(Affective) Landscapes of Emergency

Text Estefania Mompean Botias, Elena Orap, Rob Sharp

Frontline (April 2024)

Frontline (April 2024)

Border points Belarus (closed)

Border points Belarus (closed)

Border points with Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and Moldova

Border points with Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and Moldova

Russian fortifications in Crimea, Donetsk, Kharkiv, Kherson, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia Oblast and Russian regions

Russian fortifications in Crimea, Donetsk, Kharkiv, Kherson, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia Oblast and Russian regions

Energy infrastructure shelling

Energy infrastructure shelling

Shelling of Ukraine territory. All types of shelling: artillery, rocket, or air shelling

Shelling of Ukraine territory. All types of shelling: artillery, rocket, or air shelling

Nuclear threats

Nuclear threats

Environmental damage caused by Russian aggression

Environmental damage caused by Russian aggression

Landscapes of Emergency (exhibition map), 2023

Image: Estefania Mompean Botias, Elena Orap, ALICE Laboratory (EPFL)

Verified dangerous zone (mined)

Verified dangerous zone (mined)

Areas potentially contaminated by explosive ordnance

Areas potentially contaminated by explosive ordnance

Deoccupied territories 2022 (Chernihiv, Kyiv, Kharkiv, Kherson Oblast)

Deoccupied territories 2022 (Chernihiv, Kyiv, Kharkiv, Kherson Oblast)

Occupied territories before 2022 (Crimea, partly Donetsk and Luhansk Oblast )

Occupied territories before 2022 (Crimea, partly Donetsk and Luhansk Oblast )

Occupied territories after 2022

Occupied territories after 2022

Concentration and movements of Russian forces before the offensive launched on February 24, 2022

Concentration and movements of Russian forces before the offensive launched on February 24, 2022

Territorial advance and land manoeuvre combat (Ukraine)

Territorial advance and land manoeuvre combat (Ukraine)

Territorial advance and land manoeuvre combat (Russia)

Territorial advance and land manoeuvre combat (Russia)

Kharkiv

Chernihiv

Kyiv

Chernihiv

Kyiv

Our ongoing research explores the concept of emergency landscapes, focusing on the spatial practices and infrastructures that emerge under war conditions, including architectural transformation, resilience, destruction, and the intersection of human and environmental vulnerabilities. This study, initially centered on the relationship between architecture and destruction, has expanded in scope due to the continued war in Ukraine. After three years of conflict, displacement, and environmental devastation, the scale of transformation now extends far beyond the built environment. It encompasses “hyperobjects,”1 tactical media, digital sensing, and geopolitical reterritorialization – forming new landscapes of power, trauma, and uncertainty.

Architectures of Emergency

The exhibition Ukraine: Architectures of Emergency, organized by Estefania Mompean Botias and Elena Orap, emerged from months of research and analysis tracing back to the beginning of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine on February 24, 2022. As the conflict unfolded over the following months, images of war flooded our screens, showcasing a fragmented and continuous landscape of destruction. Burnt housing blocks, broken concrete, and shattered buildings all pointed to the materiality of a war unfolding through architecture. During the research for the exhibition, we began by asking: What happens to the environment when it is blown up? What does this toxic matter do to the people, plants, animals, and soil that come in contact with it, and how long will its harmful effects last? How does the devastation

impact the souls and minds of living creatures?

After the full-scale Russian invasion, Ukraine experienced a profound and disturbing transformation of its territorial landscape. Approximately 18 percent of the country fell under occupation, and a staggering 33 percent of its land was contaminated by mines and explosive ordnance, rendering Ukraine the most heavily mined nation on the planet. Alongside this inquiry, we began to question how destruction itself is seen, represented, and operationalized through the digital infrastructure of war mapping. While some areas have been successfully de-occupied and reintegrated, military operations continue along a vast stretch of 1170 kilometers. This ongoing warfare has had far-reaching consequences, resonating on a global scale. These emergency conditions and the pervasive sense of uncertainty have had a ripple effect, manifesting themselves in economic and energy crises, environmental degradation, mass population displacement, disruptions in the global food supply chain, and nuclear threats.

