Form, Function, and Freedom: A Dialogue between Frank Lloyd Wright’s and Adolf Loos’ Modern Architectural Legacies for the Future.

RobertoM.GarcíaSepúlveda

Throughout the beginning of the 20th century, architecture in Europe and North America faced disruption and reform through private dwellings. From industrial and technological advancements to new design and building approaches, architects faced a challenge to resist or adapt tothe new ways oftheturnofthecentury.Around1900,theAmerican architect Frank Lloyd Wright designed a series of homes that reflected a new American domestic architecture (Blake, 1969). These homes called Prairie Houses, primarily in the Midwest, counted with infinite residential innovations where Wright welcomed motion and dynamism. Wright identified a lack of architectural equivalency to the ideal of his nation. He believed space and freedom were the chief characteristics of the new world, the limitless space and the man on the move (Blake, 1969).

Meanwhile, Austrian and Czechoslovak architect Adolf Loos, led a deconstruction of cultural life and false luxury in Europe. His private homesbecamezonesofintimacyandretreat from social behaviour. Loos intentionally created a design disparity between the interior and the facade, often resulting in cubic forms (Sarnitz & Loos, 2022). His buildings with smooth facades and ornamentation-free surfaces, such as the Cafe Museum and House on Michaelerplatz in Vienna, provoked architectural scandals. However, while some considered Loos “an unloved and uncomfortable polemicist”, others saw him as “a particularly differentiated thinker preparing the way for the modernage”(Sarnitz&Loos,2022).

“Every great architect is necessarily a great poet” Wright stated, “he must be a great original interpreter of his time, his day, his age” (1932), andhesharedthiswithLoos.Not only through his designs, but also in his writing, Loos became one of the few modern architects that passionately questioned and criticised his culture and society, especially during a time when architecture no longer adapted or fulfilled the primal instinct of every human being, to shelter himself (Le Corbusier,

1923; Sarnitz & Loos, 2022). Loos viewed Europe and Vienna as placeswheredifferenthistoricismstylesopposedthepractical and the modern. He believed a newculturewouldautomatically lead to a new architecture, and this evolution could only be achieved through rejection and reform (Sarnitz & Loos, 2022). Thus, from Chicago to Vienna, Wright’s and Loos’ work remained intentional and rooted in a new sense of space and principles, creating room for a dialogue between their careers andlegaciesinmodernarchitecture.

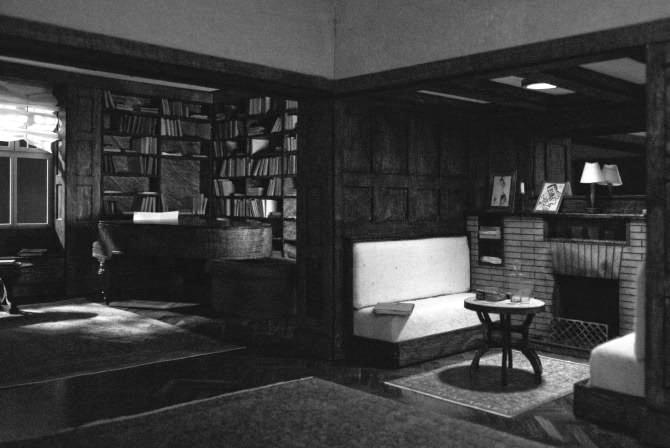

First, both developed a new centre of the house and intensified spatial contrasts. Loos’ primary concern was interior space. As seen in his Steiner House in Vienna, his interiors reflected the private character of the residents and became a cultural background for their togetherness. His Raumplan or “plan of volumes” promoted height differences according tothe room’s functions and dramatised movement through the house (Sarnitz & Loos, 2022; Risselada et al., 2008). Social areas had high ceilings, while recessed or intimate ones kept lower ceilings. Livingroomsanddiningtables,traditionallypositioned in the middle of the rooms, were shifted to the sides and along the walls, as well as fireplaces, window recesses, sideboards, and bookshelves. This created a free space in the center as the main room area where social activities were oriented(Risselada et al., 2008). Moreover, Loos’ windows serve mainly for lightingandnotforanoutsideview,contrarytoclassicalmodern architecture, as Loos considered urban living to be happening insidethehouse(Sarnitz&Loos,2022).

