2019 STAFF MEMBERS

Editorial Staff

Amanda Leiserowitz

WRITING AND DESIGN

Collette Quach

WRITING

Janel Catajoy

ART AND DESIGN

Lily Li

ART AND DESIGN

Simón Benichou

WRITING AND DESIGN

Tristan Burnside

DESIGN AND PHOTOGRAPHY

Editor in Chief

Reshma Zachariah

Editor’s Note

Thank you for picking up this book. This issue is the result of several months collectively clicking away at our computer screens.. As the Editor in Chief of Play! Magazine, I’m immensely proud of my staff and contributors for coming together to help make this happen. I’m thrilled to have been given the opportunity and support to incubate this project and see it through to fruition.

You could say that this magazine was catalyzed by my six year old self getting her hands on her first digital drawing software, pen and tablet, and never letting go. It has always been my dream to create an art book, and the Creative Entrepreneurship Internship (CEI) Program at UC Santa Cruz gave me the resources to finally make my dream a reality. I delved deeper into my interest in print media at Funomena, during my mentorship under Art Director and children’s book illustrator, Glenn Hernandez. I continued to explore print media at Chronicle Books with the help of fellow CEI intern, Shimul Chowdhury. When I brought this knowledge with me to UCSC, I encountered great interest, so I gathered a team of talented students ready to make this project happen.

In a world where the arts are serially undervalued and underfunded, the intention behind Play! Magazine is to further our education as visual artists, and push for a more holistic education in digital artistry on the UCSC campus: to provide room for growth, a safe space for feedback, and an outlet for inspiration from fellow peers. This magazine seeks to provoke the mind while showcasing our talented contributors. We represent a new generation of artists and thinkers united under the belief that all media can be consumed through a critical lens. Together, we seek to create a space where students can inspire one another while honing our craft.

Special Thanks:

Marcelo Viana Neto

Yethzéll Díaz

UCSC Art & Design: Games and Playable Media

Danette Buie

Center for Student Success, Opportunity and Equity

Glenn Hernandez

Funomena

This project was supported in part by a Creative Entrepreneurship program grant awarded by the Arts Division of the University of California, Santa Cruz.

All images contained within are copyright and property of their respective owners. Articles represent the expressed opinions of individual writers and not necessarily those of the Art & Design: Games and Playable Media Department, UC Santa Cruz, or the University of California.

PRESS PLAY // Tracklist PRESS PLAY // Tracklist

2 // Comedy in Games article by Simon Benichou, illustration by Vivian Pham

6 // Pixel Art pixel art by various artists

8 // Kilngods ceramics by Evie Chang

10 // Zeno Clash article by Kelly Lallemand

12 // Tension illustration by Morgan Tomfohr

13 // Evening Fog photography by Pace Mendoza

14 // Genre Euphoria article by Reno Rivera, illustrations by Erika Dunn

18 // 3D models by various artists

22 // A Treatise on Powergaming article by Reno Rivera, illustrations by Erika Dunn

26 // Serpent illustration by Sarah Bayrouk Gutierrez

27 // Ascending illustrations by Brandon Leung

29 // Wired illustration by Lily Li

30 // The Impkeeper illustration by Reshma Zachariah

31 // Sorcerer illustration by Janel Catajoy

32 // Learning Hmong article by Hughe Vang, illustration by Sarah B. Gutierrez

34 // Traditional Art paintings by various artists

38 // Post-Game Saudade article by Hughe Vang, illustration by Reno Rivera

43 // Sunsets illustrations by Brandon Leung and Reshma Zachariah

Variant Covers by: Ari Liu, Brandon Leung, Erika Dunn, Janel Catajoy, Reno Rivera, Reshma Zachariah

0-N1S // Janel Catajoy, UCSC ‘20

0-N1S // Janel Catajoy, UCSC ‘20

COMEDY IN GAMES

Illustration // Vivian Pham, UCSC ‘21

Comics // Richard Grillotti, UCSC MFA ‘20

From the witty writing of Portal 2 to the surreal gameplay of Katamari Damacy, games have various ways of allowing us to experience humor. But what makes a comedy game stand out? What makes you remember the hilarity, or make you want to go back and play it, finding humor despite already having experienced it? Let’s explore the different ways that games make us laugh.

Playing along with Writing

In games, we find that the easiest form of delivering comedy is through good writing. Take the Portal games, for example, namely Portal 2. You have not only some wonderfully eclectic writing, but you have the hilarious Stephen Merchant bringing immense lifte to the character of Wheatley, an apprehensive idiot who tries his best to make it seem like everything is going exactly as planned.

There’s a part where Wheatley is about to kill you. After (not so narrowly) escaping his death trap while he monologues, he begs you to come back. You have a choice here, to keep moving (the most logical action), or to actually go back and see what Wheatley has to say. You are then rewarded, not with points or a power up, but with humorous dialogue that you wouldn’t get if you were to continue on with your escape. Wheatley is surprised you came back, and begs that you kindly jump into the deadly pit before you, offering all kinds of ridiculous reasons why you would definitely want to jump into this pit. The cherry on top to this whole charade is that if you do jump in the pit, you get an achievement, Pit Boss “Show that pit who’s boss.”

