GronningenBispeparken Climate Park, Denmark

Ruchi Pathak

University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign

Introduction

Denmark is one of the leaders in the fight against climate change, pursuing ambitious targets for greenhouse gas reduction, energy transition and climate change adaptation. As part of these efforts, Copenhagen gained an innovative new urban space in 2024. Grønningen-Bispeparken is a climate park that has transformed wasteland into a lush, bio diverse green space. The park was designed by the SLA studio with rainwater management in mind. The project was awarded the prestigious Arets Arne Architecture Prize in 2025. The park integrates climate adaptation, urban biodiversity, and social inclusivity.

Gronningen-Bispeparken

Climate Park, Denmark

Project Overview

Name: Grønningen-Bispeparken

Location: Copenhagen

Area: 20 000 square metres

Commissioned by: City of Copenhagen

Architect: SLA studio

Engineer: Niras

Artistic design: Kerstin Bergendal and Efterland

Contractor: Ebbe Dalsgaard A/S

Opening: 31 August 2024

Need for the Project

Urban flooding risk: Like many other cities around the world, Copenhagen is feeling the effects of climate change more and more, especially urban floods brought on by heavy and erratic rainfall. Storm water build up had long plagued the Bispeparken neighbourhood, a residential sector in the Nørrebro district, resulting in flooded green areas and overburdened drainage systems. These difficulties highlighted the necessity of a decentralized, sustainable storm water management system.

Need for green spaces: In addition to water management, the project was motivated by the desire to improve urban biodiversity and give locals access to recreational areas. Large but underused grassy areas devoid of biological variety were present in Bispeparken prior to the intervention. The goal of the park's design was to turn these areas into a flourishing, multipurpose landscape that would manage storm water, support urban wildlife, enhance air quality, and give community members with entertaining areas.

Danish climate resilience goals: In addition, the Cloudburst Management Plan, the city's larger climate adaptation plan, seeks to reduce the danger of floods by utilizing natural alternatives. As a major part of this project, GrønningenBispeparken Climate Park was designed to use green infrastructure instead of subterranean pipes to collect, store, and release rainwater gradually.

Existing Conditions

The Grønningen-Bispeparken site was a very flat and featureless green space with little ecological or recreational significance prior to its conversion into a climate park. Due to its uniform grass lawns, lack of trees, and poor soil drainage, the area was particularly vulnerable to flooding during periods of intense precipitation. Additionally, there was little topographical variety at the location, which meant that rainwater would collect on the surface rather than be effectively absorbed or channelled.

Furthermore, the park was unable to sustain a robust urban environment due to its lack of varied flora. Wildlife had less opportunity to flourish due to the lack of pollinator-friendly habitats, native plant species, and diverse topography. People found the area less welcoming and pleasant as a result of this and the urban heat island effects brought on by the nearby buildings.

In addition to addressing floods, these pre-existing issues underscored the urgent need for an integrated strategy that would improve the landscape’s biological functions and make it more aesthetically pleasing and accessible for the local people. In order to create a dynamic, flood-resilient, and bio diverse environment that would sustainably benefit both people and the environment, the Grønningen-Bispeparken Climate Park project was created.

One of Copenhagen’s oldest social housing complexes is the Bispeparken neighborhood, which was constructed in the 1940s. The surrounding open area was meant for public use, but because to seasonal waterlogging and a lack of facilities, it was mainly unused. There were few places for residents to unwind, play, or engage in outdoor activities, which reduced the opportunity for significant communal involvement in the region.

