REVERSE STITCH

TEMPORARY AND ADAPTABLE GARMENT PATCHWORKS

RUBY LENNOX

ABSTRACT:

The advent of fast fashion in the last few decades has had detrimental effects on the planet and on our relationship with the clothing we own. ‘The average consumer buys 60 percent more pieces of clothing than 15 years ago. Each item is only kept for half as long.’ (Nijman, 2022). The clothes we buy now are not designed or produced to last and we have become accustomed to them being disposable.

At the same time, the move to off the rack clothing that facilitated fast fashion has cut the consumer / wearer off from any involvement in the creation (and consequently maintenance) of their clothing. Trends are dictated to us and we buy into them rather than having agency over the design and function of the clothes we own.

This project attempts to explore this new disposable nature of clothing while also re-opening the creation of the garment to the wearer. The clothes created by this project are temporary, fluid and only fully created through the process of being worn returning the final say in design to the wearer. Using second hand garments as the base textile and employing a selection of traditional visible mending techniques to reuse them,

the project aimed to encourage care of our garments and highlight the disconnect between the throw away trends and the physical textiles our garments are made of. Through the use of a zero-cut approach to pattern cutting the garments remain open to easy repair and repeated reuse.

All of the patterns developed and the files for the fabrication of the machine were made available online to facilitate open source interaction with the project from other makers.

3 2

INDEX:

STATE OF THE ART – 7

CONTEXT AND FRAMEWORK – 8

CIRCULARITY IN FASHION – 8

LIMITATIONS OF RECYCLING – 9

OPEN SOURCE FASHION – 10

DESIGN FOR DISASSEMBLY -13

CRAFTING TECHNIQUES – 18

VISIBLE MENDING – 18

PATCHWORK AND BORO STITCHING – 21

PLEATING AND SMOCKING – 23

PATTERN CUTTING TECHNIQUES – 25

ZERO WASTE - 25

WRAP GARMENTS – 26

BODY LED CUTTING – 27

PROJECT PROCESS – 29

PROCESS OVERVIEW – 30

STITCHING TOOLS – 32

PLEATING BOARDS – 32

SMOCKING MACHINE – 35

1ST PROTOTYPE – 36

2ND PROTOTYPE – 39

PATCHWORK CREATION – 42

GARMENT GREATION – 44

ZERO CUT DRAPING – 44

PATTERN EXTRACTION AND SIMPLIFICATION – 45

PATTERN EXPLANATIONS – 48

STITCHING LOCK AND JOINTS – 50

FINAL GARMENTS – 53

BLACK SHIFT DRESS – 54

GREEN DRAPE TOP – 60

CONCLUSION - 67

BIBLIOGRAPHY - 68

5 4

STATE OF THE ART:

7 6

CONTEXT AND FRAMEWORK:

CIRCULARITY IN FASHION:

The idea of circularity has been a widely discussed topic in the fashion industry in recent years as the environmental impacts of the industry and its waste problems have become more obvious and extensive. Despite this, it has not managed to help to curtail the ever-growing industry in any meaningful way and still remains predominantly a theoretical concept rather than a viable production method for most brands.

One of the leading organisations trying to implement more circular approaches in fashion is the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. They define a circular economy as being defined by 3 main principals: ‘eliminate waste and pollution, circulate products and materials (at their highest value), regenerate nature’ (Foundation, 2024). In this project, I wanted to explore circularity on a smaller scale and look at how we can engage with our clothes in more circular ways rather than suggesting production methods. I wanted to explore the act of dressing as a point of creation so that putting on and taking off the garment becomes a point of circular creation and disassembly.

LIMITATIONS OF RECYCLING:

One of the main limitations of circularity as I see it discussed in fashion now is the focus on recycling as the most successful way to limit waste. Not only is this often employed as a disingenuous approach by brands to shift the blame from them for their own overproduction to the customers consuming their products, but it overplays out current abilities to recycle clothing. ‘Fletcher and Grose (2012) state that the recycling of textile waste and more eco-efficient production alone do not solve the problem of an unsustainable industry, because the problem of overconsumption is not addressed at its core – it does not question the amount of apparel consumed.’ (Hirscher, 2013)

Additionally, closing the loop of production can only be done with the input of those who own a garment at the end of its traditional lifecycle, but to place the whole responsibility here undermines the much larger role of the producer and the full potential of a circular production system. Questioning the ownership of physical garments at the end of their lives in this way, encourages a similar questioning of the ownership of the ideas behind the garment - be that the design or pattern or less tangible ideas like the marketing and social

value - that offers a new way of examining the copycat culture that is driving the speed of fast fashion. To put the full responsibility of circularity on one actor at one point in the supply and use chain as recycling often does ignore the responsibility of all the other actors in that chain. I think to understand circularity as only a repetition of the existing linear system falls short of what could be a genuinely innovative, open and collaborative clothing system.

9 8

[1]

OPEN SOURCE FASHION:

Open Source Fashion is a much newer and less defined term. Initially, the open source movement focused on softwares and digital fabrication tools. While this has some relevancy in fashion now, most fashion production is still very craft based, not having developed too much technically from the introduction of the sewing machine. As a result, it is hard to see this initial movement having much widespread impact on fashion.

For me, the main impact of open source ideas on fashion is more about encouraging re-learning of the garment construction and tailoring knowledge that has been limited by industrialisation. In this way, the goal should be that the consumer of a product is no longer completely distinct from the designers and makers – and told by large advertising companies which pre-made products they should buy. This has some similarities I think with older systems of disseminating fashion trends where most people would have access to patterns or an example garment - e.g. Queen Anne Dolls - and make their own versions from this.

Being able to alter and remake as you like is integral to this and upcycling

and sharing these skills is an important was of dealing with waste, however,

I do think this is a start not the end goal. I think circularity – which open source ideas would feed into - demands a complete severing from the current linear production to consumption model, way past the minimal notion of recycling end of life garments. To truly embrace a circular model, we must relink all actors within the design/supply/consumer chains to all other points. These interactions are, I think, the grounds on which we break the Black Box model that encourages the current alienation and throwaway culture and this is where the open source movement can be really beneficial for fashion.

This also requires discussions around ownership of both the physical garments and the images and ideas produced by fashion, by moving towards a model of production that requires creation by the consumer we open up the possible outcomes and lessen the intellectual control of the designer.

11 10

[2]

DSIGN FOR DISASSEMBLY:

Design for disassembly is a well-established methodology for facilitating repair and recycling in other industries such as the automotive and electronics industries and has begun to be explored in fashion in recent years. Design for disassembly engages the designer of a product in the end of life processing of their products and helps to more evenly share the responsibility for regenerative (or at least neutral) disposal between the end user and the designer and producer.