Here, Portal 2 exhibits what you could call interactive comedy. The game sets up the joke, and you perform the punchline. The game makes you be funny. This further cements the power of Portal 2 as a comedic piece and a video game. The game

doesn’t treat you as an audience member, the game treats you the way it should, as the main character. Most of the jokes are about you or directed at you and your actions. The game has you participate in the comedy. By making you the main character in the situational comedy show that is Portal 2, you feel like you are not only surrounded by comedy, you’re a part of it.

Gameplay

This leads us to our second method of comedy, actually doing something funny. The premise of a game often dictates its gameplay. Last year’s Genital Jousting, offers a ridiculous premise of putting a penis inside another penis. Naturally, this premise lends to humorous gameplay. But it’s not always that simple. Take Octodad: Dadliest Catch, the premise of which is you are an octopus posing as a suburban father and husband. You are in charge of controlling each of Octodad’s appendages separately, resulting in you sneaking around like a sloshed Solid Snake. The wonky controls have you flopping around, no matter how hard you try to act normally. It’s exactly how an octopus would move if it was posing as suburban dad. Young Horses (the dev studio behind Octodad) had many options in tackling how the game would play, but the bumbling movement and awkward controls mesh perfectly to create an outlandishly humorous game. Not only is the premise humorous, the gameplay is as well. The gameplay informs the premise, which is not only important for comedy games, but all games.

One of the most beautiful pieces of surrealist comedy, and a key example of humorous gameplay supporting a ridiculous premise is Keita Takahashi’s Katamari Damacy. The game is about rolling up stuff into a giant ball, and when I say stuff, I mean everything. But the comedy in this game isn’t found in individual jokes, the whole game is a joke. “This is ridiculous, I can’t believe I’m doing this!” you say to yourself after rolling up your fifth human child. The game juxtaposes a relatively normal environment, featuring relatively normal items, with a ridiculous mechanic. You find yourself rolling a giant ball of stuff through a normal Japanese town, and the game treats it as such a casual occurrence. This is the essence of surreal humor, subverting expectations and creating an unpredictable and illogical world, while juxtaposing it against a seemingly normal environment, something that Octodad does as well. And the video game, as a medium, can place the player at its center, making them the star of the show, and the driving force behind the comedy.

Emergent Comedy

So the pattern we’re finding with the last three examples is that they have the player do something funny, but because that’s the only way of interacting with the world. But what about games that don’t make you be funny, but let you be funny on your own accord? Hitman, despite it’s dark premise, has a lot of humorous moments, but once again, it’s up to the player to find them. In Hitman, assassinating your target can happen in numerous ways. Yes you can shoot your target with a gun or subdue them with brute strength, but there’s something morbidly funny about instead feeding them to a hippo or making a statue look like it accidentally fell on them. All this happening while dressed as a clown or a hippie, and you can’t help but sort of chuckle in satisfaction.

A less morbid example lies in the Scribblenauts series. The game presents you with puzzles to solve, and you can write anything into your little notebook and it’ll appear. Now if the puzzle involved you transporting a man across a body of water, of course you could just write “Boat,” but what if you wrote something like “Giant Winged Lizard.” Both would get the job done.

Games with dynamic emergent gameplay like these (other examples include The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild and Metal Gear Solid V), that is to say, games that you give you problems and offer a variety of solutions, can give way to very funny moments. The game doesn’t necessarily prompt you to be funny, or reward you for making the most humorous choice but very well gives you the option to do so. The player finds a comedic solution to the open ended problem, and creates a funny moment within the game that they’ll remember. And maybe the next time they play the game, they find a different solution, perhaps more humorous than the last.

Games as Parody

There are also games that are funny because they make some sort of comment about their medium. These games could be classified as parody or meta. The Stanley Parable is another game that is oozing with comedic writing, but the story is an exploration of the meanings of choice and freedom. Almost a parody of the walking simulator genre, the performance of the narrator combined with the progressively more abstract storyline is funny, in an absurdist kind of way. The “jokes” explore the idea of existentialism, an idea that has been explored since the early 20th century, yet the medium allows you to experience these jokes first hand, making you really think about the nature of choice and decisions.

Coffee Stain Studios’ Goat Simulator, is a parody of the simulator genre. You control a goat, and that’s about it. But the environment and models are glitchy and unpolished, and the actual goat gameplay more resembles that of a destructive immortal entity than an ordinary farm animal. This is all fine though, because right from the get go, Goat Simulator is established as a parody. Even the trailer is a parody of the 2011 Dead Island trailer. We enjoy this glitchy game because it’s satire. It gives you an environment to mess around in and explore while also establishing that it is not taking itself seriously in any way. In a way, the player experiences a sense of relief, that what they’re doing is purely for comedy’s sake. We don’t have to complete objectives in any sort of time frame, we

can just mess around, and throw this goat as far across the map as we can.

