IS LEFT UNHEARD, IT’S BURNING.

Ballet

IS LEFT UNHEARD, IT’S BURNING.

Ballet

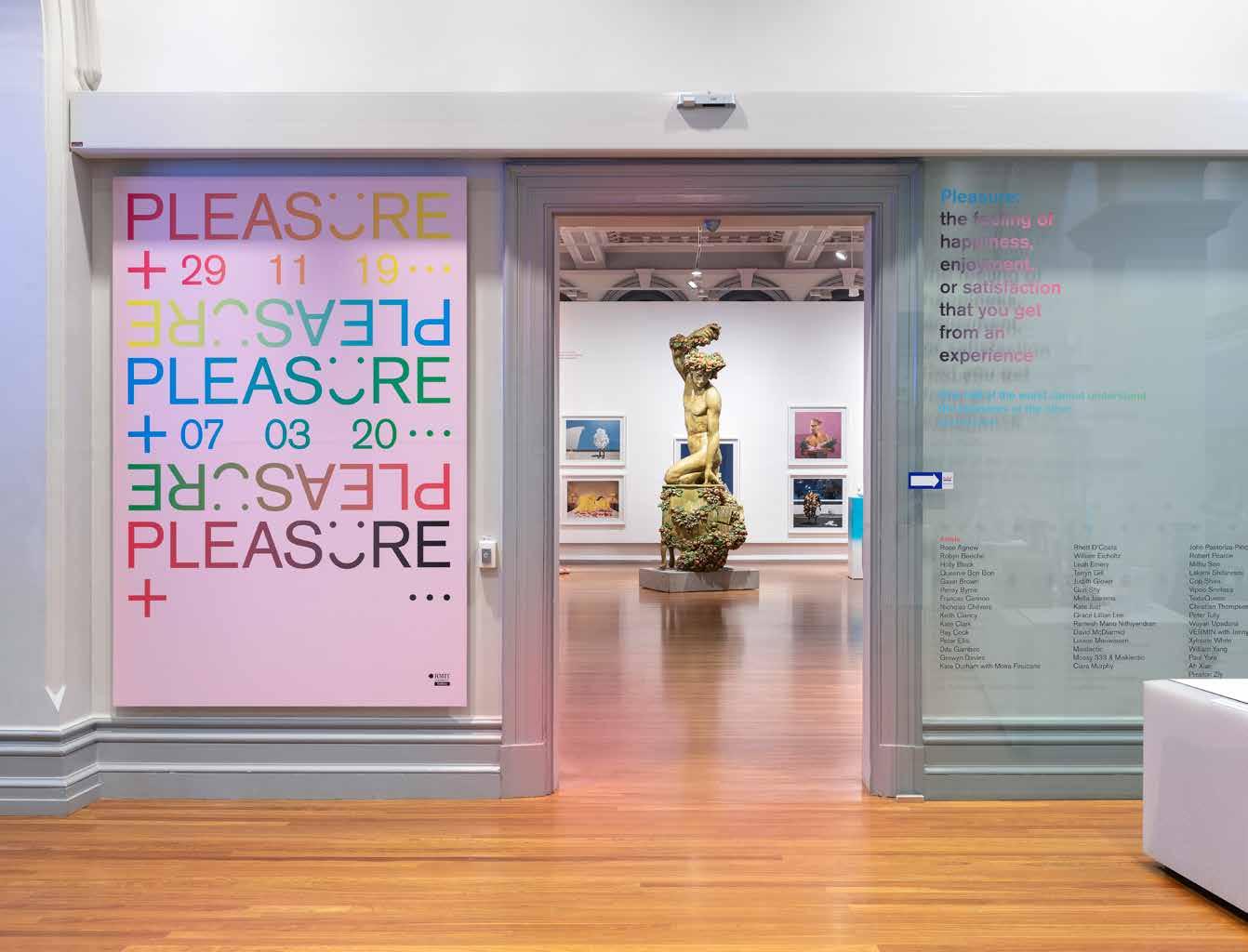

From decoration, embellishment and exaggeration to examinations of identity and beauty and its various interpretations, Pleasure explores how artists and designers have used the body as a personal, provocative and at times political canvas from the flamboyant 1980s to now.

These works of art force us to examine the body with a fresh perspective, weighing up the many complexities of what it means to be human, including disrupting gender and bodily boundaries.

This exhibition seeks to embrace frivolity, contradictions and minor perversities. Pleasure foregrounds the work of artists motivated to challenge the banalities of late capitalist society by constructing interventions that lift our spirits, produce wonder and make us laugh.

We were drawn to the outrageous, and challenging, but above all, art that treats the body with a joyful exuberance and defiant insolence. This stands in defiance to the contemporary political economy of pleasure, with its emphasis on mass production and consumption.

While many of the works in Pleasure are highly erotic or graphic in their content, they depict sexuality through an alternative lens to mainstream representations of pleasure. In a gallery context, these works provide nuanced perspectives usually silenced in the world of online pornographic culture.

Pleasure Activist Adrienne Maree Brown writes that ‘pleasure reminds us that even in the dark, we are alive.’ Be pleasured!

Installation image left to right: Kate Durham, The dress with no inhabitant, 2000; Paul Yore, Daddy’s #1, 2018; Mummy 2018; Gerwyn Davies, Bomb 2017; Opera 2017; Bed 2018; Matterhorn 2018; QLD 2014; Spilt milk, 2017; Adonis 2019; William Eicholtz, Impossible Cornucopia, 2007; Nicholas Chilvers, Puff Piece II (the Enablers), 2018; Cop Shiva, Urban Ecstasy, 2011 to present

Installation image left to right: Kate Durham, The dress with no inhabitant, 2000; Paul Yore, Daddy’s #1, 2018; Mummy 2018; Gerwyn Davies, Bomb 2017; Opera 2017; Bed 2018; Matterhorn 2018; QLD 2014; Spilt milk, 2017; Adonis 2019; William Eicholtz, Impossible Cornucopia, 2007; Nicholas Chilvers, Puff Piece II (the Enablers), 2018; Cop Shiva, Urban Ecstasy, 2011 to present

Installation image left to right Robyn Beeche, Leigh Bowery for Brutus Magazine 1984; Leigh Bowery 1984; Grace Lillian Lee, Body Sculpture: Enlightenment, 2016; Body Sculpture: Acceptance, 2016; Paul Yore, Daddy’s #1, 2018; Mummy 2018; Rhett D’Costa, Holding Hands, 2018; Bespoke, 2013; Kate Durham, The dress with no inhabitant, 2000

Installation image left to right Robyn Beeche, Leigh Bowery for Brutus Magazine 1984; Leigh Bowery 1984; Grace Lillian Lee, Body Sculpture: Enlightenment, 2016; Body Sculpture: Acceptance, 2016; Paul Yore, Daddy’s #1, 2018; Mummy 2018; Rhett D’Costa, Holding Hands, 2018; Bespoke, 2013; Kate Durham, The dress with no inhabitant, 2000

