Here are some recommended products for you. Click the link to download, or explore more at ebooknice.com

(Ebook) Biota Grow 2C gather 2C cook by Loucas, Jason; Viles, James ISBN 9781459699816, 9781743365571, 9781925268492, 1459699815, 1743365578, 1925268497

https://ebooknice.com/product/biota-grow-2c-gather-2c-cook-6661374

(Ebook) Matematik 5000+ Kurs 2c Lärobok by Lena Alfredsson, Hans Heikne, Sanna Bodemyr ISBN 9789127456600, 9127456609

https://ebooknice.com/product/matematik-5000-kurs-2c-larobok-23848312

(Ebook) SAT II Success MATH 1C and 2C 2002 (Peterson's SAT II Success) by Peterson's ISBN 9780768906677, 0768906679

https://ebooknice.com/product/sat-ii-success-math-1c-and-2c-2002-petersons-sat-ii-success-1722018

(Ebook) Cambridge IGCSE and O Level History Workbook 2C - Depth Study: the United States, 1919-41 2nd Edition by Benjamin Harrison ISBN 9781398375147, 9781398375048, 1398375144, 1398375047

https://ebooknice.com/product/cambridge-igcse-and-o-level-historyworkbook-2c-depth-study-the-united-states-1919-41-2nd-edition-53538044

(Ebook) Master SAT II Math 1c and 2c 4th ed (Arco Master the SAT Subject Test: Math Levels 1 & 2) by Arco ISBN 9780768923049, 0768923042

https://ebooknice.com/product/master-sat-ii-math-1c-and-2c-4th-ed-arcomaster-the-sat-subject-test-math-levels-1-2-2326094

(Ebook) Dead Witch Walking by Kim Harrison

https://ebooknice.com/product/dead-witch-walking-50466850

(Ebook) Dead Witch Walking by Kim Harrison [Harrison, Kim] ISBN 9780060572969, 9780451464415, 0451464419, 0060572965, B004UAVAE6, XWNMKGLPXDYC

https://ebooknice.com/product/dead-witch-walking-11985706

(Ebook) Dead Witch Walking by Kim Harrison ISBN 9780062000644, 0062000640

https://ebooknice.com/product/dead-witch-walking-2997978

(Ebook) Black Magic Sanction by Kim Harrison

https://ebooknice.com/product/black-magic-sanction-54799726

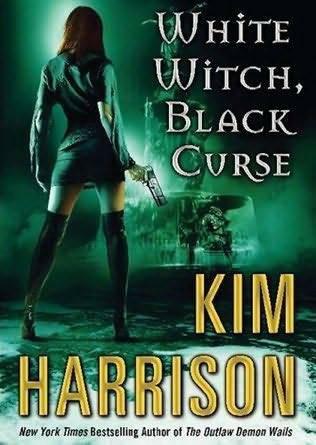

KimHarrison

WhiteWitch,BlackCurse

One

The bloody handprint was gone, wiped fromKisten’s window but not frommy memory, and it ticked me off that someone had cleaned it, as if they were trying to steal what little recollection I retained about the night he’d died. The anger was misplaced fear if I was honest with myself. But I wasn’t.Mostdaysitwasbetter thatway.

Stiflinga shiver fromthe December chill thathad takenthe abandoned cruiser, now indrydock rather thanfloatingonthe river, Istood inthe tinykitchenand stared atthe milkyplastic as ifwilling the smeared markbackinto existence. Inthe near distance came the overindulgent, powerful huffofa diesel traincrossingthe Ohio River. The scrape ofFord’s shoes onthe metallic boardingladder was harsh,andworrypinchedmybrow.

The Federal Inderland Bureau had officially closed the investigation into Kisten’s murderInderland Security hadn’t even opened one-but the FIB wouldn’t let me into their impound yard without an official presence. That meant intelligent, awkward Ford, since Edden thought I needed more psychiatric evaluationandIwouldn’tcome inanymore.Notsince Ifell asleeponthe couchand everyone inthe FIB’s Cincinnati office hadheardme snoring.Ididn’tneedevaluation.WhatIneeded wassomething-anything-torebuildmymemory.Ifitwasabloodyhandprint,thensobeit.

“Rachel? Wait for me,” the FIB’s psychiatrist called, shifting my worry to annoyance. Like I can’t handle this? I’m a big girl. Besides, there wasn’t anything left to see; the FIB had cleaned everything up. Ford had obviously been out here earlier-given the ladder and the unlocked doormakingsureeverythingwassufficientlytidybeforeour appointment.

The clatter ofdress shoes onteakpushed me forward, and Iuntangled myarms fromthemselves and reached for the tiny galley table for balance as I headed to the living room. The floor was still, which felt weird. Beyond the short curtains framing the now-clean window were the dirty gray and brilliantbluetarpsofboatsatdrydock,thegroundagoodsixfeetbelow us.

“Will youhold up?” Ford asked again, the lighteclipsingas he entered. “Ican’thelp ifyou’re a roomaway.”

“I’mwaiting,”Igrumbled,comingtoahaltandtuggingmyshoulder bagup.Thoughhe’dtriedto hide it, Ford had some difficulty getting his butt up the ladder. I thought the idea of a psychiatrist afraid of heights was hilarious, until the amulet he wore around his neckturned a bright pinkwhenI mentioned it and Ford went red with embarrassment. He was a good man with his own demons to circle.Hedidn’tdeservemyrazzing.

Ford’s breathingslowed inthe chill silence. Wanbut determined, he gripped the table, his face whiter thanusual, whichmade his shortblackhair stand outand his browneyes soulful. Listeningin on my feelings was draining, and I appreciated his wading through my emotional crap to help me piecetogether whathadhappened.

I gave hima thinsmile, and Ford undid the top few buttons of his coat to reveal a professional cottonshirtand the amulethe wore while working. The metallic leyline charmwas a visual display ofthe emotions he was pickingup.He feltthe emotions whether he was wearingthe charmor not,but those around him had at least the illusion of privacy when he took it off. Ivy, my roommate and business partner, thought it stupid to try to break witch magic with human psychology in order to recover mymemory, but I was desperate. Her efforts to find out who had killed Kistenwere getting nowhere.

Ford’s relief at being surrounded by walls was almost palpable, and seeing him release his

deathgrip onthe table, I headed for the narrow door to the livingroomand the rest of the boat. The faintscentofvampire and pasta brushed againstme-imaginationstoked bya memory. Ithad beenfive months.