Games allow us to experience things in new ways, and while comedy has existed for centuries, it’s never existed in the way it exists in games. We can be funny, we can make jokes, we can laugh at ourselves, at the world, at the characters. We can experience various forms of comedy in new ways, from surrealism, to slapstick, to black comedy. Games continue to be a medium to explore and play around with certain entertainment techniques, making us feel things we couldn’t feel in other media, and to me, that’s what makes games truly amazing.

Video Games

Mush Kelly Lallemand, Thovatey Tep, Evan Blank made for 120 SERIES Summer 2018

Writer’s Block

Brandon Leung, UCSC ‘20 made for 170 SERIES

WRITER’S BLOCK Winter - Spring 2018

Reverie

Vivian Pham, UCSC ‘21 made for CMPM 80K Winter 2018

The Birth of Venus (Above), Potatoman Portrait (Left), Richard Grillotti, DANM ‘19 LOW RES made for Pixeljam Games

Ataraxia Joyce Lin, UCSC ‘20 made for ARTG 129

“Speculative Futures’

Winter 2018

KILN GODS

Zeno Clash

An Unexpected Comfort Zone in Zenozoik

Writing // Kelly Lallemand, UCSC ‘20 Screenshots // ACE TeamZeno Clash is ACE Team’s first game, released in 2009, and built on the Source engine for those extra satisfying limp-limb physics when you send enemies flying. In the surreal world of Zenozoik, you play as Ghat, accompanied by Deadra. They flee into the dangerous outlands of the world to avoid the barrage of attacks from his siblings, among other enemies. Ghat carries a secret that could expose his parent, Father-Mother, so throughout the game he struggles with his family crisis, literally punching his family in the face. After playing ACE Team’s creative, first-person brawler, Zeno Clash, I was thoroughly impressed, mildly disturbed, and undoubtedly impacted by the experience. Now, after really appreciating the game for all the madness that it is, it is the first game I will recommend to anyone. This was not always the case; I was initially too wary of the game to play it. My friend introduced it to me, saying it was one of the best games he’s played because of how fun and bizarre it is.

I was hesitant to try it out when I saw the trippy tutorial. While the mechanics were responsive and quick, I was put off by the red hue, bird beating, and the grating voice of the teacher, Metamog.

“Keep going,” my friend persisted. “You’ll like it!” I continued to play, throwing my siblings off a bridge, firing fish guns, and running out of the semi-civilized city into the forest full of freaks, the Corwids of the Free. One corwid’s life goal is to walk in one direction for eternity and that is all the backstory the player is provided. Another’s was to be invisible, so he removed the eyes of anything that could see him. To my surprise, the more I saw, the more I embraced the strangeness and admired the imaginative game.

The game drops you right into the story, the fighting, and the colors of the surreal world. Every detail

has a purpose. ACE Team builds an incredibly rewarding aesthetic experience, whether that is the textures of the terrain, uniquely designed characters, and the insane ideas developed which produce this mechanically simple, first-person fighting game. Even the uncomfortable voice acting feels like it belongs! This is because ACE Team has accomplished the impossible: creating cohesiveness in a cacophony of insanity. Like the Corwids of the Free, the developers at ACE Team have fully embraced their creative freedoms, rejecting the conventional expectation that games must stay in between the lines in order to be wellreceived. Following this epiphany, I realized Zeno Clash is a grotesque nightmare so refreshing, it’s the game of my dreams.

A lot of interesting art and games go unnoticed because of the instinctual bias people may have against something they see during their first, brief introduction to the media. For example, they see trailers of two minute gameplay and never play the game because the art style is too strange. Maybe they like the art style of one, but never try it because it’s not their favorite genre of game. There are so many hidden gems floating around in the Indie Market; take a chance on them! They do not have to receive perfect reviews in order to provide you with a fun experience.

I implore you to explore that which does not initially appeal to you. Experience things and games that you would never expect to enjoy. Appreciate the unorthodox media for what it is and you may find you love it.

Genre Euphoria

So, let’s get the elephant out of the room—I’m trans. Hi, everyone that’s met me for the first time in the past year or so and hadn’t found out otherwise! AFAB, trans man, he/him pronouns.

For the most part, I’m stealth, and it feels pretty good. It’s not that I’m ashamed of being queer, or anything—this paragraph is right at the top of the article, after all—but there’s just a certain satisfaction in being able to politely decline people handing out flyers in the quarry and have them say “sorry to bother you, sir.” It’s pleasing to know that I pass so well that I have difficulty picking up prescriptions off-campus because the pharmacist thinks I’m a different person than my deadname.

This is the first time that I can go up to a stranger and say, “Hey, I’m a boy,” and they’ll say, “Why are you talking to me?” but also, “Yes, you are a boy.”

Well, that’s not exactly true. If you really want to think about it, the first time I passed was a few odd years ago, before my egg had fully broken. (That is, before I knew I was trans.) It was in a chatroom for one of those online avatar dress-up forums that popped up in the wake of GaiaOnline’s slow and continual demise.

I was talking with strangers, and someone called me ‘he.’