Rhett D’Costa, Bespoke 2013; Paul Yore, Daddy’s #1, 2018; Mummy 2018; Kate Durham, The dress with no inhabitant, 2000; Gerwyn Davies, Bomb 2017; Opera 2017; Bed 2018; Matterhorn 2018; QLD 2014; Spilt milk, 2017; Adonis 2019; William Eicholtz, Impossible Cornucopia, 2007; Cop Shiva, Urban Ecstasy, 2011 to present; Laksmi Shitaresmi, TERUSLAH MELANGKAH WAHAI KAKI HIPUPKU 2012 (Keep on Walking O Leg of my Life, 2012)

Installation image left to right:

Installation image left to right:

BY DESCRIBING IT. 23

The acceptance of pleasure has been a controversial part of the conduct of the self for at least 2000 years. The ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus (341-270 BC) believed pleasure to be the source of happiness, and its acceptance the key to enjoying a good life. Indeed, for him the tension embedded in the pleasure/pain binary was the inherent motivator of all behaviour. Understanding how to balance this binary has occupied much of Western (and other) philosophical inquiry since Epicurus wrote: ‘Pleasure is our first and kindred good. It is the starting point of every choice and of every aversion, and to it we come back, inasmuch as we make feeling the rule by which to judge every good thing’.1

Strangely, for much of the time since Epicurus penned the above, especially during the height of the Christian era (say 800AD up to the Enlightenment), the repression of personal pleasure was seen as the force holding ‘the good’ in place, and concomitantly the bearing of pain as a virtuous and pious duty. But with the rise of modernity this all changed, whereby the experience of pleasure (enjoyment) dropped many of its associated anxieties and moral deprecation. The eminent historian Stephen Greenblatt, in his wonderful book The Swerve. How the Renaissance Began, recounts the re-discovery of the ancient-Roman Lucretius’ two-thousandyear-old poem On the Nature of Things in the early fifteenth century. Greenblatt attributes the rise of secularism, democracy, the scientific method and the modern self (cumulatively modernity) — all, to the slow re-instatement of Epicurean ideas so eloquently articulated by Lucretius. It was a close call — almost accidental. What ‘book-hunter’ Poggio Bracciolini found, almost 500 years ago, was a copy of a copy of a copy… of Lucretius’ original manuscript, stored and forgotten (ironically given the effect it later had on conventional religiosity) in a monastery. That it survived is down to chance. Lucretius’ beautiful poem is the centre piece of Epicurean thought (and action). It not only explains the natural world as a set of accidents (swerves) but foregrounds pleasure as the key to happiness. Indeed, he opens his most beautiful poem with the first two lines:

Life-stirring Venus, Mother of Aeneas and of Rome, Pleasure of men and gods, you make all things beneath the dome2

Despite being didactic, the poem is deliberately written in a form that itself gives pleasure. Its lush and sometimes dramatic imagery is, however, balanced by an earthliness that grounds the poem in the reality of life. Its form was seemingly meant as a metaphor for the prudent management of pleasure. For Epicureans understood that the pitfalls of excessive pleasure would lead to not only pain, but deep unhappiness. Pleasure had to be measured and contextualised for it not to be overcome by excessive unfulfilled desire.

Today pleasure, in all its weird and wonderful manifestations, is central to the enjoyment of life. Yes, we live in a hedonistic society with its traps of indulgence,

Professor Julian Goddardthe end of living happily.

but if properly moderated (prudence), the resulting pleasure and happiness seem to be the main motivations for living a ‘good life’ today. We are now able to live with pleasure (and our bodies) in a more relaxed and celebratory manner than possibly ever before. As hopefully this exhibition attests.

Pleasure presents the work of a diverse group of artists who use the body to represent varying aspects of pleasure. The exhibition celebrates joy, humour, flamboyance and the outrageous in the articulation of pleasure through images of the body as created by artists. This stands in defiance to the contemporary political economy of excessive pleasure found in the mass production and consumption of banal satiation (gluttony/obesity), industrialised tropes of the gaze (porn/otherness) and the political management of delayed gratification (repression). This exhibition foregrounds the work of artists motivated to challenge the everyday of late capitalist society by constructing interventions that lift our spirits, produce wonder and make us laugh. As such, the works in this show construct a cacophony of resistance through multiple voices, diverse practices, positions and extroversions. Full of slippages, contradictions and minor perversities, this show attempts to delight and embrace difference, embarrassment and frivolity.

This strategy — resistance through celebration, especially the celebration of pleasure — while central to the intent of this exhibition is nothing new. Although there is probably more opportunity for it to succeed today given our relative tolerance and acceptance. In the late nineteenth century, a group of Parisian cartoonists, writers, raconteurs and artists gathered together with the intention of making an exhibition celebrating drawings by people who couldn’t draw. The Incoherents (Les Arts incohérents) embraced the fumisme3 spirit of the time that challenged convention and parodied everyone and everything. They were the pre-cursor of Dada (some would say the model for Dada, given how much of their ideas and forms the Dadaists copied). Their general irreverence kicked-off the anti-art movements of the twentieth century through Dada, Futurism and Surrealism to Fluxus and Conceptualism.

In a sense Pleasure carries the spirit of The Incoherents with much of the work being tongue-in-cheek but underpinned by some highly critical attitudes taking pot-shots at the conventions of contemporary society. The challenging of pomposity and convention and the celebration of difference and diversity have always been a more powerful tools than protest, in changing social mores. People seem more comfortable with humour than preaching when it comes to considering different ways of thinking, tending to respond more sympathetically to ideas that solicit empathy and participation rather than being told what they should do and think.

Pleasure is something of a Trojan horse. Inside the fun and joy of the exhibition sit serious issues such as ageism, LGBTIQA+ rights, climate change, quantum sexualities4, the role of tyranny and political repression. These strong and important considerations, usually presented in art through didactic and protestant forms of representation, are unfortunately not that popular with many people. While not trying to be popularist, this exhibition has been very well frequented and attracted plenty of positive publicity5 through its celebratory form and low-key argument. Hopefully those who visit the exhibition will not only enjoy the colour, experimentation, skills, humour and general fun, but will also dig a little deeper into the works on show and begin to question their ‘messages’ and intent. This was a definite strategy in thinking through the exhibition from its inception.

While some of the works in the exhibition may seem light-hearted, much of it is also beautiful. But again, we should not let beauty opaquely mask more serious matters, but exactly the opposite. We can learn from beauty that the realm of pleasure sits more often than not in the body. The apprehension of beauty is a feeling — possibly a sense — recognisable as pleasure. Beauty manifests through corporal pleasure, outside of the mind’s realm of rational and logically thinking. But even it is an experience that can lead to realization. Beauty is a pleasure that can remind us of, among other things, the sanctity of nature (a beautiful landscape), the joy of sensuality (beautiful bodies in all their forms), the transience of being (a beautiful moment), and of love (the beauty of friendship). If this exhibition elicits any of these, it has done its job.

Pleasure has been a pleasure. As with Lucretius’ beautiful poem, hopefully the exhibition’s form and appearance will be received likewise — pleasurably. Such exhibitions, foregrounding a pleasurable experience at the expense of more cerebral considerations, are unusual. Pleasure is itself a provocation. Something of an experiment that invites a sensual immersion that hopefully opens up ideas and allows for a myriad of differing responses.

1. As quoted in Catherine Wilson. The Pleasure Principle. Epicureanism: A Philosophy for Modern Living. Page 10. Harper Collins, 2019. Taken from Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers translated by R.D. Hicks. Harvard University Press,1931.

2. Lucretius. The Nature of Things (Translated by A.E. Stallings). Penguin Books, 2007

3. Fumisme is a term first noted by French musician and composer Georges Fragerolle in 1880 that described an attitude of mind that abhorred pomposity and practiced insolence. It was synonymous with fin de siecle bohemianism.

4. Non-binary, unfixed and indeterminable.

5. Art Almanac. 29.1.2020. pp32-34. The Australian 15.1.2020. Review section p12.

CANNOT UNDERSTAND THE Grace Lillian Lee, Body Sculpture: Enlightenment , 2016; Body Sculpture: Acceptance , 2016

PLEASURES OF THE OTHER. 29

Jane Austen

Installation image:

Rhett D’Costa, Holding Hands, 2018; Bespoke, 2013; Kate Durham, The dress with no inhabitant, 2000; Paul Yore, Daddy’s #1, 2018; Mummy 2018; Gerwyn Davies, Bomb 2017; Opera 2017; Bed 2018

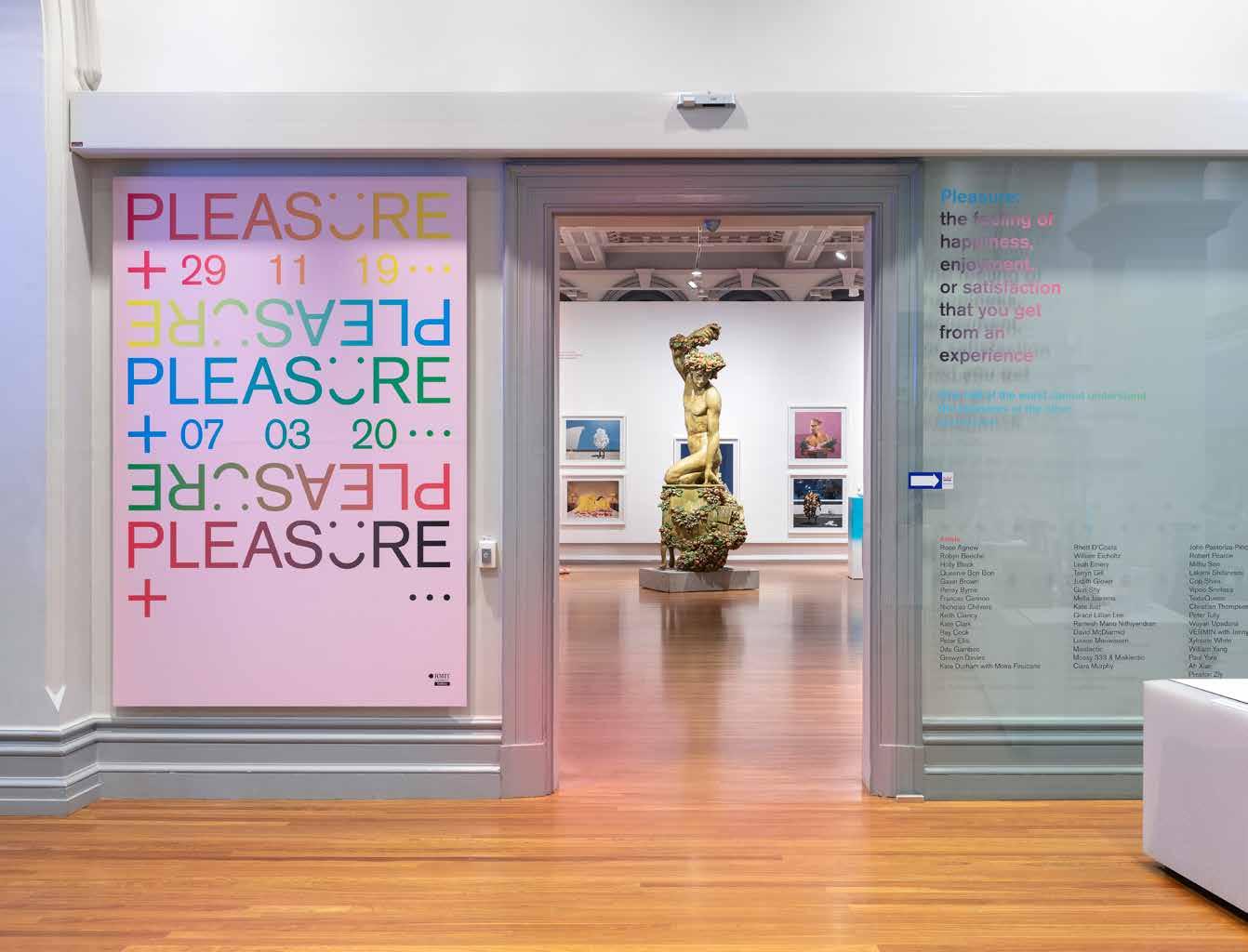

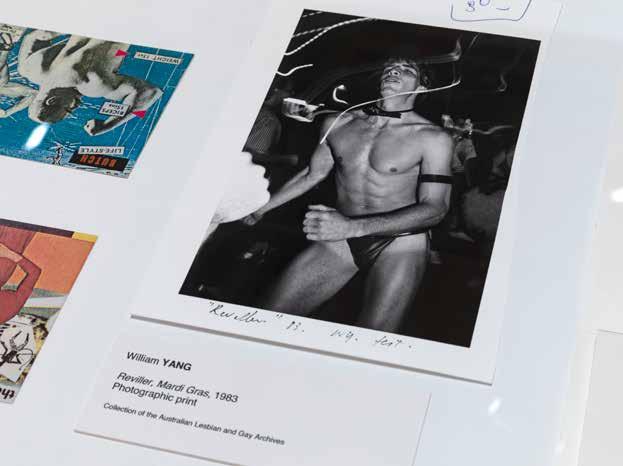

Installation image: Robert Pearce, BUTCH: A series of ultra-mundane postcards c.1982

Installation image: Robert Pearce, BUTCH: A series of ultra-mundane postcards c.1982

Pleasure might seem a trivial theme for an exhibition, but as pleasure activist Adrienne Maree Brown observed in Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good (2019) ‘pleasure reminds us that even in the dark, we are alive.’ The ability to modify and decorate our bodies to generate pleasure may not set us apart from non-human animals (is there much that does?) but it is part of the wonderful complexity of what makes us human.

