Dead in a Motel Room - Dicks

AAA Powertime - Ecco2k

Luna Llena - Arca

2

12

Make Out Music - 12 Rods

Satan-Prometheus - Gorgoroth

Death - Computerwife

Devil Moon - Car Seat Headrest

Toxic - Dog Park Dissidennts

Follow Us On Spotify!

Dead in a Motel Room - Dicks

AAA Powertime - Ecco2k

Luna Llena - Arca

2

12

Make Out Music - 12 Rods

Satan-Prometheus - Gorgoroth

Death - Computerwife

Devil Moon - Car Seat Headrest

Toxic - Dog Park Dissidennts

Follow Us On Spotify!

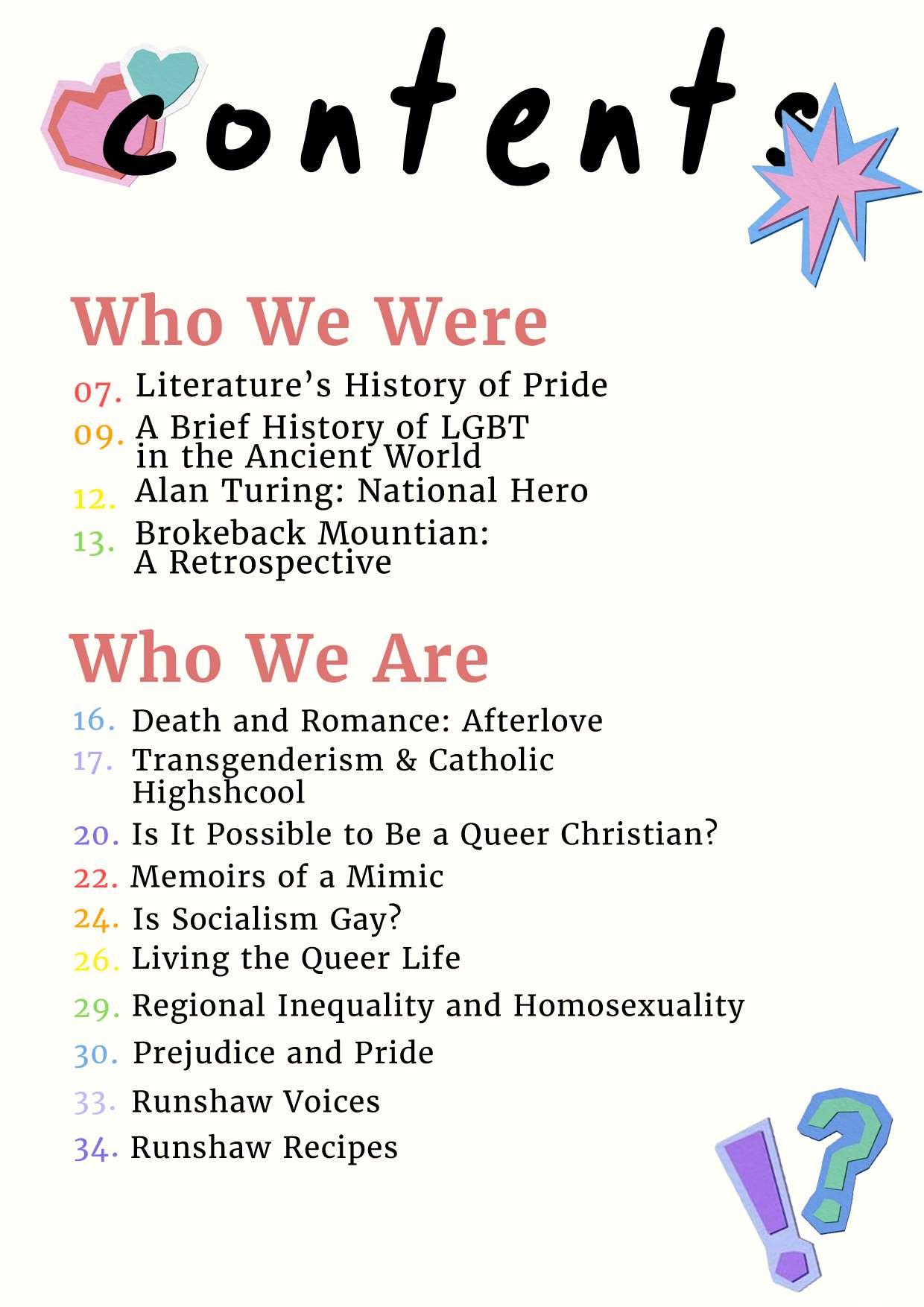

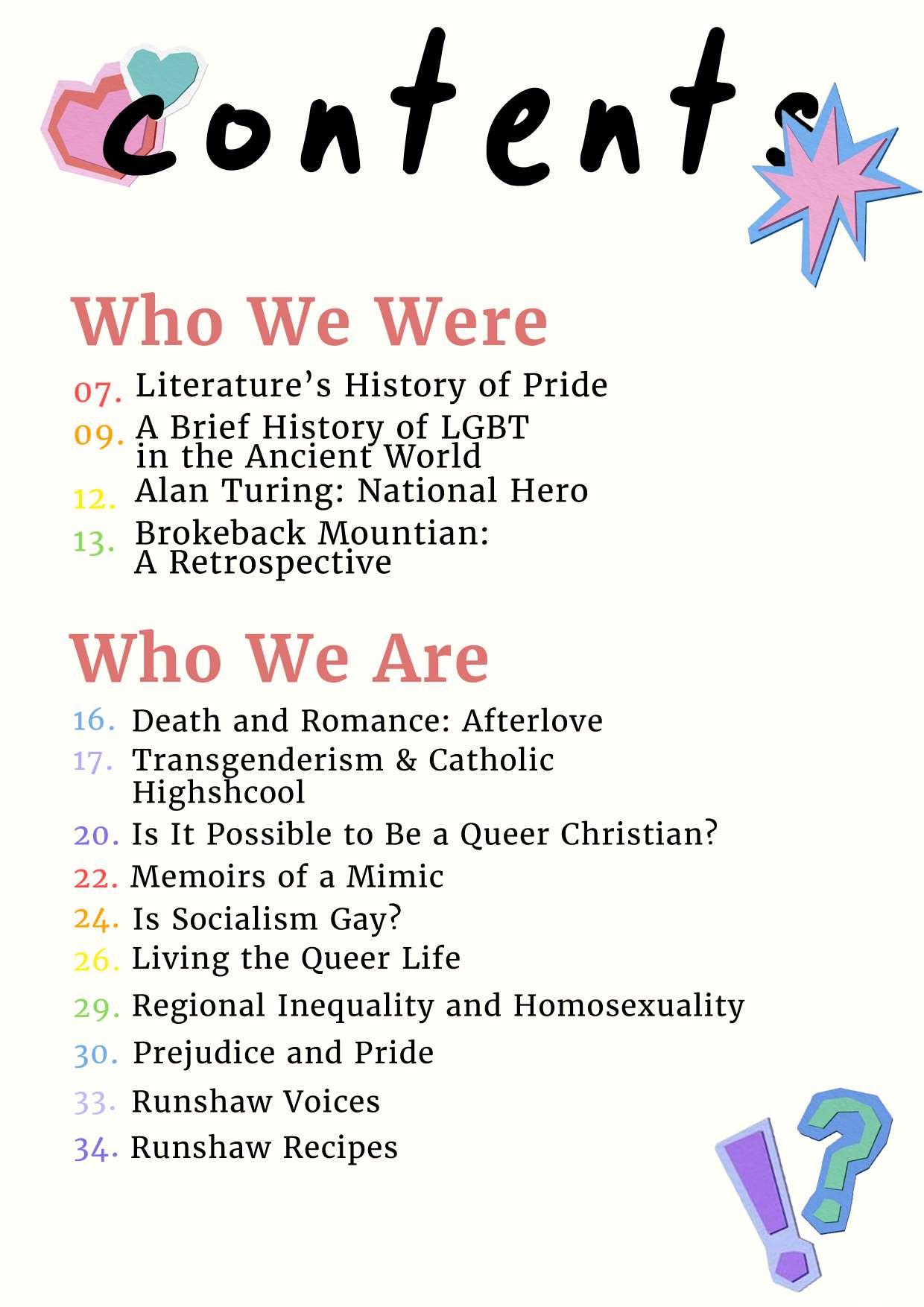

Love: shown in all different kinds of ways. Through talking and listening; closeness and space; contentment and grieving; in animals and in plants. Love is timeless and limitless and includes so many beautiful things. A great part of this is who we choose to love. The 21st century holds many iconic figures from the LGBTQ+ community. But what about the past? Who are the icons of Pride’s history? Here are a couple of my favourites…

To start with, I will go way back to the 6th century BC, in Archaic Greece. Once referred to as the ‘tenth muse’ by Plato, Sappho was a Greek poetess whom many girls identify with even today. ‘As far as I knew, there was only me and a woman called Sappho’ says Judith Butler. In fact, it is her who brought about the terms ‘sapphic’ and ‘lesbian’ from her name and her place of birth (Lesbos). Sadly, we have little knowledge of her complete works, having only found seventy fragments with complete lines. However, one particularly interesting fragment was found scribbled onto a broken clay pot, as Sappho calls upon goddess Aphrodite to come into a charming shrine ‘where cold water ripples through apple branches, the whole place shadowed in roses.’ This erotic escapade to the goddess of love is the only melê (hymn) of hers to survive. In smaller fragments, there is a pattern of how she expresses her envy of men who have the chance to talk to the girl she yearns for. ‘He seems to me an equal of the gods—whoever gets to sit across from you and listen to the sound of your sweet speech’.

What is so beautiful about her work is how little description there is of the subject, but the effect they have on the speaker. Over time, critics have argued that the poetess wasn’t writing a first-person account, but with no more evidence than if it were the other way around. Some critics decided to acknowledge that what Sappho felt for her female friends was love, but don’t hesitate to proclaim that it was ‘vulgarly sensual, and illegal’. Nonetheless, a great number of classicists go on to insist her love for women was part of what made her work so beautiful. ‘She is the proof that homosexuality is not new but as old as legends themselves.’ (Harper-Hugo Darling).

