Background Information and Recommended Plan Components

RDMP Adopted 19 October 2022

Regional Demand Management Plan Review and Update

Final Report

Disclaimer:

This report has been prepared on behalf of and for the exclusive use of Rous County Council and its constituent councils and is subject to and issued in accordance with the agreement between Rous County Council and Hydrosphere Consulting. Hydrosphere Consulting accepts no liability or responsibility whatsoever for it in respect of any use of or reliance upon this report by any third party.

Copying this report without the permission of Rous County Council or Hydrosphere Consulting is not permitted.

Acknowledgement

Hydrosphere Consulting acknowledges the Bundjalung peoples, Traditional Custodians of the lands discussed in this report and pay tribute and respect to the Elders both past and present and emerging of the Bundjalung nations.

Hydrosphere Consulting Pty Ltd Suite 6, 26 54 River Street PO Box 7059, BALLINA NSW 2478 hydrosphere.com.au

© Copyright 2022 Hydrosphere Consulting

of Country:

JOB 22-003: DEVELOPMENT OF REGIONAL DEMAND MANAGEMENT PLAN: IBACKGROUND INFORMATION AND RECOMMENDED PLAN COMPONENTS REV DESCRIPTION AUTHORS REVIEW APPROVAL DATE 0 Draft for RCC and constituent council review Kate Menzies, Nicole Fokes Robyn Campbell Mick Howland Mick Howland 29 November 2021 1 RDMP Supporting Information Kate Menzies, Nicole Fokes Robyn Campbell Mick Howland Mick Howland 22 June 2022 2 Adopted Robyn Campbell 19 October 2022

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Hydrosphere Consulting has been engaged by Rous County Council (RCC) to review and update the Regional Demand Management Plan: 2019 - 2022 (RDMP, Hydrosphere Consulting, 2018) for the next four years (2023 – 2026) on behalf of RCC and its constituent councils (Ballina Shire Council - BaSC, Byron Shire Council - BySC, Lismore City Council – LCC and Richmond Valley Council – RVC). The first stage of this project involved gathering information from each Council, reviewing feedback on the delivery of the RDMP 2019 - 2022 and opportunities for the new RDMP, as well as outcomes of a broader review to recommend a suite of initiatives for the next four year plan timeframe.

The purpose of this report is to provide recommendations for the new RDMP 2023 - 2026. The outcomes of the following tasks have been considered in this report:

• Consultation with RCC and the constituent councils.

• Review of RDMP implementation progress.

• The demand management initiatives of other water utilities.

• Current indicators of demand and losses.

• Investigation of behaviour change applications in water supply demand management.

The RDMP 2019 – 2022 describes the water supply demand management initiatives to be implemented by RCC and the constituent councils between 2019 and 2022 and includes the following seven actions with associated tasks:

• Action 1: Monitoring, Evaluation and Reporting.

• Action 2: Water Loss Management.

• Action 3: Sustainable Water Partner Program (SWPP).

• Action 4: Smart Metering.

• Action 5: Recycled Water.

• Action 6: Rainwater Tank Rebates.

• Action 7: Community Engagement and Education: 7A: Households, 7B: Schools and 7C: High Residential Water Users.

The Rous Future Water Project 2060 identifies new water supply sources to ensure long term water supply security for the Rous region. RCC remains committed to responsible water use and ongoing initiatives aimed at reducing demand Ongoing review and update of demand management activities is a key component of the Future Water Project 2060 The objectives of demand management in the region are to reduce normal consumption and average supply requirements in order to reduce the urgency of water source augmentation. Demand management actions should also aim to increase awareness of the value of water and level of customer consumption. Innovative approaches should be used to improve the success of any actions over time. Pilot programs should be used to test uncertainties and prove effectiveness of potential new or

RDMP - Background information and recommended plan components Page I

modified actions. Sufficient resources should be allocated by each council to ensure successful outcomes. The focus areas for the new RDMP should be:

1. Collection and analysis of detailed demand data accurate identification of water demand in terms of customer sectors and uses, short and long term climate influences and other drivers of demand and improved understanding of components of water losses.

2. Water loss reduction Water losses are high in the regional water supply area. A targeted program of pressure management, active leak control, pipeline and asset management and leak repairs should be implemented by the individual councils. This should be supported by improved data collection and analysis and digital integration. Residential programs should also be designed to include components which support residents to identify and repair leaks.

3. Implementation of smart metering with a short term focus on planning and developing systems and internal resources to achieve the many benefits of digitalisation such as reduced water losses, cost efficiencies due to task automation, improved service reliability and increased customer understanding and involvement across the full range of council services over the longer term.

4. Customer engagement programs targeting key sectors, schools, older properties with inefficient fittings and fixtures, household leaks or high water users with increased customer involvement, understanding and ownership of water efficiency requirements.

5. Pilot programs focusing on changing behaviour of residents to use less water to complement other supply and demand measures.

6. Pilot programs to test the community desire, costs and benefits of residential retrofit programs for household and external water uses.

The new RDMP will specify amended demand management actions and tasks for each council. The following recommendations are provided for consideration by RCC and the constituent councils

Data Collection, Monitoring and Reporting

Improved data collection and analysis of all components of the water balance is required with improved systems to capture data.

Recommendation 1: Increased effort in demand monitoring tasks is required to develop greater understanding of the outcomes of demand management programs on residential and non-residential demand over time.

Recommendation 2: The status of RDMP tasks and data on customers, water supply and consumption should be reported by all councils on a bi annual basis through the Regional Liaison Committee meetings with standing agenda items including RDMP progress, demand indicators and sharing of lessons learned.

Recommendation 3: The councils should work together to develop and implement standardised definitions of connection types to ensure consistency across the region.

Recommendation 4: The councils should work together to develop and implement a standardised metering policy across the region to assist with monitoring and reporting.

RDMP

Page II

Background information and recommended plan components

Recommendation 5: If per capita indicators are adopted/developed, the population served in each area should be estimated as accurately as possible e.g. following the release of Census results and updated as required to correspond with seasonal influences and reporting periods.

Recommendation 6: Regional demand forecasts should be updated in accordance with the Rous Future Water Project 2060 actions with more accurate data collected through the RDMP implementation.

Recommendation 7: RCC should continue to coordinate monitoring and reporting with data provided by LWUs as required by the new RDMP.

Water Loss Management

As water losses are high (although variable) across the regional water supply area, water loss reduction should be a focus of the RDMP

Recommendation 8: Water loss management is a critical component of demand reduction and current levels of losses are high. Each council should provide sufficient resources to implement their WLMPs and set targets (based on best practice indicators) and timeframes for water loss reduction.

Recommendation 9: Each council should implement a water loss management program building on existing programs and infrastructure already installed. This should include data collection and water loss analysis, district flow metering and data analysis, pressure management, active leak identification, timely leak repairs and pipeline and asset management with consistent indicator definitions across the region.

Non-residential Programs

The new RDMP should include targeted and broader delivery of the SWPP as this expenditure has been cost effective and the program provides valuable customer engagement. Promotion to high water users and specific priority industry sectors should be a focus.

Recommendation 10: SWPP promotion should continue to include case studies and cross-promotion of successful water efficiency projects.

Recommendation 11: RCC should continue to coordinate the SWPP on behalf of the constituent councils.

Recommendation 12: Constituent councils should implement a water conservation program for high water users (non residential customers) in local supply areas.

Recommendation 13: Modifications to the SWPP and eligibility criteria should be considered to make it easier for smaller businesses that are willing to participate e.g. fixture/fitting replacement, removal or lowering of demand threshold, smart metering etc.

Recommendation 14: A method of ongoing monitoring and engagement should be developed with each participating business to measure the success of SWPP initiatives.

Recommendation 15: The councils should develop improvement plans and showcase projects (across council buildings, infrastructure, operations and services) to demonstrate leadership and encourage customer water efficiency.

RDMP Background information and recommended plan components Page III

Smart Metering

As there is considerable benefit expected to result from smart metering, including synergies with other RDMP objectives/actions as well as interest from customers, smart metering should be a focus of the RDMP.

Recommendation 16: BaSC and BySC should provide information to other councils on successes, challenges and recommendations from their smart metering programs.

Recommendation 17: RCC should implement smart metering for its retail customers and work with the constituent councils to extend the program across the region either as a regional or local approach with consideration of budget, timing and planning priorities.

Recommendation 18: Consumption targets should be developed as part of the smart metering program to provide meaningful and measurable responses from the community.

Recommendation 19: Full implementation of smart metering will require significant investment, staff resources, training and a significant amount of time. It is noted that the application and benefits of smart metering and infrastructure development are not restricted to the demand management functions of each council. Implementation should consider the lessons learned from other water utilities.

Recycled Water Use

As the non potable recycled water programs in BaSC and BySC are locally driven and are not influenced by regional approaches, it is recommended that these programs continue to be implemented outside the RDMP as a supply side measure to suit the local council circumstances. RCC will continue to investigate opportunities for indirect potable reuse and direct potable reuse as part of the Future Water Project 2060.

Recommendation 20: RCC should continue to promote non potable recycled water connections to BaSC and BySC businesses (where appropriate) as part of the SWPP with rebates as part of the SWPP.

Recommendation 21: BaSC and BySC should administer their own recycled water rebates if desired (given the local plumbing enquiries and compliance requirements within their respective jurisdictions).

Rebates and Incentives

The implementation of the national Water Efficiency Labelling Scheme (WELS), for the mandatory labelling of appliances and the BASIX for new developments will continue to increase the market uptake of water efficient fixtures and appliances, particularly showerheads and washing machines. The rebate program should be modified to include a broader range of products available through rebates to reflect the needs of residential and non residential customers

Recommendation 22: Rainwater tank rebates appear to be popular within the community, particularly during dry periods. Based on feedback received during the Future Water Project 2020 public exhibition, community feedback suggests that rainwater tanks should be a component of the region’s water supply. The rainwater tank rebates do not generally provide value for money for RCC and the community and there are limited water savings particularly during extended dry periods. However, the rainwater tank rebate program provides intangible benefits such as contact with

RDMP Background information and recommended plan components Page IV

customers and stormwater detention. Due to the low cost-effectiveness, it is recommended that alternative residential customer incentives are developed to achieve the objectives of customer engagement and support, water efficiency and cost effectiveness.