The Pleasure exhibition was curated by three different people, with three different research interests. The starting point of this collaborative curatorial exercise came about via conversations we had that highlighted intersecting — and shared — interests in representations, disruptions and decorations of and to the body. We all approached the concept for the exhibition with different ideas, different backgrounds and different research but the conversation was lively and focused on how artists used the body to interpret pleasure.

We all agreed that interesting provocations arise when artists challenge the status quo in their interrogation of the human body and in assumptions of beauty and pleasure. A curatorial rationale was born.

My way into Pleasure was through my academic research. The 2018 exhibition My Monster: The Human Animal Hybrid at RMIT Gallery which I curated was a visual representation of my PhD in hybridity and the body. During my research, I immersed myself in speculative fiction and its fascination with disrupted bodily borders. I was keen to further explore the ways in which artists used the idea of the decorated and disrupted body as a metaphor and site of intimate examinations of identity.

While we live in a world where sexualised imagery is commonplace — artists have for centuries used the body as a canvas to explore identity and intimacy. Many of the works in Pleasure are highly erotic or graphic in their content. However, they depict pleasure through an alternative lens, providing the nuanced perspectives of voices usually silenced in an online pornographic culture. The artists use the body to not only embellish and adorn but also as a personal and intimate metaphor. I am fascinated by how what we consider acceptable depictions of pleasure in art has changed so rapidly. Only a few years ago, I attempted to place Dr Judith Glover, from RMIT’s industrial design program, on a broadcast public panel on design, so she could talk about her research into design and sexual health innovation. According to her research, people are more likely to own a sex toy as they get older and bodies start to fail, and we lose our sensitivity and control. The organisers were shocked by the possible discussion of dildoes on radio, and I was asked to find someone who was working in an area ‘more acceptable’. It was therefore especially delightful to feature Glover’s work in Pleasure; her bespoke BentO Box, with ceramic hand-made dildos, is about the acts of coupling, self-love and pleasure, of slowing down and exploration.

Women have always battled with pressures to blend in, and indeed, they have a lived reality of the contested space that is the very ownership of their own bodies (especially in their fertile years). When it comes to pleasure, for women the act of voyeurism neatly disengages their bodies with any heavy cultural burden to make sure their body is a constant symbol of their fertility — which has traditionally been

their currency. All bodies can take pleasure in watching acts of pleasure. Leah Emery’s In & Out with neat, polite and introspective cross-stitches — with its tradition of female craft, presents hardcore porn rather than homilies. The viewer of her work becomes a voyeur.

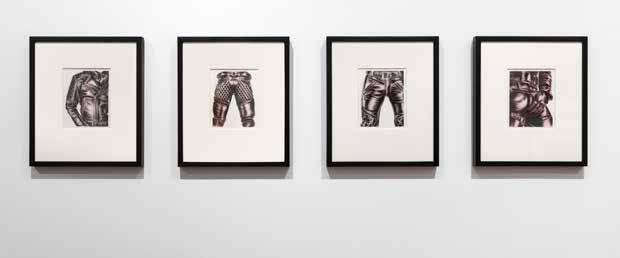

If looking is a powerful driver of pleasure, so is the imagination. The Prince and the Bee Mistress is a boxed set of 24 etchings illustrating a surreal, erotic, gothic horror fairy tale by artist Peter Ellis and writer Tobsha Learner. The subtle, almost voyeuristically private etchings depict the seduction of a young prince, who is visited nocturnally by a mysterious erotic force. These provide a wonderful, jolting contrast to John Pastoriza Pinol’s contemporary leather drawings (‘Sobriquet’ series), which reveal how in a homoerotic male context, wearing black leather clothing is a selfexpression of heightened masculinity, sexual power and an engagement in fetishism. From fairy tale to subculture, Pleasure then invites us to delight upon Gun Shy’s mixed media installation #texturalintercourse which provides viewers with pop subversion exploring fetish in the everyday normality of life. The installation beautifully illustrates the Jane Austen quote ‘one half of the world cannot understand the pleasures of the other’. Who knows what’s really on people’s minds or behind closed doors?

We can all take pleasure in the intrigue created by fragmented identities that arise from the adornment provided by costumes and decoration. From the dress-up box of childhood, to the special costumes worn for ceremonies and parades, clothes can transform us, even if only momentarily.

Yet such pleasures are rarely benign. What we wear have meanings that can be powerful; symbolic signifiers of status, wealth, gender and culture. What we choose to wear can be simultaneously an armour and an invitation and a deflection. This applies not only to clothes, but the decoration which we layer ourselves with — make up, jewellery, shoes, intimate concealed layers of undergarments and flamboyant outerwear.

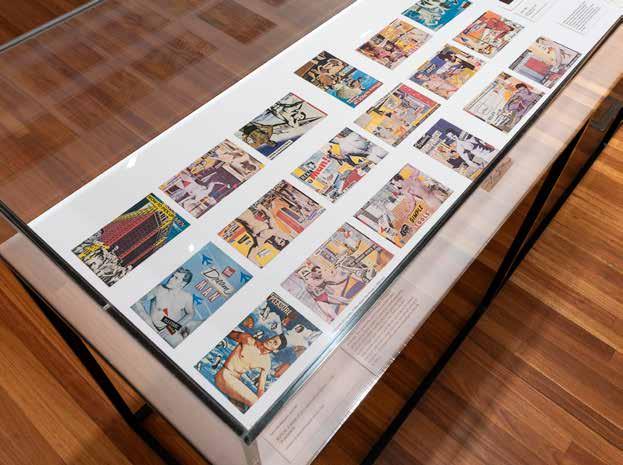

There were several reasons the curators wished to include works by David McDiarmid and Peter Tully in the exhibition. For me, it was a glistening shimmering faux bejewelled hologram brooch by Peter Tully I purchased in Sydney in the early 1990s. Tully’s work was a huge influence on me as a young art student. I was inspired by how gay artists used the pleasure and celebration of dressing up to challenge conservative social attitudes. Fashion was a provocation.

I was keen to acknowledge in Pleasure the influence that Tully and his partner David McDiarmid had in bringing gay culture into the mainstream through Mardi Gras. Together with Helen Rayment we explored artefacts, drawings and photos at the Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives (ALGA) which loaned works that helped tell the story in our exhibition of the importance of the Sydney Mardi Gras as a force for change, one that flamboyantly centres pleasure and the body. Societal change comes through cultural activities as much as legislation. The Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras was inaugurated in June 1978 as a political protest demanding gay rights. Between 1982 and 1986, with Tully at the helm, Mardi Gras also became an influential cultural movement, with flamboyant costumes, colourful and outrageous

floats, ironic humour and the visual excess of a camp aesthetic engaging an increasingly wide audience with gay liberation and identity politics.

In contrast to Tully’s brooch is Nick Chilvers’ Puff Piece II (the Enablers) a pumped up, exaggerated sculpture of sneakers where fashion and sportswear branding overlap with the cultures of pleasure, risk, sexuality, and queer subcultural identity. For Chilvers, the sneakers reflect the ideologies of commodity culture, where pleasure — and identity — can be bought.

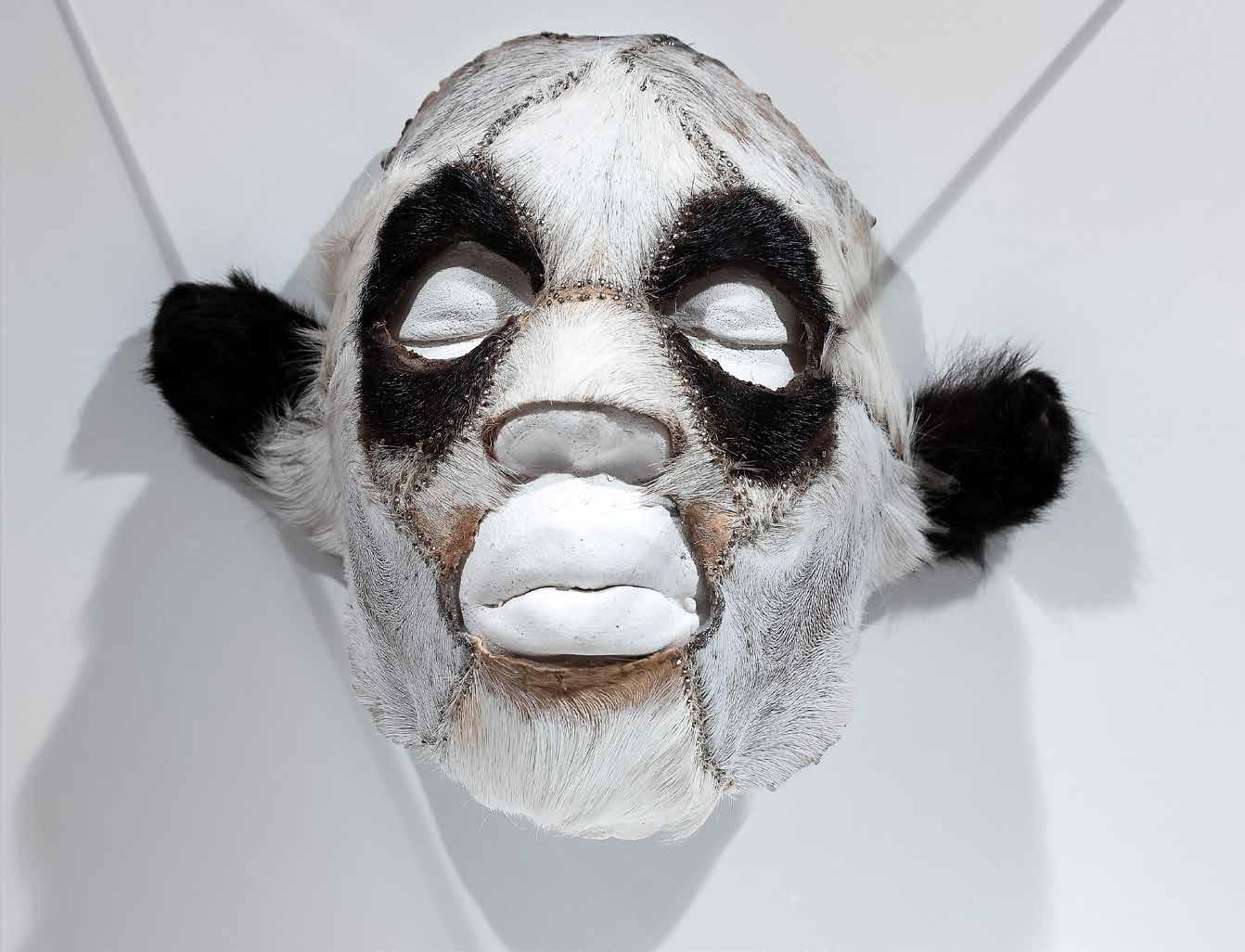

Commodity culture brings me a full circle back to the ultimate bodily disruption — that of the human and animal. American taxidermy artist Kate Clark’s Desiigner’s PANDA mask (made from bear and antelope hide) examines becoming the object of your desire. Panda is a song by American rapper and singer, Desiigner. The song’s hook is about Desiigner’s love for the BMW X6, which according to him resembles a panda bear because of its white body and tinted windows. In the accompanying music video the rapper transforms into the actual embodiment of his object of pleasure — his beloved BMW X6 — by donning a lifelike panda mask. The producers envisioned Desiigner turning into a panda — literally becoming the object of his desire — so Clark’s balance of human/animal was what they wanted. Pleasure and desire can indeed be transformative, as all good fables, fantasies and fairy tales tell us throughout history.

Installation image left to right:

@gun_shy_design (Designer), @ihateprozac (Performer) @mikewnguyen (Performer), @markgambino_ (Video), @mileslemonade (Stylist), #texturalintercourse 2019; VERMIN with Jenny Bannister, Toad a GoGo, 2019

Installation image left to right:

@gun_shy_design (Designer), @ihateprozac (Performer) @mikewnguyen (Performer), @markgambino_ (Video), @mileslemonade (Stylist), #texturalintercourse 2019; VERMIN with Jenny Bannister, Toad a GoGo, 2019

Installation image: @gun_shy_design (Designer), @ihateprozac (Performer) @mikewnguyen (Performer), @markgambino_ (Video), @mileslemonade (Stylist), #texturalintercourse 2019

Installation image left to right: Judith Glover, BentO Box, 2019; Robert Pearce, Drawing for ‘Sex Roles’ series featuring three men 1975; Sauna 1986; Artwork for article ‘The (married) Man-Trap’, 1980; Drawing for Slick Graphics’ Poster, 1982-1988; The Flogging 1981; MEN c. 1980

Installation image left to right: Judith Glover, BentO Box, 2019; Robert Pearce, Drawing for ‘Sex Roles’ series featuring three men 1975; Sauna 1986; Artwork for article ‘The (married) Man-Trap’, 1980; Drawing for Slick Graphics’ Poster, 1982-1988; The Flogging 1981; MEN c. 1980

AM ASKING PEOPLE TO BE AS

RIGOROUS IN THEIR PLEASURE

AS IN THEIR CRITICISM.

Installation image left to right: Mella Jaarsma Bale , Bale II, 2018; Kate Just, Unearthed, 2011; Misklectic and Mossy 333, I’m Here: Portrait of Mossy Jade Johnson 2017

Installation image left to right: Mella Jaarsma Bale , Bale II, 2018; Kate Just, Unearthed, 2011; Misklectic and Mossy 333, I’m Here: Portrait of Mossy Jade Johnson 2017

Bale I Bale II , 2018 (detail)

Mella Jaarsma

Installation image left to right: Dita Gambiro, Mum , 2014; Holly Block, Little Creature #1 , 2017; Louise Meuwissen, Flesh Sac (Back Pack) , 2017; Rose Agnew, Deportment for Young Ladies , 2019; Keith W Clancy, BLACK WHOLE (RMX) , 2019; Kate Just, Unearthed 2011

Installation image left to right: Holly Block, Little Creature #1 , 2017; Dita Gambiro, Mum , 2014

Kate Clark, Desiigner’s PANDA mask, 2016

Kate Clark, Desiigner’s PANDA mask, 2016

PLEASURE THE DESSERT. 73

C. Forbes

Moira Finucane The Rapture Art vs Extinction taken by Simon Schluter; Louise Meuwissen, Flesh Sac (Back Pack) 2017; Rose Agnew, Deportment for Young Ladies 2019; Keith W Clancy, BLACK WHOLE (RMX) 2019; Mella Jaarsma. Bale I, Bale II 2018; Kate Just, Unearthed, 2011; Ray Cook, Nineteen Eighty, 2006; Andrea 2002; Pearly Rose Black, Chanteuse and Artist’s Muse 2006; Mark, 2002; Gavin Brown, Running with scissors, print series, 2013

Installation image:

Installation image:

Installation image left to right: Frances Cannon, Noodles, 2016; To do the washing, 2016; I believe in God 2016; I Don’t 2016; Missiah 2016; Penny Byrne, Keep Young and Beautiful if you want to be Loved, 2011; Misklectic, Pudica 2019;

Tarryn Gill, Guardian (Self Portrait), 2017; Penny Byrne, Venus de Hoodie 2011; TextaQueen, Retribution 2019

Installation image left to right: Frances Cannon, Noodles, 2016; To do the washing, 2016; I believe in God 2016; I Don’t 2016; Missiah 2016; Penny Byrne, Keep Young and Beautiful if you want to be Loved, 2011; Misklectic, Pudica 2019;

Tarryn Gill, Guardian (Self Portrait), 2017; Penny Byrne, Venus de Hoodie 2011; TextaQueen, Retribution 2019

I believe in God 2016; I Don’t 2016; Missiah 2016 Mithu Sen, still from Breathing , 2004 84

Louise Meuwissen, See yourself in itWrestle with it 2018

Deportment for Young Ladies, 2019

Bobble

Sterling silver, hair

Thimble Sterling silver

Hair Brush

Sterling silver, ebony (reclaimed from a piano), hair

Duster Sterling silver, hair Hair Bow

Hair, sterling silver, plastic knitting needles, thread Courtesy of the artist

Leigh Bowery for Brutus Magazine, 1984 Photograph

Leigh Bowery for Brutus Magazine, 1984

Photograph Courtesy of the Robyn Beeche Foundation

Leigh Bowery, 1984 Photograph Brimbank City Council Art Collection

Holly Block

Little Creature #1, 2017

Digital photograph and fox fur Courtesy of the artist

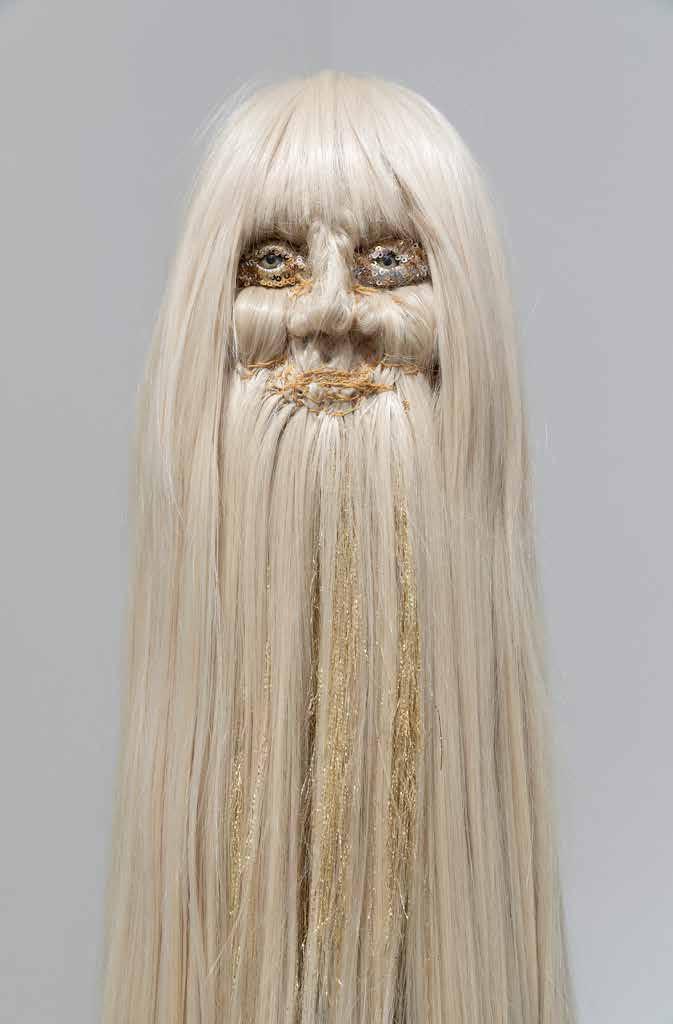

Queenie Bon Bon

Deeply leisured wear - a Coat for all occasions, 2015

Synthetic, real hair wigs, denim jacket Courtesy of the artist

Gavin Brown

Running with scissors, print series, 2013 Photographic collages

Wargames, 2015

Ink oil on canvas Courtesy of the artist

Penny Byrne

Keep Young and Beautiful if you want to be Loved, 2011

Vintage porcelain figurines, mixed media

Courtesy of Mildura Arts Centre Collection. Acquired 2013

Venus de Hoodie, 2011

Vintage resin Venus de Milo sculpture, fabric, hoodie smart phone cover

Courtesy of the artist

Nicholas Chilvers

Puff Piece II (the Enablers), 2018

Acrylic paint, plastic, moulding foam, polystyrene, and plinth

Courtesy of the artist

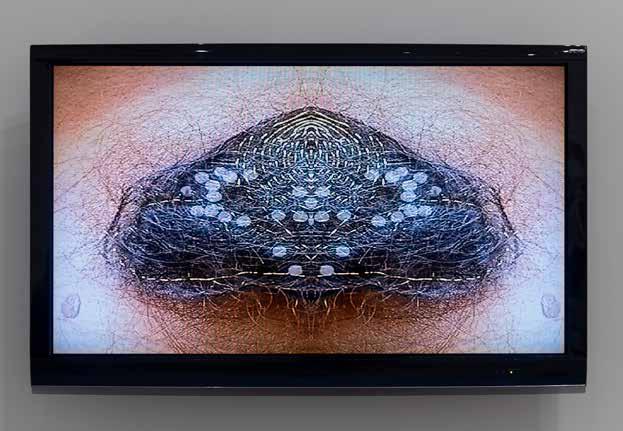

Keith W Clancy

BLACK WHOLE (RMX), 2019

Single-channel 4K video loop, stereo sound duration: 45 minutes Courtesy of the artist