My jaw clenched, and I kept my eyes on the floor, not wanting to see the broken door frame. There were smudges of dirt on the low-mat carpet that hadn’t been there before, marks left by careless people who didn’tknow Kisten, had never knownhis smile, the wayhe laughed, or the way his eyes crinkled up when he surprised me. Technically an Inderland death without human involvement was out of the FIB’s jurisdiction, but since the I.S. didn’t care that my boyfriend had beenturnedintoabloodgift,theFIBhadmadeaneffortjustfor me.

Murder was never taken off the books, but the investigation had been officially shelved. This was the first chance I’d had to come out here to tryto rekindle mymemory. Someone had nicked the inside ofmylip tryingto bind me to them. Someone had murdered myboyfriend twice. Someone was goingtobeinaworldofhurtwhenIfoundoutwhotheywere.

Stomachfluttering, I looked past Ford to the window where the bloodyhandprint had been, left likeasignposttomockmypainwithoutgivinganyprintstofollow.Coward.

The amulet around Ford’s neck flashed to an angry black. His eyes met mine as his eyebrows rose, and I forced my emotions to slow. I couldn’t remember crap. Jenks, my backup and other business partner, had dosed me into forgetting so I wouldn’t go after Kisten’s murderer. I couldn’t blamehim.Thepixywas onlyfour inches tall,andithadbeenhis onlyoptiontokeepmefromkilling myself ona suicide run. I was a witchwithanunclaimed vampire bite, and that couldn’t stand up to anundeadvampirenomatter how youslicedit.

“Yousureyou’reuptothis?”Fordasked,andIforcedmyhanddownfrommyupper arm.Again. It throbbed with a pain long since gone as a memory tried to surface. Fear stirred in me. The recollectionofbeingonthe other side ofthe door and tryingto breakitdownwas anold one. Itwas nearlytheonlymemoryIhadofthatnight.

“I want to know,” I said, but my voice sounded wobbly even to me. I had kicked the freaking door open.Ihadusedmyfootbecause myarmhadhurttoomuchtomove.I’dbeencryingatthe time, andmyhair hadbeeninmyeyesandmouth.Ihadkickedthedoor down.

A memory sifted from what I knew, and my pulse hammered as something was added, the recollectionofme fallingbackward, hittinga wall. Myhead hit a wall. Breathheld, Ilooked across thelivingroom,staringatthefeaturelesspaneling.Rightthere.Iremember.

Fordcameunusuallyclose.“Youdon’thavetodoitthisway.”

Pity was in his eyes. I didn’t like it there, directed at me, and his amulet turned silver as I gathered mywill and passed throughthe door frame. “Ido,” Isaid boldly. “EvenifIdon’tremember anything,theFIBguysmighthavemissedsomething.”

The FIB was fantastic at gathering information, even better than the I.S. It had to be since the human-run institution had to rely on finding evidence, not sweeping the room for emotions or using witch charms to discover who committed the crime and why. Everyone was capable of missing something, though, and that was one of the reasons I was out here. The other was to remember. Now thatIwas,Iwasscared.Myheadhitthewall…justover there.

Ford came in behind me, watching as I scanned the low-ceilinged living room that stretched fromone side of the boat to the other. It looked normal here, apart fromthe unmovingCincyskyline visiblethroughthenarrow windows.Myhandwenttomymiddleasmystomachcramped.Ihadtodo this,nomatter whatIremembered.

“Imeant,”Fordsaidasheputhishandsinhispockets,“I’veother waystotrigger memories.”

“Meditation?” I said, embarrassed for havingfallenasleep inhis office. Feelingthe beginnings ofa stress headache, Istrode pastthe couchwhere Kistenand Ihad eatendinner, pastthe TVthatgot lousyreception, not that we ever reallywatched it, and past the wet bar. Inches fromthe undamaged wall, my jaw began to ache. Slowly I put a hand to the paneling where my head had hit, curling my fingers under when they started to tremble. My head had hit the wall. Who shoved me? Kisten? His killer?Butthememorywasfragmented.Therewasnomore.

Turningaway, Ishoved myhand inmypocketto hide the slightshaking. Mybreathslipped from me inanalmost-visible cloud, and Itugged mycoat closer. The trainwas longgone. Nothingmoved pastthe curtains buta flappingblue tarp. Instincttold me Kistenhadn’tdied inthis room. Ihad to go deeper.

Ford said nothing as I walked into the dark, narrow hallway, blind until my eyes adjusted. My pulse quickened as Ipassed the tinybathroomwhere I’d tried onthe sharp caps Kistenhad givenme for mybirthday, and Islowed, listeningto mybodyand realizingIwas rubbingmyfingertips together astheysilentlyburned.

My skin tingled, and I halted, staring at my fingers, recognizing the memory of feeling carpet under my fingers, hot fromfriction. I held my breath as a new thought surfaced, born fromthe longgonesensation.Terror,helplessness.Ihadbeendraggeddownthishall.

Aflashofrememberedpanicrose,andIsquelchedit,forcingmybreathoutinaslow exhalation. The lines I’d made inthe carpethad beenerased bythe FIBvacuumingfor evidence, erased frommy memorybyaspell.Onlymybodyhadremembered,andnow me.

Ford stood silently behind me. He knew something was trickling through my brain. Ahead was the door to the bedroom, and my fear thickened. That was where it had happened. That was where Kistenhad lain, his bodytornand savaged, slumped againstthe bed, his eyes silvered and trulydead. WhatifIremember itall?RighthereinfrontofFordandbreakdown? “Rachel.”

Ijumped, startled, and Ford winced. “We cando this another way,” he coaxed. “The meditation didn’twork,buthypnosismight.It’slessstressful.”

Shaking my head, I moved forward and reached for the handle of Kisten’s room. My fingers were pale andcold,lookinglike mine butnot.Hypnosis was a false calmthatwouldputoffthe panic until the middle ofthe nightwhenI’dbe alone.“I’mfine,” Isaid,thenpushedthe door open.Takinga slow breath,Iwentin.

The large roomwas cold, the wide windows thatletinthe lightdoinglittle to keep outthe chill. Arm clutched against me, I looked to where Kisten had been propped up against the bed. Kisten. There was nothing. Myheart ached as I missed him. Behind me, Ford started to breathe withanodd regularity,workingtokeepmyemotionsfromoverwhelminghim.

