DANIEL

AMBROSI AI AND THE LANDSCAPES OF CAPABILITY BROWN

This catalogue is produced on the occasion of the exhibition Daniel Ambrosi. AI and the Landscapes of Capability Brown

at Robilant+Voena

38 Dover Street, London W1S 4NL

6 October – 15 December 2023

All works © The Artist

Texts © The Authors

robilantvoena.com

The twelve artworks in this exhibition, each depicting a vista created by the visionary eighteenth-century landscapist Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, or by close contemporaries, are the result of a collaboration between the digital artist Daniel Ambrosi and Robilant+Voena. Following a chance meeting with the artist in 2022, R+V suggested the landscapes of Capability Brown as a potential subject for Ambrosi; and thus the seed of this solo exhibition, the artist’s first in Europe, was sown.

The present exhibition unites R+V’s Old Master expertise and commitment to supporting contemporary artists who build upon the foundations of these Masters, with Ambrosi’s unique AI-augmented landscape art, a practice steeped in admiration for historic landscape painters.

Throughout his artistic career, Ambrosi has studied European Old Masters, taking inspiration from Poussin, Turner, Constable, Monet, Van Gogh, as well as the American School of Hudson River Artists, and from the twentieth-century, Klimt, Dali, Parrish, and Hockney. As he explains in the interview in this catalogue, lessons learnt from these artists have enriched both the form and content of his works, and he shares with many of them the same ambition for his artworks; namely, to convey the visual, visceral and cognitive experience of being in a landscape.

Although Ambrosi has imbibed lessons from Old Master landscape painters, this is the first time that he has undertaken a series of Dreamscape works based on the real-world landscapes of a master landscape designer. Bringing together the quintessentially English landscape garden as shaped by Capability Brown, with the most advanced digital tools, Ambrosi has created six pairs of works – each comprising a ’full-scene’ landscape and an aesthetically-related square-format ‘detail’ – that have a shared style of ‘dreaming’ (specific parameters within the AI technology that the artist has implemented).

