Lucy Noakes, President of the Society, on a year speaking with and listening to RHS fellows and members, identifying the Society’s principal aims and objectives for the future, and broadening advocacy work to support and champion the practice of history.

I hope that you enjoy reading our annual newsletter which is being sent to you online and in a slightly different format to that of recent years. The 2025 Newsletter is accompanied by release of our ‘Strategy for 2026-28’, which sets out the Society’s priorities and key aims for the next three years, as well as a new ‘Guide for Members’ which provides an accessible overview of the opportunities and benefits of your Royal Historical Society membership. We are releasing all three publications — Strategy, Guide and Newsletter — to coincide with the Society’s 2025 Anniversary Meeting (21 November). As well as being sent to you by email, all three publications are available on the Society’s website.

November 2025 marks the end of my first year as President. The past twelve months have been busy and important ones for the Society. Council and office colleagues have worked to develop a new strategy built on our key priorities, that will enable us to focus our resources and ensure that the Society’s future actions are as effective as possible. This is a significant time for history and the wider humanities and our new strategy seeks to address and respond to this.

We began this work in Spring 2025 with a large-scale membership survey, asking you to identify the most important concerns facing history and historians today, what you thought the Society did well, and what you would like to see us do better. Thank you to everyone who took the time to participate. We followed this survey with a number of focus groups, each involving members who represent particular categories or interests — including early- and mid-career historians, independent researchers working without institutional affiliations, and our international members — to address topics raised in the survey in more detail. Two further groups discussed the Society’s future as an advocate for history and how we best support the membership in the months and years ahead. Again, many thanks to all who took part. The thoughtful comments and suggestions from the survey and the focus groups are central to the priorities, actions and new initiatives set out in the 2026-28 Strategy.

“ We are widening and strengthening our advocacy and campaigning work. Key to this is collaborating with others, sharing ideas, resources and expertise.”

It has been a testing year for many, as history and the humanities continue to be under-valued and under-funded. The Society is keenly aware of these challenges and we are widening and strengthening our advocacy and campaigning work. Key to this is collaborating with others, by sharing ideas, resources and expertise. We continue to work closely with the Institute of Historical Research (IHR), the Historical Association and History UK, and in February 2025 we published a joint statement on the value of history and the issues facing the profession. We also work closely with the British Academy, and participate in regular meetings of their strategic forum for the humanities, which brings together representatives from learned societies and research councils. In March we demonstrated the value of history in our popular annual ‘History

and Archives in Practice’ conference, organised with The National Archives and the IHR. In June we held the latest in our series of meetings of UK historical societies, which brought together heads of 30 subject specialist societies to discuss and share advocacy strategies. We have elsewhere written on the value of history for History Workshop and the BBC History Magazine, and shared our ideas through the podcasts of BBC Radio 4’s Today Programme and BBC HistoryExtra when (in April) I spoke about the impact of cuts for the provision of history in UK higher education.

Looking further afield, we have been meeting with our sister historical associations around the world, sharing ideas and strategies, and learning about the opportunities and challenges that colleagues face. You can read about the initiatives developed by the Australian Historical Association in a post that we published in February. More recently, in November 2025, the Royal Historical Society convened a panel on advocacy at the North American Conference on British Studies in Montreal; a popular and lively successor to our panel on the crisis in the humanities at the 2024 conference. We will soon publish a summary of the key ideas developed in this session. In addition, we continue to maintain a suite of resources, including our ‘ Toolkit for Historians’ and ‘Data for the Profession and Discipline’. These guides provide links to RHS and external resources, useful when campaigning for history, and offer an up-to-date picture of history, particularly within higher education, so we may represent our subject and its practice accurately and with confidence. This public-facing work is in addition to the ongoing meetings held, behind the scenes, with historians and university managers as we seek to minimise the cuts and severe disruption caused by the present financial crisis facing UK universities.

This year we’ve also continued to work with history departments and historians across the UK, visiting colleagues at the universities of Exeter at Penryn, Aberdeen and Suffolk. Coming soon are visits to historians working at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the UCL Institute of Education (December 2025), and at Sheffield Hallam University (February 2026), with events planned for the universities of Aberystwyth, Strathclyde and the West of England later next year.

Among the many enjoyable elements of these visits is hearing from colleagues about their work and meeting with fellows and members at the receptions that now follow the public lectures, and which are such a popular element of the RHS visits programme. Further details of forthcoming visits will be available via the Society’s website and regular news updates, and I look forward to meeting as many RHS members as possible in 2026. Initiatives like these come in response to your requests that the Society is more proactive in its work outside London, where we have our office and host our in-person meetings. In line with this, in May 2026 we will hold a meeting of the RHS Council at the University of Warwick, and follow this with our annual early modern lecture, by Sasha Handley (University of Manchester), and a reception. If you work at an institution that would like to host a Council meeting and lecture in the future, please get in touch

Public appetite for history is an asset and one we must better understand and build on — not least by establishing closer connections between researchers in different sectors and making the work of historians in universities more legible to, and appreciated by, the many who enjoy history as a popular pursuit.

The numbers attending the Society’s UK-wide lectures and other events, including our London lecture series, and the annual Prothero and Anniversary lectures are a reminder — if one were needed — of the enduring popularity of history among the wider public. This was reinforced when I attended the Chalke Valley History Festival in June and saw the crowds that gathered every day to listen to historians and take part in activities. This appetite for history is an asset and one we

must better understand and build on — not least by establishing closer connections between researchers in different sectors and making the work of historians in universities more legible to, and appreciated by, the many who enjoy history as a popular pursuit. One way of doing so is to champion the excellent collaborations that currently exist. In 2025 the Society launched a new Public History Grant programme, generously funded by the Scouloudi Foundation, to support work by historians within and beyond higher education to develop projects that involve and address wider audiences.

This new grant is one of thirteen programmes in the Society’s portfolio of research funding that are currently available to RHS fellows and members. Research funding is a major part of the Society’s work and one that’s becoming ever more important as sources of ‘small pot’ funding for research continue to diminish. Appreciating and responding to these changes is a priority of the Society as we look to best support our membership and the wider historian community. The range of funding opportunities open to members of the Society is set out in detail in our new ‘Guide for Members’, released this month. We hope those who’ve joined the Society in 2025 find this a useful introduction for making the most of your association. For existing members, the Guide offers a reminder of what’s available, and highlights some recent additions to their membership of the Society.

