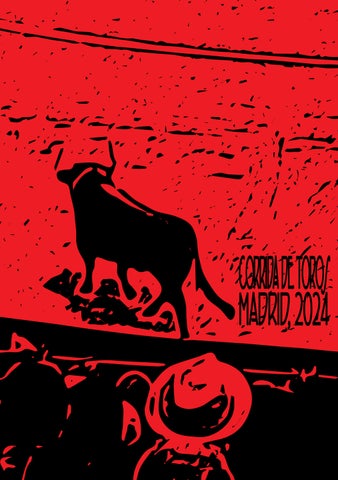

CORRIDA DE TOROS MADRID, 2024

I’m on the metro back from the corrida de toros at Las Ventas, still trying to figure out how I feel about what I’ve just seen. It was a spectacle, no doubt.

One thing I can’t stop thinking about: who are the people applauding when the steers drag another carcass off? The bullfighting team (cuadrilla), who risked their lives, (though to varying degrees it must be said)? Or the bull, who fought for his until the last blood-soaked breath?

The few sources I’ve consulted so far — an American lady sat next to me, asking questions of aficionados in Spanish, translating for me in English, Hemingway in The Sun Also Rises, Habla con Ella, a Britannica article — lead me to believe it’s mainly reserved for the fighters. If they perform well, that is.

If the bull is a good bull, and not a cowardly

bull (a manso), there is no doubt some applause reserved for him, too.

If the bull is an especially good bull, the president of affairs can grant him a pardon (indulto) which spares him the final death blow and sends him back to the ranch where he’s then put out to stud.

This is extremely rare, however. And according to animal welfare groups, the traumatised bull often succumbs pretty quickly to the injuries sustained in the ring anyway. Some retirement.

Still...there’s a lot to romanticise about the corrida de toros, if you’re so inclined.

For one, it’s an absolute visual feast. The regal matadors, draped in their striking suits of light (traje de luces) dazzle as they glide effortlessly around the bullring.

The banderilleros’ barbed flags (banderillas) adorned with the colours of their birthplace, are even more striking after being plunged into the shoulders of the bull. They protude from the writhing, muscular, blood-stained mass and flutter in the wind as he charges around the arena.

Then, of course, there’s the hard-won, balletic grace (and undeniable camp) of the matador’s movements — and the shock of the danger that each step invites.

Feet planted, red cape (muleta) flowing, they calmly and with an incomprehensible poise guide the bull for pass after pass after pass. The bull’s horns coming within millimetres of the matador’s fragile flesh. The crowd shouting: Ole! Ole! Ole!

It’s all a deadly and delicate dance of bait, charge and switch, that finally finishes with the matador whipping around away from the bull, arms aloft, suit shimmering, basking in the adulation of the crowd.

I cannot forget the bull, either. The bull, the bull, the bull. Outnumbered, outgunned, outflanked. Entirely on his own, surrounded by a whole team dedicated to his demise, with thousands more watching on and waiting with bated breath for the final blow.

The bull fights, charges, gouges, gorges, huffs, heaves, falls, rises again, or is hauled to its feet. He gives and gives and gives until there is nothing left to give. This giving is a spectacle in itself. And though I do not think I saw a Manso, I would call even a “cowardly” bull brave for what he has to endure.

There is a palpable atmosphere around the proceedings, too. A sea of flat caps and colourful pillows clutched underneath arms

on the march down to the ring. A rotunda thick with thick cigar smoke. The bellows of the cushion renters bouncing off the walls. Sunflower seeds strewn across the stone amphitheatre. The rousing sounds of the pasodoble played before each round. And equally, the deathly silence that descends all of a sudden when the matador raises their sword for the final blow. The moment of truth (hora de verdad). It is affecting. Disconcerting. Especially to the uninitiated. I wonder if, in that very moment, the bull also recognises the fate that awaits him...

“I cannot forget the bull, either. The bull, the bull, the bull.”

There’s also a lot to revile about the corrida de toros, if you’re so inclined.

It is protracted brutality. Unquestionably. I couldn’t, I wouldn’t, I won’t argue with anyone calling it cruel. You are watching death slowly unfold and you are paying for the privilege.

The bull is battered over the course of three distinct stages or “thirds” (tercios). By the last he stands bloody, beaten and utterly defeated. To see such a proud thing crumple under his own weight after one, two, three or more “death blows” is a sad sight.

To see his limp corpse unceremoniously dragged from the ring by adorned horses, leaving trails of blood in the sand, is a final indignity that’s also hard to stomach.