Fig 3: Water logged site area during monsoon season

Fig 1: Time line for the Project

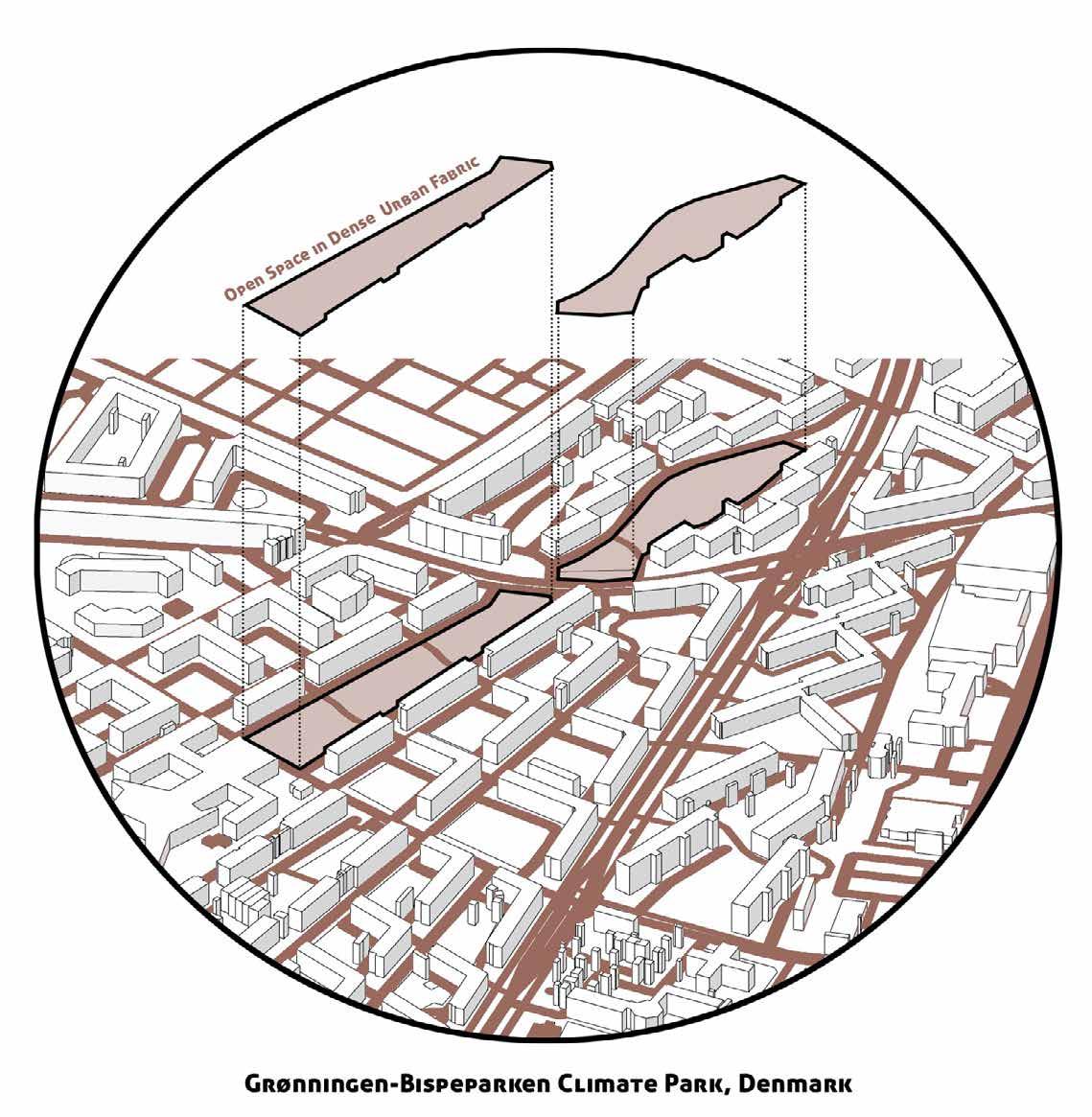

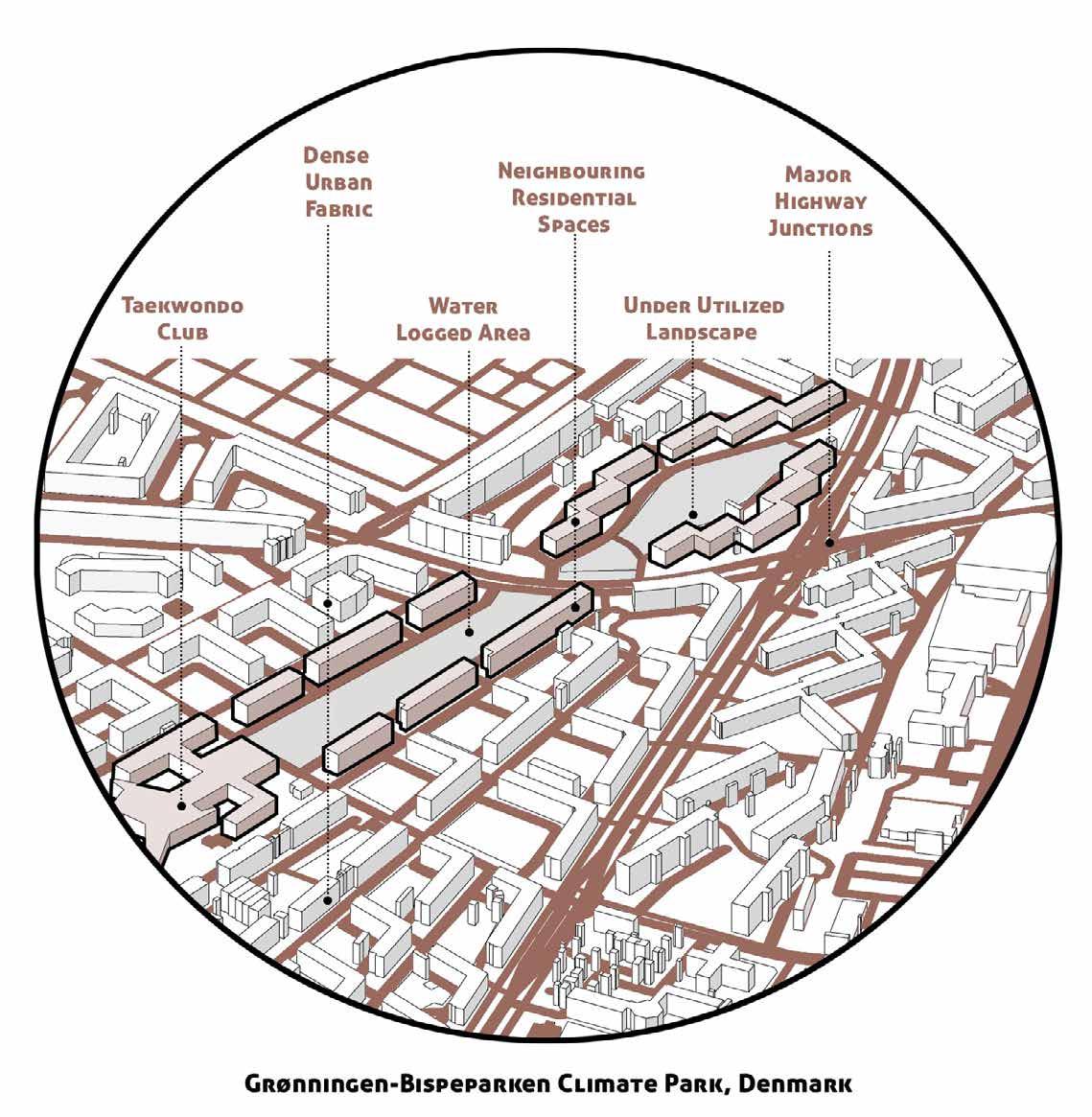

Fig 2: Dense Fabric around Grønningen Bispeparken Climate Park

Fig 4: Context of Grønningen Bispeparken Climate Park

Design Strategies

Key Sustainability Features: Storm Water Management

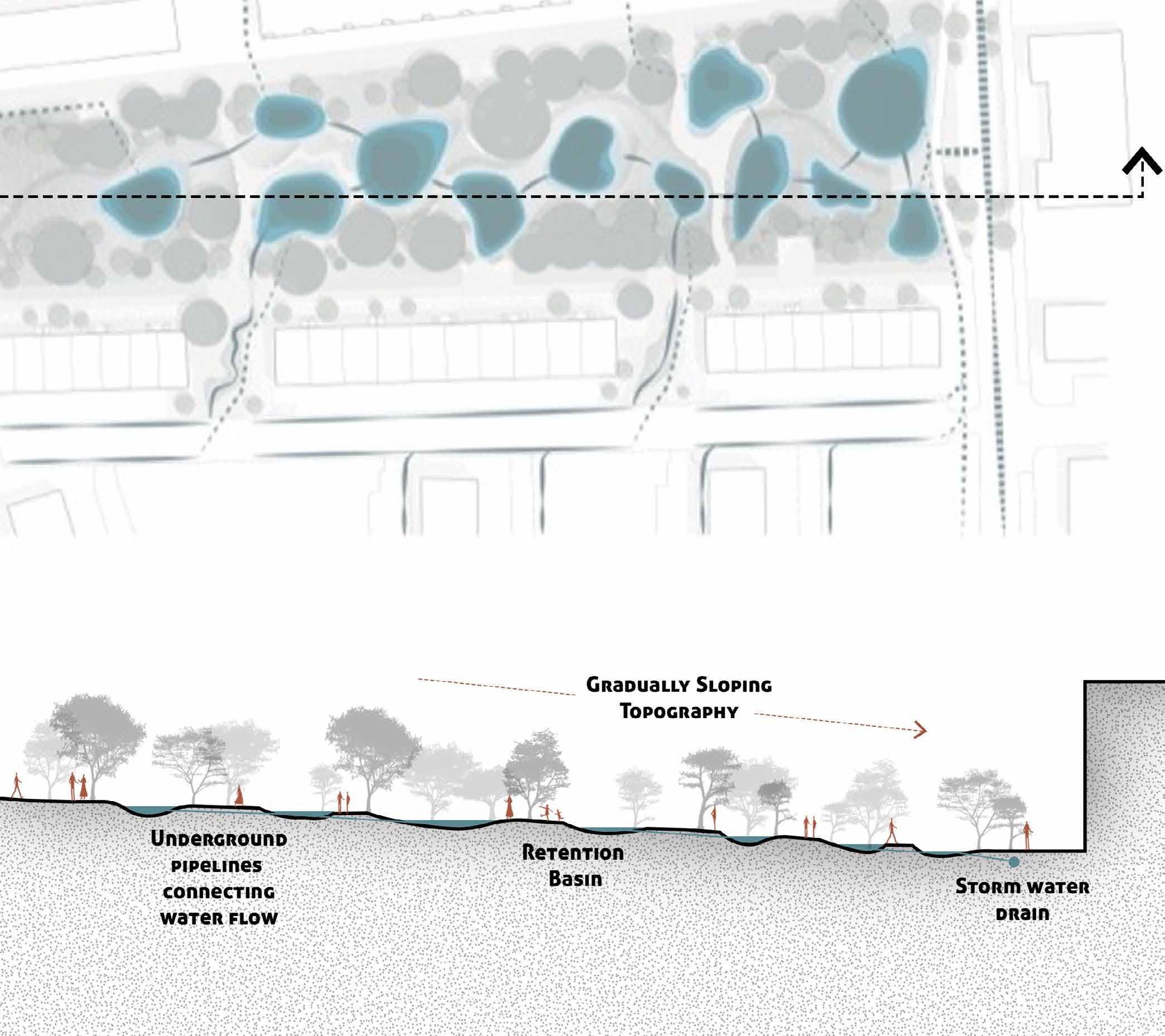

Grønningen-Bispeparken Climate Park incorporates an advanced storm water management system designed to mitigate urban flooding while enhancing natural hydrology. The park features 18 retention basins strategically placed to capture and store up to 3,000 cubic meters of rainwater, allowing for slow infiltration into the ground instead of overwhelming the city’s drainage system. Bio swales and permeable surfaces direct excess water through natural filtration processes, improving water quality and reducing runoff. The landscape’s gentle topographical variations help channel rainwater efficiently while creating aesthetic and functional water features that blend seamlessly into the public space. By prioritizing decentralized, nature-based flood control, the park serves as a model for urban resilience in the face of climate change.