Maybe it was the sense of wanting to stay anonymous in this new place, or maybe it was a quiet, secret knocking from the outside of my eggshell, but I let it happen. There was a strange power dynamic in knowing that, at any time, I could pop out and say ‘actually, I’m a girl,’ words

Writing // Reno Rivera, UCSC ‘19

Illustrations // Erika Dunn, UCSC ‘20

that now in my present form give me violent chills to type out. And I thought about it, too—okay, now I’m going to pop into chat and tell them. They just called me ‘he,’ now would be a good time to do it.

...But I didn’t. I held onto my little secret. And maybe I was a little too self-conspicuous in keeping it a secret—definitely worried myself sick over some things that the people I was talking to hadn’t given a second thought to—but a secret it was. I continued to come back to that site as ‘he,’ made friends there as ‘he,’ and grew a reputation as ‘he.’ And I enjoyed it.

Ok, let’s zoom back a bit further than that. Picture this—it’s 2013, and you’re me.

First of all, I’m sorry.

Second of all, you’re sitting at the dining room table with your very own shitty cheapo laptop. You have no spending money, and you want to play a video game. You call up your best friend (on Skype), who, with an equally cheapo laptop and no spending money, trawls through the free MMO ranking lists with you for something your combined lack of money and cheapo laptops can run together.

You pick some generic cash-grab-anime-girlfree-to-play MMO, and after some three hours of downloading on cheapo internet, you spend the next two hours in character creation making the hottest dude you can. The two of you muck around doing fetch quests for the rest of the day and then you never touch the game again.

Over the next few days, in between your daily routine of watching Vocaloid music videos and reading Harry Potter crossover fanfiction, your hot dude remains in your head. Damn, that’s a great hot dude. You have excellent design sensibilities, me. Maybe you’ll take him and make him a character of your own and he can go around in a story or something. You draw Hot Dude in the corners of your notebooks until you become great at drawing Hot Dude.

Congrats.

Now, fast forward a bit, about midway between the past two anecdotes. You’re preparing for your first ever Pathfinder campaign—your first ever tabletop RPG, for that matter. You’ve enjoyed a fair bit of rule-less forum roleplaying before, but the gamey addition of stats and RNG to your collaborative storytelling has deeply snagged hold of your interest.

As the Game Master listens to your character idea and helps you fill out a sheet, you think about what your character looks like, and sheepishly doodle Hot Dude into the character portrait space.

You’re not really that good at roleplaying live, but the campaign is a blast, and your group stays strong through the entire year. You take note of what you did well and eagerly jump at the next chance to join another game, this time with a new character.

Let’s talk about gender euphoria.

I guess to know about that, it’s important to know about gender dysphoria first, right? In its broadest sense, gender dysphoria is a pervasive sense of discomfort or unhappiness with the way one’s gender is perceived, whether that’s by the world, or by one’s own measure. This manifests in different ways from person to person. While gender dysphoria is by no means a necessity in order to transition, whether medically (through hormone replacement treatment or sex reassignment surgery) or socially (changing one’s name or pronouns, and living by them), for a lot of people it is the driving force for doing so.

In opposition of that is gender euphoria: the sense of revelry and contentment when one’s perceived gender matches up with the gender they identify with.

You might be wondering, “Oh, so does that mean cis people feel gender euphoria all the time?” Well...not quite. For a lot of cis people, being perceived as the gender they identify as is taken as a given, so it’s not as special or notable. But that’s not to say it’s impossible for cis people to experience—you don’t have to be trans to enjoy having your gender reaffirmed!

yet). It provides unrestricted access to form, not gated by the limitations of the physical human body. Very transhumanist! Unlike in real life, you rarely have to commit to how you look, allowing for a wide range of versatility in expression. Change things up regularly, or stick with something you love. This powerful form of selfexpression allows people to explore themselves in a way that the real world often makes difficult.

For someone like me that grew up in a lowincome family and didn’t have funds to buy clothing that hid all my gross body shapes, character customization gave me an opportunity to vicariously love the way I looked. I latched onto my silly Hot Dude and iterated on it, across different games and worlds and context. And then it became more than just eyecandy—it became an ideal, an version of myself that I wanted to work towards and become.

While the role of many games is escapism, it would be doing the format a disgrace to say that escapism is its only purpose. Games allow for growth and self-discovery in a low-stakes environment, and the inclusion of character customization allows the player to manifest themselves more directly within that world. Though it’s often seen as just fluff, and frequently used jokingly, creating a personalized character can be a vital part of the game experience, particularly one that can grant insight into oneself, both as a player and as a person.

So, I encourage you—spend that extra two hours fiddling with sliders to adjust your bone structure, click through every hairstyle option available, and find your very own Hot Dude (or Gal, or Enby)— whatever that hotness might mean to you.

