September 18 – December 13, 2025

Del 18 de septiembre al 13 de diciembre de 2025

Stedman Gallery

Rutgers–Camden Center for the Arts

September 18 – December 13, 2025

Del 18 de septiembre al 13 de diciembre de 2025

Stedman Gallery

Rutgers–Camden Center for the Arts

Symone Salib, Visual Artist

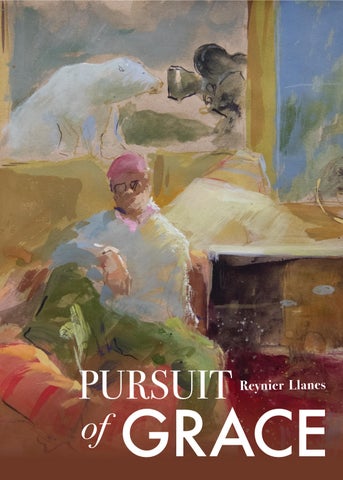

Pursuit of Grace by Reynier Llanes draws viewers in with the encouragement of reaching towards memories and dreams. To the feeling of looking to the past as a form of cultural preservation while imagining a future full of hope. Full of more than what we currently have. As a first-generation Cuban artist myself, I take in Llanes’ work with so many feelings of familiarity in ways that feel inherited from my ancestors. Figures throughout his paintings remind me of everyday people and the ways that we hold the magic within ourselves. They appear as living metaphors to the landscape of the island. They are pieces of home recalled and reimagined to remind us of the resilience of the Cuban people and visually softened with grace.

Llanes was born in Pinar del Rio, Cuba and grew up in a country where expression had to be masked. “We had to veil truth and critique behind metaphors,” he shared in a recent conversation with Elizabeth Coulter, Gallery and Collection Coordinator at Rutgers-Camden Center for the Arts. “Direct commentary on the country’s reality or political system was not allowed. That shaped my visual language.”

As someone raised by a Cuban mother, the echo of this shared reality lived through my family’s stories and ultimately their silence. This feeling of knowing and feeling unable to speak truth to power. The understanding and pain of impossible return. I have witnessed this veiled language. In Llanes’ artwork, symbolism is a language in itself. It’s a form of truth telling through brushstrokes.

In The Prayer, in the background candles are seen flickering which to me is a reminder of hope or mourning. In Cycles, a hamster wheel spins alluding to a metaphor of endlessly trying to make meaning across borders in both a literal and psychological sense. Llanes paints to document and bear witness to what it means to be someone of the diaspora.

In between Llanes’ delicate brush strokes, he creates such a clear message of nostalgia. He paints with an illusion of open-ended questions, not answers. He says, “These paintings are like a visual diary that helps me narrate my reality and respond to social conversations.” You can feel lush the landscape of Cuba and the dislocation of migration. His subjects such as “the journalist,” “the guardian,” “the poet,” are not singular people. They are examples of responsibility, of hypervigilance, and the ways we carry identity into everything we do.

They remind me of my own family, the people who watched what they said and who said it around. My Tias, who held onto our family photos and the few things they brought with them from Cuba as holy relics. How storytelling became a vehicle to preserve our families’ history and legacy and the ways silence would erase hard moments people didn’t want to remember. These roles were communal and intergenerational. Llanes has a talent for painting moments like this with tenderness, but also gravity. His figures feel luminous, but their purpose is evident. You can feel that they carry the burden of displacement, of memory, of a lifelong grief.

There is a precisely Cuban logic to the way Llanes blends reality with dream. His paintings are one where a man sings while sweeping the streets, and Roombas float through the sky. He merges magic and modern technology. This is magical realism not as a genre, but as a world view. A world view inherited from our ancestors and our history. From our ancestors who were innovative out of necessity. From the orishas and saints. From the collectives’ need to imagine freedom even when reality makes it feel impossible.

To Cubans magical realism isn’t escapism, it’s a mirror to the way we view the world. Reflecting to a deeper truth, spiritual truths of life on the island and beyond. Santería, based in Yoruba spiritual practices, is an example of the ways this is a part of the culture on the island. In Santería, orishas are symbols of nature, our deepest emotions, and ancestral wisdom. For example, deities such as Yemaya are a symbol of fertility and the goddess of the sea. She is known to be nurturing and is the mother of all. Chango on the other hand is the god of fire, lighting, and justice. He is known for being associated with emotions such as passion and protection.

Although Llanes doesn’t directly depict orishas, the visual storytelling gives a similar energy. He creates a place where nature holds spirit, that every figure and metaphor carry divine meanings. His work is a parallel for Cuban folklore and storytelling. Llanes symbolism is a nod to our heritage in this way, a familiar space where our families’ beliefs and our own imaginations blend.

Painting towards grace feels spiritual to me in this sense. Llanes’ reference to the lush landscape of the island feels like a reminder of the way our land is sacred. He through metaphorical painting shows us the duality of how the land can be threatened. It reminds me of the responsibility we hold towards the land, particularly in the midst of the effects of climate change. “The challenges we face, especially around unequal access to natural resources, demand awareness and action,” he explains. But still, he resists despair. His belief in collective imagination, in dialogue, in legacy, guides him toward hope.