The main focuses and rules for implementing this design approach according to Bogue (2007) are as outlined in the table right:

Of these, the focus on structure, material and joints translates very well to fashion. While it is predominately an approach to construction, in depth implementation will obviously impact the aesthetic design of a garment too, particularly from a material sense.

13 12

[3] [4] [5] [6]

Vezzoli and Manzini (2008) describe the main pri-

orities for designer using DfD as below:

Of these, the main focuses for this project are ‘prioritise the disassembly or more easily damageable components’ ‘engage modular structures’ ‘divide the product into easily separable and manipulatable sub-assemblies’ and ‘minimise hierarchically dependant connections among components’. These are most relevant for this project as they also require focus on the physical wear and use

of the garment and the specific repairs this requires. Additionally, considering the hierarchy / dependence of the joints used in the main structure of the garment will help with implementing innovative cutting and shaping techniques.

DESIGN FOR DISASSEMBLY IN FASHION

There are some main hurdles for the implementation of DfD in fashion that need to be addressed from both the design and production sides. While some of these may be quick fixes like picking different materials or trims, there are more complex issues regarding the construction techniques we use.

In their exploration of Design for Disassembly in a traditional men’s blazer, Gam, Cao, Bennett, Helmkamp and Farr (2011) highlighted a main problem with current garment construction, the excess of parts and combinations of materials. They found that the three jackets they disassembled took all took around 22 minutes and contained 14 individual parts (not including buttons) made from different combinations of materials and adhesives. The number of parts here makes the recycling of any of the materials in this jacket very cost and time ineffective and there-

fore increases the likelihood of it ending up in landfill. Additionally, any mixed material and anything with adhesive on is non-recyclable so even if the design was simplified very little of the jacket could be recycled.

A suit jacket is one of the most complicated garment archetypes in regular production nowadays and there are obviously garments that would be a lot quicker to disassemble. However, this example is beneficial in highlighting the some of the necessary balances needed between maintaining the specific functions of the garment and allowing it to be easily disassembled. They also found a few simple tricks for removing any need for adhesives. ‘Blind stitches were used under the collar and on the backside of the lapel to replace fusible interfacing’ (Hae Jin Gam, 2011)

Another of the main issue with design for disassembly in fashion is the use of trims. The use of trims, similar to the example above, makes the disassembly process longer and more complicated and certain trims such as rivets are impossible to remove from the fabric meaning that they and the fabric around them can’t be reused at all. Additionally, things like elastic threads, or any thread of a different composition to the fabric it is used

with means that all stitching would have to be removed before the fabric can be recycled. The effect of this is different for different trimming and depending on the quantity but it is still an important consideration..

15 14

[7]

There are some companies such as working to make trims made with design for disassembly in mind. For example Resortecs makes heat dissolvable thread so that garments can easily and rapidly be taken apart to this original pieces with little effort.

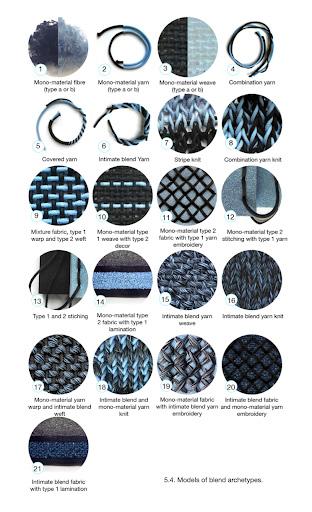

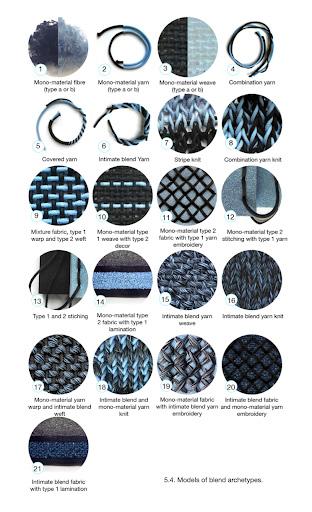

Regarding the actual textiles used in fashion, any mix blend of fibres is non-recyclable so even if the structure and joints of the garment are perfectly in line with DfD the fabric must either be used again in its pre-cut state (making it less and less useful) or be wasted. Laetitia

Forst is a researcher developing a selection of DfD textile ‘blends’ to allow for the multifunctional nature of poly-blends without drawback.

FREITAG makes screw on buttons and rivets so that the functionality of these trims doesn’t need to be lost to ensure all of the fabric can be recycled and these trims can then themselves be easily reused.

17 16

[8]

[9]

[10]

CRAFTING TECHNIQUES:

VISIBLE MENDING:

Visible mending is a catch all term for a wide range of techniques that can be used to extend the life of garments. ‘Visible mending is a textile repair approach where, instead of hiding the mend to restore it to its original state, the maker uses the repair as decoration with embroidery and hand-stitched patterns’ (Lee Jones, 2021) among other techniques. While mending was once a widely shared and practiced skill, since the advent of fast fashion it has largely fallen out of favour. It is now in a lot of instances easier and quicker to just replace a broken garment than to fix it. Visible mending aims to counter this by adding value to the signs of age and wear in a garment and encourage care and preservation. By taking the time to fix and simultaneously personalise a garment, people engaging in visible mending often find that the ‘act of mending their clothes strengthens their relationship to the item’ (Lee Jones, 2021).

As fast fashion has risen, the number of people capable of and regularly fixing their own clothes has fallen massively. One ‘survey indicated that many participants did not have the necessary skills to repair clothes and that an overall decline in repair skills was in part due to a decline in teaching the

skills in schools’ (Norum, 2013, as cited in Cassidy, 2018). Visible mending

techniques are mainly done by hand and therefore done require any machinery however they can require a selection of specialist needles and other tools.

19 18

[11] [12] [13] [14] [15]

PATCHWORK:

Patchwork is a common textile technique the around the world. There are a variety of specific patch working techniques but the basic premise is stitching small pieces or fabric together to create a full textile. It has been used for millennia for many purposes from ‘ancient Egyptians for their clothes, wall decorations, draperies and furniture’ to ‘the knights of the middle ages [wearing] quilted jackets’ (Various, 2011). Nowadays it is widely used as part of the decorative arts as well as more functional applications, particularly as part of upcycling.

BORO STITCHING:

Boro stitching is a subsection of sashiko, which refers to a range of traditional Japanese stitching technique. ‘Sashiko—frequently translated as “little stabs”— was born in Edo period Japan (1603–1868), when rural women attempted to prolong the life of their families’ tattered garments and bedding, giving rise to a humble form of white-on-indigo patchwork known as boro.’ (Halliday, 2020).

There is a selction of boro tools available to buy to make this process more accessible. These all mainly focus on helping to mark the position of the stitching points to then be sewn by hand.