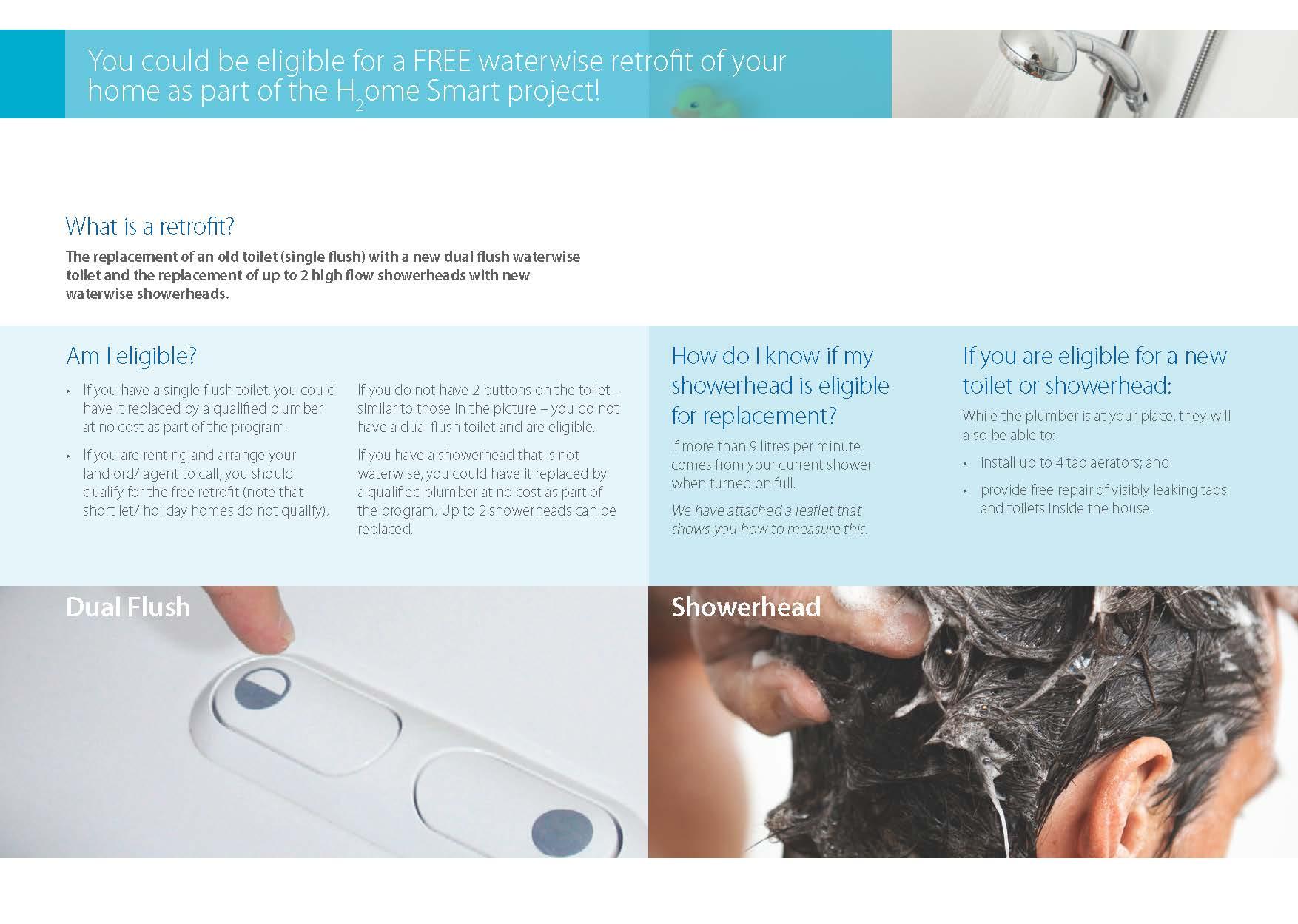

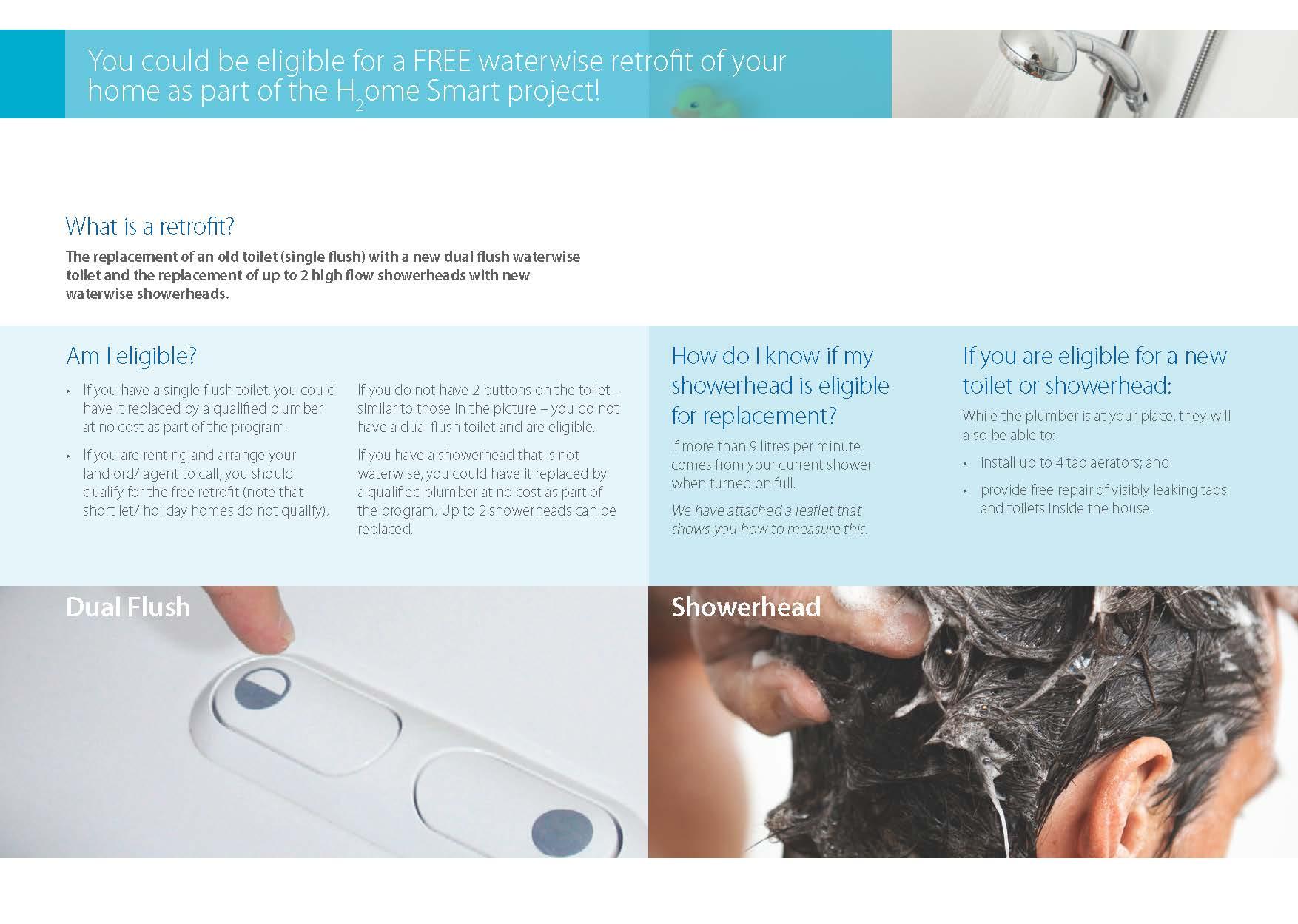

Recommendation 23: Pilot programs should be implemented to test the needs and benefits of residential retrofit programs. Pilot programs with audits and end use and fixture surveys should be implemented to allow RCC to establish baseline consumption and water use behaviour for different household types across the region, quantify potential water savings and develop targeted future incentive programs.

Recommendation 24: Incentives should be offered directly to high residential water users based on the outcomes of the pilot programs.

Recommendation 25: Programs should be considered for vulnerable or financially disadvantaged customers with older water-intensive products.

Recommendation 26: Marketing of any adopted rebate program and cross-promotion with other measures should be included to increase uptake and awareness.

Recommendation 27: As financial assistance can be used to encourage property owners to repair leaks, the undetected leak discount policies should continue with ongoing review of the expenditure and water savings. However, once a smart metering program is in place with more immediate identification of leaks, the policy should cease as leaks will be easily detected.

Residential Customer Programs

Average residential demand across the Rous supply region is higher than the NSW median although demand varies between the LGAs. The residential sector is the largest customer group in the RCC supply area with approximately 85% of connections and 76% of demand (excluding losses) (Hydrosphere Consulting, 2020c) and should continue to be a focus of the RDMP

Recommendation 28: The high residential user program should continue to be implemented using the tools developed for the RDMP 2019 2022.

Recommendation 29: A consistent regional water bill format should be considered including comparisons to regional targets and water saving advice. The bill format may need to be modified as part of the smart metering program. It should also be rigorously tested on customers before implementation as part of the residential component of the program.

Recommendation 30: RCC should continue to coordinate residential programs.

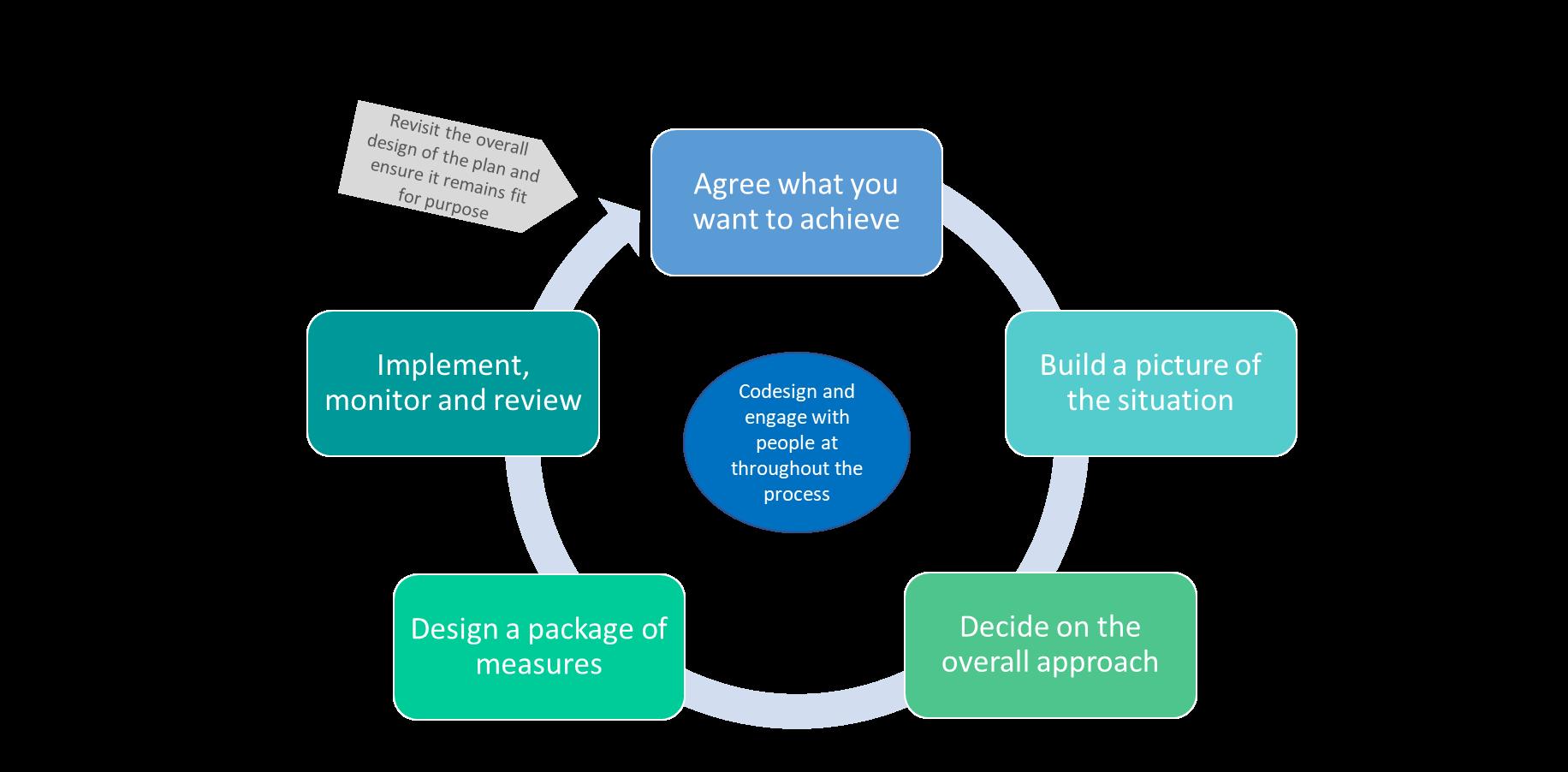

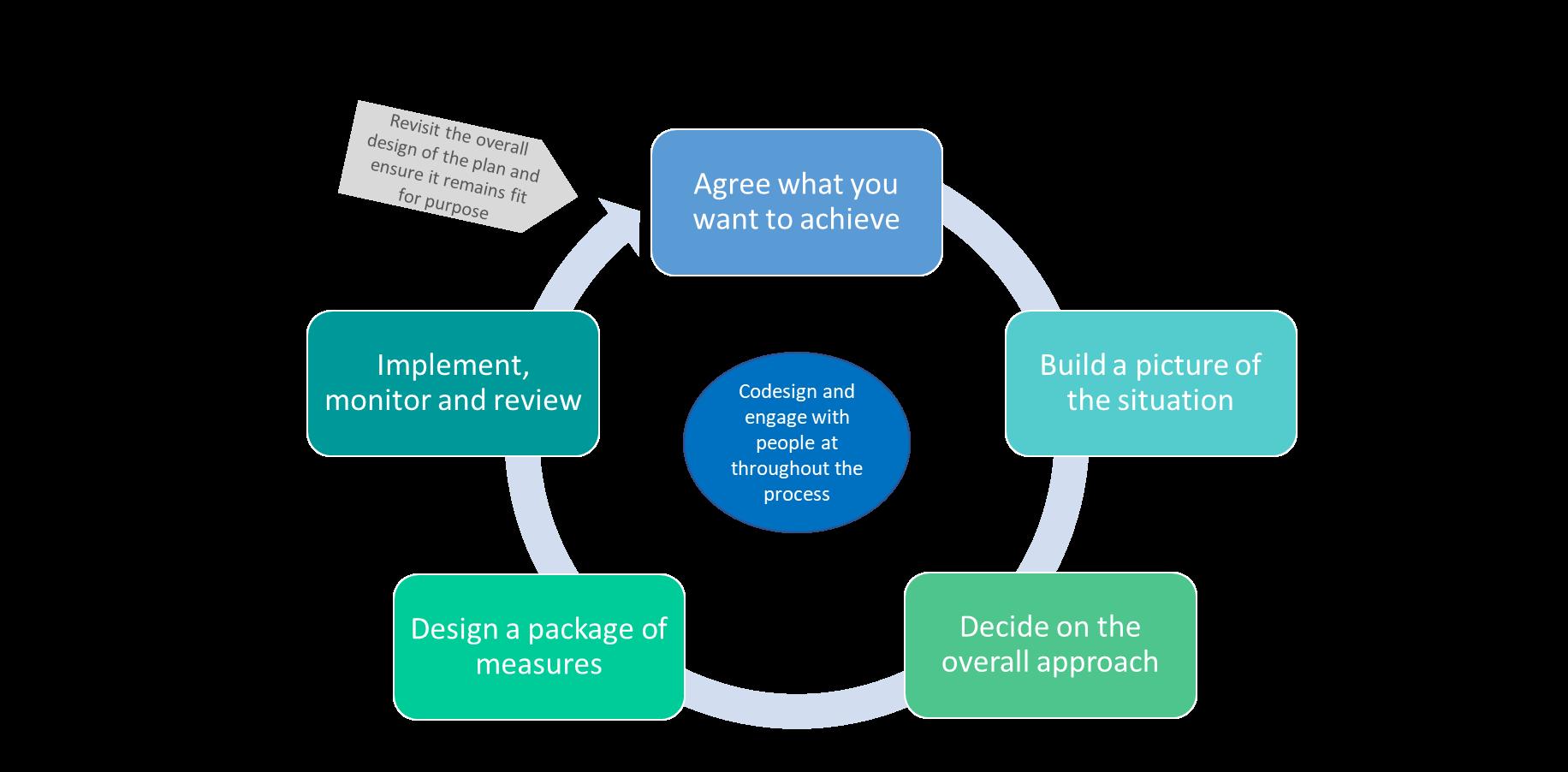

Recommendation 31: A customised pilot behaviour change program should be designed and implemented for a small sub set of the residential water supply customers in each of the four LGAs to add to the success of other water supply and demand reduction measures and ensure sustained water efficiency behaviours are identified and supported.

Education and Engagement

Education and engagement should be a key focus of the RDMP to improve the success of other demand management measures, increase water literacy and encourage water efficient behaviour.

RDMP Background information and recommended plan components Page V

Recommendation 32: RCC and the constituent councils should co-fund a regional resource for delivery of water cycle education programs including catchment health, water supply, wastewater management and stormwater management initially targeting schools but also wider community education.

Recommendation 33: RCC should continue to coordinate regional education programs.

Recommendation 34: Customer engagement should include actions that increase customer awareness of water consumption, encourage water efficient behaviours and promote the demand management program measures to increase the success of their implementation. Customer engagement would be enhanced once smart metering has been implemented.