Character customization is an excellent potential source of gender euphoria, even for people who aren’t trans (or, might not know that they’re trans

MODELING

a collection of high poly sculpts

Stillborn (Above), Man (Left, Right) Siena Mayford, UCSC ‘18

Stillborn (Above), Man (Left, Right) Siena Mayford, UCSC ‘18

Engkanto Bust

Gian Paredes, UCSC ‘19

The Wicked Witch of the Waste Reshma Zachariah, UCSC ‘19

Concept from Howl’s Moving Castle

Skelegoo Wesley Wu, UCSC ‘19

Skelegoo Wesley Wu, UCSC ‘19

A TREATISE ON POWERGAMING

Mins and Maxes

Nice title, you might be thinking.

I dig the reference.

But what does it mean?

Well, I’ll do my best to explain.

Minmaxing is a term frequently used in reference to tabletop roleplaying games, particularly during the character building stage.

If character customization involves the fluff and flavor of the character--the backstory, personality, and aesthetics--character building involves the crunch. Putting points into stats, picking out classes, filling in character sheets. It’s where the wargaming aspect of tabletop RPGs still resides. While creation and building are closely intertwined, with one often informing the other, this isn’t necessarily always the case. Fluff has no bearing on the mechanics, so the character build can be in whatever configuration the player wants.

During character creation, minmaxing refers to the act of minimizing certain parts of a character build in order to maximize other parts. For example, you lower the amount of points in your wizard’s Charisma stat in order to add more to his Intelligence, what a nerd.

While it’s primarily a term used for tabletop RPGs and other games with character creation, min-

maxing exists anywhere you have stats. Overall, it’s part of a methodology of playing games called powergaming that seeks to play in the most optimized way possible.

The Real

When I was younger, I was obsessed with being taken “seriously” as a gamer. This was around the time of the rise of the casual gamer, with the widespread proliferation and rapidly accelerating development of mobile devices making the barrier to entry lower than ever before. With it, of course, came the virulent backlash from Real Gamers-back off, mom, and put away your candy crush, this is our hobby. No girls allowed! Real games are gritty and aggressive and cool, and anything less isn’t worth consideration.

I, being an impressionable young smeet, wanted to avoid the label of being “fake”, or “casual”, or “not a real gamer”—but there was a problem. I didn’t own any consoles (besides the DS, which as a handheld, “didn’t count”), or a powerful custom PC, or really any games, for that matter. I could watch Let’s Plays of games, sure, but that wasn’t the same as playing them myself, not really. Sometimes I’d lie and say “yeah, I played that game—but it was a long time ago/it was at a friend’s place/I sold the game afterwards,” to cover up the gaps in my knowledge, but that was unsustainable. I felt guilty lying. Even if other people didn’t know, I knew. I was a fake gamer in my own eyes.

So what could I do? It’s not like playing freeware flash games was worth any sick gamer cred, and

my 300 hours in Pokémon Diamond was only really impressive to me. The answer was clear--I’d play the same games as I already played, but seriously.

I’d get involved in...The Meta. What’s a-Meta With You

Anywhere you have raisable stats, you have the ability to optimize. Sometimes, a handful of spare points can mean the difference between being able to defeat an opponent or not. And certain characters, classes, or builds benefit from having particular stats raised. Over time, players of a game figure out what the most optimum combinations of these variables will be, usually through some profane combination of trial and error in conjunction with math.

This is what’s called the metagame, or just the meta for short. Abstractly, the meta is just a way of thinking about a game beyond the context of

the game itself, but it is most frequently used in this powergaming sense of getting through content as efficiently as possible.

There is nothing inherently wrong about the existence or utilization of a game meta, and knowledge of it is important for anyone interested in playing a game competitively.

However, it fundamentally alters how you think about the game itself—and often times, games in general.

To Be A Master

Thus began my harrowing advance into the world of competitive Pokémon. I did everything I was supposed to—I researched team comps, watched strategy videos, and practiced against random strangers late into the night, all in the hopes that the little rank number under my name would raise just a little bit more.

And I sucked, really badly. I wasn’t doing very well, and all the research I needed to do in order to get better was tiring and unsatisfying.

Thinking about it, the reason I liked Pokémon to begin with wasn’t because I wanted to win against other people. I’d racked up those 300 hours in Diamond playing alone, after all. No, it was more of the fantasy of traveling across the land with a party of cute and cool monsters, having flashy battles in a world that was generally bright and optimistic that had caught my imagination as a child. The scheming mindgames of competitive, with its abstraction of pokémon into statblocks and movesets instead of individual creatures, stripped away the things I did like about the series.

And for what? I wasn’t playing because I enjoyed it, but rather that I felt like I needed to prove something. I wasn’t having fun.

And so I stopped.

Good Luck, Have...

So, what’s the point of all this?

Currently, gamer culture puts too much of an emphasis on winning and being the best. For a lot of people, this makes it so that you only have fun when you win, instead of being fun overall.

This brings forth the following train of thought: If you need to win to have fun, only “real” gamers who understand how to powergame well enough to win have fun. Conversely, if you’re not having fun, that must mean you’re not a “real” gamer.

What follows is a downward spiral—in order to become a fabled and respected “real” gamer, you force yourself to play games you don’t enjoy to hopefully become good enough to have fun.

