WURRUNGGI BIIK: LAW OF THE LAND

Public Artwork Dr Vicki Couzens, Jeph Neale and Hilary Jackman Curators Grace Leone and Jessica Clark

Public Artwork Dr Vicki Couzens, Jeph Neale and Hilary Jackman Curators Grace Leone and Jessica Clark

Public Artwork Dr Vicki Couzens, Jeph Neale and Hilary Jackman Curators Grace Leone and Jessica Clark

Public Artwork Dr Vicki Couzens, Jeph Neale and Hilary Jackman Curators Grace Leone and Jessica Clark

RMIT University New Academic Street (NAS) Public Art Commission in Collaboration with RMIT Ngarara Willim Centre and RMIT University Art Collection

Public Artwork

Dr Vicki Couzens, Jeph Neale and Hilary Jackman

Curators

Grace Leone and Jessica Clark

Bundjil Womin Djeka ngarna-ga

Bundjil asks you to come and asks what is your purpose for coming and understanding.

Bundjil was a powerful man, who travelled as an Eagle. He was the head man of the Kulin people. Bundjil taught us to always welcome guests. Bundjil asks what is your purpose for coming and understanding place.

When you are on place you make dhumbali (promise/commitment) to Bundjil and the land of the Kulin Nation.

The first dhumbali, is to obey the ngarn-ga (understandings) of Bundjil.

The second dhumbali, is to not harm the bubups (children).

The third is not to harm the biik biik (land) and wurneet (waterways) of Bundjil.

As the spirit of Kulin ancestors live in us, let the wisdom, the spirit and the generosity in which Bundjil taught us influence the decisions made on place. Do this by understanding your ways of knowing, your ways of doing, and your ways of being on place.

The Country has always been here.

We now have a marker in our landscape to remind all people (not just our ancestors and descendants) that we had a civilisation that used the resources of this land. This marker prompts us to think on the past and where we’re heading in the future. It’s a storyboard that reflects (traditionally) when you begin and when you end.

We see a lot of iconic symbols of British structures around Melbourne, but we never see anything that reminds us of our world. Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land is something iconic. It reminds me about our history: a time of chaos and the connection between the animal world and the human world, and the environment. It begins a narrative. The narrative of the First People’s land. Sometimes it can be an uncomfortable conversation; sometimes it’s a good conversation.

The Possum Skin Cloak is very much an important part of our civilisation and the changes we’ve faced. The healing properties come from the animal that it was taken from and presented to your body. It’s all connected to the animals, the plants, the seas. It’s part of the storyboard of our lives, and it goes with you on your journey. It grows with you from birth. It’s a calendar, a time capsule of your life, but it can also bring your family together, physically and emotionally. It’s your health and well-being, but it’s also your storyboard. It’s embedded into you. It’s individual, but it’s also collective.

The cloak can breathe. I would like the sculpture to remind people to slow down.

Young people need to reflect and challenge their own understanding of people and place and to question what was before the impact of colonisation. Who were the players in history? What did they look like? What did they do?

So let’s keep having conversations and scaffolding processes through the great minds of RMIT’s young people and their creativity. Let’s also keep taking leadership and ownership of the conversation. I’m privileged to be a part of this.

‘The challenge is for non-Indigenous people to delve into the history of a people that never ceded their Sovereignty. It’s not just a model of the cloak. It’s a record. It’s about respect. So when you come on someone else’s Country you understand the laws of their land.’

PARBIN-ATA CAROLYN BRIGGS am

‘Aboriginal pre-existing and continuing Sovereignties are about the relationships of authority and how that is organised around place. Sovereignty in the way that we use it here is the bridge between two ways of knowing. It’s about how we all relate to each other within a shared knowledge of place.’

PROFESSOR MARK McMILLAN

My current position at RMIT is Deputy Pro-Vice Chancellor of Indigenous Education and Engagement, chair of the RMIT Academic Board, and University Council member. None of those things are responsible for reconciliation, but all of those things are responsible for reconciliation.

Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land initially started as a conversation about how New Academic Street (NAS) would inscribe or reflect what a redevelopment is supposed to do—tell a particular story about place and about the relationships that sit within it. The project officers and people who were involved with NAS articulated that the relationship with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and place was absent. This recognition reflected the development of NAS as an idea spanning 10 years and the maturing of the institution by the time NAS was in the final stages of completion.

RMIT has moved into a positive sense of reconciliation about the future. We want to build active relationships between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. At RMIT there is not just the expectation but the institutional support and encouragement for people to situate themselves in the relationship of reconciliation. How do you commemorate or memorialise the relationship of place with Kulin today? Stacey Campton—as one of the principal drivers of reconciliation at RMIT—played a central role in addressing this question. As the driver of reconciliation at RMIT, she brought together the constellations of Grace, Jess, NAS, and Aboriginality more fully. Stacey and I worked with Jess and Grace to talk about the brief we put out to artists and creative practitioners. I distinctly remember a conversation I had with Grace where we said, ‘Let’s talk about Sovereignty as the root of reconciliation or Aboriginal Sovereignty itself’. That moment was the paradigm shift. We weren’t going to ask Indigenous creative practitioners merely to signal, but to explain their creative practice through Sovereignty. That was the change that I am

most proud of, and most proud of being able to contribute to. It wasn’t just about what the finished piece would be, but about the ways we could signal relationship in the conception of creative practice. That’s where I got very excited.

For me, engagement with Indigenous students is more than knowing that it is important or performing a structural obligation. The practice of engagement is not about burdening Indigenous students with the question, ‘What do you know about Aboriginality?’ The process of the project invited them to engage with Country on their terms as Sovereigns.

Sovereignty isn’t a Western construct. It’s a word that in English is the bridge between practices. Non-Indigenous people have used Westphalian notions of Sovereignty for assertion of control and authority. On the other hand, Aboriginal pre-existing and continuing Sovereignties are about the relationships of authority and how that is organised around place. Sovereignty in the way that we use it here is the bridge between two ways of knowing. It’s about how we all relate to each other within a shared knowledge of place.

One cannot walk past Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land and it be rendered invisible. When you see the sculpture, you cannot help but be moved by it. It invites participation. I like to stop and watch other people’s reactions—there’s always a double take. In their busyness, people walk past the figure, but then they also notice that it’s not moving. I find the double take a powerful moment of real engagement of the viewer asking what the work is, beyond admiring it for its technical or aesthetic appeal. When you look down, you see how it has been put into the landscape. You notice the plating and the design of the plating that holds it in place. The bottom of the cloak is a representation of Bundjil, which is an invitation to be with place, with the knowledge of the conditions of which the welcome is made.

Pieces like this sculpture are designed to not merely represent, they’re designed to affect. Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land is a process of absolute affect.

‘One of the best ways to recognise First Nations people is to do it visibly, and Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land is the visible representation of what Sovereignty looks like and how it feels to be walking on Country that was never ceded, Country that belongs to the Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung language groups of the eastern Kulin Nations.’

STACEY CAMPTON

I am currently the Director of Indigenous Engagement at RMIT, and previously I was the Director of the Ngarara Willim Centre, our Indigenous student service centre. Ngarara Willim is very much the central place where Indigenous staff and students gather; where we provide support services for our students, where our staff has a place to go on campus, where other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples can congregate. When I got to RMIT, it was one of the only places that felt like a space that we owned or occupied in the whole campus, if not all of our campuses of RMIT.

When discussions about the New Academic Street began, there was talk of painting a mural but it wasn’t really clear exactly where or what that mural would be. There was a lot of discussion and eventually this concept evolved from being just a space on a wall to what we have today. It took a while to get to the idea of the Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land sculpture, but it wasn’t a difficult decision to make once the argument was put forward that we have to recognise our First Nations people. It wasn’t necessarily about convincing people, it was more a case of ‘Let’s think bigger than something painted on a wall down in the third level of a building. Let’s do something spectacular.’

One of the best ways to recognise First Nations people is to do it visibly, and Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land is the visible representation of what Sovereignty looks like and how it feels to be walking on Country that was never ceded, Country that belongs to the Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung language groups of the eastern Kulin Nations. There has been a lot of work done in the last 4–5 years to make non-Indigenous people feel comfortable about Indigenous Sovereignty and self-determination. Non-Indigenous people need to take responsibility within their own schools and colleges to acknowledge that we have to share this country and we have to be in a relationship with our First Nations people.

When Vicki came to us with the Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land concept, it was absolutely perfect. It was the perfect representation of Victorian Aboriginal people. It was a perfect representation of Bundjil; what Bundjil is in a visible way.

It is also a visual representation of Sovereignty, of what RMIT are doing in the space of reconciliation and Indigenous self-determination and what the RMIT community would like to be known for. We also have Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students that come from all over—not only Victoria but all across Australia. Sovereignty for us is who we are. Sovereignty follows us no matter where we go; we know who we are as Sovereign people, we know our Country, we know our identity, we know our family groups.

I know our Indigenous students are extremely proud to walk out of Ngarara Willim to see the sculpture standing there. Every time I walk up and down Bowen Street, I see that little piece of identity that talks to me and reminds me that this huge university sits on Country that has a lot of history and that we, as a university, have honoured that in some small way. Well, I say it’s small, but really it’s 2.3 metres tall. With Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land, we’ve got something visible, something physical to refer to. We can put a flag in the earth and say to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people now that we actually matter.

As Aboriginal women, we can say, ‘I can actually see myself reflected in this place,’ and that is the concept that we kept coming back to. If you want people to come here, if you want our people to come here, if you want international students to come here, they have to see themselves reflected in this place. For us as Aboriginal people, it means just that little bit more. We’ve claimed back a little bit more of that Country and shown that we have not only every right to belong here, but we’ve shown it with grace and dignity.

The New Academic Street (NAS), a capital works project completed in 2018 was a project that transformed the heart of the RMIT University City campus; creating laneways, gardens, new student spaces, better library facilities, and public art opportunities.

RMIT University aspires to be an organisation whose community recognises the inherent value of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander traditions, cultures, knowledges and perspectives to the University—as outlined in the RMIT Reconciliation Action Plan (2016).

In 2017 the New Academic Street commissioned a permanent public art work by Dr Vicki Couzens in collaboration with Jeph Neale and Hilary Jackman. The aim of the Commission was to provide an invaluable legacy that would live beyond the project, engage meaningfully with Aboriginal cultures, and contribute to the lifeblood of RMIT’s diverse community—reflecting on the past, acknowledging the present, and aspiring towards a future Sovereign recognition. The Commission engaged with the idea of a shared future for Australia, a future founded on Sovereign recognition, one that reflects the reality that community, culture and Country are inextricably linked, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous.

The curatorial framework and brief were created to ensure the public artwork would adequately reflect and incorporate the following ideas:

Artists were encouraged to share and engage with their own Sovereignty and story, as well as the concept of Sovereign recognition through a wider lens that extends the current understanding of reconciliation with the aim of creating a shared vision for all.

