July 27 – October 30, 2022

Cover art: Meredith Leich, Animated Drawings for a Glacier-Cuttyhunk, 2021, Performance documentation photograph. © Meredith Leich

Cover art: Meredith Leich, Animated Drawings for a Glacier-Cuttyhunk, 2021, Performance documentation photograph. © Meredith Leich

July 27 – October 30, 2022

Cover art: Meredith Leich, Animated Drawings for a Glacier-Cuttyhunk, 2021, Performance documentation photograph. © Meredith Leich

Cover art: Meredith Leich, Animated Drawings for a Glacier-Cuttyhunk, 2021, Performance documentation photograph. © Meredith Leich

Roger Tory Peterson created the first modern field guide. What made it “modern” was its use of art and design to help almost anyone quickly and accurately identify birds.

Today, that might not seem such a big deal. However, at the time Peterson’s A Field Guide to the Birds was published in 1934, birdwatching— or birding—was practically unknown beyond a relative handful of academics and intrepid enthusiasts.

Peterson’s publisher was dubious about the prospects for a field guide for naming birds, especially since the inclusion of artwork increased the cover price to $2.50 per copy—a prohibitively high amount of money to pay during the Great Depression.

Both Peterson and the publisher were surprised, therefore, when the first run of 2,000 copies of the field guide sold out within a week. Three additional printings sold out within the first year. Since then, across a series of updated editions, the Peterson Field Guide to Birds has sold upwards of 15 million copies worldwide.

Today, there are an estimated 70 million birders in the United States alone. Armed with their field guides, generations of birders—doing what they love to do—have collected critically important data about the health of our bird populations. Skilled, informed and passionate

birders have been a reliable force of nature in protecting birds and the habitats upon which they depend for their very existence.

Peterson’s art mattered—and still matters—to the planet.

As the living embodiment of the field guide, The Roger Tory Peterson Institute is committed to nurturing the next generation of nature artists. More than ever, we need art—we need artists— to explore new ways to engage us in the beauty of the natural world, to bring into high relief the environmental challenges we face, and to inspire us to the recovery and redemption of the only world we have.

In fulfillment of this pledge, we are excited to launch Art that Matters to the Planet—our signature annual exhibition for interdisciplinary and cross-disciplinary artists making work at the nexus of art + nature.

In response to our inaugural call for artists, we were thrilled to receive nearly 100 submissions. Equally amazing was the number of artists who cited Peterson as an inspiration for their passion for art and nature. This response suggests that we are just beginning to tap into a wellspring of artists who, like Peterson, are channeling their passion for the natural world through their artistry.

For this inaugural iteration of Art that Matters to the Planet, we selected 15 artists, focusing holistically on their artistic practice. Taking a deeper dive into their influences, inspirations, techniques, research, and processes invites viewers to reflect even more deeply on the relationship between art, society, and nature.

For those of you who weren’t able to experience Art that Matters to the Planet at RTPI, we hope this catalogue entices you to come visit us soon. We host three major nature exhibitions each year, anchored by Art that Matters to the Planet. Each exhibition is enriched with a range of programs, featuring artists and conservationists—often in conversation with each other—taking deep dives into the interrelation between art and nature. We sponsor a number of additional programs, including an annual Plein Air Festival and an Artist-in-Residence program, providing new, emerging and even well-established artists the opportunity to spend a week or more in the company of the largest collection of Roger Tory Peterson’s art, films, photographs and papers.

Enjoy.

Arthur Pearson, CEO Roger Tory Peterson InstituteFor the past fourteen years, artist Suze Woolf has been painting burned forests throughout the American and Canadian West. In discussing her work, she describes walking through a once-familiar forest that had been recently burned, and being simultaneously devastated and riveted. The glistening blacks and blues of charred tree bark captured her attention, offering at once both a unique beauty and a terrible realization that the landscape of the forest had been forever changed.

As neither scientist nor engineer, I am more likely to contribute to changing attitudes than technical solutions. A fundamental shift in perception is much needed: we are not Masters of the Universe nor should we have dominion over our planet. We are only one type of node in an intricately connected, complex web. Many Indigenous societies shared this fundamental belief system, but they did not operate at the population scale we now face. We need new ways to engage with nature. Artwork that provokes attention is one step in the process.

Through her artistic practice, Woolf shares an absolute message about the impact of climate change. Large portraits of individual burned trees—a series entitled Burnscapes (Figure 1)—became her metaphor for the role of climate change in increased wildfires in the Western United States and Canada. Her paintings embody senses of fear, anxiety, and a strange sort of beauty. Working with wildland firefighter and author Lorena Williams, Woolf uses this body of work as an opportunity to talk to people about the climate crisis, the important role of prescribed burns, and the devastating impact of catastrophic large-scale fires.

In discussing her art, Woolf references the idea of the sublime: “I can see a lineage from landscape painters whose subject matter was the sublime—simultaneous

beauty and terror. That is certainly how I feel about climate today. I am in love the joy of the natural world and profoundly anxious about its future.” Woolf’s reference to the sublime is an apt way to think about contemporary nature art practice. As an aesthetic concept first popularized in the 19th century landscape tradition, the sublime in art refers to an overwhelming feeling one experiences when confronted with untamed nature.1 In paintings of the sublime, the intention of the artist is to produce powerful emotions in the viewer—wonder, awe, and perhaps even fear. When we experience such emotions, we consider our lives in relation to something much larger than ourselves. The artists featured in Art that Matters to the Planet compel us to do just that.

Art practice that explores humanity’s place in and relationship with the natural world is often referred to as Environmental Art or Ecological Art (Eco-art), but these terms do not necessarily encompass the range of contemporary nature art practice.2 When considering the artists featured in Art that Matters to the Planet, we find that they engage with nature in different ways, and with different messages. They encourage us to look more closely at nature so that we might better appreciate it. They share knowledge about nature to help us better understand the world around us. They raise awareness

-Suze Woolf, artistabout environmental issues in order to foster dialogue and promote change. The resulting dialogue between the artist and viewer speaks to the intuitive and transformational power of their art.

In the preface to Dr. Sacha Kagan’s seminal text on Ecological Art, Dr. Heike Löschmann, former Head of Department for International Politics for the Heinrich Böll Foundation, discusses the powerful role of art in moving us toward a more sustainable future, stating: “It is the intuitive and transformative power of art that we need to explore and bring to full bloom.”3 This transformative power is apparent in the way that artists are responding to the urgency of environmental issues by using art as activism, promoting sustainability, and encouraging us to rediscover the significance of our relationship with nature. In these ways, artists are using their practice to improve our sensibility to the complex relationships within and between nature and culture. With Art that Matters to the Planet, we hope to draw attention to the importance of art in helping to change attitudes, provoking attention, and encouraging us to engage with nature.

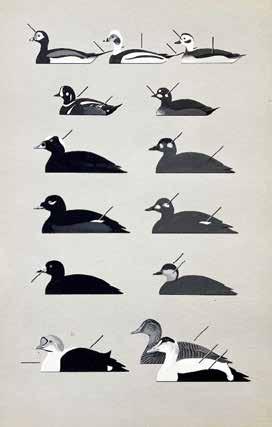

Roger Tory Peterson (1908-1996) devoted his career to art and activism on behalf of the environment. As the creator of the modern field guide—having published A Field Guide to the Birds of Western North America in 1934—he made a significant contribution to the American conservation movement. With his first field guide, he opened up a world of knowledge about the birds to non-experts, ultimately instilling in field guide users a passion for the birds. Beginning with his early field guide illustrations in 1934—depicted with a sophisticated graphic style—and evolving to striking, realistic paintings later in his career (Figure 2), Peterson’s artwork guides us on a journey to discover the beauty and wonder of nature. Throughout his career, Peterson also helped us to understand the impact of human activity on nature. He told us about the threats which birds were facing, warned us about the consequences of inaction, and affected change on behalf of the environment.

In 1954, Peterson moved to Old Lyme, Connecticut. He was drawn to the area due to an Osprey colony nesting around the mouth of the Connecticut River, and a nearby natural area known as Great Island. When Peterson moved to Old Lyme in 1954, the town had 150 nests—something like 600 summertime birds. However, a decade later, only 15 nests remained. Peterson was among the first to identify the pesticide DDT as the culprit and call for its ban. In 1964, Peterson testified

Telegraph Canyon, 2019

Varnished watercolor on torn paper

Winter Rim, 2019

Varnished watercolor on torn paper

Split, 2022

Varnished watercolor on torn paper

© Suze Woolf

Figure 1 Suze Woolf, Seattle, Washington (left to right)before a US Senate Subcommittee, calling for the strict control of DDT. Following his testimony, presiding senator Abraham Ribicoff asked what effect birds have on society. Peterson replied, “I just could not live without birds, frankly. I know that is an emotional statement. I would hate to live in a lifeless world.”