21 20

[16]

[17]

[18]

[19]

[20]

[21]

PLEATING:

Pleating is a common textile manipulation technique in which fabric is folded in on itself in some form. There are a range of ways of pleating fabrics and possible pleat shapes. Traditionally, it was a slow and painstaking process done by hand and secured with stitching, now with the digital pleating machines it can be done much easier and faster. The most commonly used pleat shapes are knife/accordion and box pleats. Pleating can be purely decorative or it can be used to add extra movement and volume where needed to a garment. With the introduction of synthetic fabrics, pleating has become easier to do and maintain as these can be permanently pleated with heat and don’t require as much securing or stitching afterwards.

SMOCKING:

Smocking is a traditional stitching technique used to gather fabric to allow stretch. It was commonly used on details like collars and cuffs before elastic.

‘When smocking, a grid pattern is drawn on the fabric. The fabric is then gathered and sewn together using a series of small, regular stitches. The gath-

ered stitches create small pleats or gathers in the fabric, giving the smocked area its characteristic appearance.’ (Martejevs, 2024). Smocking has a very decorative appearance creating geometric patterns on the fabric sections it is gathering. Similar to boro stitching, there are a range of tools available to hep with marking the stitching positions needed to create these patterns.

23 22

[22]

[24]

[23] [25]

[26]

PATTERN CUTTING TECHNIQUES:

ZERO WASTE:

Zero waste pattern cutting is a method of pattern making that aims to eliminate all waste from the cutting process. ‘With the predominant contemporary methods of fashion making the amount of fabric waste is approximately 15 percent of the total fabric used.’ (Rissanen, 2005). There are different ways of approaching zero waste cutting. For example, by eliminating most of the cutting so that the number of pattern pieces and the negative space in between them is minimised. Alternatively, using the negative space in between pieces to inform new pattern pieces.

Zero waste as an approach is a textile led pattern cutting method, as the textile available dictates the possible outcomes in a way that it does not in conventional pattern cutting. additionally, in this way, the creation of the garment and the pattern are much more interlinked than normal. Traditionally, a garment is designed (sketched) and then a pattern is made to suit this, in zero waste, the two processes have to happen in parallel.

According to Holly McQuillan - a designer working at the forefront of zero

waste pattern cutting - ‘unlike the majority of fashion design practice – where the goal is primarily to introduce a difference (Hallnäs, 2009) – zero waste fashion design could be seen as a practice concerned with solving a problem.

When engaging with the zero waste redesign of an existing garment – we know its overall desired form, but we strive to achieve something similar without making so much waste – so the design problem is the waste.’ (McQuillan, 2019).

WRAP GARMENTS:

Wrap garments predate contemporary European pattern cutting by

millennia and are still widely used. They are in some ways a more intuitive way of covering the body with cloth and require much less, if any, stitching a cutting. A wrap garment is at least partially constructed only through the act of actually being worn making it more easily adaptable to an individual’s body than most other garments.

‘Wrap clothing such as the Indian sari and dhoti, the Roman toga, or the Arabic hajk were rectangular woven pieces of fabric that remained undefined in shape until being worn and were recreated each time while dressing.’ (Lindqvist, 2016). As a result, the ‘pattern’ for these garments is more the process of putting them on and how the fabric should move around the body than a static shape as in more convention contemporary cutting.

This again is a textile led approach to garment construction, in which the aesthetic of the garment are the ‘pattern’ generated in conjunction with the wearers body not separately.

25 24

[27] [28] [29]

BODY LED CUTTING:

Kinetic pattern cutting is a type of pattern cutting developed by Rickard Lindquist to focus the movements of the 3D body more in the process of 2D pattern making. ‘The principal difference between the prevalent theory of the tailoring matrix and this human kinetic construction theory is that the latter is derived directly from how the fabric interacts with the living body instead of being derived from measurements of a static body.’ (Lindqvist, 2016). This approach focuses on the movement of the body and how the garment should be designed to enable and react to this rather than creating garments from a few specific measurements that the body will have to adapt to fit.

Subtraction cutting is a form of pattern cutting developed by Julian Roberts that creates garments through ‘the removal of fabric rather than the addition of fabric’ (Roberts, 2013). Subtraction cutting focuses on creating the space in the garment through which the body will go rather than creating a covering for the body. In this way, the result is often very organic and draped as the shape is determined through the wearing of the cloth not through design before. ‘The basic premise of Subtraction Cutting is that the patterns cut do not represent garments outward shape, but rather the negative spaces within the garment that make them hollow. Simply put, shaped holes cut from huge sheets of cloth through which the body moves.’ (Roberts, 2013)

27 26

[30] [31]

[32]

PROJECT PROCESS:

29 28

PROCESS OVERVIEW:

ASSEMBLY AND DISASSEMBLY:

The full creation process proposed by this project is illustrated in the diagram to the right. Contained within the larger circular process are different options for undoing and repeating smaller sections of the process. The garments and textiles created here should not be viewed as undergoing another full lifecycle as with upcycling but rather as undergoing short moments of alternative use. The intent is that they move between the different states – original garments, new textile, shaped garments – with fluidity and ease.

This is reflected in the textile techniques used and the way the fabric is treated. By only using running stitches, the patchworks are quick and easy to disassemble as these can be pulled out in one go when not required. They also allow for very smooth movement along the gathering lines and therefore rapid shaping and un-shaping. This also embraces the principals of design for disassembly through creating non-static objects that can be partially taken apart with minimal dependency between the different parts of the patchworks. The initial unmaking stage is the most important regarding the ease of repair of the original garments, care should be tak-

en to minimise the cuts done to prepare them for use within the patchwork. Ideally, there will only be 1 or 2 seams that require repair after use within the process to return the original garments to their initial state.

As most of the shaping for the garments is done through the gathering, there is no cutting required at all for most of the patterns presented in this project. The creation of the garments depends on the combination of the gathering, a temporary manipulation secured by the addition of toggles, and the wrap of the textile around the wearer. These are both open to adaptation by the wearer and give them final creative control of the garments.

31 30 BASE

UNMAKE COMBINE UNMAKE SHAPE UNSHAPE WEAR MEND

GARMENTS

STITCHING TOOLS:

PLEATING BOARDS:

Pleating boards are traditionally made out of thick paper of cardboards folded into the pattern desired of the pleat. They most basic of these is the accordion pleat where the paper is folded one way and then the other into parallel sections of the same width so that it resembles an accordion or fan. There are a wide range of pleating types requiring pleating boards of much more complexity but for this project, only the accordion fold is necessary.

To use the pleating boards, they are stretched out flat, and a layer of fabric placed in between two. It is important that both the fabric and the boards are taut at this point so that it fits into all of the folds evenly. Next the boards are gradually returned to their folded state ensuring that the two boards remain in perfect sync. While in this position the fabric and boards are heated and cooled so that the fabric adopts the shape of the board. When the fabric is then peeled away from the boards, it should retain the shape of the pleat over time even when washed.

