Rhode Island History

THE JOURNAL OF THE RHODE ISLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Rhode Island History

1

Published by

The Rhode Island Historical Society 110 Benevolent Street

Providence, Rhode Island 02906–3152

Roberta Gosselin, chair

Winifred E. Brownell, vice chair

Mark F. Harriman, treasurer

Peter J. Miniati, secretary

C. Morgan Grefe, executive director

publi Cations Committee

Charlotte Carrington-Farmer, chair

Catherine DeCesare

J. Stanley Lemons

Craig Marin

Seth Rockman

Luther Spoehr

Evelyn Sterne

staff

Richard J. Ring, editor

J. D. Kay, digital imaging specialist

Silvia Rees, publications assistant

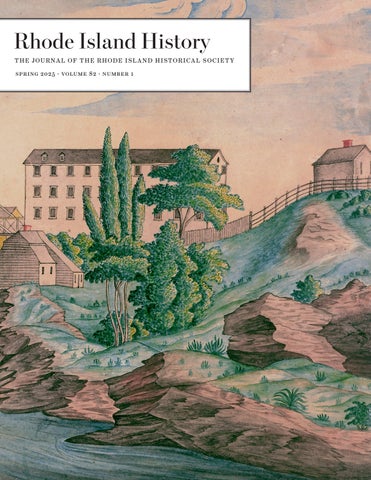

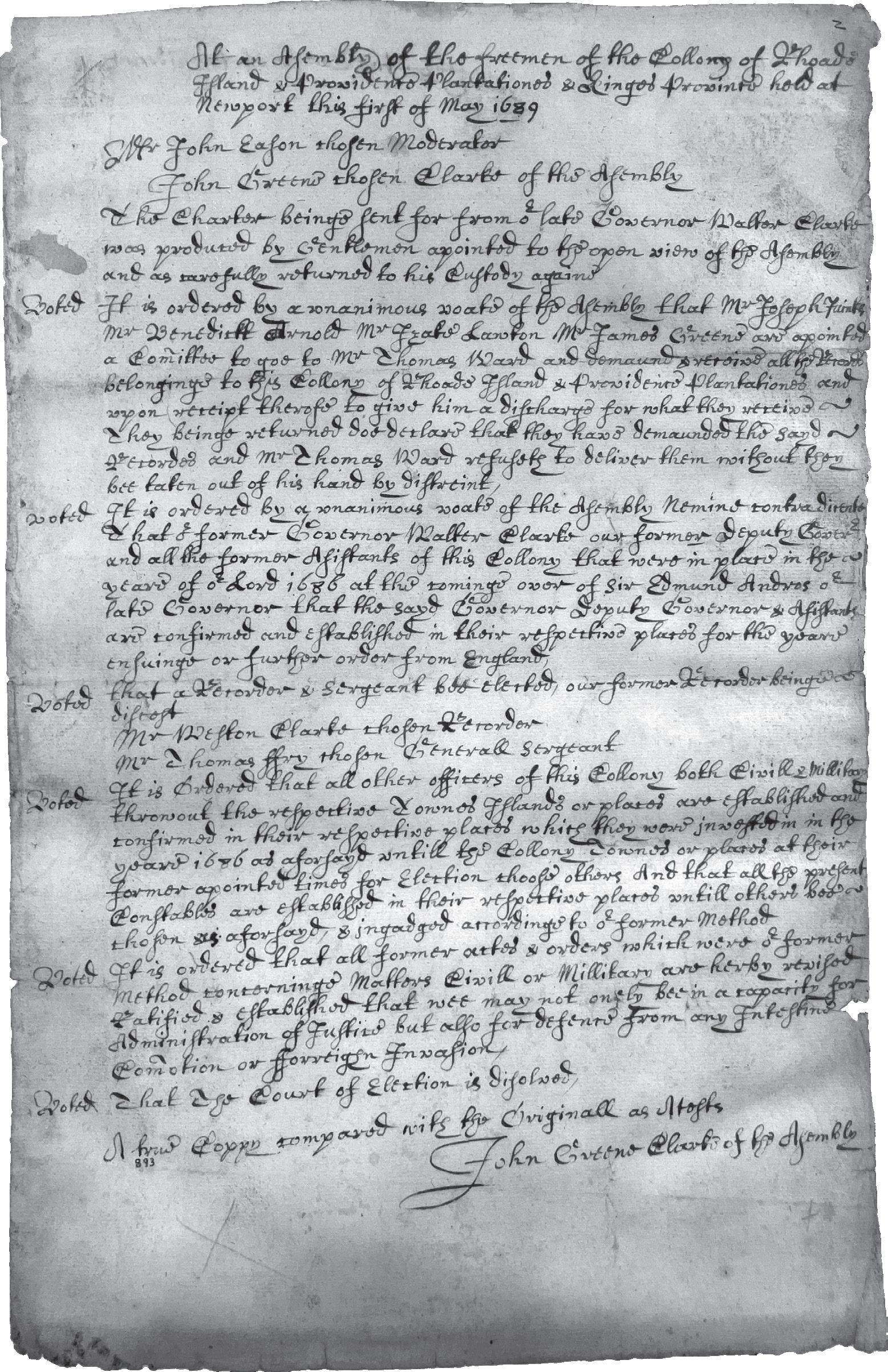

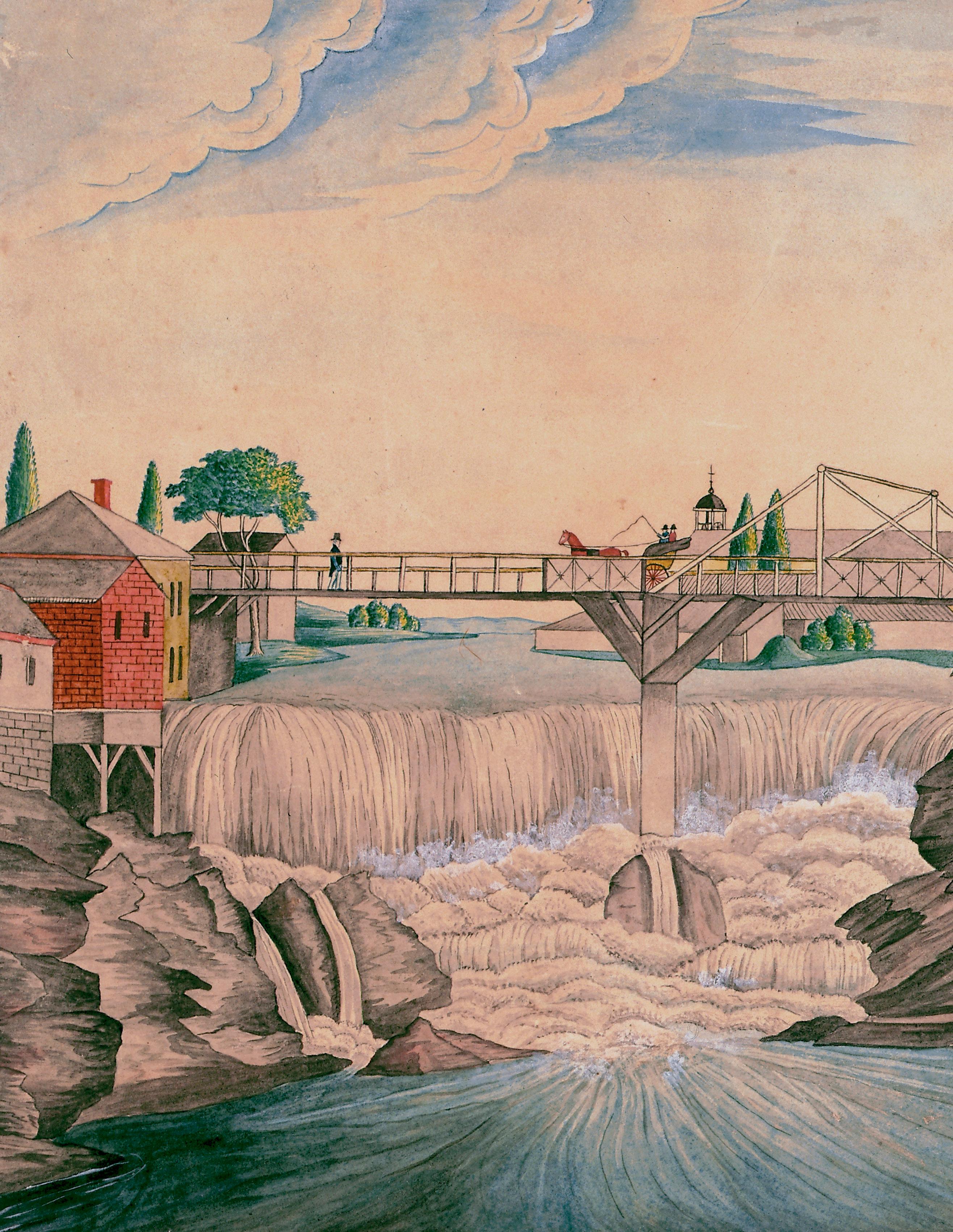

C over: Pawtucket Bridge and Falls, ca. 1810–1819. RIHS graphics paintings collection: 1971.23.1. rhi (X5) 22

3 Joseph Jenks Jr.: Seventeenth-Century Pioneer of Industry, Political Leader, and Visionary of Pawtucket Falls

Jonathan Cipriano

30 Fishermen’s Rights and the Governor’s Wall: The Birth of Recreational Shoreline Access Advocacy in Rhode Island, 1850–55 r obert g . Darst

Rhode Island History is a peer-reviewed journal published two times a year by the Rhode Island Historical Society at 110 Benevolent Street, Providence, Rhode Island 02906-3152. Postage is paid at Providence, Rhode Island. Society members receive each issue as a membership benefit. Institutional subscriptions to Rhode Island History are $40.00 annually. Individual copies of current and back issues are available from the Society for $20.00 (price includes postage and handling). Our articles are discoverable on ebscohost research databases. Manuscripts and other correspondence should be sent to editor@rihs.org.

The Rhode Island Historical Society assumes no responsibility for the opinions of contributors.

© The Rhode Island Historical Society Rhode Island History (issn 0035–4619)

JONATHAN CIPRIANO

Joseph Jenks Jr. Seventeenth-Century Pioneer of Industry, Political Leader, and Visionary of Pawtucket Falls

