CONTENTS

rize staff letter from the editors labels and limitations affirmative action & black excellence in academia

LUNCH happenings in the black community playbook efua osei, rize’s founding voice RECESS a dream blossomed

rize staff letter from the editors labels and limitations affirmative action & black excellence in academia

LUNCH happenings in the black community playbook efua osei, rize’s founding voice RECESS a dream blossomed

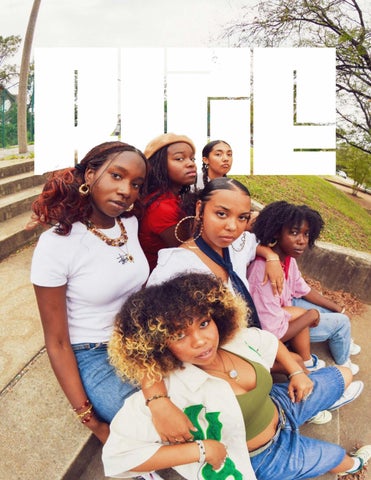

Prior to restarting RIZE, we had a desire for a creative space for Black students and were lucky enough to happen upon RIZE, a Black magazine founded on the WashU campus by Efua Osei. The combination between the pandemic and Efua graduating led to the unfortunate end of RIZE production, but we recognize the importance of having a collaborative, creative space like RIZE. Beyond being a magazine, RIZE is a third space for Black students that challeneges preconceived notions of Blackness and fosters a safe space for Black creatives to learn and grow.

For this issue we wanted to focus on the ways in which Blackness exists in educational spaces. There is an importance in creating joy and preserving identity at historically white institutions as a Black student. We aimed to center moment upon both positively and nostalgically, as well as moments that may have been more negative and regretful–both shaping who we are in the present day.

With Recess we are travelling back to days when we were able to explore and express our unapologetic joy, freedom, and blackness. Where we freely create methods of play and blend our expressions of Black culture and identity to create something new.

In Lunch, we reflect on once normal moments of opening our lunch boxes that our parents packed for us as children. Oftentimes, these foods were a product of our personal histories and cultures, representing a significant piece of who we are. We are going back to those moments and stepping into the deep rich and flavorful histories of our foods and rejecting conformity and embracing the self, who we are and where we came from; celebrating unique paths and where they intersect by sharing our food with one another.

This issue has taken a tremendous effort to put together, so we are eternally grateful to everyone who has contributed to this issue in any capacity. We hope that you will join us for what RIZE has in store in the future.

with love,

I cannot be comprehended except by my permission from “ego tripping” by nikki giovanni

I enter with joy first, Headfirst into good morning I believe in diving deep, My arms are wings, call me phoenix, I will Rise from ashes and turn clay into ceramics

I am everything

I reach into the heavens, Black, fully, I am taught, I teach Whispers and warnings

From magnolia to moss I am the soil, the sky, I am simply everything.

“She only got in becaues she’s black”.

In the lead-up to and in the wake of the Supreme Court decision that overturned affirmative action, comments like this were commonplace. Underlying the seemingly inoffensive claim that affirmative action helped or allowed Black students to get into top schools is the assumption that Black students are not as intelligent or as qualified to get into college, let alone top universities, as their white peers.

The myth that Black people only gain admission to college through affirmative action overlooks the complexity of educational access and achievement. The intention of affirmative action policies is to address systemic inequalities and provide opportunities to historically marginalized groups, including Black students navigating college admissions and campus life. These policies are not meant to, and in practice do not actually, give Black students priority over other applicants, such as those less qualified or impressive in terms of resume. The point is to allow for holistic review of applicants, considering their background, strengths, and the various elements on their academic and extracurricular resumes. Affirmative action and the inclusion of race as a consdieration for college applications does not immediately mean that all Black students lack merit or capability. Black students can and do excel academically and bring diverse perspectives and experiences that enrich the college environment; they are not accepted solely for their race but for their entire person, their overall strength as an applicant.

Research shows that Black students often face significant barriers to higher education: underfunded public high schools, limited access to advanced placement courses, . These factors can affect college readiness and application opportunities.

Affirmative action helps level the playing field but does not diminish the hard work and talent of individual students. Moreover, the narrative that affirmative action is the sole pathway for Black students perpetuates harmful stereotypes and ignores the achievements of countless Black individuals who gain admission based on their qualifications. It’s essential to recognize that diversity in higher education enhances learning for all students and fosters a more equitable society.

