ocietà italiana di Storia Militare nadir Media FvCINA DIMARTE FvCINA DIMARTE 14

ocietà italiana di Storia Militare nadir Media a cura di Flavio Carbone F C, G P A F C, G P A a cura di Flavio Carbone

S

S

FVCINADI MARTE COLLANADELLASOCIETÀ ITALIANADI STORIAMILITARE 14

Direzione

Virgilio IlarI

Società Italiana di Storia Militare

Comitato scientifico

Ugo BarlozzettI

Società Italiana di Storia Militare

Jeremy Martin Black University of Exeter

Gastone BreccIa Università degli Studi di Pavia

Giovanni BrIzzI Emerito Università di Bologna

Flavio carBone

Società Italiana di Storia Militare

Simonetta contI

Università della Campania L. Vanvitelli

Piero crocIanI

Società Italiana di Storia Militare

Giuseppe Della torre

Università degli Studi di Siena

Piero Del negro

Università di Padova

Giuseppe De VergottInI Emerito Università di Bologna

Mariano gaBrIele

Società Italiana di Storia Militare

Gregory Hanlon Dalhousie University

John Brewster HattenDorf U.S. Naval War College

Anna Maria IsastIa

Associazione Nazionale Reduci

Carlo Jean

Istituto di Studi Strategici

Vincenzo Pezzolet

Arma dei Carabinieri

Donato tamBlé

Soprintendente archivistico

Germana taPPero merlo

Società Italiana di Storia Militare

FVCINADI MARTE

COLLANADELLASOCIETÀ ITALIANADI STORIAMILITARE

L’expérience historique a favorisé la prise de conscience théorique. La raison, effectivement, ne s’exerce pas dans le vide, elle travaille toujours sur une matière, mais Clausewitz distingue, sans les opposer, la conceptualisation et le raisonnement d’une part, l’observation historique de l’autre.

R.aron, Penser la guerre, 1976, I, p. 456

Fondata nel 1984 da Raimondo Luraghi, la Società Italiana di Storia Militare (SISM) promuove la storia critica della sicurezza e dei conflitti con particolare riguardo ai fattori militari e alla loro interazione con le scienze filosofiche, giuridiche, politiche, economiche, sociali, geografiche, cognitive, visive e letterarie. La collana Fvcina di Marte, dal titolo di una raccolta di trattati militari italiani pubblicata a Venezia nel 1641, affianca la serie dei Quaderni SISM, ricerche collettive a carattere monografico su temi ignorati otrascuratiinItalia.Includemonografieindividualiecollettivediargomento storico-militare proposte dai soci SISM e accettate dal consiglio scientifico.

3

F C, G P A a cura di Flavio Carbone

LITERARY PROPERTY

all rights reserved: Even partial reproduction is forbidden without authorization but the Authors retain the right to republish their contribution elsewhere

© 2023 Società Italiana di Storia Militare

Nadir Media Srl

ISBN: 9788894698459

Sulla copertina:

Bottone della gendarmeria con scritta “Liberté Ordre Public” (1848)

Musée Carnevalet – Histoire de Paris, Collections Online

Graphic design and realization:Antonio Nacca

Print: Nadir Media - Roma • info@nadirmedia.it

09 Prefazione di VIrgIlIo IlarI

15 Introduzione di flaVIo carBone

19 « Soldats de la loi » aux armées. Les prévôtés de la Gendarmerie nationale, des origines au début du XXIe siècle, par Jean-noël luc

49 From ‘Jack of all Trade’ to ‘Master of Everything’: Changing Role of Colonial Police in Bengal, 1750s to 1920s, byaryama gHosH

83 L’exercice de la police en tenue civile : Débats et pratiques au sein de la gendarmerie belge (19e -20e siècles), par Jonas camPIon

109 L’Arma dei Carabinieri e l’intelligence: una tradizione secolare, un iter storico dal 1814 al 1950, di marIa gaBrIella PasqualInI

141 Police reform and the military in Rio de Janeiro (1831 - 1858), byanDré luIs zullI - gonçalo rocHa gonçalVes

165 Polizia e politica. Legge e ordine nel nord-ovest indiano fra Otto e Novecento, di gIanluca PastorI

197 On the front line: the police, police officers and public health in São Paulo state at the end of the 19th century, by anDré rosemBerg

7

Índice

225 Le rôle de gendarmes dans l’avènement du renseignement au GrandDuché de Luxembourg (1913-1961), par géralD arBoIt

263 Gendarmes français et auxiliaires. Acteurs et témoins de la sortie de la Grande Guerre en Macédoine, Cilicie et Syrie-Liban (1918-1925), par romaIn Pécout

283 Le Forze dell’Ordine tra il 1919 e il 1926. La sofferente stabilità dell’Arma dei Carabinieri Reali di fronte alle trasformazioni dei corpi di Pubblica Sicurezza, di flaVIo carBone

329 Ritorno alla normalità? La Legione CC.RR. di Alessandria e la ricostituzione di un apparato di polizia nel contesto post bellico (maggio – dicembre 1945), di ferDInanDo angelettI

365 De l’école à la rue. Conceptions et pratiques de l’ordre public à la gendarmerie belge (1960 – 1991), par elIe teIcHer

391 Gendarmerie in Poland. Outline of history, dianDrzeJ mIsIuk -aleksanDra zaJac

413 The Establishment of the Mexican Guardia Nacional (2012-2019): A Gendarmerie Force for Crime Wars and the Fourth Transformation of Mexico,

by JoHn P. sullIVan - natHan P. Jones

8

Prefazione

di VIrgIlIo IlarI

Il titolo di questo volume, Forza alla legge, evoca un istituto d’antico regime, ossia l’appello del pubblico ufficiale agli astanti a prestargli “man forte”, specialmente per l’arresto di un malfattore1. Nel clima della Rivoluzione francese, che attribuiva la sovranità alla nazione e la fonte del diritto alla legge, «Force à la loi» divenne però nel 1791 la «devise»2, incisa sui bottoni dell’uni forme, della gendarmerie nationale, nuovo no me rivoluzionario assunto dall’antica Prévôté et Maréchaussée3, e recepita nel 1797 sui bottoni della gendarmeria cisalpina4, prima delle altre create in seguito nelle «Repubbliche sorelle»5 e poi nei due Regni napoleonici d’Italia e di Napoli. Istituzioni, insieme al code Napoléon e al sistema giudiziario e amministrativo, sopravvissute o imitate negli stati italiani della Restaurazione. Segno non tanto della vantata impar-

Bottone della gendarmerie nationale (32e Escadron /16e Légion).

Musée Carnevalet, Histoire de Paris, Collections online

1 «Tous les citoyens sont tenus … de donner force à la loi lorsqu’ils sont appelés en son nom» (Projet de déclaration des droits naturels, civils et politiques des hommes,Article Premier, xxx. Convention nationale, 1793). Ancor oggi il «rifiuto di prestare la propria opera in occasione di un tumulto» è passibile di arresto (art. 652 c. p.).

2 Il 22 aprile 2020 il Centre national d’entraînement des forces de gendarmerie (CNEFG), la cui insegna esibisce una tigre ruggente con artiglio minaccioso, ha adottato formalmente la devise «Pour que force reste à la loi».

3 PascalBrouIllet,«‘Lecorpsleplusutiledel’État’oucommentlamaréchausséeseprésentait à la fin de l’Ancien Régime», Société & Représentations, 2003/2, N° 16, pp. 39-51.

4 https://bottonibutton.forumfree.it/?t=76242472 (consultato il 26 marzo 2022). Sulle gendarmerie napoletana e cisalpino-italica del 1797-1815, v. V. Ilari, Rassegna dell’Arma dei Carabinieri, 65, 2017, 1, pp. 211-274 e 2, pp. 219-275.

5 V. IlarI, P. crocIanI e c. PaolettI, Storia militare dell’Italia giacobina (1796-1801), Roma, USSME, 2000,

9

Forza alla legge. Studi storici su Carabinieri, Gendarmerie e Polizie Armate 10

zialità6 e apoliticità7 dell’istituzione, quanto della sua utilità e adattabilità nei più vari e perfino opposti contesti politici, sociali e ideologici8 .

Proprio l’estrema diversità dei contesti temporali e socioculturali spiega perchélostudiocomparatoe/odiacronicodelleistituzioninazionalidiapplicazione (coercitiva) della legge è meno avanzato, e probabilmente molto più complesso di quello degli strumenti militari, dove il confronto avviene anzitutto sul campo di battaglia e in secondo luogo attraverso la pianificazione, che non può assolutamente prescindere da tipologie e modelli (anche se l’attrito socioculturale ne complica sempre, e in larga misura, la concreta applicazione).

La definizione Nato della «gendarmerie-type force (GTF)», approvata il 3 marzo 2022, recita: «an armed force established for enforcing the laws and that, on its national territory, permanently and primarily conducts its activities for the benefit of the civilian population»9. L’edizione inglese di wikipedia classifica come «gendarmerie», indipendentemente dal nome proprio, ogni «military force with law enforcement duties among the civilian population». Quindi non vi rientra la «military police (MP)»10, perché questa svolge il «law enforcement» e il mantenimento dell’ordine nei confronti dei membri delle forze armate e/o

6 Il 7 settembre 1805, durante la missione svolta a Milano per organizzare il «servizio politico» della gendarmeria reale italiana, l’ispettore generale della gendarmeria imperiale, generale di brigata Étienne Radet (1762-1825) indirizzava candidamente al navigato maresciallo Masséna, nuovo comandante dell’Armée d’Italie, delle «notes secrètes à brûler après lecture» (e ovviamente conservate da Masséna) in cui lo pregava di prendere la gendarmeria «sous sa prudente protection» e di difendere «cette magistrature armée», concepita come strumento di lotta sociale della borghesia produttiva contro le «caste» parassitarie dei «ricchi» aristocratici e dei «preti». Edouard GACHOT, Histoire militaire de Masséna: la troisième campagne d’Italie (1805-06), Paris, Plon-Nourrit, 1911, pp. 13-14 nota.

7 Antonio gramscI, Passato e presente,Torino, Einaudi, 19544, pp. 23-24 [«Esercito nazionale e apoliticità (Q. VIII)»]

8 «Force à la loi» figura anche, insieme al motto «ordre public», sul recto di una medaglia coniata nel 1831 sotto Luigi Filippo (comptoir des monnaies.com, p-66191) per celebrare il ripristino dell’ordine borghese sotto la monarchia liberale nata dalla rivolta parigina del luglio 1830 («les trois glorieuses» che innescarono i moti mazziniani della Savoia e delle Romagne e la prima insurrezione polacco-lituana e bielorussa). L’icona raffigura un guerriero greco (in exomis ed elmo), che impugna con la sinistra la bandiera “liberal-nazionale” adottata nel 1831-48 (ossia col puntale a forma di gallo, invece dell’aquila napoleonica) e con la destra, armata di glaive di giustizia, cinge le spalle di una donna velata, che reca le due tavole (‘mosaiche’) su cui è incisa la parola “lex”.

