The Editor of Caravanserai is always happy to receive articles and high quality images for possible inclusion in future issues of the magazine

We welcome all contributions, but cannot guarantee to include all that we receive If you would like to submit a contribution please contact the editor at caravanserai@rsaa org uk

From the CEO

Michael Ryder

Female Leaders in Asia

The Stateless Diplomat

Mimi Malayan

Freedom on the Frontlines: Afghan Women’s Fight for Liberation

Dr Lina AbiRafeh

Remembering Ishimure Michiko

Professor Karen L Thornber

Dara Rasami: Bridge Between Two Kingdoms

Dr Leslie Castro-Woodhouse

Kim Yo Jong: The World’s First Nuclear Despotess

Sung-Yoon Lee

Gulaisha and the Women of Karakalpakstan

Annie Liddell

Louder Than Hearts: A Photo Diary

Rania Matar et al.

Did you know?

Chikai Mukai

Recent Lectures & The Reading Room

MICHAEL RYDER

International Women’s Day 2025 was on 8 March, as this issue of Caravanserai was being made ready, and Women in Asia is our theme Diversity is currently coming under attack in unexpected places, so it is particularly worth reflecting on how significant the contributions of women to Asia and to Asian studies have been

It would be impossible to do justice here to any single one of the twenty-six remarkable women in our “Female Leaders of Asia” article Instead, we have included links (for those reading this online) to additional material on each of them, so that you can explore their ground-breaking stories in more detail if you wish Similarly in “Women and the RSAA”, we have had to focus on just two of the many women who, particularly in the Society’s earlier years, took on extraordinary challenges for which they were subsequently recognised through the Society’s awards of the Lawrence and Sykes medals

A lot has happened at the RSAA since our last issue. At the beginning of February 2025, we took over the Asian Review of Books (ARB), an online platform that has been a unique contributor to the promotion of publications from and about Asia for more than twenty-five years Its daily reviews and weekly podcasts are a huge addition to the RSAA’s publications and reach. Covering the whole of Asia as it does, you will constantly find new things of interest in the ARB I hope that you enjoy this new element in the RSAA’s output David Chaffetz, a long-standing member of, and recent speaker to, the RSAA has contributed a short introduction to the ARB and its Editor, Peter Gordon, on page 50

We are thrilled to bring our long-awaited online eLibrary to members Hosted on the same “Libby” platform that supports many public and institutional libraries’ digital collections, the RSAA’s new library offers books covering a wider range of topics across Asia The collection will grow steadily as usage suggests and funding permits. If you have not tried it yet, please do.

I am sure that you will find something there that interests you Access is exclusively for RSAA members. The eLibrary includes fiction as well as non-fiction and we will be paying particular attention to books by speakers at our lectures and those reviewed in Asian Affairs or the Asian Review of Books.

Since the emergence of modern states in Asia, mostly during the first half of the twentieth century, there have been twenty-six non-hereditary female heads of state or government in the continent. Many have been icons around the world as well as trailblazers in their own countries Some came from from poor backgrounds, while others came from powerful political dynasties, and while many have had major impacts, some have also been tainted by corruption and scandal

Recognised as the first non-hereditary female head of state in the world, Khertek Anchimaa-Toka served as the Chair of the Presidium of the Little Khural of the Tuvan People’s Republic between 1940-44 She played a leading role in mobilising the resources and manpower of the republic to assist the Soviet Union in defending against German invasion. Following in the footsteps of Toka, Sükhbaataryn Yanjmaa became the first and, to date, only female head of state in Mongolia on an interim basis when she became Chairwoman of the Presidium of the State Great Khural in 1953.

Unlike the Tuvan People’s Republic and Mongolia, Sri Lanka and Thailand have both seen political dynasties dominated by powerful and influential female leaders. In Sri Lanka, Sirimavo Bandaranaike became the world’s first female prime minister as the leader of the, then, Dominion of Ceylon. A Sinhalese nationalist, Bandaranaike, oversaw the drafting of a new constitution which led to the formation of independent Sri Lanka She served three terms as prime minister, once under the presidency of her daughter Chandrika Kumaratunga, a controversial leader in her own right who spent eleven years in the presidency In Thailand, following in the footsteps of her brother, Yingluck Shinawatra became the first female prime minister of the country in 2011. Despite progressive steps by her government, her time in office ultimately ended in her removal by a coup d'état. Despite the controversies surrounding the Shinawatra dynasty, Yingluck’s niece, Paetongtarn Shinawatra, came to power in 2024 as Thailand’s youngest, and its second female, prime minister.

Two of Asia’s female leaders earned the moniker “Iron Lady” Golda Meir and Indira Gandhi became the first female prime ministers of Israel and India, respectively. Both were known for their uncompromising political stances and divisive actions whilst in office and for their roles during times of crisis. In Meir’s case, she was seen as responsible for Israel’s lack of preparedness for the Yom Kippur War of 1973, while Gandhi lead conflicts against both China and Pakistan and instituted a now much-criticised state of emergency in response to Sikh separatism

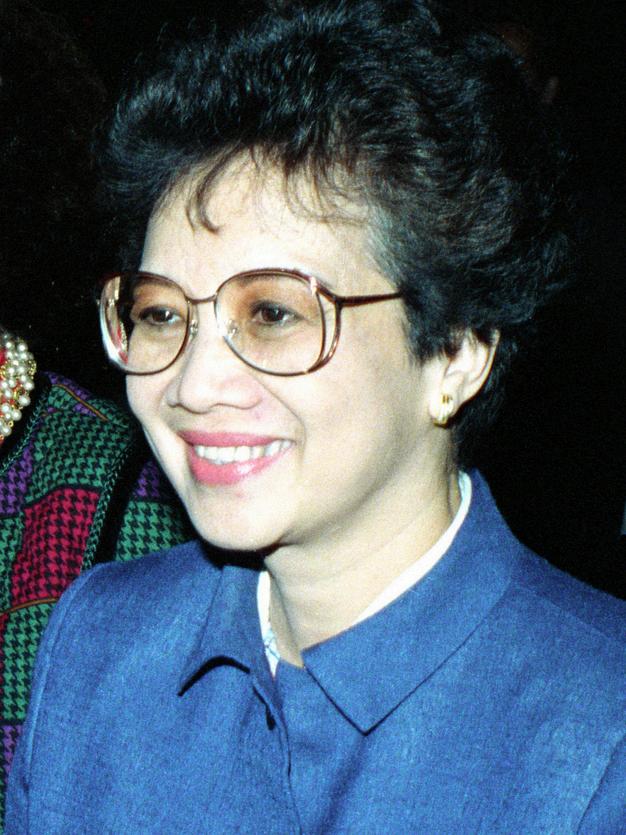

India, Bangladesh and the Philippines have all had multiple female leaders. India has seen Pratibha Patil and Droupadi Murmu step into the largely ceremonial role of president while Bangladesh has seen two long serving and consequential female prime ministers. Khaleda Zia served tens years as prime minister introducing radical political and economic reforms in her first term but overseeing a downward spiral into political crisis in her second term. Unusually, after each of her terms Zia was closely followed by Sheikh Hasina who spent two-decades in office overseeing the transformation of Bangladesh into an authoritarian state resulting in Hasina’s removal from office by a mass prodemocracy movement in the summer of last year The Philippines has also seen two consequential female political leaders in Corazon Aquino, who led the 1986 People Power Revolution which ended the two-decade rule of Ferdinand Marcos, and Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, who spent a tumultuous nine years in office marred by corruption and electoral fraud allegations.

Benazir Bhutto and Megawati Sukarnoputri both made history in the Muslim world when Bhutto became the first woman elected to head a democratic government in a Muslim-majority country (Pakistan) and Sukarnoputri became the first and, to date, only female president of a Muslimmajority country (Indonesia)

Relatively little known, Soong Ching-ling, the wife of Sun Yat-sen, was a leading figure in the Chinese government after 1949. Following the purge of President Liu Shaoqi in 1968, she and Dong Biwu, as vice presidents, became de facto heads of state in China until 1972 She survived the Cultural Revolution and in 1981, just weeks before her death, became the only female leader of the PRC when she was named Honorary President Remaining in East Asia, Carrie Lam (Hong Kong), Tsai Ing-wen (Taiwan) and Park Guen-hye (South Korea) all became the first female leaders of their respective governments within four years of each other (2013-17) Lam was a controversial figure favoured by Beijing to lead Hong Kong and oversaw the introduction of the National Security Law in 2020 Park was a change-making president restructuring government, improving North-South Korean relations and improving trade, but her reputation was destroyed when she was impeached and arrested on charges of abuse of power, bribery and leaking government secrets Sentenced to twenty-five years in prison Park was later pardoned by her successor Moon Jae-In. Tsai’s presidency, on the other hand, was largely seen as one of stability and progress

Tansu Çiller (Prime Minister of Türkiye) and Roza Otunbayeva (President of Kyrgyzstan) were both short-lived female leaders remembered for overseeing bloody periods in their countries histories in which acts by their respective security forces are believed by many to amount to crimes against humanity Three more recent presidents have left far more positive legacies in their countries; Halimah Yacob (Singapore), Bidya Devi Bhandari (Nepal) and Salome Zourabichvilli (Georgia) have all been strong advocates for women ’ s rights, prominent national leaders during the COVID-19 pandemic and, in the case of Zourabichvilli, a strong advocate for democracy and free and fair elections

Finally, perhaps one of the most famous female leaders in Asia was Aung San Suu Kyi who came to prominence during a series of pro-democracy protests in Myanmar which delivered her National League for Democracy a landslide victory in 1990 The military refused to hand over power and placed her under house arrest where she stayed for almost 15 years, making her one of the world’s most prominent political prisoners and advocates for democracy In 2012, her party won another landslide victory, and she became the State Counsellor of Myanmar (head of government). Her government drew criticism for its inaction over the Rohingya genocide in Rakhine State and, in 2019, Aung San Suu Kyi appeared at the International Court of Justice to defend the actions of the Myanmar military against the Rohingya In 2020, she was arrested again after a coup d’état that returned the military to power.

by Mimi Malayan

The one thing most people think they know about Diana Agabeg Apcar is that she was “the first female diplomat”, and yet that statement is incorrect Her accomplishments are enormous and extremely impressive; however, her appointment as Honorary Consul to Japan from Armenia in 1920 was never recognised by the Japanese government, denying her the official title. Despite that, for over a decade, before and after her appointment, she worked tirelessly on behalf of the Armenian people, rescuing around 2000 refugees escaping genocide who intended to emigrate to the United States She also wrote ten books, around 100 articles and hundreds of letters to peace activists, humanitarian organisations, religious leaders, politicians and individuals, whom she believed might influence political action in support of persecuted Armenians under Ottoman rule

Born in 1859 in Rangoon, Burma (now Yangon, Myanmar), Diana lived most of her early years within the Armenian diaspora of Calcutta (Kolkata) She attended convent school during her early years but her father’s death when she was just fourteen and other financial troubles, meant that much of her education was self-taught After her mother’s death, when Diana was twenty-two, she returned to Rangoon to live with a sister and her family. Diana was a voracious reader and wrote her first novel as a young woman “Susan” is a coming-of-age story about a young Indian Armenian woman struggling to choose the right husband.

