The Route 9 Literary Collective presents...

The Route 9 Literary Collective presents...

Wesleyan’s prose, poetry, and art magazine Fall 2024

The Lavender is Wesleyan’s student-run poetry, prose, and art magazine that publishes twice a semester. The literary magazine is run under the Route 9 Literary Collective, which also publishes a multitude of other projects including Pre-Owned, Good Condition, The John, Poems of Our Climate, The Route 9 Anthology, and more. Learn more at route9.org.

The Lavender is an homage to the fact that Wesleyan University’s official color used to be lavender. The color was changed because, according to an October 1884 issue of The Argus, lavender was not suitable for intercollegiate sports. “Lavender is not a striking color,” the article proclaimed. Well, 1884 critic, we here at The Lavender find the color incredibly striking.

Route 9 is the road that connects Middletown to the rest of Connecticut. It is the central artery of movement that every Wesleyan student, faculty, staff, and Middletown resident has driven on. It connects us and moves us forward.

Editors-in-chief: Georgia Groome and Ella Spitz

Managing Editors: Mia Foster and Nettie Hitt

Poetry Editor: Mia Alexander

Assistant Poetry Editor: Mel Cort

Prose Editor: Eli Hoag

Assistant Prose Editor: George Manes

Design Editors: Madeleine Metzger and Kyle Reims

Copy Editors: Emma Goetz, Ben Goodman, Zoe Sonkin, and Sarann Spiegel

The Team: Megan Arias, Tyler Asher, Anya Benardo, Anne Bennet, Suz Blattner, Angelina Bravo, Samara Brown, Eliza Bryson, Olivia Cohen, Ellington Davis, Katie DiSavino, Yael Ezry, Aniana Garciano, Sylvie Gross, Montana Gura, Lilly Hoefflin, Ezra Holzman, Esme Israel, Henry Kaplan, Olivia Kong, Arlo Kremen, Fae Leonard-Mann, Clara Lewis-Jenkins, Tess Lieber, Olivia Pace, Kai Paik, Charles Pasca, Alex Potts, Ellie Powell, Vandana Ravi, Ellen Ryan, Gray Sansom-Chasin, Eliza Walpert, Sarah Weber, Tae Weiss, Maisie Wrubel, Vasilia Yordanova, Ana Ziebarth

Cover Design: Nomi Kuntz

Logo Design: Leo Egger

Special Thanks to: The heroes at 72B Home Avenue and Fauver 112, all the dear friends who make this magazine possible, Oliver Egger, Immi Shearmur, Merve Emre, Ryan Launder, Alpha Delta Phi, the Shapiro Writing Center, the Wesleyan English Department, and the SBC.

Dear Reader,

We welcome you to a new Lavender issue and to a new school year! But are years, days, and moments “new,” really? Do we ever completely leave the past behind? Can we shake those old moments that still pervade our present lives?

Maybe you guys can, and if so, we applaud you for it. We can’t, so here are a few things that haunt us every day:

When I was in eighth grade, I was the head of my middle school’s newspaper. At our final assembly, I told the whole school that the work completed on the paper that year was “appalling” because I thought it had a positive connotation.

I was on the Mathletes in middle school and this kid Jonah kept interrupting while I presented my problem, so I went on my knees and said, “Bow down to King Jonah.” He ran out of the room crying and I had to chase him down the street to apologize.

Last month, my jeans got stuck in the chain of my bike at the intersection between Exley and WesShop and I had to take my pants off to get free.

I sent funny selfies to my sixthgrade crush over Google Chat every day after school, but then the next year he came out as a Trump supporter.

For the first seventeen years of my life, I would tell people that I was

artificially inseminated (instead of my mom) because I didn’t really know what it meant (skip to page 30 for the full story).

When I was nine I got strep butt (like strep throat but in my butt) and I had to hold my mom’s hand every time I went to the bathroom for a month. I then had to do two weeks of antibiotics to get rid of it, but the antibiotics gave me hives so I had to bathe in oatmeal.

In high school, I was supposed to spend a weekend upstate with my situationship, and I made an emoji key (e.g. kissy emoji = we kissed; cupcake emoji = things went further) to send to my best friend so that I could quickly notify her of any updates, and I accidentally sent the key to the situationship instead.

I wrote two chapters of a novel in fifth grade that featured a protagonist whose traumatic backstory was that his uncle was addicted to fireworks (they aren’t legal in Massachusetts, so I thought that meant they were like drugs).

We hope these hauntings resonate with all of you. We have been committed to The Lavender (and each other, in a romantic way) for three years now, and we are so grateful to everyone who worked hard to get this thang done. Let’s get to the work in this issue. It’s pretty appalling.