Throughout the year, the Society has continued to provide information and training to the historical profession. For those employed in UK higher education, there has been considerable attention on the next Research Excellence Framework (REF) which will determine future allocations of research funding. At the time of writing, much remains unclear about the terms and scope of ‘REF2029’, on which the Society continues to provide regular updates. In March, we held a webinar for historians on what it means to be a REF subject-panel member, and have continued to follow and interpret subsequent pilot exercises and policy announcements. We are delighted that Jonathan Morris has been appointed Chair, and Claire Langhamer as Deputy Chair, of the History subject panel. Both are long-standing fellows and friends of the Society and — with Barbara Bombi, the Society’s current Secretary for Research, also confirmed as a panel member — they bring a wealth of expertise and experience to the work of the REF. We await further developments and will continue to represent the interests of historians in a policy landscape that all too often seems dominated by STEM models of working. As soon as the next stages of REF2029 are confirmed, we will provide further information for our members.

Away from REF, members of the Society’s Council have been leading on discussions on the implications of Generative AI for history teaching and assessment. In September we held a symposium in Edinburgh which brought together 25 historians at a range of career stages, including students and postgraduate researchers, and with differing levels of experience of and engagement with AI technologies and practice in teaching. We are now reflecting on the insights, concerns and recommendations of those in Edinburgh who provided an initial conspectus of experience and opinion. This will include how the Society best supports those who teach history in the context of Gen AI.

You will read later in this Newsletter about the Society’s award of prizes in 2025, our grant programmes (including new awards for public history and conference panels) and our publications. You will also get first sight of some new developments in ‘Applied History’, meet the Council members elected in 2025, and hear about new appointments for our excellent Office staff. I know that many of you will have been in touch with them over the year and will be well aware of the friendly and efficient way in which they manage the multiple demands of a busy and active learned society.

“Peter Marshall was a generous scholar and colleague, and many of us will have benefited from this generosity, perhaps most notably through his

provision

of the RHS Marshall Fellowships which

since

2005 have helped students to complete their doctorates. He will be greatly missed.”

One of the more valuable historical aphorisms is the statement that we each stand on the shoulders of those who have preceded us. Over the past year I have often been reminded of the essential truth of this saying, and I am hugely grateful to all of the past Presidents and Councillors who have offered advice and encouragement, and on whose work the Society continues to build. In particular I want to remember the work and many legacies of Peter J. Marshall, President of the Society from 1996-2000, who died this summer. Peter was a generous scholar and colleague, and many of us will have benefited from this generosity, perhaps most notably through his provision of the RHS Marshall Fellowships which since 2005 have helped students to complete their doctorates. He will be greatly missed. You can read more about Peter’s life and work below, in an article by a past RHS President, Peter Mandler.

To conclude, I would like to thank three current members of the RHS Council who stand down this year — Cait Beaumont, Melissa Calaresu and Rebekah Lee — for their commitment to the work of the Society. Each of them has contributed enormously, and their time and dedication is greatly appreciated.

Lucy Noakes November 2025

Lucy Noakes is President of the Royal Historical Society and Rab Butler Professor of Modern History at the University of Essex.

To contact Lucy about the Society and its work, please email: president@royalhistsoc.org

Following the 2025 Council elections, we are very pleased to welcome three new Councillors to join the Society’s governing body. Professor Catriona Pennell (University of Exeter, Penryn Campus, Cornwall), Dr David Hitchcock (Canterbury Christ Church University) and Dr Stella Fletcher (an independent historian) will begin as Councillors in early 2026. We look forward to working with them and thank those leaving the Council on completion of their four-year term: Professor Cait Beaumont (London South Bank University) Professor Melissa Calaresu (University of Cambridge) and Professor Rebekah Lee (University of Oxford).

We also welcome those who have joined the Society in 2025, as fellows, associate fellows, members and postgraduate members. Our new fellows and members research, teach, promote and campaign for history across a wide range of sectors within the UK and Ireland and beyond.

Our 2025 survey of members was clear on the importance and benefits of being part of the Royal Historical Society. This includes ways of bringing historians into closer contact and dialogue that go beyond the Society’s current online Members’ Directory, introduced last year, and which all are welcome to join and access. We are therefore exploring new options for membership, about which you can read more in the ‘Events’ section of this Newsletter.

This month we release an online ‘Guide for Members’ which summarises the benefits of becoming a fellow or member of the Society, with links to relevant pages of the RHS website. We hope this offers a useful orientation and a reminder of what’s available to our existing membership. We will keep the ‘Guide’ up-to-date as new benefits of membership are made available.

New research funding programmes

2025 saw the creation of three new schemes within the Society’s programme of research funding. Two of these new grants — for public history projects and conference panels — are generously supported by the Scouloudi Foundation and are designed to bring together historians working within and beyond higher education. A third scheme, co-hosted with the Institute of Historical Research and the publisher DC Thomson, will provide Applied History Fellowships for post-doctoral historians looking to use their historical training and skills to gain professional experience beyond higher education. These Applied Fellowships will include funded placements with The Social History Archive, and career development and mentoring via the Institute and the Royal Historical Society.

Further awards were made this year across a wide range of career stages. These include Master’s students from groups currently underrepresented in academic history, PhD students completing their dissertations, early-career historians, and mid- and later-career researchers. Funding takes the form both of individual grants and fellowships, and support for group projects and initiatives in history teaching and research. In the financial year 2024/25 the Society was pleased to award just under £150,000 in grants to 75 historians as individual researchers and lead applicants for historical projects.

Our congratulations to the recipients of this year’s RHS Book and Article Prizes, announced in July. The 2025 First Book Prizes were awarded to Laura Flannigan for her monograph Royal Justice and the Making of the Tudor Commonwealth, 1485-1547 (Cambridge University Press, 2024) and to Jules Skotnes-Brown for Segregated Species: Pests, Knowledge, and Boundaries in South Africa, 1910–1948 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2024).

