AFTER 41 YEARS OF PUBLISHING

AFTER 41 YEARS OF PUBLISHING

At exedee we put our energy and expertise into enabling your organisation to manage process automation and digitalisation with ease … and with >99% accuracy.

Recognise any of these common business problems? We can solve them for you!

Problem #1 Problems managing inbound documents – manual data entry & processing delays and issues

Problem #2 Accounts Payable / supplier invoice processing delays and approval issues

Problem #3 Issues and challenges turning paper documents into accurately scanned files

Problem #4 Digital filing - issues trying to find specific documents in a collection of scanned files

Problem #5 Issues managing and monitoring contracts

Problem #6 Issues centralising all customer information so that everyone can find and use it

Problem #7 Conflicting & duplicate data issues in your business information

Let us show you how our eSolutions work easily, effortlessly and exactly – to solve your business problems and streamline your records and information management processes.

EDITOR: Peta Sweeney

Information and Content Specialist

Email: editor.iq@rimpa.com.au

Post: Editor, iQ Magazine

1/43 Township Drive

Burleigh Waters Qld 4220

DESIGN: Amanda Hargreaves

Graphic Designer (Freelance)

Email: olecreativeagency@gmail.com

Stock images: Shutterstock

ADVERTISING

Peta Sweeney

peta.sweeney@rimpa.com.au

EDITORIAL COMMITTEE

Stephanie Ciempka (ACT)

Peta Sweeney (QLD)

Matt O’Mara (NZ)

David Pryde (NZ)

Philip Taylor (QLD)

Roger Buhlert (VIC)

CONTRIBUTIONS & EDITORIAL ENQUIRIES

Articles, reports, reviews, news releases, Letters to the Editor, and content suggestions are welcomed by the Editor, whose contact details are above.

COPYRIGHT & REPRODUCTION OF MATERIAL

Copyright in articles contained in iQ is vested in their authors. Most editorial material which appears in iQ may be reproduced in other publications with permission gained through iQ’s Editor.

ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTIONS

iQ DIGITAL ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION

$49.50 incl GST ($) per annum for 2 issues RIMPA Global | Phone: 1800 242 611 International Phone: +61 7 32102171 To subscribe head to www.rimpa.com.au

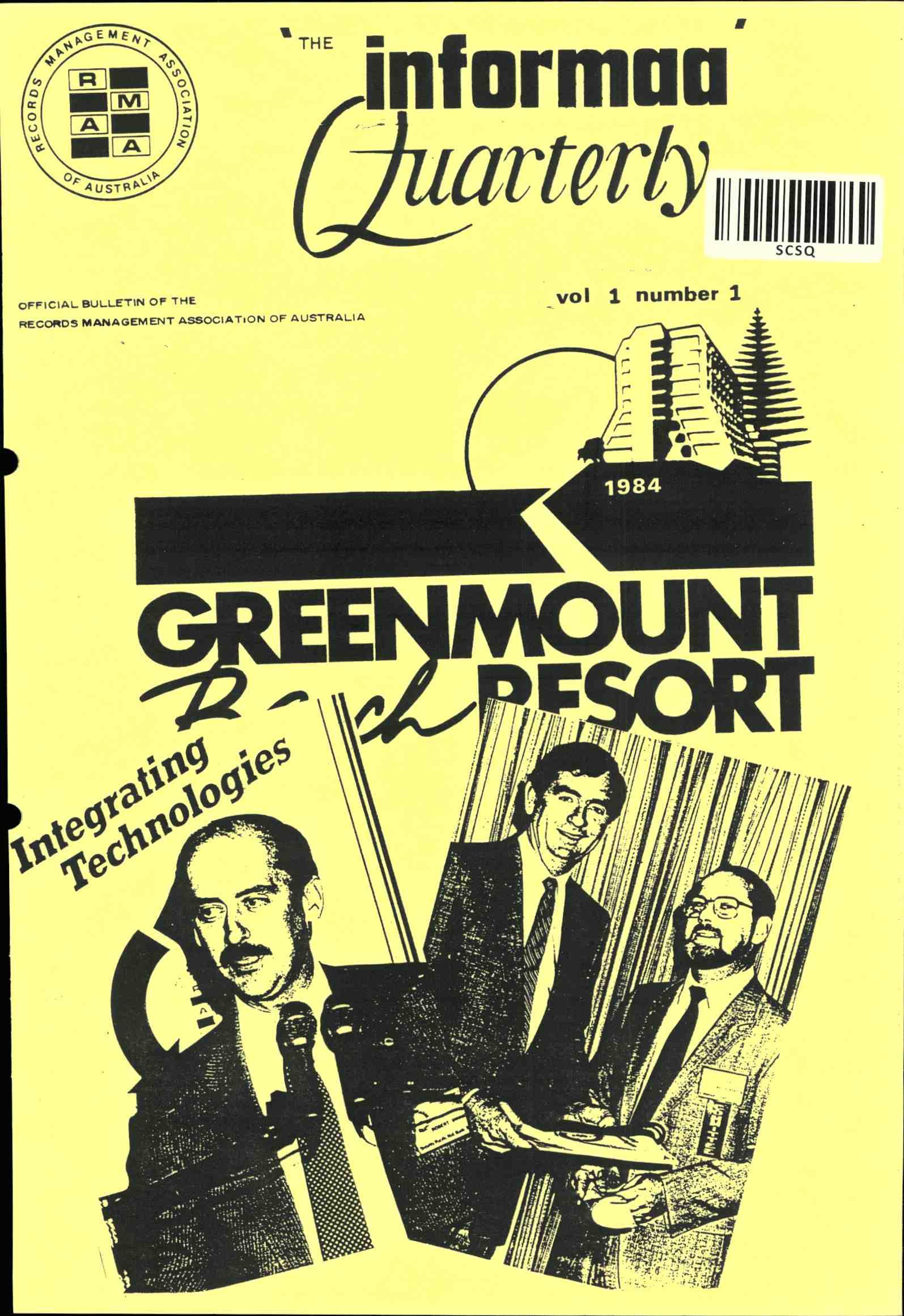

iQ ONLINE ARCHIVE

Copies of articles published in iQ since 1984 are available at the Members Only section of the RIMPA Global website, in the iQ Article Archive. The Members Only section of the website can be accessed with RIMPA Global membership.

DISCLAIMERS

Acceptance of contributions and advertisements including inserts does not imply endorsement by RIMPA Global or the publishers. Unless otherwise stated, views and opinions expressed in iQ are those of individual contributors, and are not the views or opinions of the Editor or RIMPA.

BONITA KENNEDY LIFE ARIM, CERIM, CHAIR OF THE BOARD RIMPA GLOBAL

ANNE CORNISH LIFE MRIM CEO RIMPA GLOBAL

After thoughtful deliberation, the Board of RIMPA Global has made the decision to retire our long-standing industry journal, iQ. This decision was not made lightly. For many years, iQ has been a trusted companion to our profession—capturing milestones, sharing ideas, and showcasing the voices that have shaped the world of records and information management.

However, like the profession it served, our methods of engagement must evolve. Member feedback and engagement data have made it clear: the way our community consumes content is changing. You’ve told us you want insights that are more timely, accessible, and adaptable to your working lives. In response, we are embracing new formats that allow us to deliver expert insight and professional updates more frequently and in more interactive ways. In addition, producing iQ in its traditional format has become increasingly costly— both financially and environmentally. As a member-driven association, we have a responsibility to manage our resources wisely and to reduce our environmental footprint wherever possible. By transitioning away from print-based publishing, we are supporting a more sustainable future aligned with our values. From here, our focus will shift to a dynamic mix of digital content—including fortnightly newsletters, webinars, expertled blogs, and curated online experiences. These formats not only allow us to reach more members, more often, but also reflect the cost-effective, responsive, and inclusive model we need to sustain into the future. We know that iQ has held a special place in our members’ professional journey. To honour its legacy, we will archive past editions online, preserving the knowledge, creativity, and leadership that have filled its pages.

Looking ahead, we remain as committed as ever to supporting and elevating the profession. You can expect continued access to highquality content, thought leadership, and engagement opportunities— delivered in ways that are more agile, audience-focused, and future-ready. For our valued partners and advertisers, we’re also excited to offer a fresh suite of digital opportunities, including:

• Targeted placements in our highengagement email newsletters

• Sponsored thought leadership and content partnerships

• Webinars and panel event sponsorships

• Customised digital campaign solutions We understand that change can be

You can expect continued access to high-quality content, thought leadership, and engagement opportunities—delivered in ways that are more agile, audience-focused, and future-ready.

challenging, but we believe the time is right. As we close this chapter, we do so with immense gratitude and pride. Thank you—for reading, contributing, supporting, and believing in IQ. Your support has helped us inform, challenge, and inspire thousands of professionals over the years. We look forward to shaping the next phase of our professional community with you.

Bonita Kennedy Life ARIM, CERIM – Chair of the Board

Anne Cornish Life MRIM - CEO

As we prepare this final edition of IQ, I find myself reflecting on the remarkable journey this publication has taken—through decades of industry shifts, professional advancement and shared knowledge.

Since its first issue, iQ has stood as a trusted voice, a critical resource and a reflection of our profession’s depth, diversity and resilience. Over the years, we’ve explored emerging technologies, legislative change, strategic challenges and day-to-day practice. We’ve welcomed the voices of new professionals and honoured the wisdom of seasoned leaders. Our contributors, reviewers, readers and advertisers have formed a community built on shared purpose and mutual respect. To each of you: thank you. The decision to cease publication was not made lightly. Like many of you, we’ve seen the ways in which our profession is adapting—leaning into real-time communication, embracing digital platforms, seeking content that is more interactive, on-demand and diverse in form. This final edition is not the end of the conversation, but rather a transition to new ways of engaging with the ideas and issues that matter most.