9 NATO Term: The Official NATO Terminology Database, Record 40669.AAP-06/15/39.

10 «Designated military forces with the responsibility and authorization for the enforcement of the law and maintaining order, as well as the provision of operational assistance through assigned doctrinal functions» (NATOTerm, Record 22140, approvata il 12/08/2019.AAP06/15).

della popolazione civile di un terrirorio soggetto ad amministrazione militare: anche se i compiti di polizia militare possono essere attribuiti ad una gendarmeria (come è il caso di quelle europee). Più netta, almeno in astratto, la differenza con la polizia, anche armata, e che consiste nello statuto militare, sia come arma o corpo specializzato dell’esercito, sia come forza armata autonoma. E per statuto militare non bastano la mera organizzazione gerarchica e le regole d’ingaggio; occorre anche la dipendenza,siapurenonesclusiva,dalministero della difesa. Elemento che ricorre anche nella dipendenza della Gendarmeria Europea (Eurogendfor) da un Comitato interministeriale di alto livello (Cimin) composto dai ministri degli esteri e della difesa dei sette paesi partecipanti (Italia, Francia, Spagna, Portogallo, Olanda, Romania e Polonia)11

La definizione però non risolve i problemi di identità e funzioni. Scriveva dieci anni fa Derek Lutterbeck, esaminando in particolare i casi austriaco, belga, italiano, francese e spagnolo, che le “gendarmerie”, ossia le forze di polizia a ordinamento militare con doppia dipendenza dai dicasteri degli interni e della difesa, si trovano paradossalmente a doversi confrontare con una crescente espansione dei compiti, che però accentua la tendenza verso la smilitarizzazione

11 Istituita nel 2004 per coordinare le operazioni multinazionali di gendarmeria nelle missioni Eu, Nato e Osce. Il Cimin ha sede a Vicenza nella Caserma dei Carabinieri “Generale Chinotto). Michiel De Weger, The Potential of the European Gendarmerie Force, Netherlands Institut of International Relations, Clingendael, March 23009.Florian trauner, The Internal-External Security Nexus: More Coherence Under Lisbon?, EU Institute of Security Studies, Occasional Paper 89, 2011. GiovanniarcuDI & Michael smItH, «The European Gendarmerie Force: a solution in search of Problems?», European Security, 22, 2013, pp. 1-20. Igor gelarDo, La polizia (militare) europea: Eurogendfor compie 7 anni, ma in pochi la conoscono!,Adagio eBook, 2014. Lencka PoPraVka, «La force de gendarmerie européenne», Res Militaris, hors-série, Gendarmerie, novembre 2019, pp. 1-8. M. recHtIk, M. mareš, «Evropské četnickésíly», Politické Vedy.[online].Vol.23,2020,No.1,2020,pp.202-240.DanilocIamPInI & Michael DzIeDzIc, «Assessing the Results of Gendarmerie Type Forces in Peacekeeping and Stability Operations», Militaire Spectator, Jährgang 191, Nr 3, 2022, pp. 124-139.

V. IlarI Prefazione 11

o civilizzazione o perfino verso lo scioglimento, come nel caso austriaco e belga12. A ciò si aggiungono fenomeni di segno opposto, da un lato una crescente militarizzazione delle forze di polizia a statuto civile13, e dall’altro la tendenza, anticipata dagli studi del criminologo canadese Jean Paul Brodeur (1944-2010) sulla rivitalizzazione della «haute police» nella lotta contro la criminalità organizzata14, verso l’impiego crescente di misure di polizia predittiva e preventiva15 basate sulla statistica criminologica («evidence-based policing») e di indagine basate sulle tecniche di intelligence («intelligence-led policing»16) incluso l’im-

12 Derek lutterBeck, The Paradox of Gendarmeries: Between Expansion, Demilitarization or Dissolution, Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF), SSR Papers 8, 2013. V. pure Id., «The differentiation between internal and external security, and between police and military, has been a core principle of the modern nation state.», Policing International Order, PIR 30118 (ca 2014). 2014 BusH and DoDson, «Police Officers as Peace Officers Policing from a Peacemaking Perspective»

13 Nella sterminata bibliografia sul tema, citiamo ad es. M. easton & R. moelker, «Police and Military: two worlds apart? Current Challenges in the Process of Constabularisation of the Armed Forces and Militarisation of the Civilian Police», in easton et al. (Eds.). Blurring Military and Police Roles, Boom Juridische Uitgevers, Reeks Het groene gras, Den Haag, 2010. Radley Balko, Rise of the Warrior Cop The Militarization of America’s Police Force, New York, PublicAffairs, 2013. Tobias WInrIgHt, «The history of the warrior cop. Militarized policing», Christian Century, September 17, 2014, pp. 10-12. John lea, «From the criminalisation of war to the militarization of the crime control», in S. Walklate & R. mcgarry (Eds.), Criminology and War: Transgressing the borders, Abingdon, Routledge, 2015, pp. 198-207. Tyler Wall, « Ordinary Emergency Drones Police and Geographies of Legal Terror», School of Justice Studies, Antipode, 2016, pp. 1-18. Timothy tIetz jr., « Militarizing the Police and Creating the Police State», Peace Review, 28, 2016, 2, pp. 191-194.

14 Jean-Paul BroDeur, «High Policing and Low Policing: RemarksAbout the Policing of PoliticalActivities», Social Problems, 30, 1983, 5, pp. 503-520. Philippe Robert, « Jean Paul Brodeur.APhilosopher entre deux continents», Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 53, 2011, Nr 3, pp. 311-324. Benoît DuPont, «The unique legacy of a cosmopolitan thinker.TributestoJean-PaulBrodeur»ePeterK.mannIng,«Jean-PaulBrodeuronHighand Low Policing », Champ Pénal/Penal Field, 9, 2012.

15 Emilio guIDa, «Predictive analysis. L’approccio logico-investigativo nei modelli predittivi e il ruolo dell’ampiezza geografica nelle dinamiche regionali», 2018, academia.edu.

16 Marilyn Peterson, Intelligence-Led Policing: The New Intelligence Architecture, US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of JusticeAssistance, NCI 210681, September 2005. Zakir gül, Ahmet kuHle, «Intelligence-Led Policing How the Use of Crime Intelligence Analysis translate in to the Decision-Making», International Journal of Security and Terrorism, Uluslararası Güvenlik ve Terörizm Dergisi, 4, 2013, 1, pp. 21-40. Stefano BonIno, « Intelligence e polizia sotto Copertura in Gran Bretagna: il caso della Special Demonstration Squad e della National Public Order Intelligence Unit», 2019; ID., Sicurezza e intelligence nel Regno Unito del Novecento, Prefazione di Mario calIgIurI, Soveria Mannelli, Rubbettino, 2020.

12

Forza alla legge. Studi storici su Carabinieri, Gendarmerie e Polizie Armate

piego di agenti provocatori. Temi, peraltro, non certo privi di precedenti17

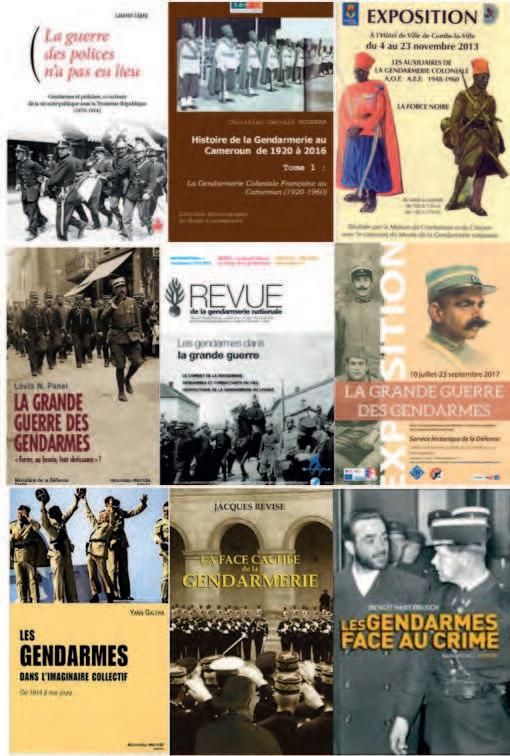

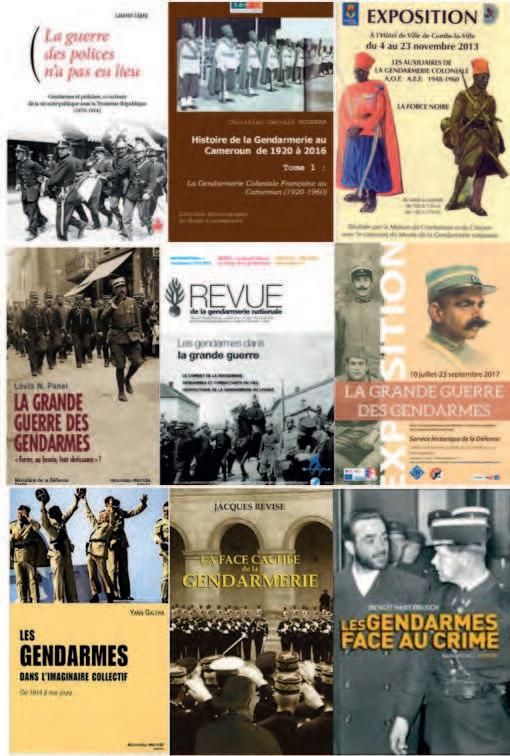

I temi e problemi che ho accennato sono ormai oggetto di una letteratura specialistica internazionale imponente, in cui gli approcci criminologici, giuridici e pratici si combinano in misura crescente con quelli storiografici, che da almeno trent’anni – anche se non ancora pienamente in Italia – hanno superato la fase meramente identitaria e acritica delle storie di corpo.Anzitutto producendo vere storie sociali e istituzionali di specifici corpi di polizia armata – penso ad esempio alle ottime monografie sulla British South African Police (BSAP), la cui possibile influenza sulla nostra Polizia Africa Italiana (PAI) meriterebbe forse di essere indagata. In secondo luogo cogliendo analogie e condizionamenti reciproci tra le polizie nazionali per contesti cronologici e geografici significativi: ad esempio nell’Europa delle guerre della Rivoluzione e dell’Impero francese, in quella dell’Età Vittoriana e Edoardiana con la nascita della polizia scientifica e criminologica, o postbellica della prima e della seconda guerra mondiale, dove i moti sociali e rivoluzionari, non più affrontabili col sistema prebellico del manforte attinto dalla truppa di leva, provocarono la formazione di forze antisommossa paramilitari (‘Black and Tan’, Palestine Police, Guardia de Seguridad yAsalto, Regia Guardia di P. S.18, Battaglioni mobili CCRR, Gendarmerie Mobile, Sicherheitspolizeinel primo, e ancora CRS e Reparti Celeri e autocarrati di P. S., e di nuovo Battaglioni Mobili CC nel secondo dopoguerra). Ma anche una storia delle polizie coloniali europee nell’Africa dello ‘Scramble’ o nella frammentazione dell’Impero Ottomano (dai Balcani al Medio Oriente), in India o nelle concessioni cinesi.

