SACREDWEB

A JOURNAL OF TRADITION AND MODERNITY 1

Robert Bolton: Modern Culture ond Rising Entropy

Ananda K. Coomoraswamy: On the Pertinence of Philosophy

Ramo P. Coomoraswamy: The Search for Authenticity

James S. Cutsinger: On Earth as it is in Heaven

Roger lipsey: The Great Work is the Small Work

Seyyed Hossein Nasr: Frithjof Schuon (1907-1998)

Kenneth Old meadow: Metaphysics, Theology and Philosophy

William W. Quinn: On Revelation, Initiation and Culture

Frithjof Schuon: Tradition and Modernity

L::U ,

"-ZF

SACRED WEB

Cover graphi c by Susan Point, TbeShaper, 1992, acrylic on canvas , detail

Cover graphi c by Susan Point, TbeShaper, 1992, acrylic on canvas , detail

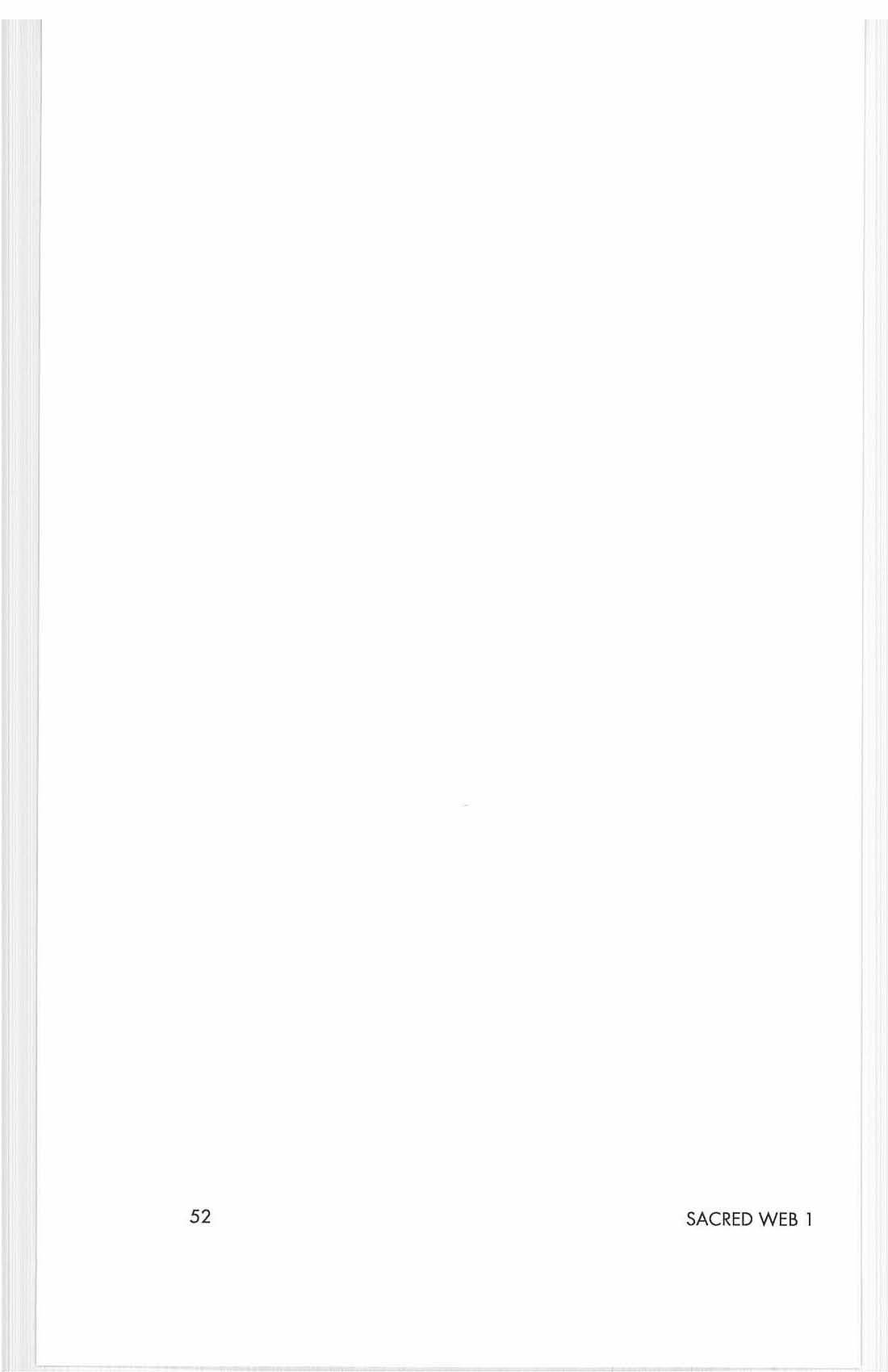

Susan Poin t, The Shape,., 1992 , acrylic on canvas

"lhis Painting is an adaptation of a traditional spindle whorl design. "111e spindle whorl is a disc tha t acts as a flywheel on the spinning device used for making woo l yarn. The spindle whorl has been tr..Ldit ionally used by Coast Salish women 10 spin and ply mountain goat wool into yarn for weaving.

111is work shows a human figure holding up the earth. 'J11e thunde rbirds (represent ing wildlife) support tbe human figure , whose hands they shape. 111e earth , in tum , has a body that supports both Ihe thunderbirds and the human figure. Ins ide the earth art:' two Ihunder lizards. (3olh thu n derbirds contain hum:m faces.

"[his painting is meant to convey the notion tbat all life is inter-re lated and that man, being the shaper of this world , must always be guided by this fact if he is 10 be a good caretake r of the planet .

SACREDWEB

A JOURNAL OF TRADITION AND MODERNITY

Publisher & Editor:

M. Ali Lakhani

ISSN: 1480-6584

Publication:

Sacred l17eb is a bi-annual p ublicat io n devoted to the study of Tradition and mod ern ity The views expressed in the journal a re th ose of th e respective authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Subscriptions:

To subscribe, pl ease mail cheque or money order to Sacred Web, 1750- 111 1 West Georgia Street, Vancouver, British Columb ia, Ca nad a, V6E 4M3: Canadian subscriptions: 515.00 per issue or S30.00 annua lly ; US subscriptio ns: S12.50 (US) per issue or 525.00 (US) annually; outside No rth America, and ins ti tu ti o nal su bscriptions: SI5.00 (US) pe r issue or S30 (US) annua ll y. Postage prepa id for all subscriptions

Subnrissions:

The editor invi tes submissions, induding articles, re views and letters. Unso licited submissions will nor be returned unless accompan ied by a se lf-addressed, stamped envelope. TIle editor reserve s the right to ed it lette rs Submissions should bemailedtotheedito r. M.AliLakhani . Sacred Web, 1750- 1111 West Georgia Street, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, V6E 4M3, or sen t bye-mai l to "Iakha l1i@Ul1iseroe.com".

Copyright:

© July, 1998. Unl ess indicated otherwise, all materials published in this issue a re copyrighted by Sacred Web and the respective contributors . The name Sacred We b and the Sac r ed Web logo a re copyrigh te d by the publisher.

Acknowledgements:

Th e publisher gratefully acknowledges each of rhe contributions in thi s issue, and, in particular, permission to reprint the follow in g: the article by Schuon and the quotati on (a t p age 14) from Stations o/Wisdom appear b y p e rmi ssio n of the author; the article by Ana nd a K. Coomaraswamy appears by perm iss io n of Rama P. CoomaraswamYi an C'Jrlie r version of t he art icle by CutSinge r was published in Dialogue & Affiance, and appear s by thei r permiss ion and that of the author; the article by Oldmeadow is excerpted from h is forthcoming book and appea rs by permission of the auth or. The artwork by Susan Point (The Sbape r) is co p yrighted by her. The graphics by Michae l Be nder (the Sacred w eb logo a nd the illustration accompanying the quotation from Schuon) were conceived by the publisher and rendered by Mic hael Bender. The publisher also thanks th e many individuals who have h elped to launch thi s journa l by donating their time and resour ces, and, in panicu la r, James We tm ore for his invaluable adv ice.

Table of Contents

Editorial

by M. Ali Lakhal1i

In this introduction 10 "SacrtXI Web", the Editor conLrasts the out looks of Tradition and mod<..-rniIY, and outlines the raison d'etTe of the journal.

The Great Work is the SmaU Work

by Roger Lipsey

In a coO\' ivia l 5('1[in8 beneath an open lea lent not far from Marrakcsh, Dr Lipsey rcO"::C1S upon Ihe objl.'Clivcs of the journal.

Frithjof Schuo" (1907·1998)

by Si.yyed l/osseill Nas r

A tribule by Dr. Nasr 10 one oflhc great expositors of Tradition

Tradition and Modernity

by Flilbjo/Sc/m on

"In the f;ICC of lhe perils o f the modern world , we ask ourselves: What mu st we do? " '!11is pape r was p reviously published under the tiLle "No Activity wilhout Truth ",

Metaphysics Theology and Philosophy

by KellIw/b Oldllleadow

What is meant by "metaphy sks" within TrJdition? Dr. Oldmeadow's lucid analysis from his fonhcorning book on Tradition expl ores this issue by contrasting mctaphysks with theOlogy and philosophy _

On the Pertinence of PhJlosophy

by A"a"da K Coomamswamy

CoomarJs"'amy's essay dis t inguishes between the different meanings of "philosophy', deBm_os the " First Philosophy· of Tr:tditional metaphysil.-s, :lnd considers the problem of -immonality"

7 9 15 19 31 53

Ancient Be liefs or Modern Superstitio ns : The Se arch for Authenticity

by Rmna P. Coo m araswa my

By what criteria can wc discern Tru t h? Arc these cri teria ob jective or subjedive' The author examines the "belief systems " of Tradition and modern ity in this p.1ssionatc plea for recourse to thc "Ancientlc-Jchings" of the great religiOUS lrJditions.

