CRITICAL REVIEW OF PRACTICE

ROBERT DAVIES

ROBERT DAVIES

PHO720 INFORMING CONTEXTS

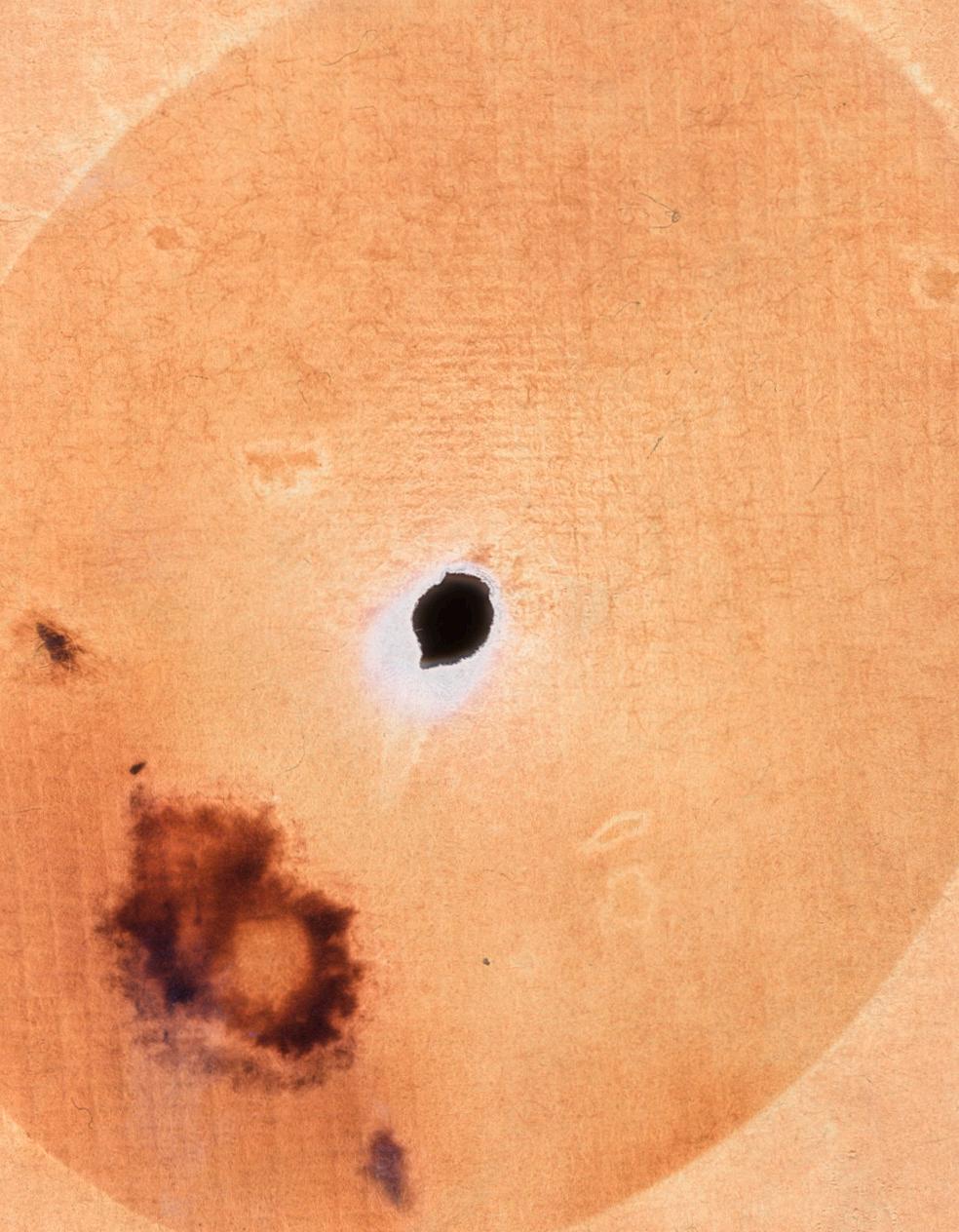

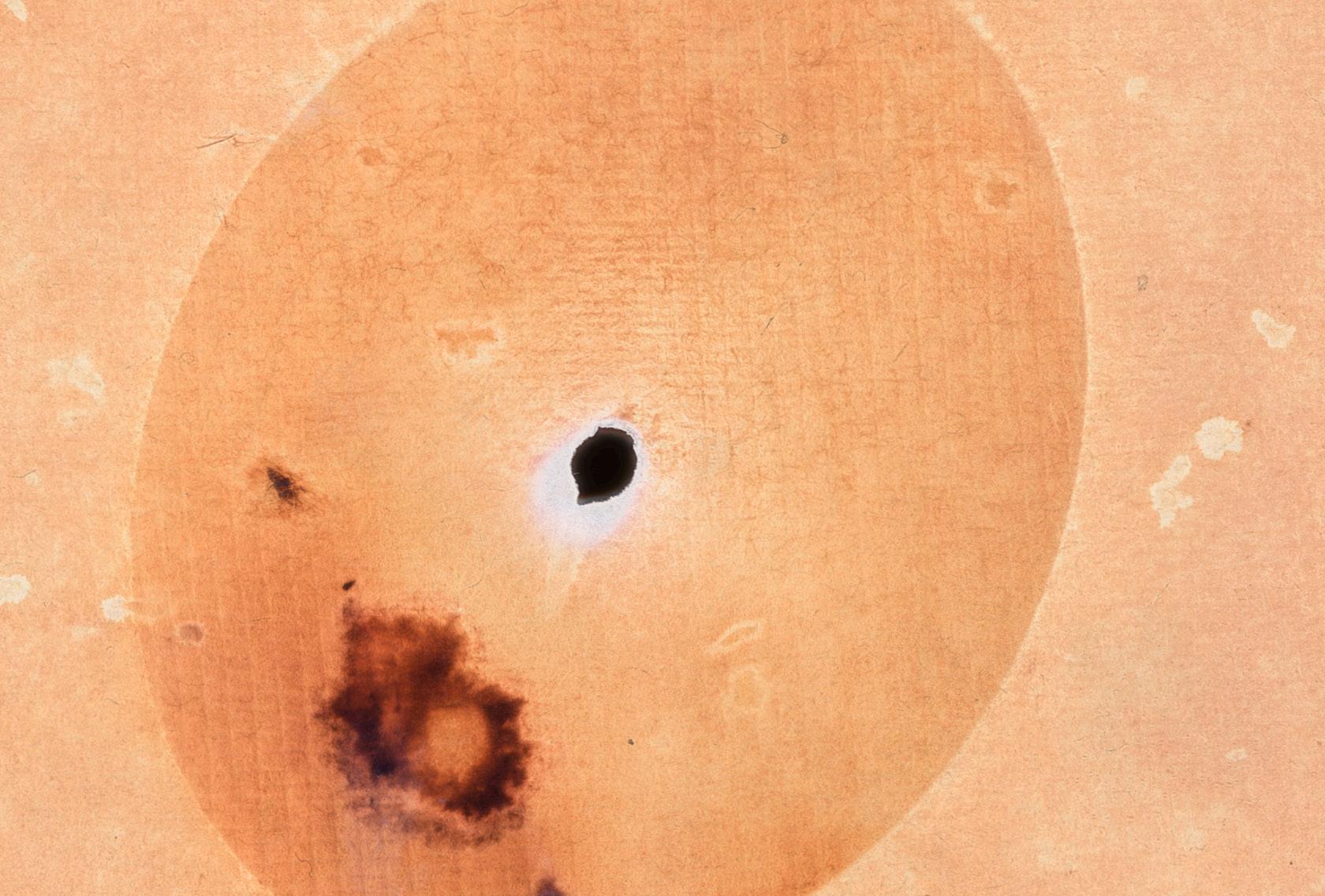

Fig.1: Davies 2023. Three hundred seconds in the sun. Cyanotype, reversed.INTENTIONS AND INSPIRATIONS

The title of my latest project Climagrams (Fig. 2) is inspired by the terminology used for various techniques and processes in cameraless photography such as ‘chemigrams’, ‘photograms’ and ‘luminograms’ (amongst many others). The climagram is also a tool widely used in meteorology to represent variables such as rainfall, temperature, and sunshine duration and therefore an apt title for a project seeking to artistically record the impact of changing climatic conditions on our planet.

By de-privileging modern day photographic apparatus, my intent is to use cameraless and lensless techniques1 to explore a photographic style freed from its “traditional subservient role as a realistic mode of representation and allowed instead to become a searing index of its own operations, to become an art of the real” (Batchen 2016: 5). I believe both the physicality and uniqueness of the photographs this genre creates will represent the very ‘real’ impact changing climatic conditions are having on our un-reproducible planet.

1. Whilst the majority of work in this project is cameraless, I did explore crude ‘lenless’ apparatus in my research.

As curator John Szarkowski said of a chemigram exhibited at the exhibition ‘A European Experiment’: “the prints are conceived as unique or semi-unique objects, rather than as the copy for mass reproductions; they are not to be regarded as windows on the world, but rather as small bits of the world itself, with their own colour and texture and shape and provenance” (Szarkowski 1967).

Concepts and theories surrounding the cameraless medium appear to have “often been subordinated or seen as marginal” (Barnes, 2018:8). This has provided me the opportunity to investigate practically and theoretically it’s significance as a genre. Using crude apparatus and various light-sensitive surfaces, my intent is to provide nature with a canvas to record itself and demonstrate that unlike the photographic negative, the Earth is not something we can make another copy from.

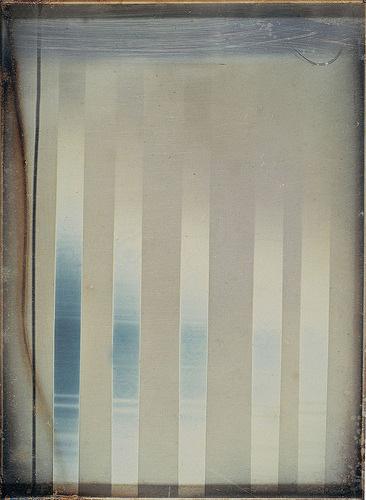

My attempt to record the climate photographically is an exploration of the relationship between science and nature, inspired by the early pioneers of photography which was “From the time of its invention…imagined as both an object of science…and a powerfully modern tool for scientific observation” (Keller 2009:20). Whilst the early calotypes of William Henry Fox Talbot and cyanotypes of John Herschel have been well documented, I have

been also been inspired by more marginal figures in photography’s history such as the French physicist Leon Foucault who collaborated with physician Armand Hippolyte Fizeau in 1844 to try and photograph light itself (Fig.4). In order to do this, they carefully exposed a silvered daguerreotype plate to three different kinds of light for different periods of time in an effort to measure their respective densities. What we see is a daguerreotype reduced to a graph, “to a picture of nothing–of nothing, that is but its own capacity to represent anything” (Batchen 2016:13). These photographs are a direct trace of their referent. What is depicted in the image, was, and is, simultaneously. Most photographs made by use of a camera will typically be a copy of their referent; the image that is captured was there, and relies upon something having been there even if non-representational. As Barthes famously said, the photograph is the “thathas-been” (Barthes 1993:77). However, with the cameraless photograph this changes; the images recorded are invisible to the eye but brought to light through the process of photographic materials and chemicals. The image shown did not exist as such, but through the magic of chemistry the photograph becomes a reality, “an emanation of that world, rather than it’s copy” (Batchen 2016: 47).

My methodology has become increasingly experimental in producing Climagrams. Throughout history, artists have been compelled to experiment in order to stumble on new genres, approaches or styles in the quest for the creation of something truly new. Inspired by photographic artists such as Barbara Kasten, who added inks as a stain or wash to create shimmering, hybrid surfaces in her Photogenic Paintings (fig.5), I have employed a range of techniques such as mixing cyanotype solutions with acrylic ink and thickening agents to retard development and therefore record longer durations of the weather over time.