Synthetic fabrics are best for this type of pleating at the are very

heat reactive. Plant based materials may hold the shape of the pleat for a while but it will not remain for extended periods of time or after washing without some maintenance or stitching to secure.

For this project, used accordion pleating boards to gather fabric to allow for rapid running stitching. Running stitching is a meticulous and time-consuming process and there are currently no machines to help automate the process (the type of stitching done by sewing machines is very different and would not allow for the ease of movement and removal required for this project).

To do this, evenly spaced holes of 5mm diameter are added to each folded section of the board, perpendicular to the folds, to allow the needle and thread to be passed through. A slit is also added to join every other hole, on alternating pairs on the top and bottom board, this allows for the board to be lifted off the fabric once sewn without catching on the stitching. The spacing and number of lines of the cuts is dependent on the desired density of stitching.

To use these boards for patchworking, the required fabric pieces should be placed in between the boards together with ample overlap. This technique will not work if the fabric inside the boards is too thick as it will affect the alignment of the holes between the top and bottom boards.

33 32

[33]

SMOCKING MACHINE:

The smocking pleater machine is a table-top machine used for adding the running stitches necessary for smocking. It works by passing fabric between 4 serrated wheels so that it is pushed onto a set of needles in a small accordion pleat. The machines are not in production anymore but it is still possible and there is limited information about their dimensions online.

Instructions for using a Princess Pleating Machine:

- Thread all the needles you need.

- Roll the fabric tightly round a wooden or plastic rod, and place inside.

- Fit the open end of the fabric between the rollers.

- Then turn one or both of the handles to steadily feed the fabric onto the needles.

- And hey presto, out comes the pleated result.

- The sides are open, so any width of fabric can be used. And the large handles give complete control. Pleat depth is about 8mm, depending on fabric thickness.

35 34

[34] [35]

1ST MACHINE PROTOTYPE:

The first prototype for the basic gear shape for the 4 wheels was designed in rhino to be printed on a desktop FDM printer. Initially, 2 small test sections were printed to ensure they turned correctly. The dimensions of these were:

- inner diameter 30mm

- outer diameter 40mm

- tooth depth 5mm

- tooth width 5mm base to 3.6mm end

- tooth array 30°

- centre cut out diameter 8mm

Despite the success of the initial test prints, it proved difficult getting the printer to work with the full-length wheels. As a result, for the first full prototype, the gears were laser cut from plywood and stacked in position. The dimensions for this were the same with and addition of 2 added inner cut outs either side of the main one of 3mm to help with the alignment. 100 of each of the 2 pieces was cut and 25 each used per gear.

The side pieces used for this machine were as shown. Enough space at the back of the machine for a dowl loaded with fabric is necessary to make feeding it through easier and smoother and a slit along on side for the excess fabric. This machine turned very smoothly and the fabric passed through very easily.

To make the needles for this machine, long doll making needles were used as a base and bent into the correct shape to match the curves between the gears. This was done both by hand with plyers and using the hydraulic press and a mould made with the CNC machine. Of the two ap-

proaches, the plyers were more successful. The mould would need to be adjusted for the curves to be deeper than the desired shape to allow for the needle to decompress after release. Both needles fit into the machine well but did not stay in place while the machine was rotating. Additionally, the gaps between the teeth were too wide to hold the them securely.

37 36

2ND MACHINE PROTOTYPE:

To ensure the needles were correct, for this second prototype, I bought a pack of needles for a Princess pleating machine – while the machines are out of production, it is still fairly easy to purchase the needles. These were much smaller than the 1st prototype of the machine so the model was scaled down to fit them. The diameter of the curve of the needle was 20mm so the inner diameter of the gear was changed to 18mm and the number of teeth was reduced to 8 to ensure they weren’t too fragile. The new dimensions are:

- inner diameter 18mm

- outer diameter 24mm

- tooth depth 5mm

- tooth width 5mm base to 3.6mm end

- tooth array 45°

- centre cut out diameter 4.8mm

3 small tests were printed of the new size using the SLA printer to check

they fit the needle correctly. There were some issues with the printer meaning the models were curved but they successful for confirming the size.

Following a few more attempts with different printing settings, 4 full length gears were successfully printed in the new smaller size and a proportional version of the sides made for the first prototype was laser cut.

When it was all constructed, the scaling down did severely limit the number of layers and the thickness of textile that could be passed through the machine. Also, as with the first prototype, when the needles were put in, the gears didn’t turn as smoothly as required and the needles tended to fall out after a few rotations.

39 38

Returning to the videos of the machine found online again, I realised that I needed to reposition the gears so that the needles would be less horizontal to try to secure them better. A few different positions and angles were tested out until a more successful setup was found.

In conclusion, for the machine to be most useful for this project, it would need to be the size of the 1st prototype. This is because to patchwork, at least 2 layers of fabric will need to be passed through the gears at most times and the smaller machine would not be capable of handling this. The next steps for developing it would be to try either printing the gears with the gaps in between the teeth at about 1mm or to laser cut with a different material for the sections in the teeth at this thickness. Additionally, it would be beneficial to cast needles at exactly the right shape and size for the machine.

41 40

PATCHWORK CREATION:

CUTTING ORIGINAL GARMENTS:

LAPPLANNING:

The process of generating the textiles for this project was based in patchworking existing garments. In this way, the only virgin materials required for the project is the thread and potentially bias tape should the maker want to bind the raw edges of their garments. It is recommended to keep the cutting to a minimum and to only follow existing seamlines to facilitate easier repair after use as part of this project.

When cutting trousers, it is best to cut the whole way down both outside seams - including the waistbacnd if possible - this will leave only a section around the waist double layered. For shirts and other tops, cut along the side seams straight through along the sleeve seams. Skirts and dresses can be cut along the back or either of the side seams.

Due to the sensitivity of the needles, when working with the smocking machine, thin fabrics only are recommended. When stitching by hand, thicker fabrics can be used. Thicker fabrics will not gather as tightly as thinner ones and care should be paid to not layer them up too thickly to ensure the full shaping can be achieved.

When using the machine, it is recommended to remove all trims, this is optional by hand. When positioning garments to be sewn, if trims are being kept in, ensure that they are not placed so that they intersect with a line of stitching as this will interfere with the gather.

It is recommended to keep the shape of you patchworked textile as close to the pattern dimensions as possible but small differences will not affect the garment. Apart from achieving the basic shape, the positioning of the garments should be used to hide as many raw edges as possible for a sleeker finish.

STITCHING:

These patterns require running stitches, this is the most basic hand stitch and can’t be done on a sewing machine.