Love, Ella and Georgia

Tribute After Tartini by Gray Sansom-Chasin

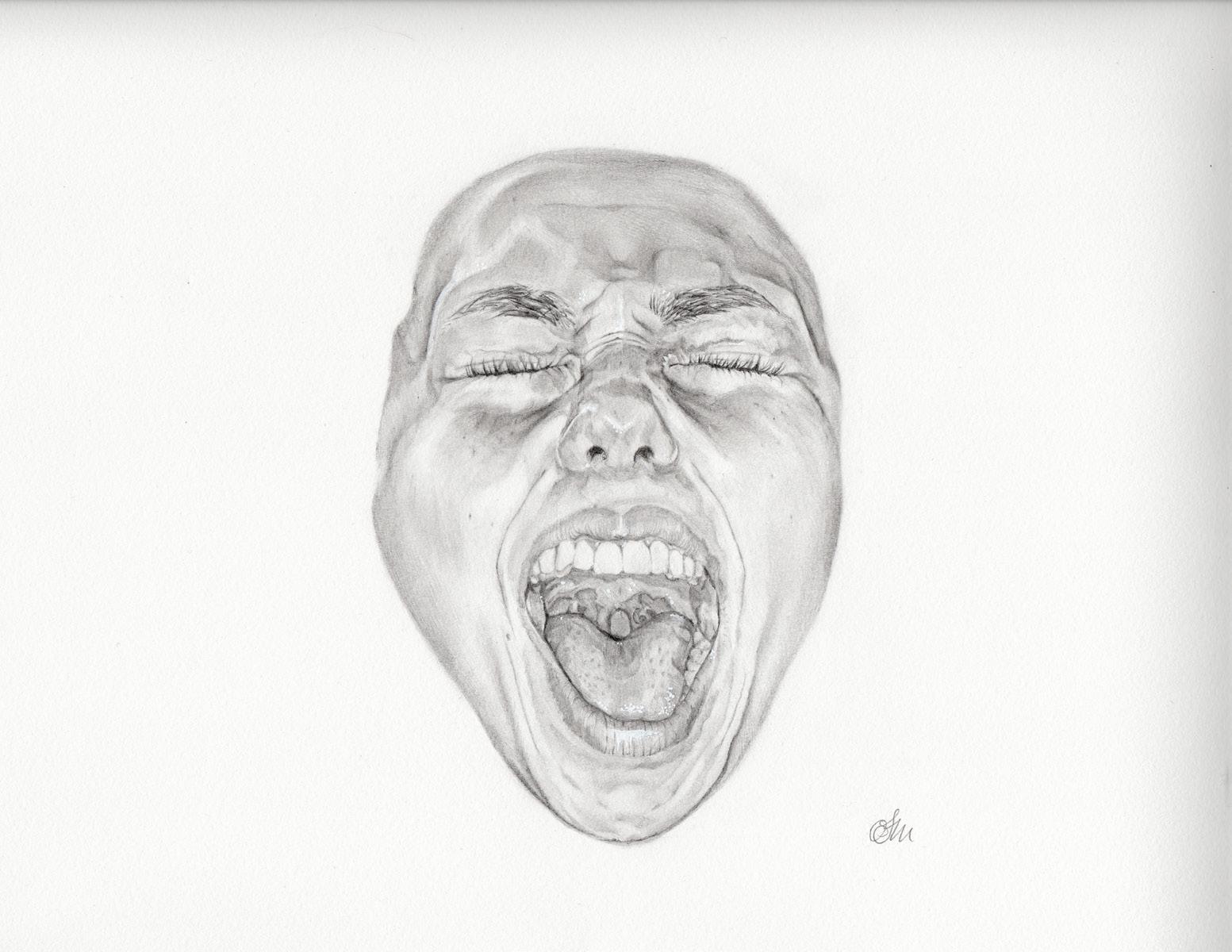

Eden Bloom

“PURPLE, OR WAS IT MAUVE?” by Kai Paik

twined by Noa Koffman-Adsit

Lauren Horowitz

Waiting For by Harry Gleicher

My second act of defiance by Mia Alexander

Sophia Molina

A projectile with a project, by Ellington Davis

Z Santilli

Programming by Ella Spitz

Pink Money by Jordana Treisman

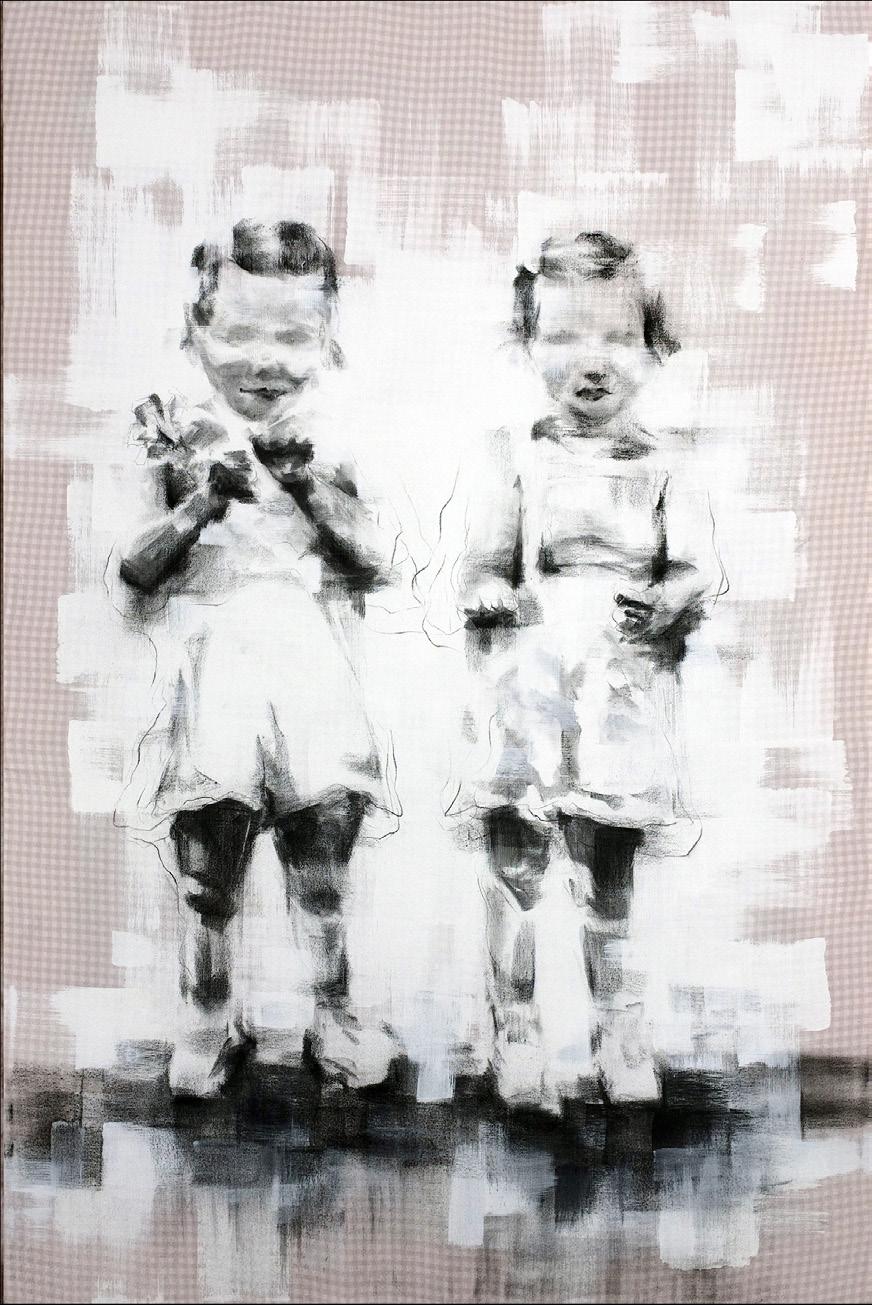

Eve Epstein

Unresolved Tension by Jalen Richardson

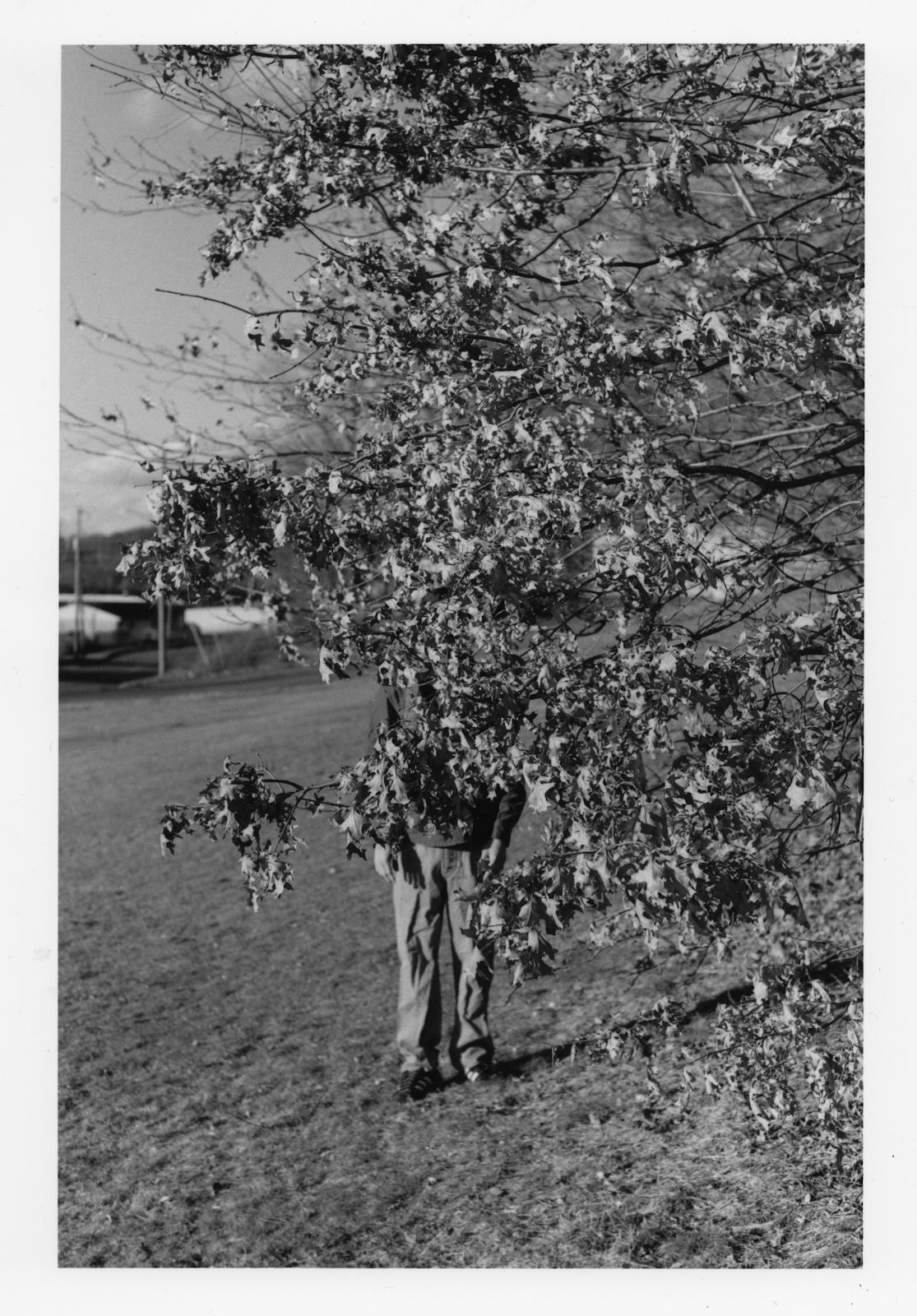

Alex Potts on the

tracks by McKenna Blackshire

Donor 1476 by Georgia Groome

audiololologist by Mel Cort

Love Letter by Abigail Grauer

séance by Olivia Kong

Shady Maple Smorgasbord Review by Efi Miller

Eden Bloom

Embergris by Shannon Lin

Eve Epstein

this is my way of bridging the gap by Sarann Spiegel

Untitled by Fae Leonard-Mann

“40 Minutes at a Dive Bar in Virgina Beach” by DZ

Down with the Collector’s Guild by Tati Wolkowitz

Sophie Jager

Shoresh Means Root by Yael Ezry

only after i’ve chosen death can i let go of what tethers me to this existence by Suz Blattner

Sestina on Blackbirds, after Wallace Steven’s Poem by Esme Israel

Last night, I dreamed the devil read me a poem. His forked tongue hissed, ringing in my ear: The profane is holy. He will give you heaven, but I, I will give you art.

So I listened, and he spoke in lost tongues, an apocalyptic prosody, a meter forged in sin, as though read from some ancient tablet buried with an immortal curse.

And now, I translate, futile forgetful prophet that I am. Was it a love poem?

Oh, infernal muse! Oh, sweet Lucifer!

Oh, eyes blazing red in the night! Unholy inspiration! Take my soul! Give me a poem!

Or maybe an elegy.

Oh, sapien flesh. Oh, mortal pen. Oh, pale anglophone mimicry. I thought the apple would give knowledge, but I was left only shame, and the echoes of a poem to rival God.

“PURPLE, OR WAS IT MAUVE?”

Kai Paik

Solemn trees swaying in elegant shapes; A speck of dust in the frayed mill house; A fervid hog, a vul’trine grouse; Miranda queths a draught of grapes.

Spirits, they keen ‘oer erstwhile wood, The hounds of Jove suborn thrice twist; ‘Curse loathen lecture doth I missed, For once at heart; hath twice as good.

Unturn it, incensed—fly, gainward wisp; O Franks hath frolicked ‘tward the sack; Keep vigil eyes, O Thoughtless Hack, Embut thy auspice, pepper lisp.

Lay belfry gauze on Javan tombs, The forthright boar’s knell sires the wind; Bereft, my Briton! All love’s but blind; Unused, an aubade echo drones.

Solemn trees swaying on curdled crust, Bear fairer fruit in borrowed shade; These hallowed halls were built to rust; Atwater’s edge all dreams may fade.