The two winners of the RHS Early Career Article Prize were William Jones for ‘“ You are going to be my Bettman”: Exploitative Sexual Relationships and the Lives of the Pipels in Nazi Concentration Camps’, published in The Journal of Holocaust Research (2024) and Michaela Kalcher whose article, ‘ The Self in the Shadow of the Guillotine: Revolution, Terror and Trauma in a Parisian Diary’, appeared in History Workshop Journal (2024).

Laura, Jules, William and Michaela received their awards from Lucy Noakes, the Society’s President, at the Prothero Lecture on 2 July 2025.

Submissions for the 2026 prize round are now invited with a closing date of 15 December 2025: please see the Society’s website for more. We expect to announce the winners of the 2026 prizes at next year’s Prothero Lecture.

We are very pleased to welcome, in late 2025, two new members of staff in the Society’s professional Office based at University College London. Hannah Elias is the new Events and Academic Engagement Officer and from December will manage the running of the Society’s lectures, workshops, panels and visits in 2026 onwards. Hannah will also be the principal contact for recipients of RHS research funding, to ensure the Society keeps in touch with grant holders during and after their awards — enabling us to communicate their activities, and findings, to the wider fellowship and membership. From November 2025, we also welcome Charlotte Cull as the Society’s new Membership and Office Administrator, with responsibility for communications with members and grant recipients.

Hannah and Charlotte join the Society’s existing staff: Philip Carter, Director; Lisa Linossi, Membership and Programmes Manager; and Sabiqah Zaidi, Governance and Finance Officer.

This November we launch the Society’s new Strategy which will inform our activities over the coming three years.

The ways in which the Society supports history and historians are closely shaped by the environment in which we work. This strategy appears at a time of considerable instability, disruption and uncertainty in the professional lives of many of our members, and especially those who teach and research in higher education in the UK and worldwide. Historians working in the galleries, libraries, archives and museums field also face funding challenges, while independent historians seek and deserve greater recognition of their work and support in accessing resources.

Our five strategic goals, from 2026 on, recognise both the turbulence and precarity which many historians now face, as well as the public popularity, potential and value of history. The priorities and initiatives proposed here enable the Society to better support the historical discipline and profession — to respond effectively to these pressures and opportunities where needs are greatest. Therefore our priorities for the Society will be to:

1

2

3

4

5

Champion, promote and celebrate historical research and expertise, to advance the creation of historical scholarship and the public understanding of history

Advocate and campaign for the value of history, and the work of historians, wherever they are located

Strengthen the profile and reach of the Royal Historical Society to support the historical discipline and its practice

Enable our fellows and members to pursue historical research through a programme of publications, funding, training, events, networking and engagement

Ensure a confident and sustainable future for the Royal Historical Society

In identifying our strategic priorities, we have engaged in many conversations: with current and former Councillors, partner organisations, history practitioners, and — above all — with our fellows and members.

With this strategy, we seek to offer a working document that results in tangible, positive developments in the Society’s contribution to historical research and practice, and discernible benefits for our membership, historians more widely, and the discipline. We therefore intend the five strategic goals to be accompanied by sustained actions and new initiatives, and that these take account of the interests and priorities of the Society’s membership and the wider historical profession.

You can read more about these goals and actions here. If you would like to contact the Society about its new Strategy, or if you would like to be involved more closely with the Society’s work, please get in touch.

The Society was very sorry to learn of the death, in July, of the historian Peter J. Marshall (1933-2025). Peter’s association with the Royal Historical Society spanned more than 50 years. Elected a fellow in 1969, Peter served as a member of the Society’s Council between 1983 to 1987, thereafter becoming Vice President until November 1991. He returned to the Council in November 1996 as the Society’s President and held this position for four years.

In this article, Peter Mandler, who served on the RHS Council with Peter from 1998, remembers Peter Marshall’s extensive and very considerable contribution to the Royal Historical Society, both during and after his term in office.

Peter was one of the most eminent historians of his generation. He certainly won all the accolades — elected a fellow of the British Academy, one of the authors in the late 1980s of the first national curriculum for history, appointed a CBE by the Queen for services to history, as well as of course his terms as a Vice President and then President of the Royal Historical Society, the latter from 1996 to 2000.

Those honours were tributes to his public service, and his public spiritedness, but also to the quality of his scholarship. Peter was one of the first generation of historians of the British Empire to begin to detach themselves from a more personal or political interest in the empire and to see it more objectively and in the round. His work focused mostly on the history of India and the ways in which the British Empire did not displace but largely worked through indigenous systems of rule; he was also always interested in ideas about empire, and particularly about the ideas of Edmund Burke in the late-eighteenth century, both about India and the Americas.

Not that Peter’s approach to empire was purely detached: he liked to remind people that he was born in Calcutta under British rule, he relished his CBE with the words British Empire in the title; but he was not sentimental and he could see the ridiculous as well as sometimes the sinister side of empire. I recall well a story he told with typical ironic amusement, of the year he spent in Kenya on national service in the early 1950s, watching Colonel Sydney La Fontaine parade through the heat and dust of his district in his ludicrous military dress uniform with the high hat topped by ostrich plumes. Peter knew then that that world was on its last legs, and he was right.

“It was instantly clear to me that the Society was then in the midst of a significant transition and that Peter was driving it.”

I was lucky enough to be appointed Honorary Secretary of the Royal Historical Society — essentially, the President’s aide-de-camp, or dogsbody — halfway through Peter’s term leading the organisation. It was instantly clear to me that the Society was then in the midst of a significant transition and that Peter was driving it.

The Society had always been a promoter and publisher of historical scholarship but in a rather clubby way, its leadership drawn from a fairly tight circle, mostly of British historians — the last non-metropolitan historian to serve as President before Peter was Robin Humphreys, the Latin Americanist, in the late ‘60s — and a lot of its time had been spent on set-piece lectures, prizes, elections to the fellowship and its library housed at UCL.

The Society had fallen behind in recognising the diversity of the discipline and the profession and the need to advocate for it with policymakers and university leaders; the History at the

Universities Defence Group (HUDG) and the Campaign for Public Sector History (PUSH) had been set up in the 1980s as campaigning bodies to fill the gap.

The period in which Peter was most active as a statesperson for his profession — from the late ‘80s to the early 2000s — was a time of significant transition as his generation was beginning to give way to baby boomers like me, much more expressive, impetuous, and full of ideas for change. On the whole Peter put himself on our side and — in his sober, low-key way, often more effective than the full-frontal assault — he dragged the Society literally into the 21st century, updating its antiquated procedures, engaging it with schools and the media and popular history, and helping to make it the vigorous and credible advocate for serious history among ever widening audiences that it is today.