Due to the tension and weight placed on the stitching by the gathering, use a double layer of strong thread. The more parallel rows of stitching you do for each line, the less the pressure will be on the individual threads. Between 3 and 6 rows of stitching is recommended for each line of the patterns. The more rows, the more pronounced and secure the shaping will be.

To do the stitching by hand, use the smocking rulers provided to mark the points where you need to stich. To avoid permanently marking the textile, use either a heat erasable pen and iron along the marks after or use marked masking tape as a guide.

To do the stitching by machine, position the fabric so that the marked line you need to stitch is perpendicular to the dowl and wind the fabric on in this position to ensure the correct alignment with the needles.

The finishing of the garment is open to the maker to decide based on their skill level and desired time taken. To embrace the most temporary version of the garment, leave the edges raw and hide them through the layering of the patchwork. This allows for the initial garments to be remade / repaired easiest and keeps the process as fluid as possible. To create a sleeker and more permeant garment, the raw edges from can be hemmed or bound.

43 42

GARMENT CREATION:

ZERO CUT DRAPING:

In order to know where the lines of stitching were needed within the patchworks, I needed to generate some basic patterns. These pre-decided garment options could then be applied to the textile patchworks rather than trying to extract shaping from random stitching done purely to secure the patchwork. This was done by draping rectangles of varying sizes around the mannequin generating shape only through gathering and securing as few points as possible. Only rectangles of calico were used with the intention that I any pattern extracted from this would be able to be used on a textile of any irregular shape that was roughly the same dimensions. As this project uses found and patchworked textiles, they are never going to be exactly the same size as the patterns so the patterns would have to have a very simple base shape that would allow for pieces extruding or slightly missing without ruining the intended design. I envisaged most of the patterns being interchangeable on the same patchworks as long as all of the stitching from the different patterns was done so the same pieces of textile were used to generate multiple drapes to ensure the sizing would match. These were 4m x 0.6m, some 1.5m x 2m and some 1.5m x 1m.

A range of 6 drapes was selected for the project, made up of different of garments. It included two tops, two dresses, one jacket and one skirt. All were very draped and voluminous aesthetically but had a decent amount of movement that wouldn’t keep the arm too close to the body or restrict leg movement despite the lack of cuts.

PATTERN EXTRACTION AND SIMPLIFICATION:

These drapes then underwent a process of extracting and simplifying in order to be used as easily distributable and repeatable patterns.

To do this, all of the marked join points and the lines for the gathering on the calico used for the drapes needed to be extracted and digitalised. This was done by measuring the distances of all the points from one corner of the calico and them inputting them into rhino like coordinates.

45 44

After a rough pattern had been generated, it needed to be simplified it to a point where it could easily be redrawn by someone without a good pattern kit. All of the angles and distances needed were measured a few key measurements were selected to be the base points for the redrawing. The points were then moved around a little to make the lines and distances more uniform. All of the distances needed to measure were converted to ratios of each other as this would allow the creation of a set of very simple rulers and stencils for redrawing them. The angles were also altered so that similar lines were fully parallel or symmetrical. For any drapes that should have been symmetrical down the middle such as the jacket, the average of the two corresponding points was found and used to get a perfectly mirrored pattern.

This process took a few tries as it was important not to move the points too much as it could damage the functioning of the pattern. However, as all of the drapes were very loose and organic I hoped that I would have enough flexibility with the exact positioning of the gathers to move them this much and still get a similar outcome.

