ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY

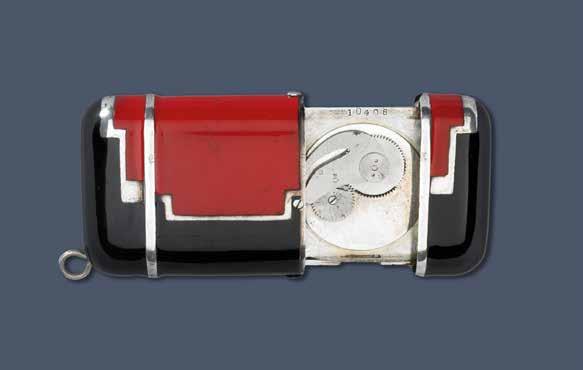

purse watch, Switzerland, c. 1930 © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Hermetic

President’s Letter

Emma Griffin on the Society’s support for history and historians during an especially difficult year for many Royal Historical Society members working in higher education.

As Emma writes here, these challenges are giving rise to new activities by the Society to advocate for the historical community. They include a greater focus on the contribution and value of history, and communication of this—and the Society’s work—to new audiences key to the future health of our discipline.

Welcometo the Royal Historical Society Newsletter for 2024 which combines a review of the principal activities of recent months, and a look ahead to new initiatives. This year’s Newsletter comes at a point of transition for the Society, as I complete my four-year term as President at our AGM in November and hand over to Professor Lucy Noakes as the incoming President. Changes to the Society’s leadership are an opportunity for review and new directions. Later in this Newsletter, Lucy writes about the Society’s recent and forthcoming programme of visits to history departments by members of the RHS Council. I know Lucy will also be in touch after she takes up the presidency to share her initial plans, in tandem with the Council, for the next phase of the Society’s work.

This year’s Newsletter is an opportunity to reflect on some of the key changes and developments in the historical profession during my presidency. There have been many stimulating and hugely enjoyable occasions when, as President, I’ve had the privilege of hosting excellent lecturers and speakers at our events; learned about innovative teaching and research; discussed historical practice with academic historians across the UK; met and corresponded with RHS Fellows and Members, and welcomed many new historians to our Society. This has all been hugely positive.

At the same time, we cannot ignore that the past four years have been ones of growing upheaval, inequality and concern for many professional historians—especially those working in UK higher education. Similar pressures are also experienced by our research students whose university careers are being negatively affected by the turmoil faced by many departments and the HE sector more broadly.

Hearing from, and working with, colleagues who face cuts and closures—to staffing, degree programmes and courses—has been a dominant, and sadly ever increasingly, feature of my time as RHS President. Our records show that, since 2021, the Society has worked with 21 different departments, threatened by or experiencing cuts, of which several have suffered repeated rounds of redundancy and retrenchment. Indeed, whilst President, my previous department entered a round of compulsory redundancy. A once occasional problem has now become business as usual.

initiatives and reforms which place additional burdens on the profession. This year, for example, we’ve seen a series of proposed changes concerning the next Research Excellence Framework (REF) for universities. In the Society’s opinion, these pay little heed to how academic historians work, and show scant understanding of the environment in which humanities research is undertaken and communicated.

“The Royal Historical Society has a responsibility to respond to, and resist, damaging reforms in our sector. This we do in a variety of ways.”

I have written before about the scale and seriousness of these threats to history as well as their very unwelcome consequences. At the root of this crisis is a series of damaging political actions that have failed to implement a sustainable funding model. The marketisation of universities—coupled with politicians’ refusal to engage with the realities of HE funding, and a talking down of the value of degrees in history—is taking a heavy toll on our members’ capacity to teach and research, and on the future security of history as a subject available to all students across the UK. It’s fair to say that the challenges we face have intensified over the past twelve months. This is due not simply to further and deeper cuts to departments, and the growing financial crisis experienced by the sector as a whole, but is also a consequence of recent government-led

The Royal Historical Society has a responsibility to respond to, and resist, damaging reforms in our sector. This we do in a variety of ways. In Spring 2024, for example, the Society spoke against proposals that books submitted for review in the next REF should be available Open Access. REF’s subsequent decision to drop this requirement in full is a very welcome outcome. We are grateful to Fellows and Members of the Society who responded to our questions relating to REF and Open Access publishing, which helped us present a strong case against this proposal.

In addition, we have continued to campaign against cuts by meeting with colleagues, engaging with university managers and the media, and via public statements. Many of you also responded to a second RHS survey, this summer, on the form and scale of departmental cuts and closures not previously brought to our attention. The results show that the extent of negative change goes much further than those cases on which we have worked. By our estimate, 40% of UK history departments have been affected by cuts and closures, with cuts falling very unequally across the sector— over 80% of the respondents from post-92 institutions reported a contraction of history provision, as did nearly 70% of those in pre92 non-Russell Group institutions.

Some of these findings are now reported

in the Society’s latest briefing—’The Value of History in UK Higher Education and Society’—published in October. As its title indicates, this work also marks a development in our approach: with greater emphasis on identifying and communicating the positive contribution of history, and a move to more proactive campaigning for our subject. October’s briefing—discussed further on pages 5 and 6 of this Newsletter—considers history’s value principally in the context of university education, with reference to strong student enrolment, professional outcomes and high levels of graduate satisfaction.

We are also continuing to work with UK politicians and policy makers. During the past year, the Society has formed a number of valuable and lasting connections with MPs and Lords keen to speak up for history and advise us on raising the Society’s profile at Westminster. You’ll find more on this on pages 7 and 8. Now and over the coming months we are working to build relationships with those MPs, with an interest or background in history, elected to parliament at July’s general election.

Race, Ethnicity and Equality in UK History. The 2018 Report presented a troubling picture of the underrepresentation and experience of Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) history students and academic staff in UK higher education, based, in part, on statistics relating to BME representation and attainment. Our Update focused on this data to trace developments over five additional years to 2022.

“One of the great pleasures of my time as RHS President is witnessing the generosity, supportiveness and commitment of the Society’s membership and the wider historical profession.”

As our political colleagues advise, when making its case to parliamentarians the Society must demonstrate history’s dual value and precarity with reference to evidence and data. This year we have focused on identifying and communicating key sources of data that enable us to chart trends relating to the historical profession. A large part of this work is generating content on aspects of the profession—such as student numbers, staffing levels and profiles, and graduate career choices—all of which can now be easily located on our website.

At the same time, an enhanced focus on data has enabled us to return to subject areas already considered. In June 2024, we published an ‘Update’ to our 2018 report,

This revealed a mixed picture. Among positive trends, we see a year-on-year increase in the number and percentage share of BME student enrolments for history undergraduate and postgraduate degrees. Also welcome is an increase in the number and percentage share of BME historians employed in UK higher education. However, the Update also identifies areas of concern, with absolute numbers of BME history students and staff still very low and the BME academic pipeline underpopulated and precarious. In 2023-24 this precarity was clearly demonstrated by the fates of two pioneering Masters’ degrees in Black History, one at the University of Chichester which closed, and one at Goldsmiths, University of London, which was reprieved at the eleventh hour. That specialist and distinctive courses like this have faced such uncertainty is further indication of the challenging year this has been for many.

