One of the human brain’s most fundamental functions is to organize its knowledge of the world into categories—classes or collections of entities or objects that are related to one another in some meaningful (to the individual) way. The five senses gather perceptions while, on the brain’s factory floor, input is assembled, sorted, and forwarded, whether to conscious attention or to a collection of perpetually updated mental representations. These, the mental representations, are the raw data on which cognition relies.

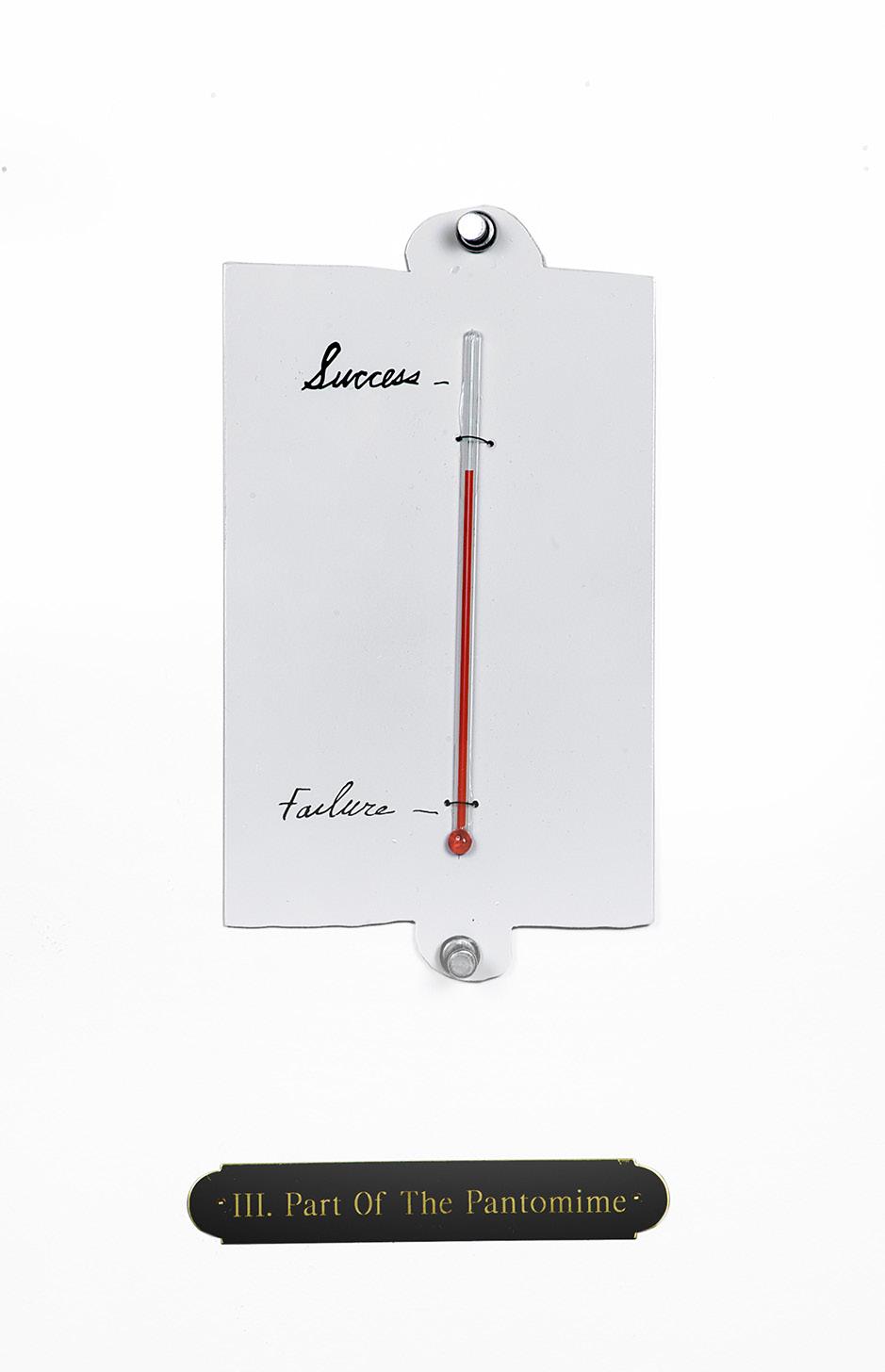

We provide structure to the semantic knowledge we acquire—for instance, about objects we perceive such as chairs, thermometers, cheese boxes, doorknobs, baby dresses—by relating them to one another either taxonomically or thematically. Objects are connected taxonomically based on functional and perceptual similarities. Take, for example, clocks, levels, and yardsticks: numbers and lines, tools for taking measure of this thing or that thing, for reckoning.

Thematic relations are different, though. They may be contingent, subjective, capricious, and, often as not, unconscious. Objects needn’t be either functionally or perceptually similar to one another in order to be grouped together by theme. Instead, they may be linked via events, random or purposeful, and co-occurrences; they may be joined ad libitum in the course of a situation, a moment, an experience, an expanse of time, or even a place. In the process, associations and triggers are embedded. Within the contours of subjectivity, in blind alleys, secret passageways, and hidden chambers of the brain, memories accumulate and later emerge—often seemingly unbidden.

