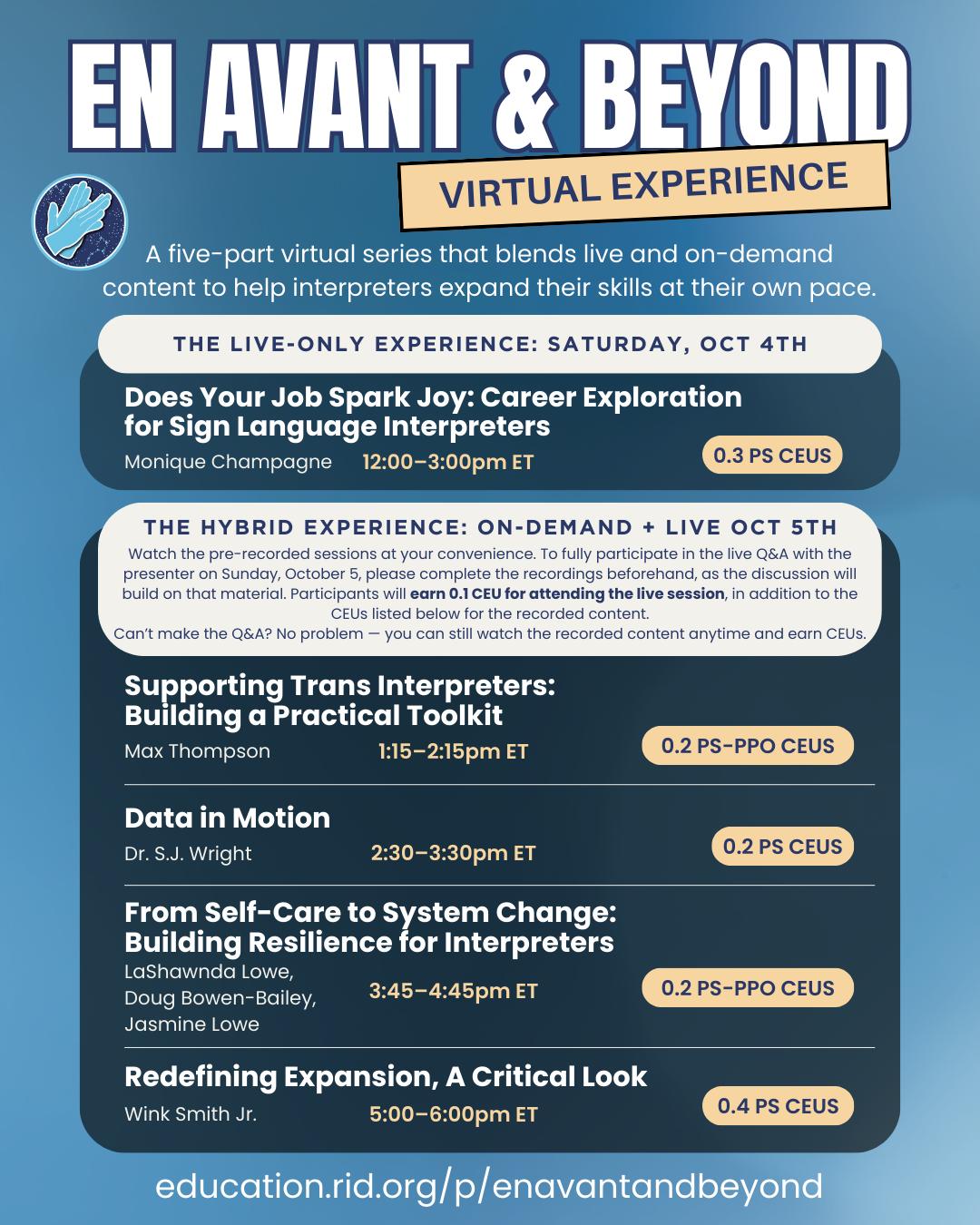

Conference Recap & Current Trends

Addressing Systemic Barriers: Accessibility and Inclusion

Amanda Kennon

Erica Alley

Laura Polhemus

The Weight of the Work: Mental Health Trends and Solutions in the Interpreting Profession

OUR TEAM

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

President | Shonna Magee, MRC, CI & CT, NIC Master, OTC

Vice President | Vacant

Secretary | Vacant

Treasurer | Vacant

Member-at-Large | Mona Mehrpour, NIC

Deaf Member-at-Large | Glenna Cooper

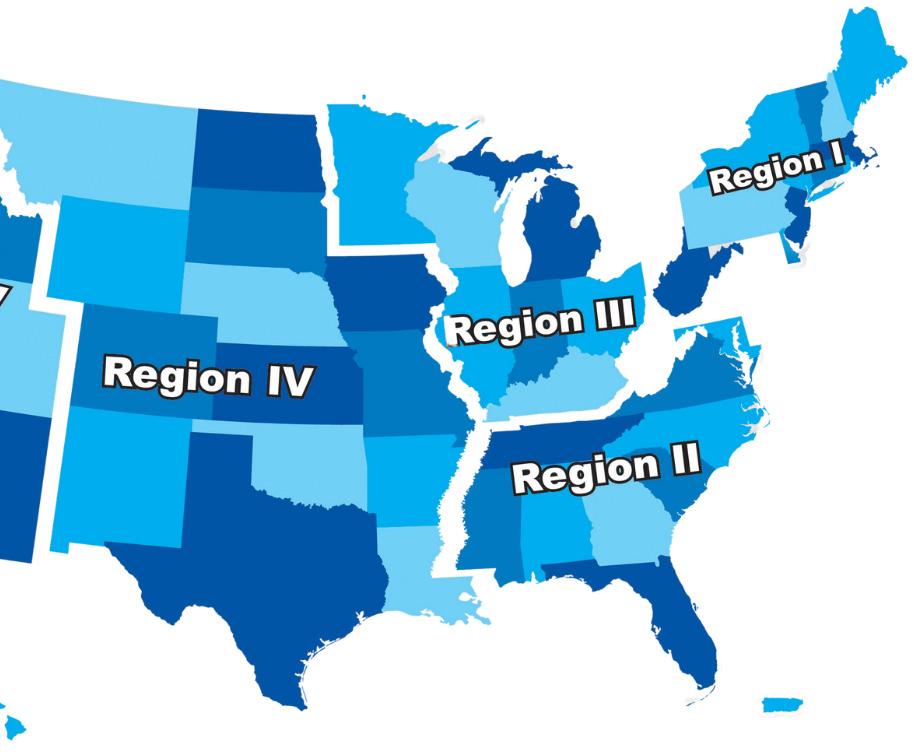

Region I Representative | Christina Stevens, NIC

Region II Representative | M. Antwan Campbell, MPA, Ed:K-12

Region III Representative | Vacant

Region IV Representative | Jessica Eubank, NIC

Region V Representative | Rachel Kleist, CDI

HEADQUARTERS STAFF

Interim CEO | Bucky Justin Buckhold, CDI

Executive Assistant and Meeting Planner | Julie Greenfield

Director of Member Services | Ryan Butts

Member Services Manager | Kayla Marshall, M.Ed., NIC

Member Services Coordinator | Vicky Whitty

CMP Manager | Ashley Holladay

CMP Specialist | Emily Stairs Abenchuchan, NIC

Certification Manager | Catie Colamonico

Certification Coordinator | Jess Kaady

EPS Manager | Tressela Bateson, MA

EPS Specialist | Martha Wolcott

Director of Research and Strategic Communications | S. Jordan Wright, PhD

Strategic Communications Manager | Brooke Roberts Davis

Director of Finance and Accounting | Jennifer Apple

Finance and Accounting Manager | Kristyne Reeds

Staff Accountant | Bradley Johnson

Human Resources Manager | Cassie Robles Sol

CASLI Director of Testing | Sean Furman

CASLI Testing Manager | Amie Smith Santiago, MS, NIC

CASLI Testing Specalist | Melissa Kononenko

Updates to RID Leadership: President Remigio Resigns

This message was originally sent to members via email on September 5th, 2025.

Hello,

Dr. Jesús Rēmigiō, PsyD, MBA, CDI Former President, RID

This message serves to announce that I have submitted my resignation. Over the years, through my service as Vice President for four years, and then President, I have navigated this journey with you - members and community. While I have navigated through this awesome journey, I have learned significantly from each of you.

I have always believed that challenges that appear can be transformed into opportunities. I am sincerely grateful to each of you who have committed your support to RID, I truly appreciate it. I would also like to thank the Board for their unwavering support through many years of service.

This was not an easy decision. It is a heart wrenching decision. I came to this decision out of a need to feel psychologically safe, to protect my mental health, and focus on my family. While I am leaving my role as President, I am not closing the door on RID forever. I am more than willing to support RID in the future if things work out and RID is in a stable condition, then I will be more than happy to lend my support. As of now, I recognize I need to prioritize my health.

I would like to thank each of you for the memories, through members, RID conferences in Baltimore and recently in Minnesota. It has been a pleasure to meet and interact with all of you beautiful people. I have learned so much from you all - our Deaf community, hearing, hard of hearing, and interpreting communities alike.