Our contributors, reviewers, readers and advertisers have formed a community built on shared purpose and mutual respect. To each of you: thank you.

In this edition, you’ll find reflections on where we’ve been and where the profession is heading. We’ve gathered voices from long-time contributors and first-time authors and curated some of the most impactful pieces for you. It’s a celebration of both legacy and future. While this may be the final printed page, the work we do—as information and records professionals—continues to matter deeply. The need for strong, ethical and future-ready information leadership is greater than ever. Thank you for being part of this story. It’s been a privilege to share it with you.

Peta Sweeney Life FRIM, CXRIM – Editor

The Council of Australasian Archives and Records Authorities have recommitted to the aims of the International Council on Archives Tandanya-Adelaide Declaration on its fifth anniversary.

The Declaration calls on archives to ‘…re-imagine the meaning of archives, to embrace Indigenous world views and to decolonise archival principles with Indigenous knowledge methods’. To mark this occasion, CAARA has released a video titled "CAARA Members Recommit to the Aims of the Tandanya-Adelaide Declaration."

CAARA’s First Nations Special Interest Group established in 2020 includes representation from eight Australian states and territories, National Archives of Australia and Te Rua Mahara o te Kawanatanga, Archives New Zealand. CAARA organisations are unified in their support for First Nations peoples, providing resources and services to our First Nations peoples and communities across Australia and New Zealand.

We support the creation of ethical spaces of encounter, respect, negotiation and collaboration and we are committed to opening up our archives. CAARA First Nations Special Interest Group.

CAARA Australian jurisdictions are working on cross-jurisdictional support for the Healing Foundation’s Principles for nationally consistent approaches to accessing Stolen Generations records.

A guide for Victorian public offices is now available.

Managing Records in Microsoft 365: A guide for Victorian public offices was developed by Microsoft 365 (M365) expert Andrew Warland to assist Victorian Government agencies in the management of records created and captured across the M365 environment.

Whether your agency is implementing or currently managing an existing M365 environment, this guidance will be a useful resource in understanding the recordkeeping capabilities and limitations of M365. This guidance will also help records managers and others to start developing a good understanding of the M365 environment. From its admin centre structure, who should have which assigned roles and responsibilities, where records are captured and stored, to recordkeeping configurations, retention policy recommendations and information architecture approaches. It covers all areas of M365 that creates and manages records including, but not limited to, SharePoint, Exchange (for emails), Teams, Purview (for compliance activities) and Entra (for access arrangements and grouping). By utilising this guidance, agencies can work towards meeting their recordkeeping requirements and compliance with PROV’s PROS 19/05 Create Capture and Control Standard and other standards and specifications. You can find this guidance on our website, as well as a new Microsoft M365 topic page for further advice. Visit prov.vic.gov.au/about-us/ourblog/managing-records-m365

ACA Pacific is a leading distributor of Document Scanners, Capture Software and Information Management solutions, designed to fast track your path to Digital Transformation. As the distributor for Kodak Alaris Scanners and Software, ABBYY solutions, Contex & Colortrac Wide-Format Scanners and GetSignature eSign solution, we can digitise just about any size and type of document, making it easy to store, share and manage business ready information. Deliver powerful benefits and real-world value to any job function and organisation.

Locations: Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, Perth, Auckland Ph: 1300 761 199 | E: imagingsales@acapacific.com.au | W: acapacific.com.au

Collaborate with confidence. AvePoint provides the most advanced platform for SaaS and data management to optime SaaS operations and secure collaboration. More than 8 million cloud users rely on our full suite of solutions including records & information management to make them more productive, compliant and secure. Locations: Sydney, Melbourne Ph: 03 3535 3200 | E: au_sales@avepoint.com | W: avepoint.com

Compu-Stor is a family-owned Australian business specialising in information and records management solutions and services. From document, media & data storage to digital scanning, business process automation and consulting services, Compu-Stor provides a wide range of solutions using the latest technologies & methodologies to deliver secure & efficient services. Through its Digital Transformation Solutions, Compu-Stor helps maximise the accessibility of information within organisations. Compu-Stor works with its customers to provide costeffective solutions tailored to their needs. Locations: Across Australia Ph: 1300 559 778 |E: sales@compu-stor.com.au | W: compu-stor.com.au

We see ourselves as your strategic business partner, not just another supplier. As the cost of running your business continues to rise and your customer’s preferred source of communication becomes digital, we have developed innovative solutions to help you adapt efficiently and effectively, not only in today’s environment but for the future. We recognise it is no longer viable to be just ‘another supplier’. Our focus is to truly understand your business challenges and strategic direction so we can support you as a trusted business partner.

Ph: 0481 009 779 | E: john.cox.ez@fujifilm.com | W: www.fujifilm.com/fbdms

Grace ensures business information is managed as the high-value asset it is, throughout its lifecycle — Capture, Control, Storage, Access, and Secure Disposal. Established in 1911, Grace operates a national network of 28 branches across every capital city and major regional centre, each equipped to provide best-in-class secure physical records and specialist digital information management solutions. Partnering with Grace ensures information is expertly managed, whilst our digital specialists provide tailored transformation pathways to increase digital maturity. Locations: Across Australia Ph: 1800 057 567 | E: GIM-sales@grace.com.au | W: grace.com.au/information

iCognition is an Australian SME and the trusted advisor of choice to our clients for enterprise-wide information management and governance, consultancy and solutions implementation. We provide IMG services and software to government, not-forprofit, education and private sector enterprises across Australia and overseas. iCognition’s goal is to ensure enterprises maximise the value of their information, while minimising cost and risk. Locations: Canberra, Sydney, Adelaide and Brisbane Ph: 0434 364 517 | E: Nicholas.Fripp@icognition.com.au | W: icognition.com.au

CorpMem Business Solutions specialises in the MAGIQ Documents EDRMS and provides a wide range of services focused on improving your business by increasing the Return on Investment (ROI) made to deliver records management. InfoVantage is our flagship software designed to create a Records and Information Management Knowledge Platform that leverages off and integrates into whatever corporate EDRMS you have implemented. CorpMem converts their clients’ corporate memory into a knowledge asset. Location: Caloundra Ph: (07) 5438 0635 | E: hello@corpmem.com.au | W: corpmem.com.au

EzeScan is one of Australia’s most popular production capture applications and software of choice for many Records and Information Managers. Solutions range from centralised production records capture, highly automated forms and invoice processing to decentralised enterprise digitisation platforms which uniquely align business processes with digitisation standards, compliance and governance requirements. Contact: Demos Gougoulas, Director Sales & Marketing | 1300 393 722

Ignite has been assisting public and private sector organisations with talent services since 1984. We provide Specialist Recruitment (IT, Federal Government, Business Support & Engineering), On Demand (IT managed services) and Talent Solutions (RPO, Training, recruitment campaigns & talent management services). For four decades, we’ve been igniting the potential of people and have built a reputation as Australia’s trusted talent advisor. Locations: Sydney, Western Sydney, Canberra, Melbourne, Perth Ph: 02 9250 8000 | E: Catherine.hill@igniteco.com | W: igniteco.com

Information Proficiency is a Records and Information Management specialist providing a full range of services and software. We cover everything IM; from strategy to daily operational processing practitioners, full managed services, technical support and helpdesk, training, software development, data migration, system design and implementations. We work with many IM products including MS365, e-signature, workflow, scanning, reporting and analytics. We also develop a range of productivity tools and connectors. We work hard to understand your requirements and implement solutions to match. Services available in all states and territories. Locations: Perth, Western Australia Ph: 08 6230 2213 | E: info@infoproficiency.com.au | W: infoproficiency.com.au

Make your business process more efficient and exact! Are process inefficiencies and data inaccuracies weighing your team down and causing errors? Do you currently achieve a data extraction accuracy of over 99%? Are you under pressure to improve outcomes while reducing costs and processing time? Are you looking for an easy, effective, and proven solution? Get the exact business process automation eSolution for your needs, with a team of dedicated experts supporting you. Talk to the Exedee team today! Ph: 1800 144 325 (Melb) | W: www.exedee.com

At FYB our customer promise is to provide secure, easy to use, leading edge technological solutions, to enable organisations to harness the power of their information so they can provide excellent services to the community. We’ve stayed true to our core beliefs—to deliver the best information governance, systems and solutions to our customers.