Of course, this isn’t universal. Some people genuinely do enjoy the challenge wrought by optimization, and that’s great for them! By nomeans am I trying to say that there’s a singular right way to enjoy games.

Instead, this is for people on the other side of that equation—for those that like slow games, or cute games, or simple ones, and for anyone who’s ever been told that they don’t really count because of it: it is fine to play the games you want at whatever pace you’re comfortable with.

After all—what’s the point in a game if you’re not having fun?

Learning Hmong

A NON-CONSUMER DEMOGRAPHIC

Disposable Games Studio is an itch.io developer that I recently found, with a catalog consisting of RPG Maker games, guides to ethical hacking, and a “Girl Gamer Soundboard”. Uhhhh, sure. But, what piqued my interest was their app called Learning Hmong 2.

I’ve understood my cultural identity as one that isn’t considered all that visible, despite how big Hmong New Year celebrations always appeared to me. Friends would ask if by “Hmong”, I meant “Mongolian”; my warm regards to any fellow Hmong readers who relate. I’m also Americanized as hell. I can’t speak Hmong; maybe this app would help?

Americanization runs deeper than language, though. I can’t relate to our traditional gender roles. There’s a lot about Hmong guys that I always resented, and so for these reasons I never had pride in being one myself.

Yet, as a game developer diving deep into Discourse, walking through Fresno’s Hmong New Year event spurred a question I never bothered before:

“Where are MY people in games?”

Unsurprisingly, maybe you’ve heard about us from a certain movie or medical book, but not video games.

Search “Hmong video games”, and one of the first results talks about Prince of Qin, a game that features Miao (read: Hmong) characters. Another refers to the Chinese Paladin series, which is apparently on Steam.

“I guess we’re big in games set in China? That’s kinda neat.”

Aside from that, though, there isn’t much Hmong content related to games I can play, let alone in game worlds that have a “modern” setting.

Writing // Hughe Vang, UCSC ‘19Illustration // Sarah Bayrouk Gutierrez,

UCSC’21“Hmong game developers” yield similarly sparse results; though not fruitless. I had pleasant surprise in finding Tiger Byte Studios, their name a play on a Hmong idiom: tsov tom, the tiger’s bite, a curse word in our language, reclaimed as “a force of transformative empowerment”, so they write. I imagined my grandfather shaking his head at that. They released a finished game! And apparently they’re working on a mech game?

“I hope it does well!”

In contrast, another result yields Hmong Trail, an Oregon Trail clone covering the Laotian Secret War. Cool! I made a Secret War game for high school too!

“...They haven’t posted since 2016.”

Starved trying to find more than 5 games to slap onto the “Hmong games list”, I searched “Hmong” on Steam and itch.io. The lonesome one result: Learning Hmong 2.

It’s not really a game. 5 pages of text buttons, with voice clips. A dictionary, at best, but not really… storytelling media.

I’m left wondering if there’s a more thorough way to find representation in games.

“Is it just search engines? Am I not looking in the right places? Or... should I engage more in my culture in games? MY games?”

There’s a lot about Hmong game developers that I never thought about, and so for these reasons I first had pride in being one myself.