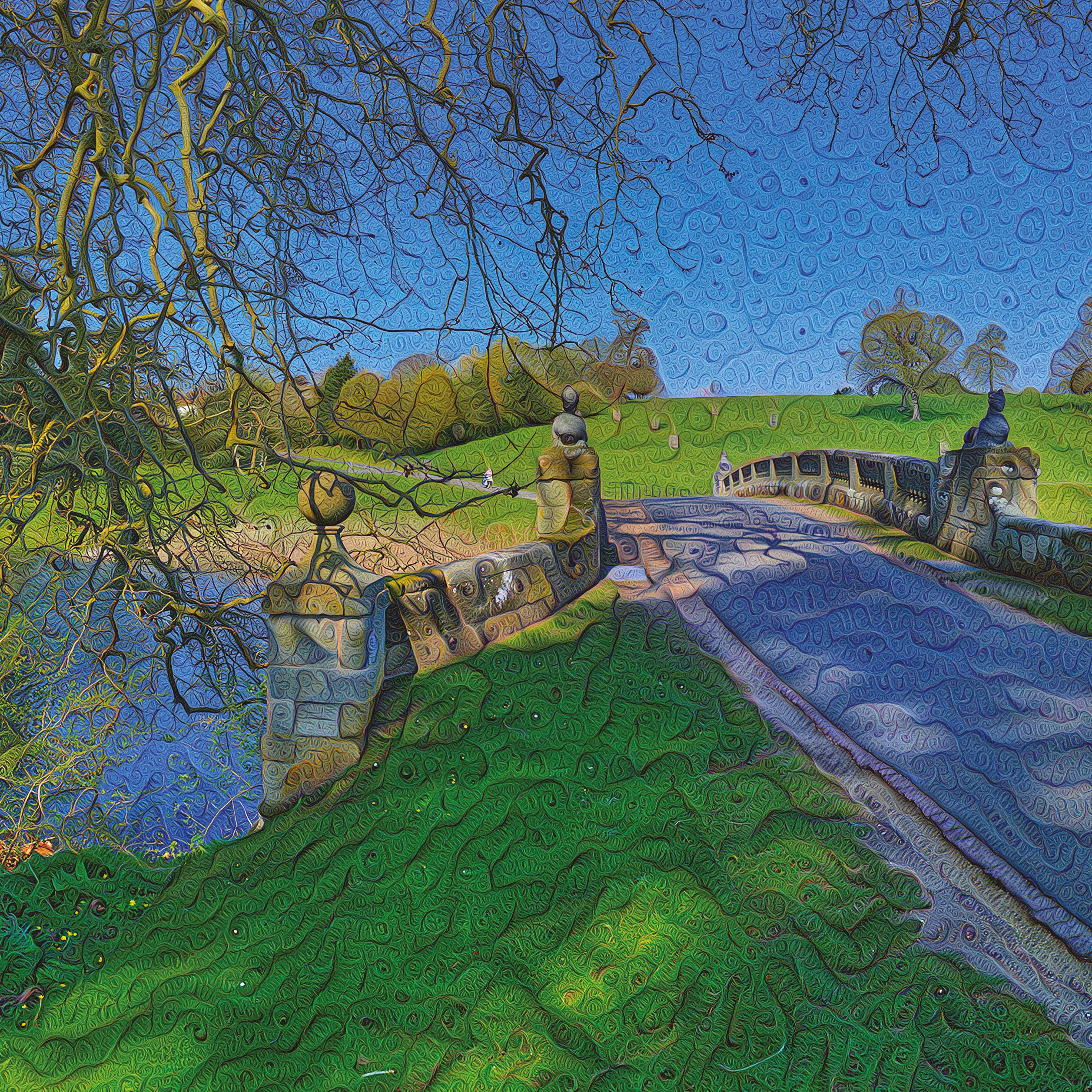

Ten outstanding estates from England are represented in the exhibition, based upon original photography captured by the artist in Spring 2023. Using a unique fusion of computer graphics and bespoke AI tools, Ambrosi offers visions of these landscapes that appear tantalisingly familiar, yet cause us to look and look again as these new interpretations unravel. Blenheim (detail), 2023

That Capability Brown himself was inspired by popular landscape paintings of his own era has proven a particular fascination for Ambrosi, reflecting the artist’s belief in the continuous interplay between the world of reality and the world as depicted by artists – an interplay that is evermore complex with the rise of digital and AI technologies in the twenty-first century. Moreover, the apparent naturalness of Brown’s landscapes – which were in fact carefully and intricately planned and manmade – prompts reflection, in the context of AI-augmentation and digital tools, on our perceptions of reality and of the creation and depiction of beauty, in the eighteenth century as in the present day. The balance of nature, man and now artificial intelligence, is a story that will unfurl long after this exhibition closes its doors.

The enduring wonder of Capability Brown’s carefully sculpted landscapes is championed in Ambrosi’s artworks, while also offering a refreshing twenty-first-century interpretation, emphasising the ability of contemporary technologies to allow us to revisit familiar themes and subjects in a novel, enlightening way. As has always been Ambrosi’s mission, these works help us to find new levels of appreciation for the world we inhabit, opening our eyes to its infinite richness.

My first degree was in architecture and, while I was a sophomore at Cornell University in the spring of 1978, one of my professors gave a public lecture about what his lab was doing on the ground floor of our design studios. It turns out that this professor, Dr. Donald P. Greenberg, was also the founder and director of Cornell’s nascent Program of Computer Graphics. What he showed us that evening utterly blew my mind and, ultimately, changed my life.

Eventually, Don invited me to join his lab as a graduate student where I became part of a group of pioneering graphics researchers who made significant contributions to the development of interactive 3D imaging systems. Since entering Don’s lab in the fall of 1981, I’ve exclusively created art that is natively digital. I’d have it no other way, especially now that after all these years, this art form is finally getting the respect and recognition it deserves.

I should add that early in my undergraduate career, I became fascinated by photography: I undertook my first photography class and discovered a love for that medium. My education was also complemented with numerous courses in architectural history, landscape architecture, urban design, and art history, all of which still inform my artwork to this day.

The motivation behind my Dreamscapes project — and that’s how I see it: as one continuous art project that is now in its twelfth year — has always been driven by a strong desire to share my own experiences of great landscapes and cityscapes. It’s hard to explain, but occasionally something magical happens when I am out in nature; I can be hiking all day in a beautiful place like Glacier National Park in Montana, and the scene suddenly comes together in a particular way that sets alarm bells ringing in my head. I struggled for decades trying to capture the sensation of the view with traditional photography, and gradually learned that it takes much more than a camera to convey that experience.

