melbourne modern

Jane Eckett Harriet Edquist European Art & Design at RMIT since 1945

ISBN 9780648422655

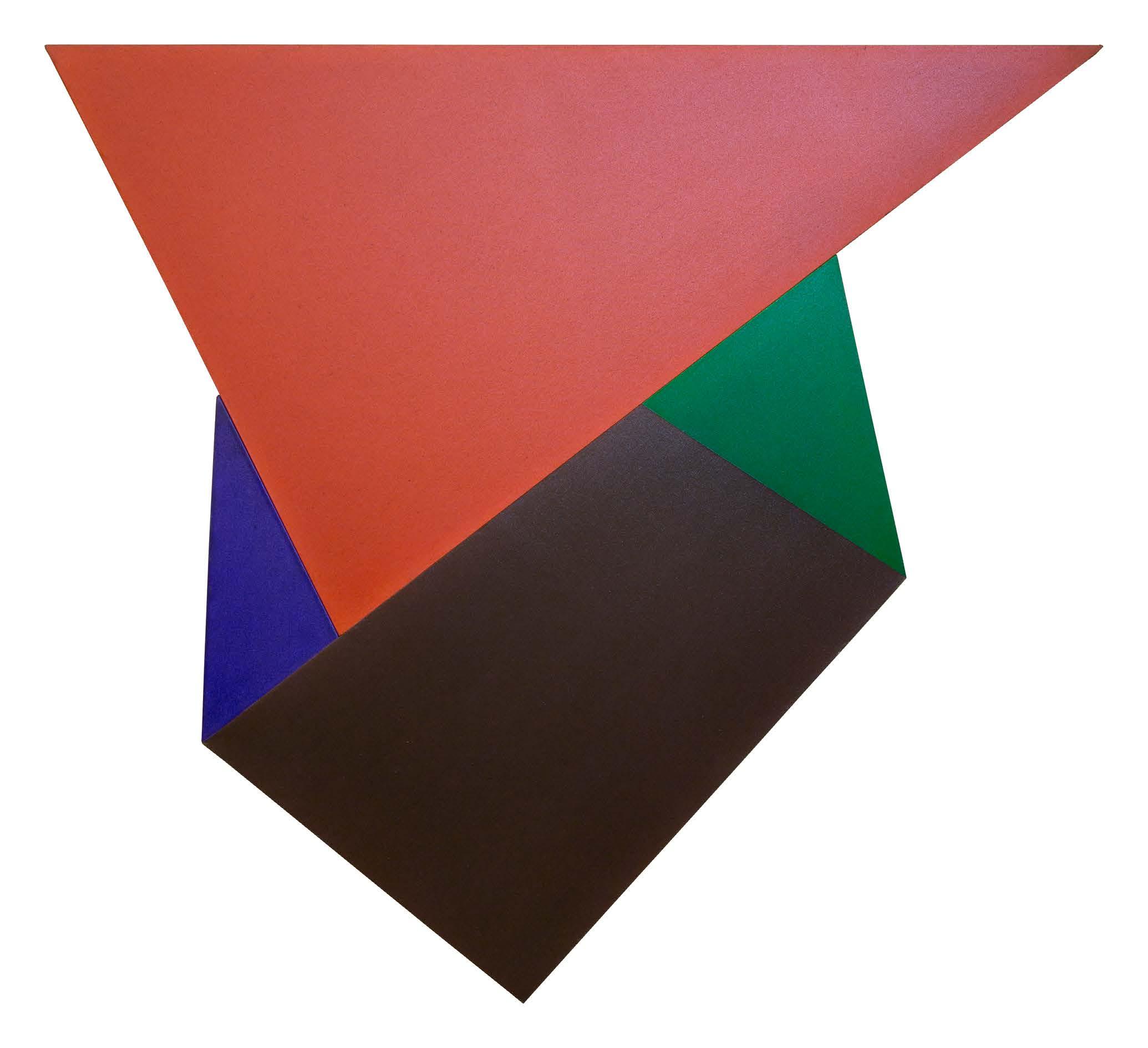

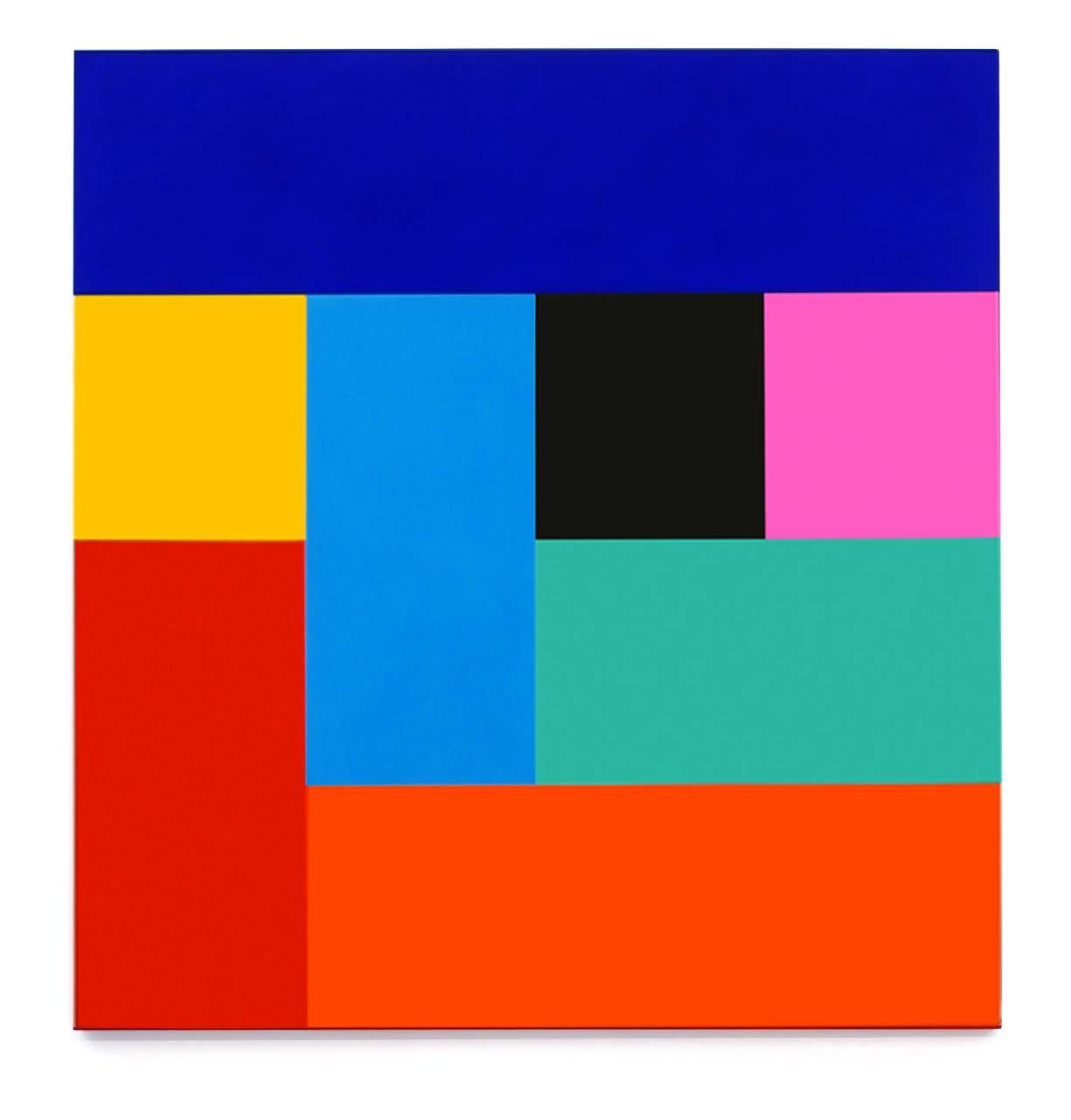

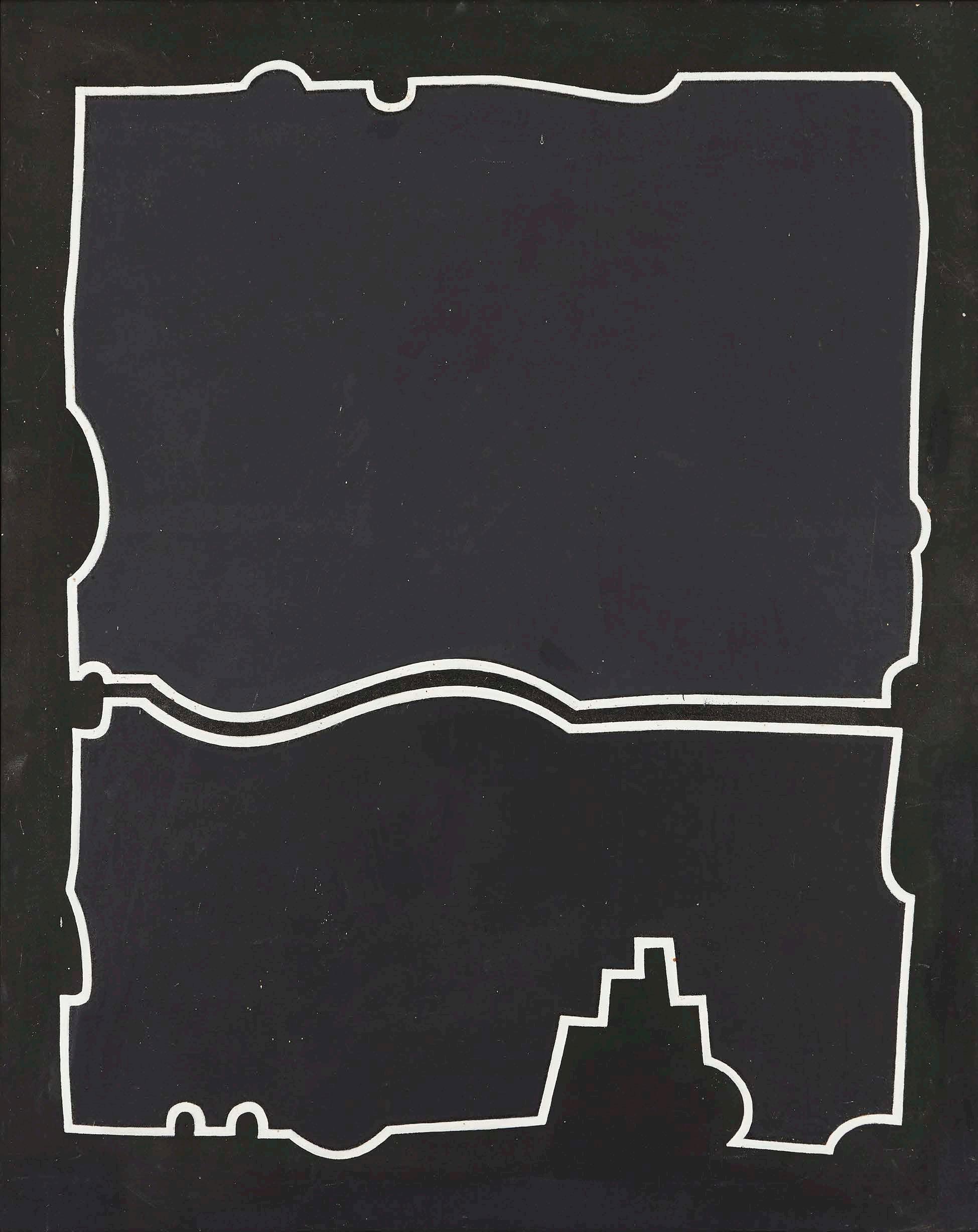

Front Cover Image

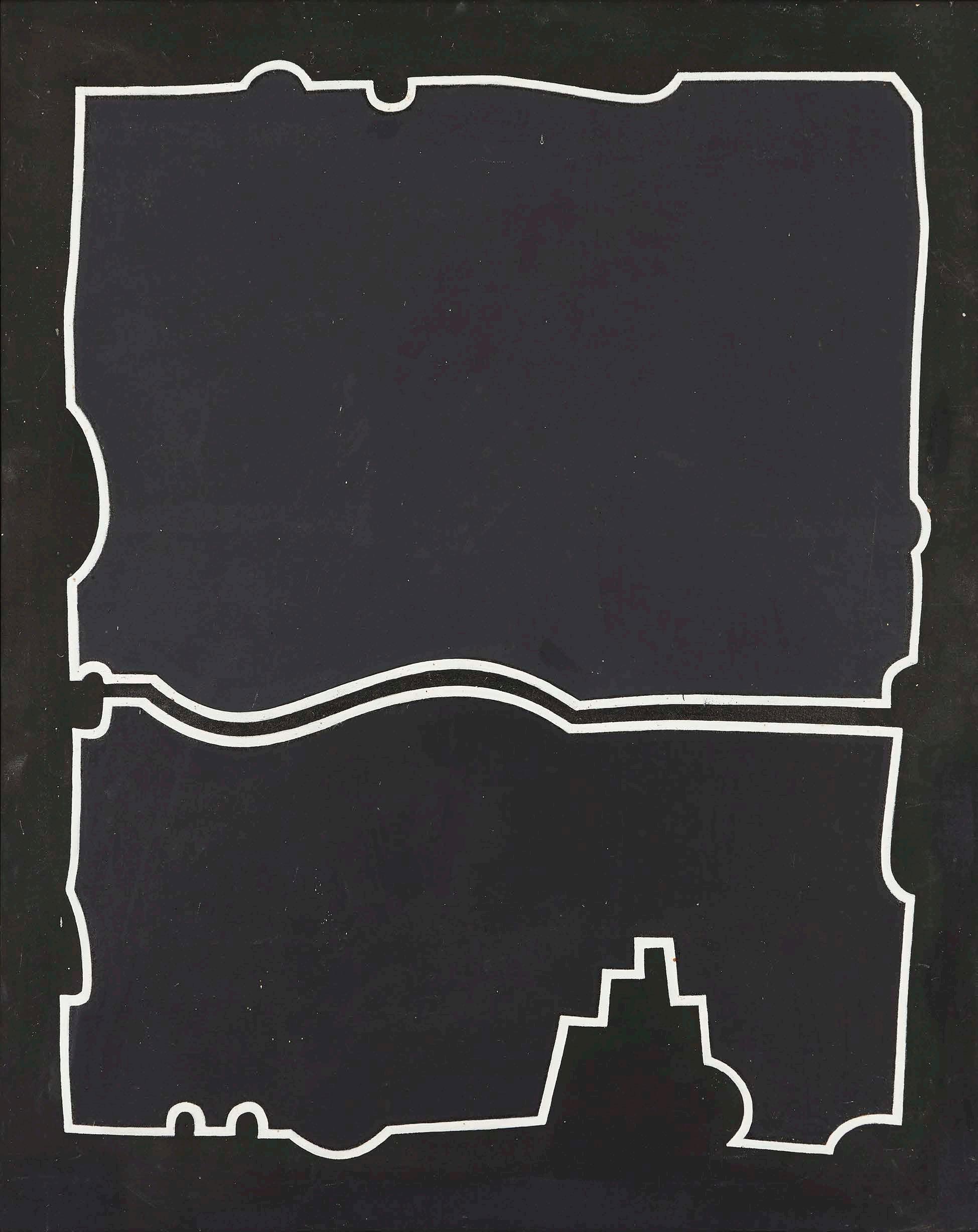

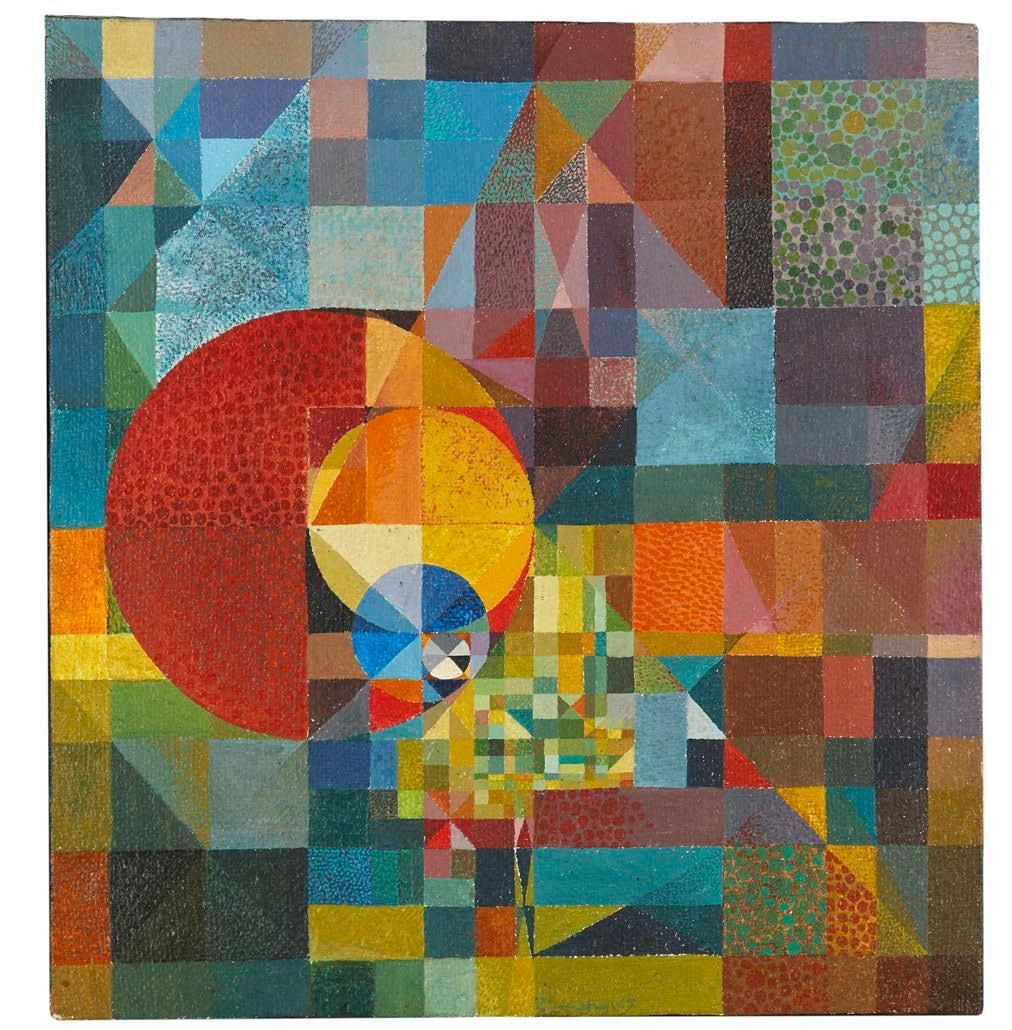

Normana Wight, Untitled, 1970 (detail), gouache on paper, RMIT University Art Collection

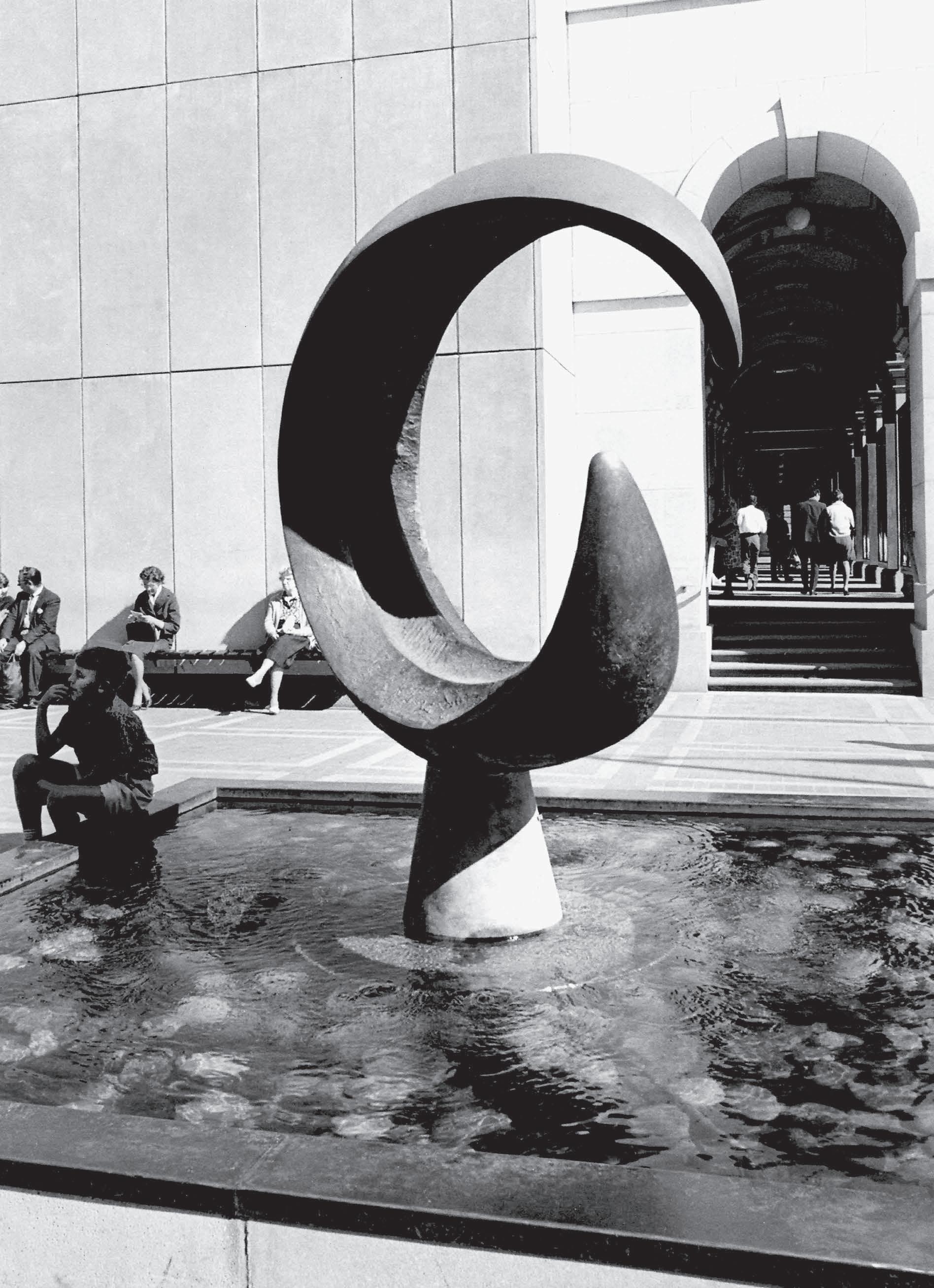

Back Cover Image

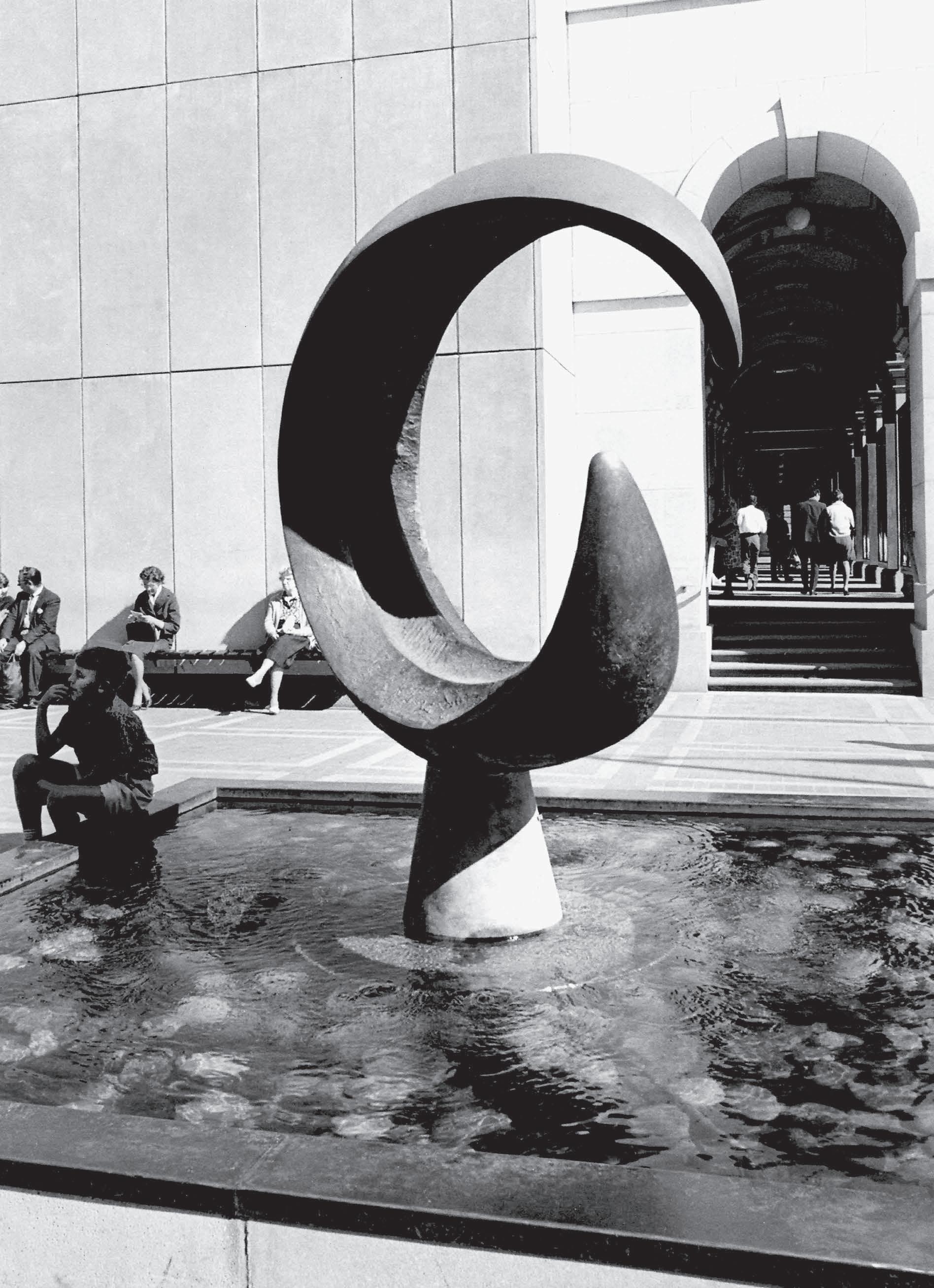

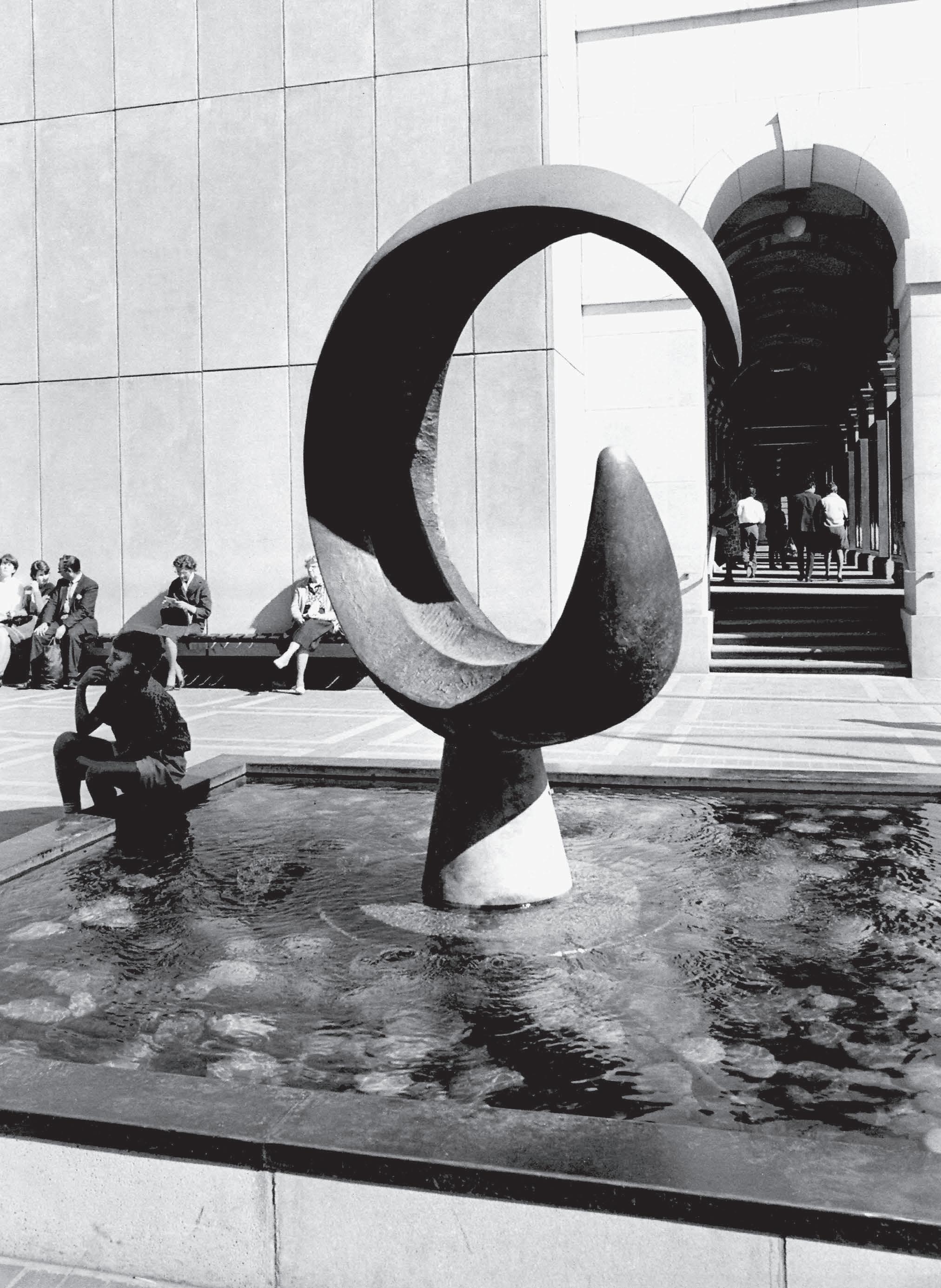

Vincas Jomantas, Landing Object II, 1971

fabricated polyester resin and fibre glass, 111.0 x 120.0 x 104.0 cm, McClelland Sculpture Park+Gallery

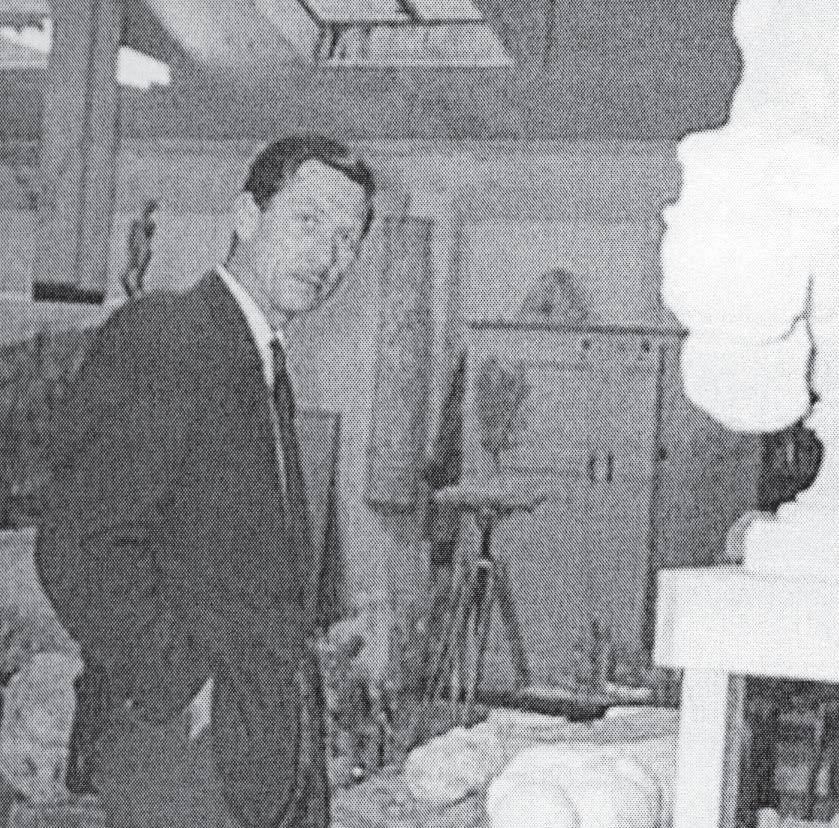

Endpapers

Wolfgang Sievers, Face to Face, 1964

State Library Victoria Wolfgang Sievers Collection

Typography

Text set in Objectiv Mk1 (Maag)

Display set in Lord Bold Lord is based on an identity designed by Viennese graphic designer Joseph Binder who studied at the Kunstgewerbeschule from 1922–1926.

ABBREVIATIONS

AGNSW

Art Gallery of New South Wales

CAE

Council of Adult Education

CAS

Contemporary Art Society (Vic.)

DIA

Design Institute of Australia

FRSA

Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts

GMH

General Motors Holden

MTC

Melbourne Technical College, 1934–1954

NAA

National Archives of Australia NGA

National Gallery of Australia

NGV

National Gallery of Victoria

NMIT

Northern Metropolitan Institute of TAFE, Melbourne

RCA

Royal College of Art (UK)

RMTC

Royal Melbourne Technical College, 1954–1960

RMIT

Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, 1960-present SLV

State Library of Victoria

TUWien

Technical University of Vienna

V&A

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

VAS

Victorian Artists’ Society

VCA

Victorian College of the Arts

VSS

Victorian Sculptors’ Society

WMC

Working Men’s College, 1887–1934

WRC

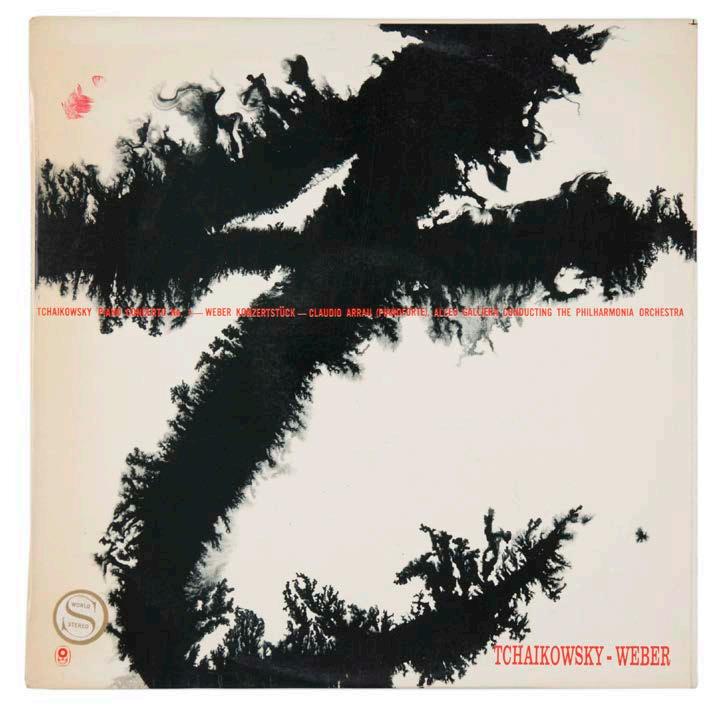

World Record Club

melbourne modern

2 MELBOURNE MODERN 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

list of works contributors artist biographies acknowledgements and photo credits CONTENTS m m

preface PAUL GOUGH introduction JANE ECKETT

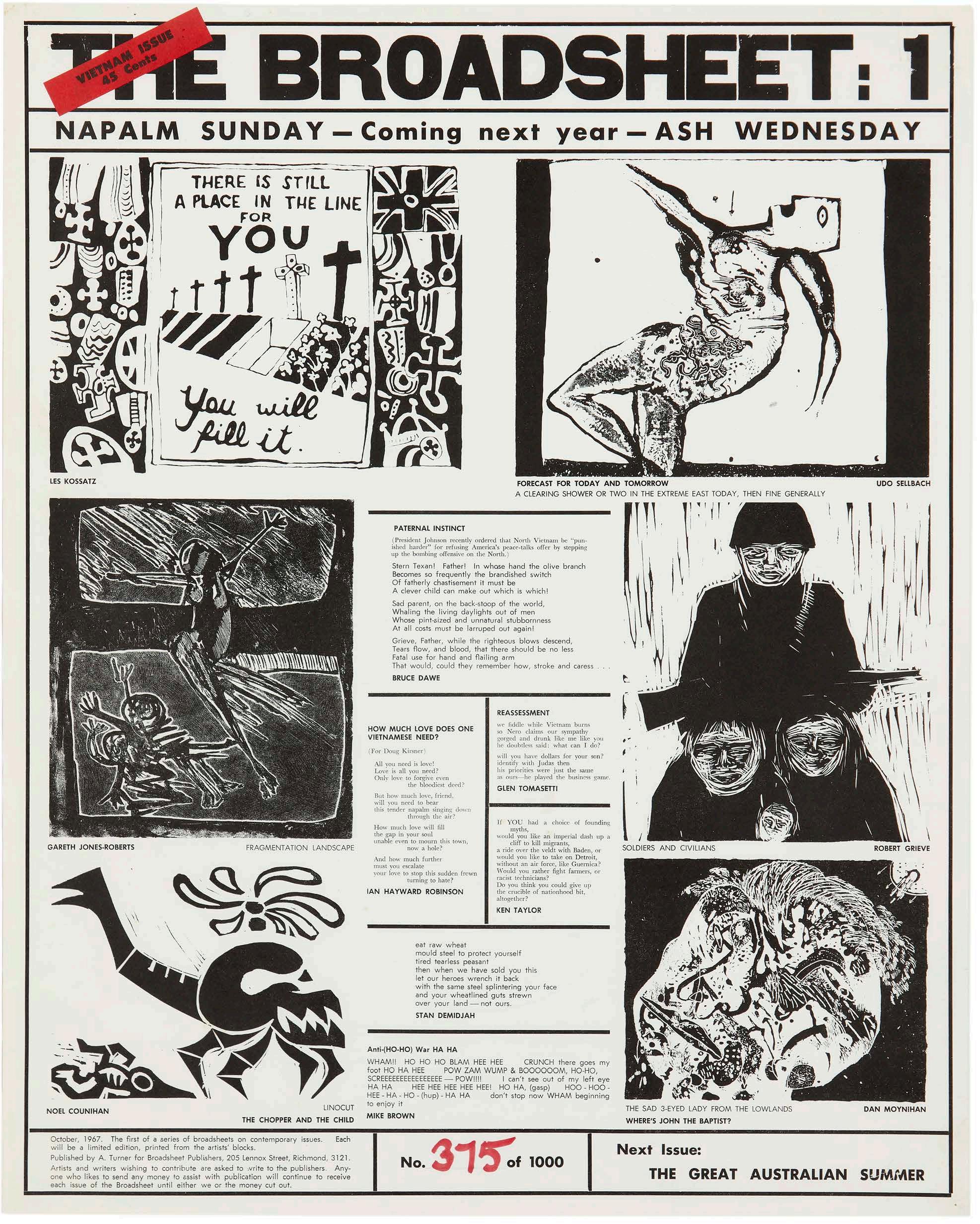

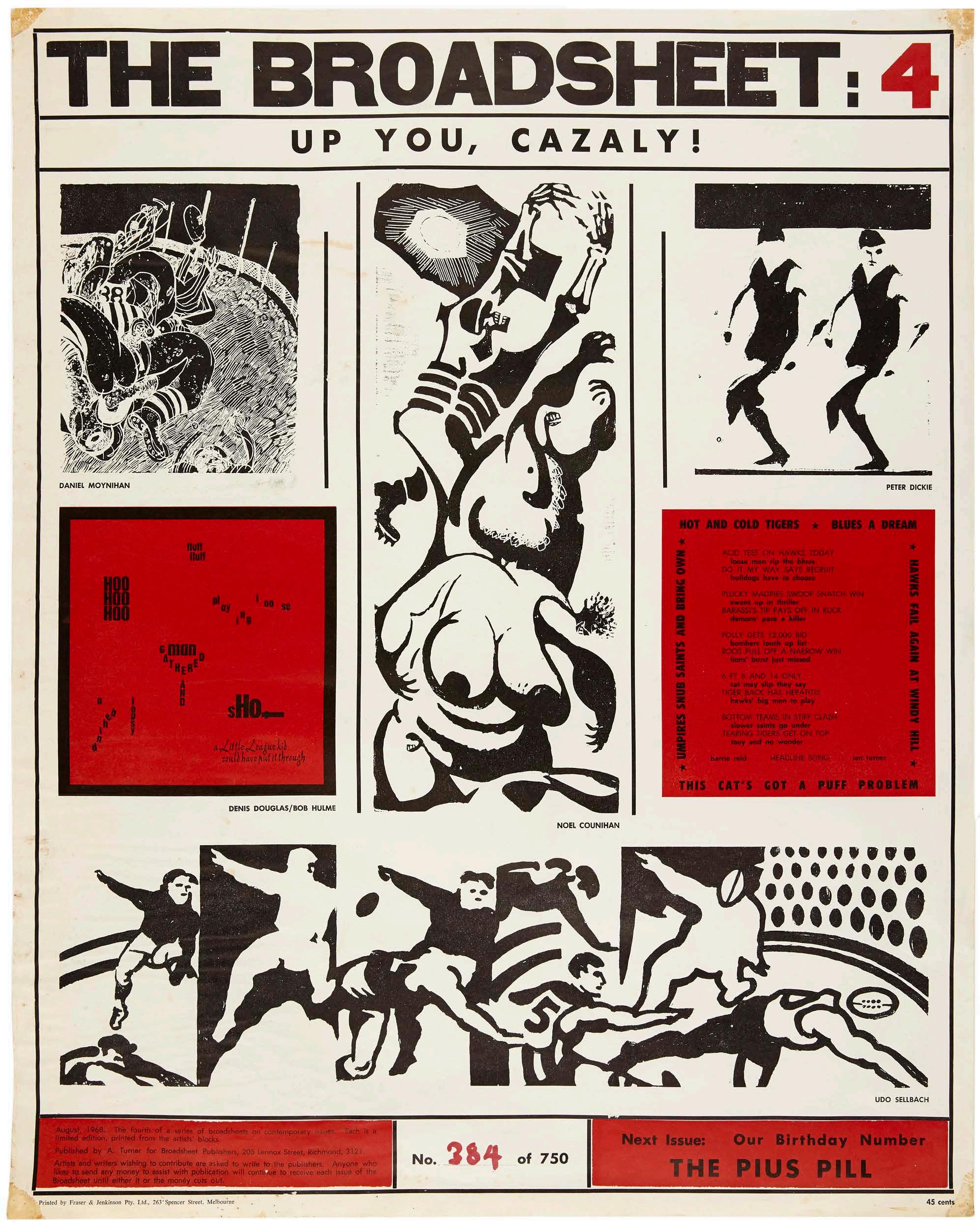

MELBOURNE MODERN 3 post-war architecture and interior design: THE FIRST ÉMIGRÉ TEACHERS victor vodicka AND THE POST-WAR TRANSFORMATION OF GOLD AND SILVERSMITHING a skilled hand and/or cultivated mind INDUSTRIAL DESIGN AT THE CROSSROADS structured eclecticism RMIT PAINTING DEPARTMENT 1945–TODAY material studies and professional practice EUROPEAN ÉMIGRÉ SCULPTORS AT RMIT printmaking AT THE ART SCHOOL OF MELBOURNE TECHNICAL COLLEGE 1948–1965 the target is man: UDO SELLBACH AT RMIT legacies HARRIET EDQUIST HARRIET EDQUIST HARRIET EDQUIST SHERIDAN PALMER JANE ECKETT VICTORIA PERIN SARAH SCOTT JANE ECKETT 8–29 30–41 42–57 58–67 68–85 86–101 102–113 114–129 130–152

4 MELBOURNE MODERN

preface

The story of the many hundreds of exiled and displaced European artists, architects and designers who arrived in Australia, and in particular Melbourne, in the grim aftermath of World War II is really quite extraordinary.

Travelling from as far as Budapest, Berlin, Kaunas, Munich, Vienna and Vilnius, they had been trained in teaching ateliers across the great European art schools and design academies.

Setting up workshops and studios in Melbourne they brought a quite brilliant constellation of ideas, approaches and philosophies into this corner of the world. Inevitably they found employment in the leading Australian institutions, many becoming teachers and technicians at the Melbourne Technical College (later renamed Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology). For the students of the day, indeed for the entire post-war culture of the city, their arrival must have been extraordinary, almost iconoclastic.

The full impact of their contribution in the disciplines and practices of painting, sculpture, printmaking, architecture, interior design, textiles, gold and silversmithing, photography, film, graphic design and industrial design –all of which RMIT still proudly teaches – has yet be fully written, but this new exhibition Melbourne Modern: European art and design at RMIT since 1945, adds a significant instalment.

In this exhibition we are privileged to share a magnificent display of contemporary art, architecture, design, gold and silversmithing from the period, as well as rarely seen archival material including documentary photographs, posters and teaching aids. These are drawn internally from the RMIT Art Collection and RMIT Design Archives, as well as external lenders whose support has been vital in realising the exhibition concept. I extend my thanks to Anna Schwartz Gallery, ARC One Gallery, Australian Galleries, Charles Nodrum Gallery, Hamilton Gallery, McClelland Sculpture Park + Gallery, Monash University Archives, National Gallery of Victoria, State Library of Victoria, University of Melbourne’s Ian Potter Museum of Art, and to the numerous private lenders – many of them RMIT alumni or family members of alumni.

Much of the work has rarely, if ever, been publicly exhibited and I applaud the curators, Dr Jane Eckett and Professor Harriet Edquist for their ingenuity and insights. I thank our wonderful gallery staff who have helped realise the exhibition, the education program and wider public engagement. And I thank deeply our patrons and sponsors, most notably the Gordon Darling Foundation who have generously sponsored this publication.

Thank you to all who have made this memorable exhibition possible, and to those inspired and dedicated practitioners and teachers of all nationalities, who escaped war-ravaged Europe to bring their unique skills, craft and creativity that has enriched Melbourne and Australia for many decades.

Professor Paul Gough Pro-Vice Chancellor and Vice President RMIT University

Opposite Gus van der Heyde, Faculty of Architecture and Building, RMIT Advanced College (poster), 1977, offset lithograph, 56.5 x 42.0 cm, RMIT Design Archives: Gus van der Heyde collection

MELBOURNE MODERN 5

introduction

Their contributions were visible at many levels: on the street, through the design of modernist apartment blocks, cafés, churches, commercial spaces and domestic dwellings, as well as public fountains, murals and screens; in the home, via furniture, textiles and hollowware; and on the body, through tailoring, fabric design and hand-made jewellery. Arguably their profoundest impact, however, was less visible for it was at the grass-roots level of education. Émigrés brought with them a diverse range of approaches and educational philosophies garnered in the art academies, ateliers, technical universities and vocational schools of Central and Eastern Europe, the Baltic States, Scandinavia, the Netherlands and Britain. Melbourne Modern surveys the contribution of European émigrés who taught at RMIT after 1945 and traces the legacy of their teaching to the present day.

A substantial existing literature highlights émigré achievements in Australian art and design.1 In 1993 Art & Australia devoted a special issue to post-war migrants, in which year also the contribution of Jewish architects since 1945 was the focus of an exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria.2 Another exhibition, The Europeans: Émigré Artists in Australia 1930-1960 at the National Gallery of Australia in 1997, remains a landmark, generating more recent surveys such as The Other Moderns, which examined Sydney’s little-known post-war European designers.3 Rex Butler and A.D.S. Donaldson’s ongoing project of the past decade has been to rethink Australian art historical narratives to accommodate émigré and expatriate artists.4 Jenny Zimmer has written extensively on individual European-trained artists, and Harriet Edquist’s many publications and exhibitions on émigré architects and designers, drawn from the rich holdings of the RMIT Design Archives, have added depth to these surveys.5

More recently attention has turned to émigré involvement in art and design education. The ARC Discovery Project, ‘Bauhaus Australia; Transforming Education in Art, Architecture and Design’, in which Edquist has been a chief investigator, has focused on this very subject and resulted in a major monograph.6 Melbourne Modern contributes to this emerging field of research by exploring in exhibition format the nature of European art education through one key institution: the former Melbourne Technical College (MTC), known since 1960 as RMIT.

The term émigré encompasses a wide range of circumstances associated with different waves of migration. It includes religious and political exiles who fled the rise of fascism in the 1930s, internees deported from Britain at the outbreak of war owing to their nationality, refugees who arrived on the cusp of and during the war, ‘displaced persons’ (DPs) unable to return home owing to the post-war redrawing of borders and the Sovietisation of Eastern Europe and the Baltic countries, and migrants who arrived after the war under assisted passage schemes or as the spouse of an Australian national. DPs account for the greatest number of artists and designers in the present exhibition, reflecting their greater numbers overall. Between 1949 and 1950 approximately 100,000 DPs arrived in Australia, generating intense debate as to how these ‘New Australians’ could best assimilate to the predominantly Anglo-Irish culture.7 In the face of such diversity in circumstances and nationalities, coupled with the Australia’s assimilationist policy, we should beware any attempt to retrospectively homogenise the émigrés. Nevertheless it can be said that all shared a similar fate of uprootedness, of immersion in two different cultures, and frequently the sense of not belonging entirely within either.

Melbourne Modern also includes artists who transcend the category of émigré but are more generally termed ‘European’. While our primary focus is on artists and designers born and educated in Europe and who arrived in Australia as practitioners, we also consider those who left Europe at a young age, as well as the Australianborn children of migrants, on the basis of their family’s cultural heritage. More broadly still we include a number of Australians who studied for extended periods in Britain and Europe. The inclusion of Britain within this broad definition of ‘European’ is a conscious reflection of Australia’s strong Commonwealth ties in the post-war decades (albeit increasingly problematic with the impending Brexit). Throughout these decades staff at RMIT referred chiefly to British educational models, while the Royal College of Art in London attracted several top students for postgraduate studies. If the term ‘European’ seems stretched to capacity, equally it disguises a multitude of national and regional differences. ‘European’ remains simply a shorthand notation; wherever possible we specify nationalities or regional affiliations.

6 MELBOURNE MODERN

In the wake of World War II, amid mass migration out of Europe, hundreds of artists, architects and designers arrived in Melbourne and profoundly changed the cultural landscape.

