Rory McMillan

Rory McMillan

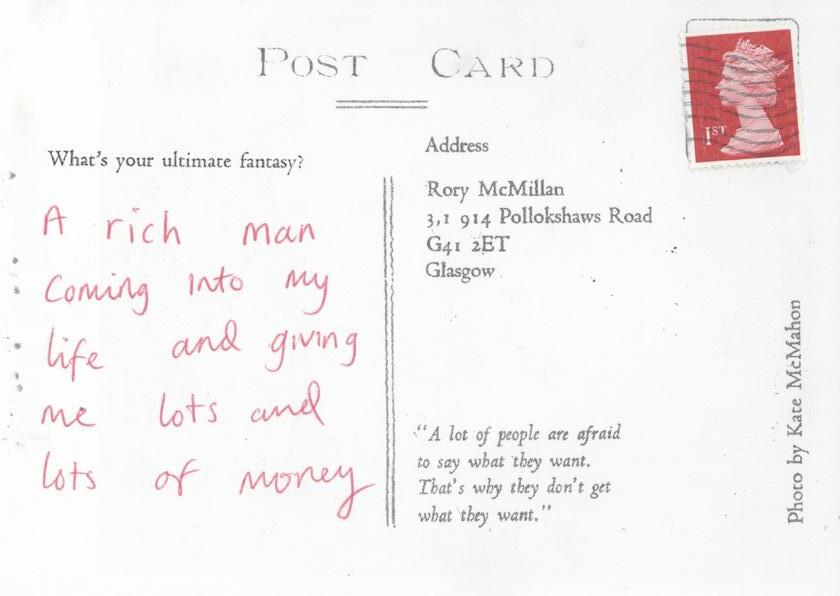

The visibility of gay culture has exposed subcultures, each of which growing to have its own myths, cultural heroes, language, and stereotypes. Gay magazines have been portraying aspects of male eroticism since the 1950s, and a sexual semiotic was created as a discreet method of communication for gay men, long before current media began picturing men as sex objects. For this work, I’ve looked at how gay men are portrayed in print, film, and art, with a focus on gay postcards collected from The James Gardiner Collection. I examine two distinct facets of gay culture: the creation of a gay semiotic mode and the male fantasy, referencing archetypal gay images as they appear in both gay media and urban enclaves.

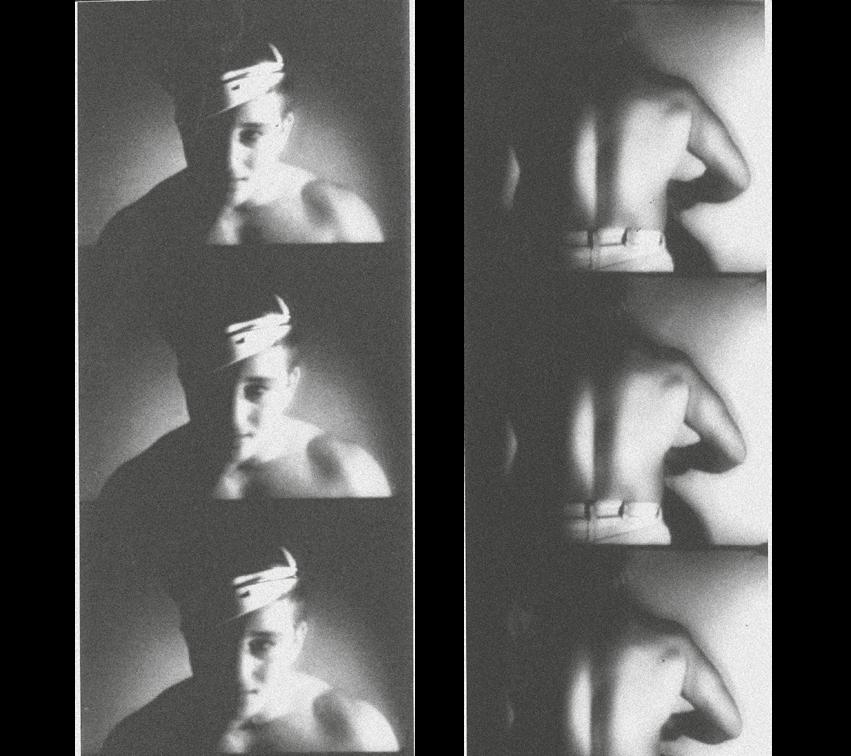

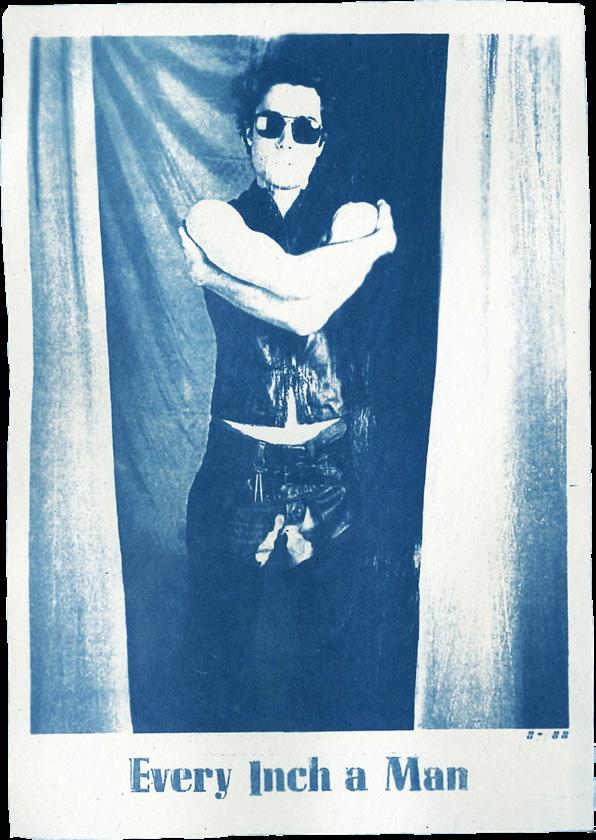

Gay culture has developed a set of public, sexual prototypes, similarly to straight culture. Men are portrayed in setups which initially were inspired by gay male fantasies depicted in gay magazines. Elements of these fantasies have been adopted into fashion, giving rise to the ‘gay look’. Albeit essentially neutral in wider culture, these adopted symbols form their own distinct connotations within the gay community. Here, I portray three archetypal uniforms, all influential in the adoption of ‘butch’ dress styles for men: the biker, the cowboy, and the sailor. During the first three decades of the 20th century, uniforms offered a fantasy for gay men, as typically men in uniform were the unavailable (or sometimes not so unavailable) objects of men’s sexual desire. Dressing up could go some way to fulfilling that fantasy, yet often these dress choices would be limited to private spaces, and so uniforms became a popular choice at the arts and drag Balls for men not looking to drag up. These images became integral in the manifestations of fantasies, frequently appearing in the work of artists, such as Tom of Finland’s erotic illustrations, or as literal characters portrayed by authors such as John Rechy (City of Night) and Larry Kramer (Faggots). This attempt to look like a ‘real man’ reflects many gay men’s desire for ‘rough trade’, it was no longer enough for gay men to ‘have men’

Fig. 1as their sexual partners; they wanted to embody these real men. It seems clear that the macho man is a reaction against effeminacy, redistributing the masculine/feminine binary, still persistent today. As this new masculinity grew in popularity, these men became considered as clones, a term widely used in San Francisco, coined by writer Larry Townsend.

Fig. 2

The clothes worn by clones were distinct from those worn by straight men, making it distinguishable from heterosexual macho men. Straight men wore this attire in an unselfconscious way, usually loosely and for comfort. The clones rejected this nonchalance and stylised these looks. Beards and moustaches were clipped, hair was kept tidy, and clothes were fitted. Gay men had to balance straight imitation with enough signifiers to still make them identifiable as real gay men. The macho look had two functions: it attracted gay men, whilst simultaneously acting as a form of self-protection. Many of these men were simply wearing the costume that experience has taught them would attract the men they found sexually attractive. Form-fitting clothing hugged the body, revealing the contours of musculature, often emphasised by not wearing underwear or shirts. A scene from Felice Picano’s novel The Lure illustrates this. Buddy Vega is sent to show Noel (working undercover for the police) how to dress to be accepted in the gay bar scene of New York: Vega told Noel ‘jeans should hang low on your hips, be tight in the ass and the legs and especially full at your basket.’

With the rise of popularity in overtly masculine forms of dress, leather became a popular choice. It projected an air of dark, brooding masculinity, with associations of the rebel, or the dominator. As leather implied stereotypical male behaviour, observers of the leather scene regarded it as archetypically masculine. It is most easily recognised by black leather items including everything from hoods to jackets, trousers, caps, and underwear. The sexual prowess and appeal to gay men of the biker look is evident in drawings and photographs in physique magazines such as Bob Mizer’s Physique Pictorial and Kenneth Anger’s film Scorpio Rising. Although typical gay media and lifestyle did not widely publicise the leather cult, instead integrating the subculture in subtle ways. A model in a magazine might, for example, wear a studded black leather wrist band or studded belt whilst holding a narcissus flower. Within the gay community, leather becomes a symbol for the unknown or the untried.

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

The fetishisation of sailors had appeal for gay men throughout the twentieth century, as one man’s recollection of the uniform during the 1920s indicates; ‘It was very flattering, quite unlike the uniform of recent times. The neck of their tunic was cut in a very rough square, which gave the wearer a very masculine appeal… The trousers were made very tight around the waist and bottoms, but baggy around the ankles. If the sailor wore no underwear, then very little was left to the imagination.’ The rise of the sailor and soldier look was marked at the turn of the Second World War, those joining to fight for their country were liberated when they were thrown into same-sex environments.

The cowboy or western look can be seen as derivative of cultural myth; it would be unlikely for an American boy growing up in the 40s or 50s not to have an American hero. As the cowboy uniform could be easily incorporated into contemporary dress, it easily grew in popularity. It is most recognised through western boots, jeans, flannel shirts, and in some instances, hats. When the image appears in gay magazines the settings are usually an imitation of barns, corrals, or fence posts. The cowboy represents the frontier and male dominated society. The cowboy lives a ‘man’s life in a man’s world.’

These archetypal images continue to exert an influence on the contemporary dress and fantasies of gay men. Today, athletic tanks, jean shorts, white socks, and workwear-oriented clothing remain as popular, and are more provocative than they initially appear. There exists a poignant irony and campiness within this aesthetic, a playful riff on masculinity stretched to the extremes. Within this visual language, a sexual premium is persistently placed on masculinity, a system familiar to any gay man who has ever perused a gay dating app. In these spaces, we often come across men who advertise themselves as ‘straight-acting’ or ‘masc’, it’s as common to list the number of times you go to the gym per week as divulging your age. While not all gays endorse the exclusion of those less masculine, the prevalent preference for masculinity within the community establishes a standard. Through embracing the complexities of gay fantasies, these archetypes persistently shape contemporary dress and ideals, continuing an ongoing dialogue between reality and desire.

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Fig. 9

End Notes

Fig. 1 William Friedkin, 1980, Cruising

Fig. 2 David Wojnarowicz, 1980, Letter to Jean Pierre

Fig. 3 Kenneth Anger, 1963, Scorpio Rising

Fig. 4 The James Gardiner Collection, 1915, A sailor from HMS Dreadnought

Fig. 5 James Bidgood, 1971, Pink Narcissus

Fig. 6 Kenneth Anger, 1947, Fireworks

Fig. 7 Colt Studio Presents, 1992, Men in Uniform

Fig. 8 Dusty, 1978, Speed, Man!