Key Sustainability Features: Urban Greening and Biodiversity

The initiative planted 4 million seeds of native plants and grasses to create a rich, biologically varied ecosystem, and also planted 149 new trees of 23 different kinds to restore and improve urban biodiversity. The local ecology is strengthened and Copenhagen’s green areas are more ecologically connected thanks to these plants, which also benefit bees, birds, and other urban species. In addition to increasing carbon sequestration, the park’s diverse vegetation offers seasonal variations in color and texture, making it a dynamic and captivating space all year round. A more natural, self-sustaining landscape that uses less water and requires less care while enhancing soil health and microclimate conditions is preferred over conventionally maintained lawns.

Key Sustainability Features: Carbon Reduction and Climate Resilience

By enhancing tree canopy cover and vegetative ground cover, the park helps mitigate the impacts of urban heat islands, therefore reducing ambient temperatures. The recently planted trees serve as carbon sinks, collecting CO₂ and enhancing air quality in addition to offering shade and cooling. The park reduces carbon emissions from pumping and water treatment systems by relying less on energy-intensive storm water drainage infrastructure. Furthermore, especially during the summer, the permeable landscape ensures a cooler and more pleasant microclimate by reducing heat absorption from hard surfaces. These initiatives show how integrated landscape design may help climate adaption in dense urban environments and are in line with Copenhagen’s larger sustainability aims of being a carbon-neutral city by 2025.