Someone had cleaned the carpet where Kisten had died for the second and final time. Not that there hadbeenmuchblood.The fingerprintpowder was gone,butthe onlyprints theyhadfoundwere fromme, Ivy, and Kisten-scattered like signposts. There’d beennone fromhis murderer. Notevenon Kisten’s body. The I.S. had probablycleaned his corpse betweenwhenI’d leftto kicksome vampire assandmybewilderedreturnwiththeFIBafter I’dforgotteneverything.

The I.S. didn’t want the murder solved, a courtesy to whoever Kisten’s last blood had been givenas athank-you.Inderlandtraditioncamebeforesociety’s laws,apparently.ThesamepeopleI’d actuallyonceworkedfor werecoveringitup,andthatpissedmeoff.

My thoughts vacillated between rage and a debilitating heartache. Ford panted, and I tried to relax, for himif nothing else. Blinking back the threatened tears, I stared at the ceiling, breathing in

the cold, quiet air and counting backward from ten, running through the useless exercise Ford had givenmetofindalightstateofmeditation.

AtleastKistenhad beenspared the sordidness ofbeingdrained for someone’s pleasure. He had died twice in quick succession, both times probably trying to save me from the vampire he’d been given to. His necropsy had been no help at all. Whatever had killed him the first time had been repaired by the vampire virus before he died again. And if what I’d told Jenks before losing my memorywas true, he’d died his second deathbybitinghis attacker, mixingtheir undead blood to kill them both. Unfortunately, Kisten hadn’t been dead for long. It might only have left his much older attacker simplywounded.Ijustdidn’tknow.

I mentally reached zero, and calmer, I moved toward the dresser. There was a shirt box on it, andIalmostbentdoubleinheartachewhenIrecognizedit.

“Oh God,” I whispered. My hand went out, turning to a fist before my fingers slowly uncurled andItouchedit.ItwasthelaceteddyKistenhadgivenmefor mybirthday.I’dforgottenitwashere.

“I’msorry,”Fordrasped,andmygazeblurringfromtears,Isaw himslumpedinthethreshold.

Myeyes squinted shut to make the tears leakout, and Iheld mybreath. Myhead pounded, and I tooka gaspingbreathonlytoholditagain,strugglingfor control.Damnit,he hadlovedme,andIhad lovedhim.Itwasn’tfair.Itwasn’tright.Anditwasprobablymyfault.

Asoft sound fromthe threshold told me Ford was struggling, and I forced myself to breathe. I had to get control of myself. I was hurtingFord. He was feelingeverythingI was, and I owed hima lot. Ford was the reason I hadn’t been hauled in for questioning by the FIB despite my working for themoccasionally. He was human, but his curse of being able to feel another’s emotions was better than a polygraph or truth charm. He knew I’d loved Kisten and was terrified of what had happened here.“Youokay?”Iaskedwhenhisbreathingevenedout.

“Fine.Yourself?”hesaidinawispyvoice.

“Peachykeen,” I said, grippingthe top of the dresser. “I’msorry. I didn’t know it was goingto bethisbad.”

“Iknew what Iwas infor whenIagreed to bringyouout here,” he said, wipinga tear fromhis eyethatInolonger wouldcryfor myself.“Icantakeanythingyoudishout,Rachel.”

I turned away, guilty. Ford stayed where he was, the distance helping him cope with the overload. He never touched anyone except by accident. It had to be a crappy way to live. But as I rocked awayfromthe dresser, there was a soft pull as myfingertips left the underside ofthe dresser top.Sticky.Sniffingmyfingertips,Ifoundthefaintbiteofpropellant.

Stickyweb.Someonehadusedstickywebandsmeareditoffontheundersideofthedresser top. Me? Kisten’s murderer? Sticky web worked only on fairies and pixies. It was little more than an irritant to anyone else, like a spiderweb. Jenks had begged off coming out here on the excuse of it beingtoocold,whichitwas,butmaybeheknew morethanhewassaying.

Myheartache eased fromthe distraction, and kneeling, Iduginmybagfor a penlightand shined it on the underside of the lip of the dresser. I’d be willing to bet no one had dusted it. Ford came close, and I snapped the light off and stood. I didn’t want FIB justice. I wanted my own. Ivy and I wouldcomeoutlater anddoour ownrecon.Testtheceilingfor evidenceofhydrocarbons,too.Shake Jenksdowntofindoutjusthow longhe’dbeenwithmethatnight.

Ford’s disapproval was almost palpable, and I knew if I looked, his amulet would be a bright red frompickingup myanger. Ididn’tcare. Iwas angry, and thatwas better thanfallingapart. Witha new feelingofpurpose, Ifaced the restofthe room. Ford had seenthe smeared mess. The FIBwould reopenthecaseiftheyfoundonegoodprint-other thantheoneI’djustmade,thatis.This mightbethe

lasttimeIwasallowedinhere.

Leaning back against the dresser, I closed my eyes and crossed my arms, trying to remember. Nothing.Ineededmore.“Where’sthestuff?”Iasked,bothdreadingandeager torealizewhatelselay hiddeninmymind,readytosurface.

There was the sound of sliding plastic, and Ford reluctantly handed me a packet of evidence bagsandastackofphotos.“Rachel,weshouldleaveifthere’saviableprint.”

“The FIB has had five months,” Isaid, nervous as Itookthem. “It’s myturn. And don’tgive me anycrapaboutdisturbingevidence.Theentiredepartmenthasbeenthroughhere.Ifthere’saprint,it’s probablyoneoftheirs.”

He sighed as Iturned to the dresser and arranged the plastic bags, printside down. Itookup the photosfirst,mygazerisingtothereflectionoftheroombehindme.

I moved the picture of the smeared, bloody handprint on the kitchen window to the back of the stack, and tidied the pile with several businesslike taps. I got nothing fromthe handprint apart from thefeelingthatitwasn’tmineor Kisten’s.

ThepictureofKistenwasabsent,thankGod,andIcrossedtheroomwithaphotoofadentinthe wall. Ford was silent as I touched the paneling, and I decided by the lack of phantom pain that I hadn’tmadeit.There’dbeenafighthereother thanmine.Over me,probably.