Peter with Jinty Nelson (1942-2024) who succeeded Peter as President of the Royal Historical Society in November 2000. Royal Historical Society archive.

Peter’s own specialism in imperial history might have been an impediment. Some of the younger, so-called ‘new imperial’ historians felt he was not sufficiently anti-imperial or attuned to the discordant interests of coloniser and colonised (though his work was all about teasing out those disparate interests, and showing how they could conflict but also how they could mesh.) Even at the height of those professional conflicts, he maintained warm relations with the younger generation and kept together a network comprising people of all views.

Before he was President, Peter had already taken a lead in pressing (sometimes gently, sometimes less so) for a more outward-facing role for the Society and for rapprochement with some of the alienated parties in HUDG and PUSH. Money was found to fund a small programme of grants for postgraduate research, and a monograph series, which had been founded by Geoffrey Elton but had gone dormant, was revived to publish early-career research. As President, Peter had more freedom — and also a lot more time, as he had taken early retirement in part to allow him to do this new job properly.

A galaxy of new initiatives unrolled under his direction. The Society’s longstanding collaboration with the Institute of Historical Research (IHR) in compiling annual bibliographies of British history was taken to a new level with funding from what was then the Arts and Humanities Research Board, digitising the many decades of annual volumes into a consolidated database, first as a CD-ROM, then as an online resource, permitting regular updates. An annual lecture in what we would now call public history was initiated with Gresham College and after his premature death in 1999 renamed in honour of the historian Colin Matthew.

Another partner, recruited by Peter, was History Today which co-sponsored a prize and a publication for the best Master’s dissertation in history. Peter developed a close relationship with Sarah Tyacke, the Keeper of the Public Records, and brought the Society into the world of data protection, freedom of information, and the thirty-year rule. The Society engaged with the relatively new Research Assessment Exercise and was able to advise the funding councils not only on history personnel but on the overall formation of the exercise in ways that accommodated the often-marginalised humanities, an important policy departure that has kept the Society at the forefront of advocacy for the humanities ever since.

Peter’s association with the Society continued long after his Presidency, not least with his generous provision of the annual RHS Marshall Fellowships, begun in 2005, to support early career researchers to complete a doctorate in history. More than 25 historians have benefited from this programme, run jointly by the Society and the IHR, and Peter maintained a close interest in recipients’ research, including that of the two PhD students who received fellowships for the final time in 2024-25.

“I sat through a lot of committee and Council meetings when Peter was in the chair and could observe the masterly way in which he both took advice and built consensus.”

I have probably forgotten many other important initiatives. What I have not forgotten is Peter’s inimitable style. I sat through a lot of committee and Council meetings when Peter was in the chair and could observe the masterly way in which he both took advice and built consensus. He would open up a subject and ask for colleagues’ views — he seemed to know just the right length of time to collect those views, just the right length of time to pause, just the right length of time then in which to propose his resolution, and just the right length of time to pause again before taking silence as consent.

Peter was always master of his brief, had always anticipated trouble or opposition, and nearly always got the result he wanted — and then, whether or not it was the desired result, he knew how to act on it. If his own temperament and generational instincts inclined him to slow the pace of change, his keen sensitivity to the way the wind was blowing — and the direction the bulk of his colleagues were shifting — impelled him to embrace change, and his tact and obvious integrity accelerated it.

In early 1999, a few months after I took office, I wrote an email to Pat Thane about Society business, at the end of which I said: ‘I’m finding my RHS job strangely compelling. Among other pluses it gives me regular contact with congenial, intelligent and professionally responsible people, which I don’t otherwise get in my anomic London life. Also I feel already that I am doing something useful. And finally,’ I concluded, ‘Peter Marshall is a complete sweetheart.’

Peter Mandler FBA was President of the Royal Historical Society between 2012 and 2016 and President of the Historical Association (2020-23). Prior to his retirement at the end of the academic year 2025, Peter was Professor of Modern Cultural History at the University of Cambridge.

A memorial event for Peter J. Marshall will take place at King’s College London on 27 January 2026, and will include presentations from former RHS Marshall Fellows, 2005-25.

Events are a major feature of the Society’s work, combining our well-established lecture programme with new activities and initiatives. They are also an excellent opportunity for historians of all kinds to come together. Events — which take place in central London and at venues across the UK, as well as online — also provide time to catch up, and to meet members of the RHS Council, at the receptions that follow. We hope to welcome you, in person or online, at one of our events in 2026.

The Society begins its 2026 events programme, on Friday 6 February, with the first in our RHS Lecture programme featuring the medieval historian Charles West (University of Edinburgh). Charles’s lecture is followed by those of the early modern scholar, Sasha Handley (Manchester), on 1 May, and the historian of modern Britain, Glen O’Hara (Oxford Brookes) on 25 September. On 1 July we host the 2026 Prothero Lecture, which is given by Rebecca Earle (Warwick), and is followed by the Society’s annual summer party. For our Anniversary Lecture (27 November) we welcome Hanna Diamond (Cardiff) who is a historian of modern France.

Our partnership lectures for 2026 — held in association with the German Historical Institute, London and Gresham College — take place in February and November. February’s RHS / GHIL Global History Lecture will be delivered on 10th of that month by Vinita Damodaran (Sussex) while on 3 November we welcome Sathnam Sanghera to give the 2026 RHS Public History Lecture.

During 2026 our London lectures will be held jointly at Mary Ward House, Bloomsbury and, in a new departure, at the Institute of Historical Research, Senate House, which reflects our close working relationship with the IHR as we collaborate in promoting the value and practice of history. As now, the Society’s London-based lectures will also be open for remote, online attendance. New in 2026 is the holding of one of our traditional ‘London lectures’ outside the capital. On 1 May, therefore, we will be at the University of Warwick for Sasha Handley’s talk which will follow a meeting of the RHS Council at the same venue. We are keen to extend this practice in 2027 and welcome offers from other institutions interested in hosting a Council meeting and RHS Lecture.