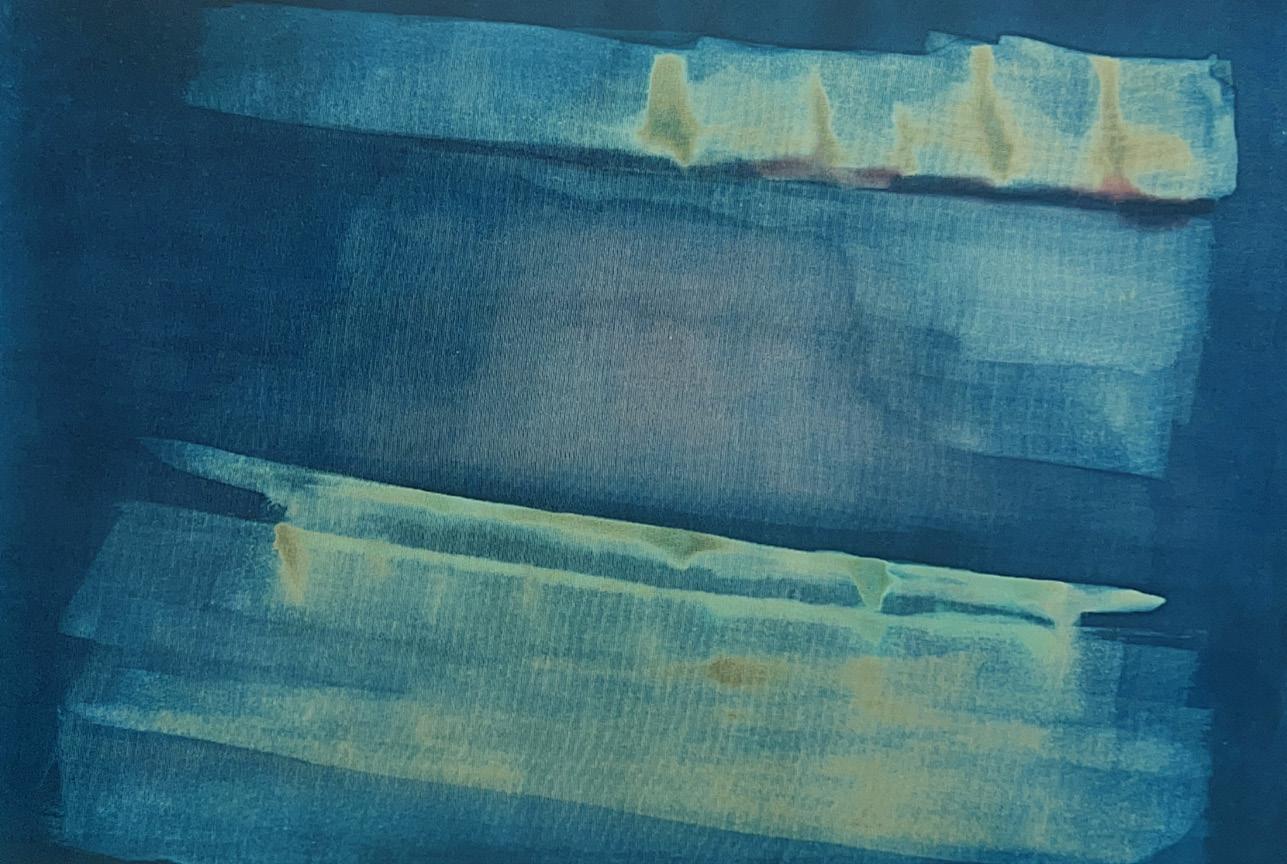

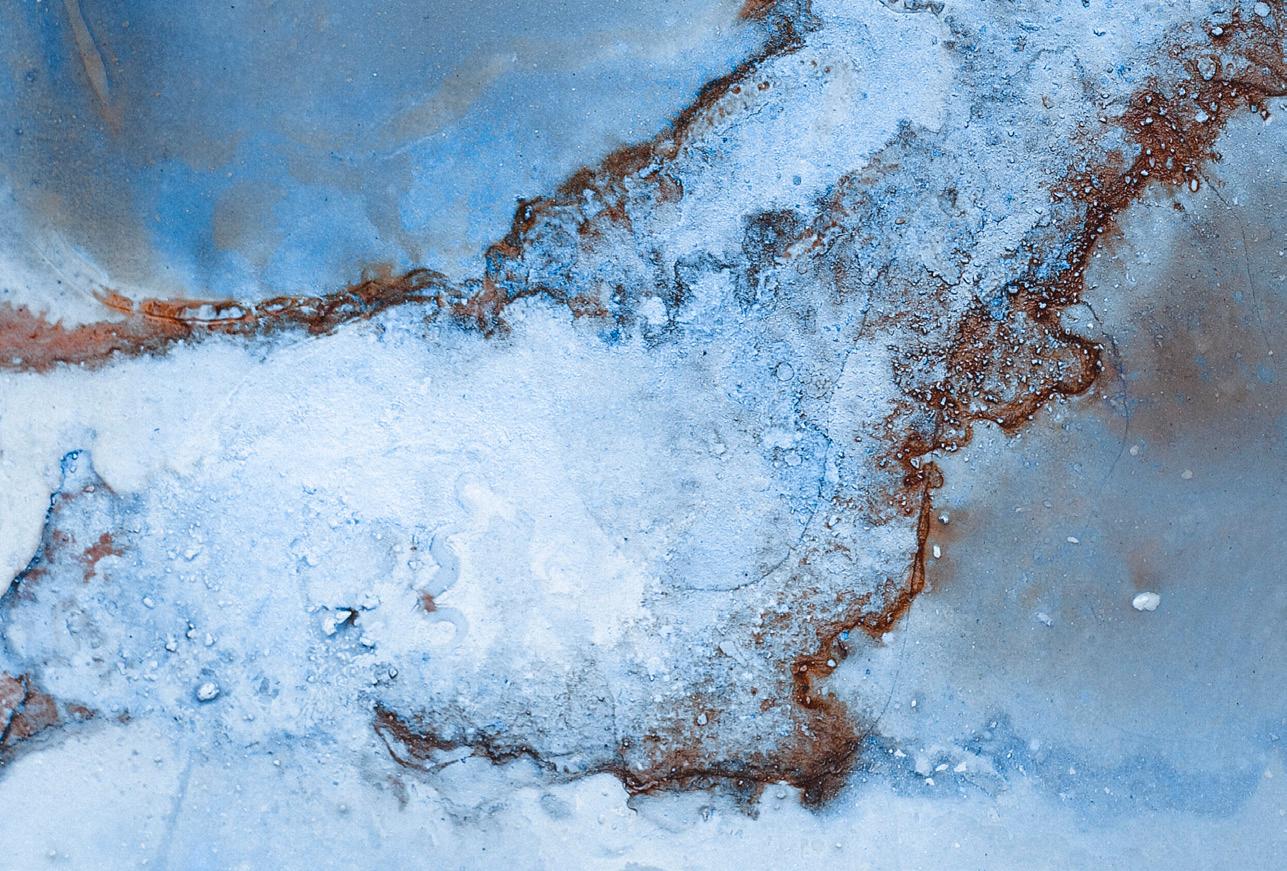

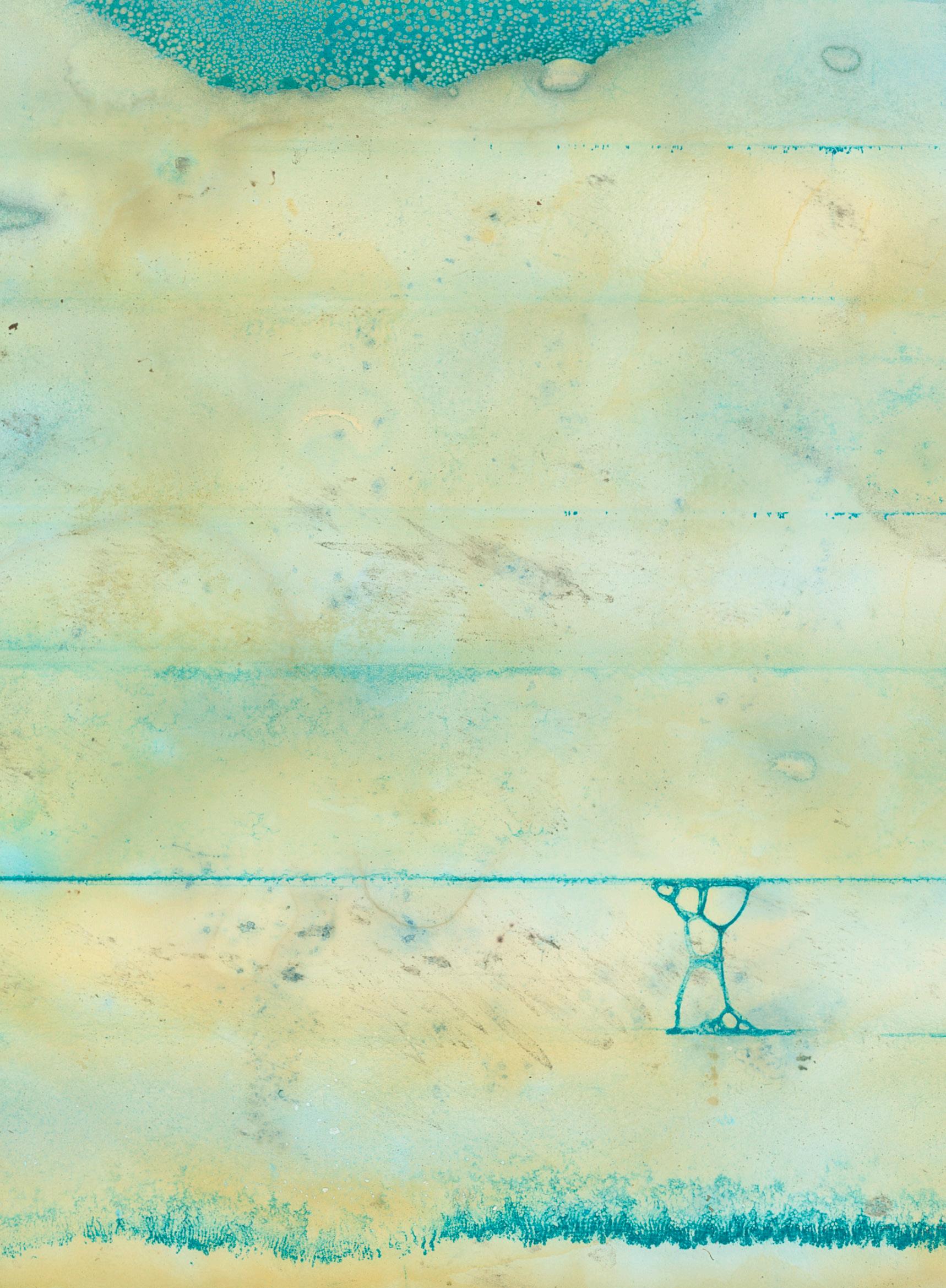

Seven days, six nights (Fig.6) shows the result of such a process, where the evaporation of the chemicals, paints and agents exposed to the elements has created what appears an aerial view of an imaginary landscape or coastline. Potassium dichromate is typically used to achieve a darker blue during cyanotype development, but in this case was prevented from mixing with the other chemicals as it was suspended in an acrylic thickening agent, creating rust-like ridges of colour. The image developed over the course of a week and is still developing as I write this review. As Régis Durand explains: “A very long exposure, for example, yields a

greater presence of the object, whose materiality seems reinforced by the duration of the ‘deposit’” (Durand 2007:243). Such exposures are not only unpredictable, but also unstable in that they are permitted to continue changing. In this sense they become alive and evolving, subject to the transforming processes of nature, just as our world is.

CONCEPTS, THEMES AND CONCERNS

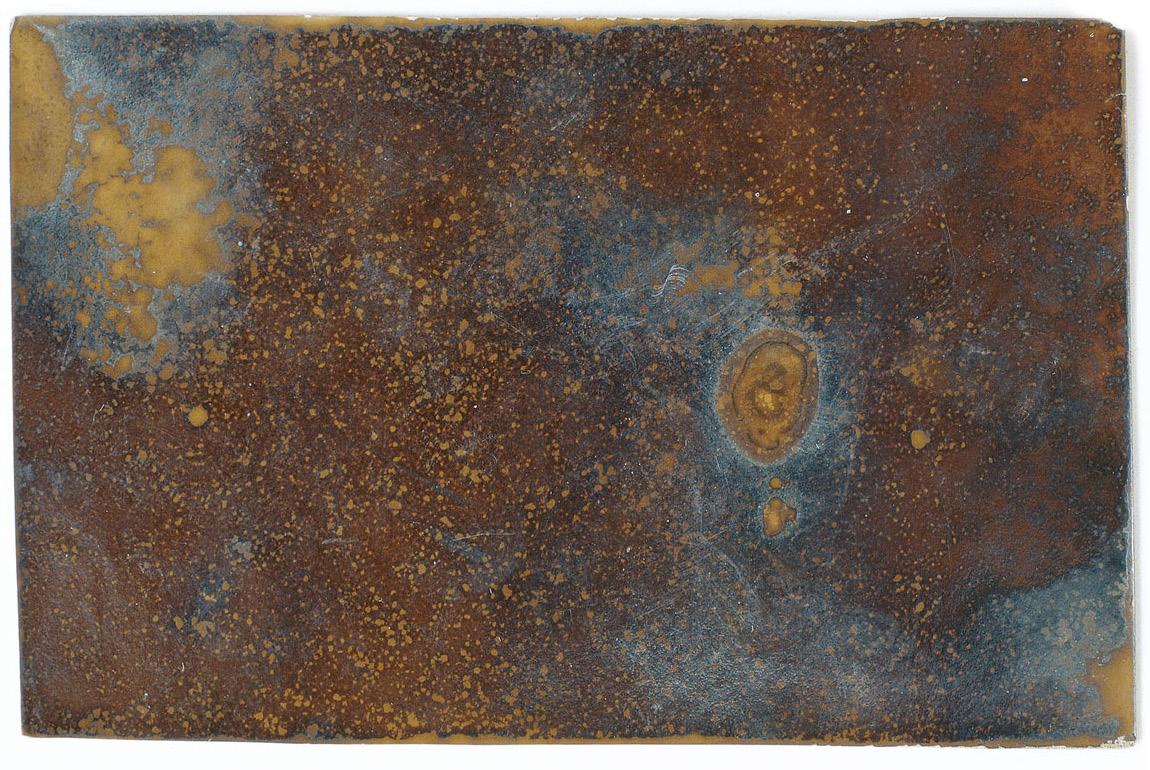

Whilst unpredictable, it would be wrong to assume that my climagrams are completely devoid of artistic intervention. My choice to create them in the first place, the choice of surface, chemicals and substances used, placement and duration of exposure are just some of the variables controlled by myself the artist. Yet they also heavily rely on the phenomena of chance. In his series of photographs called “Celestographs”, Swedish playwright August Strindberg decided that he wanted to “imitate…nature’s way of creating” (Strindberg 1894) and employed chance operations in the pursuit of artistic creation by exposing his photographic plates directly to the night sky until sunrise (Fig.7) The result was a range of exposures where stars and earthly matter seem to

move within and through one another. Whereas more ‘traditional’ photography freezes a moment in time, these images live on and perfect further an image of nature, if one not entirely intended by Strindberg.

In his series Silver (Fig.8), Wolfgang Tillmans pictures exhibit a similar material change over time. Tillmans describes these pictures as “unstable”, each representing the “result of a making” (Yazdani 2021)

and attributable to a range of human and non-human interventions and processes, both expected and unexpected. Yet the artistic choices chosen by Strindberg and Tillmans prevent these images from being mere accidents. As Tillmans says: “This word ‘accident’ is misleading. ‘The Unforeseen’ is actually much more appropriate. The unforeseen is, by definition, what you cannot plan, and that’s something that has been of great interest, and keeps art interesting for me” (Marcoci 2022: 100).