Peterson’ efforts—combined with those of Rachel Carson, author of Silent Spring, and others—resulted in the banning of DDT in the United States in 1972, leading to the slow but steady recovery of many major bird species.

Today, Peterson’s continuing influence as an artist, naturalist, and activist is evident in the artistic practice of contemporary nature artists. With their artistic practice—a combination of the influences, ideas, techniques, research, and processes which inform their art-making and activism—they promote a connection between society and nature in hopes that we are inspired to preserve it for generations to come. Like Peterson, they help us explore, discover, and fall in love with the natural world.

Elizabeth Corr, Director of Art Partnerships with the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC), emphasizes the important role of artist-activists like Peterson in communicating the realities of environmental crises: “One of the really hard things about climate change is that people struggle to imagine it, and imagine what it looks like. Artists and art have the incredible ability to break down that barrier...That allows the public to interact in a very active way, to ask questions, to have emotive responses, to feel. And once they’re feeling, they’ll be more inclined to take action on behalf of the environment.”4 Corr goes on to emphasize the importance of artist-activists in raising awareness and gaining public support for conservation issues, stating that “an artist’s distinct perspective creates new ways to engage the public on the pressing environmental issues we work on.”5

Figure 2

Roger Tory Peterson (1908-1996)

(left to right)

Sea Ducks

Gouache

A Field Guide to the Birds, 1947, plate 12

Parakeets and Small Parrots

Gouache

A Field Guide to Mexican Birds, 1973, plate 14

Gifts of the Peterson estate 2001.51.9.13, 2007.10.2.16

© Estate of the artist

One example of a contemporary artist who is engaging with environmental issues is Jenny Kendler, the founding participant in the NRDC Artist-in-Residence program. Of the NRDC program, Kendler says: “This is exactly where I want to position myself. As an artist embedded in a science-based, advocacy organization.”6 One of Kendler’s most noted works, Milkweed Dispersal Balloon, is an ongoing performance-like piece in which Kendler fills opaque, biodegradable balloons with milkweed and hands them out to communities. She asks those who receive a balloon to pop it in their neighborhood, spreading the seeds which will ultimately support monarch butterfly populations.7 Kendler’s work as an artist-activist can be considered within a variety of frameworks, whether social practice, performance art,

environmental art, ecological art, or a combination. In whichever context we choose to interpret Kendler’s work, her practice exemplifies approaches taken by ecologically concerned artists today, illustrating the powerful role they play in advocating for environmental causes.

Artists and institutions are increasingly recognizing the importance of interdisciplinary ecological art practice. In fact, a number of universities offer degree programs focused on ecological art. For example, the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque offers a program in Art & Ecology, specifically designed for students interested in pursuing ecologically minded art.8 The Nevada Museum of Art in Reno houses the Center for Art + Environment, a focused research library with archive collections from over 1,000 artists and organizations working on all seven continents.9 Since its establishment in 2008, the Center has commissioned several high-profile artworks including Helen and Newton Harrison’s climate change project, Sierra Nevada: An Adaptation (2011); Swiss artist Ugo Rondinone’s Las Vegas public art installation, Seven Magic Mountains (2016); and Trevor Paglen’s nonfunctional satellite sculpture, Orbital Reflector (2018). In the 2019 exhibition, Fragile Earth: The Naturalist Impulse in Contemporary Art, the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme, Connecticut, commissioned artists Jennifer Angus, Mark Dion, Courtney Mattison, and James Prosek to create work that responds to the natural world, demonstrating the persuasive role artists can play in advocating for the preservation of our earth.10

It is with the goal of continuing in this inquiry into the role that artists can play in advocating for the preservation of our earth that The Roger Tory Peterson Institute has inaugurated the annual exhibition of Art that Matters to the Planet. Through the exhibition, we hope to explore the ways in which artists can help to shape a more sustainable future. Artists featured in the exhibition engage with nature in a variety of ways, but all encourage us to reflect on interrelationships between society and nature. To do so, some artists incorporate scientific data and methods into their work. Some use their work to engage with the histories

of land, and tell us about the stories of peoples and cultures. Some make work based on their own personal connection with and inspiration from the natural world, in hopes that we will learn to look more closely. With their work, they investigate a variety of topics, including biodiversity, ecosystems, sense of place, sustainability, environmental activism, and protection of specific species, to name a few.

While each artist has a unique approach to engaging with nature and the viewer, all make their art from an eco-centric worldview. Artists like May Babcock, Katerie Gladdys, Michelle Schwengel-Regala, Jeanne Filler Scott, and Amy Wendland observe connections

Amy Wendland, Durango, Colorado

Supplanted [invasive, non-native], 2019 Colored pencil, Cirsium vulgare (bull thistle) herbarium sample, remounted

© Amy Wendland

Figure 3

Figure 3

between society and nature, revealing for us knowledge and systems which help us to better understand the world around us. For example, in Wendland’s Supplanted [invasive, non-native] (Figure 3), she uses an herbarium sample of the invasive bull thistle as a metaphor for the role of boarding schools in the elimination of American Indian ways of life. The stylistic elements—the black and white image, the stiff posture of the figures, and the mat and frame reminiscent of a cased photograph— indicate the prevalent photographic style of the late 19th century, referencing the timeframe that American Indian boarding schools were first established. By anthropomorphizing the bull thistle, she calls attention to the correlation between invasive, non-native plants and people, asking us to consider the devastating impact of both.

Artists like Margaret Craig, Meredith Leich, Sara Baker Michalak, Anne-Katrin Spiess, Dana Tyrrell, and Suze Woolf use their art to raise awareness about environmental issues, reaching us on an emotional level

in hopes of fostering dialogue and ultimately promoting change. Much of Anne-Katrin Spiess’ work addresses and calls attention to environmental issues. Her current project, Death by Plastic (Figure 4), is a gesture toward drawing attention to the proliferation of single-use plastics. In the summer of 2019, Spiess performed Death by Plastic for the first time in Moab, Utah. Moab is a small community with extraordinary, pristine landscapes. Tourists visit seasonally, but leave behind large quantities of trash. After discovering that only plastics #1 and #2 were being recycled, and everything else was sent to landfills, Spiess conceived of the performance piece. To perform Death by Plastic, Spiess surrounds her body with plastics bound for the landfill and holds a funeral for herself, eliciting a visceral reaction from viewers.

Artists like David Cook, Brandi Long, Michele Heather Pollock, and Ivonne Portillo encourage us to look more closely at nature so that we might better appreciate it. In Portillo’s Corianto (Figure 5), she depicts an abstracted representation of Coryanthes Panamensis, an orchid found in Colombian and Panamanian forests. The Panamanian Coryanthes attracts the Euglossa bee—a green orchid bee native to Central America—with a sweet aroma. Coryanthes’ flowers have a passage exactly designed to fit the Euglossa bee, which receives a package of pollen when crossing it to leave the flower. In Corianto, Portillo anthropomorphizes the flower by adding a figural representation—we notice a woman’s face and body on the right side of the print. She activates the composition with a vibrant yellow background accented by pale pink and green, creating for us a narrative about the Euglossa bee traveling through the passage of the flower to receive the pollen.

Figure 4

Anne-Katrin Spiess, New York, New York

Death by Plastic, 2021

Digital C-Print

© Photography by Stephanie Keith / Project by Anne-Katrin Spiess

For the artists featured in Art that Matters to the Planet, art is a personal source of healing, inspiration, and reflection, but their work also transforms us as viewers. It instills in us a sense of wonder, promotes environmental stewardship, provokes systemic change, and facilitates conversations. Through their art, we can discover how each artist interprets the minutiae and vastness of the natural world, guiding us to discover for ourselves the intrinsic value of nature.

1 The concept of the sublime as a subject matter in art was first introduced by philosopher Edmund Burke in his 1757 treatise. Edmund. A Burke, Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful: With an Introductory Discourse Concerning Taste; and Several Other Additions, Printed for Vernor and Hood, F. and C. Rivington, T.N. Longman, Cadell and Davies, J. Cuthell and 4 others in London, 1798.

2 In using the term “nature art,” we consider work by artists inspired by and making work about the natural world. Many of the artists are aligned with the practice of ecological art, but do not necessarily choose to identify themselves as such. Dr. Sacha Kagan, a leading figure in defining ecological art practice, writes that “The genre of ‘ecological art,’ as originally conceived in the 1990’s on the basis of practices that emerged from the late 1960’s onwards, covers a variety of artistic practices which are nonetheless united, as social-ecological modes of engagement, by shared principles and characteristics such as: connectivity, reconstruction, ecological ethical responsibility, stewardship of inter-relationships and of commons, non-linear (re)generativity, navigation and dynamic balancing across multiple scales, and varying degrees of exploration of the fabric of life’s complexity.”