Temi che la Società Italiana di Storia Militare aveva cominciato a saggiare incidentalmente fin dai ‘Quaderni’ del 2018 (Over There in Italy) e 2019 (Italy on the Rimland), ripresi poi nel 2021 col fascicolo speciale NAM di storia dell’intelligence militare curato da GéraldArboit e con un articolo sul fascicolo N. 12.19

Il volume, che ora pubblichiamo come N. 14 della Collana SISM “Fvcina di Marte”, è il primo prodotto del Comitato di studi di storia delle Forze dell’Or-

17 V. ad es. Jacqueline ross, University of Illinois College of Law, Tavola rotonda all’Università Statale di Milano su Storia comparata delle indagini sotto copertura negli Stati uniti e in Franca nell’Ottocento, 28 maggio 2018, presieduta da LivioAntonielli.

18 Raffaele camPosano (cur.), Il Corpo della Regia Guardia per la Pubblica Sicurezza (19191923), Ufficio Storico della Polizia di Stato, Quaderno 2020.

19 Javier cerVera gIl, «De la calle a la trinchera. El frente como escenario de lealtad y compromiso de la Guardia Civil en la Guerra Civil Española», Nuova Antologia Militare, 3, 2022, N. 12, pp. 269-311.

V. IlarI Prefazione 13

Forza alla legge. Studi storici su Carabinieri, Gendarmerie e Polizie Armate

dine formalmente costituito nel marzo 2023 nell’ambito del Consiglio direttivo della Sism e presieduto dal generale Vincenzo Pezzolet, con Maria Gabriella Pasqualini e Piero Crociani vicepresidenti e Flavio Carbone segretario. Nonché ideatore e curatore di questo volume internazionale, nato da una call for papers pubblicata il 4 gennaio 2022 su Calenda e academia.edu.

A questo volume faremo seguire, a partire dal prossimo anno, un quinto fascicolo ordinario annuale di storia militare delle polizie, curato dal Comitato, con l’auspicio che serva da modello anche per analoghe iniziative di storia specialistica. Scopo del fascicolo di storia delle polizie militari è coordinare, promuovere e internazionalizzare la ricerca italiana, tanto accademica quanto indipendente, e promuovere la storia sociale, giuridica, istituzionale e militare comparata tanto delle polizie quanto delle teorie generali che hanno presieduto e presiedono alle loro molteplici attività.

14

Introduzione

di flaVIo carBone

Questo volume ha una lontana origine legata allo sforzo della Società Italiana di Storia Militare che, da tempo, sta promuovendo la conoscenza della storia militare, abbracciando contributi che partono dall’età antica sino a quella contemporanea. Si tratta di un grande impegno per una associazione che, se mi posso permettere in qualità di membro del consiglio direttivo, raggiunge risultati importanti e costantemente grazie all’impegno del Presidente, il professor Virgilio Ilari.

Voglio ricordare in questa sede che la Società Italiana di Storia Militare fu fondata nel lontanissimo 1984 (ci apprestiamo a celebrare i quarant’anni) sotto la guida e l’impulso di un grande storico militare italiano, Raimondo Luraghi, e sin dai suoi esordi ha promosso la storia critica della sicurezza e dei conflitti, prestando “attenzione ai fattori militari ma soprattutto alla loro interazione con le scienze filosofiche, giuridiche, politiche, economiche, sociali, geografiche, cognitive, visive e letterarie”.

Dal 2020, con attenta determinazione, infatti è stata lanciata sul web la NAM

– Nuova Antologia Militare, una rivista fatta e diffusa attraverso i canali digitali ed offerta in Open Access, liberamente consultabile e scaricabile.

Si tratta di un grosso peso e un investimento di risorse che ha raggiunto un pubblico viepiù diffuso che apprezza questo approccio e la trattazione di temi distinti.

Nell’ambito delle iniziative di NAM – Nuova Antologia Militare ha avuto un buon esito il fascicolo curato da Gérald Arboit intitolato “Intelligence militare, guerra clandestina e Operazioni Speciali” al punto che lo stesso Presidente ha chiesto a chi scrive di raccogliere il testimone dall’amico Gérald e lanciare una nuova proposta con l’obiettivo di raccogliere contributi dedicati alla storia delle forze dell’ordine a statuto militare sul modello dei Carabinieri italiani e della Gendarmeria francese.

Il lancio della proposta di pubblicazione di saggi per la rivista è stato condotto attraverso diversi canali. Di questi mi preme segnalare la pubblicazione

15

Forza alla legge. Studi storici su Carabinieri, Gendarmerie e Polizie Armate 16

sul sito del CePoC1, su Academia.edu attraverso il profilo personale2, sul blog del progetto di comunicazione digitale Storia dei Carabinieri3, curato dal sottoscritto la comunicazione su Calenda.org che offre una diffusione in un ambito scientifico internazionale4, i social più professionali come LinkedIn e singole e-mail inviate a vari autori di studi dedicati alle forze dell’ordine.

L’idea era di ripetere la stessa operazione condotta da Gérald rivolta al mondo delle forze dell’ordine. In questo senso, si può rilevare come gli autori abbiano diverse provenienze e background che non si limitano unicamente al mondo scientifico, ma spaziano in ambiti differenti. A nostro modo di vedere, tali contributi arricchiscono enormemente la riflessione che quindi prende un respiro più ricco e permette ulteriori considerazioni rispetto la sola area accademica.

Complessivamente sono stati proposti 19 contributi, di cui effettivamente presentati 14 articoli. Tre di questi hanno 2 co-autori ciascuno, mentre i rimanenti 11 sono firmati da un solo autore. Se guardiamo alla composizione geografica, ci sono 4 italiani (di cui una autrice), 3 francesi, 3 brasiliani, 2 belgi, 2 polacchi (di cui una co-autrice), 2 statunitensi e 1 indiano. In questo senso ci sono due considerazioni che ci stanno a cuore: l’assenza del continente africano e di alcuni Paesi che avrebbero potuto offrire contributi e riflessioni e la presenza di due sole autrici che ci fa pensare quanto ci sia ancora da fare in termini di espansione della conoscenza soprattutto verso il mondo scientifico composto da giovani e studiose.

Per una questione più mirata ai contenuti cinque contributi sono dedicati ad una visione diacronica di questioni legate al tema principale: Luc analizza la funzione di polizia militare nell’arco della prospettiva della storia della Gendarmeria Nazionale francese, Ghosh guarda al mutamento del ruolo della polizia coloniale nel Bengala sotto controllo inglese, Campion dedica la sua attenzione a pratiche e dibattiti nella gendarmeria reale belga sul servizio in borghese, Pasqualini affronta nel lungo periodo il tema dell’intelligence condotto dai Carabinieri, mentre Misiuk e Zajac presentano una breve storia della funzione della gendarmeria in Polonia.

1 https://www.cepoc.it/archives/2733)

2 academia.edu/65960207/Carabinieri_Gendarmerie_C4P

3 Oltre al podcast che rappresenta il core business dell'iniziativa esistono altri strumenti di comunicazione tra cui il blog reperibile all'indirizzo storiacc.hypotheses.org. Tutti i contatti sono disponibili su https://linktr.ee/storiadeicarabinieri

4 Call for papers Histoire comparée des carabinieri de la gendarmerie et des forces armées pour le maintien de l’ordre public, 4 janvier 2022 (calenda.org/951149).

Altri autori affrontano territori limitati come Rio de Janeiro con le riforme di polizia 1831 – 1858 (Zulli e Gonçalves), il nord-ovest indiano fra Otto e Novecento (Pastori), la sanità pubblica in San Paolo alla fine dell’Ottocento (Rosemberg), la funzione della raccolta informativa in Lussemburgo 1913-1961 (Arboit), la gendarmeria francese in Macedonia, Cilicia e Siria-Libano 19181925 (Pécout) e la legione Carabinieri Reali diAlessandria nel 1945 (Angeletti).

Infine, i rimanenti contributi guardano alle trasformazioni nel breve/medio periodo in Italia tra il 1919 e il 1926 (Carbone), l’ordine pubblico in Belgio 1960-1991 (Teicher) e il Messico con la fondazione della guardia nazionale 2012-2019 (Sullivan e Jones).

In questo senso, pare opportuno segnalare un imprevisto, chi scrive si scusa con tutti gli autori e collaboratori, a causa di impegni professionali e familiari il progetto che avrebbe dovuto vedere la fine entro il mese di settembre 2022 è dovuto slittare di alcuni mesi in avanti e vede la stampa solamente nella Primavera 2023.

Si consideri inoltre che, inizialmente, si era ritenuto di inserire la pubblicazione all’interno dei numeri speciali (o fuori collana) della Nuova Antologia Militare mentre, più opportunamente, il Presidente ha suggerito in prossimità della chiusura del progetto di procedere alla stampa quale volume della collana “Fvcina di Marte” dalla raccolta di trattati militari italiani pubblicata a Venezia nel 1641.

Tale collana rappresenta uno dei pilastri dell’attività di pubblicazione e di diffusione della SISM, allo scopo di raccogliere e distribuire ricerche collettive o individuali a carattere monografico sulla proposizione dei soci e previa accettazione del consiglio scientifico.

Così, effettivamente, i contributi trovano una collocazione più pertinente in questa collana e, cosa che mi onora molto, consente la possibilità di garantire una maggiore diffusione attraverso diversi canali di distribuzione.