Issue XIII: Hauntings twined

Noa Koffman-Adsit

i sat down at the tattoo place and he stitched my forearm to yours.

is this what you want? i can’t tell. i’m too afraid to ask.

the first week was strange.

everything is done in tandem. next to each other. one time a stitch ripped, i think. it’s intoxicating, but we can’t hold hands, now, can we.

we went back to the tattoo man. maybe he could fix it. he stitched my arm to your collarbone, your hand to mine, a foot to a knee. patted us on the shoulder and sent us out.

i walk different, now. we roll and grope, a limb always in front, dragging us forward. it feels more efficient, i think, i said. you didn’t respond.

sometimes i’ve lost track of who is talking. who we’re talking to. where have my eyes migrated? where do they land? i’m sorry. i don’t know. i don’t know.

maybe it is more comfortable for my neck to be crooked, if our hair can be braided together. as long as mine can be as long as yours.

i can’t get a good look at your eyes. what color are they, again?

my earring got stuck in yours a few decades ago. they haven’t been unhitched from each other. i guess we shouldn’t both have been wearing hoops. hooks? i’ve forgotten.

i could kiss you, but then our mouths would be stitched together. we wouldn’t be able to talk. besides, i wouldn’t know where to start. is that my mouth or yours?

i’m afraid of you and you’re afraid of blood.

i don’t know if i like this.

i love y ou.

I’ve been stuck here for about five years now, I guess. We moved for the schools, for my boy, for the picket fence, you know, because I love the kid to death. My son and I live on an island twenty minutes outside San Francisco in an apartment building between a Christian day school and a bad Thai restaurant. Fourth floor—next to a Mexican family and what must be a hermit. Alameda is the kind of place where people stand still on the street to feel the sun on their pale faces and pray that, one day, the breeze from the estuary might just carry them to Heaven. The island is filled with reformed surfers, tech bros in Patagonia quarter-zips, bandwagon Warriors fans, and other little rabbit-hearted creatures.

It’s a pile of shit, the town. What I mean to say is that it’s built on landfill— thirteen feet of garbage at its highest point. From there, you can see the mudflats, the invasive plants eating up the shoreline, and the City. A sparkling jewel, my wife used to call it, when the sun would creep through the fog and bounce off the skyscrapers.

A few blocks from our building, a set of elderly twins linger around the towering oak trees that cast shadows on the rich folks’ homes on Central. Next to the leafy giants—really just youngsters, not even half a century old—the two make small talk and argue with each other about nothing.

No one knows their names, only their matching outfits and their permanence. They wear denim jumpsuits and New Balances on Mondays, orange windbreakers and cargo pants on Thursdays. My son nicknamed them Didi and Gogo, but I still don’t know which one is which.

I used to think they let out too much air when they laughed and their steady optimism bothered me like nothing else. There must be some booze in those brown Peet’s cups, I thought, when I ran into them for the first time. But my impression of them changed a few years ago when my son and I rounded the corner onto Park Street and saw the jesters kibitzing in matching green and yellow A’s caps. That morning, they were something like sirens to Ben, who, sporting the A’s hat I’d gotten him for Christmas the year before, ran towards them with fawn-eyes, eager to talk about the trades, the new roster, and the spring training games happening in Arizona.

“What’s up, little man?” Didi or Gogo said, still nameless at the time, the other reaching out to shake my hand with a smile. His teeth were jagged silver tiles.

“Have you guys seen Chad Bradford pitch? His arm? Isn’t that so crazy?” Ben rattled off hungrily, awaiting a response from the twins.

His hair was still blond then, tucked neatly behind his ears before settling above his shoulders. It had grown brown as he’d gotten older, but during the summers, when the sun wouldn’t set until seven, his hair had remnants of a blonder past. His full cheeks sat high on his face, a button nose pressed neatly between brown eyes too big for his little head.

I dozed off as one of them began to respond to Ben. My eyes were elsewhere as the handful of pills from the morning had begun to kick in, the warmth slowly filling my bones.

I imagined myself stuck between Alameda and Oakland, trapped on the High Street Bridge. The wind played over whatever station I’d tuned to, and I was speeding just right. Its steel road was rocking me so far from the right lane that I could have fallen off the bridge into the murky water beneath me. I felt I could fill the short span of water a thousand times over, my flesh bobbing next to the fishermen who’d only come out when the king tide rolled in.

“...Yep, yep, yep. Hey, over here!” one of the twins exclaimed, rescuing me from my rapture. “You an A’s fan?”

They let me laugh and nod to no one in particular, answering the question in silence. I knew they’d both seen my eyes turn gray like the eyes of fish that had been boiled and boiled. It felt like either one of them could’ve reached into their front jean pocket and pulled out a plastic bag dimpled by a hundred little tablets. And had they shown Ben the contents, he would have seen white pills branded with my desperate face and a series of numbers and letters. Instead, the twins matched my toothy grin with an enthusiastic display of metal, and I shook Didi or Gogo’s hand once more before continuing down Park Street.

“We’ve gotta get you to school, buddy.”

Park Street is a fleet of boba shops, nail salons, and failing Ethiopian restaurants. It’s a disservice to call it downtown, but it’s the closest we’ve got here. The only constant, apart from Didi and Gogo, is Jim’s Diner. I’ve been working as a cook at the joint for a while now. The wrinkled men who sit at the counter have told me the diner was born when good men worked at Crab Cove and the Indians lived on the West End, but it refused to die with them. The waitresses have been here since Creation, pouring burnt coffee and calling men names their wives no longer do: How you doin’, honey? Let me get that for you, baby. Little things like that. The place hums with life in the mornings.

And every morning, I gulp down little white pills from bottles labeled with other people’s names, praying God keeps the law away as I drive with fleeting consciousness down Lincoln to get to Park Street and start my shift. The griddle warms my face as the pills relax my mind. In front of the burners, I wipe sweat off my brow with a white tee perpetually stained by oil and batter and sauce. My fingers are burnt pulp, and I move with heavy feet.

This morning, I took the day off. I woke with the light, showered, shaved, threw on a white tee, slurped down a couple pills, had a drink, and put five dollars worth in the tank before driving down to South Shore. And as I crawled down the gravel path tracing the shoreline, I imagined the birds above had seen me slumped against my wooden footboard, my son asleep in the room beside mine. Or that I mistakenly told them my favorite movie and the longest I ever went without sleep and every secret I ever pinky-promised. Did they remember me before mornings like these carved wrinkles into my skin? Back when I used to come to the water with my wife and wave politely at the other families with strollers and coffee cups?

The white-bellied squirrels scurried into the ice plants as I continued past the bend where the broken pier juts into the sand. I wanted to bring my son down to feel the breeze.

I pulled into the driveway. The super’s baby sister ran naked under the sprinklers and the dogs the neighbors weren’t supposed to have ran free in the small grassy yard behind our building. As I woke Ben, a few groggy words floated from his mouth and stuck to me like cling wrap—something about baseball cards and his soccer team. I was still high. I wondered if he noticed it in my voice or in the way my eyes drifted away towards the clouds. The figure of a woman sat neatly on the horizon and I knew that we would wait on the bench beneath the birch tree and talk about nothing this afternoon.

On the bench, the wind lifted the scent of kelp and sulfur from the water. The warmth had drifted away and evanescent pinks and purples filled the sky as Ben pulled at white bark on the peeling tree. We hadn’t talked much. The cloud I saw was something else, somewhere else, entirely. A new shape for someone else to make out.

“What are we waiting for?” Ben asked as the wind pulled the last of the warmth from his skin.

Mia Alexander

was smoking a broken cigarette pawned from a drunk stranger in front of the church where I used to go to services with my Jewish father after he found me bleeding out in a bathtub he decided I needed some morals whacked into me. The stranger offered me a flame from his piss-soaked pocket— he liked me because I was young; I liked him because I thought he was as much god as that priest. When I used his lighter he said let there be light.

A projectile with a project, Ellington Davis

inertia bound only by the laws which I cannot see but know to be there. Reaching out to grab a little piece of the infinitary symbolic, which descends down with grace and intention, and is there for all well poised and willing parties.

Feeling the beat and peace without bass, only a fat synth. European disco, flirty and ovational, celebratory. To grab onto the fat and the corn and the mold and to hold on tight. As two old ladies in the sky make love, as the devil beats his wife, the rain and the shine in anti-collision.

Inertia only in the details, not greater schemes or schemas, not found in the sky. The object at rest will tend towards staying at rest. An object in motion will tend towards staying in motion. Not for the subjects, those who look to the grand and almighty and revere. We bow to you, we bow to you, may the crown sit heavy for it is not only one of us who may wear it. May our bones feel the weight of the invasion by the alien, the new, and the ill-elusive constant.

To search for that which will always be there is to look for a castle in the cellar that it contains. Russian dolls, extending with different shades of expression. Standing shoulder to shoulder like we need a good close-up on that shot. Uncomfortably cinematic, music when driving, there is a correct choice but how to decide? Obvious and concealed, a game which can be played, not with tokens only with gratitude and a pinch of salt. Acid in the throat will give cancerous results, ye be warned all those who eat more than their stomachs will afford and who can afford more than they ever thought they would.

Inertia instead interstitially, apparent under monotonic inspection, apparitions to oculus. Shining into and out of a well, never formulated intention to devour light and hark brail. Standing on the shoulders of giants, precarious floating above the folly reputable amongst all fools.