Another historical-literary figure, and a personal favourite: Oscar Wilde. Famed novelist of the Victorian era, Wilde stumbled upon his own Dorian Gray in June of 1891. His name was Alfred Douglas: a man who, unknowingly to Wilde at first, would change his life for worse. After making a connection based off wit and humour, time only increased their adoration for each other.

Having also had his wife led aside by another man, Wilde took Bosie (a juvenile nickname of Douglas’) on a trip to Brighton in October 1894. They stayed in The Metropole hotel where Bosie caught the influenza virus. As expected, Wilde lovingly nursed his partner through his entire sickness – offering him lemonade and staying by his side to help when he needed. He did this even at the risk of catching the virus himself, which, inevitably, he did. Instead of returning the favour, Bosie abandoned Wilde, booking a room in a separate hotel and leaving him to suffer alone. Wilde’s hurt was portrayed in his famous love letter ‘De Profundis’ written to Bosie a few years later. Being the romantic he was, Wilde made habit of writing love letters to Bosie and inserting them into the pockets of his suits for him to find.

Unfortunately, some letters had gone unread and remained in the pockets for Bosie’s father (the Marquess of Queensberry) to find. Queensberry grew ashamed, worried for his family name, eventually leading to a trial against Wilde, to which Bosie refused to testify or even show up for. In the end, the trial resulted in Wilde’s imprisonment for ‘Gross Indecency’ from 1895 to 1897. ‘The most terrible thing about it is not that it breaks one’s heart—hearts are made to be broken— but that it turns one’s heart to stone’ (Oscar Wilde, ‘De Profundis’) Whilst Wilde never made a recovery, dying in 1990, he is known today as one of the most influential writers for his ideas on art, beauty and personal freedom. His grave has been seen completely covered in kiss marks. As for Douglas, he died alone with only two people at his funeral.

The LGBT community has a long history, which starts with the Ancient World, extending all across Europe and throughout Asia. In Ancient Greece, the cult of the Phrygian goddess Cybele and her consort Attis flourished in 300BC, and one of its defining characteristics was the Galli; this was the transgender clergy who identified as female. It is thought that the cult originated in Mesopotamia and spread across Asia. The cult is also thought to have originated from the cult of Inanna and her clergy. However, many years before 300 BC, same-sex relationships were common in Ancient Greece. In a number of his dialogues, Plato praises same-sex relationships.

Likewise, Aristotle was indifferent to same-sex relationships. The Spartans encouraged male-male relationships in the Agoge, which was the Spartan education programme; it was thought that lovers would fight more effectively in order to protect and impress their partner. The Sacred Band of Thebes, a troop of same-sex lovers, famously proved this paradigm as they went undefeated in battle from 371 to 338 BC. 2022 marked the 1900th anniversary of the Roman Emperor Hadrian’s visit to Londinium (now named ‘London’). When Hadrian visited the city in the year 122 AD, his entourage included young men with whom he was clearly intimate. He would have been entirely open about it, and many bystanders would have thought his behaviour quite normal, if only because they themselves had same-sex relationships.

Yet, it is only recently that scholars have come to accept that such attitudes prevailed in Roman London. It is now known from documents that the Londinium of Hadrian’s time believed that same-sex relationships were normal. But it would be a mistake to regard that society as sexually ‘liberated’ or as having much in common with present-day LGBTQ values and definitions.

Photography by Gaia Kinder-Hine

Photography by Gaia Kinder-Hine

Imagine this.

Your country is fighting. It’s the second world war, bombs blitz from gloomy skies unleashing hellfire on your country. Your comrades sink with the ships at sea.

Things could not be more hopeless.

Your country is on its last legs, desperately fighting back against the relentless armada headed by the unstoppable and oppressive superpower that’s taking over the entire world. You won’t allow this. You won’t allow this oppression to dictate the lives of our children. You, and you alone, are going to make a difference.

But how?

The Enigma Code.

A complex, intricate labyrinth of code, the Germans’ impenetrable shield, defending themselves as they lay siege upon The Allies. But your superior computer knowledge beyond your peers, your ability to understand and then solve the most difficult problems in computing makes you the man for the job.

But even this, this seems downright impossible, the best of the best could not break through.

But you do it. Thanks to your dedication, your skill, you solve it, crack the technological riddle set before you.

You’re on top of the world.

You are Alan Turing: National Hero.

Eventually the Allies drop bombs on Japan and the war’s over. Finally, we can live in freedom from oppression. Which is good, being a closested homosexual man in the 1940s. Maybe slowly, you can start to be yourself.

“Gross indecency”. That’s what they called it. The crime of being who you truly are. Unbelievable that the world you saved is removing the freedom you fought so hard for.

There’s no getting out of this.

Chemical Castration. Apparently, it’s the merciful option. But to you, it’s practically a death sentence.

You lose the will to live.

