THE BAYEUX TAPESTRY’S NAZI PAST MAGAZINE BRITAIN’S BESTSELLING HISTORY MAGAZINE July 2018 • www.historyextra.com

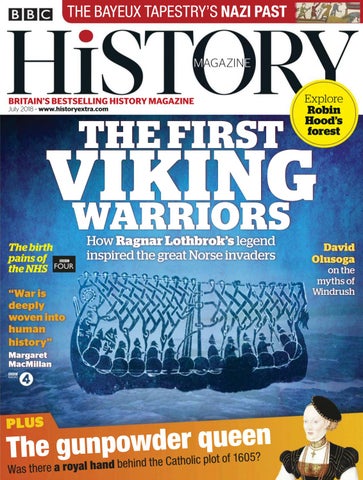

THE FIRST

Explore Robin Ho Hood’s fo orest

VIKING WARRIORS The birth pains of the NHS

How Ragnar Lothbrok’s legend inspired the great Norse invaders

“War is deeply woven into human history” Margaret MacMillan

P LU S

n e e u q r e d w o The agrouyalnhapnd behind the Catholic plot of 1605? Was there

David Olusoga on the myths of indrush