On 18 June 1889, Diana and Armenian entrepreneur Michael Apcar married at St John the Baptist Armenian Apostolic Church in Rangoon The following year the couple moved with their infant daughter, Rose, to Japan, a country recently opened to the world and bursting with opportunities for new businesses The couple had five children, but two of their three sons died. After two bankruptcies Michael suddenly died in 1906, leaving Diana with debts and three children in a foreign land Rather than return to Burma, Diana chose to redeem her husband’s debts. The family struggled, but she stabilised the business, making it successful within a few years

In 1909, the Adana Massacres of Armenians in southwestern Anatolia prompted Diana to Diana Apcar

activism. While the weakening Ottoman Empire was losing one province after another, as Greece, Bulgaria, and Macedonia slipped away during the 19th century, the suspicion and hostility of the Ottoman government towards its remaining minorities steadily grew The Hamidan Massacres of 1894-97, followed by Adana in 1909, resulted in 100,000 deaths; however, neither the Sublime Porte nor European Powers, actively meddling in Ottoman affairs, did anything to improve the situation for Armenians So, Diana put her pen to paper, writing feverishly for several years, and publishing six books arguing for Armenian self-determination. She wrote a book a year, appealed to peace societies and sent her articles to major European and American newspapers, pleading her case: Armenians’ right for “security of life and property on the soil of their own country ” She corresponded with Stanford University founder David Starr Jordan, President of Columbia University

Nicholas M Butler, US Secretary of State Robert Lansing, and dozens of othersacademics, journalists, missionaries, and politicians A hundred years before the emergence of social media, Diana had created an extensive network of connections, arguing repeatedly that if nothing were done to protect the Armenians, new massacres would be an inevitable outcome.

Her efforts were in vain. The Armenian Genocide of 1915 surpassed her worst predictions. One and a half million people were killed; hundreds of thousands of survivors fled in all directions to Syria, Lebanon, Europe, and the Caucasus Some of them continued north into Russia, only to find that country enveloped in the bloody Bolshevik revolution The refugees couldn’t go back and couldn’t travel west to Europe where World War I was raging. They chose an unexpected directionEast, taking the Trans-Siberian Railway all the

way to Vladivostok on the Pacific Ocean It took most refugees months, as they would frequently disembark the train to earn funds which enabled them to continue their journey. From Vladivostok the refugees had to get to Japan, Korea or China to sail to America. This is where they sought Diana’s help, to gain temporary asylum in Japan.

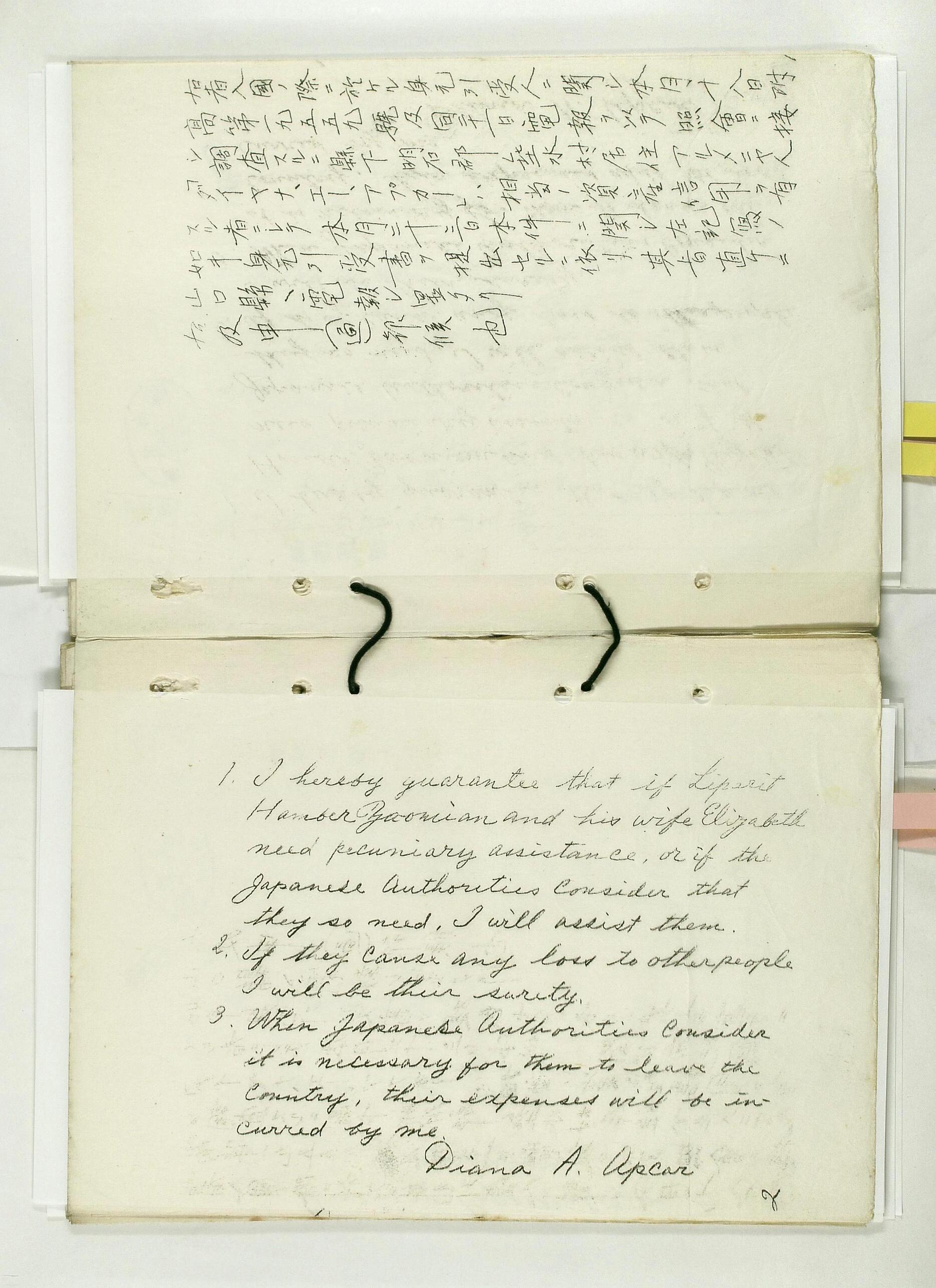

As Japan and the Ottoman Empire were on opposing sides during World War One, refugees with Ottoman passports were denied entry to Japan and were labeled “ enemy combatants.” Diana argued with the Japanese Foreign Ministry, stating that the Armenians were not Turks and had in fact been victimised by the Ottoman regime For refugees without sufficient funds to meet the Japanese visa requirements, Diana provided authorities with “guarantees” for their financial security. She rented houses to shelter them, found them jobs, and enrolled their children in school. When the American Red Cross

opened in Vladivostok in 1917, Diana became the “ manager ” of the Armenians. Once the refugees reached Japan, Diana coordinated the next phase of their ordeal: she located their relatives in the United States or found them sponsors. She assisted the genocide survivors with their identification documents and fiercely negotiated with the steamship companies for passage, booked beyond capacity for months ahead as so many vessels had been reassigned to serve in the war effort Using her own resources to help these lost souls, Diana was acting as a de facto ambassador of the lost nation of Armenia.

In 1918 Turkey was on the losing side of World War I and Russia was embroiled in its own civil war. This created a power vacuum in the Caucasus allowing for a new country to emerge. On May 28th, 1918, the First Republic of Armenia declared its independence. The country was impoverished and overrun by hundreds of thousands of

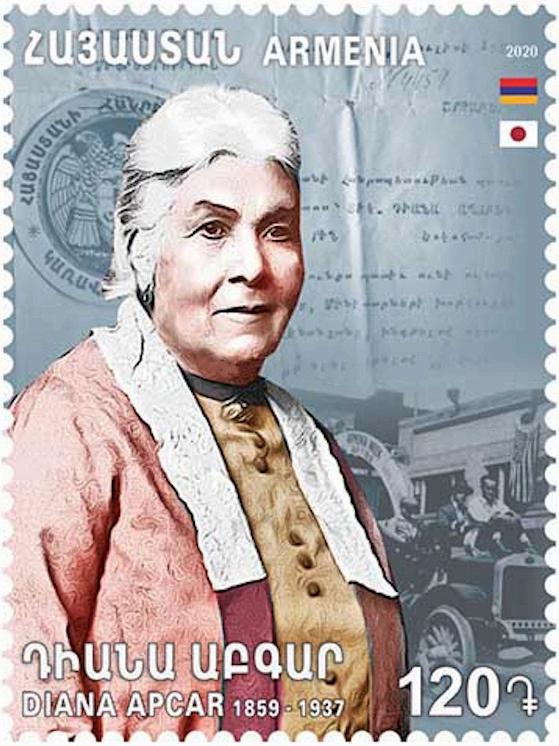

refugees Without outside support, it was destined to fail However, in July 1920, in recognition of her service to the Armenian people, Armenia’s Prime Minister Hamo Ohanjanyan appointed Diana Apcar as Honorary Consul to Japan, the first woman to ever be appointed to that post and one of the first female diplomats to be appointed anywhere in the world Sadly, while the Japanese government debated issues concerning her appointment, it failed to accept her as Honorary Consul before the Armenian Republic’s collapse In November 1920, it was absorbed into what would become the Soviet Union Despite this disappointment, Diana continued her work helping refugees, well into the mid-1920s, aiding and enabling approximately 2000 people in their quest for a new life

Both Diana and the refugees shared a vision and a hope - no matter how unrealistic - that they would overcome their obstacles: that with hard work, perseverance, and a little human compassion they would succeed Their battles were for their own survival, and that of a people and culture, despite the formidable odds against them.

