Democracy, equity and selfdetermination in U.S. Territories

Adi Martínez Román and Neil Weare Co-Founders and Co-Directors, Right to Democracy

Adi Martínez Román and Neil Weare Co-Founders and Co-Directors, Right to Democracy

Over the last year, we have worked together with people in each of the five territories, the diaspora, and other partners to begin building a movement for democracy, equity, and self-determination in U.S. territories. This report is the compilation of that work to date - from deep listening sessions in each territory, to a Summit on U.S. Colonialism at the Ford Foundation in New York, to the creation of a growing coalition to confront U.S. colonialism.

We are greatly indebted to the participants of these activities for trusting us and opening themselves to talk together about things that are often so difficult and hurtful for us to discuss. Truly seeing and listening to each other, and to create a framework of shared values and solidarity despite our different colonial experiences can only happen amongst brave people. And all of our participants have truly been brave.

The energy, emotion, and solidarity we have felt over the last year makes us optimistic that together we can co-create a new reality that challenges more than 125 years of colonialism and undemocratic rule in U.S. territories. We are stronger united than we are divided. The work continues. The future is decolonial.

Thank you. Gracias.

Si Yu’us Ma’åse’. Ghilisow.

Fa’afetai tele lava.

For more than 125 years, the United States has cloaked its colonial reality, denying democracy, equity, and self-determination to people living in its island territories. While Puerto Rico, Guam, U.S. Virgin Islands, Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa are governed by the federal government, their inhabitants are denied political rights, self-government, and self-determination. This system has been labeled as “American colonialism” by Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch. The colonial relationship between the United States and its Territories is a direct contradiction of U.S. democratic values, constitutional principles, and international human rights commitments.

The cost of this colonial relationship is high, impacting 3.6 million people in U.S. territories - 98% of whom are people of color. These consequences include:

• Population decrease of 11.6% in the last decade

• Low-income individuals denied billions in federal benefits

• Delayed disaster recovery assistance

Confront and dismantle the undemocratic colonial framework that impacts millions of people in U.S. territories.

• Undemocratic rule by an unelected oversight board in Puerto Rico

• Community/environmental concerns over militarization in the Pacific

• Veterans, elderly, and disabled denied equal access to medical care

Right to Democracy is born out of the need to build a movement for democracy, equity, and selfdetermination across U.S. Territories. Led by two visionary founders from the territories, Adi MartínezRomán and Neil Weare, the organization works to empower local communities and challenge the undemocratic colonial status quo. The organization does not take a position on status and collaborates with people of diverse status perspectives.

Our focus is to convene a diverse coalition of partners from the territories and diaspora, as well as from civil rights, social justice, and philanthropic sectors. In doing so, we aim to build a strategic, well-resourced ecosystem that will enable future advocacy efforts to succeed where past ones have failed.

People in U.S. territories should have power and agency over the decisions that impact their lives - there should be no colonies in the United States.

Created by Fajar Studio from the Noun Project Created by Fajar Studio from the Noun Projectby working collectively with people from diverse perspectives to improve understanding, co-create new meanings, and leverage collective power to achieve a common objective.

by listening with an open mind, empathizing with lived experiences, acknowledging power dynamics, and treating everyone with dignity.

through strategies that demand increased engagement, action, and accountability.

BRING ABOUT A RECKONING to address over 125 years of colonialism and undemocratic governance in U.S. territories.

OVERRULE THE INSULAR CASES and dismantle the racist colonial framework they established in order to advance self-determination and equality.

by leveraging our collective knowledge and experiences to address system-level challenges. by focusing on working together in good faith, shifting away from zero-sum politics, and centering on our shared goals experiences to address system-level challenges.

BUILD A UNIFIED COALITION across all five U.S. territories by bridging political and status-related differences to find common ground.

ENSURE THE UNITED STATES COMMITMENTS to democratic principles and international law are achieved in U.S. territories by making decolonization a mainstream issue that demands action.

CENTER DIVERSITY AS A STRENGTH in everything we do by co-creating meaning together.

Co-create advocacy strategies to engage the Supreme Court, Congress, and the Executive Branch

Confront the insidious normalization of colonialism in the United States

Build a strategic, well-sourced movement focused on achieving systemic change

U.S. Navy rule

Jones Act/ U.S Citizenship

Puerto Rico is an archipelago in the Caribbean located on the far eastern edge of the Greater Antilles, approximately 1,000 miles southeast of Florida. Prior to Spanish colonization, Puerto Rico was inhabited by the indigenous Taíno (subgroup of the Arawak) people. The Spanish colonial governance of Puerto Rico lasted from the 1500s until 1898.

The United States annexed Puerto Rico following the 1898 Spanish-American-Cuban War. This brought an end to the limited autonomy and political rights extended by Spain in 1897. After initial military rule, the U.S. Congress began extending a limited degree of self-government in Puerto Rico through the 1900 Foraker Act and 1917 Jones Act, which also recognized U.S. citizenship for the first time. Puerto Rico did not have an elected Governor until 1949. Congress approved Puerto

POPULATION

3,285,874, a 11.8% decrease since 2010

Spanish, English

LAND AREA

3,420 sq. miles, larger than Delaware or Rhode Island

DEMOGRAPHICS

Hispanic or Latino: 99%, Non-Hispanic White: .6%,

Other: .4%

43.4%, nearly 4x national average

$24,002, about one-third the national average

Rico’s Constitution in 1952, a process defined through P.L. 600 in1950. Throughout Puerto Rico’s history with the United States, local nationalist and pro-independence action and views have faced suppression, sometimes with high levels of violence and persecution.