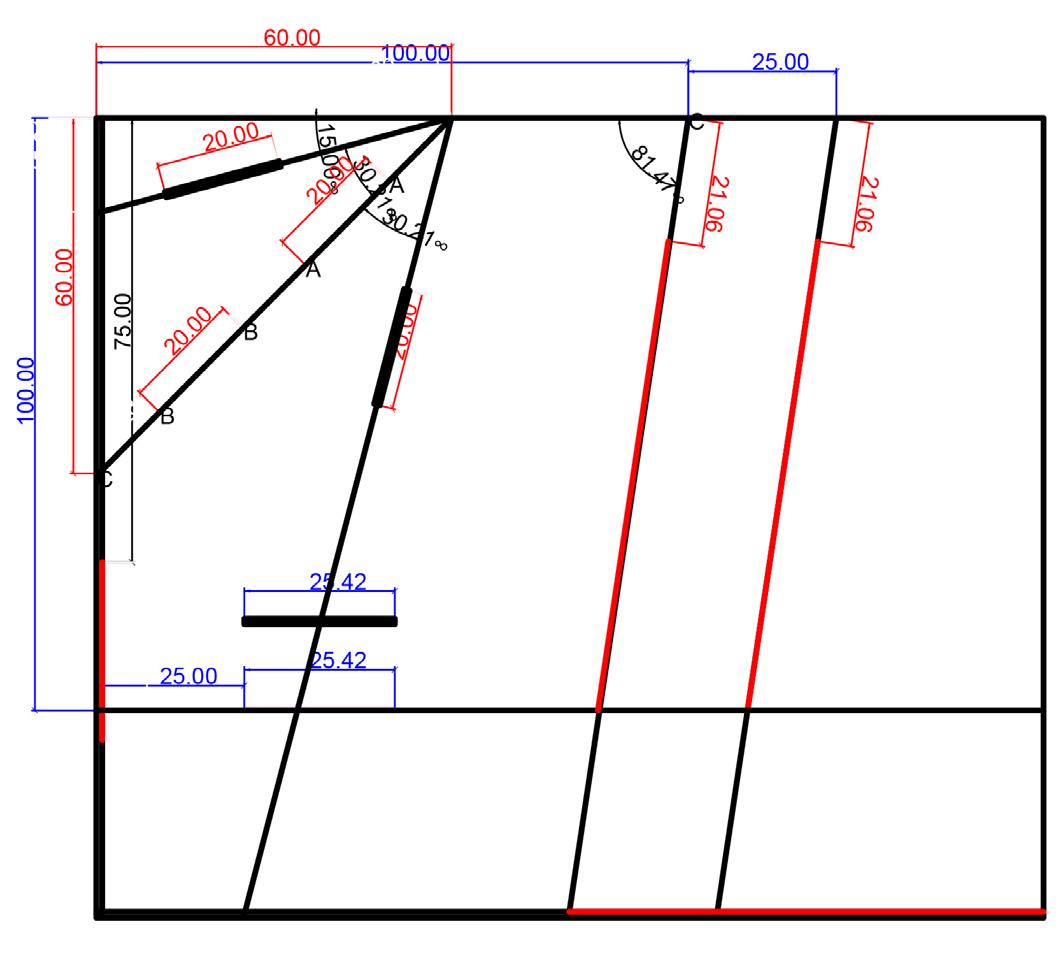

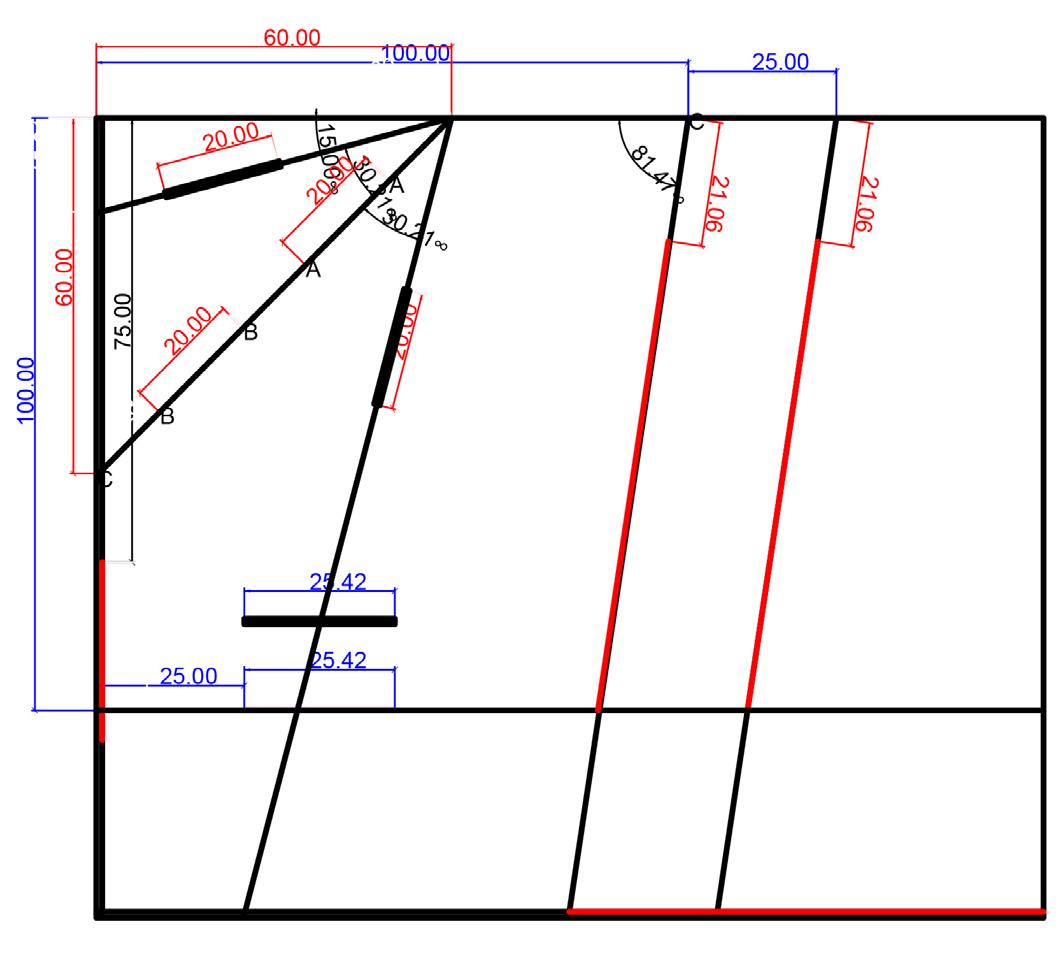

On the right page an example of this process for one of the dress drapes, the steps are as follows:

-The base pattern from the shift dress drape after it was initially put into rhino

- With all the measurements of the distances and angles:

- With the angles simplified to repeats of either 30 or 80 degrees and all main distances simplified to ratios of 20cm or 25cm:

- The pattern as it would be presented for use, black lines are the full stitching lines required to be able to do the red lines of gathering, blue lines are just needed for ease marking cuts and joints so should be traced in chalk, the letters mark join points and the thin rectangles are cuts:

47 46

PATTERN EXPLANATIONS:

In order for these to then be reproduced by other people, the pattern process needed to be explained as clearly and succinctly as possible. As the patterns and the construction process needed for this project were so distinct from conventional patterns, it wasn’t a worry that they would be inaccessible to people without prior pattern cutting knowledge.

In order to create the instructions, the process needed to be broken down into a few distinct simple steps. For the whole process of redrawing the pattern and constructing the garment, there were 6 steps (7 for the shift dress as this was the only one that required cutting).

The pattern drawing and construction are not 2 distinct phases but overlap through the placement of the locks and the gathering so that once the pattern is finished, the garment is basically constructed, just needing to be wrapped around the body.

To aid with the pattern drawing, a selection of rulers and stencils were created. In some cases, these allowed for the sections of the pattern containing the most information be accurately drawn and the rest to be extrapolated from this point. In others, they contained all of the angles and measurements needed for the patterns so that the points needed could be easily marked with minimal chance of mistake. Rulers were also mad to aid with the marking of the stitching points if this was being done by hand so that the multiple rows of stitching could be quickly and accurately marked.

These graphics are the most basic version of the instructions, they were accompanied by a pattern explanation zine with information about the textile generation process too and a detailed video tutorial showing the full assembly and disassembly process.

49 48

STITCHING LOCKS AND JOINTS:

While the garments are intended to be very fluid and temporary, there needed to be some way to keep the shaping of the garment in place for short periods of wear. This was not intended to be too secure as it needed to allow for rapid assembly and disassembly.

The garments needed to be able to be secured two distinct ways, the first was keeping the gathering in the desired places and not evenly spread across the whole line of stitching and the second was joining parts of the fabric to secure the wrap. Both of these were done with the same trim, a screw on toggle with 4 holes to pass the thread through. This was made using an open source model from Thingiverse and scaled appropriately for the thread used. The scale model is available open source on the project website.

To use this for securing the gathering, the thread at one end point of the gathering needs to be pulled so that a few loose cm can be passed through the holes in the bottom half of the lock. The top should then be screwed on and secured so that the thread can’t pass through. The thread at the other end point should

then be pulled so that the fabric in between these two points is as gathered as possible and then secured in the same way. The excess thread can be more evenly distributed between the two locks if needed but this is the simplest way.

To use them for securing the wrap is slightly more complicated. In a few of the patterns, there will be a line of stitching at most points where the locks here are needed but in some cases, it may be necessary to do a few stitches at the points indicted by the pattern. When doing extra stitching, ensure that enough thread is used to allow for at least 10cm excess to be pulled from it.

Once the stitching is in place, it should be pulled as explained above so that

a few cm can be passed through the lock. The thread from both points that need to be joined should be passed through the same lock and then secured.

These can be removed by slightly loosening the screw and pulling off, the stitching can then be lightly pulled to remove the gathering.

51 50

[36]

FINAL GARMENTS:

53 52

BLACK SHIFT DRESS:

For the final video of this project I made 2 garments using the process described above. The first, a black dress used the shift dress pattern.