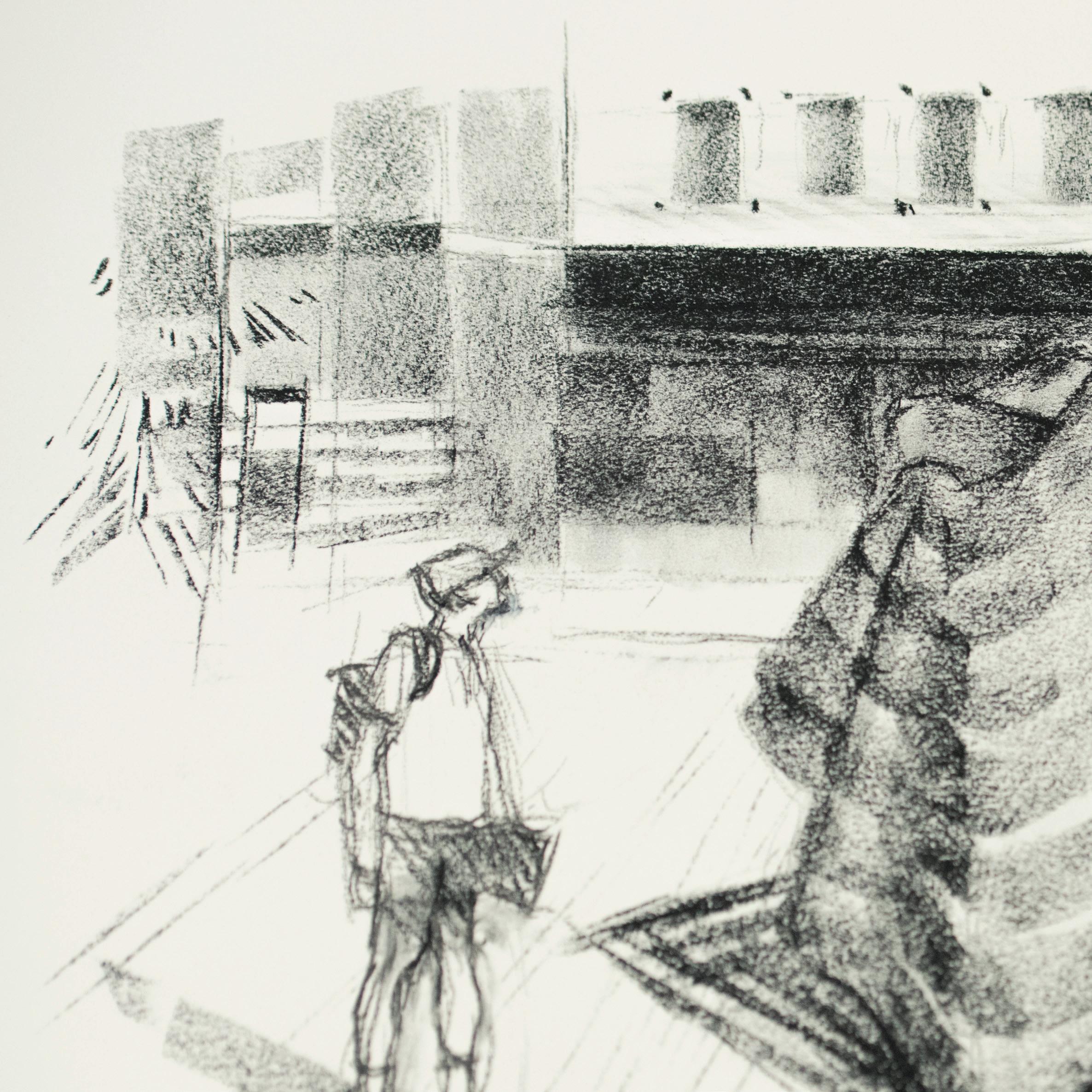

Hilary Jackman’s sketches of the artwork for the proposal (opposite and pages 19–20).

Active engagement with First Nations protocols and practices to create a public art work that engages and connects Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in the surrounding RMIT community and embraces the idea of art as a meeting place.

In the development of a proposal for this Commission, artists were encouraged to intertwine and intersect stories of Sovereignty with that of the Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung language groups of the eastern Kulin Nation, the Country on which the Commission is located within RMIT.

RMIT University’s senior Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff provided guidance in the process of this Commission. Points of reference for the concept development for this project were established through consultation with the Ngarara Willim Centre, Senior Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff, and the Ngarara Willim Student Engagement Workshop:

• A national and international platform that celebrates Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander presence, art and talent at RMIT.

• In consideration of context the Commission should create an intersection of Indigenous culture, art and technology.

• Create a dialogue with past and present in acknowledgment of those who have come before us, that pave the way to a shared future.

• Embeds story and Sovereignty.

• A learning and research environment that promotes cultural education and interaction.

• Connect with place through story.

• Reflects on tradition and embraces contemporaneity.

• The nature of the Commission should be accessible to a wide range of audiences.

• Integrates ideas of growth, change and the possibility of a shared future in dialogue within the context of RMIT.

The Project Advisory Group guided and oversaw the commissioning process and selected the final artwork to be endorsed and commissioned. The project advisory group comprised of representatives from:

• The broader Indigenous community external to RMIT

• RMIT Ngarara Willim Centre

• RMIT University

• RMIT New Academic Street (NAS) Project Office

• RMIT New Academic Street architects

• RMIT curatorial team

• RMIT students

The proposals were assessed against the following key selection criteria:

• Artistic merit and innovation of the concept

• Response to the brief and site—both physical and social

• Durability and longevity of the work proposed, with regard to materials, message and content

• Artist previous experience and/or demonstrated potential to work collaboratively on large scale site-specific public artwork

• Artist capacity to achieve the artwork within the required program, budget and Work Health & Safety Legislation

• Ability for the work to be realised in a permanent context

A Possum Skin Cloak or Spirit Cloak conjoined with a wedge-tail shaped Spirit Memory Imprint is the dual aspect form chosen to characterise and signify the conceptual intent of Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land.

Possum Skin Cloaks are significant objects of cultural expression, used in both practical daily life and for ceremony. Babies are wrapped in Cloaks, people are buried in Cloaks. Many of our treasured historical photos depict our Old People in Cloaks. After the interruption of European invasion, Cloaks have been returned to their rightful place in community, and are now iconic to the south-east of Australia.

The wedge-tailed eagle is another iconic figure in our collective Aboriginal Creation story across the south-east. Bunjil is the great Creator Spirit in this story and travels as an eagle. In this work the wedge shape of the eagle’s tail is used to infer the presence of Bunjil and the Creation Ancestors. It is described as a Memory Imprint and is in fact meant to be the representation of the residual ethereal, metaphysical imprint of the Creation Spirits ever-presence.

Here, in Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land, these two significant elements combine to embody the spiritual, conceptual, intellectual, and emotional values of Aboriginal Creation Law. Their physical realisation in place is a revealing, a bringing forth and making visible the intangible presence of our Creator Ancestor Beings: Sovereign sentinels and guardians of place; custodial stewards of Country. Our Creator Ancestor Spirits, from time immemorial, observe, guide and direct the continuous, never-ending cycle of creation.

The Work’s ongoing presence in place is intended to seed a deep cognizance of the constant, unbroken ever-presence of the Creation Spirit Ancestors. This seeded awareness will conjure and grow a heartfelt shift in perceptions and understandings of place, belonging and the shared responsibility, within the Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land, to care for our Mother Earth.

The following text is an edited selection from Dr Vicki Couzens’ PhD submission, ‘Possum Skin Cloak Story Reconnecting Communities and Culture: Telling the Story of Possum Skin Cloaks’. (Reproduced with permission)

The Possum Skin Cloak has re-emerged as a significant icon and a collective symbol of Aboriginal cultures across south-eastern Australia.

Possum Skin Cloaks tell Aboriginal stories, representing the unique and distinct tribes and language groups of south-eastern Australia. They tell stories of belonging, place, and the sacred and spiritual. The cloak is both a physical object and a symbol of knowledge. Stories of clan, kinship and Country are etched into and carried throughout a person’s lifetime through their Possum Skin Cloak.