On Earth as it is in Heaven

by james S. Cu tSi nger

This article tackles the ' cvolutionist controversy' and proposcs a basis for the reconciliation of cmanation, creation and evolution. 111C author aims "10 present an account of an cllolving world ' per ascen$unf fully consistent with thc principles presupposed 'per dcsccnsum' by mCI:tphysics and th c ology".

On Revelation , Initiation and Culture

by William n;': Qui ml

To what exlcm is it necessary 10 particiJxuc within a ' Traditionll organilation " for the purposes of spiritual initiltion , and can s uch participa tion even occur within the conditions of modernity? The author examines these issues and contrasts Inc views of Guenon and Coomara!iWamy on this suhject.

Modern Culture and Rislng Entropy

by Robert Bo lr o1/

The scienlific concep t of 'entropy' has parallels in an older a n d u n iversal metaphysical conccpt. In this essay , the author applies that concept to modern cullure In Its various manifestations ranging from the domains of economics and politiCS to art and science, and t he inrli\'iduallife

73

Contributo rs Artwork 91 115 131 139 by Susa n POint Frontispiece by M ich a el Ben d er !1lustration 14

Editorial

by M. Ali Lakhani

Tradition a nd modernity a re two separate outlooks by which to judge th e s tat e of the conte mporary world. By "Tradition " we mean soph ia perennis o r prim ordial wisdom , wh ich is not limited to any specific c ultura l or religious tradi ti on. Tradi ti onalist w rit ers have di stingui shed betwee n the te rm s "contempo rary" and "modern", t he fo rm er designating thal whi ch is of th e present age, be it traditi o nal o r modern , and the latt e r, in con trast to Tradition , designat ing "that w hi ch is cu t off from th e Transcendent , from the immut a ble principles wh ic h in rea lity govern all things and whic h are made known to man through revelation in it s most uni ve rsa l se nse" (Nasr).

To spea k of the co nt emporary world is to evoke a certa in amb ivale nce. On the one h and, we are the "c reatur es of our lim e" and so we celeb rate it s o utward accom pli shments, whi ch for th e most part are scientific and te chn olog ical. These range from the ac hievement s of medica l scie nce, lO co mputer technology, lO spa ce trav el and ot her marve ls, that almos t make us b e li eve that we are gods cap able of anything. And we ce lebrat e our apparenl maturity ev ident in ou r respect for basic ri ghts an d freedoms , and in our socia l conscie nces w hich manifest in a var iety of movements rang ing fro m mu lt icultura l and feminist to ecologica l and co nsu me rwadvocacy. On the other hand , despite the grea t p rivileges of our era-whic h , arguab ly, co nfer upon us lhe equall y great responsibility to mak e use of our gi ft s respec tfull y and for th e be tt er ment of the world and o urse lves-we ex peri ence a p ro fo u nd malaise that has bee n te rm ed "th e malaise of modernity. n

From thi s per spective, w herever mankind turn s its gaze, it no longe r

SACRED WEB 1 7

witnesses "the coun tenance of the Divine." Instead, it is confronted by a world of increasing fragmentation and spirit ual poverty; a world accultured by the hubris of science and the materialistic creed of economic exploitation undertaken in the name of "Progress", which leaves in it s wake a myriad of divisions: broken families, a n alienated and apathetic society, a pitting of man aga inst nature, and a self divided from Spiril and Intellect. Ve iled thu s from its ce lestial origin, mankind in the grip of modernity is without anchor or rudder, buffeted by the storms of its passions. Decentered man, e nslaved by hi s passions, lives in a world assaulted by th e seduct ion of hi s senses, a world of promi scu ity , consumerism, crime, corruption, bigotry, exploitat ion, disease, overpop ulation, famine , envi ronmen tal degradation, the arrogance of power, the poverty of declining va lu es, a world of increasing comp lexity and globalization, of augmented alienation and dimin ished humanity, a universe charac terized by the cog nitive and ethica l r elat ivism of postmodernism, the sclerotic dogmatism of secular and religious fundamentalism, and-what may be termed the defining feature of modernity -a loss of the sense of the sacred.

By contrast, to speak of Tradition is to admit of the Transcendent and th ereby to evoke the sacred. A centra l premi se of Traditional metaphysics is the ultimate integrity of Reality. The goa l of Traditional practices is therefore to realise Reality by d iscern ing it and concentrating upon it. It is through th e faculty of th e Intellect (whic h alone is recept ive to th e "flrst principles" of Tradition) that we can discern (or "divi ne ") that which is Real; it is through the subm ission of the lesse r (human) passions to the greater (spirit ual ) Will that we can hope to merit ultimate peace an d freedom; and it is by rediscovering our sp iritual foundation and the trust of sac redness which is our primordial herit age tha t we can begin to prop erly address the malaise of modernity.

Sacred Web h as been conceived as a journal whose aims will b e to id entify Traditi onal "first principles" and their application to the cont ingent circumstances of modernity, and to expose the false premises o f modernity from the perspective of Tradition. The journal w ill encourage and invite legitimate debate in this area and will seek to examine the interaction b etween Tradition and modernity. It is hoped th at the journal w ill be of interest to the Tradilionalist and gene ral reader alike, concerned about issues of modernity.

B SACRED WEB 1

The Great Work is the Small Work: A Response to this Journal's Mission Statement

Roger Lipsey

Roger Lipsey

At th e kind invitatio n o f Mr. Ali Lakhani, the enterprising founder and edito r of thi s new jo urnal , I respond here to the mi ss ion stat e ment (pp. 7- 8), un de r which h o miletic sign the journal goes forth. r ca nn o t promi se to respo nd syste maticall y; ha ve alway s preferred co nversat ion to o th er forms of exc hange , and p referred literature , however formal , tha t re tain s so me undercurrent of the spoken word. And so, Mr. Lakhani, c an we s it tog e th e r?-for example benea th an open te a tent at a village market not far from Marrakes h.

I remember the scene vividly even now: the worn but welcoming ca rpets and cushi ons, the tumblers filled with mint l ea and sunlight , the rich sounds, s ights, and sce nts of traditional pea sa nt Mu s lim soci ety all around-s mall vendo rs of handcrafted household goods, of herbs and of carpets and buttons, camels and donk eys; these fin e weathered face s b e neath turban s and shawls , each implying a life that had not been eas y, and had been worthwhile. Perhaps in U1e evening and through th e night we ca n att e nd a village ce remony, half religious, half conviv ial. I re memb e r a dance with magical drumming: the vi ll agers gath e red into a line, linked arms and hands , and somehow lifted and folded rhythmica lly. It w as of that very time and place , yet raised us. I was so happ y; you will be, too. All of this was and is the common fa ce o f Tradition , w hi c h s upp o rt s and warms eve n the most refined things of th e sp irit. Let us sit in such a pla ce.

They ca n be found e ven today in nearly all parts of th e world. And I think one can affirm , without being sentimen tal or "Orienta list" in th e invidious sense, that as an urban person of East or West one experiences

SACRED WEB I 9

in suc h sett ings both a deep sense o r well b eing and a stabb in g sense of loss, f o r thi s is not how one lives , nor is the thrust of the modern wo rld leading toward preservation of such things. On the contrary, such timeless environments are burning away , like the vast acreages recently reduced to ash in Indonesia , Borneo , Mexico. You have taken note of this tendency to loss in your mission state me nt.

If that is th e common face o f Tradil ion, s houldn ' t we also remember the uncommon face of il , the sc hools and tea ching/l ea rning circles in which doctr ine and practice a re pa ssed "from mouth to ear, " by sa ges who in th e ir turn s tudied with sages and so on, through the co rridors of time. Some at leas t of these lin eages lea d back to eras of Revelation or to great re novat ors by whom whole traditions were res to red to their original fres hn ess and s h arp c ut. This is a lso the realm of texts-I would willingly cap ita lize to Texts, for th e sc ripture, commentary, practice guides, reco rded myths, histories and tales, the seekers ' jou rn a ls and saints' biographi es th at make up th e library of Tradition are sac red to anyone wh o experiences the ache to be and to know , to unc o ver the Imperishabl e in the obvious fragility of our lives.

As yo u s ur e ly see, r s hare th e regard for Tradition to which you bear w it nes..<;. And ye t ... I have n eve r quite und e rstood why the vo ice ofTradition in our tim e- I su ppose I mean th e voices of Traditio nali s ts- is so often, at limes so lu xuriantly, tha t of prophetic wrath. The Traditionalist jeremiad re ca ll s its grand origina l in sc ripture associated with the prop het Jeremiah , whom th e Lord shaped into a fi e rc e, ever- renewed re minder to the people,

For, beho ld, I have made thee this day a defenced city, and an iron pillar, and brasen walls again st the whole land, again st the kings o f Judah , aga inst the princes the reo r, aga in st the priests th ereof, and against th e people of the land . fjeremiah 1.18)

Blended with the Biblical voice of wrath against the wayward people, does on e no t also hea r in our co nt em porary lamentation th e Quran ic voice:

How many generations have We d es troyed s in ce Noah's time! You r Lord is well aware of His serva n ts' s ins; He observes th e m a ll.

(Quran XV I1.17)

10 SACRED WEB 1

How best to understand th e "defenced city," the "iro n pillar" of 20'h_ ce ntury Traditionalism' It is fully voiced in the third paragraph of the mission s ta tement: " ... a wo rl d of in creasin g fragmentation and spiritual poverty; a world accultured by the hubris of science and the materialistic creed of economic expioilati o n , ... a world of promiscuity , consumerism, crime, corruption, bigotry, exploitation, disease, " and so on. One can say of this passage, I think justly , that it is to be understood as a summary of observat ions made in extenso in the writings of Rene Guonon, Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, Frithjof Schuon, Seyyed I-Iossein Nasf, and o th e r primary expo nents of the Traditional perspective. For many readers of this journal, their writings are magisterial illuminations, the greatest of which o ne will never forget; their thought and pulse enter one.