It was made of 4 garments: a jersey maxi dress, a pair of waterproof trousers, a ribbed top and a chiffon top. These were all of a similar colour for cohesion and to allow for more focus on the textures. All 4 garments were cut along as few seams as possible to gain as large a surface area as possible. the raw edges from these cuts was then bound in black bias tape to give a more refined finish.

As the machine was not working fully as intended at this point, this was sewn by hand and therefor took 2 days to do all of the required running stitches. Either 2 or 3 parallel lines of stitching was done for each line indicated by the pattern. In the end, the patchwork this garment was made from was very secure with few gaps visible between the pieces, this was enhanced

when it was worn and gravity added some more tension between the fabrics.

This pattern was the only one that required any cutting. 3 slits are needed, 2 for the neck hole and 1 for the arm hole. To reinforce this, as especially the neck hole slits would be holding most of the weight of the rest of the dress, they were hemmed with a double layer of facing in a matching colour from some scraps at the lab. This unfortunately does add a hurdle for the disassembly process, as does the binding, making this more time consuming to take apart and then potentially repair the initial garments.

55 54

57 56

59 58

GREEN DRAPE TOP:

The second final garment made was a green top used the drape blouse pattern. The instructions for creating this garment are below:

It was also made of 4 garments: a khaki raincoat, a light green tweed-look

skirt, a grey knit sweater and a pair of khaki suit trousers. These garments had a much wider range of colours and textiles than the last set which did give the final garment a more obviously patchworked aesthetic than the other garment. All 4 garments were cut along as few seams as possible to gain as large a surface area as possible. the raw edges were hidden within the layers of the patchwork where possible but no extra finishing was done.

As the machine was not working fully as intended at this point, this was sewn by hand and therefor took 2 days to do all of the required running stitches. 2 parallel lines of running stitching was done for each line indicated by the pattern. However, for added security of the patchwork and due to time constraints, 1 or 2 parallel lines of stitching done on the machine was added either side of the running stitches. In the end, the patchwork of this garment was not very secure and there were some points between the pieces that gaped slightly with some movements. Despite this, enough stitching was done for the textile to stay together while worn, disassembly was much easier for this than the black garment.

61 60

63 62

65 64

CONCLUSION:

ADAPTABILITY:

All of the patterns presented in this project should be open to easy alterations for both fit and style. They are not an exhaustive list and are a suggestion of how to use this technique to create garments. The placement and number of the stitching lines can be altered to exaggerate or minimise certain shaping points. The intensity of the gathering and the wrap can be altered to fit the wearer. Additionally, different patterns can be combined on the same patchworks to alter the textile appearance and open up new shaping options. Extra stitching can be added for more details around the existing shapes.

Garment creation should be approached openly, allowing the textile to guide more than dictating to is what it should become. The shaping will depend on a combination of the textiles used, the positioning of the stitching in relation to the textile, the density of the stitching and the wrap around the wearer’s body. The wrap of the garment is an important part of the design process of the garment and the wearer should embrace this moment of dressing as a point of creation giving them the final control of the design.

PROCESS: Overall, I am happy with the garment outcomes of this project, I think they embodied the concept well and had a genuine fluidity that was easy to manipulate. I would have liked for the machine to have been working but within the time frame available it was not possible. I think this did hinder the project quite a bit as it undermined the work to simplify the process and make it available to people with limited sewing ability. Doing so many lines of running stitches was incredibly time consuming and at odd with the intended temporary nature of the garments. Despite this, I was happy with the variety and simplicity of the pattern selection presented.

67 66

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Bogue, R. (2007). Design for disassembly: a critical twenty-first century discipline. Assembly Automation, 27(4), 285-290.

Carlo Vezzoli, E. M. (2008). Facilitating Disassembly. In E. M. Carlo Vezzoli, Design for Environmental Sustainability (p. 269). Milan.

Cassidy, D. A. (2018). Revitalising and enhancing sewing skills and expertise. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 65-75.

Foundation, E. M. (2024, April 23). What is a circular economy? Retrieved from Ellen MacArthur Foundation: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/ topics/circular-economy-introduction/overview

Hae Jin Gam, H. C. (2011). Application of design for disassembly in men’s jacket. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 23(2/3), 83-94.

Halliday, A. (2020, October 26). Open Culture. Retrieved from The Japanese Traditions of Sashiko & Boro: The Centuries-Old Craft That Mends Clothes in a Sustainable, Artistic Way: https://www.openculture.com/2020/10/the-japanese-traditions-of-sashiko-boro.html

Hirscher, A. &.-L. (2013). Open Participatory Designing for an Alternative Fashion Economy. In A. &.-L. Hirscher, Sustainable Fashion: New Approaches (pp. 174-197). Helsinki: Aalto ARTS Books.

Lee Jones, A. G. (2021). Patching Textiles: Insights from Visible Mending Educators on Wearability, Extending the Life of Our Clothes, and Teaching Tangible Crafts. Proceedings of the 13th Conference on Creativity and Cognition (C&C ‘21) (pp. 1-11). New York: Association for Computing Machinery.

Lindqvist, R. (2016). Kinetic Garment Construction: Remarks on the foundation of pattern cutting. Borås: Högskolan i Borås.

Martejevs, J. (2024). Smocking Clothes: Learn how to smock and where to find easy smocking patterns. Retrieved from Juliana Martejevs: https://julianamartejevs.com/en/smocking-clothes-learn-how-to-smock-and-where-to-find-easy-smocking-patterns/#:~:text=When%20smocking%2C%20a%20grid%20 pattern,smocked%20area%20its%20characteristic%20appearance.

McQuillan, H. (2019). Zero Waste Design Thinking Borås: Högskolan i Borås.

Nijman, S. (2022, June 21). UN Alliance For Sustainable Fashion addresses damage of ‘fast fashion’. Retrieved from UN Environment Programme: https:// www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/un-alliance-sustainable-fashion-addresses-damage-fast-fashion

Rissanen, T. (2005). From 15% to 0: Investigating the creation of fashion without the creation of fabric waste. Creativity: Designer Meets Technology conference. Copenhagen.

Roberts, J. (2013, August). Free Cutting. Retrieved from Free Cutting by Julian Roberts: https://researchonline.rca.ac.uk/3060/1/FREE-CUTTING-Julian-Roberts.pdf

Various. (2011). The Beginnings of Quilting and Patchwork in Antiquity-Two Articles on the History of the Craft. Front Royal: Seton Press.

PICTURES:

[1] Foundation, E. M. (2024, April 23). What is a circular economy? Retrieved from Ellen MacArthur Foundation: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation. org/topics/circular-economy-introduction/overview

[2] Anja Hirscher, A. F.-L. (2013). Open Participatory Designing for an Alternative Fashion Economy. In Sustainable Fashion: New Approaches (pp. 174-197). Aalto ARTS Books.

