School for Freed People Gullah Museum of Hilton Head, Hilton Head, Typology: Cultural museum Mitchelville, Hilton Head, SC Typology: Freetown Caw Caw Interpretive Center, Ravenel, Typology: Historic Rice Plantation Typology: Plantation mansion Aiken-Rhett House, Charleston, SC Typology: Plantation mansion Avery Research Center, Charleston, Typology: African American School Magnolia Plantation Gardens, Charleston, Typology: Rice plantation Pleasant, SC Typology: Plantation Boone Hall Plantation Gardens, Mt. Pleasant, Typology: Plantation Scanlonville, Mt. Pleasant, SC Typology: Historically Black Beach Typology: Rice plantation The Rice Museum, Georgetown, SC Typology: Agri-historical museum Seabreeze, New Hanover County, NC Typology: Historically Black Beach Resort Town Shell Island, Wrightsville Beach, NC Typology: Historically Black Beach Resort Town Atlantic Beach, Horry County, SC American Beach, Amelia Island, FL Typology: Historically Black Beach Resort Town Typology: Cultural museum Fort Pulaski National Monument, Savannah, Typology: Civil War Fort Years Active: 1830s 1860s Dorchester Academy and Museum, Midway, GA Typology: Historic School for Freed People Years Active: 1871 1940s Geechee Kunda Museum, Riceboro, Typology: Cultural museum Sapelo Island, Typology: Wildlife refuge Harris Neck, Townsend, GA Typology: Wildlife refuge Cumberland Island National Seashore, Typology: National park Timuacan Ecological and Historical Preserve Typology: National park Red Bank Plantation House, Jacksonville, Typology: Plantation Fort Mose Historic State Park, St. Augustine, Typology: Free-Slave Settlement Lincolnville Historic District, St. Augustine, Typology: Historically Black neighborhood Years Active: 1866 Historical Harrington School, Brunswick, Typology: African American school Typology: Historically Black Beach Manhattan Beach, Jacksonville, FL (location unknown) Typology: Historically Black Beach Resort Town Mosquito Beach, James Island, SC Burke’s Beach, Singleton Beach, Bradley Beach, Typology: Historically Black beaches Ways of Drawing a Corridor: Comparison of the idea of a heritage corridor, to the left are the clear boundaries drawn by the NPS and to the right is the mosaic of sites that dot the landscape. 11

I spent three weeks in Summer 2023 traveling from Wilmington, NC to Jacksonville, FL. I visited sites of great cultural importance to familiarize myself with the Gullah landscape. I also spent as much time as I could in archives such as the Avery Research Center, and made daily trips to the beach

neighborhoods, taking drone photographs, walking around, chatting with people, and when I could arrange it, going on walking interviews to get into the specifics. When I returned home, I tried to synthesize my notes, photos, and scans into asset maps, diagrams and thick sections.

Left to right: Penn Center, St. Helena Island, SC; Sandy Island, Murrell’s Inlet, SC; Driftwood Beach, Jekyll Island, GA

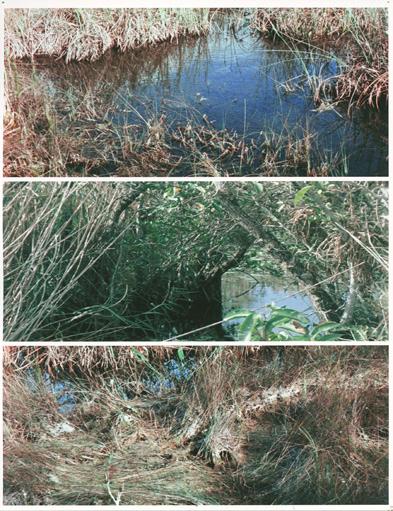

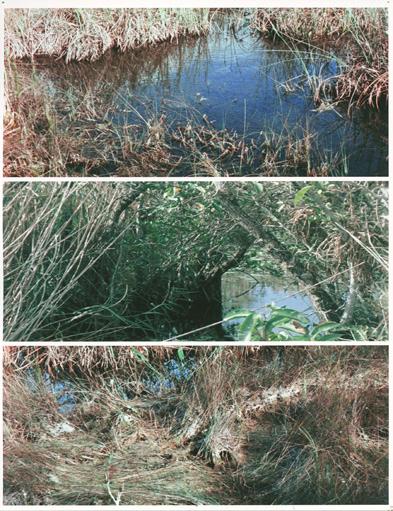

Image taken from Freeman Beach looking west towards Seabreeze. In the distance flows the Cape Fear River which is connected to the Intracoastal Waterway via Snow’s Cut, which devastated the estuarine ecology of Myrtle Grove Sound and led to increased erosion of the land of the historically Black beach town.

This drone image looks towards Mosquito Beach outside of Charleston, SC. While not a beach by traditional standards, this small African American enclave served as a key recreational ground for Black vacationers.

Left to right: International African American Museum, Charleston, SC; Fort Fisher, Kure Beach, NC; Cumberland Island, GA

Left to right: Atlantic Beach, Myrtle Island, SC; New Hanover County Public Library, Wilmington, NC; Deloris’s home, American Beach, FL

Left to right: Penn Center, St. Helena Island, SC; Sandy Island, Murrell’s Inlet, SC; Driftwood Beach, Jekyll Island, GA

Image taken from Freeman Beach looking west towards Seabreeze. In the distance flows the Cape Fear River which is connected to the Intracoastal Waterway via Snow’s Cut, which devastated the estuarine ecology of Myrtle Grove Sound and led to increased erosion of the land of the historically Black beach town.

This drone image looks towards Mosquito Beach outside of Charleston, SC. While not a beach by traditional standards, this small African American enclave served as a key recreational ground for Black vacationers.

Left to right: International African American Museum, Charleston, SC; Fort Fisher, Kure Beach, NC; Cumberland Island, GA

Left to right: Atlantic Beach, Myrtle Island, SC; New Hanover County Public Library, Wilmington, NC; Deloris’s home, American Beach, FL

FIELDWORK 12

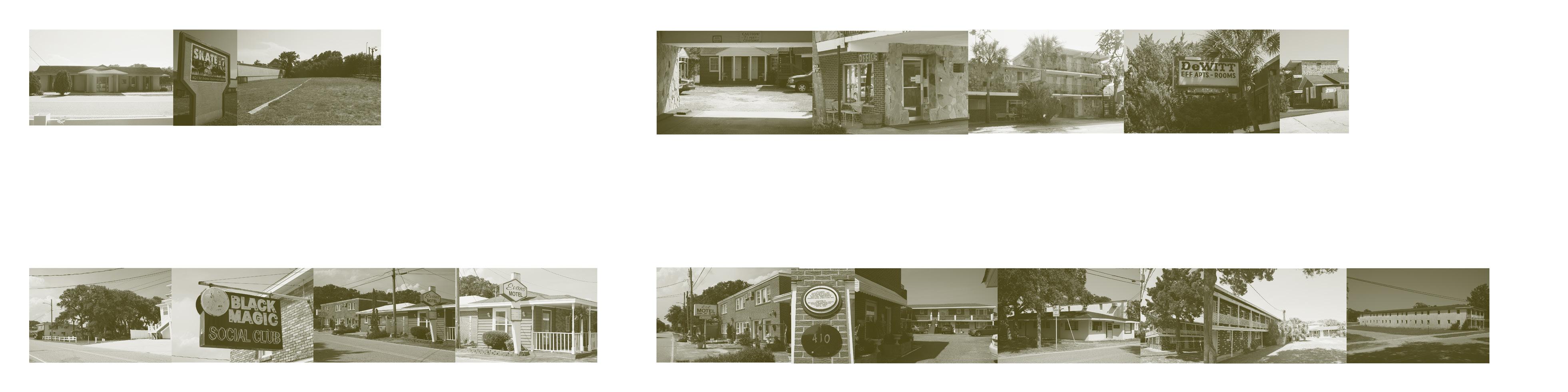

Left to right: (re)photography at Seabreeze, NC; walking interview with Carolyn, American Beach, FL; Black Magic Social Club, Atlantic Beach, SC

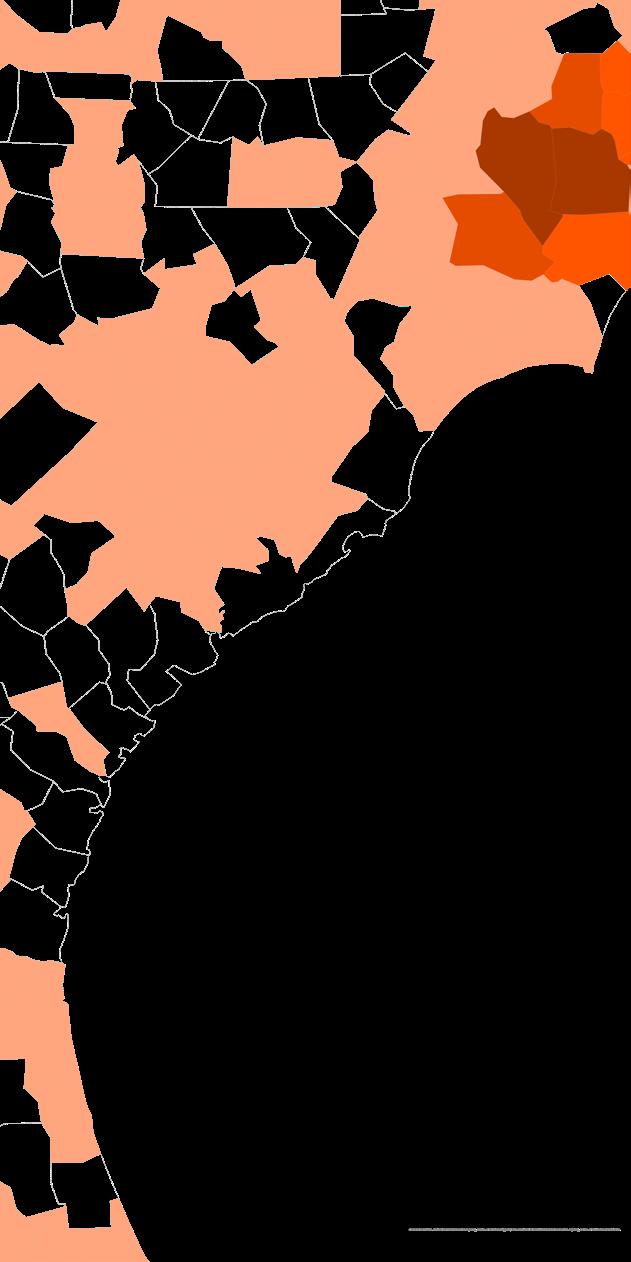

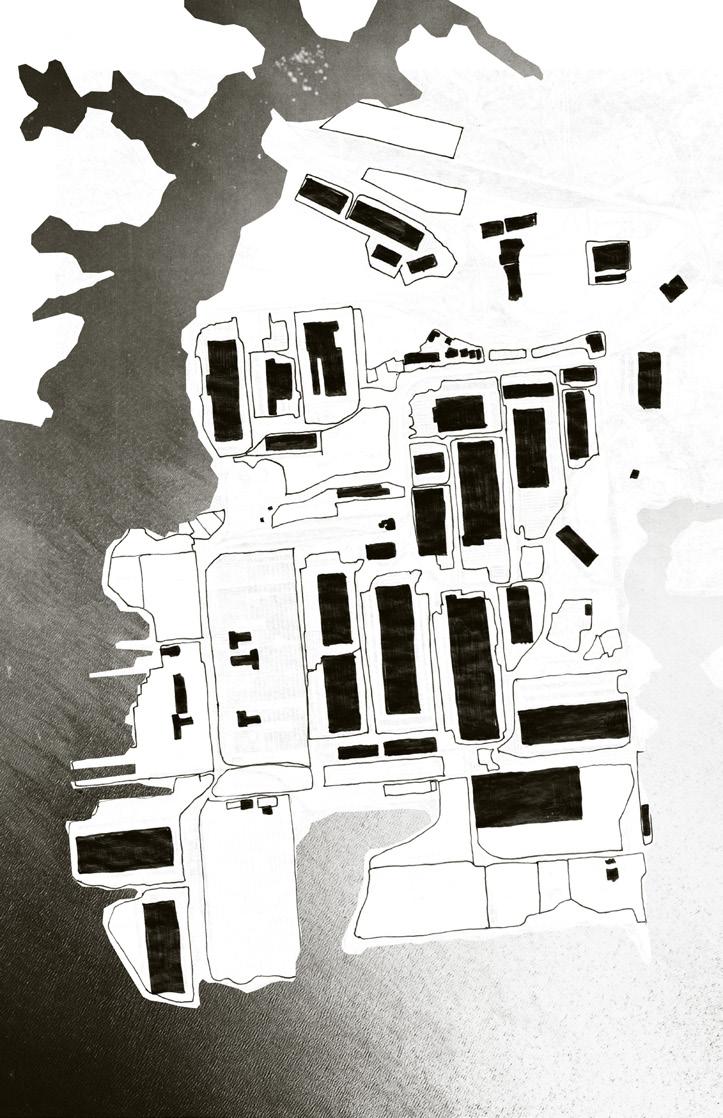

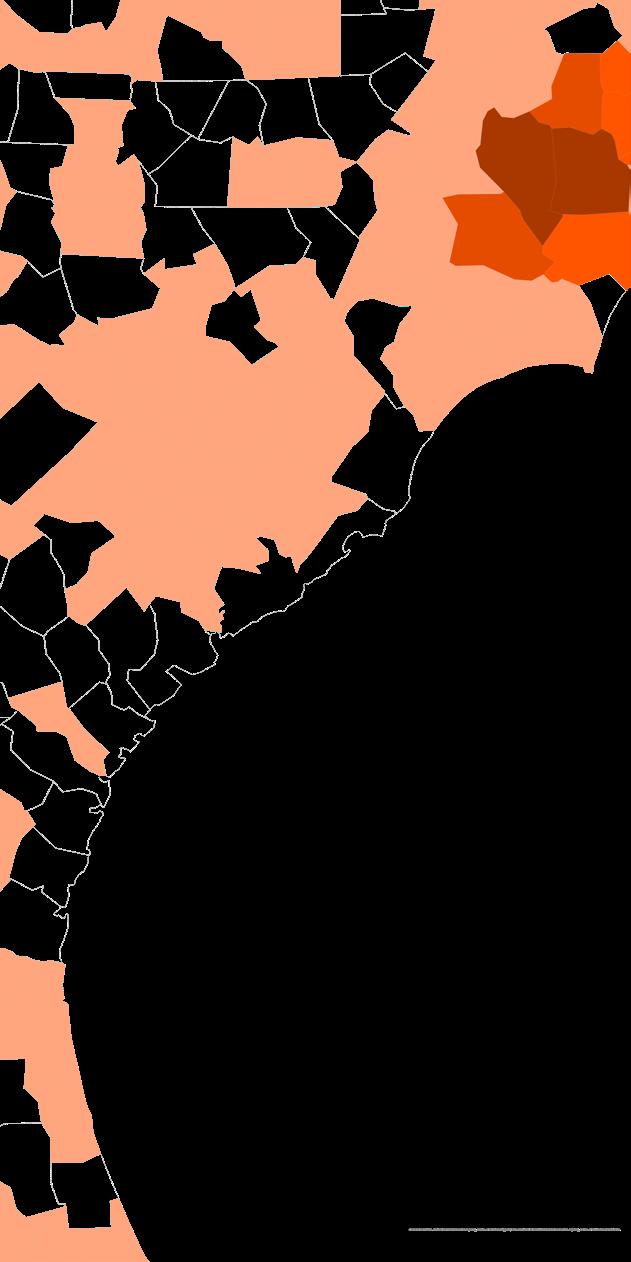

Figure-Ground diagram of Atlantic Beach, showing how the core of the neighborhood is differentiated from the surrounding Myrtle Beach.

Figure-Ground diagram of Atlantic Beach, showing how the core of the neighborhood is differentiated from the surrounding Myrtle Beach.

13

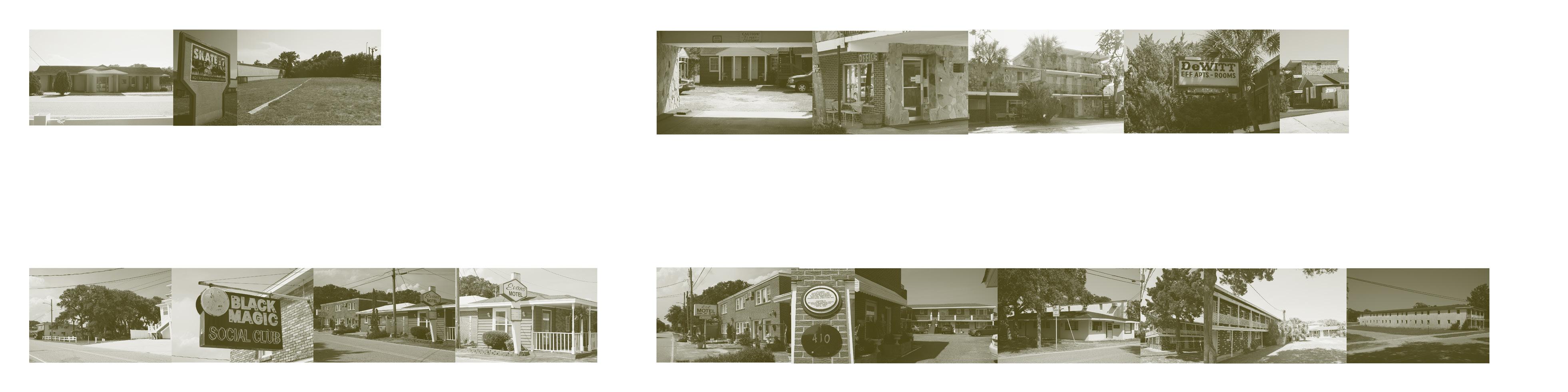

Photographs of historic Motel Row on Atlantic Beach. Sherry Suttles had advocated for its preservation in the early 2000s, and today, only a few of its historic structures remains.

Chart comparing the histories, opportunities, and challenges of three Historically Black Beach sites.

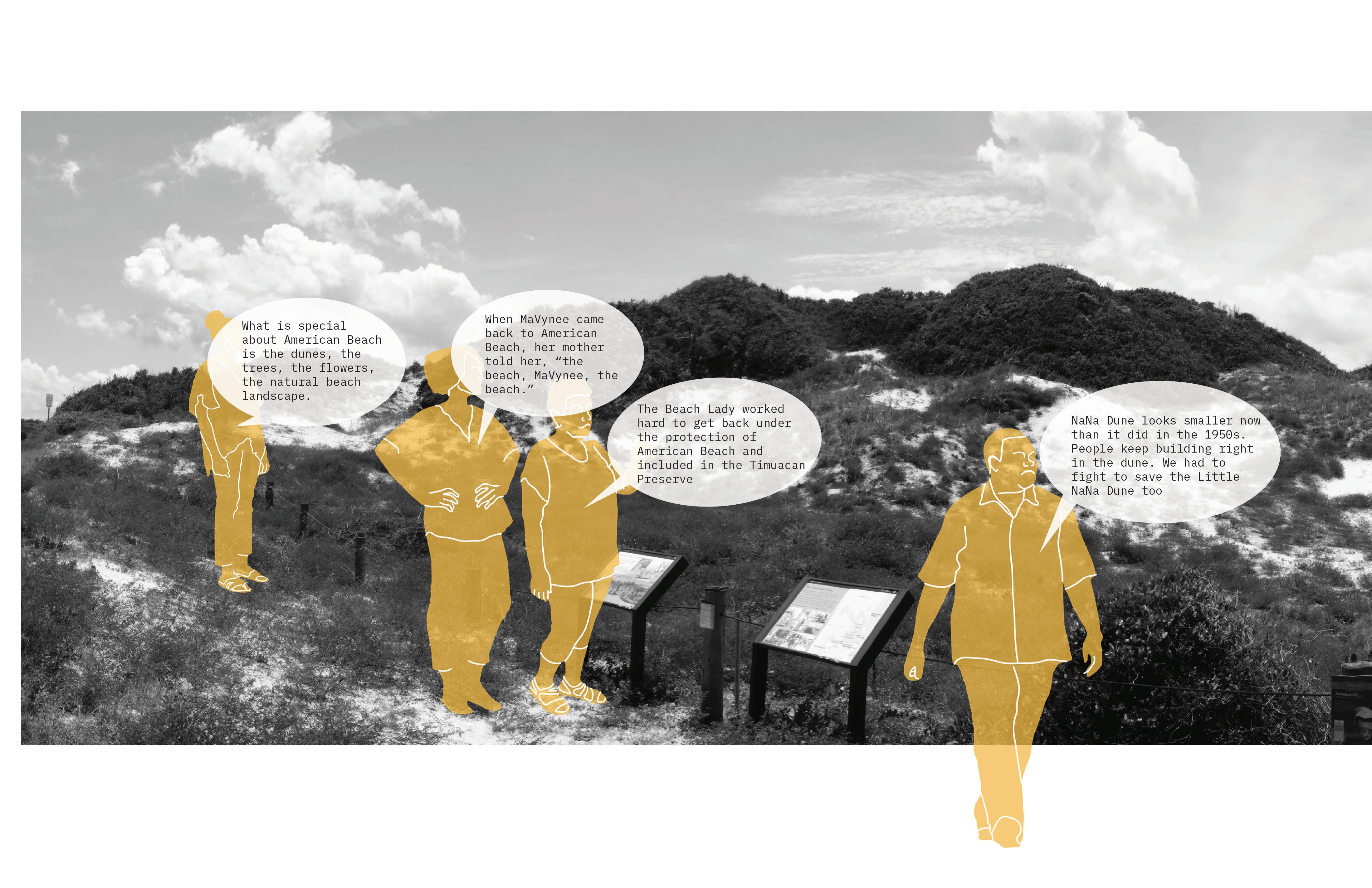

I compared the notes, stories, and opportunities of the three primary beaches in this study: Seabreeze, Atlantic Beach, and American Beach. Given the high level of vision shown by the community, the availability of historical resources, and my connections to the Florida landscape, I decided to focus my design work and analysis on American Beach, pictured to the right. The following pages refer exclusively to American Beach.

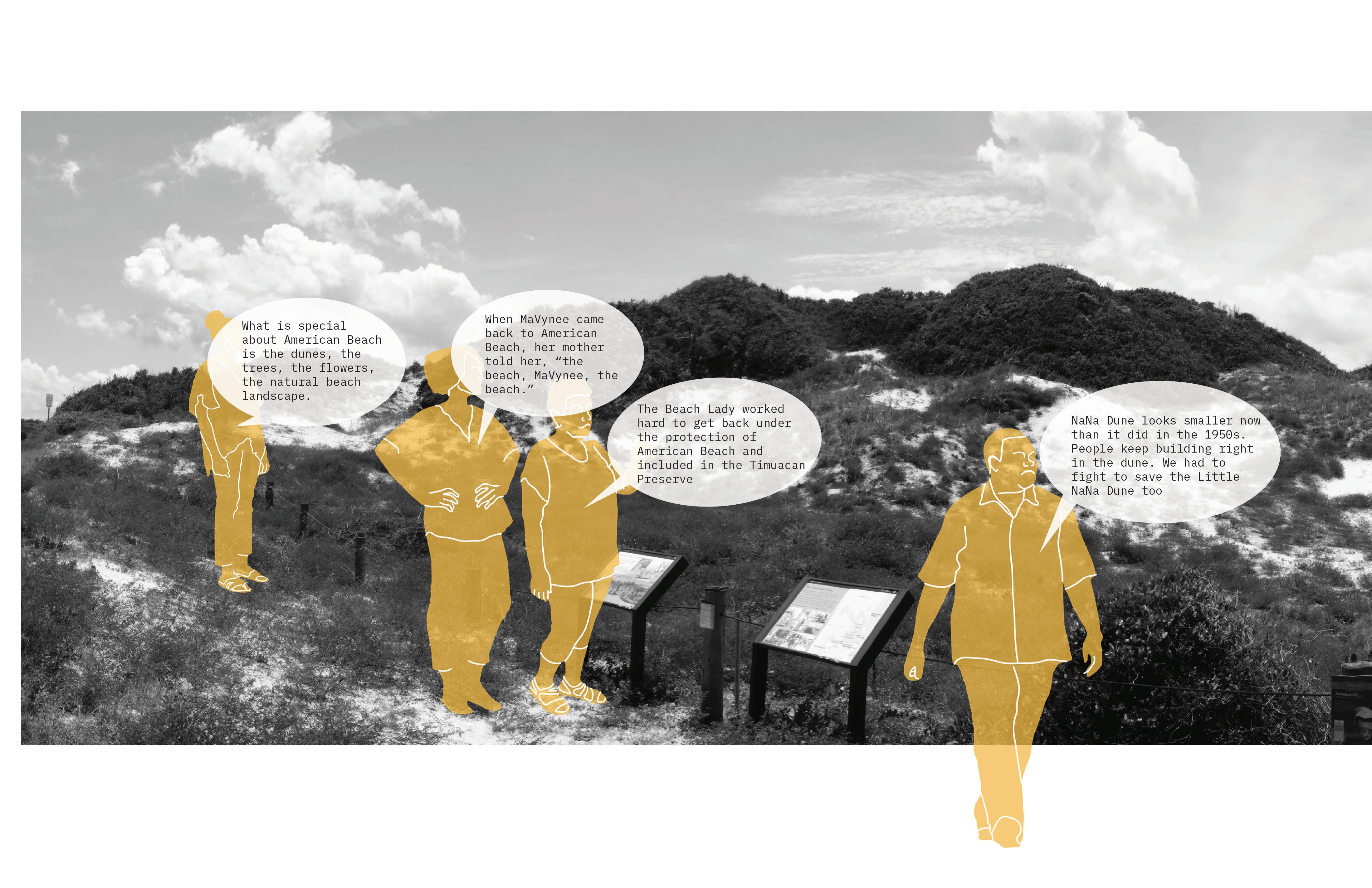

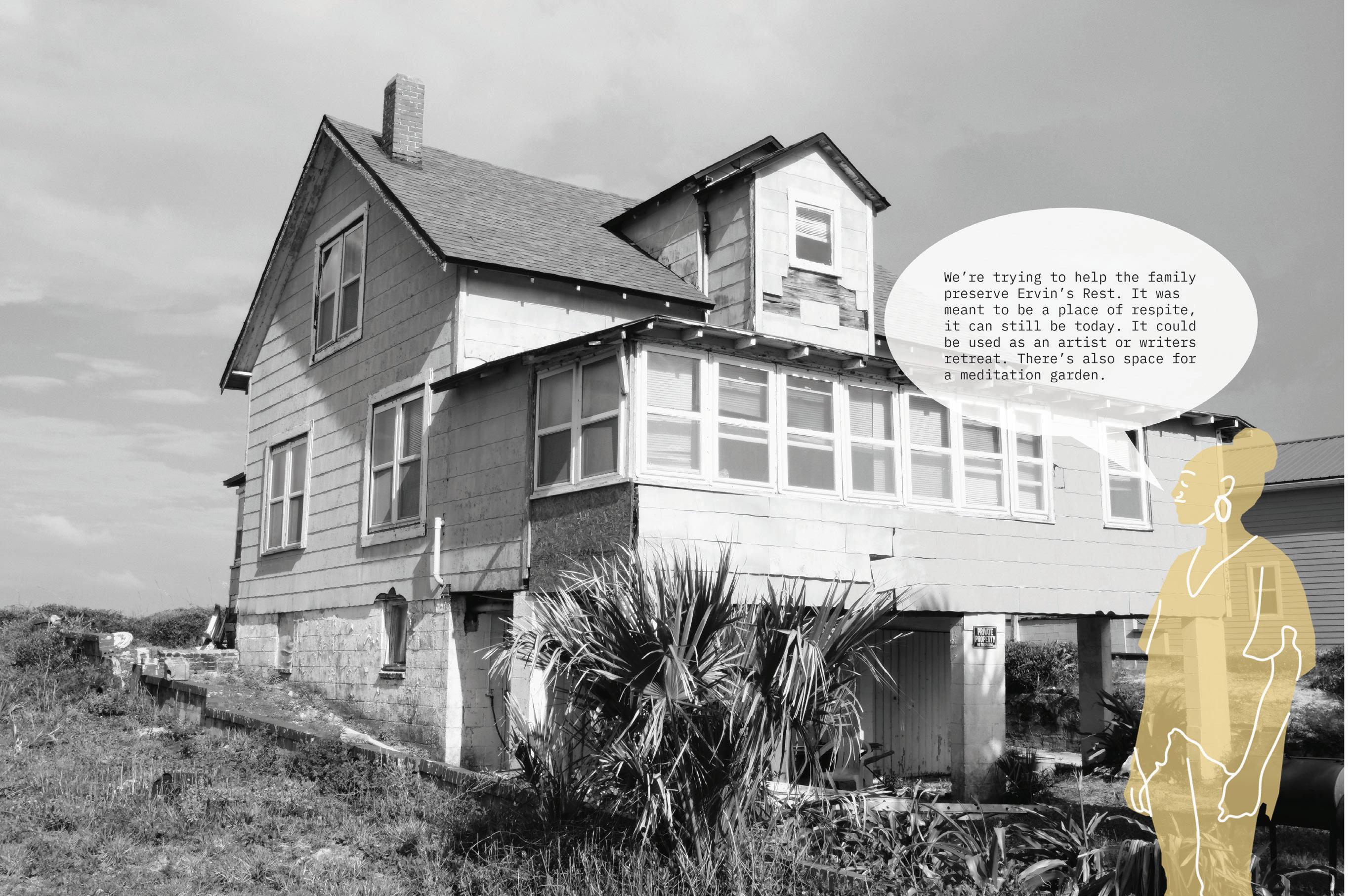

New Hanover

NC Historic Extents of Freeman Landholdings: 5,500 acres Historic Extents: 1500 acres Current Extents: >100 acres Current Extents: 115 acres Initial Land Purchase: 1937 Founded: 1937 Incorporated: 1966 Initial Land Purchase: 1935 Founded: 1940 American Beach Property Owner’s Association Formed: ~1990s Initial Land Purchase: 1855 Additional 2500 acres: 1876 Founded: 1920s Land was initially purchased by Alexander Freeman, who lived freely in New Hanover County. His son Robert Bruce purchased an additional 2500 acres. By the early 1920s, Robert Bruce’s children subdivided the beachfront properties into lots to develop a beach resort for African American beachgoers. 47 acres of land was initially purchased by George Tyson who immediately subdivided into lots for African Americans to purchase to create homes and businesses. Additional acres were purchased as the community grew and flourished. In the 1960’s, surrounding beaches decided to join under the umbrella of North Myrtle Beach. This was an attempt to incorporate Atlantic Beach into the majority community. On June 15 th , 1966, the original Atlantic Beach and Pearl Beach officially joined and incorporated as the Town of Atlantic Beach, a fully independent municipality in the state of South Carolina. Atlantic Beach is one of the better known historically Black beaches and is still an incorporated township, which provides it with the benefits of a small (shrinking) tax-base and an organized political unit. However, from my research into the Sherry A. Suttles papers, it is clear that Atlantic Beach suffers from conflicting visions about preservation. Several historic structures have been torn down in the last 30 years and large gaps in the urban fabric have created a mosaic of vacant lots. However, residents have managed to suspend develop and gentrification in their neighborhood and many lots have signs protesting the construction of high rises. Existing festivals and historical markers carry the stories of the beach. I primarily see opportunities with the vacant lots and could imagine an intervention such as a park, museum, or historical corridor that pays homage to the past while being an investment in the community’s future. It is unclear about the titles of these lots as many of these communities contend with the legacy of heir’s property and many residents are wary of any outward investment lest it lead to gentrification. American Beach is supported by a strong, dedicated network of community advocacy groups such as the Friends of American Beach and the American Beach Property Owner’s Association. American Beach also had MaVynee Betsch (AKA the Beach Lady), who was a highly visible and effective champion leading the cause of its preservation. Her leadership led to the NPS adoption of the Nana Dune system as well as to the creation of the A.L. Lewis Museum which holds the archives and narratives of American Beach. The neighborhood is well marked with historical markers and signage and the streets bear their original names of key founding figures. The Trust for Public Land has also purchased a beachfront parcel for the county to preserve and develop. The community has recently won the battle for municipal water and sewage lines to be run to the neighborhood, but community members indicate their weariness over battling for the future of American Beach and many in the community are elderly and aging as well as suffering from elevated cancer rates. Heir’s property and division over community development also slow efforts to regrow the beach’s economy. However, some key residents have indicated the desire to invest in American Beach as a research and arts hub, and have pointed to the site of Evan’s Rendezvous and Ervin’s Rest as possible renovations. Very little of Seabreeze’s history is apparent on site. The singular digital historical point shown on Google Maps which notates Roscoe Freeman’s homestead is mis-identified. A few street names is all that gives any indication of the former residents of Seabreeze and the site’s unique history. Only a few original structures remain - these can be identified because of their cinder block construction at ground level, which is in direct comparison to the stilt-raised wooden houses which are required for building in today’s floodplain. Opportunities are available because of an activist group which includes a few local historians and descendents of the Freeman family. There is potential for a park to be constructed in the marshes of Freeman Beach and there are plans for a historical marker/museum to be constructed on site. Slow development due to floodplain status and seeking to create a historical district may also offer opportunities for increased marking, preserving structures, and the creation of an interpretive landscape. In 1935, the Pension Bureau of a pioneering black-owned business – Jacksonville’s Afro-American Life Insurance Company (“the Afro”) – bought 33 acres of shorefront property on Amelia Island. A. L. Lewis, the Afro’s president, invited company employees to make use of the beach, and hosted company outings there. The Pension Bureau also had the land subdivided, and offered parcels for sale to company executives and shareowners, and to community leaders. Two later land acquisitions expanded the community’s size to 216 acres. In 1940, with many building lots unsold, the Afro offered them for sale to the wider black community. After World War II, home construction took off. Historic Extents: 300 acres Current Extents: 90 acres Beach/Location Size Year Founded/ Founding Narrative Footprint Challenges/Opportunities Potential Design Sites Atlantic Beach Horry County, SC American Beach Amelia Island, FL Freeman Landholdings Potential Freeman Beach History Park Site Evan’s Rendezvous County-owned vacant core Nana Dune (NPS) A.L. Lewis Museum Freeman Homestead Present-day Seabreeze Historic Extents of Seabreeze Historic Extents of American Beach Present-day American Beach Museum Historic Marker Site Open Space Network afforded lot Central Beachfront Urban Core Beachfront lots preserved from high-rise development Ervin’s Rest currently unoccupied but original structure is sound Evan’s Rendezvous held by Nassau County and currently in limbo

Seabreeze

County,

OVERVIEWS 14

SITE

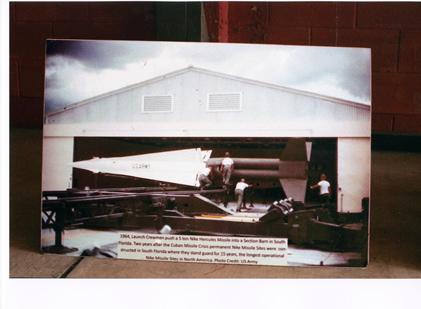

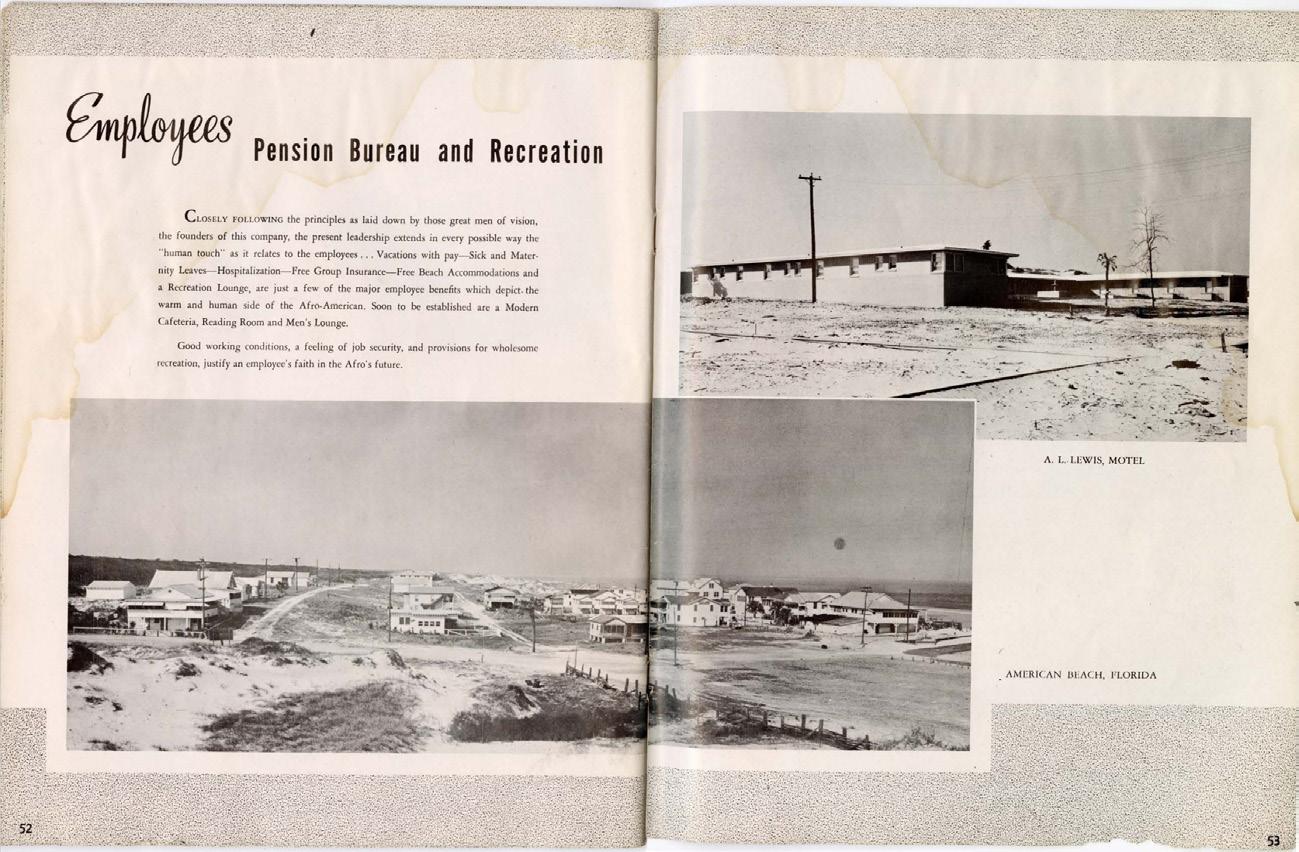

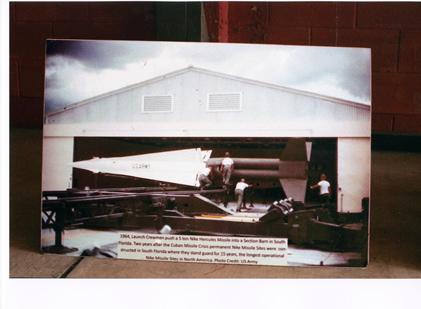

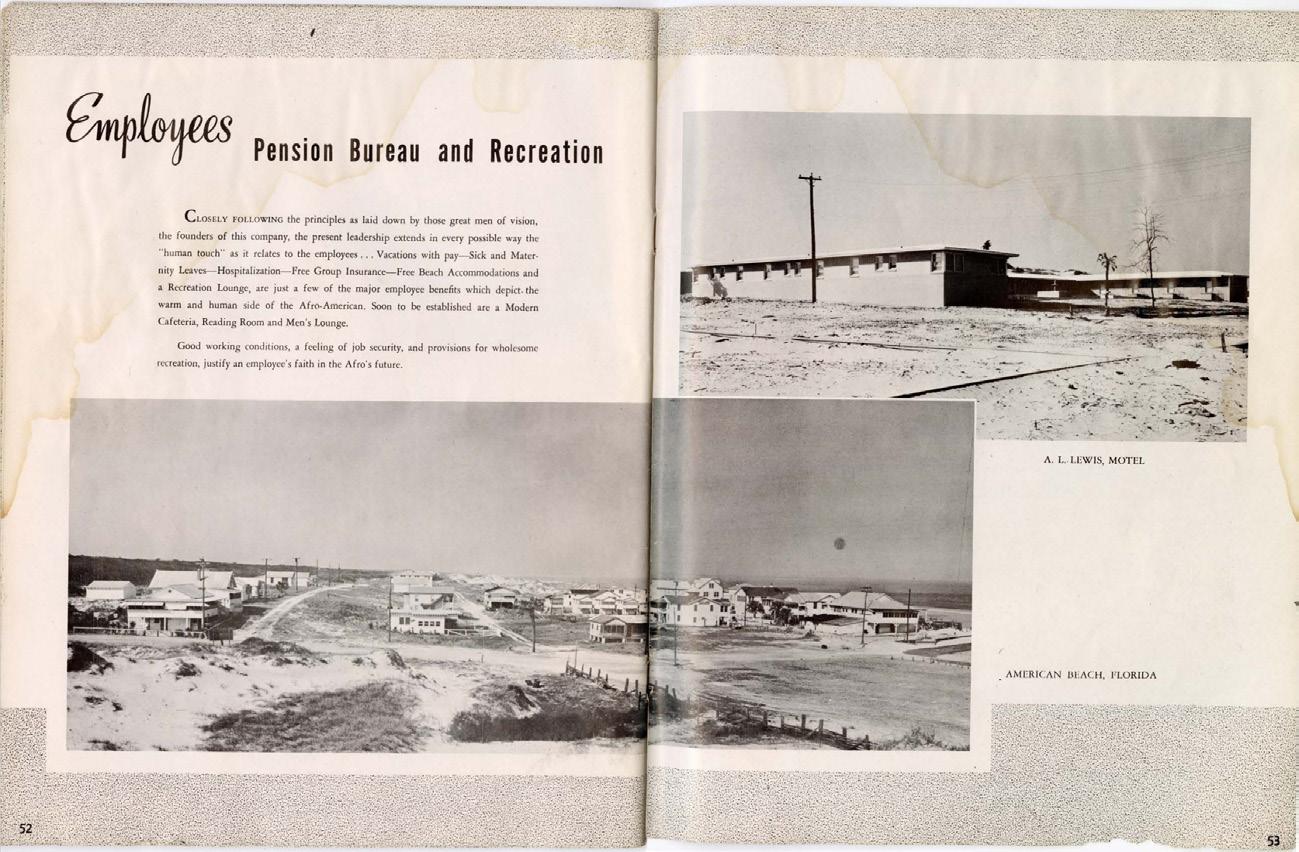

This scan was taken from the 1941 booklet celebrating the Fortieth Anniversary of the Afro-American Life Insurance Company, which was headquartered out of Jacksonville. American Beach served as a pension benefit for employees and their families until it opened more widely to the greater African American population of the south.