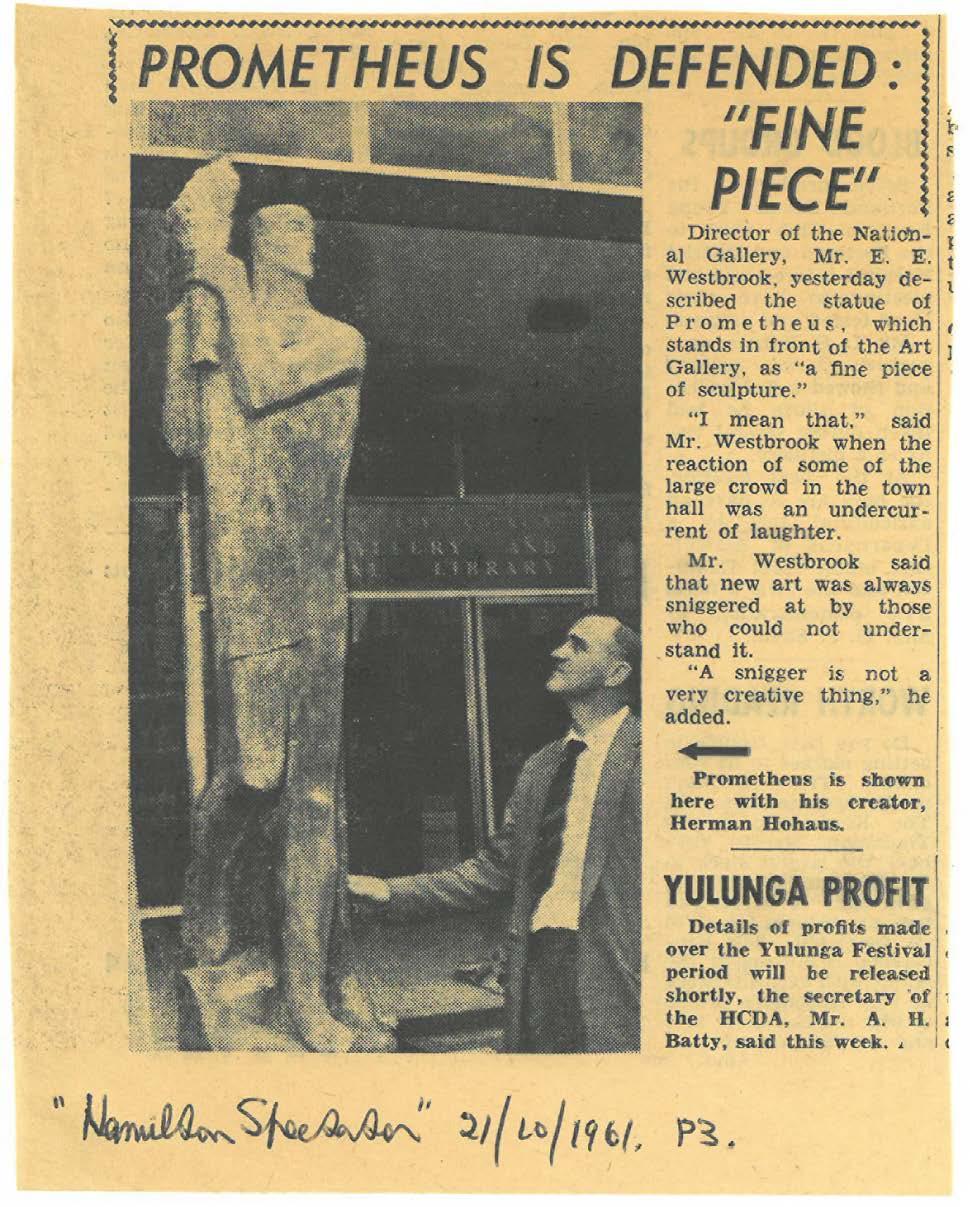

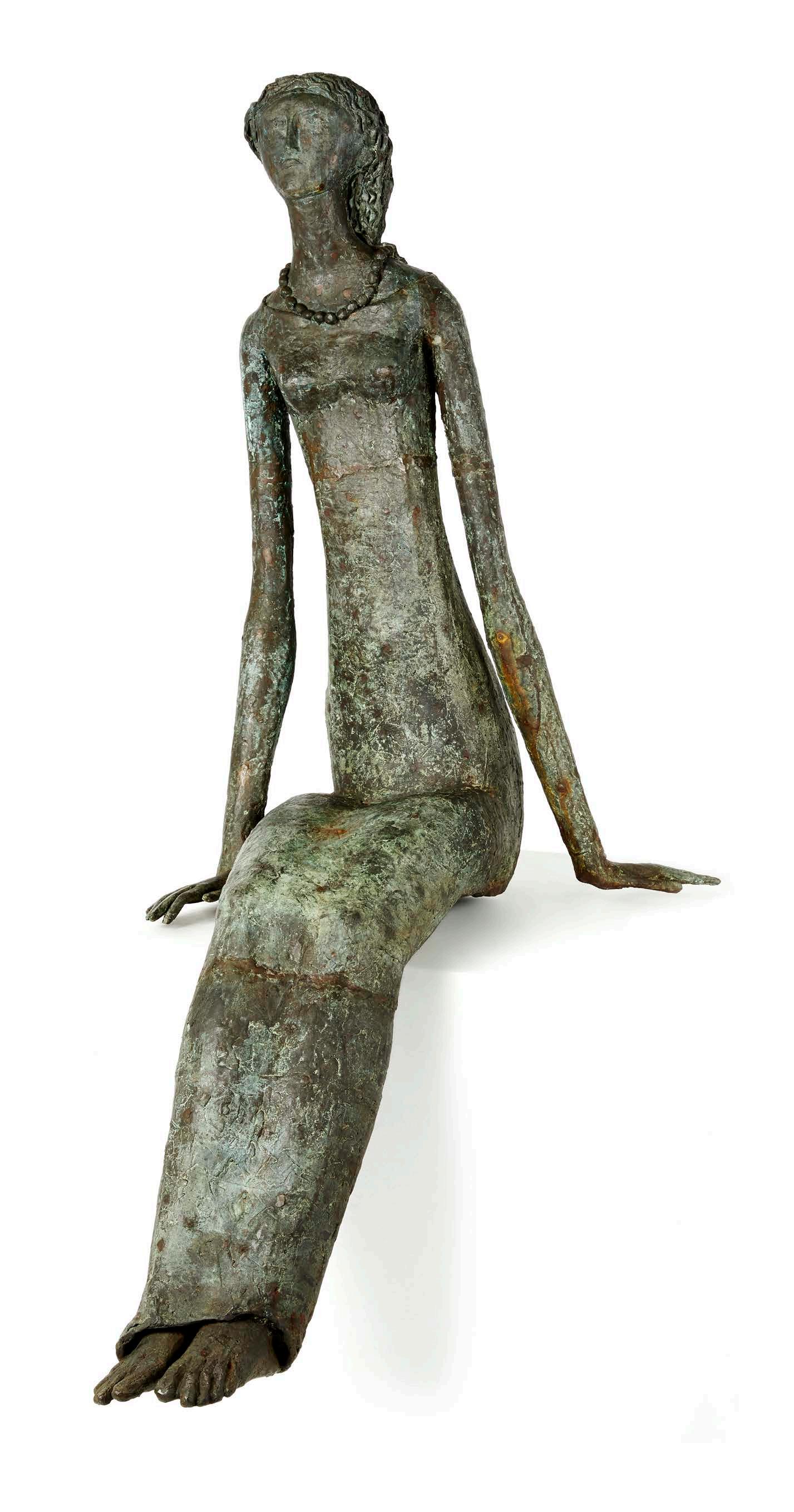

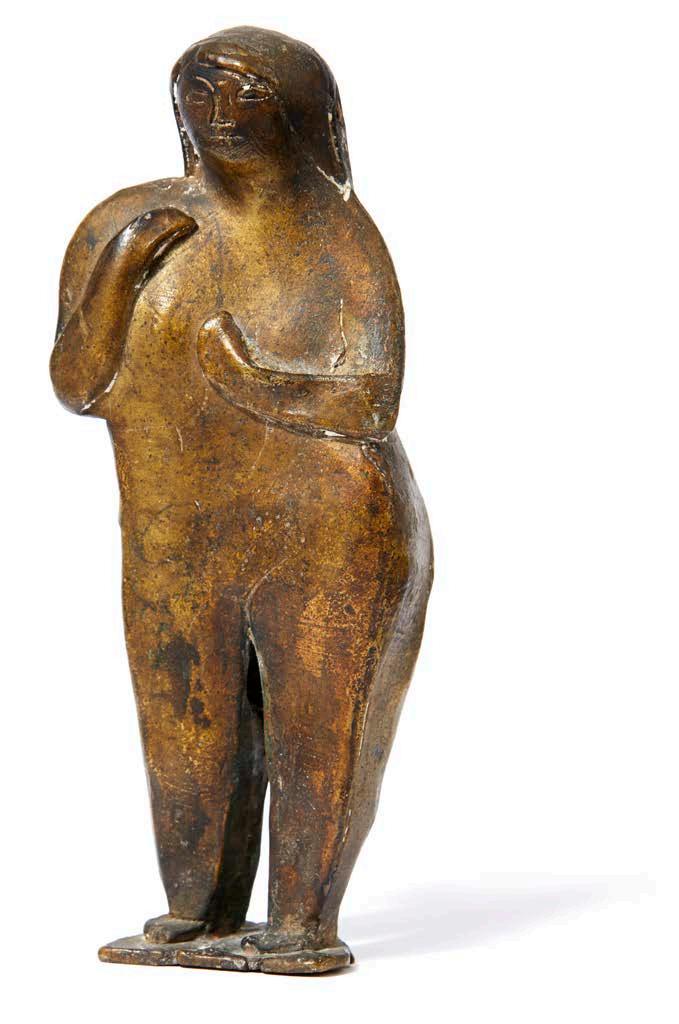

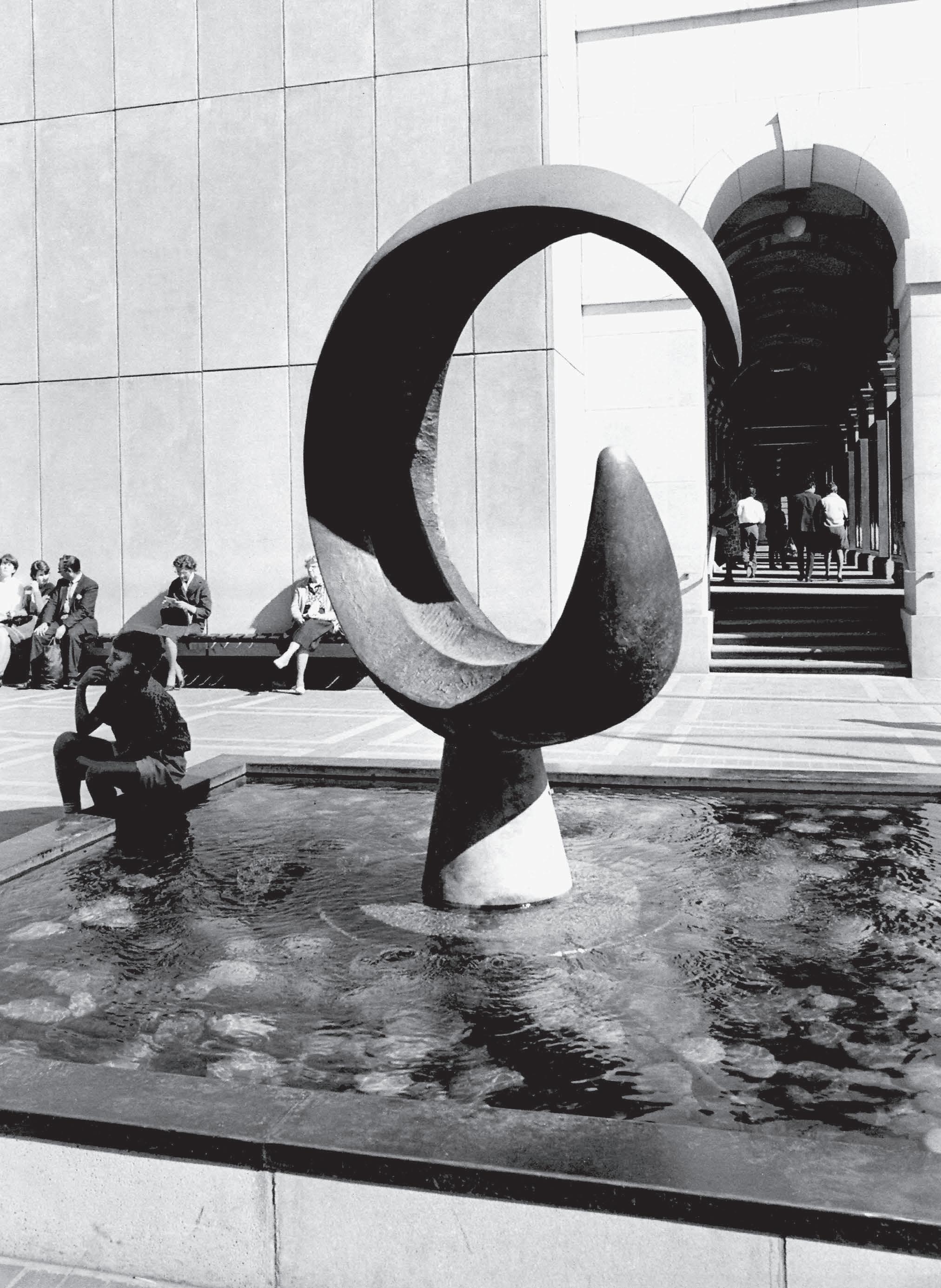

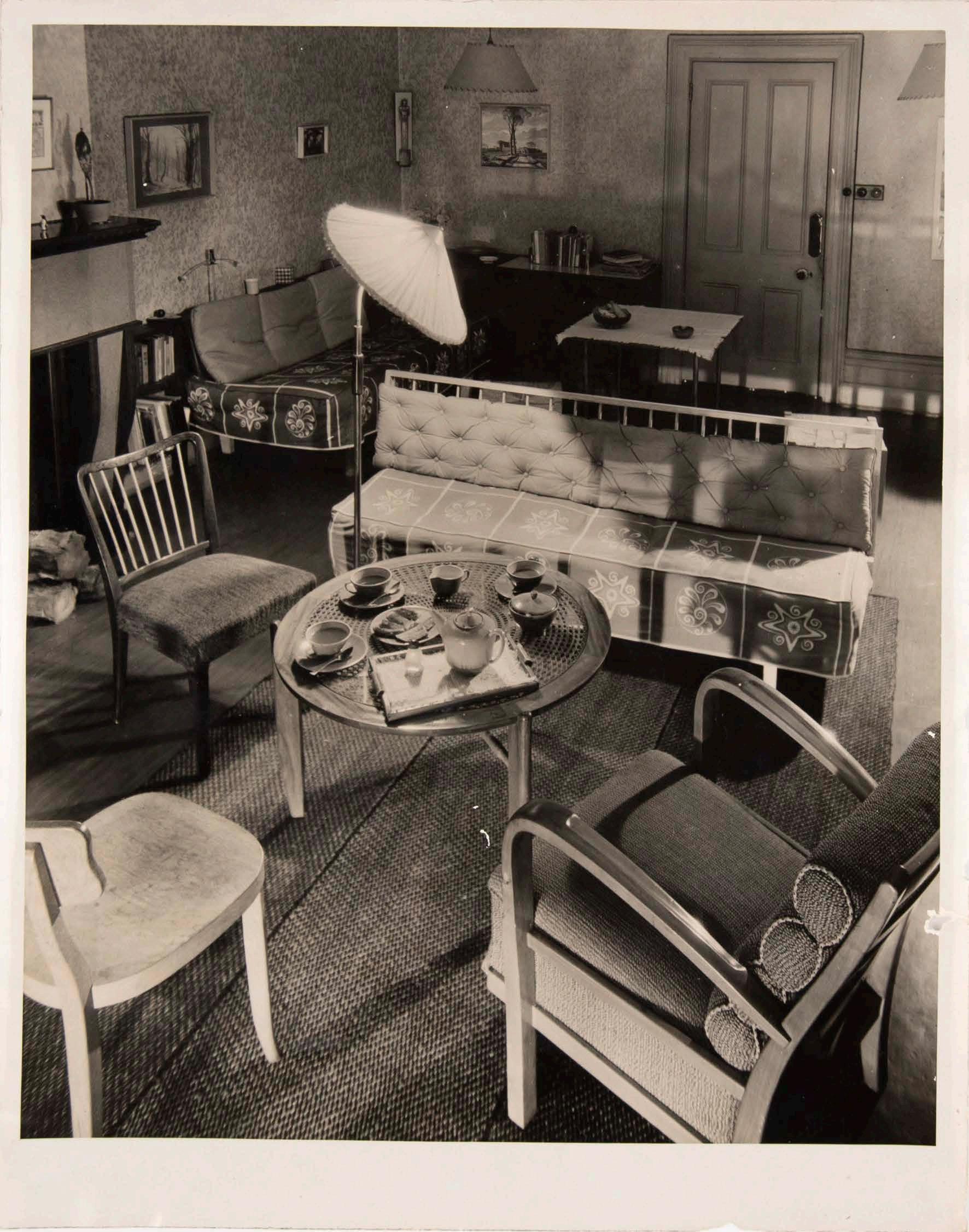

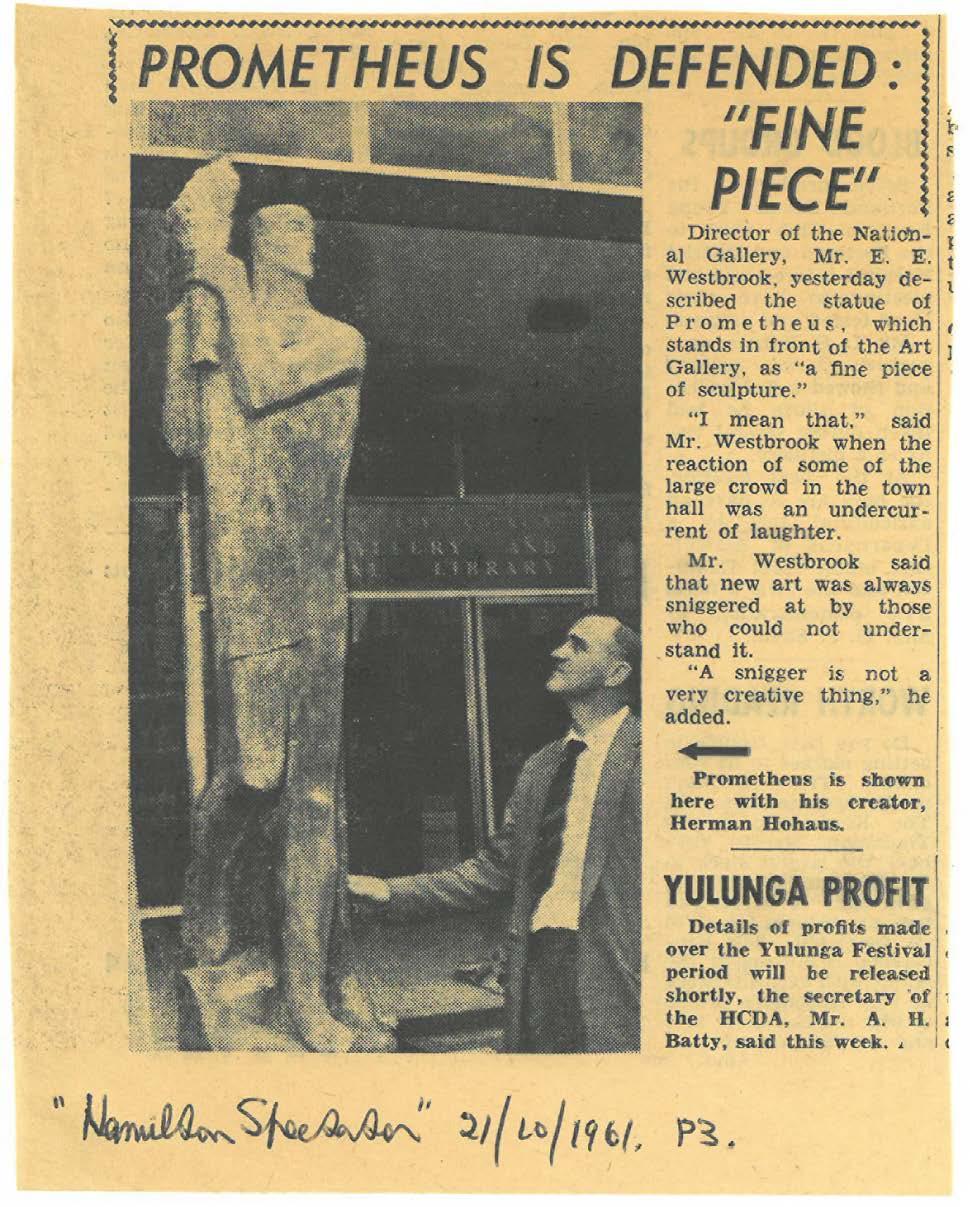

Likewise we are concerned not with a monolithic concept of modernism, but rather multiple modernisms that reflect the myriad possibilities open to artists in the interwar and post-war years. These multiple modernisms are often geographically based and stem from different historical and cultural factors. For instance, in the sculpture department Hermann Hohaus’s archaised figures are typical of those made in the immediate post-war years in Munich when sculptors rapidly distanced themselves from the sort of classical figuration deemed acceptable under the Nazis. Teisutis Zikaras, on the other hand, responded to Picasso’s cubist sculpture, which he studied first-hand in French-occupied Freiburg, finding it a viable alternative to the intense cultural nationalism of the exiled Lithuanian community with whom he lived and worked. Similarly in interior design we see a range of modernist propositions: from Sterne’s expression of pre-war Wiener Wohnraumkultur (‘Viennese living room culture’), with its flexible furniture arrangements, to Kral’s ‘sophisticated exemplars of high modernism’.8

Students at MTC in the post-war years therefore encountered a range of different modernist approaches among the teaching staff. This was enhanced by MTC’s traditional structure of learning, which allowed students to choose a broad range of subjects. Students took a selected major and elective minor subjects as well as a common core of liberal studies, including art history, history of the selected major subject, music, theatre, literature, film, social science, sociology, philosophy and psychology.9 Architects, designers, painters, printmakers and sculptors alike therefore shared many of the same instructors. This was particularly the case in drawing as it was at the basis of all courses in the Applied Art and Architecture Division (which included fine art).10 While divisions between different departments remained quite rigid during the post-war decades, and interdisciplinarity scarcely encouraged, as students progressed through their studies they nonetheless encountered a variety of teaching approaches and a range of different conceptions as to what modernism is. There is therefore no house style, or singular look to the works in Melbourne Modern. Instead, the exhibition reflects the rich variety of émigré experience coupled with student response to and remixing of these various modernist ideals.

Jane Eckett

1 See for instance Alan McCulloch, ‘Migrant Artists in Australia’, Meanjin, vol. 14, no. 4, December 1955, 511–16; Paul McGillick, ‘Sources of change: migrant art in Australia’, Quadrant, vol. 23, no. 10, October 1979, 31–6; Paul McGillick, ‘Five migrant artists in Australia’, Aspect, vol. 5, no. 1–2, August 1980, 23-5; Jenny Zimmer, ‘Five Berliners in Melbourne’, Aspect: Survey of Ethnic Visual Arts in Australia, nos. 29/30, Autumn 1984, 133–60; and among more recent contributions Andrew E. McNamara, Ann Stephen and Isabel Wünsche, ‘Case studies of modernist refugees and emigres to Australia, 1930–1950: Light, colour and educational studies under the shadow of fascism and war’ in C.P. Cruzeiro (ed.), Migrations: Migration Processes and Artistic Practices in a Time of war: From the 20th Century to the Present, Lisbon: Belas-artes, 2017, 271–89.

2 Art and Australia, vol. 30, no. 4, Winter 1993; Ronnen Goren, 45 Storeys: A retrospective of works by Melbourne Jewish architects from 1945, Melbourne: NGV, for the Jewish Festival of the Arts, 1993.

3 Roger Butler (ed.), The Europeans: Émigré Artists in Australia 1930–1960, Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 1997; Rebecca Hawcroft (ed.), The Other Moderns: Sydney’s Forgotten European Design Legacy, Sydney: NewSouth Publishing, 2017.

4 Rex Butler and A.D.S. Donaldson, ‘War and Peace: 200 Years of Australian-German Artistic Relations’, emaj, no. 8, April 2015, 1–24, URL: https://emajartjournal.files.wordpress.com/2012/11/butler_ donaldson_200-years-of-australian-german-artistic-relations.pdf.

5 Including, but not limited to, Jenny Zimmer, Inge King Sculpture 1945–1982: A Survey, Parkville, Vic.: University Gallery, University of Melbourne, 14 September–22 October 1982, and Klaus Zimmer glass artist, South Yarra, Vic.: Macmillan, 2000; Harriet Edquist and Helen Stuckey, Frederick Romberg: the architecture of migration 1938–1975, Melbourne: RMIT University Press, 2000; Harriet Edquist, ‘George Kral (1928-1978): graphic designer and interior designer’, RMIT Design Archives Journal, vol. 3, no. 2, 2013, 12–23; Harriet Edquist, ‘Vienna Abroad: Viennese interior design in Australia 1940–1949’, RMIT Design Archives Journal, vol. 9, no. 1, 2019, 6–35.

6 Philip Goad, Ann Stephen, Andrew McNamara, Harriet Edquist and Isabel Wünsche (eds), Bauhaus Diaspora: Transforming Education in Art, Architecture and Design, Parkville, Vic.: Melbourne University Press in association with Power Publications, Sydney, 2019.

7 Kajica Milanov, ‘Towards the Assimilation of New Australians’, The Australian Quarterly, vol. 23, no. 2, June 1951, 71-8.

8 See Harriet Edquist’s chapter 1 in this volume: ‘Post-war architecture and interior design: the first émigré teachers’.

9 The range of core humanities subjects differed over time; the example given here is from the 1969 prospectus, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology Calendar 1969, Melbourne; RMIT, 1969, 186.

10 Drawing seems to have led mainly by British artists such as Roy Bizley and Anthony Woodcock in the 1950s, ‘60s and ‘70s. Jenny Zimmer attests to the quiet brilliance of Woodcock, who studied in Southampton and taught life at drawing at RMIT c. 1966–79; Zimmer conversation, 14 May 2019.

post-war architecture and interior design: THE FIRST ÉMIGRÉ TEACHERS HARRIET EDQUIST 1

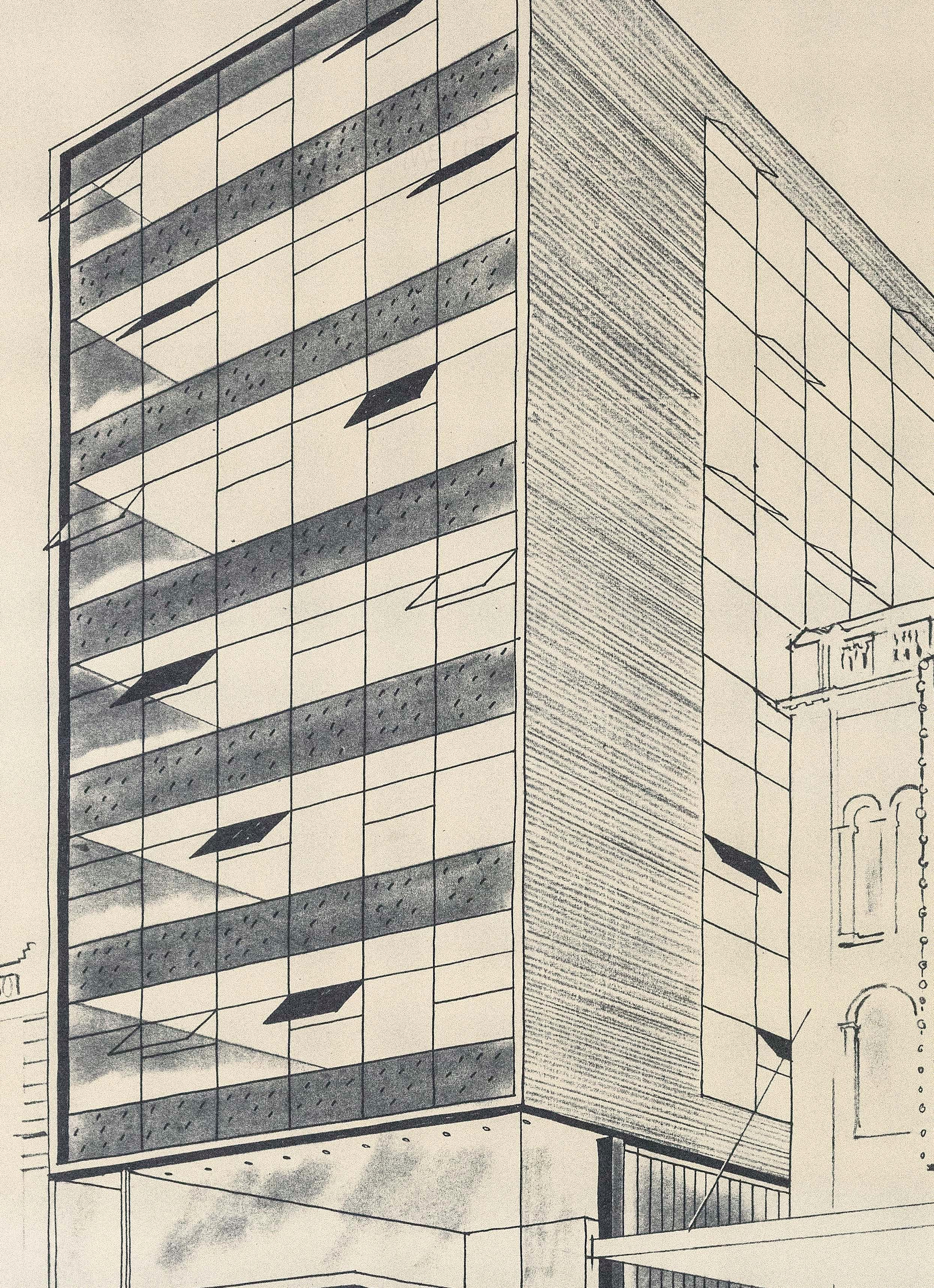

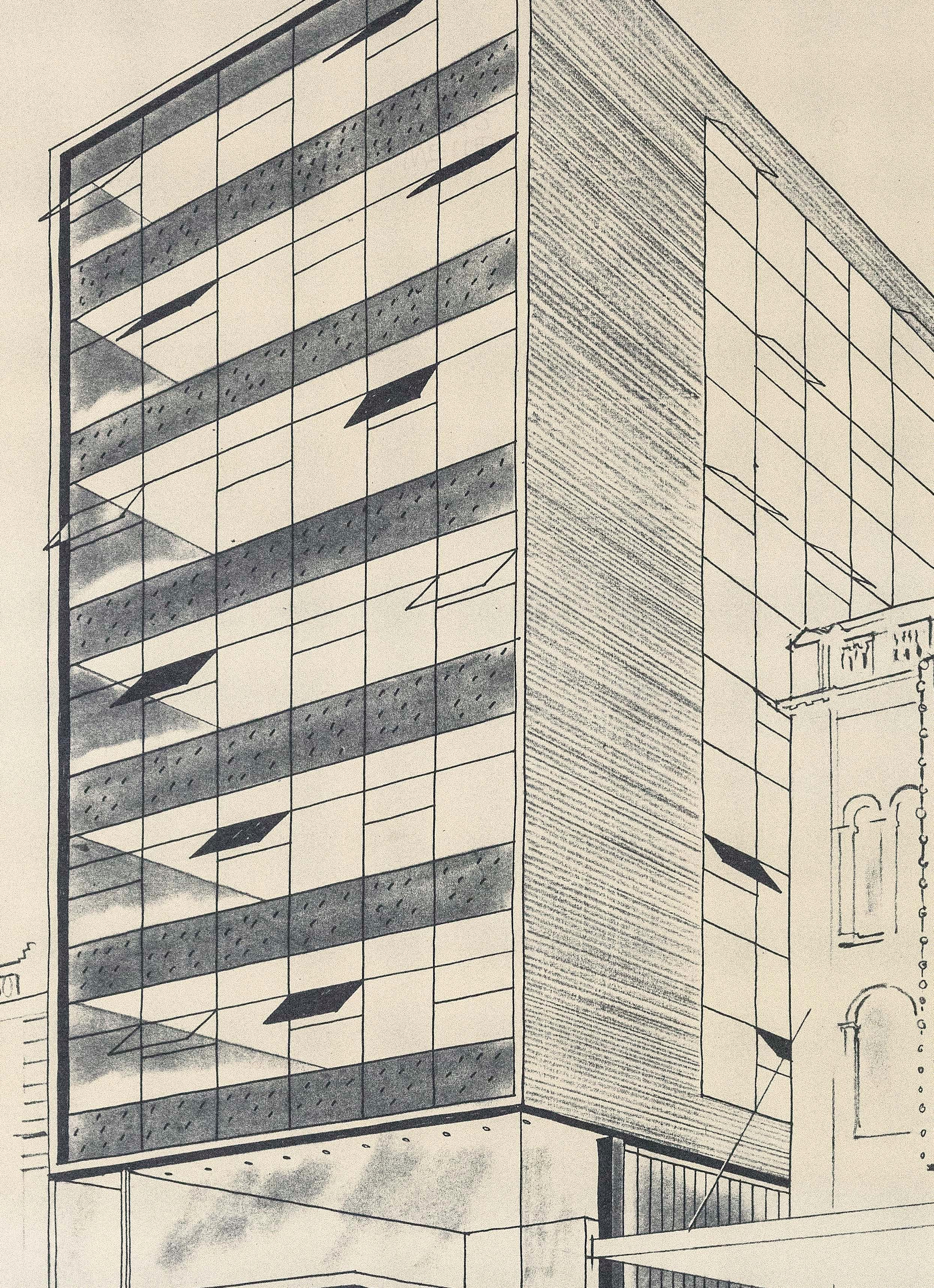

Opposite Ernest Fooks, Perspective of Commercial Building, 231–233 Bourke Street, Melbourne (detail), 1957, diazotype, image: 62.5 x 56.0 cm, RMIT Design Archives: Ernest Fooks Collection

Some of these émigrés were part-time and some full-time, and they came from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Italy, Holland, Lithuania and Latvia, Ireland and Scotland.1 Harry Winbush had been lecturer-in-charge of architecture since 1943 and whether it was his decision or Brown’s, Viennesetrained architects Frederick Sterne and Ernest Fooks and the Swiss-trained German architect Frederick Romberg all joined the staff. They were the first European designers to join Art and Applied Art after the war but they were soon followed by many more over the coming decades.

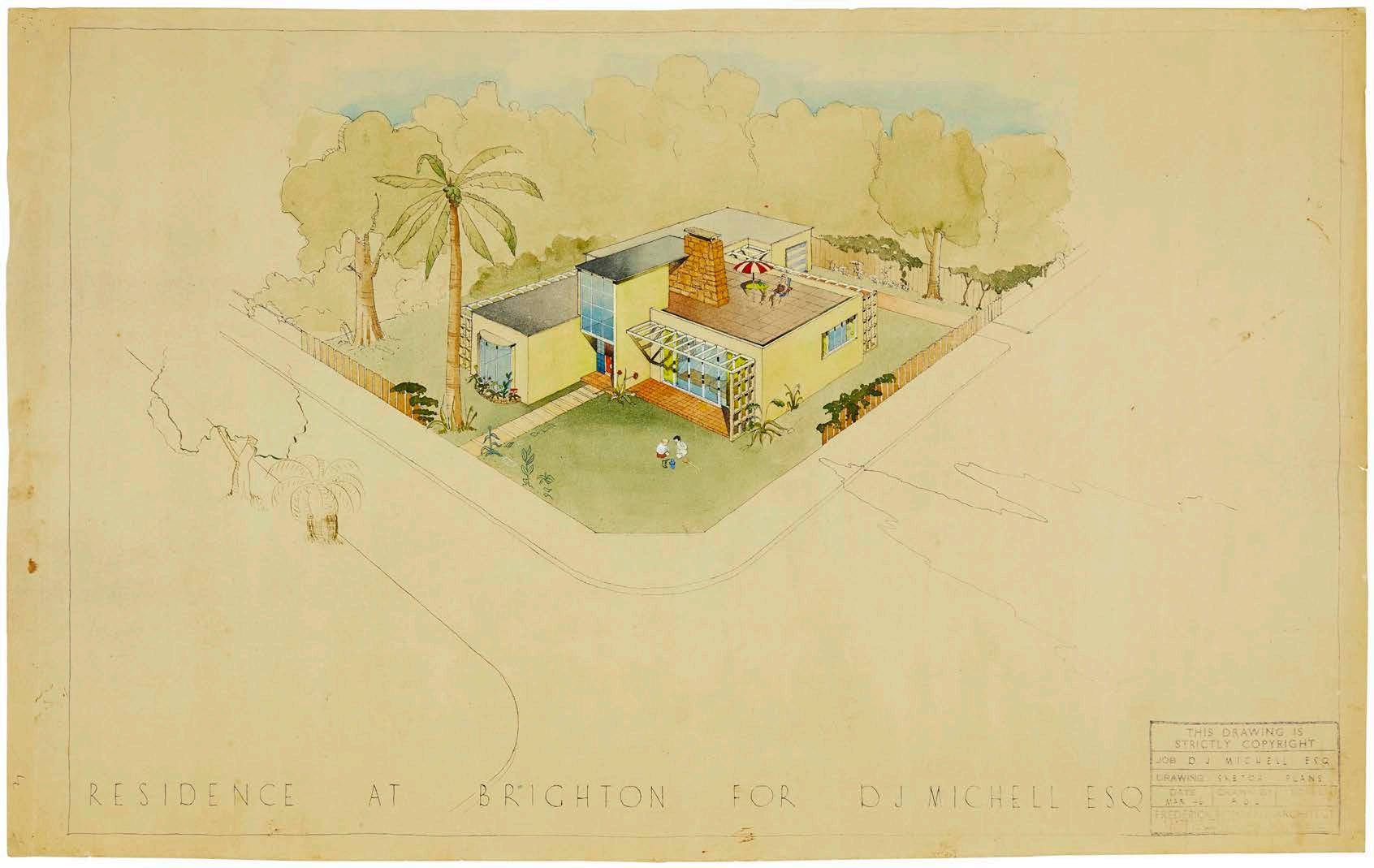

Frederick Romberg was appointed senior lecturer to teach architectural history, and his tenure was the briefest of the three; it is also the most poorly documented. He had arrived in Melbourne in 1938, a graduate of architecture from ETH Zurich, one of the most prestigious architecture schools in Europe, where he was taught and mentored by acclaimed Swiss modernist Otto Salvisberg. Romberg brought copies of his student work with him to Melbourne and had no trouble finding work with prominent architecture firm Stephenson and Turner, who appointed him job captain on their 1939 Australian Pavilion at the New Zealand Centennial Exhibition held in Wellington.2

After he left the firm Romberg set up his own practice and, with overseas financial backing, designed Newburn Flats in Queens Road, the first high-rise building in Melbourne using stripped concrete construction. When completed in 1941, the design brought Romberg some local acclaim. He also designed the unbuilt multi-storey apartment block Gloucester Apartments at the corner of La Trobe and Spring Streets for his investment company before the site was commandeered by the Commonwealth Government. Romberg and Shaw, a partnership with Mary Turner Shaw, designed Yarrabee Flats in South Yarra (1941) and several other buildings which Shaw brought into the office through her extended social networks.

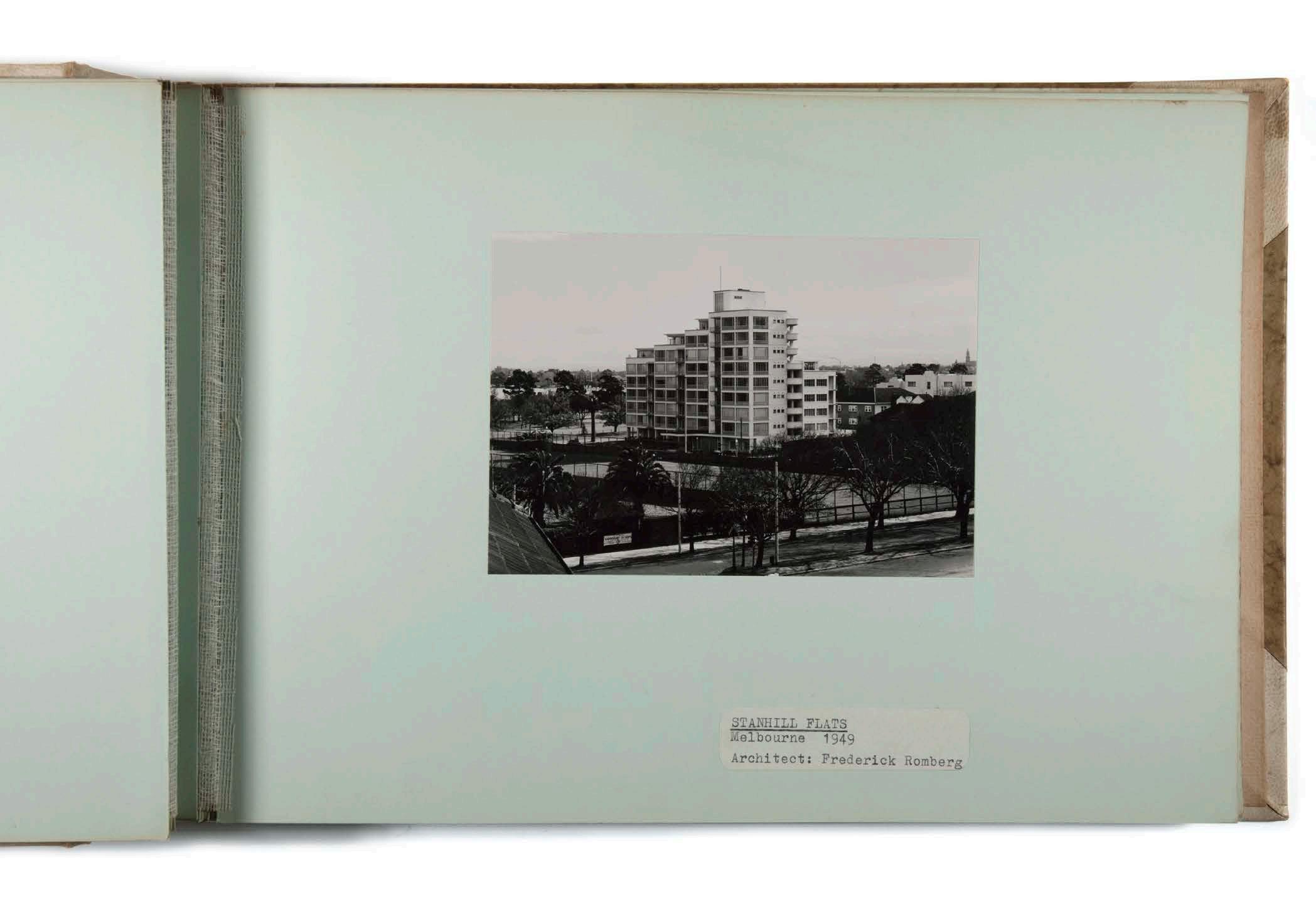

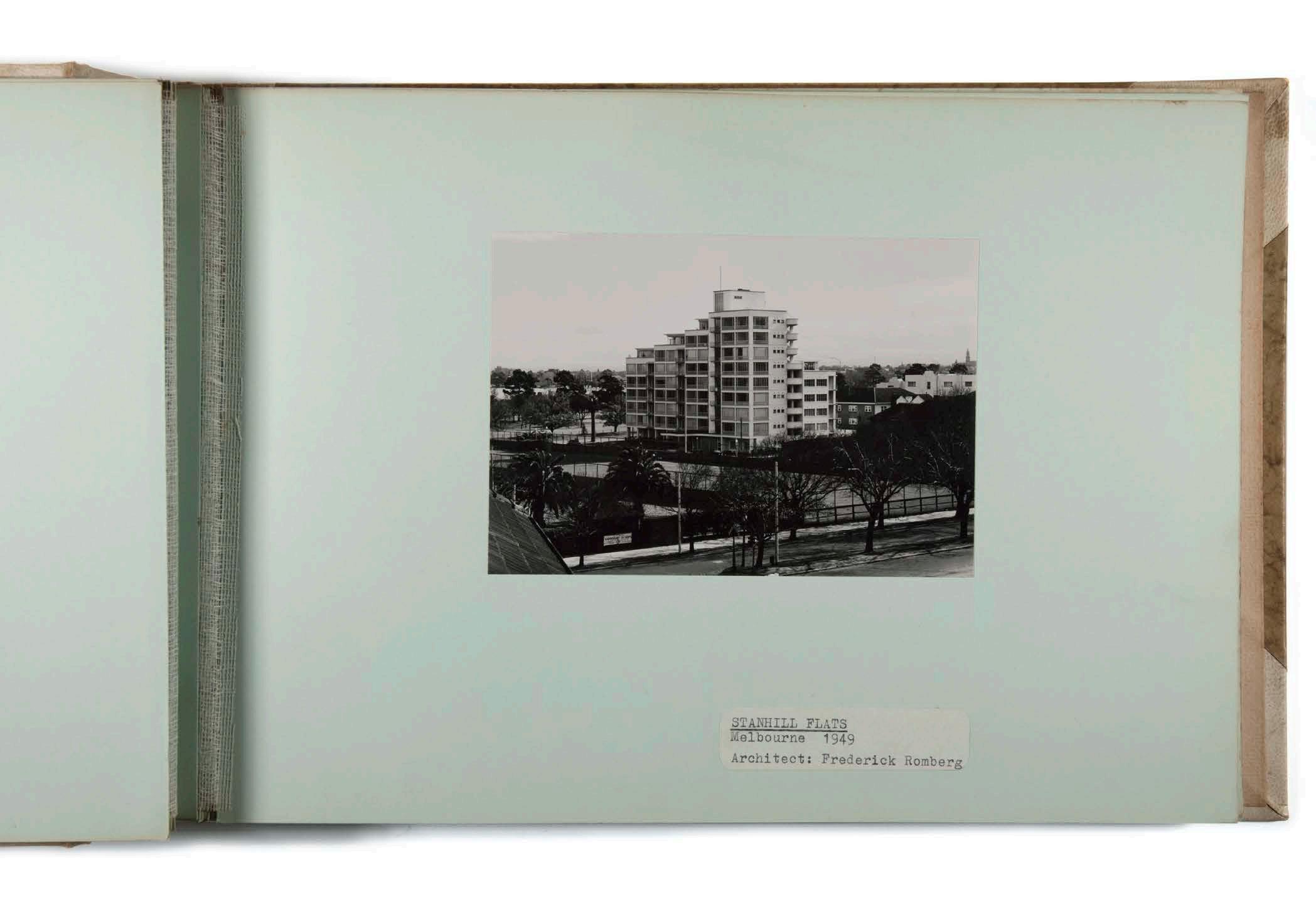

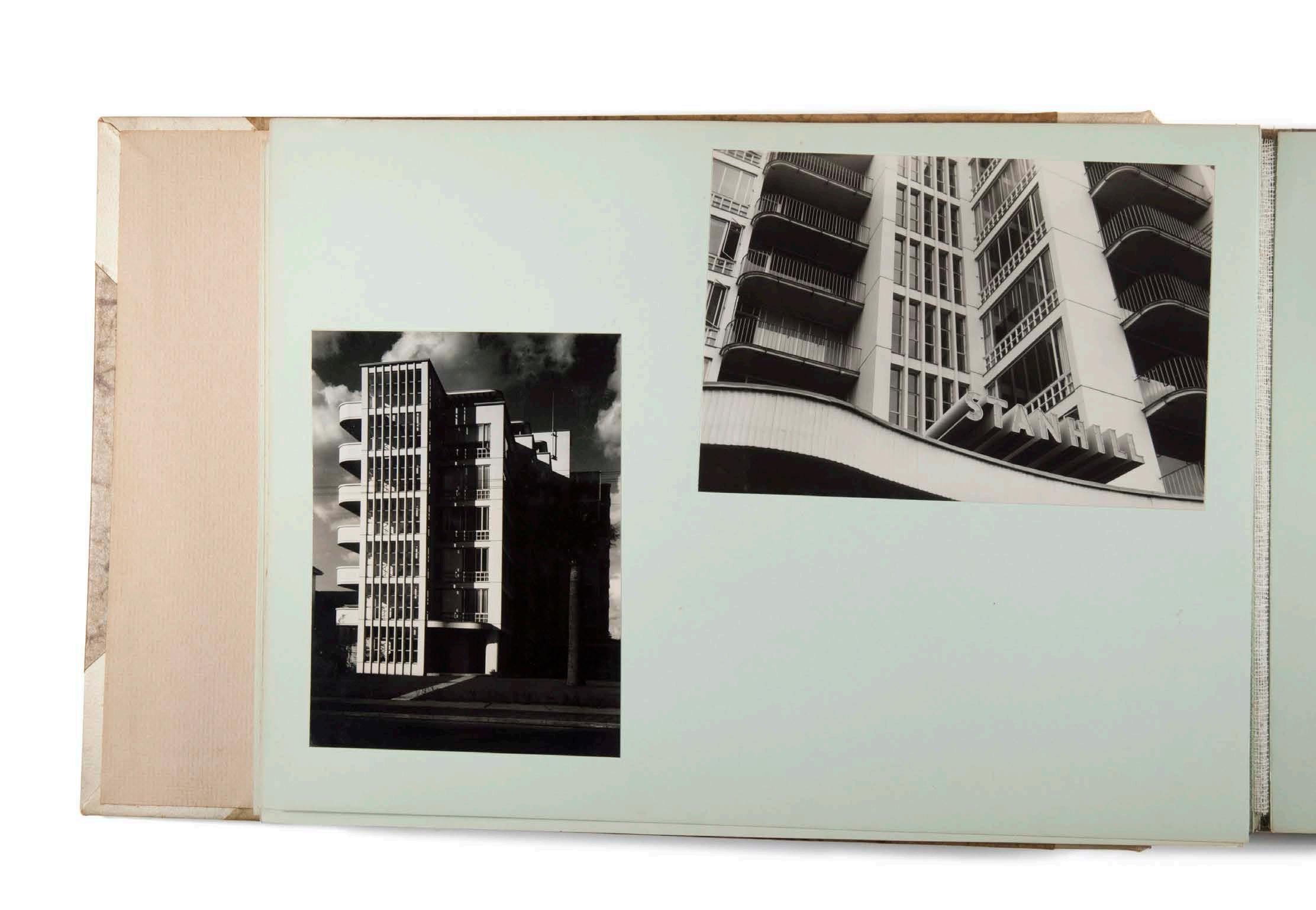

This partnership was short-lived however, and in 1943 Romberg was shipped off to the Northern Territory to work for the Allied Works Council along with other ‘enemy aliens’. On his return to Melbourne in August 1944 he lost no time in becoming a naturalised citizen. By this time, he was involved in the design of Stanhill Flats just south of Newburn,

which he had begun in 1943 for entrepreneur Polish-born Stanley Korman. Stanhill was to prove his most significant and celebrated building before the establishment of the partnership Grounds, Romberg and Boyd in 1953.

Romberg was appointed to ‘a part-time teaching assignment in the Architecture Department’ at MTC in 1945 3 The appointment highlights both the regard in which Romberg was held as an architect and the forward-looking ambition of Harry Winbush. Romberg taught architectural history and his name appeared on a 1945/46 handbook, but unfortunately neither his teaching materials nor a detailed architecture curriculum for 1945 survives, so the nature of his teaching is not known (although the 1946 copy of Banister Fletcher’s A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method in his personal collection suggests it would have followed a well-worn route).4 In 1946 Romberg left Melbourne for a visit to Europe and while he does not mention returning to MTC in his memoirs, he is listed as a part-time lecturer for 1948-49 in the university’s staff records so it is possible he continued to teach in these years.5

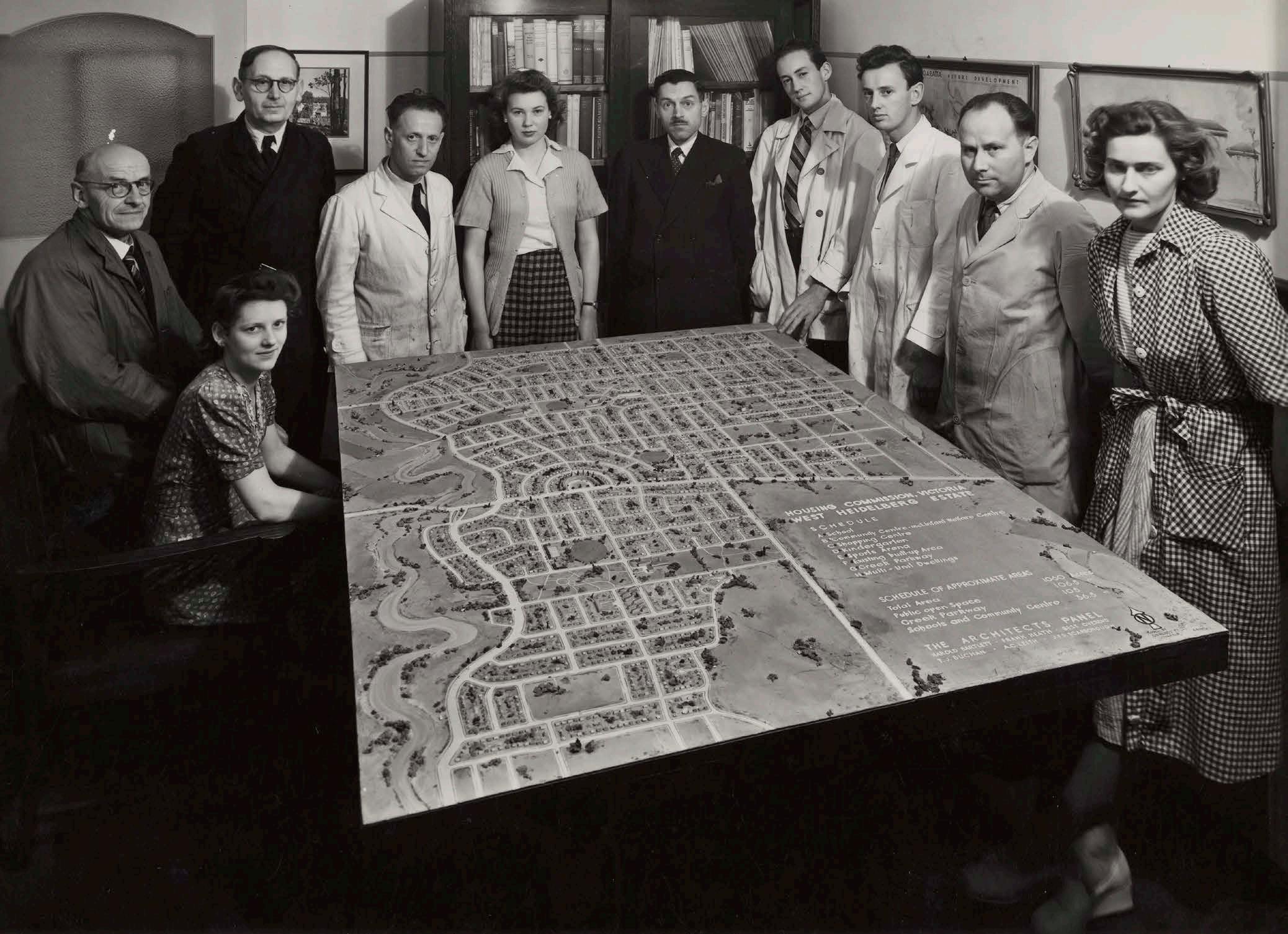

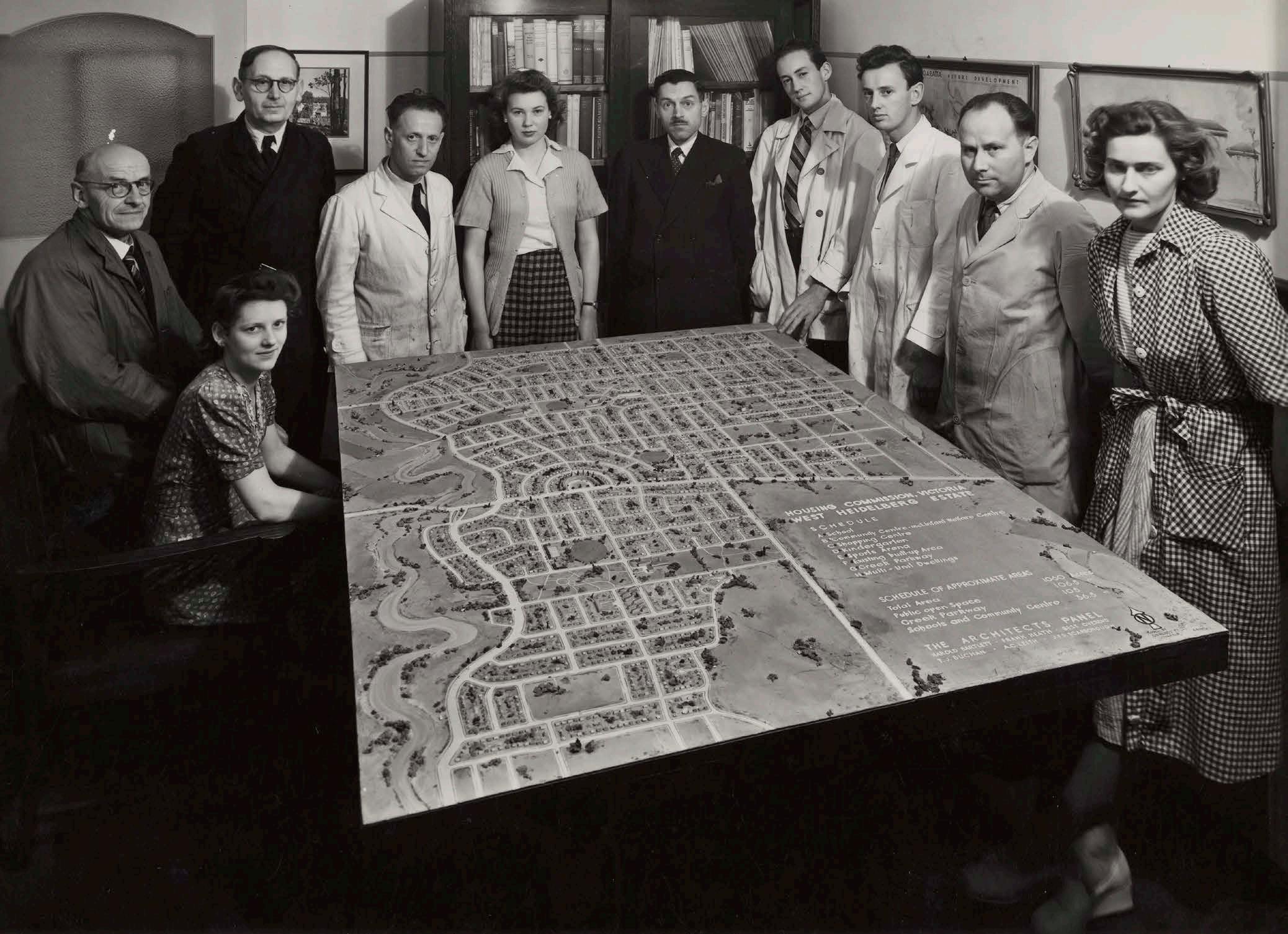

The contribution of Ernest Fooks to the architecture course is marginally better documented than Romberg’s but of quite a different nature. Fooks had arrived in Melbourne in 1939 with excellent architectural credentials. He was a graduate of Technical University Vienna (TUWien) where he obtained a doctorate in Technical Sciences in 1932 with a thesis titled Stadt in Streifen (‘Linear City’), completed under the supervision of prominent Viennese architect Siegfried Theiss. Like Romberg, Fooks brought out to Melbourne examples of his Viennese work and he quickly found a position with Frank Heath at the Housing Commission of Victoria (HCV).6 Here they were developing new towns in regional centres and new housing estates in the metropolitan area, a field Fooks knew well from his work in ‘Red Vienna’.7

At the same time, he published at least a dozen articles in the monthly Melbourne magazine Australian Home Beautiful on town planning, architecture and interior design, putting forward ideas about how Australia might benefit from Viennese experience in these areas.8 At Kosminsky Galleries, in March 1944, he exhibited his architectural drawings of European cities under the title of ‘Cities of

MELBOURNE MODERN 9

After the war Harold Brown oversaw the appointment of several émigré architects and designers in MTC’s Department of Art and Applied Art of which he was head.

Top Frederick Romberg, Perspective of Gloucester Apartments, Melbourne, 1946, gouache on tinted paper, image: 48.8 x 74.4 cm; sheet: 49.5 x 76.5 cm, RMIT Design Archives: Robin Boyd and Frederick Romberg Collection

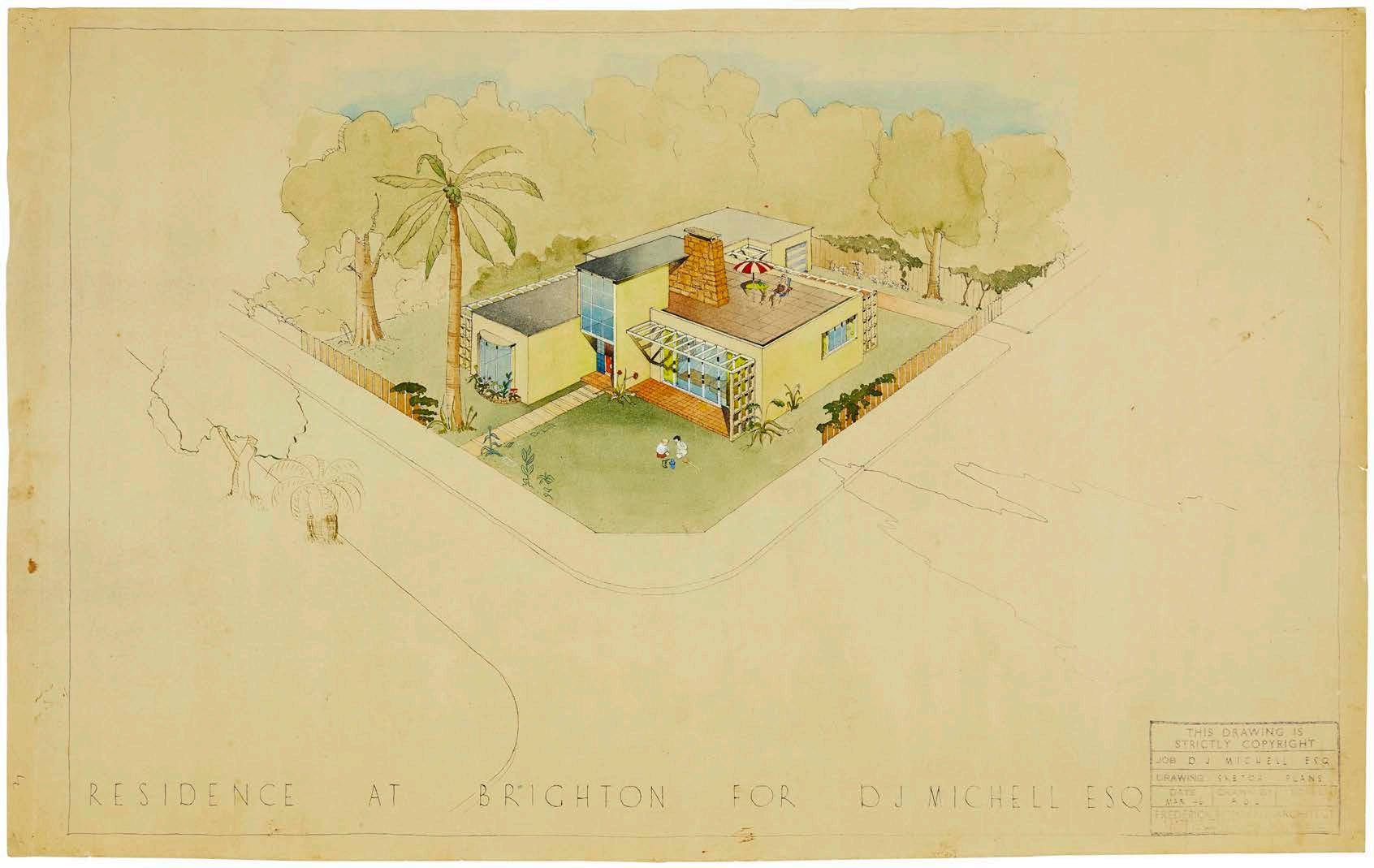

Above Frederick Romberg, Perspective of Residence at Brighton for D.J. Michell Esq, 1946, diazo-process print with watercolour, image: 43.5 x 68.5 cm; sheet: 45.7 x 73.0 cm, RMIT Design Archives: Robin Boyd and Frederick Romberg Collection

Opposite Frederick Romberg, metal tin containing student work including thesis design for the Dolder Grand Hotel, final year project at ETH-Zurich, 1937, papers, photographs, diazotypes, metal tin, various dimensions, RMIT Design Archives: Robin Boyd and Frederick Romberg Collection

10 MELBOURNE MODERN

ARCHITECTURE

POST-WAR

AND INTERIOR DESIGN

12 MELBOURNE MODERN POST-WAR ARCHITECTURE AND INTERIOR DESIGN

MELBOURNE MODERN 13

Page 12

Bottom right

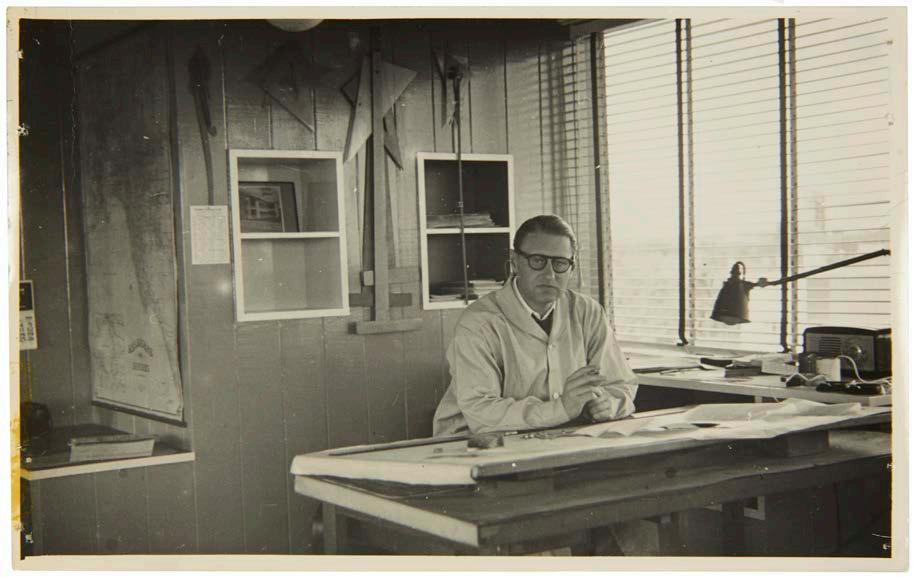

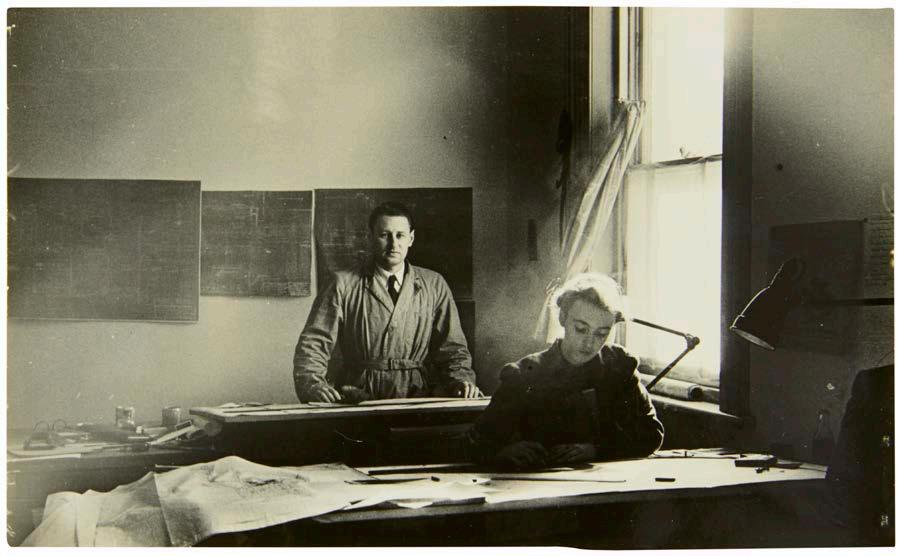

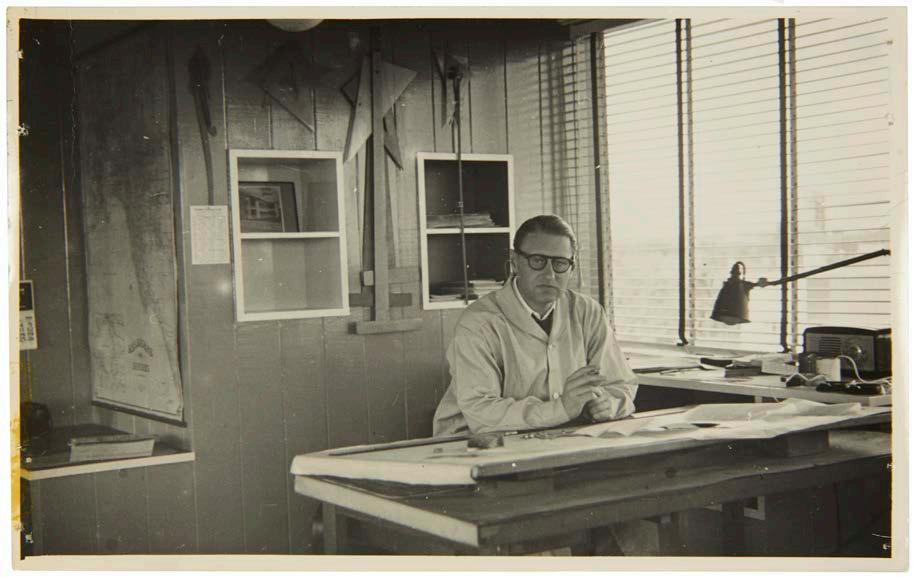

Frederick Romberg at his desk in Newburn Flats, Melbourne, 1952, photographer unknown, RMIT Design Archives: Robin Boyd and Frederick Romberg Collection.