In 2016, soon after the Supreme Court recognized that the “Commonwealth” created by the 1952 Constitution did not afford Puerto Rico any degree of sovereignty, Congress imposed an unelected seven-person Financial Oversight and Management Board that has broad powers to reject, nullify, or displace laws and regulations enacted by Puerto Rico’s elected officials. Congress has repeatedly failed to act in response to calls from Puerto Rico for self-determination and decolonization. Today, Puerto Rico is the only state or territory of the U.S. with a Hispanic majority.

87,146, an 18.1% decrease since 2010.

The U.S. Virgin Islands is an archipelago located in the Caribbean to the east of Puerto Rico on the far northwestern edge of the Lesser Antilles. Its main islands are St. Croix, St. John (two-thirds of which is now a National Park), and St. Thomas. Prior to European colonization, the Virgin Islands were inhabited by the indigenous Ciboney, Taino (sub-groups of the Arawak), and Carib people. The Danish colonization of the islands was characterized by the transatlantic slave trade and limited self-government, spanning around 300 years from the late 1600s. There were important rebellions by these enslaved people, including the 1733 Akwamu insurrection in St. John, and the 1848 rebellion in St. Croix, which resulted in a declaration of emancipation.

LAND AREA

133 sq. miles, about two times DC; 60% of St. John owned by National Park Service.

$40,408, about 60% of the national average

In 1917, the United States purchased the archipelago from the Danish for $25 million after prior failed attempts in 1902 and 1867. The U.S. Navy ruled the islands until 1931, with civilian government expanded through Organic Acts passed by Congress in 1936 and 1954. The Virgin Islands did not have an elected governor until 1970, nor a non-voting delegate to Congress until 1973, both after congressional amendments of the Organic Act. In 2010, Congress rejected a Constitution that had been approved by the Virgin Islands Fifth Constitutional Convention. The U.S. Virgin Islands is the only state or territory with a Black majority.

153,836, a 3.5% decrease since 2010

English and CHamoru 20.2%, nearly double national average

U.S. Navy rule

Guam is the largest and southernmost island in the Mariana archipelago, located nearly 4,000 miles west of Hawaii in the North Pacific. Mariana’s indigenous CHamoru people arrived approximately 3,500 years ago. Spanish colonial rule lasted from 1668 to 1898, when Guam was annexed by the United States following the 1898 Spanish-American War, and separated politically from the rest of the Mariana Islands.

In 1901, CHamoru leaders petitioned Congress for citizenship and self-government. These calls were rejected, with Navy rule lasting from 1899 to 1949, and citizenship only being recognized by the 1950 Organic Act. Among other unilateral actions, the Navy prohibited the speaking of the CHamoru language in schools and other government facilities. During World War II, Guam endured a

210 sq. Miles, about 3 times D.C.; 29% of land owned by U.S. military.

ÉriclesDEMOGRAPHICS

CHamoru: 41%; Filipino: 35.3%; Other Asian and Pacific Islander: 21%; White: 6.8%

MEDIAN HOUSEHOLD INCOME

$58,289, about 85% of the national average

First Elected Governor

First Non-Voting Delegate to Congress

brutal military invasion and occupation by the Japanese characterized by widespread killings, death, forced labor, and other atrocities.

After the war, the U.S. military seized more than half of the island, with nearly a third remaining under military control today. Guam did not have an elected governor until 1971, nor a non-voting Delegate to Congress until 1973. In the 1980s, Guam voters voted in favor of “Commonwealth” status in order to increase local autonomy and selfgovernance, but Congress failed to act. In 2019, federal courts invalidated a proposed political status plebiscite because it limited the exercise of self-determination to “Native Inhabitants of Guam.” Guam is still listed as a Non-Self-Governing-Territory by the United Nations.

47,329, a 12.2% decrease since 2010

LAND AREA

183 sq. miles, about 2.5 times D.C.

Trust Territory of the Pacific Administered by U.S.

Covenant with U.S. Signed

The Northern Mariana Islands (NMI) comprises the rest of the Mariana archipelago, consisting of fourteen main islands spanning about 375 miles. Most of the population lives in Saipan, Tinian, and Rota, which are the three southernmost islands. The indigenous Chamorro people arrived approximately 3,500 years ago, with Carolinian migration occurring during the 19th and 20th centuries. During much of the Spanish colonization of the Marianas, Chamorros in the Northern Mariana Islands were often forcibly relocated to Guam. In 1898, after ceding Guam to the U.S., Spain sold the NMI to Germany, perpetuating their political division. During World War I, Japan invaded the islands, ruling over them until the United States invaded in 1944.

Following World War II, the United States administered the islands as part of the United Nationscreated Trust Territory of the Pacific. During the 1970s, the people of the Northern Marianas Islands

POVERTY RATE

English, Chamorro, Carolinian 38%, more than 3x national average OFFICIAL LANGUAGES

U.S. HISTORY

Covenant in Full Effect

Chamorro 36.3%, Carolinian 4.8%, Filipino: 37.4%, Other Asian or Pacific Islander: 20%; White: 2.1%

MEDIAN HOUSEHOLD INCOME

$31,363, less than half the national average

First Non-Voting Delegate to Congress

negotiated a permanent relationship with the United States through a “Covenant” that established the Commonwealth of the Northern Marianas Islands in 1978. The NMI came under formal U.S. sovereignty in 1986, with immediate U.S. citizenship. The Covenant requires that certain limited aspects of the relationship between the U.S. and the NMI can only be changed by “mutual consent,” and also restricts the ownership of land to people of NMI descent.

The NMI had the power to set its own immigration rules until 2009, when Congress unilaterally shifted control over immigration to federal authorities. Congress has also unilaterally imposed minimum wage laws and made other changes that have significantly impacted the NMI’s economy. The U.S. military controls two-thirds of Tinian and uses the northernmost island of the NMI for military bombing exercises, with further military expansion planned. The NMI did not have a non-voting Delegate to Congress until 2009.