Painted Pages

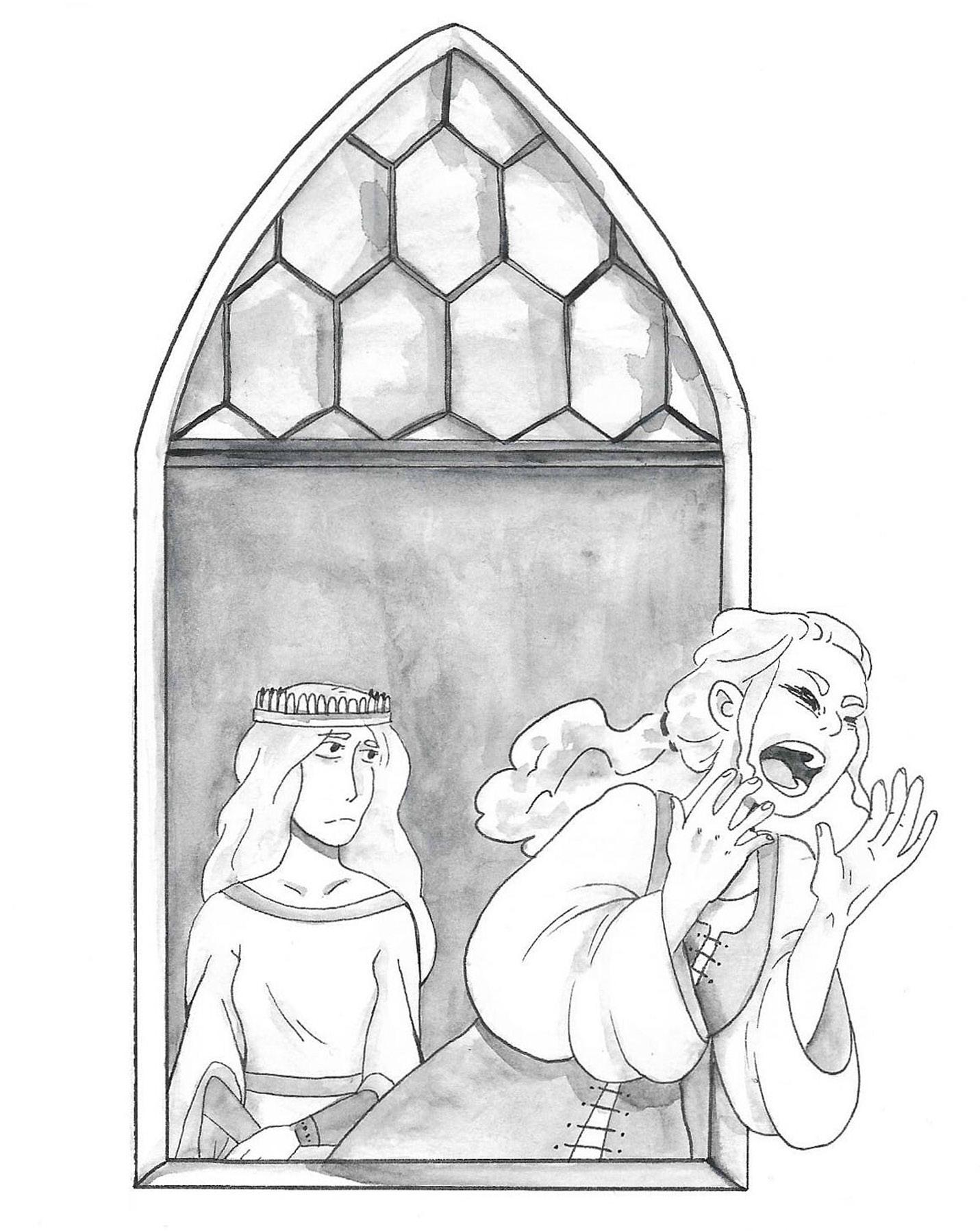

Lancelot, Knight of the Cart

original poem by Chrétien de Troyes illustration series by Amanda Leiserowitz

“Lancelot! Turn around to see who’s watching you!”

“Dear friend, may you be completely forgiven. I absolve you most willingly.”

“Sir, my lady the queen bids me tell you to ‘Do your worst’.”

Post-Game Saudade Childhood’s Endings

“Please don’t be sad.”

I was in elementary school when I first watched the ending of Magic Pengel: The Quest for Color. It is a Playstation 2 RPG in which players take the role of a Doodler, artists who control paint fairies known as Pengel, and draw Doodles that come to life and engage in rock-paper-scissors based tournament combat. Despite the game having shortcomings in its core combat system, and its fairly simple storyline, it still manages to stand out as one of my favorite games. Not just for the 3D character drawing and stat system, as robust and intelligently designed as it may be, but for the feeling of emptiness it left with me after completing the game.

Growing up isolated, no other videogame invoked loneliness in me stronger than the world left behind in Magic Pengel’s ending; intentional or not.

Pluses

While the mechanics of replay bonuses may have circulated in video games before 1995, it wasn’t until the seminal release of Chrono Trigger that these mechanics would have a commonly accepted name: New Game Plus, often shortened as NG+. In the specific context of Chrono Trigger, NG+ is used to give players the opportunity to carry over their characters’ stats, items, and abilities into a fresh game state.

Narratively, this can be interpreted as the titular player character, Chrono, being sent back in time with newfound experience to defeat the main antagonist Lavos, allowing Chrono to explore new possibilities in the form of Chrono Trigger’s multiple endings. However, what NG+ can also be seen as is an ultimate escape from something inevitable in games with save files: the exhaustion and death of game content.

Writing // Hughe Vang, UCSC ‘19

Illustrations // Reno Rivera, UCSC ‘19

With NG+, Chrono lives on forever, experiencing ending after ending, yet will never find himself in a world where time stops until the player themselves stop. Instead, it moves on forever, cycling on itself, the player able to experience the world endlessly in flow. Chrono is made eternal alongside a world ever changing, even if such change is simply a reversal of outcomes. However, for other games, a more sobering immortality awaits their player characters, in worlds left devoid of change, of discovery.

Towers

While many games would go on to iterate on NG+ and the concept of cycles, such as Demon’s Souls and its successors, others would also reject these mechanics in favor of post-game content; gameplay scenarios accessible after clearing the main story of the game. Often times, this comes in the form of singleplayer games that have a strong multiplayer component, in order to allow friends the ability to play together, even if at disparate levels of progress.

A popular example of vast post-game multiplayer is the Pokémon franchise, famous for its design emphasis on trading Pokémon and sharing the experience of the game with others. For years, the series allowed only one save file per copy of each game, presumably to prevent easier circulation of rare Pokémon among the player community. Thus, to delete the game is often a commitment; a painful one at that.

If you are a child who wants to continue playing the game after completing the main objective, and feel a deep connection to your progress and save data, you are given very difficult decisions.