For people of the diaspora grace is a tool of survival. It encourages us to move forward regardless of what comes our way. It allows us to find nuance. As Llanes puts it, “Even though the world may feel like it’s falling apart, a recurring theme throughout human history, my work remains optimistic and idealistic.” I admire this element about Llanes’ work, that although grace is not always the easiest thing to give oneself, it is necessary in a world where we reject the notion of becoming jaded. It shows us that grace is not a destination. It’s an offering. A way to keep going and a way of life.

Momentum 2025, Oil on canvas

Momentum 2025, óleo sobre lienzo

Symone Salib, Artista visual

T he Documentary 2025, Gouache on paper

El Documental 2025, Gouache sobre papel

Pursuit of Grace (En busca de la gracia) de Reynier Llanes captura al público incentivándolo a acercarse a sus recuerdos y sueños. Al sentimiento de mirar hacia el pasado para preservar la cultura y, a la vez, imaginar un futuro lleno de esperanza. Lleno de más que lo que tenemos ahora. Yo también soy una artista cubana de primera generación; por eso, la obra de Llanes me despierta un tipo de familiaridad que siento haber heredado de mis ancestros. Las figuras de sus cuadros me recuerdan a la gente común y a cómo llevamos la magia dentro. Parecen metáforas vivas que se desarrollan frente al paisaje isleño. Son piezas del hogar recordado y reimaginado, atenuadas por la gracia, que nos recuerdan la resiliencia del pueblo cubano.

Llanes nació en Pinar del Río, Cuba, y creció en un país donde la expresión debía disfrazarse. “Teníamos que ocultar la verdad y la crítica detrás de metáforas”, comentó hace poco en un conversatorio con Elizabeth Coulter, coordinadora de la galería y de la colección de Rutgers–Camden Center for the Arts. “No estaba permitido opinar explícitamente sobre la realidad del país y su sistema político. Eso marcó mi lenguaje visual”.

Criada por una madre cubana, siento el eco de su realidad en las historias de mi familia y en su silencio. La sensación de saber la verdad, pero no poder enunciarla ante el poder. La comprensión y el dolor de la imposibilidad de regresar. He visto este lenguaje encubierto. En la obra de Llanes, el simbolismo en sí es un lenguaje. Es un modo de contar su verdad mediante pinceladas.

Las velas parpadeantes que se ven en el fondo de The Prayer (La plegaria) me remiten a la esperanza y al duelo. Llanes pinta para registrar y ser testigo de lo que representa ser miembro de la diáspora.

Entre sus delicadas pinceladas, crea un nítido mensaje de nostalgia. Lo hace con la ilusión de presentar preguntas abiertas en lugar de respuestas.

“Estas pinturas son un diario visual que me ayuda a narrar mi realidad y responder a las conversaciones de la sociedad”, comenta Llanes. Se percibe el frondoso paisaje cubano y el desarraigo de la migración. Sus personajes, “el periodista”, “el guardián”, “el poeta”, no son individuos. Son ejemplos de la responsabilidad, la hipervigilancia y la presencia de nuestra identidad en todo lo que hacemos.

Me recuerdan a mi propia familia, la gente que elegía con cuidado sus palabras y frente a quién las decía. A mis tías, que cuidaron como reliquias las fotos familiares y las pocas pertenencias que trajeron de Cuba. Las narraciones, que se volvieron un vehículo para preservar la historia y el legado de nuestra familia, y los silencios, que borraron los momentos difíciles que nadie quería recordar. Estos roles eran comunitarios e intergeneracionales. Llanes retrata hábilmente estos momentos con ternura y solemnidad. Las figuras lucen luminosas, pero su propósito es evidente. Se siente la carga que llevan, el desarraigo, la memoria y el luto permanente.

Llanes funde la realidad y los sueños con una lógica precisamente cubana. En sus pinturas, un hombre canta mientras barre la calle y en el cielo flotan Roombas. La magia y la tecnología moderna se mezclan. En ellas, el realismo mágico no es un género, sino una cosmovisión. Lo heredamos de nuestros ancestros y nuestra historia. De quienes innovaron por necesidad. De los orishas y los santos. De la necesidad colectiva de imaginar la libertad aun cuando parece imposible.

Para los cubanos, el realismo mágico no es escapismo: es un espejo que refleja cómo vemos el mundo. Nos muestra una realidad más profunda, las verdades espirituales de la vida en la isla y más allá. La santería, que se basa en prácticas espirituales yoruba, es ejemplo de cómo se integra esto en la cultura isleña. Los orishas son símbolos de la naturaleza, nuestras emociones más profundas y la sabiduría ancestral. Por ejemplo, la deidad Yemayá es símbolo de la fertilidad y es la diosa del mar. Es la madre de todos, a quienes cuida cariñosamente. Por otro lado, Changó es el dios del fuego, el rayo y la justicia. Se lo asocia con la pasión y la protección.