Islid the photo behind the stack. Under itwas a close-up ofa shoe imprinttakenunder the bank ofwindows.Myheadstartedtothrob,andwiththatas awarning,Iknew somethingwas here,lurking in my thoughts. Jaw tight, I forced myself to the window, kneeling to run a hand over the smooth carpet, trying to spark a memory even as I feared it. The print was of a man’s dress shoe. Not Kisten’s. It was too mundane for that. Kisten had kept only the latest fashions in his closet. Had the shoebeenblackor brown?Ithought,willingsomethingtosurface.

Nothing. Frustrated, I closed my eyes. In my thoughts, the scent of vampire incense mixed with anunfamiliar aftershave.Aquiver rosethroughme,andnotcaringwhatFordthought,Iputmyfaceon thecarpettobreatheinthesmell offibers.Something…anything…Please…

Panic fluttered atthe edge ofmythoughts, and Iforced myselfto breathe more deeply, notcaring that my butt was in the air as primitive switches in my brain fired and scents were given names. Musky shadows that never saw the sun. The cloying scent of decayed water. Earth. Silk. Candlescented dust. They added up to the undead. If I’d been a vampire, I might have been able to find Kisten’skiller byscentalone,butIwasawitch.

Tense, I breathed again, searching my thoughts and finding nothing. Slowly the feeling of panic subsidedandmyheadache retreated.Iexhaledinrelief.I’dbeenmistaken.There was nothinghere.It was just carpet, and my mind had been inventing smells as it tried to fulfill my need for answers. “Nothing,”Imurmuredintothecarpet,inhalingdeeplyonelasttimebeforeIsatup.

A pulse of terror washed through me as I breathed in the scent of vampire. Shocked, I awkwardlyscrambledtomyfeet,staringdownatthecarpetasifhavingbeenbetrayed.Damnit. Inacoldsweat,Iturnedawayandtuggedmycoatstraight.Ivy.I’ll askher tocomeoutandsmell the carpet, I thought, then almost laughed. Catching it back in a harsh gurgle, I pretended to cough, fingerscoldasIshiftedtothenextphoto.

Oh, evenbetter, I thought sarcastically. Scratchmarks onthe paneling. Mybreathcame fast and mygaze shotstraightto the wall bythe tinyclosetas myfingertips started to throb. Almostpanting, I stared, refusing to go look and confirm that my finger span matched the marks, afraid I might remember something even as I wanted to. I didn’t recall making the marks on the wall, but it was obviousmybodydid.

I’dseenfear before.I’dseenfear brightandshinywhendeathcomes atyouinaninstantandyou canonlyreact.Iknew thenauseatingmixoffear andhopewhendeathcomes slow andyoufrantically try to find a way to escape it. I’d grown up with old fear, the kind that stalks you from a distance, death lurking on the horizon, so inevitable and inescapable that it loses its power. But this outright panic withno visible reasonwas new, and Itrembled as Itried to find a wayto deal withit. Maybe I canignoreit.Thatworksfor Ivy.

Clearingmythroat,Itriedfor anair ofnonchalance as Isetthe remainingpictures onthe dresser andspreadthemout,butIwasn’tfoolinganyone.

Smears ofblood-notsplattered, butsmeared. Kisten’s, accordingto the FIBguys. Apicture ofa splitdrawer thathad beenslid backoutofsight. Another useless bloodyhandprintonthe deckwhere Kisten’s killer had vaulted over the side. None of them hit me like the scratches or carpet, and I struggledwithwantingtoknow,butwasafraidtoremember.

Slowlymypulse eased and myshoulders lost their stiffness. I set the pictures down, bypassing the bags of dust and lint the FIB had vacuumed up, seeing my strands of red curls among the carpet fuzz and sock fluff. I watched myself in the mirror as my fingers touched the hair band in a clear evidence bag. It was one of mine, and it had held my braid together that night. A dull throb in my scalpliftedthroughmyawareness,andFordshifteduneasily.

Shit,thebandmeantsomething.

“Talkto me,” Ford said, and I pressed mythumb into the rubber cord throughthe plastic, trying to keep the fear fromgaining control again. Evidence pointed at me to be Kisten’s killer, hence the not-quite-hiddenmistrustInow feltatthe FIB, butIhadn’tdone it. I’d beenhere, butIhadn’tdone it. AtleastFordbelievedme.Someonehadleftthestinkingbloodyhandprints.

“This is mine,” I said softly so my voice wouldn’t quaver. “I think…someone undid my hair.” Feelingunreal,Iturnedthebagover toseethatithadbeenfoundinthebedroom,andasurgeofpanic rose fromout ofnowhere. Myheart hammered, but Iforced mybreathingto steady. Memorytrickled back, pieces, and nothingofuse. Fingers inmyhair. Myface againsta wall. Kisten’s killer takingmy hair out of its braid. No wonder I hadn’t let Jenks’s kids touchmyhair muchthe last five months or whyI’dfreakedwhenMarshal hadtuckedmyhair behindmyear.

Queasy, I dropped the bag, dizzy when the edges of my sight dimmed. If I passed out, Ford wouldcall someone,andthatwouldbethat.Iwantedtoknow.Ihadto.

The last piece of evidence was damning, and turning to rest my backside against the dresser, I shooka small, unbrokenblue pelletto the corner ofits bag. Itwas filled witha now-defunctsleepytimecharm.Itwastheonlythinginmyarsenal thatwoulddropadeadvampire.

Afaintpricklingofthehair onthebackofmyneckgrew asanew thoughtliftedthroughmeanda whisper of memory clenched my heart. My breath came out in a pained rush, and my head bowed. I wascrying,swearing.Pointingmysplatgun,Ipulledthetrigger.Andlaughing,hecaughtthespell.

“He caught it,” I whispered, closingmyeyes so theywouldn’t fill. “I tried to shoot him, and he caught it without breaking it.” My wrist pulsed in pain and another memory surfaced. Thin fingers grippedmywrist.Myhandwentnumb.Athumpwhenmygunhitthefloor.

“Hehurtmyhanduntil Idroppedmysplatgun,”Isaid.“IthinkIranthen.”

Afraid, I looked at Ford, seeinghis amulet purple withshock. Mylittle red splat gunhad never beenmissing, was never recorded as havingbeenhere. All mypotions were accounted for. Someone had clearly put the gun back where it belonged. I didn’t even remember making the sleepy-time charms,butthiswasclearlyoneofmine.Wheretheother sixwerewasagoodquestion.