Se mi è consentito tornare ad alcune considerazioni espresse poc’anzi, mi interessa molto segnalare una questione di grande importanza. Tale iniziativa prende anche spunto da un altro progetto molto più strutturato che fa capo da tanti anni a LivioAntonielli, studioso attento alle questioni del policing in tutti i suoi aspetti.Atale scopo nel 2012 è nato il Centro studi su “Le Polizie e il Controllo del Territorio” (CePoC)5, che ha raccolto e organizzato le numerose attività di ricerca sin dalla fine del XX secolo e che può presentare tra i suoi grandi

17 f. carBone introduzione

www.cepoc.it.

5

Forza alla legge. Studi storici su Carabinieri, Gendarmerie e Polizie Armate

successi la conduzione di convegni con grande regolarità e la realizzazione di una collana editoriale dedicata a tali convegni e ad altri studi qualificati.

In questo senso, tale iniziativa vuole essere integrativa e non sostituiva del grande lavoro svolto daAntonielli e gli studiosi che si sono raccolti intorno a lui, aprendo il panorama e offrendo differenti punti di vista e di riflessione.

Dunque ci auguriamo che questa iniziativa possa costituire effettivamente un ausilio e uno stimolo per altri studiosi e che possa lanciare nuove attività.

Effettivamente, almeno per quanto riguarda la Società Italiana di Storia Militare, della quale ho il privilegio sia di essere socio, sia ancora più impegnativo, di far parte del consiglio direttivo.

Dunque proprio basandoci su questa e su altre attività avviate in Italia e all’estero, è parso opportuno proporre un nuovo progetto aggregativo dei saperi e degli studiosi che si muovono in questo terreno così irto e pieno di insidie rappresentato dalla storia delle forze dell’ordine.

Così, all’indomani dell’ultima assemblea dell’associazione, è stato investito l’intero direttivo per ottenere un nihil obstat alla costituzione di un piccolo comitato di studi della storia delle forze dell’ordine (Co.SSFFOO) che possa raccogliere attorno ad un tavolo studiosi interessati a tale tema. Al momento il progetto vede alcuni soci della SISM farne parte e si è avviata lentamente una riflessione che possa accogliere e non escludere chi, in Italia, svolge funzioni di polizia latu sensu.

18

par Jean-noël luc Professeur émérite à la Sorbonne

résumé. Instituée à partir de 1791 à la place de la Maréchaussée, la gendarmerie française hérite de sa devancière la police des « gens de guerre » et des civils qui suivent l’armée. Des guerres de la Révolution aux actuelles OPEX, elle assume cette mission en détachant des prévôtés auprès des troupes en campagne ou stationnées en dehors du territoire national. Ce panorama analyse la réglementation de ces unités, leurs interventions au cours de plusieurs opérations, les limites de leur action et leur contribution à la militarité de l’Arme. Au-delà des enquêtes de police judiciaire, les tribunaux prévôtaux et les prisons prévôtales – deux organismes longtemps négligés par la recherche – éclairent le rôle des gendarmes comme instruments de l’État de droit et auxiliaires de la justice. Aujourd’hui, la prévôté assure des missions de police judiciaire militaire, sa tâche prioritaire, de police générale en faveur des personnels et des installations, de renseignement et d’appui. Elle est officiellement chargée de contribuer, à la fois, au respect du droit par les troupes en opération, à leur sécurité et à leur liberté d’action. mots clé. Armée, Guerre, MarécHaussée, GenDarmerIe, PréVôté, JustIce mIlItaIre, PremIer emPIre, SeconD EmPIre, Guerre de CrImée, PremIère Guerre monDIale, SeconDe Guerre monDIale, Guerre d’InDocHIne, OPEX, France.

«Noussommesenguerre,vousêtessoldatetvousn’avezpasàdiscuter», lance un officier d’état-major à un prévôt, d’un grade inférieur, qui refuse de faire fusiller des suspects, finalement innocentés. « C’est exact, rétorque le gendarme, mais si le soldat tout court exécute sans hésitation ni murmure, le soldat de la loi que je suis ne reçoit, en matière judiciaire, d’ordre que de la loi ». Et devant l’insistance de son interlocuteur, le gendarme le fait arrêter, « au nom de la loi, pour outrages à commandant de la force publique et à officier de police judiciaire, que vous voulez contraindre à une illégalité »1 . Cette altercation, en septembre 1914, illustre la volonté de l’État de droit de ré-

1 Louis Panel, La Grande Guerre des gendarmes. «Forcer au besoin leur obéissance», Paris, DMPA-Nouveau monde éditions (NME), 2013, p. 303.

19

« Soldats de la loi » aux armées. Les prévôtés de la Gendarmerie nationale, des origines au début du XXIe siècle

Forza alla legge. Studi storici su Carabinieri, Gendarmerie e Polizie Armate 20

guler le fonctionnement des armées, y compris en temps de guerre, ainsi que les entraves créées par une autre conception de l’ordre militaire. Parmi les acteurs essentiels de cette régulation, les détachements prévôtaux de la gendarmerie sont longtemps restés méconnus, alors qu’ils constituent l’un des trois rouages du système disciplinaire, avec l’organisation hiérarchique et la justice militaire. Marginalisés dans la mémoire officielle de l’Arme, qui préférait mettre en avant les prouesses de ses unités combattantes, ces détachements n’intéressaient pas davantage les historiennes et les historiens, du moins jusqu’à l’ouverture du chantier de la Sorbonne, en 20002 .

De la police de l’Ost royal à celle des soldats de la République

Au début de la Guerre de Cent ans, qui commence en 1337, le roi PhilippeV créée une juridiction et une troupe spéciales, placées sous l’autorité des prévôts des maréchaux, pour traquer, juger et punir les déserteurs, ainsi que les soldats et les autres individus coupables de pillage et d’exactions contre des civils ou des militaires pendant les campagnes. Après l’organisation d’une armée régulière, au milieu du XVe siècle, la maréchaussée devient une force permanente, implantée dans les villes de garnison. Si sa compétence est étendue, à partir de 1536, à des crimes et des délits commis par des civils, elle reste chargée, selon une ordonnance de François Ier, de « tenir ordre et police aux gens de guerre et corriger les fautes, oppressions et pilleries »3 .

2 À mon initiative, l’Université Paris-Sorbonne, devenue en 2018 Sorbonne Université, a ouvert, en 2000, un séminaire sur l’histoire de la gendarmerie. Dans le cadre d’une convention avec la Direction de la Gendarmerie nationale (DGGN), ce chantier a profité d’un partenariat fécond avec l’ancien Service Historique de la Gendarmerie Nationale (SHGN), puis avec la Société Nationale Histoire et Patrimoine de la Gendarmerie-Société des Amis du Musée de la Gendarmerie (SNHPG-SAMG). Plus de 250 travaux universitaires ont été soutenus, entre 2000et2022,auseinduséminaire,quiafournidesmatériauxà45ouvragesetà12colloques. Sur ce chantier, voir Jean -Noël Luc, «Promouvoir l’histoire académique de la Gendarmerie au début du XXe siècle», Revue Historique des Armées (désormais RHA), 295, 2019 (Laurent LóPez, dir., Être gendarme hier et aujourd’hui, en France et ailleurs), pp. 112-122. L’action des prévôtés est l’un des thèmes de recherche de l’histoire renouvelée de la gendarmerie française. Ce sujet a été jusqu’alors étudié à propos des campagnes d’Algérie (à partir de 1830), du Mexique (1862-1867), de 1870-1871, de la Grande Guerre, de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, des guerres d’Indochine et d’Algérie. Pour en savoir plus, voir la bibliographie commentée dans Jean-Noël Luc (dir), Histoire des gendarmes, de la maréchaussée à nos jours, Paris, Nouveau Monde Éditions (NME), 2016. Le panorama présenté ici s’appuie essentiellement sur des travaux, parfois inédits, réalisés à la Sorbonne, et qui ne sont pas tous cités pour ne pas multiplier les références.

3 Pascal BrouIllet (dir), De la maréchaussée à la Gendarmerie. Histoire et patrimoine, Mai-

Des membres de la maréchaussée accompagnent les troupes au cours de chacune des guerres de la monarchie. Deux règlements dits « provisoires », l’un en 1778, l’autre en 1788, chargent « le prévôt de l’armée et les détachements à ses ordres » de veiller « à la police et au bon ordre » de multiples manières. La prévôté patrouille dans les camps, elle empêche les soldats d’en sortir et elle surveillelestroupesendéplacement.Elleenregistreetcontrôlelescivilsàlasuite del’armée(vivandiers,commerçants,domestiques);ellearrêtelesvagabondset chasse les prostituées, après les avoir fait fouetter. Elle garde, dans ses prisons, les prévenus qui relèvent des « cas prévôtaux ». Elle sanctionne les soldats et les civils auteurs de certaines infractions (perturbation des distributions de vivres, maraude, etc.), en particulier par des peines « afflictives », administrées par les « Caporaux de la Prévôté »4. Par leur double fonction, policière et judiciaire, les membres de la maréchaussée, que l’opinion appelle les « juges bottés », contribuent à l’autorité du monarque sur la force armée5

Votée le 26 août 1789, la Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen confie leur protection à une « force publique […] instituée pour l’avantage de tous ». Mais pour éviter que l’État issu de la Révolution ne dépende des troupes royales ou des nouvelles gardes nationales, soumises aux pouvoirs locaux, l’Assemblée constituante le dote d’une force spéciale, en réorganisant, le 16 février 1791, la maréchaussée sous le nom de « Gendarmerie nationale ».Au nom de la séparation des pouvoirs, le nouveau corps perd le droit de juger les coupables, exercé par sa devancière depuis sa création.

Bien que les premiers textes organiques de la gendarmerie, le 16 février 1791, puis le 29 avril 1792, ne mentionnent pas, curieusement, sa fonction de police aux armées, des détachements prévôtaux sont organisés dès le début de la guerre contre l’Autriche, en avril 1792. Pendant la Première Coalition (17931797), plus de 3 000 gendarmes sont envoyés, par roulement, auprès des autres troupes pour maintenir l’ordre dans les camps, assurer la bonne marche des convois, traquer les traîneurs, les déserteurs et les maraudeurs, contrôler la distribution des vivres, enregistrer et surveiller les civils à la suite de l’armée, vé-

sons-Alfort, SHGN, 2003, pp. 14-15 ; Louis Saurel, «Les prévôtés des armées en campagne», RHA, n° spécial 1961, pp. 135-137.

4 Règlement provisoire sur le service de l’infanterie en campagne, Caen, G. Le Roy, 1778 («De la discipline et de la police dans les armées», pp. 256-268 ; «De la prévôté et de la police du quartier général», pp. 268-276), et Règlement provisoire sur le service des troupes à cheval en campagne du 12 août 1788, Paris, Magimel, 1811, pp. 64-73.