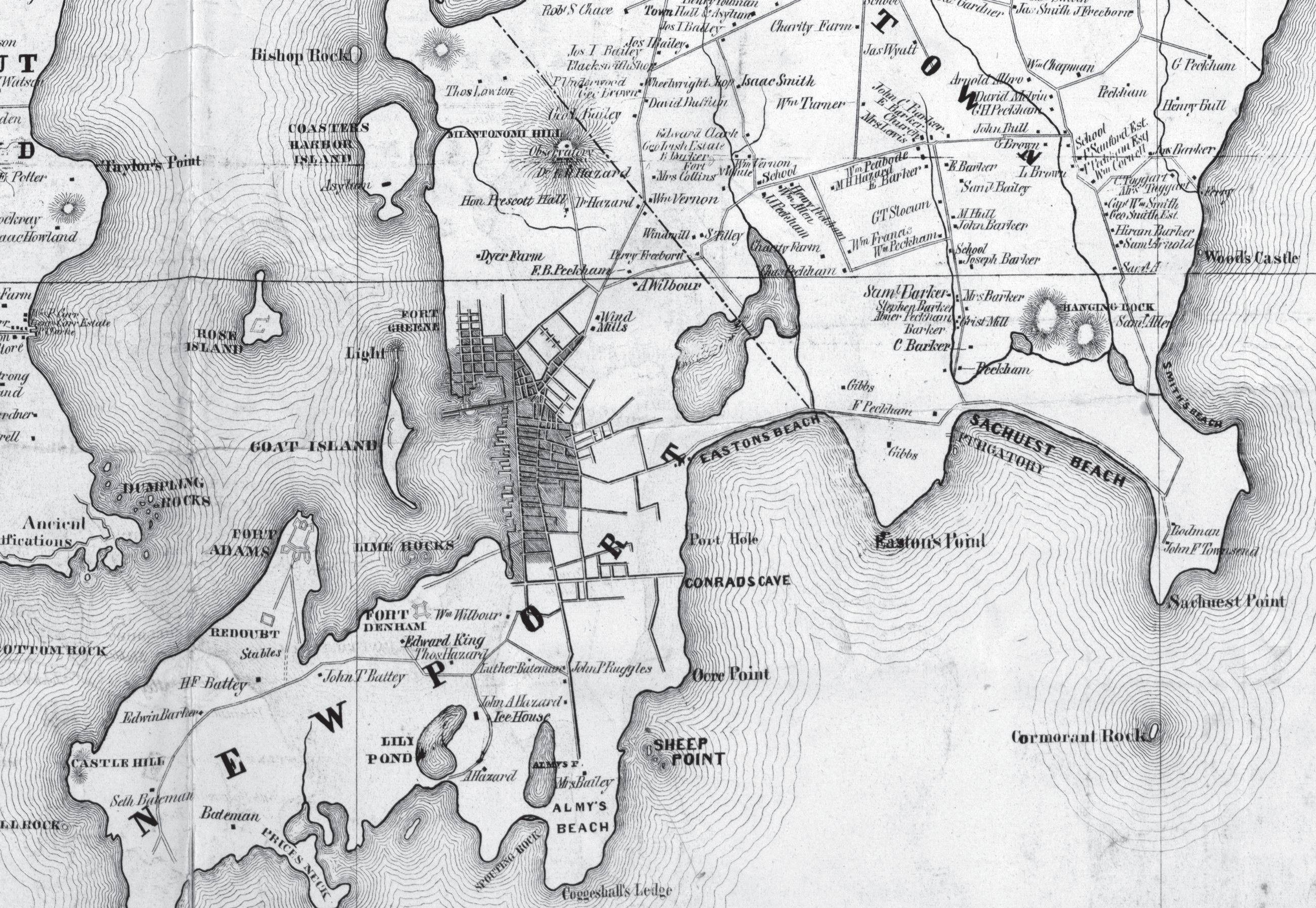

The BlaC kstone River serves as one of the many birthplaces of industrialization in North America. It flows from the headwaters located in present-day Central Massachusetts to Pawtucket Falls, where it drains into the Seekonk River, the northernmost tidewater of Narragansett Bay. In the eighteenth century, industrialists migrated to the Blackstone to utilize its waterpower. Samuel Slater, an immigrant from England, famously smuggled the most advanced textile machinery in the world into Rhode Island with the help of the illustrious Browns of Providence. He built his first mill directly north of Pawtucket Falls. A century earlier, Joseph Jenks Jr., another migrant from England, settled a short distance south of where Slater later established his mill. Athough his legacy does not match the renown of eighteenth-century industrialists, Jenks is still known in Pawtucket because he established a sawmill and Rhode Island’s first forge at Pawtucket Falls. His settlement is significant because it represents preindustrial technology and growth during the seventeenth century in southern New England.

In the late nineteenth century, soon after the City of Pawtucket was incorporated, historiography developed around “Pawtucket’s founder.” Robert Grieve wrote the first history of Jenks’s settlement in 1897, and many succeeding histories of Jenks were drawn from his narrative. In the late 1940s and into the 1950s, historians and archaeologists conducted research on the Saugus

o pposite : Pawtucket Bridge and Falls, ca. 1810–1819. RIHS graphics paintings collection: 1971.23.1. rhi (X5) 22

Ironworks located in Lynn, Massachusetts. This coordinated effort uncovered documentary and archaeological evidence, including Joseph Jenks Sr.’s workshop. Jenks, a blacksmith at the Saugus Ironworks, came to North America with his son, Joseph Jenks Jr., in search of opportunity. Together, they worked on new technologies to improve production in labor-starved New England. By 1660, Jenks Jr. struck out on his own and resided in Concord, Massachusetts, before ultimately settling in Rhode Island. His prominence in Rhode Island stemmed in part from his successful father. The skills he learned in his youth from both his father and the massive enterprise at the Saugus Ironworks helped shape the industrial future of neighboring Rhode Island, originating from Jenks building and operating the first forge at Pawtucket Falls.1

To understand the impact of craftsmen like Jenks in the seventeenth century, we need to grasp the economic realities of colonial New England. In the 1630s, tens of thousands of immigrants settled in towns along the coast. Although religious considerations motivated some, economic opportunity also drove many to participate in the Great Migration. Skilled labor was scarce in the colonies, making craftsmen in high demand. One objective of this study is to show how economic forces shaped Jenks’s trajectory.2

With a landed estate and a successful industrial enterprise, Jenks made his way into colonial political history as well. He emerged as a well-respected freeman and leader in the Rhode Island colony, with his name frequently appearing in colonial records. He

actively participated in Rhode Island’s colonial government as a deputy and assistant, overseeing important intercolonial communications, boundary disputes, and interactions with England.3 This portion of Jenks’s story frequently is overlooked, but his involvement within town and colonial governments paints a fuller portrait of who he was, in addition to his larger impact on seventeenth-century colonial politics. The following analysis presents a case study of Pawtucket’s founder within the context of a growing English Atlantic world, where industry and political opportunity shaped the trajectory of an economic migrant into a skilled artisan, industrial entrepreneur, and colonial leader in seventeenth-century New England.

A Changing Colonial Economy

Industrial development projects in New England began out of necessity. Throughout the 1630s, the economy depended on imported goods arriving with settlers from England. As immigration to Massachusetts Bay increased during the decade, thousands of newcomers brought English goods with them, including finished products such as textiles, tools, and coinage. In return, colonial merchants provided much-sought-after natural resources, primarily fur, but also cod and surplus cattle and crops. By 1640, the influx of immigrants began to recede, partly due to the precarious political situation that erupted into the English Civil War by 1642. English Puritans decided to stay in the mother country as Parliament gained more power, and many who previously had emigrated returned to England.4 Colonists felt the full impact of this economic down-

turn. The lack of ships carrying new people from the mother country caused the supply of materials, finished goods, and hard money (coinage) in New England to dwindle. As coinage became scarce, prices plummeted, making it difficult to pay debts. The economic depression of the 1640s prompted leaders to “encourage the trades and processing industries vital to the colonial economy, including bounties, special concessions and monopolies for desired projects, tax abatements, and land grants.”5 By the late 1630s, John Winthrop Jr. was coordinating efforts to fund an ironworks operation in the colonies and secured Puritan investors in England through his extensive network of connections.

Negotiations between investors and the Massachusetts General Court led to the creation of the Company of Undertakers of the Iron Works in New England. This was a private joint-stock operation. In 1645, Richard Leader replaced Winthrop as the operations manager. By that summer, he secured state-sanctioned privileges from the Massachusetts General Court, including land guarantees, tax exemptions, and militia exemptions for full employees of the ironworks. According to the agreement, if the company produced enough iron for the colony within the first three years, the Massachusetts Bay government would grant it a twenty-oneyear monopoly on ironmaking within colonial bounds.6 Winthrop originally chose Braintree as the first location for the plant, but after the leadership change, Leader purchased land in Lynn along the Saugus River. There, he established a successful blast furnace and forge. By 1648, the Saugus Ironworks was producing eight tons of bar iron per week, making it the first

heavy industrial ironworks operation in North America. Although Leader was familiar with ironworks operations, he was not a skilled craftsman and primarily served as a manager. During the mid-1640s, obtaining skilled workmen posed a significant challenge in building a successful industrial operation.7

A Skilled Workman

Joseph Jenks Sr. was born in England and baptized in 1599 at St Ann Blackfriars Parish in London. His father, John, worked as a cutler producing cutlery and weapons, while his mother, Sarah Fulwater, was the daughter of a German emigrant who also was a cutler. Jenks apprenticed with his father before disappearing from the documentary record for a time. He reappeared in 1627 when he married Jone Hearne and had a son, Joseph Jenks Jr., who was baptized in 1628. Tragedy struck the young family when Jone passed away in 1635, followed by their daughter Elizabeth three years later in 1638.8

Throughout the 1630s, Jenks worked with cutler Benjamin Stone, who specialized in producing arms at Hounslow in Middlesex to supply for the Thirty Years’ War. The English government granted Stone a monopoly for hiring Germans to train English craftsmen. While at Hounslow, Jenks forged a sword in 1636 inscribed with “JENCKES JOSEPH;” it survives at the Powysland Museum in Wales. He then moved to Northumberland for a short time, receiving state sanction for a milling operation there until as late as 1639. Unfortunately, there is no record of the mill thereafter. By 1641, he migrated to North America in Aga-

menticus (later York), Maine. He left his son, Joseph Jr., with George Hearne, his late wife’s father. Jenks probably left England because regulation and competition increased barriers to mill working. Agamenticus was first settled in the 1620s; Jenks’s skill most likely played a role in his immigration, as noted by one historian of York that he “is undoubtedly our first worker in metals, and a man of unusual ability in that occupation.”9 In 1643, Hearne passed away, leading to the assumption that Joseph Jenks Jr. immigrated to New England to apprentice with his father, as was customary for his age. Jenks Jr. would have been 15 or 16 years old. Continuing the search for skilled workmen, John Winthrop Jr. visited Maine in the winter of 1643–44 and hired Jenks to work in Massachusetts at one of the furnace operations sanctioned by the company.10 Meanwhile, after establishing sites at Braintree and Nashaway, the Saugus blast furnace was erected, and operations began in earnest by 1648. The ironworking operation at Saugus became the largest industrial project attempted in North America at the time. Establishing a productive ironworks required immense manpower, natural resources, and capital. Building a blast furnace involved significant engineering and materials. It stood about twenty-one feet high and had a base width of twenty-six square feet. Workers operated the furnace continuously, day and night, for months at a time. First, they had to dam the water to generate enough power by rotating multiple waterwheels, which powered bellows and trip-hammers. Workers added a mixture of iron ore and flux to remove impurities in the furnace. They also needed a significant amount of charcoal to fuel the furnace.

The rotating waterwheels powered the massive bellows, which blasted heat reaching over three thousand degrees Fahrenheit inside the furnace. When enough iron had melted, it settled at the bottom of the furnace. Workers tapped the furnace to allow the iron to pool into molds known as pig iron or sows, resembling the shape of a sow and her piglets. They then transported the iron to the forge, where workers reheated and pounded it using a water-powered trip-hammer. They repeated this process several times until they removed enough impurities for the iron to be considered pure enough to be sold to blacksmiths, who would then create specialty tools.11

The Jenkses settled in Lynn as Saugus became the main ironworking plant, intertwining the family’s future with the ironworks. Having a skilled blacksmith on location would benefit the company: “A blacksmith on site at the Saugus Iron Works would be vital for the production of tools in high demand. Steel-edged axes and two-man felling saws supplied woodcutters with the implements to harvest the over 3,600 cords of wood fuel needed each year to run the ironworks. Scythes provided farmers with sharp reaping tools needed for harvesting the grain that would feed the workers.”12 Jenks did not work directly for the Company of Undertakers but used his skills to secure patents and to run his own operation. By 1646, he had petitioned the Massachusetts General Court “to make experience of his abilityes & inventions” including “engines for mills, to go with water” for “more speedy dispatch of worke then formerly,” as well as a mill for manufacturing “sithes & other edged tooles” for a “new invented sawmill.”13 The general court granted

Jenks the first patent in British North America, which lasted for fourteen years. In January 1648, Jenks struck an agreement with Richard Leader and established a toolmaking mill along the tailrace of the Saugus blast furnace.14 Sawmills in New England were constructed rapidly in the seventeenth century due primarily to the lack of skilled labor. Sawpits required large numbers of people whereas sawmills could be operated by fewer people. New England towns required processed timber not only to erect homes but also to support the various craftsmen within the colonies. One way of improving technology was Jenks’s “newly invented sawmill,” which “actually may have been a mechanized way of making saw blades.”15

The Jenks millworks relied on the company’s production of bar iron. His smithing benefited the ironworks; between 1648 and 1653, the company paid him “for making and setting saws, making a broadaxe, repairing iron fixtures for the Company’s boat, and steeling axes.”16 Evidence suggests that by 1652, the Jenks operation produced saw blades for sawmilling operations in Connecticut.17 Throughout his years in Lynn, Jenks petitioned the court numerous times: in 1654 to produce “ingins to Carry water in Case of fire;” in 1655 an “engine...for the more speedy cutting of grass;” in 1667 to draw wire; and even in 1672 to coin the “making of money.”18 Jenks, a skilled smith with an entrepreneurial spirit, trained Jenks Jr., who learned how to be a successful millwright and developed knowledge of cutting-edge colonial technology adjacent to the industrial operation at Saugus.