Ph: 1800 392 392 | E: info@fyb.com.au | W: fyb.com.au

Iron Mountain Incorporated (NYSE: IRM), founded in 1951, is the global leader for storage and information management services. Trusted by more than 225,000 organisations around the world, and with a real estate network of more than 85 million square feet across more than 1,400 facilities in over 50 countries, Iron Mountain stores and protects billions of valued assets, including critical business information, highly sensitive data, and cultural and historical artefacts. Ph: 02 9582 0122 | E: anita.pete@ironmountain.com | W: ironmountain.com

iFerret is a turnkey enterprise search solution developed by iPLATINUM that works like "google" over your corporate data. iFerret enables you to find information quickly across your enterprise. Location: Sydney, Melbourne Ph: 02 8986 9454 | E: info@iplatinum.com.au | W: iplatinum.com.au

Leadership Through Data provide Microsoft 365 focused information and records management training that has been developed by information and records managers to Australian and New Zealand Records Standards. Our core offerings are designed to help Information and Records Managers make sense of Microsoft 365 so that strategy and policy can be developed with a true and accurate understanding of the platform’s capability. Our SharePoint Foundation offering helps with understanding the core of M365 before providing education in specific aspects – Records Management, Information Protection and Privacy Management, and Information Architecture. E: jacqueline@leadershipthroughdata.co.uk | W: leadershipthroughdata.co.uk

TIMG (The Information Management Group) has been in the Information Management business for more than 20 years. We are known as a company that solves Information Management problems and, as such, we remain committed to providing innovative, smart and cost-effective information management solutions for our clients. As the digital world rapidly evolves, we remain committed to helping clients accurately store, track, access, retrieve and cull data. Some of the services we offer include document conversion and digitisation (including scanning, printing and data capture), document storage and archiving solutions, sentencing, secure document destruction, Ph: (02) 9305 9596 | E: info@timg.com | W: timg.com

Objective Corporation - Powering digital transformation with trusted information. With a strong heritage in Enterprise Content Management, regulation and compliance, Objective extends governance capability throughout the modern workplace; across information, processes and collaborative workspaces with governance solutions that work with Objective ECM, Micro Focus Content Manager and Microsoft 365. Through a seamless user experience, people can access the information they need to make decisions or provide advice from wherever they choose to work. Locations: Australia: Sydney, Wollongong, Canberra, Brisbane, Melbourne, Adelaide, Perth; New Zealand: Wellington, Palmerston North Ph: 02 9955 2288 | E: enquiries@objective.com | W: objective.com.au

OpenText, The Information Company™, enables organisations to gain insight through market leading information management solutions, powered by OpenText Cloud Editions. OpenText is one of the world’s largest global software providers, delivering mission critical technology to empower 125,000 customers across 180 countries. We believe that companies of all sizes can be smarter by bringing information and automation together and delivering smarter outcomes by helping customers BUILD, AUTOMATE, CONNECT, SECURE, PREDICT and ACT. Ph: 02 9026 3400 | W: opentext.com

Since 1989, Professional Advantage has excelled as a top IT solutions provider and Microsoft Solutions Partner in Australia, specializing in modern work, cloud, security, financial management, and business intelligence for various sectors. As an exclusive iWorkplace/ Information Leadership Partner, we leverage Microsoft 365 for effective digital workspaces, information management, and data governance. Our skilled team, boasting a high NPS and long client relationships, operates across 7 offices in 3 countries, serving over 1000 clients globally. Ph: 1800 126 499 | E: enquiries@pa.com.au | W: www.pa.com.au

Founded in 2009, RecordPoint is a global leader in cloud-based information management and governance services. Our adaptable layer of intelligence offers complete insight and control over all in-place data, records, and content, enabling organisations to increase compliance and reduce costs. RecordPoint enables regulated companies and government agencies to reduce risk, achieve greater operational efficiency, and drive collaboration and innovation. Ph: 02 8006 9730 | E: salesapac@recordpoint.com | W: recordpoint.com

Votar Partner's number one priority is our clients. Working independently of all software and IT vendors, we offer our proven and specialised expertise to empower our clients to achieve their goals. Our subject matter experts can help you develop and implement practical initiatives across each stage of the information management lifecycle, ensuring that your records and information management practices support and enable business improvements, and remain relevant.

Ph: (03) 9895 9600 | E: votar@votar.com.au | W: votar.com.au

WyldLynx – We take your business personally. WyldLynx provides Information Management, Governance solutions and services using a unique blend of cutting-edge technology, real world experience and proven industry principles. This allows Organisations to manage their Information, Security, Privacy and Compliance across enterprise systems with reduced risk, complexity, and cost. WyldLynx has a reputation for delivering value through long term relationships built on trust, shared vision, and a continual investment in relevant innovation. Locations: Brisbane Ph: 1300 995 369 | E: contact@wyldlynx.com.au | W: wyldlynx.com.au

A market leader in Records and Information Management, ZircoDATA provides secure document storage and records lifecycle solutions from information governance and digital conversion through to storage, translation services and destruction. With world class Record Centres nationally, we deliver superior service and solutions that reduce risk and inefficiencies, securely protecting and managing our customers’ records and information 24 hours a day, every day of the year. Locations: HQ Braeside, Victoria Ph: 13 ZIRCO (13 94 72) | E: services@zircodata.com.au | W: zircodata.com.au

Records Solutions is an Australian-owned company, founded in 1994. Created BY Information Managers FOR Information Managers, our team provide records and information management solutions to the industry. As a software neutral vendor, our only concern when working with you is what is best for you. With a Quality Management System developed in accordance with AS/NZS ISO 9001:2016, we aim to assist you in achieving the best outcome for your project. Locations: Brisbane Ph: 1300 253 060 | E: admin@rs.net.au | W: rs.net.au

The Kenyan Archives and Records Management Association (KARMA), in collaboration with RIMPA Global, has officially launched its KARMA Talent Development Program (KDTP) - a two-year pilot initiative designed to build capability and foster leadership in Kenya’s records and information management sector.

The program connects ten early-career Kenyan professionals with ten experienced RIMPA mentors.

Running from February 2025 to November 2026, the initiative offers monthly mentoring, professional development, and project support, with the aim of strengthening local capacity and promoting international collaboration.

“This pilot program is a significant step in supporting the global growth of our profession,” said Anne Cornish, CEO of RIMPA Global.

“We’re proud to be working alongside KARMA to help shape the next generation of information leaders in Kenya.”

The program officially kicked off with the release of introductory videos, enabling mentees and mentors to connect and begin defining their goals and mentoring plans. With flexibility built in, the initiative caters to each participant’s development needs while providing structure and consistency.

RIMPA Global extends its sincere thanks to the following mentors:

- Adelle Ford ARIM

- Dr Bethany Sinclair-Giardini MRIM

- David Robinson

- Joy Siller Life ARIM

- Justin Coleman

- Leanne Dunne

“The KTDP is a dream realized for Kenya’s information management community—many thanks to RIMPA for your steadfast partnership in turning this vision into reality and for investing in the next generation of information leaders.””

- Meryl Bourke Life MRIM

- Nancy Taia Life MRIM

- Nicole Thorne-Vicatos MRIM

- Sandra Ennor ARIM

Let’s face it – information management has never been more important than it is today. As we all deal with tougher regulations and the endless flood of data, organisations desperately need skilled professionals who can make sense of it all.

That’s why we’re excited to announce our new Certification Program – designed to help you take your career to the next level.

RIMPA Global is proud to announce the launch of our comprehensive Certification Program—a milestone in our ongoing commitment to advancing the profession and supporting practitioners in their career development.