Do not slip and do not climb and saturate into the middle of re-progressive time, with a salty-sweet taste of the powdered marrow of saints. The rancor of remaining, in a valence ripping kindly through place.

Programming

Ella Spitz

Because I know when to cross the crosswalks now,

Because I feel win-wins and teeth-scraping artichoke leaves,

I have a system and everything has its place: scoop the choke; keep the heart.

Now I can round the corner, prance along your part, and keep the bounce of each loose brick.

Because I made a wish on your stray, thinning eyelash,

Because I made a hat out of pomelo leather skin,

I have a system and you’ve kept it all in place: slice the pith; slurp the heart.

Now I can fold the corner, read you your favorite part, and make the voice of each word stick.

Jordana Treisman

On April 3rd, Ohio resident Claire Hauser reached out to the local authorities to report concerns about her friend Lola Wilson, a freshman at the nearby college. Two days later, Wilson was found dead in her dorm room. According to released autopsy reports, her skin was reported to be flushed head-to-toe, and her chest swollen. Attendance records show that Lola had been marked absent in her classes for five weeks up to this point, and close friends and family reported her losing contact almost a month prior. After gaining access to the initial police report, signs of distress at the scene of the crime were abundant: walls, windows, mirrors, and even parts of the ceiling had been painted over in multiple layers of pink. Itemization of Lola’s trash and recycling bins led to the discovery that the decoration had been done entirely out of nail polish.

A student EMT, whose name has been omitted, described the scene: “Empty bottles of ESSIE and OPI filled the dorm, and the room reeked of the chemical fumes. The pink chipped off the walls and gave the air this confetti-like quality.”

In the transcription of the initial phone call to local authorities, Claire had mentioned letters sent by Lola in the months leading up to her death. Two of said letters have been leaked to the public by unknown sources, now available for viewing despite the authorities’ attempts to contain the investigation. Here they are presented to you in their unedited and untouched condition.

Letter One - September 28th (the year before)

Claire-Bear,

Well, well, well! Looks like your attempt at a disappearance was futile—I will still be bothering you, no matter how many miles away you’ve gotten!! Please: I need to hear everything about New Zealand. How is the weather? The food? The SHEEP? I hope being off the grid is nice, though I can’t imagine having the balls to do it. College has been awesome! (See attached: two polaroids of my roommates, one of a masquerade ball party, one Chess Club pamphlet.)

I’m in the classes that I want, and I got super lucky with a very nice single dorm room. What’s been the best, though, is the people. I met this AMAZING group of friends. They have traveled everywhere, seen everything. They take me to cool bars and parties, and we talk about the craziest things.

And get this: in a Dickensian twist of fate, I have been receiving envelopes of money in my mailroom, addressed to me! Not cash, or euros, or even arcade tokens, but real, legit pink money. More than all of the birthday gifts I’ve ever gotten. I’m not even sure how much I can go into detail since the facts are a little sketchy, but either through my friends or their parents (or maybe some unknown trust fund? Who knows!).

It’s super suspicious. But can you blame me? For once in my life, I would like to not be the ugliest girl in the room. No more “Slow-la,” or “Roly Poly Lolie,” or “Lonely Lola.” Think of all the words I’ll get: I will tell Michelle Redder, who sits in front of me in Philosophy, that her tag is always hanging out. I’ll ask for that off-the-menu drink at the cafe. I’ll flirt with that one boy at the fraternity parties. Oh, and the seats on the bus, and front-row concert tickets, stuff like that. Everything that comes with being beautiful.

Let me tell you something else: I really really want to try Liquid Pink, if I get enough money. How else could I try it? College is all about experimenting, anyway.

I just really feel like I’m coming into my own, you know? People look at me differently now; they talk to me. I finally feel like they see past my hair, or my acne, or literally everything else. Screw Hannah Carter: I’ll be homecoming queen from now on.

I’m sorry, this kind of turned into a rant. I’m just super excited. I’m not saying anything to my parents yet, so despite the fact that you are on a different continent than them, can you please not say anything to anyone back home? This is really huge for me and I don’t want to mess it up.

Please send me photos of the baby sheep, and let me know what farming is like. I want to hear about YOU, okay?

Your favorite debate team partner, Lola

Letter Two - December 10th

Claire,

How are you? I am dying to tell you about what’s been going on over here. Parties, boys, and my inbox is never empty. Last week, at this restaurant, the waitress fully accepted my pink money instead of regular cash because I didn’t have any on me. I’ve been waxing a lot more, trying more makeup to see if I can get more funds. The envelopes are still coming in, but there’s less pink money in them now. Still, I FINALLY collected enough that I was able to afford a whole bottle of Liquid Pink.

I’ll set the scene for you. I’ve been glamming up my dorm room: pink fluffy rug, perfume bottles, new mirrors. It looks like a Hollywood starlet’s dressing room, and sure as hell makes me feel like one. I bought the bottle at Walgreens, and I even had to pay more pink money to get into the right section, so I carried it home like a newborn baby. When I finally got to my room, I sat on my floor because it is exponentially more comfortable than those stupid dorm beds. I tried to imagine myself as pretty, and then braced myself to feel ten times that. I wondered if my legs would grow or my chin would shrink, or maybe I would simply begin to shine.

As I poured a cap’s worth into my seltzer, my stomach began to turn and I trembled a bit. I kept telling myself, embrace the pink. Let’s get fucking beautiful. And I drank it and waited.

I don’t know how to even describe it to you, Claire. The pink left this sweet taste in my throat like melted caramel, and I felt lighter than air. I looked at my hands and they were like porcelain, like a doll’s. I actually glowed.

I watched the coarse hair on my arms become the pink strands of the plush carpet. My dresser was oozing a glittery fuchsia, dripping down the

cabinet drawers. I was the version of me I see in my mind when I sleep, not even me anymore. I remember wondering if this is how we see ourselves in Heaven, if there is one.

As it faded, I was left with this residual feeling that I had the capacity to be beautiful. I’ve seen it now, Claire. And I don’t think I can go back.

Do you know how I can get more pink money? I think I’ll go to the bank tomorrow and see if they do loans. If not, I’m sure my new friends here could help out. That’s what I pay them for, anyway.

Please let me know how you’re doing. I hope the cold weather isn’t too bad for your skin.

Lola

Peers at the University have speculated that following this letter, Lola engaged with multiple fraudulent loan companies, and digital receipts show that she was able to purchase over 15 liters of Liquid Pink, an amount health experts consider to be a threat to organ health. As it is difficult to obtain, the CDC has not considered it a dangerous drug, as it is still beneficial in controlled quantities. Additionally, stock market analysis shows that the consequences for banning pink money would be detrimental to the U.S. economy.

Following the leak of the two letters, a third letter was found in Lola’s mailbox. This letter had been returned to the sender, unopened. When interviewed, Claire Hauser admitted to not giving Lola her new address or informing her of her move to back Ohio as to protect her wellbeing.

Here is the third letter, completely unedited, discovered by the SIG.

Claire,

I’m so, so, sorry that you feel like I shouldn’t write to you anymore. I know I haven’t been the best with the debt, but I SWEAR to you that I am going to pay you back. I’m just going through a really hard time right now, if you can understand that. But I guess you can’t. Do you know how hard it is to feel yourself getting uglier and uglier by the second? To watch your cheeks swell and your facial hair grow and to wrinkle? I’m sinking so hard, and now people I thought were my friends (like you) are actually not. But now I see what kind of person you are. You’re an ugly, ugly person and a horrible friend. YOU’RE SICK!!!!!! And you should be there for me right now.

I honestly have no idea what to do, Claire. The bottles are almost empty. The pink is fading from the outside in. The pink on the inside is poisoning me. There are tumors, like balls of bubblegum, everywhere. I can feel them. And my vision is tinted so badly that I can’t tell my blood from lipstick. The only way it doesn’t hurt, for me not to be scared, is more liquid pink. You understand that, right? Why I need all this money? I need the pink back. I’m trying to keep it all around me now, and fill the room with it. But the sicker I get the uglier I feel.

I want you to know how hard I’m trying. I’ve been thinking a lot recently, not like how I did in my stupid classes. I think that every day I get further from perfect. I age and become bitter and I walk towards death and away from the perfection that I once could be. But I want to change that. I want to get better, Claire. I don’t know if I’ll ever be perfect, like what I want, but I think I can get a little closer every day.

And you will all love me again. Ok?

According to financial analyst Mark Hobrick, stock in pink money is predicted to drop slightly from this incident. However, in the next couple of months, new benefits are expected to be released with the currency. Experts like Hobrick advise Americans to hold on to their shares and await a speedy rise and recovery. Despite the information being released on cases like Wilson’s, the future looks bright for pink money owners: as quipped by financial advisers across the country,

“EVERYTHING’S COMING UP ROSES.”

Unresolved Tension

Jalen Richardson

Scrupulous, my pupils are dilated Heart has been violated A vial of venom waiting for me.

Ain’t it funny, deceitfully I’m admired Receipt reservoir required To keep ‘em in check-deposit patience.

Conversations I speak from the soul, My pain seeks to be told, Haunted by cavernous consequences So ravenous common sense is, Eating all the pent-up levels Of condensation.