Dreamscapes are my solution to this challenge and are built on two key insights I had over the years. One insight (which I later learned David Hockney was exploring contemporaneously during his A Bigger Picture period) was that cameras see the world in a much more limited way than humans do. I needed to devise a computational photography technique that forces my camera to see the world the way we do: with a much wider field of view, with a much higher dynamic range (we have no problem seeing details in both the dark and bright parts of a scene), and with rich detail everywhere we look. That breakthrough, after years of experimentation, came to me in a flash in front of a canyon in Utah on September 27, 2011, which I consider the official start of my Dreamscapes art project.

The second insight was realizing that powerful landscape experiences are not only visual (seen) and visceral (felt), they are also cognitive; they make you think – about the nature of seeing, about the very essence of reality. When Google’s ‘DeepDream’ was released in 2015, I saw the opportunity to bring a cognitive element to my landscapes and, with the generous support of two brilliant engineers, Joseph Smarr (Google) and Chris Lamb (NVIDIA), in early 2016 I was granted the ‘keys to the kingdom’: a modified super-scaled cloud-based version of DeepDream that could operate successfully on my giant images. I’ve been tapping the potential of this workflow ever since, using the original AI code base, even though it was never designed to make art! In fact, DeepDream was part of a computer-vision system tasked with classifying images.

The short answer is: I know it when I see it! I choose the destination of my photo expeditions based on images I’ve previously seen that offer the mix of features I’m interested in; namely, idyllic pastoral scenes that depict a healthy balance between manmade and natural elements. But that’s just a starting point; finding precise locations where those elements come together is mostly intuitive.

As I mentioned earlier, that magic moment when the alarm bells ring in my head is both hard to predict and inexplicable. It feels more like a recognition than a discovery, as if the scene was waiting for me like an old friend. Of course, ephemeral conditions like the time of day, season, and weather add to the challenge of capturing these compositions in their best light.

The great landscape painters from history constantly inspire and enrich my work. The lessons I take from them keep growing as I continue to study the art form and visit these masterworks at museums and galleries around the world. I’ve learned about rules of composition, and the brilliant unexpected outcomes that occur when artists consciously break these rules. I’ve learned about the impact of scale and detail on creating a sense of immersion in a painted landscape. I’ve learned the value of color and how high chroma as applied by Pre-Raphaelite landscape painters, for example, transcribes particularly well to the way I see the world. And most of all, I’ve learned about the primacy of light as the driving force behind the revelation and apprehension of great landscapes.

I can set the direction of my AI, but I can’t control the details. AI is a tool for me, but it’s a tool like no other and at times it feels like a collaboration. The metaphor I like to use is this: I’m the leader of a jazz band who writes original compositions and I have a virtuoso saxophonist in my band who knows exactly where I’m going with my song, but who is going to improvise, bringing their own sensibility to the piece. In doing so, they will constantly surprise and delight me. That’s exactly what happens in the relationship with my AI. Specifically, I choose from 84 distinct ‘target layers’ in my AI’s neural network, each one of which ‘dreams’ or hallucinates with a different visual motif. I can also control four sliding parameters that determine the scale and intensity of these hallucinations. This gives me infinite variety within a finite repertoire of motifs; a bounded infinity, if you will. My job is to find the settings that are most visually compatible with the underlying source photography. Because my AI is staged on a ‘quad GPU compute server’, I can quickly test four variations at a time, at least at low resolution, before committing to the final process at full scale. With experience I am increasingly making the right choice for the full scale version the first time, but that’s not always the case.

What do you think are the challenges with AI for artists and for society, and how do you respond to criticisms of using AI in art?

As with the introduction and advance of every technology, there is disruption, fear, excitement, boom and bust cycles, adoption curves, and ultimately widespread accessibility. This pattern seems to be unavoidable and unstoppable. In the early stages, mistakes are made by both the opponents and advocates; in the heat of the onslaught, nuance is often lost as society tries to grapple with and, where necessary, regulate the use of new technology. Eventually things settle down and we all end up wondering how we ever got along without these tools.