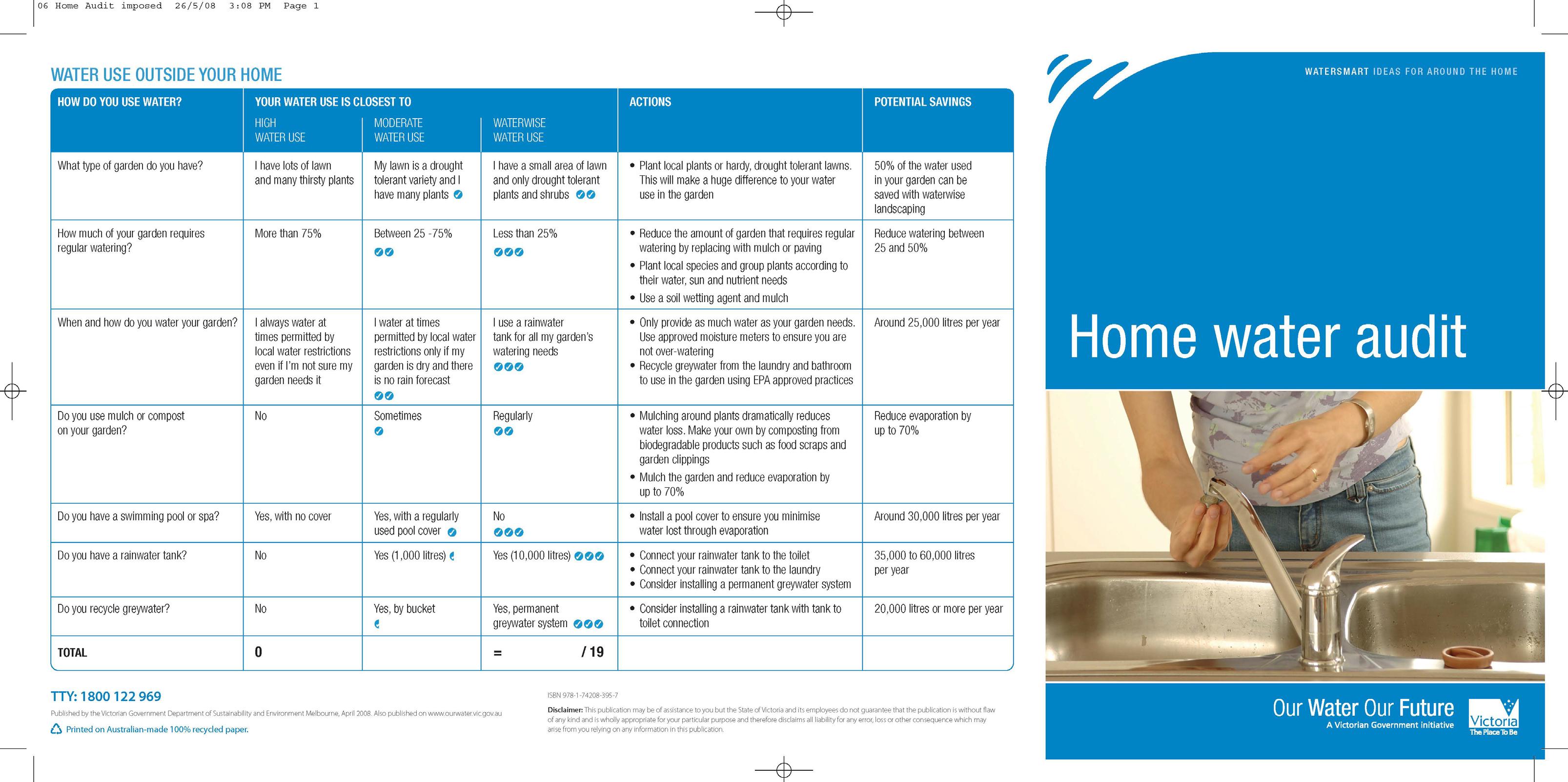

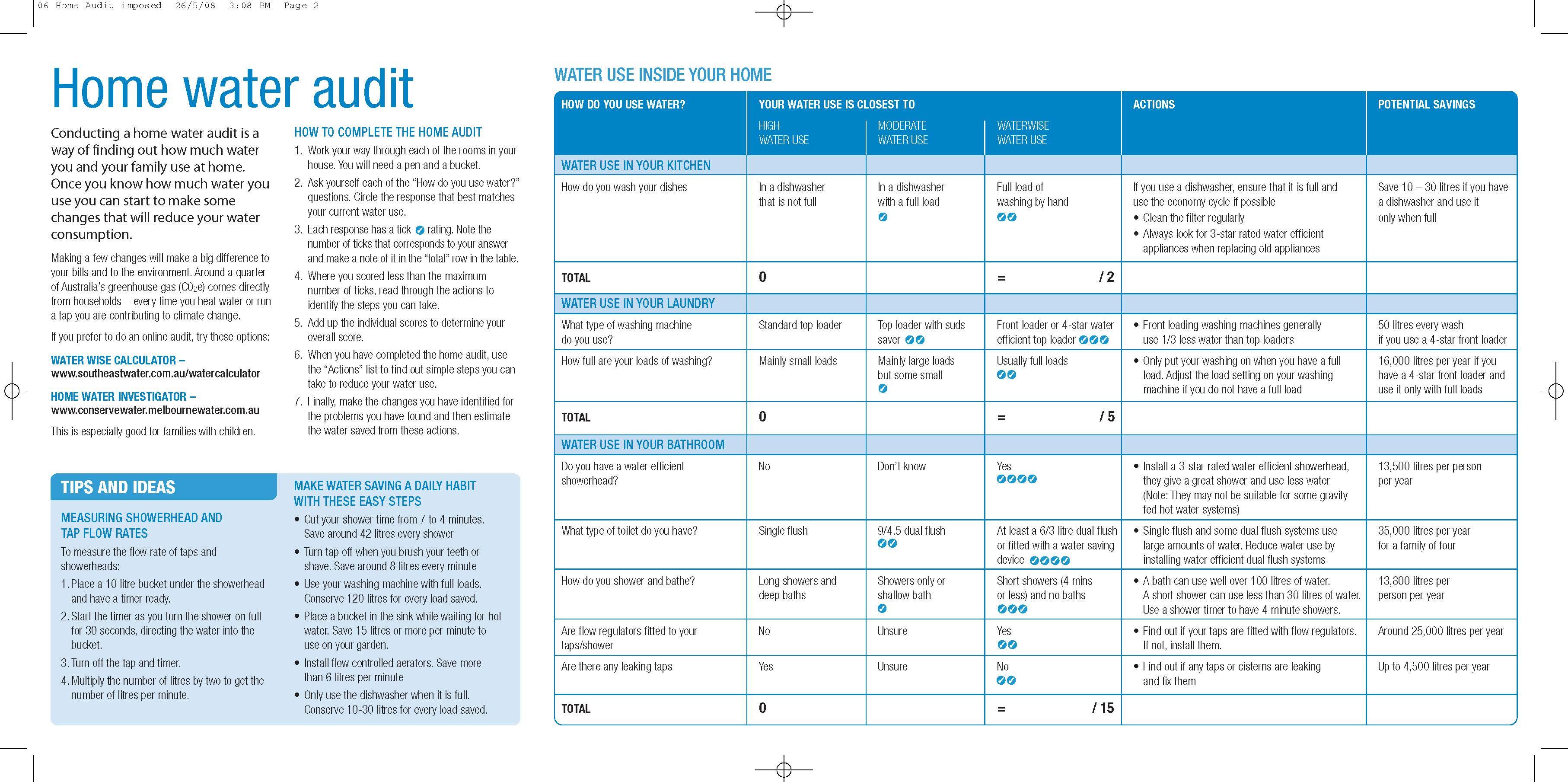

Recommendation 35: Education activities are directly linked to the customer engagement program, encouraging and supporting water efficient behaviours. Education components should be costeffective and designed to reach as many customer sectors as possible. The information available to customers (e.g. through websites, customer service centres and bill inserts) should be reviewed and updated regularly with links to consistent centralised information (e.g. from The Water Conservancy or education websites). Other cost-effective methods include the use of social media for information dissemination. Education should be undertaken in parallel with other customer engagement activities such as water use audits. General education activities should include materials targeting households, non-residential customers and high residential and non-residential users.

Recommendation 36: As school students are the customers of the future and can encourage water efficiency in the home, a targeted and well resourced education program for primary and secondary schools should be developed and delivered directly by either internal or external staff.

Recommendation 37: Education activities should include tourism accommodation providers and facilities to target the large number of visitors to the region.

Recommendation 38: Ongoing sustainable and sensible water use should continue to be promoted through voluntary permanent water conservation measures as Level 0 in the drought restriction policy to assist with promoting sensible water use, provide a link to the drought restriction policy and support other program measures.

Pricing

There are strong links between water supply pricing and water usage.

Recommendation 39: RCC should review the bulk pricing structure in consultation with the constituent councils considering demand reduction signals and mechanisms to support other demand management measures.

Recommendation 40: The constituent councils should continue to set a pricing structure that encourages demand reduction and supports the initiatives in the RDMP

Agreed Measures

The recommendations were provided for consideration by RCC and the constituent councils at a workshop with the Regional Liaison Committee in December 2021. The measures agreed at this workshop have been further developed as actions in the RDMP 2023 2026 Not all recommendations are included in the new

RDMP Background information and recommended plan components Page VI

plan which has been developed considering available budgets and human resources of RCC and the constituent councils. Multiple recommendations are combined where appropriate in the design of the new RDMP actions.

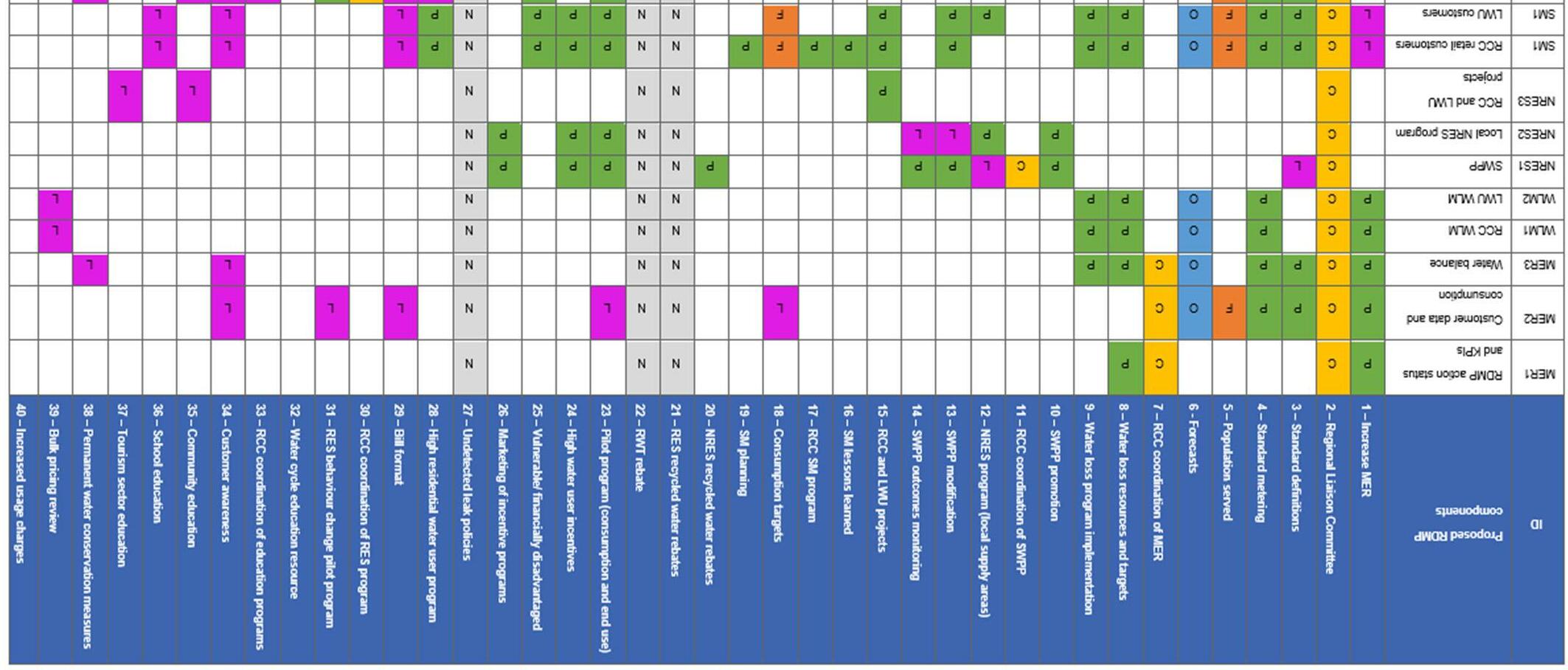

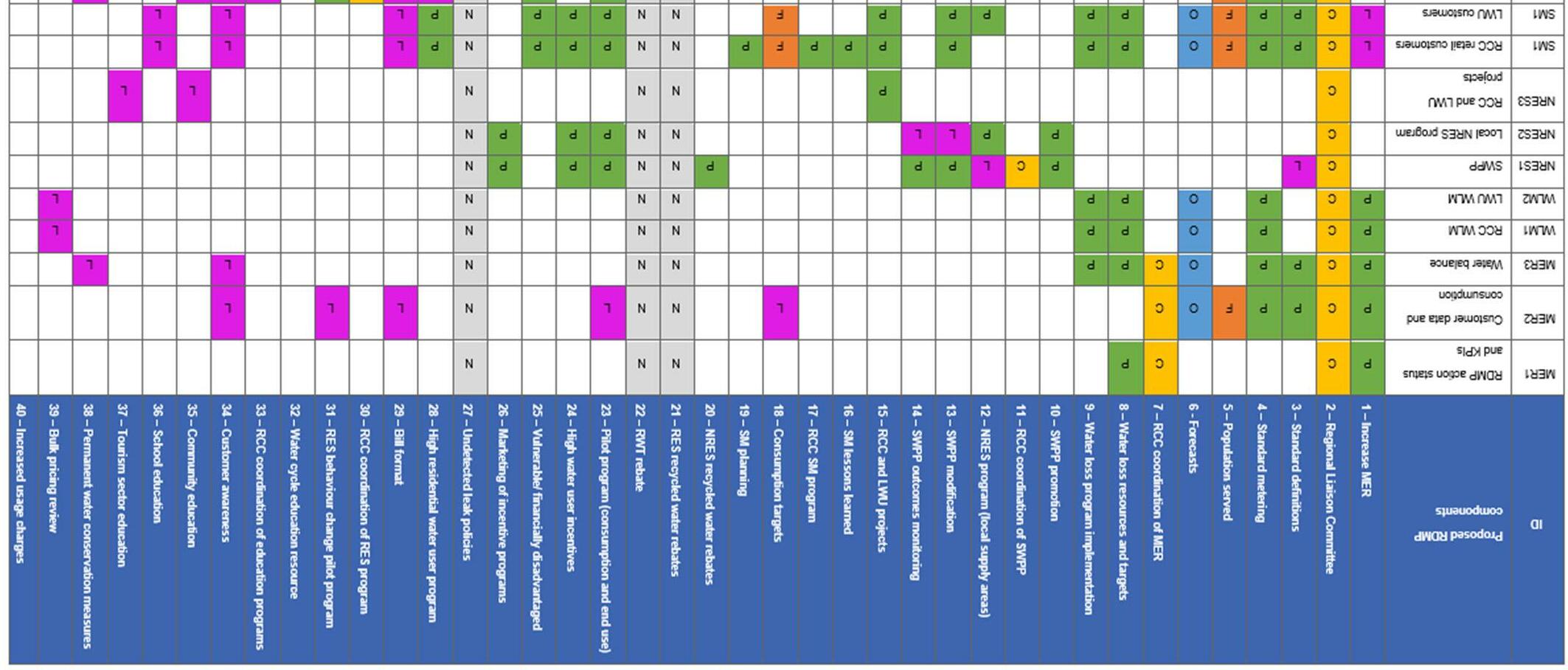

Table 1 provides the link between the recommendations and agreed RDMP components. Table 2 provides a list of actions that will be implemented separately to the RDMP 2023 2026.