Ina surge ofanger, Ikicked the dresser withthe ball ofmyfoot. The shockwentall the wayup

myleg,andthefurniturethumpedintothewall.Itwasstupid,butitfeltgood.

“Uh,Rachel?”Fordsaid,andIkickeditagain,grunting.

“I’m fine!” I shouted, sniffing back the tears. “I’m freaking fine!” But my lip was throbbing where someone hadbittenme;mybodywas tryingtogetmymindtoremember,butIsimplywouldn’t let it. Had it beenKistenwho had bittenme? His attacker? I hadn’t beenbound, thankGod. Ivysaid so,andshewouldknow.

“Yeah, youlookfine,” Ford said dryly, and Ipulled mycoatclosed and tugged myshoulder bag up.Hewassmilingatmylosttemper,anditmademeevenmadder.

“Stoplaughingatme,”Isaid,andhesmiledwider,takingoffhisamuletandtuckingitawayasif wewerefinished.“AndI’mnotdonewiththose,”Iaddedashegatheredthepictures.

“Yes, you are,” he said, and I frowned at his unusual confidence. “You’re angry. That’s better thanconfusedor grieving.Ihateusingclichés,butwecanmoveforwardnow.”

“Psychobabble bull,” I scoffed, grabbing the evidence bags before he could take them, too, but he was right. I did feel better. I had remembered something. Maybe human science was as strong as witchmagic.Maybe.

Fordtookthebagsfromme.“Talktome,”hesaid,standinginfrontofmelikearock.

Mygood mood vanished, replaced bythe urge to flee. Grabbingthe shirtboxfromthe dresser, I pushed pasthim. Ihad to getout. Ihad to putsome distance betweenme and the scratchmarks onthe walls. I couldn’t wear the teddyKistenhad givenme, but I couldn’t leave it here either. Ford could gripe all he wanted about removing evidence fromthe crime scene. Evidence of what? That Kisten hadlovedme?

“Rachel,” Ford said as he followed, his steps silent on the carpet in the hall. “What do you recall?All Igetisemotion.Ican’tgobackandtell Eddenyourememberednothing.”

“Sureyoucan,”Isaid,mypacefastandmyblindersonaswecrossedthelivingroom.

“No,Ican’t,”hesaid,catchingupwithmeatthebrokendoor frame.“I’malousyliar.”

I shivered as I crossed the threshold, but the cold brightness of late afternoon beckoned, and I lurched for the door. “Lyingis easy,” I said bitterly. “Just make somethingup and pretend it’s real. I doitall thetime.”

“Rachel.”

Ford reached outand drew me to a surprised stop inthe cockpit. He was wearingwinter gloves and had onlytouched mycoat, butitproved how upsethe was. The sunglinted onhis blackhair and his eyes were squinting from the glare. The cold wind shifted his bangs, and I searched his expression, wanting to find a reason to tell himwhat I remembered, to let go of the them-versus-us attitude betweenhumanand Inderlander and justlethimhelp me. Behind himCincinnati spread inall her mixed-up, comfortable messiness, the roads too tightand the hills too steep, and Icould sense the securitythatsomanylivesentangledtogether engendered.

My eyes fell to my feet and the crushed remains of a leaf the wind had dropped here. Ford’s shoulders eased as he felt my resolve weaken. “I remembered bits and pieces,” I said, and his feet shifted against the polished wood. “Kisten’s killer took my hair out of my braid before I kicked the door off the frame. I’m the one who made the scratches by the closet, but I only remember making them, not who I was tryingto…get awayfrom.” Myhand fisted, and I shoved it ina pocket, leaving theshirtboxtuckedunder anarm.

“The splat ball is mine. I remember shooting it,” I said, throat tight as I flicked my eyes to his and saw his sympathy. “I was aiming at the other vampire, not Kisten. He has…big hands.” A new pulseoffear zingedthroughmeandInearlylostitwhenIrememberedthesoftfeel ofthickfingers on

myjawline.

“I want you to come in tomorrow,” Ford said, his brow pinched in worry. “Now that you have somethingtoworkwith,Ithinkhypnosismightbringitall together.”

Bringit all together? Does he have anyidea what inhell he is asking? The blood drained from myface,andIpulledoutofhisreach.“No.”IfFordputmeunder,Ihadnoideawhatmightcomeout.

Fleeing,Idippedunder therailingandswungmyweightoutandontotheladder.Marshal waited inhis big-ass SUVbelow, and Iwanted to be initwiththe heater goingto tryto drive awaythe chill Ford’s words hadstarted. Ihesitated,wonderingifIshoulddropthe shirtboxor keep ittuckedunder anarm.

“Rachel,wait.”

There was the rattle of the lock being replaced, and leaving the box under my arm, I started down, watchingthe side ofthe boatas Idescended. Itoyed withthe idea oftakingthe ladder awayto leavehimstranded,buthewouldprobablyputitinhisreport.Besides,hedidhavehiscell phone.

Finally I reached the ground. Head down, I placed my boots carefully in the slush, aiming for Marshal’s car, parked behind Ford’s in the maze of impounded boats. Marshal had offered to bring meoutafter I’dcomplainedduringahockeygamethatmylittleredcar wouldgetstuckintheruts and iceouthere,andsincemycar wasn’tmadefor thesnow,I’dsaidyes.

Guilttuggedatmefor avoidingFord’shelp.Iwantedtofindoutwho’dkilledKistenandtriedto makemetheir shadow,buttherewereother things Iwantedtokeeptomyself,likewhyI’dsurviveda commonbutlethal blood disease thatwas also responsible for mybeingable to kindle demonmagic, or whatmydad had done inhis spare time, or whymymother had nearlygone offher rocker to keep mefromknowingmybirthfather wasn’tthemanwho’draisedme.

Marshal’s eyes showed his concern when I got in his SUVand slammed the door. Two months ago, the manhad shownup onmydoorstep, backinCincinnati after the Mackinaw Weres had burned his garagedown.Fortunatelyhe’dsavedboththehouseandtheboatthathadbeenhis livelihood-now sold to pay for getting his master’s at Cincy’s university. We’d met last spring when I was up north rescuingJenks’seldestsonandNick,myoldboyfriend.