Similarly, artist Marco Breuer, who “plays photography like a John Cage piano” (Durant 2007) is concerned not with how photography captures the world but with the unexplored possibilities that lie hidden in the very materiality of photography. For Breuer, the temporality of photography is not limited to the shutter’s fraction-of-a-second exposure. He is interested in stretching the sense of time that can exist in its recording life; it might take minutes, hours, or days to “complete” an image (Fig.9). Whereas “most traditional photographs record a single instant... Breuer’s accumulate scars over time” (Barnes 2018: 172).

The Surrealists believed that by applying chance to mark making artists could be released from

the constraints of rational thought and become free to express their unconscious. In Climagrams, I have utilised crude apparatus combined with photographic solutions and surfaces to draw on Surrealist ideas of automatism, or creativity that is not consciously controlled.

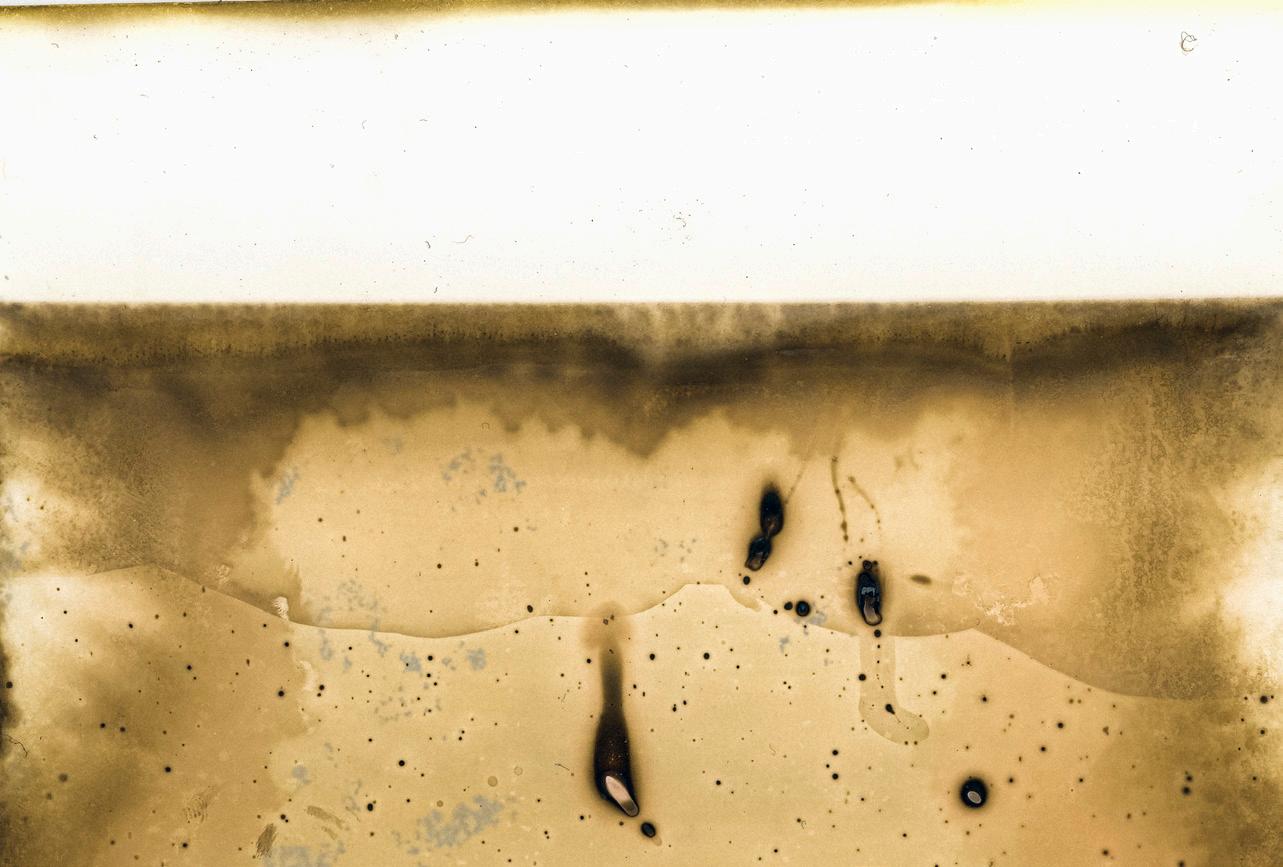

Two days of rain (Fig.10) was created by repurposing a film developing tank to develop a sheet of direct positive photographic paper (Fig.11). After the paper was placed inside the tank it was filled with a small amount of developer and left outside during the rainy season. As the container gradually filled with water throughout the day, the rising levels were recorded on the paper. As György Kepes described when discussing the purpose of the exhibition ‘The New Landscape’, which presented some of his own photograms alongside decontextualised scientific images: “The visible traces of nature’s process and structures are shown not as visible documentation of scientific facts but as rich stimulating experiences involving the whole being of the beholder” (Kepes 1951: 21). In such images, nature physically puts it’s hand onto the images, transcending the idea that a photograph must be a simple representation of reality and in their abstraction, question the distinction between scientific record and work of art.