15

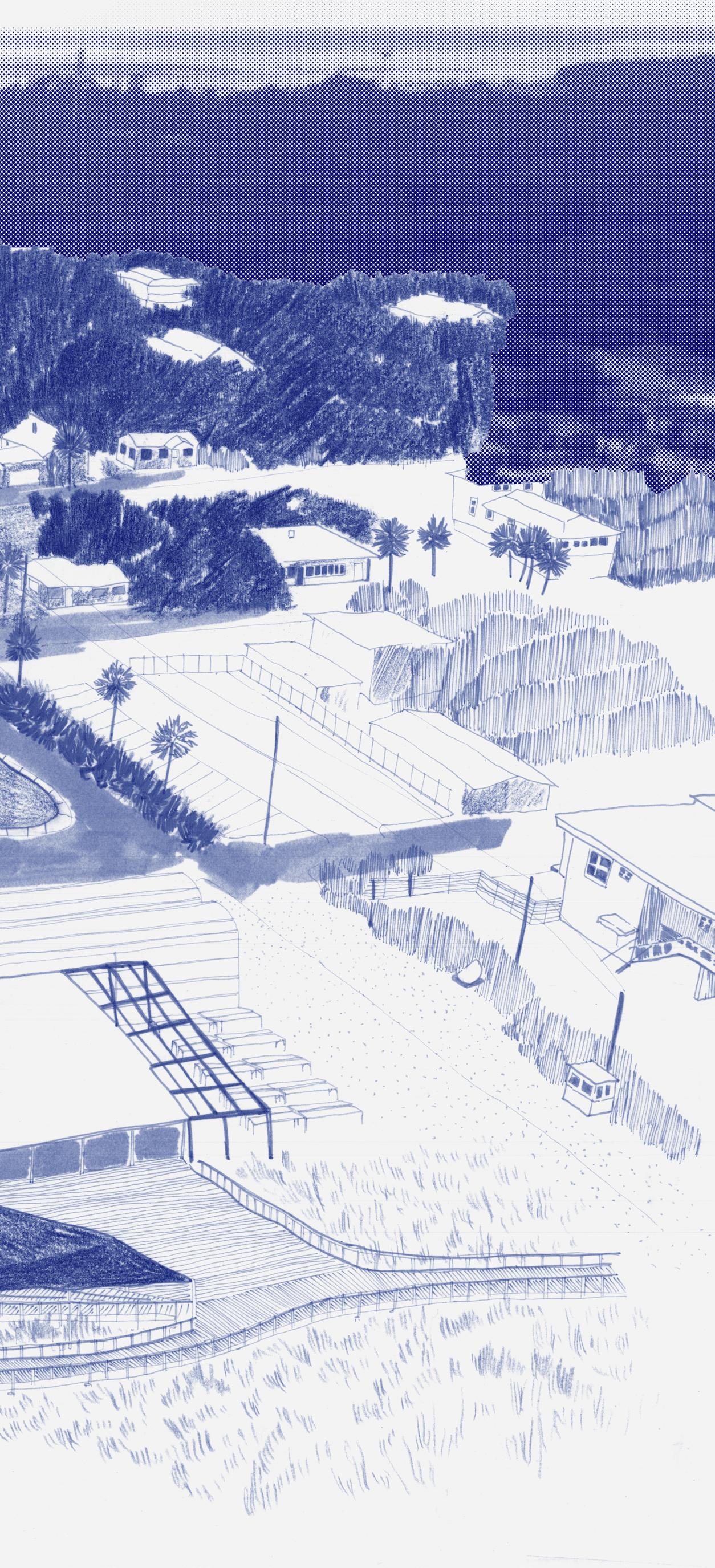

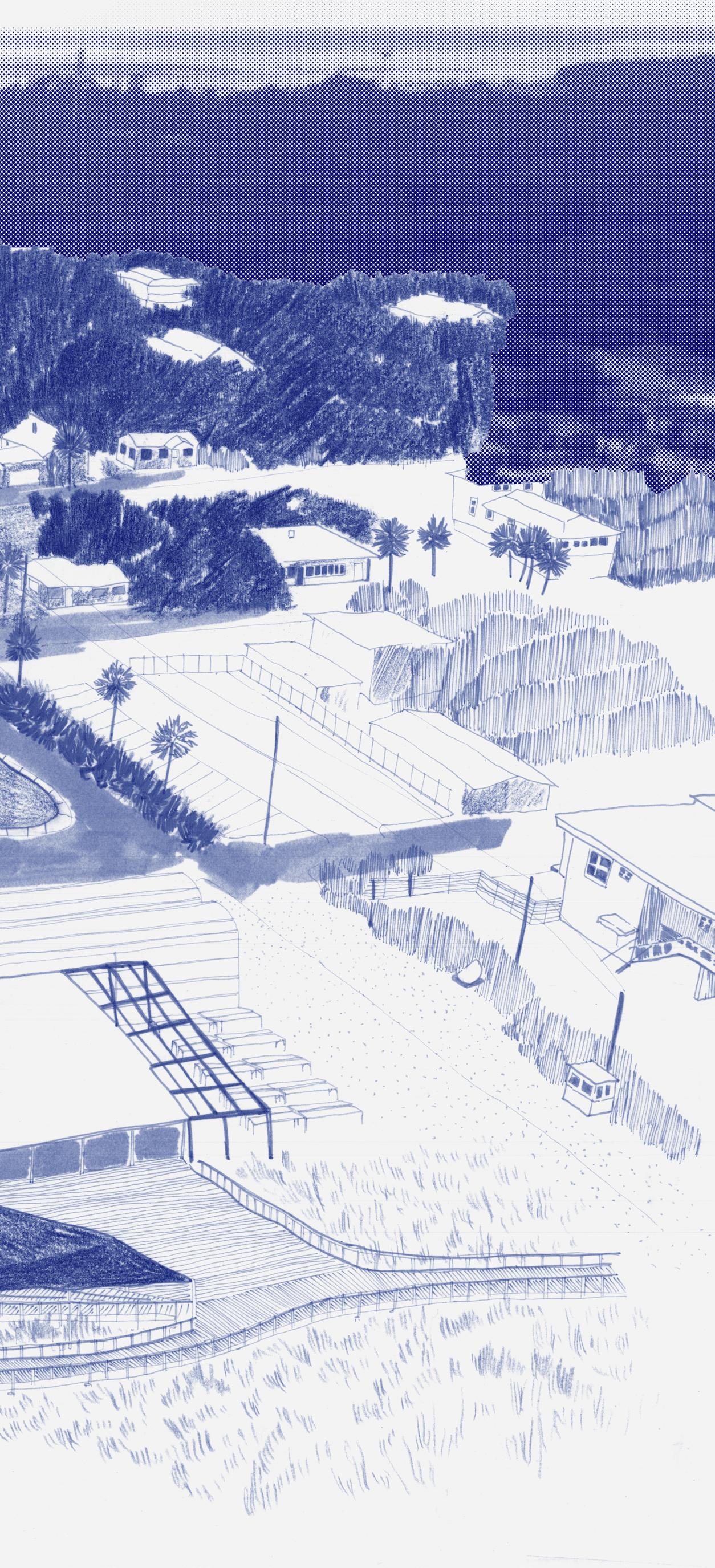

Drone footage taken of American Beach looking west towards Nana Dune.

16

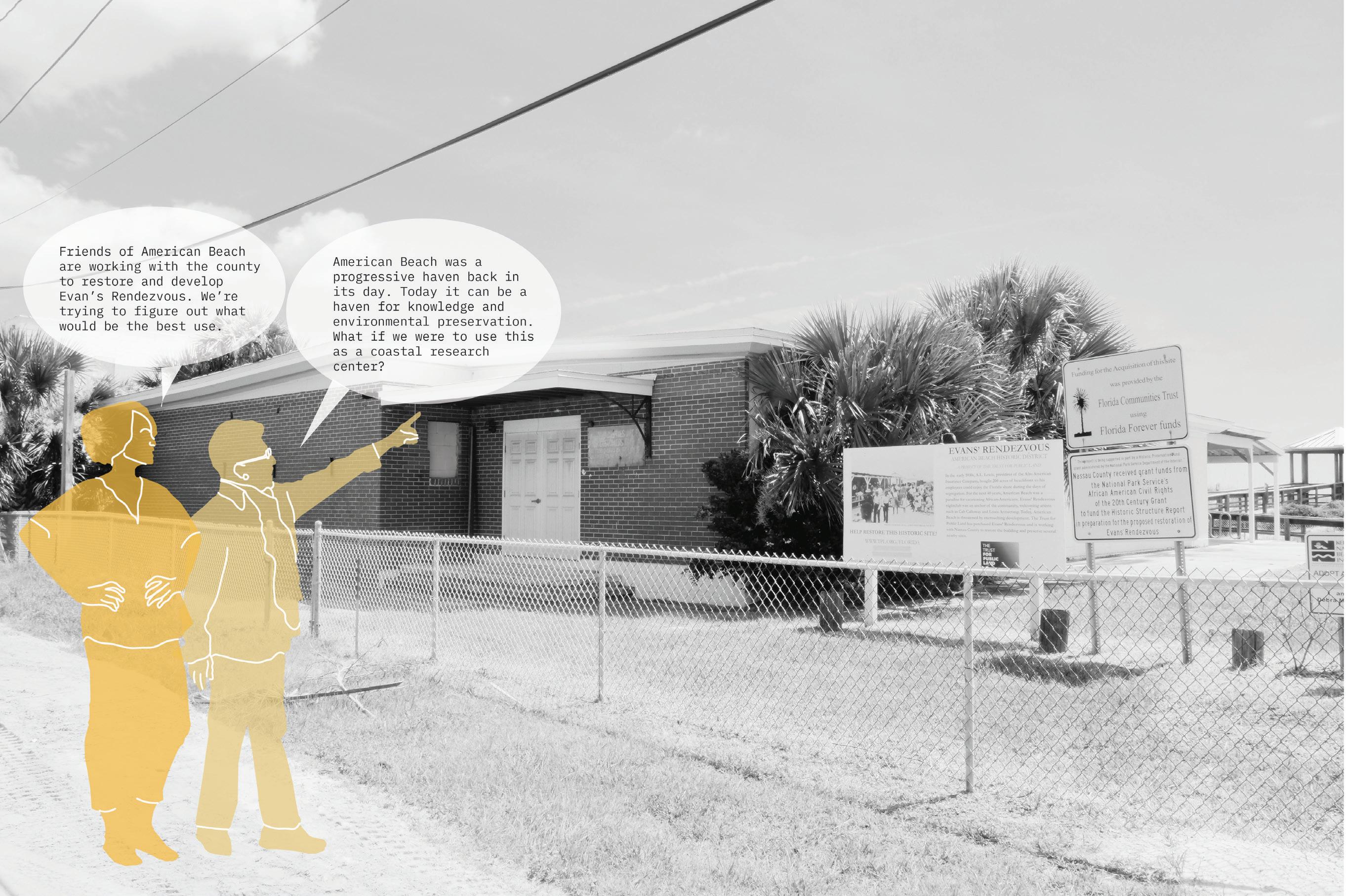

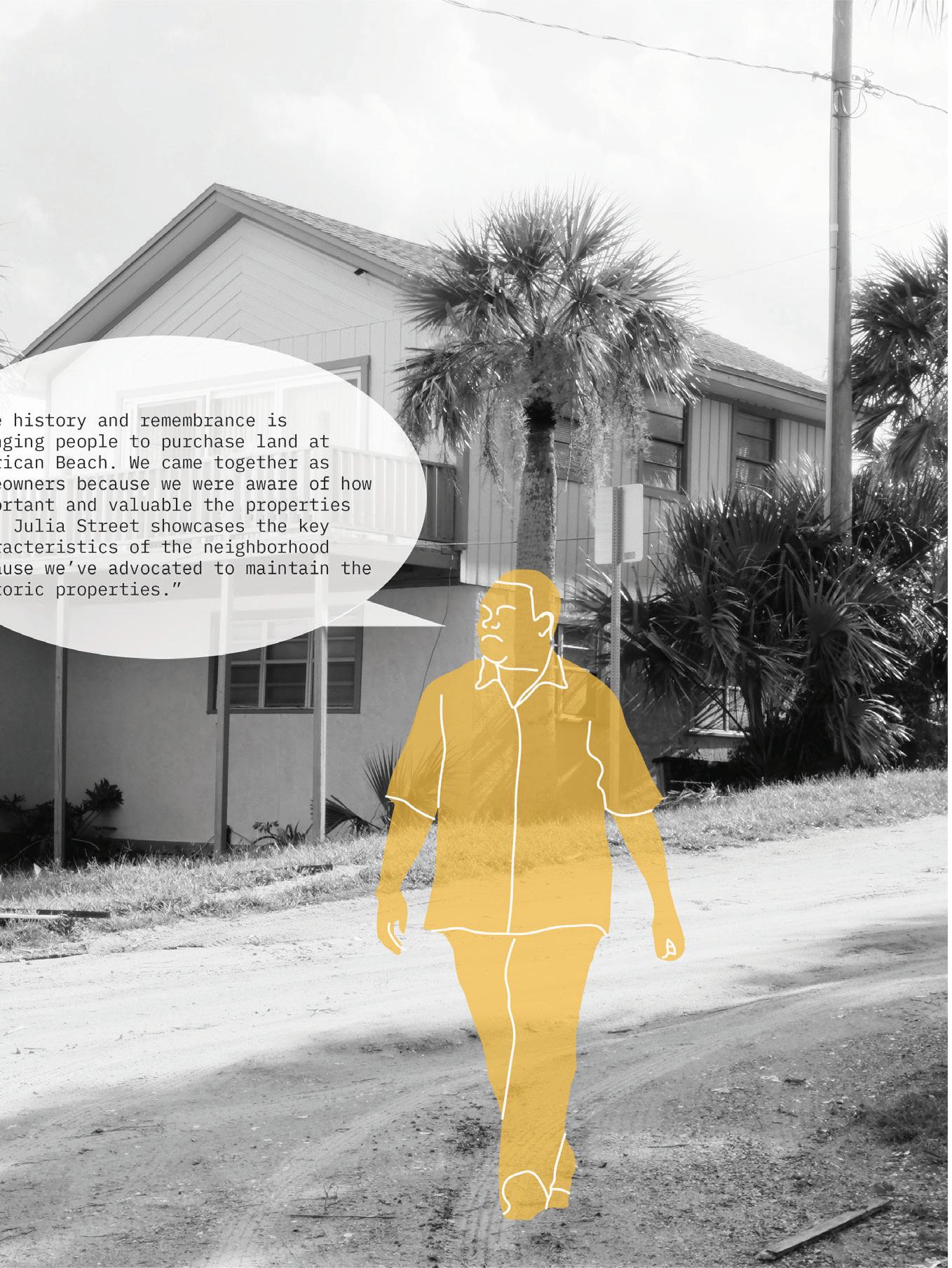

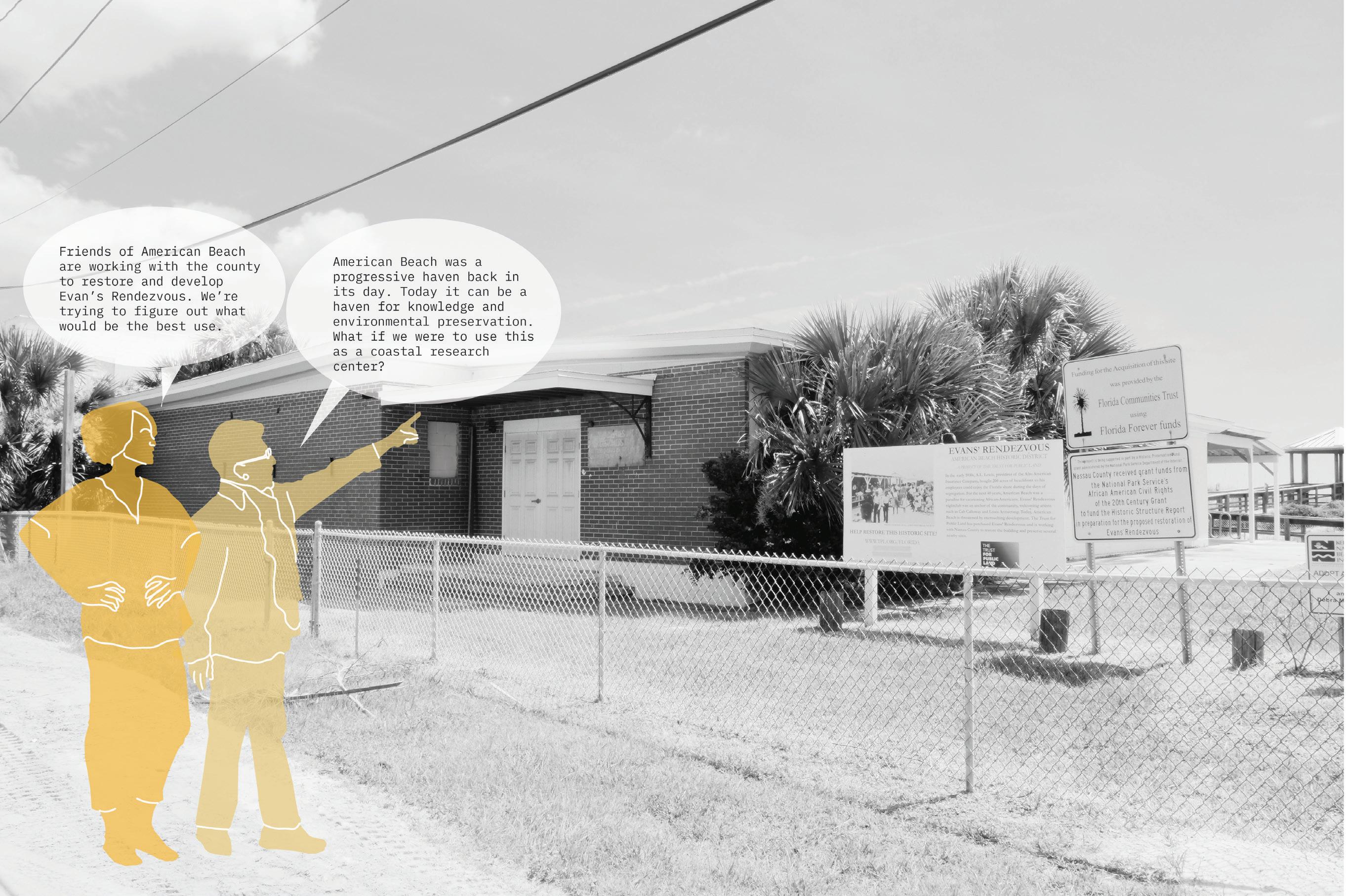

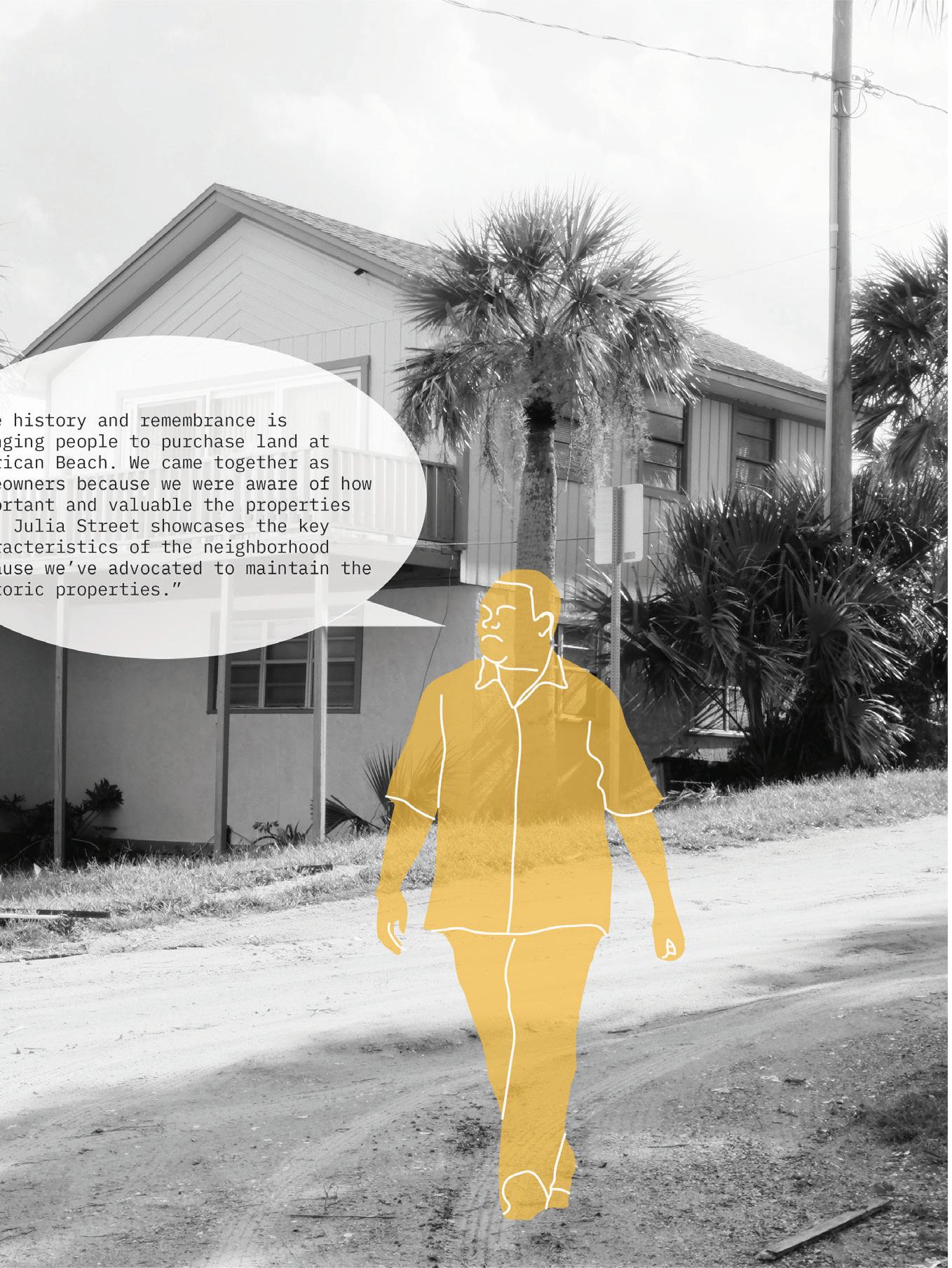

COMMUNITY INPUT

17

18

19

1919 1944 1958 1972 About 20 years prior the founding American Beach. Red contour lines mark the dune fields mid-Amelia Island. Road A1A set upon the upland spine of the island, and single road, what today Lewis Street, cuts towards the shore on what now American Beach. Had this stretch of beach been conceived as public access even before the land was purchased by A.L. Lewis? This map was published during the height of WWII, when America’s coastal landscape was concerned with potential conflict coming ashore. Despite the war effort, American Beach continued to develop and thrive. Pictured here, the shoreward blocks north Lewis Street are more densely developed than those on higher ground. NaNa Dune to the south is free from any construction. This 1958 map captures the height of American Beach’s popularity and shows thriving community built atop complex dune field more carefully rendered than previous topo maps. The structures are nestled around NaNa and Little NaNa Dune which embrace the neighborhood. Ocean Boulevard wraps around the topography, refecting care taken not to disrupt the landforms. This aerial was taken years after both the Civil Rights Act and Hurricane Dora, both of which contributed the decline of American Beach. The foredune appears have completed eroded away, perhaps still recovering from the 1964 storm or maybe another hurricane or nor’easter. The island between NaNa Dune and A1A is richly forested, giving the impression that American Beach is an enclave on an as-of-yet undeveloped island. By the 80s, the structures American Beach had reached an apparent state of decay as disinvestment the community and real estate speculation on the island increased. Rather than appearing embraced by the dunes, the neighborhood looks more like it’s being consumed by the shifting sands. The 90s were pivotal point for the community. Efforts preserve American Beach began to take off as the community members faced increasing threats of gentrification and loss of historical structures. Developments began to close in from all sides, most instrusively from the Amelia Island Plantation hotel group which consumed historic Franklin Town to the south, hemming the neighborhood. By 2005, efforts place the neighborhood on the National Register Historic Places had failed, but the community rallied around the efforts of MaVynee Betsch and the leadership the American Beach Homeowners Association. Thanks to their efforts, by 2005, NaNa Dune was incorporated into the NPS via the Timucuan Ecological Preserve. However, the entire back the dune and the coastal uplands have been fully developed into retirement/golf community. Land the north of American Beach, which had formerly been sand dunes, now developed into luxury beach communities. MaVynee Betsch had called these “waffle houses” since they all appeared have the same cookie cutter construction. Several of the historic structures have been demolished creating spate of vacancies on what was once densely developed land. Vegetation on the foredune appears make comeback. Present-day. Vacant lots have given way new construction the beach begins to regain in popularity and investment by those who wish to live on storied landscape. The residents of American Beach are now considering “what’s next?” as they think about succession of their homes and communities to their children and face an increasingly uncertain political and environmental climate. 1983 1993 2005 2023 About 20 years prior to the founding of American Beach. Red contour lines mark the dune fields of mid-Amelia Island. Road A1A is set upon the upland spine of the island, and a single road, what is today Lewis Street, cuts towards the shore on what is now American Beach. Had this stretch of beach been conceived as public access even before the land was purchased by A.L. Lewis? 1944 1919 This map was published during the height of WWII, when America’s coastal landscape was concerned with potential conflict coming ashore. Despite the war effort, American Beach continued to develop and thrive. Pictured here, the shoreward blocks north of Lewis Street are more densely developed than those on higher ground. NaNa Dune to the south is free from any construction. SITE ANALYSIS +

20

TESTS

1958 1983 2005

1972

This 1958 map captures the height of American Beach’s popularity and shows a thriving community built atop a complex dune field more carefully rendered than in previous topo maps. The structures are nestled around NaNa and Little NaNa Dune which embrace the neighborhood. Ocean Boulevard wraps around the topography, refecting care taken not to disrupt the landforms.

By the 80s, the structures of American Beach had reached an apparent state of decay as disinvestment in the community and real estate speculation on the island increased. Rather than appearing embraced by the dunes, the neighborhood looks more like it’s being consumed by the shifting sands. 1993

90s were

pivotal point for the community. Efforts to preserve American Beach began to take off as the community members faced increasing threats of gentrification and loss of historical structures.

began

close in

all sides, most instrusively from the Amelia Island Plantation hotel group which consumed historic Franklin Town to the south, hemming in the neighborhood.

but

and

Thanks to their efforts, by 2005, NaNa

was incorporated into the NPS via the Timucuan Ecological Preserve. However, the entire back of the dune and the coastal uplands have been fully developed into a retirement/golf community. Land to the north of American Beach, which had formerly been sand dunes, is now developed into luxury beach communities. MaVynee Betsch had called these “waffle houses” since they all appeared to have the same cookie cutter construction. Several of the historic structures have been demolished creating a spate of vacancies on what was once densely developed land. Vegetation on the foredune appears to make a comeback. 2023 Present-day. Vacant lots have given way to new construction as the beach begins to regain in popularity and investment by those who wish to live on a storied landscape. The residents of American Beach are now considering “what’s next?” as they think about succession of their homes and communities to their children and face an increasingly uncertain political and environmental climate. 21

This aerial was taken 8 years after both the Civil Rights Act and Hurricane Dora, both of which contributed to the decline of American Beach. The foredune appears to have completed eroded away, perhaps still recovering from the 1964 storm or maybe another hurricane or nor’easter. The island between NaNa Dune and A1A is richly forested, giving the impression that American Beach is an enclave on an as-of-yet undeveloped island.

The

a

Developments

to

from

By 2005, efforts to place the neighborhood on the National Register of Historic Places had failed,

the community rallied around the efforts of MaVynee Betsch

the leadership of the American Beach Homeowners Association.

Dune

22

23

A A’ B C D E F G H I J K L B’ C’ D’ E’ F’ G’ H’ I’ J’ K’ L’ Nassau County land Evan’s Rendezvous currently under the management of Nassau County NPS Protected Land - Timuacan Ecological & Historic Preserve C u r r e n t C C C L Foredune protected by Coastal Construction Control Line (CCCL) A A’ B B’ C C’ D D’ E E’ F F’ G G’ H H’ I I’ J J’ K K’ L L’

24

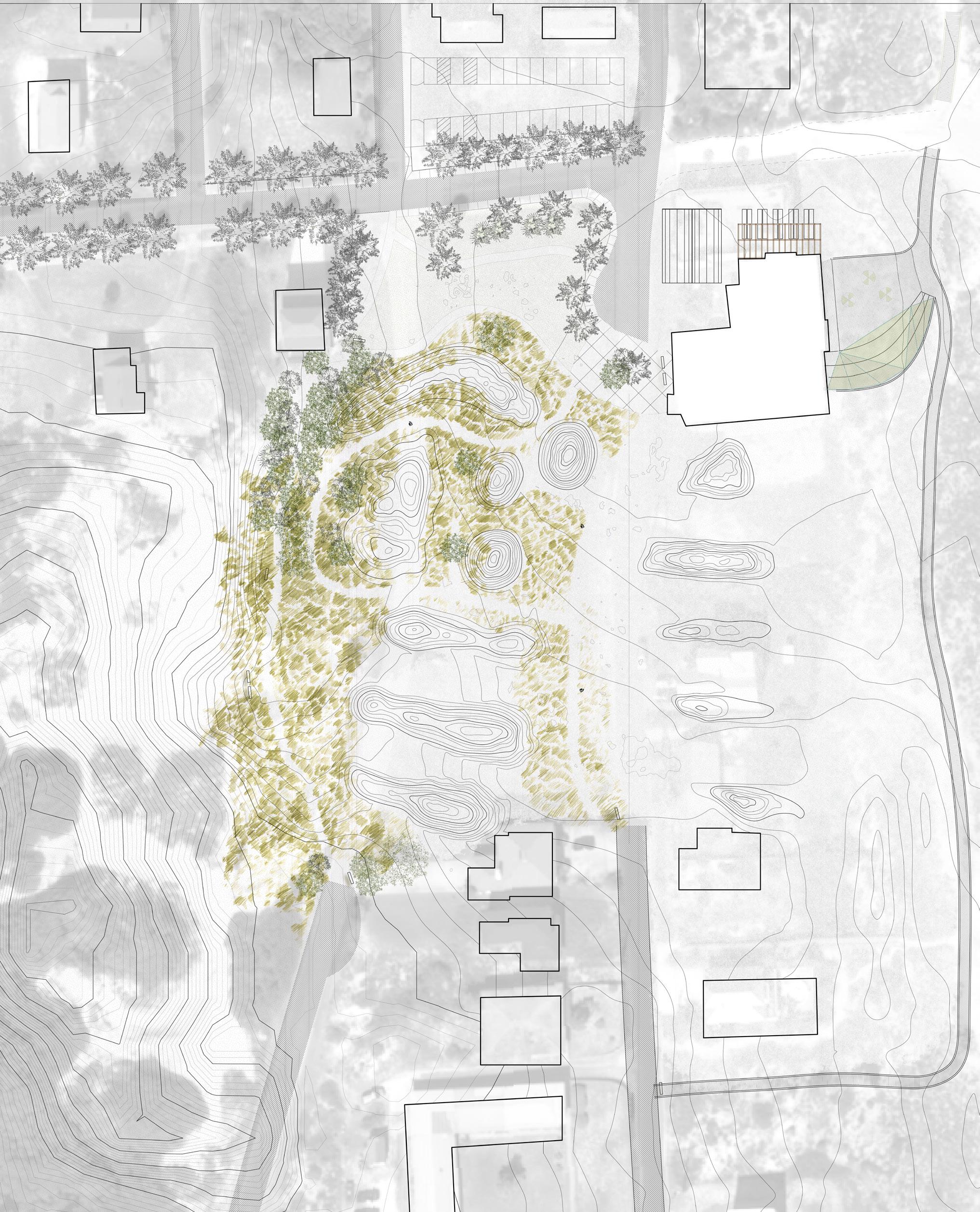

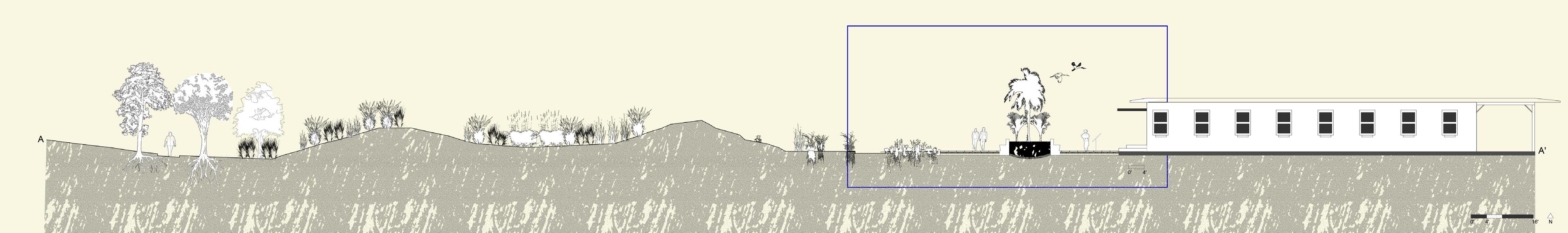

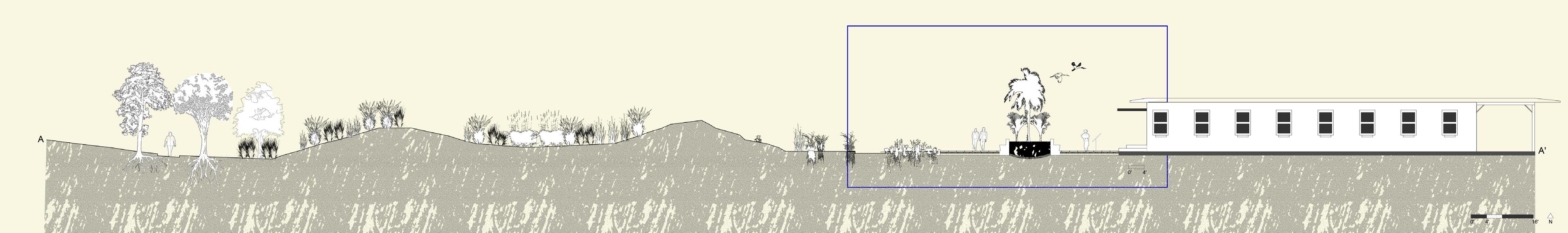

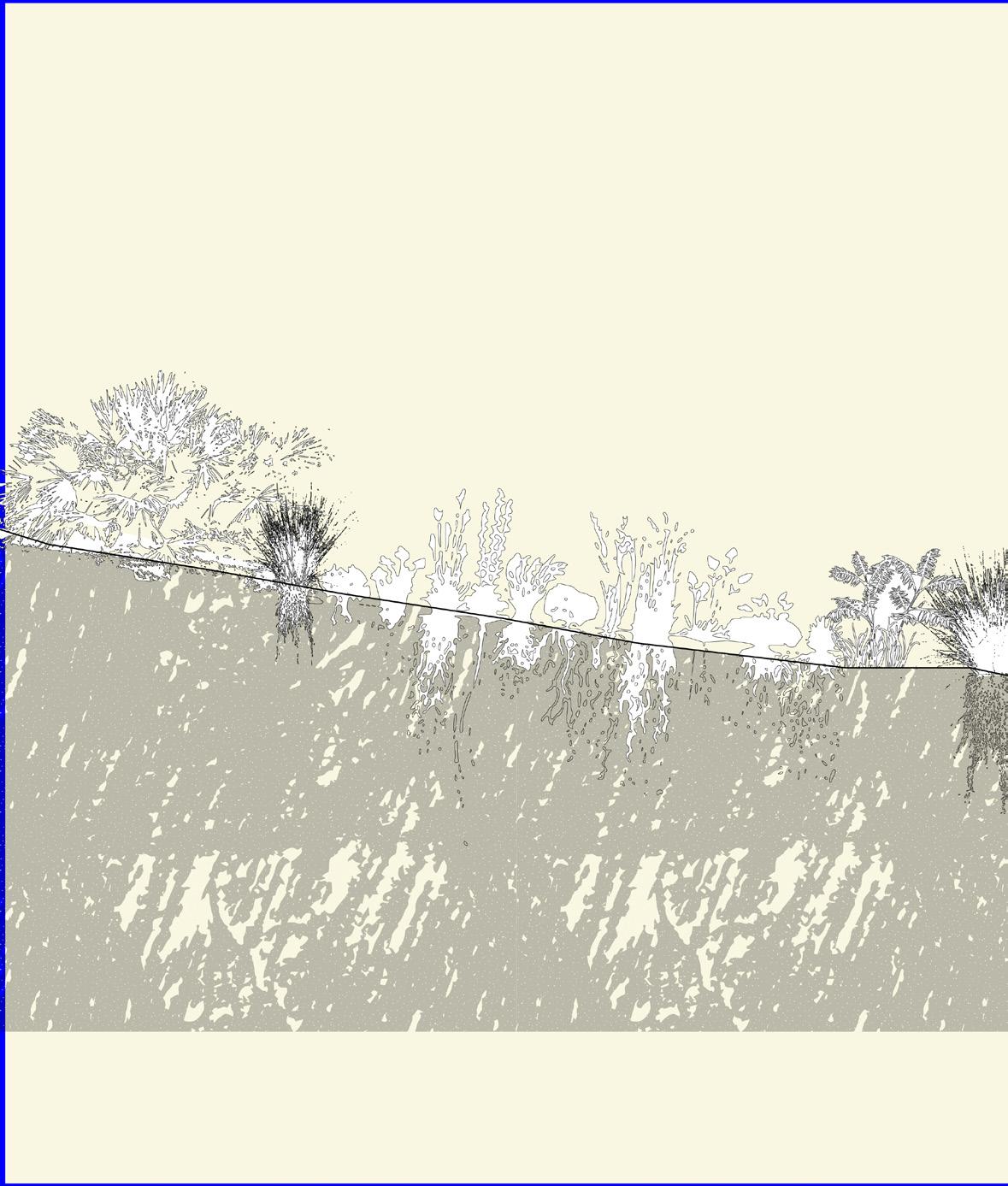

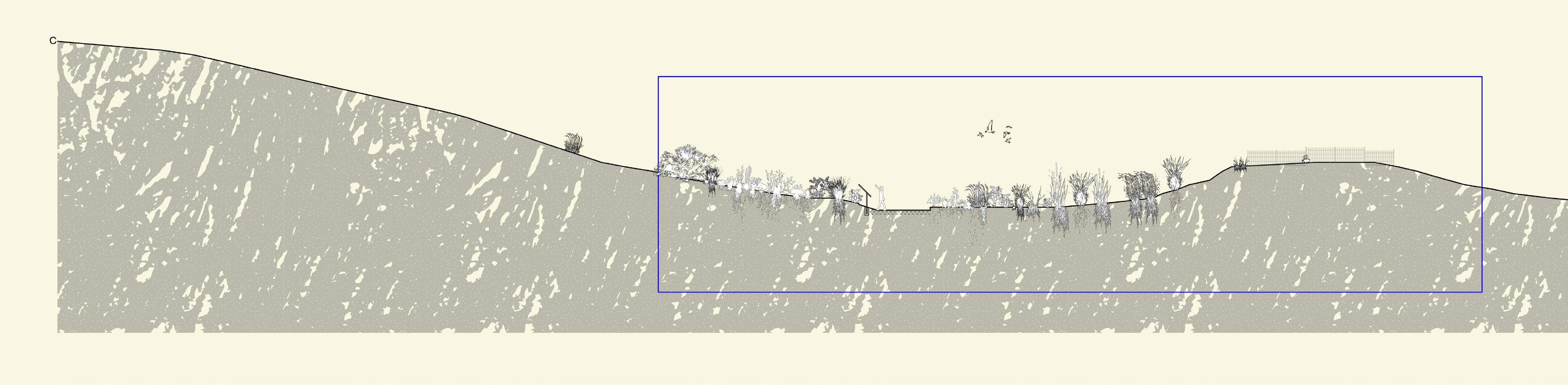

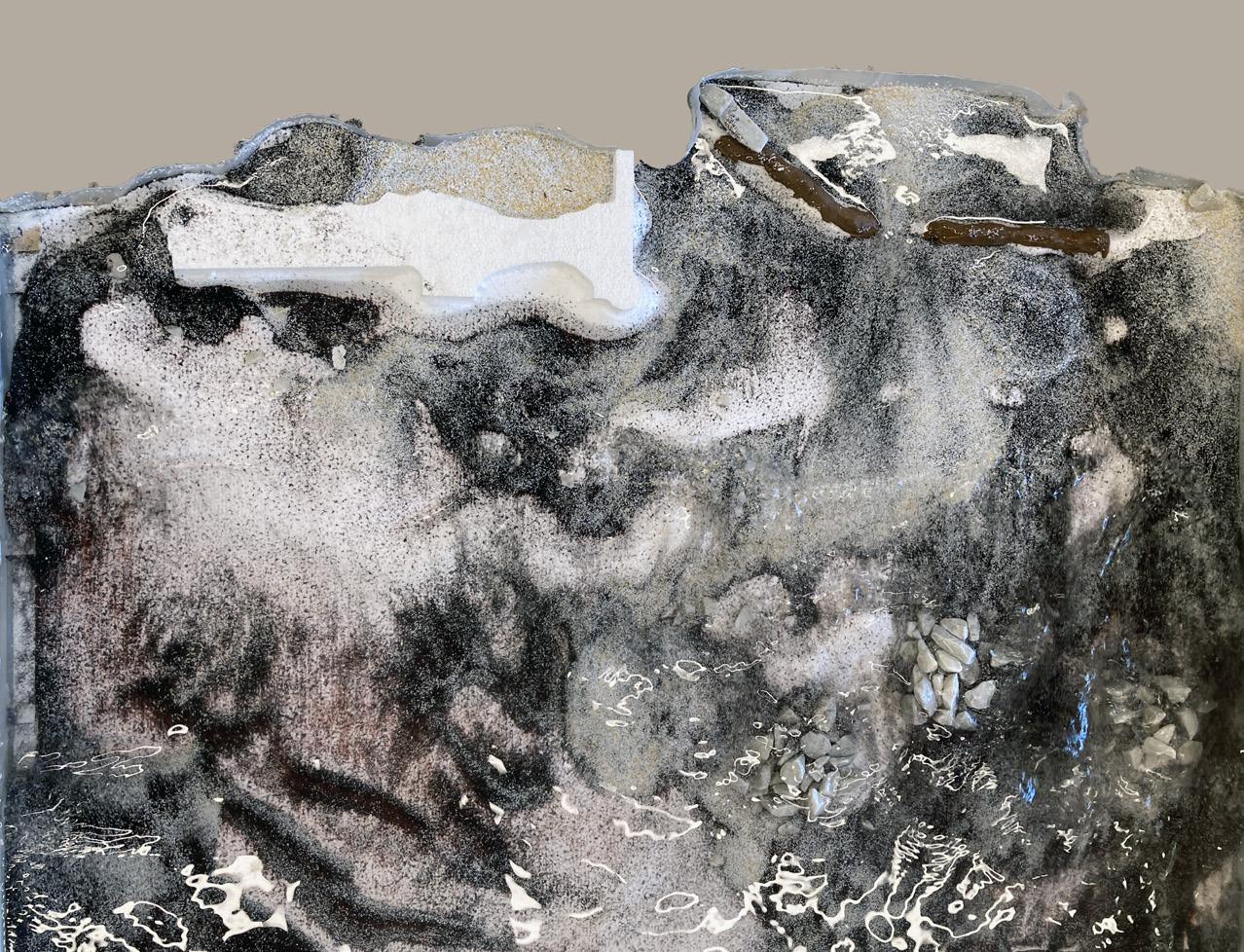

Existing Site plan and sections: Mapping control, stewardship, and development on American Beach. Wind Direction and Sediment Fields