I believe that RID will rise, if we collectively come together - RID will thrive. Thank you for being there for me during my time here.

Much love! Farewell.

Jesus

Updates to RID Leadership: Treasurer O’Regan Resigns

This message was originally sent to members via email on September 5th, 2025.

Hello Members,

Kate O’Regan, MA, NIC Former Treasurer, RID

Today is Thursday, September 4th and last night we had a Board meeting. At the meeting we discussed the Conflict of Interest (COI) review. I am extremely grateful for colleagues who informed me that even if a COI is legally minimal, the perception of a conflict of interest in our community has significant value and very real impact. I took a moment to pause, and am appreciative of that feedback.

The dilemma I have – to serve as a volunteer, and to continue working in a capacity that does serve and benefit the future of our community. At the same time as Treasurer, there are multiple aspects of perceived conflicts that I could theoretically become entangled in, despite the fact that I know the system, how it operates, and despite that – the perception overrides the reality. I value those of you who care and kindly took the time to share the harm that could be caused to several different communities – including RID members– by continuing to serve despite those perceived realities.

Last night, our President resigned for his own personal reasons. I have also communicated to the Board that I, too, am resigning. I appreciate this work, and am especially grateful for the people who are stepping up to engage with our field, and equally appreciative of those who have been engaged in our work while pushing for transformation within our organization. The strategy going forward is clear – we face an antiquated system that is rooted in archaic practices. I encourage you to please consider volunteering, please consider investing in aiding this transformation for the greater good.

I appreciate all of you, and equally – I have learned a great deal from you. I remain committed to being here in a supportive capacity for whatever you might need. I remain optimistic that membership, RID, and the future of the organization will continue to do good and welcome people to the field of ASL interpreting while practicing humility and advancing the field.

Thank you. With Love, Kate

Updates to RID Leadership: VP to President Magee

This message was originally sent to members via email on September 8th, 2025.

Shonna Magee, MRC, CI & CT, NIC Master, OTC President, RID

Hello,

I know there’s been a lot of changes happening and I wanted to confirm some of these changes and address how we will be moving forward. To recap:

Brief review of status quo

• Resignation of Secretary - March 26

• Resignation of President Dr. Jesus Remigio - Sept 3

• Resignation of Treasurer Kate O’Regan - effective Sept 10

• Section 7B of the Bylaws require the Vice President to assume the duties of the President for the remainder of the President’s term. The President’s term began September 1, 2024 and is supposed to last until August 30, 2027. The role of the President is critical to the ongoing operations of the organization.

• Section 7B also requires that vacancies which have more than half their term remaining should be filled by an election, to take place within six months of the vacancy. The first vacancy was the Secretary position - which was vacated March 26, 2025. So, the deadline for that is September 26, 2025.

• RID has sent out calls for volunteers for the nominations committee and the elections committee. Unfortunately we haven’t had any commitments due to fear of horizontal violence against volunteers in the field. We will keep trying.

First, I want to thank Kate for her service over the past four-plus years. She came on as a Board member when the entire previous Board (with the exception of a single person) had resigned. As a result, there was no institutional knowledge, no significant training on “how to be an RID Board Member”. There was just a pile of work that needed to be done - and we should all be grateful for her willingness to volunteer her time away from her work, her life, and her family on behalf of RID. We all owe her a huge “Thank You!”

Dr. Remigio, Jesus, has had a similar journey. He came into the same almost-empty Board as Vice President, and then became President. There was no one to teach, to guide, to share how things had

been done. When I became Vice President, I was fortunate to work with him. I relied heavily on his wisdom and experience on what my duties should be and how I should do them. He did not have that benefit when he started. We are grateful for his wisdom, his heart, his guidance, and his leadership over the past four-plus years.

I would like to take a moment to discuss Jesus’ reasons for his departure. He said he is leaving “out of a need to feel psychologically safe, to protect my mental health, and focus on my family”. I feel a deep sense of shame that some members of our profession have made him feel unsafe. I am sorry, Jesus. From me, to you - I am sorry that this happened. It is not okay, and we all must do better.

So, here we are… and the Bylaws dictate that I must be President.

As VP, I have always been ready to step in as President if needed…However, I did not seek the presidency for a number of reasons. I’d like to share some of these with you:

1. Right now I believe the President of this organization should be Deaf. You may or may not agree, but I believe that an organization that plays such a pivotal role in the lives and livelihoods of Deaf and hard of hearing people - from cradle to grave - should be led by someone who has a lived experience of being Deaf. Audism is real. Interpreters cause harm - either knowingly or unknowingly. Someone who is a member of the Deaf community that we serve needs to be at the helm of this organization. For far too long, the Presidency has been hearing and looked like me… we need a change.

2. My skillset and strengths are more appropriate for the Vice President role. I am a person who gets things done. I have affectionately called Mona the “heart” of the board…and I am the “checklist” of the board. That is why I ran for Vice President…so I could support a President, especially one with a Deaf perspective. My work as Vice President is not done.

So, we have a dilemma - I am forced into a role that I do not want, and that I do not believe I should hold at this time. As a matter of personal ethics, I must resign.

However, if I resign immediately, then the organization is left with only 2 executive officers, and most importantly, without a President to lead during this critical time of RID’s history. Our critical work must continue - the RID mission - which is to continue fostering the growth of the profession of interpreting. Deaf people depend on the profession and on the organization. We cannot just neglect that responsibility.

So, this is what we will do:

1. The upcoming election will have vacancies listed for four officer positions - President, Vice President, Secretary, and Treasurer.

2. I will resign as President upon the announcement of the results of the upcoming election, stepping aside so that the newly elected President can assume the role.

3. I will re-run in the upcoming election for the office of Vice President.

4. In the meantime, I will stay as interim President, working diligently with the remaining members of the Board and with our CEO, Bucky, to progress on the unfinished tasks and system

improvements that we still have on our plate. I do not want to see a new President come into office with a pile of unfinished business.

If at the end of the next few months you see the deliverables to the membership and the organization and you believe that I should continue serving as your Vice President, then vote for me in the upcoming election. If you think someone else should do the job, then vote for them. Now, let’s talk about that to-do list. Here is a brief summary:

1. The Board needs to respond to the concerns of the Deaf Caucus. I have already sent an email asking for a meeting with them. We will share the results of that meeting with the membership after it happens. I do expect the Deaf Caucus to take a leadership role in identifying and supporting candidates to become President, as well as any other vacant office that they think is appropriate.

2. There are a number of financial and administrative organizational issues outstanding that are the responsibility of Headquarters - tax filings, 990s, audits, Annual Reports, and so forth. I am working with Bucky on these issues, and we will have another update for the membership later this week with details.

3. The Board owes the membership a number of past-due meeting minutes. We are working on these, and I will provide a detailed list in my update later this week.

4. Post-conference report - you as members have a right to know how the conference went - all the numbers, all the things. This is typically included as part of the Annual Reports. I will meet with Bucky and see if we can get some preliminary numbers and results to share, while HQ staff works to produce the Annual Reports that they owe the membership.

5. The membership has asked for a special meeting; this is scheduled for November 5. I look forward to that meeting, and to being able to participate. I have reached out to Rupert Dubler, and the Board will be working with him to help identify and support an appropriate moderator for that meeting. The President is typically the Chair of membership meetings, but I do not feel that would be appropriate for this meeting, so we (the Board) will support whoever he selects. The Board will attend the meeting to listen.

6. There are a number of vacancies on critical RID committees. We need your participation in order to keep the organization moving forward. We have been working on an effort to fill committees, councils, Task Forces, Member Sections…all the groups that do the important work and advise the Board. There will be an email in your inbox within the next week which lists all the openings, and how you can step up and participate.

Thank you.

Call for Volunteer Leadership

This message was originally sent to members via email on September 3rd, 2025.

Mona Mehrpour, NIC Member-At-Large, RID

Greetings Members,

The RID Board invites you to join our Committees, Councils, and Task Forces as we continue our journey toward meaningful organizational reform. At our recent conference, we reaffirmed the Board’s commitment to a year-long initiative dedicated to removing barriers and advancing RID’s progress.

We are committed to embedding a comprehensive Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Accessibility, and Belonging (DEIAB) approach throughout the organization. For your consideration, we have attached the Scopes of Work (SOWs) for various Committees. If you are passionate about shaping the future of RID, we encourage you to explore the information and consider joining these transformative efforts. Together, let’s make 2025 a year that demonstrates our collective dedication to meaningful and lasting reform within RID!

Volunteer Leadership Groups Seeking Applicants

Bylaws Committee

The Bylaws Committee advises the RID Board of Directors regarding the organization’s governing documents. Its responsibilities include ensuring the bylaws are up to date and compliant with Robert’s Rules of Order by periodically reviewing them, proposing amendments, and assisting members with motions.

Nominations Committee

The Nominations Committee is responsible for carrying out the nomination and election process when requested by the RID Board of Directors. This includes overseeing regular or special election cycles, developing timelines, vetting candidates, and ensuring compliance with all bylaws and procedures.

CEO Search Chair

We are seeking a dynamic and impartial leader to serve as Chair of the CEO Search Committee. This vital role will help guide a transparent, inclusive, and community-responsive selection process. The Chair will work closely with the President and the external HR consultant.