Si bien Llanes no representa orishas en sus pinturas, su relato visual proyecta una energía similar. Crea un espacio donde la naturaleza tiene espíritu, donde cada figura y metáfora poseen un significado divino. Su obra va en paralelo al folclore y a las historias cubanas. De este modo, el simbolismo de Llanes es un guiño a nuestra ascendencia, un espacio en el que se fusionan las creencias de nuestras familias y nuestra propia imaginación.

Bajo esta óptica, pintar hacia la gracia me parece algo espiritual. La representación de Llanes del frondoso paisaje isleño nos recuerda que nuestra tierra es sagrada. A través de la metáfora, nos muestra la amenaza doble que puede sufrir nuestro suelo. Me lleva a pensar en la responsabilidad que tenemos con él, sobre todo, ante los efectos del cambio climático. “Los desafíos que enfrentamos requieren nuestra atención y acción, en particular, aquellos relativos a la desigualdad de acceso a los recursos naturales”, explica Llanes. Sin embargo, se resiste a caer en la desesperación. Cree en la imaginación colectiva, el diálogo, el patrimonio, y eso lo guía hacia la esperanza.

Para los miembros de la diáspora, la gracia es una herramienta para la supervivencia. Nos impulsa a seguir adelante, sin importar lo que nos suceda. Nos permite distinguir los matices. En palabras de Llanes: “Aunque parezca que el mundo se desmorona, una creencia recurrente en la historia de la humanidad, mi trabajo mantiene su optimismo e idealismo”. Eso es lo que admiro de la obra de Llanes. No es fácil otorgarse gracia y misericordia a uno mismo, pero sí es necesario en un mundo que rechaza el hastío. Nos demuestra que la gracia no es la meta. Es la ofrenda. Una forma de seguir adelante y de vivir.

Shells

2025, Oil on canvas

Caparazones 2025, óleo sobre lienzo

with Elizabeth Coulter, Gallery and Collection Coordinator

What does the notion of grace mean to you, and how does it manifest in your work?

Jumping into an art career is often fueled by idealism. For me, the closest path to utopia is through creation. Even though the world may feel like it’s falling apart— a recurring theme throughout human history—my work remains optimistic and idealistic. The title of this show is ambitious in that sense. I believe reaching for grace is essential. It’s how we open ourselves to dialogue, to understanding others. Becoming a parent has deeply shaped my worldview, influencing both the world I want to live in and the legacy I hope to leave for my children.

You frequently incorporate symbols in your compositions, like the lit candles in The Prayer, among others. What is the significance of using symbols in your paintings, and were there any life experiences that guided you to explore this mode of expression?

Symbolism has always been a part of my practice, dating back to my time as an art student in Cuba. At that time, we had to veil truth and critique behind metaphors, as direct commentary on the country’s reality or political system was not allowed. This shaped my visual language, although my concerns and critical perspective never left me. Today, I find symbolism even more engaging and fluid. It allows storytelling to emerge naturally, and I fully embrace the freedom to express and interpret feelings openly. That freedom is something I’ve learned not to take for granted.

Several of your works refer to various identities like “the collector,” “the journalist,” “the poet,” and “the guardian?” What do these characters mean to you?

These characters aren’t protagonists in a narrative; they are part of a scene. I don’t think of them as individuals with names or personalities but as figures that represent actions, careers, or energies connected to our time. I build the entire composition around them, and symbols play a strong role in shaping the scene. I’m also drawn to my African heritage, how it’s reflected in expression, posture, and presence. It is not decorative but rather recreating the images that call my attention to daily life and how they are connected to our time.

Can you share your creative process in making these works?

In this case, I worked with oils. These paintings are like a visual diary that helps me narrate my reality and respond to social conversations. The process usually begins with a study, a smaller work that allows the ideas to flow more freely from my mind to the canvas. These studies guide the larger works, though the final compositions and techniques often evolve. Across all mediums, I play with brushstrokes, mixed colors, layers, and transparency. Oils, in particular, offer a tridimensional quality where texture becomes a key expressive tool.

Many works in this exhibition suggest a disparity in access to natural resources. How do you reconcile concerns about climate change and the pressing need for environmental awareness in your work?

This is one of the issues I care about most and it’s urgent and deeply relevant. My perspective is optimistic, but not naïve. I believe the future must be imagined collectively. I often discuss these concerns with friends and family, and I hope they also feel safe sharing their concerns with me. That exchange is essential. The challenges we face, especially around unequal access to natural resources, demand awareness and action. What gives me hope is our ability to rethink our role in the world and the ultimate purpose of our existence.

Can you describe how these paintings invite introspection on the passage of time?

One of the most fulfilling parts of my work is hearing how others respond to it. When a painting evokes a memory, a feeling, or a personal reflection, I feel I’ve achieved something meaningful. That emotional connection is the highest outcome I could hope for. My take in all my art becomes secondary when faced with the interpretation of the public. The passage of time is like life itself: broad and open to interpretation. However, that concern is a constant in my practice and I’d love to hear what people think about it.

Much of your artistic practice has been centered on connection and community. What do you hope the community of the Rutgers-Camden Center for the Arts takes away from this exhibition?