Sacha Kagan, The Practice of Ecological Art, Institute of Sociology and Cultural Organization, Leuphana University, Lüneburg, 2014.

3 Sacha Kagan, Toward Global (Environ) Mental Change: Transformative Art and Cultures of Sustainability, Berlin: Heinrich Böll Stiftung, 2012, p.7.

Corianto, 2021

Monotype and woodcut on paper

© Ivonne Portillo

4 National Resources Defense Council, “Acclaimed Chicago Artist Jenny Kendler Is NRDC’s First Artist-in-Residence,” NRDC, December 15, 2016, https://www.nrdc.org/media/2014/140604.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Katie Dupere, “How One Activist Combines Impactful Art and Advocacy to Save the Earth,” Mashable, October 29, 2021. https://mashable.com/article/jenny-kendler-ndrc-artist.

8 Art &Ecology is an interdisciplinary, research-based academic program engaging contemporary art practices. Art & Ecology courses encourage students to investigate, question, and expand upon inter-relationships between cultural and ecological systems. “UNM Art & Ecology,” accessed October 3, 2022, https://ae.unm.edu/about/.

9 “The Center for Art + Environment,” Nevada Museum of Art, May 9, 2019. https://www.nevadaart.org/art/the-center/.

10 Jennifer Stettler Parsons, et. al. Fragile Earth: The Naturalist Impulse in Contemporary Art, Old Lyme, CT: Florence Griswold Museum, 2019.

FigureBrown, Kate. “‘Everything We Have, We Lose’: Activist and Artist Jenny Kendler on Climate Grief, and What Artists Can Do for the Planet .” Artnet News, March 11, 2022.

https://news.artnet.com/about/kate-brown-671.

Burke, Edmund. A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful: With an Introductory Discourse Concerning Taste ; and Several Other Additions. Printed for Vernor and Hood, F. and C. Rivington, T.N. Longman, Cadell and Davies, J. Cuthell and 4 others in London, 1798.

Dupere, Katie. “How One Activist Combines Impactful Art and Advocacy to Save the Earth.” Mashable, October 29, 2021. https://mashable.com/article/jenny-kendler-ndrc-artist.

Kagan, Sacha. The Practice of Ecological Art. Institute of Sociology and Cultural Organization. Leuphana University, Lüneburg. 2014.

Kagan, Sacha. Toward Global (Environ) Mental Change: Transformative Art and Cultures of Sustainability. Berlin: Heinrich Böll Stiftung. 2012.

National Resources Defense Council. “Acclaimed Chicago Artist Jenny Kendler Is NRDC’s First Artist-in-Residence.” NRDC, December 15, 2016.

https://www.nrdc.org/ media/ 2014/140604.

Nevada Museum of Art. “The Center for Art + Environment.” Nevada Museum of Art, May 9, 2019.

https://www.nevadaart.org/art/the-center/.

Parsons, Jennifer Stettler, et. al. Fragile Earth: The Naturalist Impulse in Contemporary Art. Old Lyme, CT: Florence Griswold Museum, 2019.

University of New Mexico. “UNM Art & Ecology.” Accessed October 3, 2022.

https://ae.unm.edu/about/.

Wallen, Ruth. “Ecological Art: A Call for Visionary Intervention in a Time of Crisis.” Leonardo 45, no. 3 (2012): 234–42.

May Babcock, Pawtucket, Rhode Island

Sara Baker Michalak, Dunkirk, New York

David Cook, Austin, Texas

Margaret Craig, San Antonio, Texas

Jeanne Filler Scott, Springfield, Kentucky

Katerie Gladdys, Gainesville, Florida

Meredith Leich, Arlington, Massachusetts

Brandi Long, Miami, Florida

Michele Heather Pollock, Columbus, Indiana

Ivonne Portillo, Barcelona, Spain

Michelle Schwengel-Regala, Mililani, Hawai‘i

Anne-Katrin Spiess, New York, New York

Dana Tyrrell, Niagara Falls, New York

Amy Wendland, Durango, Colorado

Suze Woolf, Seattle, Washington

Panel Discussion: Why Art Matters to the Planet

Brandi Long, Margaret Craig, Sara Baker Michalak

July 29, 2022

Art After 5: Sara Baker Michalak

September 14, 2022

Katerie Gladdys: Getting a Lay of the Land (virtual)

October 12, 2022

Michele Heather Pollock: Crafting the Forest Floor

October 29, 2022

“In Rhode Island Herbarium, I engage with the living ocean, and I hope that viewers in turn feel connected with the physicality of the natural world through these seaweeds embedded within handmade paper pulp. Because, it is only through knowing and loving something, can one begin to help something—and our planet needs all the help it can get.”

Place-based artist May Babcock investigates the complex relationship between nature and culture by making paper from plants, which she gathers from specific sites. Babcock begins by identifying places to collect plant fibers, sediment, water, and drawings. She then researches hydrology, plant ecologies, geological history, and human-created structures and histories—all of which inform the message of her work.

In her Rhode Island Herbarium series, seaweeds are embedded into wet paper pulp, showing the detailed texture of each plant. The hand lettering in gilded metal leaf indicates either the Google Maps, common, or Algonquian place names of the seaweed collection site. She includes the different site names in order to express the complex and diverse histories of the landscapes. A foundation of her series is the acknowledgement that all Rhode Island waters and lands were First Peoples territory prior to colonization—Narragansett, Wampanoag, Nehântick, Nipmuc, and Pequot.

May Babcock

Pawtucket, Rhode Island

Rhode Island Herbarium: Green Hill Beach #1, 2019

Artist-made paper, seaweed, gilded metal leaf

Courtesy of the artist

May Babcock

Pawtucket, Rhode Island

Rhode Island Herbarium: Machaquamaganset (Moonstone Beach), 2019

Artist-made paper, seaweed, gilded metal leaf

Courtesy of the artist

Pawtucket, Rhode Island

Rhode Island Herbarium: Namcook (Rome Point) #5, 2019

Artist-made paper, seaweed, gilded metal leaf

Courtesy of the artist

May Babcock

Pawtucket, Rhode Island

Rhode Island Herbarium: Moshassuck #2, 2018

Artist-made paper, pondweed, gilded metal leaf

Courtesy of the artist

Pawtucket, Rhode Island

Rhode Island Herbarium: Potowomut #3, 2019

Artist-made paper, seaweed, gilded metal leaf

Courtesy of the artist

“I believe that my art is about exploring humanity’s place and responsible action in the natural world. I’m hopeful that viewers of my work will reflect on all that the natural world holds, and our critical role in preserving it.”

Sara Baker Michalak’s abstract collaged works evoke dappled light breaking through a forest canopy, illuminating parts of the natural world while leaving other areas in shadow. Her compositions, colors, and forms (and occasional formlessness) suggest the feeling of the unknown. Combining representational imagery with abstract mark making, she speaks to the subjective and incomplete quality of our perceptions. She reminds us that the mysteries of the natural world are perhaps greater than our current understanding.

In her artistic practice, Baker Michalak’s materials and technique are based largely on exploring options for reducing her carbon footprint. She works primarily in collage, recycling and re-purposing materials that may otherwise be discarded. Her works are lightweight, durable, and flexible, which she achieves by layering and adhering papers or thin fabric. Her intent is twofold: to reduce her own carbon footprint, and to encourage conversation regarding how and why we make art.

“My work attempts to instill and nurture a sense of wonder in children of all ages so they can connect more deeply and passionately with the natural world and treasure its gifts. I want the viewers to be touched as I am with the beauty and wonder of nature.”

With dynamic images of birds in flight, photographer David Cook reveals the ballet-like motion of the egret’s wing, the graceful curves of a pelican’s flight, and the elegance of a Sandhill Crane. Cook’s practice is inspired by his training as a Texas Master Naturalist, a passion for the natural world, and by Rachel Carson’s book The Sense of Wonder. Carson describes a sense of wonder “so indestructible that it would last throughout life.” With his photography, Cook hopes that he can inspire others to find and nurture their own sense of wonder.

Cook’s Avian Apparitions series of photographs explores the artistry of birds and flight. By doing so, he captures ghost-like images of the birds. With Avian Apparitions, Cook asks us to consider a future in which only the ghosts of these birds remain in the landscape where they once flourished. A future where we can only imagine the gracefulness of the egret’s flight. Where we can no longer marvel at an Osprey’s hunt, or a warbler’s song. By creating ghostly images of the birds, he hopes to instill in us a greater appreciation for the beauty they add to the world.