The massiveness of the Saugus Ironworks required both skilled and unskilled manpower. Not only were

founders, finers, colliers, and smiths required, but the operation also demanded labor for mining ore and fluxing agents, felling and cutting trees in sawpits to produce charcoal, laboring on the company farm, and transporting ore, iron, tools, and other materials. Many workers were full-time employees, but a large portion of the operation involved Lynn residents who worked part-time for the company. The Jenks family lived nearby and worked with these laborers, who came from diverse backgrounds, including Puritan neighbors and indentured Scottish prisoners of the English Civil Wars who held divergent religious beliefs. Colonists lived close to Native Massachusett villages and interacted with them frequently. They traded with them, and ministers sought to convert them. The records of the ironworks reflect that two Natives, Thomas and Anthony, received two shillings each for cutting wood for services performed at the ironworks.19 The workers at the Saugus operation built crude homes for themselves, developing a company village called Hammersmith. Hammersmith primarily consisted of small log-cabin homes with thatched roofs, though some more important individuals within the ironworks had better housing. On-the-books employees, as well as indentured servants and their families, lived in Hammersmith. The Jenkses had their own homestead in Lynn and most likely lived within or adjacent to Hammersmith. Many workers did not adhere to the rigid Puritan ideal. Hammersmith quickly gained a notable reputation documented primarily by colonial court records. Violations included cursing, assault, and drunkenness, along with issues unique to Puritan Massachusetts, such as not attending church ser-

vices, sumptuary infractions, and criticizing church members.20

By 1652, Joseph Jenks Jr. met Esther Ballard, daughter of William and Elizabeth Ballard of Lynn. William and his young family migrated to Massachusetts in 1635, but he died in 1639. Elizabeth remarried William Knight of Lynn, and Esther grew up in his household.21 Both Joseph and Esther lived in Lynn and likely courted; they married by November 1652. The young Jenks couple likely contributed to the reputation of Hammersmith and resisted the rigid social conformities. In 1651, the general court passed a sumptuary ordinance declaring that the “Lord hath...declare utter detestation & dislike that men or women of meane condition...should take upon them the garbe of gentlemen, by wearinge of gold or silver lace..., or women of the same ranke to weare silke or tiffany hoods or scarves.”22 In June 1653, the court fined “Ester, the wife of Joseph Jynkes, Junior, for wearing silver lace” and others for “wearing great boots and silk hoods.”23 These infractions among the Lynn population were not uncommon, but Esther’s case indicates that the young Jenkses enjoyed a touch of opulence and finer things and did not adhere strictly to Puritan social standards.

John Gifford replaced Leader as manager in 1650, and Gifford’s tenure faced a series of legal proceedings starting in 1653. The Jenkses became involved in some fallout from property transactions. In 1654, Jenks appears in the deed records as purchasing six acres of land from George Burrill in September 1650. In 1651, he mortgaged his land to Gifford, but by 1654, Jenks had failed to make payment on the property. Gifford

had transferred the deed to Edward Richards by then. In April 1655, Jenks brought a case against Richards for damages and won; unfortunately, the court records do not detail the specifics of the proceedings.24 Joseph and Esther had their first child in 1656 while he likely still lived in Lynn and probably worked with his father in some capacity. The various property transactions and legal proceedings, along with the company’s economic troubles, must have caused anxiety for the young family.

Leaving Lynn

Evidence confirms that Joseph Jenks Jr. moved to Concord, Massachusetts, by 1660, while his father remained in Lynn. The Saugus operation began to wind down, and the Massachusetts General Court approved an ironworks in Middlesex County along the Assabet River at Concord. In 1657, Concord residents petitioned the Massachusetts General Court to build an ironworks. The colonial government granted Concord “liberty to erect one or more iron workes within the limitts of theire oune toune bounds.”25 The project required experienced workers, and the shareholders hired some employees from the Saugus operation. Joseph Jenks Jr. was among these migrant workers. He purchased twelve acres in Concord and built a sawmill and a slitting mill.26

Not much evidence recounts the operation at Concord. Edward Hartley, historian of the Saugus Ironworks, presumes that it was a bloomery operation. The bloomery required less labor and resources compared with the blast furnace technology at Saugus,

which needed large amounts of capital, resources, and manpower. In the bloomery method, smiths in the forge worked directly with the bloomery furnace; the smith had to heat the iron in the furnace hearth, then use a water-powered hammer to work the impurities out, reheat it again, and repeat the process. Although Saugus was the first successful industrialscale ironworks operation, the older bloomery method continued to dominate the colonial landscape. We can only speculate about Jenks’s time in Concord. His apprenticeship under his father, along with his own landholdings and operations in Lynn, prepared him for success in Concord. Local sawmills dotted the colonial landscape, providing townships with necessary lumber for construction. Slitting mills processed iron into long rods, which were then primarily used to create nails, highly sought after in the seventeenth century.27

Jenks’s first years in Concord faced turmoil due to the growing political uneasiness within Massachusetts. In the 1660s, the restoration of Charles II reverberated throughout the English Atlantic world. King Charles II sent commissioners in the early 1660s to rein in the maverick tendencies of colonial leaders who had governed with impunity during the chaos of the English Civil Wars and Cromwell’s lordship. A political battle developed within Massachusetts. A “commonwealth” faction of residents argued that Massachusetts charter was the foundational underpinning of their authority as a colony, and therefore Massachusetts Bay Colony was an independent entity. A more moderate faction opposed political independence from England. Still, a small coterie of royalist colonial leaders with economic

and political ties to the Crown feared accusations of insubordination and were eager to demonstrate loyalty to the new king.28

It was during the backdrop of this heightened political tension, when Jenks traveled to Lynn to obtain “plates and moulds,” that he expressed his opinions of the new king to residents and workers. His words reached the leaders of Massachusetts and provoked a heavy-handed reaction. In April 1661, authorities imprisoned him on charges of treason. Nicholas Pinion and his son Robert testified that they “did heere Joseph Jinks, jun. say that if he hade the king heir, he wold cutte of his head and make a football of it.”

Another resident noted that Jenks questioned the king with credulity, asking “is he better than another man for ought as he knew he was as good as a man as he?” Thomas Tower testified that Jenks said of the restored Charles: “I should rather that his head were as his father’s, rather than he should come to England to set up popery there.” Jenks was alluding to the regicide of the new king’s father, Charles I, in 1649. These charges were quite serious. While imprisoned, Jenks wrote a letter to the court. In it, he swore “I doo not remember” the accusations of Pinion and his son but affirmed the conversation with Tower and expressed regret “being [consisted?] of my foolishness, in taking too much liberty of my tongue” which he was “both very sorry for and ashamed of.” He remained in prison until his discharge on May 24.29

Jenks’s imprisonment reveals his tendency to voice confrontational political opinions. This loose talk posed less danger during his years in Lynn. Unfortunately, the colonial government needed to sup-

press any dissent following the restoration of King Charles II. The experience must have been unnerving for him and his family. His wife, Esther, had the sole responsibility of maintaining the household and caring for their three young children; they likely traveled to Lynn to stay with other family members during this time. The months Jenks spent imprisoned not only placed his family under stress but also delayed work at his mills, potentially jeopardizing his fledgling operation in Concord. The encounter with the law may have taught Jenks to temper his political speech, especially as he continued to build his reputation in Concord. After Jenks was released, he stayed in Concord for nearly a decade, as evidenced by Middlesex court records. In 1666, Jenks sued a local resident for failing to pay a debt. He also appears in local court records in 1667 and 1668, confirming his residence.30

Rhode Island

Joseph Jenks Jr. first appears in the Rhode Island colony records in 1669. The town of Warwick deeded him land on the Pawtuxet River. Records confirm that in March 1669, they “granted land on both sides of the Pawtuxet river on condition that he would build a sawmill and cut boards at the rate of 4 shillings and 6 pence per 100 feet. He was also to have the right to cut the trees on either side of the river for a distance of half a mile.” His residence in Warwick is corroborated by his service as foreman to a jury in 1670.31 What caused him to leave Massachusetts Bay for the Rhode Island colony? To answer this question, we need

to analyze the push-and-pull factors in context. The Puritan colonies, in general, practiced heavy-handed governments where belief informed civil affairs, such as sumptuary laws dictating residents’ dress and fines coercing people to attend congregations. We do not know how socially rigid the Jenkses were compared with the Puritan ideal, but a few clues are available. Evidence suggests that he participated in the lively social engagements of Lynn’s Hammersmith. Jenks’s wife faced fines for sumptuary infractions, which indicates that luxury likely mattered to them in their youth. They lived and fraternized with Hammersmith laborers. The 1661 imprisonment suggests Jenks was rather loose-lipped in his political views. This portrait reflects a young man who was vocal about his beliefs, spoke his mind, and could be confrontational at times.32

Jenks’s political acumen became evident after he moved to the Rhode Island colony. Civic participation in Massachusetts differed from that in Rhode Island. All colonial governments required government officials and representatives to be freemen, a status reflecting colonial civic and political standing. In Massachusetts, freemen also had to be members of the Congregational Church until 1664, and thereafter confirmed by their minister to be orthodox in their religion, which served as a gateway for increased social conformity and status. Rhode Island’s 1663 Royal Charter uniquely enshrined “full liberty in religious concernments,” and religion was not linked in any way to freeman status. To become a freeman of the colony, one only needed a competent estate and colonial approval. After arriving in Rhode Island, Jenks quickly advanced politi-

cally. In 1677, he became a freeman and participated in local and colonial government for three decades. His political and civic aptitude may have been stifled in Massachusetts.33

Jenks had an entrepreneurial ambition to provide for his family. After working at the Concord sawmilling and bloomery operation, he felt ready to take on more responsibility. Although he did not own the Concord ironworks, he probably maintained a similar relationship with the owners as his father had with the Saugus Ironworks proprietors. Jenks owned property, a slitting mill, and a sawmill. Twelve acres provided a sufficient plot of land, but by 1668, with three male heirs and six children, he needed more holdings to secure land for his family. Rhode Island may have offered more land for development and the breathing space Jenks needed to grow his family.

Economic pull factors were just as primary. In the seventeenth century, the colonies needed natural resources to spark industry and manufacture. Colonial authorities throughout New England identified a lack of skilled labor and sought to address this by subsidizing the migration of skilled workers and relying on connections with wealthy Englishmen. Grieve, in his portrait of Pawtucket, asserts that “settlers in many places would readily have offered all the inducements in their power” to lure the Jenks’s brand of inventiveness, productivity, and mill working to their locations.34 The residents of Warwick required a sawmill on the Pawtuxet, and a decent plot of land with guaranteed work in exchange would qualify as quite an “inducement.” At the same time, colonial towns needed iron. Rhode Island did not have its own

ironworks but relied on a distant operation in Raynham along the Taunton River for its supply.35 Given the numerous boundary and sovereignty disputes between Rhode Island and its neighboring colonies, Rhode Island merchants and leaders recognized the advantage of having local industries within their colonial limits.

These realities illuminate the Pawtuxet deed, which tied Jenks to the land in exchange for his sawmilling. He resided in Pawtuxet for at least a year, if not two. By 1671, it is assumed he had migrated north to Pawtucket Falls. Abel Potter owned this land, which his wife originally received through Ezekial Holliman, one of the original proprietors of Providence. Jenks purchased “sixty Akers of Land More or Lesse... Near Patucket ffales together with a Comonidge.”36 Potter lived in Warwick, and Jenks likely formed a relationship with him during his residence there.

It is probable that among the many social engagements of New England colonial life, Potter and Jenks discussed the possibility of an ironworks within the colonial boundaries. Furthermore, Jenks’s land purchase included him in the “comonidge” held by Rhode Island’s original proprietors. This land, held in trust by a group of Rhode Island landowners included in the original Providence purchase, would be accessible to Jenks at a future date.

Jenks still owned property and the milling operations in Concord. In July 1673, he mortgaged his “house & land, sawmill, & slitting mill,” situated “neere the Iron Works at Concord,” to Nathaniel Paine of Rehoboth. The deed specified that if Jenks paid Paine “five tunn of good marchantable barr iron”

within one year, the transaction would “be voyd.”37 Nathaniel was the son of Stephen Paine, one of the original settlers of Rehoboth. The Paines were heavily involved in seventeenth-century politics, trade, and land transactions within Plymouth and Rhode Island. In 1672, a year after Jenks settled at the falls and a year before he deeded his Concord land, Potter sold shares of his interest in part of Providence to Stephen Paine with Jenks as witness.38 This connection suggests a loose confederation of acquaintances among wealthy citizens and merchants; Jenks was becoming part of this network. Geographically, Jenks and the Paines were practically neighbors. The Blackstone and Seekonk Rivers formed the border between Providence and Rehoboth. Jenks’s property at the falls put him in proximity to the original settlers and merchants in the region.