Creative applications of AI are forcing artists and society at large to reconsider the very essence of creativity itself, and which aspects should be most valued: is it the time an artist spends making their art? Or the education or training they bring to bear? Or the innate hand-eye coordination they’ve been gifted with? Is it their artistic vision that matters the most, their ideas or artistic intent? The truth is technology has always been a part of art and the artists who embraced new technologies have been instrumental in advancing art throughout the ages. I understand the consternation that has arisen in the worlds of fine art, illustration, and design due to the rapid, recent development of AI. I agree that we need to take steps to ease the disruption caused by these advancements, but I’m thrilled by them and their potential for what some call ‘imagination amplification.’

Capability Brown reshaped the landscape in some ways beyond recognition from its natural and previous states. Do you see any parallels between your artistic practice and that of Brown?

Indeed! The work of Capability Brown represents the power of ideas and artistic vision; his work demonstrates the ability of ideas to shape reality. And I love how his visions were influenced by popular landscape paintings of his time, which Brown transmuted into real world landscapes that have been enjoyed by people to this very day. It’s especially poetic to me how the collective vision of Brown and his artistic predecessors continues to reverberate centuries later when I undertook this project to capture these places photographically and turn them back into landscape paintings.

When experiencing these artworks inspired by Capability Brown’s landscapes, what effect do you hope to have on your audience?

The motivation behind my entire Dreamscapes project in general and with this new collection remains pure: to share with others as fully as I possibly can the experiences that I’ve had in these special places, not just visually, but also viscerally and cognitively. Admittedly, the act of translating that four-dimensional experience into a two-dimensional art object requires bounds, a point of view, and the use of visual metaphors. But my hope is that the experience of these translated landscapes yields the same sense of joy, wonder and rebirth that I felt when I visited them for the first time in the spring of this year.

Stourhead (detail), 2023

For the art of gardening to be elevated to the rank of fine art, it had to do more than simply separate itself from every useful end. It also had to satisfy the criterion through which beautiful works are recognized. In other words, it had to imitate nature – or, rather, “beautiful nature”, which is not satisfied with reproducing the traits that render things recognizable, but goes further and assembles the traits, borrowed from the most beautiful models, into a perfect figure that is not to be found in simple nature.

– Jacques Rancière, The Time of the Landscape, 2023, p.5Well-known for his large-scale, immersive landscape artworks that blend traditional photography with computational techniques, might Daniel Ambrosi be said to ride that ‘perfect figure’ when seeking to render the landscape visible?

As Baudrillard put it some four decades ago, the Borges fable, ‘in which the cartographers of the Empire draw up a map so detailed that it ends up covering the territory exactly … has come full-circle for us, and possesses nothing but the charm of second-order simulacra’. As we move through the successive phases of the image, we are no longer surprised by the absence of a profound reality, and perhaps less so when the image is its own pure simulacrum. Nor, of course, should we forget John Berger’s adroit critique of Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews (c.1750) – whereby the ‘philosophic enjoyment of unperverted Nature’ is typically preconditioned by the possession of private land.

Today’s possession of land occurs doubly. The same landowning rights persist, but equally the new cartographers are the large corporations and start-ups photographing every inch of the globe for the generation of geographic information systems. As a counterpoint, Ambrosi has sought to improvise upon such vast systems. Not only does he create his own photographic ‘datapoints’, but he draws this data through numerous layers – stitching together a collaboration with the higher dimensional mathematics of artificial intelligence. If we think of how MRI scans render the ‘landscape’ of the body into thousands of finely sliced images, through which like a movie we can move back and forth, Ambrosi could be understood to move virtually through multiple and vast natural environments, ostensibly traversing near infinite terrains.

Jacques Rancière argues that the ‘landscape’ as a specific object is not simply some-thing, as referenced in numerous textual descriptions over centuries, but rather emerged at a specific time, coinciding with the new discourse of aesthetics. Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Judgement in 1790 offers one point of departure. Kant attributes painting as a ‘formative art’, whereby it ‘presents sensible appearance in artful combination with ideas’, which he divides into ‘the beautiful arrangement of its products’. Furthermore, he posits, this work is also undertaken in ‘landscape gardening’. Kant echoes what is already starting to be recognised (e.g. in the writings of Thomas Whately, Christian Cay Lorenz Hirschfeld, and Jacques Delille). Whately, for example, remarked: ‘Gardening, in the perfection to which it has lately been brought in England, is entitled to a place of considerable rank among the liberal arts’.