Mimi Malayan is Diana Apcar’s greatgranddaughter Since 2004, she has been researching her great-grandmother’s life and writings, in an effort to create an extensive archive, including photographs, documents, and memoirs by Armenian refugees in Japan

Find out more about Diana Apcar at https://dianaapcar.org/

In November 2020, a postage stamp dedicated to Diana Apcar entered into circulation in Armenia Designed by David Dovlatyan

Dr Lina AbiRafeh

The history of Afghanistan is one of occupation

The country had been previously occupied by the British and the Soviets, and later by their own political forces - the Mujahideen and the Taliban. The Taliban assumed power over the country in 1996, and remained entrenched until the events of 11 September 2001. The Americans, armed with the language of “liberation” of Afghan women, “occupied” Afghanistan for two decades In August of 2021 th A i t d h t

The history of Afghan women is no different. They have long suffered ideological occupations. Afghan women ’ s rights have always been highly politicised, with each political period bringing strong pushes againstor for - Afghan women ’ s rights and freedoms At the same time, each occupation has been met with strong opposition from Afghan women and their movements, whose voice and agency is once again under threat today

My book, Freedom on the Frontlines: Afghan Women and the Fallacy of Liberation, explored the complex and often contradictory experiences of women in Afghanistan living through decades of American ideological

occupation from 2001 until 2021 It examined the tension between the external narratives of women's liberation promoted by outside forces and the lived realities of women on the ground This tension, I argue, is crucial to understanding not only the past but also the precarious future of any gains made, albeit fragile In the wake of the recent US withdrawal in August 2021, the book delves into the post-withdrawal landscape to offer a nuanced understanding of women ’ s struggles and the fragility of progress in conflict zones One of the central arguments of Freedom on the Frontlines is that the rhetoric of women's liberation was often instrumentalised by the occupying forces to justify their presence and garner international support. Images of women discarding burqas, accessing education, and entering the workforce were powerful symbols used to portray the intervention as a mission to liberate “oppressed” women. The reality on the ground was far more nuanced This narrative denied Afghan women ’ s agency, obscuring the complexities of their lives More dangerously, it illustrated the limitations of externally imposed and imported change

While some women undoubtedly benefited from increased access to education and employment opportunities, these gains were often contingent on specific circumstances and subject to the whims of the occupying forces Moreover, the focus on visible markers of "progress," such as choices of attire, often overshadowed deeper issues of power dynamics, social norms, and economic realities For many women, the presence of foreign troops did not translate into genuine empowerment or a fundamental shift in their social status In some cases, the increased visibility of women in public spaces even led to heightened risks and challenges

Furthermore, Freedom on the Frontlines highlighted the diversity of women's experiences and perspectives, telling the story from the perspective of those who are most important – Afghan women themselves This presented a counter to the dominant narrative of a homogenous group of "oppressed women" waiting to be liberated This narrative ignored the agency and resilience of women who were already navigating complex social and political landscapes, actively resisting the occupation and advocating for their rights - on their terms

Unfortunately, this is not unusual The case has often been made that Western feminism thrives on the notion of “liberating brown women from brown men, ” extending well beyond Afghanistan to other so-called “developing” countries. In Afghanistan, women did not subscribe to this view and opposed the hijacking of their rights - and their lives.

Diverse, nuanced, and sometimes hidden forms of agency were often overlooked in the dominant narrative of liberation, which focused primarily on Western-defined notions of freedom and empowerment. Liberation rhetoric offered little space for Afghan women to define themselves, setting a dangerous precedent for the manner in which aid interventions are orchestrated. I argue that it is through the lived experiences of Afghan women that progress can be measured and regress can be understood The voices and stories that I included in my book moved beyond simplistic narratives of liberation to recognise the diversity of women's experiences and perspectives

My previous book on Afghanistan - Gender and International Aid in Afghanistan: The Politics and Effects of Intervention - also

examined the role of cultural and religious traditions in shaping women's lives While some traditions undoubtedly contributed to women's marginalisation, others provided crucial sources of support and community The simplistic portrayal of these practices as an obstacle to women's liberation failed to recognise the complex ways in which women negotiated and reinterpreted these social forces to suit their own needs and aspirations Often, women found ways to exercise agency within the existing social structures, challenging patriarchal norms from within rather than through externally imposed changes.

e Held, House of Wisdom, Sharjah, 2024

The withdrawal of US forces in 2021 brought these complexities into even sharper focus Today, Afghanistan continues to be increasingly precarious as the country navigates both a humanitarian and a human rights crisis. The gains made by women since 2001 are all but lost, and the $780 million the US spent to promote women ’ s rights in Afghanistan is being brought into question. Every day, there are reports of increasing restrictions on Afghan women ’ s freedom of movement, access to education, and participation in public life The resurgence of the Taliban is problematic for all Afghans, but it has been particularly detrimental to women's rights, with the imposition of strict interpretations of religious law leading to the erosion of hard-won freedoms Around seventy decrees and directives have been issued by the Taliban that directly target the autonomy, rights, and the daily lives of women and girls. For example, since the Taliban takeover, at least 1 4 million girls have been banned from attending school beyond grade six Gains made in education over the last two decades - arguable the most critical progress - have all but disappeared

The post-withdrawal reality underscores the fragility of externally-imposed change in conflict zones Sustainable progress requires more than just top-down reforms; it necessitates a fundamental shift in social attitudes and power dynamics Afghanistan cannot be reduced to a “teaching moment,” and the international community must recognise that women's empowerment cannot be achieved through military intervention or superficial changes imposed from the outside Instead, it requires a long-term commitment to supporting local actors who work to promote gender equality and social justice

The implications of the US withdrawal extend beyond Afghanistan. It serves as a cautionary tale for future interventions, highlighting the limitations of military force in achieving social and political change Future international interventions must adopt a more nuanced and context-sensitive approach to promoting human rights and gender equality around the world

Supporting local women ’ s organisations and initiatives that are working to empower women and promote gender equality is the key to making meaningful change a reality. Women have the answers and know what needs to be done in their communities, and those on the outside can support by providing whatever tools and resources Afghan women require to implement changes on their own terms.

Long-term commitment is crucial in understanding that sustainable change takes time and requires a long-term commitment to supporting local efforts This counters the short-term quick-fix method of aid deliveryparticularly in countries in crisis

My friend Aziza, a women ’ s rights leader and partner from my time in Afghanistan, was very clear in her view of the situation. “The international community let Afghanistan down. They left people in the dark about their peace negotiations or their plan to exit It all happened overnight. We moved back in time.

Twenty years of constructing a new Afghanistan is reversed in one week.”

I spoke to Aziza frequently in 2021 as the Taliban was reclaiming the country Her voice provides the foundation for the book. “Things are not going to get any better,” she told me

“We will not have achieved what we had hoped What we set out to do What we started to do. And now we have to adapt to whatever that may come in order to survive ”

The full conversation was published in Freedom on the Frontlines

Today, only one percent of women in Afghanistan feel they have influence in their communities. And today, my book feels more relevant than ever, as we witness protracted crises in Palestine and elsewhere - occupations that leave unthinkable destruction in their wake. Throughout my decades in humanitarian aid, I have argued that women and girls bear the brunt of this destruction more acutely - and for far longer Their lives continue to be upended well after the crisis has subsided

Aziza’s words underscore the gravity of the situation: “...A lifetime of work for a cause that will now be undone Everyone is in survival mode. We do not know what will come of this No woman has any choice anymore With nothing to look forward to, we are told to just deal with it, to try to live But trying to

live is different from living ”

Freedom on the Frontlines does not offer closure The fight for Afghan women ’ s rightsand women ’ s rights globally - continues It is arguably under threat now more than ever The struggle for women's liberation is not a project that can be completed through military intervention or external imposition It is a continuous process that requires a fundamental transformation of social attitudes and power dynamics The future of women's rights depends on our collective commitment to supporting local actors, addressing root causes, and learning from the complexities of the past. The stories of women in Afghanistan - their struggles and their resilience - serve as a powerful reminder of the importance of this work.

This is not just a fight for Afghanistan It is for justice, equality, and dignity for us all.