The wording in the 1673 deed to Paine indicates that the transaction depended on Jenks producing five tons of iron for the Paines. This meant Jenks’s Concord holdings served as collateral for one year. Since Jenks already had acquired the sixty acres at Pawtucket two years earlier, the Paines likely paid Potter for the land in exchange for Jenks mortgaging his Concord holdings. If Jenks could build his forge and produce the five tons of iron, the mortgage would be released. The Paines also might have supplied investment capital in the form of tools and materials to build the sawmill and forge. While the evidence is sparse and sometimes unclear, we can assert from the recorded deed and evidence of land transactions that Jenks resided at the falls most likely by spring 1672. He had sixty acres of land within Providence to

support his family and access to Pawtucket Falls to power a sawmill and forge.

Pawtucket Falls

Understanding the historical significance of Pawtucket Falls provides crucial context for Joseph Jenks Jr.’s industrial activities. The transformation of this land from an important tribal site of the Narragansett to a burgeoning center of colonial industry highlights the broader changes occurring in Southeastern New England. Various Algonquin linguistic tribal confederations inhabited the Southeastern New England woodlands. The Narragansett and Pokanoket both claimed rights to this land and used it for hunting, planting, and seasonal migration. The name Pawtucket derives from Algonquin for “place of the falls.” The falls served as a wading point for travel and a site to fish during the spring fishing season. Colonial settlement changed how this land was conceptualized and utilized. The English introduced their ideas and practices of property, sedentary settlements, monocrop agriculture, domesticated animals, fencing, and their legal system.39

When Roger Williams negotiated land rights with the Narragansett sachems in 1636, they included the lands from the “Pautuxet River” in the southwest, to “Neotaconkonitt Hill” in the northwest, to the “Rivers & fields of Pautuckett” in the east.40 Throughout the first decades, the proprietors of Providence distributed the land and began to settle. In 1765, much of the land from Pawtucket Falls to east of the Woonasquatucket was separated into the town of North Providence—

where Pawtucket in its jurisdictional bounds was a growing village. The City of Pawtucket was not incorporated until the late nineteenth century. When Jenks arrived in 1671, he was not the first colonial settler within present-day Pawtucket boundaries. However, his residence at the falls marked the first industrial enterprise utilizing its natural waterpower. His settlement attracted workers and other millwrights to the falls, leading to its growth as a village in the succeeding decades.

Upon arrival, the Jenks family needed to build the infrastructure for a homestead, sawmill, and forge. By this time, his eldest son, Joseph Jenks III, was an adolescent and assisted his father in construction. Jenks erected a wooden-frame house adjacent to the falls, where the Boys & Girls Club building stands today at 53 East Avenue. This likely occurred within the first months of settlement, followed shortly by the construction of the sawmill. Developing the forge was a complex process. It included damming the water at the falls and channeling the flow to rotate waterwheels. The waterwheels needed to be constructed and implemented to power both the bellows and the triphammer. To power the bloomery, Jenks likely “placed the ore in a small hearth with a charcoal fire blown with bellows.... Carbon monoxide from the fire reduced the ore to solid iron, and impurities in the ore simultaneously formed liquid slag.” Then, he “took a ball of white-hot iron and slag (the bloom) from the hearth and hammered it to consolidate the iron and expel the slag.” This process culminated in wrought iron, which was used for creating intricate shapes (think of a wrought-iron gate) or parts for “machinery and mech-

anisms.”41 Other labor included processing the lumber into tall mounds or pits and overseeing the laborintensive task of producing charcoal. Bog iron ore had to be mined from local swamps and transported to the forge. Secondary sources mention workers migrating with Jenks who would have built lodgings as well. These structures probably were temporary housing, perhaps similar to those in the Hammersmith village of Saugus. Unfortunately, this assertion is inferential, as no documented evidence exists of who and how many workers initially migrated with Jenks.42

Bog iron ore was plentiful at the local mineral spring adjacent to the Moshassuck River, about a mile and a half from the falls. Jenks was familiar with this process, as most of the iron at Saugus was mined from local swamps. Today, this area lies near where Mineral Spring Avenue crosses the river, just southeast of the Lorraine Mills. Seventeenth-century Providence town records consistently reference a “great swamp” that stretched from “Mineral Spring Avenue in Pawtucket to the North Burial Ground in Providence.”43 Maps provided by the National Park Service highlight the mineral spring/great swamp. One park ranger asserts

“based upon the map and the general geography of the region, that seems like the most logical location of the swamp where they were collecting the bog iron.”44 Multiple secondary sources indicate that Jenks erected a sawmill and Rhode Island’s first forge sometime before 1675, when King Philip’s War broke out across New England.45 Pokanoket, Narragansett, and Nipmuc warriors swept across Southern and Central New England that fall, razing and destroying colonial settlements, including Jenks’s home, sawmill, and forge.46 After the war receded in Southern New England with Metacom’s death in 1676, Jenks returned to the falls and had to rebuild his house and sawmilling operations. These were constructed within a few years; by 1679, “Joseph Jenckes & ye sawmill” was rated in the Providence records, indicating that Jenks had already resumed sawmilling.47 In 1678, the town council voted to “Settle at ye ffalls and there abouts a perpetual Comon for the Townes ffree fishing...and stake out a perpetual Convenient high way from ye Towne to ye Comon.” Jenks’s residence and sawmilling operation put him adjacent to the falls, potentially placing him in conflict with this plan. Gregory Dexter’s prop-

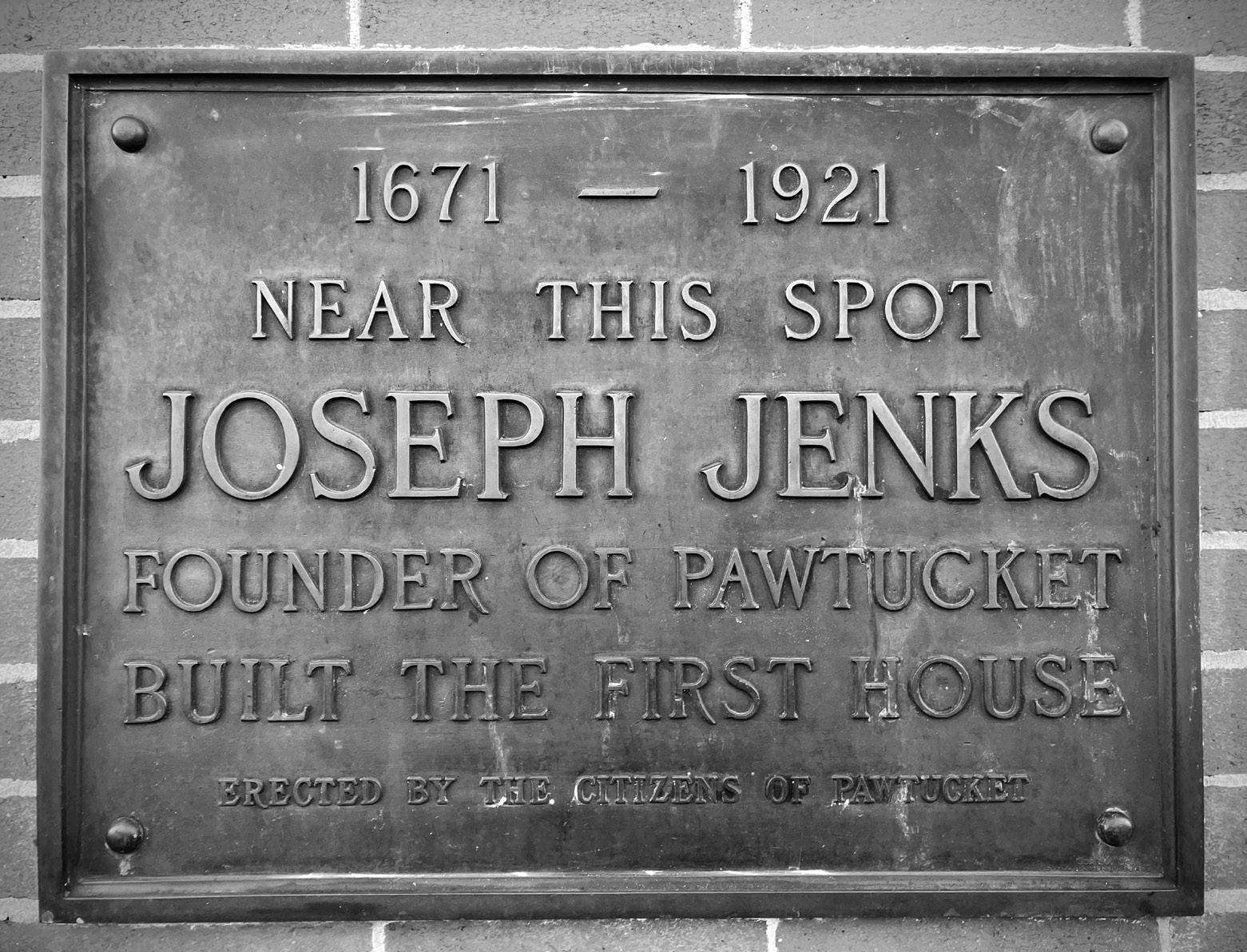

Image of Jenks site plaque taken by the author, location is 53 East Avenue, Pawtucket, RI.

erty was adjacent to Jenks’s and also would be affected by a highway to the falls. Both men probably attended the town meeting on April 27, “whereas there have been long debates this day about pautuckett ffalls.”

Placing a road and proclaiming eminent domain on Jenks’s property drew a guarantee from the town that if “any damage Come to mr Dexter or Jiencks theire landes there abouts,” they promised to “make them reasonably Sufficient sattisfaction out of ye Townes lands Elce where.” Jenks’s prime location along the Rehoboth/Pawtucket highway at the falls involved him with town residents. Townspeople visiting the fishing commons witnessed Jenks’s rebuilt sawmill. Jenks and his family probably fished with the townspeople, forming connections and building trust with Providence residents.48

Sawmilling likely served as the main source of income for the Jenks family following King Philip’s War due to the high demand for lumber to rebuild homes destroyed during the conflict. Finished boards could be transported just north to Providence along the highway or more easily along the Seekonk River from Jenks’s sawmill to the towns of Rehoboth and Providence farther to the Narragansett Bay towns. Throughout the 1680s, the settlement grew in size and stature. In 1679, Jenks “gave unto Joseph Woodward of this towne foure Acares of Land,” perhaps as a fulltime worker for the mill. In 1681, Joseph’s half-brother Daniel left Lynn and joined the Pawtucket Falls settlement “whereby he may learn and perfect his Trade of his Brother Joseph jenckes.” By 1685, sawmilling remained an integral part of his falls operation when the town requested “twenty shillings in boards belong-