recommended

components Page VII

RDMP Background information and

plan

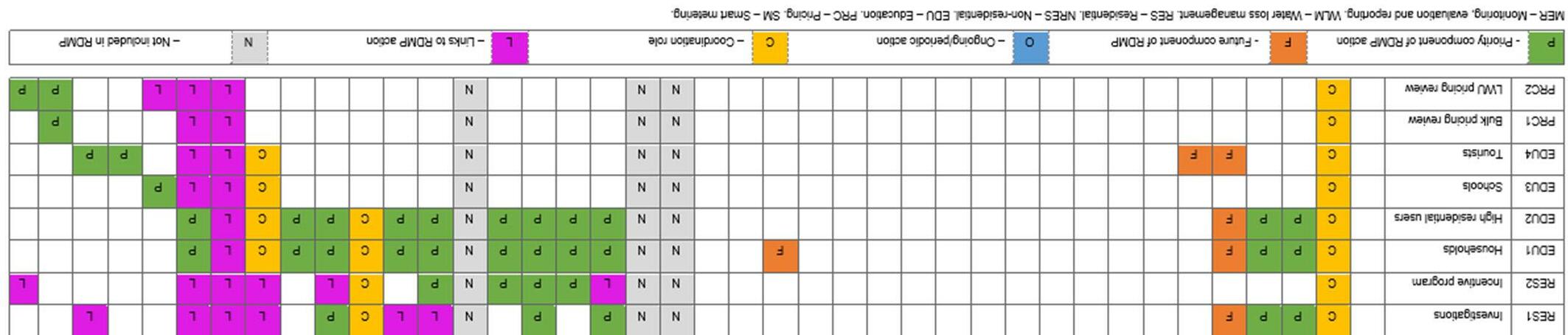

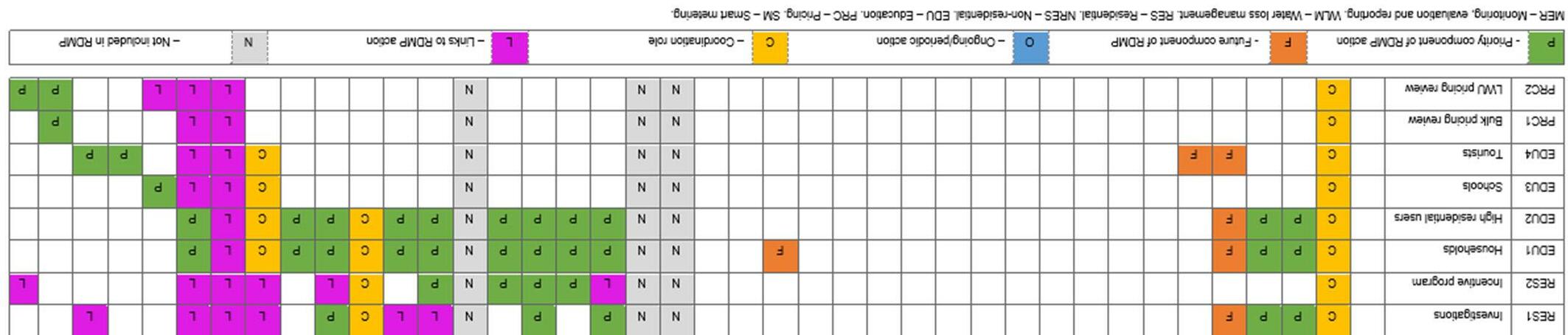

RDMP - Background information and recommended plan components Page IX Table 1: Recommendations and agreed RDMP components ID Component 1Increase DMR 2Regional Liaison Committee 3Standard definitions 4Standard metering 5Population served 6Forecasts 7RCC coordination of DMR 8Water loss resources and targets 9Water loss program implementation 10SWPP promotion 11RCC coordination of SWPP 12NRES program (local supply areas) 13SWPP modification 14SWPP outcomes monitoring 15RCC and LWU projects 16SM lessons learned 17RCC SM program 18Cons umption targets 19SM planning 20NRES recycled water rebates 21RES recycled water rebates 22RWT rebate 23Pilot program (consumption and end use) 24High water user incentives 25Vulnerable/ financially disadvantaged 26Marketing of incentive programs 27Undetected leak policies 28High residential water user program 29Bill format 30RCC coordination of RES program 31RES behaviour change pilot program 32Water cycl e education resource 33RCC coordination of education programs 34Customer awareness 35Community education 36School education 37Tourism sector education 38Permanent water conservation measures 39Bulk pricing review 40Increased usage c harges Monitoring, evaluation and reporting RDMP action status P C C L N N Customer data and consumption P C P P F O C L N N L L L L Water balance reporting P C P P O C L L N N L L Non-residential programs SWPP C L P C L P P P N N RCC and constituent council property audit C L L P L L N N L Residential customer programs Investigations C P P F N N P P L L L C P L L L L Incentive program C N N L P P P L P C L L L L L L Education and engagement Households C L L F F N N L L L P L P C L P C P P P High residential users C L L N N L L L P P P C L L C P P P Schools C N N P C P L P P Tourists C F F N N C P L P P P Priority component F Potential future RDMP action O Ongoing/ periodic action C Coordination role L Links to RDMP action N Not recommended

RDMP - Background information and recommended plan components Page X Table 2: Demand management actions to be implemented by RCC and the constituent councils separately to the RDMP ID Component 1Increase DMR 2Regional Liaison Committee 3Standard definitions 4Standard metering 5Population served 6Forecasts 7RCC coordination of DMR 8Water loss resources and targets 9Water loss program implementation 10SWPP promotion 11RCC coordination of SWPP 12NRES program (local supply areas) 13SWPP modification 14SWPP outcomes monitoring 15RCC and L WU projects 16SM lessons learned 17RCC SM program 18Consumption targets 19SM planning 20NRES recycled water rebates 21RES recycled water rebates 22RWT rebate 23Pilot program (consumption and end use) 24High water user incentives 25Vulnerable/ financially disadvantaged 26Marketing of incentive programs 27Undetected leak policies 28High residential water user program 29Bill format 30RCC coordi nation of RES program 31RES behaviour change pilot program 32Water cycle education resource 33RCC coordination of education programs 34Customer awareness 35Community education 36School education 37Tourism sector education 38Permanen t water conservation measures 39Bulk pricing review 40Increased usage charges Monitoring, evaluation and reporting Demand forecasts L C L L F P C L N N Water loss management RCC water loss management L C L L P P L N N L L Constituent council water loss management L C L L P P L N N L L Non residential programs Local non-residential customer program C P P L L N N L L L L L L Smart metering RCC retail customers L C L L F O L L L L P F P N N L L L L L L L L Constituent council customers L C L L F O L L L L L L F L N N L L L L L L L L Pricing Bulk pricing review C N N L L L L P Retail pricing review C N N L L L L L P P P Priority component F Potential future RDMP action O Ongoing/ periodic action C Coordination role L Links to RDMP action N Not recommended

RDMP Background information and recommended plan components Page i CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. DEVELOPMENT OF THE RDMP 2019 2022 3 3. FEEDBACK FROM COUNCILS 5 4. RDMP IMPLEMENTATION STATUS 7 5. REVIEW OF CURRENT PRACTICE 11 5.1 Customer engagement and education 17 5.2 Permanent Water Conservation 18 5.3 Rebates and Incentives 20 5.4 Undetected Leak Policy .................................................................................................................... 21 5.5 Water Loss Management 21 5.6 Pricing 22 5.7 Smart Meters ..................................................................................................................................... 23 5.8 Municipal Water Use 27 6. BENCHMARKING 28 6.1 Residential demand .......................................................................................................................... 28 6.2 Water Losses 28 6.3 Pricing 29 6.4 Expenditure ....................................................................................................................................... 30 7. BEHAVIOUR CHANGE 33 7.1 Current Behaviour Change Practice 33 7.2 Focus Groups 35 7.3 Recommended Approach 36 8. RECOMMENDED RDMP COMPONENTS 40 8.1 Recommended RDMP Objectives 40 8.2 Recommended RDMP Approach 40 8.3 Water Efficiency Targets 41 8.4 Target Customer Sectors 41 8.5 RDMP Focus Areas .......................................................................................................................... 41

REFERENCES 43

ABBREVIATIONS 46

APPENDIX 1 DEMAND MANAGEMENT MEASURES CONSIDERED IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE 2014 FUTURE WATER STRATEGY 49

APPENDIX 2 NOTES FROM MEETINGS WITH COUNCIL STAFF 59

APPENDIX 3 RDMP IMPLEMENTATION STATUS 61

APPENDIX 4 BENEFIT COST ANALYSIS ...................................................................................................81