“Birds have wings; they’re free; they can fly where they want when they want. They have the kind of mobility many people envy.”

- Roger Tory Peterson David Cook

Austin, Texas

Goose Spirit, 2021

Photograph Courtesy of the artist

David Cook

Austin, Texas

Goose Spirit, 2021

Photograph Courtesy of the artist

David Cook Austin, Texas

Soaring Pelican, 2021

Photograph Courtesy of the artist

David Cook Austin, Texas

Soaring Pelican, 2021

Photograph Courtesy of the artist

David Cook

Austin, Texas

Roseate Spoonbill, 2022

Photograph Courtesy of the artist

David Cook

Austin, Texas

Roseate Spoonbill, 2022

Photograph Courtesy of the artist

David Cook Austin, Texas

(left to right)

Crested Caracara, 2021 Egret, 2021

Photographs

Courtesy of the artist

David Cook Austin, Texas

(left to right)

Crested Caracara, 2021 Egret, 2021

Photographs

Courtesy of the artist

David Cook Austin, Texas

Brown Pelican, 2021

Photograph Courtesy of the artist

David Cook Austin, Texas

Brown Pelican, 2021

Photograph Courtesy of the artist

David Cook

Austin, Texas

White Ibis, 2022

Photograph Courtesy of the artist

David Cook

Austin, Texas

White Ibis, 2022

Photograph Courtesy of the artist

David Cook Austin, Texas

Sandhill Crane, 2021

Photograph Courtesy of the artist

David Cook Austin, Texas

Sandhill Crane, 2021

Photograph Courtesy of the artist

David Cook

Austin, Texas

Blue-winged Teal, 2021

Photograph Courtesy of the artist

David Cook

Austin, Texas

Blue-winged Teal, 2021

Photograph Courtesy of the artist

David Cook Austin, Texas

Great Egret, 2021

Photograph Courtesy of the artist

David Cook Austin, Texas

Great Egret, 2021

Photograph Courtesy of the artist

“My intent is to create work that will engender thought about the relationship between humans and their surroundings. Underlying imagery for me is about other worlds, and the portals between; worlds under the microscope or among the stars, drains, conduits and black holes.”

Margaret Craig’s degree in Biology has been a major influence in the aesthetic and ecological context of her work. With an absolute message about protecting the planet, Craig asks us to contemplate the ways that humans affect the environment. By doing so, she hopes that we will consider what humans of the past have left behind, and how we can create a better future by changing our habits.

Craig’s otherworldly sculptures look like something we might see under the ocean, or under a microscope. Her delicate sculptures and wearable “creatures” are created from repurposed plastic trash. With them, she imagines a future in which aquatic evolutions arise from the plastic trash in the oceans. Her recent work addresses the bleached reef—a leading cause of climate change—with the pale coloration intended to evoke this devastated environment. By creating works made from repurposed plastics, Craig uses the medium as the message: recycle, reuse, and conserve.

Courtesy of the artist

Margaret Craig

San Antonio, Texas

Creature from the Bleached Lagoon, 2022

Performance documentation photograph

Margaret Craig

San Antonio, Texas

Creature from the Bleached Lagoon, 2022

Performance documentation photograph

Cast acrylic etching, repurposed plastic light, mixed media

Courtesy of the artist

Margaret Craig San Antonio, Texas

Murano Critter Alternative Evolution, 2021

Margaret Craig San Antonio, Texas

Murano Critter Alternative Evolution, 2021

Margaret Craig

San Antonio, Texas

Alternative Evolution Creature, 2020

Cast acrylic etching, repurposed plastic light, mixed media

Courtesy of the artist

Performance documentation photographs Courtesy of the artist

San Antonio, Texas

The Albatross, Vegas, 2018

Performance documentation photograph

Courtesy of the artist

Margaret Craig“The monarchs have been on the earth for almost two million years, but human activity is killing them. I hope my art will inspire others to conserve and protect the monarch butterfly, as well as the myriad other species that depend on milkweed.”

In Milkweed Sanctuary, Jeanne Filler Scott depicts a lively scene in which an adult monarch butterfly, a monarch caterpillar, milkweed bugs, a soldier beetle, and a spotted cucumber beetle converge on milkweed plants. She invites us to explore the monarch’s habitat by painting in detail the plants and activity in the foreground, while the background field and trees recede into the distance. Filler Scott utilizes a realistic style reminiscent of Dutch vanitas paintings. In vanitas paintings, Dutch painters incorporated butterflies to remind us of the fleeting nature of life. Filler Scott’s butterfly has a different message, highlighting the need for preserving the monarch and their habitat.

Springfield, Kentucky

Milkweed Sanctuary, 2020

Oil on panel

Courtesy of the artist

Jeanne Filler ScottOf all the world’s butterflies, only the monarch makes a two-way migration as birds do. Unlike other species of butterflies, monarchs cannot survive the cold winters in northern climates. The monarch knows when it is time to travel south for the winter, flying as far as 3,000 miles to reach their winter destination in the forests of central Mexico.

On our land in Kentucky, we have large patches of milkweed growing undisturbed for the monarchs and other creatures that depend on these plants. This includes other species of butterflies and moths, such as the milkweed tussock caterpillar or milkweed tiger moth. The monarchs and other insects that feed on milkweed leaves have evolved to tolerate the sticky white sap, which contains toxic chemicals to deter mammals and most insects from eating them. Other insects that rely on this plant, such as milkweed bugs and red milkweed beetles, use the toxins for defense. However, the flowers of the milkweed plant do not contain toxic chemicals, so bees, flies, and butterflies can safely feed upon the nectar.

Most monarch butterflies live for two to six weeks, but the generation of monarchs that migrates lives for six to nine months. This is because the last generation of the year does not become sexually mature as adults. They can live longer than the other generations because they overwinter in a cool location, which slows their metabolism. The butterflies cluster on trees for the winter, each tree hosting thousands of individual butterflies, which cover the branches and trunks. In the spring, they become mature, mate, and lay eggs as they migrate north, starting the first new generation of the year.

The monarch butterfly population has declined by 90 percent since the 1990s. The causes of the decline include habitat loss from intensive agriculture and urban development, and the use of pesticides and herbicides which kill milkweed, as well as other flowering plants that adult butterflies feed on. Climate change is another factor, as altered weather affects the patterns and timing of migration.

Springfield, Kentucky

Study of monarch caterpillar and adult butterfly, 2020

Pencil on paper

Courtesy of the artist

Jeanne Filler Scott“I endeavor to make art that awakens curiosity: transforming spectators into participants yearning to explore their surrounding environments, perhaps developing individual and collective strategies to connect and co-exist with the world around them.”

Katerie Gladdys creates installations, sculptures, and performance art which examine how we create a sense of place. Her practice is informed by research in geography, environmental studies, forestry, ethnography, agriculture (specifically food systems), and community activism. She sees community as both a resource for the creation of knowledge and scholarship, and an opportunity to engage with and contribute to society. With her installation, Thy Neighbor’s Fruit, Gladdys asks us to consider how nature informs our relationships with places and with each other.

With her practice, Gladdys emphasizes the importance of sharing knowledge about and experiences with nature. As part of her installation for Art that Matters to the Planet, and in partnership with the Jamestown Public Market and Cornell Cooperative Master Preservers, RTPI and Gladdys hosted a jam-making event for volunteers in the Jamestown community. “Jammers” gathered to learn how to preserve blueberries, and to learn about the relationship between food preservation and sustainability. During the jam-making event, members of the Jamestown community contributed to the audio narrative that accompanied her installation.

Gainesville, Florida

Thy Neighbor’s Fruit, 2010-now

Shelves, jars of jam, audio

Courtesy of the artist

Katerie Gladdys and Douglas Barrett in cooperation with and with special thanks to Steve Reagan, Project Leader, Choctaw and Sam D. Hamilton Noxubee NWRs

Red-cockaded Woodpeckers were once considered common throughout the Southern pine ecosystem, which covered approximately 90 million acres before European settlement. The birds inhabited the open pine forests of the southeast from New Jersey, Maryland and Virginia to Florida, west to Texas and north to portions of Oklahoma, Missouri, Tennessee and Kentucky. Many pine forests have all but disappeared due to European settlement, widespread commercial timber harvesting and the naval stores/turpentine industry in the 1800’s. Early to mid-1900 commercial tree farming, further destruction of forests due to urbanization and agriculture contributed to further declines in the RCW population landing them on the endangered species list. Much of the current habitat is also very different in quality from historical pine forests in which RCWs evolved.