In his contemporary AI-renders for his exhibition of artworks based on the landscapes of Capability Brown, we might want to suppose Ambrosi has added to such perfection, having ‘transposed’ our viewpoint through the hyperreal light of the Californian sky. Whatever one’s sensing of these works, at stake is the question of ‘unity in variety’. As Rancière explains, this tension is critical to the emerging discourse of landscape gardening and the ‘picturesque’ in the 18th century.

Capability Brown, for example, a noted influence for Ambrosi, was instrumental in moving away from the formal, symmetrical gardens popular of the period. Instead, Brown introduced a style of design that sought to emulate natural beauty, albeit in a highly curated form. Ambrosi seeks to uphold Brown’s ability to curate unity in variety, or to ‘shape reality’. Yet, interestingly, Brown was criticised by his peers. For some, his gardens were considered too smooth and undulating, lacking in curiosity and concealment. As Rancière puts it, ‘the gaze must be bounded in a way that does not allow it to see the limit of what it is looking at. There must be a limit that conceals the limit’. For Ambrosi, the ‘limit’ that conceals the limit of the pictured space is arguably the limitlessness of AI, which reveals a whole new vista; it places us in a very different timespace.

The emergence of the 18th century landscape discourse is bound up with a tension between the liberal and mechanical arts. ‘The latter,’ Rancière remarks, ‘produced objects that served the needs of human beings, while the former provided pleasure to those whose spheres of existence extended beyond the simple circle of

needs’. Today, the crafted and mechanical are of apiece in an art practice such as with Ambrosi, which in turn produces new effects of the picturesque and the grand (terms typically forgotten from Kant’s aesthetics, as opposed to the much-used terms of beauty and the sublime):

The picturesque tends toward its own overcoming, toward a state in which the happy combination of varied objects is abolished in a holistic effect: the grandeur that reduces this variety to a unity that neutralizes the individuality of the objects and their qualities. The same process erases likewise the usual link between cause and effect, according to which a particular spectacle produces the corresponding effects of pleasure or pain.

[…] …this “grandeur” produces a specific effect: rather than the landscape seeming vaster than it actually is, it is now the mind that is enlarged. The way travelers describe it, this enlarging of the mind first manifests itself in a state of stupor and unnamable happiness.

– Jacques Rancière, The Time of the Landscape, 2023, p.54As Ambrosi describes in interview, when a scene suddenly comes together (or, we might say, when we encounter its ‘grandeur’) it sets ‘alarm bells’ ringing in his head. Traditional photography, he remarks, struggles to capture such pensive moments, hence his remarkable travels through the multi-dimensionality of a longterm provocative and collaborative AI practice.

For centuries a recurring ‘dream’ theme for artists, the magnificent art of the English Landscape Garden is neither locked in the past nor old-fashioned. One only needs to walk the ground, such as at Stowe or Stourhead, to find their unforgettable ‘sense of place’ is alive and well.

An engaging exhibition involving artificial intelligence at Robilant+Voena’s London gallery offers an original take on much-loved, well-watered views. In his first solo UK show, California-based digital artist Daniel Ambrosi is making waves, motivated by a passion for the history of landscape painting. Ironically, ten of his twelve artworks feature ‘artificial river’ landscapes dreamt up by ‘Capability’ Brown.

To mention the celebrated 18th-century engineering pioneer in the same sentence as AI seems surreal. Everyone visiting Blenheim for the first time stops in awe to query the sheer scale of Brown’s man-made lake. ‘How did he do it?’ This same question will undoubtedly spring to mind on first sight of Ambrosi’s astonishing Dreamscapes

In the first instance, armed with a compact camera,1 the artist works at speed, taking dozens of photos of the source scene. Later, he employs computer graphics techniques to stitch them into one seamless high resolution panorama. Then, with the help of AI-image transformation technology, he showcases his personal response to that chosen vista.