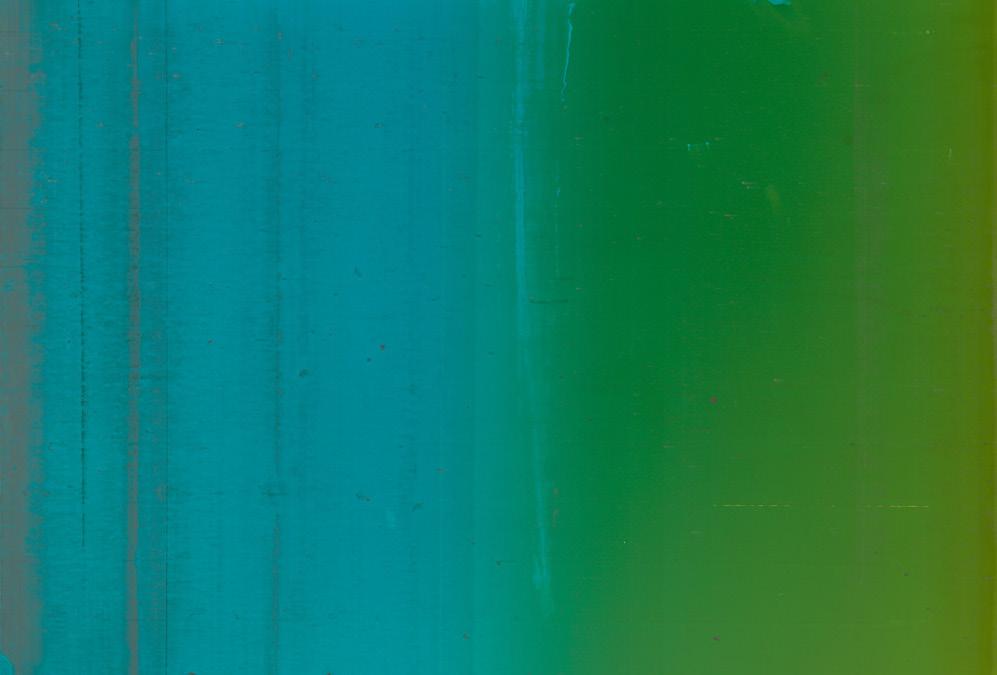

Vilém Flusser describes a need “to create a space for human intention in a world dominated by apparatus” (Flusser 2000: 75). He posits the camera as a programmable apparatus that, paradoxically, programs the photographer who uses it. Charlotte Cotton also recognizes that to a certain degree “technologies themselves are ‘authoring’ the images we see” (Cotton 2015: 4). One contemporary cameraless photographer who shuns this domination by technology is Gary Fabian Miller who has returned to what he designates as a “lost turning” in photography’s history during the midnineteenth century. Photography has, in his reckoning, become a “stunted” practice, now “more debased than it’s ever been” as it becomes more technologised and instrumentalised (Mellor 2001: 136). Miller now experiments with the possibilities of light and colour as both medium and subject (Fig.12) and as David Chandler explains: “Whereas for other photographers light is a source, a beginning, for Fabian Miller light is the work, it is something to direct and control, and importantly to feel” (Chandler 2001:25).

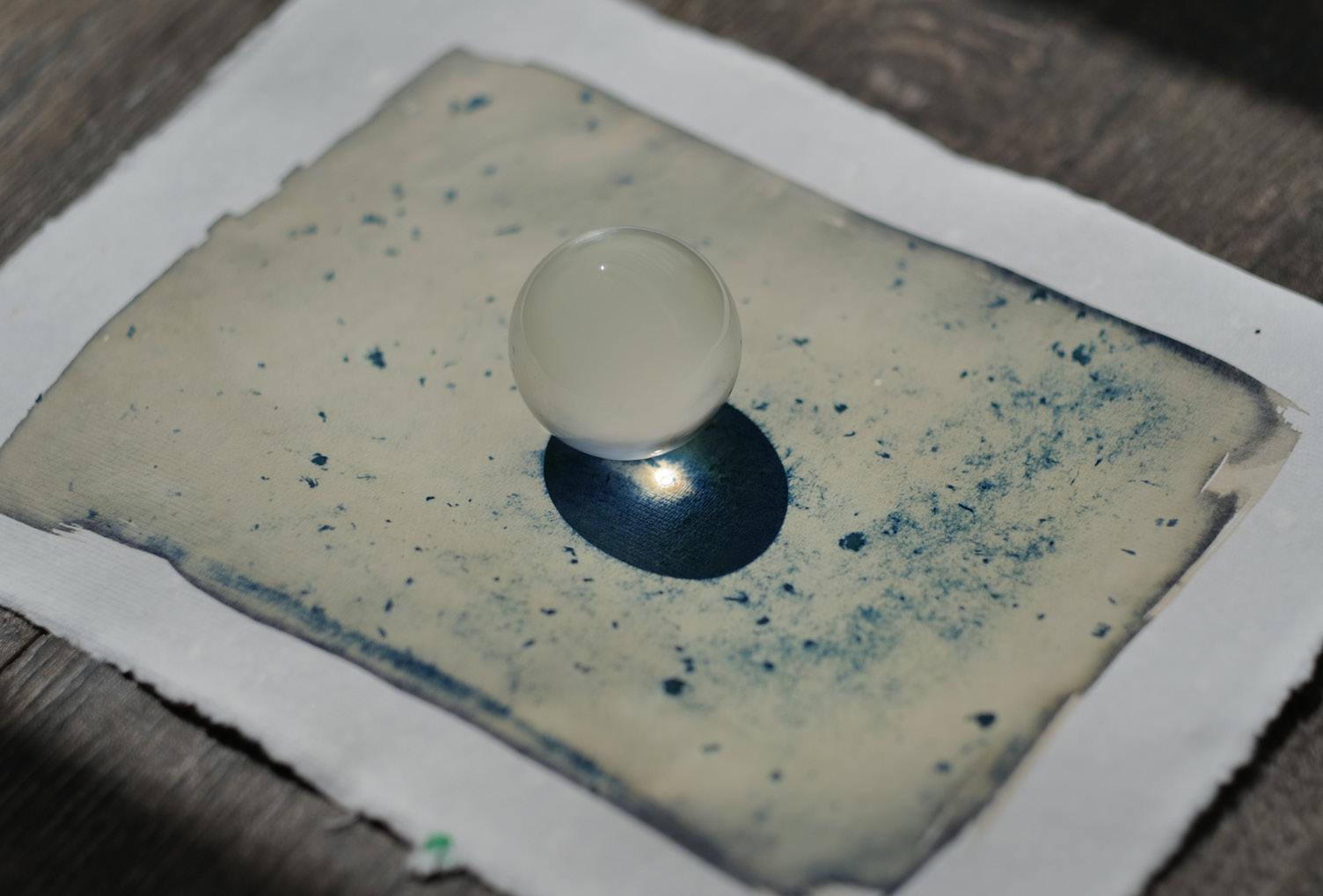

In my picture, Three hundred seconds in the sun (Fig.13), I placed a spherical glass prism onto a sheet of wet cyanotype coated homemade paper for five minutes.

Under the intense equatorial midday sun, the rays were focussed, burning a hole in the paper and changing the colour of the chemicals (Fig. 14,15).

In favour of technology, I embrace collaborating with nature. Alphonse de Lamartine declared that photography “is better than an art, it is a solar phenomenon in which the artist collaborates with the sun” (quoted in Gernsheim 1962: 65). Photographer Chris McCaw also works with the sun, and his series Sunburn (Fig.16) explores both it’s creative and destructive power. Although his work is not camerless, he uses custom made apparatus, in which the intense light of the sun is focused to the extent that it physically scorches the film. In this collaboration between artist and subject, the sun becomes an active participant in the printmaking.

The historic references to photography’s beginnings are also apparent in this work. The world’s earliest surviving photograph made by Niépce was an eight hour long exposure, describing the movement of the sun as the buildings were being lit by two directions showing morning and afternoon light in the same image.

I have similarly tracked both morning and afternoon passages of the sun in my climagram, From sunrise to sunset (Fig.17). It was made with a ‘Jordan’s Sunshine Recorder’ from the 1960’s (Fig. 18,19), essentially a metal cylinder with two pinhole apertures either side which record the morning and afternoon sun on a piece of light sensitive paper. As with Miller’s and McCaw’s work, we can see how time is an important component “not just the long exposures but also sequential and seasonal time, temporalities that can only be understood as experiences of and in nature” (Batchen 2016: 38)

Being “in nature”, is a common part of the methodology for many cameraless artists such as Susan Derges. Her work explores the idea that natural patterns are the signs of deeply hidden affinities – visible signs that point to the invisible. Working outdoors at night

is comprised of a cast iron base with hinged adjustable mount for angling the main barrel (according to latitude). The barrel is provided with a lid to emit sunlight and contains a small pinhole opening either side to let in the traversing sunlight. A piece of photographic paper is placed within the barrel and the transit of the sun is exposed onto the paper, thereby plotting its journey throughout a day.

and submerging photographic paper below the surface of a river, she then exposes them to a microsecond of flashlight. The process embraces chance and the final result can only be seen after processing. As with Tillmans work in Silver, these are no mere accidents. “The Unforeseen” is a better definition for Derges work too.