The creation of Possum Skin Cloaks is part of the ongoing cycle of singing up Country and keeping Country strong. It generates a sense of recognition and acknowledgement of place, and leaves a lasting legacy with south-eastern Aboriginal communities and across mainstream Australia. Whilst we teach cloak-making in the practical sense, it is the experience of making and wearing; learning language, cultural stories and knowledge; and coming together in community and connecting with each other, culture and song lines that initiates a healing journey for all who join in.

In a cloak-making workshop, different generations interact. These community workshops facilitate interactions and transgenerational engagement, creating opportunities for the transference of knowledge, for listening to stories, being given responsibilities, and the strengthening of family and kinship networks. Making Possum Skin Cloaks triggers a need to find out more about them: How were they

made? Where and how were materials sourced? What is our language for possums, cloaks? What ceremonies did we use them for? Who wore them? These questions, in turn, trigger the need to learn more about other related cultural knowledge and practices.

Possum Skin Cloaks were a vital part of Aboriginal people’s lives in preEuropean times. Cloaks were used in daily activity, to keep warm, to sleep in and to carry babies.

To make a cloak was a very labour-intensive and time-consuming process. The skins were gathered, stretched and cured, incised with designs, and sewn together with kangaroo sinew, with some Cloaks comprising 50 or more skins.

To capture the possums, the men would seek them out in trees with hollows, where possums nest. Once ascertaining there was a possum or two in residence, the men would make notches, with a stone axe, into the lower part of the tree’s trunk. The hunter would place a rope around his waist and the tree trunk, and lean back into the rope to create tension and act as a kind of sling. He would then ascend the tree using the notches he had already cut as foot and hand holds, and make more as he climbed. Once the hunter was near the hollow, he would beat a club on the trunk or branch where the hollow was, scaring the possum out. He would club and grab it or cause the possum to fall to the ground below, where the rest of the hunters would be waiting to capture and finish the possum off. Sometimes smoke was used to ‘smoke’ the possum out of the tree.

As the skins were gathered, they were stretched and cured by both men and women. The women carried, in a small possum bag, up to 300 handmade wooden pegs that were used to stretch and peg the skin on a piece of flattened bark. Once stretched, the skins were scraped with a sharpened shell or stone implement and cured with smoke, ash and fat to make them ready for use. The skins, once prepared, were sewn together with kangaroo sinew by the women. The sinew was obtained by the men, being extracted from the tail or hind leg of the kangaroo. The sinew had to be chewed to break it down into thin threads for use in the sewing of the skins.

During the process of sewing the skins together and after the cloak was completed, the designs depicting clan and Country affiliations were incised into each skin. A sharpened mussel-shell implement was generally used, or, sometimes,

a stone blade or knife. The incising process, as well as the practice of rubbing animal fat into human skin with natural body oils, made the skins more flexible for wearing. Wear and daily use also made the skins more supple. Ochres were used to colour the skins or selected designs and decorate the cloaks.

Possum flesh was eaten and roasted in fires. Whole skins were used as water carriers and storage containers. Small bags were hung around the neck to carry pegs used for stretching out and preparing skins for use. Fur was rolled with hair to make string. String and skin pieces were used to create body adornment items such as necklaces, armbands, headbands and dance belts. For sport, possum skins were sewn together to make a ball that was used in ‘marngrook’—a game of keepings off between two teams, using the feet and hands—the progenitor of modern-day Australian Rules football. The jaw bone of the possum was hafted to a wooden handle to produce an engraver, which was used to carve designs into wooden implements. Nothing was wasted.

Each individual had a Possum Skin Cloak. As a child outgrew being carried by his mother, a cloak was made for them that was theirs from birth to death. The cloak, growing as the child grew, became their life story, a living visual biography. Skins were added and scored with markings that depicted clan and Country. Symbols were added as their life unfolded, marking pivotal events: initiatory rites of passage from childhood to adulthood, from girl to woman or boy to man; marriage; the birth of children; and so on. In this way the cloak became powerfully connected to an individual. The time spent in the gathering of resources and making the cloak, as well as their ceremonial and spiritual significance, contributed to the high esteem and economic value of Possum Skin Cloaks.

Cloaks were present at ceremonies, with their role and uses ranging from shrouds to percussion instruments. The women bundled their cloaks over their knees and used them for percussion, drumming and singing. At intertribal gatherings, the markings on the skins that displayed who you were and where you came from were especially relevant. In these ceremonies and uses, we see the importance and centrality of Possum Skin Cloaks in the celebration of the esoteric. Through the contemporary revitalisation of Possum Skin Cloaks, we see them used in many ceremonies, including newly regenerated initiatory practices.

Whilst the cloak you wore was a personal item, cloaks were also specifically made for trade and were valuable items. They were important gifts in establishing relationships, maintaining of diplomatic relations and resolving disputes with neighbouring tribes.

Establishing a relationship with visitors is a fundamental Aboriginal protocol. The exchange of greetings, information about the visitors, informing visitors of their rights and responsibilities, and giving gifts was a common practice.

Whilst the impact of European colonisation was devastating to Aboriginal people, we sought innovative ways to accommodate dealings with the Europeans into our established systems. With the coming of these strangers, new economic opportunities arose for Aboriginal people. Cultural items were sold as souvenirs for their practical uses, and many Europeans received gifts of value such as weapons, cloaks and baskets. Possum Skin Cloaks and baskets in particular were prized for their usefulness to the Europeans who were spreading rapidly across the country.

There are only fifteen skin cloaks located in museums within Australia and overseas. European anthropologists collected most of the cloaks, found in museums overseas, during field trips to Australia in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

How many cloaks may have survived in private and family collections is a mystery that’s yet to be investigated. As part of the Possum Cloak Story vision of returning cloaks to community, there was a mandate to reconnect communities who have connections to cloaks held in collecting institutions in Australia and overseas.

The Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land public artwork was commissioned in 2017. Dr Vicki Couzens conceptualised the piece with co-collaborators Jeph Neale and Hilary Jackman.

The public artwork combines two important cultural markers: A Possum Skin Cloak sitting on a base that evokes the Spirit Memory Imprint Shadow of a wedgetailed eagle’s tail. Dr Couzens articulates the intent of the artwork:

‘These two significant elements embody the spiritual, conceptual, intellectual, and emotional values of Aboriginal Creation Law. Their physical realisation in place is a revealing, a bringing forth and making visible the intangible presence of our Creator Ancestor Beings: Sovereign sentinels and guardians of place—custodial stewards of Country. Our Creator Ancestor Spirits from time immemorial observe, guide and direct the continuous, never-ending cycle of creation.’

Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land is made out of spheroidal (grey) cast iron which was chosen because of its physical properties such as high strength, durability, low maintenance and the capacity to endure in the environment without need of protection. Sandcasting was the process used as sand is able to withstand the significant heat of molten iron.

The early stages of the project were all about creating a model of the artwork: making the Possum Skin Cloak plus a life-size model and the base on which it would stand. The next phase involved scaling up the life-size model, creating a plaster master that had both the form and texture of the final artwork. The procedure of turning the plaster master into the finished cast-iron public artwork is a series of processes (The Casting).

The process of casting requires 3 steps (continually going from a positive form to a negative form and repeating) to get from the plaster master to the final form. Due to the material and size of the finished artwork it was necessary to work in panels, making an already complex process even more difficult.

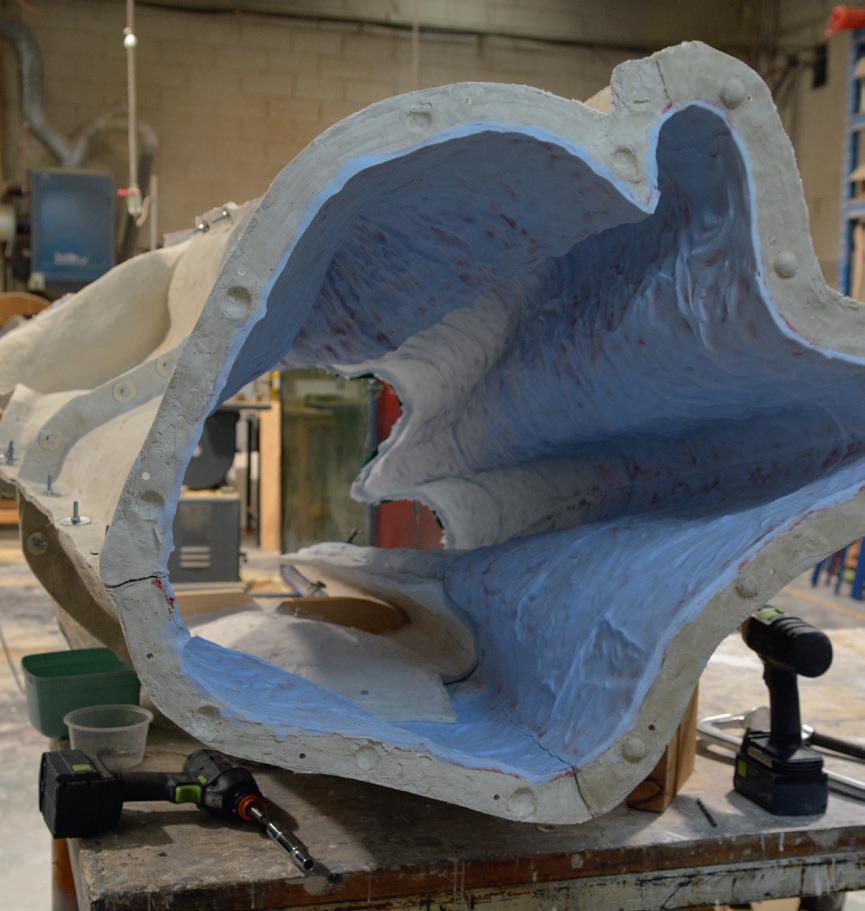

Step 1: The silicon-rubber moulds: From the plaster master (positive form) silicon rubber moulds are created (negative form) of both the inside and outside of the plaster master.

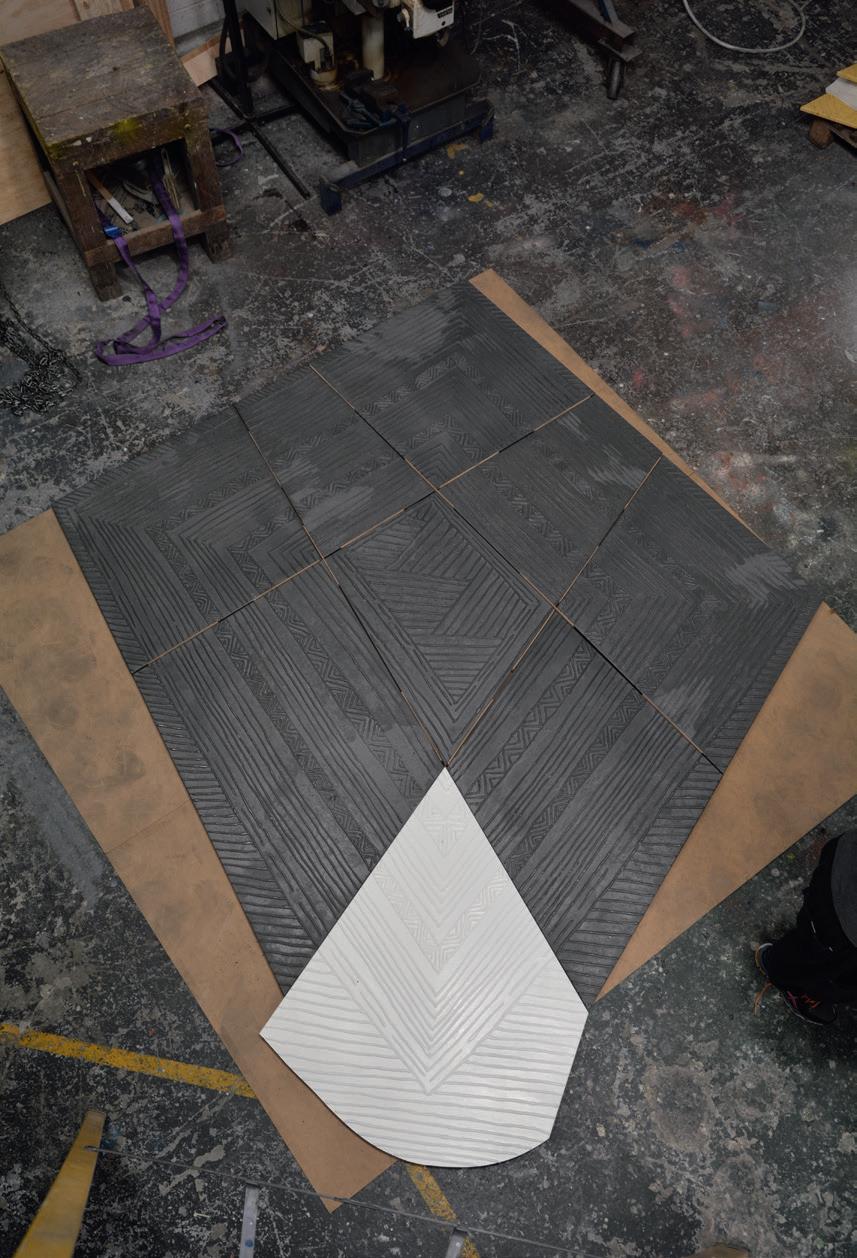

Step 2: Sand-casting patterns: Cast into the silicon-rubber moulds are the sand-casting patterns (positive form). These were then cut up into numbered panels in preparation for the final process.