5 Jacques LorgnIer, Maréchaussée, histoire d’une révolution judiciaire et administrative, 2 tomes, Paris, L’Harmattan, 1995 et 2000.

21 J.-n.

luc « SoldatS de la loi » aux arméeS. leS PrévôtéS de la Gendarmerie nationale

Forza alla legge. Studi storici su Carabinieri, Gendarmerie e Polizie Armate

rifier les poids et mesures des commerçants, garder les prisonniers en instance de jugement, etc.6. La plupart de ces missions étaient d’ailleurs prévues, malgré plusieurs imprécisions, par le règlement de 1792 sur le service de l’infanterie en campagne, qui reproduit de nombreux articles du règlement de 1778, déjà cité7 . La grande loi organique de la gendarmerie, celle du 28 germinal an VI (17 avril 1798), tient compte de ce dispositif : elle rappelle que l’Arme, d’abord créée « pour assurer, dans l’intérieur de la République, le maintien de l’ordre et l’exécution des lois » (article 1er), doit également fournir, « en temps de guerre, des détachements destinés au maintien de l’ordre et de la police dans les camps et les cantonnements » (article 215)8. Le même texte annonce un règlement du service de ces détachements (article 221), qui ne verra pas le jour. Seule la gendarmerie des nouveaux départements de la rive gauche du Rhin bénéficiera, sur cette question, de l’instruction spéciale du 29 floréal an VII (19 mai 1799), rédigée par son organisateur, le général Wirion, l’un des inspirateurs de la loi de Germinal. Ce texte se signale à l’attention en rétablissant une justice prévôtale, au moins partielle, malgré le principe de la séparation des pouvoirs, puisqu’il prescrit d’organiser des tribunaux prévôtaux – non mentionnés dans le règlement de 1792 – pour punir les auteurs d’infractions parmi les civils attachés à l’armée9 .

Les prévôtés, d’un Empire à l’autre

La prévôté intéresse particulièrement Napoléon, qui souligne son utilité pour réguler l’armée dans une lettre envoyée, en 1812, au maréchal Berthier. Le gendarme n’est pas un homme à cheval ; c’est un agent qui doit être créé dans chaque poste, parce que ce service est le plus important, qui doit être chargé de la police sur les derrières de l’armée et ne doit pas être employé ni en sauvegarde [protection d’une ville non occupée], ni pour les escortes. Deux à trois cents hommes de cavalerie de plus ou de moins ne sont rien. Deux cents gendarmes de plus assurent la tranquillité de l’armée et le bon ordre.10

6 Louis Saurel, art. cit., p. 137.

7 Règlement provisoire sur le service de l’infanterie en campagne du 5 avril 1792, Paris, Magimel, 1808 («De la discipline et police dans les armées», pp. 140-146 ; «De la police du quartier général», pp. 146-152).

8 Jean-Noël Luc (dir.), Histoire de la maréchaussée et de la gendarmerie. Guide de recherche, Maisons-Alfort, SHGN, 2004, p. 287 et 293.

9 «La prévôté aux Armées», Le Cahier Toulousain, s.d

10 Lettre du 26 juin 1812, Correspondance de Napoléon Ier , Paris, Imprimerie impériale, 1859-1869, tome XXIII.

22

23

J.-n. luc « SoldatS de la loi » aux arméeS. leS PrévôtéS de la Gendarmerie nationale

Forza alla legge. Studi storici su Carabinieri, Gendarmerie e Polizie Armate 24

Sur le terrain, les missions des prévôtaux gagnent en importance au fil des campagnes du Consulat, puis de l’Empire, avant même d’être partiellement récapitulées dans le règlement de Schönbrunn sur le service des troupes (1809), destiné à l’«Armée d’Allemagne », engagée contre l’Autriche pendant la guerre de la Cinquième Coalition. Ce règlement reprend, parfois mot pour mot, les prescriptions des textes, déjà cités, de 1792 et de 1778. Réapparue, on l’a vu, dans l’instruction de 1799, la justice prévôtale est à nouveau mentionnée dans celle de 1809, qui charge des « tribunaux prévôtaux » d’appliquer « les peines de police et correctionnelles » à des civils à la suite de l’armée (vivandiers, blanchisseurs, domestiques) coupables d’une infraction11 .

La gendarmerie de la Grande Armée est une institution hiérarchisée. Elle est pourvue d’un Grand Prévôt, rattaché à l’état-major (le général Jean-Baptiste Lauer, entre 1805 et 1813, puis le général Étienne Radet), ainsi que de grands prévôts et de prévôts, respectivement affectés auprès des principales armées et de chaque corps d’armée. Les éloges adressés, en 1808, par le maréchal Davout, gouverneur temporaire du duché de Varsovie, au général Saunier, grand prévôt du 3e corps d’armée, confirment l’étendue des fonctions de la prévôté, bien audelà de la seule surveillance des militaires : « il me tient au courant de tout ce qui se passe […], il est instruit de l’arrivée de tous les voyageurs, des motifs qui les amènent dans le duché, de ce qu’ils rapportent, des bruits qui circulent, et généralement de tout ce qu’il peut être important de savoir »12

L’ordonnance du 3 mai 1832 sur le service des armées en campagne développe, avec plus précision, les missions des prévôtés évoquées dans les textes antérieurs.

La gendarmerie remplit à l’armée des fonctions analogues à celles qu’elle exerce dans l’intérieur. La surveillance des délits, la rédaction des procèsverbaux, la poursuite et l’arrestation des coupables, la police, le maintien de l’ordre, sont de sa compétence et constituent ses devoirs (article 169). Les attributions du Grand Prévôt embrassent tout ce qui est relatif aux crimes et aux délits commis dans l’arrondissement de l’armée. Son devoir est surtout de protéger les habitants du pays contre le pillage ou toute autre violence (article 171).

11 Extrait du règlement provisoire pour le service des troupes en campagne, imprimé pour l’armée d’Allemagne, Schönbrunn, Imprimerie impériale de l’armée, 1809 («Vivandiers, blanchisseurs et marchands à la suite de l’armée», pp. 171-176 ; «Police et discipline», pp. 177182 ; «Répression des délits», pp. 182-184 ; «Gendarmerie», p. 184-189). Sur les tribunaux prévôtaux, voir p. 182, 183, 185, 186.

12 Jacques-Olivier BouDon, L’Empire des polices. Comment Napoléon faisait régner l’ordre, Paris, Vuibert, 2017, pp. 211-222.

En réaction contre l’encombrement des tribunaux militaires par des affaires mineures, comme les infractions commises par des commerçants, lors des expéditions en Morée (1820), en Espagne (1823) et en Algérie (1830), le texte de 1832 étend le pouvoir répressif des prévôts. Désormais, ces officiers de gendarmeriepeuventinfligeruneamendede50francsmaximumauxvagabonds et autres civils présents à l’armée sans permission et de 100 francs maximum aux marchands malhonnêtes et aux tenanciers de cabarets ouverts en dehors des heures réglementaires13 .

Le Second Empire consolide l’organisation de la prévôté à travers deux textes fondamentaux, bien plus précis que les précédents. Le décret organique de la gendarmerie du 1er mars 1854 consacre à cette formation trente-deux articles (505 à 536), dont certains répètent, mot pour mot, ceux du texte de 1832, par exemple à propos de la désignation d’un « Grand Prévôt » ou des amendes infligées à des civils14. Le code de justice militaire du 9 juin 1857 signale que la juridiction prévôtale ne peut exister que lorsqu’une armée opère à l’étranger – une condition qui sera maintenue par tous les règlements ultérieurs. Il reconnaît aux prévôts, dont les verdicts sont sans appel, le droit de juger seuls, assistés d’un greffier, choisi parmi les sous-officiers de gendarmerie. Il étend leur compétence aux prisonniers de guerre non officiers coupables de « contravention de police » ou d’infractions à la discipline, et il élève le niveau des sanctions jusqu’à 200 francs d’amende et six mois de prison, pour les militaires comme pour les civils15 .

La filiation établie par l’ordonnance de 1832 et le décret organique de 1854 entrelesmissionshabituellesdepoliceadministrativeetjudiciairedesgendarmes et celles qu’ils assument auprès des armées positionne les prévôtaux comme des instruments de la loi et des auxiliaires de la justice. Chargée du service de « force publique » aux armées, selon la formule du décret de 1854 (article 536), la prévôté ne demeure pas moins une institution d’exception, et à double titre. D’une part, car elle ne peut être organisée qu’à l’occasion d’un conflit ; d’autre

13 Ordonnance sur le service des armées en campagne. Règlement du 3 mai 1832, Limoges, E.Ardant, C. Thibaut, s. d., p. 168-177.Auparavant, un règlement de 1823, non retrouvé, reproduisait largement le texte de 1809.

14 Jean-Noël Luc (dir.), Histoire de la maréchaussée et de la gendarmerie, op.cit., pp. 323-327.

15 Code de justice militaire pour l’armée de terre du 9 juin 1857, Paris, Lavauzelle, s.d., pp. 1516, 21 et 60. Pour rester dans la logique de ce panorama, on signalera simplement l’existence de textes ultérieurs sur le service en campagne de la gendarmerie, inspirés par les réorganisations de l’armée française, et notamment les instructions des 25 octobre 1887, 18 avril 1890, 13 février 1900 et 31 juillet 1911, cette dernière en vigueur lors de la Grande Guerre.

25 J.-n.

luc « SoldatS de la loi » aux arméeS. leS PrévôtéS de la Gendarmerie nationale

Forza alla legge. Studi storici su Carabinieri, Gendarmerie e Polizie Armate 26

part, car elle réunit, comme la maréchaussée, des prérogatives policières et un pouvoir de justice, mentionné, on l’a vu, dès les textes organiques de 1799, 1809 et 1832.