Despite my better judgment, we’d been out more than a few times, realizing we had enough in commonto probablymake a good go of it-if it weren’t for myhabit of gettingeveryone close to me killed. Not to mention that he was coming off a psycho girlfriend and wasn’t looking for anything serious. The problemwas, we bothliked to relaxdoingathletic stuff, rangingfromrunningatthe zoo to ice-skatingatFountainSquare. We’d keptitfriendlybutplatonic for two months now, shockingthe hell outofmyroommates. The lackofstress fromnotwonderingwill-we, won’t-we was a blessing. Curbing my natural tendencies and instead keeping our relationship casual had been easy. I couldn’t bear itifhegothurt.Kistenhadcuredmeoffoolishdreams.Dreams couldkill people.Atleast,mine could.Anddid.

“Youokay?”Marshal asked,hislow voicewithhisup-northaccentheavywithworry.

“Peachy,”ImutteredasItossedtheboxwiththeteddyontothebackseatandwipedacoldfinger against the underside of my eye. When I didn’t say anything more, he sighed, rolling his window downto talkto Ford. The FIB officer was makinghis wayto us. Ihad halfa mind to accuse Ford of asking Marshal to drive me here and back, knowing I’d probably need a shoulder to cry on, and though he wasn’t my boyfriend, Marshal was a hundred percent better than taking my raw turmoil backtoIvy.

Ford looked up as he angled to my door, not Marshal’s, and the tall man behind the wheel silentlypresseda buttontoroll mywindow down.Itriedtoroll itbackup,buthe lockedthe controls

andIgavehimadirtylook.

“Rachel,” Ford said as soonas he closed the distance betweenus. “Youwon’tbe outofcontrol for evenaninstant.That’show itworks.”

Damnit, he had guessed whyIwas afraid, and embarrassed thathe was bringingthis up infront of Marshal, I frowned. “We don’t have to do it at my office if you’re uncomfortable,” he added, squintingfromthebrightDecember sun.“Nooneneedstoknow.”

Ididn’tcareiftheFIBknew Iwasseeingtheir psychiatrist.Hell,ifanyoneneededcounseling,it was me. But still…“I’mnot crazy,” I muttered as I angled the blowingvents to me and myhair flew upfromunder myhat.

Ford puta hand onthe openwindow ina show ofsupport. “You’re probablythe sanestpersonI know. You only look crazy because you’ve got a lot of weird stuff to deal with. If you want, while you’rerelaxed,Icangiveyouawaytokeepyour mouthshutaboutanythingyouwantunder justabout anycircumstance. Completelyconfidential, betweenyouand your subconscious.” Surprised, I stared athim,andhefinished,“Idon’tevenhavetoknow whatyou’rekeepingtoyourself.”

“I’mnotafraid ofyou,” Isaid, butmyknees feltfunny. Whathas he figured outaboutme thathe isn’tsaying?

Shifting his feet in the slush, Ford shrugged. “Yes, you are. I think it’s cute.” He glanced at Marshal and smiled. “Bigbad runner who cantake downblackwitches and vampires afraid oflittle helplessme.”

“Iamnotafraidofyou.Andyou’renothelpless!”IexclaimedasMarshal chuckled.

“Thenyou’ll doit,”Fordsaidconfidently,andImadeanoiseoffrustration.

“Yeah, whatever,” Imuttered, thenfiddled withthe ventagain. Iwanted to getoutofhere before hereallyfiguredoutwhatwasgoingoninmyhead-andthentoldme.

“Ihavetotell Eddenaboutthestickysilk,”Fordsaid,“butI’ll waituntil tomorrow.”

My eyes flicked to the ladder, still propped against the boat’s side. “Thanks,” I said, and he nodded, responding to the heavy emotion of gratitude I knew I must be throwing off. My roommate would have time to come outwiththe Jr. Detective Kitshe probablyhad stashed inher label-strewn closetandtakewhatever printsshewanted.Nottomentionsniffingthecarpet.

Ford smiled at a private thought. “Since youwon’t come in, how about me comingover tonight about…six?Somewhereafter mydinner andbeforeyour lunch?”

Istaredathimfor hisbrazenness.“I’mbusy.How aboutnextmonth?”

He ducked his head as ifembarrassed, buthe was still smilingwhenhe metmygaze. “Iwantto talktoyoubeforeItalktoEdden.Tomorrow.Threeo’clock.”

“I’m picking my brother up at the airport at three,” I said quickly. “I’ll be with him and my mother therestoftheday.Sorry.”

“I’ll see you at six,” he said firmly. “By then, you’ll be home trying to get away from your brother andyour mom,readyfor somerelaxation.Icanteachyouatrickfor that,too.”

“God!Ihateitwhenyoudothat!”Isaid,messingwithmyseatbeltsohewouldtakethehintand goaway.Iwas more embarrassedthanangrythathe’dcaughtme tryingtoevade him.“Hey!” Ileaned outthewindow asheturnedtogo.“Don’ttell anyoneIhadmyfaceonthefloor,okay?”

Frombesideme,Marshal madeawonderingsound,andIturnedtohim.“Youeither.”

“No problem,” he said, thunkingthe SUVinto gear and movingforward a few feet. Mywindow wentup,andIloosenedmyscarfas thevehiclewarmed.Fordslowlymanagedtheslushyruts backto his car, pullinghis phone fromhis pocketas he went. Rememberingmyownphone, onvibrate, Idug mycell outofmybag.Scrollingthroughthemenutoputitonring,Iwonderedhow Iwas goingtotell

IvywhatIrememberedwithoutbothofusflakingout.

Witha small noise ofconcern, Marshal puthis SUVbackinto park, and myhead came up. Ford was standing beside his open door with his phone stuck to his ear. A bad feeling began to trickle throughme whenhe started backto us. Itgrew worse whenMarshal puthis window downand Ford stoppedbesideit.Thepsychiatrist’seyescarriedaheavyworry.

“That was Edden,” Ford said as he closed his phone and returned it to his belt case. “Glenn’s beenhurt.”

“Glenn!” I leaned over the center console toward him, getting a good whiff of the scent of redwood coming off Marshal. The FIB detective was Edden’s son and one of my favorite people. Andnow hewashurt.Becauseofme?“Isheokay?”

Marshal stiffened, and Ileaned back. Ford was shakinghis head and lookingatthe nearbyriver. “He was off duty investigating something he probably shouldn’t have. They found himunconscious. I’mgoingtothehospital toseehow muchdamagehe’ssufferedtohishead.”