Wipe down all the windows That water goes in a basin— Lotta sewage to waste in…

Got a couple people in mind when I’m on vacation Lots of empty space and This block-headed place is vacant

Guess I’ve been forsaken Awoke by the indignation I’m broken, insane, and shaken

Used to being ghosted But now that the gas is lit, A vessel is being hosted, Blind I was passionate,

I’m pitching my fork I gotta lot to uncork This what you get when you screw with me

I’ll show you a demon—Diabolic, Peek into a brain when it suffers… Melancholic, Tunnel vision, Hear an echo, will I let go? Not a chance, see the blood on my hands already.

Alex Potts

McKenna Blackshire

i sat down on the rail road tracks & drank a bottle of wine, clear my mind— this old lady came up to me, she said:

i’ve got a plane where do you want to be? the first time we went up in the sky i was certain i’d die.

i ran to france with nothing but a cigarette & a hat there was a naked girl with a pretty guitar all we did was smoke her art.

i want to see her again, but she swam to the stars! goodnight!

stained glass windows left behind tell the stories of forgotten time i look in the fragments, in techni-colors, i am trapped.

i don’t know what it takes to not forget. can i do anything nothing at all? you’ll forget then isn’t it the end? i want to write about everything i can’t recall.

a bottle of wine, the railroad tracks, no—you can’t go back.

a flower & an expectation to last. the disco disguises a disco for the dead.

Lauren Horowitz

Lev Rubinowitz transferred to my elementary school in the fourth grade. He wore knitted sweater vests and adults called him “precocious,” which was enough to explain why he seemed to know everything that the rest of us squirming, unsophisticated children didn’t. He had technically been a year ahead at his previous school but, for reasons unknown to me, was required to repeat fourth grade upon entry to my crunchy granola, Kumbaya-caroling educational institution.

One thing I heard about him during that first year was how he already knew everything in our curriculum. He already knew how to add and subtract fractions, how to use commas, where each of the fifty states were. He already knew what happened at the end of A Wrinkle In Time and Charlotte’s Web and Harry Potter. Many of the kids resented him for this. I chose to exercise caution. Lev was in a different class section when school began, so our interactions were minimal. I saw him out in the garden, stealing leaves off the stevia plant. By the wooden lunch tables, still damp from the last Los Angeles drizzle, he boasted about what song he was learning to play on the viola or told some joke that I didn’t understand.

One of the adult-sounding terms that Lev brandished was “screwed up.” I remember talking to Dad in the kitchen and, in a fleeting moment, deciding to adopt some of this grown-up vernacular to describe how something was, in my humble opinion, very screwed up. His eyes widened a bit, clearly shocked. Dad proceeded to lovingly inform me that this was actually not a very nice thing to say. As someone who cared painfully about the maintenance of my niceness, this pointer pierced me like an arrow to the heart. It also cemented my distrust of Lev, the source of not-nice things.

On the first day of fifth grade, I saw Lev’s name pinned onto the same homeroom door as mine. When we were assigned to be desk partners, Lev grinned from across the table, his pencil box encroaching on my side. During class, he blabbed incessantly to me in a hushed scream, stopping at nothing to disrupt my focus, the very goody two-shoes attentiveness which had garnered me blue ribbons and gold stars. How could someone know so much about the world I didn’t and nothing about the one I did?

As the target of his attention, I felt shamefully implicit in his class disruptions, as if they were somehow my fault or of my doing, that the burning red

which tinged the tips of my ears was hard proof of my culpability. I was, in a way that wouldn’t be deciphered until years later, flattered. But what cut through any sensation of delight was my loathing for his utter disobedience and how it reflected back onto my face in scarlet splotches. I decided that Lev embodied everything I wholeheartedly denounced. He was annoying, pretentious and disruptive to the class, a ticking time bomb with tight curls.

Valentine’s Day had a certain rhythm. We each prepared various valentines—cards, Fun-Dip, candy necklaces—and delivered them to every student in the class. My school was big on inclusion. But this year, something felt off. It wasn’t until my best friend Carrie told me to open my backpack that I finally understood why. Inside of the front pocket was a CD in a clear case. On its surface was a myriad of doodles, abstract and ornate. Within the dense jungle of squiggles, I noticed a graphite outline of a heart. For once, I actually understood what the boy was trying to tell me. It filled me with an ocean of dread.

At home, I reluctantly put the CD on and listened—very quietly—to the songs he compiled for me. I think it was mostly slow rock. But my memory of what the mixtape actually contained was hazed over by the panic of receiving such a thoughtful gift. Part of me felt undeserving of it, I’m sure. I shoved the mixtape into my stash of Valentine’s Day loot in hopes that the gummy worms and candy hearts would somehow mask the intensity of his romantic gesture.

A couple of hours later, I heard a knock at my bedroom door and my dad’s head poked in. He asked me if I’d gotten anything good, prodding around my stash, and I asked myself if I should tell him. Eventually, somehow, the mixtape was in his hands. I couldn’t tell if he looked pleased or skeptical. I, for a fact, looked like a nervous wreck, unsure of what to say or how to react to this token of affection. Dad awkwardly said, “Lev’s mom was just asking us how the valentine was received…” I had no words.

At school, I managed to maintain my composure and kindly thank Lev for the gift. But at home, the mixtape haunted me as if it was the boogeyman himself. As long as it remained in my bedroom, I felt as if my head was trapped in a tank of filling water. I don’t know whether it was the guilt of Lev’s feelings being unrequited or that I simply felt unprepared for this level of romantic intensity, but one day, the sight of the mixtape became unbearable.

With trembling hands, I shoved the mixtape into the box of now stale Valentine’s candy and hurled the box into the trash can outside before fleeing the scene. But even after unburdening myself of all remnants of February 14th, I couldn’t help but wince internally. Days later, I regretted the decision entirely.

The cavernous remorse I felt for throwing away Lev’s gift still echoes within me whenever I think about it. He and I became good friends in middle school and still are. I know few other people as talented, inspired, and smart as Lev. He goes to a music conservatory in London, playing shows every chance he gets, and I look forward to seeing him whenever we’re both home. We always have so much to talk about, yet, to this day, we’ve never discussed the mixtape. My silence is mainly selfish. I’m scared to admit what I did. I doubt Lev even thinks about it anymore, but the possibility that the mixtape might still exist, intact and unharmed, in the faraway folds of his memory, consoles me. Even more than knowing that, I wish I could go back and carefully listen to the songs he chose and admire the doodles he created. I could accept the love he offered more gracefully now than I could then, but no boy has come close to Lev’s gift on any Valentine’s Day since.

In the first quarter of the year with No visuals. just confusion BEÄM

Amidst a palimpsest of arisals

The idea of a chair is set aflame— Self-serving—

With no material falter.

Mulled over in the queen of streets, One arises as conditioned— Needing not to feed the flamed, But choosing to anyway.

We all, moorers of barely-floating graves, Swept under the uncertain white washes of viscous descent.

Another frame away,

Attached to his tongued ties,

A man slices his licks width across

A one hundred and ten degrees apart. Split open and leaking fabric. Drapes are made of these. And a man runs his fingers through them chalked.

Simultaneously, in a ceramic tub somewhere in Connecticut, A girl bleeds brown tears semi-professionally, Euphorically smacked but short-legged as always. The bath water again, remembering slowly how to flow adrift. The girl, again, forgetting where her warmth ends, seeks refuge at a Kentucky fried chicken

where the American dream is fried not with oil, but reserpine air.

Citizens, demanding god-given suffrage, under the mirage of free will and free rights suckle on the supple teats of suffering, chastised by the state; its 4 unit nucleus. For me they did away with veto decades ago, now, confronted with the illusion of choice in the face of situation, a mandatorily united front forms out of fear and ignorance, and those who speak out are once more made drapes of.

I’ve called upon the first 20 years of the so-called forever-interpreted-and-reinterprited-herkunft, and rested upon the creased contours of its dined cloth in silent sobs madness and confusion. unbeknownst to what extent rocks decay of palms to soothe the weight of ephemerality and spiral jetties.

I’ve seen great minds crumble to that of a sickly child. ruminating on linguistic games and the falsehood of smug knowledge and caricatures and endless thirst for success and sex and coach-class martyrdom, nonchalance, and thicker skin, thicker blood, thicker soup.

In our incessant choice to suffer we leave our arrows in, demanding to know who shot them, with what bow, made by whom, from what tree, festering what needn’t be so, if, evermore.

Yet I, on a pedestal of skeptic asceticism,

Issue XIII: Hauntings who, not for compassion nor milk nor motherly-love, endemic voyeur of doom and impending hubris, who mindlessly rips skin, cartilage and all manners of feathers, who out of the fear of the neo-gods that engulf the modern age, thirst without cessation, without means for an end, with no visuals, and ample confusion.

Donor 1476

Georgia Groome

I know very little about Mike—I’m not even technically supposed to know his name. I was conceived in 2002 when artificial insemination was not very common. The information that was offered about sperm donors at that time pales in comparison to the extensive reports that are now available. From what I understand, many contemporary sperm donor profiles include names, voice samples, videos of them at their current age, and sometimes even contact information. I have none of this. All I know is what was included in Mike’s file, which describes his features, his medical and genetic history, and a few of his interests. Also, a picture of him when he was two years old. If you zoom in really tight on the photo, you can make out the text on the cake placed in front of him: “Happy birthday, Mike.”

I know that he is a singer, a guitarist, and a drummer. His favorite color is green, his favorite food is lasagna, his favorite music is rock, his favorite animal is a tiger, his favorite movie is “Backdraft,” his favorite song is “Plush,” and his favorite play is “Tommy.” He has a dog, and he drives a Supra.

