5 minute read

Why We Wrote Leave No Man Behind

By CAPT George Galdorisi, USN (Ret.)

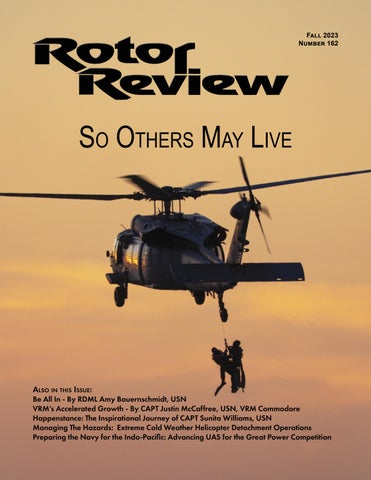

The subject of this issue of Rotor Review is “So Others May Live.” It is also the twentieth anniversary of when my partner (the late Tom Phillips) and I came up with the original germ of an idea to write our book Leave No Man Behind: The Saga of Combat Search and Rescue. I thought this was the time to tell, as Paul Harvey famously said, “The rest of the story.”

First, this isn’t about selling copies of the book. For those of you in the San Diego area, it is available at the NHA Office, the Coronado Public Library, and elsewhere. For others further afield, we are mindful that other libraries have a copy.

Here is the journey that Tom and I began, and it happened, to no one’s surprise, at our NHA Symposium. Full disclosure, it was on Friday night, the last day of the Symposium, and as the old saying goes, “When you drink enough beer, anything is possible.”

During the 2003 NHA Symposium in San Diego, we decided to write a book about the history of combat aircrew rescue. It became a five-year labor as we discovered the astounding ups and downs in the saga of combat aircrew rescue, and a rich heritage and history which completely surprised us. We wouldn’t trade the experience for anything. Here is why we wrote the book.

There has never been a time in history when it was good to be a POW: From the life sentence in the slave galleys of antiquity, to dungeons of medieval times, to appalling prison hulks of the Napoleonic Era, to the shame of Andersonville and similar northern prisons of our own Civil War, to starvation, disease, and even cannibalism of the Japanese POW Camps, or the Katyn Forest and Malmedy Massacres of POWs in Europe in World War II, to the brainwashing of Korea, to the unspeakable isolation, torture, and cruelty of the Hanoi Hilton, in living memory.

But today, there may not be any POWs. Prisoners have already been tortured, dismembered, and dragged through the streets, and beheaded while screaming for mercy on the internet for billions to see.

For that reason, today’s CSAR crews must live up to the imperative to “leave no man behind” as never before. But will they be as ready as CSAR crews in past conflicts?

We wrote the book to tell the riveting stories of astonishing rescue missions over the years, and to show how the discipline grew despite repeated setbacks, as technology, doctrine, tactics, and techniques evolved gradually into the skill sets of today’s military. The March 2011 crash of the Air Force F-15 Strike Eagle over Libya and the recovery of one of the two crewmen via a Marine Corps TRAP Mission was a stark reminder of the criticality of having CSAR forces always formed and ready for every military mission where our aircraft go in harm’s way over enemy territory.

The most important lesson learned from Vietnam era combat rescue was the dramatic improvement in performance when Navy combat rescue units, after four years of frustration, finally shed all other collateral missions and dedicated their entire focus to the sole mission of combat aircrew rescue. Just as our book hit the shelves, USD AT&L, the Department of Defense’s chief weapons buyer, declared that we don't need dedicated CSAR forces, and that any helicopter in the area will do just fine.

Then-Secretary of Defense, Robert Gates, was fond of saying the department didn’t have the money to buy what he called “exquisite weapons.” He made this point repeatedly in speeches across the country. But we believe that with a DoD budget now in excess of $850 billion a year, if the nation buys only one exquisite weapons system, it should be a CSAR platform that can snatch our warriors from the clutches of the enemy. Likewise, if our helicopter pilots and aircrews, who have CSAR among many other missions, achieve an exquisite degree of proficiency in only one mission, it must be CSAR. Our people deserve nothing less.

Our young volunteer airmen join up with an implicit understanding that, if they get stranded behind enemy lines, the nation has the best combat rescue capability possible and will stop at nothing to go get them before they fall into enemy hands. Dare we as a nation have it any other way?

Perhaps enough has been said. “So Others May Live,” is our core competency as Rotary Wing Naval Aviators. There are lessons learned the hard way that we should mind lest they happen again. That’s why we wrote Leave No Man Behind: The Saga of Combat Search and Rescue and would write it again today.

There has never been a time in history when it was good to be a POW: From the life sentence in the slave galleys of antiquity, to dungeons of medieval times, to appalling prison hulks of the Napoleonic Era, to the shame of Andersonville and similar northern prisons of our own Civil War, to starvation, disease, and even cannibalism of the Japanese POW Camps, or the Katyn Forest and Malmedy Massacres of POWs in Europe in World War II, to the brainwashing of Korea, to the unspeakable isolation, torture, and cruelty of the Hanoi Hilton, in living memory.