Fig 5: Design Strategies

Fig 6: Aerial View of the Park

Ruchi Pathak. University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign

Fig 7: Circulation Pathways and Landscape Features

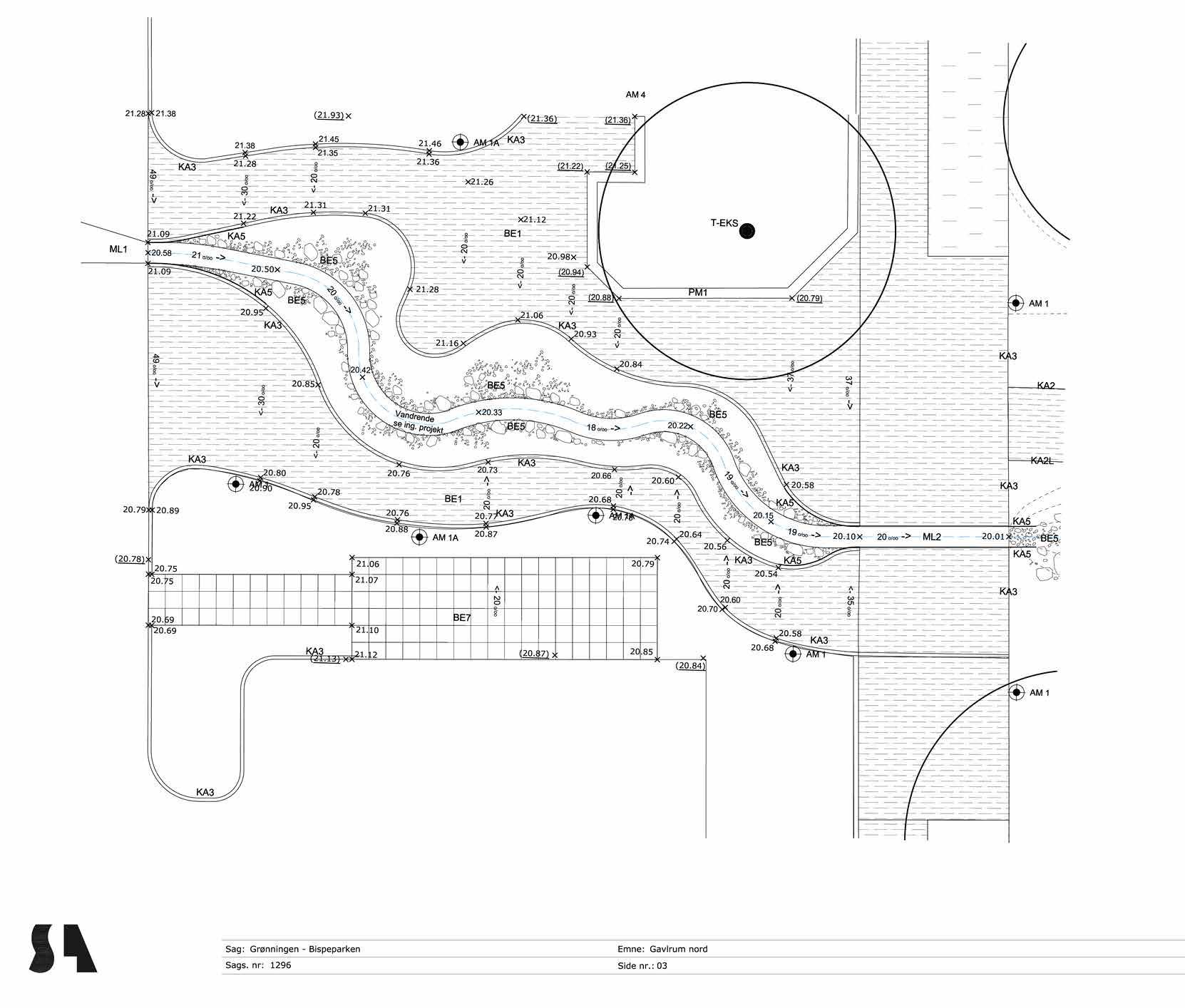

Fig 8: Plan of the Park

Landscape Features

Bispeparken-Grønningen Topographical changes are a fundamental design concept used in Climate Park to improve public use and storm water management. The environment was altered to naturally route precipitation into retention zones by combining low-lying basins with higher parts, rather than creating a park that is typically level. During periods of high rainfall, these depressions serve as makeshift water storage spaces, limiting localized floods and permitting slow penetration into the soil. By slowing down water flow, the winding bio swales and planted channels remove pollutants and lessen the strain on Copenhagen’s drainage system. This nature-based technique blends in well with the park’s public areas, unlike traditional storm water solutions that sometimes depend on subterranean pipes, making climate adaptation an engaging and visually appealing experience for guests.

In addition to serving a hydrological purpose, the park’s varied flora and soft, organic shapes give both locals and tourists a warm and engaging atmosphere. Instead of having a strict, geometric design, the roads meander across different types of terrain, providing a dynamic and captivating experience. In order to provide dry, pleasant settings even in inclement weather, seating areas are positioned strategically along higher terrain. By fusing urban infrastructure with the natural surroundings, the park’s ecological character is strengthened via the use of natural materials like wood, stone, and wild plants. In addition to being robust and useful, these landscape interventions make the area aesthetically pleasing and socially inclusive, strengthening ties within the community and promoting urban biodiversity.

Fig 9: Landscape Features

Fig 10: Transformation due to water features in Monsoon

Material and Construction

To reduce its environmental effect and increase longevity, the Grønningen-Bispeparken Climate Park places a high priority on low-impact building methods and sustainable materials. By using locally sourced stone and salvaged wood for the hardscape features—like pathways and seating areas—the carbon footprint related to extraction and shipping is decreased. Rainwater can soak into the ground through permeable surfaces like green infiltration zones and gravel pathways, which stop runoff and preserve natural water cycles. Furthermore, the design reduces the amount of asphalt and concrete, which raise embodied carbon emissions and cause urban heat island effects. The park serves as an example of ecologically sensitive urban construction as it incorporates durable, low-maintenance materials that gradually minimize resource usage.