A New Benchmark of Professional Excellence

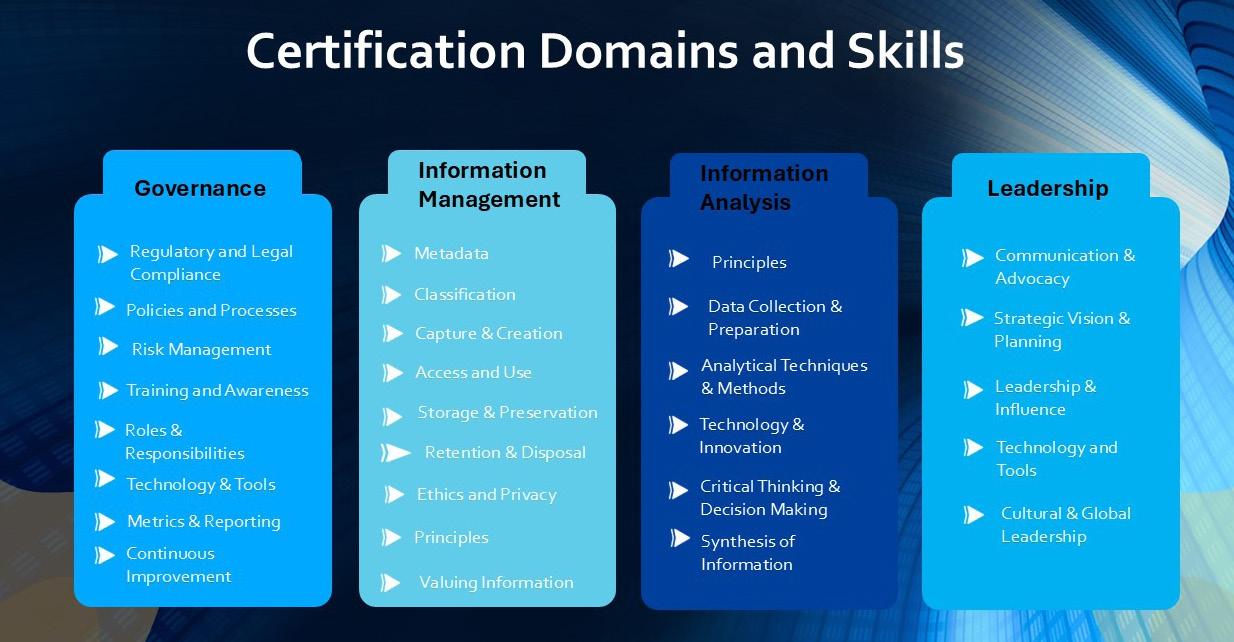

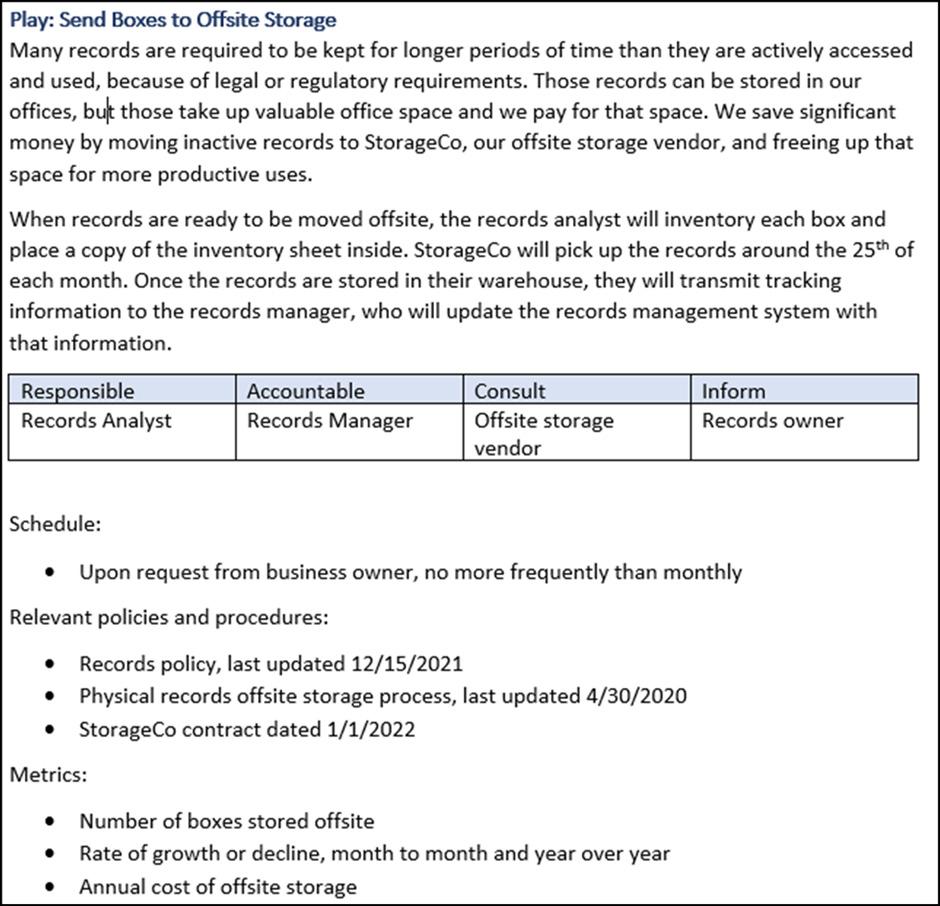

The RIMPA Global Certification Program was developed through extensive research and member consultation, this program establishes a clear framework for validating the capabilities of information management professionals across four key domains. See Figure 1: Domain Capabilities Framework.

This comprehensive framework doesn’t just acknowledge technical proficiency; it recognises the multifaceted nature of modern information management roles that increasingly demand business acumen, strategic thinking and leadership capabilities alongside traditional information handling skills.

Three Levels of Professional Excellence

We’ve created three certification tiers that recognise your growing skills and experience. Whether you’re newer to the field or a seasoned veteran, there’s a certification level that fits where you are in your career journey.

Experienced Level (CERIM)

This entry-level certification acknowledges practitioners who have demonstrated fundamental capabilities across all four domains. At this level, professionals can:

• Explain governance principles to internal customers

• Apply basic information management concepts and lifecycle knowledge

• Support analysis processes with fundamental techniques

• Develop foundational leadership skills in information management

Skilled Level (CSRIM)

The intermediate certification recognises practitioners with robust expertise and practical experience. These professionals demonstrate:

• Proficiency in implementing governance frameworks

• Strong ability to implement systems and manage information-related risks

• Skills in applying analysis techniques to solve real-world problems

• Capability to lead IM teams and align practices with organisational goals

The highest tier of certification distinguishes practitioners who demonstrate exceptional mastery. These professionals exhibit:

• Expertise in strategic governance leadership and policy development

• Advanced capabilities in strategic planning and driving IM innovations

• Leadership in information analysis methodology development

• Influence on organisational and industry-level IM strategies

The Certification Process: Accessible and Rigorous RIMPA Global has partnered with Robinson Ryan, a respected assessment provider who also supports DAMA certifications, to deliver a certification process that is both accessible and maintains high standards of integrity. The certification journey follows these steps: The examination is structured to assess realworld application of knowledge rather than mere theoretical understanding. For the Experienced level, a 60% pass mark is required, while Skilled and Expert levels require 70% and 80% respectively, reflecting the increasing depth of capability expected at each tier. See Figure 2: Certification Journey.

We also recognise the accomplishments of our existing professional members and have established a straightforward transition pathway.

All current professional members (at 1 April 2025) can opt into the new certification program for just $25 (including GST), receiving a complimentary three-year certification aligned with their current membership status:

• Associate Members (ARIM) will transition to Experienced Certification (CERIM)

• Chartered Members (MRIM) will transition to Skilled Certification (CSRIM)

• Fellows (FRIM) will transition to Expert Certification (CXRIM)

This transition opportunity has been extended until the end of August 2025, providing enough time for current professional members to gain certification without undergoing the examination process.

Certification is valid for three years, after which renewal is a streamlined process involving a shorter 30-minute examination focused on current trends in the field. Practitioners seeking to upgrade to a higher certification level can do so at any time by paying the upgrade fee and completing the certification process for their desired level. The certification program encourages continuous professional development, ensuring that RIMPAcertified practitioners remain at the forefront of evolving information management practices and technologies.

In today’s competitive job market, having recognised credentials can make all the difference – both for you and your employer.

RIMPA Global has established a transparent fee structure that reflects the value of certification while remaining accessible to practitioners at all career stages. The fee structure varies based on certification level and RIMPA membership status, with special pricing available for practitioners in developing information management countries. While the investment required may vary, all practitioners can expect returns in terms of professional recognition, career opportunities, and personal development. For those looking to upgrade their certification level, upgrade fees apply, and if successful a further three-year certification period will commence.

Why bother getting certified? In today’s competitive job market, having recognised credentials can make all the difference – both for you and your employer.

• Verified Expertise: Certification provides independent validation of your skills and knowledge, differentiating you in a competitive job market.

• Career Advancement: Certified professionals often enjoy enhanced career opportunities and greater mobility across sectors.

• Professional Development: The certification process itself encourages continuous learning and skills enhancement.

• Industry Recognition: A digital badge and certificate demonstrate your commitment to professional excellence.

For Employers:

• Quality Assurance: Certification helps identify candidates with verified capabilities in critical information management functions.

• Risk Mitigation: Certified practitioners bring standardised knowledge of compliance requirements and best practices.

• Return on Investment: Organisations benefit from the improved performance and strategic thinking that certified professionals bring to information management challenges.

• Competitive Advantage: Teams with certified professionals are better positioned to leverage information as a strategic asset.

RIMPA’s next step is to actively promote the certification program to external stakeholders, particularly those involved in recruitment and workforce planning. Our goal is to clearly communicate that certification is a reliable indicator of capability, and we will be mapping certification levels to commonly advertised roles in the industry. This will allow employers to better match their job requirements with certified professionals.

Integrity and Accessibility at the Core

The RIMPA Global Certification Program has been designed with integrity and accessibility as guiding principles:

• Independent Assessment: Partnership with a third-party examination provider ensures objective evaluation of capabilities.

• Reasonable Accommodations: The program provides appropriate adjustments for practitioners with documented needs, ensuring equitable access to certification.

• Transparent Appeals Process: A clear process exists for addressing examination concerns or other certification issues.

• Ethical Framework: All certified practitioners commit to upholding RIMPA Global’s professional standards and code of conduct.

Make your expertise official and join a network of recognised professionals who are shaping the future of our industry.

The Journey to Certification: Years in the Making The development of this certification program represents the culmination of extensive work by dedicated RIMPA Global staff and members:

• In late 2022, a Status Upgrade Review Working Group was established to create more streamlined pathways for members seeking professional status.

• This group’s comprehensive report, submitted to the Board in May 2023, contained 21 recommendations informed by research and member feedback.

• The Status Implementation Working Group formed in August 2023 then worked diligently to implement these recommendations, focusing on creating a modern, transparent upgrade process and future-proof certification program.

• Between January and April 2025, RIMPA Global and Robinson Ryan collaborated to develop exam questions, create policies and rules, and establish the technical platform for the certification process.

• In February 2025, the RIMPA Global Board endorsed the revised status upgrade and certification model. This thorough, member-driven approach ensures that the certification program truly reflects the needs of the profession and establishes a meaningful standard of excellence.

Ready to take the plunge? We’re inviting all RIMPA members and information management pros to get on board with certification. It’s your chance to make your expertise official and join a network of recognised professionals who are shaping the future of our industry.

Whether you’re an experienced practitioner looking to formalise your expertise or newer to the field and seeking to establish your professional credentials, the RIMPA Global Certification Program offers a pathway to recognition that aligns with your career aspirations.

Congratulations to the professional members who took advantage of the transition period and secured their certification at the transitional rate. From 1 July 2025 all practitioners seeking certification will need to complete the full certification process, including examination.

For practitioners who aren’t yet RIMPA Global members, certification is available to you but it is an ideal time to join the RIMPA community to receive the discounted price and gaining access to not only the certification program but also the wealth of resources, networks, and professional development opportunities that RIMPA Global membership provides.

RIMPA Global will be sharing detailed information about the certification application process for new applicants and the pathway for upgrading certification levels. We will also be hosting information sessions to answer questions and guide practitioners through this exciting new program.

The RIMPA Global Certification Program marks a significant evolution in our profession’s journey. By establishing clear standards of professional excellence and providing a structured pathway for recognition, we are not just acknowledging the capabilities of today’s information management practitioners—we are helping shape the future of our profession.