Fig. 9 Physique Pictorial, 1964, Volume 13, Number 4

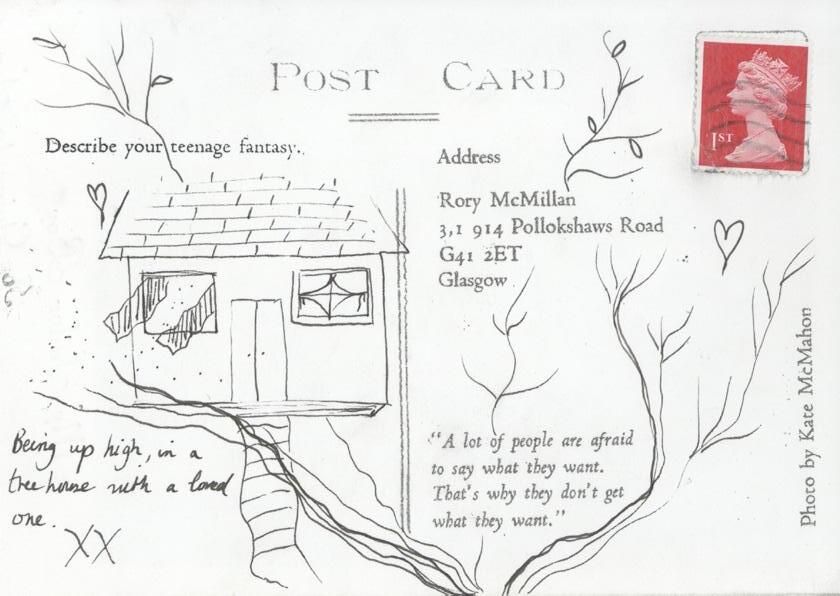

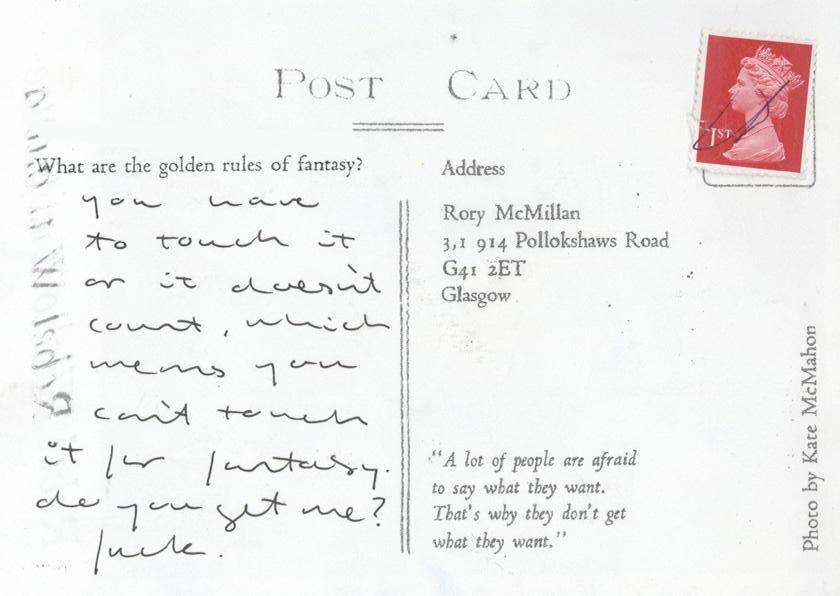

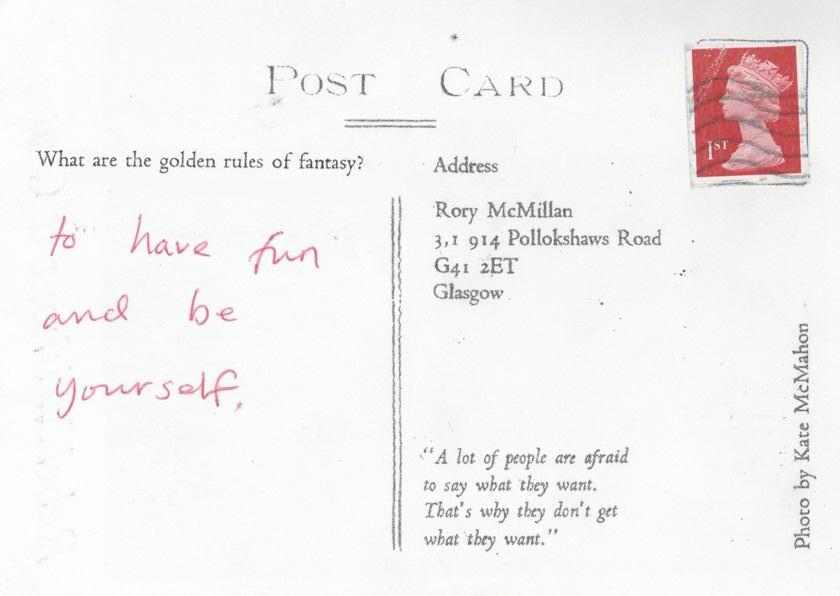

Bedtime Stories

2023/24 by Rory McMillan

With thanks to Kate McMahon for photography, Graham Peacock for modelling, and to all those who participated in this project.