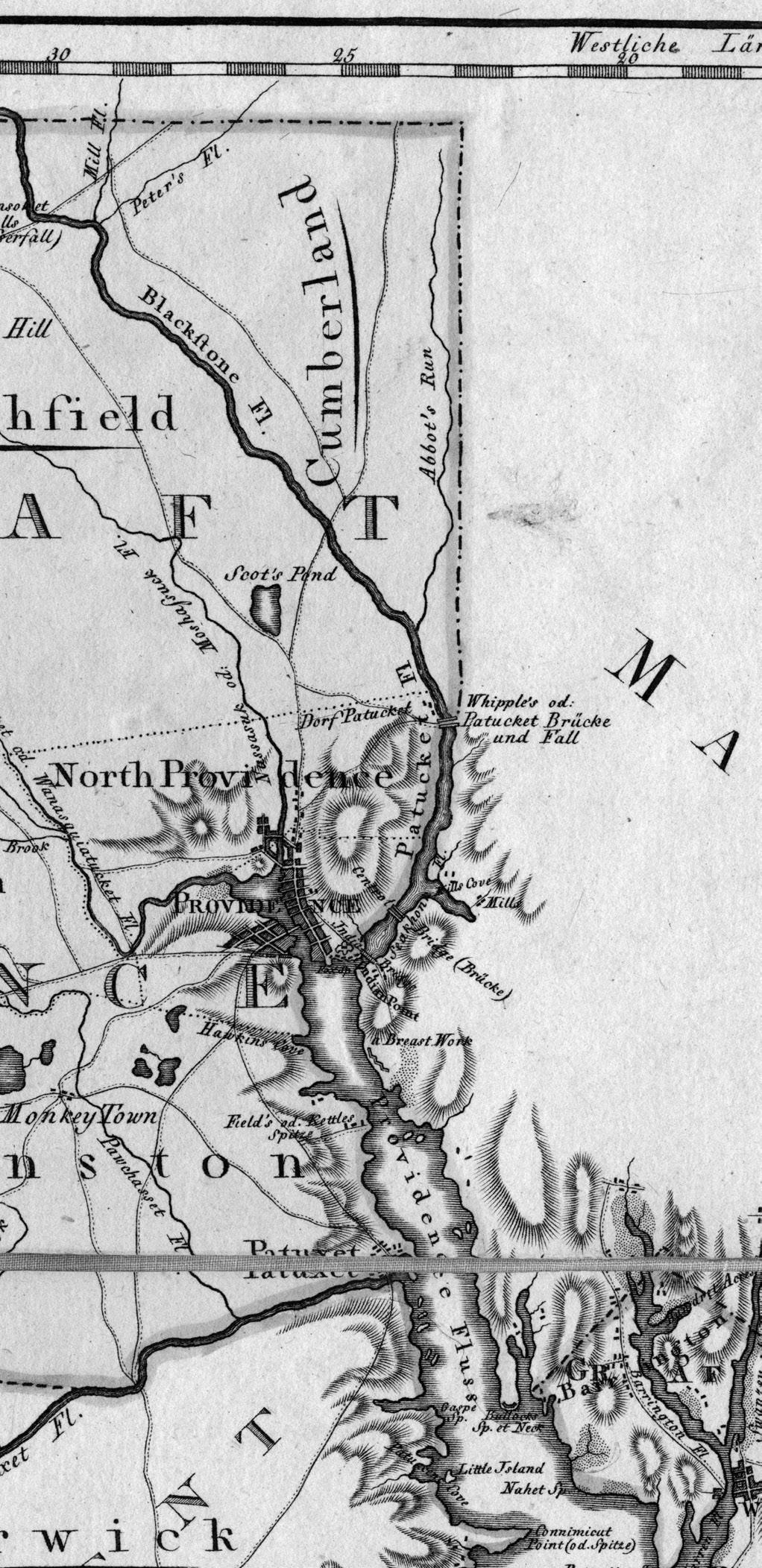

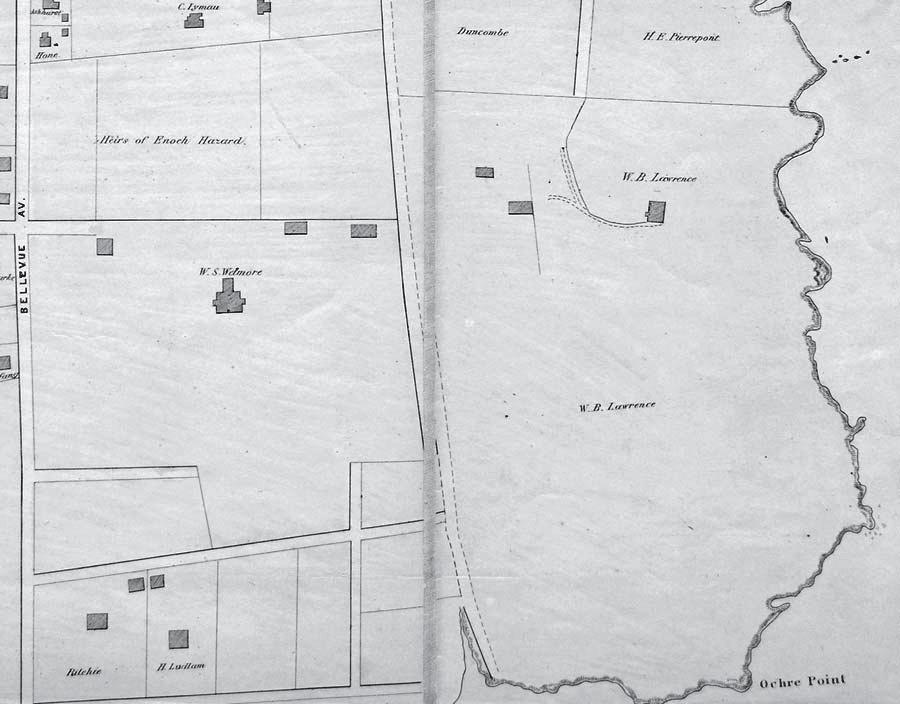

Detail of “Rhode Island” from the Ebeling-Sotzmann Atlas Von Nordamerika (Hamburg, 1797). “Patucket Brücke und Fall” (Pawtucket Bridge and Falls) in the center on the Massachusetts line.

ing to ye Towne” be delivered to Town Recorder John Sanford as payment for debts owed to him.49

Rebuilding the ironworks operation took some time. In January 1684, Jenks petitioned the town for the “Re building of my Iyron woorks” as well as “the liberty to make [use] of any lodgemine...in this towne-

shipe...that is not yet layd out [unto] any pertiqueller person....” This “lodgemine” presumably referred to making use of any common lands or original proprietor rights to lands containing bog iron ore. The ironworks operation was back online by 1688, when Jenks’s estate assessment included this entry: “my fordge.”50 The demand for iron among Rhode Island farmers and craftsmen included tools such as “chains for hauling logs, ox-plows, and carts, or for oaken buckets that hung in the wells, and also barrel hoops, locks, latches, and other ironwork for new houses.” Shipbuilding, a growing New England industry, required metal for “small anchors, bolts, and a variety of metal fittings for shipyards.”51

Pawtucket Falls grew into an important center of industrial production, and the Jenks family prospered as the colony’s agricultural and merchant industries expanded. In 1688, Providence estates underwent tax assessments, including those of Jenks and his two sons, Joseph III and Nathaniel, totaling thirteen shillings and two pence. This assessment included fortysix acres of land for Jenks, four for Joseph III, and two for Nathaniel, with “purchhis Right” on the land held in trust by the original proprietors; numerous domesticated animals for each, including cattle, horses, and pigs; “my sloope littell improved, my saw mill...”; and “my fordge.”52 The Jenks family continued to grow, multiply, and achieve success in Pawtucket. Through their daily interactions and business dealings with townspeople, merchants, and fellow landowners, the Jenkses earned the trust of their neighbors and gradually integrated themselves into a network of influential elites who held political power.

Joseph Jenks Jr., Freeman

Jenks’s move from Massachusetts to Rhode Island brought him under the jurisdiction of a new colonial government. Rhode Island’s Royal Charter of 1663 established a central colonial government with executive authority vested in the governor, his deputy, and ten assistants or magistrates. These offices, along with locally elected deputies from each town, formed the General Assembly of Rhode Island. The Rhode Island colonial town served as the nucleus of local civic authority. Roger Williams founded Providence as a communal democratic experiment where “all the heads of families would meet to decide what direction the community should take.”53 Over time, this evolved into regular town meetings that maintained a large degree of autonomy during the first decades of settlement. The Royal Charter continued to grant some degree of local autonomy, but town meetings had to include colonial assistants.54

The Rhode Island colony operated as a limited democracy. Freeman civic status, an English institution, connoted the ability to participate in civic and political life in the seventeenth century. Since the Rhode Island government functioned as a mixed government system, residents could obtain freeman status in both town and colonial capacities. Town freemen could vote for local appointments (town council, constable, etc). Freemen of the colony could vote for governor, assistants, and deputies to represent them from the towns and hold colonial office.55

On May 1, 1677, the Rhode Island General Assembly voted to admit Joseph Jenks and five others from

Providence as “freemen of this Collony.”56 He had an estate within the town and either petitioned the colony for permission or received a recommendation from officers of Providence. Jenks now could participate in voting for the civic leadership of his town, and colonial representatives could even hold office. In 1679, he was elected deputy to the colonial general assembly and served on the colonial trial court.57 In 1680, he was elected as an assistant, one of ten chosen to serve in an executive capacity for the colony under the governor and deputy governor. He was reelected to this post annually through 1686 and again from 1689 to 1691, 1695, 1696, and 1698.58

The growth of colonial Rhode Island did not happen in isolation. The New England colonies were connected to the mother country, and much of Jenks’s civic career involved colonial issues tied to the larger English Atlantic world. Throughout his years in office, Jenks served both Providence and Rhode Island in numerous capacities, playing a role in local matters and participating in Rhode Island’s larger political history, especially in the last two decades of the seventeenth century. Below, we will explore a sample of examples highlighting his political tenure, thereby illustrating his leading role within Rhode Island colonial civic life and his ascension politically.

Jenks’s first year in government as a Providence deputy focused primarily on intercolonial land disputes over the former Narragansett Country and the Mount Hope peninsula.59 In July, he joined a committee with six other assembly members, the governor, and the deputy governor. Their responsibilities included responding to a letter from King

Charles II earlier in the year. The committee had to establish “that a true account may be rendered his Majesty concerning Mount-hope Neck” and “That an account soe farr as we are able, may be given to his Majesty concerning the late warr with the Indians.”60 The committee completed the letter on August 1. The authors assessed Mount Hope’s arable land and value and also asserted that “wee humbly conceive by your Majesty’s gracious Charter to us granted... within which limmitts the said lands called Mounthope Neck...is situated.” They argued the boundaries of the 1663 Royal Charter, which stipulated that “the easterly bounds whereof [Narragansett Bay] extends itself to the eastward of the said Bay three English miles.” The authors addressed the Narragansett Country, accusing Massachusetts and Connecticut of “endeavor[ing] to insult over your loyall people, and have forbidden us the exercise of your Royall pleasure,” and of “consult[ing] to dispose of the said Province lands, as their conquest.” They ended with a plea, asking that “such of this your Collony, that want settlements, may be supplyed out of those vacant lands, unsettled in your said Province, before any others.”61 Appeals to authority from Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut over Narragansett Country continued throughout the following decades.

Jenks’s competence as a representative quickly earned him esteem. As stated above, in 1680 he was elected colonial assistant. In this role, he served as one of ten advisers to the governor on administrative matters. Assistants met with deputies and the governor to form the general assembly, where colonial laws were legislated. They sat on the state courts and managed

administrative duties under the governor’s purview, including auditing, writing correspondence, enacting legislation, and handling boundary issues. They assessed taxable assets and served on town councils, helping to affirm deeds and wills and to administer town business. At the first general assembly meeting, where Jenks was elected an assistant, he was “chosen and empowered to purchase and procure a bell...for giving notice, or signifying the several times or sittings of the Assemblys and Courts of Tryalls, and Generall Councills.”62

Much of the assembly’s time focused on local matters. Rhode Island towns celebrated their autonomy and frequently resisted top-down colonial authority. Municipalities in Narragansett Country refused to accept the colonial government’s jurisdiction. In October 1681, the assembly voted that Jenks “goe to Kings Towne and require and receive the engagements of the Wardens and officers lately chosen in said towne.”63 At a following general assembly meeting in June 1682, Jenks reported that the inhabitants of Kingstown “evaded” their responsibilities. This insubordination “if not timely prevented” was “likely to bee prejudiciall to this Collony.” The assembly responded with resolve by appointing two “Conservators of the Peace” to maintain the abrogated responsibilities of the Kingstonians. They also required a delegation to “conveane the inhabitants” of Kingstown to “read the severall acts of the Generall Assembly for the raising of money for the payment of the Collony’s debts” and to enforce that “townesmen doe elect all their officers respectively.”64 Ultimately, Kingstown did not fully cede to Rhode Island jurisdictional authority until 1696.65

Jenks’s role in Providence also demanded much of his time. As an ex-officio member of the Providence Town Council, Jenks had to serve as a Providence councilman while fulfilling his duties as a colonial assistant. In a July 1680 meeting, the town council addressed the issue of wolves, which consistently plagued colonial New England by “causing ye great damage of our inhabitants.” The council voted that “ye whosoever killleth ye wolves...shall have for Each wolfe (so killed) upon demand payed to them by our Town Treasurer Twenty shillings in Cuntrey pay.” Jenks was among the residents responsible for levying the tax for the wolf bounty. He also took charge of levying taxes for Providence various times throughout his tenure.66

In 1685, King Charles II died, and his brother, James II, ascended to the throne. James prioritized asserting imperial dominance over the New England colonies. Starting in 1685, he worked to implement a unified administrative state known as the Dominion of New England. The king appointed Sir Edmund Andros as royal governor. In June 1686, Edward Randolph, secretary of the dominion, arrived in New England and delivered a letter of quo warranto to Rhode Island and Connecticut. This letter required both colonies to submit their charters to royal authority. Instead, Rhode Island leaders appointed a committee, composed of the governor, deputy governor, Jenks, and three others, to “draw up our humble address to his Majesty,” and to Randolph. The assembly initially resisted the request to submit the charter and pleaded that it should be upheld “both in religious and civil concernments.”67 But, as with other New England colonial governments,