As well as Warwick, the Society will be visiting historians at the universities of Sheffield Hallam (18 February), Aberystwyth (May), Strathclyde (October) and the West of England (December). Visits are an opportunity to meet those who research and teach historically across a university (many of them now working outside traditional history departments) as well as the many archivists, community and public historians with whom they collaborate, and — importantly — members of the Society from the region. Each visit will include an RHS-sponsored guest lecture and the 2026 Visits programme will include a presentation by David Stack at Sheffield Hallam, with details of those speakers joining us at Aberystwyth, Strathclyde and the University of the West of England available in the near future.

In addition, on 16 April, the Society cohosts the 2026 ‘History and Archives in Practice’ conference, with The National Archives and Institute of Historical Research. We’re delighted that HAP26 takes place in Sheffield, in partnership with the University of Sheffield Library, in a programme dedicated to historians’ and archivists’ work to effect civic and social change.

Alongside its programme of lectures, visits and conferences, the Society hosts regular workshops to provide focused support for historians. For 2026 we offer events relating to career paths outside higher education, as well as workshops for history educators facing up to course closures and loss of research time. To accompany the Society’s new Applied History Fellowships, we will also run sessions on historians’ skills and their value to employers.

This year a considerable number of RHS members have spoken of the importance of coming together as historians — especially at a time when cuts and restructures leave many feeling more isolated. The Society has an important role here in bringing together its members, often in more informal in-person meetings, which we look to initiate and develop in the coming months. Further details of these sessions and our 2026 programme of workshops will be circulated from early in the new year.

For more on what’s available in 2026, please see the ‘Events’ pages of the Society’s website. All our events are recorded and are available as videos and audio recordings to watch or listen to again. We look forward to seeing you in the coming months.

The 2025 volume of Transactions (Seventh Series, Volume 3) is published in November and will be sent to members of the Society as a print or online edition, based on their preference for receiving this publication.

In the following notice, the co-editors of Transactions, Jan Machielsen and Paul Readman, report on 12 months with Transactions and on the latest volume.

It’s been a year of progress for Transactions. In January, Paul Readman joined Jan Machielsen as co-editor, restoring the editorial team to its full complement. This was just as well, since the volume of business dealt with by the journal has continued to increase, with the 2025 volume being the largest yet published by TRHS in its new guise. Heft, however, is not everything. The quality of the articles we have published — across the whole range of history and all geographical areas — remains outstandingly high.

Autumn 2025 also marks our first complete year as a fully Open Access journal, which means authors publish without charge and new content is as accessible as possible. As a result, our readership is growing. Downloads of articles from our website have increased significantly over the past year: the September figures, for example, are 50% higher than for those of the same month in 2024. While new editions of the journal appear annually (each November), individual articles are published on FirstView as soon as they are ready.

Transactions is a distinctive journal. We continue to publish the revised text of lectures delivered at Society meetings, for those who seek to publish in this way and following peer review. Most of our articles, however, start life as unsolicited submissions. Indeed, we welcome submissions from historians of all kinds and all career stages: from PhD students to professors emeriti, from independent scholars working outside university departments, to established academics working within them. Authors also reflect the interests and priorities of an international community of historians who are engaged with collections worldwide. We are proud of the diversity of Transactions authors and are keen to see this increase further.

We are proud, also, of our Common Room section, which has established itself as a unique feature of the journal. The Common Room is a place for intervention on matters of pedagogy, policy, and public uses (and abuses) of the past; for methodology, historiography and the craft of historical writing; for roundtable discussions and debate; for experimentation, provocation and reflection; for contributions that don’t quite ‘fit’ the standard categories used by academic publications. One recent example was the celebration ‘in thirteen articles’ of a former President of the Royal Historical Society, Jinty Nelson (1942-2024), cherished to the memory of so many of us. If you have an idea for a Common Room piece, don’t hesitate to contact the editors. We’d be pleased to hear from you.

Jan Machielsen is Reader in Early Modern History at Cardiff University

Paul Readman is Professor of Modern British History at King’s College London

This year the Society has published five monographs in its New Historical Perspectives book series, on subjects ranging from medieval English guilds to the lure of Western Ireland and Scotland, and women’s lives in apartheid South Africa.

2025 also saw publication of the 25th title in the NHP series, with all volumes published in print and free Open Access editions by University of London Press. Titles in the series have now been downloaded on nearly 200,000 occasions.

Print discounts of 30% are available to all RHS fellows and members on this year’s new volumes, and all other titles of the NHP series via University of London Press (UK, EU and RoW) and University of Chicago Press (North America).

To take account of this offer please apply the discount code: RHSNHP30. All 25 titles in the series are also available as Open Access downloads and in a Manifold digital reader edition.

In 2025 the Society has published three volumes in its Camden Series of scholarly primary editions, including The Papers of Admiral George Grey, edited by Michael Taylor (June, which is available Open Access from the Society) and A Collector Collected. The Journals of William Upcott, 1808-1823, edited by Mark Philp, Aysuda Aykan and Curtis Leung (November).

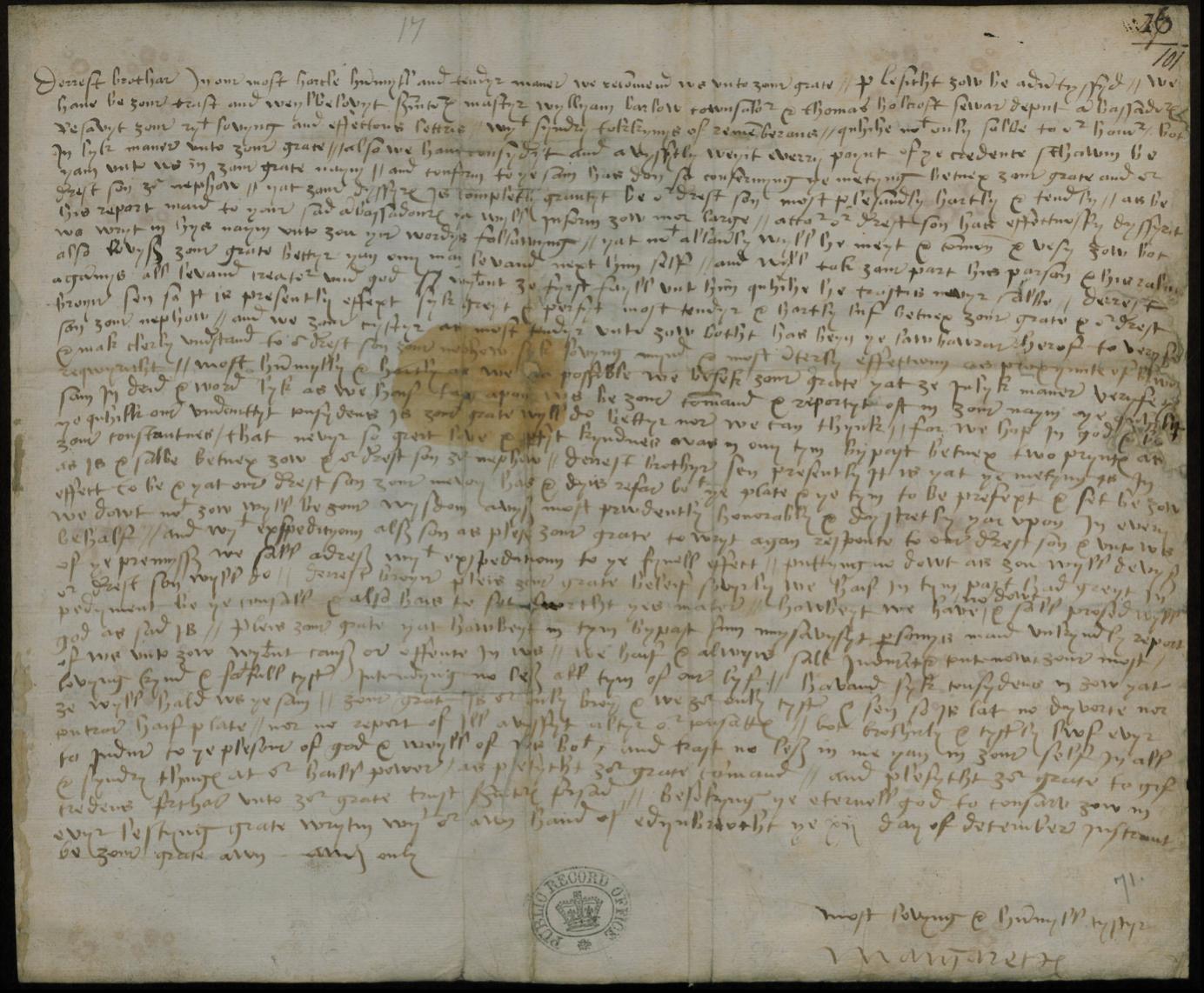

In August, we published Helen Newsome-Chandler’s edition of the holograph letters of Margaret Tudor (1489-1541), which Helen introduces in the next article in this Newsletter.

Our next titles in the New Historical Perspectives and Camden series are Organised Militarism in Interwar Britain The Navy League and the Air League of the British Empire, by Rowan Thompson (published in April 2026) and The Correspondence of Katherine Jones, Viscountess Ranelagh, 1640-1690, edited by Evan Bourke (June).

2026 will also see publication of the first titles in the Society’s new book series, ‘Elements in History and Contemporary Society’.

Part of Cambridge Elements, short monographs from CUP, our new series explores the value, use, discourse, and impact of history in contemporary society and culture – drawing attention to the roles played by a variety of institutions and individuals in the making and use of historical knowledge. All titles in this new series will be funded by the Society to appear Open Access.

Here, Helen Newsome-Chandler introduces her volume in the Royal Historical Society’s Camden Series, The Holograph Letters of Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scots (1489-1541), which was published in August 2025.

This volume presents the surviving holograph correspondence of Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scots as a stand-alone edition for the first time. The 111 holograph letters (written in Margaret’s own hand) and 4 ‘hybrid’ letters (written by a scribe, with a postscript or subsection by Margaret herself) form an unprecedented epistolary archive, featuring the largest collection of holograph correspondence written in English or Scots of any medieval or early modern queen.

Born on 28 November 1489, Margaret Tudor was the eldest daughter of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, king and queen of England. On 8 August 1503, Margaret married James IV, king of Scots, at Holyrood Palace, Edinburgh, as part of the Treaty of Perpetual Peace — a treaty which served to secure peace between England and Scotland after centuries of hostility and warfare.

This union ‘was one of the most important diplomatic alliances made during Henry VII’s reign, and it is through this marriage that the kingdoms of England and Scotland were eventually united in Margaret’s great grandchild, James VI of Scotland and I of England. However, despite playing such a pivotal role in the establishment of the Tudor dynasty and in European politics and diplomacy in the early sixteenth century, Margaret has received substantially less scholarly and public attention than her kin.’1 Margaret, is, however, deserving of attention in her own right.

Margaret Tudor was a prolific letter-writer: 247 letters and diplomatic memorials (also known as ‘articles’ or ‘instructions’) written in her name survive today.

This substantial archive has not gone unnoticed. Muriel St Clare Byrne, in the introduction to her edition of the Lisle Letters (1981), noted that ‘[t]he amount of correspondence with which Queen Margaret of Scotland bombarded her brother […] and all the important persons who had to be cajoled or bullied into doing what she wanted, has to be examined to be believed.’2 In spite of this, there has never been a standalone edition of Margaret Tudor’s correspondence before the present volume, published in August 2025 in the Royal Historical Society’s Camden Series.

Due to restrictions of space, it has not been possible to include all of Margaret Tudor’s surviving letters in my new edition. My Camden volume therefore presents a subset of Margaret’s letters and focuses on the most exceptional part of her epistolary archive: 111 surviving holograph letters (written in Margaret’s own hand) and 4 hybrid letters (letters written by a scribe which feature a subsection or postscript written in Margaret’s hand), written in English and Scots.

“ The unprecedented archive presented in this edition has the potential to provide new understanding of the communicative practices, education, and political and diplomatic activities for medieval and early modern queens for whom we have few, or no surviving letters.”

These 111 holograph letters form the largest collection of holograph correspondence written in English or Scots of any medieval or early modern queen hitherto discovered. In contrast, only 10 holograph letters (written in English) survive for Margaret’s younger sister, Mary Tudor Brandon, queen of France (later duchess of Suffolk). The unprecedented archive presented in this edition therefore has the potential not only to shed new light on the life, character, and voice of Margaret Tudor, but to provide new understanding of the communicative practices, education, and political and diplomatic activities for medieval and early modern queens for whom we have few, or no surviving letters.

Margaret’s holograph and hybrid letters are written across a 38-year period and document much of her life as queen of Scots. The first surviving letter was sent to Margaret’s father, Henry VII, shortly after her marriage to James IV at Holyrood Palace, Edinburgh, in August 1503. Margaret’s final letter was sent to her brother, Henry VIII, king of England, in March 1541, some five months before she died of a suspected stroke at Methven Castle on 18 October 1541.

Margaret Tudor’s surviving letters provide a fascinating insight into the day-to-day challenges that she faced as queen of Scots, especially following the death of her first husband, James IV, who was killed by Henry VIII’s army at the Battle of Flodden on 9 September 1513. For example, Margaret often wrote to Henry VIII complaining that she was facing financial difficulties and

was forced to live like ‘a powr Ientyl vhoman’ (poor gentlewoman), because she struggled to receive regular payment of the rents of her dower lands. Margaret also frequently commented in her letters that she was greatly ‘mystrustyd’ (mistrusted) by the lords of Scotland, who often suspected that Margaret’s allegiances lay with England, and that she was actively conspiring against Scotland’s interest (which, on occasion, she did).

Margaret also regularly wrote to Henry VIII and his noblemen to protest of the mistreatment she received from her second and third husbands, Archibald Douglas, sixth earl of Angus, and Henry Stewart, first Lord Methven, who regularly stole the rents from her dower lands.

For example, in February 1537, Margaret wrote to her brother, noting that Lord Methven had ‘spendyd my landes and profetes a pon hys avne kyn and fryndes In sych sort that he hath made them ope and pwt me In to gret dettes vysche vylbe to the sowm of viijm markes scotyes mony’ (spent my lands and profits upon his own kin and friends in such sort that he hath made them up and put me into great debts which will be to the sum of 8000 marks Scots money).

“Margaret’s letters also evidence her own political ambitions.”

However, the letters also highlight the important role that Margaret Tudor played in Anglo-Scots diplomacy in the early sixteenth century. Margaret was frequently called upon by John Stewart, second duke of Albany (who governed Scotland on behalf of Margaret’s young son, James V, king of Scots) to write to Henry VIII and his noblemen to seek a renewal of Anglo-Scots peace.

In a letter sent to Henry on 9 December 1521, for example, Margaret requested that: ‘ȝe vol for my sake and request and for the viel of the kyng my son your nefew that the pees betwxt your sayd rawlme and thys may be prolongyd vhol saynt Ions day at mydsomar or forthar at your plesur’ (ye will for my sake and request for the wellbeing of the king my son your nephew that the peace betwixt your said realm and this may be prolonged while Saint John’s Day at Midsummer or further at your pleasure).

In 1534, Margaret even wrote on behalf of her then adult son, James V, to organise a diplomatic meeting between James V, and his uncle, Henry VIII. Margaret’s letters also evidence her own political ambitions. Following the death of James IV at the Battle of Flodden in September 1513, Margaret became the regent of Scotland, and was responsible for ruling Scotland on behalf of her young son, James V (who at the time of his father’s death was only 17 months old). This move situated Margaret in an unusual position of power for a late medieval queen, but it was contingent upon her remaining a widow. When Margaret married Archibald Douglas, sixth earl of Angus, in secret in August 1514, she was forced to relinquish the regency to John Stewart, second duke of Albany.

However, for the next 12 years, Margaret actively sought to regain the regency and the power and status that she had previously held. For example, in September 1517, she wrote to the border warden Thomas Dacre, second Baron Dacre of Gilsland, articulating her desires to ‘haue all the rwlle’ (have all the rule) and reassume her control of the regency and Scottish government. Margaret briefly regained some control of the Scottish government when she had her son declared of age to rule independently in August 1524, but she swiftly lost this power when her second husband, Archibald Douglas, sixth earl of Angus, returned to Scotland after being exiled in France.

One of the most distinctive aspects of Margaret Tudor’s holograph letters is their unusual linguistic composition. To date, research into the anglicisation of Scots in the late medieval and early modern periods has shown that Scottish writers regularly adopted features of English into their writing. There is, however, ‘significantly less documentary evidence of English writers adopting Scots linguistic forms into their writing in these periods’.3 Margaret Tudor is the only writer identified by A. J. Aitken in his study of the pioneers of Scots to exhibit such a pattern.4 Margaret Tudor’s letters are thus somewhat unique because she incorporates the use of Scots linguistic features into her writing at certain points in her life.

“ The decision to standardise Margaret’s language in line with modern practices would in effect bleach Margaret’s epistolary voice, removing any opportunity to study her unique linguistic practices.”

The language of Margaret’s letters may pose some challenges to modern readers, as they are presented semi-diplomatically in the edition, preserving the original spelling, punctuation, deletions, and insertions used in the original manuscripts.

However, the decision to standardise Margaret’s language in line with modern practices would in effect bleach Margaret’s epistolary voice, removing any opportunity to study her unique linguistic practices and the role that Scots and English played in her dual identity as queen of Scots and princess of England. In an effort to overcome these challenges, the Introduction of my Camden edition includes a discussion of Margaret’s use of Scots and particularly challenging terms are glossed in the main transcriptions. In addition, an appendix offers a glossary of key terms and an introduction to the Scots language and historical varieties of English.

The edition also provides a substantial introduction which explores the archive of Margaret Tudor’s correspondence, including a discussion of what letters have not survived and the value that Margaret Tudor herself placed in holograph writing. This is followed by a discussion of the language of Margaret Tudor’s holograph correspondence, as well as an analysis of the materiality and delivery of her letters. The volume also includes a detailed biography, to enable readers to better understand the complex political and cultural context in which Margaret’s letters were originally written.

Finally, the edition concludes with a handlist of Margaret’s remaining extant correspondence (Appendix 3), which includes scribal letters, copies of original letters, and foreign language letters. This is the first time such a handlist has been published, and I hope that it will enable readers to access the rest of Margaret Tudor’s correspondence that is not included in the volume.