He is a Catholic, and he can speak both English and Spanish fluently. He plays rugby, volleyball, basketball, and football but only watches basketball and football. He has two brothers who were reported as twenty-eight and twenty-one at the time. He got a 1230 on his SAT. He had a 3.3 GPA in high school and a 2.5 GPA in college. He majored in economics and Spanish and minored in business. He was working on his bachelor’s degree when he donated his sperm; I don’t know his exact age, but he must have been in his early twenties.

He never served in the military. He’s right-handed. I know the measurements of his hands, fingers, neck, chest, inseam, waist, sleeve, wrist, hat, and shoe (remarkably, he has size thirteen feet). He is six foot two, two hundred pounds, and has O+ blood. He has normal vision and average-set eyes. They are oval and light blue. His eyebrows, nose, cheekbones, ears, mouth, and teeth are all more or less medium/average. His chin is square and strong. He has thick, curly blond hair. He has slight dimples and a slight Adam’s apple. His personality type is ENTJ. His parents are both German. He has no medical complications or issues. He has one tattoo and three warts. He told his interviewer that he wanted the money to buy himself a stereo system.

His academic goal is to get a master’s in business, his professional goal is to gain a dynamic position in sales or recruiting, and his personal goal is to love and be loved.

This is all that I know.

Mom paid Mike extra to stop donating his sperm. I don’t know how many half-siblings I have; I just know that I’m the youngest of us all. Mom guesses that there are between eight and twelve of us, but that’s an arbitrary number. She doesn’t want to know—the thought that I have siblings freaks her out— and I have no real interest, either. Not that I could find out if I wanted to, anyway. Once, Mom said, “If you ever fall in love with someone who was born within five or so years of you and was conceived by a sperm donor around the New York area, get a genetic test, just to be sure.” Unintentional incest—that would suck. I have no romantic conceptions of Mike as my father or these hypothetical siblings as siblings or any of us as resembling any kind of family. But some of the people who do resemble family for me don’t share that same detachment. For example, when Mom got pregnant, Nana couldn’t wrap her mind around it. She couldn’t fathom the idea that I wouldn’t have a father, and more so, that people would know I didn’t.

“She suggested that I tell you that your dad died in 9/11,” Mom said. “I said, ‘That doesn’t even make any sense. Georgia will be born in 2003. The math is all off,’” and Nana said, “I don’t know. Maybe the Afghanistan war, then.” Mom laughed as she told me this. “What pictures would I even show her of this father?” Mom joked, mimicking the rest of the conversation. “She’s so fucking crazy.”

audiololologist

Mel Cort

n I watch it slip trip n fall

lttrs off th waywrd, pitterpatterin, kerplnkin out th wazoooooo.

decibl by dcibl b dcblbdcl, soundn lik

Love Letter

Abigail Grauer

We are two monsters. You are a ghost and I And I I

I am blood wrapped in sinew and spine and flesh, Tearing at my hair and wailing in the halls, And praying to shrines of malice and hope.

You are my soul wrapped in a death shroud; I am the white dress at your wedding.

My soles are worn thin from the short walk to hell, And your garbage is sick of receiving my letters.

I would beg you, if you would only listen: Get on my knees and pray, Drink the blood on my walls like wine, Eat the shirt you left in my drawer, Choking on thread and spitting out bloody teeth for postage.

You are pouring my heart with your cornflakes, Tying your shoes with my envy. I want to wash every lone sock in your house, water your plants, feed your dog, and Wander the halls of my heart while I scream.

In the Book of Maccabees, Judith fights for her people by seducing and sleeping with an enemy general. She beheads him before he wakes up the next morning.

Lady Macbeth is the wife of a timid Danish lord in Shakespeare’s Macbeth. She is often deeply frustrated by her husband’s lack of bravery, and tries to take matters into her own hands before ultimately killing herself.

Madame Defarge avenges her sister, who was raped and murdered by noblemen, by knitting the names of similarly wealthy families and determining who dies by the guillotine.

but can you hear feel their fingers touching soiled, dewy earth once again, at last resurrected, these brilliant, glowing temptresses, given over to violence amidst the wilting, radiant flowers that cleanse you and i

i hope you remember those whokeeptheharvestforthemselves/whositonthronesofgoldandlie/whowillloveandloveuntiltheystabourchest/ whoprayuponagoodgodwhilewecurseacruelfather/whopoundinandoutofourbodiesandthencallusthebitch/

find them so that their blood may burn forever i’m telling you to go out AND LIVE

o judith, you of honeyed seduction

you knew you were a creature of beauty you knew he desired you you knew the path that would make you a murderer you knew you could slice off his head, like you would slice up fruit, the multicolor juices flooding how different from son of god himself except that you exchanged pleasure for an unHOLY salvation

and you, lady macbeth in your savage, unGODLY skull lies an empty conscience you prayed upon your god for power and easy lies

you prayed upon spirits to unsex you. what did you ever mean?

you were asking for fear and silly womanly nerves to be ripped away can you understand that many of us can be equally just as delicate as violent as beautiful as angry as radiant as hateful

madame defarge your pleasure blooming as a guillotine sees their heads divided from their body the blood of their marrow dripping into the grainy cobblestone

o child of guiltlessness your innocence unbroken until your sister was ravaged wrecked reaped cries go unheard, uncomforted so you continue your knitting like a good Christian wife

yeah, so keep the veil on, keep signing that accursed cross BECAUSE WHEN HAS YOUR god EVER FOUGHT FOR YOU?

Shady Maple Smorgasbord Review

Efi Miller

Among the rolling fields of Pennsylvania’s pious and pastoral Amish country lies a haven of hedonism and gluttony. The sprawling fields are parted by a warehouse-like quasi-industrial but also quasi-colonial structure. Only in such a niche religious area would be the largest all-you-can-eat buffet in America. Slithering through the masses of Mennonites I pile my plate with whoopie pies, scrapple (a fried meat brick), ready-to-order pancakes, and gravy—till the grease slides down my fingers, loosening my already-precarious grip. The dangling chandeliers appeared to have consumed most of their design budget, as everyone sits on sticky pleather seats and rests their elbows on discolored plastic tables. In the dining room, families bite into their piles of slime, partaking in a holy feast, ignoring the fact that they just violated the fifth deadly sin. An annoying person would comment on how this temple of bile is a microcosm of America with its capitalism and obesity, but I can’t hear them over the sound of my own plate of gloop swishing around my mouth.

Embergris

Shannon Lin

Flames lashed out of the metal barrel into the August heat. Liu Ren-jing watched the joss paper curl and blacken in the fire. A stack of more paper rested in her blanketed lap. When the fire began to calm, she folded up another sheet. The yellow paper was coarse and dusty under her weathered fingertips, and the square of silver glinting in the summer sun. She tossed the paper. It caught on the lip of the furnace before tumbling onto the asphalt. Ren-jing had parked her motorized wheelchair an arm’s length away—any closer and she risked setting her lint-covered blanket on fire—but her aim was still far from reliable. Folded joss paper littered the ground in front of her like large, crumpled flowers blooming in the cracks of the road.

This was the first time in decades Ren-jing had burnt offerings for the dead. She remembered one Hungry Ghost Festival of her childhood clearly. It was a mundane memory: the scent of smoke, the burning of incense, the heat. Her uncles laying out plates of chicken and bowls of rice. Her father pouring rice wine into ceremonial cups. Her mother propping up incense sticks on the offering table.

Yet, as many of her other memories had begun to dwindle, this one had remained with stubborn clarity. Perhaps that was why she had decided to go through the trouble this year, after spending almost her entire adult life agnostic.

Perhaps it was out of selfishness. Ren-jing was eighty-nine. It wouldn’t be much longer until she became a ghost herself, if such a thing were possible. In the seventh month of the next lunar year, maybe she would be among the wayward spirits bursting from the gates of hell—the starving and restless with no family to give them offerings. The last time she had seen Ren-jun was at their mother’s funeral, with her teenage niece trailing behind him. That was more than forty years ago. Ren-jing wondered when her brother had decided she wasn’t worth the trouble anymore. Was it when she transferred out of medical school to study marine biology on the other side of the country, without telling anyone? Was it when she stopped making the trip up north for Chinese New Year? Was it when he had to resort to looking up her work email in the university directory just to tell her the date of their mother’s wake? If Ren-jun had once believed they should keep in contact—whether out of love or duty or inertia—he’d definitely stopped after what happened with the whale.

Ren-jing tossed another piece of paper toward the fire. There would be no one to do this for her after she passed. She convinced herself it didn’t matter as she watched the paper land in the barrel and send up a shower of sparks. The idea of an afterlife was already far-fetched, let alone a ghost economy with joss paper as legal tender. Yet, her hands found the next sheet in the stack and started folding it up anyway.

What is this all for?

The question wormed its way into her mind as she watched the orange flames writhe under the light breeze. She was wasting money—real money—to set ghost money on fire. Her parents surely must have gotten their fill of tributes from Ren-jun every Tomb Sweeping Day. But maybe he was already dead.

She looked down at her bony hand, at the creases around every knuckle, at the creases in the paper as she pinched it between callused fingers. The back of her hand was a splatter of liver spots from decades of dives and field work. She wondered if his looked the same.

Ren-jing leaned into the next throw. Her back popped. The paper landed neatly in the center of the ashes.