His head. Ford meant his brain. Someone had beat himup. “I’mcoming, too,” I said, reaching for myseatbelt.

“I can drive you out,” Marshal offered, but I was winding my scarf back up and grabbing my bag.

“No, but thanks, Marshal,” I said, my pulse fast as I gave his shoulder a quick touch. “Ford’s goingoutthere.I’ll,ah,call youlater,okay?”

Marshal’s brown eyes were worried, and his black hair, tight to his skull, hardly shifted as he nodded. Ithad beengrowinginfor onlya few months, butatleasthe had eyebrows now. “Okay,” he echoed,notgivingmeanygrieffor ditchinghim.“Takecareofyourself.”

I exhaled, glancingonce at Ford, waitingimpatientlyfor me, thenbackto Marshal. “Thanks,” I saidsoftly,andgavehimanimpulsivekissonthecheek.“You’reagreatguy.”

Igotout, and, pace fast, followed Ford to his car, mythoughts and stomachchurningatwhatwe might find at the hospital. Someone had hurt Glenn. Sure, he was a FIB officer and ran the risk of injuryall thetime,butIhadafeelingthisinvolvedme.Ithadto.Iwasanalbatross. JustaskKisten.

Two

We’ll take the nextelevator,” the tidywomansaid withanoverlybrightsmile as she pulled her confusedfriendbackintothehall andthesilver doorsslidshutbeforeFordandme.

Wondering, Iglanced atthe huge lift. The thingwas bigenoughfor a gurney. Ford and Iwere the onlytwopeopleinhere.Butthenthewoman’sharshwhisper of“Blackwitch”cameinjustbeforethe doorsmet,tellingmeall Ineededtoknow.

“TheTurntakeit,”Imuttered,tuggingmybagbackuponmyshoulder.

Besideme,Fordedgedaway,notenjoyingmyangryemotionsasIfumed.Iwasn’tablackwitch. Okay, so myaura was covered withdemonsmut. And yeah, I’d beenfilmed last year beingdragged down the street on my ass by a demon. It probably didn’t help that the entire universe knew I’d summoned one into an I.S. courtroom to testify against Piscary, Cincinnati’s top vampire and my roommate’sformer master.ButIwasawhitewitch.Wasn’tI?

Depressed,Istaredatthedull silver panelsofthehospital elevator.Fordwasadarkblur beside me, his head bowed as I stewed. I wasn’t a demon to be pulled back to the ever-after when the sun rose, but my children would be-thanks to the illegal genetic tinkering of the now-dead Senior Kalamack. He had unknowinglybrokenthe checks and balances thatelves magicked into the demon’s genome thousands of years ago, effectively allowing only magically stunted demon children to survive. The elves named the new species witches, tellingus lies and convincingus to fight demons intheir war. Whenwe found outthe truth, we abandoned the elves and demons both, migratingoutof the ever-after and doingour best to forget our origins. Whichwe did admirably, to the point where I wastheonlywitchtoknow thetruth.

Ceri had filled in the gaps of Mr. Haston’s sixth-grade history class, having been a demon’s familiar beforeIrescuedher.She’dreaduponitbetweentwistingcursesandplanningorgies.

No one knew the truthbutme and mypartners. And Al, the demonIhad a standingteachingdate with every Saturday. And Newt, the ever-after’s most powerful demon. There was Al’s parole officer, Dali. Mustn’t forget Trent and whoever he’d told, but that was likely going to be no one, seeing that his dad’s breaking of the genetic roadblock had been a stupid thing to do. No wonder they’dkilledall thegeneticistsattheTurn.Toobadthey’dmissedTrent’sdad.

Ford jiggled on his feet, then, looking embarrassed, he pulled a black metal flask from a coat pocket,twistedoffthetop,tiltedhisheadtotheceiling,andtookaswig.

WatchinghisAdam’sapplemove,Igavehimaquestioninglook.

“It’smedicinal,”hesaid,acharmingshadeofredashefumbledrecappingit.

“Well, we are ina hospital,” Isaid dryly, thensnatched it. Ford protested as Itooka sniff, then touchedittomylips.Myeyeswidened.“Vodka?”

Looking even more embarrassed, the slight man took it from my unresisting fingers, capped it, and tucked itaway. The elevator chimed and the panels slid apart. Before us was a hallwaylike any other inthebuilding,withitslow-matcarpet,whitewalls,andbanister.

My worry for Glenn came rushing back, and I lurched forward. Ford and I bumped as we got out, and Ifelta washofchagrin. Iknew he didn’tlike to touchanyone. “CanIsteadymyselfonyour elbow?”heasked,andIglancedatthepockethehaddroppedtheflaskinto.

“Lightweight,”Isaid,reachingoutfor him,careful totouchhimonlythroughhiscoat.

“I’m not drunk,” he said sourly, linking his arm in mine in a motion that held absolutely no romance, but rather, desperation. “The emotions are sharp in here. The alcohol helps. I’m in

overload,andI’drather feel your emotionsthaneveryoneelse’s.”

“Oh.” Feelinghonored, I strode forward withhimand past the two orderlies pushinga hamper. Mygoodmoodsouredwhenoneofthemwhispered,“Shouldwecall security?”

Ford’sgriptightenedwhenIspuntogivethemmyopinion,andthetwoskitteredawaylikeIwas theboogeyman.“They’rejustafraid,”Fordsaid,hisfingerstighteningonme.

We continued down the hall, and I wondered if they could kick me out. The beginnings of a headache pulsed. “I’m a white witch, damn it,” I said to no one, and the guy in a lab coat coming towardusgaveusacursoryglance.

Ford was lookingpale, and Itried to calmmyselfbefore theyadmitted him. Ishould step up my effortstofindamuffler for him-other thanalcohol,thatis.

“Thanks,”hewhisperedas hepickeduponmyconcern,then,voicestronger,headded,“Rachel, yousummondemons. You’re good at it. Get over it, thenfind a wayto make it workfor you. It’s not goingtogoaway.”