Alan Turing, a hero to his country, committed suicide not long after. He saved them, and they killed him for the crime of being himself.

But we’ll make sure he won’t be forgotten. We’re in the present. Things have changed, we have changed.

Alan Turing, you will be remembered.

Released in 2005, Brokeback Mountain gained a range of differing responses from people all around the world and sparked controversy with its “explicit” and LGBTQ+ content explored within the movie. Set in 1963 Wyoming and spanning the course of 20 years, the film follows Ennis Del Mar (played by Heath Ledger) and Jack Twist (played by Jake Gyllenhaal) who are hired to work as shepherds up on Brokeback Mountain and while working, develop both a sexual and emotional relationship with each other.

When leaving, the two fight and part ways, with Ennis returning home to marry his fiancé Alma (played by Michelle Williams) and Jack moving to Texas and marrying Lureen (played by Anne Hathaway). After four years they reunite, and Jack tries to persuade Ennis they should create a life together, but is ultimately rejected, as he refuses to leave his family behind. He reminds Jack of how America’s harsh views on homosexuality will continue to drive a wedge between their dreams.

This extremely emotional and heart-breaking romance was aided not only by its captivatingstory, but the raw, harrowing performances from the cast, making sure to leave you in tears by the end of the film. But why was it so controversial? Upon release, Brokeback Mountain received many reviews both positive and negative, from critical acclaim to outrage amongst groups of people who did not agree with the film’s subject matter. In fact, the film wasbanned from Utah and China for its content and storyline. It was also not accepted at the Cannes

or New York film festivals due to what seemed to be a problem regarding censorship. Some audience members even walked out of the film after the sex scene as they believed it to be “an act that should only be carried out between a man and a woman”.

When interviewed about whether or not they wanted to see the movie, some men claimed they feared it would turn them gay. It wasn’t just audience members who had an extreme reaction to the movie either. Once they had heard about the story and content presented in the film, Michelle William’s Catholic high school disowned her as a graduate as she did not “represent the values of the institution” and “promoted a lifestyle” they disagreed with. This discriminatory behaviour towards the movie was unfortunately common amongst groups, with the biassed views being targeted at cast members at interview panels, including Heath Ledger being told Ennis and Jack’s love for each other was “disgusting”.

However, not all reactions to the movie were this extreme and archaic in their nature. Despite these reviews, many many people actually loved the movie for both its representation and tragic, engaging story. Many LGBTQ+ audience members praised the film for straying away from stereotypes (such as the comedic side character) and focusing on the character’s emotions, as it presented them as “real people’’. It has been cited as “the most romantic movie ever made” and ultimately deserves as much praise as possible; the Oscars would go on to play a part in this.

The 2006 Oscars saw Brokeback Mountain gain its well-deserved recognition with eight nominations including Best Actor, Best Supporting Actor, Best Supporting Actress and Best Picture. However, it only won three Academy Awards: Best Original Score, Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Director for Ang Lee. Despite these wins, further controversy sparked when Brokeback Mountain lost to Paul Haggis’ ‘Crash’ for best picture, causing an uproar as people claimed it had been robbed of a deserved win. In my eyes, all members of the cast deserved an Oscar for their incredible performances, with Heath Ledger standing out as an obvious winner.

Brokeback Mountain has gone on to be one of the most well-known LGBTQ+ films of all time, with its story being so influential that it would help spark crucial debates about gay marriage over the years after its release. It would also go on to influence more LGBTQ+ cinema, helping pave the way for films such as Call Me By Your Name, Moonlight and Carol, which have also received great acclaim amongst awards shows and audience members alike. It is clear to see that Brokeback Mountain had a large impact on LGBTQ+ cinema we see today as well as the world around us, challenging hostile views and providing the representation needed to make a change. Through its phenomenal acting, memorable scenes and raw emotion, Brokeback Mountain has certainly earned its place as one of the most remarkable, moving romances of all time.

The book ‘Afterlove’ is about two girls who meet during a school trip and fall for one another. Tragically, their time is cut short, and the couple are separated by death. As the one who remains living battles with the loss of a love with so little time to blossom, the other has to fight her own war as she comes to terms with her death and becoming a reaper, someone who escorts the souls of the deceased to their final resting places.

The book is beautifully written and the love between the two is that of a fairy-tale as they fight to find one another again following their separation. The representation in this book gives me hope that one day there will truly be widespread inclusion for all, and we can come to accept that

I think what resonated most for me at least, is how the two girl the experience sexuality and discover their own place in this world. The fact Ash falls in love but has been hurt by it so many times really shows the reality of the way queer women fall in love, sometimes with the wrong people, only to turn the corner and find the right one. In a way, I suppose, it can be said for all relationships, but for queer women this is an entirely new narrative. Finally, we all have a book to relate to, with good representation free of stereotypes. The beating heart of this narrative is our queer couple, Ash Persaud and Poppy Morgan, which is truly comforting and gives me hope to find my other half the same way these two do, although I wouldn’t mind less death!