As I’ve mentioned throughout these responses, the interaction with the audience, how meaning emerges when the work meets new minds, is central to my practice. Beyond that, I believe deeply in access: access to art, to different career paths, to new perspectives. Institutions like the RutgersCamden Center for the Arts play a vital role in creating those opportunities. My own life changed the first time I met real artists at my school or visited an art museum. That’s why I’m passionate about offering workshops and engaging with the community. Not just because I have a background in teaching, but because it feels natural to me. When access to culture and education is made possible through social mobility and justice, lives are transformed, and communities grow. I truly believe in the pursuit of that kind of beauty.

El pasado, presente y futuro 2021, watercolor on paper

El pasado, presente y futuro 2021, acuarela sobre papel

con Elizabeth Coulter, Coordinadora de la galería y su lección

¿Qué significa para usted la gracia y cómo se manifiesta en su trabajo?

Por lo general, uno se lanza a una carrera artística impulsado por el idealismo. Yo creo que el camino que más nos acerca a la utopía es el de la creación. Aunque parezca que el mundo se desmorona, una creencia recurrente en la historia de la humanidad, mi trabajo mantiene su optimismo e idealismo. En ese sentido, mi exhibición tiene un nombre ambicioso. Considero que es esencial acercarnos a la gracia. Es lo que nos permite abrirnos al diálogo y entendernos entre nosotros. Ser padre marcó mucho mi visión del mundo. Influenció tanto el mundo en el que quiero vivir como el patrimonio que espero dejarles a mis hijos.

Sus composiciones están cargadas de símbolos; por ejemplo, las velas encendidas de The Prayer (La plegaria), entre otros. ¿Cuál es la relevancia de usar símbolos en sus pinturas? ¿Vivió alguna experiencia que lo llevara a explorar este modo de expresión?

El simbolismo siempre fue parte de mi práctica artística, desde que estudiaba arte en Cuba. En esa época, debíamos disfrazar la verdad y la crítica con metáforas, ya que no estaba permitido opinar abiertamente sobre la realidad del país y su sistema político. Esto dejó una marca en mi lenguaje visual; sin embargo, nunca dejé ir mis inquietudes y mi visión crítica. Hoy en día, el simbolismo me parece aún más interesante y fluido. Permite que la narración surja con naturalidad y da libertad para expresar e interpretar los sentimientos abiertamente. Acepto esta libertad y me lanzo de lleno a ella. Entendí que no debo subestimar su importancia.

Varias de sus obras refieren a identidades, tales como “el recolector”, “el periodista”, “el poeta”, “el guardián”. ¿Qué representan estos personajes?

Los personajes no protagonizan una narración: son parte de una escena. No los considero individuos con nombres y personalidades, sino figuras que representan acciones, profesiones o energías ligadas a la actualidad. Construyo toda la composición centrándome en ellos, y los símbolos determinan en gran medida la escena. También me interesa mucho mi ascendencia africana, y cómo se ve reflejada en expresiones, postura y presencia. No es meramente decorativo: recreo imágenes que me remiten a la vida diaria y a cómo se relacionan con los tiempos que corren.

¿Cómo es el proceso creativo detrás de estas obras?

En este caso, trabajé con óleos. Estas pinturas son un diario visual que me ayuda a narrar mi realidad y responder a las conversaciones de la sociedad. Generalmente, empiezo con un estudio, una obra más pequeña que deja fluir las ideas con naturalidad desde mi mente hacia el lienzo. Aunque los estudios sirven de guía, la composición y la técnica evolucionan en la obra final. Algo común a todos los medios que uso es el juego de pinceladas, las mezclas de color, las capas y las transparencias. En particular, los óleos dan tridimensionalidad y la textura se vuelve una herramienta clave para la expresión.

Muchas de las obras expuestas insinúan la desigualdad de acceso a los recursos naturales. ¿Cómo integra en sus pinturas la inquietud por el cambio climático y la necesidad de despertar conciencia ambiental?

Este es el problema que más me importa y que considero más urgente y relevante. Soy optimista, pero no ingenuo. Creo que tenemos que imaginar el futuro colectivamente. Con frecuencia, comparto mi preocupación con amigos y familiares, y espero que ellos se sientan cómodos contándome sus inquietudes. Esas conversaciones son esenciales. Los desafíos a los que nos enfrentamos requieren nuestra atención y acción, en particular, aquellos relativos a la desigualdad de acceso a los recursos naturales. Encuentro esperanza en la capacidad de repensar nuestro rol en el mundo y el propósito de nuestra existencia.

¿De qué modo estas pinturas invitan a la reflexión acerca del paso del tiempo?

Una de las partes más gratificantes de mi trabajo es ver la respuesta que suscita. Cuando una pintura evoca un recuerdo, sentimiento o reflexión, creo que logré algo valioso. El mejor resultado posible es esa conexión emocional. Mi visión de mis obras pasa a segundo plano cuando surgen interpretaciones del público. El paso del tiempo es como la vida misma: es amplio y de libre interpretación. De todos modos, es una preocupación que aparece siempre en mi práctica artística, y me encantaría saber qué opinan los demás.

Gran parte de su obra se centra en la conexión y la comunidad. ¿Qué reflexión le gustaría que se lleve de esta exposición la comunidad de Rutgers-Camden Center for the Arts?