Sous le Second Empire, puis sous la Troisième République, des détachements prévôtaux sont envoyés sur tous les théâtres d’opérations, en Europe (Guerre de Crimée, 1853-1856, Campagne d’Italie, 1859, Guerre de 1870187116), au Moyen-Orient (Expédition du Liban, 1860-1861), au Mexique (1861-1867), où le nombre de déserteurs augmente beaucoup après les progrès de la guérilla à partir de 186417, et, lors de l’expansion impérialiste, en Afrique et enAsie, où les prévôtés constituent parfois le noyau des futures gendarmeries coloniales. Quelques témoignages tirent de l’ombre les prévôtaux engagés dans la campagne de Crimée. En juillet 1854, un zouave de passage à Gallipoli, ravagé par le choléra et les trafics, et visiblement influencé par le discours officiel des alliés, admire l’un de ces militaires, qui surveille, « en tenue irréprochable », un bazar largement déserté : Sans l’intervention du gendarme français, l’Occident échouerait dans tous ses plans de réforme en Orient […]. Le gendarme déblaie le terrain et inspire aux masses populaires le respect de l’ordre. […]. Toute la canaille cosmopolite, le rebut de la société occidentale, qui s’est réfugié en Turquie, tremble devant la buffleterie jaune.18

La même confiance inspire la réclamation, en août 1855, par le commandant de la place de Constantinople, de l’envoi de 50 gendarmes au lieu de 13 : L’uniforme du gendarme fait toujours une forte impression sur l’esprit du soldat. Je pense, par ce moyen, arrêter le commerce d’effets, qui ruine la discipline et démoralise le soldat, et empêcher aussi la maraude dans les vignes.19

16 OlivierBottIn, La Guerre de la gendarmerie. Des gendarmes aux gens d’armes (1870-1871), mastère I, sous la dir. de J.-N. Luc, Paris Sorbonne, 2010.

17 Benoît HaBerBuscH, «L’emploi de la gendarmerie au Mexique (1861-1867) : force prévôtale ou force de sécurité intérieure ?», RHA, 258, 2010, pp. 3-13 ;Adrien KIPPeurt, La Gendarmerie au Mexique (1861-1867), Force publique, Revue de la SNHPG, 7, 2012.

18 Cité par Marie-Hélène DeBIès, Du pays des Chouans à Sébastopol. Jean-Michel Gangloff (1802-1871), La Crèche, Geste éditions, 2010, p. 221 (les bandes de l’uniforme du gendarme étaient alors de couleur jaune).

19 Édouard EBel, «La Gendarmerie pendant la Guerre de Crimée», Carnet de la Sabretache, 158, décembre 2003, pp. 180-184.

27 J.-n.

luc « SoldatS de la loi » aux arméeS. leS PrévôtéS de la Gendarmerie nationale

Forza alla legge. Studi storici su Carabinieri, Gendarmerie e Polizie Armate

Zoom sur les prévôtés au cours des deux guerres mondiales

Au cours de la Grande Guerre, 17 800 gendarmes territoriaux sur 22 000 constituent, par roulement, des unités prévôtales, pourvues de 6 000 hommes à partir de 1915, et qui perdront en tout 450 de leurs membres. Pendant la « Grande Retraite » de la fin du mois d’août 1914, les prévôtaux couvrent le repli des troupes, rassemblent des éléments épars et remplacent des cadres hors de combat. Lors de la première bataille de la Marne, au début de septembre 1914, ils reçoivent l’ordre de « maintenir les hommes sur la ligne de feu et [de] forcer au besoin leur obéissance ». Tout au long du conflit, ils surveillent les voies de communication pour garantir la fluidité de la circulation des soldats, des munitions et des approvisionnements, une obsession du commandement. Leur contribution à l’écoulement des flux sur la « Voie sacrée » pendant la bataille de Verdun leur vaut d’ailleurs plusieurs félicitations.Après les combats, ils assurent la police du champ de bataille, où ils arrêtent les auteurs de larcins sur les cadavres et où ils récupèrent les corps, ainsi que les armes. Ils participent également à la lutte contre l’espionnage et à la gestion des prisonniers20 L’armistice de 1918 n’interrompt pas leur travail, puisqu’ils restent chargés du maintien de l’ordre aux armées pendant la démobilisation et de bien d’autres missions au cours de la longue sortie de guerre, comme le repérage du matériel militaire abandonné ou volé21 .

Un détour par l’Armée d’Orient, implantée à Salonique à partir d’octobre 1915, révèle l’ampleur des missions de police assumées par la prévôté six cents ans après sa création. Le maintien de l’ordre et la discipline restent ses objectifs prioritaires. Ses hommes traquent les déserteurs, dont le nombre augmente avec l’allongement de l’expédition. Ils contrôlent les cabarets et les maisons de tolérance officielles. Ils assistent les médecins pendant les vaccinations et les tests d’urine, destinés à vérifier la prise régulière de quinine, que les soldats vivent comme des brimades. Comme les civils sont considérés comme des espions potentiels, les gendarmes enquêtent, par ailleurs, sur les responsables locaux, afin de pouvoir signaler les suspects et les francophiles au 2e Bureau. Ils interviennentdanslavieéconomiqueendélivrantdesautorisationsàdesmaisons

20 Louis Panel, La Grande Guerre des gendarmes, déjà cité, p. 95-114, 347-383, 593, et, du même, «La gendarmerie nationale francese nella prima Guerra Mondiale», dans La Grande Guerra dei Carabinieri,acuradiFlavioCarBone,MinisterodellaDifesa,ComandoGenerale dell’Arma dei Carabinieri, Ufficio Storico, 2020, pp. 206-213.

21 Sur les gendarmes dans la sortie de la Grande Guerre, voir l’étude de Romain Pécout dans ce numéro.

28

de commerce, non sans essayer de favoriser les exportations françaises, et en contestant les prix, jugés exagérés, des marchands autochtones. Ils contribuent, plus largement, à l’instauration du nouvel ordre français en désarmant la population villageoise et en obligeant les habitants à enlever les ordures des rues et à se faire vacciner contre le typhus et le choléra. L’arrêt des hostilités ne met pas fin à cette pluriactivité. Comme sur le front français, les prévôtaux de l’Armée d’Orient participent à l’organisation du départ des hommes et du matériel, première étape de la démobilisation22 .

Vingt ans plus tard, pendant la « Drôle de guerre », les 5 000 prévôtaux et leurs 300 officiers contribuent toujours à la discipline des troupes, « force principale des armées », comme le rappelle le règlement de discipline général de 1933. Dans un contexte marqué par la démoralisation des soldats, la peur du défaitisme et la hantise de l’espionnage, la prévôté apparaît d’abord comme un instrument de contrôle de la zone des armées. Ses hommes répriment une circulation militaire et civile anarchique, qui inquiète beaucoup l’état-major ; ils arrêtent des déserteurs ; ils enquêtent sur la reconstitution, réelle ou fantasmée, de réseaux communistes. Le déclenchement des opérations, à partir du 10 mai 1940, élargit leur rôle à l’orientation des unités en repli, à la participation à des combats isolés et à la gestion de la retraite désordonnée des autres soldats, des civils et des services publics. Lors de la panique de la mi-mai 1940, et alors que les prévôtés de la IIème armée refoulent plus de 16 000 fuyards, de nombreux chefs d’état-major rendent hommage à cette troupe particulière. Mais quand la débandades’accentueaprèsladéfaitedelaSomme,le7juin1940,lesprévôtaux sont emportés, à leur tour, par « ce fleuve humain en crue », selon le témoignage de l’un des leurs23. La France libre renoue avec l’organisation traditionnelle d’une force armée en dotant ses unités de deux prévôtés, l’une pour encadrer les soldats français présents en Grande-Bretagne, l’autre pour suivre les troupes engagées, à partir de 1942, en Afrique du nord, où les gendarmes participent également aux combats. L’exploitation des archives prévôtales nuance l’image idéaliséedesForcesFrançaisesLibres,enrévélantl’existencedefortestensions, politiques, idéologiques et raciales24 .

22 Isabelle Roy, La Gendarmerie française en Macédoine pendant la Première Guerre mondiale, Maisons-Alfort, SHGN, 2004, pp. 29-37, 57-75, 118-126, 188-192.

23 Aziz Saït, les Prévôtés, de la «Drôle de guerre» à «l’Étrange défaite», doctorat, sous la dir. de J.-N. Luc, Paris-Sorbonne, 2012, chapitres V à VII et XIV.

24 Vincent LHomeau, Les Prévôtés de la France libre, 1940-1944. Discipliner «L’autre Résistance», Force publique, Revue de la SNHPG, 9,2014.

29 J.-n.

luc « SoldatS de la loi » aux arméeS. leS PrévôtéS de la Gendarmerie nationale

Forza alla legge. Studi storici su Carabinieri, Gendarmerie e Polizie Armate

Le gendarme prévôtal, enquêteur, magistrat et agent pénitentiaire

Ces responsabilités particulières méritent un développement autonome, car elles positionnent la prévôté comme un maillon essentiel de la chaîne judiciaire aux armées. Les fonctions d’officier de police judiciaire militaire sont d’abord exercées par les seuls commandants des formations prévôtales, puis également par d’autres officiers et, même, pendant la Grande Guerre, par les sous-officiers. Tous ces militaires sont alors qualifiés pour collecter les informations relatives à une infraction à travers des interrogatoires, des perquisitions, des saisies et des arrestations. Pendant l’occupation d’une partie de l’Espagne, entre 1809 et 1814, ils enquêtent, par exemple, sur des détournements de fonds par deux généraux, la falsification de la farine importée de France, la profanation d’objets de culte et des viols25.Au cours de la conquête de l’Algérie, à partir de 1830, ils interviennent, notamment, à propos des duels entre soldats, de l’abus d’alcool, des vols de marchandises appartenant à l’armée et des pillages perpétrés par la troupe26

On dispose d’une vue d’ensemble sur les infractions commises par des soldats, en l’occurrence parmi ceux du Corps expéditionnaire français en Italie, grâce au registre d’écrou de la prison prévôtale de Naples, entre juillet 1944 et septembre 1945 : plus du tiers (37 %) des 373 militaires incarcérés sont accusés de désertion, 18 %, de viol, 14 %, de vol et de pillage, et 3 %, de meurtre ou tentative de meurtre. Souvent favorisés par l’abus d’alcool, les homicides volontaires sont généralement provoqués par des humiliations ou des rivalités à propos d’une femme ou associés à des viols ou à des tentatives de viol27

Les riches archives des prévôtés du Corps expéditionnaire français en Extrême-Orient (CEFEO) renseignent sur la gestion de certains crimes commis dans le cadre d’une guerre de décolonisation. Interrogé par les prévôtaux après la découverte, en mai 1946, du corps d’un coolie, son supérieur, un brigadier-chef, reconnaît qu’il a l’habitude de frapper les ouvriers quand « ils mettent de la mauvaise volonté pour travailler ». Après l’avoir arrêté, pour « coups et blessures ayant entraîné la mort », les gendarmes remettent le cadavre à un

25 GildasLePetIt, Saisir l’insaisissable. Gendarmerie et contre-guérilla en Espagne au temps de Napoléon, Rennes, Presses Universitaires de Rennes (PUR), pp. 116-117.