The Red-cockaded Woodpecker is very particular about the trees and forests they inhabit. The woodpeckers prefer pine trees aged sixty and over and unlike other woodpecker species build nests in living trees infected with red heart rot. Red heart rot does not kill the pine tree, affecting only the physiologically inactive

heartwood. Additionally, the RCW prefer pine forest that does not have a lot of understory created by immature hardwoods and brush. Both prescribed and naturally occurring fires maintain the southern pine ecosystem keeping the woodlands open for nesting and foraging for food. Today, many southern pine forests are considered timber plantations where trees are planted close together and not subjected to regular burnings resulting in a dense pine/ hardwood forest.

Creating habitat for the Red-cockaded Woodpecker is a priority for the United States federal wildlife refuges in the southeastern US. “Restoring” a mature pine forest to presettlement condition initially involves locating and mapping mature pine species suitable for RCW nesting sites, removing young hardwood trees and brush followed by prescribed burning. Prior to European settlement, Native Americans and natural processes such as fires started by lightning kept these pine ecosystems healthy. The mission of US wildlife refuges is conservation and preservation of wildlife and their ecosystems. Wildlife refuges serve their communities as places of recreation. Presentday communities and stake holders that surround the refuge often use these lands for hunting and recreation as well.

Balancing the missions of conservation and public engagement can often be challenging

Coming Soon…, 2017

Documentation of an intervention at Sam D. Hamilton Noxubee National Wildlife Refuge, Brooksville, MS; mixed media and silkscreen and text pamphlet

Courtesy of the artists

when the community is not informed or educated about the landscape changes even if those changes benefit ecosystem biodiversity. When understory and brush are cleared to make way for Red-cockaded Woodpecker habitat, citizens often are alarmed and a lack of explanation of this process can potentially create conflict between the refuge and communities that they serve.

At Sam D. Noxubee National Wildlife Refuge, loblolly pines form an ecosystem critical to Red-cockaded Woodpecker conservation. The average lifespan of a Loblolly pine is 120-150 years. At Noxubee, many of the pines where the RCW live are approaching the end of their life span necessitating the development of new nesting habitats on land that will need to be cleared of brush and small trees. Noxubee National Wildlife Refuge is a local and regional destination for hunting, hiking and watching wildlife.

In collaboration with refuge personnel, an artist and a designer created the project, Coming Soon…, responding to the need to alert and inform the public about land that potentially will be developed as RCW habitat in a way that inspires curiosity and support for this important process. Initially, the refuge surveys land to determine potential Red-cockaded Woodpecker habitat. Mature Loblolly pine trees whose circumference is greater than the arm span of

an adult, are identified. Literally, if one cannot hug the tree, then the pine is tree is old enough to be a nesting site.

The team then designed a poster of a Redcockaded Woodpecker image scaled three to four times larger than the size of an actual RCW for visual impact on passing vehicles and pedestrians. The posters are printed on cotton paper that is not only durable, but also biodegradable for minimal environmental impact. The woodpecker posters are then affixed to pines that potentially could serve as nesting sites. Aluminum nails which do not damage the trees were used. The resulting installation of posters in the forest is visible from the road and alerts passerby of future changes in the landscape. The artwork reminds the public of the importance of the Red-cockaded Woodpecker as a keystone species in southern pine forests.

“I aim for wonder, imagination, and even humor as means of creating a receptive state in which to consider a frightening future—to create a light in the darkness.”

Meredith Leich is an animator, watercolorist, and installation artist whose work explores cities, place-based histories, and climate change. All of her work responds in some way to the climate crisis, which she approaches through scientific research and visual exploration. Seen here are photographs documenting Leich’s projects Animated Drawings for a Glacier (2018-2021) and At the Currents’ Edge (2022). With both projects, she projects animated drawings onto dark surfaces with the intent of shedding light on the tremendous past and future power of the glacier to shape the world.

In the photographs seen here, we notice the dramatic contrast between the bright lights of the projections and dark backgrounds. While the projected light is the focal point, we can also explore the background scenery. In all cases, the moving water has become softly blurred, while the still elements–including rocks, seaweed, and a thick metal chain–are in sharp focus. This element helps us to consider the passage of time, invoking in our imaginations the long timescale of glacial motion.

Meredith Leich

Arlington, Massachusetts

Animated Drawings for a Glacier-Cuttyhunk, 2021

Performance documentation photograph

Courtesy of the artist

Meredith Leich Arlington, Massachusetts Animated Drawings for a Glacier-Cuttyhunk, 2021 Performance

Meredith Leich

Arlington, Massachusetts

Animated Drawings for a Glacier-Kennicott, 2018

Performance documentation photograph

Courtesy of the artist

Meredith Leich

Arlington, Massachusetts

Animated Drawings for a Glacier - Flow, 2018

Charcoal drawing; artifact of the animation process

Courtesy of the artist

Meredith Leich

Arlington, Massachusetts

At the Currents’ Edge, 2022

Performance documentation photograph

Courtesy of the artist

I created At the Currents’ Edge (2022), a site-specific video projection, for a light festival in the coastal village of Skagaströnd, Iceland. I was inspired by the 2021 scientific observations that the Gulf Stream, which contributes to Iceland’s habitability, is slowing down and could collapse, a change that would drastically shift weather patterns on both sides of the Atlantic. Both frightened and enthralled by these powerful ocean dynamics, I created in response a hybrid watercolor-animation and experimental video collage that echoes the forms of gyres, meanders, eddies, and streams of the ocean’s currents, and I projected the video onto a found brass boat propeller at Skagaströnd’s coast, looking west over the Atlantic.

“I truly believe the one true way to preserve what we call our home is to first re-establish that relationship to nature. My work brings the viewer into an environment where they feel safe, a place where they can be silent and ponder for a time with nature.”

Brandi Long’s practice is inspired by the natural world: its beauty, ragility, and perseverance in the face of obstacles. Through her work, she reminds us that nature can teach us about ourselves. Each piece serves as a metaphor for life, a self-portrait, and a time capsule that preserves the beauty of nature. Her practice is a testament to the spiritual connection that she feels with nature, and through it, invites us to discover for ourselves a similar connection. Long’s fairytale-like sculptures are stories within themselves, revealing layers of detail and complexity as we explore. For example, in Real Happenings, bees gather around honeycomb and dried flowers which sprout from the pages of a book. The moment, frozen in in time, invites us to explore: we notice the delicacy of the bees’ wings, and the gradual deterioration of the flowers. With her sculptures, Long reminds us that life is short and fleeting, and to cherish every moment.

Artist Statement

Brandi Long

Nature is in everything … in the sizzling sun, the boundless sky, in the rolling hills and vast oceans. Nature is what we hear and feel…

Caressing whispers blowing in the wind. Dewdrops lying lovingly on the skin.

Nature is what we know…

Beautiful, fragile, it brings peace and serenity to all.

Nature is a muse

My artistry evokes all that she gives me.

Brandi Long Miami, Florida

Real Happenings, 2022

Embroidery, polymer clay, organic material, found object

Find time for stillness because life changing moments arise in tranquil spaces.

Rebirth, 2022

Embroidery, polymer clay, organic material, found object

Nothing ever leaves us until it has taught us what we need to know.

Brandi Long Miami, Florida

(left to right)

Courtesy of the artist

Brandi Long Miami, Florida

(left to right)

Courtesy of the artist

Miami, Florida

As Above So Below, 2022

Fabric, polymer clay, found object

Twisted and tangled, swaying in the waves. A magical labyrinth with tentacles green. We search for things unseen.

Courtesy of the artist

Miami, Florida

Among the Leaves, 2020

Embroidery, organic material, found object

Sometimes you will never know the value of a moment until it has become a memory.

Courtesy of the artist

“Now I am a nature artist, yes, but I think I am also an environmental artist as well. Everything works together to point out the normally unseen things living their lives around us, to make people look more closely at the natural world, all in an attempt to stir in viewers the same sense of wonder I get when I stumble upon a new mushroom, or find a gloriously green patch of moss after a rain. I believe we will save nature if we love it.”

Since moving to the woods in 2008, Michele Heather Pollock has become increasingly fascinated by the forest ecosystem. For several years, she took long walks in the woods almost daily, in all seasons and weather. She then used what she observed as inspiration for her studio work. In 2018, she developed a rare autoimmune disease called Scleroderma. Because Scleroderma has made it difficult for her to continue walking in the woods, she creates physical souvenirs of her old life in the woods while the memories are still fresh.

Pollock–a self-taught amateur naturalist–makes art as way to explore, discover, observe, and remember the natural world around her. Spending time in the woods became an essential part of her process: walking in the woods, watching things emerge, grow, go to seed, and die back, photographing tiny treasures, and journaling. With her art, she shows us the often-unseen things that live their lives parallel to ours. For example, in Forest Floor, she re-creates mosses, lichen, leaves, and mushrooms, providing us with a glimpse into the biodiversity of the forest.