Dismissing the merits of Black students reduces their accomplishments to mere quotas, which undermines their true contributions to academia and beyond.

Affirmative action gained significant traction with President John F. Kennedy’s Executive Order 10925 in 1961, which mandated that government contractors take affirmative steps to ensure that all applicants are treated equally without regard to race, color, or national origin. This was a direct response to the pervasive discrimination faced by Black Americans and other minorities in various sectors, particularly in employment and education. In subsequent decades, affirmative action faced significant pushback and legal challenges, leading to a series of court rulings that shaped its application. States like California and Michigan implemented bans on affirmative action, arguing it constituted reverse discrimination. Others in favor of affirmative action see it as essential for leveling the playing field and fostering a more equitable society.

In the world of academia, in the aftermath of the 2023 Supreme Court decision overturning affirmative action, we see how, despite the argument that affirmative action was doing more harm than good in making admissions more equitable, diversity in incoming student populations has been greatly impacted, especially as it pertains to the rates of Black students in top institutions.

At top institutions across the United States, the population of Black incoming students has decreased: at Harvard, from 18% for the class of 2027 to 14% for the class of 2028. At Brown University, from 15% for the class of 2027 to 9% for the class of 2028. At Amherst College, from 11% for the class of 2027 to a staggering 35 for the class of 2028. WashU is no different than these other institutions: the percentage of Black students admitted for the class of 2028 is considerably smaller than for classes and years past: between 2023 and 2024 the population of Black admitted students decreased four percent, from 12% to 8%. On its own that drop is notable, but even in the context of all the racial demographics of the admitted student population for the class of 2028, we see that no other group saw such a drastic drop in representation— the number of Asian and Hispanic students each decreased by 1%, and the number of white and the number of unspecific race/ethnicity increased, respectively, by 1% and by 5%.

On one hand, it’s easy to see these numbers as confirming the idea that Black students are not actually more qualified than white or other applicants, but the reality is that the removal of race as an explicit factor only makes it easier for schools to limit access to Black students who are just as qualified if not more, as many Black students often go above and beyond in pursuit of higher education, exemplifying Black excellence. Zaire Johnson and Nia Johnson are two inspiring Black students whose academic excellence and leadership earned them acceptance to prestigious Ivy League schools in 2023.

Zaire Johnson, stood out as a student from Philadelphia with a passion for debate and community service. Throughout high school, Zaire maintained a high GPA while participating in numerous extracurricular activities, including serving as captain of the debate team. His involvement in debate not only sharpened his critical thinking and public speaking skills but also instilled in him a deep appreciation for discourse and advocacy. Zaire was also committed to community outreach, volunteering with local organizations to promote educational equity and mentorship for younger students. His dedication to uplifting others and fostering a supportive environment in his community played a significant role in his college applications, ultimately leading to offers from several Ivy League schools, including Princeton and Columbia.

Nia Johnson, from Chicago, also made headlines with her acceptance to Yale University. Nia’s academic journey was marked by her commitment to excellence, as she excelled in Advanced Placement courses and consistently achieved top grades. Beyond academics, Nia was an active leader at her school, serving as president of the student government. In this role, she worked to address issues affecting her peers, advocating for mental health resources and promoting inclusivity within the student body. Nia’s leadership extended into her community, where she engaged in various service projects aimed at helping underserved youth.

Both Zaire and Nia exemplify black excellence, especially in the realm of academia, a world that is usually coded and understood as elite, white, and exclusionary. They demonstrate that hard work, resilience, and a commitment to service can lead to extraordinary opportunities and refute the myth of Black inferiority in higher education.

Once full of hotdog winters, and baked potato silence, Feast for us.

This semester, the Black community at Washington Univer sity in St. Louis made significant strides in education and pro fessional development. The Association of Black Students, ABS, set the tone for the year with their theme, Elevate,” aiming to create structures and resources tailored to the academic and personal growth of Black students. ABS hosted impactful events, including voter education sessions and a development workshop focused on building LinkedIn profiles and resumes. These initiatives highlighted the organization’s commitment to empowering members of the community through knowledge and career readiness.

The WashU chapter of the National Society of Black Engi, also made waves this semester by attending Conference in Houston, Texas, from November 13-16. This annual gathering brought together thousands of Black tech professionals and students, fostering invaluable opportunities for networking and knowledge sharing. Members of WUNSBE connected with recruiters, met industry leaders, and felt the power of being surrounded by Black leaders in technology shaping the future of innovation. This empowering experience left students eager for next year’s conference and reinforced their mission of academic excellence, professional success, and positive community impact.