[3] Martijn van Strien, V. d. (2016). OPEN SOURCE FASHION MANIFESTO . Retrieved from opensourcefashionmanifesto: http://www.opensourcefashionmanifesto.com/

[4] Makers Unite. (2024). Retrieved from Makers Unite: https://www.makersunite.eu/

[5] Martijn van Strien, V. d. (2016). OPEN SOURCE FASHION MANIFESTO . Retrieved from opensourcefashionmanifesto: http://www.opensourcefashionmanifesto.com/

[6] Openwear. (2010). Issuu. Retrieved from Openwear Brand Manual: https://issuu.com/openwear/docs/openwear_brandmanual

69 68

[7] Hae Jin Gam, H. C. (2011). Application of design for disassembly in men’s jacket. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 23(2/3), 8394.

[8] Technology. (2022). Retrieved from Resortecs: https://resortecs.com/technology/

[9] F-ABRIC - THE BUTTON. (2015, August 21). Retrieved from FREITAG: https://media.freitag.ch/en/fabric/button

[10] Forst, L. (2020). Textile Design for Disassembly: A creative textile design methodology for designing detachable connections for material combinations. University of the Arts London, London.

[11] Khounnoraj, A. (2020). Visible Mending :Repair, Renew, Reuse The Clothes You Love. Quadrille Publishing Ltd.

[12] Jones, L. (2021). The E-darning Sampler: Exploring E-textile Repair with Darning Looms. TEI ‘21: Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction (pp. 1-5). New York: Association for Computing Machinery .

[13] Buss, R. (2016, July 11). Monday Morning Inspiration/Visible Mending . Retrieved from Rhonda’s Creative Life: https://rhondabuss.blogspot. com/2016/07/monday-morning-inspirationvisible.html

[14] Visible Mending - Jeans. (2019, January 28). Retrieved from Simple Living Toowoomba: http://simplelivingtoowoomba.weebly.com/simple-living-blog/ visible-mending-jeans

[15] Bookhou. (2021, August 4). Bookhou. Retrieved from Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/p/CSJ-q9Lrj1k/?utm_medium=share_sheet&epik=dj0yJnU9M3E5dEtlWllPdkloaV9TakJEMWRrWjdMMXJ2aXZtRXkmcD0wJm49Z0hteXBwOElFQW1ZY04xNVJjaUpPUSZ0PUFBQUFBR1l4aEE4

[16] Digital Patchwork. (2023). Retrieved from A New Kind of Blue: https://anewkindofblue.com/#patchwork

[17] Niasunset. (2018, February 27). Sashiko / Boro. Retrieved from A CUP OF TEA WITH THIS CRAZY NIA: https://acupofteawithnia.wordpress. com/2018/02/07/sashiko-boro/

[18] (n.d.). Retrieved from pinimg: https://i.pinimg.com/originals/aa/f1/64/aaf164931e0af5f3fcdabcfbbe8be020.jpg

[19] Japonés antiguo Boro Sashiko ropa de dormir, chaqueta Indigo Kimono, Reversible Meiji Era 1900s Patchwork Yogi, IB20235018N11 noragi haori (2024). Retrieved from Etsy: https://www.etsy.com/es/listing/706689265/japones-antiguo-boro-sashiko-ropa-de?epik=dj0yJnU9NWZudFdySm0tdWhZY3hwVnFwRnFaVVc3QTVLclNmY0smcD0wJm49UExseVdTM3RlRGd4ekNEZUNpT3VsdyZ0PUFBQUFBR1l4a2ow

[20] Sashiko Graph Acrylic Stencil, 1cm spacingSashiko Graph Acrylic Stencil, 1cm spacingSashiko Graph Acrylic Stencil, 1cm spacing Sashiko Graph Acrylic Stencil, 1cm spacing. (2024). Retrieved from A Threaded Needle: https://www.athreadedneedle.com/products/sashiko-graph-acrylic-stencil-1cm-spacing?_ pos=24&_sid=0a60d4247&_ss=r&variant=47964742615316

[21] Sashiko Sampler Textile Lab “Block” . (2024). Retrieved from A Threaded Needle: https://www.athreadedneedle.com/collections/beginner-kits-small-sashiko-projects/products/sashiko-sampler-textile-lab-block

[22] ISSEY MIYAKE PLEATS PLEASE FRAGRANCE GIVEAWAY (2013, October 7). Retrieved from In My Bag: https://www.inmybag.co.za/2013/10/07/

issey-miyake-pleats-please-fragrance-giveaway/

[23] Boston, M. (n.d.). Woman’s blouse. Retrieved from Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/27866091421632074/

[24] Gallery. (2024). Retrieved from Sacresue: https://www.sacresue.com/gallery

[25] (2024). Retrieved from Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/114278909288138647/

[26] Contemporary Smocking Techniques. (2013, November 28). Retrieved from The Cutting Class: https://www.thecuttingclass.com/contemporary-smocking-techniques/

[27] McQuillan, H. (2016). Twinset. Retrieved from Holly Mcquillan: https://hollymcquillan.com/portfolio/twinset/

[28] Bajwa, S. (2023, December 5). The Contradiction of National Clothing. Retrieved from Brown History: https://brownhistory.substack.com/p/the-contradiction-of-national-clothing

[29] Lindqvist, R. (2017). Motive part II: Systems of garment construction. Retrieved from Ataca: https://atacac.com/book/chapter2.php#chapter2-1

[30] Lindqvist, R. (2017). Motive part II: Systems of garment construction. Retrieved from Ataca: https://atacac.com/book/chapter2.php#chapter2-1

[31] Subtraction Pattern Cutting with Julian Roberts. (2013, October 25). Retrieved from The Cutting Class: https://www.thecuttingclass.com/subtraction-pattern-cutting-with-julian-roberts/

[32] Roberts, J. (2013, August). Free Cutting. Retrieved from Free Cutting by Julian Roberts: https://researchonline.rca.ac.uk/3060/1/FREE-CUTTING-Julian-Roberts.pdf

[33] Zhang, C. Y. (2021, March 27). I Made a Thousand Pleats Using a Handmade Pleating Board. Retrieved from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?app=desktop&v=Vtetgj41-A8

[34] The Princess Pleater. (n.d.). Retrieved from Princess Pleaters: https://www.princess-pleaters.co.uk/

[35] Read Pleater 24-Row Maxi pleater: Professional Smocking Made Easy. (2024). Retrieved from Sewing Machine Outlet: https://www.sewingmachineoutlet. com/products/read-24-row-maxi-pleater

[36] alexberkowitz. (2021). Threaded Cord Toggle. Retrieved from Thingiverse: https://www.thingiverse.com/thing:4344834/apps

71 70

72