Como mencioné anteriormente, una parte esencial de mi práctica artística es la interacción con el público y la creación de significado tras el contacto de la obra con nuevas mentes. Más allá de eso, soy un defensor acérrimo del acceso al arte, a distintas trayectorias profesionales y a nuevas perspectivas. Las instituciones como Rutgers-Camden Center for the Arts desempeñan un papel central a la hora de crear dichas oportunidades. Mi vida cambió desde que conocí artistas de verdad en la escuela y visité un museo de arte por primera vez. Por eso, me apasiona dar talleres y vincularme con la comunidad. Además de tener formación de profesor, es algo natural para mí. La movilidad social y la justicia dan acceso a la cultura y la educación; eso transforma la vida de muchas personas y hace que las comunidades crezcan. Creo de verdad en la búsqueda de esa belleza.

Silvia Spitta, Professor Emerita of Spanish and Comparative Literature Dartmouth College

From his early coffee paintings in Cuba, to last year’s two exhibitions, Passages at the Gibbes Museum of Art in South Carolina and Timeless Origins at the Polk Museum of Art in Florida, Reynier Llanes continually has evolved and transformed his artistic practice. Since his move to the US South in 2007, his artistic activity has increased. He returns time and again to certain themes, such as rural life in Cuba, the Orishas and folklore of his childhood, migration to the US, the pandemic, and now, more recently, the Black Lives Matter protests. Many large, almost monumental oil paintings might first appear as coffee paintings or watercolors. As the title of this exhibition at the Stedman Gallery, Pursuit of Grace, suggests, Reynier Llanes’ oeuvre has been marked by the search for beauty as well as the hauntings of memory and that of the beings that surround all of us and whose presence we intimate.

Llanes’ focus on the transcendent, the invisible and intuited, the ghostly and the hauntings of memory that dominate many of his paintings is balanced by an equal emphasis on the tactile and the sensual. No object is unworthy of being honored in a still life. In particular, he favors the objects and foods that evoke the past. As the Spanish “recordar” from re (again) and cor (heart) has it, to remember is to pass a memory through our heart once again. When we remember we feel. While the 90 miles that separate Cuba and the US is most often represented as fraught with perils—as in Cuban-American artist Sandra Ramos’ famous engravings and installations which show exiles swimming to Florida surrounded by sharks, or the sea floor full of skeletons of the drowned—Llanes’ coffee painting SOS (2015) is ludic. It shows a young boy in a straw hat, floating on an old tire in the sea. He is asleep yet continuing to hold his artist’s brush. Despite his dire straits, the boy is nowhere near drowning but rather he is placidly being pulled along in his precarious raft by a snail while a cafetera is steaming with fresh coffee on the stern.

As Llanes recalls, he owes the idea of using coffee as ink to a lucky accident when he spilled some on a canvas and was fascinated by the effect. Given that he grew up and became an adolescent during the Special Period—an extended period of economic depression that began in Cuba in 1991—to paint with coffee as ink reflects resourcefulness necessitated by extreme scarcity, and a respect for finite resources, as well as its social, economic, and environmental influence.

Llanes’ coffee paintings set this artist in the tradition established by Brazilian artist and photographer Vik Muñiz, who rendered the children he saw living on the plantations of St. Kitts with sugar. Using brown sugar, his portraits serve as a fierce critique of the exploitation and slavery that characterized sugar plantations in the Caribbean and elsewhere during the colonial period and well beyond. Like sugar, coffee too was grown on plantations and depended on slave labor.

Llanes’ coffee paintings are delicate; their sepia tone reminds us of old photographs. Coffee, as Llanes would have it, is in the DNA of every Cuban: his Evolution (2015), which shows a series of cafeteras connected like a backbone or a DNA sequence, has become a recurrent image in his works. As his The Town Fountain (2015) underlines, coffee is at the center of Cuban social life and memory.

Earth toned coffee paintings are in tune with the rural life in Cuba that Llanes recalls and which he painted repeatedly. They are of family members who built imaginary worlds and told him many fables while he was growing up. But he also painted the life and impossible dreams of young jíbaros or farmers. One painting, Immersed in Passion (2013), shows a young man contemplating the future in a straw hat, drinking coffee and smoking a cigar. More somberly, and as if to signal the Cuban exodus from the rural areas, Passport (2014) shows a pile of old shoes.

But the hunger so many suffered during the Special Period is also referenced. The lack of meat in Cuba is represented quite ironically: cows are shown as beautiful and dignified animals in several still lifes. Repeatedly he paints cows, recalling his rural upbringing and the fables his grandfather would recount. He painted many of the cows with corn on their heads and some of them with small figures riding them. An oil painting, Ochosi (2015), in brilliant colors shows the Orisha of hunting (from the pantheon of deities in Yoruba tradition that became Santería in Cuba) lovingly holding a cow not a deer or any other animal that is typically hunted. Blue Grass Hill (2019), in a pastel color palette, is dominated by a field of blue grass which is the preferred pasture of cattle raised for beef. A white cow can be seen on the horizon in the distance.