Step 3: Iron castings: The sand-casting patterns were used to form a negative shape into the sand into which cast iron is poured to finish up with the final pieces (positive form).

Once the cast-iron panels were returned to the studio from the foundry, the next stage was assembly of the panels to form the cloak, the attachment of the Cloak onto the base and then the treatment of the cast iron to give it its finish (patina) and then the installation in at Bowen Street at RMIT’s city campus

Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land is 2.3 metres in height and weighs over 2.5 tonnes

‘The intention was to change the conversation. Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land is an insertion in the built space. It is an expression and assertion of Sovereignty and Aboriginal ever-presence. I was very comfortable with changing the conversation and wanted to make sure we did with a very strong message in a very open space.’

DR VICKI COUZENS

The process to construct the cast-iron base required the initial creation of a positive image using MDF with the textural markings/pattern created using liquid nails. The resulting patterns (positive image) were sent to the iron foundry and went through a sand-casting process. The finished cast-iron tiles were mounted on a steel supporting frame. The final tile had to be fitted at the end to the form of the fitted Cloak. (Pictured:

Dr Vicki Couzens gathered together over 60 possum skins to create the Cloak. She used an historic image of Kaawin Kuunawarn (1820-1889) the Chief of the Kirrae Wurrong tribe, also known as King David and Hissing Swan, as the inspiration and model for the final work. The image shows Kaawirn Kuunawarn standing in a dignified and stately manner as befitted his role and status as a Senior Elder. This stance informed the intent of the artwork in the shaping of the Cloak. The possum skins were stitched together with a synthetic sinew to emulate the original process using untanned skins and kangaroo sinew. (Pictured overpage: Dr Vicki Couzens with her daughter, Jarrah Bundle sewing the possum skins together)

‘One of the things about making sculpture is that the material that you use has to suit the idea of the work. We couldn’t actually use a Possum Skin Cloak, so for us to get the same effect it was a little bit like poetry where you use words to infer things without directly saying them. And this is what we had to do to achieve the same sense of the materiality of the Possum Skin Cloak.’

JEPH NEALE

Jephe Neale created a computer-generated model of a figure with a proud stance. Two models were made: one life-size for the real Possum Skin Cloak to ensure the correct form and draping and the second model as the tool to scale up the work. The waterjet cut layers were covered with chicken wire to imitate the form of the Cloak.

(Pictured overpage: Jeph Neale, Jarrah Bundle and Dr Vicki Couzens draping the Cloak around the form)

The next stage in the process was to create plaster master of the form. Suspended horizontally on a gantry (to use gravity to support the wet plaster), the model was covered in plaster saturated hessian. The final images show a comparison between the life-sized and the real size of the artwork. (Pictured: Hilary Jackman working on the plaster)

The objective was to make the external surface look soft so that it appeared like fur. Hilary Jackman created this external texture by hand, squirting plaster through her fists to produce a tactile, haptic surface on the outside of the Possum Skin Cloak. (Pictured overpage: Hilary Jackman experimenting with the texture of the outside of the Cloak)

‘Vicki always gets us involved right at the beginning, which opens up possibilities. Plus, we’ll come up with an idea or materiality or something that’s outside the square. We enjoy inventing new things and working through how a work might be done or what materials we can use. It’s just so enjoyable and the ideas flow. They just materialise.’

HILARY JACKMAN

The process to get to the final cast iron, required a series of steps. This first step was to create a negative mould of the master which was done using silicon-rubber moulds backed with polymer activated gypsum to hold the silicon rubber rigid. These moulds were created as re-joinable sections.

The next stage was to form the positive sand-casting patterns inside the assembled negative silicon rubber moulds which would eventually go to the foundry. Pads (blocks) were added to the inside of the sand-casting patterns to facilitate the assembly of the finished work. These sand-casting pattern panels were made out of fibreglass and polymer activated gypsum.

The sand-casting patterns were then sent to the foundry where they went through the process of turning the positive sand-casting patterns into a negative into which cast iron was poured to finish up with the final positive form.

The final artwork was built from the bottom up. All of the panels required grinding to fit them together again because the of the uneven contraction of the cast iron as it cools.

The panels were assembled by using stainless steel plates to attach one to the other; the plates were bolted on and then welded. Stainless steel was chosen because of longevity. (Pictured: Jeph Neale fitting and grinding the panels)

‘Realising ideas into a physical medium in a place where you can affect the conversations happening at RMIT and in the wider world, affords me the opportunity to get that story, conversation, or point out there. A lot of my work is about making a difference and creating change and trying to evoke feelings and experience and engagement.’

DR VICKI COUZENSTo prepare the base to mount the finished Possum Skin Cloak, the final panel of the Spirit Memory Imprint Shadow with protruding bolts to support the cloak was put into the steel frame. The cloak was then suspended and fitted in two parts: the main cloak and the remaining panel (the inside flap of the cloak). (Pictured on the following pages: Jeph Neale fitting the Possum Skin Cloak to the base)

To achieve the rust-coloured finish (patina), the Cloak was sprayed with a light solution of hydrochloric acid to start the rusting process. It was kept wet for several days to allow the rust to take hold and then a light spray of fish oil was applied to slow down the rusting process.

The assembled artwork weighed over 2.5 tonnes and was 2.3 metres tall. The most important aspect of transporting the finished artwork, was to ensure the structure was secure and balanced (i.e. it would not tip over).

‘The concept is one of a spiritual and ethereal presence, so not necessarily real in a physical way. The sculpture embodies the spirit of Country and the Law of the Land as a conduit and visual manifestation. It’s the same principle with the memory shadow on the ground. It’s that sense of the memory of presence—the impression that it’s always been there and that the Law of the Land and the spirit of Country has risen up and you can actually see it for a moment in time.’