LAND AREA

49,710, a 10.5% decrease since 2010 DEMOGRAPHICS

76 sq. miles, slightly larger than DC

Samoan: 89.4%; Asian and other Pacific Islander: 11.4%; White: .8%

$28,352, about 40% of the national average

American Samoa comprises the eastern islands of the Samoan archipelago, located about 2,500 miles southwest of Hawaii in the South Pacific. Its main islands are Tutuila, Aunu’u, the Manu’a islands, Rose Atoll, and Swains Island. The indigenous Samoan people have inhabited the islands for 3,000 years.

The United States acquired American Samoa through Deeds of Cession with the islands’ traditional leaders in 1900 and 1904. Navy rule lasted from 1900-1951. While American Samoans initially understood they were U.S. citizens following the transfer of sovereignty to the United States, in the 1920s the Navy informed them that they were considered “non-citizen U.S. nationals.” This contributed to the 1920s Mau protest movement, which sought citizenship and self-government. Congress failed to act on citizenship, and it took until 1951 to transition to civilian government under the Interior Department.

In 1960, Interior approved an American Samoan Constitution, along with a revised Constitution in 1967 that incorporates protections for communal land and the matai system that are a core part of the Fa’a Samoa, or Samoan way of life. American Samoa did not have an elected governor until 1978, nor a non-voting Delegate until 1981. American Samoa remains subjected to the nearly unlimited power of the Department of Interior and is recognized as a Non-Self-Governing-Territory by the United Nations. It is the only state or territory that is majority Pacific Islander.

AMOUNT PEOPLE IN U.S. TERRITORIES PAY IN FEDERAL TAXES

65 THOUSAND VETERANS WITH SERVICE CONNECTED DISABILITIES 25 THOUSAND *WORKING TO BE RE-LISTED. UN-RECOGNIZED NON-SELFGOVERNING TERRITORIES UNDER U.S. JURISDICTION, NOT INCLUDING PUERTO RICO*

There is no basis for the present colonial governance of the territories in the U.S. Constitution or international law. Instead, its foundation lay in a series of overtly racist Supreme Court decisions known as the Insular Cases. These cases broke from prior Supreme Court precedent to deny the full application of the Constitution and justify colonial rule over the people of Puerto Rico, Guam, and other so-called “unincorporated” territories.

In the Insular Cases, the United States Solicitor General justified the denial of equality and selfdetermination because in his view the people of these new island territories were “savage and half-civilized … people,” calling their lands – and by extension their people – “not … parts but possessions” of the United States. These distinctions were necessary, in the Justice Department’s view, to preserve “Anglo-Saxon liberty as enforced and illustrated by the Anglo-Saxon race.”

The Supreme Court adopted this racist language and explicit white supremacy, with the Justices calling residents of the island territories “alien races” and “savage tribes,” cautioning that they were “absolutely unfit” to receive the same rights enjoyed by people in Anglo-Saxon majority states or so-called “incorporated” territories. The Justices did not even entertain the idea that the residents of the newly acquired territories should have any say over their future relationship with the United States or that there should be limits on the power of Congress to rule them.

More recently, Supreme Court Justices from across the ideological spectrum have condemned the Insular Cases. Justice Neil Gorsuch declared that they “deserve no place in our law” because they “have no foundation in the Constitution and rest instead on racial stereotypes.” Justice Sonia Sotomayor agreed, recognizing the Insular Cases were “premised on beliefs both odious and wrong.” Yet the Supreme Court has failed to overrule them, in part because the Department of Justice continues to actively rely upon and defend them. All of this reflects perhaps the most insidious aspect of the Insular Cases - the creation of a culture of acceptance and normalization of an undemocratic colonial framework grounded in overt racism.

This anti-democratic relationship presents a threat not just to the people living in U.S. territories, but to the United States as a whole. Colonialism contradicts the core democratic and constitutional values that define the United States, as well as basic notions of human rights. The idea that whole communities within the United States can be singled out and denied their political rights based solely on who they are or where they live is dangerous to all.

None of this would be tolerated for any other community in the United States or country in the world. It should not be considered acceptable for people living in U.S. territories.

SCAN OR CLICK THE QR CODE FOR OUR FULL REPORT ON EACH OF THE FIVE TERRITORIES:

Following the launch of Right to Democracy in April 2023, our immediate focus was to conduct a Listening Tour that consisted of a series of intensive, in-person community dialogues throughout all five U.S. territories. From June through October 2023, Right to Democracy convened 17 community dialogues, with over 200 participants across all five U.S. territories.

•

•

•

• Representatives of youth organizations

• Community leaders (Eastern, including Vieques and Culebra)

• Community leaders (Western)

• Health and Eldercare Professionals

• Experts, leaders, and activists focused on environmental issues, disaster recovery, and climate change

• Labor union leaders

Right to Democracy developed a methodology for these community dialogues in partnership with El Enjambre, a Puerto Rico-based organization that uses popular education techniques to structure dialogues and co-creative gatherings. The goal of the community dialogues was to create safe spaces where participants from diverse backgrounds and status perspectives - ranging from pro-statehood to pro-independence - could have open and honest conversations about how they understood their

relationship with the United States and the impacts living in a so-called “unincorporated” U.S. territory had on their lives. The sessions explored what participants understood colonialism, citizenship, and decolonization to mean, and invited participants to share their ideas on how to transform such realities through democratic, inclusive, and unifying processes. Furthermore, the dialogue sessions helped identify policies, ideas, and strategies to build collective power.