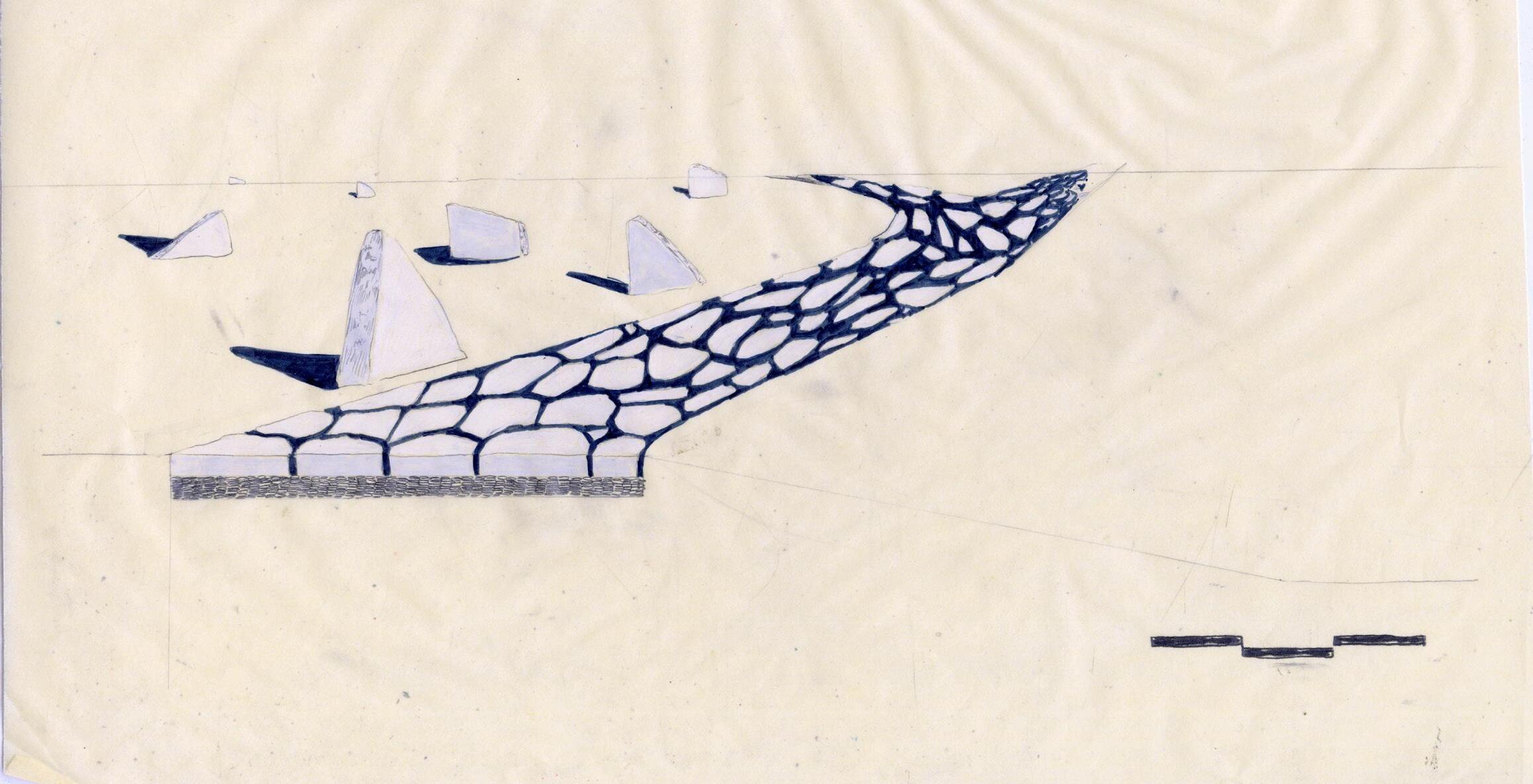

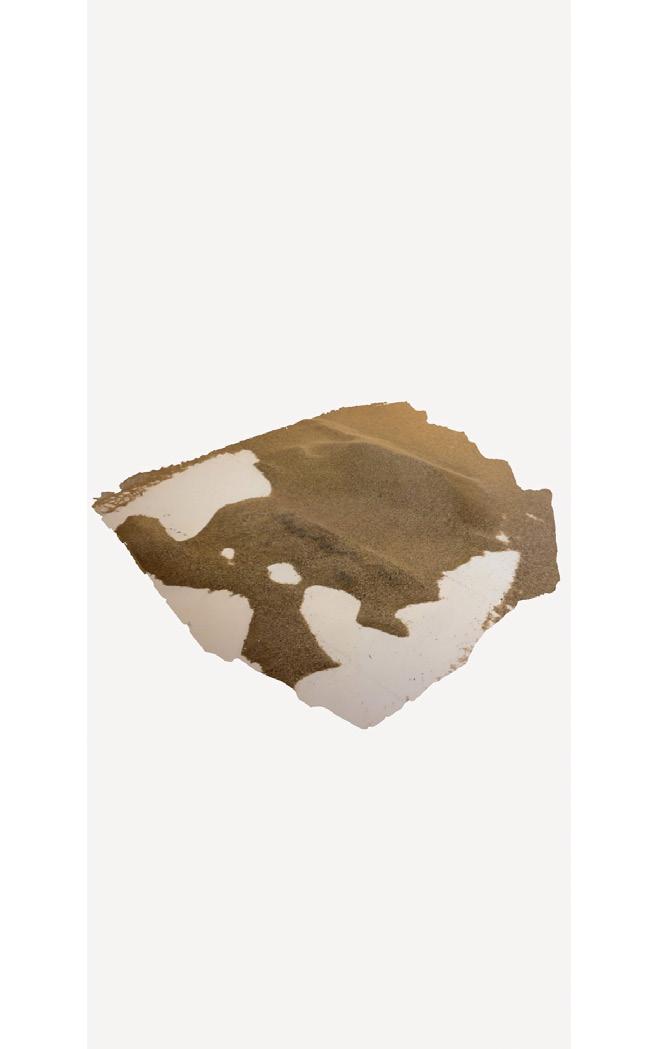

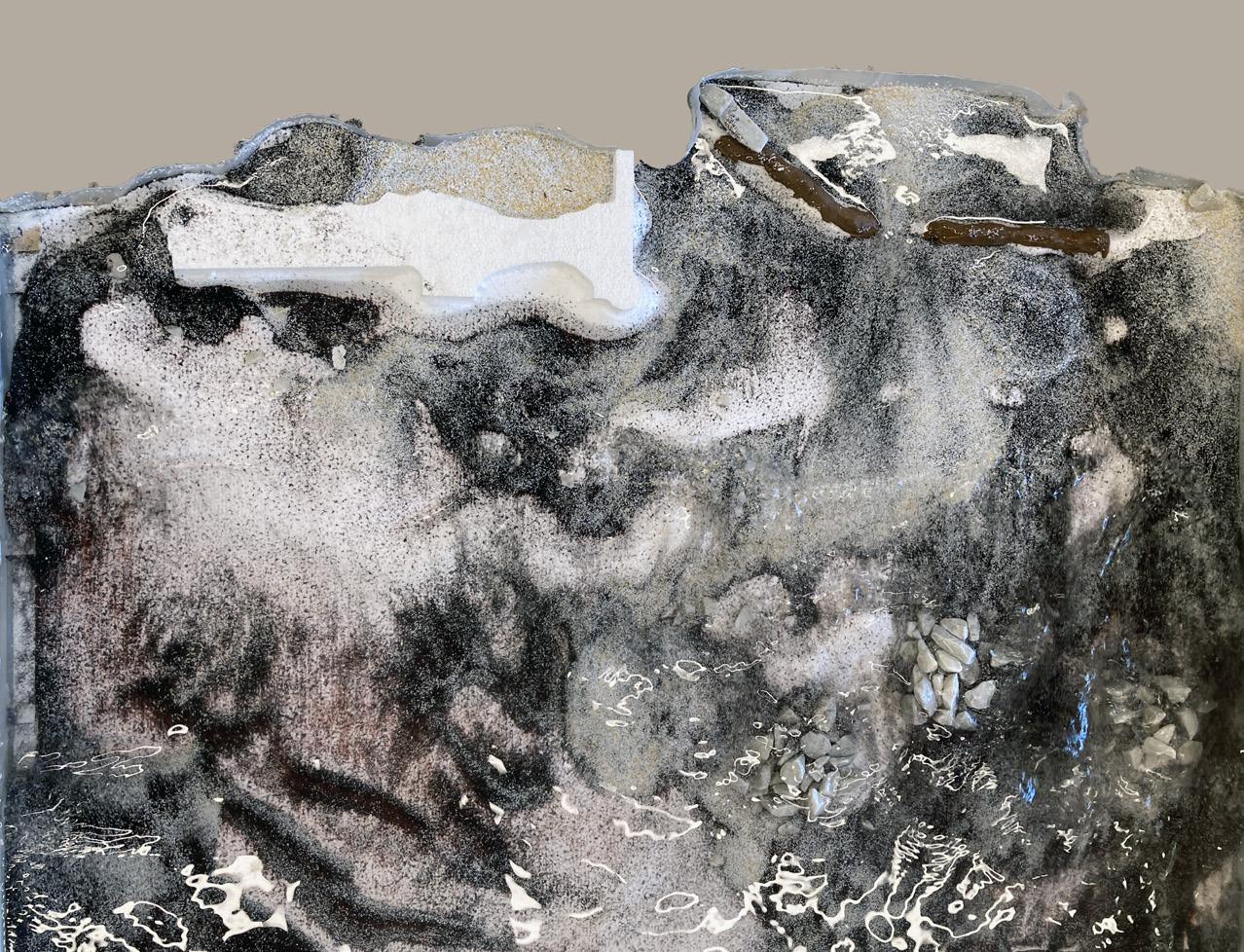

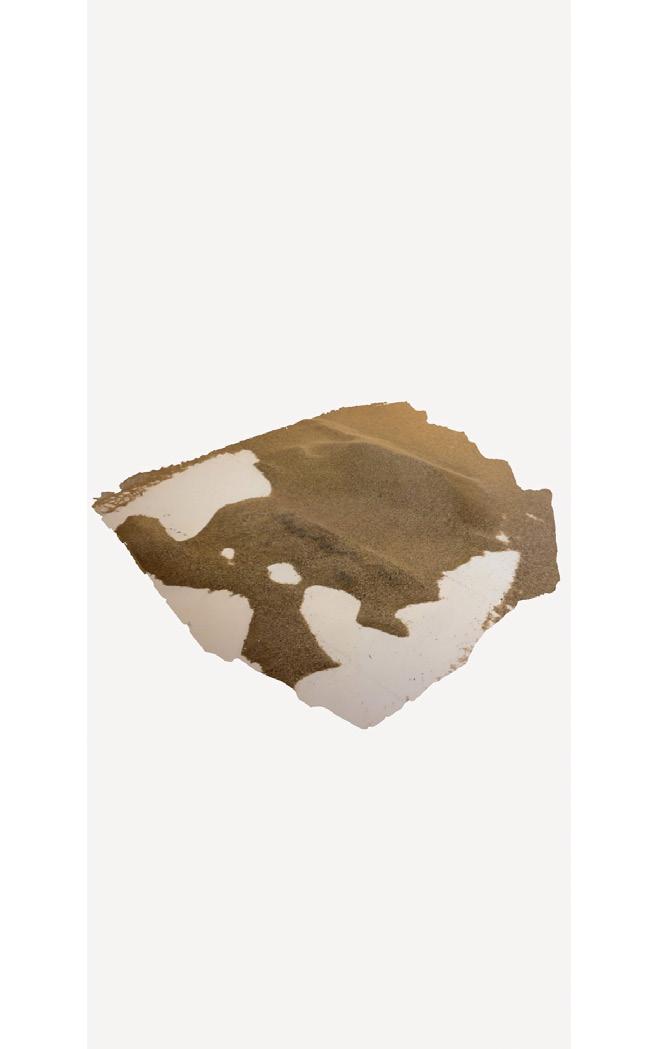

Dune Table Tests: The idea to reinvigorate Nana Dune as a secondary dune using an artificial primary dune field was tested using a dune test table, a funnel set up with an industrial fan to approximate the aeolian transport processes. A perpendicular dune form was determined to be the most efficient at sending sand across the field. These results were 3D scanned and used in my Rhino modeling.

25

Contributing historic structure*

Contributing historic structure* removed since 1998

Non-contributing historic structure*

Proposed boundaries of the American Beach Historic District*

Current location of the Coastal Construction Control Line**

Proposed for removal/relocation

Extant Dune - protected/managed by NPS

Remnant Dune topography

* Ddetermined from Historic Resources Survey of American Beach conducted in 1998 as part of its application to the National Register of Historic Places

** Determined by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, this line is trending westward

- all contours at 1ft interval N 100’ 200’ NaNa Dune

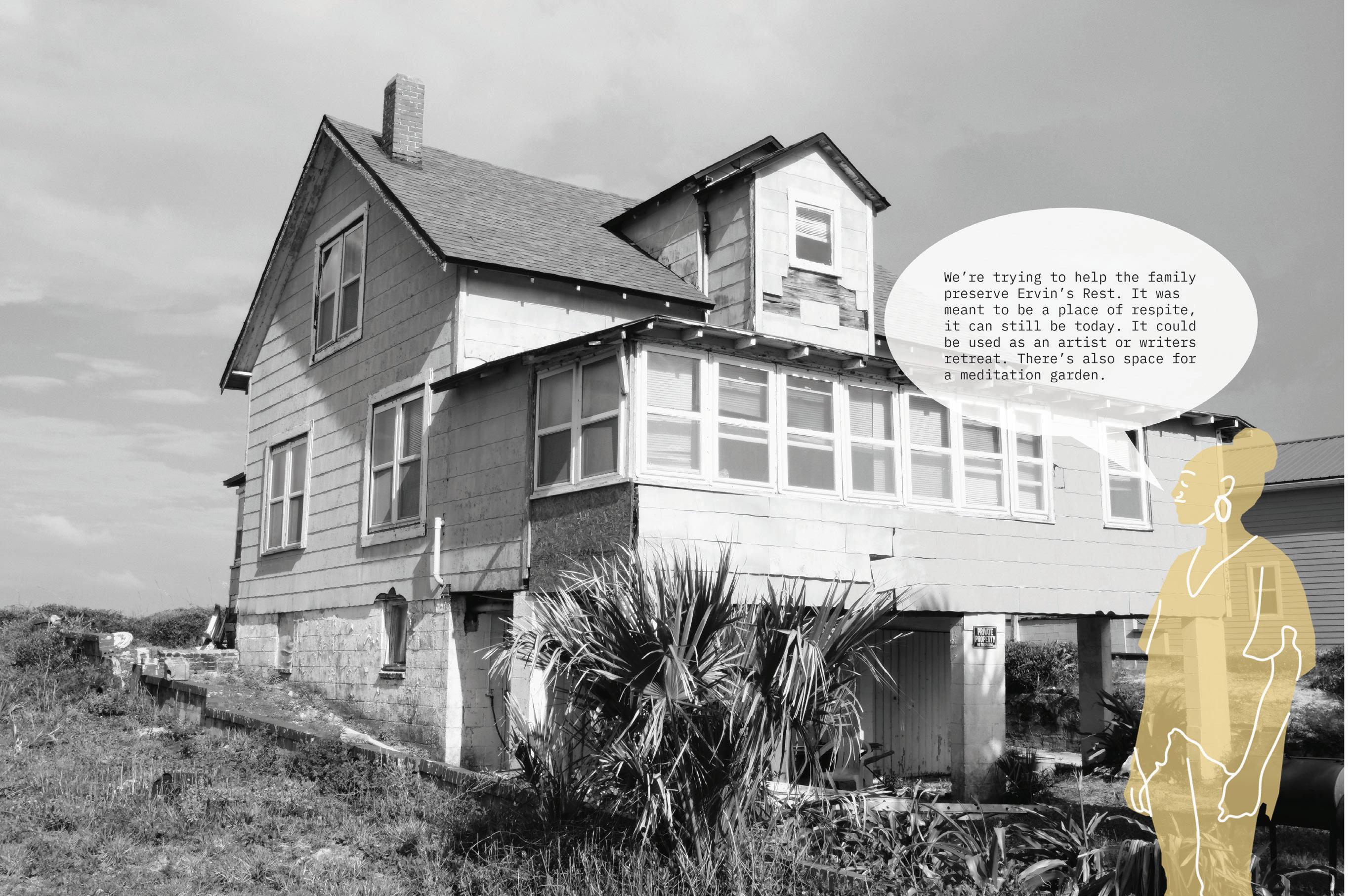

Ervin’s Rest

Public

Access, including OSV

Note

Evan’s Rendezvous

Current

Beach

Julia

Lewis Street American Beach Motel long term rentals Little NaNa Dune G r e g g S t r e e t O c e a n B o u l e v a r d Proposed Circulation Diagram 26

A.L. Lewis Museum

Street connects to A1A

Implementation TImeline

Remove

Relocate

5500 Gregg Street is listed as having been constructed in 1958 adjacent to Evan’s Rendezvous. On the National Register of Historic Places application, the lot is referred to as “Sweet Tooth,” suggesting that it may have been a soda shop or snack bar. It is unclear if the existing structure is the same as the one noted in the 1998 report. Interviews with residents indicated that the building does not hold historical or community signi cance. e structure today is in a state of disrepair, with the roof caving in as evident from Google Earth aerial views.

e structure should be removed to focus restoration resources on the Rendezvous and also to open up public space for the beach access approach.

0-1 years

If community gives approval of removal plan, demolish within 1st year of implementation.

Reuse of Materials

e structure is composed of CMUs, which can be repurposed for hardscaping projects. Larger pieces can be used as pavers for the patio of Ervin’s Rest.

Smaller, crushed pieces of concrete or RCAs (recycled concrete aggregate) can be used in lieu of more traditional materials such as oyster shells and limestone and can line parking lots and trails.

In place of the CMU structure would be space for a dune nursery, a comfort station, concession stand or other desired beach commodity. In the case of the design proposal, I suggest a dune nursery and small comfort station.

Remove

5524 Gregg Street was formerly Tino’s Restaurant. It is unclear when it was demolished and returned to the housing market. e lot has since been developed into a newly constructed 3 story beach house directly in between NaNa Dune and the beach. e structure is in front of the Coastal Construction Control Line, suggesting that it is at high risk of damage from dramatic erosion events.

e structure should be relocated to enable sediment transport to continue to ow to feed the protected dune structure and also to ensure that the home is at a reduced risk of damage from hurricanes.

~3-5 years

Given the di culty of either buying out the landowner or nding a new plot of land, the plan to relocate this home can happen in the mid-term.

Alternatives could be to remove the garage structure on the ground oor to allow sediment to move in front of the house, but the building is still in direct danger of erosion and wind damage from hurricanes.

sediment carried by prevailing easterly winds are blockedby3

suggested placement

Historic images of the roads in American Beach indicate that they were unpaved, compacted sand. Infrastructural improvements such as asphalt paving have been added in the last few decades, but the concretization of roads in front of NaNa Dune present an obstacle to the necessary aeolian transport processes which feed the dune.

Given the lack of structures that require road access, I suggest removing the indicated portions of the roads to allow sediment to move freely across the landscape and reduce vehicular tra c.

~1-5 years

e section of Ocean Boulevard could be removed immediately, but depending on the relocation of 5524 Gregg Street, the portion of that road would need to remain intact for access to that home.

Removing the streets expands the potential area for a park and restores connections between the beach and the dune without removing access to arterial roads. Homes to the south of the removed area would still remain connected via pedestrian and bicycle trails

Disturbance Plan: My design is fairly low impact in terms of existing structures, but given the sensitive nature of development in this neighborhood, I made this diagram to show the rationale behind the removals and relocations that I suggest to reinvigorate Nana Dune.

Structure 5500 Gregg Street 5524 Gregg Street

of Ocean Boulevard and Gregg Street

Rationale

Segments

Remove or Relocate?

Implementation

Plan

storyhouseonforedune

moveable comfort station similar to those on Assateague Island nursery beds

27

PROPOSED DESIGN

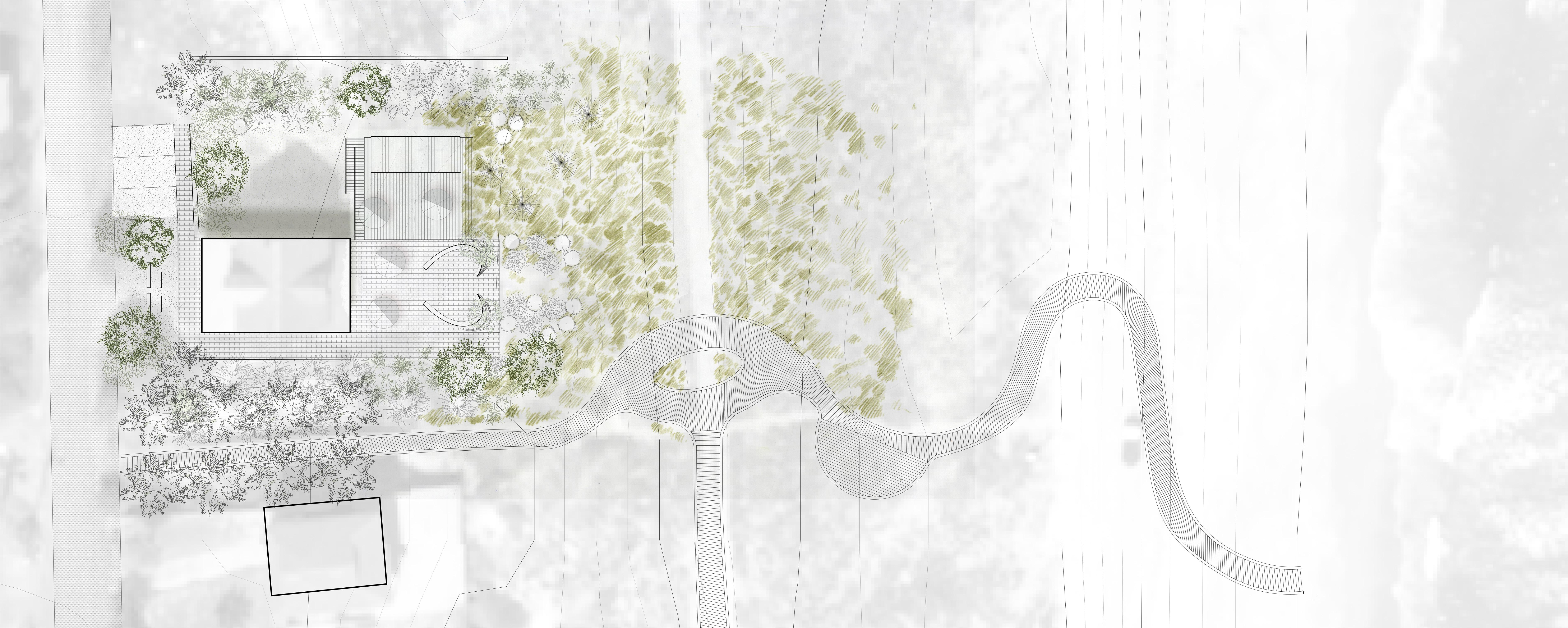

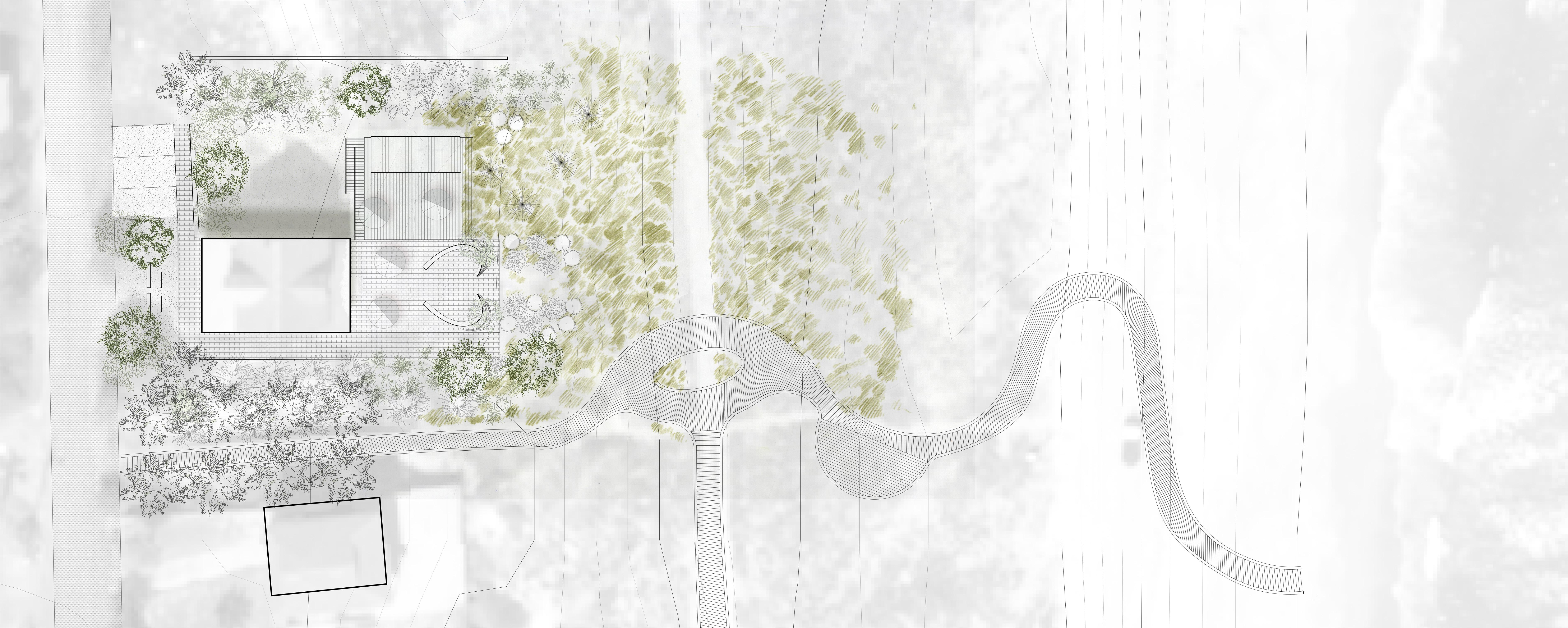

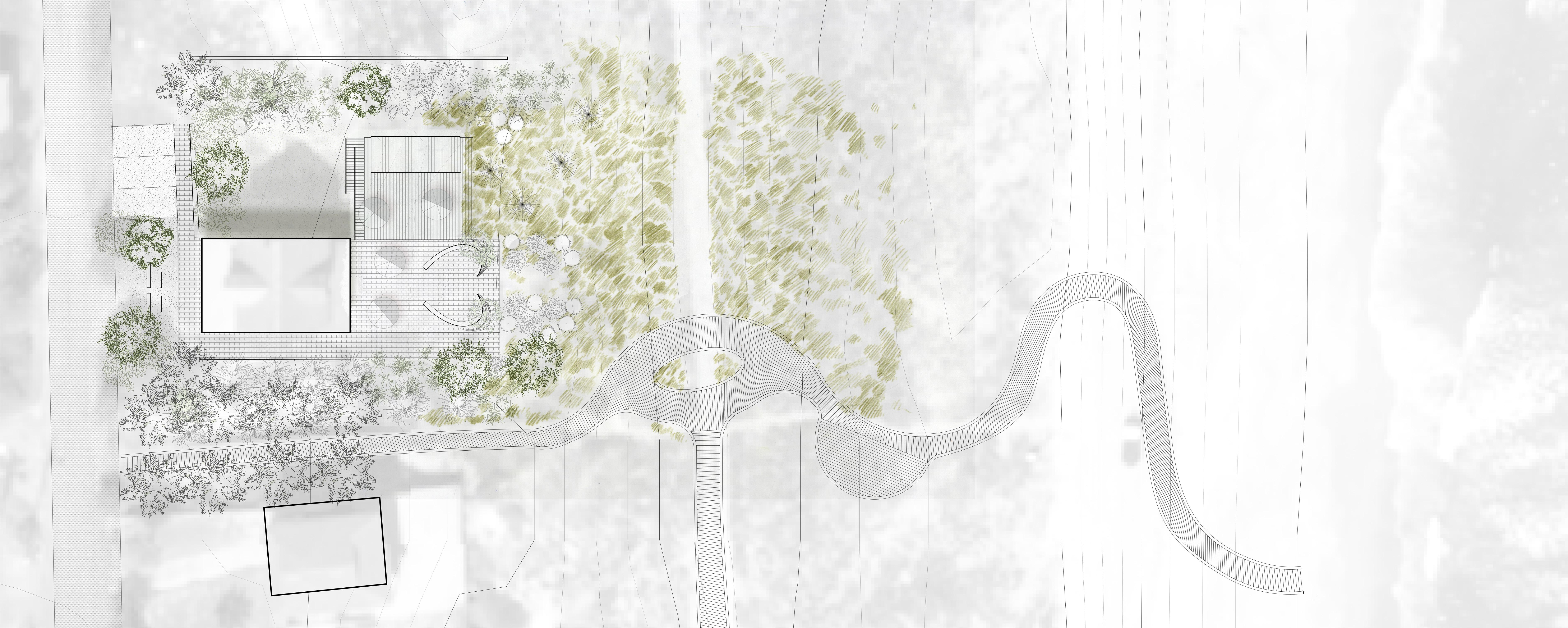

My design proposes a few simple moves focusing on increasing accessibility for both community members and visitors, highlighting natural processes such as aeolian transport, and creating spaces for gathering for visitors and neighbors alike.

I focused on two primary sites within American Beach: Ervin’s Rest, to the north, and Evan’s Rendezvous/Nana Dune to the South.

28

29

Ervin’s Rest

Ervin’s Rest sits on the foredune of American Beach. One of the suggested programs for this property, which is still family owned but not lived in, is to use it part-time as a Retreat for artists and writers and part-time as a gathering/contemplation space for the community.

Given this interior/exterior life, I have prioritized a balance between access and privacy, using the reversed front/back orientation of the house to create an oasis type gathering space for community members in the ocean-front backyard while also making a moment to rest and reflect at the streetfacing front of the house for visitors to the beach.

A boardwalk, which has been graded to ensure accessibility, snakes to the south of the house and opens up at what used to be the Village Way Road, revealing a glimpse of the old road and creating a public gathering space. This new boardwalk both connects to the beach, giving elder community members a way to walk down to the beach, and stretches to the south to create a new pedestrian walkway.

A C C’ G G’ D’ E’ D E B

30

0’ 16’ 32’ N F’ F A’ B’ 31

32

33

A’ A 0 N 4’ 16’ B 0 N B’ 4’ 16’ 34

0 4’ N 0 4’ N 35

0 C N 4’ 16’ C’ D’ D 0 N 4’ 16’ 36

0 N 4’ 16’ E’ E F’ F 0 N 4’ 16’ 37

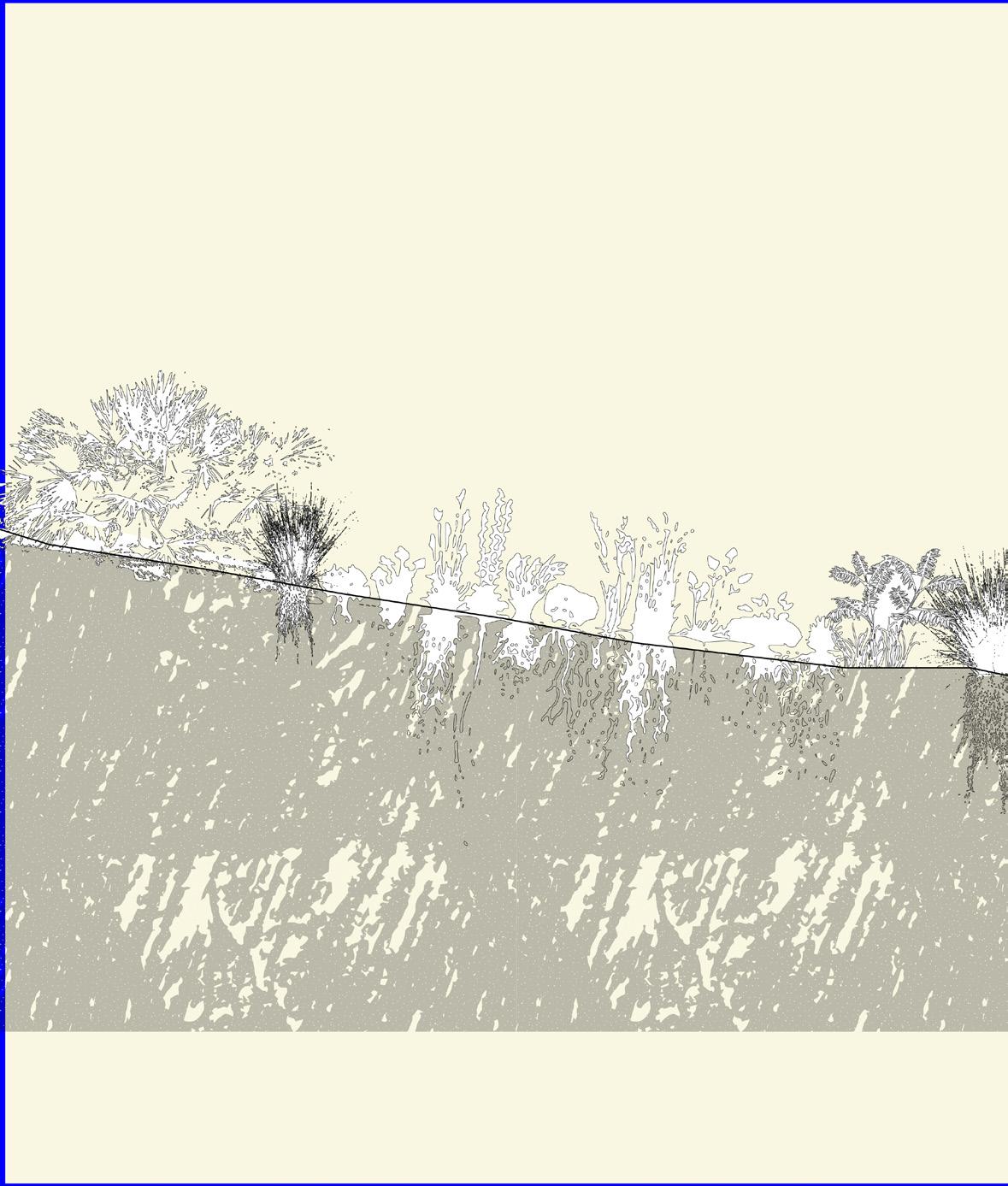

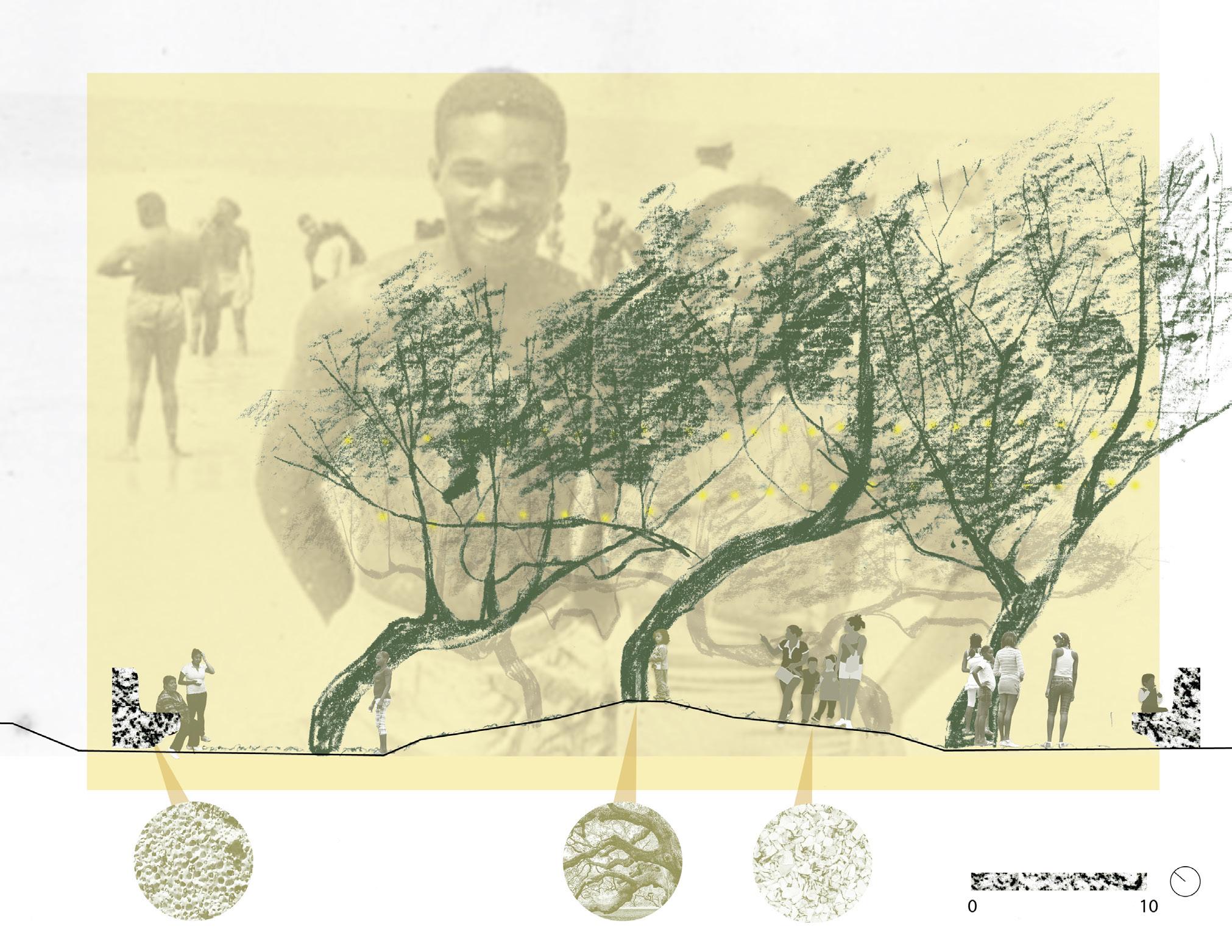

Nana Dune Park

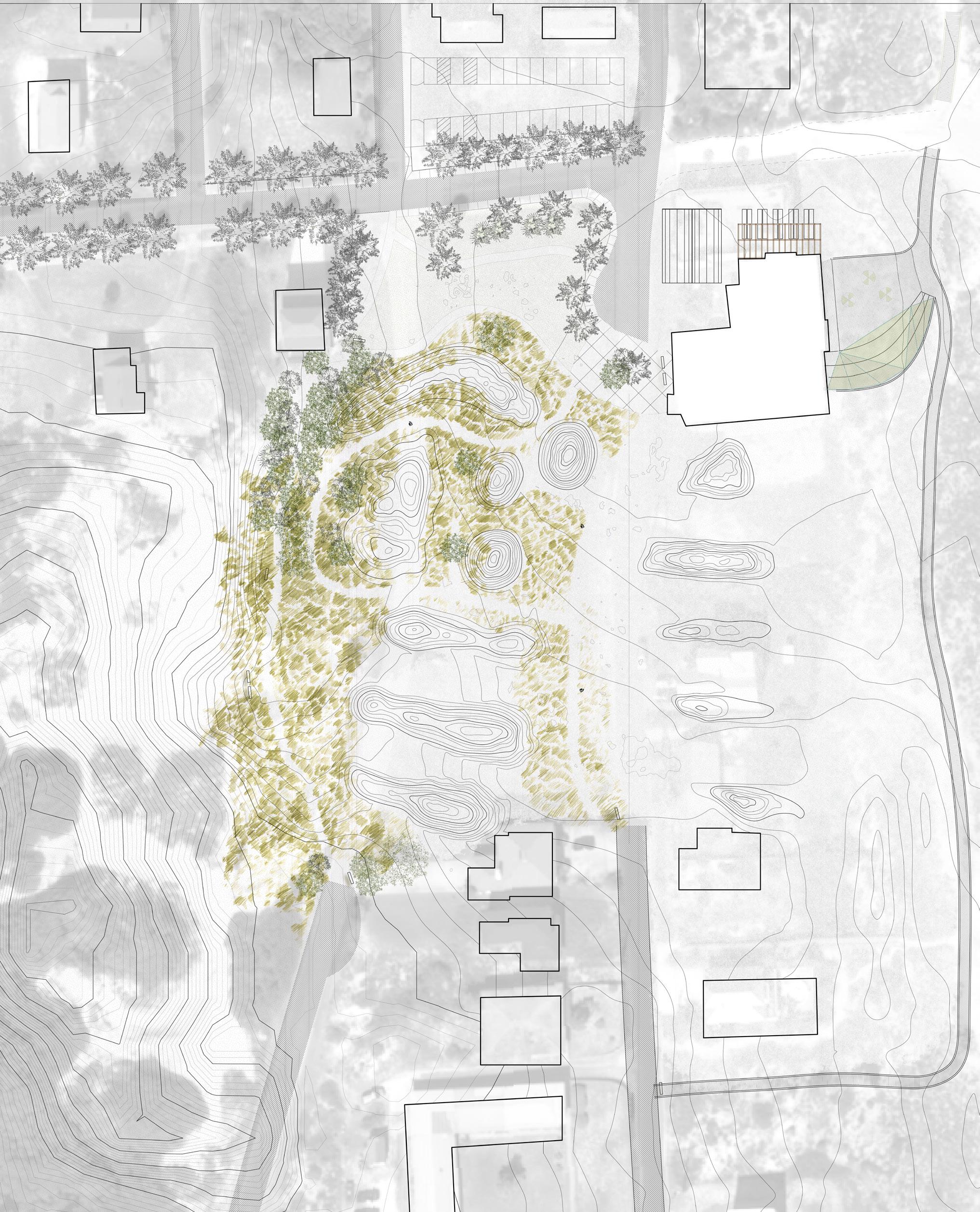

To the south is Nana Dune, which, in terms of Florida topography, sits like a mountain overlooking the beach. In photos from the 1940s, Nana Dune creates an identity for the beach, acting as a wayfinding point as well as a way to get a vantage point on the island. Residents of the beach speak with a veneration about the 65’ dune, which is the largest remaining in the state, yet they’ve identified that over the years it’s shrunk and more and more of the land behind and in front of the dune is purchased and developed. Today the dune is fenced off and currently, the county holds the vacant land directly in front of the northern end of Nana.

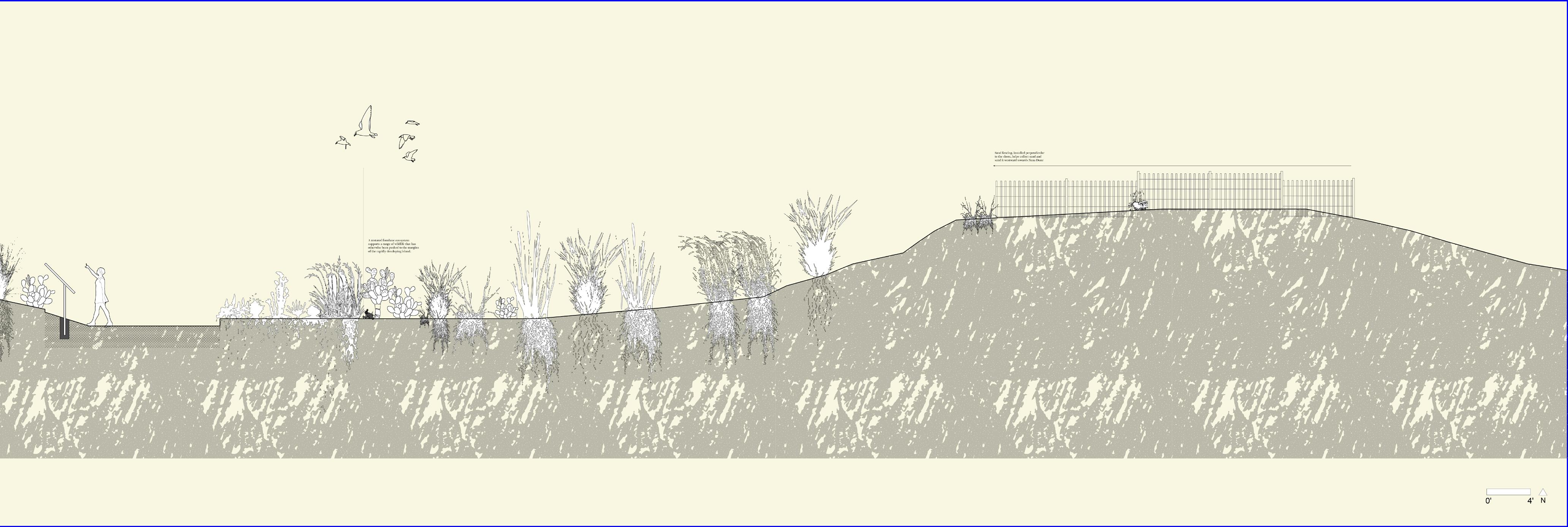

In the spirit of the central tenets of accessibility, adaptability, historicity, restoration, recognition, and plurality, my proposed design for Nana Dune prioritizes circulation of people, wind, and sediment (fig. 33 + 34). I have closed off the two North/South roads which run in front of the dune to relieve the front of the hard pavement. Instead, the boardwalk crosses through the beachfront side of Evan’s Rendezvous meeting at a decked gathering space and then continues southward to connect back to the road.

A softened path system runs through the new park, snaking around small feeder dunes that reference the old topography of Amelia Island. The new path is created and reinforced through the continued movement of people through the dunes, allowing people to interact with a part of the dune while simultaneously providing for sediment to move westward and feed Nana. Grasses mark the edges of this soft path, their roots reinforcing the edge and evoking the coastal strands that came before.

At the northwestern edge of the park is Founder’s Grove, a memorial grove dedicated to community leaders both past, present, and future. The red bay and oak trees create a shaded walk and are punctuated by didactic points to help guide visitors.

While I did not design the renovation of Evan’s Rendezvous, which is a historic juke joint and concession stand, residents have identified the structure as a potential coastal research center. I have taken this suggestion and have applied it towards a dune research and restoration center. A small dune nursery will sit where a former CMU building once stood, creating an new economics focused on restoration.

16’ 32’ N A D E G G’ D’ B B’ C’ A’ E’ I’ I J J’

38

39

40

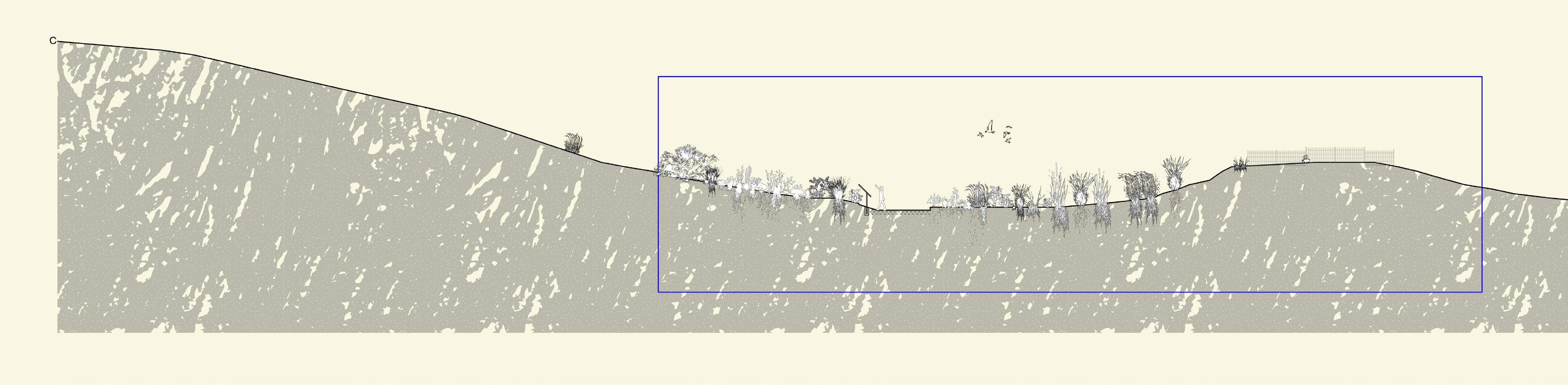

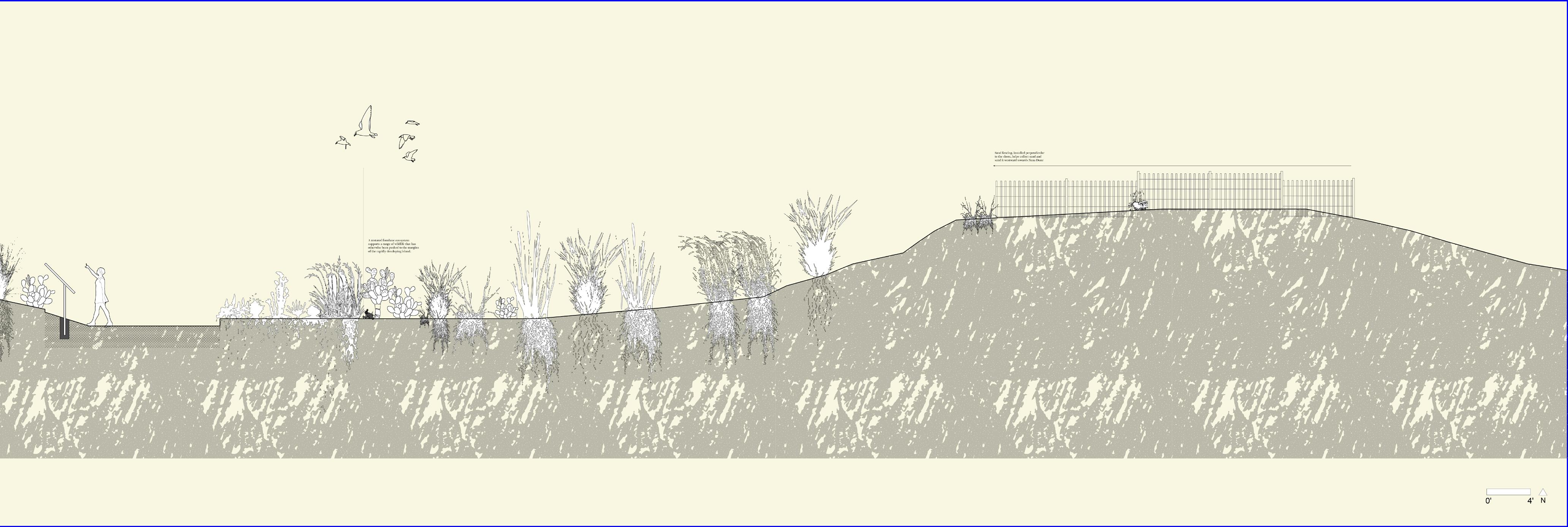

Left: View looking towards the west over Nana Dune Park.