DR VICKI COUZENS

The base of the public artwork was set into the decking and had adjustable feet to level it up as it needed to sit completely flush with the deck. The scale and positioning of Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land was chosen so that it would have a presence in the centre of RMIT’s city campus and to engender the feeling that people traversing or using the courtyard are in the presence of and in the space of the artwork and that its presence is a continual and ever-present echoing of Indigenous Sovereignty and Law.

‘Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land, is the foundation in which our Being, our living, our place and belonging exists. It tells us how the world is made, how the world works and the laws for living in it.’

DR VICKI COUZENS

Artist, VC Indigenous Research Fellow, RMIT University

Launch Speech: Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land Sovereignty

Ngatanwarr

Mayapa Wangan ngootyoong wanyoo Boon Wurrung ba Woi Wurrung ngalam meen, wooroowooroomeet koorookee ngapoon, ngarrakeetoong ba Meerreeng-ee watnanda-warr deen makatepa

I make Respect for the Boon wurrung and Woi wurrung Ancestors, Elders, Community and Country on where we gather today.

Sovereignty, what is sovereignty?

When I was beginning to put together the Expression of Interest for this commission, my first question to myself was what is sovereignty? What does the dictionary say? What do I think sovereignty is and what does it mean for Aboriginal people collectively?

Sovereignty is a state of Being—it is an internal experience and state of Being. It is who I am as a sovereign Gunditjmara person. As a sovereign Gunditjmara person I live in a state of Being Gunditjmara; it is who I am. I have never ceded my identity; my worldview is through my sovereign Gunditjmara lens, ‘always was, always will be’ as the saying goes.

And sovereignty is an external experience—it is the society, the dominant cultural state we live in.

I researched definitions in several different dictionary sources.

Sovereignty: The quality or state of being sovereign, of having supreme power or authority.

Or, Supreme and independent power or authority in government as possessed or claimed by a state or community.

Some synonyms for sovereignty: supremacy, jurisdiction, dominion, preeminence, prepotency, sway, ascendance, primacy, power, tyranny, predominance, authority, control, influence, rule.

These words seem to aptly describe an underlying attitude, when we think that the society we live in today is shaped by and seeded from the colonial British Empire mindset with its well-designed and established practices for colonising other countries. This colonial mindset is pervasive and inherently woven into the very fabric of the culture of the institutions, government structures and social mindset of this nation.

We are all aware of the massive negative impact ‘colonisation’ continues to perpetrate on our communities.

Another definition of sovereignty I found seemed to better fit our Aboriginal ideas and aspirations of sovereignty.

Sovereignty: Rightful status, independence, or prerogative.

Some of the synonyms for this definition are: autonomy, independence, selfgovernment, self-rule, home rule, self-legislation, self-determination, non-alignment, and freedom.

Antonyms to the state of self-determination and self-government are hegemony and colonialism.

Freedom! My home Country has been stolen, colonised, pillaged and exploited, my Old People and Ancestors fought and died defending our inherent Sovereign rights…

Sovereignty in the Dictionary of Aboriginal English means our place as First Peoples of this Country; it means our collective belonging to place, our innate and inherent rights to autonomous and self-determining Being.

Sovereignty is living in accordance to the Law of the Land.

RMIT Bundyi Girri Strategy* and the Ngarara Willim Centre must be wholeheartedly thanked for the opportunity to create this work. It is through the work of the many who have gone before us and those that carry the fight forward now that challenging colonial thinking and the colonial mindset has given rise to

* RMIT is looking to play a leading role in creating a new relationship between Indigenous and nonIndigenous Australia through the Bundyi Girri project. This is an RMIT initiative that aims to transform the cultural values of the University. With its name taken from the Wiradjuri words for ‘shared future’, the project aims to create an environment where all non-Indigenous staff and students, foreign and domestic, can understand their place in a shared journey of reconciliation.

the establishment of the Bundyi Girri Strategy. The University now has an inclusive way into the future that foregrounds and privileges First Nations epistemologies, our ways of Knowing, Being and Doing.

Because of this we are celebrating a work that speaks to First Nations Sovereignty, a conversation that we couldn’t have had even as recently as five years ago in the ways we can today. I want to acknowledge and offer my deep appreciation of the leadership of the University in being change agents in what is the time of change, the time of sharing that is leading to the transformation of Australia into a matured nation.

Sovereignty is living in accordance with the Law of the Land.

Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land, is the foundation in which our Being, our living, our place and belonging exists. It tells us how the world is made, how the world works and the laws for living in it.

Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land is a manifestation of the eternal, the everpresence of continuous, concurrent creation. Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land is the Law of the Universe.

We, humans, with all other creatures, are singular parts of a greater interconnected stream of consciousness, existing within and as part of the continuous creation.

This work is a manifestation of the beautiful, the immense and amazing, the inexorable and implacable presence of Creation: the ever-present, the timeless and continuous concurrence of Aboriginal Ancestral Creation. It is a representation and a reminder of the spiritual nature of our existence; it represents the ethereal; it is a call to reconnect with spirit, with place, with Country. It is Sovereignty of Aboriginal Peoples as First Peoples in this Land.

It is magnificent, in the presence of the Old People.

This awe-inspiring creation was made possible through a long-term collaborative relationship with my two very dear friends Jeph Neale and Hilary Jackman. Their experience in all things design integrity, sculpture, colour, materiality—the list is endless—has made this work possible. Our collaboration has grown over almost 15 years and allows for deep understandings in the work

we do. It is Jeph’s genius that sees this work realised in its physicality. His absolutely convoluted and detailed brain machinations, and his ability to innovate and invent makes all things possible. A big and deep thank you to you both. I have learned so much and love you and love your work.

Last but not least, to Grace and Jess who have worked so hard on this New Academic Street project: many thanks for your hard work through this complicated and long project.

Thank you to my Old People, my Elders and family.

‘Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land rises from a memory imprint that conjures Bunjil, the Great Creator Spirit. The large-scale Possum Skin Cloak signifies the ever-presence of First Nations people, the significance of Indigenous knowledges, and the law of the land. Its embodiment of place, of protection and Sovereignty invites us to take pause, stop, and connect with Country—the land that connects all of us.’

JESSICA CLARK

Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land represents many things. It embodies a spirit of Country and place. It reflects Aboriginal knowledge and Indigenous peoples status as First Nations people.

It also represents RMIT’s commitment to reconciliation and building a shared future with our Indigenous staff, students, and community. As a University, and a community of thought-leaders and world-shapers, we are passionate about continuing our journey towards sustainable and genuine reconciliation. This commitment is outlined in our Dhumbah Goorowa Reconciliation Plan 2019–2020. This plan articulates how we will progress Indigenous self-determination by developing strong bonds with Australia’s First Peoples through our institutional values, policy and practice, and supporting staff and students in their personal understanding of and connection to Indigeneity.