But is there no danger here--<langer perhaps of a certain self-satisfaction, of pride in knowing the names of the devil? Is there no momentum here , by which one adds insult to injury with a cer tain relish-as if each term further distanced one from the dreadful reality to which it refers?

Practical redemptive wo rk is relentlessly day-to-day , w he th er one seeks at least a littl e to redeem and dignify one 's poor self, or to co ntribute to the lives of othe rs, or to con front resourcefully some cha ll enge on th e larger scales of society and planet. We live under what one wi se tea c her ca lled "the law of sma ll increments, " by which we gain or Jose a littl e eac h day. I am saying, then, that to inventory th e fearful s in s and stupidities o f modernity must never give pleasure, and that the Great Work is the sma ll work, th e day-to-day work. This need not-a lthough it canforce a narrow perspective. One need not-although one doe,s-.lose one's awareness of th e unutterabl e grandeur of Creation and of its Divine Author as one altends to the innumerable details of any sma ll redemptive work. O n the contrary, every reading from a sac red book, every meditation, every communal effort can be a step toward Reality in the sense conveyed as a prayer in Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 1.3.28:

From the unreal lead me to th e real!

From darkness lead me to light!

From death lead me to immortality!

I wonder w hether modern history is merely, and ahjec tl y, a d ivers ion from whatever course events might have taken , had we been wiser. I SACRED

I 11

WEB

wonder whether scie nce and technology are essentially si nful , in that they ca nn Ol bur d ivert u s from what th e mi ss ion statement properly ca lls a sense of th e sacred. In its second paragraph , the sta teme nt see ks to deal fairl y with the contempo rary wo rld by remembering some of o ur achievements-medical scie nce, for example, and s p ace tr ave l w h ich has g iven us ou r first good look at our p lanetary home. But those acknowledgments are drained by a s hort and te ll ing ph rase to the effec t tha t these thin gs provoke an ev il : they "almost make us believe that we are gods capab le of any th ing. " Is th is rea ll y so? Admitte dly , the phrase "maste rs of the universe" has been co in ed, by wits in o u r own c ulture , to describe young financial wizards who ha ve made quick fortunes and fee l on top of the world. But abou t that very com muni ty, a witty novel was written a nd wid ely read , Tom Wolfe's Bon/ireo/the Vanities , w h ic h rath er puts the m in th eir p lace. I do no t th ink that m any o f u s const rue this dangerous world as good proof t h a t "ye sh all be as gods" (Genesis 3.5) or that we are anything lik e gods. Too much AID S, too mu c h ca nce r, too mu c h war, too much poverty, too many frightening eco logica l porte nts , too much socia l d is location, too much violence and noise in th e popu la r arts, too man y se lf-serving po lit ica l leaders. Thi s is my own li st.

But th ere a re more se ri o us questions to as k of modern history and o f our c u rren t cu llUre: i f they are not a diversion into utt er da rkness-if the y are, as a lmost a lways in human affairs, a chiaroscuro throug h which we must of n eces..o:;; ity find our way-t h e n what genera l pe rspec tive might make se n se? And h ow can love and knowledge of Tradition co ntribute to human welfare?

I can n o t a ltogether aband o n the Jud aeo-Ch ristian conviction o f an unfold ing na rrati ve, suffu sed w it h Divine love and intent but offe re d entire ly into our hands by the Good Lord, and b y His will s ubj ec l to ou r ind ividual and co ll ective choices. In thi s li gh t , I do not perceive scie n ce and tec hn o logy as monstrous- h ow cou ld I do so as I write on a firstrate comp ut e r, com muni cate hy e-mail w ith the editor of thi s jou rnal , answer the te lep h one from tim e to t ime, and e xpect eas il y to join friends this eve ning who live at 15 miles' distance across the river? If we c hoose poor ly, science and technology w ill indee d p rove to ha ve bee n mons trou s-not intrinsically so, but In ou r hands. This is, of course, a cl ic he; that does no t mea n it is untrue

We have reache d a s ta ge of cu lture in whic h qua ntit at ive scientific

12 SACRED WEB 1

observation has at last ca ught up with Pasca l's premon itory ver ti go as he co nt e mplate d the "two infinitudes, " t he infinitely s ma ll and th e infinit ely g rea t. This stag e is, lik e all prior stages of c ulture , a fi e ld of choice in which mu ch if not all depends on th e w isdom of ou r choices. What , th en, is th e role of Tradition? Each of us who cares w ill perhap s answer this question a liul e differently. The mission stat eme nt of this promising new jou rnal speaks of th e need "to id entify Traditional 'first principl es' and th ei r applicat ion to the co ntingent of modernity, and to exp ose th e fa lse premises of modernity ... ." Thi s is surely sensib le. But do it with love, by which I mean do it pati ently , with an eye not only to th e Truth but 10 peop le here and now , and n ot on ly to "p eo pl e h e re and n ow" but to thi s very p e rson whom you address and whom you might al so feel and kn ow. Do not permit th e awesome beauty o f sc ripture, and eve n of reli gious practice, to lure you away from co nt act with thi s thinking, feeling flesh that we are.

So mew here in his writings, Coomaraswa my reca ll ed the title of Oliver Go ldsmith 's late 18m-ce ntury play , She SlOOps 10 Conque r He c ited it , as you ca n imag in e, not as a matter of theater history but to mak e a larger point. The s toop into the real tex ture of life that he adv ised remains binding on all who h ave been to u ched and cha nged by our enco unt e rs with Tradition. That "descent, " as you well know , ushers us int o a realm of sac red paradox where the way up is th e way down (Heracle itus), where th e fulfillment of th e highest is consummated through its con ta ct and poss ibl e union with o rdinary things.

Well, Mr. Lakhani, we have occupied this breezy tent through mu ch of th e day and co ns um e d ou r fair share of mint tea. It is s ur e ly tim e to ta ke leave. I value our fra ternal co ntact and tru st that thi s wi ll not have been ou r only o ppo rtunity to exc hange. We can me et later, as I suggested, in th e vill age-but on second th ought , I mu st return to the city where I ho p e to find a pia no to wo rk further o n th e four-voice fu g u e by).S. Bach that has lately give n me no sleep.

SACRED WEB 1

13

"W hat separates man from divine Reality is the s light est of barriers. God is infinitely close to man , but man is infinitely far from God. This barrier, for man , is a m ounta in , which he must remove w ith his own hands He digs away the earth, but in vain, the mountain remains; man however goes on d igging in the Name of God. And the mountain vanis h es. It was never there."

Frith)o! Schuon from "S tations of Wisdom "

Frlthjof Schuon (1907 -1998)

Frlthjof Schuon (1907 -1998)

14 SACRED WEB 1

Frith jof Schuon (1907-1998)

by Seyyed Ho ssein Nasr

On May 5, 1998 , Frithjof Sc hu on breathed h is last in hi s home in Bl oo mington ) Indiana after a protracted illness and was buried in a forest n ear hi s home. He died in the ea rl y hOllrs of the morning in great peace, conscio us to almost the last moments of his life, moments spen t in an arm chair nea r his bed while invoking the Divine Name to which he had d e di cated hi s whole being since his yo uth . SellUo n was born in Ba ste, Sw itz erland of German parents in a family of musicians. Af(er his early educat ion in Ba sle where instruction was carri ed out in German, his fam il y moved to Mu lh o u se where he rece ived a French educa tion , thereby ga ining perfect mas tery of bo t h languages which became t he main vehicles for the ex press ion of his teachings in lat er life.

Afte r serv ing in the Fren ch he moved to Paris where he embra ce d Is lam and lea rn e d Arabic. H e then journeyed to Nort h Afri ca to mee t the great Alger ian Sufi mas ter, Sh aykh Ahma d al-'Alawi a nd later went to Cairo to meet Rene Guenon whose works had con firmed his own ea rl iest intui ti ons and God-given knowledge abou t metaphysics, tradition, the unity of tmditio nal truth and the nature or th e modern world. After adverse experiences du ring the Second World War, Sc hu on sett le d in Lausanne where for forty years he expounded the tMhs of tradition and pres ided ove r th e spi ritu al orde r or Sufi larfqah which he h ad founded as a branch of th e Shiidhi li yyah Order into which h e had been initiated by Shayk h al- ' Alawi. In the 60s , afte r v isio ns of the Holy Virgin, he added the name or Maryamiyya h to the sun Order which he had founded in Europe in the 1930s. Sha ykh ' IsiiAhmad NOr ai - Din al -S hiidhili al -Da rqawi al-'Alawi al-Maryarni , as he was known to the circle o f hi s

WEB 1 15

SACRED

discip les, received see ke rs from not o nl y Eu ro pe a nd America but also fro m throughout th e Islamic wo rld a nd he also had C hri sti an discip les and followe rs as we ll as Buddh ist a nd Hindu ones. Attracted strongly to th e b eauty of the primord i al tradit ion of th e Native Ameri ca ns, he sojourned twice in th e 1960s to America before leavi ng Europ e pe n nanently for the American Mid west in 198 1, whe re h e was to se ttl e. He passed the res t of his days in Bloomington , Ind iana, w he re d es pit e so me turm oil around him h e con ti n ued wi th sere n ity a nd d etachmen t to w rite major wo rks and to guide num ero us m en and wo m e n from near and far s piritually .

