Design & Innovation at a Crossroad

Delft, Netherlands, 6‐7 August 2024

Design & Innovation at a Crossroad

Delft, Netherlands, 6‐7 August 2024

Roel KRABBENDAM, M.Ed B.Arch NCARB LEED AP a

a

Fielding Graduate University

Monocultures of identical K‐12 classrooms proliferate from the Sahara to the Himalayas, and they certainly remain the norm in the United States. Yet evidence suggests high teacher dissatisfaction and low student engagement. Can re‐imagining existing school environments powerfully engage students and teachers, without rebuilding them from scratch?

Proposed here are schools delivering visceral experiences supported by diverse environments. These schools would be physically re‐organized as communities of practice, with like‐minded teachers working together in workspaces that build community, promote identity and support collaboration. When teachers surrender their private classrooms, those spaces can diversify to more powerfully support teachers in engaging students.

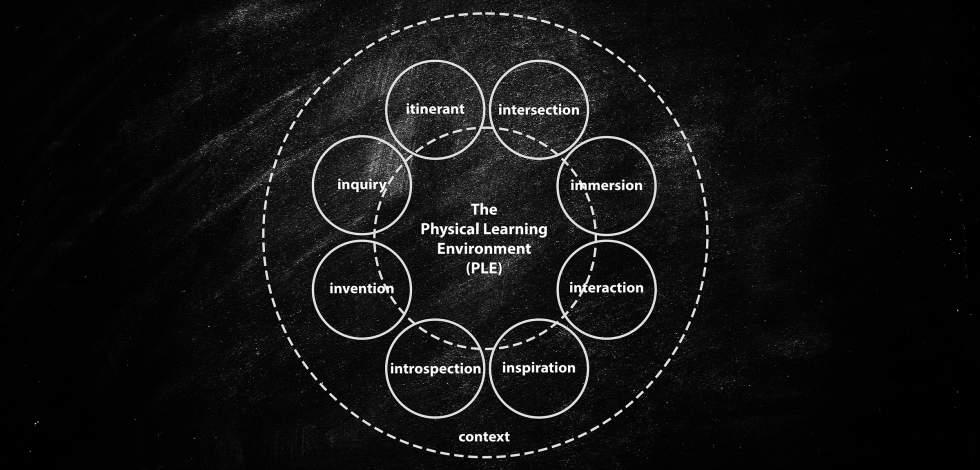

What could these rooms become? Nine categories of learning spaces are identified, generating 60 spatial archetypes to replace identical classrooms with a diverse ecosystem.

What broader lessons for design management stem from this work? Compared to the templates and precedents often referenced in design, the arch‐typological approach presented here offers tremendous benefits:

Adding depth: contributing deeper research over a timespan independent of immediate project‐driven concerns.

Reducing risk: ensuring the outlines of an approach without eliminating agency, and local variation.

Focusing design effort: defining the field of play to concentrate energies on the unique aspects of the problem at hand.

Keywords: archetypes, typologies, communities of practice, educational ecosystem, K‐12 school facilities design, pattern language, student engagement, teacher attrition

* Corresponding author: Roel Krabbendam | e‐mail: hkrabbendam@fielding.edu

Copyright © 2024. Copyright in each paper on this conference proceedings is the property of the author(s). Permission is granted to reproduce copies of these works for purposes relevant to the above conference, provided that the author(s), source and copyright notice are included on each copy. For other uses, including extended quotation, please contact the author(s).

The advent of 21st Century Learning (Trilling & Fadel, 2009) had a positive effect on public school in the United States, with alternatives to traditional pedagogy now common, individualized and project‐based learning more prevalent, and high school drop‐out rates continuing to decline. (NCES, 2021, Table 219.70). Nonetheless, persistent problems plague the system, particularly regarding the teacher and student experience. The first question addressed in this paper will be, how can the school facility make a difference?

With 13,318 separately administered public school districts, 90,922 traditional public schools, 7,547 public charter schools, 30,492 private schools and 691 virtual schools (NCES, 2021, Table 105.50), the public school system in the United States is decentralized, economically diverse and varied in performance. The second question addressed in this paper will be, given the wide disparity in this system, can ideas be presented so that schools can apply them flexibly, to fit their circumstances?

Recognizing that under‐resourced schools bear the brunt of systemic dysfunction, and that construction and renovation can be prohibitively expensive, the third question contemplated here will be whether any facility‐based proposal can possibly help those most in need of innovative solutions. Finally, some lessons for design management will be drawn from this work.

Teacher attrition in the United States is double that of high‐performing school systems in Europe and Asia (Sutcher et al., 2016), and it is costing between $1B (Haynes et al, 2014) and $8B annually (Garcia & Weiss, 2019; Strauss, 2017). Since school funding is largely local, resources are spread unevenly. Poorer schools bear the brunt of these issues.

Considerable evidence shows that [teacher] shortages historically have disproportionately impacted our most disadvantaged students and that those patterns persist today. Nationally, in 2013–14, on average, high‐minority schools had four times as many uncertified teachers as low‐minority schools. These inequities also exist between high‐poverty and low‐poverty schools. When there are not enough teachers to go around, the schools with the fewest resources and least desirable working conditions are the ones left with vacancies. (Sutcher et al., 2016, p. 5)

Signs of teacher dissatisfaction are not scarce, and strikes among school employees are becoming increasingly frequent (USAfacts, 2023). Dissatisfaction is the most common reason teachers give for dropping out. A Learning Policy Institute report implicates the lack of “school culture and collegial relationships, time for collaboration, and decision making input” (Sutcher et al., 2016, p. 52). Anecdotal evidence implicates monotony, boredom, stasis, and confinement (Kruse, u.d.), and a profound sense of isolation also figures prominently:

Much of our work is done in silos, which sometimes consist of just one person. Teaching can be incredibly isolating. ...We write learning outcomes alone, design activities alone, and teach behind a closed door. We reflect, review assessments, and enter statistics alone. How can we build communities of practice when our work is often done in isolation? (Brown & Settoducato, 2019, p. 10)

Research has shown that a strong sense of community reduces burnout (McCarthy, 1990), that collaboration reduces burnout (Kanayama et al., 2016), that innovation (the opposite of monotony) increases as emotional exhaustion decreases (Koch & Adler, 2018), and that spatial mobility improves affect (Heller et al., 2020).

Something more systemic has affected the lives and professional conduct of American teachers in the last decades, however. Concern regarding international competitiveness, expressed by the 1983 report A Nation at Risk, for example, inspired increased standardization and accountability within the educational system, and spurred a standardization, commodification and corporatization of the K‐12 curriculum that stripped teachers of their agency and identity. Au (2011) argued that this standardization of teaching disempowered and deskilled teachers. To the extent that this paradigm prevails, it is not difficult to understand the erosion of both identity and job‐satisfaction among public school teachers. If the school facility is to have a positive impact on the teacher experience, then it will be to re‐empower them, increase their agency, support collaboration, strengthen their sense of community and re‐invigorate their sense of identity.

The student experience

Student disengagement has also proved persistently problematic in the United States. For the purposes of this study, Schlechty (2011) offered the most useful definition of engagement: attention, commitment and persistence all focused on something that delivers meaning. Zyngier (2008) distinguished between cognitive, affective, and physical disengagement, and concluded that affect identified through observation was not a reliable indicator of cognitive engagement. The Gallup Student Poll (2016) provided student self‐reporting data, showing 74% of students engaged in grade 5, but only 33% of students engaged in grade 12.

In contrast, the California School Climate, Health and Learning Survey System (CalSCHLS, 2021) reported 72% of 9th and 11th graders motivated to learn, but only 27% reporting their activities to be meaningful. Csikszentmihalyi and Schneider (2000) identified a similar problem with the emotional experience of students in school almost 2 decades earlier:

Despite the seemingly dull nature of the activities that students are most commonly asked to do, they still feel more challenged in academic classes than in other classes. Even so, they do not appear to find most of their academic classes interesting or enjoyable. Academic classes are positively associated with challenge and importance to future goals, but they do not foster enjoyment, positive affect, or motivation. (p. 163)

They reported that academic classes offered importance with anxiety and boredom, art classes offered joy without importance, and only computer science and vocational courses offered both joy and importance. Schools commonly force students to choose between value and joy.

Even the best of these statistics indicate that public school in the United States is not engaging a quarter of its students, who have their minds elsewhere. A school facility that positively impacts the student experience will inspire engagement. This is fundamentally different from a facility focused on “achievement”, even as greater achievement is the expected outcome.

The average age of a public school building in the United States is 49 years old (NCES, 2024). These schools were built before the personal computer, the internet, Wi‐Fi, and the codification of 21st Century Learning. They constrain the activities they host within a rigid matrix of rooms and supporting systems and they bend life inside them to their own limitations. Replacing them is often impractical, however, due to issues of siting, cost, phasing, and student displacement during construction.

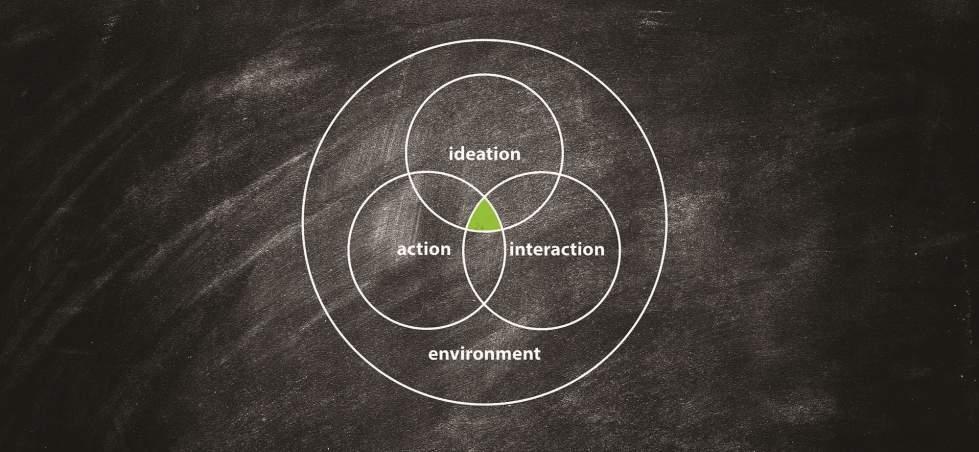

Can space even make a difference? Describing public school design guidelines intended to support healthy eating, Huang et al. (2013) identified 10 domains of environmental influence on the issue (e.g. water access, signage, on‐site food production, aesthetics), each with design strategies offering affordances (school garden), avoidances (replace vending machines), arrangements (prominent salad bar), and ambiance (introduce music) to support that domain. This team demonstrated specifically what every architect understands and environmental psychology has maintained for over half a century: that environmental design impacts the action, interaction, and ideation that takes place in a space. Architect Patrick Pouler (1994) wrote:

Space is neither innocent nor neutral: it is an instrument of the political; it has a performative aspect whoever inhabits it; it works on its occupants. At the micro level, space prohibits, decides what may occur, lays down the law, implies a certain order, commands and locates bodies. (p. 175)

What kinds of affordances, avoidances, arrangements and ambiance would simultaneously support teacher satisfaction and student engagement? What kind of school is this? Not, in any case, the complexes of identical classrooms and isolated teachers so common across the world today.