Environmental Impacts

The park has significantly improved the ecological health of the area by restoring native vegetation, increasing tree canopy cover, and creating new habitats for urban wildlife. The introduction of wetland plants, flowering meadows, and pollinator-friendly species has enhanced biodiversity, supporting birds, bees, and small mammals. The integrated storm water system reduces urban runoff and water pollution, ensuring that excess rainwater is filtered naturally before entering nearby waterways. By reducing reliance on artificial drainage infrastructure, the park also contributes to Copenhagen’s broader sustainability goals of carbon neutrality and climate resilience. These environmental benefits make the park an important model for other cities seeking to implement nature-based solutions in urban settings.

Fig 11: Construction Drawing of Landscape Features

Fig 12: Section through the park

Social Impacts

The previous site of Gronningen Bispeparken was a bare land which restricted the use of the space. However, the new space was designed keeping in mind the social integration and congregation qualities. Along with ecological design, equal priority was given to the social component of the design. The integration of the park area with neighbouring structures and communities helped enhance the quality of life for people. There was no other planned green space in the same area. Thus the Gronningen Bispeparken was an important congregation point in the neighbourhood. The path was designed with multiple pathways and seating spaces which encouraged interaction of people. The pathways directed the flow and circulation of people around the entire space without isolating any particular space. The multiuse areas served as flexible and inclusive spaces for all the public. Multiple play areas, relaxation spaces and fitness installations help create a great example of social infrastructure in the Copenhagen region.

Community Involvement

To guarantee that the park satisfies the requirements of the neighbourhood, the project placed a strong emphasis on community co-creation and public involvement from the beginning. The design was greatly influenced by citizen input sessions and stakeholder workshops, which gave planners insight into the community’s worries about accessibility, floods, and recreational areas. Based on suggestions from the community, public art, interactive exhibits, and designated gathering places were included to create a space that is both socially and climate-resilient. A closer bond between the community and its surroundings was also fostered by the introduction of educational programs that taught locals about storm water management, urban biodiversity, and climate adaption techniques. In addition to encouraging local users to actively maintain and care for the park, this participatory method guarantees long-term management.