Throug hout his lo ng life, Schuo n kept away from the limel ight and always e mph asized t he primary of hi s message over everyt hin g e lse. But hi s numerous works , bo th books and art icles written (exce pt for som e poems, an ea rl y treatise and his autobiography) in Frenc h , soon mad e him a celebrated nam e among tho se inte res ted in gaining a d eepe r un de rsta nding of metaphysicS, the esoteric sign ifica nce of re li gion and th e co nditi ons for an au th entic spi ritual life. H is exposi ti on of the "tr a nsce ndent unity of religions n , auth entic metaphysics, tr aditi o n al ant h ropology, t he traditional do ctr in es o f art, esoterism a nd spiritu ali ty, and th e profo und est c riti cism of th e mo d e rn world mad e a deep impact upon numerous people in both Ea s t a nd West, and far beyond t he ci rcl e of hi s immediate di scip les.

Schuon was not on ly a peerless metaphysician and pill ar of uni ve rsal ort ho doxy and trad it ion, but also a remarkable artist, both painter and p oe t. Endowed wi th the innate gift o f percei ving th e "metaphysica l transp arency of forms" , he produced a large numb er o f p aintings o f an iconic nature a nd also many d epi cti ng tr adi ti o n al Na ti ve American themes. He also wrote two vo l umes of poetry in Ge rman in h is youth and a vo luminous co ll ect ion in the las t part of hi s life which summari ze in poetic form his teac hin gs on both th e m e taphy sical and o p e rative pl anes. H e also composed some English poe try and a numb e r of poems in Arabic in the tradition o f classica l Su fi sm.

Schuo n was wi th out doubt th e foremost expositor in th e latte r half of this cent u ry of the philosophia perennis as we ll as t he soph ia perennis, esote rism and tr aditi o nal metaphysics and ex po und ed th e inner meaning o f diverse religious forms and their transcendent unity in a unique and ma tc hl ess manner w hile always emp ha siz ing the necessity of pre-

16 SACRED WEB 1

serving orthodoxy and following a single orthodox tradition. While the major expositors of traditional teaching s before him , Guenon and Coomaraswamy , emp ha sized doctrine , Schuon never cease d to emphasize in addition to doctrinal matters the importance of sp iritual practice and the cen tral significance of the attainment of spi ritu al virtu es. One cannot in fact read his works and understand them fully w ith out being driven by an inner categorical imperative to choose an authentic sp iritual path and to follow it faithfully. His writings are in reality not only the fmit of theoretica l metaphysical knowledge but also and p rim ar ily of realization of the highest order.

His death marks the departure from this world o f a light of exce ptiona l glow and dazzling brilliance . He leaves behind, however, after sixty-five years of intellectua l and spiritual activity , not o nl y a sp iritua l order, but also a vast corpus of writings which are peerle ss in their depth as well as universality . a corp us con taining tea chings which are at once universal , essenti al, ortho dox and of the greatest practica l sp iritual import. Hi s inHu ence in lands as far apart as Malaysia and Sweden, Ameri ca and Sou th Afri ca is great and his writings have been If"'dnslated already into many l anguages. The light of his presence here on earth is bound to shi ne in land s near and far, and perhaps to an even greater extent than when he was a li ve , long aft e r he had left thi s lowly plan e for th e exalted height s of the Divine Empyrean.

SACRED WEB 1 17

raQi Allahu 'anhu wa 'a nn a bihi.

18 SACRED WEB 1

Tradition and Modernity

by Frilhjoj Schuon

The purpose of this congress l is of the most extreme importance, since it conce rn s, direc tly o r indi rectly , the des tiny o f mankind. In th e fac e of perils of the mod em wo rld, we ask ourselves: Wbalmust we d o? This is an empty quest io n if it be not founded upon antecedent ce rtainties , for ac tion co unts for not h ing unle ss it be the ex press io n of a knowing and also a manner of being. Before it is possibl e to e nvisage any kind of remedia l activity , it is ne cessary to see thing s as they are , even if, as th ings turn ou t, it costs us much to do so; o n e must be conscious o f those fundamen ta l t ru th s th at revea l to us the va lues o f proportions of things. If one 's aim is to save mankind , one mu st first know w hat it means to be a man ; if one wishes to defend the s pirit, o ne must kn ow what is s pirit. "Before doing , one must be, " says the proverb; but without kn owi ng , it is imposs ibl e to d o. "The soul is all that it knows, "as Aris totle said.

In o ur lime one h as ofte n h ea rd it sa id that in order to fight against male ri a li srn--o r mat e riali s t pseudoide ali sm-a n ew id eo logy is ne e ded , one capable of stand in g up to a ll seductions and assaults. Now, the need for an ideo logy or t he wish to oppose one ideo logy to anothe r is already an adm iss ion of weakness, and a nything und e rt ake n on this basis is false a n d doomed to defeat. What mus t be done is to oppose truth purely and

I. This paper was originally wri{{en by SeilUon for a co ngr ess conve ned in Japan in 1961, which dealt with the crisis of modernity. The text was subseque ntly published under the title "No A ct l vlly wllbolll in the l'l:nguin antbology titled "!beSwo ,.d O/G l IOsis" (edited by Ja cob Ncedh!m an ). A version of Ihis paper formed th e text of Sc h uon 's message to th e Hothk o Co ll oqu ium on and Actioll H, held a t Ru thko Ch apd , in Ilus lon, Texas, in July 1973, and wa s read to th e parti c ip,lIl lS by Scyyed Il osscin Nasr

SACRED WEB 1

19

simp ly to the false ideologies , that same tnlth that has always been and that we cou ld never invent for the reason that it exists outside us and above us, The wo rld is obsessed w ith "dynamism" as if this consti tuted a "categorical imperative" and a uni ve rsa l remedy and as if dyn amism had any meaning or positive efficacy outside truth.

No man in his senses can have th e intention of merely subs tituting one error for another, whethe r "dynamic " or otherw ise; before speaking of force and effec ti veness one must th erefore speak of truth and nothing else. A truth is powerful in measure as we assimilate it; if the truth does n ot confe r on us the strength of which we stand in need, this only goes to prove that we have not re ally grasped it. It is not for truth to be dynamic, but for ourselves to be dynamic in function of a true co n victio n . That whic h is lac kin g in the prese nt world is a profound knowledge of the nature of things; the fundamenta l truths are always there, but they d o not impose themselves in actual prac tice because th ey cannot impose themselves on those who are unwilling to accept them.

It is obvious that here we are concerned, not wi th the quile ex ternal data with which experimental s c ience ca n possibly provide u s , but with realities which that science does not and indeed cannot handle and which are transmitted through quite a different channe l , that of myth o logical and metaphysical symbol ism. The symbo lica l language of th e great traditions of mankind may indeed seem arduous and baffiing to some minds, but it is nevertheless perfectly intelligib le in th e li ght of th e orthodox commentaries; symbolism-thi s point must be stresse d-i s a rea l and rigorous science, and nothing can be more naiv e th an to suppose that its apparent naivety springs from an immature and "pre logical " mentality. This science , whi c h can properly be described as "sac red ," quite plainly does not have to adjust itself to the modern experimental approach; the realm of revelation, of symbolism, of purse and direct intell ec tion , stands in fact above both t he physical and th e psychol og ica l realm s, a nd consequently, it lies beyond the scope of so-called scient ifi c methods. If we feel we cannot accept the language of t raditi ona l symbolism because to us it seem') fanciful and arbitrary . this s ho ws we have not yet understood that language, and certainly not that we have adva nc ed beyond it.

Not hing is more mis lead in g than to pretend, as is so glibly done in our day , th at th e re ligi ons have compromised themse lves hopel ess ly in the course of centuries or that they are now pla yed out. If one knows what

20 SACRED WEB 1

a religion really consis ts of, one also knows that the religio ns cannot compromise themselves and that they are ind ependent of human doings; in fa c t , nothing men do is able to affect th e lraditi on<l l doctrines , symbols, or rit es. The fact that a man may exploit religion in orde r to bolster up nationa l or private interests in no wise affects religion as such. In Japan, Shinto , for examp le , was latterly made to serve political ends, but it was in no wise compromised in its e lf by thi s fact , nor co uld it be. Its symbols, rites, traditions, moral code, and doctrine remain what they always were, from th e "Divine Epoch" down to our ow n times; and as for an ex hau sti ng of th e religions, one might speak of thi s if all men by now be co me saints or Buddhas. In that case only co uld it b e adm itted that th e re ligi ons were ex h a usted , at least as regards th eir forms.

Tradition s p eaks to each man the language he can comp re hend, provided he wishes to li ste n The latter pro viso is crucial, for tradition , let it be re peated, ca nn o t "become bankrupt"; rather is it of th e bankruptcy of man th at one shou ld speak, for it is he that has lost all intuiti on of th e s up e rn at ur al. It is man who ha s let himself be deceived by th e dis cove ries and inven ti ons of a falsely tota lit arian science; that is to say, a science th at d oes not recogn ize its own proper limits and for tha t same reason misses w hat ever lies beyond those limits.

Fascinated alike by scie ntifi c phen omena and by th e erroneous conclu s ions h e draw s from th e, man has ended by being submerged by hi s own c rea tion s; h e will not realize that a traditional message is s ituat ed on quite a different plane or how much more real that p lane is, and h e allows himself to be dazzled all the more readily since sc ienti sm provides him w ith all th e exc us es he wants in order to ju s tify hi s own atta c hm e ntt o th e world of appea rance and to hi s ego an d his conseq u e nt flight from th e presence of the Absolute.