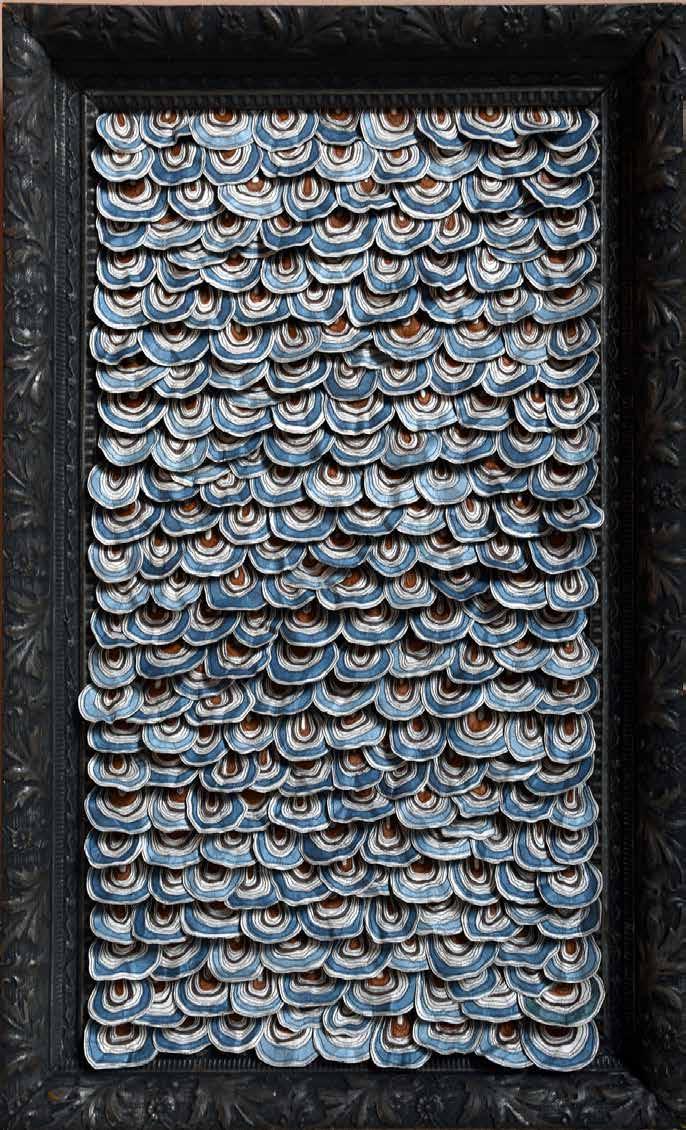

Michele Heather Pollock

Columbus, Indiana

Forest Re-framed #1: Turkey

Tail Mushroom, 2021

Machine quilted paper, hand sewn assembly

Forest Re-framed #1: Turkey

Tail Mushroom is an assemblage of hundreds of machine quilted paper

turkey tail mushrooms. The pieces are hand-sewn together to re-create the way turkey tail mushrooms grow together on logs in nature.

Courtesy of the artist

Michele Heather

Pollock

Columbus, Indiana

To Know This Place, 2022

Machine stitched paper/ fabric, acrylics, hand embroidery

Courtesy of the artist

To Know This Place dives deeply into a sense of the place where I live and work, the woods I love and miss, my new relationship to it, my sense of loss, and the experience of relearning and rediscovery.

The titular piece in the body of work, To Know This Place, is a large accordion-fold book featuring paper/fabric images of various spots along my most frequent woods walk, highlighting specific flora and fauna that I have seen there. Each image is made of machine quilted mono-printed papers, and fabric stained with mud from my woods, plus machine stitched “drawings,” acrylic and watercolor paints, and hand embroidery. I mount each image on a single accordion-fold page that features field notes from my journals typed on an antique typewriter. The piece is part quilt, part artist book, part nature journal, and part field guide.

Michele Heather Pollock

Columbus, Indiana

Forest Floor, 2022

Machine stitched paper/ eco-dyed fabric, hand embroidery

Courtesy of the artist

Forest Floor is an eco-dyed upcycled linen tablecloth which has been machine quilted.

Various forest floor elements are contained within, including hand embroidered mosses, beaded lichen, quilted paper leaves, and paper and fabric sculpture

mushrooms.

Since I can’t go to the woods much now, I’ve begun to ask myself: what it would mean to bring the forest into the studio? Forest Reliquaries are a literal re-framing of nature, a re-contextualization into man-made vessels. Think terrariums. Think museum specimens. I’ve been collecting antique boxes, canning jars, bell jars, old books, damaged frames. From my years of woods-walking I have thousands of photos of the tiny things I found. Now I’m using machine quilting, hand embroidery, beading, and new paper and fabric sculpture techniques to re-create tiny bits of the forest in my studio. Collected and displayed together, they comprise a cabinet of curiosities honoring my love of the forest floor.

Michele Heather Pollock

Columbus, Indiana

Forest Reliquary #1, 2021

Machine quilted, hand embroidery, beading, sculpture.

Akin to a terrarium or something found in a Cabinet of Curiosities, Forest Reliquary #1 captures tiny handmade paper mushrooms and hand-embroidered moss in an antique glass jar.

Courtesy of the artist

Columbus, Indiana

Forest Reliquary #2, 2021

Machine quilted paper, hand embroidery.

An antique tin box holds a tiny treasure: machine quilted paper mushrooms and hand embroidered moss.

Courtesy of the artist

Michele Heather Pollock

Michele Heather Pollock

Columbus, Indiana

Forest Reliquary #3, 2021

Machine quilted paper, hand sewn assembly.

Housed in an antique cigar box, Forest Reliquary #3 holds a colony of machine quilted paper Turkey Tail mushrooms.

Courtesy of the artist

Michele Heather Pollock

Michele Heather Pollock

Michele Heather Pollock

Columbus, Indiana

Forest Reliquary #4, 2021

Machine quilted paper, hand embroidery, beading, sculpture.

Housed in an antique tin box, Forest Reliquary #4 holds tiny paper mushrooms, handembroidered and beaded moss, and quilted paper leaves.

Courtesy of the artist

Columbus, Indiana

Forest Reliquary #7, 2021

Machine quilted paper, hand embroidery, beading, sculpture.

An old wooden box that once contained port wine now holds a small part of the forest floor, including a recycled cardboard tree stump, quilted paper leaves and ferns, paper mushrooms, and hand-embroidered and beaded moss.

Courtesy of the artist

Michele Heather Pollock

Michele Heather Pollock

Columbus, Indiana

Every Leaf on Every Tree, 2022

Eco-dyed wool felt, hand quilting, hand embroidery

In my woods, I have counted at least 27 different species of native trees. As homage to these trees, and the importance of them in my life personally and in the life of the local ecosystem, I have re-created a single leaf from each of these trees. I collected leaves from each tree and made acrylic prints. These prints were used to make patterns from which I cut the leaves from used coffee filters dyed with watercolors. I hand-embroidered the vein structures into the paper leaves with cotton thread. Every Leaf on Every Tree showcases these biologically accurate embroidered leaves against a piece of handquilted wool felt eco-dyed with leaves from these same trees.

Courtesy of the artist

Michele Heather Pollock“Since time immemorial, indigenous peoples have known how to leave a respectful trace.”

Barcelona-based Colombian artist Ivonne Portillo’s art celebrates the diversity of the peoples and landscapes of Latin America. With abstract representations of landscapes and nature, she emphasizes the historical memory of indigenous peoples, many of whom structure their worldview around reciprocal relationships between humans and nature.

Portillo’s woodcut prints transform the shapes of the earth and its textures into carved and engraved topographies. Forests, mountain ranges, and bodies of water are distilled to line and color, with intersections, adjacencies, and layering reflecting their natural counterparts. Her prints represent diverse landscapes, much like the Latin American lands which shelter 60 percent of the planet’s biodiversity.

In Portillo’s woodcut prints, the materials speak of the interdependent relationship between nature and society. Paper and burlap–plant fiber materials used by humanity for millennia–represent the basic and essential. The metallic colors represent the mineral richness of the earth: precious metals that were transformed by the indigenous goldsmiths of these territories. The art of wood engraving integrates these two materials, creating a unique imprint in each work and leaving a trace on the essence of the earth, just like people do when they inhabit a landscape.

Ivonne PortilloBarcelona, Spain

Achikanain, 2020

Woodcut and collage on burlap

Achikanain means “footprint” or “trace” in Wayuunaiki, the language of the indigenous Wayuu people who inhabit the northern tip of South America. This woodcut prints a trace representative of a diverse landscape, much like the Latin American lands which shelter 60 percent of the planet’s biodiversity.