Dr Lina AbiRafeh is an activist, academic, and aid worker recognised as one of the world's leading women's rights experts. She has worked on gender issues in developing and humanitarian contexts around the world for nearly three decades

Find out more on her websitehttps://www linaabirafeh com/

*all images included in this article were taken by the author during her time in Afghanistan between 2002-2006

by Professor Karen L Thornber

Often referred to as the “Rachel Carson of Japan,” Ishimure Michiko (1927-2018) was one of Japan’s most prolific environmental writers and engaged environmental activists A native of Minamata, a village on the Shiranui Sea in western Kyushu, for more than half a century Ishimure struggled tirelessly for justice for individuals and families afflicted with Minamata disease, a highly stigmatised, disfiguring, debilitating, and sometimes lethal neurological condition caused by severe mercury poisoning In 1932, a chemical factory in Minamata owned by the Chisso Corporation had begun using mercury catalyst in the production of acetaldehyde. By the mid-1950s, people in Minamata and the surrounding areas began exhibiting symptoms similar to those of acute anterior poliomyelitis, and in 1968, the Japanese government declared Chisso’s release of methylmercury into the waters by Minamata the cause of Minamata disease Yet even today, Minamata patients, their families, and activists continue to struggle for recognition, including in such works as Scottish comic-book writer Sean Michael Wilson and Japanese artist Shimojima Akiko’s graphic novel/manga The Minamata Story: An EcoTragedy (2021)

Ishimure’s experiences were like those of many rural female intellectuals and not dissimilar from those of many of the women I discuss in my book Gender Justice and Contemporary Asian Literatures (2024). Ishimure shared with a German critic in the early 1980s that as a woman in rural

Ishimure Michiko - Asahi Shimbun Company Photographer: Hirabayashi Publishing

Minamata, she was criticised for reading and that “ women in Minamata were only valued as workers, not as agents of academic and literary life” (Komatsubara 73). Moreover, Japanese literature has long been Tokyocentric, and literary figures generally have had to become connected in the metropolis before receiving recognition

Yet these and many other obstacles did not prevent Ishimure from either writing or activism Her creative oeuvre is substantial: fifty volumes of novels, poems, plays, children’s stories, and essays, many of which are included in her seventeen-volume collected works (Ishimure Michiko zenshū, Complete Works of Ishimure Michiko, 2004). Among her best-known writings is her Minamata trilogy. Published in 1969, Kugai jōdo: Waga Minamatabyō (Sea of Suffering and the Pure Land: Our Minamata Disease),

the trilogy’s first volume, has been reprinted dozens of times in Japanese, including in publisher Kawade Shobō Shinsha’s Sekai bungaku zenshū (Complete Collection of World Literature, 2007) Sea of Suffering discusses the first fifteen years of the Minamata tragedy The narrator of this volume includes accounts of her own interactions with Minamata patients and experiences fighting corporate and government bureaucracies that refused to acknowledge their suffering She also incorporates moving stories of Minamata patients in their own voices and those of their families and friends. In addition, she contextualises the experiences of the Minamata villagers, discussing pollution incidents elsewhere in Japan and the world Kamigami no mura (Villages of the Gods), the second part of her Minamata trilogy, serialised between 1970 and 1971, takes the reader to the December 1970 Chisso stockholders meeting. The third part, Ten no uo (Fish of Heaven), was published in 1974 Both Villages of the Gods and Fish of Heaven focus on the suffering of Minamata patients and the

struggles of these individuals and other concerned parties against the Chisso Corporation and the Japanese government Also noteworthy is Ishimure’s Noh play Shiranui (2003), a requiem to the victims of Minamata disease.

To be sure, Ishimure’s contributions were quickly recognised outside of Japan In 1973, for instance, she received the Ramon Magsaysay Award from the Philippines, sometimes referred to as the Asian Nobel Prize, given annually since 1957 to persons “who address issues of human development in Asia with courage and creativity, and in doing so have made contributions which have transformed their societies for the better ” And many scholars of literature and the environment, regardless of nationality, are familiar with the name Ishimure Michiko. Papers addressing her work are regularly given at environmental literature conferences in the United States, Europe, and East Asia But very few outside Japan/Japanese studies have read much of her oeuvre This is because

Ishimure’s writings – with the exception of Tsubaki no umi no ki (Story of the Sea of Camellias, 1976, trans 1983), Tenko (Lake of Heaven, 1997, trans 2008), Sea of Suffering (trans. 1990), Shiranui (trans. 2016), Anima no tori (Spring Castle, trans October 2025), and several short pieces – have not yet been translated, and the majority of extant translations are into English and German, leaving readers not proficient in these languages with no direct access to her work.

This inaccessibility is especially unfortunate given the relevance of Ishimure’s narratives far beyond Japan. For instance, as I argue in “Ishimure Michiko and Global Ecocriticism” (2016) and Ecoambiguity: Environmental Crises and East Asian Literatures (2012), both Sea of Suffering and Lake of Heaven illuminate two of the greatest challenges facing environmentalists, indeed societies worldwide: the readiness with which even the most obvious environmental damage is disavowed, particularly evident in Sea of Suffering; and the limits of ecological resilience, an underlying concern of Lake of Heaven

Many literary works that address humaninduced environmental disruption portray dismissals of this damage - acquiescing to it by denying and dismissing the responsibility for and knowledge of (potential) ecodegradation –as a common response to and facilitator of compromised ecosystems In some texts, disavowal plays a central role: certain narratives accentuate the extent to which governments, corporations, citizens’ groups, and individuals will go to refute that environmental degradation exists or, when overwhelming evidence to the contrary makes such denial impossible, to reject responsibility for it, minimise its seriousness, and strive to

expunge it from public consciousness Sea of Suffering highlights this process The novel accentuates the disconnects between obvious physical evidence (landscapes that are clearly polluted; people who are unquestionably disfigured) and the behaviors (disavowals, including both active denials and conscious indifference) of many in the Japanese government, the Chisso Corporation, and residents of Minamata and the surrounding towns. Sea of Suffering also devotes significant attention to alternatives, contrasting denials of Minamata disease with the great compassion for the afflicted demonstrated not only by the families and close friends of Minamata patients but also by the Japanese medical community and sometimes even by members of groups known primarily for their disavowals

For its part, Lake of Heaven, written three decades after Sea of Suffering and in a nation and world of increasingly threatened ecosystems, is one of many narratives that contrast the relative resilience (endurance and revivability) of nature, whether individual species or the nonhuman more generally, with the ephemerality of people and their cultural artifacts These narratives call attention to those parts of the nonhuman that withstand or recuperate from damage imposed by people, and those that exhibit resilience in the face of blizzards, typhoons, and shifting tectonic plates Yet any number of these writings, including Lake of Heaven, despite their seeming optimism about the prospects of the nonhuman, in fact leave the extent of nature’s resilience ambiguous. Ishimure’s novel describes the visit of Masahiko, a young Tokyo composer, to what remains of his grandfather Masahito’s hometown of Amazoko (bottom of heaven), a village in Kyushu that thirty years earlier was buried under a lake created by a dam. Amazoko is fictional, but it is modeled after the actual Kyushu village of Mizukami, which was submerged by the Ichifusa Dam Although Lake of Heaven in many places highlights the parallels between the pre- and postconstruction landscapes and underlines the differences between Japan’s cities and its mountain regions, the novel also makes clear that the latter are in jeopardy These landscapes have for the most part withstood and overcome the changes people inflict, but Ishimure’s novel suggests that environments will not be able to do so forever, at least not in a form that can readily sustain human endeavor

Today, Japan’s Minamata Disease Museum (est. 1988) explicitly devotes itself “to

collecting and preserving documents, as well as disseminating knowledge about Minamata Disease in order to build together a world aware of human rights violation, where environmental issues such as Minamata Disease would not occur again ” Similarly the Minamata Disease Municipal Museum (est 1993), also in Minamata, bills itself as using displays and storytellers to “exhibit and tell the history and present situation of Minamata disease and the hard situations that patients experienced, such as the suffering and discrimination, in order to prevent the reoccurrence of disastrous pollution like Minamata disease ” Much of the success of these museums, and of Minamata’s reinvention, beginning in the 1990s, as a “model environmental city,” is a result of the tenacity of Ishimure and other Japanese writer/activists, who refused to capitulate to much more powerful forces in industry and government and provided inspiration for future generations.

Professor Karen L Thornber is a cultural historian and scholar of Asian literature and media at Harvard University

Reference - Komatsubara, Orika “The Role of Literary Artists in Environmental Movements: Minamata Disease and Michiko Ishimure,” International Journal for Crime, Justice, and Social Democracy 11(1) 2021: 7184.

by Dr Leslie Castro-Woodhouse

The city of Chiang Mai is often described as Thailand’s “northern capital ” Travelers might pick up on a few marked differences between the Thai culture they encounter in Bangkok versus that of Chiang Mai. For instance, the distinct northern linguistic accent elides hard “ r ” sounds to soft “h”es, and has other aspects pronounced enough that in days past, Siamese officials visiting from Bangkok had to hire translators The local cuisine’s curried khao soi and vinegar-brined beef dishes hint at the region’s long colonial entanglements with Burma. Then there’s the fluttering sigh of the

traditional saw violin and shimmering gongs that figure so prominently in the region’s traditional music. And then of course, there’s the veritable trademark of Chiang Mai: the rainbow of traditional, striped phasin skirts still worn by local women

While many Thais typically explain away these features as mere regional differences, their actual significance goes much deeper What is today Thailand’s northern region was once - a scant hundred years ago - a sovereign kingdom called Lanna. How Lanna became part of Thailand is, I suggest, best embodied in the story of one woman: Dara Rasami (18731933), a Lanna princess who married the king of Siam. Her story is key to understanding how Thailand retained its sovereignty while every one of its Southeast Asian neighbors fell to European colonial domination

Lanna and Siam: Constellations and Alliances

Until the early twentieth century, Lanna wasn’t so much a single polity as an evershifting constellation of city-states ruled by a set of Buddhist monarchs who shared familial connections They married the daughters of neighboring kings, creating a network of alliances linking Lanna together The earliest iteration of Lanna arose in the thirteenth century and lasted until Burma colonised the region in the mid-1500s By the 1770s, Lanna’s people had had enough, and allied themselves with the “southern” kingdom of

Dara’s official portrait, taken during her 1909 visit to Chiang Mai (Photo courtesy of the National Archives of Thailand)

Siam, the better to throw off the yoke of their shared enemy, the Burmese. Following their joint victories over the Burmese, Siam’s newfound Chakri dynasty built a new capital city at Bangkok, while Lanna rebuilt their capital at Chiang Mai, repopulating the old city with ethnic groups resettled from the uplands. But soon, new players came on the scene, unsettling both the region’s balance of power, and the alliance between Siam and Lanna

Europeans had begun encroaching into Southeast Asia from all directions in the early nineteenth century To Siam’s east, the French were moving into Vietnam and Cambodia; to the south, the Dutch and Portuguese had colonised much of Indonesia; to the west,

Britain had begun its slow-motion conquest of Burma. As anxieties rose among the Siamese elite in Bangkok, Lanna’s rulers saw only opportunity in British officers’ hunger for beef cattle and teak timber profits

So when a rumor reached Bangkok in 1883 that Queen Victoria herself wished to adopt a young Lanna princess - just as she had adopted Maharaja Duleep Singh from the PunjabSiam’s King Chulalongkorn was duly alarmed He immediately tapped his half-brother, Prince Phichit Prichagorn, to journey 362 miles to Chiang Mai on a critical secret mission: to secure the princess as the Siamese King’s consort That princess was Dara Rasami, who was at that time nine years old With a gift of diamond earrings to the King

and Queen of Lanna, the deal was sealed But there was a not-so-secret catch: to bring Lanna firmly under Siam’s control, and stave off European colonisers for good.