Rhode Island eventually submitted to the new king’s authority. Only a month later, Jenks and Providence leaders confirmed this inevitability and recommended to the assembly “that our minds ar that ther be a surender or prosterating our Charter and the priviledges...unto our gratious sovereign lord King James the second.”68

The Dominion of New England was much different from what Roger Williams had envisioned. The new government was “highly centralized and oligarchic in character.” Rhode Island as a county of the dominion was represented by seven justices.69 Jenks and many other locally elected leaders did not participate in the new government (and probably were not invited to). They did not align with the same circles as the well-connected social elite who “liked its authoritarian quality, its bestowal of power on gentlemen of the place..., without sullying them with a requirement of being elected.”70 In fact, it may have centered more around wealth and influence rather than views on its “authoritarian quality.” All but one justice hailed from outside Providence and mostly represented the largest, wealthiest town of Newport. Jenks’s power centered in his locality, in the trust built in his local northern Providence where he had lived for years, where he hired workers, fished with neighbors, and performed marriages. He was a well-respected craftsman and businessman within the community. His deeds upheld democratic principles of local governance. He was not of the aristocratic-adjacent leaders that came to power during the period of the dominion and therefore maintained his individual capacity as a townsman. Overall, the dominion generally was ineffectual in Rhode Island

as it struggled to be implemented in its entirety.71 Its short reign was toppled in April 1689, when the Glorious Revolution swept King William and Queen Mary into power, overthrowing James II and quickly dismantling the dominion’s rule in Rhode Island. In response to the unfolding events in England, Bostonians revolted and deposed Andros. In Rhode Island, Walter Clarke and John Coggeshall, the prior governor and deputy governor in 1686, encouraged all freemen to meet in Newport on May 1, their traditional election day, to reassume their “ancient privileges.”72 When May 1 came, those in attendance wrote a resolve that “we can do no less but to declare that we take it to be our duty to lay hold of our former gracious privileges in our Charter contained, and so to continue the government, always yielding obedience to the Crown of England, and manifesting our allegiance thereunto.”73 The charter was then taken out of hiding from the former Governor Clarke, presented “to the open view of the Assembly,” and returned to his safekeeping. This occasion, which one historian notes as a “self-styled assembly,” was the first official meeting of the general assembly since its dissolution in 1686.74 Not all freemen were pleased with this hasty decision. Many royalists in the colony refused to observe the restoration of the 1663 charter.

During the May 1 assembly, “Mr. Joseph Jencks” was appointed to lead a “committee” with three others to retrieve the records of the colony. But, upon confronting their keeper, Thomas Ward, he “refuseth to deliver them without they be taken out of his hand by distraint.”75 Ward was not alone in resisting; Francis Brinely, the chief justice of the Rhode Island Court

under Andros, wrote in February 1690 that things had gotten out of control: “We can never govern ourselves with justice nor impartiality, unless there be a good government established here, as in the other Plantations.”76 As 1689 came to a close, the “republican” faction that included Jenks and other popularly elected representatives was successful in its assertiveness. They had their royal charter and the people behind them.

Eight months following the May 1 assembly, Jenks and several others sent a petition to the new monarchs justifying their actions:

“to extend your fatherly care in the granting a confirmation to our Charter, which although it was submitted to his late Majesty, nevertheless it was not condemned nor taken from us; and therefore since the late Revolution, concerning Sir Edmund Andros, his being deposed from the government, we your Majesties’ subjects, being destitute of government, saw cause under grace and favor, to re-assume the government according to our Charter, the 1st of May last past, being the Election day appointed by our said Charter, in which Assembly it was ordered, that the former Governor, Deputy Governor, and Assistants that were in place in the year of our Lord 1686....”77

Since the charter never was officially revoked, leaders in Rhode Island argued that since they were “destitute of government,” reverting to the Royal Charter was the most just, logical, and expedient remedy. These leaders knew what they were doing and took advantage of

the power vacuum in the American colonies created by the 1689 revolution. In actuality, they staged a peaceful coup—one that technically was legal since their charter had not been officially revoked. The ascension of William and Mary thrust England into a war with France. How the colonies would be governed was not their top priority in the immediate aftermath of the revolution. The gamble worked, and by 1690, the Rhode Island colonial government had fully resumed operation under its 1663 Royal Charter.

Two decades after the death of Metacom, colonial boundaries on the eastern line of the colony, where the Pokanoket originally had lived, still caused intercolonial flare-ups.78 One such flash point over the disputed land occurred in 1695. On July 2, the general assembly appointed a group including “Mr. Joseph Jencks,” to “run the eastern line of our Colony...according to the best of their understanding.”79 Jenks and his party journeyed to the boundary line with Massachusetts Bay and confronted the Freetown residents. Commander John Saffin, a leader of the Massachusetts colony, met the Rhode Island delegation late in the afternoon and “demanded to know the cause of their coming thither.” Jenks, the “chief speaker,” responded that they were there to run the Rhode Island boundary line. Jenks also asserted that they should read the queen’s letter to the colony so that “his Majesty’s Subjects in these parts might know their duty and privileges” according to the colonial boundaries under Rhode Island’s Charter. Saffin claimed that Jenks and his party were trying to “stir up the people.” He continued his discussion with “long winded Jenks” for most of the night and only managed to dismiss the

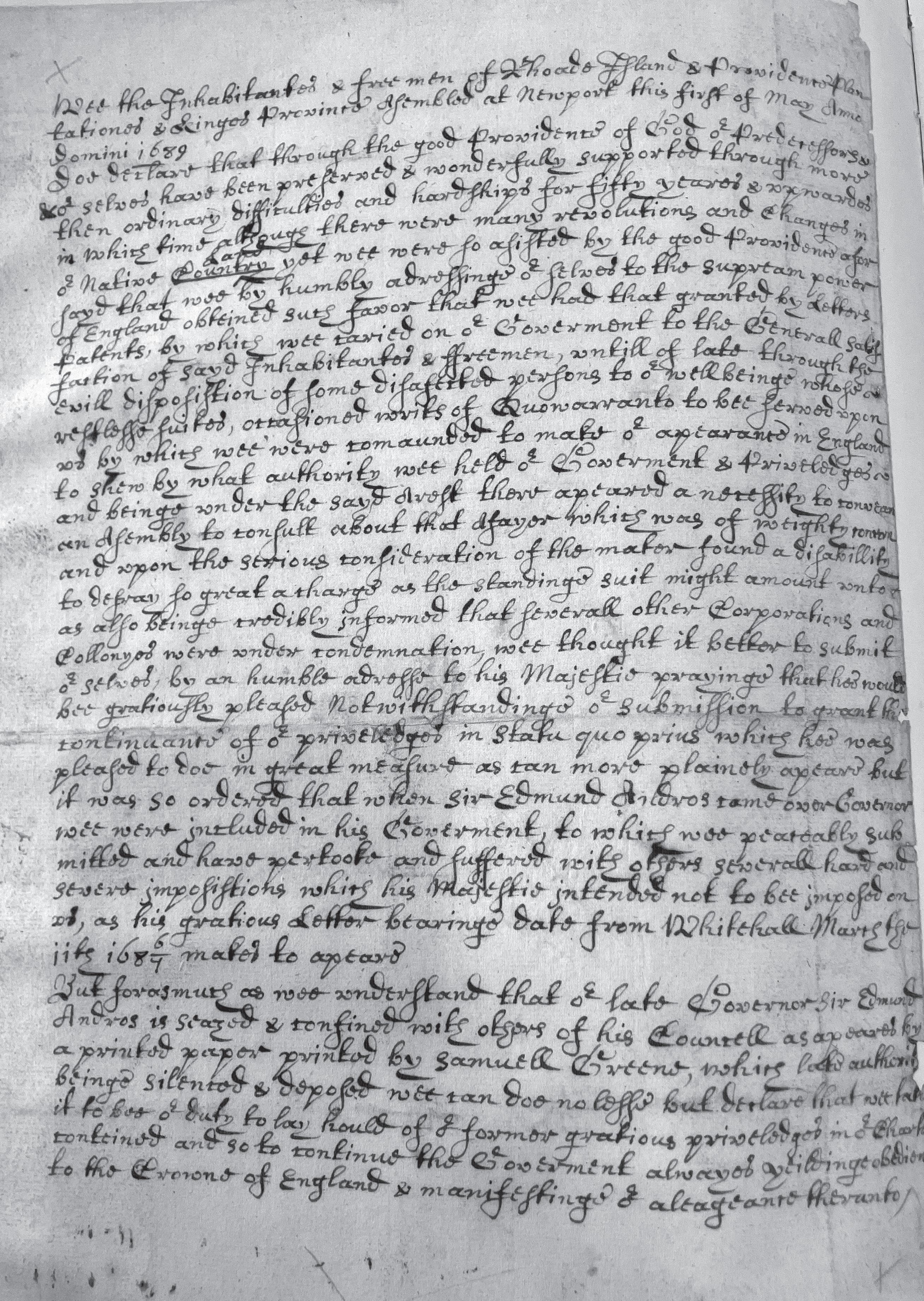

l eft: The Rhode Island General Assembly’s declaration dated May 1, 1689. Records of the General Assembly, State Archives, Providence, RI. Image taken by the author.

r ight: The Rhode Island General Assembly’s minutes dated May 1, 1689. Records of the General Assembly, State Archives, Providence, RI. Image taken by the author.

Rhode Islanders the next day. Saffin reassured the leaders of Massachusetts that “there is not one in ten of all the people in these parts...that desire to be under Rhode Island Government.” Jenks, an aging leader in his late sixties, embodied a general vitality and a commitment to civic duty. This instance also hints at his outspoken and argumentative personality reminiscent of his 1661 imprisonment, although probably somewhat refined over almost two decades of leadership experience. This event highlights Jenks’s belief in the mission of his colony: that those technically within the boundaries of Rhode Island should “know their duties and privileges;” that they too could participate in a more robust civic atmosphere.80

Jenks played a role in creating a bicameral legislature, a major shift in the colony’s government that reflected both English political traditions and the colony’s growth. In 1696, the number of colonial deputies increased as more towns joined Rhode Island. While serving as an assistant, Jenks and the general assembly passed a law establishing an upper house composed of the governor, deputy governor, and assistants, as well as a lower house of town-elected deputies. This change addressed “a great hindrance in the Managing of the Publick Affairs of the Government.”81 Ineffective tax collection and growing demands from localities led to the adoption of this new system, which thereby elevated the role of the Deputies.82 This bicameral structure continues to this day, with the upper and lower houses evolving into the modern State Senate and House of Representatives.

By the early 1700s, Jenks, in his seventies, began to slowly retreat from holding colonial office. He served

in a local capacity on the town council and in different town offices. His name continued to appear in local records in performing marriages and recording deeds. In 1708, he drew up his will, “being now Very aged & by Reason of age become weake of body.” He was still alive in 1713, working with his sons to help erect the first bridge over Pawtucket Falls, which connected Rehoboth and Providence. As earth was needed to support the construction of the bridge and more construction widened the river, a trench was beginning to be dug to the western side of his settlement as an avenue for fish to swim upstream. The falls were changing, and throughout the following decades, the growing Pawtucket village would attract more milling operations. Jenks in his final years undoubtedly spent time reflecting on how much the settlement had grown in the previous four decades. He died in 1717, at the presumed age of 89.83

All of his sons followed in his footsteps by holding public office. Joseph Jenks III surpassed his father’s record of service, boasting twelve terms as deputy of Providence, including two as speaker of the House of Deputies. He served as an assistant from 1708 to 1712. For all but one term from 1715 to 1727, he served as deputy governor under the stalwart leadership of Samuel Cranston. After Cranston’s death, Jenks became governor of the Colony of Rhode Island, serving from 1727 to 1732. His second son, Nathaniel Jenks, achieved the rank of major in the colonial militia, served in various capacities as deputy and town councilman, and helped build the Pawtucket bridge. Ebenezer, continuing Rhode Island’s tradition of religiously divergent leaders, became a minister for the

First Baptist Church. His youngest son, William, known as Judge William Jenks, also participated in local and colonial government, serving as chief justice of the Providence County Court and playing a significant role in boundary negotiations with Massachusetts in the 1740s. Joseph Jenks Jr. left “unto my Two sons, namely, Ebenezer and William: my Cole house and halfe of the fforge to be Equally betwene them two.”84 This implies that Jenks had partnered with another investor in the forge as it continued to grow well into the eighteenth century. All of his daughters married peers within their esteemed social class, including the Tefts, Whipples, Scotts, and Browns of Providence. The second and third generations continued to grow, and the Jenks legacy had become woven into the fabric of Rhode Island.