People spea k of a duty to make oneself usefu l to SOCiety, but they neglect to ask th e question whether that society does or does not in itse lf possess the usefulness that a human soc iety normall y shou ld exhibit , for if th e individual must be usef ul to th e collec tivity , the latter for its pan mu st be usefullO the individual , and one must never lose sigh t of th e fa c llh at th ere ex is ts no higher u sefu lness than that wh ic h e nvisages the final ends of man. By its divorce from traditional truth-as primarily perceivable in that "flowering fonh " that is revelation-society forfeits its own ju stification, doubtless not in a perfun c tor il y an imal sense, but

I 21

SACRED WEB

in the human se nse. This human quality impli es t hat the collectivity . as suc h , ca nnot be t he ai m and purp ose of the individua l but th at, on th e cont rary, it is t he indi vid ual who , in his "solitary sta nd " before th e Absolute and in the exercise of hi s s upreme functi o n, is the aim of purpose of co llect ivity. Man , w h e ther he be co nce ived in th e plural o r th e s ingular, o r whet h er hi s func tion be direc t o r indirect , s ta nd s like "a fragment o f absoluteness" and is made fo r th e Abso lut e; he h as no other cho ice before him. In a ny case, o n e ca n de fin e the socia l in terms of truth , but o ne c annot define truth in terms of the soci al.

Refere n ce is o ft e n made to th e "se lfis hn ess" of those who busy th e mse lv es wi th sal vation, and it is s aid that in stead of s aving onesel f one oug ht to save ot hers; but this is a n absurd kind o f argume nt , s ince e ither it is impossibl e to save others, or e lse it is poss ib le to s a ve them but o nly in v irtue of our own sa lvati on o r o f our own e ffort towa rd sa lva t ion. No man has ever d one a se rvi ce to anyone else whatsoever by remain ing "a ltru is ti c all y" attac h ed to hi s own d efec ts. He who is capable of be ing a sa int bu t fail s to beco me such cert ainly will save no o ne e lse; it is s heer hypoc risy to conceal one 's ow n weakness and s p iritual luk ewarmness behind a screen o f goo d wo rks be li eved to be indi s p e nsabl e and of abso lute va lu e.

Another erro r, closely re lated to the o n e ju s t po in ted o ut , consis ts in s upposing that con te mplative spi ritua li ty is opposed to a ction o r renders a man incapab le of ac tin g , a bel ie f that is beli e d by a ll the sacred sc riptu res and especially by the Bhagavad-gita. InJapan the exa mpl e of sain ts s uc h as Shotoku Tais hi , Hojo To kimun e, Shinran Shan in , and Nich iren prov es-if proof is needed-that s piritu a lit y is neit he r oppo se d to action no r dep e nd e nt up o n it , and a lso that sp irituality le ads to t he mos t perfec t ac tion w h eneve r circ um s ta n ces require it , ju st as it c an al so, if ne cessa ry, turn away from th e urg e to action when no immediate aim im poses the nee d for it.

To c ut off man from th e Abso lute a nd reduce him to a co ll e c ti ve p henom e non is to d e pri ve him of a U rig h t to exis te nce qua man If man deserves t hat so man y efforts s ho u ld be spen t on hi s beha lf, th is c annot be s imply becau se he exists, ea ts, and s leeps o r because he likes w hat is pl easa nt a nd h ates what is unpl easant , fo r th e lowes t of the anima ls are in s imil ar c ase wilhout bei ng considered for thi s reaso n our e qu a ls and treate d ac cordingly. To th e objection that man is di stingu ish ed from t he

22 SACRED WEB I

animal by hi s intelligence , we will answer that it is precisely thi s intellec· tual superi ority that the social egalitarianism of the mod ern s fails to tak e into account, so mu ch so that an argument that is not appli ed consist· ently to men cannot then be turned against the animals. To th e objection that man is distinguished from animals by his we will answer that th e complete ly profane and worldly "c ulture " in qu es tion is nothing more than a specifically dated pastime of the human anima l; that is to say , thi s culture can be anything you plea se, while wa iting for th e human animal to s uppress it altoge t her. The capacity for absoluteness that characterizes human inte ll ige nce is th e only thi ng conferring on man a right of primacy; it is only this capacity that gives hi m the right 1O harness a horse to a ca rt. Tradition, by its above -worldly chara cter, manife sts the rea l super iority of man; tradition alone is a "human ism" in th e positive se nse of the word. Antitraditional culture, by th e very fact that it is without th e se nse of the Ab solute and even the se nse of truth-for these two things hang together---cou ld never confer on man that unconditional value and those indisputable right s that mod ern humanitarian ism attributes to him a priori and without any logical justification.

The sa me co u ld a lso be expressed in another way: When p eo ple s p ea k of "c uiture," th ey generally think of a host of contingencies, of a thousand ways of use less ly agitating the mind and disp ers ing o ne's attention , but th ey d o no t think of that prinCipl e that a lone co nfe rs lawfuln ess on human work s; this principle is the transcendent tmth, whence springs all genuine culture. It is impossible to defend a culture effectively-such as t he tradit ional cu lt ure of Japan , which is one of t he mo st precious in the world-without referring it back to its spiritual princip le and without seeking ther e in the sap th at keeps li fe going. Agr ee ment as b etwee n cultures mean s agreement on sp iritual principles; for truth , despite great differences of expression, remains one.

Many p eo pl e of our time reason along the foll ow ing lin es: The religions--or the differing spir itua l perspectives within a given religi oncontrJ.dict one ano ther, therefo re they cannot aU be right ; co nsequently none is tru e. Thi s is exactly as if one said: Every indivi dual claims to be " I," thus th ey ca nnot all be right ; consequently non e is " I. " Thi s examp le show s up th e absurdity o f the antireligiou s argument, by re ca lling th e real analogy betw ee n the inevitable external limitation o f reli giou s languag e an the no less inevitable limita tion of the human ego. To reac h

SACRED WEB 1 23

this conclusion, as do the rationalists who use the above argument, amounts in practice to denying th e diversity of the knowing subjects as also the div e rs ity of aspects in the objec t to be known . It amounts to pretending that there are neither pOints of view nor aspects; th a t is to s ay , that there is but a s ingle man to see a mountain and th at th e mountain has but a si ngle side to be see n. The error of the subjectivist and relativist philosophers is a contrary o n e. According to them, th e mo untain would alter its nature according to whoever viewed it; at one time it might be a tr ee and at another a stream. Only traditional me taph ysics does justice both to the rigour of o bjectivity an d to th e rights of subjectivity ; it alone is able to explain the unanimity of the sacred doctrines as well as the meaning of th e ir formal divergencies.

In so und logic, to o bserve the diversity of re ligions s hould give rise to the opposite co nclu s ion , nam e ly: Si nce at all periods and among all p eoples religion s are to b e found that unanimously affirm one absolu te and transcendent reality, as also a b eyo nd that receives u s a cco rding to our merit or kn ow le dg e-or according to our demerit and ignorance-t here is reason to co nclud e that every re ligio n is right , and all th e more so s ince the g rea test me n ha ve walked the ea rth have bo rn e witness to s piritual tnahs. Il is possible to admit that a ll the mat eriali sts ha ve been mistake n , but it is not poss ible to admit th a t all the fo und ers of re li g ions, all the sa in ts a nd sages, have been in e rror and h ave le d ot h e rs into error ; for one had to admit that error lay with them and not w ith th os e who contradi cted them , mankind itse lf would cease to offe r any interest, so that a belief in progress or in th e possibility of progress would become doubly absurd. If th e Buddh a or Christ or a Plotinu s or a Kobo Dai sh i were not inte lligent , th e n n o one is intelligent, a nd there is no s uch thing as human intelligence.

The di vers ity of re li gions , far from proving the falsen ess of al the do ctrines concerning the s upernatur a l, s hows o n the con trary th e suprafo rm al character or reve lation and the fo rm a l c haracter of ordinary human understanding ; the essence of rev e lation-or enlig ht enme nt-is o ne , but human nature requires d iversity Dogmas or other symbols may co ntradict one anther ex te rnall y, but they conc ur internally .

Howbe it , it is easy to fo re see the following objecti o n : Even if it be admitted that there is a pro vide ntial and ine sca pable cause underl y ing th e di vers ity of re li gions and even th ei r exote ric in co mpatibilit y in ce r-

24 SACRED WEB 1

tain cases, ought we not then to try to get beyond these differences by creating a sing le universal religion? To this it mllst be answered first that these differences have at all times been transcended in the various tericism and second that a religion is not something one can create for the asking. Every attempt of this kind would be an error and a failure, and this is all the more certain inasmuch as the age of the great revelations had closed centuries ago. No new religion can see the light of day in our lime for the s imple reason that time itselfl far from being a sort of un iform abs t raction, on the contrary alters its value according to eveIY phase of its development. What was still possible a thollsand years ago is so no l onger, for we are now liv ing in the age known to Budd hi st tradi tion as "t he laner limes." Howeve r, what we are able to do and must do is to respect a ll of the religions-but without any confusing of forms and without ask ing to be fully understood by every believer-whi le waiting till heaven itse lf wills to unite those things that now are scattered. For we find ourselves on the thresho ld of great upheavals, and what man himse lf has neither the power no r the right to rea lize will be realized in heaven, when the time for it shaH be ripe.

The world is full of people who comp lain that they have been seeking but have not found; this is because they have not known how to seek and have only looked for sentimentalities of an individualistic kind. One often hears it said that the priests of such and such a religion are no good or that they have brought relig ion itself to naught, as jf this were possible or as if a man who selVes his relig ion badly did not be tray himself exclusively; men qu it e forgel the timeless va lue of symbols and of the graces they veh icle. The saints have a t all times suffered from the inadequacy of certa in priests; but far from think ing of rejecting tr adition itself for that reason, they have by thei r own sanctity compensated for whatever was lacking in the contemporary priesthood. The only means of "reforming" a religion is to reform oneself. It is indispensable to grasp the fact that a rite vehicles a far greater value than a personal virtue. A persona l initiative that takes a religious form amounts to nothing in the absence of a traditiona l framework such as alone can justify that ini tiative and turn it to advantage , whereas a rite at least will always keep fresh Ole sap of the whole tradition and hence also its principal efficacy-even if men do not know how to profit thereby.

