Drew Brantley

By Tom Bradbury

By Mark Sinatra

By Austin Brady & Martin Urdapilleta

By Jonathan Bernstein, Jennifer Rossan & Cameron Posillico

The firm maintains a diverse, businessoriented practice focused on investment funds, litigation, corporate, real estate, regulatory and compliance, tax and ERISA.

Drawing on the experience and depth of our lawyers in these distinct areas, we can leverage each lawyer’s industryspecific knowledge to help our clients succeed. This collaborative approach brings to the table a collective insight that contributes to sensible, efficient resolutions, and allows us to remain attentive to the cost and time sensitivities that may be involved.

Sadis’s clients include domestic and international entities, financial institutions, hedge funds, private equity funds, venture capital funds, buyout funds, commodity pools, and numerous businesses operating in various industries around the world.

BY PAUL MARINO SADIS & GOLDBERG

As summer winds down, it is hard not to reflect on the first half of 2025—what has happened, what has not, and what might still lie ahead. From my vantage point, (that is transactions and credit deals in the middle and lower middle market) this year has felt a lot like the Beatles tune: “Getting Better.”

• The optimist in me (channeling Paul McCartney) says things are getting better. Deal flow has picked up meaningfully. We are seeing more LOIs, and even when we are not winning mandates, we are getting more looks. Deals are moving—not at warp speed, but with intent. There is real momentum.

• But the realist (maybe cynic?) in me—call it the John Lennon voice—reminds me that things have been slow; slow enough to think they have nowhere to go but up. For example, many middle market investment banks had their worst year-over-year returns in recent memory, despite a modest uptick from the bottom of 2023–24. Moreover, while it is true that deal volume has increased—it is also true that fewer deals are closing because selectivity rules the day. Efficient capital is chasing great companies—because good enough just is not

good enough.

Nonetheless, activity is on the rise and things are looking up.¹ Therefore, I guess it all depends on whether you are a McCartney-ite, or a Lennonite (I posit most of us are both at one time or another). Still, some backwards-looking data may give us a forward-looking edge. Let’s dig in.

Sellers are still reluctant. Many are making too much money to be compelled to sell—and they

certainly do not need to. This has widened the bid/ask spread, especially for companies with $2M+ in EBITDA, where owners are dissatisfied with valuations being offered in the market. Owners spent years hearing about premium multiples and frothy deal activity. Now they face buyers burdened by higher interest rates, tighter credit, and more cautious underwriting. Multiples are lower, rollover asks are higher, and earnouts are more common. After taxes, fees, and reinvestment options, sellers often feel short of their goals—and they are choosing to wait.

Nevertheless, this standoff has an expiration

date. A major shift—a drop in rates, a spike in buyer demand, or a recovery in valuations—could bring sidelined sellers back. Conversely, if valuations deteriorate further or if a broader economic downturn threatens company performance, “good enough” offers may start to look very attractive.

The resolution of trade negotiations with America’s top partners is a meaningful tailwind for companies reliant on foreign inputs. Tariffs and supply chain unpredictability have (somewhat but are expected to) compressed margins and made long-term planning difficult. Today, it appears there is greater policy clarity, businesses can lock in pricing, renegotiate supplier terms, and invest with more confidence.

Stable trade terms also boost investor confidence and improve the cross-border M&A environment, particularly for those sourcing or selling globally.

Predictability translates into operational confidence and stronger valuations.

For sponsors focused on manufacturing, retail, or just about any global supply chain business, the picture is still emerging. Expect some short-term margin pressure as companies digest remaining tariff costs, and slightly higher prices; and expect more efficient operators—which usually means leaner headcount. Good for inflation, but not good if you are the individual terminated.

However, the optimist in me sees job displacement as a uniquely American dynamic: efficiency breeds entrepreneurship. Those bold enough to build fill gaps in the market.

As trade and tax policy settle, regulatory focus will sharpen. I expect agencies like the SEC and FINRA to take clearer, more predictable stances and pare

back aggressive proactive regulatory review.

While not directly affecting the private deal space, I would love to see Sarbanes-Oxley scaled back enough to incentivize more IPOs. Public listings bring valuation transparency, an outlet for investors to realize liquidity (at higher multiples mind you)—and will relieve pressure in the private markets (look at the growth of secondary funds— the growth isn’t a coincidence, it is because there is a lack of liquidity). Nonetheless, I have to believe — many LPs will nudge their GPs to merge platforms/ portfolio companies and seek an exit—and if the regulatory environment is friendly, the exit might be through an IPO (or SPAC) to optimize valuation and liquidity.

Another issue to watch is the slow and steady march of private investments entering the public realm.5 While I am all for democratization of financial markets (it is one of the reasons why the USA’s markets are successful) I am unclear as to the success of illiquid investments in public markets. Large public PE companies own, operate and sell platform companies (and let’s face it, most large PE firms are becoming insurance holding companies— using cash flow from the insurance to fund their platform investments) but many of the smaller and less liquid funds will undoubtedly struggle. The outcome is unclear, however if history is any predictor of future results, there will be issues, which will then result in a regulatory overreach (see, e.g., SARBOX).

Regulatory and compliance is important (think of a baseball game with no rules and umpires—chaos would ensue); but compliance overreach stifles innovation and creates risk-averse cultures. The

best businesses stay on strategy—and away from strategy drift. If you are a GP/IM—stick to your knitting—stay in your lane, do what you say you are doing as per your documents; take a cue from Yul Brynner in the epic movie, Ten Commandments: so it is written, so it shall be done.⁶

Few things move sentiment like MEG: Meat, Eggs, Gas. Food and fuel prices shape how Americans perceive the economy—and their leaders.⁸

When these costs fall, consumers breathe easier. Discretionary spending ticks up. Business optimism returns. Lower input costs give SMBs room to reinvest, hire, and expand. The ripple effect is real.

On my recent family drive down the East Coast, I saw gas averaging $2.75–$3.15. If prices drop another 20–30%, that’s a meaningful tailwind—not just for the economy broadly, but especially for lower- and middle-income Americans.

One benefit of being at a middle-market law firm: we see most of the field. We see deals from billiondollar companies and funds down to micro-cap deals and independent sponsors, we’re hearing the same thing across the board—activity is up.

Even bankers we speak with, from top-tier to smaller shops, all report more activity on sponsor, deal and investment side. That’s often the first signal that momentum is building.

On August 3, the Wall Street Journal reported the busiest deal week since 2021.10 That urgency usually

starts at the top and trickles down. As sellers and buyers start feeling the momentum, inertia kicks in—and the whole market starts moving.

While the bid/ask spread remains a challenge, LOIs and IOIs are up. Add in a bit of policy certainty (tax reform done, trade deals nearly finalized), and the table is set for a broader M&A acceleration across all tiers.

If urgency returns—and I think it is—that energy helps normalize valuations. Sellers will give up chasing 2021 highs. Buyers will trust they’re not overpaying. Confidence, not exuberance, is the fuel we need.

Bain’s Midyear 2025 Report shows strategic M&A up 11%—no surprise, given public companies’ strong balance sheets and stock currency. Interestingly, industrial M&A is off 15%, likely due to tariffs. Nevertheless, that space could rebound quickly, especially with the new tax bill’s generous expensing provisions.11

I am bullish. The next 12–18 months could be exciting.

Whether you are a McCartney optimist or a Lennon realist (or both); whether you clash against the numbers or just want to get in your car and go, the market feels like it is starting to hum again, which is just what I needed: signs of life in M&A. Let’s go!

A Little League Lesson That Still Works

I recently met with a friend’s daughter—a bright

recent college grad seeking career advice. I found myself returning to something I wrote years ago, rooted in Little League wisdom from Coach Richard Kropp in Stamford, CT.