Conclusion

Joseph Jenks Jr.’s life exemplifies the transformation of an English economic migrant into a key figure in Rhode Island’s industrial development and political class. His industrial education at Saugus, under his father’s guidance and among a diverse group of workers, not only honed his technical skills but also exposed him to the broader socioeconomic dynamics of early colonial industry. Jenks’s hands-on experience in milling operations across colonial bounds, from Lynn to Pawtucket Falls, equipped him with the knowledge and expertise to found a successful settlement. His keen assessment of Pawtucket Falls as an ideal site for his sawmill and forge profoundly influenced the trajectory of Rhode Island’s industrial

development. His decision to settle there did not happen in isolation but was shaped by the larger forces of the expanding English Atlantic economy, which rewarded skilled artisans capable of capitalizing on available resources. The colony’s growing demand for industrial labor allowed ironworkers such as Jenks to thrive, planting the seeds of a future industrial economy at the falls. Rhode Island, founded by dissenters who valued liberty of conscience and democratic governance, proved a fertile ground for someone with Jenks’s temperament. His success in industry facilitated his rise in the colony’s political sphere, where his leadership helped shape both policy and civic governance, cementing his place at the forefront of Rhode Island’s most pressing colonial matters. Jenks looms large in Rhode Island’s history, but his fuller legacy has been overlooked. Researchers of industrial history tend to focus on succeeding generations, including Samuel Slater, the Wilkinsons, and the era of the first industrial revolution in America, with brief mention of Joseph Jenks Jr. While details of his forge and smithing operation at the turn of the seventeenth century are lacking and perhaps should spark further archeological research, ironworking in Pawtucket continued to play a large role in the local economy years after Jenks’s death. His sons continued their ownership and production at the forge, and Pawtucket Falls became synonymous with iron. This legacy influenced Oziel Wilkinson’s move to Pawtucket. When Samuel Slater came to Pawtucket, he relied on Wilkinson’s metalworking and engineering in building the first water-powered cotton mill in America.85

It is important to note that Jenks’s story of immigration from Massachusetts to Rhode Island was not only economically but also politically motivated. The trajectory of New England industrial history would have looked different had not the political atmosphere in Rhode Island been less stifling compared with that of Massachusetts in the 1660s. In Rhode Island, Jenks was welcomed as a freeman, trusted by his neighbors, and quickly rose through the colony’s political ranks. The depth of confidence he gained among his peers and constituents by consistently being elected and participating at the forefront of discussions—whether it be in resisting the Dominion of New England, staging a peaceful coup following the Glorious Revolution, negotiating boundary disputes, or presiding over the creation of a bicameral legislature—embodies his views on political life as supposing to be democratic, active, and robust. He actualized this belief through-

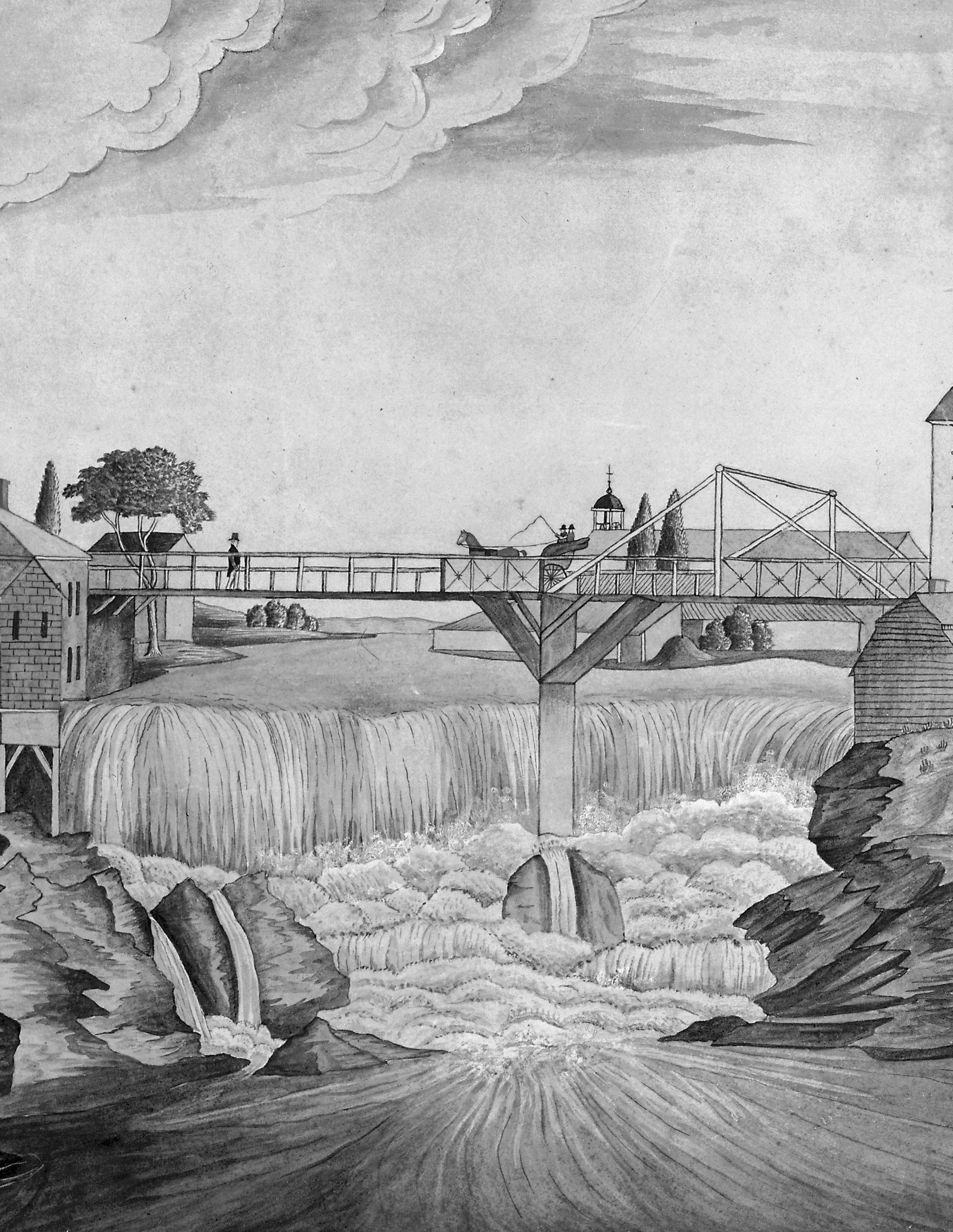

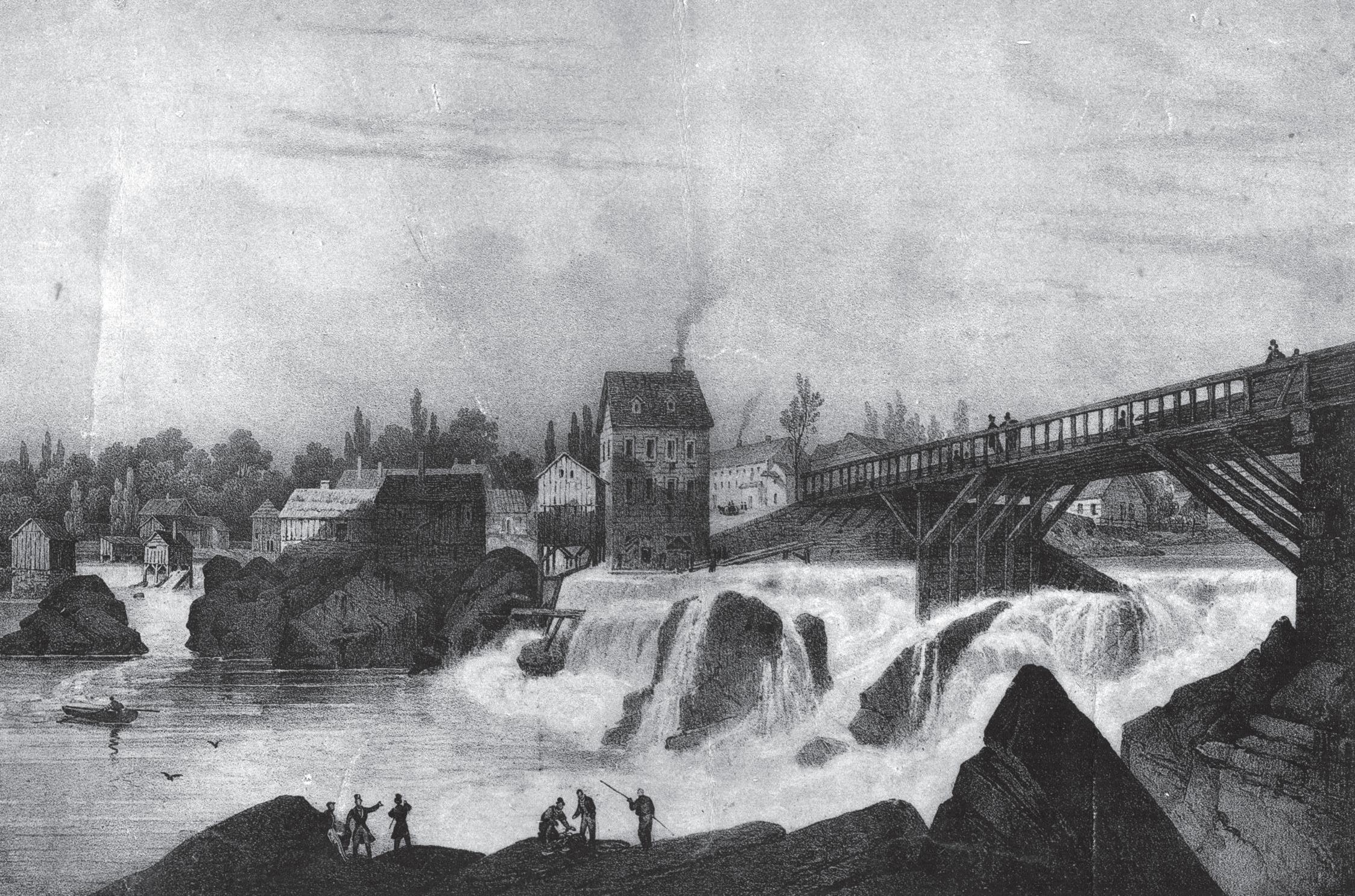

Print representing Pawtucket falls in 1815, courtesy of the Old Slater Mill Association in Pawtucket, RI. The artist is Jacques-Gerard Milbert.

notes

1. Robert Grieve, An illustrated history of Pawtucket, Central Falls, and vicinity: a narrative of the growth and evolution of the community (Pawtucket, RI: Pawtucket Gazette and Chronicle, 1897), PDF, https://www.loc.gov/item/86139384/; Slater Trust Company, Pawtucket, RI Pawtucket, Past and Present; Being a Brief Account of the Beginning and Progress of Its Industries and a Résume of the Early History of the City (Pawtucket, RI: Slater Trust Company, 1917), PDF, https://www.loc.gov/item/17003765/; John Williams Haley, The Lower Blackstone River Valley; The Story of Pawtucket, Central Falls, Lincoln, and Cumberland, Rhode Island; An Historical Narrative (Pawtucket, RI: Lower Blackstone River Valley District Committee of The Rhode Island and Providence Plantations Ter-

out his career, and passed this trait onto his children as their political successes surpassed his own.

Joseph Jenks Jr. is memorialized throughout the City of Pawtucket; a street near the original settlement and a middle school currently bear his name. He is buried at the historic Mineral Spring Avenue Cemetery with his sons. Industrial entrepreneurs, such as the Wilkinsons and Samuel Slater, followed in his footsteps and built upon his industrial vision. The Jenks clan continued to play a significant role in Rhode Island’s history and has since multiplied and migrated to every corner of the United States. Today, countless family histories proudly trace their lineage back to Joseph Jenks Jr., settler of Pawtucket Falls.

Jonathan Cipriano is a social studies teacher at Slater Middle School in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. He earned his bachelor’s degree in history from Rhode Island College and is currently pursuing a Master’s in American history at Gettysburg College.