Likewise, in most of Wright’s Prairie houses, he kept a central element taller than the rest, often a double height area, that became the new heart of the house. These spaces became a mystical source of life within the home and central heating systems from where the other rooms andwingswouldextendto the ends. (Blake, 1969). Wright’s idea of the ‘utility-core’, where he centralised most services and systems for efficiency and flexibility, becameaninnovationtomodernarchitectureand aprecedentforhislaterpowerfulradialplans(Pfeiffer,2004).

Second, both boosted liberation from architectural limits and encouraged dynamism. After Loos’ stay in America, “the land of unlimited possibilities”, between 1893 and 1896, he returned to Vienna, criticising superficial ornamentation and

redefiningmodernlife(Sarnitz&Loos,2022).Whenquestioned about his work on the Turnowsky Apartment in Vienna and TristanTzaraHouseinParis,Loosrepliedthathisarchitectureis modern with a cultural understanding of flexibility and openness. “I love it when people arrange their furniture as they (not I) need” LooscommentedinhisessayOrnamentandCrime (1913) “it is completelynaturalandwholeheartedlyapprovingif they bring old paintings, beloved memories, things tasteful or tasteless. I design human interiors, not inhumane ones,”. He applied no restrictions on the occupants and allowed them to makehomestheirown(Sarnitz&Loos,2022).

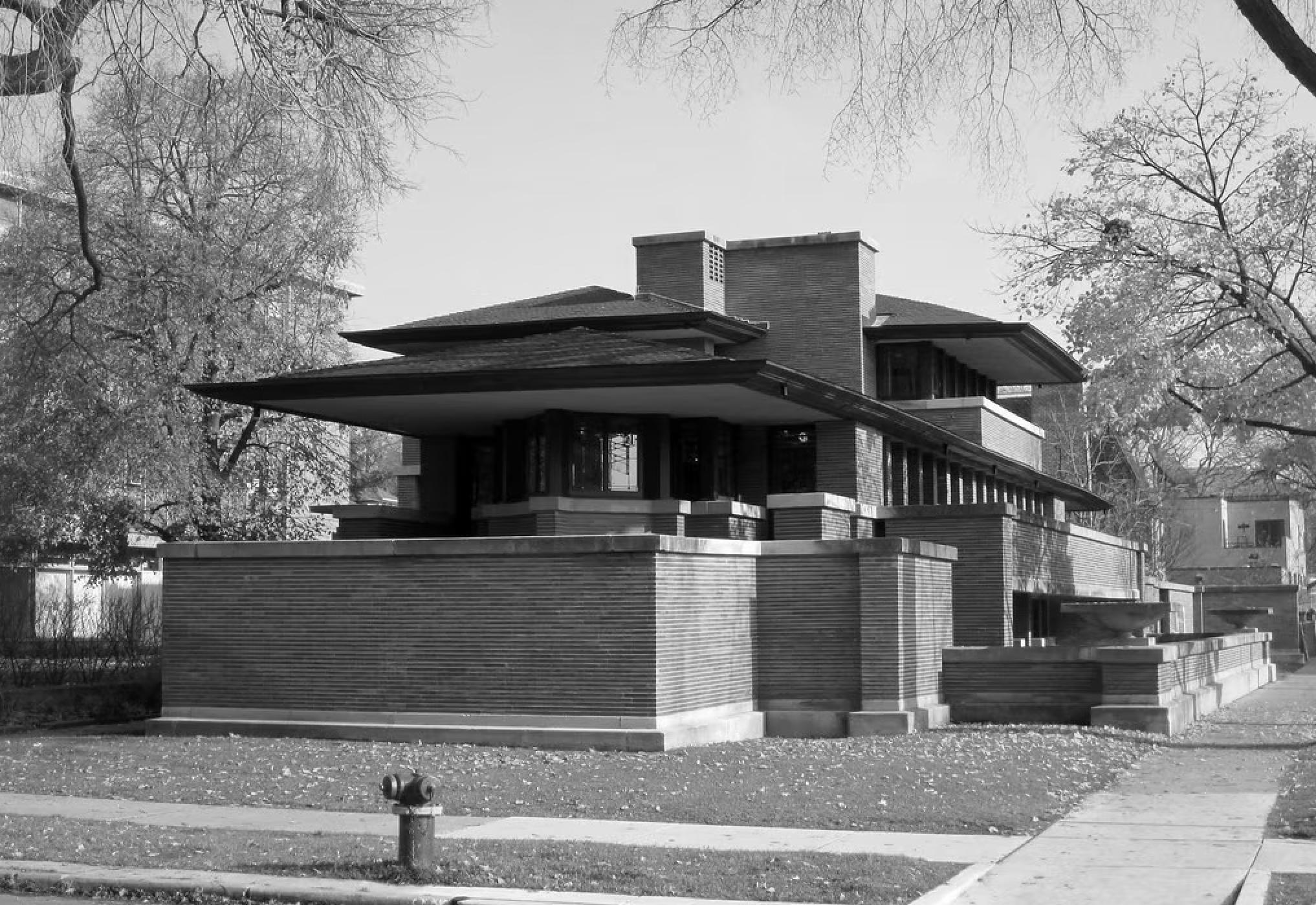

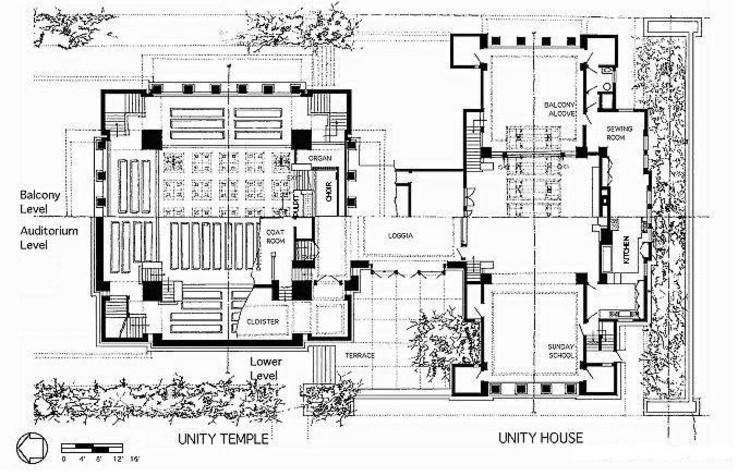

Similarly, Wright’s dismembering of the traditional box became one of the most critical architectural “discoveries” ever when the conventional concept of the room existed unchallenged. Through his residential work, Wright left symmetry behind and fostered a new dynamic and poetic asymmetry, as seen in his Winslow House and Robie House (Blake, 1969; Brooks, 1979). Furthermore, some of his later works such as the Larkin Building and the Unity Temple, influenced architecture atthebeginningofthetwentiethcentury With innovative plans, spatial organisation and geometric ornamentation, Wright achieved a new sense of freedom where the reality of the building no longer consisted of the walls and roofs, but the space within (Pfeiffer, 2004; Blake, 1969). It was in Unity Temple when, as Wright recalls, he achieved a new architecture that could be free. He called this “organic architecture” where the interior space drew closer to the landscape outside, and the distinction between exterior and interiorvanished(Pfeiffer,2004).

Third, bothhadaharmoniousapproachtonaturethrough naturalmaterialandexpansionwithinthelandscape.Throughout his childhood, Wright was immersed in music, poetry, literature andphilosophyathome,aswellasnature,workingathisuncle’s farm. He recalls these as his most formative years, which later profoundly influenced his principles and values(Pfeiffer,2004). As influenced by traditional Japanese architecture, Wright radically re-imagined the American home and architecture by following a dominant horizontal line rather than a vertical one, cultivating a life where man could be in harmony with nature ratherthanstandingaboveoragainstit(Blake,1969).

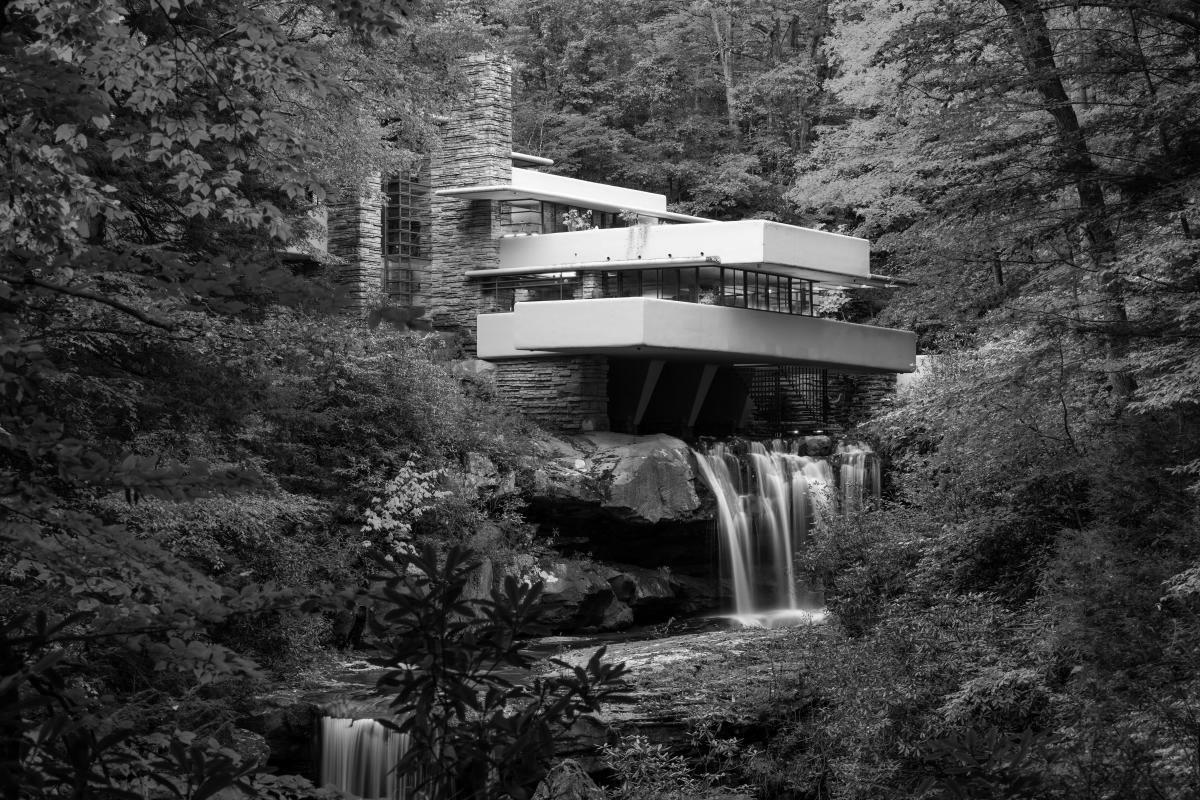

Through low proportions, broad overhangs, and gently sloping roofs in an extended horizontal line, Wright’s “earth-hugging prairie style” introduced a way to co-exist with the environment (Pfeiffer, 2004). His work blended into nature and accentuated its qualities as he had a deep consciousness of the landscape around him and its beauty worthy of recognition. His work Fallingwater, a private residence and weekend home for the Kaufmann family designed in 1935, was considered as “the best all-time work of American architecture” by the American Institute of Architects (Architectural Digest, 2024). He believed nature was the only body of God we see, therefore the closer man associated himself with nature, the greater his personal, spiritual and physical well-being (Brouce, 2024; Pfeiffer,2004).

Similarly, Loos felt a deep and respectful wonder of nature (Risselada et al., 2008). He believed the pleasure of natural material should replace theappreciationofornament.As seen in his Moller House, Villa Muller, and Khuner Country House across Europe, Loos opted for simple materials, such as natural stone and hardwood, showing their affective value in a moral sense rather than anaestheticone(Sarnitz&Loos,2022). This way and through his Raumplaun, Loos made spatial “luxury” available and affordable to anyoneindependentlyfrom high-quality construction materials and room sizes (Sarnitz & Loos,2022).

Similarly, Wright appreciated natural materials in a time when brick was plastered, wood was painted, and concrete was covered. In his Winslow House, one of his earlier residential works in 1893, materials were used in their pure state, keeping an elegant dignity not known in a time of ornamentation and overstatement(Pfeiffer,2004).

Ultimately, there is one more principle to consider between their work. Many of Wright’s renowned works had different forms, from suburban homes to churches, offices to skyscrapers. However, a strict loyalty and force remained consistent: human values. InWright’sbookATestament(1957), he describes humanity as the light of the world and recalls his aim for a more “humane” architecture throughout his career. Through his “organic architecture”, Wright’s work kept a continuous and integral harmony with humanity and its

environment. Designing buildings that could stand in time to their place and mankind, not mere fashion or style (Pfeiffer, 2004). Like Loos’ criticism of liberating society from impractical architecture, Wright aspired to elevate middle-class Americans and respond to their challenges through “humane” architecture, technology and romance (Sarnitz & Loos, 2022; Pfeiffer,2004).

In the article “Regarding Economy”, editor Bohuslav Markalous compiled some of his conversations withLoosabout his work. “Homes should never be finished”, he recalls, “they should be in constant motion and development, state of change, as man” (2008). Like Wright, Loos also reflected humanity in his work. He tore down the masks from facadesandkeptallthe richness in the interior (Risselada et al., 2008). This way, and through their modern work,botharchitectsintroducedsocietyto a new way of life in the face of rising large cities. For Wright, this meant cities and buildings that are healthy, humane, and harmonious. For Loos, this meant a cultural deconstruction, practicality,andintimacy

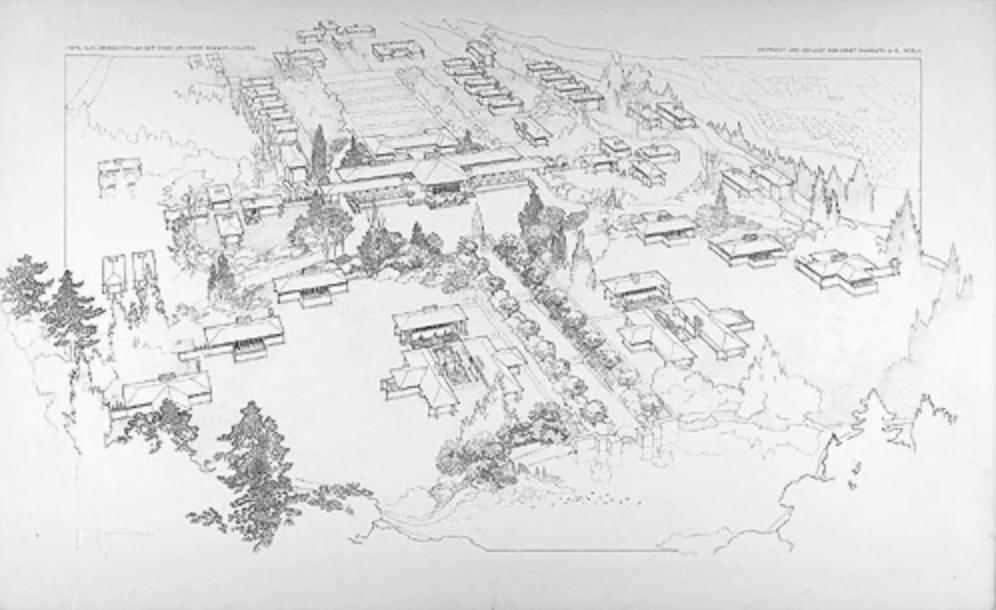

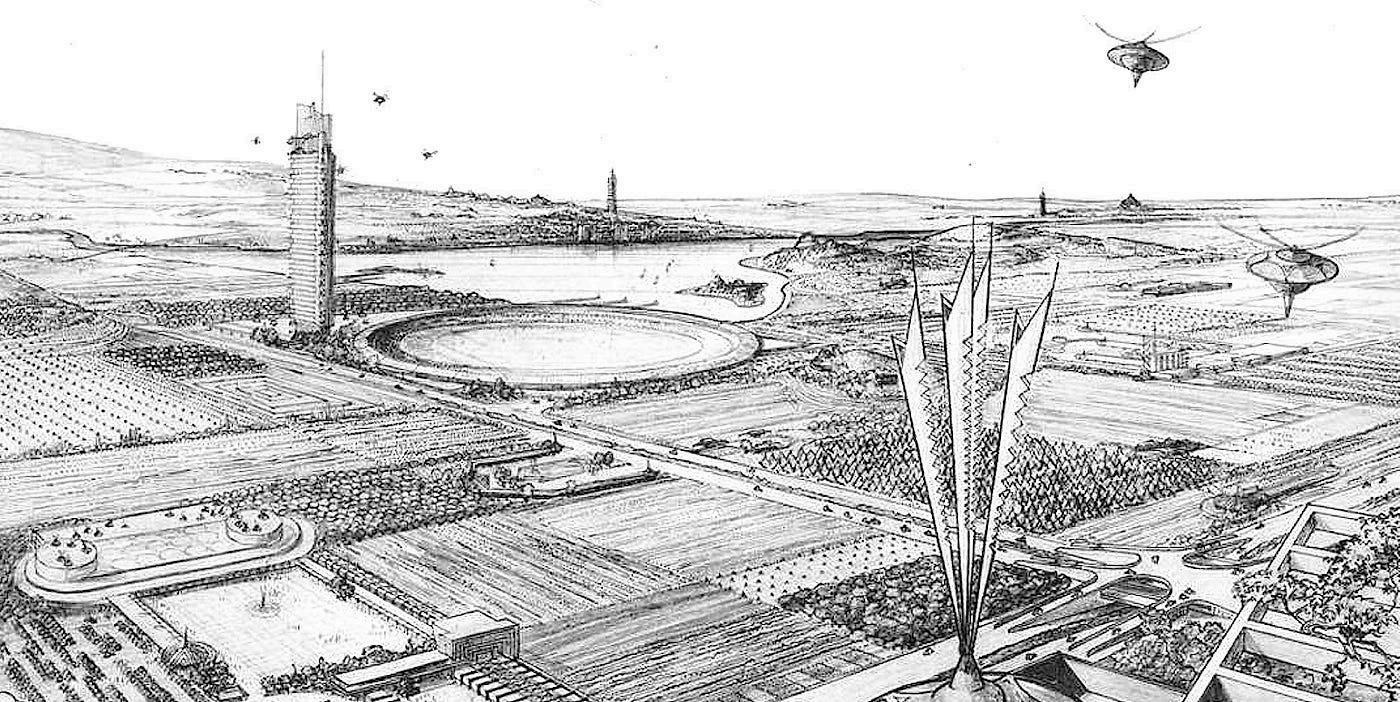

To conclude, one of Wright’slatestprojectsin1958,The Living City, consisted of a utopian solution to cities’ increasing unhealthy environment, crowdiness and imminent fall. Due the vast amount of land across America, his hypothetical was situated in the landscape of the countryside, surrounded rolling hills, expansive prairies, lakes, and rivers (Pfeif 2004). While Loosdidnothaveadetailedproposalforautopian city, his writing and work principles emphasised simplicity quality construction, and honesty. Despite the century between their work and now, one could tell their principles are timeless and still relevant to society nowadays. With efficient designs, affordable and functional housing, critique to consumerism,and sustainability, it is possible to face current local and global challenges and improve our ways of building. It is relevant to consider how modern architecture would benefit us in our time. Allinall,ifwearetomoveforward,wemustfirstlookback.

Bibliography

ArchitecturalDigest.“InsideOneofFrankLloydWright’sFinal-EverDesigns|UniqueSpaces| ArchitecturalDigest.” YouTube,16Jan.2024,www.youtube.com/watch?v=6L7NnZWeW-s.

Blake,P.(1969) Frank Lloyd Wright: Architecture and space.Baltimore,Md:PenguinBooks. Branscome,E.(2020).GivingVoicetoaBuilding:ACriticalAnalysisofAdolfLoos’sLandhaus Khuner ARENA Journal of Architectural Research,5(1).doi:https://doi.org/10.5334/ajar.186.

Brooks,H.A.(1979) Frank Lloyd Wright and the destruction of the box.JournaloftheSocietyof ArchitecturalHistorians,38(1),pp.7–14.doi:10.2307/989345.

Brownlow,M.(2024). The Loos House on Michaelerplatz.[online]www.visitingvienna.com.

Availableat:https://www.visitingvienna.com/sights/winter-palace/loos-house/.

ChiaraTestoni(2022). 10 Frank Lloyd Wright houses to visit in the United States [online] Domusweb.it.Availableat: https://www.domusweb.it/en/architecture/gallery/2022/03/22/from-prairies-to-usonia-10-frank-lloyd -wright-houses-to-visit-in-the-united-states.html [Accessed5Mar.2025].

LandmarksIllinois(n.d.). Unity Temple.[online]LandmarksIllinois.Availableat: https://www.landmarks.org/unity-temple/.

LeCorbusier(1923). Towards A New Architecture NewYork:Brewer,Warren&Putnam.

Loos,A.(1913) Ornament and Crime.TranslatedbyR.C.G.

Milnarik,E.(2018). William Winslow House and Stable.[online]SAHARCHIPEDIA.Availableat: https://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/IL-01-031-0097.

Perez,A.(2010a). AD Classics: Unity Temple / Frank Lloyd Wright [online]ArchDaily Available at:https://www.archdaily.com/64721/ad-classics-unity-temple-frank-lloyd-wright.

Perez,A.(2010). Gallery of AD Classics: Frederick C. Robie House / Frank Lloyd Wright - 6. [online]ArchDaily.Availableat:

https://www.archdaily.com/60246/ad-classics-frederick-c-robie-house-frank-lloyd-wright/5037de24 28ba0d599b0000a8-ad-classics-frederick-c-robie-house-frank-lloyd-wright-photo?next_project=no.

Pfeiffer,B.B.(2004). Frank Lloyd Wright, 1867-1959: building for democracy Köln;LosAngeles: Taschen.

Overstreet,K.(2020). Gallery of Adolf Loos and the Beginnings of European Modernism - 1. [online]ArchDaily.Availableat:

https://www.archdaily.com/972624/adolf-loos-and-the-beginnings-of-european-modernism/61a2af0 3f91c810572000002-adolf-loos-and-the-beginnings-of-european-modernism-photo.

Risseladaetal.(2008) Raumplan versus Plan libre : Adolf Loos/Le Corbusier Rev andupdated Englished..Rotterdam:010Publishers.

Sarnitz,A.andLoos,A.(2022) Adolf Loos, 1870-1933: Architect, cultural critic, dandy.Köln: Taschen.

Silvestre,B.(2024) Lecture 4: The Heroic Period of Modern Movement, Commonality and Difference in Interwar Europe. [Lecture] AR4005. Architecture starts with seeing. Kingston University.22October.

Steiner,D.(2025). Frank Lloyd Wright.[online]Steinerag.com.Availableat: http://www.steinerag.com/flw/Artifact%20Pages/PhRtS144wasmuth.htm [Accessed5Mar.2025].

StudioAdamCaruso(2024). Professor Adam Caruso - ETH Zürich [online]StudioA.Caruso. Availableat:https://caruso.arch.ethz.ch/news.

Wood,H.S.(2017). Rethinking Frank Lloyd Wright - Hannah Sloan Wood - Medium.[online] Medium.Availableat: https://woodhannah.medium.com/rethinking-frank-lloyd-wright-958e2897ad8b [Accessed5Mar. 2025].

Wright,F.L.(1932). An Autobiography: Frank Lloyd Wright.

Wright,F.L.(1957). A Testament.

* I acknowledge using Grammarly to improve my grammar and writing style, not to generate content for the essay