The personal is political: Dara’s role in the palace

Once she had reached puberty, Dara made the long journey to Bangkok to join the king’s harem of royal queens, consorts, and concubines in 1886 Although she ultimately spent nearly thirty years in Siam’s royal palace, her status for the first few years was anything but certain Although political marital alliances were common among the elites of both Lanna and Siam, the bride’s role was often fraught with danger, as she served as both diplomat and hostage in her new husband’s home. It was no different for Dara Rasami, whose cultural difference from the Siamese presented an additional hurdle Among Siam’s most elite women, Dara’s differences were hard to miss. Instead of the short haircut sported by Siamese consorts, Dara wore her long hair Lanna-style, pulled up in a bun on top of the head Instead of chongkrabaen leggings, Dara and her ladies wore striped, wraparound phasin skirts Her northern accent was hard for the other consorts to understand, and they taunted her for smelling “like fish paste,” a favorite Lanna condiment

Young Dara suffered so much from repeated humiliations that the king himself intervened, ordering the other palace women to ease up, lest Dara decide to return home. Since a royal consort could opt to leave her service in the palace any time (until she had a child), at that moment Dara could have gone back to Lanna if she wanted to. But the king feared that such a move would devastate Siam’s alliance with

Lanna, leaving them open to British colonisation. Despite these hardships, Dara was resolute in her commitment to the role she played for her home kingdom.

Two years later, Dara had a daughter by the king, cementing her place in the court As a new mother, she was granted a new house of her own in the palace, where she gathered an entourage of a dozen Lanna ladies-in-waiting In Dara’s household, she and her attendants could freely speak, dress, and eat in northern style Despite the challenges of being ethnically different in the homogenous Siamese palace surrounding them, they maintained Dara’s distinctive Lanna style throughout her palace career.

Dara’s life and career in the Siamese palace

Sadly, Dara’s only daughter - like many infants and young children born to royal consortsdied at only three years of age during one of the many waves of illness that periodically swept through the inner palace She and King Chulalongkorn would have no other children. And that could very easily have been where Dara faded into the background among the other 150 royal consorts and queens in the palace. But in the face of her daughter’s loss and her own exile from her distant homeland, Dara persisted. When a female cousin died leaving two small children behind, Dara brought them into her household to raise as her own She and her ladies were skilled musicians and dancers, and she organised a Thai orchestra among the palace women And despite the teasing Dara had endured years earlier about Lanna’s strange foodways, the “mieng” snacks her ladies sold from her residence’s back steps were a hit among the Siamese consorts

Dara was also intellectually curious, employing a “reader” in her household to keep her abreast of current events. Dara’s friendship with Prince Damrong, widely regarded as the “father of Thai history,” sparked a lifelong interest in Lanna’s ancient history and culture Dara became involved in palace photography through her friendship with another consort, Lady Erb Bunnag, who featured Dara prominently in her palace images Erb and Dara were also among the select number of consorts King Chulalongkorn moved to his new palace in Bangkok’s Dusit district in 1901.

Dara and Lanna’s place in a Siamese hierarchy of civilisations

Dara’s career trajectory was emblematic of Siam’s changed relationship with Lanna. Although Siam’s elites looked down on Dara’s Lanna identity, her presence effectively raised L ’ i h Vi i i i d

hierarchy of civilisations they were building While Siam’s other ethnic groups figured in the lower echelons of this racial pyramid, Lanna ranked just below the Siamese at its apex.

We can see Lanna’s place in this civilisational hierarchy in the Thai adaptation of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly When the king’s brother, Prince Narathip, overheard a Puccini aria while touring Europe in 1906, he decided to create his own version of the story called Sao Khrua Fa (Thai for Miss Butterfly) In his version, the American naval officer becomes a Thai soldier, and the tragic heroine – ? A woman of Lanna, of course Sao Khrua Fa sold out Bangkok theatres for months when it opened in the summer of 1909.

Dara and the construction of Lanna identity

Since then, repeated productions of Sao Khrua

Fa for film, television, and stage have perpetuated the trope of the delicate “northern” woman in Thai popular imagination But although Dara herself provided musical and dance expertise to the production, she missed its opening While the play spread the stereotype of the beautiful but naive Lanna woman amongst Bangkok theatergoers, she was building Lanna identity in Chiang Mai in her first return visit since leaving home in 1886

Palace elites had exposed Dara to the new ideas they were encountering about what it meant to be a “modern” and “civilised” nation As Siam built its own hierarchy of civilisations parallel to that of Victorian-era Europeans, Dara witnessed how other ethnic groups within Siam’s territories fared in the rankings - that is, far below the Siamese, who put themselves at the top of the pyramid At the time, her homeland was being rapidly absorbed into the modernising Thai state If Lanna’s uniqueness was to survive, someone needed to actively promote its cultural heritage - and Dara Rasami was ideally placed to embrace that role.

During her 1909 tour of Lanna, Dara spent several months visiting Lanna’s remaining local chiefs, restoring crumbling temples, and building a new, Bangkok-style, royal cemetery for her Lanna ancestors. Before her return to Bangkok, she threw a week-long festival, for which she built a boxing arena, movie theatre, and hospital Local women changed their hairstyles to match Dara’s “Japan-style” pompadour, and began wearing Victorian blouses with their phasin skirts - a style still closely identified with Dara Rasami today

Dara’s promotion of Lanna’s culture and economy

After King Chulalongkorn’s death in 1910, Dara returned to Chiang Mai to become a major Lanna booster, leaving a lasting impact on the local economic and cultural landscape. At her residence, she set up schools of weaving and dance where local girls from all social classes could learn traditional Lanna cultural forms Her historical interests took her on multiple horseback journeys into the mountains and forested valleys to collect local Lanna knowledge Dara even set up an experimental farm in Mae Rim to find cash crops Lanna’s farmers could sell to Bangkok markets

Lanna’s place in the new Thai nation-state was further solidified when the Thai railway line reached Chiang Mai in 1922, shrinking the journey from a perilous six-week overland journey to an overnight trip by sleeper train. Soon Bangkok arrived - including Siam’s next two kings, Rama VI and VII. When the Thai queen was photographed wearing a Lanna phasin, Lanna became briefly “cool” among mid-1920s Bangkok elites

Dara died at age sixty in 1933, having seen her homeland transition from sovereign kingdom to Thai province But as visitors to Chiang Mai can attest, Dara’s influence is still visible there today, in the popular Lanna cultural practices that she kept alive.

Dr Leslie Castro-Woodhouse is a scholar of Thai history and a seasoned editor and book coach through her company Origami Editorial. With a background spanning both business and academia, she was previously managing editor of Asia Pacific Perspectives at the University of San Francisco and is the author of “Woman between Two Kingdoms: Dara Rasami and the Making of Modern Thailand”.

by Sung-Yoon Lee

Vignette

We stood stiff, eyes fixed obsessively on the barren landscape before us called North Korea

Sir John Scarlett, former Chief of Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service, was the first to break the silence. “What’s going through your mind?” he asked

“Profound sadness,” I mumbled

It was a clear, bitingly cold morning in late January 2023. On the last of a five-day visit to Seoul, we, a handful of visitors from the US and the UK, found ourselves standing at Panmunjom, the inter-Korean border village, peering into Kaesong, by North Korean standards a relatively affluent city It was the only visible sign of civilisation for miles

A few tall, bleak-grey buildings stood as if they had defied the laws of nature and sprouted from the unpromising grounds. A shell of the former inter-Korean industrial park complex stretched horizontally from the cluster of colourless buildings One wore a prominent charred mark, the after-effect of the demolition of the adjacent North-South Joint Liaison Tower, an office building maintained entirely with South Korean taxpayer money until its theatrical demise in front of the cameras in 2020.

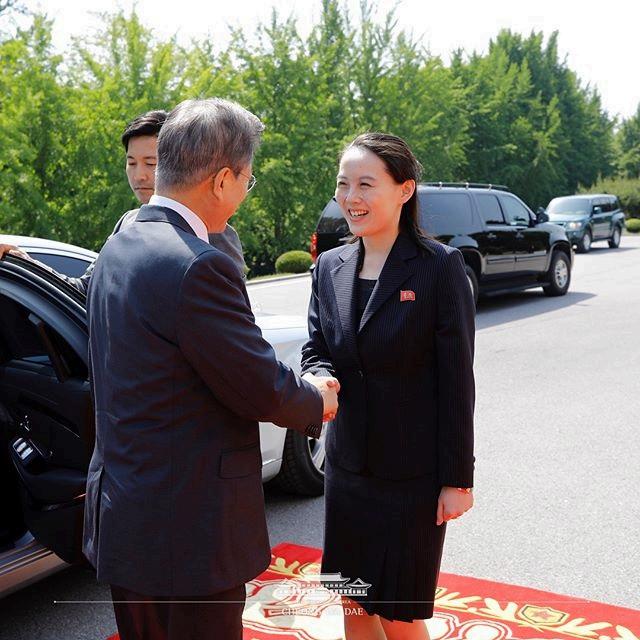

That June, Kim Yo Jong, the supreme dictator’s outspoken sister, threatened to destroy the “useless” building and deploy troops into the border area It was a game of psychological pressure versus South Korea, immeasurably richer and freer than the North and, thereby, markedly more risk averse Three

days later, demolished it was, reaffirming Ms Kim’s status as the top official in charge of external affairs of the brutish dynastic regime into which she was born.