Ambrosi commenced his project by exploring ‘the finest view in England’2 – Blenheim. With the April weather far from promising, he left marker stones for his tripod at one affecting viewpoint where, should the light improve, he would return. Unbeknown to Ambrosi, Brown had proposed a Gothic bathhouse, ‘Rosamund’s Bower’, in this exact location. This romantic idea, and memorial of Henry II’s love for his mistress, would take advantage of both prospect and history. Though his plan never materialised, it is intriguing to discover that Ambrosi intuitively sensed the magic of that space.

As luck would have it, a sudden outbreak of sunlight enabled exciting image capture, the first step in creating a five-metres-wide, back-lit showpiece. The resulting work, Blenheim, presents an impressive, immersive fantasy in rich saturated colour, reminiscent of the 1950’s widescreen Todd-AO vision, that heightened technicolour, panoramic cinema experience.

Grand Chatsworth in sparkling, spring sunshine with cottonwool clouds, and Chatsworth Cascade are equally charged. Step closer to inspect a verdant stage populated with garden visitors, as if statues in a lively tableau.

If Brown, the so-called ‘Shakespeare of Garden Arts’ is the author of the setting, then Ambrosi is the director in this production. An accentuated rhythm, and uplifting control of colour and tone reminiscent of David Hockney, draws attention to Brown’s Spartan palette of trees, shrubs, and daffodils. His contemporary orchestration of light is equally rewarding.

Brown was schooled in the pursuit of visual pleasure by paintings of Claude Lorrain, Nicolas Poussin, and Salvator Rosa. He developed a practical, formulaic approach, intending onlookers to pause and contemplate pleasing contours in a harmonious ’unified whole’, and instructing his men to ‘Keep all in view very neat.’ Two and a half centuries later, Ambrosi brings surviving elements of that ‘whole’ into sharp focus. He invites us to explore every lake edge and oblique approach road. His mark-making in Stowe brings a dynamic texture redolent of Van Gogh’s emotive brushwork, drawing the eye to the cedar and then freely up the hill to the Gothic Temple of Liberty.

Notice the lone, mazy oriental plane guarding Brown’s dappled bridge in Compton Verney, where the artist branches out and crosses over into another strange, photomosaic paradise. A variety of patterning somehow lends heroic form. Investigate in Charlecote the deeply engraved bark of veteran oaks surrounded by tangled blades of grass. One senses the breeze blowing the rushes and rippling the water in Petworth. Here is epic space for every feature tree and clump to shine. In Bowood lace-like alders, once planted by Brown to conceal lake-ends, confirm this never-ending ‘river’. Intimate inspection reveals Ambrosi’s vast, multifaceted mesh, as if Nature’s network of living organisms hidden underground has surfaced.

Given a problem to solve by collaborators, it is said Brown originated the phrase: ‘I shall go to bed and sleep on it.’ These Dreamscapes, just as dreams, may prove perplexing to process. Is this really AI, or has Ambrosi played God? Has he created, by doubling layers in close-up, a wonderfully weird, Gothic world? Seen from a distance, are his novel landscapes quite simply divine?

Borrowing a line from Alexander Pope, banker Henry Hoare was moved to laud Brown’s ‘unfailing eye’: ‘He paints as he plants.’ Ironically, Hoare’s masterpiece, Stourhead, made the greatest impression on Ambrosi. He arrived early, not a soul around and was captivated the minute he laid eyes on the iconic classical landscape, veiled in mist. A ‘dreamy’ style of AI hallucination proved best for communicating his emotions in that rare moment of mystery. Stourhead stands out, as Ambrosi avowed, ‘It really felt like walking through a dream!’

Capability Brown had one dream – ‘to finish England.’ Given Ambrosi’s comparable sensibility and compositional skill, combined with AI potential, one wonders if that Elysium might eventually be fulfilled? Perhaps it could be said that Ambrosi ‘paints with his eye and his apps’. In the great tradition of landscape art, he makes us look. We end up being memorably immersed in his bright, imagined, spacious Arcadia beneath azure skies.

Sheffield Park (detail), 2023

Sheffield Park (detail), 2023

Six pairs of aesthetically-related artworks are presented; each pair consists of one landscape-orientated light box and one square fabric print.

Each light box displays a ‘full scene’ Dreamscape, which appears to be a photographic reality from a distance but reveals itself to be a digital fantasy up close.

Each fabric print is a ‘double dose’ Dreamscape, which is visibly dreamlike from a distance but reveals a secondary pass of ‘dreaming’ at a finer scale.