Poppy Morgan and Ash Persaud are a beautifully crafted couple, who complement each other perfectly and seem to balance and encourage each other to try something new or expand their lives. The positive representation is relatable not only to queer women but the entire community and beyond, through their healthy but also beautiful relationship connecting with all who read this book.

It’s Friday now and the 5th day I’ll bargain with my mother, hustle the price for her to let me stay home from school. Same method as usual. I’ll cook dinner, Mum, I’ll sweep. I’ll hoover.

I don’t want to do PE today—ball-dancing: girl-boy.

This will never happen again; I’ll wash the dishes.

I waited up all night, nurturing a hunger-induced stomach-ache (for realism) and staring at stark blue light for seven hours to induce red-shift in my sclerae and a convincingly gaunt gaze. In the morning, I mimicked the limbo of lethargy and waited until just 5 minutes before rush-to-the-bus o’clock to trudge down the stairs and confess how horribly ill I feel. There are pros and cons to this.

Pro: she is too busy tending to my brothers for verbal dueling and scalding spitfire profanities, at the moment.

Con: she won’t be so busy later.

I haven’t been eating much recently. For most girls, the goal here is conformation. I describe my own goal as ‘ironing-board’ to my mother, and she calls me ridiculous. She says I have birthing hips, which makes my stomach belch as if a baby just kicked at it.

My hair is black, now. Black-blue. School is angry about it, but having darker hair gives a more rugged appearance. Noticeable eyebrows make you more imposing, as dysphoria asserts.

To my father’s dismay, it has also been chopped short and curled. I’ve never seen him cry, but his first time seeing the state of it is the closest it has and will ever come; brutally overt about it, he says it’s horrible, tells me (as he always has) how people would kill for beautiful long blond hair like mine. But, the sacrifice means that unfamiliar men in public tend to swap out the usual ‘sweetheart’ for the more camaraderie ‘mate’ nowadays.

High-cost, low-profit.

Girls still aren’t allowed to wear pants at school. I am all doom and gloom and squares (personality, joy, and colour are all feminine: be grey or be girl), walking to class in a frumpy pleated skirt and socks pulled up past the knees (I refuse to shave my legs) and the boys find it hilarious.

Begging to the world to look, look, at you—and not at a refraction of themself and their view—preordains you to humiliation. This will become your primary emotion; epitomise femininity or have your personhood to your peers be analogous to a jester in costume, in front of his court.

This changes, when you change your name.

The humiliation is not so external anymore, no, you internalise it until it cauterises your fingerprints. People stop talking to you—they don’t know you anymore, don’t know how to—but their eyes pierce relentlessly, and unwaveringly, and the emanating blood seeps from your pores like sweat. Walking to class leaves you sweltering and panting and wishing the ludicrous coat you wear (even in summer, be sick not seen) would gain autonomy and strangle you where you stand.

It doesn’t.

Hour-by-hour until the day is over and day-by-day until the week is over, I compress my chest (and my breath) neatly within one-of-two cheap binders and quietly skulk alongside the only people who don’t look at me like a three-legged lion. They see my old name but say my new one—and that must be enough, because I might just go insane without the company.

Consequential fabrications of this still reside, internally.

But now, in college, my hair colour changes by the month and is loose, unbridled around the shoulders. I wear green joggers most days, and swap out crystals from my necklace, an externalised emblem of my mood.

This means that I must announce my transness to each new teacher, student, and friend—and that I still suffer abdominal ache on the bus journey home each evening, courtesy of my continued adornment of unforgiving binders.

This also means that I know who I am now, and I refuse to shun it for your convenience. I am Jackson (or Jae, to my family, or Leaf, to my lover), I am transgender; I am everything I ache for, and everyone who got me here.

I am one month on Testosterone, now, and on the path to being me.

‘This also means I know who I am now, and I refuse to shun it for your convenience. [...] I am everything I ache for, and everyone who got me here.’

Certainly, Christianity has a reputation for homophobia and anti-queer teachings that has spread throughout today’s society, but exactly how accurate is it? To examine this claim, we must also examine the history and doctrine of one of the biggest religions on the planet to see if this reputation is deserved.

Undoubtedly, the Bible has explicit rules about homosexuality that absolutely cannot be denied, but it must be considered how important these rules are to Christianity. There are hundreds of laws that the Bible sets out for Christians, such as not cutting hair, not being near women on their periods, and not wearing linen or wool clothing, but these are little followed in Christianity, so why do some place such emphasis on opposing the queer community? Arguably, the roots of the problem with Christianity and the LGBTQ+ community lies not with the doctrine of the religion itself, but with those who twist and corrupt it to suit personal agendas.

Historically, Christianity evolved from the ancient religion of Judaism, which has had a significant effect on its doctrine today, most notably in the nature of the Bible. The Old Testament, the first part of the Bible, is compiled of mainly Jewish scripture, with the most relevant part being the prophecies predicting the coming of the Messiah, who Christians believe to be Jesus, and this is the main reason it is included in the Christian Bible. Interestingly, all the scripture commonly used against the LGBTQ+ community is found in the Old Testament, including the most infamous verses such the Leviticus “man must not lie with man,” leading to questions of how relevant it is to Christianity itself.