Frank Shaw’s ReConsider exhibition is a sort of cabinet of curiosities in which objects, artworks and their various, individual components, are not exotic, resonating of far flung lands; rather, passengers of inward journeys across time, they’ve returned home, changed. Quicksilver, acutely personal memories, like ghosts glimpsed as fugitive shadows in one’s peripheral vision, comprise the intangible substance of a given work. An object seems to stand for something essential—a memory, an emotion— and, at the same time, contradicts or perhaps transcends its own essence.

The majority of the materials in the exhibition were salvaged from Frank’s family farm.

My father died. Despite promising to take all his treasure with him, it remained. What had been invisible, untouchable, became present as an enormous task and a gift. (Frank Shaw)

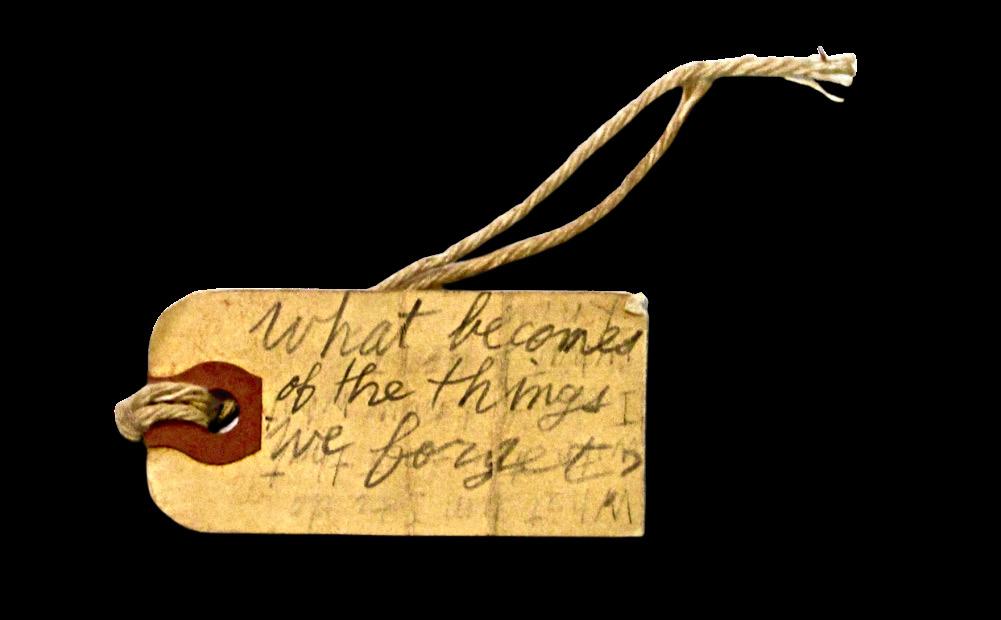

Excavated from barns, tool sheds, and the basement, the objects are, in some cases, altered; in others, they are left as is, possibly even in a state of disrepair, decay, or incompleteness. Throughout the galleries, enigmatic, poetic titles attached to objects provoke questions, conundrums. Items are grouped in accordance with, one suspects, a continuously shifting organizing principle rooted in memory, which is often, in itself, a wholly unreliable witness.

The exhibition is, among other things, a shell game of thematization and taxonomy. In isolation, the four clocks in the work titled, In Good Time (2020, pictured right), are immediately evocative of their primary function: they visualize the incremental passage of time. They look like clocks: round faces, numbers positioned at regular intervals, hands. Perceptual confirmation becomes second nature. These items belong together: taxonomy. And yet, One Handed Clock (2020) begs to differ. The hour hand is stuck at 10 o’ clock. The minute hand has vanished altogether. 34,432 Days (2021-22), a basket filled with desiccated flowers, their scent long since vanished, whispers wryly, “Memento mori.” Themes emerge: clocks as sentinels, clocks as symbols of mortality, loss, and the fleeting nature of time and life: vanitas

There is a poignant efficiency to Frank’s displays; careful consideration is given to practices of possession, acquisition, divestiture, and even destruction superimposed on this shambolic constellation of things. In sum, the objects seem to constitute a painstaking inventory intended to somehow materialize the intangible: hopes, wishes, misunderstandings, fears, awakenings, loss, dreams. Gallery by gallery, a scattershot catalog of a life and the infinite number of lives nested within it unfolds across walls and floors and aligns neatly along shelves.