Despite significant differences in the history, experience, and status perspectives of participants – both across and within territories – the community dialogues identified broad areas of common ground in how participants thought about concepts like democracy, colony, citizenship, how they understood their relationship with the United States, and what a path forward for decolonization should look like.

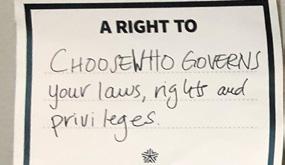

All the sessions in the different territories stressed the notions of rights, participation, speech, and freedom. Participation in the decision-making processes was a main issue stressed across the board. Having a voice and being able to speak up was repeated in all groups as fundamental importance in any democracy, or as part of the right to democracy.

The term colony produced similarly strong reactions, with all participants relating it to the unequal power relations between the U.S. and the territories. Dependency, lack of decisional power, subjugation, extraction and domination were the main characteristics mentioned by all the participating groups. Also, in all the dialogues participants related the colony to feelings of inferiority and manipulation .

Citizenship is related to having rights and being acknowledged as a full member of a social body or community, of a country or specific society. At the same time, all groups acknowledged in some way or another how the idea of citizenship can also exclude those that are not considered, or allowed, to be citizens. Most participants focused on U.S. citizenship and not on citizenship as an abstract term. Most of them also agreed on using the term “second-class citizenship” when referring to their experience of citizenship in the territories.

The following terms were the most used among the participants: abusive, based on dependency (especially on federal funds, economic dependency), fosters displacement, toxic. In all territories diverse metaphors were offered to illustrate it as an unequal and unbalanced relationship.

There is also discrimination in the way laws and policies are applied in the different territories. Participants from each territory expressed concern about climate justice, the lack of food sovereignty, and the importance of protecting the local culture and identity.

The high cost of living, food prices, and other goods (low quality and high costs), lack of affordable housing, lack of job opportunities, and lack of health services in general, and mental health services in particular, were also common denominators.

There is a common concern among all the territories about displacement and the out-

migration of the local population. This has produced family separation and diasporic societies from all the island-territories. Militarization and in-migration of new populations has also led to changes in the community that are not always welcome or desirable. In the Pacific territories, security and environmental issues tied to militarization and the possible conflict with Asian countries were amongst the most important challenges mentioned by participants.

When asked about positive aspects of the relationship with the United States, the results focused mainly on freedom to travel, especially to the United States where many family members live, and on access to federal funds. While federal funds were acknowledged as a “positive” aspect when considering the needs of the population, some also viewed them as a source of dependency, signaling to participants the need for systemic and sustainable solutions.

EDUCATION in its different forms, expressions, and modalities was emphasized as the main element of a decolonization process. This education, however, must be a popular, critical, and ‘decolonial’ one. It should use the language of the people, be unbiased, and explain in clear terms the different possible decolonized futures. These educational strategies should be present both inside and outside schools and educational institutions. The creation of courses and curricula that focuses on the topic of colonialism and decolonization; the development of educational material, from articles and books to art, songs, documentaries and movies, and the use of media (radio, television, Internet, podcasts), were suggested in the different dialogues. The education process must include a clear and comprehensive discussion of all the core concepts necessary in the decolonization process (citizenship, colony, democracy, Insular Cases, among others).

to inform, mobilize, and promote a decolonization movement and initiatives was repeated across the groups. This was viewed as particularly important for engaging young people.

. People should be able to speak for themselves with freedom, without being judged. The whole process of decolonization, from organizing meetings, assemblies, marches, to written documents and formal meetings with political figures must include meaningful representation of the people. According to all the groups, the process must be transparent, inclusive, clear and trustworthy, with participation from the grassroots to other levels of civil society.

Find or create a common ground among all the island territories that allows the formation of a coherent unity, a “power bloc,” a “coalition” that works together for a common purpose. While each territory is different from each other, there are commonalities that should be emphasized in order to build a unity of purpose and solidarity among all. Social media, virtual meetings, developing common documents and activities, and visits among participants from all the territories were emphasized across the sessions.

Each of the groups recognized the importance of engaging people from the territories living stateside, both because that population now exceeded the population still

living in the territory and because that population had political power and representation in the communities they lived that could help elevate issues faced in the territories.

. All the groups pointed to the importance of identity as a necessary aspect for decolonization. The importance of recuperating and protecting local knowledge and languages, especially in the Pacific islands (NMI, American Samoa, and Guam) but also mentioned in the U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico. This cultural aspect is tied to, and also includes, the protection of the land as expressed in land rights, areas considered “sacred grounds,” and traditional practices (like artisanal fishing, among others) that are impacted because of federal regulations related to the U.S.

military or are in danger because of real estate or tourist “development” and expansion.

Participants emphasized ecological consciousness in most sessions. Participants recognized the out-sized impact of climate change to all the island territories through more frequent and higher intensity hurricanes/typhoons/ cyclones, as well as sea-level rise, droughts and high temperatures. Supporting local and native solutions and initiatives for mitigation and adaptation was mentioned by participants as imperative for sustainability and resiliency of territorial ecosystems.

Participants recognized the importance of creating more opportunities and mechanisms to connect

the younger and older generations together. In the case of Puerto Rico this was viewed as critical given its large population of older residents, which also impacts some other territories like the NMI. Older generations have much experience and knowledge to share. But the energy, openness to change, and new ideas from the youth must be listened to, valued, and included throughout the whole process.

, like the most recent popular protests against Governor Ricardo Roselló in Puerto Rico, and the civil disobedience practiced against the military bombings in Vieques, were mentioned as examples of “¡no más!” or “¡basta ya!” (¨enough¨) moments that are important for the decolonization process. This was not only shared in the Puerto Rican sessions but also in the Guam, NMI and Virgin Island ones.