For many school districts, the resources to effect change exist. The United States spends at least $60B annually on school construction (Jackson & Johnson, 2021). However, pressing expenses overwhelm these existing funds. The United States General Accounting Office reports the following:

The 100 largest school districts, which serve approximately 10.4 million students, identified security (estimated 99 percent), monitoring health hazards (94 percent), and completing projects to increase physical accessibility for students with disabilities (86 percent) as their high priorities (Nowicki, 2020, p. 23)

The 2021 International Existing Building Code (306.7.1) codifies some of these priorities, for example, by requiring that up to 20% of construction costs be dedicated to accessibility. Concurrently, school shootings dramatically reinforce the emphasis and expenditures on security in the United States, and the increased reliance on digital technologies drives enhanced wireless connectivity. Any pragmatic strategy to supercharge the power and effectiveness of the learning experience and better support teachers and students through the Physical Learning Environment (PLE), must minimize the inordinate costs of construction that this nation has demonstrated it must spend elsewhere.

We have a system in the United States that drives out too many starting teachers, that fails to engage a quarter of its constituents, that is housed in an infrastructure that constrains innovation, and that is designed to be financially inequitable, leaving under‐resourced districts to their own limited devices. We need better ideas.

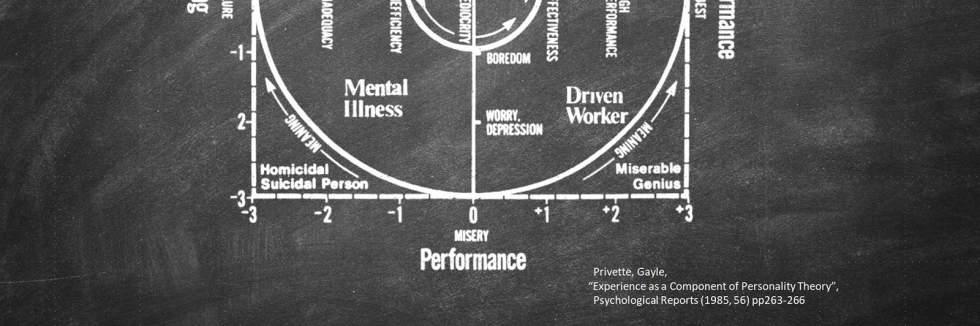

Where to start? Consider the following four square diagram plotting performance against emotional experience:

Figure 1 An experience model of feeling and performance (Privette, 1985, p. 264). Highlights in green by the author.

Proposed in 1985 by Dr. Gayle Privette at the University of West Florida, this diagram illuminates the importance of matching profound effort with positive emotional experience. Effort must be matched by joy if a person is to achieve Flow and Self‐actualization. Hard work in a joyless context, easy joy without accomplishment, or giving up entirely and in misery all lead to psychological disaster. Consider this in the context of school.

There can be no doubt that schools demand peak performance from their students. High stakes testing regimes enforce performance in the United States. When, however, do schools take institutional responsibility for the quality of their students’ emotional experience? Social Emotional Learning (CASEL, 2020), ECOLE (Glaser‐Zikuda et al., 2005) and FEASP (Astleitner, 2000) are well‐known frameworks and methodologies attending to student emotions, but these approaches emphasize socialization over joy, flow or self‐actualization, and none reference the

PLE, so entrenched is the idea of the self‐sufficient classroom. Despite this recognition of emotion as fundamental to learning, Mainhard et al. (2018) found that student emotions remained up to the teacher:

8042 student ratings of 91 teachers indicated that a considerable amount of variability that is usually assigned to the student level may be due to relationship effects involving teachers. Furthermore, the way that teachers interpersonally relate to their students is highly predictive of student emotions. In sum, teachers may be even more important for student emotions than previous research has indicated. (p. 109)

Curriculum includes objectives, learning experiences, the organization of those experiences, and evaluation (Tyler, 1969). As the political system imposes objectives, and standardized testing defines evaluation, teachers naturally focus on learning experiences and their organization. Megan Power, ambassador fellow of the US Department of Education expressed this exactly when she wrote in 2019:

No longer is the focus of good teaching mainly on delivering content. Rather, a good modern teacher is a designer of experiences. Teachers today aren't expected to be experts in everything; they're more often part of dynamic teams that combine their experiences, skills, and passions to help elevate all students' learning. (Power, 2019, para. 16)

How then to help teachers offer experiences that match effort with joy? Here, the educational environment becomes salient. If an experience may be modelled as thoughts, actions and interactions enacted within an environment, then the optimal experience would fully engaging all of these dimensions. The environment in this model is available to powerfully contribute to the equation. This understanding certainly calls into question the international standard of repetitive, traditional classrooms. Are these classrooms truly all we may ask of schools in our effort to support teachers and engage students?

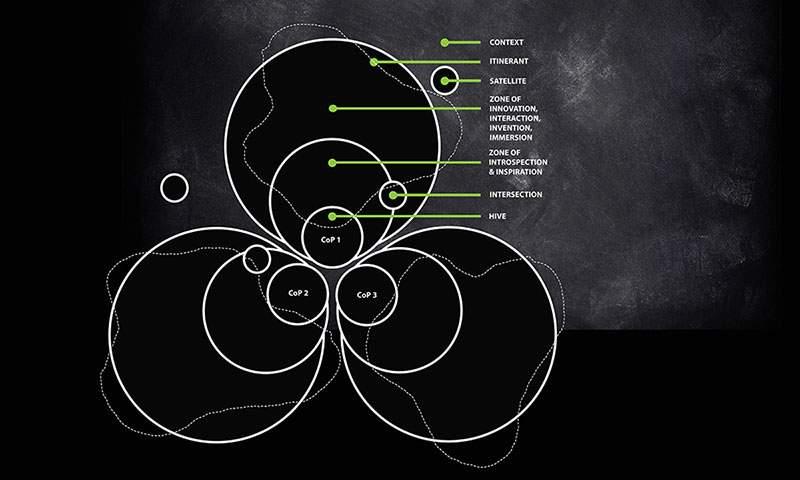

It is the teacher experience that sets the thoughts expressed in this paper into motion. One contribution a building can offer isolated teachers craving community, identity and collaboration is space for Communities of Practice (CoP). Coined by Jean Lave and Étienne Wenger, the term was inspired by their interest in the situated learning offered by apprenticeships through “legitimate peripheral participation” (Lave, 1991, p. 63), and the role that played in identity development:

The construction of practitioners' identities is a collective enterprise and involves a recognition and validation by other participants of the changing practice of newcomers‐become‐oldtimers. Most of all, without participation with others, there may be no basis for lived identity. (Lave, 1991, p. 74)

Wenger‐Trayner and Wenger‐Trayner (2015) defined communities of practice (CoP) as “groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly” (p. 2). Members of a CoP share a domain (some specific area of interest), share a practice (activities directed towards specific goals), and define themselves as a community (identification with the group).

The term has been understood primarily in psychosocial terms and associated with the potentially fickle nature of human relationships. Grossman, Wineburg and Woolworth (2001), for example, described the result of their 2 year effort to create a teacher’s community in an urban high school as “fragile” (p. 944). Collaborating between classrooms and across disciplines despite an unforgiving school schedule proves tremendously challenging.

There is nothing fragile about a physical CoP. The model proposed here pulls teachers out of their private classrooms and offers them individual workstations in a “hive” among their peers with the space and tools to collaborate. Planning tables, incubator space for more extended projects, conference space and storage are prominent. Materials can be shared and duplication minimized. A help desk makes space for student/teacher interactions and offers space outside of the curriculum‐driven context of more formal venues. Acknowledging the vitality bestowed by contact with the outdoors, doors opening outward to a patio furnished with work surfaces and Wi‐Fi complete the scenario.

Darling‐Hammond et al (2017) addressed the opportunity this way:

Collective work in trusting environments provides a basis for inquiry and reflection into teachers’ own practices, allowing teachers to take risks, solve problems, and attend to dilemmas in their practice. (p. 10)

Furthermore, sustained, active, professional development, creates a collaborative culture that results in a form of collective professional capital that leverages much more productive, widespread improvement in an organization than would be possible if teachers worked alone in egg‐crate classrooms. (p. 23)

To an under‐resourced school, this way of organizing and supporting teachers outside of the classroom may seem fanciful or better suited to new construction projects, in which the school facility can be completely reconsidered. Where is an existing school without the funds to build from scratch to find space for hives? How can physical CoP be incorporated into existing schools without massive and unaffordable renovations? These schools are most affected by problems of teacher attrition, and least prepared to solve them.

The question is not trivial. To make space in existing schools for hives, both space‐based and schedule‐based strategies may apply. Empty and under‐utilized space may be re‐purposed, occasional activities like lunch may be re‐imagined, and outdoor space may be more extensively utilized. Adding one period to the school day reduces the number of classrooms required at any one time, hybrid schedules reduce daily student attendance, and internships and out‐of‐school activities reduce classroom utilization. Every school has unique constraints, but an open‐minded approach that avoids preconceptions may yet prevail.

How is the CoP a catalyst for the ideas that follow? Consider the implication of pulling teachers out of their own classrooms. Hosting them in hives at the heart of CoP liberates their classrooms from conformity, enabling an entirely new paradigm of diverse learning environments. The following section explores these implications.

If teachers settle in Hives, and classrooms can diversify, still the question remains: what would these learning environments become? Woodman (2016) and Baars et al. (2022) both concluded that learning environments are rarely re‐arranged for pedagogical purposes. The possibility that a neutral, re‐arrangeable space (the traditional classroom, for example, but with light, stackable furniture) would most economically support teaching and learning proves to be a fiction. Needed here is a typology of diverse and specialized possibilities, a set of archetypes to draw from. Thiis‐Evensen (2001) recalled the definition of archetype from the Greek as “first form” or “original model”, the basis for all future variations and combinations. He noted that archetypes have three requirements:

• They must be classified “in a concentrated overview”.

• They must be described, in order to demonstrate their potential.

• They must be a cross‐culturally recognizable language of form. (p. 17)

A menu of educational archetypes is not a new idea. Educational Facilities Lab (EFL) asserted this in 1968:

The wealth of new options in designing a school program must be considered with this focus: how, in a particular situation and with the available resources, can each individual student be given a set of experiences, which will best facilitate his own education. (Gross & Murphy, 1968, p. 14)

As detailed by Gross and Murphy (1968), the EFL proposed learning spaces of diverse scales grouped thematically (communications barn, flexible subject matter suites, science/math cluster or barn, career skills cluster or arts barn), with concepts that included a “teacher planning centre” in each cluster, the library imagined as “an intellectual supermarket” (p. 58), and television imagined as a source of inspiration. The EFL focused on flexibility, proposing moveable partitions without acknowledging the trouble they cause in terms of maintenance and acoustics. However, the EFL more than 50 years ago made the fundamental steps of moving teachers out of classrooms and into planning centres, and breaking down schools into thematic suites.

Alexander et al. (1977) proposed a typology or “Pattern Language” of 253 essential spaces in scales ranging from the regional, “the Countryside”, to the personal, “Marriage Bed” to the particular, “Half‐Inch Trim”. A number of their patterns pertain to schools, including “Network of Learning”, “Adventure Playground”, “Children’s Home”, “Alcoves”, “Child Caves”, and “Secret Place” and “Shopfront Schools”. Alexander viewed large, consolidated schools and the economic arguments that sustain them with suspicion, failing to celebrate their potential to offer greater experiential variety by virtue of their size.

Moore and Lackney (1994) more specifically addressed patterns within school, identifying “27 patterns for the design of the next generation of American schools” (p. 39). They organized their patterns into 4 categories: Planning Principles, Building Organizing Principles, the Character of Individual Spaces, and Critical Technical Details. Yet, their presentation is abstract, without suggesting in any depth what is done and what is experienced within these patterns.

Thornburg (2004) proposed just four “primordial learning spaces” (p. 1): campfires (information from sage or shaman), watering holes (learning among peers), caves (conceptual development through introspection and study), and life (learning from experience). These typologies are evocative, but too reductive to signal how these primordial spaces might deliver on their promise. Are there different types of campfires or watering holes? How does school use “life”? The typology is silent.

Nair and Fielding (2005) borrowed directly from Thornburg to propose 25 design patterns that included Campfire, Watering Hole, Cave Space, Learning Studio, Welcoming Entry, Student Display Space, Home Base, Lab, Art/Music/Performance, Physical Fitness and Casual Eating Areas. Regarding their intent, they cited Alexander’s search for a timeless Pattern Language as inspiration, but wrote:

Our pattern language differs from Alexander’s in that we wanted to create an actual, usable design vocabulary for schools as a living, changing thing‐similar to the spoken and written language that changes as cultures grow and change‐but one that everyone can use. (p. 2)

Nair and Fielding expanded the vocabulary of patterns, and applied them more specifically to what happens in school. In a critique, however, Jelacic (2008) cited this specificity for diminishing the opportunity for community involvement and creativity emphasized by Alexander. Christopher Alexander et al. (1977) explained this about their search for a language of building patterns:

Each solution is stated in a way that it gives the essential field of relationships needed to solve the problem, but in a very general and abstract way‐so that you can solve the problem for yourself, in your own way, by adapting it to your preferences, and the local conditions at the place where you are making it. (p. xiii)

A useful pattern language must be specific enough to be evocative without being so prescriptive that it stymies creativity. This exactly is the beauty and the utility of an elegantly articulated archetype.

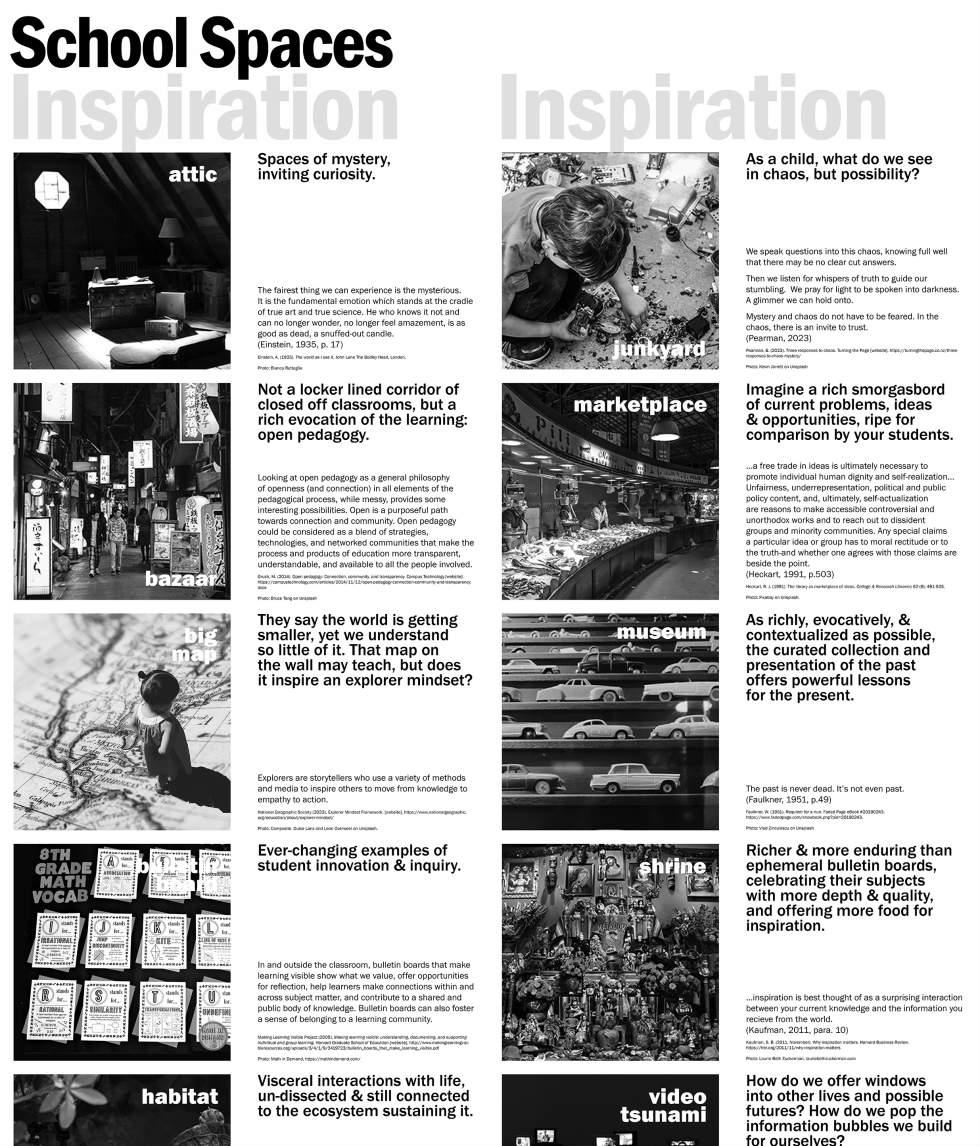

Proposed here are nine categories of learning environment, based on how they support learning. Each category in turn suggests a set of archetypes for the actual learning spaces, which combined form a new typology of learning spaces. The categories are proposed as follows:

A more detailed explanation follows:

To step into a room is to immerse mind and body in a poem pregnant with meaning. As the philosopher of space Gaston Bachelard wrote 65 years ago, “Forces are manifested in poems that do not pass through the circuits of knowledge” (Bachelard, 1958/1994, p. xxi). Our sensations, our possibilities for action, our intentions and our moods are all subject to these forces. In a room, therefore, we are offered the opportunity to make meaning, and thereby, to teach. Is it far‐fetched to suggest that learning French while cooking crêpes might proceed with more gusto and engagement than enduring repetitive recitations in some petrified classroom? Are cafeterias designed for antiseptic efficiency not a lost opportunity to explore culture? Could we imagine them as food festivals instead? Auditoriums for immersive multimedia presentations, black boxes for digital presentations, sandboxes for working dynamically in groups, situation rooms to understand systems, and even tents as satellites of outdoor learning offer similar opportunities to captivate students with immersive experiences.

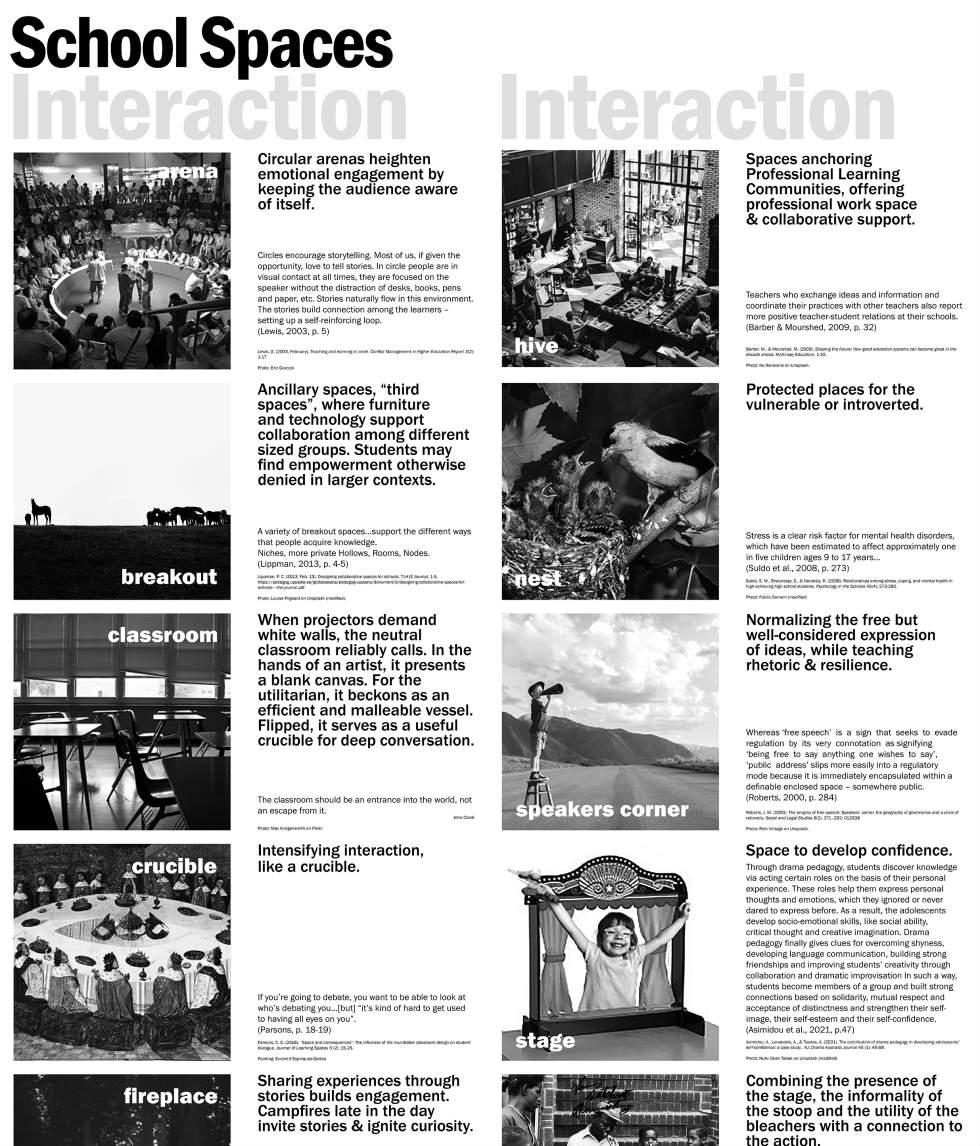

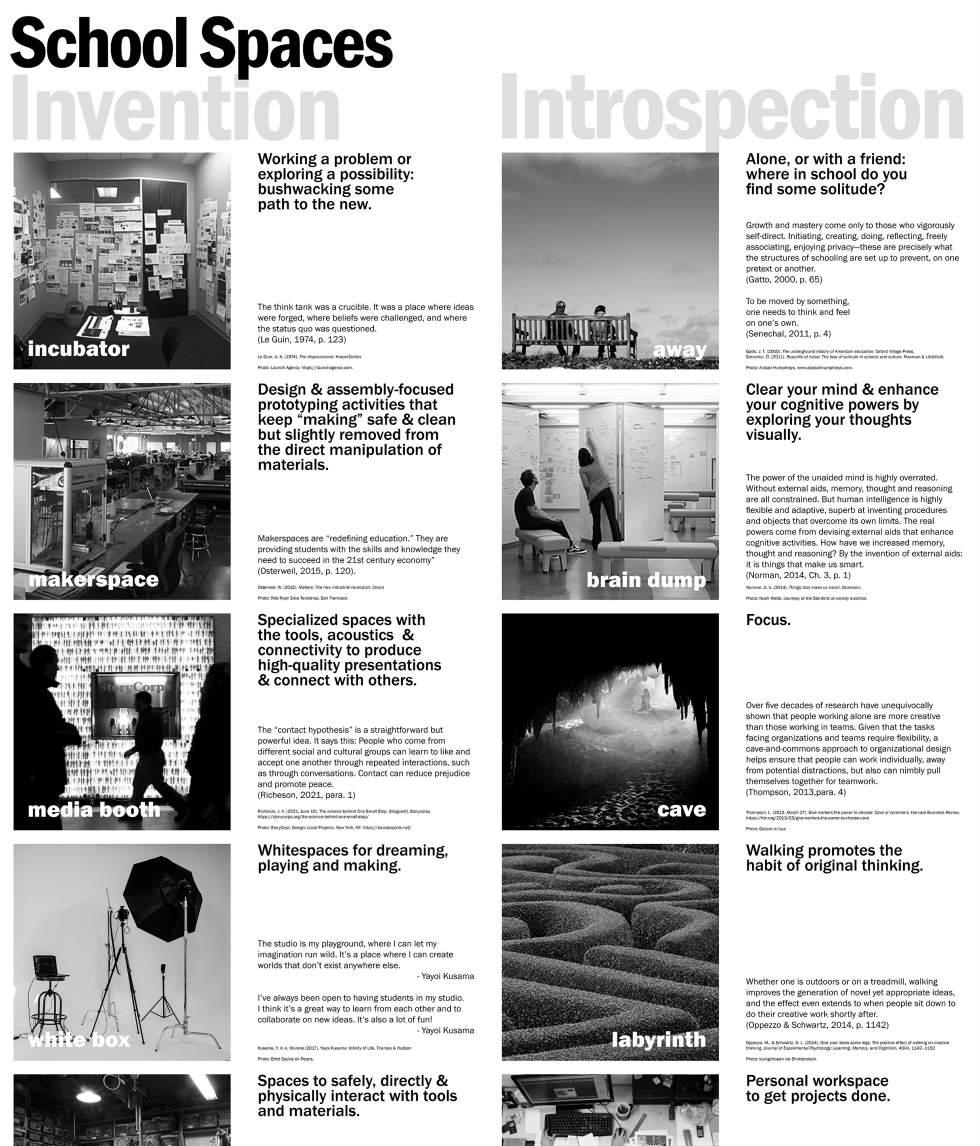

Spaces structure the ways in which we engage with each other, and this can be managed with intention. If traditional classrooms were structured as a grid of tables and chairs to facilitate Teacher/Student communications and discourage Student/Student disruption, this has long been subverted by pulling chairs into circles. The Harkness Method of roundtable classes codified this into student‐led conversations (Polm, 2019), turning classrooms into crucibles in which no student could disengage. Arenas for socially engaged presentations, fireplaces for curiosity‐inspiring storytelling, small nests to support more introverted students, stoops for semi‐social work, hives for collaboration with peers, and speakers’ corners to inspire self‐confidence can similarly structure interactions for pedagogical purposes, facilitating and amplifying specific interactions.

Classrooms everywhere demonstrate how seriously teachers take their duty to inspire. Their rooms are papered with maps, quotes, admonishments, art, calendars, models, and more. Spaces can also inspire in subtler ways. Recall perhaps the power of a childhood attic to add mystery and inspire curiosity, especially if the space rewards you with treasure. Likewise, junkyards inspire experimenting and thinkering (Kozlovsky, 2007); markets inspire comparison (Ideas! Opportunities! Colleges! Literary themes!); big maps inspire adventure; habitats inspire a connection to nature; and video arrays offer tsunamis of possibility. Bulletin boards inform in an ephemeral way, shrines honour a legacy more permanently, and learning paths tantalize with the allure of a shopping street.

Spaced Learning (Das, 2021) demonstrated that students need to pause in order to consolidate their learning. They need time to think, or even to not‐think. “Only ideas won by walking have any value,” wrote Friedrich Nietzsche in Twilight of the Idols (1889/1997, p. 10), an argument for walking labyrinths in schools. Caves (temporary spaces to work alone undisturbed), brain dumps (places to document and explore what is on your mind), workstations (permanent work space), and anyplace where individuals are offered solitude to engage in personal reflection likewise deserve a role in school.

Invention spaces are hubs of creativity within the school environment. They offer respite from following recipes, memorizing material or doing as you are told. To be meaningful, it must invite tinkering and thinking together (Poce et al., 2019), and help students bushwhack a path to learning. Thus, makerspaces for assemblies, media booths for audio‐visual production and transmission, white boxes (studios) for other expressive arts, incubators for organizing ideas and workshops for working directly with materials, all earn a place in school. These spaces foster a culture of exploration and experimentation.

Schools undoubtedly call students to ask poignant and pointed questions. The focus placed on Curiosity by 21st Century learning speaks to the idea that answers rarely find purchase without an instigating question, and are most valuable when they spur new questions. Thus, if we claim a place in schools for help desks, labs, stacks, computers and wonder walls, it is not simply to simplify answer‐giving but to teach curiosity and encourage question‐asking

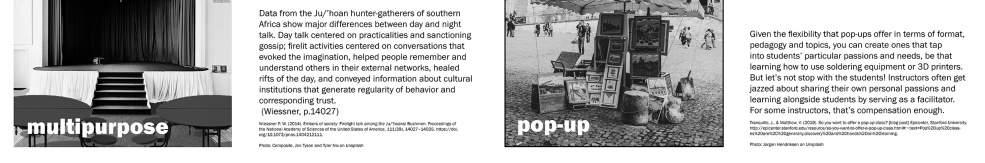

Nothing claims attention like surprise and change (Berlyne, 1951). Itinerant learning environments capitalize on this powerful neurological impulse. There is a reason in retail for the unpredictable appearance and disappearance of pop‐up stores; they engage the audience. The unexpected arrival of a cabinet of curiosities can be as attention grabbing as the tinkle of an ice cream truck. A book cart can liberate books from Dewey Decimal jail and present them thematically instead of by number. A classroom bus can connect abstract lessons with the world at‐large, bringing learning to unconventional locations in order to enhance the overall educational experience. Itinerant elements can also continue to solve practical problems of not enough classrooms. Working from carts, teachers can transform any space into a venue for their specific pedagogic purposes. These elements add surprise and variety to the learning environment, both harbingers of engagement.

Whether financially driven or pedagogically purposeful, combining uses into a single space can increase utility, deepen meaning, and facilitate engagement. A library is useful, but a library café invites students to linger. A cafeteria and auditorium often sit empty, but a cafetorium invites greater use and reduces construction costs. The gym auditorium and the multipurpose room do the same. Intersecting spaces can also cater to different learning preferences within a single environment. Consider the bar restaurant, a pattern taken from the ubiquitous Apple computer stores, where there is space to learn alone, or seek help at a genius bar.

What surrounds a school can be richly conceived to support learning. Wilderness offers complexity, risk‐taking and relationship to what Gregory Bateson called “The Pattern That Connects” (1979, p. 21). Gardens connect lessons in design and biology with lessons in grit and effort. Parks offer pause specifically invoked in descriptions of spaced learning (Das, 2021). Fields, wild or striped for games, invite relaxation and play. Finally, the surrounding Community is typically rich in resources if school will extend a welcome. Even schools in wintery locales might heed the lessons learned from the tuberculosis scares of the last century in which students were bundled up to be taught outdoors all winter long, regardless of the cold and snow (Fesler, 2000).

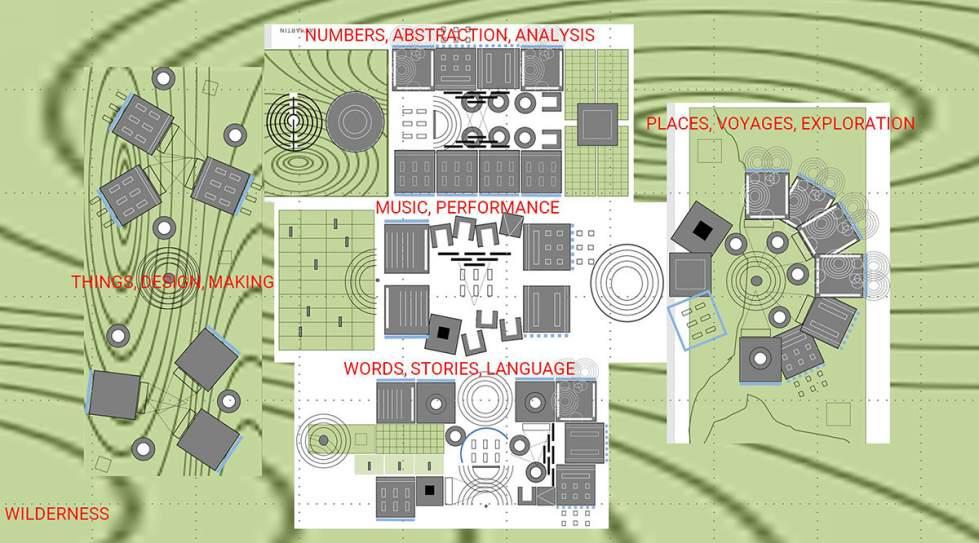

5: The Educational Ecosystem, a language of learning environments. See Appendix A for a more detailed presentation.

These 9 categories of learning environment were the distillation of an effort to imagine 100 new types of learning environments that could replace the traditional classroom. The goal was arbitrary and assumed unattainable, 65 spaces were ultimately proposed, and 5 did not survive scrutiny because they duplicated a learning experience or offered a tepid one. This sample size was sufficiently large that a search for categories was required to understand and to explain what was proposed. 6 types of experiences and 3 types of spaces were ultimately identified through sorting.

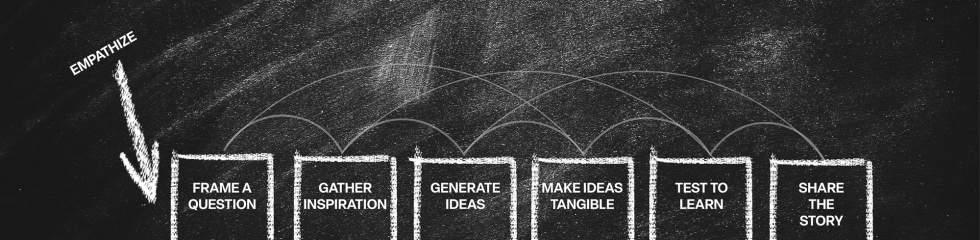

Retracing the path to these results, an expansion of the normal iterative design process comes into focus. Solving the problem of teacher attrition through the lens of facility design also generated a solution to a second problem: student disengagement. If a design process typically seeks an efficiently iterative path from problem to solution, (and where fees are small, the less iteration the better), the process here took that first solution and asked: “what are the implications”. That secondary question recognized the systemic nature of the terrain and unleashed a tremendously creative search for new learning environments, ultimately showing that both students and teachers could be well served by this approach. This value‐added result further supported the solution to the original problem: teacher discontent.

Noteworthy here is the nature of the solution to the secondary problem: learning environments. Rather than explicitly identify specific solutions, the results are expressed as a typology of archetypes that leaves tremendous latitude to future projects. As a reference for design, an arch‐typology offers much richer data than a template (500 students x 1 class / 25 students = 20 identical classrooms), and a far richer palette of ideas than a precedent (this school is designed as houses, this one as teams, this one as forts…). Communicating the potential of the archetypes through name, imagery and descriptive text became extremely important, as did organizing and systematizing the results. Ingold (2012) described the design role exhibited here elegantly:

Let us allow then that designing is about imagining the future. But far from seeking finality and closure, it is an imagining that is open‐ended. It is about hopes and dreams rather than plans and predictions. Designers, in short, are dream‐catchers. Traveling light, unencumbered by materials, their lines give chase to the visions of a fugitive imagination and rein them in before they can get away, setting them down as signposts in the field of practice that makers and builders can track at their own, more laboured and ponderous pace. (p. 29)

This approach understands the design of public schools as a social creative process (Warr & O’Neill, 2005). Typologies offer significant benefits to a social process by quickly educating individuals new to the problem, and enrolling them in a bounded instead of an open‐ended search for solutions. Typologies reduce risk by mapping and bounding the creative search, but also by what they represent: the product of considerable research extending far

beyond what any single design project could muster, without imposing the limitations of specific precedents. They offer embodied knowledge with space for interpretation and adaptation.

It is important to acknowledge, at the time of this writing, one last crucial but missing step to this design process. Based on work by Barrett (2015) and Baars et al. (2022), an instrument stands ready to test the utility of physical CoP and the Educational Ecosystem (See Appendix D), and a workbook is now available to guide a series of Participatory Design Workshops (Stewart, 2014). That work, however, remains incomplete. Not until these ideas undergo systematic evaluation in the field can they be characterized as a solution and not a hypothesis. This presentation is an invitation, extended from across the Atlantic, to evaluate it and test it here.

Figure 6: Design thinking: when working with systems, empathize deeply, organize carefully, and consider the implications. Original source: https://www.ideou.com/blogs/inspiration/design‐thinking‐process

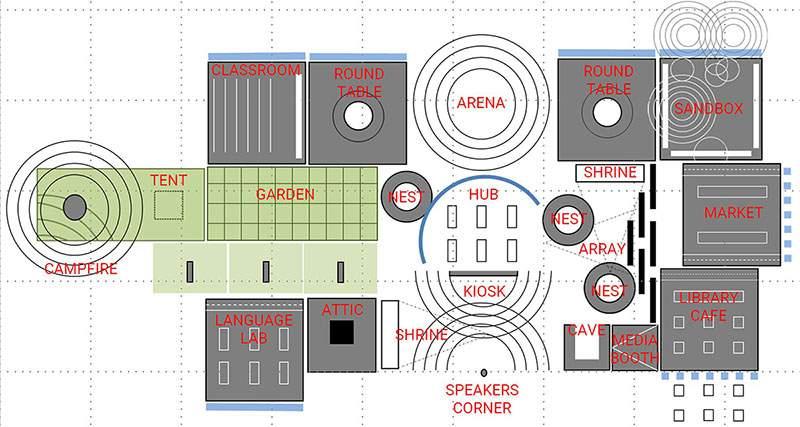

Proposed here are 9 categories of educational environment, and a typology of archetypes, that may be called into service if teachers occupy CoP and classrooms are freed to diversify. This model stands in stark contrast to the prevailing monoculture of repetitive classrooms that we traditionally understand as a K‐12 school. The diversity of spaces recommended here might be better understood as an ecosystem, an Educational Ecosystem.

The claim is not that that the arch‐typology presented here is exhaustive. Rather, it stands as a model and invitation to all schools, especially legacy schools without the resources to radically re‐build, to re‐imagine their existing facility with these archetypes or others of their own invention. A classroom can be re‐imagined as a crucible, a marketplace, or a sand box. A locker‐lined hallway can be re‐imagined as a learning path. Students and teachers now confined to a single room could be moving among this rich diversity of environments. With some space and time, teachers could be mentoring, collaborating and building a community of practice.

This paper began with problems perhaps specific to the American context, a preoccupation with legacy 20th century schools, and a concern that schools could do more to balance a focus on performance with positive emotional experiences; with joy. Four questions were posed:

Can the school facility make a difference in addressing teacher dissatisfaction and student disengagement? Can possible interventions be presented in such a way that affords flexibility in their implementation? Can facility‐based interventions even help under‐resourced schools? What does this mean for Design Management?

The combination of physical CoP and the Educational Ecosystem demonstrates how moving teachers out of their private classrooms can become a catalyst for a dramatically diversified learning environment. As an arch‐typology, the Educational Ecosystem affords flexibility and choice to schools that implement it. Articulated as well were

strategies by which legacy schools might make space for CoP and re‐imagine the use of their existing classrooms, without dramatic and expensive renovations.

Most usefully, this presentation represents a model of school applicable to K‐12 schools anywhere, old or new. Appendix B, for example, shows the results of an early experiment exploring how a new school might become organized as CoP, using an earlier version of the Educational Ecosystem. Appendix C applies it to an existing school. If teachers are better supported by physical CoP, and if students are truly more engaged in a diverse educational environment, then this model of K‐12 school has far‐reaching implications for K‐12 schools everywhere.

Ecosystems are already commonplace, of course, even in legacy schools Consider the tremendous variety of athletic spaces they offer. The gyms, weight rooms, tennis courts, squash courts, handball courts, pickle ball courts, basketball courts, fronton courts, baseball fields, football fields, softball fields, soccer fields, field hockey fields, lacrosse fields, running tracks, swimming pools, and elaborate playgrounds for younger students, demonstrate how rich and diverse the athletic ecosystem is. Why would the academic ecosystem be any less engaging?

What does this effort suggest for Design Management? First, arch‐typologies offer powerful starting points for design thinking that avoid the problems of templates or precedents. Arch‐typologies bring more investigation and design thinking to the problem than many time and fee constrained design efforts can bear, and if carefully and evocatively prepared, offer an engaging and instructive tool to educate stakeholders and enrol them in the design process. Templates offer no research or imagery to fuel the imagination and precedents, in contrast, can be misused to replicate the status quo. They may foreclose rather than invite invention.

Second, arch‐typologies also reduce risk, efficiently drawing boundaries around the field of inquiry so that the problem is never open‐ended and creative energy is quickly focused on a discrete set of solutions. Arch‐typologies offer stakeholders a map to what might otherwise be a bewildering terrain.

Third, especially when dealing with complex systems like education, it may prove useful to explicitly consider the implications for the system of a design solution. In this case, the solution to the original problem of teacher discontent was the catalyst for a secondary effort to imagine new learning environments and re‐engage K‐12 students. That second student‐focused effort now offers an immensely persuasive justification for the original teacher‐focused solution.

Anecdotally, if these ideas do survive testing to find an enduring place in the design of K‐12 schools, I believe that it will not just be because they promise powerful results, but because they do not eliminate conventional results. Conventional spaces like classrooms and cafeterias and auditorium included among the archetypes validate client preconceptions, a precondition to opening their minds to change. Validation by the quotidian client and not the open‐minded progressive client will be the true sign of systemic change.

Alexander, C., Ishikawa, S., & Silverstein, M. (1977). A pattern language: Towns, buildings, construction. Oxford University Press.

Astleitner, H. (2000). Designing emotionally sound instruction: The FEASP-approach. Instructional Science, 28(3), 169–198. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003893915778

Au, W. (2011). Teaching under the new Taylorism: high-stakes testing and the standardization of the 21st century curriculum, Journal of Curriculum Studies,43:1, 25-45, DOI: 10.1080/00220272.2010.521261 Retrieved 24 Mar, 2024 from https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2010.521261

Baars, S., Schellings, G.L.M., Krishnamurthy, S., Joore, J. P., den Brok, P. J., & van Wesemael, P. J. V. (2021). A framework for exploration of relationship between the psychosocial and physical learning environment. Learning Environments Research, 24, 43–69. Retrieved 17 Mar, 2024, from https://doiorg.fgul.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/s10984-020-09317-y

Bachelard, G. (1994). The poetics of space. (M. Jolas, Trans.). Beacon. Original work published 1958 as La poetique de l’espace.

Barrett, P., Davies, F., Zhang, Y., & Barrett, L. (2015). The impact of classroom design on pupils’ learning: Final results of a holistic, multi-level analysis. Building and Environment, 89, 118-133. Retrieved 17 Mar, 2024, from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2015.02.013

Bateson, G. (1979). Mind and nature: A necessary unity. E. P. Dutton. Berlyne, D. E. (1951). Attention to change. British Journal of Psychology, 42(3), 269. Brown, D. N., & Settoducato, L. (2019, Winter/Spring). Caring for your community of practice: Collective responses to burnout. LOEX Quarterly, 45(4), 10-12. Retrieved 17 Mar, 2024, from https://commons.emich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1346&context=loexquarterly California School Climate, Health and Learning Survey System. (2021). California Secondary School Climate Report Card 2020-21 https://calschls.org/docs/sample_secondary_hs_scrc_2021.pdf CASEL. (2020). Our work. https://casel.org/our-work/ Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Schneider, B. (2000). Becoming adult: How teenagers prepare for the world of work Basic Books.

Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/teacher-prof-dev Das, S. (2021, August 6). Spaced learning: A neuroscience-based approach to maximize learning outcome. [web page]. eLearning Industry. https://elearningindustry.com/spaced-learning-neuroscience-basedapproach-to-foster-knowledge-retention

De Bono, E. (1970). Lateral Thinking. Penguin.