Left: View looking towards the west over Nana Dune Park.

41

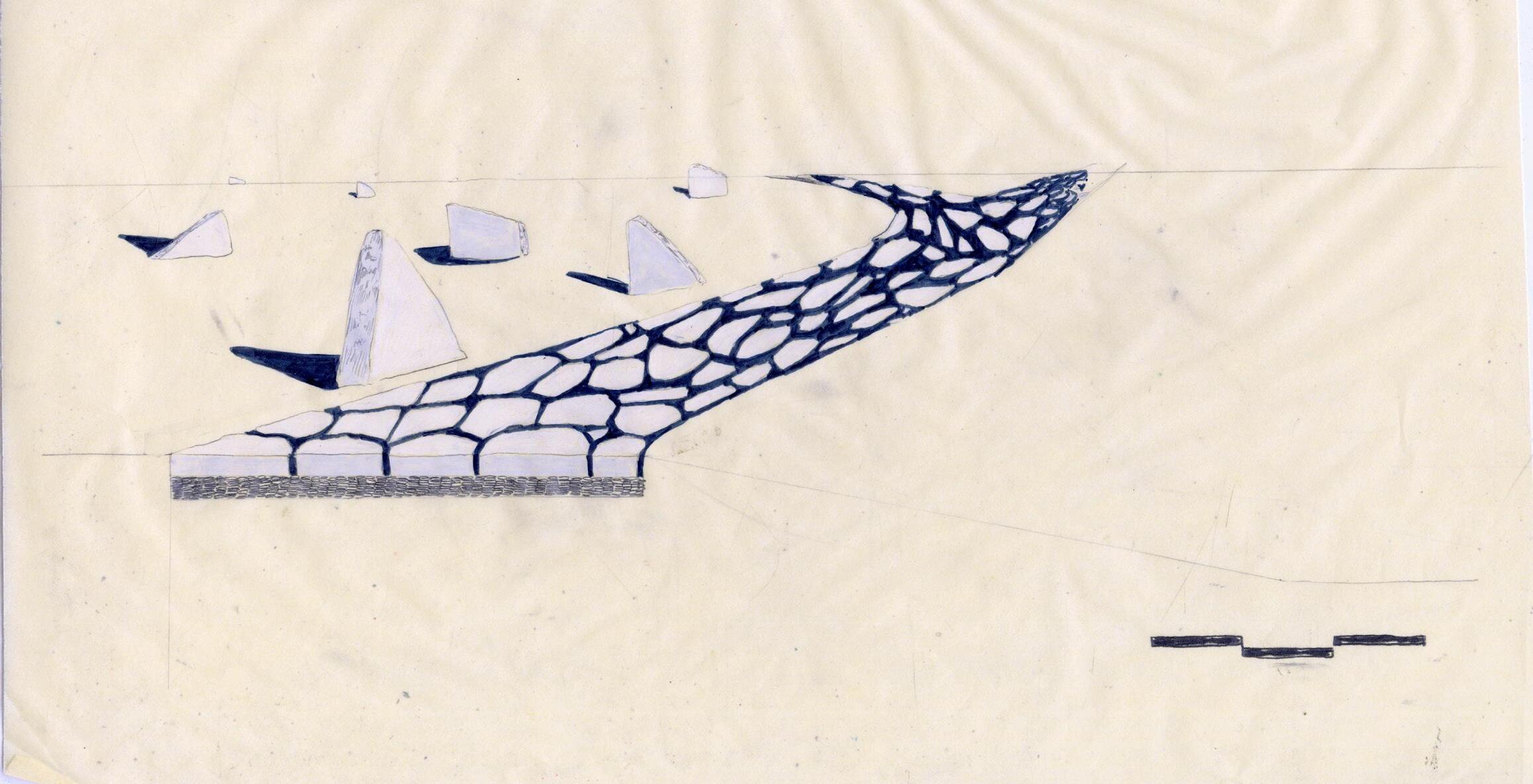

Top: Quick sketch imagining a view from between the new foredune saddles towards Nana Dune.

42

43

44

45

46

47

4' 16' N 0' D' D N 16' 4' 0' E E' 48

N 16' 4' 0' I I' N 16' 4' 0' I I' N

49

16' 4' 0' J' J

Research Studios

50

51

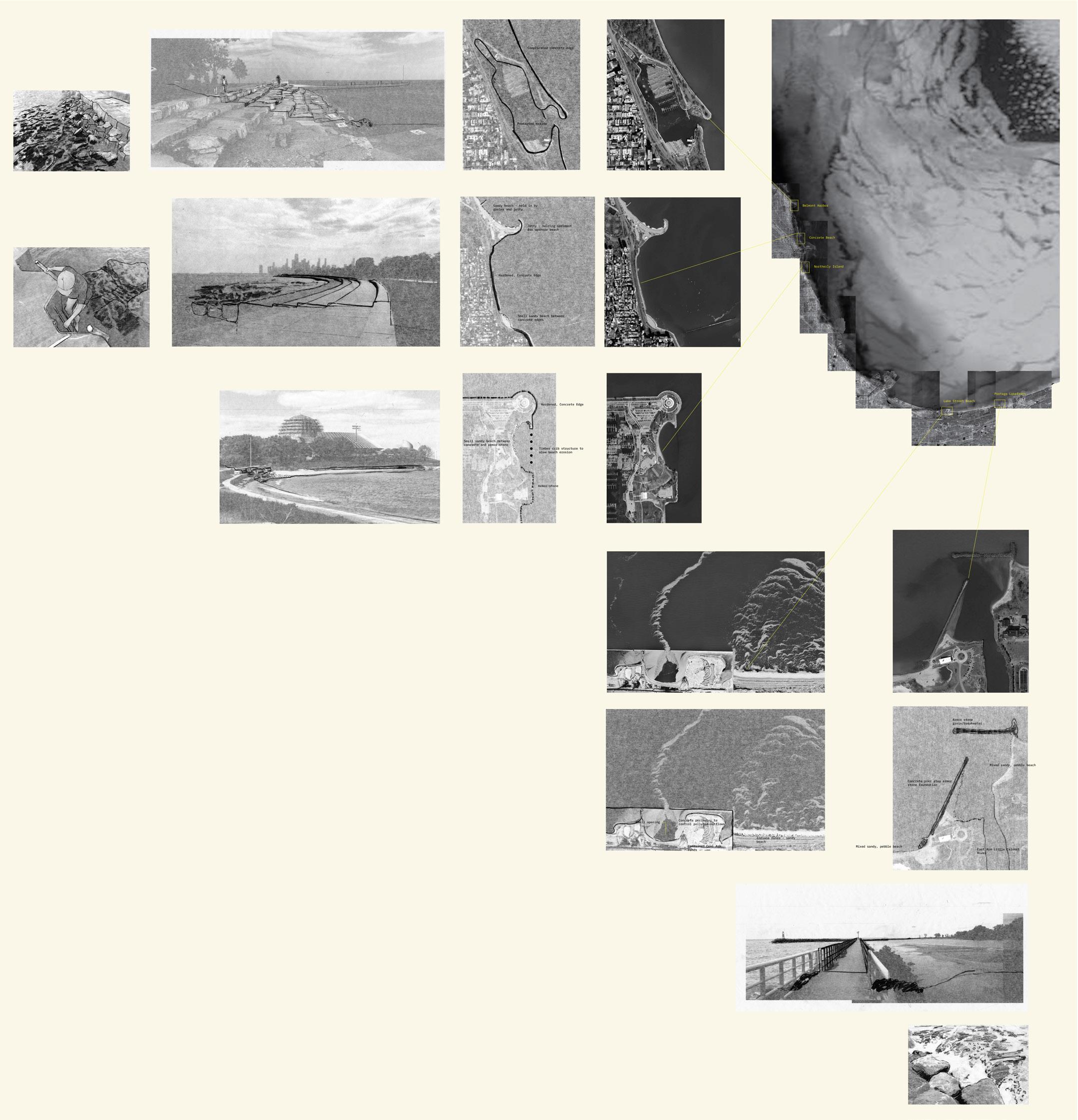

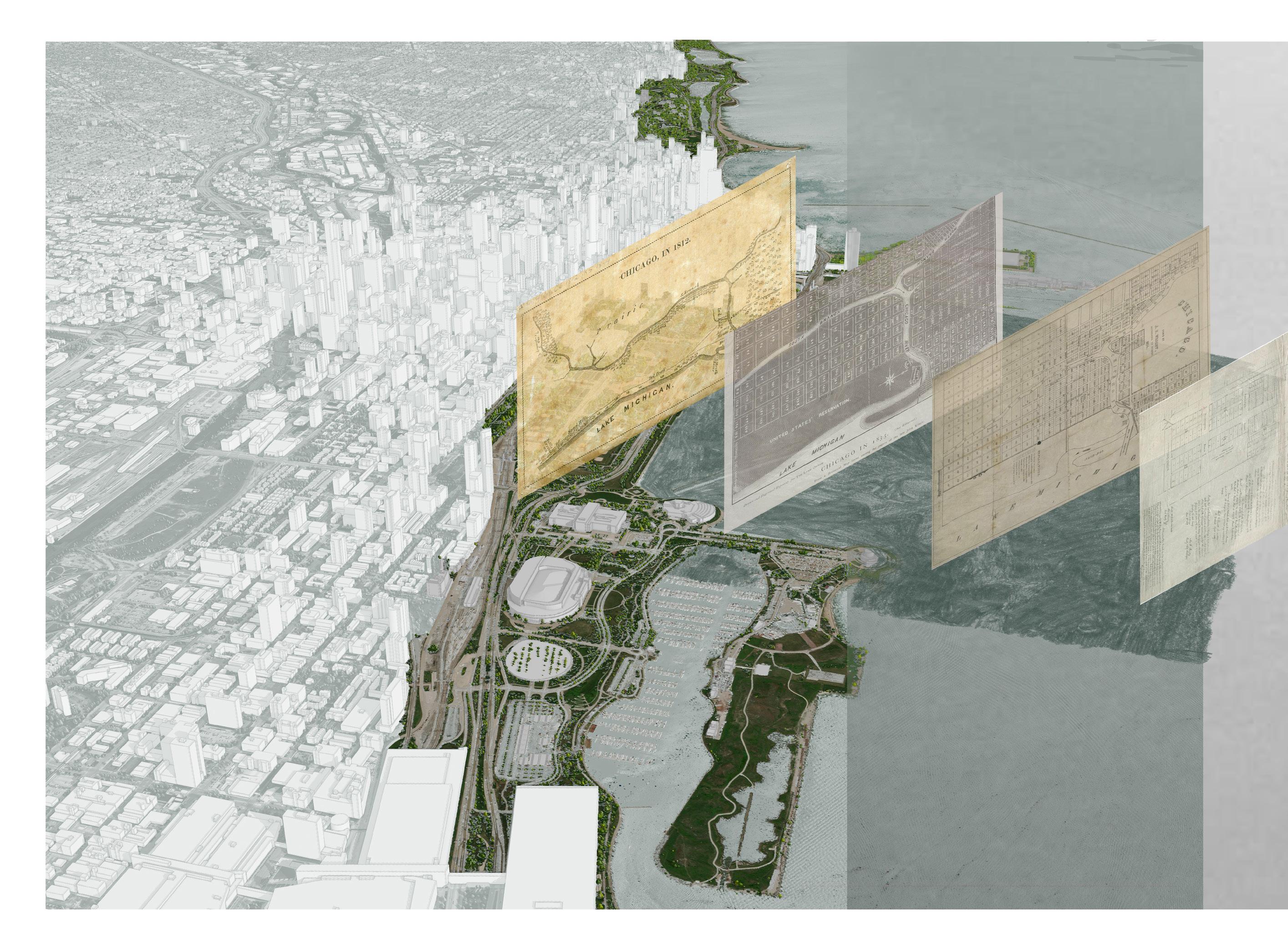

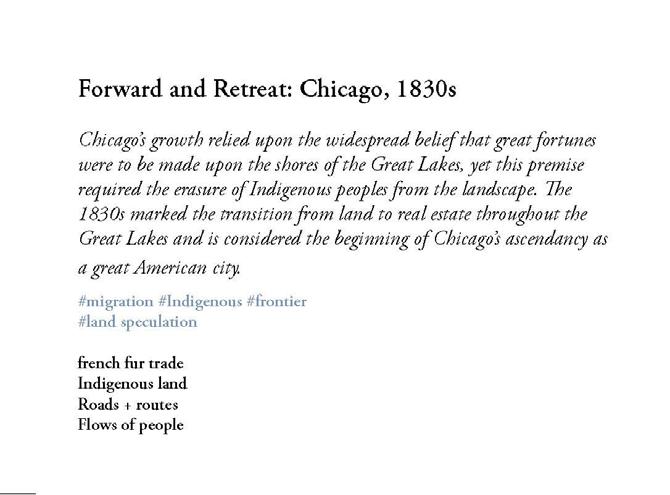

A History of the Edge

Work created as part of Fall 2023 LAR 8000 studio Professor:

Erin Putalik

Chicago, IL, USA

“A flat landscape simply is, with an intensity which excludes you as you stand and gaze. You are in the presence of something which seems to radiate courage and independence. Something eccentric, also, which refuses to perform beauty in predictable ways. Unvarying, and perhaps a little absurd in its stubborn insistence. And all the more loveable for that.”

Noreen Masud, “A Flat Place”

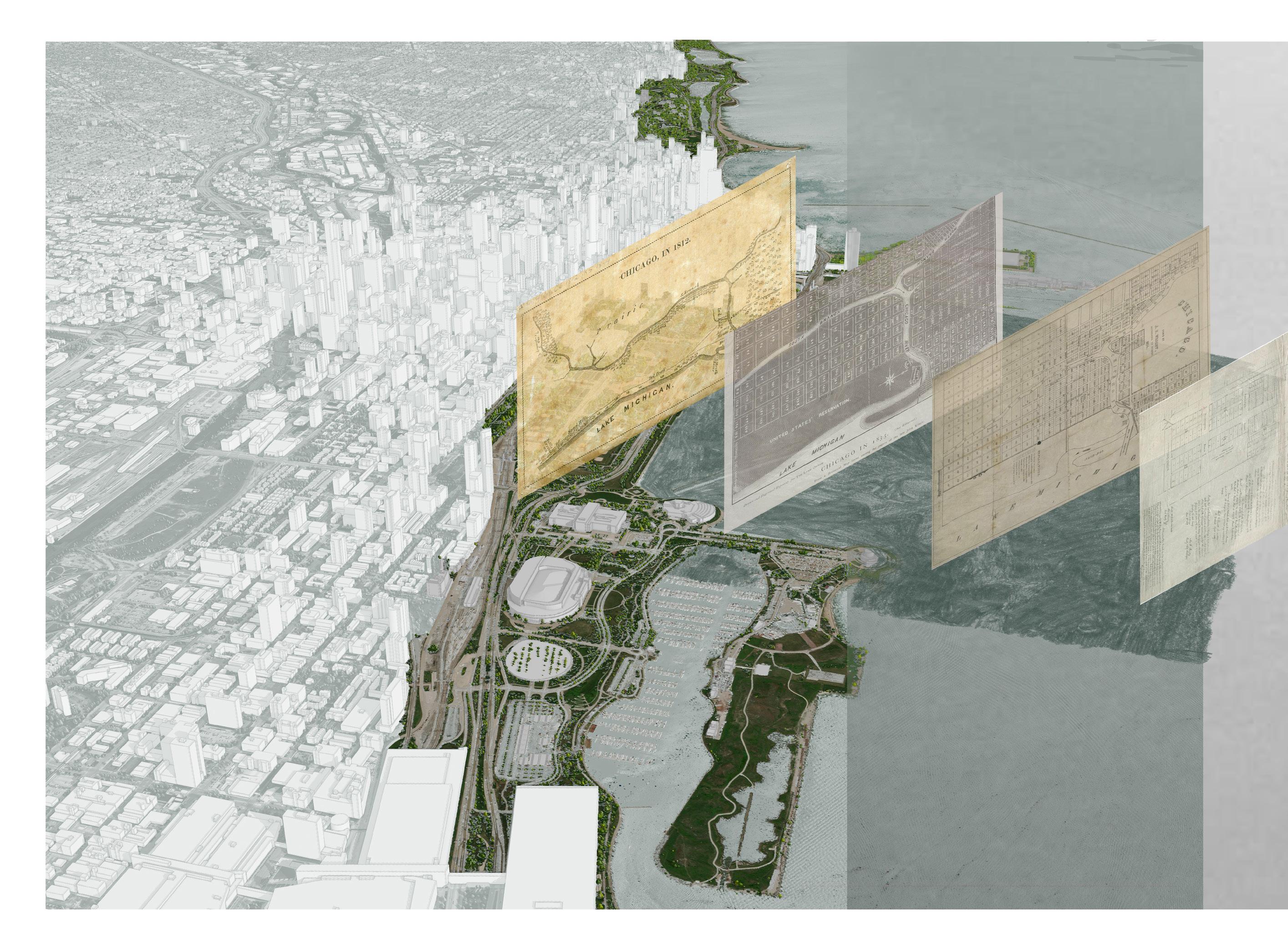

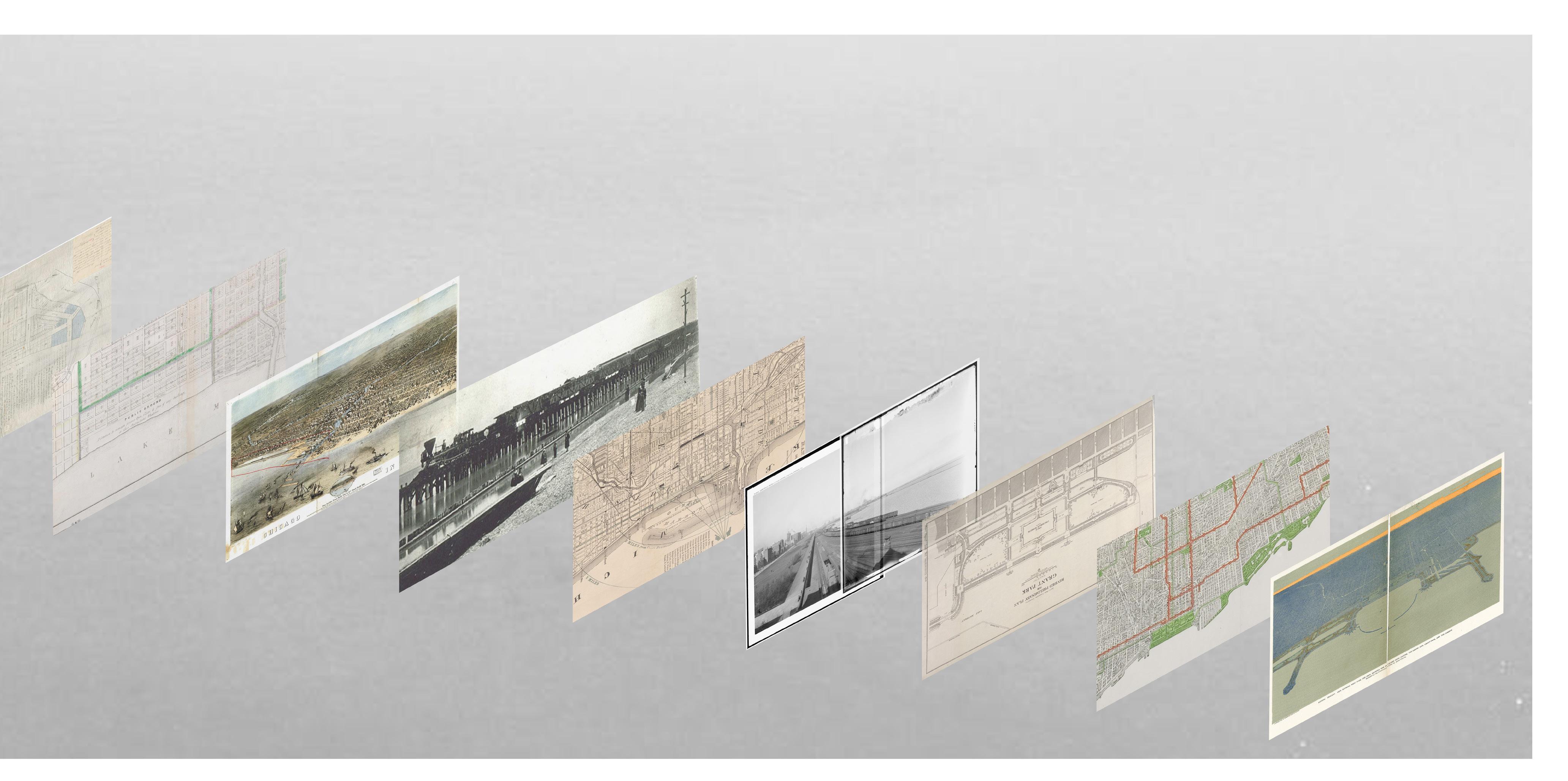

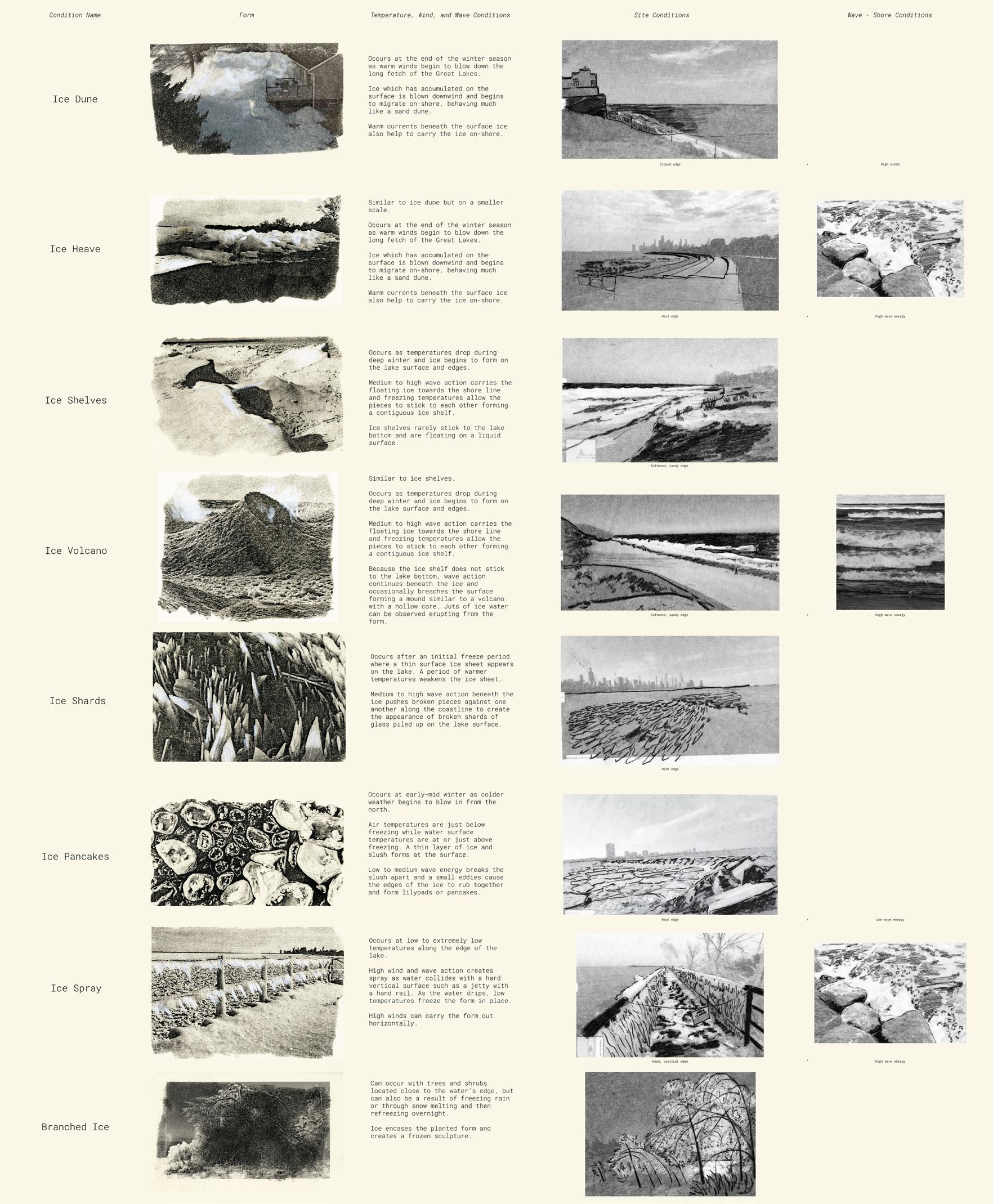

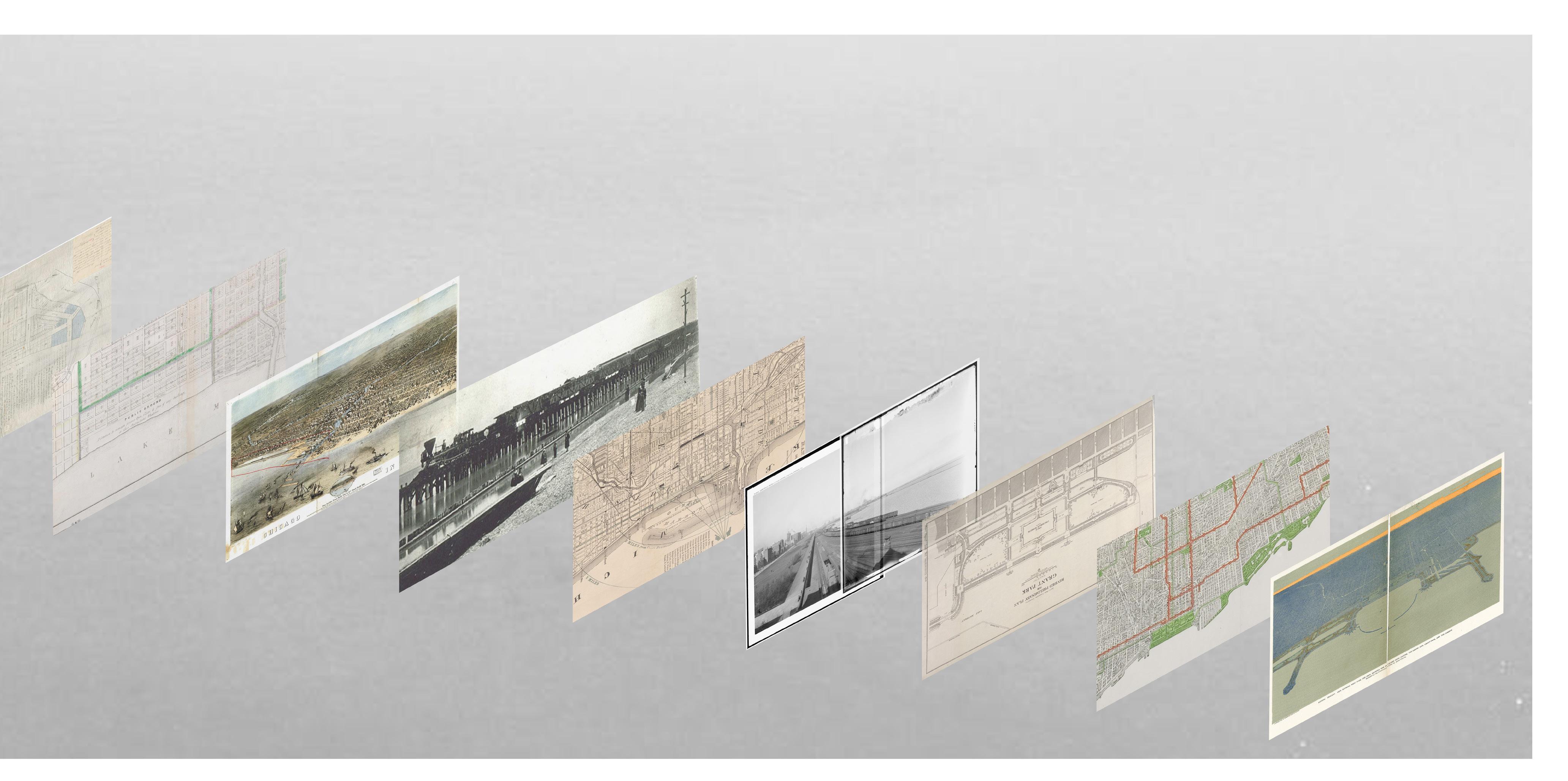

My project is titled, “A History of the Edge - A Proposal to Reclaim a Public Lakefront through the Manipulation and Exposition of Ice Forms.” I was interested in the triadic relationship between the lake, identity, and everyday lifespecifically, how each of these converge on the edge of the city and competes for space. In the spirit of the studio, which asked us to consider sand and its political economy, I chose ice as my material form of study. Ice touches upon all three of these forces, but it also relies upon a concatenation of global climatic conditions which speaks to our present age of living in an atmospheric commons.

For my site, I chose the Chicago Harbor, which frames Grant Park. Siting my project at this central location speaks to the legacy of expositions that Chicago has hosted, specifically the Columbian Expo of 1893 and the Century of Progress Expo of 1933. Both of these expo’s demonstrated grand visions which played out over constructed terrains on the lakefront. The combination of these interests turned into a semester’s long exploration of the many forms that ice takes in a dynamic lake system that also asks the question: what is the next expression of Chicago’s public lakeshore and how would it look if it were guided by material processes as well as by a desire to witness the changing character of winter over the next Century of Progress.

52

xx 53

54

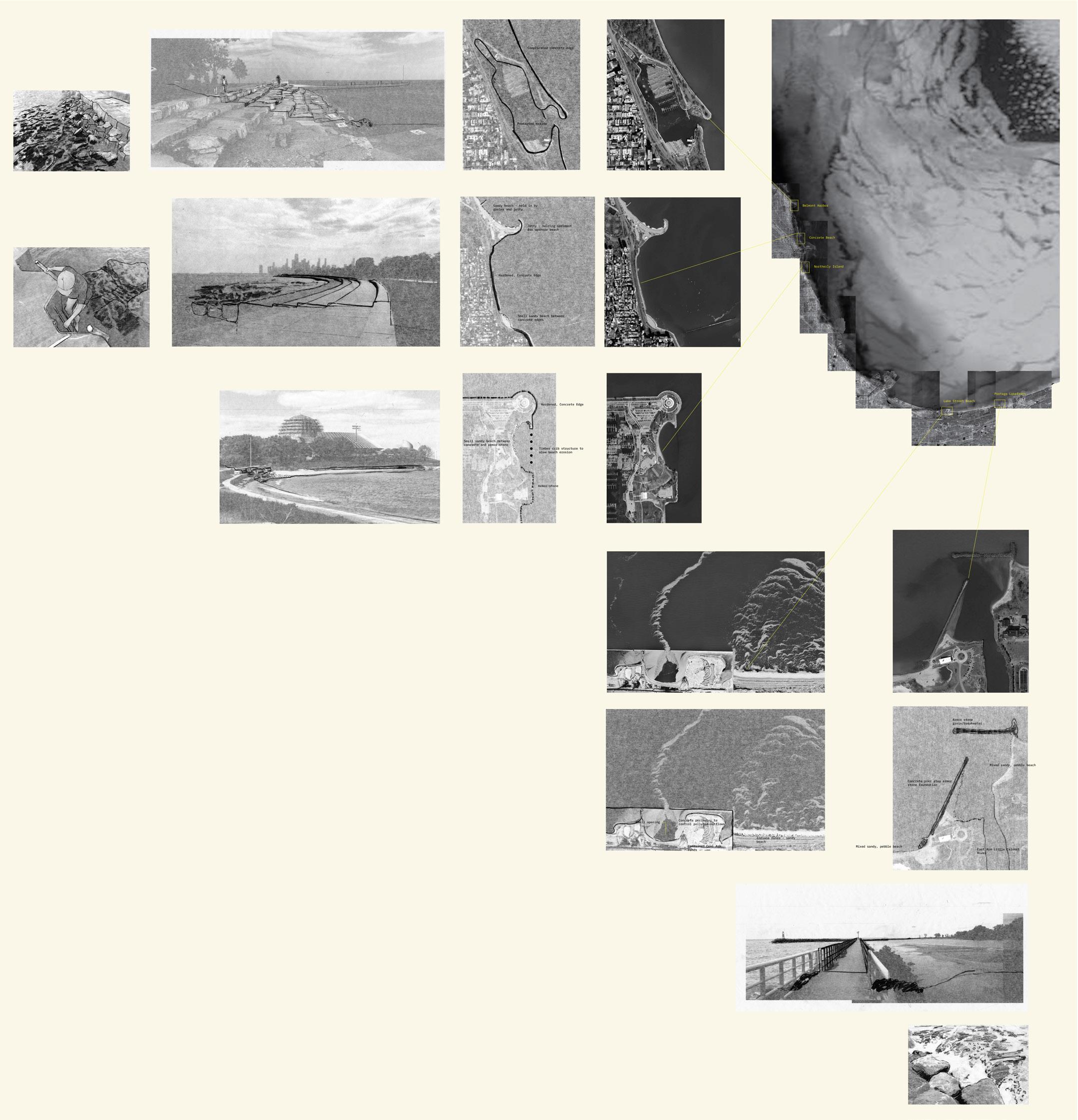

Map created by teammates, Adrian Robins and Maggie Nell, who combined edited DEM and topobathy layers with shoreline typology, sediment type, and wind data to create a map that questioned the consequential relationships of these hydromorphological inscriptions in the landscape. This map was critical for my pivot towards examining the legacy of ice on the shore of Lake Michigan.

Scores on the Southern Shore: The first part of the studio was completed in groups to create a series of maps, or in the case of my group, an atlas of the Southern Shore of Lake Michigan. Working under the general umbrella of scores and scoring, my maps traced the in/out migration in the many forms that it has marked the Chicagoland area, looking in particular at the Great Migration and the transferrence of the US South into Chicago’s South Side.

55

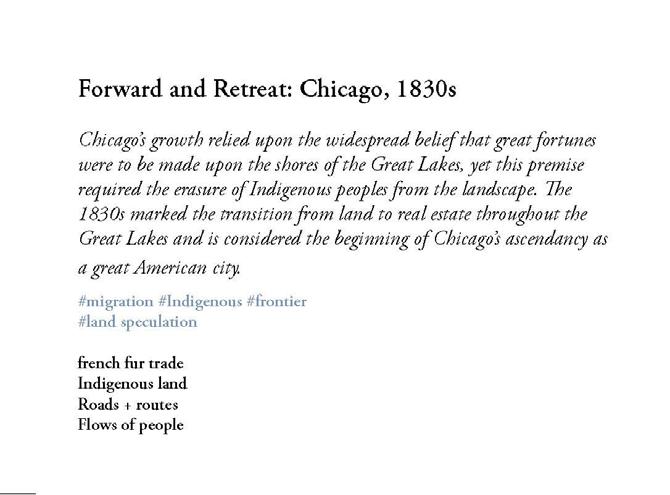

Ice dynamism on the lakeshore: In the second exploration of this studio, I began to trace the presence of ice on Lake Michigan, hoping to understand the cycles of freezing that mark the lakeshore. While ice cover is trending downward, the balance shifts according to global atmospheric conditions such as El Nino and La Nina. Using snapshots from NOAA and images posted on Google Maps, I catalogued the specific forms that ice takes along the lakeshore to begin to understand the dynamics that wind, temperature, and wave action can make.

56

57

Test 1

Coastal Infrastructure: Breakwaters

Placement logic: Armor stones were placed upon existing high points in the nearshore topobathy of the Chicago Harbor.

Results: The breakwaters placed in front of the harbor, which is protected by existing breakwaters, produced sandy sediment build-up between the two edges. Water was able to move through and over the stones, but sediment was deposited when the waves reflected back.

The breakwaters which were placed at an angle in front of Northerly Island acted differently than expected. Sediment travelled along the spine of the breakwaters and flowed into the marina behind Northerly Island, which filled up rapidly with sediment.

Test 2

Coastal Infrastructure: Clumped Breakers

Placement logic: Armor stones were placed as small islands off the harbor lakeshore.

Results: The small islands had some small effect of building up sandy sediment in the mid-range between the harbor and the islands. A small sandbar seemed to be forming, but the overall effects were minimal and did not provoke much excitement in their forms.

Test 3

Coastal Infrastructure: Jetties

Placement logic: Armor stones were placed at even intervals perpendicular to the shore to create a jetty effect.

Making a Lakeshore: As we shifted into an analysis of the material economies that mark the Lakeshore, I continued to look at the relationship between shoreline morphology, sedimentary movement, and ice forms. While the bathymetry of Lake Michigan is surprisingly ill measured, I created a digital model of the downtown Chicago harbor using nautical chart depths. I routed an exaggerated version of the harbour and used it as a foundation surface on our sediment table. I ran tests looking at the impact of hard infrastructures on the lakeshore and tried to erase them using sediment. I used the results to design a new lakebottom for the harbour that focuses on highlighting nearshore lake processes, the drawings of which are shown on the following spread.

Results: The jetties accumulated sediment as is consistent with real world groynes and jetties. Sandy sediment began to build up along the spine of the armor stones and created triangular shaped beaches between the features. Perhaps the most interesting result was the beach that began to build up between the harbor and the northern edge of Northerly Island.

Test Coastal Placement Results: vertical surface are run shape the Paddle Speed: 50% Wave Frequency: 1.5 sec Travel Range: 40 degrees

Northerly Island

Northerly Island

Northerly Island

Chicago Harbor

Chicago Harbor

Chicago Harbor

58

Coastal Infrastructure: Existing

Placement logic: None

Results: The model itself has a very large vertical exaggeration, so I ran water over the surface as is. The features that were created the most interesting to me visually. This also revealed forms that seem to mimic the shape of the shoreline. Beaches built up along breakwaters.