Whereas Derges is usually there present for the whole of her process, I sometimes purposefully neglect and detach myself from the creative process for considerable amounts of time. A week in a waterway, (Fig.16) is the result of a cyanotype and acrylic ink coated canvas which was submerged in a waterway outlet and left for two weeks with no attention from myself. Again, Surrealist ideas of automatism are at play, with the lack of intervention on my part emphasising film theorist André

Bazin’s statement that “All the arts are based on the presence of man, only photography derives an advantage from his absence” (Bazin [1945] 1960: 7).

IN SEARCH OF THE UNFORESEEN

During my research, I have discovered that there is far less literature concerned with cameraless photography than compared with other genres such as

fine art, portrait, documentary or landscape.

John Szarkowski acknowledged this prejudice claiming: “the camera is central to our understanding of photography…cameraless pictures…are of interest primarily as exercises that anticipate or further explore discrete and partial aspects of photography’s potentials” (Szarkowski 1989:15). Whether it can really be considered a valid form of photography is in some ways a debate about language and terminology and how it influences our understanding of the subject (and the world at large). As Wittgenstein said: “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world” (Wittgenstein 1921). If the world in question is that of photography, perhaps difficulty in assigning meaningful subject terms to nontraditional formats has denied its vast range of conceptual and physical abilities, explaining why cameraless photography has found difficulty in acceptance. My use of the definition climagram whilst adding to the plethora of cameraless nomenclature, is also a demonstration of it’s inherent breadth.

The lack of literature itself on cameraless photography appears a complex problem rooted in the personal and cultural biases of the art, photographic, and publishing establishments. As Blank states:

“The reigning cultural and critical sensibilities have diminished the impact of those who choose to work with cameraless formats” (Blank 1990: 96-100). He goes on to explain how this bias has a foundation historically in the less-than-enthusiastic reception of photography by the art world as a whole, and subsequently with the photographic community’s refusal to accept cameraless processes as a valid expression of the photographic medium (Ibid). Genre definitions are challenged further by cameraless practitioners such as Pierre Cordier, the ‘father of the chemigram’, whose work has always been difficult to classify, and raises the question of affiliation from an art-historical point of view. As he states: “I put some distance between myself and the notion of photography, hoping to be welcomed within the world of painting, because in fact I am neither a painter nor a photographer, but a bit of both.” (Barnes 2012: 10).

Regardless of classifications, I believe that opportunities were missed at the conception of photography that could have allowed it to be a genre recognised in its own right. As the work of cameraless photographers both past and present demonstrates, with traditional processes and materials we can challenge “human perspective, rationalised space, three-dimensional illusions, documentary truth and

temporal fixity” (Batchen 2016: 47). This return to the fundamentals of photography provides a way for mysteries to be uncovered, not by accident but through discoveries which are unforeseen.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BARNES, Martin. 2018. Cameraless Photography. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd (In association with the Victoria and Albert Museum).

BARNES, Martin. 2012 Shadow Catchers: Camera-less Photography. London: Perseus Distribution Services.

BARTHES, Roland. (1993) Camera Lucida: Reflections on photography. London: Vintage Classics.

BATCHEN, Geoffrey. 2016. Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph. Germany: Prestel.

BATCHEN, Geoffrey. 2014. ‘Photography: An Art of the Real’ in: What is a Photograph? (ed.) Carol Squiers. Munich: DelMonico Books-Prestel.

BATCHEN, Geoffrey. 2012. Photography and Authorship. Still Searching blog, Winterthur Fotomuseum, October 7.

Available online: http://blog.fotomuseum.ch/2012/10/4photography-and-authorship [accessed March 30 2023].

BAZIN, André.1960. ‘The Ontology of the Photographic Image’. In: Film Quarterly, Vol. 13, No. 4. The University of California Press.

BENJAMIN, Walter. 1936. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Available at: https://www. marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/ge/ benjamin.htm [accessed 3 February 2023).

BESHTY, Walead. (2009) ‘On the Conditions of Production of the Multi-Sided Pictures Works (20062009)’. In: The Edge of Vision: The Rise of Abstraction in Photography. (ed.) Lyle Rexer. New York: Aperture Foundation.

BLANK, PETER P. 1990. The Impact of Personal and Cultural Bias on the Literature of Cameraless Photography: Difficulties in the Literature Search and the Librarian’s Response. Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America, 9(2), 96–100. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27948206

[accessed 7 April 2023].

BURBRIDGE, Ben. 2015. ‘All that is Solid Melts into Air: Early Scientific Photography and Modern Art’. In: Revelations: Experiments in Photography. (ed.) Ben Burbridge. London: Mack.

CHANDLER, David. 2001. ‘Introduction’. In: Tracing light. (ed.) David Allan Mellor and Garry Fabian Miller. Maidstone: PhotoWorks.

CORDIER, Pierre. 2012. ‘Meet the inventor of the Chemigram: Pierre Cordier’. In: Musee, June 13.

Available at: https://museemagazine.com/culture/ art-2/features/meet-the-photographer-pierre-cordier [accessed 7 April 2023].

COTTON, Charlotte. 2015. Photography is Magic. New York: Aperture.

DURAND, Régis. 2007. ‘Event, Trace, Intensity’. In: David Campany. Art and Photography. London: Phiadon Press.

DURANT, Mark Alice. 2007. Marco Breuer: Early Recordings. Available at: https://saint-lucy.com/essays/ marco-breuer-the-material-in-question [accessed 1 April 2023].

ELKINS, James. 2009. What Photography Is. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

FLUSSER, Vilém. 2000. Towards a Philosophy of Photography. (Translated by Anthony Matthews). London: Reaktion Books.

FRIED, Michael. 2008. Why Photography Matters as Art as Never Before. New Haven: Yale University Press.

FUNKE, Jaromir. 1927. “Man Ray”. Fotograficky Obzor (Photographic Horizon) 35.

GERNSHEIM, Helmut. 1962. Creative Photography: Aesthetic Trends, 1839-1960, New York: Bonanza Books.

GREEN, Charles. 2001. The Third Hand: Collaboration in Art from Conceptualism to Postmodernism. University of Minnesota Press..

KELLER, Corey. 2009. Brought to Light: Photography and the Invisible. London: Yale University Press.

KEPES, György. 1951. The New Landscape. Arts & Architecture 68.

KRAUSS, Rosalind. 1986. The Originality of the AvantGarde and Other Modernist Myths. USA: MIT Press.