26 Damien Lorcy, Sous le régime du sabre. La gendarmerie en Algérie, 1830-1870, Rennes, PUR, 2011, pp. 169-176.

27 DimitriRoulleau-GalaIs, La Prévôté, une solution efficace face aux comportements du corps expéditionnaire français en Italie de 1943 à 1945 ?, master I, sous la dir. de J.-N. Luc, Paris-Sorbonne, 2007, p. 67.

30

31 J.-n.

luc « SoldatS de la loi » aux arméeS. leS PrévôtéS de la Gendarmerie nationale

Forza alla legge. Studi storici su Carabinieri, Gendarmerie e Polizie Armate

médecin, vietnamien, de l’hôpital de Cholon, qui conclut, après l’autopsie, à un décès par éclatement de la rate sous l’effet de coups de poing. Le viol et l’étranglement, en 1947, d’une jeuneAnnamite, retrouvée nue et à demi enterrée, sont plus difficiles à élucider. Les villageois expliquent aux enquêteurs qu’ils avaient eu peur de sortir de leurs paillotes la veille au soir, malgré les appels au secours de la victime, car un homme ivre et nu circulait dans le village.Après la découverte, près du lieu du crime, de pièces d’uniforme de la Légion, les gendarmes inspectent, sans succès, les paquetages des détachements du 1er Régiment Étranger de Cavalerie (REC) stationnés dans les environs. En poursuivant leurs investigations à l’infirmerie, ils repèrent un légionnaire portant « des égratignures fraîches, faites par des ronces », et dépourvu de short, de chemisette et de képi. Soumis à un interrogatoire, le suspect avoue son double crime28 .

Des gendarmes peuvent également juger les auteurs de certaines infractions, puisque les tribunaux prévôtaux – qui fonctionnent peut-être auparavant –sont mentionnés, on l’a vu, dès les règlements de 1799 et de 1809. Même s’ils constituent surtout « une soupape de délestage des conseils de guerre […] pour les affaires mineures », ces tribunaux font ressortir, symboliquement, la dignité et l’indépendance des officiers de gendarmerie en tant qu’hommes de loi et représentants de l’État de droit. C’est dire la déception de ces cadres au cours de la Grande Guerre, dont les opérations se déroulent essentiellement sur le territoire national, où la justice prévôtale ne peut pas être organisée29. En revanche,lestribunauxprévôtauxmissurpied,àpartirde1916,enMacédoineet en Serbie, jouent pleinement leur rôle.Au-delà des vagabonds et des prisonniers de guerre non officiers, ils jugent, en fait, tous les civils, attachés ou non à l’armée, en infraction avec la réglementation des déplacements, du commerce et de l’hygiène publique. Selon la faute commise, la sanction peut être une amende, un travail forcé, une peine de prison ou la fermeture d’un établissement commercial30. Les tribunaux prévôtaux organisés au Levant pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale sont encore plus actifs, car leur compétence est étendue à l’ensemble de la population locale pour de nombreuses questions relatives aux intérêts français. Ainsi ont-ils jugé plus de la moitié des affaires traitées par la justice militaire entre 1941 et 194331. Dans d’autres contextes, où ces tribunaux

28 Pierre-Yves Le Quellec, L’Exercice de la police judiciaire par les prévôtés du CEFEO au Vietnam (1946-1954), master II, sous la dir. de J.-N. Luc, Paris-Sorbonne, 2012, p. 65 et 81.

29 Louis Panel, op. cit., pp. 299-303.

30 Isabelle Roy, op. cit., pp. 99-102.

31 HelènedeCHamPcHesnel, La Déchirure : guerre fratricide en gendarmeries, Levant 19391945, Vincennes, Service Historique de la Défense (SHD), 2014, pp. 190 sq

32

particuliers ne sont pas organisés, des prévôts peuvent intervenir dans les autres cours militaires à titre de magistrat, commissaire-rapporteur, juré et même avocat.

Déjà prévues dans les règlements de 1799, 1809 et 1832, les prisons prévôtales, longtemps négligées par les chercheurs, constituent un dispositif crucialdumaintiendel’ordreauxarmées,etquiimposeauxgendarmesuntravail souvent considérable. Cent cinquante d’entre elles ont fonctionné pendant la Grande Guerre, dans des locaux disparates (étables, caves, églises). Installées à tous les niveaux, de la division à l’armée, elles ont reçu, au total, une population hétéroclite de 150 000 personnes : justiciables des tribunaux militaires, ou de droit commun, et condamnés à de courtes peines, soldats et civils, hommes et femmes, Français et étrangers. Décrite comme « le cauchemar des officiers et des gendarmes », la surveillance de ces établissements de fortune, d’où les évasions sont fréquentes, représente le premier motif des punitions infligées aux prévôtaux, qui n’aiment pas évoquer cette mission32

Aux yeux de plusieurs gendarmes, les enquêtes sur les infractions commises par des militaires contre des civils, et la punition des coupables, sont d’autant plus nécessaires qu’elles peuvent contribuer à supprimer ou, au moins, à réduire l’hostilité de la population à l’égard des troupes d’occupation.

« Protéger les habitants du pays contre le pillage et toute autre forme de violence »33 : les prévôtaux, pionniers de la doctrine « Gagner les cœurs et les esprits » ?

Bien avant la théorisation de cette stratégie, la protection des habitants des territoires occupés est considérée comme un atout pour contrecarrer l’influence des opposants à la présence française. « On ne peut attaquer avec succès toutes les causes du brigandage [la guérilla] qu’en réprimant sévèrement les actes irréguliers de la troupe », assure un général de l’armée d’Espagne en 181134. EnAlgérie, au XIXe siècle, le même raisonnement conduit des gendarmes à protéger des indigènes, leurs bêtes et leurs cultures contre des soldats ou des colons violents ou malhonnêtes. L’impartialité et l’efficacité des agents de l’administration française – du moins de certains d’entre eux – sont officiellement présentées

32 Louis Panel a tiré de l’ombre cette «oubliée de la Grande Guerre» dans l’ouvrage déjà cité, p. 304-315.

33 Ordonnance du 3 mai 1832…, op. cit., article 171, p. 169.

34 Gildas LePetIt, op. cit., p. 118.

33 J.-n.

luc « SoldatS de la loi » aux arméeS. leS PrévôtéS de la Gendarmerie nationale

Forza alla legge. Studi storici su Carabinieri, Gendarmerie e Polizie Armate 34

comme l’un des moyens de convaincre les habitants qu’ils sont mieux défendus contre les abus qu’à l’époque des Ottomans. Pour régler « le grand problème de la domination », résume, en 1856, le commandant de la gendarmerie d’Afrique, il faut « prévenir le plus insignifiant déni de justice » et « défendre [la population] quand elle devient victime d’un délit ou d’une erreur »35. Pendant la Grande Guerre, on retrouve le même projet en Macédoine, où la prévôté de l’armée d’Orient espère séduire les populations locales en se montrant plus efficace et plus juste que les polices turque ou bulgare36 .

Au cours de la Guerre d’Indochine, les enjeux des relations avec la population locale conduisent les prévôtaux à souligner explicitement l’irresponsabilité d’un grand nombre d’autres soldats. Pour le commandant du poste de Bac-Ninh, en juillet 1952, la recrudescence des attentats aux mœurs, tolérés par une grande partie des officiers du corps expéditionnaire, « porte, non seulement préjudice à la renommée de notre armée, mais sont exploités utilement par l’ennemi ». À la même époque, le responsable du poste d’Hadong dénonce l’ébriété de 90% des militaires « rencontrés en ville », fiers de leurs « cuites mémorables, où la solde est bue en une soirée », ainsi que leur comportement « agressif et hargneux », avant de rappeler les conséquences négatives de ces actes : « c’est sur ces faits et gestes que s’appuie la propagande antifrançaise du Vietminh »37 .

Ce tableau serait cependant incomplet s’il ne s’étendait pas aux divers obstacles rencontrés par les gendarmes détachés auprès des armées.

Les limites de l’action des prévôtés

Elles résultent d’abord de la faiblesse numérique des détachements : 400 hommes pour la campagne de Russie (1812), 160 hommes en Algérie (1833), 158 au Mexique (1867), 315 en Macédoine (1915-1918) ou 264 en Indochine (1947). Comment des effectifs aussi réduits – leur insuffisance est un leitmotiv des rapports – pourraient-ils contrôler des milliers ou des dizaines de milliers de soldats : 650 000 pour la GrandeArmée de 1812, 114 000 à l’armée d’Orient, en 1916, et 90 000 en Indochine, en 1949.Au cours de la campagne de Russie, par exemple, les prévôtaux sont impuissants face aux pillages commis par une multitude de soldats mal ravitaillés. Ils ne parviennent pas davantage à

35 Damien Lorcy, op. cit., pp. 171, 284-287.

36 Isabelle Roy, op. cit., p. 82 sq

37 Pierre-Yves Le Quellec, op. cit., p. 5 et 105.

35 J.-n. l

«

uc

SoldatS de la loi » aux arméeS. leS PrévôtéS de la Gendarmerie nationale

Forza alla legge. Studi storici su Carabinieri, Gendarmerie e Polizie Armate 36

garantir la sécurité des villes occupées, ni à empêcher l’incendie de Moscou38

Les maigres effectifs des prévôtés entravent d’autant plus leur action que leur polyvalence, accrue par les demandes des états-majors et par les emplois abusifs, freine leur réactivité en matière de police judiciaire. En 1940, deux officiers proposent d’ailleurs de remédier à cette situation en organisant, soit une « brigade de recherche » spécialisée, soit une « gendarmerie du droit », auxiliaire de la justice aux armées et distincte d’une « gendarmerie de combat », chargée du maintien de l’ordre et de la participation aux opérations39

L’indulgence abusive ou la corruption de certains prévôtaux peuvent également réduire leur efficacité. À Salonique, en 1916, deux d’entre eux refusent de régler leur consommation, puis de contraindre au paiement deux autres militaires, qui déclarent publiquement vouloir « faire comme les gendarmes »40 ! En Indochine, des prévôtaux participent au trafic des piastres, ferment les yeux sur un convoi de riz illégal en échange d’une bouteille de Cognac ou ne poussent pas les investigations contre des soldats brutaux qu’ils fréquentent quotidiennement. La formation insuffisante de certains jeunes gendarmes et leur faible expérience de la police judiciaire retardent également des enquêtes. Le commandant de la prévôté du Centre-Vietnam – qui semble ignorer les difficultés du recrutement – réclame, en 1951, une vraie sélection des prévôtaux, « investis d’une mission délicate », qui leur impose d’être « des hommes solides, irréprochables et connaissant à fond le métier ». La gendarmerie, conclut-il « se doit d’envoyer au corps expéditionnaire ce qu’elle a de meilleur »41