There’s a certain bloodlust or mob mentality in some of the crowd too. They hiss and boo if they deem the bull or fighter too cowardly

or if they think everything is taking too long.

I’m told (by a few boys I meet on a basketball court later) that there are some nationalist tendencies in that crowd as well. A little reading and research makes it clear the bullring has become a battleground for competing visions (and histories) of Spain.

On the left many socialists see bullfighting as a barbarous relic of a bygone era — something that has no place in a modern-day, progressive, EU-centric country.

On the right the conservatives of the Popular Party (PP) and Vox claim it’s a cherished and indisputable part of Spanish culture, history and identity1.

“the bullring has become a battleground for competeing visions and histories of Spain.”

It’s hard to ignore the echoes of Spain’s fascist past in this, given that the Popular Party was founded by a minister who served under Franco, and that Franco himself loved bullfighting — often using it as a metaphor for a homogenous nation, identity and race.

One cannot ignore the literal echoes of the fascist anthem Cara al Sol (Facing the Sun) either, which bounded around the Plaza de toros de Palma in Mallorca in 2019, when bullfighting returned to the island after a brief ban2 .

Returning to the spectacle in the ring: it seems to me there’s an underlying unfairness

to the whole thing. Admittedly, on a scale of crimes against morality, unfairness doesn’t really stack up against the cruelty, brutality or murder on show. But if we’re talking crimes against sportsmanship — and for many this is a “sport” — it seems to me a most egregious sin.

Though bulls are reared with great care and in relative luxury, in the hours before the fight they are isolated, kept in dark cages and, if you believe the welfare groups, drugged, starved and beaten. To rile them up and make for a good show, perhaps. But the impact is also debilitating. It sways the odds in favour of the matadors.

This unfairness persists throughout each tercio — a “tragedy in three acts”. First with the picadors, who lance the bull from horseback, damaging its neck and shoulder muscles, making it harder for him to raise his head (and so, his horns) to defend himself.

Next, with the banderilleros, who plant pairs of barbed sticks in the same areas to further weaken the muscles and further compromise the bull’s defences.

And lastly, with the matador. Walking out for the “third of death” (tercio de muerte) the matador is primed to take the ultimate advantage of the bull’s weakened state.

Their first port of call is to wear the bull down further by goading him into a few final charges. Once they feel the bull is sufficiently fatiuged, tbe matador prepares, at last, to put him out of his misery. We reach the hora de verdad.

The matador stands square in front of the panting bull. They cock their arm up and

pinch their sword. It’s as if there’s almost a line extending from their eye, over their hand, down the length of their thin blade and towards the bull.

The crowd falls silent. The matador steadies themself. The bull takes his last few breaths and the crowd holds theirs. Then, in one sudden motion: the cape draws out one last charge, the bull darts forward and the matador lunges, plunging their sword in a small opening between the bull’s shoulder blades.

If done correctly, this blow severes the aorta and causes a near-instant death. Getting it right requires extreme precision. Only one of the six bulls I saw required one strike.

That bull was instantly stunned. He stumbled backward and inhaled. His eyes rolled up into his head. His final exhale was a torrent of thick, dark blood. He collapsed in a lifeless heap. It was an awful sight. I choose that word carefully.

“If there is any glory to be found in death in the bullring...it is certainly not found here.”

The other bulls needed multiple strikes. They were finally finished off by a puntillero, whose job it is to administer a coup de grace by plunging a blade into the bull’s skull.

These sights of protracted, inelegant, botched punishment before a clumsy, rudimentary final blow were altogether horrible. If there is any glory to be found in any death in the bullring — and that is a big if to begin with — it is certainly not found here.

All of this was racing through my head, in one form or another, as I rose from my concrete slab of a seat and picked my way through the seeds and abandoned pillows that littered the aisles of the ampitheatre.

It was a violent and vile spectacle, yet there was a great deal of beauty and grace in it too. I saw bravery and cowardice. Poise and chaos. Skill and incompetence. Pride and shame.

Suffice to say, I was conflicted about the whole thing. Suffice to say, I’m still conflicted about the whole thing. I try now to find some sort of clarity, some sort of certainty, by asking myself if I’d attend another bullfight, given the chance.

The confusing truth that delivers me neither certainty nor clarity:

I would. But I wouldn’t feel good about it.

1 Guillem Martínez, “How the far right in Spain has seized on bullfighting to make its point”, The Guardian, 2019.

2Stephen Burgen, “Fascist anthem played as bullfighting returns to Mallorca”, The Guardian, 2019.