As AI becomes more dominant in our culture undermining the real/unreal divide, Llanes has incorporated this presence in his paintings—but always in ludic form. Similarly to the ghostly presences in so many of his paintings, it too is largely invisible. Many of the corn cobbs on the heads of the cows in the Queen Yolanda (n/d) and other paintings of cows have computer plugs protruding from them. Revelation shows a cow’s head with a brilliant aura but perhaps to reflect on the increasing mechanization of dairy farming today; when we look closely, we see a small computer plug at the center. Increasingly, as digital dominates our lives, computer plugs protrude from baguettes, watermelons, and other fruits in Llanes recent works. Climate change is addressed by paintings where papayas serve as igloos, ski jumpers fly over snowless landscapes, and a little bright yellow bird sits atop a rusty oil barrel.

Three paintings stand out in my mind for the beauty and lightness—the grace with which Llanes has begun to touch on fraught situations. The first, Suns under the Moon (2020) is perhaps the most moving representation of the pandemic I have seen. It shows a group of masked doctors treating a patient outside under a moonlit sky. They are in a field of sunflowers and there is no patient other than the sunflowers searching for light under the moon. In You are Here (2022) a newborn is wrapped in a flowing white baptismal cloth being lovingly held by a figure that is barely intimated and who is standing in a city in ruins. While this painting represents our extreme vulnerability when we are born, another more hopeful painting is Home (2022). With it, Llanes departs from the agonistic longing for home in the works of many Cuban exiled artists, such as Ana Mendieta, who literally burned her silhouette into the ground and who returned to Cuba to engrave her presence in the caves of Jaruco. Unlike Mendieta for whom Cuba was always home, for Llanes, we are all transcendentally homeless, yet at home in the universe. Home, then, shows a woman alone in the universe surrounded by bright stars and galaxies. We are all there with her. We are equally homeless but at home in the sheer beauty of the universe.

Silvia Spitta, Profesora emérita de Español y Literatura Comparada, Dartmouth College

Desde sus primeras obras pintadas con café en Cuba hasta sus dos exhibiciones del año pasado, Passages (Pasajes) en el Gibbes Museum of Art de Carolina del Sur y Timeless Origins (Orígenes atemporales) en el Polk Museum of Art en Florida, la práctica artística de Reynier Llanes evolucionó y se transformó sin cesar. Tras su mudanza al sur estadounidense en 2007, el volumen de su producción creció de manera vertiginosa. Ciertas temáticas son recurrentes: la vida rural en Cuba, los orishas y el folclore de su infancia, la emigración, la pandemia y, en el último tiempo, las protestas de Black Lives Matter. Muchos de sus óleos de gran escala, casi colosales, se parecen a primera vista a sus pinturas con café o acuarelas. Como indica el título de esta exhibición en Stedman Gallery, Pursuit of Grace (En busca de la gracia), la obra de Reynier Llanes lleva la marca de la búsqueda de la belleza y la persistencia de la memoria y de todos los seres que nos rodean, cuya presencia evocamos.

Lo trascendente, lo invisible e intuido, los fantasmas que dominan muchas de sus pinturas, se equilibran con un énfasis en lo táctil y lo sensual en igual medida. No hay objeto que no sea digno de figurar en una obra de naturaleza muerta. Sobre todo, usa objetos y alimentos que evocan el pasado. Recordar, término compuesto por “re” (nuevamente) y “cor” (corazón), es cuando un recuerdo pasa por nuestro corazón una vez más. Cuando recordamos, sentimos. Las 90 millas que separan a Cuba de Estados Unidos suelen representarse plagadas de riesgos, como en los grabados y las instalaciones de la artista cubano-estadounidense Sandra Ramos, que muestran exiliados nadando hasta Florida rodeados de tiburones y suelos marinos llenos de esqueletos de los ahogados. Sin embargo, SOS (2015), una de las obras que Llanes pintó con café, es tanto sensual como lúdica. Lejos de la inclinación agnóstica de gran parte del arte del exilio, presenta a un joven con un sombrero de paja que flota sobre un neumático en el medio del océano. Aunque está dormido, se aferra a su pincel. Está en graves apuros, pero descansa plácidamente mientras un caracol tira de su precaria balsa y una cafetera italiana o cafetera anuncia con su vapor que el café está listo.

Llanes recuerda que la idea de usar el café como tinta surgió accidentalmente cuando volcó l a bebida sobre un lienzo y quedó fascinado por el resultado. Dado que creció y se convirtió en adolescente durante el Período Especial —un prolongado período de depresión económica que comenzó en Cuba en 1991— el hecho de usar café como tinta refleja la ingeniosidad que los cubanos tuvieron que desarrollar para sobrevivir a la extrema escasez de esa época. Pero también demuestra un respeto por los recursos limitados, así como por su influencia social, económica y ambiental.

Las pinturas en café de Llanes ubican a este artista en la tradición establecida por el artista y fotógrafo brasileño Vik Muñiz, quien representó a los niños que veía mientras vivía en las plantaciones de azúcar morena en San Cristóbal, y cuyos retratos sirven como una crítica contundente a la explotación y la esclavitud que caracterizaron a las plantaciones de azúcar en el Caribe y en otros lugares durante el período colonial y mucho tiempo después. El café también se cultivaba en plantaciones y dependía de la mano de obra esclava.