Furthermore, the main root of Christianity is the New Testament, as it describes Jesus’ life, death and rebirth, who of course is the figurehead of the religion. This part of the Bible has the most influence in Christianity today, which is significant when considering queer theology as it does not mention anything about homosexuality in the New Testament. In fact, the central message in Christianity is to spread love to absolutely everybody - “love thy neighbour,” and this includes the LGBTQ+ community, showing beyond doubt that Christian’s are encouraged to spread love and inclusion through their religion.

To conclude, whilst the Old Testament has many rules against queer culture in Christianity, the latter parts of the Bible, which holds more weight for Christians, teach a religion of love and diversity that makes it possible for any member of the queer community to become a Christian, no matter its widespread and undeserved reputation as prejudiced.

‘The roots of the problem [...] lies not within the doctrine of the religion itself, but with those who twist and corrupt it’

Millie Cast

Art by Katie Noble

Art by Katie Noble

Batesian mimicry is the process by which a hunted animal creates the illusion of danger, increasing the chances of survival by camouflaging against a background of toxic creatures or predators, and what I thought I saw before me then.

I’d claim a shared mindset though defiantly oppose my personality with the boys around me, who’d cast out of themselves whatever stomach-emptying insults came to mind and wore uniform expressions of angry, stoic, obnoxious men. Fights happened often, a battle to prove who was the mimic and who, the hunter. I’d lifted both arms and both fingers to the sky, showing the world what black and blue lettering I’d had stamped across my eye clearly reading “heterosexual.” and snarled through broken teeth at teachers corralling us down corridors, to be released at the cry of the bell.

Into overbrimming classrooms, in which I’d learn the breadth of my competition, the richness of the prize: manhood. At the twitch of a finger packs of hounds would loosen themselves upon any of our number, finding their evident homosexuality an afront to all masculinity. And so, each of five friends a lethal danger to the other, we patrolled like dogs to cure any love with shock therapy. Images of lethal injections gradually became videos of beheadings, and worse yet, for fear that our loyalty to all morality might be questioned.

A refusal to lose the right-to-bruises drove boys to be men, delivered along that path with the addition of an inability to vomit regardless of sight, smell, or sound. Men shed blood, sweat, and alcoholic piss only, anything else and a boyfriend was implied.

Once, I’d put myself between two raging bulls, hands outstretched. Delivering a slap to the face of he who’s will would have proved him the hunter. The next day I was told that I impressed by my emotional maturity. Pride hurt, I revealed a set of teeth that would never again form a row. I vowed to never again act the hero.

Every year my ego swelled at the thought of once-again becoming a worse, more harmful human being. My peers became familiar with the superiority of the Machiavellian in every historical context, according to a self-described villain.

But

I met him

Years having passed.

For the first time in longer than I’d wish to remember I wanted to be close to another boy, and yet his eyes narrowed with every mention of a scar I’d given. My damage did not impress this one.

As our acquaintance-ship began dissolving, I found myself desperate; willing to throw everything and my life away for a person who would not grant me honest competition.

I reflected on the time I’d wasted, in a year I would certainly never see him again. In months I learned to apologize, abandoned everyone I’d known, hid my scars. I’d have done anything to have him, most of all I’d fight, as if that wasn’t the easiest option.

Once I’d rushed headfirst into battle, clad in long-awaited perception of justice. Revealing myself to retain basic empathy in defence of the person I cared for most, at first I was met with confusion as to how I could sympathize with boys so unlike men. What remained of my ego was shredded by a sea

of complaints. Each and every person wielding the uniform critiques as if love was subject to the whims of logical debate.

Boys who’d called themselves my friends found the most sensible option, to cut out someone cowardly enough to protect someone important to them.

Ignoring the teacher’s whims, throngs pressed around me seeking blood from an offered heart. Snapping and barking at every step I took. It was a surprise to the school when I outcast myself from that classroom, marching through the uneasy gaze of the group I had once mocked with.

I could finally unite my mind in abject defiance of the boys around me, could cast my self far outside from the social sphere they inhabited. Fights mutated into arguments, ceaseless slurry of poorly worded reminders that a gay existence was a threatened one. I raised my eyes to a familiar sight, a wingless angel in sunlight. For the first time in my life someone chose to guide my hand into theirs, gazed with authentic contentment not given before by even a singular of dozens of friends.

The competition never ends. But at least I’ll never hide again.

Relations between socialism and the gay world have been long and varied. Conflict between the two from the socialist perspective have existed from near the point of socialism’s conception, with multiple denigratory perspectives on homosexuality posited: from theories about relations between people of the same sex being an aristocratic affliction stemming from the disaffection and boredom with all other kinds of (heterosexual) carnal vice common amongst the decadent and self-indulgent youth of the nobility; to the idea that homosexuality was exceptionally prevalent amongst members of the petty bourgeoisie because of the contradictions that gradual capitalist decay sowed amongst this stratum of society; and that the proletariat and lumpenproletariat were given over to homosexual relations because the economic conditions they lived under made (nominally normal) heterosexual lives impossible — and various other explanations. There have also been (often reactionary) tendencies amongst gay liberationist movements to disregard socialism as homophobic or inadequately equipped to provide meaningful advances for gay people.