Fesler D. M. (2000). Open-air schools. The Journal of School Nursing: The Official Publication of the National Association of School Nurses, 16(3), 20–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/105984050001600303

Filardo, M. (2016). State of our schools: America’s K–12 facilities 2016. 21st Century School Fund. https://fileseric-ed-gov.fgul.idm.oclc.org/fulltext/ED581630.pdf

Gallup, Inc. (2016). Student poll https://www.sac.edu/research/PublishingImages/Pages/researchstudies/2016%20Gallup%20Student%20Poll%20Snapshot%20Report%20Final.pdf

Garcia, E. & Weiss, E. (2019, March). The teacher shortage is real, large and growing, and worse than we thought. Economic Policy Institute. https://files-eric-ed-gov.fgul.idm.oclc.org/fulltext/ED598211.pdf

Gläser-Zikuda, M., Fuß, S., Laukenmann, M., Metz, K., & Randler, C. (2005, October). Promoting students' emotions and achievement-Instructional design and evaluation of the ECOLE-approach. Learning and Instruction 15(5), 481-495. DOI: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.07.013

Gross, R., & Murphy, J. (1968). Educational change and architectural consequences. Educational Facilities Laboratories. https://files-eric-ed-gov.fgul.idm.oclc.org/fulltext/ED031061.pdf

Grossman, P., Wineburg, S., & Woolworth, S. (2001). Toward a Theory of Teacher Community. The Teachers College Record, 103, 942-1012. http://www.tcrecord.org/Content.asp?ContentID=10833

Hargreaves, A., & Fullan, M. (2012). Professional capital: Transforming teaching in every school. Teachers College Press.

Haynes, M., Maddock, A., & Goldrick, L. (2014, July). On the path to equity: Improving the effectiveness of beginning teachers. Alliance for Excellent Education. Retrieved 17 Mar, 2024, from https://all4ed.org/wpcontent/uploads/2014/07/PathToEquity.pdf

Heller, A. S., Shi, T. C., Ezie, C. E. C., Reneau, T. R., Baez, L. M., Gibbons, C. J., & Hartley, C. A. (2020). Association between real-world experiential diversity and positive affect relates to hippocampal–striatal functional connectivity. Nature Neuroscience, 23, 800–804. Retrieved 17 Mar, 2024, from https://doi-org.fgul.idm.oclc.org/10.1038/s41593-020-0636-4

Huang, T. T., Sorensen, D., Davis, S., Frerichs, L., Brittin, J., Celentano, J., Callahan, K., & Trowbridge, M. J. (2013). Healthy eating design guidelines for school architecture. Preventing Chronic Disease, 10 http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd10.120084

Ingersoll, R. M., Merrill, E., Stuckey, D., & Collins, G. (2018). Seven trends: The transformation of the teaching force–updated October 2018. CPRE Research Reports. Retrieved 17 Mar, 2024, from https://repository.upenn.edu/cpre_researchreports/108

Ingold, T. (2012). Introduction: The perception of the user–producer. In W. Gunn & J. Donovan (Eds.), Design and anthropology (pp. 19-33), Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315576572-7

Jelacic, M. (2008). Review. The language of school design: Design patterns for the 21st century. Children, Youth and Environments, 18(2), 278-281

John, L. K. (2018, May-June). The surprising power of questions. Harvard Business Review https://hbr.org/2018/05/the-surprising-power-of-questions

Kanayama, M., Suzuki, M., & Yuma, Y. (2016, June 14). Longitudinal burnout-collaboration patterns in Japanese medical care workers at special needs schools: A latent class growth analysis. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 9, 139-146. Retrieved 17 Mar, 2024, from https://www.dovepress.com/longitudinal-burnout-collaboration-patterns-in-japanese-medical-care-w-peerreviewed-fulltext-article-PRBM#

Keigher, A. (2010). Teacher Attrition and Mobility: Results From the 2008–09 Teacher Follow-up Survey (NCES 2010-353). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved 17 Mar, 2024, from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2010/2010353.pdf

Killingsworth, M. A., & Gilbert, D. T. (2010, November 12). A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science, 330, 932. www.sciencemag.org

Koch, A., & Adler, M. (2018). Emotional exhaustion and innovation in the workplace: a longitudinal study. Industrial Health, 56(6). DOI: 10.2486/indhealth.2017-0095 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326302877_Emotional_exhaustion_and_innovation_in_the_workpl ace_a_longitudinal_study

Kozlovsky, R. (2007). Adventure playfrounds and postwar reconstruction. In, M. Gutman & N. de ConinckSmith, (Eds.). Designing modern childhoods: History, space, and the material culture of children; An international reader (pp. 1-35). Rutgers University Press. https://www.adventureplay.org.uk/RK%20Adventure%20Playground.pdf

Kruse, M. (u.d.) 20 plus tips to avoid teacher burnout. [Blog entry]. Reading and Writing Haven. https://www.readingandwritinghaven.com/how-to-beat-teacher-burnout-practical-tips-to-try-today/ Lave, J. (1991). Chapter 4, Situated learning in communities of practice. In L. B. Resnick, J. M. Levine, & S. D. Teasley (Eds ), Perspectives on Socially Shared Cognition (pp. 63-82). American Psychological Association. Retrieved 17 Mar, 2024, from https://ecologyofdesigninhumansystems.com/wpcontent/uploads/2012/12/Lave-Situating-learning-in-communities-of-practice.pdf

Mainhard, T., Oudman, S., Hornstra, L., Bosker, R. J., & Goetz, T. (2018, February). Student emotions in class: The relative importance of teachers and their interpersonal relations with students. Learning and Instruction, 53, 109-119

McCarthy, M., Pretty, G. M. H., & Catano, V. (1990, May). Psychological sense of community and burnout. Journal of College Student Development, 31(3), 211-216. Retrieved 17 Mar, 2024, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232559885_Psychological_sense_of_community_and_burnout#full TextFileContent

Moore, G. T., & Lackney, J. A. (1994). Educational facilities for the twenty-first century: Research analysis and design patterns. Center for Architecture and Urban Planning Research, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED375514.pdf

Nair, P., & Fielding, R. (2005). The language of school design: Design patterns for 21st century schools. DesignShare.com.

National Center for Education Statistics (2021). Table 219.70. Percentage of high school dropouts among persons 16 to 24 years old (status dropout rate), by sex and race/ethnicity: Selected years, 1960 through 2021. Digest of Education Statistics https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d22/tables/dt22_219.70.asp

National Center for Education Statistics. (2024, February 15). Nearly one-third of public schools have one or more portable buildings in use. [press release]. Retrieved 20 March, 2024, from: https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/spp/results.asp#school-facilities-dec23-chart-3

Nietsche, F. (1997). Twighlight of the idols, Or, How to philosophize with the hammer. (R. Polt, Trans.). Hackett. Originally published in 1889.

Nowicki, J. M. (2020, June). K-12 Education: School districts frequently identified multiple building systems needing updates or replacement. United States Government Accountability Office. GAO-20-494 Public School Facilities. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-20-494.pdf

Poce, A., Amenduni, F., & De Medio, C. (2019). From tinkering to thinkering: Tinkering as critical and creative thinking enhancer. Journal of E-Learning and Knowledge Society, 15(2), 102-112. https://doi.org/10.20368/1971-8829/1639

Podolsky, A., & Sutcher, L. (2016, November). California teacher shortages: A persistent problem [brief]. Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/productfiles/California_Teacher_Shortages_Persistent_Problem_BRIEF.pdf

Polm, M. (2019, October 24). Using the Harkness Method to teach the news. [web page]. Close-Up Washington DC. https://closeup.org/using-the-harkness-method-to-teach-thenews/?gad_source=1&gclid=CjwKCAiA1fqrBhA1EiwAMU5m_-uUYWK8DpPwv3Fd1Y2yabmtUFaUQudPBbPBcDw1Mkavhh2c_Tp2hoCDGUQAvD_BwE

Pouler, P. (1994). Disciplinary society and the myth of aesthetic justice. In B. C. Scheer & W. F. E. Preiser (Eds.), Design review: Challenging the urban aesthetic control (pp. 175-186). Chapman and Hall. Power, M. (2019, July 1). Teamwork by design. Educational Leadership 76 (9). Retrieved 24 Mar, 2024 from https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/teamwork-by-design

Privette, G. (1985). Experience as a component of personality theory. Psychological Reports, 56, 263-266. https://journals-sagepub-com.fgul.idm.oclc.org/doi/epdf/10.2466/pr0.1985.56.1.263

Schlechty, P. C. (2011). Engaging students: The next level of working on the work. San Francisco, CA: JosseyBass.

Shah, S. (2016). Movement and growth through the adult development stages: Factors that can facilitate shifts. [Dissertation] HEC Paris – Oxford Saïd Business School. Stewart, S. (2014). Design research In D. Coghlan & M. Brydon-Miller (Eds.). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Action Research (pp. 245-247). SAGE Publications. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446294406.n105

Strauss, V. (2017, November 27). Why it’s a big problem that so many teachers quit—and what to do about it, Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2017/11/27/why-its-a-bigproblem-that-so-many-teachers-quit-and-what-to-do-about-it/

Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2016). A Coming Crisis in Teaching? Teacher Supply, Demand, and Shortages in the U.S. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Retrieved 17 Mar, 2024, from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/coming-crisis-teaching

Thiis-Evensen, T. (2001). Archetypes in architecture. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. Thornburg, D. D. (2004, October). Campfires in cyberspace: Primordial metaphors for learning in the 21st century. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 1(10), 1-10. https://homepages.dcc.ufmg.br/~angelo/webquests/metaforas_imagens/Campifires.pdf

Trilling, B. & Fadel, C. (2009). 21st century skills; Learning for life in our times. San Francisco, CA: JosseyBass.

Tyler, R. (1969). Basic principles of curriculum and instruction. Chicago, Il: University of Chicago Press. United States Census Bureau (2017). Public Education Finances: 2015 Table 9. Capital outlay and other expenditure of public elementary–secondary school systems by state: Fiscal year 2015 https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2017/econ/g15-aspef.pdf USAfacts. (2023, October). How often do teacher strikes happen? [web page]. https://usafacts.org/articles/howoften-do-teacher-strikes-happen/ Warr, Andy & O'Neill, Eamonn. (2005). Understanding Design as a Social Creative Process. Creativity and Cognition Proceedings 2005. 118-127. 10.1145/1056224.1056242. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/221629731_Understanding_Design_as_a_Social_Creative_Process Wenger-Trayner, E., & Wenger-Trayner, B. (2015, June). Introduction to communities of practice: A brief overview of the concept and its uses. [web page]. Retrieved 17 Mar, 2024, from https://www.wenger-trayner.com/communities-of-practice/ Woodman, K. (2016). Re-placing flexibility. In K. Fisher (Ed.), The translational design of schools (pp. 51–79). Sense Publishers.

Zyngier, D. (2008). (Re)conceptualizing student engagement: Doing education not doing time. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24, 1765-1776.