Page 12

Middle right

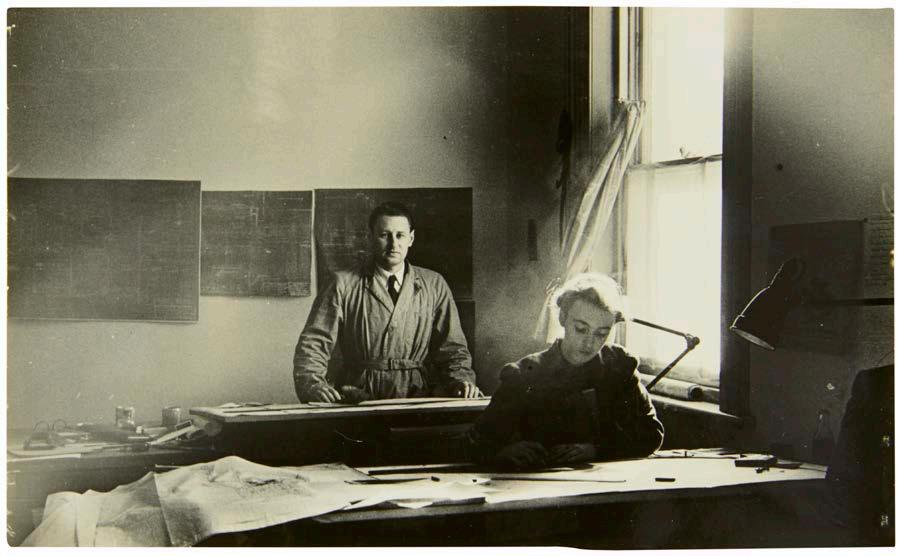

Frederick Romberg and Berenice Harris in the office at 1 Latrobe Street, Melbourne, c. 1947–49, photographer unknown, RMIT Design Archives: Robin Boyd and Frederick Romberg Collection.

Page 12

Middle left

Frederick Romberg and Horrie Clayfield, building manager for Stanley Korman, at the Stanhill construction site, 1949, photographer unknown, RMIT Design Archives: Robin Boyd and Frederick Romberg Collection.

Page 12

Top

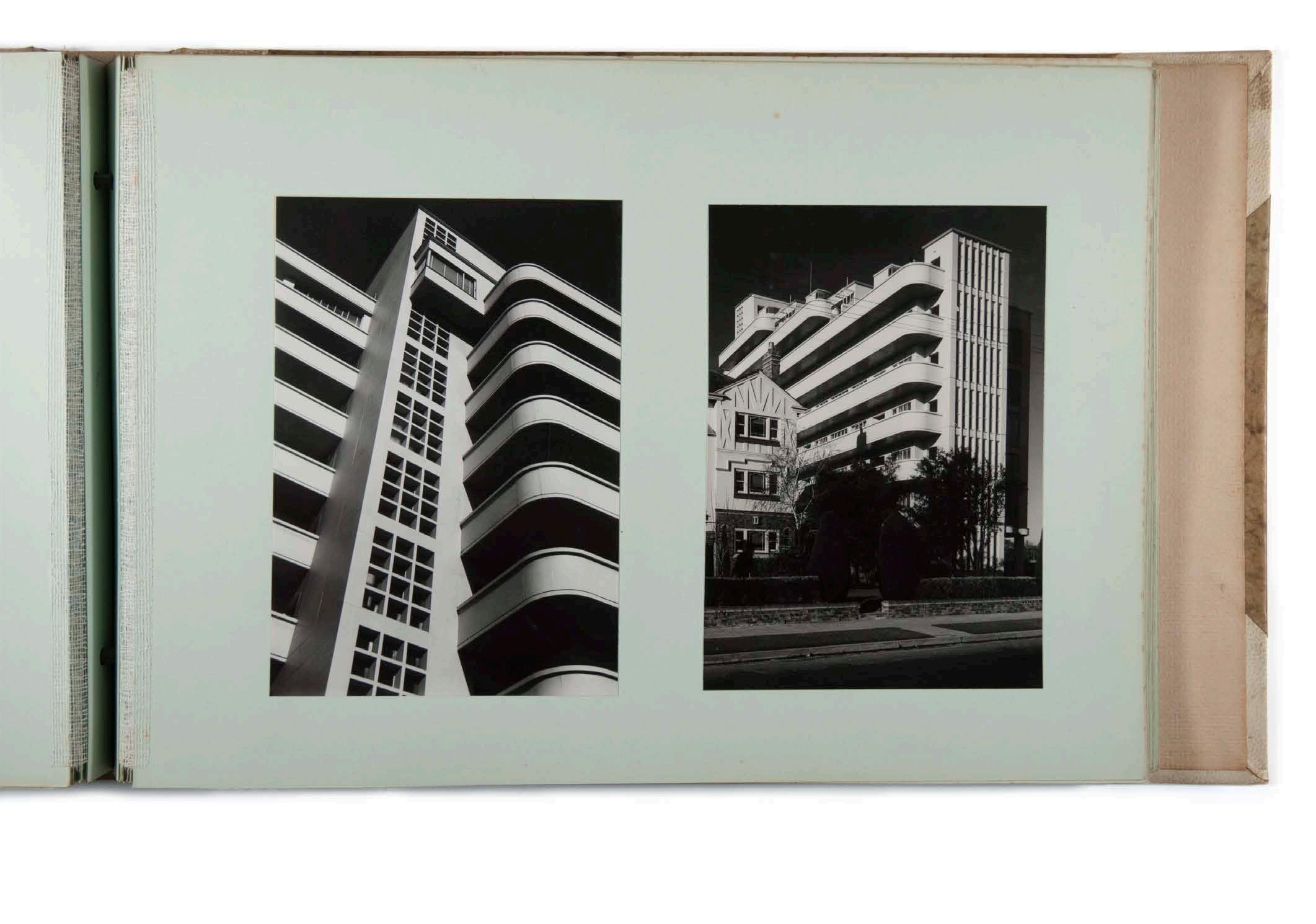

Frederick Romberg, Stanhill Flats, Melbourne, 1949, photographs mounted in album titled Frederick Romberg 1939–1950, photographer: Wolfgang Sievers, RMIT Design Archives: Robin Boyd and Frederick Romberg Collection

Page 13

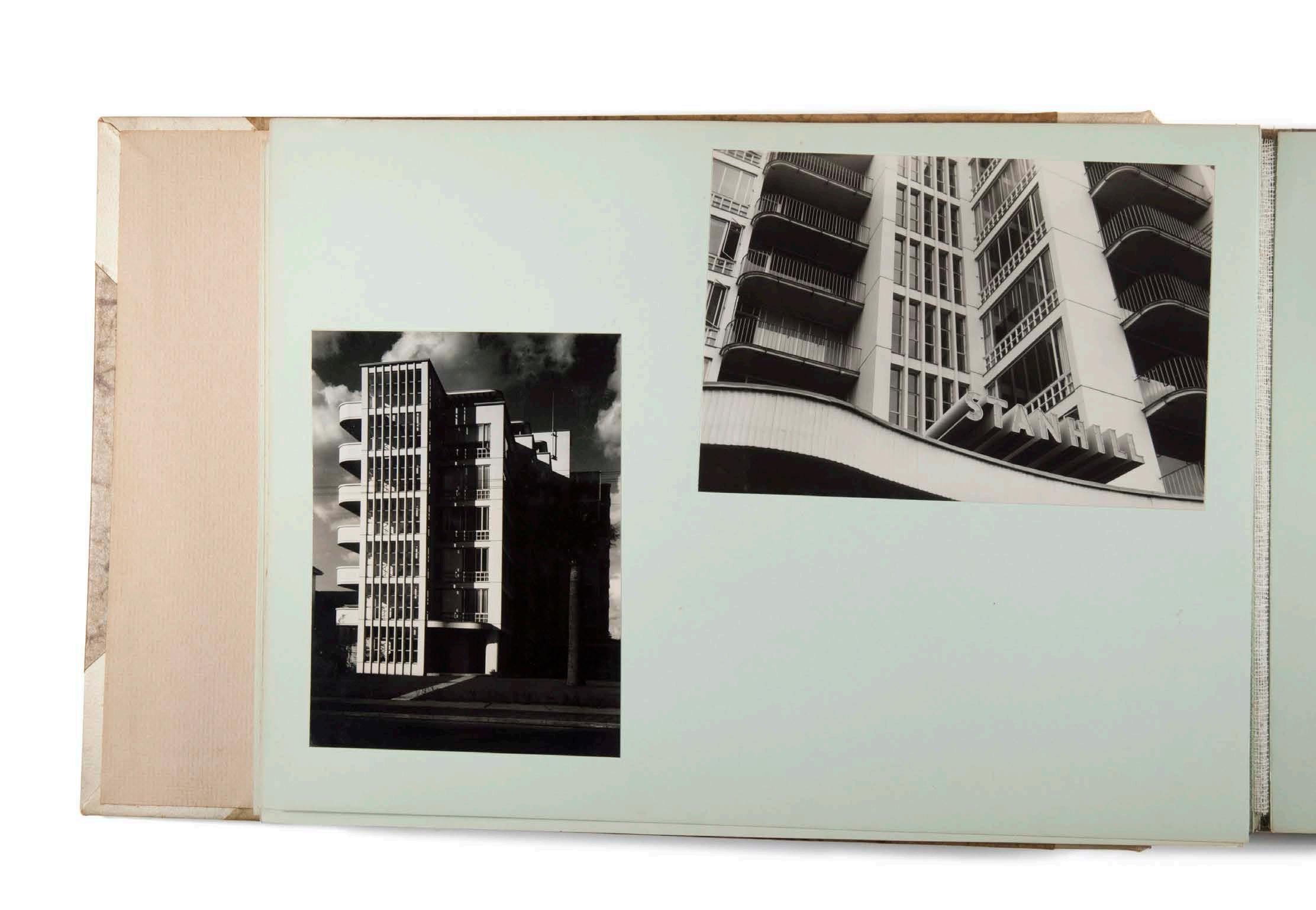

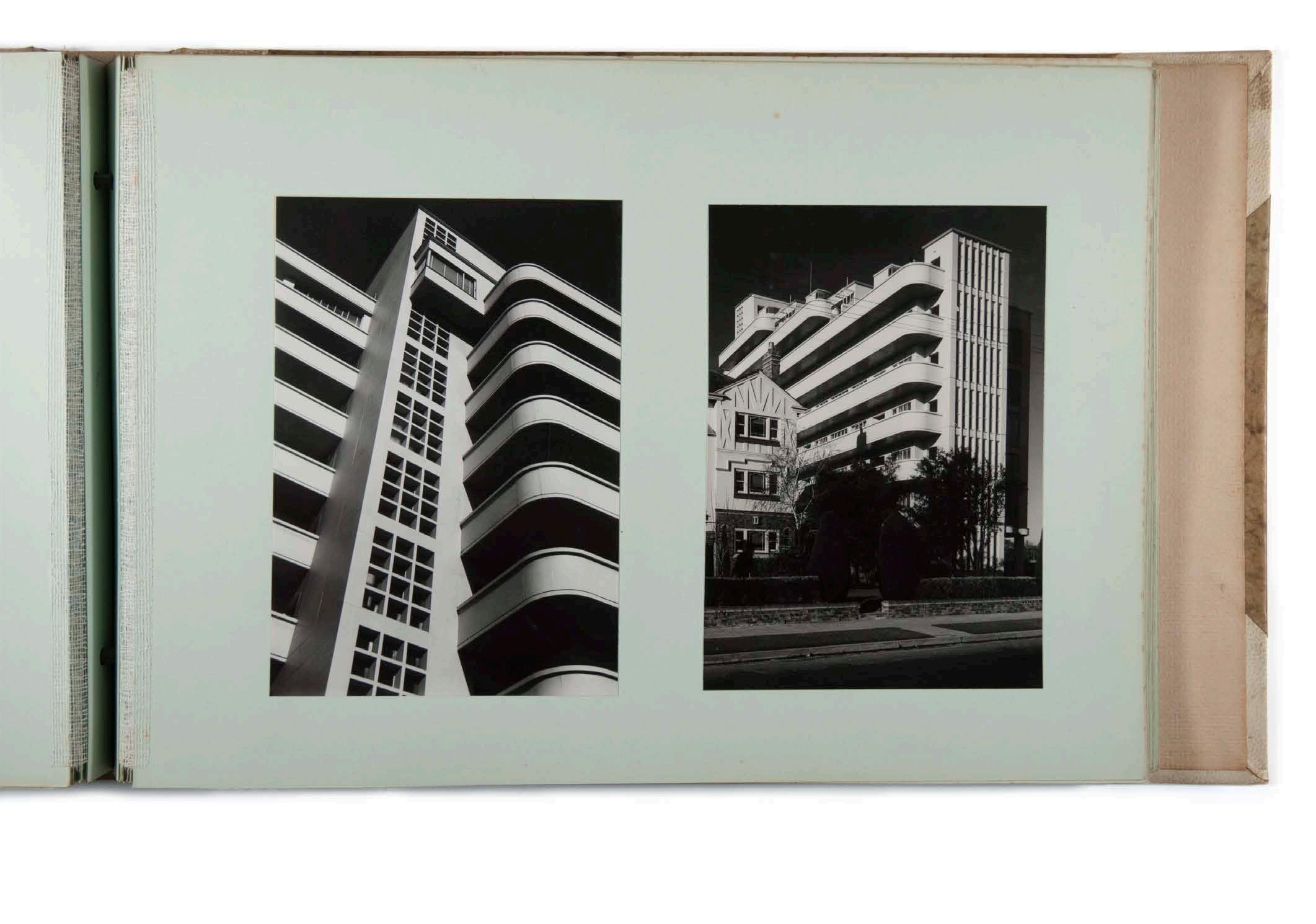

Frederick Romberg, Stanhill Flats, Melbourne, 1949, photographs mounted in album titled Frederick Romberg 1939–1950, photographer: Wolfgang Sievers, RMIT Design Archives: Robin Boyd and Frederick Romberg Collection

14 MELBOURNE MODERN

ARCHITECTURE AND INTERIOR DESIGN

POST-WAR

Opposite top Office of Frank Heath, Melbourne, with staff assembled around a plan of the Housing Commission, Victoria, West Heidelberg Estate (Ernest Fooks standing fourth from left), c. 1940–42, Commercial Photographic Co., State Library Victoria: Harold Paynting Collection

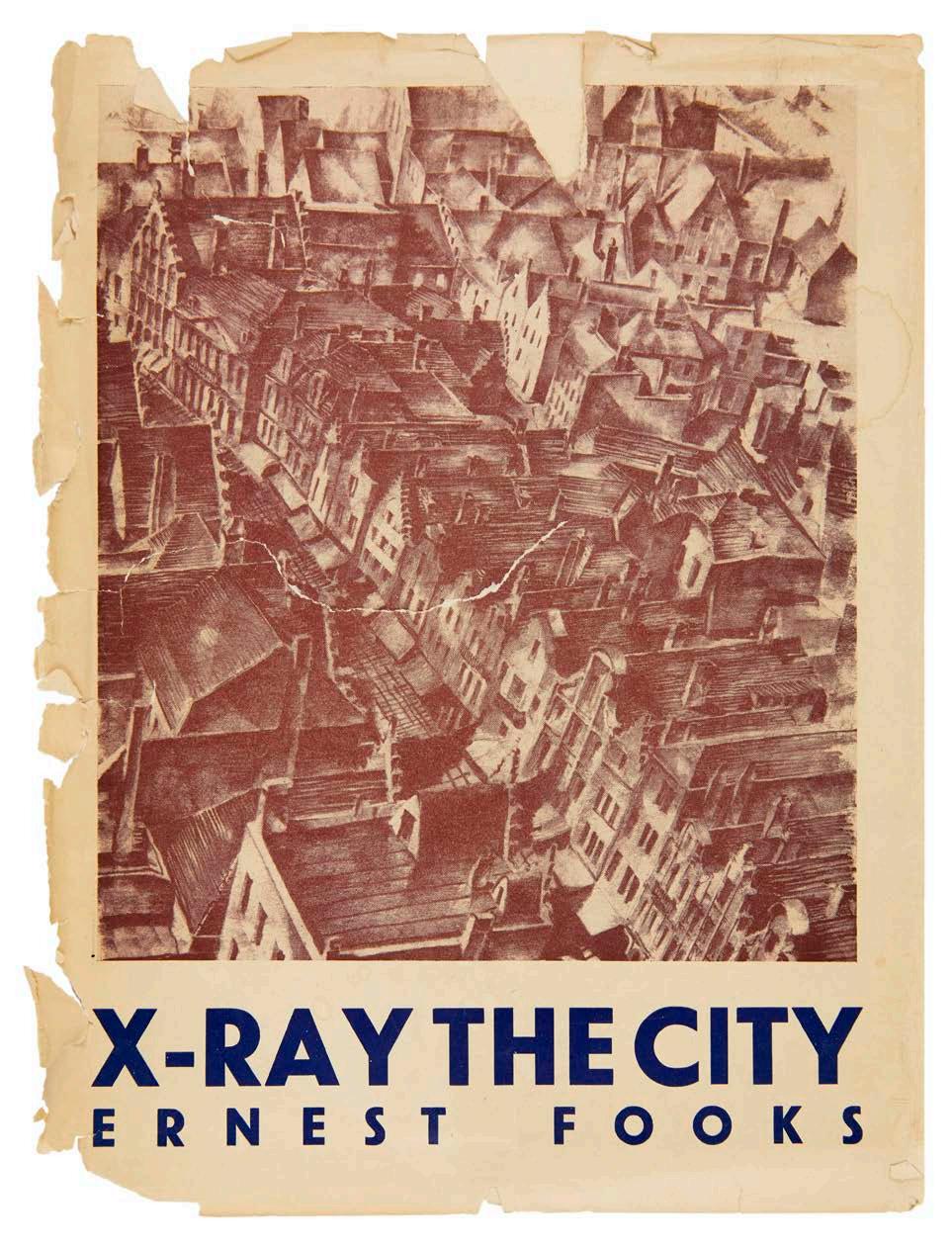

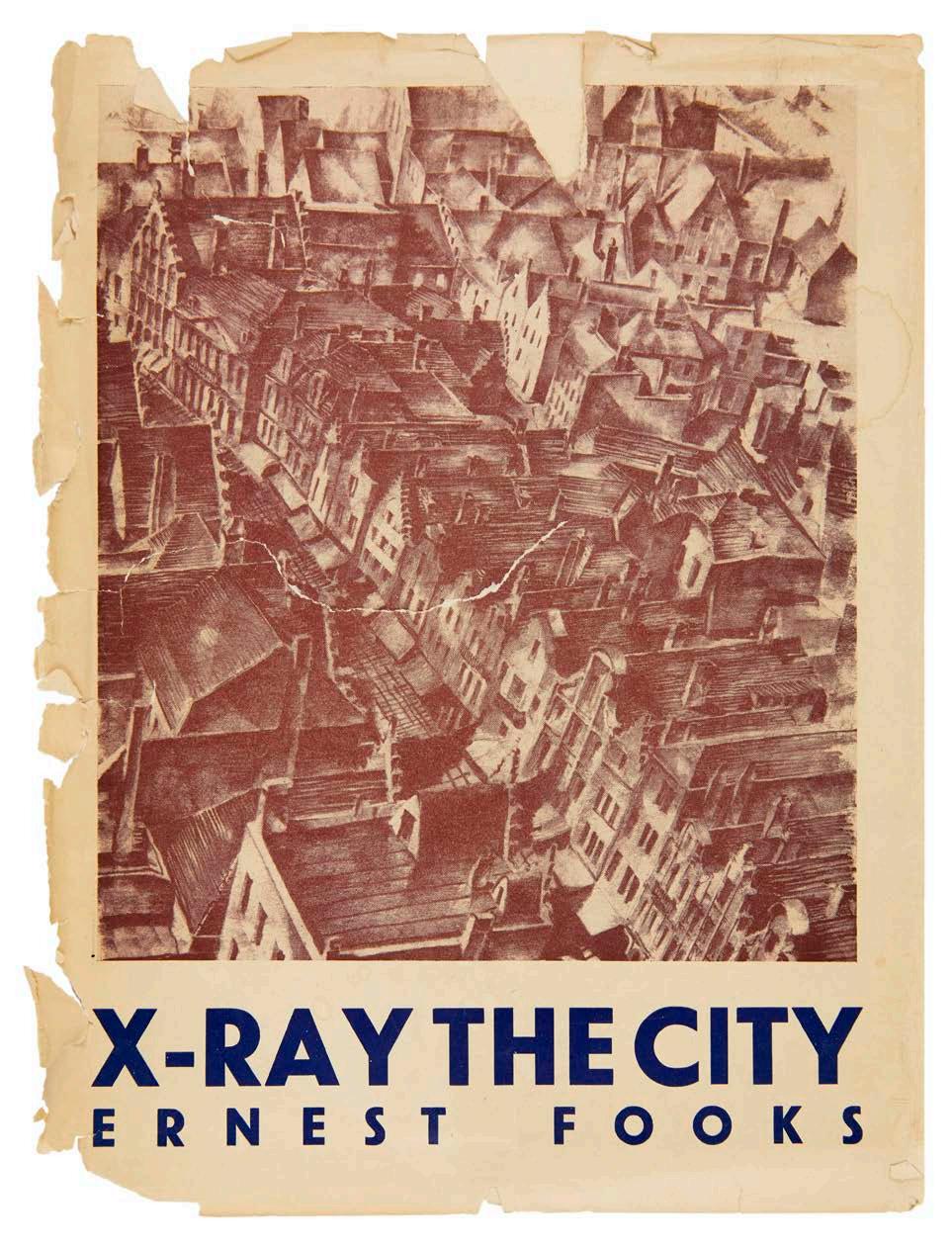

Opposite right Ernest Fooks, X-Ray the City! The Density Diagram: Basis for Urban Planning, with a foreword by Dr H.C. Coombs, 1946, Ruskin Press, Melbourne, RMIT Design Archives: Ernest Fooks Collection.

Right Melbourne Technical College Diamond Jubilee exhibition, Arts Building (Building 2), town planning display, 1947, photographer: Lyle Fowler, State Library Victoria: Harold Paynting Collection

Yesterday’, to critical acclaim. In 1946 he published his important urban study X-ray the City! The Density Diagram: Basis for Urban Planning!9 It was probably off the back of either this publication or the earlier exhibition that Fooks was appointed part-time lecturer in Winbush’s architecture department. He developed the new subject of Town Planning, which he taught for several years. Departments of Town and Country Planning had been established at the University of Sydney in 1947 and University of Melbourne in 1951 as responses to Australia’s rapid post-war urbanisation, and the MTC was characteristically pro-active in modernising its courses similarly to prepare its students for the new realities of a rapidly increasing population and industrialisation. Like the army of part-time teachers at the College, Fooks’ name does not appear on the annual prospectuses, so his teaching activities are hard to document.

In 1947 however, to celebrate the College’s Diamond Jubilee, Art and Applied Art mounted an exhibition in Building 2 of student work across all its disciplines. The various rooms designed by the students to showcase their work were recorded by photographer Lyle Fowler. The display included town planning, and it is reasonable to assume that the work was by Fooks’ students. Their scheme was divided into two parts: ‘what we have’ and ‘what we need’. The three photographs under the first section show small views of an industrial landscape, a congested city, and a poor neighbourhood. The larger, visionary scheme shows a design for an irregular greenfield site with sports oval flanked by housing (detached houses and apartments), a hospital, school, shopping precinct and factories serviced by a railway line and car parking, while photographs show modern housing and high rise urban buildings. The scheme displays the typical suburban template of Fooks and Heath at HCV for ‘housing formulated to provide proximate population of workers to new perimeter factories, on greenfield sites’ and indicates the nature of Fooks’ curriculum, fusing European experience with Australian circumstance.10 For all that, the important contribution Fooks made to MTC architecture was quickly erased: when Granville Wilson came to publish the centenary history of RMIT’s Faculty of the Constructed Environment in 1987, his account of town-planning begins in 1966.11

Frederick Sterne’s architectural education is something of a mystery but by 1930 he was enrolled at TUWien in economics and administrative law, prerequisites for registration as an architect.12 At the same time he had established a modest practice in interior design and his work began to appear in European architecture and trade journals. His most significant known work was an interior scheme for one of the houses that formed Josef Frank’s 1932 Vienna Werkbundsiedlung, which indicates that he was an active participant in the socialist city’s massive inter-war building programme. After he arrived in Melbourne in 1938 Sterne, like Romberg and Fooks, had no trouble finding work in a progressive Melbourne architecture firm – in this case Leighton Irwin, where he remained for the duration of the war.

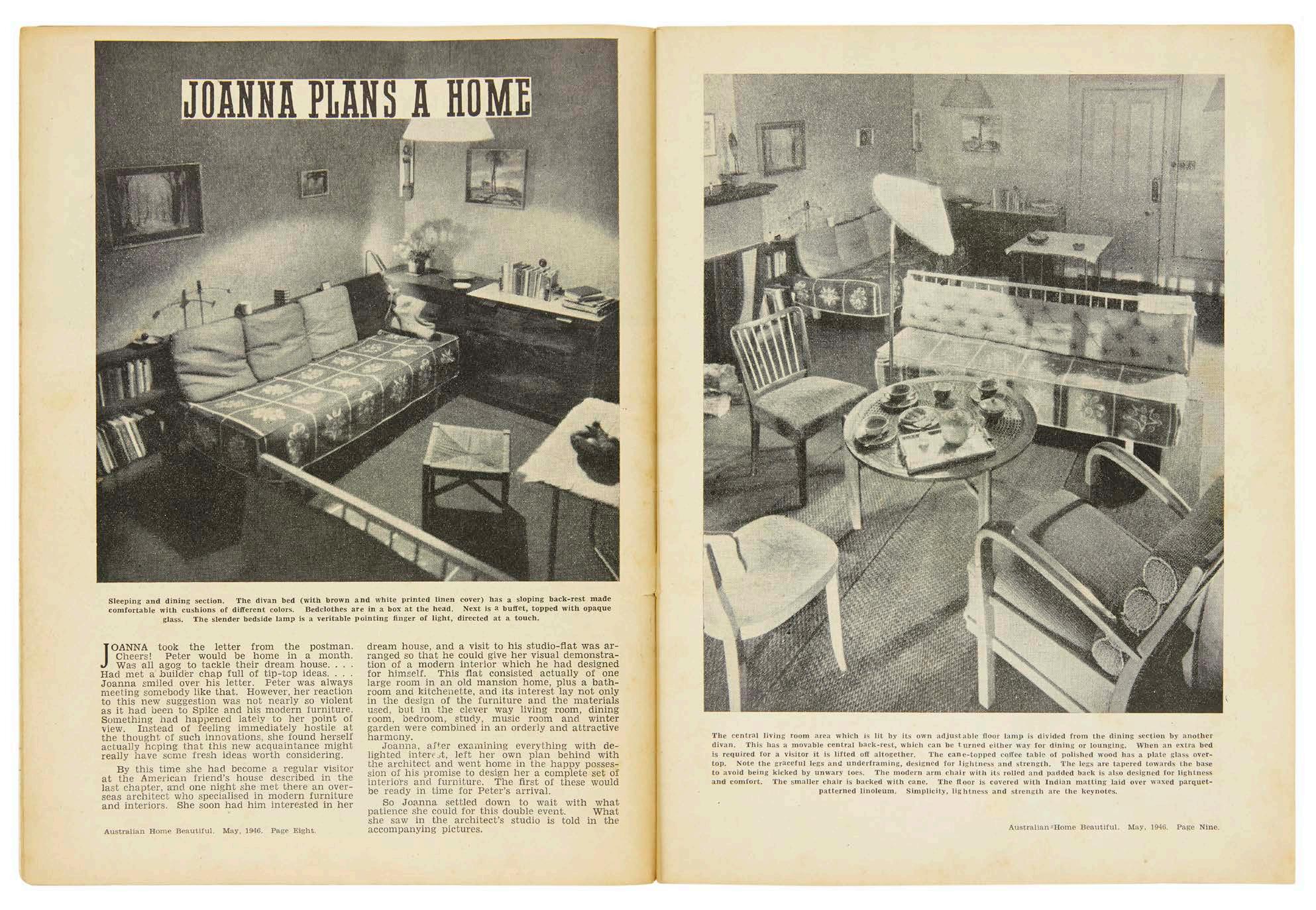

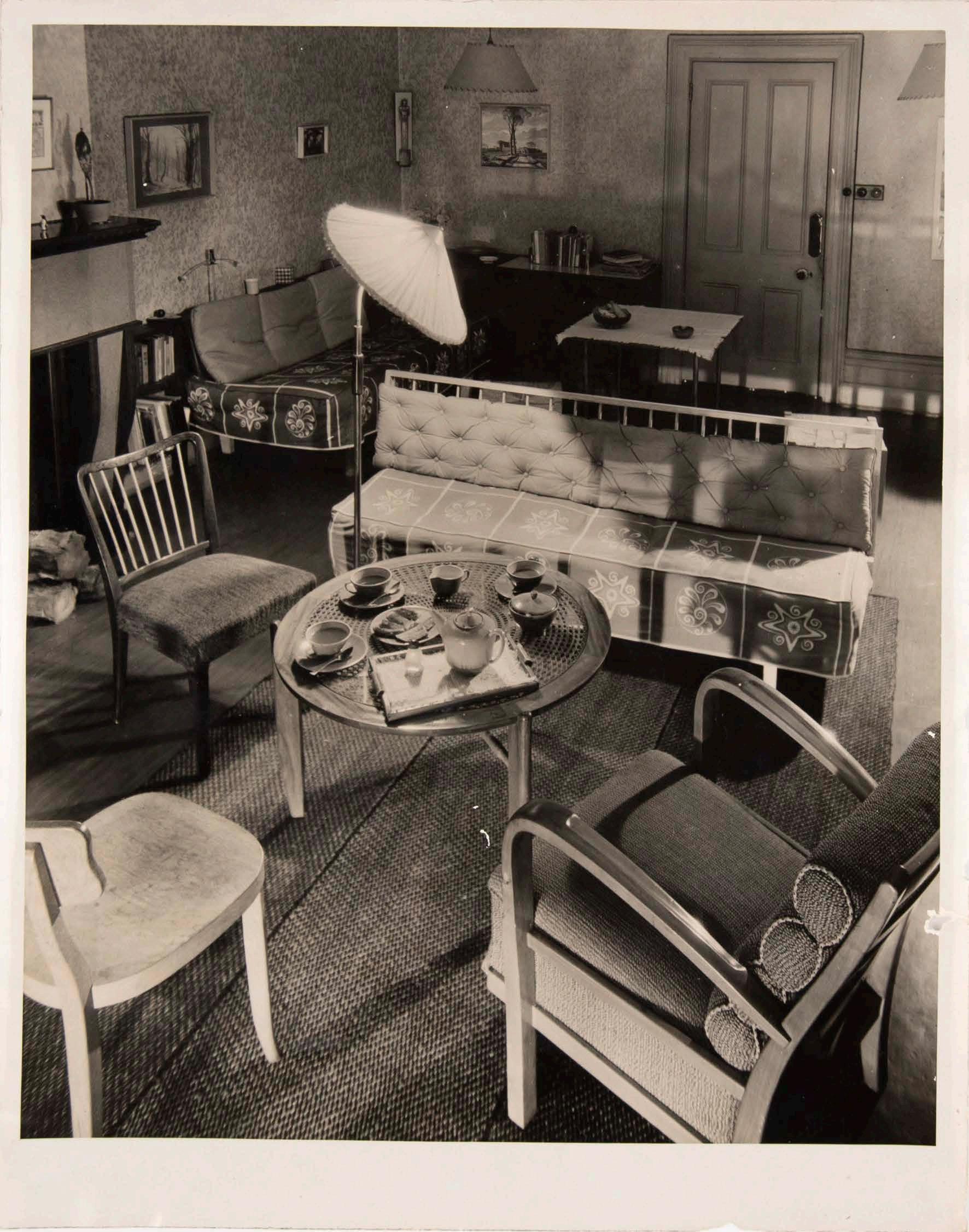

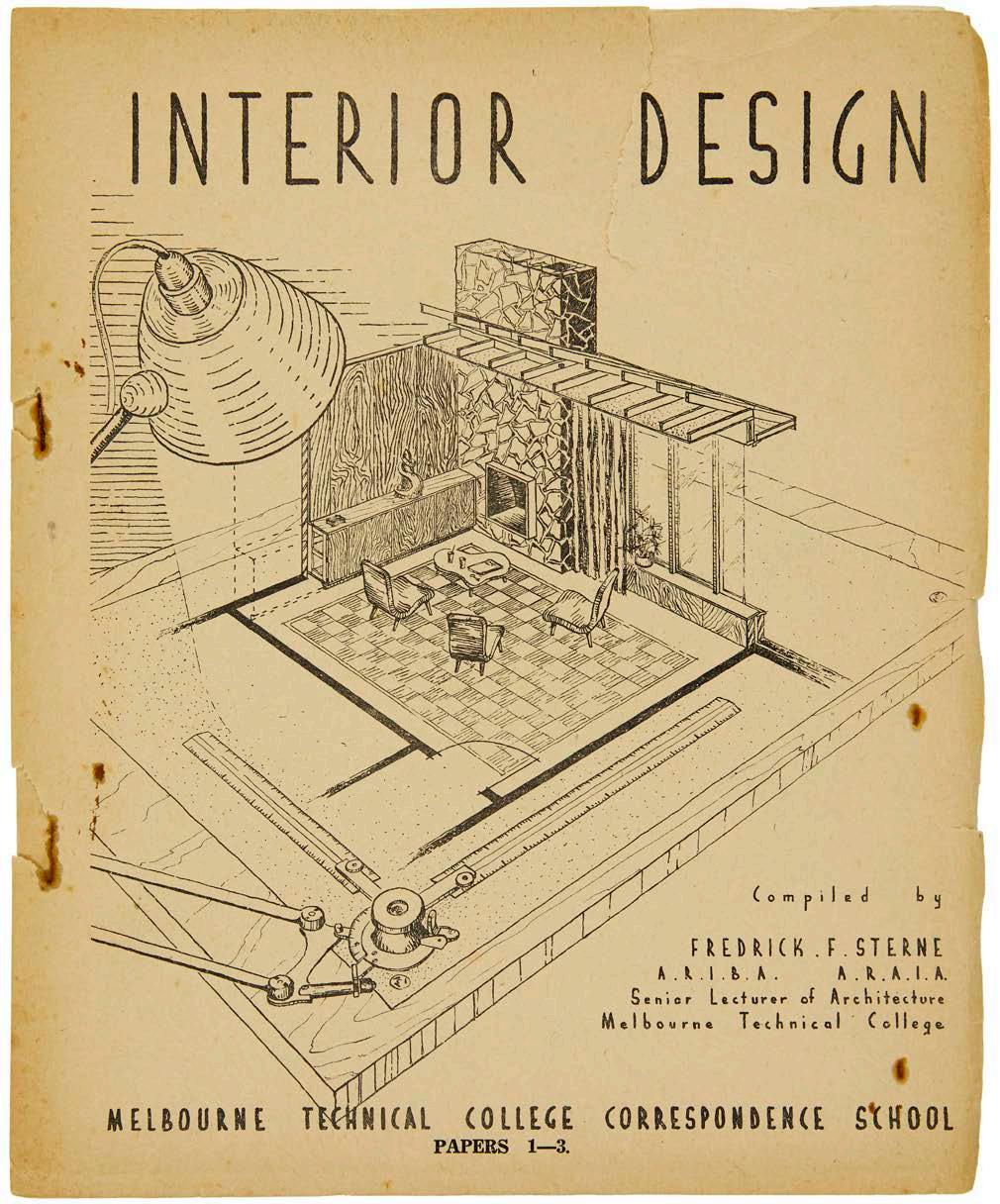

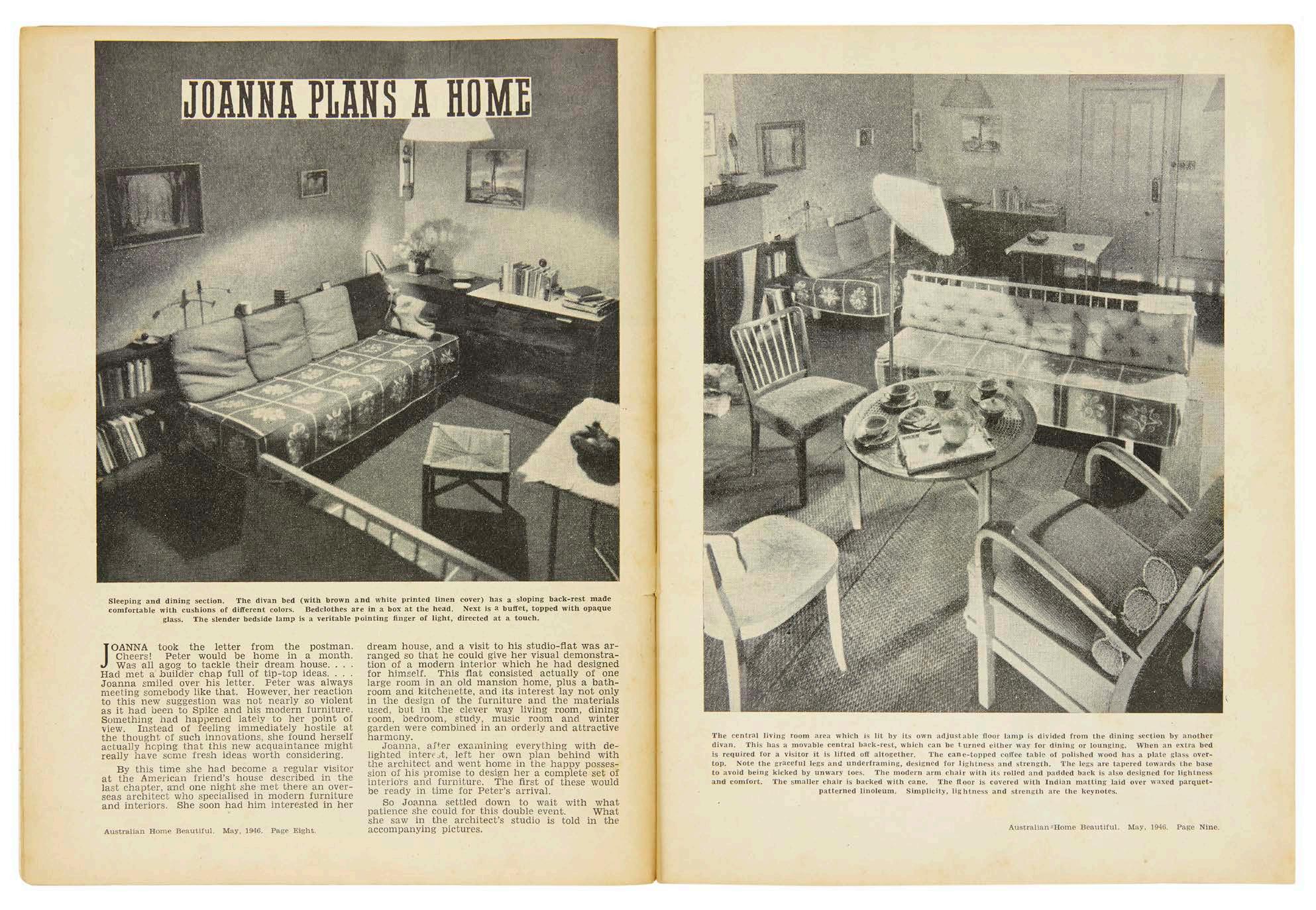

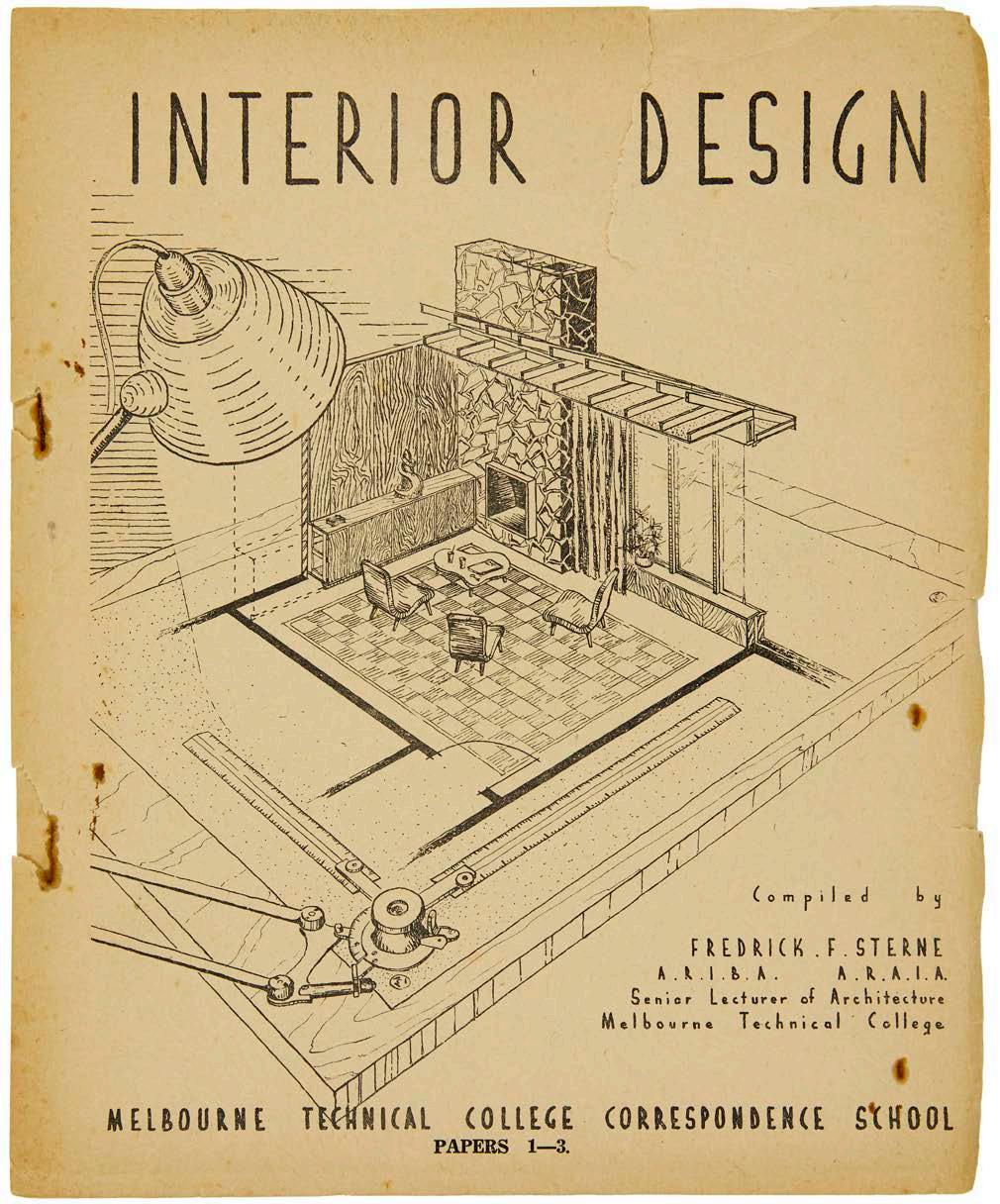

During 1945 and 1946 Sterne became familiar to readers of Melbourne’s Australian Home Beautiful through a series of articles he co-authored with long-standing journalist Mary Jane Seymour, which dealt with the interior design of the post-war house.13 Sterne’s illustrated contributions were infused with the ethos of Wiener Wohnraumkultur (‘Viennese living room culture’) that marked the particularly Viennese contribution to Australian modernism.14 It was probably on this basis that Sterne was brought into MTC as principal lecturer in architecture with a brief to transform its Interior Decoration course into Australia’s first Interior Design course.

Interior Decoration had been on the MTC curriculum for years and by 1936 it was divided into three subjects: Interior Decoration, Interior Decoration History, and Interior Decoration Design.15 By 1947 the prospectus listed two subjects: ‘Interior Decoration, Design’ and ‘Interior Decoration, Presentation and Rendering’.16 But in 1949 we find Sterne’s four-year Associate Diploma of Interior Design, which was planned as a ‘comprehensive’ course with ‘equal emphasis … placed upon design, construction and business administration’.17 It would seem that design had been implicit in the Interior Decoration course from the 1930s, but under Sterne it assumed the professional nomenclature and status it still enjoys. 1947 staff records show that Sterne was a parttime lecturer in the Department of Architecture, teaching Interior Design students design, building construction, specification and professional practice. He became full-time

MELBOURNE MODERN 15

16 MELBOURNE MODERN POST-WAR ARCHITECTURE AND INTERIOR DESIGN

Opposite top Frederick Sterne and Mary Jane Seymour, ‘Joanna Plans A Home’, Australian Home Beautiful, May 1946, pp. 8–11, RMIT Design Archives: Frederick Sterne Collection

Left

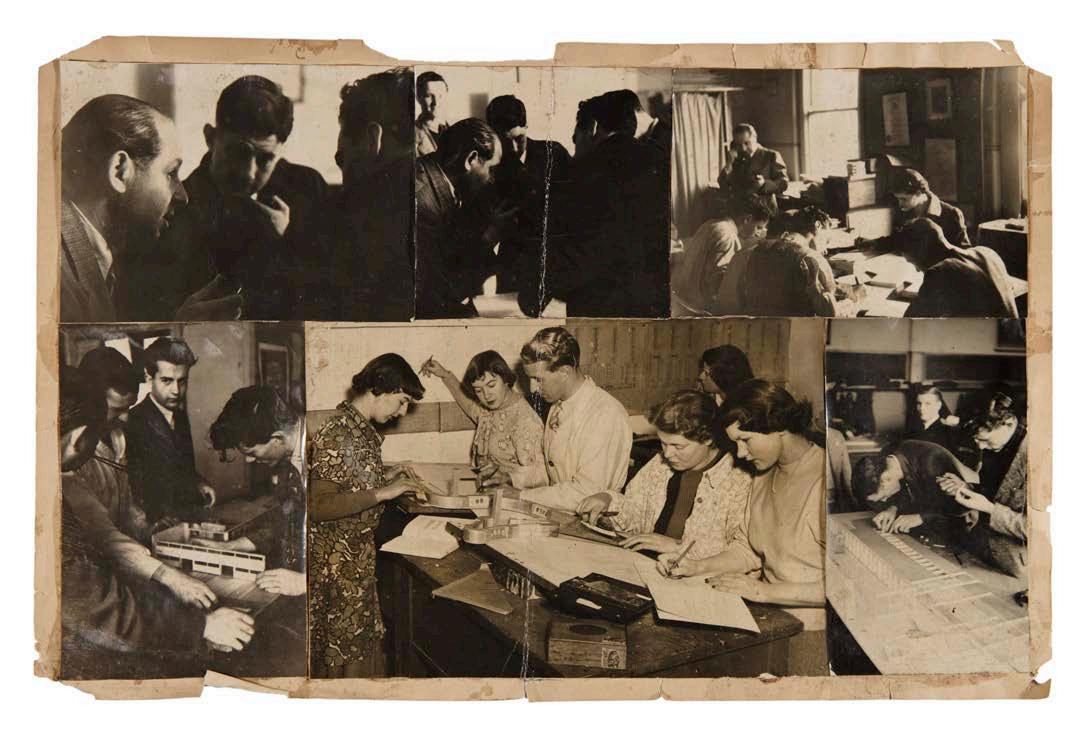

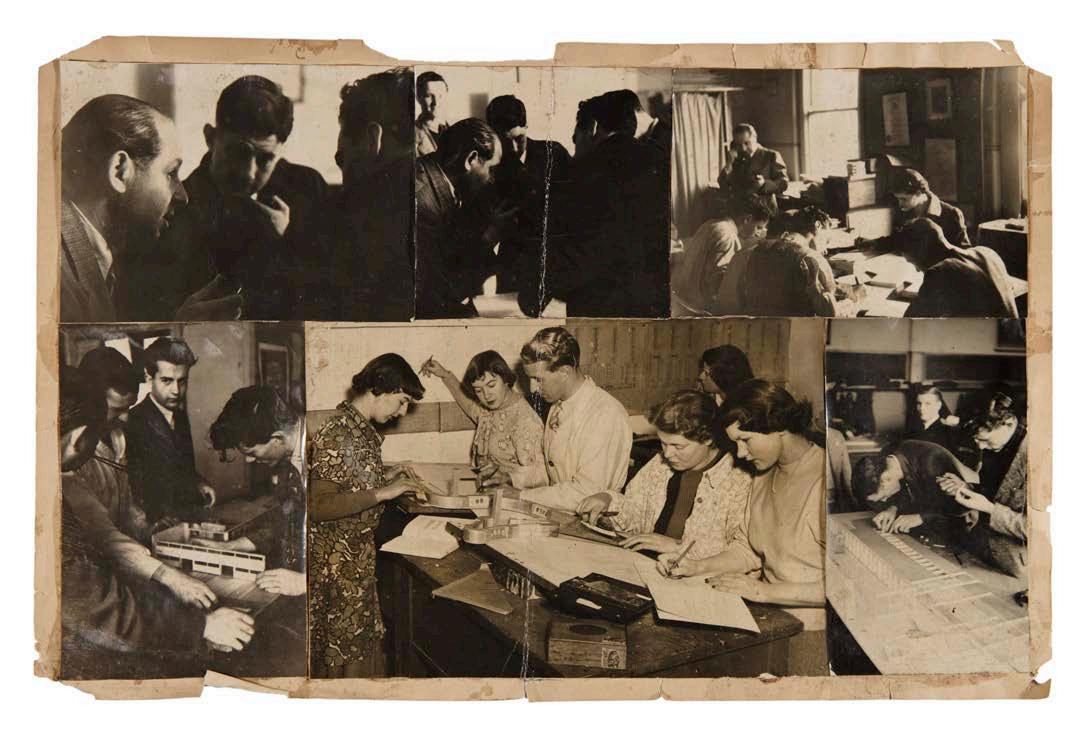

Melbourne Technical College Interior Design students at work, collage of six photographs, c. 1947–51, photographer unknown, RMIT Design Archives: Frederick Sterne Collection

Opposite below Frederick Sterne and Mary Jane Seymour, ‘Joanna Plans A Home: Furniture is Designed for Dining Room and Hall’, Australian Home Beautiful, July 1946, pp. 27–30, RMIT Design Archives: Frederick Sterne Collection

in February 1948, in which year he wrote the new curriculum for Interior Design.18 He also wrote the correspondence course for Interior Design for the College’s large cohort of correspondence students.

Sterne’s influence seems to have extended to recommending fellow émigrés to teaching posts. For instance, by 1949 Fritz Rosenbaum, a Viennese émigré architect, was teaching part-time; he was probably recruited by Sterne.19 A pianist as well as a lateral thinker, Sterne installed a piano in the lecture room and ‘demonstrated the similarities between various classical themes and methods of building construction’.20 This apparently endeared him to students, as reflected in his obituary in the MTC magazine Jargon, in 1951: ‘Having seen much in his travels, and being a lover of culture and all the arts, Mr. Sterne was an inspiration to students, among whom he was held in high esteem’.21 Granville Wilson confirms this, recounting that Sterne, or ‘Uncle Fred’ as he was known, was ‘regarded highly’ by the students.22

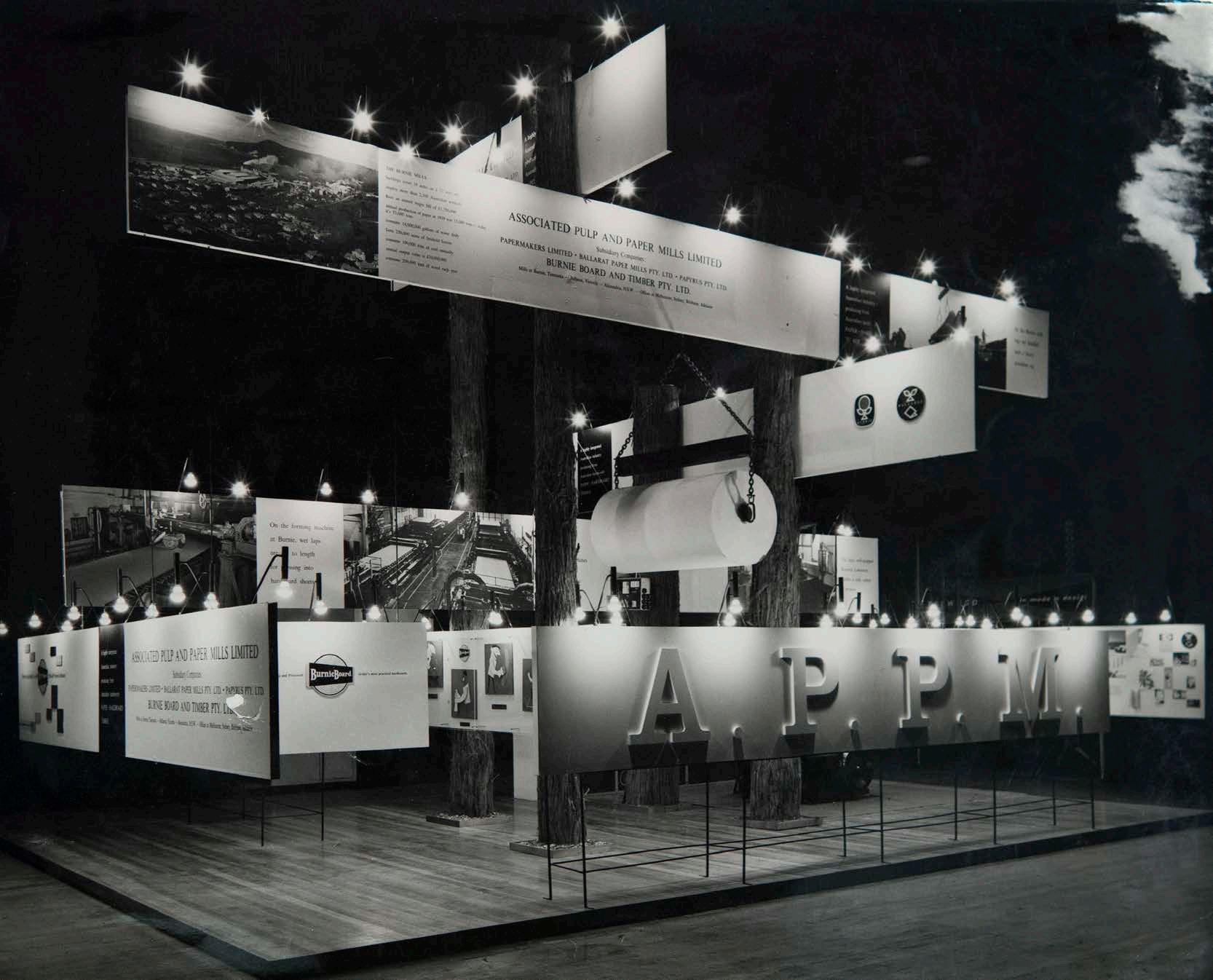

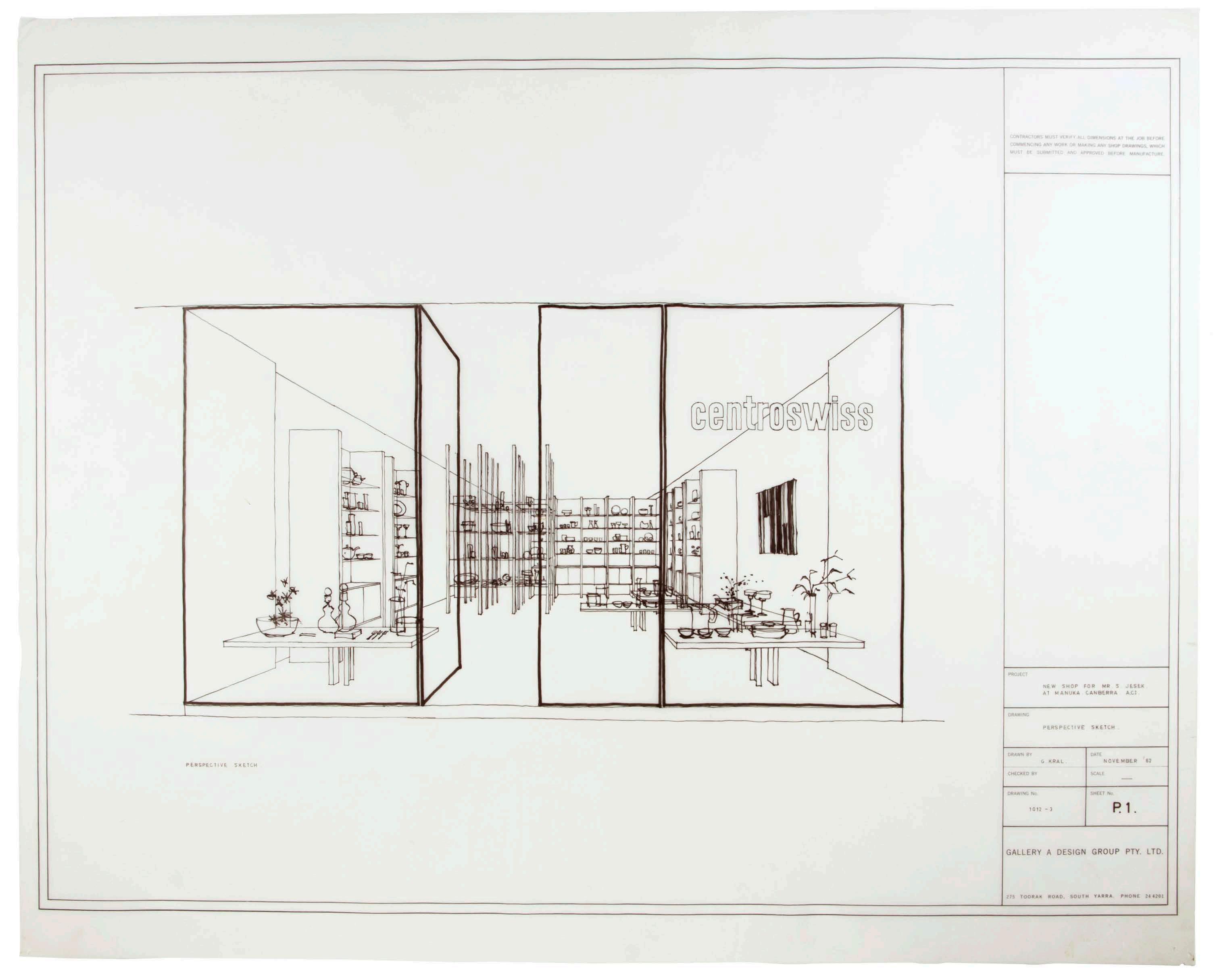

It was not until the end of the 1950s that another émigré from Europe came in to teach, albeit briefly, in Interior Design. Little is known about Czech-born George Kral’s education and training in Europe before he emigrated to Australia in 1950, but in his active years from 1956 to 1978 he was at the forefront of Melbourne exhibition design, interior design and graphic design practice.23 By the mid-1950s he was collaborating with German émigrés Gerard Herbst and Wolfgang Sievers as well as English-born architect Bernard Joyce, local designer Clement Meadmore, and entrepreneur Max Hutchinson. In association with these colleagues Kral designed cafés, shop interiors and exhibitions that were sophisticated exemplars of high modernism. The only example from this significant body of work published in the architectural press, however, was the small Caprice Café in Collins Street, of which Architecture and Arts noted in 1957: ‘the Caprice relies purely on the downright elegance of brass, pure white plaster and bricks’.24 Indeed, it was elegance which set Kral apart from his Melbourne contemporaries whose modernist interiors while worthy, experimental and interesting were rarely elegant or displayed such an innovative use of materials as Kral’s. The sheer elegance

of the Esquire Café in Canberra, unerringly captured in photographs by Wolfgang Sievers, differentiates Kral from his design peers. So too Kral and Joyce’s interior for the Australian Pavilion at the Fourth Tokyo International Trade Fair, hosted by JETRO (Japan External Trade Organisation) in April 1961, which with its over-scaled photographs and light boxes, reflective surfaces and lavish use of black, was at the forefront of design for Australian overseas trade pavilions.

Gallery A was established by Max Hutchinson and Clement Meadmore in 1959 in Flinders Lane as a gallery and furniture showroom, and soon Joyce and Kral added a design studio to its stable of offerings. Kral, who was an accomplished graphic designer, designed its corporate identity. By October 1962 the Gallery A Design Group Pty Ltd (as it was known) and Gallery A itself had moved to prominent premises on Toorak Road, South Yarra.25 Headed by Kral, the design studio brought together interior design, architecture, graphic design, photography and product design, and on some of its projects – such as the fit-out of a new Sportsgirl store featuring bright yellow joinery – Kral’s students at RMIT would join the design team. His brief tenure at RMIT coincided with that of Joyce, who had joined the staff in 1961. In that year Kral was a guest lecturer in Industrial Design and in the Department of Architecture and Building and was also appointed lecturer in Architectural and Interior Design.26

Romberg, Fooks and Kral were all sessional teachers and their long-term impact on curriculum development at RMIT is hard to gauge. Sterne’s contribution was more substantial and hence can be documented. Like Vodicka and Herbst (see chapters 2 and 3), he had a significant role to play in the development of the course of which he was head and, like them, his legacy lives on today.

MELBOURNE MODERN 17

18 MELBOURNE MODERN POST-WAR ARCHITECTURE AND INTERIOR DESIGN

Opposite page Frederick Sterne apartment, living and dining room separated by divan upholstered with Frances Burke’s Crete fabric, c. 1946, photograph: Sutcliffe Pty Ltd, RMIT Design Archives: Frederick Sterne Collection Above

Frederick Sterne apartment, study and music room c. 1946, photograph: Sutcliffe Pty Ltd, RMIT Design Archives: Frederick Sterne Collection Left

Frederick Sterne, Interior Design: Melbourne Technical College Correspondence School, Papers 1–3, c. 1948, printed course notes, RMIT Design Archives: Frederick Sterne Collection

MELBOURNE MODERN 19

Above

Right George Kral (standing) and Clement Meadmore at Gallery A, Melbourne, c. 1959–63, photographer unknown, RMIT Design Archives: George Kral Collection

Pages 22–23

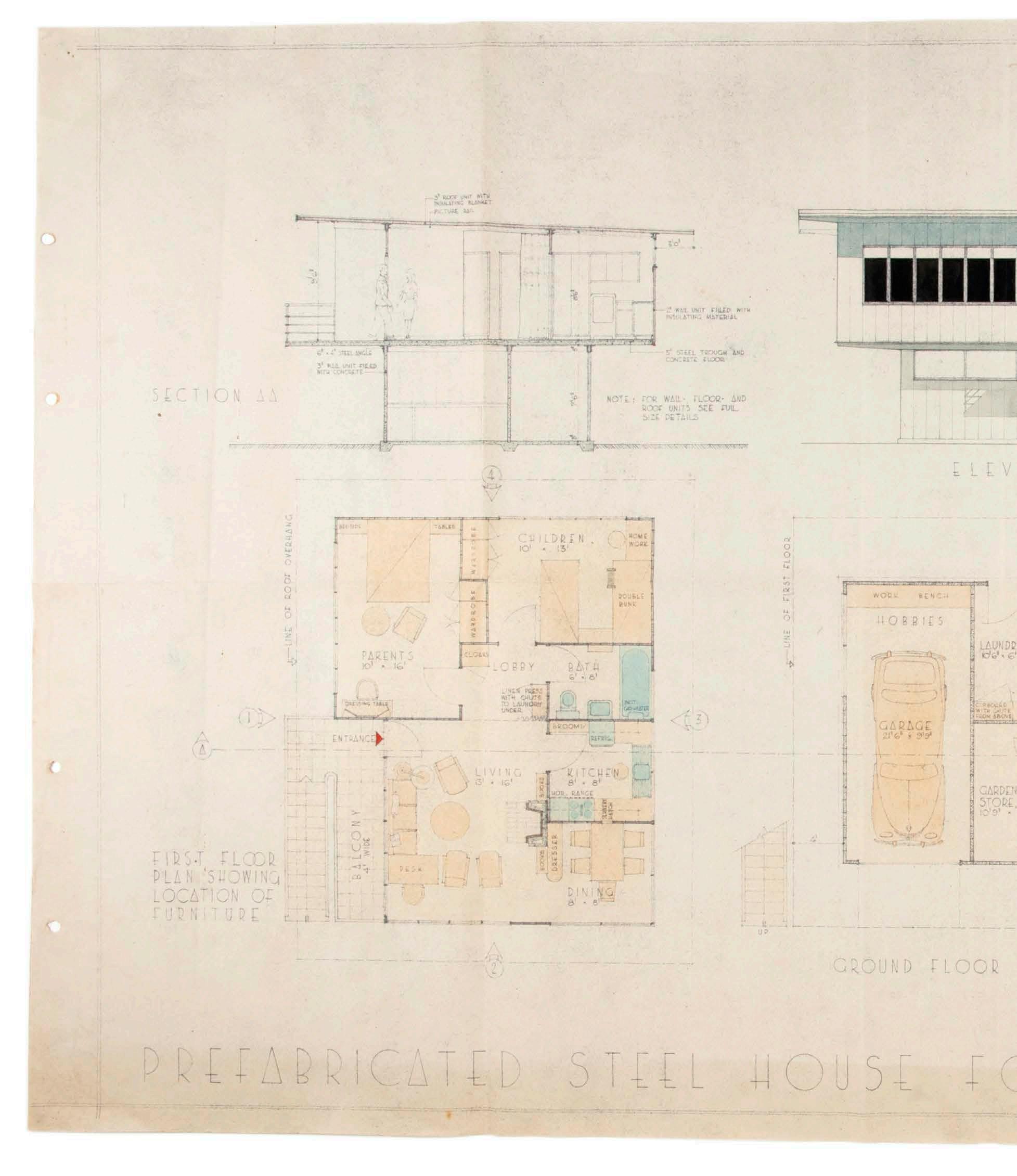

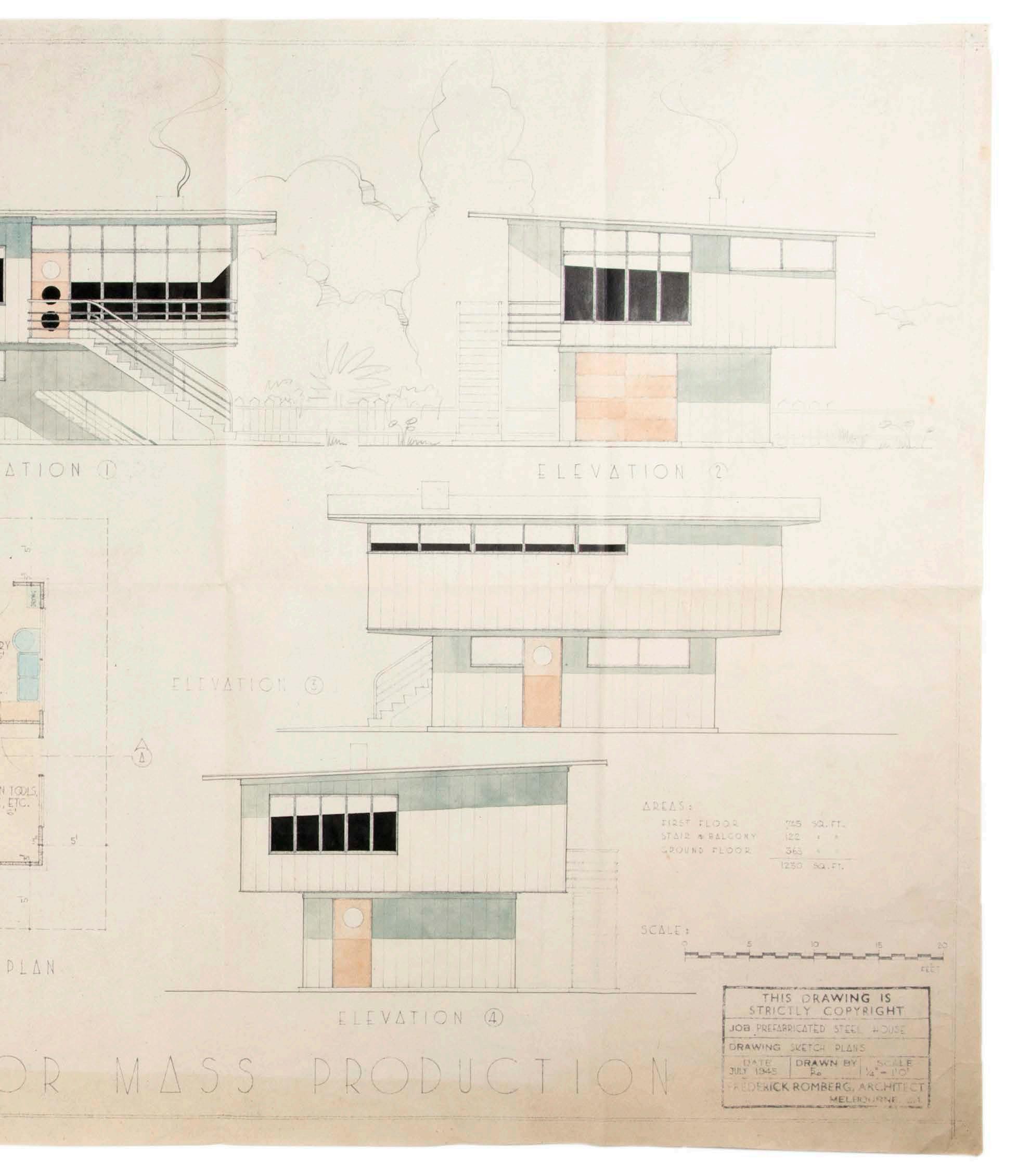

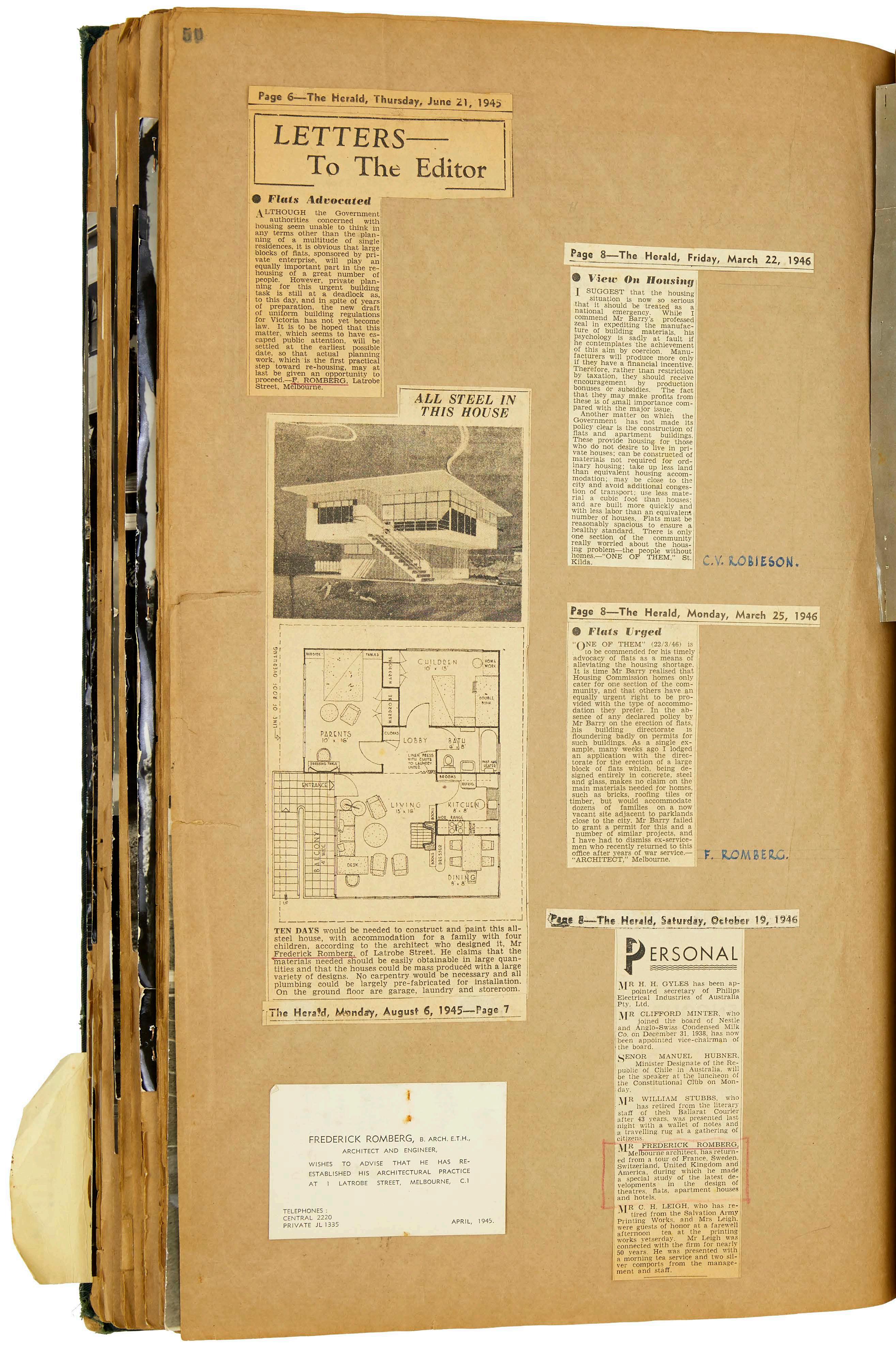

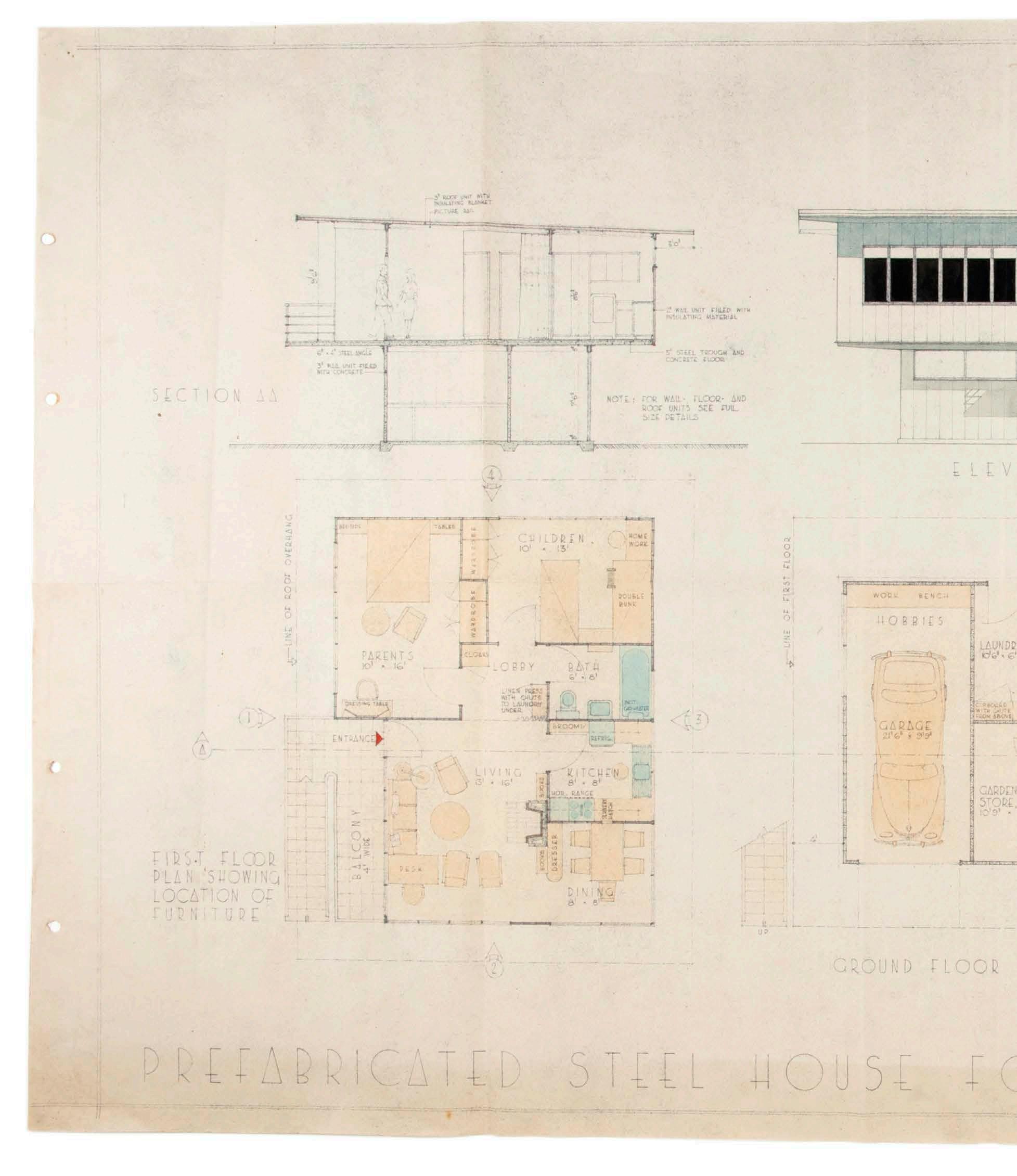

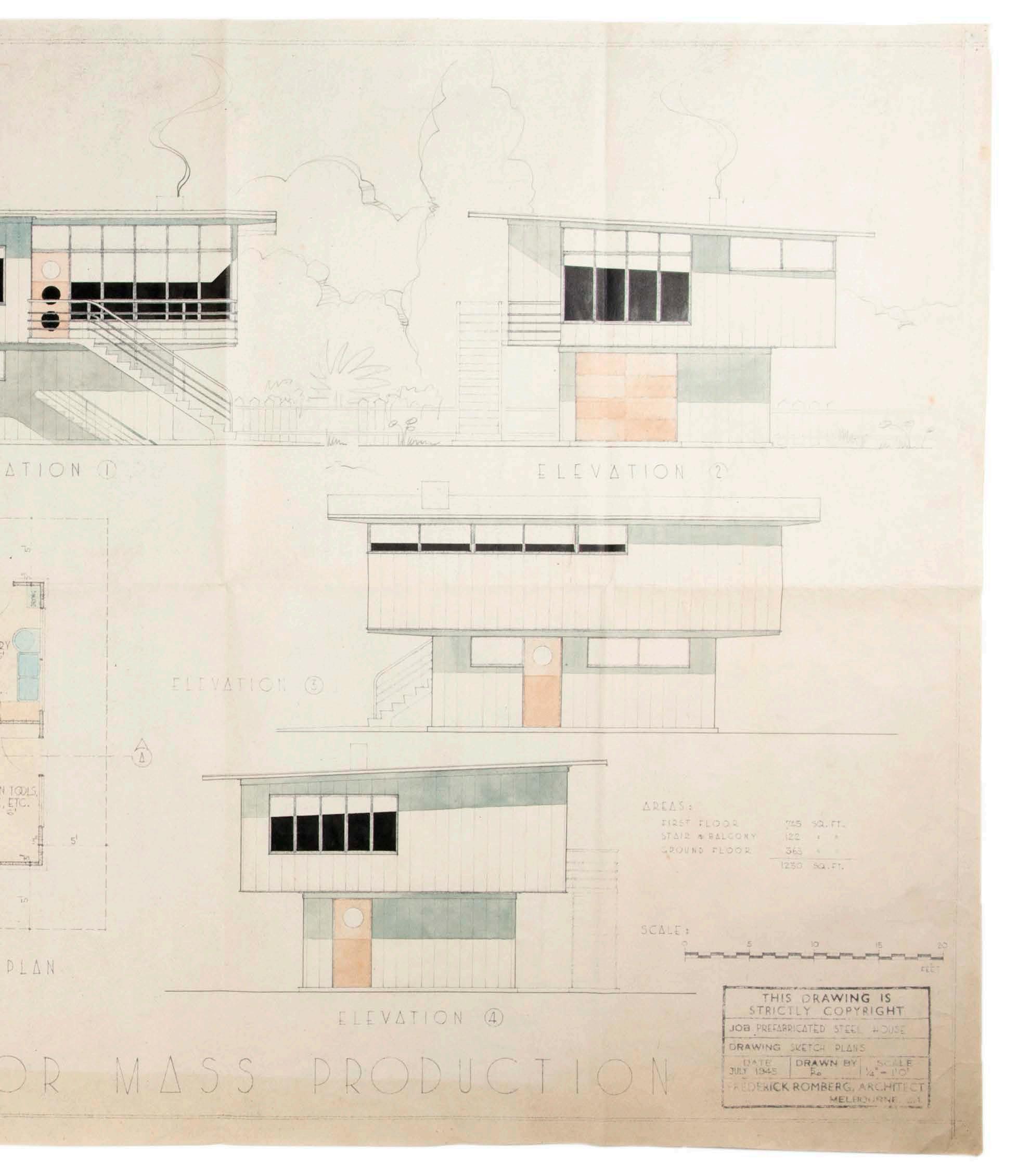

Frederick Romberg, Plans for Prefabricated Steel House for Mass Production, 1945, diazo-process print with watercolour, 55.3 x 98.0 cm, RMIT Design Archives: Robin Boyd and Frederick Romberg Collection

Pages 24–25

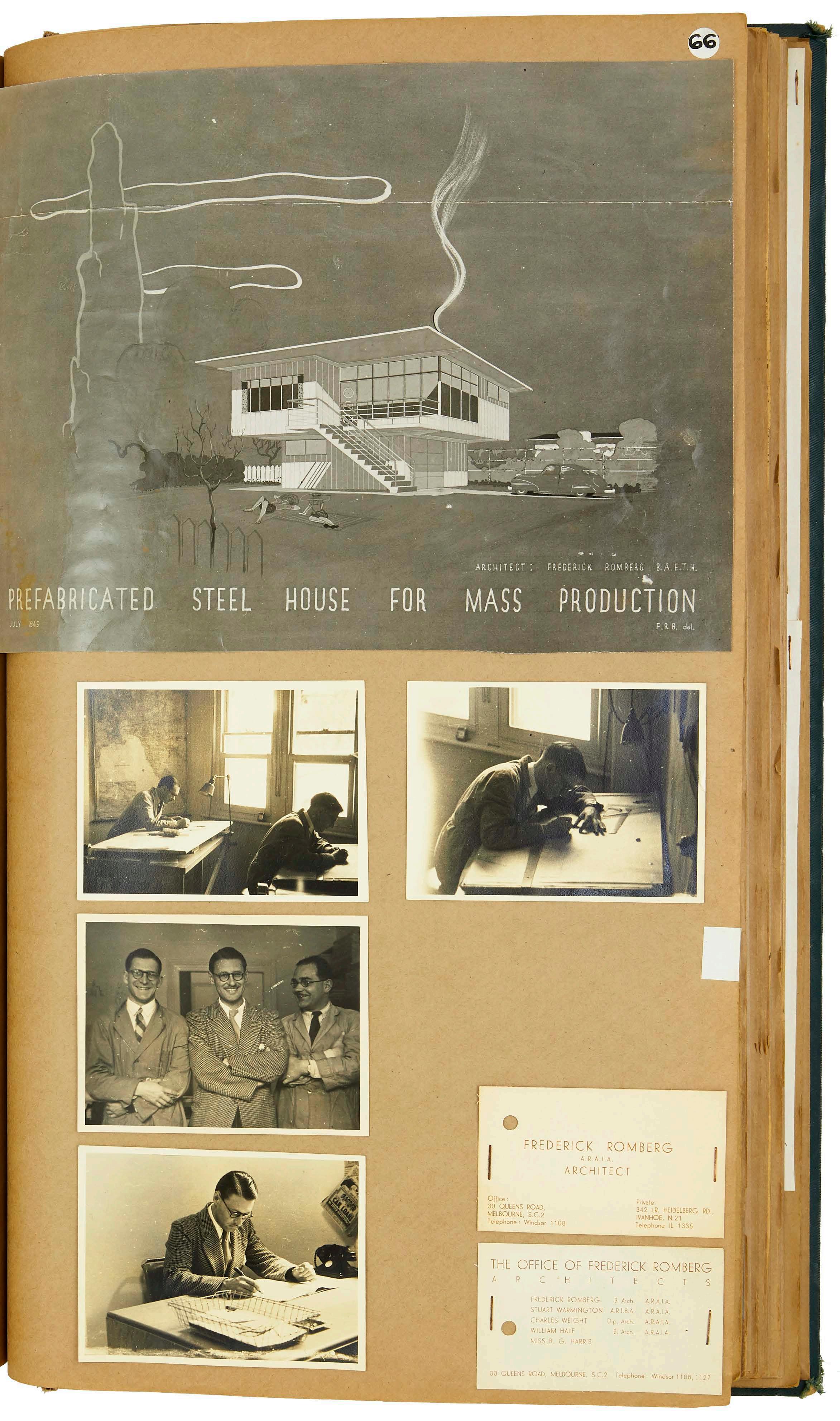

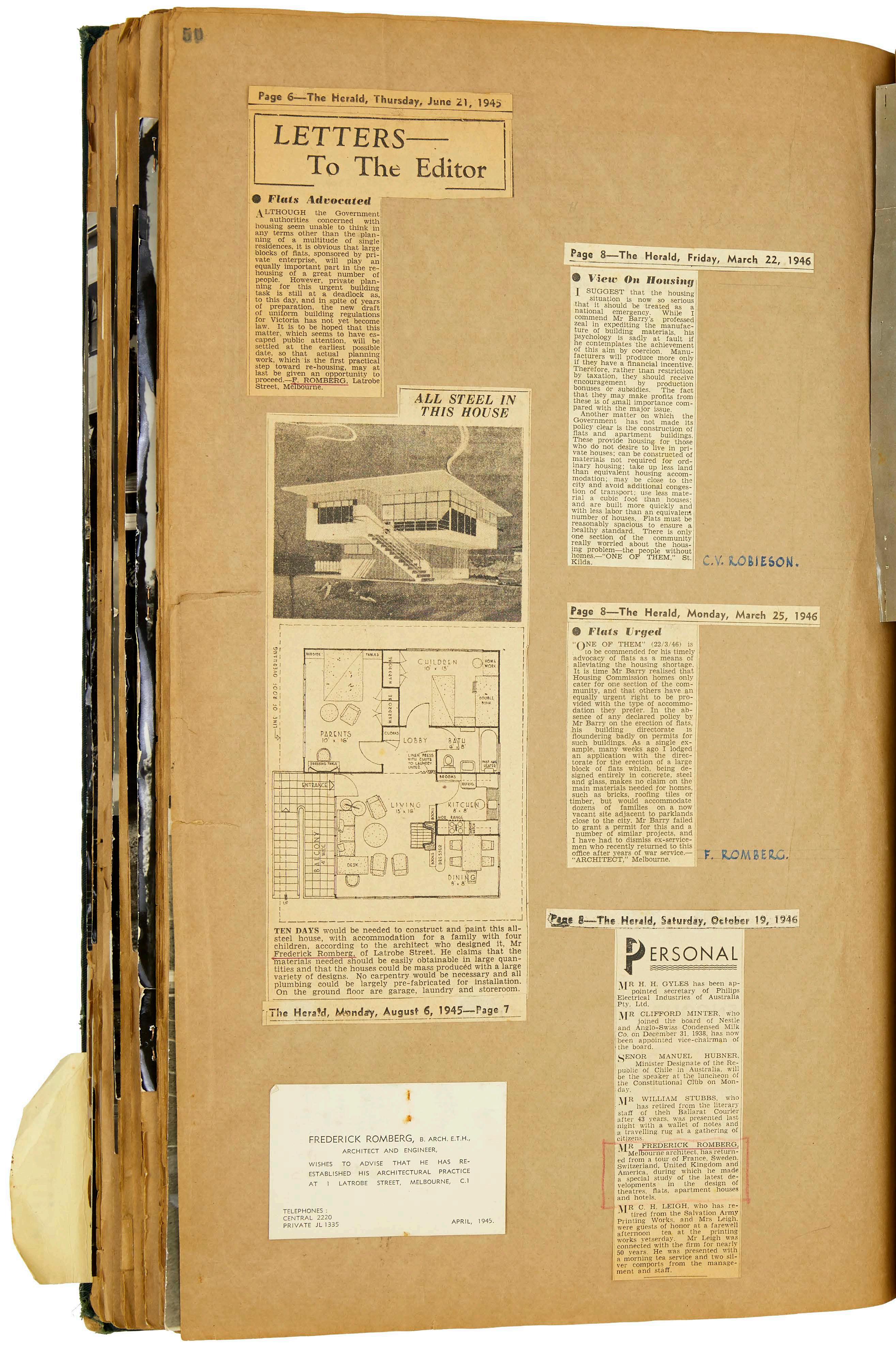

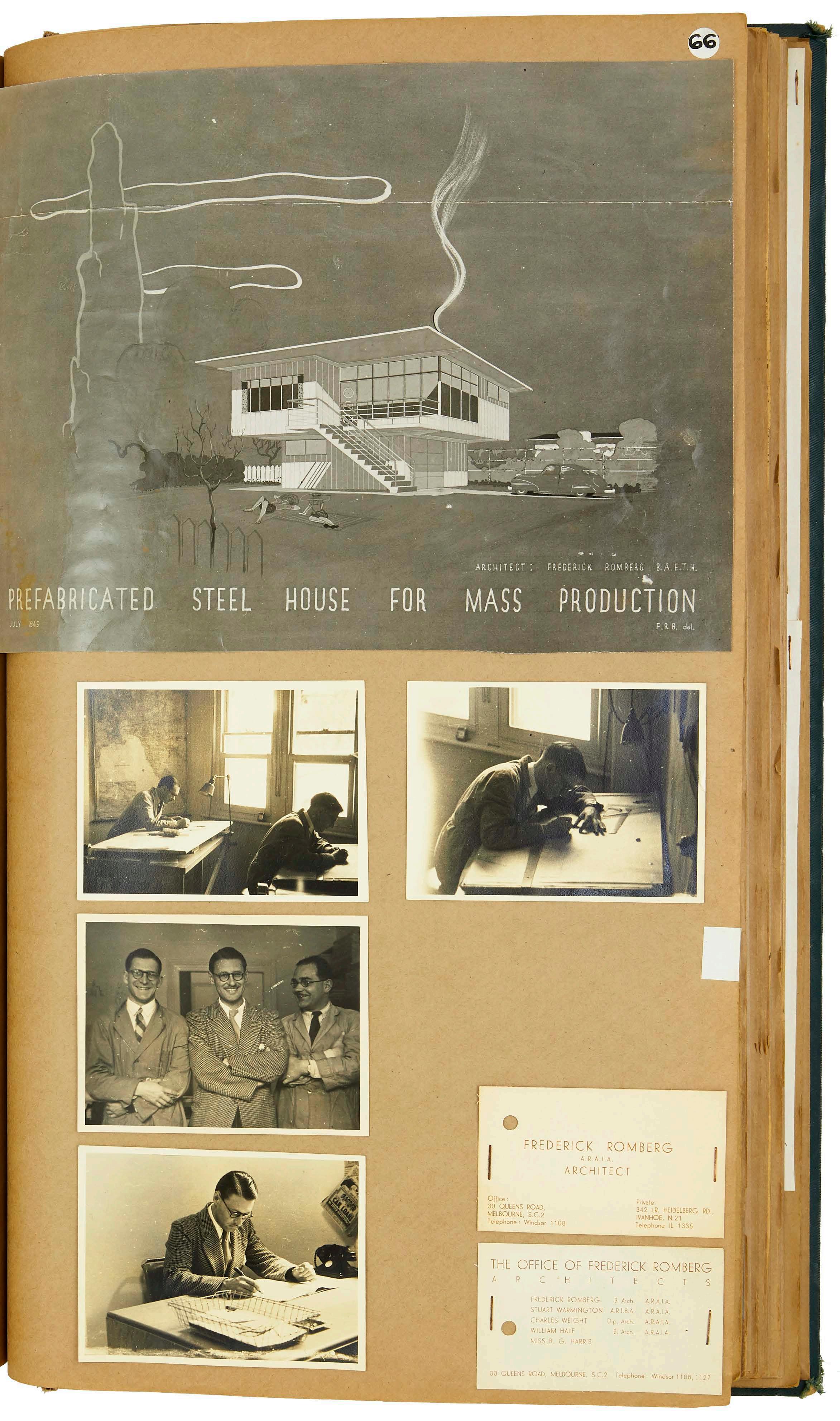

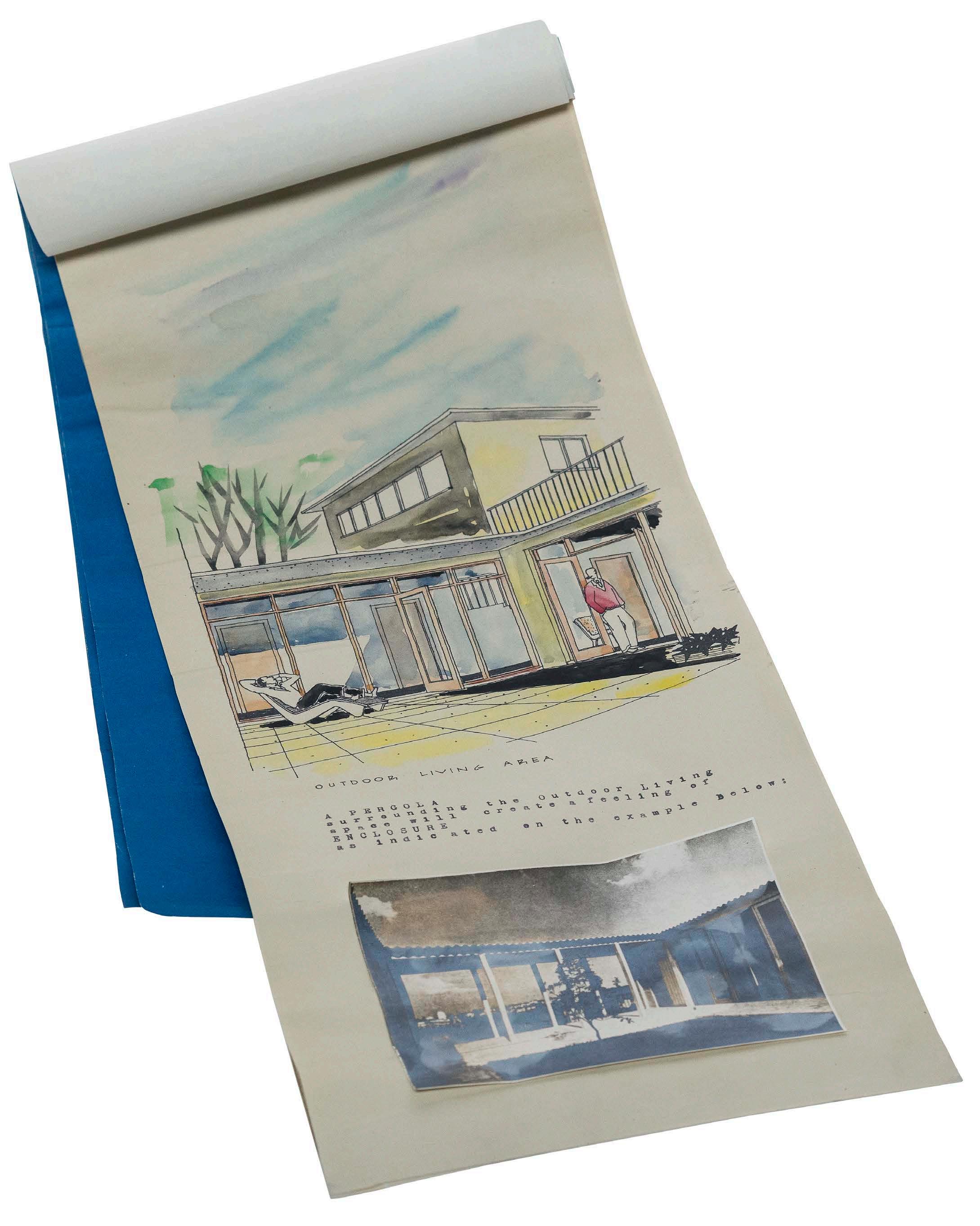

Frederick Romberg, Architectural scrapbook, 1938–1953, 1980–1992, photographic paper, ink, paper, 32.5 x 52.0 cm (closed), RMIT Design Archives: Robin Boyd and Frederick Romberg Collection

20 MELBOURNE MODERN POST-WAR ARCHITECTURE AND INTERIOR DESIGN

George Kral and Bernard Joyce (designers), Interior of the Australian Pavilion at the Fourth Tokyo International Trade Fair, 1961, photographer unknown, RMIT Design Archives: George Kral Collection

1 Harriet Edquist, ‘The Shaping of Design’, in Philip Goad, Ann Stephen, Andrew McNamara, Isabel Wünsche, Harriet Edquist, Bauhaus Diaspora and Beyond. Transforming Education Through Art, Design and Architecture, Carlton, Vic.: Miegunyah Press, 2019, 196–212.

2 Harriet Edquist, Frederick Romberg. The Architecture of Migration 1938–1975, Melbourne: RMIT University Press, 2000, 15–17.

3 Quotation from Frederick Romberg, ‘Before Gromboyd: An Architectural History’, typescript memoir, 1986, RMIT Design Archives, Romberg and Boyd Collection, 0020.2008, box 51.

4 Granville Wilson, Centenary History. Faculty of Environmental Design and Construction. Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, Melbourne: RMIT, 1987, 17.

5 The information from staff lists was kindly supplied by Catrina Sgro, RMIT University Archives, 11 April 2019. RMIT’s archival records for the early period are incomplete: often staff lists held in RMIT Archives, lists published in the annual Prospectuses and the evidence of staff and students themselves, do not align and one has to make a best guess. For example, while there is evidence in Romberg’s archive that he taught at WMC in 1945–46, his name does not appear in the RMIT Archive’s employment lists for those years.

6 Harriet Edquist, Ernest Fooks, Architect, Melbourne: School of Architecture & Design, RMIT, 2001; Catherine Townsend ‘Ernest Fooks in Vienna’, The House Talks Back, Melbourne: MSD Masters Exhibition, Melbourne School of Design, 2016, 4-11.

7 David Nicholls, ‘Fuchs, Heath and the HCV’, The House Talks Back, 16-17.

8 Australian Home Beautiful (AHB) articles include ‘Simplicity in furnishing a small house’, AHB, 1 May 1940, 25–7; ‘An Architect Visits Norway’, AHB, 1 July 1940, 24–6; ‘Function and Beauty should combine in Interior Design’, AHB, April 1942, 12–3, 33; ‘Form follows function. The fundamental principles of interior decoration’, AHB, June 1943, 19–21; ‘Yesterday and Tomorrow. Town Development Past and Future’, AHB, February 1944, 6–9 (part 1) and March 1944, 6–10 (part 3); and ‘The blight of a crowded city’, AHB, April 1946, 12–3.

9 Ernest Fooks, X-ray the City! The Density Diagram: Basis for Urban Planning, with a foreword by H C Coombs, Melbourne: Ruskin Press, 1946.

10 Nicholls, ‘Fuchs, Heath and the HCV’, 16.

11 Wilson, Centenary History, 41.

12 Harriet Edquist, ‘Vienna Abroad: Viennese interior design in Australia 1940–1949’, RMIT Design Archives Journal, vol. 9, no. 1, 2019, 26, 35. In Sterne’s obituary in Jargon, it was stated he studied ‘at the technical college in Giessen, Germany, and at the universities

of Prague and Vienna, where he graduated as an architect’ and that he ‘was also awarded a diploma in Interior Design’; ‘Frederick F. Sterne’, Jargon: Melbourne Technical College Annual Magazine, 1951, 51.

13 Mary Jane Seymour and Frederick Sterne, ‘Joanna Plans Her Home’, Australian Home Beautiful, May 1946, 8–11; ‘Joanna Plans Her Home’, AHB, June 1946, 12–14; ‘Joanna Plans A Home: Furniture is designed for Dining Room and Hall’, AHB, July 1946, 27–30; ‘Joanna Plans A Home: Discussion on Furnishing a Bedroom in Modern Style’, AHB, August 1946, 27–30; ‘Joanna Reviews Her Plans’, AHB, November 1946, 20–22.

14 Edquist, ‘Vienna Abroad’, 4-35.

15 Melbourne Technical College, 1936 Prospectus, Melbourne: MTC, 1936, 16.

16 Melbourne Technical College 1947 Prospectus, Melbourne: MTC, 1947, 173.

17 Melbourne Technical College 1949 Prospectus, Melbourne: MTC, 1949, 155.

18 This information was kindly supplied by Catrina Sgro, RMIT University Archives, 11 April 2019.

19 Fritz Rosenbaum’s name appears in the Part Time Instructors Record Book for 1949 teaching evening class in Interior Design.

20 Wilson, Centenary History, 25. An open piano with sheet music is depicted in the photograph of Sterne’s South Yarra flat published in Australian Home Beautiful, May 1946, 11.

21 ‘Frederick F. Sterne’, Jargon: Melbourne Technical College Annual Magazine, 1951, 51.

22 Wilson, Centenary History, 25.

23 Harriet Edquist, ‘George Kral (1929-1958): Interior designer, graphic designer’, RMIT Design Archives Journal, vol. 3, no. 2, 2013, 12–23 and Harriet Edquist, ‘George Kral and the Gallery A Design Group’, in Goad et al., Bauhaus Diaspora, op. cit., 201–2.

24 ‘Three coffee lounges’, Architecture and Arts, no. 52, December 1957, 43.

25 The chronology of the Gallery A Design Group has been extrapolated from the dated drawings of the Gallery A Design Group in the RMIT Design Archives.

26 This information was kindly supplied by Catrina Sgro, RMIT University Archives, 11 April 2019 and sourced from a letter of application for Lecturer in Interior Design, Department of Architecture and Building 21/07/1961), RMIT Archives Collection Series 1999/057/210 - Personal Files (terminations – pre1990 inclusive).

MELBOURNE MODERN 21

ENDNOTES

22 MELBOURNE MODERN

ARCHITECTURE AND INTERIOR DESIGN

POST-WAR

MELBOURNE MODERN 23

24 MELBOURNE MODERN

MELBOURNE MODERN 25

POST-WAR ARCHITECTURE AND INTERIOR DESIGN

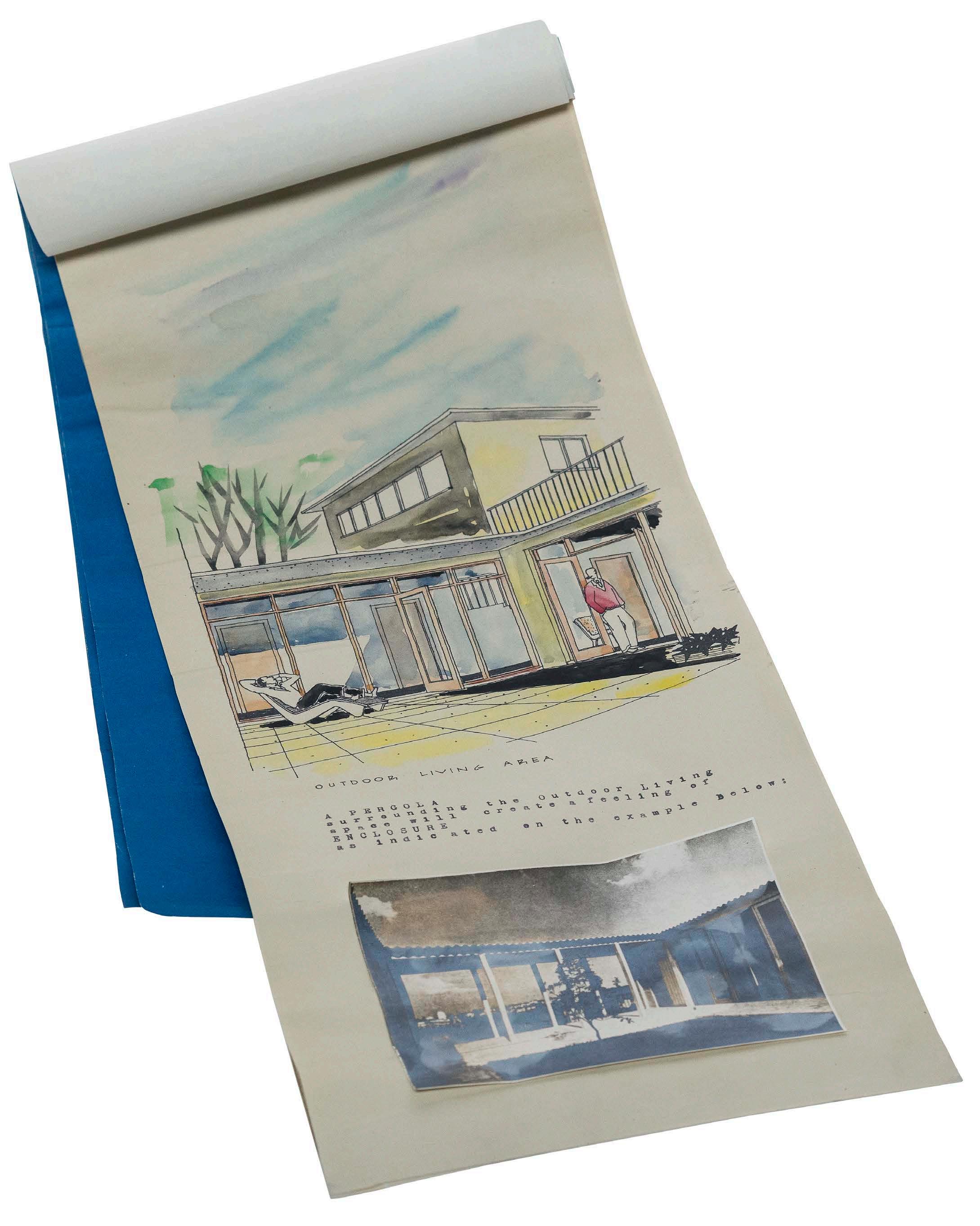

Ernest Fooks, Analysis Sketch Plans of Proposed Residence in Cantala Ave Caulfield, 1951, diazotypes, photographs, typescript, stapled in covers, 51.0 x 22.0 cm, RMIT Design Archives: Ernest Fooks Collection

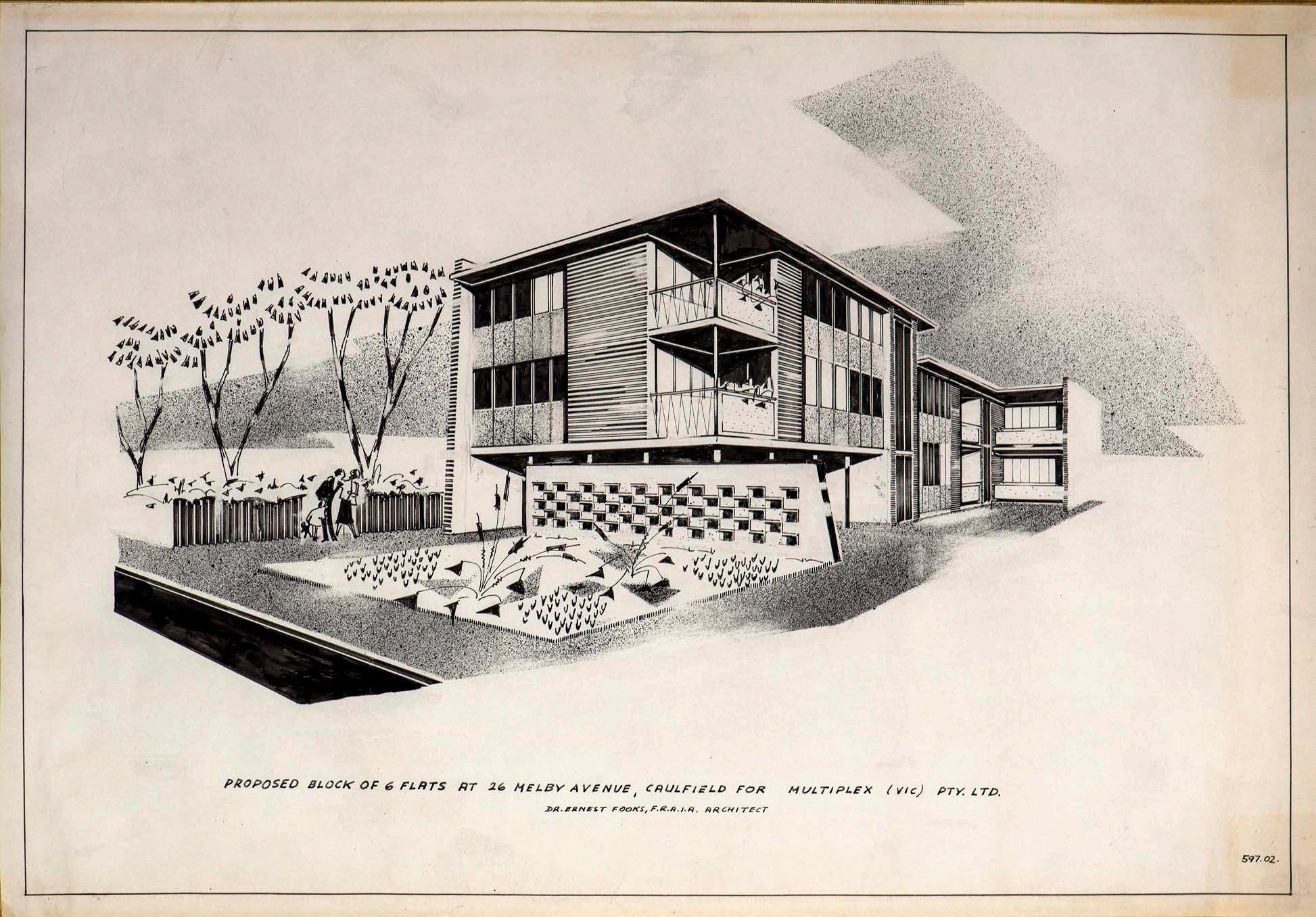

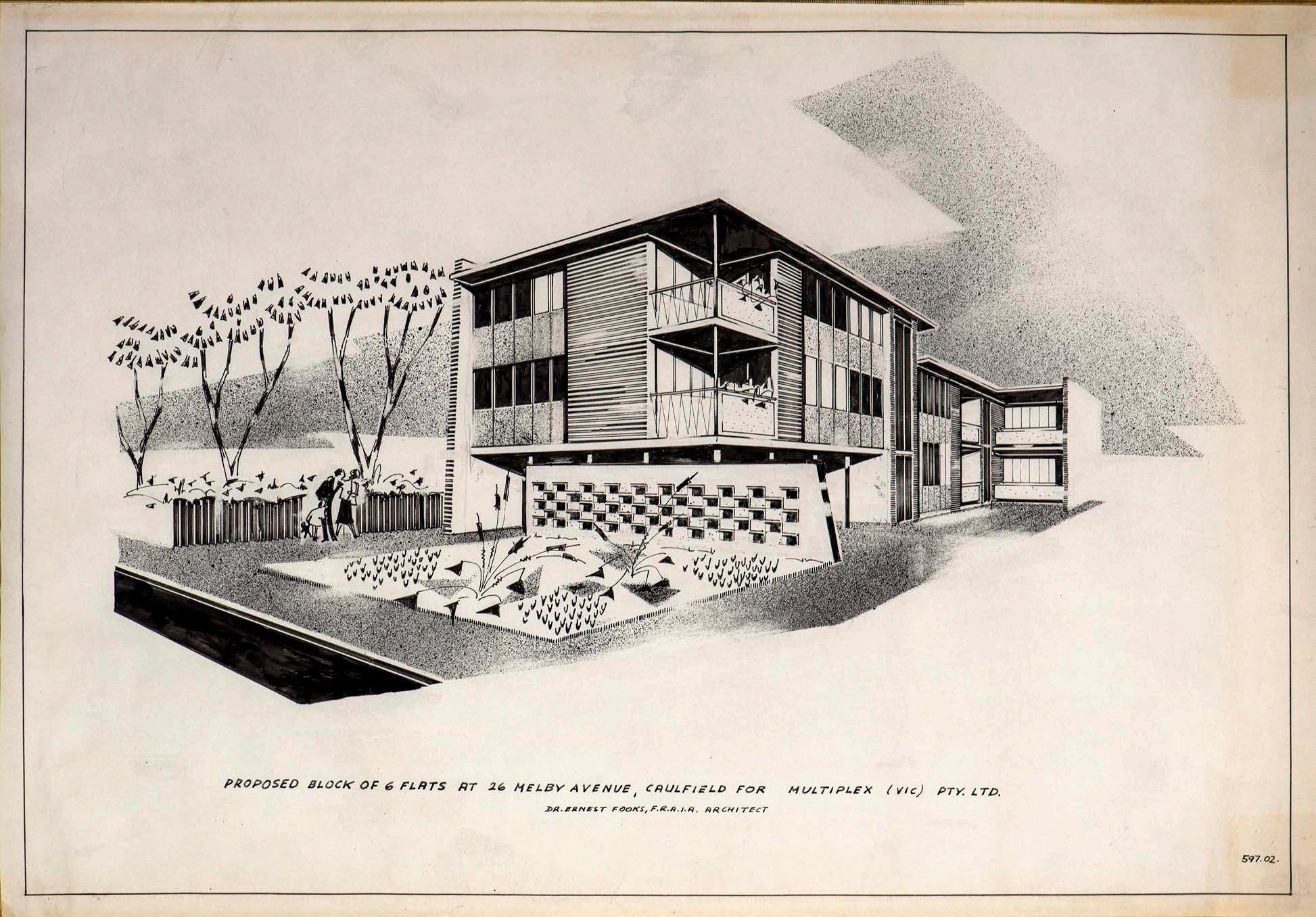

Opposite Top

Ernest Fooks, Perspective for Proposed Block of 6 Flats at 26 Melby Avenue, Caulfield for Multiplex (Vic.) Pty Ltd, 1960, pencil, pen, ink on paper, image: 46.5 x 67.5 cm; sheet: 50.5 x 71.7 cm, RMIT Design Archives: Ernest Fooks Collection

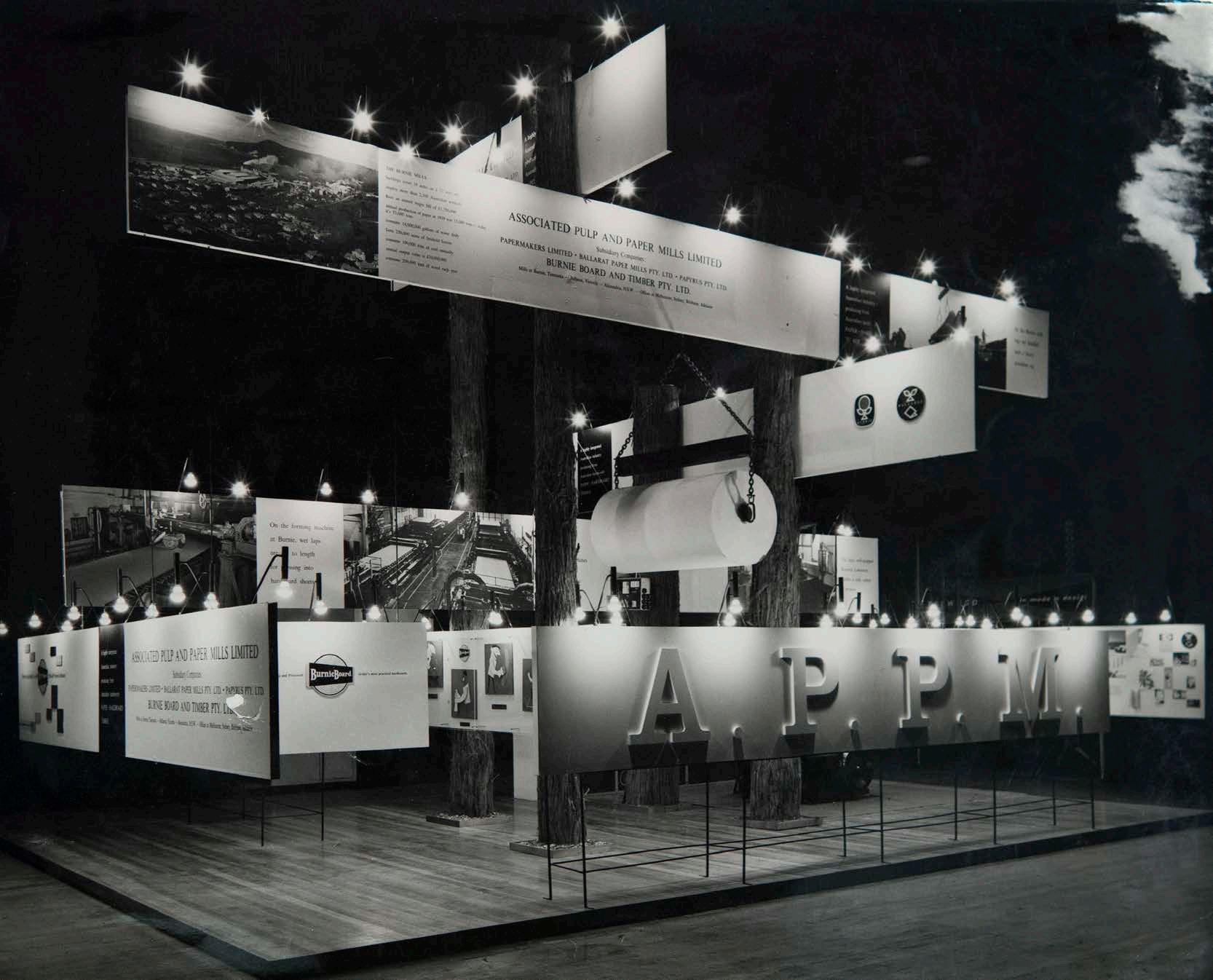

Opposite Bottom

George Kral, Associated Pulp and Paper Mills (APPM) Exhibit, 1958, photographer: Wolfgang Sievers, RMIT Design Archives: George Kral Collection

26 MELBOURNE MODERN

MELBOURNE MODERN 27

Above George Kral for the Gallery

A Design Group, Corporate design proposal for Allan’s World of Music, 1971, ink, cardboard, letterpress printing, plastic comb binding, clear plastic covers, 39.3 x 35.3 cm (closed), RMIT Design Archives: George Kral Collection

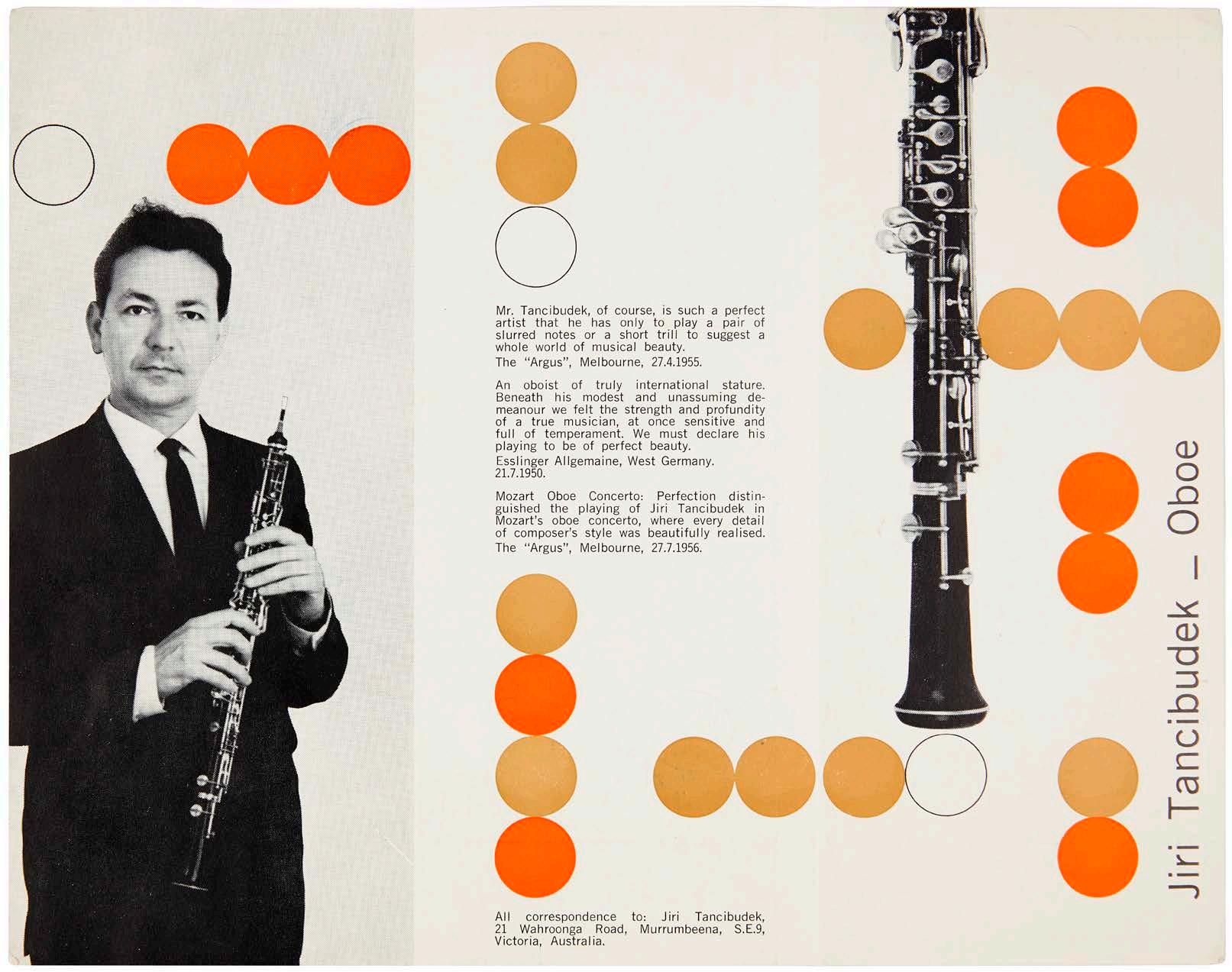

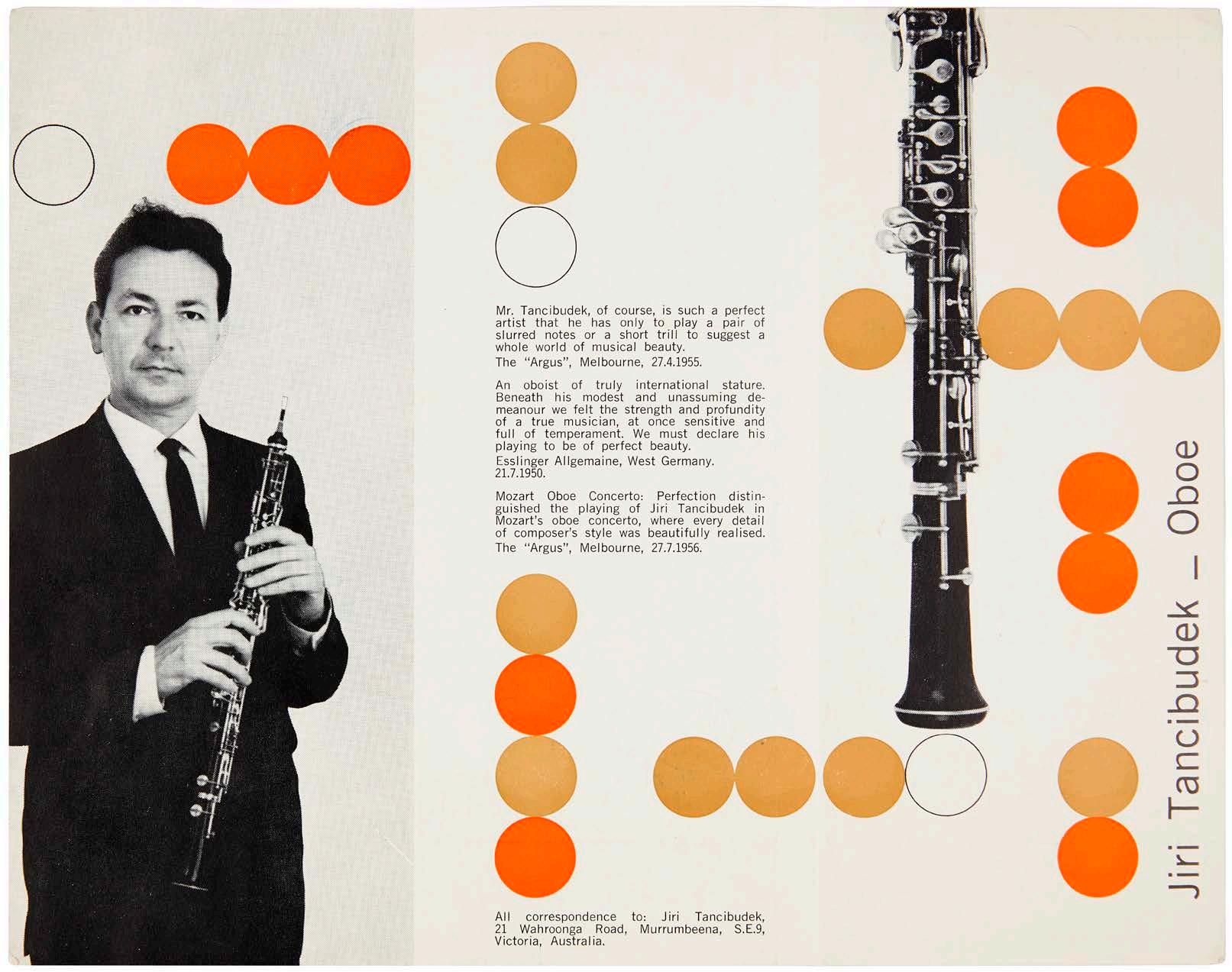

Left

George Kral, Jiri Tancibudek - Oboe, c. 1962, double sided colour printed brochure, 22.5 x 28.5 cm, RMIT Design Archives: George Kral Collection

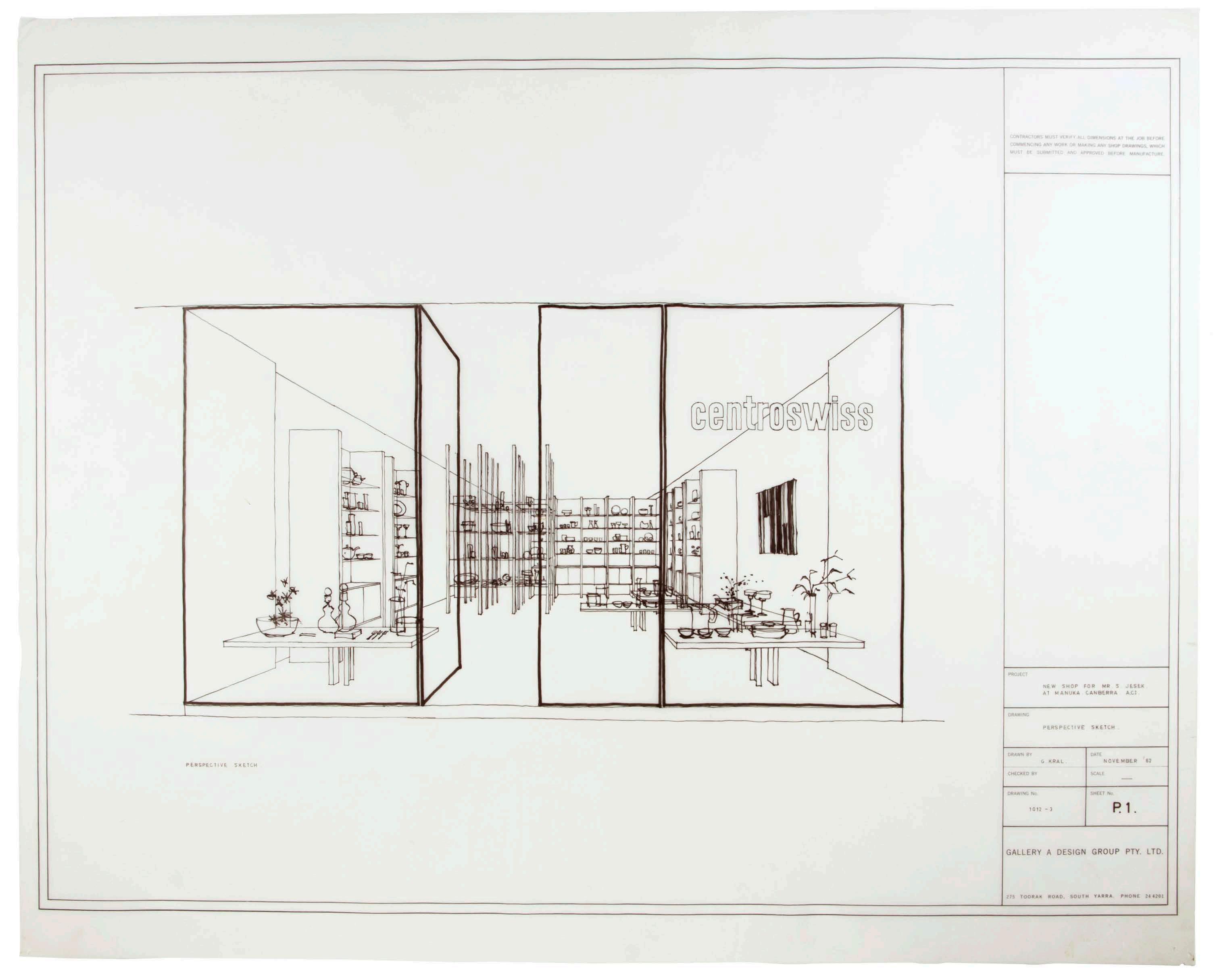

Opposite George Kral for the Gallery

A Design Group, New shop for Mr. S. Jesek at Manuka, Canberra, ACT (perspective sketch of Centroswiss homewares), 1962, ink, pencil, acetate, image: 55.0 x 73.5 cm; sheet: 60.7 x 75.0 cm, RMIT Design Archives: George Kral Collection

28 MELBOURNE MODERN POST-WAR ARCHITECTURE AND INTERIOR DESIGN

MELBOURNE MODERN 29

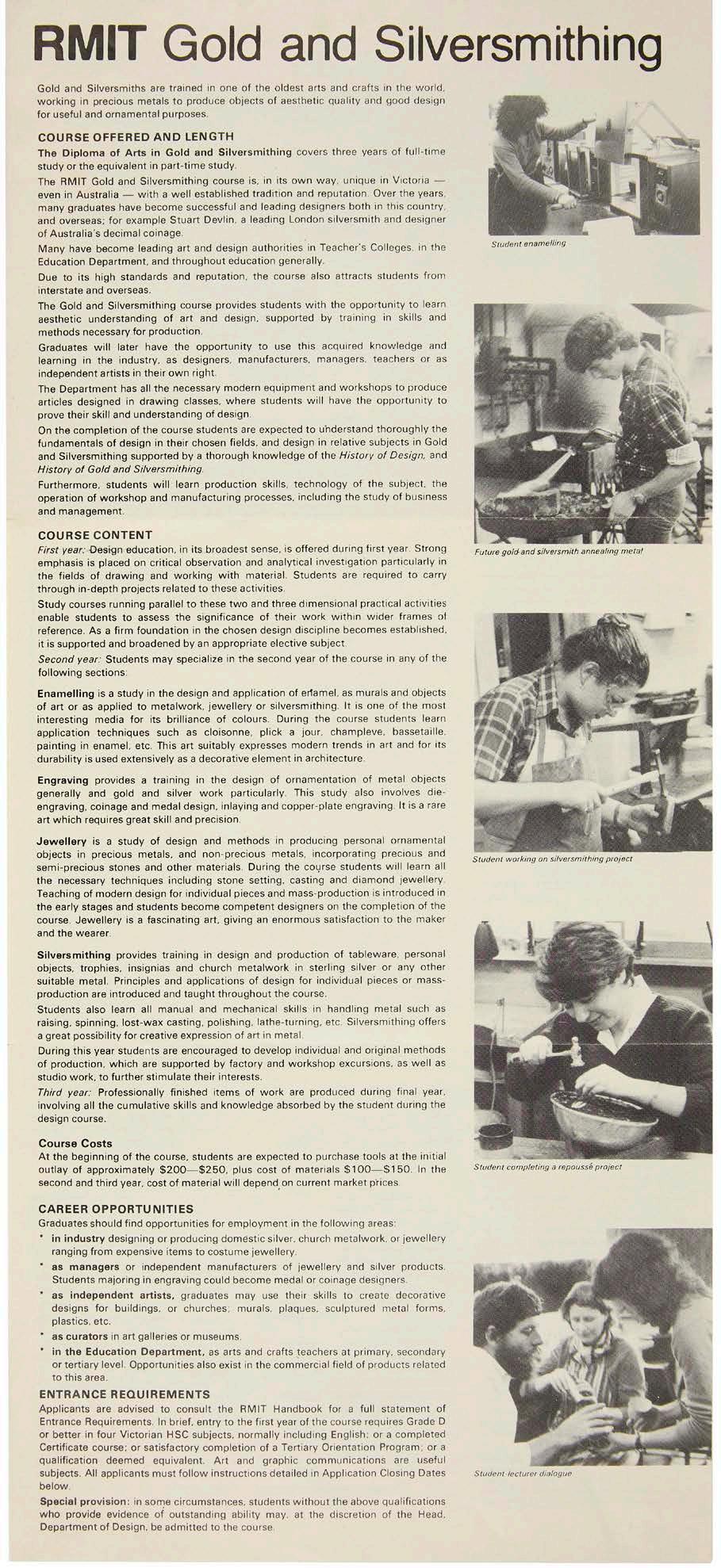

victor vodicka AND THE POST-WAR TRANSFOR MATION OF GOLD AND SILVERSMITHING HARRIET EDQUIST 2

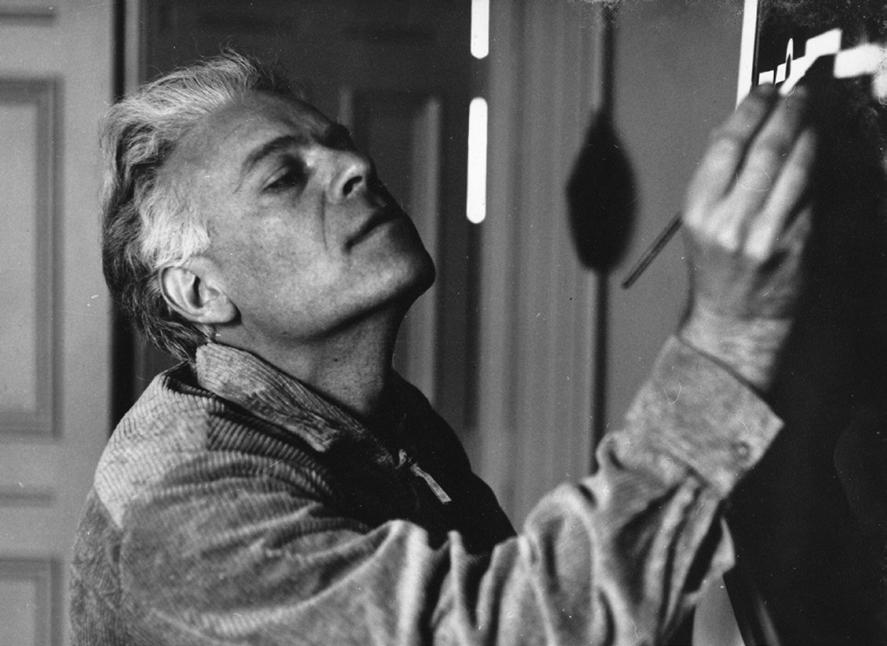

Opposite Robert Baines as a student at work on a silver brooch, 1970, Max Williams Photography Studio, RMIT Design Archives: Victor Vodicka Collection

One of Greenhalgh’s first appointments was Vaclav (Victor) Vodicka, a Czech goldsmith who had migrated to Australia in 1950 after the Communist takeover in Czechoslovakia. He joined RMTC in 1955 and over the succeeding years transformed gold and silversmithing into the leading course of its kind in Australia.

According to Vodicka, gold and silversmithing at RMIT went back as far as 1927 ‘when the art-metal certificate was established on a part-time basis’.1 In 1930 when Englishborn artist T.F. Levick was head of the Department of Art and Applied Art, a subject called ‘decorative metalwork’ was taught by E.G. Cousins. By 1936 Harold Brown, trained at Ballarat School of Mines, had become head of the Department and the newly named ‘art metalwork’ was taught by N.H. Ferguson. During the war the record appears incomplete, but enamelling was introduced in 1940 and four years later ‘art metalwork’ was still on the syllabus. It remained there, taught by silversmith Lawrence R. Ferguson until 1953. Ferguson taught ‘full-time students and a number of part-time students (hobbyists) who had been enrolled to boost gold and silversmithing numbers and justify its existence’.2 In 1951 one of these was sculptor Inge King, who attended evening class and learnt silversmithing and gem setting; her work, exhibited from 1951, showed ‘Celtic, Assyrian and Aztec influences’.3 In 1952 the first four Diplomates from Ferguson’s course graduated, after which Ferguson left to study in England.

The change came in 1954. Alfred Simm, who had joined the College the previous year, replaced Ferguson and the course was rebadged ‘gold and silversmithing’. Simm was an English jeweller who had come to Australia with his family in 1953.4 According to The Herald, who quickly profiled his work at the College, he was a Fellow of the Royal Society of the Arts (FRSA) and had obtained the National Diploma of Design (NDD).5 The NDD was introduced in Britain in 1946, when the Ministry of Education reorganized British art and design education. Under this system students took a Ministry’s Intermediate Certificate in Art and Crafts followed by the NDD.6 The NDD was one of the pedagogical models later referenced by the RMIT School of Art, which generally looked to England for clues about educational reform in art

and design. The 1955 prospectus indicates that Simm was still in gold and silversmithing, though in February of that year he returned to England.

Vodicka was appointed to the position in August 1955. What the students did between February and August is anyone’s guess; possibly Vodicka was already teaching and was appointed to fill the vacancy created by Simm.

The first visual evidence of silverwork produced by College students is a slide dated 1955 in Vodicka’s archive.7 It shows a silver cylindrical vessel and cover produced by a student who would have studied under Simm. Vodicka recalled the course at this time included two Diploma students, and this piece is presumably by one of them.8 What this evidence suggests is that Vodicka inherited a tiny but established course that had produced capable graduates, and he built from there. Simm seems to be important in this history, for it was he who was responsible for the transition out of the old-fashioned, Arts and Crafts inspired ‘art metalwork’ to the more professionally focused ‘gold and silversmithing’. And here the model was another English institution: the Royal College of Art (RCA), which had upgraded its course structure and suite of awards in 1948-49 to include gold and silversmithing.9

Students who graduated in 1956 would have had both Simm and Vodicka as teachers and their work, recorded in slide format among Vodicka’s papers, included a candelabra, chalice, mug, and a drinks set comprising a silver jug and beakers on a tray. Vodicka’s first Diploma students graduated in 1957; their pieces included a coffee pot, teapot and mug in classically inspired modernist form. Some slides are identified by the student’s name: G. Hildebrand, for example, designed and produced a rose bowl and a lidded box, the exterior surface of which was highlighted with a raised, abstract linear decoration.10

The most illustrious of Vodicka’s students in 1957 was Geelong-born Stuart Devlin. Devlin was a precocious talent who, by the age of 13, had hand-built a silver tea service. After school he trained as a teacher at Gordon Technical College and was therefore bonded to the Education Department. By 1956 he was in Melbourne teaching at Prahran Technical College and in 1957 also undertaking

MELBOURNE MODERN 31

In 1955 sculptor Victor Greenhalgh succeeded Harold Brown as head of the Department of Applied Art at what was then RMTC.

MELBOURNE MODERN 32

AND SILVERSMITHING

POST-WAR GOLD

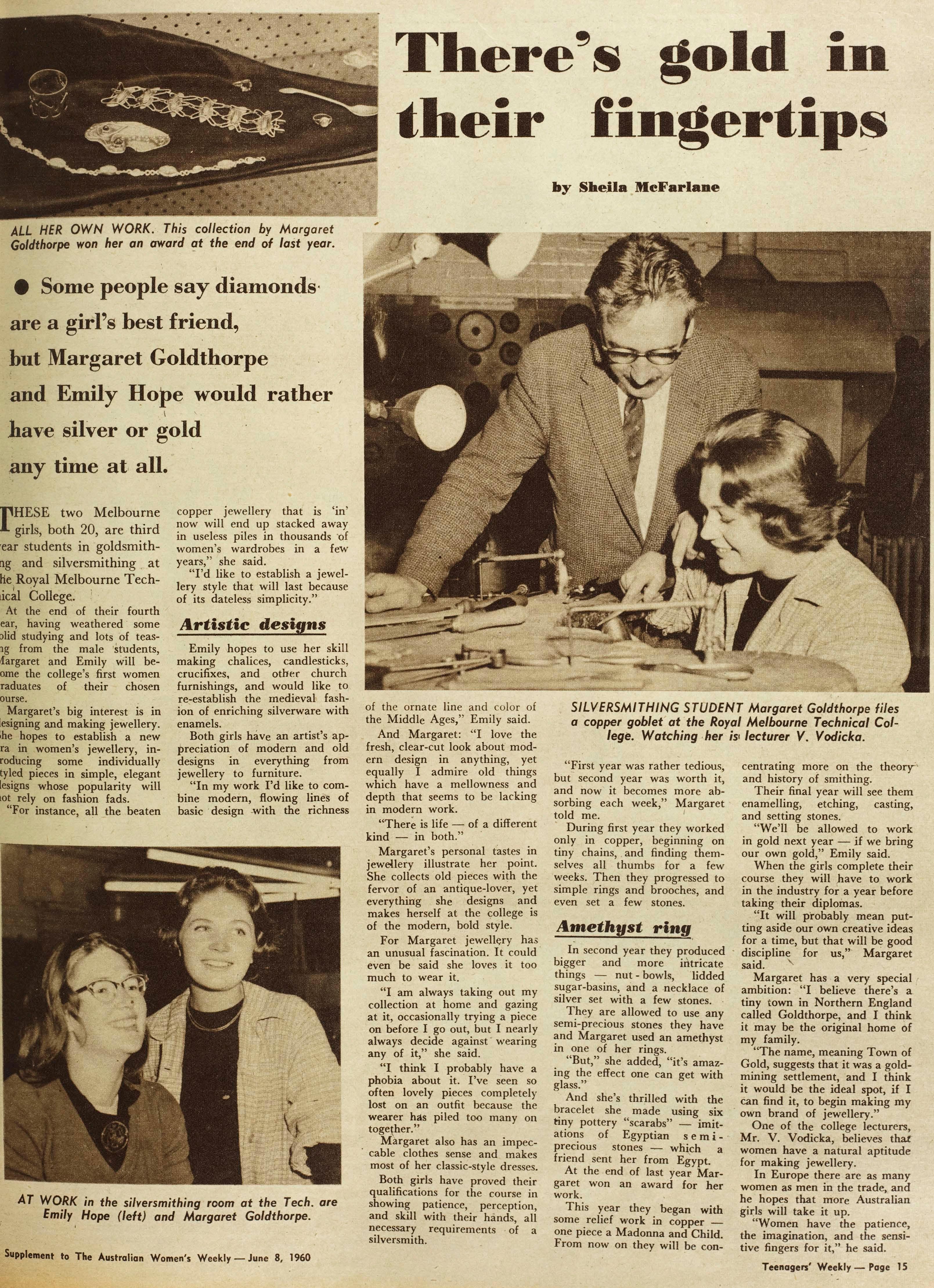

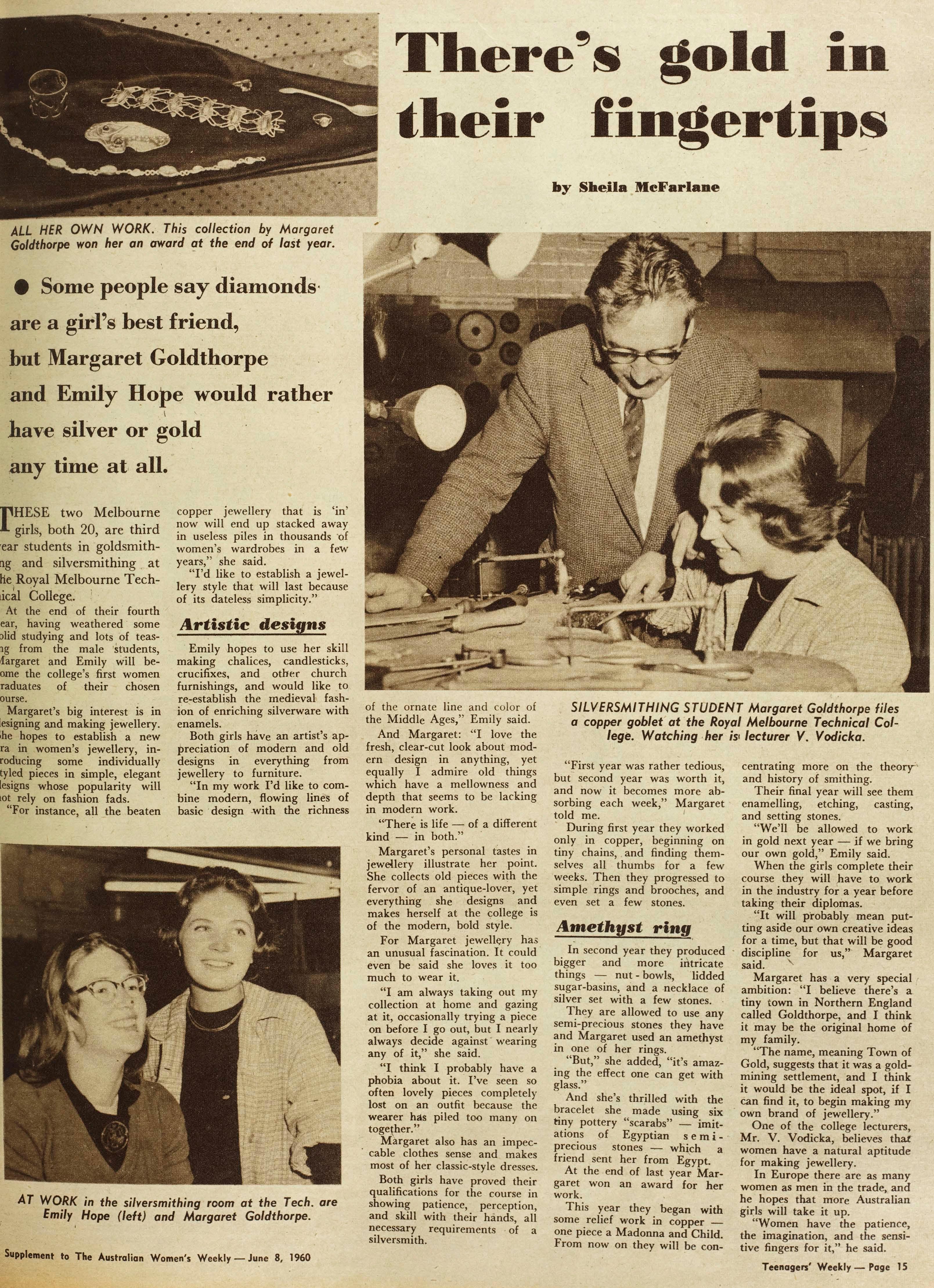

Opposite Victor Vodicka with Emily Hope and Margaret Goldthorpe, in Sheila McFarlane, ‘There’s gold in their fingertips’, Australian Women’s Weekly, 8 June 1960, Teenagers’ Weekly supplement, p. 15.

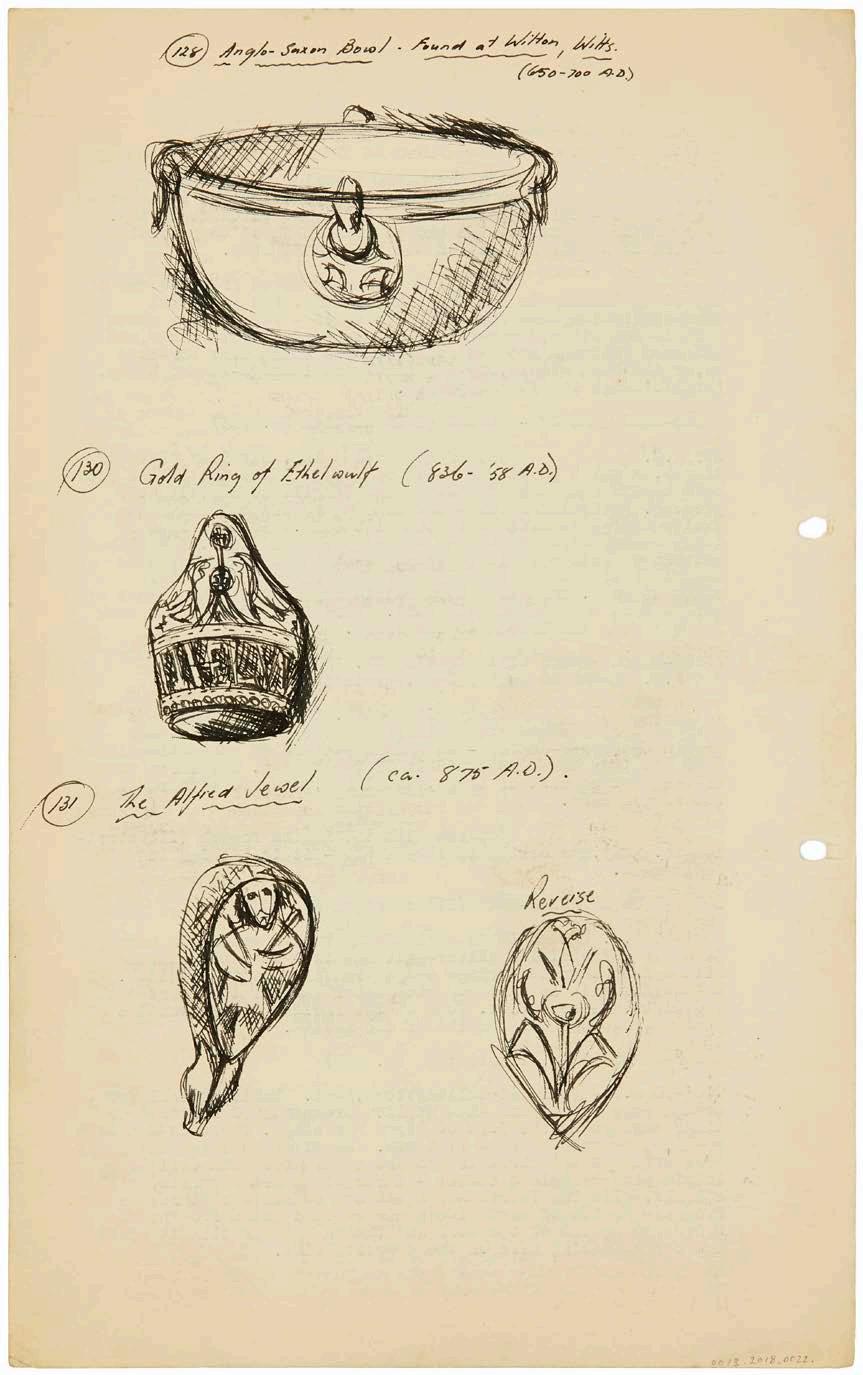

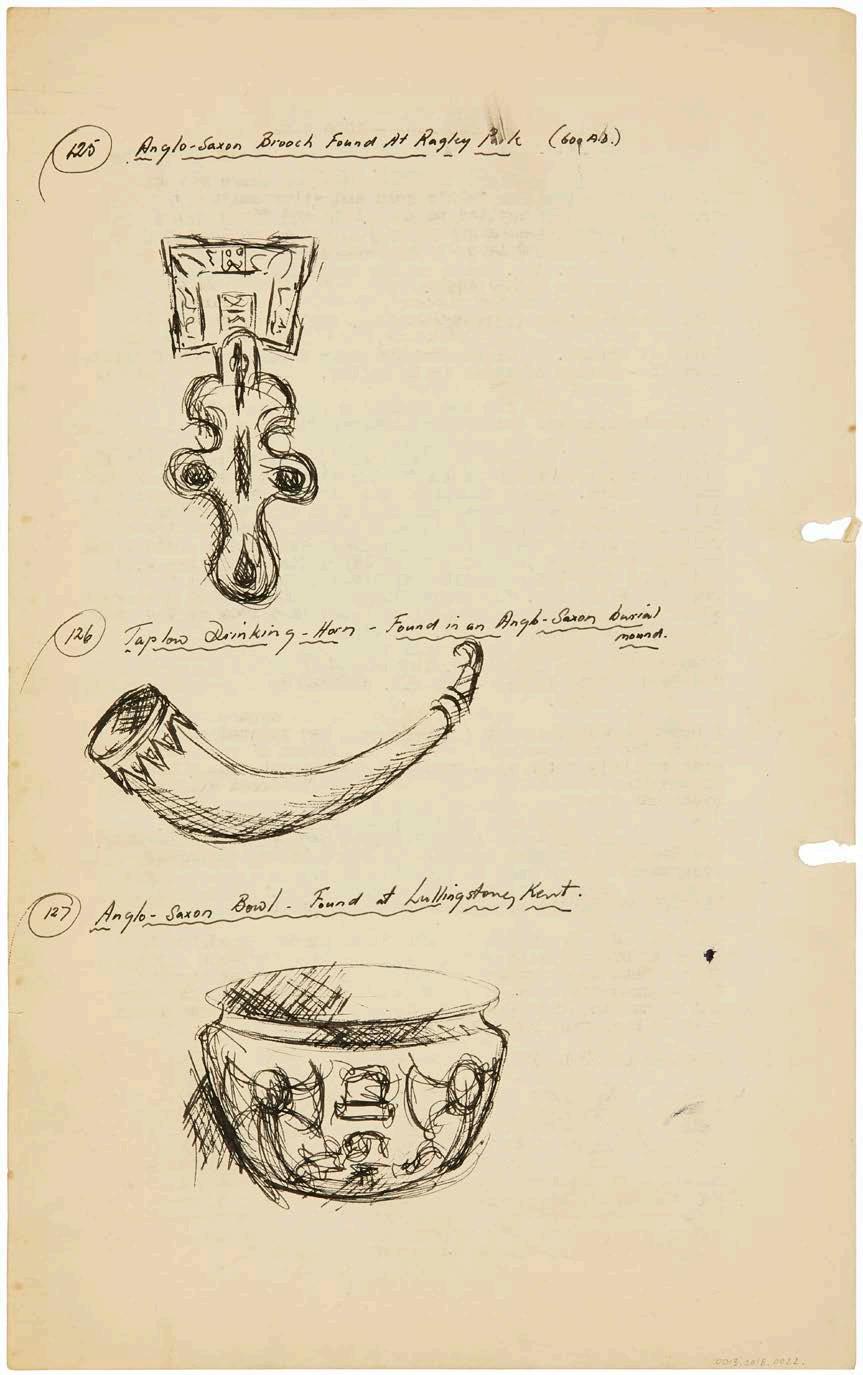

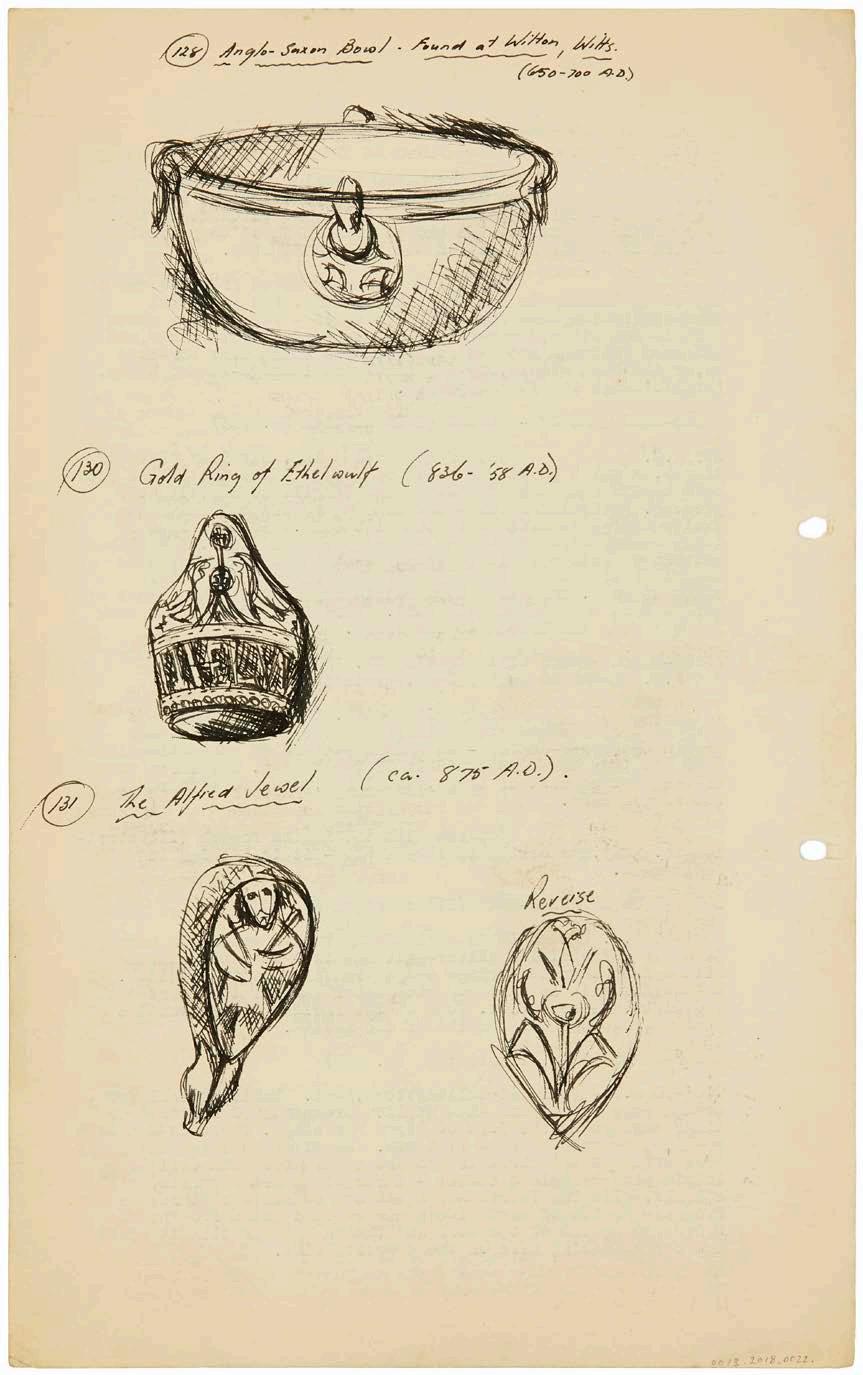

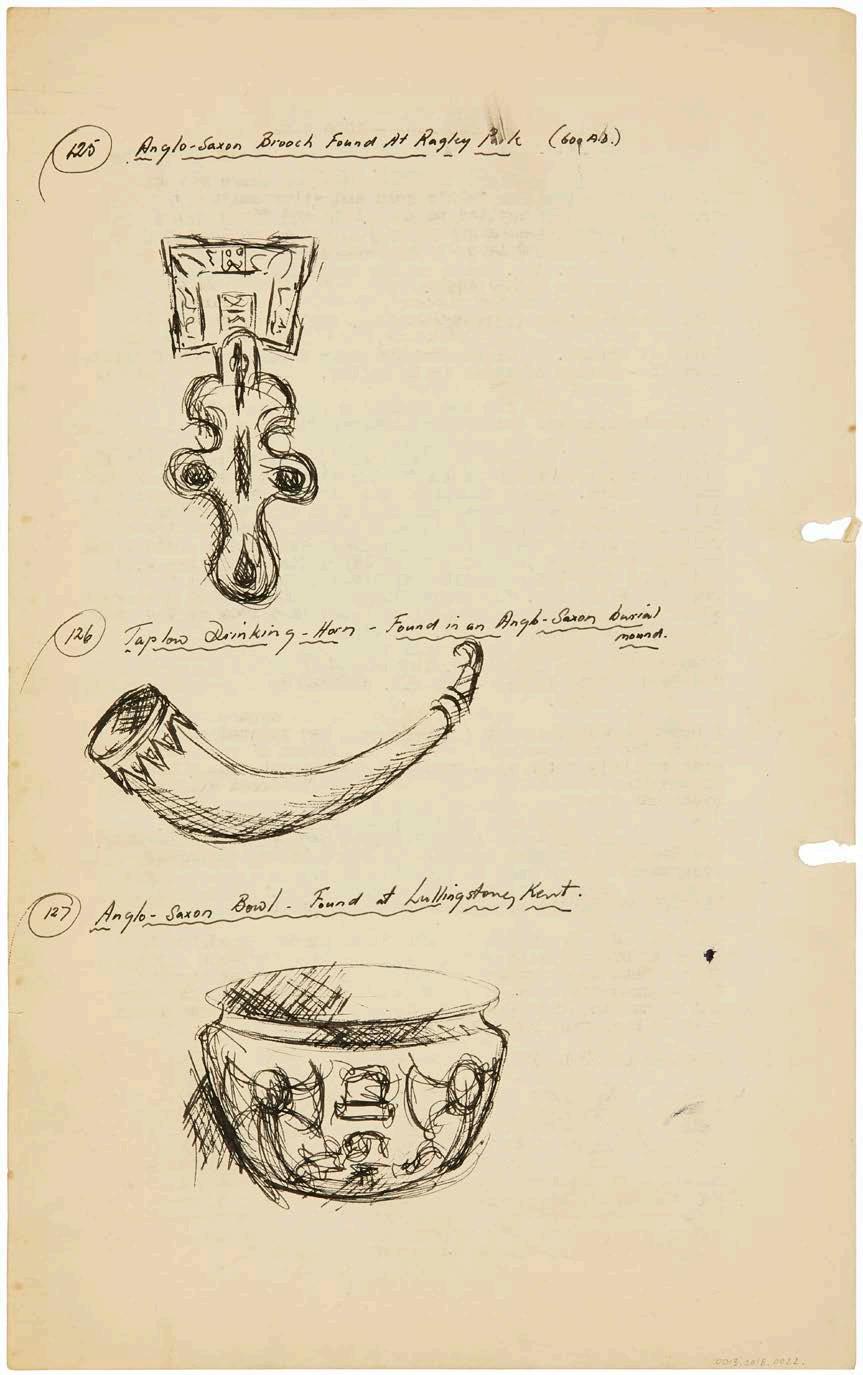

Left Victor Vodicka, Anglo-Saxon brooch found at Ragley Park 600 AD and Anglo-Saxon bowl found at Wilston, Wilts. 650-700 AD (leaves from a manuscript history of gold and silversmithing), pen and ink on paper, c. 1964, 33.5 x 20.5 cm each, RMIT Design Archives: Victor Vodicka collection.

Vodicka’s Diploma course, completing it in a year. There was very little that Vodicka could have taught him, as is clear when we compare his graduating piece – an angular gilding metal and Bakelite teapot which seems to anticipate the 1980s – with the standard fare of other students.11 After numerous awards and scholarships Devlin won the commission to design Australia’s first decimal currency in 1964 and thereafter became one of the most successful goldsmiths in Britain, where he spent the rest of his life. Vodicka kept a proud eye on Devlin’s career as the number of press cuttings in his archive attest.

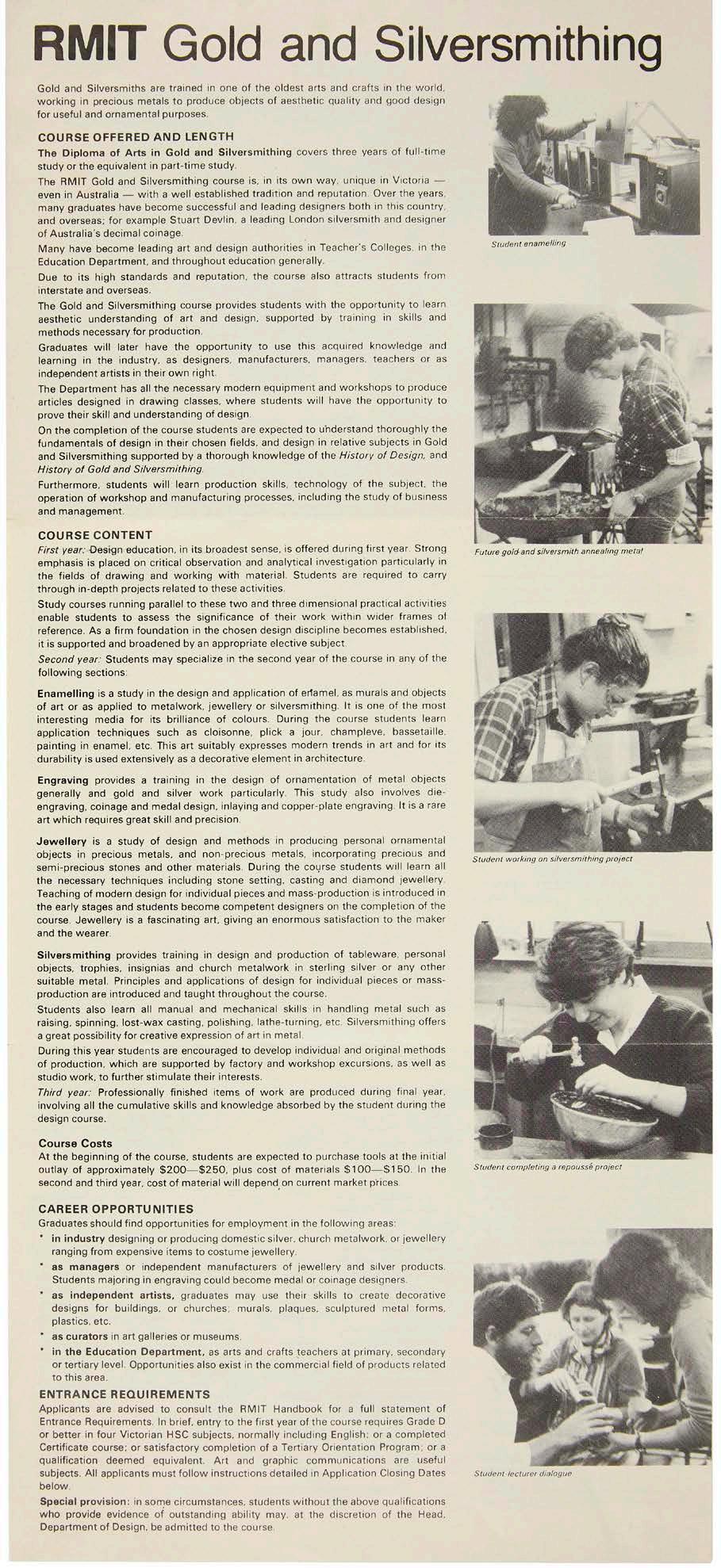

In 1958 Emily Hope and Margaret Goldthorpe became the first women to enroll full time into the course. As they were not attached to the Education Department Vodicka was encouraged to write a full-time curriculum.12 A battered piece of paper in his collection lists the projects the students could embark on in 1960, covering flatware, holloware, tableware, a ‘television lamp’ and jewellery pieces such a necklace, pendant, ring, bracelet and brooch. Goldthorpe specialised in jewellery and won an award for her work, and it may well be that her success prompted Vodicka to ask for a jeweller to join him on the staff. While Vodicka had included jewellery in the course he saw himself primarily as a silversmith, and so in 1960 he persuaded Greenhalgh to fund a part-time jeweller to teach the evening classes. Wolfram Wennrich, a highly accomplished goldsmith who had received his training in Hamburg after the war, took on this role becoming full time in 1963.13 Wennrich and his family had been sponsored by Melbourne jeweller Max Hurwitz to migrate to Australia in 1953.

From 1962 to 1964 Vodicka doubled the intake of students and concurrently reduced the numbers of parttimers. At the same time the ambition and standard of work produced by the students leaped. Throughout the 1960s Vodicka expanded the course with more specialised subjects: design in 1963 and history of gold and silversmithing in 1964. The Vodicka archive holds a folder containing an illustrated typescript of a history of goldsmithing and silversmithing which suggests he contemplated publishing a text book for students.14 In 1969 a subject ‘research in methods of production’ was introduced in third year. According to

MELBOURNE MODERN 33

34 MELBOURNE MODERN

Vodicka, this subject included a dissertation at the end of the year which ‘considerably improved the standard of the course and influenced the design generally’.15 These innovations parallel and were influenced by contemporary changes in international design education, particularly those in Britain which followed in the wake of the Coldstream Report of 1960.16 According to Kate Aspinall, the Coldstream Report marks ‘a graspable moment of displacement in the British art world. It represents a shift between an educational system based on disciplined studies of techniques and crafts to one based on conceptual thinking and design’.17 Among the report’s recommendations was mandatory history courses taught by qualified historians. Extracts from Coldstream were included in Victor Greenhalgh’s 1961 ‘The First Report of the Place of the School of Art, RMIT in the Structure of Art Education in Victoria’.18 Within this context Vodicka’s inclusion of ‘history of the subject’ in gold and silversmithing (which was in fact a fixture of all art and design courses) and his introduction of a specialised design subject and research thesis are pertinent, as is Greenhalgh’s appointment of art historian Margaret Garlick (now Margaret Plant) as senior lecturer in the History of Art in 1968 – the first such appointment in an Australian art school. Miloslav ‘Dismas’ Zika, who had arrived from Prague with his family in 1949, also taught history part-time.

The character of the art school was shaped by its common courses shared by all students; they undertook professional training in their chosen discipline but also studied across the spectrum of classes the school offered. So, for example, Robert Baines who commenced in 1968 recalls: …in Complementary Practice we had lecturers like Vincas Jomantas and Ernesto Murgo in sculpture, James Meldrum and Andrew Sibley in painting, Nornie Gude for life drawing and Dr. Zika for Art History. It was a broad Fine Art experience.19

Marian Hosking recounts similar memories. Her education at RMIT ‘was thorough in technical skill and with a broader fine art ethos’.20 Art history was taught by Garlick and Zika, the latter of whom ‘brought the decorative arts to the forefront, he had a theory that at certain times the plastic arts led and

challenged accepted practice. Studying a so-called lesser art, this was very empowering’.21

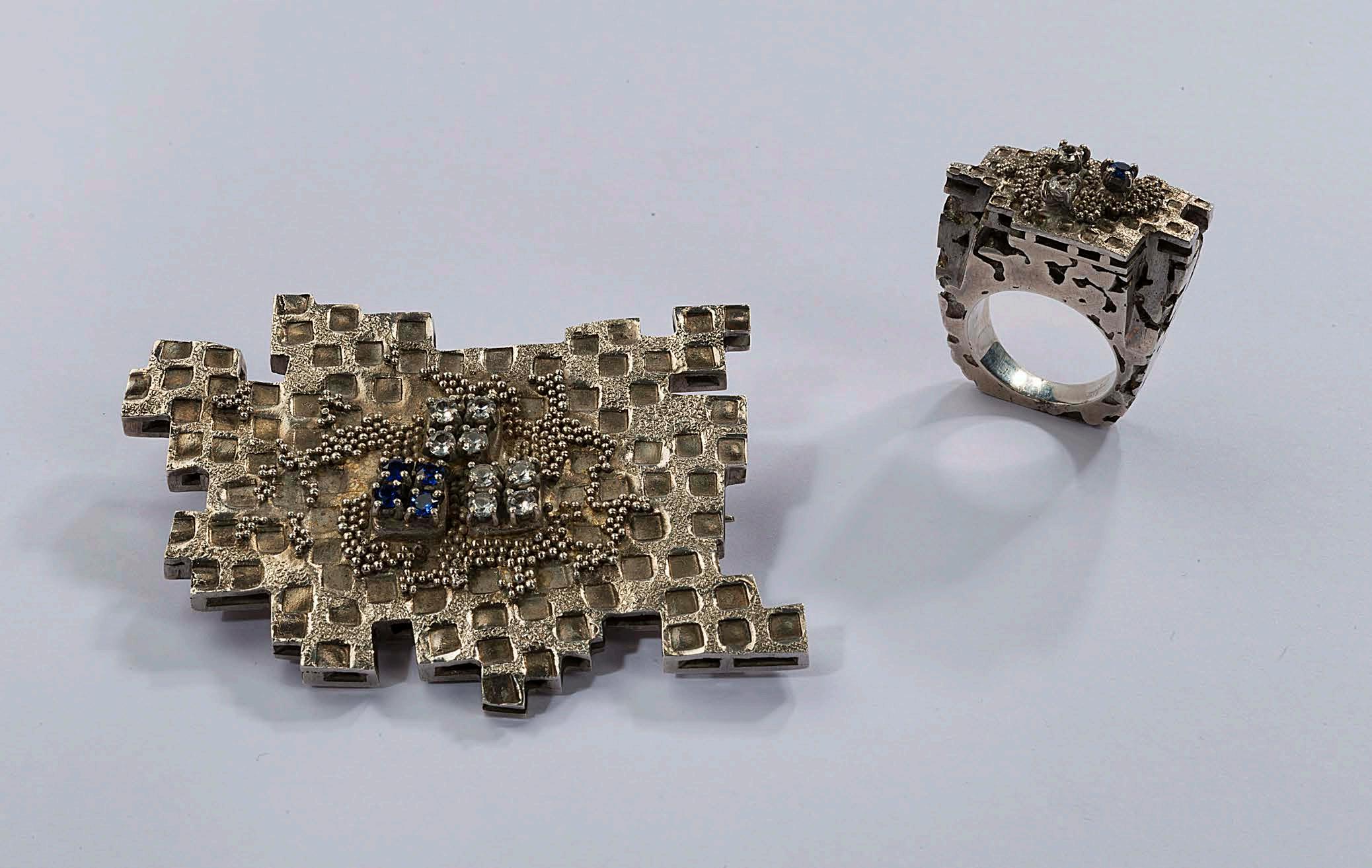

Like his RMIT colleagues Tate Adams in Printmaking and Gerard Herbst in Industrial Design, Vodicka kept his students in the public eye through articles in the press and through awards, competitions and exhibitions. Named awards were a feature of RMIT and were offered by gold and silversmithing in the 1960s if not earlier. In 1962/63 W.E. McMillan, a friend and admirer of Vodicka’s work at the College, instituted an acquisitive award for outstanding student work, and in 1966 Vodicka held a student competition to design a medal for the winner of the McMillan prize. The W.E. McMillan Collection inspired other acquisitive awards and together they represent today a unique record of almost 60 years of student work at RMIT. Students were also encouraged to enter the Made in Australia Awards. Two foolscap sheets in the Vodicka archive list student prize winners from 1965 and 1966 for named prizes with monetary awards, and about 40 entry forms for these competitions from the 1960s and 70s indicate the ambitious benchmarks set for the students.

Prizes supplied by industry included the M. Hurwitz annual award for jewellery; Dunklings award for silversmithing; K.G. Luke annual award for the best second year student in silversmithing; L. Puzsar annual award for the best second year student in jewellery and the L. Puzsar special award for jewellery. These were professional Melbourne gold and silversmiths in whose workshops talented students could find employment after graduation. Melbourne had a rich tradition of successful manufacturing jewellers, such as Dunklings, established in the 1880s, and it benefitted after the war from an influx of émigré craftspeople expert in traditional methods of hand crafting jewellery. Hurwitz for example had arrived in Melbourne in 1939 and established himself as a manufacturing jeweller and dyemaker in Crossley Lane. In his workshop could be found ‘craftsmen from Italy, Poland, Russia, Greece and Latvia as well as diamond-setters from France and Germany’, and he employed RMIT graduates such as Robert Baines.22

In 1967 Vodicka organized the first student exhibition in B8, the exhibition room in the Art Department’s Building 2.

MELBOURNE MODERN 35

It contained work made over the previous five years, including Robert Cranage’s Water Jug, 1962, Howard Tozer’s repousse Vessel, n.d., and Gregor Scarlett’s Teapot with wooden handle, 1967. Governor General Lord Casey and Lady Casey visited their exhibition during a brief stay in Melbourne, generating considerable publicity.23 In 1968 there was an exhibition at jewellers Paul Bram, which suggests that under Wennrich jewellery was surging ahead.

The development of gold and silversmithing at RMIT absorbed post-war influences from both Scandinavia and Germany. Vodicka and Wennrich were not immune to this, and their own work developed in parallel with their students. For example, Wennrich exhibited in Melbourne and Sydney together with his recent graduates Marian Hosking, Norman Creighton and Rex Keogh in 1974.24 Vodicka kept pace with contemporary silversmithing and maintained a small

practice undertaking commissions for the university and external clients such as the College of Nursing and Romberg’s Lutheran Holy Trinity church in Canberra.

Graduates from the Vodicka and Wennrich years included Raymond Stebbins, Australia’s first Professor of Gold and Silversmithing, Tozer, an expert enameller who led the teacher-training program at Melbourne State College; Creighton and Keogh, who were influential in the formation of the Meat Market Craft Centre in Melbourne in 1977; Baines, who has played a major role in Australian gold and silversmithing since his graduation in 1970; and Hosking, who, like Baines, is a ‘Living Treasure: Master of Australian Craft’. They have been followed by other significant practitioners such as Su san Cohn and Margaret West, each succeeding cohort of graduates building on the legacy of its first émigré teachers Vodicka and Wennrich.

36 MELBOURNE MODERN

Page 34

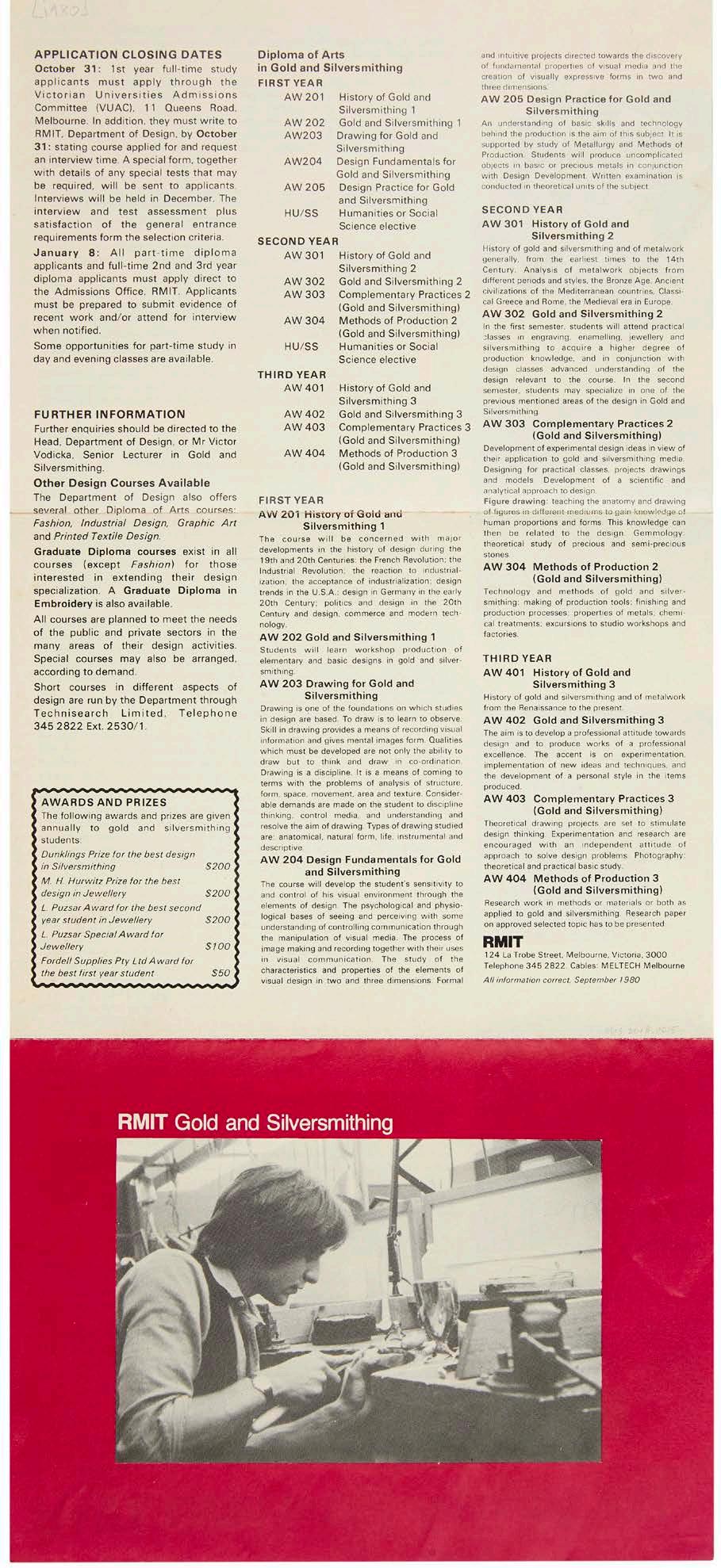

Top RMIT Gold and Silversmithing (prospectus), September 1980, brochure, 45.8 x 20.6 cm, RMIT Design Archives: Victor Vodicka Collection.

Bottom left

Exhibition of work by RMIT Gold and Silversmithing staff and students at RMIT School of Art, Building 2, October – November 1967, photographer unknown, RMIT Design Archives: Victor Vodicka Collection.

Bottom right

Victor Vodicka, Silver lamp for the College of Nursing, Australia, c. 1950’s, photographer unknown, RMIT Design Archives: Victor Vodicka Collection.

Page 35

Victor Vodicka, RMIT commemorative plate, 1971, copper, enamel, 15.4 cm diameter, RMIT Design Archives: Victor Vodicka Collection.

Page 36

Top left

Peter Gertler, Untitled (pair of boxes), 1973, sterling silver, felt, eye: 4.7 x 4.0 x 4.0 cm, lips: 4.4 x 4.0 x 4.0 cm, acquired through the Dunklings Prize for Silversmithing, 1973, RMIT University Art Collection: W.E. McMillan Collection.

Top right

Kevin George Eastwood, Flexible bracelet, 1966, sterling silver, 19.8 cm length, RMIT University Art Collection: W.E. McMillan Collection.

Lower left

Howard Tozer, Vessel, 1964, silver plated and gilded gilding metal, 8.5 x 11.4 x 11.4 cm, RMIT University Art Collection: W.E. McMillan Collection.

Lower right

Norman Creighton, Neckpiece, 1968, sterling silver, 25.0 x 22.4 x l.0 cm, RMIT University Art Collection: W.E. McMillan Collection.

This page

Norman Creighton and Neita Bartlett with Creighton’s Neckpiece, 1968, which was awarded the Max Hurwitz Prize at RMIT’s special awards for art. Press photograph: ‘A winning necklace for another winner’, The Age, 11 July 1969, p. 11.

ENDNOTES

1 Victor Vodicka, handwritten notes to his opening speech given at a seminar about the gold and silversmithing course in 1978, Victor Vodicka collection, RMIT Design Archives, 2.

2 Vodicka, opening speech given at a seminar about the gold and silversmithing course in 1978, 2.

3 The Age Art Critic, ‘Contemporary work in exhibition’, The Age, Melbourne, 21 October 1952, 2; see also Margaret Vine, ‘Jewellers and Jewellery: European trained, made in Australia’, in Roger Butler (ed.), The Europeans Émigré artists in Australia 1930–1960, Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 1997, 197.

4 Alfred Simm, arrived Melbourne per New Australia 26 February 1953, application for assisted passage to Australia under the United Kingdom and Australian Government Agreement, Melbourne: National Archives of Australia, MP210/2, 1953/38/132/SIMM A/A/J.

5 ‘Woman’s World: Jeweller’s art’, The Herald, Melbourne, 27 April 1954, 14.

6 John Vernon Lord, Hywel James, Gillian Naylor, ‘Post-war curriculum and assessment: Coldstream, Summerson, art history and complementary studies’, in Jonathan Woodham and Philippa Lyon (eds), Art and Design at Brighton 1859-2009: from Arts and Manufactures to the Creative and Cultural Industries, Brighton: University of Brighton, 2009, URL: http://arts.brighton.ac.uk/ arts/alumni-and-associates/the-history-of-arts-education-inbrighton/post-war-curriculum-and-assessment-coldstreamsummerson-art-history-and-complementary-studies (accessed 6 April 2019).

7 Victor Vodicka’s archive was donated by his son Peter Vodicka to the RMIT Design Archives in 2018.

8 Vodicka, opening speech given at a seminar about the gold and silversmithing course in 1978, 3.

9 Victor Greenhalgh notes the importance of the RCA and Cooper Union School of Art in his 1961 report, ‘The First Report of the Place of the School of Art, RMIT in the Structure of Art Education in Victoria’, Victor Vodicka collection, RMIT Design Archives.

10 The slides are in the Vodicka collection, RMIT Design Archives.

11 Illustrated in Carole Devlin and Victoria Kate Simkin (eds.), Stuart Devlin. Designer Goldsmith Silversmith, Woodbridge, Suffolk, England: ACC Art Books Ltd, 2018, 15.

12 Sheila McFarlane, ‘There’s gold in their fingertips’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 8 June 1960, 15.

13 RMIT Archives Employee History Cards (2001/084) for Wolf Wennrich state he was appointed 17 July 1963 as a temporary lecturer in jewellery. This temporary position ceased when he resigned in 1979; see also Edquist, ‘The Shaping of Design’ in Goad et al., Bauhaus Diaspora, 205–06.

14 ‘History of Goldsmithing and Silversmithing’, typescript, Victor Vodicka collection, RMIT Design Archives.

15 Vodicka, opening speech given at a seminar about the gold and silversmithing course in 1978, 8.

16 William Coldstream, ‘First Report of the National Advisory Council on Art Education’, London: H.M. Stationery Office, 1960.

17 Kate Aspinall, ‘The ‘Pasmore Report’?: Reflections on the 1960 ‘Coldstream Report’ and its legacy’, Art School Educated Conference, Tate Britain, 11–12 September 2014, URL: https:// www.academia.edu/8524265/The_Pasmore_Report_Reflections_ on_the_1960_Coldstream_Report_and_its_Legacy (accessed 24 February 2019). Greenhalgh cites Coldstream in his ‘First Report’.

18 Greenhalgh. ‘The First Report’, Appendix F.

19 Robert Baines, email correspondence with Harriet Edquist, 13 July 2017.

20 Marian Hosking, email correspondence with Harriet Edquist, 22 July 2017.

21 Marian Hosking, email correspondence with Harriet Edquist, 22 July 2017.

22 As jeweller Kim Bartlett noted in Kylie Davis, ‘Like father like son’ (profile of Kim and Jay Bartlett), Duo, 11 July 2017, URL: http:// duomagazine.com.au/style/like-father-like-son/ (accessed 24 February 2019).

23 ‘The next move will be to Lord Casey’s’, The Sun, 28 November 1967, 8.

24 Untitled article, Craft Australia, vol. 4, no. 1, 1974, 8–9.

MELBOURNE MODERN 37

38 MELBOURNE MODERN

Opposite top Wayne Guest, Brooch, 1976, sterling silver, 9ct yellow gold, titanium, 4.0 x 3.0 x 1.0 cm, RMIT University Art Collection: W.E. McMillan Collection

Opposite below Margaret West (known as Margaret Jasulaitis 1960–82), Sculpture, 1974, sterling silver, titanium, 8.2 x 8.2 x 3.0 cm, RMIT University Art Collection: W.E. McMillan Collection

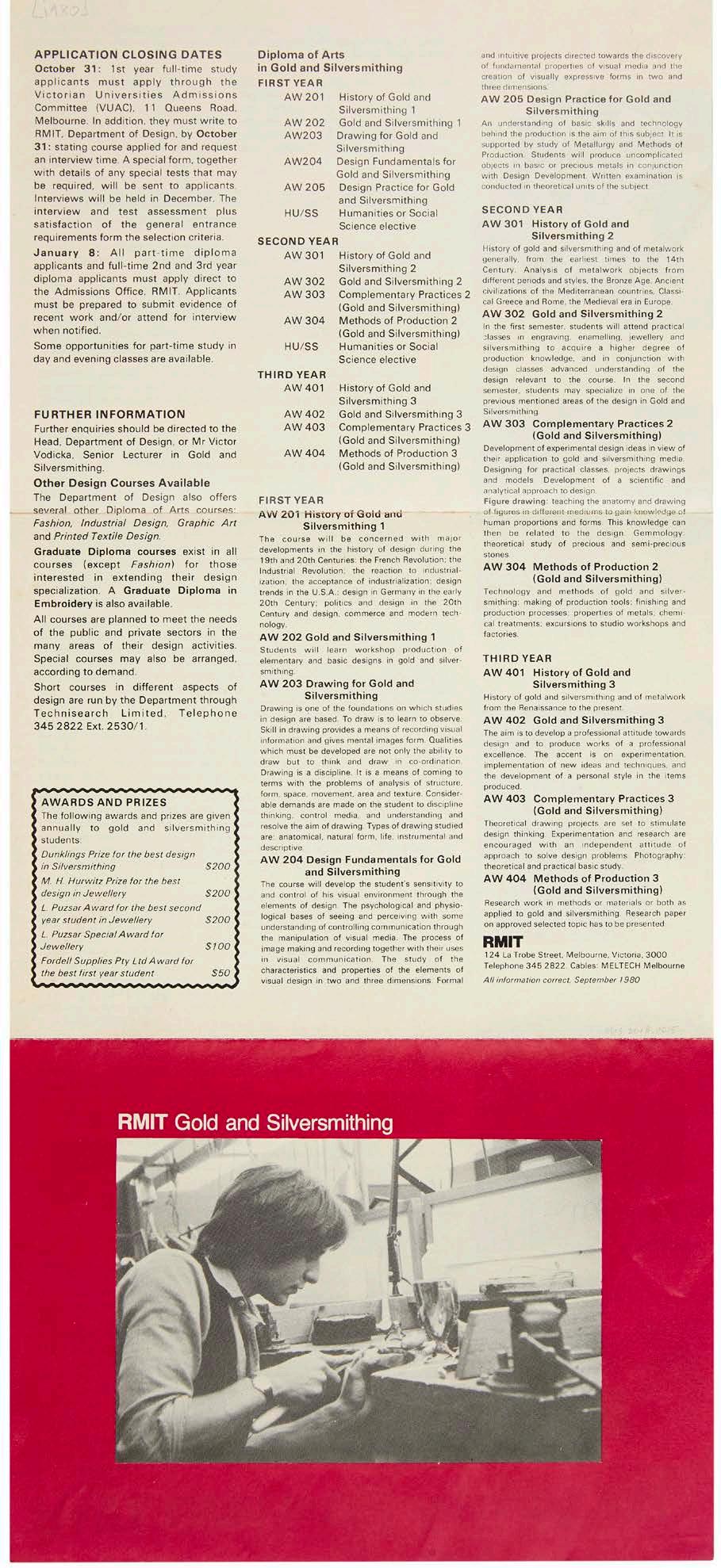

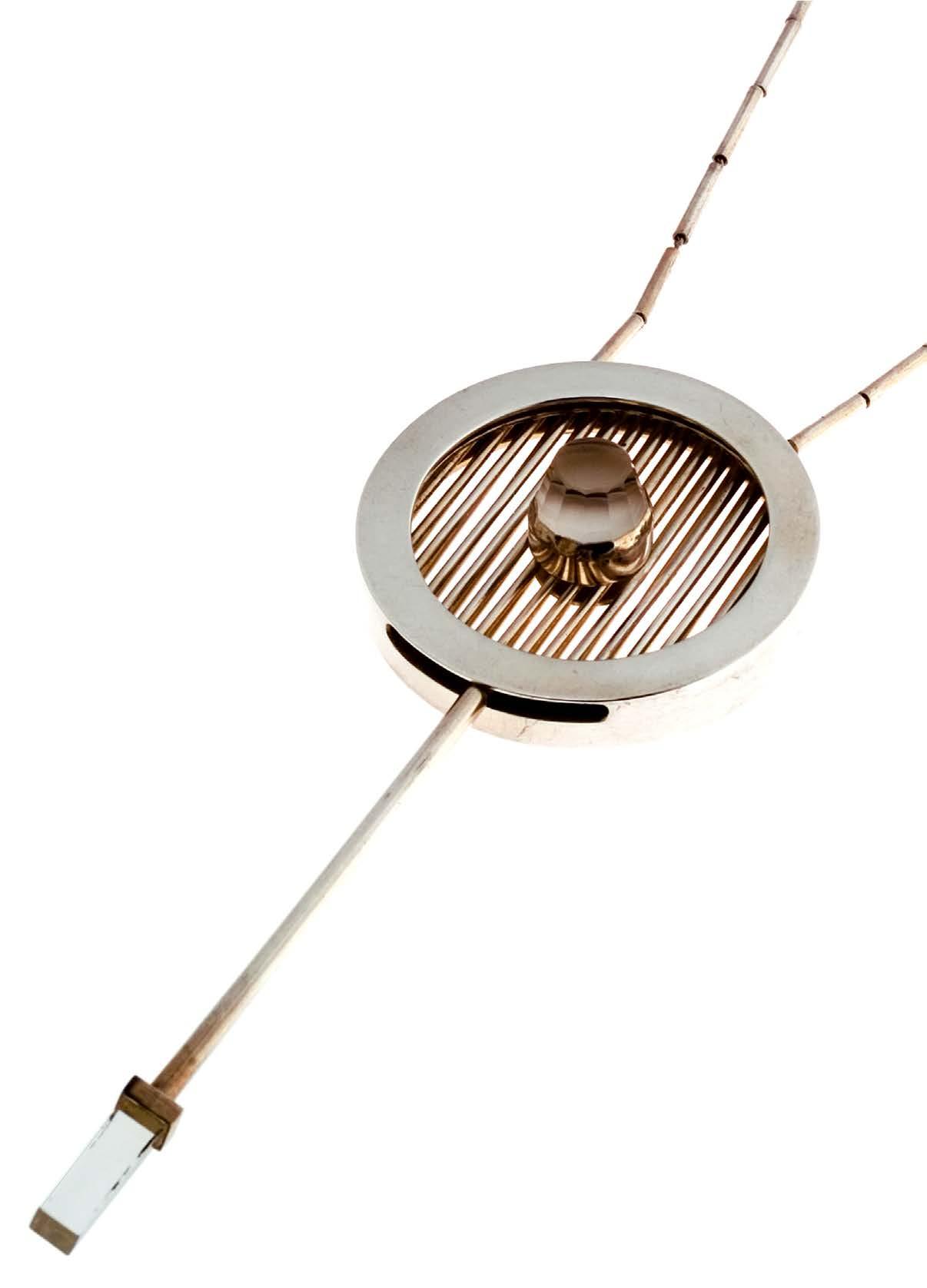

Left John Stirling, Kinetic necklace, 1971, sterling silver, quartz crystal, 49.0 x 6.1 x 2.0 cm, RMIT University Art Collection: W.E. McMillan Collection

Right Margaret West (known as Margaret Jasulaitis 1960–82), Collier, 1975, sterling silver, titanium, stainless steel, 25.7 x 12 x 2.2 cm, RMIT University Art Collection: W.E. McMillan Collection

Page 40

Top Marian Hosking, Chocolate Bracelet, 1969, sterling silver, 2.0 x 2.0 x 1.0 each unit, collection of the artist

Below

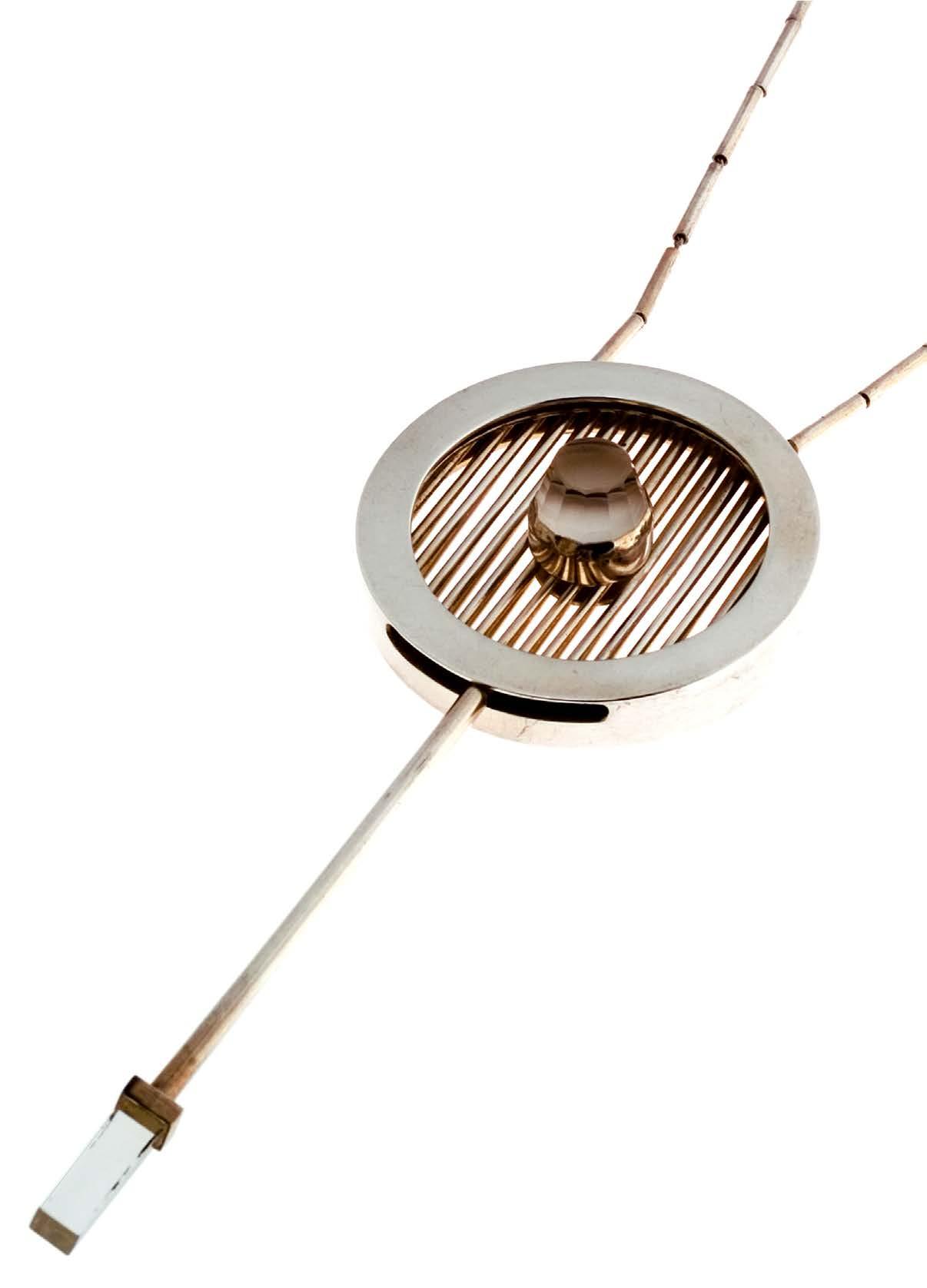

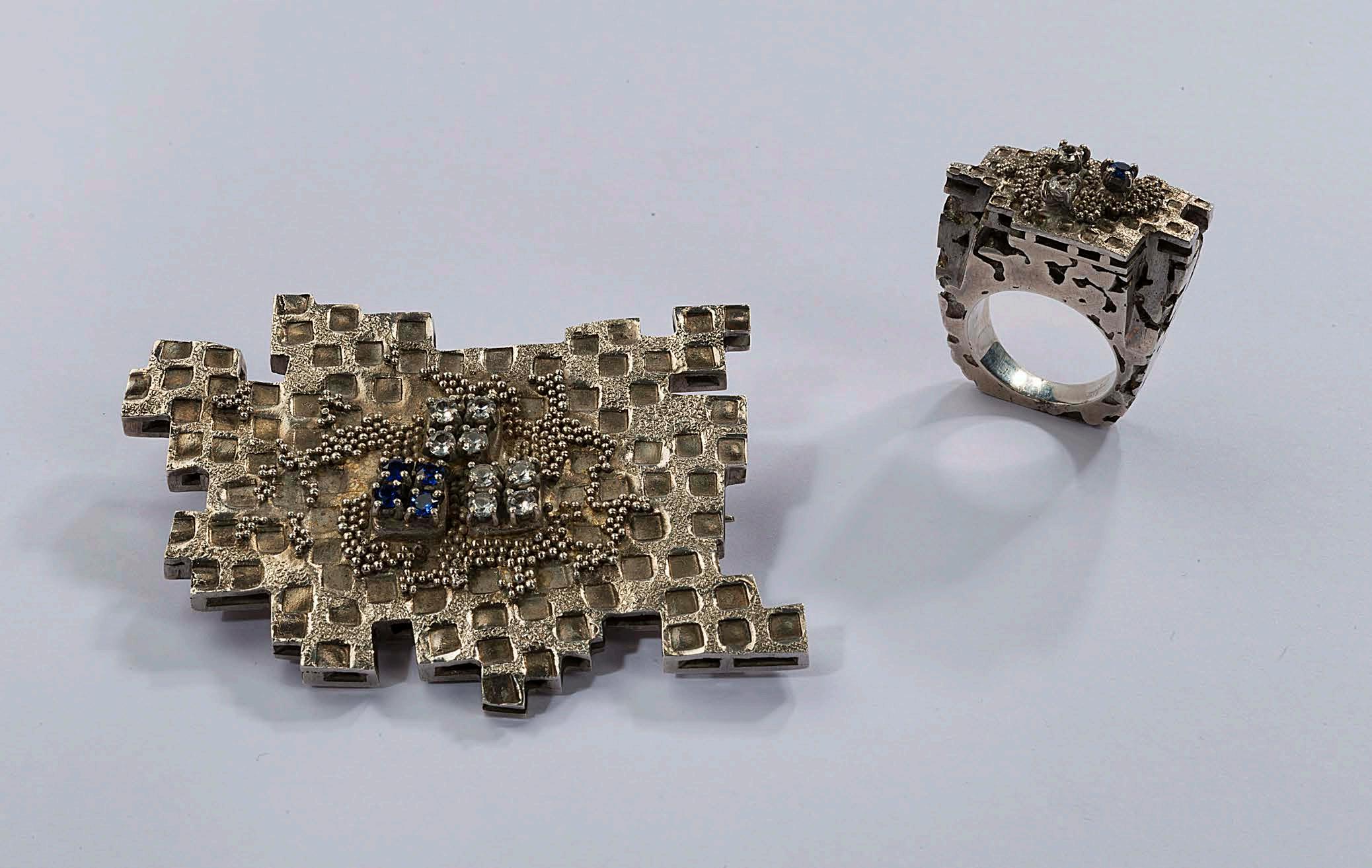

Robert Baines, Brooch and Ring, 1970, silver, corundum, rhodium plate, brooch: 5.0 x 6.7 x 1.2 cm; ring: 3.8 x 2.6 x 1.3 cm, RMIT University Art Collection: W.E. McMillan Collection

Page 41

Robert (Bob) Keith Cranage, Water Jug, 1962, Silver plated gilding metal, 24.6 x 13.2 x 13.2 cm, RMIT University Art Collection: W.E. McMillan Collection

MELBOURNE MODERN 39

40 MELBOURNE MODERN

3 a skilled hand and/or cultivated mind? INDUSTRIAL DESIGN AT THE CROSSROADS HARRIET EDQUIST

Opposite Radios designed by students of RMIT industrial design (detail), unknown photographer, RMIT Design Archives: Gerard Herbst Collection

In 1947 MTC celebrated its Diamond Jubilee.

To mark the occasion, the College published Sixty Years, in which it noted the work it had done to fit students to meet the increasingly technological demands of the post-war world, deftly interweaving the College’s motto perita manus mens exculta (‘a skilled hand, a cultivated mind’) into its summary of achievements:

Technical advances have increased our mastery of our environment, minds and hands have had to be trained that our sum-total of knowledge, skill and culture might be worthily increased.1

Although it has waxed and waned over the years the ‘cultivated mind’ part of the equation has always been part of RMIT’s mission, even if the view of education as handmaiden to industry has often predominated. And one way of thinking about the Industrial Design programme after the war is as a battleground between skill and culture.

Among the celebrations to mark the Diamond Jubilee, Art and Applied Art mounted an exhibition in the Arts Building (Building 2) showcasing the work of students across its numerous art and design programmes. Reviewed favourably, the industrial design display attracted special comment:

The industrial design section is particularly notable. The students who arranged it have made an excellent job with everyday materials and transformed a bare room into an exhibit of first-class interest. This display should be an object lesson to the organisers of all exhibitions. It shows what could be done with the Exhibition Building, for instance, if it were intelligently handled.2

Lyle Fowler’s photographs of the minimalist industrial design exhibit show product development (an iron and an electric kettle) from sketch to prototype with an emphasis on design for industrial production. Industrial Design had been established at the College in 1939, the first such course in Australia, and after the disruption of the war it produced its first graduates in 1948-49; presumably this was their work.3

A year after the exhibition German-born designer Gerard Herbst was hired as a sessional teacher in the course. He was at the time art director of the large industrial concern Prestige Fabrics in Brunswick, and his specialties were in poster, textile, communication and exhibition design.

Herbst had arrived in Melbourne in 1939, sponsored by his Jewish friend Kurt Jacob, for whose family he had worked in Munich and had assisted after Kristallnacht in November 1938. His education and training prior to professional work are not clear but on his immigration papers he described himself as a ‘window dresser’ (later crossed out and changed to commercial artist) and he had worked in that field in Germany during the 1930s.4 Jacob, who had left Munich earlier to establish a branch of the family music store in Sydney, organised a position for Herbst as assistant to the advertising manager at Prestige. In 1942, like thousands of other so-called ‘enemy aliens‘ Herbst joined a labour unit for the Australian Defence Force and he did not return to Prestige until demobilisation in 1945.

In the meantime Prestige, founded as a luxury lingerie manufacturer by George Foletta in 1922, had turned to the manufacture of woven silk for parachutes and other military uses. Having invested in new weaving equipment, Foletta decided to develop this side of the business and produce fine textiles for the fashion industry. Foletta appointed Herbst art director of the new concern, a position he held until 1955. He was in charge of Prestige’s overall design, promotion and advertising, and responsible for providing a unifying vision for the company’s brand. Herbst established a design studio where young designers with different skills collaborated on projects, a practice model more commonly associated with commercial graphic design studios. By the early 1950s the staff included Viennese-born Susan Copolov (formerly Tandler) who had studied art at MTC. Herbst was particularly interested in advertising and marketing and, while he produced innovative, sparsely modernist displays himself, he also harnessed and encouraged the talents of others. From 1949 to 1951 he collaborated with cinematographer Geoffrey Thompson of Cine Service on three short, highly innovative films for Prestige, one of which, Language of Design, was shown at the International Textile Exhibition at Lille, France in 1951. He also commissioned German-born modernist photographer Wolfgang Sievers to produce promotional material for Prestige. One of Sievers’ most celebrated photographs depicts Herbst standing on a cliff overlooking the sea at Black Rock, holding aloft a

MELBOURNE MODERN 43

Below right

Prestige Fabrics Ltd. designer and MTC graduate Susanne Tandler (later Susanne Copolov), from Vienna, with miniature mannequins draped in Prestige fabrics for exhibition in Textile International display in Lille, France, 1951, photograph: Gerard Herbst, RMIT Design Archives: Prestige Fabrics, Gerard Herbst Collection

Opposite above and below Melbourne Technical College Diamond Jubilee exhibition, Arts Building (Building 2), industrial design display, including a display showing the development of an iron and an electric kettle from sketch to prototype, 1947, photographer: Lyle Fowler, Harold Paynting Collection, State Library Victoria

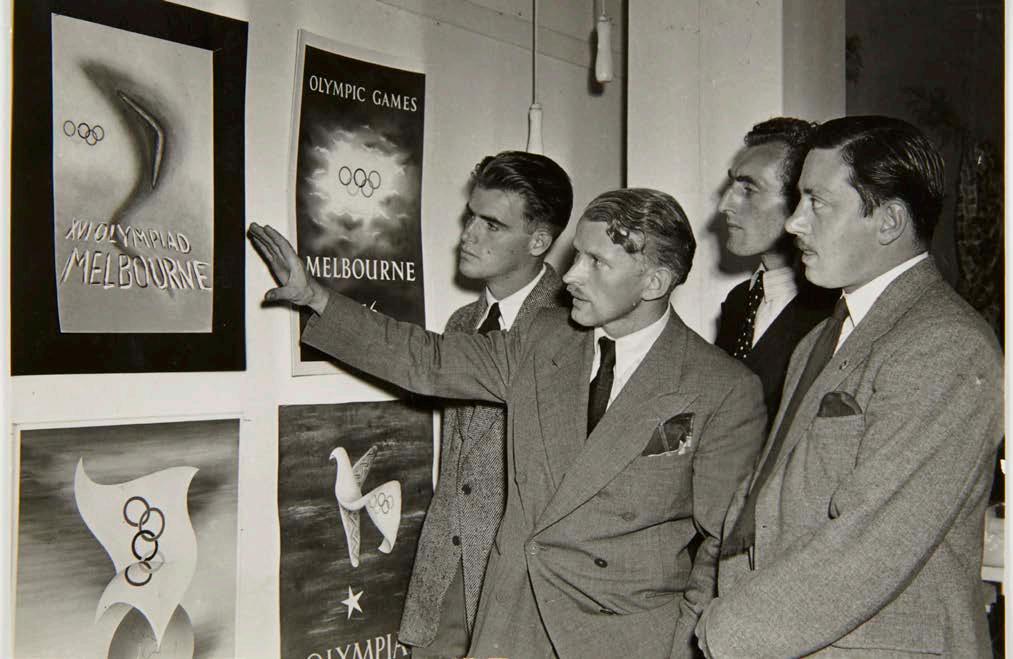

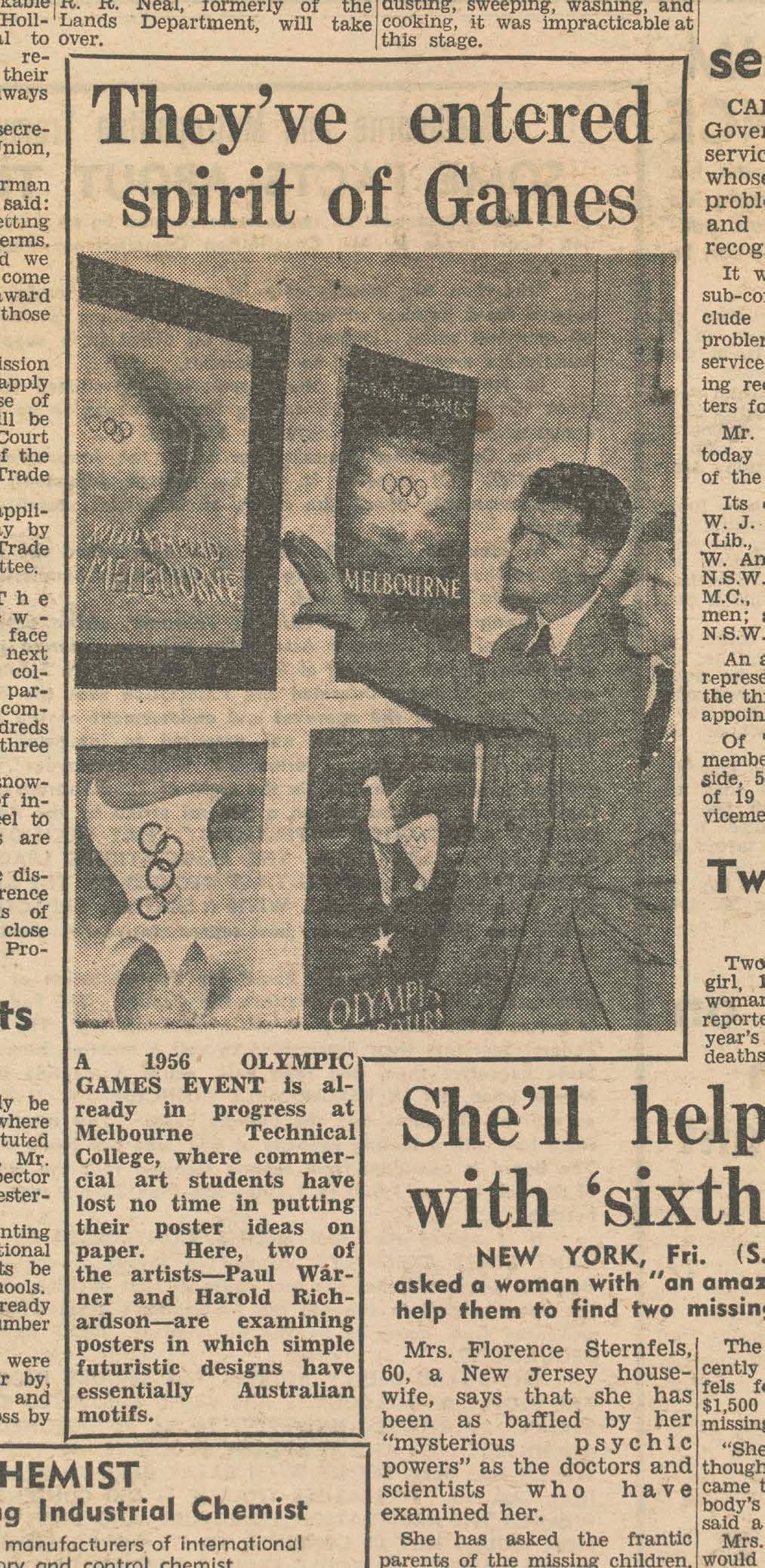

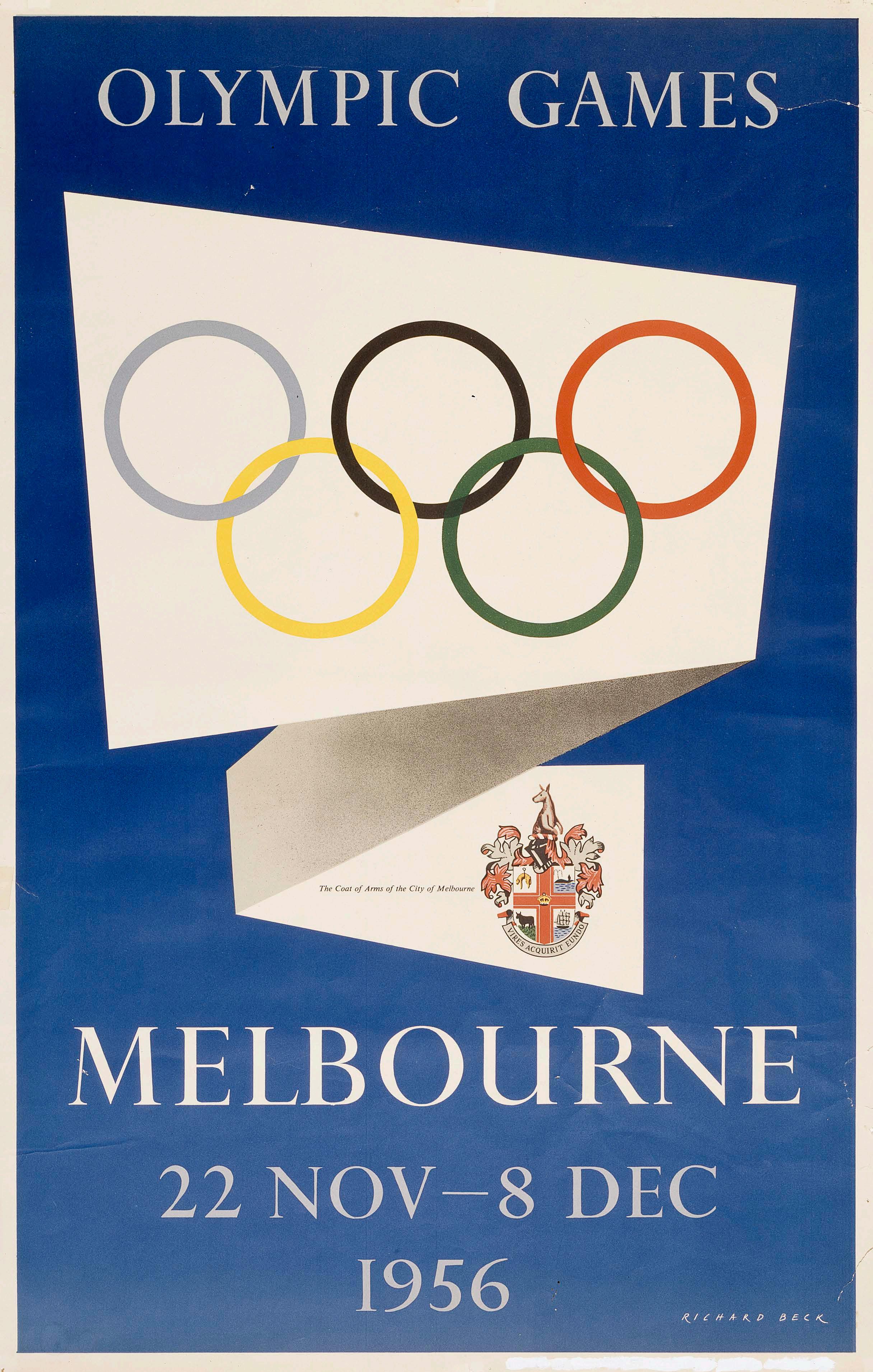

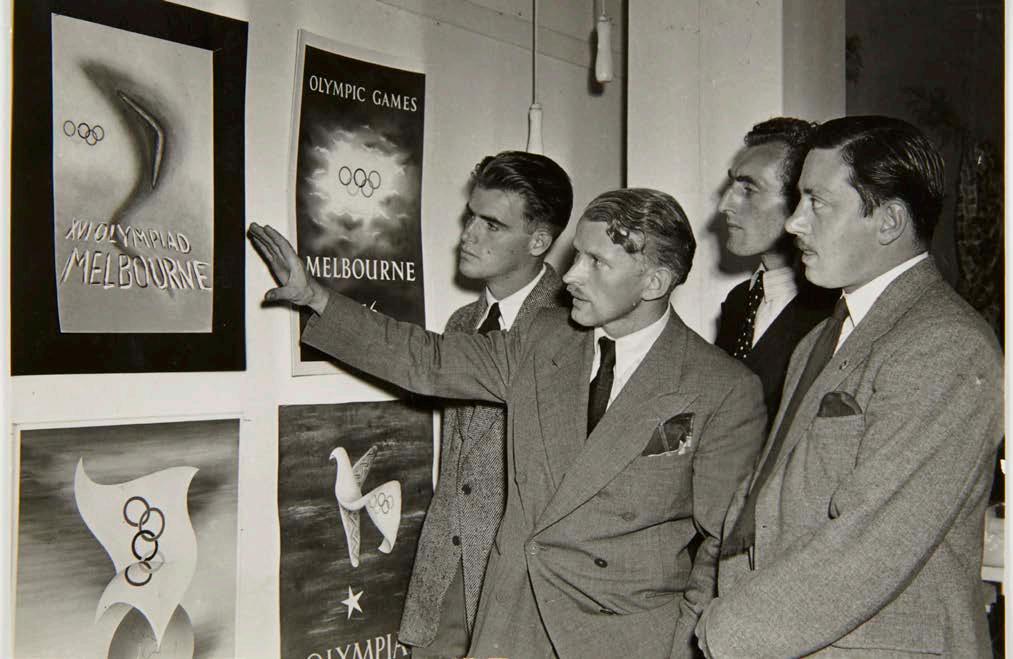

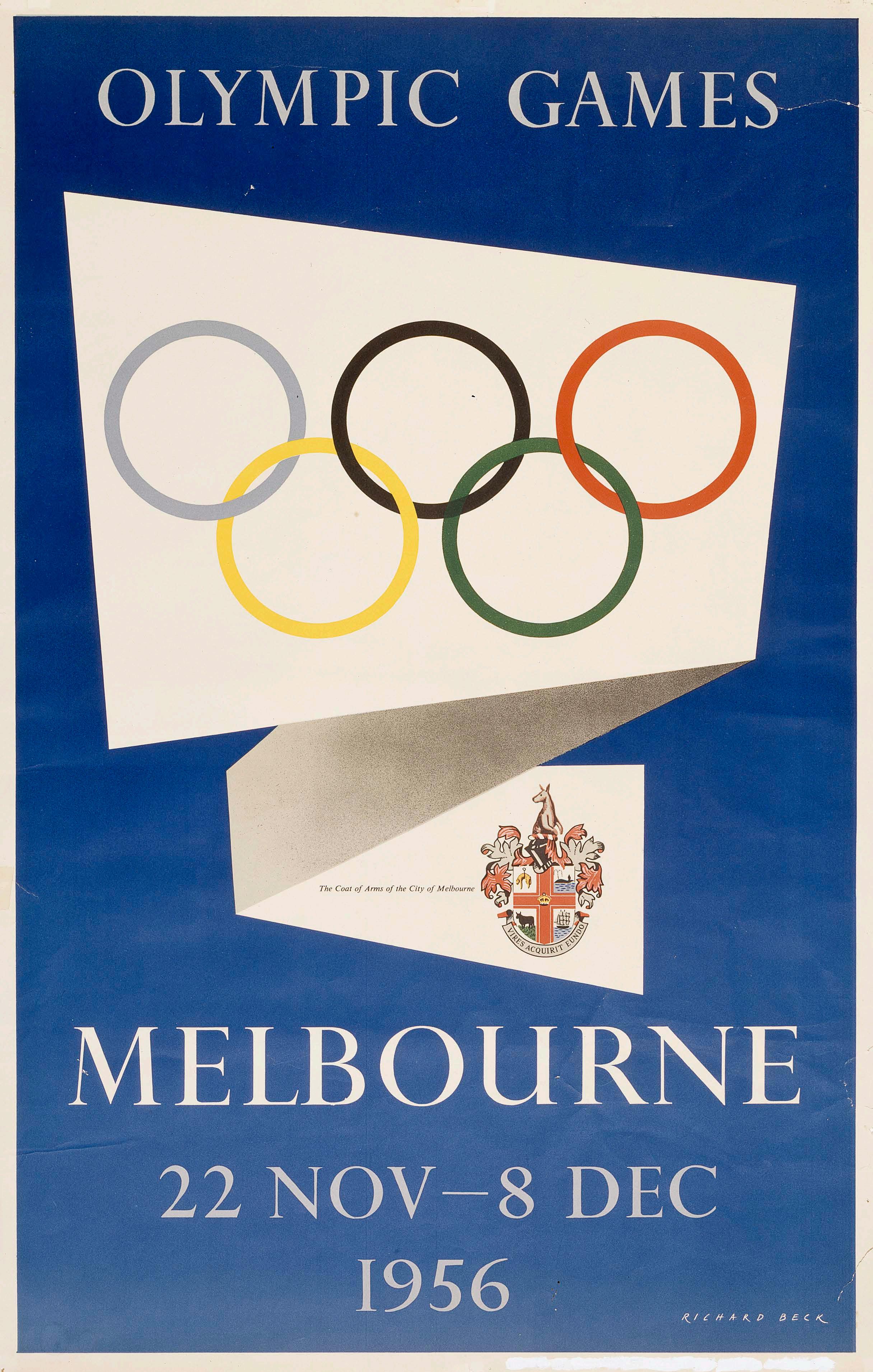

billowing length of Prestige fabric with a floral motif.5 It is a commanding image of victory and freedom. Herbst was not a product designer and had not been trained in product design, so his classes with the evening students at MTC from 1948 focused on two-dimensional design. For instance in 1950 he set them a project to design a poster for the 1956 Melbourne Summer Olympics (Melbourne having been announced the 1956 host city in April 1949). An article in The Argus featured the students’ ‘simple futuristic designs’, accompanied by a photograph of students Paul Warner and Harold Richardson examining the posters.6 Two of the designs featured a rippling Olympic flag –possibly echoing Herbst’s choreographed displays at Prestige Fabrics – and two featured boomerangs. Three years later The Herald illustrated one of the rippling Olympic flag poster designs of 1950, noting that its designer David Seaton was now working in London and quoting Herbst, who lamented ‘the Australian public was unaware of its capable people in the field of industrial art and design’ and that ‘Australia could ill afford to lose these people continually’.7 Herbst’s 1950 student project and his public comments of 1953 were prescient. In 1954 the Melbourne Olympic Organizing Committee commissioned poster designs from five artists. English-born Richard Beck won the commission with a poster that is one of the most celebrated and internationally acclaimed design objects produced by the Games. As John Hughson has noted, Melbourne wished to present itself as a modern, southern city in counterpoise to the northern hemisphere, and Beck’s poster fulfilled this ambition brilliantly by dispensing with the classical athletic male figure, ‘instead offering a sparse geometrical design said to depict an invitation card’.8 Yet Beck’s design of a tri-fold white invitation card against a blue background was in many respects pre-empted by Herbst’s students, whose posters were similarly non-figurative and balanced a simple central motif (be it boomerang or rippling flag) against a plain background and simple capitalised text. Whether Beck was aware of the MTC student designs is unclear (there is no record of the designs among his archive and his own employment at the College only commenced in 1956) but Herbst’s initiative and his students’ response to his design brief warrant attention.

After more than a decade of teaching part-time, Herbst was appointed full-time senior lecturer in industrial design in 1960. He filled the vacancy left by Edward Heffernan, who had moved to Geelong to take up a position as head of Art and Design at the Gordon Technical College. Heffernan was typical of most industrial design teachers at the time in that he was trained in fine art rather than applied art (Heffernan was a graduate of the National Gallery School, had studied with George Bell, and had been teaching at MTC since 1946). Herbst, on the other hand, was experienced in working in industry through his employment at Prestige and his appointment presaged the professionalisation of industrial design teaching at RMIT.

Throughout Herbst’s term as a full-time teacher at RMIT, the certainties of the post-war modernist project were unravelling, and visions of an infinitely perfectible, technologically crafted world had come under stress. In addition, the 1960 Coldstream Report advocated for a broader pedagogy in art and design schools than one simply focused on preparing students for industry.Now skills were not enough: students had to learn to think conceptually and broadly. This tension between skill and mind, which in RMIT’s motto are conjoined, seems to have formed a core of Herbst’s thinking even at Prestige. While he appointed staff for their skill he also pushed them into a much deeper engagement with the context and genesis of their work.

In 2000 Herbst published Formgestaltung at RMIT Australia circa 1960: Recollections of a design pedagogy, a manifesto of sorts comprising excerpts from School prospectuses, Herbst’s essays and thoughts, photographs, examples of student work, exhibitions, curricula and design competitions.9 Its range and eclecticism evinces strongly his ethos of design teaching. He was not a trained teacher

44 MELBOURNE MODERN

INDUSTRIAL DESIGN

MELBOURNE MODERN 45

Left Gerard Herbst (centre, arm raised) with MTC industrial design students Paul Warner, Harold Richardson and David Seaton studying their designs for Melbourne Olympic Games posters, 1950, photograph: The Argus, 1950 RMIT Design Archives: Gerard Herbst Collection.

Below ‘They’ve entered the spirit of Games’, The Argus, Melbourne, 18 March 1950. Detail of above.

Opposite Richard Beck, Olympic Games Melbourne, 22 Nov – 8 Dec 1956, 1956, colour lithograph, photo-lithograph, image: 95.2 x 60.0 cm, sheet: 106.0 x 65.2 cm, National Gallery of Victoria.

and his approach was personal. Some ideas were based on Bauhaus models which came to him through publications; others came from his wide reading in sociology, urbanism and design, and from institutions such as the Ulm School of Design in Germany. His 1968 article ‘Redeeming the Machine’ suggests he was familiar with Ulm’s work in ergonomics. He encouraged his students to think critically of the world around them. He was as critical of industry and its impact on the environment as he was concerned that his students engage with it as designers. Lewis Mumford was one of his favourite writers – those he called ‘mentors’ – and his students found themselves rather to their surprise working their way through The City in History and other key Mumford texts. Bruce Hall, who entered his final year in 1960 and had been taught by post-war staff like Heffernan, recalls that: [Herbst’s] approach was quite different, he encouraged projects of a social nature, eg. alternatives to galvanized dust bins, moulded power plugs with handles... His approach did bring criticism from Ron Rosenfeld IDIA. Gerard was a bit erratic, jumping from one idea to another [but] he did influence me… I tried to think outside the box.10

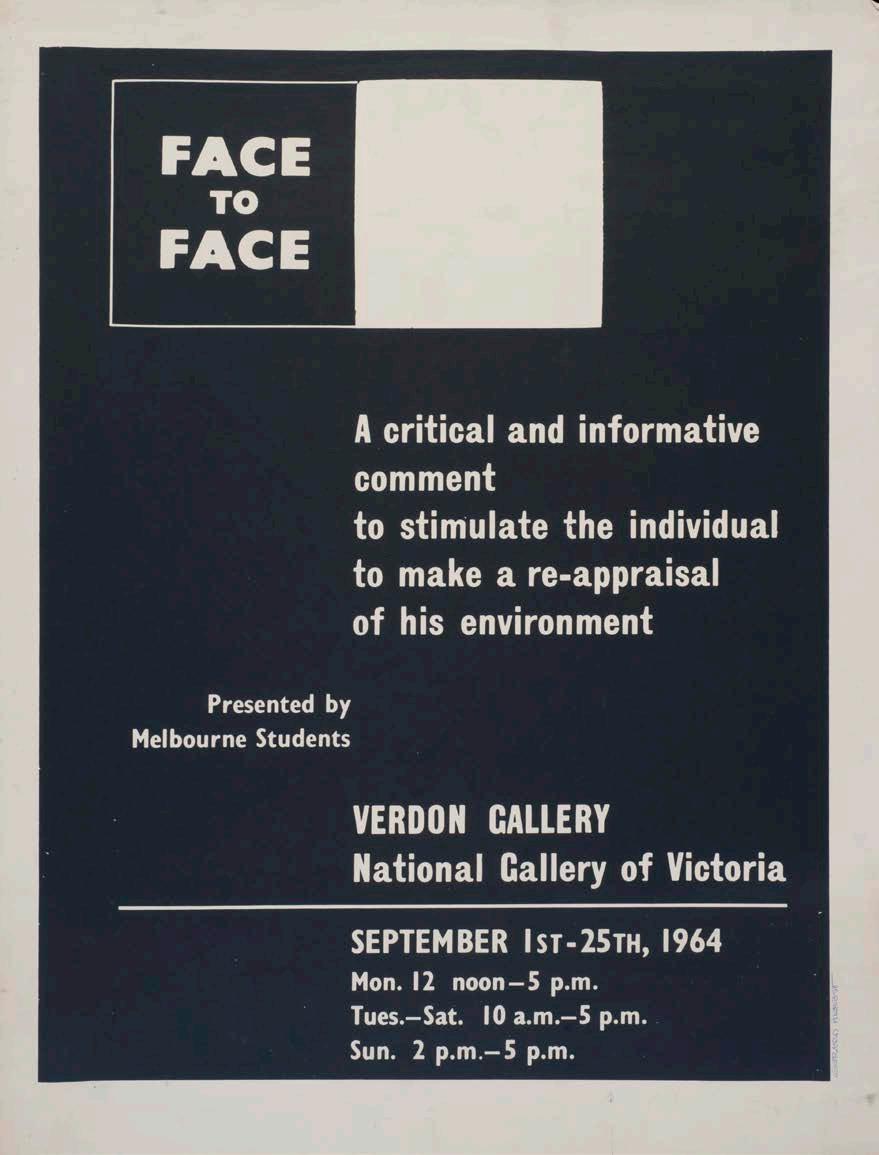

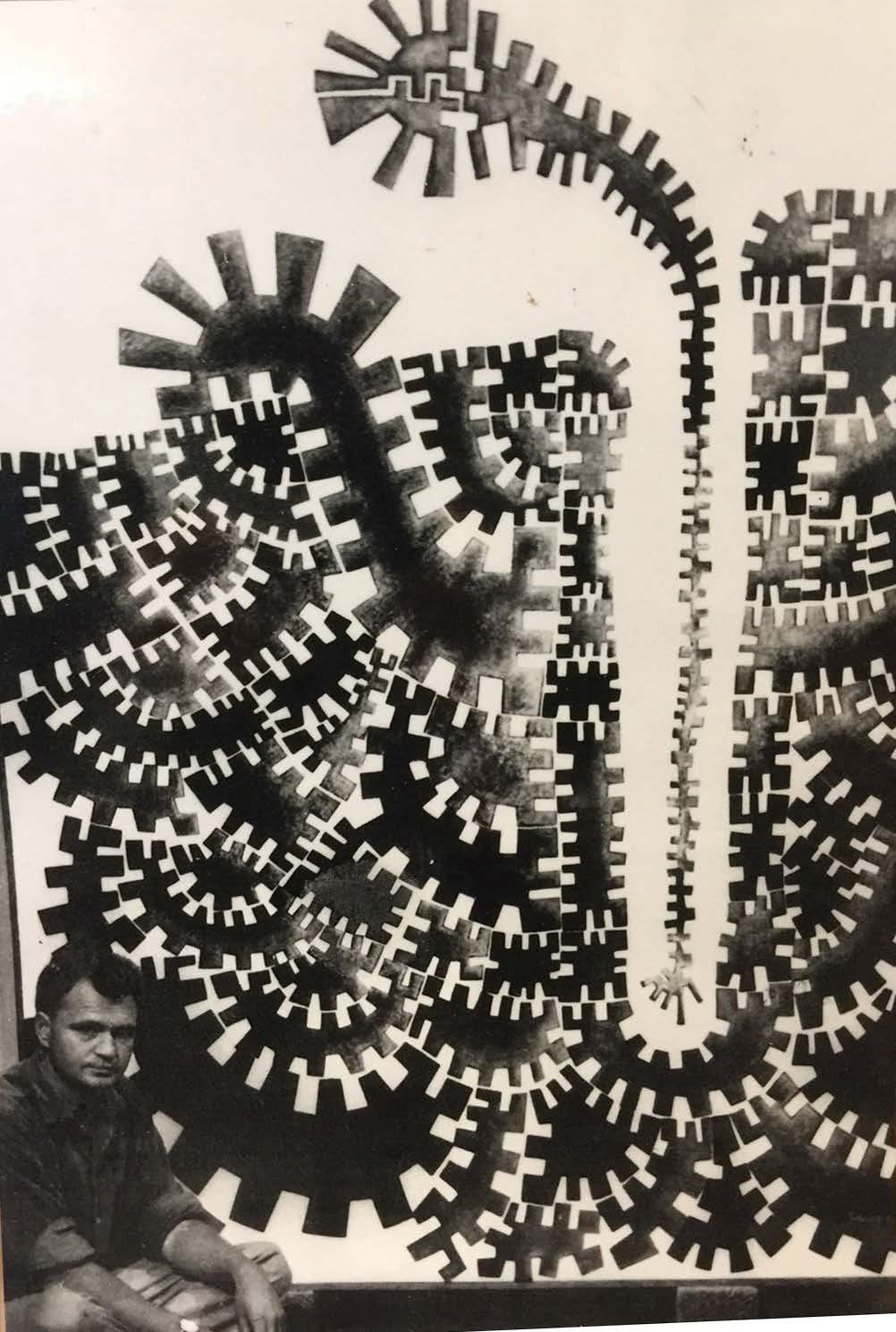

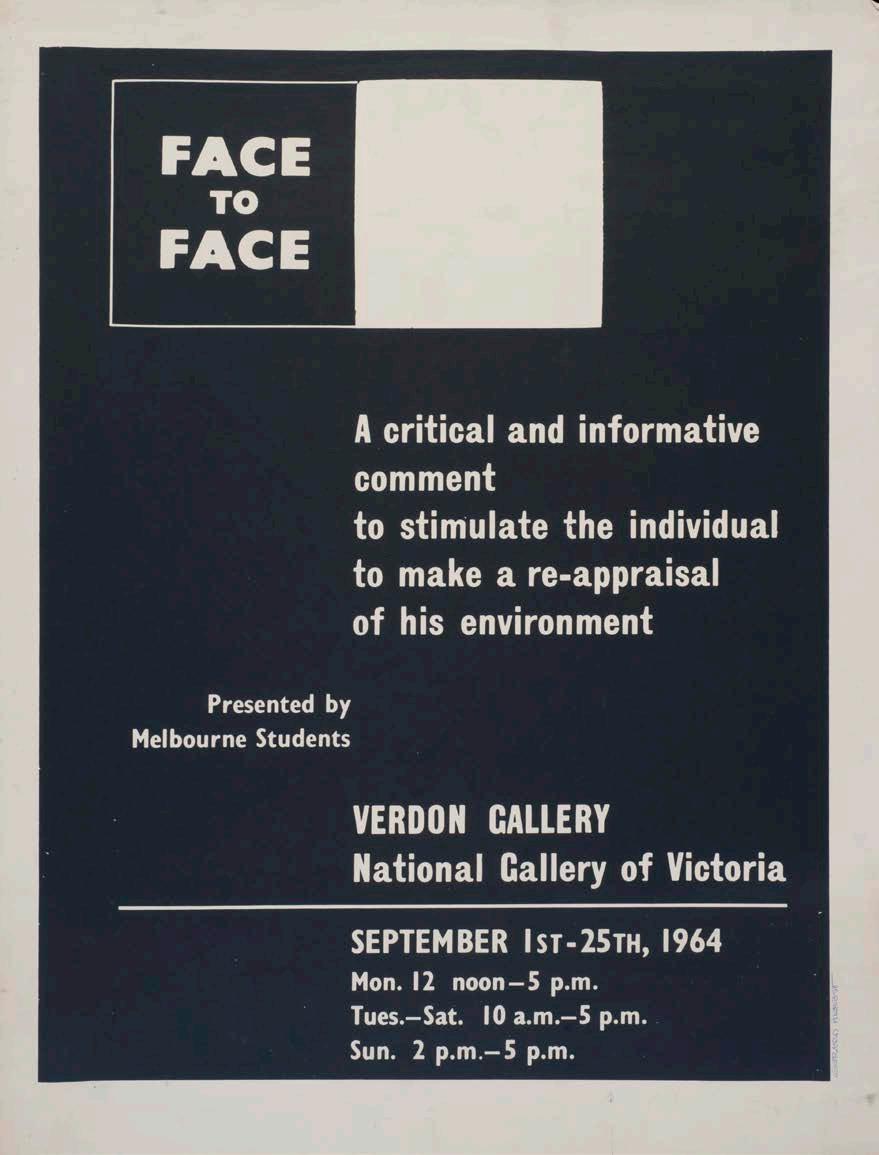

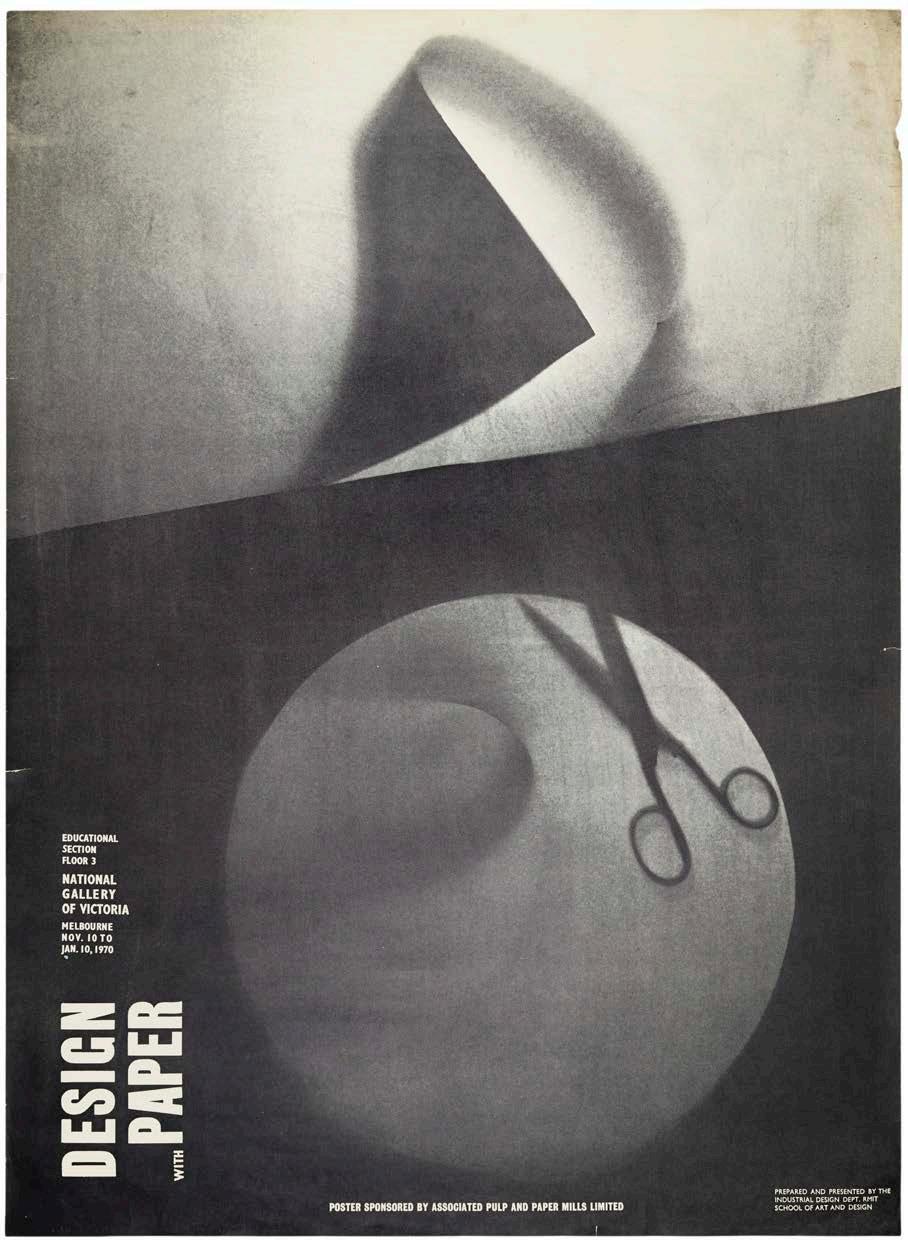

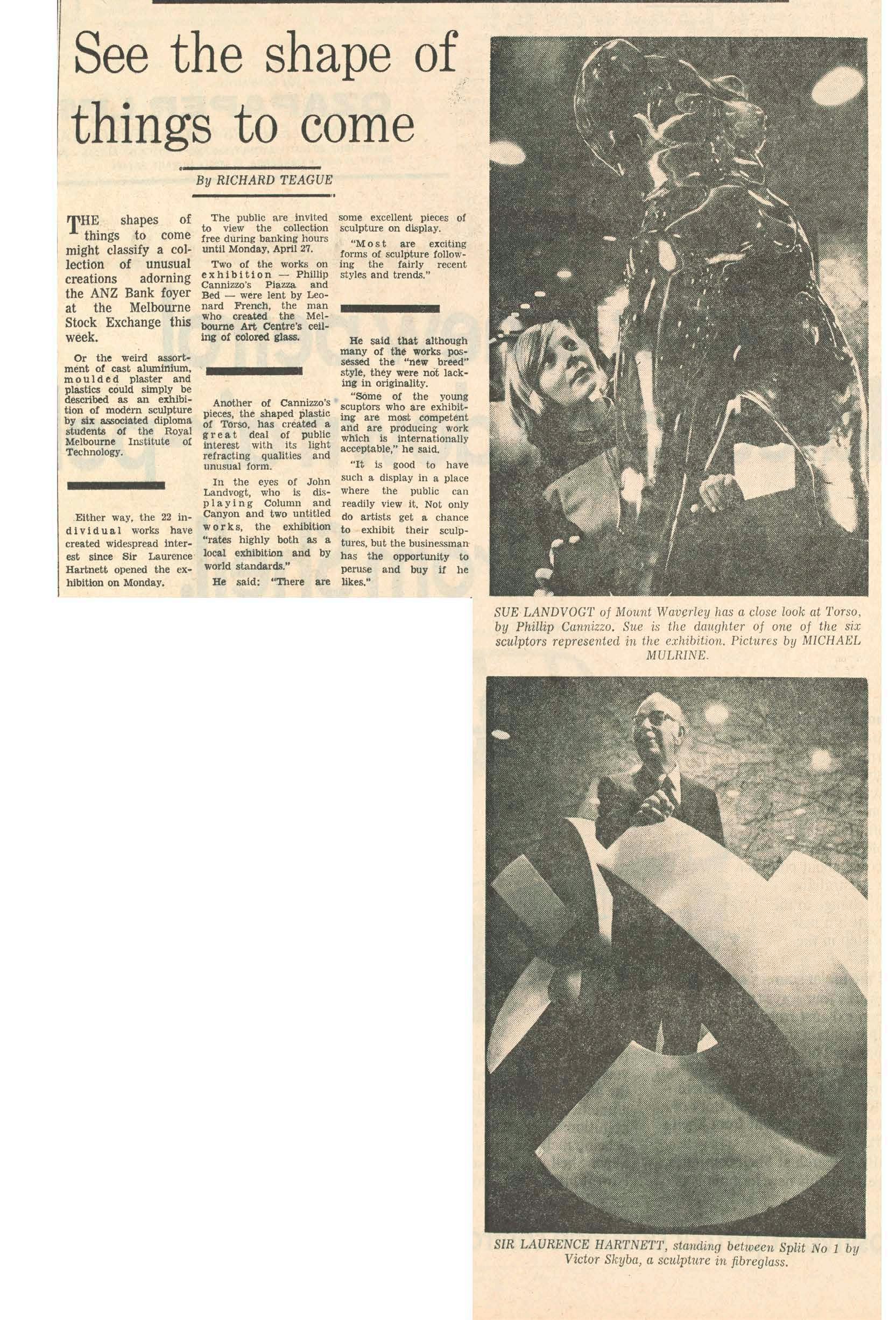

Herbst’s belief in design’s social agenda was the focus of the first of three public exhibitions that he and his students curated in Melbourne that showcased their skill and their thinking. Face to Face at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) in September 1964 was designed to direct attention: ... to some of the dangerous practices that threaten our society. It is based on opinions expressed by the world’s most eminent thinkers, and on aesthetic evaluations made by Australian educationalists. Its aim is to challenge all responsible citizens to make a re-appraisal of existing senses of values.11 Here we can see the echoes of Mumford. This theme continued the following year, when Herbst collaborated with RMIT’s Technology Theatre Department to produce a black and white film, Negatives Positives, which aroused considerable interest when first shown at the Victor Greenhalgh tribute exhibition, ‘Decade’, in July 1965.12 Negatives Positives encapsulates Herbst’s views on life and education. It juxtaposes, as its title suggests, two opposing

46 MELBOURNE MODERN

INDUSTRIAL DESIGN

MELBOURNE MODERN 47

Above Face to Face exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria, in the Verdon Gallery (now State Library of Victoria), organised by Gerard Herbst and RMIT industrial design students, September 1964, photograph: Wolfgang Sievers, State Library Victoria: Wolfgang Sievers Collection

Left

Gerard Herbst, Face to Face exhibition poster, 1964, offset lithograph, 75.3 x 57.0 cm, University of Melbourne Art Collection: Gerard Herbst Poster Collection

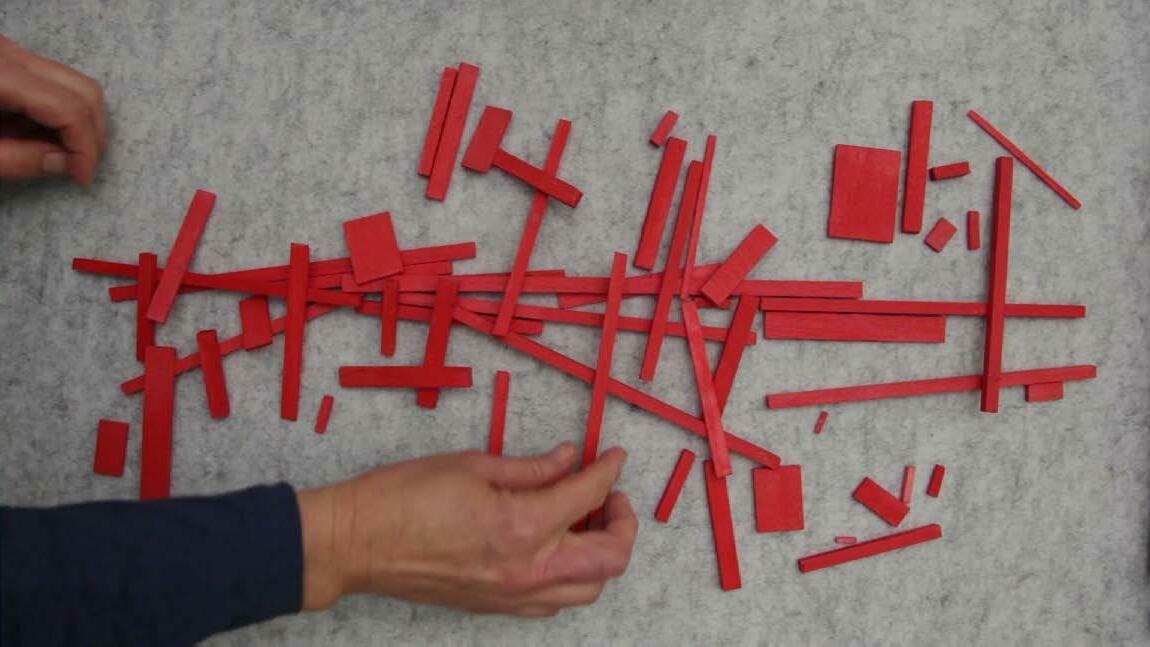

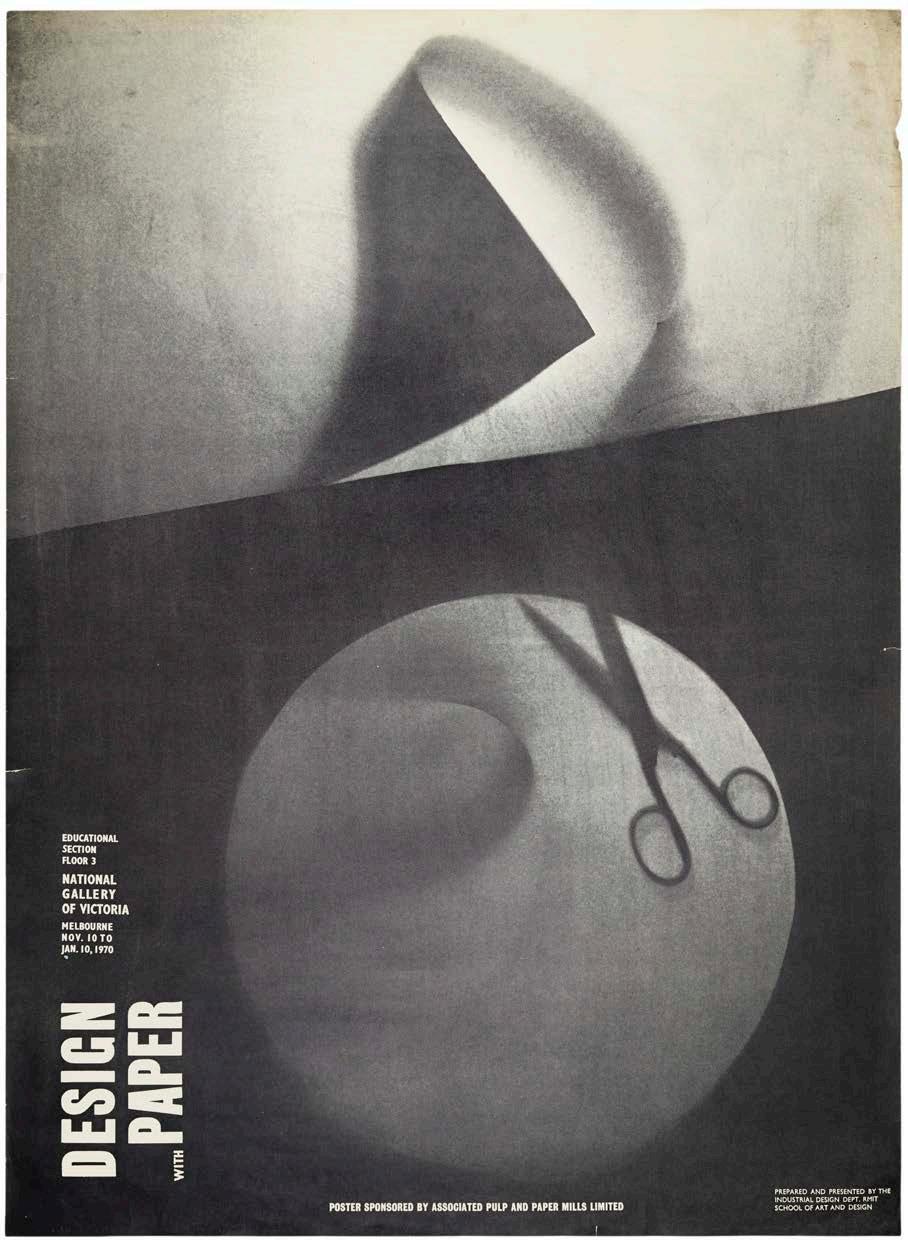

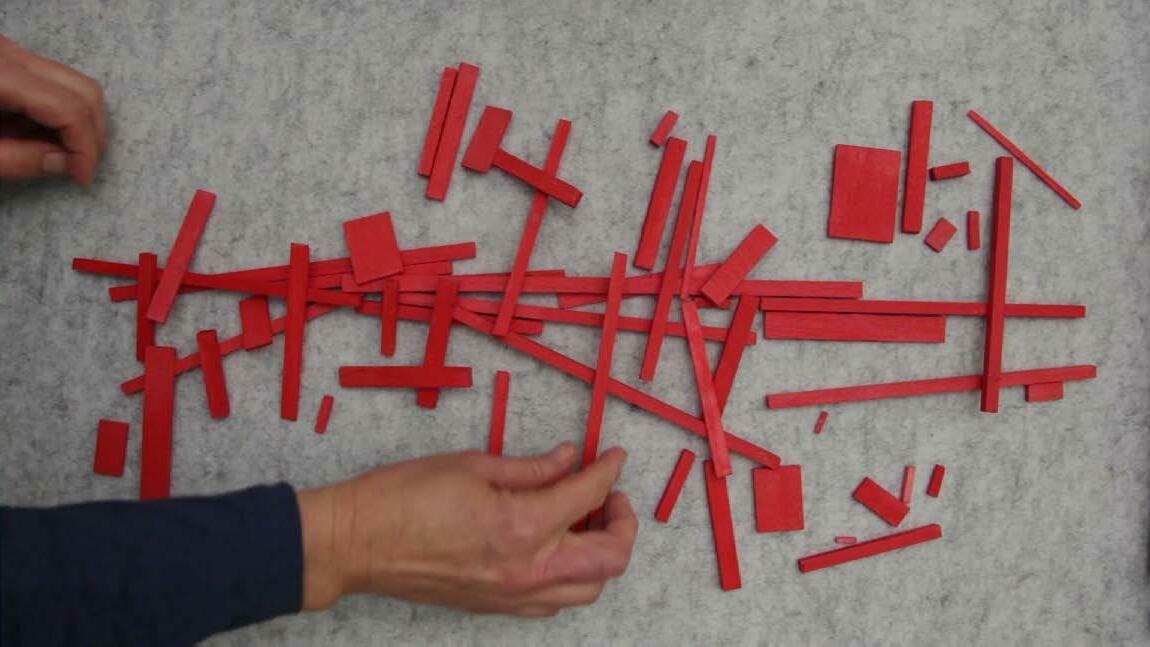

Opposite top Gerard Herbst, Design with Paper exhibition poster, 1969, offset lithograph 98.6 x 73.2 cm, RMIT Design Archives: Gerard Herbst Collection. Design with Paper was presented by RMIT’s Industrial Design Department at National Gallery of Victoria, November 1969 – January 1970

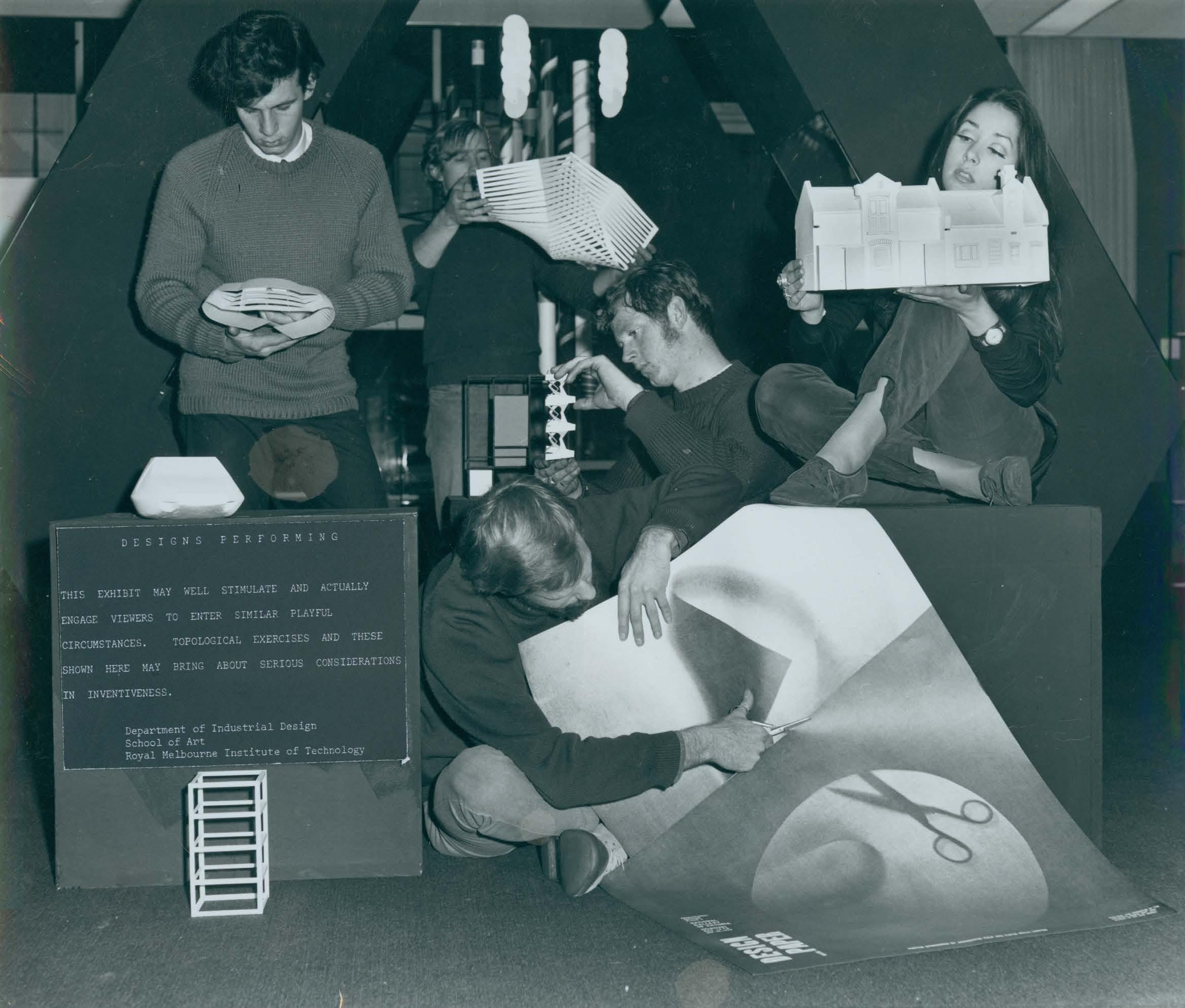

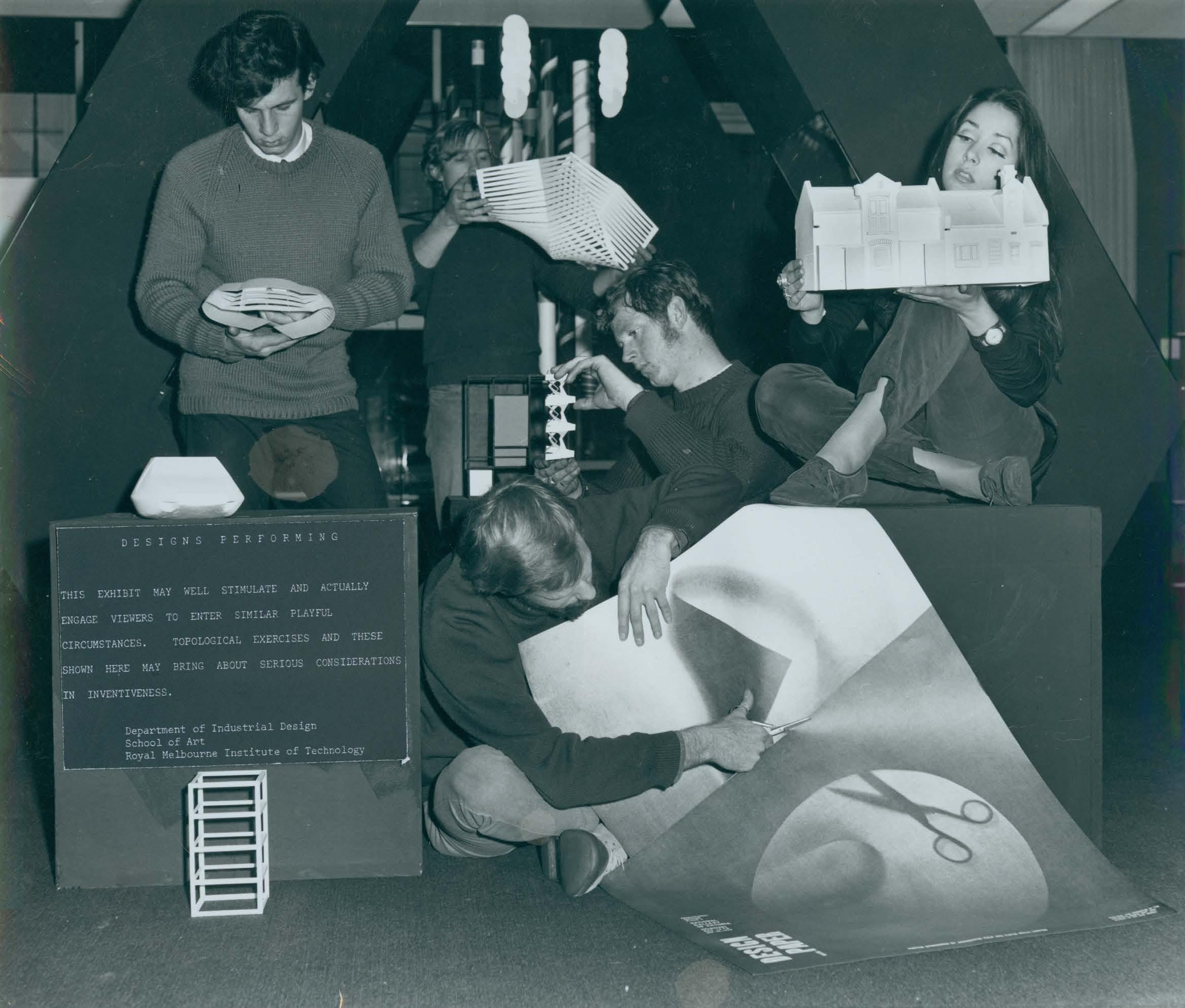

Opposite below ‘Designs Performing’, Design with Paper publicity photograph of RMIT industrial design students with paper exhibits, 1969, photograph: Gerard Herbst, RMIT Design Archives: Gerard Herbst Collection

48 MELBOURNE MODERN

MELBOURNE MODERN 49

50 MELBOURNE MODERN

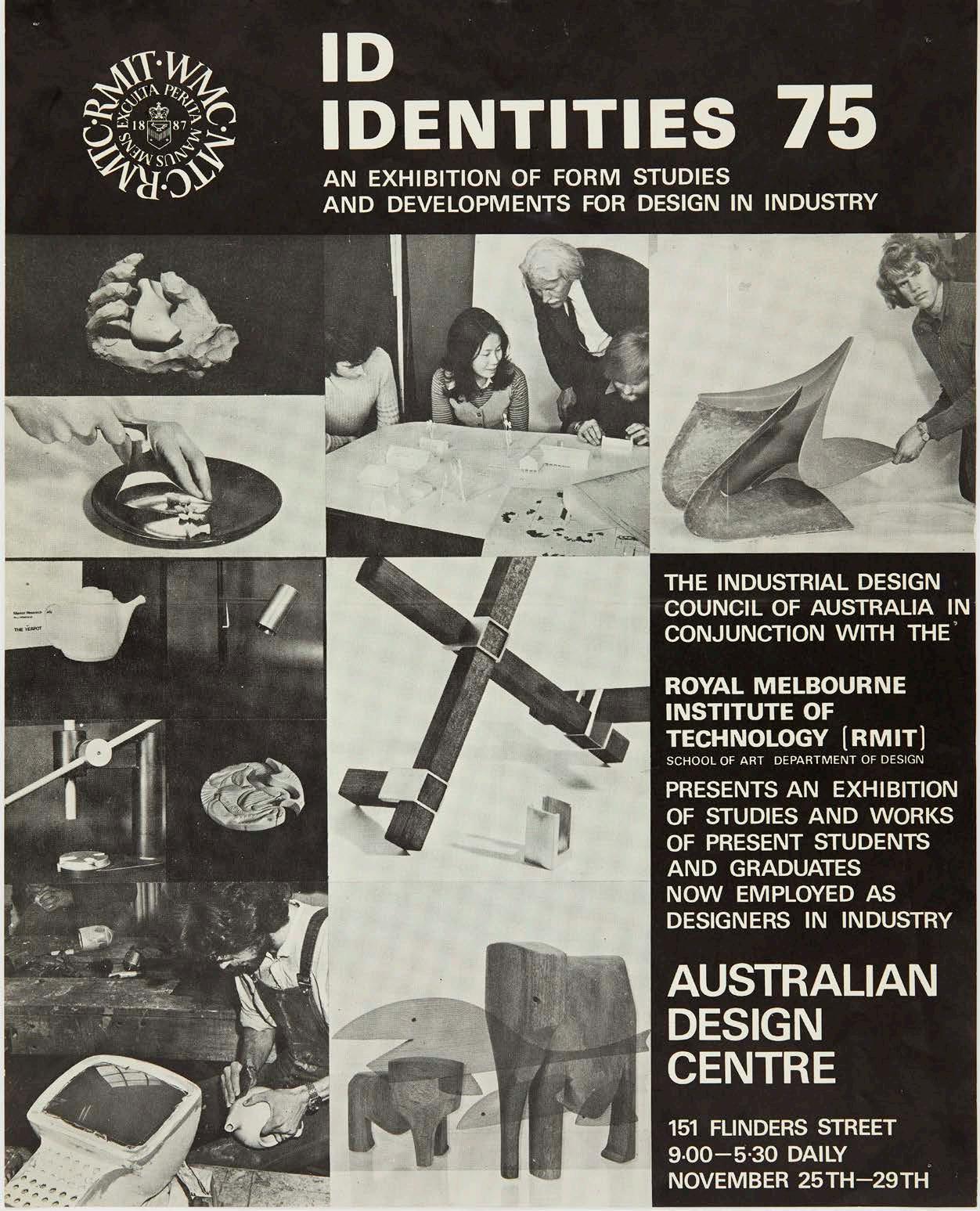

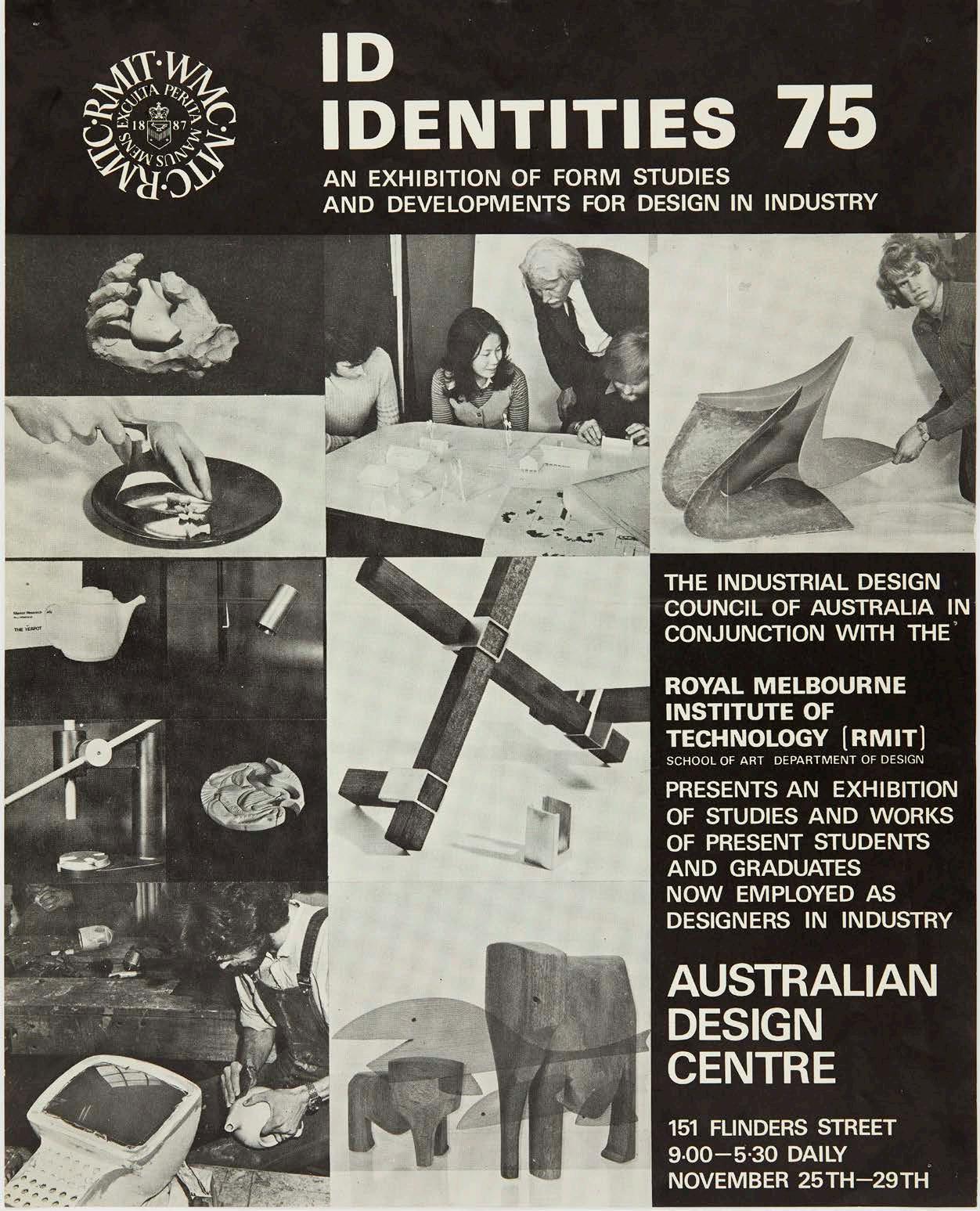

Opposite above left Gerard Herbst, ID Identities 75: An Exhibition of Form Studies and Developments for Design in Industry, exhibition poster, 1975, offset lithograph, 39.9 x 32.0 cm, RMIT Design Archives: Gerard Herbst Collection

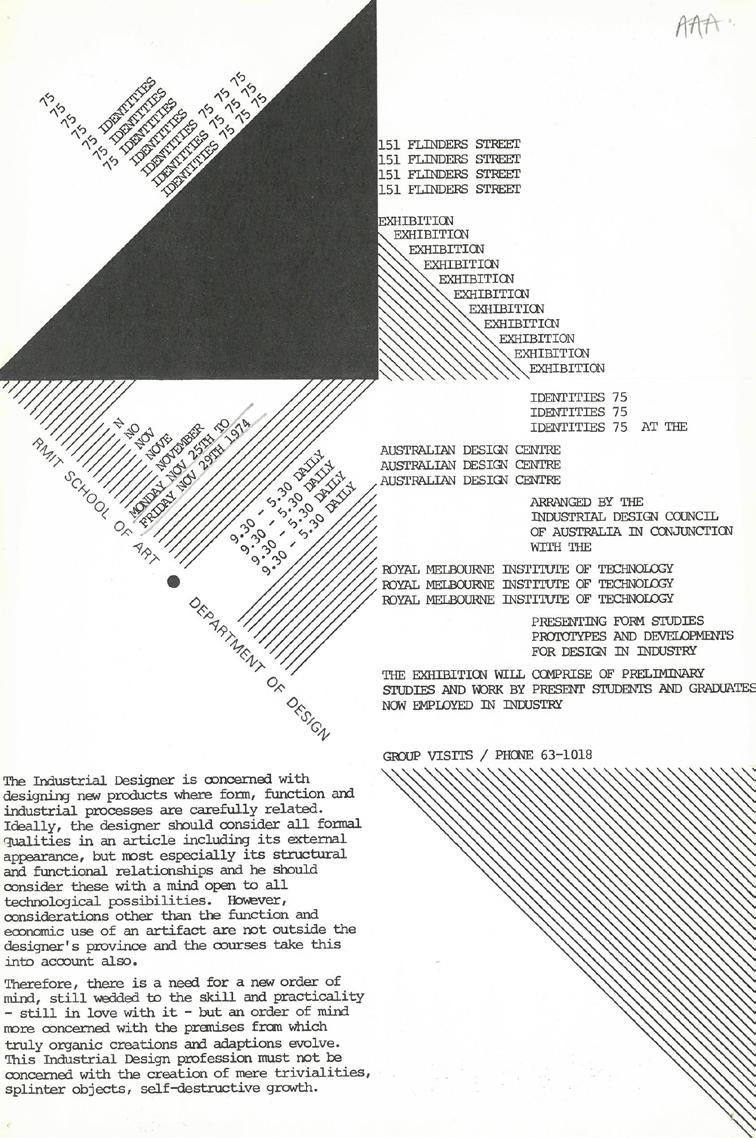

Opposite above right Gerard Herbst, ID Identities 75 press release from RMIT School of Art, Department of Design, 1975, single sheet with typeface, 33.0 x 20.0 cm, State Library Victoria Opposite below Industrial design class at RMIT, 1964. Back Row: Andrew Moran, Geoff Putnam, Derek Clark, Andrew Dixon, William Kemp, John Buckley. Front Row: unknown, Robert Gilbert, Lotars Ginters, Paul Dillon, George Nikas. Photograph attributed to Lionel Suttie, collection of Ian Wong

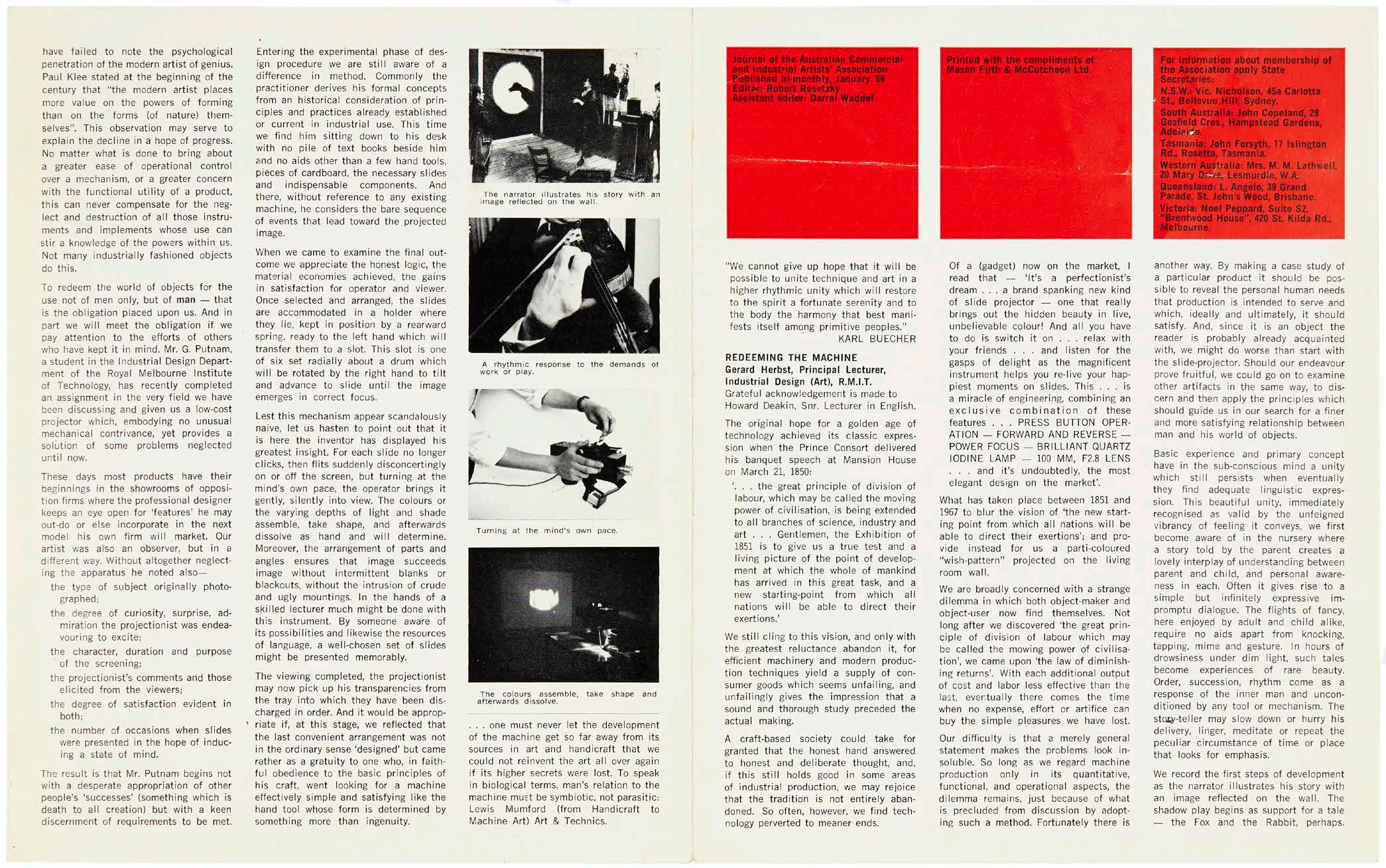

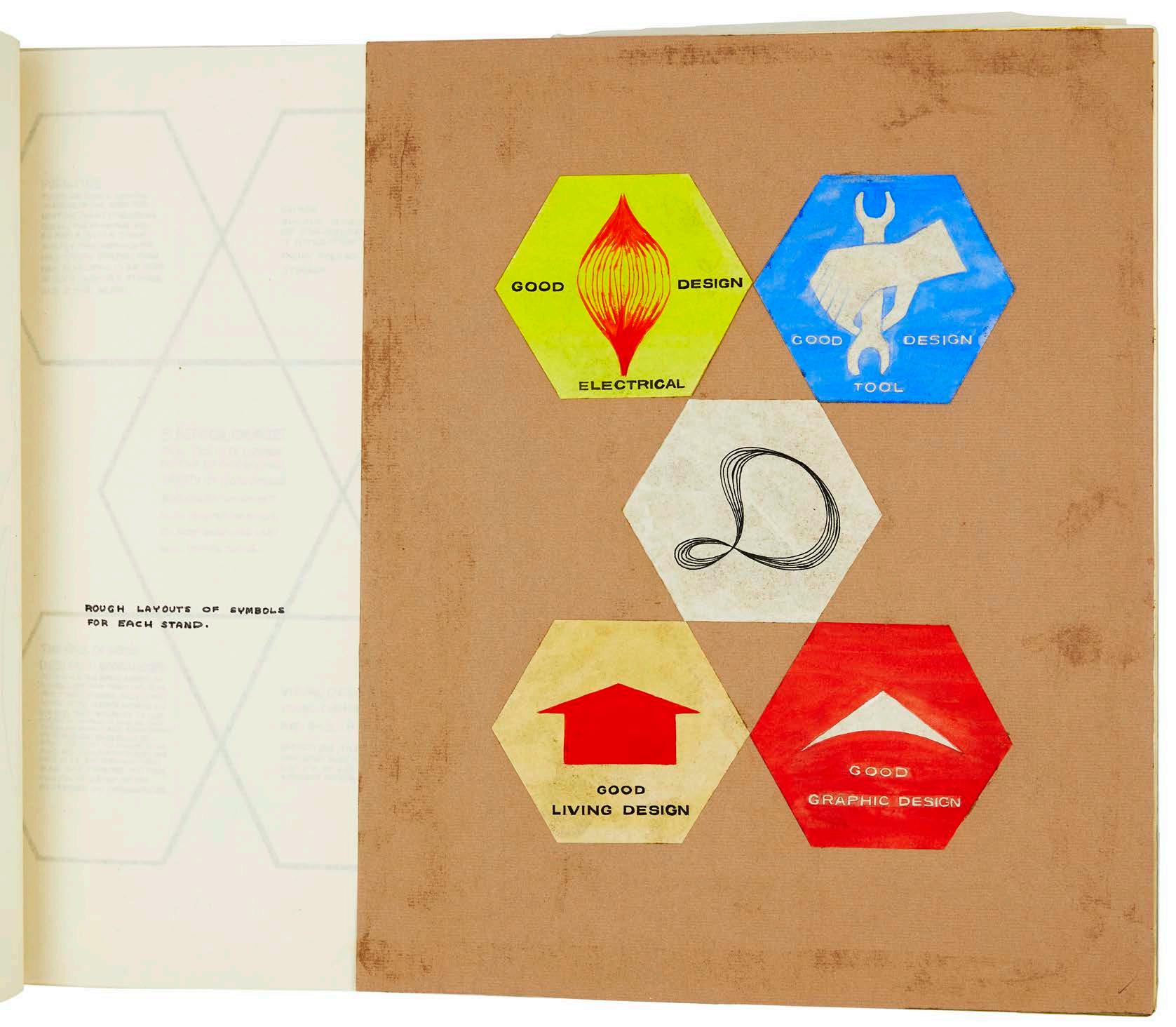

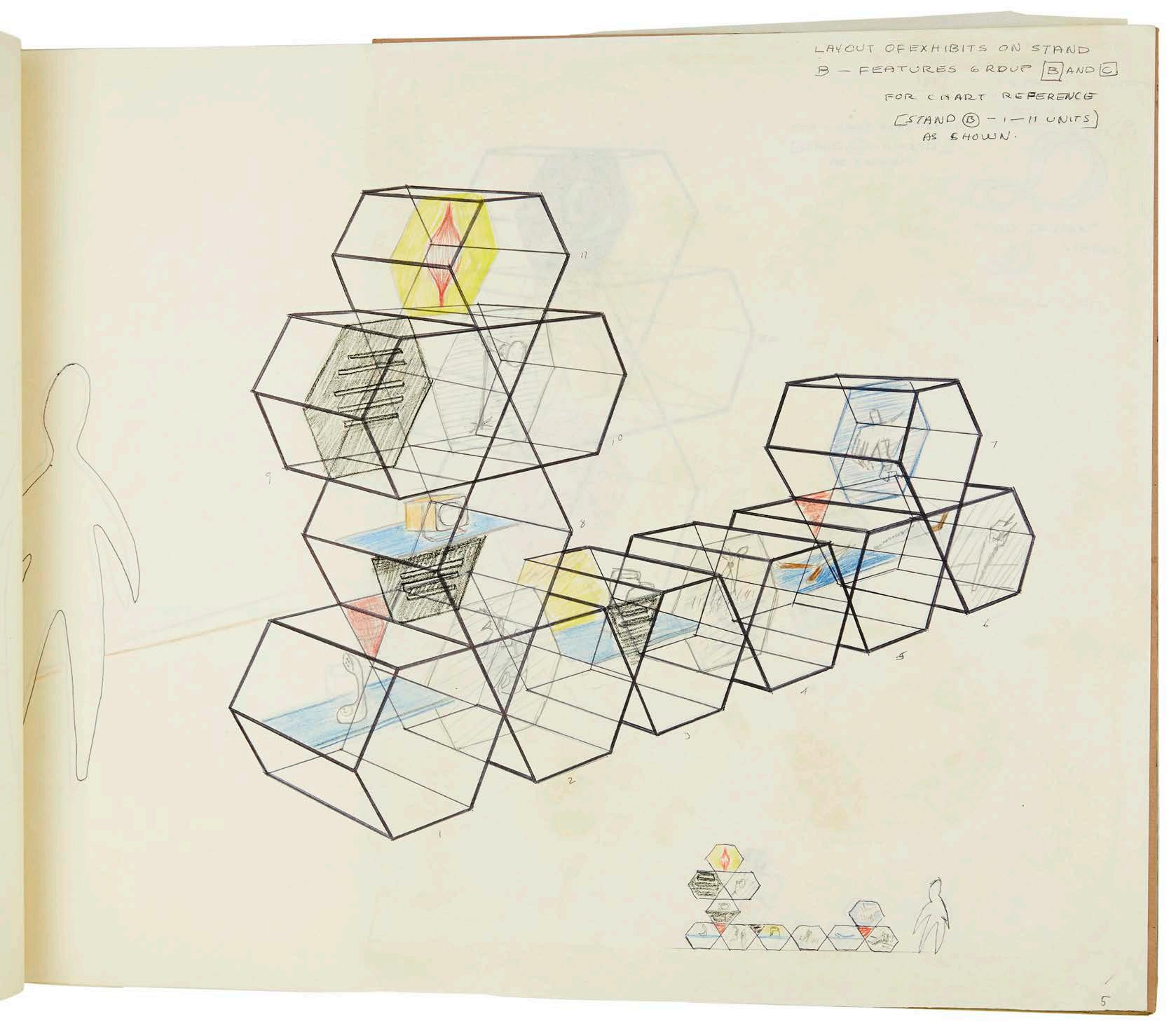

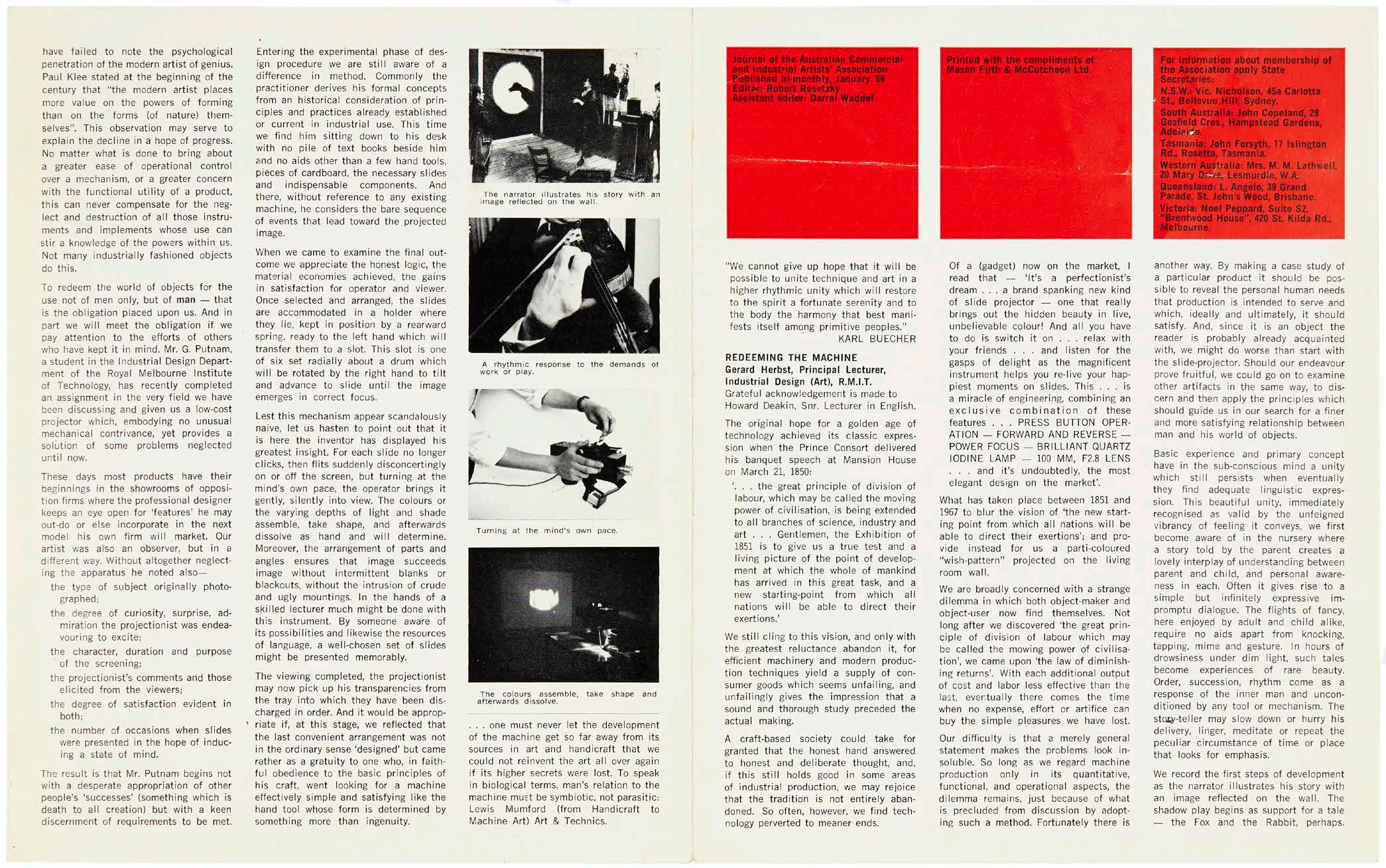

Above Gerard Herbst, ‘Redeeming the Machine’, Journal of the Australian Commercial and Industrial Artists’ Association, January 1968, RMIT Design Archives: Gerard Herbst Collection

Below

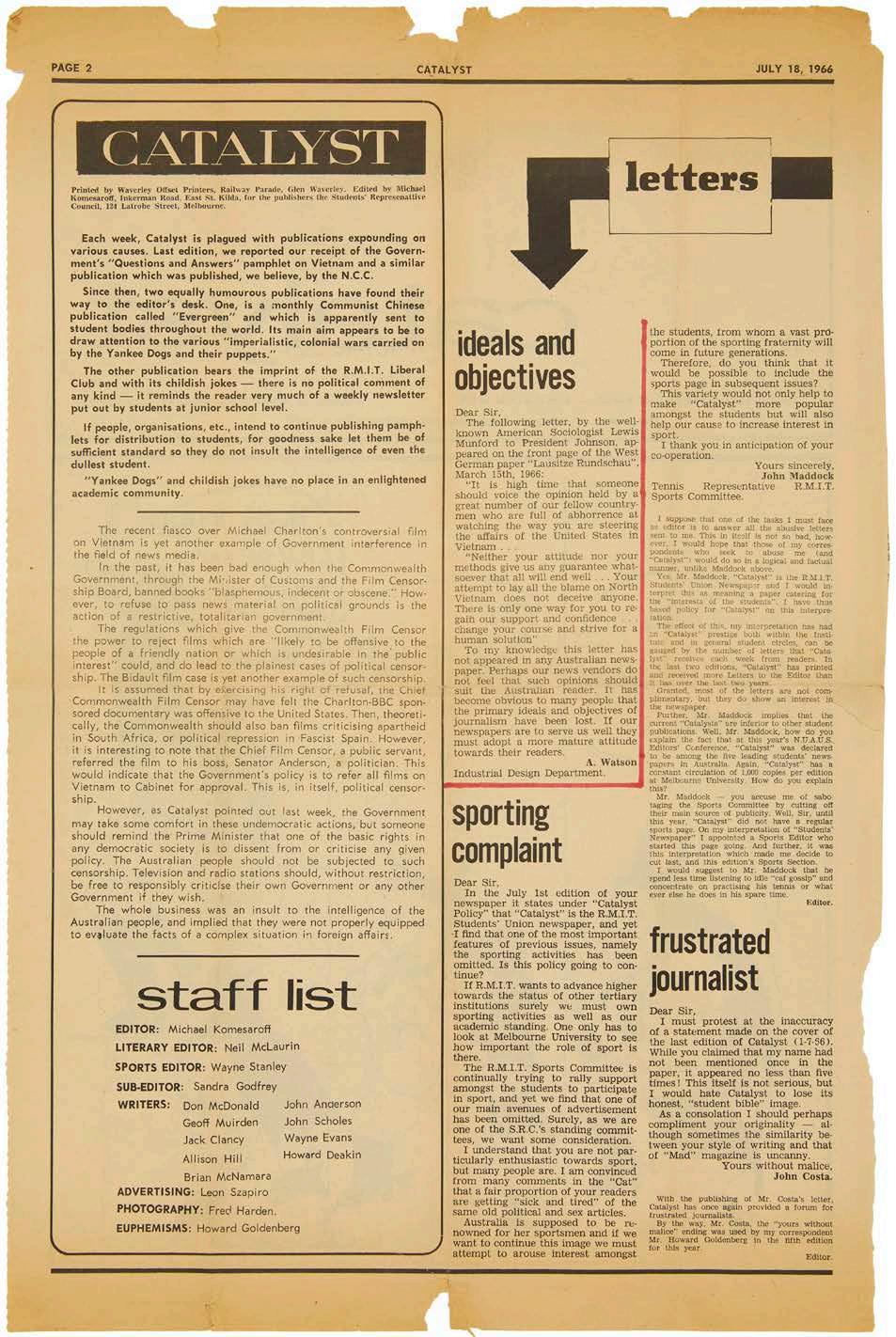

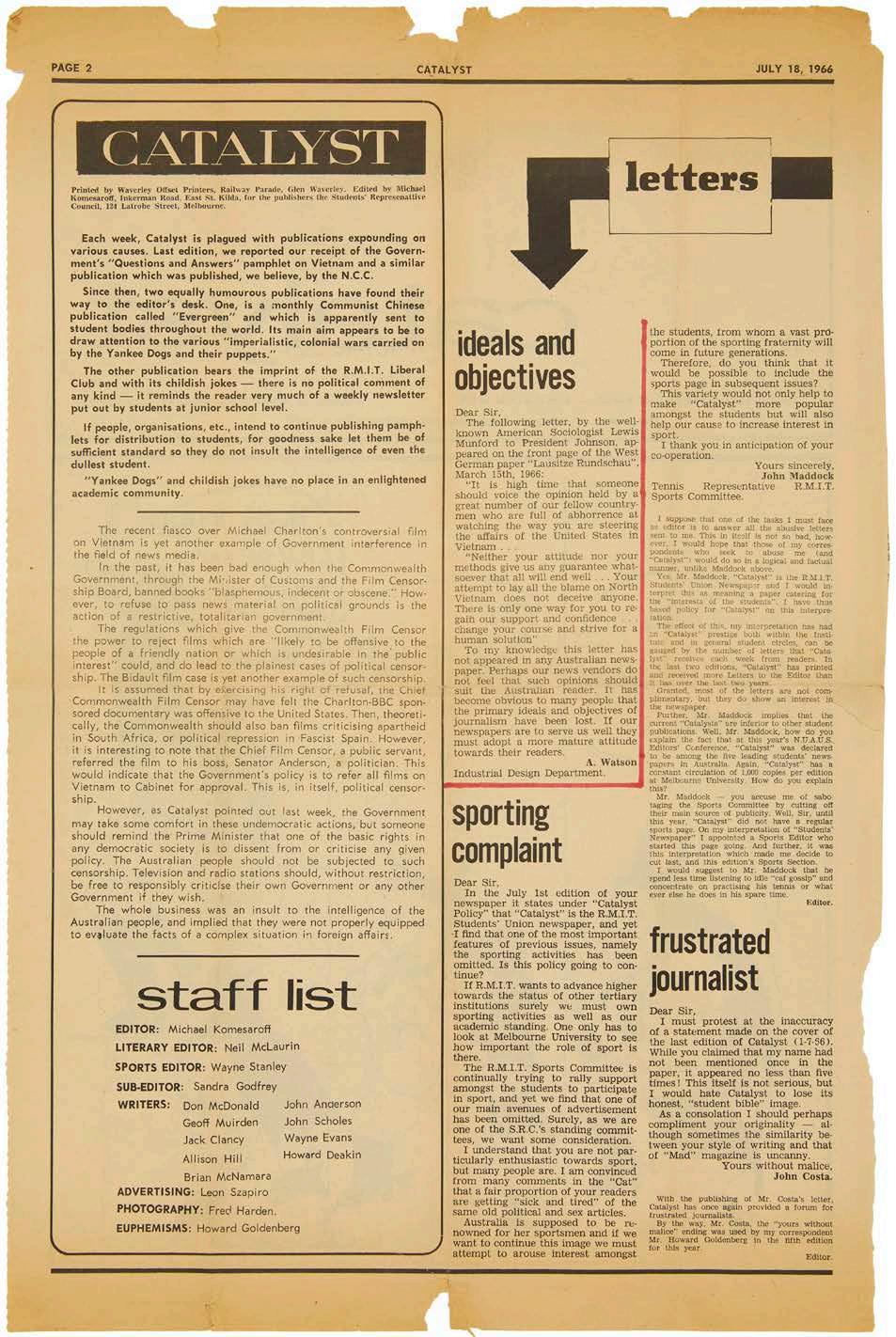

A. (Athol) Watson, ‘Ideals and Objectives’ (letter to the editor), Catalyst: Student Newspaper of RMIT, vol. 22, no. 8, 18 July 1966, p. 2, RMIT Design Archives: Gerard Herbst Collection

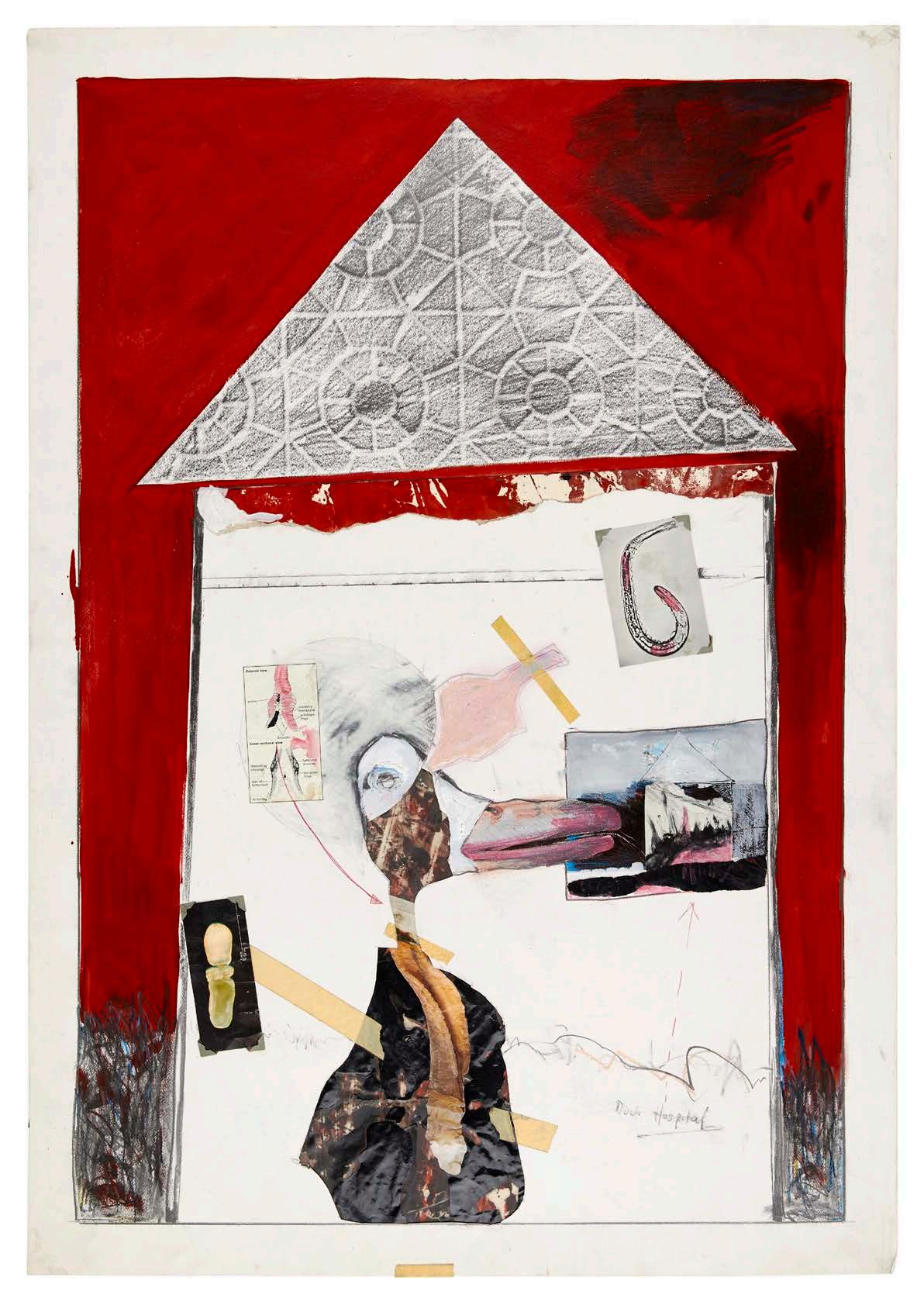

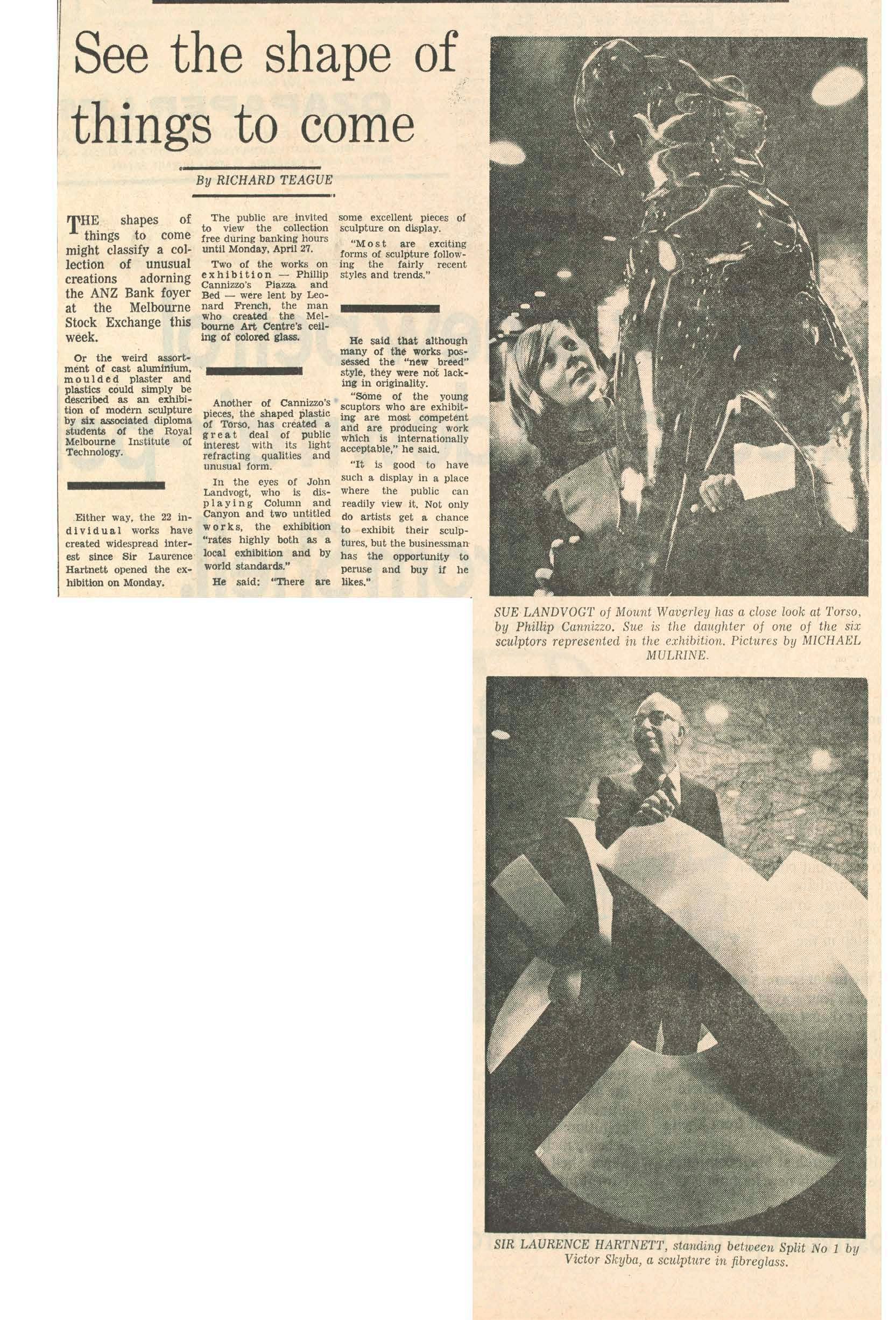

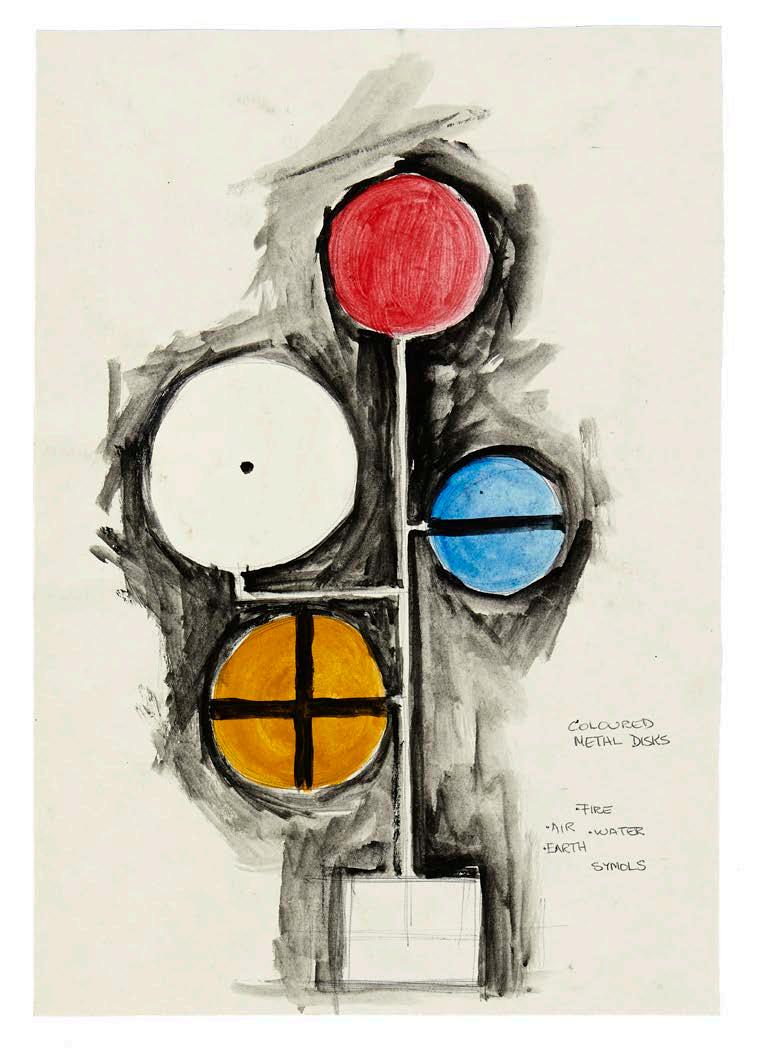

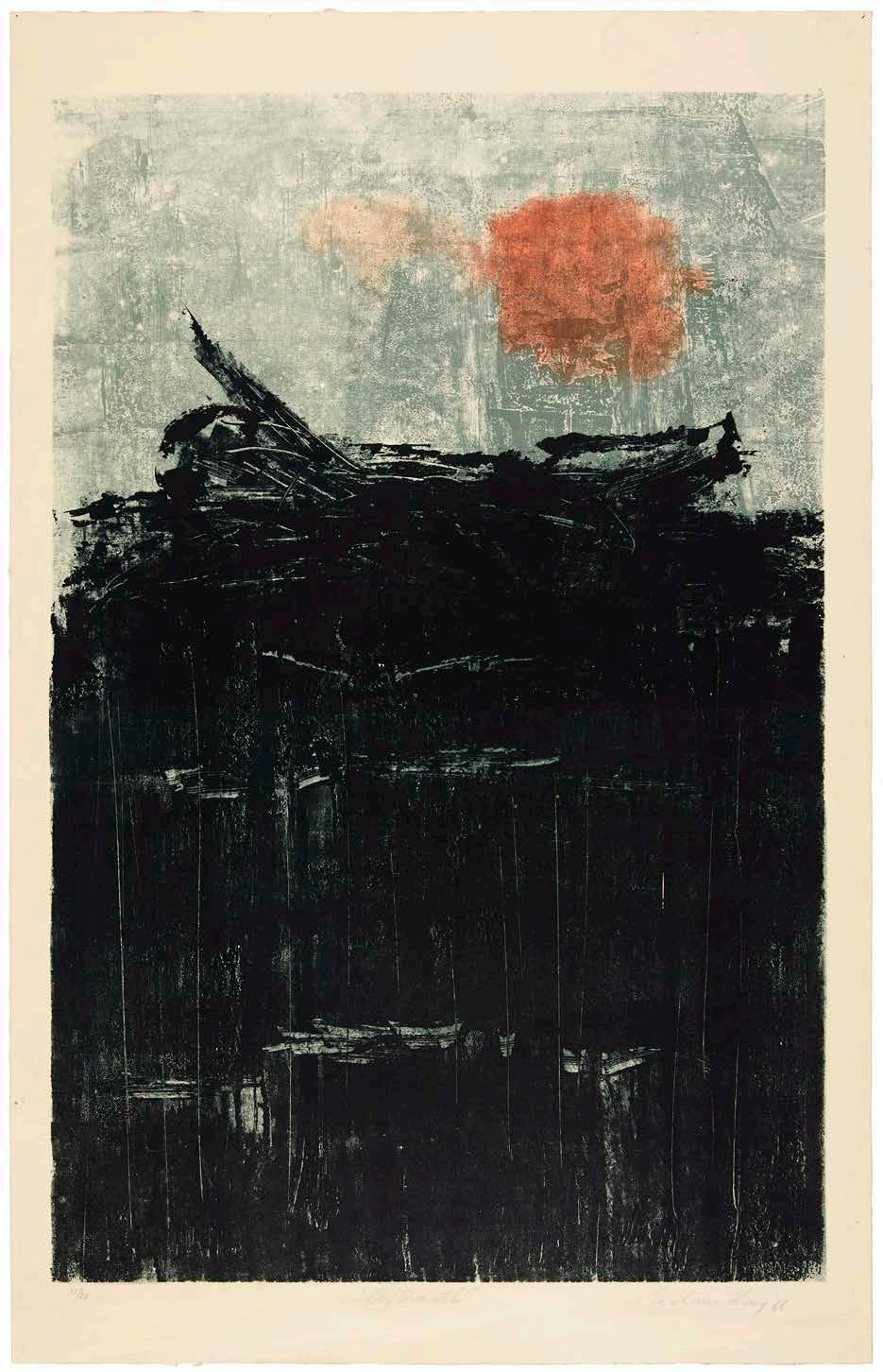

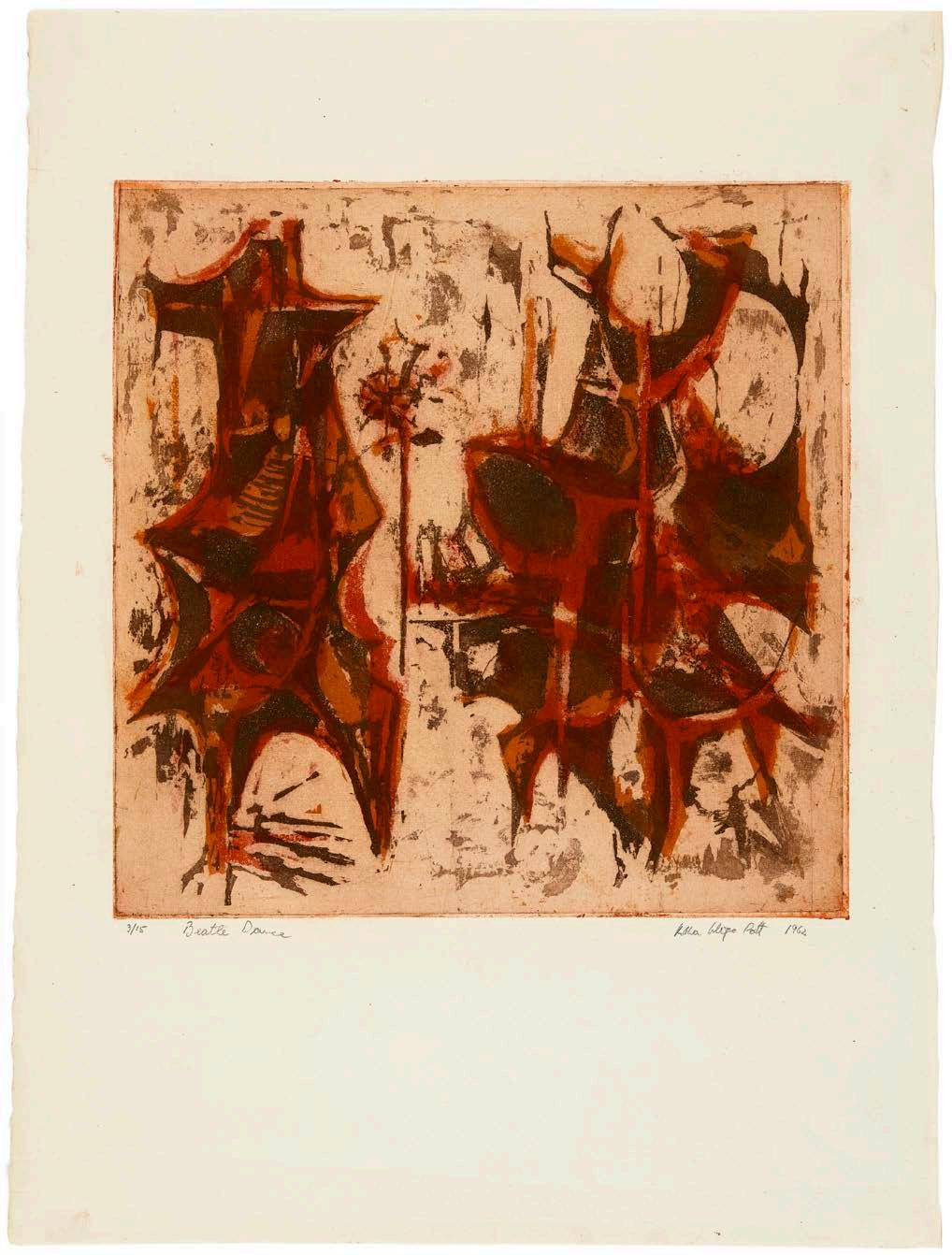

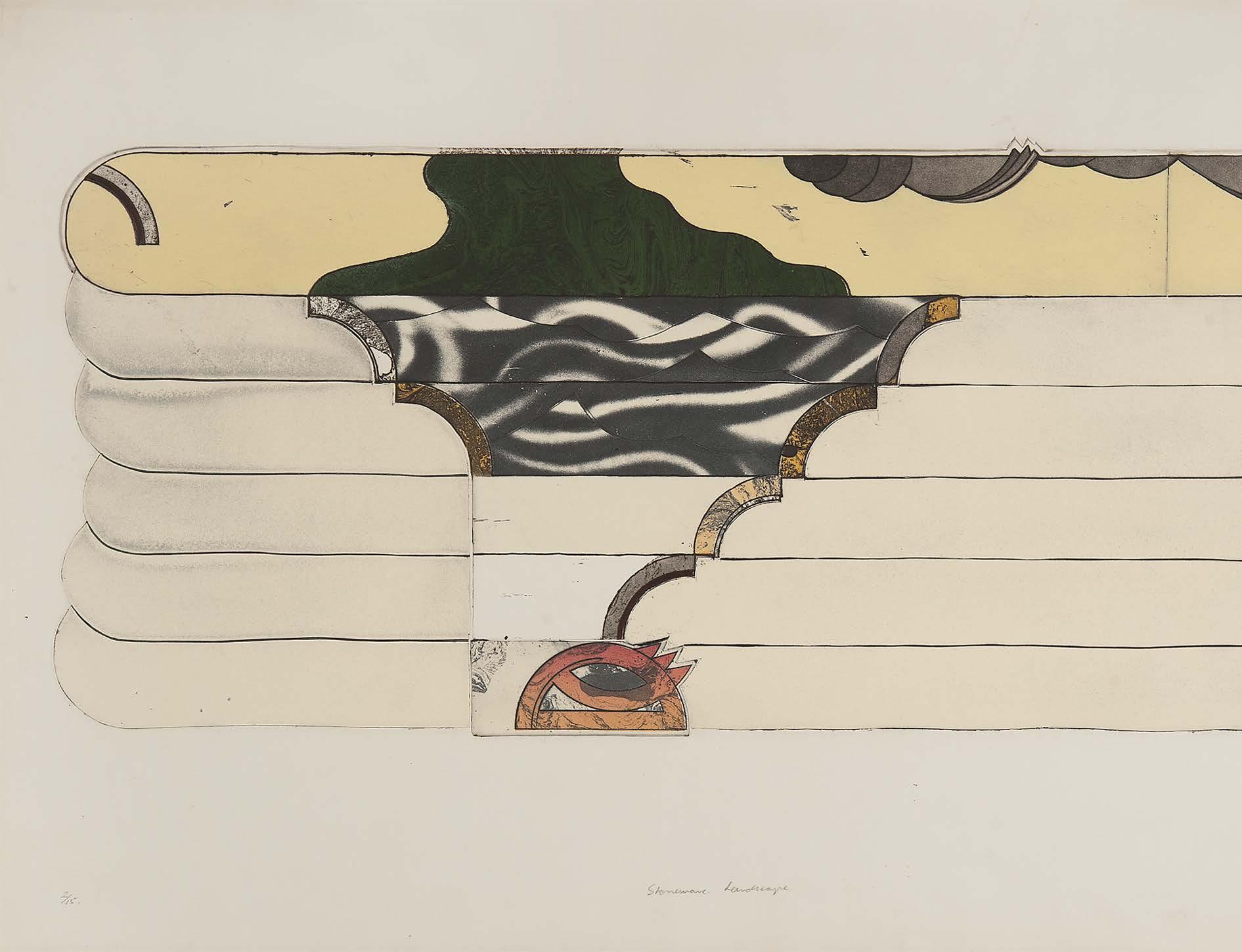

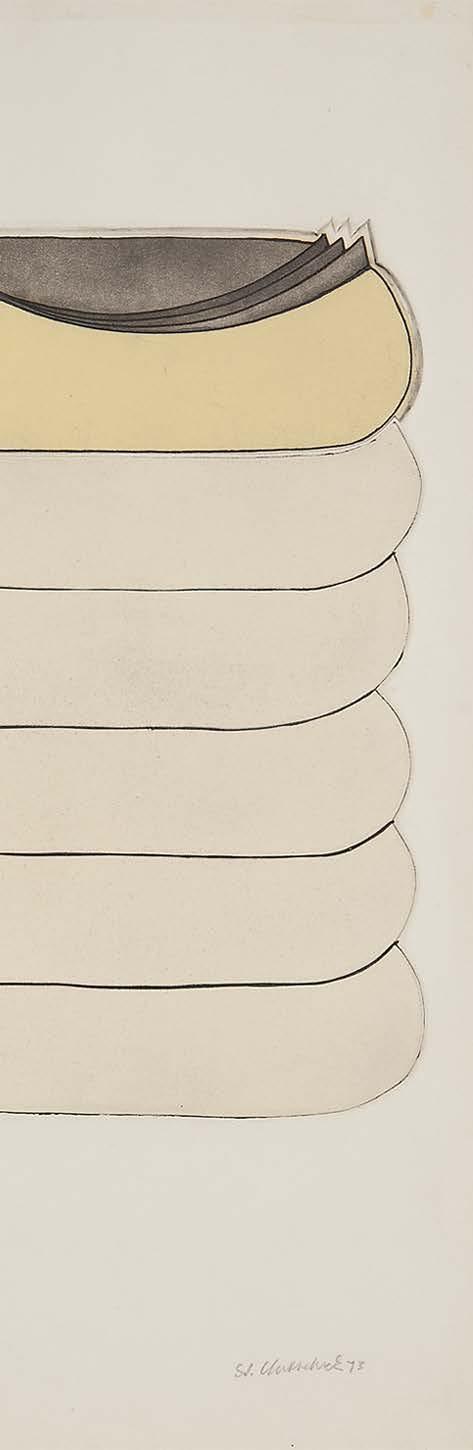

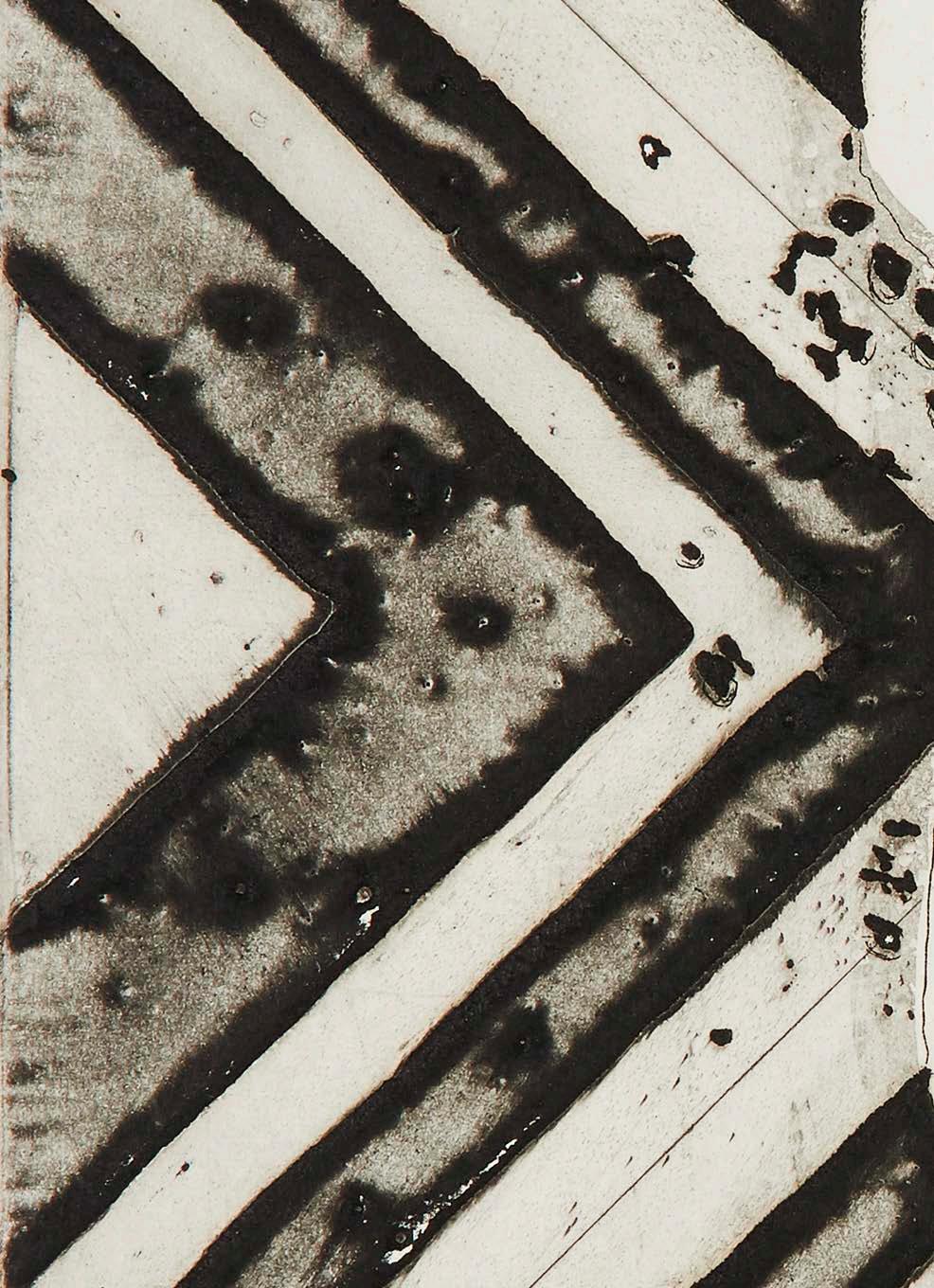

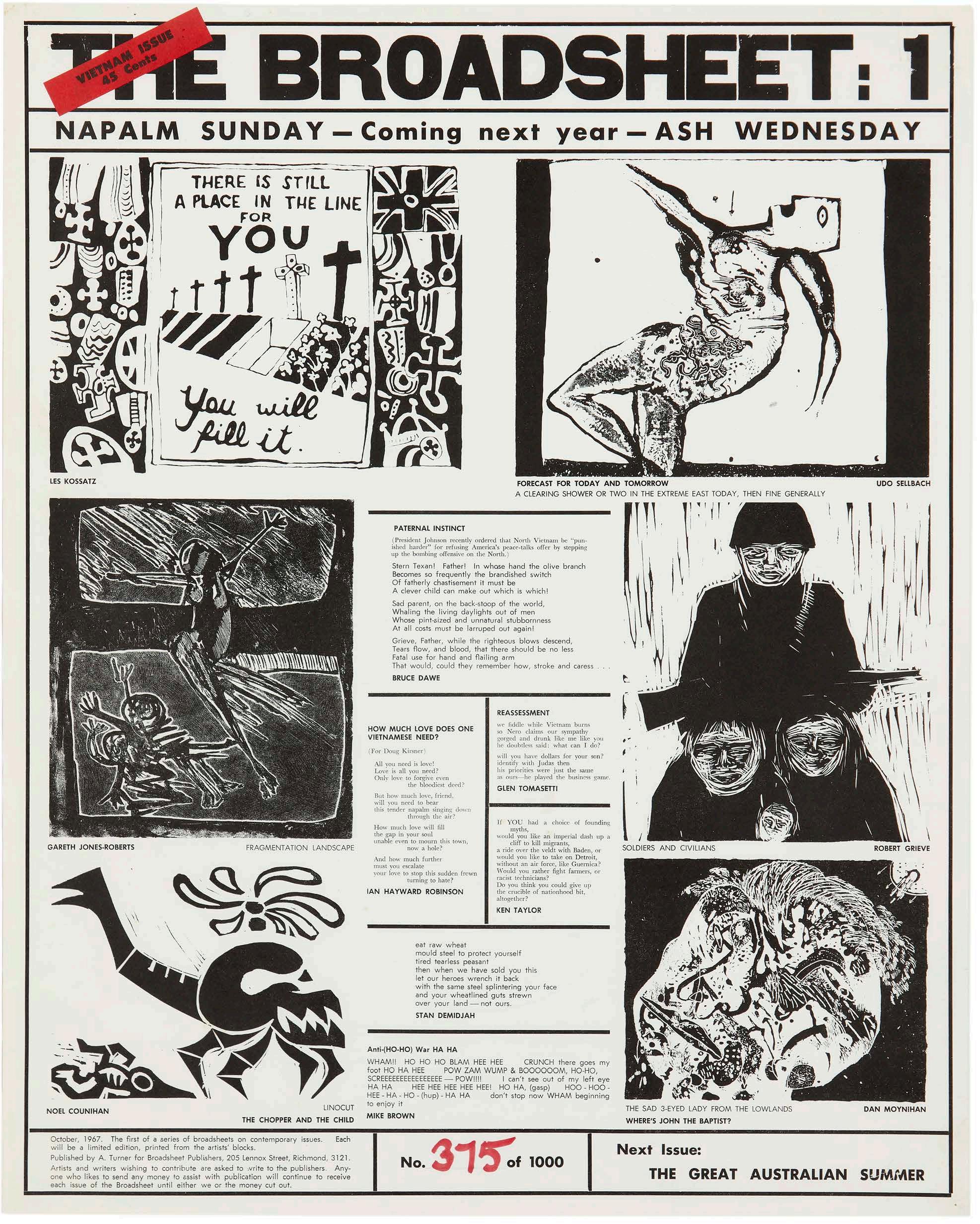

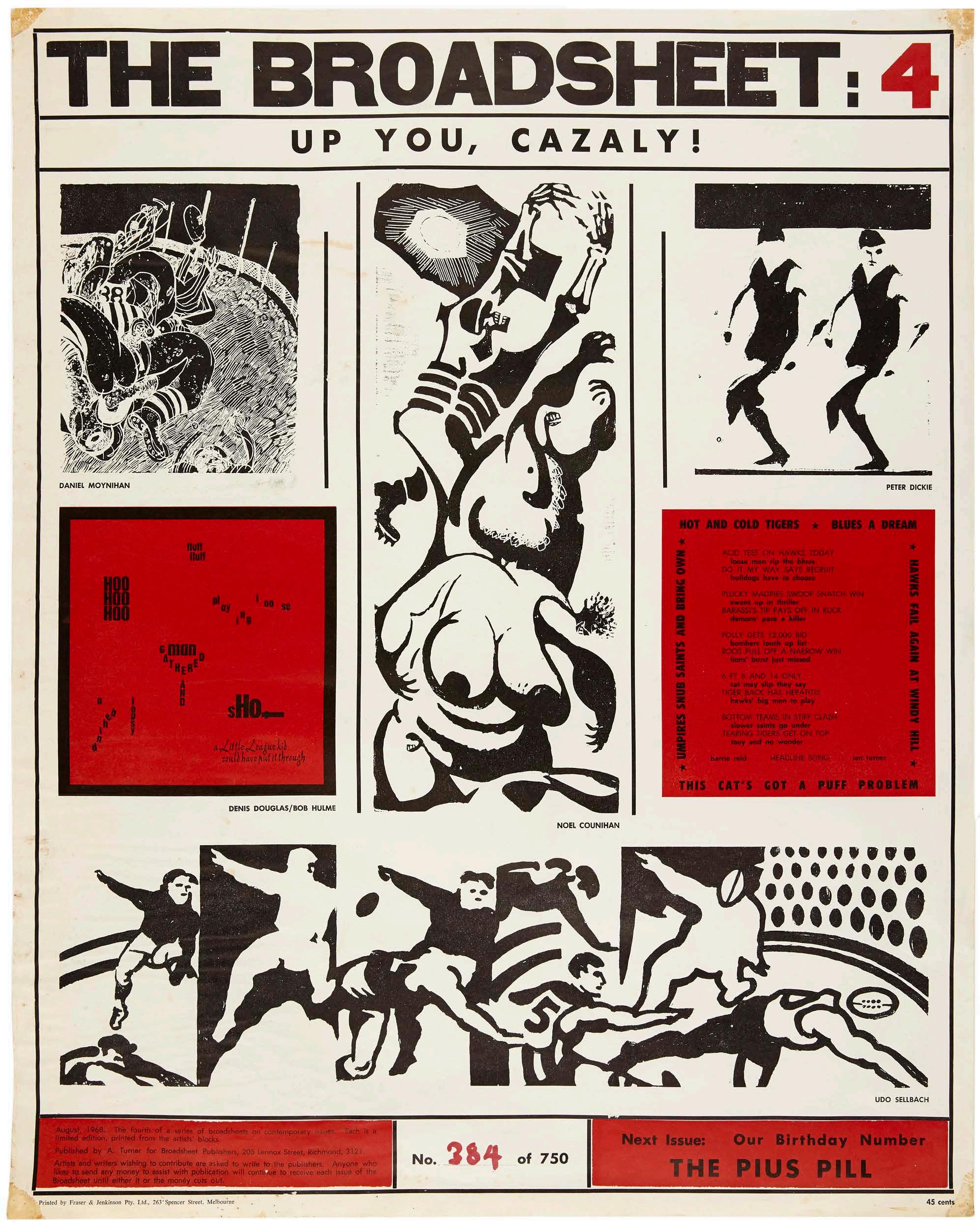

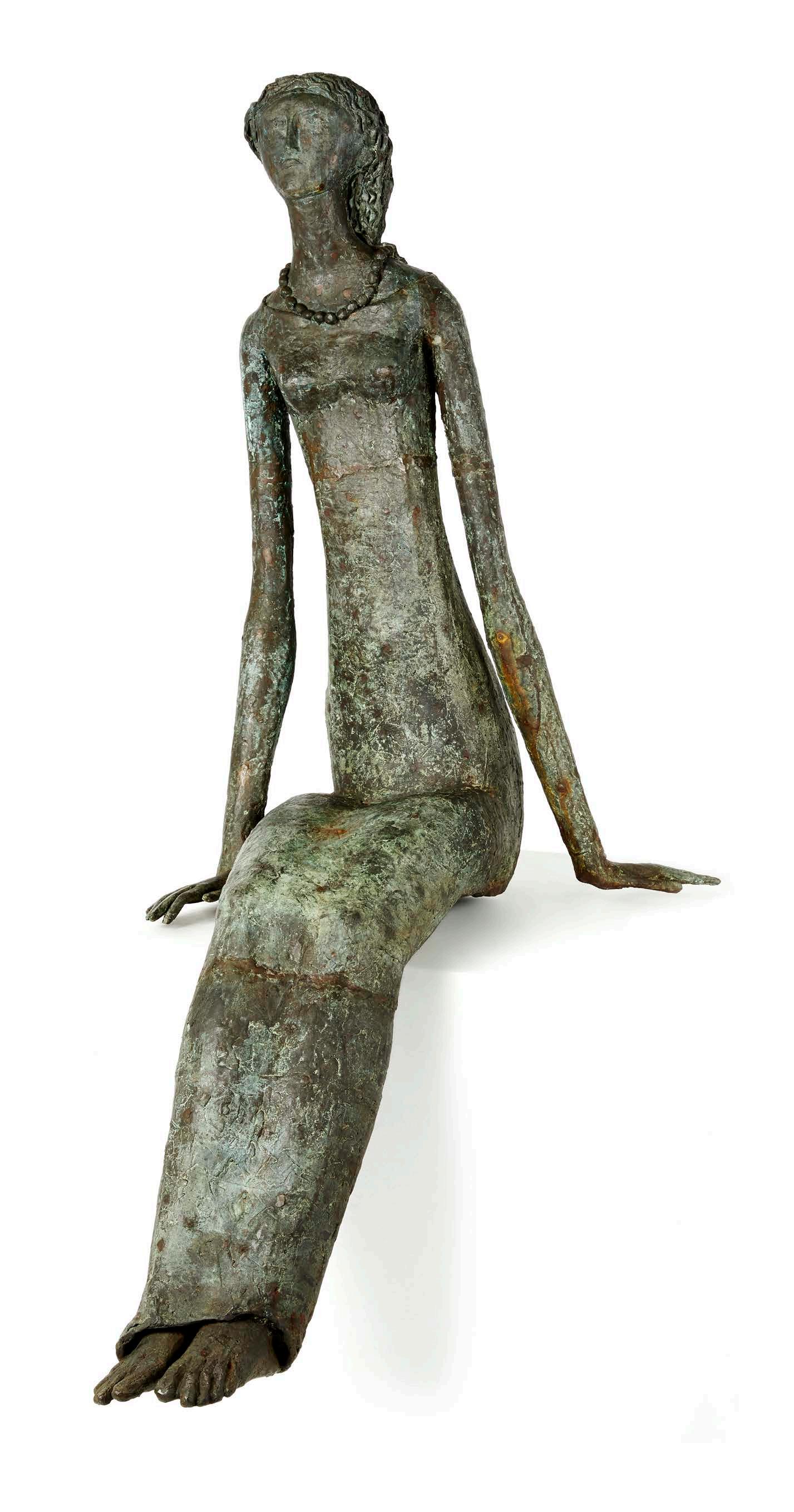

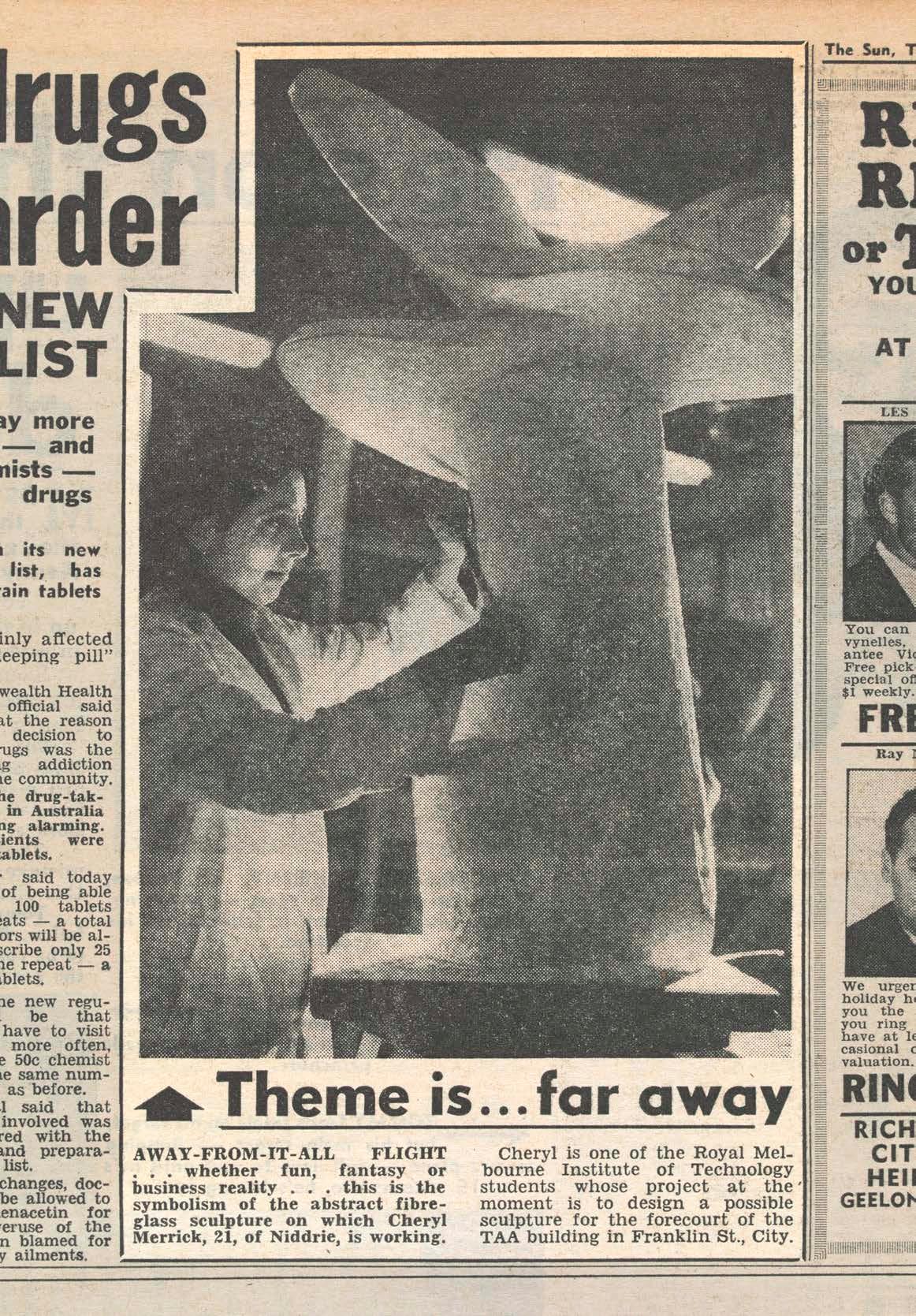

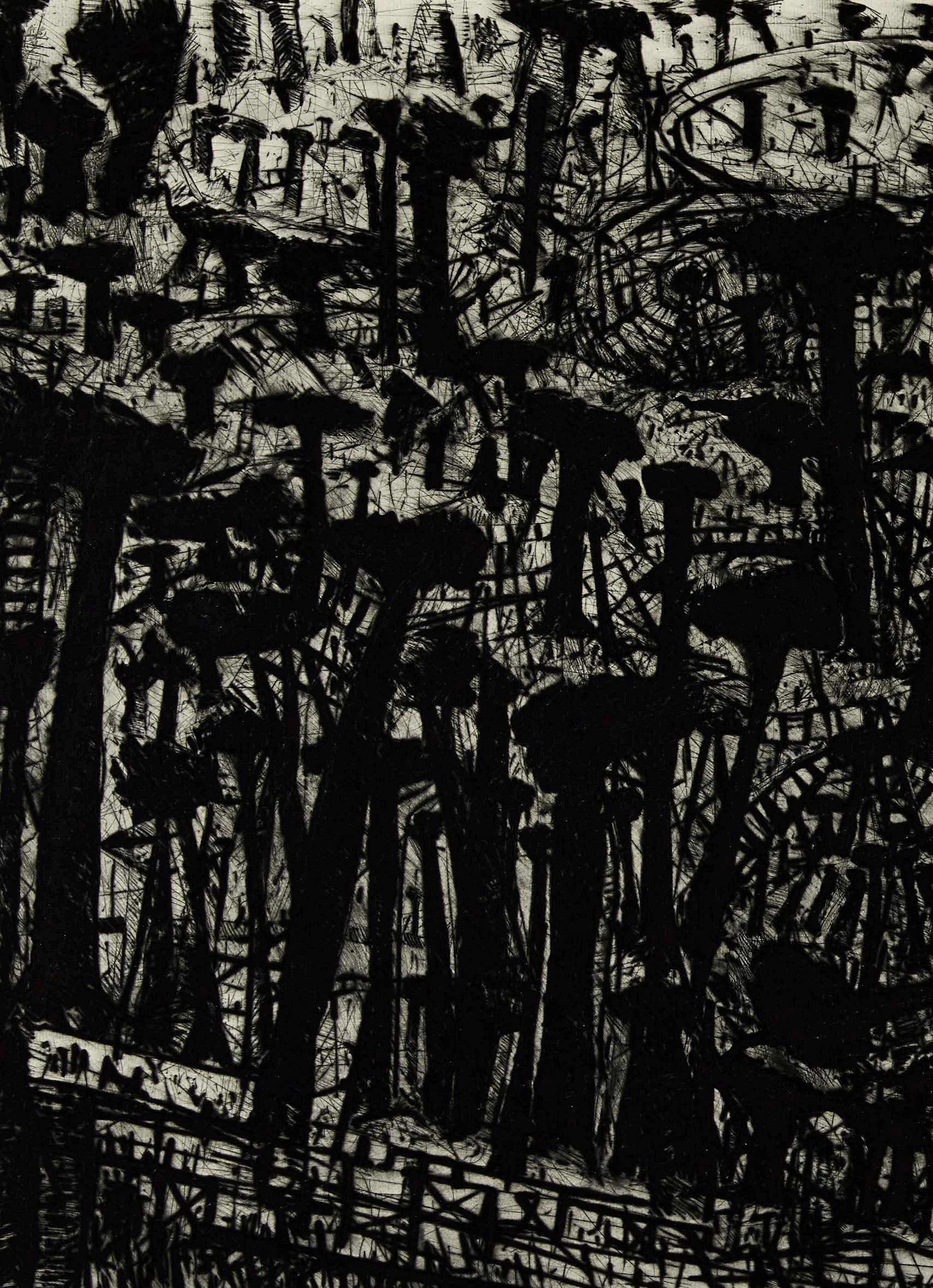

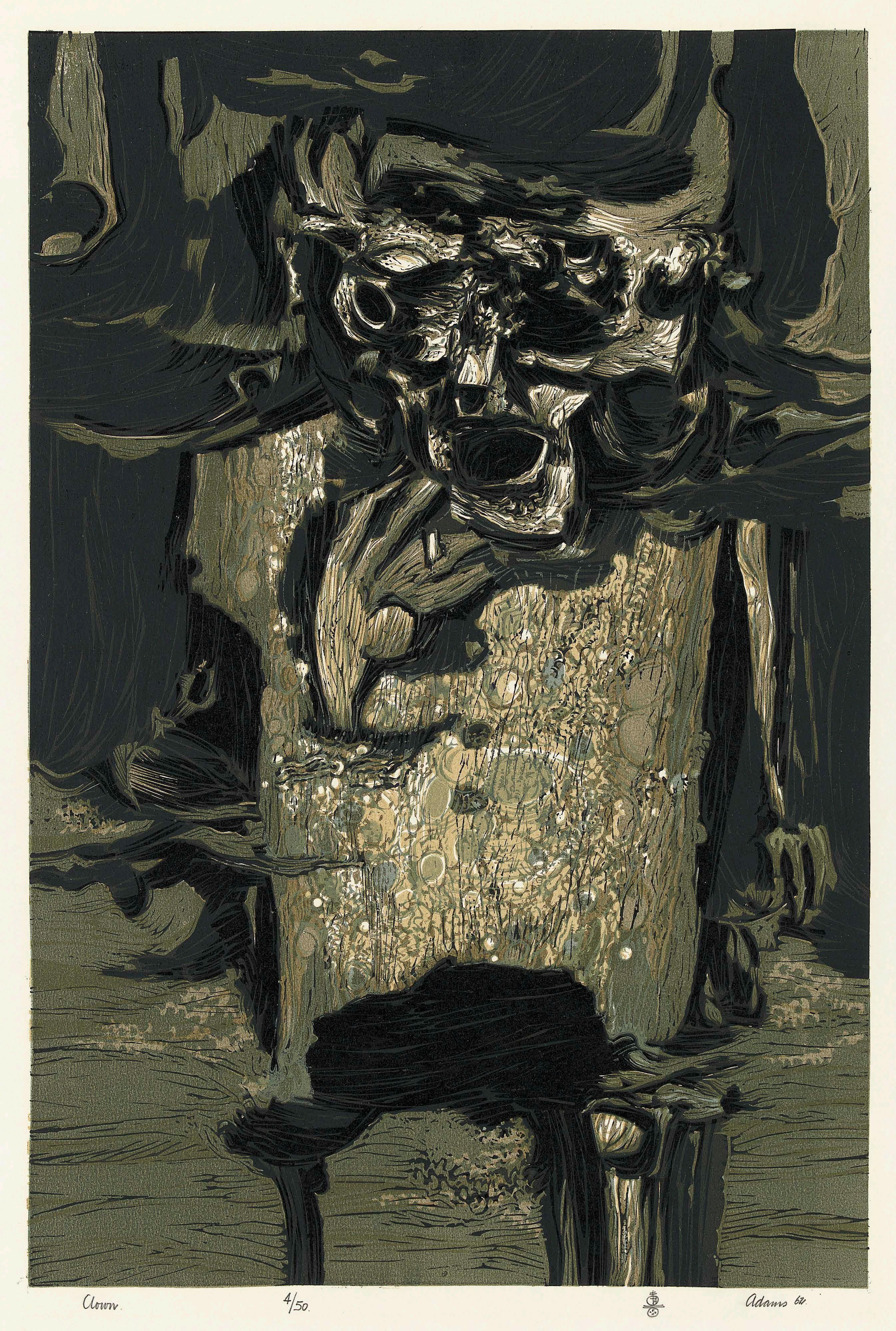

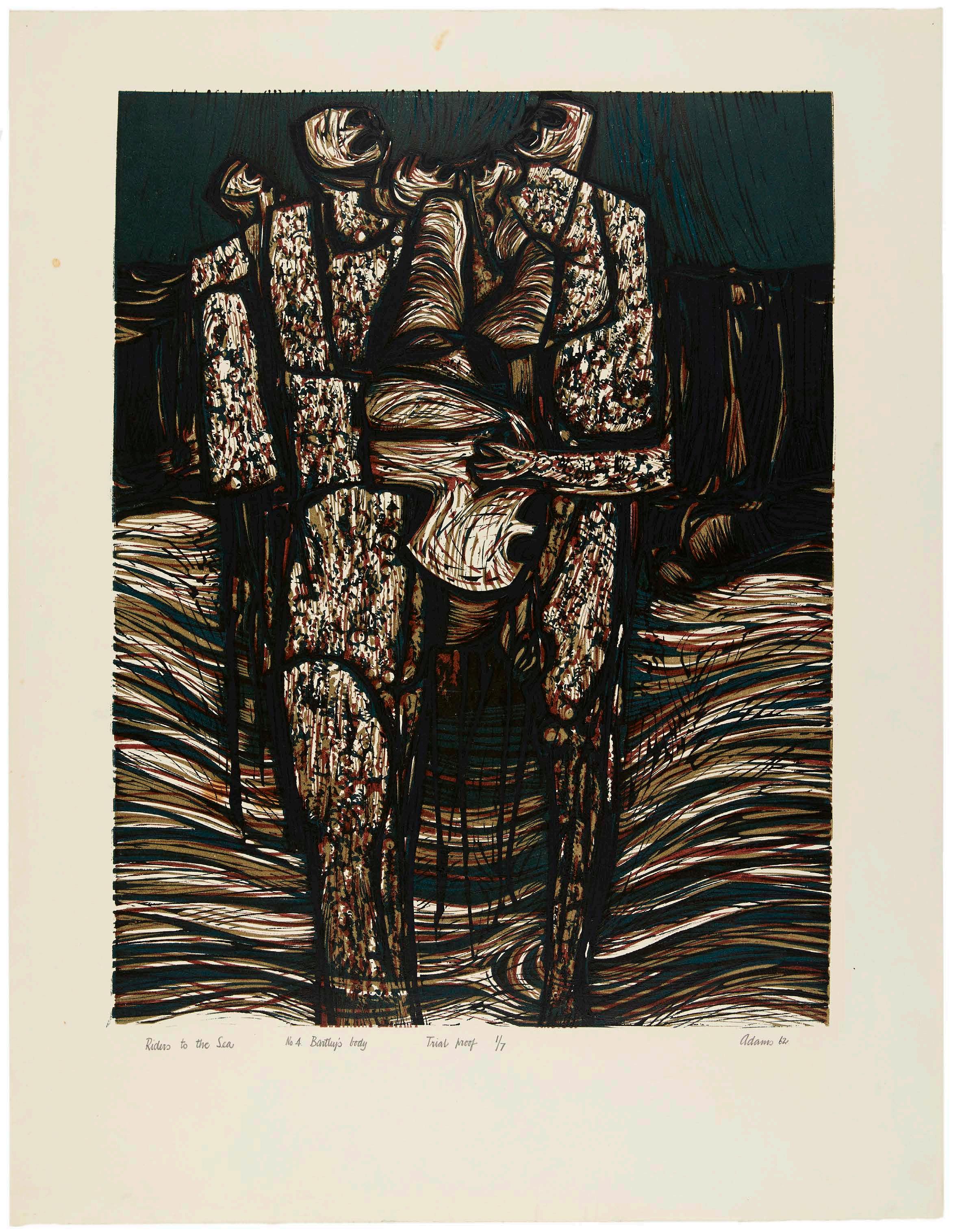

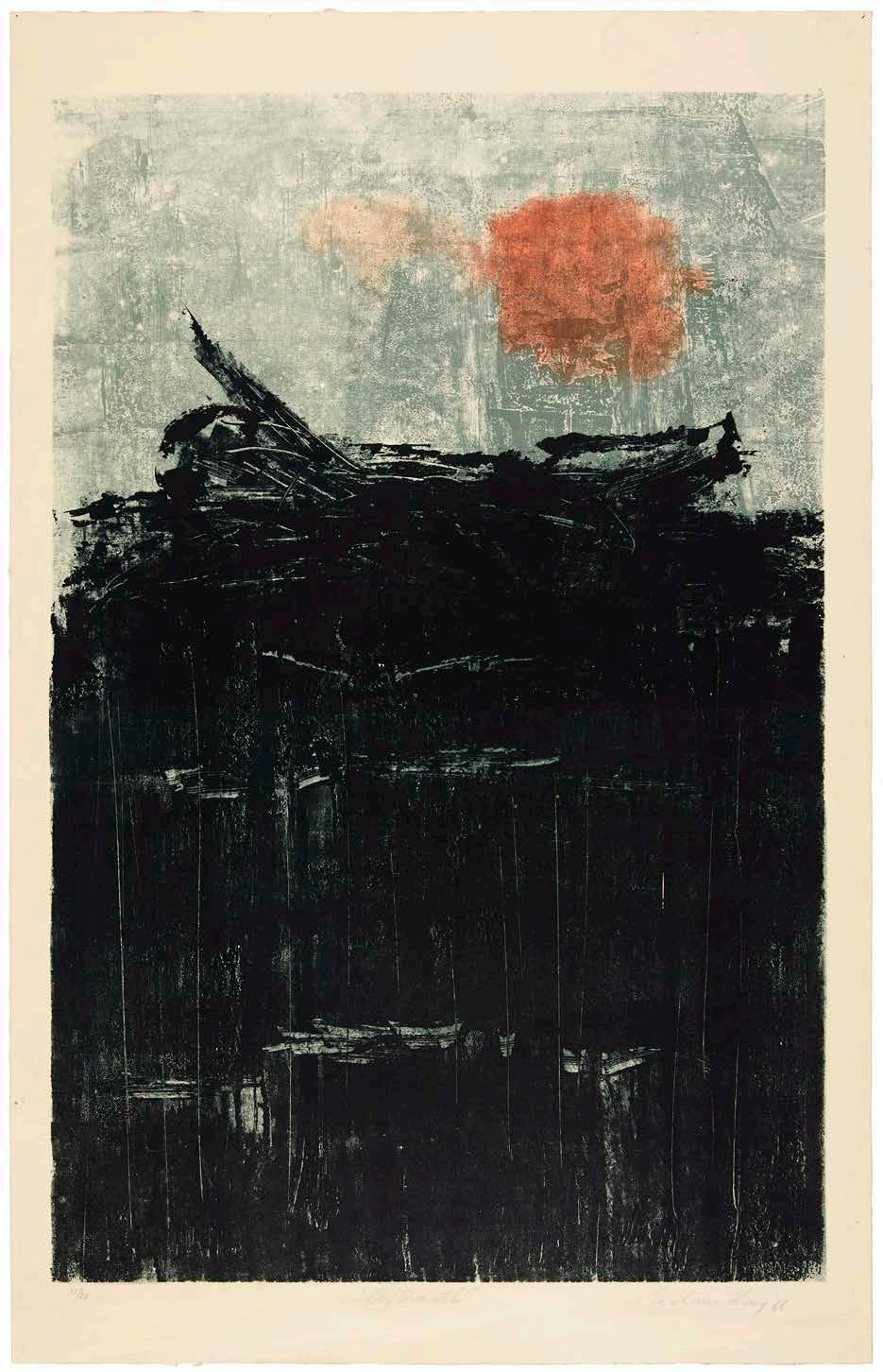

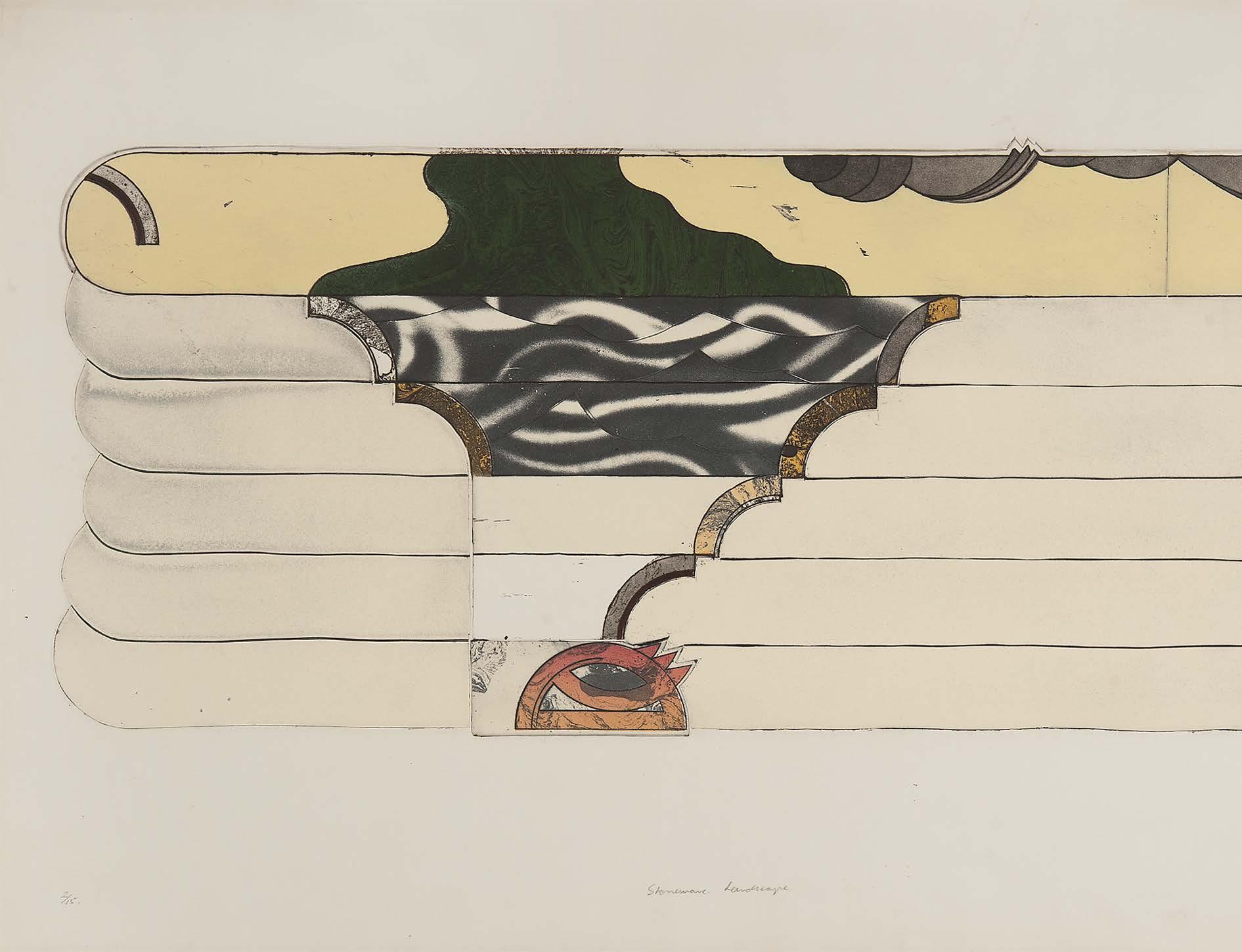

MELBOURNE MODERN 51