• Diversity Council

• Deaf Advisory Council

• Council of Elders

• DeafBlind TaskForce

• Audit Committee

• Certification Committee

• Conflict of Interest Committee

• Interpreting in Spiritual Spaces

• Professional Development Committee

Confronting Horizontal Violence: Turning Challenges into Opportunities

Dr. Jesús Rēmigiō, PsyD, MBA, CDI Former President, RID

The recent Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) conference in Minnesota provided both inspiration and challenge. While the gathering offered rich opportunities for connection and growth, it also shone a light on an ongoing issue in our profession: horizontal violence.

Horizontal violence, broadly defined, refers to harmful behaviors that occur within peer-to-peer relationships. In the interpreting field, this can manifest in many ways from subtle undermining of colleagues to overt hostility. These behaviors may not always be visible to those outside our profession, yet their impact on interpreters, the Deaf community, and the integrity of our professional culture is undeniable.

Reflections from the Conference

At the conference, I witnessed a courageous willingness among colleagues to begin naming and addressing this issue. Honest dialogue is rarely comfortable, but the fact that these conversations are happening speaks volumes about our collective commitment to growth. That openness gave me hope. It also reminded me, however, that much work remains in building environments grounded in accountability, respect, and trust.

The Need for Education and Accountability

One of the most significant takeaways for me was the pressing need for training and workshops dedicated to addressing horizontal violence. Professional development in this area can provide us with the language, strategies, and tools we need to navigate conflict and to cultivate healthier professional relationships.

Equally important is accountability. As interpreters, our responsibilities extend beyond linguistic skill. The way we treat one another must reflect integrity, compassion, and respect. Establishing clear expectations for conduct and committing to hold ourselves and one another accountable is essential if we are to foster a professional community where everyone can thrive.

Challenges as Opportunities

While horizontal violence presents undeniable challenges, it also offers us an invitation: to transform difficulty into growth. What might happen if we viewed difficult conversations as catalysts for change? What if we approached our peers with the same compassion, equity, and respect that we strive to

bring to our work within the Deaf community?

The conference reminded me that although the experience of horizontal violence may differ for each individual, our collective response can be powerful. By acknowledging the problem, investing in education, and fostering accountability, we can reshape our profession into one that is stronger, healthier, and more resilient.

Moving Forward Together

The path ahead will not be easy, and progress will require commitment from all of us. Yet I believe that if we face these issues directly, we can transform moments of pain into opportunities for healing and change. By cultivating respect, practicing empathy, and engaging in honest dialogue, we can create a professional culture where horizontal violence has no place.

The RID conference gave us a glimpse of what is possible: a profession courageous enough to confront its challenges and resilient enough to transform them into opportunities. Let us continue this vital work together.

A Final Question

So I leave you with this: “How can we, as interpreters, transform the harm of horizontal violence into opportunities for accountability, growth, and a more compassionate profession?”

Take a moment to reflect on it. Our future as a profession may depend on how we choose to answer.

PRESIDENT’S REPORT: Committing to End Horizontal Violence in Our Field

Shonna Magee, MRC, CI & CT, NIC Master, OTC President, RID

Over the past year, one of the clearest themes to emerge in our profession is the challenge of horizontal violence. This is not new to our field, yet it continues to show up in ways that harm individuals and weaken our collective strength as a community of interpreters.

Dr. Jordan Wright’s research has highlighted this in sobering terms. Many of our colleagues’ responses in his data reveal painful experiences where professionals have been torn down, not by systems or external forces, but by one another. At our own national conference in July, Dr. Wright himself became a recipient of horizontal violence. His scholarship, designed to benefit the entire field, was not only questioned, but someone attempted to undermine it publicly in ways that were neither constructive nor collegial.

We also see this pattern in how our headquarters staff are treated. These are dedicated professionals who work tirelessly to keep RID functioning, often in the face of overwhelming demands. Yet too often, their reward has been hostility, personal attacks, and an onslaught of criticism. Instead of being uplifted for holding our organization together, they are worn down by horizontal violence from the very membership they serve.

The Board of Directors has not been immune, either. As volunteers, Board members commit countless hours to the work of governance, only to be met with assumptions, hostility, suspicion, and disparagement. This climate has made it increasingly difficult to recruit individuals to serve in leadership and board roles. Many members tell us plainly that they do not want to be the next target.

This cycle of infighting is unsustainable. If we continue to turn inward and attack one another, our profession and the communities we serve will be the ones to suffer

A Call for Change

It is time for us to commit, as a community, to ending horizontal violence. This means:

• Choosing to assume the best of one another, rather than the worst.

• Engaging in dialogue and questioning rather than accusation or attack.

• Calling out horizontal violence when we see it, not to shame, but to interrupt harm.

• Calling one another in with compassion, guidance, and accountability so that together we can model a healthier way of working.

I want to acknowledge my own part in this. Earlier in my career, and during times when personal challenges weighed heavily, I did not always show up as the colleague I wanted to be. There are people to whom I owe apologies, because I approached situations defensively or unprofessionally

rather than with generosity. Looking back, I see how harmful it was to assume the worst in others instead of extending trust. I am committed to doing better, and to encouraging others to do the same.

Looking Forward

Our profession is at a turning point. We can either continue the cycle of mistrust and division, or we can choose to build each other up. Supporting one another’s growth does not mean avoiding accountability. It means holding one another to high standards with respect and dignity, recognizing that we are all still learning, and that the learning never ends.

The future of RID, and of our field, depends on our ability to shift from tearing down to building up. Let us commit together to ending horizontal violence. Let us be courageous enough to call it out when we see it, and compassionate enough to call each other back into community. By doing so, we strengthen not only ourselves, but also the Deaf communities we serve.

Region I Report

Christina Stevens, NIC

Region I Representative, RID

Conferences are my favorite time of the year. I enjoy chatting and learning alongside my colleagues from all over the country. This year’s conference also brought me back to some of my RID “roots”. The first RID conference I attended was a Region 3 conference in 2010, where?? Minnesota! I was part of the support staff for that conference. During that conference I started my networking journey, I am still in contact with many of the people I met in 2010. It was great to reconnect with them again this year.

This year part of my board duties was to help oversee the Dennis Cokley Cafe run by NOVIN. It has been a huge honor for me to work with Kate O’Regan and continue the legacy she began in 2019 at the National Conference in Rhode Island. With the support from NOVIN we are able to continue to provide support. The Cokley Cafe is a place for students, recent graduates and first time attendees to come together in conversation. Each morning we would gather, have some coffee, and chat about what was happening at the conference, questions about the profession and networking. I want to personally thank the NOVIN team for their work this year.

Now the sad news. I am arriving at the end of my term on the RID Board. It has been a huge honor and joy to be your Region 1 Representative for the past several years. This is not quite goodbye- this is now an opportunity for YOU! For the next few months I will be working with the Affiliate Chapter Presidents to start finding the next Region 1 Rep! Is that you?? Is volunteering on the national level something that you have been considering? Shoot me an email and let’s chat! Region1Rep@rid.org

Two white women standing on a very busy blue patterned carpet. Christina is wearing a navy blue blouse with polkadot see through short sleeves and grey pants. She has shoulder length hair that is pulled towards the back. Janice Cagan-Teuber Former Region 1 Rep from MA is holding a cane. She is wearing an olive green jacket, gray v-neck shirt and green skirt. She has glasses and the blue RID Conference lanyard. Both women are smiling.

Former GVRRID President Eliza Fowler and Christina Stevens stand in front of the exhibit hall Sorenson green sign. Eliza has glasses and shoulder length brown hair. She is wearing a grey button sweater, and blue blouse, with plaid pants. Her purse is across her body. Christina also has a bag across her body and you see her conference badge near her arm near her hip. Christina has her arm on Eliza’s shoulder.

individuals stand in a

Region IV Report

Jessica Eubank, NIC

Region IV Representative, RID

Hello Region IV! I wanted to take the opportunity to update you on the Region Meeting that happened on Thursday July 31st at the National Conference in Minnesota. We had a total of 26 people from our region attend the meeting. It was wonderful to see you all, some again and some for the first time.

Communication

Communication in the Region was an important topic of discussion. Some members expressed concern that they do not see any direct communication from me. As Region Representative my form of communication has been to send updates to Affiliate Chapter (AC) Presidents with the assumption that Presidents will then share that information with their members. However, there were a few concerns raised with this method. One, it is not always clear to Presidents if I meant for them to share the information with members or if it was meant as just an update for AC leadership. Two, AC Presidents are volunteers and may not check their inboxes frequently enough to share the information with their members in a timely manner, especially for events. And three, not all members who live in the geographical area of Region IV have an active AC or their AC currently does not have enough board members to function efficiently so they will not receive updates distributed through ACs. I appreciate this feedback, and am working on a new communication approach that will be more widely distributed without placing additional burden on our volunteer leadership. To those members who do not have an active AC in your state, you do not have to be a resident of a state to join its AC. For those of you wanting to get connected I encourage you to reach out to an active AC in a neighboring state if you are able!