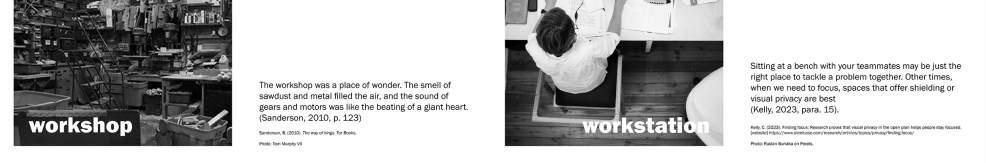

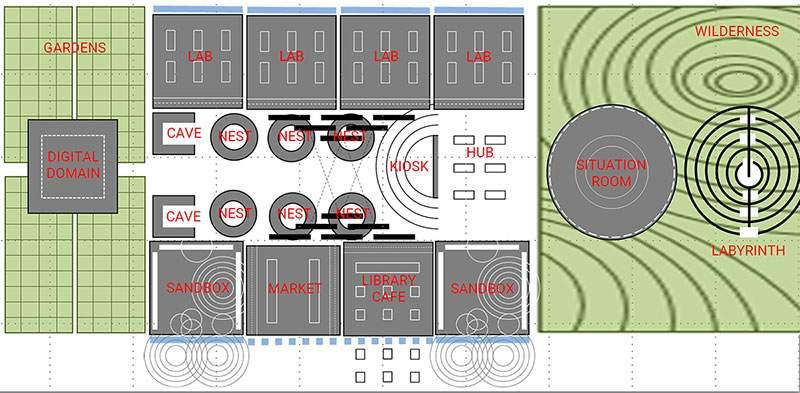

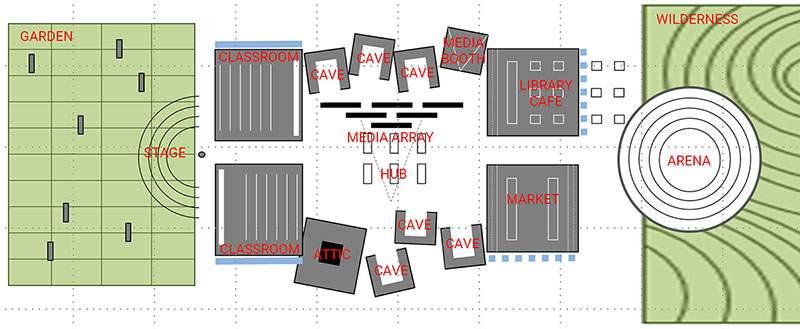

A game to imagine a new school with computer icons representing the spaces of the Educational Ecosystem yielded the following results, a far cry from the repetitive classrooms of the traditional school. In these experiments, learning experiences that seemed specific to the theme of the CoP were rather intuitively selected and arranged, often with the Hub (later renamed the Hive) central to the effort. Icons were not strictly proportional, and so the relationship between elements is of more importance, as is the selection of which elements to include.

7. A Community of Practice based on words, stories and languages. The premise here is that teachers of traditional subjects like Language (English and others) and Social Studies all share a commitment to stories: a common language.

8. A Community of Practice based on numbers, analysis, and abstraction. The mathematician, the statistician, the scientist may find common ground for collaboration here. Contemplation and experimentation are powerful themes.

9. A Community of Practice based on places, voyages, exploration. Here the image of exchanging stories around a literal campfire proved most poignant and emotionally engaging.

Figure 10. A Community of Practice based on music and performance. Practice, performance, and access to resources and the outdoors are prominent themes.

In these early experiments to test the mechanics of a Participatory Design Workshop, it became immediately apparent that the results would very likely not be architecturally revolutionary. In fact, these experiments first suggested that existing, legacy schools might be very receptive to the transformation into Communities of Practice. Many iterations proved similar to standard double‐loaded corridors common to public schools. The big difference lies is in the variety of uses, the central zone of inspiration incorporating the Hub (now Hive), and access to and use of the outdoors.

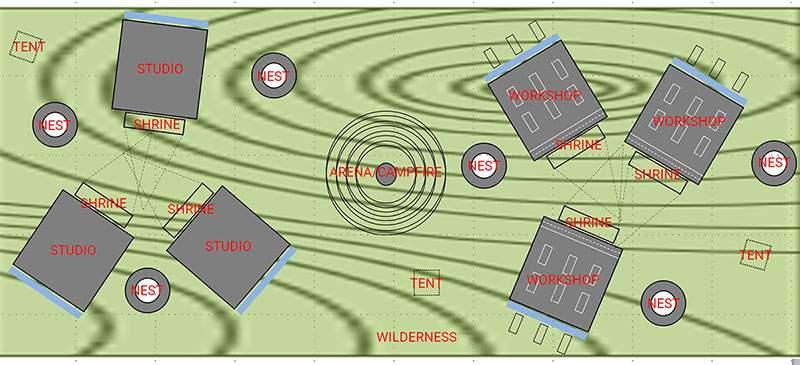

One instance suggested that focusing a CoP on the Hive might not be universally accepted. In the case of a CoP based on objects and making, in which individual workshops or studios drove the curriculum, an entirely different approach emerged:

11. A Community of Practice based on objects and making. Individual studios and workshops supplanted the idea of a central Hive with an Arena imagined for both presentation and exhibition.

The question of how a school combining all of these CoP might coherently come together proved consequential. Repetitive, identical classrooms naturally arrange themselves along orderly corridors and around interior courtyards. What kind of order or system might be found in juxtaposing these disparate CoP was by no means obvious. Nonetheless, the prevalence of rooms the size of a typical traditional classroom within the Educational Ecosystem imposed a matrix‐like quality to the combined result, while still leaving room for innovation. This exercise was a far cry from practicing architecture, but it began to suggest an architectural character.

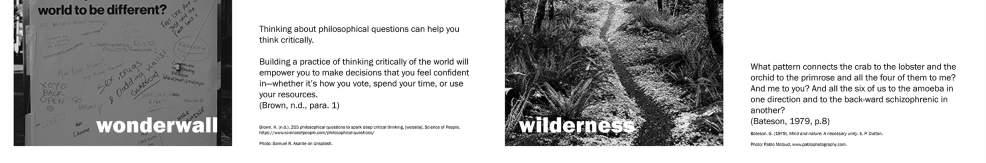

Can a legacy school be re‐imagined as Communities of Practice? This experiment reconsiders the plan of a grade 7 and 8 junior high school built in the 1950s and renovated in the 1990s. This experiment highlighted a number of interesting nuances of the Educational Ecosystem.

1. With 6 Educational Ecosystem (EE) archetypes that fit into standard classrooms, the existing organization of combined 7/8 teams occupying groups of 8 standard classrooms and 2 science rooms already offered the full diversity of applicable archetypes.

2. While 20 teachers per hive is a bit tight, finding just 3 rooms for hives appears not to be overly onerous. However, adding storage, conference, incubator and lounge/snack space to the Hives would require a more detailed analysis beyond the scope of this experiment. The space was not readily apparent.

3. The EE definitely brought greater diversity to the academic classrooms, which were originally identical. Due to the extensive whiteboards already built into the classrooms, they already operated more as sandboxes or 21st century multi‐focus rooms than sage‐on‐the‐stage traditional rooms.

4. The perimeter heating system stymied any attempt to gain outdoor access from individual learning spaces.

5. The EE brought greater meaning to the circulation system, with pop‐ups, wonder walls, a learning path, breakout spaces, and graffiti wall all added to what were simple locker‐lined corridors.

6. The EE added meaning to exterior courtyards, with an arena, garden, big map, tent, field, and habitat.

7. The EE did not add much diversity to already specialized spaces, with art rooms and workshops already available. A junkyard and makerspace was one exception.

8. The EE re‐imagined the library, with fewer stacks, and more rabbit holes (computers with unique programs). The proximity to the cafeteria made a library café less useful, though some beverage availability might be convenient and appreciated.

9. The cafeteria served as a multi‐purpose room, hosting events like dances and serving as a study hall. Inserting additional program would have been counterproductive.

10. The black box was imagined as a multi‐projector, virtual learning environment similar to SMALLab. Whether the expense and available programming justifies multiple venues in a single school requires additional investigation.

11. Incubator space seemed best offered to the teachers for regular curriculum development. It was not immediately apparent how individual or small groups of students could be given such a room for extended periods of time for project work, except for a period at a time.

12. Museum space requires further consideration. How can space possibly be afforded for static display? Who would manage dynamic display, and to what end? Display along a Learning Path seems more realistic. One exception is if a museum is imagined as more ephemeral, as when a college fair or career fair or science fair gets set up in the Gymnasium, though it would then be characterized as a marketplace.

13. Running a single roundtable discussion in a crucible of 25 students is challenging. Splitting the room into two tables makes the tables more manageable, but results in acoustic conflicts between the adjacent tables. Whether a sound absorbing partial partition would be sufficient to address the noise but still allow a single teacher to supervise both tables requires some investigation.

14. This library was too small to realistically serve as a marketplace, offering broad perspectives on singular themes. However a small scale effort to group books by theme instead of number could be considered. As book collections become smaller, it becomes harder to mount these kinds of comparative productions.

15. The auditorium at the heart of the school is a community resource hosting events unrelated to school. The adjacent lobbies, hallways and cafeteria needed to remain flexible, but could host pop‐ups, temporary kiosks, temporary food festivals and temporary displays.

In general, the EE offers a richer classroom experience, richer public spaces and a richer outdoor environment. For teachers, the possibility of strongly supported collaboration in hives remains fundamental to this idea but also challenging in practice. Here, space for individual workstations appeared to be available, but incubator space, conference rooms and storage remained elsewhere. Noted in this experiment is the possibility of teachers remaining in now diverse classrooms, or the possibility of teachers circulating with most of their curriculum on their laptops, all without the benefit of hives. Offering teachers no practical home base seems unrealistic, but if a laptop is all they need than this deserves further investigation.

The possibility of reducing digital infrastructure requirements for under‐resourced schools by offering more powerful and engaging real‐world experiences does seem realistic to a point. A roundtable discussion in a crucible might very well prove engaging without the addition of a projector and HDMI input from a laptop, and similarly for many of the other spaces considered here. The addition of this infrastructure would certainly add to the utility of the spaces and to the richness of the experience, and sufficiently resources schools would consider nothing less, but if the alternative is a corridor of neutral classrooms without technology or a diverse ecosystem without technology then the hypothesis remains intact that the latter would greatly enhance engagement.

How do we evaluate whether an existing educational environment, re‐organized as Communities of Practice (CoP), and diversified via the Educational Ecosystem, would be more engaging than the original? Proposed here is a pre‐ and post‐workshop survey to gauge changes in the perceptions of an existing school by stakeholders offered the opportunity to re‐imagine their existing school.