It’s in difficult times that one sees the true nature of our community. One of the great pleasures of my time as RHS President is witnessing the generosity, supportiveness

and commitment of the Society’s membership and the wider historical profession. This is evident in many ways, including the dedication of my fellow RHS Council members who give their time fully and voluntarily to defend and champion the discipline. Likewise, those who share their expertise at events hosted by the Society, or as mentors for RHS training or publishing programmes; and the many colleagues, at all career stages, who’ve been in touch during my presidency, to offer advice, ideas and experience.

This community element is hugely important for the Society’s, and the discipline’s, continued success. It’s one we’ve therefore sought to enhance in 2024 with two initiatives to facilitate greater networking. In June we hosted a meeting of 35 UK history societies to discuss our shared interests and priorities, and to plan future gatherings of organisations and groups that are vital for the health of our discipline and are now being asked to do ever more. You can read more about our work with history societies on pages 11 and 12 of the Newsletter. Our second venture, launched in September 2024, is an online RHS Members’ Directory. Here members, who wish to opt in to this service, may list their research interests and areas of specialism. The Directory is available to all members of the Society, and we hope it enables you to make connections with fellow historians in your field and to build new professional networks.

Finally, and in addition to professional networking, we have continued to welcome newcomers to the Society—be they new members or first-time attendees at one of our public activities. All RHS events are special, of course, but this year’s ‘in conversation’ with the broadcaster and author Greg Jenner (held in February) was especially memorable. This was not just for Greg’s insights on public history, but also for the breadth of his very sizeable in-person and online audience— ranging from professional historians to freelance history writers, podcasters, and

many of Greg’s younger readers and listeners. Events like this speak powerfully to the popularity, vitality and value of history which the Society must champion in other areas of its work.

To close this Letter I’d like to thank Simon MacLean and Emily Robinson who step down as councillors in November, as well as Andrew Smith, who first joined Council as our Honorary Director of Communications in 2019 and has performed unstinting service for the Society in a variety of roles since. Their contribution to the Society has been considerable and is greatly appreciated.

As this year’s Newsletter was going to press we received the very sad news of the passing of Professor Dame Jinty Nelson, who was President of the Royal Historical Society between 2000 and 2004. Elected a Fellow in 1979, Jinty joined the Council in 1994 and was appointed the Society’s first female President six years later. As President, she delivered a superb series of lectures exploring ‘England and the Continent in the Ninth Century’. Her contribution to our organisation is today remembered by the Society’s Jinty Nelson Fellowships which provide support for innovative history teaching.

In addition, to her work for the profession, Jinty was of course both a hugely respected historian of early medieval Europe, and a teacher of enormous generosity, talent and dedication. Jinty trained and inspired generations of historians to enter the profession, and we will miss her greatly.

November 2024

Emma Griffin is President of the Royal Historical Society and Professor of British History and Head of School at Queen Mary University of London.

President of the RHS since 2020, Emma completes her term in November 2024 when she is succeeded by Professor Lucy Noakes from the University of Essex. To contact Emma or Lucy about the Society and its work, please email president@royalhistsoc.org

The Value of History

In October 2024, the Society published ‘The Value of History’, a briefing on the state and contribution of history in UK higher education in the 2020s. While drawing attention to the cuts affecting many departments, this publication also sets out history’s strengths and the value of studying the subject at university.

The briefing marks a broadening of the Society’s advocacy work to support historians by championing the contribution of history within education, and more broadly.

As a supporter of history and historians, the Royal Historical Society is the first place to which many practitioners turn when their capacity to teach, research and communicate comes under threat. Since the early 2020s, the number and severity of these threats has grown considerably.

News of cuts makes for difficult reading. However, a discipline under siege is not the full picture. In our support for historians, the Society must also demonstrate and communicate the value of history in education and national life. Given the current situation, it’s unsurprising that positive messages are not being heard as clearly as they might. This is a situation compounded by negative, and misplaced, political commentaries on the value and purpose of a humanities education. In response, the Society seeks to better promote history’s contribution and worth, both as a subject for study and an important dimension of civic and national life.

It’s interventions of this kind that underpin ‘The Value of History’, released in October 2024. The briefing highlights the strength of our discipline, in terms of uptake, popularity and outcomes. This is an important message to remember, reiterate and for the Society to develop in the coming months.

Despite fluctuations in student numbers, history has long been, and remains, a major subject in UK higher education. For over a decade, more than 40,000 students have annually enrolled on history undergraduate or postgraduate degree courses.

History repeatedly appears in or around the top 10 of ‘non-STEM’ subjects chosen by undergraduates, with enrolment figures similar to those for degrees in accounting, economics, finance, health studies, marketing and politics. History is similarly a major subject in schools and colleges. In 2024, it was the fifth most studied A-Level. Enrolments at A-Level are up more than 5% since 2020 while those for GCSE are now 25% higher than in the late-2010s—far exceeding the increase in GCSE students in the round. History’s popularity at 16-18 years is welcome and alerts us to the need for many of these students to go on to study the subject at university. This is clearly a vulnerable transition point in the pipeline. But it’s also one to benefit from positive messaging, directed towards audiences—such as prospective history undergraduates, their parents and teachers— with whom the Society has not traditionally engaged.

For those who do decide to study history at university, the experience is positive. Responses to the UK’s annual National Student Survey consistently score history very highly in terms of intellectual challenge and the quality of teaching. Eight out of ten respondents in 2024 are confident that the skills acquired in their history degree will serve them well in the workforce—a level higher than many more overtly vocational programmes.

Having entered the labour market, and contrary to popular rhetoric, history graduates perform strongly in terms of employability and earnings. Government data (June 2024) shows 87% of history graduates ‘in sustained employment or further study’ five years after completing an undergraduate degree, placing them ahead of graduates in subjects including politics, computing, economics and forensic science, and just behind those in business, management, physics and the biosciences. Median earnings for history graduates are also above those for students in media, psychology, social policy and education.

There are many ways to measure the value of history. In the coming months, the Society will work with members and the wider historical community to identify qualities such as skills, training and the pleasure of acquiring historical knowledge and understanding. There is work to better appreciate value within the university, in line with contemporary approaches to teaching and research that are often at odds with popular, but anachronistic, images of the history student or lecturer. In this way, we hope to reassure future history students so they might pursue their interests with confidence, while providing academic historians with material to encourage these choices. In turn, history’s value extends beyond the university to encompass public recreation as well as civic and democratic health. Defining this broader worth will equip the Society to speak with new audiences to whom we need to convey the value of our discipline, its practice and practitioners.