If things were otherwise or if spiritual values were to be found ou tside

25

SACRED WEB I

the sac red trad iti o ns, the function of th e sai n ts would ha ve been, not to en li ve n their religion , but rather to abolish it , and there would no longer be any reli gio n left on ea rth , o r e lse on the con trary there would be re li gions b y the million , which amo unts to th e same thing s; and th ese milli ons of p e rso nal p se udorelig ions would th emse lves be ch a ng ing at every minute. The re ligi o ns an d th eir orthodox deve lop m en ts-suc h as the various traditiona l sc hoo ls of Buddhism-are inalienab le an d irreplaceable legacies to which nothing essent ial ca n be added and from whi c h noth i ng essen ti al can be subtra ct ed. We a re here, not in ord er to ch a nge th ese things, but in o rd er to understan d th em and reali ze th e m in o ursel ves.

Today two da ngers are threatening religion: from the outside, its destruc ti o n-were it o nl y as a result of its genera l desertion-an d from the in sid e, its fal sificat ion. The latte r, wit h its pseudointellectual pretensions and its fallacious professions of "refo rm ," is immeas urably more harmfu l than all th e "s uperstit io n" and "co rrupti on" of whic h , rightly or wrongly , th e re prese nta ti ves o f the tr aditional patrimonies have been accused ; thi s herit age is absolutely irrepl aceab le, and in th e face o f it men as such are of n o account. T radition is abando ned, no t because peop le are n o longer ca pabl e o f understanding its language, but because they do not wish to unders tand it, for thi s la nguage is made to be understood till th e end of the world; tra diti on is falsified b y reducing it to flatness on the plea of making it more acceptable to "our time," as if one co uld-or s h ou ld-a ccommodate truth to error. Admittedly, a need to rep ly to new qu es tions and new forms of ign ora nce can always arise. One ca n a nd must exp l ain the sac re d doctrine , but not at th e expense of that w hich gives it its reason for existing , th at is to say, not at the expense of its truth a nd e ffectiveness. There could be no question , for i nstance, of adding to th e Mahayana or of replacing it b e a new vehicle, su c h as would n ecess arily be o f pure ly human invention ; for the Mahayana-or s ha ll we say Buddhi sm'-is infinite ly su ffi cie nt for th ose who will give th emse lves the trouble to loo k high er th an their ow n heads.

One point that has been already mentioned is worth recalling no w beca use of its ext reme imp ortance. It is quite ou t of the question that a "r eve lation, " in th e full sense of th e word 1 should arise in our tim e, o ne comparab le , th at is to say , to the imparting of one o f the great sutra s or any o th er primary scripture; the d ay of revelations is past on thi s globe

26 SACRED WEB 1

and was so already long ago. The inspirations of th e sa int s are of another order, but these cou ld in any case never falsify or invalidate tradition or intrinsic orthodoxy by claiming to improve on it or even rep lace it, as some people ha ve sugg es ted. "Our own time " possesses no quality that makes it the measure or the criterion of values in regard to that which is timeless. It is th e timeless that, by it very nature, is the measure of our time, as indeed of all other times; and if our time has no place for authentic tradition, then it is se lf-condemne d by that very facl. The Buddha's message, like every other form of the one and only truth , offers itse lf to every period with an imperishable freshness. It is as true and as urgent in our day as it was two thousand years ago; the fa ct that mank ind finds itself in the "latter days," the days of forgetfulness and decline, only mak es that urgency more actua l than ever. In fact, th ere is nothing more urgent, more actual, or more real than metaphysica l truth and its demands. It alo ne can of it5 own right fill the vacuum left in the co ntemporary mentality-especially where young people are co nce rn ed-by soc ial and political disappointments on th e one hand and by the bewildering and indigestibl e discoveries of modern science on the other. At th e risk of re pe tition let the following point be s tressed, for to doubt it would be fata l: To search for an "ideology" in the h o pes of filling up that vacuum-as if it were simply a maller of plugging a hole-is truly a case of "pulling the cart before the horse ." It is a case of subordinating truth and sa lvation to narrowly utilitarian and in any case quite externa l ends, as if th e sufficient cause of truth cou ld be found somewhere below truth. The suffic ien t cause of man is to know the truth, which exist5 outside and above him; the truth cannot depend for its meaning and ex istence on the w ishes of man. The very wo rd "ide ology" shows that truth is not the principal aim people have in mind; to use that word shows that one is scarcely concerned with the difference between true and false and that what one is primarily seek ing is a mental deception that will be comforta ble and workable , or utilizab le for purposes of one 's own choosing, whic h is tantamount to abolishing both truth and intelligen ce.

Outside tradition th ere can assuredly be found some relative truths or views of partial realities, but outside tradition th ere does not ex ist a doctri ne that catalyses absolute trut h and transmits liberating notions concerning lota l reality. Modern science is not a wisdom but an accumula-

WEB I 27

SACRED

tion of physical expe rim e n ts coup led w ith many unwarrantable conclusions; it can neither add nor subtrac t anything in respect of the total truth or of mythological or othe r symbolism or in respect of the principles and experiences of the s p ir iLU allife.

One of the most insidious and destruct ive illu sions is the belief that depth psychology (o r in other words psychoanalysis) has the slightest connection wi th spi ritual life, wh ich these teachings persistently fa lsify by confusing infe ri or elements with supe rior. We cannot be too wary of all these attempts to reduce the values vehided by tradition to the level o f phenomena su pposed to be sCientifi ca lly controll able. The spirit escapes the hold of profane science in an absol ute fashion. It is not the positive results of experimental science that one is out to deny (a lways assuming that th ey really are positive in definite sense) by the absurd daim of science to cover everything possib le, the whole of truth, th e whole of the real; this quasi-relig ious claim to totality moreover proves the falseness of the point of departure. If one takes into account the very limited realm within which science moves , the least one can say is that nothing justifies the so-ca lled scientific denials of the beyond and of the Absolute.

If it be essentia l to distinguish between th e realm of religion or traditional wisdom and that of experimen tal science, it is also essentia l to di st inguish betw ee n the intellect, wh ich is intuitive, and reason , which is discursive ; reason is a limited faculty, w hereas intellect opens out upon th e Universal and the Divine. For metaphysical wisdom, reason only possesses a d iale ctical, not an illuminative, usefulness; reason is not capable of grasping in a concrete way that which lies beyond the wo rld of forms , though reason is able to reach further th an imagination . A ll ratiocination condemns itself to ignorance from th e moment it claims to d ea l with the roots o f our existence and of our sp irit.

We all know that the need to accou nt for things in terms of ca u sality, as felt by modern man, is apt to remain unsatisfied in the face of the ancient mythol og ies; but the fa ct is that attempts to explain the m y thologica l order w ith the aid of rea son ings that are necess arily arb itrary and vitiated by all sort of prejudices are bound to fail in any case. Symbol isms reveal their tru e meaning only in the light of the contem plative inte lle ct , which is analogi ca lly represented in man by th e heart and not by the brain . Pure inlellecl-or intuition and suprarat iona l intelligence--ca

n 28 SACRED WEB I

flo we r o nl y in t he framework of a traditiona l orthodoxy, by reason of the co mpl e men tary and th e refore necessary re la tion sh ip between intellectio n and re ve lati on.

The fundam en ta l int e ntion of every religion or wisdom is the fo ll owing: first , d isce rnm ent betwee n the real an th e unreal , an d th e n conce ntration up o n th e rea l. One could also render this inte nti o n otherwise: truth and th e way, prajna an d upaya , do c trin e and its corres p ond ing me th od. One must kn ow that the Absolut e or th e Infinite-wh at ever may b e th e na mes given it by respec tiv e tradition s-is what gives se nse to our existence, just as onc must know that the essen ti al co nt e nt of life is the co nsc iOll sness of th is supreme reality , a fa ct that expla in s th e parl LO be played by co ntinual prayer; in a word we live to rea liz e th e Absolute. To rea li ze th e Absolute is to think of it , und e r one fo rm o r anot he r as indicated by revelation and tradition , by a fo rm s uch as th e Japanese nembutsu o r th e Tibetan Om man; padm e hum or the Hin du japa-yoga, n o t forgetting th e Christian a nd Islami c invocatio ns , s uc h as the J esus Praye r a nd the dhikr of the derv is he s. Here one will find some very diffe ren t mod a lities, not only as betwee n on e religio n a nd another bu t also w ithin th e fold of eac h re ligion , as can be s hown , for instance , by th e differe n ce b e twee n Jo d o Shins hu and Ze n . Howeve r thi s m ay be, it is on ly on th e basis of a ge nuin e spiritual life that we can e n visage any kind of exte rn a l action with a view to defendin g truth and sp iritu a lity in the world.

All th e traditi o nal e10c trine s agree in this: From a s tri c tl y s piritu a l po int of vi ew, th o ugh not nec essa rily from other much more re lative a nd th e refore less important points of view , mank ind is becoming more and more co rrupt ed; th e id eas o f "evo lution ," o r "progress, " and o f a s ingl e "civ iliza ti o n " are in effec t the most pern icious pseudodogmas th e world has ever produ ced, for there is no newfound e rror that does n o t eage rl y attach its ow n cl a ims to the abo ve beli efs. We say not that evolution is no ne xi s te nt , but that it ha s a partial and mo s t ofte n a q uit e ex ternal app licability; if th ere be evo lutio n on the o n e h a nd , th ere are dege neration s on th e ot he r, a nd it is in any c ase rad ica ll y false to s upp ose th a t ou r ancesto rs were intellectually , s pirituall y, o r mo ra Uy our infe rio rs. To su ppose thi s is the mos t c hildish of "optica l delusions "; hum an wea kn ess ahers it s style in the co ur se of history , but not its nature. A question th at n OW arises is as follows: See ing that humanity is decaying in escapa bl y SACRED WEB I

29

and seei ng that th e final crisis with its cosmic consumma tion as fo retol d in t he sacred b oo ks is ine vitab le, what then can we do? Does an exte rnal activity still have a ny meaning?