Region Conference

The last Region IV conference was in Albuquerque, New Mexico in 2018. In the past two years I have had a few discussions with AC Presidents about hosting a Regional conference, and there are two camps in which the ACs typically fall. Either they are very interested in hosting a Region conference but their ACs are too small to independently support the logistics of attempting to host the Region, or their ACs are already committed to hosting state conferences on a biennial basis and are not able to also commit to hosting a Region Conference. One idea offered is to host a virtual conference. Other Regions have had success with virtual conferences, so this is absolutely a possibility. Another idea was instead of hosting a fully virtual conference we could have ACs host a “watch party” where members could get together with their own local ACs and watch the main presentation together virtually and then discuss with their in person colleagues. I love these ideas and am excited to discuss them further! Members also expressed interest in at the very least hosting a Region Business Meeting even if we do not have a full conference since it has been several years since our last Region Business Meeting.

Region Finances

Discussing the conference led to a question about finances and whether or not the Region could financially sponsor a conference rather than rely on individual ACs to take on the financial burden of hosting. Our Region does currently have a balance of just over $6,000 and it is possible to use that money to fund a conference. However, an important piece of financially protecting the Region is that any decisions that use our Region funds must be made unanimously by our AC Presidents. A simplified version of the process is that I as Region Representative do not decide how to use the funds, instead I must propose to the Region IV Presidents Council why I would like to access the fund, including the purpose and amount. All active ACs must then vote yes and sign an agreement with the details. Members asked if during my term I have used Region funds for anything, and the answer is no I have not. I did request to use Region funds to pay for a licensed Zoom account to host meetings, but not all Presidents agreed. I am currently working with RID HQ to see about options for Zoom licenses under our non profit account. So we can use Region funds to support a Region IV conference if all of the active ACs in our region support the idea.

Looking Forward

Conference was an excellent opportunity to see many of you and have good discussions and feedback on what you would like to see in our Region. However, not everyone from our Region was able to attend the conference. And our Region is unique in that it is geographically massive and due to the rural nature of many of our states interpreters often work in small pockets or in isolation. I recognize that connecting across the Region is very difficult. Please know that as much as I try to stay up to date on what happens, as our front line workers who see the daily needs of your community I really do rely on you for information about what is happening throughout our Region. I am here to support you and I am here to listen to your concerns. If there is anything you would like to discuss you are always welcome to email me at region4rep@rid.org. I look forward to continuing to serve you for the remaining year of my term, and am excited to see the ways in which our Region can thrive. En Avant!

View photos from the 2025 RID National Conference here!

Did you take a headshot at our 60th Birthday Gala? It is now ready to download! Click here to find and save your photo. When you share on social media, be sure to tag us and use the hashtag #RIDAnniversaryGala2025 so we can see your amazing pictures!

Thank you to Sander Kenwood Photography for capturing these fantastic images!

FROM OUR MAL: Reflections on a Year of Service & Growth

Mona Mehrpour, NIC Member-At-Large, RID

It has been one year since I last submitted an article for VIEWs, and what a year it has been. Stepping into the role of Member At Large on the Board of Directors was a challenge I underestimated, and I quickly realized the weight of responsibility that comes with serving this organization. Yet, through each challenge, I have grown, learned, and recommitted myself to the interpreting field and the communities we serve.

This past year has shown me the fragility and resilience inherent in our work. I have seen firsthand, through our members, Member Sections, and Affiliate Chapters, the dedication and passion that fuels RID. I have also seen gaps, moments of disconnect between leadership and membership, moments that reveal the need for trust, transparency, and purposeful dialogue. These experiences, while difficult, have been invaluable lessons in humility, accountability, and the power of service.

I have learned the importance of diverse leadership, not simply in background, but in perspective, experience, and connection to those we serve. I have witnessed the challenges of navigating privilege, systemic barriers, and entrenched ways of thinking, and I have come to understand that growth requires courage: the courage to have hard conversations, to confront difficult truths, and to continue pushing forward despite frustration or setbacks.

Even in the face of overwhelming moments, I am inspired by the commitment I see around me. Our organization is undergoing necessary change, and while the process is often messy, it is also filled with opportunities for innovation, creativity, and reflection. I remain dedicated to serving RID, to learning from each experience, and to helping the organization evolve in ways that truly reflect its purpose and values.

Being on the board is not easy, it is complex, challenging, and at times exhausting. But it has also been a year of deep growth, connection, and reaffirmed purpose. I am proud to be part of this work, committed to the future of RID, and ready to continue contributing to an organization that serves as a cornerstone of our profession and our community.

I would like to take this opportunity to invite all members, not just those within RID, but within the broader Deaf community, near and far, to engage in understanding the vital role of interpreters. This is an invitation to witness and support Deaf community members thriving, whether Deaf, DeafBlind, DeafDisabled, hard of hearing, late-deafened, or our hearing counterparts, as we coexist in accessible communication. I encourage members to actively participate in shaping what RID can give back, creating an organization that truly reflects and supports both its members and the wider community we serve.

Who We Are

RID’s purpose is to serve equally our members, profession, and the public by promoting and advocating for qualified and effective interpreters in all spaces where intersectional diverse Deaf lives are impacted.

Our Mission

VMRID is the national certifying body of sign language interpreters and is a professional organization that fosters the growth of the profession and the professional growth of interpreting.

Our Vision

We envision qualified interpreters as partners in universal communication access and forward-thinking, effective communication solutions while honoring intersectional diverse spaces.

Our Values

VThe values statement encompasses what values are at the “heart” or center of our work. RID values:

• the intersectionality and diversity of the communities we serve.

• Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Accessibility and Belonging (DEIAB).

• the professional contribution of volunteer leadership.

• the adaptability, advancement and relevance of the interpreting profession.

• ethical practices in the field of sign language interpreting, and embraces the principle of “do no harm.”

• advocacy for the right to accessible, effective communication.

Call for Motions

This message was originally sent to members via email on September 9th, 2025.

The next membership business meeting will be held on January 10, 2026. The meeting will be held on Zoom, and registration links will be shared closer to the meeting date. This meeting is an opportunity for our members to present, discuss, and vote on motions that impact our organization, and we encourage you to join us!

If you are interested in submitting a motion, there are a few important dates to keep in mind. Motions that impact the RID bylaws must be shared with the membership 90 days prior to the meeting. Motions that do not impact the bylaws must be shared with the membership 60 days prior to meeting. In order for headquarters and the bylaws committee to receive and review the motions before disseminating to the membership, we must receive all proposed motions in accordance with the timeline below.

Motions Timeline:

• Motions that impact the Bylaws must be received by September 26 at 11:59 pm ET

• Motions that do not impact the Bylaws must be received by October 24 at 11:59 pm ET

• Motions received after October 24 at 11:59 pm ET are considered “from the floor”

Motions will be received and reviewed by the bylaws committee. To submit your motion(s) please use this link.

As in previous years, we will collect opinions from various groups including the RID Board, headquarters, and pertinent committees. Opinions will be posted at least 30 days prior to the business meeting.

We strongly encourage either the motion maker or the seconder to be present at the meeting to discuss the respective motion. If neither individual is able to attend, RID recommends that a representative is present on the behalf of the motion maker. Whether a representative is there or not does not impact if your motion is discussed on the floor of the business meeting.

Please note that you will be required to provide all information (motion, rationale, and fiscal impact) in both ASL and English. If your motion impacts the Bylaws, you need to show an “edited” version of the Bylaws (including deletions as strike-outs, additions, changes, etc.), including the Article and Section numbers.

Please send questions and concerns to motions@rid.org

Deadlines and Important Dates

• September 26, 2025 at 11:59 pm ET: Submit motions that do impact RID Bylaws.

• October 8, 2025: Motions that impact bylaws are shared with membership.

• October 24, 2025 at 11:59 pm ET: Submit motions that do not impact RID Bylaws.

• November 7, 2025: Motions that do not impact bylaws are shared with membership.

• November/December, 2025, time TBD: A Town Hall for members to discuss motions.

• December 12, 2025: All motions will be available to members for review.

• January 10, 2026 from 12 - 5pm ET: Virtual Membership Meeting

SCL JTA Phase 1 Launched –Laying the Foundation

Sandra McClure

Sandra McClure (she/her), has been a professional American Sign Language (ASL)-English interpreter with specialty certifications in legal interpreting and K-12 education since 2009. She is also an educator and mentor. Sandra earned her PhD in Interpretation and Translation Studies at Gallaudet University and her dissertation focused on ASL-English Interpreters’ Preparation Practices in Legal Settings: Perspectives of Professionalism. She holds a Master of Science in ASL-English Interpreting: Interpreting Pedagogy from the University of North Florida and a Bachelor of Arts in Criminal Justice from Northern Arizona University. Additionally, she has three Associate degrees which include interpreter training and criminal justice. Additionally Sandra currently serves as the co-vice chair for the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) Legal Interpreters Member Section (LIMS) and previously served as the chair and Region II representative.

Group picture from SC:L JTA meet up in July 2025

CASLI is pleased to announce the launch of Phase 1 of the Specialist Certificate: Legal (SC:L) Job Task Analysis (JTA)! Late July 2025, CASLI successfully brought together 13 Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) and met with CASLIs new psychometrician team at Dainis & Company to begin this important work.