Courtesy of the artist

Ivonne Portillo

Barcelona, Spain

Madre Blanca, 2020

Woodcut and collage on paper

“Patagonia is called the White Mother by her children,” wrote the Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral in her verses to the remote land. The White Mother sees 47 great glaciers grow on her ice of the Austral Andes, including Perito Moreno, the ever-moving colossal frigid glacier.

Courtesy of the artist

Barcelona, Spain

Woodcut on paper

In the mid-nineteenth century, Colombia had 139 square miles of glaciers at the summit of its mountains. Today, there are only 14 square miles. In less than two centuries, the country has lost 90 percent of its glacier areas In the second half of this century, the six glaciers that are left will disappear, including Cocuy.

Courtesy of the artist

Ivonne Portillo

Barcelona, Spain

Cattleya aurea, 2021

Woodcut and digital on paper

From Costa Rica to Argentina, the genus Cattleya paints the forests of Latin America with color. Cattleya aurea is the only yellow species with red “lips”–petals that function as a color guide for their pollinators. This species grows on treetops in the lowland forests of Colombia.

Courtesy of the artist

Ivonne Portillo

Barcelona, Spain

Acacallis, 2021

Watercolor and woodcut on paper

This piece is named after an orchid from the amazon: Acacallis cyanea. Orchids possess an important ecological role since they provide food for pollinators and contribute to the nutrient and water cycles of ecosystems. Deforestation, glyphosate spraying, and unrelenting harvesting threatens them.

Courtesy of the artist

Barcelona, Spain

Corianto, 2021

Monotype and woodcut on paper

Coryanthes panamensis, an orchid found in Colombian and Panamanian forests, attracts the Euglossa bee–a green orchid bee native to Central America–with a sweet aroma.

Coryanthes’ flowers have a passage exactly designed to fit the Euglossa bee, which receives a package of pollen when crossing it to leave the flower.

Courtesy of the artist

Ivonne Portillo“My wish: For people to look more closely at and care for nature.”

As a kid growing up in Wisconsin, my favorite books were field guides. Their combination of words and images helped me make sense of the world, and inspired me to learn more about the natural history of my home range as well as any place I visited. During college, I chose degree programs in Entomology and Wildlife Ecology, and often drew my subjects as a learning tool. A professor saw my drawings and offered me a job as a scientific illustrator in his taxonomy lab, setting me on a path to not just become a scientist, but to also be a science communicator. After fifteen years illustrating biology and medicine, I shifted into fine art, still keeping natural history stories at the core of my projects.

In 2017, I participated in the National Science Foundation’s Antarctic Artists & Writers Program, which afforded me seven weeks at McMurdo Station, Antarctica. My project proposal was to SCUBA dive to explore the marine ecosystem, draw while underwater, then return to the studio to create artwork to connect people to this remote and extreme environment. My underwater field sketching–in a dry-suit, with three pairs of gloves, in 28-degree water, under seven feet of solid sea ice–was definitely the most extreme length I’ve gone to for SciArt, but also the most rewarding. The resultant artwork included a series of paper flags with metalpoint drawings serving as a “field guide to the super cool inhabitants of this supercooled habitat.”

- Michelle Schwengel-RegalaThe sculptures and drawings in Frozen, Floating offer windows into Michelle Schwengel-Regala’s expedition to McMurdo Station, Antarctica with the National Science Foundation’s Antarctic Artists & Writers Program (NSF Award #1645127). These installations were originally created while Schwengel-Regala participated in the 2018 fishcake x Box Jelly Artist in Residence program in Honolulu, Hawai‘i

This knitted aluminum wire sculpture is a scale model of the portal in the sea ice Michelle traveled through to enter and exit the marine realm. At the beginning of each dive season, heavy equipmentoutfitted with a four-foot auger excavates a hole through seven feet of fast ice at each dive site. The holes are then surrounded by a shack to shelter divers and attendants from the outside elements.

Humans are not adapted to living underwater. With a history of asthma, Schwengel-Regala was unsure how her lungs would react to being submerged in such cold conditions. During her 33 dives she had to suspend her fears and push her limits. These knitted bubbles represent her breaths, her vital signs, her sighs of relief. The rising bubbles indicated which way was up, toward the lone hole in the ice through which she could return to the surface, to the land, to the realm of humans.

Description

Michelle Schwengel-Regala

Mililani, Hawai‘i

Flags

Flags serve as means of communication. In and around McMurdo Station, swatches of fabric attached to bamboo poles convey crucial information: red or green flags trace safe paths across land or sea ice, blue flags highlight subnivean features (i.e. fuel lines), and black flags warn of danger. The durable bamboo poles became the equivalent of trees in this otherwise plantless landscape.

In nature, red is often interpreted as an aposematic alert; in Antarctica it has more positive connotations, requiring that Michelle recalibrate her associations with the color. During one snowmobile outing across sea ice, conditions deteriorated to the point that the horizon was obscured by blowing snow, no geographical landforms could be seen, and the red flags at regular intervals were the only form of reference for wayfinding. There even came a point with such limited visibility that only the closest flag could be made out through the white-out conditions. Without that red beacon, would they have found their way back to safety?

Mililani,

These works on paper offer glimpses of a few ice and life forms Schwengel-Regala experienced in the underwater realm, again using the flag format to convey information. With admiration for the metalpoint drawings of da Vinci and Durer, Schwengel-Regala has brought this technique into her modern repertoire but in a unique combination—using the same waterproof paper she used as a field biologist. The metals used for these drawings are silver, copper, aluminum, and gold. Lines made with the first two will experience a subtle color shift over time, a natural result of exposure to the atmosphere.

Drawings are grouped by their respective dive locations. Each site had a unique complement of creatures and ice formations.

Courtesy of the artist

Metalpoint drawings on white flags

Arrival Heights (18k gold)

- anchor ice - in shallow depths, supercooled water forms crystalline plates on the substrate and around this bush sponge (Homaxinella balfourensis)

Little Razorback (copper)

- close-up texture of nudibranch (Bathyberthella antarctica)

- polychaete worm (Flabegraviera mundata) Turtle Rock (aluminum)

- close-up of crinoid (Promachocrinus kerguelensis)

- brinicles - formed on the bottom of the ice ceiling when supercooled fresh water seeps into the salt water and freezes

- close-up of pores in green sponge (Latrunculia biformis)

Intake Jetty (silver)

- dragonfish eggs (Gymnodraco acuticeps)

- pteropod mollusk (Clione antarctica)

- close-up of oral arms of jelly (Diplulmaris antarctica)

- narcomedusa jelly - (Solmundella bitentaculata)

Checkered flags help divers orient to the overhead ice hole.

Blank flags hold space for the Antarctic discoveries yet to be found.

Michelle Schwengel-Regala

Mililani, Hawai’i

Displayed together: Red Flag Installation White Flag Installation

Courtesy of the artist

“I firmly believe that if enough of us implement slight but substantial shifts in consumption habits, and stop using products whose harvesting or production causes environmental problems, we can have a significant impact on the health of the planet.”

Conceptual land artist Anne-Katrin Spiess is interested in spaces–both physical and psychological–and how the two relate to one another. In her artistic practice, she creates site-specific projects in remote landscapes. Her projects exist only for a few hours or days at a time before they are disassembled and the landscape returned to its original condition. Many of the materials that she uses are collected or borrowed from nature and then later left to return to their natural cycles. She carefully introduces man- or machine-made materials as subtle reminders of human civilization. Because of her close connection with nature and land, and because of the deep sense of responsibility she feels towards the planet, much of her work addresses and calls attention to environmental issues. One such work is her performance piece, Death by Plastic, seen here.

New York, New York

Death by Plastic (Funeral Procession), New York City, 2021

Digital C-Print

Photography by Stephanie

Keith / Project by AnneKatrin Spiess

Courtesy of the artist

My ongoing environmental concerns led me to address single-use plastic pollution. For decades, prosperous nations sent their plastics to China. China’s recent refusal to accept these materials is a wake-up call for all countries faced with a glut of plastics and a lack of infrastructure to process them. We need to make a significant paradigm shift and be willing to change our habits–as consumers, as product and packaging designers, and as corporations. My current project, Death by Plastic, is a gesture toward drawing attention to the proliferation of single-use plastics.

In the summer of 2019, I performed Death by Plastic for the first time in Moab, Utah. Moab is a small community with extraordinary, pristine landscapes. Tourists visit seasonally, but leave behind large quantities of refuse. I had been creating art in the area for twenty years when I discovered that only plastics #1 and #2 were being recycled and everything else was sent to landfills. I felt like I had been hit by lightning. After a sleepless night, I decided to build a clear casket where my body would lay covered by plastics #3, #4, #5, #6 and #7, which were no longer being recycled. The work was photographed on the Moab landfill, where the plastics would eventually end up.