Each pair of adjacent artworks utilises the same initial dreaming style, but that style is upscaled in the fabric print in order to accommodate the second dose of AI-interpretation.

All artworks in the following pages are linked to an interactive zoomable browser to enable viewing of each image in full detail; click on the artwork to launch the zoomable version.

Blenheim, 2023

LED perimeter-lit dye-sub fabric print

203.2 x 487.6 cm (80 x 192 in.)

Stowe, 2023

Ambient-lit dye-sub fabric print

121.9 x 121.9 cm (48 x 48 in.)

Edition of 5

Chatsworth, 2023

LED perimeter-lit dye-sub fabric print

198.1 x 365.7 cm (78 x 144 in.)

Chatsworth Cascade, 2023

Ambient-lit dye-sub fabric print

182.9 x 182.9 cm (72 x 72 in.)

Edition of 3

Charlecote, 2023

LED perimeter-lit dye-sub fabric print

116.8 x 213.3 cm (46 x 84 in.)

Edition of 3

Compton Verney, 2023

Ambient-lit dye-sub fabric print

121.9 x 121.9 cm (48 x 48 in.)

Edition of 5

Petworth, 2023

LED perimeter-lit dye-sub fabric print

121.9 x 243.8 cm (48 x 96 in.)

Edition of 3

Bowood, 2023

Ambient-lit dye-sub fabric print

121.9 x 121.9 cm (48 x 48 in.)

Edition of 5

Prior Park, 2023

LED perimeter-lit dye-sub fabric print

121.9 x 243.8 cm (48 x 96 in.)

Edition of 3

Sheffield Park, 2023

Ambient-lit dye-sub fabric print

182.9 x 182.9 cm (72 x 72 in.)

Edition of 3

Stourhead, 2023

LED perimeter-lit dye-sub fabric print

198.1 x 365.7 cm (78 x 144 in.)

Stourhead Temple, 2023

Ambient-lit dye-sub fabric print

121.9 x 121.9 cm (48 x 48 in.)

Edition of 5

Daniel Ambrosi (born 1958) is a California-based visual artist specialising in digital and AI-augmented art. He studied at Cornell University, where he received a Bachelor of Architecture and a Masters in 3D Graphics. During the 40 years since graduating, he has practised digital art, and starting in 2015, with engineering assistance from Joseph Smarr (Google) and Chris Lamb (NVIDIA), developed an enhanced version of Google’s ‘DeepDream’ technology, that has allowed him to create his large-scale immersive Dreamscape series.

Ambrosi’s practice is deeply informed by the history of landscape painting, finding particular inspiration in the works of the grand format landscape artists of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe and the later nineteenth-century Hudson River School artists.

Ambrosi’s works have been shown in exhibitions and art fairs across the United States and in Europe; his work has recently been acquired by the Museum of Contemporary Digital Art (MoCDA), and in 2019 he was a finalist of the Lumen Prize for Art and Technology.

Sunil Manghani is Professor of Theory, Practice and Critique at University of Southampton and a Research Fellow of The Alan Turing Institute. He is managing editor of Theory, Culture & Society, and Co-Editor of Journal of Visual Art Practice. His books include Image Studies; Zero Degree Seeing; India’s Biennale Effect; and Farewell to Visual Studies. He curated Barthes/Burgin at the John Hansard Gallery, and Building an Art Biennale and Itinerant Objects at Tate Exchange, Tate Modern.

Steffie Shields MBE, garden photographer, writer and historic landscape consultant. She is a member of Garden Media Guild and Professional Garden Photographers Association, and Cambridge ICE tutor, Madingley Hall (2007-2016).

Steffie is the author of Moving Heaven and Earth: ‘Capability’ Brown’s Gift of Landscape (2016) and was advisor to both the national 2016 ‘Capability’ Brown Tercentenary Festival, and the More4 TV series Titchmarsh on Capability Brown. In the same year, Steffie was co-curator, with Hal Moggridge OBE, of the contemporary photography exhibition: Lenses on a Landscape Genius - Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown

A Vice President of The Gardens Trust, and Chairman of Lincolnshire Gardens Trust, in 2018 Steffie received an MBE for services to conservation and heritage.