This Listening Tour has served to confirm, complement, and complete our ideas on the values sustaining our work and the way to structure our strategies. We were able to confirm that while each U.S. territory has unique people and histories, many of the perceptions about U.S. colonialism are strikingly similar. In spite of the differences between territories, there are broad areas of common ground.

defense of indigenous rights, language, cultural traditions, local knowledge and practices. We see how our work will necessarily be connected to a wider process of collective healing that will take time, but that needs to move with urgency.

A consistent theme was describing territories’ relationship with the United States as “toxic” and “abusive,” “extractive” and “second-class” treatment. The effects of this relationship were also identified by participants, such as dependency, feelings of inferiority, insecurity and lack of self-worth. This has led to a stronger understanding of the need to support strategies that give a strong emphasis on identity, the

The role of the U.S. military was also an important and consistent theme. Even though some territories have more military presence than others, high levels of military recruiting is ubiquitous. There is a general sense of questioning: What would a demilitarized society look like? What would the economic, political, social, and ecological effects be in each of the territories? We can keep exploring these kinds of questions in our cross-territorial dialogues and other initiatives, which offer high potential for learning and advocacy opportunities.

In spite of the differences between territories, there are broad areas of common ground.

Concern over corruption in local territorial governments is another common theme, which is often viewed as a consequence or symptom of the colonial relationship. This sustains a fundamental aspect of our theory of change: that the practice of colonialism is inherently dehumanizing and creates divisions among people in the territories, fostering toxic interactions that must be overcome. This insidiousness also impacts the government that is forced to operate within a colonial framework. This is also seen in how certain segments of society who perceive themselves to benefit from aspects of the colonial relationship can also become defenders of the undemocratic status quo.

The harms of the colonial relationship lead many to leave their respective islands. Most often this is in search of better jobs and opportunities

stateside. But it is also to access services and benefits denied to them if they stay home. The failure of the undemocratic colonial relationship is evident by the 11.6% loss of population in U.S. territories over the last decade. There is a strong sense about how the people of each territory have become diasporic societies, with more of the native population now having to live “outside” their homeland. “Displacement” was a term used to encompass the break up of families and support networks in the territories, impeding development of the social and economic capital needed to build sustainable communities. It was also characterized by a sense of community loss, pain, and longing for return, as well as a failure to take into account the local communities’ needs.

It was commonly held in all territories that any decolonizing effort needs to be based on the

experiences and aspirations in the territories, and that a movement will need to look to the territorial colonial experience as reference for action. We will always emphasize that any of our efforts will be based on approaches that take seriously people’s languages, cultures, knowledge, and ways of being. This requires resources to build greater grassroots engagement and organizing in each territory, as well as communications through social media platforms, podcasts, and other forms of artistic expression. Building an educational curriculum that allows for knowledge transfer and solidarity building across territories is also critical.

One of the most notable things we realized was how often it would be impossible to guess from the statements being made which territory they came from or which age group. The commonalities between territories and between different demographics were that powerful. The colonial experiences from the Caribbean to the Pacific reflect important common denominators which can bring opportunities for intergenerational healing and avenues of collective action. We have seen that building common ground is not only possible, but a necessary starting point in order to build a movement for democracy, equity and selfdetermination. We are determined to do just that.

One of the most notable things we realized was how often it would be impossible to guess from the statements being made which territory they came from or which age group.

Right to Democracy has also hosted a series of powerful cross-territorial conversations that highlight both areas of common ground and differences between each territory. They have also established important professional and personal connections between people who are focused on similar issues in each territory, creating opportunities for learning and solidarity.

Art Competition Panelists - RtD hosted an Art Competition titled “Express Yourself Contest: What does Democracy Mean To You?”, inviting young people in the territories to present their views on democracy through the visual arts, words and music.

Typhoon Webinar - The first interterritorial conversation had experts from the U.S. Territories discuss challenges faced by Guam and NMI following Typhoon Mawar and how shared experiences might contribute to finding common ground and solutions.

Art Competition Panelists - RtD hosted an Art Competition titled “Express Yourself Contest: What does Democracy Mean To You?”, inviting young people in the territories to present their views on democracy through the visual arts, words and music.

Typhoon Webinar - The first interterritorial conversation had experts from the U.S. Territories discuss challenges faced by Guam and NMI following Typhoon Mawar and how shared experiences might contribute to finding common ground and solutions.

Veterans Panel -This virtual encounter gathered veterans from the U.S. Territories to discuss the challenges faced by them and their families, identifying common experiences and possible areas of collaboration.

Interterritorial Local Governance and Transparency Panel -The first in-person panel hosted by RtD aimed to discuss the challenges shared by the U.S. territories with regards to transparency in their local governments and how it ties to a colonial framework that dictates U.S. spending in the territories.

On October 25-26, 2023, Right to Democracy convened an historic, two-day Summit on U.S. Colonialism in New York City, co-hosted by the Ford Foundation, Democracy Fund, and the J.M. Kaplan Fund. The Summit was the culmination of our Listening Tour, which laid the foundation for connecting and inviting dozens of partners from the territories. From the states, we also invited diaspora, civil rights, social justice, and philanthropic partners.

The theme of the Summit was “Democracy, Equity, and SelfDetermination” – three core concepts that emerged from our Listening Tour. Recognizing that the topic of colonialism is rich and expansive, we focused in a more targeted manner on the undemocratic colonial framework that denies people a say in the decisions that impact their lives and the inequities this creates. We structured and approached the conversations through the lens of our values, which include building common ground, respecting differences, provoking change, staying focused, and avoiding toxicity.