To this it mu s t be a nswe red that an affirmation o f the truth , or any effort o n behalf oftm th , is never in va in, even if we cannot from beforehand meas ure the value of the outcome of suc h an activity. Moreove r we have no c ho ice in the ma tte r. Once we know the tmth , we must li ve in it and fight for it; but what we mu st avoid at any price is t o let ou rse lves bask in illu sio ns. Even if, at thi s moment , the horizon see ms as d ark as pos sibl e, o ne must not forge t that in a p e rhaps unavoidabl y distant future the victory is ours and ca nnot but be ours. Tmth by its very n atu re conque rs all o b sta cle s: Vincit omnia ve ri/as

There fore , every initiative taken w ith a view to harm o n y be tw een th e differe nt cultures and for the defense of spir itua l values is good, if it has as its basis a recog nition of th e great principa l of truths and consequently also a recognition of tradition or of the traditions.

"Wben tbe inferior man bealS talk about Tao, be only laugbs a t iI; it would not be Tao if be did notlaugb as iI tbe self-evidence of Tao is taken for a darkness. " These words o f Lao-tse were never more t imely than now. Errors can not but be , as long as their qu ite relati ve possibility h as not reach ed its ter m; but for the Absolute errors ha ve nev e r been and neve r sha ll be. On their own p la ne they are wha t they are , but it is the Chang e less that sha ll ha ve t he final say.

30 SACRED WEB 1

Metaphysics, Theology and Philosophy*

by Kennetb S. Oldmeadow

, .. {nllb is tbe ultimate goal oj the whole universe and the con/emplalion oj Imlh is the esselllial activity of wisdom

5t Thomas Aquina s!

7be proof of the Still is the sun: if tbou require the proof, do nOI avert thy face

Rumi t

71)e possession of ail tbe sciences, if unaccompallied by the know/edge of tb e best, Will more often than not frljure tbe possessor

Plato 1

The In/inite is what it is; one may understand II or nol lilldersiand iI . Metaphysics cannot be tClugb/LO everyone bill, if it could be, there would be no albetsm

Frithjof

"Me taphysics is th e finding of bad reasons for what we believe upon inst inct.'" This Bradleian formulation , perhaps o nly half-se rious , s ignp os ts a modern conception of metaphys ics shared by a good many peo-

111i s article is a revised excerpt from a forthcoming book , provisionally titled "Traditi onalism

I. 51. Thomas Aquinas , quoted in Selmon's Undersland(Ilg Islam (Allen & Unwin, Londo n , 1976) p133fn2.

2. Iturni in Whitall Perry 's A Treasury ojTraditiOl/a/ Wisdom (A ll en & Unwin, London , 1971 ) 1'750.

3. Plato in Perry's A Treasury oj Tmdillonal Wisd om, Ibid. p731.

1 . Selmo n , Spiri tual PerspeClives and Human Facts (Perennial Books, London, 1%7) p50.

5. From F.H Bradley Appeanm ce and Reality quoted by S Hadhakri shnan: "Reply to My Critics" in P.A . Sc hUpp (cd) The Philosophy ojSarvepallf RadhakrishllmJ (Tudor, New York , 1952) p791.

SACRED WEB 1 31

pie, philosophers and oth erw ise. Th ere is, of course, no single modern philosop hica l posture on the natu re and significan ce of metaphysics. Some see it as a kind of residual b li ght on the tr ee of p hil osop hy, a feeding-ground for obsc urantists and love rs of mumbo -jumbo. Others grant it a more d ignified s tatu s' It is one o f those words, like "dog ma " or "mystical ," whic h h as been pejora te d by ca reless and ignorant usage. The word "metap hysics " is s o fraught wit h hazards, so h edged about wit h phil osophical disputation , and so s ulli e d by popular u sage that we shall have to take so me ca re if the prop er se nse in which th e tr aditionalists use the word is to become cl ea r. So me ope rationa l definitions of seve ral cru cia l terms w ill provide th e starting-point. Th e elu cidatio n of the traditionali st conce ption of metaphysics will be structu red around three questions: Wha t is metaphysics? What is its relations hip , in terms of procedu res, c riteria and ends , to ph ilosophy? And to th eology' Su bsequently a sub ordinate question wi ll come into foc us: Why have th e traditionalists see n fit to expose to the publi c ga ze certain metaphysical principles and esoteric insights previously the exclus ive preselVe of th ose s piritu all y qualified to understand th e m'

Witho ut a cl ea r definition of terms certai n misunderstandings will be more or less inevitab le. T he foll owing words in th e traditi onali st vocab ul ary mu st be understood precise ly: Tradition and tradition, Revelation,/ntellect, gnosis, metaphYSiCS, and mystical.

Tradition: T he pri mordia l wis dom, or Truth , immut ab le and unform ed. tradit ion: A forma l embodim ent of Truth under a particu lar mytho logical or re ligious gu ise w hich is transmitted through time; or th e ve hi cle for the transmission of this fo rmal embodiment; or the process of transmiss ion itse lf.

Revelation: A prov iden ti al Message from the Divine which, entering the world of tim e and space, must take on a ce rt ain form , and from whic h issues a mythologica l or religiou s trad ition.

Intellect : When ever the traditio nali sts use th is word or its derivatives it is not to b e un derstood in its modern a nd popular sense of "me nt al power. " Rath er, it is a precise technica l term taken from the Latin intellectus and from mediae va l sc holasticism: that fa c ulty whi c h perceives the trJnscend-

6. For some d isc ussion of this term by a modern ph il osop her sec J. I lospcrs An Inlroductfon 10 Philosophical Analysts (Routledge and Kegan Pa ul , London, 1956) pp21 Iff.

32 SACRED WEB 1

ent. 7 Th e Inlellect re ce ives intuition s and apprehends realiti es of a s uperph enomena l orde r We remember Me ister Eckhart 's s tat ement: "There is some thin g in th e sou l wh ich is uncreate d and un c reata bl e thi s is th e ln te llec t. "ij It is, in Sel1Uo n 's wor d s, "a recept ive faculty a nd not a productive power: it does not 'c rea te'; it receives an d tran s mits. It is a mir ror."9 The In te ll ect is an imp erso n al, unconditioned, receptive faculty, wh e nce the ob jectivity o f intell ect io n . It is "that w hich participates in th e divine Sub jec t. ,," Marco Pallis remind s u s that the belief in this transcendent fa c u lty , capable of a dir ect c onta ct wit h Reality, is to be found in all traditi o n s under var ious name s. II

Gnash;: "The wo rd g no s is . .. refers to supra-rational and thu s pure ly inte ll ective , knowledge of metacosmic realitie s. " 12 It must not be confu sed with th e hi sto ri c al phenomenon of gn os tici s m , th e G ra eco-O ri e nt a l s yncretism of la tt e r classical time s. 13 Its San s krit e quival e nt is jiian a , knowle d ge in its full es t se nse , what Eckhart calls "divine knowledge .'

Metaphysic: We s hall turn to thi s term in some d etai l prese nt ly bu t fo r th e moment the fo ll owing caps ul e definition from Nas r wi Usuffice: "Metaph ys ics, w hi ch in fa c t is one and s hou ld be n amed me tap hys ic ... is th e scie nce of the Rea l, of the o rigin and end of thing s, of the Absolute and in its li ght , th e re lati ve. " 14 Si milarl y metaphysical: "concerni ng univ ersa l realities co n s idered ob jec tively. "ls

Mystical: "co ncerning th e sa me realities considered subje c ti vely, that is, in re lation to the conte mplative so ul , in sofar as th ey e nt e r int o co nta c t with it. "16

As Guenon obseIVe d more than once m e taphy sics cannot prope rly a nd stri ctl y be defined, for to define is to limit , whil e th e d oma in of me taph ysics is the Real and thu s limitle ss. Consequently, me tap hy sics

7. Sec M. Lings What fs Sufism' ( Allen & Unwi n, London , 1975) p18.

8. Qu oted in M. Lings A Sufi Saini oj the Twclllielh Cen llllY (Unive rsi ty of Ca lifornia Press, Berkeley , 1971) p 27

9 Schuon , SUI/ fOIlS oj Wisdo m ( Perennial Books , London , n d .; reprin t John Murray , Lond o n , 1961) p 2 !.

10 ibfd. ; p88.

11. M. Palli s q uoted in Perry 's A Treasury oj Tmdflfolllll Wisdom , Op.cil. p733

12. Sc h uo n , Understandillg I slam, op.cfl. pI!).

13. See Sc huon , To /la ve a Center pp67-68. See al so Schuo n , Roots of the 1·luman Condit ion (World Wisdom Books, Bl oo mington , 1991) pplO- ll .

11. 5. \1 Nas r Mall (II/d Nature (Allen & Unwin, London , 1976) pSI.

15 Selmon, Logfc (lmi Transcendence (Harper & Row , New York , 1975) p204fn9.

SACRED WEB 1 33

"is truly a nd absolutely unlirrtited and canno t be confined to any formul a or any system."l7 Its subjec t , in th e words of J o hn Taule r, is "that pure knowledge th at knows no form or c rea turely way."IH This must always be kept in rrtind in any attempt at a "definition " which must needs be prov is ional and incomplete. Let us return to th e passage in wh ich Nasr expla ins the nature of metaphysics:

It is a science as strict and as exact as mathematics and with the same clarity and certitude, but one which can only be: attained through intellectual intuition and not s impl y through ratiocination. It thus from philosophy as il is uSlwlly understood. Rather, it is a theorfa of reality whose realisation means sanctity and spiritual perfection, and therefore can only Ix: achieved within the cadre of a revealed tradition. Metaphysical intuition can occur everywhe re-for the "spirit bloweth where it listeth"-but the effective realisation of metaphysical truth and its application to human life ca n only be achieved within a revealed tradition which gives efficacy to certain symbo ls and rites upon which mClaphysics must rely for its realisation.