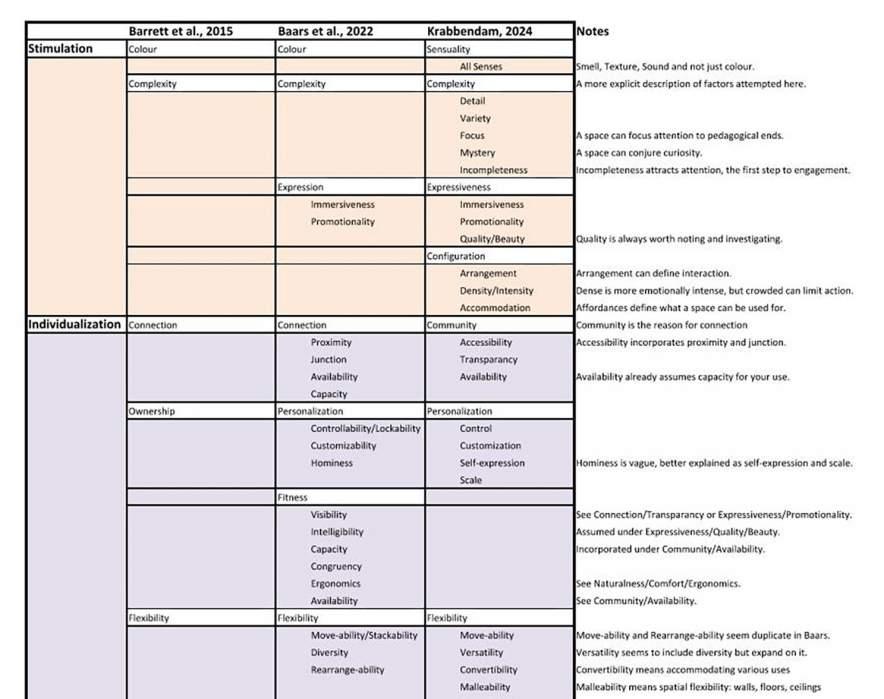

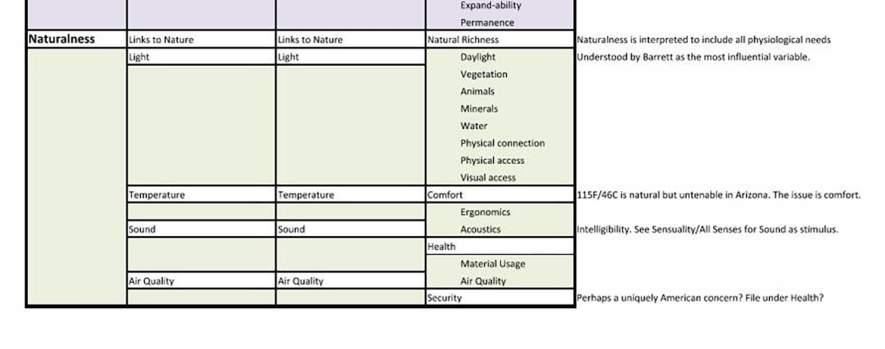

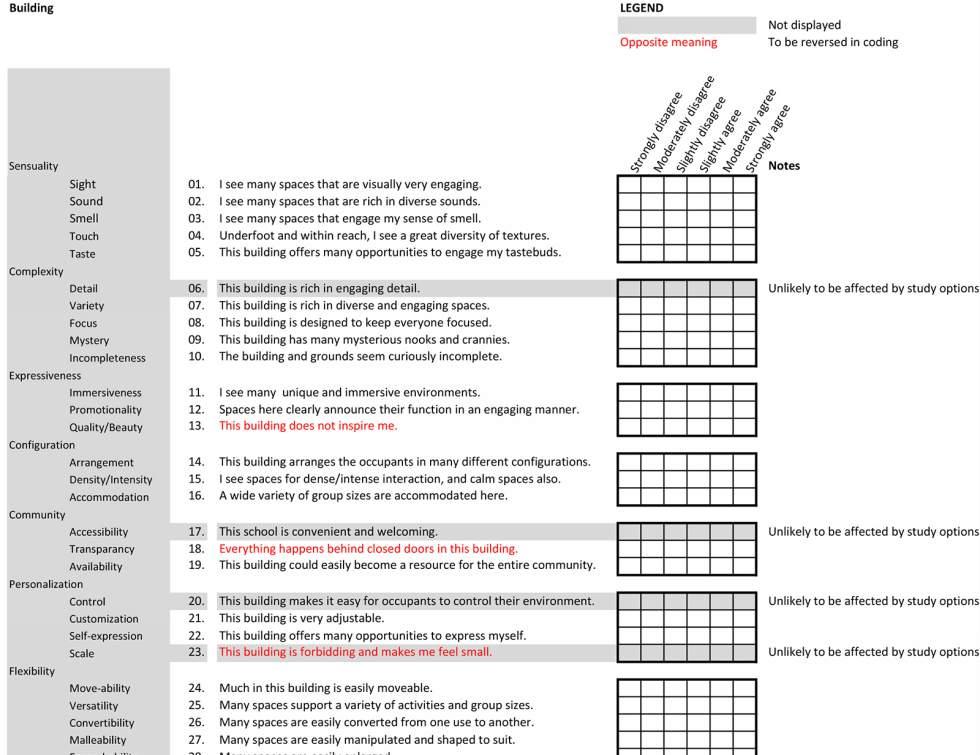

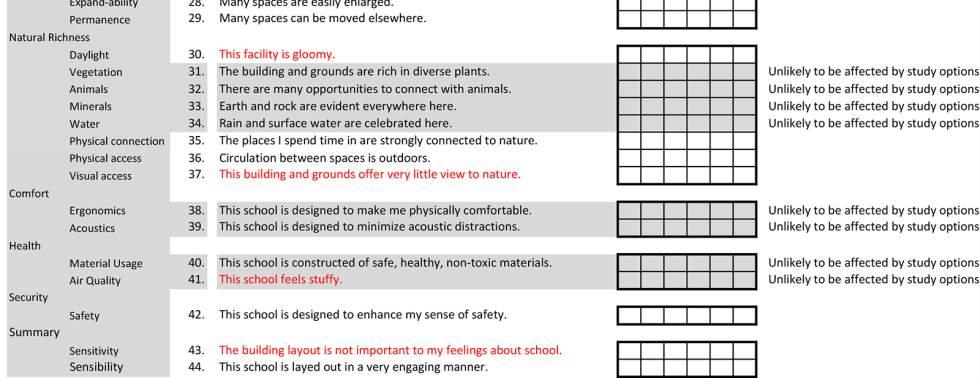

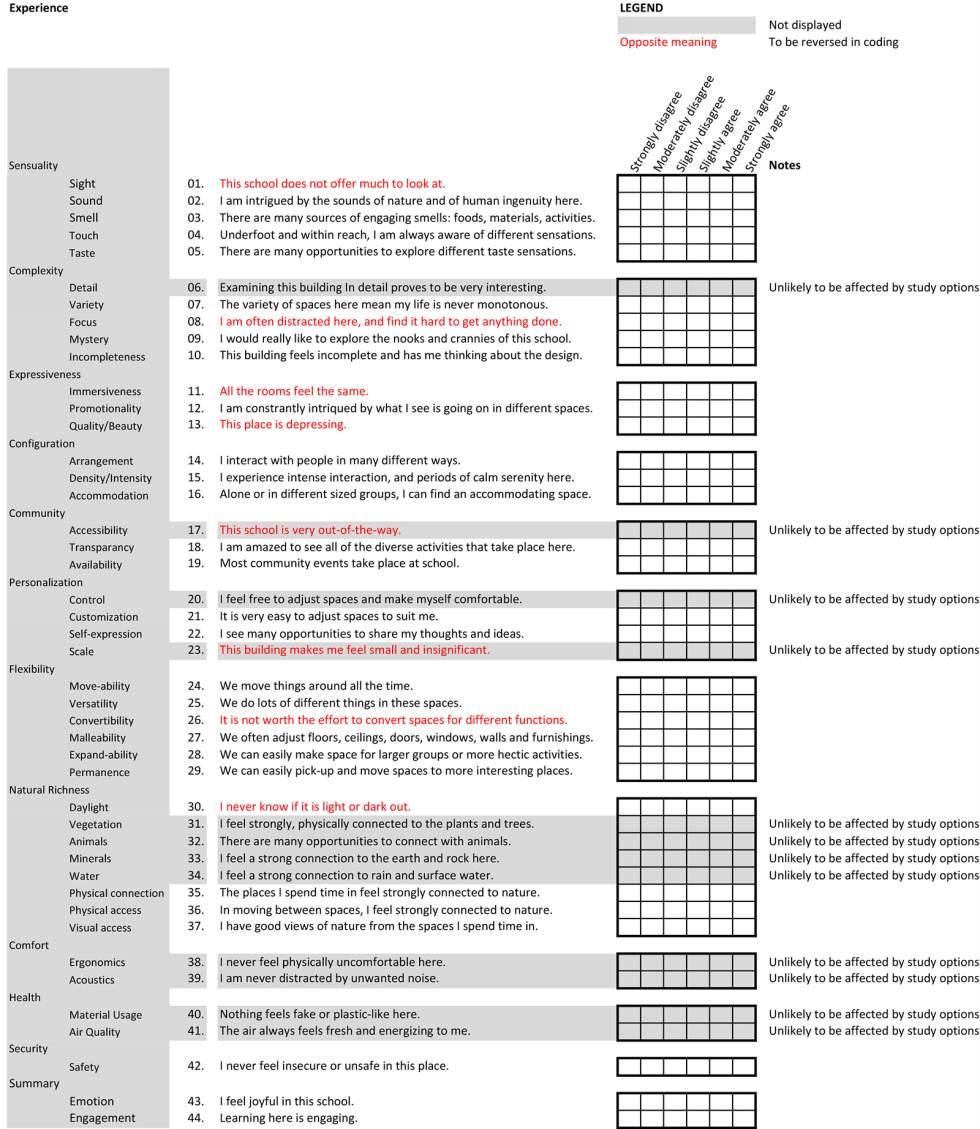

Barrett et al. (2015) laid the foundation for this instrument with a detailed statistical analysis of classroom sensory impacts presumed to affect learning. They arranged these sensory impacts into three “design principles”: Stimulation, Individuality and Naturalness (SIN). Baars et al. (2022) adopted these design principles in their work linking the Physical Learning Environment (PLE) with the Psychosocial Learning Environment (PSLE), though slightly modifying the assignment of sensory impacts. Proposed here are further adjustments to those assignments, still within the SIN framework:

The proposed test recognizes a difference between the perception of a physical space or building and the quality of the occupant experience. For each of these perspectives, questions address each of the sensory impacts identified above. Sensory impacts that are unlikely to be affected by the study design are shaded in grey, as are descriptive cells that would not be visible to study participants.

Please focus your imagination on the school building and the environment. Please register the extent to which you agree with the following statements:

Please focus your imagination on your experience of the school. Please register the extent to which you agree with the following statements:

As a pre‐test, this survey is intended to gauge participant feelings about their existing school facility. After an explanation of Communities of Practice and the Educational Ecosystem, and a Participatory Design Workshop in which participants are offered the opportunity to re‐imagine their existing school, the post‐test would gauge their feelings about that re‐imagined school. A workbook and complete design of the study is available from the author.