BY MATT O’MARA FRIM, CXRIM

In October 2024, I had the incredible privilege of attending ARMA International’s InfoCon conference in Houston, Texas – all thanks to the generous RIMPA scholarship.

Valued at $8,000, this scholarship covers flights, accommodation, and full registration to one of the world’s premier conferences for information professionals. It’s an opportunity that I can honestly say has been a career highlight – and one that I’d encourage every RIMPA member to consider applying for.

If you’re even thinking about applying for the RIMPA scholarship, do it. The opportunity to attend InfoCon provides far more than just a ticket to a conference –it’s a platform to grow professionally, connect globally, and bring fresh insights home.

Held at the vast George R. Brown Convention Center, ARMA InfoCon 2024 drew over 900 attendees from across the globe. Houston – known as “Space City” and home to NASA’s Johnson Space Center – was a fascinating backdrop. Arriving to 31-degree heat from a cool New Plymouth spring was just the beginning of an experience packed with professional insight, thought leadership, and genuine connection.

One of the most surprising and fascinating aspects of Houston is its extensive underground tunnel system. Spanning over six miles (9.7km) and connecting 95 city blocks, this climate-controlled network lies approximately 20 feet (6 metres) beneath the bustling streets of downtown . It’s not only the largest collection of underground tunnels without a subway in the United States but also a vital part of the city’s infrastructure . Originally developed in the 1930s to link two movie theaters, the tunnel system has evolved into a subterranean cityscape . Today, it connects office towers, hotels, banks, corporate and government offices, restaurants, retail stores, and even the Houston Theater District . The tunnels house over 500 businesses, including numerous dining options and shops, serving thousands of downtown workers and visitors each day . Navigating the tunnel system is made easy with colorcoded maps and wayfinding tools throughout . Access points are primarily located within connected buildings, with only a couple offering direct street-level entry . The tunnels are typically open to the public on weekdays from 6:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m., providing a convenient and comfortable way to traverse downtown Houston.

For visitors attending events like ARMA InfoCon, the tunnel system offers a unique and efficient means to explore the city, connect with fellow professionals, and experience the vibrant culture that thrives beneath Houston’s surface.

InfoCon’s speaker lineup was nothing short of outstanding. One standout was astronomer Dr. Phil Plait, who drew compelling parallels between space data and the future of information management. His talk was both intellectually exciting and deeply relevant to the data-driven world we work in.

John Montel, CIO at the U.S. Department of the Interior, reinforced the value of strategic thinking, executive engagement, and investing in education and training – particularly during digital transitions. Other sessions provided deep dives into Microsoft Purview, SharePoint, and Copilot, reflecting the sector’s growing emphasis on managing records in place using cloud-based tools. Information governance was a recurring theme, with practical insights into enhancing governance practices using emerging technologies – a hot topic across our industry.

Beyond the impressive sessions, the real power of InfoCon lies in the connections you make. Meeting peers from around the U.S. and the world – and discovering that many of our challenges are shared – was both validating and inspiring. The social events built into the program were just as valuable, offering casual opportunities to share experiences, ideas, and solutions. And yes, everything really is bigger in the States – from the convention center to the meals!

Winning the RIMPA scholarship didn’t just open the door to a world-class event; it opened my eyes to the global nature of our profession. Whether it’s the adoption of AI, transitioning from paper to digital, or navigating hybrid environments, the core challenges are often universal. Being at InfoCon allowed me to engage directly with thought leaders, discover new tools and methods, and return with actionable knowledge to benefit my own work – and, I hope, to share with the wider RIMPA community.

If you’re even thinking about applying for the RIMPA scholarship, do it. The opportunity to attend InfoCon provides far more than just a ticket to a conference – it’s a platform to grow professionally, connect globally, and bring fresh insights home. Attending InfoCon also offers RIMPA a valuable lens into how other associations operate, what’s coming next in our field, and how we can learn from international best practice. Finally, I want to extend a heartfelt thank you to RIMPA and the scholarship selection committee. Being chosen was a true honour – one I’ll never forget and an absolute career highlight.

BY DAVID ROBINSON AND STEPHEN CLARKE MRIM, CSRIM, RIMPA GLOBAL AMBASSADOR

Has Information Management improved over the last 40 years? Are the various decision makers in organisations making better decisions based on complete record sets in 2025 compared to 1985? These are the questions we’ve pondered over as a profession with traditional Information Management (IM) thinking and disciplines being diluted through deprofessionalisation of the industry, reduction in further educational qualifications and theoretical knowledge, with many experienced IM staff, with indepth knowledge of paper based and digital systems now steadily leaving the profession is it time to think differently on how we can help our organisations to improve decision making by providing more complete and accurate records through both new human and machine modes of practice.

While the digital age began earlier than the 1980’s it was still in its ‘toddler’ stage in the average office

setting in the 80’s. Paper based records and manual processes to manage them ruled the day. Large postal bags of mail, date stamping, handwritten inwards mail registers, library cards to manage file locations and photocopies of correspondence if more than one staff member needed to know about the correspondence that day was what was going on. Organisations who were at the cutting edge were converting archived records onto microfilm and had a mainframe computer to mark file locations by staff initials and were installing the facsimile machines (original electronic transmission) but didn’t have many places to send facsimiles to yet. Looking back at this time we would generally say that staff had a high level of awareness of their responsibility to retain a copy of outwards correspondence on the official file as well as making (handwritten) notes to record significant meetings or telephone conversations. Personal computers, mobile phones etc were expensive and limited in functionality and not really in the office yet. In conclusion,

the limited choice of medium to create and capture records into the official recordkeeping system did, in the majority of cases work and the decision makers in organisations made decisions based on complete sets of business records. The rise of personal computers and internet really saw the digital revolution explode from the 1990’s.

Most IM teams in 2025 are struggling daily to manage records what are received centrally. Outside of official systems records can be in any application with often scant regard for whether they fully integrated, or not, with centralised or ‘authorised’ corporate systems. Social media has been with us since the early 2000’s in a business context and still is mostly outside of these official systems. Specialist teams in ‘Digital or Data’ have formed and we’re hearing that traditionally IM teams are being merged into these new teams whose management may, at best have a token knowledge of records disposal, naming conventions,

business classification etc.

Technology remains at the forefront of the modern office. IT budgets are huge and ever expanding on the promise of delivering greater and greater efficiencies, yet it only drives contextual records further apart. We had the concept of ‘big data’ a few years ago which made all manner of claims, yet we now are told part of this could be redundant, obsolete trivial (ROT) data. Artificial Intelligence (AI) being the latest technology to emerge promising to remove repetitive, repeatable tasks from employees. We’ve also seen a sidelining of records management as we moved into the 2000s between information management and data governance, and perception that records management only applies to information, not data. A common phrase is a ‘Tradesperson is only as good as their tools’ however in a modern organisation its been the tools that have let employees to create and store records all over a modern workspace. Employees exit an organisation and either leave records in personal accounts, or worse delete everything. Central

recordkeeping resources are too thin on the ground to be able to meaningfully capture what is needed. It doesn’t help that organisations compound this issue with the cognitive dissonance of a ‘keep everything’, with the periodic ‘delete/overwrite everything’ approach, based on format, or system, regardless of the business value of the records.

Since the 1980s, the creation and capture of records has undergone significant conceptual evolution, yet professional practice has not consistently kept pace with theoretical development. Foundational models such as the records lifecycle and the records continuum have offered foundational frameworks for understanding the management of information from creation to eventual disposal or preservation. These models, however, are heavily predicated on the assumption that staff actively create records in a deliberate and structured manner, in the first place, and consistently

capture them into designated official systems. In practice, this assumption often proves flawed. The reality of everyday organisational behaviour shows us that many records of evidential or business value are either not being created at all, for example, critical decisions made informally and never documented beyond a whiteboard or, when they are created, are not captured in a manner that supports long-term findability or reuse, (e.g. thermal image printouts), or with inadequate naming conventions, minimal metadata, and/or poor contextualisation mean that even when records do enter formal systems, they remain difficult to retrieve and interpret. This disconnect between theory and practice highlights a fundamental challenge for the profession: without renewed emphasis on the conditions and behaviours underpinning record creation and capture, especially in increasingly decentralised and digital work environments, the value of even the most sophisticated theoretical models’ risk being undermined by poor implementation on the ground.

"Digital practice has blurred these boundaries, everyone with a PC became their own (usually untrained) de facto records manager."

In our workplaces we have witnessed the shift in practice, as the creation and capture of records has transformed from a paperbased paradigm, where records were a tangible physical artefact, to a complex, digital environment in which records are fluid, distributed, and often ephemeral. In the paper world, recordkeeping was a more deliberate and observable act; documents were physically filed, formally registered, and controlled within structured systems. Digital practice, however, has blurred these boundaries, everyone with a PC became their own (usually untrained) de facto records manager.

The act of record creation is now embedded within everyday business processes and applications, emails, chat messages, collaborative documents, and transactional systems, making the distinction between a high value and lowvalue records less visible and more difficult to manage without deliberate intervention. This shift has necessitated a re-examination of traditional recordkeeping concepts and has exposed the limitations of relying on staff to consciously and consistently create and capture records into official systems.