Later, at a lavish lunch of various cuts of the fabled snowflakes-speckle-marbled, primegrade Korean beef back in Seoul, I muttered on

“Just by sheer luck, I was born south of the border, in the late-1960s South Korea was a desperately poor and hungry nation back then But I was fortunate enough to have a good education and a good life ”

I took a deep breath, overcome by guilt at both self-dramatisation and spoiling the gluttonous mood.

“But in North Korea, everything is hereditary. Not only power at the very top that’s handed down to the next generation, but everything else: hunger, misery, terror, oppression, privation, and insidious political classification

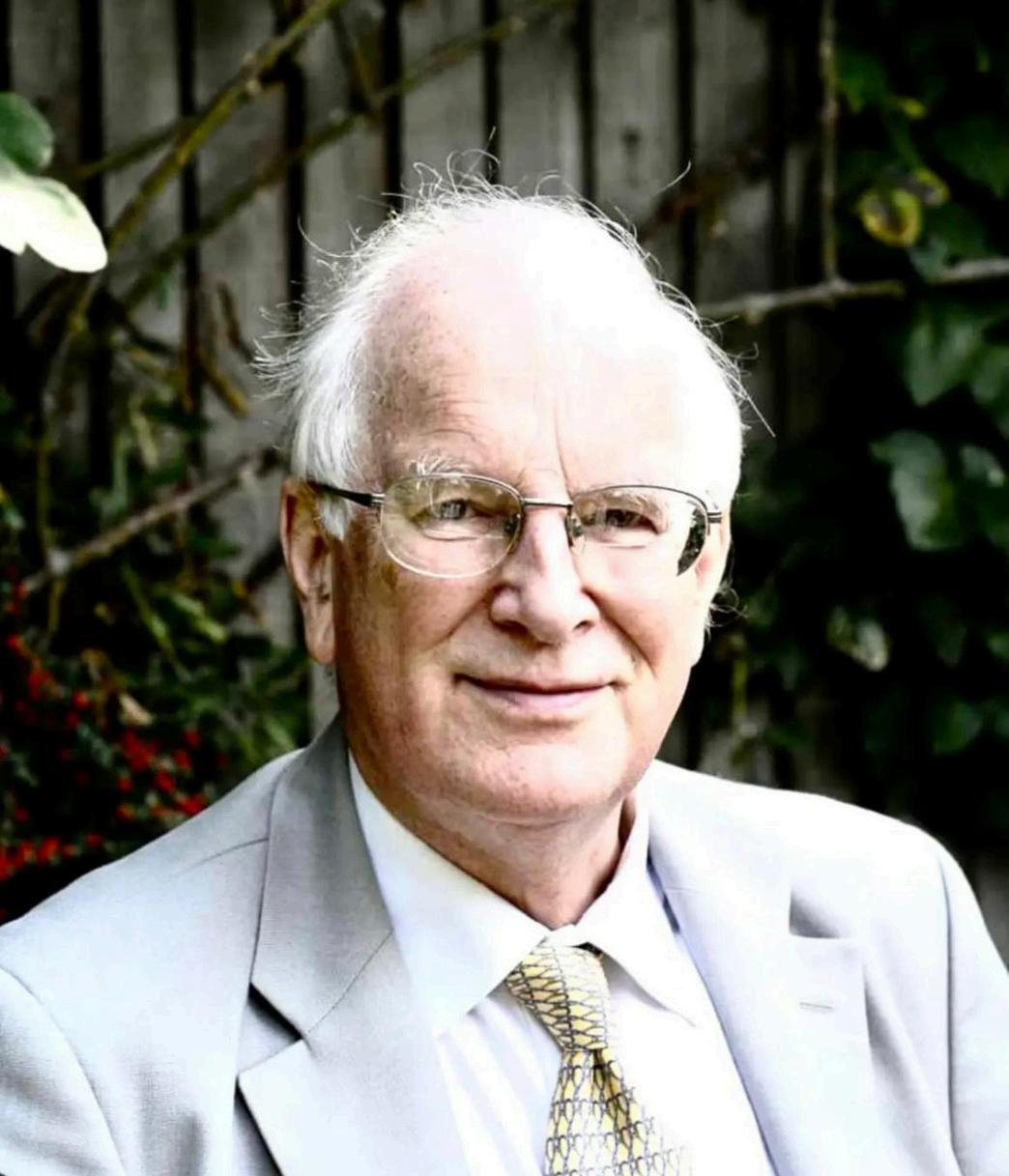

Second InterKorean Summit 2018, meeting between President Moon Jae-in and Kim Yo-jong. Cheongwadae, Blue House.

upon birth Over the past century, going back to Japan’s colonisation of Korea in 1910, the vast majority of people living in North Korea have known nothing but tyranny. It’s such a tragedy ”

No one at the table raised an objection

Out of this macabre, male-dominated, medieval-like milieu has emerged a powerful, young, female figure - the supreme dictator’s younger sister who is also his most trusted aide, adviser, propagandist and spokesperson: effectively a “co-crime boss” of the Kim sibling’s ossified totalitarian dynasty

Young, beautiful, smart, and acerbic, Ms Kim exercises real power often with a vituperative verbal twist, demeaning her targets with custom-made insults She is a tyrant-in-waiting prone to making threats of nuclear strikes against the South, her power checked neither by term limit nor the separation of powers but only by her brother She is undoubtedly the most powerful woman in North Korea and, arguably, all of Korean history and, possibly, even world history. Simply, she is the most dangerous woman in the world today

Yet, at first, few saw in her such ominous potential. If anything, she was viewed with a mix of gawkish obsession and suppressed condescension when she made her debut on the world stage by visiting South Korea for the Winter Olympics in February 2018. The public’s unsophisticated perception was all contrived, that is, elicited by the North Korean propaganda queen herself After all, her family excels in “weaponising weirdness”determinedly cultivating a “ crazy dictator”

image with an outlandish cult of personality and external hostility Why? Because their strange mix of medieval mores and buffoonish bellicosity, without fail, transforms the hitherto “mad man ” into a very reasonable chap the moment he steps out of his cocoon and engages foreign leaders, officials, and journalists, often beaming smiles and uttering reassurances like peace, rapprochement, and denuclearisation

All three generations of Kim leader have excelled at this art form and, collectively, have gained tens of billions of dollars in cash and material aid with the periodic put-ons

In South Korea, Ms Kim maintained a mysterious-but-charming, imperious-butcourteous demeanor Not once did she speak to the media or to the public. Simply by showing up to the opening ceremony and sitting with her chin up above and behind the US Vice President and his wife, she showed the world who was the real VIP.

She had insisted on this optically strange seating arrangement, threatening to walk if her South Korean hosts failed to comply That she, the younger sister of the North Korean leader, brought an invitation letter for the South Korean president, which she personally delivered to him during her visit to the presidential office the next morning, confirmed her status as the messenger of peace Above all, it confirmed her brother’s noble intentions; a peace-prone statesman now finally willing to part with his nuclear arsenal. Just by showing up in the South, she paved the way for her brother’s dramatic image makeover with a series of summit pageantries featuring the leaders of China, South Korea, and the United States

Yet, as in the past, this round of political drama proved just that, an exciting chimera. The formerly courteous princess from Pyongyang soon turned rather discourteous.

She ridiculed South Korean leaders variously as a “frightened dog barking” or “idiots” who parrot the US and called Joe Biden “senile.” In over fifty written statements, she has insulted the South Korean leadership, cabinet, military, and public with biting vitriol, while pledging eternal support for Vladimir Putin and the “heroic army and people” of Russia But beyond her routine day job as her nation’s chief spokesperson, propagandist, and foreign policymaker, her greatest achievement to date has been as the supreme censor over the entire Korean peninsula.

Shortly past 6am on 4 June 2020, Ms Kim issued a statement calling on South Korea to pass a new law that criminalises the sending of leaflets that human rights activists - many of them emigres from the North - fly across the border into the North via balloons She made a

point to call these activists “human scum ” and “trash ” Four hours later, the presidential office in Seoul gave a briefing implying her wish would be accommodated Ten minutes later the Unification Ministry announced it would work on such a bill With rare alacrity and unity, other agencies, including the Ministry of National Defense, chimed in

The very next day, ruling party lawmakers started drafting the new bill. Criticism from civic groups within South Korea and international bodies, including the United Nations, poured forth Lord David Alton, a senior Member of the British Parliament, called the South’s new legislation a “Gag Law ” US Congressman Michael McCaul issued a scathing statement: “A bright future for the Korean Peninsula rests on North Korea becoming more like South Korea - not the other way around ”

President Moon Jae-in attends the opening ceremony of the 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics with US Vice President Mike Pence and Kim Yo Jong Image courtesy of Blue House, Republic of Korea

Yet, the South Korean administration, enjoying a supermajority in parliament, pressed ahead and passed the law that December The maximum punishment for violation was three years in prison and a 30 million won fine (at the time about $27,000) While Ms Kim had called for a ban on leaflets, the South Koreans went several steps further and outlawed sending any item with even minimum exchange value, for example, a bar of soap, toothpaste, medicine, etc Ms Kim’s victory was historic It shall forever be remembered as the first-ever case of the North extending its stifling censorship across the border into the South - a feat that even Ms Kim’s grandfather, father, and brother could not accomplish And she achieved it so seemingly effortlessly.