Para Llanes, el café está en el ADN de todos los cubanos: Evolution (Evolución), del 2015, presenta una serie de cafeteras conectadas como una columna vertebral o una secuencia de ADN. Esta imagen aparece recurrentemente en su obra. Como remarca The Town Fountain (La fuente del pueblo), del 2015, el café es el núcleo de la vida social y la economía cubanas. Las pinturas de café son delicadas. Sus tonos sepia nos recuerdan a las fotografías antiguas.

Los tonos tierra combinan con la vida rural cubana que Llanes recuerda y pinta con frecuencia. Sus pinturas en café representan a los familiares que le relataron mundos imaginarios y fábulas cuando era niño. No obstante, también pintó la vida y los sueños inalcanzables de los jóvenes granjeros y los jíbaros. La pintura del 2013 Immersed in Passion (Sumergido en la pasión), muestra a un joven con sombrero de paja que contempla el futuro mientras bebe café y fuma un cigarro. La pintura del 2014 Passport (Pasaporte) es más sombría y expone una pila de zapatos viejos, quizá señalando el éxodo de las áreas rurales cubanas.

Asimismo, también hace referencia a la hambruna del Período especial. Representa con ironía la escasez de carne en Cuba: varias de sus naturalezas muertas presentan a las vacas como animales hermosos y nobles. Las incluye en reiteradas ocasiones, remitiéndose a su infancia rural y las fábulas que su abuelo le contaba. Muchas de estas vacas tienen maíz en la cabeza, y algunas están montadas por pequeñas figuras. Un óleo de colores vivos, Ochosi (2015), representa al orisha de la caza, una de las deidades de la tradición yoruba que conforman la santería cubana. En la pintura, Ochosi abraza cariñosamente una vaca en lugar de aferrarse a un ciervo u otro animal de caza. Con una paleta de colores pastel, la composición de Blue Grass Hill (Colina de pasto azul), del 2019, está dominada por un campo de pasto azul, la hierba predilecta para alimentar al ganado bovino. En el horizonte se divisa una vaca blanca. La inteligencia artificial domina cada vez más nuestra cultura, socavando la división entre lo real y lo irreal. Llanes la incorpora, aunque siempre desde un lugar lúdico. Su presencia es casi invisible, al igual que la de tantos otros fantasmas representados en sus obras. Sin embargo, muchas de las mazorcas que llevan en la cabeza las vacas de Queen Yolanda (Reina Yolanda, s/f), y de otras pinturas de vacas, tienen enchufes de computadora sobresaliendo de ellas. En Revelation (Revelación) vemos la cabeza de una vaca rodeada por un aura brillante. Podría ser una reflexión acerca de la creciente mecanización de la industria láctea puesto que, al mirar de cerca, se puede apreciar un enchufe de computadora en la frente de la vaca. A medida que lo digital domina nuestras vidas, en sus pinturas recientes los enchufes de computadora salen de baguettes, melones y otras frutas. Para explorar el cambio climático, en sus obras representa iglús hechos de papayas, esquiadores que saltan sobre montañas sin nieve y un ave amarilla que se posa sobre un barril de petróleo oxidado. Hay tres obras que se destacan, a mi parecer, por su belleza y luminosidad, esa gracia con la que Llanes comenzó a abordar temáticas complejas. La primera es Suns under the Moon (Soles bajo la luna), del 2020: puede que esta sea la representación más conmovedora que haya visto de la pandemia. Un grupo de médicos con barbijo atienden a un paciente bajo la luz de la luna. Están en un campo de girasoles. No hay paciente alguno: solo los girasoles que buscan la luz en la noche. La pintura del 2022 You are Here (Estás aquí) presenta a un bebé recién nacido que está envuelto en un pañuelo blanco de bautismo. Una figura difusa carga al bebé en un abrazo amoroso frente a una ciudad en ruinas. Esta obra representa lo vulnerables que somos tanto al nacer como en la actualidad. Ahora bien, un lienzo con una mirada más esperanzada es Home (Hogar, 2022). En él, deja de lado el anhelo combativo de regresar al hogar que suele aparecer en el trabajo de los artistas cubanos exiliados. Por ejemplo, Ana Mendieta quemó la forma de su figura en el suelo y regresó a Cuba para grabar su presencia en las cuevas de Jaruco. Mendieta nunca dejó de añorar su hogar en Cuba. Por el contrario, Llanes cree que todos somos vagabundos y nuestro hogar es el universo. En consecuencia, Home presenta a una mujer sola en el espacio, rodeada de estrellas brillantes y galaxias. Todos estamos allí con ella como vagabundos cuyo hogar es el universo en su inagotable belleza.