Over the latter half of the twentieth century Philip Coolidge Brooks’ original 1940s records lifecycle model[1] dominated records management practice and conceptualised recordkeeping as a linear sequence, from creation, active use, semi-active storage, to eventual archives or destruction. While appropriate in the context of physical records, this model proves increasingly inadequate in digital environments, where records are continually reused, revised, repurposed, and remain active across multiple business contexts and systems. In response, the records continuum model has emerged as a more dynamic and integrated conceptual framework. Various records management thinkers and authors arrived at the continuum solution, but Frank Upward’s model is generally considered to be the foundation of modern recordkeeping theory[2] The Continuum theory acknowledges that records can exist

simultaneously in multiple states, being both current and archival, both business and evidential, depending on their use and interpretation across time and space. However, this model too assumes that records are being consciously created and managed from the outset. The disconnect between theory and organisational reality remains a persistent challenge. Both the lifecycle and continuum approaches are built on the foundational premise that records will be captured at or near the point of creation into a designated, controlled environment. Staff frequently bypass formal systems due to perceived complexity, time pressures, or lack of awareness. Records are generated but left stranded on desktops, shared drives, or within transient communication tools. The practicalities of modern work environments, and reliance on decentralised digital collaboration, mean that records are often not consciously identified, let alone consistently managed.

Compounding this issue is the poor application of naming conventions and metadata standards. Even when staff do attempt to capture records, inadequate or inconsistent naming makes information retrieval difficult. Without structured metadata or contextual tagging, records become effectively invisible within repositories, undermining their long-term accessibility and usability. Information professionals frequently encounter systems bloated with poorly titled documents, lacking version control or contextual clarity, which significantly hampers enterprise search and discovery functions. This is further exacerbated by human error and misfiling, and a failure to capture file or store records at all, e.g. records sitting in individual email inboxes, or spread amongst several. In the digital era, where documentation can, and should, be seamlessly embedded into business processes, the failure to generate records at the point of transaction or decision represents a significant gap in governance maturity. Even when records are created, they are frequently not captured with adequate metadata, rendering them contextually opaque and

disconnected from the broader business information landscape. Metadata, whether system-generated or user-applied is essential to make records findable, relatable, and useful over time. Without it, the intrinsic value of a record is diminished, and its potential to support business, legal, and historical needs is compromised. This gap between record creation and meaningful capture highlights the urgent need to refocus professional practice from implementing a single technological platform towards automation, supported by behavioural and cultural change.

A renewed emphasis on embedding recordkeeping into business workflows, supported by automation, intuitive interfaces, and behavioural design, is critical.

Overall, the digital transition has challenged many of the assumptions that underpinned traditional records management. The profession must now move beyond outdated models and adapt its practices to fit real-world organisational behaviour. A renewed emphasis on embedding recordkeeping into business workflows, supported by automation, intuitive interfaces, and behavioural design, is critical. Recordkeeping must also be reframed not merely as compliance, but as an enabler of business performance, transparency, and knowledge continuity in a complex and evolving information landscape.

If you’re out at a social gathering and there are people you don’t know its inevitable that you’ll be asked ‘so, what do you do for work?’ and in response you have to go into details to explain what IM which usually results in a puzzled expression. Why is it that colleagues in other corporate functions such as Accounting, Communications or Human Resources are readily understood and not ours?

It maybe the time for IM to give up and better describe the value of our corporate function delivers. So next time you get that question say something like ‘I help my work make evidence- based decisions’ instead. Isn’t that the real reason why employees make and access records to check information and/ or use them to make business decisions? Ok, we may retrieve a nice report we created occasionally just to admire it but why don’t we just let go of describing what we do and just tell them what the outcome is ‘evidence-based decision making.’

Management apathy to support good recordkeeping existed in 1985 and is mostly still present today. While we like to think that we have their support, in truth its more real to start from the point that we don’t. Having worked through the rise of the digital age and the decline of paper as a records medium the explosion of data and digital tools has seen an ‘unchecked’ loss of central control and accessibility to most records. Employees still make business decisions whether they have full or limited access to records.

Looking back now from 2025 there seems to be a shortage of a key ingredient for a success, when implementing new technology platforms, in the lack of focus on the human element of addressing employee psychology. This is usually limited to training staff to use the new technology or providing educational IM initiatives. For example, employees arrive at the training session, delivered online and many just do their regular work while the Trainer delivers the material because the participants aren’t fully invested and engaged, which isn’t the Trainor’s fault. Its largely due to a poor workplace culture that believes records aren’t important. Organisational psychology, which is the study of human behaviour in business that focuses on applying psychology principles to improve workplace effectiveness and employee well-being[3] needs to be fully engaged to truly empower the workforce. Traditionally this is done from the top down in an organisation from Management, Human Resources or Change

Transformation teams however by also engaging this from the bottom up as well with psychology tools such as ‘job crafting’[4] an organisation can meet halfway to rapidly change workplace culture. Addressing this as a first priority to build a good recordkeeping workplace culture is a must. While technology plays its part, its still too heavily relied upon as the focal element at the expense of the people factor being organisational psychology.

Humans can change behaviour when fully engaged and motivated with belief in the outcome. Our parklands used to be practical useable with dog owners not picking up their pooch’s waste and people used to place all household waste into a single landfill bin. Enough people changed and believed in a better way and now environmental outcomes are vastly improved. Changing the workplace culture to ‘move the dial’ from a poor recordkeeping culture to good one is possible too. Psychology and specifically organisational psychology has the means to influence a good recordkeeping culture for most employee’s behaviour but it is more a marathon than a sprint. Job crafting is one proven method that can open employee thinking around self, task

Job

crafting is one

proven

method that can open employee thinking around self, task or relations to allow them to redesign their work to make it more meaningful to them and their team. This increases their satisfaction, commitment and enjoyment of their job. But it can’t just come from top-down thinking, so we need to engage lowerlevel employees and build up towards the top to make significant change. or relations to allow them to redesign their work to make it more meaningful to them and their team. This increases their satisfaction, commitment and enjoyment of their job. But it can’t just come from top-down thinking, so we need to engage lower-level employees and build up towards the top to make significant change.

While 1985 recordkeeping had limited technology by today’s standard with records mostly on paper and microfilm media and over a century of repeated work practice to ‘keep a copy’ now appear to be quite comprehensive compared to 2025. In 1985 though we were just told that it’s done this way and we mostly did it. The record creation ‘digital genie’ escaped the bottle in the 1990’s and is still loose today. So, the challenge now for us as a profession is do we still have the fight to take on the apathy towards us and present an improved applied model of recordkeeping to our organisation and individual employees? One that helps re-capture the ‘digital genie’ and return them to the bottle of comprehensive compliant recordkeeping?

So, in conclusion, over the past four decades, the evolution from paperbased to digital work environments has dramatically changed the nature of records creation and capture, yet Information Management practice has struggled to keep pace. While traditional models like the lifecycle and continuum provided structured approaches to managing information, they were built on assumptions that no longer hold true in decentralised, digital workplaces where records are inconsistently created, poorly contextualised,

"To build a sustainable IM culture, organisations must move beyond technical solutions and invest in workplace culture change, engaging staff at all levels."

and often never captured at all. Technology has enabled data proliferation but undermined recordkeeping coherence, with critical business decisions increasingly undocumented or lost in fragmented systems. This disconnect demands a fundamental shift, from systems-based IM thinking to human-centred, behavioural approaches that focus on the psychology of recordkeeping. To build a sustainable IM culture, organisations must move beyond technical solutions and invest in workplace culture change, engaging staff at all levels, embedding IM into workflows, and reframing recordkeeping not as a ‘tick-box’ exercise, but as a vital enabler of evidence-based decision making. Just as society changed its behaviours to improve environmental outcomes, so too can workplace behaviours shift, if the profession embraces organisational psychology as the key to revitalising modern recordkeeping practice.

Stephen Clarke MRIM, CSRIM, RIMPA Global Ambassador and J. Eddis Linton Award winner 2012, is an Information Management and AI Consultant. Stephen has had many senior roles in Information and Data Management, been a Chief Data Officer, and the Chief Archivist of Archives New Zealand, a career highlight of 20 years as senior NZ Public Sector. Stephen has been a strong advocate of standards for many years working with Standards Australia and NZ since 2007,and for ISO since 2010, and has co-developed standards such ISO 15489, ISO 13028, ISO 16175, and the ISO 30300 series.

REFERENCES

David Robinson - With more than 38 years of experience in the records / information management industry, David has worked in all levels of government to guide agencies to make the most out of their information assets. David is responsible for the redevelopment of the information management program at City of Greater Geelong and has led implementations of information management solutions at government agencies. With a passion for job crafting, storytelling and all things historical David is making it fun again to work in information management.

[1] Brooks, Philip Coolidge. “The Selection of Records for Preservation.” American Archivist 3, no. 4 (October 1940): 221–234.

[2] Upward, Frank, Sue McKemmish, and Barbara Reed. 2011. “Archivists and Changing Social and Information Spaces: A Continuum Approach to Recordkeeping and Archiving in Online Cultures”. Archivaria 72 (December), 197-237. https://archivaria.ca/ index.php/archivaria/article/view/13364

[3] ChatGPT

[4] Vol 40 – Issue 3 – November 2024 issue of iQ - The RIMPA Quarterly Magazine of the Records and Information Management Practitioners Alliance.

BY GUY HOLMES

In a somewhat startling projection, researchers and analysts are warning that by as early as 2026, the world may face a shortage of high-quality data to train artificial intelligence (AI) systems.

The engines of today’s AI, particularly large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini depend on an evergrowing diet of text, images, audio, and video to become smarter, faster, and more capable. But this well is beginning to run dry.