Summit participants represented a wide range of perspectives and preferences when it comes to the issue of political status, from statehood, to independence, to other options. Rather than focus on these differences, we worked to create a safe space that would permit us to explore areas of common ground that could serve as a foundation for forward progress. Participants reflected a diverse range of backgrounds, from community activists, artists, attorneys, academics, and more. The goal was to work towards the creation of a strategic, well-resourced ecosystem so that future advocacy efforts can overcome the obstacles faced by past efforts.

Building on our approach from the Listening Tour, we structured a dynamic and highly participatory event. By engaging the active participation of all present, we were able to co-create meaning together, build understanding and trust, and create powerful emotional bonds of connection and solidarity.

Day one of the Summit was hosted by Covington & Burling LLP, one of Right to Democracy’s pro bono partners. Nearly 50 people from the territories and their diaspora participated in working sessions to build understanding, solidarity, and cocreate diverse strategies to confront the colonial

framework. The second day was hosted by the Ford Foundation, with leaders from philanthropy meeting with participants from the first day to engage funders in building a new ecosystem and movement focused on advancing democracy, equity, and selfdetermination in U.S. territories.

This CHamoru/Chamorro concept, “to make good,” centers the importance of cooperation and reciprocity to create harmony. These concepts were reflected during the Summit discussing the challenges the imbalanced relationship with the U.S. presents and community efforts to restore harmony and make things right.

Participants were divided among five tables by territory, with each group working as a team to compose a picture portraying their thoughts on the relationship of their territory with the United States. Afterward, each territory introduced its participants and explained the meaning of their picture. While

Participants next explored the prospect of working together cross-territorially and with stateside-based partners to confront the colonial framework that affects each territory. They were divided into groups that included representatives from each territory to discuss and identify commonalities around the

each group had differences and specific challenges in how the imbalanced relationship with the U.S. presents, it was notable how many similarities there were between each territory. Participants shared powerful moments of realization and empathy throughout the conversation.

challenges faced and the opportunities to advance democracy, equity, and self-determination.

Participants expressed many shared challenges. When asked to pick the most important challenge in the territories, the biggest challenge emphasized by all groups is the mindset of disempowerment

and division caused by colonial governance. The result is that along with a lack of education and awareness about the relationship with the United States, there can be culturally internalized feelings of dependency, cynicism, opportunism, and acceptance. Addressing challenges in the states, the groups emphasized that most people in the United

States do not even realize the colonial nature of the territorial relationship, leading to a lack of interest or engagement in the needs of the people of the territories. If most people in the United States do not recognize there is a problem to begin with, finding a path towards a systemic solution is difficult.

• Focus on climate justice and the environmental impacts of colonialism and militarization to build power at the local, national, and global level.

• Develop educational materials and a curriculum on U.S. territories that can be used within and across territories, as well as stateside.

• Co-create a manifesto or declaration on what democracy, equity, and selfdetermination looks like for people in the territories.

• Emphasize the arts, social media, and communications technology as a way to engage people where they are at, raise awareness, and organize action.

• Recognize the importance of Right to Democracy serving as a convener to help build, sustain, and grow a crossterritorial movement.

Participants next worked to co-create a strategy for driving change. They formed groups based on interest area, focusing on five categories: Litigation, Policy Advocacy, International Law & Indigenous Rights, Education & Media, and Organizing.

Participants identified as a main strategy to pursue litigation to overrule the racist Insular Cases, and challenge other discriminatory and inequitable treatments under federal law.

☐ Develop a cross-territorial pipeline for identifying new legal theories and cases

☐ Mobilize engagement of allies through amicus briefs

☐ Leverage relationships within and between Bar associations

☐ Connect litigation to broader decolonization efforts

☐ Use as a platform for policy advocacy and media engagement

Participants proposed the creation of a cross-territorial working group of civil society members to develop a shared policy agenda that can influence decision-making at the Federal Level.

☐ Develop a shared policy agenda through inclusive deliberation that can be advanced collectively

☐ Promote learning, sharing, and collaboration across territories and with state-side allies

☐ Develop processes and metrics to measure progress

☐ Keep independent from political parties and government officials

☐ Elevate existing networks, both within territories and the diaspora

Participants proposed co-creating a collective declaration that incorporates elements of a truth and reconciliation process.

☐ Identify specific groups and individuals who represent diverse territorial voices to provide first-hand accounts of the challenges faced

☐ Leverage international law and indigenous rights to bring about change at local and federal level

☐ Promote local and federal legislation to protect indigenous land use and cultural rights

☐ Develop a cross-territorial database and provide translation services

☐ Elevate and facilitate the participation of indigenous veterans

Participants identified as main strategies to create a territorial curriculum and establish a media syndicate.

☐ Create content library and resource database to share our diverse knowledge among territories, the diaspora, and beyond

☐ Develop a media guide on U.S. territories similar to GLAAD’s LGBTQ media guide

☐ Tap into diverse communication channels – social media, art institutions, academic, news, film

☐ Organize concerts, festivals, theatrical performances, and other in-person events to promote education/ engagement

The strategy in this group is to bring people together in solidarity, including communities and existing networks, in territorial and diaspora levels.

☐ Determine who are the stakeholders, identify champions (grassroots leadership and diaspora), ensuring indigenous allies are included

☐ Articulate bottom-up spaces to discuss organizing strategies and build trust.

☐ Develop a multilingual database of resources

☐ Focus on building connectivity in the outreach

☐ Calendarize escalated actions, establish rules of engagement and build capacity - from outreach to transportation

Among some of the special moments of the Summit were a series of impromptu cultural activities that helped break up the intense working sessions.

Participants were

Frances Sablan, Executive Director of Marianas Alliance of NGOs, leading participants in a traditional cultural dance from Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands.

Joe Maae leading participants in a traditional Samoan cultural dance.

surprised with a “parranda de plena” during the Summit dinner, sponsored by Salomé Galib.

Frances Sablan, Executive Director of Marianas Alliance of NGOs, leading participants in a traditional cultural dance from Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands.

Joe Maae leading participants in a traditional Samoan cultural dance.

surprised with a “parranda de plena” during the Summit dinner, sponsored by Salomé Galib.

Day Two of the Summit took place at the Ford Foundation in NYC. During the morning session, participants from the philanthropic sector and other allies had the opportunity to learn more about each of the five territories and engage in conversations with diverse civil society leaders working in each territory. A representative from each territory presented the pictures each group created the prior day, reflecting both the diversity and uniqueness of each territory, but also the common threads that draw them together. Throughout the day’s

In the afternoon session, participants drilled down on the role that media and philanthropy can play in driving narrative and cultural change, as well as on specific advocacy and organizing strategies. The Summit concluded with a conversation on what it will take to build an ecosystem focused on advancing democracy, equity, and self-determination.

conversations, lessons and highlights from Right to Democracy’s Listening Tour were interspersed with personal reflections from territorial leaders. Given a general lack of knowledge in philanthropy about U.S. territories, philanthropy participants shared that they learned more about the territories in one day than they had in their whole lifetime. The energy and solidarity in the room was palpable, as leaders in philanthropy intermixed with leaders from each of the five territories throughout the day.

In this conversation, participants recognized how the existing narrative of normalization of the colonial status quo has served as an obstacle to advancing democracy, equity, and self-determination in U.S. territories. They acknowledged the need for the United States to first recognize there is a colonial problem in order to achieve any meaningful systemic change.

The conversation on media and education began with reports from the Listening Tour and Day One working sessions on Education and Media. New York Times Magazine reporter Sarah Topol, author of the tour de force article “The America That Americans Forget,” also spoke on the challenges of reporting on Pacific territories while examining how the military buildup in Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands impacts communities of color who lack representation in the life-and-death decisions that impact their lives. Her article focused on Roy Gamboa, a veteran from Guam who Right to Democracy is representing in future litigation challenging the racist and undemocratic framework governing U.S. territories.

The conversation on philanthropy and narrative change centered around an important article in Inside Philanthropy by Ana Marie Argilagos, President of Hispanics in Philanthropy, Deanna James, President of the St. Croix Foundation, and Sarah Thomas Nededog, former Chair of Payu-ta and Pacific Islands Association of Non-Governmental Organizations (PIANGO) titled It’s Time for Philanthropy to Recognize and Address “American Colonialism.” Deanna James emphasized the need for a greater focus on place-based philanthropy to more holistically address the community challenges presented by a history of U.S. colonialism. Sarah Nededog highlighted the need to build greater philanthropic and nonprofit infrastructure and capacity in the Pacific, where to date philanthropy has been all but absent. There was a consensus that philanthropy needed to do more to support systemslevel change in U.S. territories, rather than just addressing crises as they arise.

Source: Foundation Directory, Population based on 2020 Census (adapted)

The conversation on advocacy and organizing began with lessons from the Listening Tour and presentations from the Day One work sessions on Litigation, Policy, International & Indigenous Rights, and Organizing. Gustavo Sánchez and Edoardo Ortiz of IZQ Strategies and Reframe, who have conducted

national and local polling on overruling the Insular Cases, the denial of parity in federal benefits in U.S. territories, and the undemocratic imposition of PROMESA in Puerto Rico, also presented on the need to build greater data, polling, and organizing infrastructure in U.S. territories.

The final conversation of the Summit was on the role philanthropy could play in supporting the growth of an ecosystem focused on promoting democracy, equity, and self-determination for people in U.S. territories. Jerry Maldonado, Vice President of Programs at Policy Link, Lourdes Rosado, President of Latino Justice, Erika Wood, Senior Program Office for Civic Engagement and Government at the Ford Foundation, and Sean Raymond, Senior Associate at Democracy Fund engaged with the participants in a conversation on what obstacles and opportunities were present in philanthropy. They also focused on what lessons could be learned from how other politically marginalized groups have successfully used movement-building to grow power

Some key insights from this conversation included:

• The need for philanthropy to better include territories within existing programmatic silos and/or create a new category for anti-colonial work.

• The necessity of a “field catalyst” like Right to Democracy to coordinate and facilitate movement building.

• The need for place-based philanthropy in U.S. territories, including the creation of a Community Foundation or other philanthropic intermediary for Pacific Territories.

They also pointed to lessons from movements to end felon disenfranchisement, advance LGBTQ rights, and elevate indigenous rights across the United States as examples of power-building that people in U.S. territories could draw from.

The Summit concluded with powerful personal testimonies that invited a call to action.

The Summit created a powerful space for connection and bonding between people that, even while living so far away from each other and in such diverse cultures, felt immense and immediate familiarity, solidarity, and love for each other. We laughed, we cried and we danced together, all the while co-creating strategies and hope for effective systemic change for our communities. Furthermore, to present our shared realities and discuss challenges with philanthropy and U.S. based organizations and allies, powerful

realizations and learnings served as seeds for the creation of a true ecosystem for democracy, equity, and self-determination in the territories. The bonds created in two days of working together are an invaluable source of strength that Right to Democracy is committed to keep nurturing and cultivating, as they are the “glue” that can sustain a movement to confront the racist and undemocratic colonial framework that affects the territories and democratic governance in the U.S. as a whole.

Leila Staffler, a former NMI Legislator from Tinian, shares the impacts of militarization on her family and community, and her life-long efforts to build upon and protect their cultural rights and identity.

To continue the work and the momentum achieved through the Listening Tour and Summit, Right to Democracy has supported the creation and development of a coalition focused on building a new crossterritorial movement.

To build solidarity amongst the people of American Samoa, the Northern Marianas Islands, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands in order to challenge the colonial framework established under the law and policy of the United States.

A non-colonial future relationship with the United States is achieved in our lifetime by the people of American Samoa, the Northern Marianas Islands, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands through a process of democratic self-determination.

▶ Build a strong foundation centered on solidarity, trust, and shared values that allows the Coalition to scale and expand its scope of impact in a sustainable manner.

▶ Grow the Coalition to include leaders and organizations from each territory and throughout the United States that reflect a broad diversity of experiences, expertise, backgrounds, and perspectives.

▶ Embrace common ground while respecting differences in order to avoid divisions that have historically held back efforts to challenge the colonial framework in U.S.

▶ Strengthen the internal capacity of Right to Democracy to support the Coalition, in particular by expanding staff in the area of communications, community directors in each territory, and ecosystem management.

▶ Secure financial resources to facilitate future in-person gatherings of coalition members from different territories.

▶ Provide financial support for Coalition member organizations, both in the territories and stateside, to be able to better integrate a system-level focus on challenging the colonial framework into their existing areas of work.

The dismantling of U.S. colonialism requires change at multiple levels and one place that it must start in our own communities, across the U.S. insular empire, where we have to agree that each of us deserve more than what we have now, and together assert that our rights to self-determination, our rights to determine our own distinct paths be respected and supported.

A group like Right to Democracy can help be that network to help us each elevate our own understanding of our situations, by continually looking to other colonized territories of the U.S. So that we see our own destiny linked to theirs and vice versa.

I look forward to the day when it becomes natural for people in Guam and the CNMI to wake up in the morning and wonder what people in Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Island and American Samoa are doing that day. And for those in other time zones, surrounded by other oceans to do the same for us in the Marianas.

Source: Bevacqua: The right to democracy | Pacific Daily News

The baseline rules were to build common ground, respect differences, provoke change, stay focused and avoid toxicity. It provided a very safe and comfortable space for us to share and challenge each other but also provided a platform to express frustration and pain and offer solutions for healing and growth.

I became uninhibited to share problems and triumphs as a local girl from Guam. I found that there were so many common problems among the territories whose people were exhausted from waiting for this promise of equality. I also concluded that as islanders do, we all compromised many rights to stay in our territorial island nations because of cultural pride and wanting to be a part of the change that would someday make good with what we perceived to be owed.

Source: Shared vision, shared goals, shared struggles | Pacific Island Times

Profa. Luisa Seijo Maldonado and Prof. Pedro Cardona Roig

Es innegable que la descolonización requerirá de un proceso largo y complejo. Sin embargo, el encuentro evidenció la voluntad de movernos a la autodeterminación. Unidas, las personas que representan a estos territorios determinaron que desde su unión puede surgir un movimiento que conduzca a la gobernanza que merecen.

La organización ya comenzó a aportar a este sueño con iniciativas que incluyen el cambio de narrativa acerca de las conversaciones sobre el colonialismo. No menos importante es la lucha en los tribunales por eliminar los casos insulares y la continuidad de estrategias para señalar el colonialismo y por qué es un obstáculo fundamental para la justicia que merecen las cinco islas.

Source: La urgencia de la autodeterminación de los territorios | El Nuevo Día

Because American colonialism has long relied upon conquest and division, prioritizing community becomes a particularly powerful strategy in decolonization efforts. By convening delegates from all of the five American territories, the Summit reinforced the importance of leveraging community in the process of confronting our colonial relationship to the United States. For most of us, this was the first time that we participated in a forum with representatives from all 5 of the U.S. territories present in order to explicitly challenge American colonialism and encourage critical and generative dialogue. The opportunity to do so, allowed us to feel seen in our anti-colonial struggles, seeded hope and both deepened and expanded networks of solidarity. Coming together to teach and learn about the similarities and differences of our territories allowed us to strategize, engage in visioning sessions, and craft solutions to the colonial conundrum we all face. Participants recommended creating a territorial curriculum, a media network and guidelines, and legal campaigns. These outcomes left many of us with a desire to see consistent and continued engagement with Right to Democracy around self-determination efforts in the future.

Source: Confronting Colonialism Together, Virgin Islanders Attended Right to Democracy Summit in NY | The St. Thomas Source

Learning about the similarities and differences between the territories was a healing experience for many, with various attendees moved to tears as emotions ran high from the intergenerational trauma rooted in genocidal colonialism and slavery. For advocates that have worked on ending U.S. colonialism for decades, as well as for people just learning about second-class citizenship, the summit was also at times a form of group therapy to know that they are not fighting these battles alone. The days of isolation into territorial silos separated by oceans are over, as the leveling influence of the internet is the key difference from 1994. Working together over thousands of miles and time zones via Zoom meetings or other social media mediums, brings optimism and light to replace pessimism and darkness for those dedicated to democracy and self-determination.

Source: NMI participates in historic U.S.

Andra Samoa and Ken Aiono

The first thing we can say about this event is that it provided an unhindered and safe space for us to express and discuss the situations and challenges we face in American Samoa. Even with our different cultures, our islands are facing very similar realities in several aspects. Problems with the one-sided relationship with the United States, and the threat that this represents to local economic development, local entrepreneurship and the environment; the laws and policies imposed that markedly increase the cost of living, the loss of rich cultural traditions, the painful separation of families that leave to the mainland and the powerlessness felt when decision-making that impacts our daily lives are made by others are a few of the things that we share.

Source: Op Ed about the Summit on U.S. Colonialism | Document

Territory Summit in New York | Marianas Variety