This supreme science of the ReaL.is the only science that can distinguish between the Absolute and the relative, appearance and reality Moreovcr, this sc ience cxiSL'I, a s the esoteric dimension within every orthodox and integral tradition and is united with a spiritual method derived totally from the trddition in question. I?

This view of metaphysics accords w ith the traditional but not modern conception of p hil osophy-of philo-sophia, love of w isdom as a practical concern. In India, for example, philosophy was never only a matter of epistemo logy but an ali-embraCing sc ience of fi rst principles and of the true nature of Reality, and one wedded to the spi ritual diSciplines provided by relig ion. The ultimate reality of metaphysics is the Supreme Identity in which a ll oppositions and dualities are resolved, those of subject and objec t , knower and known, being and non- beingi t hu s a Scrip tur al formu lat ion s u ch as "The th ings of God knoweth no man , but

16 ihid. Schuon is, of co urs e, not unaware of the linguistic and connotative ambig uilcs surrounding thi s term. See Schuon 's SPfrlllltd Perspeclives, op.cfl. p86fn See also S.H. Nasr 5ufi Essays (Allen & Unwin , London, 1972) p26 fn5. For an exte nd ed traditionalist discussion sec W Stoddart: in Ranjit Fernando (cd) 7beUnalllmous Tradflfoll (Sri Lanka Institute ofTmditional Studies, Colombo, 1990pp89-95.

17. R. Gucnon: "Orienta l Metaphysics · in Jacob Needleman (cd) 7beSwordof>Gnosts (Pengu in Books, Baltimore, 1974) pptl3-41.

18. Quoted in C. F. Kelley Meisler Eckhart on Divine KI/Ow/edge (Yale University Press, New tla ven, 1977) p-i.

19. S.H. Nasr, Man (md Nature pp81-82. See ,llso Coomaraswamy's undated letter to Selecled le/lers oj Ana/Ida K. Coomaraswamy (cds: Rama Coomardswamy an d Alvin Moorc , jnr.) pIO: - tra ditional Me taphysics is as much a Single and inva riable science as mathematics."

34 SACRED WEB 1

the Spirit of God.' w As Coomaraswamy remarks , th e philosophy , o r metaphysics, provided the vis ion , and religion th e way to its effective verificat ion and actualisation in direct experience. 21 Th e cleavage berween metaphys ics and philosophy on ly appears in modern limes.

The nature of metaphys ics is more easily gras ped through a cont rast with philosophy and theology However, severa l genera l p o in ts ne e d to be estab li s h e d b e fore we procee d. Because the metaphysical realm lies "beyond " the phenom e nal plane the validity of a metaphys ical prin c iple can be ne ith e r proved nor disproved by any kind o f e mpirical d e monstra ti on, by refe rence to material realities. 22 The aim of metaphysics is not to prove anything whatsoever but to make doctrin es in le lligibl e a nd to demonstrat e their conSist e ncy.

Secondly , metaphysics is concerned with a dire c t apprehens ion of reality or, to put it different ly, with a recognition of th e Absolute and o ur relati o ns hip to it. It thus takes on an imp erative c haracter for tho se capable of me taphy s ical di sce rnment.

l11e re quir ement for us to recognise th e Absolute is its elf an :Ibsolu te o nei it co nce rn s man as suc h and not man under s uc h and suc h co nditi ons. It is a fundamental aspect o f human dig nit y, and especially of that intelligen ce which denote d state of man hard 10 obtain ," that we accept TrUlh becau se it is tr ue an d for no ot her reason .l.I

Furth ermore, because metaphysics is attuned to the sacred and the divine , it dem a nds so me thing of those who wou ld unlock it s mysteries:

If metaphysicS is a sac red thing , that means it could not be limited to the frJmework of the play of the mind. It is illogical and dangerous to talk of mctaphysics wit ho ut being pr eoccu pied with the moral concomitances it req uir es, the criteria o f which arc, for man, his behaviour in relation to God and to his neighbour. <1

Thirdly , metaphysics assumes man 's capacity for abso lut e and ce rtain

knowledg e :

20. 1 CoriTltbltms 11.11. '[he Absolute may be called God, the Godhead, nirgun a Brahman , the Tao, and so on, accord in g to the voca bulary at hand See Schuon, Light 011 the All cle' ll Worlds (Peren ni al Books, Lo ndon, 1966) pp96-9fnl for a co mm e nt ary on the use o f - and Selmon, Log ic and Trans cendence, op.cl f for a si milar discussion of "Allah " .

21. A.K. Coomaraswamy : "A Le cture o n Co mp ara ti ve Religion " q uo ted in Roge r Lip sey (cd) Coo maraswamy: Ilis Life and Work ( Bo lling cn, Princeton, 19n) p275. Also see an d We stern in Lipsey (ed) Coomaroswomy 2: Selected PCljJers, Me taphysfcs ( BoHinge n, PrinceLO n , 1977)

22. Sec R. Guc no n : op.c lt p53

23. Sc h uon, In /be Tracks o[ Buddbism (Allen & Unw in , Lond o n , 1968) p33 .

24. Schuon, Sp iritual PerspecUues, op .cit pI73.

SACRED WEB 1

35

111e capaci ty for objec tivity and for absoluteness is an anti cipated and existential refutation of al! th e ide o logies of d o ubt: if man is able to doubt, thi s is because certitude exists; likewise the very notion of illu s ion proves that man ha s access to reality ... lf doubt co nfo rmed to the rea l, hum:!n intelligence w ou ld be d eprived of its sufficient reason and man would be less than an a nimal , s in ce the intelligence o f animals docs not expe rience doubt concerning the reality to which it is proportioned. lS

Metaphys ics, therefore , is immutabl e and inexorab le, and the "infallible standard by which not only religions, but stiJI more ' philoso phies' and 'sci e nces' mu s t be 'corrected ' " .a nd inte rpreted. ,, 26 Metaphysics ca n be ignored or forgotten but not refuted "precisely b ecause it is immutable and not re lated to change qua c hange. "" Metaphysica l p rin c ipl es a re tm e and va li d once and for all and not for thi s parti c ular age or men ta lity , and co uld not, in any sense, "evolve ." They can be val ida ted dire c tl y in the p le nary and unitive ex peri ence of the mysti c. Thus Martin Lings can write of Sufism-and one co uld say the same of any intrinsica ll y orthodox tradi ti onal esoterici s m- that it has the right to be inexorabl e because it is based on certainties and not o n o pinion s. It bas the obligation to be inexor-dble because mysticism is the so le reposit ory of Truth, in the fullest sense, being a bove a ll concerned with the Absolute, the In fini te and the Et erna l; and - If the salt have lost its savour, wherewith shall it be salted? " Witbout mystic ism, Reality would have no vo ice in the world . There would be no record of t he true hierarchy , and no witness th a t it is continually be in g violate d 21

One might eas ily substitute th e word "meta physics" fo r "mys ticism " in this passage, th e fo rm er being th e fo rm a l and "objective" aspect of the "subjective " expe rience Howeve r, thi s is not to lose sight of th e fa ct that any and every me taphysical doctrine will take it as axiomatic that every fonnulati o n is "but e rror in the face of th e Divine Reali ty itselfj a provisi o nal , indispensa bl e, sa lutary 'error' which, howeve r, contains a nd comm unicat es the virtu a lity of th e Truth."29 With th ese considera tion s to th e fo refro nt we

25. Selmon, Logicand Transcendence, op.ctt. pl3. See also Selmon Esolerism as Principle and as \Vay ( Perennia l Books, inndon, 1981 ) ppl5ff.

26. LeIter to ).H. Muirhead, Augu st 1935, in Se lected Lellers of AKe; Op.ci l p37.

27. S. J I. Nasr Sufi F.ssays p86. See Sctmon, S/a/iolls oj Wisdom , op.c il . p1\2.

28. M. Lings What iSSlIfrsm ' p93.

29. Selmon , Spiritua l Perspectives, op.cit. ppI62- 163. Cf. AX Coomarasw am y: "".a nd every belief is a heresy if it be regarded as the truth, and nol simply as a s ignpost o f the truth. W Sri Ramak ri sh na and Religious Tolera nce in Cooma raswamy 2: Selected Papers, op.clt. p38. See also Sc h uon, SufISm: Veil and Qutnlessence(Wo rld Wi sd om Books, 1981) p2

36 SACR ED WEB 1

can turn to a comparison , firstly , of metaphysics and philosophy .

In a di sc u ss ion of Sh an kar a's Advaita Vedanta, Coomara swa my exposed so me of th e crucia l d ifferences between metaphysics and modern phi losop hy:

The Vedanta is not a in the current sense of the word , but only as the wo rd is used in the phrase Pbilosophia Perenflis Modcm phi losop hies arc closed syste ms , employ ing th e method of dia lectics, and taking fo r granted that oppos ites ar e mutually exclusive In mode rn phil osophy things arc either so or not SO; in eterna l philosophy th is d e pends upon our point of view. Metap h ysics is not a syste m , but a consistent doctrine; it is not merel y concerned with conditioned and quantitativI: experie n ce but with universal possib ility ,.IO

Modern European philosophy is diale c tica l, which is to say analytical and rational in its m odes. From a traditi o nali st poinr of view it mi g ht be sa id that modernist philosophy is anchored in a mis understanding of th e nature and rol e of reason ; indeed, the ido latry of reason could hardly have ot herwise ari se n . Sc hu on spo tlights some of t he streng th s a nd deficien cies o f t he ra ti ona l mode in these terms: