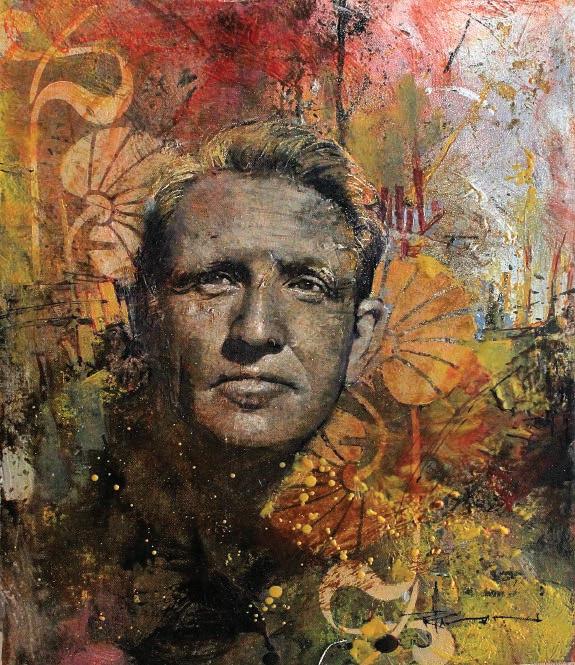

Robert Hagan

Copyright1 © Robert Hagan 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by reviewers, who may quote brief passages in a review.

ISBN2

Library of Congress Control Number _______________

Add any permissions and credits here, including: Permission to use material from other works

Credits for illustrations or photos

Credits for cover design and images [highly encouraged]

People who worked on your book, such as your editor, designer, proofreader, or indexer

Printed in ___country___

[Optional] Published by Publisher Name [if you have one]

[Optional] Physical address or email [encouraged so that others can get in touch to request permission to use passages from your book]

Visit your website URL here

INTRODUCTION

PART 1

1

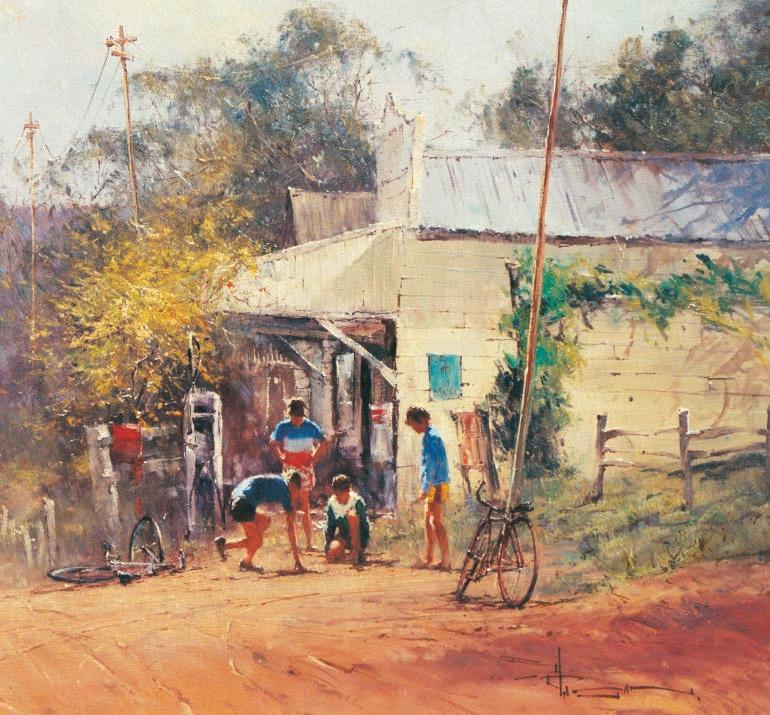

CHILDHOOD IDYLL ON THE BEACH Chapter 1 Absorbing Color and Shape with my Mother 4

PART 2

MY BOYHOOD ADVENTURES

Chapter 2 Mark Twain Would be Proud 22 Chapter 3 Rollin’ on the River 36 Chapter 4 Bananas, Runaway Trucks and Snakes! 48

PART 3

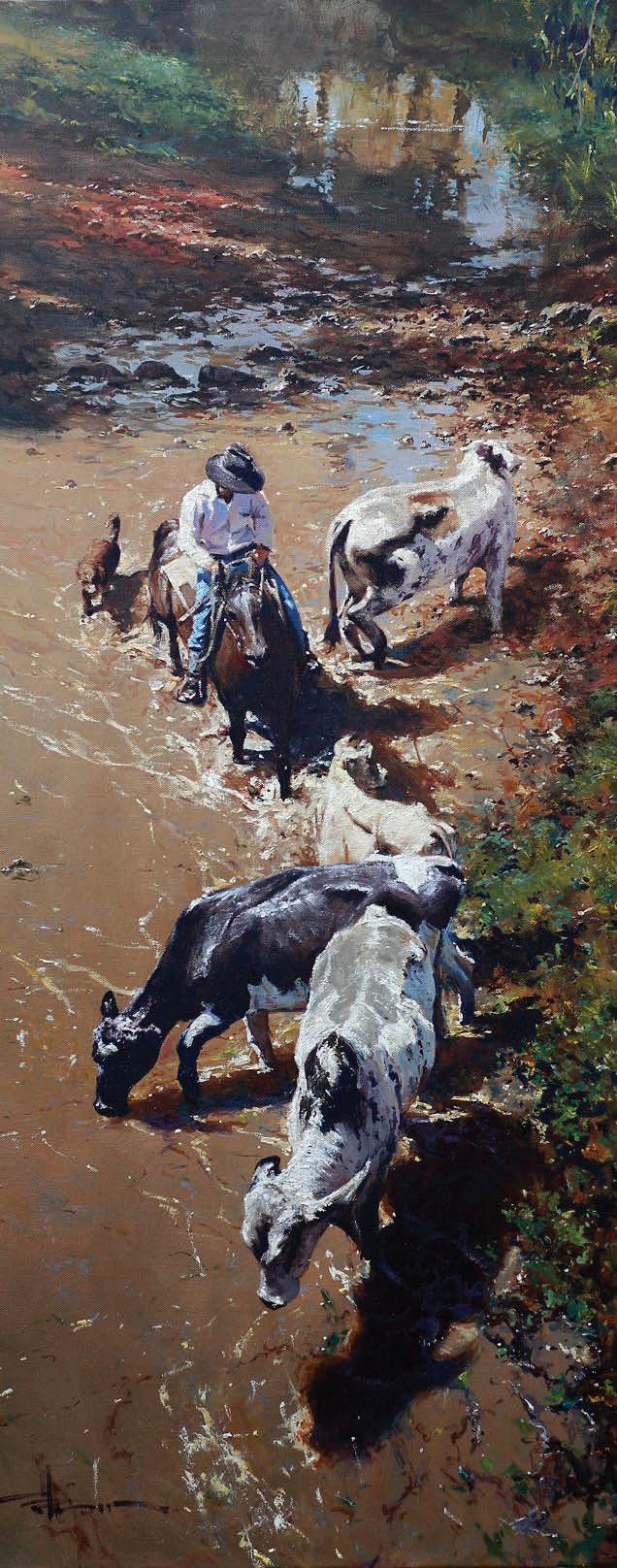

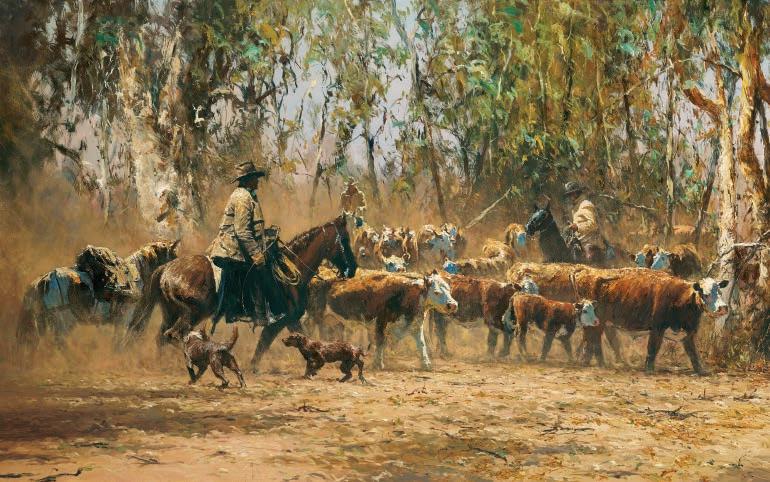

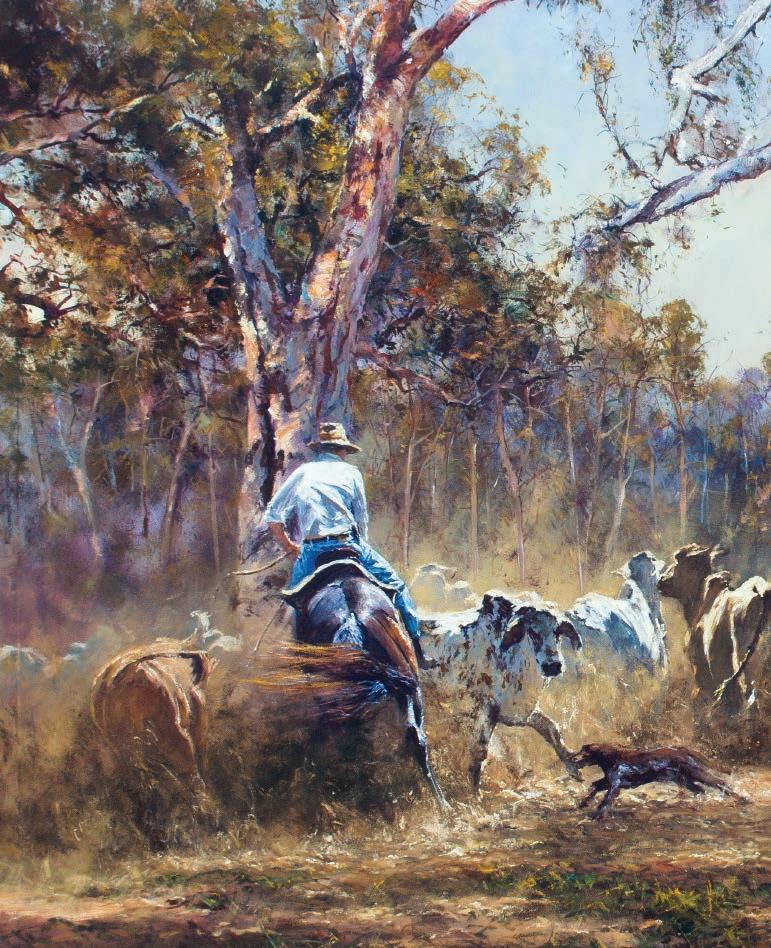

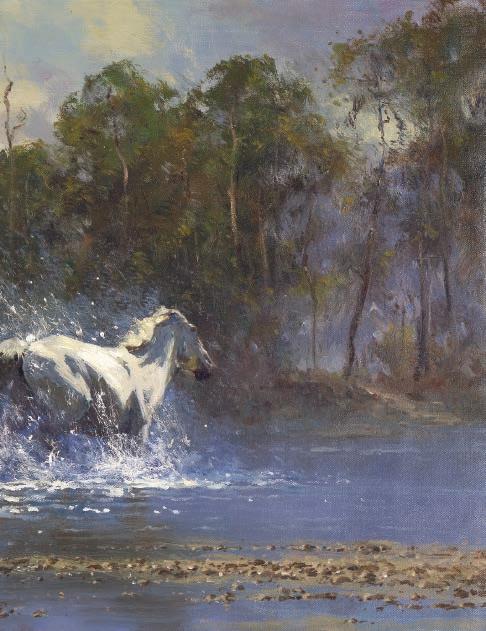

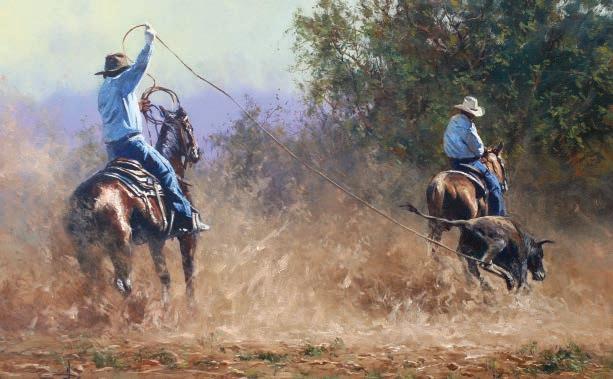

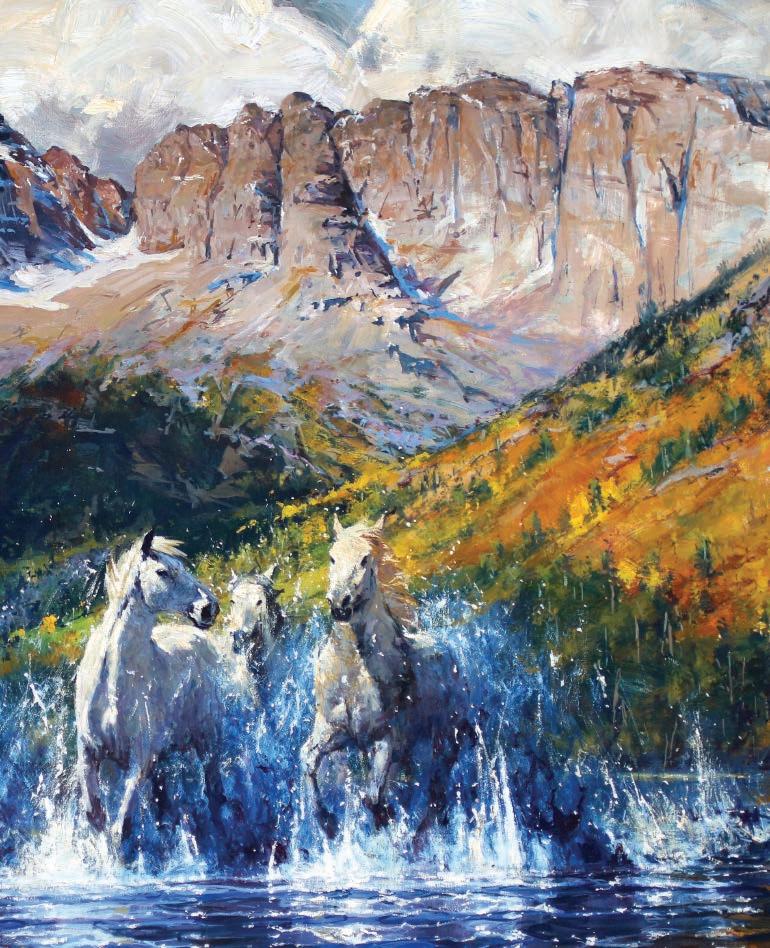

LEGENDARY AUSTRALIAN HORSEMEN Chapter 5 Cutting Cattle Aussie Style! 62 Chapter 6 Brumbies! Run Wild, Run Free 90

PART 4

AN EDUCATION AND AN ATTEMPT ON MY LIFE Chapter 7 School: A Wake-Up Call 110 Chapter 8 The Rail Boss Tried to Kill Me! 116

PART 5 CITY SLICKER BLUES Chapter 9 See You in Court, Hagan! 124 Chapter 10 Last Rites in the Burns Ward 136

PART 6

EXPLORING THE SOUL OF ART Chapter 11 In Search of My Artistic Honesty 140

CONTENTS

PART 7

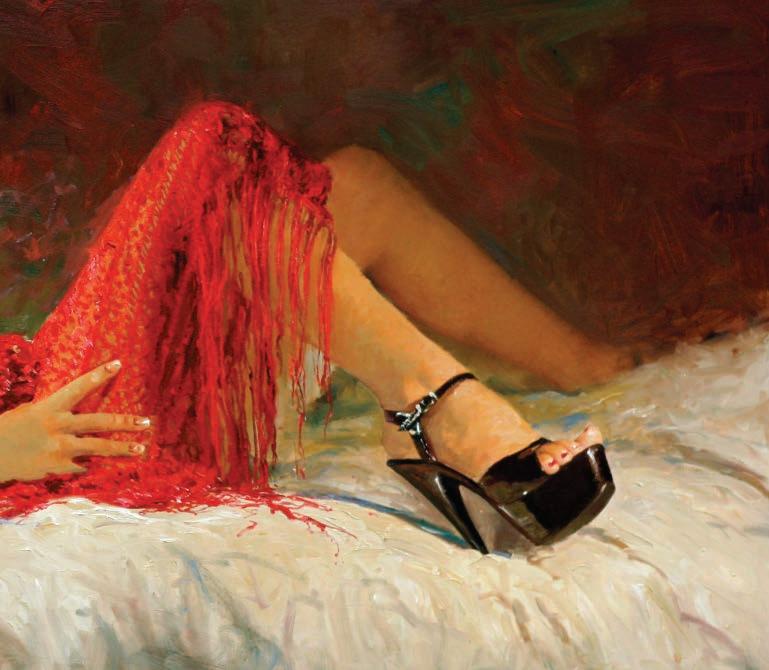

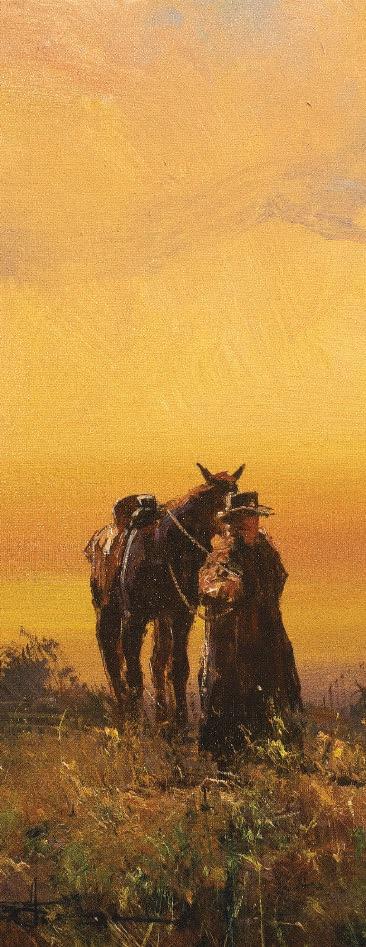

ROMANTIC FIGURES IN THE LANDSCAPE Chapter 12 Avoiding That “Stuck-On” Look 154

PART 8 RESURRECTION Chapter 13 A Car Crash: And I Get By with a Little Help from my Friends 192 Chapter 14 The Eighties Were a Dream 200

PART 9

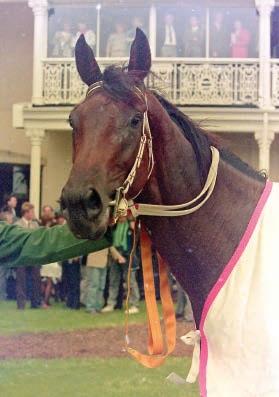

YACHT RACING MEETS HORSE RACING Chapter 15 The Americas Cup: Action at Sea 208 Chapter 16 Giddy-Up! I Go Racing! 214

PART 10

GIT ALONG LITTLE DAWGIES Chapter 17 222 I Go West! Chapter 18 Tatonka! The Power and Glory of Bison 282 Chapter 19 Mustangs and Mules! 310

PART 11 RESOLUTION Chapter 20 Where I Am Today 364

INTRODUCTION

Robert Hagan was born in Murwillumbah, New South Wales, Australia in 1947 and spent his robust childhood in and about the beautiful Tweed Valley.

Five years at Murwillumbah High School rewarded him with several concussions on the football field and a scholarship to Newcastle University. Four years later, he graduated with an Arts Degree in Economics and a Diploma in Education, which sent him off to teaching.

Robert married and divorced, taught high school in the rural regions and then moved to Sydney. His first exhibition in 1964 at the Woollahra Galleries, he says, largely unsuccessful.

His move to Sydney was horrendous. He suffered major burns to his body; had a serious car accident and had the dubious pleasure of “helping” put a stop to stock market short selling, when he was dragged before the Courts for doing exactly that thing.

At 28, he took a year off and “went Bush” trying to sort out the painting bug that he says “plagued him from childhood”.

At age 31, Hagan taught himself to paint. He recalls it being the most frustrating period ever. “I had no clue what I was doing and stubbornly sought no help whatsoever from anyone other than two great Australian artists from the past”.

His big breakthrough came on Sydney’s Freshwater Beach where he stood in anger after three years without have made progress. He made the simple observation that learning begins with the first step, not the fiftieth!

Robert says, “Nature is expressed in its simplest form at the seaside — sky, water and beach. I worked out that just three colours are needed to replicate it. Just three!”

He sold his first painting as a professional at a school charity art show for 150$. It was a beach scene with sky, water, sand and a fishing rod upright in the sand. After that, for two years he painted every sort of life and mood on the beach, especially kids fishing with dogs, seabirds and pelicans.

He bought a house in Harbord on the Sydney’s Northern Beaches, and then rented a cottage among the coconut trees on the beach in Thailand. He returned to Australia periodically, and also lived in the UK where he painted the different colors of the northern hemisphere.

His first book of paintings of Australia was published, and he had many sell-out exhibitions from 1980 to 1988 at premier galleries including the Noella Byrne Gallery in North Sydney and the Sydney Hilton. By this time, Robert was painting “just about everything.”

Robert married again and his first son, Joe, was born in 1985. The next year he was commissioned to paint some typical Australian scenes to hang in the office of the incoming Premier of New South Wales, Barrie Unsworth.

Seeking a new challenge, Robert threw his brushes at the America’s Cup battle taking place off Fremantle, Western Australia.

He bought part ownership in a racehorse called Research, which went on to become the Horse of the Year in 1989. He says he then became Father of the Year, when his second son, Graeme, was born.

Hagan moved to San Diego in 1991 to paint the America’s Cup battle and soon published his second book of Australian paintings. In 1995 he again painted the America’s Cup and won the one and only competition he ever entered — an International Maritime competition, held by the Mystic Seaport Museum, Connecticut.

By then Robert had established a presence in select US galleries; had two more books published in association with the International Artist Group; gave seminars on painting; was invited to judge art competitions in Los Angeles and continued with his own exhibitions. His paintings now included the Western genre.

On days when he was not painting, he fished in Mexico, lost golf balls and enjoyed the “Thank God It’s Friday” ritual at the pub.

In 1989 the Hagan family returned to Australia for his sons’ education. He returned to Australian-themed paintings and published another book, as well as delivering a number of instructional seminars.

He transitioned into making instructional videos, which in turn led to discussions on making a TV series about painting. A test video of his sons playing rugby turned into a 25minute pilot of Robert painting two girls in the “bush” using a selection of brushes, including a common household toilet brush! A friend from Channel 9 thought the pilot had some promise.

Hagan let that bake, while he went off to Thailand to build a hotel, but he returned to the film project and by 2005, with the help of his buddy from Channel 9, and some other “pretty clever” people with cameras and microphones, he had a pilot ready and entered it into the Moondance Film Festival in Hollywood. He won an award for the film and signed a contract with Discovery HD to produce ten 30minute travel-themed episodes about painting called Splash of Color for international screening. Afterwards, Hagan made more TV pilots aimed more at art than travel.

In 2017, Robert sold his business in Thailand and built a studio complex/ house and other facilities there in readiness to dive back into painting. He travelled to the USA and, after scaling some rugged terrain in Utah and chasing genuine cowboys around Kansas, he had a mountain of fantastic new material that set his passion for painting alight.

In January 2019, with unsettling images coming out of China, Hagan decided it was time to leave Thailand and move again, this time to the USA, where he says he is now painting better than ever. His two sons haven’t fallen far from the tree and he alerts us to watch out for another wave of Hagan art!

CHILDHOOD IDYLL ON THE BEACH

ABSORBING COLOR AND SHAPE WITH MY MOTHER

My brush with imagery began when I was a toddler playing beside my Mother in the warm waters and on the sandy spits that made up the estuary of the Brunswick, as it flowed to the Pacific Ocean.

North and south of this Big River’s mouthwere miles of white sandy beaches that were perfect for a young Robert learning to enjoy fishing and surfing.

My most vivid memory of that time was of the sun’s warmth, the feel of the sand, the blue sky and the brightness of the light.

I remember my Mother, with skirt somehow hitched up casting out her line and pulling in flapping, silvery whiting from the shallows around us. It was heaven. I felt totally safe and life was a wonderful adventure.

Memorizing color, shape and emotions

In retrospect, even as young as I was, I began to understand important lessons. My first “take” from those idyllic days on the beach, was the color of the sun, which I now know to be a light soft yellow, and of thin, glassy water, which I now know to be a very high key pastel blue.

It also struck me, as my Mother energetically swung her line over her head, that her figure made a triangle shape; I guess from how she tucked up her dress to avoid getting it wet. But that shape was planted in my head and, in painting, shape is important.

Then there was the color of her skin – a light gray tinted with pink. That color was embedded in my brain and it seems, for good reason.

The last take-away was, and is, the memory of the experience – a simple, daily adventure beside my Mother. k

Seeing with romantic eyes

My Mother’s close friend, Kit, would join her to fish and to while away the lazy hours. She helped oversee me at the same time. I can still visualize them chatting away together and adopting those special female poses that only women seem to be able to achieve.

It’s not hard to paint women when I have those memories to fall back on. Later in this book, I will reveal more about how I paint women. But, if you look into them, you will see that in these romantic works there is more softness in the color, in the play of tones and in the bleeding edges than in my other types of paintings.

They all involve water, with the midday sun ones having a dreamy passiveness about them; just as I experienced way back then, while sitting playing in the warm salty water.

“Summer’s Warmth”,

BOYHOOD ADVENTURES

MARK TWAIN WOULD BE PROUD

As I said in my Introduction, our family moved a lot. First, to the teacher’s residence in Main Arm, outside Mullumbimby, about 15 miles inland from idyllic Brunswick Heads. It was these years that made me who I am today.

This region was, and still is, undulating dairy and small-crop land, and the way of life was peaceful. But for me, then age six or so, this was Adventure Land. There were small creeks and hidden groves populated by colorful finches and enriched by the surprising flutter of bush quail. This was my introduction to wet, tropical bush in all its green, and more green, nature.

When I was nine, we moved to Chillingham and this is when things really got underway for me.

This little hamlet, at the base of Mount Warning, sits huddled in a narrow valley surrounded by steep hills draped in emerald green rainforest that was energetically drained by Rouse Creek — every boy’s dream place!

Chillingham boasted only 15 homes; a small butcher shop; general store; sawmill; trucking business and a community – wait for it – School of Arts! The town had just enough elements of urbanization to add

to a young boy’s understanding of complex living systems; but enough of Mother Nature’s gifts to make life a total, amazing adventure. In those days, this was Tarzan Country to me, with a bit of Dick Tracy, and even the Ponderosa, thrown in! A real mix, to say the very least, although today’s boys might be imagining Jumanji, Harry Potter or the Mandalorian!

With my fantasy land that I called Shanghai, a pocketful of small stones and Trigger, my black kelpie dog, by my side, I was Tarzan, ready to take on everything the rugged hills could throw at me.

Absorbing the color of weather

Beneath the shadow of Mount Warning the days were a mix of heat, humidity and afternoon thunderstorms — with vivid blue morning skies, a build-up of puffy white cumulus clouds at midday followed by a regenerating downpour of gray rain at three or four-o’clock in the afternoon.

After eight years living with this weather pattern, I accumulated some pretty intense mental pictures of what rain looks like and of the clouds in the startling blue skies. There were many, many images that imprinted themselves on me during these formative years. Those enduring memories form the basis of what, and to a lesser extent, how I paint. And, so, my passion for storytelling was born.

These stories were a conglomerate of nature and people.

Peaceful co-existence

With a population of only 40 people at the time, Chillingham was small enough for me to see how people differ, yet how they coexist; individual families working together for some sort of common good. My Father, as the teacher for the valley’s elementary youth, enjoyed a privileged position as the “go to” man for things of a written nature. For just about all the other residents, work meant farming and working the land. Those of us who have insight into that world know that it comes with a real understanding of life, and how it should be presented in paint.

For some, working the land meant logging the hills to feed the little sawmill or farming the bananas on the hillsides. For others, it meant packing the fruit into the boxes that came from the sawmill. Then the boxed bananas were trucked to the railhead in Murwillumbah for their long journey by train to Sydney.

During school breaks I worked in the banana industry and it certainly gave me some unique insights. For one thing, I quickly found I had to look carefully where I put my feet when clearing the trash from the base of the banana “stool” because this was where snakes like to hide, and a bare foot offers little protection from a pair of poison-laden fangs!

I lived with color all around me

Bananas are colorful. They sprout large, vivid green luxuriant leaves on their way to producing first green, then yellow bunches of fruit. As the leaves grow, they turn orange then brown to finally fall and collect at the base of the stool. With the leaf debris cleared away from the base the rich red volcanic soil is exposed.

As well as hoeing around banana plants, I helped the men cut and manage the banana bunches to the flying fox that shot them to the packing shed. I helped and watched — whether in the banana fields or on the beach, I was always gathering information. In retrospect, even as young as I was, I began to understand important lessons. I know I absorbed all the rich colors that bananas display due to the super fertile volcanic soil, plenty of sunlight and 70 inches of rain a year!

Lessons from Popsy the cow

I did other chores too. We had a family cow called Popsy and it was one of my many jobs to herd and milk her twice each day. She fed on the grass adjoining the road and would wander wherever her whim would take her.

Chillingham, being in an enclosed valley, was very cold in winter when the grass would be covered in frost. In my bare feet at 6 a.m. it was torture to walk along the dirt road and over the frigid grass to find and retrieve her. That being said, I gained an acute understanding of what a lifting early morning mist looks like, and how the subtle grays would become vivid colors a few hours later.

Popsy also taught me how a cow looks like, first while running then turning to charge at me, especially after she’d calved and was in protective mode. Later, I had no problem extrapolating that behavior into powerful, action-packed paintings of bulls.

My banana job was by the grace of George Chittick who, apart from fathering at least six children, had a mixed farm with a boundary that began beside the general store and ran way into the hills behind. I spent most of my boyhood on his farm. Besides working on the bananas in my holidays, I intermittently fed the pigs; rounded up the 50 or so cows; fed the chickens and picked the peas, beans and tomatoes on his river flats. I also rode the odd small bull, and at night I shot the rats in the barn as they scurried away from stealing grain from the bin to the safety of the darkened rafters.

My dog Trigger

I had great memories of boyhood that left indelible impressions on me, for instance roaming with my dog Trigger. He was a cross kelpie mixed with “something else”; but to a 10-year-old, his breeding meant nothing. He was my best mate and was by my side whenever I left the house. To this day I still have a dog.

The hills behind our house rose to a mountainous escarpment forming the remnant outer rim of a volcano, the core of which is Mount Warning. I basically lived in what’s left of a 20,000 foot volcano! This was serious Tarzan terrain and was where Trigger and I went exploring.

With all its rain, strong sunlight and rich red volcanic soil, anything would spring to life. The local joke was, you could stick a pencil in the ground and it would sprout.

In the pioneering days this was demanding cedar logging country and the folks who settled there were as rugged as the bullocks that they used for hauling out the massive logs — they were as tough as nails. The pioneers cleared the narrow alluvial river flats to make way for small-cropping. They selected eastward hill slopes for bananas and the land in-between for dairy cattle; but ninety per cent of the terrain was too tough and densely treed for farming.

There was cold, refreshing spring water bubbling out of holes in the ground; deep turquoise and green freshwater crayfish hiding in the mountain streams; macadamia nuts growing wild; red, blue and green rainbow lorikeets flashing above, while at my feet, just to keep me focused and alert, writhed some of Australia’s most poisonous snakes. Trigger was particularly on the lookout for them and although this was serious snake country, I wasn’t bitten once. It was a magic world!

After I was old enough for an air rifle, I counter-attacked the snakes as they found their way from their dark hideaways to the exposed, warm rounded rocks that broke up the gully beds. I would creep up as close as possible and “ping” them, and occasionally even got one. Pigeons also “went down” and were roughly cooked over a fire. Trigger was the operational ground force for retrieving the prey. He was multi-talented — hunter, stalk er, retriever, round-up dog and a reliable 2IC to me, but above all, he was a gifted fighter. He learned the hard way, fighting off seasoned pack farm dogs, which would ambush him when he or I strayed into their territory. But, at age six, he knew the tricks.

Big Red meets his match

One fight stands out as truly masterful. There was a red dog that had badly beaten Trigger a few times, taking off half his ear in one encounter, but Trigger was not fazed. There was a steep embankment in “our” territory that dropped down about 12 foot that Trigger had obviously studied and included in one of his many war strategies. That embankment was to prove pivotal and conclusive in his last encounter with Big Red. It was nasty, ferocious and bloody with not one inch given by either dog as they rolled and locked onto each other in a tangle to the death. At least, that’s what it seemed to me; but I knew I couldn’t do anything other than spectate and trust in Trigger’s fighting ability.

In the midst of snarling, biting and deadly jaw locks, Trigger very cleverly and skillfully moved the action towards the steep drop-off and, in one almighty body throw, slammed into Big Red and launched him into space off the embankment to crash onto the hard rocks below. With a gargled yelp Big Red struggled to his feet, emitted some more painful cries and limped off. Trigger stood proudly at the edge, wounded and in pain, but he barked a hero’s bark and returned to me for congratulatory support.

When you witness something like that, the memory of your dog’s ways stay with you forever. Although today I own a Pekinese, who clearly doesn’t have the form of Trigger, he does have commitment and undying loyalty to me — and in the end that is what matters.

So, just like bush horses, dogs have many ways of being our friends. The dogs that work cattle and sheep amaze me with their skill as they act upon the various nonsensical whistles and unintelligible yells from the farmer, only to masterfully round up and drive a herd into a pen half-a-mile away. My brother, David, man aged a sheep farm and while sitting solo on the back of a pick-up he could command his dogs to round up 600 sheep and drive them into a yard near the shearing shed. The dogs loved it. These memories are indelible.

... and so, my passion for storytelling was born.“Trigger Triumphs”, oil on canvas, 12” x 16”(31 x 41cm) “

ROLLIN’ ON THE RIVER

The local river was a magnet. I think my love of water in its many expressions comes from my activities in Chillingham and on the beach at Brunswick Heads. One was a stream and the other a sea, but both had so many moods.

As I said, afternoon thunderstorms were regular summer events, with the downpour hitting around 3-4 p.m. almost every day. 60 to 100 inches of rain a year is a lot of water for a small stream at the bottom of multiple interlocking hills to handle, especially during a short time. So if every boy’s dream is to build a canoe and run a flood, then that was right up my alley!

Running the flood

I used a sheet of old corrugated roofing iron; the end of a banana box; one cleat; a few nails and some tar scraped off the bitumen road — and that was all I needed to make a canoe. The cleat went at the front, the box end at the back and the corrugated sheet was folded and secured to both using nails. The tar was used as waterproofing to fill the gaps and, with Trigger barking from the sodden bank, I pushed off into the swirling water, instantly battling for control.

The stream would flood anywhere from 10 yards wide to a raging 40-50 yards wide. The current was seriously wild with whirlpools and rips at every bend. From where I entered the water, I had about 800 yards before the surging water would smash the canoe into the wooden bridge, so I had to bail before that, or be sucked under the water and likely not survive. So it was a “run the flood with consequences” if I didn’t get it right!

Sometimes, I encountered a flash flood with the water rising very quickly, adding more danger to an already dangerous adventure. At 1314 years of age, boys are reckless and daring and see everything as a challenge to be overcome. That was me. So off I went, paddling left then right to steer away from the banks and exposed trees that took the brunt of the brown current as it quickly swirled around the previous bend. I had a few close shaves, but whatever commonsense I had told me to bail out and swim when I could see the bridge looming too quickly for me to make it to the bank in the canoe. On those occasions a few days later I would find the canoe a mangled and twisted clump lodged ten feet up in a tree! But it was fantastic fun and very memorable.

In calmer times, the bridge over the stream was our diving board into our own “swimming pool”, and I spent many wonderful days with my mates as we launched ourselves off the bridge into the cool waters below and generally mucked around. (Sadly, the original wooden bridge is long gone, being replaced by a characterless concrete one.) We built rafts from logs shipwrecked on the banks or that had been pushed up against trees. We navigated the rapids on these rafts and generally tried to destroy them in the process.

There were sections of the river where the water was relatively still and deep with gentle aprons of grass on each side, and there were other sections compressed and fast flowing with steep banks on each side. Each configuration had its own rewards for adventurous boys.

Chillingham flood, 1954

Chillingham flood, 1954

Eyeballing a snake

Snakes often crossed the river and were an issue at times, especially when we were swimming or just paddling around nonchalantly. Once, I was quietly cooling off by ducking my head under the water and at the exact moment I lifted my head to the surface I saw a good-sized

black snake waddling its way across the water towards me and flashing his forked tongue, like traffic lights, as a signal for me to get out of the way. I complied by dropping back under the water, letting him pass quietly overhead.

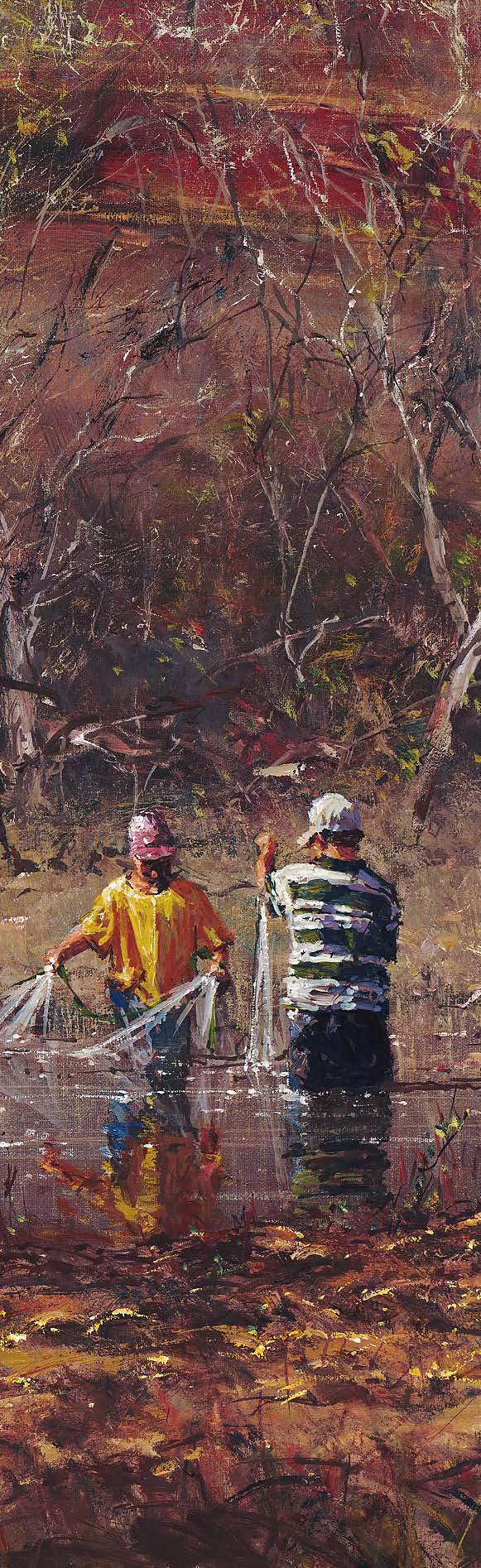

Explosive fishing!

In the deep holes there were perch, which are a delicious type of freshwater cod. They were very cunning, and hard to catch. No-one really mastered the technique of catching them, and yet they were quite plentiful. Local farmer, George, though, had a unique way

of bagging them. He would throw a stick of gelignite into the water, stunning the fish long enough to scoop up enough for a few dinners. It was pretty entertaining to watch and gave new meaning to the art of fishing.

Collecting river stones paid dividends

The river stones were rounded through attrition and during floods were swept downstream by the swollen currents. The bigger the flood the more the stones moved. Small ones had color; some yellow, some red; but the rarest color was blue. I took a fancy to these and after each flood would walk the sides of the stream, spot them and put them in my pocket. This became a hobby because they were unusual and rare. Over time I had a few boxfuls stored under the house.

One day, I noticed some visitors walking the stream banks, stopping to pick up stones and repeating the action. I approached one of them and asked what they were looking for. One of them showed me the blue stones in his bag, to which I told them I had boxes of them! One thing led to another and I ended up with 10 Australian Pounds in my pocket, which, at that time, was a bag full of money, and certainly more than the three shillings in wages that George gave me for working on the farm!

Wonderful waterfall

Of course, for an adventurous boy every river or stream must have a waterfall; preferably one that can accommodate a good jump or dive from height. And there was one on the nearby Limpingwood Road, about half a mile from the bridge or, to put it another way, eight minutes ride on my 24inch bicycle!

This waterfall was a real gem. I spent many hours lounging around on the rocky platforms above the falls only to jump into the refreshing rock pond ten feet below to cool off. I’ve returned there over the years and based a number of my paintings there.

. . . boys are reckless and daring and see everything as a challenge to be overcome. That was me.“Taking Aim”, oil on canvas, 30” x 24” (76 x 61cm) Circa 1991

BANANAS, RUNAWAY TRUCKS AND SNAKES

Iloved my boyhood time with farmer George and his family and the farming chaos that ensued. It was hard work but as funny as anything can be. George and his wife, Dorothy, seemed to manage the farm by default. Their only routine was set by the cows, which voluntarily headed to the milking shed at around 3 p.m. each day – something my Popsy failed to do!

The family house was big and sprawling with bedrooms off the center hallway. It also had a generous veranda along two sides that gave a view over the cultivated river flats and up to the partially forested hills. The verandah was partially sheltered by large trees and was the perfect place for George to sit and bark orders to anyone who came near him.

Car as chicken coop

I remember that every four or five years, George would buy a new Humber Super Snipe which, to the unknowing, was the best made-inEngland car (other than the Rolls Royce) that money could buy at the time. How he managed to afford this was beyond me, considering the daily bedlam of his farm.

After a few trips to town crammed full of banana boxes, this magnificent car was invariably left abandoned under the trees with its windows down to “keep it cool.” This, of course, was an irresistible invitation to all the chickens running free and it didn›t take long for them to take up roosting inside the car and leaving their “deposits” on the leather seats and burnished Elmwood finishes.

As a boy, these little things stayed in my head and provide a generous library of farm-based human stories on which to reflect.

Introducing . . . the back end of a horse

George had two huge brown draught horses with long manes and white socks that he intermittently hooked up to a plough or sled, or some other bit of equipment, to advance one of his farming projects. Eventually, instead of the horses, he bought a grey Ferguson tractor to use on the river flats. But, to my great satisfaction, he continued to harness the horses to the wooden sled to navigate the steep muddy climb up to the

banana plantation. I loved sitting on the roughly constructed sled and watch with wonder the massive, muscular, sweaty hindquarters of the horses in front as George navigated, with grunts and slaps of the reins, our way up the slippery bush track to the packing shed. As a ten-yearold then, that was what animal power was all about.

Tractor incoming!

As much as the horse images stuck in my head, so too did the demise of the tractor or, more accurately, one of them! George liked to park things where he left them so the tractor could be found anywhere, often hitched to a trailer.

Imagine this picture. As I said, the family house sat on top of a hill with the road to Chillingham encircling it and cut into the incline before arriving at the general store. One day, the tractor sat hitched to the trailer, with its grey fluted nose pointed at the road below. Acting under George’s yelled instructions from the verandah his farmhand, Slippery, unhitched the trailer. The instant he pulled the bolt, the tractor first inched forward, then picked up speed until its steely mass followed its gray nose plummeting down the hill in a perfectly straight line until it became airborne and crashed headlong onto the road below!

George’s yelling increased in tempo, volume and vernacular as his steel horse plunged to meet its end. Slippery returned verbal fire at George, waved his arms in the air and casually wandered off with his dog.

I remember so many funny, colorful and simple moments like this!

Go milk that bull, boy!

For instance, my first ride on a small bull. George liked to tease me; he was a natural joker who let life just wander by. He taught me how to milk a cow but first mischievously herded a bull into the stall for me to milk! Anyhow, I enjoyed my impromptu rides on the calves but progressing to a bigger bull was a step up for my 12 years. If the ground hadn’t been covered with a thick mattress of kikuyu grass that broke my fall, I reckon I would have been carted home with a very bruised rear end.

Learning to stay on a horse

George didn’t own riding horses but neighbor Rawson did and when I was 12 I learned to ride bareback. Lance Rawson, his son, was my schoolmate and he taught me everything he had gleaned from watching others work and ride horses. So, I learned on the run, and by accident!

Needless to say, I quickly found out a few things about horses that made me respect them. I rode bareback until I worked out the rhythm of the horse’s movements, and if the canter was bruising on the backside the gallop bounce was flirting with disaster.

Lance and I occasionally rode into the hills along cattle tracks, through bushy enclaves onto open paddocks and through the creek and stream beds.

Horses are power units with a disposition and a way of managing anyone on board. If they sense a novice they will play up and if you don’t know how to respond correctly, they will accelerate their displeasure to the bucking-off stage.

My early experience with horses only scratched the surface of what a relationship can be with them — as you will discover when, 30 years later, I bought part shares in a truly remarkable racehorse that wiped the floor with the rest of the field!

Backbreaking work in the fields

George’s farm had about 600 x 50 yards of river flats adjoining the creek of our valley that he would periodically plough and prepare for tomatoes, peas or beans. Irrigated, they would thrive under the hot summer sun. Picking and getting these to market was the problem. George had a hard time rounding up his family to help, since they knew how hard the work was and they preferred to do anything but that. So whenever he could round them up for free he did, but I was paid, as was every outsider who contributed their labor.

Bent over for five or six hours is truly backbreaking. The first to cave-in was usually George. Rarely sporting a shirt above the shorts that were tied in place with string, George had a remarkable torso. His overall color was a pink, turning to brown where there were clusters of freckles; but his entire upper body was covered in ginger hair, front and back! If it was a sight to behold way back then, but 40 years later, when I caught sight of him walking up the hill to the farmhouse, he was truly an even more remarkable spectacle! All George’s hair had grown longer and turned to a blond-white transforming him into the elusive Abominable Snowman.

Anyhow, back to the crops. When he tired, shortly after getting everyone to start picking, George would disappear among the rows of peas or whatever, only to be given away when an unexpected reddish mass breaking up the greens of the peas was spotted. It was George sprawled between the rows, fast asleep, obviously overburdened by the pressure of the multiple responsibilities of running the farm. The cash from the crops generally resulted in a new piece of farm equipment, so it all worked somehow.

'Digger' Brim’s truck

The Brims family owned the trucks that lumbered to the Murwillumbah train station every week laden to the hilt with boxes of bananas, and any other produce that needed shipping. Like most family trucking businesses, repairs, mechanical work and works-in-progress were done at the side, or behind, the main shed/garage. 'Digger' Brims and I must have been about 13, when we decided to try to fire up an old topless Whippet that had seen its best days well and truly many years earlier. 'Digger' reckoned it only needed some gas and a battery to get it going. It needed a bit more than that, but it eventually blasted into life, rocking and rolling spasmodically as a result of only four of its six cylinders working. It had tires with some air and, like George, its overall tint was ginger from the rust that had set in. With the steering wheel reduced to four spokes and using a few banana boxes as seats, we set off down a slope and onto the wet grassy flat beside the river. With a lot of spluttering, smoke and noise, and not much movement, we lurched forward back and forth, churning the grass and bogging the wheels in the wet soil until we hit a dry spot! Then for some reason, the other two cylinders decided to fire up just when Digger had his foot flat to the floorboards and the old Whippet took off like a rocket. My banana box went from under me, dumping me on the floor, while Digger held onto the wheel for grim life, but steering it straight into the river! And that was the end of the Whippet!

Camping out

During our ten years in Chillingham, until I was 16, for a change of scenery and to fish, we would occasionally pack up the car with camping and fishing gear and head to the coast, which was a good 90 minutes away.

The tent would be erected, stretcher beds opened, gas lamps made ready and the other paraphernalia put in place. There was Mother, Fa ther, my older brothers David and John, the youngest one, Laurie and, of course, Trigger.

There is nothing quite like walking along an open beach breathing fresh salty air with fishing rods in hand, a dog bounding around in front of you and the excitement of wondering what may end up on the hook. There is something very special about being part of a family and doing things together. Casting the line out over the waves, feeling the water splash to your waist, retreating to the beach and waiting with your finger on the line in anticipation of a bite, is universally special. Catching fish and cooking them in the early evening over a wood fire with the people most important to you adds meaning to being part of a family. The glow and crackle of a fire, the smell of freshly cooked fish and the general rawness of the occasion, made it into a Tarzan family adventure for me.

Recollections of these times are framed in the context of emotion, smell, and mood rather than shapes, color and contrast. That's why we need to paint what is in the back of our heads at times.

I am a captive of my experiences

There are many more stories I can tell; but the point is they all have relevance to what I do now each day as an artist. One way or another, most artists recount their own experiences in their art and I'm a captive of my experiences. In fact, I revisit them whenever I need inspiration so I never have issues wondering what to paint. I simply close my eyes and return to the library of moments stored in my head. If you look at my paintings, you will see all these elements of my life, but with other people as the actors.

LEGENDARY AUSTRALIAN HORSEMEN

CUTTING CATTLE AUSSIE STYLE!

Not all the best equine experiences take the form of trail-riding or horse racing.

A horse cutting cattle from a herd displays a different ability — sheer animal-to-animal instinct. The horse anticipates the movement and likely direction of the steer and cuts it off, forcing it to go where it should. The stockman performs a passive ballet, directing the exchange with leg and foot pressure. Amazing understandings take place between rider and animal.

If my paintings of men with horses have something special about them then I guess it comes from my unique time around them. As you will see, 30 years later my horse horizons were broadened when I bought a part share in a truly remarkable racehorse that wiped the floor with the rest of the field.

BRUMBIES! RUN WILD, RUN FREE

There is something powerful about the free spirit of the horse. Theirs is the nature of pure wildness, of free running with an air of tamelessness. The Brumbie epitomizes what we imagine freedom to be. Even when they are being rounded up in the treacherous Australian High Country, we see the fiery ballet between liberty and dominance; between stubbornness and the crack of the stockwhip. Brumbies embody the challenge of the wild. The free spirit of the horse is magnetic and is something I attempt to nurture in my paintings.

First, the narrative builds in my mind into a very real story and I paint to capture it in a tangible way. I am transported through familiarity to evoke the sights, sounds and smells of the environ ment; the bush-hardened muscles sculpted on precipitous slopes; the coarseness of manes and tails, the huffing and puffing through flared nostrils as they gallop at full charge in a mad dash away from their pursuers. All this fosters a potent connection that brings the vision to life — an image we all have in our minds of what it truly means to Run Wild, Run Free!

EDUCATION AND AN ATTEMPT ON MY LIFE

SCHOOL: A WAKE-UP CALL

School was more of a pain than a pleasure, but it had to be en dured for better or for worse. I was every bit an average student from elementary all the way thru to high school graduation. I had little incentive to do anything exceptional, so I did the bare minimum.

I was happy to remain unnoticed except on the rugby football field where my combat instincts went into overdrive – more on this else where in this chapter because I DID learn lessons playing rugby that stood me in good stead for the challenges in life that I faced and still face today.

So, truthfully, the only academic interest I had at school was in tech nical drawing which, to all intents and purposes, is really not that aca demic. I found drawing easy, and the need for exactness and three-di mensional thinking was exciting and refreshing. I consistently achieved top marks for this subject.

Art was part of the curriculum but I never took it up, not through lack of interest, it’s just that the opportunity never presented itself. I recall my brother David, who was five years older than me, returning home from college for the holidays and painting a very intriguing water color of the waterfall near Limpinwood. David did it on the spot and I was very impressed with its simplicity; the natural colors used and his attention to detail. He had brilliantly captured a scene that I knew

very well, and his painting sparked something in me. David made a few sketches of the waterfall, one of which I managed to find, and it is rep resented here.

David had painting in his veins and for a number of years had been sending drawings responding to an “Are you an Artist?” advertisement on the back of a monthly magazine. I hadn’t taken much notice of this diversion until he painted the watercolor. I was about 15 years old then and it did ignite something in me. Although painting never became part of my high school studies, it was something that was emerging in me, as we will see.

Wake-up, son!

My real challenge during high school came at the end of the final year. Until then I had achieved only the bare minimum results that allowed me to stay on. In fact, I was encouraged to leave school a number of times by both my Father and the school careers advisor.

As the final statewide exams loomed, I came to the realization that if I didn’t “pull my finger out” (as the expression goes), I might well be packing shelves in Woolworths for the rest of my life.

One teacher took me aside and told me quietly, but firmly, “Hagan, you have been sea-gulling your entire time here. Better wake up son!” “Hell,” I thought, “this is serious!” Coming second-last in class wasn’t going to be good enough. So, I sought advice on what to do from a teacher friend at another school. He said, “Time is short; you need to get the previous five years’ worth of exam papers and work out the topics most examined, then study them and hope you get questions on those!” Since I had done virtually nothing for five years, this was all news to me.

I skipped school for two months and instead spent my time in the town library, catching up on five years’ worth of indolence. I made my topic selections and prepared like crazy for those, and only those. A High-Risk Strategy!

When the exams came, I crossed my fingers that I would get questions on my five chosen topics. As luck would have it, I hit pay dirt across all subjects and went from almost last in the year to almost first! Phone-calls were made to my Father with mutterings to the effect that, there must be a mistake. There wasn’t. And after leaving school, I boarded the passenger section of the famous fruit train and travelled to Sydney armed with my results. I applied for a scholarship to Newcastle University. Which I got!

The beginning of my interest in art

I moved to Newcastle at 17 and boarded in a house that backed onto a coal train railway line, so I learned to sleep to the sounds, associated trembling and shudders of the coal hoppers as the trains rumbled past.

University was pretty boring and I fell back into my detached ways, preferring to do something else. That “something else” was the beginning of my interest in art. I began looking at things around me with one eye closed. In retrospect, I was flattening the scene to identify interesting interplays of color and unusual compositions. This advanced to me “boxing” the view with my fingers — framing the scene. I didn’t know where this was going, I just liked discovering different juxtapositions of shapes and colors.

During my first three months at university, I organized a truck to retrieve and bring to the house some tree trunk sections I saw on the roadside. I bought a hammer and chisel and started to chip away carving various head shapes. At the same time, I bought some raw tent canvas and oil paints and started fiddling with them. I knew nothing about surface preparation at the time, so the canvas just absorbed the paint, and I gave up.

For the next four years I did just enough to graduate and idled away my time at the pub. During holiday breaks I worked at the steel mill. I had one harrowing experience during this time however that made me think a little more deeply about life, as you will see in the next chapter.

It turns out, that to win you have to dig deep

The game of Rugby is a great teacher. From about age nine I played rugby for my school every Saturday in Murwillumbah and I enjoyed it. (I enjoyed even more consuming the after-game meat pie and malted milkshake in the Astral Cafe.) By the time I got to High School, I knew a bit about ball handling, running with it and tackling. I was a pretty aggressive, mongrel player or, to put it politely, I had a bit of Irish in me. I realized early on that to win one needs to dig deep. Our Team Coach immediately earmarked me for the role of hooker in the middle of the scrum, which was where a lot of the “biff” went on. He wrote in the School Yearbook that I showed courageous tackling and could be relied upon to intercept any player attempting to run the ball.

In rugby, the two opposing packs of forwards push and grunt their way to dominance and for possession of the ball, and when we got it, I hooked the ball back with my boots for our next attack. When a player on the other team got the ball, my job was to bring him down! Quite a bit of fighting went on and I spent considerable time on the sidelines after being sent off for some ungentlemanly infringement, or recovering from being knocked out by someone else’s ungentlemanly infringement! I finished high school with a few trophies for Best and Fairest, but I learned much more from Rugby.

My tenacity and willingness to put my head in places where most would not, nor should not, won me praise on the field of combat and went a long way to prepare me for the demands of turning myself into a worthwhile artist. No lessons, just pure determination to get it done, and to do whatever heavy lifting was required in the pursuit of turning five thousand brushstrokes into something, not just recognizable, but desirable. This is what struggling in the middle of the scrum, fighting for the ball and being knocked out a few times, prepared me for. Rugby taught me more about life than school.

I was a member of the 6.7 Team of thirteen-year-olds (measured by weight; in this case six stone seven pounds). We finished our season undefeated. After playing seven inter school games, only 11 points had been scored against us, while we managed to score 67.

One particular game stood out and was widely acknowledged as one of our school’s finest games. I will never forget it. We played highly rated, top shelf team, Woodlawn, at Ballina in unpleasant, rainy conditions on a soaked field. It was war right to the end. We charged headfirst into each other through the mud, with the determination to concede not one inch. The score was nil all after an hour and the game was abandoned just before full time.

I was at the age when the kind of gallantry, guts and determination needed to prevail at rugby stuck in my young head. Being undefeated is Big Tent stuff for young minds. I guess that’s why I find contact sports are best represented in the mud – because I know the feeling; it doesn’t come any harder. So, if school taught me anything, it was that life was not just about winning, it was about conquering.

That rugby game is going on in my head to this day.

THE RAIL BOSS TRIED TO KILL ME!

Tired of being a sweeper and conveyor belt cleaner at the steel mill, I sought work as a laborer on the upgrade of the TransAustralian railway. The money was good, I was young and I felt the exercise wouldn’t hurt. So off I went on a one-way ticket to Ivanhoe, in western New South Wales. A few kangaroos, plenty of rabbits and a variety of poisonous snakes and spiders inhabit this flat and barren scrub country. The original, and only, reason men went there at all was to search for gold, otherwise they just passed through on their way to somewhere better.

I got off the train at a small shed that served as the Ivanhoe railway station. It was a railhead with a dead line on which sat a few convert ed livable railcars around which were about 25 small, frail huts called humpies which were about 8 x 4 feet in area. A demountable served as the kitchen and Ivanhoe town (and the pub), were about a mile-and-ahalf away over the scrub country. I was assigned a hut and told to report to the demountable, ready to work, at five in the morning. The men were a collection of misfits and criminals overseen by the camp Supervisor, Ferdy who, I soon found out, was totally unstable; bordering on the insane. I don’t know whether the steel plate he had in his head had anything to do with it, but I thought whatever caused it possibly did.

I was put on an “extra” gang of anywhere between 20-30 men. We were transported to the worksite in the back of a truck.

Toiling on the railroad

My job was swinging a sledgehammer and knocking in the “dogs” that secured the steel rail to the sleepers supporting them. If your sledgehammer glanced off the dog, a slither of red-hot steel would fly off and, hopefully, not land in your socks or those of your sledge- ham mer partner! Being yelled at hastened my learning.

Daily temperatures reached around 110F, or more, but we had a target to complete each day before we could call it quits at about 6-7 p.m. so we worked about 12-14 hours a day, six days a week.

Returning to camp we were offered to opportunity to be dropped off at the Ivanhoe pub and walk home, or go directly to the compound. Most went to the pub, ate, drank too much and set off to camp over the scrub, falling over, arguing and, at times, fighting on the way. This scenario was repeated each day. It was unruly, basic and bordered on the primeval — and it nearly ended my life.

An incendiary shut-down

At Christmas, about six weeks into my stint there, the camp was temporarily downsized to six men, including me, and we were reassigned to fettler work. This meant running along the track in a mo torized trolley to spot and restore parts in need of repair.

On his way out of camp, Ferdy closed and locked down the demountable kitchen and disconnected the electricity so we were basically reduced to the existence of early man! This outrage prompted me to write a letter of complaint to the Commissioner of Railways in Sydney, outlining our predicament; after all, Christmas in Australia is high summer. I sent a copy of the letter to the newspapers, including our signatures.

About a week later, a cloud of dust slowly emerged from the distance, growing in volume as the vehicle responsible for it approached the camp. It pulled up and two well-attired men emerged and approached us asking for Robert Hagan. Being poorly dressed, but having manners, I declared myself to be that person and asked why they sought me. My letter was in their hand. We were told the power would be restored and the kitchen unlocked for us. With that, they returned to the car and disappeared in another cloud of brown dust.

The next day a handyman from Ivanhoe turned up to restore the power and remove the lock on the facilities, enabling us to return to civ ilized living. We were good for the next six days riding the rails, replacing sleepers and promptly getting off the track before the daily train roared over us.

Be careful, Bob!

Everything changed the afternoon Ferdy and the gang returned. Ferdy was sour and very moody, snarling at me when near and mutter ing under his breath. He was clearly extremely angry with me. One of the guys let slip that Ferdy and a few of his cronies “had it in for me” because of the letter and the heat he’d received from the bosses. “Be very careful, Bob”, he said.

I kept to myself the next day, swinging the sledgehammer in the sweltering heat and surviving another day. After two months I had become very fit, muscled and tanned and believed I was reasonably capable of handling myself in a fight, but not for what was coming my way!

On its way back to camp the truck dropped Ferdy and his boys off at the pub while the rest of us went on to camp. I cleaned up, ate and went to my humpy to retire. Half asleep, I heard a developing ruckus as the boys staggered and yelled as they approached camp. The humpies were lined up in rows about 10 feet apart and were basically a simple wooden frame with plywood sheeting, a tin roof and a small window and a door. The bed was very small and basic with the bedhead hard against the wall opposite the door.

The noise went on as the men passed by, continued for a bit then everything went silent. That is a little bit weird, I thought, but reckoned they had split and gone off to bed. Not so! I heard some muf fled noise and scraping and moved my head to one side of the pillow to listen more intently when the section of wall where my head had been an instant before, splintered apart from the blow of a pair of monstrous steel sleeper tongs! The heavy tongs missed my head by a fraction and if I had not moved, I would not be writing this today.

Making my escape

I leapt from my bed, threw open the door and ran behind the humpy, only to see two figures hastily disappear into the darkness. Thinking this may not be the end of the attack, I smartly gathered up my few belong ings and ran into the scrub. I could see a few lights go on at Ferdy’s train carriage as I headed towards the rail line and the little railway station that had been my original entry point. Beyond that was a small culvert where I took refuge and camped that night. The next day, I slipped out and jumped the daily train as it stopped momentarily on its way east to Sydney. A close shave!

You might wonder how this and the stories that follow have anything to do with my painting. Well as I said earlier, we are a product of our environment and experiences. This particular experience taught me to measure the landscape very well before acting. In painting terms, it means do your homework meticulously before taking up the brush. Know the subject if you want to avoid a pair of heavy tongs crashing into your skull!

The heavy tongs missed my head by a fraction...

SLICKER BLUES

SEE YOU IN COURT, HAGAN!

graduated from university in 1970 only to find myself in more trouble. How I survived my twenties I really don’t know. What I DO know is that the following events were pivotal to my becoming an artist with the determination, life experience and work ethic I have today.

My first mistake

In my last year of University, I brainstormed how to make money. At the time, the stock market was dominating the Australian news and millionaires were being made every day. I wondered if, perhaps, the market might offer an opening for me that would help things along, especially given how hard it had been to generate funds working on the railways! I thought, you can’t beat a pocketful of money to get a flying start in life! So, I found a phone-box, flipped through the phonebook, found the listing for the biggest stockbroker and made a call to buy and sell a few stocks. Without any security or screening, other than my name and address, my order was taken and I became part of the fren zied Wild West Stock Market, as it was then called!

Within a few weeks I had made A$30,000, mostly by choos ing the easiest way forward, which was to sell stock and then buy it back. Little did I know that, legally, I was skating on very thin ice! I had stumbled into what was then a very guarded and exclusive area of trading that was reserved for experienced and highly qualified

professional traders — and that was definitely not me! But my initial successes led me to make a very adventurous trade which, after the dust settled, resulted in the stockbroker being bloodied, my actions be ing referenced in a Royal Commission into the Securities and Exchange industry, and a few years later, my appearance in court.

I go before a judge

The court experience was memorable in a few unusual ways. Prior to appearing in the court-room the constabulary had to ensure I harbored no ill intent by way of weaponry on my person. They had me remove my watch and keys but allowed me to keep my false teeth in place!

Another notable variation from the norm came following my request to the judge to allow me to stay overnight in a place other than the officially designated holdover facility made of steel. “Where, then, would the defendant wish to stay?” asked the judge of my coun sel? I whispered, “Well, the Travelodge, top of town, would be nice, and it’s close-by”. The Crown was asked if it had any objection, and the prosecutor replied, “Well, no your honor. The defendant appears every time he is called”. So, I was given the okay to stay in a fancy hotel at the Crown’s expense for the duration of the trial instead of spending it in a cell. In a break from legalese, my counsel commented,

“Geez, that’s a new one”!

The result of the case was an adjustment to Australian trading laws and a firm slap on my wrist with instructions to behave myself! But it was the impending civil proceeding that had me in the hole for millions of dollars that sealed my move away from a regulation type life to one based on freelancing in the dark forest!

My top gun lawyer

My solicitor, after lamenting the situation I had gotten myself into and the steep challenge he faced to extricate me from the tangle, told me there was possibly one person only who had the skill to dull the crossfire coming my way and restore order to my heavily compromised existence. He was right. My Queen’s Counsel turned out to be brilliant.

“QCX” had been a shining star of the legal world and was heavily tipped to advance to the very top of that profession. Except, through a devastating tragedy he had lost his entire family and that caused him to spiral downwards into a lost life of alcohol abuse and indolence. By the time I navigated the liquor bottles cluttering the narrow staircase of his chambers to meet him, he had not donned his wig for at least three years. There was no secretary in the anteroom, nor did I think there ac tually was one, given the mountain of folders and files that had amassed on the furniture. I stood there and called if anyone was there. “Come in

here, son”, was the gravelly reply. “Push that stuff off the chair son. You know you’re in deep shit, don’t you?” — I nodded in agreement. “Go on, tell me your story then”, he asked. I managed to get what I could out, and must have tilted my head in an endearing way while doing so because the next day my solicitor told me I was extremely fortunate because “QCX” was going to take me on as his client. It seems “QCX” felt I had inadvertently and innocently wandered into an area of business that was infested with questionable practices and ethics and I was likely to be chewed up and spat out by the system. Thankfully, he saw it as a David and Goliath battle.

It was a pretty surprising moment for the Crown prosecuting team and the judge when “QCX” appeared in the courtroom wearing his disfigured, moth-eaten wig and announced that he would be defending me. So, the matter began and the press made sure the high-profile bro kerage house, and the young troublemaker being sued by them, were reported on and that the system was duly protected.

Eventually, the prosecuting team got what they wanted — an adjustment to Australian Exchange Law, and, over a beer in the nearby pub I was told it wasn’t personal, just something that had to be done! The backstories to all this are hilarious and eventful, to say the least, but that’s for another day!

Rediscovering art

Needless to say, after this costly defeat in court I had to make adjustments to my life plan. The trajectory I had set needed recalibrating, given the likelihood of my modest teaching wages being garnished for the next 100 years! But here’s where destiny called again. While waiting for the wheels of justice to crunch me up and spit me out, I was posted to teach at a great little country high school in Wauchope, NSW and it was there that I rediscovered my leaning towards art.

The land around Wauchope was given over to dairy farming, with some cattle raising, timber milling and, in the adjacent uplands, pota to farming thrown in. The area had farmhouses, barns, milking bails, old tractors and other farming paraphernalia sprinkled about. It was a bigger version of Chillingham with more Farmer George Chit ticks! Lucky for me it was a 25-minute drive to the beach and gave me the opportunity to reconnect with my earlier experiences that environment offered.

What happened there was important to me. Although I had just married and was as happy as a kid in a candy store, I was unsettled by the pending civil court case and its dire consequences to my/our future prospects. When that circumstance finally played out and the conse quences of my actions became clear to me, I asked myself if I could visu alize teaching for the rest of my life — and the answer was a resounding NO! Given that, I then asked myself, “What can you do then, Bob? What do you have that is special to you, AND that you like to do?”

The answer lay in front of me. I had a sketchpad with drawings of the farmhouses, barns and ploughs that I made in my free time, all from the immediate area and a few from the nearby beach. I had consciously drifted back into doodling with images and framing things of interest. I was just doing this as a sort of pastime/ hobby. I had no plan around it until then!

Art is your best way forward, mate

‘Shrubby’, one of my fellow teachers, told me his brother-in-law, Terry, was to stay a night on his way to Sydney and suggested, since he was a sort of arty-creative type, that a beer with him would be worth having. After a case or two of beer, first sitting then crashing prostrate under the “drinking tree”, it was confirmed by Terry that art was my best way forward.

Terry was a strong believer in instinct as the best star to follow and insisted I clear my backyard of the baggage and get to Sydney and make it work from there. I didn’t bother gathering up the sodden sketches the next day — I had greater things to do!

My first Sydney exhibition was a flop

These two events, the prospect of a zero future in the regular world combined with the resurgence of my art instinct, pointed me in a new direction, especially since my marriage had unfortunately fallen victim to the strain and bleakness of the court.

I was transferred to a Sydney school and, through Terry, had my first exhibition at the Woollarha Gallery with Les Burcher. Needless to say, even though a few did sell, it was mostly a flop.I had swapped my pencil for a common ballpoint pen using figure eight squiggles to sketch some pretty unexceptional images, while I poked a bit of oil paint around for some likewise basically nothing results. But I had made a start. Terry introduced me to his journalist mates and everyone agreed that I should push on! And so, I did.

Little did I know that, legally, I was skating on very thin ice!

LAST RITES IN THE BURNS WARD

Ipushed on with purpose and diligence until, one day, my house was engulfed in flames and I became a human torch!

They say dogs don’t understand time! Maybe it’s true, but an inspired artist working away with colors, brushes and some toxic fumes absolutely loses track of time. Five minutes becomes one hour; one hour is one day! It was only the smoke in the room that alerted me to the fire raging in the kitchen. So, on a hot New Year’s Day in 1975, I learned that it would have been far better for me to have smothered the flames, or deployed the contents of a fire extinguisher, instead of trying to manhandle a pot full of flaming oil off the stovetop though a spring-loaded insect screen door! Needless to say, the rush of incoming oxygen, and the quick snap back of the door, ended in my inheriting the full volume of the boiling oil over my partially covered body. I was nicely alight, from top to toe.

After my frantic yells for help, and some quick-thinking neighbors who called an ambulance, I found myself in hospital lying in a bath full of ice and enjoying the hallucinations of a powerful painkiller.

I had 30 per cent third-degree body burns with about 30 per cent second and first-degree burns, which together put me in a very precarious position that I might not survive.

A burns ward is not a happy place

There is a smell that permeates everything in a burns ward and, for their own wellbeing, nurses are rotated out of there after four weeks. Body bags outnumbered the survivors. After four days, even morphine couldn’t dull the intense pain as the burned areas returned to life — but

the areas that were just “meat” were worse. A priest came to my bed side and in a low, modulating voice recited the last rites. It seemed I was done for. I certainly felt that way — but being only 25, I was strong, with years of roaming the bush of Chilingham behind me to add that X factor!

I was very close to going out and at one stage actually wished I would, just so the pain would stop. At that instant I realized life really was a gift not to be taken lightly and that if I could somehow get through it, I would look very hard and fast at making sure I set my com pass on true North — and nothing else!

“Do or die, mate. Get out of here and get it right”, I said to myself.

Do or die!

After much skin grafting, applications of the miracle ointment silver sul fadiazine and daily bathing, my full body bandages were removed and I exited hospital in a wheelchair to, with great haste, renew my life challenge.

First, I had to learn to walk again and with a lot of rolling around in the ocean I came good. But not well enough to paint. So, it was back to teaching for me and the frustration of not having the opportunity to paint full time.

I did know what I wanted to do though and by no small measure.

THE SOUL OF ART

IN SEARCH OF MY ARTISTIC HONESTY

decided it was time to clip the edges of art and look into its soul. I spent time at the Art Gallery of New South Wales admiring, then trying to reverse engineer, the Australiana paintings that appealed to me. Having experienced how fragile life can be, after the fire and the car crash, I knew I had to sort out this bug in me — and fast.

Australian artist, Arthur Streeton’s works appealed to me be cause of the simplicity and certainty in his compositions; his insight into floating colors and tones and the unique tree shapes and topography that characterize his work. The Australian landscape was in my cross hairs.

Streeton’s work was the best. He used bold, yet measured strokes; colors that were exact in hue and value and a composition that commanded and challenged the passerby. Streeton was, and will forever be, the benchmark of what the Australian landscape looks like in paint. He got it between the eyes every time — his was a one-pass take. He was a rare talent indeed and so I, like most Australian artists starting out today, felt that everything began where he left off.

As well as Streeton, I was captivated by the exceptional works of another Australian artist, Norman Lindsay, particularly his robust yet sensitive sketches and his juicy oil paintings of voluptuous women in various role-plays. I wasn’t enamored so much of the narratives, more by how he engineered the outcome and his technical astuteness.

So, while teaching, I created the environment in which to paint in my spare time. I kept to myself and simply drove forward without a formal

structure yet hoping I could somehow make it all work.

I asked myself, why do people buy art? I went to art auctions thinking I would learn something about what motivated people to part with their hard-earned money in exchange for a bit of paint or pencil scratched onto a surface.

Searching for MY look

I went to a few art galleries, believing these would tell me more about the art market. I spent hours going nowhere. I was determined to do it basically alone and unaided. I had a belief in the back of my head that if I could learn in this way then whatever I came up with would be MY technique and MY look.

Years later, I am happy to say that has happened. I do have my own style of painting and way of interpreting the world but, I must admit I could have made it much easier on myself had I attended art classes!

In retrospect, I liken my learning to paint pathway to being seated in a dark room in front of a thing called a piano and being told to play Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata without ever having heard it before, nor ever having played the piano before. Painting is really that hard.

I ask, how on earth did Streeton and Gruner do it?

I must have been about 12 when I had my first inkling that I was maybe wired a bit differently from the other kids. No one gets sucked into a

particular painting, of all things, at that age, but I did.

The work was so real; its authenticity mesmerized me. Just a man sitting on a log at midday in the Australian landscape. Later, l was to learn the painting was Streeton’s, The Selector’s Hut

That painting was the first rocket to hit me!

What stunned me was that someone had somehow been able to capture a moment in time that gave meaning to this land and the Australian man on the land. It was the clear way he delivered the story that impacted me. The colors were not the colors around me then, but I had seen these colors in the Grafton, New South Wales area, so I knew they were RIGHT. And the single gum tree was RIGHT, as was its umbrella canopy. I had SEEN that tree. The woodcutter too was RIGHT because I had seen that man working elsewhere, on dairy farms and in the sawmill down the road. His clothes and hat were just RIGHT. At 12 years old, I was enamored of the story being told and puzzled that it was in paint!

That painting stayed in my head and resonated in that part of my brain that was unusually wired.

Later, I was to see more of Streeton’s works. Beach ones that were also dead right — just what I had seen while fishing and playing around the beaches on the New South Wales North Coast. Streeton brought the black and white photos of the day into color along with the life that was around me. He intrigued me and subliminally challenged me.

I wanted to try to do this, but my life’s trajectory was heading in the wrong direction. I needed to go right, but I was heading left. The far North Coast was all agriculture — few residents escaped the region. But when I landed my scholarship to Newcastle University and left on the banana train, I still carried in my head all the rich images of the life I had lived on the North Coast and those memories have served me to this day.

As you will read elsewhere, I faced a number of intersections in art — all of which had to do with chipping away at the bug I had in my head about the Streeton paintings. But it wasn’t until I went to the NSW Art Gallery in Sydney, that my wiring really powered up and began to steer my brain and feet in another direction.

And then there was Gruner too

The second rocket hit when I was standing in front of Elioth Gruner’s Spring Frost, totally consumed by its scenic perfection, the narrative and that bloody light . . . how . . . did . . .he . . .do . . . that? I knew I had to do

A tent, a gun and my materials

I became increasingly frustrated; finally decided to quit teaching and “go bush” to sort out this art bug once and for all.

I was living alone so had no hesitation about inflicting my problem on others; so, I would be the only one to suffer in the pursuit of au thenticity.

I drove off full of hope and excitement, to a place called Tabulum, inland from Casino on the far north coast of New South Wales. I had a tent, a gun and my equipment.

A year later, full of disappointment and even greater frustration, I threw in the towel and returned to teaching, convinced it was my lot in life, and told myself to forget about painting as the basis of my being

How in the hell could this be done? Two artists with dumbfounding ability doing the seemingly - at least from my position - impossible?“Just Sultry”, oil on canvas, 24” x 72” (61 x 183cm) Circa 2012

ROMANTIC FIGURES IN THE LANDSCAPE

AVOIDING THAT “STUCK ON” LOOK

This brings me to what I call romantic type paintings. As a mere male it is hard to project my thoughts into a scene of a young lady in jeans and t-shirt looking at some ducks floating around in a stream. If there IS a crossover of emotions in terms of what I would feel if I were her, then I think it would be purely accidental. But if she had a flowing pink dress with some frills and her hair was tied with ribbon and she was standing with a slight lean to her body and instead of farm ducks there were white swans, then my imagination would conjure up a storyline mostly based on my Mother and the few old movies I saw featuring women in a similar situation.

Since I never had a sister and was raised mostly in a bush village with few girls, my base from which to understand the young lady’s feelings, emotions and hopes is very slim indeed. As a result, I tend to be rather narrow in the way I paint women, depicting them in a very old-worldly, celebratory way; I guess in the image of my Mother. Images gleaned from toddler Bob’s memories!

I avoid showing their faces; preferring to see the head turned slightly away, and the hair, touched with a ray of sunlight, stirring the need to see her expression while at the same time camouflaging my shortcoming.

So, my paintings today are still very much who I was and how I felt back then but, I must confess, I really haven’t learned much more about women since then. On the flip side though, by not declaring any knowledge of female psychology and, minimizing the painting situations I could put women in, I’m staying safe from the crossfire I would otherwise surely get.

As I mentioned previously in this book, if you look into these ro mantic paintings of women, you will see a softness in the color and more play of tones and bleeding of edges than in my other types of paintings. They all involve water with the midday sunny ones having a dreamy pas siveness about them; much as young Robert experienced sitting in the warm salty water way back then. I guess I learned enough then to do just enough to bring the viewer into my world without turning on the light to show them what they saw.

Integrating the figure

There’s a huge engineering gap between painting a figure in the landscape and painting a landscape with a figure. That both require an ability to faithfully represent the shape is a given; it’s in knowing how to integrate the figure so that it avoids that dreadful “stuck-on” look that is crucial!

Those who paint the landscape with a figure are generally preoc cupied with the nuances of a producing a good landscape painting. The figure is dropped in after much of this tedious work is done and, in order to protect all that hard work and not clash or disturb it, the figure is kept small relative to the painting. So the landscape controls the figure. Whereas, I bang in the landscape first, wipe away the area for the fig ure, then rough it in showing its highest and lowest values. The painting evolves from there — moving from figure to setting and vice versa.

An explanation

The integration process involves a step-by-step strategy. There are setting and subject elements. The setting elements go in first and are left at their middle value. The subject elements go in next and they are left at their middle values as well. From then on, all elements are advanced simultaneously in color and value to the end. Eventually, the greatest variation in both mass and value are displayed in the SUBJECT, leading to an orderly finish to the painting.

The importance of drawing

I was born with some natural ability to draw. I can’ t cartoon draw — that ’s a different skill again! I place a mental grid over the image I ’ m copying and simply follow the image where it crosses the grid boxes. It ’s a case of practice and it can be learnt but it is important to get the shape right.

Successful self-education is predicated on a huge dose of tenacity, self-belief and patience. I chose this way, thinking that as it’s mostly a trial and error process I would find my own way of painting. After 40 years of painting professionally it seems to have worked!

Successful self-education is predicated on a huge dose of tenacity, self-belief and patience.

RESSURECTION

CRASH . . . AND I GET BY WITH A LITTLE HELP FROM MY FRIENDS!

Then, at 12.30 a.m. on Wednesday March 16th, 1978 I woke from an unconscious state to bright lights and the whirling sound of helicopter blades hovering overhead. My little 190 SL sportscar was a wreck, and the lady who’d been with me was somehow not in the passenger seat.

The Cahill Expressway heading north out of the Sydney CBD and leading onto the Harbor Bridge is a two-lane tunnel, the road carving a semi-circle, both lanes heading in the same direction. My companion and I had been enjoying an evening of song and dance with the car’s top down allowing the refreshing night air in our faces, when we were suddenly confronted by the headlights of a car coming straight at us in the wrong direction around the curve! The inevitable collision happened and we wound up in hospital.

There has to be something to fate — the first time that a head-on collision was to happen in the one-way Cahill Expressway tunnel had it had to involve me!

X-rays show a cracked skull and, judging by the multiple images I could see while my brain was trying desperately to focus, the diagnosis was that all was not well upstairs.

A slow recovery, accompanied by a slide into uncertainty and negativity, called an end to teaching, and any other type of work, for a time but, oddly, it provided me another circumstance in which I could return to painting.

Unlocking the secrets to my art

After the Cahill Tunnel accident, I endured a three-year harrowing time before I had the opportunity to paint. My visits to doctors, neurosurgeons, psychiatrists and lawyers, culminated in a highrisk showdown scarily similar to the movie, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest.