water+ wisdom Australia India

All life depends on access to water. This reality is part of the shared consciousness of Australia and India. Both were part of the supercontinent Gondwana 100 million years ago, sharing in East Gondwana, the Indo-Austra lian plate for 40 million years until about three million years ago.

The residue is a geology that has an ancient connection. Australia and India now share similarities of high rainfall variability, long established practices of customary water management and competing demands for water from different sectors.

The Ganges and the Murray-Darling, for example, share the acute strains of flowing through multiple countries and state jurisdictions respectively, and both support vital food bowls as well as other primary production.

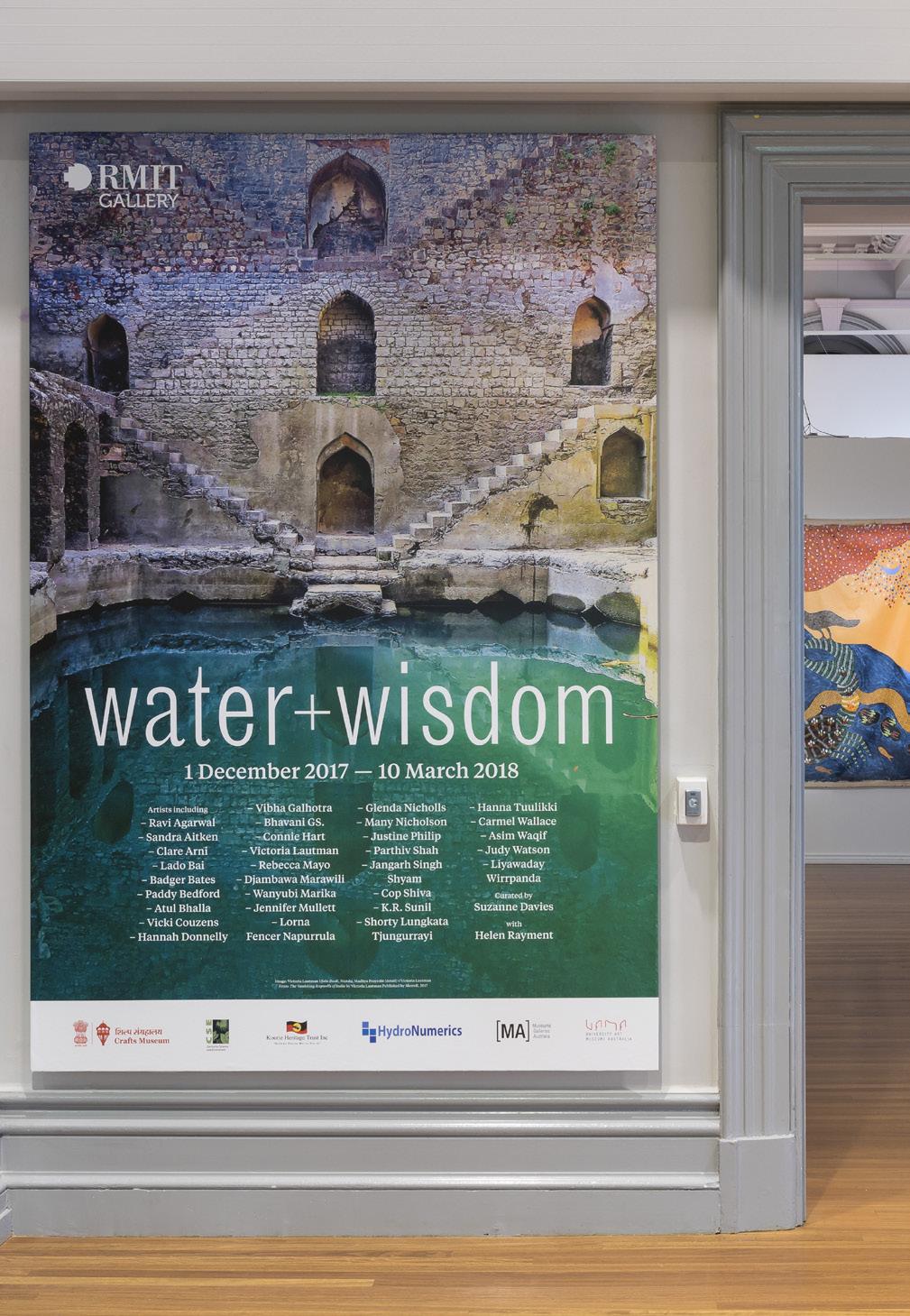

The exhibition water+wisdom: Australia India (1 December 2017 – 10 March 2018) looked at the importance of natural waterways in our everyday lives, and explored how artists, writers, researchers and filmmakers in both countries continued to tell the story of the stewardship of water through creative activities.

In 1999 the Australia-India Council supported an initiative that brought together two Indigenous Australian artists, Djambawa Marawili and Liyawaday Wirrpanda, and two Indian artists, Jangarh Singh Shyam and Lado Bai, to create a collaborative work of art. They began making a painting at opposite ends of a large canvas to create a landscape of hills and forests inhabited by mythical animals. As they approached the middle, the question of how to conclude was resolved when they collaborated on painting the river, confidently exploring each other’s territory. The work, and its resolution, was a symbol of shared interest in each other’s landscape, and revealed a shared knowledge of the importance of water.

Page 3

Cop Shiva

The Water Agora series, 2015 – present 26 digital photographs, Courtesy of the artist

Page 4

Installation view, water + wisdom Australia India, RMIT Gallery. Photo Mark Ashkanasy, 2017

water+wisdom: Australia India showcased the work of more than 40 creative practitioners and researchers to relay stories about the importance of water. They covered topics such as: spiritual practice, the economy, transportation, the flow of diasporas and family relationships; weaving connective threads of the rich cultural, economic and ecological flow of water across two continents which were once linked.

In the neutral but thought provoking space of RMIT Gallery, we explored the ramifications of poor water management and it’s far-reaching consequences. The artists featured told dramatic stories in regards to river pollution and destruction.

We ignore the responsibility to the waterways at our peril. Poetic responses to practical realities encouraged deep reflection about our own relationships with the most precious resource we all share, although not all equally: the access to clean and plentiful water. Much is at stake.

In shaping the exhibition, we relied extensively on research by experts from India and Australia to augment customary knowledge regarding water stewardship on both continents. In dialogue with transdisciplinary water experts across RMIT University and the wider industry, we liaised with academics, researchers, engineers and architects.

The outcome was multi-layered in approach, and energetic in its outcomes. We thank our collaborators and the artists involved.

Water is a political issue but the human connections to water across cultures are forceful. In water+wisdom: Australia India, we contemplated the greatness of water in our lives to bring to the fore a focus for the future.

Suzanne Davies and Helen Rayment76 x 60 cm,

Water = life. What happens when we run out?

As part of RMIT Gallery’s water+wisdom: Australia India exhibition, an important international symposium on 2 March 2018 provided an opportunity to be inspired, network and explore ideas about creative responses to ancient wisdom regarding water.

We asked artists, researchers and activists how they continue to tell the story of the stewardship of water through their work. We wondered what could be learned from traditional knowledge to prevent a water crisis similar to that which recently threatened Cape Town.

Indian activist Parineeta Dandekar, who recently received the Vasundhara Mitra award in the activist category for her work in river management, river rejuvenation and river conservation, presented the symposium’s keynote address.

These edited extracts from all the speakers’ presentations reflect the range of insights into ways we might work creatively to ensure the constant supply of earth’s most precious substance, that is water.

Parineeta Dandekar

Coordinator, South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People

Vibha Galhotra

Conceptual artist, represented in exhibition

N’Ahweet Carolyn Briggs

Indigenous language specialist and Boonwurrung Elder and researcher represented in exhibition

Aunty Di Kerr

Wurundjeri Elder and researcher represented in exhibition

Rueben Berg Victorian Environmental Water Holder Commissioner

Dr Matthew Currell

RMIT Senior Lecturer, Hydrogeology and Environmental Engineering

Dr Justine Philip

PhD Ecosystem Management, Museum Victoria Associate and represented in exhibition

Dr Sandra Brizga

River Management specialist and researcher represented in exhibition

Deborah Hart Arts-focussed activist and writer

Glenda Nicholls

Artist represented in exhibition

Carmel Wallace

Artist represented in exhibition

Judy Watson

Artist represented in exhibition

The water+wisdom symposium was held in front of a capacity audience from 10am-4 pm on 2 March 2018 at RMIT Storey Hall, 336 Swanston Street, Level 7, Green Brain Conference Room.

Eel Trap, 1987 natural fibres, 34 x 93.5 x 38 cm approx. Koorie Heritage Trust Collection

Eel Trap, 1991 natural fibres; reeds, 29.2 x 92.5 x 35 cm approx. Koorie Heritage Trust Collection

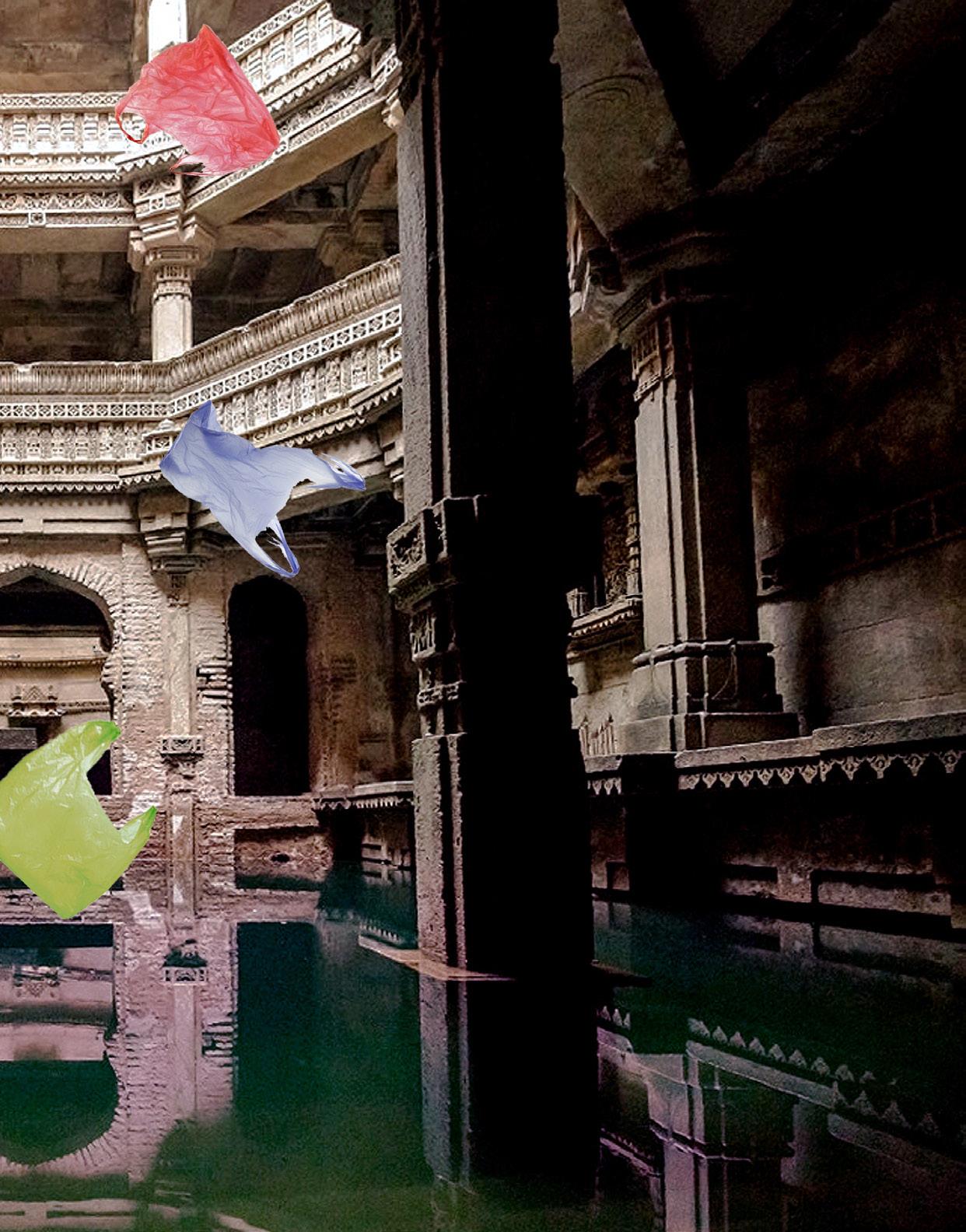

Parthiv Shah

A.N.O.M.A.L.Y. 1, 2016 digital photograph, 47 x 66 cm, Courtesy of the artist

Parthiv Shah

A.N.O.M.A.L.Y. 1, 2016 digital photograph, 47 x 66 cm, Courtesy of the artist

The first image that comes to mind when talking about Indian rivers is that they are dry, polluted and abused. Fortunately and unfortunately, it is not a binary. The mighty Ganges is often shown as an extremely polluted river worshipped by devotees, but that is not the whole reality. Ganges means “she who flows”, and other river names around the world such as the Rhine, Tigris, Mississippi and Yada, also relate to a river that flows. Today, however, one of the things that has been completely taken away from the river is its flow.

Brahmaputra, part of the Ganges basin, is one of the largest rivers in India and contains more than 130 species of fish. It faces extreme conflicts between states when its water is shared. While it may be a distress year for one state or another, it is always a distress year for the river itself because a river never gets its water.

Around the world, water stress is increasing. The per capita water availability is declining rapidly and, much like in Australia, India still has affluent urban areas which receive immense amounts of water. But we have a large number of poor households in rural and urban areas, which do not get the minimum amount’.

We need to appreciate our traditional linkage with water. In India we have 27 major river systems, each defined by the mountain system from which it emerges. We have the Himalayas up north, which forms a very different category of river to those in the west. The Ganges is one of the largest river systems in the world, and while its basin is supposed to be very polluted, it is home to more than 150 fish species and supports one of the largest deltas in the world as well as one of the biggest contiguous mangrove forests. India is a land of contrasts and our rivers reflect this. It is not about dead rivers or alive rivers, it is about rivers which are dead and alive at the same time.

A friend of mine took a canoe ride from one of the origin points of a river to its confluence with the Ganges. We thought he would see a dead river suffering dry stretches and extreme pollution, but he came back with stories of astounding diversity, of fisher folk making a living from the river out of species that we thought were extinct. Those are the secrets that rivers hold when they are with the community, and when the community is in touch with the river.

On the topic of rivers in India, the life land of India actually flows below its surface. Ground water rather than river water sustains most rural agriculture, as well as the rural and urban water supply. I believe ground water is abused more than rivers throughout the world, because ground water as a resource is completely ungoverned. We have not been able to govern something that is beneath the ground. With increasing technologies to make drilling easier, there are more and more exploited aquifers throughout the country. This is water that has sustained the growth of crops for food production and drinking water systems throughout the country. If we are not able to govern this properly, it is going to become an even bigger problem in India.

Pollution has had a chronic effect on the health of rivers in India, with nearly 63 per cent of all sewage flowing into Indian rivers untreated. Another big issue right now in India is green power. We have a large number of hydropower installations throughout the country, one after the other. This means that if one hydropower project does not have too much impact on the river ecosystem, another will.

I am part of an activist advocacy group which is made up of local people who are affected by the dams which are coming into their backyards and potentially cutting off source water to irrigation fields. Indigenous groups and forest-dwell ing communities are leading on the ground, and I am trying to help them in their struggles. In a recent case, a group of women successfully stopped the World Bank from investing in one of the biggest projects in India. In another, a group of Buddhist monks protested against a planned dam which would have affected their monastery’s water supply. That is power of the people.

Flooding in India, and many places, is celebrated. Or it was before we were told that flooding is a menace. Today, the Chenab River is completely dry because we have damned it so much and used it up. When a river dries, its stories dry too. After a generation, we will not remember the stories of the river.

US-based Indian activist Parineeta Dandekar recently received the Vasundhara Mitra award in the activist category for her work in river management, river rejuvenation and river conservation.

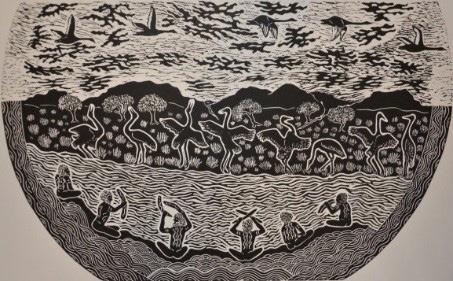

Djambawa Marawilli (Yolngu), Liyawaday Wirrpanda (Dhudi Djapu), Jangarh Singh Shyam (Pardhan Gond) & Lado Bai (Bhil)

A collaborative painting by Australian and Indian indigenous artists, New Delhi, 1999 Acrylic on canvas, 182 X 500 cm, Collection of the Crafts Museum, New Delhi

Djambawa Marawilli (Yolngu), Liyawaday Wirrpanda (Dhudi Djapu), Jangarh Singh Shyam (Pardhan Gond) & Lado Bai (Bhil)

A collaborative painting by Australian and Indian indigenous artists, New Delhi, 1999 Acrylic on canvas, 182 X 500 cm, Collection of the Crafts Museum, New Delhi

As an artist working in India, it is clear that there are very urgent issues about water affecting us on a global scale. In this time of urbanisation, nuclearisation and negotiation, we tend to forget or ignore our living environment, one which is rapidly disappearing as we slip through the episodes of construction, building and so-called development. My work lies at the intersection of Utopia and Dystopia, employing realities based on the latter state of the environment to construct your Utopian counter-figure through visual aesthetics. I reflect on how urban living, which is growing and is unstoppable all over the world, is impacting the atmosphere.

India is a very old community, as is Australia, and I don’t think I would be wrong calling ourselves indigenous. But we have been colonised, and then we have changed our cultures. We have forgotten our culture, or we have become confused in our present time.

I was invited by Coach, an Indian artist-led association in Delhi, to create an art object from waste collected during its Greener Town project which was aimed at cleaning up the Yamuna River, a holy river that attracts a lot of religious activities. It was heartbreaking to realise that this was not sewerage but a river, a cesspool where now only one or two per cent of the river water actually flows into the river bed in Delhi. We are diverting the rivers for the dams and other things, and is changing the whole ecology of the river.

We come from an indigenous society with traditional ways of looking at, and engaging with, rivers. But now it is a toxic river, and we are a data-driven society living in an urban world. How do we deal with this? I began documenting this problem and decided to take my canvases to the river to create a performative act that would actively engage people in conversation. The result was a number of canvases being created using sediment from the river. This sediment is very important in keeping the ecology of the land as a lot of minerals are transported this way. But now it is just contaminated sediment and a polluted surface. I made more and more works, but was aware I needed to take the conversation

Vibha Galhotra River Map, 2016 glass and bugle beads, cable, silver wire, 271.8 x 182.8 x 25.4 cm Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

further by displaying in galleries and other public spaces. As an artist, I look at aesthetics, humor and satire of my time and try to bring them into my work in different ways. Sometimes people think these are tar paintings or oil paintings; I call them action paintings, like Jackson Pollock, but with the river sediment of my time.

The national anthem of India boasts of the country’s national resources, of the Vindhyan and Himalayas ranges, and the Yamuna and Ganga (Ganges) as two great rivers that travel through the landscape and bring a lot of minerals with them. It is hypocritical to use this national anthem in today’s time, because now the rivers are completely polluted and contaminated by sewage. That is what inspired me to situate the canvas with the sediment in a pile of dung while the national anthem plays to a celebration of national wealth.

In another of my works, I represent the very fragile ecosystem of the rivers through a map of the rivers which was based on data that represents river beds, some of which have dried up. It aims to show how this contamination is coming back into our lives. It’s a circle. If we don’t take care of our environment it will hamper our health, which is something we are all concerned about. Many diseases are being discovered, and contaminated rivers are carrying a lot of viruses which we don’t even know about yet.