Landscapes of Destruction

The number of ruined and damaged buildings – and even cities – illustrates the irreparable harm caused to Ukraine’s infrastructure, environment, and cultural identity. Ruined cities, once shaped by the people who inhabited them, continue to undergo reconfiguration in their absence. The debris remains in an ongoing relationship with the environment and the landscape, becoming an evident political agent of the conflict. Material artifacts of war can provide crucial evidence for understanding complex and

often hidden histories, as we can read events, document experiences, and store information recorded in materiality.2

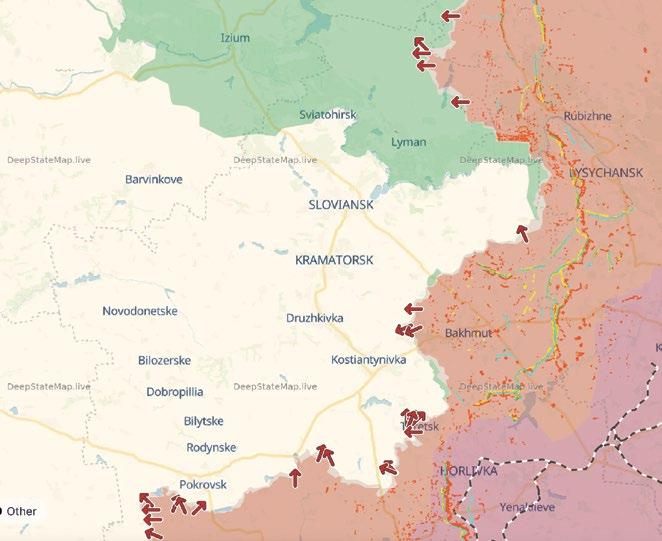

Critically, digital cartographic platforms such as DeepStateMap and Air Raid Alert overlay these material absences with speculative futures – superimposing destruction, front lines, predicted strikes, radiation levels, and simulated nuclear fallout zones over the terrain in a process of rapid modification. In this way, the digital interface does more than merely represent the damage; it symbolically and emotionally enacts it, reinscribing the trauma spatially and temporally. This raises questions about the ontological status of war-torn space. Can a city, once it has been reduced to ruins – no longer a fixed entity but a dynamic site of memory and history – still be considered a city? Or does it instead become a “hyperobject”: distributed and hauntingly persistent across digital, material, and affective realms?

Traces of the Past

The ongoing war is a hybrid conflict that operates on multiple levels – military, ecological, cultural, and cartographic. Both historical and contemporary maps play a role in the media when it comes to territorial speculations and colonial narratives, contributing to the construction of competing realities and questioning Ukraine’s right to exist. The Russian mapping service Yandex contributes to propaganda by keeping older satellite images of the Donbas region online. These images show the area before it was destroyed, erasing the devastation from its cartographic narrative. The Central Election Commission coined the term “territorial

Images: DeepStateMap.Live (above), Screenshot on Air Alert!

uncertainty” to describe the situation of losing control over the territory of the Kursk region. The linguistic regime of power does not allow Russian citizens to use the word “war,” only an alternative: “special operation.”3

Meanwhile, platforms such as Air Raid Alert serve the opposite purpose – not to erase violence but to embed it into everyday life. The real-time display of air raid warnings, potential shelling, and missile carriers at sea produces a temporal cartography of fear and anxiety. These alerts constitute a geography of threat in which the event is always imminent – sometimes merely anticipated, sometimes devastatingly fulfilled. This dynamic reflects what Brian Massumi calls the “affective event”: a condition where perception and emotion are mobilized not only by what has happened, but also by what might happen. 4 Within this affective terrain, emergency management is not separate from perception – it is embedded in the design of the warning system itself. Each siren or visual signal becomes part of an infrastructural choreography of governance, where civil defense protocols, psychological conditioning, and digital interfaces converge. The population is not just informed; it is positioned – physically and emotionally – within a system of constant readiness, a cartography of vulnerability and response.

In Ukraine, the reliance on satellite imagery from allies and commercial companies such as Maxar introduces further geopolitical asymmetries. The visualization of war becomes conditional, often filtered through corporate and political agendas. For instance, Maxar’s temporary restriction of satellite data to Ukrainian analysts 5 raised critical issues about how

Every day maps: A Graphical representation of the battlefield development (above) and the Air Alert! Application (below) provide real-time information on civil defense threats across all regions of Ukraine. These alerts include notifications on missile and drone attacks, the risk of artillery strikes in frontline areas, as well as potential chemical and nuclear hazards.