Perhaps her vile putdowns and unreasonable demands are somewhat easier to stomach because they come from a beautiful young woman rather than her portly, less photogenic, male sibling. The unexamined sexism inherent in so many of us - both men and womenworks to her regime’s advantage; that is, she can get away with a lot more than her dourlooking brother. In due course, Ms Kim will wear a charming smile and engage her nation’s adversaries. At that moment she will capitalise on the widespread tendency on the part of her interlocutors - who are mostly significantly older men - to patronise young women Naively thinking that she is more malleable than her brother or that they themselves, by virtue of their own wisdom and charisma have “influenced” her, the wish to believe in her good intentions will stay firm.

For now, she will continue to bolster her dynasty’s cult of personality while showcasing her brother’s achievements and, cleverly, his adoration for his little daughter The girl, since

2022, has often been sighted next to her father at memorable family outings like an intercontinental ballistic missile launch or a night-time military parade. The wholesome father-daughter ensemble in effect is a diplomatic Multiple Launch Rocket System; that is, it fires at adversaries several self-serving messages all at once: “We’re a dynasty and have all the time in the world You are bound by term limits and will be forgotten in four to five years ”

In manipulating her foes to resign themselves into accepting her nation’s nukes as an immutable reality, she reaffirms a reality at once sinister and grim like the daily lot of her people: “The supreme leader obviously loves his daughter, doesn’t he? He’s not crazy enough to start a nuclear war, is he? Maybe we’ll all just have to learn to live with a nuclear North Korea…the nature of the regime notwithstanding ” Yet another victory it shall be for the dystopian dynasty.

Sung-Yoon Lee is a Global Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and author of “The Sister: The Extraordinary Story of Kim Yo Jong, the Most Powerful Woman in North Korea”

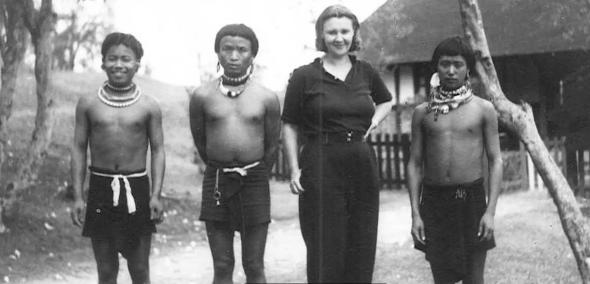

by Annie Liddell

“I saw the flood in 1939, when the Amu Darya River was so powerful that its banks were falling away into the water Before the flood came, there had been some sort of mist that indicated that water was on the way Some schoolboys and I were playing close to the river, but we had to flee as the ground began to crumble As we ran, that part of the bank collapsed into the river at such a great speed…

At that time there were no bridges and the Amu Darya was like heaven I was an excellent swimmer, but I was still cautious about swimming in the fast-moving water The boys were more daring and swam further out into the Amu Darya, but it was extremely dangerous Once when I was swimming, one boy kicked me in the face leaving me

me with a scar My grandmother sobbed ‘You were so gorgeous’.”

Gulaisha Esemuratova has been many things in her 94-years of life: journalist, women-rights activist, poet, and daughter of an ‘ enemy of the people’ Though Gulaisha’s face has been softened by the strong summer heat and the bitter cold winters of Karakalpakstan, her quick humour and ready gold-toothed smile make it easy to envision her as a strong-willed feminist living in the outback of the Soviet Union. Yusup, her 72-year old son, sits beside her holding her hand - one worn from years of domestic work, labour in the fields and her writing. Gulaisha tells tales of her childhood

and early career as a journalist, pausing at times for Yusup to translate; she corrects him sharply whilst he tenderly pats her hand, reassuring her that he is telling her stories properly.

Though many women in Karakalpakstan have lived through dramatic transformations, Gulaisha is exceptional to have survived to such an age and experienced these changes in unique ways, as a writer and pioneering advocate for women ’ s rights Born just after the Central Asian Soviet Republics were established and the collectivisation of the 1920s, Gulaisha has experienced the post-war economic shifts, the breakdown of the USSR, and the establishment of independent Uzbekistan in the 1990s All of these political re-organisations have profoundly changed people’s lives, especially those of women.

Karakalpakstan has, to some extent, been insulated from these developments due to its distance from major Central Asian cities. The Autonomous Republic of Karakalpakstan is situated in western Uzbekistan and is most known, perhaps, as the site of the former Aral Sea and Amu Darya Delta – now the world’s youngest desert The stash of forbidden art masterpieces from across the former USSR in the Savitsky Museum in Nukus, the capital of Karakalpakstan, is a compelling illustration of this However, the Amu Darya Delta, Karakalpakstan and its neighbouring region Khorzem, have also been at the forefront of change given the dramatic decline of the Amu Darya river and the desiccation of the Aral Sea to less than a tenth of its size in only seventy years The Aral Sea Crisis has led to economic decline, outward male labour migration and a heavy burden on the women left behind

By the time Gulaisha was born, the Second

Cultural Revolution was catalysing huge changes; Soviet collectivisation and the 5-year plans led to a vast expansion of cotton production in Khorezm and Karakalpakstan. However, these plans were poorly conceived leading to harsh labour conditions as workers struggled to meet impossible quotas Moreover, poor agricultural practices and irrigation infrastructure resulted in increasingly high rates of soil salinisation Alongside these economic shifts, significant social changes were underway that revolutionised gender

From the early 1920s, the "Hujum" ("Attack" in Arabic) campaign of the Soviet Government pushed for profound changes to the practice of religion, traditions and the social roles of women The campaign circulated propaganda against social practices deemed oppressive to

women: bride prices, the traditions of women's seclusion and veiling. These campaigns often had quite tangible impacts, in particular the ‘burqa’ burnings. In the 1920s, women were encouraged to discard their veils in mass burnings across cities in Uzbekistan as a symbol of liberation However, there was strong backlash from some men with some party supporters reported to have attended the rallies only to replace veils the next day In more remote areas, like the Amu Darya Delta, resistance was more pervasive, and pre-Soviet cultural practices endured into the 1950s

Women’s participation in Soviet social and economic life was supposed to mirror that of men ’ s. This ranged from universal schooling through to full labour participation, especially in the cotton fields. While this offered women some economic independence, it came at the

cost of harsh labour conditions for poor pay and led to the loss of female cultural traditions, notably embroidery in Karakalpakstan

For Gulaisha, competing with the boys in her class was normal and encouraged at home (Gulaisha means ‘alive flower’ which seems quite fitting), but not all families encouraged girls to be so outspoken Growing up, she was well aware of the substantial issues facing young Karakalpak women, including neglect from their husbands and the risk of being kidnapped as brides by Turkmen – a practice still theatrically performed to this day In particular, she recalls the hardships of the 1950s when, as a young journalist, her reporting on poor conditions for women was banned by officials. In 1954, Gulaisha worked on a newspaper, ‘The Young Leninist', which sent her to Moynaq - a small fishing village now symbolic

of the Aral Sea disaster Everyone warned her "Gulaisha, you will freeze to death (there)." Gulaisha chuckles at the memory and then says seriously, "They sent me to the remotest region because I am a daughter of the enemy "

Yusup elaborates, Gulaisha’s father, his grandfather, was "the last king of the Karakalpak people” Having led key revolts against the Soviet Red Army, he was shot by the KGB, along with his 14-year old son This family trauma has instilled in Gulaisha a fierce determination, but also a lifetime of fear, knowing that being a daughter had saved her from the same fate, and that her sons might not receive the same mercy Despite this, Gulaisha has spent her life campaigning for women ’ s rights and their place in society She set up her own women ’ s newspaper in Karakalpakstan which she proudly references as we talk

From the 1960s, for Gulaisha and others in the Aral Sea Region, it became clear that ecological conditions were rapidly deteriorating, which was soon accompanied by economic stagnation

in the 1980s across the Soviet Union When Gorbachev became General Secretary in 1988, his push for greater openness emboldened the first discussions of the Aral Sea Crisis and a return to some religious freedoms, with a dynamic shift as women took up head scarfs again When Uzbekistan gained independence in September 1991, it marked a precarious shift once more for women and their futures

When I asked Gulaisha for advice for young women facing an uncertain future, particularly in the context of escalating water scarcity and in a time when female rights around the world are under threat, she said, “I am a Karakalpak writer, 94 years old As a representative of the Karakalpak people, I must convey this message to my children: Be honest and brave in telling the truth, because in the end, we all die as human beings Look at the Aral Sea - it’s gone, but whose soul hurts? No one ’ s. ”

Annie Liddell is a co-founder of Project Amu Darya which created an award-winning documentary about the Amu Darya Delta.

