RitaMcGrath

The Perils of Great Success

Introduction

Most of the time, bringing an innovation to life doesn’t work out. But sometimes, in a magical moment, product-market fit is achieved, the market responds and there is a glorious period of success. But the thing we don’t talk about much is that this very period of success contains within it the seeds of future disappointment and even irrelevance.

The relationship between success and failure (I\II)

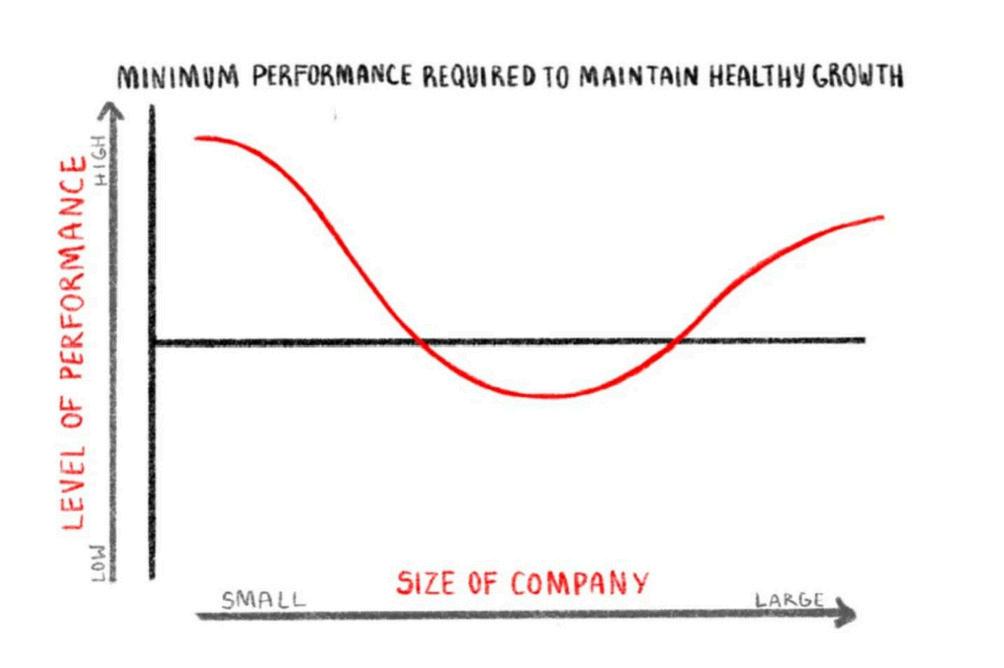

Jeff Severts, a corporate veteran and now innovator at the University of Chicago has an interesting stage model for the evolution of companies. In a business pamphlet (because he claims he hates business books), he suggests that companies go through four predictable stages as they evolve. His foundational model looks like this:

The relationship between success and failure (II\II)

Here’s the problem as he identifies it: we think that performance is steady over the life cycle of a company. But in reality, there is a fascinating period where a company can let its performance slip, but due to a number of factors – momentum, inertia, the time required for competitors to copy and others – it can underperform but still keep its market dominance.

Another take on the same phenomenon, this time from Steve Jobs (I\III)

Steve Jobs was once asked his view on why incredibly successful companies struggle so much to sustain their success once the initial wildly successful offering no longer can carry the firm. I thought his answer was fascinating and it points to a similar phenomenon that Severts observed (this was in the difficult period for Jobs after he had exited Apple and before his triumphant return in the late 1990’s):

McGrath

Another take on the same phenomenon, this time from Steve Jobs (II\III)

Thought Sparks

Well, for PepsiCo, [having sales and marketing people in charge ] might have been okay. But it turns out the same thing can happen in technology companies that get monopolies like, oh, IBM and Xerox. If you were a product person at IBM, or Xerox… when you have a monopoly market share, the company is not any more successful if you make a better product. So, the people that can make the company more successful are sales and marketing people and they end up running the companies. The product people get driven out of decision-making forums. And the companies forget what it means to support the product genius that brought them to that monopolistic position in the first place…. And they really have no feeling in their hearts usually about wanting to really help the customers. So that's what happened at Xerox. The people at Xerox PARC used to call the people that ran Xerox toner heads. The toner heads would come out to Xerox PARC and they had no clue about what they were seeing.

Another take on the same phenomenon, this time from Steve Jobs (III\III)

As a company grows, the proportion of people involved in exploiting an existing advantage relative to the people engaged in either building a potential new advantage or transforming away from an exhausted one is likely to be much larger. Unless carefully managed, this can create a power imbalance in which the demands of exploitation completely overwhelm the need to build for the future.

Is this inevitable? No. Does it require skillful leadership? Yes.

In the work I’m doing for my new book, I’m finding these patterns of recurring success leading to failure to be more common than one might think, a reason that the average lifespan of a large company runs around 40 years. What is a solution? Adopting the new strategy playbook, making innovation a proficiency and adopting permissionless organizational forms. Not easy or natural, but entirely doable. This is among the challenges we work with companies to address.

https://thoughtsparks.substack.com/