Where Did You Grow Up

Damsel

2016, oil on paper board

Chancellor Antonio D. Tillis Art Collection

Manufactured 2017, oil on canvas

Chancellor Antonio D. Tillis Art Collection

Where Did You Grow Up 2017, oil on canvas

Black Pearl 2017, oil on canvas

Active 2018, oil on canvas

Chancellor Antonio D. Tillis Art Collection

The Guardian 2019, oil on canvas

It’s You 2020, watercolor on Paper

Wordsmith 2021, watercolor on paper

The Poet Sketch 2021, oil on Masonite

Chancellor Antonio D. Tillis Art Collection

El pasado, presente y futuro 2021, watercolor on paper

Temperature Says 2023, gouache on paper

The Link 2024, oil on canvas

Peacemaker 2024, oil on canvas

The Collector 2024, oil on canvas

The Journalist 2024, oil on canvas

Damisela

2016, óleo sobre cartón

Colección de arte del rector Antonio D. Tillis

Fabricado

2017, óleo sobre lienzo

Colección de arte del rector Antonio D. Tillis

Dónde creciste 2017, óleo sobre lienzo

Perla Negra 2017, óleo sobre lienzo

Activo

2018, óleo sobre lienzo

Colección de arte del rector Antonio D. Tillis

El Guardián 2019, óleo sobre lienzo

Eres Tú 2020, acuarela sobre papel

Poeta 2021, acuarela sobre papel

Boceto del poeta 2021, óleo sobre masonita Colección de arte del rector Antonio D. Tillis

El pasado, presente y futuro 2021, acuarela sobre papel

La temperatura dice 2023, gouache sobre papel

El Vínculo 2024, óleo sobre lienzo

Pacificador 2024, óleo sobre lienzo

El Recolector 2024, óleo sobre lienzo

El Periodista 2024, óleo sobre lienzo

The Prayer 2025, oil on canvas

The Documentary 2025, oil on canvas

Momentum 2025, oil on canvas

Sing to Me, sister 2025, oil on canvas

Shells 2025, oil on canvas

Sketch Book 2025, gouache on paper

Queen Bee 2025, oil on canvas

La Plegaria 2025, óleo sobre lienzo

El Documental 2025, óleo sobre lienzo

Momentum 2025, óleo sobre lienzo

Canta para mí, hermana 2025, óleo sobre lienzo

Caparazones 2025, óleo sobre lienzo

Cuaderno de bocetos 2025, gouache sobre papel

Abeja reina 2025, óleo sobre lienzo

A ntonio D. Tillis, Chancellor

John D. Griffin, Dean

Vanessa Cubano, Manager of Special Projects

Carolyn Jane Scott Charitable Trust

Cyril Reade, Director

Katy Resch, Assistant Director

Elizabeth Coulter, Gallery and Collection Coordinator

Amy Hoke, Arts Education Coordinator

Tatyana Romero, Graphic Designer

CATALOG DESIGN

Q uynh Mai

REYNIER

Reynier Llanes, Visual Artist

Patricia Diaz, Studio Manager

Rutgers–Camden Center for the Arts’ exhibitions, education, and community artist programs are funded in part by New Jersey State Council on the Arts/Department of State, a partner agency of the National Endowment for the Arts; Rutgers The State University of New Jersey, and other generous contributors.

RCCA appreciates support from the Office of the Chancellor and the Office of Civic Engagement. Special thanks to the Department of Visual, Media, and Performing Arts: Kenneth Elliott, Chair; Zulma Rodriguez, Administrative Assistant; Stass Shpanin, Program Director; Allan Espiritu, Head of BA and BFA in Visual Arts; Oludare Oredipe, Print Manager.

This programming is part of the Rutgers–Camden Year of the Arts celebration, sponsored by the Office of the Chancellor.

314 Linden Street, Camden, NJ 08102

RUTGERS UNIVERSITY–CAMDEN

A ntonio D. Tillis, Rector

John D. Griffin, Decano

Vanessa Cubano, Gestora de proyectos especiales

Carolyn Jane Scott

Charitable Trust

STEDMAN GALLERY

RUTGERS–CAMDEN CENTER FOR THE ARTS

Cyril Reade, Director

Katy Resch, Subdirectora

Elizabeth Coulter, Coordinadora de galería y colección

Amy Hoke, Coordinadora de educación artística

Tatyana Romero, Diseñadora gráfica

DISEÑO DEL CATÁLOGO

Q uynh Mai

REYNIER LLANES STUDIO

Reynier Llanes, Artista visual

Patricia Diaz, Encargada de estudio

Las exposiciones, la educación y los programas para artistas de la comunidad del Rutgers-Camden Center for the Arts (RCCA) están financiados en parte por el New Jersey State Council on the Arts/Department of State, una agencia asociada del National Endowment for the Arts, Rutgers, la universidad estatal de New Jersey, y otros generosos donantes.

RCCA agradece el apoyo de la Oficina del Rector y la Oficina de Participación Cívica. Agradecemos especialmente al Departamento de Artes Visuales, Multimediales y Escénicas: Kenneth Elliott, presidente; Zulma Rodriguez, asistente administrativa; Stass Shpanin, director del programa; Allan Espiritu, Jefe de Licenciatura y Licenciatura en Bellas Artes en Artes Visuales; Oludare Oredipe, Gerente de Impresión.

Este programa se lleva a cabo en el marco del Rutgers–Camden Year of the Arts, con el patrocinio de la Oficina del Rector.

GALLERY, FINE ARTS BUILDING

314 Linden Street, Camden, NJ 08102