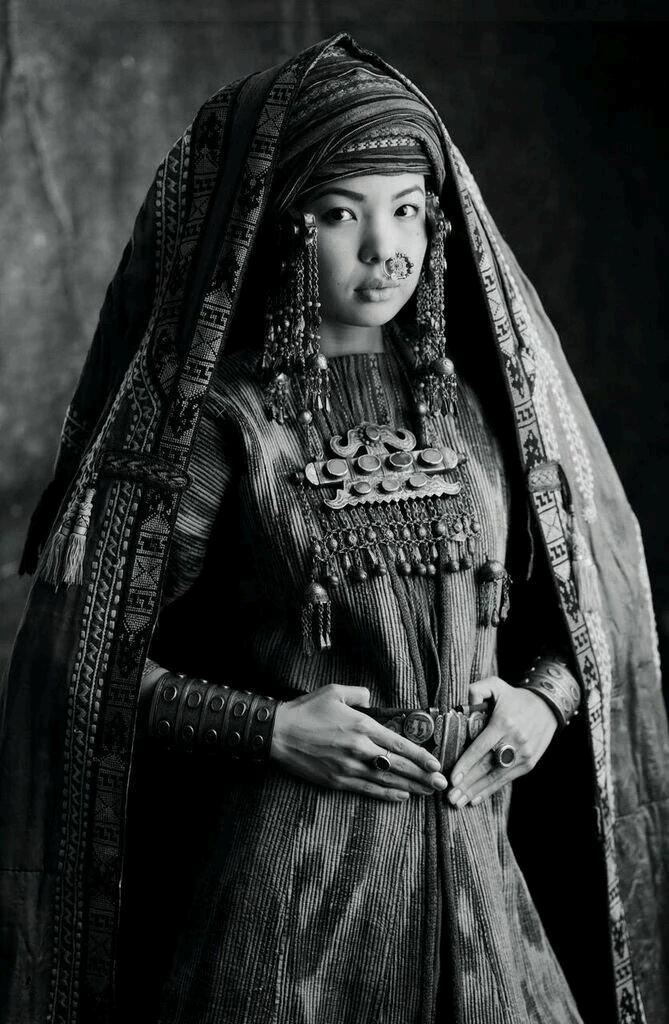

curated by Rania Matar

Presented by The Middle East Institute Arts and Culture Center, in partnership with Tribe, a non-profit publication and platform focused on documenting photography, film, and video from the Arab world, Louder Than Hearts features the work of ten women artists who capture the resilience, strength, beauty, and creativity of women in the region, often in the face of great adversity.

The Egyptian, Iranian, Jordanian, Lebanese, Palestinian, Saudi and Yemeni photographers represented in the show explore the diversity of experiences and personal narratives told by women across a vast geographic area. Each

project showcased is deeply personal, each story distinct Yet together, these works underscore the shared humanity of women, weaving together the threads of personal and collective life experiences while providing insights into the artists' perspectives and realities, as well as their strengths and vulnerabilities.

The exhibition reveals the role of both the photographers and their protagonists as trailblazers and catalysts for change in their communities, providing a portrait of women in the Middle East as voices of peace, courage, and hope

Victoria from My Mother’s Gun series, 2015 by Carmen Yahchouchi Victoria holding her own weapon from the Lebanese civil war of 1975–1990 Mothers are still haunted by those memories Part of a series that captures the enduring impact of the Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990) on women, highlighting their pivotal roles in the middle of chaos and devastation

Whore, 2016 by Heba Khalifa From the Homemade series which explores female identity, body image, and societal pressures through evocative visual narratives in which vulnerability leads to empowerment and shared experiences transcend societal constraints

Dome of the Rock, Theatre Back Drop, 2017 by Tanya Habjouqa From the “Birds Unaccustomed to Gravity” series which maps the psychic and physical boundaries shaping Palestinian lives under occupation It explores the tensions within landscapes and characters etched into the lives of the occupied and occupying populations. The series traces the losses and victories defining Palestinian existence, revealing confrontations, liberations, and the forging, holding, and remembering of space.

Inner Resistance, Occupied West Bank, Za'tara, 2013 by Tanya Habjouqa From the “Occupied Pleasures” series, a multidimensional portrayal of humanity’s ability to find joy amid adversity in the West Bank, Jerusalem and Gaza, utilising a sharp sense of humor about the absurdities produced by a 57-year occupation

Farah (In Her Burnt Car), Abey, Lebanon, 2020 by Rania Matar - part of the series: “Where Do I Go? 50 Years Later” Farah was part of Lebanon’s young generation who took part in the October 2019 uprising against corruption and mismanagement Farah’s car was burnt in the protests The photograph immortalises the car in an act of resistance

Participating artists: Rehaf Al Batniji (Gaza), Tasneem Alsultan (Saudi Arabia), Thana Faroq (Yemen/Netherlands), Tanya Habjouqa (Jordan/US), Shiva Khademi (Iran), Heba Khalifa (Egypt), Safaa Khatib (Palestine), Rania Matar (Lebanon/US), Newsha Tavakolian (Iran), Carmen Yahchouchi (Lebanon)

The title was adopted from a poetry collection on love and loss by Lebanese poet Zeina Hashem Beck These images were displayed at the MEI Art Gallery in Washington DC from May to October 2024

Chiaki Mukai is a Japanese cardiovascular surgeon and astronaut who became the first Asian woman in space Before being selected by the National Space Development Agency of Japan (now called JAXA), Mukai held an number of positions at a range of hospitals and institutions including becoming Assistant Professor at the Department of Cardiovascular Surgery at Keio University In 1985 she was selected as an astronaut and after intensive training and research flew on the Space Shuttle Columbia in 1994 During this mission she conducted eighty-two life science and microgravity science experiments In 1998, she became the first Japanese citizen to have two spaceflights when she flew on the STS-95 mission onboard the Space Shuttle Discovery

(pictured below) After her second flight, Mukai continued supporting space exploration working as deputy mission scientist for the STS-107 mission. She has since held positions as a Visiting Professor at the International Space University, Director of the Space Biomedical Research Office of JAXA, Director of JAXA’s Centre for Applied Space Medicine and Human Research and an advisor to JAXA’s Executive Director and Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology From 2015, Mukai has been the Vice President of Tokyo University of Science Japan has long struggled with gender inequality but that hasn’t stopped trailblazers like Chiaki Mukai from leading world-changing research and smashing the glass ceiling.

Transcripts of our most recent talks and panel discussions are available to download on the RSAA website, where you can also access recordings from our YouTube channel

Raffello Pantucci is an internationally acclaimed foreign and security policy expert This lecture explores China’s growing influence across Centra Asia based on more than a decade of writing, research and travel. The lecture provides an insig into Beijing’s expanding economic, cultural and political power, offering a deeper understanding the transformative effect of China’s foreign policy vision and its economic and trade policies

Scholar of Asian history David Chaffetz tells the story of the steppe raiders, rulers and traders who amassed power and wealth on horseback from the Bronze Age through to the twentieth century Drawing on a wealth of primary sources - in Persian, Turkish, Russian and Chinese - Chaffetz presents a ground-breaking new view of what has been known as the “Silk Road”, and a lively history of the great horse empires that shaped civilisation

*A recording of this event is not available

Dr Yu-Ping Luk delivered an exclusive introductory talk to a group of RSAA members exploring the background to the Silk Roads exhibition and its contents. The exhibition offered a unique chance to see objects from the length and breadth of the Silk Roads From Indian garnets found in Suffolk to Iranian glass unearthed in Japan, they revealed the astonishing reach of these networks

PROFESSOR EMERITUS JENNY WHITE, ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR SEBNEM GUMUSCU AND HANNAH LUCINDA SMITH

This online panel discussion was the first in our new series Power, Legitimacy and Influence: The Future of Asia which will run over the next two years and cover six long-standing regimes and leaders in Asia that have had and continue to have huge influence outside their own borders, shaping the region and its trajectory This event was guest moderated by Dr James Ryan and examined the rise of the AKP and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the resultant democratic backsliding and the use of Islamic nationalism to shape contemporary Turkish politics It also considered what impact these domestic developments are having on Türkiye’s foreign policy, particularly in relation to the Middle East.

The Reading Room gives RSAA members the opportunity to discuss a book with its author or another specialist commentator. As well as the chance to discuss excellent new books about the hugely diverse countries and regions of Asia, these meetings are great opportunities to connect with others in the RSAA network who share your interests.

Throughout history, the Indian Ocean has been an essential space for trade, commerce, and culture. Every European power has sought to dominate it Now, after a lull in the postwar period, control of major shipping routes has once again become a critical aspect of every rising state’s ambition to be a global power

Darshana M Baruah shows how governments from Washington, DC, to Nairobi and Canberra are expanding their interests in the region The Indian Ocean is resource rich, strategically placed - and home to over two billion people Island nations have become more important than ever, with Madagascar forming ties with Russia and the Comoros with Saudi Arabia It is also through the region that China engages with Africa and the Middle East This is a compelling account of the geopolitical significance of the Indian Ocean - showing how the region has taken center stage in a new global contest

Darshana M Baruah is a fellow with the South Asia Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace where she directs the Indian Ocean Initiative. Through the Initiative, Baruah convenes the annual Indo-Pacific Islands dialogue bringing together the islands of the Indian Ocean and the Pacific to highlight and discuss issues of importance to island nations Baruah’s primary research focuses on maritime security in the Indo-Pacific and the role of islands in shaping great power competition Her work examines the impact of maritime security in foreign policy engagements, naval strategy, maritime partnerships in the Indo-Pacific, and island agency in shaping great power competition.

In this thought-provoking new work, historian Justin M Jacobs challenges the widely accepted belief that many of Western museums ’ treasures were acquired by imperialist plunder and theft His account re-examines the allegedly immoral provenance of Western collections, advocating for a nuanced understanding of how artefacts reached Western shores. Jacobs examines the perspectives of Chinese, Egyptian and other participants in the global antiquities trade over the past two and a half centuries, revealing that Western collectors were often willingly embraced by locals. This collaborative dynamic, largely ignored by contemporary museum critics, unfolds a narrative that may lead to hope and promise for a brighter, more equitable future.

Justin M Jacobs is Professor of History at American University, Washington DC He specialises in China and the Silk Road, teaching courses on modern China, the Japanese empire, the history of archaeological expeditions, world heritage sites, and voyages of exploration in the Pacific.

The RSAA’s journal, Asian Affairs, is published with Taylor & Francis which entitles RSAA members to a 30% discount on any full priced CRC Press or Routledge book.

To redeem this discount please login to your RSAA account via our website. Once you have logged in you will see a blue button entitled “Show Code”, click on the button to reveal the discount code. To use the code click “Use Code” on the right hand side of the blue button. This will take you directly to the Routledge website and automatically apply your discount code to any full priced book that you’d like to purchase. You can also just copy and paste the discount code into the “Enter Promo Code” box during checkout on the Routledge website.