4

Northerly Island

59

Chicago Harbor

60

61

The Shedd

The Field

The Shedd

The Field

A A’ B’ C’ B C 62

Adler Planetarium

Art Insitute

Perspective 1 Perspective 2 Perspective 3 63

Lakeshore Drive

N 64

Eastern Cottonwood

Eastern Cottonwood

10’ N N 65

Dry-stacked Limestone

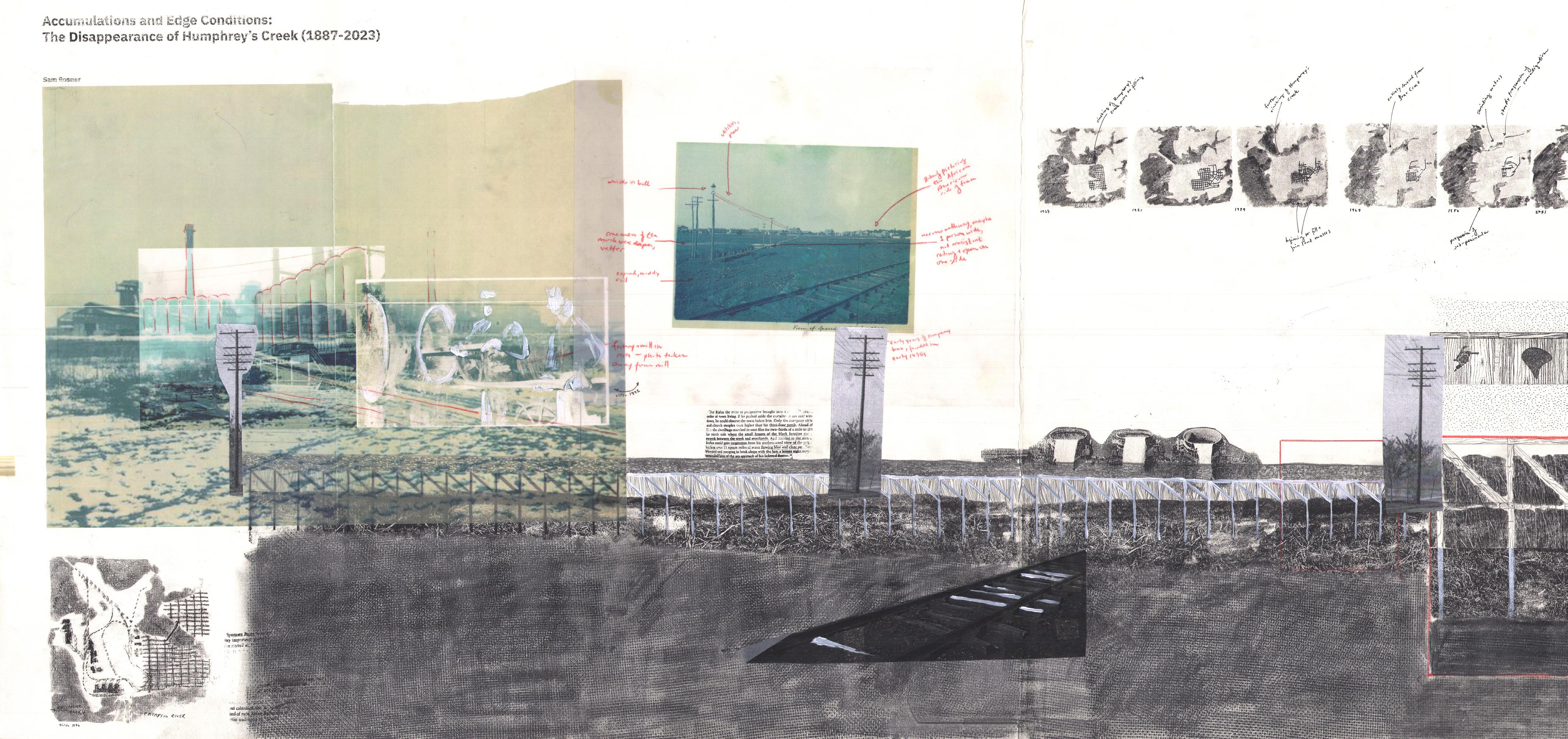

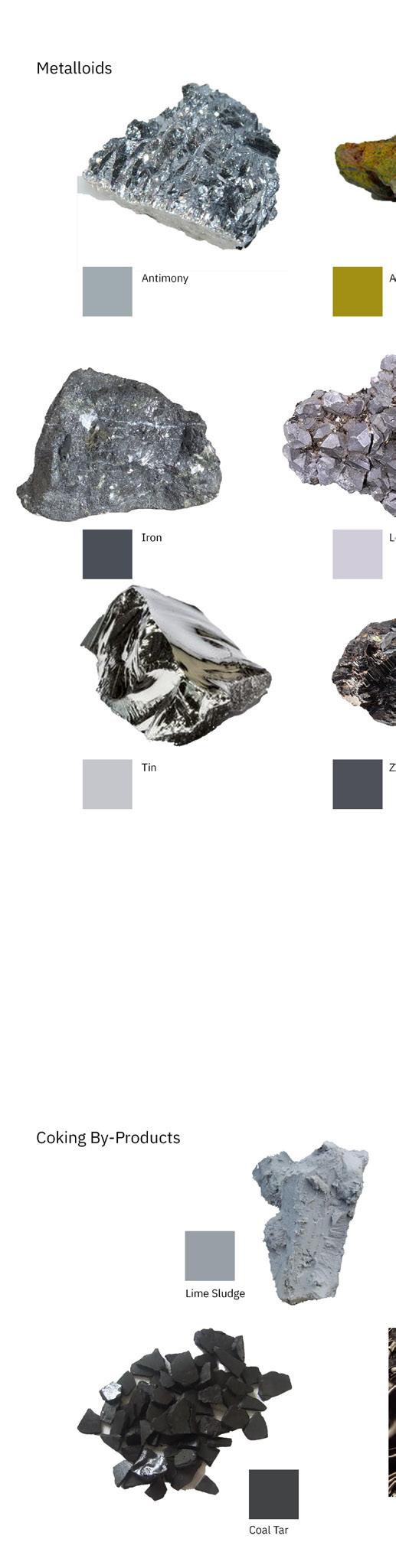

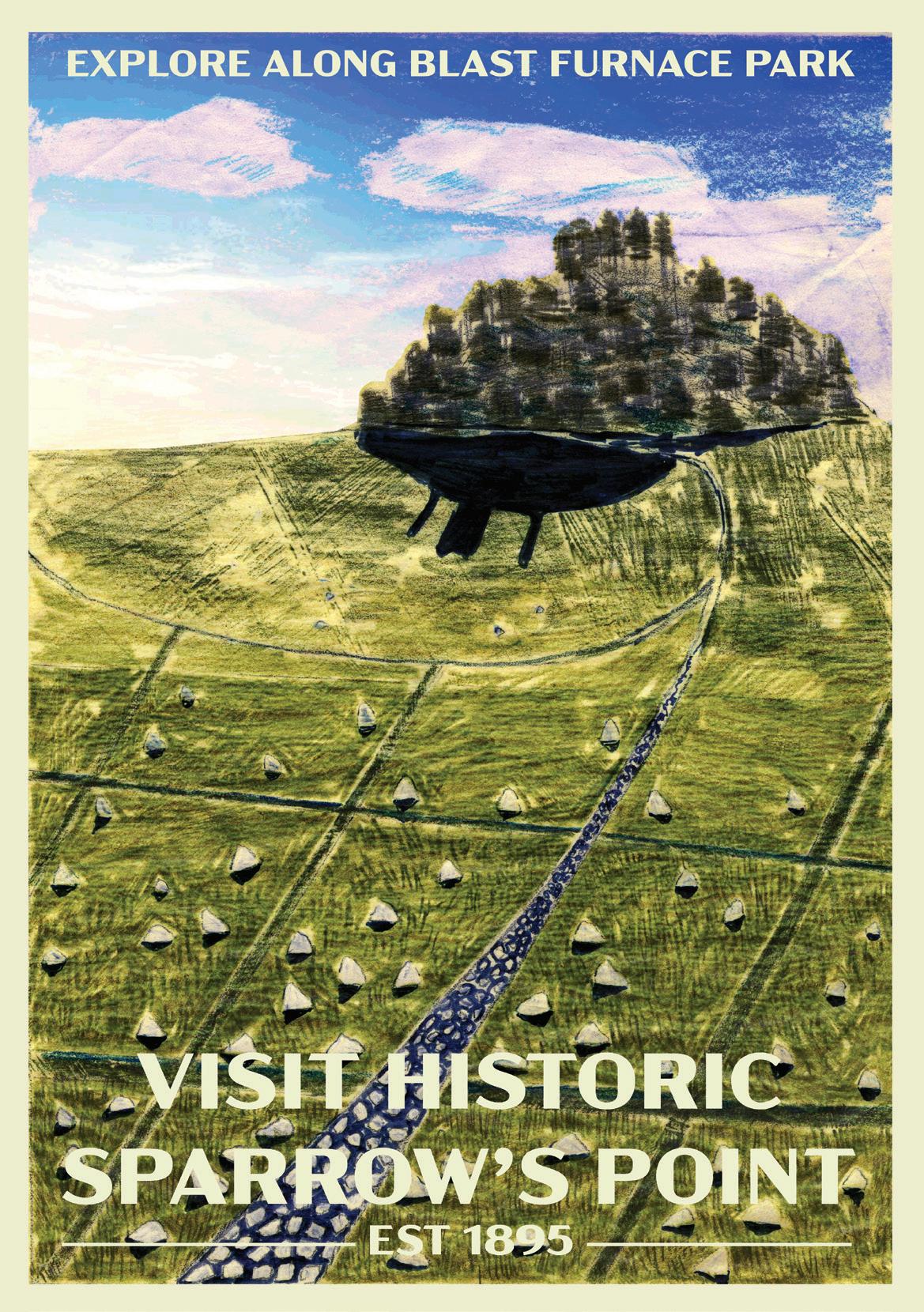

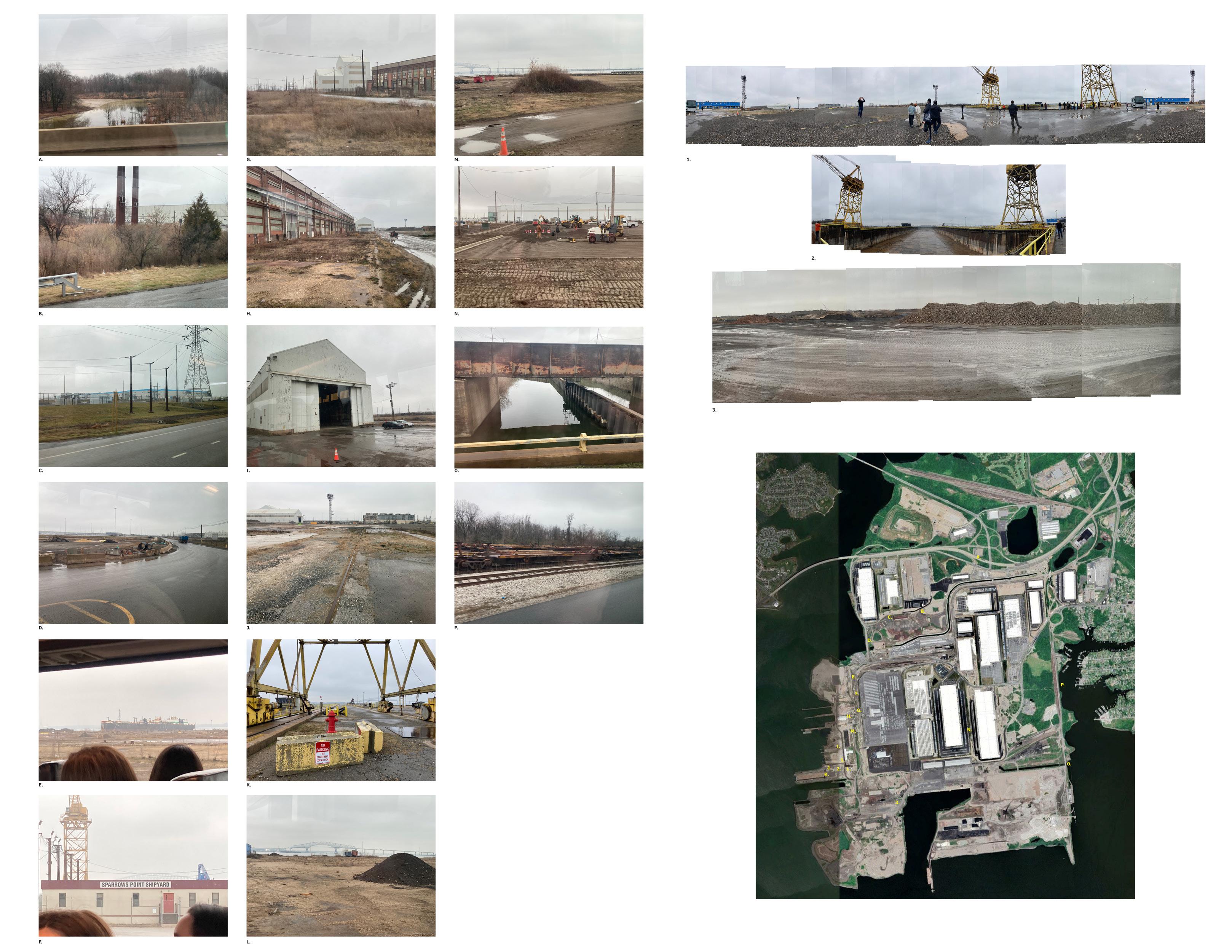

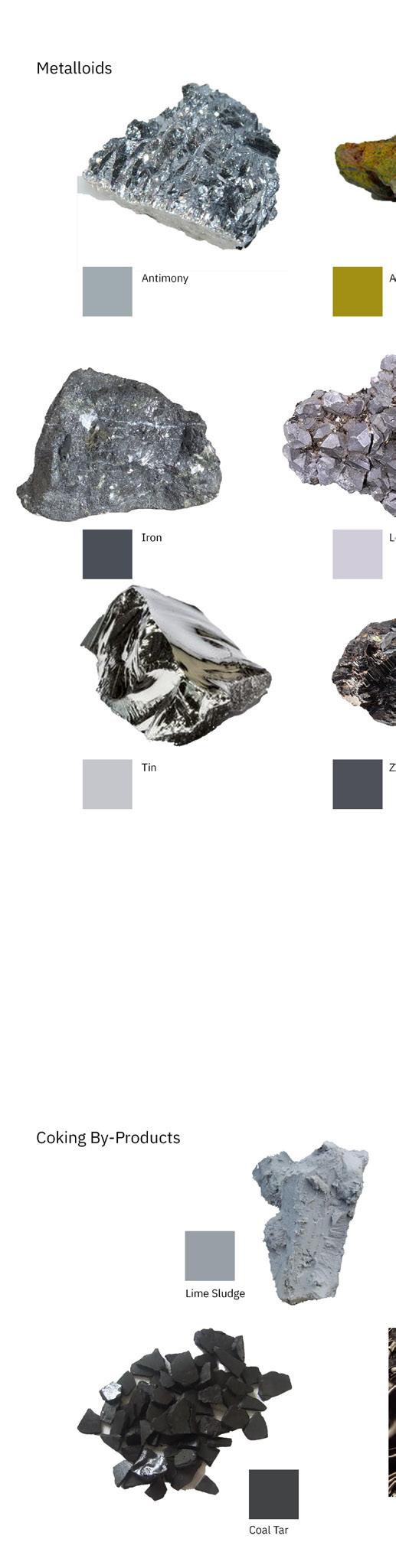

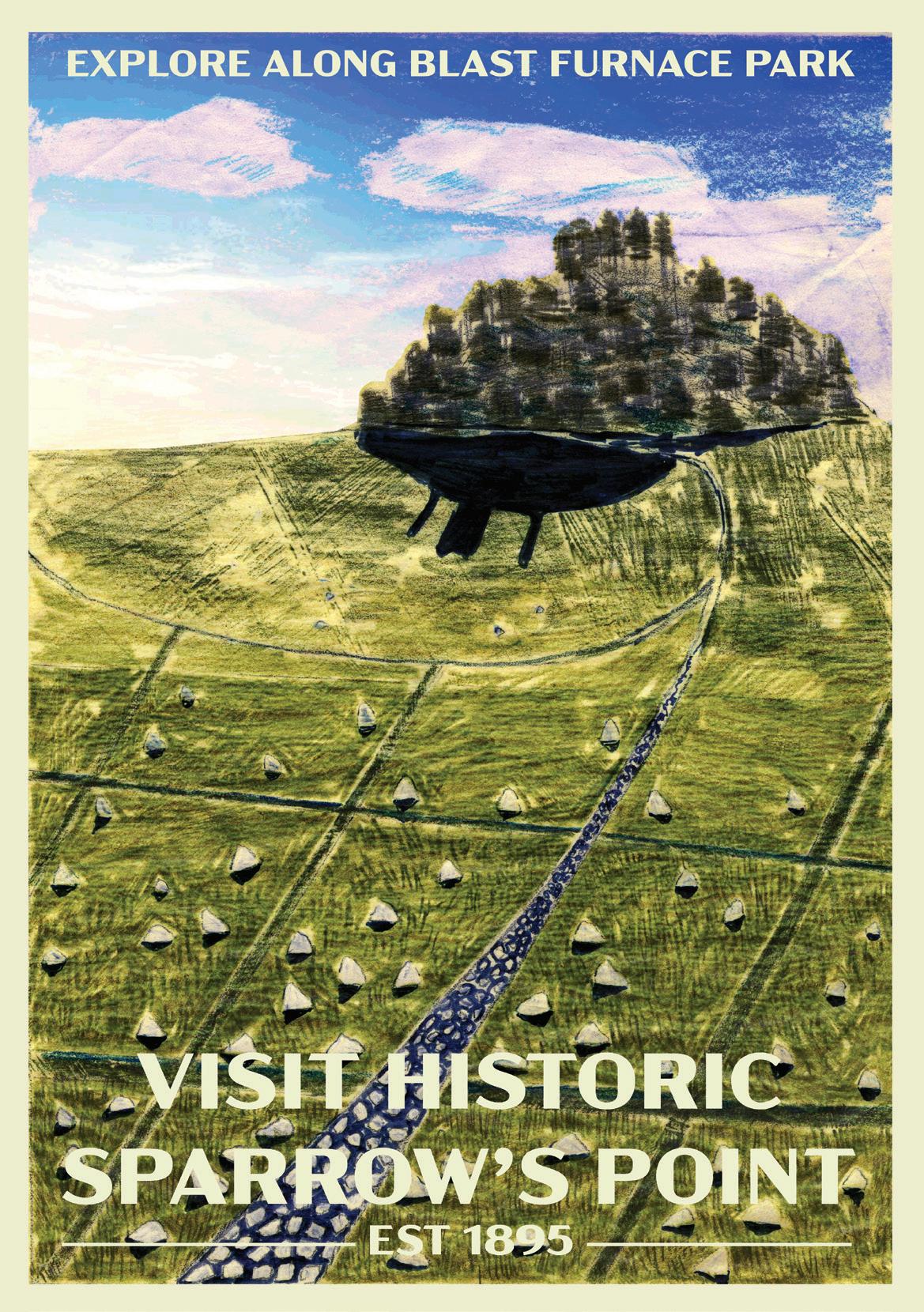

Learning from Company Towns: The Post-Industrial Landscape of Sparrow’s Point

Work created as part of Spring 2023 LAR 7020 studio

Professors: Brian Davis, William Shivers, Taryn Wien

Baltimore, MD, USA

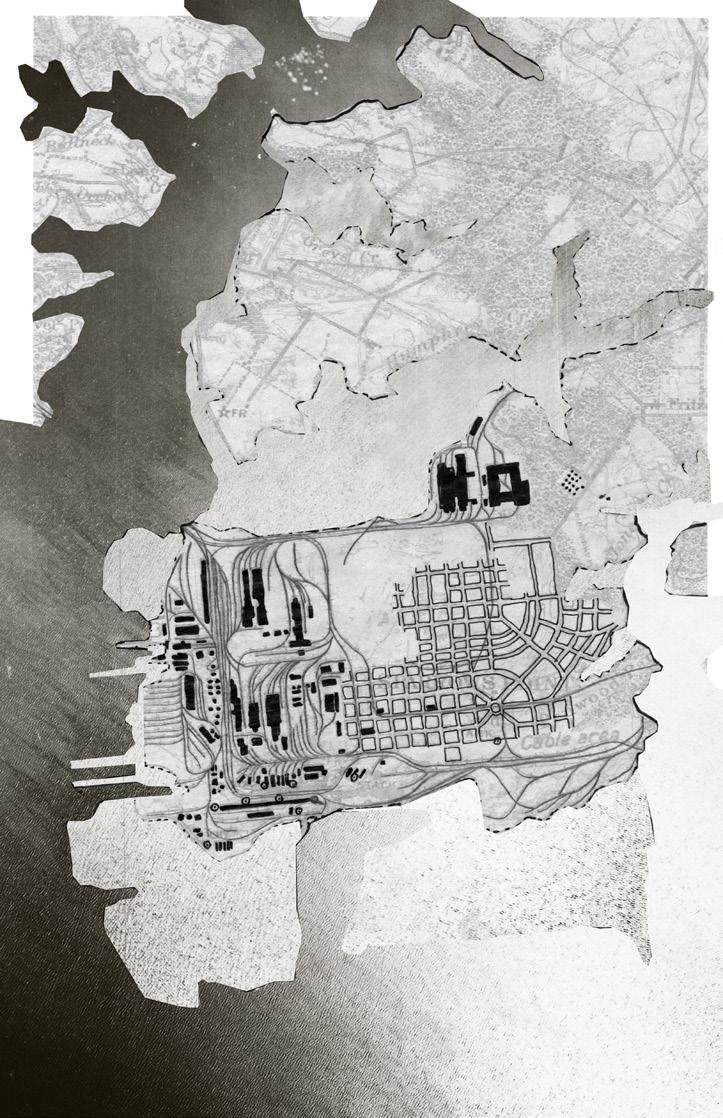

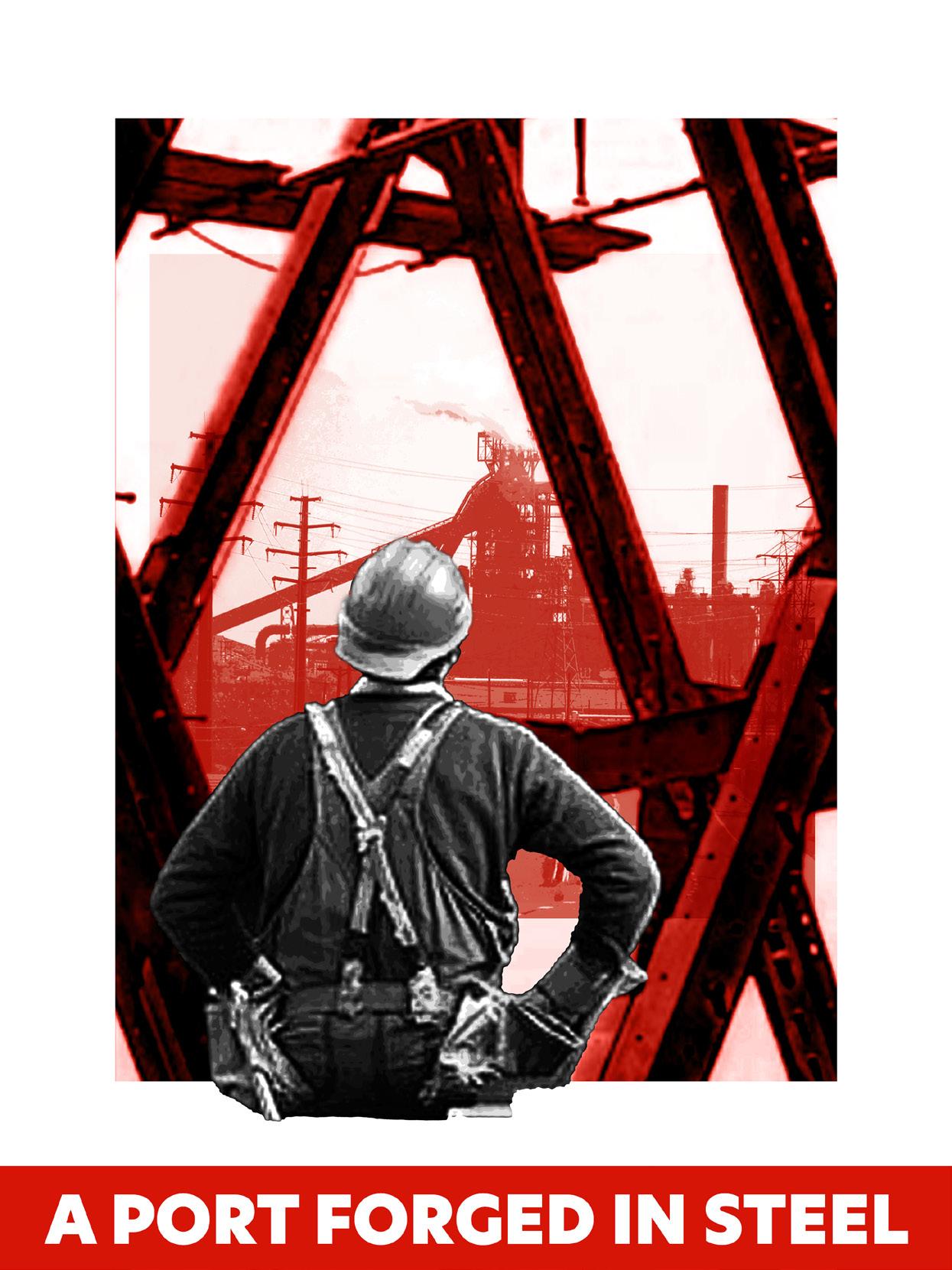

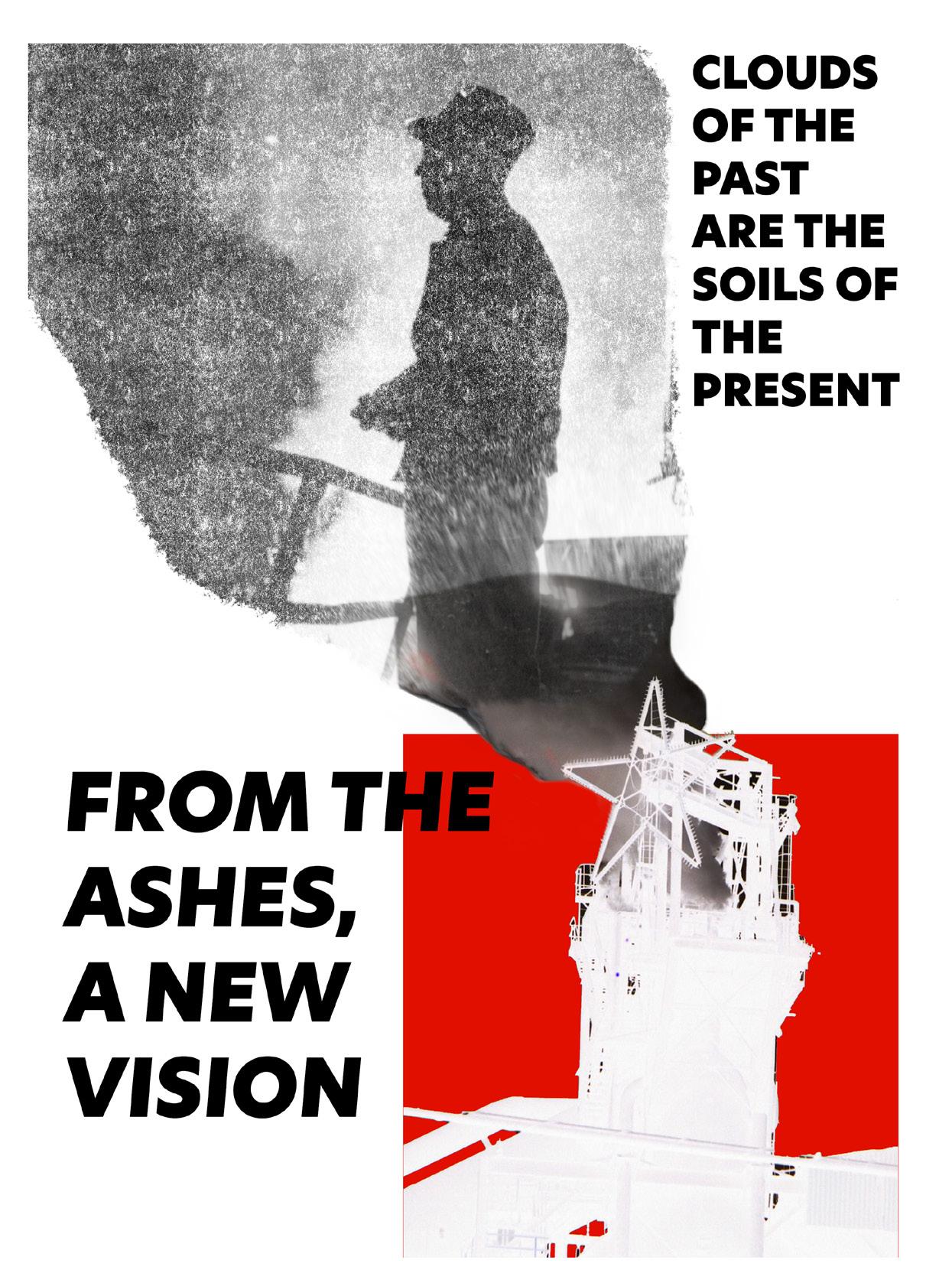

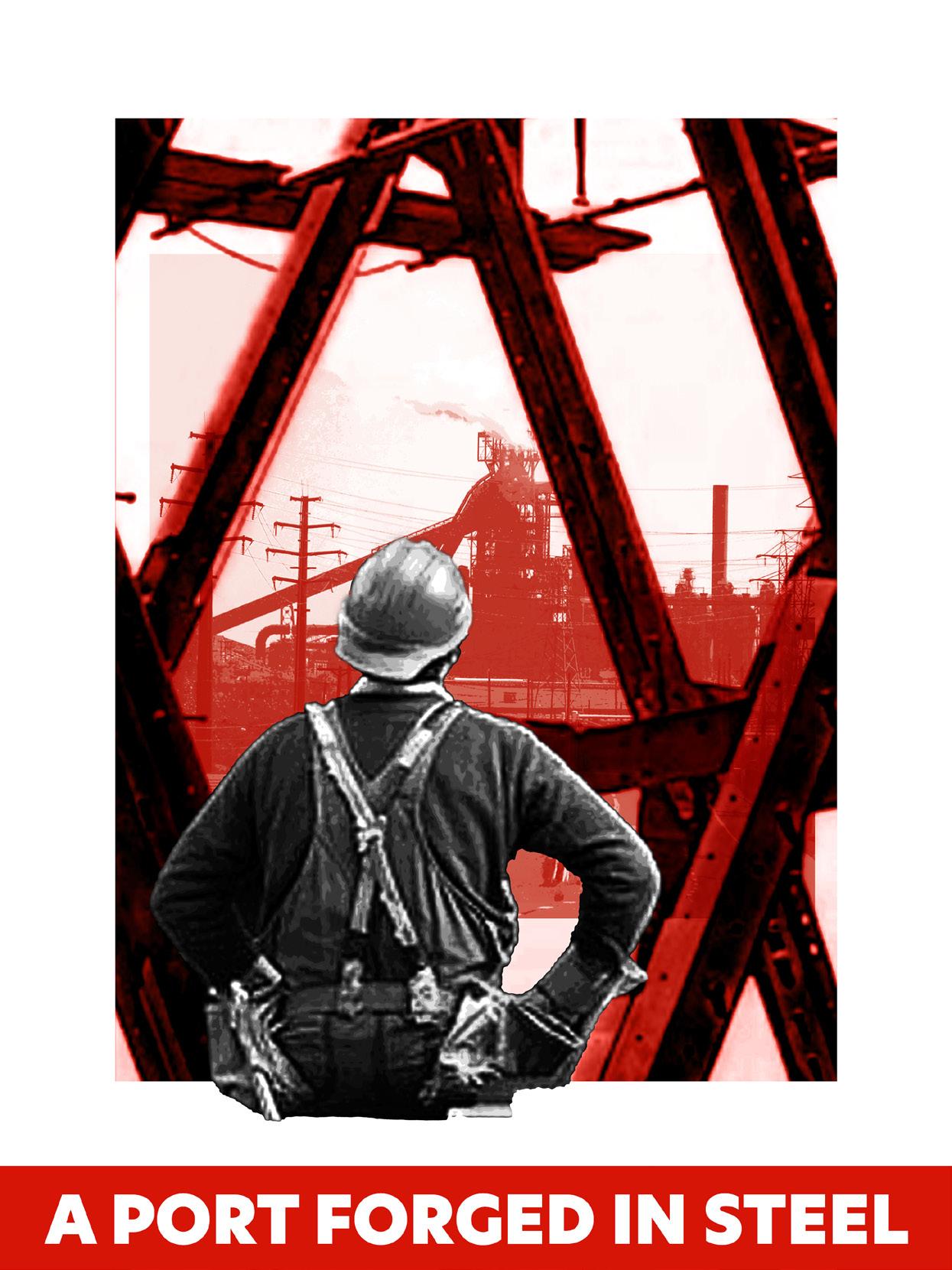

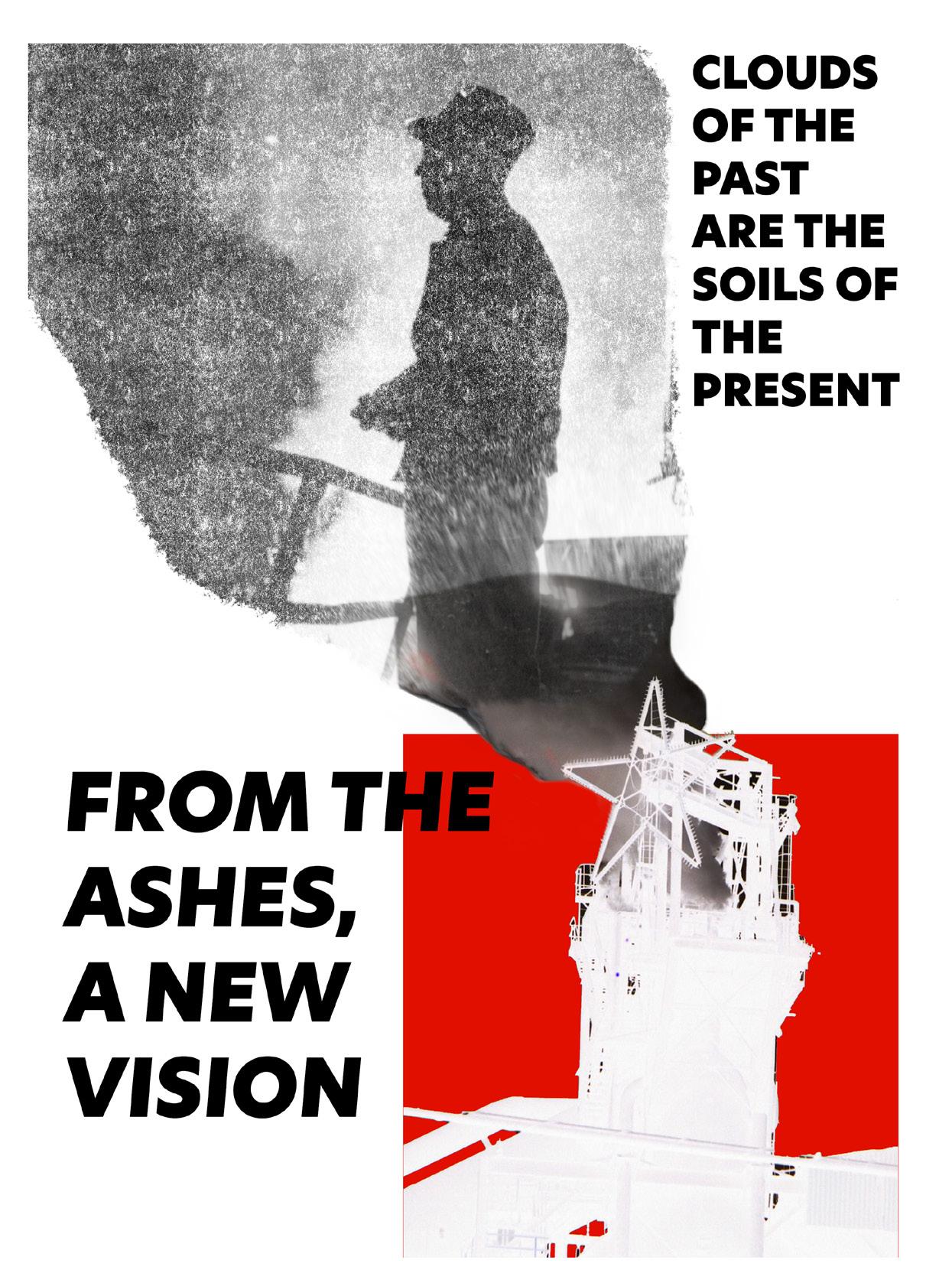

“A port forged in steel.” For 125 years, Bethlehem Steel, located on the peninsula of Sparrow’s Point, was a major producer of steel and metal goods in the United States. The mill at its height employed nearly 30,000 workers, with many of them housed in the company town that was also located on the peninsula. If someone were to ask a Baltimoreon in 1923 if they thought steel would ever leave the Patapsco River coast, it would have been unthinkable. As the mill waned at the tail end of the 20th century, the town disappeared, buried in the shadow of the ‘Big L’ Blast Furnace and under piles of slag and industrial waste. Today, the 3300 acres of Sparrow’s Point is on course to become an industrial corporatescape, built to accommodate the global logistics and distribution needs of a vast array of mega-corporations such as Amazon and Home Depot. As we look towards the future of Sparrow’s Point, Tradepoint Atlantic neglects to see itself in the major folly of Bethlehem Steel - crafting a landscape based upon the needs of today’s capital titans without regard to the health and long-term welfare of its constituent communities.

My project seeks to learn from the company town of Sparrow’s Point and suggest a corporate landscape that accounts for its own exit. As the industrial glacier retreats, we’re left to contend with its odd remnants and toxic erratics. I ask, “What if companies were mandated to plan for their sunset years and are tasked with leaving the land better than they found it?” Sited on the future former footprint of the McCormick logistics center, my project imagines one piece of this remediated Sparrow’s Point and lays the traces of its industrial past across a vast meadowland in a monument to the structures that once dominated the landscape. My proposal moves to privilege the scale of the body, a radical shift in a place that has always prioritized the scale of capital.

66

67

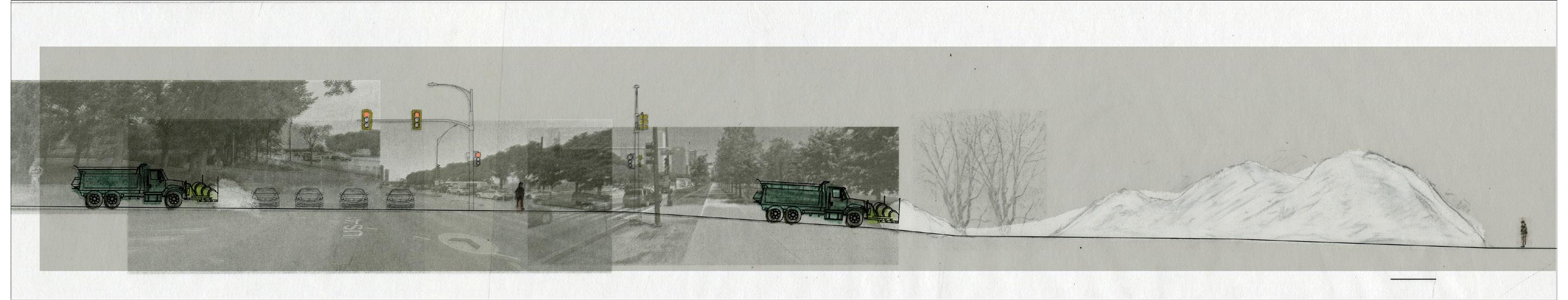

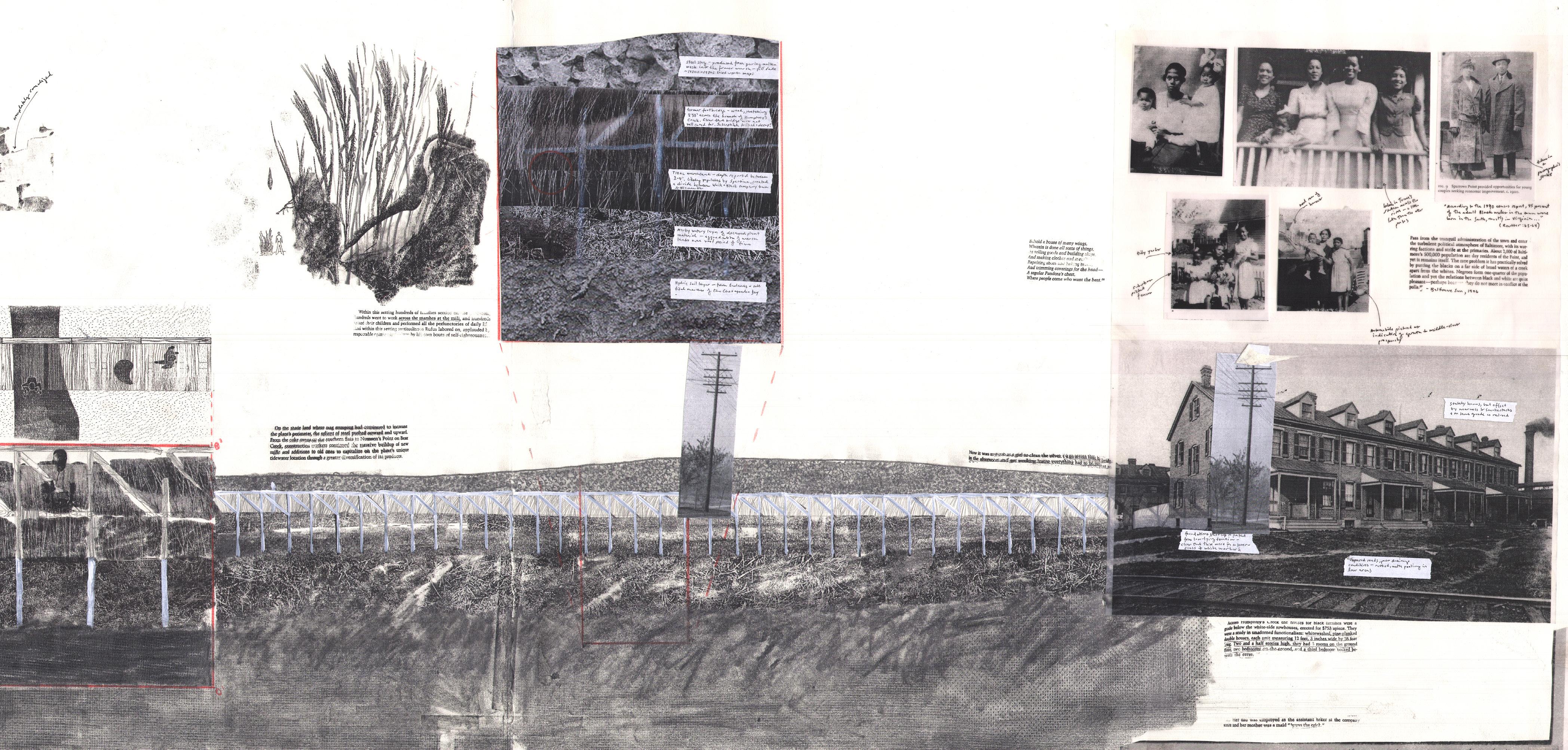

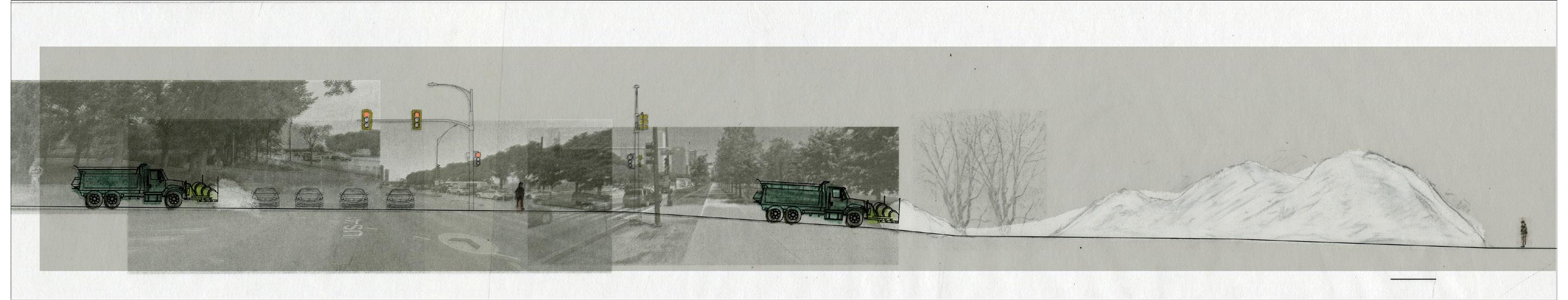

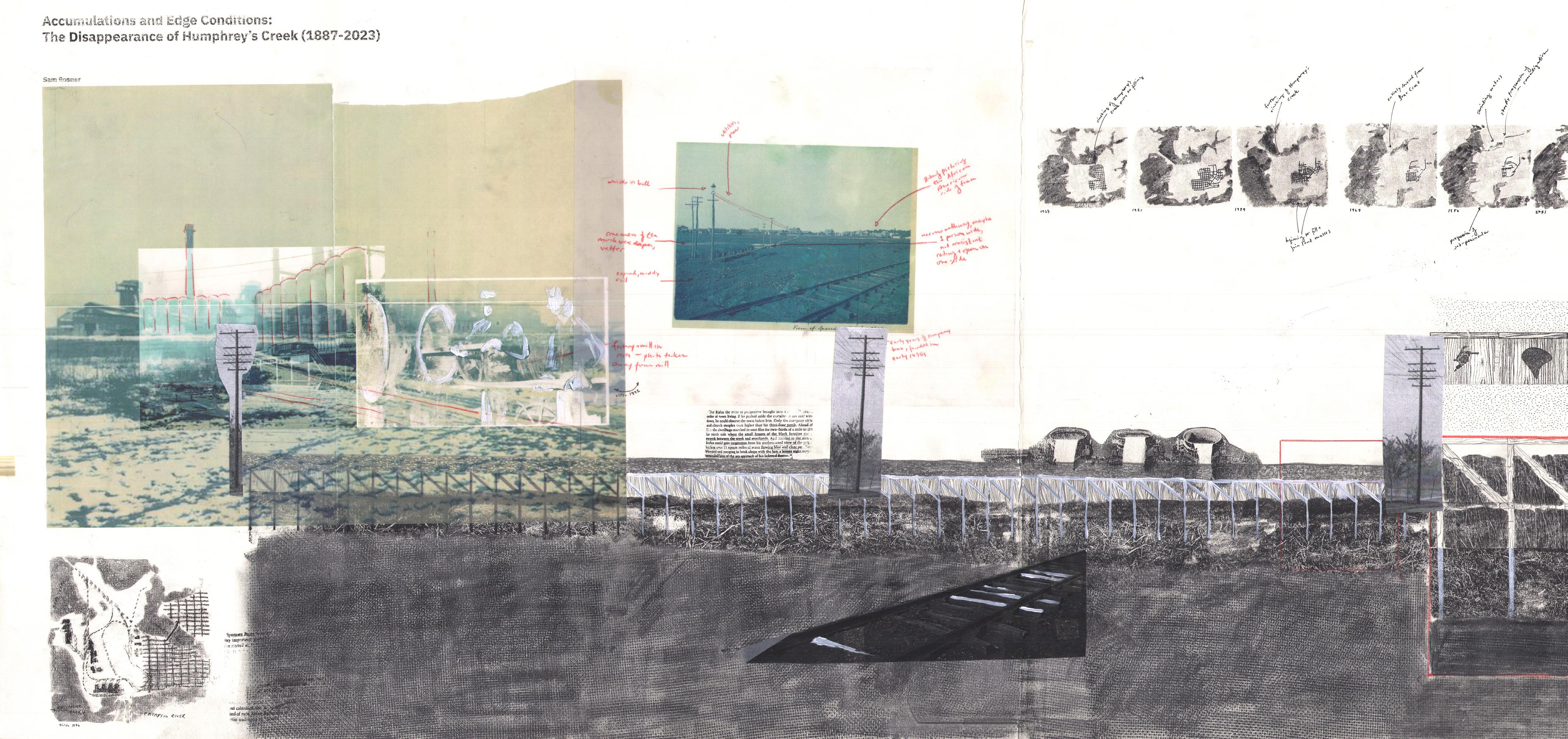

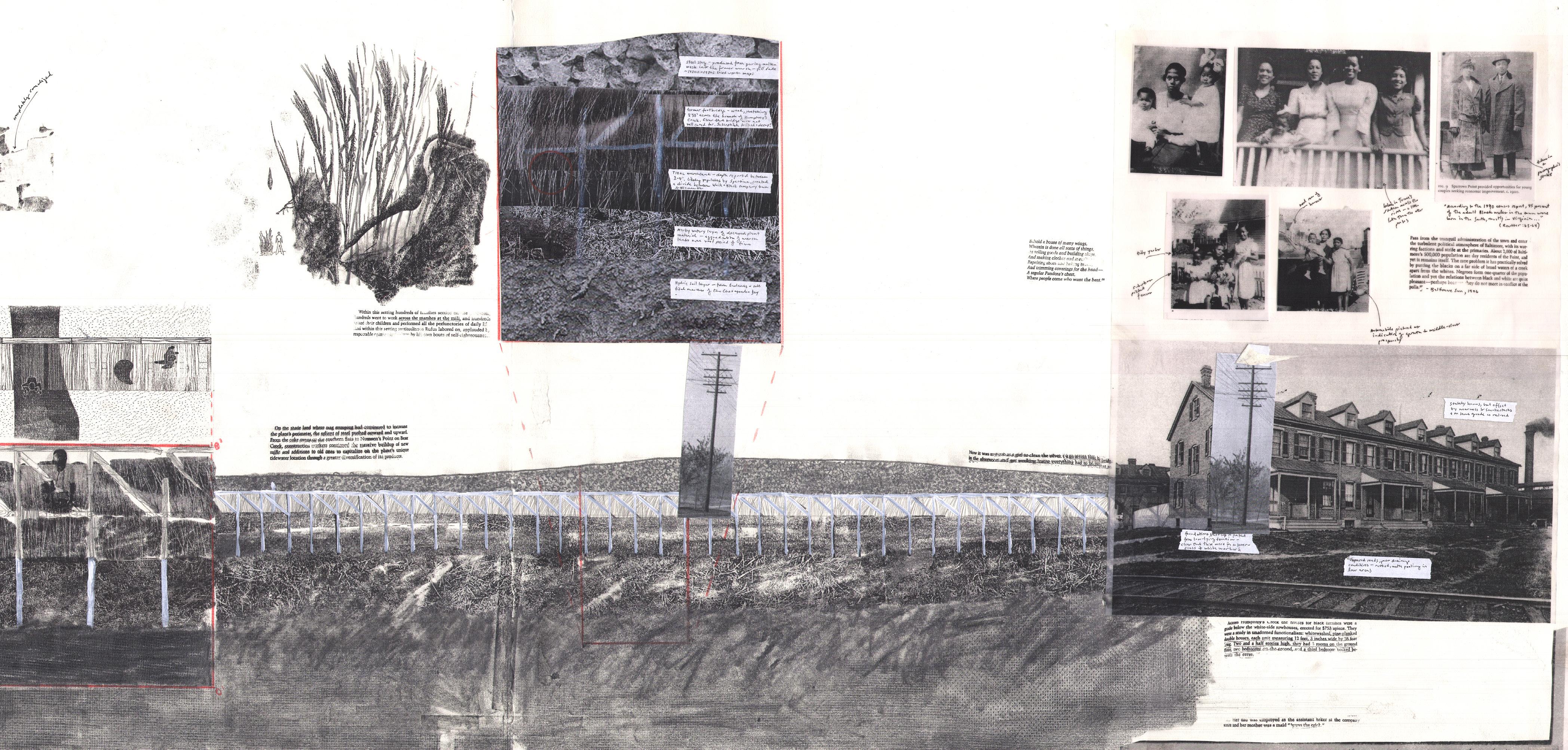

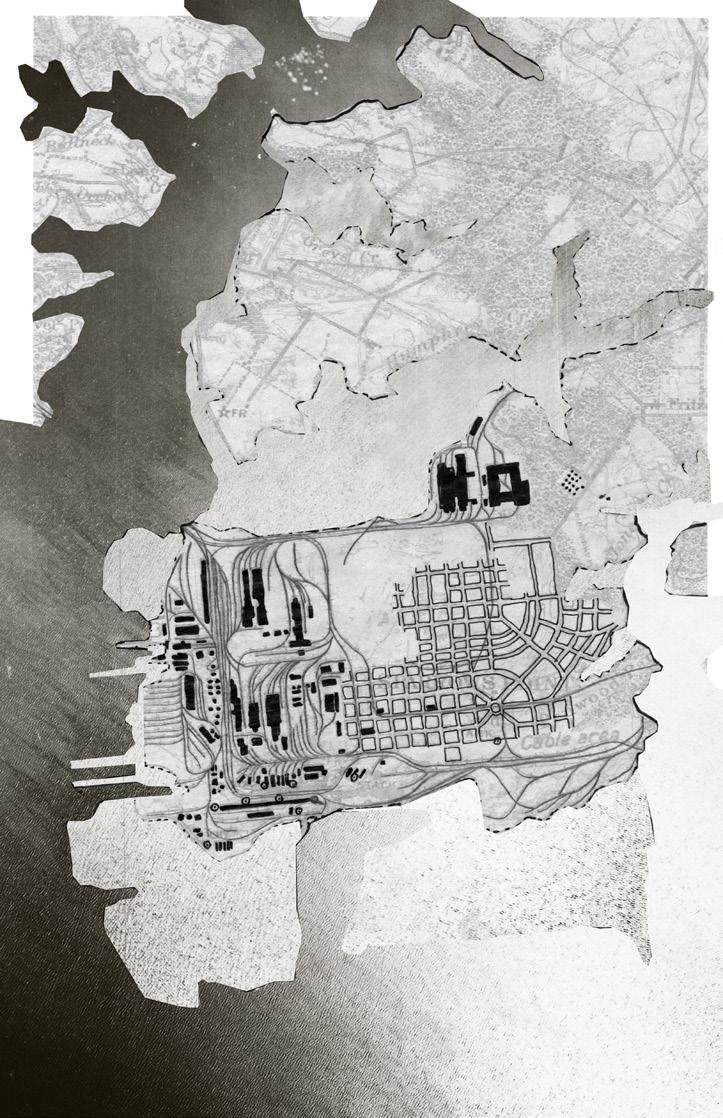

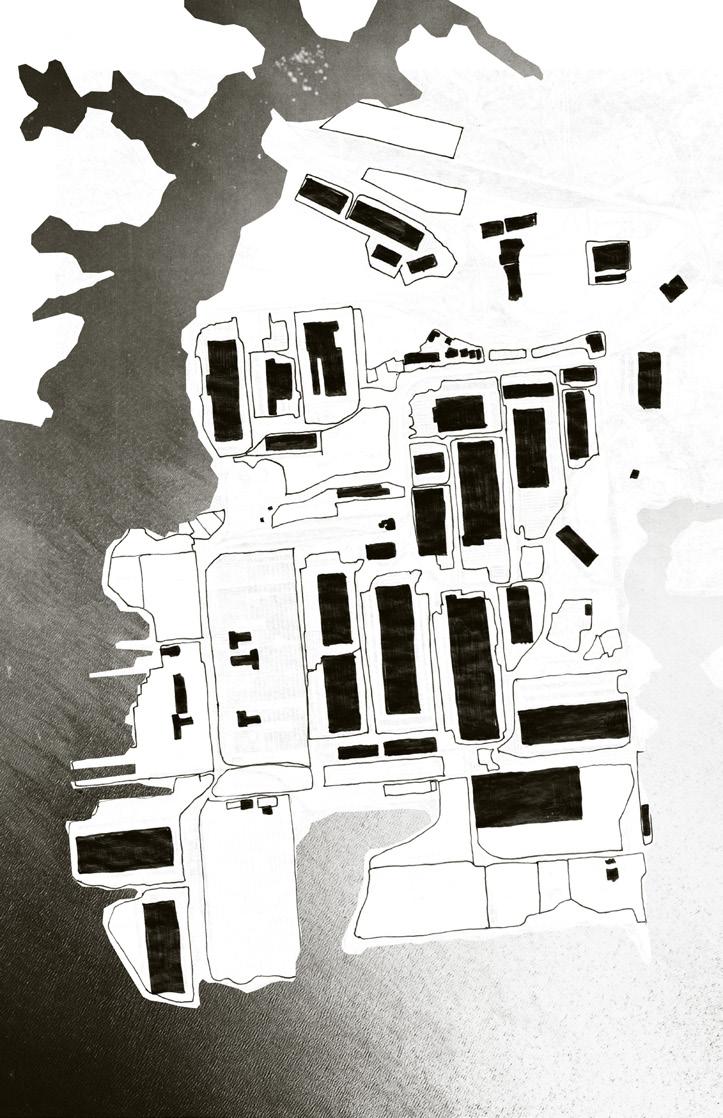

A Stream Lost: This studio began with a deep section that was cut somewhere along Bear Creek, a small stream off of the Patapsco River to the east of Baltimore. After looking at historical nautical charts of the area, I selected a former stream that used to cut through Sparrow’s Point, a former steel mill and present-day Superfund site. My research into the lost stream showed that it had once been a dividing point in the former company town, separating White workers from Black workers. Over the first few decades of the life of the mill, the stream was quickly filled with steel slag and was built on top of to add more worker housing. This section explored the idea of cutting through this site that is so marked by labour, race, and industrial waste.