Dernier obstacle, et de taille, à l’action des prévôtés : l’hostilité des autres soldats, irrités par les pouvoirs policiers et judiciaires accordés à des militaires non combattants, et le refus, par de nombreux officiers, des entraves à leur autorité sur leurs hommes, dont ils peuvent tolérer, bon gré, mal gré, les excès. Mutisme, invectives et coups ne sont pas exceptionnels, surtout quand la solidarité des chefs soude l’unité face au gendarme verbalisateur. « Le rapport du Grand prévôt est sans pudeur ; c’est bien un rapport de gendarme », proteste un commandant des troupes d’Algérie, en 183342. Traumatisés par l’horreur des tranchées, les poilus s’indignent, eux aussi, devant les injonctions de ceux qu’ils traitent d’embusqués, en rappelant, avec ironie, que « le front commence au

38 Jacques-Olivier BouDon, op. cit., pp. 216-218.

39 Aziz Saït, op. cit., chapitre IX.

40 Isabelle Roy, op. cit., p. 81.

41 Pierre-Yves Le quellec, op. cit., p. 43.

42 Damien Lorcy, op. cit., p. 142.

dernier gendarme » ! Tenace, l’image persiste dans la mémoire littéraire de la guerre. Dans Les Croix de Bois (1919), Roland Dorgelès ironise sur la surveillance des aubergistes par les prévôtaux : « ils sautent la patronne ; comme ça elle est parée contre les contraventions, et eux ont la croûte ». Dans La Main coupée (1946), Blaise Cendras se moque des « gens d’armes de métier, qui ne voulaient pas aller se battre »43. Que sont les gendarmes, d’ailleurs, pour certains cadres de l’armée ? Des coursiers ou des « valets de chambre », proteste l’un de leurs officiers. Au Tonkin, en 1948, et alors qu’un gendarme colonial assiste un prévôtal dans son travail, le chef de bataillon commandant le secteur donne l’ordre « d’embêter ce petit merdeux qui enquête à Phong-Tho, afin qu’il n’obtienne aucun renseignement ». L’un des prévôts du corps expéditionnaire déplore d’ailleurs que sa mission soit « incomprise, parce que trop nombreux sont les officiers qui méconnaissent le rôle de la Prévôté auxArmées » 44

Si les hauts responsables militaires défendent le plus souvent les prévôtaux, ils peuvent aussi ménager les officiers qui s’en plaignent : « on aura soin, qu’à l’avenir [le Grand prévôt] ne se fasse pas le trompette des délits que commettent les soldats autour de leurs cantonnements », répond, en 1832, le chef d’état-major de l’armée d’Algérie à un autre général, tout en invitant les chefs de détachements à mieux surveiller leurs hommes45. Le choc des mutineries de 1917 dissipe cependant ce genre de réserves. Le 11 octobre, Philippe Pétain, commandant en chef des armées françaises depuis le mois de mai, apporte un soutien appuyé aux membres des prévôtés : Au cours de récents incidents, des militaires des armées se sont laissés aller à proférer des injures et même à exercer des violences graves contre les gendarmes. Des officiers et sous-officiers ne sont pas intervenus immédiatement de toute leur autorité. Ces faits dénotent un fâcheux état d’esprit, qui ne doit pas être toléré. Comme leurs camarades des autres armes, les gendarmes remplissent avec conscience et dévouement leur mission.46

Mais après la victoire, les missions prévôtales ne sont pas moins évacuées d’une mémoire nationale chargée d’exalter les souffrances et le courage des poilus. À l’exception des moments forts de la revendication – vaine – de la carte d’ancien combattant pour les prévôtaux, au cours des années 1930 puis 1950,

43 Louis Panel, op. cit., pp. 384, 531-532, et, pour les citations, Yann Galéra, Les Gendarmes dans l’imaginaire collectif, de 1914 à nos jours, Paris, NME, 2008, pp. 85-98.

44 Pierre-Yves Le Quellec, op. cit., p. 27.

45 Damien Lorcy, op. cit. p. 175.

46 Louis Panel, op. cit.,p. 452.

37 J.-n.

luc « SoldatS de la loi » aux arméeS. leS PrévôtéS de la Gendarmerie nationale

Forza alla legge. Studi storici su Carabinieri, Gendarmerie e Polizie Armate

la mémoire gendarmique ne fait guère mieux jusqu’au début du xxIe siècle47 Quand elle n’oublie pas, le plus souvent, les prévôtés de la Grande Guerre, elle retient surtout leurs missions de contre-espionnage et de renseignement, plus consensuelles et plus valorisantes que l’arrestation et la détention de soldats coupables d’infractions.

La prévôté, instrument et symbole de la militarité gendarmique, de la fin du XVIIIe siècle aux OPEX

L’histoire des prévôtés éclaire également la militarité originale de la gendarmerie48, qui a été enracinée dans l’armée par la Révolution et par les régimes suivants. L’héritière de la maréchaussée fournit des troupes combattantes dès le début des guerres révolutionnaires, à partir d’avril 1792, puis pendant la Guerre d’Espagne, entre 1809 et 1813. La loi de Germinal an VI (1798) lui attribue, en plus, la prérogative de l’ancienne Maison militaire du roi : « prendre toujours la droite et marcher à la tête des colonnes » (article 152). L’ordonnance de 1820 confirme son statut militaire en la définissant comme « l’une des parties intégrantes de l’armée » (article 2). Enfin, le décret organique de 1854 accentue cet arrimage en reconnaissant à l’Arme la possibilité de constituer des unités combattantes (article 536) et en la rattachant au ministère de la Guerre pour le contrôle de « toutes les parties du service » (article 73). La « nature mixte » de ce service maintient cependant le corps « dans les attributions » de trois autres ministères : l’Intérieur, la Justice, la Marine et les Colonies (article 5).

La gendarmerie emprunte alors à l’armée ses hommes, son encadrement supérieur, son organisation hiérarchique, ses équipements, ses uniformes, ainsi qu’une partie de sa symbolique, de sa culture professionnelle et de son mode de fonctionnement. Mais cette forte influence des standards militaires ne doit pas faire oublier qu’elle reste une force dédiée principalement à la sécurité intérieure, et non aux champs de bataille. Si les engagements de ses unités combattantes, peu nombreuses, contribuent à sa militarité, ils ne la résument pas. Il est donc vain de vouloir évaluer l’identité militaire de la gendarmerie à l’aune du seul critère de sa participation au combat, considéré comme « le but final

47 Yan Galéra, op. cit., pp. 121-132.

48 Jean-Noël Luc, «Histoire d’une identité militaire particulière. La militarité de la gendarmerie française, de la Révolution au début du XXIe siècle», dans Hervé DréVIllon et Édouard EBel (dir.), Symbolique, traditions et identités militaires,Vincennes, SHD, 2020, pp. 173-186.Voir également La Gendarmerie, les gendarmes et la Guerre, dossier de Force Publique, 1, février 2006.

38

39 J.-n. l

« S

uc

oldatS de la loi » aux arméeS. leS PrévôtéS de la Gendarmerie nationale

Forza alla legge. Studi storici su Carabinieri, Gendarmerie e Polizie Armate 40

des armées », selon la célèbre formule du colonel Ardant du Picq, dans un ouvrage posthume publié en 188049. Un tel raisonnement masquerait les diverses missions militaires que cette institution assume depuis sa création50, y compris en temps de paix, à côté de son engagement, prédominant, dans la police de la société.

Dès son origine, la gendarmerie française fonctionne effectivement comme une force armée complémentaire des autres troupes, avant, pendant et après les opérations. Pendant les périodes de paix, elle assure la police des militaires en intervenant, entre autres, dans l’organisation de la conscription, le contrôle des permissionnaires, l’administration des réserves ou la protection des convois de munitions. L’entrée en guerre accroît ses contributions au rassemblement, à l’équipement, au transfert et au contrôle des troupes. Des gendarmes peuvent, en plus, se battre, au cours de certaines campagnes, au sein de formations préexistantes ou d’unités créées pour l’occasion51. Et l’Arme continue d’assumer des missions militaires après la fin des hostilités, en participant, à plusieurs niveaux, à la transition vers le temps de paix, y compris dans les régions libérées ou occupées52 .

La contribution essentielle de la gendarmerie au bon fonctionnement de

49 Charles ArDant du PIcq (1821-1870), Études sur le combat, Paris, Hachette et Dumaine, 1880, p. 7.

50 Ces missions se sont d’ailleurs amplifiées depuis le milieu du XXe siècle. À côté des unités maritimes, créées à partir de 1791, le corps s’est alors doté d’autres formations spécialisées rattachées aux armées (gendarmeries de l’Air, de l’Armement, de la Sécurité des armements nucléaires). La mise en œuvre des doctrines du continuum «paix-crise-conflit armé» puis «sécurité-défense» a, par ailleurs, augmenté la participation de la gendarmerie à la Défense opérationnelleduterritoire(DOT),auxOPEXetàlaluttecontreleterrorisme.Simultanément, ses effectifs se sont accrus, jusqu’à représenter, en 2011, 43 % de ceux des armées, dont le volume a diminué, et la moitié de la réserve opérationnelle. Au début du XXIe siècle, les textes officiels relatifs à la défense nationale rappellent sa «vocation à participer à la défense du territoire» et sa capacité à fournir un «appui essentiel» aux armées (article 53225-6 du Code de la Défense et Livre blanc Défense et Sécurité nationale, Paris, DILA, 2013, p. 96).

51 Formationspréexistantes:gendarmerieàpieddelagardeimpériale(GuerredeCrimée),garde républicaine mobile (campagne de 1939-1940), gendarmerie mobile (Guerre d’Algérie). Unités de circonstance : régiments à pied et à cheval (Guerre de 1870-1871), 45e bataillon de chars légers (1939-1940), légions de garde républicaine de marche (Indochine), commandos de chasse (Algérie). Sur les engagements combattants de la gendarmerie française, voir Laurent LóPez (dir.), La Gendarmerie, ses emblèmes et ses faits d’armes, dossier de Histoire et Patrimoine des gendarmes, 16, 2e trimestre 2019.

52 Sur l’exemple de la sortie de la Grande Guerre, voir l’étude de Romain Pécout dans ce numéro.