(below)

Destroyed panelka buildings in Borodianka, Kyiv region (above); Hyperobjects: The town of Chasiv Yar in Donetsk Oblast was completely destroyed during the war (below).

Images: Kateryna Malaia and Philipp Meuser (above), Radio Svoboda (below)

cartographic visibility is controlled, distributed, and weaponized. The widespread use of drones provides a novel perspective on the landscape, yet it simultaneously accelerates the potential for enhanced surveillance and carrying out targeted attacks.

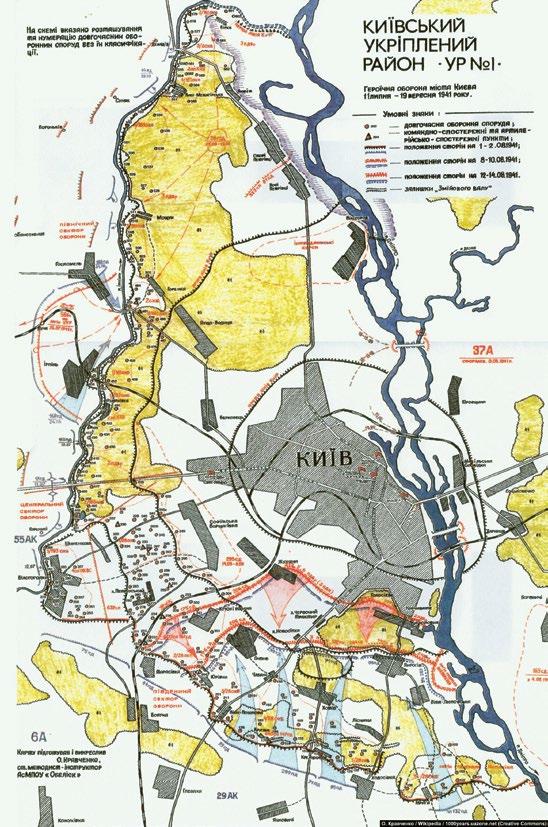

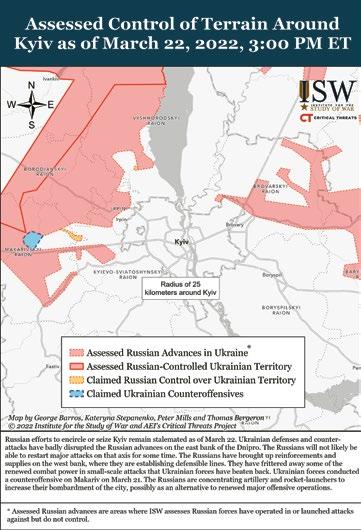

Our research engages with comparative historical cartography to investigate the ways in which wartime conflicts are mapped, starting with the Second World War. We examine how certain regions appear as recurring sites of violence, traced through overlapping layers of maps. The methodology involves analyzing the visual language employed in the maps, including shapes, colors, lines, and other design elements, to understand how meaning is constructed. The study considers the choice of subject matter highlighting what is represented, what is emphasized, and what is omitted. Soviet cartography developed a strong visual language in its representations of the Second World War. Ukrainian cartography, shaped by different historical and political contexts, is in the process of forming its own visual language in response to recent conflicts and spatial reconfigurations.

According to geographer Peter Collier, the relationship between warfare and cartography was more intimate in the twentieth century than in any previous era. 6 With the development of satellite imagery and the current use of surveillance drones, we can trace the impact of technology on mapping techniques as we see new kinds of cartographic practices appearing. Furthermore, comparing the maps of different periods leads to a discussion of mapping as an active agent of cultural intervention.7 Some recent episodes of ideological speculation on

The defense of Kyiv in 1941 (above) and in 2022 (below)

Images: Museum of War, Kyiv (above), The Institute of the Study of War (below)

cartography, including the annexation of Ukrainian territories and labeling them as “new regions of Russia” without factual borders, claiming that a 400-year-old map proves that Ukraine is not a real country, while failing to notice that it has “Ukraine” written on it.