This prediction is not a dystopian fantasy, it’s a wake-up call. As the data that has traditionally powered AI becomes exhausted, organisations must prepare for a new era where private, proprietary, and internal data becomes the fuel that drives AI innovation. And this transition offers significant opportunities for organisations ready to embrace it. Most of today’s large AI models are trained on publicly available data: websites, books, open-source code, forums, social media, news articles, and more. While vast, this corpus has limits. Much of the high-quality content has already been absorbed into existing models, and growing legal and ethical concerns are restricting further harvesting. At the same time, what’s left online tends to be either redundant or low in informational value. As a result, the utility of public data is diminishing, and the ability to continue scaling models using this approach is reaching its limit.

Yes, new data is always being created on the internet, but the models are now keeping pace with this creation. New photos on Instagram that are used to train AI image generation models took years to ingest and be integrated into the systems of today, but now these systems like ChatGPT are absorbing this data and information almost as fast as it is created. What the world does not realise is that prior to the cloud existing almost all data worth keeping was recorded onto backup tapes. The cloud is the fundamental bedrock that has allowed AI to grow at the rate it is now growing – as it provides the compute and storage that allows these massive models to scale and continue to grow. But prior to the cloud, the data created by corporates was largely written to offline technology meaning the AI models and cloud have never seen a large part of our world’s historical content. This challenge, however, presents a powerful new opportunity. Every organisation sits on a reservoir of internal data that has typically been used for record-keeping, compliance, or reporting. This includes everything from documents and spreadsheets to emails, call transcripts, PDFs, and images. Unlike public data, this internal information is deeply specific to the organisation.

It reflects its customers, its processes, its language, and its knowledge, making it incredibly valuable for the next phase of AI development. Using internal data to train or finetune AI models isn’t just a technical upgrade — it’s a strategic move. It enables the creation of custom applications that truly understand the nuances of your organisation. For example, a legal firm might create

Using internal data to train or fine-tune AI models isn’t just a technical upgrade — it’s a strategic move.

an AI tool capable of summarising case notes in its own format, while a manufacturing company could use historical data to forecast maintenance needs or optimise supply chains. Even something as straightforward as an internal chatbot trained on company policies can reduce the burden on HR and operations teams. But making this data usable for AI requires more than just uploading it to a model. Most enterprise data isn’t AI-ready. It’s scattered across silos, stored in outdated formats, or buried under layers of confidentiality.

The first step is understanding what data exists and where it lives. That means conducting an internal audit, identifying key information assets, and bringing structure to chaos. This might include scanning paper documents, extracting data from PDFs, consolidating emails, or tagging files with metadata to improve discoverability. Once this groundwork is done, security and governance take centre stage. Organisations must ensure that data privacy, legal compliance, and access controls are embedded into the AI development process. Sensitive data needs to be handled with care, especially where customer information, employee records, or financial details are involved. This is where good data governance practices, long championed by information managers, become vital enablers of innovation.

Organisations should also consider the long-term lifecycle of their information. Archiving strategies that have traditionally focused on regulatory retention can now be reimagined through the lens of usability. It’s no longer just about storing documents for years; it’s about structuring them in a way that AI systems can extract value over time. Metadata becomes a crucial asset, not just a tag. The ability to understand when, why, and how a document was created and in what context becomes essential to training AI that can reason, reference, and act.

With internal data cleaned, secured, and structured, organisations can begin to explore how to combine it with publicly available sources in a meaningful and safe way. This hybrid approach, when done right, yields powerful results. Public data can offer general context, definitions, industry benchmarks, and reference materials, while internal data delivers the specificity needed for precision. Together, they allow AI to respond intelligently and appropriately to queries that require both background knowledge and contextual awareness.

One effective technique for this is called Retrieval-Augmented Generation, or RAG. Instead of retraining a model from scratch, RAG allows AI to access relevant internal documents at the moment of a query. So when someone asks a question, the system finds the most applicable documents and uses them to inform its answer all without permanently absorbing sensitive data into the model. It’s secure, scalable, and effective. Some organisations may choose to fine-tune a model directly on their internal data. When taking this

approach, they should consider techniques such as masking sensitive fields or using synthetic data to avoid exposing confidential information. Whichever path is chosen, it’s important that the AI infrastructure is deployed in a way that meets data residency, privacy, and cybersecurity requirements. This could mean using private cloud environments, keeping the AI systems on-premises, or adopting zero-trust frameworks.

Adopting AI doesn’t mean replacing people, it really means amplifying the impact of the people.

Building these systems often involves a multidisciplinary effort. It requires collaboration between IT teams, records managers, legal counsel, and business stakeholders. The AI initiative should not be driven solely by technologists. It must be grounded in a deep understanding of the business goals, user needs, and regulatory context in which the data lives. It’s in this collaborative space that records professionals and

information managers play a vital role, ensuring that data quality and information integrity are upheld as AI development progresses. The rewards of leveraging internal data for AI are far-reaching. Decision-making becomes faster and more accurate as AI surfaces insights from across the organisation. Productivity improves as routine tasks like summarising documents to generating reports that can all be handled by machines. Customer experiences become more personalised and responsive, driven by an understanding of past interactions and behaviours. Perhaps most importantly, this shift transforms data from a passive archive into an active, strategic resource. Imagine your AI model knowing everything about your organisation form its inception, it is an incredibly powerful notion, and one that is now becoming reality. There are cultural benefits too. When employees see their knowledge and workflows reflected in AI tools, they become more engaged in the technology. Data quality improves, digital skills grow, and innovation becomes part of everyday work.

The organisation begins to develop what might be called an “AI-ready culture” — one that embraces change and continually looks for better ways to use information.

Adopting AI doesn’t mean replacing people, it really means amplifying the impact of the people. It allows skilled professionals to focus on critical thinking, creativity, and relationshipbuilding, while the AI handles the grunt work. For example, a policy analyst might use an AI tool to scan thousands of pages of regulatory text and surface relevant passages, freeing up time for interpretation and strategy. A customer service representative could access a dynamic knowledge base trained on previous cases to resolve inquiries more quickly and accurately.

• Enhanced decision-making

• Automation of repetitive tasks

• Increased employee satisfaction

• Competitive differentiation and barriers to entry

• Improved and personalised customer experiences

That said, the journey isn’t without its challenges. Integrating legacy systems, aligning stakeholders, and developing the right mix of skills can take time. There may be resistance from staff concerned about automation or overwhelmed by new tools. And while costs can be managed with the right planning, there will be an upfront investment in infrastructure, training, and data preparation.

Addressing these challenges requires thoughtful change management. Staff need to understand not just the technology, but the vision behind it. Communication, training, and transparency are essential. Leaders must demonstrate how AI will support people, not sideline them, and create opportunities for staff to participate in shaping how the technology is introduced. This collaborative approach builds trust and leads to better outcomes.

But for those willing to make the leap, the results speak for themselves.

Proprietary AI models grounded in internal knowledge are not only

more useful, they’re also harder for competitors to replicate. They give organisations a durable advantage in markets that are becoming more data-driven and automated every year. In time, these models could even become licensable assets themselves, opening up new revenue streams or partnership opportunities. For professionals in records and information management, this moment represents both a shift and an opportunity. The principles of good information governance — accuracy, integrity, accessibility, retention — are now central to AI success. The ability to classify data, ensure compliance, manage metadata, and track usage has never been more relevant. Information professionals are uniquely positioned to lead in this space, helping to bridge the gap between compliance, operations, and innovation.

As AI capabilities grow, so too will the demand for well-curated, explainable data. Regulators and customers alike will expect transparency and accountability from AI systems. This means that organisations will need clear documentation of how data was collected, processed, and used in model training or augmentation. Records professionals, with their long-standing expertise in documentation, auditability, and lifecycle management, are essential to meeting these expectations. In the past, data was something we kept “just in case.” It was a safeguard, a record, a box to tick. But the role

of data is changing. In the AI era, data becomes an engine — a source of power that fuels growth, insight, and transformation. And as the supply of usable public data begins to dwindle, internal information will become the most valuable asset many organisations have. Now is the time to prepare. Audit your data. Protect it. Organise it. Activate it. Because the future of AI won’t just be trained on the internet. It will be trained on you and your own personal and corporate data.

Guy Holmes is the Founder and CEO of Tape Ark, a company revolutionising legacy tape data access and migration. With a background in geophysics and decades in the oil and gas sector, Guy launched Tape Ark to modernise outdated, costly storage practices. A passionate advocate for Artificial Intelligence, he sees Tape Ark as a bridge between legacy data and AI-driven analytics. He shares insights on his podcast Tape Ark 3D: Deep Diving into Data. Guy holds degrees in Geophysics and Technology Management, and is a graduate of the Australian Institute of Company Directors. He has a proven track record in growing start-ups and turnaround ventures across tech and information management sectors.