I use little trinkets and bells in my work a lot. These are all sown together by other women in the community where I work. I draw on the canvas underneath, then they deconstruct this by adding ‘ghungroos’(small metallic balls), and this creates a different image. It is a kind of satire on the commerce-driven art ecology. It is also inspired by presenting an image that has been formed because of the contaminated elements in the water. It starts as one form and then completely changes into something else.

I find some people don’t want to talk about negative issues, especially environmental issues, because they find it boring. So I try to engage them by making the object and trying to carry on the discussion. Some of my works show the new constructions being built around the river, changing the whole sovereignty of the land and replacing the natural forest with a concrete forest.

New Delhi-based conceptual artist Vibha Galhotra’s large scale sculptures address the shifting topography of the world under the impact of globalisation and growth.

One of the most important cultural practices I learned when I was young was the importance of explaining where you came from, and who your family is. This cultural practice remains very much an important reminder of my family’s history and culture. Another crucial part of our cultural memory is the relationship between water and family. While my grandparents came from two different regions, their connections to water formed an important part of our continuing cultural connection. Both the Murray River and the Edwards River had a large impact on their lives. You need to understand the diaspora, the movement of Aboriginal people in their own lands, and how they would move from one place to the other. We seem to think about it as coming from other places or country, coming into their land or other parts of the world, but people forget that Aboriginal people were exposed to that diaspora, and that was a part of the breakdown of family structures.

The rivers provided the lifeblood of our families, and relationships with the rivers continued to play a role in their families’ lives for many generations. For my grandparents, it gave them opportunities to work and support their family, and eventually they were able to purchase a small property on the banks of the Edwards River. This was where I had my happy years. The river enabled my grandparents to sustain their family and provide protection for them and other families that grew up there as the riverbank population expanded. It provided access to drinking water, and also water for washing clothes, cooking, everything you had to do with water. The river also supported a small garden in a growing community. Murray Cod was plentiful, as were Yellowbelly and Murray Perch, and there was also access to wild game, kangaroo, possum and pigeon. My grandparents were proud to give their address as the riverbank in the 1930s, and you think about those things.

My grandfather’s country was dominated by the bay, swamps and rivers around the coast of Melbourne. The Boonwurrung was a language group with a large confederacy known as the Kulin. The Kulin Nation included the area surrounding Melbourne, including the Goulburn River and up further to the mountains. The word “wurrung” means language, how you speak. The word “boon” means “to speak with no lips” and translates to mean that anyone could only talk the language of the Boonwurrung when they entered their country.

People of the River Aunty Di Kerr (video still) documentary film, duration: 21 minutes Coordination: Evelyn Tsitas Cinematography: Timothy Arch Editing: Karen McPherson Produced by Arch Creative Speakers: N’ahweet Carolyn Briggs, Indigenous language specialist and Boonwurrung Elder and Aunty Di Kerr, Wurundjeri Elder

It’s very important that we understand people and place, and those things that are important to our survival, because it is about giving context to people and river. The importance of water and its relationship to traditional owners is best explained in relationships with seasons. The Boonwurrung and other Kulin Nations believe that there were six or seven seasons, each season defined by plants, animals, stars, and the moon, and the relationship between the river and the sea. This is our voice. This is our connection. This is a privilege for you to be able to share in these stories.

I think we’re pretty good at understanding how we fit ourselves within place, and the technology of those skills that have sufficed for more than 230 years that the colonials have been on this country. It is about that meaningful connection to who we are. It is about that spiritual relationship to land, waters, and who we are, and how we play out those stories in our land. Each of the seasons is a journey cycle that accompanied them. We are defined by the relationship between the land, moon, and waters. In our traditional beliefs, the importance of water and the waterways was demonstrated throughout with the assistance of Waarn, the black raven. Waarn was the keeper and protector of our waterways while Bundjil was our creative spirit who presented himself as an eagle.

I believe one of the most important contributions that we can all make is to begin to understand that we do have a shared history. And this shared history helps define and guide the way we should protect the lands and waters. One way is to understand the way in which the knowledge of the first peoples can guide the policies and programs that can protect our cultural landscape. As the Chairperson of the Boonwurrung Foundation, we have been established to promote the history and culture of the Boonwurrung, and we are very happy to begin a conversation about a rich history and culture in an integrated, meaningful manner. These two guiding principles are what the Boonwurrung Foundation aims to promote: a meaningful engagement about a shared sense of our history and knowledge.

Boonwurrung Elder and Traditional Owner N’Ahweet Carolyn Briggs is an indigenous language specialist and Chairperson of the Boonwurrung Foundation.

I’m the eldest in my family line, so I’m a senior Elder of my family line. We don’t have any generations before us, so we have young Elders in Wurundjeri. I take my role very seriously, and part of that is about law and customs, caring for country and the waterways. My three main waterways are the Birrarung Valley, Merri Creek and the Maribyrnong River.

My mother and grandmother always spoke fondly about the Merri Creek and Maribyrnong River in particular. They talked about what they did as women many years ago, and how each river and riverbank was full of life. They didn’t need anything. They did lots of women’s business. My mum was a maker of the feather flowers which I have continued with my own girls and my granddaughters. Their stories about the Maribyrnong River, about them harvesting, fishing and joyfully playing and enjoying their country, were amazing. I remember them all so fondly, and I tell my grandchildren about them. When I travel around my country with my grandchildren, I am always teaching by telling them, “This is your river. This is your country.”

Connection to country is very important to us. Our country is our mother, and I believe that the rivers and the waterways are her veins. So we have to look after her, or she’ll die. I have seen lots of changes over the years and parts of the waterways down here were changed when they built on marshy land.

The bay is only about 10,000 years old. The mouth of the bay is actually a beautiful waterfall, and underneath it’s still there. We still have beautiful country, and it’s hard when you are in a main city to visualise what it was, and to keep it clean, and to look after it.

We have a green team that looks after our country and I have worked with only a few of them. It’s very important that everybody takes on that journey. Water sustains life. It sustains us all. Automatically we turn the tap on and don’t even think about it. We get in the shower and we love it, and I admit that I’m one of those who takes longer than seven minutes, but you don’t think about it because it’s there.

My grandmother was born on Coranderrk Mission, which is in Healesville. I’m really proud of the women of my tribe. They were strong. They were resilient.

Aunty Di Kerr (video still)

documentary film, duration: 21 minutes

Coordination: Evelyn Tsitas

Cinematography: Timothy Arch

Editing: Karen McPherson

Produced by Arch Creative Speakers: N’ahweet Carolyn Briggs, Indigenous language specialist and Boonwurrung Elder and Aunty Di Kerr, Wurundjeri Elder

They worked in market gardens, basket weaving, doing lots and lots of things to keep the family going. Up in Healesville near Coranderrk Station is Badger Creek. I go there at the beginning of every year with my sister and we do a Water Ceremony to help us get through the year and to be strong. If we struggle any time during the year, we go back there. Water Ceremony is about committing yourself to caring for country and thanking our ancestors. We always need to thank our ancestors, and I do that every day. We all need to do that.

I was recently down at a confluence of the Merri Creek and the Birrarung, which is where our initiation grounds were. It was really dirty. It was full of plastics and all sorts of things. I was very sad. We need to teach people the consequences of not looking after things. Years ago, when we all cared for country and spoke out, we were called greenies. We were considered really weird people. I spoke to someone the other day about that and I said we’re still considered weird people. It is sad that people look at us that way. Because when you think about it, we are caring for everybody not just for ourselves. We also care for our water because she is our mother. Everybody should care for their mother and her health. So it is important that we do that together. We need to walk as one, because we all belong here.

The only thing is that we have law here, traditional law. Our laws are very simple. They are not to harm the land or the waterways, and not to harm any children. That’s all we ask of visitors on country. That law is over 60,000 years old.

Wurundjeri Elder Aunty Di Kerr has made a life-long contribution to her community in the areas of health, welfare, education and land rights.

My family comes from Warrnambool, south west of Victoria, where we have a very strong connection with water and traditional knowledge and its connection to water. Down there the aquaculture system has been recorded to be about 6000 years old, which makes it one of the oldest in the world. There are people who used to manage the waterways there, manipulating them to help us catch eels, the Kuyang, which are a key resource for our people. They would manipulate all these different creeks, change the way the water flows with different levels of water and different pathways so they could control where and when the eels would move. They then placed woven grass eel traps to catch them and then smoke the eels to provide a ready supply of food throughout the year.

This aquaculture system enabled people to live very easily within the landscape and it is not a new thing that we are looking at manipulating our waterways in this way. It’s something that has a very strong tradition here in Australia and across the world among indigenous peoples. There is great wisdom in understanding what knowledge there is, and in recognising those things in a landscape that demonstrates that knowledge.

When we think about rivers in Victoria today, most people probably imagine places where the rain falls and fills up, where fish live and water goes along and eventually heads into the sea. Having now spent some time in this role, I believe people who use our waterways don’t think of rivers that way. To them, they are just a channel, a drain to get water from one place to the next. Actually, many of our systems, many of our waterways in this state are running in reverse. They run the opposite of what they would have done naturally for thousands of years. For example, in winter there would be lots of rain, and the waterways and rivers used to fill up with water and move along. In summer it would become very hot, so there was not much water going through those rivers. Today things actually run the opposite to that because we dammed everything up. Now in winter they capture all the water and store it in these gigantic, massive dams so none of the water really flows along the rivers like it used to. In summer now when it gets really hot and the farmers need water to feed their crops, they have to ring up the people who manage the dams and say, “We’re down here at the other

end of the river and we need some water”. They let some water out and it flows down the river during summer.

That’s why the Australian Government instituted this thing called environmental watering, where farmers can use some of that water that was used by irrigators. On that point, it is really important we have this water because none of us are growing enough food in our backyards and we need farmers to be producing these things. But we do need to ensure that the environment is being looked after too.

We are now working with traditional owners to figure out the best ways to do some of these things. Aboriginal people have knowledge about these places, about what plants should be growing here and if they’re not, how can we change our watering to make sure those plants come back? They know where fish should be at this time of the year and if they are not there now in the way they’ve been for thousands of years, how can we adjust our water management system so those fish return? We are drawing from that knowledge, that wisdom across thousands of years, to ensure we have not totally decimated our landscape. We are never going to return it to how it was thousands of years ago, but we can enhance it and make it closer to that, and ensure we have healthy waterways.