You could transfer your Pokémon to another game or storage application, which cost money (and probably an argument with stingy/confused parents or guardians).

You could also delete your data and play the game over with a new file, given you have the heart to delete your Level 100 favorites.

You could ALSO wait patiently for the next version of Pokémon to be released, though the wait could take years, and also you wouldn’t be able to know if your favorite features from the current game will stay intact.

In middle school, when I first played Pokémon Diamond, I chose the easiest option: complete the post-game storyline, then play through the endless challenge of the Battle Tower.

Along with completing the Pokédex, the Tower is the last meaningful content to complete in a playthrough of the game.

The Battle Tower features gauntlets of randomly determined opponent trainers that you can battle with alone, with friends, or with NPC allies. I played a good while along and with the NPC characters, but eventually it gets stale. You recognize the reused lines that characters give every battle, and realize all the fights you encounter feeling the same, unlike the hand-designed content of the main game.

Looking back as an older person makes me see the appeal of challenges such as Nuzlocke runs, in which players commit to simulating permanent deaths to their party. These sorts of challenges are ephemeral and force players to restart and renew their playthroughs of the game. They feel the same endearment they do as a normal playthrough of Pokémon, but avoid the stagnation of the post-game content, where your attachment grows while nothing changes in return. But that’s not how these games were designed

to be played; there are many incentives given, such as real world event-exclusive Pokémon and multiplayer modes, that encourages players to maintain their save files for long periods of time after the games’ ending.

Having never completed the Battle Tower and returned to my player’s hometown, their mother unchanged from the start of the game, I stopped playing Pokémon Diamond.

Homes, Returned to Dust

A relative gave me Magic Pengel over a decade ago. In many, many ways, Magic Pengel’s structural make-up is very similar to Pokémon, the only difference being Pengel’s drawing mechanic substituting for Pokémon’s catching mechanic. You are able to draw Doodles, trade Doodles, and battle against friends with Doodles. It makes sense, then, that Magic Pengel would share the same problem of post-game content exhaustion like Pokémon.

In Magic Pengel, the player character finds themself in a kingdom in which color gems, the main resource used in drawing Doodles, are treated as currency and taxes. However, despite the inclusion of the player as a character, the plot of the game centers not around them, but around the orphans Zoe and Taro. The goal of the game is to participate in Doodle tournaments to help pay off Zoe and Taro’s debt to their homeland. Should the player fail, the siblings will be forced to leave their home. Throughout the game, the siblings also work towards finding their lost father, the famed Doodle artist Galileo, and uncover a deep conspiracy within the kingdom in the process.

Revisiting the narrative today, I realize that there are a few weaknesses that I hadn’t noticed as a kid. From details such as Zoe being unable to use Pengel due to lacking purity of the heart, despite much more sinister characters holding this very ability, to moments of grating voice acting, the game would have probably been much less impactful had I played the game as an adult now.

But despite this, even as a child, the fantasy of the game left a strong impression on me as an mortifying premonition of the housing crisis’ and rampant capitalism that we experience in our present day reality. And from this attachment, I felt invested in the plight of these characters. As sappy as it may be, I had truly believed that I was Zoe and Taro’s only friend, in a world that had alienated them from their ability to contribute to society. I wanted to help them reclaim their rights to their homeland.

This feeling is what devastated me during the ending of Magic Pengel.

After the final boss, the kingdom’s reign falls, the debt now cleared. Despite a harrowing and deadly final act, the game ends on a positive note, every protagonist surviving the end of the game. It was set up to be a happy ending. Zoe and Taro wouldn’t have to worry about eviction anymore. They would stay around and cycle through their 3 dialogue lines indefinitely forever, right?

“I’m so glad we became friends. Take care,” Zoe says during the credits. Galileo never having appeared, the orphans left to go find their lost father in the world beyond the game.

Saudade

In Portuguese and Galician, saudade is a word that expresses melancholy and longing for things lost that may never return. I imagine that I may not be the only one who experiences this in video games; at its most common form, it’s the feeling that occurs when a game loses its magical quality, when the seams give away to the machine underneath. This is what each iteration of Pokemon eventually ends up becoming; unless you become devout in competitive play, you reach a point in which the world stops moving and progressing, and you are left with no choice but to start anew, whether with a new file or the next entry in the series.

What made Magic Pengel special is its own simple variant on saudade. Every time your player character wanted to create a Doodle, the most fundamental mechanic of the game, you would talk to Zoe and Taro. They help you manage all the essential functions of the game, including saving the game. No matter how you feel about their characters, they are a permanent feeling fixture of the game; symbols of familiarity and safety.

But it is during the post-game where saudade is most felt, where the home once greeting you with friends is now empty and lonely. You wonder how your friends are doing, knowing that they will never return home. Will they ever find their father? Will they ever send letters to you? And you gently weep, knowing that things have changed irrevocably, that they can never remember you, because it is a game, and games are machines that never grow beyond their bounds. And it is being trapped in these bounds that makes us imagine and long for possibilities, for infinite game worlds, that will never exist.