One afternoon at practice, I asked Mr. Kropp how he became such a successful businessman. (Side note: he is a great man who has a lot of personal and professional success—retired in his mid-tolate 40s coached little league for his kids and for a longtime afterwards.) Here is what he told me: there are three things that you need to do to make you successful in business (as he put it better than ninety percent (90%) of the people that you work with):

1. Show up on time,

2. Show up every day, and 3. “Show up” every day.

When I pointed out that #2 and #3 were the same, he smiled and said, “You’ll understand once you start working.” What he meant was when you show up to work—be ready to work—do not occupy space (or as another friend’s dad used to say, “don’t be a fresh air inspector”). (Mr. Kropp also told me I talked too much and should become a lawyer or stockbroker.)

Years later, I still live by it. Whether selling water and coffee door-to-door (my first job out of college) or helping run a law firm—showing up on time, showing up every day, and showing up ready to grind, makes all the difference, it matters.

Mr. Kropp’s advice rings as true today as it did in June of 1985.

1 To quote the late great Jim Morrison: “I’vebeendownsoverydamnlong,itlookslikeuptome.”

2 Should I Stay or Should I Go, The Clash, Combat Rock (1982). Released as a double A-sided single. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Should_I_Stay_or_Should_I_Go

3 London Calling, The Clash, London Calling (1980). Released as a single. The album is often listed as a top ten rock and roll albums of all time (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rolling_Stone%27s_500_Greatest_Albums_of_All_Time)

4 I Fought the Law, Clash (originally released by the Crickets), The Cost of Living (1979); in 1989, during Operation Just Cause, the U.S. military surrounded the Apostolic Nunciature in Panama while trying to capture Manuel Noriega, the strongman of Panama. U.S. forces blasted loud rock music—including “I Fought the Law” by the Clash—to put pressure on Noriega to give himself up. (Tran, Mark (April 27, 2010). “Manuel Noriega – from US Friend to Foe”. The Guardian. London) (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I_Fought_the_Law. Visited, 7/30/2025)

5 Wall Street Journal, “How One Big Private-Equity Fund Makes Its Numbers Incomprehensible” (https://www.wsj.com/finance/investing/how-one-big-private-equity-fund-makes-its-numbers-incomprehensible-5268657e?st=gqSydW&reflink=article_email_share) (visited 8/13/25)

6 Yul played Ramses II— the antagonist, so only model compliance only after this phrase.

7 Lost in the Supermarket, Clash, London Calling, 1979 (When Joe Strummer wrote this song, he was truly inspired by the bewilderment of shopping at the International Supermarket, with his then girlfriend and her family).

8 Obviously, zero is not an option unless you are running for mayor in NYC and you believe that you can spend other people’s money (of course until it runs out). Also, similar to bond yields: yields up/price down but instead CCI: MEG down/CCI up.

9 I am unclear if there is a song that conjures up a movie scene more than this song and Fast Times at Ridgemont High (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y5oPZFDci80&list=RDy5oPZFDci80&start_radio=1); if you know you know.

10 Even the Wall Street Journal recognizes this issue ((https://www.wsj.com/business/deals/its-a-scorching-hot-summer-for-deals-on-wall-street-vacation-can-wait-38c8e3c0?mod=Searchresults_pos1&page=1 (visited, 8/4/2025))

11 https://www.bain.com/insights/m-and-a-midyear-report-2025-separating-signal-from-noise/ (visited, 07/31/25)

12 One from the Vault is a live album by the Grateful Dead, recorded on August 13, 1975, at the Great American Music Hall in San Francisco, California, for a small audience of radio programmers. It marks the first time the Dead played Blues for Allah live in its entirety and recorded. It’s a memorable album for me because it was the first Dead album I bought as a senior in HS at Westhill, HS in Stamford CT.

PAUL MARINO Partner

Sadis & Goldberg pmarino@sadis.com

Paul Marino is a partner in the Financial Services and Corporate Groups. Paul focuses his practice in matters concerning financial services, corporate law and corporate finance. Paul provides counsel in the areas of private equity funds and mergers and acquisitions for private equity firms and public and private companies and private equity fund and hedge fund formation.

BY DREW BRANTLEY FRISCH CAPITAL

Unfortunately, this is a call that we get all too often, which can ultimately lead to many deals falling apart.

When selecting a capital provider, there are a lot of factors to consider: the type of capital they deploy (equity or debt), how involved they will or want to be post close, have they worked with Independent Sponsors in the past, industry experience, your economics, and much more. But one of the most important factors to consider is a capital provider’s

“certainty to close”.

Certainty of close is just that, the probability of a capital provider’s ability to close a deal.

Independent Sponsors are naturally enthusiastic about their deal. In life, when we are enthusiastic about something, we are naturally drawn to others that are enthusiastic about the same thing as well.

As an Independent Sponsor, it’s important not to get sucked into the trap of confusing a capital

“Drew, we were about 60 days down the path toward close working with a capital partner that was interested in the deal, then they backed out. We were only really talking to them.”

provider’s interest with their certainty of close.

Let’s break this statement down into more detail and help provide you with some thoughts to help you avoid this pitfall.

Capital Providers have money that they need and want to put to work. Their job is to find good deals and companies to invest in. Naturally, they are going to want to see as many deals as possible to be able to find the right one. So, if an Independent

Sponsor or Investment banker says, “Hey I have a deal with these criteria, would you be interested in learning more?”; if there is a remote possibility that it could fit their investment criteria, a capital provider is going to say, “Yes”. Even if they think it’s not going to be a fit, most capital providers would rather see the deal, than not see the deal.

Now here is where it gets tricky. Once someone turns an NDA and starts reviewing information, undoubtedly, they are going to start asking

questions. Often one question and answer lead to another. Due diligence questions take time to answer. Before you know it, you are 4 weeks down the path answering questions for a capital provider that said they were “interested”, only to find out that when it goes to committee or the patriarch, they are going to be a pass for a reason they have known since day 1.

While this is not necessarily nefarious on behalf of the capital provider, it can be very frustrating for an Independent Sponsor to try to get their deal closed in a timely fashion.

Raising capital is difficult. It takes a lot of time, energy, and effort. In addition, you have to have thick skin. You are going to hear a lot of “no’s” before you get to a “yes.” Regardless of whether you raise the capital yourself, or work with something like us, Frisch Capital, a specialist in raising capital for Independent Sponsors, the goal is to reach out to enough parties to have multiple capital providers interested early in the process. Having multiple interested parties allows you to have choice in who you select as your capital partner.

Choice can allow you to do four things:

1. Select your partner(s) based on who you feel is going to be the best fit for you and your deal.

2. Select the capital and capital structure that you feel will set you up for the best chance of success. Keep in mind, just because you have sources and uses in your model doesn’t mean that it is going to match how a capital provider needs or wants to put capital to work in your deal.

3. Negotiate better economics.

4. Provide you with some additional “certainty to close” because you have backups in place should something happen and a capital provider you select walks away.

Most Independent Sponsors want to be able to call a capital provider, have quick conversation, send them a few materials and then within a week get an email saying, “Hey we are in and will fund the deal, no questions asked.” Reality is much different. Realistically the process to get a capital provider to provide you with a proposal to do your deal can take between 3-6 weeks depending on the capital partner, their process, and what information is available at the time. So be prepared to give capital providers time to review the materials, without pressing them too much to make a decision. You do not want to push someone away because your timeline is unrealistic.

This timing should also be considered regarding when you engage third parties such as attorney, accounting firms, placement agents to help with the capital raise and more. Most service providers want to get involved earlier rather than later. Many such as Frisch Capital and Sadis and Goldberg LLP are happy to work with you on costs, engagement structure etc. so that you do not have to spend a bunch of money on the front end. By engaging with service providers earlier than you need them it allows for them to plan, prepare and clear the path internally on their side to be able to meet your timeline for the deal. A good rule of thumb is 2-4 weeks before the Letter of Intent is going to be in place give them a call and give them a heads up you have a deal that is coming soon.