Yet capitalist society has — apart from its own degradation of homosexuals — frequently merged the socialist or proletariat interest with gay interests to attack both in one fell swoop. We can see this in the Lavender Scare of the late 1940s to 1960s, a period of congressional investigation-led of gay people working for the US government which resulted in the firing and forced resignation of many and culminated in the social ostracization of those discovered to be gay. The Lavender Scare destroyed lives across the USA — socially, economically and mortally, with several people committing suicide in the wake of the decimation they had been subjected to. Hence, it’s significant that the Lavender Scare was bound inextricably with the Red Scare, (the similar hunt for and destruction of suspected communists within America) with the Scares both an indelible part of the Cold War and with the same rhetoric and the same investigators being reappropriated for both purposes.

Despite the frequently fraught relationship between gay and socialist causes, the class enemies of both movements often see some inexorable link between the two. And it’s true demonstrably that socialism, despite all the antagonism, repeatedly improves the gay condition when put into practice. The 1917 October Revolution in Russia resulted in the repeal of previous legislation criminalising homosexuality, and the introduction of Hugo Chávez’s government resulted in gains for gays in Venezuela. Furthermore, gay groups often have embraced socialism wholeheartedly: a prominent example being the group Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners, a group of largely communist gays and lesbians who supported South Wales miners during the 1984–85 strikes.

What drives this conflict? Why did Cuba post-1959 revolution see the increased persecution of gay people, but in 2022 legalised same-sex marriage after an overwhelmingly positive referendum result, (due in part to Mariela Castro, Fidel Castro’s niece and Raúl Castro’s daughter, campaigning for LGBT rights)? Why did the USSR decriminalise homosexuality in 1917, only to recriminalise it in 1934? How can these contradictions be explained?

It’s necessary to understand that socialism has never been uniform in its approach to any issue. The root of these conflicts lie in broader and more fundamental principles which, likewise, are often not agreed upon. Clashes over the nuclear family, the role of men and women, to what extent reform and revolution should occur, whether power should be centralised, whether national identity and worldwide class consciousness can co-exist, if traditional conservative values are antithetical to communist revolution (and so on) all impact how same sex relations are viewed, and each have hundreds of years of sometimes bitterly differing rationale behind them. It hence stands to reason that the issues of gay rights and socialist liberation are complexly and sometimes contradictorily intertwined.

‘It’s true demonstrably that socialism, despite all the antagonism, repeatedly improves the gay condition’

I don’t know how it was for others but it’s safe to say being Bi can be an experience and a half. At least it was for me in high school as someone who realised fairly early it ended in a disaster. My first attempt at coming out ended in me vehemently denying it as a rumour because of the high school culture of being a queer person.

Anyone who was brave enough to come out was given the societal cold shoulder of the school. By the end of the year it was long forgotten that I could ever be a queer person and I wasn’t the target of teenage prejudice. How could anyone honestly be happy living a life in hiding who you are though?

Eventually it got easier to accept that you simply had to hide it for fear of your peers treating you as a social pariah. After high school I eventually gave up living a shadow of a life for fear of the way others would look at me and I came out as bi; my family already knew but for the first time I had friends who I knew wouldn’t judge me in a community where I wouldn’t be the outcast. Throughout my life, I’ve come to a realisation that as a community we will always pick and choose what parts of ourselves to accept and sacrifice what parts of ourselves we can’t to accept to fit our narrative: the way we planned our lives to be with those guiding us. After this I decided to give up on other people’s perceptions influencing my life plan and just ‘be’. It gets exhausting after a while to live a half life due to the pressure of those around you.

Even as I came out there were still these echoes from all angles telling me who I could and should be, the stereotypes that should have been long forgotten. The fact is I will never be “straightened out” and I refuse to “pick a side” nor am I “hyper-sexualised”. I won’t be told who I can be and what the boundaries are when set out by other people who don’t know me, my story or who I am. By imposing the stereotypes that come with coming out, it results in alienation for young people and creates a hatred of the institutions that perpetrate these stereotypes and reflects the fact that there is no proper education about being queer in this world. Our education system should reflect the needs of all of those within it, not simply the ‘mainstream’.

Art by Katie Noble

Art by Katie Noble

Art by Ellie Wrght

Art by Ellie Wrght

Feelings towards homosexuality have pro gressed, changed, and shaped over the years in various different places around the world. The UK happens to be one of the countries where attitudes towards homosexuality have undergone significant changes over the years. But while it is true that attitudes have changed, there are still some discrepancies in opinion and acceptance between different regions with in the country.

Gay, Queer, Trans, Girl… I have been called all these names over the years, but here’s the thing, I’m not any of those things and I’m not offended by being called them, I am very much an ally (of the lgbtq+ community – not the name callers, though I may have funded bullies over the years through their stealing of my dinner money). But it leaves me to think, why do people use terms like this in jest, when they are not funny, and what impact does it have on our community when it is said?