Working on this edition of Margaret Tudor’s holograph and hybrid letters has been both the largest challenge I have ever encountered, but also a delight. I have loved reading and interpreting Margaret’s unusual language and getting to know the tenacious and unyielding character that comes through in her writing. I hope that readers enjoy Margaret Tudor’s letters as much as I have.

1 Helen Newsome, ‘“[An] old battle constantly re-fought”: Why language matters when editing early modern women’s letters: A case study of the holograph letters of Margaret Tudor, queen of Scots’, Women’s Writing, 30.4 (2023): 337352, 339

2 Muriel St Clare Byrne, The Lisle Letters, 6 vols (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981) I, 65.

3 Helen Newsome, ‘“[An] old battle constantly re-fought”, 341.

4 Adam Jack Aitken, ‘The Pioneers of Anglicised Speech in Scotland: A Second Look’, Scottish Language, 16 (1997): 1–36, 28.

Helen Newsome-Chandler is a historical linguist, with expertise in late medieval and early modern women’s writing and epistolary culture. Her recent publications include contributions to Women’s Writing, Renaissance Studies, Royal Studies Journal, and The Edinburgh History of the Book in Scotland, vol. I: Medieval to 1707

Fellows and members of the Society may purchase print copies of The Holograph Letters of Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scots (1489-1541) at the reduced price of £16 per volume from Cambridge University Press.

To order a copy please email administration@royalhistsoc.org, marking your email ‘Camden’. The online edition is available from CUP as one of 385 volumes in the Camden Series of scholarly primary editions available free to fellows and members of the Society. Similar print discounts and online access are available for other recent Camden volumes in the series.

Recently published Camden titles include:

• The Household Accounts of Robert and Katherine Greville, Lord and Lady Brooke, at Holborn and Warwick, 1640-1649, edited by Stewart Beale, Andrew Hopper and Ann Hughes (2024)

• Allen Leeper’s Letters Home, 1908–1912. An Irish-Australian at Edwardian Oxford, edited by David Hayton (2024)

• The Last Days of English Tangier. The Out-Letter Book of Governor Percy Kirke, 1681–1683, edited by John Childs (2023)

• La Prinse et mort du roy Richart d’Angleterre, based on British Library MS Harley 1319, and Other Works by Jehan Creton, edited by Lorna A. Finlay (2023)

For details of how to access online the complete run of Camden volumes (1838-2025) and of Transactions (1872-2025), which are benefits of Society membership, please see our new ‘Guide for Members’.

18 November 2025: Launch of the Society’s ‘Strategy, 2026-2028’ and ‘Guide for Members’.

21 November: RHS Anniversary Lecture, with Jane Ohlmeyer (Trinity College Dublin): ‘ Visible | Invisible: Voices of Women in Early Modern Ireland’, preceded by the Society’s 2025 AGM.

10 December: RHS Visit to historians at the UCL Institute of Education and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, with a guest lecture by Heather Ellis (Sheffield): ‘Hunger, Health and Hope: A History of School Meals in Britain’.

31 January 2026: Closing date for applications for the new Applied History Fellowships, with the Institute of Historical Research and DC Thomson.

6 February: RHS Lecture, with Charles West (University of Edinburgh): ‘“Alike in Appearance but not in Scope”: Queens and the Making of Medieval Europe’.

10 February: RHS / German Historical Institute Lecture in Global History, with Vinita Damodaran (Sussex): 'Decolonising the Natural History Collections of Empire'.

18 February: RHS visit to historians at Sheffield Hallam University, with a guest lecture by David Stack (Reading), 'Well-being: a Historian's Perspective'.

March: Launch of the call for the RHS Public History and RHS Panel Grants, 2026-27, supported by the Scouloudi Foundation. This is the second year of a new programme to support collaborations between historians working in and beyond higher education, and conference attendance by historians with no access to institutional funding.

16 April: ‘History and Archives in Practice, 2026’ at the University of Sheffield Library: a day conference on the theme of ‘Shaping Societies, Improving Lives: the Impact of Archives and Historical Research’.

9 April: Publication of the 26th New Historical Perspectives volume: Organised Militarism in Interwar Britain: The Navy League and the Air League of the British Empire, by Rowan Thompson. Rowan’s is the first of three monographs to appear in the NHP series in 2026.

1 May: RHS Lecture, with Sasha Handley (Manchester): at the University of Warwick.

May: Launch of the call for the Society’s Jinty Nelson Teaching Fellowships for 2026-27 and annual Funded Book Workshop Grants for mid-career historians.

May: RHS visit to historians at Aberystwyth University.

June: New Camden volume: The Correspondence of Katherine Jones, Viscountess Ranelagh, 16401690, edited by Evan Bourke. The first of three volumes to appear in the Camden series in 2026.

1 July: 2026 Prothero Lecture, with Rebecca Earle (Warwick): followed by the Society’s annual summer party.

July: Award of the 2026 RHS First Book and Early Career Article Prizes.

Officers of the Society, from November 2025

• Professor Lucy Noakes, President, president@royalhistsoc.org

• Professor Clare Griffiths, Vice President

• Professor Barbara Bombi, Secretary for Research

• Dr Kate Bradley, Secretary for Publications

• Dr Adam Budd, Secretary for Education

• Dr Emilie Murphy, Secretary for Advocacy and Public Engagement

• Professor Matthias Neumann, Treasurer

Councillors of the Society, from November 2025

• Dr Catherine Feely

• Dr Stella Fletcher

• Professor Karen Harvey

• Dr David Hitchcock

• Professor Mark Knights

• Professor Iftikhar Malik

• Dr Helen Paul

• Professor Catriona Pennell

• Professor Olwen Purdue

• Dr Jesús Sanjuro-Ramos

The Society’s Office, based at University College London

• Philip Carter, Director, director@royalhistsoc.org

• Lisa Linossi, Membership and Programmes Manager, membership@royalhistsoc.org

• Sabiqah Zaidi, Governance and Finance Officer

• Hannah Elias, Events and Academic Engagement Officer

• Charlotte Cull, Membership and Office Administrator

• General enquiries: administration@royalhistsoc.org

• Social media / Bluesky: @royalhistsoc.org

• RHS News Circular: a weekly digest of RHS activities and of external history events sent to your in-box.

• RHS Members’ Directory: a listing of 3500+ members of the Society and their work to facilitate connections between historians: https://directory.royalhistsoc.org/login/