2. Margaret Ellen Newell, From Dependency to Independence: Economic Revolution in Colonial New England (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998), 57–58, e-book accessed September 3, 2024.

3. Rhode Island (Colony), Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, in New England, Printed by order of the General Assembly, John Russell Bartlett (Providence, RI: A. C. Greene et al., 1856–1863) (hereafter referred to as RI Records).

4. Newell, 51–55.

5. Ibid., 55.

6. Hartley, 93

centenary Committee Inc./E. L. Freeman Co., 1937) First Edition; Susan Marie Boucher, The History of Pawtucket (Pawtucket, RI: Pawtucket Public Library, 1986). The coordinated efforts of the mid-twentieth century produced two important works regarding Joseph Jenks and his time at Saugus: E. N. Hartley, Ironworks On the Saugus: The Lynn and Braintree Ventures of the Company of Undertakers of the Ironworks in New England (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1957); William A. Griswold, Donald W. Linebaugh, and United States National Park Service, Saugus Iron Works: The Roland W. Robbins Excavations, 1948–1953 (Washington, DC: National Park Service, US Department of the Interior, 2010) (hereafter referred to as Saugus Iron Works).

7. Ibid., 128.

8. William Bradford Browne and Meredith B. Colket, The Jenks family of England; supplement, compiled under the terms of the will of Harlan W. Jenks, deceased (1956), 4–6; Stephen P. Carlson, Joseph Jenks, Colonial Toolmaker and Inventor, ([N.p.: Eastern National Park and Monument Association, 1981), 3.

9. Charles Edward Banks and Angevine W. Gowen, History of York, Maine, Successively Known as Bristol (1632), Agamenticus (1641), Gorgeana (1642), and York (1652), (Baltimore: Regional Publishing Company, 1967), 142.

10. Browne and Colket, 6–8; Carlson 3–6; Saugus Iron Works,

174–176. Browne and Colket argue Jenks Jr.’s migration after his grandfather’s death as well as David Benedict, Elizabeth J. Johnson, and James Lucas Wheaton, History of Pawtucket Rhode Island: Reminiscences & New Series of Reverend David Benedict: Origins of Pawtucket, East Side (Pawtucket, RI: Spaulding House Publications, 1986). Benedict was the nineteenth-century minister and local Pawtucket historian who communicated with descendents of the Jenks family.

11. Hartley, 171–184.

12. Saugus Iron Works, 178.

13. Massachusetts, Nathaniel Bradstreet Shurtleff, and Massachusetts General Court, Records of the Governor and Company of the Massachusetts Bay in New England: Printed by Order of the Legislature (Boston: W. White, 1853), V3: 65, (hereafter referred to as Massachusetts Records).

14. Carlson, 9; Hartley 127–128.

15. Saugus Iron Works, 180; Richard Candee, “Merchant and Millwright, the Water Powered Mills of the Piscataqua,” Old Time New England, 60, no. 220 (Spring 1970): 138.

16. Carlson, 10.

17. Saugus Iron Works, 182

18. Boston Records Commissioners, Second Report of the Records

Commissioners: Boston Town Records (Boston, 1877), 118; Massachusetts Records, V3: 386, V4 Pt. 1: 233–4; Ibid., V4 Pt. 2: 528 quoted in Carlson, 13–15.

19. We do not know the status of Thomas and Anthony. What obfuscates their status is that following the Pequot War of 1636–7, many Pequots were subjected to servitude throughout New England, by both Indigenous nations and English colonists: Margaret Ellen Newell, Brethren by Nature: New England Indians, Colonists, and the Origins of American Slavery (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015). At the same time, if they were not subject to servitude, ministers in New England such as John Eliot sought to impose Christianity on Native villages and to coerce them into assimilation while Native peoples continued to adapt: James Axtell, The Invasion Within: The Contest of Cultures in Colonial North America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985); Neal Salisbury, “Red Puritans: The ‘Praying Indians’ of Massachusetts Bay and John Eliot,” The William and Mary Quarterly 31, no. 1 (1974): 27–54; Jacqueline M. Henkel, “Represented Authenticity: Native Voices in Seventeenth-Century Conversion Narratives,” The New England Quarterly 87, no. 1 (2014): 5–45.

20. Hartley, “Chapter 10.”

21. “Family of William Ballard of Lynn with wife Elizabeth,” in The Great Migration: Immigrants to New England, 1634–1635 (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society) V1: 148. PNG accessed on July 25, 2024.

22. Massachusetts Records, V3, 243.

23. Alonzo Lewis and James Robinson Newhall, History of Lynn, Essex County, Massachusetts: including Lynnfield, Saugus, Swampscot, and Nahant (Boston: J. L. Shorey, 1865), V1: 233.

24. Massachusetts Land Records, 1620–1986, Essex, Deeds 1639–1658, Vol.1: 54–55; Essex County Court Records, 1648–1655, image 494, accessed August 20, 2024; Carlson 11–12 also references the court proceedings as “vague”; it is clear that Jenks received damages upwards of seven pounds, but as to why is unknown.

25. Massachusetts Records, V4, pt.1: 311

26. Hartley, 278; “Deed from Joseph Jenks to Nathaniel Paine,”

Massachusetts Land Records, 1620–1986, Middlesex Deeds V4, 487–490, accessed August 24, 2024.

27. Hartley, 153; Benno M. Forman, “Mill Sawing in Seventeenth Century Massachusetts,” Old Time New England 60, no. 220 (1970): 116, PDF, accessed August 24, 2024.

28. Paul R. Lucas, “Colony or Commonwealth: Massachusetts Bay, 1661–1666,” The William and Mary Quarterly 24, no. 1 (1967): 88–107. For a broader discussion on the geopolitical situation in an Atlantic context: Jenny Hale Pulsipher, Subjects unto the Same King: Indians, English, and the Contest for Authority in Colonial New England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005).

29. Massachusetts State Archives Collection, colonial period, 1622–1788, V102 “Political 1638–1700,” 28a–34a, images 458–469, accessed August 25, 2024.

30. Middlesex County Court Records, Card index to court papers, Gr-Mem 1636–1785 images 2961–2965, accessed June 22, 2024; Middlesex County Court Records, Court papers - Folios 27–60 1647–1672, Folio 40 Group 3 Image 580, accessed June 22, 2024.

31. Grieve, 34.

32. For a general analysis of Puritan society in practice: Francis J. Bremer, The Puritan Experiment: New England Society from Bradford to Edwards (Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England, 1995). Hartley also discusses the social life of the workers and their families at Hammersmith and their inflated number of court appearances in great detail: Hartley, 202–207.

33. There is much debate over freeman status in seventeenth-century Massachusetts, but it is undoubtedly clear that legally, the Bay Colony required a religious component: Robert Emmet Wall, “The Decline of the Massachusetts Franchise: 1647–1666,” The Journal of American History 59, no. 2 (1972): 303–10; B. Katherine Brown, “The Controversy over the Franchise in Puritan Massachusetts, 1954 to 1974,” The William and Mary Quarterly 33, no. 2 (1976): 212–41. For Rhode Island, the Rhode Island Secretary of State’s website created an annotated version of the Royal Charter for educational purposes, and it is just as useful for anyone to quickly and efficiently read and analyze the document in its

entirety: “Rhode Island Royal Charter, 1663,” Rhode Island Secretary of State, accessed August 23, 2024. To understand freeman status in Rhode Island: Patrick T. Conley, Democracy in Decline: Rhode Island’s Constitutional Development 1776–1841 (East Providence, RI: Rhode Island Publications Society, 1977, reprinted 2019), 46–48; Patrick T. Conley, “A History of Election Tickets in Rhode Island,” Small State Big History (website), February 23, 2024, https://smallstatebighistory.com/a-history-of-election -tickets-in-rhode-island/

34. Grieve, 37.

35. Carl Bridenbaugh, Fat Mutton and Liberty of Conscience: Society in Rhode Island, 1636–1690 (Providence, RI: Brown University Press, 1974) 79.

36. Providence. Record Commissioners, Daniel F. Hayden, William G. Brennen, and William C Pelkey, The Early Records of the Town of Providence, V. I-XXI ... Printed under authority of the City council, edited by Horatio Rogers, George Moulton Carpenter, Edward Field, and William E. Clarke, (Providence, RI: Snow & Farnham, city printers, 1892–1912), V4: 6–7, accessed August 22, 2024 (hereafter Providence Records).

37. “Deed from Joseph Jenks to Nathaniel Paine,” Massachusetts Land Records, 1620–1986, Middlesex Deeds Vol. 4, p 487–490, accessed August 24, 2024.

38. Providence Records, V3: 285.

39. “Pawtucket Falls” National Park Service, accessed August 22, 2024. Many scholars continue to use the larger distinction of Wampanoag confederation to relate information on Southern New England Indigenous peoples, but the Pokanoket are the tribal nation that resided in the region of this study; for more, see: Students of Roger Williams University, Pokanoket: The First People of the East Bay (Bristol, Rhode Island), PDF booklet, http://www .drweed.net/PokanoketBooklet.pdf. Scholarship on how colonial English and Native cultures changed by interacting with the environment includes William Cronon, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England, 1st rev. ed., 20th Anniversary ed. (New York: Hill and Wang, 2003); Neal Salisbury, Manitou and Providence: Indians, Europeans, and the Making of New England, 1500–1643 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982).

40. Roger Williams, “Memorandum of original deed for Providence, December 10, 1666,” Rhode Island Secretary of State Catalog, accessed August 23, 2024. Throughout the past few decades, recent scholarship has brought new perspectives of the “Providence Purchase” that question and help reorient understandings of how the lands of Providence, and all of Rhode Island, were obtained throughout the first decades of colonization: Anne Keary, “Retelling the History of the Settlement of Providence: Speech, Writing, and Cultural Interaction on Narragansett Bay,” The New England Quarterly 69, no. 2 (1996): 250–86; Jeffrey Glover, “Wunnaumwáyean: Roger Williams, English Credibility, and the Colonial Land Market,” Early American Literature 41, no. 3 (2006): 429–53.

41. Without archaeological evidence, it is tough to recreate the operation that Jenks had built when he first arrived: Robert B Gordon, American Iron, 1607–1900 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996) 7–10, 14; he describes it as most likely a bloomery operation 65–66. There is a deposition from an 1812 federal court case of Benjamin Jenks that recounts the forge probably a century after its original construction: “Seargent’s Trench: Deposition of Benjamin Jenks,” The Flyer, Old Slater Mill Association, Vol III, no. 5 (May 1972): 11.

42. Grieve, 38, infers that he was able to operate a successful business “with work-men trained in his father’s shops at Lynn.” Grieve was unaware of Jenks’s residence in Concord, but it does not deter from the fact that Jenks and his firstborn would not have been able to build and operate a sawmill and forge by themselves.

43. Grieve, 41.

44. Mark Mello, Slater Mill Historic Site Park Ranger, email message to the author, January 21, 2024.

45. Grieve; John Osborne Austin and George Andrews Moriarty, The Genealogical Dictionary of Rhode Island; Comprising Three Generations of Settlers Who Came before 1690, with Many Families Carried to the Fourth Generation (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1887), and David Benedict mention this. Unfortunately, there is no documentary evidence confirming Jenks was able to erect a forge and sawmill prior to the war; this history seems to have been passed down orally through generations and reiterated through Benedict but cannot be confirmed.

46. After the Puritan-led forces mounted a horrific attack upon the neutral Narragansett in December, the Narragansett confederation entered the war on the side of Metacom. They were led by the fierce sachem Canonchet, who during the spring of 1676 initiated an offensive through the Blackstone River Valley. Jenks’s forge, sawmill, and all the houses in the vicinity were destroyed. Jenks likely joined his fellow Providence residents and fled to Aquidneck Island to wait out the war. Recent scholarship of King Philip’s War is fascinating and helps to reorient our understandings of the conflict: Lisa Tanya Brooks, Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip’s War, Henry Roe Cloud Series on American Indians and Modernity (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018); Christine M. DeLucia, Memory Lands: King Philip’s War and the Place of Violence in the Northeast, Henry Roe Cloud Series on American Indians and Modernity (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018); Daniel R. Mandell, King Philip’s War: Colonial Expansion, Native Resistance, and the End of Indian Sovereignty (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010).

47. Providence Records, V15: 189.

48. Ibid., V8: 25, 28.

49. Ibid., V8: 55, 107, 152.

50. Ibid., V17: 14, 119.

51. Brindenbaugh, Fat Mutton 79–80.

52. Providence Records, V17: 119.