Language is constantly evolving through our own moral progress and understanding of the world as a collective society. The word Gay, appeared in the

English language in the 12th century, its primary meaning was joyful or carefree, bright and showy, in the 14th century it attained associations with being carefree with morals, a Gay woman was a prostitute, a Gay Man a womanizer. Its association with homosexuality came when identifying young male prostitutes for male clients as Gay Boys. In the nineteen fifties and sixties it carried this dual meaning, appearing in subculture in a knowing ambiguity and a wink. In the nineteen nineties and lad culture the word becomes a slur, someone calling something or someone gay is showing disrespect or hostility or identifying something is rubbish.

‘Hopefully

one day our language will reflect a society that values and celebrates differences in their entirety, rather than reflected ingrained prejudices that impact on our pride.’

So language is always evolving, but it’s important to realise, there isn’t a vote overnight where everyone agrees certain words now mean certain things and not other things (although if you want to pretend there is, grab a dictionary and some tippex and go nuts!); a word doesn’t have a score about how ok it is to use, it’s all about context. The context is the situation within which something exists or happens that can help explain it. Context can change the meaning of language. Which brings us to intent, the words themselves should not have the power to offend, it is surely how they are used, but these things are never just black and white when one sense of a word is used to identify a group of people then using that same word in a derogatory or negative sense, it’s just unhelpful. It shouldn’t be controversial, nobody is saying you can or can’t use words in certain contexts and as shown with the example of ‘gay’ there can be positive change to the context but it’s still important to be responsible for how they might be perceived.

Our language is like a river that can never be frozen, we will never be able to control it completely but we do have a responsibility as a modern day society to police our language. We must protect marginalised groups from these slurs that have derived from semantic change and new words and phrases being coined. Hopefully one day our language will reflect a society that values and celebrates differences in their entirety, rather than reflected ingrained prejudices that impact on our pride.

What do you and the Pride Club do?

Make an open and comfortable space to create a social environment.

What made you think of running the Pride Club?

I used to run an LGBTQ+ club in high school, so I decided to take on this role to organise it in a college setting.

What can the club do for questioning young people?

We create a social environment people can share their stories and educate themselves. By doing this, hopefully we can help people better understand and learn perhaps about themselves and how to be an ally and a supportive friend should anyone they know come out to them.

How does Runshaw currently support LGBTQ+ people?

Runshaw does not accept any hate and they have a safeguarding report system in place. When applying, there is the option to change your name and pronouns on the system to accomodate your identity.

What do you and the club hope to achieve?

We hope to have more educational activies for next year, and more external activities so we can reach

out to the rest of the Runshaw community and involve everyone.

Is there any advice you would give to young people in college?

You don’t need to have everything figured out yet, give it time! There is no rush into labelling yourself.

Any events going on?

Movie Night! We have had two speakers recently: Tanya from Lancashire Sexual Health Serivces and Ash from the Hate Crime Police Department. For Pride History Month, Kahoots were run to create a fun and open environment.

Where do you run?

We are in M602 on Thursdays from 11:20 to 1:20.

Any social media?

The club is part of the Runshaw Enrichment Team, so they post any upcoming events on the Instagram and Twitter: @runshawenrichment

For our Pride Issue, we spoke to Franky, the head of Runshaw’s LGBTQ+ club, to find out about Runshaw is currently doing to support its students!Runshaw’s Pride History Month Display

Hannah Glover

Makes 16 - 15 mins prep, 35-40 mins cooking

Ingredients

- 225g butter

- 450g caster sugar

- 140g dark chocolate

- 5 eggs

- 100g plain flour

- 55g cocoa powder

Instructions:

- Heat the oven to 190C, 170C Fan, or Gas Mark 5

- Line a 20cm x 30cm baking tin with baking paper

- Melt the butter and the sugar together in a large pan

- Once melted, take off the heat and add the chocolate stirring untul the chocolate has fully melted

- Mix in the eggs, then stir in the flour and the cocoa powder

- Pour the brownie mixture into the lined tin and bake for 35-40 minutes, or until the top of the brownie is firm

- Take it out of the oven and leave it to cool in the tin

- Take the brownie out of its tine and cut them into 16 squares to enjoy!

Ingredients

- 20g butter

- 2 gloves of garlic, crushed

- 300g arborio risotto rice

- 1l chicken or vegetable stock

- 200g ham, chopped (optional)

- 200g frozen peas (optional)

- 100g broccoli, boiled (optional)

- 60g cheese, grated, plus extra to serve

Instructions:

- Heat the butter in a large frying pan

- Add the garlic and cook for 1 minute

- Tip the rice into the pan, stir to coat it in the butter

- Add a ladleful of stock, stir

- Once absorbed, add more stock. Continue doing this until all the stock has been absorbed and rice is cooked

- Tip in the peas, cheese, ham, and broccoli (and any additional ingredients), stirring everything together

- Season with black pepper, then serve with garlic bread.

With this recipe, you can add pretty much anything! Some other things that can be added are: Sweetcorn, bacon, carrots, mushrooms, and peppers