APPENDIX 5 REGIONAL DEMAND DATA 91

APPENDIX 6 BEHAVIOUR CHANGE CURRENT PRACTICE AND LITERATURE REVIEW 97

APPENDIX 7 BEHAVIOUR CHANGE FOCUS GROUP REPORT AND OUTCOMES ................................99

FIGURES

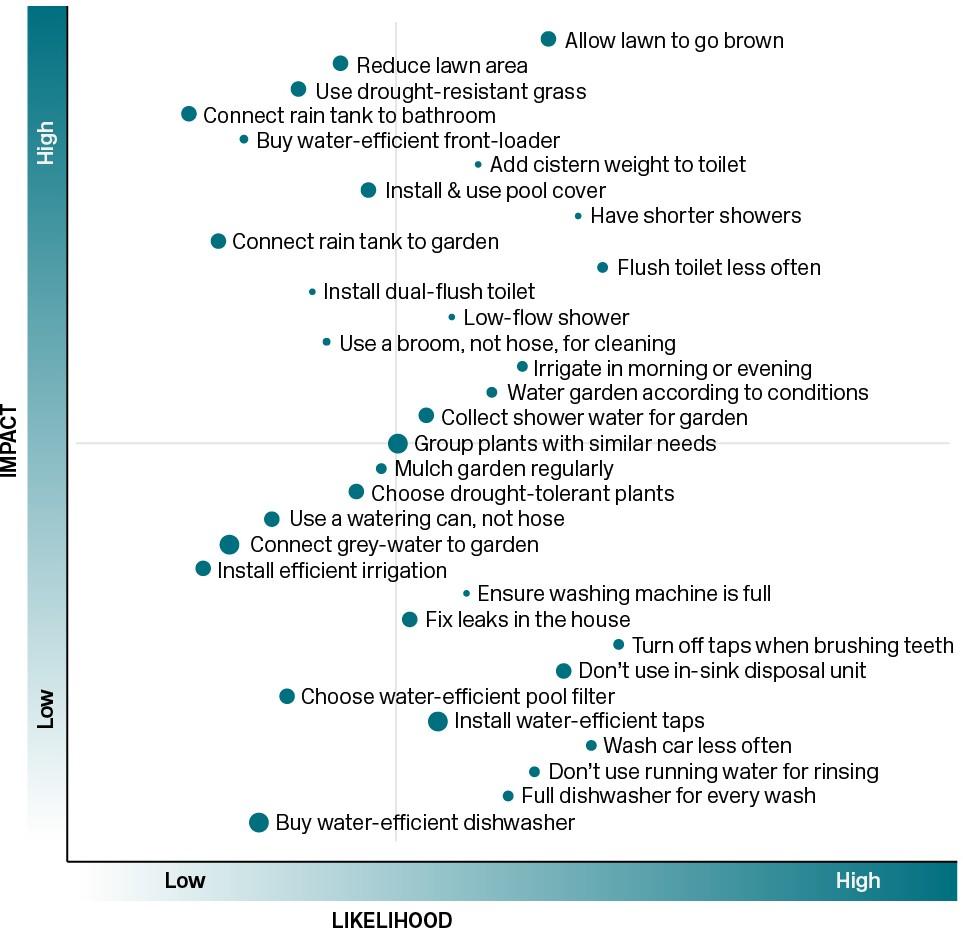

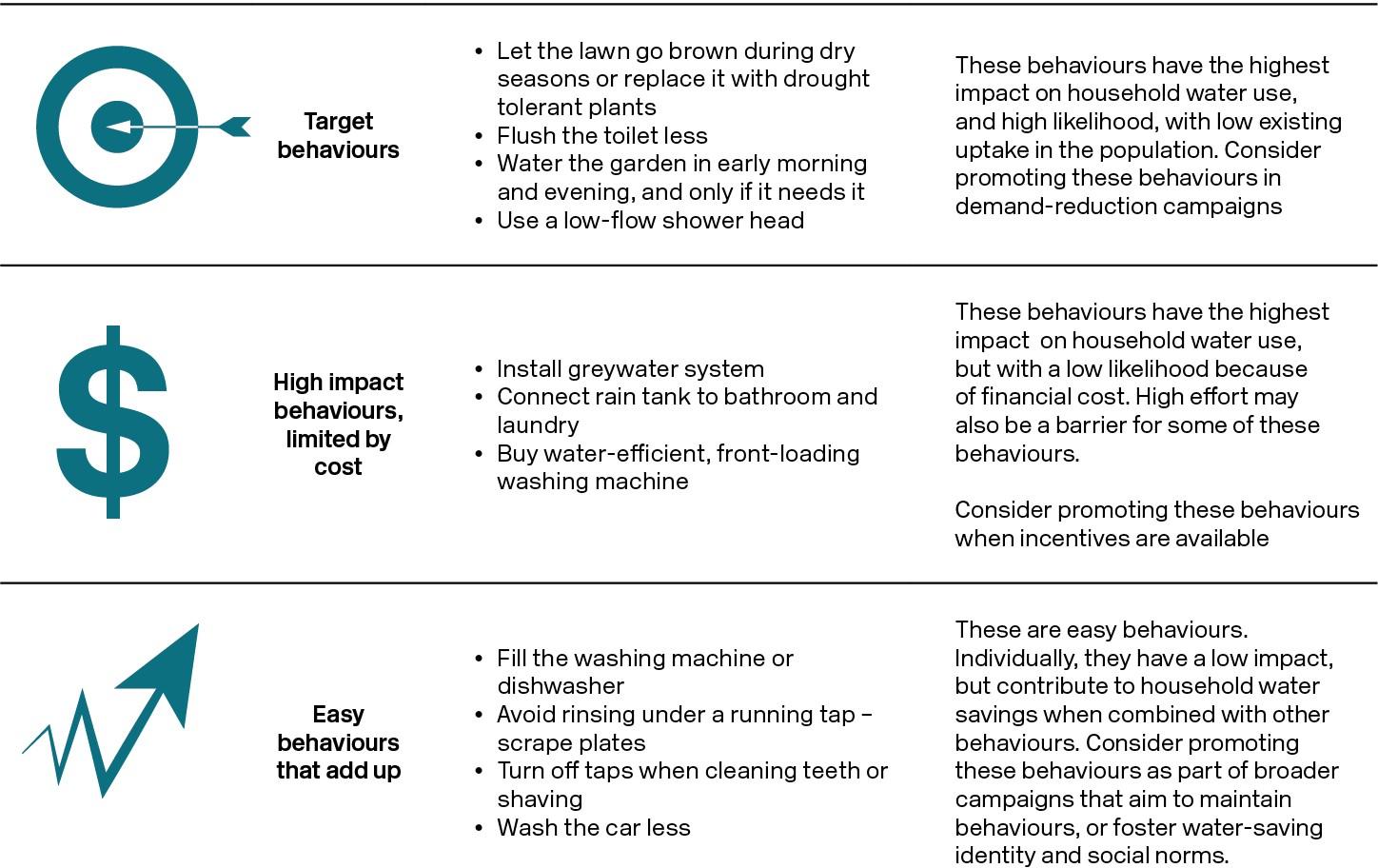

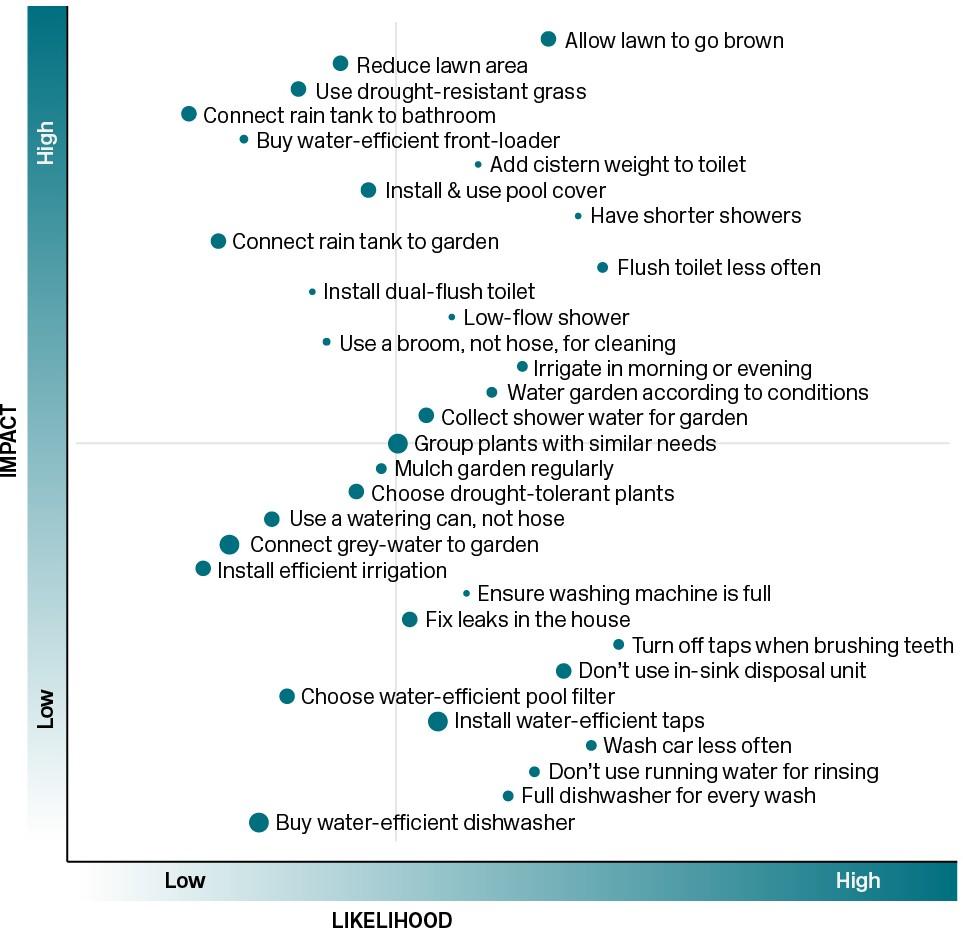

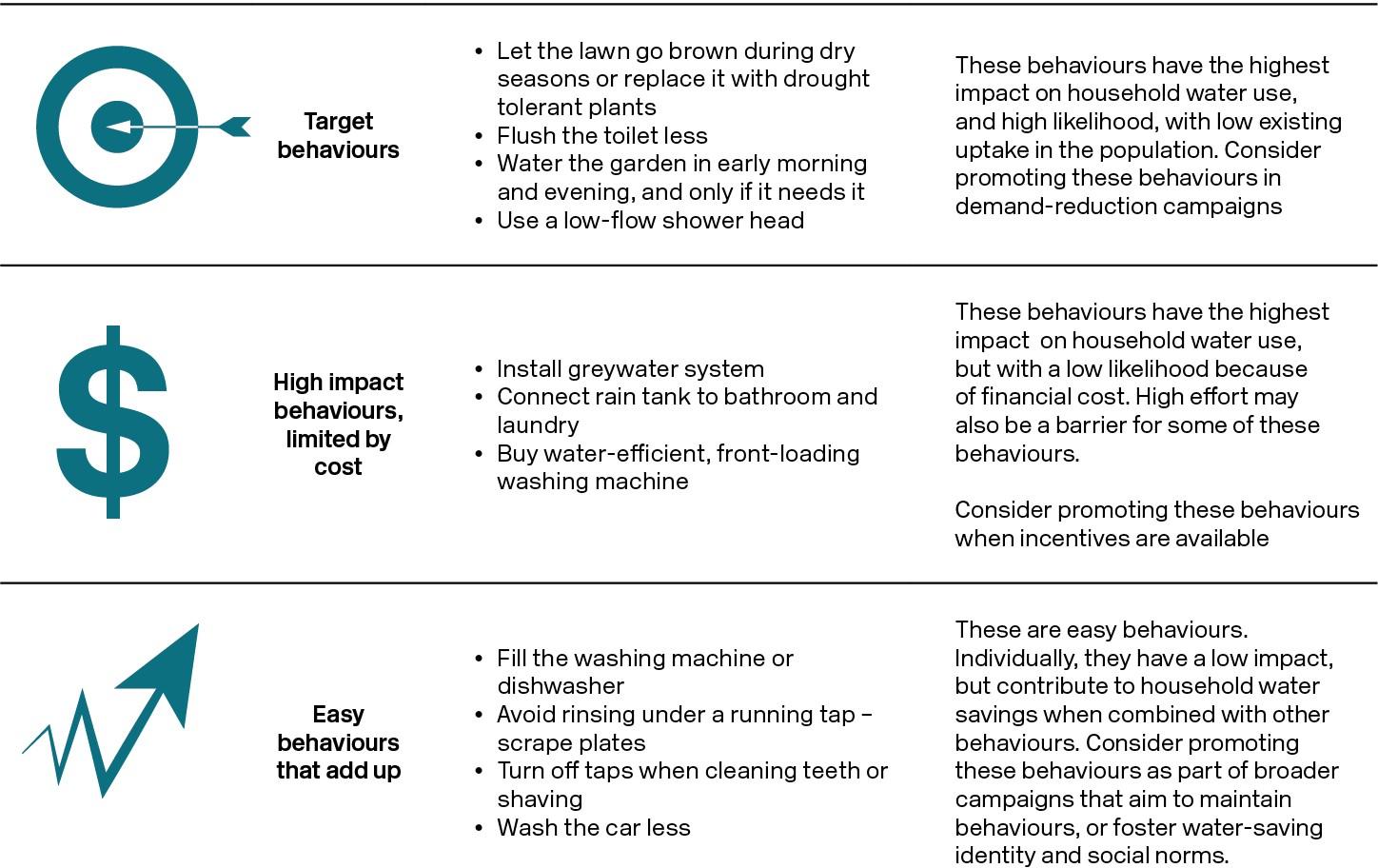

Figure 1: Rous region every day water saving measures ............................................................................... 19

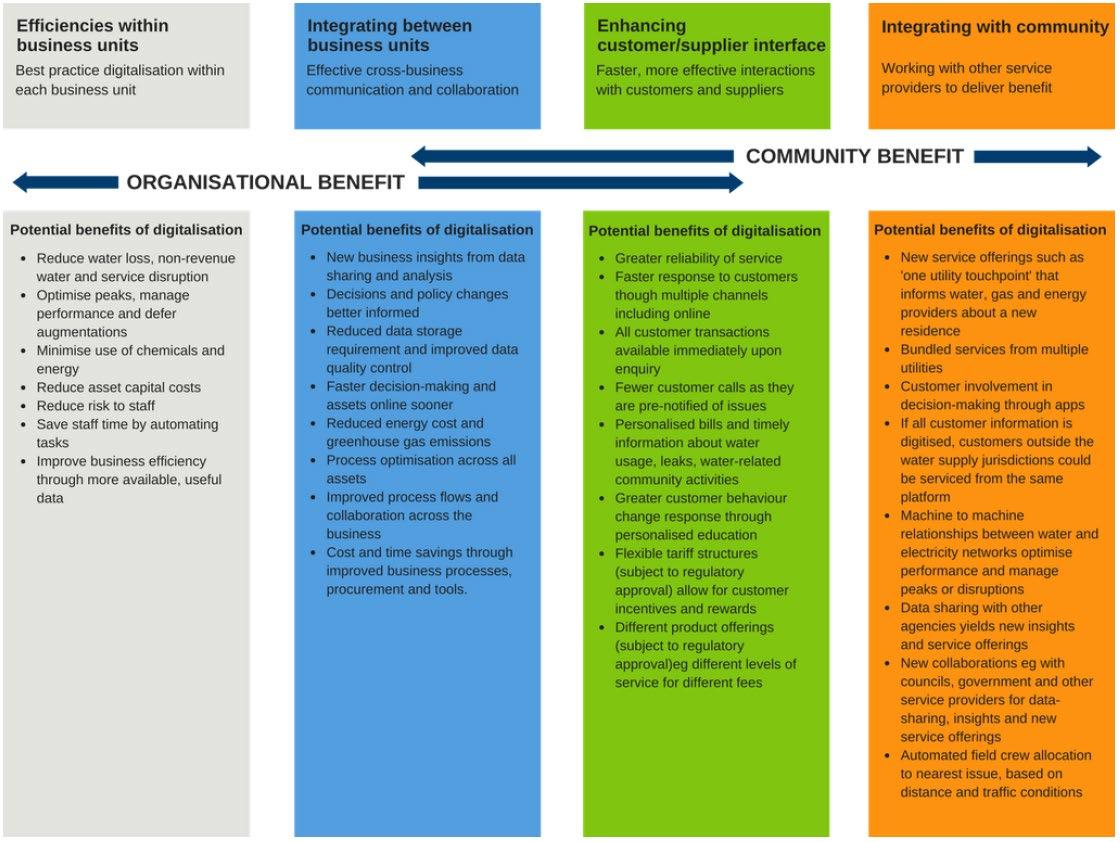

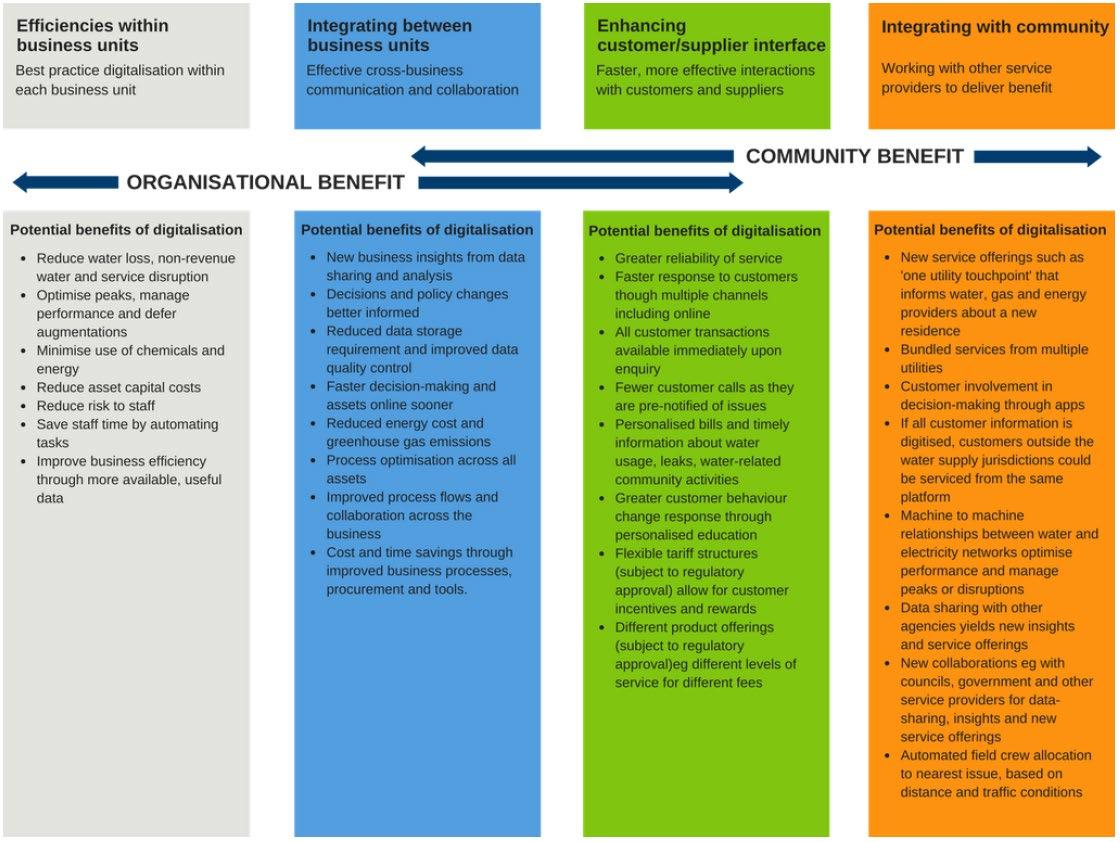

Figure 2: The four components of a mature digital water utility, from an internal focus (left) moving to an increasingly external focus (right) 26

Figure 3: RCC annual expenditure demand management 31

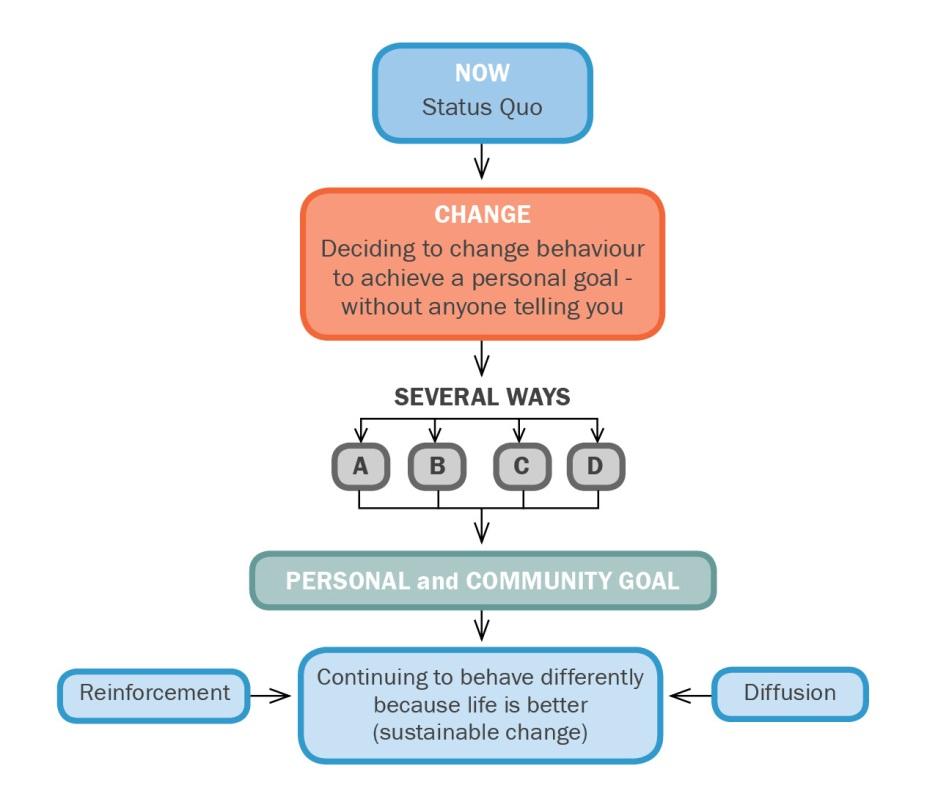

Figure 4: Options for bringing about change ................................................................................................... 33