In November of the same year, my body rested in the casket–filled with fishing nets and single-use plastics–as a gondola carried it silently across the canals of Venice, Italy. Venice is facing similar issues to Moab, but on a larger scale. Thousands of tourists visit the city daily, leaving behind tons of waste–much of which is single-use plastic bottles. In July of 2021, I performed Death by Plastic in my hometown of New York City as a funeral procession down Fifth Avenue.

New York, New York

Death by Plastic (Funeral Procession), New York City, 2021

Digital C-Print

Photography by Stephanie

Keith / Project by AnneKatrin Spiess

Courtesy of the artist

We are gathered here to mourn the state of the planet, our home, a place where climate change is causing torrential rains and scorching fires.

Have you noticed?

We are here to mourn oceans and rivers filled with plastics and debris.

We are here to mourn beaches which are no longer pristine. We are here to mourn the fish who are feeding off microplastics rather than plankton.

We are here to mourn the whales who are dying with their bellies full of plastic.

We stand here in the realization that we each ingest a credit card worth of plastic every week through the foods and drinks we consume, and that those microplastics may end up in human placenta and sperm.The very essence of human life is in jeopardy.

Unless we come up with alternate solutions to single-use plastics, the very composition of our bodies will be irreversibly changed and the planet we live on will be so toxic and polluted that life as we know it will no longer be possible. Please join me in the procession.

New York, New York

Death by Plastic (Funeral Procession), New York City, 2021

Digital C-Print

Photography by Stephanie

Keith / Project by AnneKatrin Spiess

Courtesy of the artist

Interdisciplinary artist Dana Tyrrell utilizes repurposed and reclaimed elements in his works on paper, sculpture, installations, and paintings. He does so as an individual gesture toward reducing the excess of commercially available art-making materials, as well as a reaction against the wider commodification of art. For his installation, Erosions, Tyrrell incorporates postcards of Niagara Falls, painted over with white RustOleum. His intent in doing so is to draw attention to the Love Canal toxic waste disaster from the late twentieth-century.

Love Canal–a residential neighborhood in Niagara Falls, New York–was originally the site of an abandoned canal that became a dumping ground for chemical waste in the 1940s and ’50s. Tyrrell, a lifelong resident of Niagara Falls, has family who lived in Love Canal until it was deemed too toxic in the 1970s. With Erosions, Tyrrell juxtaposes the environmental tragedy of Love Canal with the nearby tourist destination of Niagara Falls by painting over postcards of the latter. The result is a disruption of the intended viewing of the picturesque postcard, asking us to consider the prioritization of economic growth over environmental and community health.

Dana Tyrrell

Niagara Falls, New York

Erosions, 2021

Acrylic and Rust-Oleum gloss enamel paint on postcards

Courtesy of the artist

“I seek to humanize the natural world, and naturalize humans. I wish to remind the viewer to respect the earth, walk lightly, thank the universe for wonders known and unknown.”

Amy Wendland’s practice is inspired by plants. Through them, she creates a narrative about the intersection of humans and the natural world. Each of us may experience and perceive plants in different ways, whether through culturally applied meaning, symbolism, or scientific understanding. Her artworks address the various ways in which we give meaning to plants, investigating both the scientific and social aspects of nature.

In her works, Wendland uses herbarium samples which were deaccessioned from Fort Lewis College in Durango, Colorado. She includes both plants and their labels, telling us where and when the plant was collected, as well as who collected it. For example, she adheres a narrowleaf cottonwood branch from 1968 to her paper, drawing fresh leaves, catkins, and bark found in the same area which the branch was originally collected.

While conducting field work for her botany series, Wendland became acutely aware of the surroundings where she found plants. For scientific accuracy, she records soil and rock types, companion plants, exposure and altitude. And she always finds trash. From the side of Old Highway 3 in Durango, Colorado to the high valleys of the Tien Shan mountains in Uzbekistan. Where she finds plants, she also finds evidence of human disregard.

Durango, Colorado

1959 Burn examines wildfire ecology. In the original work, the Spineless horse brush herbarium sample was collected from the 1959 Morefield fire burn area. Intact forest duff was rendered in paint and pencil, while the plant was drawn by burning the paper, illustrating the cycle of growth, catastrophic change, and renewal.

Courtesy of the artist

Amy Wendland

Durango, Colorado

Supplanted [invasive, non-native], 2019

Digital print

Botanical manifest destiny. The herbarium sample in the original work was obtained from a former American Indian boarding school, now Fort Lewis College. Introduced to eastern North America during the colonial era, bull thistle migrated westward in the 1800s.

Cirsium vulgare’s vigorous adaptability pushed native plants to near extinction.

Courtesy of the artist

Amy Wendland

Durango, Colorado

Populus angustifolia, Redux, 2020

Populus angustifolia

herbarium sample, colored pencil

This narrowleaf cottonwood branch was cut from a tree in 1968. Fifty-two years later, fresh leaves, catkins and bark were collected from the same area. Rendered from observation directly on the surface of the sample, the drawings are a resurrection, a redux of life and color to the ancestor tree.

Courtesy of the artist

Amy Wendland

Durango, Colorado

Roadside: Penstemon barbatus and Found Glass, 2022

Watercolor, colored pencil, found glass

Roadside perennials: beautiful plants and discarded trash. I found this dormant Penstemon barbatus on a frosty February morning, State Highway 3, Durango, Colorado. Below was a broken bottle. Looking closely, I saw it read: design pat. Feb. 16th, 1885. The plant is perennial, the trash eternal.

Courtesy of the artist

Amy WendlandI began collecting the debris I found, dutifully recording location and date like some sort of obscene category/ line on an herbarium label. This spring I completed the first piece in this “trashed” series: Roadside - Penstemon barbatus and Found Glass.

I found the dormant Penstemon barbatus on a frosty February morning. Below was a broken bottle. Looking closely, I saw it read: “design pat.’d Feb. 16th, 1885.” I lovingly rendered the penstemon and mounted the trash below. Later that July, heavy rains washed the hillside away and the plant was gone. But the glass remained.

(bottom)

A photograph of Paeonia intermedia, found high on a snowy mountainside in Uzbekistan. Next to it was a lid, cut free from a can with a knife. Translated, the Cyrillic text reads “Russian Army Super Food.”

Courtesy of the artist

“As neither scientist nor engineer, I am more likely to contribute to changing attitudes than technical solutions. We need new ways to engage with nature. Artwork that provokes attention is one step in the process.”

While Suze Woolf’s paintings of burned trees and artist books from beetle-killed trees look very different, they are inspired by the same theme: the impact of climate change on the natural world. Woolf’s paintings capture the char patterns on trees found in burned forests throughout the American and Canadian West. In this body of work, Woolf draws our attention to the role of the warming planet in the frequency of catastrophic fires in the West.

Woolf’s artist books made from beetle-killed trees accentuate the hieroglyphic “scribing” of bark beetles. By doing so, she likens the marks to a script that we cannot read. Woolf crafts her books to contrast the rough and delicate textures of the materials, while also informing us about the processes that created them. The works serve as a meditation on the beauty of the natural world, as well as an opportunity for us to learn about the effects of certain bark beetle species on Western forests.

Suze Woolf

Seattle, Washington

Winter Rim, 2019

Varnished watercolor on torn paper

A burned tree from the Fremont National Forest on Winter Rim, above Playa

Summer Lake in south central Oregon.

Courtesy of the artist

Suze Woolf

Seattle, Washington

Telegraph Canyon, 2019

Varnished watercolor on torn paper

A burned tree totem that shows both char and bark beetle galleries from Zion National Park in Utah.

Courtesy of the artist

Suze Woolf

Seattle, Washington

Split, 2022

Varnished watercolor on torn paper

I saw this tree on Carleton Ridge south of Missoula, Montana. Exposed to high winds blowing sandy soil near the top of the ridge, its surface was like a smoothed stone sculpture.

Courtesy of the artist

Suze Woolf

Seattle, Washington

Bark Beetle Book XXV: Outbreak, 2019

Log, handmade Japanese paper (Unruyu kozo; chiri); iron-oxide dyed non-woven viscose; nylon thread

Chiri means “leftover” in Japanese, referring to small bits of bark leftover in the paper. The red circular areas are rubbings representing beetle kill in the Quesnel Timber Supply Area of British Columbia between 19992016.

Courtesy of the artist

Bark Beetle Book XI: Teanaway Log, 2017

Fir-engraver-inscribed wood; wire-edge bound with linen thread; magnets

Bark Beetle Book XXXV: Base Pairs, 2020

Branch with bark beetle galleries, offset printed pages of handmade and commercial papers, iron-oxide dyed felt, clasp