68

69

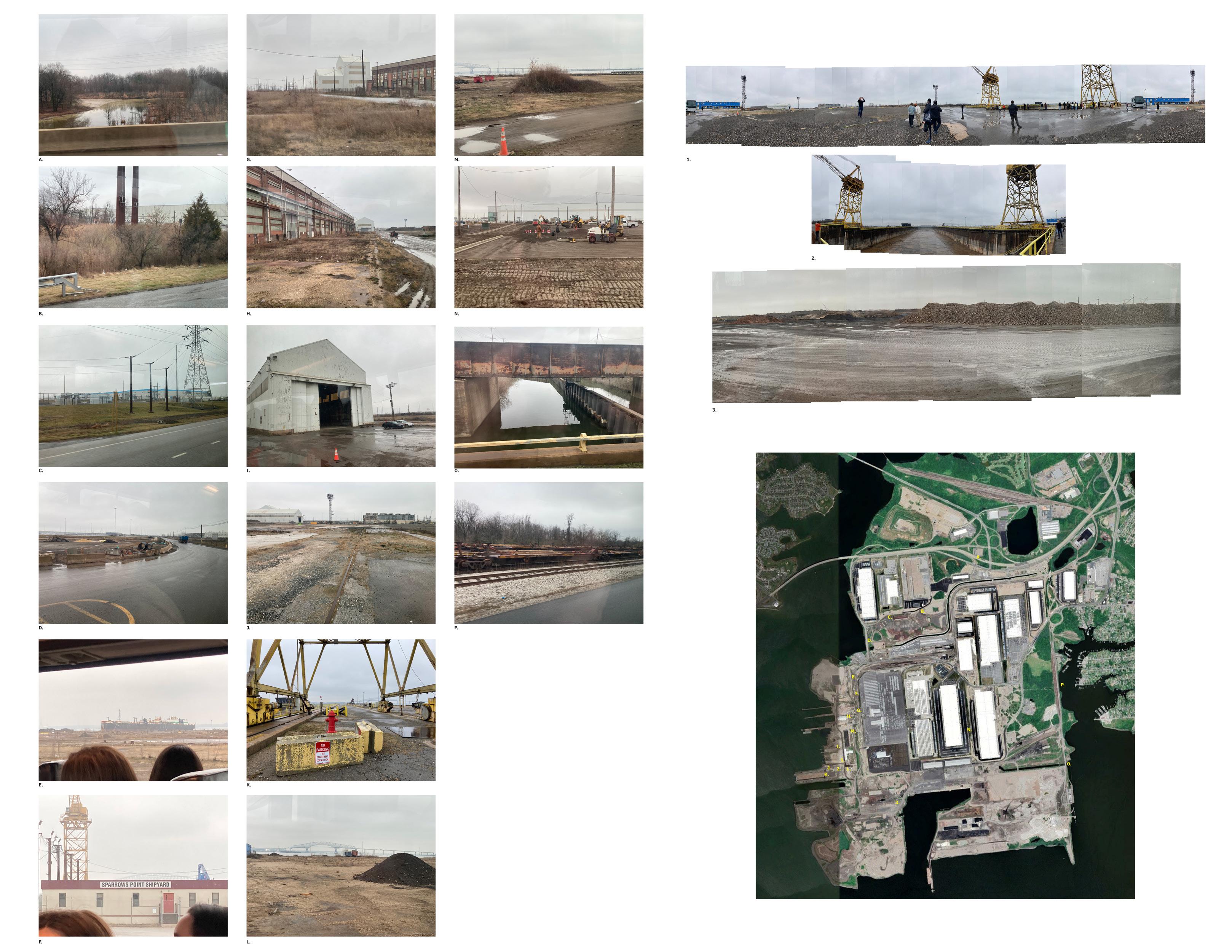

Post-Industrial Field Work: Our class took a trip to Baltimore and visited the industrial landscape of Sparrows Point which today looks like the surface of the moon, so marked by waste and attempts towards remediation. The images and diagrams on this page are a result of this fieldwork and seeks to understand the chemical and structural traces of the now long-gone steel mill.

70

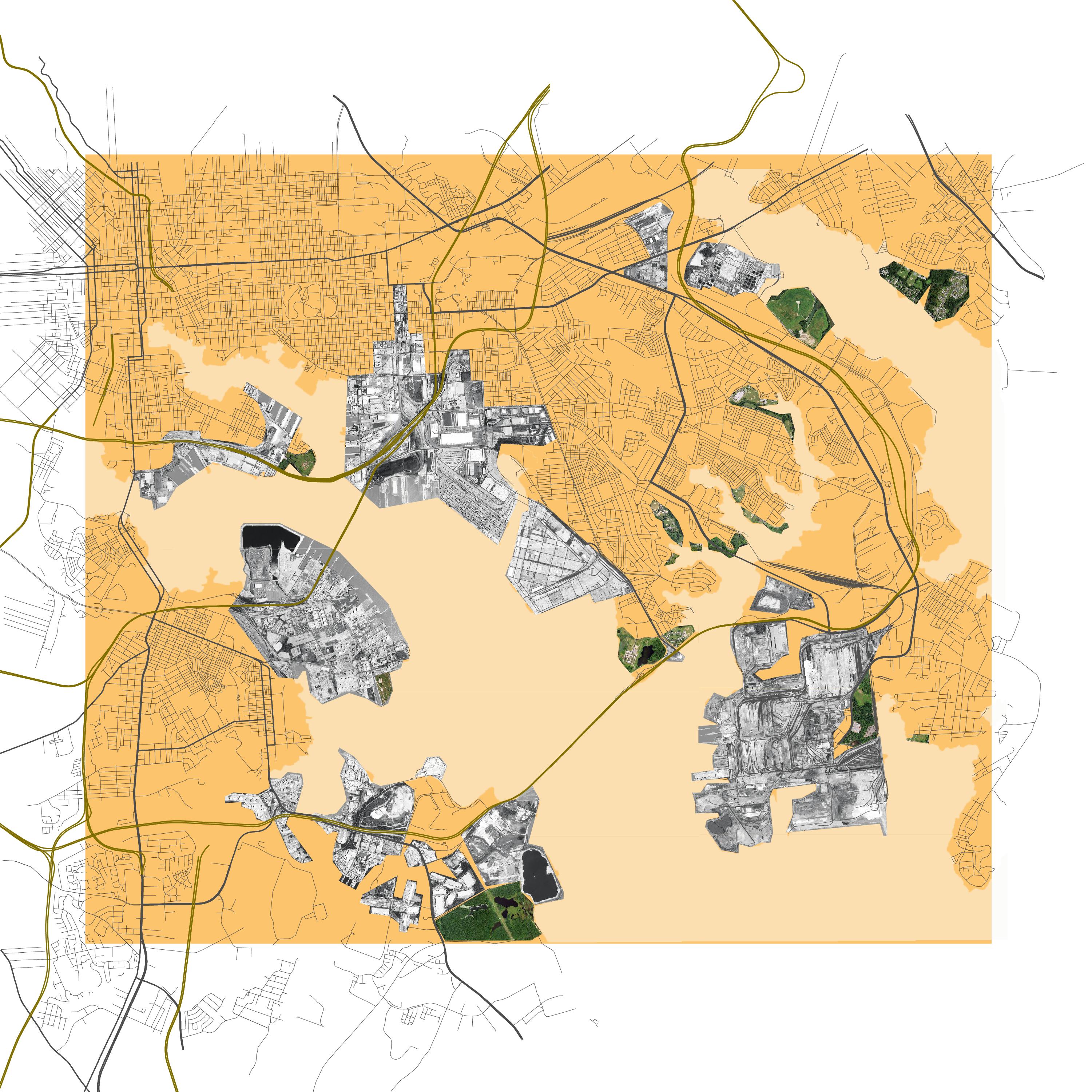

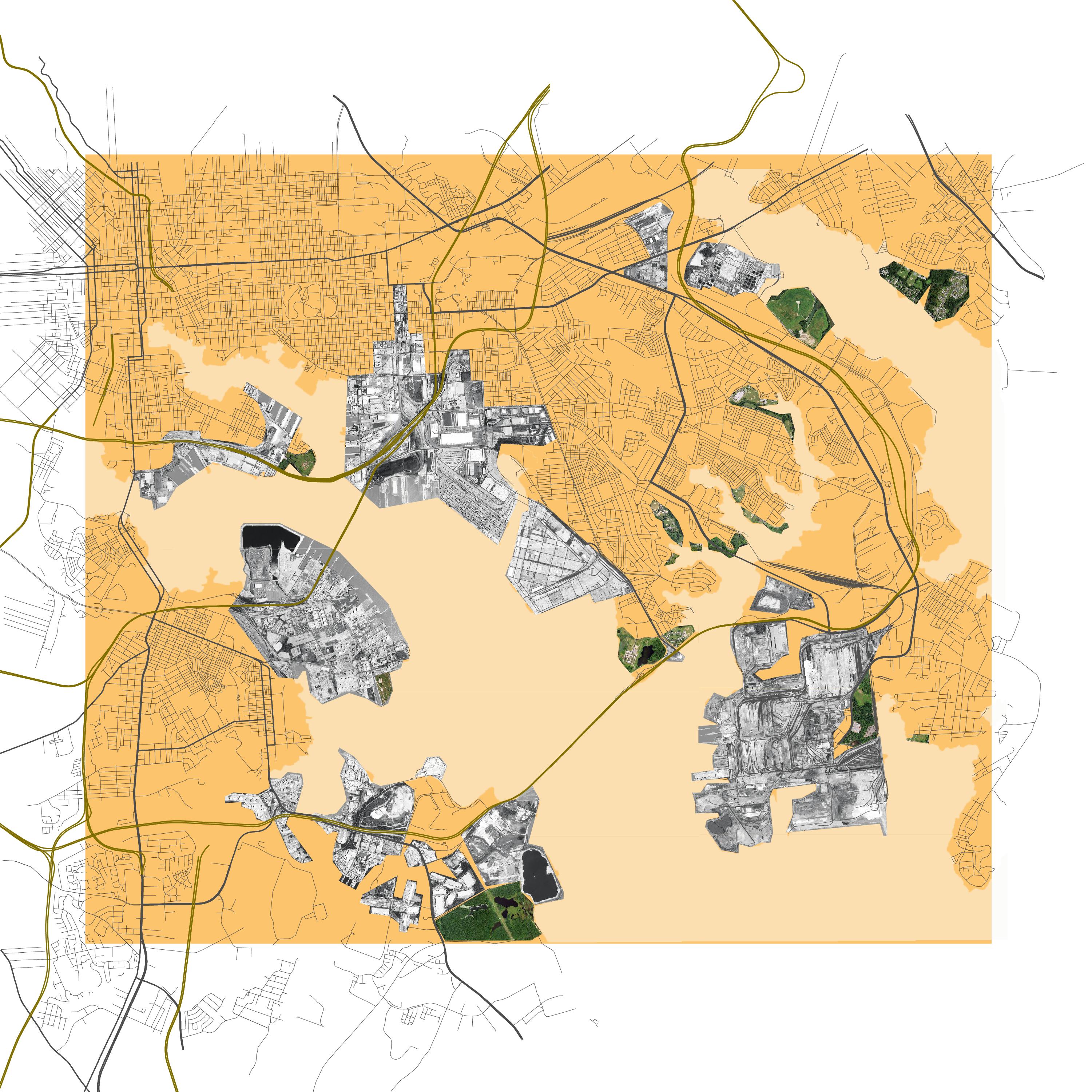

Contours sourced from 2015 USGS CoNED Topobathy DEM The darkest contour line represents ~5’ of sea level rise. Sparrows Point’s coastline has been built up and armored over the years, and with the exception the its eastern edge, the peninsula appears to be more less protected from rising sea levels. How can this relative place resiliency be folded into the more vulnerable residential communities Turners Station and Dundalk? This quick study of the current conditions Sparrows Point combines the monumental size of the new building footprints (TPA brags that the McCormick building is the largest footprint on the Atlantic coast), with the much smaller, though multiple footprints the piles of slag and other excavated material that is awaiting remediation or removal. Tradepoint Atlantic’s Master Plan conceives Sparrows Point as grid fungible lots. They have been “remediating based upon planned usage” strategy that allows them to remediate piecemeal depending upon whether the land will be used for recreation or for heavy industry. In many cases, this strategy will mean pouring large concrete caps further flattening the ground plane. The human body dominated this scale, totally overwhelmed by the vastness concrete and large, windowless logistics centers. This combined map begins to tell the story of exploitation on Sparrows Point while also showing the explosion of scale indusrial usage of the peninsula. Overtop the former company town are hulking, impersonal logistics centers. This total erasure of the company town misses key opportunity to learn from the landscapes of the industrial past. Can future vision Sparrows Point begin repair the relations between community, place, and industry? The grid, railroads, and building footprints are drawn from 1931 map of Sparrows Point and shows the Steel Mill’s Company Town its peak point of expansion. The large, kidney shaped blank space the center the filled, former Humphrey’s Creek, which disappeared around 1925. Over the next 90 years, Sparrows Point would balloon as land mass, pushed southwards through the dumping of dredge and steel slag. Though may seem hard to believe given today’s landscape, Sparrows Point was once home to about 9000 residents. This value study based on 1994 aerial view of the peninsula. The constructed land to the south of the Blast Furnace has burnt, charcoal-like quality, perhaps due the particulates from the exhaust cloud. This aerial view complicates the ground plane, showing not flat, broad expanse, but as highly pock-marked and complex surface. This contrast to the glossy, flattened depictions of the ground utilized by Bethlehem Steel and now Tradepoint Atlantic that have made easy to imagine as exploited, “standing-reserve” space. Former Humphrey’s Creek inlet Cloud emanating from the primary Blast Furnace, which was built 1986 and deconstructed 2014, marking the end of steel production Sparrows Point The former Blast Furnace site now vast parking lot waiting area for BMW and Volkswagen cars shipped from Europe The eastern edge remains the most park-like, formerly used as golf course and now planned to be used as country park. The northern extent Humphrey’s Creek was also filled and channelized into Tin Mill Creek, whose outflow site is now considered Superfund site 1”=15,000’ 1”=15,000’ 1”=15,000’ 1”=15,000’ 1”=15,000’ 1”=15,000’ 71

Towards De-Growth in a Growth-Oriented Landscape: As I shifted into design, the idea of a company town rang in my ears. After reading into de-growth theory and practices, I wondered what it would take to move Sparrow’s Point towards a truly post-industrial future that would pay homage to the many lives that this peninsula has led. The timeline on the left follows the industrial history and branches off to imagine the shifts in advocacy and policy that would enable the peninsula to become an industrial heritage park. The posters above mark key points in the campaign towards this de-growth future and take inspiration from Soviet-era graphic design to capture the large-scale shifts needed to transform the trajectory of this extraction lanscape.

72

73

~300’ 350’ 13’

28’ 235’ 298’

~875’

x

tall

Company Town Block Unit (1895)

“Big L” Blast Furnace (1978)

D Street Housing Unit (1931)

Big L Mound

74

Blast Furnace Park: xx

Restored Wetland

Drift Mowing Field

Restored Wetland

Drift Mowing Field

75

Company Town grid mown paths - ~12’ wide

0’ 2’ 6’

6-8’ clean soil to cap a layer of geotextile

Contaminated steel slag + industrial sediment, depth unknown

Schizachyrium scoparium

70 miles of tracks currently run through Sparrow’s Point. Repurposed rail ties are used to line pathways through the landscape

76

Solidago sp.

Mown pathways offer a variety of choices across the meadowed landscape

A berm gently sets the path back to meet the wetland grade.

6’ 2’

77

Sassafras albidum

0’

Design Research

78

79

Coastal Parklands: Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument

Location: Dorchester County, Maryland, USA

Managers: Brian Davis, Marantha Dawkins Role: Student Research Assistant Work currently in progress.

The Coastal Parklands team is an interdisciplinary effort to assess and design nature-based infrastructures for three National Park Service (NPS) sites that are at a high risk of inundation from sea level rise caused by anthropogenic climate change. This research team is composed of members coming from organizations such as the NPS, the US Army Corps of Engineers, The Nature Conservancy, UVA, UPenn, and is also in conversation with descendants of Harriet Tubman as well as federally recognized Indigenous tribes. The Coastal Parklands team is now at work assessing and designing for the Jacob Jackson Homesite as part of Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument (HATU).

As a more senior member of the student research team, I have managed a small team of three students to create drawings and timelines that relate to the ecosocial history of the nearly 500 acre homesite. Together, we have produced drawings that tell the story of Harriet Tubman’s early childhood in Dorchester County, MD specifically, but have also begun depiciting the direct relations that enslaved people had with the landscape both while labouring and also while seeking passage to the north.

Jacob Jackson was a free Black man living in Dorchester County in the 19th century, an era that was dangerous to African Americans both free and enslaved. Jackson was familiar with the Ross/Tubman family as the families would have met while working on the land. Jackson hid his literacy from the White community and was therefore able to smuggle messages from Harriet to her brothers and famously aided in her rescue of them in the 1850s.

Today, the homesite is all but disappeared, with only traces of fields and ditches and sparse remains of settlement to indicate the rich human history of this place. The site sits between .5’ and 2’ above MSL and is predicted to see sea level rise hit about 2ft above MSL by 2050, effectively erasing the site entirely. Our work as the Coastal Parklands team is to interpret this changing landscape and aid in the protection of key historical sites through manageable nature-based infrastructural interventions. The work is aimed to be wrapped up by October 2024.

Continuum of Sea Level Rise: This map, made in collaboration with Marantha Dawkins, shows the edge of land and water as a murky boundary on which key historical sites sit tenuously. As seen through this carefully edited DEM, the land of Dorchester County has long sat at the edge of submersion.

80

81

82

83

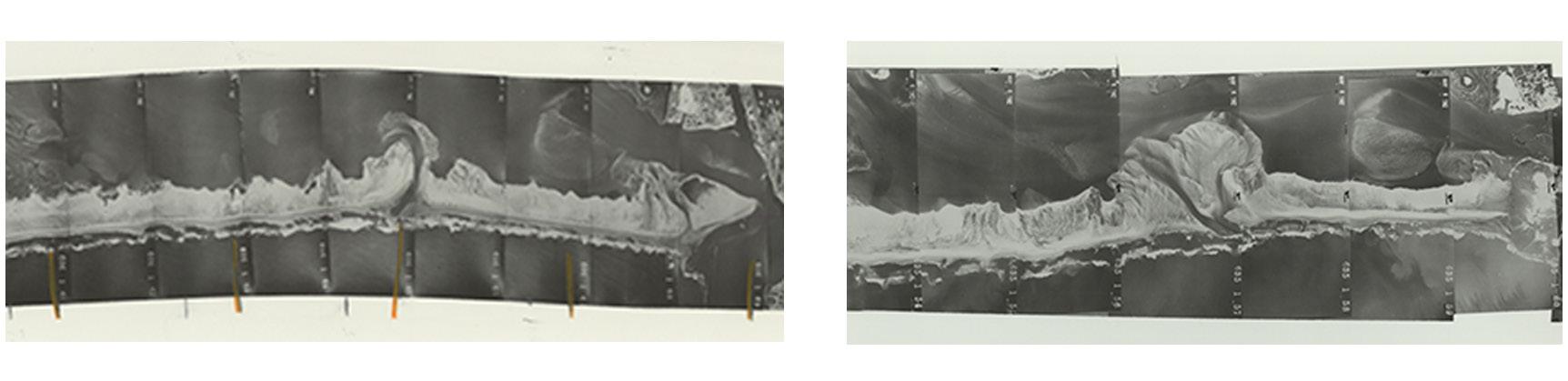

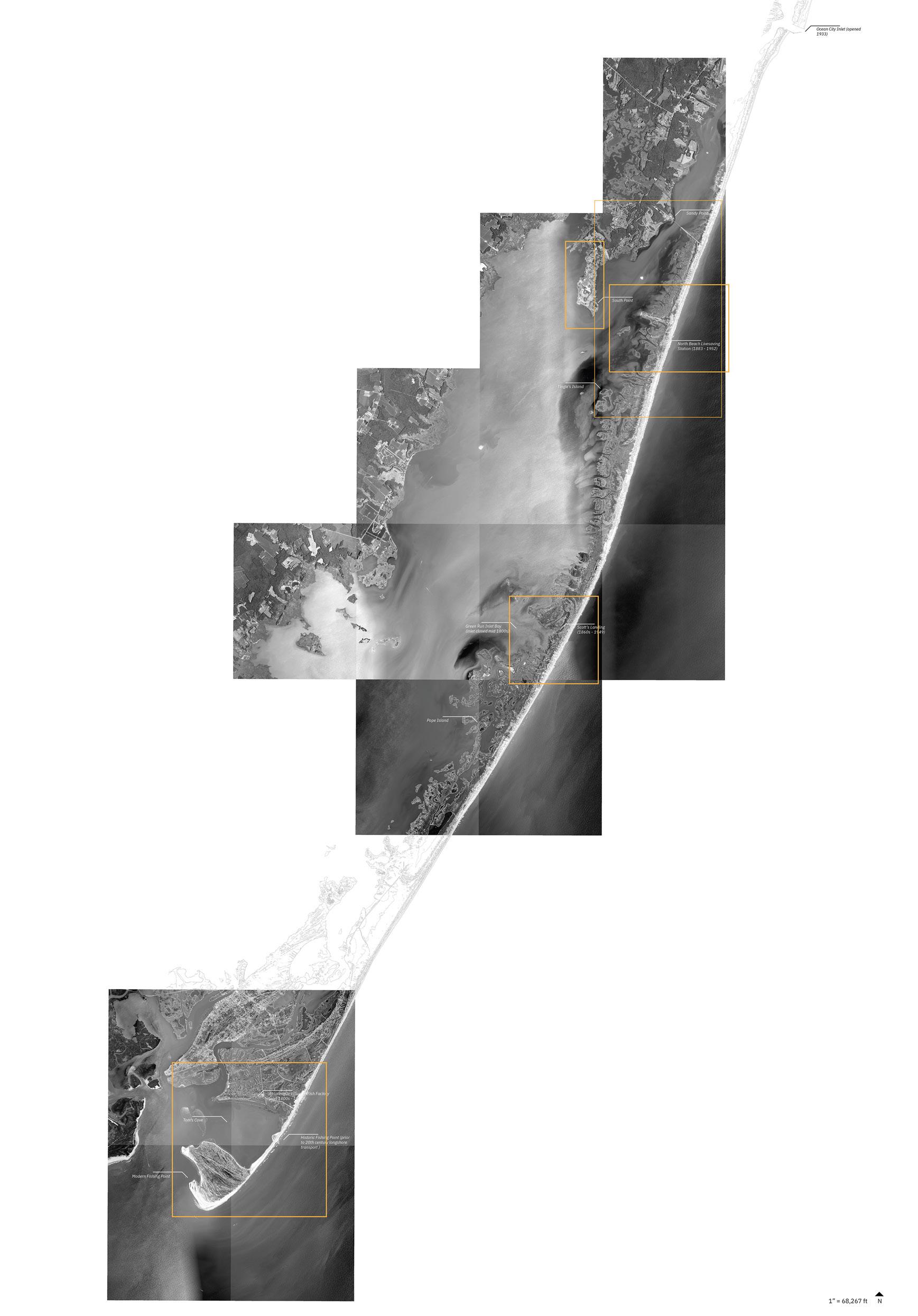

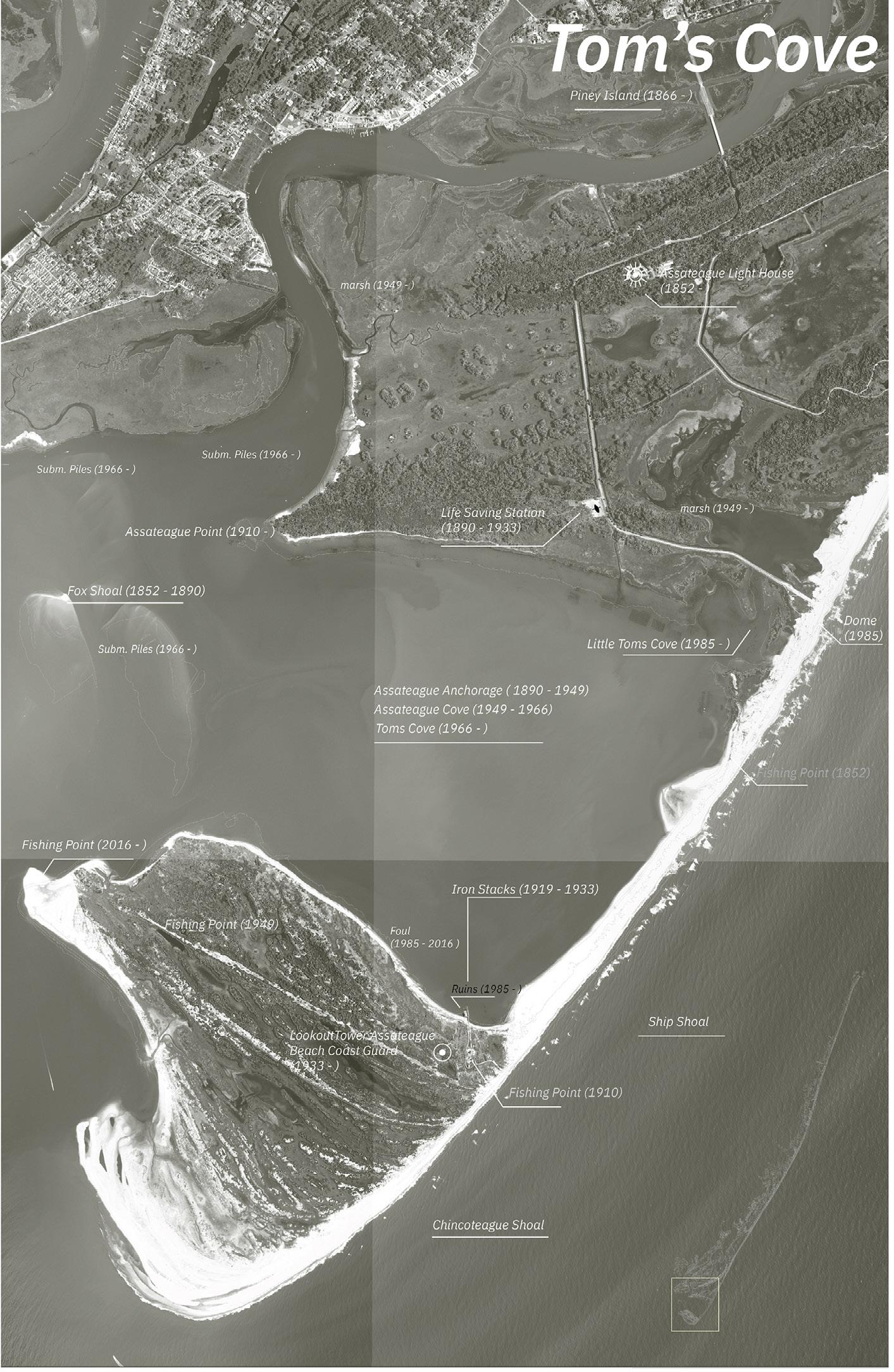

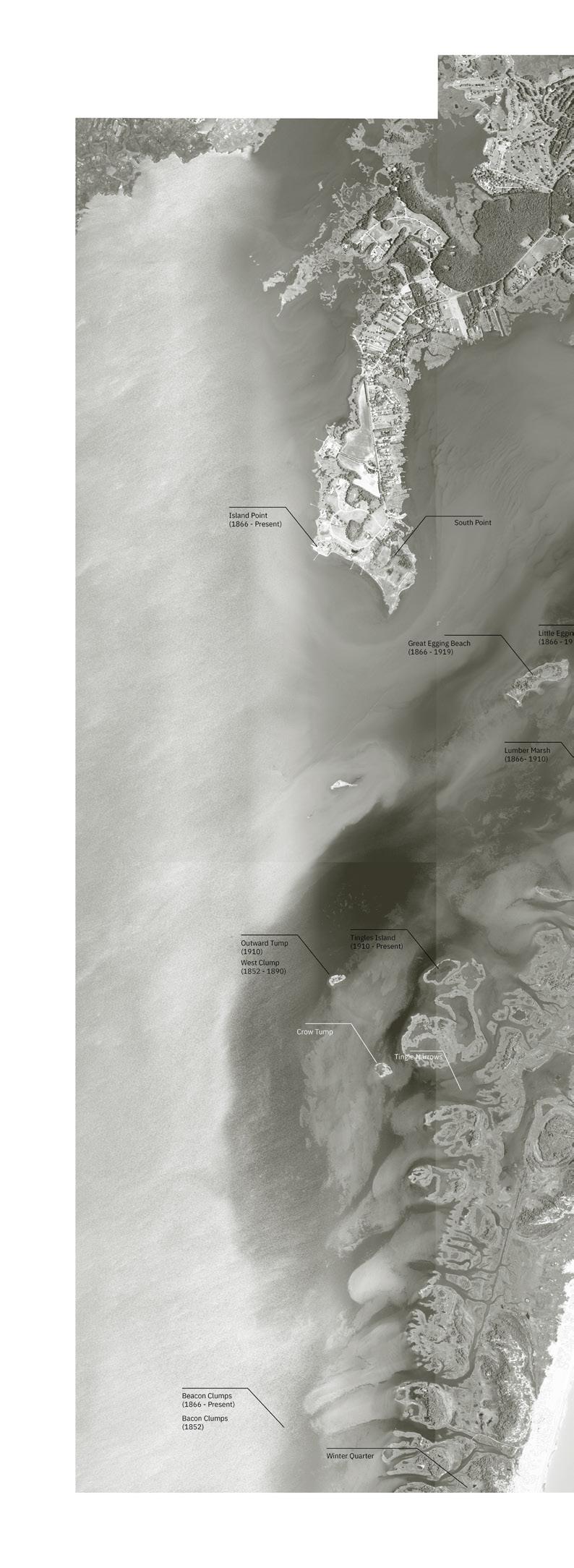

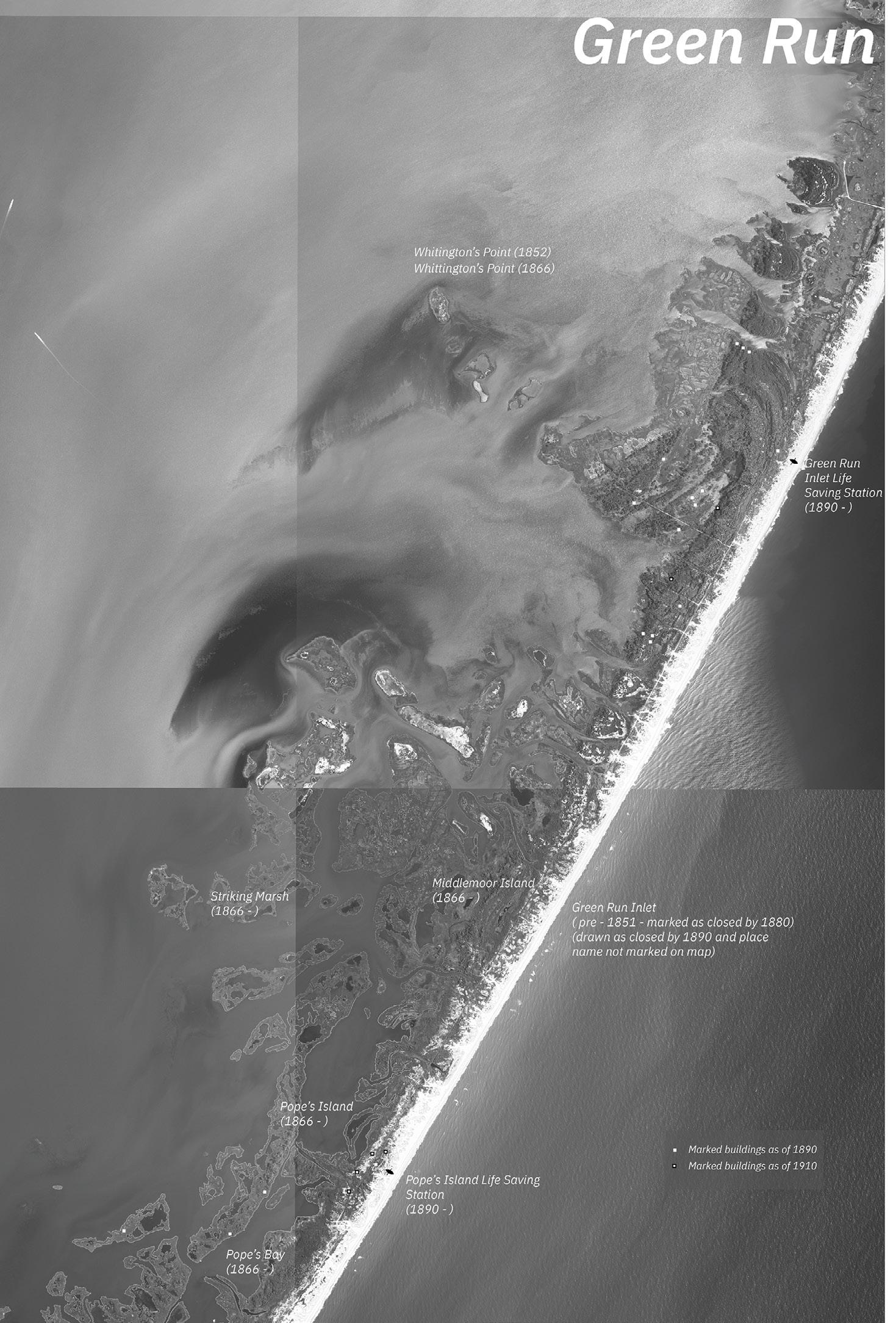

Coastal Parklands: Assateague Island

National Seashore

Location: Assateague Island, Maryland + Virginia, USA

Managers: Erin Putalik, Brian Davis, Marantha Dawkins

Role: Student Research Assistant

Work took place between January 2023 - February 2024

Published report forthcoming.

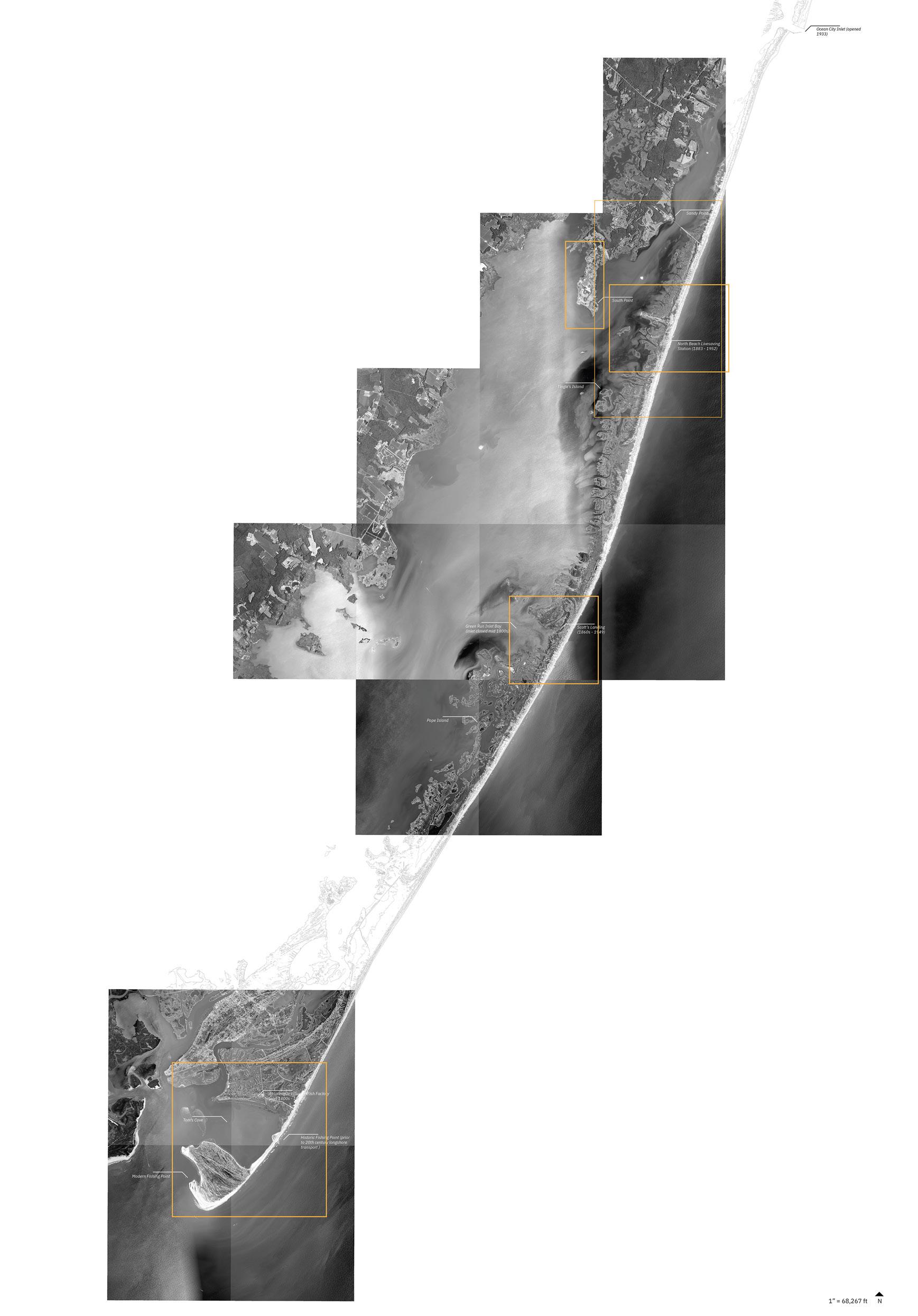

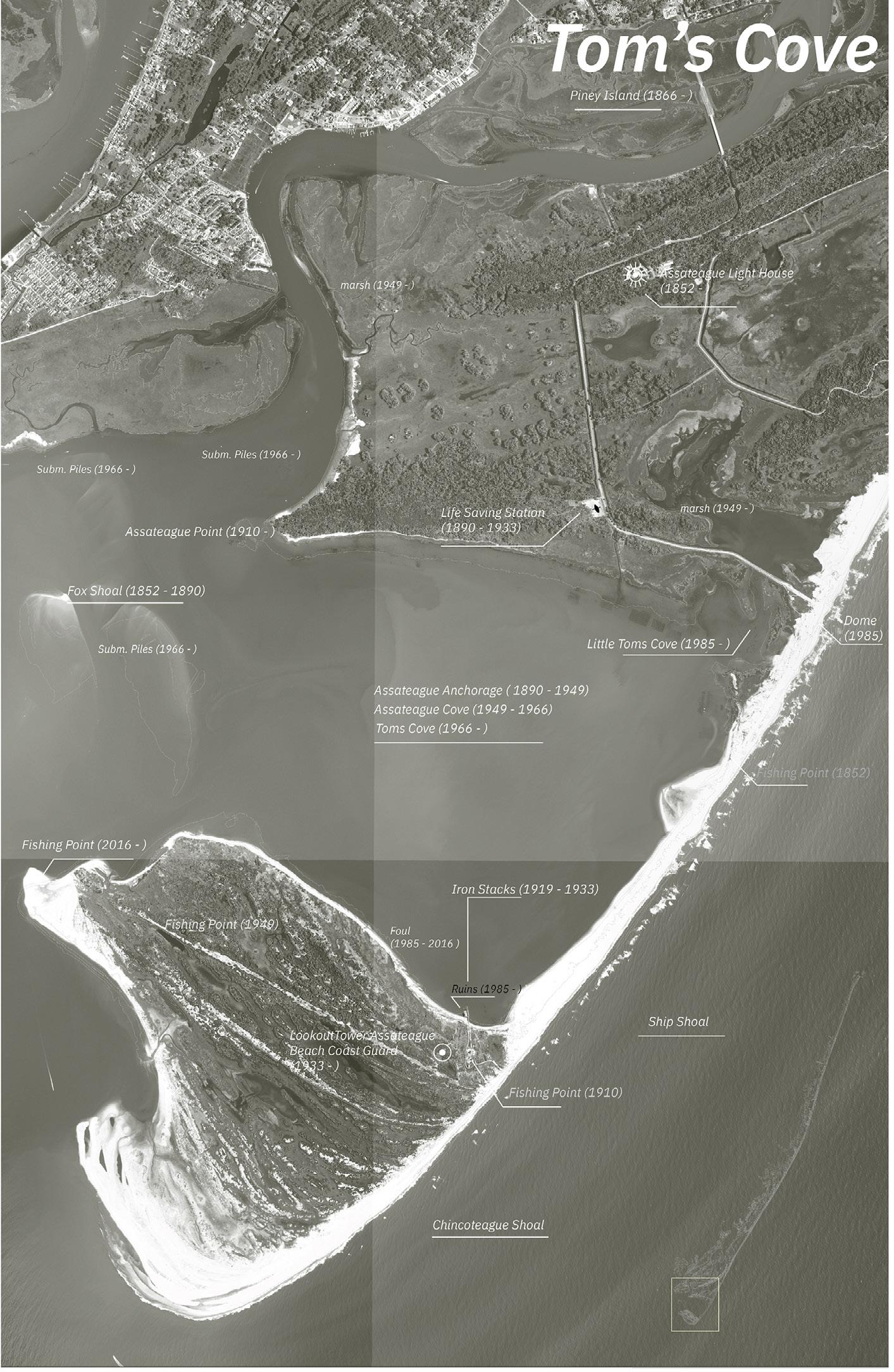

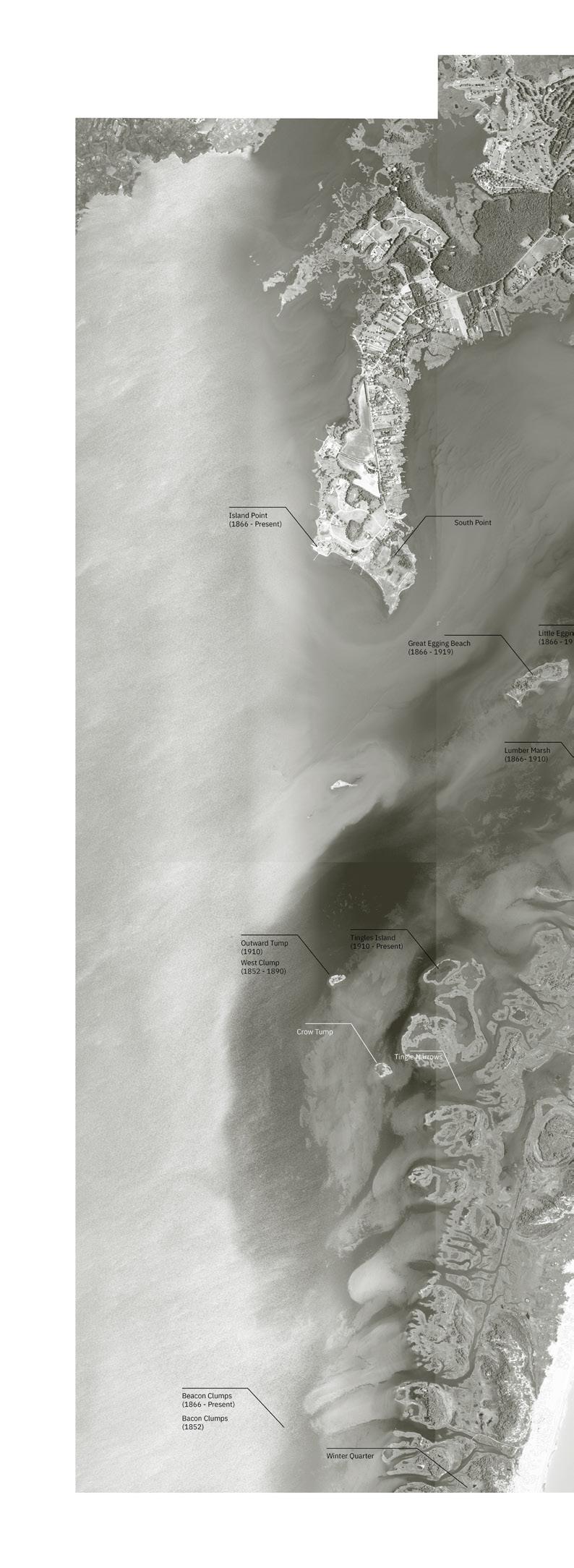

The Coastal Parklands team is an interdisciplinary effort to assess and design nature-based infrastructures for three National Park Service (NPS) sites that are at a high risk of inundation from sea level rise caused by anthropogenic climate change. This research team is composed of members coming from organizations such as the NPS, the US Army Corps of Engineers, The Nature Conservancy, UVA, and UPenn. The first of these sites of study was Colonial National Park, home to historic Jamestown. I joined this research team as we began work on Assateague Island National Seashore, an unruly barrier island along the Delmarva Peninsula that for centuries has been made and unmade by natural processes such as hurricanes, longshore transport, and aeolian transport.

I worked on the cultural history of Assateague with my manager, Erin Putalik. As part of my duties, I completed a literature and visual culture survey of the barrier island to build a library of references for life on this narrow stretch of land. Key to this

process was a deep dive into historic charts and the changing sense of place that occurs so suddenly through overwash events and more slowly via sediment transport that can be traced through historical drawings and place names.

I identified and visited archives that hold materials about the early and administrative life of this park and interviewed Joe Fehrer Jr., who is the son of Joseph Fehrer, the head of land acquisitions in the early days of the park’s becoming.

From this rich repository of material and oral histories, I worked alongside the infrastructural design team to enrich their understanding of the ecosocial history of this place and help determine the placement of infrastructure that could most effectively protect the fragile artifacts of human history on the island.

My final duties were to write up our findings and help deliver the report which will soon be published by NPS.

A brief write up of this research was written by myself and Erin Putalik and is published in KERB 31.

1962 After 1962 Nor’easter 84

An excerpt featuring some of the historical positioning I wrote for the forthcoming report on our group’s findings from our research on

85

Assateague.

86

Shifting Sands, Shifting Sense of Place: These maps trace the changing place names that were recorded over a century of nautical charts. Some of the changes are gradual, but others, such as the moving end of Fishing Point demonstrate the malleability of naming on an ever shifting shoreline.

87

In the Plantation Cemetery

Location: Fluvanna County, VA, USA

Independent Study, Fall 2022

Instructors: Beth Meyer, Allison James

Published in October 2022 by the Hoosac Institute.

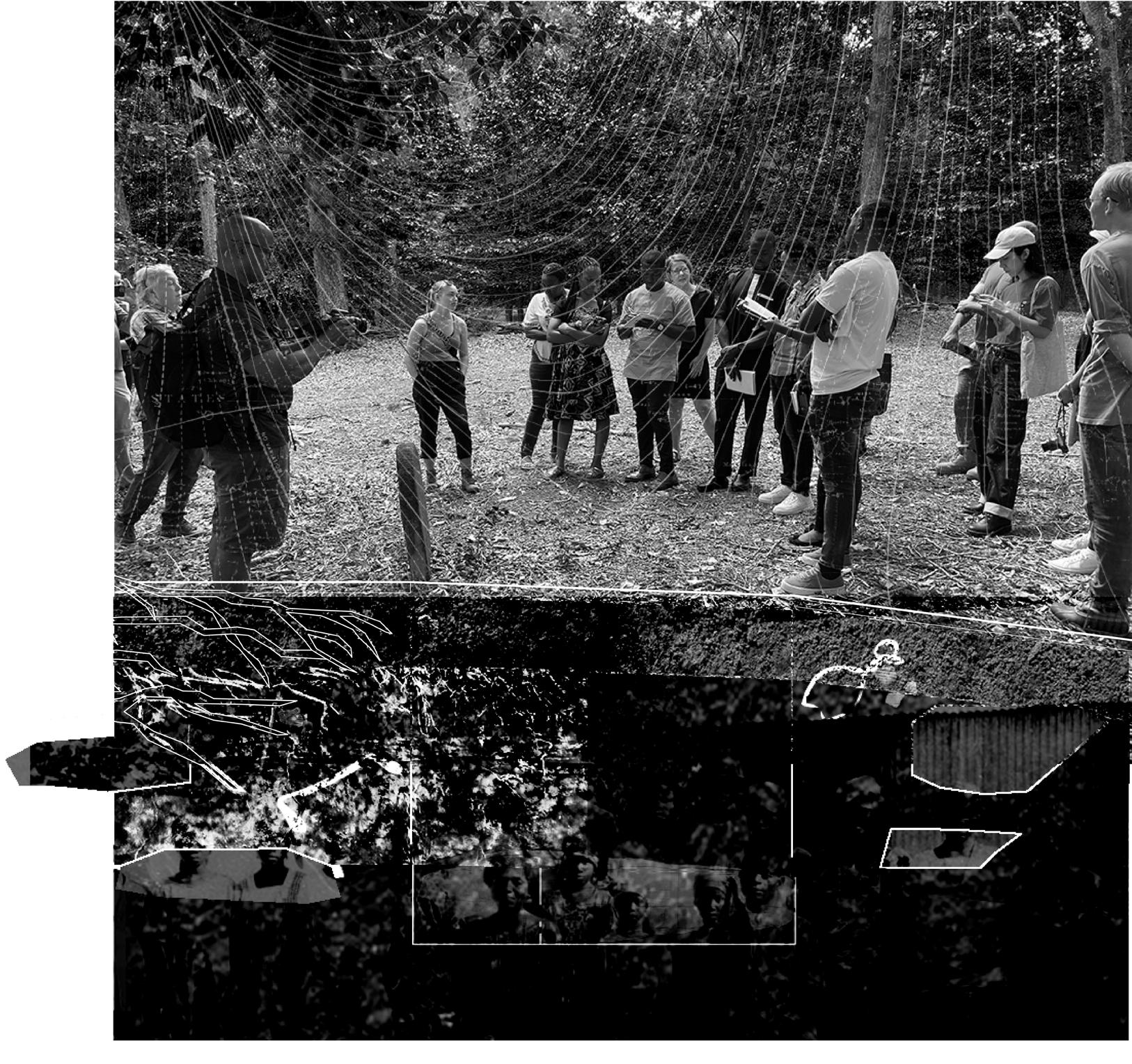

This essay is records a once in a lifetime encounter between a group of students from the University of Liberia, who are visiting Virginia and Washington D.C. as part of a field school organized by Allison James (a Cultural Landscape Preservationist and consultant for the World Monuments Fund), and Horace Scruggs, a descendant of Ben Creasy who was enslaved by John Hartwell Cocke on Bremo Plantation in Fluvanna County.

The drawings accompanied the essay which is excerpted here:

“Could Ben Creasy have ever dreamed of this moment? Could he have imagined this congregation of people, of family members and long-lost loved ones, gathered at his final resting place. Could he have imagined this bridging of oceans of time, oceans of suffering, oceans of history. Gmawlue read on, his Liberian accent inflecting Peyton Skipwith’s words with the warmth that two centuries of expatriation would give to his ancestors.

The fact of our presence, standing here together, is reason enough to believe that there is hope for the future. This group of students travelled across the Atlantic to return to Virginia in search of connections and networked histories embedded within our shared cultural landscapes. At this place they found traces of ancestors who survived bondage and endured the difficulties of building a country. We did not talk about it, but a brutal and bloody Civil War marked the childhoods of many of Liberia’s youth. 20 years later, these students – Thomas Gmawlue, Alexander Dash, Gayflor Wesley, Harriet Gaye, Lorpu Flomo, John Delphin, and John Lissa- are picking up the pieces and are looking towards the past to rebuild their country in a way that acknowledges the complexity of Liberian identity.

The letter comes to a close. Gmawlue reads the last, brief sentence from Peyton’s first correspondence as a Liberian, “Direct your letters to Monrovia.” We will heed this direction. Our work together is just beginning.”

Fork Union

Bremo Farm

Enslaved Cemetery

Remains of Chapel

Grace Episcopal Church

Sal’s Italian Restaurant

JamesRiver

Fork Union

Bremo Farm

Enslaved Cemetery

Remains of Chapel

Grace Episcopal Church

Sal’s Italian Restaurant

JamesRiver

88

89

90

91

.

Finding Virginia’s Freetowns

Location: Albemarle County, VA, USA

Summer Research Assistant 2022

Managers: Suzanne Moomaw, Lisa Goff

Collaborator: Logan Parham

Role: Researcher, Curator, Exhibition Designer

EXHIBITION

AUGUST 24 – SEPTEMBER 8, 2022

Elmaleh Gallery, Campbell Hall, UVA School of Architecture

Largely undocumented are the 50 or more Freetowns that flourished in Central Virginia from the middle of the nineteenth century, when they were occupied by free Blacks; through Reconstruction, when they were joined by settlements of emancipated Blacks; and into the twentieth century, when they continued to provide a measure of security and self-determination for Blacks circumscribed by the violence of Jim Crow. Many of these communities, centers of Black endurance and achievement, have vanished. But they live in collective memory, and in traces on the landscape.

This research project is a collaboration of faculty, staff, and students from across the University of Virginia who have been documenting, researching, and meeting with community members to find Freetowns in Albemarle, Buckingham, Fluvanna, and Orange counties. Their central goal is to unearth the history which has been lost to development, migration, and memory through studying plantation records, historical maps, tax filings and records, photographs, newspaper archives, oral histories, and other documents held by UVA’s Special Collections and local historical societies. The research team has highlighted the particular and unique stories about how Freetowns were built and sustained across time in the most challenging of conditions.

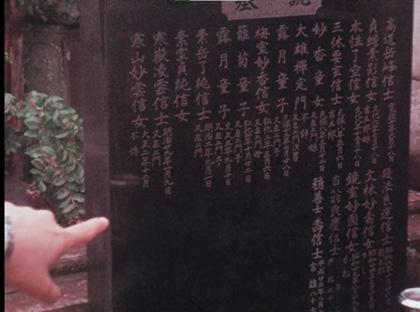

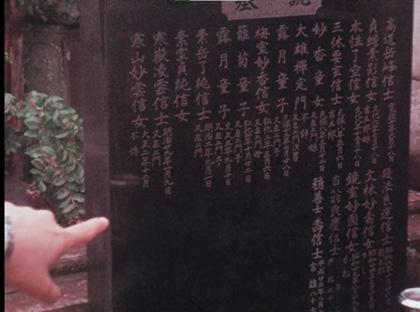

Mt. Carmel Baptist Church was erected in 1873, serving the Black population of Browns Cove. A small graveyard is located the rear of the building. Henry and Gladys Barbour are laid to rest here and using the census records as reference, we can see that they were husband and wife, having grown up just few houses down from each other. At the trail entrance at Patricia Ann Byrom Forest Preserve is memorial erected in 2016 by the Blue Ridge Heritage Project. It lists the family names of those who were evicted and displaced during the creation of Shenandoah National Park. While many narratives paint these mountain families as being low-income and living in dilapidated conditions, wide variety of households made up these communities. The Vias, listed on this plaque, posed major threat to the evictions process, taking their case to the courts and delaying their departure. While there are very few records of Black families being displaced during this process, the Park’s census records capture only landowners, so there is large probability that Black families who were boarders were not enumerated as living in park land. The story of Massie Tyree shows glimpse into the rich lives of the Black community in the White Hall region. Born to newly freed woman on the Early Plantation, Massie grew to become major landowner Doylesville who managed farm and opened series of successful businesses including local jazz club and dance hall. Browns Cove Browns Cove Shenandoah National Park Patricia Ann Byrom Forest Park

92

Mt. Carmel Baptist Church and its adjacent schoolhouse form the civic center of the Browns Cove Freetown community. While the church is still in operation, the schoolhouse across the river has been converted into private home. Tarry’s Tourist Camp would have drawn people from all over the Crozet area for music, dancing, and games. It was washed away during the 1942 flood which damaged many structures and roads along Browns Gap Turnpike. Doylesville Cove White Hall 93

1937 1957 1966

94

Changes in Land Use: These simple drawings attempt to trace the reforestation of Brown’s Cove as plantation agriculture began to leave the landscape, narrowing the band of farms into a smaller valley gap.

1980 1990 95

96

97

98

99

Foundation Studios

100

101

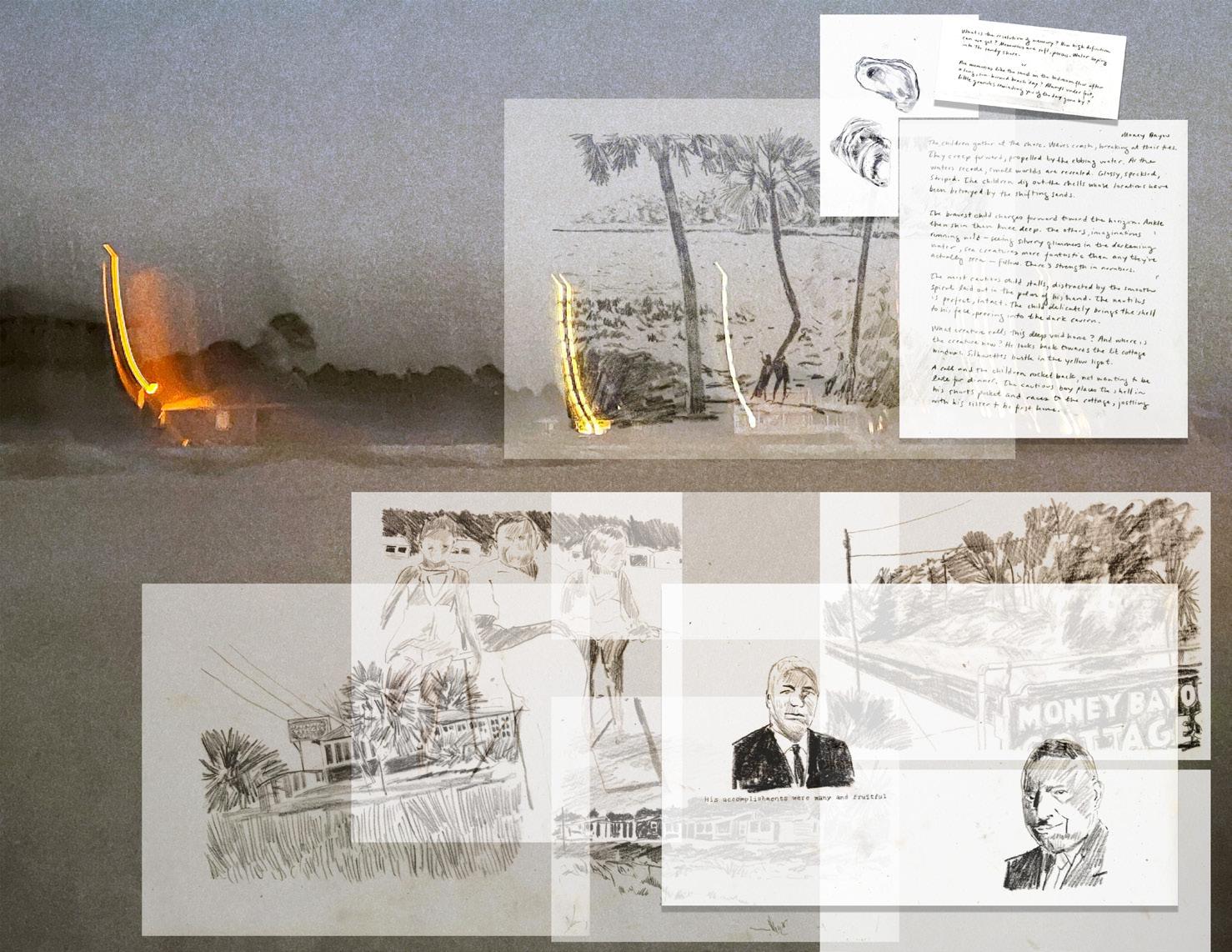

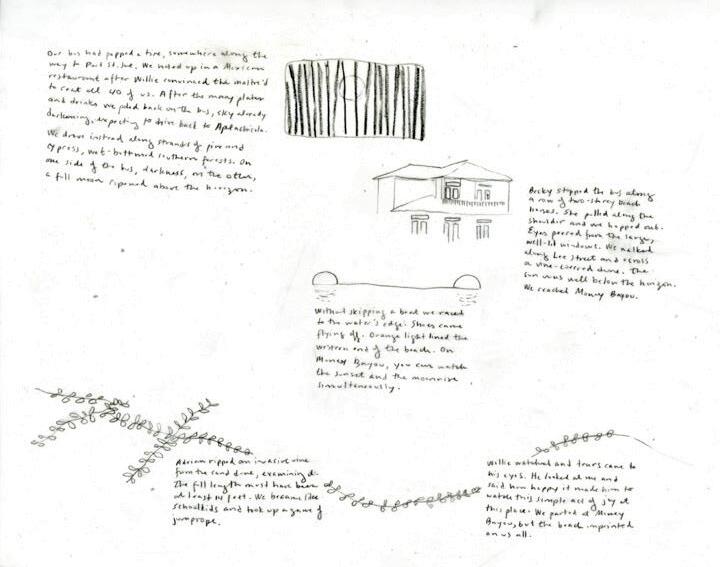

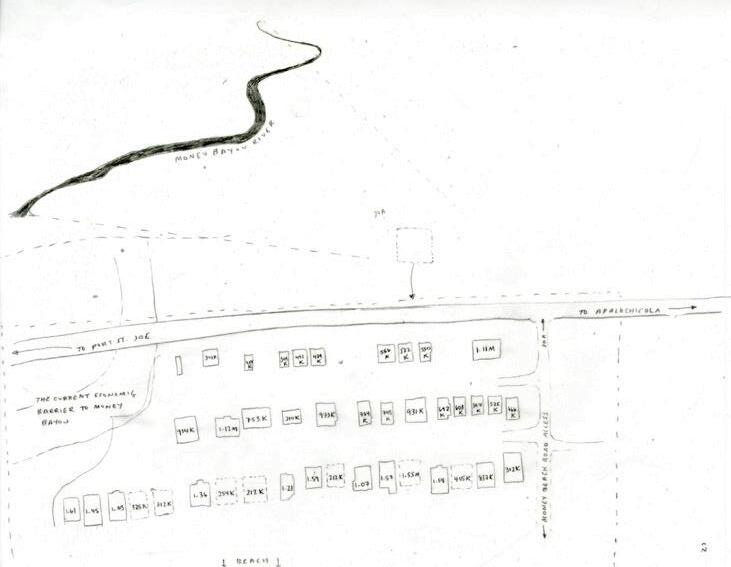

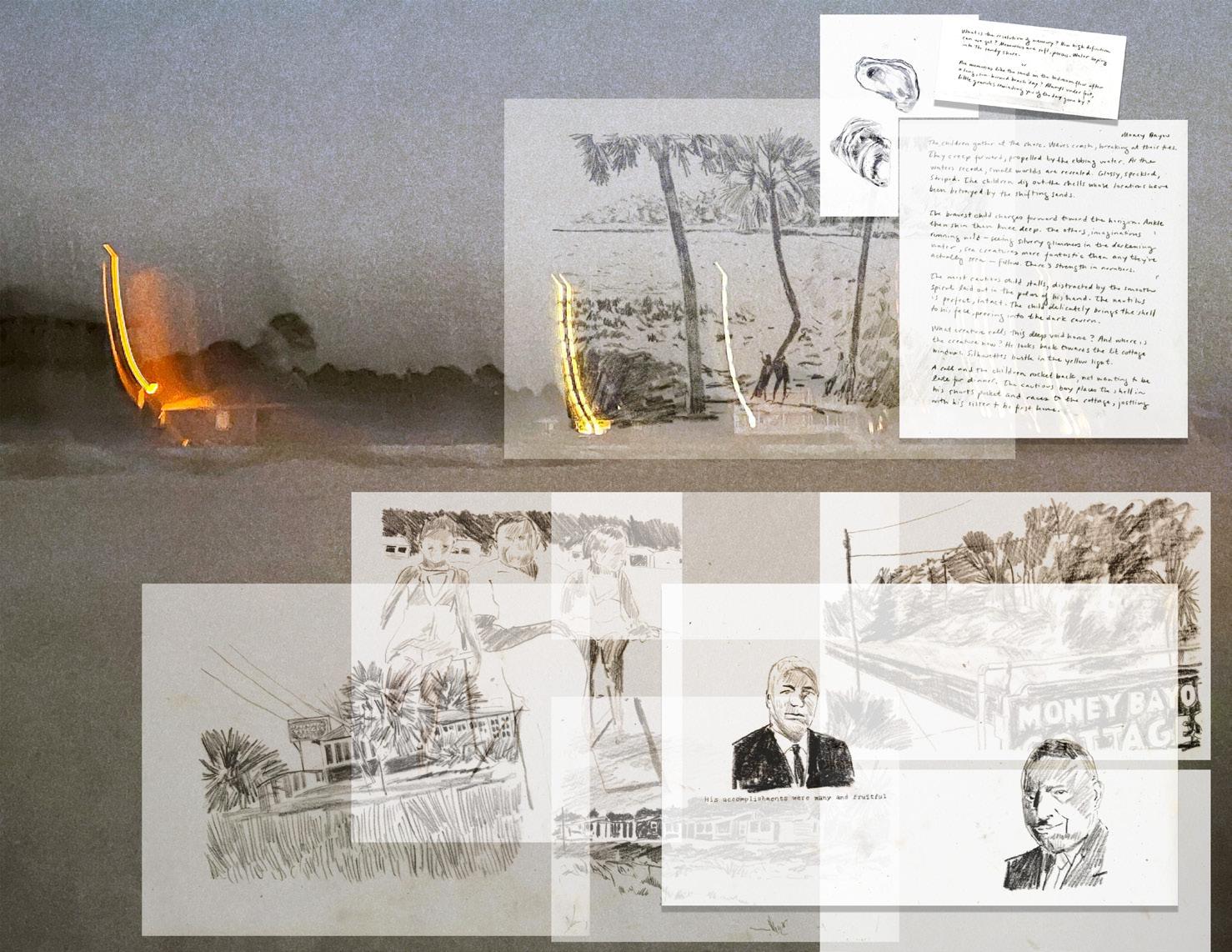

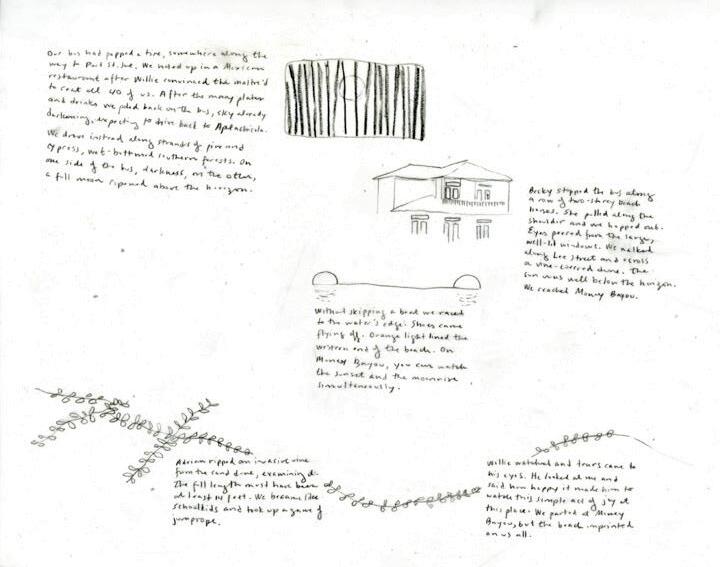

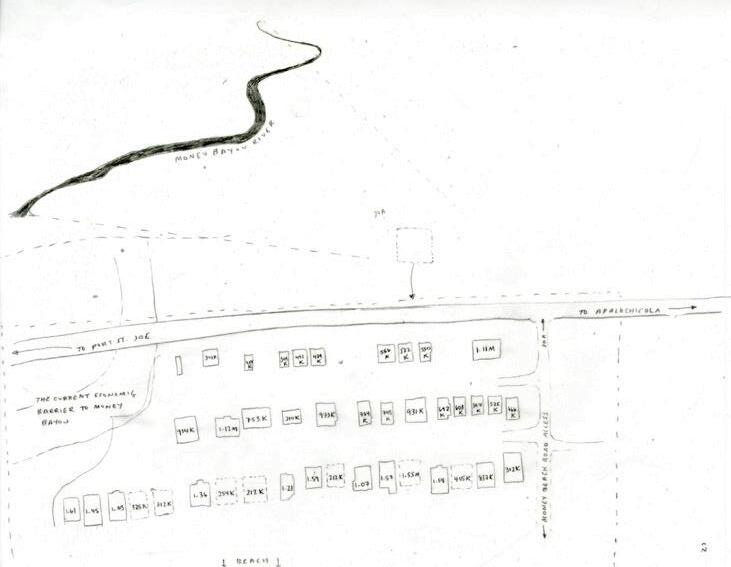

Eclipsing Memory at Money Bayou Beach

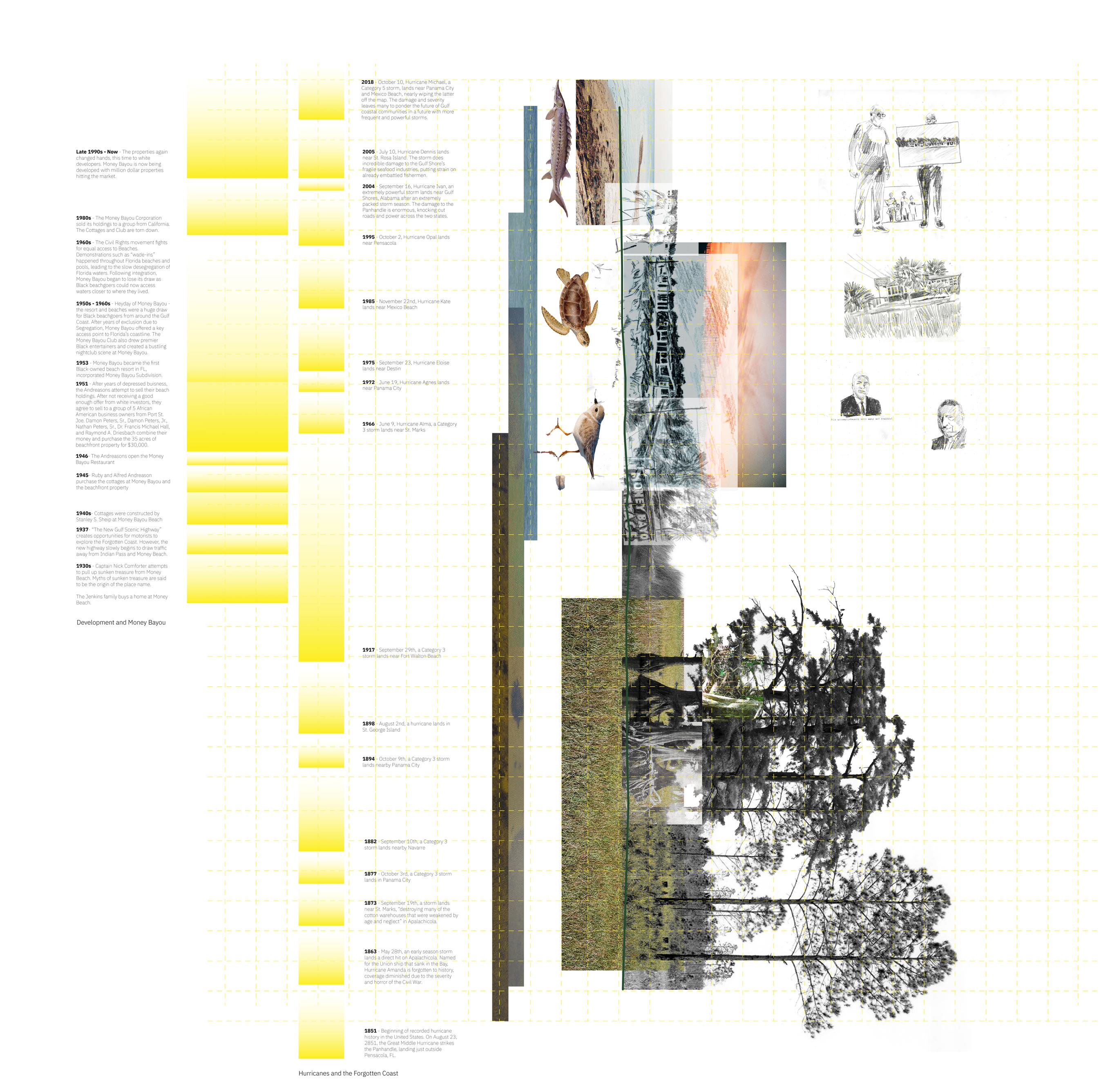

Work created as part of Fall 2022 LAR 7010 studio Professors: CL Bohannon, Rebecca Hinch, Michael Luegering

Apalachicola, FL, USA

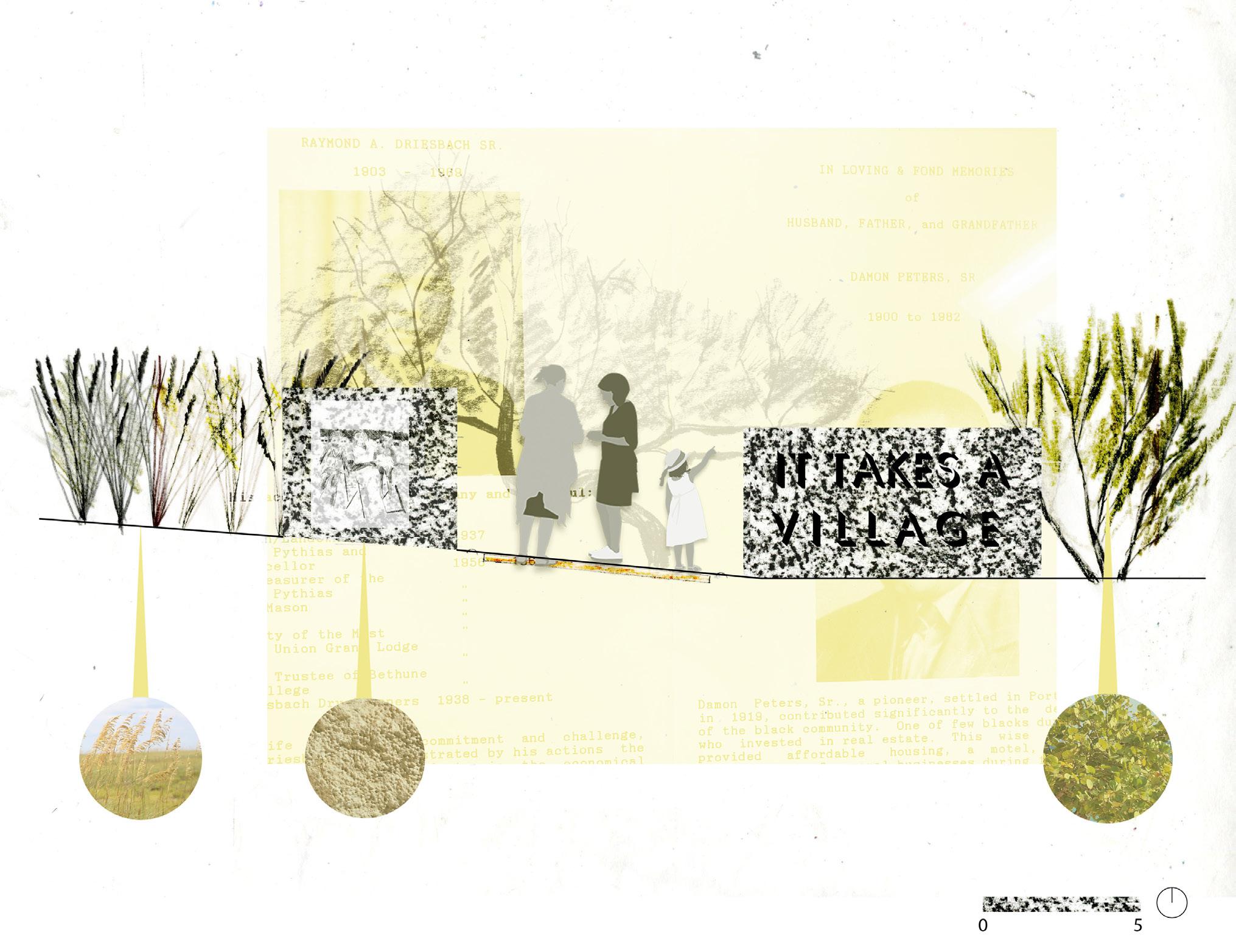

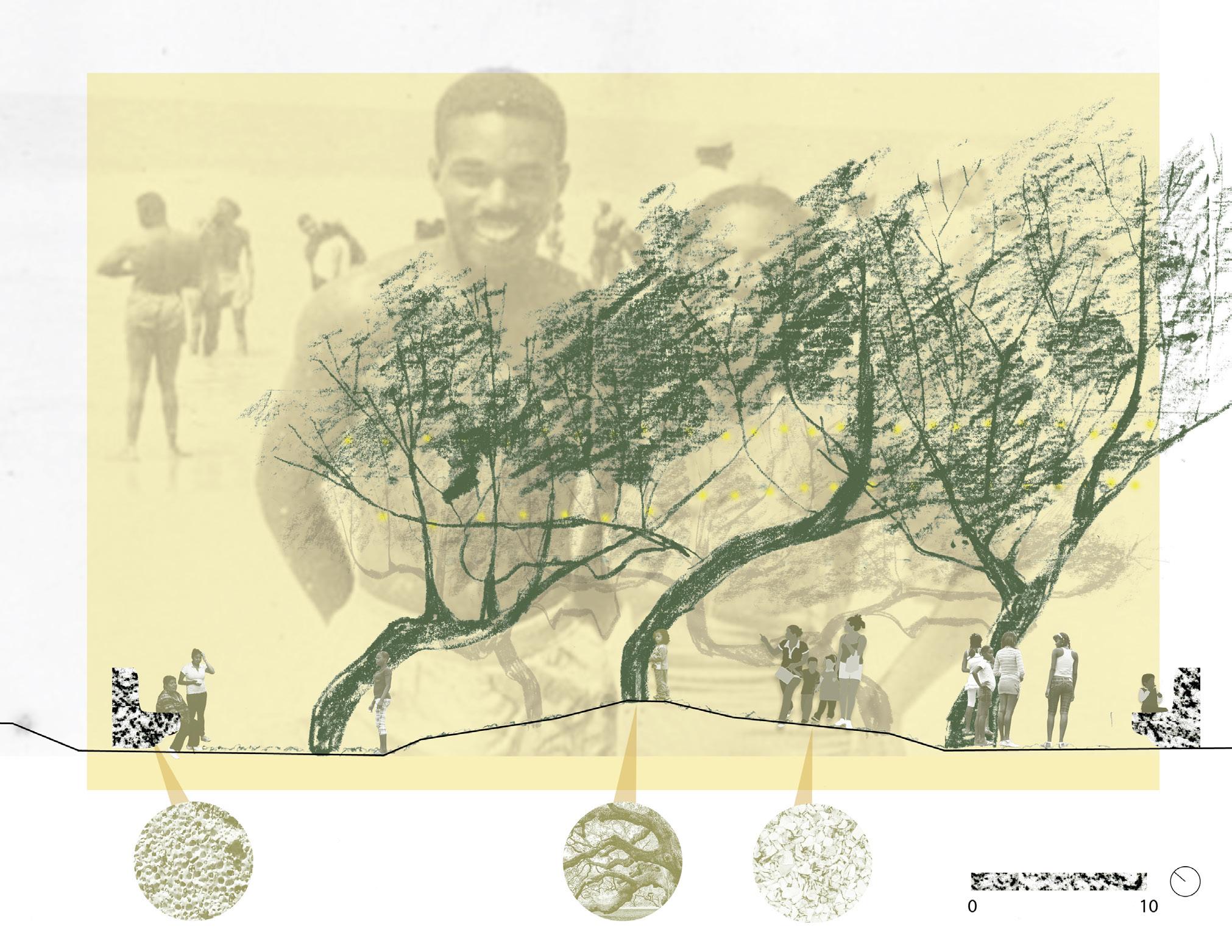

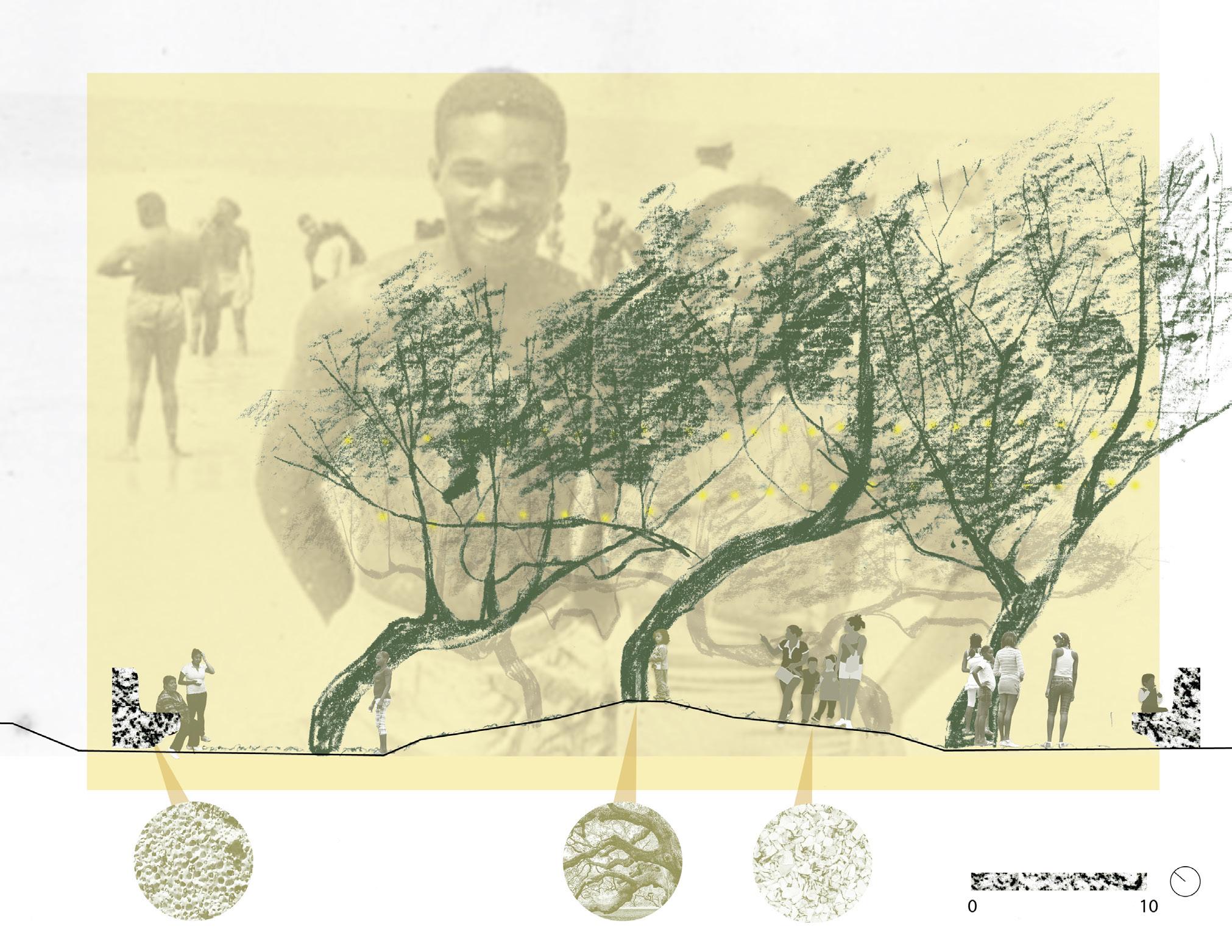

Money Bayou sits between the Port St. Joe and Apalachicola on the Gulf Coast of Florida. In 1951, after years of being denied access to Florida’s waterfront, the Black business community invested in 33 acres of beachfront property and opened the Money Bayou resort which served Black patrons throughout the Gulf coast until the end of legal segregation in 1964. Today, access to the beach is made difficult by the lack of public points of parking or comfort facilities and the beach is surrounded by million dollar vacation homes, mainly owned by White families.

Through interviews, site visits, and archival research, I drafted a design that would strengthen connections between Money Bayou and the Black communities of the Forgotten Coast, center the beach within the larger narrative of Black resiliency and joy during the Jim Crowe era, and restore the ecological health of the dune system on which this history was held.

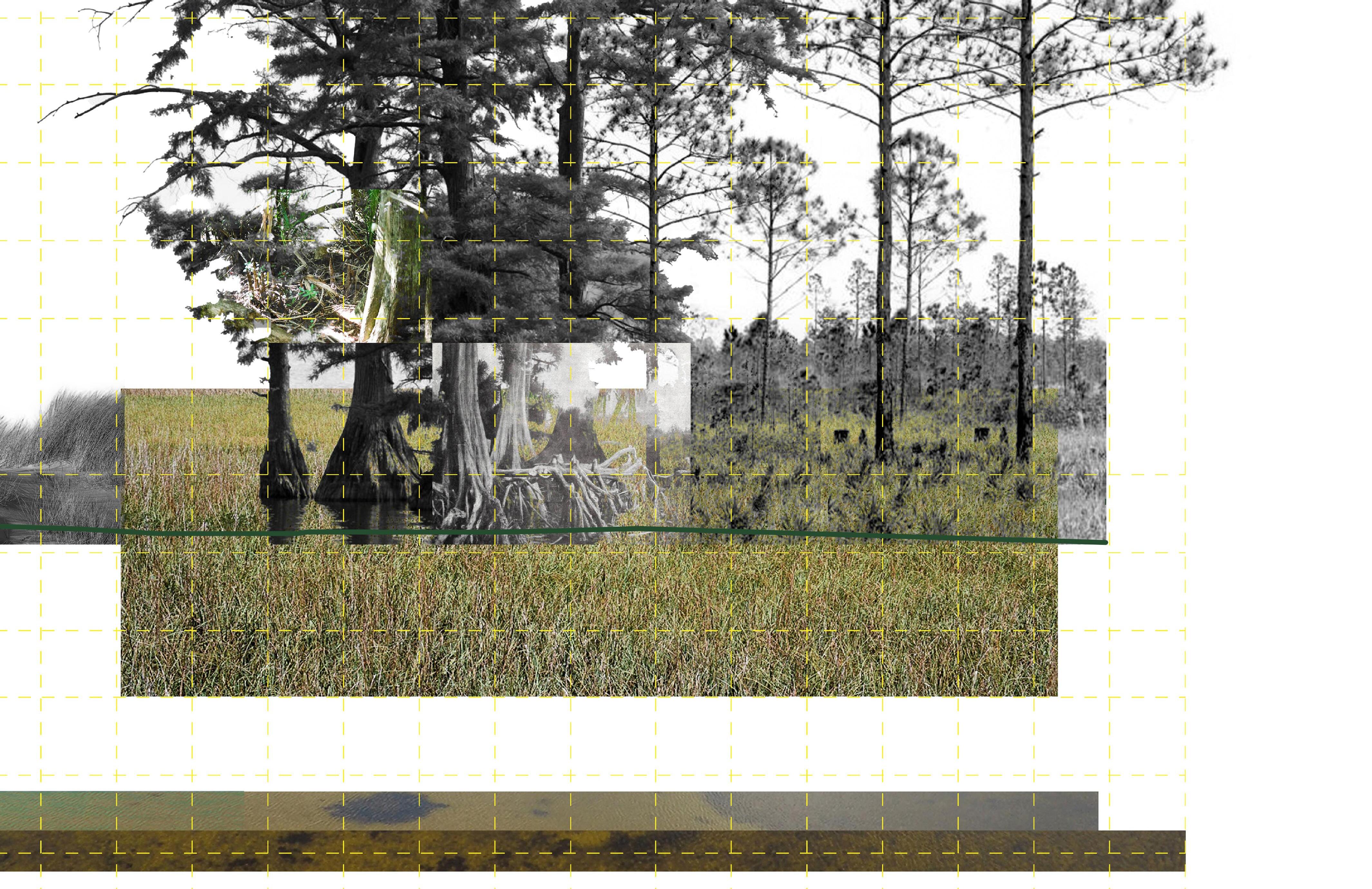

Port St. Joe Apalachicola Money Bayou Gulf of Mexico Social Context Ecological Context St. Joseph Bay State Buffer Preserve Money Bayou River Brackish, Estuarine Money Bayou’s Thick History

102

Black

Spaces on the Florida Coasts: These diagrams looked at the spread of Black beach spaces along the Florida coast. These small slivers were African American destinations during Jim Crow for families who were seeking recreation and respite from the Florida heat. However, the journey to these beaches could be arduous, as sun-down towns created danger for families who needed a pit stop on the sometimes 5+ hour journey to the nearest beach.

103

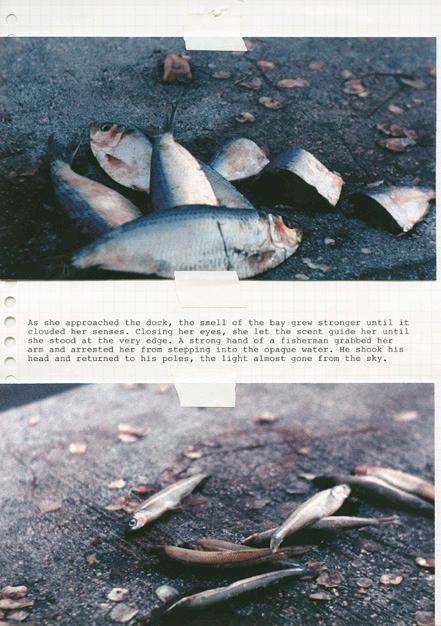

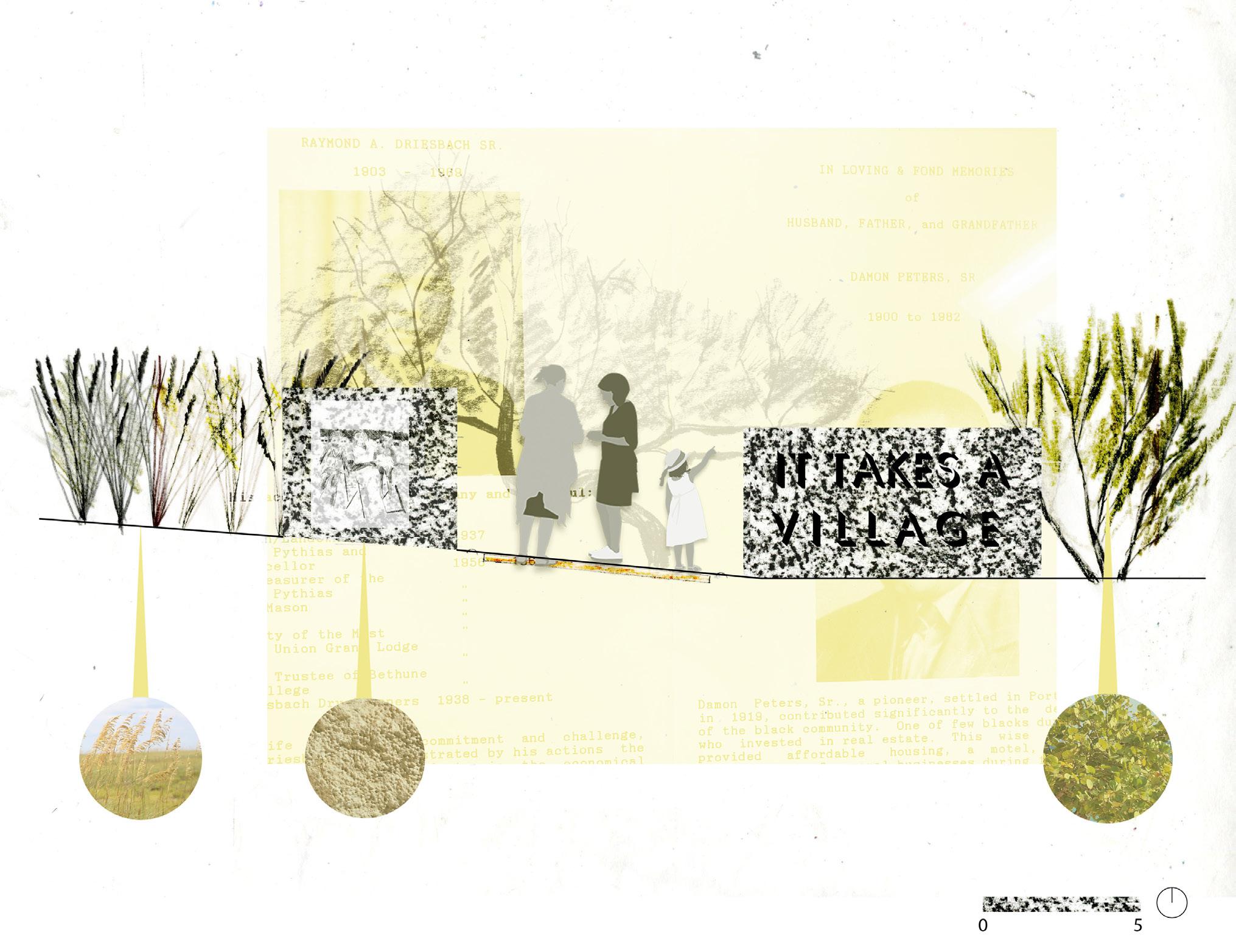

Together we sat in the George Washington High School Museum, gathered together with the shared goal of preserving the memory of the Forgotten Coast. Nathan Peters, stands at the front of the room, surrounded by shining, smiling faces school portraits, family photos. He is gracious with his memory, with his stories. He has undertaken the enormous project of tracing the lives of the many people who had walked through the halls of GW High School. But perhaps more importantly, he is documenting the legacy of Black joy. Tantamount to this task is the story of Money Bayou, complicated account of self-determination. Peters begins, “Before 1940, there were no Black beaches in Florida.” Those who are familiar with the Florida coast know the importance of the water’s edge. To have no beach access to be severed from the state’s best public resource. The result of this deal was the declaration that the beaches of the Forgotten Coast were no longer off limits for the Black community. Money Bayou drew people from across the state and as far and wide as Louisiana, Georgia, and Alabama. The five cottages stood as testament to this immense pride and joy of being able to offer this strip of ocean to the community. Peters continues, “In 1951, the business community of Port St. Joe bought piece of beachside land. Five people Damon Peters, Sr., Damon Peters, Jr., his uncle Nathan Peters, Sr., Dr. Francis Michael Hall (the community dentist), and Raymond A. Driesbach gathered together $25,000 to purchase 33 acres, including five cottages, from white family. The deal went down in the dark of night, after which the white family fled, fearing retribution for the sale.” Lexicon Ownership the condition of being in possession of an object, land, or memory; having sense of obligation and care Authorship the condition of in being in position to inscribe one’s identity and experience onto place or object; to have the power of mark-making; to have the ability to write one’s story Readership - the condition of being a reader and find connections between different pieces of text; being able to see the inscriptions left in place Unfolding the act of revealing or disclosing to find the crux or heart of something Embedding the act of inscribing or of making an impression, especially onto a landscape Emerging to be about to burst out, to have lot of potential, to be on the cusp Translating to tell story to someone who not part of your community or to tell story that you’ve gleaned without having directly experienced the event this often results in misunderstandings, confusions, losses of detail, but also makes more complex the relationship between authorship and readership 104

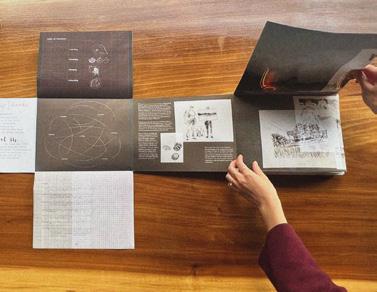

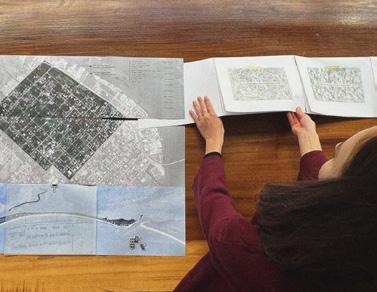

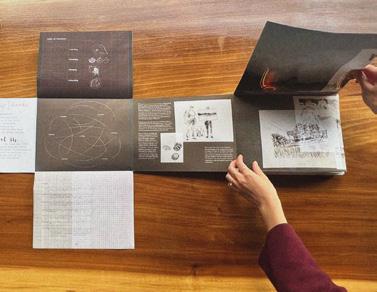

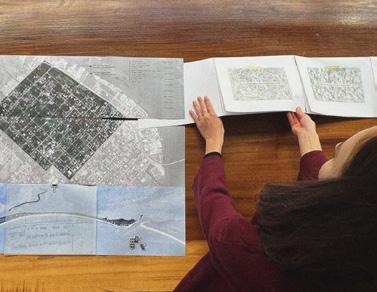

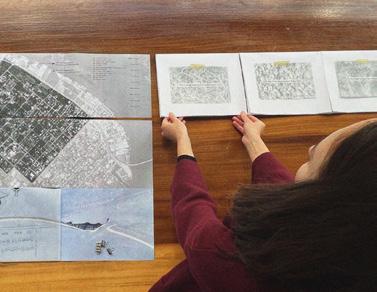

Prior to delving into site design, we worked in groups to process our field work from our time in Apalachicola. My group, which included Gina Lee and Ariana Arenius, focused on drawing the feeling of home. Gina and Ariana looked in particular at the front garden and backyard spaces of the Hill Community and I looked at Money Bayou as the space of vacation home. We created an accordion fold book that tied together these different home-spheres and included a diagram to show how the pieces fit together.

The book was sent off to our community collaborators in Apalachicola.

105

Dunes

C C’ A E’ B D D’ E Educational Center + Comfort Station Bus Parking

Picnic Lawn

Picnic Lawn

Gathering Grove

Restored Dune Grassland

Balancing Social and Ecological Needs Gathering Space Pine Preserve Wildlife

106

Pineland Preserve

Entrance to beach/interpretive landscape

Corridor Dunes

Proposed Money Bayou Memory Park Plan 107

C

Parking Lot with Accessible Spots and Bus Parking

Didactic Dune

D

Central Gathering

108

D’ Education Center + Comfort Station

B B’

Existing Preserved Coastal Pineland

Central Gathering Grove

A’

Existing Preserved Coastal Pineland Walking Path

Community Lawn

C’

B B’

Existing Preserved Coastal Pineland

Central Gathering Grove

A’

Existing Preserved Coastal Pineland Walking Path

Community Lawn

C’

109

Gathering Grove

Area of Focus: Marking time, making a sense of place

E Transition Zone from Beach to Park

Letting time bend live oaks to create intimate pockets of space

Preserved

Coastal Dune

Oolitic limestone seats will eventually wear away, creating an index of use

Oolitic limestone markers with images and text engraved onto them and placed at the southern bounds of the park create a sense of arrival/departure.

Dune grasses and shrubs protect the upper dune while also creating a visual pinch point, heightening the sense of anticipation.

Uniola paniculata

110

Caulerpa lentillifera

E’

Upper Dune Plantings

Central

Gathering Grove

Community

Lawn

Education

Center + Comfort Station

Area of Focus: Gathering at the center, recentering community

Crushed shell mulch creates a soft footing, reflecting moonlight in the evening

Area of Focus: Reclaiming public access through parking

Celebrating existing palms on site

Sabal palm Coco palm Saw palmetto Pygmy date palm

Accessible Parking

111

Placemaking through historical references

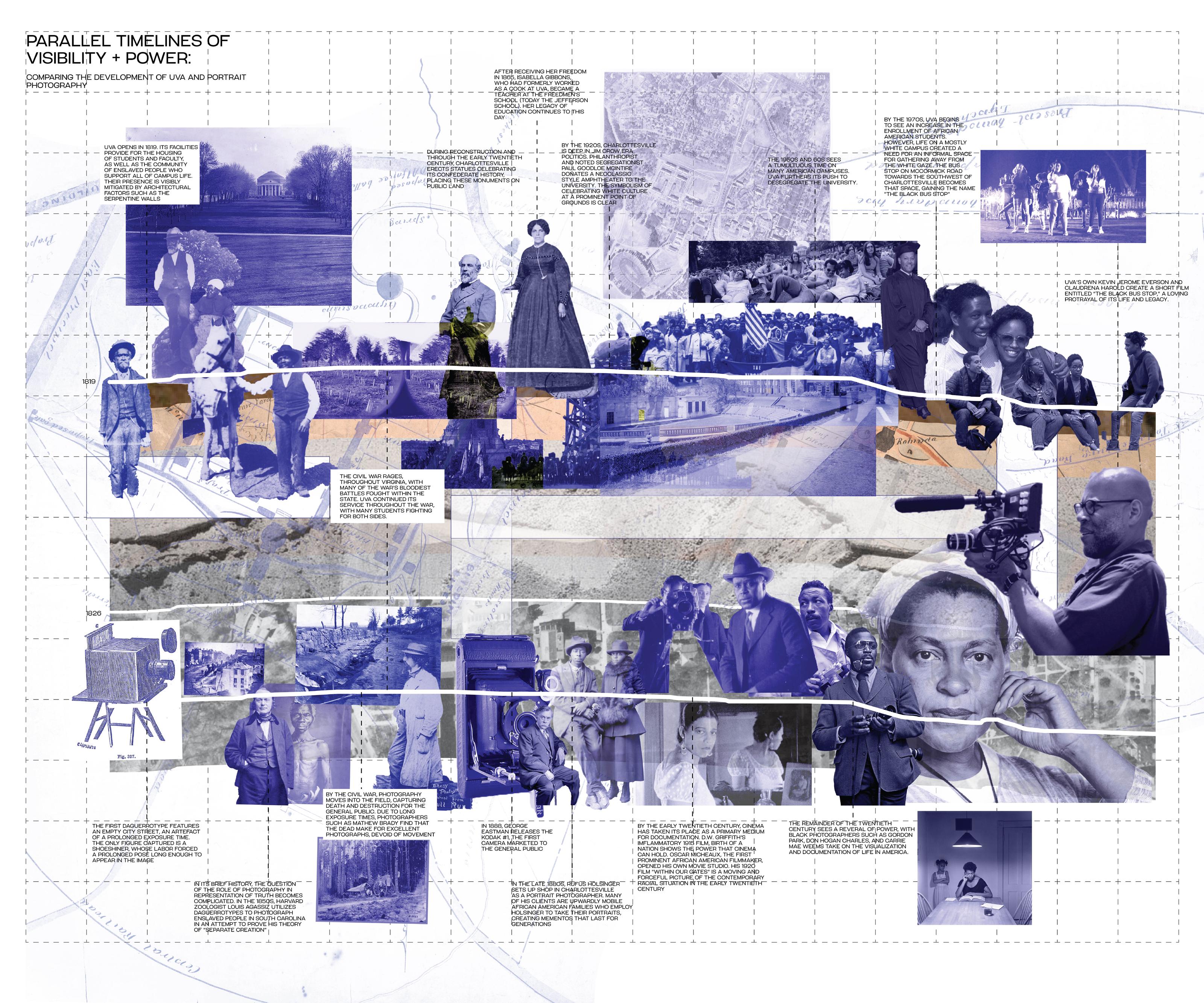

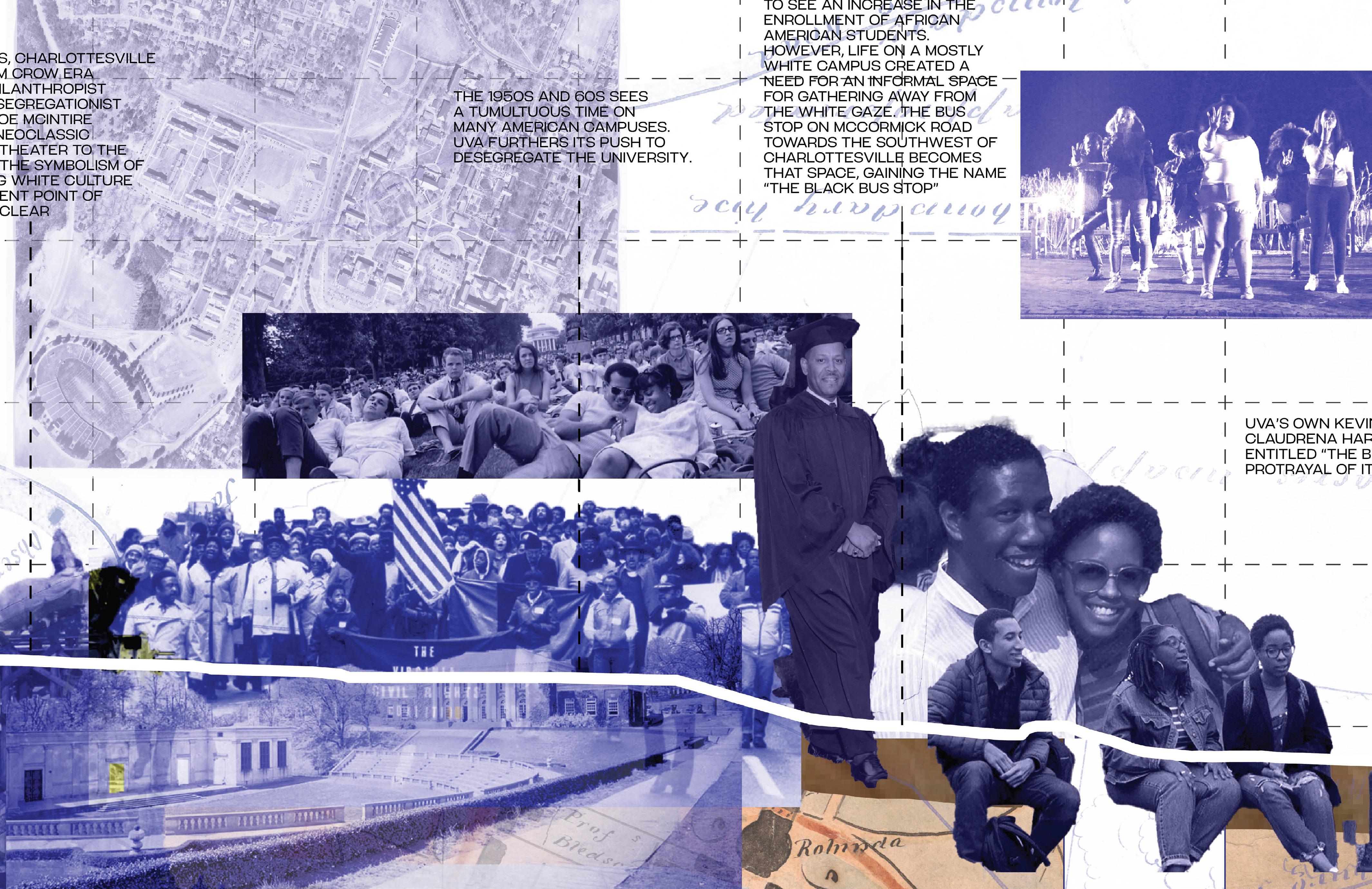

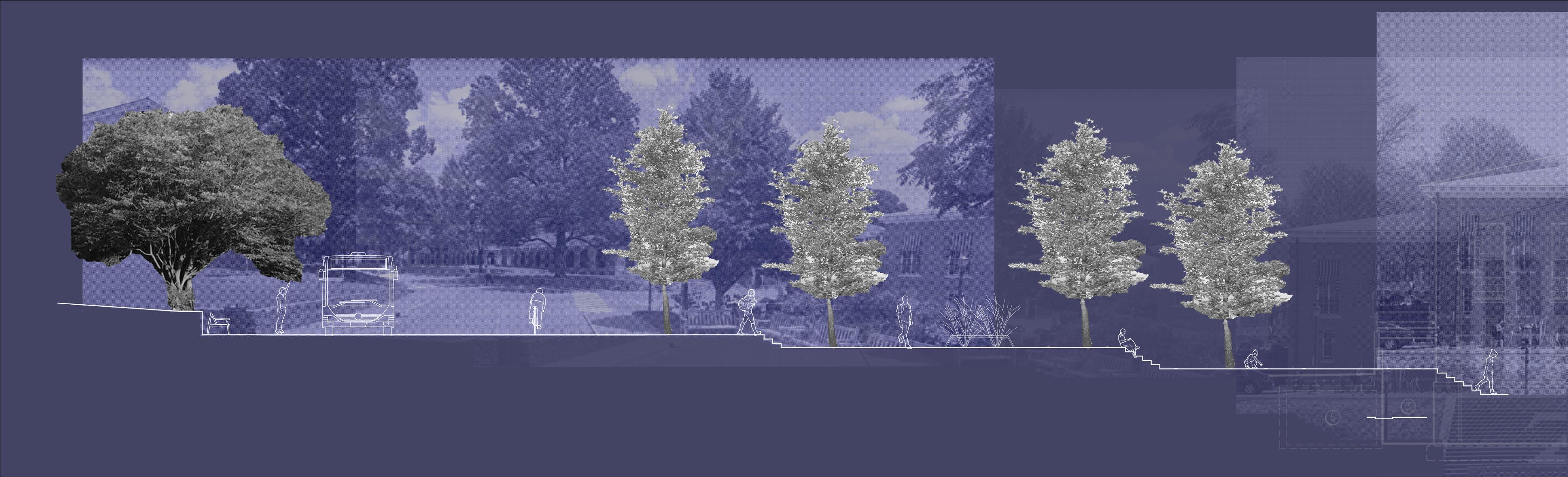

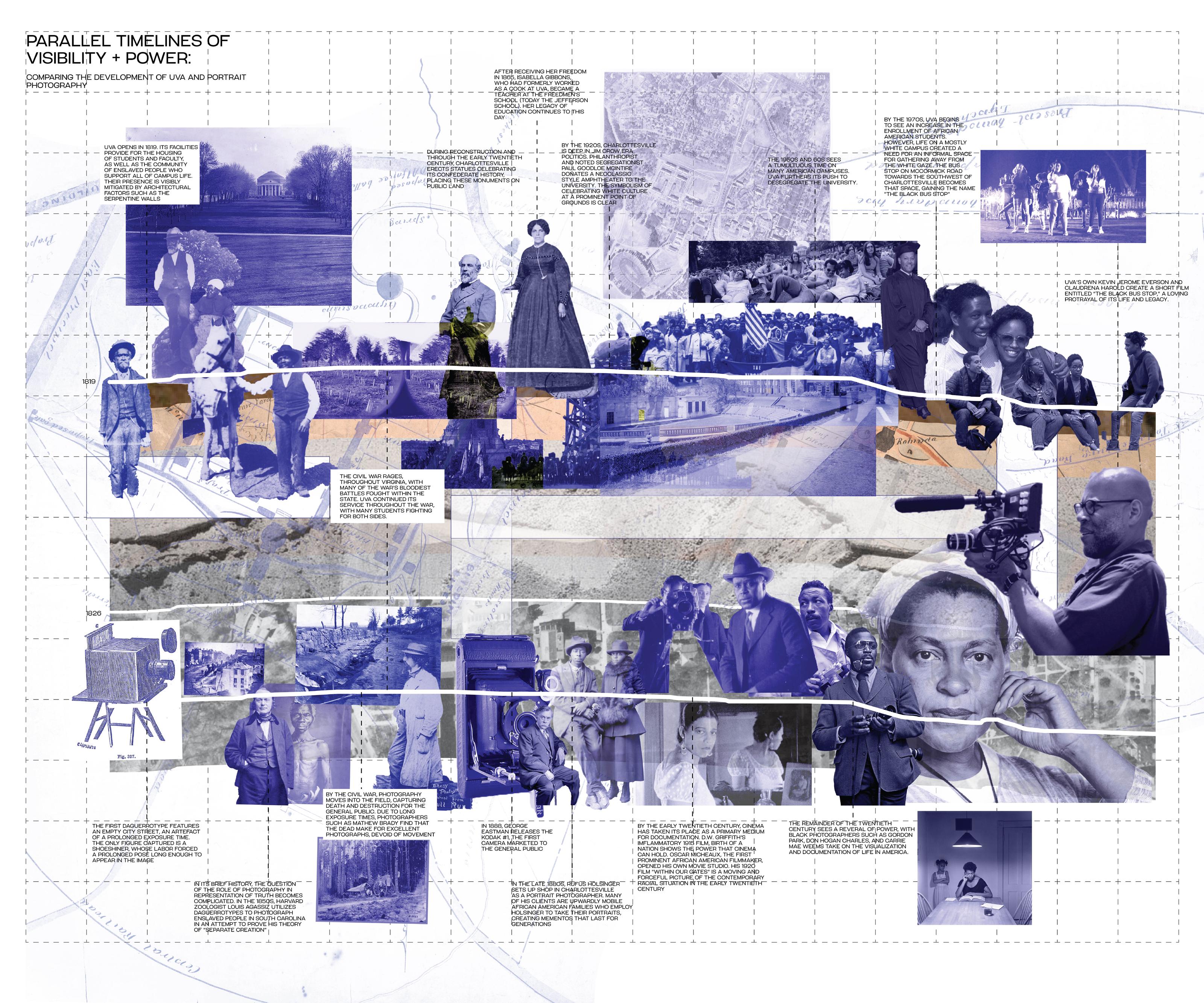

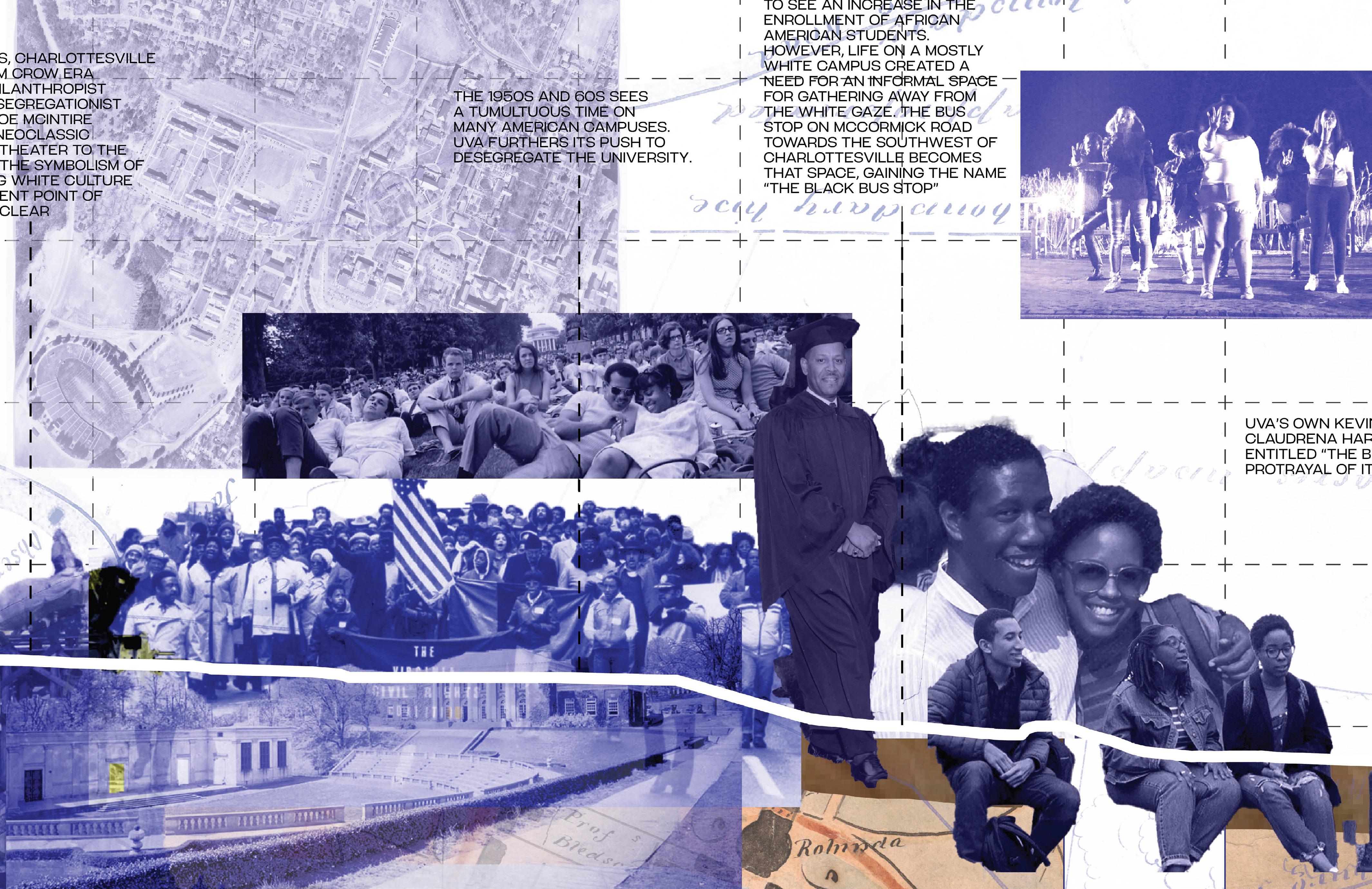

Visibility and Power at UVA’s Black Bus Stop

Work created as part of Spring 2022 LAR 6020 studio

Professors: Beth Meyer, Emily Wettstein, Scott Mitchell

Charlottesville, VA, USA

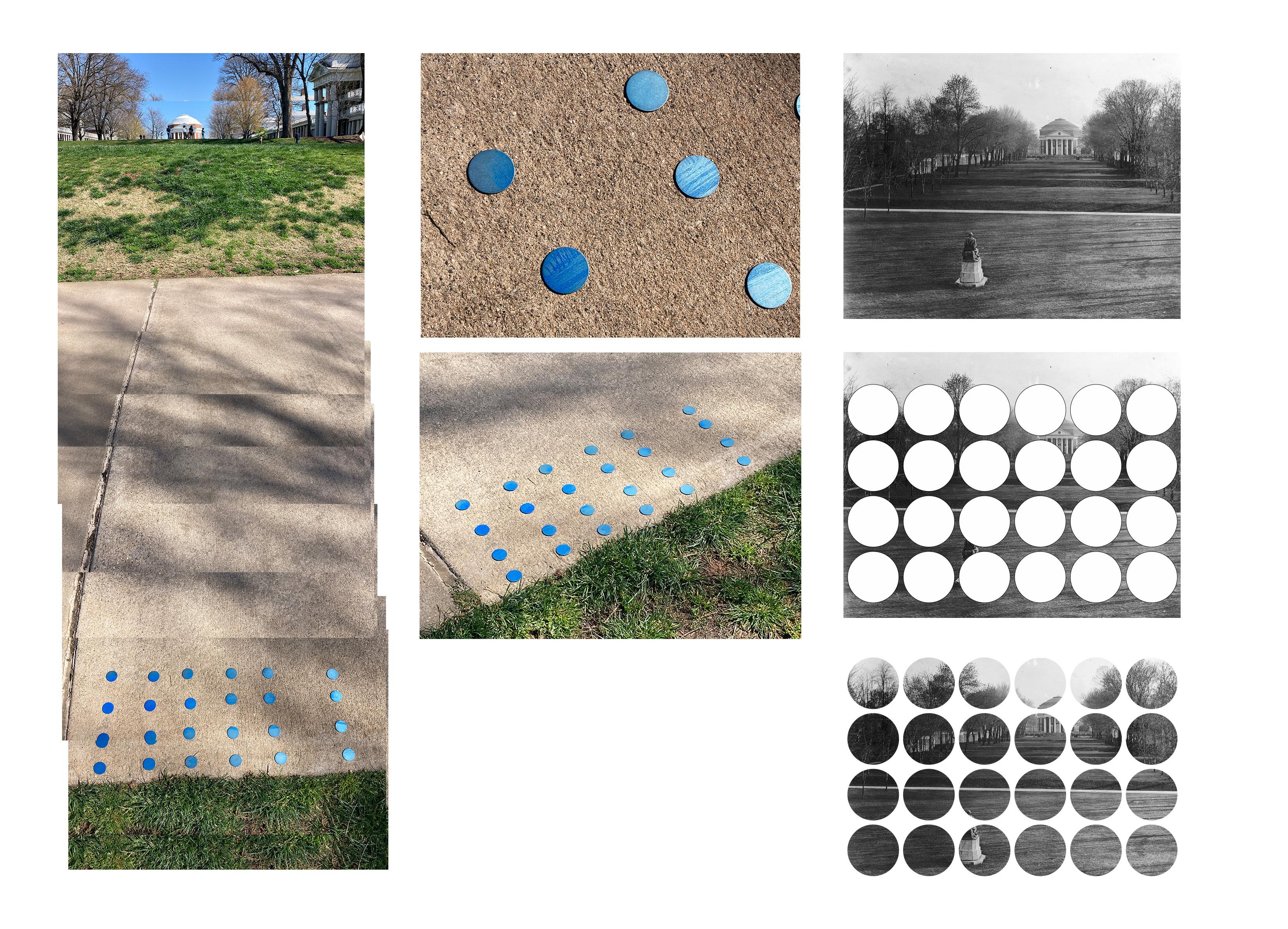

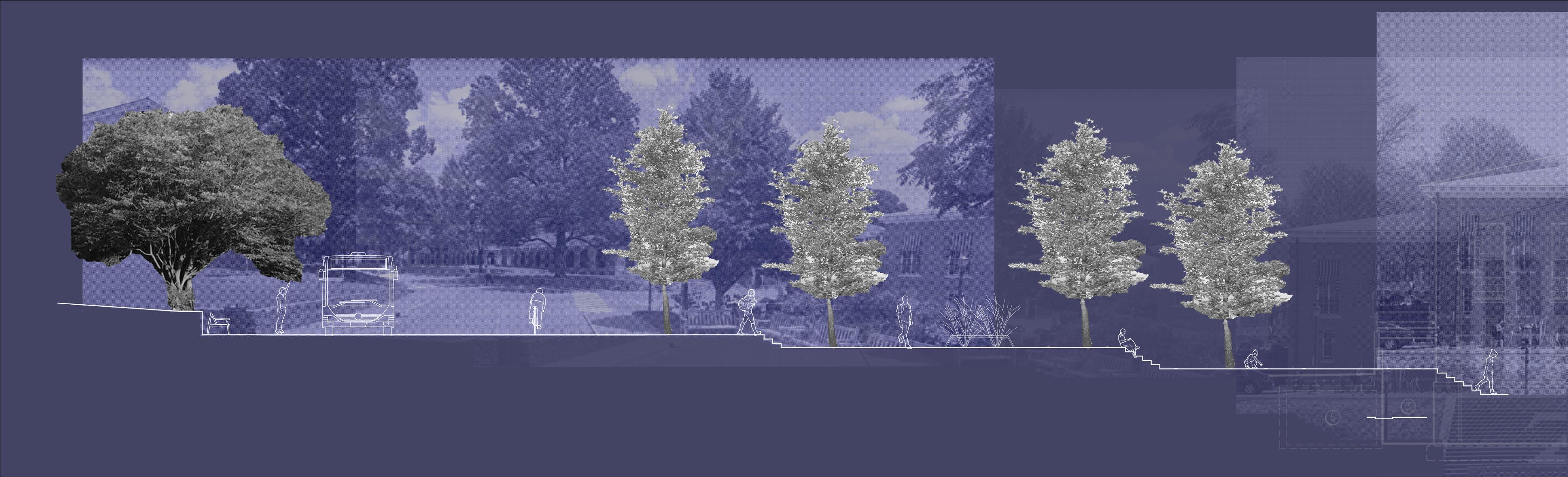

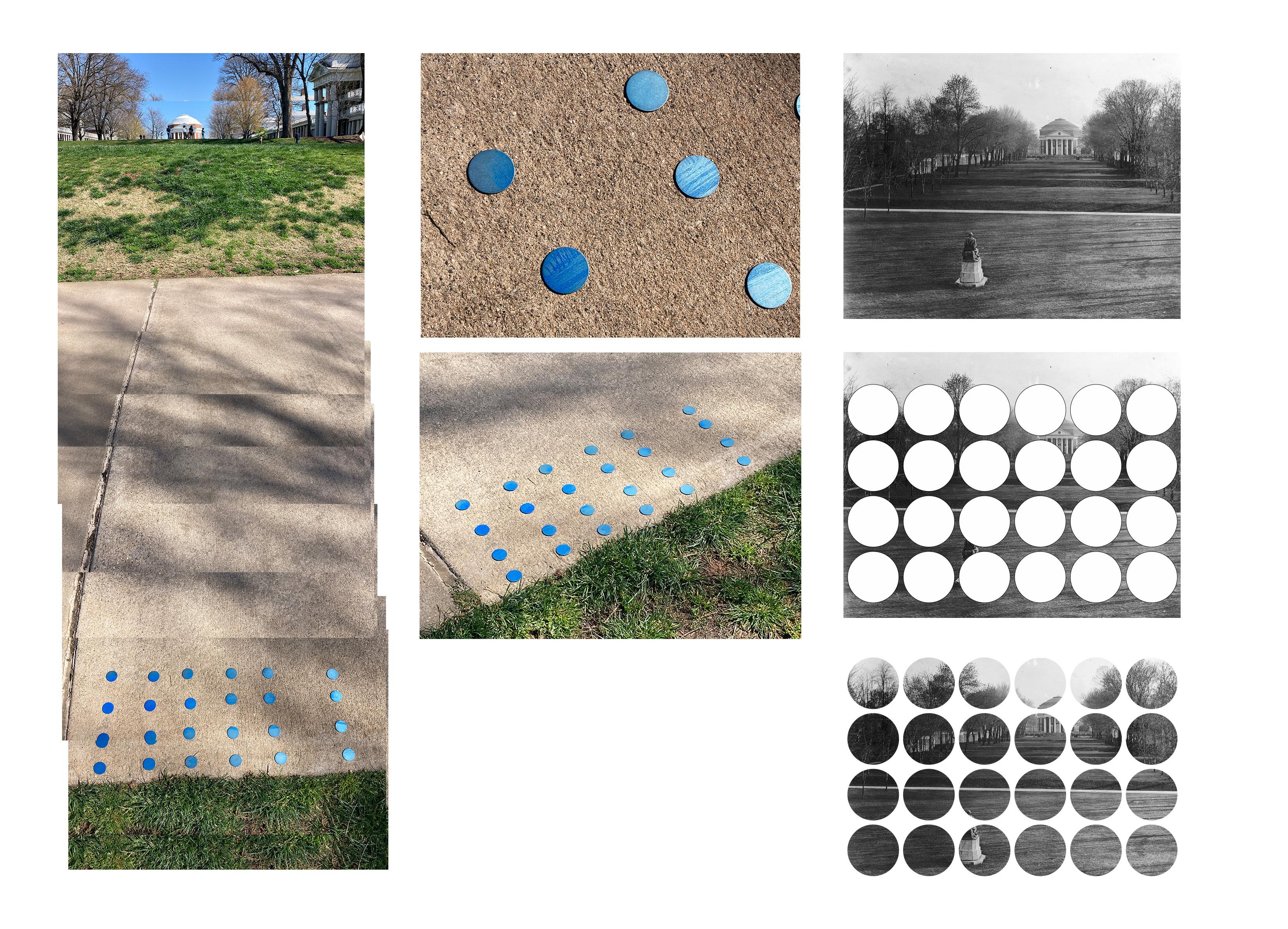

Following the two axes created by the Rotunda and Monroe House, a plantation building pre-dating the University, my concept for the Black Bus Stop considers the photographic chiasmus: “we see because they are visible, they are visible because we see.” The relationship between a photographer and their subject has been evolving throughout the long history of portraiture. Although photography can capture a certain grade of accuracy and objectivity, its usage has been anything but. Through my design work with the Black Bus Stop, I am exploring the power relationships between what is visible and what is invisible.

The Black Bus Stop sits at a threshold of visibility, centrally located on McCormick Road, but out of the gaze of the surrounding buildings. It hides in plain sight, innocuous during the day, but throughout its lifetime, at night it became a site where black students

would gather to be seen by their friends and peers. My design approach extends the bus stop across McCormick Road, down the slope, and along the graded path which marks the historic end of the South Lawn. A field of glittering steel discs, etched with fragments of portraits of both Charlottesville African American community and those shot by black photographers are embedded along this walk, chronologically ordered from east to west. Through this design gesture, this pedestrian corridor becomes a transect through both time and space: walking along this path, one can catch glimpses of faces, hands, clothing. Along this same path, cor-ten steel retaining walls emerge from the earth like breaching whales, slowly rising up to seated height before plunging again beneath the ground.

Arriving at the plaza, the steel discs flow up and along the three raised

terraces, arriving at the historical Black Bus Stop and its stone wall. The cor-ten steel bench seats rise from the granite paving as though they were peeled from the ground itself. Hydrangea and maple leaf viburnum are arranged in planters surrounding the benches, carving out spaces for both conviviality as well as for privacy. This pairing of planting and seating creates a variety of opportunities for students and community members to determine the extent of their visibility. Black tupelo trees rise from the terraces, providing shade and privacy while also repairing the canopy along the South Lawn. Finally, inset ground lights are scattered through the plaza, mimicking the steel discs, but at night creating a critically needed well-lit space for gathering and waiting for the bus.

112

113

114

115

MainStreet

Grounds diagram. Dark blue indicates existing canopy condition.

Dotted lines are pedestrian pathways and the shaded zone indicates the topographic boundaries of the historic core.

Rotunda

Monroe House

SouthLawn

Black Bus Stop

Amphitheatre

Rotunda

Monroe House

SouthLawn

Black Bus Stop

Amphitheatre

Canadahistorically black neighborhood