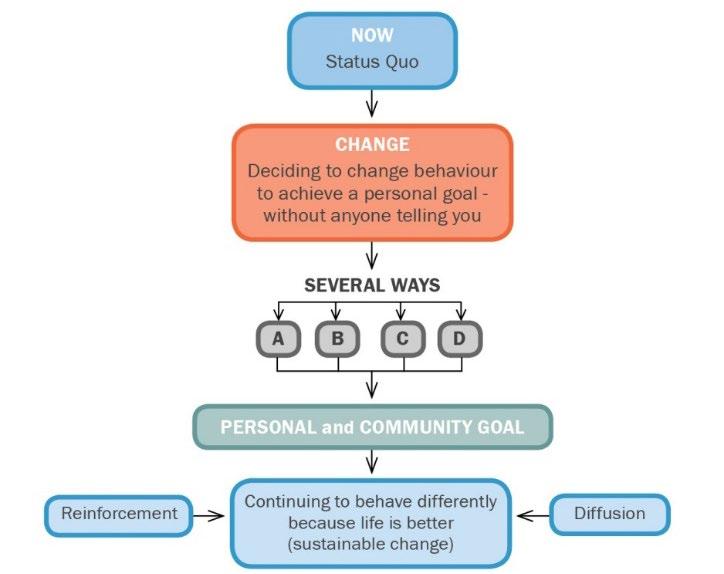

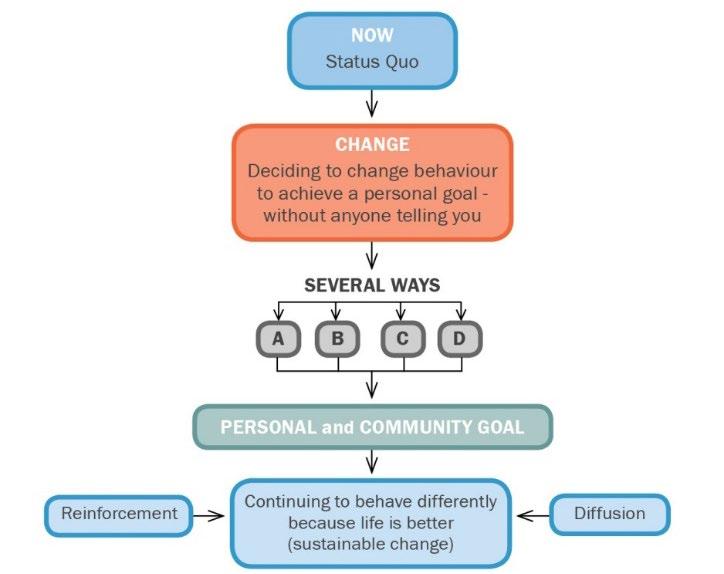

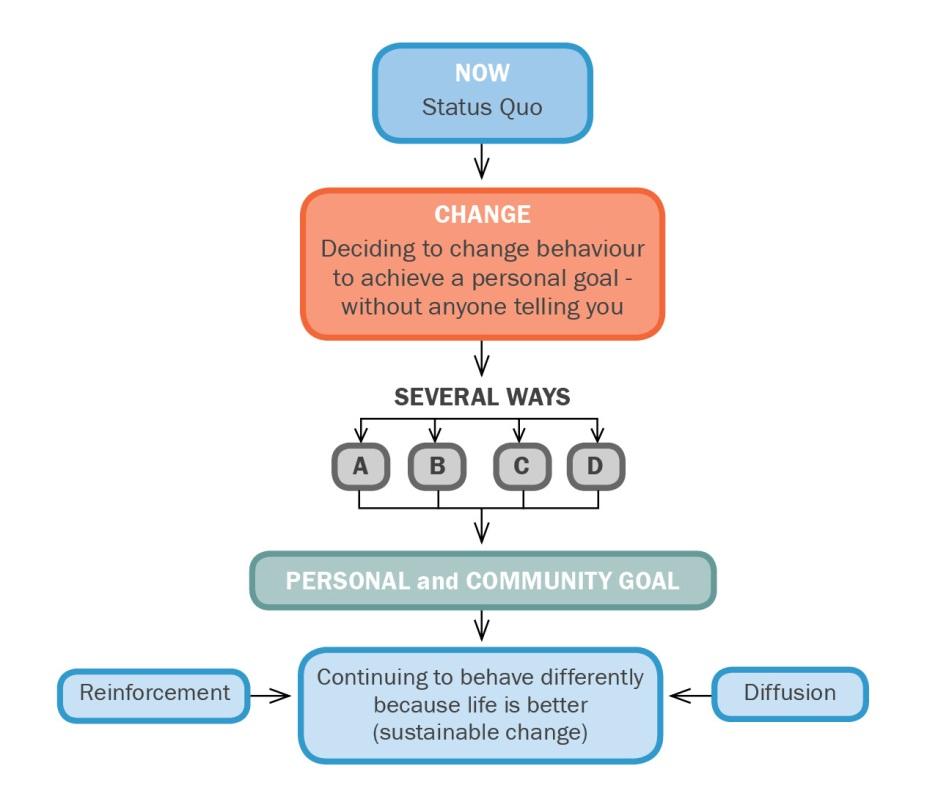

Figure 5: The conditions surrounding voluntary behaviour change 34

Figure 6: The benefit of the implement, evaluate, learn and adapt process 38

Figure 7: The potable town water supply balance ........................................................................................... 92

Figure 8: Regional demand and connected properties: 2012/13 2019/20 94

Figure 9: Regional residential consumption and total demand per connection: 2012/13 2019/20 95

TABLES

Table 1: Recommendations and agreed RDMP components IX

Table 2: Demand management actions to be implemented by RCC and the constituent councils separately to the RDMP .......................................................................................................................................................... X

Table 3: Adopted demand management strategies 3

Table 4: Summary of demand management measures for selected NSW LWUs and south east Queensland 12

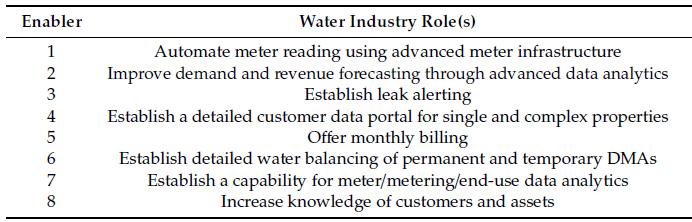

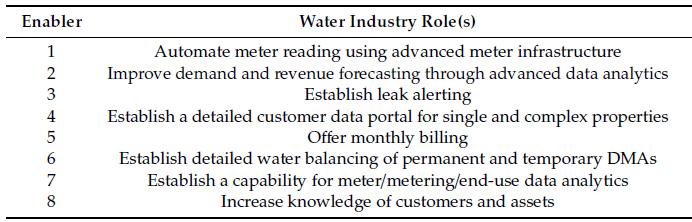

Table 5: Enablers (changes required) to enable benefits to be achieved from digital water metering ........... 25

Table 6: Comparison of average annual residential water demand in the region (2019/20) 28

RDMP Background information

recommended plan components Page ii

and

Table 7: Comparison of water losses (2019/20) 29

Table 8: Comparison of water supply tariffs in the region 30

Table 9: Comparison of demand management expenditure (total programs and administration/staff) 32

Table 10: Demand management measures implemented by RCC prior to 2014 52

Table 11: Potential new demand management measures considered in the 2014 Future Water Strategy 57

Table 12: Status of RDMP actions ................................................................................................................... 64

Table 13: Cost benefit analysis existing SWPP and rainwater tank rebates 84

Table 14: Demand management annualised costs TSC 86

Table 15: Cost benefit analysis rebates (CVC and CHCC) .......................................................................... 89

Table 16: Water supply connected properties (total regional and local supplies) 2019/20 93

Table 17: Permanent population served by water supplies 2019/20 93

Table 18: Potable urban water demand in the region (total regional and local supplies) 2019/20 ................ 94

RDMP Background information

recommended

components Page iii

and

plan

1. INTRODUCTION

Hydrosphere Consulting has been engaged by Rous County Council (RCC) to review and update the Regional Demand Management Plan: 2019 – 2022 (RDMP, Hydrosphere Consulting, 2018) for the next four years (2023 – 2026) on behalf of RCC and its constituent councils (Ballina Shire Council – BaSC, Byron Shire Council – BySC, Lismore City Council – LCC and Richmond Valley Council – RVC)

RCC provides bulk water to the following constituent council local government areas (LGA):

• BaSC, excluding Wardell and surrounds.

• BySC, excluding Mullumbimby.

• LCC, excluding Nimbin.

• RVC, excluding Casino and all land west of Coraki.

Bulk water supplied to these areas by RCC is delivered to the customer through the networks of each local Council (BaSC, BySC, LCC and RVC). RCC also provides water supply services to rural and urban connections direct from the bulk supply trunk main system (retail customers).

Demand management has been an integral part of RCC’s bulk water supply planning and management since 1995. These ongoing demand management initiatives have been successful in reducing water demand by approximately 50% over the last 25 years from average 484 kL/a/connected property (MWH, 2014a) to 248 kL/a/connected property (Hydrosphere Consulting, 2020c) despite an 80% increase in customer connections. Increased water efficiency and demand management strategies have reduced or eliminated many of the non essential uses of water from everyday life, meaning that it is now harder to achieve sustainable long term reductions in demand (this is termed ‘demand hardening’).

Appropriate urban water conservation is a required outcome of the NSW Best Practice Management of Water Supply and Sewerage Framework and the Water Management Act 2000 (as well as the National Water Initiative). In non metropolitan areas in NSW, water is supplied by the local water utility (LWU), which in most cases is the local council. Demand management and water conservation measures are implemented by LWUs using a suite of measures usually defined in a Demand Management Plan or in its Integrated Water Cycle Management (IWCM) Strategy.

The Best Practice Management Framework has been streamlined with checklists from the 2007 best practice guidelines superseded by the 2019 checklist for IWCM Strategies and 2014 Checklist for Strategic Business Plans. The checklists require demand management measures to be assessed including pricing (the responsibility of individual councils), a review of the current program and potential new non build water conservation measures with respect to their cost effectiveness (leakage reduction, pressure reduction, other losses, communication, permanent water conservation measures, retrofit etc.), the impacts of BASIX, open space irrigation, metering and billing.

The Rous Future Water Project 2060 identifies new water supply sources to ensure long term water supply security for the region. The Future Water Project builds on extensive investigations undertaken by RCC over the last few decades to identify potential source augmentation options and enable selection of a preferred long term strategy. The Future Water Project 2060 is RCC’s IWCM Strategy (Hydrosphere Consulting, 2021a) which documents the outcomes of detailed investigations undertaken regarding potential source

RDMP - Background information and recommended plan components Page 1

augmentation options and implementation scenarios. The constituent councils are also developing water supply strategies for the local supplies.

This report addresses the IWCM checklist requirements relating to water conservation measures. Demand data are also included in the regional demand forecast (Hydrosphere Consulting, 2020c).

The first stage of this project involved gathering information from each Council, reviewing feedback on the delivery of the RDMP 2019 2022 and opportunities for the new RDMP, as well as outcomes of a broader review to recommend a suite of initiatives for the next four year plan timeframe

The purpose of this report is to provide background information and recommendations for the new RDMP. The outcomes of the following tasks have been considered in this report:

• Consultation with RCC and the constituent councils.

• Review of RDMP implementation progress.

• The demand management initiatives of other water utilities.

• Current indicators of demand and losses

• Investigation of behaviour change applications in water supply demand management.

The new RDMP will specify amended demand management actions and tasks. This report provides a summary of the RDMP 2019 2022 and recommended changes based on the outcomes of the above tasks. The recommendations are highlighted in bold italic text throughout this document Not all recommendations will be adopted in the new plan which will be developed considering available budgets and human resources of RCC and the constituent councils. Multiple recommendations may be combined where appropriate in the design of the new RDMP actions.

Page 2

RDMP Background information and recommended plan components

2.

DEVELOPMENT

OF THE RDMP 2019 - 2022

As part of the development of the Rous Future Water Strategy in 2014 (MWH, 2014a), demand management options were reviewed including a strategic level cost benefit assessment. A benefit cost analysis of the demand management options (MWH, 2014b) weighed the cost of investment in demand management initiatives against the benefits accrued from three perspectives – the utility, the customer and the community (where the community combines both the utility and the customer). Assumptions for each measure including water savings, uptake and costs are provided in MWH (2014b). Any demand management measure with a marginal cost lower that the cost of source augmentation options being considered at that time were considered further as part of demand management cases (“Current Demand Management” and “Enhanced Demand Management”). The measures considered in 2014 are summarised in Appendix 1

Water efficiency was identified as Key Action 1 in the 2014 Future Water Strategy to affirm RCC’s ongoing commitment to the enhanced demand management initiatives with cost effective measures to achieve greater water efficiency. The 2014 Future Water Strategy (MWH, 2014a) predicted that enhanced demand initiatives will help delay and downsize future water sources required for the region. The enhanced demand management initiatives were reviewed by the Regional Water Supply Agreement Liaison Committee –Demand Management Working Group in 2017/18 and actions were optimised for the current (2019 – 2022) RDMP (Table 3, shaded green).

Table 3: Adopted demand management strategies

Demand management strategy

Residential initiatives

Rebates – rainwater tanks

Comments

Not considered cost effective in the 2014 Future Water Strategy but the program has broad community support.

Rebates – recycled water Program has been reviewed with consideration of recycled water scheme development.

Rebates – showerheads

Rebates have been offered since 1996. Water efficient showerheads are now readily available and the opportunity to replace inefficient showerheads is reduced.

Adopted strategies for RDMP 2019 –2022

Rainwater tank rebate program to continue in current form with active promotion.

Enhanced promotion of rebates where recycled water is available.

No additional action included in the RDMP 2019 - 2022

Water Efficiency Labelling Scheme (WELS), Building Sustainability Index (BASIX)

Programs are mandated by the NSW Government.

No additional action included in the RDMP 2019 - 2022

RDMP - Background information and recommended plan components Page 3

Demand management strategy Comments

Permanent low level restrictions

Not considered feasible with current legislation.

Adopted strategies for RDMP 2019 –2022

Increased promotion of voluntary measures (Voluntary Permanent Water Savings) is included in the RDMP 20192022

Non residential initiatives

Enhanced Blue and Green Business Program

The effectiveness of program has been reviewed and modifications have been developed.

Open space water efficiency

Constituent council initiatives

Water loss reduction

June 2016 study found low level of usage and low number of customers in the region.

Sustainable Water Partner Program (SWPP) targeting high water users with water efficiency plans, rebates, recognition program and increased engagement.

Not included in the RDMP 2019 - 2022

Local Water Utility (LWU) (constituent council) demand management plans

Strategic and regional approach to water loss management is critical to the success of the RDMP.

Not required as each council will implement actions from the RDMP.

Community Engagement and Education

Community engagement and education – schools

Community engagement and education – households

Programs have been successful but need to be matched to available resources.

Actions are required to increase understanding of household water consumption.

The RDMP actions will improve accuracy and understanding of water loss components and target leakage reduction.

Not included in the RDMP 2019 - 2022

Other initiatives

Smart metering

The status of current initiatives across the region and available technologies have been reviewed. Ongoing review of available technologies is required.

The RDMP 2019 - 2022 includes an overarching program of education to be delivered through schools.

Actions aim to provide increased awareness of consumption patterns and potential for water savings for all households and will also target residential customers with high consumption.

Smart metering program to be developed and optimised in the RDMP 2019 - 2022 as this is a potentially highly effective technology to identify leaks and high consumption.

RDMP - Background information and recommended plan components Page 4

Source: Hydrosphere Consulting (2018)

3. FEEDBACK FROM COUNCILS

Meetings were held with engineering, management, community engagement and operations staff from the councils to obtain feedback on the progress of the RDMP, challenges faced and actions to be included in the new RDMP. The outcomes of these meetings are provided in Appendix 2. The feedback from the RCC and constituent council staff can be summarised as follows:

• There is a lack of staff resources across the region which has delayed the implementation of RDMP actions.

• The councils generally agree that regional consistency is required for customer metering and definitions to aid in more accurate demand monitoring. There are significant challenges with developing a consistent system due to the variation in system capability, council policies and the lack of resources.

• The constituent councils provide limited community engagement regarding water saving measures and instead rely on and refer to information provided by RCC. During the drought of 2019/20, the councils were actively involved in communication of restrictions, particularly for local supplies.

• Only BaSC and RCC have a residential consumption target (160 L/person/day). Other councils indicated a need for smart metering before targets can be set, monitored and communicated appropriately.

• All councils are interested in smart metering as both a local and regional approach and have either implemented a local program (BaSC) or developed a pilot programs (BySC), planned to implement a local program (RCC) or are interested to see the outcomes of other programs before committing to the expenditure (LCC and RVC).

• Water loss reduction appears to be a key focus for each council but implementation is hampered by the lack of resources and the widespread nature and high cost of the program.

• BaSC has incorporated recycled water supply as a long term water source. BySC is implementing recycled water schemes on a local and opportunistic basis and is likely to focus on environmental flow releases in future. LCC and RVC are not planning to implement recycled water schemes. RCC will investigate potable water substitution as a long term component of the regional water supply strategy.

• Rebate and incentive programs are not actively promoted by the constituent councils and they rely on RCC to implement these programs. The constituent councils are unlikely to implement a rebate program for rainwater tanks in their LGAs if it is not managed by RCC. The low cost effectiveness of rainwater tank rebates is recognised but the councils also recognise the customer water savings and general community support for rainwater tanks. It is also recognised that an increased rebate would further reduce the cost effectiveness of the program.

• There is limited support for rebates for internal water efficient fixtures and fittings as these are mandated by NSW Government requirements for new developments and readily available on the market However, there is general support for a review of potential incentives with an increased understanding of water consumption patterns, cost effectiveness and expected success.

RDMP - Background information and recommended plan components Page 5

• There was general interest in supporting lower socio economic areas to improve water efficiency.

• There was general support for the re introduction of region wide school education programs addressing whole of catchment issues.

• There was some support expressed for a review of bulk water supply pricing to increase water efficiency signals.

• There is general support for RCC to lead and manage residential and non residential demand management initiatives across the region but also a need to provide clear responsibilities for implementation.

• While there is support for a delivery model where RCC leads the implementation of the proposed demand management initiatives, some actions remain the responsibility of the constituent councils. For example, actions such as implementing leakage detection, water loss management, pricing and smart metering are captured in internal business plans and budgets of the constituent councils and will be implemented alongside RCC’s demand management actions.

This feedback has been considered in the recommendations for the new RDMP.

RDMP Background

components Page 6

information and recommended plan

4. RDMP IMPLEMENTATION STATUS

The RDMP describes the water supply demand management initiatives to be implemented by RCC and the constituent councils between 2019 and 2022 and includes the following seven actions:

Action 1: Monitoring, Evaluation and Reporting

Action 2: Water Loss Management.

Action 3: Sustainable Water Partner Program (SWPP)

Action 4: Smart Metering

Action 5: Recycled Water.

Action 6: Rainwater Tank Rebates

Action 7: Community Engagement and Education: 7A: Households, 7B: Schools and 7C: High Residential Water Users

Each action included tasks to complete in order to fulfil the objectives of the actions A review of the progress of each action and its related tasks, expenditure and key performance indicators is provided in Appendix 3

Implementation of the RDMP actions has been hampered by a lack of human resources available within RCC (particularly during 2019/20 with a changeover of the Water Sustainability Officer) and the constituent councils (with staff changeover or deployment on other initiatives). Other actions (e.g. the SWPP and community engagement/ education) have required significant effort in the early planning and engagement stages including customer liaison and are only producing results in later years of the RDMP. Some implementation progress has been affected by COVID 19 restrictions. The implementation of standardised definitions of connection types and demand reporting across the region has been delayed by the lack of council resources which has had a flow on effect delaying other actions (e.g. water loss management and development of targets). The implementation of a regional approach to smart metering has not been successful as the councils have developed local programs and there has been a lack of regional coordination. Digital technology such as smart metering would improve the ability to monitor and report demand and increase customer interaction which are expected to result in more effective water saving measures. The take up of rebates and incentive schemes is likely to be higher during dry weather with the largest number of rebates provided during 2019/20 when extended dry periods were experienced

For the current rebates offered and the SWPP actions in the RDMP 2019 - 2022, the annualised costs per kL of water saved by the councils and their customers have been calculated based on the net present value (NPV) of the net expenditure and the predicted water savings. This calculation provides an indication of the relative investment for each action as a function of water saved to enable comparison between the actions on a cost basis. The data and calculations are provided in Appendix 4

The rainwater tank rebates do not provide a financial benefit to RCC (for expenditure of public funds) apart from the lowest level of rebate ($200 for a 3 kL tank without outdoor use only). The benefit to the customer generally increases as the tank size increases and indoor plumbing is included, but the benefit to RCC generally decreases, reflecting the increasing rebate offered. The SWPP is cost effective for the councils and customers which reflects the program’s focus on the actions with the largest water savings. The

RDMP - Background information and recommended plan components Page 7

achievable water savings for other programs (education, smart metering etc.) are uncertain. Significant variation is expected amongst customers, LGAs and would also be influenced by other measures implemented. Water savings from programs implemented by the constituent councils (smart meters, water loss management) will depend on investment, network configuration, customer mix, etc. The influence of tourists on water usage is a significant factor in the RCC region. Although some water savings can be hardwired, short term visitor behaviour is typically difficult to influence, unless there is a crisis such as a drought.

Similar findings have been reported for other LWUs (e.g. Tweed Shire Council (TSC), Clarence Valley and Coffs Harbour City Council) as discussed in Appendix 4

The following recommendations are provided from the review of the status of RDMP implementation and the benefit cost analysis undertaken for this project:

Recommendation:

• Increased effort in demand monitoring tasks is required to develop greater understanding of the outcomes of demand management programs on residential and non residential demand over time.

• The status of RDMP tasks and data on customers, water supply and consumption should be reported by all councils on a bi annual basis through the Regional Liaison Committee meetings with standing agenda items on RDMP progress, demand indicators and sharing of lessons learned.

• The councils should work together to develop and implement standardised definitions of connection types to ensure consistency across the region.

• The councils should work together to develop and implement a standardised metering policy across the region to assist with monitoring and reporting.

• If per capita indicators are adopted/developed, the population served in each area should be estimated as accurately as possible e.g. following the release of Census results and updated as required to correspond with reporting periods.

• Regional demand forecasts should be updated in accordance with the Rous Future Water Project 2060 actions with more accurate data collected through the RDMP implementation.

• RCC should continue to coordinate monitoring and reporting with data provided by LWUs as required by the new RDMP.

• Water loss management is a critical component of demand reduction and current levels of losses are high. Each council should provide sufficient resources to implement their WLMPs and set targets (based on best practice indicators) and timeframes for water loss reduction.

• SWPP promotion should continue to include case studies and cross-promotion of successful water efficiency projects.

• RCC should continue to coordinate the SWPP on behalf of the constituent councils.

• Constituent councils should implement a water conservation program for high water users (non residential customers) in local supply areas.

RDMP Background information and recommended plan components Page 8

• Modifications to SWPP and eligibility criteria should be considered to make it easier for smaller businesses that are willing to participate e.g. fixture/fitting replacement, removal or lowering of demand threshold, smart metering etc.

• A method of ongoing monitoring and engagement should be developed with each participating business to measure the success of SWPP initiatives.

• BaSC and BySC should provide information to other councils on successes, challenges and recommendations from their smart metering programs.

• RCC should implement smart metering for its retail customers and work with the constituent councils to extend the program across the region either as a regional or local approach with consideration of budget, timing and planning priorities.

• RCC should continue to promote non-potable recycled water connections to BaSC and BySC businesses (where appropriate) as part of the SWPP with rebates as part of the SWPP.

• BaSC and BySC should administer their own recycled water rebates if desired (given the local plumbing enquiries and compliance requirements within their respective jurisdictions).

• Rainwater tank rebates appear to be popular within the community, particularly during dry periods. Based on feedback received during the Future Water Project 2020 public exhibition, community feedback suggests that rainwater tanks should be a component of the region’s water supply. The rainwater tank rebates do not generally provide value for money for RCC and the community and there are limited water savings particularly during extended dry periods. However, the rainwater tank rebate program provides intangible benefits such as contact with customers and stormwater detention. Due to the low cost-effectiveness, it is recommended that alternative residential customer incentives are developed to achieve the objectives of customer engagement and support, water efficiency and cost effectiveness.

• Pilot programs should be implemented to test the needs and benefits of residential retrofit programs. Pilot programs with audits and end use and fixture surveys should be implemented to allow RCC to establish baseline consumption and water use behaviour for different household types across the region, quantify potential water savings and develop targeted future incentive programs

• Consumption targets should be developed as part of the smart metering program to provide meaningful and measurable responses from the community.

• The high residential user program should continue to be implemented using the tools developed for the RDMP 2019 - 2022.

• A consistent regional water bill format should be considered including comparisons to regional targets and water saving advice. The bill format may need to be modified as part of the smart metering program. It should also be rigorously tested on customers before implementation as part of the residential component of the program.

• RCC and the constituent councils should co fund a regional resource for delivery of water cycle education programs including catchment health, water supply, wastewater

RDMP Background information and recommended plan components Page 9

management and stormwater management initially targeting schools but also wider community education.

• RCC should continue to coordinate regional education programs.

• RCC should continue to coordinate residential programs.

• Education activities should include tourism accommodation providers and facilities to target the large number of visitors to the region.

RDMP Background information and recommended plan components Page 10

5. R EVIEW OF CURRENT PRACTICE

Hydrosphere Consulting (2020a) provided a comprehensive review of current practice for consideration by Tweed Shire Council (TSC) in its review of demand management initiatives Additional information has been collected from other LWUs to enable comparison with the Rous regional approach. Where data are adequate, RCC’s level of investment has been benchmarked against other LWUs considering factors such as demand and customer numbers (Section 6.4).

The review of current demand management practice conducted for TSC (Hydrosphere Consulting, 2020a) found that demand management programs are influenced by legislation, state and local government structure, human and financial resources, local needs/issues, climate influences, regulation and socio economic factors. Water utilities which are separate from the local council (such as Sydney Water and in Victoria where water utilities are supported by the state government) and metropolitan water utilities are often more supported by other levels of government and have more resources to implement demand management actions and different needs to regional water utilities such as RCC and the constituent councils. Given these influences and drivers, it is considered appropriate to focus this review on NSW non metropolitan water utilities with a similar climate to that of the Rous region (i.e. the NSW North Coast). Where relevant, comparisons to the experiences of other NSW LWUs which actively implement demand management initiatives

Demand management practice in south east Queensland has also been reviewed. Seqwater is the bulk water supply authority for south east Queensland and is responsible for sourcing, storing, treating and distribution of potable water to over 3.3 million people (Seqwater, 2020) compared to approximately 117,000 people in the constituent council areas. The Water Security Program (Seqwater, 2016) is Seqwater's plan for providing the region's drinking water over the next 30 years, including during times of drought and flood. The program details the demand management activities being implemented in the region. Demand management activities are implemented by Seqwater, south east Queensland water service providers (Unitywater and Urban Utilities), local government and the Queensland government. Seqwater operates a much larger water supply network than RCC and many of Seqwater’s customers live in metropolitan areas. For these reasons, the demand behaviour and demand management approach in south east Queensland are not directly comparable to the Rous region. Similar to NSW, the Queensland government legislation stipulates that water efficient taps and showers are required in all new residential buildings and water efficient toilets are required in all new buildings. Local governments are responsible for water conservation education and water efficiency in Council buildings, facilities and operations. Water service providers implement pressure and leakage management, metering and billing and water carter facilities such as fixed fill stations and metered hydrant standpipes to account for water use. They also provide information and community engagement about indoor and outdoor water efficiency These aspects of demand management are comparable to NSW LWUs

A summary of the demand management measured of NSW water utilities (local councils) and south east Queensland is provided in Table 4 and discussed in the following sections

RDMP - Background information and recommended plan components Page 11

Table 4: Summary of demand management measures for selected NSW LWUs and south-east Queensland

RCC and constituent councils Yes, mainly through website. Some community events e.g. Water Week, Residential high water users program. SWPP.

Yes Yes –rainwater tanks, SWPP

Yes – by constituent councils

WLMPs have been prepared but not fully implemented

Yes – by constituent councils

Dual reticulation available in Ballina, Lennox Head and Byron Bay

Yes – Ballina. RCC pilot program 2014 17 with 10 businesses. BySC pilot program 2021 – East Mullumbimby

Refer Section 4 and Appendix 3

Tweed Shire Council1 ‘Target 160’ campaign. Information on website.

Yes Showerhead, toilet and tapware rebates, top water user program

Yes No Yes Open space irrigation and industry usage

No TSC demand management plan was reviewed with a new program framework adopted March 2021.

Page 12

RDMP - Background information and recommended plan components

LWU Customer engagement and education

Permanent water conservation measures

Rebates and incentive programs

Undetected leak policy Water loss management Best-practice pricing Potable water substitution Smart meter program

Comments

Clarence Valley Council2

Information on website, facilities tours, Waterwise schools program

Yes Showerhead, toilet and rainwater tank rebates, water efficient partner program (>5 ML/a)

Yes Infrastructure renewal, WLMP to be developed.

Best-practice pricing

Coffs Harbour City Council2 Information on website, facilities tours, Waterwise schools program

Bellingen Shire Council3 Information on website, Waterwise schools program, Savewater Alliance

Yes Showerhead and toilet rebates, water efficient partner program (>5 ML/a)

Yes Infrastructure renewal, WLMP to be developed.

Yes Urban reuse for urban open space and agriculture

Pilot program to be developed and implemented

Regional Water Efficiency Plan adopted 2020 (shared bulk water supply)

Yes Washing machine rebate Yes Leak detection and repair, pressure management

Yes Urban reuse for urban open space and agriculture

Pilot program to be developed and implemented

Yes Dual reticulation for new residential development

No Unable to obtain additional information from Council

Page 13

RDMP - Background information and recommended plan components

LWU Customer engagement and education

Permanent water conservation measures

Rebates and incentive programs

Undetected leak policy Water loss management

Potable water substitution Smart meter program

Comments

Page 14

Permanent

Rebates and incentive

Undetected leak

Water

Best-practice

Potable

Smart

RDMP - Background information and recommended plan components

LWU Customer engagement and education

water conservation measures

programs

policy

loss management

pricing

water substitution

meter program Comments

Information on

Yes Showerhead, dual flush toilet and rainwater tank rebates Yes Metering reservoirs and

water loss User pays pricing Recycled

No

Nambucca Valley Council4

website

monitor

water from sewage treatment plant used for agricultural purposes

Limited investigation into demand management as water supply is considered to be secure5

Waterwise

Yes

Yes

Unknown

Kempsey Shire Council6

schools program

No

Unknown User pays pricing

Unknown Unable to obtain additional information from Council

spray gun heads, tap flow restrictors, showerheads), Business water efficiency program

Unknown

Yes - with significant price increases between 2003 and 2014 (step 1 usage charge in 2021/22 is $3.80 per kL)

Yes - open space irrigation and agriculture

at

Point to inform leak detection program.

5-year average residential demand is 121 kL/property p.a. which is attributed to high usage charges

Page 15

RDMP - Background information and recommended plan components

LWU Customer engagement and education

Permanent water conservation measures

Rebates and incentive programs

Undetected leak policy Water loss management Best-practice pricing Potable water substitution Smart meter program

Comments

Eurobodalla7 Information on website Yes Showerhead exchange, washing machine and dual flush toilet rebate, free installations of water saving devices (hose spray guns, pre-rinse

Active leak detection

Trial

Potato

Example south east Queensland Councils9,10,11

Information on website, school and community education programs and stakeholder engagement

No Conservation credits program and turf removal program

Yes Pressure and leakage management undertaken by water service providers, system loss programs

Tiered pricing Gold Coast desalination plant, western corridor recycled water scheme

No -

School and community education programs. Business education program. Community education program. Residential high water users program

No Incentive schemes and targeted marketing encouraging water-saving products.

Yes Water loss reduction program, pressure management, water meter replacement program

User pays pricing Recycled water schemes

supply water for irrigation of agricultural and sporting fields, parts of Seqwater have access to Gold Coast desalination plant

Smart water meter solutions project, Unitywater completed trial of smart meters and opted against them

-

Sources: 1- Hydrosphere Consulting (2020a), 2- Hydrosphere Consulting (2020b), 3 Bellingen Shire Council (2012), 4- Nambucca Valley Council (2021), 5 - pers. Comm. Richard Spain, (2021), 6 - Kempsey Shire Council (2021), 7 –Hydrosphere Consulting (2021b), 8 – Seqwater (2017), 9 - City of Gold Coast (2019), 10- Redland City Council (2014), 11- Logan City Council (2017).

Page 16

RDMP - Background information and recommended plan components

LWU Customer engagement and education

Permanent water conservation measures

Rebates and incentive programs

Undetected leak policy Water loss management

Best-practice pricing Potable water substitution Smart meter program

Comments

Seqwater8

5.1

Customer engagement and education

Since the millennium drought in Australia, it has been recognised that it is important to develop relationships with water customers to increase the effectiveness of water saving initiatives The Water Services Association of Australia (WSAA) has undertaken customer research which shows that water efficiency remains an important issue for Australian customers (even during non drought periods) and many want their water utility to support them to do more (WSAA, 2019a). Water demand education and awareness activities promote the uptake of water efficiency measures and highlight water wastage, but also engage the community to be better advocates for water conservation and protection, with the expectation that water is supplied, delivered and used efficiently. A substantial array of information on water saving tips is available on LWU websites. Social media is also becoming more common for communication of water topics. Seqwater has launched a three year community education and engagement program which will build community knowledge. The ‘Realities of Rain’ awareness campaign supports the three year program and asks people to use water wisely and prepare for the possibility of drought. The campaign includes an online hub with information, surveys, engagement opportunities and water conservation measures (Seqwater, 2021) Other large Australian water utilities have implemented similar customer engagement programs e.g. Hunter Water Love Water campaign, Sydney Water’s Customer Hub (Hydrosphere Consulting, 2020a).

Coffs Harbour City Council (CHCC), Clarence Valley Council (CVC), Kempsey Shire Council and Bellingen Shire Council have partnered with the NSW Department of Education and Cascade Environmental Education Centre to deliver the Waterwise Schools program (based on the program developed by Water Corporation, WA) which provides teaching and learning opportunities for primary schools. The Waterwise Schools Program provides participating schools with free promotional resources, competitions and a ‘waterwise’ accreditation if the schools include water education in their curriculum, participate in national water week, promote community awareness and have developed an action plan. The program is professionally delivered to schools via specialist water educators working for Cascade Environment Centre (Hydrosphere Consulting, 2020c).

The Gold Coast City Council ‘School Water Saver Program’ is available online only and includes worksheets, lesson plans, activity sheets and teaching resources for early childhood, primary and senior grade levels. The lessons discuss water as a valuable resource, the sources of water, using water wisely under urban demand management, alternative water sources such as recycled water and sustainability. Lesson plans for grades two, four and seven align with the Australian curriculum.

Seqwater delivers a comprehensive water education program and online portal called ‘Up a Dry Gully’, aimed at primary and secondary school teachers and students. Learning experiences are held at major Seqwater dams and water treatment plants and cater to primary and secondary schools, TAFE and university groups, as well as professional delegations and community groups.

The RDMP school education action involves external partners delivering school education programs rather than council resources with limited participation from schools.

Other common methods of raising awareness and promoting water efficiency include:

• Water saving information on water bills

• Tours of water supply and sewer facilities for schools and members of the public.

RDMP Background information and recommended plan components Page 17

• Consumption targets campaigns (e.g. TSC’s ‘Target 160’ [L/person/day] campaign)

• Water saving programs or audits targeting high residential or non residential users

• Assisting businesses (non residential customers) to prepare Water Efficiency Management Plans.

Recommendations:

• Customer engagement should include actions that increase customer awareness of water consumption, encourage water efficient behaviours and promote the demand management program measures to increase the success of their implementation. Customer engagement would be enhanced once smart metering has been implemented.

• Education activities are directly linked to the customer engagement program, encouraging and supporting water efficient behaviours. Education components should be cost effective and designed to reach as many customer sectors as possible. The information available to customers (e.g. through websites, customer service centres and bill inserts) should be reviewed and updated regularly with links to consistent information (e.g. from The Water Conservancy or education websites). Other cost effective methods include the use of social media for information dissemination. Education should be undertaken in parallel with other customer engagement activities such as audits. General education activities should include materials targeting households, non residential customers and high residential and non residential users.

• As school students are the customers of the future and can encourage water efficiency in the home, a targeted and well-resourced education program for primary and secondary schools should be developed and delivered directly by either internal or external staff.

5.2 Permanent W ater C onservation

Unlike other Australian states (e.g. Victoria, ACT), NSW legislation restricts the implementation of permanent water conservation actions to voluntary measures. Most NSW coastal water utilities have implemented permanent (voluntary) water efficiency measures, although the components are variable. For example:

• MidCoast Water has a ‘summer water savers’ voluntary program to help residents be waterwise during the summer through tips and promoting WELS.

• Permanent water conservation measures are imposed by many of the NSW local councils. The most common component of these measures is restrictions on unattended hoses during daytime (e.g. 10:00 am to 3:00 pm)

• Permanent water conservation measures were in place in south east Queensland from December 2009 until 2013 These were introduced by the former Queensland Water Commission (the agency formerly responsible for setting water restriction policy and coordinating water infrastructure projects in the state) following extended periods of drought and water restrictions in the preceding decade (Seqwater, 2016)

• RCC and the constituent councils have adopted “every day water saving measures” (Figure 1)

RDMP Background information and recommended plan components Page 18

Figure 1: Rous region every day water saving measures

Recommendation:

• Ongoing sustainable and sensible water use should continue to be promoted through voluntary permanent water conservation measures as Level 0 in the drought restriction policy to assist with promoting sensible water use, provide a link to the drought restriction policy and support other program measures.

RDMP Background information and recommended plan components Page 19

5.3 Rebates and I ncentives

There is a natural trend towards water efficient fixtures and fittings driven by market, regulation and customer preferences. Water efficient fittings and fixtures are now readily available and the benefits of replacing inefficient fittings and fixtures through rebates are therefore reduced. The reduced effectiveness of rebates is being recognised by most water utilities and in many cases these programs are being phased out or modified to increase uptake.

The rebate programs of NSW LWUs are continually evolving with market forces and community preferences. Rainwater tanks provide opportunities for reduction in demand during normal climatic conditions (i.e. when household rainwater tanks are refilled by rain). During droughts, the effectiveness of rainwater tanks diminishes with larger tanks able to store more water for dry periods. The BASIX requirements will address any demand reduction opportunities from rainwater tanks in new developments and rebates can assist with encouraging water efficiency in non BASIX houses. Many rainwater tanks in the Northern Rivers region failed in the drought of 2019/20 and customers relied on town water supplies during these times. In addition, rainwater tanks installed as part of BASIX for internal uses are required to include potable water top up systems.

In NSW, the use of a rainwater tank is not recommended by the State Government for drinking, cooking or personal washing if there is a potable supply available. Studies (e.g. McBeth, 2011) conclude that water use of houses with rainwater tanks is highly variable with water savings dependent on many factors, not simply the tank volume and connections. McBeth (2011) noted that people who install large tanks yet do not connect them for all of house use, seem to develop high water use habits, with high rates of demand for reticulated water when the tanks are empty. The analysis and evaluation of water meter data before and after installing a rainwater tank (by RCC as part of a 2020 rebate survey) reiterated the complexities of water consumption, demand and identifying opportunities to maximise water savings associated with rainwater tanks The RCC survey also found that 28% of the respondents would have purchased a rainwater tank without the rebate. The impact of an incentive on someone who would have made the change anyway (e.g. bought a rainwater tank) is called free riding in the behavioural economics literature Rainwater tank rebates are being phased out by many LWUs due to the low cost effectiveness (refer Appendix 4). Most water utilities include policies on rainwater tank use in urban areas even if there is no rebate offered. Many NSW councils offer other rebates including:

• New for old showerhead exchange/rebate

• Dual flush toilets

• Taps/tapware

• Aerators/flow controllers.

• Outdoor watering fittings. There are many products on the market designed to reduce water use through either inadvertent wastage (e.g. a hose connection bursting off the hose) or reduced consumption (e.g. through design of sprinkler heads). The Water Conservancy website (Smart Approved WaterMark - The Water Conservancy ) provides information on certified water efficient products for leaks, glasswashers, greywater, pool and spa, garden, plumbing, watering, cleaning, car washing, bathroom, rainwater and analytics.

RDMP - Background information and recommended plan components Page 20

Sydney Water is proposing a stronger focus on water conservation and efficiency (with investment of $23 million p,a. which is considered to be a low cost for Sydney Water) through measures such as (DPIE, 2021):

• Supporting households to save water, such as buy back programs for inefficient appliances, installation incentives and maintenance services for rainwater tanks, free repairs to leaky taps and fittings, and helping people to use water more wisely (and make better use of stormwater) in their gardens.

• Encouraging businesses to save water, including water saving action plans and audits, replacement programs for inefficient commercial appliances and help to find and fix leaks.

Recommendations:

• Incentives should be offered directly to high residential water users based on the outcomes of the pilot programs

• Programs should be considered for vulnerable or financially disadvantaged customers with older water intensive products.

• Marketing of any adopted rebate program and cross-promotion with other measures should be included to increase uptake and awareness.

5.4 Undetected L eak P olicy

Many water utilities provide reductions for high water bills due to undetected leaks. The aim is to incentivise customers to fix leaks they might otherwise ignore RCC, LCC, RVC have adopted similar policies with varying conditions and refund amounts) Some LWUs also apply a process to alert customers of higher than normal water meter readings

Recommendation:

• As the financial assistance can be used to encourage property owners to repair leaks, the undetected leak discount policies should continue with ongoing review of the expenditure and water savings. However, once a smart metering program is in place with more immediate identification of leaks, the policy should cease as leaks will be easily detected.

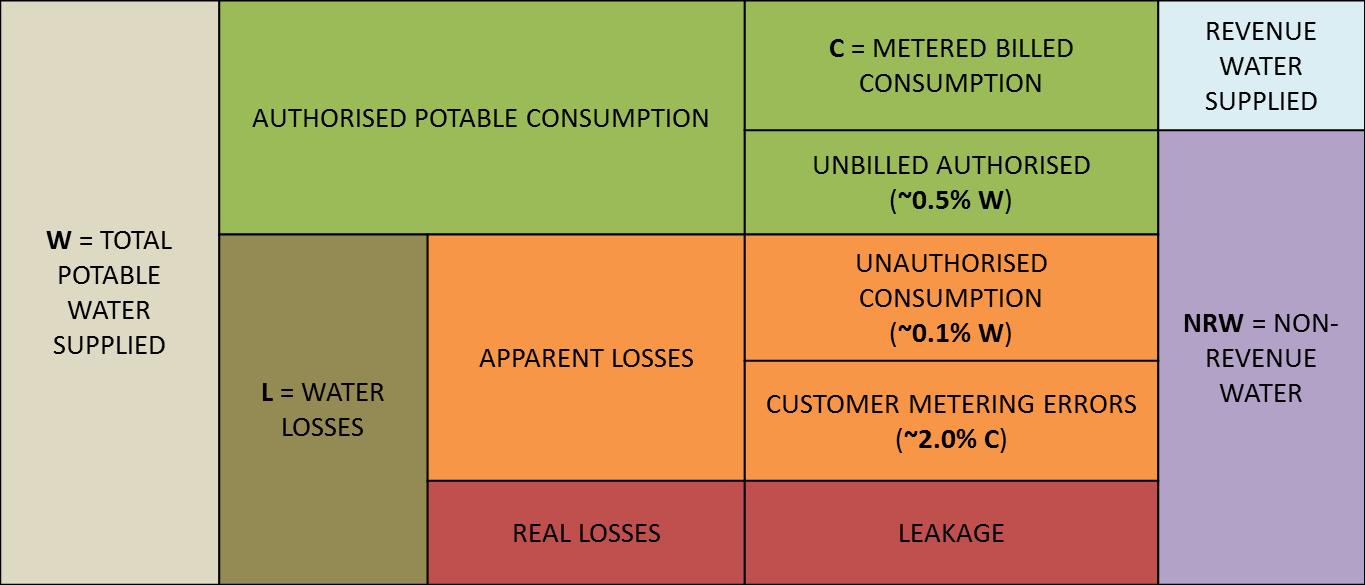

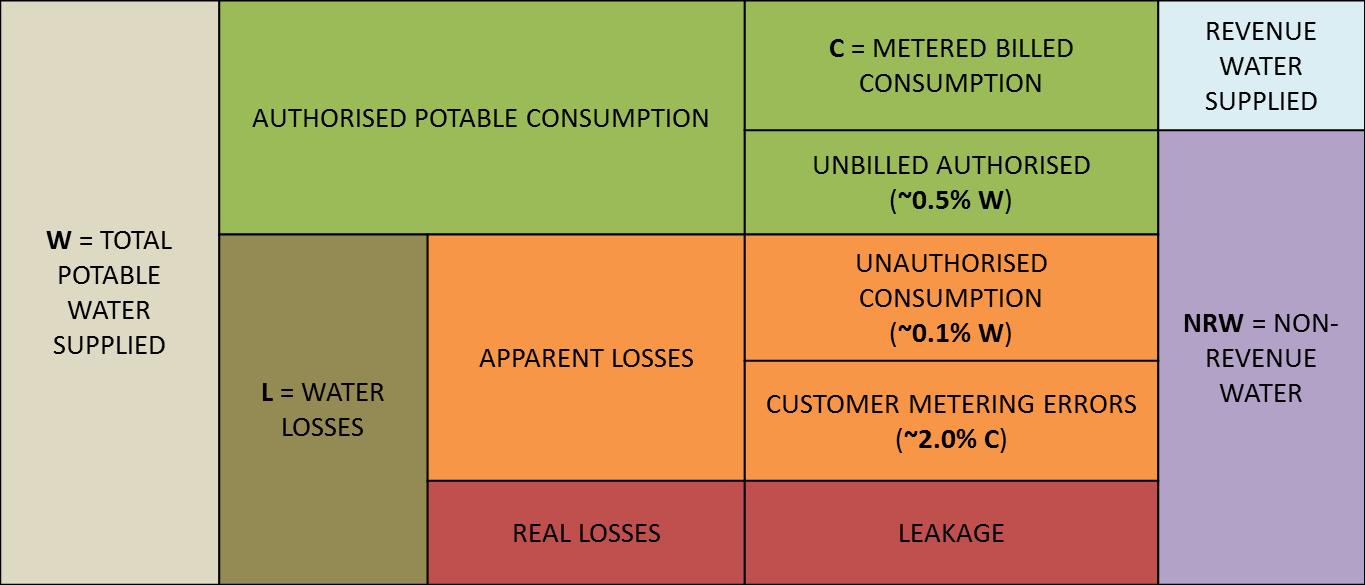

5.5 Water Loss M anagement

The International Water Association Water Loss Taskforce (WSAA, 2019b) has developed Four Pillars of Leakage Control. The pillars represent best practice for reducing real losses and promote four different strategies that can be used to minimise leakage. These include:

• Pressure management the rate of leakage and new burst increases with pressure (including cyclic pressures).

• Active leakage control requires monitoring of flows in a metered area to identify leaks and repair before they become a greater issue.

• Pipeline and assets management includes material selection, installation, maintenance, rehabilitation and replacement, and commonly associated with renewals.

• Speed and quality of repairs repairs should be done quickly and to a suitable standard.

RDMP Background information and recommended plan components Page 21

Mains renewals are usually targeted and the elimination of background leakage is an unaccounted benefit of this expenditure. As it is neither practical nor cost effective to renew all mains, some leakage is unavoidable. The implementation of pressure management has a positive impact on the other strategies used to control leakage (e.g. active leakage control, asset management and repairs) and can be used to reduce the annual ongoing costs of the leakage program. Sectorisation of the system to create district metered areas or zones is another method of facilitating leak detection Some councils separately meter districts allowing them to detect potential leaks and estimate their general location when analysing water balances. District metering areas (DMAs) are made up of a discrete number of properties and are usually bounded by closed valves so they can be monitored and managed as separate areas. DMAs are used in most countries around the World and they have been extensively proven to assist in reducing leakage in a water supply network (Watercare, undated). Emerging trends targeting reducing water losses from leaks include installing smart meters in houses and cloud based management software e.g. TaKaDu which shows real time data of meters and uses predictive analytics to detect potential leaks.

Pressure management is a fundamental strategy to leakage control. It is widely accepted that pressure management has the benefit of reducing NRW and frequency of bursts and leaks (WSAA, 2019b). In 2011, WSAA completed a three year study into leakage and pressure management, finding that pressure management has a three fold benefit water conservation, reducing costs to the water utility and improving outcomes for the customer. Pressure reduction is most commonly achieved through the implementation of DMAs coupled with pressure zoning.