This important step brought together a diverse group of subject matter experts to identify and refine the tasks, knowledge, and skills required of interpreters working in legal settings. Their work resulted in a strong, research-based framework that reflects today’s professional standards and will guide the next steps in test development.

The next stage of JTA will focus on a national validation survey, gathering input from interpreters and stakeholders across the country to ensure that the framework represents the full breadth of the profession. Furthermore, this will help develop the blueprint of future SC:L assessment. We are excited for this and please be on the lookout for the survey in the near future! To continue this critical work, we are actively seeking funding to support Phase 2 and beyond.

We also want to extend our gratitude to those who made Phase 1 possible:

• CASLI Board of Directors – for providing start-up funding

• Interpretek – for their generous financial support

• KIS (Keystone Interpreter Solutions) – for their support with interpreting logistics

CASLI has already invested $60,000 in this effort, and with the generous support of partners like Interpretek and Keystone Interpreter Solutions, we have built a strong foundation. To complete the JTA and develop the new SCL exam, we estimate an additional $500,000–$750,000 will be needed for the next phases.

This is a pivotal moment for the future of legal interpreting. If you or your organization can contribute, or if you know of potential funding sources, please contact us at Testing@CASLI.org or SCL@CASLI. org. Your continued engagement and support are essential as we take the next steps in developing an updated, valid, and reliable SC:L exam for our profession. Together, we can ensure that Deaf individuals have access to qualified interpreters in every corner of the legal system.

Lastly, CASLI has implemented a page dedicated to the ongoing progress we are making with SC:L (Specialist Certification: Legal) https://www.casli.org/scl-specialist-certification-legal/

Conflicted about Conflicts of Interest?

Roger Williams

LISW-CP/S, RID CT, NAD 5, QMHI-S

Mr. Williams is the owner of Hands On Interpreting, LLC, a private practice specializing in consulting and training related to the needs of deaf adults in the mental health system. Until his retirement in 2023, he was employed as the Executive Director of the Spartanburg Area Mental Health Center with the South Carolina Department of Mental Health. He received his B.S.W. from the Rochester Institute of Technology, his M.S.W., specializing in community mental health, from the University of Illinois and completed coursework towards a doctorate at the University of South Carolina, College of Social Work. Mr. Williams is licensed in Florida and South Carolina as a Licensed Independent Social Worker – Clinical Practice/Supervisor and holds an RID Certificate of Transliteration and an SCAD/NAD IAP Level 5 and has been recognized at the state and national level for his leadership in mental health services within the Deaf community.

For many non-profit organization discussions and decisions about conflicts of interest are both frequent and complicated. RID is no different. In the recent past, concerns about conflicts of interest, both real and perceived, have led to resignations and recriminations. The nature of non-profit groups like RID, which aim to serve the greater good, means that it is common for these conflicts to arise. But not all such conflicts are cause for concern, although they should be examined and evaluated. They are part of professional life, and the key is how they are identified, disclosed, and managed.

There is a conflict of interest when personal interests (financial, relational, or professional) have the potential to influence professional decisions. As a working interpreter, a workshop presenter, the spouse of a deaf adult, and the parent of four deaf adults, I have a personal and professional interest in the actions of RID. I benefit when RID has standards for certification and my family benefits when those standards demand competence and quality. But the presence of such a conflict would not automatically mean it would be inappropriate for me to serve in a leadership capacity, as I have in the past. Such conflicts arise far more often than we might think, and most are manageable with the right strategies.

These can run the gamut from hiring or mentoring someone you already know, accepting a gift from a client, or serving on multiple boards that sometimes overlap in purpose. These are all situations that can happen to any professional. None of them inherently mean corruption or unethical behavior. What matters is how openly and responsibly they are addressed.

Example 1: We Work in a Small World

Suppose there was a situation where an interpreter applies to work on an educational contract where their sibling is a teacher. The potential for favoritism is real, but the solution is not to automatically bar the interpreter from the assignment. Instead, the interpreter should disclose the relationship, and the agency can assign a neutral reviewer to monitor evaluations. By providing transparency and oversight, a potential conflict is avoided, and concerns can be managed.

Example 2: Vendor Relationships

Suppose an interpreter has a long-standing friendship with the owner of a local interpreting agency and is part of a decision-making group selecting vendors for a conference. Without disclosure, this could look like favoritism. But by openly declaring the relationship and recusing themselves from the vendor selection vote, the interpreter avoids bias while still contributing their expertise in other areas of the project. The conflict is not erased, but it is ethically managed.

Example 3: Dual Roles and Commitments

Imagine an interpreter who both teaches in an Interpreter Training Program and also serves on a credentialing task force. At first glance, it might appear that this is a direct conflict that disqualifies them from participation. But this would exclude individuals who have vital experience and knowledge. Mitigation might involve ensuring that the interpreter does not grade or recruit their own students for the credentialing pilot program, while allowing their broader expertise to benefit the task force. Separation of duties protects integrity while preserving valuable contributions.

Organizations in other fields recognize this reality. They rely on disclosure policies, independent reviews, and structured safeguards like compartmentalization of privileged knowledge and segregation of duties. These tools do not eliminate conflicts; they make sure conflicts do not erode trust or integrity. Interpreting is no different. Instead of assuming that a colleague with a potential conflict is acting in bad faith, we should ask: Has it been disclosed? Are appropriate mitigation steps in place? Is there transparency in decision-making?

This shift in mindset is crucial for our field. Interpreting already faces challenges of trust, credibility, and accountability. If we treat every conflict as a disqualification, we risk losing experienced professionals and discouraging open dialogue. Worse, we create a culture of suspicion instead of collaboration. By contrast, when we acknowledge that conflicts exist everywhere, and emphasize management over punishment, we foster an environment of honesty and integrity.

Leaders set the tone, but every interpreter contributes to this culture. The goal is not to shame colleagues for having conflicts, but to hold one another accountable for handling them responsibly. That means encouraging disclosure, respecting established policies, listening to concerns about conflicts, and supporting one another in navigating gray areas with professionalism, and choosing recusal or alternatives when appropriate. Being conscious of how a potential conflict might be perceived places an additional responsibility on those in leadership positions to be mindful even when outside of formal settings, ensuring that privileged information is not inadvertently disclosed in social settings.

Conflicts of interest are inevitable. How we respond to them is a choice. Let us take a page from Brené Brown and her call for us to assume a positive intent from all, supporters and critics. Let us choose transparency over secrecy, education over condemnation, mitigation over vilification, and accountability over accusation. Our profession will be stronger for it.

5 Mitigation Strategies Every Interpreter Should Know

• Full Disclosure – Be upfront about any relationship or interest that could appear to affect your work. Transparency is the first step to trust.

• Recusal – Step back from decisions where your objectivity could reasonably be questioned. Let others handle that piece.

• Separation of Duties – Divide responsibilities so no one person controls every step of a process, especially in hiring, evaluation, or credentialing.

• Independent Oversight – Involve neutral reviewers or committees to provide an extra layer of accountability.

• Documentation – Keep a record of disclosed conflicts and the steps taken to manage them. It demonstrates accountability and builds confidence in the process.

A Laboratory in Real Time: An Autoethnography of the National Conference Plenary

Dr. S. Jordan Wright

I attended the 2025 RID National Conference to do what many of us say we want more of: present actual data. As Director of Research and Strategic Communications, I have spent the last year conducting a study on the state of the ASL interpreting industry. The study lasted 11 months, included 19 focus groups, and a 70-question survey with over 2,000 respondents. This national study, the largest of its kind, makes clear that we are staring down a generational cliff, systemic inequities, racism, and widespread horizontal violence. Sobering findings, yes - but essential ones. What I did not expect was that my plenary would become the research laboratory in real time. Within the span of three hours, nearly every behavior our dataset flagged—gatekeeping, elitism, performative disruption, horizontal violence, and resistance to evidence—was acted out on stage and in the audience. It was, in effect, a laboratory in real time. For that, I must extend some thanks: the disruptors provided a case study as vivid as it was unintentional.

The Open Mic

For those who did not attend the conference, each morning began with an En Avant session, a reimagining of the traditional keynote. The original communication access set-up included a Certified Deaf Interpreter (CDI) for hearing presenters, and open captions. I worked with the Conference Access Coordinator well in advance to secure the most appropriate and qualified voicing team to align with the level of scientific content to be delivered. Given the varying stages of ASL mastery among attendees, it was vital to me that everyone receive equal access and that the focus remain on the data.

The open mic was designed as a platform for dialogue and layered access. Instead, it became theater. A few participants interrupted my presentation, stood up from the audience, and requested the audio from the open mic be turned off. I held a vote with the live audience on the matter. The result was a 50/50 split: half wanted the open mic on, half wanted it off. Ultimately, the open mic was turned off. I invite you to consider the question at the core: when presenting to an audience of diverse language modalities and access needs, what does true access for all look like? When we say we are in an “ASL space”, do we agree to actively exclude those who are new to the field, paraprofessionals who may not yet be fluent, hearing professionals who are blind, parents of Deaf children beginning their journey, or Deaf, Hard of Hearing, DeafBlind, and DeafDisabled individuals who are also new signers or prefer spoken languages?

Now, onto actual crises. According to the study’s findings, we have a three-year window before interpreter shortages reach public crisis level. This year alone, 153 students, first timers, and emerging signers attended the national conference, the next generation watching closely. What did they see? A performance of exclusion masquerading as authority. For a profession allegedly concerned with recruitment and retention, this was less of a welcome and more a lesson in how to alienate new blood.

Official Language and Misuse

In 2015, members of RID voted to establish American Sign Language as the official language of all RID conferences and meetings (Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf [RID], 2020). This action was reaffirmed at the 2017 biennial conference and incorporated into the Policies and Procedures Manual under the section governing national conferences. The motion was intended to provide clarity and consistency by designating ASL as the baseline language of proceedings, ensuring shared access for participants.

Scholars of language policy have long noted that declaring an official language is not meant to restrict communication, but to guarantee a baseline of access. Tove Skutnabb-Kangas (2000; 2013) describes official language status as a floor, not a ceiling: it secures rights but does not eliminate the presence of other languages. Her broader work on linguistic human rights underscores that restricting minority or signed languages under the guise of official policy can amount to “linguistic genocide” (Skutnabb-Kangas, 2000, 2009). In her view, equitable policy is not merely symbolic, it is essential to protect against exclusion in education, legal systems, and civic life. International examples abound: Canada’s Official Languages Act (1969, revised 1988) established English and French as co-official languages to ensure access, even as dozens of other languages thrive across the country. Post-apartheid South Africa recognized eleven official languages in its 1996 Constitution, a move designed not to exclude but to broaden participation. In fact, South Africa recognized South African Sign Language as the twelfth official language of the country in 2023 — whereas the United States has yet to legally recognize ASL as an official language, and in March 2025 codified only English into recognition (usa.gov, 2025). The European Union designates twenty-four official languages, guaranteeing access to its legal and political processes, yet daily work continues in whatever languages are most practical (Canada, 1988; South Africa, 1996; European Union, 2013). While other countries have expanded official languages to widen participation, the United States narrowed to one — and RID, in miniature, had already rehearsed the same move, a prototype of regression disguised as principle. Across contexts, the designation of an official language is about securing participation, establishing a minimum, but not silencing alternatives. At RID, however, the baseline was distorted into a ceiling, and access was weaponized as restriction.

Understanding that history makes the plenary episode all the more perplexing. Declaring ASL the official language of RID conferences was intended to ensure Deaf participation, not to deputize language police. No one strolling the Champs-Élysées is smacked with a baguette and theatrically escorted to the Bastille for daring to hold a conversation in English instead of French. Official status sets a norm; it does not prohibit participation. If Canada can provide government services in English and French while Mandarin and Cree flourish, if South Africa can expand its official languages to twelve, and if the European Union can operate with twenty-four, surely RID can survive an open mic without declaring it heresy.

Official languages guarantee access to the proceedings, not a linguistic purity test in the hallways. In

the same way, ASL must remain the baseline at RID conferences to ensure Deaf participation and the spirit of access. That history is vital; however, weaponizing “ASL space” to silence voice access, or open mic, confuses official status with linguistic policing.

Our own community shows the opposite every day. Marlee Matlin delivered her Oscar acceptance speech in spoken English, sparking controversy at the time, yet she has built a decades-long career in both ASL and English across stage and screen. Justina Miles of Super Bowl fame moves fluidly between ASL on stage and spoken English in media interviews. Heather Whitestone, a former Miss America, primarily uses spoken English in her public life. Matt Maxey and Sean Forbes as Deaf musicians use both ASL and spoken English, while Haben Girma, an internationally recognized disability rights advocate, navigates ASL, ProTactile, Braille, and speech to reach audiences worldwide. Deaf public figures, professionals, and everyday citizens have long navigated multiple modalities, whether embraced or contested. Professional conferences that outlaw the very diversity Deaf leaders embody are not protecting equity; they are staging its funeral.

It is also worth noting that since the ASL motion was adopted, national conference attendance, and therefore revenue, has steadily declined. As the famous statistical saying goes: correlation does not imply causation, but the trend is difficult to ignore. One could be forgiven for running the statistical regression of these variables, if they were inclined to do so. If the profession is serious about attracting and retaining new members, then every policy that narrows participation ought to be examined with evidence, rather than slogans.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006) sets a simple but powerful standard: Deaf people have the right to participate fully in society, and that right requires interpreters (and other avenues of access) to make participation possible. What is often missed is that access works in both directions. If access is genuine, it must also include hearing people who do not sign but are part of the same event or discussion. Their ability to participate is also protected (NDC, 2025).

This is the purpose of making ASL the official language of RID conferences. Official status is meant to guarantee a common baseline of access, not to restrict other forms of communication. When “ASL space” is turned into a weapon to silence voice access, or open mic, it no longer protects access. It erodes it. Applause in the moment may feel satisfying, but it comes at the expense of the very principle we claim to uphold.

Disruptions and Silencing

Midway through, an audience member interrupted to demand the immediate inclusion of a Black, Indigenous, Person of Color (BIPOC) CDI, accusing the talk of being whitewashed. Representation and equity matter profoundly. At the same time, equity is not advanced by distracting from data with improvised protest.

The irony is sharp here, as the upcoming section in my report already contained extensive findings from BIPOC interpreters. By interrupting, the disruptor drowned out those very voices. In the name of amplification, the data itself was muted. Worse still, the demand disrespected the very professionals it claimed to champion. To insist that any CDI—let alone one drawn into a highly technical plenary at the last moment—be inserted without preparation is to treat Deaf interpreters as interchangeable tokens rather than as specialists whose expertise requires context and readiness.

Equally troubling, this was not even an established evidence-based practice. The idea of placing a CDI alongside a Deaf presenter appears to have been invented at this conference, without precedent in policy, without research to support its efficacy, and without respect for the preparation such work requires. Interpreter scholars have long emphasized that effective access requires planning and preparation, not improvisation. Napier (2011; 2016) demonstrates that Deaf and hearing interpreter teams work best when they are briefed and coordinated, not conscripted mid-session.

RID’s own Policies and Procedures Manual is silent on such a configuration, and no empirical study in our field identifies it as a standard of practice. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006) affirms the right to full access, but it also underscores that such access must be organized, transparent, and effective. The American Psychological Association’s Guidelines for Accessible Presentations for professional meetings specify that interpreters and access providers must be contracted in advance with sufficient time for preparation (APA, 2021). The Professional Convention Management Association’s standards emphasize the same: lastminute substitutions compromise both the provider and the audience (PCMA, 2018). None of these frameworks support the notion of conscripting a CDI mid-session to satisfy optics.

True equity requires planning, standards, and readiness. What occurred instead was invention in the name of optics. That is not progress by any stretch of the imagination; it is exploitation disguised as advocacy.

When Data Becomes “Wrong”

The declaration soon followed that my inclusion of BIPOC (or IOC as some participants in the study prefer; I defer to the lived experiences of individuals to inform us of appropriate naming conventions) findings was “wrong.” Not because of flawed methods. Not because of weak analysis. Simply because of my positionality as presenter.

This betrays a profound misunderstanding of how research operates. Social sciences have long recognized that empirical inquiry into marginalized groups is often conducted by those outside the group. What matters is rigor, transparency, and accountability. Were this not so, entire disciplines would collapse. It is essential to clarify that I do not claim to speak on behalf of BIPOC/IOC interpreters, nor to substitute their voices with my own. My role, rather, is to report the perspectives entrusted to the study in a way that both preserves their integrity and renders them accessible to a broader readership. In other words, the findings are theirs; the responsibility for translating those findings into research discourse is mine as Principal Investigator of this study.

Our own field illustrates this truth. William Stokoe (1960), a hearing linguist, is often credited with legitimizing ASL as a language in the eyes of academia. Dennis Cokely (1992), also hearing, and not an interpreter, helped construct the early frameworks of interpreter education and professional discourse. Their positionality did not erase their contributions; their work endures because of its substance and influence. At the same time, neither should be viewed as infallible. Both produced work that, while groundbreaking, also reflected the limitations and biases of their time. To acknowledge their contributions is not to sanctify them, but to recognize that the value of scholarship must be measured in rigor, not in identity nor their belief systems.

This idea is hardly unique to interpreting. Across the social sciences, thinkers have long grappled with the question of who may produce knowledge. Michel Foucault (1969) observed that knowledge is always tied to systems of discourse and power, not simply to personal identity. Pierre Bourdieu (1986)

emphasized the role of cultural and social capital in determining who is “heard” and who is ignored. Clifford Geertz (1973) advocated for “thick description” as a way to capture cultural nuance through reflexivity and methodological care. None of these scholars argued that only insiders can create valid knowledge. What they did argue is that any claim to knowledge must be held accountable to standards of rigor, transparency, and ethics.

Paulo Freire (1970), in Pedagogy of the Oppressed, reminds us that “to speak a true word is to transform the world.” Transformation requires both lived experience and empirical evidence in dialogue with each other. To sever one from the other diminishes both. To insist that only those with insider identity may present insider data is not equity; it narrows the discourse and collapses into gatekeeping cloaked in rhetoric. In scholarly terms, it is the difference between privileging standpoint to the exclusion of method, and recognizing that the two must remain in productive tension. Both are necessary, neither is sufficient alone. Or, to borrow from Bourdieu, it is the mistake of treating cultural capital as if it were scholarly capital. Identity may grant access and insight, but only methodological rigor transforms those insights into knowledge capable of reshaping practice.

Leadership Under Pressure

Imagine, for a moment, standing in front of more than five hundred people. Half the room is demanding that you shut something down immediately, while the other half is demanding that you let it continue. Each side believes they are defending access and equity. Every decision you make will be remembered, repeated, and judged not only by those in the room but also by the hundreds more who will learn about it afterward.

If you were in charge, what would you do? Leadership is rarely about consensus. It is about making decisions that serve the long-term interests of the profession, even when they are unpopular. Was the decision (that I was forced to make) to turn off the open mic ultimately the wrong one? Reasonable people will disagree. In hindsight, I see it as a choice born from optics rather than evidence. A structured forum could have preserved access while avoiding chaos. What I would have done differently is insist on process: an open mic with clear time limits, facilitation, and translation protocols. Instead, the decision that was made placed me as the plenary speaker in the crosshairs of competing factions, a predicament wildly outside of any recognized conference norm. The American Psychological Association and the Professional Convention Management Association both maintain rules of order precisely to prevent speakers from being put in this position. No speaker should be forced to shoulder that burden, and no profession that claims maturity should allow it to happen again. Taken together, the laboratory comedy of errors support Napier’s (2018; 2019) notion that ASL interpreting is a profession in waiting – for the past six decades– since it cannot seem to rise to meet the standards of what is widely agreed upon to be a profession, as evidenced in the presentation I made under the purview of social research (Wright, 2025).

That moment represented the abdication of leadership. More importantly, it reflected a broader pattern in our field: the habit of privileging opinion, tradition, and optics over evidence. The totality of our national study, over 2,000 survey respondents and 19 focus groups, demonstrates a shocking lack of empirical grounding for much of what we do as a profession. Policies are often enforced without data, practices are repeated without validation, and norms are policed without evidence of their efficacy. Look where that approach has brought us. When I remarked during the plenary that “it is a well-known phrase that interpreters eat their young,” the majority of the audience laughed. The laughter was telling: it signaled recognition, even acceptance, of horizontal violence a dysfunction so

entrenched that it has become humor (e.g., Roberts, 1983; Duffy, 1995). Humor revealed recognition, but also resignation. That is the cost of substituting opinion for evidence. If we continue to laugh at the collapse rather than confront it, the plenary itself will be remembered not only as a disruption but as a laboratory in real time, exposing what happens when a profession mistakes performance for practice. The generational cliff is no longer abstract; it is accelerating toward us. Who will remain to carry the field forward?

Conclusion: A Case Study in Real Time

The premise of this study has always been clear: to use data to enforce, debunk, or establish standards of practice. Too often, our field relies on inherited “good ideas” or opinions as if they were evidence. Many of these conventions, such as rigid two-hour minimums or automatic team assignments, have calcified without ever being empirically tested for efficacy. Behavior itself can become “accepted practice” simply because it goes unchallenged.

I say this not only as a researcher but also as a Deaf professional. Across years of presenting at national and international conferences — academic, medical, scientific, and professional — my expertise and role have been respected, and layered access has been assumed as the norm. In these spaces of prestige, communication is enriched by multiple modalities: International Sign alongside national sign languages, captions, and aurally delivered languages through interpreters and open mics, all coexisting without controversy. For example, when I was invited to speak at Clin d’Œil in Reims, France, this layered approach was not debated; it was expected. As a professor, I have carried the same principle into my classrooms. At Universities in which I have taught, and elsewhere, access for Deaf youth is never conditional on conformity to ASL purity. We honor the modality each student relies on, and we provide it. Open mics and parallel streams of communication often become a form of universal design, ensuring access not only for those scaffolding ASL as a second language but for all students. By contrast, in this plenary, ironically among my own community, my communication choices were dishonored and my position undermined. The U.S. clings to a feral fixation on ASL purity that is uniquely provincial when placed against global practice. What happened here was not progressive, not even neutral; it was regressive.

Jemina Napier (2015) argues that interpreting must be recognized and regulated with the same rigor as other professions if it wishes to claim legitimacy. That standard is incompatible with ad hoc invention on the plenary stage. Professions earn their authority through tested practice, not performance. If interpreting wishes to stand as a profession alongside law, medicine, education, and nursing, then our conduct at professional convenings must meet the same standards of rigor, civility, and preparation. No physician would tolerate a colleague inventing new clinical procedures on stage in the middle of a medical congress. No bar association would allow members to improvise rules of evidence in the middle of oral argument. No educational association would conscript teachers into a session without context or preparation. Yet here, a field that claims professional status tolerated behavior that was, by global standards, quite frankly, barbaric.

The behavior was not only beneath the standards of professional associations, it was beneath the standards we owe one another. A professional association that tolerates improvisation in place of preparation, disruption in place of discourse, and optics in place of evidence forfeits its claim to the very word “professional.”

Lastly, thank you for this impromptu laboratory. I recognize passion is indispensable, but passion

without professionalism is an experiment without controls: unpredictable in the moment and ultimately unusable. RID’s stated purpose is to serve equally our members, the profession, and the public by promoting and advocating for qualified and effective interpreters in all spaces where diverse Deaf lives are impacted. In that plenary, we did not come close to achieving it, and that failure, more than any individual disruption, is what should concern us most.

References

American Psychological Association. (2021). Guidelines for accessible presentations at APA meetings. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood.

Cokely, D. (1992). Interpretation: A sociolinguistic model. Linstok Press. Duffy, E. (1995). Horizontal violence: A conundrum for nursing. Collegian, 2(2), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1322-7696(08)60093-5

European Union. (2013). Languages and translation in the EU institutions. Publications Office of the European Union.

Foucault, M. (1969). L’archéologie du savoir [The archaeology of knowledge]. Gallimard. Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Herder & Herder. Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures. Basic Books. Napier, J. (2011). Here or there? An assessment of video remote signed language interpretermediated interaction in Australia. Journal of Applied Linguistics and Professional Practice, 8(2), 133–153. https://doi.org/10.1558/japl.v8i2.133

Napier, J. (2016). Challenges in interpreting research. In B. Nicodemus & L. Swabey (Eds.), Advances in interpreting research (pp. 1–22). John Benjamins.

Napier, J. (2015). Sign language interpreting: Theory and practice in the 21st century. In H. Mikkelson & R. Jourdenais (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of interpreting (pp. 361–376). Routledge. Professional Convention Management Association. (2018). PCMA professional meeting standards. PCMA.

Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. (2020). Policies and procedures manual. Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf.

Roberts, S. J. (1983). Oppressed group behavior: Implications for nursing. Advances in Nursing Science, 5(4), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/00012272-198307000-00006

Skutnabb-Kangas, T. (2000). Linguistic genocide in education—or worldwide diversity and human rights? Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Skutnabb-Kangas, T. (2009). Linguistic human rights. In M. Denison & J. Hess (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of language and identity (pp. 140–157). London, UK: Routledge.

Skutnabb-Kangas, T. (2013). Linguistic diversity and biodiversity: The threat from killer languages. In T. Skutnabb-Kangas & R. Phillipson (Eds.), Social justice through multilingual education (pp. 31–52). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

South Africa. (1996). Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. Government of South Africa. Stokoe, W. C. (1960). Sign language structure: An outline of the visual communication systems of the American Deaf. Studies in Linguistics, Occasional Papers, 8. University of Buffalo.

United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. United Nations. www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf

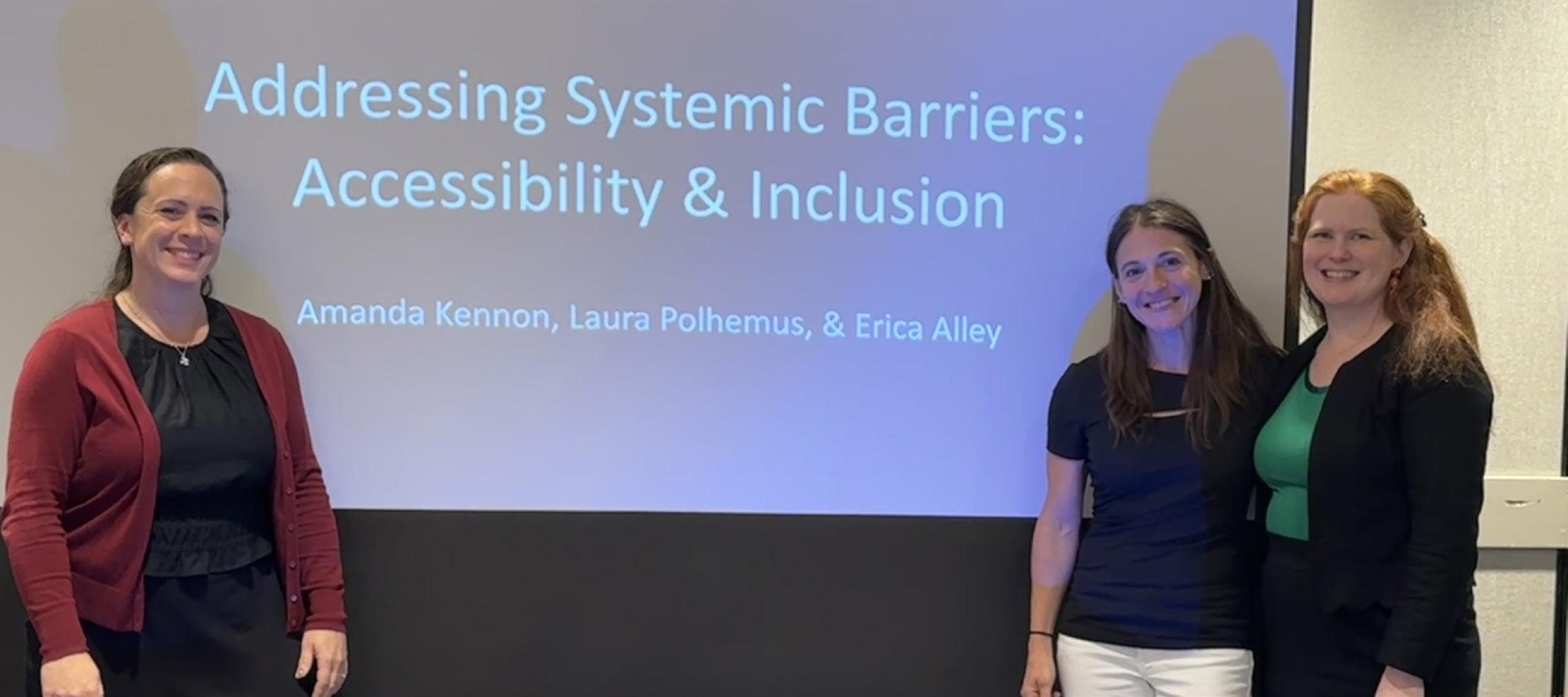

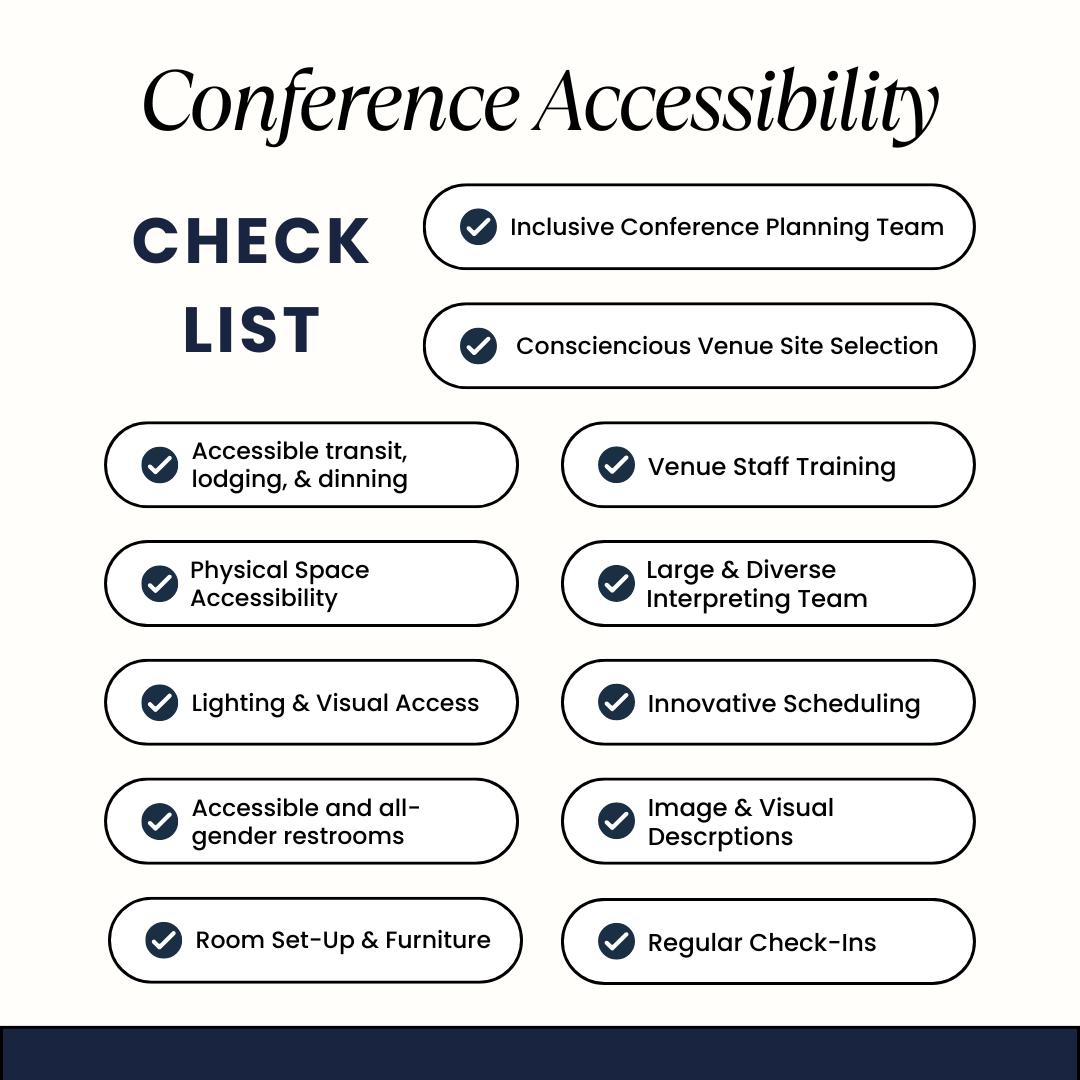

Addressing Systemic Barriers: Accessibility and Inclusion

Amanda Kennon MA, NIC

Erica Alley PhD, NIC Advanced

Laura Polhemus PhD, NIC Advanced, BEI Advanced

Amanda Kennon is a freelance ASL-English interpreter, mentor, and presenter who identifies as neurodivergent and has chronic health conditions that can feel disabling, including migraines and fibromyalgia. Dr. Laura Polhemus, who was diagnosed with ADHD during her PhD program, is an Assistant Professor at Bethel University who also struggles with Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. Dr. Erica Alley works in the Health Equity Strategy and Innovation Division at the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) as the Sign Language Interpreting Lead and a member of the Policy and Systems Change team. After diagnosis with multiple sclerosis, Erica began researching the experiences of interpreters with disabilities and the strategies we apply to our work. Amanda and Laura are researching neurodiversity in the interpreting profession, sharing their work and related resources @SLINeurodiversity (FB/ IG).

Image description: Laura, Erica, & Amanda- three white hearing interpreters with hidden disabilitiesstanding in front of the screen with dark blue title slide with “Addressing Systemic Barriers: Accessibility & Inclusion” in large white text and our names in smaller white text

What began as a shared interest-shaped by experience, enriched through conversation, and strengthened by ongoing research - has evolved into passion for a topic that calls for further inquiry

Addressing Systemic Barriers: Accessibility and Inclusion was presented at the 2025 RID National Conference as a Community of Practice (CoP) to confront challenges, share knowledge, and develop guiding principles for interpreting work. These principles must be considered through a disability justice lens, which recognizes disability not as an individual deficit but as a product of societal structures that create disabling environments. As Sins Invalid (2019) states, “there is no neutral body from which our bodies deviate” (p. 10). Disability justice emphasizes cross-disability and the principle of “Nothing About Us Without Us.” Ladau (2021) reinforces this, noting that “all too often, people with disabilities are relegated to the sidelines in conversations about issues that directly affect us” (p.144). During the session, disability was reframed through a social model lens, moving beyond the medical model in order to see disability as a vital part of intersectional identity.

This session aimed to generate actionable strategies for increasing accessibility and inclusion in the interpreting field. Given the action oriented goal of the on-site discussion, the Whova App was utilized in advance in order to survey the upcoming conference attendees. In response to the question “What would make the interpreting field more accessible for neurodivergent interpreters as well as those who identify as having a disability?,” participants stressed the importance of addressing ableism, removing systemic barriers, and expanding education. They also sought to cultivate an environment grounded in respect, empathy, kindness, understanding, and an appreciation for varied needs.

During the session, approximately 84 participants engaged in collaborative discussions centered around the overarching question: “What individual and collective actions can we take to foster greater accessibility and inclusion in the interpreting field?” Topics of discussion are summarized below.

Navigating Barriers

Interpreters who identify as neurodivergent or having a disability often encounter systemic barriers within the field, including ableism, gatekeeping, and gaslighting. Navigating decisions to address barriers is a skill that is developed through experience. For example, an interpreter with a nonapparent/invisible disability may decide to avoid self-disclosure when interpreting in an environment in which they have had a negative experience. People with disabilities know that their personal choices can carry professional risks; therefore, a great deal of critical thinking goes into each decision.