Memoryscapes

Mapping war is not only a form of analysis but also of memorialization. The physical transformations of landscape become both evidence and memory. Mapping these sites becomes a process of preserving and interpreting trauma. Our project analyzes case studies of communities affected by the war, the emergence of architectural practices, and the tangible material traces of debris as narrative and cartographic agents. By integrating participatory mapping and collecting testimonies through interviews, the project contributes to inclusive knowledge production and informs policy-making processes in post-traumatic contexts. The pilot phase is situated in communities within Kyiv Oblast that were directly affected by the war in 2022, particularly those engaged in reconstruction efforts. Participatory mapping adds a human dimension to the spatial data of the postwar landscape. Following the insights of “new materialisms,” we understand ruins and war remnants as

1 The term “hyperobjects,” coined by philosopher Timothy Morton, describes things that are so massively distributed in time and space that they are difficult for humans to fully comprehend or perceive. In the context of war and environmental devastation, “hyperobjects” refer to how war is not just a series of local events, but part of a larger, often overwhelming system of trauma, ecological collapse, and global politics that extends far beyond immediate visibility. See Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World, Minneapolis MN 2013.

active agents, or “thing-power,”8 that shape the (post)emergency environment.

Digital platforms, by contrast, can flatten this agency into abstractions. DeepStateMap, for example, may visually indicate an “occupied” zone with a shade of red, yet without acknowledging the layered ruin, loss, and memory embedded in its ecosystems. Thus, while these platforms are indispensable for tactical navigation and public awareness, they must be critically read in conjunction with situated, embodied, and affective mappings. This is where a practice of counter-cartographies comes in: hand-drawn maps, sketches by displaced persons, and breath-mapped territories. These are not about strategic control, but about presence, memory, and survival. The act of redrawing – not on the totalizing form of a satellite map, but through oral archives, or on paper, through the memory of one’s steps, fears, and hopes – generates another kind of knowledge.

Mapping the Uncertain

Exploring how war physically transforms spaces and understanding how maps are used to document, analyze, and critique these transformations is central to our research. From the lived simulation of military front lines to the collective wailing of air raid sirens, the war in

2 Susan Schuppli, Material Witness: Media, Forensics, Evidence, Cambridge MA 2020.

3 Bruno Latour, “Is Europe’s Soil Changing Beneath Our Feet?” in: GREEN 2, 1.2022, War Ecology: A New Paradigm? pp. 85–89. Available online: geopolitique.eu

4 Brian Massumi, Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation, Durham NC 2002.

5 Tim Zadorozhnyy, “Maxar Technologies restricts Ukraine’s access to satellite imagery amid US halt to intelligence sharing,” The Kyiv Independent, March 7, 2025, on: kyivindependent.com

Ukraine is fought not only on land but also in cartographic narratives. These digital cartographies are “performative acts” – they do not merely describe the war event but actually create and sustain it. They shape what is visible and thinkable. Thus, historical cartographic comparison, participatory mapping, and archival materials are essential tools for assembling, challenging, and enriching the dominant visual narratives of conflict. Finally, we return to our initial question: How could we map not only what is gone, but what is still emerging – precariously, hopefully – from within these (affective) landscapes of emergency?

Estefania Mompean Botias is an architect and urbanist currently pursuing a PhD at the ALICE Laboratory of EPFL. Her research explores the ambivalences of emergency conditions and investigates how emergencies transform spatial and regulatory frameworks.

Elena Orap, an architect from Kyiv, moved to Switzerland after the 2022 invasion. She collaborated on the research project at ALICE, and is currently a grantee at Documenting Ukraine at the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna. Rob Sharp holds a PhD in Media and Communications from the London School of Economics and Political Science, and is Assistant Professor at the University of Sussex, researching solidarity in Europe amid Ukraine’s ongoing war.

6 Peter Collier, “Warfare and Cartography,” in: Mark Monmonier (ed.), History of Cartography, Volume 6: Cartography in the Twentieth Century, Chicago 2015, pp. 1696–1700. Available online: press.uchicago.edu

7 James Corner, “The Agency of Mapping: Speculation, Critique, and Invention,” in: The Landscape Imagination: Collected Essays of James Corner, 1990–2010, New York 2014, pp. 197–239.

8 Thing-power, as defined by Jane Bennett, is the ability of objects and materials (non-human entities and objects) to act to exert force and to have an impact on their surroundings and on human beings. Bennett argues that inanimate objects such as rocks, water, machines, and even commodities have a form of agency and vitality of their own. See Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things, Durham NC 2010.