As the VCE sponsor of RMIT’s New Academic Street project, I am particularly thrilled to see Wurrunggi Biik take up its place in the heart of our city campus.

I have been engaged with the New Academic Street development from its inception. Back in 2011, a team of RMIT staff led by the Property Services met to discuss how to transform and activate the city campus, and our presence on Swanston Street. These discussions morphed into the New Academic Street project which, in 2012, saw Carey Lyon, Director of the architectural practice Lyons, lead a consortium of architectural practices of RMIT alumni to reimagine the centre of our City campus.

The resulting design has rejuvenated our University and created inspirational, collaborative and colourful spaces for students and staff. RMIT’s New Academic Street officially opened in 2017. Spanning 32,000 square metres of indoor and outdoor spaces, it has fast become a precinct where thousands of students study, socialise and collaborate every week. It is appropriate that Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land takes its place in the centre of this precinct on Bowen Street.

Thank you to all of the RMIT funding bodies that supported this public artwork—the New Academic Street Project, Property Services Group, the RMIT Art Fund and RMIT University Art Collection and our Vice-Chancellor Martin Bean.

Thanks also to the immensely creative people who brought Wurrunggi Biik to life: artist Vicki Couzens, her collaborators Jeph Neale and Hilary Jackson, and curators Grace Leone and Jessica Clark.

My hope is that this stunning artwork will draw people together, spark reflection, and signify RMIT’s commitment to building a shared future, one that reflects the reality that people, custom and Country are inextricably linked.

The installation of Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land on our CBD campus, is a powerful statement of Aboriginal Sovereignty.

I’m honoured that as RMIT’s Chief Operating Officer, I’ve been given shared custodianship of this piece of public artwork—in partnership with the artist Vicki Couzens, Traditional Owners of this land and the RMIT University Arts Collection. As the daughter of an artist and someone who is deeply committed to reconciliation with our First Nations people, it’s not lost on me how powerful art can be in shaping the conversations we need to have, to build the society we wish to create.

Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land presents each of us with an opportunity to explore our own personal connection to Country. I look forward to the enduring and prominent presence of Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land at the centre of our RMIT city campus—which aligns with our reconciliation agenda being at the centre of RMIT’s identity and decision-making.

Let’s be proud of this, let’s not just walk by, let’s stop and reflect.

‘Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land is a public artwork that will transform our current understanding of reconciliation and promote an environment for a shared future for all through the founding principle of Sovereignty.’

GRACE LEONE

Many people have been instrumental in the realisation of the Wurrunggi Biik: Law of the Land public artwork as well as the making of this publication. While we are unable to mention everyone, we would like to take this opportunity to thank you all for your contribution. In particular we would like to acknowledge the following people.

RMIT University: Alice Alberico (Project Officer, Capital Works Property Services Group); Parbinata Carolyn Briggs AM (Elder in Residence); Jon Buckingham (RMIT Gallery Collections Coordinator);

Stacey Campton (Director of Indigenous Engagement);

Di Cohen (NAS Project Manager); Professor Peter Coloe (VCE Sponsor of RMIT’s New Academic Street (NAS));

Jedda Costa (Ngarara Willim Student Representative);

Dr Vicki Couzens, (Artist, VC Indigenous Research Fellow); Suzanne Davies (Director, RMIT Gallery, 2018);

Abena Dove (RMIT Union Representative); Aunty

Kerrie Doyle (Associate Professor Indigenous Health);

Jeremy Elia (NAS Project Office Director); Sarah Firth (RMIT Union Representative); Professor Julian Goddard

(Head of School, School of Art, 2018); Dionne Higgins (RMIT’s Chief Operating Officer); Aunty Diane Kerr (Wurundjeri Elder); Professor Mark McMillan (Deputy

PVC Indigenous Education and Engagement); Ben Palmer (Project Manager, Capital Works); Janeene Payne (NAS Project Office Student Engagement and Events Manager); David Shaw (Senior Advisor, Health, Safety, Security); School of Art.

All images reproduced with permission.

Cover image: Matt Houston Photography

pp. 2–3: Matt Houston Photography; p. 4: Grace Leone/Parbin-ata Carolyn Briggs; p. 6: Matt Houston

Photography; p. 13: Matt Houston Photography; p. 17: Matt Houston Photography.

THE COMMISSION

pp. 18–19: Illustration by Hilary Jackman; p. 21: Illustrations by Hilary Jackman; p. 23 and p. 25: Image capture from Law of the Land, RMIT video; p. 27: Visual poem by Vicki Couzens.

THE PROCESS OF MAKING

pp. 28–29: Photograph by Jeph Neale and Hilary Jackman; p. 30: Matt Houston Photography; pp. 38–95: Photographs by Jeph Neale and Hilary Jackman.

THE LAUNCH

pp. 96–97. Photograph by Moorina Bonini; p. 101 Matt Houston Photography; p. 105: Matt Houston Photography; p. 106 Matt Houston Photography; p. 111 Matt Houston Photography; p. 114 Matt Houston Photography.

Aboriginal languages are oral and sometimes there are different spellings and/or spelling systems across different languages.

External to RMIT: Peter Felicetti (Felicetti engineering); Hilary Jackman (artist); Carey Lyon (Lyon Architects);

Jeph Neale (sculptor).

RMIT University acknowledges the people of the Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung language groups of the eastern Kulin Nation on whose unceded lands we conduct the business of the University.

RMIT University respectfully acknowledges Ancestors and Elders past and present.

RMIT also acknowledges the Traditional Custodians and their Ancestors of the lands and waters across Australia where we conduct our business.

Published in 2020 by the Bowen Street Press

Bowen Street Press

Building 9, Bowen Street

RMIT University

Melbourne Victoria 3000 www.bowenstreetpress.com.au

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or in any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter of 10% of this book, whichever is greater to be photocopied by any education institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Copyright text © individual credited authors

Copyright illustrations and photography © See Image Credits, p. 112

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia

ISBN: 978-1-922271-02-0

Book production: In collaboration with the Bowen Street Press team and Grace Leone

Text design and typesetting: Christopher Black

Cover design: Grace Leone

Printed and bound in Australia by Valiant Press

‘Sovereignty is living in accordance with the Law of the Land.’

DR VICKI COUZENS