PALMER, Daniel. 2017. Photography and Collaboration from Conceptual Art to Crowdsourcing. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

MARCOCI, Roxana. 2022. Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear. New York: The Museum of Modern Art.

MELLOR, David Allan and MILLER, Garry Fabian. 2001. Tracing light. Maidstone: PhotoWorks.

REXER, Lyle. 2009. The Edge of Vision: The rise of Abstraction in Photography. New York: Aperture Foundation.

SNYDER, Joel. 1980. ‘Picturing Vision’. In: Critical Inquiry, Vol. 6, No. 3. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

SNYDER, Joel and ALLEN, Neil Walsh. 1975. ‘Photography, Vision and Representation’. In: Critical Inquiry, Vol. 2, No. 1. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

SONTAG, Susan. 1977. On Photography. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

STRINDBERG, August. 1894. On Chance and Artistic Creation. As translated by Kjersti Board for Cabinet, no.3. 2001. Available at http://www.cabinetmagazine. org/issues/3/i_strindberg.php. [accessed 29 March 2023].

SZARKOWSKI, John. 1989. Photography until now. New York: The Museum of Modern Art.

SZARKOWSKI, John. 1967. A European Experiment. Press release (April 28th). MoMa.

WITTGENSTEIN, Ludwig. [1921] 2001. Tractatus LogicoPhilosophicus. Routledge.

YAZDANI, Sara R. 2021. ‘Wolfgang Tillmans’s Abstract

Mediations and Other Ecologies’. In: After Image, Volume 48, Issue 2. University of California Press.

FIGURES

Fig. 1: Robert DAVIES. 2023. Three hundred seconds in the sun. Cyanotype, reversed. Private Collection: Robert Davies.

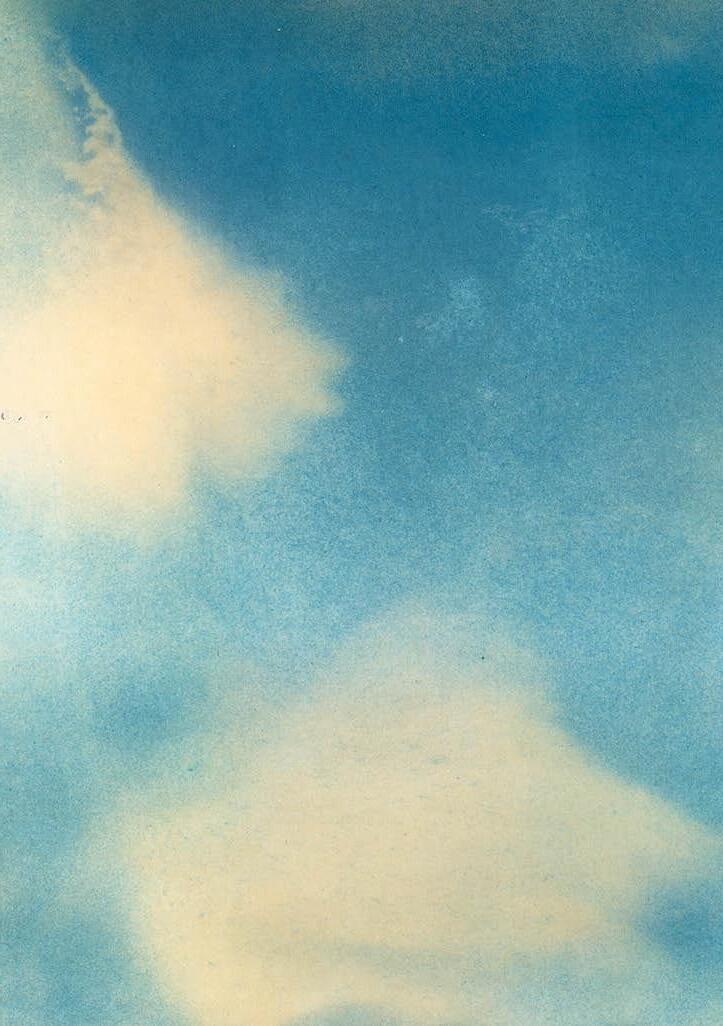

Fig. 2: Robert DAVIES. 2023. Half an hour in a tropical shower. Private Collection: Robert Davies.

Fig. 3: Robert DAVIES. 2023. A day in stormy weather. Private Collection: Robert Davies.

Fig. 4: Jean Bernard Léon FOUCAULT. 1844. Spectre solaire. Available at https://imagesociale.fr/3485 [accessed 1 March 2023].

Fig. 5: Barbara KASTEN. 1976. Untitled 76/6. Available at http://barbarakasten.net/photogenic-painting [accessed 23 February 2023].

Fig. 6: Robert DAVIES. 2023. Seven days, six nights. Private Collection: Robert Davies.

Fig. 7: August STRINDBERG. 1894. Celestograph. Available at: https://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/3/ feuk.php [accessed 5 March 2023].

Fig.8: Wolfgang TILLMANS. 2013. Silver 124. Available at: https://www.galeriebuchholz.de/exhibitions/wolfgangtillmans-2013-berlin#_ec=images||31 [accessed 27 February 2023].

Figure 9: Marco BREUER. 2012. Untitled (C-1210). Available at: http://www.resettheapparatus.net/corpuswork/manipulations-of-photographic-paper.html [accessed 6 April 2023].

Fig. 10: Robert DAVIES. 2023. Two days of rain. Private Collection: Robert Davies.

Fig. 11: Robert DAVIES. 2023. A film developing tank is used to collect rainfall and develop a 4x5 sheet of drirect positive paper. Private Collection: Robert Davies.

Fig. 12: Gary Fabian MILLER. 2018. Here on the edge of things. Available at: https://www.garryfabianmiller.com/ work/view/here_on_the_edge_of_things [accessed 6 April 2023].

Fig. 13: Robert DAVIES. 2023. Three hundred seconds in the sun. Private Collection: Robert Davies.

Fig.14: Robert DAVIES. 2023. A spherical glass prism is placed on a sheet of homemade paper coated with wet cyanotype solution for 5 minutes in the midday sun. Private Collection: Robert Davies.

Fig.15: Robert DAVIES. 2023. The white mark is where the prism was placed. The burning changed the colours of the cynaotype solution. The paper was subsequently washed and fixed. Private Collection: Robert Davies.

Fig.16: McCaw 2010. Sunburned GSP#428 (Sunset / Sunrise, Arctic Circle, Alaska). Available at: https://www. chrismccaw.com/sunburn [accessed 6 April 2023].

Fig. 17: Robert DAVIES. 2023. From sunrise to sunset. Private Collection: Robert Davies.

Fig.18,19: Jason CLARKE. 2023. Early Twentieth Century Jordan’s Pattern Sunshine Recorder by Casella, London. Available at: https://jasonclarkeantiques.co.uk/products/ early-twentieth-century-jordans-pattern-sunshinerecorder-by-casella-london [accessed 1 February 2023].

Fig. 20: Robert DAVIES. 2023. A week in a waterway. Private Collection: Robert Davies.