BY IAN HICKS

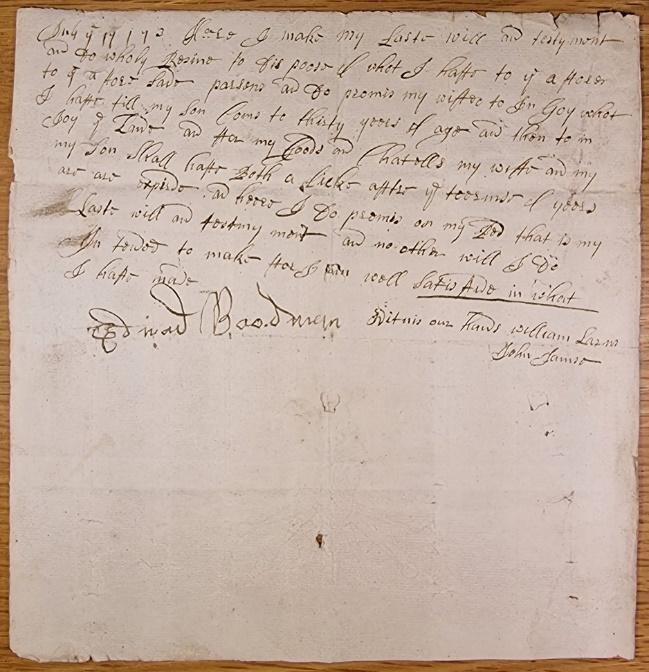

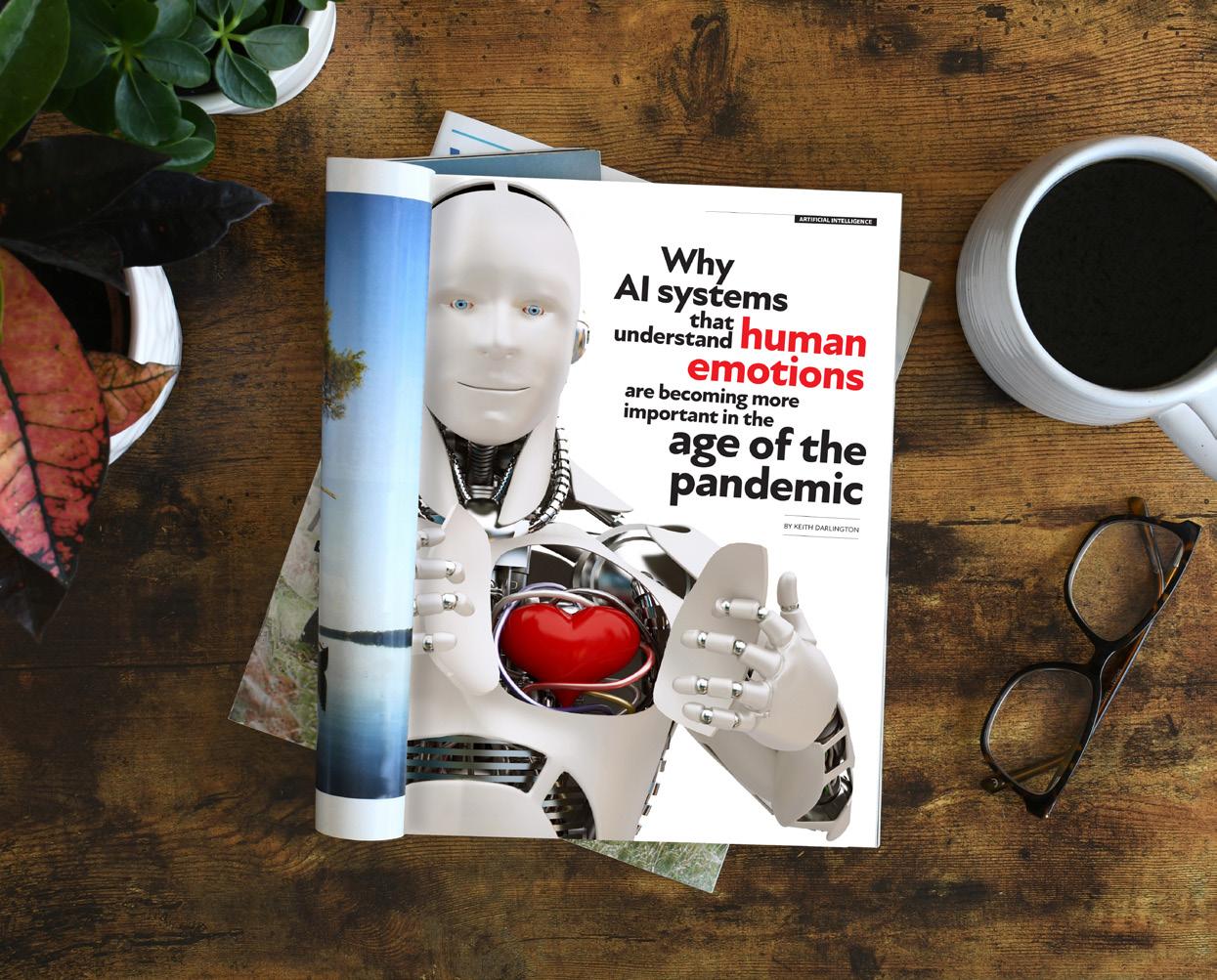

Ian Hicks draws from his master’s in Archive and Records Management dissertation to explore what emotions users feel while handling original documents and how important these are to their experience and how these compare to looking at digital copies.

Acknowledgement: This article appears with permission of ARA (UK and Ireland) and the author. The article was first published in the ARC Magazine, No. 398 May-June 2024.

Our fundamental purpose as archivists (and archive conservators) is to preserve the documents (and in some cases objects) that record the history of our communities, preserving the original facts and information. We do this so people can call on this information now and in the future for a multitude of purposes and reasons.

The recent furore round the proposal by the Ministry of Justice to destroy original documents, in favour of a digital only approach, broached to a wider public the pros and cons of digitisation and why preserving originals is important from a technical ‘fail-safe’ perspective. Few of those putting forward consultations on the matter looked at the impact on users –particularly the loss of ‘wonder’ and emotional affect when literally holding history in their own hands. My research focusses specifically on this aspect of user experience – and who do we preserve archives for if not our users? The research for my masters was certainly not the first in the heritage sector where there have been several studies exploring user emotions. I found, however, that there had been little work on the role that emotions play when conducting historical research with original manuscripts, apart from a study conducted by Anastasia Varnalis-Weigle in 2016, ‘A Comparative Study of User Experience between Physical Objects and Their Digital Surrogates.’

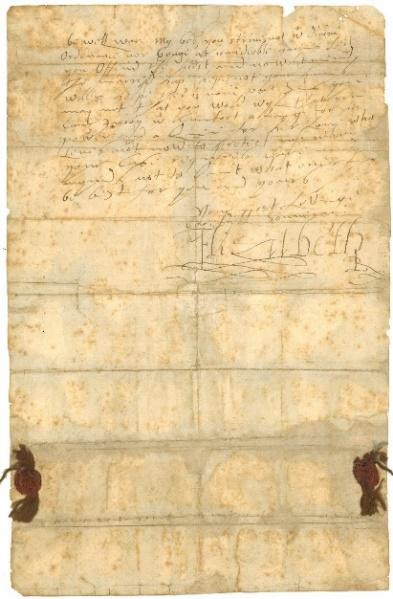

For my research, I audio-recorded interviews of 50 visitors to the archives and local studies at the Wiltshire & Swindon History Centre (WSHC) while they handled original documents and viewed digital copies. The participants were asked to explore three documents - an eighteenth-century will from our probate collection. This collection has been digitised and is available on Ancestry.co.uk (we do not produce the originals anymore); this was chosen because wills are heavily favoured by genealogists – who account for a high proportion of our users, and also because the document is small and looks like it was handwritten by the testator and signed by him.

See Photograph A: The will of Edward Bodman, WSHC, MS P5/1725/3.

The second document is a rolled map, dated 1841, in which the participant had to unroll to view it. This gave them an element of exploring and discovery. Again, this document has been digitised and is available on a website called ‘Know Your Place: Wiltshire’ (we do not produce the originals anymore).

See Photograph B: 1841 Tithe Map of Hankerton, Wiltshire, WSHC, MS T/A Hankerton.

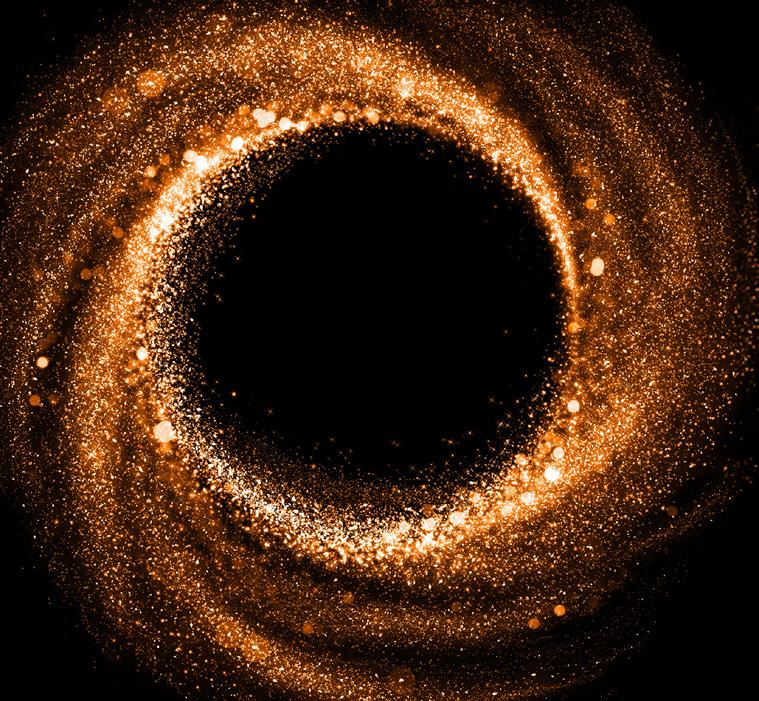

The third and final document was a letter from Elizabeth I. This document was chosen, because it was written and signed by a well-known historical figure, who the participants, it was hoped, could connect with. It was intended to provoke an emotional response, which the will or map could not provide – an emotional response being unlikely due to the non-family nature of the document. It also has two small wax seals with fabric embedded in the wax. This allowed the participant to engage with other intrinsic values of documents that digital copies could not otherwise provide.

See Photograph C: Queen Elizabeth I letter, undated, WSHC 1946/4/2K/1.