Please see the Society’s website for copies of this briefing.

The Royal Historical Society at Westminster

Concern over university funding has grown increasingly pronounced this year. The future of UK higher education, including the provision of degree subjects in the humanities, is now on the political agenda. Since autumn 2023, the Royal Historical Society has been meeting with UK parliamentarians: to raise awareness of the threats facing history departments, and the consequences of cuts and closures for students—as Philip Carter explains.

Overthe past twelve months, the Society’s public statements on history and UK higher education have drawn attention to a growing disparity. On the one hand, history as a subject remains significant, popular and performs strongly in terms of professional outcomes for graduates. On the other, we see ever greater pressure on history departments experiencing cuts to staffing and closures of courses and degree programmes.

The Society has long been aware of this discrepancy between the vitality of history as a discipline (which extends well beyond higher education) and the unregulated and inadequate infrastructure of the university sector in which certain departments grow rapidly at the expense of others.

In recent months the broader crisis in university funding, long experienced on the ground, has finally broken through to public attention.

With this comes greater appreciation that the current situation has political origins and requires a political response. Since autumn 2023, the Society has been meeting with UK parliamentarians to bring our concerns and analysis to their attention. These meetings also introduce the Society and its work to parliamentarians. In this way, we look to develop working relationships with MPs, members of the House of Lords, and established parliamentary networks such as the All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) for Archives and History.

Between late 2023 and the calling of this year’s general election, the Society met with MPs and Lords across the party divide. Our meetings involved representatives of government, the shadow front bench, chairs and members of the Education Select Committee, and heads of APPGs for our discipline and for Higher Education. When making contact, we have prioritised parliamentarians in key roles, as well as those with expertise in parliamentary procedure to assist the Society in making effective interventions via members, through debates and questions on the floor of the House or in committee.

In the majority of cases our contacts have previous or ongoing connections with academic history and publishing, including a number who are Fellows of the Society. One such was the late Lord (Patrick) Cormack who provided us with a number of contacts in the early stages of the Society’s parliamentary work and who sadly died in February 2024. Lord Cormack’s generosity and commitment were considerable and his support for the Society will be missed. Away from Westminster, we’re also very grateful to other members of the Society who have shared their experience of working with parliamentarians—either as historians communicating research or as professional staff in the Commons and Lords who’ve guided us on procedure. Following this year’s general election, we have compiled a register of newly elected MPs with a professional or personal interest in history, with a view to building our networks now that parliament has resumed after the 2024 party conference season.

A primary concern when meeting parliamentarians is to demonstrate the instability that’s currently being experienced by historians in UK higher education, and the damage being done as cuts deepen. Students now risk being denied opportunities to take up history at university, as course closures pare back subject areas available for study.

Departmental closures in turn make history degrees increasingly inaccessible, especially to the very large—and growing—number of students unable to live away from home. For many parliamentarians this situation comes as something of a revelation, being at odds with their own experience of university. As we explain, the situation today is much more precarious and uncertain than for previous generations. Deregulation of departmental admissions in the 2010s, coupled with nonengagement with the deteriorating state of university funding in the present decade, are political decisions that necessitate action.

It is not sufficient simply to raise concerns. The Society understands the need to demonstrate—especially to audiences less disposed to listen—the value of historical study and research, and the personal and societal benefits these bring. By placing greater emphasis on the value of history (as set out elsewhere in this Newsletter) we look to raise the profile of the discipline and the Society at Westminster; to develop relationships with a new Commons membership; and to work more closely with, and support, existing parliamentary networks such as the APPG Archives and History.

In return we ask that politicians do not pit history against other sectors of UK higher education. This is a false dichotomy few historians recognise. To have the best chance of tackling the challenges facing us, we need to appreciate and involve historical understanding and skills, working in tandem with other disciplines. Each current challenge, however seemingly removed from history as a subject, has a past from which we can profitably understand, interpret and learn.

Philip Carter is Academic Director of the Royal Historical Society. Sketch the Palace of Westminster, iStock Images, credit: Tatiana54

Royal Historical Society Visits, Past and Future

Earlier this year, RHS councillors concluded their latest round of visits to history departments across the UK. This was followed, in autumn 2024, with the Society’s call for its next series of departmental visits to begin in the Spring.

Lucy Noakes—the Society’s incoming President from November 2024—reviews this latest set of visits, and their value to the Society, and looks ahead to new encounters and discussions with colleagues in 2025.

Meeting with fellow historians is among the most enjoyable and valued activities undertaken by the Society’s Council. Earlier this year, councillors completed their current programme of visits which began at Edge Hill University, Ormskirk. This was followed by meetings with colleagues and postgraduate students at the universities of Northampton, Kent, Canterbury Christ Church, the Highlands & Islands, and Hertfordshire (in 2023), together with York, York St John, and Brunel in 2024. In each case, departments had requested a visit following an open call from the Society.

In autumn 2024 we invited applications for a next round of day visits to start from Spring 2025. Over the coming few months, we’ll confirm this new programme and seek to accommodate as many requests as we can.

In my role as President of the Society, from November 2024, I look forward to taking part in this coming series and to meeting members of history departments across the UK. This won’t be my first experience of an RHS visit, however.

Each meeting ends with a public lecture delivered by a guest speaker of the department’s choosing. In September 2023, I was delighted to attend the day’s activities and give the closing lecture at the University of the Highlands & Islands’ Centre for History at Dornoch.

Prior to the lecture, each visit combines meetings with academic staff and research students to discuss a department’s profile and activities, as well as plans and concerns. Given the challenges faced by many departments, the Society’s latest round has focused on the threats to individual centres, as well as the profession and discipline more broadly. Visits also enable RHS councillors to speak with university senior managers. Here we set out the contributions made by academic historians to their institution and wider community. The work, creativity and dedication of the staff we meet is truly impressive. Councillors are keen to inform university leaders of this, and the high regard in which colleagues are held by the Society and the wider profession.

Visits also provide an opportunity for department members to come together

in person. There is time for socialising and catching up, not least between colleagues much of whose professional contact remains remote and online. There’s also a chance for historians outside of the history department—those working in law, business, economics or medical faculties, for example—to attend and make connections that often prove difficult without occasions such as these. Appreciating the breadth of historical expertise and practice across a university is an important part of the Society’s preparation for each visit. RHS councillors are very aware of their need to welcome historians working in higher education, and related sectors, in whatever departments or organisations they’re located.

Closing lectures are a chance to welcome first-time visitors to a department, as well as to learn about the current research of

“Each visit is an opportunity for councillors to listen and learn from our hosts.”

In addition, visits offer time and space to reflect on topics, chosen by our hosts, relevant to the profession and discipline. Recent panel discussions have considered historians’ engagement activities beyond the university; public perceptions of history; the discipline’s contribution to regional economic and civic development; partnerships between academia, heritage and conservation; curriculum reform; and history’s future within UK higher education. These are key subjects for the Society, and visits provide councillors with fresh perspectives on topics discussed as part of RHS committee work.

Finally, each visit is an opportunity for councillors to listen and learn from our hosts—notably about how the Society is perceived; how we develop our support for members and the profession; where we should direct resources; how we enhance our advocacy work; and the role and purpose of a modern learned society. These sessions are extremely valuable and will remain central to the new programme from 2025.

speakers. The Society is very grateful to those who have given papers as part of our latest round. Lectures are an important way for the Society to extend its in-person events well beyond London where the RHS has its office. This is vital if we are to be a truly national organisation, and it will be an important objective for my term. Huge thanks are also due to Emma Griffin, the Society’s outgoing President, who has led each of these visits and has revived the RHS practice—post lockdowns—of meeting with colleagues across the UK.

As I take up the Presidency, I look forward greatly to the next round of Royal Historical Society visits from 2025; to learning more about the exceptional work and expertise that exists in centres across the UK; and to meeting as many members of the Society as I, and fellow councillors, are able. Details of the forthcoming series, and lectures, will be circulated in the near future. I hope to see you, and to discuss the work of the Society, at one of these events.

Lucy Noakes is Rab Butler Professor of Modern British History at the University of Essex and President-Elect of the Royal Historical Society.

Lucy takes up the Presidency of the Society on 22 November 2024 and will lead the next set of RHS visits from Spring 2025.

The Royal Historical Society is one among many historical societies in the UK that work to support the study, research and communication of history. Societies are a core element of a national infrastructure that facilitates historical practice.

As many historians experience institutional cuts, societies are taking on greater roles to support the historical profession. Here, Barbara Bombi introduces new work at the RHS to bring societies together, to exchange advice and experience.

In June 2024, the RHS invited leaders of 35 UK history societies to discuss their respective organisations and the role of subject specialist associations in supporting our discipline. Our attendees reflected the broad spectrum of societies: from those dedicated to broad categories of historical analysis (the Economic, and Social History societies, for instance) and practice (the British Association of Local Historians or Oral History Society); to associations representing specialist subject fields, chronologies and area studies (including, among many others, the British Society for the History of Science, the London Medieval Society and the German History Society).

Creating a Network of UK SocietiesHistory

The RHS currently works with a number of UK organisations, for example in funding awards and prizes or collaborating on special initiatives such as the creation of Fellowships for Ukrainian Scholars in Exile, which it undertook in 2022. By convening a half day event in June 2024, the RHS sought to bring together the UK’s most prominent

“One of the most striking features of this year’s gathering was the sheer range of organisations that make up the subject specialist sector, and the extraordinary commitment and creativity that their volunteer leaderships bring to the discipline.”

national societies, appreciative of our shared interests, priorities and concerns. Central to this first session was an opportunity for heads of organisations to meet informally. In turn, we have since created an online network to enable society leaders to keep in touch between future annual gatherings.

One of the most striking features of this year’s event was the sheer range of organisations that make up the subject specialist sector, and the extraordinary commitment and creativity that their volunteer leaderships bring to the discipline. Public and specialist events, research funding, secondary and primary publications, membership, exhibitions and professional guidance are just some of the activities of UK history societies. As several speakers noted, the pressures now faced by many professional historians, within and beyond higher education, are leading to a growing number of calls for support from specialist and area studies societies.

These demands come at a time when societies face new challenges of their own. Journal publishing—a key activity of societies—is, for many, a principal source of

income. The emergence of new open access models from publishers, whereby journals are financed through ‘read and publish agreements’ rather than by institutional subscriptions, risks both significant cuts in societies’ income and the capacity to publish authors who do not belong to institutions that make up these new agreements. Cuts to income place not just specialist publishing, including scholarly editions as well as journals, at some risk; they also reduce societies’ ability to fund new research at a time of increasing demand from and inequality within UK higher education.

June’s meeting therefore addressed alternative forms of income generation and membership growth, not least as a means of easing the burden on time-pressed volunteers who govern our history societies and oversee their many activities. Society finance; how best to support the historical profession; membership growth and diversification; and raising the profile of societies and their role are topics to which we will return, in detail, at future meetings.

More immediately, and via our new network, the Royal Historical Society will communicate policy initiatives, circulate developments within academic publishing and make available data relating to history in UK higher education as this is released. The environment in which history societies operate is changing and brings new demands. However, and as our first gathering of leaders made clear, we will be better able to navigate through collaboration and dialogue. History is made hugely richer by the work of its many subject specialist and learned societies, and I look forward to continuing this conversation.

Barbara Bombi is Professor of Medieval History at the University of Kent and Secretary for Research at the Royal Historical Society.

Doing History in Public

Over the course of 2024 the Society has been running a series of workshops entitled ‘Doing History in Public’, led—and introduced here—by the RHS Council member, Andrew Smith. Workshops have brought together historians with experience of public engagement, together with specialists from related sectors such as museums and galleries, publishing, and print and broadcast media.

There is now a growing expectation that historians work with community groups and communicate their research to broader audiences beyond universities. Less common is advice and guidance on how we do—in public—history that’s valuable, ethical and supportive of historians and those with whom they work.

In2024 the Royal Historical Society hosted a series of workshops on the theme of ‘doing history in public’. These workshops, or ‘consultative conversations’, serve to highlight the intersections between historical scholarship and public engagement, and the challenges and opportunities therein. No longer reserved for senior academics, public engagement is now often expected of historians at all career stages. With these workshops, the Society seeks to understand how best to support historians in this area of academic activity.

Our workshops explore different platforms for engagement and bring together members of the Society experienced in, for example, trade publishing or working with the print and broadcast media, along with invited

specialists from sectors integral to public history. This has helped ensure broad and representative participation from historians of varying backgrounds (both personal and professional) and at different career stages.

Each conversation has taken place according to the Chatham House rule, allowing contributors to openly discuss their experience—positive and negative—of ‘doing history in public’. We look to identify common themes and concerns, as well as future recommendations for action and guidance by the Society, to better support those who wish to undertake public history or promote their research to new audiences. But above all, we hope to provide an environment that’s respectful of different professional affiliations and encounters, from which RHS councillors can learn more about a pressing issue for historians.

Our first workshop (held in April 2024) considered the role of Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums in shaping collective memory and public engagement with history. This conversation provided insights into the expectations and requirements of the ‘GLAM sector’, and how these are best negotiated with academic historians when partnerships are forged. We considered the need to make collections accessible and engaging, as well as the tension between meeting public expectations and maintaining a pedagogic role. Co-productive work, involving historians and community partners, was also discussed, with guidance from our specialist witnesses to involve all partners equally and from the start of a project. Attendees from the museum sector highlighted their need to square historical complexity with communicability, while also fostering curiosity and a desire to learn more beyond an exhibition. Historians have much to offer here, but need to approach public history alert to the expectations and purpose of historical content in galleries and museums.

Our second workshop (June) looked to the intersection of historical research and print media, from the perspective of journalism and book publishing. Historians shared their experience of writing trade books, as well as for newspapers and popular history magazines, emphasising the importance of balancing academic rigour with public accessibility. Writing for broader audiences often involves simplifying complex ideas without compromising historical accuracy or nuance, especially in a publishing environment in which digital platforms are increasingly prevalent. Participants also discussed the potential risks and hazards of ‘doing history in public’, especially in high-circulation and high-profile print formats. Academic contributors noted the variable, and sometimes inadequate, levels

within documentary broadcasting, many of which take place away from the camera or microphone as specialist content advisers. More than the other platforms explored in this series, broadcasting enjoys a particularly wide range of options and starting points for the historian looking to work publicly. This is especially so with the rise of history podcasting which—as our contributors to this format reminded us—can be performed well, and communicated widely, without extensive professional support or specialist technology.

“Our workshops explore different platforms for engagement and bring together members of the Society experienced in, for example, trade publishing or working with the print and broadcast media, along with invited specialists from sectors integral to public history.”

of support available from their institutions for those taking up public-facing roles. This is especially so when dealing with controversial topics; what one participant usefully called ‘hard hat’ areas of historical debate.

A third and final workshop in the series (September) considered broadcast media, with reference to audio and visual formats, scripted and live. This session brought together historians, commissioning editors, producers and podcasters. Together we delineated the numerous roles for historians

Since completing these workshops, I and my co-hosts from the RHS Council—Olwen Purdue and Cait Beaumont—have been reviewing our discussions. From this will come guidance from the Society on the scope, activities, practice and, yes, potential problems faced by those seeking to ‘do history in public’. By speaking with experienced public history practitioners, as well as those with whom they work in related sectors, we aim to equip historians with the resources necessary to engage confidently and ethically with the public. In this way, we seek to ensure and continue history’s capacity to inform and enrich public discourse.

Andrew Smith is a councillor of the Royal Historical Society and Director of Liberal Arts at Queen Mary University of London.

Supporting Mid-Career Historians: Funded Book Workshops

In 2024, the Royal Historical Society held the first sessions of its Funded Book Workshops—a new programme to support mid-career historians currently completing a second or third monograph. The scheme enables recipients to bring together specialist readers of their choosing, for a day, to discuss a manuscript in detail.

Jennifer Aston was one of two recipients in the first year of this programme. Here Jennifer reports on her workshop and its contribution to developing her manuscript.

In January 2024, I was fortunate to host six scholars—Rosemary Auchmuty, Amy Erickson Maebh Harding, Jane Humphries, Rebecca Probert and Sharon Thompson—at the Society’s office in London to discuss my book manuscript: Deserted Wives and Economic Divorce in 19th-Century England and Wales: For Wives Alone. This writing project was unusual as it was co-authored with someone who was not only dead, but who I had never met.

In 2021, I began work on (what should have been) a journal article about section 21 of the Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Act 1857. This small piece of legislation made a significant impact on the lives of tens of thousands of deserted married women as it gave them the ability to apply to their local magistrate or police court and, for just a few shillings, revert their legal status to that of a feme sole. In other words, a section 21 order gave a married woman, who had been deserted by her husband and who was maintaining herself, total control over her property as well as the ability to contract, to sue and be sued, and to make a last will and testament. Despite their importance to women in the mid-nineteenth century, section 21 orders had remained largely unexamined given an absence of a central registry of cases and the loss of magistrates’ court records.

One notable exception to this was the work of Olive Anderson, a Professor of History at Westfield College, later Queen Mary and Westfield. I had stumbled across two articles written by Anderson in the late 1990s, but

although footnotes promised a forthcoming book, sadly further searching only revealed her obituary written by Anderson’s daughter, Harriet, in early 2015. The obituary revealed that Anderson had left behind an incomplete typescript. After a trip to read it and meet Anderson’s daughters, we agreed that I would integrate my research to update and complete the surviving typescript.

Any book project is challenging, but combining research methods at thirty years’ remove and the voices of two historians born seven decades apart is especially so. Above all, I was certain that the deserted wives and their stories should be at the heart of the book: the recovery of their experiences could not be lost in the rediscovery of Anderson’s manuscript. The RHS Funded Book Workshop helped me to do all of that, and more. The six scholars shared not only their thoughts on the technical and legal points of the manuscript, but also their advice on how to weave Anderson’s original research with my own, sometimes contradictory, opinions. My book is published in November 2024, and I hope readers will agree that it makes an important contribution to the fields of legal, economic, social and women’s history, as well as having an interesting writing partnership.

Jennifer Aston is Associate Professor in Law at Northumbria University and the recipient of an RHS Funded Book Workshop Grant for 2023-24.

Promoting Wellbeing through History Teaching

Launched in 2023, the Society’s Jinty Nelson Teaching Fellowships encourage the development of innovative history teaching in UK higher education.

In this article David Stack, from the University of Reading, reflects on his recent study of wellbeing and history teaching which was supported by a Teaching Fellowship in 2023-24.

The challenge of student wellbeing is familiar to all of us working in higher education. Even before the pandemic interest in this area was growing, and since 2020 it has become a mainstream concern in many institutions. One aspect of this challenge that troubled me was the apparent gap between institution-level commitments to wellbeing and the pedagogic practices of individual disciplines. How, I wondered, does the structure and delivery of a degree impact the wellbeing of our students?

I was keen to delve into this problem and wanted to do so specifically in relation to history, for two reasons. First, experience in various cross-disciplinary roles had taught me that students most strongly identify with their discipline or department, rather than wider university structures; thus, to be successful, I assumed, wellbeing needed to be pursued at this level. Second, I wanted to explore how the growing interests of historians in wellbeing as a research question might align with teaching considerations.

This was where the Royal Historical Society’s Jinty Nelson Teaching Fellowship proved invaluable. Other funding opportunities would not countenance a discipline-focused project. The Society’s scheme allowed me to look specifically at the experience of students on history degrees.

My initial aim was to develop a dedicated wellbeing module, which could provide a template for history departments across the sector. The question of the optimal place in the curriculum for such a module was left open, but the working assumption—based around wellbeing concerns related to the transition to university—was that it would be aimed at first-year undergraduates.

The project undertook two main pieces of research: a survey of just over 100 current undergraduate students, enrolled on the History BA and related joint degree programmes at the University of Reading; and a scoping study of wellbeing practices in about 90 UK history departments or their equivalent. This research was only possible because the Teaching Fellowship allowed me to employ a doctoral student, Abbie Tibbott, who undertook much of the work.

The survey, which was conducted anonymously and online, asked 15 questions, with a mixture of set and open text answers. The areas covered included: a wellbeing self-assessment (on a scale of 1 to 10); a ranking of concerns and areas in which students felt they needed help; awareness of departmental and central university support systems; and student views on the potential for a wellbeing module as part of a history degree programme. The participants were all full-time students, overwhelmingly aged 18-21 years old, and made up of first year (43), second year (39), and third year (21) undergraduates.

The scoping study looked at the websites of universities offering history degrees, and sought to establish a point of contact, with

responsibility for the wellbeing of history students, and evidence of wellbeing concerns and initiatives. Each point of contact was invited to provide further details, and any reflections they wished to share.

The results of both the survey and the scoping study—which are discussed in more detail in my recent article for Transactions of the Royal Historical Society—provided pause for thought. The survey pointed towards a body of students who were no more than averagely happy, and often struggled with stress (60%), mental health (40%), motivation (more than half), and time management (around a third). There was some evidence that wellbeing declined — and certainly was not obviously enhanced— across the three years of their degree. The scoping study showed a great range of understanding and initiatives around wellbeing in history departments, with an overwhelming focus on entry year students, and questions of transition.

In processing these results I was led back to wider literature on wellbeing and reassessed some of the anticipated outcomes of the project. My starting point that wellbeing is best pursued at the level of the discipline was confirmed both by the general literature and responses to the survey, which highlighted, in different ways, the centrality of the curriculum as the one consistent element in students’ lives which can influence behaviour.

The idea of creating a dedicated wellbeing module, however, was not supported. The scoping study suggested that no history department runs such a module at present, and that those who have experimented with wellbeing drop-in sessions experience very low levels of engagement. Even if such a module could be made to work it would silo wellbeing into one spot in the curriculum and reinforce the tendency to see wellbeing as a one-off, transitional event.

“I wanted to explore how the growing interests of historians in wellbeing as a research question might align with teaching considerations.”

Rather than develop a standalone module, therefore, the research led me to conclude in favour of pursuing a strategy of curricular infusion, in which wellbeing becomes a standard consideration in module design by all staff. Receipt of an RHS Teaching Fellowship, 2023-24, made it possible to consider the problem of wellbeing specifically as it related to history students. This, in turn, led to a revised understanding which will inform my future teaching practice and hopefully that of others too.

David Stack is Professor of Modern History at the University of Reading and the recipient of an RHS Jinty Nelson Teaching Fellowship for 2023-24.

Launched in 2023, the Fellowships support innovative history teaching in UK higher education. The Fellowships, awarded annually, are named for Dame Jinty Nelson (1942-2024), President of the Royal Historical Society between 2000 and 2004.

In October 2023, the British Library suffered a massive cyber-attack by a criminal gang who stole data and destroyed critical infrastructure. A great many humanities academics in the UK—and plenty beyond— have been affected in some way, if only through their inability to access the Library’s online catalogue. The cyber-attack is just one recent episode to highlight how closely connected, and potentially vulnerable, scholarly life is to contemporary events.

with members of the younger generation wearing Hanfu along with matching traditional hair ornaments. This trend is aided by the Xianxia 仙俠 TV dramas that have overwhelmed Chinese screens. Blending historical and mythical stories, these dramas become an important source where young Chinese learn about the past and traditions of their country. Mass culture, youth culture, and fashion—these are the elements that can shape a population’s historical consciousness and identity.

In autumn 2024 the Society launched a new publishing series: ‘Elements in History and Contemporary Society’. The series is part of Cambridge Elements— collections of short monographs published online and in print by Cambridge University Press. ‘Elements in History and Contemporary Society’ will explore the intersection of past and present via studies of historical legacy, practice and debate.

Here, the series editors—Richard Toye and Vivienne Xiangwei Guo—introduce ‘Elements in History and Contemporary Society’ and invite submissions for the first round of titles.

‘Elements in History and Contemporary Society’

A New Publishing Series

Climate change, the rise of Artificial Intelligence, the threat of authoritarianism: all are trends and actions that can impact both our ability to write history and the kinds of history we want to write.

Our readiness to draw on the past likewise remains a constant, if evolving, feature of contemporary life. To take one example: in recent years, Hanfu 漢服—China’s traditional Han-style clothing typically composed of a loose yi 衣 (upper garment) and a skirt-like shang 裳 (lower garment)—has become popular with young Chinese. China’s historical sites, parks and even streets are often teeming

Modern day political and societal debates are often in urgent need of historical contextualisation. The arguments that rage on social media may seem unprecedented in their intensity and vitriol; yet the sense of standing on the edge of the abyss is something that is familiar from many times and places past. This is not to say that history simply repeats itself or that there is no need for concern. But historical understanding can help us better appreciate which aspects of contemporary life are new and which are not. Similarly, when historians reflect on the environment and practices of their own work (such as the ubiquitous, and unquestioning, reliance on online catalogues) they become better able to assess their effects and so develop the discipline.

There is much to be gained from close assessment of the value, use, discourse, and impact of history in contemporary society and culture. In response, the Royal Historical Society has recently launched a new publishing series, ‘Elements in History and Contemporary Society’. Its purpose is to draw attention to the roles played by a variety of institutions and individuals in the making and

use of historical knowledge. The series will cover a wide range of topics and engage with different geographical regions and historical periods, while addressing four principal themes:

1. Uses of the past in contemporary politics, ideology and/or public policy.

2. Contemporary institutions of historical knowledge, including archives, museums and/or education.

3. New technologies and historical knowledge such as digital humanities and new media.

4. Memory, mass culture and public opinion.

As editors, we are excited to be involved in this new initiative—not least because of our own interest in the interplay of history and contemporary life. Richard specialises in the study of Britain’s role within a global and imperial context from the late nineteenth century to the present day. Vivienne’s research focuses on the intellectual, political, and cultural history of modern China, particularly the history of China’s intellectual elites in the late-nineteenth and twentieth century.

The new series, however, will not be confined to areas of our expertise. Titles in the series will address questions of use, understanding

politics, teaching, the media and community history), where discussions of the value and application of historical knowledge are especially prominent.

In keeping with the Elements model, each volume in the series will be a concise and topical intervention, limited to 30,000 words and published by Cambridge University Press within 12 weeks of approval of the final manuscript. This ensures each title’s responsiveness and contribution to contemporary debate. Thanks to support from the Royal Historical Society, all books in the series will appear Open Access, with no charge to authors. This will ensure that the topics and debates covered in the series will be as accessible and widely read as possible.

Titles in ‘Elements in History and Contemporary Society’ are not intended to be polemical or, necessarily, controversial. Nevertheless, they will be argument-driven, persuasive and passionate. That is to say, writing for the series will be a different type of exercise to writing a research monograph. Authors will highlight, illustrate and illuminate issues and make their case about why they matter and what ought to be done.

“We encourage contributions from those working in sectors beyond higher education … where discussions of the value and application of historical knowledge are especially prominent.”

and the value of history, and be open to discussion in any culture or region worldwide. Similarly, we encourage contributions from those working in sectors beyond higher education (including heritage, public policy,

As editors, we now invite submissions for the series, with the first titles in the series to appear from 2025.