As her hand came back to rest on the stack of paper, it felt just as thick as when she had first bought it. The idea of dedicating it all to her long-dead parents, her maybe-dead brother, and the hypothetical horde of hungry spirits still felt hollow in her mind. With every new sheet, Ren-jing tried to conjure the image of someone she knew who could conceivably be dead. It would be good exercise for the brain. Something to stave off the forgetfulness.

Big Uncle. Middle Uncle. Cousin with the bowl cut. Associate professor whose office was across from mine. The PhD student with the round glasses. My other PhD student, the one who drove out with me to that beaching. The distressed oyster farmer who lent us the raft to go inspect the carcass. The department secretary who coordinated the transport. The crane operator who ended up needing a bigger crane. The truck driver who was driving the body through Tainan City toward the dissection site.

The dead whale that exploded before it could arrive.

The buildup of gasses in the decomposing body, combined with the subtropical heat, was too much for the rotting skin to contain. Early in the morning, as the sun was just beginning to rise, the whale burst on the back of the truck. Entrails rained down onto Section 4 of Ximen Road, right outside Su-Su’s 24-hour Grocery. The parked mopeds and nearby storefronts were plastered with several tons of blood. It was the finale to a logistical nightmare that had begun when a call came in about a sperm whale beached in the next county over.

Forty-seven-year-old Associate Professor Liu Ren-jing had rushed out to Taixi Township that morning after several hours of lobbying with the wildlife conservation agency and her department head to allow her to take the whale onto land for a necropsy. When she arrived and saw the massive corpse bobbing in the ocean, she realized this was the largest whale to ever wash up on the shores of Taiwan in recorded history. The studies she could perform, the papers she could write—this whale represented possible breakthroughs in cetacean research—and her career. She’d been snubbed in the consideration for tenure and full professorship for the sixth year in a row.

She needed this to go right.

When the pair of university-arranged 40-ton cranes finally pulled up to the shore, Ren-jing had helped to secure the sperm whale to the hooks. They tried to lift the body from the water tail-first. The pulleys ground to a halt with the sound of wire straining against metal. Refusing to give up, Ren-jing arranged for another 120-ton crane. It would take until the afternoon—and more money out of the department budget—for it to arrive on such short notice.

With the strength of the three machines combined, the whale finally emerged from the water. He was immense. Large white scars the size of buses spanned his gray skin. His mouth was stained with his own blood and hung open to reveal a row of sharp teeth, each the length of her forearm. The whale sagged between where the cranes were secured so that his body formed a wave; as he rose higher into the air, Ren-jing could almost picture him swimming through the clouds.

As they lowered him onto the truck bed, his body crushed the vehicle entirely.

Another call, another four hours, another expense out of the department’s funds. By the time the 100-ton truck pulled up onto the pier, the sun had set. They finished loading the whale onto the bed in the late evening. It was too dangerous to transport him in the dark. The drive to the Sicao Wildlife Refuge, where the necropsy would take place, would have to wait until tomorrow morning.

Ren-jing was not there when the whale exploded in the street. She was in Sicao, setting up the tools she needed for the coming dissection.

Forty-two years later, Ren-jing still remembered the stench when she first arrived on the scene. It was as if every fish in the sea—and even the sea itself—had died on Ximen Road. The smell of ammonia and blood clung to her as she helped the sanitation workers gather the intestines from the asphalt. It festered as the American film crew came in and asked her to recount the story in her broken English for their documentary. The scent of dead fish reeked every day as she spent the following year in Sicao studying the carcass, preserving its eyes, its teeth, its bones…

And it lingered as she faced the backlash from other researchers, the government, and her own university.

The clean up on Ximen Road was costly for the local government, and the accident made for bad press. The documentary highlighted her team’s struggles with transporting the body. The footage of Ren-jing’s stuttered speech came with English captions that accentuated her broken grammar. The film also featured the opinions of American researchers, who placed the blame on Ren-jing’s team for the explosion. They cited the failed lift by the tail and the back and forth with the trucks as having caused internal damage to the whale’s body; the long exposure to the sun accelerated decomposition in the carcass. They concluded that the incident was a result of her mishandling of the body. There was even a stir in online public forums that the incident was a test for a newly developed bioweapon. The university scrambled to save its image by issuing an apology, which also attempted to quash the outlandish rumors. Ren-jing was allowed to continue her research on the carcass in Sicao—but by the time she retired eighteen years later, she’d never advanced past associate professor.

The humiliation still stung, after all this time.

Ren-jing leaned back in her wheelchair. Looking back, that whale’s death had perhaps the most profound effect on her life out of everything she’d experienced. She cradled the stack of joss paper in her hands. She tossed a few more for her parents, more out of obligation than belief. They had kept in very little contact after she’d left their hometown to study marine biology in Tainan. They were an important part in her life by virtue of being her parents, but Ren-jing did not have the time to kid herself anymore; her relationship with them had ended long before their deaths. The same went for Ren-jun, if he was actually dead. The fact she did not know was damning enough. A few more papers for him, then, too.

But the rest of the stack, Ren-jing decided, she would reserve for the whale. After all, who could be a hungrier ghost than the spirit of a 16-meter-long, 60-ton sperm whale? Four decades later, no one spoke of the explosion. The skeleton gathered dust in the university’s marine conservation center. Hardly anyone still remembered him, and Ren-jing was sure to be the first to pay tribute to him like this. She was the only one close enough, senile enough, irreverent enough to bother.

Folded paper clanged against the barrel wall before dropping into the fire. Ren-jing watched the smoke swirl up from the fire, dancing above the burning offerings—a hungry ghost made real. As a steady cloud coalesced, she began to picture a form in the churning smoke. The flickering wisps above the furnace formed a tail. Rising higher, the smoke swelled into a dense mass of a head, broad and imposing. A pair of tendrils became a set of flippers. A wayward puff formed a dorsal

hump. Before long, Ren-jing was watching the phantom of a sperm whale swimming in the undulating waves of the summer breeze.

It had been a long time since she last laid eyes on him, but Ren-jing recognized that crooked jaw, that nicked fluke, that bulbous head. While the smoky creature was far from the gargantuan beast he had been in the flesh, he was familiar.

Surely, it was a trick of the eye. Or the fumes were finally getting to her. Her memory had begun to fail her more and more frequently, too; she had grown used to feeling the borders of her mind. This was a product of senility—a late-onset schizophrenia, perhaps—an amalgam of all the sperm whales in her decades of study. A hallucination. Imaginary. Impossible.

The wind whipped. The whale’s mouth split open. And as the burning embers crackled and popped, Ren-jing heard the distinctive clicks of a sperm whale coda.

You are even smaller than you were last.

Ren-jing gazed up at him with wild eyes, shoving her bifocals closer to her face. A large eye peered down at her—a dark pupil ringed by an ashen gray sclera. The same, dead eye that had stared at her on the necropsy table, that now rested in a jar of formalin in the basement of the Department of Life Sciences.

“You were already dead when I found you, how…?” The air was dry and hot. Her voice rattled from years of intermittent use.

I was watching even so.

“The dissection. We couldn’t leave you there—you saw what happened; you were a hazard. It was a miracle no one was injured in the end.” She expected to feel silly, but the conversation felt real. “…Your body was invaluable to my research.”

The wisps of a wrinkled eyelid blinked slowly.

When one dies, the small feast. You were doing the same?

Ren-jing paused. “Yes, I suppose that’s one way to look at it.” She hesitated for a moment, trying to find the words. Was he angry with how his body was used? “I…took you apart to learn from you. To preserve you. Your bones, I reconstructed your skeleton—it’s an incredible specimen.”

She sighed. “It took me the better part of a year to finish working on you.” It was a dark spot in her memory. As the documentary came out and the complaints began to pile up, she had retreated into the work of preserving the whale. It had been difficult, and on a scale far larger than anything she had ever done, but it was something she had become determined to do well.

The whale in the smoke bobbed in the breeze.

The birds were so many. They ate also. It took her a minute to catch on. “Ah, yes—the wildlife refuge,” she finally said. “I originally wanted to perform the necropsy in the university, you know. But I was forced to take you to Sicao instead. The black-faced spoonbills and the ibises, they’re endangered and the wetland is one of their few protected habitats—but I had to get one of my students to stand watch over your guts, to shoo them away.”

The two lapsed into silence.

Ren-jing stared at the whale—the accursed, magnificent whale that had changed her life. If this really was him, there was something she wanted to confirm with him. The warmth of the fire blended into the heat of the day, yet under the blanket and against the pleather seat of her wheelchair, Ren-jing’s body felt cold. Instead, it was her mind that burned intensely with a single question.

“You were struck by a ship, weren’t you?”

The whale’s mouth closed into what looked like a blubbery smile. Yes.

Ren-jing already knew the answer. She had known the answer for more than forty years. A few days into the necropsy, she unearthed two broken vertebrae near his dorsal hump, right where his body had burst. The flesh around the wound was a deep wine-purple with bruising. No one had listened.

But she finally got confirmation of what she had always known was true—from the whale himself, no less. Ren-jing felt an ancient knot in her chest finally come undone.

After the pain, I could not swim. The tide pushed me onto that shore of oysters.

The whale closed its eyes.

And then, death.

Ren-jing let out a cough of a laugh. Then another. Then a course of laughter began to rattle in her ribcage. Her lungs, once strong with the endurance of a frequent diver, now exhaled the breaths of a long-forgotten mirth. The wind whistled along with her, splitting the smoke of the whale’s jaws into a wide grin. The edges of her eyes began to wet with tears—from the smoke or the laughter, she wasn’t sure—and her vision became a vast, gray blur.

As Ren-jing wiped her eyes and released one last laugh, the smoke dissipated into the summer breeze.

Issue XIII: Hauntings

this is my way of bridging the gap Sarann Spiegel

on evenings in which i’m a split-open cadaver, poked and prodded i think of you, who plucked the liver from my belly and gnawed at the lining of my long intestine. from you i learned not to flinch at the brush of fingers inside my rib cage.

i no longer fear the scavengers. i hear the love in their cries and am glad i can satiate the hunger eating at them. this way, we are both devoured. i would cut the flesh from my calf to feed you any day.

tonight, the first-years slice into my heart and fearing they’ll muck up the workings, know this: i may love you best with my guts in your mouth.

Fae Leonard-Mann

Catching up, caught up, it is a cycle, isn’t it? When the wind blows, you know I am by your side. Watching.

I don’t even care if it is not where you want me to be. I am beside you. I have been beside you for seven months now.

You might not know this. Not explicitly, no. But you sense it, don’t you? When you feel a breeze on the back of your neck. When the trees sway.

I should not sum it up as easily as this. It is deflating the importance. It is summarizing.

Let me clarify: I am not what you think I am. You cannot imagine what I really am.

Let me point to what is important: I am looking out for you. Every second of every day.

It is not as simple as the fact that I love you (although this is true). It is not as simple as the fact that I am always by your side (although in a sense, I am). I am with you when you need me most.

Like two months ago, when I saw you crying at the train station.

Did you notice how the air got warmer? The spring scents of cherry blossoms got sweeter, hauntings hushed? I hope you did.

I should listen to the rushing winter winds. As they soar past, they always make me shiver. They warn me to forget, like they do. Yet every time, I call myself back to you.

I am without self, selfish nonetheless.

“40

You were hot

And I was overheating

And we were seated next to each other in a dive bar in Virginia Beach

Like two packets of instant ramen on the same shelf

And all around us people were dancing in circles

Like a less-than-circular blunt rotation

Your eyes screamed at me let’s get out of here. I wanted to get out too but I kind of liked the atmosphere in the bar but you were hot so I went along with it anyway

And we clung to each other like warm blind creatures in the backseat of the Uber

while our one sober friend sat in the front seat with the chain-smoking driver working out how to split $35.95 between 2 Venmos and a PayPal.

It was a little past eight

But the sun had already dimmed to the lowest setting

Sending braided streaks of orange and pink down the endless ocean

Sex is fun, but love is expensive

And I would be paying dearly.

Gone were the days of magazine collages and scrapbooks

Because you were a whole live newspaper clipping

A real media sensation straight from the source

And you said don’t think about him but I was thinking about my cousin

The closest facsimile of your smile

Geminal, we were two souls of the same wing

But you were gone before the castles fell

That we had left behind in the sand; You tore your gaze from the fire

And I remain at the hearth.

Issue XIII: Hauntings

Tati Wolkowitz

We went to Cimetière du Père Lachaise last fall to visit Jim Morrison’s grave. At the peak of September, the heart of the cemetery meant total isolation from the treeless streets of Paris, a funny stand-in for the sprawling parks I was beginning to achingly miss. Violet and I entered from the side gate into the labyrinth of mismatched mausoleums and rusted delicate gates. Perverted tourism can be sweet sometimes, I thought, as we played one way Marco Polo with our class.

Jim’s grave was a shrine littered with guitar picks and concert stubs and portraits of the man resting below the earth. Rosaries and liquor bottles and cigarette butts formed pathways surrounding the sanctum junkyard for another rock star member of the 27 Club. It seemed to me that this was the perfect spot for a sentimental person to part with totems and amulets, worthless to an unassuming eye. We spent a while considering material eulogies before adding new footprints to the wasteland of weeds and wild grass covering Jim’s neighbors whose names, I realize, we never did learn.

My mom got her genes tested this week and supposedly isn’t predisposed for Alzheimer’s. Thank god, I think when she tells me, though the concept of knowing otherwise terrifies me completely. From far away I silently think, “I probably am though, all that Ashkenazi blood and everything.” Five years ago, my grandparents’ friend’s brother died from Alzheimer’s. They traveled all around the world trying to find the perfect place to lay his ashes and landed back in Newark, unsuccessful, with a full urn. When they stopped for gas on the drive home, they placed it on the cab bulb and forgot about it for the first time in a week. The second the car drove off the urn fell and shattered into a gutter off 117th street and when they realized, the somber dam collapsed and they couldn’t help but laugh. They’d traveled all the way to the Swiss Alps to say goodbye but somehow it was better this way. He’d really be an Upper West Sider forever.

Emilia drove up to see the homecoming game when her school was the visiting team and I cheered along with the high school girls in blue. My best friend stained her hair green that day with the blue hairspray and my brother’s tongue matched from cotton candy dye. I won colored gumballs at the ring toss and a kazoo from the raffle and kept them in the painted ceramic box my great grandmother let me take from her own Riverdale Alzheimer’s suite, cozied up next to the dying rose petals I was supposed to throw in with her coffin. I’ve added a lot of junk to that box since: song lyrics sung to me while my dad

strummed along on the guitar, photo booth pictures from middle school parties, beads bought off fishing ports. I don’t treat any of them especially well and I hardly ever visit. They’re only evidence that I’ve always been afraid to forget even idle moments of inconsequence that I scavenge, instead, for weathering reminders that it all happened, that we were really here.

When I was younger, I used to agonize over what I’d take from my apartment before climbing down the rickety fire escape in case it were to all burn away in a moment. I’d settle on that ceramic box and sometimes, I still do. It feels sort of futile though, after seeing Jim’s littered tombstone. What does he want with paper flowers and recycled lyrics now? They don’t speak like the hundreds of lipstick stains covering the limestone of Alain Bashung’s grave just down the hill but we flock to both and imitate the gestures that came before. Footprints, then, might leave sweeter traces of pilgrimage. And besides, what are trinkets to the dead if not us tourists’ reactions to waste, impermanence, and landfills?

Yael Ezry

Like the slow tap-tapping from my spine into my feet, my fingers through my scalp, The natural spinning into three— I once explained that k’tev (Three letters, three sounds)

Compose “letter,” “to read,” and “to write.” That we once understood That we cannot separate Letters from meaning, The sound from the tone.

Shoresh means root. There used to be a blossom tree here, In front of my apartment, but Sandy Knocked it over onto someone else’s car.

I am reminded that we once devised That “tree” has the same shoresh as “strength,” “Bones,” and “to advise” (The car was alright, But they cut down the tree—they put up Metal scaffolding around the building by December).

There is Ch’ai; which spins into “life,” “Wild animals,” and “revive.” Spelled out, it means “to live.”

I wonder if the deer up the road understood That my too-muchness died like a sapling, Tapping from the faucet, exhausted in the sand.

I wonder if she too, as a wild animal, Watched the eclipse and knew that everything ends— If she knew that its branches may extend, If she, too, knew that the root of “moon,” yareakh, Is also “The wanderer.”

Lavender only after i’ve chosen death can i let go of what tethers me to this existence

Suz Blattner

even when the music that begins rest is the same, the body remembers what the mind cannot. /crawl into adirondacks but wicking the woods spreads water like poison; instead tilt back/ and taste the sky; let the rain bite skin; forget ache and disappear as the world obscures in smoke.

/die in the storm where soil crawls and whispers. slip of wind and water grasp the deceptive eye.

a honey tongue used to sing chant—choke

sever stems

the dislocated mind oozes into/ humming on the sidewalk when no one can hear all the heat of the day is defeated by the nerves that press on torn souls. note that echoes continue even as tune is lost with body.

freeze until matter is forgotten

and a body a man trails through the street on an illumination. his pathway supposed to tame human courtesy but only encouraging a man to lose body where light shines

at day the sun rises for everyone but him. he joins the tire tracks, /fuel and opossum intestine his blood meaning no more than the reflection of headlights/

bones pop—/shatter/ sunpeaks and work stirs but they scream when body reaches mind forgetting the mutilation only occurred before death twisted.

/the unknowing/

Sestina on Blackbirds, after Wallace Steven’s Poem Esme Israel

He rode over Connecticut In a glass coach. Once, a fear pierced him, In that he mistook The shadow of his equipage For blackbirds.

One, three, four fat blackbirds

Watching from Connecticut’s Black birches, tracking his equipage. Their blackbird wings were phosphorescent, the coach Rattled beneath their glow. He mistook Them for shadow, sang a quick hymn.

Eyes, eyes upon him. He imagined blackbird Eyes above, imagined they mistook His fleshy form for wax worms found in Connecticut Beehives, the glass coach His hive, his honey breath bee-equipage.

The birds pecked his equipage: Two trunked horses, him And the glass coach, Glass means little to a blackbird. The deep ponds of Connecticut, Glossy eyes, shadows he mistook

For darkness. Once he took Too quick a look at his equipage, Saw his own shadow in the hard Connecticut Ground. Sight struck him. The blackbirds Sat above the coach,

Skeletal coach, While he sat beneath them, mistaking Birds for tools of travel. The blackbirds Marked his great age, And sang a high hymn In the Connecticut

Night, in the dark, death Mistook him

For a dozen Connecticut blackbirds, and passed on.