Many Black organizations maintained an interest of art and creativity this semester! ASA, the African Students Association organized a visit to the St. Louis Art Museum, where members explored Narrative Wisdom and African Arts. They also hosted an Arts and Activism Roundtable on November 20th, which highlighted how artists use mediums like fashion and visual art to challenge societal norms and spark change. These events celebrated the intersection of culture, creativity, and activism.

Black Anthology the long-standing Black student production at WashU, is well underway, with their highly anticipated theme reveal scheduled for December 6th. Meanwhile, Noir WashU’s first affinity space for Black creatives, facilitated powerful conversations this semester, including a roundtable on AI and art. They hosted the Artist Link Up on October 25th, which connected local St. Louis creatives in a celebration of Black artistry and expression. Noir is also producing a zine titled Shades of Joy, an open submission project celebrating Black creativity and emotion. Additionally, the Sam Fox School Black Students Network brought a hands-on element to creativity with biweekly paint-and-sip sessions, new crochet workshops, and a web design workshop in partnership with NSBE

This semester was a vibrant celebration of Black community, culture, and connection at WashU. ASA celebrated Africa Inkululeko: Freedom, Empowerment, A highlight of the week was the guest speaker, Tomi Adeyemi, an award-winning author of the bestselling Children of Blood and Bone. Adeyemi’s powerful words inspired attendees to embrace their heritage and

ABS hosted a retreat from September 20th-22nd at YMCA Trout Lake! The Muslim Students Association added to the semester’s sense of community with their Slimsgiving event on November 15th. Featuring food, games, prizes, and plenty of laughs, the event brought friends together in a joyous celebration of Thanksgiving. Additionally, the Black Men’s Coalition (BMC) and Black Women and Femmes Collective (BWFC) came together to host a mini-golf night before Thanksgiving break, a fun and lighthearted event that brought the community together for some pre-holiday joy.

the founding voice of rize.

I am Efua Osei, a Washington University in Saint Louis alumni who graduated in 2021. During my time at WashU, I studied African & African American Studies. I originally founded RIZE Magazine during my sophomore year and released a total of three issues in 2019. I have a Ghanaian background but was raised in Dover, Delaware. Since graduating, I’ve been working as a project manager in Chicago for three years. Much of my time is invested in creative work such as writing, photography, and graphic design. Although I enjoy many creative pursuits, I consider myself a writer first and foremost. My current writing is centered around music, focusing on interviews and reviews.

As an AFAS major, I spent a lot of my time in special collections, where I developed a deep appreciation for the rich Saint Louis history found in items like pictures, newspaper clippings, and magazine archives. I was often inspired by archival materials and fascinated by how they preserve the past. One item I came across was The Black Collegian, a Black student newspaper published at WashU around the time of the 1968 Brookings Sit-In. Seeing The Black Collegian showed me that WashU once had a newspaper or magazine centering its Black students. This inspired me to bring back a space where Black writers, photographers, artists, and musicians on campus could come together and create something meaningful for themselves.

WHAT DID YOU ENVISON FOR THE FUTURE OF RIZE AFTER YOU LEFT?

The excitement I felt from the responses to RIZE on campus made me envision it as some thing that could expand to involve other universities, becoming a source of Black student media for Saint Louis. More than anything, I hoped for RIZE to continue and grow beyond my time at WashU.

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO CREATE SPACES LIKE RIZE FOR BLACK STUDENTS AT HISTORICALLY WHITE INSTITUTIONS?

Many creative spaces on campus aren’t specifically for White students, but they are still predominantly White. Black students deserve spaces where they can take up space and share their artistic vision. At WashU, this is especially important because many Black students focus on paths that don’t center creativity, like medicine. A space like RIZE offers an outlet for Black students to express themselves and fulfill their creative needs.

CAN YOU SHARE MOMENTS IN YOUR LIFE WHERE YOU EXPERIENCED PURE, UNAPOLOGETIC JOY, AND HOW THEY SHAPED YOUR IDENTITY?

I’ve experienced the most pure, unapologetic joy with my friends and while working on RIZE. When I’m in creative settings, exchanging ideas with others, I feel heard and seen. Creating brings me the greatest happiness and is a core part of who I am.

WHAT IS THE SIGNIFICANCE OF EXPRESSING BLACK JOY AND FREEDOM IN SPACES WHERE BLACK EXPERIENCES ARE UNDERREPRESENTED AND MISUNDERSTOOD?

If we lived in fear of expressing ourselves in spaces where we are underrepresented or misunderstood—which is most spaces—we would always be hidden. Expressing Black joy and freedom in these spaces displays a sense of fearlessness that’s essential for Black people to become comfortable with. Expressing joy shows we’re not afraid of rejection, bringing us closer to loving ourselves and embracing our joy.

HOW DO YOUR CREATIVE OUTLETS CONTRIBUTE TO YOUR FREEDOM, JOY, AND BLACK IDENTITY?

My creative outlets are deeply rooted in myself and my Blackness. My first pieces of writing stemmed from my experiences, and even now, when I write about music, it’s about music that resonates with me personally. A lot of my creativity is shaped by my experiences as a queer Black person. Everything I create is an extension of myself, affirming my identity and joy.

A lot of people struggle with expressing their creativity and putting it out into the world, but you have to start somewhere! Be open to inspiration from anything around you—whether it’s going on a walk, listening to music, watching a movie, or spending time with people you care about. Most importantly, check in with yourself and do things you genuinely enjoy.

we are creatures of the day of an ever radiant sun of pavement and scraped knees toothy grins and untied laces

contentment was a thing close by on swing-sets and merry go rounds

we reminisce hastily of slapping feet and exhilarated breaths and laughter unrestrained, but do not allow ourselves to ponder too long. obligations call.

but could we again jump until our soles burn? and until rope makes rhythm? sing and skip and run, with our hearts in spirited tandem? could we forget ourselves for just a moment, in a return to the play we know best?

You saw it in elementary, in small and timid classrooms. Often being one of the only Black faces in a monocultural space— circumstances unnoticed to you, a boy too naive to see the systems set against him.

In the absence of the familiar was a profound isolation, a feeling you could hardly explain to yourself at the time.

But that loneliness remained, tucked away to follow you into adolescence. Growing older imparted harm that could not be rectified. You internalized those feelings, cut after tiny cut; walking into your advanced literature class on the first day of school and being told you were in the wrong place; your instructor informing you how surprised they were by your performance on an assessment, only to apologize for confusing you for another student who “looked just like you”. Classmates claiming you don’t act Black, teachers commending your articulation, peers asking where you’re really from, as if being American wasn’t enough.

As a child, to be told you don’t have what it takes to excel in classes that challenge or to be excluded altogether, to be on the other side of implicit bias, is to wither away any semblance of intrinsic value that little body can hold.

Jared Chinyere

Through years of struggle within this system, you’ll discover what a dream truly means. It means opening the door for yourself, sitting at the table, and

A dream is never truly finished, nor is it individual. It starts from the soil, from the asphalt and concrete of city streets, and the impact of its sowing resounds across the nation. It is the struggle for better education, attending a recognized university, creating a life for yourself. An individual dream can only be attained by realizing the collective one. A dream can be suppressed, momentarily subdued to the point of triviality. It can dry up, crust over, or sag like a heavy load. But hiding away in that dark corner, unwavering, the dream cannot be extinguished or reckoned with. In waiting, it sturs—like the hustle of Mary Jane dance shoes on wooden ballroom floors, the chorus of voices booming from the base of an obelisk in Washington, the syncopated rhythms of drums and saxophones flooding Manhattan clubs.

As with all things hidden away, there comes a point when it shows its face, unapologetically, with the vicious force of nature itself. The infernal pulse of flames lighting up the skies of Minneapolis, hordes of black fists brimming the streets in memoriam of justice. This force powers a dream, the struggles of Black men, women, and children everywhere condensed to the point of eruption. With this power, you’ll ignite a fire that can only be found in a human soul to build temples of tomorrow and scale mountains unknown, recognizing that the unimaginable is already in your grasp.

A dream doesn’t fade, flicker out, or wither away. It explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes. explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes.explodes. explodes.

Models

Nadiyah Ahmed

Lulu Allie

Erin Amankwaah

Amanna Bagwu

Zach Babers

Tobi Daramola

Aaliyaa Genat

Toni John

Brandon McCrow-Bennett

Josephine Ofori-Apau

Nora Perry

Scarlet Reo

Harlem Taylor