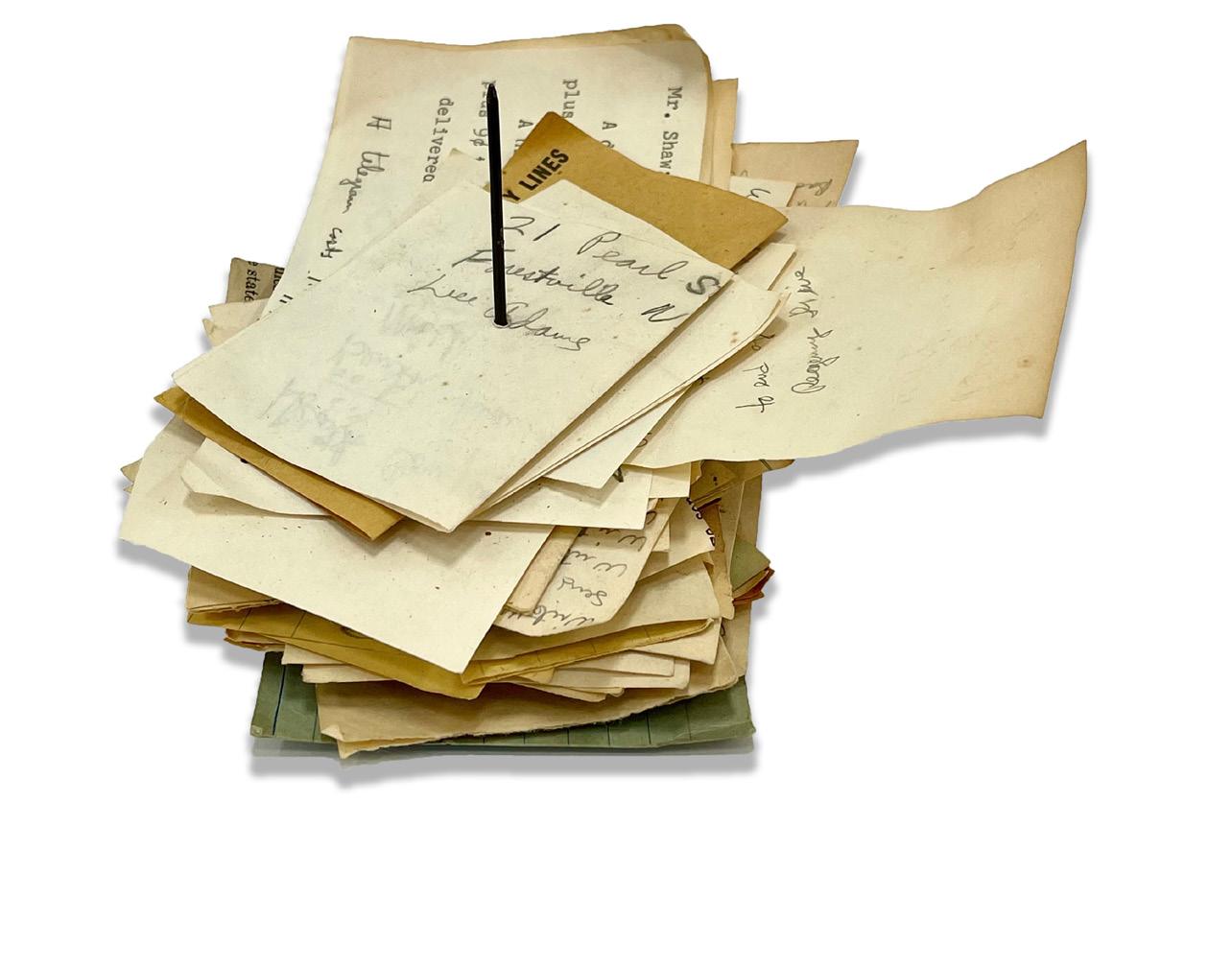

As the excavation proceeded, “One thing,” recalled Frank, “led to another: thermometers to yardsticks, yardsticks to compasses, compasses to words.” Lists were made:

Listing seemed the best form. It’s mundane and poignant: recording things needed; noting what mattered in one manner or another. Old lists are a window: showing concerns of a day, a moment. Lists are also intimate: written not for display, but for memory’s sake. (Frank Shaw)

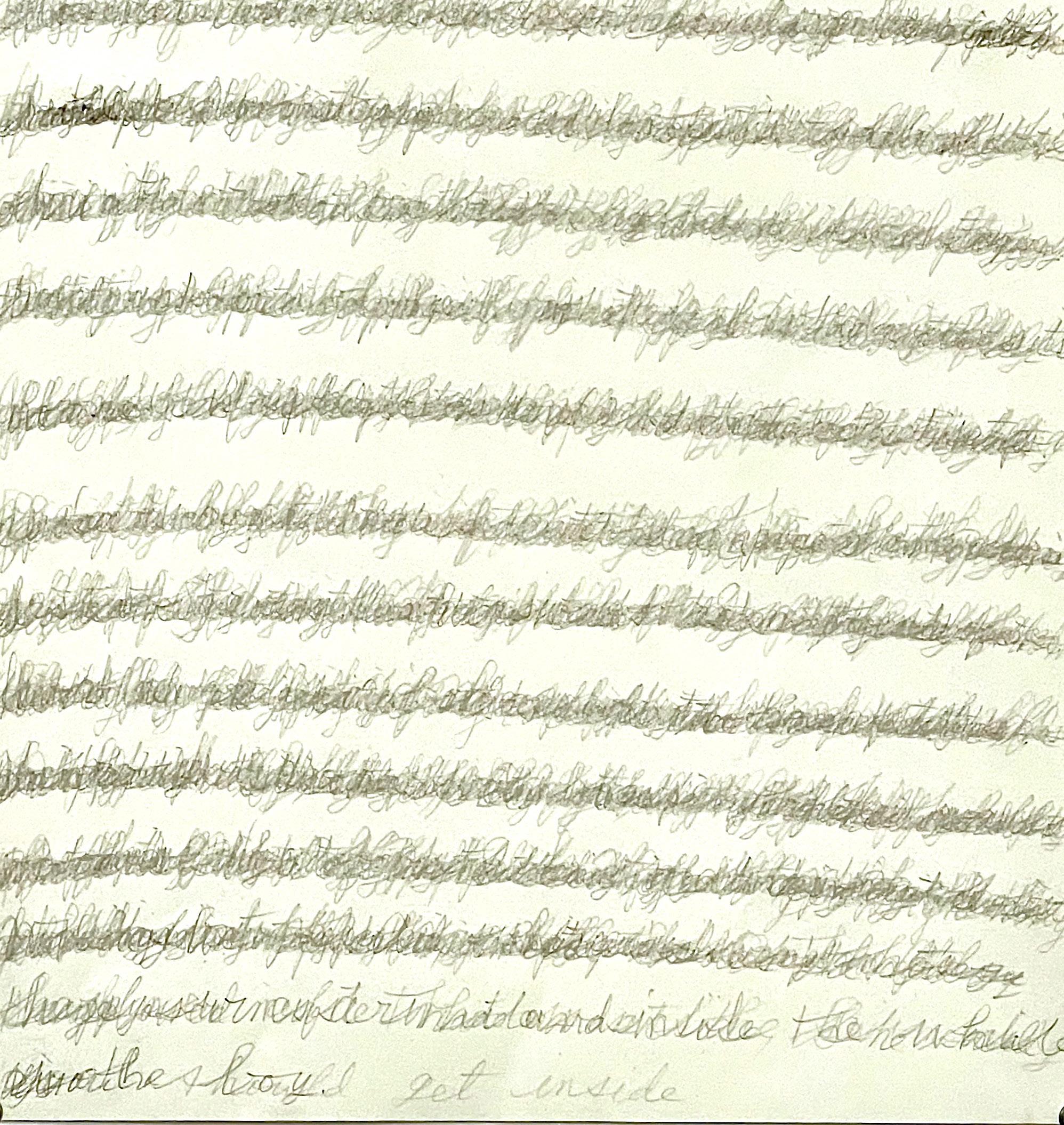

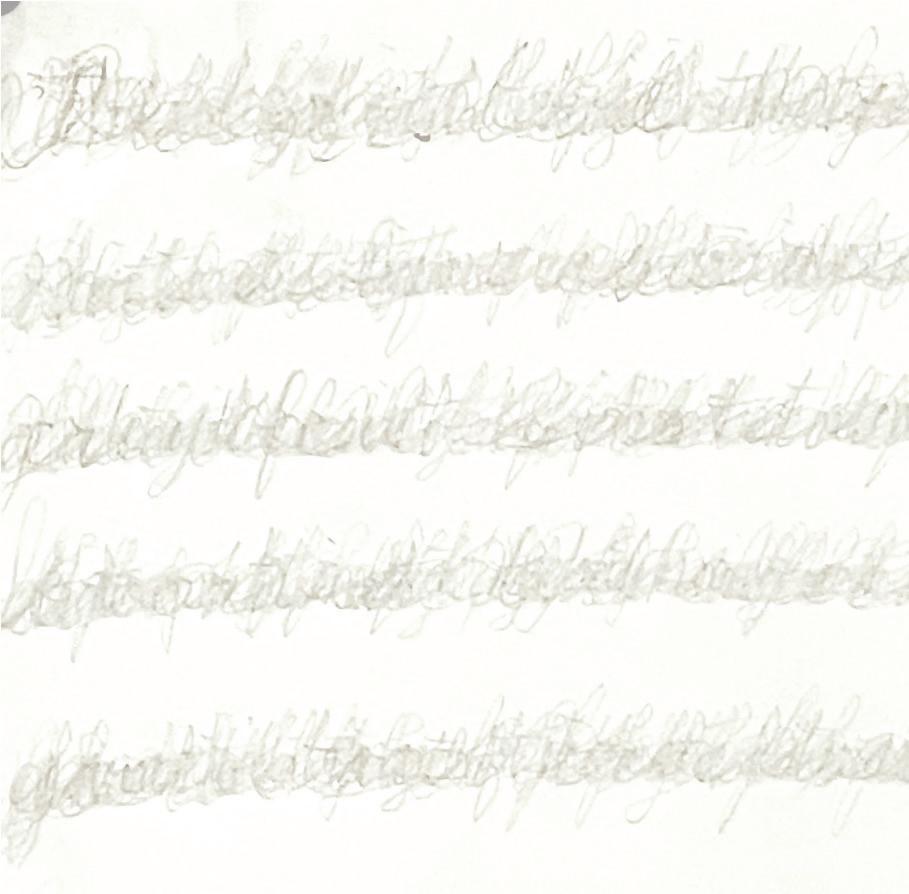

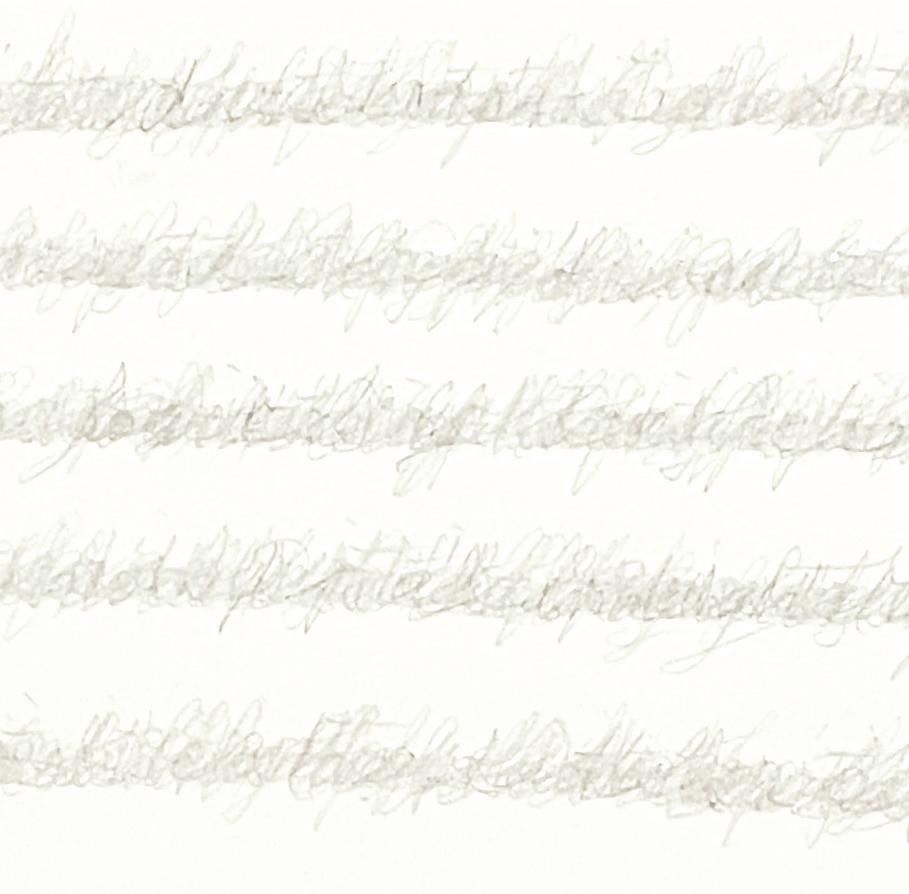

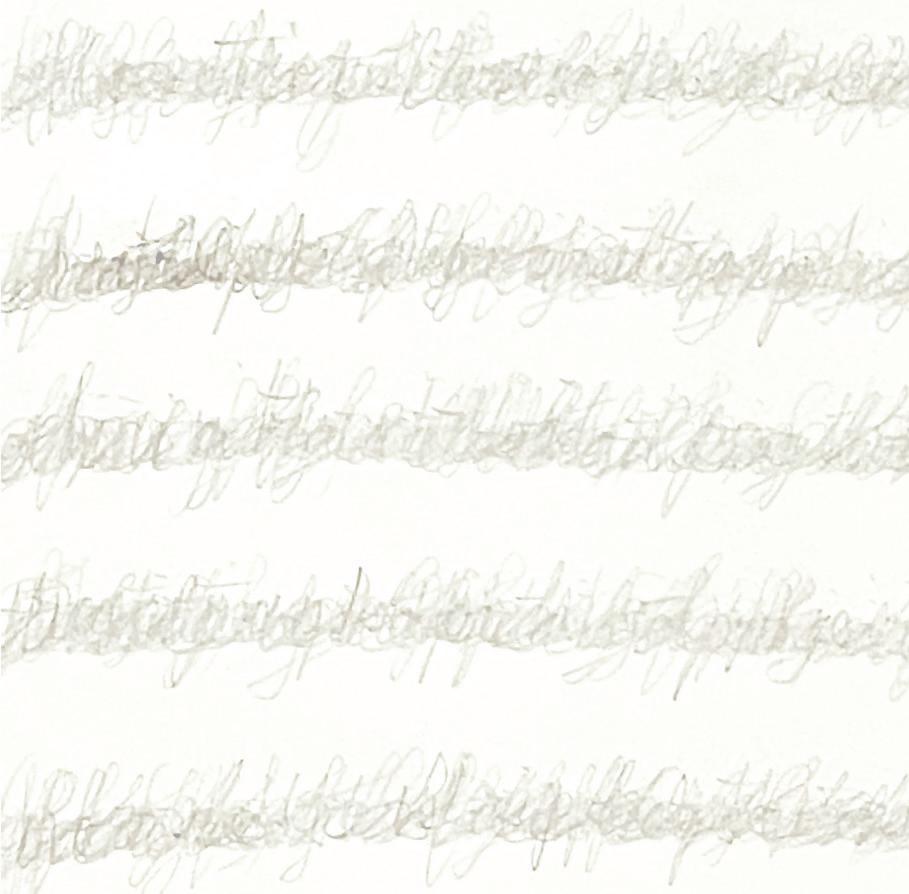

Reckoning (A Trace of What It Was), a complex work produced over a span of five years, from 2017 to 2022, attempts the unattainable: to fabricate in list form a narrative that transcends temporality. Reckoning was born of an earlier piece, Indecipherable Days (2018-19). Both artworks arose from a revelation that the house the family was selling “was not one, but many,” Frank explained. “There were 12 houses existing simultaneously. Each house became a list.”

Written in cursive, the lists are composed in prose form. They are liquid, lyrical meditations on the appearance, condition, function, location, and/or significance of an object like a wind-up music box and a barrel for burning trash and material such as peeling paint, plaster and lath, and dust. As the inventory proceeds, apparitions are summoned. They couple, replicate, separate, and lodge between the cursive lines. The fragmentary character of each line mimics the disjointed nature of memory.

Eventually, the physical sorting and redistribution of the estate concluded. Displayed throughout the galleries, select items, most in altered or denuded states, quietly interrogate complex conceptions of inheritance and value in a fretful, ambient chatter: “What is my mnemonic / aesthetic / emotive / cognitive / practical value?” “What is my worth?” inquires object after object.

Meaning and value may be coaxed from a three-legged stool missing two of its legs in So We Go (2018) because it is displayed in close proximity to Yesterday was Tomorrow (2022) in which five wooden chairs wait between rustic, wooden doors to accommodate a sitter. The catch—or is it a trap?—is that two of the chairs are seatless and the doors open to dead ends. Into the surface of one of the doors are impressed letters, words, clipped phrases like fragmentary secrets overheard through keyholes and cracks and then stamped into the wood. Above the display, white and brown porcelain door knobs spell out the title of the work, Yesterday was Tomorrow, in anachronistic Morse Code: dash dot dash dash pause dot pause dot dot dot and so forth like otherworldly tapping on a table at a séance.

From Frank’s list, “Texts that I seem to carry more than other things read,” “Burnt Norton” from TS Eliot’s, “Four Quartets” is plucked, its words held fast, pinned in place—moths, not butterflies—here and there throughout Yesterday was Tomorrow:

Footfalls echo in the memory Down the passage which we did not take Towards the door we never opened Into the rose-garden. My words echo Thus, in your mind. But to what purpose Disturbing the dust on a bowl of rose—leaves I do not know. Other echoes Inhabit the garden. Shall we follow?

Other texts Frank carried: James Joyce’s Ulysses and Finnegans Wake, Virginia Woolf’s The Waves and To the Lighthouse, Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, The Consolations of Mortality by Andrew Stark, Why Time Flies by Alan Burdick, Wallace Stevens’ Notes from Adagia, Poetics of Space by Gaston Bachelard, Remarks on Colour by Ludwig Wittgenstein, Whitman, Dickinson, Oliver… The list is a code we cannot crack. Themes do rise to the surface, however: something about time; something about objects and memories being activated in specific places; something about our relations to certain objects being acutely sensory and bodily; something about memory being unstable.

The 13 different thermometers of It Was Evening All Afternoon (2013, pictured left) measure, elucidates the artist, “success, happiness, time and objectivity among other things.” The title of each piece in this suite is a phrase from the poem, “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” by Wallace Stevens, which ponders sensations. Sensations, as we know, have the capacity to trigger memories—often random and surprising ones. The red line of a single, numberless thermometer in The River is Always Moving (2013) surges upward from the low mark, “Yesterday,” to the high mark, “Tomorrow.” Here, sensation is mercurial. I Do Not Know Which to Prefer (2013) consists of eight thermometers of different lengths, also bereft of lines or numbers but seemingly mostly running hot, mounted above block text which reads rather faintly, “THE OBJECTIVE ABSOLUTE TRUTH.”

Assorted Fetishes, Relics, and Conundrums (2015-22), a mixed media display in Gallery 5, has a catchall aura about it. Here, it is as if sensation and memory have collided and parallel, lengthy, and meandering

family and personal narratives have scattered on impact. Entire histories—of people and objects—have been condensed to an assortment of essential ingredients like reversing a recipe or a magic spell. A scrap of leather, a snippet of desiccated rubber, a stub of electrical wire, and an irregular, rough-edged piece of wood that didn’t make the cut: each odd remnant, like a sliver of bone from a martyr’s skull or a patch of fabric from a holy monk’s rough-woven tunic, demands to be obsessed over or revered—or both. These vestiges may signal loss or incompleteness but, conversely, they may also, muses the artist, “tell of hope or fear. Or both.”

A bit of wire evokes a person who could, with that wire, solve an electrical problem. The scrap of leather kept, speaks of hope; it might patch a worn glove or shoe, the fear that the glove will be torn. (Frank Shaw)

In this field of emotional and sensate exploration, fetish and relic seem to oppose one another across an invisible line of potential misunderstanding. What is the difference, after all, between paying homage and idolizing? Devotion and fanaticism? Veneration and obsession? Glorification and fetishization? The conundrums are as inevitable as the vexing awareness of mortality that sheaths each object like a layer of fine dust.

The titles of artworks are effective, evocative, endearing, and/or elusive. In some instances, they offer light comic relief; in others, puzzlement. Often directly descriptive, they nevertheless tease, hint at more, here and there offering a possible solution to a quandary (or quandaries) posed by materials, objects, and artworks: Relic: Doll in a Box, Fetish: Three Rulers, Relic: Spirit Level (Ancestor 3F), Fetish: Twine, Relics: Shrouded Forms, Fetishes: Sacred Scraps, Relics: So We Go…

Many of the relics are also questions: Why was it kept? Was the item not crossed off the list ever procured? If I can’t solve an electrical problem, what is the value of the wire? (Frank Shaw)

A work titled, So It Goes (2022), consists of a series of galvanized metal pails, none still watertight, connected to one another in descending order, from largest to smallest, with sisal garden twine. The piece invites easy metaphors of containment and loss and suggests relationships between objects, artworks, and ideas like a crafty matchmaker. The pails had been in the barn when Frank’s parents purchased the farm. Even then, they no longer fulfilled their particular function but had been retained, at the least as talismans of pragmatism: “Waste not, want not,” they warn. In sum, So It Goes has the air of a Rube Goldberg device for distilling memory or a demonstration of how we recall an event differently each time we remember it until eventually, what we are recalling is the last time we recalled the event.

Each artwork in ReConsider, in its way, explores the essence of memory as well as the process of learning to remember. Indeed, parents teach their children how to construct coherent, autobiographical memories through a technique of elaboration. A parent’s elaborative style—or the lack thereof—has tremendous bearing on the nature of the memory-narratives their children will go on to produce, even decades later. Parents model remembering by using orienting and evaluative techniques; details give form and depth to memories; emotions and subjective experience help the child locate themselves within a given memory. In the galleries, details have been shuffled, repurposed. The result is the prevailing, ambivalent conundrum: “Whose memories are these?”

A Salvaged Dream (2018, pictured right), is a repository, a reliquary of inherited—or appropriated—memory. It consists of four models constructed from distressed wood, four iterations of a cottage that had been built by Frank’s father’s father in the 1930s

alongside Canadice Lake in northwestern New York. When the city of Rochester claimed the site for a reservoir in the ‘40s, the cottage was disassembled and stored in a small barn on the grandfather’s property until the mid-1960s, when the artist and his father moved it 40 miles away to their own barn. The material was stored carefully with the expectation that the structure would at some point be rebuilt.

Significantly, the four models of the modest dwelling are built from scrap wood other than that retained from the original cottage. Frank refers to the cottage as a “mythic structure.” It was, for his father—

A place always golden in his memory. A pile of planks possessing power I did not understand, an importance I could not comprehend.” He both hoped to reassemble it and dreaded doing so… Later, I learned that my parents honeymooned there in the 40’s.

According to family legend, the place was built with the foreknowledge it would be disassembled, so nails were pounded only halfway. That’s the legend. (Frank Shaw)

His design of the models was based on his 90-year-old mother’s recollection and a blurry photograph. A Salvaged Dream is a phantom and a memory, inherited and reified.

Arguably, the concept of heritage is grounded in exclusion: assigning value to some things while disregarding others—all of which is undertaken based on a set of indeterminate, often expressly subjective criteria. In this regard, lists and heritage share some common features: both rely on selection, decontextualization, and recontextualization to create new relationships, themes, and taxonomies.

Removed from the barn and set in the studio, these things spoke differently. Separated from the chaos, form and character and story emerged. (Frank Shaw)

Debra Thimmesch is an art historian, activist, independent researcher and scholar, writer, critic, editor, and visual artist. She writes and teaches about art through the ages, mentors graduate students in the history of art, and is attuned to current endeavors to radically re think and reframe the pedagogy of art history. Her writing has appeared in Art Papers, The Brooklyn Rail, and Blind Field Journal. Her BA in art history is from Wichita State University; master’s and doctoral work in art history; the University of Kansas.

Shaw received his BFA in Painting from the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, Rhode Island and an MFA from Yale University School of Art in New Haven, Connecticut. His paintings have recently been featured in the United States Embassy Art in Embassies Program in Bridgetown, West Indies. His work has also been exhibited in numerous exhibitions including Artspace Gallery, Lindsborg, KS; Project Gallery, Wichita, KS; Webster University, St. Louis, MO; Butler County Community College, El Dorado, KS; Wichita State University, Wichita, KS; Emporia State University, Emporia, KS; Nancy Lurie Gallery, Chicago, IL; Marilyn Pearl Gallery, New York, NY; and the Salina Art Center and the Land Institute, Salina, KS.

The Haunt 2019-22 Wood 19” x 47” x

Inheritance 2015-22 Mixed media 30”x 384”x 30”

A Salvaged Dream 2017-2022 Mixed media

x 72”x

The Answers 2017-2020

Mixed media

x 26” x

The Hallowed 2018-19

ensemble of mortises and tenons

x 300”

Reckoning A Trace of What It Was 2017-2022

Ink on vellum, 12 units each 26” x 17.75”

34,432 Days (pictured above) 2021-22

Mixed media 29” x 24” x 20”

The Code 2020 Wood and graphite 7.5” x 25” x 1”

121 days 2022 Mixed media 29” x 30” x 24”

Love Means Everything 2014 & 2021

Ink on paper, 33 individual sheets each 22” x 17”

It Was Evening All Afternoon 2013

Mixed media, 13 individual thermometer units. dimensions variable.

(Un)Certainty 2014

Graphite on wood, 8 individual units dimensions variable.

Short Long Long Short 2015 & 2018 Graphite on wood. 8 individual units 25” x 49”

Head and Heart 2015 Wooden levels. 4 individual units, dimensions variable.

Between Us We See The Whole Picture 2014 Two 34” yardsticks 8” x 34”

Either Neither Both 2014

Paint on wood, 3 individual units, each 3.75” x 7.25” x .75”

To Find The Heaven Below (pictured right) 2014 5 compasses dimensions variable. Atonement 2016 Yardstick, paint, marker 36”

Yesterday Was Tomorrow (doors and chairs) 2022 5 wooden chairs, 4 wooden doors Overall dimensions approx. 80” x 300” x 30”

So We Go 2018 3 wooden stools 9” x 104”x 31”

Stories We Were Told (Mantel) 2022

Mixed media 101” x 77” x 23”

There, Then 2022 5 units 23” x 114” x 28”

Indecipherable Days 2018-19

Graphite on paper, 15 sheets 18” x 12”

Happened

Might Have and What Has

Assorted Fetishes, Relics, and Conundrums

2015-22

Mixed media.

dimensions variable.

Green metal locker

Large glass bell jar

Ensemble of mortises and tenons

Oil cans

Glass reflector beads

Jars of barn dust, desiccated rubber bands, rotten string, piano ivories Letters

Rusted wire bulb cages

Small mechanical gizmo

5 wrapped glass insulators

Small wooden spools

Rusted metal cans

4 ancient light bulbs

4 Baby Ben clocks

Used, but still good, drier switch

Small homemade electrical switches

Radio Ear (good one year) battery

Tenon and pin

Desk spike of completed jobs Mysterious wand

Several broken folding rulers Doomsday switch

4 couples comprised of rope and pulleys

1 couple comprised of broken pulleys with no rope

1 pulley with rope

Doorknobs

Scraps of wood and metal

Iron faucets

Pipes

Wooden spirit levels

Old mirrors

Metal kettle

Assorted bits of hardware

Scraps of leather and rubber

Balsa wood model planes

6 galvanized pails

Bundle of old sisal

Old rubber bushing with attached mailing label

Miscellaneous peculiarities

Friday, Oct 7 | 5-7 PM | Opening Reception | ReConsider

Salina Art Center | FREE

Please join us in celebrating the opening of ReConsider by artist Frank Shaw. Special introductory remarks by Saralyn Reece Hardy, the Marilyn Stokstad Director at the Spencer Museum of Art, followed by remarks from Shaw at 6 PM. This event is free and open to the public.

Saturday, Oct 22 | 10-11:30 AM | MAGIC, STORY, LESSON: Writing with Art

Lori Brack | Art Center Warehouse Education Studio | Registration required, $45

After a brief introduction to the exhibition and time for personal viewing and reflection, individual pieces in Frank Shaw’s ReConsider will provide sources and subjects for original writing. This workshop is based on the idea that a writer “may be considered as a storyteller, as a teacher, and as an enchanter,” according to literary virtuoso Vladimir Nabokov. Teen and adult writers will look at examples of poems and prose that use the magic-story-lesson content and then write a draft in any form they choose with those ideas in mind.

Wednesday, Oct. 19 | 12:15 PM | Art Byte

Darren Morawitz | Salina Art Center | FREE

Bring your lunch and join Darren as he takes just 30 minutes to investigate a single piece of art in the gallery. These small bytes of art information inspire conversations around viewing, interpreting, and discussing contemporary art in all forms. This interactive conversation will surely leave you feeling inspired and confident about your next visit to an art museum. A new piece of work is discussed each month while you enjoy your lunch break.

Friday, Nov. 4 | 5-7 PM | Opening Reception | ReConsidering; a project by Salina South & Central High School students

Salina Art Center | FREE

Using prompts from artist Frank Shaw and inspired by Shaw’s exhibition, ReConsider, students engaged in active dialogue with members of their family or community to create ReConsidering. Each team of students explored private collections while gathering oral stories and translating those stories into written text to accompany individual displays. View these displays in our gallery from Nov. 1 - Dec. 30, 2022.

Thursday, Nov 10 6-7 PM | Walk & Talk with Frank Shaw

Salina Art Center | Registration required, $10

Explore ReConsider through a special gallery tour led by the artist himself. Shaw will be available to discuss his process and answer questions.

Saturday, Nov. 12 | 10-11:30 AM | MEMORY, MEMOIR, MEMORIAL: Writing with Art

Lori Brack | Art Center Warehouse Education Studio | Registration required, $45

What are the relationships between our private visions of the past, our personal life stories, and how we remember those we love who have died? In this workshop, teen and adult writers will look at examples of memoir, memorial, and memory writing. After an introduction to Frank Shaw’s ReConsider exhibition, writers will select a piece or pieces that reflect one or more of the three ideas and write a draft of a poem or short prose piece that reflects and interprets the work of art as a doorway into their own memories, life stories, and remembrances.

Wednesday, Nov. 16 | Art Byte

Darren Morawitz | Salina Art Center | FREE

Bring your lunch and join Darren as he takes just 30 minutes to investigate a single piece of art in the gallery. These small bytes of art information inspire conversations around viewing, interpreting, and discussing contemporary art in all forms. This interactive conversation will surely leave you feeling inspired and confident about your next visit to an art museum. A new piece of work is discussed each month while you enjoy your lunch break.

Catalog published by Salina Art Center to accompany the exhibition ReConsider | Frank Shaw

242 S Santa Fe Ave

Salina, Kansas 67401

September 28 - December 31, 2022

Essay by Debra Thimmesch

Design by Hannah Crickman Photos courtesy of the artist Installation by Frank Shaw, A. Mary Kay, and Daniel Picking

Founded in 1978, the Salina Art Center is a 501(c)3 creating exchanges among art, artists, and audiences that reveal life. Accredited by the American Alliance of Museums, the Art Center’s galleries, Art Center Cinema, and Warehouse are located in the heart of downtown Salina, KS. Learn more online at www. SalinaArtCenter.org.

Supporters include artists, educators, and community members who envision a center to engage people in art experiences of quality, relevance, and significance to our global community. A heartfelt thank you to our patrons, sustainers, advocates, and benefactors for their generosity.

Salina Art Center exhibitions and programs are supported in part by donors, members, underwriters, foundations, the Salina Art Center Endowment Foundation, and the City of Salina.

Reconsidering; a project by Salina South & Central High School students is funded by the Greater Salina Community Foundation.

| info@salinaartcenter.org