Ihuffed, readyto tell himhe had no rightto sound so highand mighty, butturninga liabilityinto anasset was exactlywhat he had done withhis “gift.” I gave his arma squeeze, thenstarted whenI saw Ivy, myroommate, bendingover the nurses’desk, notcaringthata male orderlyhad justwalked into a wall watching her. Her black jeans were low and tight, but she had the body of a model and couldgetawaywithit.Thematchingcottonpullover wascuthightogiveaglimpseofher lower back as she craned to see what was on the computer. In deference to the cold, her long leather coat was draped over the counter. Ivy was a living vampire, and she looked it: svelte, dark, and broody. It madeithardtolivewithher,butIwasnopicniceither,andweknew eachother’squirks.

“Ivy!” Icalled, and her head turned, her short, enviablystraighthair withthe gold tips swinging asshecameup.“How didyoufindoutaboutGlenn?”

Ford’s shoulders slumped, all his tension slipping from him as he held my arm. He looked happy.Buthewould,seeingthathewaspickingupmyemotionsandIwashappytoseeIvy.PerhapsI might invest ina little talktime about IvywhenFord and I got together again. I could use his insight intoour uneasyrelationship.

I wasn’t Ivy’s blood shadow, but her friend. That a vampire could be friends with anyone without sharing blood was unusual, but we had an additional complication. Ivy liked both boys and girls, mixing blood and sex into one and the same. She’d been clear that she wanted me, too, in any capacity, but I was straight, apart froma confusingyear of tryingto separate blood lust fromgender preference. Thatshe’d bittenme more thanonce hadn’thelped. Ithad seemed like a good idea atthe time. The rush froma vampire bite was too close to sexual ecstasy to dismiss, and it had taken me thinking I’d been bound to Kisten’s killer to wake me up. The risk of becoming a shadow was too great.ItrustedIvy.Itwasher bloodlustIwasworriedabout.

So we lived together in the church that was also our runner business, sleeping across the hall from each other and doing our best to not push each other’s buttons. One might think Ivy would be ticked offafter wastinga year chasingme, butshe had a blissful happiness thatvampires didn’toften find.Apparentlymytellingher Iwasn’tever goingtolether sinkher teethintome againwas the only wayshe’d believe Iliked her for her and notthe wayshe could make me feel. Ijustadmired the hell out of anyone who could be that hard onherself and still be so incrediblystrong. And I loved her. I didn’twanttosleepwithher,butIdidloveher.

Ivy came to meet us, her small lips closed and her slimboots silent on the carpet. She moved witha memorable grace, and there was a slightgrimace onher usuallyplacid face. Her features held a slight Asian cast, having an oval face, a small nose, and a heart-shaped mouth. It was seldomshe

smiled, afraid the emotionwould breakher self-control. Ithinkthat was one ofthe reasons we were friends-I laughed enoughfor bothof us. That, and the fact that she thought I could find a wayto save her soul whenshe died and became anundead. Right now, I was just lookingto find the rent money. I’dgettomyroommate’ssoul later.

“Edden called the church first,” she said by way of greeting, her thin eyebrows high as she spottedFord’sarmlinkedinmine.“Hi,Ford.”

Themanreddenedattheliltshe’dputinher lastwords,butIwouldn’tlethimtakehisarmback. Ilikedbeingneeded.“He’shavingtroublewiththebackgroundemotion,”Isaid.

“Andhe’drather beabusedbyyours?”

Nice.“Doyouknow whatroomGlennisin?”IsaidasFord’sarmslippedaway.

She nodded, her darkeyes notmissinga thing. “This way. He’s still notconscious.” Ivyheaded downthehallwaywithusintow,butwhenwepassedthedesk,oneofthenursesstood,determination onher no-nonsenseface.“I’msorry.Novisitorsexceptfamily.”

Apangoffear wentthroughme, notbecause Imightnotsee Glenn, butthathis conditionwas so serioustheywouldn’tletanyonein.Ivydidn’tslow down,though,andneither didI.

The nurse started after us. Mypulse quickened, butanother waved us on, thenturned to the first nurse.“It’sIvy,”thesecondnursesaid,asifthatmeantsomething.

“Youmeanthe vampire who’s-” the firstnurse said,butshe was pulledbacktothe deskbefore I heardtherest.IturnedtoIvy,seeingthather palecomplexionhadshiftedtopink.

“Thevampirewho’swhat?”Iasked,rememberingher stinthereasacandystriper.

Ivy’sjaw tightened.“Glenn’sroomisdownhere,”shesaid,avoidingmyquestion.Whatever.

An unexpected sense of panic hit me when Ivy made a sharp left into a room and vanished behind the oversize door. I stared at it, hearing the soft sounds of delicate machinery. Memories of sitting with my dad as he took his last, struggling breaths swam up, then more recent, of watching Quenfightfor hislife.Ifroze,unabletomove.Behindme,Fordstumbled,asifIhadslappedhim.

Crap. Iflushed, embarrassed thathe was feelingmymisery. “I’msorry,” Igushed as he stood in the hallwayand held up a hand to tell me he was all right. Ithanked God Ivyhad alreadygone inand wasn’tseeingwhatI’ddonetohim.

“It’s okay.” His eyes were weary as he came close again, hesitant until he knew I had the old painsafelytuckedaway.“CanIaskwho?”

Iswallowedhard.“Mydad.”

Eyesdown,heguidedmetothedoor.“Youwereabouttwelve?”

“Thirteen.”Andthenwewereinside,andIcouldseethatitwasn’tthesameroomatall.

Slowly my shoulders eased. My dad had died with nothing to save him. As a law enforcer, Glenn was getting the best of everything. His father was in the rocker pulled up to his bedside, ramrodstraight.Glennwasbeingtakencareof.Eddenwastheoneinpain.

The small, stockymantried to smile, buthe couldn’tdo it. Inthe few hours since learningabout his son’s attack, his pale face had acquired wrinkles I’d onlyseenhints of before. Inhis grip was a winter hat, his short fingers working the rimaround and around. He stood, and myheart went out to himwhenheexhaled,thesoundcarryingall hisfear andworry.

EddenwasthecaptainoftheFIB’sCincinnati division,theex-militarymanbringingtotheoffice the hard, succeed-against-all-odds determinationhe’d gained inthe service. Seeinghimdownto the bare bones of himself was hard. The lingering questions in the FIB as to my “convenient” amnesia concerning Kisten’s death had never occurred to Edden. He trusted me, and because of that, he was oneofthefew humansIabsolutelytrustedinreturn.Hisson,unconsciousonthebed,wasanother.