Part of that is also about ensuring there is water for cultural practices as well. Water is not just about sustaining things and providing food. Sometimes it is also about ceremony. Many cultures around the world recognise the value of water and culture, so there are some really great opportunities in looking more at the connections between water and traditional owner knowledge.

Rueben Berg is the first Aboriginal Water Commissioner to be appointed to the Victorian Environmental Water Holder. He is a Director at Westernport Water, a member of the Water for Country Project Control Group and has held a range of senior positions including Founder/ Managing Director of RJHB Consulting and a Founding Director of Indigenous Ultimate Association and Indigenous Architecture and Design Victoria.

Badger Bates (Paakantji)

Warrego-Darling Junction, Toorale, 2012 linocut print, 56 x 75.5 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Broken Hill Regional Art Gallery

Badger Bates (Paakantji)

Mission Mob, Bend Mob Wilcannia 1950s, 2009 linocut print, 57.5 X 90.7 cm

Courtesy the artist and Broken Hill Regional Art Gallery

I have a particular connection with certain types of water bodies as most of what I work in, research and teach is about underground water, or ground water, such as springs and wells. In 2010 I was fresh out of my PhD and just got my first job as a hydrologist working in a big consultancy in Melbourne. They had been working on some of the modelling and input to the Murray-Darling Basin Plan as it was being developed. Everyone was nervous to see how the plan was going to be received by communities and there were plenty of discussions after it was released. Irrigators living in rural communities were filmed by the media burning the plan, because it was proposing to take water out of the irrigation system and return it to the environment to try and save the health of the ecosystems in the Murray-Darling Basin. Plan changes were made so the amounts of water that were going to be diverted from irrigation licenses back to the river system were reduced, and a new plan agreed on in 2012. The plan is set to kick in at 2019.

The problems of the Murray-Darling Basin plan are not just confined to that region or that particular issue. Anything to do with water and water management always seems to create conflict. It’s worth noting indigenous perspectives on water, and I think there is something that people who are arguing over water rights maybe ought to learn from those previous cultures.

One of the proposals to improve water management in places like the Murray-Darling Basin was the “unbundling” of land and water rights so that water can be traded independently of land where you live. So, if a farmer decides that he/ she doesn’t want the excess water, they can trade it to someone else who decides that they do need it. This idea of a water market was supposed to result in water going to the highest value uses. I believe this “unbundling” has essentially allowed big players to come in and start buying up huge water licenses and speculate on the water market at the expense of ordinary people.

What else do we see happening in the Murray-Darling Basin? We have a real problem with carp herpes virus affecting the European carp in this waterway. Virologists have developed a cure that they say can infect the fish with a virus which kills the carp, but nothing else in the ecosystem. I see this as a problem because when carp die, they suck the oxygen out of the water and this will lead to massive blackwater events. Some UK academics have also looked at the virus and

suggest that, with a couple of small mutations, it could jump species and create an ecological crisis. That’s concerning, and I’m not a virologist. But it relates back to my earlier point that we ought to learn from our indigenous people and their cultures. This carp issue arose partly due to the fact the species was introduced by European fishermen throughout the basin in different areas for various purposes involved with fishing. This idea of translocating a European species and turning a river here into what it was like back in England is part of why we have imbalances in our river systems, and a lack of wisdom going into our planning with water. Our indigenous peoples managed the landscape here in Australia and we can learn a lot from their cultures. Land management practices here prior to European settlement were thrown out the window, with disastrous results in the early decades following European arrival.

Our indigenous people moved the focus from land use to land care. They thought long term and believed in leaving the world as it was. They were active not passive, striving for balance and continuity to make all life abundant, convenient, and predictable. Author Bill Gammage got it right when he said, “We have a continent to learn and if we are to survive, let alone feel at home, we must begin to understand our country. And if we succeed one day we might become Australian.” I think if you want to go wisdom and water, don’t look forward, look back.

Mathew Currell is a lecturer at RMIT University in the School of Engineering. His teaching and research are predominantly in the fields of hydrology, geochemistry, and environmental engineering. His research focuses on using environmental tracers, modelling and other techniques to understand the effects of various activities and processes on groundwater such as mining, agriculture, land use change, climate change, and pollution. Mathew is a fluid speaker of Mandarin and has a particular interest in water pollution and other environmental issues in China.

The dingo’s ability to guide people to water and to locate water sources above and below ground has been an important part of dingo human interactions for thousands of years, and deserves to be fully acknowledged in the contemporary Australian story. Dingo human conflict has been central to the colonial process. Over the past 230 years, dingoes have become both culturally and physically marginalised Australia wide. They form a role within an Aboriginal society as a cultural keystone species spanning back perhaps over 10,000 years or more, and this has become almost invisible.

The dingo was listed as a threatened species in 2004, and prior to that most dingo research was funded by agricultural boards as opposed to cultural boards. Such as, looking at the dingo’s livestock conflicts and how to solve them. My research examined the positive influences the dingo has had on human society, and water turned out to be a central theme. Australian cartography marks numerous waterholes and water courses all across the continent, with many named Dingo Soak, Dingo Creek, Dingo Gap, Dingo Rock. Names that are based on the myths and legends, artworks and songs of the Aboriginal people.

But these are far from just mythic representations. They had grounded and complex Aboriginal knowledge systems relating to underground rivers and locating places where the water reaches up closest to the earth’s surface. Often aided by the diggings of a dingo and sometimes just by finding the claw scratches on the surface of dry river beds. I found a surprising number of historical records in the archives describing how dingoes had led colonial explorers to life saving water sources.

Dingo water knowledge was greatly valued in traditional Aboriginal society and stories, but it has been notably absent from scientific records of dingo human interactions. This might be because there has been a positive value that has been attributed to the dingo and its feral status in Western science. Or it could be, in fact, that elements of this story are secret knowledge and so it’s only possible for us to catch a glimpse into the dingo’s place in Aboriginal Dreamtime. They feature prominently in songlines which, in Western ethnographic discourse, are best described as alternative ways in which cultures dream and map space.

Justine Philip Young dingo in the Pilbara desert, 2017 digital photograph, 39 x 59.5 cm, Courtesy of the artist and AMRRIC

Justine Philip Young dingo in the Pilbara desert, 2017 digital photograph, 39 x 59.5 cm, Courtesy of the artist and AMRRIC

Linguist Merrill Parker wrote, “The travels of the first dingoes are told and retold until they forge memory paths, which take people to water and food and explain how people arrived in the land and where they will finally go. Ancestral beings created water sources, dug up soaks and transformed the landscape. In this mythic terrain, the ancestors were shape shifters, moving from dingo to human form and back again. They were capable of giving birth to dingo or human young.” Parker says that in the myths, the dingo was described as a powerful dreaming deity, creating vital water holes. Good, deep ones that would serve several language groups. God-like, the dingo’s power was tempered with kindness as they thought to make the wells deep so that other people will come here and drink from it.

There are mythic accounts of dingoes disappearing back into the earth and transforming into rainbows, providing layers of connection between the dingo, water and land through accounts of the rain, rainbows, land, burrows and waterholes.

Many paintings feature dingo dreaming, tracing sacred sites on traditional land as a central theme. In many there is a round water hole somewhere in the painting. While travelling through Canning Stock Route last year, I took a photo of Well 35. The Aboriginal name for the well is Jarntu, the local name for dingo. This is the site of the ancestral mother dingo, a sacred site with healing powers. Jarntu’s pups live in the rock holes and soaks surrounding the area linked by a series of underground tunnels.

Another photo dating back to 1924 shows three women with dingoes draped around their waist, like garments of clothing. It is recorded that dingoes have greatly extended and supported women’s contribution to the traditional economy and food supply. Connections between dingoes, land, water and people include the multi-species sharing of these vital water sources. Important Dreamtime stories provide recognition, not just of the value of our precious water sources, but also of our human animal commonality, mutual dependencies and importantly, our mutual vulnerabilities.

Dr. Justine Philip has a PhD in Ecosystem Management, focusing on the Australian dingo in environmental history and cultural heritage. She has a Masters in animal science, covering animal ethics, policy and law as well as a B.S. in Scientific Photography. She is interested in human animal interactions in Australian and New Zealand history and heritage, and collects archival, narrative, and visual sources that examine indigenous ecological knowledge systems in colonial history.

Australia and India have a special and ancient relationship, with a long term geological history that makes this a fairly intimate connection. This connection, first described by Austrian geologist Dr Edward Suess, starts with understanding the basics of plate tectonic. That is, that the outer layers of the earth have a crust that is broken up into a number of distinct plates that are floating in a sea of magma. Australia and India are on different plates, so if we take those assumptions and go back 250 million years, the geologists’ current understanding is that there was a super continent known as Pangaea. But 200 million years ago it broke into two parts, Eurasia to the north and Gondwana to the south. The continents didn’t stay still, with the plates moving, floating in the sea of magma. Gondwana broke up and the continents moved to the north. So initially, Australia and India were next to each other, but by 100 million years ago they had separated quite spectacularly, although still in the southern hemisphere. Then India jetted off to the north at a fairly rapid speed and Australia shuffled sideways. India kept moving north and crashed into Eurasia, ending up against it and pushing up what we now know as the Himalayas. The evidence, pieced together from fossils of strange creatures and a plant glossopteris, the tongue fern, which grows in all the Gondwana countries, indicates that the bits of Gondwana once fitted together. That sets the context for where India and Australia came from in geological history, but where they are today is somewhat different. With the plate tectonics and the continental drift, Australia is sitting in the middle of its own plate. Not having collided with anything, it is tectonically stable. Australia has a very dry climate, a flattish topography, and material that is being eroded and washed off rocks which have been there for eons. This has led to major iron ore deposits and red soil. Red earth.

India, by contrast, formed the highest peaks on earth with the Himalayas, while the southern part of India, the Indian Peninsula, contains Gondwana rocks similar to those we find in Australia. The Himalayas have experienced massive erosion down the glaciers, with landslides pushing huge volumes of sediment which then provide the matrix for the development of ground water and water wells. They also produce very fertile plains for agriculture, whereas on the peninsula in India’s south the rocks are older. In fact they are meteoroid rocks

which came off the Gondwana formations. Australia also has volcanic rocks, in the western part of Victoria, but they are much more recent and thus we are still sitting on a hotspot of a different type.

The climates now are different. Australia has some major deserts as a result of the circulatory currents while India, in a different latitude, has a wetter climate and more rainfall. Rivers are not just a matter of rocks and soil, they are the interaction of that topography with water. So we end up with river systems that are similar but different.

In terms of management, the Ganges covers a number of other countries whereas the Murray–Darling is found in only one country, albeit crossing a number of states and territories. However, its management is still often difficult and controversial. In terms of human impacts, we have much less people in Australia so some of the pressures are less. There is less pollution coming to the rivers but we also have very dry rivers, so there is a lot of pressure on water. India, meanwhile, has a very large population but also lots of water.

An interesting point about Australian rivers is that investigations have established that Australia now is drier than it was tens of thousands of years ago. It’s like traffic. If you have a huge amount of water, you need a big river. If you have a tiny bit of water, you need a small river. And the meanders can be very tight, whereas with a lot of water the meanders have to be very wide. Our climate was wet but we have descended into aridity. In terms of understanding our rivers, we have to look at those in India to show how the process formed ours. Australia and India were both once part of Gondwana, and the river systems in both countries reflect past legacies and current processes, and have some similarities and some differences.

Sandra Brizga has more than 30 years’ experience in River Catchment and Coastal Management, working as an independent River Consultant since 1995. Sandra has qualifications in Geography, Geomorphology, Environmental Law and Finance, and previously pursued a career in academia. Her publications include a book on river management and current and previous board and committee memberships include the Fraser Island World Heritage Area Scientific Advisor Committee, the Port Philip CMA and various other government boards.

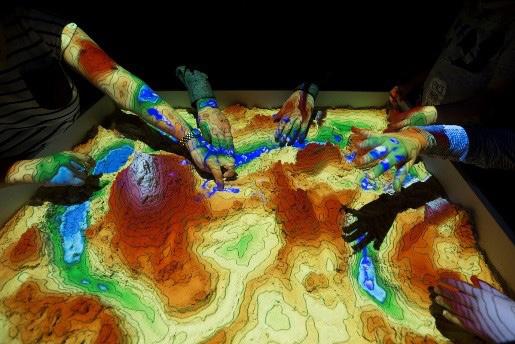

Developed by the UC Davis’ W.M. Keck Centre for Active Visualisation in the Earth Sciences, the UC Davis Tahoe Environmental Research Centre, Lawrence Hall of Science, and ECHO Lake Aquarium and Science Centre

Coordination for RMIT Gallery: Dr Jonathan Duckworth & Ross Eldridge (CiART)

As the co-founder of Climarte (2010) and ClimActs (2013), my aim is to harness the creative arts to draw attention to the urgency of climate change. There are so many ecocidal stories now, and I would like to talk about ways in which our water is threatened by the same industries that are threatening the climate.

One example was when we went to the Pilliga Forest to help the community blockade which had been going on there for months, with hundreds of people protesting to stop forests being bulldozed by big business. We were also going to be appearing as guest artists in the Water Bow, which was a Janet Laurence installation in Sydney, exploring all the ways in which water in Australia was being used. The forest site sits above a major recharge zone to the Great Artesian Basin and scientists were warning that if the planned 800 wells ended up reducing the pressure, water would no longer flow to the surface.

We joined the others and there were seven climate guardians blockading the part between the forest and the drillers when the police arrived. We said, “Look, we are so sorry, we understand you should really be concerned with the community, this shouldn’t be your job to come and arrest a group of angels trying to protect a forest and a major recharge zone. But, here we all are, none of us really want to be here.” Two guardians left, but the rest of us were mothers and grandmothers who felt strongly about this, and we were charged and ended up in the New South Wales court. Fortunately, the magistrate did not fine or imprison us but said the next time the police came and we were in the way of bulldozers, that was when we had to move. He was amazing, but we were very lucky because we could have gone to prison for two years for protecting everything.

That’s really where I want to interrogate this idea of power. Increasingly we are seeing the same companies behind fracking, and they are recognising the writing is on the wall with the use of fossil fuels in energy, so they’re looking at all these other ways. We are seeing a really interesting power dynamic, and the fact we are all tied into this economy, we all have opportunities to divest and to hold our political leaders to account. It’s like we have this opportunity to finally get a little more brave.

Another recent performance was an installation for the opening of the Lorne Sculpture Biennale, called Coal Requiem. This was an example of where we

had an opportunity to be paid to come and appear and do something quite spectacular and unashamedly political. It absolutely helped fund our work and that was a really wonderful one because we wanted to raise awareness of the rising sea levels, of the ways in which forests pump water through inlands. So with all of our performances, we do put out quite a lot of important information. In fact, when we were in Paris we got away with a lot more than we should have because there was a state of emergency ban, but we were there as part of the Cop 21 arts festival as well and used incredible imagery of angels as climate guardians to protect and blockade.

Our group uses different acts to get across our messages. Some of these are satirical, such as a coal diggers act, with one of my favorite alter egos being Coral Bleach, a billionaire coal digger. And we have the medieval astronomers from the flat earth institute, and I am Chancellor Carbonaceous in another role. We have different people who come in and out of these roles, so when you show up at events, there’s the government’s independent experts. It’s awkward. They have to go a very long way in history to find scientists who will support their world view. We also have the Frackers’ Guild where we are obsessed with everything sub-strata and we walk around going oink, oink, oink. But, we have a brisk trade in saints and body-parts and biblical relics, so we’ve teamed up with the fracking industry. The aforementioned climate guardians are the poignant act but it is effective because even people who really would like to lock you up can’t help laughing.

Deborah Hart is an arts-focused activist and writer who spent 16 years working in development roles within Australian leading arts and cultural organisations before turning her energy to environmental issues. She co-founded Climarte in 2010 and ClimActs in 2013 and her book, Guarding Eden, was published in 2015 by Allen & Unwin. In it, she explores what ordinary Australians are doing in attempts to safeguard nature and humanity’s future.

I’m a river girl from Swan Hill in Northern Victoria. I grew up around the mighty Murray River, or Milloo. I’m multi-clan Aboriginal custodian of this land, and the second of nine children, six boys and three girls. My mum’s country is the Coorong area in South Australia, and my dad’s country is around Yorta Yorta country. My family storyline comes from the footprints of my ancestors who have handed down blueprints of their craft to my elders. They have passed this knowledge on to me. Today, those blueprints are reflected in our family practice and in my own art practice in many different art forms.

As Aboriginal people, we connect to country through the environment, using traditional and contemporary methods to produce culturally relevant pieces of art or craft. The inbuilt knowledge and skills handed down from our ancestors gives us a storyline. Women and fishing have always been important to me, as I grew up in a fishing family. Over the years, I acknowledged the hand-fishing technique used by my maternal grandmother and the pole-fishing technique used by my paternal grandmother.

As the years flow on, I’m learning more about my craft, around net making and using that knowledge to create artwork in different forms, while also building on my other skills to complement the styles. My weaving is my connection to country. My net-making processes and techniques continue to be in keeping with the weaving and knotting process of bygone days. I’m not sure what happened, but I believe my ancestors set me on the journey with the nets for a reason.

I’m not really a water person. Growing up on the banks of the Mighty Milloo, we were told by our Elders to “stay away from the water because a bunyip will get you”. Because of that bunyip, I’m not a good swimmer. I have heard that in Swan Hill, where the bridge goes across to where we used to live, there were great big caves under the water. I’m not sure if they were underground rivers, but that’s where these giant cod fish or animals lived.

I loved fishing as a young person. Growing up near the waterways gave me a sense of being grounded when I needed healing. It also meant that we had food. Fish, crayfish and yabbies. I once read a Wiradyuri story of how the first man and woman came about, with men being made from clay and women found in the water. I asked my mother why water was so important to women

and she replied, “Water is life”. I asked her why and she said, “Babies are born in water. If there’s no water, there’s no life.” That made sense to me. Without water, our babies will die.

When I first started net weaving, I was told women didn’t make nets, but my father encouraged his six daughters at an early age to go outside the box of female duties and explore the special gifts we each had. While I’m weaving these nets, I think a lot about my Aboriginal ancestors and how they would have had to find the fibres to make the string to make the net, to drag the waters to collect the fish, to feed the family or feed the mob. Or if it was used as a bird net, to catch ducks.

Growing up on the river, I remember the flowing water was blue back then, clear blue and sometimes crystal green. That’s just over 50 years and what has happened in that time? How difficult it would be now to go to country to find the grasses to harvest, to make the strings, to make the nets. I wonder if the grass fibres would be brittle from chemicals being used on the land? We have found that environmental wear-and-tear on the land is damaging the plants. This makes it hard to find the right grasses to weave with now, and it is not easy getting to our harvesting places.

I go to the store and buy cords and fibres to make modern nets or I find recycled materials like electrical cords. I actually have some great big reels of carpet string that my mum was able to collect somewhere. That’s the thing about our people today. We adapt. We adapt to what’s around us. And that’s the same with our weaving. We use whatever we can find.

Artist Glenda Nicholls was taught to weave by her mother and grandmother. Now a grandmother herself, she aims to ensure her knowledge is passed on to her own descendants. In 2015 Glenda won the $30,000 Deadly Art Award, Victoria’s richest indigenous art prize for her work, A Woman’s Rite of Passage.

Glenda Nicholls (Waddi Waddi/Yorta Yorta/Ngarrindjeri) Milloo (Blue Net), 2015, jute string and dye installation dimensions variable, Courtesy of the artist

Just as physical experience is a vital part of my creative process, so too is the gathering of knowledge, both oral and written. It is important to know our history, that of people who inhabited the land before us. Stories bind us to our home territories. They strengthen our sense of belonging and our will to protect the environment.

Much of my artwork references water and fishing. In the two places that I have called home, both have lakes in their hinterlands and major evidence of traditional water knowledge. I was born in Majura and spent my childhood on the banks of the Murray River, swimming in its waters, often in the irrigation channels that run from the river to the fruit blocks. Just north is Lake Mungo where my family would regularly go to visit relatives who had sheep stations in the vicinity. Mungo has been without water for 15,000 years, yet it retains its shape. There is no doubt it was a lake, with its flatbeds and surrounding dunes and lunettes. It is a sacred site of world significance, containing some of the oldest human remains and artefacts. Its dry lake bed, though, could also be viewed as a portent for the future.

The place that I have called home for most of my life, though, is Portland in south west Victoria. Portland is home to a large lobster fishing industry, and I have referenced its dome forms and used its discarded plastic and ropes in much of my work. Close to the north east of Portland lies Lake Condah and the Mount Eccles lava flow, or Budj Bim, which once flowed out to the sea. Budj Bim is a landscape of world significance, due to the permanent settlement and extensive eco-culture system by the Gunditjmara over a period of at least 6,500 years along the lava flow between Darlots Creek and the Fitzroy River. This was well before the pyramids and Stonehenge. As a feature of Winda-Mara’s Budj Bim Tours Initiative, one of its roles is to provide a focus for relating stories of the Budj Bim landscape, the technology developed by Indigenous people over thousands of years to farm and process eels. Also, about the interruption to that way of living on the land as it was colonised by European farmers in the 19th century, and recent efforts to reclaim traditional water knowledge.

In 2007, Vicki Couzens and I built a stone sculpture called Kurtonitj as part of the Regional Arts Victoria statewide project about water use, called Fresh & Salty. We built our sculpture in a paddock, sandwiched between land containing

cultural artefacts and the remains of stone eel traps and houses built by the original inhabitants. Ancient structures that had been demolished were graded into five stone piles and we used one of these piles to make a positive contribution to this landscape and community. We were thinking of our work on one level in terms of reconciliation, and the finished sculpture has become a focus for what’s possible in terms of developing positive reciprocal relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

We needed to utilise something that referenced water knowledge and farming technologies of both Indigenous and colonial cultures, so stone from the volcanic landscape of south west Victoria seemed an obvious choice. On the Kurtonitj site, both cultures had farmed using this stone from the Mount Eccles lava flow, or Budj Bim. The Gunditjmara built their sophisticated and extensive system of eel traps, channels, and holding ponds, while colonial farmers constructed walls to contain their flocks of sheep and lay their herds of cattle. The spiral in our sculpture was inspired by the coiling technique of the woven eel baskets while the passage between the spirals harks back to the eel channels and weirs constructed by the Gunditjmara. Building this wall with stones from the ruins of ancient Gunditjmara homes and eel traps was our way to pay homage to Indigenous culture and knowledge. The spiral form, one that rises from and returns to the ground, represents the essence and continuity of life. Our artwork is an attempt to visualise a path forward through collaboration and reconciliation, while recognising Indigenous communities past and present. Artist Carmel Wallace has a PhD from Deakin University in the field of a multidisciplinary exploration of place and its ramifications for environmental ethics and awareness. She has undertaken residencies including SymbioticA, an artistic laboratory in the School of Anatomy and Human Biology at the University of Western Australia. Her work has been acquired by institutions and galleries including the National Library of Australia, the State Library of Victoria, the Baillieu Library at Melbourne University and the National Gallery of Australia.

My family are Waanyi people from north west Queensland. Riversleigh Station is where my grandmother was born, and it is an important place for the study of fossils. Lawn Hill Gorge is within that area, a subterranean basin of beautiful water which punctures the surface of the skin of water with little bubbles trickling up through fissures in the limestone.

Lawn Hill Gorge is a sacred place for the Waanyi people who perform traditional ceremonies and celebrations there. They believe that if you tamper with the water, pollute it, or take it for granted, the rainbow serpent Boodjamulla will leave and take the water with him. My grandmother told me this story after she asked her mother, Mabel Daley, about Lilydale Springs. Mabel, my great-grandmother, said, “The rainbow dried it up”. In fact, the person on the property at Lilydale Springs had used dynamite to try and extract more water and there is now only a trickle left.

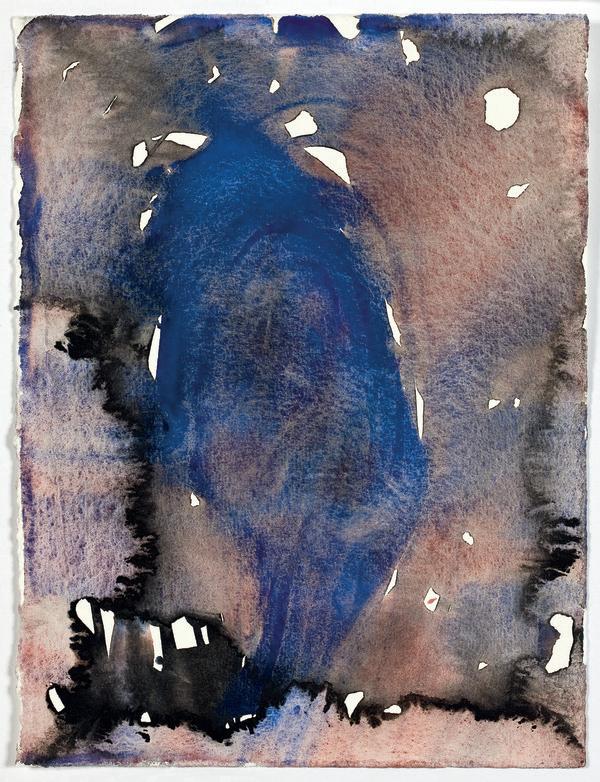

One of my Lawn Hill Gorge paintings called Water Line is based on my family history. Once, for many reasons, we had to run away from the station but my great grandmother Mabel caught a fish. My grandmother told me it was so big that she would hold it and it would go all the way down her back. She said she gave us the flesh off the backbone, the best of what she had. So, I use that as a symbol of Aboriginal women trying to keep together culture and country and family, holding them safe.

Many of my artworks are water related, including some I made when I had an artist in residency in India. One I made in Rajasthan, called Drawing With Dirty Water, was in fact completed with the use of water that other artists were cleaning their brushes in. It was the idea that the water almost became an alchemy, changing the process to make something magical. I used the washed out water sediment from other artists’ brushes.

For the Venice Biennale I was thinking about what were known as the red tides in Sydney, where too much nitrogen and not enough oxygen was causing this effect like the blue-green algae contamination. As this work was for Venice, I also imagined the arteries of the canals being sort of like the body, the metaphysical body, carrying this sludge and sediment. I also felt that this lagoon type area had been broken up for the large cruise ships to come through, and wanted to show how that has affected fishing practices for people in that area.

gorge drawing 7, 2001 pigment on paper, 20 x 19.5 cm Purchased through the RMIT Art Fund, 2013 RMIT University Art Collection, Accession no: RMIT.2012.40

Some other works highlight beauty such as when I was literally canyoning down Bell Creek Gorge, north of Sydney, through a really narrow chasm of water, and the sun hit the water in a particular way. It was a beautiful area to go through. And the Great Artesian Basin which shows ground water which I believe is a precious jewel. In fact, ground water is the hidden jewel under a lot of Australia. Another of my paintings, Blue Pools, relates back to my family history and growing up in Queensland. A place we used to go to in the rainforest area had beautiful blue pools.

Another water related piece called Water Spout came from a dream I had where a water spout was coming towards us and there was a large conch and valer shell. The spout created a large trench as it made its way towards us and we all had to scatter. In its wake were these large shells. Another time, during a residency in New Zealand, I painted the Waimakariri River which is a major river delta that flows out through Christchurch but carries pesticides. And there was that whole idea of shoal and driftnet in other works that look at passages of water between Aotearoa and Australia.

The catching of fish and the threat of the driftnets or the ghost nets, which have been used up north, was another theme of mine. When I was working with the community in Tennant Creek, there was a mine pool at a place called Noble’s Nob. If you ever see the pools or bodies of water around mines, they are actually really beautiful looking, but they contain all sorts of toxic sludge.

Influential indigenous artist Judy Watson was born in Mundubbera and now lives and work in Brisbane. She is best known for her painting and printmaking. Her catalogue of work explores her Aboriginal heritage. On her mother’s side, her ancestors are the Waanyi people of north west Queensland. In 2016, the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) commissioned Judy to create a public artwork for the gallery’s entrance.

Badger Bates (Paakantji)

Mission Mob, Bend Mob Wilcannia 1950s, 2009 linocut print 57.5 X 90.7 cm

Courtesy the artist and Broken Hill Regional Art Gallery

Vibha Galhotra Manthan, 2015 single channel, digital video projection duration: 10:43 minutes

Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Sandra Aitken (Gunditjmara)

Eel Trap, 2013 plastic hay bale twine 33.5 x 85.5 x 38.7 cm approx. Koorie Heritage Trust Collection

The Sewage Pond’s Memoir, 2013

single channel video duration: 06:30 minutes Courtesy of the artist

Clare Arni

Kumbh Mela, 2013 Sundarbans, 2015 – 2016 Varanasi, River Ganga, 2013 digital archival prints 40.6 x 50.8 cm and 50.8 x 40.6 cm Courtesy of the artist

Herbert Basedow

Wongapitcha women carrying dogs which they hold across their backs to enjoy the warmth of the animals’ bodies, Central Australia, 1924 photograph printed from glass plate negative 50 x 40 cm

NMG Macintosh collection, JL Shellshear Museum, University of Sydney

Badger Bates (Paakantji)

Warrego-Darling Junction, Toorale, 2012 linocut print 56 x 75.5 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Broken Hill Regional Art Gallery

Paddy Bedford (Gija) Dingo Springs, 2004 ochre on canvas 180 x 150cm Private Collection, Melbourne Courtesy of William Mora Galleries, Melbourne

Atul Bhalla

Looking for Dvaipayana, 2013 photographic performance 12 photographs: 53.5 x 59 cm each

Courtesy of the artist and Vadehra Art Gallery, New Delhi

Vicki Couzens (Kirrae Wurrong & Gunditjamara) & Carmel Wallace Kurtonitj, 2007 outdoor stone sculpture dimensions variable Courtesy of the artists and Regional Arts Victoria Documentation photographs by Bindi Cole Chocka (Wadawurrung)

Hannah Donnelly (Wiradjuri) Long Water, 2017 video and sound installation duration: 11:02 minutes

Courtesy of the artist

Vibha Galhotra River Map, 2016 glass and bugle beads, cable, silver wire 271.8 x 182.8 x 25.4 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Bhavani Gs Journey to the River Cauvery, 2012 single channel video duration: 24:55 minutes

Courtesy of the artist

Connie Hart (Gunditjmara)

Eel Trap, 1987 natural fibres 34 x 93.5 x 38 cm approx. Koorie Heritage Trust Collection

Connie Hart (Gunditjmara) Eel Trap, 1991 natural fibres; reeds 29.2 x 92.5 x 35 cm approx. Koorie Heritage Trust Collection

Henry King

Aboriginal Fisheries, 1880-1900 photograph printed from glass plate negatives 50.8 x 60.9 cm Collection of the Museum of Applied Arts and Science, Powerhouse Museum, Sydney

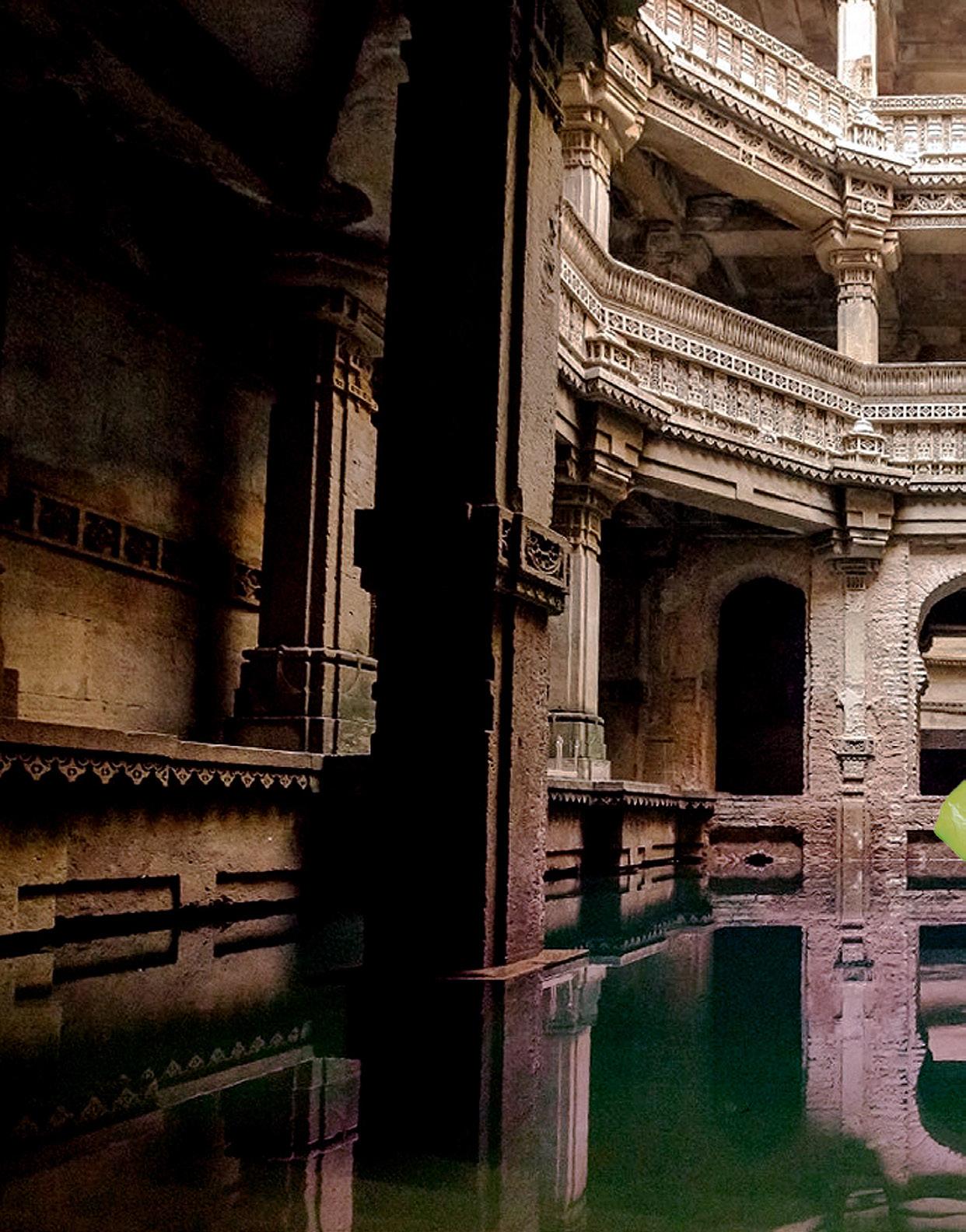

Victoria Lautman

Ujala Baoli, Mandu, Madhya Pradesh, 2014 digital photograph 76 x 60 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Victoria Lautman Chand Baori, Abhaneri, Rajasthan, 2013 digital photograph 60 x 76 cm Courtesy of the artist

Victoria Lautman

Sai Nath Ji Ki Baori, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, 2016 digital photograph 60 x 76 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Victoria Lautman

Navghan Kuvo, Junagadh, Gujarat, 2015 digital photograph 60 x 76 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Victoria Lautman Mahila Baag Jhalra, Jodphur, Rajasthan, 2014 digital photograph 76 x 60 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Victoria Lautman Panna Meena Ka Kund, Amer, Rajasthan, 2014 digital photograph 60 x 76 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Victoria Lautman Van Talab Baoli, Amer, Rajasthan, 2016 digital photograph 76 x 60 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Victoria Lautman Lolark Kund, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, 2013 digital photograph 76 x 60 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Victoria Lautman

Batris Kotha Vav, Kapadvanj, Gujarat, 2015 digital photograph 76 x 60 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Djambawa Marawilli (Yolngu), Liyawaday Wirrpanda (Dhudi Djapu), Jangarh Singh Shyam (Pardhan Gond) & Lado Bai (Bhil)

A collaborative painting by Australian and Indian indigenous artists, New Delhi, 1999 acrylic on canvas 182 x 500 cm Collection of the Crafts Museum, New Delhi

Wanyubi Marika (Rirratjiᶇu) Three Waters, 2013 natural pigments on bark 181 x 59 cm

Purchased through the RMIT Art Fund, 2013 RMIT University Art Collection Accession no: RMIT.2013.36

Rebecca Mayo Bound by Gorse (Ulex europeaus), 2017 gorse and digital print installation dimensions variable Courtesy of the artist

Jennifer Mullett (Gunai/ Kurnai/Monero/Ngarigo)

The Great Gunai Fisherman, c.1990 lithograph print 36.6 x 43.5cm Koorie Heritage Trust Collection

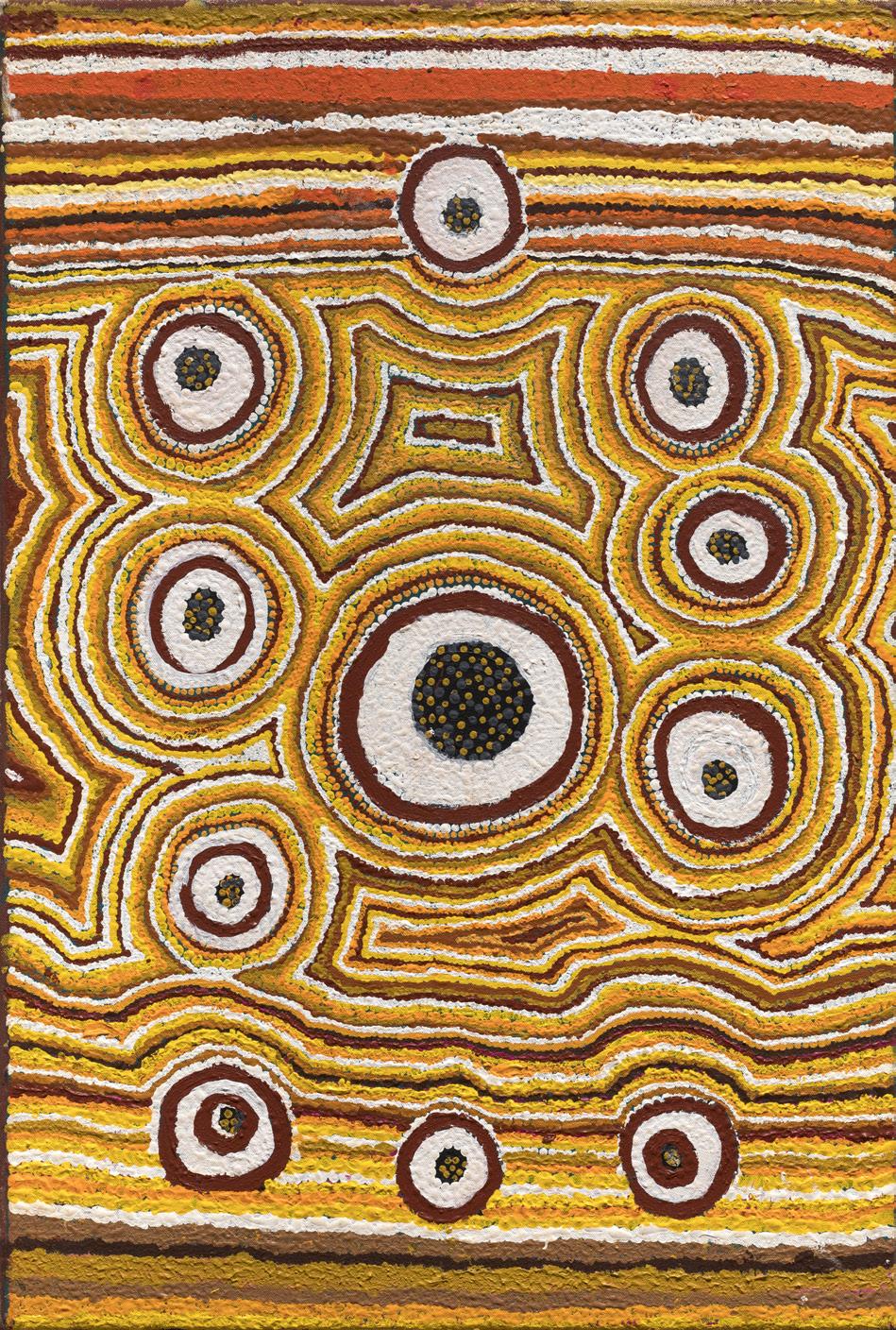

Yulyurlu Lorna Fencer Napurrula (Warlpiri/Ngaliya) Water Dreaming, 1998 synthetic polymer paint on canvas 80 x 50cm Collection of the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory

Glenda Nicholls (Waddi Waddi/Yorta Yorta/Ngarrindjeri) Milloo (Blue Net), 2015 jute string and dye installation dimensions variable Courtesy of the artist

Mandy Nicholson (Wurundjeri)

Map of Port Philip Bay (on kangaroo skin), c. 2000 kangaroo skin and paint 128 x 80 cm

Koorie Heritage Trust Collection

Sophia Pearce (Barkandji) and Jock Gilbert Fishtrap at Culpra Station: A Barkandji Story of landscape digital photographs Courtesy of the artists and Culpra Milli Aboriginal Corporation

Justine Philip Pilbara from the air, 2017 digital photograph 60.5 x 44.0 cm Courtesy of the artist and AMRRIC

Justine Philip Young dingo in the Pilbara desert, 2017 digital photograph 39 x 59.5 cm

Courtesy of the artist and AMRRIC

Parthiv Shah A.N.O.M.A.L.Y. 1, 2016 digital photograph 47 x 66 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Parthiv Shah A.N.O.M.A.L.Y. 2, 2016 digital photograph 51 x 66 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Parthiv Shah

A.N.O.M.A.L.Y. 3, 2016 digital photograph 41.5 x 66 cm

Courtesy of the artist

The Water Agora series, 2015 – present 26 digital photographs Courtesy of the artist

K.R. Sunil Chronicle of Disappearance - Documentation of vanishing water bodies in Kerala, 2016 digital photographs courtesy of the artist Commissioned by Visual Arts Gallery, India Habitat Centre

Donald Thomson Burrmilakili’s husband with young dingo, Tjirrmango (Echidna), in Arnhem Land), 1936 photograph printed from glass plate negative 40 x 50 cm

The Thomson Collection, Museum Victoria

Donald Thomson Burrmilakili with young dingo, Tjirrmango (Echidna), in Arnhem Land, 1936 photograph printed from glass plate negative 40 x 50 cm

The Thomson Collection, Museum Victoria Shorty Lungkata Tjungurrayi (Pintupi)

Dingo Dreaming, 1972 synthetic polymer paint on composition board 56 x 53 cm

Private Collection, Melbourne

Hanna Tuulikki SOURCEMOUTH : LIQUIDBODY, 2016 three screen film and sound installation, vocal composition, choreography, visual score

Courtesy of the artist Commissioned for Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2016 and supported by the National Lottery through Creative Scotland, the British Council, Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop and CCA Glasgow

Kutiyattam choreography: Kapila Venu

Videography: Darren Warren Sound: Pete Smith Costume design: Emily Millichip Production: Amy Porteous and Beinn Watson

Asim Waqif

Maintain - Scavenge from the HELP series, 2011 single channel video duration: 15:30 minutes Courtesy of the artist

Asim Waqif

Andekhi Jumna, Delhi, 2011 Single channel video of performance: recycled plastic bottles, LED and battery, boats and drummers

Duration: 6:24 minutes Courtesy of the artist and Yamuna Elbe Project

Judy Watson (Waanyi) sacred water, 2010 pigment, pastel and acrylic on canvas

212 x 213 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Milani Galleries, Brisbane

Judy Watson (Waanyi) tennant creek, 1999 blood wood gum on paper 24 x 19 cm

Purchased through the RMIT Art Fund, 2013 RMIT University Art Collection Accession no: RMIT.2012.41

Judy Watson (Waanyi) gorge drawing 7, 2001 pigment on paper 20 x 19.5 cm

Purchased through the RMIT Art Fund, 2013 RMIT University Art Collection Accession no: RMIT.2012.40

Judy Watson (Waanyi) water body, 2012 Three channel film Duration: 04:04 minutes Courtesy of the artist and Milani Galleries, Brisbane

Wendy Wise (Walmajarri/Nakarra/Mulan) Walkali, 2002 acrylic on canvas 75 x 50 cm Private collection, Melbourne

Unattributed artist Night Fishing, 1864 chromolithograph 45.7 x 49.1 cm Koorie Heritage Trust Collection

Unattributed artist

Aboriginal Fisheries, 1880-1900 photograph printed from glass plate negatives

50.8 x 60.9 cm

Collection of the Museum of Applied Arts and Science, Powerhouse Museum, Sydney

People of the River documentary film duration: 21 minutes

Coordination: Evelyn Tsitas Cinematography: Timothy Arch Editing: Karen McPherson Produced by Arch Creative Speakers; N’Ahweet Carolyn Briggs, Indigenous language specialist and Boonwurrung Elder and Aunty Di Kerr, Wurundjeri Elder

Sandbox

Developed by the UC Davis’ W.M. Keck Centre for Active Visualisation in the Earth Sciences, the UC Davis Tahoe Environmental Research Centre, Lawrence Hall of Science, and ECHO Lake Aquarium and Science Centre

Coordination for RMIT Gallery: Dr Jonathan Duckworth & Ross Eldridge (CiART)

Putuparri

documentary film duration: 1:37:00

Courtesy of Ronin Films

Journey to the River Cauvery, 2012 single channel video, duration: 24:55 minutes, Courtesy of the artist

ISBN: 978-0-6484226-2-4

Appreciative thanks to the participating artists and their representatives for their generous support, insight and commitment to the context of the exhibition. Appreciate thanks also to: Milani Galleries, Brisbane; the Museum and Art Gallery Northern Territory; The Koorie Heritage Trust; The Crafts Museum, New Delhi; William Mora Galleries, Melbourne; The Donald Thomson Collection and Museums Victoria; The J.L. Shellshear Museum, the University of Sydney; AMRRIC; Hydronumerics, Melbourne; Broken Hill Regional Art Gallery; Culpra Mill Aboriginal Corporation; Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney; Gunditj Mirring Aboriginal Corporation; Winda Mara Aboriginal Corporation; Regional Arts Victoria; the State Library of Victoria Digital Collection Archive; UC Davis’ W.M. Keck Centre for Active Visualisation in the Earth Sciences; the UC Davis Tahoe Environmental Research Centre, Lawrence Hall of Science, and ECHO Lake Aquarium and Science Centre; Dr Jonathan Duckworth, Director – CiART; Ross Eldridge, Senior Programmer - CiART; Stefan Greuter, Co-Director - CGDR); Ronin Films; Visual Arts Gallery, India Habitat Centre; Vadehra Art Gallery, New Delhi; Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Opening night speaker: Professor Mark McMillan, Deputy Pro Vice-Chancellor Indigenous Education and Engagement, RMIT Water+wisdom symposium speakers: Parineeta Dandekar, Coordinator, South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People; Vibha Galhotra, Conceptual artist; N’Ahweet Carolyn Briggs, Indigenous language specialist and Boonwurrung Elder; Aunty Di Kerr, Wurundjeri Elder; Rueben Berg, Victorian Environmental Water Holder Commissioner; Dr Matthew Currell, RMIT Senior Lecturer, Hydrogeology and Environmental Engineering; Dr Justine Philip, PhD Ecosystem Management, Museum Victoria Associate; Dr Sandra Brizga, River Management specialist; Deborah Hart, Arts-focussed activist and writer; Glenda Nicholls, Artist; Carmel Wallace, Artist; Judy Watson, Artist.

Acting Director: Helen Rayment

Senior Communications & Outreach Advisor: Evelyn Tsitas

Collections Coordinator: Jon Buckingham

Installation Coordinator: Nick Devlin

Installation: Fergus Binns, Christian Bishop, Beau Emmett, Ford Larman

Gallery Operations Coordinator: Megha Nikhil

Gallery Assistants: Mamie Bishop, Kaushali Seneviratne, Maria Stolnik

Exhibitions Assistant: Meg Taylor

Catalogue Coordinator: Helen Rayment

Catalogue Editor: Evelyn Tsitas

Text Editor: Vicki Hatton

Catalogue Design: Dianna Wells Design

Catalogue Photography: Mark Ashkanasy

Catalogue published by RMIT Gallery December 2018

RMIT University

344 Swanston Street Melbourne

GPO Box 2476 Melbourne Victoria Australia 3001

Tel: +613 9925 1717 Fax: +613 9925 1738 Email rmit.gallery@rmit.edu.au Web www.rmit.edu.au/rmitgallery

Gallery hours: Monday–Friday 11–5 Thursday 11–7 Saturday 12–5. Closed Sundays & public holidays. Free admission. Lift access available.

RMIT University acknowledges the people of the Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung language groups of the eastern Kulin Nations on whose unceded lands we conduct the business of the University. RMIT University respectfully acknowledges their Ancestors and Elders, past and present. RMIT also acknowledges the Traditional Custodians and their Ancestors of the lands and waters across Australia where we conduct our business.

Page 61

Justine Philip Pilbara from the air, 2017 digital photograph, 60.5 x 44.0 cm, Courtesy of the artist and AMRRIC

Page 62

K.R. SUNIL

Born Kodungallur, Kerala, lives Kerala India

Chronicle of Disappearance - Documentation of vanishing water bodies in Kerala, 2016 Digital photographs, Courtesy of the artist, Commissioned by Visual Arts Gallery, India Habitat Centre