Richard Toye is Professor of Modern History at the University of Exeter.

Vivienne Xiangwei Guo is Lecturer in Modern Chinese History at King’s College London.

For further details of the Society’s ‘Elements in History and Contemporary Society’ series, and how to submit a proposal for a short monograph of up to 30,000 words, please see the Elements page on the Royal Historical Society’s website.

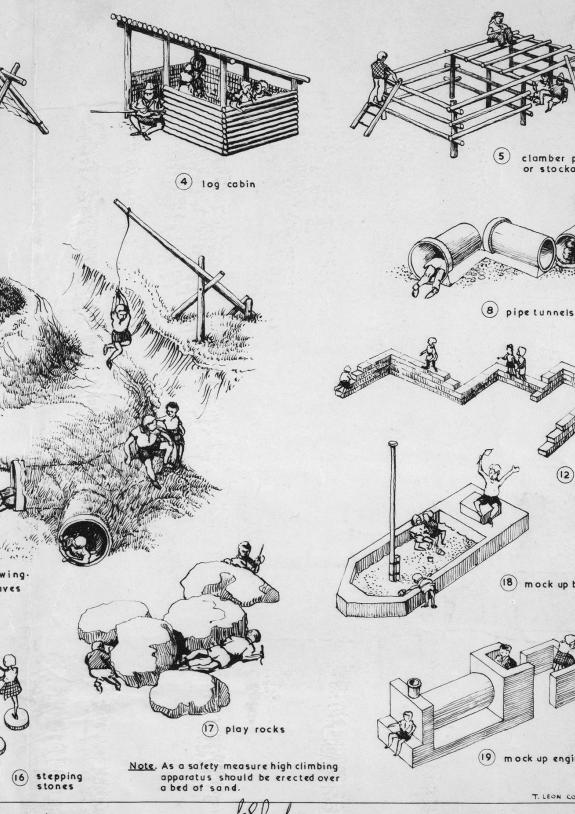

Suggestions of Improvised Equipment for Children’s Play by R.B. Gooch, National Playing Fields Association, 1956, The London Archives, CLC/011/MS22287

Designed for Play

In his new book, Designed for Play. Children’s Playgrounds and the Politics of Urban Space, 1840–2010, Jon Winder considers the history of the children’s playground and the wider social, political and environmental concerns such spaces have addressed.

Jon’s monograph appeared in July 2024, part of the Royal Historical Society’s ‘New Historical Perspectives’ series for early career historians, published by University of London Press.

InJanuary 1858, Charles Dickens launched the Playground and Recreation Society in London. Dickens hoped that the organisation would create dedicated play spaces for poor children, away from the temptations and evils he felt that children encountered in the street. A year later, parliament passed the Recreation Grounds Act which specifically permitted the creation of playgrounds for children.

This combination of high-profile advocacy and enabling legislation may seem like the obvious starting point for a process that has resulted in more than 26,000 children’s playgrounds across the UK today. However, by May 1860 the Playground and Recreation Society had unceremoniously folded and few public spaces in London included dedicated recreation grounds for children. Elsewhere the picture was similarly mixed. Several gender-segregated playgrounds had been created in Salford and Manchester in the 1840s, while conversely a small number of

public parks barred children from entering altogether.

From this inauspicious start, my book— Designed for Play. Children’s Playgrounds and the Politics of Urban Space, 1840–2010, published in the Society’s New Historical Perspectives series—charts the rationale, form and function of children’s playgrounds over the course of almost two centuries.

The book offers new insights into the histories and geographies of childhood, welfare, philanthropy, education, nature, landscape and urban design. The playground has seldom been explicitly endorsed by central government and as a result Designed for Play draws on the dispersed archives of philanthropic, municipal, commercial and voluntary actors to highlight the convoluted journey of the playground: from obscurity to popular ubiquity and back towards a place of somewhat aimless eccentricity in the twenty-first century.

In tracking the ideas and actions that have sought to direct children’s playfulness, we find that these environments have long acted as a site where social, political and environmental values have been played out and contested.

In the 1890s, the philanthropic reformers created children’s garden gymnasiums, segregated by age and gender, in the poorer districts of London. By the 1920s, manufacturers such as Charles Wicksteed & Co. were selling robust metal swings and slides to municipal authorities who were intent on facilitating children’s carefree and energetic play in parks and on housing estates.

During the mid-twentieth century, the National Playing Fields Association did much to promote standardised playground provision and actively campaigned against children playing in the street. At the same time, modernist architects and landscape designers experimented with the ideal playground form as they created the architecture of the welfare state. From the 1970s, sociological research, anarchic thinking and the adventure playground movement all challenged conventional practices. By the turn of the century, playgrounds were increasingly presented as a problem to be solved, often sites of danger and decay rather than childhood possibility.

Throughout this story, the term ‘playground’ has proved sufficiently flexible to accommodate changing attitudes to childhood and diverse play space forms. At the same time, such spaces have proved a means to explore wider historical themes and their impact on the built environment. From landscape architect Fanny Wilkinson and psychologist Mabel Jane Reany to campaigner Marjory Allen and sociologist Margaret Willis, the playground has also been associated with pioneering women who reimagined and redefined spaces for play.

The long history of the playground likewise provides a unique example of shifting welfare interventions in the urban environment. A diverse set of actors across philanthropic, voluntary, municipal and commercial arenas have sought to influence the built form of cities, ostensibly to shape children’s health and wellbeing, while also seeking to address urban and imperial anxieties, generate profit and gain political capital.

In twenty-first-century Britain, the politics of the playground are far from settled. It seems obvious to state that children play in playgrounds, but they are not the only places where children do so. High-profile campaigns, including ‘Make Space for Girls’ and ‘Playing Out’, continue to contest historical assumptions about children’s place in the city, challenging car-centric, maledominated public space design.

Designed for Play provides important historical context for present-day policymakers and campaigners, encouraging deeper reflection on the assumptions and values that shape children’s place in public space. It also shows that seemingly novel calls for the reintroduction of nature into cities, and the creation of wilder childhoods, have a long and complex history.

Jon Winder is a Postdoctoral Research Associate on the Wellcome-funded ‘Melting Metropolis’ project at the University of Liverpool.

Along with all 20 titles in the NHP series, Jon’s book is accessible as a free Open Access text, as well as in paperback print and Manifold online editions.

Print discounts of 30% are available to RHS Fellows and Members on this and all titles in the NHP series, via University of London Press (UK, EU & RoW) and University of Chicago Press (North America). To take up this offer, please apply the discount code: RHSNHP30.