Kate Clark

Desiigner’s PANDA mask, 2016 Bear and Springbok hide, plaster cast Video duration: 4:03 minutes Mask courtesy of the artist Video courtesy of the artist and Iconoclast Productions

Frances Cannon Noodles, 2016 Ink on paper

To do the washing, 2016 Ink on paper

I believe in God, 2016 Ink on paper I Don’t, 2016 Ink on paper

Missiah, 2016 Ink on paper Courtesy of the artist

Ray Cook

Nineteen Eighty, 2006 Andrea, 2002

Pearly Rose Black, Chanteuse and Artist’s Muse, 2006 Mark, 2002

Photographs Courtesy of the artist

Rhett D’Costa

Holding Hands, 2018

Inkjet photographic print on paper

Bespoke, 2013

Inkjet photographic print on paper Courtesy of the artist

Gerwyn Davies Bomb, 2017 Opera, 2017 Construction, 2017 Bed, 2018 Matterhorn, 2018 QLD, 2014 Spilt milk, 2017 Adonis, 2019

Photographs Courtesy of the artist

Kate Durham

The dress with no inhabitant, 2000 Metal, shell, wire. Courtesy of the artist

William Eicholtz

Impossible Cornucopia, 2007 Synthetic glazed polymer, cement Courtesy of the artist

Peter Ellis and Tobsha Learner

The Prince and the Bee Mistress, 1986 Edition: 15/15

Plate 1: Title page, The prince and the bee mistress

Plate 9: Chinese 5th century Plate 10: The prince’s room Plate 11: The swarm

Etching, aquatint, soft-ground, drypoint, sugar-lift, photoetching, plate-tone and relief printing on paper from copper and zinc plates

Printed by Bill Young, assisted by Elizabeth Milsom

Published by Peter Ellis

This publication was assisted by the Visual Arts Board of the Australian Council Collection of the artist

Leah Emery

Animal Queendom (2), 2018

Embroidery thread on aida cloth

In & Out, 2016

Embroidery thread on aida cloth Courtesy of the artist and Michael Reid Sydney + Berlin

Dita Gambiro

Mum, 2014 Synthetic hair, iron, hair clips Collection of Konfir Kabo, Melbourne

Tarryn Gill

Guardian (Self Portrait), 2017

Mixed media including EPE foam, hand stitched fabric and synthetic hair, fringing, artificial eyes

Private collection, Melbourne

Judith Glover

BentO Box, 2019

Maple and Walnut boxes, porcelain dildo and leather wrap, porcelain jug, platter, cups and silky oak chopsticks Courtesy of the artist

@gun_shy_design (Designer)

@ihateprozac (Performer)

@mikewnguyen (Performer)

@markgambino_ (Video)

@mileslemonade (Stylist)

#texturalintercourse, 2019 Mixed media installation

Courtesy of the artists

Mella Jaarsma

Bale I, Bale II, 2018

Mixed media installation. Includes four works on paper, digital print on fabric, bark cloth, bamboo

Courtesy of the artist

Kate Just

Unearthed, 2011 Epoxy resin, wire, cloth, wood Courtesy of the artist

Grace Lillian Lee

Body Sculpture: Enlightenment, 2016 Cotton, cane and feathers

Body Sculpture: Acceptance, 2016 Cotton, cane and feathers

Purchased through the RMIT Art Fund, 2016 RMIT University Art Collection

Want a dance costume, c. 1984-85

Singlet and boxer shorts, hand painted Donated to AGLA by Stephen Allkins

Collection of the Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives

Louise Meuwissen

Flesh Sac (Back Pack), 2017

Embroidery on salvaged materials including wool, polyester, glass, plastic, shell, wood, nylon, poly-fibre fill

Dimensions variable

See yourself in it- Wrestle with it, 2018

Knitted polyester/cotton balaclava, glass beads, Swarovski crystals, plastic beads, mirrored glass, high vis reflective ribbon, cotton, cotton thread, polyester thread, lurex thread, nylon thread, polystyrene, cotton wadding, nylon stocking, adhesive, steel, powder coated stainless steel

Courtesy of the artist

Misklectic Pudica, 2019 Resin, gypsum and pigment

Courtesy of the artist

Misklectic and Mossy 333

I’m Here: Portrait of Mossy Jade Johnson, 2017

Single channel HD video duration: 3:56 minutes

Produced and directed by Misklectic Spoken word written and performed by Mossy Jade Johnson Music score by Bokonon

Filmed by Misklectic and Melina Aguad

Edited by Misklectic Courtesy of the artists

Ciara Murphy 80kgs, 2019 Steel nails, cotton 80kgs, 2019 Video duration: 7:00 minutes

Filming: Caitlin Hunter Courtesy of the artist

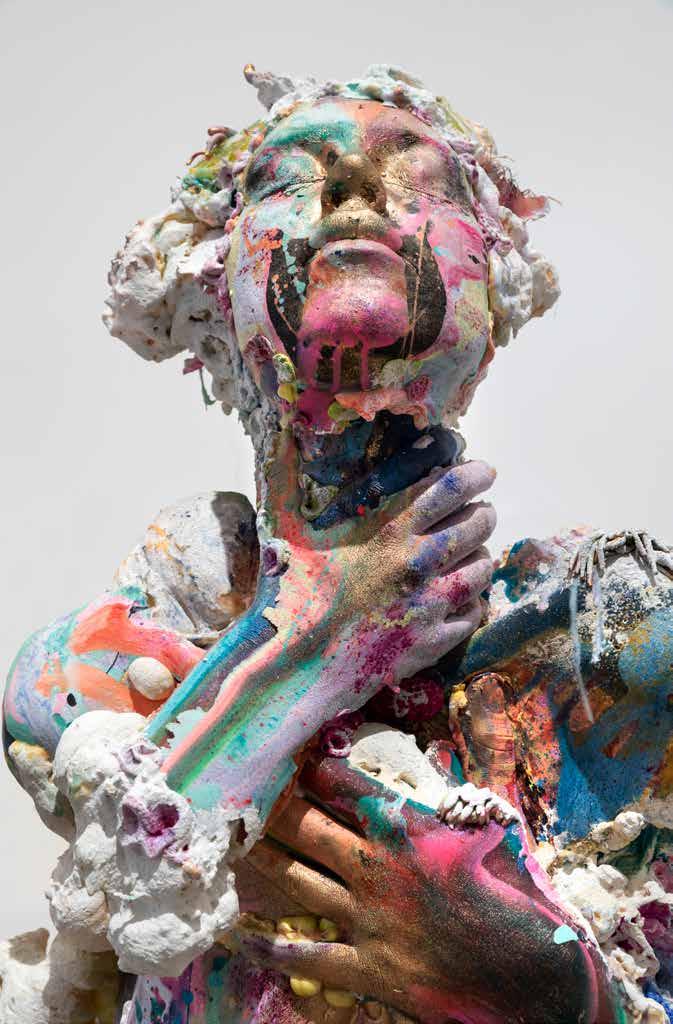

Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran

Untitled figure 11, 2016

Earthenware, polystyrene, glaze, Indian human hair, porcelain, enamel, shells, wooden beads, false teeth

Untitled figure 12, 2016

Earthernware, glaze, gold lustre, platinum lustre, resin, shells, wooden beads

Courtesy of The University of Melbourne Art Collection. Purchased by the Ian Potter Museum of Art, 2017

John Pastoriza-Piñol

Sobriquet 14 Jacket, 2019

Sobriquet 8 Arse, 2019

Sobriquet 12 Crotch, 2019

Sobriquet 5 Crotch, 2019

Watercolour on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Scott Livesey Galleries

Robert Pearce

BUTCH: A series of ultra-mundane postcards, c.1982 18 postcards

Collection of Robert Buckingham and John Betts

MEN c.1980 Acrylic on canvas Collection of Robert Buckingham and John Betts

The Flogging, 1981 Acrylic and mixed media on paper

Artwork for article ‘The (married) Man-Trap’, 1980 Watercolour, collage and mixed media on paper

Drawing for ‘Slick Graphics’ Poster, 19821988 Watercolour, Ink, coloured pencil on paper

Drawing for ‘Sex Roles’ series featuring three men, 1975 Pencil on cardboard

Sauna, 1986 Pastel on paper

RMIT Design Archives, Robert Pearce Collection. Gift of Anne Shearman

Mithu Sen

Breathing, 2004 Video duration: 3:18 minutes

Courtesy of the artist

Laksmi Shitaresmi

TERUSLAH MELANGKAH WAHAI KAKI HIPUPKU, 2012

Keep on Walking O Leg of my Life, 2012 Aluminium casting, bronze casting, polyurethane, paint, gold plating Collection of Konfir Kabo, Melbourne

Cop Shiva Urban Ecstasy, 2011 to present Photographic series Courtesy the artist

Vipoo Srivilasa

The Curse of Plenty, 2019 Porcelain and mixed media Courtesy of the artist

TextaQueen Retribution, 2019 Fibre tip pens, coloured pencil and synthetic polymer paint on cotton paper Courtesy of TextaQueen

Christian Thompson (Bidjara) Ellipse, Polari, 2014 C-type print Courtesy of the artist and Sarah Scout Presents, Melbourne Peter Tully Holographic crown brooch, 1991 Mixed materials Private collection, Melbourne

Rosella Design Mardi Gras Float / Costume design, 1985 Pencil on paper Collection of the Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives

Wayan Upadana

Glob(BABI)sation, 2013

Painted polyester resin, stainless steel water tab, stainless steel base, car paint Collection of Konfir Kabo, Melbourne

VERMIN with Jenny Bannister

Toad a GoGo, 2019 Cane toad leather and mixed media Wig styling: Steve Munroe

Courtesy of the artists: Jenny Bannister and Lia Tabrah

Xylouris White Daphne, 2017 Video duration: 5:19 minutes

Courtesy of the artist and Bella Union

Ah Xian China China – Bust 82, 2004

Cast porcelain with hand-painted underglaze decoration

Collection Museum of Old and New Art (Mona), Hobart, Australia

William Yang

Stephen Allkins, c.1983-85 Photograph

Reveller, Mardi Gras, 1983 Photographic print

Jock Allen, Peter Tully and Carlos Bonicci, 1985

Photographic print

Collection of the Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives

Paul Yore

Daddy’s #1, 2018

Found materials, wood, sequins, quilting thread, cotton, felt, jewellery, synthetic hair, synthetic fur, zips, feathers, wool, plastic beads, towel, synthetic flowers, lace, buttons, stuffing

Mummy, 2018

Found materials, wood, felt, wool, embroidery cotton

Courtesy of the artist and Neon Parc

Preston Zly

Firebird, 2019 Leather, plastic, rubber, feathers, crystals, gold leaf

Joy, 2019

Photographer: Samantha Jarrett Creative Director: Bianca Christoff Model: Marissa Shoe designer: Preston Zly Courtesy of the artists

Pleasure

Curated by Julian Goddard, Helen Rayment and Evelyn Tsitas

RMIT Gallery 29 November 2019 – 7 March 2020

The curators would like to thank the participating artists, private lenders and galleries for their generous support and commitment to this exhibition. A number of artists went the extra mile, and contributed to our opening night performances above and beyond all expectations. It was a pleasure to work with them all!

We would like to especially mention, Gun Shy and the performers who made opening night so memorable @ihateprozac, @mikewnguyen and their stylist @mileslemonade; also Kate Durham, Jenny Bannister and Lia Tabrah for their creative generosity; William Eicholtz and the Fashams team who worked a logistical miracle; RMIT colleagues John Pastoriza-Pinol, Judith Glover, Rhett D’Costa and Nick Chilvers for their unflagging enthusiasm for the exhibition and contributing to the public programs.

Appreciative thanks also to Professor Paul Gough, PVC DSC; Paula Toal, Head, Cultural and Public Engagement and Lynda Roberts and our colleagues at RMIT Creative.

Curator, RMIT Galleries: Helen Rayment

Manager Public Engagement: Evelyn Tsitas

Engagement Officer: Elise Barton

Operations Coordinator: Megha Nikhil

Operations Officer: Verity Hayward

Exhibitions Assistant: Thao Nguyen

Production Coordinator: Nick Devlin

Installation Technicians: Robert Bridgewater, Beau Emmett, Ari Sharp, Simone Tops

Administration Assistants: Narinda Cook, Michelle Sakaris and Madeline Tzevakos

RMIT Gallery / RMIT University www.rmitgallery.com 344 Swanston Street Melbourne Victoria 3000 Tel: +61 3 9925 1717 Fax: +61 3 9925 1738

Email: rmit.gallery@rmit.edu.au

Gallery hours: Tuesday-Friday 11-5 Saturday 12-5 Closed Sundays, Monday & public holidays. Free admission. Lift access available.

e-Catalogue published by RMIT Gallery June 2021. Online publication.

Graphic design: Sean Hogan of Trampoline

Catalogue editors: Helen Rayment and Evelyn Tsitas

Catalogue photography courtesy Mark Ashkanasy

RMIT University acknowledges the people of the Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung language groups of the eastern Kulin Nations on whose unceded lands we conduct the business of the University. RMIT University respectfully acknowledges their Ancestors and Elders, past and present.

RMIT also acknowledges the Traditional Custodians and their Ancestors of the lands and waters across Australia where we conduct our business.