At some point you are going to have to select

a capital partner. Unfortunately, you can’t run multiple parties right down to the day of closing. This means when you select a capital partner, you will go exclusively with them and stop talking to others. But if the group you selected backs out for some reason, you will have other backups available to call to see if they are still interested. This can save you weeks or even months by not having to start all over again with someone new. This is the greater certainty of close that many people are seeking in their transactions.

While this seems simple enough, if you do this you are going to have to tell people, “sorry but I have chosen to go in another direction”. You want to be very careful about how you communicate your process to capital providers to avoid burning any bridges. To set yourself up for the greatest chance of success and try to keep friends and not make enemies, consider the following:

1. Communicate clearly to capital providers your timeline and process.

2. Let capital providers know what information they will have access to and don’t be afraid to say, “we do not have that at this time, but after

we select a partner that will be available to you.”

3. Be honest and transparent with capital providers. If they can do something to improve their proposal, ask and give them the opportunity. If you would not select them regardless of an improved proposal, let them know that you want to be respectful of their time and do not want to ask them to go back to improve their offer knowing that you are already going in a different direction.

4. Say Thank You!

5. Don’t take it personally if someone says NO.

6. When a capital provider passes on a deal, a pass is typically not an invitation for you to try and convince them they made the wrong decision. Simply say thank you and move on!

While there is a lot more nuance to finding and selecting a capital partner then just these simple points, these are guiding principles that can help you maintain relationships and hopefully find a partner that you are excited to work with and most importantly help you get certainty of close!

Securities offered through GT Securities, Inc. (Member FINRA, SIPC)

DREW BRANTLEY Managing Director

Frisch Capital Partners drew@frischcapital.com 706-227-4144

Drew is a serial entrepreneur having started 5 businesses, sold a few and still owns some. He knows what it’s like to be in your shoes. He sees the Independent Sponsor model as the method executives and industry experts can take to own and run already established businesses. He now dedicates his career to helping individuals buy companies, find greater success and live life on their own terms.

Jarrett Wood, a Principal at SharpVue Capital, has built his career in private credit and equity with a focus on the lower middle market. Based in Raleigh, NC, SharpVue was founded in 2016 and has steadily expanded its investment platform. Since joining in 2018, Jarrett and his colleagues have raised multiple funds, including an SBIC vehicle and the recently launched Fund III, which is targeting $250 million in commitments.

SharpVue invests primarily in companies with $2–8 million of EBITDA, often family- or founder-owned businesses at an inflection point. The firm typically deploys $3–15 million per deal, combining debt and equity capital, and supports growth through follow-on investments. Its ability to provide a full capital solution has been particularly valuable for independent sponsors, allowing them to focus on underwriting and execution rather than assembling financing from multiple sources.

In the lower middle market, success often comes from helping companies professionalize—building sales and marketing functions, improving financial reporting, and investing in systems. Private credit provides flexibility, enabling management teams to reinvest free cash flow into

growth rather than being constrained by amortization schedules. Over time, as companies scale, SharpVue works with partners to optimize cost of capital, often introducing senior bank financing once the business has achieved greater stability.

The firm also places a strong emphasis on alignment with sponsors and management teams. Whether through board seats, observation rights, or active engagement, SharpVue takes a partnership-driven approach. With its combination of credit discipline and equity orientation, the team is focused on driving long-term enterprise value rather than short-term gains.

With strong roots in the Southeast and deep experience across market cycles, Jarrett and the SharpVue team continue to see significant opportunity in private credit. As traditional banks retreat from smaller company lending, SharpVue is positioned to fill that gap, providing flexible capital and thoughtful partnership to growing businesses.

BY TOM BRADBURY

This article explores how organizational culture, long dismissed as an intangible “soft” factor, is now recognized as a measurable driver of execution and financial performance. It examines how leaders — including those in private equity — are reframing culture as a core element in operational strategy, value creation, and long-term success.

Thesis:

The central argument is that culture is not merely an HR concern but a powerful, quantifiable infrastructure that shapes organizational alignment, decision-making, and sustainable growth. By adopting more sophisticated ways to measure culture—beyond engagement scores and turnover—leaders can link it directly to value creation and use it as a repeatable lever for competitive advantage across companies and portfolios.

Conclusion:

• Organizations that shift cultural measurement from anecdotal to data-driven tools gain sharper governance and execution insight.

• Embedding culture analytics in ongoing performance monitoring helps leadership teams strengthen operations, reduce risk, and accelerate results.

• Viewing culture as a form of capital enables businesses — including PE-backed companies — to systematically protect and grow enterprise value.

• The strategic intelligence of an executive overlay to traditional financial and HRIS data will align GPs, Operational CEOs and investor objectives.

equity and high-performance sectors, the rules for value creation have evolved. For too long, the organizational levers that determine how a company works—from leadership alignment to shared execution rhythm—were dismissed as secondary “soft” issues, considered less quantifiable and less critical than operational levers or financial structure. But as the most sophisticated General Partners (GPs) and operating leaders have discovered, these organizational dynamics—what can now be more precisely captured as organizational intelligence or business intelligence—are anything but soft. In fact, they often spell the difference between an underperforming asset and a portfolio outlier.

Today, the operational frontier is defined not just by operational effectiveness, but by measurable organizational intelligence. In practice, this means connecting workforce dynamics directly to enterprise value, risk mitigation, EBITDA growth, and superior exit multiples. The ability to quantify, benchmark, and optimize these dynamics— transforming them from perceived intangibles to repeatable levers of value—is no longer a competitive edge but an investment imperative.

In the fiercely competitive world of private

The greatest challenge, and opportunity, facing today’s GPs is to draw a clear, evidence-based line from organizational intelligence to financial outcomes. In the past, so-called “culture” was often measured by engagement scores or employee sentiment, but lacked the granular connection to margin, deal execution, and strategic acceleration that busy deal teams and operating leaders require.

This is rapidly changing.

Advanced analytics have enabled leading private equity firms to map specific dimensions of human capital ROI (HCROI) directly to metrics that matter— not just to HR, but to investors and boards:

A top leadership team that operates with shared clarity on priorities, roles, and protocols can make strategic decisions swiftly and avoid costly drift. In contrast, when alignment is weak, organizations bog down in committees, misinterpretation, and second-guessing. This slows EBITDA improvement and constrains effective scaling.

When each level of the organization understands “who does what, with whom, to deliver what,” it eliminates execution drag. Clear definition of accountabilities and reporting lines sustains throughput and diminishes resource waste— contributing directly to higher operating margins.

Predictable, disciplined execution cycles ensure major initiatives don’t stall after board approval. When the cadence of communication, reporting, and course-correction is established, not only do strategic rollouts gain velocity, but mid-course corrections become easier—protecting timelines and minimizing slippage in target achievement.

The real potential of an organization is realized

when workforce focus is channeled toward valuegenerating initiatives. A distracted, misaligned, or reactive workforce squanders investment; a mobilized one creates outsized returns with the same resources.

The collective mindset and discipline around KPIs, accountability, and shared purpose determine whether a company’s performance peaks at mediocrity or reaches top-quartile benchmarks. A cohesive system here ensures sustained performance against strategic plans.

None of these dynamics operate in the abstract. Each can now be measured, benchmarked, and—increasingly—engineered to support both operational and financial objectives throughout the deal lifecycle.

Misconceptions persist. The term “culture” is still treated as an HR codeword: employee engagement, a line on the Mission statement, or the aesthetic of a company’s workspace. While these can offer signals, they’re just surface proxies. The real substance is below the surface, embedded in business routines, information flows, decision rights, behavioral norms, and the day-to-day translation of strategy into execution.

Organizations that treat these aspects as strategic—tracking them systematically—gain a formidable advantage. Consider the challenge for

a GP facing two prospective assets: both show similar historical EBITDA and operational KPIs, but one has measurable gaps in leadership alignment and decision tempo, identified through analytic overlays that map directly to value drivers. The GP with organizational intelligence can anticipate post-close friction, price risk accordingly, or design focused interventions to unlock latent asset value.

Conversely, post-close, a clear picture of organizational health answers the critical questions: Are teams mobilized around the right priorities? Are leadership disagreements holding up key decisions? Are organization-wide communication flows enabling or stalling execution? When tracked, these variables allow for leading indicator management—intervening before financials show lagging pain.

Traditional HR systems—such as ADP, Workday, or

BambooHR—serve foundational needs in payroll, compliance, and records. But they stop short of surfacing the intelligence required by today’s valuefocused investors and operators. What changes the equation is the deployment of analytics overlays: platforms or processes designed to integrate with existing systems, harvest targeted feedback (quantitative and qualitative), and synthesize it into actionable dashboards that correlate directly with business KPIs.

Modern overlays provide:

• Execution-focused dashboards: Realtime displays that tie organizational metrics (alignment, clarity, accountability) to financial drivers like margin improvement, employee churn, or project velocity.

• Alignment scans: “Pulse checks” across leadership and business units, identifying pockets of friction, communication breakdown, or misinterpretation of strategic intent before they become systemic.

• Cross-functional effectiveness reports:

Mapping how teams actually collaborate (versus how they’re supposed to), ferreting out hidden barriers to operational throughput.

• Enterprise-level benchmarks: Rolling up insights portfolio-wide to spot common limiting factors, shape capital allocation decisions, and drive the spread of best practices.

This strategic intelligence enables both proactive risk mitigation and aggressive identification of value creation opportunities.

For GPs, the business case is now proven and multidimensional. Four core advantages accrue with the adoption of rigorous organizational intelligence:

Organizational analytics enhance pre-deal assessment with deeper visibility into execution risk—often revealing misalignments, bottlenecks, or unique strengths that aren’t visible on a standard diligence checklist. This reduces the odds of post-close surprises, supports more confident underwriting, and can identify undervalued assets with hidden upside potential once HCROI is optimized.

After close, instead of relying on intuition or generic playbooks, fact-based diagnostics pinpoint where

focus and intervention will produce the greatest business outcome. Whether that’s accelerating a newly-minted CEO’s organizational clarity, helping reset decision rhythms, or shoring up teams ahead of growth initiatives, these interventions become repeatable levers to move the value needle.

As buyers become savvier, they demand proof of not just performance but resilience—evidence that execution risks have been neutralized and that any step-up in value is sustainable. Business intelligence overlays arm deal teams with compelling narratives (and hard evidence) to de-risk premium multiples or allay skepticism during diligence.

The transformative power of new intelligence isn’t limited to individual assets. By aggregating insights across the portfolio, GPs create an institutional capability for continuous monitoring, risk management, and opportunity identification. Systemic issues can be flagged early, and best practices can be systematically spread—raising the baseline of value creation across all portfolio companies.

Operating CEOs face heightened pressure to turn strategy into bottom-line results. However, the internal mark of a high-performing CEO is their

ability to see—often in real time—where teams are aligned or drifting, where priorities are understood or miscommunicated, and where initiative momentum is stalling or surging.

Organizational intelligence tools put these insights at CEOs’ fingertips, enabling:

• Alignment across top teams, ensuring strategy isn’t interpreted differently in silos.

• Real-time feedback loops that surface readiness for key initiatives before resources are wasted.

• Clear measurement of initiative velocity, facilitating corrective intervention well before numbers miss.

• Insight into communication gaps or role confusion that may drag on margin or revenue execution.

This clarity makes CEOs better coaches, frees up time previously lost to firefighting, and allows for proactive, precision-based management of both strategy and talent.

The beauty of the new business intelligence paradigm is the quantification: For every dimension measured—alignment, clarity, accountability, communication—firms can calculate, over time and across assets, the impact on HCROI, EBITDA, retention costs, and revenue velocity.

For example:

• Improved alignment and leadership clarity

mean faster decisions on new product rollouts, reducing time-to-market and capturing incremental revenue.

• Clear operational cadence allows companies to act on opportunities faster than lessdisciplined rivals, directly boosting competitive advantage and, in many cases, allowing expense optimization by eliminating redundant meetings or processes.

• Enhanced accountability lowers voluntary turnover and the hidden costs of rehiring and retraining, while ensuring critical deliverables meet board expectations.

Incremental improvements, tracked consistently and managed proactively, can add measurable basis points to operating margin and help nudge enterprise value upward—results that reverberate at the exit.

Deploying these intelligence overlays is increasingly seamless. Adoption typically follows five steps:

1. Integration with existing HR systems to pull foundational data.

2. Collection of targeted leadership and team feedback on areas that directly map to value creation or strategic objectives.

3. Construction of customizable dashboards that translate these metrics into business terms relevant to GPs and CEOs.

4. Establishment of automated, real-time alerts for emerging frictions, alignment drift, or surging strengths.

5. Ongoing monitoring of organizational health through regular “pulse” surveys, workforce analytics, and feedback sessions.

The result: continuous, unobtrusive insight that powers informed decisions without disrupting operational cadence.

The real power of business intelligence is realized when discipline is maintained:

• Avoid overreliance on generic engagement surveys that miss nuances in business-critical behaviors.

• Resist investing in large-scale system overhauls driven by technology rather than operational need.

• Ensure that every tracked variable is unambiguously linked to business value— tailored to the unique investment thesis, sector context, and operational priorities.

• Do not allow “organizational intelligence” to become a new catch-all phrase. Instead, focus on contextualizing and actioning only those

insights directly tied to strategic and financial outcomes.

For private equity firms and performance-driven CEOs, the measurement and management of workforce dynamics isn’t just a nice-to-have—it’s a structural imperative. Today’s market demands resilience, executional precision, and faster value creation, making organizational intelligence the linchpin of deal success.

For GPs, business intelligence increases alpha by raising risk visibility and sharpening post-close intervention. For CEOs, it provides the clarity, focus, and momentum needed to actualize strategic aims and create outsized returns.

Organizational intelligence is no longer a mystery, nor is it “soft.” It’s a measured, structural asset— an engine for sustainable growth and competitive outperformance.

TOM BRADBURY Founder and CEO

Broad-Gauge

Broad-Gauge specializes in providing metrics to Middle Market leaders and Private Equity stakeholders that quantify organizational culture and effectiveness. When implemented, these metrics provide actionable insights that impact an organization’s financial performance typically with an initial payback in less than 1 year.

BY MARK SINATRA

Maximizing return on investment (ROI) is crucial after acquiring a portfolio company. The stakes are high, and the pressure is on to ensure the acquisition not only boosts the portfolio but also delivers long-term value. However, it’s important to take the time to understand what you’ve bought and review each

part of the business so you can make deliberate, well-thought-out changes.

During this review, it’s essential not to overlook the HR component. The portfolio company must have the right people, processes, and systems in place to enhance talent management and deliver a strong

ROI. Partnering with a professional employer organization (PEO) experienced in company acquisitions can help you achieve this outcome as you consider the following changes:

While it isn’t always necessary to change members of the senior team after an acquisition, it is quite common. According to AlixPartners, as many as 75% of portfolio company CEOs leave after a PE acquisition.1 Besides finding a new CEO, you might also need to hire for other key roles, such as CFO. In some instances, existing employees may be ready to step up and fill these positions.

Updating the succession plan will also help maintain a steady supply of senior leaders. By evaluating leaders’ readiness for larger roles, you can identify the need for development programs to prepare them for these positions.

Changing the makeup of teams and departments is sometimes unavoidable after a portfolio company acquisition. Whether you need to pursue layoffs, permanent job eliminations, or the realignment of entire departments, restructuring can be an effective way to reduce costs and improve efficiency.

Beyond layoffs, job rotations can be advantageous as they enable employees to develop new skills and potentially improve their productivity. Additionally, by reviewing individual job descriptions, you may discover that making changes at a granular level can help ensure each employee is optimally positioned

for future success.2

To align the portfolio company with its new strategic direction post-acquisition, a culture change may be necessary. This could involve reassessing and potentially changing the company’s core values and ways of working. A trusted PEO can provide the HR guidance needed for an effective culture change, including strategies for hiring individuals who fit the desired new culture.3

As you evaluate the company’s culture and consider possible changes, be sure to assess the following:

• Decision-making processes

• Company policies and HR practices

• Team dynamics and interactions

• Communication channels and overall transparency

Amid potential layoffs, restructuring, and revamping the leadership team, it’s also a good idea to evaluate compensation and benefit plans to ensure they properly motivate employees and align with new strategic goals. This review could lead to the following changes:

• Revising salary structures to ensure market competitiveness

• Updating promotion criteria and performance evaluation methods

• Adjusting performance-based bonus and stock option programs

• Implementing flexible benefit options to address employees’ diverse needs

Benefits are a critical component of total rewards. In fact, an Aflac study found that 53% of employees would accept a job offer with slightly lower pay in exchange for better benefits.4 By upgrading the portfolio company’s benefits program, you can potentially reduce expenses while enhancing your ability to attract and retain talent. A PEO partner can be invaluable here, as it possesses the expertise and negotiation power to help you design an affordable benefits program that employees truly value.5

To effectively hire, pay, and manage a workforce, you need robust infrastructure and systems that support employees and keep the company in compliance with evolving labor laws. Even if a new portfolio company already has some HR technology, it’s wise to evaluate its effectiveness and identify any gaps. Additionally, you might find opportunities to integrate the company’s existing HR technology with the systems you already have in place across your portfolio. These may include:

• Applicant tracking system (ATS) for recruitment

• Payroll system

• Employee onboarding platform

• Benefits enrollment and employee self-service portal

• Online training system

There are several HR systems to choose from, but you don’t have to be an expert. A PEO can be instrumental in evaluating your current HR tech stack and ensuring the portfolio company has the best HR systems and support to manage every HR activity, from hiring to offboarding.6

Implementing strategic HR adjustments after acquiring a portfolio company is essential for its long-term success. By building the right team, fostering a positive culture, and optimizing HR processes, you can strengthen your portfolio and maintain high levels of employee engagement and performance. Aspen HR provides the expertise and resources to help you get it done, affordably and with exceptional quality. Contact us to learn how we can help enhance HR operations in your portfolio companies.7

For more insights on the HR factors to consider in your roll-up strategy, get your copy of The New CEO’s Guide to HR.8

1 https://hbr.org/2023/11/private-equity-needs-a-new-talent-strategy#:~:text=About%20three%20out,after%20the%20acquisition

2 https://aspenhr.com/top-3-ways-to-empower-new-hires-and-ensure-their-success/

3 https://aspenhr.com/5-critical-reasons-smbs-must-hire-for-culture/

4 https://www.aflac.com/docs/awr/pdf/2023-trends-and-topics/2023-aflac-awr-the-state-of-workplace-benefits-and-enrollment.pdf

5 https://aspenhr.com/peo-for-portfolio-companies/

6 https://aspenhr.com/hr-tech-platforms/

7 https://aspenhr.com/contact/

8 https://aspenhr.com/5-hr-changes-to-consider-after-a-portfolio-company-acquisition/

SINATRA CEO AspenHR

Mark Sinatra is the CEO of Aspen HR, where he leads the strategic direction and growth of the company. Prior to Aspen HR, Mark was CEO of Staff One HR, where he led the company through a period of substantial growth highlighted by achieving the Inc. 5000 list of fastest-growing companies for four years in a row, and culminating in Staff One HR’s sale to its largest privately-held competitor, Oasis Outsourcing, in December 2017

BY BORIS POGIL

As important as it is for a company to have its financials in order, the same can be said when it comes to taxes. When contemplating the sale of a business, a seller should consider the value that a Tax Factbook can bring.

What exactly is a Tax Factbook? It’s a comprehensive report that summarizes the tax profile of a business, typically prepared before a sale or merger. It includes detailed information about the company's tax structure, historical tax filings, audit history, and tax attributes.

By investing in a Tax Factbook, a seller may benefit in many ways. One such benefit is the ability to identify tax issues or red flags ahead of a planned sale/merger so that the seller can correct the issues before they arise in due diligence. For example, if a company has not historically filed sales tax returns in states where it should have, the company may consider entering into voluntary disclosure agreements with the states prior to the start of due

diligence. By doing so, the company strengthens its tax profile and eliminates potentially thorny tax issues that may cause a buyer to become hesitant during the due diligence process or delay the closing.

Another notable benefit of a Tax Factbook for the seller is that it can reveal or highlight a company’s tax attributes that enable it to obtain a higher selling price. For example, a company may discover that it has larger NOLs or tax credits than anticipated, or that its tax profile favors one type of transaction structure over another – such an asset sale instead of a stock sale.

Ultimately, a Tax Factbook has many benefits. It can enable a seller to command an increased sale price, it can eliminate tax “problems,” and it can help streamline the sale process by bringing to light all material tax matters that a buyer would care about when conducting tax diligence on a target company.

BY JAVIER DAVILA O15 CAPITAL PARTNERS

Private credit has emerged as one of the fastest-growing segments in alternative investments, driven by the secular pullback of traditional bank lending and the persistent institutional demand for yield, downside protection, and portfolio diversification. One increasingly important borrower profile within this asset class is the independent sponsor-backed company — a middle-market business that relies on a sponsor who raises capital to acquire a business on a transaction-by-transaction basis rather than from a committed blind pool (funded sponsors).

Traditional banks have historically had high lending standards even for traditional sponsor-backed platforms, and even higher standards for sponsors without a committed fund. So, independent sponsors often turn to the private credit market to serve as their primary source of capital to consummate acquisitions. While the independent sponsor model offers compelling opportunities for private credit lenders, it also introduces distinct risks and structural considerations that differ from sponsor-backed deals involving well-capitalized traditional private equity funds. The following article walks through each stage of the private credit investment process, highlighting key factors that attract or deter us from underwriting an independent sponsor-backed deal.

A private credit manager’s origination pipeline is built on deep relationships — with investment banks, advisory firms, management teams, and of

course, sponsors themselves. When a borrower is backed by an independent sponsor, we pay close attention to the quality of the sponsor’s deal sourcing channels. Independent sponsors who consistently source proprietary or semi-proprietary deals in attractive industries often add significant value to the transaction, minimizing auction-driven price competition. Furthermore, independent sponsors who regularly source investment opportunities across the same industry exhibit sector expertise and relationships which cannot be replicated.

Proprietary deal flow from sponsors who consistently bring relationships that wouldn’t otherwise be in a formal auction process is beneficial. Independent sponsors with a history of sourcing high-quality platform businesses or wellexecuted add-ons develop a tangible track record, especially if they can demonstrate attractive returns from prior exits. A strong, reliable base of co-investors or family office relationships serves as credible capital backers and gives us confidence the sponsor will have the capital to close and support the borrower post-closing. Often, we support an independent sponsor by making an equity coinvestment in the transaction ourselves, but we prefer to do that alongside other equity capital providers as well. On the contrary, transactions where the sponsor is still shopping for a meaningful portion of the total required equity as we approach closing is concerning.

We focus on conducting extensive due diligence on

both the company and the independent sponsor in parallel early on. Diligence on the company typically includes an industry assessment, an evaluation of the company’s management team, a view on the overall quality of the asset, sustainability of the company’s cash flows, competitive positioning

across the industry, and exit opportunities. Financial due diligence via a quality of earnings analysis is key to determining the nature of adjustments to Adjusted EBITDA and underwrite to the true earnings power of the business. We prefer to see predictable revenue streams and defensible

margins. Free cash flow conversion is critical as cash flow must be strong enough to service debt comfortably over the term of the credit. We typically engage a third party to conduct an industry market study for sectors we are less familiar with. Cyclical businesses or those exposed to risks from rapid disruption are less attractive. Beyond the sponsor, the company’s management team and day-today operators are critical. We prefer when key management retains a meaningful equity rollover stake to ensure increased alignment and buy-in.

Diligence on independent sponsors typically includes an understanding of their depth of operational expertise, alignment of interests, and their ability to weather downside scenarios. Understanding an independent sponsor’s experience and investment track record is extremely important. Examples of prior transaction experience across the same sector is ideal, and any evidence of value creation plans from prior exits gives us comfort. The sponsor’s own capital contribution, either direct equity or rolling fees, signals alignment too.

Independent sponsors who are former operators themselves often roll up their sleeves post-closing, which we value highly. A meaningful seller equity rollover indicates the founder believes in the company’s upside potential and provides extra cushion for the lender. Plus, it shows the seller is supportive of working alongside the independent sponsor to drive future growth. A streamlined investor group helps ensure clear governance and faster decisions when challenges arise. An independent sponsor’s transaction should be wellcapitalized without using too much leverage at the onset, an adequate equity cushion is extremely important.

Key considerations when preparing a term sheet and ultimately negotiating a credit agreement are outlined below. Each of the unique features of an independent sponsor’s transaction is considered when negotiating terms.

• Leverage: Lower middle market transactions tend to have more conservative leverage, but leverage could creep up for sizeable businesses with significant EBITDA and a conservative equity cushion at higher valuations.

• Security: We typically require first-lien security on all assets. For asset-light businesses, we push for robust cash flow sweeps and strong financial covenants.

• Covenants: Independent sponsor-backed deals often receive financial covenants packages similar to those received by borrowers backed by funded sponsors. We strive to keep financial covenants market given the company’s size and scale, historical performance, and perceived industry risks.

• Equity Backstop: Some lenders negotiate “springing” equity contributions if performance deteriorates. Although this may not always be available given the independent sponsor’s primary capital providers.

Healthy debt service coverage ratios with a clear runway to cover interest and amortization with ample cushion are attractive. Stress testing management’s and the independent sponsor’s financial projections model gives us a view of potential scenarios which may impact future leverage and debt service coverage. Independent

sponsors are typically open to reasonable limits on additional debt, distributions, and relatedparty transactions. If there is a seller note that was required to close the transaction, we ensure it’s deeply subordinated with minimal current pay requirements, if any. Overly aggressive earnouts are typically a challenge for us to get comfortable with, especially if the expectation is that future earnouts will be paid with incremental debt financing rather than the company’s internally generated free cash flow. If significant portions of the consideration are tied to future earn-outs, that creates a certain level of uncertainty.

During the approval process, our entire investment committee shares their input on the risks and merits of the borrower. Plus, we question the assumptions used in our scenario analysis to confirm comfort with the underlying projected performance of the business. Underwriting to sustainable free cash flow generation is paramount. After building a relationship with an independent sponsor and building good rapport, we’re seeking confidence the independent sponsor will stand by the company through a rough patch. No one can guarantee the company’s positive financial performance, but we should feel assured the independent sponsor we’re backing is someone who will make good decisions during difficult times to help guide the business.

Sponsors with thoughtful investment memos, robust third-party diligence, detailed analysis, and conservative projections win trust. Many independent sponsors roll their fees into equity — a trend we view favorably. Over time, following the

closing of several transactions, there are market terms associated with transaction economics. An independent sponsor willing to engage early and work transparently through our credit committee process can facilitate the broader financing process. Sponsors with multiple active transactions and limited capacity to help underperforming portfolio companies can be a challenge to drive investments to closing.

Private credit managers take active portfolio monitoring very seriously as any impairments across the portfolio may negatively impact current fund returns and future fundraising efforts. With independent sponsor-backed borrowers, this discipline is even more critical because the margin for error can be thinner than with large, committed fund managers.

Financial reporting, including timely delivery of detailed monthly and quarterly financials, is a top priority. In many cases, the private credit lender sits on the board, providing early insight into potential issues, especially after making an equity co-investment. In the absence of an equity coinvestment, it is typical for a private credit lender to receive a Board observer seat depending on the terms of the credit facility. Along with this board representation comes information rights and access to receiving information in a timely manner alongside the rest of the board members.

Early warning indicators like declining financial performance, customer churn, reimbursement changes, contract losses, or margin erosion are key operational KPIs worth tracking. A sponsor’s

engagement with management post-closing and their proactive approach to adding value is worth noting to provide comfort throughout the term of the investment.

The best sponsors communicate potential issues just as early as recent wins and work collaboratively with lenders to find accommodative solutions to issues which are in the best interest of the company. Sponsors who proactively adjust forecasts throughout the year gain trust by consistently setting and achieving realistic budgets.

In the case of performance declines, it’s helpful to confirm the independent sponsor has the investor relationships required to support the borrower in the near term. A private credit lender is more likely to continue supporting the business with incremental capital in those cases where an independent sponsor demonstrates the ability to inject more equity.

Some independent sponsors are fantastic dealmakers, but not the best operators as they may check out shortly post-closing, especially if they move on to managing another investment or the burdens associated with raising a formally committed fund. If the independent sponsor is incentivized to chase maximum exit valuations at the expense of debt service, that can create misaligned incentives and cause tension. Alignment of interests throughout the investment period is helpful across all investors, both credit and equity alike.

The final test is the borrower’s ability to refinance or sell at a value that comfortably clears the debt

and generates acceptable risk-adjusted returns for the lender. Private credit lenders are actively seeking attractive market returns from each of their investments. Although it’s expected that some credit investments will be smoother than others during the life of the investment, it is also expected that at exit a private credit firm will realize an acceptable return on its investment. Maintaining investments with low probability of default, loss given default, and exposure at default are paramount for realizing attractive returns. If any of these metrics appear to increase over the life of an investment, it’s prudent to consider taking a proactive approach to addressing the reasons why and consider making any changes to the terms of the credit agreement, if applicable.

Independent sponsors with a clear value creation plan post-closing, professionalized financials, and a track record of successful exits often lead to a successful refinancing opportunity or eventual sale. Certain industries such as healthcare, education, and business services, where there are significant industry tailwinds and multiples generally remain resilient are often favorable. Continuity across the management team with limited turnover throughout the investment, and a team who can run the business independently if the independent sponsor is less hands-on is always preferred.

Weak exit markets can present a challenge for private credit investors. If the underlying business is in a sector that suddenly faces valuation compression or other industry-specific challenges, that increases refinancing risk. Independent sponsors who push for short flips may underinvest in the operational improvements that drive long-term value. Most private credit investors

typically underwrite to 5-7 year hold periods, and would expect investments throughout their hold to increase the long-term equity value of the business at exit.

Borrowers backed by independent sponsors can be an excellent fit for private credit investors who understand the nuances of these transactions for several reasons. These investments often come at attractive yields with tighter covenants. Plus, the opportunity for equity co-investments allows for increased alignment between the lender and the entrepreneur. An independent sponsor’s ability to contribute real operational value can create additional downside protection. Conversely, private credit investors with experience financing transactions for independent sponsors can prove to offer a significant amount of support and guidance to independent sponsors throughout the lifecycle of the investment, especially for first-time independent sponsors.

Ultimately, our goal is to ensure that we underwrite not just the company, but also the people behind the business, including the independent sponsor — with an emphasis on alignment, integrity, and capacity to support the borrower through good times and bad.

Several investment opportunities alongside independent sponsors come with the associated risks of an undercapitalized independent sponsor throughout the life of the investment and lack of institutional infrastructure. These transactions generally require higher vigilance, rigorous diligence and additional structural considerations. Independent sponsor-backed transactions are a distinctive niche within the broader private credit landscape. These transactions offer compelling risk-adjusted returns when properly structured but demand disciplined origination, thorough diligence, and robust monitoring. The most successful investments are those where the borrower, the sponsor, and the lender are aligned, transparent, and committed to building real enterprise value and equity value — deal by deal.

JAVIER DAVILA Principal o15 Capital Partners

o15 Capital Partners is an alternative investment firm providing capital to companies led by and serving undercapitalized communities. We believe that private capital, when deployed with intention, can generate strong returns and lasting impact. Javier is a Principal at o15 Capital Partners and is primarily responsible for originating and executing private credit & equity investment opportunities, as well as portfolio management.

BY SETH LEBOWITZ SADIS & GOLDBERG

Section 1202 of the Internal Revenue Code1 permits, under certain conditions, eligible taxpayers2 to exclude from their gross income certain gains from the sale or exchange3 of “qualified small business stock.” The ability to exclude gains from gross income –which means that such gains are effectively exempted from federal income taxation– is a powerful tax planning tool that can make an attractive investment even more attractive on an after-tax basis. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (the “OBBBA”), signed into law by the President on July 4, 2025, made several taxpayer-friendly changes to the “qualified small business stock” rules. Below is a discussion of these changes in the context of the operation of Section 1202.4

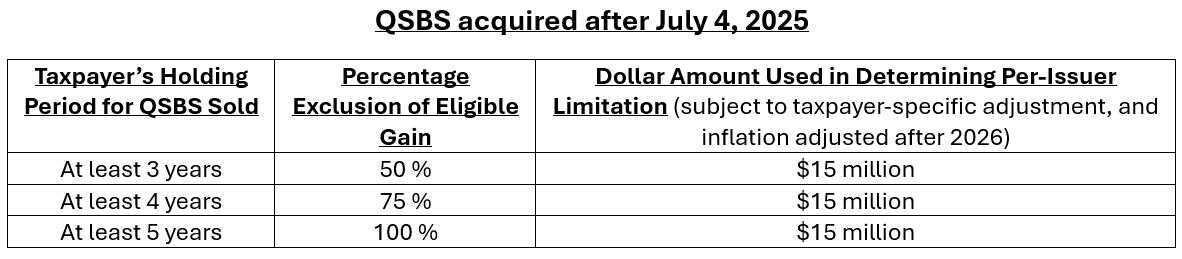

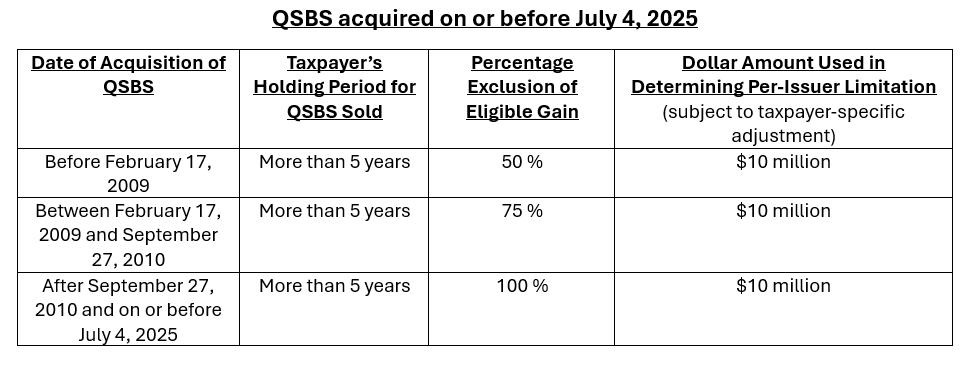

Holding Period(s).5 In general, a noncorporate taxpayer who holds QSBS for a specified holding period can exclude 100% of the gain realized on the sale of such stock.6 For QSBS acquired on or before July 4, 2025 (the “Applicable Date”), the taxpayer must have held such QSBS for more than 5 years in order to be eligible for the 100% exclusion7, and an otherwise eligible taxpayer that held QSBS for any shorter period generally would not be eligible for any exclusion. The OBBBA changed this holding

period requirement to allow a 50% exclusion of the gain from sale of QSBS held for at least 3 but not as many as 4 years , a 75% exclusion of the gain from sale of QSBS held for at least 4 but not as many as 5 years, and a 100% exclusion of the gain from sale of QSBS held for 5 years or more.8

Under pre-OBBBA law (and for current and future sales of QSBS that was acquired on or before the Applicable Date) an otherwise eligible taxpayer who sold QSBS after, say, 4 years and 11 months was not permitted any gain exclusion at all. For QSBS acquired after the Applicable Date, such a taxpayer would

be eligible for a 75% exclusion after a holding period of 4 years and 11 months, and for a 100% exclusion after a holding period of 5 years or more.

Per-Issuer Limitation. The amount of gain from the sale of QSBS otherwise eligible for exclusion from gross income by a taxpayer is not unlimited. Rather, the selling taxpayer must determine whether and to what extent the gain otherwise eligible for exclusion is subject to the “per-issuer limitation.” As its name suggests, this limitation is applied by a taxpayer on an issuer-by-issuer basis; that is, a taxpayer who

sells QSBS issued by multiple corporations would calculate this limitation separately for each such issuing corporation. Only the amount of otherwise eligible gain that does not exceed the per-issuer limitation is permitted to be excluded from gross income in whole or in part under Section 1202. The per-issuer limitation is the greater of (i) a specified dollar limit and (ii) 10 times the aggregate adjusted bases of QSBS of that issuer sold during that taxable year.

The OBBBA increased the specified dollar limit for dispositions of QSBS that was acquired after the Applicable Date. For QSBS acquired on or before the Applicable Date,9 the specified dollar limit applicable to a taxpayer with respect to a particular QSBS issuer for a taxable year is $10 million, reduced by the aggregate amount of gain previously taken into account by the taxpayer under Section 1202 in prior taxable years with respect to QSBS of the same issuer.

For QSBS acquired after the Applicable Date, the specified dollar limit applicable to a taxpayer with respect to a particular QSBS issuer for a taxable year is $15 million,10 reduced by the sum of (i) the aggregate amount of gain previously taken into account by the taxpayer under Section 1202 in prior taxable years with respect to QSBS of the same issuer and (ii) the aggregate amount of gain previously taken into account by the taxpayer under Section 1202 for the taxable year and attributable to stock acquired on or before the Applicable Date.

The “greater of” rule used to determine the perissuer limitation is obviously taxpayer friendly, and the increase from $10 million to $15 million as enacted by the OBBBA adds to this taxpayer

friendliness. Worth noting in this context, although it is a pre-existing rule rather than one enacted by the OBBBA, is a special basis rule used for purposes of Section 1202, including for purposes of the perissuer limitation. Under this special basis rule, in a case where a taxpayer transfers property (other than money or stock) to a corporation in exchange for such corporation’s stock, the basis of such stock in the hands of such taxpayer shall in no event be less than the fair market value of the property exchanged. Without this special basis rule, a taxpayer that contributes low-basis but high value property to a corporation in exchange for QSBS would have a lower per-issuer limitation in connection with a later sale of QSBS of that corporation.

The effective dates of the OBBBA’s changes to the holding period rules and per-issuer limitation can potentially cause confusion, because multiple dates are referenced –the date of acquisition of the QSBS, the date of disposition of the QSBS, and the date the OBBBA became effective. An illustration of the dates of applicability of these rules (simplified for ease of use) is shown in the two charts.

Definition of QSBS. In order to take advantage of Section 1202 and the holding period and perissuer limitation changes made by the OBBBA that are discussed above, a taxpayer must in the first place own stock that meets the definition of QSBS.11 The OBBBA made a significant taxpayerfriendly change that affects the definition of QSBS issued after the Applicable Date. QSBS generally is defined by reference to the taxpayer who acquires, holds, and later disposes of the stock, as well as by reference to the corporation that issues such stock. In order to be classified as QSBS, (1) the stock must

be stock of a C corporation12; (2) the corporation that issued the stock must have been a “qualified small business” as of the date of issuance; (3) the stock must have been acquired by the taxpayer at its original issue (either directly from the issuing corporation or through an underwriter) either in exchange for (i) money or property other than stock, or (ii) as compensation for services provided to such corporation (other than as an underwriter of such stock) and (4) during substantially all of the taxpayer’s holding period for such stock, such corporation must meet an “active business” requirement.13

In order to be classified as a “qualified small business” at the time of issuance of stock, a

corporation must meet a maximum “aggregate gross assets” test under which its aggregate gross assets, determined in accordance with specified rules in Section 1202, may not exceed a specified dollar value at any time prior to the issuance of such stock14 and may not exceed that specified dollar value immediately after the issuance (taking into account amounts received in the issuance).

The OBBBA increased the maximum dollar value used to determine qualified small business status to $75 million, from $50 million under pre-OBBBA law. Thus the potential qualified small business status of a corporation that issues stock after the Applicable Date is tested using a $75 million maximum for aggregate gross assets, whereas the potential

qualified small business status of a corporation that issued stock prior to or on the Applicable Date is tested using a $50 million threshold for aggregate gross assets. The OBBBA’s increase in the size of a potential qualified small business is very taxpayer friendly, as it allows some businesses that would not have qualified previously to qualify, and it also potentially facilitates a higher per-issuer limitation for certain shareholders because shareholders generally will have the opportunity to contribute property of greater value, or a larger amount of cash, in exchange for stock without violating the

limit on the issuing corporation’s aggregate gross assets.

The changes to the QSBS rules made by the OBBBA will provide additional opportunities to taxpayers such as founders and employees of, and investors in, start-up and small businesses to make equity investments in a way that, if all required conditions are met, could end up providing them with significant tax savings on the sale of appreciated stock.

1 Referred to hereafter simply as “Section 1202.”

2 Special rules apply to noncorporate taxpayers that are partners of partnerships that own qualified small business stock. For purposes of illustrating the recent changes to Section 1202, this article focuses on a direct owner of stock rather than a partner of a partnership that owns stock.

3 For brevity, a “sale or exchange” is hereafter referred to simply as a “sale.”

4 Due to the focus on changes made by the OBBBA, not all aspects of Section 1202 and its application are discussed herein. Other aspects of Section 1202 and its application, as well as the interaction between post-OBBBA Section 1202 and Section 1045 of the Internal Revenue Code, will be addressed in the future.

5 Section 1202 contains several special rules for determining the acquisition date of stock for QSBS purposes, which are not discussed herein.

6 Subject to Section 1202’s per-issuer limitation, discussed below.

7 Applicable to QSBS acquired after September 27, 2010. There exists under pre-OBBBA law a 50% exclusion and a 75% exclusion for QSBS acquired prior to a specified date in 2009 during a specified period in 2009 or 2010 prior to September 28, respectively, and these exclusions will continue to be available to otherwise eligible taxpayers post-OBBBA, but they are not discussed in the main text of the article because they are much less frequently applicable to sales of QSBS in 2025 and beyond.

8 The contrast between “more than 5 years” and “5 years or more” is noteworthy even though it would only affect sales that occur after a holding period of exactly 5 years.

9 Whether QSBS was acquired before, on or after the Applicable Date, the specified dollar limit is reduced for married taxpayers filing separate income tax returns.

10 This dollar amount will be adjusted for inflation starting after 2026.

11 Pursuant to rules not discussed herein, under certain circumstances, stock acquired upon conversion of QSBS, and stock received in certain tax-free transfers may be treated at least in part as QSBS.

12 QSBS must have been originally issued after the date of enactment of the Revenue Reconciliation Act of 1993.

13 Certain stock redemptions of stock by the issuing corporation within the 4-year period beginning on the date that is 2 years before issuance of stock that otherwise would be QSBS can turn such issued stock into non-QSBS, i.e., into stock that is not eligible for the Section 1202 exclusion.

14 This test is also applied to any predecessor of the corporation whose status as a qualified small business (or otherwise) is being determined

Sadis & Goldberg

slebowitz@sadis.com

Seth Lebowitz is a partner in the firm’s Tax group. Seth advises clients on the taxefficient planning and execution of a broad range of transactions, with a particular focus on the formation, operation and investing activities of private equity and hedge funds. Seth has experience with: Domestic and international tax issues relating to fund structuring

• Joint ventures and partnerships

• Corporate and real estate investing

• Lending Securities trading

• Distressed investing

• Financial Products

BY ROBERT CROMWELL SADIS & GOLDBERG

Over the past decade and a half in particular, the growth in importance of the private credit markets for completing middle market business acquisitions and for providing post-acquisition working capital lines of credit has been a huge driver of middle market business growth and expansion. Acquisition funding and working capital facilities provided by the nonbank lender is frequently an irreplaceable staple in the business plans of independent sponsors and committed capital funds. For legacy

owner operators as well, nonbank lenders step up to provide working capital to grow operations, or to keep operations afloat when the going gets tough.

While non-bank debt can provide flexibility, speed, and access to capital in situations where traditional banks are unwilling to lend, it also comes with its own set of challenges, some of which may not be fully appreciated until after the financing has closed. In this article, we highlight a series of issues that can arise when using non-bank debt financing,

with the goal of helping borrowers avoid pitfalls and understand possible optimal approaches.

You’ve heard this attorney’s lament before: I wish you had involved me before you signed the letter of intent. The dynamics at play that lead to that scenario frequently are understandable. However, the dynamics at play with a loan or credit facility

commitment letter with a nonbank lender may be quite different.

The lender may earn a commitment fee or other substantial fee when the letter is signed, notwithstanding that the “commitment” is entirely conditional at that time. If the ultimate loan amount that the lender is willing to underwrite is reduced, is that loan commitment fee then reduced? What if the conditions ultimately cannot be satisfied? If the initial payments upon signing are tied to projected

costs, are costs realistic? Are the costs open-ended? Are the terms related to the loan underwriting generic, and if so, does this indicate a risk that the lender will not understand the credit well enough to sign off on the underwriting? We have seen all of these issues in signed commitment letters that we received only after signing, and we have seen would-be borrowers get burned by a subsequent disconnect between borrower and lender after the commitment letter has been signed.

We have occasionally seen lenders that cannot deliver the funding and we have occasionally seen lenders that seem more interested in the fees they earned by signing the commitment letter than actually completing the transaction. Less disappointing, but possibly equally troublesome, borrowers may not fully understand the negative covenants, the borrowing base maintenance requirements, the security requirements and/or the other deliverables summarized in a commitment letter until after (post-signing) review with their legal counsel. Broadly speaking, commitment letters should be reviewed and negotiated in a similar fashion as the actual credit agreements, and the focus should include ensuring that conditions precedent are realistically achievable and potentially narrowing any material adverse change or other type of lender discretionary outs.

How restrictive are the financial covenants, operational restrictions, and reporting requirements in the loan documentation? How much room is there for hiccups or worse in the

business plan? Do any of the following actually conflict with the business plan, or will they be overly onerous to fulfill:

• Total leverage/debt service coverage/fixedcharge coverage ratios;

• Borrowing base coverage (and exclusions);

• CapEx limitations;

• Asset sales requiring lender consent;

• Onerous reporting obligations such as weekly borrowing base certificates or rolling 13-week cash flow forecasts

• Etc.

What will happen when the covenant package that seems workable when agreed to turns out to be prove too restrictive in practice, or upon some small level of underperformance relative to the business plan? This is where understanding the lender’s reputation is key. It is not simply a matter of “are they loan to own?”—probably not, although that is a question to consider. It is more a combination of two key factors:

• Does the lender understand your business, and how committed are they to seeing you succeed?

• What is the lender’s approach to waiving defaults and restructuring covenants—does the lender approach this as an opportunity to extract exorbitant fees and juice its returns to borrower’s detriment and possibly such that the default cycle is designed to continue, or do they take a more reasonable approach designed to bring the loan back on track based on reasonable requirements?

What can borrowers do to address these possibilities? Running performance models against

all maintenance requirements and deliverables using realistic downside scenarios is one important step. Frank discussions with the prospective lender and due diligence on the lender’s track record are perhaps more important.

Receivables-based financing, such as factoring arrangements or asset-based loans (ABL) frequently are utilized for working capital liquidity. The same as with other types of credit facilities, these arrangements should be closely scrutinized to assure they deliver the result that the borrower expects.