Recent and Forthcoming Royal Historical Society publications, 2024-25

Transactions of the Royal Historical Society (Seventh Series, Volume 2)

December 2024

Allen Leeper’s Letters Home. An Irish-Australian at Edwardian Oxford, edited D.W. Hayton (Camden Series, Fifth Series, Volume 67)

July 2024

The Household Accounts of Robert and Katherine Greville, Lord and Lady Brooke, at Holborn and Warwick, 1640-1649, edited Stewart Beale, Andrew Hopper and Ann Hughes (Camden Series, Fifth Series, Volume 68)

December 2024

Jon Winder, Designed for Play: Children’s Playgrounds and the Politics of Urban Space, 1840–2010 (New Historical Perspectives)

July 2024

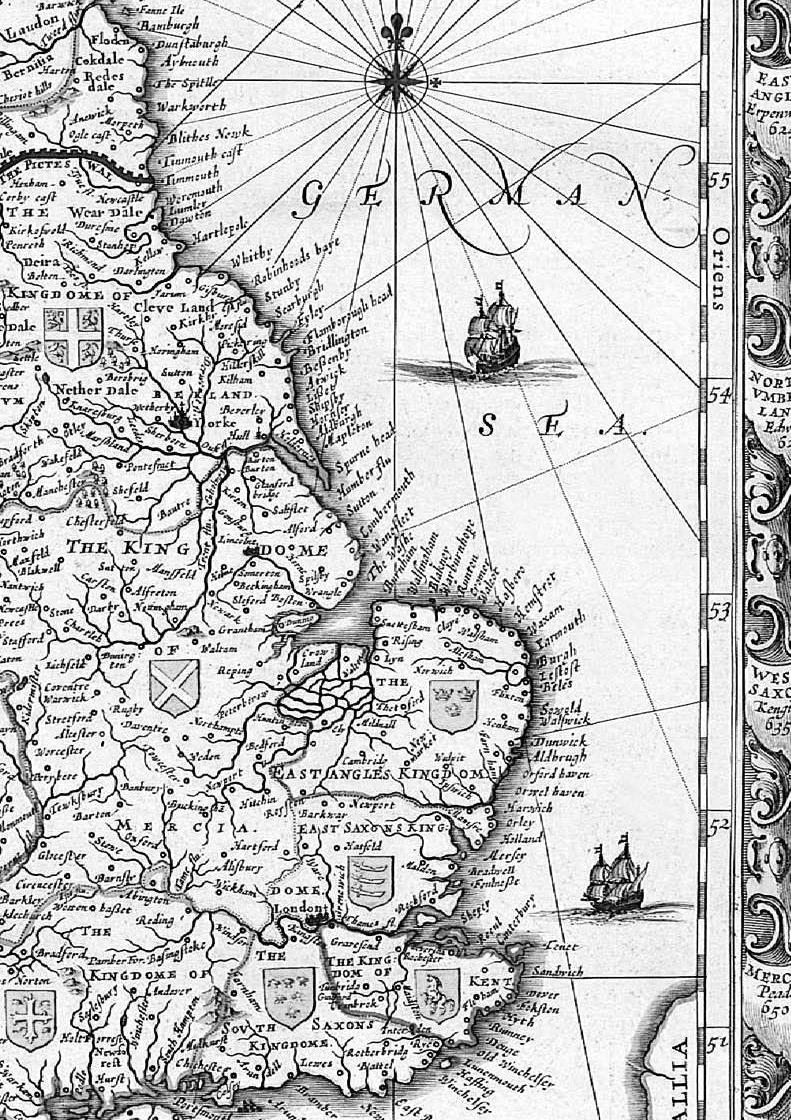

Martin Spychal, Mapping the State. English Boundaries and the 1832 Reform Act (New Historical Perspectives) September 2024

Maria Cannon and Laura Tisdall eds., Adulthood in Britain and the United States from 1350 to Generation Z (New Historical Perspectives) November 2024

Rachel E. Johnson, Voice, Silence and Gender in South Africa’s Anti-Apartheid Struggle. The Shadow of a Young Woman (New Historical Perspectives)

March 2025

For further details of these and other titles, please see the Publications pages of the Society’s website.

Emma Griffin, RHS President (2020-24): An Appreciation

In November 2024 Emma Griffin completes her term as President of the Royal Historical Society. Jane Winters looks back on Emma’s contribution and some of the challenges and her achievements over the past four years.

Emma took over as President of the Society in autumn 2020, while the Covid pandemic was still causing disruption to our personal and professional lives. An immediate challenge was to continue to steer the Society to new ways of working, with a focus on making events and activities available online to the widest possible audience. As face-to-face events and meetings once again became possible, Emma has remained committed to this widening of access. The positive results can be seen in the hundreds of people who now attend Society webinars on topics as diverse as how to produce scholarly editions and the use of AI in history teaching.

The pandemic was not the only challenge that Emma had to address. History, like other humanities disciplines in the UK, has increasingly suffered from under-investment, the closure of courses and job losses. Increased advocacy for the discipline, both in public and behind the scenes, has been one of the hallmarks of Emma’s presidency. Under her leadership, the Society has developed a multifaceted approach, which combines practical assistance with both public statements at particular points of crisis and a wider campaign to demonstrate the value of history for our society and culture. Among the resources that Emma has developed with the RHS Council are the regularly updated ‘Toolkit for Historians’, which brings together materials that have proven useful for historians facing significant change to their professional lives; and annual

data on the history profession in the UK, which is used to counteract uninformed narratives of decline for the discipline.

Emma’s practical responses to hardship and lack of opportunity also include new Master’s Scholarships for students who are underrepresented on programmes in the UK (eight were awarded in 2024-25, with support from the Past & Present Society and the Scouloudi Foundation). Throughout her term, Emma has worked to bring together organisations concerned with history, ensuring that their collective impact in key areas is greater than could be achieved individually.

Emma has still found time to develop and enhance the Society’s activities in other areas. Membership categories have been revised, with the introduction of a new Associate Fellowship designed, in part, to recognise the contributions of professional historians working outside higher education. Membership of the Society, across all categories, has risen by 35% between 2021 and 2024. Support for early career researchers remains central to the work of the RHS, but there has been a new focus on research funding for historians at all career stages, including dedicated awards for mid and later career scholars.

Finally, the RHS publishing programme has been reshaped and enhanced under Emma’s guidance. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society has been relaunched, and a new short-form monograph series, ‘Elements in History and Contemporary Society’, appears in autumn 2024. This is designed to promote the value of history and engage with important debates that require a historical perspective, complementing the advocacy work that is such an important part of Emma’s legacy as President.

Jane Winters is the Society’s Vice-President for Publications and Professor of Digital Humanities at the School of Advanced Study, University of London.

© Royal Historical Society 2024, except where explicitly stated.

THE ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY

ADVOCATES for historians and the value of history

BUILDS connections between historians of all kinds

CELEBRATES the diversity of our historical communities

CHAMPIONS environments in which history may flourish

FACILITATES historical enquiry through funding and publishing