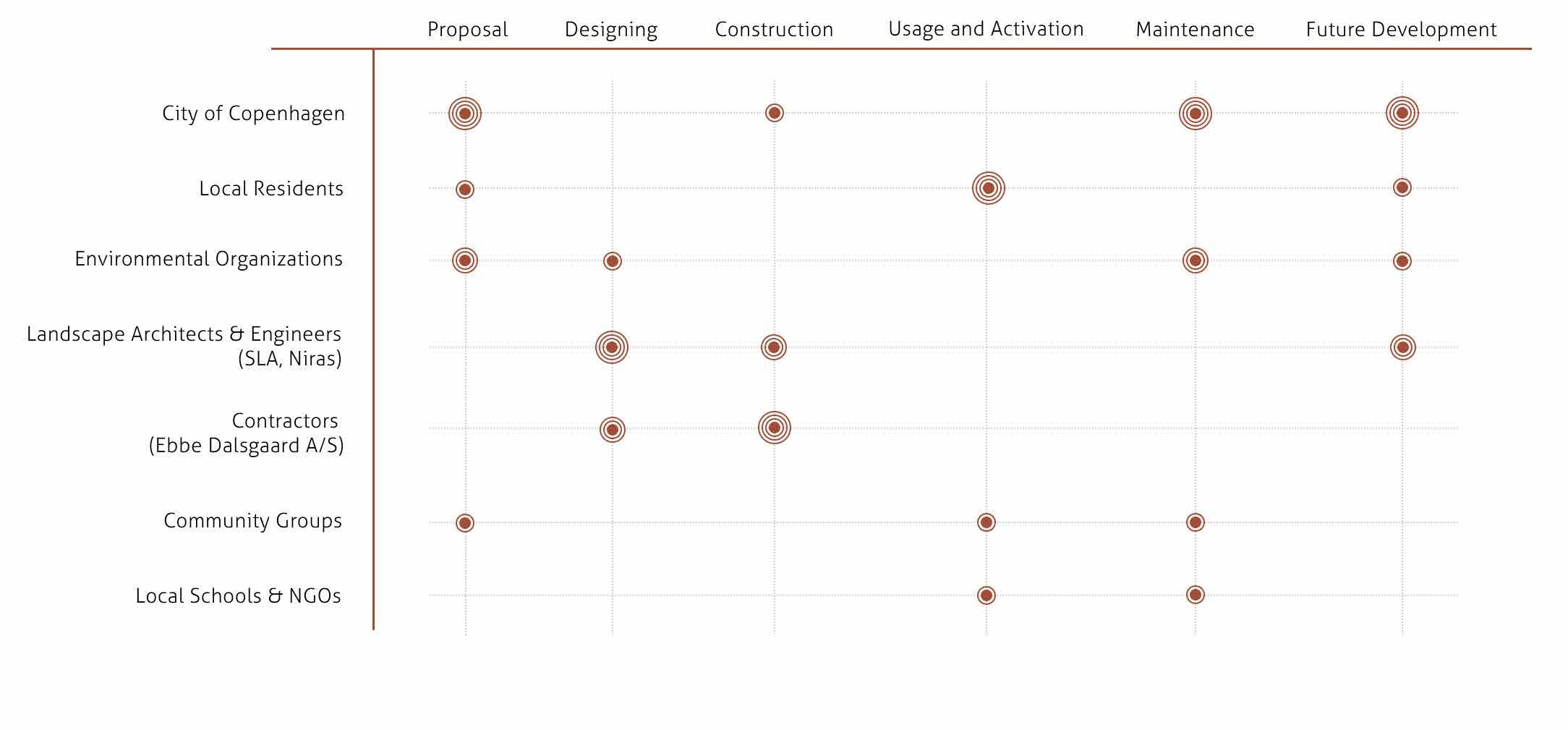

Stakeholder Role in Project

1. City of Copenhagen

Funding, policy, and climate strategy alignment

2. Landscape Architects & Engineers Design and implementation of storm water solutions

3. Local Residents

4. Environmental Organizations

Economical Impacts

Participatory planning and feedback

Biodiversity conservation and ecological assessments

Beyond its environmental impact, the project has revitalized public space, making it more inviting, inclusive, and functional for a diverse range of users. The park now serves as a hub for social interaction, recreation, and outdoor activities, improving overall well-being in the neighbourhood. Increased green space and improved air quality contribute to physical and mental health benefits for residents. Additionally, the park’s transformation has led to a rise in local property values, demonstrating the economic benefits of sustainable urban design. By making the area more attractive to both residents and visitors, the project also stimulates local businesses and cultural activities, fostering long-term economic resilience.

Fig 13: Stakeholders involved in Various Phases

Fig 14: Stakeholders and their Role

Fig 15: Community engaging with Park

Future Vision and Challenges

Looking ahead, Grønningen-Bispeparken Climate Park aims to serve as a living laboratory for urban climate adaptation, continuously evolving to address emerging environmental and social challenges. Future plans may include enhancing biodiversity corridors, integrating smart water management technologies, and expanding community-led ecological initiatives to ensure long-term sustainability. However, maintaining the park’s delicate balance between ecological function and public accessibility remains a key challenge. As climate change intensifies, more extreme weather events, such as prolonged droughts and heavy rainfall, could test the resilience of the storm water management system. Additionally, ensuring continued community engagement and long-term funding for maintenance will be essential for preserving the park’s ecological integrity and social value. By embracing adaptive management strategies and fostering cross-sector collaboration, the park can remain a model for sustainable urban landscapes and inspire similar climate-resilient projects worldwide.

Ruchi Pathak

University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign